Aghssan

Fifth edition

Aghssan is a magazine that aims to bring together actions, stories, ideas and alternatives around questions related to arts, ecology, new media and their entanglement with social and political issues.

The magazine is a project of kounaktif, superimposed on the various actions led by the collective to make access to culture possible for a wider audience.

Kounaktif is a collective and a cultural platform founded in 2018. As a collective, we work to share various areas of knowledge and skills, weave social bonds via arts and culture, and develop creative and critical abilities in the fields of visual and sound arts, philosophy, new media, and DIY practices. These practices are perceived as tools of resistance against imposed realities. Kounaktif’s DNA is expressed at the intersection between arts, technology, and ecology through creative and critical expressions, alternative pedagogies, and the production of knowledge. We constantly promote collective intelligence and collaboration through our programs in the form of discussions, round tables, creative labs, exhibitions, participatory workshops, concerts, and open mics.

After researching international agricultural policies and their impact on local policies in North Africa, delving into the issue of female agricultural workers, and highlighting the importance of ecological and environmental agriculture, the Tabi3a 3.0 project, in its third edition, decided to focus on the pressing issue of water problems in Morocco today. Morocco is currently experiencing severe drought threatening its food security and sovereignty, forcing us to confront a serious water shortage. This is not only due to a lack of rainfall but also because of the depletion of groundwater resources caused by excessive and irresponsible usage by some landowners. This includes the excessive use of water by swimming pools, exotic fruits, and also due to public policies that fail to safeguard water against multinational companies that continue to exploit the Earth's wealth.

In the third edition of the Tabi3a 3.0 project, a series of meetings were held with researchers and experts on the water situation, public policies adopted by the state to retain water and food sovereignty. Animated design capsules were also created, addressing the dilemma of pesticides and their dangers to human, animal, and environmental health in general. Additionally, urban agriculture workshops were organized, inaugurated with film screenings and discussions about the role of native and non-genetically modified seeds in preserving water and the environment.

In this fifth issue of Aghsan magazine, we will shed light on the water situation in Morocco before and after colonization, traditional irrigation methods adopted by farmers in remote areas, and the concept of hydrocolonialism or water colonization. We will explore the role water plays in internal and external political conflicts as it transitions from its natural role as a vital resource to a weapon for dominance.

Contributers to this issue of Aghsan magazine, which is part of the Tabi3a 3.0 project, include : Mahmoud Maamar Kawthar Fernane Youssef El Idrissi Youssef Soumairi

Designed by : Chaimae El Yacoubi

Posters by : Omar Bouazzaoui

Translated by : Lamyaa Ouarit

Coordinated by : Youssef Aaroui

Language Editing : Saad Hmihem

Colonialism of Water refers to practices with a colonial nature that prevailed during the colonial period in Morocco. During this period, colonial powers transformed cooperative features and social systems developed by Moroccans over centuries to manage water resources. They altered these systems to serve their agricultural colonial projects. In contemporary times, Colonialism of Water refers to practices adopted by institutions or organizations engaged in commercial or agricultural activities exploiting water resources in a specific local community. These practices deprive the community of benefiting from its water resources and expose them to exploitation due to mismanagement.

An example of contemporary practices falling under this concept is the Israeli authorities' extraction of groundwater and distribution to settlements and farms in the occupied West Bank. This practice exacerbates water scarcity for Palestinians, impacting their ability to access water resources for agricultural needs.

This management approach is characterized by a colonial nature, considering the superior position of these organizations or companies that exploit water resources under the guise of local investment. This is done without consideration for the needs of the local population.

Morocco was never considered a rich country in terms of water resources. It experienced modest rainfall, often scarce, with each century in Moroccan history witnessing fluctuating periods of drought and rain scarcity. This can be attributed to Morocco's geographical location in Africa and its exposure to climatic influences from the Sahara Desert. Water, therefore, became a crucial element around which social and political conflicts revolved. Moroccans innovated various systems for collective water management, considering Morocco's climatic reality. These systems were characterized by a "democratic" nature and creative engineering techniques implemented by local communities through cooperation and collective effort, minimizing water usage without depleting or hindering its renewal.

The arrival of French and Spanish colonizers and their treatment of Moroccan land as a wheat reservoir for ensuring France's self-sufficiency led to the dismantling of local water management practices. The colonizers, particularly the French settlers, used modern means to extract water from the water table to compensate for the rainfall difference between Morocco and their home country. Water, which was once a socially significant element for Moroccans, transformed into an economic production factor benefiting a parasitic colonial class on Moroccan soil and a foreign country.

The conflict over water became a manifestation of tensions between Moroccans and French settlers. The French deprived Moroccans in certain regions of water sources for the benefit of their lands. In 1937, this led to the Wad Boufekrane events in Meknes, where Moroccan authorities killed dozens of protesters opposing the diversion of Wad Boufekrane's water for the benefit of French farmers.

