30 minute read

MIDNIGHT DOUGH

TAISIA KITAISKAIA

I. Babushka’s

Advertisement

When my grandmother created the sourdough starter, she knew that it was good. She made it from wild yeast at our dachya. Yeast that traveled over the blackberry patches in the yard of our summer house, and the wooden cupboards in the kitchen and the warped planks of the floor, the wild strawberries and their white flowers running alongside the cabin. Babushka fed the sourdough as she fed her yogurt and sauerkraut and all her children, and when the sourdough threatened to escape its jar, she put it in the cool cellar next to the potatoes growing eyes, and patted its head. The sourdough was wild from the chickens she beheaded and her swims with her husband and son

and daughter — my mother — in the vast lake. Their dog, moppy and tough, rode in a basket on their motorcycle; one family on one motorcycle. This yeast circled the fresh jams from those blackberries, the yeast of armpits and the banya, where they all slapped each other with birch branches to wake the skin. Yeast from the hairy domovoi, the house spirit that looks after every Russian home.

After her husband died young and Babushka sold the dachya, the sourdough lived on in her apartment. The starter ate the asbestos in the walls and the lead in the water, the throat clearings of the man upstairs and the sounds of children playing against the wall with the building’s sole basketball. My grandmother put the jar out overnight to ferment for the next day’s bread, and the sourdough heaved and ate the sound of the city and the dreams of the scurvied pines along the streets. When my mother and sister and I came to visit and slept in Babushka’s bed (she took the couch), Babushka made us blini — buttery crepes — in the mornings, and then sent us home with a hearty loaf of sourdough rye.

My babushka never questioned the sourdough, because she was good, and the family curse had passed her over. She was a cheerful and innocent woman all her life, and though the curse had ruined her childhood and killed her husband with a heart attack at 40, it would never touch her.

My mother knew the many tragedies in our family well, but she first heard of the curse shortly before our family left the Soviet Union, when she visited my greataunt to say goodbye.

Babushka’s sister, Auntie Klara, said her stomach had been talking to her for weeks. By day, she was staggered by stomach pains. At night, she would hear a low voice in her belly.

“I heard the voice, Elena,” Auntie Klara said. “It told me to repent.”

Mama’s aunt looked small and withered in her armchair. The Persian rugs mounted on the walls turned the house dark, and Mama could barely see her aunt. Klara was not a spiritual woman. She had raised her children to have practical jobs, and she did not believe in nonsense.

“The doctor told me to see the znaharka. The znaharka did something with her teeth, something with a knot. She said I needed to apologize to the voice.” The znaharka, a woman-who-knows, said that the voice was the spirit of Auntie Klara’s daughter-in-law. Klara’s son was a promising young pilot who had been killed by the secret police a decade ago, and his wife felt that Auntie Klara had neither loved nor grieved him.

Auntie Klara apologized to her stomach, to the wife of her son. “I no longer hear her voice,” she said. “But of course, it’s all to do with what happened in the labor camp.”

Mama’s eyes were blank.

“Ah, your mother never told you.” And so, my Auntie Klara told the story.

Babushka’s father, a clergyman from Ukraine, was sent to a Siberian labor camp during the revolution. Oleg was fortunate to keep his wife and children in a little house nearby, spending nights at home and working in the camp during the day. Famine everywhere. The potatoes, cabbage, and radishes in their little garden plot were not enough to feed the family.

Oleg was harvesting his potatoes one fall evening when a camp officer rode by

on his horse. “Bring those potatoes to my house tonight,” the officer ordered. Oleg could not obey, his own family would starve.

The next day, Oleg reported to camp empty-handed. The officer shot him on the spot.

My great-grandmother Maria — talented with roots and herbs, words muttered at a doorstep — put a curse on the officer and his family.

The curse worked: all four of the officer’s sons died in the war, and the officer died too, a painful and mysterious death.

But the curse came back to my family. Both of Maria’s sons died also. Only her two girls survived — my babushka and Auntie Klara.

