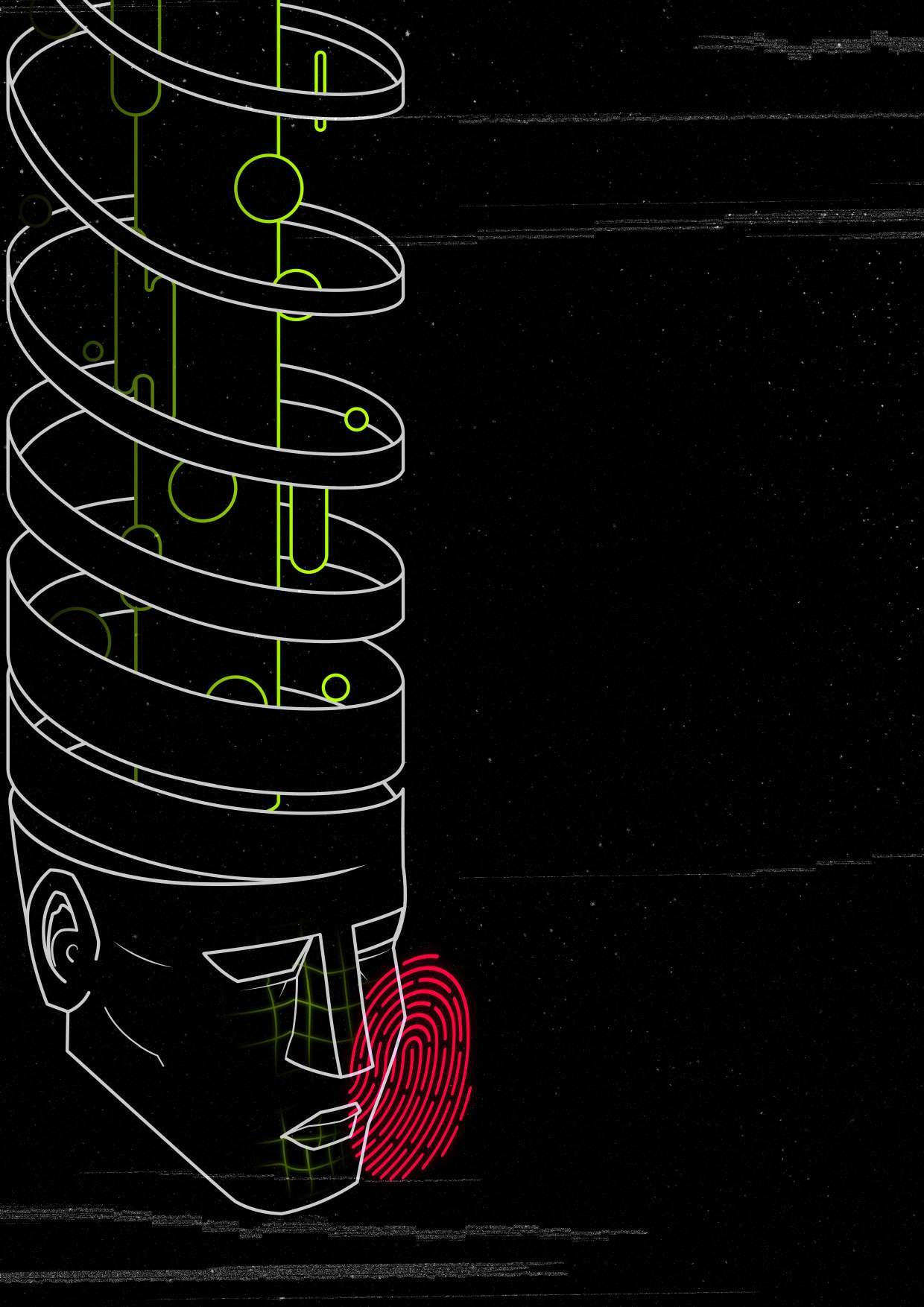

Kounaktif is a cultural platform founded in 2018. It aims to create a space for sharing knowledge and skills, weaving social bonds via Art and culture, and developing creative and critical capacities in the fields of visual and sound arts, philosophy, new media and DIY (Do it Yourself!) practices. These practices are seen as tools of resistance against imposed realities.

Kounaktif’s identity is based on the intersection between arts, technology and ecology through creativity, education and dissemination. It constantly promotes collective intelligence and collaboration through its programmes in the form of discussions, exhibitions, participatory workshops and concerts.

Aghssan is a magazine that aims to bring together actions, stories, ideas and alternatives around questions related to arts, ecology, new media media and their entanglement with socio-political questions.

The magazine is a project led by Kounaktif and it's superimposed on the various actions led by the collective to make free access to cultural production.

