PROTECTING LOCAL ECONOMIES, REGIONAL IDENTITY, AND OUTDOOR RECREATION

PLUS: GOLF COURSES REIMAGINED, LONG ISLAND GETS A GREENWAY, AND A FRESH LOOK AT JUNETEENTH

Return the Favor: Become a Monthly Donor

Help us connect everyone to the benefits and joys of the outdoors with a recurring monthly gift. It’s easy, automatic, and secure.

Our members make our work to create parks and protect public land possible.

START TODAY

tpl.org/monthly

Wolcott Community Forest, which is adjacent to Wolcott Elementary School in Vermont, is frequently used by local children for outdoor recreation and education. CHRIS BENNETT

We’re partnering with communities to transform former golf courses into thriving outdoor oases that are accessible, biodiverse, and working to fight climate change.

The Long Island Greenway will stretch from Manhattan all the way to Montauk. At 200 miles long, it will bring 27 communities within a 10-minute walk of the outdoors. And when complete, it will change how Long Islanders and New Yorkers play, commute, and live healthy lives.

Working lands such as forests, farms, and ranches are an important part of our conservation efforts toward climate resilience. These places also support local economies and regional identities.

“The relationship we have with local food— we want to have that with timber.”

~ SARAH

IN THE GIVING TREES , PG. 48

With a variety of ways to give, we offer something to suit everyone.

Use the envelope bound inside this magazine to send your gift, or donate online and learn about more ways to give at tpl.org/support .

Share your love of nature and outdoor adventures with someone you care about. Make a difference and honor a friend or loved one with a tribute gift.

Donate $2,000 or more annually and receive the recognition due a champion, such as invitations to special events and insider updates on our projects. Call 415.495.4014 or email champions@tpl.org to learn more.

Consider including us in your will or estate plan, learn about the benefits of designating retirement funds to TPL, and explore other tax-wise ways to give. Call 202.856.3748 or email plannedgiving@tpl.org to learn more.

Car recycling benefits both people and the environment by conserving natural resources, reducing pollution, and lessening energy consumption. Call 855.500.RIDE (7433) or visit tpl.org/cars to get started.

Simplify your charitable giving and meet your philanthropic goals by giving through your donoradvised fund. Learn more at tpl.org/daf. Scan with your mobile device’s camera to make a gift today!

Trust for Public Land depends on your support. You make our work possible.

tpl.org/support

From the President · 11

Our departing CEO shares a message of gratitude and expresses faith in TPL’s future.

Board Spotlight · 12

Get to know Kenneth Wong.

First Look · 13

Advice for beginning birders, a tour of climate-smart TPL parks, historymaking tribal lands work, and a conversation about equity and climbing the world’s tallest peak.

On Topic · 58

A compendium of insightful book, show, and podcast recommendations to bring you closer to the outdoors.

TPL Near Me · 60

A Dallas, Texas, high school student on the healing power of her community park.

Member Center · 62

Offices · 63

Trail’s End · 64

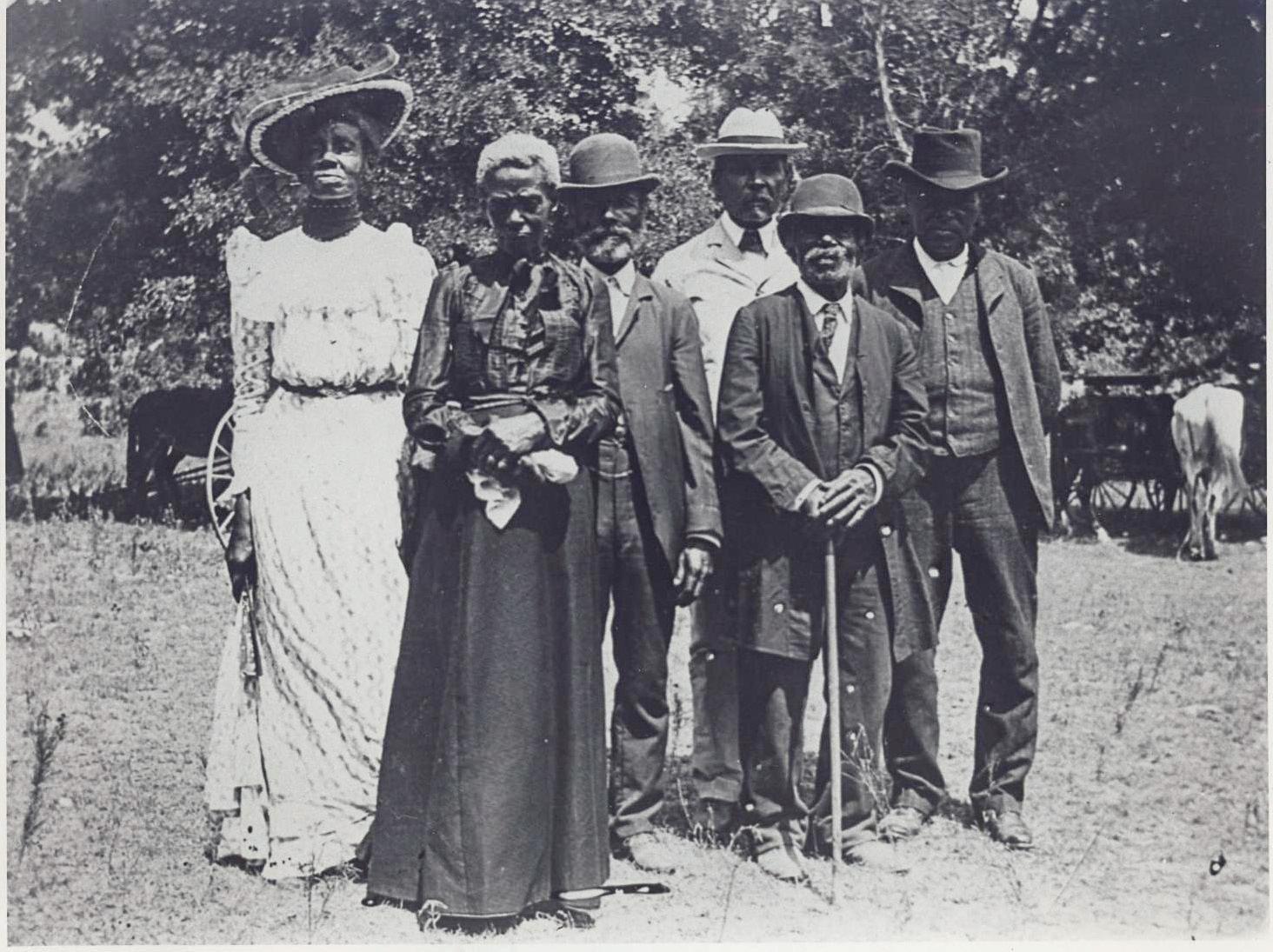

Juneteenth has more to do with public lands than you might guess.