Soon Maria herself grew ill. She called my babushka to her deathbed. Maria had always seen the potential in her daughter, an open vessel.

When Maria began to whisper strange words into her daughter’s ear, my grandmother ran away. She knew that her mother wished to pass on a writhing thing, like a knot of snakes, to her. My grandmother ran out of the house in her cotton dress and her bare feet, all the way up the hill. She hid in the weeds and saw a green vapor rise from the chimney of her mother’s house. Her mother was gone.

That’s how it was: my greatgrandmother Maria, a rigid figure sketched in charcoal: straight lines, black eyebrows, rage and power inside. My innocent great-grandfather Oleg digging out his potatoes, greenish from the black soil. The sound of horse’s hooves, and the sky greenish with gray around the green, like a hard-boiled egg. A storm that did not break but pressed down, flattening the earth and the sad government houses and the deserted grass.

My grandmother, the little girl in the cotton dress and bare feet, never did inherit her mother’s gift, those writhing snakes. But the curse had already done its work.

For hadn’t my grandfather, Babushka’s husband, died so young? And hadn’t Auntie Klara’s son, the young pilot, been murdered? And wouldn’t Auntie’s daughter, with the cold eyes and the mathematics degree, soon die of cancer at 37? And hadn’t Auntie’s husband spent his last days struggling with a brain tumor?

“And Sveta, too,” Auntie Klara said, speaking of my sister. “Hasn’t she always been a strange child?” Auntie Klara recalled how as a six-year-old, my sister — with the help of a neglected boy in our apartment building — dismembered a frog in the nearby creek.

My mother left her aunt’s house in anger, but she took Sveta to see a shaman before we left for America. As soon as they walked into the shaman’s cramped room, all the candles went out.

The curse was stitching itself through the generations, like an aging woman with failing eyesight embroidering the family cloth. Who knew where the blind woman would next stab the needle, and pull the thread taut?

II. Mama’s

Our father was settling into his doctoral program when my mother arrived in Los Angeles. Thirty years old, in a leather jacket and with incredible hair, Mama brought the two children, some clothes, and a bit of Babushka’s sourdough starter. The sourdough was the one living reminder she would have of her mother for years to come.

Over days of international flights, trapped in a glass jar inside a sweater

inside another sweater, the sourdough was feeling feisty.

When we got to our new apartment, a clean beige place with no personal effects, my mother stirred the starter to calm it down, then put the jar in the refrigerator. The starter burbled next to the clean nice American foods, the milk, plastic bag of grapes, butter. As if making an altar, Mama arranged the little red wax cheeses from the plane, saved in her purse, around the feet of the jar. The fridge hummed with menace and then peace, like an old dog.

Mama did not make bread that first year, and the sourdough languished behind the weird wax cheeses no one liked. She thought it would make her too sad to smell that old smell, and she was so sad already. For a while the starter burbled and made bubbles and holes in itself, trying to grow. Then it went flat and quiet.

Instead of making bread, my mother ate ice cream sandwiches and looked out the window at the clipped green lawn behind the graduate student housing, constantly worked over by sprinklers. She worked for minimum wage at a lab, treating vials of cancerous cells with different chemicals. When the researchers tried to make her clean the vials, she used her painful English to remind them of her biochemistry degree. No one would tell her what to do. She picked us up from daycare and lugged our laundry down to the basement and folded our nice clean socks.

On nights when she couldn’t sleep, my father snoring in bed besides her, Mama wondered when she would meet the domovoi, the gruff hairy man taking care of the house (or making mischief, depending on his mood). She’d seen him many times in her mother’s apartment and dachya. A bit like a sasquatch, but more squat. She had not heard any stomping in the middle of the night and wondered if they even had domovoi in America. She missed her mother, remembering her silhouette in the snowy street as the taxi pulled away. She read bedtime stories to her children, practicing her English, and worried about what her aunt had said.

Now Mama knew for sure what was wrong with Sveta. As a baby, she had cried and cried, she hated being dressed, she hated being naked. She hated being touched. In Russia, Sveta had locked our cousin up in the bathroom for hours, and in America, she didn’t get along with anyone.

