2 minute read

FALLING BODIES

DEBORAH PAREDEZ

I am not alone in watching my body giving up its truths, the dark taint of the dye job giving way to the gray, the fallen breasts, the slope and folds of my mother-marked belly mound.

Advertisement

I’m not yet fifty and already I’ve outlived some I’ve seen naked, the lovers I left, the children I watched die. I’ve long known how to look for the bullet left lodged in the chamber when unloading the gun.

My aim isn’t so good nor my vision. It’s getting harder and harder to read without pushing the page farther from my eyes.

I haven’t seen Tía since before

the outbreak, only the sign outside the nursing home proclaiming its name: Buena Vida.

In another time of plague, Galileo observed the speed of falling bodies, how, no matter the differing weight of two objects, falling is an equalizing force. Imagine them, he wrote, joining together while falling.

Sometimes when you watch someone die the only sound you hear is your own shredded breath. Other times only their ragged gasps rending the garment of this realm.

I watch the circling hand touch every number, hear the seconds stacking themselves into minutes hours days weeks months, the teetering years collapsing behind me, before me.

I’ve had to give up running since I tore something in my hip the same one where years ago I rested the baby and years before that I dipped and flared on the dancefloor.

My back now gives way when I bend over to pull the load of soaked clothes from the machine. The doctor

says only resistance and movement will begin to repair what’s torn.

At the end of the march I bend toward the ground with the others kneeling in silence for eight minutes forty-six seconds, spinning hover of helicopter blades and my daughter’s fidgeting hands the only sounds I hear.

At the end of his life, halfblinded by cataracts, Galileo still found a way to measure the distance between bodies scattered across the sky, observed the ways the moon rocked itself back and forth as if saying no against the night.

My daughter watches her dancing body on the video she’s made in the living room. Another brown girl has filmed us all kneeling. Another woman’s daughter has taken a cell phone video of a man as he is murdered in the street.

All the girls watching.

When we watch, we watch someone, someone maybe we love or someone maybe we don’t even know, someone who is someone’s grown child dying under the knee of another, the sound we hear is his muddled breath, his crying out for his mother, long gone and risen and rocking and rocking and rocking him still.

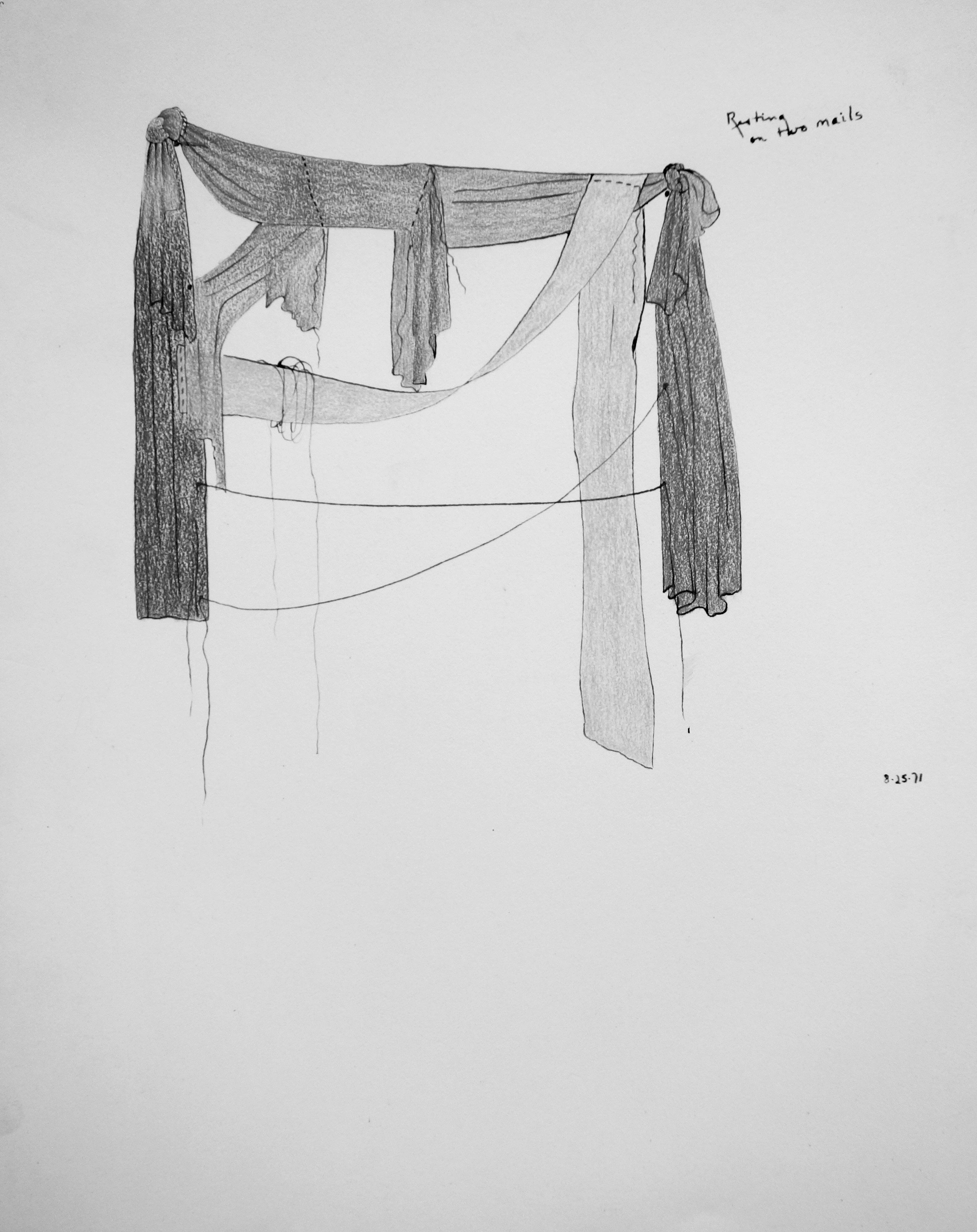

Pages from the Journal of Rosemary Mayer, 1969–1971. Courtesy of The Estate of Rosemary Mayer.