april 2007 Hortensia Völckers An Instrument for Every Child Armin Zweite Deterioration of Art — Who Cares? Wilhelm Genazino Momentary Numbness. On Begging. Kathrin Röggla The Revenants Nikola Richter We Children from the Unemployed Petting Zoo Otfried Höffe European Community of Values? Polish Miracles Martin Pollack Nobility Peter Oliver Loew Lumpex Radek Knapp Hans Kloss Pawel Dunin-Wasowicz On Saksy Emir Imamovi´c Taking Memory to the Streets Hanns Zischler Journey to the Interior Nico Bleutge Air News Committees 4 9 12 14 19 23 27 29 29 31 32 37 38 42 43 german federal cultural foundation

kulturstiftung des bundes

stork ➝ eastern border ➝

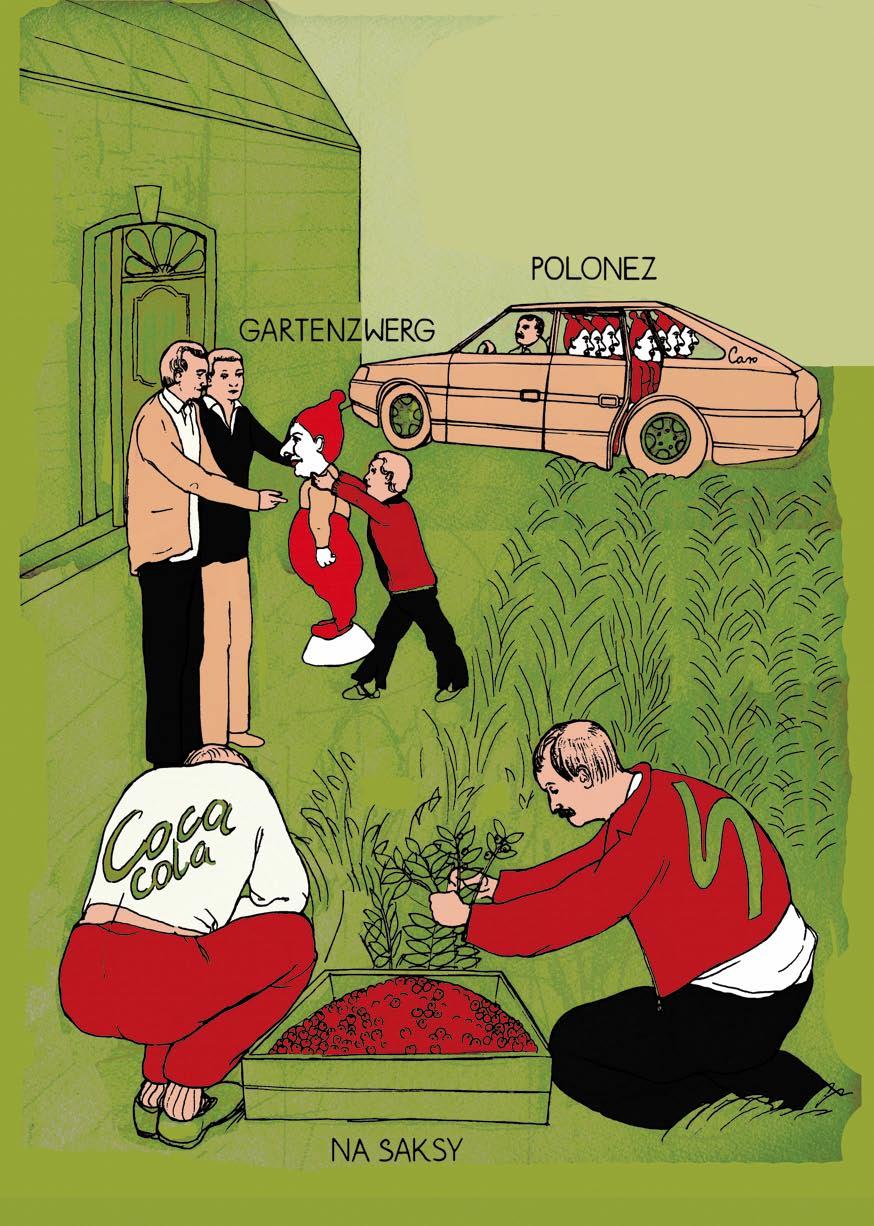

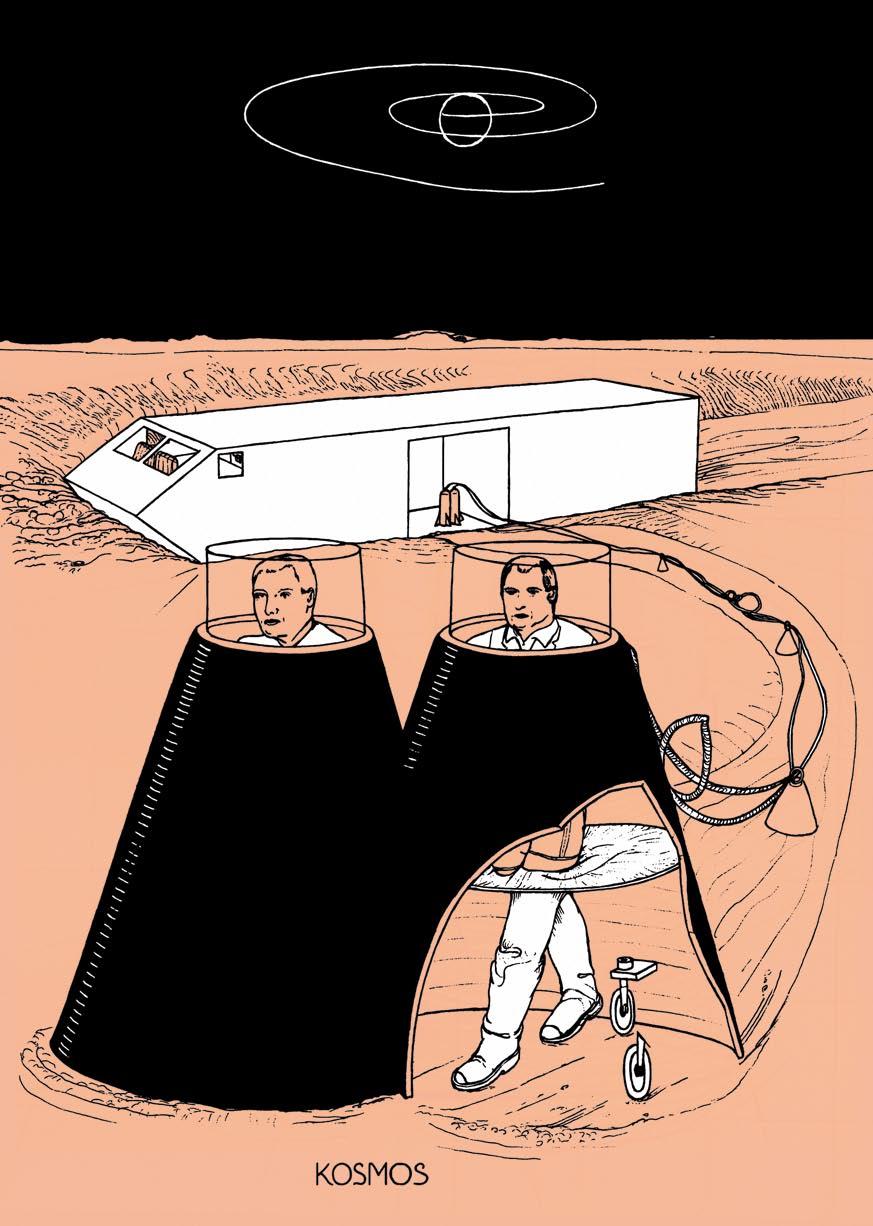

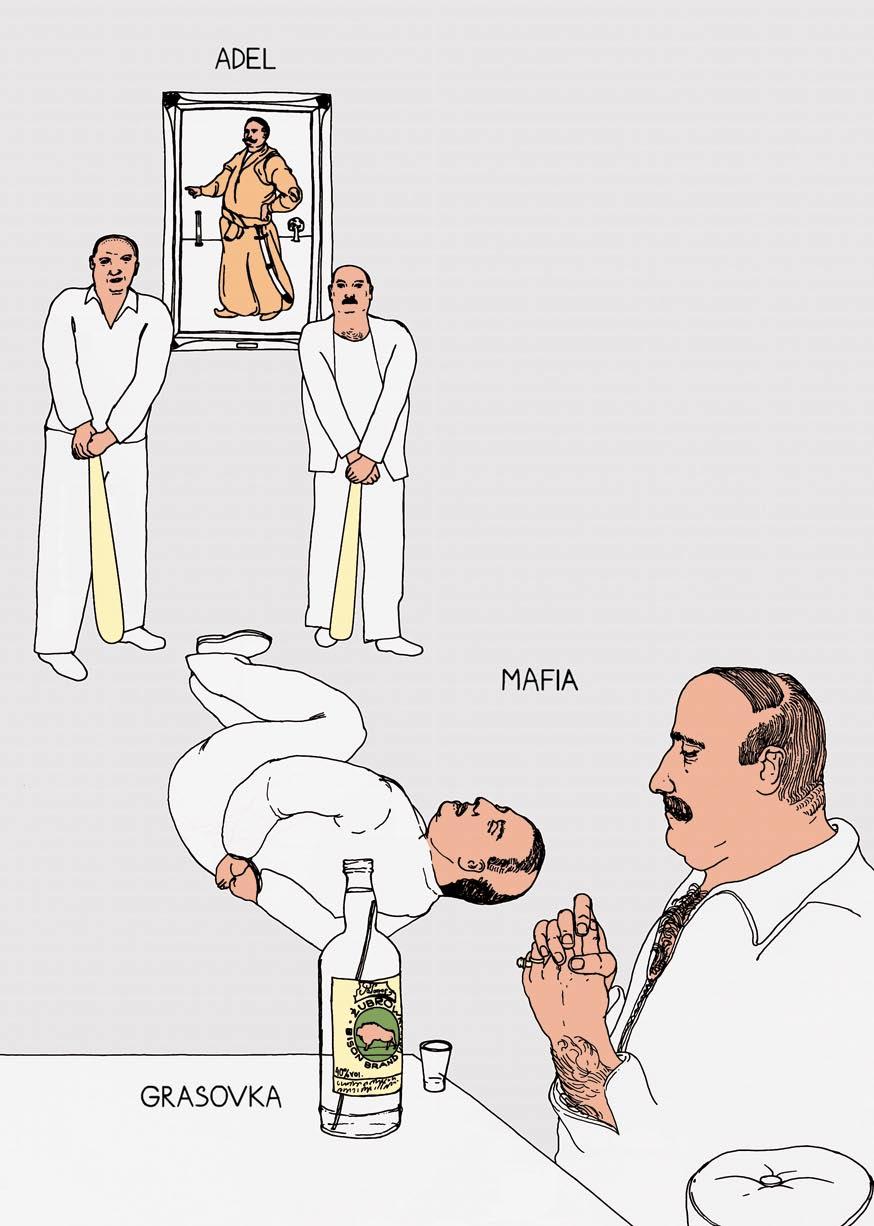

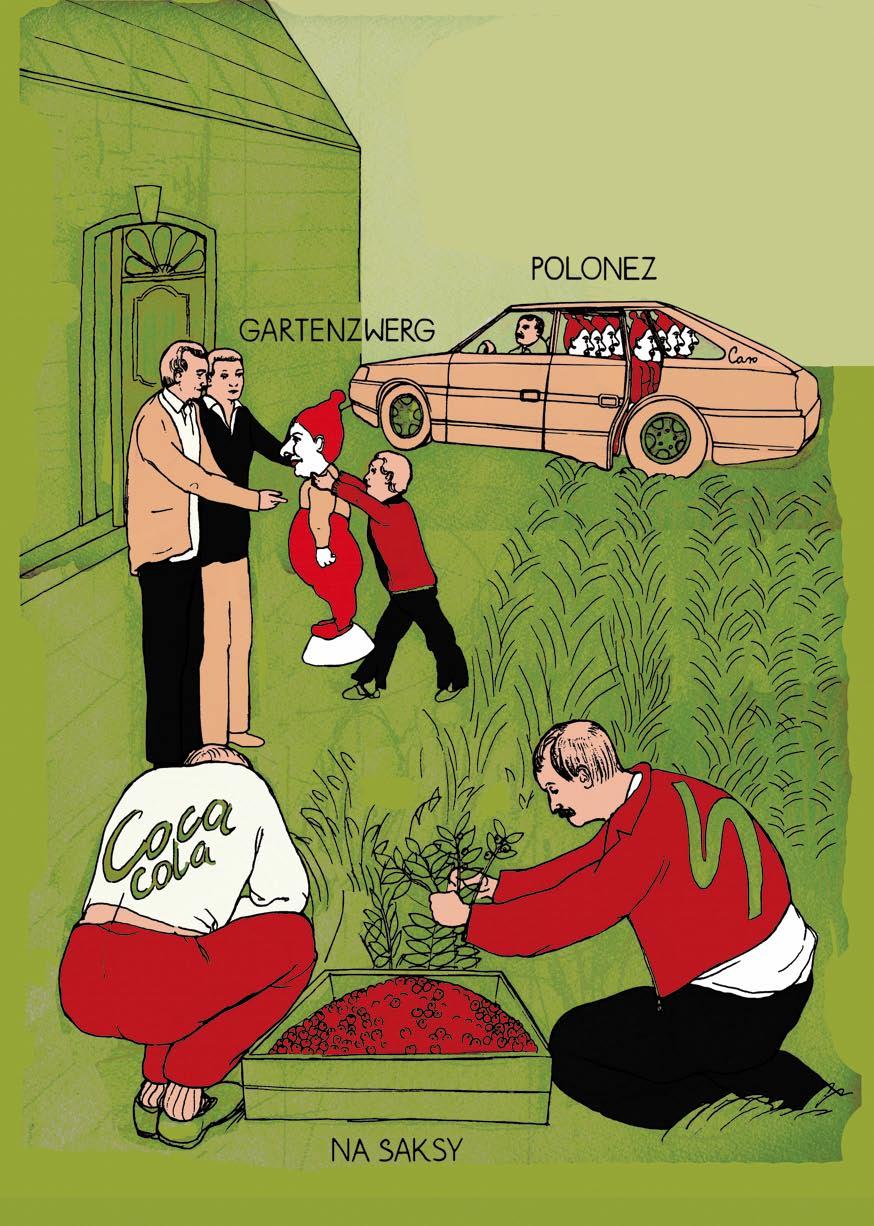

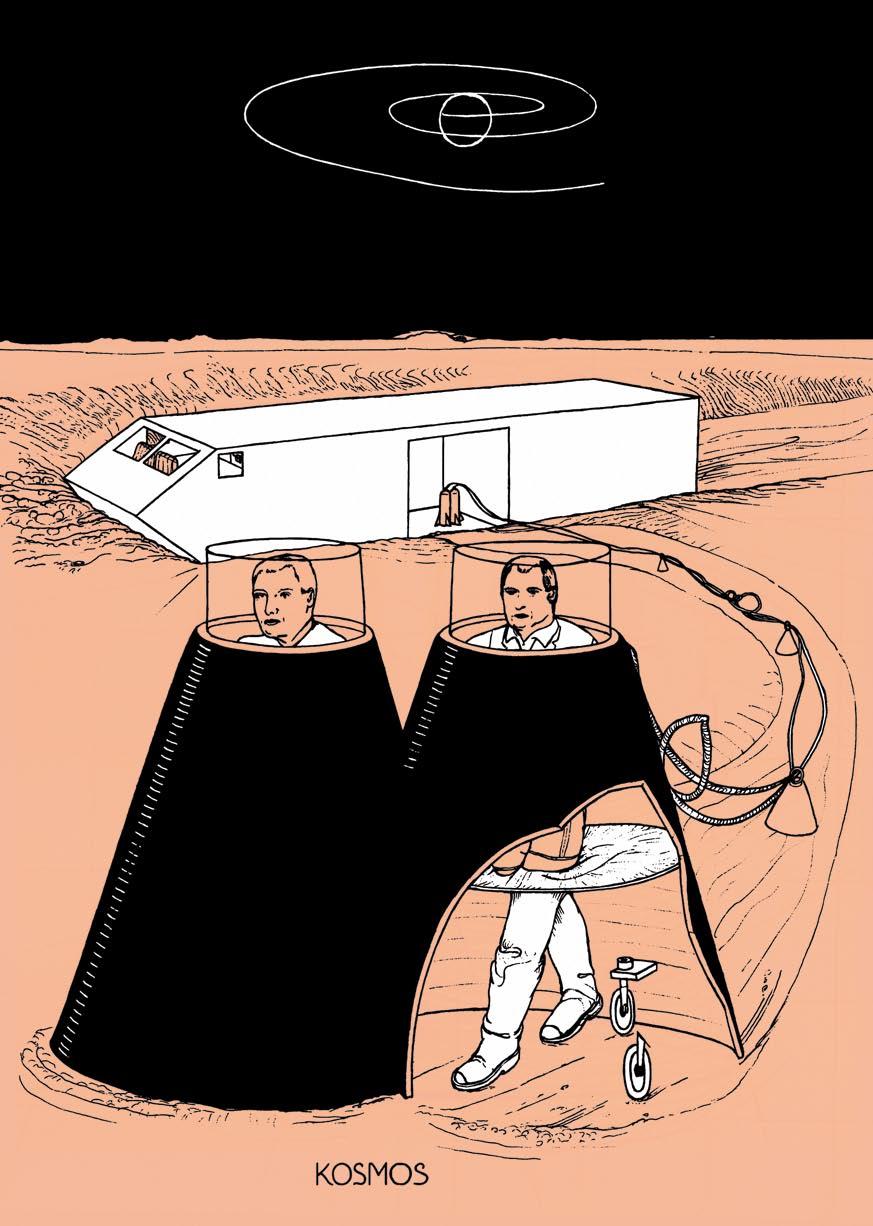

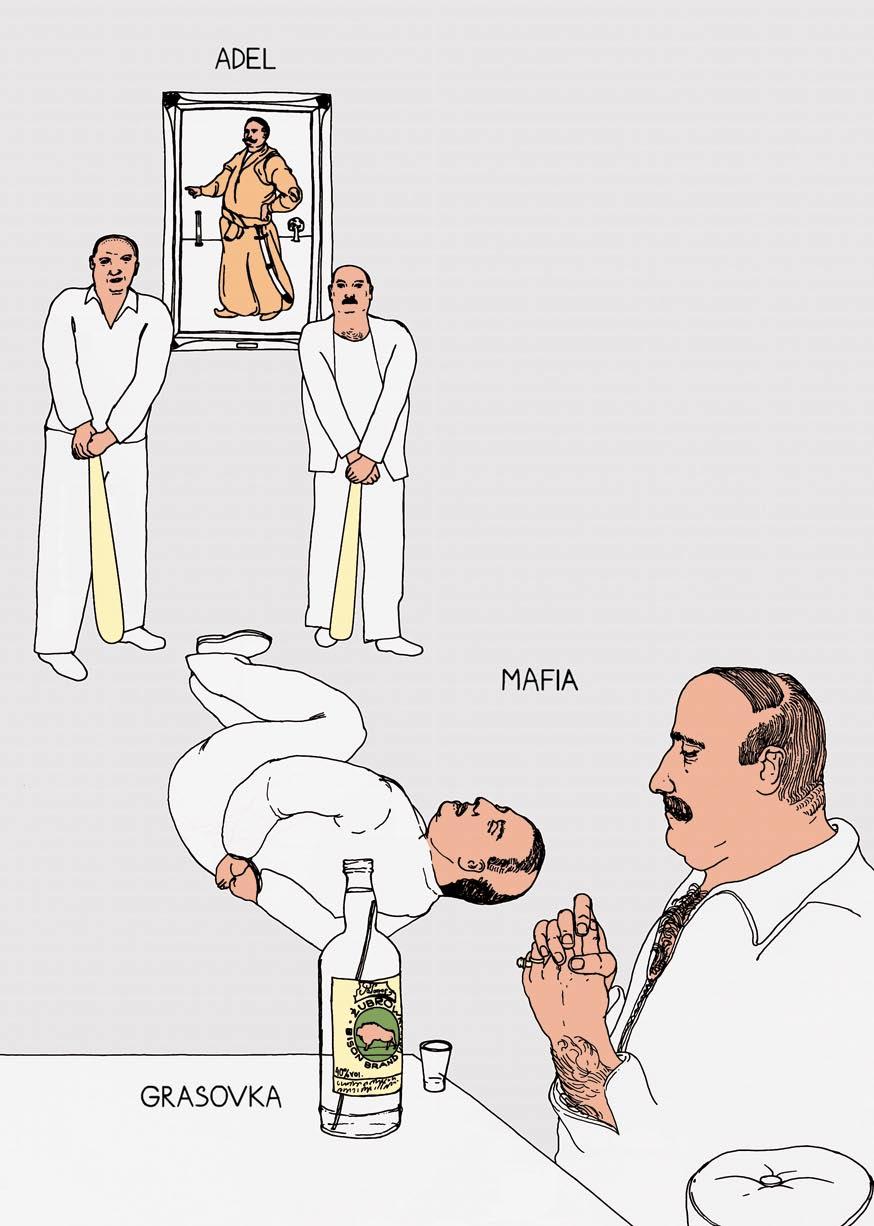

The German Federal Cultural Foundation never shrinks away from representing or supporting controversial positions. In fact, its focus on several thematic areas in the field of contemporary art and culture has required a readiness to challenge popular opinion and initiate debate. However, the projects in this issue are an exception to the rule as no one could raise serious objection to them, though they would have never left the drawing board without a bit of help. A former German president once claimed that our society needed a ‹jolt›. In view of the unarguably dreadful situation of cultural education in Germany, such a ‹jolt› could be created by a project to teach 200,000 children how to play a musical instrument in the coming years. And though the efforts will be focused on the Ruhr region as the European Capital of Culture 2010, we hope the project will have long-lasting effects that go far beyond the borders of the Ruhr region. If we do not convey cultural achievements and skills to younger generations, and if we do not enable them to foster and continue this heritage through their own efforts, the debate concerning how to preserve our historic cultural institutions could soon be pointless [ p. 4 ] . >>> In light of a dynamically expanding entertainment and event industry which is constantly encroaching on the activities of cultural institutions like theatres and museums, our loss of cultural competence is not the only danger facing art and culture. The artworks themselves are at risk of being lost forever. Only recently has the public become aware that century-old and modern works of art are in poor condition and require immediate restoration measures. Armin Zweite presents several impressive examples of contemporary art that do not only illustrate the current situation from an expert’s point of view. He also addresses the ‹ethical› problem of restor ing contemporary artworks whose short lifespans seem to have been intended by the artists [ p. 9 ] . With its Programme to Preserve and Restore Mobile Cultural Assets, the Federal Cultural Foundation hopes to increase public awareness about this problem and help find new ways of solving it. >>> Art enthusiasts have paid relatively little attention to the cultural heritage preserved in museums and collections of natural history. With his project Journey to the Interior, Hanns Zischler attempts to integrate these treasures of natural history into an interactive medium that takes the public on exciting new journeys into the secret world of museum storerooms [ p 3 7 ] . >>> All the drawings by Maciej Sienczyk in this issue were created as part of the German-Polish cultural projects organized by Büro Kopernikus. They illustrate the world of Polish Miracles — a compilation of articles by German and Polish writers. We have provided a selection of humorous examples on pages 27 31. >>> This issue also includes two new literary pieces by Wilhelm Genazino and Kathrin Röggla who were asked by the Federal Cultural Foundation and the Suhrkamp Verlag to describe their visions of the Future of Labour [ p. 12 ] . Nikola Richter, who is per sonally familiar with society’s ‹precariat›, investigates what young people think about the future of labour and how they’ve expressed their ideas in cultural projects on p. 19. >>> In contrast to Wolfgang Reinhard’s article in our last issue, the well-known philosopher Otfried Höffe is quite optimistic regarding the chances of shaping a European community of values — the topic of a conference organized by the Federal Cultural Foundation [ p. 23 ] . Emir Imamovi ´ c’s report on the erection of a monument in downtown Sarajevo demonstrates how difficult such an undertaking can be, and more importantly, how precious cultural education is in a democratic society.

editorial 3 editorial