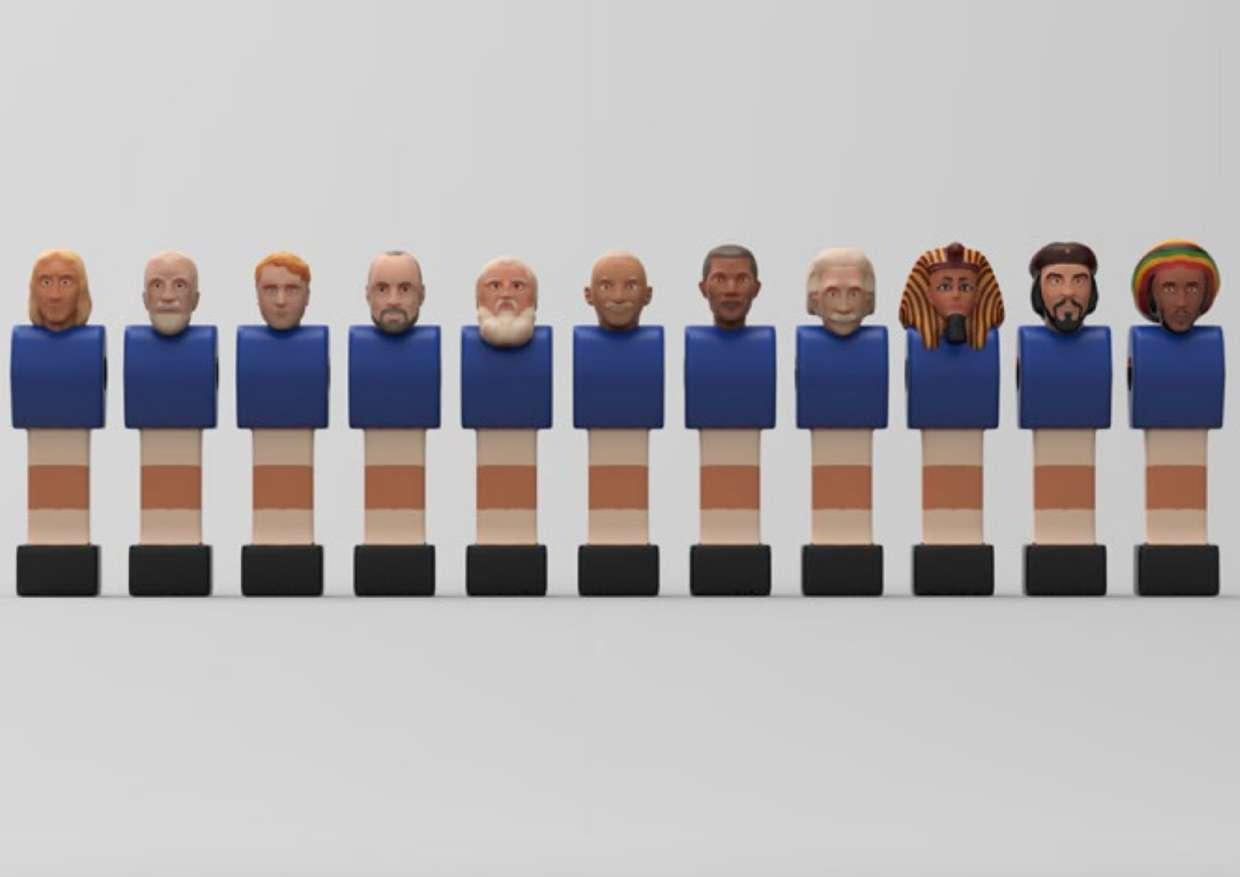

In the global society today, we are submerged in a westernized way of doing, of being, of thinking, and even of imagining the world(s). Mohamed ElManjra in 1990 pointed out that “our recent history is still colonized. [...] [We] enjoy only nominal independence. In short, decolonization is still a remote target. It will take decades befores it materializes.»

In fact, our inner spaces are also subject to domination and power struggle. Our multilayered identities are constantly confronted to nationalistic and global narratives that reduce the complexity into one-dimensional reality. We are taught in our universities that philosophy and arts began in the West. This linear way of approaching history, philosophy and arts shaped our perception. This perception imprisoned us in thought and imagination.

What does it mean to decolonize our imaginaries ? Is it thinking inside new electric and liquid paradigms that allow flow and include intensities ? Is it the exploration of non-linear (hi)stories, multiple beginnings and endings, juxtaposition of cultures ?

In this edition of Aghssan, we are uniting forces, gathering ideas and artworks that highlight these ideas that challenge the mainstream current that dictates one-way of doing, of thinking, of being, of imagining.

PS : All texts are written in their original language. We intentionally mixed texts in Arabic, French and English to invite the readers to break out from the usual schisms.

The issue of decolonization entangles at least political and epistemological viewpoints. Within the African continent, what does decolonization of knowledge mean after the independence of its countries? As a philosopher, and like many other thinkers, I am interested in the margins of what is perceived as knowledge. Indeed, academic and classical European knowledge is glorified in Western culture, excluding other types of knowledge, especially in the Francophone context, according to a vertical master plan.

Moreover, the “fields” (“champs”) of European classical knowledge resemble the “bocage” as a type of agricultural organization where the fields are bordered by hedges, even though North American universities based their cursus on objects and “studies” rather than disciplines. By tackling decolonization of knowledge horizontally, starting with literature, arts, including fine arts and music which are important elements in order to grasp the philosophical meaning of decolonization

of knowledge.

First, we need to understand what colony is. It’s a space where colonized people are globally “de-symbolized”, as if they have no abilities to rationally think and do something like the colonizers. One of the other tools of domination is also marked by the sense of orientation and cartography. Cartography of the world where the North is always portrayed at the top, and South at the bottom - and also encyclopedic knowledge in the 18th century that consisted of mapping and hierarchizing knowledge – gives an orientation in terms of aim, process, norm, legitimacy etc. In this sense, a border was created between the metropolitan knowledge and the knowledge of the colonized that is regarded either as dangerous or invalid, as a kind of the wrong or of the ignorance.

In order to tackle the hegemony of these orientations and cartographies, we do not need to re-orient or re-create new cartographies,

we need to give up cartographies and become radically disoriented. Disorientation means questioning norms and standards of knowledge without any prejudice. It is not necessary to build another encyclopedic cartography of what is valid and invalid, or to depend on a higher order from which we take legitimacy. Disorientation requires us to give up our old compass for finding new landmarks and diving within the uncertainties of the world.

Furthermore, knowledge in its European conception is based on “impensés” or unseen principles. Knowledge was considered as a kind of vision, so, what was privileged was the vision over the other senses, in so much as the vision pre-supposes distance between the eye and what it sees. For example, to refer to the 18th century, we name it «Enlightenment». So, we obviously conceive knowledge in terms of vision. This is why the anatomy has been developed with the dissection of corpses, to see under the skin. Then, the body was considered under the prism of mechanism, then technology. Thus was born the idea of a mechanical body, as if the body was a lively machine.

In this sense, Europeans and Westerners, who believe themselves at the peak of knowledge, have ignored, not only for centuries, but during millenia, practices that are established on the examination of the living body as a whole. Surgery became an hegemonic paradigm of care, ignoring another paradigm founded on touch, contact and living organisms. The West excluded flows and circulation, crucial in Chinese medicine from its approach. And that is mostly due to the fact that Western culture is obsessed to see through its technological devices the validity of any knowledge on the human body.

There’s also another important aspect that requires our attention, more political than epistemological. Within the whole Western world, knowledge is regarded as a capital, and not as a circulation. When we conceive knowledge as a circulation, we are not obsessed with what we produce, but also of

what we receive from “Others”. No matter who these others are, that is to say, others who are undifferentiated. It is a way to say that hospitality is a way to increase our knowledge and to share it with others instead of thinking, a priori, that Others since always live in ignorance, without art, without literature and, at last, without science.

Thus, there is a large variety of ignorance, simply because absolute ignorance does not exist. Absolute ignorance is a fantasy of the virgin land from which knowledge will develop. One of the examples of ignorance can be found through resistance, internal resistance - which makes us know something, but we know it without internally knowing it (par ailleurs), like a dead knowledge, something that we wont use because of our internal boundaries. In this sense, all sorts of knowledge necessarily include some forms of ignorance - or blindness, i.e if we perceive Chinese medicine not as true medicine but only as massage, we miss its value. That means we have a resistance here - hence the necessity to disorient ourselves to allow the flow beyond our internal blindness produced by our blockages and our prejudices. Everybody, even any Nobel Prizewinner, needs to be open minded and to accept this fact. It is better to develop knowledge with “others” than to stay in the “entre-soi”.

It is not enough to be open minded. Knowledge is produced inside of capitalism. So, what is being looked at as knowledge, now, is what is profitable to the companies. Well, non-profit knowledge, widely located in the global South, is being marginalized, even totally excluded from the sphere of valuable knowledge. This is one of the reasons, I think, that people from Guadeloupe or New Caledonia, for instance, are opposite to any vaccin anti-Covid. They take heed to capitalism more than to knowledge.

