On Yom Kippur 5734 (October 6, 1973), the State of Israel faced an unexpected attack by a coalition of Arab states, led by its neighbors, Egypt and Syria. Caught by surprise on the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, Israeli soldiers and reservists were quickly mobilized to defend their country.

As the fiftieth anniversary of the Yom Kippur War approached, The Leffell School reached out to our community, inviting Yom Kippur War veterans and others impacted by the war to share their recollections and experiences with our Leffell School students and the larger community. It is through these very personal memories – stories told by those who lived through the war or their family members – that our students and those of us too young to remember the war directly can best learn and gain valuable insights about this crucial moment in Israel’s history. Through their words, we learn about the harsh realities of war and the extraordinary bravery of the men and women who fought in it, while looking toward the future and maintaining our tikvah, our hope. We pray for a lasting peace in Israel and around the world –a time when the words “המחלמ דוע ודמלי אל”that our children will no longer learn war, will transform from prophecy to reality.

Joseph Arkin

Amir Azkireli z”l

Tzvi Bar-Shai

Micha Ben-Hillel

Yechezkel Calif

Amos Elazari

Rabbi Michael Graetz

Clive Gurwitz

Mike Guy z”l

Rabbi Richard Hammerman

Andrew Lester

Haim Linder

Opher Pail

Moti Pasternak

Alan Queen

Benny Reichman

Giora Romm z”l

Barbara Bernhard Scharf

Jose Spiwak

Dr. Igal Zuravicky

Todah Rabah, The Leffell School | Hartsdale, New York

הבר אנעשוה - ד״פשת ירשת א״כ

“Nation shall not lift up sword against nation, neither shall they learn war anymore”

,ברח יוג לא יוג אשי אל" "המחלמ דוע ודמלי אל

We are grateful to those who generously submitted stories for this collection and acknowledge other members of our kehilah who also served, volunteered, or were otherwise impacted by the Yom Kippur War, including:October 6, 2023

JOSEPH (YOSKE) ARKIN

as recalled by his wife Oney Arkin Friend of a Leffell School familyOn Saturday, Yom Kippur morning around 9:00 a.m., there was a telephone ring in our house. Most unusual on that holiday. It was a female soldier, instructing Yoske to report. Yoske asked if the matter was very important, because he was not feeling well. Yes – so he made preparations, got his stuff, ate a breakfast that I prepared for him, despite the Yom Kippur fast. He went outside to call our neighbor, who was a reserve soldier in the air force – did he receive any notification? No. Then we started to see cars racing on the road out of Zahala, where many high-ranking officers lived. In 1973 Yoske served in the branch of the army called Haga, which dealt with civilians possibly affected by a military episode or war. There was a special identification on the soldier's uniform. (Nowadays there is a different, special unit to protect and serve civilians.)

Yoske had just celebrated his 46th birthday on Rosh Hashanah. He had actively served in the War of Independence (1948-9), Suez (1956), the Six-Day War (1967) and various training activities over the years. He knew that you go and do, according to the directions of the army. His rank was 2nd Lieutenant. Several of the men serving in Haga were embarrassed by the identification on the uniform, but Yoske's reaction was to do his best at whatever service was required.

Yoske, as an officer, was in charge of an emergency "supply depot" in Akir (Kiryat Ekron). I can imagine that his placement was the result of several factors – an officer was required, and Yoske knew the area very well, born and raised in Mazkeret Batya (Ekron). Furthermore, the air force base of Tel Nof (originally a British air base in the Mandate years) was very close by. The contents/supplies stored in the depot were intended for emergency civilian use.

Yoske was able to drive home every 3 days or so, for the night. He told me a very special story. The depot where he was stationed was evidently poorly ventilated. Yoske's feet were affected – itching, discomfort, pain. On one of his drives back home, through a village, he noticed a sign in front of a house: dermatologist/ doctor. He gave it a try, was warmly received by the doctor, received instructions and medication. The doctor refused to be paid!

AMIR AZKIRELI Z"L as recalled by his brother-in-law Zvi Segal Extended family of Leffell School students

Amir was killed on the second day of the war on 9.10.73. He and the entire tank crew who were all reserve tank commanders were killed in the central sector in Sinai. It was difficult to extract his tank and it took a long time before they succeeded to bring him back to Israel.

Because of his courage and fortitude, Amir received the Itur HaMuppet, the Medal of Distinguished Service military decoration after his death.

TZVI BAR-SHAI Grandfather of Leffel School students and alumniMy Milchemet Yom HaKippurim

We’ve all seen movies about the fighting and destruction. We all should understand that war is horrible. Everyone loses but sometimes, like when your country is attacked on the holiest day of the year, it is necessary. I didn’t do anything different from all the hundreds of thousand other Israelis who served.

I had made Aliyah to Israel in March of 1968. I spent 6 months on Kibbutz Ma’ayan Tzvi (near Zichron Ya’akov) learning Hebrew and working in the fields. It was a fabulous experience. Though I loved Kibbutz, the open air, friendly people, hot sun and hard work, I knew that that commune lifestyle was not for me so when I finished the Ulpan (language studio) I moved to Jerusalem and registered for the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

That year many people I knew from the States came for their Year Abroad Program at the Hebrew U. I hung out with them and other Americans for a while but then realized that if I wanted to be Israeli I’d have to serve in Zahal, the Israel Defense Forces. So, I went to the Induction office and asked what my military status was and because I was not native Israeli, they thought I was looking for a way out. They started listing to me all sorts of ways to avoid or postpone serving. So, I told them no; I wanted to serve and how could I get in? They then gave me an induction date and, in February 1969, I became an Israeli soldier. I served three years in one of Israel’s elite Sayerret units (Egoz) and in addition to Sayerret training I was trained as a combat medic.

After my discharge I started working for a Scandinavian furniture company, assembling and delivering furniture during the day, and in the evening as a Youth counselor at a community center. After a while I told them I was leaving to work with one of the Jewish Agency’s summer youth programs and they hired a replacement for me. A very cute young Persian girl named Etty. When she came in for me to brief her about the job it was love at first sight. We started dating in June 1973 and about

three months later I proposed marriage to her on October 5th 1973. The next day I had been invited to celebrate Yom Kippur with her family and we hadn’t yet had a chance to tell anyone. I was with her father and brothers in their Beit Kenneset (synagogue) when things became strange. People were getting up one by one and leaving. Cars were driving through the streets (something that never happened on Yom Kippur at the time).