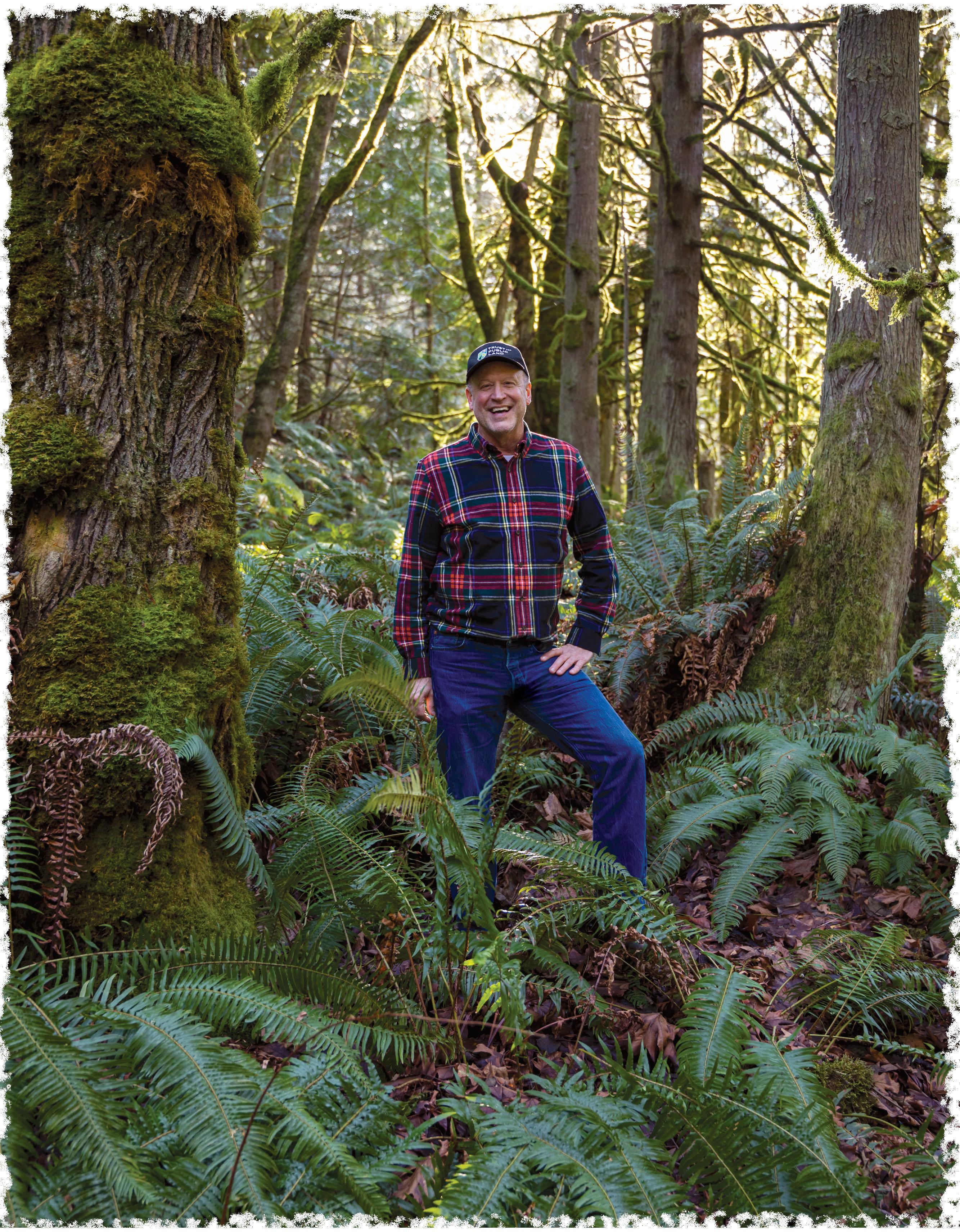

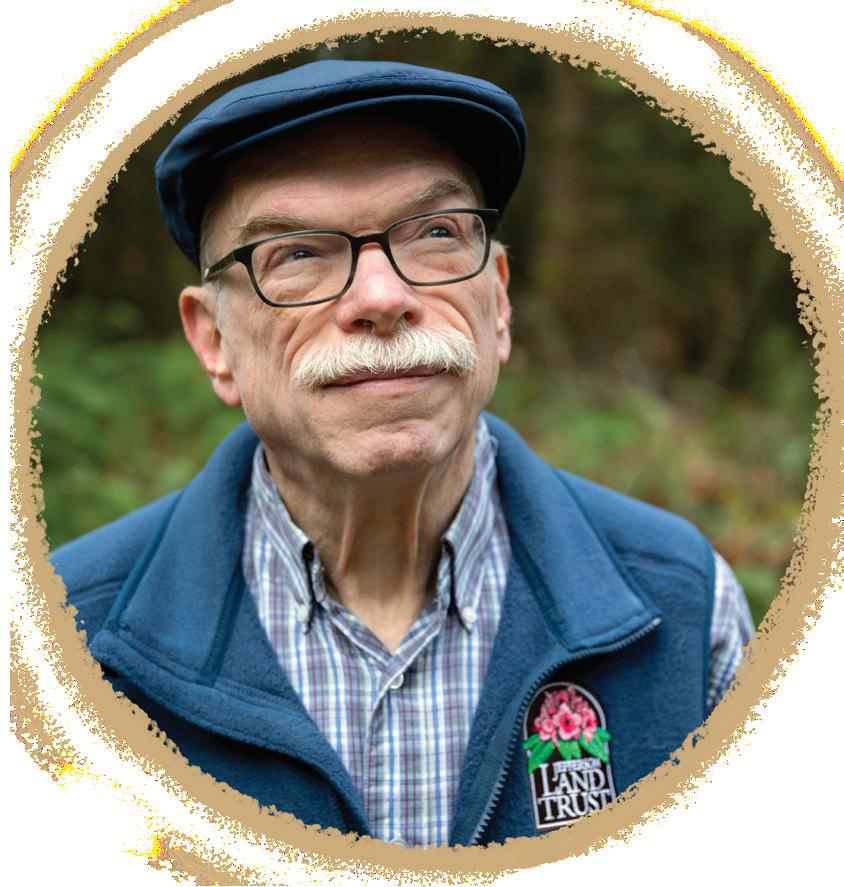

on the cover

TPL Senior Director of Field Programs

Richard Corff marvels at the towering trees and lush growth along a trail near Washington’s Chimacum Ridge Community Forest.

RICH REID

Besides being a gathering place for events and recreation, Panorama Park—which affords an incredible view of Pikes Peak— brings much-needed green infrastructure to a community that has suffered longstanding inequities, such as being about 7 degrees hotter than surrounding neighborhoods. In 2022, TPL completed the renovation of this 13.5-acre park, which features 250 newly planted trees, 20 shade structures, a splashpad, and a hammock zone where residents can find respite from intense summer weather. Even the bike course, shown here, helps retain and manage stormwater. Read more at tpl.org/panorama-story and discover 10 TPL parks that are models for green infrastructure across the country in this issue.

Page · 16

Chelan County, Washington

Once privately owned and closed to recreational use, the striking sandstone spires of Peshastin Pinnacles State Park are now open to climbing enthusiasts forever. Thanks to TPL, Chelan-Douglas Land Trust, and other partners, the park welcomes thousands of climbers and hikers every year to experience the beauty of the Central Cascades and Wenatchee Valley. In this issue, hear from members of Full Circle Everest, the first all-Black team to summit Mount Everest, on the joys and challenges of mountaineering.

Page · 20

At San Geronimo Commons, a golf course turned community green space nestled in the forested hills north of San Francisco, a major landscape renovation is under way. The changes, which are returning the site to a more natural state, will greatly benefit both people and wildlife. Rather than pesticide-treated grass that requires irrigation, drought-hardy native plants are being added. Wild creeks that were previously forced underground will see daylight for the first time in decades. And residents can now use the site for a wide variety of outdoor recreation. Read more about TPL’s work transforming golf courses into natural areas in this issue.

Page · 26

Become a Conservation Champion and help Trust for Public Land connect even more people to nature. With your annual leadership-level contribution of $2,000 or more, you’ll receive invitations to special events and insider updates on our projects and conservation strategies. Learn more about the impact you’ll have as a Conservation Champion. Contact us at 415.495.4014 or champions@tpl.org.

tpl.org/champions | champions@ tpl.org

Join us online for project updates, stunning photos, and inspiring stories.

Follow us on social media:

@trustforpublicland

@TheTrustforPublicLand

@the-trust-for-public-land

@tpl_org

TrustforPublicLand

Be sure to tag us in your posts!

Sign up for our emails: tpl.org/email-signup

And listen to our podcast, People. Nature. Big Ideas. tpl.org/podcast

executive editor & publisher

Jennifer Ramsey

editorial director

Deborah Williams

managing editor

Amy McCullough

staff writers

Lisa W. Foderaro

Amy McCullough

designers Rachel Andrade

Miya Su Rowe

Ben Whitesell

media production manager

Elyse Leyenberger

As I write my final Land&People letter as Trust for Public Land’s president and CEO, I’m filled with gratitude, hope, and faith in TPL’s future.

I joined TPL six years ago because I was inspired by the organization’s unwavering commitment to equity—the cornerstone of our mission in connecting everyone to the outdoors. I’ve carried that sentiment with me throughout my journey here. It is our people and our collective vision for a better future that drives us forward. It is our hope in action. What an honor it’s been to work alongside staff, supporters, partners, and advocates who’ve helped this extraordinary organization achieve so much. Together, we’ve accelerated our land protection efforts to enhance economic and recreational opportunities. We’re spearheading a movement to make Community Schoolyards® projects a national standard. And we’ve strengthened our focus on equity with our Black History and Culture program and our Tribal and Indigenous Lands program. Our work has connected millions of people to vital green spaces, bringing opportunities to connect with nature and each other and instill a deeper sense of community. Every park, trail, community forest, landscape, or schoolyard adds to our collective power of hope in action.

for the benefit of expanded public access to the outdoors and enhanced biodiversity, their hope for climate resilience and a sustainable recreation-based economy is self-fulfilling (page 26).

Every TPL project reflects our “community at the center” commitment. Our work doesn’t just change landscapes; it changes lives.

Our work is made possible by the involvement and support of people who, like us, believe that grassroots efforts can generate national impacts. We’ve built trust and credibility through our community-led approach to placemaking that’s positioned our leadership to drive national momentum in securing federal policies like the current EXPLORE and Outdoors for All Acts. More mayors and parks departments are signing TPL’s 10-Minute Walk® pledge. And we’re leading a nationwide movement to grow awareness and support for parks as critical infrastructure and climate-smart solutions.

© 2024 Trust for Public Land. All rights reserved. 10-Minute Walk, Community Schoolyards, Conserving Land for People, Conserving Nature Near You, Creating Parks and Protecting Land for People, Fitness Zone, Land for People, Land&People, LandVote, Northwoods Initiative, Our Land, Outside For All, Parks for People, Parks Unite Us, ParkScore, The Trust for Our Land, Trust for Public Land, TPL, and all other names of Trust for Public Land programs referenced herein, as well as their logos, are registered or common-law trademarks of Trust for Public Land.

When students design their own Community Schoolyards projects, the results are far more than new playgrounds. By participating in this work, children experience the power of civic engagement; they develop a sense of responsibility to their neighbors and a pride of collective effort. They have a hand in making their communities more climate resilient and experience the wonders of nature in safer, cooler, greener play spaces (page 16).

