The Swansea Applied Linguistics Journal

Issue 6, Autumn 2023

Issue 6, Autumn 2023

Welcome to the 6th issue of The Swansea Applied Linguistics Journal. For any new readers joining us, this is a student-run journal that allows our best and brightest students from Swansea University’s Applied Linguistics department to show off their first-class work from their first to final year. All the work you are about to read has each achieved a mark of 70 and above – a most impressive achievement. Once again, the 2023 issue offers a wide selection of work from all corners of the Applied Linguistics discipline, from Language Teaching Methodology, Psycholinguistics, Language in the Media, Forensic Linguistics, and many more!

As with all things, there come challenges. With the continuation of industrial action and implementation of marking boycotts, we students had to once again adapt to a new academic environment. So, to see such an output of first-class work despite these difficulties fills my heart with pride as this year’s editor. This journal strives to celebrate outstanding work, and this year is certainly no different.

Should you have any queries about any of the work featured in this issue, please feel free to email us at lingjournalswansea@gmail.com or DM us on our Twitter account @SwanseaApplied.

Chloe Williams Editor

Editor

Chloe Williams

Assistant Editor

Martin Lee-Paterson

Proofreaders

Ellie Dickinson

Hannah Roddy

Martin Lee-Paterson

Photography

Swansea University

Staff Advisor

Dr Alexia Bowler

If

If you would like to join the editorial team for our next issue, don’t hesitate to contact us via our email.

Should you have any feedback, ideas, queries, or concerns about this issue or the journal in general, pleas contact us using the details below.

To

To students and staff alike, we thank you all for your continued support year after year.

1 Year

Language Teaching Methodology

Sida evaluates language teaching strategies in textbook grammar lessons

Mythbusters

Juwerya discusses the myths and perceptions surrounding the use of non-standard dialects

Language in Mind

Cerys identifies the types of aphasia two patients present with

2nd Year

Language Teaching in Context

Sida evaluates how a learner’s language proficiency is measured in a case study

Child Language and Literacy

Angharad highlights how children view differences in dialects

Angharad critically evaluates a set of publications where applied linguists and practitioners have worked in partnership

Madison explores the effects and differences between working memory and long-term memory

3rd Year

99 Second Language Acquisition

Rachel reviews recent studies in L1 attrition

11 Second Language Acquisition

Hannah reviews studies of working memory in bilingualism

134 Language in the Media

Rebecca uses corpus analysis to investigate Brexit discourse in editorials

18 Forensic Linguistics

Celyn analyses linguistic tools for attributing authorship

Sida Cong, 1 year

Evaluation and analysis of textbook pages for a grammar lesson focusing on “can, have to, must” and the negative forms

According to Scrivener (2011, p. 129), teachers can apply “present-practice” pattern to English grammar teaching. Specifically, presenting grammar requires teachers to show rules and give accurate explanations to learners. Practice focuses on restricted output and authentic output, and “authentic output is also known as production or simply as speaking or writing skills work” (Scrivener, 2011). The pattern of English grammar teaching is known as Present, Practice, Production (PPP). In this essay, I will evaluate and analyse the textbook pages given in the order of PPP, discuss the strengths and weaknesses in the grammar focus, and find ways to improve upon them. A brief discussion of how the materials relate to the concept of Global Englishes will also be included.

Starting with a direct explanation of the grammar without any context clues is not recommended in English teaching. Learners need some examples to get lexical information about the grammatical items. The article “Are Traditional Ways Of Learning The Best?” (Scrivener, 2011, p. 40) shows example sentences including the target grammatical items. Besides, on Page 41, Exercise 4 shows six example sentences that use these items to express necessity and possibility. Teaching with examples can help learners distinguish between items and prepare to learn the relevant grammar formally.

Correct examples of grammar in use should be shown during the presenting process. There exists a brief and clear statement of grammar rules with positive examples on Page 134. In addition, it is recommended that the presenting stage show the learners highly relevant grammar rules only. For example, the modal verb “can” has two meanings one expresses the possibility of doing something, and the other expresses the ability to do something. The

focus on grammar within these textbook pages allows learners to revise and distinguish the use of “can”, “have to,” and “must” as modal verbs expressing present obligation. The meaning of “be able to do something” does not belong to the grammar focus in this lesson. Practice and production

Production is also a type of practice that is more creative and gives learners more flexible ways to use grammar as opposed to other activities such as drills, which are easier to control by teachers and get predictable answers from learners. Practice for English grammar learning is encouraged to contain both meaningful and structured exercises. Exercise 5A on Page 40 shows a sentence completion task, which requires learners to use the target grammatical items. This task focuses on the form of the grammar.

6A on the same page is a writing activity including grammar practice. Learners are asked to use “can “, “have to,” and “must” as well as their negative forms to write sentences according to the context given in 5A. It is also a structured task. As mentioned

above, writing skills work is a kind of production. The instructions for 6A contain “work in pairs”, which according to Nation (2008) belongs to Shared Tasks. The benefit of such instruction makes it possible for partners to help each other complete the task. According to Ur (2012), Free discourse requires learners to complete speaking or writing tasks about a certain topic, but there is no instruction to use the target grammar. Thus, as a free discourse task, 6B is more flexible than a controlled practice and can focus more on the meaning of the grammar. The task requests the learner to give explanations and reasons for their opinions and gives them the opportunity to use the target grammar naturally. For example, if one of the learners says home-schooling is a good idea, he might give the reason that the students “don’t have to” wait for the school bus.

Since “students might need to use the grammar in both speech and writing” (Ur, 2012), grammar presentation should include International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) transcriptions of the grammatical items. The textbook pages only demonstrate how to

pronounce “have to”, which is inadequate for the learners. Negative examples are as essential as positive examples in the explanation as they stress how the grammar is allowed to be used within the rules. On Page 134, there are no negative examples such as “can(‘t)” and “must(n’t)” when the subject in the third person singular is missed in the statement. In addition, there are some subtle differences and overlaps between “can” and “must”, “can’t” and “mustn’t”, which have not been explained at all.

Weaknesses to do with the subject in the third person singular are not limited to the presenting stage, and there is no practice for this usage in the whole grammar lesson. A learner should know that a modal verb will not change form with a change of subject or number. Furthermore, the production tasks are too restricted by the topic of home-schooling, which results in limited space for learner output and makes the task boring.

The following text will focus on one of the weaknesses mentioned above and state some of the author’s own ideas. To improve the weakness of the missing third-person singular subject and make its usage clear to the learners, teachers can give some accurate examples and set a gap-fill drill. An example such as “Monica must get home before 8 pm” or, “Monica get home before 8 pm” might be used. After receiving the responses from the learners, the teacher should then ensure all of the learners clearly understand this.

The concept of Global Englishes (GE) builds on World Englishes and English as a Lingua Franca (ELF), and states that all speakers of English own English. To evaluate the relations between English teaching materials and GE, the Global English Language Teaching (GELT) framework was created. In GELT, the target conversation partners should be NESs (Native English Speakers) and NNESs (Non-native English Speakers), which is demonstrated in the picture shown on Page 41 featuring non-native Englishspeaking children. The target culture in GELT is a mixture of

different cultures, and on Page 41, about Exercise 7A and 7B, the examples and discussion topics given contain cross-cultural communication elements. These two exercises also include materials from various countries in which English is spoken, rather than just those that speak it monolingually, therefore further aligning with GELT principles.

References:

Nation, I. S. P., & Newton, J. (2009). Teaching ESL/EFL Listening and Speaking. New York: Routledge

Scrivener, J. (2011). Learning teaching: the essential guide to English language teaching (3rd ed.). Macmillan Education.