Despite declaring independence in 1956, most governments, except for the government of Mr. Abdullah Ibrahim, continued the planned agricultural policies of colonization. The focus was on supporting large farmers and "beneficial" agricultural regions like Chaouia and the west, directing irrigation policies to these areas.

In 1967, the country initiated a dam policy, aiming to irrigate a million hectares with water by the end of the century. By 1999, seventyfive dams were built in the country, with a total capacity of approximately 14 billion cubic meters. The Unity Dam near Ouezzane, inaugurated in the mid-90s, was the flagship project of this policy, being the second-largest dam in Africa at the time. However, in the mid-90s, due to consecutive years of drought, it became apparent that the dam policy did not provide a genuine safeguard against the threat of drought. Moroccan agriculture suffered, and the conditions of the dams deteriorated due to drought, siltation, and dust, reducing their water efficiency.

Returning to Moroccan agricultural policies

after independence, the state did not support Moroccan agriculture to ensure food security for Moroccans. Instead, it directed its policies to regions dominated by fruit and citrus farming for export to European and Western countries. This paradox becomes evident as Morocco cultivates products that consume large quantities of water to benefit countries with greater water resources than Morocco. These countries are inclined to preserve their water sources and secure their agricultural needs from other countries without incurring additional environmental and water costs.

Despite the concerns raised by environmental organisations, the state reinforced these directions through agricultural plans like the Green Morocco and Green Generation. These plans aim, as announced, to increase agricultural production and create a rural middle class. However, experts argue that the real goal of these plans is to boost agricultural exports, bringing hard currency and profits to a narrow class of large farmers. These products are agricultural and water-intensive, unsuitable for the Moroccan climate and environment.

In response to the formidable challenges posed by water scarcity in Morocco, a coalition of organizations and initiatives dedicated to environmental and water issues has put forth a set of solutions. Among the most prominent recommendations is the imperative to adopt more economical irrigation methods, recognizing that the agricultural sector is the largest consumer of water in Morocco. These organizations advocate for transitioning away from crops ill-suited to the Moroccan climate and demanding excessive water. Instead, they promote the cultivation of crops using natural, unmodified, and local seeds known for their adaptability to the local climate.

At the infrastructure level, there is a pressing need to establish desalination plants, especially for major Moroccan cities that face water shortages during the summer. Cities such as Casablanca, El Jadida, Saharan cities, Berkane, and Laayoune fall into this category. The Moroccan government, responding to

the critical effects of drought on vital regions, has initiated a project to transfer water between the Sebou River and the Bouregreg River, leveraging excess water from the western region to benefit the central region. Simultaneously, the government has swiftly implemented an urgent three-year water program.

Despite the urgency of these measures, some observers consider them delayed. Regardless of the technical aspects of the projects, critics argue that the state has not demonstrated genuine commitment to transforming agriculture in Morocco and addressing its direct impact on the water sector. They contend that Morocco persists with agricultural policies inherited from the colonial era, reinforcing them through programs like the Green Morocco and Green Generation, despite criticisms and concerns raised by various environmental and water-focused organizations.

The premise is simple: all living beings require water for survival. Water stands as an indispensable resource for human life and ecosystems, playing a pivotal role in economic development. Its significance extends beyond sustaining life; water is crucial for the advancement of agriculture, as well as other industrial and service sectors.

However, beyond its role as a life sustainer and contributor to national development, water can also be wielded as a tool of domination and coercion. It serves as a potent instrument that one state can use to exert influence over another or that a political system can leverage against its adversaries.

The concept of hydro-colonialism encapsulates

Water, beyond its role as a life source, emerges as a tool intricately woven into negotiations of power dynamics and dominance at the state level. As early as the 1980s, the intelligence agencies of the U.S. government foresaw potential water-related conflicts, particularly in the Middle East and North Africa.