Hortensia Völckers, Alexander Farenholtz [ Executive Board of the Federal Cultural Foundation ]

by hortensia volckers

an instrument

change through culture — Culture through change. Essen and the entire Ruhr region, with its 53 cities and communities, used this motto for its successful bid to become the European Capital of Culture 2010 — a title it will share with the Hungarian city of Pécs and Istanbul. The cultural ‹beacons› of the Ruhr region — theatres, museums, the Ruhrfestpiele, Triennial, Short Film Days, Zeche Zollverein, count less major and fringe events, socio-cultural projects and multi-cul tural institutions — will soon undergo explosive growth, heralding the decline of the old Ruhr region, demonstrating the struggle and splendour of its transformation and presenting its plans and visions for the future.

A capital of culture? Is this hype really necessary, sceptics ask. Don’t we already have enough spectacles, festivals, glitzy events and long mu seum nights? Do we really need more subterranean adventure land scapes, floating cultural islands and coalmines converted into concert halls and art studios? When the show ends, what will remain behind, what will continue to strengthen culture in the long term? Let me re spond with a dream:

One summer day in 2010, the Ruhr region’s largest football stadium will be packed with students from the first four grades of primary school. Every last seat will be taken, the playing field will be filled with people. Parents and local dignitaries will have a hard time squeezing in be tween the masses of children sitting on the bleachers, the stairs, in the aisles. Opening their canvas bags and instrument cases, they will then perform the premiere of a piece they had prepared for three years. A rhapsody for 200,000 children, a melange of etudes and improvi sation, a demonstration of what they learned from talented, imagi native teachers in three years of music classes. A suite of etudes and improvisation based on the world of childhood experience — songs sung to them by their grandparents who came from Italy, Spain, Kurdistan, Anatolia, or who immigrated to the mining cities from Galicia more than a century ago. Also the popular music of today, radio schmaltz and immigrant a cappella, Turk rock and classical snatches, Shakira and Grönemeyer, the latest teen rap and the rock’n roll their parents grew up with. The songs they sang together in pre school and the strange melodies they invented themselves. Along with these, they will chirp, whistle, rattle and sing the sounds of their daily lives — the honeyed violins in the TV commercials, the rising cheer of a football game, traffic noises, cartoon sounds, music they hear from the apartment next door, police sirens, rumbling machines demolishing the last factory in their neighbourhood, shouts on the playground, ship whistles on the river port, shopping mall Muzak, plopping tennis balls and screeching tram wheels, the subtle hum of a church organ and the calls to prayer from the mosques. All of this mixed together into a collage of sound based on traditions, classical and pop music, order and chaos. It will truly be a concert like no other, a gigantic fète de la musique, an event that will continue to resonate in the region for a long time, as the preparation alone will have taken three whole years.

This is a dream, my dream, but it could turn out differently. The two hundred thousand children might decide to perform at all the public spaces and parks in the Ruhr region, thousands of small groups, per forming their piece on one day at the same moment, or perhaps over a period of days, self-organized and decentralized. Nothing is set in stone. They can decide for themselves.

The dream has become a project — and is almost fully financed. An in strument for every child in the Ruhr region — an undertaking so im mense that most people can’t believe their ears when they first hear about it. Not only because of the 50 million euros the project will cost in the end. This project has already created logistic, legal and educa tional problems which pose a serious challenge to cultural agencies, primary schools and music schools. Where are they supposed to find that many qualified music teachers? Who is going to convince parents from so-called ‹educationally weak› social classes that their small monthly contribution to this project is well-invested? How can we expand the range of instruments to include the foreign sounds famil iar to the immigrant population? How do we gain the support of school directors who are faced with even more organizational prob lems and how can we motivate teachers to spend extra time during their day to work with trained instrumentalists from the music schools? Do we need to launch a promotional campaign for the par ents and neighbours who will have to endure the musical mania of their children’s trumpeting, horn-blowing and fiddling for three years — and hopefully longer?