La pire des situations c’est quand tu rêves dans la culture de l’autre, tu goûtes selon les critères de l’autre et que tu le fais d’une manière inconsciente et que tu considères au fond de toi-même que le dominateur ou l’ancien colonisateur est et reste la source du savoir. Mais il ne faut pas que le concept de l’Autre soit un voile qui nous cache une autre réalité ; car quand on prend conscience de la présence de cet autre dans notre façon d’imaginer, d’aimer, de haïr ou de créer le premier réflexe, naturel diront certains, est celui de le rejeter. Le rejeter comment ? Rejeter ne doit pas non plus passer sans être vue et revue avec précision. Comment a-t-on absorbé l’autre au point où il est devenu une partie de notre identité voire l’identité même?

Il n’y a pas que le dominateur qui inculque ou inocule sa culture au dominé, le dominateur aussi est fasciné par le dominé, par sa culture et sa manière d’être et de voir le monde. Nous avons eu au Maroc l’exemple des portugais qui avaient habité la ville de Mazagan, l’actuelle El Jadida et qui, à leur retour au Portugal, avaient été rejetés par les habitants de Lisbonne, car ils les considéraient comme des marocains ; on les appelait d’ailleurs ainsi. Ils ont été obligés de quitté le Portugal et sont allés s’installer au Brésil en fondant une nouvelle Mazagan et ils continuent à ce jour de célébrer des fêtes annuelles où ils se rappellent de leur vie au Maroc. L’autre exemple est celui des Français du Maghreb qu’on appelle communément ‘’Pieds Noirs’’, ils ne sont certes ni Maghrébins ni français, car ils sont un produit des deux cultures, mais ils continuent à ce jour de rêver de leur vie au Maghreb.

Ceci pour dire que personne ne peut obliger autrui à embrasser sa culture. La différence avec les dominés c’est qu’ils adoptent la culture du dominateur de plein gré et il arrive le jour où ils sont pris d’un sentiment de culpabilité. Alors ils se ruent sur leur corps et tentent d’arracher l’Autre, celui qui les a habités et qui les a transformés. C’est à partir de ce moment qu’un sentiment de perte prend naissance et qu’un retour vers un moi

fictif est entamé. Nous n’avons qu’à reprendre les écrits d’Albert Memmi (Statut de Sel ou Portrait du colonisé), ou encore les travaux de Franz Fanon pour s’en rendre compte. L’un et l’autre, Memmi ou Fanon, étaient l’exemple du colonisé qui vécut sa situation en tant que tel. Ils tentaient de revenir vers ce moi imaginaire, un moi fabriqué par l’idéologie nationaliste teintée de marxisme simpliste de l’époque.

En usant du concept de l’acculturation, en vogue au lendemain des indépendances, et compris comme une absence de culture et non pas comme enrichissement, Franz Fanon avait exhorté les intellectuels maghrébins et négro africains à rejeter la culture occidentale et à revenir au patrimoine local. Ce retour aveugle à la culture d’origine ne prenait pas en compte la mise en place d’une pensée régressive et passéiste. Ce que Fanon et bien d’autres intellectuels issus de la culture coloniale, n’avaient pas saisi à l’époque, c’est que l’Occident avait bien pris place dans les imaginaires. Qu’il était devenu une partie de notre culture, celle que nous avons construite au fil des temps. Vouloir nettoyer nos corps, nos esprits et nos âmes des résidus de la souillure occidentale (comme il plait à certains islamistes de dire aujourd’hui) revenait à se mutiler culturellement et mentalement et sombrer dans une schizophrénie insurmontable. La culture française dont il était question dans les états du Maghreb au lendemain des indépendances, n’a jamais été un cadeau offert gracieusement par le colonialisme, mais bel bien une appropriation que nous avons arrachée tout comme l’indépendance ne serait-ce que celle des esprits.

Vouloir effacer ce moment crucial de notre devenir d’un revers de la main, c’est sortir de l’histoire et vagabonder dans la jungle des identités aveugles.

© Sofiane Byari, “Conversation between dualities”, acrylic paint, wood, mirrors, 100x60 cm, 2019

© Sofiane Byari, “Conversation between dualities”, acrylic paint, wood, mirrors, 100x60 cm, 2019

It would be interesting if we begin with the general definition of what’s decolonization, where it began and the major movements. According to me, there are two main decolonization movements, the one took place in the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s, which was a fight against colonial forces in Africa and Asia. This can be described as a national fight against a colonial power occupying a territory. The later resulted in the Tricontinental movement, which rejected both the American liberal social model and the Soviet social model and demanded a third model of development based on the reality of the countries of the southern hemisphere. This is the first major decolonization movement. And the second decolonization movement is what’s currently happening.

For example, there is a south-african researcher named Ndlovu-Gatsheni who speaks of decolonization in terms of Insurgency and Resurgence. Insurgence is the struggle of colonial power which occured

in the 60s and 70s, and the Resurgence, which is the reappearance of the decolonial issue in Africa, the Maghreb and Europe. The current idea of decolonization claims that even decades after our independence, there is still colonial continuity, which we call «colonialism without colonization». Colonization consists of invading territories, colonialism is about the invasion of mindsets, societies, of knowledge and lifestyle. It’s something that deeply affects society because it is embedded deep within us that it becomes unconsciously inherent to our psyche and behaviors.

Then we have a third conception of decoloniality which originated from Latin America. The current decolonial debate emerged from South American countries such as Colombia, Peru and Argentina. It’s a theory in philosophy and social science which argues that Western modernity did not appear in the 17th and 18th centuries, it started when the European «discovered» Latin America. That’s when colonial thinking emerged and

the colonial system was created based on race and species classification and social categorization. This Latin American thinking evolved during the 1980s and the 1990s, and when we’re referring to decoloniality, we’re mostly referring to this Latin American perspective. They argue that, instead of the dichotomy of modernity-tradition, modernity itself is a colonial thought. So, in order to eradicate colonial thinking we must review and question our perception of modernity.

In fact, there is more than a way of thinking and living. When we speak about decolonization of arts, we can mention the definition of the moroccan writer and poet Omar Berrada, and he refers to it as a «fight for our self-reinvention», it allows us to invent something totally new and that belongs to us, as people from the ex-colonized countries.

Most of the researchers and artists who wanted to build something out of decolonial thought in Morocco, found themselves either in prison or exiled in Europe. We can say that the decolonial effort to build something has failed due to political reasons. Within my research practice, I am trying to embed this decolonial thought in my research methodology by outlining techniques that fit more with the Moroccan context.

One of the residues of colonial power in Morocco (and North Africa) is showcased in the use of french and the necessity of speaking that language in universities and even administrations. And those who are unable to meet the western criteria within the art field find themselves marginalized within their own countries. This leaves us giving much effort and energy to understand and know about the western ways of doing and thinking, which creates a gap and doesn’t allow us to dig more into our own pre-colonial culture.