Ur, P. (2012). A course in English language teaching (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Non-standard dialects have been derided as imprecise and incorrect, and hence not equal in value to the standard language, which is regarded as more prestigious (Gordon, 2012). In this essay, I will argue against the myth that non-standard dialects are deficient. Firstly, I will discuss the preconceptions and attitudes that influence our views on dialect, and people's perceptions as to what speaking a non-standard dialect entails. As a result, perceptual dialectology, which aims to discuss public perceptions of dialects, will be a focal point in the first section. Secondly, I will draw on evidence that shows how non-standard dialects are perceived as linguistic diversion in education, and how nonstandard dialects are frequently connected to negativity and speech-correction. This section will argue that non-standard dialect variations do not reflect a lack of educational understanding, but rather the failure of educational intuitions to put resources in place to promote diversity in language varieties. Finally, I will discuss how non-standard dialects are perceived on

a global scale, their significance in conversations about linguistics compared to standard dialects, and how they reflect certain cultures, as well as their importance to different social groups.

The study of how non-linguists evaluate dialect diversity is known as perceptual dialectology. As a result, this section will concentrate on these dialect perception issues and how they present the distinguishing of standard and non-standard dialects as problematic and subjective. In many societies, this distinction has been reinforced by prejudices and ideological biases. For example, Boughton’s (2006) study assessed how people from a variety of French dialects perceive one another and discovered social prejudices between regions. There were particularly noticeable prejudices for and against dialects from the West and Centre, as well as the capital Paris, which hosts the country’s standard dialect, and common social attitudes were supplied when applying the correct dialect to location. For example, when applying dialects to north and east regions, social prejudices were equated. Similarly, Iannàccaro and Dell’Aquila’s (2001) research on European dialect

perception focused on geographical location and discovered that people perceived dialects differently depending on which part of the country they originated from. The perception of language played a minimal role, but depending on where an individual came from and their language community, those who shared a language variety were less prejudiced than those who spoke different dialects. These findings support the idea that social views influence how we perceive dialect variations, and that “non-standard” dialects are considered to be entirely acceptable in particular social contexts. With these social biases in mind, one cannot reasonably describe dialect variations as deficient. For example, Bucholtz et al. (2007) highlighted perceptual dialectology variations within California. Their results revealed that Californian dialect distinctions were characterised by linguistic and stylistic traits connected with a particular area rather than just regional location. These considerations demonstrate that dialects can be more culturally and regionally proclaimed and are not synonymous with deficiency.

Regarding the varieties of dialect that exist in our society, Fridland and Bartlett (2006) highlights that our perception of dialects can be personal matters through assessments of correctness and pleasantness. Their findings demonstrated that those from southern American states evaluated their own correctness of speech lower than those from other American states, but they did not perceive their own accents as less pleasant or those from other states as more pleasant. This shows how dialects can be understood depending on characteristics. Labelling what we perceive to be a non-standard dialect as wholly insufficient may thus be inaccurate. On the contrary, we should recognise that it is difficult to maintain a standard dialect given the many different variations thereof within a language’s larger speaking community, a community which is already in itself subject to change. For example, Robinson’s (2007) research shows just how grammatically diverse usage of the verb ‘to be’ is in English dialects spoken across the UK. There are numerous cities especially in the north that use the form ‘were’ for both singular and plural, whereas those in the south use the distinction ‘was’ and ‘were’ for singular and plural subjects. This highlights dialectal variation across the United Kingdom and shows

how unwieldy the concept of a standard dialect has become. Conversely, respecting and identifying that these linguistic variants are part of a homogenous group and hold significant social value is crucial in dealing with negative perceptions of non-standard dialects.

Furthermore, it is important to understand the historical evolution of dialect variations has seen several become the ‘standard’ and some fall out of favour. Maxwell’s (2006) study highlights that dialect variation within the Slovak speech community has been exacerbated by political and ideological factors. These influences have been observed to spread throughout the region and have had an impact on the development of their language. As a result, a range of dialects have emerged from historical factors, and speakers’ dialogue preferences have been linked with the same political issues. The perceptions of nonstandard dialects can extend beyond the goal of being defective, and countries have developed to recognize the standard dialect. However, according to Preston (1999) regional dialect diversity has become influential prior to historic and structural influences on 17

language development. This corresponds to the Clopper and Pisoni (2006) study, which found that regional location and geographic mobility had an impact on determining where a person sounded like they were from as well as adding perceptions to dialects. These findings show how dialects, whether regional or historical, are objects of cultural significance, and that, discarding those we consider to be non-standard makes it more. Non-standard dialects in Education:

Within the educational field, the perception of a non-standard dialect has become increasingly negative. The belief is that students who speak a widely prevalent and approved language variation are often in a better position in the classroom than those who speak a different variety (Hart Blundon, 2016). For instance, Cushing’s (2021) study highlighted that Standard English in classrooms is ingrained as part of school policies. Teachers are compelled to utilise Standard English in the classroom, and students are expected to follow this standard in their education. This perspective highlights how children observe from a young age that their dialect is less prestigious, and this unjust judgement can have an impact on

how children understand what it means to have a dialect. Similarly, Messier’s (2012) research conducted on Ebonics English varieties found that efforts to employ these dialects in the classroom have seen difficulty and resistance due to institutional and cultural biases towards Standard English. This emphasises how the narrative of non-standard dialects being inferior is deeply recognised and embedded in the educational field. However, moving towards inclusivity and promoting nonstandard dialects in areas such as education can help shape people's understanding of what it means to have a non-standard dialect. Tan and Tan (2008) examined sentiments towards non-standard English in Singapore and discovered that they were linked with substantial social affiliations. Their findings indicated that non-standard English should be integrated into schooling to promote a better awareness of language issues. This could foster a better understanding of what a non-standard dialect entails and can raise the standing. of non-standard dialect usage from a deficiency to an alternative means of linguistic communication. Labov’s (1972) study found that BEV’s (Black English Vernacular) syntax involved complex structures such as deletion of the final vowel

structures which require significant grammatical skill. Likewise, Green (2002) discovered that AAVE (African American Vernacular English, formally BEV) used concepts such as be form and bin verbs to emphasise varied meanings, and that adverbs are unnecessary in this situation. This highlights an interesting case on how grammar is marked in different dialects. This further demonstrates how non-standard dialects, abundant as they are in grammaticality, cannot simply be presented as defective or simplified versions of English in the realm of education. As a result, by broadening dialect comprehension in education from standard to different varieties, students can better understand dialects, allowing them to be less prejudiced and recognise the linguistic differences seen in diverse cultures. Therefore, modifying the perspective of a non-standard dialect in schools can have a lasting effect on generations to come.

Non-standard dialects on a global scale:

Non-standard dialects have a global impact by providing a shared language to communities and social groups. A study by Jaffe (2000) demonstrated how AAVE orthography indicates the

genuineness and originality of the language, as well the importance it holds in the social context of a community, in comparison to standard language variations, which may not represent intimate personal engagement with language use. This underlines the belief that non-standard dialects and language variations have important cultural significance. Similarly, Mufwene’s (2015) research on creole language showed that numerous varieties of the language existed in the community, demonstrating the unstable character of languages in changing, multicultural environments. Mufwene (2015) also commented on how shifts in language variation may be directly or indirectly caused by colonisation. These findings show the significance of linguistic variations across many cultures, and that the dialects people choose to speak can be the result of either distancing themselves from or collectively acknowledging as a community the discrimination they have faced.

The view that non-standard dialects cannot become globally significant can be refuted by research demonstrating the importance of non-standard dialects in running parts of society. Zhu and Grigoriadis’s (2022) research discovered the importance of Chinese

dialect varieties and how they affect economic development and government spending. This shows how having an array of dialects inside a country can foster progression. This finding also shows that non-standard dialects can help rather than hinder the societies we live in.

Conclusion:

In conclusion, there are numerous possible arguments against the myth that a non-standard dialect must necessarily be deficient. For example, one can better understand how people judge non-standard dialects through linguistic frameworks such as perceptual dialectology. Furthermore, non-standard dialects within a country have significant regional or historical importance, which is sometimes overlooked when applying perception to dialects. As a result, viewing a non-standard dialect as deficient can be reductive. Additionally, investigating the role of education in defining standard and non-standard dialects might help to debunk the idea of more and less acceptable language varieties. Changing how nonstandard dialects are discussed in an educational context may also help combat the aforementioned myths and improve their standing

amongst students. Lastly, realising that non-standard dialects have an innate connection with the individuals who speak them is crucial, and being mindful of how their language variants are evolving allows for a deeper understanding of the non-standard dialect's community.