My dream of a musical ‹social sculpture› stretching across an entire re gion would have dissolved into a series of smaller nightmares had we not known it was indeed possible. For this dream has a history. It be gan five years ago when Manfred Grunenberg, the director of the Bochum Music School, walked into the meeting room at the ‹Foun dation for the Future of Education›, a project established by the ‹Community Bank for Loans and Gifts› (GLS ) which is one of the pi oneers of ethical-ecological banking in Germany. He was trying to collect a half million euros for the project An Instrument for Every Child, which, as he put it, was «a counterpart to the Deutsche Tele

kom’s plan to provide all primary school children access to a compu ter by 2006». In cooperation with the city’s music schools, Grunen berg hoped to offer all children in primary and special schools the op portunity to learn an instrument of their choice. He was able to secure the half million euros. Bochum, though strapped for cash as all Ger man cities are, agreed to fund the expansion of the music schools, and since then, the musical network has been rapidly expanding thanks to a coalition comprised of municipal agencies, the Foundation for the Future (which purchased all the instruments with the proceeds acquired from the sale of privately donated Stradivari), the children’s families who contribute 15 or 25 euros per month, and last but not least, the primary school teachers who participate in the first intro ductory year of musical instruction. The cooperation between gov ernmental institutions and the citizens functions well, yet anyone who has been involved in a similar project knows how difficult, time-con suming, and potentially conflict-ridden such constructions can be. But the network is stable and growing.

And now the plan is to expand the network across the entire Ruhr region. How did this come about? Let me at least tell my part of the story. Last spring between March and June, my colleague Antonia Lahmé and I made several reconnaissance trips to the Ruhr region. We wanted to find out if the Federal Cultural Foundation could contribute any thing worthwhile to the ‹Ruhr Cultural Capital 2010›. We met with cultural department heads who had dreamed of a ‹systematic ap proach to cultural education› for years and spent their time after work singing in a choir. We drove through Essen-Katernberg in a police car, not because it was dangerous, but because the officer who was assigned the area knew all the kids by name, even those whose names were difficult to pronounce. We walked through closed coal mining areas decorated with modern artworks and listened to the quips of a nostalgic taxi driver who described it as «artificial respiration» for a place he and his colleagues used to work, suffer and live. We stum bled across disputes of professional competence while walking down the linoleum-lined corridors of a brick Gothic cultural affairs depart ment. At the university, we learned that 800 children from 46 nations receive free instruction from students. Beneath the obsolete winding towers at the Carl Mines, we met with a pastor who grew up next to the windmills along the Lower Rhine. For the last twenty five years, he had devoted his life to looking for work for young people — and had no intention of stopping anytime soon. We spoke with a school director who hoped to instil a ‹new religiousness› in children. Togeth er with theatre directors, he now cooperates with volunteer street workers to get kids off the street and develop a secular, theatrical ‹Canon for City Inhabitants›. At the Philharmonic Orchestra in Essen, we sat among nervous parents whose children — Italians, Russians, Turks, Germans — could find their way through the back stage labyrinth with their eyes closed. We visited a reconstructed min ing floor at the mining museum and went to a street in DuisburgMarxloh, where one can find everything one needs for a Turkish wed ding and where a handful of extremely active women have collected enough money to fund the construction of Germany’s largest mosque. Standing in front of a half-constructed glass palace in Duisburg, we asked ourselves whether this city was the right place for ‹Germany’s largest casino›. And sitting on a plastic sofa in an old roundhouse, we were told that the architecture in Mülheim was as mixed as its pop ulation. That was why it was so difficult to develop a cultural pro gramme that appealed to everyone.