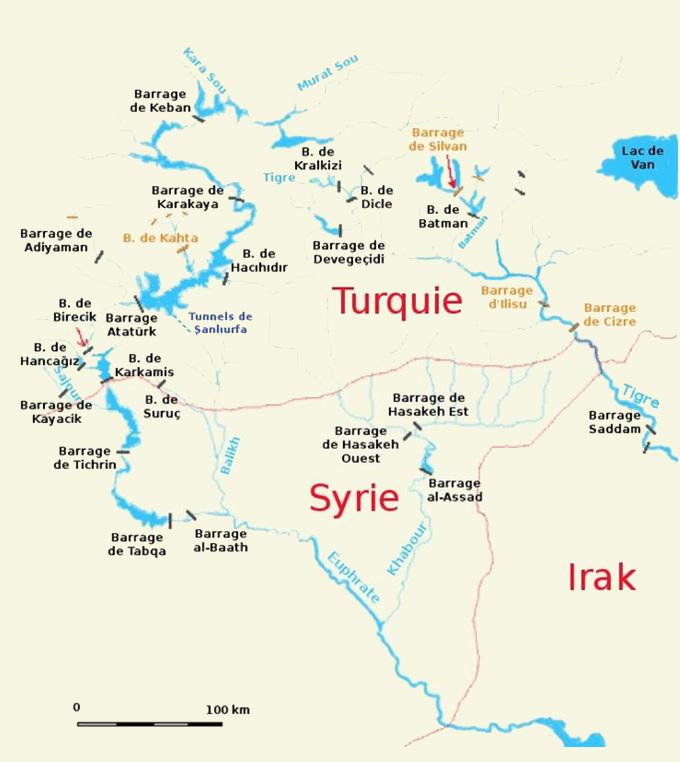

Global examples abound, showcasing conflicts and negotiations where water becomes a means of exerting pressure. In 1990, Turkish authorities threatened to reduce the flow of the Euphrates River into Syria unless the Syrian government tightened control over its borders to stem the passage of Kurdish rebels. Three years later, Saddam Hussein, the former president of Iraq, was suspected of poisoning water reserves in the Ahwaz region, inhabited by his Shiite opponents in the southern part of the country.

the utilization of water as a means of exerting pressure on countries with the objective of colonizing new territories—what is often referred to as water colonization. This colonization process is not confined merely to the physical; it extends to shaping ideas and perceptions surrounding water.

The objective here is to delve into this concept through examples and experiences drawn from various countries worldwide. By doing so, we aim to illuminate the diverse forms of both material and symbolic domination facilitated by the strategic use of water. Additionally, we will spotlight instances at the national level, particularly examining the history of water privatization under colonial administration.

Dams of the Upper Tigris-Euphrates Basin Source: X. Guimard

Furthermore, the Arab-Israeli conflict since the 1960s provides another prominent example of inter-country conflicts over water. From the early 1960s, the Golan Heights, located on the Syria-Israel border, was perceived as an emblematic area.

It marked the origins of the main rivers flowing through the region, from the Syrian-Israeli border upstream to Jordan downstream. Recognizing its strategic significance, the Arab League devised a hydraulic development project aimed at redirecting water from this plateau and controlling it as a means of pressuring the State of Israel and impeding its development. A few years later, Israel waged war against Syria, leading to the occupation of this plateau, subsequently recognized by the United Nations as part of Israeli territory.

To cite just a few examples, the mobilization of water as a pressure tool runs parallel to the mobilization of diplomatic and military force. In fact, water security is as strategic as military security and state sovereignty.

Golan Heights Source: France 24 (2019)

Examining the history of water privatization in Morocco leads us to consider certain significant periods, notably those before, during, and after colonization. Before 1912, water was perceived as a gift from God, accessible for free, and managed through community management. In ancient medinas, water supply was facilitated through communal fountains, sourced from springs. Channels, both open and covered, were constructed for its distribution. At the entrance of the medina, the "Nadhir" represented the community in terms of water management. Larger quantities were sourced from underground reservoirs called "Metfya," filled with rainwater. Communal facilities like hammams and mosques were utilized for hygiene purposes. Access to water was collectively shared for domestic consumption and other purposes, such as site work.

The culture of individual water connections gained prominence in the lives of Moroccans after the establishment of colonial administration. For "hygiene" reasons, the colonizers advocated reconfiguring water mobilization systems. Urban and legal measures were introduced to realize this vision. The urban planning project for new cities on the outskirts of old medinas relied on individual potable water connections. In 1914, a new decree defined water sources as

decree by the Ministry of the Interior mandated their formation. Driven by demographic growth, major programs were launched to generalize access to potable water. One such initiative was the social connection program, receiving substantial funding and technical support from the World Bank. Individual water connections became more common, transforming the water resource into a commodity subject to the laws of supply and demand, rather than remaining a collective good accessible to all.

Starting in the 1970s, particularly with the introduction of motor pumps, irrigation underwent a transformation. In various places, such as oases, there was a growing trend towards private access to irrigation water. Historically, oases were established around collective water management, particularly through the khettara system. This system involved mobilizing water from a source to the palm grove through an underground drainage channel with a gradient that allowed for the free flow of water. Near the fields, a basin was constructed to store the water before distribution based on the irrigators' turns and rights. Water was collectively owned, in varying quantities, by all participants in the creation of the khettara and those who held plots within the palm grove.

However, collective access to water faced threats due to the degradation of this system in various oasis areas. The introduction of new techniques for accessing groundwater further accelerated this process. Irrigators could mobilize significant quantities of groundwater to irrigate their plots without having to wait for a collective turn. Subsidies provided under the Green Morocco Plan (2008) also facilitated private access to water. Farmers could access public support to create wells and access groundwater freely. The proliferation of solar panels further encouraged irrigators to extract water from greater depths. The capacity to access this water at significant depths varied depending on the financial resources of the irrigators, raising questions related to social differentiation in water access, the fragmentation of collective water management,

and the sustainability of the resource.

