KounaKtif is a collective and a cultural platform founded in 2018. as a collective, we are worKing on sharing various areas of Knowledge and sKills, weaving social bonds via arts and culture, and developing creative and critical capacities in the fields of visual and sound arts, philosophy, new media and diy practices. these practices are perceived as tools of resistance against imposed realities.

KounaKtif’s dna is expressed through the intersection between arts, technology and ecology through creative and critical expressions, alternative pedagogies, and production of Knowledge. we constantly promote collective intelligence and collaboration through our programmes in the form of discussions, round tables, creative labs, exhibitions, participatory worKshops, concerts, open mics.

aghssan is a magazine that aims to bring together actions, stories, ideas and alternatives around questions related to arts, ecology, new media and their entanglement with socio-political questions.

the magazine is a project led by KounaKtif and it's focused on the various actions led by the collective to to maKe cultural productions accessible.

The current issue intends to crystallize «DAMJ», a project that aims to connect territories, communities and disciplines - while inviting artists-artisans and researchers to reflect on the dualities of center-periphery, space-psyche, interiority-exteriority of spaces and beings.

In an attempt to outstrip the dual towards the multiple duos, a unique assemblage emerges and allows fluid interactions between the center-s and their boiling margins, between the exteriority and interiority of disciplines, territories and beings. The gap between the art of Fabrication and the fabrication of Art indicate a power game between the war machines and the State*. These machines allow us to chew the exteriority, facing the process of State digestion of interiorities that shape our processes of perception. In this sense, the affective tissue is a sort of arrow that pierces the being with intensities - resisting to a hegemonic center like an Ego, a Capital, a State or a City Center - squirting from occult margins of the unconscious, of a repressed desire for the bond, of a gnosis that transcends knowledge and ignorance, of a rhizomatic fountain of life and death. Drawing continuous lines and curves, crisscrossing boundaries, tinkering with manifolds and intertextuality, and simultaneously, barricading bridges while digging tunnels.

*«It

La fin du XXème siècle accélère la transformation des mentalités et des techniques. L’expansion urbaine décolle alors brusquement et l’usage général de l’automobile multiplié par dix le rayon de l’agglomération, saturant les voies menant vers les centres, dont l’accessibilité se réduit, et suscitant des noyaux urbains périphériques qui assurent une part croissante de l’interaction. Cette fragmentation du cœur des cités en plusieurs foyers distincts, ce débordement résidentiel et usinier sur des distances de plus en plus grandes font peu à peu de la ville une entité abstraite dont les habitants ne saisissent plus qu’avec peine l’unité, dont ils ne connaissent qu’un nombre limité de quartiers, en dépit du réseau de transport de masse (chemins de fer, tramways, autobus) qu’on y édifie à la hâte.

Ain Sebaa conçu en période coloniale à l’image des cités occidentales s’hérissait comme périphérie en barres et des tours où s’entasse une population désurbanisée, dont les deux pôles d’existence se trouvent également altérés et ont perdu en leur solidarité. La vie collective de la communauté urbaine ou de quartier, le réseau d’interaction sociale qui justifiait le groupement des habitants se trouvent distendus spatialement, tandis que la vie individuelle et familiale achève de se dépersonnaliser au profit du temps de la machine urbaine qui en règle chaque minute. Par ailleurs, la promiscuité - entre voisins comme dans chaque famille - anonymise la vie quotidienne et, sans doute, l’individu luimême.

Personne ne conteste la réalité de la prolifération urbaine aujourd’hui. Une ville est d’abord proliférante : même assoupie au fin fond d’une campagne, il y a en elle une force de prolifération. C’est le terme qui semble le plus adapté pour définir l’existence urbaine. Les termes techniques de développement, d’expansion des villes paraissent beaucoup trop sages. Le terme ‘prolifération’ convient bien mieux parce qu’il traduit le caractère violent, puissant du phénomène. Qu’il s’agisse de la mégapole, des villes moyennes ou des petits villages, l’extension est évidente. En outre, le phénomène est permanent : il se produit dans ces différents espaces depuis que les villes existent. Certes les causes apparentes peuvent être radicalement différentes : c’est bien la pauvreté, la pénurie, l’oppression économique et politique qui animent la prolifération. La prolifération urbaine cause certainement des risques. C’est qu’avec elle que peuvent aussi se développer des éléments négatifs, toxiques pour l’humanité : la pollution d’abord, mais aussi l’oppression économique la plus sauvage, ou bien la volonté acharnée de repli sur soi. La prolifération urbaine n’est pas qu’une question technique, technologique, économique, financière, mais bien un phénomène culturel, une question de valeurs.

Comme la dernière poussée de la vague qui s’infiltre dans toutes les anfractuosités ou qui lisse immédiatement la plage de sable, la prolifération urbaine butte sur les obstacles, les contourne, les retourne, passe de l’envers à l’endroit et réciproquement. C’est la notion

même de la centralité qui éclate. Il n’y a plus de centre, ou mieux, il existe une centralité fluctuante dont l’exemple le plus significatif est celui de la « ville dans la ville ». Ainsi l’opposition entre espace public et espace privé - caricaturée par les villes privées aux franges de la ville (ville verte, Casa-finances, Pôle de Mazagan…) revendiqué par l’invasion publique de l’ensemble résidentiel - peut-être exploré de l’intérieur avec la description des « territoires singuliers ». Il semble que l’essentiel se joue sur ces frontières, que la vérité ou l’erreur se trouvent à la limite, à la jonction. Ce qui importe, c’est de questionner les marges, de s’intéresser à ce qui se passe à la frontière. La marge n’est pas seulement la périphérie physique des villes. La marge nous la portons en nous-mêmes, c’est la limite entre notre expérience sensible et la réalité du lieu. La marge c’est tout ce que nous avons renvoyé dans l’ordinaire, le banal, le trivial. Tout ce sur quoi nous portons un regard « inattentif » : le quotidien, les passages, etc. Il s’agit tout de même d’un regard et que l’expérience reste sensible. Autrement dit, que c’est sans doute dans ce qui paraît le plus banal, le plus ordinaire, le plus trivial, que nous avons toutes les chances de trouver « ce qui nous rend semblables ». C’est dans les franges explorées que l’on retrouve le sens de la ville. C’est pourquoi l’étude de la prolifération urbaine, malgré son désordre apparent, peut nous apporter l’essentiel, car ce qui nous rend semblables est justement ce qui nous permettra de définir le « vouloir vivre en commun ». Sinon nous resterions à la surface des clivages (périphérie/centre, privé/public, communautaire/intime, local/global, etc.) et à leur violence. Encore faut-il mener une étude pas seulement technique, sociologique, ethnographique, technologique, économique, mais une étude sensible de l’expérience singulière de l’espace.

Le territoire urbain est le lieu de « processus fictionnels ». L’imaginaire des villes est ce qui explique et justifie la prolifération urbaine. La projection imaginaire, l’aspiration au jeu, l’inventivité récupératrice, la force des mythes urbains montrent que le moteur principal des transformations des villes est cette faculté proprement humaine de désirer le territoire. Il ne s’agit pas seulement d’une pulsion individuelle. Le caractère urbain (territorial) lui donne cette dimension spécifique d’aspirer à la médiatisation, c’està-dire d’appeler invinciblement l’altérité.

Bien entendu, cette projection imaginaire et

désirante a une face cachée et une face claire. Elle peut appuyer une réaction, une révolte silencieuse qui consiste à rejeter l’altérité. Mais elle peut aussi être à la source de multiples hybridations urbaines, qui permettent une appropriation collective de l’espace. Nous pouvons considérer que l’espace, c’est ce qui ouvre, ce qui rend manifeste, qui fait voir, qui fait paraître, qui dévoile, qui montre la vérité. C’est ce qui oblige les corps à coexister, à être ensemble et simultanément. Grâce à lui, nous existons les uns pour les autres. L’espace est ce qui rend public et commun, ce qui apparente : nous vivons dans le même espace, nous avons quelque chose en commun ; nous sommes tenus d’apparaître, donc de coexister. Étudier l’espace, c’est étudier les différentes manières dont les hommes conçoivent leur coexistence, leur vie publique, leurs rapports mutuels, mais aussi leurs relations au temps et à l’histoire.

Les médiateurs, et ce depuis plusieurs années, explorent et interrogent les liens entre action artistique et développement urbain. Les cultures urbaines se montrent, n’en déplaise à certains, davantage au pluriel et en continuel changement. Pluralité des langues, des origines, des couleurs, des saveurs, des croyances et des styles. Le lieu de l’action – la scène – c’est la ville. Mais la ville de Casablanca n’est pas un champ clos, encore moins un décor. Elle est bien plutôt le lieu géométrique et la condition de la rencontre. Mieux : elle est l’agent actif, l’acteur privilégié d’une alchimie subtile, une transmutation véritable qui s’opère sous nos yeux. La ville, creuset immense, fabrique de l’innovation sociale. Il n’est pas aujourd’hui d’exploration plus fascinante que celle de ces territoires urbains où s’inventent au quotidien de nouvelles formes de solidarité, où des pratiques, dont la rencontre se féconde réciproquement, pour donner naissance à des formes culturelles inouïes que, dans notre impuissance à les définir, nous appelons, faute d’un meilleur terme, « cultures émergentes » ou « cultures jeunes ».

Bien entendu, cela se fait tout seul. Partout, à chaque instant, des équipes sont à l’œuvre. Leur diversité a de quoi déconcerter l’observateur. Tel projet émane d’une institution reconnue, s’appuie sur des professionnels de la culture et dispose de moyens appréciables. Tel autre s’inscrit en marge de l’institution, voire en révolte contre elle. Les uns, dont le crédo est « l’égalité d’accès à la culture », s’efforcent d’éliminer les obstacles qui empêchent des populations entières de rencontrer la création. D’autres s’intéressent d’abord aux pratiques sociales,

aux cultures d’origine, à la créativité des gens et choisissent de mettre en péril les pratiques savantes dans l’espoir de les faire évoluer. Mais toutes ces équipes ont un point commun : elles ne se résignent pas à l’inacceptable ; elles ont fait le pari que la ville est l’accoucheuse des expressions culturelles de demain ; mais elles savent que c’est un accouchement difficile et elles ne rendront pas les armes tant que les pouvoirs publics n’auront pas assumé toutes leurs responsabilités. Car il serait vain de chercher ici une main invisible, pour parler comme les économistes classiques, sorte de Providence qui, en dehors de toute intervention collective, prendrait spontanément en charge la régulation du système. C’est pourquoi ces militants des cultures urbaines nous interpellent, nous toutes et tous, sans relâche. C’est aussi, il est nécessaire de procéder à une enquête minutieuse sur la réalité des cultures urbaines.