Acquiring 30,000 acres of forest in Maine’s Katahdin region is hope in action because it not only expands public access in the region, but it’s also important for environmental and economic health, and it’s sacred to the Penobscot Nation. When the largest land return between a U.S.-based nonprofit and a tribal nation is complete, the Penobscot will again be connected to Wáhsehtәk w (page 18), the land central to their identity and culture.

When communities like San Geronimo in Marin County, California, reimagine former golf courses

As I prepare to pass the baton, I know this isn’t the end of the race but a continuation. Each of us plays a vital part in this team effort. We must keep pushing forward with vigor because our work is vital to our individual happiness and the well-being of our nation.

As we approach the elections and the national discourse intensifies, I take great solace in the fact that our work, rooted in hope borne of action, bridges divides among us. At TPL, we’ve always believed in the transformative power of land to bring people together. That’s never been more relevant, and because of it we can look to the future with hope.

Thank you for joining me as a fellow TPL supporter. I am profoundly grateful to be a part of the TPL community, and eager to continue to support and champion this critical work.

diane regas president & ceo

diane regas president & ceo

chair

Lucas St. Clair

Jodi Archambault

J. Franklin Farrow

Mickey Fearn

Jody S. Gill

Allegra “Happy” Haynes

Alex Martin Johnson

Jennifer Jones

Chris Knight

Christopher G. Lea

Joseph E. Lipscomb

Eliot Merrill

Ignacia S. Moreno

Julie Parish

Michael Parish

David Poppe

Thomas S. Reeve

Diane Regas

Laura Richards

Ted Roosevelt V

Lex Sant

Anton Seals Jr.

Sheryl Crockett Tishman

F. Jerome Tone

Taylor Toynes

Jerome C. Vascellaro

Lindi von Mutius

Keith E. Weaver

Susan D. Whiting

Florence Williams

Kenneth Wong

A RECENT ADDITION to our National Board of Directors, Kenneth Wong is deeply experienced in real estate and has held numerous high-profile positions. During his 40-plus-year career, he’s developed all types of buildings and places, including theme parks, affordable housing complexes, cruise ships, and master-planned communities. Today, Wong is chief operating officer of Related Companies and cofounder of energyRe, a leading renewable energy development company with projects across the United States. His diversified business experience, track record of creating places for people, and entrepreneurship in energy transition make him a unique member of TPL’s community. We asked him why Trust for Public Land is deserving of his time and energy.

What initially brought TPL to your attention? I was always aware of TPL at a distance and had a vague impression of it doing good things—boy, I had no idea! A few years ago, I began a personal quest to find an organization I could invest in, and that’s when I discovered how amazing this organization is.

What particular project or initiative speaks to your values and goals? There are many, but the topper is TPL’s Community Schoolyards® initiative. As someone who has worked in cities and real estate development my entire career, it is the ultimate crossroads of themes that matter: providing safe, clean, outdoor space for all (including kids), reducing heat islands, filtering urban runoff, improving health outcomes, and using the planning and design process to create ownership by the community. Climate change is truly the largest-scale threat to our future, and while every TPL program and initiative is making a difference, schoolyards have the potential to change the world for many people fast.

What types of challenges do you think TPL is uniquely poised to address? TPL is peoplecentered and values-centered. It builds solutions that produce both immediate results and longterm endurability. There are other fantastic

National Board of Directors since 2023

organizations in the conservation space, but TPL is extraordinarily skillful in this way.

What are you most looking forward to achieving as a member of TPL’s national board? I’m most excited about helping TPL scale its best work as powerfully and quickly as possible. I also want to build bridges. We need to find like-minded partners, not just in the nonprofit sector, but with universities, research centers, governments, and across the private sector, to magnify our impact.

On a personal note, how do you most enjoy connecting to the outdoors? Nature and the outdoors have always given me a sense of peace, strength, and connectedness. I love big nature that makes me feel small (mountains, ocean, a desert, a deep forest), as well as little pockets of nature like city parks and squares that connect me to other people. I’m lucky to have access to the outdoors year-round, and to share all those experiences with family and friends. I don’t take it for granted one bit, and that makes me even more passionate about the mission of TPL: we need to help connect everyone to the outdoors.

Famed marine biologist Sylvia Earle said,

“We are at a point in time where we have a choice. Imagine if you didn’t have the facts about what the problems are. Imagine if you didn’t have the solutions. But you have both.” By helping create community green spaces such as Historic Fourth Ward Park in Atlanta, Georgia, TPL is addressing the problem of climate change with smart design solutions that prevent flooding, limit pollution, and cool communities—all while providing places to play. Also see page 16.

TURN THE PAGE FOR: Avian Advice for Beginning Birders

Historic Land Return in Maine

A Climbing Conversation with Full Circle Everest

Birding provides opportunities to experience nature in a deep, fulfilling way—and it can connect you to a whole community of outdoor enthusiasts too. Follow these pro tips to get started, and you’ll soon be appreciating avian life all around you.

By Amy McCullough with Tykee James

To bird expert and advocate Tykee James, birds are all about joy. He felt his first jolt of winged wonder at age 18, when he witnessed a female belted kingfisher (above) leap off a cattail and sing as it flew across a creek. He was mesmerized. “That bird made nature come to life,” says James (left). This is what birders call a “spark bird,” the species that ignites your interest. And finding yours is just one of several ways to ease into the activity known as birding. Here are a few more pointers to get you started:

1. Start where you are. Whether you’re at home, in a park, or even in a parking lot, there are birds to be seen. You don’t have to go far. You only need to be curious, spend a little time, look around, and be prepared to appreciate what you see. Keeping it simple helps demystify the practice. And while you don’t need special gear, binoculars are a helpful tool.

2. Find your spark bird. As a TPL supporter, you’re very likely a nature lover. While you’re enjoying whatever activities take you outdoors, look for birds. Sooner or later, you’re bound to see one that trips your trigger. Take its picture and identify it with the help of a field guide, another bird enthusiast, or an app (see tip #5). Once you know which bird wowed you, learn more about it.

3. Set a realistic goal. James recommends starting with a “familiar five,” as it’s likely you know at least a handful of birds already. Identify five species you’re comfortable with; then move to a familiar 15 and so on. But try not to get overwhelmed. “It’s not the knowledge of birds

that makes you a birder,” says James. “It’s the joy you have about birds and how you share it.”

4. Notice the details. James says there’s a lot to be gained from paying attention to the little things when observing birds. “‘Small brown bird’ describes a lot of birds,” he notes. Notice that the little brown bird also has a white bar above its eye, and a little black bib, and a yellow beak, and it’s bigger or smaller than this other bird you know. “All of a sudden these details start to collect,” says James.

5. Take a class and/or download an app. Many birding groups offer in-person and online courses. Enroll in one—or download one of the many free apps. James likes Merlin Bird ID for beginners because it includes real-life photos of birds in their habitats. And it can help you narrow down species by taking factors such as time of year, your location, and migration routes into account. But James cautions sound-only IDs because birds are excellent mimics.

6. Tell your bird story. And ask others for theirs. “I always go back to the idea that everybody has a story about birds,” says James, “whether it’s about the robin in your garden or the cardinal you hear on your commute.” Find your own bird story, tell it, and make a space for others to share theirs.

7. Get engaged. Consider recording your observations in an online database like eBird, or participate in events such as the Audubon Christmas Bird Count or the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Great Backyard Bird Count. These activities offer a way to engage with other birders and support research that relies on community input.

8. Support birds at home. Bring birds to your yard or neighborhood green space by adding feeders or birdhouses. Such offerings welcome local and migrating species and make for easy birdwatching—from your own window or on a daily walk, for instance. Be sure to provide a diverse mix of seeds and follow other best practices, such as cleaning feeders and raking hulls to prevent the spread of disease.

9. Enjoy the moment.

In the end, don’t forget to acknowledge the journey these creatures make and enjoy the moment. “Birds are going all across the hemisphere,” says James, “and the fact that one stopped in a tree near you and did a little ‘tweet’ before going on in its flight, being in that moment is absolutely magical.”

Turn to page 26 to read about how we’re improving wildlife habitats in California.

Tykee James hosts the podcast On Word for Wildlife, is cofounder of the Freedom Birders movement, and was an organizer of the first Black Birders Week in 2020. A former government affairs coordinator for the National Audubon Society, he is currently co-chair of Amplify the Future, which supports environmental education, and board president of the DC Audubon Society, which is in the process of changing its name.

One of the touchstones of spring is the biannual migration of songbirds. TPL’s efforts have helped conserve many important migration paths. Here are a few locations that offer stunning birding opportunities. And don’t worry if you miss the current migration, which winds down in June. These parks and wildlife refuges have plenty of year-round residents too, from songbirds and shorebirds to hummingbirds and hawks.

By Lisa W. FoderaroIn May, all manner of warblers, thrushes, vireos, and flycatchers show up at this sprawling refuge along a 50-mile stretch of coast in southern Maine. One of the most beautiful sites in the preserve is Timber Point, a peninsula south of Portland where some 270 species of birds have been recorded.

This 485-acre green space along the Chattahoochee River, just 40 miles from Atlanta, is a terrific place to see migrating songbirds such as northern waterthrushes, Cape May warblers, and Canada warblers. The woodlands, thickets, and river draw breeding warblers too. And keep your ears open for the squeaky dog-toy sound of the brown-headed nuthatch, which lives among pines in the southeastern U.S.