Realizing that something bad was happening I asked one of her brothers to drive me to my home on the other side of the city and sure enough there was a “stav shemoneh” (emergency mobilization notification) on my door. I grabbed my ready pack with my military gear, was driven back to my girlfriend’s home, and broke fast early. I said goodbye to everyone - her mother threw water on me as I left (a Persian custom of some kind for good luck and safe return) - and went to my reserve unit’s mobilization point. They had not been prepared and we were equipped poorly (there was a lot of equipment lacking) but off we went to our assigned goal of protecting Israel’s eastern border with Jordan. We waited but early the next day our mission changed. King Hussain of Jordan decided not to come to the party, and we were reassigned to the northern Syrian front.

We were an armored battalion comprised of tanks, armored personal carriers (APC), and jeeps with recoilless cannons on them, but all the vehicle carriers were taken so we had to drive on our tracks all the way up to the Golan Heights; a difficult task. We actually lost some vehicles and soldiers were injured losing control on the long hard drive up. We were, I think, one of the first reserve battalions to engage the Syrians who had infiltrated deep into Israeli territory. We fought for 5 weeks till a ceasefire was called. We had pushed their armies back beyond the Golan Heights and into Syria. My unit was almost called upon to attack the Syrian position on top of Mount Hermon

(which they had taken from us) but instead a regular army unit, Sayerret Golani, was assigned to do it and my girlfriend’s cousin and a high school friend of mine were killed fighting in that assault.

During those five weeks, as a combat medic, I treated several wounded soldiers. We were fortunate in that there weren’t many despite the fighting. I myself was protected inside an APC; I think they saw me, the medic, as a first aid kit that had to be protected and preserved till there was a need. I do remember one incident where in the middle of an ongoing battle and barrage I had to leave the APC and go out and treat an Arab soldier. A very surreal situation. Despite the raging battles going on, Israeli civilians wanted to do what they could to make the soldiers lives better so one day, during a lull in the fighting, we were in our APC, which is open on the top, all of a sudden a dozen or so whole grilled chickens came flying over the top and into the APC. These civilians had driven up to the combat front with home cooked food for us and distributed it as they could to us. But these lulls could be as dangerous at the ongoing fighting. In one of them we were suddenly artillery barraged, a few of my fellow soldiers were lightly wounded; but a soldier, with whom I had done the Combat Medic’s course, was killed.

After the ceasefire I was finally given leave (medics were the last to get leave as we were few and far between and they couldn’t spare us) and I went back to Jerusalem to my girlfriend and her family. They were elated to have me back safe. They fed me (of course) and we finally had the chance to tell them of our engagement. I then made a call to my parents back in New York. I said “hi, Mom, Dad, I’m alive; and, oh yah, I’m getting married!” One of my future brothers-inlaw then drove us to the Kotel Ma’aravi (the Western

Wall) and I prayed Gomel (a prayer of thankfulness when surviving a dangerous situation). The next day I hitchhiked all the way from Jerusalem back to Syria where I had left my battalion.

Unfortunately, when I got there another unit was there, Battalion 7, a regular army tank battalion. When I asked one of the officers where my Battalion was they told me Egypt. Overnight they had taken my unit to Egypt to replace two units of a similar type who were destroyed when Arik Sharon, then Commander of the Southern front (later Prime Minister), battled to cross the Suez Canal.

So, on my way down to Egypt, I went back to Jerusalem and spent another night with my future wife and her family. The next morning, I got up and hitchhiked to Stay Dov airport. I fanaigeld (Yiddish for deviously) my way onto a flight to Tassa, a large airbase in the middle of the Sinai Peninsula, which we had just recaptured from the Egyptians. When I got there I had no idea what to do. The Battalion 7 officer just said they were in Egypt, but Egypt is a big place. I had no idea how to find them. So, I left the airbase and sat on the side of the road trying to figure out what to do next when a supply truck drove by and suddenly hit its brakes a few hundred feet down the road and then backed up to me. “Hey you, Bar-Shai, get in the truck” the guy next to the driver shouted. Turns out that this was, by chance, a supply truck from my unit and the guys in the truck recognized me and brought me back to our new Egyptian base. We stayed in Egypt another three months as part of the forces surrounding the Egyptian 5th Army which Zahal had cut off from retreat. I did get some more time off, among which were two days so I could go to Jerusalem and finally get married. My parents and sister flew in for the wedding, which was lovely and different, in part because many men came with their

weapons which were piled in a corner but also because we mixed my wife’s Persian traditions with my Ashkenazi traditions out of respect for our parents.

During this time, since most of the able-bodied men were drafted, men and women who were not took on their jobs. My wife filled in as a substitute teacher in high school, while the students also filled in some civilian jobs. Some of her students delivered the mail. I had been writing postcards (cards with the address on one side and the content on the other), to my girlfriend/ wife all this time. They were “love letters” typical of all young soldiers from the front. The student “postmen” of course read the cards and then all the students knew of their teacher’s relationship with me.

We finally got pulled out of Egypt and went back to Israel hopefully to be demobilized. We thought the discharge date was to be March 8th ’74 and my now wife arranged a surprise party for me at our home in Jerusalem with our friends, most of whom had served and already been discharged. But while they waited Assad, President of Syria, redeployed his army in a way that looked like he would again try to attack Israel, so I wasn’t released and the welcome home party went on without me.

I was finally demobilized at the end of March after six months of fighting. I lost some friends in the fighting and my wife lost a cousin. All in all, over 2,600 Israeli soldiers were lost and as the saying goes “there but for fortune go I”.

I am married still to Etty whom I’ve been with for these last 50 years. We had three children; the eldest of which is the mother of three of our grandchildren who are all students at Leffell, the oldest of which just graduated and is hoping to enlist in Zahal next year.

MICHA BEN-HILLEL Friend of a Leffell School familyFifty years have passed since Yom Kippur of 1973, that dreadful and fateful day when at 2:00 p.m. a siren echoed throughout the country. The radio announced the waging of heavy battles along our borders with Egypt and Syria.

I was a 28-year-old reservist in the paratroopers brigade and I was sure I would be recruited within the next few hours. In the evening, I kissed my wife Pnina and my two infant sons, Noam (two years old, and Yotam just three months old) and boarded the bus that took me and my comrades to our army base.