Les cultures urbaines ont eu à faire face à tous ceux qui ne voient de salut que dans l’enfermement et dans l’exclusion et qui se réfugient dans une conception passéiste et frileuse de l’identité culturelle. Car nous avons appris avec Paul Ricœur que l’identité véritable consiste à rester fidèle à soi tout en évoluant, et précisément parce que l’on évolue, alors que rien n’est plus redoutable ni plus mortifère que cette fausse identité qui consiste à refuser tout changement, par fidélité à une « nature » que l’on finit par trahir en prétendant la sauvegarder.

La ville bouge, nos perceptions urbaines changent. Alors qu’hier la ville s’organisait autour d’un centre unique, l’espace urbain, en croissant de manière exponentielle, nous offre aujourd’hui de multiples centralités, alentours, îlots intermédiaires, qui rendent à la fois plus complexes et plus stimulantes les nombreuses connexions entre ces espaces. L’évolution urbaine a profondément modifié nos perceptions, et plus largement nos représentations du monde. Cette perception est devenue chaotique et brisée, rendant obsolètes les seules visions figuratives. Donner à voir la ville, la vie, le monde, ne serait plus la succession linéaire de différents points de vue, mais bien l’approche globale de la diversité, en bousculant et l’espace et le temps, comme une quête spirituelle d’un paradis impossible.

Mais ce n’est pas seulement le morcellement de la ville et ses nouvelles organisations qui ont modifié la manière de l’écrire. Ce sont aussi les énergies qui l’habitent. La capacité de dispenser de l’énergie, d’en recevoir de l’autre, de la lui rendre à son tour. Tout un univers d’échanges et de confrontations qui fabriquent la ville, qui créent la vie, qui construisent le monde.

Les arts, les images et les actions culturelles sont le reflet de ces fragmentations et de ces énergies qui dirigent aujourd’hui le champ de la création et de nos représentations visuelles. Mais c’est le fil conducteur de tout ce qui s’y fait qu’il faut savoir apprécier. Les arts, les images et les actions reflètent la diversité des acteurs, des situations. C’est dans cette diversité que se développe la vie, dans l’esprit mosaïque et les effets d’écho.

Découvrir ce qui est constitutif de la ville d’aujourd’hui – et peut-être ainsi mieux prendre la parole dans la cité -, c’est cerner les énergies et les éclatements qui annoncent les nouveaux modes de vie et de perception, c’est se laisser entraîner dans de multiples itinéraires visuels qui explorent et anticipent nos réalités.

Mais au-delà de la ville qui nous phagocyte et nous dévore, et au-delà des instances qui occultent et méconnaissent l’intérêt que revêtent l’art et la culture dans la ville d’aujourd’hui, apparaît l’urgence du retour au petit et au proche. En disant cela, je pense à la vidéo et au court et moyen métrage réalisés par des citoyens qui ne sont pas nécessairement des réalisateurs professionnels qu’il convient de les appeler des acteurs. Je pense aux petits bouts d’histoire, aux petits studios de tournage et de montage, aux petites salles d’art, aux petits théâtres, aux petites bibliothèques et librairies de quartier… Car ce qui compte, ce n’est pas le beau, le bon, le vrai, mais le plutôt le juste.

(c) Salima Hamrini, Cap Spartel, 2018, promontoire de la côte du Maroc, situé à l’entrée sud du détroit de Gibraltar, à 14 kilomètres à l’ouest de Tanger.

abdelhamid belahmidi

2+2 =?

The answer to this math problem may seem obvious. Yet, the equation “two plus two” had earlier been used to give illogically the result of five (2+2 =5). The concept evolved centuries ago in philosophy and literature, most notably used in the 1949 dystopian novel “nineteen-eighty-four” by George Orwell, to indicate the control of thought therefore the reality of societies. «Where is the sea?” is a dystopian narration, which writes the destiny of a character, who, through the door of the sea, gets into the world we live in. Smothered in walls or lost in streets, he faces black screens, and unlimited cycles of information. His day continues in a loop in search of reality.

His journey narrates the story of a connected society and the effect of simplistic information, which is mistaken for knowledge nowadays. The abundance of digital media contents makes it harder to retrieve useful information on social networks.

The story explores how information is misguided on social media to influence users’ behaviors, and how social networks are already a tool for brainwashing; now used as defense mechanisms against mind and knowledge. “Where is the sea?” is a personal quest for lost human values in a myriad of swampy ignorance, and eagerness to know both our subjectivities and the objective world. Seeking the sea, the individual is looking for the sea within, always there yet with its tides, constantly moving.

(c) Abdelhamid Belahmidi, «Where is the sea» series; All lost, the stranger attempts to overcome this manipulation to deduce his true reality; 1/12; 2021.

(c) Abdelhamid Belahmidi, «Where is the sea» series; Like sea sand that moves, he is back to where he came from. Is he the same as he was?

(c) Abdelhamid Belahmidi, «Where is the sea» series; All lost, the stranger attempts to overcome this manipulation to deduce his true reality; 1/12; 2021.

(c) Abdelhamid Belahmidi, «Where is the sea» series; Like sea sand that moves, he is back to where he came from. Is he the same as he was?

For so long the only thing I knew of Morocco was my dad’s hometown: Larache. A place in which my memories are all washed in blue hues; the hazy blue of the sky, the rich blue of the buildings, doors and steps in town and the crystal blue of the ocean’s waves crashing against the rocks all along Antlantico. My image of Larache can never be unbound from the sea.

But the sea is not the only shade of water. Though, it offers us many fruits, it can not quench our thirst, nor water our crops. What if water is away from the shore? In rivers, or falling from the sky?

CONVERSATION

10/11/22

513M ABOVE SEA LEVEL

- Tell me a little bit about who you are, where you are…a little bit about you.

Hello, hello. Hello. So my name is Mbarek Benghazi.

I live in a small village, south of Morocco it’s called Mhamid El Ghizlane, it’s the last oases before the desert and I do the work of a local guide. First I want to thank you for having with me this conversation.

- No thank you Mbarek! Can you tell me what is your favorite place or favorite thing in M‘hamid?

You’re welcome, Jessica, you’re welcome. So about my favorite place, where I live… It’s to be in a place faraway from civilization, and it’s connected with nature. And, yes, that’s what we have here, that’s why we live in M’hamid. It’s a place very quiet and very spiritual and for sure, my most favorite place is mostly when I go to the desert and in an area very isolated and far away, that’s is the most important to me.

My most favorite time is sundown. We see an amazing and magical color between the sand and sky, the color of the sand changes, you see every second it changes at the sunset… really I can’t explain, it’s so hard to explain you know?

You really have to be in the desert to feel that. It’s really something touching. The sunrise also, but the sunset? The sunset is more wow. Also in the night, late in the night when you can see the stars. It’s like therapy for me. I watch the stars, the galaxy, how they are moving, shooting stars. It’s very very very beautiful. Every time in the desert is beautiful.

- Can you tell me a little bit about the history of M’hamid? You mentioned it’s the last oasis before the Sahara. So what does that mean in terms of history and society?

Great question. So M’hamid is the last oasisbeforethedesert,yes,sothedesert starts directly when you are in M’hamid.

It was the meeting of the caravan crossing the desert, and other caravans coming from the Atlas and the others coming from the north of Morocco too. Mostly they were coming for commerce,passingthroughtotradethingsfrom across the Sahara - Mali,Timbuktu,Algeria, and many other places. They would bring things from here to North of Morocco, and they would bring things from North to here. And, before, it was a very very important place because of the climate. It was very green, the oases were very green and there were a lot of date trees. People could stop here, have a break, have water from the river because before the river always had water in the valley, so it was a very very important place. It’s an old story. People also had animals and land for agriculture, vegetables and grass for animals. And other, nomadic tribes would have animals toocamels, goats. So this is the story of M’hamid.

- And what is it like now?

It’s kind of, life has changed because people, thepeoplenowtheyhavetobeabletochange, they have no other choice because the first reason is the border, the second reason is climate change. The climate changed a lot, and we can really see that and feel it. Now there’s not enough water anymore, no rain, and the nomad people who live in the desert they are able to come to the town and do other jobs, and also the people living in the oases in M’hamid we don’t have enough water to cultivate, for agriculture, so we had to be able to change the way of life. So it’s very different than before, now people have another way to live, developed tourism, making a camp in the desert to have people experience the desert at night with camels.

A few hotels and guest houses, the economy of the town turned into tourism. If no tourism people would have no job because nomadic life has finished,agriculture is finished, no caravan any more, no water. So only this chance.

- So when, when would you say it changed the most in terms of the water and not being able to do agriculture? Like, how long ago was that change?

About 15 years ago, there was still a little bit of water. I mean to do something. So people who had a well, they could have water..they could have water even if it was not so good…so good for agriculture. It was salty water, but it’s okay. If, at least, I can have some water to do something, you know, like, if it’s not functioning for this plant it can function for another…it’s better than nothing.

But, I mean, after this time it was very, very hard because now the salty water is going very

deep. Very, very deep. So people have no chance anymore to have water. And the treeofthedates, theyhaveverylongroots, very long, so they’re looking for water in the ground, under the ground. And now it’s very, very long. Very long, very deep. They don’t have any water anymore because it’s very, deep, too deep. And very dry, very dry, the soil now, so we can see that, well, here in M’hamid, they are on the way to die. It’s like a cemetery in some places. It’s like a cemetery, really. A lot of palmaries are dying. Yes. And the reason is the water from the river, because in the Dra’ Valley, in the past, there was always water in the river, so there was water under the ground, but still water always, because there is water in the river.

But when they built the dam, the water stopped. Not any more water in the river, and with no rain. Water comes only with, like, a big system.

Andyearbyyearthewaterunderground went very dry, and today there is not any more water and no rain. It’s a very hard time that we have for the earth and for agriculture and also for the plant in the desert. And we feel that, and we touch that, it’s very difficult.

For our oases in M’hamid it’s very, very difficult. Because the desert will advance more. The sand will come more and not only because M’hamid is

We have a barrier, now, yes, but when this barrier disappears, no more water. So, like, in no time, it will disappear and then the sand will move very deep; to the atlas and to the big cities and maybe to Europe. Maybe. But the water will come back. That’s our wish.