We spoke to approximately 200 people during our search for a project. And somewhere along the way, we fell in love with the Ruhr region — a place still attached to so many clichés. We loved the jumble of drab cities with the remnants of their industrial past, the green islands of the cities to the south with their new middle-class joggers and the run down quarters in the northern cities with their quaint sayings (I think my fontanel’s gonna pop!), the patchwork garden communities and the kiosks on every other street corner, the warm-hearted frankness at the counters. But above all, we were impressed with the diversity of the civil interest groups, foundations and community centres which were established in more prosperous times and have survived the hard times thanks to the tremendous dedication of many. We found out what this country of complainers is constantly demanding. Excel lence. We found it in schools where 80 percent of the students have an immigrant background, all of whom speak excellent German. We encountered it in libraries equipped with the most modern techno logy and run by friendly and helpful staff. We recognized it in thea tre and orchestra directors who were dedicated to their art, felt privi leged to do what they do, and saw it as their duty to «give something back».

This is when we came across An Instrument for Every Child in Bochum with its amazingly well-functioning cooperation between the city and its citizens, patrons and musicians, a model of collaboration that con tinually generates long-term renewal. An Instrument for Every Child in the entire Ruhr region — it would be an impossible undertaking without cooperation. It could only be realized with political focus and the necessary funding, the cooperation of schools and municipal pol iticians, as well as the support of state agencies and sponsors. Accord

4 cultural heritage

for every child

ing to its statutes, the aim of the Foundation is to support and initiate innovative artistic and cultural projects, at best, in an international context. But is it the task of a national cultural foundation to devote itself to the musical literacy of a region? Nobody thought of this when the Foundation was being planned. Strange — or perhaps not. Every one knows that the great cultural traditions and ‹national treasures›, the cultural beacons that shine far beyond our own borders — the Theatertreffen, the documenta, the music festivals — and the many institutions and places which carry the ‹World Cultural Heritage› logo are useless if we don’t support the legatees, if the beacons don’t shine beyond the suburbs, if we don’t continually ‹re-mould› our treasures to fit the times. We’ve heard it said again and again — cul ture is the place where we talk about, describe, sing and surmount the barriers of the world we live in. Culture is the place we ask the ques tion ‹how do we want to live together?› — a question discussed and decided on by politicians, and ideally, with everyone. However, in order to participate in this discussion about society and its potential, we as a society have to learn to speak the language — the public and political language and also the language of the arts.

Perhaps this is the most extensive and costly innovation we have to sup port — working on the aesthetic ‹basics›. The Federal Cultural Foun dation has already taken steps in this direction with a wide range of smaller and large projects, including the Dance Plan Germany (in cooperation with community, state and federal institutions) and the New Music Network. Even with the ‹PISA shock›, Rütli Oath and the Rhythm is it! euphoria behind us, we still have a long way to go to en sure that all children in Germany are integrated into our fractured, multi-dimensional, national and globalised culture, that they are aesthetically educated to the point that they know what’s coming out of their iPods and PC s, that they can analyse and evaluate the sym bols being used to influence them, that they know how the sounds, images and stories they encounter in their daily lives are produced, and that they learn how to produce them themselves. Zoltan Kodály, the founder of Hungary’s great kindergarten and school music tradi tion, once claimed «Not being musically inclined is something you learn«. And indeed, it takes tremendous effort to prevent children — and adults — from singing, from wanting to learn how to play an in strument, from using their imaginations and creating something with others instead of playing Second Life all by themselves.

We teach our children to read and write so they can express their will and communicate with others. We teach them mathematics and sci ence so they can understand and shape the world. No one questions this, people call for optimisation and politicians attempt to follow through. However, musicians, painters, writers, cultural policy-mak ers and parents have to constantly provide reasons why aesthetic edu cation is important to our children. Do we always have to justify what we know — from Book III of the Politeia, Rousseau, and the reform pedagogues of the 1920s and1970s — that culture and art are elements of public life, as indispensable as politics, economy and architecture? Do cultural policy-makers have to defend what has been common knowledge since biblical times? According to the book of Genesis, the first city required four professions: a developer, peasant, forger and singer. Apart from bearing children and cooking, the Bible names all the areas of human activity that each individual and society at large must master in order to survive and live: building, agriculture, in dustry — and culture. Culture involves learning about our origin, en visioning the future, cultivating feelings and celebrating community. These are things we have to learn and practice. Throughout the course of history, they have become as varied, complex and difficult to mas ter as molecular biology, systems theory, the uncertainty relation and computer science. The scientific revolutions sparked by the theory of evolution, astrophysics and psychology with its counter-intuitive dis coveries have become the basis of our civilization. They necessitate a lengthy learning process. And the same applies to art — its liberation from cultural affairs, the weakening normative power of idealistic systems, images and sounds, the specialization of ‹autonomous› art and its departure from the mainstream. And on the other hand, the increasing possibilities of technical reproduction that have led to the commercialisation of those images and harmonies, the growing per fection of the cultural industry. We must train our eyes and ears to recognize and process all of this. And we require complex learning processes. However, it all begins with learning how to read and write. And democracy means no one is left out.

Things have changed since PISA in this respect — or so we’re told. But only ‹since PISA ›. I welcome the educational alliances which are cur rently being formed in many places in Germany, such as efforts to in clude dance training in school curricula, influenced by the inspiring film Rhythm is it!. And it doesn’t hurt that brain researchers are prov ing with colourful CAT scans something we’ve known all along — that performing music is one of the most complex challenges to our brains (and bodies!). A musician reads the music, transforms the notes into neural commands to a myriad of organs, muscles and ten dons, pays attention to the instructions from the conductor or the lead guitarist, listens to the other players and simultaneously adjusts his/her performance within a fraction of a second. This is an extreme

form of multitasking involving the brain, fine motor skills and per ception. In Manfred Spitzer’s book Musik im Kopf (Schattauer 2005), inspired by his love of music and an inexhaustible thirst for know ledge, he claims that music is the only process that literally engages the entire brain: the cerebral cortex, limbic system, hippocampus and the brain stem.

Music-making increases IQ , social skills and math grades — these are the kind of neuro-physiological findings that gradually make it into the newspapers. Taking young people and motivating them to partici pate in an ambitious community project strengthens their team spirit, willingness to work and self-confidence. Getting children to sing in a choir — as the touching blockbuster The Chorus demonstrates — is a powerful integrative tool for re-socializing ghetto hooligans. Dancing at work is beneficial — and may well be introduced in the German corporate world before long. BMW and RWE have shown their man agers Rhythm is it! (motivation!), and Mercedes sent its customers thousands of copies of Sacre du Printemps — a symphonic cultural event featuring dancers from Neukölln, district of Berlin.

It is good to hear that a humanistic education is the soundest founda tion for becoming a well-rounded person even in a computerized society of knowledge. But did we really need consultants and managers to tell us this? Children who make music are well-balanced, have bet ter social skills and a higher IQ — this is true and important. Above all, the language they speak is universal. The oldest flute ever discov ered by palaeontologists is as old as the first cave drawings and rudi mentary tools. Music is probably older than language and its funda mentals as the most physical form of communication that penetrates the very cells of our body and resembles the animal-like sounds of desire and combat. Its rhythm is anchored in the movement of our body and its instinctive sense of time. In contrast to the fine arts and more so than theatre and poetry, music is the only activity with which we can transcend ourselves — into our deepest emotions and in har mony with others. It is the most abstract art form that creates the strongest connection — because of its physical effect and its expres sion in performance with others, the act of making music together. Music cannot make us better people. It is simply a way of perceiving the world, transporting ourselves into the world. It is both exhilarating and exploitable, which is why Plato warned rulers about it and why the music industry is one of the largest branches of the economy. Music can excite and soothe, heal and sedate, it can be a catalyst for social emancipation («We shall overcome») and an apocalyptic hymn («…until the world lies in ruins»). And for this reason, too, we should learn its alphabet, semantics and grammar as thoroughly as we learn to read words and numbers.

But let me return to the school children who will soon be carrying their bulky guitar and trombone cases to school. The assortment of instru ments at their disposal is impressive — the violin, cello, double bass, trumpet, trombone, flute, clarinet, French horn, guitar, mandolin, ac cordion, recorder — in combination, everything is possible: children’s symphony orchestras, string quartets, jazz bands, punk rock groups and folk music ensembles. We are currently working on expanding the range of instruments to include those from other cultures, such as the Turkish long-necked lute saz or the Russian balalaika. From past experience, we can expect that An Instrument for Every Child — Ruhr 2010 will produce its own group of young stars — and in following with the typical bell curve, there will probably be a great number of children who never make it further than «Dona, Dona» or the «House of the Rising Sun». The same applies to ‹conventional› reading and writing. Some children are destined to write poems all their lives while others write SMS messages, some read Joyce and others read the BILD newspaper, or not even that. Musical instruction will inspire some to explore Beethoven’s highly individualised quartets, others to compose the eternally recycled harmonies of pop music, and others to experiment with sounds, combining traditions and styles to create new musical worlds.