On the night between October 15th and 16th our regiment was the first force that crossed the Suez Canal on small rubber boats and landed on Egyptian soil. It was a decisive move that led to a faster end of the war. But before ceasefire was reached, our platoon was involved in a battle over an Egyptian post. Painfully one of my friends was killed when running towards the trenches. Twelve other soldiers were injured and I, as a medic, had to take care of some of them.

Over 2600 Israeli soldiers and many more Egyptians lost their lives during this war. It was the last war between the two countries. The positive outcome of the war was the signing of a peace treaty which has prevailed. War is a terrible thing that must be avoided.

YECHEZKEL CALIF

Cousin of a Leffell School student

םוקממ ונזזו הקספה ילב ונילע ורי ,תונוידב יניס רבדמב ונייה

ונממ םיקלוח ףרשנו עגפנש ילארשי סוטמ וניאר רקובב ,םוקמל

תא וניאר ,עגפנ אל דחא ףא לזמב ,הב ונייהש הללוסל ולפנ

היה שא תחת לכה ,םתוא ץלחל םהילא ונצרו םיחנוצ םיסייטה

דחא םישק דאמ תוברק ויה .םיסייטה ולצינו ונלצינש לודג לזמ

רשג רוציל ידכ ץאוס תלעת תא תוצחל בדנתהש ונלש םיניצקה

ידוהי היה הרקמב אוה ,גרהנ םירצמ ןוויכל וצחי םיקנטהש בדנתהל אבש יאקירמא ונייה אל יכ ,ועגפנש םילארשי םילייח לש םישק דאמ תוארמ ויה

אל ,םינכומ ונייה אל

We were in the Sinai desert in the dunes. They shot at us non-stop and we moved from place to place. In the morning we saw an Israeli plane that was hit and burned; parts of it fell into the battery we were in. Luckily no one was hurt. We saw the pilots falling and ran to them to rescue them. Everything was under fire. It was very lucky that we were saved and the pilots were saved. There were very difficult battles. One of our officers who volunteered to cross the Suez Canal to create a bridge for the tanks to cross in the direction of Egypt was killed. He happened to be an American Jew who came to volunteer.

There were very difficult scenes of Israeli soldiers being injured, because we were not prepared. The war was a complete surprise. We were not prepared. We did not shower for about a month. Food was sent occasionally.

AMOS ELAZARI

as recalled by his son-in-law Michael Stein Grandfather of Leffell School students

Amos Elazari often says that he was born twice on Yom Kippur, as his birthday is September 25th and often falls (as it does this year) on Yom Kippur.

His unit was one of the last to deploy, and as such knew the severity of the situation. He deployed and his wife Tchiyah didn’t hear from him for a few months, assumed he was dead and moved in with her parents, until she found out he was commanding troops in the Sinai.

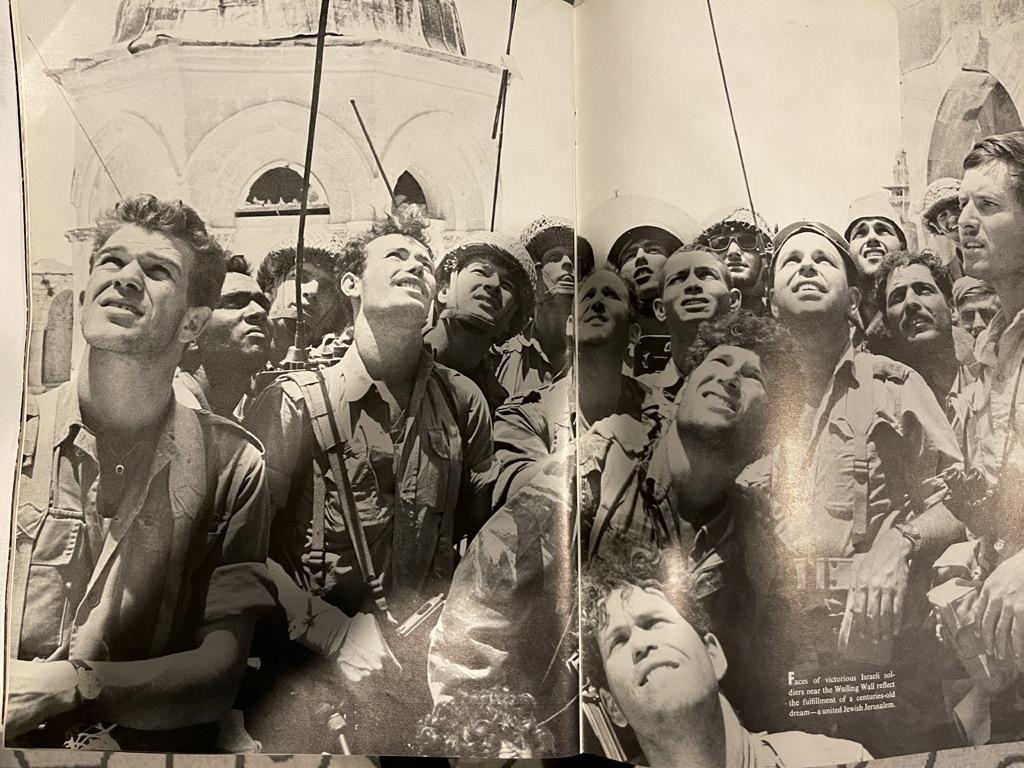

The top left photograph is from Life Magazine taken on June 7 1967 after his unit conquered Jerusalem. He is the second from the left in the front row (4th from the left overall). And a more recent picture.

RABBI MICHAEL GRAETZ

Uncle of Leffell School students

Father of a Leffell School faculty member and grandfather of Leffell School students

Excerpt of A YOM KIPPUR WAR DIARY

(from: Conservative Judaism, Vol. XXIX, No. 4, Summer, 1975)

Note: The full article may be read on Rabbi Graetz’s website and can be accessed at https:// en.michaelgraetz.com/ideas-and-research/significantevents/a-yom-kippur-war-diary/

Sunday, October 14, 1973. The call came in the evening. Join the military Hevrah Kaddisha in Tel Hashomer. Not knowing what to expect, I went with my commander, a member of my shul. At Tel Hashomer I met the group I was to be with for seventy-two days. At first they were suspicious of me, but I did look Jewish (beard and tzitzit). A small room, with a sliding door leading into a larger room. We were to wait there overnight, then take the plane to Refidim at five in the morning.