Reference list

Boughton, Z. (2006). When perception isn’t reality: Accent identification and perceptual dialectology in French. Journal of French Language Studies, 16(3), pp.277–304. doi:

https://doi.org/10.1017/s0959269506002535

Bucholtz, M., Bermudez, N., Fung, V., Edwards, L. and Vargas, R. (2007). Hella Nor Cal or Totally So Cal? Journal of English Linguistics, 35(4), pp.325–352. doi:

https://doi.org/10.1177/0075424207307780

Clopper, C.G. and Pisoni, D.B. (2006). Effects of region of origin and geographic mobility on perceptual dialect categorization. Language Variation and Change, 18(02). doi:

https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954394506060091

Cushing, I. (2021). Policy Mechanisms of the Standard Language

Ideology in England’s Education System. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 22(3), pp.1–15. doi:

https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2021.1877542

Fridland, V. and Bartlett, K. (2006). Correctness, Pleasantness, and Degree of Difference Ratings Across Regions. American Speech, 81(4), pp.358–386. doi:

https://doi.org/10.1215/00031283-2006-025

Gordon, T. (2012). Relevant linguistics: A Textbook for Language Teachers. Charlotte, Nc: Information Age Pub. Green, L.J. (2002). African American English: A Linguistic Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hart Blundon, P. (2016). Nonstandard Dialect and Educational Achievement: Potential Implications for First Nations Students. Canadian Journal of Speech-Language Pathology & Audiology, 40(3).

Iannàccaro, G. and Dell’Aquila, V. (2001). Mapping languages from inside: Notes on perceptual dialectology. Social & Cultural Geography, 2(3), pp.265–280. doi:

https://doi.org/10.1080/14649360120073851

Jaffe, A. (2000). Introduction: Non-standard orthography and nonstandard speech. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 4(4), pp.497–

513. doi https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9481.00127

Labov, W. (1972). Language in the inner city: Studies in the Black English vernacular. Philadelphia: University Of Pennsylvania Press.

Maxwell, A. (2006). Why the Slovak Language Has Three Dialects: A Case Study in Historical Perceptual Dialectology. Austrian History Yearbook, 37, pp.141–162. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/s0067237800016817

Messier, J. (2012). Ebonics, the Oakland resolution, and using nonstandard dialects in the classroom. The English Languages: History, Diaspora, Culture, 3.

Mufwene, S.S. (2015). The emergence of creoles and language change. In: N. Bonvillain, ed., The Routledge handbook of linguistic anthropology. New York; London: Routledge, p.pp. 362-379.

Preston, D.R. (1999). Handbook of perceptual dialectology: Volume 1. Amsterdam: J. Benjamins.

Robinson, J. (2007). Regional voices: Non-standard grammar.

[online] The British Library. Available at: https://www.bl.uk/british-accents-anddialects/articles/regional-voices-non-standard-grammar.

Tan, P.K.W. and Tan, D.K.H. (2008). Attitudes towards nonstandard English in Singapore1. World Englishes, 27(3-4), pp.465–479. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467971x.2008.00578.x

Zhu, J. and Grigoriadis, T.N. (2022). Chinese dialects, culture & economic performance. China Economic Review, 73, p.101783. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2022.101783

Aphasia is a language disorder characterised by difficulties in speech production and communication. This can affect many aspects of language including phonology, morphology, syntax, and semantics (Code, 1989: 2). Aphasia is caused by damage to the brain, particularly in the left hemisphere as this is where speech and language production and processing is located (Sedivy, 2019: 69). A typical way in which the brain can be damaged resulting in language difficulties and more specifically aphasia is due to strokes. Damage to specific areas of the brain can result in different types of aphasia presenting varying severities and symptoms. The differences in symptoms for differing aphasia categories can be observed and used in diagnosing aphasia patients. This essay will define and characterise three types of aphasia, Broca’s, Wernicke’s, and Anomic aphasia. This information will then be applied to data

from two aphasia patients, aiming to diagnose them with a specific type of aphasia.

One type of aphasia affecting speech and language production is Broca’s aphasia. Broca’s aphasia, also known as expressive aphasia, motor aphasia, syntactic aphasia or agrammatic aphasia (Berndt and Caramazza, 2008: 3) is a type of non-fluent aphasia and is caused by damage to the Broca’s area, located in the left frontal lobe of the brain (Code, 1989: 4). This type of aphasia is characterised by slow speech with frequent pausing and difficulty in choosing which words to use (Sedivy, 2019: 69). Broca’s aphasia can also be identified through shorter sentences/phrases, simplified syntax and a reduction in function words and functional morphemes (Cutler, 2005: 57).

Another type of aphasia impacting language in patients is Wernicke’s aphasia. This is a fluent type of aphasia and is caused by damage to the Wernicke’s area, located in the left temporal lobe

of the brain (Sedivy, 2019: 71). Similar to Broca’s, and most types of aphasia, patients with Wernicke’s aphasia have difficulties in finding the right words to use. Unlike Broca’s aphasia patients, they are able to speak fluently. This results in speech that is fluid and continuous but lacks substance and relevant meaning often resulting in nonsensical speech or what Pallickal and Hema (2020) refer to as “neologistic jargon” (p1140).

The final type of aphasia to be discussed is Anomic aphasia. This is another type of fluent aphasia and can be cause by damage to the left hemisphere of the brain. Anomic aphasia is characterised by the patient’s inability to retrieve lexical items from their lexicon (Andreetta et al, 2012). Despite difficulties in retrieving words and some instances of pausing throughout speech, anomic aphasia is still considered a fluent type of aphasia due to frequent production of full, coherent sentences without error (Bar-On et al., 2018: 884).

Unlike other types of aphasia, anomic patients often produce wellformed, grammatically correct, and relevant speech however there is a significant difficulty in finding the words to use which causes

speech to be produced slower and less fluidly (Andreetta et al, 2012).

In order to identify what type of aphasia a patient has a Mean Length of Utterance (MLU) must be calculated. This is the average number of words or morphemes that are uttered by patients at a given time (Sedivy, 2019: 207). To find the Mean Length of Utterance, the number of words or morphemes uttered are counted and divided by the total number of utterances. In this analysis, nonlexical utterances, fillers, and unintelligible utterances will not be counted and will not contribute to the Mean Length of Utterance. This includes utterances such as ‘mhm,’ ‘oh,’ ‘xxx,’ and ‘Au’.

These utterances do not carry significant meaning in what the patients are trying to articulate therefore omitting them from the analysis will clarify the data making the MLU calculation more reflective of the type of aphasia present in each patient. Utterance such as ‘yeah,’ ‘okay’ and ‘alright’ however, have been counted towards the MLU as these reflect more meaning in the patients’ speech. Repetition of the same words multiple times consecutively have also been discarded from the data and will be counted just

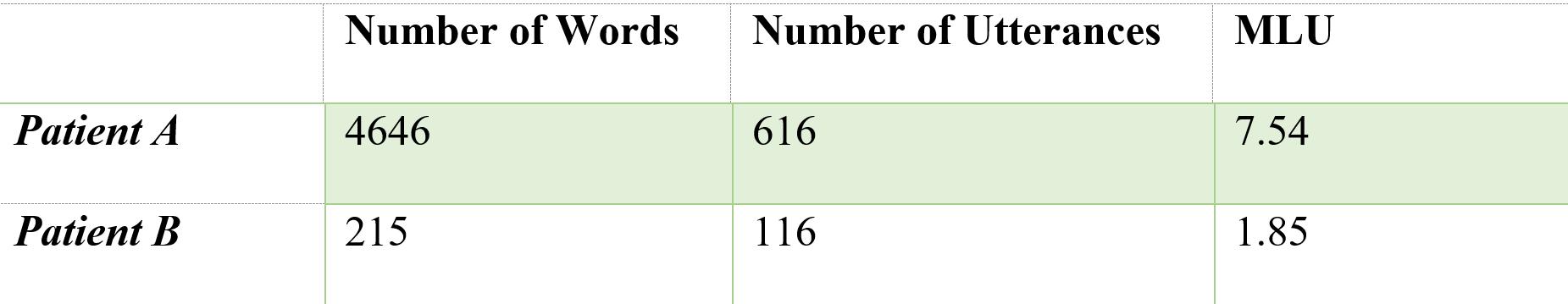

once. For example, “Queen Queen Queen Queen” will be counted as “Queen” i.e., one utterance instead of four. It can be useful to investigate both patients’ data comparatively before analysing each of them individually. Below is a graph and table presenting the number of words and utterances spoken by each patient, followed by a graph presenting their respective MLU’s.