The analysis above reveals how the manipulation of water can go hand in hand with the manipulation of military force in negotiating power relations. The concept of hydro-colonialism is of great importance in highlighting this aspect of water, beyond its well-known role as a vital resource. If wars have often been portrayed as the result of negotiations over certain energy sources or strategic areas, water also appears to be at the core of these conflict triggers. This use of water as an instrument can occur at the inter-country level, as seen in various cases such as the IsraeliArab conflict, but it can also take place within a single country. This is where the example of pressure exerted by Saddam Hussein's regime on its political opponents comes into play.

Manipulation can also occur at the level of perception. The French colonial administration did not merely act on a material level to secure a role in the management of Moroccan water as an investment opportunity for French companies. They also sought to influence the perception of water consumption methods, suggesting that the new methods introduced by the colonialists were more health-conscious than the traditionally used methods by Moroccans. This further facilitated colonial domination over the Moroccan state, not only through military force but also through economic means via water companies. This constitutes another level of insight that the concept of hydro-colonialism has helped elucidate.

(..) every time our skin goes under, It’s as if the reeds remember that they were once chains

And the water, restless, wishes it could spew all of the slaves and ships onto shore Whole as they had boarded, sailed and sunk Their tears are what have turned the ocean salty, (..) The audacity to arrive by water and invade us If this land was really yours, then resurrect the bones of the colonizers and use them as a compass Then quit using black bodies as tour guides or the site for your authentic African experience Are we not tired of dancing for you?

- "Water" - Koleka Putuma

- "Water" - Koleka Putuma

The colonial power didn’t only invade territories, or imposed with brutal force exploitation of resources, it went much deeper through a denigration of culture, distortion of our representations, language, collective memory and history and overall imaginaries. In the Moroccan context, cities have been used for experimental urban planning and architecture by French architects. From a European modern perspective, the medina is perceived as a confusing and illogical space, hence the necessity to control it, encircling it in a geometrical space that can be readable.1

Intending to avoid the mistakes made in Algeria and Tunisia, the general Lyautey used subtler tactics to maintain power while avoiding resistance, and for that matter, he labeled our cultural and urban heritage as something inferior, related to the past, that we must get rid of if we want to progress as a country, while the “modern” ways are related in our imaginaries to the future, to a path that we must forge in order to progress as a nation and individuals. This domination is rooted in Descartes cogito “I think therefore I am” which creates a split in our awareness and puts the beingness behind the thought, fostering rigidity

in our sense of identity. This perception is influenced by an inferiority complex, anchored in an epistemological domination.

If you remove colonialism physically without removing it epistemically, it will not disappear.

This way of understanding the world is still present, even in the form of Hegelian dialectics, stating that history is inevitably a combination of a thesis, an antithesis, and a synthesis, progressing like the arrow of time. This myth of progress of homo faber has been debunked when we began to see the results of the machine of progress built on extractivism and exploitation, creating damage to ecosystems, to the land and the sky, to human and non-human life alike, creating further scarcity and enlarging the gap between the rich and the poor.

Hence the necessity to slow down and go back to precolonial times, and to discover our ancestral technologies—not to cry in nostalgia but to reclaim our histories to take our sovereignty back, as a nation, as people, and as organizations. This includes also the way with which we handle water infrastructurally, and perceive it symbolically and poetically.

1 Le Maghreb urbain : Paysage culturel entre la tradition et la modernité

URL : https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/euro/2012-v8-n1-2euro01518/1026641ar/#:~:text=En%20adoptant%20les%20 principes%20de,service%20de%20la%20domination%20coloniale.

- Sabelo J. Ndlovu - GatsheniIn this sense, our sense of identity has totally shifted,2 from being understood in terms of vibrancy, fluidity, and resonance with the environment, to being fixated and localized in the mind, as a rational ego. This epistemological and ontological dominion of our plural and fluid identities has been challenged by the notion of tidalectics, introduced by the poet and scholar Kamau Brathwaite, which intends to go beyond dialectal movement towards the end of history. It rather describes "the movement of the water backwards and forwards as a kind of cyclic... motion, rather than linear.” 3

Tidalectics open to us the underrated possibility to think and feel in circles and even in spirals, like the ebbs and flows of the sea. Our ancestors were so much in tune with the natural cycles that their understanding of time was circular and radial, indicating an intuitive grasp of tidalectics, which has been erased and perceived as unscientific. This erasure occurred because European philosophers began to detach from their roots, traditions, emotions, and overall cut ties with any spiritual understanding. This confinement led people to be individuals with a cold and egoic mind, completely detached from the land as a womb, the community as a family, and, most importantly, their emotions. We all know how the scientific mind didn’t create only beautiful technologies but also the nuclear bomb and justified slavery and racism ( “scientific racism”) using scientific means.

