QUEER BODY

[they.them]

Boston Architecture College

Queer Body Queer Place

Master of Architecture

December 2023

Becker Schmidt M. Arch Candidate

Yufan Gao Thesis Faculty

Karen Nelson Dean, School of Architecture

becker schmidt they. them

BIOGRAPHY

Becker - architectural designer and ceramicist - sees architecture as a vessel to facilitate well-being and community. A background in industrial design and urban reslience informs their thoughtful, multi-scalar design approach. Their ceramic practice, rooted in tactile exploration, enriches their architectural work by adding an intimate, hand-crafted quality to larger projects.

All endeavors yield spaces that are not only functional but deeply human. Becker is committed to an architectural practice that listens to and represents its occupants, fostering a sense of belonging and honoring individual and community needs.

M.Arch Candidate

The Boston Architectural College

320 Newbury St Boston, Massachsetts, USA

notes on gender

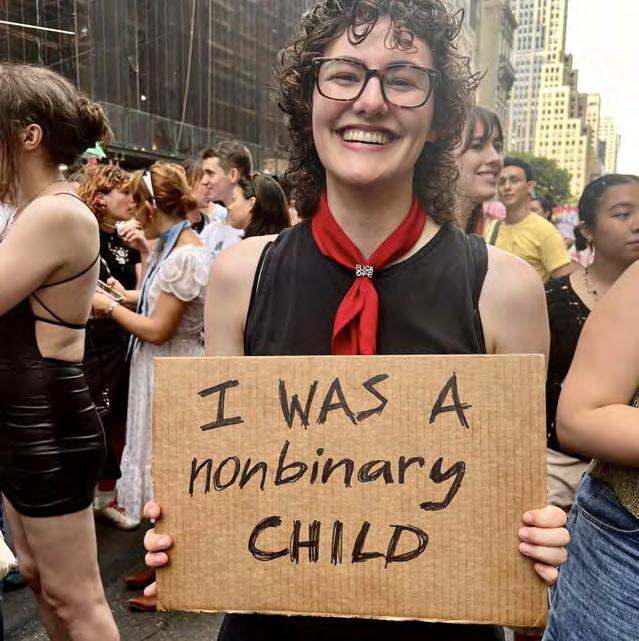

like you, I am a human. Perhaps not like you, my pronouns are they/ them. My identity evolved beyond one assigned to me at birth. I have come to know myself - and the body that holds me - as I have unfolded in time and space. My architectural and artistic pursuits aid in my becoming.

I am one of many gender-queer persons continually looking for belonging in space. This thesis is an attempt to capture that longing, express that pursuit, and advocate for the enhanced visibility of trans people in public space.

This thesis does not aim to justify trans identities, the validity of our pronouns, or our bodies. It exists to celebrate what we already know as gender nonconforming individuals - that trans people have always existed and always will. That we have a right to live freely, openly, and safely. That when the world doesn’t see us or celebrate us, we see and celebrate ourselves. This thesis seeks to honor our resilience, our creativity, and our unwavering ability to create place.

notes on limitation

the history presented in this thesis is limited to post-colonial Boston, as much of pre-colonial queer history has been lost in the genocidal violence of colonialization. Boston is located on the traditional and ancestral land of the Massachusett, whose land was violently stolen and never ceded. I pay respect to the people of the Massachusett Tribe, past and present, and honor the land itself which remains sacred to the Massachusett people.

I acknowledge that my identity as a white, cisassumed person limits the intersectional identities I can speak to with individual authority. Although secondary research includes more diverse representation, due to time and resource limitations, the in-person primary research conducted only includes a total of seven white transmasc, transfemme, and nonbinary voices. I hope to expand upon my research and the voices it represents in future iterations of the project.

glossary of terms

Cis-gender²

Describing a person whose gender identity matches the gender they were assigned at birth.

Delocalization1

The indefinite replication of the configurations of key relationships associated with one queer site or node to another, possibly in a distant locale - a sor t of multiple place-making.