At Tel Hashomer I saw for the first time many of the things that were to become commonplace. The file of the dead soldier, the plain wooden coffin draped in the flag of Israel, rubber surgical gloves, masks, the unforgettable smell of death. I wondered how I would do it. Could I look at a dead body and take it? I was supposed to photograph faces for the files. Could I do it?

With all the talk about the war by those who had already served one week in the North, there was an impressive aura of seriousness. No Catch-22 or M.A.S.H. here, no hint of irreverence, no black comedy. This was the Hevrah Kaddisha, a holy task, a great mitzvah, hesed shel emettrue loving kindness-since there could be no possibility of any ulterior motive. The recipient of our acts could in no way pay us back or make it worth our while. I peeked through a crack in the sliding door to see if I could see blood, a body. If I couldn’t take it, would I quit? I saw something, took a deep breath and walked away. Well, I survived. Better not think about it. Try to sleep.

IDF Paratrooper CLIVE GURWITZ

MIKE GUY Z"L

CLIVE GURWITZ

MIKE GUY Z"L

as shared by his wife Rachel Cousin of Leffell School students

We were newlyweds (May 1973). The horrifying Yom Kippur is still etched in memory. Yom Kippur, for me, will never be the same again. The cantor in our synagogue was drafted into the army in the middle of the service and then the alarm started and we turned on the radio. Mike was drafted the next day. Mike belonged to the paratroopers who were supposed to land with helicopters beyond the enemy lines They sat for about a week in Kidron near Tel Nof base (a large air force and paratrooper base south to Rehovot) and waited for a mission. I came to visit him every day (in a car whose headlights were painted to keep the blackout) thinking that the next day he will be sent to the front. On one of the visits Edmond, Barbara, and the baby Ilana joined. After about a week they were flown south and were on the first plane that landed in Fayed military air base beyond the Suez Canal. Mike said that there was a great fear of anti-aircraft fire Their job was to guard the captured base While they were at the airport,,a team from the Mossad arrived with the purpose of surveying the abandoned Egyptian outposts and looking for intelligence materials Mike knew a few of his friends and joined them. They found a lot of intelligence material The Egyptian soldiers had a large supply of mango juice. The smell of the corpses remained in memory with the smell of the juice. From that day Mike couldn't drink mango juice. They continued to patrol,defending the area that was largely conquered, and captured many Egyptian captives that were in the area waiting to fight.

I don't remember exactly how long he stayed in the army. I only remember that it was a very long and traumatic period At the beginning of the war, we were all convinced that like the Six Day War, this too would be over quickly. The sad truth about the high price we paid in losses was revealed later. Despite the victory on the battlefield that began as a complete surprise, this war is remembered as a great national trauma.

Note from Mike’s cousin: Mike also had a long and illustrious career in the Mossad (over 30 years). Only bits of his accomplishments are known. When he passed away, his funeral was attended by over 350 people and the speakers included Ephraim Halevy, a former head of Mossad. He is one of Israel’s unsung heroes.

זאו הליפתה .תרחמל סייוג קיימ

םיקוסמב תוחנל םירומא ויהש םינחנצל ךייתשה קיימ יווקל רבעמ .בייואה

וכיחו ףונ לת סיסב דיל ןורדק בשומב הכורא הנתמהב ובשי םה אוה תרחמלש הבשחמב םוי םוי ותוא רקבל יתאב .המישמל

.תקוניתה הנליאו הרברב דנומדא ופרטצה םירוקיבה דחא .םחלנ

דיאפב תחנש ןושארה סוטמב ויהו המורד וסטוה עובשכ ירחא

שאמ דאמ לודג ששח היהש רפיס קיימ .ץאוס תלעתל רבעמ ןמזב .שבכנש סיסבה לע רומשל היה םדיקפת .םיסוטמ דגנ

הרטמב אבש דסומהמ תווצ עיגה הפועתה הדשב ויה םהש

.ןיעידומ ירמוח שפחלו ושטננש םיירצמה םיבצומה תא רוקסל רמוח ואצמ םנמאו םהילא ףרטצהו ולש םירבח ריכה קיימ

ץימה לש הלודג הקפסא התייה םירצמה םילייחל .בר יניעידומ

תופוגהש חירו וגנמ

.וגנמ ץימ התש אל קיימ םוי ותואמ .ץימה חיר םע ןורכזל ראשנ

RABBI RICHARD HAMMERMAN Grandfather of Leffell School students

In 1973, in addition to my position as Director of Collegiate Activities for United Synagogue, I was serving as High Holy Day rabbi at a small synagogue in Wycoff, NJ; an "off-shoot" of a larger Conservative synagogue in Fairlawn, NJ. We met at a borrowed site. Before services began, one of the members informed me and my wife Sharon about the beginning of what came to be known as The Yom Kippur War. We had little information.... but added our fervent prayers for Israel's safety. Having experienced the miraculous 1967 "Six-Day War," we were concerned - but not overly worried about Israel's safety. Unfortunately, the Yom Kippur War, due, in no small part, to Israel's "miraculous victory" in 1967, was caught ill prepared for the surprise invasion. The losses were grave. Israel needed more than our prayers. It needed the last minute infusion of emergency arms and munitions from the USA which saved it from utter disaster.

It took Israel many years to recover psychologically from this almost fatal tragedy. Indeed, in addition to too many who were killed in battle, there were, and are, many soldiers who experienced severe physical and mental trauma during the war, from which they have yet to recover. We happened to meet one of those former soldiers.... who found solace living and acting as a taxi driver in Frankfurt, Germany. Jewish history takes many turns....

May God give us the strength to continue to strengthen the hands of our brothers and sisters in Israel to work for peace, and secure Israel's safety and democracy.

OPHER PAIL Grandfather of a Leffell School student

I enlisted in the IDF Armored Corps in February 1972 and volunteered to join an elite reconnaissance unit patrolling the eastern bank of the Suez Canal. Our unit sent daily reports about the massive buildup of Egyptian troops on the border and their preparations for war to the Southern Command, Military Intelligence Directorate,x and Ministry of Defense. The reports were all ignored, along with so much other evidence that war was imminent.