- 15 years ago is not

And now it’s like everything is looking for water; humans, the roots of the date palms, the plants in the I understand, how much does rain affect this? Like can the issue rain?

So I mean, yeah, a little rain would help, but not for a long time. I mean it will be helpful yeah, but what we need more is the river, water comes for us from the river. Becausealittleraincannotgoverydeep

underground. But the river always brings water, a lot of water also goes under the ground and then we have a lot of water than in the wells and oases.

So, yeah, if we have a river that’s a sign of a good year, we say. But also the rain, it helps.The most that we hope for in the future is if the dam can be opened.Then the water can come back and restore the river. Because water comes from different areas, like from the snow in the Atlas Mountains and from other rivers. So yeah. So we hope it rains and water comes in the river, this will help lift a bit.Yeah.

- So, the rain and snow starts in the mountains, and comes down the rivers, down the valley and all the way to M’hamid, to the river and the underground rivers too. And now, there is not so much snow yet in the mountains.

Yes, exactly, it’s very sad.Very sad. But that is the only way that things can improve for us, I think, with the rain coming from the mountains, because otherwise, with so little water it will be difficult and cost a lot of money to go so deep underground with machinery and a lot of things and, you know? So it’s the only way, we must be careful for nature and have the balance, to have the rain and the seasons, that’s it. Otherwise, it’s difficult. Inshallah, the water will come back.

- Inshallah!

7/11/22

2750M

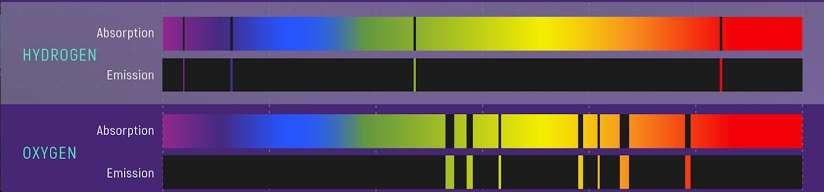

Okay. Yes. Okay, when you observe only the stars, the Sun has a signature of, of variables, okay? And when we have a planet eclipsing, a part of the light comes from the star. We know that the planet has an atmosphere, and the atmosphere of the planet has a signature and when you have it eclipsing we name it ‘transit’: planet and star ‘transit’.

And after that, [the planet] passes behind the star and from the differentiation, we can deduce the composition of the atmosphere of the planet. It’s named the spectroscopy of the transit. Yes. And from that, we can deduce the composition of the planet’s atmosphere, yes, of the planet’s atmosphere.

- Andso, sothis,you couldonly knowwhenyou haveaneclipse?

Yes, it’s the method of transit. It’s like an eclipse. Of course, it’s not like the eclipse of our sun and moon, because the diameter of the moon and the Sun, it’s the same. But if we have just very small transits, we can deduce and detect the exoplanet’s atmosphere by this method.

- Withspectrography?

We can detect by photometry first. When we have transits, just to measure the diminishing of the light coming from the star.

- Okay..?

We have the period of the transit. And from the diminition [difference] we can deduce from there that there is an exoplanet near this star. If we can go deeply in the analysis [with a telescope] for example, we can do this spectroscopy of the transit. When the planet starts to cross the star [its sun] we can make a differentiation between the light before, and after the eclipse, and then we can deduce the composition of the planet.

- andwoulditstillproduce thesignatureofcolorswhich representelementssuchas nitrogen,oroxygen or water?

Yes, from this we can deduce the signature. If you are interested in that, I have one of my students, Jamila Choukar who just defended her PhD in this topic, to explain this phenomenon.

-It’ssointeresting.Thank you.

«A poverty curtain has descended right acrossthefaceofourworld,dividingitmaterially and philosophically into two different worlds, two separate planets, two unequal humanities, one embarrassingly rich and the other desperately poor.» Mahbub ul Haq (1976), The Poverty Curtain: Choices for the Third World global political economy. Dependency theory emerged in the 50s under the direction of Raul Prebisch, Director of the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America Prebisch and his colleagues, their research found that economic activity in richer countries frequently resulted in major economic problems in poorer countries. Such a possibility was not expected by neoclassical theory, which claimed that economic expansion was advantageous to everyone, even if the benefits were not always distributed equitably.

People today don’t have to look far to identify inequalities, regardless of where they live. Living conditions vary widely across the globe; for example, the average income in North America is 16 times that of Sub-Saharan Africa. Our individual experiences develop amid massive global transformations and disparities, and these circumstances determine how healthy, wealthy, and educated each of us will be in our lifetimes. Yes, our individual efforts and life decisions do count. However, data show that these factors are significantly less influential than the one fundamental element over which we have no control: where and when we are born. This single, absolutely random aspect has a significant impact on our living conditions. so what makes some countries wealthier than others, and why the economic growth in developed countries did not translate into growth in the less developed countries? One of the theories that try to explain these global disparities is dependency theory, known also as the core/periphery dependency.

Amid concerns about the wealth gap and inequalities between developed and developing countries, emerged dependency theory and became a crucial analytical tool for examining development and underdevelopment in the

Dependency theory arose as an intellectual movement in response to modernization theory, a quasi-evolutionary economic development model that proposed that nations progressed linearly through successive stages of growth. One of the principal proponents of modernization theory, William Rostow, postulated five distinct stages of economic growth, starting with «traditional» agrarian cultures and ending with an urbanized national economy focused on the mass production of consumer goods. Prebisch and Andre Gunder Frank questioned Rostow’s assumption of a global economic system that would enable all countries to effectively transition through these stages, arguing that Rostow’s model presupposes a false dichotomy between «traditional» and «modern» civilizations.

Dependency theorists split into two strands: the Marxist and non-Marxist frameworks. Scholars such as Mahbub ul Haq and Raúl Prebisch have approached the question of dependency from a non-Marxist perspective.

They recognized that the international economic system has benefits to provide to help the global South’s development requirements and that the developed world should help these needs since it is in their best interests. They regard the presence of a shared North-South interest as implausible, given the South’s incapacity to change the system. while the likes of André Gunder Frank, Theotino dos Santos, and Immanuel Wallerstein’s views on dependency reflect a Marxist orientation.

Frank argues that The capitalist system has established a rigorous international division of labor and that this divide controlled the economic, political, social, and cultural values of the dependent states in accordance with the interests of the dominant powers. This division will continue to exist because it serves the function of draining surplus capital from dependent states for the advantage of dominant states. a comparable split occurs inside the developing countries. Frank argues that the most remarkable achievements of development in undeveloped countries were recorded when their relations with rich countries were the weakest, using Argentina, Brazil, Mexico, and Chile as examples during the Napoleonic wars and the two world wars.

Despite scholarly conflicts, dependency theorists have a core belief: the world is divided into two halves, the center-industrialized countries and the periphery/underdeveloped countries, and that this structure occurs inside a state. While they do not always employ the term center/periphery, their approach to the international system remains consistent. They claim that trade between the center and the periphery is characterized by uneven exchange, resulting in the underdevelopment of the periphery. They are all in agreement that the rise of the global capitalist system is linked to thirdworld underdevelopment.

CORE/ PERIPHERY IN EUROPE: CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPE AND WESTERN EUROPE

Countries in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) act as the periphery in Europe. It is vital to highlight that CEE includes a wide range of countries, each with its own set of historical, political, and economic traits. Nonetheless, most CEE nations share the availability of cheap and partly unskilled labor, which leads to lower-end integration into the European transnational production chain and, eventually, dependency on the European core. Mis- or under-industrialized systems inherited from pre-1989 regimes, as well as failed attempts at democratization and decentralization during the transition period, offered further fertile ground for the emergence of dependent structures. . Amin sees parallels between Eastern Europe

and Latin America by referring to the former Eastern Bloc countries’ ‘LatinAmericanization.’

According to Amin, among the core countries of the European Union (EU), Germany benefits the most from CEE’s current subordination. Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria all rely heavily on Germany as their primary export market. Despite industrialization, wages in these countries remain a fourth of those in Germany, and industrial ownership remains concentrated in the hands of European and German investors in particular.

Multinational firms hold about 80% of all productive assets in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia, while employing less than 30% of the local labor force. . While EU integration and foreign investments have aided industrialization, led to technology transfer, and increased productivity, Germany has reaped the lion’s share of the benefits, both directly in terms of expanding its own export markets and indirectly through spending on regional infrastructure that benefits German trade interests. This unequal distribution of the gains of trade integration has led to increased resentment in the afflicted nations with anti-European groupings and conservative nationalistic movements (e.g., Poland and Hungary) portraying themselves as attractive defenders of national interests.

• The growing fence between the U.S. (core) and Mexico (periphery) to prevent the entrance of unauthorized immigrants.

• The Demilitarized Zone between North and South Korea.

• Air and naval patrols on the waters between Australia and Southeast Asia and between the EU and North Africa to keep out unwanted immigrants.

• The UN-enforced border separating the Turkish north and Greek south of Cyprus, known as the Green Line.

The core-periphery concept is not constrained to a global scale. Sharp disparities in wages, opportunity, access to healthcare, and other factors frequently exist between

local or national populations. Some of the most blatant examples may be seen in the urban housing sector. Many individuals in rural regions see prospects in cities and take action to move there, despite the fact that there aren’t enough jobs or homes to sustain them. According to the UN, almost one billion people today live in slum conditions, and the majority of the global population increase is occurring on the periphery.

Rural-to-urban migration and high birth rates in the periphery are resulting in megacities (cities with more than eight million inhabitants) and hypercities (cities with more than twenty million people). Slum sections in these cities, such as Mexico City or Manila, can house up to two million people, with minimal infrastructure, severe crime, inadequate health care, and tremendous unemployment. Another example is the slums of Anacostia so close to the powerful and the rich of Washington, D.C.’s center city. Or the slums of Rio di Janeiro also known as Favelas, and as a Moroccan, I cannot omit the bidonvilles of Casablanca (shanty towns).

Many countries starting from the 1960s, witnessed slum clearances and the mass construction of ready-to-occupy housing by the state in the developing world. This type of formal housing typically consisted of minimal sized houses or flats designed to produce the lowest possible cost per unit while meeting standards set by laws that translated professionals’ views on how the urban poor should live. Such dwellings usually left a dissatisfying difference between the views of “those who decide and those who have to live with it”. These units were typically positioned far from metropolitan centers, where property was inexpensive, and relied on inadequate infrastructure and transportation links. Beneficiaries included families with incomes below a certain threshold and/or those displaced by slum clearances. People were never consulted about the site, design, building standards, or management of their own housing.