Deterritorialization of queer groups¹ the loss of identifiable queer sites and nodes, and thus substantial por tions of the local queerscape, through homophobia, capital, or environmental deterioration.

Gayborhood²

A neighborhood primarily made up of LGBTQIA+ residences, businesses, and entertainment.

Gender dysphoria²

a profound dissatisfaction with one’s physical and/or mental state, caused by discrepancies between one’s gender identit y and gender assigned at birth.

Gender euphoria

the experience of profound joy with one’s physical and/or mental state caused by the congruence between one’s gender identit y and gender assigned at birth.

Gender ideology

a term invented by the Catholic Church rooted in anti-trans rhetoric to dehumanize transgender people.

Nonbinary2, 3

a gender identit y that is open to a full spectrum of gender expressions, not limited by masculinit y and femininity. It is a catchall term for people who don’t exclusively identif y as male or female.

Queer²

An umbrella term describing anyone who identifies as something other than heterosexual/cis-gender.

Queer appropriation of space¹ the transformation of formerly homophobic and heteronormative social and physical space (whether public, private, or derived rom electronic media) for social relations that suppor t or enhance opportunities for homoerotic and allied communality and eroticism.

Queer community/communities¹

a full collection or select subset of queer net works for a particular territory, with relatively stable relationships that enhance interdependence, mutual suppor t, and protection.

Queer network¹

a shif ting set of relations and exchanges, involving more than two people, with a positive or impar tial relationship to homoeroticism within a globalizing political economy that includes some kind of homophobia; networks can be defined by combinations of identities, desires, sensibilities, interests, locations, and proximities.

glossary of terms

Queer node¹

a set of par ticularly important or strategic queer sites for the ongoing functioning and contact of some of the networks marginalized in heteronormative political economies.

Queer placemaking¹

the use and casual or purposeful modification of a site or set of sites by queer net works, which marks their irregular or ongoing presence.

Queer site¹

a point in physical space where there is contact and exchange involving at least t wo people and where there is a positive or impar tial relationship to homoeroticism within a broader environment that includes some kind of homophobia; sites can exist for a moment or can be more stable.

Queer space¹

an expanding set of queer sites that function to destabilize heteronormative relations and thus provide more oppor tunities for homoerotic expression and related communality.

Queerscape¹

a physical landscape that harbors queer sites and queer space, where resistance to heteronormative constraints and a diversity of homoerotic relations intensify, cumulatively, over time.

Queer territorialization¹ relatively secure place-making across landscapes that cumulatively challenges constraints on queer communities, homoeroticism, and the dominance of