In the shadow of Albuquerque, the Valle de Oro National Wildlife Refuge (pictured above) hosts an impressive

variety of bird life, from Swainson’s hawks, western kingbirds, and northern rough-winged swallows in spring and summer to northern harriers, horned larks, and Savannah sparrows in fall and winter. The refuge is a mix of hayfields, desert, and bosque, a cottonwood forest habitat that flourishes along rivers and streams in dry regions of the United States.

To fuel their amazingly long migrations, songbirds need food and water. Two properties in the southern Sierra Nevada, Hanning Flat and Desert Springs, provide both in abundance. Lark sparrows, Savannah sparrows, horned larks, prairie falcons, and golden eagles are found in the grasslands at Hanning Flat, while its higher-elevation pine-oak woodlands welcome Cooper’s hawks and sharpshinned hawks. Twenty miles south lies Desert Springs, which attracts neotropical birds flying north. Western tanagers move through in large numbers, as well as blue grosbeaks, black-headed grosbeaks, and a half dozen species of warbler.

When you enjoy the simple pleasures of a park—a shady spot to read or the sight of a duck gliding across a pond—you might not be thinking about what’s going on behind the scenes in the service of climate resilience. But at TPL, we are. When we design and build parks with residents and partners, we incorporate all kinds of climate-smart green infrastructure to improve resilience to heat, floods, and other threats. In doing so, we’re creating a replicable model for park development nationwide. Here are some of our most impactful green spaces— all of which couple function with form in a big way.

By Amy McCullough Illustration by Nate PadavickLos Angeles, CA

The Central-Jefferson and Quincy Jones Green Alley networks near South L.A.’s Central Avenue jazz district turned 11 underused alleys into safe, shaded pedestrian routes featuring trees, flowering vines, and colorful murals. They’re also engineered to manage stormwater, capturing more than 1.5 million gallons per year and replenishing underground aquifers that provide water to a region increasingly at risk of drought.

Bozeman, MT

This award-winning park and nature sanctuary—which is home to over 100 species of birds—undid heavy damage from prior industrialization. Now, its 60 acres include a restored riverfront, regenerated wetlands, and natural streams that greatly improve local water quality, plus a community garden to feed residents.

Greenbelt | Dallas, TX

| Denver, CO

Once a trash-strewn vacant lot, this 5.5-acre park, which serves 42,000 nearby residents, is now a restored native shortgrass prairie with an outdoor classroom, walking trails, interactive play spaces, and art designed with local students. It also features a central arroyo that collects and cleans stormwater before releasing it.

This ambitious greenbelt will include three new TPL parks and a 17-mile trail stretching across southern Dallas, adding vital green space for nearly 200,000 residents who increasingly face recordsetting heat. Climate-smart features include native rain gardens and lighting that’s 100 percent solar-powered, which will save $71,000 in electricity costs over the next 20 years See page 60 for a deeper look at the greenbelt’s first park.

Peace Park

St. Paul, MN

Residents of nearby Skyline Tower once had scant access to green space. Now, the community enjoys a climate-smart park with playing fields, bike paths, two rain gardens, a playground, and features that collect and filter 1.5 million gallons of runoff annually, keeping polluted water from flowing into the Mississippi River.

Rockefeller Park Cleveland, OH

Once complete, this renovated park—the city’s largest, covering 200 acres—will connect five nearby neighborhoods to the outdoors and to the Cleveland Cultural Gardens, a series of public gardens celebrating the region’s ethnic diversity. A watershed restoration at Doan Brook will also address dangerous stormwater flooding

WACA Bell Park | Chicago, IL

Based on ideas sourced from residents, TPL worked with partners to reinvent this once-vibrant park, which serves 9,487 residents within a 10-minute walk. Its transformation includes new trees, which will combat rising temperatures in an urban heat island, permeable surfaces that reduce flooding, and upcoming solar panels that will power lighting and Wi-Fi throughout the park.

Dundee Island Park | Passaic, NJ

Previously underused, this park— which serves 20,160 residents within a 10-minute walk—was transformed with local input and now includes a boat launch, soccer field, community garden, and walking trails. And its climatesmart design accommodates Passaic River flooding events, mitigating damage to surrounding neighborhoods.

The Pacific School Brooklyn, NY

This project, which reduces neighborhood flooding and pollution of nearby Gowanus Canal, is among several Community Schoolyards® projects to be completed with New York City’s Extreme Weather Task Force. It’s capable of managing 1.2 million gallons of rainwater a year, enough to cover a football field in 4 feet of water.

Historic Fourth Ward Park Atlanta, GA

Part of the Atlanta BeltLine—a 22-mile green space network— “H4WP,” as it’s known, gives people a place to cool off, play, and enjoy outdoor gatherings—all while providing safety against floods that previously inundated surrounding communities. The park’s infrastructure can decrease peak stormwater flow by as much as 44 million gallons of rainwater per day.

Communities are at the core of TPL’s mission. In Maine, Trust for Public Land’s Indigenous partners are playing a critical role in advancing important—and historic—land conservation.

By Maulian Bryant, Penobscot Nation Tribal AmbassadorAs director of natural resources for the Penobscot Nation, Charles “Chuck” Loring Jr. has a lot on his plate. Lately, he’s been working with Trust for Public Land toward restoring nearly 30,000 acres to the Penobscot Nation—acres that are central to his tribe’s identity. When achieved, it will be the largest land return between a U.S.-based nonprofit and a tribal nation in history.

Protecting this land, called Wáhseht әk w by the Penobscot (and pronounced “WAH-seh-teg”), will ensure preservation and Indigenous stewardship of the tribe’s ancestral homelands and sacred waters. It will also greatly enhance public access to Katahdin Woods and Waters National Monument, benefiting surrounding communities and enhancing the region’s outdoor recreation economy for years to come.

The Penobscot’s natural resources department oversees the management of these lands. Pretty consequential. But Chuck— who I’ve known for years as a fellow tribal member, a former

high school classmate, and now, as a professional colleague— sees his role as an opportunity to be both an important voice for his people and a crucial partner to TPL. “The most significant challenge is fundraising,” he says. “There are not many federal programs that exist that work with the Penobscot Nation’s desire to gain back ancestral homelands.”

Many of us grew up within large families that take great pride in our tribe’s outdoor traditions. We are taught from a young age about hunting and fishing and, most importantly, that harvesting game is part of the balance and reciprocity of the relationship between all living things. These are core values for our people: sustainability, sustenance, respect, trust, and the knowledge that the health of the natural world is ingrained in everything.

Those values are reflected in the magnitude of what this project means for our tribe. Located in the heart of the Penobscot Nation’s territory, the land carries profound importance for our people, who rely heavily on the Penobscot River and consider it a valued member of our community. “We are looking at this as a significant landscape-scale restoration project where we can let the forests heal from their previous industrial uses and focus on improving fish habitat, as well,” says Chuck.

But this partnership with Trust for Public Land to regain our ancestral land is not just about restoration and growth. It is about healing. The lands heal from generations of misuse. The Penobscot people heal from generations of theft and disruption of connection to these places of our creation stories. When we can harvest game and medicine or do ceremony in sacred places where our ancestors did these same things, our connection is restored, and our communities and families are given new life. Our tribe finds a great amount of joy and hope in what this collaborative land return means.

I haven’t met with a single tribal citizen whose eyes didn’t light up at the prospect of us gaining back the Wáhsehtәk w parcel.”

– CHUCK LORING, PENOBSCOT NATION DIRECTOR OF NATURAL RESOURCES

“This land back work is some of the most rewarding and important work I’ve been involved in,” says Chuck, who also serves as an advocate for our tribal administration and councilors. He sees its value on a regular basis: “I haven’t met with a single tribal citizen whose eyes didn’t light up at the prospect of us gaining back the Wáhsehtәk w parcel,” he reflects.

Chuck finds himself focused on the sacredness of the land itself and what it means to protect it; for him, it’s an opportunity to practice that same reciprocity that comes from being in balance with nature—a reciprocity he learned about as a boy, sitting in the forest, feeling the breeze, and appreciating the peace and stillness of the hunt.

Now, as a key spokesperson for TPL’s Wáhsehtәk w land back effort, Chuck gets to weave together his life experience as a Penobscot tribal citizen and his education in forest operations. “As a tribe that relies on sustainable timber harvesting for our main source of income, Wáhsehtәk w affords us more opportunities now and in the future to provide for our people’s needs while also returning our ancestors’ land into our care,” he says with enthusiasm.

“We once had claim to all of this land, which ultimately dwindled,” he continues. “We held that land in our minds in perpetuity. We are not your typical landowner. We have no record of development of any of our current lands; we are not a threat to shoreland or wetlands. We are responsible stewards, guided by our ancestors, elders, chief, and council

to do the right thing by our land for our people.” It’s a sentiment shared by many members of our community.

Diane Regas, TPL’s president and CEO, agrees: “Trust for Public Land recognizes the profound and vital significance of returning land,” she says. “It’s not just an isolated act, but a deep acknowledgment and reaffirmation of a timeless bond, a rich history, and a promising future.”

Though there are certainly obstacles to progress, our tribe is cautiously optimistic and hopes that through storytelling and cultural exchanges, we can fully express to potential funders and supporters how much this land means to our people—past, present, and beyond.