Two hundred thousand school children will soon discover that it is pos sible to perform together, which is something many will realize is not possible in Second Life. The curriculum in 1,000 primary schools will be expanded to include an additional activity which cannot be learned using a machine, but only through individual and group practice. A medium with which six-year-olds who haven’t yet mastered the basic vocabulary can communicate, an ‹art› that one can learn and perform simultaneously. A sound we enjoy hearing as we pass by these strange buildings where our future is being formed. In the past five years, there hasn’t been a project I have treasured more than An Instrument for Every Child

� cultural heritage

Hortensia Völckers is the Artistic Director of the Federal Cultural Foundation.

history ➝

theft ➝

h i storic e x hi bitions [sele ction]

At its 10 th joint session on 9 10 November 2006, the Federal Cultural Foundation’s jury granted funding totalling 7. 4 million euros to 51 new projects. Several of these are exhibitions based on culturally historic themes, a selection of which we have listed below.

treasures of the liao — china’s forgotten nomad dynasty Archaeological exhibition Artistic director: Adele Schlombs I Concept and content: Shen Xueman (CHN) I Venues and schedule: Museum of Far Eastern Art, Cologne 27 January – 22 April 2007 I Museum Rietberg, Zürich (CH), 13 May – 15 July 2007

The Kitan were nomadic horse-riding warriors who controlled north ern China around the year 1000 AD . They ruled a territory that stretched from Mongolia to Manchuria and as far south as presentday Beijing. They referred to themselves as the ‹Liao Dynasty› and their military prowess put fear into the heart of the Chinese Song Dynasty. Although dismissed by Chinese historians as the ‹Barbarian Dynasty›, the treasures of the Liao testify to its awe-inspiring splen dour and display a unique synthesis of nomadic and Chinese tradi tions. During the 10th and 11th centuries, the Liao Dynasty was the most powerful dynastic line in Eastern Asia and even maintained trade relations with countries on the Baltic Sea. This exhibition is the first of its kind in Europe to present approx. 200 pieces of art which were discovered in the autonomous region of Inner Mongolia in re cent decades. Some of the most impressive exhibits include the cere monial death armour of the Princess of Chen, who died in 1018 AD , and that of her husband, as well as precious antiques from the treas ure of the White Pagoda.

a historic friendship Exhibition on Prussian-Russian relations in the 19 th century Curator: Wasilissa Pachomova-Göres (RUS/D) I Participants / artists: Burkhardt Göres, M. Dedinkin (RUS), S. Androsov (RUS), N. Vernova (RUS) I Venues and schedule: State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, October 2007 – January 2008 I Martin Gropius Building, Berlin, March – June 2008

This exhibition follows up on the two major exhibitions MoscowBerlin, Berlin-Moscow, shown in 1997 and 2002. While the first exhibi tions emphasized the volatile relations between Germany and Russia in the 20th century, the current exhibition will focus on Prussian-Rus sian relations during the first half of the 19th century. The close dy nastic relationship between the Hohenzollern and Romanov lines had a long-lasting impact on practically every area of society and ini tiated a period of extremely fruitful cultural exchange. For the first time, outstanding artworks from this period will be transferred from and to Berlin and St. Petersburg for an exhibition that will provide viewers the opportunity to directly compare the works. Several pieces will be publicly displayed for the first time since the former Soviet Un ion officially returned them to Germany. Although this exhibition touches on some recent cultural-political issues, its historic perspec tive demonstrates how cultural exchange can benefit political and social relations. The cooperation between the State Hermitage in St. Petersburg, other Russian cultural institutions and the Foundation of Prussian Palaces and Gardens Berlin-Brandenburg will help consoli date German-Russian cooperation and build trusting between Ger man and Russian museums.

origins of the silk road Cultural-historic exhibition

Curators: Christoph Lind, Alfried Wiecorek I Participants / artists: Wang Bo (CHN), Mayke Wagner, Zhang Yuzhong (CHN) I Venues: Martin Gropius Building, Berlin; Reiss Engelhorn Museums, Mannheim; Überseemuseum Bremen (Bremen Overseas Museum) I Schedule: 1 January 2007 – June 2008

This exhibition features approx. 180 well-preserved antiques excavat ed from graves found in the Taklamakan Desert in the far western re gions of the People’s Republic of China. They provide evidence of the historically unique cultural transfer from Central Asia to the Medi terranean. For those who once lived in relatively inaccessible regions, it was quite normal to interact with other cultures on the Eurasian continent. Although many in Germany are familiar with the Silk Road as one of the longest trade routes in human history, very few are well-acquainted with this Far Eastern region and its intercultu ral civilisation. This cultural-historic exhibition was made possible through the tremendous cooperation of Chinese archaeologists and the colleagues from the Curt Engelhorn Foundation and the Reiss Engelhorn Museums in Mannheim. The exhibition will open at the Martin Gropius Building in Berlin.

confrontation and dialogue: german art of the cold war

1945 1989 Exhibition Curators: Stephanie Barron (USA), Eckhart Gillen I Artists: Gerhard Altenbourg, Georg Baselitz, Joseph Beuys, Anna and Bernhard Johannes Blume, Carlfriedrich Claus, Lutz Dammbeck, Hanne Dar boven, Felix Droese, Hartwig, Ebersbach, Hans Haacke, Bernhard Heisig, Peter Herrmann, Werner Heldt, Jörg Immendorff, Anselm Kiefer, Martin Kippenberger, Astrid Klein, Gustav Kluge, Mark Lammert, Wolfgang Mattheuer, Harald Metzkes, Marcel Odenbach, A.R. Penck, Sigmar Polke, Nuria Quevedo, Raffael Reinsberg, Gerhard Richter, Katharina Sieverding, Rosemarie Trockel, Werner Tübke, Günther Uecker, Wolf Vostell and others I Venues and schedule: Los Angeles County Museum of Art (USA), 11 January – 5 April 2009 I National Museum of German Art and Culture, Nürnberg, Mai – July 2009 I Neue Nationalgalerie Berlin, September –December 2009

This exhibition will feature about 180 works of art-historical signifi cance — paintings, sculptures, photography and installation art — all of which were produced in East and West Germany between 1945 and the end of German division in 1989. It will explore the conflict of competing images of humankind and ideological concepts in the confrontation and dialogue between the opposing political systems in Germany. Jointly organized by the American head curator of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Stephanie Barron, and the Ger man exhibition maker Eckhart Gillen, it will be the first American ex hibition to present German art history during the era of German di vision in an all-German context. The exhibition will open in Los An geles in 2009, marking the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall. During the second half of the commemorative year, the exhibi tion will be shown at the National Museum of German Art and Cul ture in Nürnberg and the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin.

the tropics — equatorial perspectives or: paradise is right around the corner Exhibition and accom panying events Curators: Alfons Hug, Viola König, Peter Junge, Anette Hulek I Artists: Rachel Berwick, Mark Dion, Candida Höfer, Beatriz Milhazes, Julian Rosefeldt, Thomas Struth, Pascale Marthine Tayou, Guy Tillim and others I Coopera tive partners: Goethe-Institut, Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil (BR) I Venue and schedule:Martin Gropius Building, Berlin, April – June 2008 The ethnological exhibits in this exhibition present the tropics as they were viewed before they were socio-geographically classified as be longing to the so-called ‹Third World›. Westerners often associate the term ‹tropics› with lush exoticism — a cliché reinforced by traditional art from the equatorial regions of the world. Although we generally recognize their highly spiritual content and strong emotionality, these works have an aesthetic quality which has long been overlooked. In recent years, contemporary artists have begun to re-examine the trop ics — a mythically-charged subject that reflects the patterns of our distinctly western perception. With works by 25 contemporary artists and pieces from the collections at the Ethnological Museum, this ex hibition will illustrate the artistic complexity and aesthetic wealth of the tropics, as well as encourage new approaches in the cultural dia logue between the northern and southern hemispheres.

8 cultural heritage

deterioration of art– who cares?

The condition of many pieces in Germany’s museum collections is alarming. Most museum-goers seldom have the chance to see these endangered artworks. The Federal Cultural Foundation and the Cultural Foundation of German Länder have jointly launched a Programme to Preserve and Restore Mobile Cultu ral Assets. During the next five years, this programme will help fund model projects that restore works of art. One of the key goals of this programme is to increase public awareness of the dramatic situation, and using several examples, present new solutions for saving our cultural heritage. The art historian Armin Zweite explains that century-old artworks are not the only ones in danger — many pieces of contemporary art are also in urgent need of restoration.

by

armin zweite a

few weeks ago, an artwork by Damien Hirst, one of the most prominent figures of YBA (Young British Art), changed hands for a phenome nal 20 million dollars. The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991) is a large glass case containing a tiger shark preserved in formaldehyde. The new owner clearly didn’t invest in suf ficient preservation measures. Now the cadaver is beginning to disintegrate which has forced Hirst to catch another tiger shark and recreate the piece.

The original didn’t even survive twenty years. Although this may be a very unique and spectacular case, it is a telling example of a phenom enon now threatening the field of contemporary art. It involves a myriad of conservation and restoration problems, the consequences of which public collections have only begun to analyse in the past dec ade with the prospect of exchanging information at the international level. Apparently one of the reasons for this precarious situation is the fact that everything is possible today — not only in terms of the forms of representation, motifs and styles, but also in the use of heteroge neous materials and highly diverse, often experimental techniques. Furthermore, we are noticing that many other genres besides painting are affected by this problem. Collections of contemporary art not only feature sculptures and photography, but also video pieces, con ceptual art, environments, ready-mades, installations, kinetic exhibits, etc. All of these works are promoted, marketed and collected under the category of ‹Art›, which entails that they survive the present and ideally continue to be valued and aesthetically appreciated in the fu ture.

Since Duchamp, Warhol and Beuys, there seems to be no end to the continually expanding definition of art. A large percentage of these works end up being shown and often permanently stored in museums. It is now one of the special tasks of public collections to preserve, maintain, study and present these works. This wouldn’t be worth fur ther thought if we weren’t being bombarded with such an explosive increase of problems in such a short span of time. As the example of Damien Hirst’s work demonstrates, we are now facing a qualita tively different situation than two or three generations ago when one could generally assume a finished artwork wouldn’t need restoration so soon.

There are many reasons why this problematic situation has arisen. We have recently noticed a growing tendency to use working methods that consciously differ from conventional methods and, at times, do so to an absurd degree. Artists constantly experiment with new forms of expression and design and use unusual materials in order to create something that has never been seen before. Regardless of what the in herent message is, artists always attempt to make it memorable, ori ginal and unique so that they are heard over the Babel of overheated discourse in the contemporary art scene.

Let us look at a few examples. In his wall sized works, Anselm Kiefer uses a wide variety of materials, including ashes, lead, sunflowers, ceramic elements, wire, photos, hair, glass, dried leaves and the like. Their size, complex surfaces, fragility, and weight of over several hun dred kilograms make handling and installing such works especially difficult. For example, after the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao pur chased and displayed the works, the museum curators deemed it too risky to put them in storage. They left them where they were and built a concealing wall, behind which these immobile monstrous artworks remain today. In effect, they were forced to relinquish valuable exhi bition space. Kiefer’s oeuvre may represent a borderline case, but an

extreme material fetishism that harbours unforeseeable dangers to the works in terms of their preservation seems to be ubiquitous.