So Sveta was cursed, and the other daughter — she wriggled out of my mother’s arms and out of the curse and sped down the streets on her bicycle, and never came back, not really. The girl had been so shy back in Russia, what happened to her? Here, she was so easy with the new language, her skin tan and her hair blonde in the playground sun. Lost to my mother already, loosed to America.

No, my mother did not want to make bread. She let the sourdough starter get all flat in the fridge, and it took her a year to feed it again. Instead she made khvorost, sweet dough cut into strips, fried, and sprinkled with powdered sugar. She made savory meat and cabbage pies, or fish and potato pies, with beautiful cutouts in the crust like the carvings of medieval Rus. She made kisel, a sour jelly drink, for hot days. But she did not make bread.

After a year, doubting that the starter could live again, my mother began to feed the sourdough. As the creamy mass came alive and gave off its odor, my mother remembered all of it, her whole childhood: the dachya, the wood planks, the

Rosemary Mayer, Untitled, 8.25.71, colored pencil and colored marker on paper, 12 x 9 inches. Courtesy of The Estate of Rosemary Mayer.

wild strawberries, their white flowers, the birch twigs, the smell of pines from her mother’s apartment balcony. She wept and made bread, and when she was done weeping and the bread was baked, she was pleased by the golden color and the hollow sound when she thumped the loaf on its back.

She fed the sourdough regularly now, worrying a bit that the starter somehow carried the curse, or maybe that exposure to Sveta would taint the yeast. But the bread was delicious.

My family moved away from California and up further north, close to the latitude of Siberia. Like coming home, but at a distance. Eventually Mama left the days of khvorost and fish pies behind, she was done hosting and entertaining my father’s graduate students and working in labs. She was going to grow her hair out as long as it would go, and she would have dogs and she would make bread and she would read.

Sveta stayed strange as she got older, but that was to be expected. This truth was a difficult one to eat, but Mama got used to it. The curse had done its work, and now all Mama could do was tend to the goodness of the daughter around the demon. Even when the demon strolled and paced back and forth across the house, or sat in her daughter’s stomach, indigestible.

My sister wanted to be a fashion designer, so my parents sent her to design school. She got into cocaine and was sent back home. She was hot in a way that made people want to ruin her, and even in Alaska, where there are no people, she found a way to sleep around with the worst men imaginable. From the age of 20, she lived permanently in my parents’ basement, smoking weed and watching TV or going manic and writing bad poetry. She wore leggings with exploding suns on them, and whenever I visited home, she would gnash her teeth and hide in the basement. Right before I was about to fall asleep, she would come in, turn on all the lights, and rifle through my bags. What was she looking for?

“It’s like she sees the goodness in you, and it makes her seethe,” said my mother.

The demon theory. My mother and sister watched horror movies deep into winter nights. The movies corroborated what they felt to be true about evil. I didn’t know what was true, but I didn’t spend a lot of time at home, just in case.

But there was always hope, and the hope grew like sourdough. Sometimes going flat and quiet and untouched, and sometimes massaged, worked through, given something to eat. It seemed the thread of the curse had emerged in our family, made its one stitch, and moved on.

III. Mine

One winter when I was old enough to care about bread, my mother gave me some of her starter. I swaddled the jar into my luggage. Like my mother’s starter, the sourdough flew with me into the cold of the sky and the clouds and then into the heat of baggage claim. My girlfriend, Teresa, and I took it home. And like my mother, I put the jar in the fridge, though for me, it was among old pickles and dried-out Swiss cheese and spilled soy sauce. One day, I said to myself, one day, I will clean the fridge.

Unlike my mother, I was excited about the starter. In my bland little American life, I wanted to be close to something rich and yeasty and strange and, yes, sour. I wanted to eat meaningful, ancestral bread. I was in Texas and I did not know

my neighbors and I did not have family nearby and I just couldn’t wait. The bread was delicious from the beginning, even though my first dough was too wet, and the loaf barely rose. But I kept going, and my loaves were emerging golden from the oven.