A self-reliance approach seeks to transfer management of local resources and their productive use in the hands of mainly autonomous economic policymakers. It differs from the sometimes misguided objective of ‘catching up’ or ‘greening’ the economy, questioning whether pursuing the core nations’ growth path under present global capital accumulation dynamics is both economically and ecologically realistic. Importantly, it does so without conjuring anti-modernization themes. One of the most important parts of self-sufficiency is the

temporary withdrawal from global economic institutions, which is also regarded as crucial by many supporters of dependency theory. Self-reliance expands on the paradigm of dependency by noting the obstacles imposed by core nations on the periphery. However, under self-reliance, neither capital flows nor global trade contacts should be fully eliminated, but rather exploited to further the superordinate aims of the impacted country.

The strategy avoids autarky or selfsufficiency narratives while emphasizing the environmental effect of global trade ties, the necessity of regional forms of economic cooperation, and the development of local value chains. It also seeks to avoid the emergence of any new type of core-periphery dependence as a result of rapid and new capital accumulation. This would include altering production patterns as well as confronting the cultivation of the consumerist mindset and the objective of attaining ever greater degrees of materialist lives. This is extremely important since the type of consumerism embedded in the core nations’ economic models and cultures hinders any efforts to achieve the global community’s aims of providing a stable climate and environment.