During the Yom Kippur War itself, I participated in various defensive undertakings in the Sinai. Immediately after the war, I was assigned to train new tank officers as over 600 tank officers were killed in action. I lost 30 friends among the 2,700 IDF soldiers killed in action during the war. I left active duty in August 1975 and served in the IDF Reserves as a Tank Company Commander until December 1979.

During the early morning hours of October 7th, 1973, Defense Minister Moshe Dayan said that “the third temple is in danger.” This sense of pessimism, which was not shared by the generals, was unfounded and counterproductive. Indeed, the notion that “the Yom Kippur War seems to have been Israel’s closest brush with destruction” is inaccurate.

While on the first day of the war (October 6th) the Syrians managed to penetrate the weak Israeli defenses in the southern part of the Golan Heights, their plans, which Israel knew well in advance, were not to proceed towards the Sea of Galilee (much less to advance farther south to destroy Israel) but rather turn north and take the entire Golan Heights. As it turned out, IDF reserves quickly arrived and the Syrians lost three successive battles on October 7th, 8th, and 9th, and thereafter completely retreated.

Similarly, the Egyptians limited their ambitions to take over a narrow strip of about five miles along the eastern bank of the Suez Canal, and then try to leverage this

initial success diplomatically. They never dreamed of destroying Israel. And Israel knew every single detail of the Egyptian military plan. The Southern Command launched a counter offensive on October 15th, encircled Egypt's Third Army and brought Egypt to its knees.

Many military historians believe that Israel's military triumph in Yom Kippur was greater than the Six Day War victory. That may be true, but in a broader sense not one but three winners emerged in the aftermath of the war, as I see it. Israel secured a precious peace agreement with Egypt, signed in 1979, after five bloody wars were fought between the two countries from 1948 to 1973. Egypt won back its pride, which was dealt a significant blow during the Six Day War, as well as the entire Sinai Peninsula in the peace agreement with Israel. And the U.S. pulled Egypt away from the Soviet circle of influence.

A few days ago, on the eve of Yom Kippur 2023, exactly 50 years after the war began, my army unit held a reunion in Latrun, near Jerusalem. Amazingly, almost everyone showed up including many who presently live abroad, like I do. Absent, of course, were the young souls who never returned from the battlefield, who were deprived of the opportunity to marry, build families, develop careers, and have children and grandchildren. The parents of the fallen have long passed, but their brothers, sisters, nieces, and nephews were there. We hugged and cried and reminisced – it was a very moving experience.

Many books have been published about the Yom Kippur War. My personal favorites are Elusive Victory by Colonel T. N. Dupuy and The Yom Kippur War by Abraham Rabinovich. I encourage students who are interested to take a look.

Thank you for the opportunity to send my story.

GIORA ROMM Z”L

Grandfather of Leffell School students

Editor’s note: In 1969, Giora Romm, an Israeli Air Force fighter pilot was captured and held captive for several months when an Egyptian missile exploded beneath the tail of his Mirage IIIC fighter plane. The Mirage fighter plane and Romm’s time in captivity is referenced in his account of the Yom Kippur War below.

Excerpt from Solitary: The Crash, Captivity and Comeback of an Ace Fighter Pilot

It’s three p.m. on a Saturday when I line up on Runway 33 at Tel Nof. I am Yachin Kochava’s number two, and our target is the Budapest outpost at the northern tip of the Suez Canal, toward Port Said. I am sitting in a Skyhawk plane loaded with eight quarter-ton bombs, and when I look to my left I see Uri Bina and Roni Tepper also lining up on the runway to complete the formation. There is nothing remarkable about any of this except in regards to me. Although I am number two, I am the commander of the squadron, the 115th Squadron, and when I take off, it will be the first time in my life that I am flying a Skyhawk.

In the history of military aviation, only three pilots have made their first sortie in a new aircraft on an operational flight. I am about to be the fourth. Just an hour and a half ago I entered the cockpit of this completely unfamiliar plane for the first time, and now I’m about to take it up in the air, fully loaded with bombs, to attack a target in an area where battles are raging.

Three days earlier, Lieutenant Colonel Ami Goldstein (Goldy), the squadron commander, was killed in a training accident. That evening, when I returned to my home in Hatzor, I found a message that Benny Peled, the air force commander, wished to speak with me. As usual, he got right to the point: Be here tomorrow at seven-thirty a.m. I’m appointing you commander of the 115th Squadron.

I drive to the Tel Nof air base where the squadron is stationed, to see Ran Ronen, the base commander, who was the one who’d insisted that I be given the command of the 115th Squadron. I’ve known Ran for many years. He was my commander in the 119th Squadron during the Six-Day War. He was the commander of the flight school when I was a flight instructor there for two and a half years. And most important, on September 11, 1969, he

was Tulip One, the leader of the Tulip formation, when I was Tulip Four, who did not return.

“Ran” I say as soon as the meeting starts, “You may not know this, but I have never flown a Skyhawk.”

“I know, Giora,” he replies. “But I still want you, and nobody else, as the squadron commander. We have a funeral tomorrow. Afterwards, on Thursday and Friday, you’ll get acquainted with the squadron, and on Sunday, you’ll start a conversion course on the plane. A week from now no one will even remember that you’d never flown it before.”

“Are you sure?” I ask him.

“Giora, it wasn’t easy to appoint you. There are people in the force with more seniority than you who’ve been waiting to obtain a squadron command, and Benny was hesitant to break the regular order. I want you! … Come on, since you’re here already, come with me to see Nechama, Goldy’s wife.”

“His widow, Ran, his widow.”

At seven-thirty the next morning in his office, Benny Peled doesn’t waste any time on sentimentalities. One commander was killed; another commander is taking his place. Life goes on, end of story. We speak for about ten minutes. No mention is made of the possibility that war could erupt in a couple of days. The subject of captivity is mentioned briefly, but Benny is the only one who brings it up. He says he will tell the Chief of Staff at their next work meeting that he’s appointed a former POW to be commander of a combat squadron. I’ve never had an opportunity to tell Benny about the crises that I’ve been struggling to overcome ever since my return to operational flying, and the subject doesn’t come up now either. I’d planned to find a time to talk to him about it, but now is certainly not that time. Nor is there any point in discussing any technical issues regarding the squadron. He and I both know that my knowledge of the Skyhawk and its operations is basically nil.