And as a father to a young daughter, Chuck is certainly looking ahead. He feels a responsibility to make things better, just as his family felt while he sat as a boy in a hunting stand, listening to the forest and the lessons of our ancestors carried on the breeze.

Maulian Bryant has been Penobscot Nation Tribal Ambassador since 2017. She is working closely with TPL’s Federal Affairs team to help identify funding sources for the Wáhsehtәk w land return. Show your support for land conservation across the country by making a gift today at tpl.org/land&people learn more @ TPL.ORG/TRIBAL

Embracing the joys and challenges of climbing— including breaking down racial barriers—with the first all-Black team to summit Mount Everest.

Last fall, TPL Northwest Director Mitsu Iwasaki (right) was joined in conversation by three members of Full Circle Everest, the first all-Black team to summit Mount Everest. Together with seven other people of color, expedition lead Philip Henderson and mountaineers Demond “Dom” Mullins and Adina Scott climbed the highest mountain on Earth in May 2022. Read an excerpt from their enlightening discussion with Iwasaki about inclusion and equity in outdoor recreation, presented in partnership with Seattle Arts and Lectures.

MITSU IWASAKI: What is Full Circle?

PHILIP HENDERSON: Full Circle is about giving back. In the early ’90s, when I started working in the outdoor industry, I realized that there were people out there who wanted to know about camping and hiking and skiing and climbing. They just didn’t know how—at least from my community.

MI: How did this team come together?

DOM MULLINS: It was all sort of happenstance. Philip was kind of a unicorn—this African American dude who worked in the outdoor industry for 30 years. Philip had the opportunity to meet, by chance, all these other athletes that wound up being part of our project.

ADINA SCOTT: I did a trip to Denali in 2013 . . . Philip was there. Fast-forward a while, I get this phone call [from Phil]:

“Hey, how ya doin’? We’re going to Everest. You coming?”

I think a lot of the people on the team have a similar phonecall-coming-from-out-of-the-blue story.

PH: When I was building the team, it wasn’t like, “I’m going out to find 10 Black people to climb Everest to make a point.” All of our paths just happened to [cross]—everybody has a story. Our lives were just there, so we made it happen.

MI: Climbing is a lot of work. There’s a bit of suffering in there—and a lot of time and resources invested. There’s also a great deal of joy in it. What is the joy that you find in climbing?

AS: To me, it’s become really integral in spending this time outside, and with people, and in places that are magical. Finding the right people to do it with, there’s nothing like it.

DM: I grew up in Brooklyn. I didn’t know anything about wilderness. I learned about wilderness when I was in the army. I fell in love with it, but it didn’t even have a name for me. It was like, “This is army stuff.” Stacy [Bare, a fellow climber] introduced me to mountaineering. Part of the joy of climbing for me was realizing that I had an education that

was conducive to all of that. I learned how to climb with a veterans’ group. It became a vehicle for community for me, after service, and also to get myself into the sort of exciting trouble that I missed.

PH: The joy in climbing to me is just that I like doing things with my hands. It’s the technical aspect and the problem solving. As well as, if you’ve ever had birds flying below you, to me that’s one of the joys of climbing. Being outdoors . . . I’m just peaceful. I’m happy. I’m free.

MI: For Full Circle, there is an incredible amount of responsibility in representing your community—and a sense of not having space to fail. Can you talk about that?

AS: I think the really scary thing about showing up publicly and showing up out loud is that people are going to think what they think. People are going to judge a community based on [us]. We do have expertise. Everybody there has a lot of experience. But it’s like, “Did I show up right? Are my

The joy in climbing to me is . . . the technical aspect and the problem solving. Being outdoors . . . I’m just peaceful. I’m happy. I’m free.”

–PHILIP HENDERSON, FULL CIRCLE EVEREST EXPEDITION LEAD

Climbing is a lot of work. There’s a bit of suffering in there—and a lot of time and resources invested. There’s also a great deal of joy in it.”

–

MITSU IWASAKI, TPL NORTHWEST DIRECTOR

MITSU IWASAKI, TPL NORTHWEST DIRECTOR

crampons good?” All of those extra anxieties. The outdoor industry can be a pretty darn judgy place at times, and sometimes it’s for good reasons [such as safety], and sometimes it’s not. Being confident in our own abilities is kind of hard.

MI: Can you talk about what it means to be different among often intimidating and exclusive climbing communities?

DM: Particularly in mountaineering, I know we all have had experiences where we find ourselves the only person of color in a whole situation. I had become accustomed to having that type of experience in other institutions—in my professional life, when I was in the military. When I encountered that in the outdoor community, it was actually funny to me, because I didn’t realize it at first. I had become so used to it. It was other people who noticed it before I did.

Now is a productive moment in the outdoor industry, where we’re starting to have conversations about how to make these spaces more conducive to diverse peoples. It’ll lead to better outdoor education, and it’ll lead to better rapport and even earnings for the companies in the outdoor industry. It’s a win-win situation for everyone involved.

PH: When I started working at NOLS [National Outdoor Leadership School], I was the only Black American instructor there for six years. None of my coworkers—in the office or in the field—looked like me. But whatever is in the past is in the past. We want to normalize being in the outdoors and that connection to the outdoors. I can blame all the things that happened previously, but if I don’t change that moving forward, then that’s on me. [I can] provide [that experience] for someone else because I know what the benefits are. So that’s full circle.

Trust for Public Land recently completed the first phase in a complex land protection project that offers an array of benefits for people and wildlife in Colorado and beyond.

Planes and plains come together on the unique piece of land known as Bohart Ranch, part of which TPL protected last fall. Located east of Colorado Springs, the site includes a remote runway known as Bullseye Auxiliary Airfield, a critical training area for the U.S. Air Force; the wide-open skies above the ranch are also used by the Air Force Academy.

Protecting the site from encroaching development is important for a variety of reasons. Beyond the airfield, an active cattle ranch—maintained by multiple generations of the same family—helps sustain the area’s economy and identity, as cattle ranching is the lifeblood of many rural communities. (The same family will continue to lease and steward the land moving forward.) Plus, the rolling grasslands and miles of streams at Bohart Ranch provide native habitat to over 200 plant species and iconic fauna such as bison and elk.

An outcome of the SOAR initiative (which stands for Security, Open space, and Agricultural Resilience), the protection of this 11,900-acre property was a collaborative effort with partners such as The Nature Conservancy, and it’s

been many years in the making. “Through the SOAR initiative, we have a once-in-a-generation opportunity to make major progress in securing the natural, economic, and cultural vibrancy of the Colorado Springs region,” says Jim Petterson, TPL’s Mountain West region vice president.

This is the first acquisition in a multiphase project that will result in the permanent conservation of the entire 75-squaremile ranch. In one more boon to local communities, the Colorado State Land Board will direct the proceeds from this and related projects toward its mission to support public education. “You know you’re onto something when a project emerges that conserves important wildlife habitat and open space, supports agricultural production, provides muchneeded funds for public education, and enhances national security," adds Petterson. Turn to page 48 to learn more about our conservation of working lands.

We couldn’t achieve our commitments to climate, equity, community, and health without their generous financial contributions to our mission and our work. Thank you for helping us connect everyone to the outdoors.

Community Schoolyards® initiative & Parks for People | Boston, Massachusetts; Los Angeles, California; & Denver, Colorado

Transformation of ‘A‘ala Park | Honolulu, Hawai‘i

Community Schoolyards® initiative | California; Pennsylvania; Washington, DC; & Washington State

Wildfire Resilience Initiative | Southern California

Park Creation & Accessibility | Nationwide

Dalio Center for Health Justice support of the Community Schoolyards® initiative | Brooklyn & Queens, New York

Community Schoolyards® initiative | Los Angeles, California Tribal Schoolyards projects | Nationwide

Since its transition from golf course to public green space, San Geronimo Commons has become a beloved setting for the community, including runners from the nearby San Domenico School, who enjoy the rolling terrain and beautiful scenery.

In California, communities and partners are working with Trust for Public Land to turn former golf courses into resilient, biodiverse sanctuaries where wildlife can thrive and more people can connect with nature.By Amy McCullough

In the snug, emerald valley of San Geronimo, California, three words mark a paved trail in thick white chalk: “You’ve got this!” Written by the coach of a local high school cross-country team, the message was meant to encourage runners during a recent race. But it’s indicative of much more. It reflects the positive attitude and proactive manner of a community that’s working together to meet the challenges of climate change.

The 157-acre site where these words appear, once an 18-hole golf course, has been undergoing a transformation since 2018, when Trust for Public Land bought it and began working with residents to best realize its next iteration as a community asset. Soon after, irrigation stopped, and a grand and complex effort to restore the landscape began. And in the months and years to follow, people started visiting the site for a wide variety of uses.

San Geronimo Commons, as this public space is now known, is one of three former privately owned golf courses TPL is helping reimagine along the California coast—an area plagued in recent years by extreme heat and devastating weather events such as floods and wildfires. Marin County Fire Chief Jason Weber puts it bluntly, “It seems like a year-round business of disasters,” he says. “It has certainly changed in the last 10 years. You can’t say ‘the new norm’ anymore. It’s really just the normal.”

That reality is why communities are partnering with TPL to make the most of their landscapes—and gaining a host of benefits for wildlife and people in the process.