That’s what life felt like then: warm, golden loaves that would keep on coming. Nothing evil would ever happen to me. Someone once told me I looked like a trophy wife. Can a trophy wife be the recipient of a Siberian labor camp curse? I didn’t think so. Strife and famine belonged to the old country. I had gone to college, and grad school. For a while I hadn’t had enough money, but now I did. My friends and family were healthy; no one died. Teresa was wonderful. My parents were okay with her, and I was grateful that I wasn’t in Russia, where I could be jailed — or worse — for dating a woman. I was moving along the track of life, my retirement account and savings growing, my debt decreasing. I was young, I had nothing to worry about. I would go on meeting friends for drinks and having my little moments of elation, my pockets of unevil magic. So I reasoned with my belly and my brain.

And then, two months after I’d flown home with the sourdough, Teresa left me, and pain pressed in on my house. It came in through the windows, it came in through the doors and the cracks in the old house. It came in such a way that I knew it had always been there, and always would be. Like everyone else, I would eventually lose every precious thing in my life.

When I turned over the blind woman’s embroidery, I saw that the back was thick with thread. The neat stitches on the other side were an illusion. In reality, the whole cloth was covered. There was no place that was not cursed.

Teresa wore her hair in a French braid, and her mother was from Spain. We understood long childhood plane rides and speaking another language. She had notebooks covered in glittery butterflies like a child, and her eyebrows were almost always furrowed, leaving a permanent crease. The rest of her skin was smooth, almost transparent — you wouldn’t think she was nearly 32. She looked like a wise 12-year-old. She was a bit pigeon-toed, and I would joke to the doves that roosted outside our bedroom, “She’s here! She’s here, your very own cousin!” Teresa’s face was either laughing or not laughing, perfectly serious or perfectly playful. She drank two cups of coffee every morning, getting very caffeinated and excited about her projects, then crashing out on the couch for the afternoon. I liked holding her lightly around the wrist when we went on walks, kicking up leaves.

Oh, Teresa of the many charms! Of course someone would fall in love with your butterfly notebooks and pigeon toes and bony wrists. It only took three weeks for her, at a winter artist residency. When Teresa picked me up from my holiday visit in Alaska, she had just gotten back from New England. I thought we were being progressive and interesting, spending the holidays apart: me with my family, and her making art in the woods. That was very foolish of me. That place was romantic. A handful of artists and writers, candlelit dinners, snow and cabins. Of course, Teresa would leave me for someone she’d met there. “How predictable,” I

Rosemary Mayer, Moon Tent , October 2, 6:45 p.m – October 3, 5:27 a.m., 1972. Courtesy of The Estate of Rosemary Mayer.

told her, in a bitter moment during our breakup, which was spread out over several days like a soiled garment spread out on a railing.

When I first met Teresa, she reminded me of a young woman who played the upright bass in my middle school orchestra. This creature had the small, compact body of a gymnast, the square face and fingers of a man, and a blonde horsey ponytail. She had to stand up on a stool to play the bass, and she did it expertly and with great expression.

Teresa was like that. She had a magical, nerdy quality that made you sure she’d ridden horses as a girl, and an intellectual rigor that blew away any notions of quaintness. She read queer theory in bed long after I’d fallen asleep, and she was successful, having received an NEA grant for her sculptures made from twigs and other natural flotsam and jetsam.

“Is that how you think of it?” she’d say in her Spanish accent, shaking her head. “Flotsam and jetsam?”

“The most charming and profound flotsam and jetsam!”

And she would throw me to the bed with her surprising strength, bite the fat part of my arm, and leave me there.

Maybe I wasn’t the best at describing her work; maybe that was one of my failures, or a symptom of a larger failure.