It is expected that patients with a lower Mean Length of Utterance will have non fluent aphasia i.e., Broca’s aphasia while patients with a higher MLU are expected to have a fluent type of aphasia i.e., Wernicke’s or Anomic aphasia.

Figure 2: Table displaying both patients’ number of words and utterances spoken and their MLUs.

Figure 2: Table displaying both patients’ number of words and utterances spoken and their MLUs.

Another useful tool when diagnosing aphasia patients is to look at the relevance of the patients’ responses to the prompts given by the investigator. It is likely that patients with Wernicke’s aphasia will have fewer relevant responses while responses from those with Broca’s or Anomic aphasia will be mostly relevant.

It is likely that patient A has anomic aphasia as they have an MLU of 7.54. This is evidence that they have a type of fluent aphasia e.g., Anomic or Wernicke’s as Broca’s aphasia patients tend to have lower MLUs. It is unlikely that they have Wernicke’s aphasia

due to their score of 100% of relevant responses to the investigator’s prompts. This shows a level of comprehension that is only observed in patients with Broca’s and Anomic aphasia. Wernicke’s patients tend to experience disruptions in comprehension (Berndt and Caramazza, 2008: 249) meaning it would be unlikely for a Wernicke’s patient to produce 100% relevant responses. This can be found in the following example from the transcript when the investigator asks the patient to describe making a cheese and pickle sandwich.

It is evident from this example that the patient is able to comprehend and understand the task given and produce a relevant response with accurate grammar which is common for patients with anomic aphasia (Andreetta et al, 2012: 1788).

Further evidence supporting the diagnosis of Patient A with anomic aphasia can be found in the analysis of the frequency of different word classes in their speech. Many functional word classes such as determiners, conjunctions, pronouns, and prepositions are retained in this patient’s speech. Bird et al (2002) note that anomic patients have a very high frequency of function words whereas a deficit in function words tends to be found in other types of aphasia. Below is a table and pie chart illustrating the frequency of content and function words in Patient A’s speech.

As illustrated by the pie chart, there is a roughly even split between the number of content and function words spoken with function words making up 44% of the patient’s speech. The use of function words can be observed in example 1 when the patient uses conjunctions, determiners, and prepositions. Deficits in function words tend to be found in agrammatical types of aphasia (Broca’s).

This patient clearly does not lack function words in their speech therefore the deduction can be made that they have anomic aphasia

Patient B is likely a Broca’s patient. This can be deduced from the

low MLU score of 1.85. A mean length of utterance this low indicates that the patient has a non-fluent type of aphasia i.e., Broca’s. The patient’s percentage of relevant responses also supports their diagnosis of Broca’s aphasia. 63% of Patient B’s responses to the investigator’s prompts were relevant. This level of comprehension is fairly common in Broca’s patients, auditory comprehension skills tend to be somewhat retained (Nielsen et al, 2019: 3) hence the lower percentage than that of the anomic patient but a higher one than that which would be observed in a Wernicke’s patient. An example of a relevant response from Patient B can be seen below.

While this response is not very in-depth and consists of one-word utterances, it should be noted that it is relevant to the question

asked therefore displaying comprehension skills in the patient. However, there are also examples of the patient giving answers that are not relevant to the prompt. Such as:

The patient has once again given very short answers, which is common in Broca’s aphasia (Cutler, 2005: 57) and their answer is not necessarily relevant to the prompt given by the investigator. This shows a lack in their comprehension and understanding skills however, over half of their responses can be classed as relevant confirming that they have Broca’s aphasia as opposed to Wernicke’s. Patient B’s use of content and function words also support the diagnosis of Broca’s aphasia. Some function words are retained in their speech such as determiners, conjunctions and pronouns,

however there are very few in comparison to Patient A and there is a noticeable lack of prepositions. Bird et al (2002) note that Broca’s patients tend to have difficulty retrieving function words while content words such as verbs, nouns, adjectives and adverbs can be retrieved more easily. The figures below show Patient B’s use of content and function words.

Patient B

Number of Function Words

21%

Number of Content Words

Number of Content Words

79%

Number of Function Words

The pie chart illustrates Patient B’s heavy favouring of content words over function words with function words making up just 21% of Patient B’s speech. No function words are found in the previously provided examples however they can be observed in lines such as “well everything anything yeah” and “them and them”. This patient’s lack of function words in their speech supports the diagnosis of Broca’s aphasia.

To conclude, out of the three types of aphasia discussed in this essay, distinct symptoms of each can be identified and applied to patients. It is clear that Patient A has anomic aphasia due to their high MLU score, high percentage of relevant responses and frequency of function words in their speech. It has also been deduced that Patient B has Broca’s aphasia highlighted by their very low MLU score, significant number of relevant responses to prompts and severe lack in function words.

Andreetta, S., Cantagallo, A., & Marini, A. (2012). Narrative discourse in anomic aphasia. Neuropsychologia, 50(8), 1787–1793.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.04.003

Bar-On, A., Ravid, D., & Dattner, E. (Eds.). (2018). Handbook of Communication Disorders: Theoretical Empirical, and Applied Linguistics Perspectives. De Gruyter, Inc.

Berndt, R. S., & Caramazza, A. (2008). A redefinition of the syndrome of Broca's aphasia: Implications for a neuropsychological model of language. Applied Psycholinguistics. 1(3). 225-278.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716400000552

Bird, H., Franklin, S., & Howard, D. (2002). ‘Little Words’ – Not really: function and content words in normal speech and aphasic speech. Journal of Neurolinguistics. 15(3), 209237.

Code, C. (1989). The Characteristics of Aphasia. Taylor & Francis Group.

Culter, A. (2005). Twenty-First Century Psycholinguistics: Four Cornerstones. Taylor & Francis Group.

Nielsen, S, R., Boye, K., Bastiaanse, R., Lange, V, M. (2019). The production of grammatical and lexical determiners in Broca’s aphasia. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience. 34(8). University of Copenhagen.

https://doi.org/10.1080/23273798.2019.1616104

Pallickal, M. & Hema, N. (2020). Discourse in Wernicke’s aphasia. Aphasiology. 34(9). 1138-1163.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2020.1739616

Sedivy, J. (2019). Language in Mind (2nd Ed.). Oxford University Press.

Sida Cong, 2nd year

According to Housen and Kuiken (2009), complexity, accuracy and fluency (CAF) have been generally used in linguistic research to evaluate oral and written productions, which can reflect learners’ language proficiency. Based on Daniel’s oral production video, which is excerpted from his IELTS speaking test (Ross IELTS Academy, 2022), this essay will evaluate how the author measured Daniel’s CAF and why she chose the activities (displayed in Appendix B) from the textbook (Liz & Soars, 2000) to develop Daniel’s CAF specifically. Besides, some discussion about elements in the test prompt which related to Global Englishes ideals will be included.