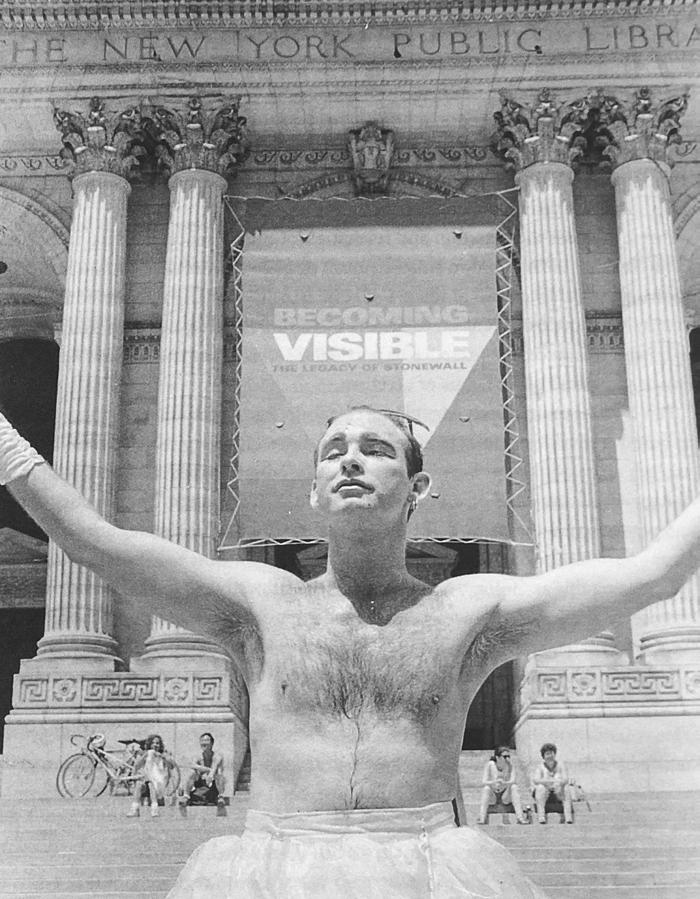

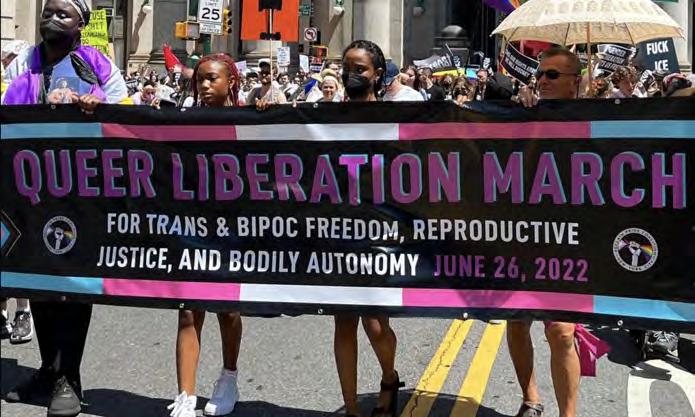

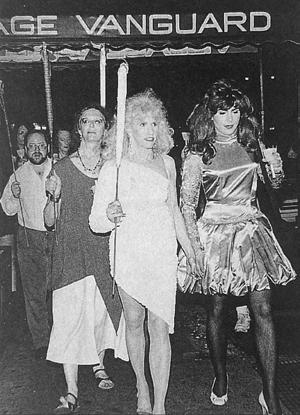

Stonewall4

a historical event. On June 28th, 1969, Stonewall, a gay bar in New York City, was raided by police, resulting in an uprising of LGBTQ+ protestors fighting against police brutalit y for six days, ultimately igniting the gay rights movement. Transgender (trans)² of, relating to, or being a person who identifies with a gender identit y and/or expression that differs from their assigned sex at bir th.

1Ingram, Gordon Brent, Anne-Marie Bouthillette, and Yolanda Retter, eds. Queers in Space Communities, Public Places, Sites of Resistance. (Seattle, WA: Bay Press, 1997), 447.

2Davis, Chloe O. Queens English: The LGBTQIA+ dictionary of Lingo and Colloquial Phrases. New York, NY: Clarkson Potter, 2021.

3Bongiovanni, Archie, Tristan Jimerson. A Quick and Easy Guide to They/Them Pronouns. Portland, OR: A Limerence Press Publication, 2018.

4Library of Congress. N.D. “Research Guides: LGBTQIA+ Studies: A Resource Guide: 1969: The Stonewall Uprising.” Library of Congress Research Guides. https://guides.loc.gov/lgbtqstudies/stonewall-era.

THESIS STATEMENT

Queer Body; Queer Place is an interactive architectural environment that harnesses the material properties of clay and fabric, influenced by atmosphere and body, to reflect the transformative power of the genderqueer experience.

Inflatable structures are placed on site, manipulated, moved, and interacted within. Community members then use clay to build a cob encasement around the inflatable. In doing so, the queer place becomes monument and the inflatable moves to create queer place within a new area of the city.

RESEARCH DISMANTLING BINARY SPATIAL ASSUMPTIONS

QUEER GEOGRAPHY

QUEER PHENOMENOLOGY

DISMANTLING SPATIAL ASSUMPTIONS GEOGRAPHY PHENOMENOLOGY

DISMAN TLING SPATIAL

-. . . .. ..

