8 minute read

THE SANDBOX

ANNETTE WEISSER

When Aron was beginning to walk, Nora took him to the playgrounds around Echo Park and Silver Lake. On weekday mornings, these playgrounds were usually populated by pale pink toddlers and their nannies, most of whom were Latina. Nora noticed how they arrived, one by one, pushing the kids in expensive strollers, settling down at the picnic tables. It wasn’t the same group every time, but after a while Nora recognized many of them, especially two older women with long gray hair that they wore sometimes in tight braids down their backs, sometimes clipped around their heads Frida Kahlo–style. The nannies presided over the younger, chattier kids who could have been their daughters.

Advertisement

They laughed in Spanish and shared huge amounts of Salvadoran and Mexican food that they brought for themselves in plastic bags while occasionally feeding the kids healthy snacks from colorful Tupperware boxes. They showed each other cell phone images of their own children and grandchildren, catching up on what was happening in their lives, while their charges played more or less unsupervised in the sandbox. They clearly coordinated these outings, stealing some private time from their employers, making good on the long hours on public transport that they weren’t usually paid for.

Sometimes a kid got in trouble, for example, by falling down the concrete steps that lead down into the sandbox. The kid would start to cry, inspiring others to cry, too. Aron would usually take advantage of the distraction and grab whatever toy he had laid eyes on, making the other kids even more upset. Nora would watch these scenes from afar and wait for one of the nannies to sort out the situation. Every time this happened, she noticed an unwillingness, a slight hesitation, before one of the nannies got up. But as soon as the nanny would pick up the distressed toddler, all that went away immediately, and she would comfort the child with professional amenability.

That would be the moment when Nora came in, chiding Aron for taking the other kid’s toy, prying it from his little brown hand, shooting him a glance that was meant to say: I know this isn’t a big deal, and I’m only doing this because this is what’s expected of me, I hope you understand.

The symmetry of the situation — the woman shushing the red-faced toddler on her arm, his blue eyes overflowing with tears, and Nora wrangling Aron, his black eyes angry over the loss of the toy — made her wonder every time if the other woman was aware of it as well. The easy legibility of it, the way it renders race and class relations in this city completely obvious. Nora would smile at the nanny, trying to convey a vague sense of complicity. They would both return to their positions across the playground, the nanny to the others at the picnic table, Nora to her corner in the shade and her iPhone.

It’s a late September morning and already the sun has lain siege on the city for many hours. The heat has penetrated every corner, even the shadiest ones. Nora takes Aron to the playground because she can’t stand the heat inside their apartment, and from here she plans to head to the air-conditioned public library for a couple of hours. At the playground, the usual gathering of nannies, but apart from them and Nora, no other parents show up on this sweltering Friday morning. As soon as the nannies arrive, they diligently put sunscreen and hats on the kids before releasing them into the sandbox. Would they do the same for their own children, Nora wonders.

“Mexicans don’t use sunscreen,” is what a Mexican American social worker once told her, before the adoption, when she was a caregiver and the Department of Children and Family Services was responsible for Aron’s well-being.

“Because we’re stupid. Make sure you

do.”

But Nora doesn’t use sunscreen either, out of a vague indifference for her own, and now, by extension, Aron’s wellbeing. Why she rarely flosses, protects herself against UV-radiation, or still

smokes when basically all her friends quit years ago? Working-class fatalism, she explains to herself.

But that’s not the only reason.

“You don’t have any sense of the future,” an old boyfriend told her more than once. And it’s true. To Nora, the future is a grayish fog, into which all the little arrows that the people of the present send off simply disappear. If a meteorite hit the Earth, or a nuclear power plant imploded, or war broke out, or climate change rendered life on earth into a drawn-out agony, a sunburn — even a bad one — would be of no concern anymore. All her life, Nora found it hard to negotiate these apocalyptic scenarios with the petty nuisances of everyday life.