Furthermore, by reconnecting to the movement of the sea as circular and spiral-like, we begin to grasp a deeper layer of time beyond the linear perception of birth and death. This reshapes all our thinking-feeling processes. This is possible only when we recognize emotions as valid perceptions of reality and the collective unconscious as a vast reservoir of hidden energy-knowledge that the ratiocinating mind cannot grasp. If, in symbolism, emotions and the unconscious are associated with water, it is because of the fluidity, depth, and movement on the surface (waves, tides, etc.) that we can draw inspiration from. As we all know, water covers 71% of Earth's surface, and the human body is about 60% water; this high percentage underscores the vital importance of water—not only for our survival but also for our intellect

and perceptual apparatus, to be permeated with watery understanding, specifically in terms of time perception as circular and radial, and identity as fluid and plural.

Hydrocolonialism isn't solely about using water for military and exploitative purposes - as it is the case currently, when we see, for example, Israeli companies investing in avocado in Morocco (which is in reality an investment in underground water)4 or a French company still handling water pipelines in Morocco-5 but this

2The important thing was not identity, but the energy supposed to govern vital phenomena and animate behaviors. The quintessential human was defined by their richness in vital energy and their ability to resonate with the myriad living species that populated the universe, including plants, animals, and minerals. Neither fixed nor immutable, they were characterized by their plasticity." (Achille Mbembe - "African metaphysics allows us to think of identity in motion"

URL : http://bit.ly/3gR3zpm

3Mackey, “An Interview with Edward Kamau Brathwaite,” 44; Brathwaite, “Submerged Mothers,” 48–49. Recent work has returned to his theory; see Hessler, Tidalectics.

4Morocco Is World’s 9th Largest Avocado Exporter Amid Water Scarcity

URL : https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2023/08/357238/ morocco-is-worlds-9th-largest-avocado-exporter-amid-waterscarcity

5Lydec (Lyonnaise des Eaux de Casablanca), 51% of it belongs to Suez, which has been bought by Veolia in 2022. And Amendis, which also belongs to the French group of Veolia.

Before the French invasion of Morocco, water was viewed as a divine gift. Communities had collective water distribution systems and relied on ancestral technologies, such as the Khettara system. Water was considered sacred in most indigenous cultures, playing a central role in purification rituals or in prayers of asking Anzar6 or Allah for rain. In this precolonial era, societies exhibited strong collective bonds, often following the notion of 'Ubuntu,' which means 'I am because we are.' This integrative approach extended to the relationship between individuals, the environment, and the cosmos.

This pre-birth attitude can be understood phenomenologically when we go back to our mother’s womb, and observe how we literally were gestated in the warm waters of our mother, and being fed from our mother’s food, moods, thoughts and environment. Until the weaning happens, our physical machinery had to function by being exposed to air (symbol of the mind), which at first, hurts the lungs. The act of being thrust into the world can be perceived as a forceful and abrupt transition - that can be fractally extrapolated on the ways with which Westerners have been weaned by killing God in their psyche, and systematically disconnecting from their heart and any sense of transcendence, while coldly engaging in imperialistic quest.

We can find an echo of this understanding, for example, in the Sumerian notion of freedom, which they called Ama-gi7, which can be literally translated as, “going back to the mother/ nature”8 , which basically means going back to a state of union with the motherly waters and by extension the cosmos at large. The notion of freedom in the European renaissance has been completely shifted, by re-orienting our attention towards the future, progress and moving

forward - considering the past as bad, uncivilized and futile, which unleashed disdain towards anything rooted in the ground, in tune with the natural cycles, namely the indigenous societies and women bodies. This deep shift has introduced new and totally divided ontology and epistemology, which has been reflected on the ways with which we inhabit the Earth and live with ourselves and each other. Among these ways, perceiving the land as a space that we can exploit by extracting resources, and water later on, as a commodity instead of being a gift from nature/God or an actual vital right.

This shift pushed the whole world to be led by Western values of “freedom”9, progress, modernity and privatization of everything, which by extension, disconnects us from the reality of the real natural world, as Bruno Latour advocates to reintroduce in social sciences the notion of “Gaïa” instead of Earth, because it reflects that She is an actual being, and this mythological understanding of natural phenomena as deities or beings in paganistic/aniministic societies is what allowed the ancients to have this sacred bond with their environments.

This leads me to question the lack of real political action to protect our natural and vital resources, which - in my opinion, is rooted in an outdated paradigm of profit and progressive economic growth, which overlooks the actual natural world which holds the real vital values, and floods our imagination with greed, instead of abundance, biodiversity and balanced Eden (Gaïa). According to Bruno Latour, political action is still not efficient to tackle ecological issues because « for the moment… affects are not aligned to the point of creating automatisms… There is a lack of imaginaries capable of feeding political passions »10.

6Amazigh deity of rain.