BINARY ASSUM PTIONS

P spheres + shortcomings

ublic Space, and our built environment overall, has primarily been built by white men. Everything from rooms, to buildings, to parks, to the zoning guidelines from which they are created, have been designed from a cisgender, racist, and heteronormative perspective, framing white male cis-heterosexuality as the norm - marginalizing, alienating, and vilifying those who do not conform.5

In American culture, men have traditionally been associated with the exterior and granted the freedom to move openly in the public realm while women have been associated with the interior, the domestic, and the private, and those who exist outside the binary have not been considered. The urban built environment is one of hard edges, imposing structure, and monumental scale that aggrandizes power, capital, and industry - all qualities culturally associated with the masculine.6

Seen as nurturing, cooperative, subjective, and emotional, the stereotypical woman is defined as domestic. However, even in such a space, she does not have authority. Language such as homemaker and housekeeper, master bedroom, head of the table, man of the house, man cave, and breadwinner reinforce ideas of male ownership. “A homemaker has no inviolable space of her own.”7

The spaces associated with women - the kitchen, the laundry room - are spaces of service. In this way, “the house [becomes] a spatial temporal metaphor for conventional role playing.”8

Queer people, who are not considered within the built environment, have carved out spaces for themselves in the margins between private and public. Places like nightclubs, coffee shops, pride parades, and gayborhoods have been created

5Catterall, Pippa, and Azzouz Ammar. Rep. Queering Public Space: Exploring the Relationship Between Queer Communities and Public Spaces. London, UK: Arup, 2021.

6Rendell, Jane, Barbara Penner, and Iain Bordan, eds. Gender Space Architecture: An Interdisciplinary Introduction. (London: Routledge, 2000).

7Rendell, Jane, Barbara Penner, and Iain Bordan, eds. Gender Space Architecture, 2.

8ibid

by queer people for queer people when others did not consider, nor believe in their right to spacepublic, private, or otherwise. These places provide community and resources. They celebrate freedom of expression and embrace marginalized identities. However, such places are diminishing in number and, even within them, white cis-normative prominence infringes on their inclusivity.

Both the glorification of the masculine in the public realm and the emphasis on femininity in the domestic realm, are dehumanizing in their veneration. The exclusion of transgender, gender non-conforming, nonbinary, or gender-queer people in the built environment denies their existence and forces them to define space for themselves. Such gendered architectural realms encourage the fragmentation of our built environment and reinforce assigned cultural roles. It segregates public and private and heteronormativity from queerness, preventing growth, unity, and knowledge exchange, further emphasizing the marginalizing nature of the heteronormative white male gaze.

We need to complicate the relationship between the lines that divide space.9 “ “

the space between

the distinction between oppositional directions - inside or outside, left or right, east or west - is not neutral nor is it static. Cultural ideologies give meaning to oppositional directions and their meanings shift as ideologies change over time. Two oppositional points form a line that creates a division. “It is lines that give matter form and that create the impression of surface, boundaries and fixity.”10 Within the moving of this line, lies the space that dismantles our ideas of binary relationships, spatial and otherwise.

Gender is a social construct that evolves over time. The points of “male” and “female”, what qualities they possess, and therefore the binary line they create, continually changes throughout history. To exist as a genderqueer person is to deny a falsely perceived fixity and expose the blurred line. It is to exist both in-between and outside of the gender binary; it is to exist in the margin.

The margins we exist in do not remain dormant nor dark. We revere and respect them. Queer people “come to [our] space through suffering and pain, through struggle. We know struggle to be that which pleasures, delights, and fulfills desire. We are transformed, individually, collectively, as we make radical creative space which affirms and sustains our subjectivity, which gives us a new location from which to articulate our sense of the world.”11 Queer people operate from the fringes with force, carving and blossoming in the in-between of cisheteronormative spheres. We are not given space, we create it for ourselves. When our places are taken, we build them anew.

The places we create are incredibly wholesome and loving. It is in the home where a mother proudly

9 Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, objects, Others. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006), 13.

