9 781940 660523 5 1 2 0 0 > ISBN 978-1-940660-52-3$12.00 LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS QUARTERLY JOURNAL : DOMESTIC no . 28

Books to Think With From Library Distributed by the University of Chicago Press www.press.uchicago.edu

Why Fiction Matters in Contemporary China David Der-wei Wang “Wang illustrates that poetic allusion and ambiguity are ways of o ering alternative truths. In China, then, fiction matters as an alternative way of and a response to speaking truth—dark as it is, Chinese fiction begets hope and light.”

Off Limits New Writings on Fear and Sin Nawal El Saadawi Translated by Nariman Youssef “The leading spokeswoman on the status of women in the Arab World.”—Guardian “Nawal El Saadawi writes with directness and passion.”—New York Times Paper $19.95

—Barbara Mittler, Heidelberg University The Mandel Lectures in the Humanities at Brandeis University Paper $35.00

Christmas and the Qur’an Karl-Josef Kuschel Translated by Simon Pare “A passionate endeavor to understand the di erent narratives given around the Christmas story (or stories) and put these in context.”—New Arab Paper $19.95 Reynard the Fox Retold by Anne Louise Avery “Adding mischievous contemporary twists, Avery has wonderfully refreshed the medieval collection and shows how these traditional animal fables, with their large and lively cast of characters and their wicked and seductive protagonist, have lost none of their truth-telling power.”—Marina Warner Cloth $30.00 From the From

To place an ad in the LARB Quarterly Journal, email adsales@lareviewofbooks.org unpress.nevada.edu collectionlive-wirefull of characters who aren’t afraid to bare their souls.”

Sara NoviĆ, author of Girl at War “One of the systemcruelillogical,ourguidebooksstraightforwardmosttocomplicated,andoftenimmigrationI’veread.”RoquePlanas, HuffPost “Murray makes it reading.”essentialItfromsheltermaintainforimpossiblereaderstotheofdistancepolitics...isabsolutely “A significant and Branchliterature.”environmentalliterature,Montanaliterature,AmericanontocontributionwelcomescholarshipwesternandMichaelP. , author of Rants from the Hill

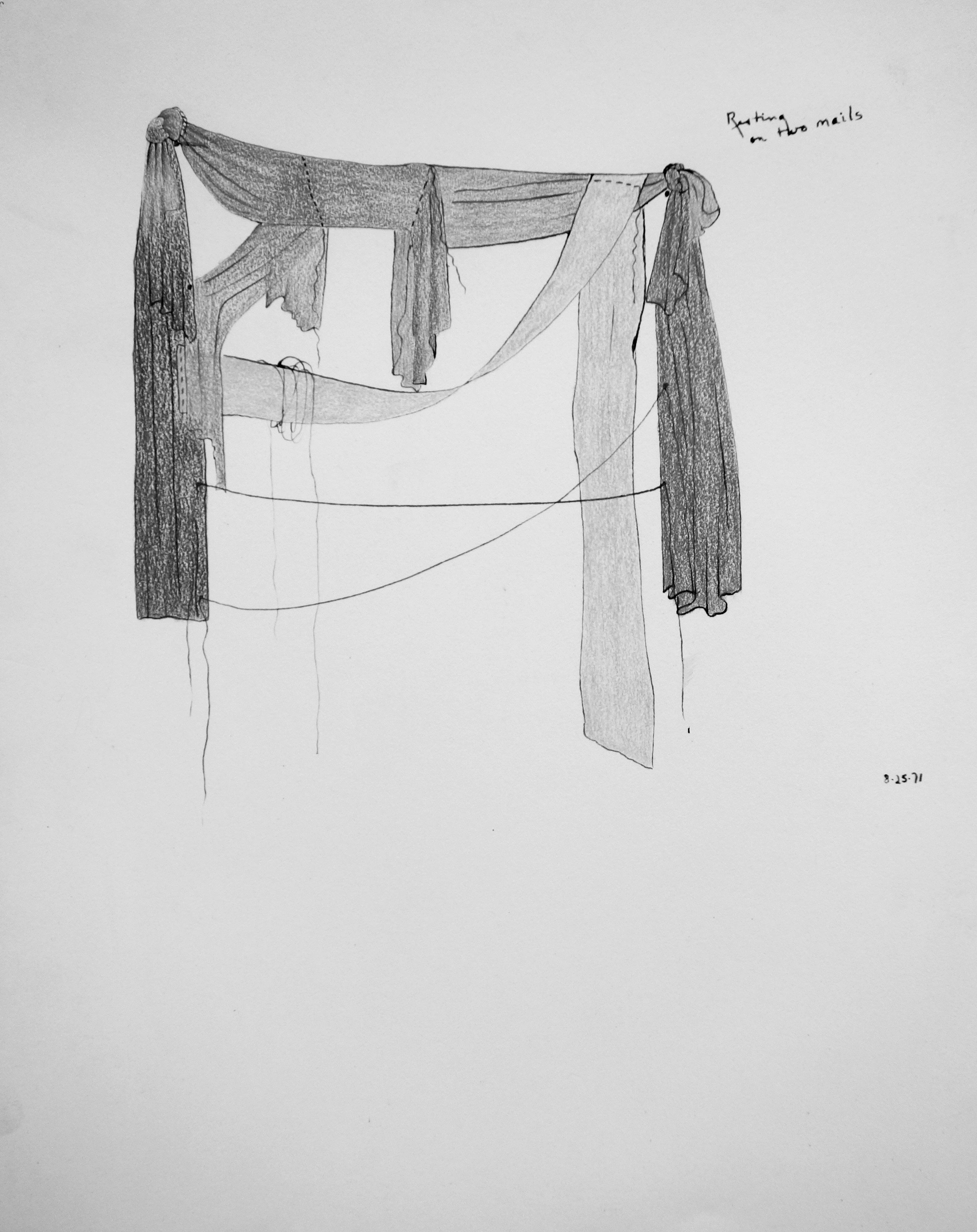

PUBLISHER: TOM LUTZ EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: BORIS DRALYUK MANAGING EDITOR: MEDAYA OCHER CONTRIBUTING EDITORS: SARA DAVIS, MASHINKA FIRUNTS HAKOPIAN, ELIZABETH METZGER, CALLIE SISKEL ART DIRECTOR: PERWANA NAZIF DESIGN DIRECTOR: LAUREN HEMMING GRAPHIC DESIGNER: TOM COMITTA ART CONTRIBUTORS: JA'TOVIA GARY, ROSEMARY MAYER, REYNALDO RIVERA PRODUCTION AND COPY DESK CHIEF: CORD BROOKS AD SALES: BILL HARPER EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR: IRENE YOON MANAGING DIRECTOR: JESSICA KUBINEC BOARD OF DIRECTORS: ALBERT LITEWKA (CHAIR), JODY ARMOUR, REZA ASLAN, BILL BENENSON, LEO BRAUDY, EILEEN CHENG-YIN CHOW, MATT GALSOR, ANNE GERMANACOS, TAMERLIN GODLEY, SETH GREENLAND, GERARD GUILLEMOT, DARRYL HOLTER, STEVEN LAVINE, ERIC LAX, TOM LUTZ, SUSAN MORSE, MARY SWEENEY, LYNNE THOMPSON, BARBARA VORON, MATTHEW WEINER, JON WIENER, JAMIE WOLF COVER ART: ROSEMARY MAYER, UNTITLED, 1971, COLORED PENCIL AND GRAPHIC ON PAPER, 17 X 14 INCHES. COLLECTION OF THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, MODERN WOMEN’S FUND. COURTESY OF THE ESTATE OF ROSEMARY MAYER. INTERNS & VOLUNTEERS: NICOLE LIU, ELLIOT SCHIFF

Fresh Reads This Fall “A

BuzzFeed

The Los Angeles Review of Books is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. The LARB Quarterly Journal is published quarterly by the Los Angeles Review of Books, 6671 Sunset Blvd., Suite 1521, Los Angeles, CA 90028. Submissions for the Journal can be emailed to editorial@ lareviewofbooks.org. © Los Angeles Review of Books. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Los Angeles Review of Books. Visit our website at www. Thelareviewofbooks.org.

Distribution through Publishers Group West. If you are a retailer and would like to order the LARB Quarterly Journal, call 800-788-3123 or email orderentry@perseusbooks.com.

LARB Quarterly Journal is a premium of the LARB Membership Program. Annual subscriptions are available. Go to www.lareviewofbooks.org/membership for more information or email membership@lareviewofbooks.org.

LOS ANGELES REVIEW OF BOOKS no . 28 QUARTERLY JOURNAL DOMESTIC ISSUE

Michael David-Fox, Georgetown University “Brooks introduces the reader to wondrous dimensions of Russian cultural creativity. By breaching the distinction between low and high culture, he reveals how popular themes and imagery permeated great works of literature and the arts, leavening their serious-minded discourse with doses of magical thinking and imagination.”