What was my largest failure? I was, perhaps, her dull corporate bride. But I had been proud to support Teresa. I liked that my steady paycheck meant she could clear her slate of freelance gigs and go to residencies or conferences or a weeklong trip to New York City when she wanted. It gave meaning to my hours at the office, to think of her at home, reading under the yellow light of a table lamp, while the sky darkened in my office. Teresa made fun of me here, too, saying I was trying to recreate the patriarchy, but I was forgetting that she actually had her own money. “Generational wealth, baby,” she said, kissing me under the ear. She liked my nascent jowls.

“Yeah, but you don’t pay rent.”

“That’s because you insist on me not paying rent.” And Teresa would get up, taking her book of incomprehensible and formidable theory, and go make couscous to appease me.

I knew Teresa, and I knew she would not be back. She was a quick, decisive person, and she had made her decision. One early February morning, she rolled her suitcase out of our door and gate. With her French braid she looked like a child going off to school. Only her expensive boots gave her away as a grown, beautiful woman, about to get on a plane, about to meet a new lover.

Back inside the house, the dough I’d made the night before was pushing past its plastic wrap. And so I made my grief bread, and as soon as it was done went on the first of many long, desperate walks around the neighborhood, determined to spend as little time as possible in the house, with the mugs Teresa had left behind. I was an unwanted bit among other unwanted bits, and the sourdough starter.

I had a nightmare that Teresa came back as a weird grub-baby creeping along the living room floor toward me. I slept poorly, not used to being alone. I lured people, platonic and otherwise, to my bed so I could sleep. And ran out of the house first thing in the morning, almost gasping for air.

It was March, past midnight, and I had stayed up late. When I turned off all the lights and got into bed, I remembered that I had to knead the dough again and let the starter belch.

I did not like going into the dark kitchen alone. I did not like turning on the light and anticipating the dashes of cockroaches on the floor, in the sink, creeping over the clean, drying dishes with their disgusting feet, depositing their egg sacs on our countertops, ducking into the food disposal for wet scraps. But I was not ready for what was to come, which was so much worse.

When I had kneaded the dough and took the lid off the starter jar, I saw a face straining in the sourdough, a suffering face, not unlike an anthropomorphized moon in a children’s book. I quickly put the lid back on, but it was too late, because the demon was already standing next to me: a middle-aged man with long gray greasy hair, one side of his mouth malformed, revealing his black rotting teeth. His small eyes were all black with no whites, just like in the horror movies my Mama and sister love.

The demon smiled at me with his evil mouth.

Then he put his hand in the food disposal, flicked the switch to On, and made me watch.

I staggered over to the dining table where my dough was rising again in its bowl, and sat down. Why didn’t I run back to bed? Somehow I couldn’t.

There was a paw on my shoulder. Not the demon’s mangled hand, but the heavy warm hand of the house dweller, the spirit of the house, the domovoi. I’d never seen a domovoi before, but I recognized him immediately: a little stooped in the shoulders, a little depressed. A sensitive man with no one to talk to.

The domovoi sat down in the chair across from me at the table and folded his arms in front of him, like a man waiting for his beer at a bar. Or a chaperone. He had appeared so that I would not be alone with the demon, and that was kind of him. But it was a little much to be meeting both of them at once.

I had assumed that my house did not have a domovoi, due to my culturally impoverished American life. No mythical Slavic being would want to inhabit it. Maybe the domovoi had arrived with the starter? Had a bit of domovoi been collected wild from the air of my parents’ house, along with the yeast? Or maybe this was my grandmother’s domovoi, the one from the dachya.

The domovoi was gentle as an animal, and I took a deep breath. I could hear the demon’s hand dripping blood on the kitchen floor, and I stared at the patient, hairy arms of the domovoi. Patient as grass, patient as death itself, as a relative sitting with a little crying girl at a birthday party.

So I remembered what the Buddhists say, how you must have tea with your demons. And I said to the demon, without looking at him:

“Okay. Come over. Please have a seat.”

And he sat next to the domovoi, so that I was facing him, and the domovoi was between us like a couples counselor.

I put the kettle on to boil, set out three cups and three bags of green tea.

I appreciated that the demon kept his mangled hand under the table. When I finally looked at him, it took all the bravery I had.