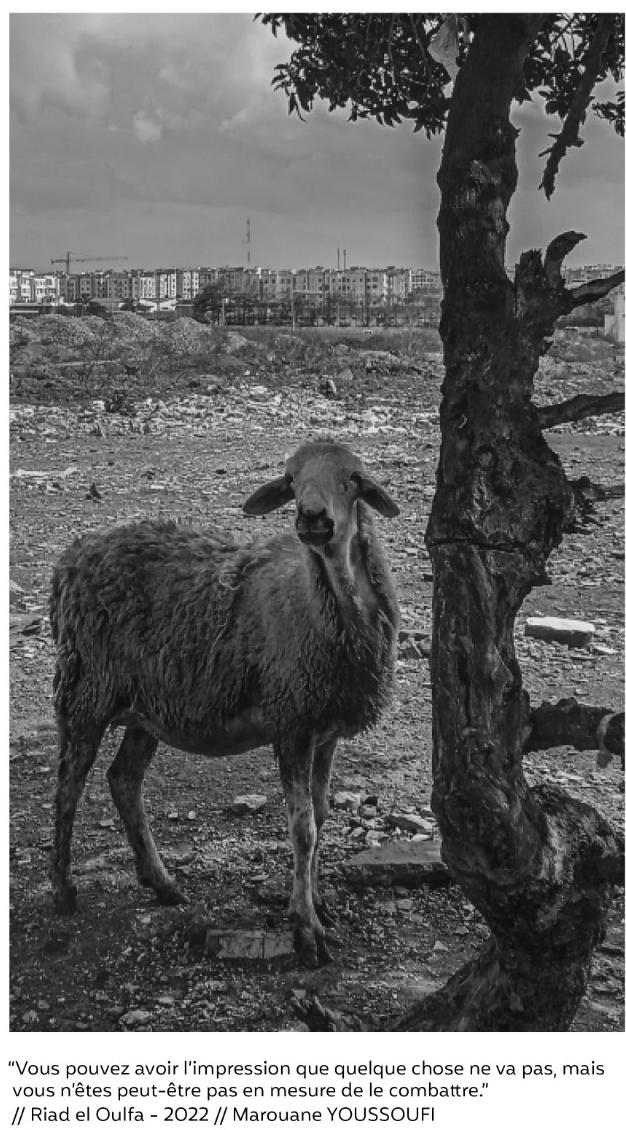

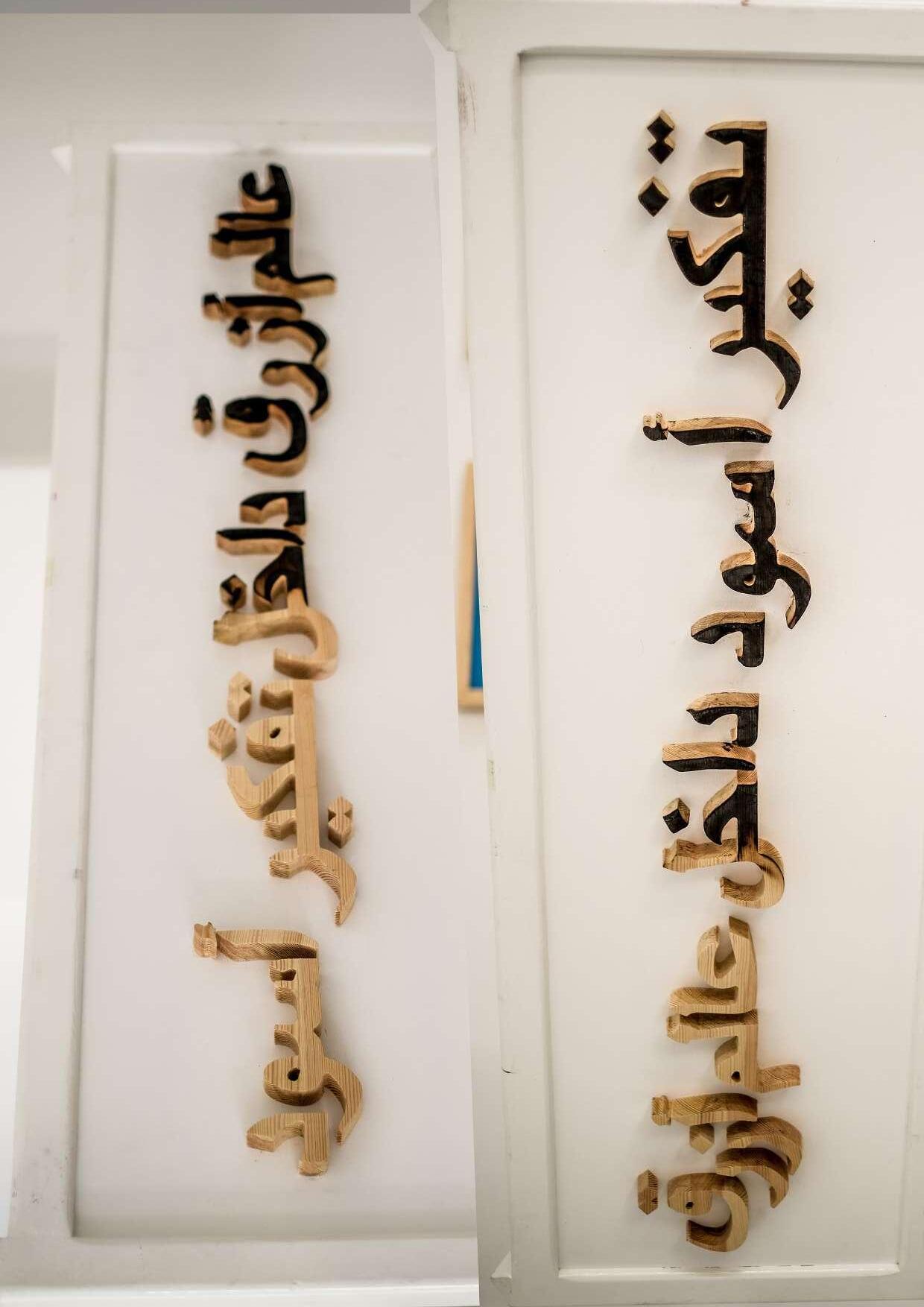

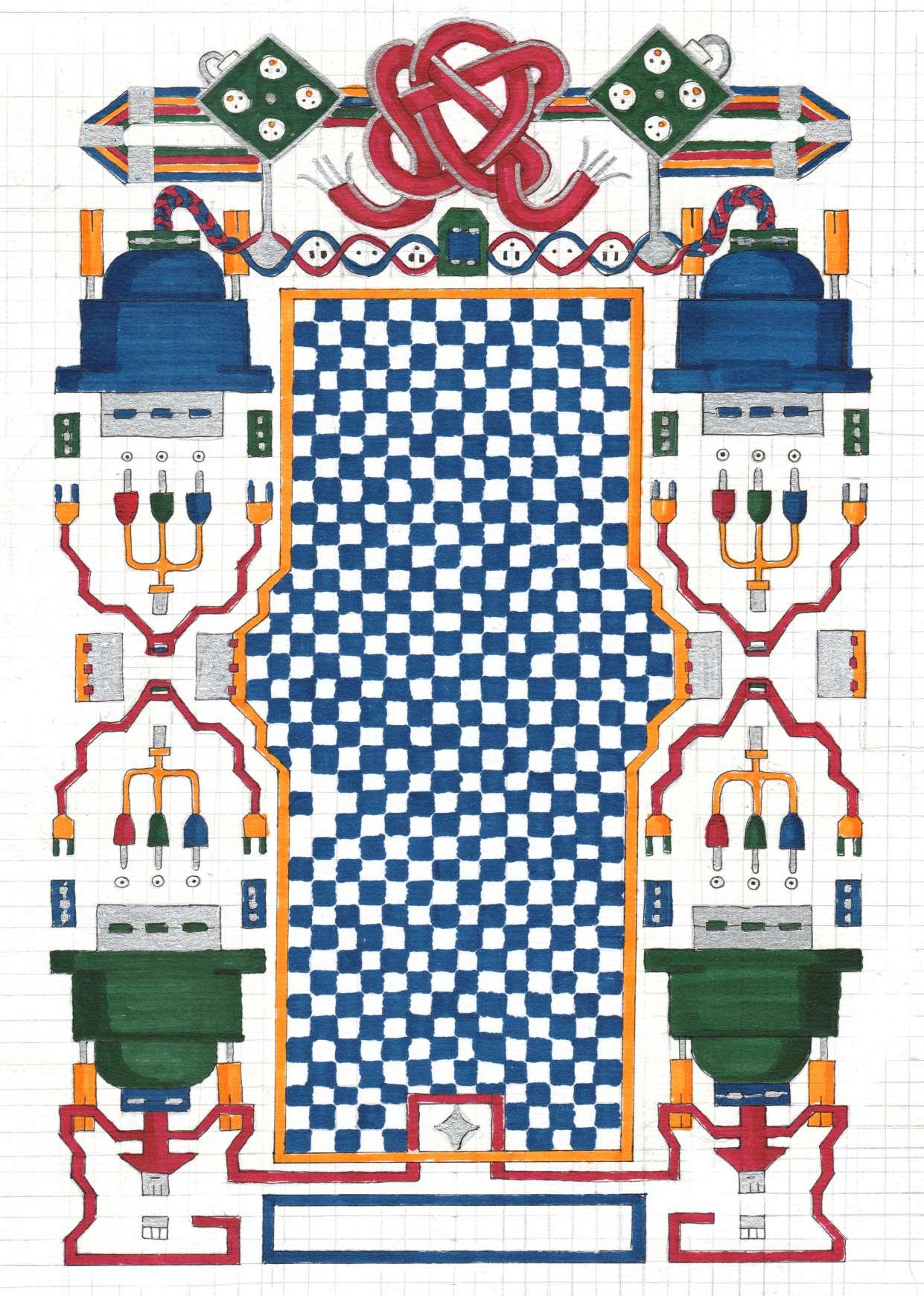

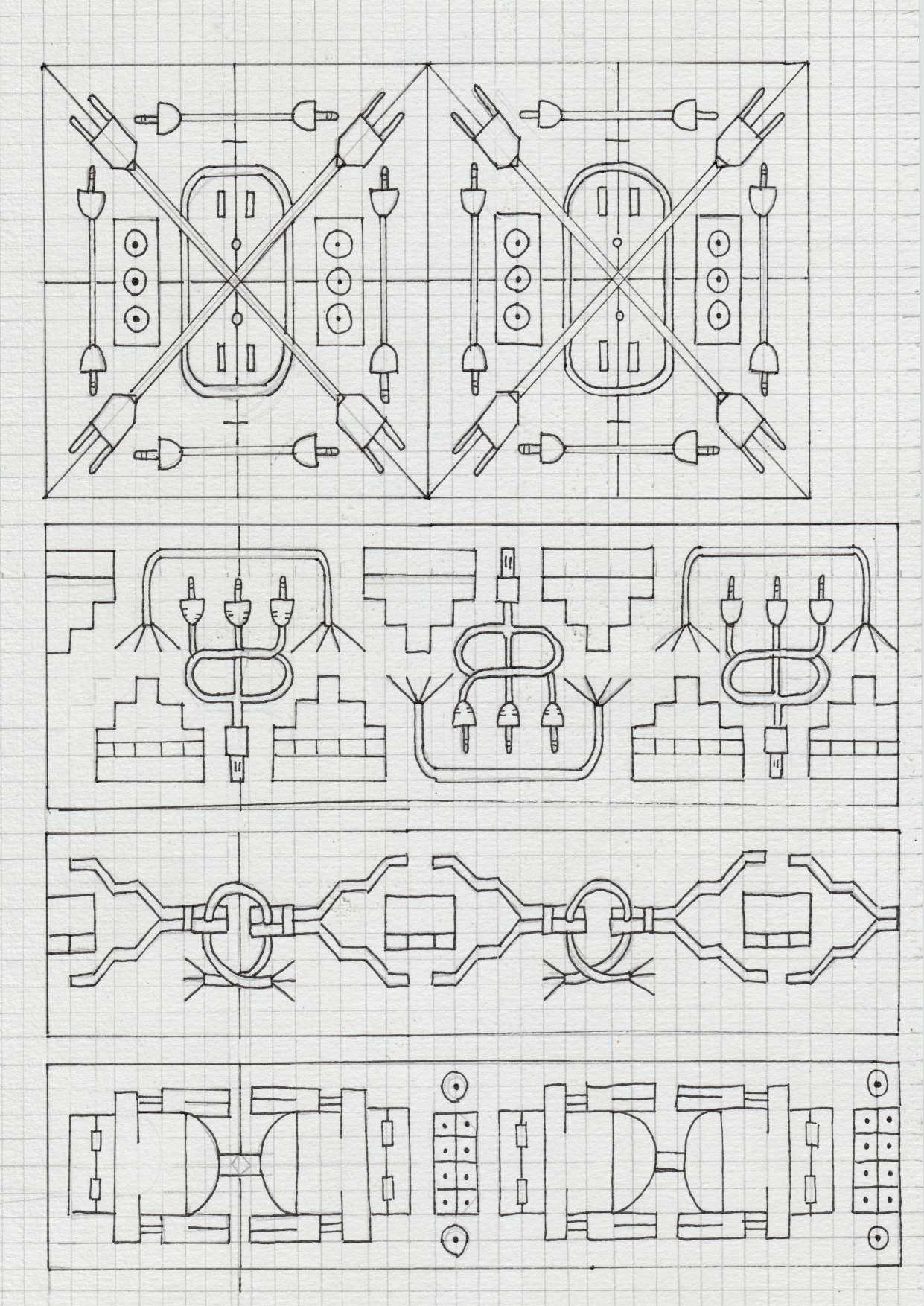

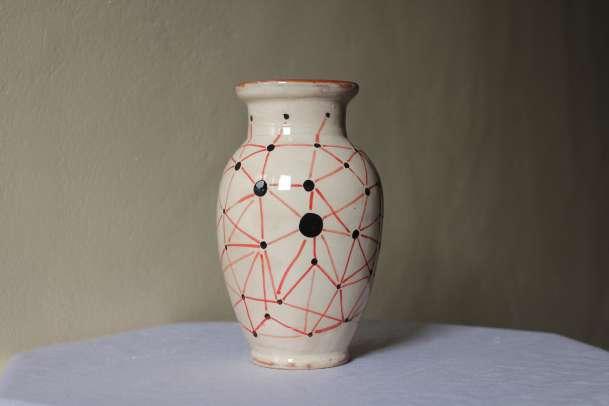

Durant ma résidence avec le projet DAMJ, j’ai pu travailler sur le relation entre psyché et espace que j’ai traité avec un artisan durant la période de la résidence artistique à Chefchaouen, au sein du projet DAMJ. Un processus, dans lequel j’ai intégré mes idées et ma pratique artistique avec un autre langage, le langage d’un artisan. Ce dernier fabrique des objets matériels, qui peuvent être soit fonctionnels soit décoratifs. L’artisan pratique un métier, grâce à ses expériences et aptitudes, afin d’atteindre les niveaux d’expression d’un artiste.

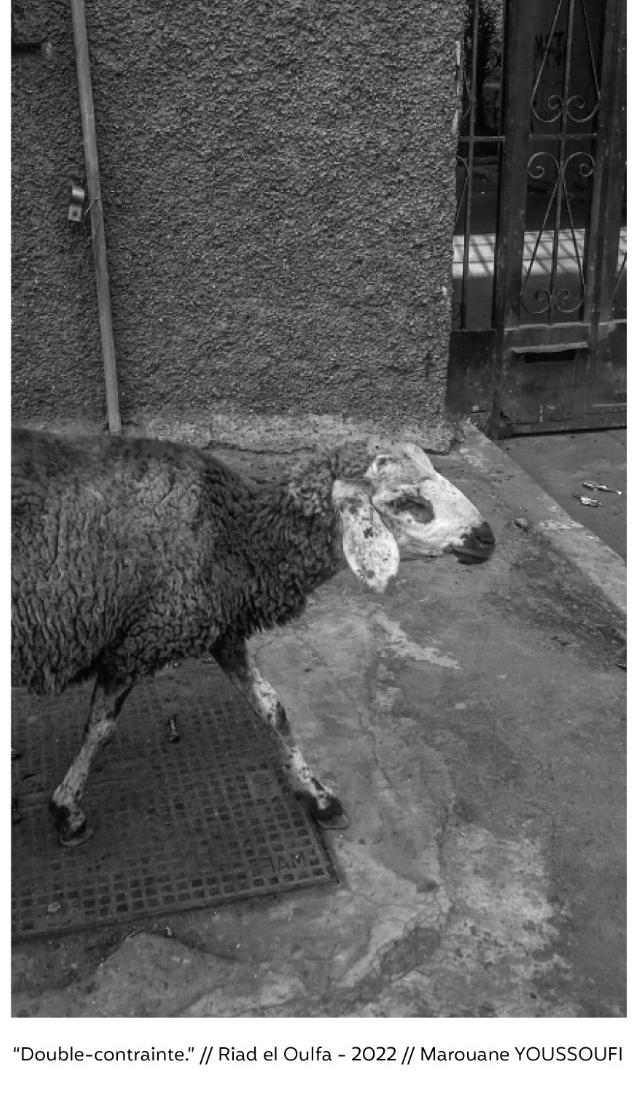

Le sujet sur lequel nous avons travaillé gravite autour du fléau du suicide dans la ville de Chefchaouen. Après des recherches, j’ai réalisé qu’il y a trois aspects principaux qui indiquent le phénomène croissant du suicide à Chefchaouen, dont le premier étant les conditions sociales qui montrent que le processus de culture de cannabis a affecté les relations sociales, qui montre également une croissance de l’individualisme dans les douars et sont ainsi devenus des conflits au sein de la société.

Le concept théorique que nous avons investigué Mohammed Bouali et moi-même, trouve racine dans ces questionnement : Comment pourrait-on décrire et exprimer le processus

d’intéraction entre espace et psyché à travers une recherche visuelle et artistique ? Quel intérêt à décrire les processus imaginatifs et créatifs impliqués dans l’activité artistique et artisanale?

D’après des témoignages dans la médina de Chefchaouen, des réponses écrites et des enregistrement que j’ai faits sur terrain, la recherche était basée au début autour des citations partagées entre les Chefchaounis, qui représente plus ou moins la diversité de pensée des gens au sein d’un seul espace qu’est la ville bleue. Avec l’écriture, on a essayé de poser quelques idées à table, structurées sous forme de schémas, afin de creuser plus et arriver à un commun accord. La recherche n’était pas facile; il était également difficile de poser des questions aux gens au sein de la ville. Pouvoir trouver un équilibre entre les gens et l’artisan Mohammed Bouali fut le grand défi que j’ai eu durant la période de recherche, car c’était difficile au début que j’entame une recherche avec un artisan.

L’une des différences qui se sont présentées durant la subtilité de l’artisan à travers son travail, se concentre sur l’accessoirisation et la fonctionnalité plus que sur l’esthétique et l’idée, je peux même dire qu’il développe des réponses qui ne sont pas des réponses. Cependant, comment je vois personnellement la recherche artistique, c’est de pouvoir structurer les idées - se poser des questions, et, se concentrer après sur la création des œuvres.