Material fetishism? No, this is not about material fetishism, neither in Kiefer’s works, nor those by many other artists. Knowing the artist’s intention in using certain materials in a certain way is clearly essential to understanding the reason for such conglomerations of various substances. Meaningless rubbish is suddenly instilled with meaning and significantly influences the message of the work. Think of the pieces by Beuys (grease, felt, honey, fat, flowers, newspapers), Dieter Roth (chocolate, spices, cheese, sausage, mould), Wolfgang Laib (rice, beeswax, pollen) Kounellis (coal, beetles, soot, coffee, jute), Mario Merz (fruit, brushwood, newspapers). The list goes on and on. It is often the visual effect of many of these works which barely have an ephemeral validity (and are often not intended to). They decom pose and crumble within weeks or months, sometimes several years, and as they fade away, we become especially aware of the precarious condition of such works. Suddenly, we feel they should be preserved for posterity, although this may not have been intended when they were first envisioned and created.

Kinetic works are only regarded as art when they are moving, clanking and clicking. Problems occur when engine units fail, obsolete mate rials wear out, ball bearings jam up, the joints of various materials break with the constant vibration, or the built-in objets trouvés simply stop working. Eventually, the works have to be repaired and compo nents replaced. However, which preventative and restorative meas ures can we take without changing the character of the piece and en dangering its integrity and authenticity?

Questions like these also apply to works completed within a set period of time, i.e., slide, film and video projections. In such cases, we have to decide to what degree the authenticity of a piece depends on the pro jection devices and their specific arrangement in the room. However, does it make sense to equate the identity of a work with things that cannot be preserved in the long-term? Is the hardware only of techni cal relevance, or do conceptual, aesthetic and historical aspects play a key role?

For the sake of time, let us take only a cursory look at the other genres and forms of media. For the past twenty years, curators have been faced with what seems an unsolvable conservation problem concern ing poster-sized colour photos, though some manufacturers provide a colour-guard guarantee of 100 years. Furthermore, many are scep tical of their irreversible bonding with acrylic glass and the now wide spread use of the Diasec process. And what about the large illuminat ed cases which Jeff Wall and many other artists create? Due to the in tensity of the lamps, there is no way to prevent the slides from fading with time, nor do we know for sure whether digital data material is a viable long-term solution for creating equivalent, identical-looking remakes. A possible consequence of this technology is that the con cept of originality is starting to become obsolete. There have already been copies of works displayed in exhibitions which were not person ally created by the artist — Bruce Nauman’s early neon works, for ex ample, have been revamped using this practice for years.

Of course, a great deal of progress has been made. At the suggestion of Wulf Herzogenrath, the Federal Cultural Foundation recently fund ed a project to preserve and restore early works of video art which not only resulted in significant findings, but also restored and digitalized

9 cultural heritage

a limited selection of outstanding video works of the 1960 s and 1970 s, preventing their permanent loss and enabling future generations to view them. (40yearsvideoart.de — Part 1, Rudolf Frieling and Wulf Herzogenrath (eds.), Ostfildern 2006).

Let me point out that in extreme cases, there is practically no time to waste before preventative measures have to be taken to preserve the pieces — which means restoration must begin almost immediately after the completion of the artwork. Whether this is the artist’s intention is a different question altogether. However, those who exhibit, market and preserve such works are sure to face some major problems sooner or later.

The difficulties mentioned above dramatically multiply with installa tions. In this genre, the problems inherent to the materials and sub stances combine with problems resulting from the free and potentially variable character of these multi-part works. Often specially created for a particular exhibition, such works have to be stored in suitably sized storage rooms. If not sooner, this is when the first complications arise — especially when the artist is unavailable or unable to take the necessary precautions. In addition to preservative, aesthetic, historic and pragmatic problems, there are also problems of a legal nature (droit d’auteur and droit moral) which result when complex environ ments are presented in a new situation. This is currently the focus of a controversial discussion concerning what should be done with the ‹Block Beuys› in Darmstadt in view of the upcoming renovation of the museum. What is the role and responsibility of a museum in such cases? What established parameters can it fall back on?

Does the museum endanger the identity of a work or perhaps funda mentally call it into question if it totally reconfigures the ambience? Can it partially or even totally destroy a work by exhibiting it in a new situation? Or are we possibly dealing with alternative versions and ap pearances of a work whose meaning basically remains the same even when its outward character has changed? When a curator and restorer modify a work, can it still be considered authentic or does the ‹work› become more a concept than a physical entity?

In any case, it seems necessary to ask the artist as quickly as possible about his/her materials, techniques, intended message or meaning, etc. Max Doerner and Ralph Meyer began doing this years ago. More recently, Heinz Althöfer, Erich Gantzert Castrillo, Carol MancusiUngaro and others have followed their example and have done signifi cant groundwork, compiled enlightening results and established the basics. All of these approaches and profound findings were often tied to individual people and institutions and were publicized at a much later time and only to a limited extent. Only recently has an interna tional exchange of data and information taken place which may now enable others to find a more reliable basis for upcoming measures and decisions. In 1997, the Netherlands Institute for Cultural Heritage provided a wonderful example of such an exchange when it organized a landmark symposium based on this issue, the results of which were published in 1999. (Modern Art: Who Cares? An interdisciplinary re search project and an international symposium on the conservation of modern and contemporary art, eds. Ijsbrand Hummelen & Dionne Sillé. The Foundation for the Conservation of Modern Art and the Netherlands Institute for Cultural Heritage, Amsterdam 1999)

In 1999, the International Network for Conservation of Contemporary Art (INCCA ) was created as a platform for discussing the problems I have already outlined on an international level (www.incca.org). Its

founding members include the Netherlands Institute for Cultural Heritage mentioned above, the Tate Gallery, the Restoration Centre in Düsseldorf and a number of museums in Spain, Italy, Austria, Bel gium, Denmark, Poland and the United States. The members of the network provide each other access to as -yet unpublished materials. So far, they have jointly gathered data on more than 180 contempo rary artists. The symposium in Amsterdam spawned a series of followup conferences, but at the moment it seems the number of new ques tions and problems is increasing disproportionately to the number of approaches to solving them.

The Internet and electronic media have made it possible to exchange information very quickly — an essential requirement for discussing realistic measures for countering the deterioration of contemporary art on an international basis and developing strategies of prevention, conservation and, if necessary, restoration, revision and even re-pres entation. Above all, it is possible to sharpen public awareness regard ing a myriad of problems which one cannot generally ascribe to the transience of the materials or the artist’s negligence or technical in competence. Rather, they are partly inherent contemporary art, de termine its aesthetic appearance and character, and, to a certain ex tent, are an essential feature of the genre. In short, fragility and the unrestricted structure of current aesthetic production have shaken the postulate of permanence which has long propagated the idealistic concept of art. This is not especially surprising in light of today’s frame of mind in which doomsday scenarios play a significant role in such fields as ecology and economy. The complicated materials and conceptual structures of current art production reflect a polarity in corporated in these works — on one hand, the attempt to enlighten, and on the other, a gradual movement toward spiritualistic syncre tism. On one hand, the evocation of horizons of emancipation, and on the other, the regression to the mythical and mystical. According to Jean Clair, artwork conservation is the last surviving aristocratic profession, yet in view of this conflicting situation, there is little use arguing whether he is right.

10 cultural heritage

Prof. Dr. Armin Zweite has been the director of the Kunstsammlung NRW (K20) since 1990 which he expanded in 2002 to include K21 (Art of the 21st Century). He has also been the commissioner of the São Paolo Biennial several times. Armin Zweite is a member of the curatorial panel for the Programme to Preserve and Restore Mobile Cultural Assets.

Europe Fair ➝

by wilhelm genaz ino

momentary numbness. on begging.

the train was waiting in the station. It was early evening and the blue- and white collar workers were hurrying to catch their train. With tired faces, they looked for a quiet niche where they could relax, which wasn’t easy because the train was overcrowded. Their exhaustion was all that was left from a long day of work. Many of them began to eat and drink. They pulled out pieces of pizza, pretzels and sandwiches from their bags. They probably weren’t very hungry, but ate and drank because it would help them get through the last sprint of a long day, a waste of time sitting in a smelly train going home. The train suddenly jerked forward. Most of the commuters looked out the windows, although there wasn’t much to look at besides cranes, signal booths and grey shrubs alongside the tracks.

The sliding door opened and a beggar entered the car. He was in his mid-forties and didn’t make a very shabby impression. But the gloomy look in his eyes told of the long conflict between his need and shame. His face was drawn, grey, bitter, chiselled with deep wrinkles. With a serious expression and an outstretched arm, he shoved his paper cup in front of each passenger. He wasn’t successful, which really didn’t surprise me. Not a single passenger searched their pockets for a coin. The women were best at giving him the brush-off. Affronted, they turned their faces to the window and stared at the drab scene outside. Obviously he had caught these people at the wrong time. He didn’t think that they might simply want to forget their hard day at work and enjoy a few precious moments of peace and quiet. And then a pushy beggar has the gall to disturb this pathetic home -bound retreat! From his contemptuous expression, he clearly blamed everyone he begged from. They had a job, he had a paper cup. They had good rea sons to feel exhausted, he was only irritable. Common beggars believe that other people are secretly involved in their downfall. Their atti tude seems especially inappropriate because they have no way of find ing out what everyone else has and what they don’t. Being so resent ful, most beggars refuse to acknowledge the fact that the people they beg from are also strapped for cash. They have expensive children, pay exorbitant rents, the next instalment is coming up, they’ve already cancelled their next holidays — there’s not much left for beggars. The lack of success makes beggars belligerent. They grumble or insult those who don’t give anything or enough. And consequently, they themselves are treated with contempt. Many beggars complain that they’re always insulted, even by people from whom they don’t ask for money.