The moroccan painter Chabâa says that the decolonial movement is a return to self -moroccan one- but also the individual self. We shouldn’t oppose the individual to a big structure in power. In fact, one of the ways through which we can resist the hegemony

of the Western thought isn’t by opposing individuals and power structures. I mean by that, allowing a multitude to emerge, those who defend colonial taxonomy and the individuals who are opposed to it are both supposed to express their ideas, from this friction we can truly create something that is rooted and authentic to our own context. There is for example the moroccan anthropologist Zakaria Rhani who is very critical towards this idea of decoloniality and post-coloniality, he argues that we mustn’t put ourselves in a break with these things but rather being in a critical continuity. By critical continuity, he means documenting ourselves while being radically critical, and being present within our society. We must then for sure revist the canon, but also be consciously part of a critical continuity. Besides, we shouldn’t just criticize things then start all over again. We must place ourselves in an ethical continuity that will allow us to move forward. Time spent decolonizing our past will serve as a launching pad free of any useless questions around the fake dichotomy between modernity and traditions.

We for sure recommend creating a local alternative to western culture; we have to interact with it, criticize it, and benefit from it. But most of all, we need to do some research about our own culture. A society without research breeds ignorance. And I don’t mean ignorance regarding formal education, but regarding the future. So we need to recognize previous works instead of taking inspiration from someone outside of ‘our’ reality -which is not wrong in itself -, but there were countless experiments here. For example, the experiment I’m currently working on in the psychiatric hospital of Casablanca; I would like to see psychiatry students in Morocco to acknowledge these experiments in order to immerse themselves in their reality.

© 560 Zoom, «Taxi Kebir», 4-tapes recorder installation, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dTpoL6EYHUc

on observe ce qui est de plus intime chez nous avec les yeux de l’autre on ne peut que construire une vision de l’identité qui est fantasmée. Une décolonisation épistémique n’est pas une Tabula Rasa de tout ce qui nous est transmis de l’autre, mais plutôt un regard critique des conditions de production de la chose transmise. Un regard décentralisé des sentiers de la domination moderne et des traditions intellectuelles occidentales.

, , , ,

Dernièrement, la nouvelle tendance, des sciences humaines et des études culturelles a ouvert une nouvelle brèche dans l’étude des rapports de force entre cultures et visions du monde. La thèse principale de celleci est qu’un processus de décolonisation impose un engagement qui a vu le jour en partie avec Frantz Fanon ou Césaire dans un contexte de réaction à l’occident lui-même. Par décolonisation, on fait référence à tous les processus de déconstructions des biais et stéréotypes que le colonialisme a construits autour des cultures “indigènes”. La notion de l’imaginaire est centrale, car on parle souvent de la décolonisation des imaginaires, c’est-àdire le processus par lequel le subconscient collectif se libère de nombreuses images figées sur sa culture et sa place dans le monde moderne. L’imaginaire comme ensemble hétérogène de données ne peut être que lié aux formes d’être de la société. Il est une composante qui fait partie d’un ordre du fait social et anthropologique qui régit la vie du collectif et de l’individuel. Il ne suffit pas alors de porter l’attention sur l’imaginaire, car

il est l’expression d’une structure profonde de principes. Ces principes se fondent sur les deux dimensions ; épistémologique et métaphysique. La décolonisation des imaginaires entend une décolonisation systémique, il s’agit d’une conscience profonde des structures sous-jacentes qui déterminent le logiciel de l’imaginaire d’une culture, à savoir la structure métaphysique - c’est à dire l’ensemble des croyances qui déterminent la vision du monde et la structure épistémologique qui fonde la nature du savoir (scientifique ou non) produit.

Par décolonisation épistémologique, j’entends l’ensemble des processus qui nous permettent d’examiner les procédés de la production du savoir. Autrement dit, développer les principes épistémologiques pour une souveraineté intellectuelle de la culture décolonisée. Ceci implique une conscience historique de la culture et des modes de domination. Une décolonisation épistémologique nous donnera les clés d’accès à notre imaginaire. Du moment où

On peut penser que pour faire cela, un retour à la tradition, dont l’image est une création purement coloniale, s’impose. Mais ceci ne peut être vraiment légitime que si on a les moyens pour comprendre cette tradition. Le choc colonial crée une distance entre l’identité transmise et l’identité vécue. Un peuple qui n’a pas accès à son histoire ne peut que réclamer un simulacre de tradition. Dans l’idéal, un puisement dans l’héritage idéel peut nous aider à comprendre la posture de notre culture dans le monde et les principes fondateurs de son développement. Le monde de la tradition nous est étranger malheureusement, car l’on ne peut plus faire la différence entre ce qui exogènes et ce qui est endogène dans les regards qui relisent cette tradition. Cherchons alors dans le vécu, car c’est lui seul qui incarne et métamorphose les valeurs qui ont régi notre vie sociale depuis des millénaires. Prenons par exemple l’usage de l’expression «utiliser la raison”, dans la darija cette expression (ﻚﻠﻘﻋ ﻡﺪﺧ) prend un sens différent de l’usage actuel qui implique que le fait d’utiliser la raison, c’est pour comprendre. Dans notre contexte, cette expression implique une forme de sagesse et de bienveillance dans la prise de décision, ce qui veut dire qu’elle n’est pas détachée de l’acte éthique. Cet exemple nous dit beaucoup sur la structure de notre imaginaire autant plus qu’il peut être un début pour un travail de réflexion sur la valeur de la raison dans notre culture et notre espace linguistique et symbolique.

les valeurs occidentales prédominent les cultures du monde au point que ces cultures ne peuvent plus s’appréhender qu’à travers les yeux d’un occident savant. Une décolonisation des valeurs est primordiale, car ce sont les valeurs décolonisées qui permettent l’émergence d’une pensée décolonisée.

En somme, une décolonisation n’est possible qu’à travers une examination des conditions épistémologiques de la production du savoir et aussi des fondements métaphysique de ce même savoir. La science est un procédé explicatif constitué d’outils techniques d’investigation et d’expérimentation. Néanmoins, les sciences sociales peuvent porter en elle-même des cadres idéologiques qui amplifient encore plus l’emprise et la domination et les exemples de l’Histoire ne manquent pas. C’est pour cela que dans le cadre d’une épistémologie décoloniale que le penseur doit voir l’applicabilité des procédés scientifiques sur les cultures étudiées. Par exemple, la question du regard du chercheur dans l’anthropologie est-elle efficiente ? Doit-on familiariser le regard pour mieux comprendre quelques phénomènes spirituels ou mystiques ? Ce regard, est-il seulement de l’ordre du témoignage ou implique-t-il la question linguistique ? La traduction dans l’étude du phénomène, ne met-elle pas une distance entre le chercheur et son objet ? Qu’en est-il de la séparation entre sujet et objet dans ce genre d’études. Voilà quelques questions qui peuvent nous aider pour comprendre comment on doit approcher le phénomène culturel complexe. Enfin, décoloniser une culture, c’est décoloniser une vision du monde qui nous mettra en face-àface devant notre reflet, ce dernier pour qui on demande au moins le droit de contempler, sans intervention, avec tout ce qui est beau en lui et tout ce qui est laid.