He had those black eyes, but sometimes the ink would drain from them and I’d see blue eyes with red vessels, wrinkles. His gray hair hung down straight down

Rosemary Mayer, Mooring Knot, 1978, olored pencil and graphite on paper, 15 1/8 x 12 inches. Courtesy of The Estate of Rosemary Mayer.

his torso, and he wore a flannel shirt and light blue jeans.

The evil one and the good one stared at each other, and at me, but there was no animosity, only kinship between them. The comfort of childhood friends. They both laughed when I offered them tea, the domovoi through his hairy hand and the demon behind his mangled one, which he politely put away after dripping blood on the table.

As we drank our tea, I had an eerie feeling, the color of my great-grandfather’s potatoes and my great-grandmother’s soul rising from the chimney. A raw color, wild and uneasy. When my grandmother made her starter, had she caught this uneasiness along with the yeast from the air? She had mixed it in with her hands, and it had fed us. It was ours.

The curse, blind as a potato.

The curse, hard as a turnip.

All things buried in the earth, wanting to come out when they’ve been nourished.

The domovoi reached over and patted me on the back. The three of us blew on our tea and looked at each other.

The domovoi reminded me of a mournful dog my family had once had, before we really understood dogs. Mournful but quiet. Muffled. He was wearing a faded olive green T-shirt with a small hole near the collar. He had the face of a bearlike creature and the air of a gentle uncle, the kind who mopes around the house when he visits, doesn’t know how to talk about his feelings, and helps you put up a bookshelf.

The demon had the air of a demon.

Even quietly drinking tea, the demon was relentless. He stared and grinned at me with his broken face. He dribbled blood on the floor. In the demon’s tattered hand, in his inky eyes were all the visits he would make for the rest of my days, all the deaths to come. Again and again I would have that cold feeling in my belly as I made my midnight dough.

At least the domovoi was easy to love. I wanted to go out in a boat with the domovoi, eat crackers with him by a lake, wanted to watch movies with the domovoi and have him wordlessly explain algebra, his hairy fingers drawing figures in the air. I could imagine us clipping our nails together in the tub. He would be a good bather; he’d know how to bathe himself and others.

I did not much care for the demon. The closer I looked, the more the demon looked like a punk farmer, with his flannel shirt and jeans and irreverent long hair. What was he, German? Wisconsinonian? A thespian? A dilettante?

I thought these things as I looked harder into his face. “Oh, Jesus,” I said, and his eyes filled up with ink again, and he grinned and I saw his rotten teeth which seemed to be moving larvally.

And then I knew what I needed to do.

“Breathe into my face,” I said to the demon. “Get close.”

And he did. He put his face into my face, his face of rot and pain, and in his exhale his face seemed to dissolve around me. I smelled decay and old wells and dead grass, I smelled stone and asphalt and dirt. I smelled rain in a village, an old pail. Loam. Lakewater, and a boat with the water sloshing through it. And then nothing. It was like a cloud had passed. When I opened my eyes the demon was gone, it was just me and the domovoi.

The domovoi raised his eyebrows and shuffled off into the dark part of the house. In bed, my breathing slowed. I had outsmarted the demon, maybe even the

curse. For the rest of that night I slept well, proud of myself.

But the demon did not go away. The domovoi stuck around, too.

I threw the starter away after that first night, but later I dug it out of the trash. It was too precious a connection to my mother and grandmother, to the dachya.

So I kept making bread, and as I kneaded, the demon and the domovoi would lurk.

Sometimes I played classical music to keep us company. The demon seemed to like it, especially Chopin. He danced with the domovoi, a slow dance at a middle school party. The demon’s mangled hand dangling from the domovoi’s shoulder, the domovoi with his hands around the demon’s waist.

They danced sweatily; I had turned off the AC. I yawned and went back to bed.