She brought a book but not enough water for herself and Aron. They would need to move on to the public library very soon. She can’t wait to get out of this vicious heat. But Aron looks happy; he’s busy building volcanoes in the sandbox and trying to get the other kids interested in his project. Two of them use their hats as buckets to move sand around. Nora recedes further into the shade of the recreation center right next to the playground.

She’s now almost out of Aron’s sight.

She stretches out on a concrete bench that had retained a tiny bit of its early morning cool. She can feel the cool through her summer dress, and her body relaxes into it. She takes off her sunglasses to read, but even in the shade the whitehot light irritates her eyes. She slips them back on. The heat around her turns from viscous to solid, inescapable. She longs for the cool, quiet reading room of the library, or simply the next Starbucks. Fragments from last night’s dream return: a tiny baby bobs on top of very regular waves. Nora’s in a row boat, and the baby drifts further and further away. Nora rows frantically to rescue the baby, but the boat doesn’t move an inch. Then she realizes that the waves are made of plywood, and the boat is fixed on a metal contraption at the center of a stage. From out of the darkness, an audience watches her futile attempts to save her baby, now disappearing behind the painted horizon …

Nora wakes up from an eerie, growling sound and immediately notices that the light has changed. Is it already that late? How long had she been sleeping? Startled and guilty, she jumps up to check on Aron. She sees him standing in the middle of the sandbox, mortified, looking up the jungle gym.

The nannies crouch on top of it.

Two squat on top of the plastic roofs at both ends. Two more lurk on top of the monkey bars. The older woman stands at the top of the slide, very straight, arms outstretched. They all face the same direction: toward the sandbox, where their employers’ children run in a dense group from one end to the other and back again, like performers in a Modern Dance piece.

Tiny performers eager to get it right.

Aron sees his mother reappear from out of the shade and turns toward her, but Nora cannot move. She cannot take her eyes off the spectacle of the crouching nannies. Now she can see that the nannies’ mouths are wide open, and that the growling sound is emanating from these … cavities in long, unison waves.

They look like fierce, angry goddesses.

The children continue their choreographed movement while Aron looks at Nora, his big eyes filled with horror,