Hardback

essays 11 QUEEN OF REPS (ON SPACESHIP EARTH) by Elvia Wilk 32 AGAINST GRACE by Julian Randall 52 SANCTUARY UNMASKED: THE FIRST TIME LOS ANGELES (SORT OF) BECAME A CITY OF REFUGE by Paul A. Kramer 73 HIGH FEMME CAMP ANTICS by Jenny Fran Davis 104 EXCERPTS"MAGIC"&"MONUMENT",FROM LOVE IS AN EXCOUNTRY by Randa Jarrar 125 WHO DO YOU SERVE WHEN YOU SERVE YOURSELF? CONSUMER LABOR, AUTOMATION, AND A CENTURY OF DOMESTICSELF-SERVICELABOR by Mackenzie Weeks fiction 37 IN ANOTHER LIFE by Miki Arndt 89 MIDNIGHT DOUGH by Taisia Kitaiskaia 119 THE SANDBOX by Annette Weisser 130 THE COAST by Colin Winette poetry 31 VIKINGS by Carl Phillips 49 TWO POEMS by Sylvie Baumgartel 85 FALLING BODIES by Deborah Paredez 116 BLUE WILLOW by Armen Davoudian no . 28 QUARTERLY JOURNAL : DOMESTIC CONTENTS

346 pages | 32 b/w illustrations, 16 43073.indd124/02/202043073.indd1 Resource Radicals ofSenseTheMuñozEstebanJosé Edited

Richard Wortman, Columbia University 2019 ISBN: 9781108484466

The Firebird and the Fox Russian Culture under Tsars and Bolsheviks Jeffrey Brooks, Johns Hopkins University “Brooks brings a lifetime of learning to bear in his new interpretation of Russian and Soviet culture in its most creative century. He is able to suggest how a variety of cultural elds over time grappled with the same set of recurring Russian dilemmas, distilling the powerful motifs that writers, artists, and intellectuals repeatedly embroidered into their works. No one who studies or loves Russian culture can afford to ignore this book.”

December

dukeupress.edu FromPetro-NationalismtoPost-ExtractivisminEcuador TheaRiofrancos Resource Radicals PLAYTHEINTHESYSTEMANNAWATKINSFISHER ofSenseTheMuñozEstebanJoséBrown Edited and with an Introduction by Joshua Chambers-Letson and Tavia Nyong’o Wld i ck dtheisorder dofesire PressUniversityDukefromBooksNew The Play in the System The Art of Parasitical Resistance ANNA WATKINS FISHER Wild Things The Disorder of Desire JACK HALBERSTAM Perverse Modernities Utopian Ruins A Memorial Museum of the Mao Era JIE LI Sinotheory The Sense of Brown JOSÉ ESTEBAN MUÑOZ JOSHUA CHAMBERS-LETSON and TAVIA NYONG'O, editors Perverse Modernities Resource Radicals From Petro-Nationalism to Post-Extractivism in Ecuador THEA RIOFRANCOS Radical Américas Utopian MEMORIALA MUSEUM OF MAOTHEERAJIELI Ruins Lesley Stern Diary of Lesley Stern a Detour Diary of a Detour LESLEY STERN Writing Matters! dukeupress.edu FromPetro-NationalismtoPost-ExtractivisminEcuador TheaRiofrancos Resource Radicals PLAYTHEINTHESYSTEMANNAWATKINSFISHER ofSenseTheMuñozEstebanJoséBrown Edited and with an Introduction by Joshua Chambers-Letson and Tavia Nyong’o Wld Things J ck Halberstam dtheisorder dofesire PressUniversityDukefromBooksNew The Play in the System The Art of Parasitical Resistance ANNA WATKINS FISHER Wild Things The Disorder of Desire JACK HALBERSTAM Perverse Modernities Utopian Ruins A Memorial Museum of the Mao Era JIE LI Sinotheory The Sense of Brown JOSÉ ESTEBAN MUÑOZ JOSHUA CHAMBERS-LETSON and TAVIA NYONG'O, editors Perverse Modernities Resource Radicals From Petro-Nationalism to Post-Extractivism in Ecuador THEA RIOFRANCOS Radical Américas Utopian MEMORIALA MUSEUM OF MAOTHEERAJIELI Ruins Lesley Stern Diary of Lesley Stern a Detour Diary of a Detour LESLEY STERN Writing Matters! dukeupress.edu FromPetro-NationalismtoPost-ExtractivisminEcuador TheaRiofrancos Resource Radicals PLAYTHEINTHESYSTEMANNAWATKINSFISHER ofSenseTheMuñozEstebanJoséBrown Edited and with an Introduction by Joshua Chambers-Letson and Tavia Nyong’o Wld Things J ck Halberstam dtheisorder dofesire PressUniversityDukefromBooksNew The Play in the System The Art of Parasitical Resistance ANNA WATKINS FISHER Wild Things The Disorder of Desire JACK HALBERSTAM Perverse Modernities Utopian Ruins A Memorial Museum of the Mao Era JIE LI Sinotheory The Sense of Brown JOSÉ ESTEBAN MUÑOZ JOSHUA CHAMBERS-LETSON and TAVIA NYONG'O, editors Perverse Modernities Resource Radicals From Petro-Nationalism to Post-Extractivism in Ecuador THEA RIOFRANCOS Radical Américas Utopian MEMORIALA MUSEUM OF MAOTHEERAJIELI Ruins Lesley Stern Diary of Lesley Stern a Detour Diary of a Detour LESLEY STERN Writing Matters!

The Domestic has also shifted in the larger sense of the word. We have just endured an exhausting election and the future of our nation is foremost in the news, our conversations, and our collective conscious. Our attention has been rapt by houses outside of our own: our chambers of government, and of course, the White House. This issue of the LARB Quarterly Journal grapples with Domesticity in all of its forms. In “Queen of Reps”, Elvia Wilk counts her way through quarantine, rethinking her own life and work. Poet Julian Randall remembers when President Obama sang “Amazing Grace” and wonders about the state of Black existence amid the brutal realities of the past year. Paul A. Kramer presents a deep investigation on the history of Los Angeles as a sanctuary city. In her short story, “In Another Life”, Miki Arndt explores the life of a grandmother-for-hire in contemporary WeJapan.hope this issue and these pieces offer a different perspective on domesticity. After a year like 2020, we might all be tired of the same old view. Medaya

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR cecile pineda entry without inspection a writer’s life in el norte UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA PRESS ugapress.org if we were electric Stories Patrick Earl Ryan isbn paperback9780820358079$19.95 • flannery o’connor award for short fiction • entryinspectionwithout A Writer’s Life in El Norte Cecile Pineda paperback $24.95 isbn 9780820358468 • crux: the georgia series in literary nonfiction • stories IF WE WERE ELECTRIC PATRICK EARL RYAN if Stories Patrick paperbackisbn for•

We had planned for a Domestic-themed issue long before there was any sign of a pandemic, when the prospect of millions of people staying inside for six straight months was something beyond impossibility. How strange then to put together an issue dedicated to domesticity in the midst of an enormous realignment of our domestic lives, which have suddenly become our work, social, and recreational lives.

| Translated by Joyce Zonana Winner of the Global Humanities Translation Prize “A long overdue translation of Jóusè d’Arbaud’s neglected Provençal masterpiece.”

Find more books on

New from Indiana University Press Wherever Sold American democracy: iupress.org/politics

by Jóusè d’Arbaud

-The Honorable John Lewis democracy is a privilege that we must defend at all costs

The Beast, and Other Tales by Jóusè d’Arbaud

| Translated by Joyce Zonana Winner of the Global Humanities Translation Prize “A long overdue translation of Jóusè d’Arbaud’s neglected Provençal masterpiece.” —Sandra Beckett, author of Crossover Fiction: Global and Historical Perspectives nupress.northwestern.edu

“We live in an age that demonstrates the powerful need for ethics in government. Democracy is a privilege that carries with it important responsibilities for the people and their representatives. As we look back on this era and determine the future of this nation, Dr. Long Thompson’s book will be a resource for Americans who are seeking ways to secure our democracy and our future as a nation.”

Available

—Sandra Beckett, author of Crossover Fiction: Global and Historical Perspectives nupress.northwestern.edu

The Beast, and Other Tales

Books Are

Bold

“Goode is open and assertive with his opinions, but his tone is humorous, even facetious at times. . .

—Foreword Reviews

Bold and Beautiful Books

Translated into English for the first time, this internationally bestselling biography is timed for the 250th celebration of Beethoven’s birth. “Smart, brave, and deeply knowledgeable. Opera criticism does not get better than this.”

The definitive book on Ruth Asawa’s fascinating life and her lasting contributions to American art. “Moss Roberts’s elegant and approachable translation provides an excellent introduction to one of the most important Confucian classics.”

The classic oral epic about the African hero Mwindo, which has important implications for the comparative study of African culture.

. An entertaining and deep industry text.”

The definitive book on Ruth Asawa’s fascinating life and her lasting contributions to American art. “Moss Roberts’s elegant and approachable translation provides an excellent introduction one of the most important Confucian classics.”

—Lawrence Kramer, author of The Hum of the World: A Philosophy of Listening

“Moss Roberts’s elegant and approachable translation provides an excellent introduction to one of the most important Confucian classics.”

Translated into English for the first time, this internationally bestselling biography is timed for the 250th celebration of Beethoven’s birth. “Smart, brave, and deeply knowledgeable. Opera criticism does not get better than this.”

—Olivia Milburn, Professor of Chinese, Seoul National University Translated into English for the first time, this internationally bestselling biography is timed for the 250th celebration of Beethoven’s birth. “Smart, brave, and deeply knowledgeable. Opera criticism does not get better than this.”

—Olivia Milburn, Professor of Chinese, Seoul National University

Bold and Beautiful Books

The definitive book on Ruth Asawa’s fascinating life and her lasting contributions to American art.

