HOW GREEN SPACE IS NURTURING NEIGHBORHOODS IN CHICAGO PLUS: TPL’S IMPACT ON NATIONAL PARKS, COOL SCHOOLYARDS IN DALLAS, AND PARK-BUILDING TO BRIDGE DIVIDES NATIONWIDE

IS DECEMBER 3

DONATE THROUGH MIDNIGHT ON TUESDAY, DECEMBER 3, AND YOUR GIFT WILL BE TRIPLED.

Your year-end, tax-deductible contribution will protect beloved outdoor places and create new ones for future generations.

Thank you for your support!

How

With Black culture and public land as tools for change, Chicago leaders are building fruitful relationships with TPL’s help.

From combatting climate change to improving health and learning outcomes, Community Schoolyards® projects are a sustainable solution to the nation’s need for more parks.

Because of an ambitious plan that involves residents in its visioning and construction, India Basin Waterfront Park serves as a model for enhancing communities and reducing displacement.

With a variety of ways to give, we offer something to suit everyone.

Use the envelope bound inside this magazine to send your gift, or donate online and learn about more ways to give at tpl.org/support .

Simplify your charitable giving and meet your philanthropic goals by giving through your donor-advised fund. Learn more at tpl.org/daf.

The holiday season is the perfect time to share your love of nature and outdoor adventures with others. Make a difference and honor someone special with a tribute gift.

Donate $1,000 or more annually and receive the recognition due a champion, such as invitations to special events and insider updates on our projects. Call 415.495.4014 or email champions@tpl.org to learn more.

Consider including us in your will or estate plan, learn about the benefits of designating retirement funds to TPL, and explore other tax-wise ways to give. Call 202.856.3748 or email plannedgiving@tpl.org to learn more.

Car recycling benefits both people and the environment by conserving natural resources, reducing pollution, and lessening energy consumption. Call 855.500.RIDE (7433) or visit tpl.org/cars to get started.

Scan with your mobile device’s camera to make a gift today!

Trust for Public Land depends on your support. You make our work possible.

tpl.org/support

From the President · 11

Dr. Carrie Besnette Hauser, TPL’s new president and CEO, shares what drew her to the role and how she connects to our mission.

Board Spotlight · 12

Get to know Anton Seals Jr.

First Look · 13

Camping tips from a pro, transformation at scale through our Community Schoolyards® initiative, growing America’s national parks, and a conversation about health and the outdoors.

On Topic · 58

A roundup of insightful book, film, and podcast recommendations from partners and staff.

TPL Near Me · 60

Small-business owners in Trinidad, Colorado, look to Fishers Peak State Park for a brighter future.

Member Center · 62

Offices · 63

Trail’s End · 64

Parks can connect us to family and friends in sometimes surprising ways.

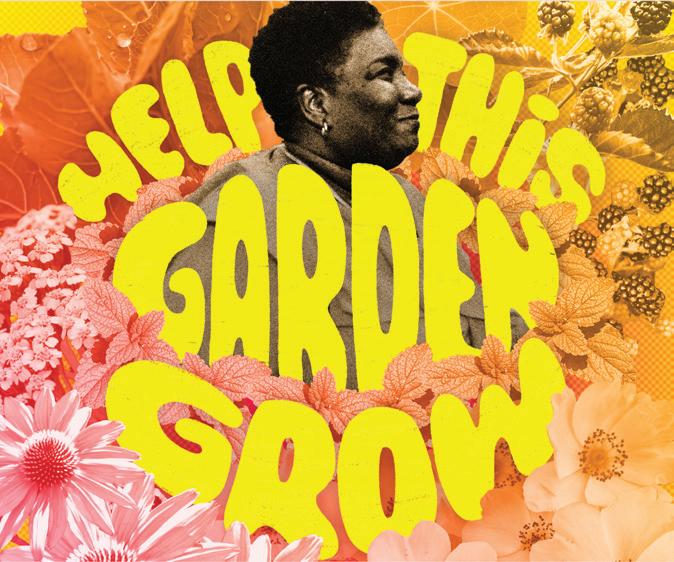

on the cover

Naomi Davis, founder and CEO of nonprofit Blacks in Green, stands in the Mamie Till-Mobley Forgiveness Garden, which TPL helped improve, on Chicago’s South Side.

Photo: Gracie Hammond

One of the original National Scenic Trails established by Congress in 1968, the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) features some of the most beautiful and diverse terrain in the western U.S. It traverses 26 national forests and seven national parks. Trust for Public Land has protected over 50,000 acres along the trail, with more in the works, ensuring this special route will continue to thrive for future generations of hikers to enjoy. In this issue, discover more National Park Service sites TPL has helped expand.

Page · 16

Trust for Public Land’s Community Schoolyards® projects are vibrant green oases where kids can play and learn outdoors. If all of our nation’s schoolyards were improved in this way—and opened to the community after hours—80 million people would have access to a new park within a 10-minute walk of home. In Dallas, Texas, we talked to students, teachers, and residents to learn how they’ve benefited from these safe, climatesmart green spaces. Read more about TPL Community Schoolyards projects in this issue.

Page · 42

Once completed, India Basin Waterfront Park will total over 10 acres and close a critical gap in the San Francisco Bay Trail, bringing green space to the more than 35,000 residents who live within a mile of it. Planned park features include local art, a floating dock for recreational water use, and landscape restoration to benefit wildlife and combat sea level rise. The best part? It’s being built by—and with direct input from—the people who love it most, reflecting their community’s rich history and identity and providing lasting economic and health benefits for generations to come. Read more about this remarkable park in this issue.

Page · 50

tpl.org/champions | champions@ tpl.org

Become a Conservation Champion, and help us connect even more people to the outdoors with your annual leadership-level contribution of $1,000 or more.

Discover the impact you’ll have as a Conservation Champion by contacting us at 415.495.4014 or champions@tpl.org.

Join us online for project updates, stunning photos, and inspiring stories. Follow us on social media: @trustforpublicland

@TheTrustforPublicLand

@the-trust-for-public-land @tpl_org

TrustforPublicLand

Be sure to tag us in your posts!

Sign up for our emails: tpl.org/email-signup

And listen to our podcast, People. Nature. Big Ideas. tpl.org/podcast

executive editor & publisher

Jennifer Ramsey

editorial director

Deborah Williams

managing editor

Amy McCullough

staff writers

Lisa W. Foderaro

Amy McCullough

Deborah Williams

designers

Rachel Andrade

Miya Su Rowe

Ben Whitesell

media production

manager

Elyse Leyenberger

media coordinator

Amber Garrett

© 2024 Trust for Public Land.

All rights reserved. All In for Outdoors, Community Schoolyards, Connecting Everyone to the Outdoors, Conserving Land for People, Conserving Nature Near You, Creating Parks and Protecting Land for People, Fitness Zone, Land for People, Land&People, LandVote, Northwoods Initiative, Our Land, Outside For All, Outside Matters, ParkEvaluator, Parkology, Parks for People, ParkReviewer, ParkScore, ParkServe, Parks Unite Us, 10-Minute Walk, The Trust for Our Land, Trust for Public Land, TPL, and all other names of Trust for Public Land programs referenced herein, as well as their logos, are registered or common-law trademarks of Trust for Public Land.

Whether in Colorado’s high Rocky Mountains, where I live now, or in Arizona’s Grand Canyon, near where I grew up, I’ve always felt a profound connection to the outdoors.

From climbing to the Mount Everest basecamp and summiting Mount Kilimanjaro, to rafting iconic and fragile rivers, to daily walks with our dog, Gracie, nature has been a cornerstone of my life. These experiences have reinforced my belief that access to nature is essential and must be championed for all. I’ve dedicated my career to public service, community engagement, and the promotion of equitable access to education and the outdoors.

I’m honored to join Trust for Public Land as its next president and CEO. TPL forges paths—both literally and figuratively—to bring the benefits of outdoor experiences and nature to millions, including and especially those who haven’t always seen themselves reflected in our shared public spaces.

It will be a privilege to build upon the successes of my predecessor, Diane Regas, whose leadership significantly enhanced TPL’s impact nationwide and elevated the national conversation about the power of parks to create equity and opportunity for communities everywhere. As a national organization, TPL must scale its work to connect more people to the benefits and joys of the outdoors while also tailoring its approach to the hyperlocal needs of each community. Two projects that resonate deeply with me illustrate this balance.