10 Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology, 14. 11 Hooks, Bell. Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black. (South End Press, 1999), 209.

compliments her son’s makeup, in the ballroom where drag kings perform for their community, and in the bedroom where a lesbian cares for her partner after their top surgery, where we choose to honor one another. Our places are thoughtful and caring, joyous and beautiful. All of this is overlooked when society is more interested in paying service to the fear of the unfamiliar than the humanity in a united community.

Prejudice squanders our collective potential for freedom. It prevents us from learning about others, and in turn ourselves. A cis-heteronormative world fears queer people because it fears the uncertainty of a life without the parameters of the binary. As Alok V. Menon has said, “they see us dare to exist freely and fear what they think they cannot have.”12

The margins are a place of opportunity as well as resistance. In proclaiming our identities and unapologetically exercising our right to public space, we show the world who queer people are. We become the representation other queer people need to discover themselves. In the act of resistance, we expand the space between.

Queer . -

geo graphy

S history: erasure + defiance

pace is defined by its users and once it has been defined, holds the history of the actions that gave it its meaning. To move within space that has not been created nor historically used for your demographic, means to exert force onto the existing spatial restrictions and to find expression within the confines of an existing space.13 Unless the pattern of “space-invasion”14 is consistently recurrent, the existing historical marks of the space will erase the temporary nature of its occupants.

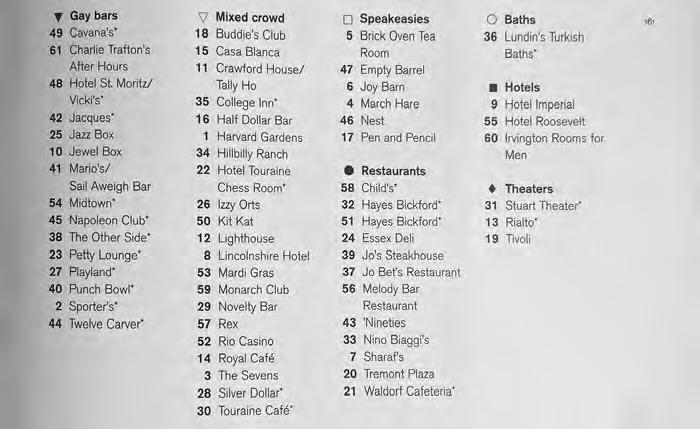

Queerness was criminalized in America for the majority of the 20th century. Queer places were the underground, the ball, the nightclub and the bathhouse. They were privately-public, enclosed spaces in the outside world that allowed them, even if in secret, to exist as human beings free to express their identities and desires. Queer places in these times were also the streets, the parks, jails, the aids ward, the mental hospital. Public space for queer people often meant they were violated, victimized, and incarcerated because they dared to exist outside of the cis-heteronormative social code.15