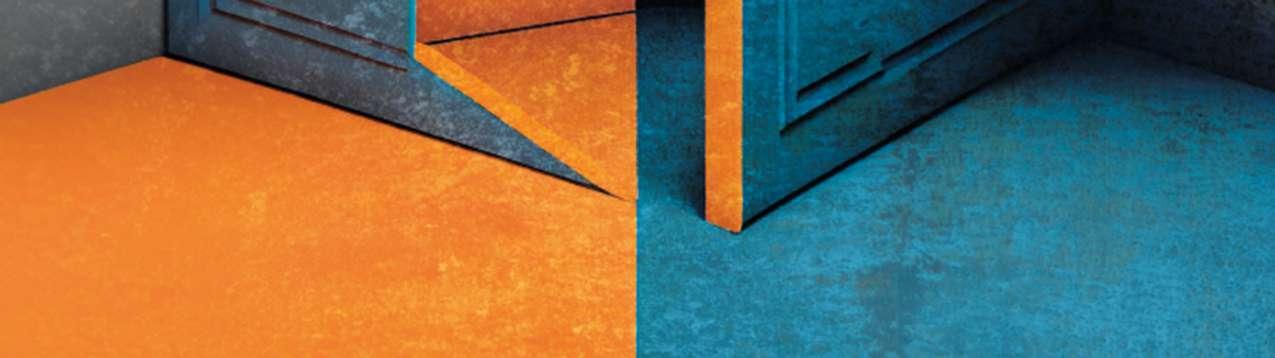

Après plusieurs recherches et propositions, nous sommes arrivés au point de réaliser problématique qui lie et délie espace et En noir et bleu, ces quatre planches combinant traits et écriture, nous avons essayé d’intégrer spectateur dans l’œuvre même; ces oeuvres ont pour objet de faire réagir et questionner de la peur, la démotivation et comment pessimistes perçoivent ces situations.

La deuxième œuvre, qu’est une installation bois sur le sol, est le résultat d’une collaboration artistique-artisanale. Chaque phrase est dans une interface “monde bleu au sein d’une pensée opaque”, “monde opaque d’une pensée bleue”. Notre ambition bouleverser ce fléau dissipé entre les murs de la ville.

En effet, le choix de créer avec devient au fur et à mesure ma pratique artistique, étant un jeune artiste dans la recherche l’amélioration, toujours dans l’expérimentation, ces derniers années je me suis focalisé une recherche concernant la poésie populaire routière ; en particulier les moyens de transport au Maroc. Nous avons la marge du moyen transport routier, une mobilité de messages, signes et d’identités. Autant de supports qui communiquent chez nous au sein vie sociale par une transmission de messages iconiques, plastiques, et littéraires.

(c) Anas Guermouj et Mohammed Bouali, Sans Titre, 40x40cm (4). Oeuvre réalisée dans le cadre du projet DAMJ. Photo prise par Omar Kassimi

(c) Anas Guermouj et Mohammed Bouali, Sans Titre, 40x40cm (4). Oeuvre réalisée dans le cadre du projet DAMJ. Photo prise par Omar Kassimi

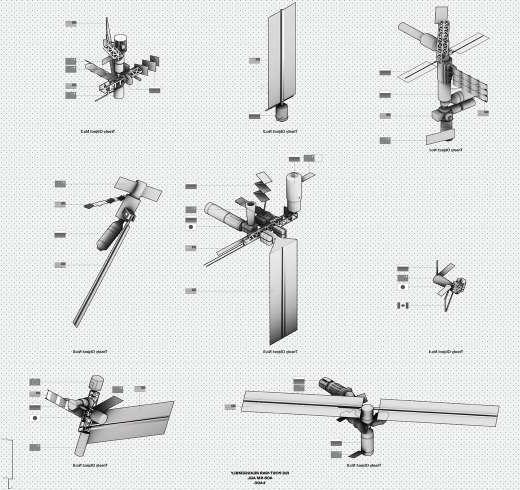

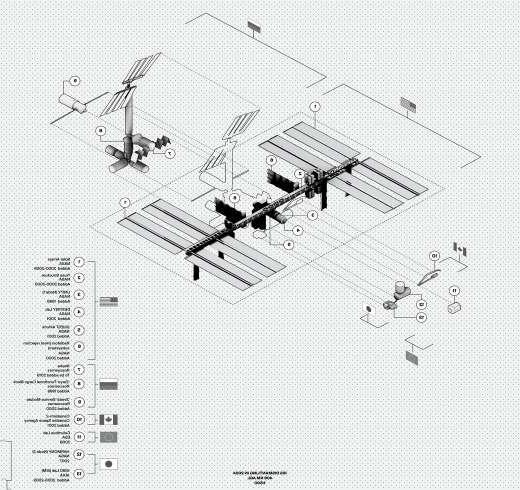

developed atThe University of British Columbia’s School of Architecture and LandscapeArchitecture. Research committee members: Scott Sorli, Sara Stevens, Fionn Byrne

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty maintains that an object launched into space remains the jurisdiction of the launching state. As a composition that fuses together objects launched from various states, the International Space Station is a physical embodiment of a space treaty.

Once an object in space is broken apart, its fragments remain the jurisdiction of the launching state.

At 408 km above ground level, the Lower Earth Orbit’s relative proximity to the Earth’s surface makes it the ideal altitude for mass surveillance. Satellites at this height are cheaper to operate and can be controlled from the ground, or by satellites operating in higher orbits.

The Lower Earth Orbit contains many smaller orbits which increases the chance of collision with other objects, and especially with space junk which can strike at speeds up to 57600 km/hr. The Kessler Syndrome increases the potential scale of this destruction and fragmentation.

This episode begins when the International Space station is decommissioned in 2024.

While the space treaty is falling apart, separate space stations for Russia, China, and the US have quietly been under construction. Newly formed space militaries further imperialism’s reach into space.

By 2030, the 1967 Outer Space Treaty is considered archaic, and international cooperation in space ends. Space War I results in the destruction and fragmentation of the International Space Station’s components, leading to a cluttered landscape of space junk from various jurisdictions littering the Lower Earth Orbit.

In an attempt to reestablish international cooperation in space and clean up the post-war landscape, a new treaty sends an international group of humanitarian garbage collectors into Lower Earth Orbit to fuse together the remnants of Space War I. The new treaty objects (composed of space trash) fuse together small particles of space junk, making their jurisdiction ambiguous.

In order to prevent further conflict in space, the United Nations sends humanity’s most valuable artifacts into Lower Earth Orbit, where they will be preserved in the dust-free, duty-free newlyformed space junk capsules.

Once the artifacts are in space, they can be watched via live feeds from earth.

The humanitarian space garbage collectors are selected to stay aboard the new stations in order to guard the works; and to continue to consolidate space junk to their objects as they travel through orbit—essentially becoming part aid worker, and part space prospector.

The value of space is thus made tangible through the displacement of a cultural object 408 km above the earth’s surface. With the object, humanity’s gaze is extended into the vertical periphery, where it can monitor the decisions of governments and corporations.

“How do you have “Kindness Always” on your trotro and you are fighting me over coins?!” is the statement I heard in a public bus that first ignited my interest in Mottonyms [Joseph Oduro-

Frimpong, 2013 coined this term).

Trotros are what we as Ghanaians call the cheapest mode of transportation (public uses) in the country. “Tro” means penny and history has it that people will make the statement “I don’t have tro” to explain why they are using that mode of transport.

Over the years it has grown in identity and representation but the one thing that has always remained constant are the mottonyms. Mottonyms are the BOLD inscriptions and statements most car owners and drivers paste behind their cars. They vary in message ranging

from Social, political and religious sentiments with hints of humor and a dash of crass when necessary to make a point. Coming back to the first story shared, the statement of this lady was enough to not just cause a spread of laughter in the vehicle but to actually stop the driver’s mate from asking further about the coins. That’s the power of mottonyms and what that taught me that day is that not only is the driver allowed to raise social consciousness with his or her words but they’re also expected to be held accountable by those very words.

From that experience, the One Way Vision project was conceived, growing from the observation of these writings to the photographic choices that most owners selected to accompany these words. What did they mean to the average Ghanaian and how did they negate the common notion that “Ghananaian do not like to read and that to hide valuable knowledge from us, hide it in a book”. A statement that does not consider our knowledge sharing past of oral knowledge transmissions and knowledge sharing through other physical mediums i.e dance, songs and storytelling.

In the mid-1980s to the late 1990s, The Mirror, a Ghanaian weekly newspaper, featured a satirical column under the banner ‘Woes of a Kwatriot’. In a piece titled No Big English, Kwatriot lampooned Ghanaian politicians’ communicative incompetence (and/or linguistic arrogance) in explaining economic policies and realities to nonEnglish speaking Ghanaians1. In that essay, Kwatriot explained that he had borrowed the paper’s title from an inscription on a commercial vehicle. In explaining what “might have inspired the inscription” (Yankah 1996:1), Kwatriot speculated it might have resulted from a government official’s Big

graphic image to the outside and while still allowing visibility to the exterior from the interior. Its micro-perforated material makes it so you can see an image from the exterior. You can see out, but viewers on the outside only see your graphic.

This idea carries across not just visually but sentimentally as my mind during the project (ongoing) wanders around the human nature of projecting one thing and hiding our real inner workings.

English or ‘verbose English’ used to explain simple economic plans to people from the driver’s hometown. Although Kwatroit’s inference of the possible motivation for the inscription may not be entirely correct, what is clear is that this interpretation cues us to how the inscription is situated within the driver’s everyday personal experiences. [Except from Joseph Oduro’s Cry your own cry paper].

The project title ‘One Way Vision’ stems from the printing technique which is used in creating the photographs for the public vehicles and its accompanying calligraphic lettering. The printing technique itself relies on the tiny holes in the printing paper that allows for light entering into the paper, creating the reality of seeing from inside but not outside. One Way Vision provides a

beya othmani

Handsdoing,handsmaking,handsteaching,handslearning.Twohands learnwhattwohandsteach.Willthetwolearninghandsrememberthe gentle caress of theyoung hand?

As early as 1882, one year after the declaration of Tunisia as a French protectorate, a net of institutions and organs to study and reform crafts production was created. They were deployed in order to modernize craft techniques, monitor and improve the quality of crafts production. Their actions were centralized in 1933 through the creation of an overseeing institution, the Office for Tunisian Arts (OAT), which in addition to being responsible for the development of the crafts industry was also dedicated to inventorying, studying, preserving so-called tunisian arts and training artisans.