In southern Chattanooga, Tennessee, residents of historically underserved neighborhoods have been physically cut off by an old, unused rail corridor as a renaissance in the city’s nearby South Broad area unfolded in plain sight but out of reach. But TPL is changing that: from our advocacy efforts and relationship building in Alton Park, we secured a new $20 million EPA grant for that community and are now transforming that railway barrier into the green Alton Park Connector trail, designed and activated through our uniquely cooperative,

community-centered approach that reflects local identity and needs.

Similarly, in the Bayview–Hunters Point neighborhood of San Francisco, California, India Basin Waterfront Park is a shining example of centering community while creating recreational opportunities and addressing environmental justice. As you’ll read on page 50, the park’s groundbreaking Equitable Development Plan aims to prevent displacement and ensures that residents who have been deeply involved in planning and building this beautiful space will benefit from it for generations to come.

Trust for Public Land’s work addresses urgent challenges. Green spaces are essential for everyone’s well-being, for managing stormwater and reducing urban heat, and for capturing carbon and providing environmental resilience to combat climate change.

Parks also bolster democracy, address social isolation, and bridge divisions, as highlighted in the On Common Ground profiles from East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana, that you’ll read in this issue (page 26).

As the organization moves into its next 50 years, your support will help advance TPL’s mission to protect and create all kinds of special outdoor public places and spaces.

With optimism and determination, I look forward to our journey together to shape the future of our communities and the health of our planet. I am eager to lead TPL into its next chapter, continuing to innovate, advocate, and collaborate to make the outdoors accessible and welcoming for all.

Carrie Besnette Hauser, PHD president & ceo

chair

Lucas St. Clair

Jodi Archambault

J. Franklin Farrow

Mickey Fearn

Jody S. Gill

Anita Graham

Carrie Besnette Hauser

Allegra “Happy” Haynes

Alex Martin Johnson

Jennifer Jones

Philip June

Chris Knight

Christopher G. Lea

Joseph E. Lipscomb

Eliot Merrill

Ignacia S. Moreno

Julie Parish

Michael Parish

David Poppe

Thomas S. Reeve

Laura Richards

Ted Roosevelt V

Anton Seals Jr.

Sheryl Crockett Tishman

F. Jerome Tone

Taylor Toynes

Jerome C. Vascellaro

Lindi von Mutius

Alvin Warren

Keith E. Weaver

Susan D. Whiting

Florence Williams

Kenneth Wong

National Board of Directors since 2024

AS LEAD STEWARD AND COFOUNDER OF Grow Greater Englewood, Anton Seals Jr. comes to Trust for Public Land’s National Board of Directors with a wealth of experience in community organizing, operations, and strategic planning. Established in 2017, Grow Greater Englewood uses food economies and land sovereignty to help residents of Chicago’s South Side grow and thrive— much like the land they activate as farms, gardens, and community green spaces. Seals got involved with TPL while organizing the upcoming Englewood Nature Trail, a public green space that will anchor the nation’s first agro-eco district (read more on page 32). We asked what inspired him to join our board.

How did you first hear about TPL? From the Bloomingdale Trail project (also known as The 606). I’ve witnessed the ongoing growth of this organization since then. TPL has a collective of committed and inspired people who continue to expand the work of conservation and land stewardship.

What part of TPL’s work most reflects your own values and goals? Community, health, and climate are essential to work we are doing on the South Side of Chicago and align with TPL’s core mission. At Grow Greater Englewood, we believe in long-term efforts to create holistic communities. We aim to improve the overall well-being of life within spaces that were historically marginalized and have degraded air and water quality and limited services.

TPL and its broad network across the U.S. can further the conversation, informing the public interest and building trust. The value of collective work and responsibility—also known as ujima, or the third principle of Kwanzaa—is where I see inroads.

What challenges do you think TPL is uniquely poised to address? First, addressing the evolving

public health crisis in our country by providing access to nature. But also, TPL can bring more voices to the conservation table and redefine the work we do as an essential need of all communities. I see TPL making sure we have a much more racially diverse sector that helps steward Mother Earth.

What are you most looking forward to achieving as a member of TPL’s board? Making sure that I continue to center voices that are critical to defining conservation, sovereignty, and open spaces in the 21st century. The preservation of Black land and communities in America is crucially important to the future of our country.

How do you most enjoy connecting to the outdoors? Being a native Chicago kid, I had the pleasure of growing up a couple blocks from Lake Michigan. Now, I want to work with people repurposing urban land across the country to instill stewardship of the outdoors in others.

learn more @ TPL.ORG/SEALS

TURN THE PAGE FOR:

Pro Camping Tips for Fall

Leveling Up Schoolyards

Building a Network of Outdoor Allies

In the conservation classic A Sand County Almanac, author Aldo Leopold wrote, “When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” His words exemplify what TPL sets out to achieve when we protect land at beloved natural areas such as Zion National Park— ensuring access to spaces that enrich the human experience and connect us to the outdoors in a meaningful way. By leading complex projects with a variety of partners, we ensure remarkable public lands are available to communities nationwide, fostering a love of nature and respect for the outdoors that will grow well into the future. Learn more about our work to protect land at national parks on page 16.

The prospect of sleeping outside—even in the refuge of a tent—can be daunting for those new to camping. Follow these handy camping tips from a seasoned pro for a cozy, comfortable, and memorable outdoor experience.

With L.L.Bean’s Lindsey Johnson

Lindsey Johnson is no stranger to the outdoors. As an Outdoor Discovery Program Coordinator with TPL partner L.L.Bean, she heads expeditions ranging from hiking and kayaking to archery and stand-up paddleboarding in eastern Pennsylvania. For Johnson, a great day at work includes showing others the joy of being outside. Here, she shares her best camping advice for fall and beyond.

1. You needn’t go far. “One of my earliest outdoor memories is setting up our tent in the backyard and learning the ropes from my dad,” says Johnson, who recommends going somewhere you’re comfortable with to start—even if that’s your yard. If you’re outside, you’re closer to nature than you are in your bedroom, she notes. If that feels too pedestrian, locate your closest state park with a campground and start there.

2. Separation from the cold, hard ground is key to your comfort. A sleeping pad goes a long way in keeping you warm and ensuring a good night’s sleep. “For a foam pad, I recommend using one with a metallic layer to help retain heat,” says Johnson. Inflatable pads, on the other hand, can provide more cushion. For the best of both worlds, she suggests stacking one of each for extra comfort plus insulation.

3. Mind your fabrics and layers. When it comes to clothing, Johnson likes to have a base layer, a mid-layer, and an outer shell. The layer closest to your skin should wick perspiration away. Silk, bamboo, and many synthetics are good at wicking; cotton, not so much. Synthetics blended with natural fibers, such as wool or alpaca, have the added bonus of being antimicrobial, so they resist odor. Your mid-layer—fleece is a common

choice—is for insulation. And the outer layer, such as rain gear with vents, should keep environmental moisture out but also be breathable.

4. Don’t underestimate your water bottle. Johnson’s favorite cold weather hack? Use your water bottle as a foot warmer: “On a really cold night, I’ll heat up some water on the campfire while I’m getting ready to turn in,” she says. She then fills her bottle with the warm water, sticks it in her sleeping bag, and lets it radiate through the night. “It’ll warm your toes right up,” she attests. Slip a sock or neck gaiter around the bottle to ensure you won’t get burned if it’s too hot at the start.

5. Be creative. Lots of home items can be repurposed in your camping kit. An old toolbox might become a first aid kit or a caddy for cooking utensils. A doormat you’re about to retire can do wonders at keeping dirt outside your tent—and is a good reminder to leave your boots outside. Johnson likes to bring shower caps for packing shoes in at the end of a trip, especially if it’s muddy where you’re headed.

6. Get tactical about toiletries. If you’re easing into things at a campground with more facilities, such as showers, Johnson’s must-have item is a toiletry organizer. She recommends a water-resistant, hanging version with clear or mesh pockets, which make it easy to see and grab what you need.