. An entertaining and deep industry text.”

—Olivia Milburn, Professor of Chinese, Seoul National University Translated into English for the first time, this internationally bestselling biography is timed for the 250th celebration of Beethoven’s birth. “Smart, brave, and deeply knowledgeable. Opera criticism does not get better than this.”

The classic oral epic about the African hero Mwindo, which has important implications for the comparative study of African culture. “Goode is open and assertive with his opinions, but his tone is humorous, even facetious at times.

.

The classic oral epic about the African hero Mwindo, which has important implications for the comparative study of African culture. “Goode is open and assertive with his opinions, but his tone is humorous, even facetious at times. . . . An entertaining and deep industry text.”

The classic oral epic about the African hero Mwindo, which has important implications for the comparative study of African culture. “Goode is open and assertive with his opinions, but his tone is humorous, even facetious at times. . .

—Foreword Reviews

. An entertaining and deep industry text.” —Foreword Reviews

—Lawrence Kramer, author of The Hum of the World: A Philosophy of Listening and Beautiful Books

—Lawrence Kramer, author of The Hum of the World: A Philosophy of Listening and Beautiful Books

Bold

—Olivia Milburn, Professor of Chinese, Seoul National University

.

—Lawrence Kramer, author of The Hum of the World: A Philosophy of Listening

—Foreword Reviews The definitive book on Ruth Asawa’s fascinating life and her lasting contributions to American art. “Moss Roberts’s elegant and approachable translation provides an excellent introduction to one of the most important Confucian classics.”

—Richard Walker, author of Pictures of a Gone City

“A tour de force of the Bay Area. This book is witness to the way everyday people shape the city from the ground up.”

Devin Stauffer, University of Texas at Austin “An excellent resource for authors seeking to understand their legal rights responsibilities.”and

“There is no one better to ask than Marion, who is the leading guide in intelligent, unbiased, independent advice on eating, and has been for decades.”

—Lydia Pallas Loren, Lewis and Clark Law School

www.ucpress.edu

“Examining shipboard mutinies with startling clarity, this is maritime history at its rollicking best.”

—Vincent Brown, author of Tacky’s Revolt

—Kirkus Reviews

For Fall Reading showscan Devin Bold and Beautiful Books For

—Mark Bittman, author of How to Cook Everything “The gig economy is a failure, Schor sharply chronicles—but not one that can’t be redeemed by ‘cooperation and helping.’”

“In this timely volume, Bartlett shows that Aristophanes’ comedies can deepen our understanding of the hazards of democracy.”

Rosemary Mayer, Untitled, 8.26.71., Colored pencil and colored marker on paper, 12 x 9 inches. Courtesy of The Estate of Rosemary Mayer.

essay

An influencer I follow on Instagram posts female-focused self-help con tent about boundaries and expectations during quarantine. She says it’s okay not to be productive during this unprece dented time. She says we should be kind and forgiving to our bodies. She says we should be wary of wasting our energy. She posts up to 30 times a day. I look at every single upload, clinging to the reassurance even as I loathe the basicness. I eat it up like butter — butter, a formerly unhealthy ingredient that scientists recently deemed healthy after all. I’m jealous of this influ encer, this person who seems to have a definitive idea of what life’s healthy ingre dients are. OF REPS SPACESHIP EARTH)

THE QUEEN

11

(ON

ELVIA WILK

los angeles review of books 12 Day 50-something or 60-something of quarantine in Brooklyn. I wake up and look at Instagram. I hardly notice the sound of constant sirens outside any more. My partner, A, is probably in the kitchen chopping or cleaning, or may be he’s having coffee and reading a book on the fire escape. I roll out of bed and head straight to my command station: the computer, where I spend several hours trying to concentrate on pumping out words. Eventually there is lunch, after which there is the dishes, after which I do a workout video in front of my computer.

Remember your breath, yogis, the onscreen instructor with calves like onion bulbs says. He’s talking to the group of people doing the workout with him in the pre-recorded video but he’s also talking to me, implicitly. Which makes me a yogi too, implicitly. My fellow yogis in the video are a diverse bunch, “all shapes and sizes.” One of them is not thin, which is supposed to be inspiring. This isn’t really yoga. It’s some yoga postures as a preamble to three circuits of crunches and squats. As a grand finale we go through the asanas while holding five-pound weights. I watch the yogis in the video wincing and grunting. Just four more! You got this … I notice one of the yogis cheating, she’s only doing every other rep. I wonder when this video was recorded. It must have been in a time a place where people were allowed to be in the same room together. This makes me wistful, but then I remember that I pre fer to work out alone anyway. I don’t want anyone to see me wincing and grunting or skipping reps. I don’t want a witness to my work.Mywork ethic is a major problem. This is the big lesson of quarantine. I have no structuring principle for how to spend my time besides work. Sans any “life” events outside the domestic vacuum to outline my days, the work problem has become a problem. The issue is not simply that I’ve filled the hole left by social and professional routine with extreme work ing hours instead of something nice. It’s not even that work is the only way I know how to “cope.” It’s that my productivity it self has lost its telos. I can no longer figure out what I’m working toward. The future is a blank space; it always has been; once you understand this, your ordering princi ple falls apart. ¤ I have no muscles that have developed through play or manual labor — just countable reps. I write a certain number of words today; I answer a certain num ber of emails today; I do a certain num ber of lunges. I lunge — “a sudden thrust forward of the body,” as if to seize prey — and then I retract without grasping anything in my jaws. Just the lunge and the act of lunging. A certain number of lunges. A certain number of calories. A certain number of recreation hours. And then the day is over. A, for instance, is very productive too. He gets work done. Only he doesn’t seem to exalt it as his ordering principle for be ing alive. Taking a day off can be nice for him; the meaning of life does not disin tegrate as soon as the disciplinary struc ture is removed. He doesn’t panic like I do when interrupted at the desk, because you can’t interrupt something that isn’t sacred. Free time does not provoke an existential spiral. For me, anything that isn’t quanti fiable productivity can only be construed as procrastination. There’s no “life” that is not a means to an end of — ?

los angeles review of books 14 Over dinner, which we have tacitly decided is a meal I do not eat while sit ting at the computer, A and I have con versations about the meaning of work and why we do it. Lockdown has given us all this time to talk about how we spend our time. I maintain that there is work and then there is work — there is the thing capitalism makes me do to feed myself, and then there is the thing I do because it gives my life meaning. I’m a writer; my work is supposed to be meaning-making, so often these overlap. But I have to be lieve I’d do the latter kind of work no mat ter what. Of course, as soon as I say these things, the distinction between types of work dissolves into a sea of Right Reasons questions.I.e.,Would you truly work if you didn’t have to? How do you differentiate between the work that is sacred and the work that is profane? Is any work sacred under neoliberal capitalism? Is there such a thing as Labor of Love that has not been recuperated? Where did you get this Protestant work ethic; you’re a Jew? What’s really the driving factor, artistic expression or desperation for recognition? Couldn’t you find meaning in something less excruciating? What would happen if you took a day off? Why, and what, are you always counting? Where is pleasure? Are you squashing all the pleasure out of something that you really do want to do, just by dint of counting it in the form of reps? If it’s what you “want” to be doing, why does it feel and look so much like punishment?Onenight after dinner we watch my favorite childhood movie, The Princess Bride. In one scene, the princess’s true love, Westley, is being tortured by the princess’s evil husband in a dedicated underground chamber. Westley is laid out on a rack called “The Machine,” a device with special suction cups that suck out fu ture years of the victim’s life, causing ex cruciating pain. The machine whirrs and Westley writhes on the table, while the torturer observes his responses dispas sionately and takes notes. “I’ve just sucked one year of your life away,” the torturer in forms Westley after the first bout is over. “What did this do to you?” He asks ear nestly. “Tell me. And remember, this is for posterity.”I’vealways identified with the tortur er as much as Westley. The torturer is a sadist, but he is also a scientist who has spent his entire life inventing this evil device, and he genuinely wants to quan tify what it does. Posterity is an inside joke with myself: when I’m really strug gling to get something done, I tell myself, “Remember, this is for posterity.” So I take a quick look at Instagram and then I pros trate myself upon The Machine. ¤ One way to make sure I’ve done my reps for the day to keep lists of all my tasks. Everything goes on the same list because everything has to get done. Shower, eat, write a friend, write a colleague, talk about my feelings, call my dad, write an email, write an essay, write a diary, write a new list ofSomethingtasks. on my list that is not work, but that is on the same list and so has become ontologically flattened into work, is to record a video message for my friend’s birthday. Given the quarantine situation, her kind husband has invited almost 100 people to upload pictures and videos to an app where she’ll be able to