Housen and Kuiken (2009) argued that there exist plenty of definitions of CAF and summarized a definition which is believed by most linguistic researchers. Complexity is the hardest one to comprehend among the three concepts. It contains cognitive complexity and linguistic complexity. Cognitive complexity is mainly determined by learners’ subjective feelings, while linguistic complexity focuses on the system and features of L2 itself. The definition of accuracy has the least controversy, which can be described as the evaluation on the amount of errors. Fluency can represent overall language proficiency, which especially measures “smoothness” of oral and written production (Housen & Kuiken, 2009).

Considering the definition of CAF and calculations of the measurement applied by Ogawa (2022), the author calculated each index of CAF. The statistics helped the author to evaluate Daniel’s CAF comprehensively. Table 1 shows the factors the author considered in the evaluation and the statistics. There are two terms needing explanations in the table.As-unit refers to TheAnalysis of

Speech, which can be defined as “a single speaker’s utterance” (Foster et al., 2000). According to McCarthy and Jarvis (2010), MTLD is known as the measure of textual lexical diversity, which can be calculated automatically by a web tool called TEXTINSPECTOR (http://textinspector.com/workflow).

Note. Adapted from Ogawa (2022, p. 7).

In the study done by Ogawa (2022), the score of CAF can be relatively accurate after using the same calculations on a large amount of data. The author didn’t rely on the statistics in Table 1 completely because she had to evaluate Daniel’s CAF only through

Table 1. Statistics of CAF measuresone cut of his oral production. However, the statistics provided different aspects of Daniel’s linguistic performance in some ways.

The first problem the author met in the evaluation process is it is difficult to measure cognitive complexity. There is little linguistic background information of Daniel. Besides, external factors of complexity like the topic of the test question can also influence his oral production. The statistics cannot be reliable because there exist fortuities in one set of data. Especially, accuracy was just confirmed by percent of error-free AS-units. There were selfrepairs, pauses and repetitions which can influence the judgement on accuracy. Another problem worthwhile to be mentioned is the author could not ensure the degree of Daniel’s confidence on the speaking test. If he felt nervous, he probably could not perform as naturally as he practiced by himself. It’s another tough issue for the author to consider. Finally, Daniel was given one minute to take notes for his monologue task in the test. What if he could just answer that question immediately?

Global Englishes include Word Englishes and English as a lingua franca (ELF) (Galloway & Rose, 2015). Galloway and Rose (2019) also created Global English Language Teaching (GELT) to analyse the relations between English teaching materials and GE. Considering the whole speaking test, the questions mainly focus on topics in common daily life, which are understandable for the candidate without any obstacle of cross-cultural communication. As such, this provides evidence for the presence of the ELF in the test. In addition, Daniel was asked some questions about his country. In this case, it provided Daniel sources and information which he can recall from his experiences in L1. GELT encourages to regard L1 as a resource for language learning. The author proposed to add some questions related to different cultures, which will increase the degree of difficulty but can help candidates enlarge their view to the world and express their opinions towards different cultures in L2.

As Scrivener (2011) argued, teachers should know the definition of the achievement aim clearly and set up possible and appropriate achievement aims. Daniel will take another similar speaking test in three months, which means his English learning should focus on oral production. Based on the evaluation of Daniel’s CAF, there come out three achievement aims. First, about complexity, Daniel will be able to master more vocabulary about daily life and be more familiar with more grammatical items. Second, Daniel will produce a higher portion of error-free utterances. Third, Daniel is expected to be more confident to speak English, with less hesitations.

This paragraph will evaluate Activity Directions 1.4 on page 43 of the textbook. According to Hunter (2012), there are a lot of limitations of language teaching at present. On one hand, teachercentred classrooms commonly appear, which means there are less opportunities for learners to output target languages. In this case, learners can hardly develop their fluency. On the other hand, to

focus on natural conversation practices alone leaves no space to improve learners’ complexity or accuracy. Based on the materials given, the author did some adjustments by adapting the communitive methodology of “Small Talk” (Hunter, 2012). The basic intention of creating “Small Talk” is to make learners practice conversations by themselves and make the teacher an observer, who will give feedback and corrections after speaking activities (Hunter, 2012). With no interruption of the flow, learners can develop their fluency. In Activity Directions 1.4, there is a restricted topic- “Directions”. It can be classified as Meaningfocused Output according to Nation (2007). During the preparation for the speaking task, Daniel can get familiar with some new vocabulary related to daily life. By describing different positions on the map, Daniel can get opportunities to practice different grammatical items. Nation and Newton (2009) stated that activities focusing on fluency should be meaning-focused, familiar to learners and support learners to improve their language proficiency. Daniel can choose any position on the map to give descriptions in English orally, and his partner won’t know “where Daniel is” until they finish the conversation. Thus, the activity is meaningful. The

topic “Directions” was under the tag of “Everyday English”, which means to be familiar to learners. Time pressure can help Daniel to improve his speed fluency and produce less pauses. The colourful map makes the activity more engaging, which can motivate Daniel to learn English.

Practice 3 on page 39 is based on Grammar Point 3 on the same page. It follows the strand of “Language-focused Learning”. The learning focus is a grammatical item - Demonstrative Pronoun “this, that, these and those”. The achievement aim of this activity is that learners can use the four grammatical items to compose sentences accurately. Analysing Daniel’s oral production transcription in Appendix A, the author found that Daniel made more errors in using functional vocabulary than other types of vocabulary in the test. Therefore, this activity is helpful for Daniel to develop his accuracy. Scrivener (2011) pointed out that learners should take a series of steps to master each new grammar item. The whole process can be briefly described as exposure, noticing, understanding, practicing, using and memorizing new grammar items, which can be achieved by using the “Present-Practice-

Product” (PPP) grammar teaching framework (Scrivener, 2011).

Before Practice 3, there are listening materials which contain the new grammar items. The materials and the examples the teacher show with flash cards can be regarded as opportunities of exposure. The exercise in Grammar Point 3 can make Daniel notice the grammar items specifically. By stating and explaining the grammar rules given in the textbook, the teacher provides opportunities for learners to understand them. The practice in this activity makes learners ask and answer questions about the facts of their classroom by using new grammar items, which belongs to a drill (Scrivener, 2011). The drill can help Daniel to get familiar with new grammar items orally. The teacher should listen to learners carefully while they are speaking and then “use error awareness and correction techniques” to make the activity focus on accuracy (Scrivener, 2011).

Practice 1 on page 37 shows a communicative activity as Scrivener (2011) defined. It is a Meaning-focused Output activity. The pair work contains an exchange of information because Student A and Student B are required to use different pictures to make up conversations. There exist information gaps between two

students in a pair. Therefore, the activity is meaningful, which meets the first condition of fluency- focused activities. Before Practice 1, learners are required to do tasks based on new relevant vocabulary and new grammatical items- prepositions used to describe the positions of stuff. In this case, learners’ familiarity with new linguistic items can be improved. Time pressure is a direct way to focus on fluency in language learning activities. Considering the possible length of conversations learners can create, learners should be given 40/30/20 seconds by practicing the same conversations as Scrivener (2011) encouraged. No interruption of flow caused by the teacher is needed. The scores of Daniel’s CAF show that Daniel has obvious weakness with fluency. The teacher can make some tailored learning plans for him like asking him to do more time-limited speaking tasks after class. Besides, the teacher should give more positive feedback to help Daniel develop his confidence to speak English.

CAF is not an ideal measurement to evaluate learner’s language proficiency, although it has been generally used. The author has

addressed several problems which caused difficulties to give scores on Daniel’s CAF. Both subjective factors and objective factors influence CAF, which makes it not totally reliable to evaluate language proficiency. The evaluation of Daniel’s CAF directly influences the learning activities designed for him to improve his spoken English. Technically, the author should get more background information about Daniel himself and his English learning experiences. Language acquisition cannot avoid considering subjective factors. In addition, standard indices of CAF for different levels of language proficiency have limited authentic data to reference. Linguistic researchers should work on improving CAF either by adjustment or creating a new framework to collect data and do calculations, which can make this measurement more authentic to be widely used.