Mary Churchill, the aforementioned cross-country coach, says training at San Geronimo Commons (SGC) has provided her team with an enhanced appreciation for nature and a connection to their community. “Students see an area being used by the public, their neighbors, their classmates, and shared with animals,” she explains. “They are also aware that we work in collaboration with the fire department to use the area.”

She’s referring to Chief Weber and his staff, who have turned the former golf course clubhouse into the Marin County Fire Department’s administrative headquarters. Weber, a strong advocate for the restoration project, says the new natural area is in alignment with Marin’s vision, noting that more than 50 percent of land in the county is preserved for open space.

“The community saw pretty early on the value of the property for public use and public safety.”

– MARIN COUNTY FIRE CHIEF JASON WEBER

He sees an added bonus, since the fire department will be more centrally positioned than in their previous headquarters, greatly improving response times, which is more important than ever for this region. “The community saw pretty early on the value of the property for public use and public safety,” Weber observes. He’s glad the fire station is at a local nexus too: “The community gathers here pretty regularly,” he says, citing a weekly food pantry, track meets, cycling events, even a recent car show. “Everyone’s finding so many uses for the property as a commons, and it’s good for us to interact.”

Churchill, who teaches biology in addition to coaching, says SGC “has everything: hills, trails, vistas, and great parking,” adding that it’s not only beautiful but also feels safe. Her student athletes agree. George Kunze, a graduating senior, describes the site as “a pleasant, secluded area to train and race in where I’ve made a lot of valuable memories.”

Of course, not everyone was on board. Alexa Davidson, a lifelong resident of the area and executive director of the nearby San Geronimo Valley Community Center, says there was a sense of real loss for people who had used the space as a golf course. Homeowners who’d grown accustomed to having a manicured golf course outside their doors are also adjusting.

Davidson and other local leaders embraced the community engagement process and saw the site’s evolution as a time to do a lot of listening. They focused on being good neighbors, asking, “How can we support each other?” And as residents enjoy more regular access to the land for walking and recreation—and the broader community sees new possibilities at the property—attitudes are shifting.

Erica Williams, a senior project manager at TPL, says community engagement efforts and transparency about the process, including a monthly newsletter, helped assuage some concerns. The pandemic also played a role: “It represented a paradigm shift,” she says, “with property users reaching out to express their gratitude for the land and deep appreciation for its natural beauty, easy access, and trails.” Many neighbors have since come forth as land stewards, offering to help however they can: “They really are very in touch with the land and care about it,” says Williams. “We’re not philosophically opposed to golf,” she adds. “There was just an incredible restoration opportunity that also had a lot of community benefits.”

The acquisition also connected San Geronimo Commons to four adjacent green spaces: Roy’s Redwoods, Gary Giacomini Open Space Preserve, Maurice Thorner Memorial Preserve, and French Ranch Preserve. That connectivity not only expands recreational opportunities for the public; it also improves wildlife habitat, enhancing the region’s biodiversity and climate resilience at once.

A return to native plants is part of that resilience. Restoring the region’s natural grasslands will help mitigate climate change, as their deep root systems hold carbon, reducing the amount of greenhouse gases released into the atmosphere. And reconnecting waterways to the floodplain will create a moister landscape that is resilient to fire. “That’s where the restoration piece is really important as a climate benefit,” says Williams.

Chief Weber agrees: “We’ve been able to prove that this space can be used for public access, along with fire protection.”

Current community uses for the site include a food pantry (right), where an estimated 750 individuals receive groceries each week.

Coach Mary Churchill (below, in blue) and runners from the nearby San Domenico School regularly train on site.

In Marin County hotel bathrooms, prominent signs recommend keeping shower durations to five minutes or less in the name of water conservation. A rest area near Salinas displays a similar “every drop counts” message on a placard near the vending machines. Clearly, this is a state with water issues— and a population concerned about usage.

“Certainly, from the standpoint of water conservation, that’s a very glaring example of how this work is beneficial,” says Williams. Removing fertilizer and pesticide from stormwater runoff is another collateral benefit of transitioning golf courses to natural landscapes. In addition to being better for residents, cleaner water is hugely important to fish populations.

Anna Halligan of Trout Unlimited (TU), a national nonprofit and important TPL partner on the SGC project, explains how the watershed restoration will benefit both endangered coho salmon and threatened steelhead trout: “One thing that we know is really beneficial for fish is reconnecting the stream

channel with floodplains,” she says, which is what TU is helping achieve in the San Geronimo Valley. For other wildlife, too, such as birds, insects, amphibians, and mammals, “there’s this really great opportunity to create seasonal wetlands.”

The golf course had previously covered—literally, with dirt—much of Larsen Creek and directed its water into a holding pond, which was then used for irrigation. Now, TPL and Trout Unlimited are redesigning the landscape to hold water for as long as possible, which will protect the community from natural disasters.

A restored, naturally functioning floodplain means a more saturated water table, increased fire resilience, and better flood protection. “We want to have that buffer for those big weather events,” says Halligan, noting that natural streams allow fish refuge from strong storm flows, “so it’s not all just rushing downstream.”

Another aspect of the project will specifically benefit coho salmon. “There’s a limit to how far they can get upstream right now,” says Halligan, TU’s north coast coho project director.

San Geronimo Creek, one of the waterways that runs through the property, provides roughly 40 percent of the available coho spawning habitat in the entire Lagunitas Creek watershed, and TU is working with TPL to restore this creek, maximizing the Bay Area’s largest remaining coho salmon run.

California has committed to the goal of conserving 30 percent of its lands and coastal waters by 2030, known as the 30x30 initiative. The transformation at San Geronimo Commons “checks that box right out of the gate” Halligan notes— as do TPL’s other golf course restoration projects in the Golden State, all of which support climate resilience.

As TPL Climate Director Brendan Shane puts it, “While each location is unique, these large sites provide amazing opportunities for each community to address climate risks. The same restored natural landscapes that improve habitat, biodiversity, and water quality can buffer against coastal storms, manage extreme precipitation, and recharge groundwater supplies. These restored public landscapes also capture and store carbon in their forests, wetlands, and soils—helping address the root cause of climate change.”

“These large sites provide amazing opportunities for each community to address climate risks.”

– TPL CLIMATE DIRECTOR BRENDAN SHANE

About 150 miles down the coast, Tim Frahm, also with Trout Unlimited, leans over a bridge and joyfully points out a juvenile steelhead trout in the Carmel River.

Here, the Monterey Peninsula Regional Park District (MPRPD), Trust for Public Land, and TU are partnering with the California State Coastal Conservancy and others on an ambitious riparian (riverside) restoration that will improve 40 acres of habitat along 1 mile of the river.

Formerly Rancho Cañada, a 36-hole golf course, the land was purchased by TPL and granted to MPRPD, who—like the Marin County Fire Department—moved their headquarters to the clubhouse, even converting the prior pro shop into a Discovery Center focused on environmental and cultural education. The golf course property adds a 185-acre parcel to Palo Corona Regional Park, a significant open space on California’s

Trout Unlimited is working with TPL to restore Larsen Meadow (above and opposite) and other parts of the Lagunitas Creek watershed to support wildlife such as coho salmon.

central coast. And the transition will heal the landscape from prior damage, help prevent flooding, and provide new opportunities for recreation.

Christy Fischer, TPL’s conservation director for coastal Northern California, describes the project as “stunningly successful”: stunning because it very easily could not have happened. Previously the executive director at the Santa Lucia Conservancy, Fischer and MPRPD General Manager Dr. Rafael Payan each heard about the possibility of the golf course purchase on the same day—and both reached out to contacts at Trust for Public Land, knowing we’d have the expertise to help.

Facing competition from developers for both the land and the water, the groups needed to move quickly. They had a mere two and a half weeks to get under contract on the property—including a $100,000 deposit. That was before the challenge of raising an almost $11 million purchase price in 12 months. It seemed impossible, but TPL marshaled the resources necessary to quickly close the deal. And “off to the races we went,” says Payan.

Rethinking the resource of the Carmel River—which had previously provided irrigation to the golf course—was key, says Fischer. Frahm, who serves as TU’s central coast steelhead project manager (and happens to be Fischer’s husband), realized there was an opportunity to dedicate the irrigation water back to the river, enhancing its natural flow to the benefit of fish and other wildlife. A healthier, more natural Carmel River also means better resilience to the effects of climate change and cleaner drinking water for surrounding communities.

Much like the quest for funding, the proposed floodplain restoration at the former Rancho Cañada site requires plenty of creativity—not to mention flexibility.

“This is going to be a process-based restoration, where we create the footprint; we provide revegetation; but then the river is going to start carving her own locations,” says Frahm. Designs of this type used to attempt to keep rivers structurally in the same place, he explains. “Happily, we’ve evolved away from that.”

Frahm consistently refers to the river as “she” and “her”— an affectionate habit that reveals his close relationship with the landscape. Jake Smith, MPRPD’s planning and conservation program manager, describes the site with a similar rapture. When recommending the hike to Inspiration Point— which provides a bird’s-eye view of Carmel Bay—he advises planning in plenty of time for “blissing out” at the top.

And he’s similarly excited about discussing the forthcoming restoration, which is where the creativity comes in. The restoration team had to come up with new ways to allow the river to meander since they weren’t starting with a blank slate, given considerations such as nearby homes, existing roads, and the park next door.