For sites with pit toilets, always bring extra toilet paper and hand sanitizer—and secure your personal items when visiting. If your phone, sunglasses, or wallet fall in, “it’s essentially impossible to retrieve them,” says Johnson. Going even more rustic? Take a collapsible shovel, dig a hole, do your business, and cover to leave no trace.

7. Hone your fire game. “I look at fire building as an art form,” says Johnson. “Everybody can do it, but with practice you get to be more of a master at it.” She’s a fan of teepee-shaped fire construction and advises starting with smaller pieces of wood. Her best insider kindling trick is to empty your dryer lint and bring it along. “It catches really fast and is super easy to pack.” Another DIY fire-starter is wine corks soaked in rubbing alcohol. Of course, always ensure there isn’t a burn ban in your area, and use local firewood to reduce the spread of invasive insects.

8. Go with the glow. An easy hack Johnson shares is hanging glow sticks from your tent zippers. “When you get up in the middle of the night to visit the bathroom, you’ll easily find your tent and won’t have to fumble around for the zippers in the dark,” she says.

9. Don’t trip. “Pool noodles are a great way to eliminate the tripping hazard of your tent lines,” says Johnson. Just slice one open along the long side and slide it over your tent lines. The brighter the color, the better.

10. Duct tape is a camper’s best friend. “I always bring a roll tucked in with my supplies,” Johnson shares. When she’s packing extra light, she wraps multiple layers of duct tape around her water bottle, where it naturally ends up on adventures when you might need it. “Use it for a quick tent tear or pole repair, hang a strip at your site as a fly trap, even use it as a last resort for a pesky splinter when you forgot your tweezers.”

11. Engage with nature. “I really like nature journaling,” says Johnson, “and all you need is a piece of paper and a pencil or pen. You can do whatever you want as long as you’re taking the time to observe and reflect on the natural world.”

Another way to engage is to learn something new, whether it’s with field guides or a nature app. “I walk around the campsite, and if I see a flower I’ve never seen before or hear a beautiful bird call, I take a picture or record it,” explains Johnson. While she acknowledges it’s also good to unplug (and you should plan for some phoneless time), a photo or recording can lead to later discoveries.

What could be more fun and empowering than preparing a feast over an open fire with your campmates? A campfire dinner is more than a meal; it’s an event. Here are two of Johnson’s favorite cool-weather dishes, plus a few pointers for success: Chili Food for Chilly Times

• Measure spices out in a bag before leaving home.

• Precut your vegetables so they’re ready to toss in a pot.

• For a group, bring a variety of toppings and let everyone choose their own adventure: shredded cheese and tortilla chips, fresh cilantro and onions, sour cream and Fritos—or all of the above.

• Slice a banana down the side, leaving the peel on.

• Fill it with whatever you want—the sky’s the limit! Suggestions include: – chocolate sauce or pieces – fresh berries or preserves – marshmallows

– peanut butter or chopped nuts

• Wrap it in foil and toss it over the fire.

• Cook for a few minutes; then carefully extract with tongs and allow it to cool.

• Unwrap the foil, grab a fork, and eat it right out of the peel.

Illustration by Nate Padavick

TPL regularly works to secure lands for national parks, scenic trails, monuments, and historic sites?

Here are some of our biggest achievements over the years.

PACIFIC CREST TRAIL

Preserved 50,000+ acres of trail corridor, ensuring recreational access, habitat connectivity, and climate resilience

VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK

Protected a remote ecosystem and an array of cultural sites with 16,000+ acres saved at Pohue Bay

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK

Added 400 acres in the park's largest restoration project to date, expanding visitor access and improving critical wetland habitat and biodiversity

WESTERN U.S.

ZION NATIONAL PARK

Protected 6,700 acres in and around this beloved park, including the iconic Narrows Trail

NICODEMUS NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE

Expanded the oldest and only remaining post-Civil War Black settlement west of the Mississippi River

CUYAHOGA VALLEY NATIONAL PARK

Created this very popular 33,000-acre park, providing opportunities to bike, hike, and paddle for 3 million annual visitors

Protected 100,000+ acres across 14 states-including Maine’s Bald Mountain Pond-benefiting people, wildlife, and climate adaptation

SAGUARO NATIONAL PARK

Saved 2,200+ acres, enhancing access for recreation and preserving wildlife habitat along with many cultural sites

MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK

Preserved key properties in MLK’s childhood neighborhood, visited by millions per year

EASTERN U.S.

TIMUCUAN ECOLOGICAL AND HISTORIC PRESERVE

Saved 100+ acres at Black Hammock Island, a beloved recreational and historic site that supports climate resilience

Our mission to address park equity and improve climate resilience across the country begins with a thoughtful big-picture strategy that puts playgrounds to work.

By Lisa W. Foderaro

For years, Trust for Public Land has pioneered a new way of thinking about often-overlooked schoolyards. Their typical blank asphalt offers little to spark the imagination, and it bakes in the sun and floods in the rain. But our Community Schoolyards® initiative swaps out blacktop for garden beds, native trees, up-to-the-minute play equipment, and outdoor classrooms, transforming recess and turning school grounds into neighborhood parks.

In just the past five years, we’ve ramped up the program and extended its reach to include 50 school districts in more than a dozen states. But the need is so great—and the potential of schoolyards to address equity and climate change so promising—that TPL has embarked on a new strategy. For the first time, we are advocating on all three levels of government—federal, state, and local—with a coordinated strategy on a single priority policy issue: scaling our Community Schoolyards program to become a national standard.

At the state and local levels, there is perhaps no better example of advocating on all fronts than in Los Angeles, California. Only a few years ago, we struggled to convince the school district there to sign off on even a single schoolyard renovation.

That was before Francesca de la Rosa and Juan Altamirano entered the fray. De la Rosa, TPL’s California green schoolyards campaign manager, methodically set out to expand and support the Living Schoolyards Coalition, a group of L.A. nonprofits that includes TPL. Meanwhile, Altamirano, director of government affairs for TPL’s California program, worked the halls of the state capitol, convincing officials to dedicate $120 million to a new statewide green schoolyards program, highlighting its urgency. “We have moved the needle in both getting broader buy-in from the Los Angeles school district and pushing policies forward across the state to advance comprehensive greening,” says de la Rosa.

The result? Five TPL schoolyards are currently in the works in L.A.—plus an additional 40 renovations being led by partners across the district, some of which will adopt elements of our Community Schoolyards model. The model emphasizes climate resilience, educational outcomes, and park access—with schoolyards available to the wider community after school and on weekends.

For Danielle Denk, TPL’s Community Schoolyards initiative director, investing in schoolyards has never been more important. One hundred million Americans don’t have a park within a 10-minute walk of home, including 28 million

When you cross the line into an underfunded school district, there is a very stark reality of inequity. We’re leveraging every single tool in our toolbox to change that and give all children inspiring green spaces to play and learn.”

– DANIELLE DENK, DIRECTOR OF TPL’S COMMUNITY SCHOOLYARDS ® INITIATIVE

children. Add to that the persistent inequities that plague public schools and our nation’s mental health crisis, and the transformation of schoolyards into green spaces that do double duty as neighborhood parks is clearly a win.

“When you see the state of school facilities in a high-wealth community, they have been able to invest in high-quality amenities and green spaces that support learning,” she says. “But when you cross the line into an underfunded school district, there is a very stark reality of inequity. We’re leveraging every single tool in our toolbox to change that and give all children inspiring green spaces to play and learn.”

Until now, funding for Community Schoolyards projects has come mostly from school districts, private philanthropy, and in large cities such as New York, water departments eager to support green infrastructure (think rain gardens and absorbent turf fields). But asking school boards to cover a substantial portion of the costs is tricky since we prioritize districts serving low-income populations.

To unlock funding at the state level, we lobby for continuing, dedicated sources such as lottery revenue or sales tax. “The gold standard would be new stand-alone programs for schoolyards, durably funded by legislatures or approved by voters through ballot measures,” explains David Weinstein, TPL’s western conservation finance director.

Weinstein and his team are also exploring existing state education and conservation funding streams while pursuing one-time appropriations for individual schoolyard projects. One recent success came in Oakland, California, where voters in 2020 approved a $735 million bond for public schools. TPL successfully advocated for a $6 million share to help pay for new schoolyards. And just this year, we launched new programs in 10 states to lobby for additional funding.