los angeles review of books 16 watch them on her birthday. It’s possible to see what other people have uploaded so far. Before recording a video, I watch some of the other video messages. One of our mutual friends has made a lovely one: she’s sitting in a bathtub and extolling the virtues of the birthday girl, whom she dubs “The Queen of Pleasure.” I smile. It’s true! This friend is wonderfully adept at enjoying life. She knows how to live in a body in time, how to maximize joy as its own end, and I dearly love this about her. I get emotional thinking about friends I haven’t seen in so long, who are all Queens of something. The Queen of Finding the Hilarious. The Queen of Even Keel. The Queen of Gathering Us Together. The Queen of Optimism and Ambition. I must be a Queen of some kind too, I think. What Queen am I? The Queen of Time Management. The Queen of Third Draft of an Essay. It is I, The Queen of Reps.Joy in a certain type of work must be a timeless thing. At least it was timeless, before work was stolen from us, so maybe it’s not timeless after all. That would have been the kind of work that is about the perpetuation of life. Reaping the hay, feed ing the family, reproducing ourselves and each other. Tending the garden. Taking care. That is not the kind of work that is easily countable as reps, although people — such as my influencer — have found many ways to commodify it. Women were made to do most of the labor-of-life for the last few centuries, so maybe there is a reason I dislike uncountable care work, fa voring the numerable kind with accolades. My mom, a professor at a big Midwestern university, says that her great est challenge is teaching undergraduates that learning doesn’t have to be a misera ble chore. She wants them to understand that work is not the opposite of entertain ment. She wants them to experience joy in reading, writing, and thinking instead of feeling like that’s what you have to get done so you can go to the movies or a kegger. But then, my mom also complains that she puts so much energy into teach ing, unlike her male colleagues, and that her teaching work is never fully appreciat ed. No one is counting her hours. ¤ I take a break from writing this to look at Instagram. My influencer has just made a video where she describes herself proudly as “really crushing it” during lockdown. She says we need to give ourselves credit when we’re doing well. I tap through to a series where she asks people to post their “smallest wins” of the day. Think of your smallest win today, then think of something even smaller. What does it mean to win? She doesn’t say. The implication, I assume, is that life might be a rat race but that we’re only truly in competition with ourselves. Winning at life is nothing glamorous — it’s just about getting better in small ways every day. Getting better means being healthier and less miserable? I can't help but think that the concept of winning seems to counter what it describes, since you can’t actually beat yourself unless you are also beaten. My small win today is my only win today, because I don’t know any other concept of winning: I worked and then I worked out, even though I didn’t want to. But then I see that lots of the small wins people are posting in response to the influencer’s story are things like taking a shower and eating a healthy bowl of or ganic grain. So winning, or at least small

— RACHEL JAGARESKI, FOREWORD REVIEWS new in paperback BOB DYLAN: HOW THE SONGS WORK by Timothy Hampton “This is an essential Dylan book and unlike any other. Hampton left me with a deeper appreci ation of Dylan’s uniqueness…his lyrical and poetic brilliance, his many voices.”

DISTRIBUTED

pretations

DISSIMILAR SIMILITUDES: DEVOTIONAL OBJECTS IN LATE MEDIEVAL EUROPE by Caroline Walker Bynum “Dissimilar Similitudes glides through history and iconog raphy …Its probing essays original, revisionist inter that illuminate avenues for further study.”

are

— DEAN WAREHAM, AUTHOR OF BLACK POSTCARDSBY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS / ZONEBOOKS.ORG FALL 2020

Courtesy of The Estate of Rosemary Mayer.

ELVIA WILK

¤ One of my friends used to have a shitty boyfriend who always insinuated that she was lazy for not working enough. “It’s true,” she told me, “it’s not like I work very much. But I’m making enough money to live on. So, what’s the problem? I don’t get it. I thought not working was what we were working for.” ¤ I’ve had an autoimmune issue for at least 10 years. It was finally (sort of) diagnosed a few weeks before quarantine. The ver dict: I have lazy lungs and I haven’t been getting enough oxygen this whole time. In January a doctor gave me an asthma inhaler, an allergy pill, and a few nasal sprays, and within weeks my debilitating pain and fatigue became, miraculously, infuriatingly, confusingly, suddenly, man ageable. Ironic: While the world is ailing and my city is dying, I have more energy than ever before. I marvel at the extent of my newfound ability, my changing limits. My max five reps become 10 become 20. I always wondered what I’d do if I were suddenly able, and here I am, #blessed with this energy and this privilege, this time … ¤ When I was in my final year of art school, depressed and trying to finish my thesis exhibition, I called my dad to complain about how everyone seemed to be do ing less work than me but making better art. I spent most of my time in my win dowless studio agonizing and doodling; outside, the Good Artists were chainsmoking and chatting. I’d make 100

19 winning, is about not working? It’s about self-care?Instagram-style

“self-care” is for the rich and white, even the influencer is woke enough to know that. Self-care is something you pay for. It’s reproduc tive labor you do for yourself, because you don’t have to do reproductive labor for anyone else instead. But if I stopped looking at Instagram I would have time to take a shower. I’m a well-off white wom an and my boyfriend is making me dinner in our nice apartment from the groceries we paid to have delivered. Maybe I could construe not taking care of myself as an act of resistance. I used to fantasize I was Kurt Vonnegut whenever I worked on fiction. He was my favorite author, whose strict writing schedule is well known. He took reps very seriously because he was con cerned with posterity. But then I read his biography and I had a hard time main taining the fantasy. Turns out the reason he was able to lock himself in the study and clack away on his typewriter for sev eral hours every morning is that his wife was making food and taking care of his children and answering his letters. During his sanctified writing hours, nobody, not his wife, not his three biological children, nor his three adopted children — whom he chose to adopt —were allowed to knock on the door. A often brings me snacks while I’m at the computer. He might kiss my cheek, but he doesn’t say anything because he knows I get agitated when interrupted. I reach blindly for the carrot stick he’s placed beside me. I realize he’s done the dishes and swept the house while I’ve been emailing. I worry that I’m winning at being Kurt Vonnegut.

I read a report about the climate. It says even now, in the midst of COVID-19, when travel is at a record low — when humans are doing probably the most we will ever be willing to do to — the results are not nearly enough to make a dent in the catastrophically upward-sloping tem perature trajectory graph. And in fact, in some freak turn of events, the global tem perature is maybe going to rise this year, because of a decrease in the layer of pol lution surrounding the planet, which, de spite its toxicity, has actually been helping Earth cool off.

A asks if I want to go with him to the community garden to drop off some com post. We have to take it to the garden now because the city has suspended organic waste collection in order to spend more money paying police to harass unhoused people sleeping on the subway. I shake my head and tell A I want to stay home and write. I tell him I’m writing in my diary, so it sounds like a healthy activity, but actual ly it’s an article about climate change that I hope gets published and paid for. After he leaves the house, I spend an hour won dering whether going to the community garden is a better use of time than sitting inside and writing about the importance of community gardens. My ordering prin ciple short-circuits. I take another shower

Some of my classmates were probably geniuses. Others managed to parlay the genius myth to their advantage. Others were just rich or from famous families, so it didn’t matter. Others were ahead of me in a different way: they understood that creative work also happens when your ass is not in the chair and they saw no pur pose in self-punishment. And others were probably working as hard as I was and just not making such a big deal out of it. They realized that artists are not supposed to look like we’re toiling this hard. Our labor is supposed to be mysterious exceptional labor, in service of making exceptional timeless objects, etc. In retrospect, I’m guessing we all felt bad about how much we were working or not working. In retrospect, it’s obvious that the 10,000 hours rule is just anoth er weapon for individualizing our pain. We’re millennials and artists; we've always known meritocracy is a farce. But we nev er figured out how to redeem ourselves beyond work, and we experience our feelings of failure in isolation. We don’t know how much we’re supposed to work, how much we’re supposed to seem like we work, how much we’re supposed to “enjoy” work. Do What You Love is an even more insidious farce. We experience our small wins and our big losses alone. Hoarding them, then belittling them. Nothing we can do is enough but trying this hard is both pointless and embarrassing.¤

One of my teachers required all her students to spend 40 hours in the studio each week. She’d clearly read that Malcolm Gladwell book. Just show up, she im pressed upon us, even if you don’t have any ideas, because that’s the only way some thing will happen. You have to be there when the inspiration hits. The more you sit there trying to work, the more you’ll eventually get done — a variant of the classic “ass-in-chair” writing advice. Or a variant of the motivational gym poster: “10% inspiration, 90% perspiration.”

los angeles review of books 20 drawings or whatever, but invariably their work would be cleverer and much cool er. “Well, honey,” my dad told me, “some people are geniuses, and the rest of us just have to work harder.”