Ce travail de décolonisation nous aidera à comprendre la structure métaphysique qui régit le socle des valeurs de notre société. Nul ne peut nier quand dans le monde cosmopolite

© Youssef El Idrissi, “Subaquatic Landmarks : Unconscious (T)errors”, screenshot from video art installation, analog TV, water, 2 squares of glass, red LED, dimensions variables, 2021.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wvhbawuZC2M

J'ai eu du mal à choisir une pièce de l'ensemble de mes créations qui serait plus adéquate à cette ligne de réflexion. Mais il se trouve que ce mal est assez cohérent, ce déficit qu'on éprouve généralement devant chaque confrontation au "multiple".

Ce mal est assez cohérent, il est la condition de l'expérience de cet échange, et agit en tant que réponse primaire à notre rassemblement pour une quête identitaire commune. Il est le point de réunion, pour tous les esprits subissant les retombées d'une ex-domination, aux justes moments où on tente son évasion, son émancipation, aux esprits condamnés à un éternel départ.

Je prends cette chance, non pas pour parler culture mais pour parler art. Il s'agit bien de deux choses bien différentes, sinon contradictoires. L'art et la culture sont deux champs qui divergent autant que cette divergence est ce qui fonde leur union. Je souligne l'absence d'un fond académique postcolonial qui ne s'arrête pas seulement à l'anthropologie et l'ethnographie et qui inclurait les champs purement créatifs et artistiques. Selon ce postulat je trouve significatif qu'on parle du moment créateur au sein d'une culture, de chercher à voir ce que l'agression coloniale a semé jusqu'aux involutions des subjectivités appartenant à cette culture dominée.

Oui, on nous a appris aux universités que l'art et la philosophie sont nés en Occident. L'école produit en partie l'oppression d'une mémoire historique par l'imposition d'une histoire étrangère, face à laquelle l'acte de création même dans ses tendances les plus anhistorique ne peut que se replier à l'infini. J'ajouterai qu'il est ainsi plus facile pour un individu venu dudit premier monde, de l'Occident, d'être artiste que pour celui qui vient du Sud. Ce dernier est contraint de toucher le sol même sur lequel il marche, car à ce sol, on a substitué une carte, la carte s'est décomposée sur le sol, et désormais le sol et la carte ne font qu'un.

Il est d'une irritation ultime quand on ne peut être artiste qu'au milieu d'une langue autre, d'une histoire, et d'une configuration psychogéographique tout à fait autre.

En ce monde qui ne passe que par le filtre de l'altérité. On est dans un paradigme où " le médium est le message", dans lequel le créateur honnête, vit dans le risque de s'anéantir à force de devoir se mettre sur un double front, saisir sa réalité d'abord, et guetter par la suite la chance d'un langage assez adapté pour l'articuler. Comment gérer ce destin excessif? Faut-il assumer son émasculation? soit construire, nouer sa sensibilité et son intelligence sur des terrains qui dépassent tout ce qui fait sens, avec l'espérance d'une nouvelle écologie affective à venir, la naissance de nouveaux capteurs et vecteurs de lecture, d'une herméneutique et une phénoménologie alternative.

Nabil Himmich

Inspired by Arthur Kleinman’s The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing, and the Human Condition , as well as Rene Addlakhas’ Deconstructing Mental Illness, An 1 Ethnography of Psychiatry Women And The Family , the following ideas aim to outline a short essay 2 exploring different approaches which demonstrate the biomedicine discourse as a non-universal socio-cultural system. This short essay will be divided into three different parts: To begin we shall explore Kleinman’s concepts of how the experience of disability relates to culture and social structures. Following that, the next paragraph shall give a broader theoretical analysis based on Addlakha’s work concerning the deconstruction of the complex of superiority of the western biomedical discourse of mental illness. Finally we shall close up with a dive in into feminist theory dealing with the construction of psychopathologies.

Published in 1988, Kleinman’s The Illness Narrative is a fine piece of medical

anthropology that invites us to look at the deeper meanings of syndromes and disorders. In the first chapter of his book, he distinguishes between three key terms: illness, disease and sickness. Relating to the point of view of the patient, illness is what he labels as the reaction of the patient and their close and extended environment to the diagnosis and its symptoms. (p.5). On the other side, disease refers to the diagnosis given by the practitioner which tries to label the problem within the biomedical model. A model the author regards as too narrow as it is presented as a “mere technical issue… an alteration in biological structure.” (p.5). The last important label he refers to is sickness, a term midging both the perspective of the patient as well as the practitioners. This very last one, mirror’s the “...reflection of political oppression, economic deprivation , and other social sources of human misery.” (p.6). The preceding three categories give us a great first sight not the complex dimensions that involve health, however, a deeper dive is required. The

following paragraph will allow us to dig into a pool of theoretical frameworks that zoom into the power position of the Western biomedical system within the international scientific scene as well as the roots of its creation.

Placed at the top of the hierarchy of knowledge, the Western biomedical scientific system finds itself in a privileged position. Addlakha explains this statut as a result of the myth of the scientifical neutral and “value free” qualities associated with it. These very pseudo-qualities allow it to be the model that other non-Western medical systems are compared to. (p.46,2008). She further explains that the socio-cultural foundations of the Western biomedical discourse are just as existent and elaborate as other nonWestern ethnomedical systems. As a matter of fact, she brings out various contemporary social anthropologists who have laid out clear theories that underline the link between society and medicine. In order to explain this relationship she uses the Robert Stauss’s model which lays it into two categories: sociology in medicine vs. sociology of medicine. Without examining the medical practices of the profession , sociology in medicine takes care of bringing more light into matters of “medically defined problems and objectives, such as the nature of patient compliance to medical regimens or cultural notions of health and illness.”(p.47, 2008). Our focus will be rather on the other category of the sociology of medicine (in the sector of psychiatry) since it is the one that digs deeper into the roots of the European and North American knowledge production of the cultural aspect of western biomedicine historically as well as ideologically. One of the two adepts of this second school of thought that she brings to the surface are Kleinman and Rhodes’ who deconstruct the universalistic discourse of biomedecine whereas they link it to various concepts

such as “biological reductionism,mindbody dualism,objectivism, individualism and impersonalism.”(p.48,2008). These very values remind us of varying currents of ideas that have left an undeniable effect upon modern medical culture. Further names of the social constructivists that are put on the table are Michel Foucault, Michael Taussig or David Armstrong. Yet the author reflects on such an interpretation as being slightly too extreme, Addlakha opens up to us about a preferred interpretation of hers being the middle ground between which she refers to as biomedical hegemony and politico-sociocultural hegemony (referring to the social constructivists). She mentions various names as Kleinmann , Byron Good, and Engels whose approach is more based on a “biopsychosocial model”; an approach which “neither denies the objective reality of disease nor … privileges the biological over and above the social.” (p.48, 2008).