In Washington, DC, Jessica Montoya, TPL’s senior director of park equity and federal relations, says a grant program through the U.S. Department of Education would provide critical support for schoolyards. We’re working closely with New Mexico Senator Martin Heinrich, a champion of revitalizing schoolyards, to get support for a bill that would unlock such federal funding.

Montoya is also encouraged that in April of 2024, the Biden administration hosted the first-ever White House Summit for Sustainable and Healthy K-12 School Buildings and Grounds (to which TPL was invited): “We see the administration moving toward more energy-efficient, health-focused schools, and community schoolyards are a great complement to that.”

While the horizon for state and federal funding may be long, and progress is sometimes delayed, TPL staff are fully

JOE SORRENTINO

invested in the work happening on the ground, in the present. Elizabeth Class-Maldonado, the Pennsylvania program director, holds monthly meetings with the Philadelphia school district to maintain momentum. “It’s about showing up,” she says. To date, TPL has completed 15 schoolyards in the city and recently identified three more projects. (Watch a related video at tpl.org/bregy.)

In Sacramento, California, Altamirano has kept the pressure on. Fresh off the success of securing $120 million in state funding, our California team set its sights on a $10 billion school facilities bond being negotiated for the November ballot. As part of this effort, the L.A. teachers’ union got on board, and an editorial in the Los Angeles Times championed the idea, calling the “desolate state” of many schoolyards a “hazard to kids and an environmental injustice.”

“When we first started, we weren’t taken seriously,” Altamirano recalls. “That didn’t deter us. We continued to advocate and organize and wound up with 16 members of the state legislature signing a letter that said they, too, wanted support for community schoolyards.” Thanks to TPL’s efforts to rally support, these projects will be eligible for up to $7.3 billion in grant funding. And we’re building on that momentum at all levels of government and at sites across the country. After all, our public schools already own 2 million acres of land. With Community Schoolyards projects, we can make the most of it.

Turn to page 42 for a deep dive into our Community Schoolyards projects in Dallas, Texas.

When it comes to enjoying the outdoors, it’s not just about finding your place; it’s about finding your people.

One of the biggest barriers to equity in the outdoors is access. But it’s hardly the only one. Here, TPL’s editorial director, Deborah Williams, joins our new health director, Dr. Pooja Sarin Tandon (above), in conversation about how to overcome those barriers—and what it really takes for people to feel welcome outside. Even when we achieve our goal of putting a quality park within 10 minutes of every person in this country, the unfortunate reality is that many people still won’t go. As a practicing pediatrician, Tandon thinks a lot about how we can remedy that situation. It starts, she says, by shifting people’s perceptions of nature and their sense of belonging in it. Ironically, it wasn’t until adulthood that she began to question her own views on the topic.

DEBORAH WILLIAMS: What changed about your perception of nature as you got older?

POOJA TANDON: I broadened my definition of what “outdoorsy” means. Until this became a professional passion for me, I viewed outdoorsy within a typical American or Western framework of what you’d see in an outdoor retailer catalog: rock climbing, camping, activities that take place in the wilderness or faraway outdoor places. Then, as my professional work about the importance of connecting children to nature evolved, I recognized the importance of nearby nature and different ways people, especially children, can connect with nature. I reflected on my own childhood.

You describe your upbringing in your 2022 Ted Talk: “The Power of Belonging in Nature,” and it doesn’t sound as if you felt particularly outdoorsy. I was born in India and spent most of the first 10 years of my life in a pretty urban area in the city of Lucknow. I never went hiking there. I don’t remember ever being in the woods, and I don’t think I even knew what camping meant. But here’s what I did do: We lived in a second-story apartment, and we had a rooftop terrace, and I spent a lot of time up there. In the summertime when it was too hot to be indoors, we would set out cots and sleep under the stars. I have slept on that terrace more than a hundred times.

Do you think experiences like sleeping on the terrace, taking walks around the neighborhood, or having family picnics in the park are ways people experience nearby nature without realizing it?

Yes. It’s a way of connecting with nature that is often undersold and that we don’t always highlight. We should encourage each other to recognize those moments when we find ourselves in nature—to stop and enjoy them. Even these brief respites bring great mental and physical health benefits.

In your Ted Talk, you also bring up the idea of nature mentors and allies, that it’s not only about helping people discover where—but also with whom—they feel safe and inspired outdoors. Can you expand on that?

Sure. I’d describe nature mentors as people who encourage

and guide us into new experiences in nature. Even if you can’t show someone how to use a compass or read a map, you can be a mentor by lending them gear or urging them to examine the veins in a leaf or listen to the sound of the wind. Likewise, we all need one or more nature allies: those folks who are always game to accompany us on an outdoor excursion. Whether we seek out guidance or give it, we become part of a virtuous cycle of outdoor allyship—and those allies are crucial to our having positive experiences outside, which means we’re more likely to do it again.

Your new book, Digging Into Nature [cowritten with Dr. Danette Swanson Glassy], is grounded in your research about the correlation between nature access and health, but it’s really a practical guide for parents and caregivers. Why was that focus important to you?

We’ve seen patients and families from so many different lived experiences, backgrounds, and resources, and we wanted this book to be of service to people facing a range of barriers. That could be anything from their zip code and what their neighborhood has to offer to the physical health status of family members or their own individual health situation, as well as their cultural perceptions about what being outdoors can and should look like.

What I love about the park prescription movement is that it’s a formal acknowledgment that healthcare providers and institutions have a role in connecting people to nature because nature has a role in promoting health and well-being.”

– DR. POOJA SARIN TANDON, TPL HEALTH DIRECTOR

The metrics for proximity and quality of green space that TPL uses are very relevant. And we know from TPL’s and others’ work that having parks and building trails is not enough. This idea of “if you build it, they will come” has been debunked. Different barriers require different solutions.

Can you elaborate—and give an example of a solution?

Most people, no matter their geography or socioeconomics, can relate to the barrier of time poverty. In the book, we acknowledge that many families are juggling jobs, school, homework, activities, and other priorities. So even if they have the desire to go outside more, it’s just hard to fit it into their schedule.

We have a section in the book about this, and we offer some simple ideas. Think about the activities you’re already doing and see if there’s an opportunity to do them outside. Take homework or reading outside, whether to your porch or a nearby park, for example. Kids might otherwise spend that time at the kitchen table or at a desk in their bedroom. You can still get the schoolwork done while also getting your daily dose of fresh air and nature.

You talk a lot in the book about how outdoor playtime, particularly, facilitates children’s development. Interactions in the natural world support all kinds of milestones and the acquisition of life skills. We address the different realms of development—speech, motor, behavioral, emotional.

In the early years, the outdoors offers really unique opportunities for developing motor skills that are hard to create indoors. For example, uneven, inconsistent surfaces

offer challenges at the fine and gross motor level, whether that’s jumping off a log when you’re 2 or climbing a tree when you’re 6. There’s something unique about running through a field uninhibited. Think about the exuberance and motor skills that come from being able to do something in an unconfined space. You can’t find that indoors.

For children of all ages, including teenagers, immersive experiences in nature evoke a sense of awe and attention restoration—those are developmental opportunities in the cognitive and emotional realm that are hard to find inside.

Beyond the nuclear-family level, there are also systems-level solutions. One of these, the concept of park prescriptions, has been gaining momentum. What are your thoughts on the trend toward time spent outdoors as literal medicine?

As physicians, we think about the things that impact our patients’ health. We should prioritize talking to them about getting outdoors and moving their bodies. What I love about the park prescription movement is that it’s a formal acknowledgment that healthcare providers and institutions have a role in connecting people to nature because nature has a role in promoting health and well-being.

But, like any advice from a doctor, people don’t necessarily follow it, especially if it’s in a form that’s generic, like, “Spend X number of minutes outside per day.” That’s where having support from our community is critical for motivating us and helping us overcome our unique barriers to getting outside.

We’re partnering with the Ocmulgee National Park and Preserve Initiative, the Muscogee Nation, and the National Park Service to bring Georgia its first national park.