7 Assyriologist Samuel Noah Kramer has identified it as the first known written reference to the concept of freedom. Referring to its literal meaning “return to the mother”, he wrote in 1963 that “we still do not know why this figure of speech came to be used for “freedom.”

8By the Third Dynasty of Ur, it was used as a legal term for the manumission of individuals. It is related to the Akkadian word anduraāru(m), meaning “freedom”, “exemption” and “release from (debt) slavery”.

9 Understood as a separation from traditions, land and ancestral wisdom.

10Bruno Latour, Nikolaj Schultz, Memo on the new ecological class, Les Empêcheurs de penser en rond, 2022.

«The main objective of the article is to raise awareness about the issue of water stress in Morocco and emphasize the importance of taking urgent measures to sustainably manage water resources while balancing water use in agriculture and avoiding overexploitation of groundwater. The ultimate goal is to preserve the country's precious water resources to ensure a sustainable water supply for future generations.»

Water stress has become a major global challenge, an undeniable reality that affects both nations and individuals. Over the past decades, water demand has seen exponential growth, with this significant increase since 1960 being the result of several factors, including rapid population growth, ongoing industrial expansion, intensified agricultural irrigation, and a growing demand for energy.

According to a recent report by the World Resources Institute (WRI), the Middle East and North Africa are among the regions most severely affected by water stress, with 83% of the population facing extremely high water constraints. Morocco, located at the crossroads of North Africa and the Middle East, is not immune to this reality and remains vulnerable to the impacts of climate change.

Unfortunately, in Morocco, the problem of water deficiency is often attributed to insufficient or reduced precipitation, whether in the form of rain or snow. Climate change is frequently identified as the primary cause of this situation. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that governance and authorities overly focus on these meteorological factors, while historical efforts have primarily centered on water supply development and expansion, including the use of new technologies such as desalination, neglecting the crucial importance of managing and controlling available water resources, particularly given the already limited reserves. While variations in precipitation have a significant impact on Morocco's water resources, it is essential to examine other critical factors contributing significantly to this issue, such as the imbalance between water supply and demand and its management. It is crucial to recognize that population growth, expanding agriculture, and industrial development exert substantial pressure on already limited water reserves.

Currently, the agricultural sector in Morocco is the largest water consumer, representing approximately 87% of the total consumption of our groundwater resources, while the rest is allocated to other activities and drinking water supply. However, it is essential to note that agriculture contributes only about 13% to 14% at most to the GDP. This disparity highlights

a glaring imbalance in the use of our water resources.

To illustrate how our water resources are distributed and managed, let's take the example of date palm production and cultivation. According to the latest program contract signed between the National Agency for the Development of Oasis and Argan Trees (ANDZOA) and the government, one of the key objectives of upgrading the palm sector is to plant an additional 2 million trees by 2030, with 3 million already planted. The goal is to accelerate production in arid areas characterized by low and irregular precipitation.

However, a crucial question arises : where will the water necessary to achieve these ambitious goals come from? Who will bear the cost? This presents a major dilemma because it primarily endangers fossil aquifers, a nonrenewable resource. Overexploitation of fossil aquifers can lead to their depletion, with severe consequences for the entire ecosystem and the communities that depend on it, including a decline in water table levels, deteriorating water quality, and land subsidence.

This situation underscores the urgent need to rebalance water use in the agricultural sector and implement sustainable strategies to preserve our water resources. We are at a stage where immediate action is necessary to address the current situation, which involves not only exploring technological solutions but also implementing rational and resource-appropriate management actions. Water management must also consider the legislation governing this field, as it directly affects the economics of water. This is where the key lies in addressing the current crisis and ensuring the sustainable management of our water resources.

In conclusion, this situation urgently highlights the need to restore balance in water use in the agricultural sector while deploying sustainable strategies to preserve our precious water resources. The future of our nation depends on our ability to act responsibly, raise awareness, legislate, and innovate to ensure a sustainable water supply for future generations.

All the information in this research paper was extracted from the mouths of men aged between eighty and ninety years old. They generously gifted me with every letter or story with joy and delight. They are the ones who welcomed me into their mud homes or accompanied me to the irrigation channels, passionately narrating the stories of the canals flowing with the waters of the sacred valley. I deliberately refrained from extensively using references from those who preceded me in the same subject, opting instead for oral narratives or rare manuscripts. They informed me that the wise of their time were the architects of these techniques and organizations that structured the oasis by managing the waters of the valley from its natural course to a cultural heritage through effective management. Every piece of information compiled today may become a treasure for our descendants one day.

﴾ And We have sent down blessed rain from the sky and made grow thereby gardens and grain from the harvest ﴿

-Surah Qaf, verse 9-

-Surah Qaf, verse 9-

"The water tells the story of the community, and the community tells the water."

Water heritage in the oasis regions is considered one of the most important factors that contributed to expanding the oasis along the banks of the Draa Valley. This was achieved through the rationalization of the water of the Draa Valley using traditional irrigation channels and the khataras, which constitute the lifeblood of the oasis's prosperity.