Closing up this brief literature review on the theoretical notions of the relationship between mental illness/health issues and society; the feminist perspective presents itself as rather critical to many of the theories. Linked with their depiction of the health system as male dominated ; the feminists question various definitions of psychopathologies, always linking them to the patriarchal nature of society. Beyond challenging certain psychopathologies, they mainly view mental illness as a product of the inequalities and various violences that women suffer from in society rather than it being a construct. Speaking of gender asymmetry, the political oppression of women remains at the heart of the feminist theory concerning the construction of mental illness.

1 Kleinmann, Arthur. The Illness Narratives: Suffering, Healing and the Human Condition, Basic Books, New York, 1988, pp. 4–28.

2 Addlakha, Renu. Deconstructing Mental Illness: An Ethnography of Psychiatry, Women, and the Family. Zubaan, an Imprint of Kali for Women, 2008

make them beautiful make them proud make them furious make them crowned little boy high little girrrl wise/ wild every fever burns by all every season smells our fall damages are useful in a game try to fix me, ain’t no blame if there’s a chance of you trying to catch the truth, without lying on my lips, silent whispers hush now, a bloody prayer a single shot, all is quiet now

AS THE WINTER FREEZES DEEPER

BITE ME HARDER

WE ARE CLOSE TO (...)

AS THE WINTER FREEZES DEEPER

BITE ME HARDER

WE ARE CLOSE TO (...)

AS THE WINTER FREEZES DEEPER

BITE ME HARDER

WE ARE CLOSE TO (...)