21 and have a glass of wine. I win. ¤ The documentary Spaceship Earth comes out two months into quarantine. It’s about one of my favorite historical uto pias, Biosphere 2. In the 1960s, a group of performance artists and countercul ture enthusiasts got together and started the Theater of All Possibilities, an arttheater-business venture that would last decades. Funded by a billionaire oil mag nate, they first built a ship and traveled the world, buying land, constructing a hotel, holding theater performances, and docu menting themselves. Their collective work culminated in the 1987–1991 creation of Biosphere 2, a giant glass structure in the Arizona desert. The biosphere contained a closed-loop life-support system, which eight people lived inside for two years. Biosphere 2, resembling a Bucky dome crossed with a Victorian green house, was equal parts performance art, science fiction, and science project. To create its internal ecosystem, the bio sphereans first traveled the world collect ing plant and animal species they chose to populate their world in captivity. Once inside the biosphere they subsisted (al most) off farmed food and recycled air and water, a feat intended as the first ever dress rehearsal for a sustainable human habitat in space. They also intended it as a consciousness-raising stunt to spread awareness about the environmental dev astation that might someday force hu manity off-world — Biosphere 1 being the original planet Earth. I have been invited to guest-teach a masters class on Zoom about storytell ing in times of crisis. The students have seen Spaceship Earth, so we talk about Biosphere 2. I ask leading questions about whether the documentary gives a bal anced portrait of the project and its po litical flaws, for instance, its colonial and biblical undertones. I ask whether anyone feels nostalgic for an imaginary past when utopian thinking seemed possible, at least for some. One of the students points out that it’s hard to have nostalgia for a past where the future was eight white people in a dome filled with exotic species they stole from around the world. As an assignment, I’ve asked the stu dents to briefly describe a future scenario where the world is still in quarantine, but things are different. Not better or worse, just different. A basic science-fiction exer cise to think beyond the utopia/dystopia binary. It seems like most of them have not done the assignment. They have re acted negatively to its implications. The gist of the reaction is: How could you ask us to imagine a future? Who do you think has access to the future? You think we get to de cide what’s going to happen? Why should we lend our imaginations to the people in com mand? I can see their faces frowning in the little boxes on the screen. I can’t blame them. I have the same questions. I think about my yoga workout vid eos, about the pointedly diverse bunch of yogis selected to be in each class. I imag ine a yoga class in a Biosphere. I imagine my living room is full of the plant and an imal species of the world, ones I special ly handpicked for my quarantine zone. I imagine there are no plant or animal spe cies left in the world except for the ones I preserved. I wonder whether there could be an anticolonial/decolonial biosphere. I wonder whether imagination can be total ly uncoupled from prediction, and wheth er future thinking is always going to be in the service of power, or whether it’s ELVIA WILK

I laugh, because I know exactly what he means. But then as soon as we hang up, I pull out my phone and look up the

“I was treating my desk like a com mand center,” he says. “Every few hours I would feel the need to sit down, buckle in, and get all the news. Like I could get some control if I knew what was going on. But I’m not in command of anything.”

los angeles review of books 22 possible to imagine a future in a way that can’t be instrumentalized. Welcome, yogis. One student brings up her favorite moment from the Spaceship Earth doc umentary: when one of the biosphere ans calls her therapist from inside the dome. Frozen inside her insular, fakenatural world, she casts a line outside — she makes contact with Biosphere 1, to ask for psychiatric support. It’s funny, be cause I’ve also described that same scene to my own therapist. I’ve told my therapist that ever since she and I have had to stop meeting in person, I feel like we’re living in different biodomes. I’ve spent several sessions with her talking about pandemic and climate change and Biosphere 2. In one session, I ask her whether I talk about politics too much in therapy. She says that in classical psychology, too much talk of politics is supposed to be in terpreted as an avoidance tactic. But she has come to believe that not mentioning politics in therapy is the real avoidance tactic, especially right now. How could we pretend there is an inside without an outside? How could the global not be the personal, the geopolitical not be the psychological? How could the pandemic, which has changed time and the future, not change my time and my future? ¤ After they survived for two years, the bio sphereans left their habitat. Steve Bannon bought the whole complex in the interest of profit-driven research. The Theater of All Possibilities was never allowed back. ¤ Sometimes I take a tiny break from work and go into the other room, the only other room, and say hi to A, because he doesn’t mind me interrupting him. A little visit. One day I ask him if he’s sick of his room. Maybe he wants to switch rooms with me? Of course, I’m sick of this room, he says. Are you sick of your room too? Yes, I say, but I’m sick of both rooms. I’m sick of room We know we need to get out of the house. We rent a car and drive to the beach, to the Rockaways. The shore is cold and windy on the day we’ve chosen, but it’s gloriously empty. The sunlight is yellow in the early afternoon and the pale water dissolves into pale sky where there should be a horizon line. A reads a book and I sit a few feet away, scooping sand with my feet (even though I feel like I should be reading too, because reading a certain number of pages counts as a cer tain number of reps), and chatting on the phone with a friend in California. My friend in California tells me that he started quarantining even earlier than most of us, because he had a normal flu and didn’t want anyone else to catch it — a concept that seems like it should be the norm now that we know it’s possible to just stay home rather than go to work when sick — and he’s feeling pretty good about isolation. He attributes his decent mental health to the fact that he limits his computer time each day, holding back his urge for constant updates.

23

ELVIA WILK most recent death statistics. I read about a person who is supposed to be in com mand telling the nation’s citizens to drink bleach.“Spaceship Earth” was a concept made popular in the 1960s by Buckminster Fuller. It encompasses the idea that Earth is our only survival system and that we are all its crew. We have to work together to pilot the thing — to stay alive. If the met aphor holds today, who is in the command center? It is certainly not I, the Queen of Reps. But if work is not my ordering prin ciple, how will I manage to stay in com mand of anything at all? Today, some of the Biosphereans still work together on a farm in New Mexico called Synergia Ranch. The last shot of the documentary Spaceship Earth shows them drinking wine together around a table on the ranch at twilight, laughing and maybe reminiscing. I’m jealous of their ability to reminisce about something. I wonder how they’re doing now, under quarantine. ¤ What a luxury it is to live in this apart ment and having all this time to toil with my mind. I wouldn’t be able to spend my time this way had I not had that costly education, the network based on privilege. Posterity is an incentive, but so is the ob ligation I feel to maximize this silly luck. I keep looking for “good” things to spend my work ethic on. Because of the autoimmune factor, less on the surface now but still “underly ing” as far as conditions go, I’m not sup posed to go places full of people or touch surfaces or breathe common air. That means that any work I can do with altru ism in mind involves more time on The Machine. I accept that the only way we’re going to abolish a system where people are forced to risk their lives to go to work is for people like me to do work, so here we go.Some evenings I join a Zoom meet ing run by an organization that assists asylum seekers in filling out immigration applications, and I spend a few hours do ing reps on behalf of someone else. I lis ten to the testimony of an asylum seeker who’s endured unspeakable things and I wonder what she thinks of the concept of the future.Another day I make a countable number of phone calls to elderly people in my neighborhood to ask if they need help and not a single person says yes; I donate $25 to a bail fund; I sign a petition for canceling rent. A and I volunteer to teach a Zoom class to kids who are stuck at home and need edu-tainment. We plan a 40-minute class about climate change, waste, and composting and teach it re peatedly to groups of K-5 kids, who turn out to have an impressive grasp of global warming. Most sessions are full of 10 or 15 students, but due to some glitch in the sign-up system, our final class is attended by only one student. She’s a six-year-old named Dorothy and she’s very shy. Dorothy’s dad keeps trying to get her to sit still in front of the screen, plying her with snacks and promises of playtime afterward, but he seems harried. While we’re teaching, we can see him in the background doing the dishes with anoth er small child slung around his hip. We feel like keeping Dorothy occupied for a little while is the least we can do. But when we get to the part of the lesson on composting, we ask Dorothy whether she knows what global warming is. She bursts into tears and ducks under the table. I can’t blame her.

Of course, from the perspective of posterity, Ingeborg Bachmann is not an unknown woman. She wrote that book. ¤ I try to take a rest when I start to feel overwhelmed. That’s what the influencer recommends: You don’t have to be burned out to take care of your body. But something strange happens lately when I pause the reps. I get incredibly drowsy and fall into a deep sleep. It feels like I have no choice, like I’m drugged and dragged under con sciousness level. It doesn’t matter how much I’ve slept the night before or how tired I feel. Whenever I decide to stop working, I pass out. My therapist says this sounds like a traumatic stress response. She suggests I listen to a radio interview with Laurie Anderson, in which Anderson talks about being in a terrible plane crash. I listen to the interview. Anderson says she didn’t stop flying after the crash, but when she gets on a plane now, she becomes cataton ic. She’ll get in her seat and be fine before takeoff, but as soon as the engine revs up her whole body goes slack and she sinks

los angeles review of books 24 ¤ A magazine asks me to write a short piece in response to Italo Calvino’s Six Memos for the Next Millennium, a series of texts Calvino wrote in the 1980s about the qualities he believes are unique to litera ture and which will carry us through the next millennium. My assignment is to write about his first memo on Lightness, in which he says you can’t write about this heavy world with a heavy hand; you have to treat the gnarly stuff with delicacy and wit. I find this 600-word assignment ex cruciatingly difficult to write. I try to ex plain importance of lightness, but every word is an anvil. I want to learn this lesson from Calvino, I really do. But I’ve never known how to do anything besides to try harder, hit harder, keep lunging. I sit and stare at The Machine and tell myself to unclench my teeth. I used to live with a certified genius writer who would spend three days party ing and come home fucked up and sleep for 14 hours and then wake up and write an essay with flashes of brilliance that an editor would help get into shape over the course of a few weeks and that would be published to great acclaim on Twitter, all while I was working 8:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. in the next room on a single difficult text. We all know someone like this, but nobody thinks of themselves as that kind of person. Is that person “lightness”? Sometimes I get angry with myself for not being able to produce words and A gets frustrated with me too. He asks whether I really have to work until I have nothing left. He lists my accomplishments. He says he loves my writing but that I can’t be re duced to what I produce. He says I have intrinsic value as a human being. I nod, but I don’t know what the hell he’s talking about. I don’t have low selfworth, I’m just not sure I exist. I have to do some mark-making as evidence. But you have evidence, he tells me, and points to himself.Afriend sends me a quote from Ingeborg Bachmann’s book Malina. “I don’t think about growing old, just about one unknown woman who follows anoth er unknown woman. […] I don’t know myself any better at all, I have not grown any closer to myself. I have only watched one unknown woman slide further and further into another.”