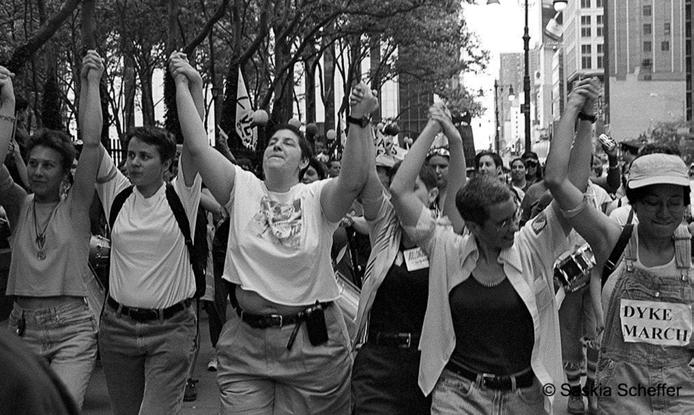

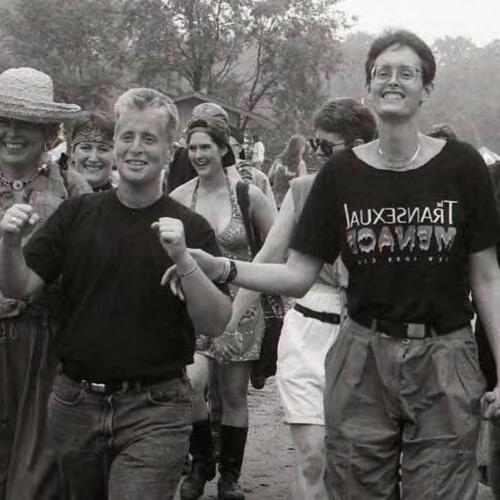

Our queer ancestors fought to establish and maintain their right to space; they fought to bring us out of the underground and into the open. It is because of them - especially trans-women of color - that LGBTQIA+ rights have expanded. “The 1969 stonewall riots and the act up and queer nation actions marked three exceptional points in an ongoing trajectory of increased purposefulness in queer community building and place-making.”16 Queer protesting led the fight against AIDS. It let to the federal decriminalization of same-sex intercourse (2003) and the federal legalization of same-sex marriage (2015).17 We owe our visibility, acceptance, and legal protections to the queers who came before us.

13 Ingram, Gordon Brent, Anne-Marie Bouthillette, and Yolanda Retter, eds. Queers in Space.

14 Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. (Routledge, 2006).

15 Fitzgerald, Tom, and Lorenzo Marquez. Legendary Children: The First Decade of RuPaul’s Drag Race and the Last Century of Queer Life. (Penguin Publishing Group,2020).

16 Ingram, Gordon Brent, Anne-Marie Bouthillette, and Yolanda Retter, eds. Queers in Space, 47.

17 “Human Rights Campaign: Extremists at CPAC Laid Bare Hatred at Root of Vile Legislation Targeting Trans People,” Human Rights Campaign, March 6, 2023, https://

www.hrc.org/press-releases/human-rights-campaign-extremists-at-cpac-laid-bare-hatred-at-root-of-vile-legislation-targeting-trans-people.

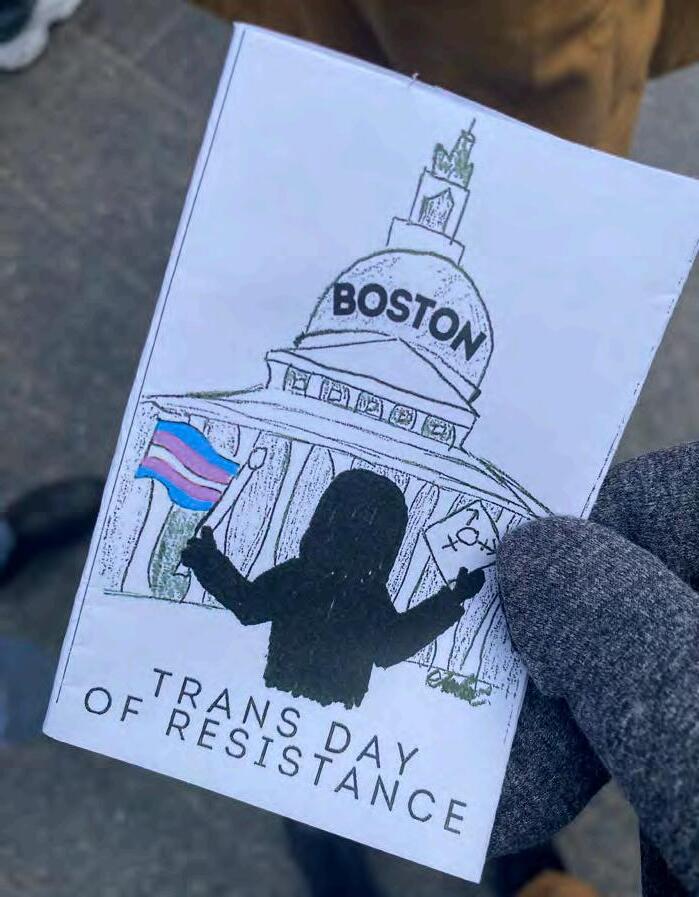

19 However, trans people have always and will always exist. We will continue to demonstrate, to declare ourselves in public space. Protest is at the core of our history and, therefore, at the core of every place created by queer people. In a time where our rights are unstable and trans people, especially trans people of color, are violently targeted, it is essential to orient, map, and mark our existence in physical space. 18 “2023 Anti-Trans Bills: Trans Legislation Tracker,” n.d., https:// translegislation.com/.