The world is rife with human-made wonders: consider the Egyptian pyramids, Chichén Itzá, or the moai of Easter Island. Lesser known—but equally fascinating—are the Ocmulgee Mounds in modern-day Georgia, which TPL is working to level up into a full-fledged national park.

Constructed around 900 CE by a cultural group known as the Mississippians—ancestors of the Cherokee and Choctaw Nations, among other Indigenous peoples—the Ocmulgee Mounds have served various purposes, such as housing village chiefs and acting as funerary sites. The mounds evolved over time to accommodate roughly 60 towns (or chiefdoms) comprising the Muscogee Nation, also known as the Creek or, in their own language, Mvskoke (pronounced “mus-KOH-gee” in English).

Now, this land—which has been inhabited by humans for 17,000 years—could become Georgia’s first national park. TPL, in partnership with the Muscogee Nation and the Ocmulgee National Park and Preserve Initiative, is working to elevate the site from national historical park to national park—a move that would contribute an estimated $206.7 million annually in tourism.

The title indicates a certain cachet; our best-known natural attractions, national parks provide scenic destinations, preserve history, protect crucial ecosystems, and often limit consumptive uses such as mining.

Such designation would also honor the Muscogee Nation by establishing a cooperative approach to management that includes both the tribe and the National Park Service. This plan recognizes the tribe’s rich history in the area and pays respect to Indigenous cultural knowledge.

Improvements will enhance the existing historical park and connect it to nearby Bond Swamp National Wildlife Refuge, creating a grand 23,000-acre park along the Ocmulgee River.

Since the 1990s, TPL has preserved nearly 3,000 acres of land that will be integrated into the new national park— signifying our deep recognition of what this area has meant to previous and current generations and what it will mean well into the future.

Turn to page 16 to learn more about our work securing lands for National Park Service sites.

would like to thank the following supporters.

We couldn’t achieve our commitments to climate, equity, community, and health without their generous financial contributions to our mission and our work. Thank you for helping us connect everyone to the outdoors.

For their partnership and support of TPL’s Community Schoolyards® initiative. Guided by their social purpose platform, Mission Every One, Macy’s has helped transform public schoolyards into community parks nationwide, ensuring healthy, livable communities for generations to come. To date, more than $3.7 million has been raised, directly impacting nearly 10,000 students and providing access to green spaces for over 285,000 community members.

Through its Corporate Citizenship program, Northrop Grumman has contributed $1.15 million to enhance community well-being through support of TPL’s SOAR (Security, Open space, and Agricultural Resilience) initiative, Tribal Community Schoolyards Pilot Program, and California Community Schoolyards ® projects. In doing so, Northrop Grumman has helped conserve over 11,000 acres of land for environmental sustainability and national security and transformed schoolyards into culturally relevant spaces to learn and thrive.

For their support of TPL’s transformational work to increase access to public green space in Dallas, Texas. Oncor’s $1 million gift represents their longstanding commitment to our mission and will help us bring more than 17 miles of new trails and three signature parks to historically underserved neighborhoods, providing access to nature for nearly 200,000 residents who don’t currently have a park or trail within 10 minutes of home.

Community Schoolyards ® initiative California; Pennsylvania; Washington, DC; & Washington State

Chattahoochee RiverLands Gateway Park Atlanta, Georgia

Woody Branch Park & Judge Charles R. Rose Community Park Dallas, Texas

Community Schoolyards ® projects, Trails initiative projects & Community Forests

South Dakota & Washington; Maryland, Montana, Utah & Wisconsin; & Maine

Elementary School Gardens Newark, New Jersey

Sierra Nevada Land Conservation Program Northern California

Community Schoolyards ® projects New York City & Colorado

How ParkS and community engagement are HelPing americanS find common ground.

Story

When Levar Robinson and Stanley Spring greet each other, it’s with a hug—the kind with tight arms and a long embrace. But a year ago, they were complete strangers.

The two men came together during an effort by the Recreation and Park Commission for the Parish of East Baton Rouge (BREC) to solicit community input for a 10-year systemwide park plan. The project was supported by a community engagement grant from Trust for Public Land, funded by the Walmart Foundation. TPL also guided park practitioners in tried-and-true community engagement strategies, providing more than six months of training to BREC staff. Similar efforts have been completed at eight other sites nationwide as part of TPL’s On Common Ground program—and the results will be published so others can learn from and emulate them.

The park system in East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana, has an extraordinarily eclectic list of facilities. It includes everything from your typical neighborhood park to a water park with a surfing simulator and even a velodrome—one of an estimated two dozen cycling arenas still operating in the country.

And then there are golf courses, lakes, a zoo, an equestrian center, and an RV campground all spread across the parish. There are 175 parks in total for a locality of 450,000 people. To inform its next-decade planning effort for all of these sites, the

parks department put together its most diverse community advisory group yet, with input and support from TPL.

The 15-member community advisory council helped BREC shape a plan that was presented to voters ahead of this year’s tax election. With funding assistance from TPL, BREC was able, for the first time in its 75-year history, to compensate community members with $1,000 stipends as part of an effort to supplement time spent away from work and ensure members from low-income neighborhoods were included.

The strategy was a success, with representation that better reflected the population. The department received applications from across the parish, which is made up of 47 percent Black residents, 47 percent white residents, and smaller communities of Latinx, Asian, and Indigenous residents. When it comes to divisions among racial groups, locals say there’s a lot of “history.”

East Baton Rouge Parish desegregated schools under a court order in 1970—16 years after the landmark 1954 Supreme Court Brown v. the Board of Education ruling declared segregated schools to be unconstitutional. It was a divisive time, and remnants of those tensions still exist today.

This park-planning effort aimed to facilitate cooperation despite that history and take steps toward easing those tensions.

Under guidance from TPL, leaders from BREC intentionally assigned council members into pairs that cut across lines of difference—paying particular attention to racial and geographic diversity—to maximize interactions between people from different parts of the city and life backgrounds and to build bridges across historic divides.

Each pair of partners was tasked with organizing an “Imagine Your Parks” event at a local BREC facility to collect feedback from residents on the 10-year plan. In addition to helping formulate the surveys, they worked to spread the word about the effort.

At each event, council members distributed surveys asking East Baton Rouge Parish residents to consider parks and facilities as well as programming their communities could benefit from. Residents were asked questions such as, “How can BREC’s facilities contribute to a more resilient community, especially considering flooding and extreme heat?” Or “What would creating a more inclusive and equitable system look like to you?”

In less than a year, the council members went from untrained volunteers to BREC ambassadors collecting data and sharing messages from their communities, an achievement that wouldn’t have been possible without TPL’s support. And in the end, lasting friendships have flourished between council members—people like Levar Robinson and Stanley Spring—who say they wouldn’t have crossed paths outside of this process.

“I didn’t expect Stanley and I to click,” Robinson, 46, told a room full of colleagues as he affectionately pointed to his council partner. The room erupted in laughter when Robinson made this declaration.

“I think they laughed because they identified with what Levar said,” Spring, 72, explains, referring to the nervous tension of working with someone who comes from another part of the parish—someone with a different cultural background and lived experience. “I had reservations when I first met Levar,” says Spring, but in the first five minutes, they hit it off. “It was just like that,” he says as he snaps his fingers.

Robinson is the founder and CEO of Fathers on a Mission, a local nonprofit community organization; he’s a Black man who was born and raised on the north side of Baton Rouge, the historically Black, working-class side of town, which he describes as underserved. Spring is white and a retired litigator from the south side of Baton Rouge, the more affluent and white part of town.

Says Robinson, “Even as a grown man, because of past experiences and trauma, you don’t necessarily know what’s going

to be the outcome of [collaborating with] someone new.” He found himself questioning if Spring would accept him and his opinions: “Is he going to be okay with what I feel, how I think?” Robinson asked himself. But that quickly changed once they spent a little time together.

Spring was asking himself the same questions. “I looked around at all the different people, and I was really nervous about it, but when I got to know them and got that mutual understanding, we got rid of that polarization,” he notes.

Spring acknowledges that if it wasn’t for parks, he and Robinson would never have met. Robinson agrees. But due to this experience, they’ve exchanged numbers and keep in touch. “When you intentionally invest in parks programs to bring people together, bonds form,” says Cary Simmons, who leads the On Common Ground program as TPL’s director of community strategies.