In Tunisia, where the exact same model of craft reform initiated by Lyautey in Morocco was replicated, the French authority disguised those disciplinary mechanisms as humanitarian gestures and framed them as part of their mission civilisatrice. Furthermore, the French administration often framed its action as a purifying one and the idea that the preprotectorate colony was contaminated and

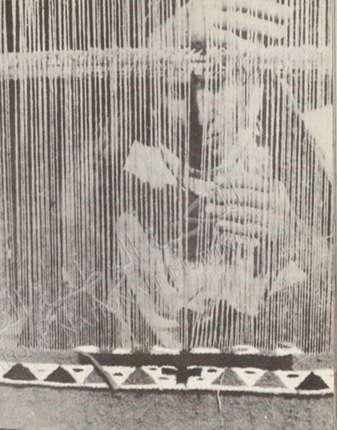

Photograph of an official from Office forTunisianArtsexplaining the maquettetoaweaver,inRevault,Jacques.“TapisTunisiensàHaute Laine Et à Poil Ras.” Les Cahiers deTunisie, no. 21-22(1958): 119–38.

impure was a recurring trope. The director of the OAT described in a text the state of carpets before the French intervention as compromised, contaminated, degenerate and even used the term bastard. The use of this exaggerated terminology gives a feeling of urgency and almost gives a purpose to the colonial intervention. The concept of contamination was often employed when referring to the state of crafts after the introduction of chemical products in production processes but it was also used to refer to the taste of artisans and the aesthetics of their work.

The director of a regional center of the OAT wrote in 1951 about artisans that “they possess an innate artistic sense; they «feel» the beautiful but, except for a tiny minority they are unable, due to lack of artistic education, to create a work of pure style. Often, for a tiny decorative detail, for an easily avoidable technical error, the harmony

of a composition is spoiled.” One is left to wonder what is the “pure style” the author is referring to? And who is actually qualified to detect it if not its creators (the natives)? I am reminded here by the words of Fanon. He described how colonial powers perceived the native as a “corrosive element, destroying all that comes near him; he is the deforming element, dis-figuring all that has to do with beauty or morality”. Thus the tarnished hands of artisans had to be tamed, trained, versed, accustomed and formed to the “pure” stylistic demands of the protectorate.

The French administration asserted its hegemony by establishing artificial canons of pure vs bastard tunisian arts. This action was carried by a dense institutional fabric and a whole field of studies supported by the publication of journals such as the Cahier des Arts et Techniques d’Afrique du Nord and the Revue Tunisienne, the organisation of congresses and exhibitions and the creation of museums. Installed first in the capital at three different locations, the Office for Tunisian Arts was quickly expanded by the creation of centres in cities such as Kairouan, Nabeul, Sfax, Gafsa, Gabès, Djerba, Sousse, Tozer and Bizerte. These centers hosted museums of tunisian arts coupled with cooperatives for the sale of products, guaranteed by a label issued through a stamping service. A brand, TUNISIA, was created in 1934 and the OAT was responsible for issuing labels on carpets, mats and embroidery and only stamped goods that met the required standards of quality were allowed to be exported. The transformation of a territory into one brand controlled by the colonial authority was attuned to the sophisticated methods developed by the protectorate to dominate and expropriate. The foundation of the trademark TUNISIA gave the French colonists the power to symbolically decide what could be labeled Tunisian and what could not. I find the name of the label an ironic coincidence as I am reminded of the equation stated by Aimé Césaire in his essay Discourse on Colonialism “colonisation = thing-ification”.

Among many areas of intervention of the Office for Tunisian Arts, textile was a predominant one. During its 20 years of activity, 350 maquettes of carpets and 600 motifs had been catalogued. Those studies were used to reproduce historical artworks, readapted to the taste of modern consumers, which in turn were used as prototypes to be emulated by weavers. The intervention of the administration extended to domestic spaces where French officials regularly visited artisans in their own homes to monitor the production. The first photograph shows an official of the French administration explaining a carpet maquette to a weaver in her own home. The new artifacts produced under the control of the colonial institution would serve as authentic historical sources on which the new crafts production emerged. Under this new order, craftsmanship as a potentially creative, social, emancipatory and esoteric activity was amputated, truncated, becoming the mere production of objects, to be either sold and/or exhibited. With that one can lament the disappearance of the artisan as a living archive, an active body and vehicle of knowledge, as a nod in a net of relationships, in a chain of knowledge transmission and production.

Two hands learn what two hands teach.Two handsrepeatwhattwohandsinstructandlegify. Thegentlecaressdissolvesinthereproductionof the movement commanded.

The weaver’s hands appear in the foreground. They seem dislocated from her body, holding onto the threads. The threads keep the hands afloat. The threads and the hands are together making one into a carpet while the weaver in the background watches. She watches as the hands and threads weave themselves into a concealing screen. Reciprocally, we watch her, hiding behind threads like a prisoner, hands clutching to the thread, pleading for release. We are offered one last glance before she disappears under the labour of her own hands. A last look at her face and her hands and the threads before the carpet eats-up all the visible space.

With the establishment of a regime of invisibility of the artisan’s labour, one that transformed the artisan into a nameless, faceless, fantomatic concept, a whole iconography of “the artisan at work” started to appear. In this emerging repertoire of images and descriptions, representations depicted the artisans performing manual labour, often emphasising the movements of the hands. These recurring representations are inseparable from the context in which they were produced and it is impossible not to draw a connecting line between those representations and the underlying dynamics of labour that they reinforced. The attention given to the hands of the artisan symbolically anchored the artisan in the realm of pure productivity. The emphasis, through the hand, on the corporeality of the artisan was also perhaps related to the perceived lack of intellectual capabilities and intentions of indigenous craftsmen. An attitude that was common at the time of the protectorate.

«Long before being artists, we are artisans; and all fabrication, however rudimentary, lives and likeness on repetition, like the natural geometry which serves as its fulcrum. Fabrication works on models which it sets out to reproduce; and even when it invents, it proceeds, or imagines itself to proceed, by a new arrangement of elements already known. Its principle is that «we must have like to produce like».»

Henri Bergson - Creative Evolution

During the last two years, I have been investigating how space -built and naturalimpacts our psyches and social structure, and slowly I came to the realization that psyche, body and the social structure are spaces themselves, which allow any interaction between these complex structures to occur. Psyche, body and world are all part of space. Space enwraps everything material and immaterial, and it’s the essential super-infra-structure allowing anything to happen, both transcending the elements and immanent to them.

DAMJ project (arabic word for “Integrate”) intends to connect territories, disciplines and communities; and go beyond the classical separations of Space and Being between center and periphery; body and psyche; self and environment. This reflects and it’s well formulated in the duality between art and craft.

In the collective book «Unconscious Dominions», Richard Keller reminds us that «for sociologist Stéphabe Bernard, European settlers in Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco found psychological «shelter in the caste barriers separating» the French and Muslim populations. These caste barriers were crucial to «European psychology» as «the inferiority imposed on the Muslims» appeared «to the colonizer as the justification of his presence in the colony, as the condition of his settlement in the country, and as the safeguard of the privileges attached to his social condition. (...) as the protagonist in MoroccanauthorDrissChraïbi’sautobiographical novel LepasséSimple«We, theFrench, are in the process of civilizing you, the Arabs. Badly, in bad faith,andwithnopleasure.Because,ifbychance you come as our equals, I ask you: in relation to whom or what will we be civilized?»

In fact, this colonization of the mind-heart system led to the creation of what Fanon calls «the colonial lumpenproletariat» and what the Algerian poet and musician Kateb Yacine calls «the évolués» - the disenfranchised population of broken masses who sought not to compete with the colonizer but to replace him - the colonized elite, destined for frustration, sought the improvement of its own condition through compromise with the French and the rejection of native values, producing powerful forms of alienation and self-hatred.

The colonized elite permeates the art world, leaving artisanal practices as folklore to the touristic gaze, for artistic exploitation, invisibilizing individuals within a system claiming to be fair. The craft world is dominated in a way that it’s fixed in an old past in which it’s impossible to actualize - but only to comply with the hegemonic project of westernization-modernization. The word native, etymologically comes from natus, past participle of nasci (Old Latin gnasci) «be born» related to gignere «beget» (14c.) and it also meant «person born in bondage, one born a serf of villein.» (the mid-15c.).

The native, the colonized, the artisanal, the indigenous, the black, the enslaved, the outdated seem to be in a time-bondage due to the structural unbalance inherent to the current Western hegemonic model that invaded physical locations and bodies - but also, more subtly, leaves deep traces and wounds, inject emotions, and spread beliefs on hidden inner places, in the unconscious.

Using an interdisciplinary and decolonial methodology, the purpose is to understand how communities and individuals are drastically impacted by the space they inhabit, but also how to have some agency within these spaces. Throughout the research, we realized that the colonial residues in our ways of Being led to the recreation of centers consisting of metropoles where the capital flows, and less «important» places such as the rural areas like the rurban city of Chefchaouen - the province where we find the highest rate of suicide, and at the same time, it’s a world-wide known touristic destination.

“As Fanon’s reference to the squeezing of France into North African bodies suggests, the trauma produced by racism and colonialism is not merely in the mind. Revealing the intimate connections between the psyche and the soma, Fanon describes the difficulties that the disruption of his psyche caused to his bodily schema when he relocated to France. Following Merleau-Ponty, Fanon describes the bodily schema as the lived body by and through which one takes up the world. The body as lived is not the body as consciously reflected on; such reflection has already turned the body into an object for thought. As lived, by contrast, we do not think our bodies through their various activities and movements. The body as lived is the unthought means by which I am an active agent in the world. As Fanon explains, “[a] slow composition of my self as a body in the middle of a spatial and temporal world—such seems to be the [bodily] schema. It does not impose itself upon me; it is, rather, a definitive structuring of the self and of the world—definitive because it creates a real dialectic between my body and the world.”

(Sullivan, Shannon (2004). Ethical slippages, shattered horizons, and the zebra striping of the

Perceiving the unconscious as a space itself has been brought by Fanon and later permeated the Western postmodern philosophy and humanities, and especially the duo Deleuze and Guattari. They describe the unconscious not in figurative or structural terms, but in mechanical and spatial ones. The unconscious becomes a factory instead of a theater, and the challenge is no longer to identify, interpret, and channel but to locate, map and release. Locate, map and release what exactly? Models and energetic impulses that shape emotions of inferiority-superiority, that splits the mind into the dual, generates the power struggle; by releasing, we give space to the act of listening, to allow innerouter growth, to bond in fluid and rhizomatic manner, to incorporate the complexity of the flux, to dance on nomadic iterations, and perceive through the fractalization of Being.