GELT should master both language teaching theories and language learning theories. The definition of CAF has variety of versions stated by linguistic researchers, but there is one which can provide a basic notion (Housen & Kuiken, 2009). The definition can connect CAF with language learning as three aspects of achievement aims. How to develop CAF is still an obstacle facing

language teaching. There are few activities which can develop complexity, accuracy, and fluency simultaneously. Teachers need to run activities with different focuses to make the three aims balanced. Different materials have different advantages, and it is important that teachers choose suitable materials and design activities to make effective use of them. There is one goal that by the end of a period time English learning (for Daniel, it refers to three months), learners should achieve the original achievement aims, which needs teachers to plan how to help learners to make progress gradually and monitor them regularly. For example, teachers can provide quizzes in class to check learners’ English skills. Finally, teachers should encourage learners by giving positive feedback because motivation is a powerful resource in language learning.

Boggs, J. (2020). ALE200: Language Teaching in Context: Week 6 notes [Google file]. Google File.

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1ClealSrzDiyBPdP25M4IYexwwvESO04QOTeyOqc2uk/edit

Foster, P., Tonkyn, A., & Wigglesworth, G. (2000). Measuring spoken language: a unit for all reasons. Applied Linguistics, 21(3), 354–375. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/21.3.354

Galloway, N., & Rose, H. (2015). Introducing global Englishes.

Housen, A., & Kuiken, F. (2009). Complexity, Accuracy, and Fluency in Second Language Acquisition. Applied Linguistics, 30(4), 461–473. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amp048

Hunter, J. (2012). “Small Talk”: developing fluency, accuracy, and complexity in speaking. ELT Journal, 66(1), 30–41.

https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccq093

Liz., & Soars, J. (2000). New Headway English Course. Elementary Student’s Book. Oxford University Press.

McCarthy, P. M., & Jarvis, S. (2010). MTLD, vocd-D, and HD-D: A validation study of sophisticated approaches to lexical diversity assessment. Behavior Research Methods, 42(2), 381–

392. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.42.2.381

Nation, I. S. P., & Newton, J. (2009). Teaching ESL/EFL listening and speaking. Routledge.

Nation, P. (2007). The four strands. Innovation in Language

Learning and Teaching, 1(1), 2-13.

https://doi.org/10.2167/illt039.0

Ogawa, C. (2022). CAF indices and human ratings of oral performances in an opinion-based monologue task. Language

Testing in Asia, 12(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-

022-00154-9

Rose, H., & Galloway, N. (2019). Global Englishes for language teaching. Cambridge University Press.

Ross IELTS Academy. (2022, August 13). IELTS Speaking test band score 2.5, 2022 [Video]. YouTube.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7vzC-qMb0jQ&t=292s

Scrivener, J. (2011). Learning teaching: the essential guide to English language teaching. (3rd ed.). Macmillan Education.

How children view differences in dialects

Many child development researchers wonder whether young children notice differences between dialects – that is, how a person speaks a particular language based on where they are from - and if so, whether that affects the child’s opinion of that person. Two studies examined a group of 5–6-year-old children and how they viewed dialects. The children were asked to sort dialects of English into categories. They were given their own home dialect –the type of English they heard at home, a regional variation –spoken by a first language English speaker, but from a different area, and a second language variation – English spoken by a first language speaker of another language. Results showed that the children were able to tell the difference between their own dialect and the second language variation, but not between the second language and regional variation or the home and regional

variation.

What the researchers did

• The researchers carried out two experiments on separate groups of 5–6-year-old children from Ohio. One asked the children to consciously sort dialects into categories, while the other asked them to link each dialect to cultural items, such as houses or clothing.

• The three dialects used in the experiments were a home dialect; in this case Midland American English, a regional variant (meaning different dialect); Northern British English, and a second language variant; Maharashtran Indian English.

• In Experiment 1, 36 children were split into three groups. Each group was tested on two of the three dialects, for example: Group 1 was tested on the home versus regional dialect, Group 2 on the regional versus second language dialect and Group 3 on the home versus second language dialect.

• The experiment started with a training phase, where each group heard recorded sentences in their two dialects and were simultaneously shown green and purple puppets, which would move when they were supposedly speaking. A sentence would play, and the child would be told, for example, green puppets sound like this.

• The next step was a test phase, in which new sentences were played, and the children were asked to match them to the puppet.

• In Experiment 2, 36 children who had not taken part in Experiment 1 were split into three groups by the same categories as Experiment 1, and each group was played the same training sentences as in the previous experiment.

• This time, the children were asked to link the dialects to cultural items, such as houses.

• The children would be shown two pictures, one showing something that was familiar to them, for example, a house that was common where they lived, and one that was unfamiliar, for example, a mud hut. The children were then played a sentence in a dialect and asked which picture the dialect belonged to. What the researchers found

• Experiment 1 showed that most of the children matched the puppet to the correct dialect in the home versus second language dialect contrast, but in the other two conditions (home versus regional dialect and regional versus second language dialect), the number of children who answered correctly was no higher than would be expected by chance.

• This suggests that, overall, the children were not able to pick out anything specific in the home versus regional and regional versus second language dialects that helped to differentiate between them, and may just have been choosing an answer at random.

• It is important to remember that each experiment was done on a completely different set of children, meaning that the results would not have been affected by the children having picked up information from a previous experiment.

• The overall findings of this study show that, at this age, while the children are not always able to knowingly sort dialects into categories, they can make judgments on how similar or familiar someone is to them based on their speech.

• The results imply that as children start school, they are still in the process of learning what makes accents and dialects similar or different to their own. This could be useful for teachers who want to understand more about how young children interact with new peers and how they communicate as a result of information they pick up from each other’s accents. More research is needed to determine at which point children start to acknowledge these differences in peoples’ speech.

Reference Wagner, L., Clopper, C.G., & Pate, J.K. (2013). Children’s perception of dialect variation. Journal of child language, 41(5), 1062-1084.

https://doi:10.1017/S0305000913000330

Angharad John, 2nd year

Report on and critically evaluate a set of research outputs/publications from projects where applied linguists and practitioners have worked in partnership

This essay will examine the research outputs from a Research Excellence Framework (REF) Impact case study in the health domain. Undertaken by the University of Nottingham’s School of English, the study is titled: Raising Awareness of Adolescent Health Communication (University of Nottingham, 2014). The aim of this research was to “enhance practitioner-patient communication” (University of Nottingham, 2014, particularly when it came to adolescents and young people, and to better understand the ways that teenagers express worries they have about their health.

The Health Language Research Group was set up in 2002, which was an “interdisciplinary sub-group” (University of Nottingham, 2014) of the Centre for Research in Applied

Linguistics (CRAL). The research team in this group consisted of Ronald Carter, Professor of Modern English Language, Svenja Adolphs, Professor of English Language and Linguistics and Dr Louise Mullany, Associate Professor in Sociolinguistics (UoN, 2014). The researchers developed working relationships with Dr Aidan MacFarlane and Dr Ann McPherson, who were paediatricians working in the NHS at the time, and the co-creators of the Teenage Health Freak website (Teenage Health Freak, n.d.). This website allowed teenagers to submit health-related questions which were then answered by GPs (UoN, 2014). These questions were converted into data for one output of this research, which was a 2-million-word corpus created from the roughly 113,000 healthrelated questions that were submitted via the ‘Ask Doctor Ann’ (THF, n.d.) function (UoN, n.d.). When submitting the questions, adolescents were also able to specify their gender and age by using a drop-down list, however this was not essential. The corpus used this data to break down the words most commonly used, as well as the median number of words in questions sent by each age and gender.