The Skyhawk is primarily a plane meant for striking ground targets, while I’m coming from years of flying intercept missions and being in aerial dogfights. It’s the

start of the workday. Benny has an entire air force to run and isn’t free to indulge in idle chitchat (and at this point I know nothing about the growing tension with Syria and Egypt).

“Go on, go meet the pilots, take over the squadron and start commanding it. Good luck to you.”

And so, life’s never-ending rollercoaster now leads me to yet another unexpected destination - the Skyhawk squadron building in Tel Nof.

Goldy was an especially popular and beloved commander, and the air of shock and grief is palpable. I introduce myself to all the squadron pilots who are there – a few I know from my time in the air force so far, but many are new faces to me. The deputy squadron commander shows me around the facilities, and by then it is afternoon.

A large crowd stands over Goldy’s freshly dug grave in the Kiryat Shaul cemetery. I observe the people gathered at the funeral, my new role having yet to fully sink in. Anat and Nili, the squadron secretaries, lay wreaths on the grave, their eyes red from crying. The honor guard fires off three rounds, and the throng begins to disperse. Small clusters of mourners trickle past me and shake my hand, whether in congratulations or polite rebuff I can’t be sure.

The next day, Friday, seems completely normal at first, but the state of alert soon begins to rise, and by nightfall, with the High Holy Day of Yom Kippur setting the mood, I decide to stay and sleep at Tel Nof, on the couch in Omri Afek’s home in the family quarters.

The blare of the siren at seven in the morning essentially marks the start of the three weeks of the Yom Kippur War. It’s the Six-Day War in reverse. Syrian and Egypt have launched a surprise attack. We suffer major loses. In the conference room with Ran, we are informed that at 11:30 the air force will strike the Syrian air force on the ground, and each commander immediately rushes to his unit. This is the order for Operation Negiha (“Ramming”) and I must see to all the preparations for the 115th Squadron to smoothly carry out this order. Obviously I’m going to have to find a way as soon as possible to do a

quick flight to familiarize myself with the aircraft. In the midst of all the hubbub, I dispatch one of the pilots to my home in Hatzor to fetch my flight suit and special flight boots. Mickey Schneider, the squadron’s safety officer – who six days later would fly with me on a strike mission in Syria, be hit by a surface-to-air missile and fall into a grueling eight-month captivity –goes and comes back with flight gear for me: helmet, oxygen mask, G-suit and torso harness – the piece of gear with which the pilot attaches himself to the ejection seat and parachute.

Golda Meir and Moshe Dayan decide that the strike is a mistake, so the whole “Ramming” plan is off the table. This means, at least, that I have time to instruct that one plane have all its external cargo unloaded so I can take a little flight to get acquainted with my squadron’s aircraft.

Avraham Yakir, one of the youngest fellows in the squadron, escorts me to the plane and explains the main points to me. “Our Skyhawk is different than all the others. It’s the most modern plane in the air force, equipped with the most advanced systems.”

Everything a person would normally learn in ten days I must absorb in just fifteen minutes. Yakir helps me get hooked up to the communications system, goes over the layout of the cockpit, explains how to get strapped in, how to operate the various systems, how to start this up. And then he climbs down and takes the ladder with him. As he would tell me a few months later, not long before he was killed in a training accident, he thought all along that this whole thing was some kind of practical joke.

I start up the plane, carefully taxi over to takeoff position and run through all the necessary checks, but then I can’t close the cockpit canopy. Repeated explanations are offered to me over the squadron radio, but try as I might, I can’t shut the thing. A pickup truck drives up with Yakir riding in it. He mounts the wing, climbs toward the cockpit and shows me that in American planes there are certain actions – such as closing and locking the canopy - that are accomplished by sheer elbow grease, unlike in the French Mirage, where a much more delicate touch is used. Now I line up on the runway and request permission for takeoff. It’s Saturday, at exactly two p.m.

“Peach, Egyptian planes are en route to attack the base. Do not take off! Return to your position immediately!”

I return the Skyhawk 410 to the position from which I took it. Yakir is waiting for me in the underground shelter where planes are kept protected from airstrikes, and he drives me back to the squadron. Pilots in full flight gear, clutching maps and aerial photos, are standing in front of the squadron building ready to go to the planes. I stop one of them and ask where he’s headed.

“Our formation is going to attack Egyptian forces that are trying to take the Budapest outpost.”

I take the maps and photos from him. “Who is the leader?” I ask.

“Kochava,” he tells me. Yachin Kochava was my first student in the pilot training course.

“Yachin,” I say to him, “as of this minute I am your number two. This is my first flight in a Skyhawk. After takeoff, it’ll take about twenty minutes to reach Nahal Yam. In that time I’ll learn to fly this plane, and if I have any questions, you’ll answer them.”

Kibbutz Nahal Yam is on the north shore of the Sinai Peninsula. In one of the long nights with Aziz, he kept prodding me to divulge the purpose of the tall antennas at Nahal Yam. In a short while, I’m going to begin the final run to the attack from these antennas, whose purpose is just as mysterious to me now as it was then. And now I am back on the runway again, already asking Kochava what the takeoff speed should be for the heavy configuration in which we are flying.

“Raise the nose at 125 knots,” he tells me. “Take off at 150 and you’ll be fine.”

Now we’re airborne and I’m still trying to orient myself in this unfamiliar cockpit, fiddling with the knobs that adjust the height of the seat and pedals, and trying to identify the multitude of buttons on the stick, which is so different from the one I’m used to in the Mirage. My eyes are busily scanning the cockpit in an effort to figure out what all the switches are, but at the same time I am pleased to see that I am exactly where I should be in the formation. It’s a huge relief to see that the basic act of flying a plane is second nature for me at this point.

Over the controller’s channel I hear Shlomo Levy from the 113th Squadron, the Mirage squadron, the squadron of which I was the deputy commander until just a few days

ago, leading a formation on intercept patrol over the Suez Canal region. For a few seconds I can’t help envying him while I contemplate my peculiar situation, thinking that where I rightfully belong is at the head of that formation instead of Shlomo. But I can’t let myself get caught up in self-pity, for I must keep studying the interior of the Skyhawk cockpit, my new home in the sky.