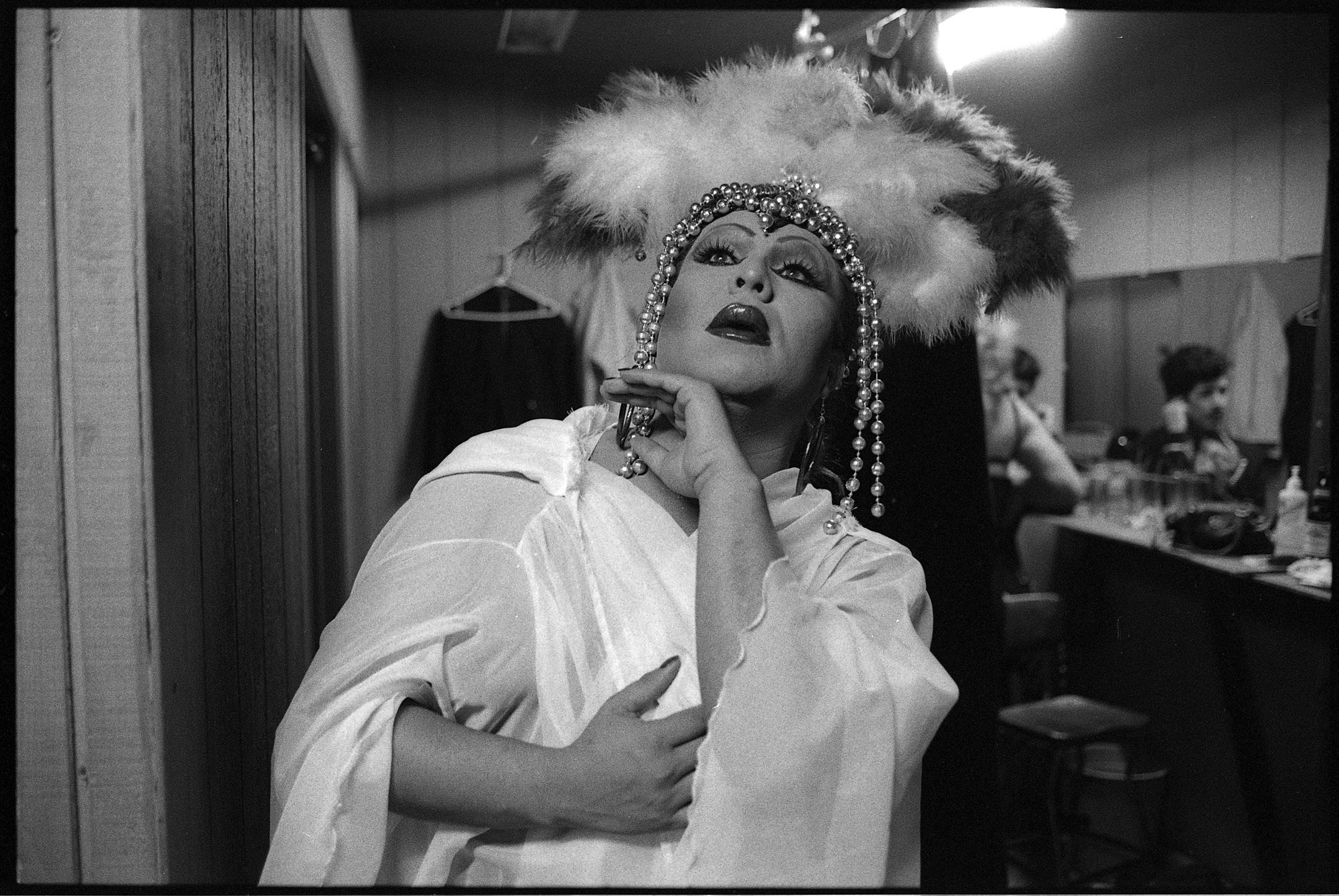

Reynaldo Rivera, Untitled (Cynthia and Juan, Downtown Los Angeles), 1991. Courtesy of the artist.

or amazement. Nora can’t tell from the distance.

Then, the growling abruptly stops. The women close their mouths, and after a short while they reopen them again simultaneously. Now light emerges from within. The light climbs up and then out of their mouths, dripping from their chins, and dissolves into the air.

Little by little, the bright daylight returns.

Nora feels Aron’s gaze on her, and his expectation for her to do something, anything, but she is mortified. Then there’s a loud bang behind her back. She swirls around and sees that the office door of the recreation center has flung wide open. An employee pushes a wheelbarrow, piled high with crates of water bottles, out of the office and toward the basketball court.

“Want one? It’s a hot day today!” He plucks a bottle from an open crate and throws it at her. Nora tries to catch it, but her hands grasp nothing, and the bottle rolls away from her on the tiled floor.

“Sorry for that,” the guy says over his shoulder and pushes the wheelbarrow through the open door of the basketball court.

Nora bends down to grab the bottle.

When she looks up again, the nannies are gone. Or rather, they’re back at the picnic table, and a heartbeat later they storm down the steps and into the sandbox because one of the kids has a bloody nose. The girl cries hysterically, and the other kids chime in, driving each other into a screaming frenzy. Now their nannies are all over them, wiping wet faces, blowing noses, providing water and snacks, calming the kids in their care.

The screaming ebbs away.

“What happened,” Nora asks Aron as she picks him up and carries him toward the concrete bench. “I don’t know,” he says, “suddenly the sun was gone. And you were gone, too.”

“Where were you,” he says in a neutral tone, and instead of answering Nora hands him the water bottle. They both take deep sips from the bottle until it’s empty. Then Nora gathers Aron’s toys from the sandbox, straps him into the stroller and leaves the playground.