In order to irrigate thousands of hectares of cultivated land, the Draa Valley is considered the pulsating heart of human life, the source of human settlement, and agricultural activity. The ancient Draa inhabitants sought to create a complex and systematic water network to divide surface and groundwater, taming the flow of the valley's water among the tribes, palaces, and religious lodges.

The valley's water is evenly distributed among all residents, and the khataras have sacred customs that they have documented in manuscripts or on gazelle skins, preserving them in the collective memory of the Greater Draa inhabitants.

These customs are passed down from generation to generation to manage these irrigation channels among the agricultural lands. There were several traditional tax agreements and obligations that had to be respected to this day.

Water organizations have witnessed conflicts among the Draa inhabitants, and it was necessary to find a suitable solution to fairly divide the water's time among its owners. The water of the Draa Valley is bought and sold, documented in agricultural land contracts. For example, a farmer may buy an orchard without the water from the saqiya, or he may buy both the orchard and his share of water. This share could be a quarter, eighth, half, or a specific portion of the time allocated to him.

From these tribal customs of water distribution, it is understood that they were based on the sundial (for daytime) and the water clock (for nighttime) or celestial signs (to determine the allocated time for each person to exploit the saqiya's water)."

Water Elders"The water is the organizer and structure of the social fabric, serving as the anchor for the stability of individuals."

All tribes rely on one person in the division of canal water, known as the "Saqiya Operator." This person is a wise and dignified individual among the tribe members and is often a just guardian of the Book of God in the distribution of canal water among the tribe's inhabitants. All the "chiefs of the tribe," whether settled or nomadic, are familiar with him, and he is the same person who becomes significant during the distribution of inheritance among families. Sometimes, he may be appointed to oversee the irrigation water, its excavation, and maintenance.

The water sheikh or Water elder, is well acquainted with the names of canals and pathways, as well as the "musaarif" (distribution) and the number and proportions of water shares. Additionally, he knows where the "aqawak" originates and where it ends. The water sheikh is keen on organizing surface water in a complex manner, from the valley, main canal, to the small canals (distributors), until it reaches the "jannat" with a system known as "al-nawba." The latter must be respected, and the one coming next

STAR TECHNOLOGY

﴾ And landmarks. And by the stars, they are guided ﴿

-Surah An-nahl, verse 16-

must not close the water of the canal until they put a little straw in the water, symbolizing a symbolic message that the allotted time has ended.

Undoubtedly, the expansion of the oasis east and west would not have occurred without the division of the land and the excavation of canals. The technique of supplying water to the oasis from the "aqawak" at the top of the valley, passing through the main canal and then the "musaarif," is what enabled the construction of palaces, huts, and human settlements within the oases.

In periods of consecutive years of drought and low precipitation, the number of water sheikhs in the oasis community significantly decreases for several reasons: either due to migration, death, the failure to inherit this ecological culture, or neglect of canal maintenance. The latter has led to submersion in sand and waste, as evident in most storage canals along the roadside. Fortunately for us, we have found some individuals with a good understanding of the history of water among them.

Water sheikhs relied on star technologies, specifically astronomical time, to ascertain the seasons, directions, and the Qibla direction for prayer. This method was also employed to allocate the appropriate proportion of water to each farmer. The nightly determination of the irrigation ratio was based on the positioning of stars from sunset to dawn. A star becomes visible during the Isha prayer, another emerges after the Isha prayer, and a third is distinguished by its radiance at dawn. Utilizing these stars and celestial signs, the night is divided into quarters, thirds, halves, and dawn in accordance with tribal customs. Additionally, the time of dawn is established by the crowing of the rooster.

The daytime is also divided based on solar and astronomical timing, encompassing the period from sunrise to noon. Furthermore, the half-day from Thursday afternoon to Friday afternoon is regarded as a complete day.

Some elderly individuals still retain recollections of this process, albeit not with absolute precision. Despite thorough research, we were unable to pinpoint this technology precisely, although all indicators affirm its existence. Nevertheless, it appears that those proficient in interpreting such signs were often scholars, mosque muezzins, or experts associated with ancient mosques.

The Tinsa process is a very simple time calculation method. It involves a brass vessel with a very small hole in the middle. This brass vessel is placed in a container of water, and something is gradually immersed inside the container until it sinks completely, referred to as "kharuba." This process is repeated each time to adjust the allocated time for each farmer. The water sheikh monitors this process and knows the subsequent or upcoming shift.

Taqdam is a very simple process that relies on light and shadow. A person stands or positions themselves well, facing the sunlight so that their shadow is cast on the ground. In the second stage, another person marks the end of the shadow. Then, the person standing upright aligns themselves with the direction of the shadow, placing the first "foot," followed by the second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh. The number of steps is used to determine the time and, consequently, the water allocation ratio for the irrigated area for each person. The distance covered by the steps varies between shadow and sunlight based on the seasons, expanding or contracting accordingly.