18 The thinly veiled rhetoric about “protecting the children” does nothing to hide a very clear message: right-wing lawmakers intend to eliminate trans people from the public sphere.

[…] “The ‘Women’s Bill of Rights’ would erase trans recognition by the federal government.”

As of December 6th 2023, the day I am writing this, 591 anti-trans bills have been proposed in 49 states. 85 of them have passed, 377 of them are active and, thankfully, 129 have failed. They “seek to block trans people from receiving basic healthcare, education, legal recognition, and the right to publicly exist.”

20Ingram, Gordon Brent, Anne-Marie Bouthillette, and Yolanda Retter, eds. Queers in Space Communities, Public Places, Sites of Resistance. (Seattle, WA: Bay Press, 1997), 20.

we are everywhere! “ “

- a stonewall-era rally cry

21 Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology, 7. 22 Ibid. 23 Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology, 7.

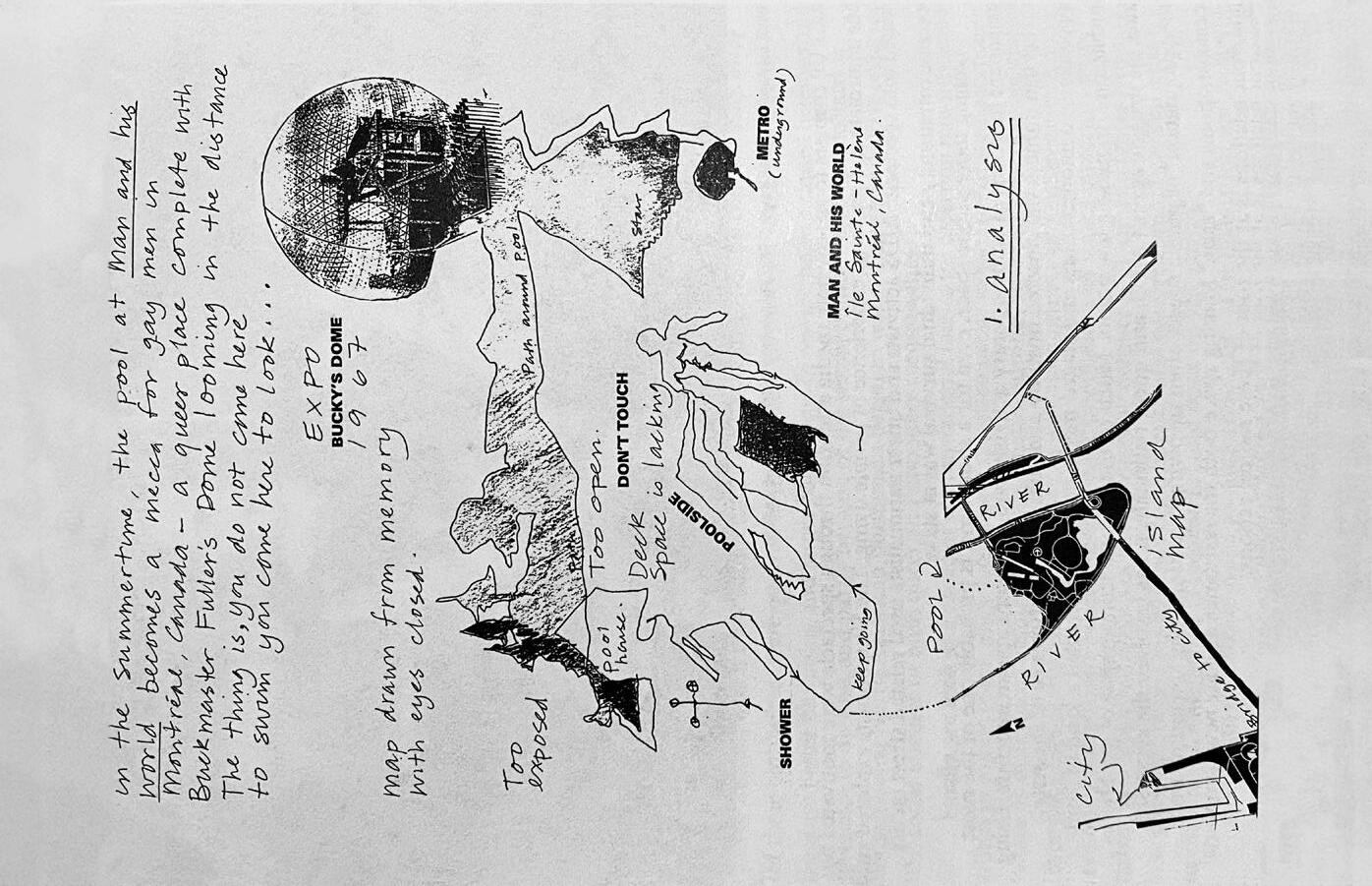

Gender and space dynamic is deeply influenced by culture and geography. To understand space and gender, we have to look beyond the physically spatial and look to the intangible, theoretical, social, and cultural geographies that influence human relations. Queer geography exists parallel to the assumed “default” geography of cis-heteronormativity. To identify queer place is to orient oneself in the direction of identity, to find commonalities from one queer orientation to another, and to mark the queer experience in space and in time.

To grow up queer in a cis-heteronormative world is often to be disoriented. Therefore, to become oriented is to navigate from a point of disorientation. This process can often feel like moving through an unfamiliar dark room. One rarely follows a direct path to the exit, instead feeling their way around until they come upon an object - in this case a door knob - that enables their exit and establishes their orientation. The indirect “line” formed in the pursuit of this inner knowing could be considered a mapping of queer orientation.22

The feeling of disorientation is how we find ourselves searching for, going toward, and creating queer place. When we follow this “field of intuition”23, we are drawn to specific “objects” within our range of perception. By following the lines that attract us, which often deviate from the standard, we meet others who have followed their own lines. We call this cluster, formed by way of similarly deviant-line followers, a queer place.