I’m afraid this current attitude toward beggars is rooted in the way the National Socialists ‹solved› the beggar problem. On February 23, 1937, SS Director Himmler called for the arrest of all individuals whose «anti-social behaviour endangered the general public». The majority of these were petty thieves, tramps, gypsies, door-to door salesmen, skivers, prostitutes, ruffians, complainers, ‹idlers› — and also beggars. Less than a year later, on January 16, 1938, Himmler issued a more se vere decree to arrest any individual belonging to this group ‹without warning› and immediately incarcerate them at the Buchenwald con centration camp. Interestingly enough, though Himmler’s decrees were meant to safeguard the ‹public order›, they made no secret of al so providing the system a fresh supply of workers it urgently needed. The farming industry in the 1930 s was desperately lacking workers whom Göring promised to deliver with the help of a four-year plan. In a presentation by SS Oberführer Greifel, the director of the ‹FourYear Plan Department› in the ‹Reichsführer SS personal staff›, he ex plained: «In light of the strained employment situation, our national work ethic demanded we seize all the idlers and antisocials, who would rather vegetate and make our cities and streets unsafe than participate in our nation’s working life, and force them to work.» Today, we still feel uncomfortable with the old Nazi practice of threatening to arrest those whose ability to work was confirmed by a doctor and yet who «refused job offers…on two occasions…without good cause or began the job only to have quit shortly thereafter without any valid reasons.» Granted, our current government does not threaten to arrest and send people to a concentration or work camp, but ‹only› reduce or revoke its financial support. What still remains of the Nazi practice is a con cealed sympathy for the state’s hard-handedness. And, in fact, this sympathy is not always concealed. There are people who remind beg gars that they would have long been sent to a work camp if the Nazis were still in power. The Düsseldorf homeless newspaper «Fiftyfifty» quoted a street worker who claimed «the basic idea of homeless news papers» is to «preserve people’s dignity so that they don’t have to beg». This would mean that poverty or homelessness is no reason to feel ashamed, but rather the fact one has to revert to begging. Destitution

does not strip away one’s dignity, claim the privation ethicists, but wearing one’s hardship on one’s sleeve does. Logically, the newspaper «Fiftyfifty» encourages people to «only buy from authorized sellers who do not beg». Could there be a slight hint of the former Nazi deni gration of beggars in this objection?

Young beggars have found an especially conspicuous alternative to play ing the role of the traditional ‹beggar›. They avoid the problem of having to approach people on their own by joining a beggar’s group. You might see six or seven of them lying or sitting at the entrances of tram stations among half-empty beer bottles, dogs, sleeping bags and foam mattresses. They shout, tell jokes, laugh loudly and sometimes make fun of the smartly dressed people walking by from whom they hope to receive some spare change. They work hard at demonstrating an artificial cheerfulness. The signal they wait for is the rattling coins falling into the change slot at the ticket automats. One of the young people stands up and ambles over to the automat. He hopes the pas senger will leave their change behind. But if the passenger takes it, the beggar stops him: «S’cuse me, could I mooch a little money off ya?» The line is supposed to sound cool or funny, but never seems to have that effect. The ‹normal› passer-by extremely dislikes this form of beg ging — he feels like he’s being pushed into a corner. In his opinion, there’s nothing funny about begging.

Why are we so quick to stay at a safe distance from those in need? Tat tooed and pierced beggars probably have the least success because they lack a display of humiliation in the face of defeat. The typical altruistic citizen doesn’t want anything to do with these kind of selfmutilated freaks. Consequently, the self-mutilated beggar is not only rebuked for begging, but also for mutilating himself. The grungy, scruffy-looking, drunk, or confused beggars are the hardest hit. In the eyes of the well-meaning public, they don’t even have a basic idea of how serious their profession is and how much discipline is required to succeed at it. Most donors expect beggars to have a professional work ethic. If this ethical code is visibly violated, the beggar will have to reckon with aggression instead of compassion. He will have to lis ten to the typical lecture — Find a respectable job! I don’t give any thing to freeloaders! Why don’t you brush your teeth first! Hardly anyone realizes that beggars come from a similarly complicated social background as non-beggars.

I once asked a rather untrustworthy-looking beggar about his situation. He said, «I’m ninety percent physically handicapped, I got open wounds on my legs and two by-pass operations behind me. I get 103 30 euros of welfare a month, I’d like to work, but I’m not allowed to.» The man wears the same dirty jogging trousers every day, the same worn-out sneakers, and the same dark-grey (formerly lightgrey) Bundeswehr socks. People who give him money have to endure his presence for a moment, as his odour is less than pleasant. Could it be that this somewhat unsophisticated man doesn’t realize that his appearance may discriminate him as much as his social downfall? We’d have to say yes, especially if we observe another beggar at work in a reputable pedestrian shopping arcade not far away. This is where one can find those expensive boutiques that cater to a corresponding clientele. And the beggar fits into this glitzy environment, as well. He doesn’t even look like a beggar. He lives in a small town about 70 km away and travels to the big city on Saturdays because he has a ‹normal› job during the week which is poorly paid. And that’s his problem. He resembles the young employees who are strolling through the arcade with their families, buying an ice cream for their kids or drinking a quick cappuccino. People are a bit taken aback by this well-dressed beggar because they can’t believe that he’s ‹that› desperate. The risk he’s taking is high. If someone from his hometown happens to catch him begging, his reputation will be ruined. He is also unusual in an other way. Normally, beggars aren’t very talkative. The shock of their downfall still follows them around and they behave as one would ex pect — ashamed, humiliated, reserved.

This small-town Saturday beggar, however, is happy to answer my ques tions. He only has a part-time job. He lives in a cramped two-room apartment with his wife, who is now expecting her second child. He doesn’t want to be lumped together with normal beggars. He doesn’t even look like a beggar, but more of a man in dire financial straits who will do whatever it takes to improve his family income. He explains that this extra ‹pin-money› will go to purchasing a monthly ticket for the S-Bahn, without which he wouldn’t be able to commute to his workplace.

12 labour

the labour reports for the last days

The Future of Labour programme has asked writers to set out on a literary expedition into to day’s working world and report their findings. Wilhelm Genazino and Kathrin Röggla [see p. 14 ] take very different angles in their reports on people they have encountered who have become liquidators of a capsized working society. We thank both authors for allowing us to be the first to publish their pieces. In August 2007, the Suhrkamp Verlag will publish Schicht! Arbeitsre portagen für die Endzeit (The Labour Reports for the Last Days), a compilation of writings by Bernd Cailloux, Dietmar Dath, Felix Ensslin, Wilhelm Genazino, Peter Glaser, Gabriele Goettle, Thomas Kapielski, Georg Klein, Harriet Köhler, André Kubiczek, Thomas Raab, Kathrin Röggla, Oliver Maria Schmitt, Jörg Schröder and Barbara Kalender, Josef Winkler, Feridun Zaimoglu and Juli Zeh. [Approx. 300 pages, Frankfurt 2007 , ISBN: 978-3- 51 8- 1 2508-3 ]

The hardest strain on him is not the begging, but rather the high degree of wasted effort. In other words, begging is largely psychological — humiliating oneself is not as difficult as the psychological strain of constantly spinning one’s wheels. The small-town beggar claims that begging is only a temporary but necessary, self-induced anaesthesia. It works for him because he’s a hundred percent sure that this trying phase in his life won’t last forever. He tells me that his wife isn’t as good at enduring it as he is. While he’s here begging, she’s at home, sitting on the edge of the bed, crying. Sooner or later, he’ll find a full-time job — of that he’s certain. It’s not the first time he’s had to revert to unusual measures. As a child, his parents didn’t give him an allowance, so he earned money delivering newspapers early in the morning before school. While he talks with me about his childhood, he steps away every so often and approaches passers-by who seems promising. Back then, delivering newspapers was rather unusual and his more affluent school friends used to make fun of him because of it. «I’ve had to deal with discrimination since my childhood.» Suddenly, his communi cative ‹method› pays off. After sharing a few words with an elegantlydressed retired woman, she hands him a 5 euro note. That will pay for one quarter of his monthly ticket. A moment later, he throws a criti cal glance at one of his ‹colleagues›, a black man, probably from Afri ca. Kneeling, the man is prostrate with his face almost touching the ground. He covers his head with his hands — a paper cup is next to him. It’s impossible to talk or even look at the man. «That much hu mility is repulsive», the small-town beggar comments.

There’s a large street festival going on at the other end of the city. The weather is nice, people are in a good mood. They snuggle up together on wooden benches, drink wine, talk animatedly and are full of faith in the world. Naturally, there are beggars here, as well, and they’re just as affected by it. That’s to say, very few go away with empty pockets. An extremely self-conscious looking beggar stands by himself in the midst of all the tables lined along the shopping street. He looks to be about 30 or 35 and makes a generally unkempt impression. He’s good looking, yet doesn’t know how to capitalize on his attractive face. In fact, his shoulders are slumped, he looks intimidated as if he were a child who had just been reprimanded in the middle of a wide pedes trian zone. The worst thing about him is his self-made sign which he holds against his chest. Made of white cardboard no larger than the top of a shoebox, it reads «PLEASE », handwritten in red capital letters. It is so apparent that this sign is the reason for the beggar’s lack of success.

It’s hard to say why this is. The cheerful festival-goers look down on him in derision. Some people insult him as they pass, hissing curses or swear-words which clearly hurt his feelings. He probably thinks this improper confrontation is a test of courage. He forces himself to en dure the humiliation. There’s no other way to explain why he doesn’t simply leave. Even the children run around him and poke fun at him because he’s the only one here who isn’t drinking and laughing. The giggles from the children are perhaps the key to understanding the situation. The beggar has no chance of succeeding because he is the only one resisting the festival cheer. The people punish him for ru ining their mood. His attempt to generalize his misery backfires on him. The others are far from acknowledging this kind of metaphysi cal trickery, let alone rewarding him for it. The beggar’s moralizing crusade becomes a fiasco. In his Christ-like role, the man is completely isolated from everyone else. Perhaps he never realized that when fac ing a large crowd, a single beggar is always unsuccessful. Someone should explain to him that begging is not only a matter of being iso lated, but also isolating those from whom he begs.

Beggars can create a moment of awareness in people when they ap proach them alone. If successful, their appearance can shock the pas sers-by so deeply that they are moved to generosity. In this way, the (successful) beggar and the (successful) giver form a momentary rela tionship, they form a unit. The jovial giver is at least as sensitive as the unfortunate beggar. There is a brief moment of epiphany when they have to place themselves in the beggar’s shoes. It’s when they sudden ly realize that they could fall from the ranks of the wealthy by some unfortunate accident someday and find themselves in the ranks of the needy. This luckily-averted catastrophe is what impels givers to ex press their thankfulness.