Sun Foot End of shadowThe rural community consists of several social groups with varied origins, including the "Iznassen," "Lmarbtin," and the aristocracy known as "Ait Atta." It was imperative for these groups to live under the shade of social solidarity, necessitating interaction and integration into a unified human structure, away from conflicts and property violations. They had to contract in the name of the "Qasr Al-Qasba." This tribal cohesion is based on shared interests and participation in mutual benefits. Al-Nawba is the designated time period for each individual or canal entering the oasis. It

Ouled Mohamed

branches between the members of the tribe and the oasis in distributing water according to tribal customs. For example, the "Saqiya AlMazouya" has 12 nawbas and irrigates 180 hectares of the irrigated area per acre, a specific proportion of the canal water. The "Nawba" is tightly divided and has been contracted for centuries, remaining in effect to this day despite consecutive years of drought and the absence of valley water. However, during flourishing periods, the same customs and traditions in water distribution resurface.

Day and night

Ouled Mohamed Massoud Day and night

Government Day and night

Nouba Jdida Day and night

El Attawia Day and night

Amechriken Day and night

Mubdia oula Day and night

Mubdia tlania Day and night

Moharrira Day and night

Taqdam is a very simple process that relies on light and shadow. A person stands or positions themselves well, facing the sunlight so that their shadow is cast on the ground. In the second stage, another person marks the end of the shadow. Then, the person standing upright aligns themselves with the direction of the shadow, placing the first "foot," followed by the

second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh. The number of steps is used to determine the time and, consequently, the water allocation ratio for the irrigated area for each person. The distance covered by the steps varies between shadow and sunlight based on the seasons, expanding or contracting accordingly.

It was a tradition among the residents of the oases to depend on individuals with substantial experience in prospecting for groundwater and precisely digging wells. Typically, these individuals were local farmers whose expertise lay in traditional groundwater prospecting. They would identify the suitable location with great precision, employing primitive tools to discern the piece of land with water. Using a branch from an olive tree, they would carefully inspect the land until the branch tilted towards the spot it was drawn to, signifying the discovery of the water source. This marked the commencement of well-digging activities.

The inhabitants of the oases extensively use wells to exploit groundwater for various purposes, including irrigating crops, drinking, and daily use. Wells play a significant role in irrigating crops during the summer periods when surface water is scarce. They also serve a hydrological role. See types of wells.

The first type is wells located inside homes, palaces, and citadels. These are communal wells often used for daily drinking for humans and animals, as well as for household purposes. Women use them to avoid the hardship of carrying water over short distances due to their narrow and deep characteristics underground.

The second type is distributed along the sides of the road between oases or on roads leading to the desert. Both humans and animals quench their thirst from these wells. Their unique geometry varies, and near these wells, small tanks are often placed to pour water into, providing hydration for sheep, goats, and camels. They are designed with the purpose of providing rest for passersby or small caravans passing through to markets or neighboring tribes.

The third type is wells used for irrigating crops and green areas. They are often communal and solidarity-based. Each owner of an acre has a dedicated well, and they rely on traditional methods. However, in the early seventies, oasis inhabitants started using

In the collective memory of the oasis inhabitants, a powerful connection exists between the land and the sky, between humans and popular sanctities. Celebrations during the harvest, supplications during years of famine and drought, or offerings such as the sacrifice of sheep or goats as a token of gratitude or repentance for human sins—all reflect the human inclination to create beliefs that provide solace in times of weakness or to offer sacrifices to appease nature. All these multifaceted symbols share a common meaning: that the oasis inhabitants have crafted for themselves a sacred refuge to turn to in times of both joy and adversity. They craft a Tagnja statue from reeds in the form

The fourth type is the wells of mosques, initially used for the purpose of mosque construction and providing water for workers during its construction. They are also utilized for drinking, ablution, and bodily purification. These wells are commonly found in all ancient mosques in the Draa region.

of a woman adorned with various colors— yellow, red, and green. The head of this statue takes the shape of a "Mghrafa," embellished as a beautiful, radiant girl, lifted amidst the crowd. They then sing :

Tagnja, Tagnja, oh my Lord, let the rain fall...

Tagnja, Tagnja, oh my Lord, let the rain fall.

Tagnja, O mother of hope, towards God's mercy it has come...

Tagnja, O mother of hope, towards God's mercy it has come.

The matter reverberates ; it is one of the oldest rituals practiced.

Pictures of the ancient mosque in Amzrou, city of Zagora

morocco-is-worlds-9th-largest-avocado-exporter-amid-wa

Lyonnaise des Eaux

https://www.erudit.org/fr/revues/euro/2012-v8-n1-2-eu

ro01518/1026641ar/#:~:text=En%20adoptant%20les%20principes%20 de,service%20de%20la%20domination%20coloniale