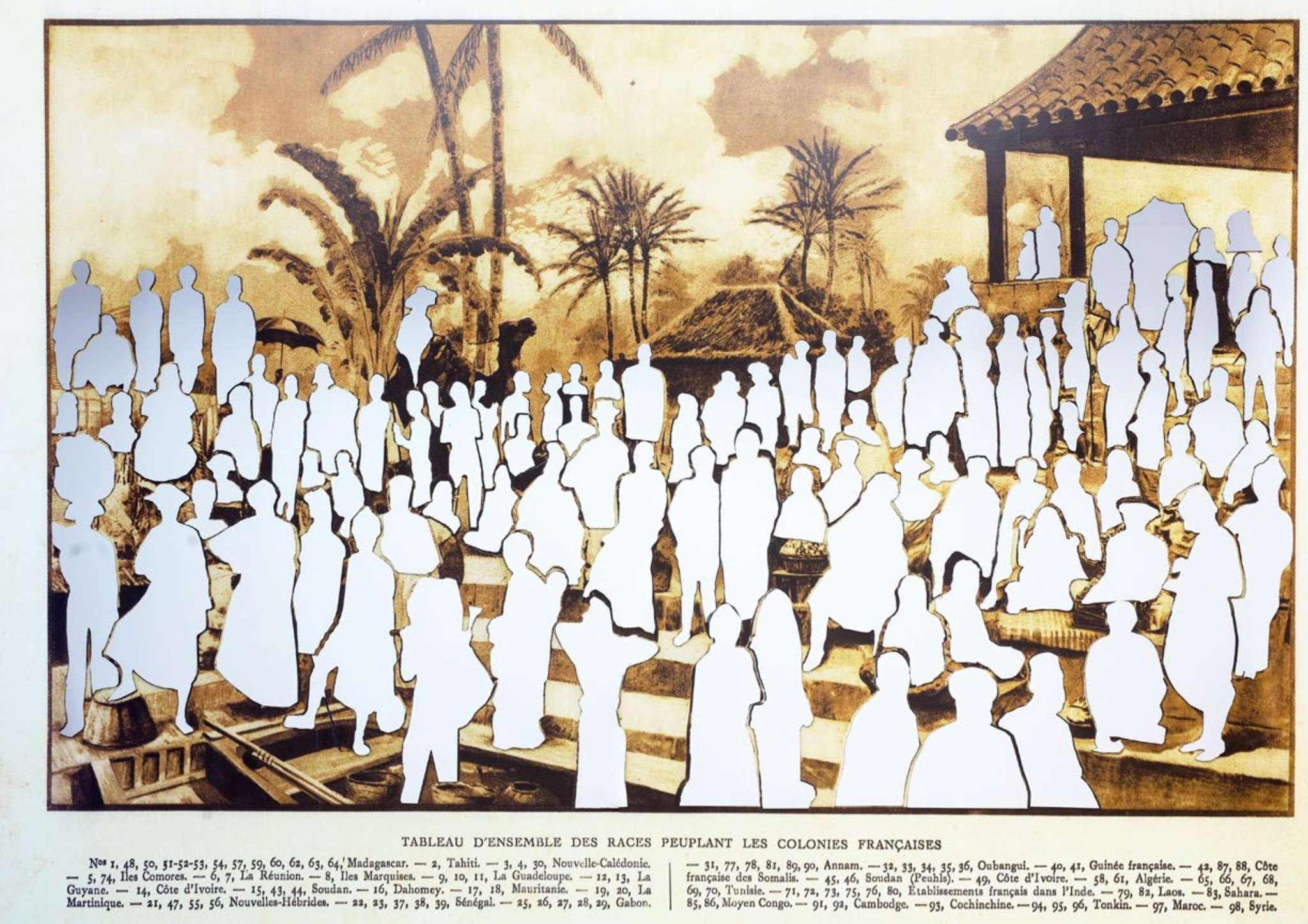

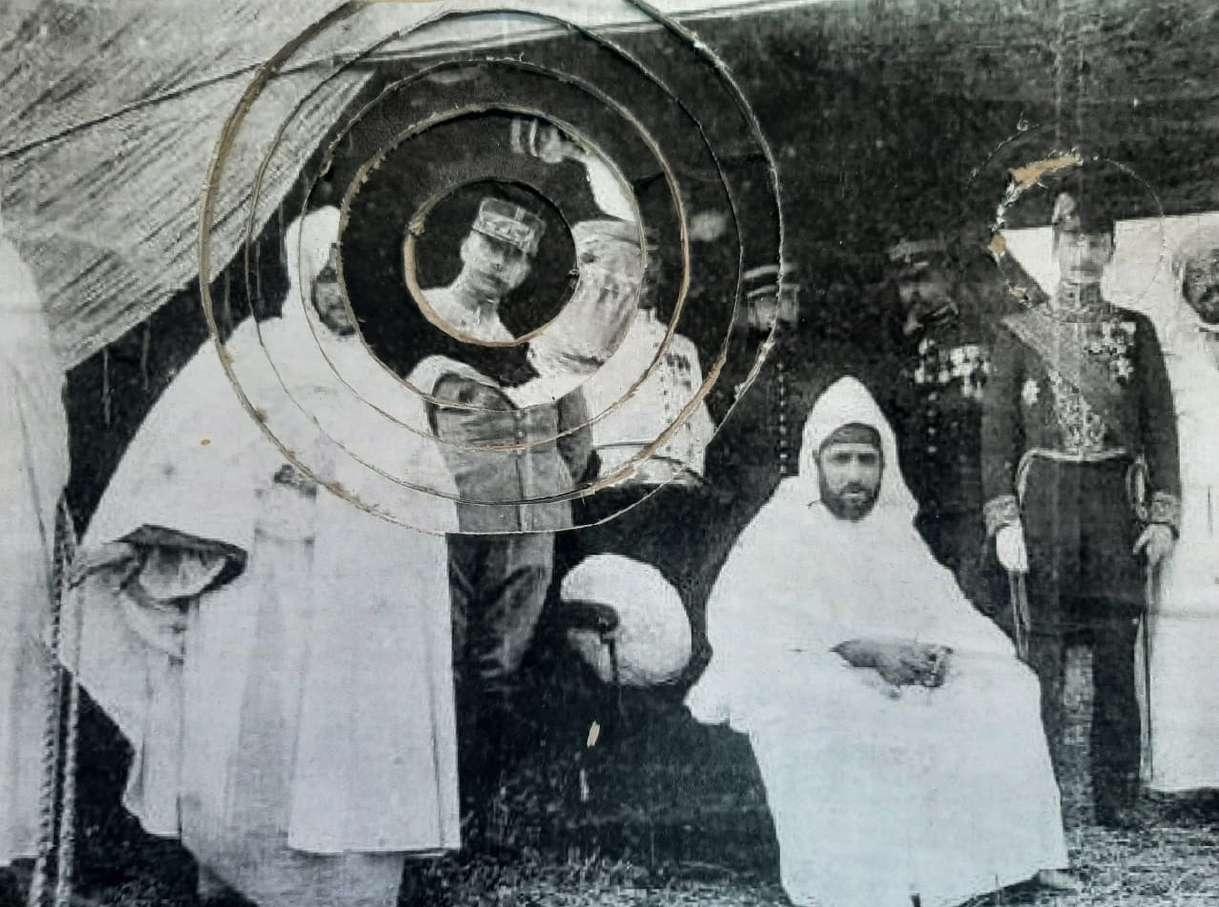

© Youssra Raouchi, "Refining History", printed on layered cardboard, 29 x 42 x 1.5 cm, 2021.

© Youssra Raouchi, "Refining History", printed on layered cardboard, 29 x 42 x 1.5 cm, 2021.

Je suis colonisé.e, tu es colonisé.e, mais surtout nous sommes le pilier de la colonisation.

Il me semble qu’avant de parler de la décolonisation des imaginaires, il nous faudra comprendre qu’est-ce que la colonialité et comment quelque chose comme l’imaginaire peut être colonisé. À quoi penses-tu quand tu entends le mot colonisation ? Des hommes blancs qui construisent des autoroutes ? Des nassaras qui veulent t’apprendre ce qu’est une personne moderne ? Une bande de sociologues féru.e.s, obsédé.e.s par le “c’était mieux avant” ? En tout cas, c’est ce que je pensais, il y a encore quelques années. En explorant le sujet, j’ai découvert dans la pensée décoloniale, un outil d’une grande puissance, qui m’a permis de voir le monde et de me voir sous un jour nouveau.

La colonisation est un état d’esprit que nous portons en nous, il dessine et définit ce que nous voyons, nos valeurs, nos rêves, nos identités,

mais aussi notre imaginaire. Au-delà du fait historique qui s’étale sur une période fermée, la décolonisation politique à donné naissance à un continuum colonial qui lui survit encore aujourd'hui. Construit sur une hiérarchie stricte, aux sommets, nous y trouverons les pratiques et les connaissances des sociétés occidentales. À la base, toutes les sociétés qui ne reprennent pas les schémas exacts sur lesquels se sont construites ces dernières. Nous avons tendance à penser d’abord au droit, à l’économie et à la technologie, des sphères ou la colonialité peut-être parfois évidente et certainement attendue. Mais en m'intéressant à la construction des identités genrées à travers une approche décoloniale, j’ai constaté l’existence de la colonialité dans des recoins plus intimes de mon esprit.

Entre autres, l’imaginaire, ce deuxième monde, un univers interne dans lequel tous les murs sont malléables et extensibles, où il n'y a théoriquement aucune limite. On y puise des images, de l’espoir, on y dessine des chemins,

on y invente des futurs. Il est le champ d'où éclot nos rêves, où nous pouvons imaginer de nouvelles réalités, une société en paix où il fait bon vivre. Pourtant, ton imaginaire et le mien sont aussi formés par des bâtiments et des chemins que nous avons appris à voir comme indispensables, sans lesquels nous pensons que nous ne pouvons pas avancer, rêver, espérer ou nous projeter dans le futur. On en oublie l’infini de notre créativité. C’est dans ces structures que nous retrouvons la colonialité. Elles sont construites par notre entourage social, nos croyances, l'histoire que nous apprenons, elles-mêmes touchées par cette colonialité. Nous reproduisons cette hiérarchisation des valeurs en ayant comme objectif d'atteindre le sommet, donc les valeurs occidentales, tout en vivant dans la peur d’être traître à notre culture en négligeant la tradition. Quelle conséquence cela a-t-il sur nous et sur la société ? Malgré la multiplicité de nos vies, souvent, nous nous retrouvons à vouloir reprendre les chemins que nous avons intériorisés à travers les discours de la société. Soit un homme mon fils, soit une femme ma fille! Sans rien ajouter à ces affirmations, il y a une avalanche d'idées préconçues qui viennent à l'esprit. Il y a la bonne façon d’être une femme ou un homme qui serai authentique, et la mauvaise façon qui serai donc falsifiée. Réfléchir à la possibilité de les optimiser, de les adapter ou d’imaginer de nouvelles manières, semble perdu dans le mal d’ÊTRE.

Je suis une personne marocaine, ayant grandi comme beaucoup, entre ce qui me paraissait être le choix de la modernité ou le choix de la tradition. L’un excluant l’autre, le premier est considéré comme une trahison ; la personne moderne est occidentalisée donc contrefaite. Le second est vu comme le choix de la “vraie” marocanité, de la pureté et de

l’honneur, mais semble être hors d’atteinte et ne correspondre à aucune réalité. Il est une image déformée entre orientalisme, féminité soumise et virilité haineuse. La colonialité est de ne pas pouvoir imaginer l’existence d’un troisième choix, qui serait authentique, prônant l’être complexe, résultant à la fois de la tradition, de la modernité et d'aucun des deux, en osmose avec l’état actuel de la société qui n’est ni celle d’avant, ni une copie des autres.