Approaching Nahal Yam, we descend to a low altitude. With Kochava’s help, I activate the ammunition switches and we accelerate toward the Budapest outpost. Kochava calls over the radio, “Pulling!” and in tandem with him, for the first time in my life, in a fully loaded Skyhawk, I pull up to execute a bombing pass the likes of which I’ve never tried before. At 6,000 feet we both roll over on our backs and have the outpost in sight. It’s easy to spot the Egyptian amphibious armored vehicles emerging from the sea and heading for land. When we all come out of the bombing pass and join up in neat formation, Uri Bina says to me, “Two, your bombs did not release.”

We’re coming back up on Nahal Yam, and now I turn around to try another bombing pass, alone this time. This will be the second bombing pass I am ever attempting with the Skyhawk’s advanced bombing computer, a system I’d never used until ten minutes ago. I can hardly make heads or tails out of the abundance of information contained in the image on its gunsight. This time I gently guide the sensitive aiming point on the gunsight’s sophisticated Head-Up display, and when I press the button to drop the bombs I feel the plane vibrate as all eight are released.

From far to my left, from the direction of Port Said, a surface-to-air missile zooms my way. I dive until I’m practically licking the ground, and the missile loses its way and explodes in the dunes. I return to Nahal Yam, join my new companions, and we’re on our way home to Tel Nof.

Kochava calls for a fuel check. Roni Tepper and Uri Bina both report 4,500 pounds. Now where can the fuel gauge in the Skyhawk be? I eventually locate it in the bottom right corner of the front panel. It reads 1,800 pounds. I realize immediately that I failed to activate the fuel transfer from the reserve tanks to the main tank.

I report 4,500. I’m not about to humiliate myself by letting it be known that I don’t know how to transfer fuel. In the French-made Mirage, fuel transfer from the

external fuel tanks is automatic, but these American planes must have a special switch for this somewhere. Where the hell is the switch for the fuel tanks? I can’t find the bloody thing. Now the fuel gauge shows 1,600 pounds. I reach behind me with my left hand and, moving clockwise, systematically proceed to flip all the switches in the cockpit to the “on” position. At El Arish, at 20,000 feet, the needle drops to 1,400 pounds. And then, suddenly, thank god, it starts to rise. The fuel from the reserve tanks is making its way to the main tank. I make a mental note that when I’m back on the ground I’ll have to see just which switch accomplished this neat trick.

“Two, one-fifty,” says Kochava in the frugal language of aerial communications. And now I’m circling Tel Nof and stabilizing my plane at a speed of 150 knots on the final approach to make my first ever landing in a Skyhawk. The landing is simple. The plane’s wheels caress Runway 36 the moment they touch it, and I quickly clear off the runway and taxi back to the underground shelter. I’m in a hurry. I have no time to waste. This looks like war. I have a squadron to command and I haven’t had a moment yet to step back and ponder my extraordinary situation. But before I can stop to consider the implications of being thrust into this new aircraft after my experience in captivity, I have a squadron to lead in which I don’t even know half the pilots, nor can I remember the technical officer’s name, and when we went looking this morning for Kobi the adjutant, so he could attend to all of the urgent administrative matters, we learned that he’d skipped out the day before and gone home to Haifa.

All the squadron and unit commanders from the base assemble for a “command group” meeting with Ran late that evening. When the meeting is over, I stay behind to speak with him privately. “Ran, I know that you appointed me to command the squadron and I thank you for that, but war probably wasn’t part of the game plan. If you want, find yourself a commander with experience in the Skyhawk and I’ll go back to the Mirages.”

For reasons I will never fathom, Ran looks at me and says: “I want you to continue. Go back to the squadron and continue as commander.”

I turn on my heels, get into the car that until Wednesday belonged to Goldy, and return to that black hole — the 115th Squadron, in the Yom Kippur War.

BARBARA BERNHARD SCHARF Grandmother of a Leffell School studentMy Service to Israel During the Yom Kippur War

We lived in Boston when the Yom Kippur War broke out in Israel. My husband had started his medical training at Harvard and I was continuing my nursing studies at Boston University (BU). We were glued to the news and felt helpless as we saw Israel initially struggle. A doctor friend of ours dropped by and encouraged us to volunteer through the American Association of Physicians for Israel. Without hesitation we gave our names. I had been a nurse in the first Intensive Care Unit (ICU) at Johns Hopkins Hospital where I graduated with my diploma in 1971. Considering the name of the organization specifically addressed doctors, I did not expect to be called. Within a week, I was called to serve with a group of ICU and Operating Room (OR) nurses along with orthopedic surgeons. I informed my professors at BU and my employer that I was volunteering to serve as an ICU nurse in Israel and prepared for my service. Our American team met in New York and began our somber journey on El Al as Israel surrounded the Egyptian’s third Army in the Sinai and President Nixon declared the highest state of emergency for the United States. We landed in Paris to refuel. Our plane was surrounded by the Gendarme (French police) and we were not allowed to disembark. We arrived safely in Israel and were whisked away to a hotel training site in Hertzlia for orientation and assignments. I was assigned to work in Haifa at Rambam Hospital’s newly opened ICU along with an OR nurse. Several nurses and doctors were assigned to work with Prisoners of War (POW). The Egyptians had left their wounded in the Sinai desert and there were many requiring amputations because their wounds were unattended for so long. A few of the physicians assigned to the POWs decided to return home. This was very controversial. Most of us felt we would accept that assignment and spare the Israelis from having to care for those who sought their destruction.

In Haifa I immediately reported to the ICU. I had to walk through construction in order to ascend the stairs to the unit. I was warmly received and ready for work. It was the end of the third week of the war and the nurses were working twelve-hour shifts with no time off. I was concerned about language challenges as my Hebrew was very limited. Fortunately, medication orders were written in English and the nurses spoke English to help me with orders for patient care. I was immediately impressed by the youth of the patients as ICUs typically are dominated with older people with chronic illnesses. What a price Israelis pay in sending their strapping young men to defend their country. There were two rooms with patients: one for

limb and internal injuries and one for burn victims on ventilators. I was usually assigned to the burn room as the patients were sedated and I could just talk to them in English knowing it was good stimulation but not necessarily effective communication. I was told these soldiers served in tank battalions and the enemy (Syria was in the war from the north) missiles supplied by Russia were penetrating the tanks and causing severe burns before escape was possible. We had many family members visiting and the nursing and medical staff supported them with the utmost compassion. I really felt Am Israel Chai.