In the nine very different communities where TPL tested its strategies, data shows participants grew closer together through programming and collaboration at parks. “We saw that over a diverse range of communities coming from backgrounds across geography, ability, race, and income, not only did people come closer together,” Simmons notes, “but they also enjoyed themselves and said working in these mixed groups felt like they were making a positive impact in their communities.”

The experience had a positive impact on staff, as well: “I learned more in the first five months of working with my community advisory council about different communities and areas in this parish than I have in my 18 years working in recreation,” says Katrina Coots Ward, BREC’s partnership and development director, “because you really have to engage with the community.”

“i learned more in tHe firSt five montHS of working witH my community adviSory council . . . tHan i Have in my 18 yearS working in recreation.”

– KATRINA COOTS WARD, BREC PARTNERSHIP AND DEVELOPMENT DIRECTOR

Robinson and Spring co-organized their event at a BREC golf course. About 60 people—parents and children—attended on a cold Sunday in January. Parents filled out surveys while their children enjoyed free snacks and competed to win cash prizes. Children and teens were split into age groups and each given a putter and five golf balls; whoever got closest to the hole won a prize. Spring says he was happy with the turnout, especially considering the weather.

Now, as the national election is just around the corner and the advisory council program winds down, Spring and Robinson say they will continue collaborating. Spring recently applied to join the board of directors at Fathers on a Mission, which offers resources to help fathers become positive roles models for their loved ones and in their communities. Spring

“iS He going to Be okay witH wHat i feel, How i tHink?”

–

LEVAR ROBINSON, COMMUNITY ADVISORY COUNCIL MEMBER

and Robinson, who both have children, hope to develop a program that uses golf to get dads and sons together to build stronger relationships.

“If folks aren’t working in the same profession or go to the same church or in the same community, then they’re likely in their own silos. All we had to do . . . was offer the bridge, and everyone in our committee is crossing it and connecting and forming friendships,” says Ward, who facilitated advisory council meetings and served as a liaison between members and park leadership.

TPL’s Common Ground Framework, a first-of-its-kind resource, proves with academic rigor that parks can and do bring people together.

Employing community advisory councils is one of more than 50 engagement strategies that Trust for Public Land

“i looked around at all tHe different PeoPle, and i waS really nervouS aBout it.”

– STANLEY SPRING, COMMUNITY ADVISORY COUNCIL MEMBER

includes in the framework, which guided their efforts in East Baton Rouge Parish and the other pilot sites. It asserts that green spaces are inherently inclusive places that foster belonging, and that the shared experience of engaging in park planning strengthens social ties and creates connections among residents.

Meaningful and authentic community engagement was a priority for Trust for Public Land’s work with BREC and an integral part of the program’s success. Park directors often attended meetings, and advisory council members saw their concerns and suggestions taken seriously and reflected in proposals. Members of the advisory council knew BREC Superintendent Corey K. Wilson not just by name but by face, for example, because he was a regular attendee.

“ParkS HelPed me oPen uP to more PeoPle.”

– DR. EVELYN THOMAS, COMMUNITY ADVISORY COUNCIL MEMBER

Staff from BREC—with support from Trust for Public Land advisers and an outside consultant TPL hired—also facilitated complex discussions between advisory council members about race, class, and the equitable distribution of resources. These conversations, which took place over several months and meetings, were important to ensure that every community in the parish was included as they developed the 10-year plan.

Getting out into the field was an eye-opening experience for many council members. They took a daylong tour of parks they had never visited. “I didn’t know there were so many parks,” says Dr. Evelyn Thomas, an advisory council member.

Thomas grew up in a rural area where she says backyards were the closest thing to parks. When she moved to Baton Rouge, she told herself she would never move away. Parks became safe spaces where she could meet people and grow her community.

“Parks helped me open up to more people,” says Thomas, who was paired with Rex Cabaniss, 68, a prominent local architect and urban planner, both with deep community roots. Together they organized a Mardi Gras–themed event where kids were encouraged to enter contests and win prizes.

Dr. Evelyn Thomas (left) and Rex Cabaniss planned a Mardi Gras–themed event to solicit feedback on local parks from Baton Rouge residents.

Thomas, a Black woman, is a community advocate in North Sherwood Forest, a historically Black neighborhood that in recent years has seen more Latinx and Asian neighbors move in. A registered nurse with a Ph.D. in human behavior, she’s also a Doctor of Divinity and the senior pastor at the local interdenominational ministry.

Residents of North Sherwood Forest come to her for advice on a range of issues, from guidance on dealing with landlords to other forms of conflict resolution. Recently, a community member working to bring outdoor lighting to a neighborhood park reached out to ask if Thomas could help.

As a council member, Thomas was able to contact facilities leaders, which accelerated the process. The park now has tall lighting posts that illuminate the grounds after dark.

“If I wasn’t connected to BREC, then I would not have known who to contact and what person to follow up with,” Thomas shares.

She says she feels a sense of accomplishment knowing she was a small part of a process to help the community feel safer at the park and hopes more people will visit it now.

Thomas’s advisory council partner, Cabaniss, a white man, says it was inspiring to be part of the committee. As a member of numerous organizations and boards in Baton Rouge, Cabaniss is used to seeking community input on projects. “Organizations often talk about being collaborative with citizens,” he says, but this project “really walked the talk of serving the mission to enhance the quality of life in Baton Rouge.” That’s exactly the type of deep community engagement TPL is cultivating with its On Common Ground program.

What Trust for Public Land’s work with BREC has proved is that if you invest in programming and planning to bring people together around parks, you develop camaraderie and leaders.

“It doesn’t surprise me at all because parks are natural settings for community building,” says Simmons. The interactions fostered in parks enable people to express their unique identities, offering neighbors a fresh perspective on their community through a different and new lens, he explains.

Even though these bonds can happen organically—for example, residents of Baton Rouge might spark conversations and discover mutual interests while waiting to ride the waves at the surfing simulator or renting a kayak at the swamp— parks departments can also cultivate meaningful exchanges between locals through intentional programming.

Through its On Common Ground pilot projects—and its 50-plus years of community-centric green space creation—TPL has found that parks are capable of transforming neighborhoods into truly engaged networks, bridging divisions that might otherwise tear us apart.

The research findings from the other On Common Ground sites mirrored what’s happening in the East Baton Rouge Parish: programming at parks can lead to the development of social connections, cohesion among participants, and increased civic participation.

Once participants make that connection, there’s a ripple effect that continues to spread. Levar Robinson and Stanley Spring, for example, started collaborating around parks and now will continue working together to address concerns that go beyond green spaces.

Amid heated political debates in East Baton Rouge Parish and nationwide, parks have the potential to be neutral and welcoming spaces where people can come together. That’s why Simmons says he hopes other communities will look to the success of BREC and follow suit.

“The human connection we have with our parks and public spaces is one of the things that just continues to bond us all universally,” says Simmons. And he’s not just touting an idealistic theory. Thanks to the efforts of TPL and partners, the proof is in the parks—and the people they bring together.

“tHe Human connection we Have witH our ParkS and PuBlic SPaceS iS one of tHe tHingS tHat JuSt continueS to Bond uS all univerSally.”

– CARY SIMMONS, TPL DIRECTOR OF COMMUNITY STRATEGIES

Jorge Rivas is a firm believer in the power of storytelling and visual communications to inform and move people into action. He has been recognized with a GLAAD Media Award and medals from the National Association of Hispanic Journalists for his investigative reporting.

With Black culture and public land as tools for change, Chicago leaders are building fruitful relationships in their communities.

BY ARIONNE NETTLES · PHOTOS BY GRACIE HAMMOND

– CAROLINE O’BOYLE, TPL ILLINOIS STATE DIRECTOR

Last April, as Chicago shook off the lingering effects of winter, Douglass Park on the city’s West Side gleamed with signs of spring and renewal.

The grass in the ample 162-acre park had returned to a vibrant shade of green, the trees were no longer barren and dull, and flowers were starting to bloom. That included the yellow daffodils in the park’s renovated 18-hole miniature golf course, which TPL helped create.

While this attraction may be new to some, it’s actually a return to its original use—but for a later generation.