Décoloniser l’imaginaire revient à identifier et déconstruire ces structures qui emprisonnent notre univers. Sortir des circuits de vie fermée qui brident notre capacité à créer, notre capacité à NOUS créer. Décoloniser notre imaginaire, c'est toujours opter pour la troisième voix, celle dans laquelle toi et moi pouvons nous créer de toute pièce. C’est se délester de la peur de perdre notre identité en étant critique vis-à-vis de notre histoire. Mais c’est surtout être capable de faire la différence entre ce qui est l’Histoire, et ce que sont les discours historiques qui nous immobilisent dans une recherche de pureté culturelle et identitaire vide de tout sens. Finalement je pense que décoloniser l’imaginaire, c’est se donner de la crédibilité, ce que nous sommes capables de créer dans notre imaginaire n’a nul besoin d'appartenir à la tradition ou à la modernité pour être digne d’être accouché par nos esprits. Nous sommes des êtres intelligents avec des capacités de brassage phénoménales; nous pouvons appartenir à plusieurs mondes, et les concilier paisiblement. Alors osons réinventer le centre depuis les marges.

« Ne reste pas ici, c’est du n’importe quoi. Tu seras mieux avec des gens civilisés »

These are the words of a relative of mine who was advising me to leave the bled and return to the West, to europe or australia. It was amid a loud fight between this family member and another which (seemingly) occurred for no reason in the summer of 2019 on the streets of Kenitra near l’khbazzat. I told him that Europeans, and by extension of its empire, ‘Australians’ were not civilised in any way. He looked at me, shook his head and changed the conversation topic.

This intergenerational interaction seems a long time ago on paper, or in a Western linear temporal sense, but the interaction and memory of it stays with me. What does it mean to stay or not? What does it mean to be civilised? Do we hate ourselves? Or is it a recognition of the Empire?

A cousin says : « au moins t’es tranquille làbas » on a regular basis.

Là bas, australia

Recently on Invasion Day1, I spoke with an

Aboriginal Elder at the 50th anniversary of the Tent Embassy, the world’s longest ongoing protest site. As we were listening to a speech, he asked which ‘mob’ I was from, a term used by Aboriginal people to ascertain which tribal group/lands one is connected to. I told him my parents were mostly African. He raised his fist in the air.

Resisting the colonial state, Uncle Michael Anderson, was one of four men who set up the Aboriginal Embassy in 1972 calling for land rights and sovereignty at a time of global formalised ‘decolonisation’ and Black and Third World anti-imperial movement. A Black power activist, he spoke of one of the two flags they attached to the Embassy to show and connect the struggles of Aboriginal peoples to a pan-African anti-imperialism. He calls it the African international unity flag (the black, green, red striped pan-African flag) that represented ‘the people, the land, and the blood shed by First Nations people on this continent’. The global anti-imperialist struggle is spoken about alongside and sometimes replaced by a lexicon of settler colonialism, and an individualised apolitical identity/ culturalist politics he says, exacerbated by the rapidly changing technology of the 21st century.

From the importance of using Agraw in the Hirak Rif, Jerada, Imider to the documenting and incorporating culture, expansion of capitalist authoritarianism, land grabs and erasure of tribal lands in Morocco, the imperial projects and ambitions of ‘the masters’ are increasingly more obvious, or connected?

About the layers of colonial thought in Morocco

In explaining Amazighness vs. Arabness, the limits in the language we possess to talk about these things to other First Nations people becomes entangled. But I tried through a story: I spoke of some in my family and their insistences on identifying as Arab. In the story that I told, I spoke of my great-grandmother who left her tribal lands in the Sahara in the early twentieth century and settled in Kenitra. She spoke only her Amazigh dialect, similar to Tachelhit, and lived in the ‘quartiers des Sahrawis’, a community of people from the south near Agadir to the Saharan region where a border now lies between the Moroccan and Algerian nation-states, reminders of a colonial past in the present. Also, a reminder of this was language and a reference to the Arab outside of the community. When my grandmother entered the community, they referred to her as the Arab. My father born in this quartier, never learned the language his grandmother’s region, nor did he feel at home in Kentira as a dark-skinned afro-Amazigh, he used to always say ‘I don’t look like them, I don’t talk like them, I am not Arab’.

I only know these details because of a family project inspired by the work of our generation in documenting the language, culture, politics, histories, sound, music, echoes and vibrations of ways of living actively eroded by state and global empire which seeks to monetise a depoliticised culture under a racialized and stratified late-stage capitalism. And while social media has helped us (as a broader

populi) share, seek, exchange, and have access to information, it has also brought about questions of a new/different interdependency between human and machine, between labour and automation, between human and space, between human and time and so on. These conditions, as Achille Mbembe reminds us, lay bare a dynamic, one where the ‘masters’ don’t need ‘slaves’ anymore thanks to machines. These shifts in human power relations have a global effect on us all, but of course this is a topic of ongoing discussions outside of this text.

Whenever my father spoke of his homeland, he spoke of it in disjointed ways, repressed it in many ways. It was not until recently in 2021, with the popularisation of Aboriginal rights and land back initiatives, when we spoke about the disappearance of this wealth of knowledge that our family, our people, hold that the connection, for him, was made between Aboriginal struggle and dispossession on this continent and Amazigh rights and the political nature of them. This re-understanding reminds me of Fanon’s account of resistance where the colonised subject must free themself from the dead weight of the past, thus rejecting that past and building themself. And Verges’ understanding: how every attempt to find a revolutionary beginning must choose how to conceptualise the relation between different conceptualisations of time. In our different contestations of linear time, there’s power in repetition, mimicry, invention, slowness, ongoing practice, and cyclic time.

Can we reignite or perhaps reimagine a ‘Third World’ transnational solidarity that Mehdi Ben Barka advocated for, that Fanon and other revolutionaries of the decolonial period advocated for, one of colonised peoples that can lead us to our respective but collective liberations?

1 Invasion Day marks the day Europeans landed on the shores of Gadigal land now known as Sydney. It is a day of mourning and survival for Aboriginal people. It is also ‘Australia day’ the national day of ‘celebration’ chosen by the Australian state.

promise of an archive", a speculative

https://www.yasminebenabdallah.com/kounaktif-promise-archive

A speculative triptych, “The promise of an archive” traverses the disappearance and erasure of the Moroccan public archives, the colonial displacement of videos, and finally the prayer for a solar flare for things to go back to how they never were. The three-channel installation invites questions around the current state of our public archives, its relationship to colonization and continuing neo-colonial dynamics, as well as a call for reinvention and for decolonized imagined futures.

(c) Yasmine Benabdallah, "The

triptych.

(c) Yasmine Benabdallah, "The

triptych.

second edition

ContributOrs :

560 Zoom

Abdeslam Ziouziou

Abir Gasmi

Bahia Bennouna

Constance Leon

El Mahdi Lyoubi

Fatine Aarafati

Hafsa Rmich

Heba Hage-Felder

Hind Moummou

Kawthar Benlakhdar

Loutfi Souidi

Mohamed Hamdouni

Moulim El Aroussi

Nabil Himmich

Nouh Fettah

Saïda Essafiri

Selma Kossemtini

Seloua Luste Boulbina

Shehrazade Bloul

Simohammed Fettaka

Sofiane Byari

Yasmine Benabdallah

Yousra Rouichi

Youssef El Idrissi

Designer : director of publication :

Youssef El Idrissi

Omar Bouazzaoui

second edition