I worked in this ICU for three weeks. We were reduced to eight-hour shifts. The nurses were so grateful, as were people we met on the streets. It was alarming to see no young men in the streets. I first visited Israel in March 1973. Israelis were still riding high on their tremendous victory in the Six-Day War in 1967. The mood on the street was now very somber. As my time in Israel progressed the hostilities stopped. Most of the new admissions to the ICU were soldiers involved in road accidents as they traveled on official business or tried to return home on leave. The word was that soldiers felt invincible after surviving on the battlefield. They did not drive carefully. At the end of my service, I had grown close to my fellow nurses. We wore white uniforms and nursing caps. The head nurse presented me with an Israeli nursing cap with the Mogan David Adom emblazoned on the brim and I gave her my Johns Hopkins cap.

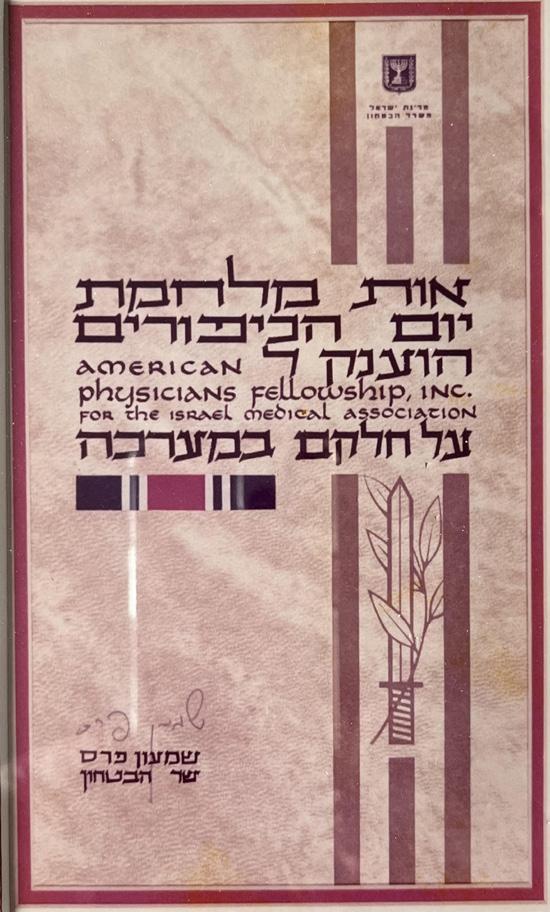

Upon my return to Boston one of my proudest moments was upon receipt of the Yom Kippur war medal and a certificate of recognition for my service during the war signed by Shimon Peres.

JOSE SPIWAK

as recalled by his niece Amy Baskt Uncle of a Leffell School student

My family settled in Bogota, Colombia after the Holocaust. They were very Zionist. Due to the political instability in Colombia members of my family moved to the USA.

My uncle Jose Spiwak was a doctor in LA. He did his residency in a military hospital. When he heard about the war he decided to fly to Israel to be a medic. He called my aunt who asked him if he was on his way home from work and he said no he was on his way to Israel. While in Israel treating patients who were injured, he by chance met with our cousin Eytan Porat who was a young soldier in the war. He was injured and lost three fingers. They embraced and were so happy to be together.

DR. IGAL ZURAVICKY

as recalled by his daughter Darya Pollack Grandfather of a Leffell School student

DR. IGAL ZURAVICKY

as recalled by his daughter Darya Pollack Grandfather of a Leffell School student

My father was born at the tail end of WW2 in September 1945. His parents fled Poland and were on the run for the entirety of the war (the vast majority of my father's extended family on both sides perished at the hands of the Nazis). My father's father died of complications of malaria and malnutrition shortly thereafter but my father and my Baba (paternal grandmother Miriam) returned to Poland after the war and waited until 1948 to safely and legally immigrate to Israel.

My father grew up in Ramat Aviv and was a communications officer in the Central Command unit of צה״ל He served his routine service but ultimately came to the United States in the mid-to-late 1960s for university where he met my mother at Columbia JTS. Despite completing his service, my dad returned to fight for Israel in two subsequent wars: 1967 and 1973.

In September 1973, he was in Israel for a short 4-day visit with my Baba — a birthday getaway — along with my mother and my oldest sister (then a baby of only 8 or 9 months old; today she is nearly 51), during the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War. They were living abroad in Switzerland at the time, where my father completed medical school. If you were to ask my parents directly, they would tell you that on the night of Kol Nidre 1973, while my mother went to (or prepared to go to) services, my father observed the gathering of soldiers and armored cars in the streets and heard rumblings about the onset of war. Following a surprise air raid that sent my father, mother, Baba, and sister into a bomb shelter, my father informed my mother that their vacation was about to take an unexpected turn as he was leaving to rejoin his unit and fight. My father set off to fight early in the day on Yom Kippur, leaving my American mother and their (then) infant daughter with my Baba.

Because the planned visit was so short, he had not yet had the opportunity to report to his unit before the war broke out and therefore they did not know that he was in Israel and so he was not formally mobilized. When the war started he simply took off toward the front (determined to defend Israel) and was directed to go north. Initially, he was grouped together with other reservists who were residing abroad and was assigned to hunt tanks with shoulder missiles. Some time (days) later — in a blur from combat — my father was pulled out and transferred to his former unit of the Central Command on the Jordanian

border (where he was stationed during his regular service back in 1963-1966 as an officer). Continued presence on/ near the Jordanian border was key in case the Jordanians joined the war because that part of the country was very vulnerable to attack.

After 6 long weeks away fighting, my father returned to my mother, sister, and Baba in Ramat Aviv. It had been a long 6 weeks for them too but after the war’s conclusion and reuniting they were quick to return back to their prior life, albeit forever changed by the experience.

A PRAYER FOR THE STATE OF ISRAEL

Avinu she-ba-shamayim, rock and redeemer of the people Israel: Bless the State of Israel, the first flowering of our redemption. Shield it with Your love, spread over it the shelter of Your peace. Guide its leaders, ministers, and advisors with Your light and Your truth. Help them with Your good counsel. Strengthen the hands of those who defend our holy land. Deliver them, crown their efforts with triumph. Bless the land with peace and its inhabitants with lasting joy. And let us say: Amen.