The contents of the corpus were then judged against “CRAL’s multi-million word general English holdings” (UoN, 2014). This allowed researchers to identify terms that had a proportionally high usage (Harvey et al., 2007). From this, it was found that the most common topics queried were: sex, pregnancy and relationships; body parts; body changes; weight and eating; smoking, drugs and alcohol (UoN, 2014). An encyclopaedia containing 100 words on these topics was then created to aid health practitioners. The aim was for it to bring to light any trends in “adolescent sociolinguistic style and register” (UoN, n.d.). It showed the frequency of use of each word across different genders and age groups, as well as some examples of how the words were used in context. Some challenges faced while creating the encyclopaedia included converting the data from spreadsheet into XML (that is: Extensible Markup Language (FileInfo, 2022)) format, as well as finding and deleting duplicate messages that were sent on the same date (UoN, n.d.). Correction of spelling as often as possible was also necessary (UoN, n.d.). Obviously, in some cases this would have been difficult or even impossible, depending on whether the word was intelligible or distinguishable from another similar word which would have made

sense in the same context.

The third output of this project was a booklet designed to be accessible for a practitioner audience, and to provide health practitioners with more information on how adolescents express health worries, titled “Am I Normal?” (Harvey et al., 2007). It explains the background of the Teenage Health Freak (Teenage Health Freak, n.d.) website and the corpus, and points out that previously, sexual health research has found that young people will often use “vague terms and euphemisms” (Harvey et al., 2007) when talking about their body, however, while using the website they explained their concerns in “meticulous detail” (Harvey et al., 2007). It also advises that practitioners could learn useful communication lessons by analysing this bank of health language (Harvey et al., 2007). It was hoped that this publication would contribute to the “continuous professional development” (UoN, n.d.) of groups of practitioners within the NHS, while also being useful to adolescents, parents and teachers.

Until this point, not much linguistic research into adolescent health had been carried out. It was also noted that GPs generally wanted to better understand how young people viewed health and illness (UoN, 2014). The researchers’ decision to analyse the online communication was therefore an effective one for several reasons. Firstly, typing out questions anonymously online is a far less daunting prospect for a self-conscious teen than trying to articulate concerns to a doctor or parent face-to-face, especially if they are worried about the adult asking them uncomfortable questions in return. Being able to submit questions anonymously makes it more likely that the adolescents would share what is genuinely bothering them, meaning that the data would show a much wider picture of adolescents’ real concerns, not just what they would normally be willing to share with an adult. This also applies to the type of words they might use. When talking to adults, words considered rude or taboo might be avoided, but as mentioned in Harvey et al. (2007), more direct anatomical language is included in the questions. This shows that a corpus made up of online submissions more accurately reflects natural adolescent language and perspectives, as opposed to, for example, one made up of words used by adolescents in a

doctor’s surgery. Furthermore, the reach of this project was fairly wide. As the data was gathered online, there were no geographical barriers that stopped teenagers from providing questions. The 113,000 responses resulting in a 2-million word corpus indicates the moderately large scale of the project.

The main problem being addressed in this study was health practitioners'’ lack of knowledge of adolescent communication, and how best to respond to this style. As a result of the research, GPs stated that they felt more informed, and were able to engage “more effectively and confidently” (UoN, 2014) with teenage patients. Several GPs who read the ‘Am I Normal?’ (Harvey et al., 2007) booklet commented that it gave them more “knowledge and insight” (UoN, 2014) into adolescent communication. They also explained that the booklet helps to highlight the fact that teens often have “hidden agendas” (UoN, 2014) and concerns when consulting with GPs, and it details the best ways to make young patients comfortable enough to have conversations about said agendas. Ideally, the most successful outcomes for young people from this study would have been more effective treatment, or feeling less

intimidated and instead better understood by their health practitioner. This could then result in more positive attitudes towards talking to a GP, and improve overall confidence in the NHS. These comments exhibit that, according to the practitioners at least, the real-world challenges that were being addressed in this research were done so successfully.

In terms of ethical aspects, there is a question over whether teenagers were aware their questions would be collected and used for research purposes. As the Teenage Health Freak Website is no longer live, it is difficult to determine whether anything was displayed on the ‘Ask Doctor Ann’ (THF, n.d.) function explaining this. As the questions are anonymous, this would not be such a serious problem, but it is a particularly sensitive area given that these are the questions of minors.

It is mentioned that this research was carried out as a result of “demands” (UoN, 2014) from GPs, so it could be inferred that relationships between practitioners and researchers were initially strained. It is arguable that the main priorities of each group would

be different from each other. This would have not been a significant issue for earlier research as the Teenage Health Freak website was designed by GPs, who obviously understood the values of GPs’, for example, strict protocol and patient confidentiality; hence the anonymity of the questions submitted. It would therefore be more interesting to know where they stood on the ethics of research, and whether it was explained on the THF website that these questions would be recorded and analysed. The NHS is a huge stakeholder in this research, not necessarily in financial terms, but the outcomes of this research would make significant differences. Good results from the research would lead to better relationships with young patients and parents, and even a more positive overall image. There is even the potential for better funding, although this is a bold, oversimplified statement to make given the complexity of the NHS structure. The project also worked in collaboration with Medikidz (Medikidz, n.d.), a company which makes accessible health materials for children and young people, who managed to secure £42 000 worth of funding from the Horizon Digital Economy Research Institute (UoN, 2014). This is another

example of differing values and priorities working in partnership, as Medikidz is an “enterprise” (UoN, 2014) which has to consider making profit, while the NHS and researchers would have had the service they were providing as their main focus.

In terms of dynamics, researchers are likely to have faced pressure, as they were the ones providing the - arguably overdueservice to GPs. The GPs also had vested interest in this research; many might have felt on a personal level that they want to learn to communicate better with adolescents. Particularly if they work with them often, their job could have become easier and more rewarding with the better knowledge on how to communicate with them effectively.

In conclusion, the research for this REF Impact case study did succeed in identifying common linguistic patterns of adolescents when discussing their health and anatomy, and as a result was able to give guidance to practitioners on how best to communicate with young patients.

FileInfo. (2022, March 13). .XML File Extension. FileInfo.com.

XML File Extension - What is an .xml file and how do I open it? (fileinfo.com)

Harvey, K.J., Brown, B., Crawford, P., Macfarlane, A., McPherson, A. (2007). Am I normal?’ Teenagers, sexual health and the internet. Social Science & Medicine (65), 771–781.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.04.005

Medikidz. (n.d.). Medikidz. Medikidz. http://www.medikidz.com/

Teenage Health Freak. (n.d.). Teenage Health Freak. Teenage Health Freak. http://www.teenagehealthfreak.org/

University of Nottingham. (2014). Raising Awareness of Adolescent Health Communication. Research Excellence Framework 2014, Impact Case Studies.

https://ref2014impact.azurewebsites.net/casestudies2/refservic e.svc/GetCaseStudyPDF/31746

University of Nottingham. (n.d.). Teenage Health Freak Corpus: Overview. Centre for Research in Applied Linguistics.

Teenage Health Freak Corpus: Overview - The University of Nottingham

University of Nottingham. (n.d.). Health Communication and the Internet: An Analysis of Adolescent Language Use on the Teenage Health Freak Website. Centre for Research in Applied Linguistics. Health Communication and the Internet: An Analysis of Adolescent Language Use on the Teenage Health Freak Website - The University of Nottingham

University of Nottingham. (n.d.). Teenage Health Freak Corpus: The data Transformation Process. Centre for Research in Applied Linguistics. THFdataPreparation - The University of Nottingham

University of Nottingham. (n.d.). Teenage Health Freak: The data Transformation Process. Centre for Research in Applied Linguistics. THF Encyclopedia - The University of Nottingham

Madison Allardyce, 2nd year

Madison Allardyce, 2nd year

In this study I explore the effects and differences between memory systems. Simply, memory consists of the remembrance and recollection of information (Klein, 2015). However, from a more academic approach, the concept of memory involves three major steps:

(1) learning – new information is gathered and encoded into our memory,

(2) storage – the encoded information is then stored to maintain continuity,

(3) retrieval – when we decide to remember the piece of information, we retrieve it from our memory (Klein, 2015). For my research, I specifically investigate the use and comparisons between working memory and long-term memory.