They also had to remedy issues caused by the landscape’s former use as a golf course. That includes cutting away earth to lower the floodplain, dropping it as much as 15 feet in places.

Bringing the landscape down to the water table will create an accessible, drought-resistant water source for wildlife and provide greater capacity during storms—including an increased ability to capture and retain sediment—which is important to climate resilience.

Smith adds that a “nice wide, wet, intact riparian corridor also has the potential to buffer a lot of the negative effects of fire.” In other words, a healthy river and functioning floodplain mean better protection from wildfires. If a fire starts on one side of the Carmel River, for instance, a saturated landscape could help keep it from spreading to the other side.

The restored Rancho Cañada property will, in effect, act as “a kind of Swiss Army Knife to really mitigate a lot of climate change impacts and increase our capacity to adapt or respond to those events,” says Smith. This is great news for local communities, as flooding and wildfires are both top of mind for residents in California.

Much of the removed earth will be mounded in a manner that’s “sympathetic with the landscape,” according to Frahm, meaning the restoration aims to re-create a natural topography. The project team is also carefully considering the needs of wildlife, removing invasive species and adding native veg-

“One of our driving motivators, like TPL, is to reach and provide services to underserved, underrepresented, and under-resourced communities.”

– DR. RAFAEL PAYAN, MONTEREY PENINSULA REGIONAL PARK DISTRICT GENERAL MANAGER

Dr. Rafael Payan (opposite) and the Monterey Peninsula Regional Park District are partnering with TPL and Trout Unlimited to maximize water quality, steelhead trout habitat, and flood safety of the Carmel River (inset).

etation for a healthier ecosystem with improved refuge and new food sources.

Like San Geronimo Commons, Rancho Cañada fills a missing piece in a checkerboard of conserved land, in this case between Los Padres National Forest along the Big Sur coast north to Fort Ord National Monument near Monterey. Smith sees such connectivity as providing wildlife with a “pressurerelease valve,” allowing species access to more habitat if theirs is adversely impacted by an event like wildfire. He mentions black bears as one animal that has endured challenging circumstances by taking advantage of such openings.

Humans take advantage of new routes into nature, as well. Already, visitors can be seen walking dogs at the former Rancho Cañada site, pushing strollers along former golf cart paths, and generally enjoying the property—even though it’s

just getting started. Some parts are open now but will close during upcoming phases of construction, while other areas that are currently closed will open. “We’re designing it to maintain access,” says Smith, noting that its final design will strive to serve all ages and mobilities.

Payan is likewise concerned with equity and accessibility. “One of our driving motivators, like TPL, is to reach and provide services to underserved, underrepresented, and under-resourced communities,” he says. He hopes the park will become a beloved natural area to all in the region, from the Salinas Valley’s agricultural workforce and their families to elderly residents from nearby retirement communities to members of local Indigenous groups.

Payan, who is of San Carlos Apache and Mexican descent, is also interested in preserving local cultures and educating users of the park through interpretive signage and educational programming. He says the community overall has been very supportive, and keeping residents informed of the project’s progress and benefits is one of his primary goals.

“It’s easy to see what resonates with people when you start ticking off all the things that this multibenefit project does,” adds Frahm. “Reducing flood risk for the retirement community living upstream? That’s a big deal. Protecting a domestic water source? That’s a big deal. Creating a favorable, stable environment for threatened steelhead trout and other wildlife? That’s a big deal.” And while partners like the MPRPD, Trout Unlimited, and the California State Coastal Conservancy are invaluable to seeing it through, all agree this is truly an “if not for TPL” project.

Decisions about the restoration at NCOS, led by Dr. Lisa Stratton (above right), are made to optimize habitat for a variety of wildlife, including western snowy plovers, tidewater gobies, and Baja California tree frogs (from top to bottom).

It takes all of two minutes on a trail with Dr. Lisa Stratton, director of ecosystem management at the University of California Santa Barbara’s Cheadle Center for Biodiversity and Ecological Restoration, to see the strength of community at North Campus Open Space (NCOS). This is where TPL secured 64 acres of a former golf course for a wetland restoration that is benefiting residents—including students of all ages—and endangered shorebirds.

Stratton, who showed up on a bicycle and with a backpack full of aerial site images, sees a familiar face and shouts, “Hi, Jim!” at a birder passing by. “Hi, Greg!” and “Hey, Jeremiah!” are soon to follow, and each interaction focuses on birds, from American bitterns and black-crested night herons to killdeer, sandpipers, and pipits.

Jim, who’s carrying a large scope, is on his way to (hopefully) view a horned lark, causing Stratton to exclaim, “Oh!

I gotta see that. That’s a new bird for us. Cool.” Jeremiah, encountered a bit later, explains that the lark is a juvenile so not as recognizable, or so he’s heard on the birding grapevine.

Stratton is overseeing the restoration at North Campus Open Space—which ceased being Ocean Meadows Golf Course in 2013, broke ground in 2017, and fully opened to the public in 2022—and is the property’s biggest ambassador, according to Alex Size, TPL conservation director for Southern California.

Indeed, it’s not uncommon to hear her described as a force of nature—or, rather, a force for it. As Mark Holmgren, former curator of the Cheadle Center’s vertebrate collections, puts it, “Lisa is a unique person, able to blast ahead and ignore obstacles that hold normal humans back.”

Though retired from UCSB, Holmgren has continued working closely with Stratton as a member of the local Audubon chapter’s science and conservation committee. “We take on issues locally that are meaningful to birds,” he says, which has led to many discussions about how to best restore the NCOS site, located on Devereux Slough, to provide for shorebirds at risk of losing habitat due to climate change.

Western snowy plovers are one example; Belding’s Savannah sparrow is another. The former breed on sandy shores, using beach material to build nests. The latter is a wetlanddependent species that resides in Southern California’s coastal salt marshes year-round.

Holmgren began conducting bird surveys at the property in 2011, when it was still a golf course—and while, in fact, he was simultaneously golfing. “We were having so much fun watching birds that we gradually weened ourselves off the golf,” he says with a chuckle. Data shows that the restoration has, without a doubt, improved bird diversity. “We have more variation in habitats,” he observes. “Now we have freshwater riparian, salt marsh, grassland, coastal sage scrub, and vernal pool habitats”—all of which also serve other wildlife.

Beaming from under a bucket hat, he reports that the beach at Devereux Slough has the largest population in the county of breeding western snowy plovers; more than 60 nests have been recorded annually. Belding’s Savannah sparrows have also been documented breeding on-site.

“Another thing we’re really proud of,” says Stratton, “is that we have two populations of federally endangered plants here”: Ventura marsh milkvetch and salt marsh bird’s beak. It’s not just about putting native plants in the ground, she says. It’s about asking, “How can we create these unique ecological niches for different organisms?”

And, as with the other former golf courses, NCOS connects with adjacent natural areas—such as Ellwood Mesa, a 137-acre overwintering site for monarch butterflies that TPL and partners protected in 2005—linking more than 600 acres of land. “The connections are as important as the open spaces themselves,” comments Holmgren. “Because if one area is hit by fire or disease or some other kind of calamity, wildlife needs those corridors to quickly recolonize.”

In 1965, developers added an estimated 500,000 cubic yards of soil to Devereux Slough to create the nine-hole course, essentially covering up a natural estuary. Once TPL bought the land and conveyed it to UCSB, removing and rethinking some of that fill was an early step in planning North Campus Open Space.

Stratton says they excavated 350,000 cubic yards of earth, likening the effort to a ballet of machine operators. Nearby residents—many of whom are university faculty—were mostly very supportive of the changes, she says. In recent years, new arrivals have even told her they moved here because of the project.

“But,” she continues, “the public had to psychologically conceive of the change. Guiding that change and communicating [about it] was more of a nuanced challenge.”

Both Holmgren and Stratton credit the project’s genesis, in part, to Duncan Mellichamp, an emeritus professor of chemical engineering at UCSB and a onetime member of TPL’s California Advisory Board. “He realized this is part of what institutions can do: preserve open space and manage it,” says Holmgren. “It has created a fabulous perception in the community.”

“Thanks to you guys and other groups,” adds Stratton, “there was bond money available.” By “you guys,” she means TPL—specifically our expertise and leadership in supporting environmental ballot measures, which can result in important funding for projects like hers. Rachel Couch, a project development specialist with the California State Coastal Conservancy who worked on both Rancho Cañada and North Campus Open Space, describes it this way: “Everyone wanted to be a part of such a cool idea to undo the damage that the golf course had done to this coastal watershed.”

Horned larks are one of many bird species to visit NCOS.

Stratton identifies several climate benefits tied to the restoration, which is ongoing, but points to one very convincing piece of evidence: “All these people don’t have to buy flood insurance anymore,” she says, gesturing to a line of houses adjacent to NCOS. “We dropped flood elevations by a foot and a half, which took all these people out of the danger zone.” While protecting nearby communities, they also designed the wetland so it can become tidal for longer during rain events, knowing that as sea levels rise, such topographical changes will protect the salt marsh habitat. Much like the floodplain restoration at Rancho Cañada, it does this by lower-

“All these people don’t have to buy flood insurance anymore.”