My parents are competitive people. They have the same job as each other — they’re academics in similar fields — which means there is always a measuring stick handy. Work is undoubtedly the fami ly ordering principle and we do not give much credence to small wins. Technically my dad is retired now but he still writes an article or reads someone’s dissertation or gives a lecture every day. Once I asked him what is the meaning of life and he told me learning and curiosity, which I think is laudable and true but which I think is only part of the truth, given the family emphasis on recognition and ac complishments. Life is about the work of meaning-making itself but it’s also about someone noticing that we’re doing all this fucking work. Otherwise does it exist? Do we? When I call my mom at a given mo ment and ask how she’s doing, the first thing she usually says is a variant of “Oh, you know, buried under work.” Buried is how she’s doing. It’s the only way to do. She and my dad are often working top ics related to ethics and social justice, so there is a moral imperative justifying this work being done. But for my mom, there is an extra moral component because she’s a woman and it was a battle to get where she is, so her success is its own justifica tion. I inherited the embattled feeling of that second wave, even though the battle itself isn’t exactly mine. The belief that work will be there for me even if all else falls apart is also part of my inheritance. After every breakup or romantic rejection, I call my mom in tears in order to receive her reliable instruction to work through it. She tells me to write about my feelings and to channel my en ergy into other projects. I must not give up, I must process and parse the mess, I must harvest meaning from it, I must find my way back to myself through la boring by myself I must gain recognition elsewhere to remind me that I exist, even when there is no lover to assure me. And she’s right: work always works. Work will always take me back.¤

los angeles review of books 26 into a coma-like trance. “My mind shut down,” she says of the last time this hap pened. “My mind protected me from be ing there anymore.” After I listen to the radio interview, I ask my therapist what is the meaning of life. She says she is not going to give me an answer, not because she doesn’t have some ideas, but because I’m so desperate for someone to tell me that I’ll lunge at whatever she gives me and never let go. ¤ When I was sick I had an excuse for needing to rest; when I had a social life I had an excuse to take a break; without these premises I realize the flimsiness of those stopgaps, and the ridiculous impov erishment of a life in which everything not work is a procrastination tactic or an excuse.Ireturn to my influencer, who I need to believe really does want the best for me. She agrees that I have to put my ass in chair if I’m going to be really crushing it during quarantine. But if I really want to crush it, I also have to get my ass out of the chair and do 500 reps and then drink a liter of water, set healthy boundaries for my relationships, and forgive myself for everything I’ve ever done.¤

Why would they be, when Biosphere 3 is right here? ¤ One of my art teachers in college sympa thized with my inability to leave the stu dio until I made something good (with no criteria for what that would be). He said the problem was that I couldn’t get out of my own head enough to let things flow. He said I was too worried about what peo ple would think. He gave me some advice, which allegedly comes from Duchamp: When you first start making art, every time you look over your shoulder you see all your crit ics standing there and watching what you’re doing. Eventually, if you keep working, you look over your shoulder and find your friends standing there. Then one day you look behind you and find only yourself looking over your shoulder. But finally, one day, you look behind you and see nobody there at all. I have never been able to verify that Duchamp said this. But I get the lesson, which is that it takes a lot of time to learn to rid oneself of other people’s opinions and voices and create something that isn’t about pleasing anyone or getting attention. The lesson is that a true artist makes work for no one else but — no one? Posterity? The lesson is that good work comes from within. I used to find this a helpful image, but now it creeps me out. Who is this person with no body behind her? One unknown woman slides further and further into another … I don’t think the influencer has the same goal as Duchamp. She wants some one to be looking over her shoulder at all times. And here I am, anxiously looking. One day she posts a quote that says: “We don’t need to come out of quarantine skin ny, we just need to come out alive.” I nod. I’m grateful for this post. I really do not feel like doing any lunges or squats right now. I should rest and unplug … I should step away from the Machine … I should indulge in some organic grains … this is me, listening to my body and being kind to myself … this is what it must be like to know what the ingredients for a good life WILK

27

I write half a short story about a group of office workers living in outer space. There’s nothing glorious about their sit uation; they’re just working way more re motely than the rest of us remote workers.

Characters are supposed to have motives: “Give everyone something to want, even if it’s just a glass of water.” One person in the group says the story is an interesting take on quarantine, but that she doesn’t think millennials are interested in outer space.

They’re employed by a software company that has sent a portion of its workforce to space in perpetuity, basically as a public ity stunt. The employees-cum-astronauts have agreed to the arrangement just be cause having an office in space is more in teresting than a regular office. I send the story to my writing group, which meets weekly instead of monthly now, because we’re all stuck at home, so we have time to show up. The group seems unsure whether the premise of the story is sound. They are not convinced wheth er it’s plausible that people would sacri fice their whole lives to live in space with their colleagues without a very good rea son. The group has a point. There’s a rea son I haven’t been able to finish the story.

ELVIA

los angeles review of books 28 are … the right way to cope … Then I flip to her next post. It says: “There’s no right way to Whatcope.”is “cope”? Is it the same as “exist”? To exist, you need an ordering principle, similar to what the influencer calls “priorities.” Here are some priori ties — work, money, posterity, love, selfcare, saving the world, fun. However: If I don’t have time to do all these priorities before dinner, I’m going to have to figure out how to rank them, that is, how to pri oritize. But this is impossible because all of them are necessary to be a person who exists.Incredibly, some days I feel like I al most get the balance right. Giddy: I’ve done enough work of all kinds, real and recreational. I’ve attended to all the prior ities. This is what winning feels like! The healthy butter! On those days of success, I fantasize about going on vacation. Maybe I’ve “earned” a holiday! The allure of vacation is slightly dif ferent during the pandemic; it might also be a misplaced desire for “a time when everything around us wasn’t dying.” But when the fantasy hits, it hits hard. I just have to say the word “vacation” to A to get us going. Sunburn, he says. Fruit, I say. Hot, overripe, fruit. Fruit that we eat from each other’s hands. ReadingSwimming.all day and falling asleep in the sun Lemon trees. Sweat. We smile. Then one of us points out that we have everything we need and that missing vacation because of the pandemic is really a very pathetic thing to complain about.For me, the fantasy has always been the point anyway. The possibility of exit. In truth vacation scares me, because on vacation, time slides toward death with out any notches to help a person keep a grip. One feels a moral imperative to “not work” on vacation that can be very op pressive. What if one gets an idea? What if one feels the need to make a mark on life while everyone else is playing bocce? What if one wants to play bocce and real izes one never wants to go back to work? One gets so drowsy in the heat. ¤ An artist friend of mine is having diffi culty being productive in quarantine. We talk on the phone about how stagnated we feel, no matter how much time we put in. She also has the added distraction of motherhood, because she had a baby last year. Do you think you could ever be hap py if you stopped doing work completely to just be a mom? I ask her. Of course, she says, and I’d love it. But I’d have to kill myself. ¤ When I was very young, I believed that all my thoughts were being recorded some where in a giant book, and that when I died the book would be given to me to read in the afterlife. For this reason I tried to think in third person, past tense: She looked across the room and saw the dog ly ing under the tree … she didn’t want to eat dinner but dad said it was time to eat … she was sleepy that day … it seemed fun to her … so that it would read like a story when it was all put together someday. I don’t know where I got this idea, but I know I was very afraid of dying and that I could only imagine my own death if I knew my

29 whole life would be safely preserved in a book.At some point, I realized nobody was going to write this book for me, and that any evidence of my existence is going to be of my own making. I realized I have no choice but to try to make it, even though it is never going to be as sublime as the book of all thoughts.

I, the Queen of Reps, sit at my desk cranking out words, take a break to kneel on the floor next to my desk and lift my leg a hundred times, then back to the desk to eat some calories A lovingly puts within my reach. I take a shower and tell myself it is a Small Win. I walk from one room into the other room and back again. I search for a new ordering principle. I find none. I’m on a spaceship but I’m not in the command center. Is there a com mand center? Just another room. This very room. Luckily, when I entered the room, A was there, backlit by sunshine with a book in one hand, his uncut quarantine hair spiral ing into fresh curls, watering the plants …

ELVIA WILK

Rosemary Mayer, October Ghost, 1981, Wood and ribbons, dimensions unknown , installed in the artist's studio.

Courtesy of The Estate of Rosemary Mayer.

31

The Vikings thought the wind was a god, that the eyes were holes. A window meant a wind-eye, for the god to see with, and at the same time through. I used to hate etymology —

What’s the point, I’d whisper: I was quieter back then, less patient, though more easily pleased. I am pleased to have been of use, I used to say to myself, after sex with strangers. Leaning hard against the upstairs window, I’d watch them make their half proud half ashamed-looking way wherever, and if it was autumn — whether in fact, or only metaphorically — I’d watch the yard fill with leaves, then with what I at first thought was urgency, though it usually turned out just to be ambition. I’d leave the window open, as I do now — if closed, I open it — then pull the drapes shut across it, which of the many I’ve tried remains the best way I know, still, to catch a wind god breathing.