“I wish you all would stop rustling around in the middle of the night,” I said with some malice later that spring, when I woke up to another night of their carousing. The demon and the domovoi were drinking mezcal. The mezcal had been made by a woman from Mexico, a friend of a friend, and I hadn’t even tried it yet — but they had almost emptied out the bottle. Laughing, slapping each other on the shoulders. The demon’s hand looked like a withered octopus, but it no longer bled.

“I am ready to sleep,” I told them. “In general. Like, I am ready for you to be gone.”

They tried to focus their drunk, little eyes on me.

“Can you please, please go away for a little while?”

They burst into laughter.

“Okay, enough of this,” I said. “Let’s go on a walk.”

We headed outside in the dark. I’m not sure what I was thinking — maybe I was hoping to lose them out there.

The demon and the domovoi continued to carouse on the sidewalks. The domovoi pointed at the moon with reverence; the demon slapped his hairy hand away and leered and laughed at the moon. He thought the moon was hilarious.

The demon scampered on his feet and good hand down the street, picking up leaves. He brought the leaves back in his good hand and scattered them over the head of the domovoi, trying to make it pretty.

We wandered around for a while, stumbling into each other.

After a few loops around the park they started to get tired and droopy, and the demon even started whimpering, from the cold I guess.

“There, there.” I pet the demon awkwardly on his flannel shoulder, using the back of my hand, and led them back to the house.

I left them in the guest bathroom to sleepily comb each other’s hair with their fingernails, picking out insects and eating them, perhaps.

Soon it was summer, I couldn’t host those two anymore. The demon, at least, needed to go.

“I know you will come back,” I told the demon. “And when you do, you will be welcome,” I added with gritted teeth.