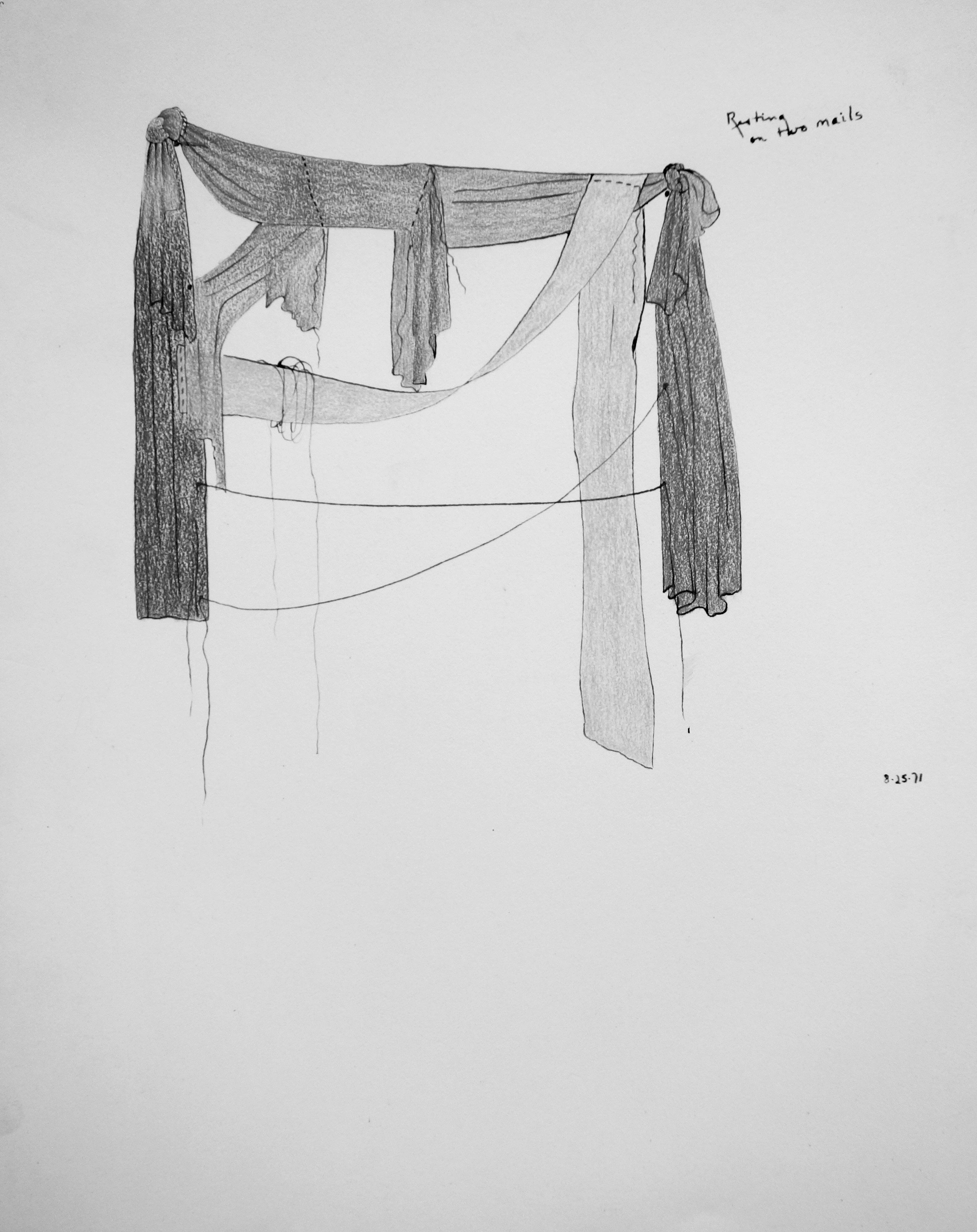

Reynaldo Rivera, Untitled (Performers, La Plaza), 1992. Courtesy of the artist.