“When I first moved here in 2001, I used to take my grandsons over there to play,” says Sheila McNary, an executive member of the North Lawndale Community Coordinating Council (NLCCC), which along with Trust for Public Land, was involved with the project. Back then, “it was just a regular miniature golf course,” says McNary, who remembers its green turf and a fountain spouting water.

After the early 2000s, however, the course was ignored and fell into an unusable state, depriving neighbors of a conve-

nient and fun outdoor activity. There hadn’t been any upkeep of the facility—resulting in peeling turf and other hazards caused by neglect and extreme Chicago weather—leaving an inoperative space McNary describes as “totally messed up.”

Enter Haman Cross III, a successful artist from North Lawndale who wanted to reimagine the course as a community asset. Cross connected with the NLCCC to make it a reality, knowing they could assemble the right stakeholders; the NLCCC, in turn, invited Trust for Public Land to collaborate and provide expertise. Together, they held weekly planning meetings with residents.

Today, the course is the opposite of a mess: the bright reds, blues, and yellows that highlight each hole add contrast to the lush greens of Douglass Park—named after 19th-century abolitionists Frederick and Anna Douglass—inviting visitors to come in, enjoy nature, and explore the park’s features. Beyond the fresh turf and crisp colors, a view of the Chicago skyline peeks from behind the trees.

The park has more than 200 species of birds, and Cross wanted to honor them with an avian-inspired design focus.

Local teenagers worked with Cross, architecture professors, and staff from the Lincoln Park Zoo to design each hole with a special theme to feature one of these unique birds and their habitats.

This project was one way TPL could help advocate for the North Lawndale neighborhood in Chicago, explains Illinois State Director Caroline O’Boyle. But doing so for Chicago communities means letting local organizations like the NLCCC lead.

In any town or city, residents who wish to improve their neighborhood are the authorities about what is or isn’t needed. Trust for Public Land’s role, O’Boyle says, is being a connector for resources, building support for ideation, and often being a liaison between community leaders and government officials.

In this vein, TPL works as an ally, a friend, and a collaborator with organizations like the North Lawndale Community Coordinating Council as their guide. But much like an Oscarwinning supporting actor can make a great film, TPL’s involvement is crucial to the overall success of these projects.

“We got a seat at the table for the Douglass Park golf course

THEY’LL PLAY A ROUND OF MINIATURE GOLF. THEN THEY’LL GO FISHING IN THE BROOK, AND THEY CAN GO SWIMMING IF THEY WANT.”

– SHEILA MCNARY, EXECUTIVE MEMBER OF THE NORTH LAWNDALE COMMUNITY COORDINATING COUNCIL

project, and then I just started showing up for meetings, asking what else can we do?” says O’Boyle. “It was just a matter of meeting people, listening to what their goals and ambitions were, and figuring out how TPL can help.” That often includes the important aspect of identifying funding mechanisms (in this case, support from TPL, the City of Chicago, and L.L.Bean).

McNary says she wanted Douglass 18 Miniature Golf Course to be a place for community connection, an anchor, a mainstay where kids can hang out or adults can relax after a long day at work—pointing out the lack of other similar options nearby. What’s more: it’s affordable at only $5 per game, plus weekly discounts on certain days.

Since the renovated course opened in 2021, she’s seen young people, especially, take advantage of this updated amenity— including hundreds of day campers from Chicago Park District cultural centers. “They’ll play a round of miniature golf,” she says. “Then they’ll go fishing in the brook, and they can go swimming if they want.”

Numerous studies show that safe, quality green spaces and exposure to nature improve people’s physical and mental health, and Mount Sinai Hospital, Saint Anthony Hospital, and

Schwab Rehabilitation are all nearby. McNary, who’s a nurse, says the course has already been helpful for those seeking treatment and rehabilitation. “[Schwab] brings some of their patients over to play,” she says, noting that all but three holes are ADA accessible.

The course has been open for three seasons, and this year, the NLCCC is opening a concession stand, which McNary hopes will attract even more visitors. Proceeds from the stand will support the mini golf course and employ and train neighborhood youth.

About a mile away, tucked between residential streets not far from busy Ogden Avenue, WACA Bell Park broadcasts cheer from behind a protective fence. The basketball court, with its paint reminiscent of the Chicago flag’s red stars and light blue stripes, is flanked by a long bench plus short colorful stools on one side and picnic tables in a tree-filled section on the other. Those trees are newly planted and, like this renovated park, are expected to grow and flourish in the coming years.

Lola Jenkins, Westside Association for Community Action (WACA) vice president, says this space has a long history, but she’s excited for what’s ahead. Basketball games, rollerskating, and mixers for older community members are just a

few of the events North Lawndale residents enjoyed over the summer. And coming soon, lights and Wi-Fi powered by solar panels will help keep activities going after sundown.

Jenkins’s parents created WACA in the early 1970s as an intervention-based organization that used mentorship to address and reduce youth violence. When Jenkins and her sister took the baton, they decided to focus on prevention. That’s why WACA has recently honed its focus to offer even more to the community in the form of wraparound services that help at-risk individuals’ entire families.

“We’re nothing without community partnership—that’s any organization, especially one that’s grassroots or community based,” Jenkins explains. “And TPL has been really instrumental in assisting us, fostering that collaboration by driving this process for the [basketball] court and taking it to a place, honestly, that we didn’t even consider to be imaginable.”

One specific way TPL’s partnership helped was by creating what Jenkins describes as a truly inclusive input process, one in which North Lawndale residents were able to share their thoughts about what the space should offer. The feedback loop was very intentional. After residents shared their thoughts, those ideas were transferred into designs that WACA could then show community members during subsequent meetings. Then, WACA would get more feedback, and the same would happen again.

This kind of process, Jenkins explains, is rare. Oftentimes, inclusion is something organizations claim to deliver but may not prioritize. But this renovation is the culmination of many ideas from many people, a feat that was accomplished, in part, due to TPL’s involvement.

The idea for picnic tables and nontraditional seating not often seen at a basketball court stemmed from community feedback and a desire to be able to use the court area to gather for meals, for example. It was a way to make WACA Bell Park even more of a welcoming space—a safe space for residents.

“I think the feedback that has been the most heartfelt is that sometimes in situations like this, where there’s a lot of change happening within a community, a lot of people feel like there’s just an illusion of inclusion, and their thoughts or feelings aren’t really being taken into consideration; their ideas won’t be heard,” says Jenkins.

This process was different, and the focus on true involvement means the new WACA Bell Park will more fully serve its community.

WE’RE NOTHING WITHOUT COMMUNITY PARTNERSHIP . . . AND TPL HAS BEEN REALLY INSTRUMENTAL IN ASSISTING US, FOSTERING THAT COLLABORATION . . . AND TAKING IT TO A PLACE, HONESTLY, THAT WE DIDN’ T EVEN CONSIDER TO BE IMAGINABLE.”

– LOLA JENKINS, WESTSIDE ASSOCIATION FOR COMMUNITY ACTION VICE PRESIDENT

Dr. Jocelyn Imani is TPL’s national director of Black History and Culture, a role she describes as “chief dot connector.”

That’s because Imani’s position leads her to intimately know and understand the work of TPL partners and friends across the U.S.—and to notice the various opportunities to connect leaders working throughout these cities.

Imani’s role also means she oversees two distinctive types of projects: those that are Black historic sites and those that are using Black culture for change. She sees harnessing the impact of Black culture and public land as an important marker of what’s happening in Chicago and what other organizations can do for their communities to prevent violence, create safe spaces, and battle food insecurity.

One project that sits in both buckets of TPL’s Black history and culture portfolio is the Mamie Till-Mobley Forgiveness Garden in West Woodlawn, a neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side. TPL helped make improvements to the garden and is supporting related efforts through its Equitable Communities Fund. Till-Mobley made international news and became a face of

the civil rights movement when in 1955, her 14-year-old son, Emmett Till, was kidnapped, tortured, and killed by white supremacists in Mississippi. She bravely put her son’s body on display at his funeral—so the world would have to reckon with the truth of what happened to him. And she spoke out against racial injustice and worked as an activist and educator until her death in 2003.

Now, an abundance of perennial flowers fills Mamie’s namesake garden along with freshly planted trees. While the garden is meant to honor the past, it’s also purposeful about the community’s present. There are places throughout for people to sit and think, paths for walking, and opportunities to stop and smell the flowers.