Baddeley (2010, 2012) describes working memory as the temporary storage of small amounts of information over brief periods of time. Working memory is located in the pre-frontal cortex of the brain (Conway et al., 2005). This is where complex goal-directed human behaviour is studied (Conway et al., 2005). Within this system there are two main components: domain specific skills, and domain general capability (Conway et al., 2005). Domain specific skills include practices such as grouping and rehearsal (Conway et al., 2005). These practices are also found when using short term memory (Baddeley, 2010). Short term memory describes the temporary storage of information; however, the role of working memory goes beyond this simple storage (Baddeley, 2010, 2012). The role of working memory includes general cognitive control and executive attention, which provides techniques that can be applied practically to activities (Conway et al., 2005; Baddeley, 2010). This means that working memory is domain general (Conway et al., 2005). Baddeley and Hitch’s model (1974) explains that working memory is controlled by the central executive, which is where information is stored (Baddeley, 2010, 2012). This element is important during complex activities as it

allows the individual to switch attention and concentrate on different stimuli (Conway et al, 2005). Within the central executive, there are three structural components where information is stored (Baddeley, 2010, 2012). This element is important during complex activities as it allows the individual to switch attention and concentrate on different stimuli (Conway et al, 2005). Within the central executive, there are three structural components where information is processed (Turner & Engle, 1989). First, there is the phonological loop (Baddeley, 2010, 2012). This is where speechlike information is stored and where (sub)verbal rehearsal processing is achieved (Baddeley, 2010). It is suggested that it is more challenging to recall a sequence of words when the words contain similar sounds (Baddeley, 2010). Then there is the visuospatial sketchpad, which processes visual and spatial semantics in real life and reading (Baddeley, 2010, 2012). Finally, there is the episodic buffer, which was added later in Baddeley and Hitch’s (1974) model (Baddeley, 2010). This component temporarily stores visual and auditory information and is linked to long term memory (Baddeley, 2010, 2012).

I chose to use an operation span task (OSPAN) to measure

working memory capacity. OSPAN tasks are used to predict the level of complex cognition of individuals and their memory performance (Conway et al., 2005). An OSPAN task consists of two tasks: a word or digit span activity (in this study a word span) in accompaniment with a secondary task (in this study a maths task) (Turner & Engle 1989). These tasks were originally designed from Baddeley and Hitch’s (1974) theory of working memory, whereby they identify the importance of a memory system that can temporarily store information whilst other mental activities are taking place (Conway et al., 2005). Participants are shown sequences of maths equations, which are answered with a true/false answer, followed by a word, usually a concrete noun with 4-6 letters, to remember (Turner & Engle, 1989). Once the sequence is complete the participant records the words they can remember in order that they appeared. The combination of the ‘to-beremembered’ target stimuli (word span) and a demanding processing task (maths equations) stops participants using memory strategies, including rehearsal and grouping, allowing researchers to grasp a full picture of their participants working memory capacity (Conway et al., 2005). The results of these studies

highlight that there is no significant difference in performance between the sexes, working memory decreases as age increases, and working memory is lower when a participants’ second language (L2) is used in the experiment (Conway et al., 2005; Baddeley 2012).

The other task included in my study is a continuous visual memory task (CVMT) which measures long term memory (Paolo, 1998). Within long term memory there are two main systems: declarative memory and procedural memory (VanPatten et al., 2020). The declarative memory system is located in the hippocampus and other medial temporal lobe (MTL) (Ullman, 2016). This area of the brain is where: language is learned, knowledge and experiences and linked together, and where information and events are remembered (Ullman, 2016; VanPatten et al., 2020). More specifically within the MTL, the perirhinal cortex contributes to object recognition, the para-hippocampal cortex contributes to spatial recognition, and the hippocampus contributes to higher-level concept recognition (Ullman, 2016). The procedural memory system is based in the frontal, basal-ganglia circuits (Ullman, 2016). Processes including learning motor and

cognitive skills and learning to predict probabilistic outcomes are done in this area of the brain. Declarative memory acquires knowledge quicker, therefore explicit instructions and attention on stimuli increases learning in this system (Ullman, 2016). However, procedural memory processes knowledge quicker, therefore implicit, complex instructions increase learning in this system (Ullman, 2016). Research has proven that both memory systems decline through age as memory plateaus after adolescence and procedural memory decreases in adulthood (VanPatten et al., 2020). Ullman (2016) discovered that women rely more on declarative memory because higher levels of oestrogen result in better declarative memory. Due to this, men tend to use more procedural memory (Ullman, 2016). Research also shows that early language learners (L2) rely more on procedural memory, whereas later language learners rely on declarative memory (Ullman, 2016).

CVMT measures visual learning and declarative memory (Paolo, 1998). It removes the motor component linked with drawing tasks and decreases verbal labelling that may appear on tests involving simple geometric shapes (Paolo, 1998). In a continuous visual memory task, a series of shapes appear on a

screen (in this study 112 pictures were shown). Participants are required to state whether the picture is new or old; this promotes the use of their long-term memory (Paolo, 1998). Unlike Ullman’s(2016) discoveries CVMT are not influenced by gender or education, which is supported by Trahan and Larrabee’s (1988) test model (Paolo, 1998). However, Paolo’s study (1998) showed the CVMT results were largely influenced by age. Furthermore, PiliMoss et al. (2019) identified that declarative learning is the main predictor of accuracy in comprehension tasks.

The first task, to conduct my study, was to develop a research question: How do the effects of working and long-term memory differ, in relation to various demographic factors?

After this, I began to create my experiment. I used gorilla software to clone the OSPAN and CVMT tasks into my experiment (Gorilla Experiment Builder, 2016). Furthermore, I provided an information sheet, consent form, and background questionnaire at the beginning of the experiment to provide the participants with information about the experiment, choice to participate, and give information about themselves - which would later be compared.

Due to the cloning, I made alterations to each section in order for them to correspond with what specifically I was investigating. For example, in the questionnaire I included questions about the participants’ age, sex, education, first language (L1), and potential second language (L2). Moreover, I changed the OSPAN task to consist of 42 sequences, three sets of 2-5 sequences sorted randomly, and ensured that 50% of the maths equations were correct (Turner & Engle, 1989).

Once my experiment was complete, I sent the experiment to multiple friends and family members via various social media platforms and email. Overall, 30 anonymous participants were collected and categorised accordingly:

Figure 3.1

12

18

Male Female

60% of participants were female and 40% were male.

The age of the participants ranged between 19-75. I separated the participants’ ages into 4 groups to later compare.

Undergraduate degree Postgraduate degree Other

School until age 16 School until age 18

FigureMost of the participants have an undergraduate degree (30.3%).

The other forms of education by the participants include: RMN and specialist practitioner diploma level, Registered Nurse qualified 1991 pre-degree, and City and Guilds C&G 015 in agricultural engineering.

Majority of the participants’ first language is English (93.3%).

Figure 3.430% of the participants have reported that they can speak another language.

4.1 OSPAN Task

Table 4.1.1

Table 4.1.1 shows the results from the target stimuli in the OSPAN task. The y-axis represents the words in the task (42) and the x-axis shows the results from the participants. The highest participants scored 41 (97%) and the lowest scored 4 (10%). The average score of the participants was 31 out 42 (74%).

Table 4.1.2 highlights the results from the secondary processing task in the OSPAN task. The y-axis shows the number of equations in the task and the x-axis represents the results from the participants. The highest score was 42 (100%) and the lowest score was 22 (52%). The average score of the participants was 37 out of 42 (89%).

Table 4.2.1 displays the results from the continuous visual memory task. The y-axis shows the number of pictures that appeared in the task (the total number was 112 therefore the axis was rounded to 120). The x-axis represents the results from the participants. The highest score was 98 (87%) and the lowest score was 49 (43%). The average score of the participants was 74 out of 112 (66%).