The intimate, or what I’d call the para-doxical, beyond doxa, the point that joins two (or more) totally different universes - or in Lacanian terms «the knot» - is understood by the philosopher Sloterdijk in a properly architectural model of a series of interior spaces shared, cosubjectives and inter-intelligents obliged to take part only in dyadic or pluri-polar groups which exclude any monad closed on itself. The intimate challenges the power struggle, the closed linear system, the dual and the different oppositions found between colonizer-colonized, dominantdominated, black-white, art-artisanal, center-periphery - it points out to our humanity, and more broadly, to the nondual life-force that permeates existence.

This opens the door to specific geometries of the psyches that intersect with the spatiality of the physical world in a rhizomatic unfolding, allowing to map the Body without Organs, releasing the flux of energy, reshaping the fluid identities - and where the madness, the schizophrenia, and the various psychological complexes have to be released instead of neutralized, where the necessity lies in allowing the cleavage without losing in rationality. To release is to transform the striated inner space into a smoother one.

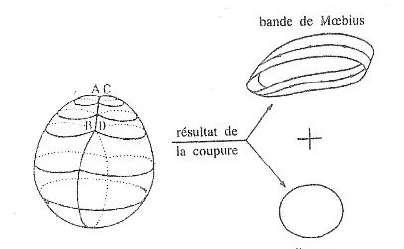

In topological terms, Lacan tried to go beyond the world of representationq in the classical sense, and instead of perceiving any duality between subject and object, the interior and the exterior, he describes the subject as included in itself and includes the object, which is radically heterogeneous and in the outside

through the cross-cap, which is an abstract object whose mathematical definition preceded its representation; it is a presentation of the projective plane. It is the fact of showing that the inside and the outside are one and the same thing which gives the value to the cross-cap.

«(...) words and letters have been invented by a positive effort of humanity, while space arises automatically, as the remainder of a substraction arises once the two numbers are posited. But, (...) the infinite complexity of the parts and their perfect coordination among themselves are created at one and the same time by an inversion which is, at bottom, an interruption, that is to say, a diminution of positive reality.”, H.Bergson - Creative Evolution

In fact, the intimacy between beings, locations and dreams is a proximity where the external and the internal worlds can communicate freely - either in the sexual act, the confession to a close friend, remembering one’s dreams and ideals, or freeing oneself from the linearity of the Western models of knowledge.

We have been dispossessed from our lands, roots, culture, ideals and more dangerously, of our conceptions of proximity and intimacy, of our notions of time and space. And the dilemma that remains isn’t to create or invent ‘new’ solutions, but to invert the directionalities related to the ideas such as progress (time) and development (space) - to interrupt, to diminish positive reality in order to slow down, get closer, meditate and remember within the spaciousness of negative reality, and allow the intimacy to emerge between the individuals and their intrinsic complexities, which will put us closer to the world, others and paradoxically also to ourselves. We are meant to remind ourselves of the multiple ways of being and doing - the multiplicity that is embedded in our African and native cultures and cities. The maze, the fractals, reaction-diffusion - the non-linearity, complex geometries are all reflected in vernacular design - and they are somehow an echo from a distant future reflecting physical and immaterial pathways that we are meant to remember and connect to if we are eager to face the ongoing challenges of our inner and outer cities.

cable frameMarkers and pencil on paper, 2022.

(c)Fatine Aarafati, Ornamental

This is an informal conversation between Youssef El Idrissi (co-founder of Kounaktif, artist, editor-in-chief of AGHSSAN magazine) and Léopold Lambert (writer, architect and editor-in-chief of The Funambulist, a bimestrial magazine dedicated to the politics of space and bodies)

Youssef : Hello Leopold, from your position, how do you conceive the duality and this relentlessness between center and periphery - notably where you are currently in France? How is this confrontation between center and periphery taking shape in France?

Léopold: I’m compelled to find similarities across scales in the way this dependency of peripheries towards centers is operating, with the idea that it’s probably a colonial scheme. If we take the French example, there is a similarity in a sense that France thought of itself as a metropolis on which depends an entire empire across the world, with its colonies. White France like to imagine that French colonialism ended in 1962 with the final liberation of Algeria, but of course, it’s still much active today, whether through neocolonial structures such as we call «Francafrique» in Sub-saharan and Saharan West Africa, but also with the colonies that France didn’t change the nomenclature for and still calls them «overseas territories», namely Martinique, Guadeloupe, Guiana, Kanaky, part of Comoros, and part of Polynesia that France still dominates. In that case what we call “the center” can be as far as it could be on the globe: if you take Kanaky for instance, we are almost at half the circumference of the Earth. Of course this shows the absurdity of this center-periphery relationship, and often, what are deemed “peripheries” occupy their own centers.

Similarly on the scale of France itself as a country, there is a centrality that is imposed from Paris to the rest of the country. There is even a name for a part that isn’t Paris called

«Province» not provinces in the plural, but «the» province, the territory that isn’t Paris, i.e., the center—coming from a small town I can tell you how much it pisses me off to hear this! And then within cities themselves, the largest cities and even the smaller ones - there is still this relationship between the city center where the economic, cultural and political life happens and the working class, in particular the racialised working class, has been relegated to live in the margins of cities, as a sort of reproduction of the geographical scheme of power dynamic that the metropolis and the colony operate.

At that point, it may be important for me to speak about my own positionality. I’m someone who lives in the city center of… Paris (of all cities) and regarding some parts of your question, it would be more appropriate to ask someone who lives and may have grew up in the “banlieues» to reply. What I can perhaps point out is towards what I call «the colonial continuum». For example when speaking about social housing complexes where we found racialised working class whose family have been colonial subjects, their habitat is geographically, physically and architecturally reproducing similar circumstances and conditions that the one that the colonial empire had colonized

people. And another aspect of this continuum can be found not only in the construction of habitat and the organization from colonized to racialized bodies in space but also the systematic destructions of such habitat.

Youssef : In France, the periphery brings together specific social groups - immigrants, the middle class and the working class - while the center brings together a much more privileged class; how can we deal with this and break down this wall that creates this social, economical and even racial segregation mainly due to spatial separation?

Léopold : Now, concerning the solutions, recommendations and what sort of politics and action shall we support to counter this colonial scheme of domination, is first, to think less in terms of center-peripheries, but in terms of centerS and peripherieS. Taking seriously the fact that whatever we are speaking about, the idea of geographical points where whatever we are considering - political, economical, cultural dimensions and that can be many other things - but whatever domain we are considering, I think it’ll be probably fair to consider, there will be always a geographical point of convergence of intensity that we call center, and perhaps more we are considering to cultivate a pluricentric way of organizing space and geography and politics, the more we will be into something that can be more reachable than the scheme that we are living in at the moment. At the world scale, it involves an important effort of decentering and recentering. If we talk about knowledge production for example, and my own practice in editing The Funambulist from a place like Paris, this often means considering this center as an obsolete one (except perhaps in what it can bring to the anglophone world, considering we’re publishing in English), and considering instead many other centers of knowledge production at the scale of the world. One of the places where I have felt that the most, in my own subjectivity, has been Johannesburg.

located generally in the North ‘validate’ if a knowledge is real, true or accurate? How knowledge production - from its conception to its diffusion and consumption - is used as a tool of domination? And how does your concept/ idea of «colonial continuum» integrate this idea of knowledge production - in contrast or in parallel with production of goods in capitalistic society?

Léopold : I would love to think that this is only a problem for us situated in the North and that people in the Global South (i.e., most people in most parts of the world!) have already moved on from this colonial hierarchy. But it’s true that it might yet be the case, and that old ideas die hard, in particular when places like North America or the United Kingdom still have an infrastructure of knowledge production (universities being the main parts) that attracts many people of the South.

In May 2022, we published an entire issue around that topic. It was entitled “Decenter the U.S.” and it argued that, even within our circles of anti-racist, anti-colonial, and queer struggles, we are too influenced by the U.S. “software” (for lack of a better word) and we should instead try to pluriversalise our influences and ways of framing problems.

Youssef : Speaking about centers of knowledge production, how do the few ones

As for my concept of “colonial continuum,” what could be useful about it is the bridges it allows us to create between different spacetime. And it’s not because it’s called the “colonial” continuum that what navigates within it cannot be anti-colonial forces. For instance, a generation of Kanak leaders studied in France during May 1968 and used their experience back home to form the Kanak independence movement that was very close to liberating the country in the 1980s. Similarly, an Algerian author like Kateb Yacine who wrote his novels in French was speaking of the coloniser’s language as “spoils of war.” So sometimes, what is being produced within the colonial infrastructure may very well be used to subvert it. Those dynamics are very complex of course, and that’s also why it’s one thing to speak about all of this abstractly, it’s another to practice the decentering and recentering.

Fatine Arafati, artist

Youssef El Idrissi, artist and researcher

Fouzia Chafik, artist

Beya Othmani, curator

Youssef Zaoui, artist & cultural worker

Rashid Ben Addi, writer

Oussama Ait Ouahi, artist

Kwassi Darko, artist & curator

Dana Salama, designer & organizer

Ahlam Shaimi, researcher

Anas Guermouj, artist

Marouane Youssoufi, artist & organizer

Mustapha Azzouz, artisan

Pierre de Lohéac, artist

Abdessamad Khadiri, researcher

Jessica El Amal, artist & curator

Abdelhamid Belhamdi, photographer

Salima Harimini, photographer

Abdelbaki Belfaqih, anthropologist

Yassine Aharaz, artisan

Mohammed Bouali, artisan

Léopold Lambert, architect & writer

Khalid Bouaalam, artist

This publication is within the framework of «DAMJ» project, part of Youth-Led Initiatives, part of the program All-Around Culture, led by L’Art Rue (Tunisia), and cofunded by the EU.

This publication is printed also thanks ot the support of Prince Claus Fund grant (Building Beyond Mentorship).

The implementation of the art-artisanal residency «DAMJ» has been successful thanks to the implication of «Centre Culturel de Chefchaouen» and its dedicated staff.

We want to thank our collaborator «Mahal Art Space» that allowed us to exhibit the works produced after the residency, and held collaborative workshops and discussions during the exhibition. Kounaktif is supported by The European Endowment for Democracy.

Youssef El Idrissi

Follow us : /kounaktif @damj_project @koun.aktif

Maha Tirraf

Maha Tirraf