VIKINGS CARL PHILLIPS

essay 32

AGAINST GRACE JULIAN RANDALL

For those who don’t remember or chose to forget, there is a video of an ashhaired President Barack Obama singing “Amazing Grace” in a church in South Carolina. Everyone behind him is Black and draped in long church robes, deep purple like elegies. It is the summer, and everything is slick; it is the summer and a toll must be paid. From my room in Philly the wi-fi is shaky, and everyone behind Obama flits between tulips and bruises, depending on the lag. There is a funeral going on that seems to have been going on all year. Obama opens his mouth, he says a new version of what we always say about goodness, about possibility. Nobody says the word “assassination,” nobody says

33 “betrayal,” everyone sings along. The song stutters in like a wave and nobody says forgiveness but it’s implied and encour aged. I sink sweat into the mattress, I look at the window and think about mercy. I leave the clip on a loop and all along the internet some folks say it is one of the best speeches of Obama’s presidency. I rise to get a glass of water I have been thinking about for over an hour and I can see the outline of myself on the bed; it is June, I can see myself evaporating. More unites Black people than song, and less unites Black people than nonBlack people seem to believe. I, for in stance, am related to zero percent of the Black people I have been asked if I am related to, I don’t know most people’s Black co-workers or the “guy that used to date my cousin.” I know very few peo ple in the grand scheme of things, and I prefer it that way. What does unite every Black person I’ve ever known — whether they phrased it this way or not — is at least once in their life, being compelled to thank or forgive white people for some thing that a Black person could never do. If the roles were reversed, they would have killed us. Silence is not always silent, but it is always a form of gravity. Grace is also not always silent. Sometimes it is a tooth falling into a palm, and that palm never curdling into a fist. Let me backtrack: Once when I was seven, I was in the process of losing a tooth. Everyone knows that this process can take a while, and it had been weeks of this canine threatening to break its teth er once and for all from my small body. One day during recess, I was a seven and a white boy was seven and all the vio lence we had ever intended prior to that day was theoretical; fights were a sound we made with our mouths; we always won and never bled. Even when he did actu ally punch me, I don’t remember it as a fight. Rather, the fist arrived as a curiosity, a question asked in the eye of the storm that was the world. But maybe I misre member, maybe he knew exactly what he was doing. Regardless, the little tether snapped, and my mouth tasted like cop per and then like a mouth again. I caught the tooth; I didn’t swing back; I feigned thanks for relieving me of the burden of it. Thanks to him, I no longer had to won der when the tooth would fall out. This is not the youngest age I can remember things, but it’s maybe the oldest thing I have ever remembered: the moment when I realized that I could win this fight, but I also knew that I would lose in some larger and more irretrievable way. I told my fam ily what happened, I told them it was an accident and maybe believed it. Even as a child, I managed to reach into that well of goodness, I reached for the religion of be lieving the best of people who put blood in my mouth. I was Black, I was good, I got to stay where I was put. I placed the tooth beneath my pillow, in the morning there were two faded dollar bills, pulped and soft like feathers. The memory feels almost too cinematic — that tooth fall ing into my palm; a single slow hailstone that never melted, but disappeared all the Insame.the two most famous clips I know of, Obama has a tendency to start singing be fore he starts singing. Obama is measured, graceful, clearly hyper aware of what his voice can and cannot reasonably pull off. He doesn’t just start belting but kinda two steps his way into it like an Uncle wading into a soul train line. In the clip of him at the Charleston funeral he is shaking his JULIAN RANDALL

los angeles review of books 34 head, a mightcouldbe under his tongue, as he says “Grace” over and over again, like it’s pulling him toward something. The whole thing seems almost spontaneous, who am I to say it wasn’t? Those first notes come out flat if we’re being honest, but maybe the song is tired too. A storm can only rage in memory for so long, or so I’m told.The history of “Amazing Grace” as a song is a story of transformation, but it has been told out of order so many times that the bones of it have healed crooked ly and now the grace is less about healing than it is a history of manageable pain. Part of the mythos is true: John Newton, the writer of the song, did eventually be come an abolitionist, and he did write it as a result of being the captain of a slave ship passing through a storm that threat ened to drown him but through which he passed. He stayed in the slave trade for another five years after finding religion, convenient. He wrote the song rough ly 24 years after the storm, for him, had passed, convenient. In the version that me and some of my homies grew up with, everything is a bit more immediate, some of us even were brought up believing, as I did, that Newton wrote the song with the storm still rolling over him. Epiphany is funny like that; it can be made to look very spontaneous even with the dead lying at one’s feet. The summer that Obama sang was belligerently hot, death made it hotter. I remember what it was that summer — watching Obama call the names of those assassinated by the coward Dylann Roof, saying they “found that grace.” I remember wondering if this was the fate of Blackness to be shot by a stranger you prayed over. I remember learning the cops brought him some Burger King; I remember not even having the energy to perform surprise. Heat is a strange government, it can make you beg for rain, it can make you thank the storm.Forgiveness, or something like it, has always been prescribed as Black people’s superpower. whiteness necessarily has a parasitic relationship with that forgive ness. I’m done indulging it. If I am quiet it is only because I have spent my adult hood trying to pry the blood-thick leech of white folks wants out of my throat. I will be asked to forgive again and again. I will try. I will fail and fail because some times I want to survive. whiteness cannot sustain its allegiance to moral mediocrity, but I wish that wasn’t my problem; I de serve for it not to be. I do not doubt the grace of Black peo ple; it is in many ways the only reason I am still alive. I would like though, to divorce grace from what I feel compelled to, but cannot forgive. The ways that such com pulsion follow me and most of the people I love, the storm unending and eventually teaching nothing but the pedagogy of its own persistence. I feel compelled to say something: one of the great tragedies of whiteness is that it seems one goes to the grave without a true calculus for how of ten they have been spared. I have no such luxury. In a more perfect version of my self, I have Grace for so much less — or at least for something different — and am more alive for it. I reach for that other me, that version, I fail to reach him every time. I feel compelled to say this as well, there are perhaps no tragedies of whiteness it self. Tragedy implies a choice was with held, and whiteness always has a choice and it will always choose the path of my destruction. I pledge to respond in kind. I say it around the leech in my throat that throbs, “Sorry, sorry, sorry.”

JULIAN RANDALL

What I’m striving toward, failing toward, bleeding toward, is a practice of freedom that I don’t need to preface by saying, “It ain’t much but,”. I demand of myself and those around me a freedom where it is not dismissed as conspiracy theory when I name what I have abso lutely seen happening before me, around me, because of me. That last one is prov ing harder than it sounds, the arm of for getting is as long as a country, but narrow as a gaze, meager as the imagination of white folks who sit in police cars and state houses and restaurants and department meetings and classrooms united by their instinct to punish Black folks for living, loving, styling, flexing, imagining, and forgiving ourselves, and them too, most if not all of the time. When they can not punish us, they punish those we love, when they cannot punish them, and even when they can, they punish themselves.

35

In my mind, the grace that is made synonymous with the obligation to forgive the unforgivable is always pronounced with a lowercase “g”. Since 2015, I don’t know if I believe in true freedom anymore.

Some of us pass under storms and learn almost nothing truly, and resolve that this is miracle, and miracles happen to and are the rightful property of folk who we de cide every day deserve to be free.

white supremacy is a death cult, a religion for the feral and those taught to aspire to that feralness if only to pretend it will ease the jaws we were born in. I grow weary of epiphany, it’s nearly June again, I am tired of the rain, I am tired of waiting for it to be God enough.

It sounds like a destination rather than a constant process, and it sounds that way because we love destinations in America.

MIKI ARNDT

My name is Rimiyo and I’m a grand mother. I’ll be 65 in November.

37 fiction

In one life, I have a daughter. Kanae is 35 and a dental hygienist. Her husband Shota is 42 and he works with comput ers. He’s explained to me what he does, something about data, but I can never re member. My granddaughter Rika is seven. She calls me Obaachan. We watch music shows and she teaches me the dances. My joints don’t move the way they used to but we’re happy together when we dance. Kanae says the way Rika smiles with all of her teeth, reminds her of me.

IN ANOTHER LIFE

In another life, I have two sons. Their names are Kosuke and Kohei. They’re in their late 30s, one a lawyer and the other in real estate. It’s hard to tell them apart.

They have a father, Koichi. We’re about the same age. He is my husband. He has no sense of humor and murmurs his words, as if speaking with a mouth full of mouth wash. I get tired of asking him to repeat himself. I never would’ve picked such a man but I have no choice in this matter. My son Kohei has a wife, Chikako, who works as a receptionist at his agency. They have a son, Haruto. He is three, hyperac tive and obsessed with trains. He calls me Baaba. I sit with him and we create elabo rate scenes of accident and rescue togeth er, using his toy figures and speaking in funny voices that make him giggle. Koichi murmurs in the background toward us. I pretend not to hear him. In another life I have a far better hus band, Hiroaki. I see him twice a week. He texts me what he wants for dinner and I pick up the ingredients at the supermar ket. “Sukiyaki is not as enjoyable alone,” he would say, while he thanked me. He missed home-cooked meals after his wife died. He asked me about my other fam ilies and remembered my stories better than I did. He was curious to hear how Rika was doing, what Haruto was learn ing in school. He laughed heartily at my impressions, particularly of me mimicking soft-spoken Koichi. We don’t have any children, Hiroaki said he never wanted them but now he wondered whether he made the right choice. In another life, I have a daughter. Her name is Maya and she’s 43. I heard that she lives in London with her husband and their daughter. I don’t even know her daughter’s name. Maya doesn’t know about my other families, just like I don’t know about hers. Maya’s father left us when she was five, and Maya left me when she was 18. I don’t see myself in Maya, al though she alone shares my blood. I’m a far better grandmother than I ever was a mother. Maya hadn’t liked to be touched or held, and it still surprises me when Rika hugs me, or Haruto reaches for my hand when we go for our walks. Would they do that if they knew who I really was?