–

ing water levels. “Instead of being bermed behind a sandbar,” says Stratton, “it becomes tidal, which drops the water level by about 5 feet.” Couch puts it more simply: “It basically just provides more room for the water to go.”

Guillermo Rodriguez, TPL’s California state director, says these projects “bring critical green infrastructure to landscapes and communities that need it, with benefits ranging from increased public access and flood control to reviving critical habitats.”

He notes that TPL is also providing technical assistance to a local land trust in Palm Springs, where three contiguous former golf courses will be developed into a nature preserve.

North Campus Open Space during restoration (inset) and recently (opposite), showing much-improved water capacity. Planting native species such as purple sage (right) was an important part of returning the NCOS landscape to a natural state.

All of this intentional, thoughtful design is why Stratton uses the term “rewilding” with caution, noting it can give the impression of letting something go, with little to no management. “We’re making conscious decisions,” she says, which is true of each of these former golf course sites.

TPL’s Christy Fischer makes a similar point, noting that “golf courses left to their own devices go to hell in a handbasket really quickly,” typically with invasive species running rampant. In essence, deliberate effort, planning, and cooperation are needed to best serve wildlife and people.

Plus, we can’t truly go back to a pristine, “wild” state. From agriculture and ranching to golf courses and development, people have been affecting these landscapes for centuries. What we can do is learn from the past and strive for healthy, functioning ecosystems moving forward. In Holmgren’s words, “History informs restoration, but it doesn’t necessarily dictate restoration.”

The educational aspect is key. Exposure to restored landscapes teaches such ecological lessons, and there are plenty of students who will benefit, from children at Lagunitas Elementary School and West Marin Montessori Preschool near San Geronimo Commons to attendees at environmental education programs led by the Santa Lucia Conservancy at Rancho Cañada—and certainly by college students at UC Santa Barbara. “Doing this through the university has been special beyond what we ever anticipated,” Holmgren remarks.

Stratton agrees: “Being on campus is our biggest asset. We are a place with 5,000 new students every year. They’re out here collecting data; they’re getting that field experience.” It’s become a living laboratory that’s engaging students who are otherwise often divorced from the land around them. “There are about 30 classes that use the space in some way,” says Stratton—“not just ecology and biology, but also writing courses, anthropology, field trips.”

The site also serves as a route for Isla Vista Elementary School students, who bike through NCOS on their way to

school each morning. And there are two nearby preschools that use the site for outdoor education, even helping plant native species and watching them grow.

UC Santa Barbara is also working with members of the local Chumash community to raise awareness about Indigenous land management, such as controlled fire. “Cultural burning was a really important practice here,” says Stratton, who conducted a burn in partnership with the Chumash in fall 2023. “We want to bring back their practices and help highlight how sustainable they are while educating people and engaging the community in their value and importance.”

When asked about her favorite use of the site, Stratton pauses, then says, “I think birding is really cool because there are new discoveries all the time, but I’m really proud that it’s used for all this different education.”

And she’s particularly moved by the experience of her own students. “They go into this environmental studies program, and all they hear about is disaster,” she says. But many have told her that working on the NCOS restoration made them feel something unfamiliar: hope. “This made them feel like they made a difference.”

It’s a feeling that recalls those three encouraging words written by the cross-country coach: You’ve got this. When it comes to fighting climate change, we do have this—we can, that is, if we work together to conserve land with resilience in mind.

See page 58 for reading and viewing recommendations from community members and partners in this story. For more on birding, turn to page 14.

Amy McCullough is senior writer and editor for Trust for Public Land and managing editor of Land&People magazine. She is also the author of The Box Wine Sailors, an adventure memoir.

From Manhattan to Montauk, Trust for Public Land’s Long Island Greenway will fill a major gap in a statewide corridor for hiking and biking while supporting local economies, combatting climate change, and connecting 27 communities to the outdoors.

By Bradford McKee · Photos by Tara Riceproposed off-road alternative off-road proposed on-road alternative on-road existing on-road existing off-road

The first 25-mile section of the Long Island Greenway will lie in reach of 250,000 residents. It will begin in Nassau County at Eisenhower Park, then run east to Bethpage State Park and continue into Suffolk County to Brentwood State Park. Construction is planned to start in 2025, but more funding is needed to make the full trail a reality. Help us bring projects like the Long Island Greenway to communities across the country. Donate at tpl.org/land&people.

In late 2020, the State of New York provided a way for anyone to hike or bike its vast expanse almost entirely— almost. Despite two routes totaling 750 miles, the Empire State Trail, the nation’s longest multiuse state trail, stopped short of Long Island. Between Manhattan and Long Island’s tip near Montauk, not far from some of the world’s most beautiful beaches, there was still no trail. It’s this glaring omission that TPL’s Long Island Greenway proposes to remedy.

A new trail stretching 200 miles, the Long Island Greenway will provide 27 communities with greater access to green space and connect to 26 existing parks, all while offering New Yorkers an escape into nature. And it will link residents of Long Island, including those in Brooklyn and Queens, to the Empire State Trail (inset, left). Urban trails like the Long Island Greenway are also important for mitigating growing climate risks.

Of course, building the Empire State Trail was no easy feat. It took almost four years, 58 construction projects, and $297 million to become a reality. But trail advocates still quickly took note of—and issue with—Long Island’s omission. “That’s 8 million people you’re not serving,” says Danny Gold, TPL’s project manager for the Long Island Greenway. He adds that the greenway will connect to communities that don’t currently have easy access to trails.

Someone close to the early planning process for the Empire State Trail surmised that Long Island’s dense development would be prohibitively difficult to navigate. According to Gold, TPL challenged that opinion. Difficult maybe, but not impossible. In 2018, as the Empire State Trail was under construction, TPL conducted a study. It concluded that a multiuse trail extension on Long Island was, indeed, feasible. And the island’s density could be seen as making an even stronger case for the trail: more people to reach with its benefits.

Multiuse trails like the Long Island Greenway support climate resilience in many ways. Reducing greenhouse gas emissions is a major one. Long Island is carpeted with cars— more than 2 million of them. Nassau and Suffolk County drivers are said to travel 70 million daily vehicle miles. And three-quarters of them drive to work alone. If a portion of these people swapped their gas-powered commutes with active transportation alternatives provided by the new trail, such as walking or cycling (or by using it to more easily access public transit), Long Island could see a meaningful reduction in carbon emissions.

Then there’s climate mitigation in the form of green infrastructure along the trail. For example, TPL recently transformed a roadside stormwater ditch into a thriving native landscape and rain garden near the proposed greenway at Edgewood Oak Brush Plains Preserve. It can soak up the heavier downpours global warming brings to the region, and the palette of plants—such as milkweed and native mint—is a magnet for pollinators. The addition of plants and trees also cleans the air, mitigates high temperatures, and captures carbon—while providing cooling shade for trail users. Exposure to green space also nurtures people’s passion for the outdoors, raising awareness and cultivating climate advocates of all ages.

That study positioned Trust for Public Land to spearhead the Long Island Greenway—an ideal match, as creating trails under challenging circumstances is one of the things TPL does best. And there is plenty of incentive: Extensive multiuse trails bring numerous benefits, such as improving public health, generating new economic activity, and reducing environmental hazards such as air and water pollution and—the big one—greenhouse gas emissions. And they make excellent community amenities, enabling active transportation. People can commute, run errands, visit friends, go out to dinner, and engage in other routine activities without having to use a car.

While it’s a great advantage to Long Island residents that the greenway will connect to so many communities and parks, the complexities and nuances of mapping such a route can’t be overstated. For TPL project planners, route-finding is among the most critical—and technically challenging—steps.

“If you’re thinking about laying out a trail in an urban landscape like Long Island, existing linear features are one of the best ways to connect people,” says J.T. Horn, director of Trust for Public Land’s national Trails initiative. “When there’s a rail line or a utility corridor, it can be used for a dual purpose,” he explains. In fact, the existing 10-mile North Shore Rail Trail, which runs between Port Jefferson and Wading River on Long Island, follows a former train route turned electric path. Trust for Public Land is working with the Long Island Power Authority to share similar right-of-way access for stretches of the Long Island Greenway.

The Long Island Greenway effort, which is projected to cost $114 million and is actively fundraising, needs to win support among public officials and agencies in Brooklyn, Queens, the counties of Nassau and Suffolk, and in multiple Long

Island towns and villages. There is also the broader public to enroll in favor of the idea: the landowners, residents, and businesspeople who will find themselves near the greenway route. And of course, there is an urgent need to raise millions of dollars for the project from various federal and state programs, grantmaking organizations, and individual donations small or large.

Mike Lieberman, who strategizes planning and development for the Long Island Greenway as senior program manager for community trails in TPL’s New York State office, has carved the greenway’s planning into five sections. As TPL implements them, there could be a dozen concurrent construction projects in multiple locations and on various schedules, all working toward completion.

The built terrain of Long Island is quite complex. It’s densely populated and developed, with few pedestrian or cycling routes as alternatives to some of the state’s most hazardous roads—the roaring expressways, parkways, and highways built chiefly as rapid conduits in and out of New York City. As Lieberman puts it, the Long Island Greenway project “sounds almost impossible—and is also the perfect fit for TPL.”

The Long Island Greenway sounds almost impossible—and is also the perfect fit for TPL.”