“It's really those three r’s,” says Naomi Davis, founder and CEO of Blacks in Green. “Reflect, relax, and remember that there is a higher way forward.”

Blacks in Green (BIG) is the environmental and economic organization that created the garden and is also renovating the adjacent Till family home into a museum and theater. Davis says she wants visitors to be able to pull from TillMobley’s spirit of forgiveness.

"As mere mortals, we’re always caught up in some kind of drama: somebody said something or did something, or we felt slighted, or they shouldn’t have done that, and we’re easily offended inside of our sort of daily drama,” Davis notes. “But how many of us could call on ourselves to forgive that kind of perpetration?” she asks, referring to Till-Mobley’s experience.

Something else Davis was aware of while dreaming up the garden was the prevalent narrative that Black neighborhoods are filled with violence. That narrative also extends to the idea that they lack the kind of calm, peaceful spaces that Blacks in Green is creating.

“People rarely associate us with that system change and transformational mission,” Davis explains. “But it’s fundamental to our work; we’re changing the narrative of what it means to be Black in America, where Black communities are synonymous with beauty, prosperity, comfort, and joy.”

Trust for Public Land supports Blacks in Green’s mission for change. “Naomi talks about ‘followship’ a lot,” says O’Boyle,

“meaning the act of listening and responding, rather than speaking first or leading. And I think we’re a good follower.”

The Mamie Till-Mobley Forgiveness Garden is just one of 16 planned throughout the West Woodlawn neighborhood that will focus on local luminaries of the Great Migration. In support of that larger effort, TPL helped BIG purchase two plots for additional gardens, and as BIG cultivates these spaces, they will also be connected by greenways. This is what Davis calls “G.O.D.” or “garden-oriented development.”

“It’s designed to be an ecological anchor, meaning we are building an oasis of resilience against the harms of [the] climate crisis, which after all, hit our communities first and worst,” Davis says.

Imani echoes this sentiment, describing the work of TPL’s partners in Chicago as “an example of using culture to deter gentrification, fight against climate change, defend our children, or whatever the bottom-line thing is; we’re leveraging Black culture as a means to connect.”

WE’RE CHANGING THE NARRATIVE OF WHAT IT MEANS TO BE BLACK IN AMERICA, WHERE BLACK COMMUNITIES ARE SYNONYMOUS WITH BEAUTY, PROSPERITY, COMFORT, AND JOY.”

– NAOMI DAVIS, FOUNDER AND CEO, BLACKS IN GREEN

In Compton, California, gardener Johnny Fajardo saw the power of urban land to feed his community. In working to sustain that situation, he developed his own potential too.

Created in 2013, Compton Community Garden (CCG) occupies a mere 900 square feet, but its impact on food justice is significant: each of its 66 garden beds can feed a family of four for a year. And its impact goes beyond sustenance, with donation drives that incorporate home essentials and volunteer days when anyone can help garden or join activities such as guided meditations, nutrition workshops, and intro-to-gardening classes.

But the future of this small-but-mighty garden was in jeopardy when, after 10 years in operation, the landowner decided to sell it. The community rallied to save it, raising $500,000 in small-dollar donations in a single week (the average gift was $26). Trust for Public Land contributed, too, as the garden’s largest donor. (The property is now held by the Los Angeles Neighborhood Land Trust, where it remains community owned.)

It was during that fevered period of organizing and fundraising that Fajardo, CCG’s head gardener, connected with TPL. "The TPL team were true allies and friends in a moment of uncertainty for our garden,” says Fajardo.

The “followship” O’Boyle mentions is also at play in TPL’s relationship with Grow Greater Englewood (GGE) and Anton Seals Jr., its lead steward (a.k.a. executive director) and cofounder. A nonprofit with the motto “community health is wealth,” GGE has many Chicago-area projects based around food justice that work with agriculture and land development.

But it was the creation of the Englewood Nature Trail—turning an abandoned railroad track into an elevated recreation area in the Englewood neighborhood on the city’s South Side—that brought GGE and TPL together.

The trail will be a 1.75-mile dedicated right-of-way where people can walk and bike safely, with accessible ramps, and

“Their guidance and resources helped us organize a global community and protect our green space in perpetuity— and sparked my personal interest in advocating for land trusts as a pathway to true community ownership.”

Not long after, Fajardo joined TPL at the 2023 Land Trust Alliance Rally in Portland, Oregon, an international conference of land conservation practitioners, and has since taken a role as California community advocate with GreenLatinos, an environmental justice organization.

“I had the opportunity to speak with some of the most thoughtful and experienced environmental and community leaders,” Fajardo says of the event. “Listening to the shared struggles we face across cultures and communities—and how leaders are addressing these issues democratically and inclusively—brought clarity to me in how I wanted to move forward as a professional organizer, communicator, and leader.”

“He grew,” says Dr. Jocelyn Imani, TPL’s national director of Black History and Culture, who sees TPL’s role as going beyond land conservation to include development and networking. In fact, she feels a responsibility to introduce people and organizations—such as Compton Community Garden and our partners in Chicago—that could benefit from the type of shared learning and collaboration Fajardo describes.

“Johnny got access to a profession that he’s trying to make waves in that he didn’t have prior to TPL” she says. And that’s where an investment in both land and people matters— because both go on to support communities over time.

featuring murals, sculptures, and mosaics throughout its design. When possible, existing trees along the trail will be preserved, and new trees will be planted throughout the 17-acre green space—something residents expressed was a priority during public meetings. And it will serve as the nation’s first agro-eco district, transforming vacant lots into an urban agriculture zone.

Seals, who now serves on TPL’s National Board of Directors (see page 12), says GGE had been networking with other organizations to get the project going when he first connected with TPL. He describes having the wisdom and support of TPL staff—especially that of O’Boyle—as extremely helpful. “That’s how you allow for a natural relationship to grow,” he says.

THE WAY THAT BLACK PEOPLE— BLACK AMERICANS IN PARTICULAR WHO ARE DESCENDANTS OF THOSE WHO WERE ENSLAVED—RELATE TO LAND, IT IS A UNIQUE KIND OF ONGOING HEALING PROCESS.”

The project to transform the railroad track had been a goal of residents for years. For Seals, this kind of development speaks to the heart of how Black people, like those who live in predominantly Black Englewood, relate to land.

The ideology that land is public, and that people are stewards of it—are a part of it—and are integrated into a larger ecosystem is rooted in Indigenous and African belief systems, he explains. The history of land in America and how enslaved Black people both worked on it and, at one time, were denied the ownership of it creates a specific relationship. That connection makes projects such as the Englewood Nature Trail even more meaningful.

“The way that Black people—Black Americans in particular who are descendants of those who were enslaved—relate to land, it is a unique kind of ongoing healing process,” he says. “Our work is around putting our flag in the ground and saying, ‘We don’t need to move.’ That’s what preservation is all about.”

The connectedness of GGE’s urban farm cooperative is an example of such stewardship: its network of Black farmers— as well as those from other communities of color—helps build food-related businesses along 59th Street; a weekly farmers’ market on a nearby corner sells locally grown food and other products to residents; and this now-essential corner will also be the entry point to the Englewood Nature Trail.

Preserving not only land, but the investment and interest in these projects, is how leaders say they create their own change. This correlation is not lost on O’Boyle.

“Land is power, land holds meaning, land holds history, land holds culture—all those things,” she says. “Especially with leaders like Naomi and Anton, they’re staking a very specific claim, the sort of cultural history of the neighborhoods that they’re living in.”

North Lawndale, Englewood, and West Woodlawn are all Chicago neighborhoods with Black residents whose lives collectively build up the essential telling of the city.

“You can almost tell the story of Chicago through what’s happening in those neighborhoods,” O’Boyle explains. “And our partners are very intentional about claiming the Black history of those neighborhoods and making them places that are going to be thriving for the people who are living there now.”

“Honestly, in terms of TPL’s nationwide goals, Chicago is kind of a crown jewel,” says Imani. “It’s a community-wide effort with multiple nonprofit partners working together toward the same goal over multiple projects and over long periods of time.” And it’s a type of collaboration that should and can be modeled.