With this in mind, we can easily observe how and to whom the good will of givers is distributed. Generally, beggars who only display their wretchedness are unsuccessful at motivating people to give. There are other beggars, though few, whose technique is immediately noticeable

and are quite successful at taking advantage of the predominant mood of the moment, even if it’s only an amateurish artistic display of juggling with three balls. People thank them for it with generous donations, not in compassion with the beggar and his neediness, but as an expression of their high spirits. A young accordion player is the most successful. He can’t play well, but the music is fast and lively. And he plays the music people know and like. His performances are short so that he can play for a large number of pub and restaurant guests. You could say that the accordion-playing beggar has the best marketing strategy. He completely ignores the fact that he is in a terri ble plight. Concealing this is the secret to his success.

I’m surprised that this article turned out to be a criticism of the beggar as such (and not the act of begging). Actually, the beggar is what mo tivated the criticism, that is, many beggars are incapable of begging. They lack the intuitive understanding of their profession and of those from whom they ask for help. Therefore, it stands to reason that some sort of institutional counselling could provide assistance to those who enter the begging profession. What kind of support could they receive? As of yet, there are no statistics regarding the number of peo ple who are forced to earn their living solely from begging or improve their regular income with begging. In a society that often refuses to look truth in the face, we have to wait ten to twenty years before a problem is politically acknowledged. We generally have to wait an other ten years until politicians finally address the problem. This is how long it will take until our political parties, employment agencies and community colleges to accept the fact that begging is a profession and the more training beggars have, the more effectively they can practice it. Who or what is hindering us from establishing schools for beggars? The clientele already exists — sitting and lying around ev erywhere.

One of the main focuses of a beggar’s training should be learning a skill with which he or she can entertain audiences. A beggar should learn how to perform for people, maybe with a mobile pocket theatre, or, if he only has three plastic rings, throwing them up in the air and catch ing them again. The artistry helps direct the people’s attention away from one’s wretched predicament. Teaching beggars to suppress their compulsion to lie is also very important. Why can’t a beggar say, «I’m in a terrible situation and could really do with a few euros»? Why does he tell you instead «I just lost my wallet with over 300 euros and need some change to buy a train ticket to visit my mom»? If someone is go ing to beg from you, you don’t want to be so obviously lied to. The problem is that beggars believe they need a good reason to beg. We should show them that being homeless and hungry is reason enough.

Beggars’ schools would have an enormous political effect. The beggars would take consolation in the fact that they were no longer completely left on their own. Of course, we will never have such schools in this country. Our nation’s vanity would never tolerate schools for beggars. We would rather get used to poorly trained beggars and torture them with ineffective debates about the lower-class.

Wilhelm Genazino, born in Mannheim in 1943, began his career as a freelance journal ist, after which he worked as an editor for various newspapers and magazines (e.g., Pardon). In 1977, he wrote the Abschaffel trilogy which marked his breakthrough as a writer. Genazino has received numerous literary awards, such as the Kranichsteiner Literature Award conferred by the German Literature Fund [see p. 38 in this issue] and the most prestigious German literature prize in 2004, the Georg Büchner Award by the German Academy of Language and Poetry. His most recent novel, Mittelmäßiges Heimweh, was published by the Hanser Verlag in 2007. Wilhelm Genazino resides in Frankfurt.

13 labour

the revenants

by kathrin roggla

[ ... ] 2. berlin e

ven catastrophes have to be created, this i know from catastrophe sociol ogy, it’s a project that takes centuries, a societal project. for example, a successful smallpox epidemic doesn’t just happen by itself, it has to be well organized, tremendous effort is required, investing in the wrong areas, neglecting the right areas, and a bunch of experts whom everyone relies on too much. this applies to major catastrophes as well as to minor, everyday catastrophes, the ones people call catastrophes ‹in a figurative sense›. these, too, require careful preparation, a setting, they cannot exist outside the context of the economic, political and legal forms of organization within a society. perhaps the centuries are not their source of strength, though their roots go back that far, shorter spans of time suffice to create the necessary conditions, yes, it often comes down to the small, insignificant changes like the intro duction of the credit card in 1968 or instalment plans in the 1960 s. yes, personal bankruptcy, for example, or private financial insolvency which could be caused by other forms of bankruptcy, but in this case, should be viewed in and of itself, is very similar to bankruptcies of larger legal entities in that it is jointly brought about through the ef forts of society and the individual. and that’s a lot of work. i’m not only talking about the contracts that have to be drawn up, institutional conditions, meetings with bank employees and branch office managers, developing advertising brochures and financing models, not even the economic downturns that play a role in the whole process. a society has to first embrace the basic idea that debt is acceptable. it has to come up with the idea of fictitious money, along with a cer tain calculation method, an economic rationality in connection with surplus production and profit-mongering. it has to be able to incor porate future prospects into business calculations in such a way that they appear to already exist. to produce poverty, one must also pro duce the moral categories responsible for dragging each indebted in dividual deeper into debt. the production of insecurity has to exist as do certain neo-liberal values. people have a generally positive attitude toward investing — a rather modern, unfounded belief that we can create security by permanently investing in ourselves, in our future. on top of this is the coupling of one’s personal value with one’s prop erty, the diverse forms of which derive from various historic sources, ranging from protestantism to the advertising industry. and then something creeps into the equation which is always very helpful for producing catastrophes — a large degree of negligence — economic calculations, social security plans, data protection, psychological sta bility, all of which produce legal ‹grey areas›, those ethereal visions of last chances, quick profits, of lucking-out-this-time, of ‹blossoming landscapes in the east›. and then it happens, for which an inflated real estate market is just as helpful as casinos, and is commonly called a ‹credit accident›. according to the credit counsellor’s botanic textbook, the typical causes include unemployment, divorce and illness. person al bankruptcy is right around the corner.

western societies — europe, japan, the united states — are extremely successful at producing these ‹figurative› catastrophes. we could even say that there’s an overproduction, though strictly speaking, this pro duction reaps no profits and actually works against the basic market principles of these societies. yes, it immobilizes, kills, destroys capital, transforms it into a chasm of red ink, cutting off large sections of the population from access to free trade and the blessed mechanism of self-regulation fathered by adam smith. for this reason, it eventually became necessary to counter this overproduction of crises, to set lim its, that is, offer possibilities of reducing one’s debt. the americans de vised a declaration of bankruptcy and in japan and several european countries, personal insolvency was born — an option formerly re served for large legal entities such as companies, states, etc. which re quired a new form of arbitrator, the credit counsellor.

now here they are, small-time experts in bankruptcy, this sub-species of insolvency whose most prominent representative in all likelihood is still balzac because, in his writings, he endowed the small-time bankrupt with a self confidence that hardly exists today. the private bankrupt who no one would like to see as a vanguard, as a frontrun ner of society, the private bankrupts who are always overshadowed by the money-gobbling giants of the new economy, industrial bankrupts,

[excer pt]

state bankrupts, although they do the basic work and without whom no larger bankruptcy is conceivable — but what kind of work is that? one might ask — and of course, how could one not regard this crisis production and its subsequent management as the heap of work it re ally is? strangely enough, both processes involve money acquisition, it simply flows in different directions. whether it involves special of fers with which people hoped to save money, a refinancing plan with better conditions that only accelerated their financial ruin, special deals at casinos or hot stock options, real estate speculation which really seemed a sure thing, or the tedious processes that follow — dis tribution, instalment plans, deferment plans. profit-oriented mentality is usually one of the reasons why people take out a loan that even tually causes their ‹credit accident›. at a personal level, the first step, of course, is to lose money. Since only a fraction of the population is filthy rich, this is not very difficult. today we quickly consider the option of going into debt which is constantly promoted by all the current investment hype. but when we go to the grosse hamburger strasse 18 in berlin-mitte, or ‹dilab e.v.› on the rigaerstrasse in friedrichshain or to ‹julateg finsolv› in köpenick, then we’ve already completed the first phase, the money is long gone. we sit there and wait for a long time. we’ve heard of peo ple waiting six months, although the employees are said to be quite motivated. operated by non-profit umbrella organizations, these pub licly financed credit counselling agencies are usually overcrowded, i experienced it first hand — 40 to 70 new debtors usually show up at the preliminary information meetings, all of whom hope to declare personal bankruptcy a route only a few are allowed to take. yet who knows who you’ll encounter here? is it a hybrid of a public offi cial and vengeful god, or an employee and prosecutor? nowadays there is all this talk of employees who really tow the line for you, and then you can never find them. we all hear so much about customer service, yet we are still confronted with help-desk hygiene. yes, we’ve left our hopes behind, we’ve left our tricks behind, but we haven’t left the waiting rooms behind. nor have we left behind the incessant meet ings, the conversations to convince ourselves that there’s still a way of getting ourselves out of this mess somehow. one thing is for sure, no one wants to belong to that group of grubby debtors who we’ve all heard about, who we constantly hear about. those grubby debtors who are supposedly all around us, the hartz 4 clientele oozing out of our ears so to speak. nor do they want to be la belled as someone who complains they don’t earn what they deserve, and no matter what they do, they simply can’t earn it. at least some people here are true berliners who can say, «da war ick so kleen, da bin ick unter de teppich geloofen, so kleen war icke» (i was so small i could run underneath the carpet, that’s how small i was). or «det hab ick verkackeiert», (i screwed up) or «versaubaselt» (messed up), but people like me don’t even have that to fall back on. i’m sitting on the other side of the table anyway, facing the situation straight on, or as i’ve just discovered, from above.

from above, they’re offices — apartments converted into offices. the rooms on the first floor of this prefabricated housing estate in köpen ick look ordinary, there are potted plants in the rooms and in the cor ridor. there are the caritas offices in an old building in berlin-mitte with a view of ben becker’s carriage house, ground-floor courtyard apartments converted into offices in friedrichshain where nobody wants to live, or a drab administrative building. in any case, rooms that previously served other purposes, converted rooms, sometimes with an additional waiting room like at a dental practice, sometimes it’s only a small hallway, but still gives you that dentist feeling. the plural is what keeps you occupied. the downpour of thousands of small stories, they cancel each other out almost immediately, they seem to get drowned out by the others because they are all basically the same. i just realized how quickly this happens: how often you hear practically the same stories about miscalculations, endless streaks of bad luck, misfortunes and divorces, forgotten maintenance pay ments, bouts of unemployment, and now here i am, one of countless other journalists looking for those stories that stand out from the rest. you tell yourself that’s what people want to hear, extraordinary stories,

14 labour

that very special story, throwing a wrench in the works that are kept operating by the experienced credit counsellors, a story that shows them in a different light, makes an impression, somehow. one they’d take home with them and tell their families. because it’s a story that really goes to show…but what?