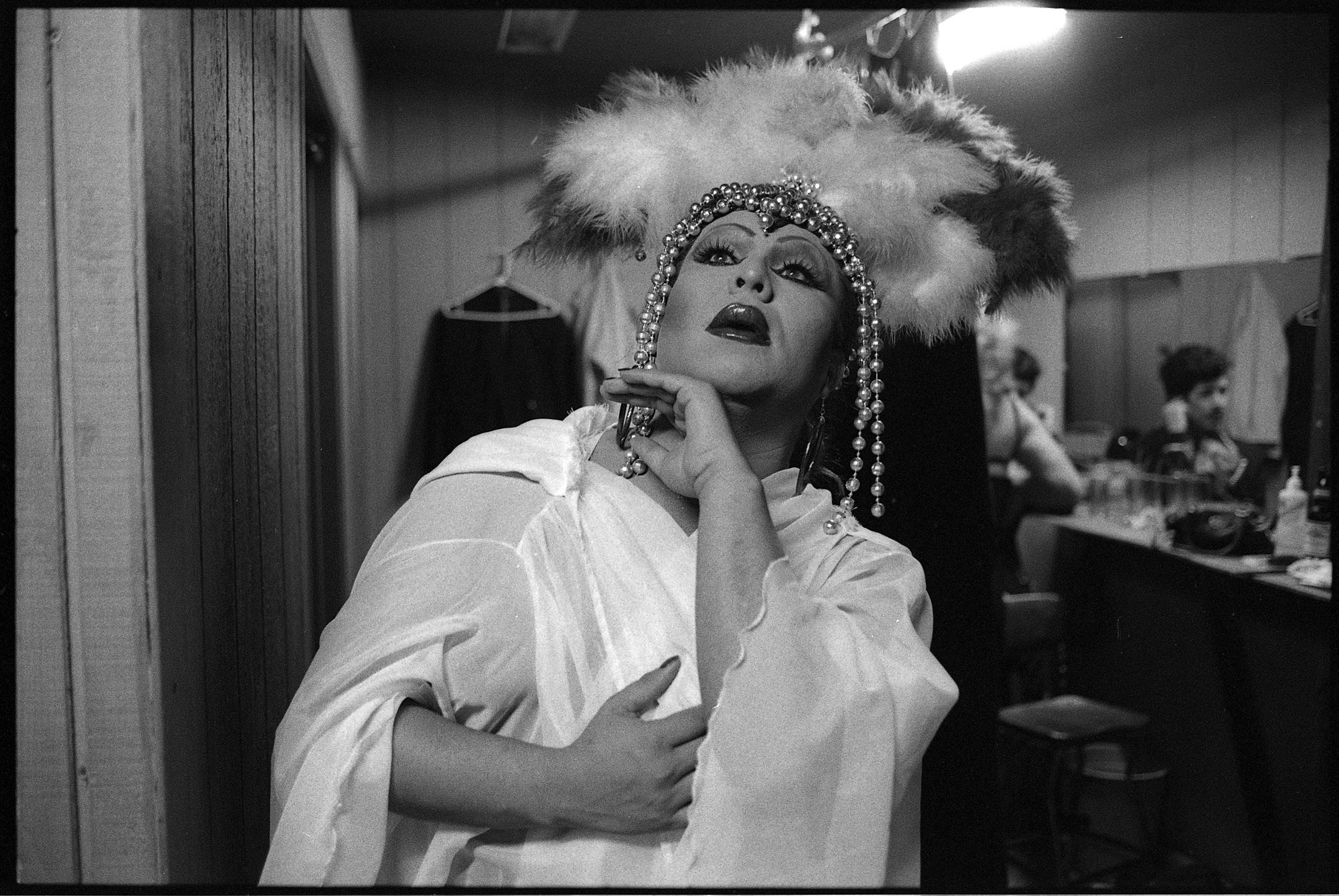

Reynaldo Rivera, Untitled (Two Girls, Los Angeles), 1994. Courtesy of the artist.

I left the two beings to say their goodbyes. In the nights to come, I heard the domovoi knocking around, a little melancholy to be alone again. He busied himself with the sink faucet, making it leaky and then making it unleaky, turning the ice maker on and off, reorganizing my tea selection to his liking (the faces of the tea boxes pressed together, as if kissing). He sampled little bits of my bread loaves approvingly. I thought of him having his midnight tea alone, missing his demon friend, like a sasquatch in a lonely diner.

I went to work and schemed for the future and made bread loaves, each more beautiful than the last, each design cut into the top more intricate. I felt the promise I had felt before — growth, mastery, life yielding to me like dough. The feeling of knowing how to handle it, when to let the dough rest and when to approach. Drinking from the goblet of metaphor again, the golden liquid in my veins, making sense of things.

Often, I was appalled to think about a conversation I’d had with my mother that winter, before Teresa left.

“Life is very difficult,” she’d said one night after dinner.

And I had said: “In what way?”

My ancestors had wondered about the meaning of life. They were philosophers, holy men, authors. Before Siberia, before the labor camp and the potatoes and the curse, my great-grandfather Oleg sat at a rough wood table, like the one I had shared with the demon and the domovoi, and thought about his sermon.

Oleg barely notices the plate of blini and the pitcher of cream his wife places in front of him. Small windows of the log house letting in some dappled light. An icon in one of the corners. Children playing outside, making the sounds children always make.

My great-grandfather, deep in thought. Revolution coming for them, and then famine, but not yet. Maria pouring tea from the samovar, her intelligent and sturdy movements, her hard shoes on the wooden floor. Stomping out the shadows under her shoes with every step.

Maria asks Oleg a question about his tea. He stares at her with a benign, cloudy look. She shakes her head, pours cream into his tea from the pitcher. “Ah, the cream,” he says, “thank you.” She smiles to herself, and a fat fly follows her back to the stove. (A century later, Teresa would bring me tea and I’d register the cup minutes later. Was that why she left me? Oh Teresa, how had we even come to know each other? Your family from one end of Europe, mine from a place where the fields smelled bitter and hot with trampled grass. How could you have left me, when you knew how alone and strange I was, under the corporate bride exterior?)

Cottonwoods and birches by the wooden fence, a horse snorting in the neighbor’s yard. Handsome horse, Oleg thinks. Irritable though. The sermon would begin with an image of horses … But not the white horse and the black horse, like in Plato. Too simple. Such morality disgusts me. The sermon must be about the beauty of the horse.