I talk to Hiroaki about my families. I apologize about using his time to talk about myself, but he reassures me that’s what couples do, it’s more natural this way. He asks if I have feelings for my fam ilies, and I say yes. I’ve always been honest, though you might think it funny from my line of Asidework.from the families, I have the occasional wedding or funeral to attend as a relative. I’ll do one-off meetings with younger women who want advice on rela tionships and how to deal with a trouble some mother-in-law. One of my clients is a hikokomori. His name is Kei and he’s 22. He’s confined himself to his studio apart ment that barely fits his futon and a coffee table. His clothes are in a box and his floor is littered with soda bottles, empty ramen containers, and cigarettes. He sleeps off his days and plays video games until the morning. His family said Kei had been close to his grandmother and was never the same after she died. When my agency told me Kei’s fam ily had loved my profile, I tried to turn down the job. I had heard of hikikomori, and found it creepy that these men hid from society. My supervisor, Takeda-san, reminded me that I had been reluctant to meet Hiroaki as well. I had only wanted grandmother roles and wasn’t interested in pretending to be a wife. Takeda-san had assured me that Hiroaki just wanted to talk. “He lost his wife two years ago, his high school sweetheart. You can meet him in our office. If you don’t like him, I’ll send him someone else.”

los angeles review of books 38

Now Takeda-san insisted. “I know this is unusual, but this boy needs guid ance. The family read through your re views, your profile, and said you reminded them of the grandmother he lost. His mother said she’ll go to his house with you, so you’ll be more comfortable. He’s agreed to a few sessions. Tell me yes?”

A few Septembers ago, I was sitting on a park bench eating my onigiri when I spot ted two boys fighting in the sandbox. One boy held the other boy’s toy plane high above his head, taunting him. A group of mothers gossiped nearby, engrossed in conversation and unaware of the escalat ing conflict. I walked over to the children. I can’t recall what I said to them but I made the bigger boy return the plane to his smaller friend and told them stories until they were both laughing and playing together again. I walked back to my bench satisfied. Then a man in a gray suit walked over and handed me his business card. “I’m Takeda. I saw how you handled those kids, and they’re not even your own. I know this might sound strange, but are you looking for work? We’re looking for grandmothers. A good one is hard to find.”

I became an expert in scheduling, so I could babysit my grandchildren, meet Hiroaki for dinner and attend events for the agency. These commitments were al ready a lot, with the names and histories, birthdays and occupations and favorite foods. I took notes on my phone to re member conversations. I taught Rika how to write and Haruto how to use chop sticks. We’re not supposed to develop at tachments to our families but it was hard not to.I’ve asked my least favorite husband Koichi about his other roles (he’s from a rival agency) but he doesn’t like to break character. He was tight-lipped about his commitments, saying he had to protect the family’s privacy. Kanae, my daughter, worked with a couple families and was a stand-in wife for corporate events. I met her years ago at her wedding. I was her aunt for the night and we bonded imme diately. She was the bride of a gay man who wanted to appease his parents with a traditional wedding. In our family, she was the wife of Shota, who lost his wife in a car accident when Rika was only two. When applying for her kindergarten, Shota rented Kanae for the interviews. Rika took to Kanae, and Shota start ed booking her more often. When they needed a babysitter, Kanae referred me to join their family as a grandmother. We’ve been a family since. Kei though, was another matter. He played video games silently while his mother attempted conversation. All he granted us was a nod, no eye contact. His mother apologized on our way out. “We would like you to come again,” she said, checking my face for my reaction. “I’m sure this is different from your usual work,

39

¤

MIKI ARNDT

I didn’t realize that being a grand mother was something I had wanted until Takeda-san offered it to me. Maybe it was an experience I hadn’t earned, but I want ed to give it a try. I had never imagined anyone would want to rent me but I trust ed the density of his business card, printed on expensive paper. I followed him back to his office. Takeda-san regaled me with stories of the families he had worked for, other people’s children he had raised, widowed women he had comforted. By the time I left, I had taken my profile picture and signed a contract, officially a grandmother-for-hire.

I owed Takeda-san for discovering me.

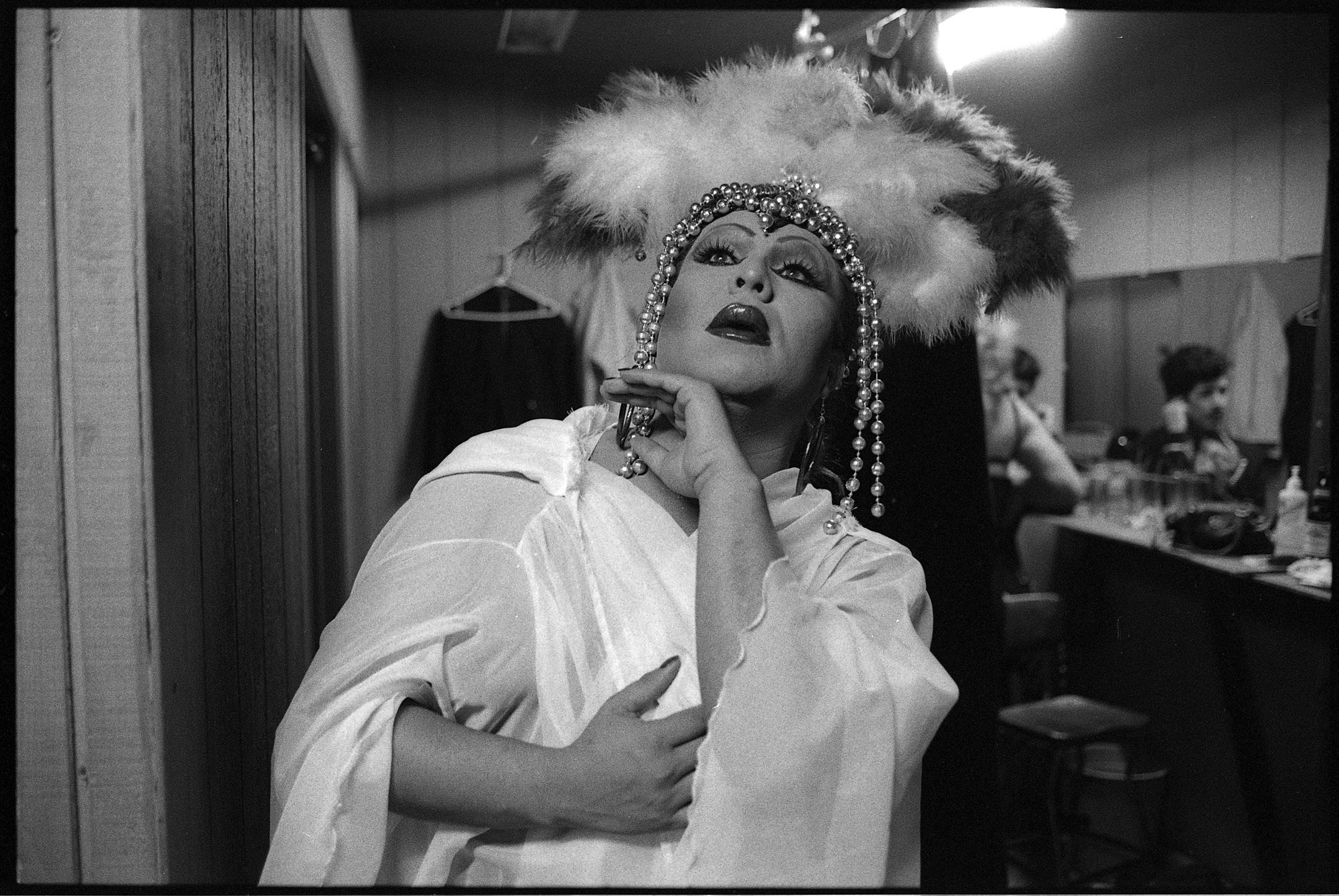

Ja'Tovia Gary, An Ecstatic Experience, 2015. Courtesy of the artist and Womxn In Windows.

“Today we’re going to spend a good time together,” I announced, while Kei continued playing his game. “Did you hear anything I said during my last visit?” Kei ignored me. “Okay,” I said. “Show me what’s so good about this game,” I picked up a con troller. “Teach me how to play and I’ll beat you. If I do, talk to me, even if it’s for a minute.”Keilooked at me with surprise. I had made“I’vecontact.never used this before but I learn quickly,” I added. Kei’s voice was faint and raspy, like the creaking of an unoiled machine. He spoke in quick staccatos, and I pretend ed to hear everything he said. Then we spent the next three hours playing video games. We didn’t say another word. This was probably not what I was hired for but I had enjoyed the game and at least he opened his mouth. The following week, he asked about my zabuton. I brought my own cushion because his room looked like it hadn’t been cleaned in years. But I couldn’t say that.“It grounds me.” “I“How?”havea lot of lives, a lot of families. This zabuton is a constant. This is a re minder that I’m still the same person, no matter who I’m with or where I am.”

“Or maybe you just don’t want to sit on my floor,” he said. “That too,” I admitted. I cleared away the soda cans, making room for my cushion. I actually looked forward to playing video games with him. I was competitive and I might be able to beat him with more practice. Maybe I needed to visit him twice a week instead. “Maybe you can visit me twice a week,” he mumbled as I was leaving. “Are you starting to feel fond of me?”