The formation of one place attracts the formation of others, creating a queer “layer” within a spatial landscape. While queer places are clustering, other layers within a given landscape are also forming.

Interaction between layers leads to the declustering, dispersal, and re-clustering of others.

When the dominant layer within our spatial landscape is cis-heteronormative, queer place is often pushed out and places that once held thriving queer communities are forgotten and unmarked. Queer place can be mapped both spatially and over time as its formation has had to adapt to social and spatial opposition.

“ “

the question

of orientation is

not about how we find our way, but how we come to feel at home.

“Mental-maps” cognitively mark the places we associate with queerness. As I continue to become oriented in my queer identity, I continue to mentally “map” the places that facilitate my discovery. These places are physical, but the shape, the taste, the color of them exist in the folds of my memory and the form of my identity. The map of my queer identity can be physically traced from a pottery studio in Chicago, to a bench in Barcelona, to the places in Boston that make me feel like I am coming home to myself. The cognitive significance of these physical places can be mentally traced by the curiosity I felt meeting a nonbinary person for the first time, by the flush a woman’s compliment brought to my cheeks, by the validation I experience in my trans-for-trans relationship.

appingas an action, not a nounspeaks to the active nature of geography. It lives as fluidly as the humanity that draws its boarders. If finding orientation is finding home, mapping is our way of marking the journey.

morientation, mapping + monument

“Mental-maps” trace individual orientation. When they overlap in physical space, we identify commonalities in subjective experiences and make queer claim over a given landscape. “Each urban and rural queer scape embodies numerous subjective maps of spatialized social relations, […] both current and remembered.”24 The spatial network defined in relationship to our queerness “defines the points where a person’s friends, lovers, potential sex partners, and allies can be found, and where danger may exist.”25 It is where we find orientation and build community.

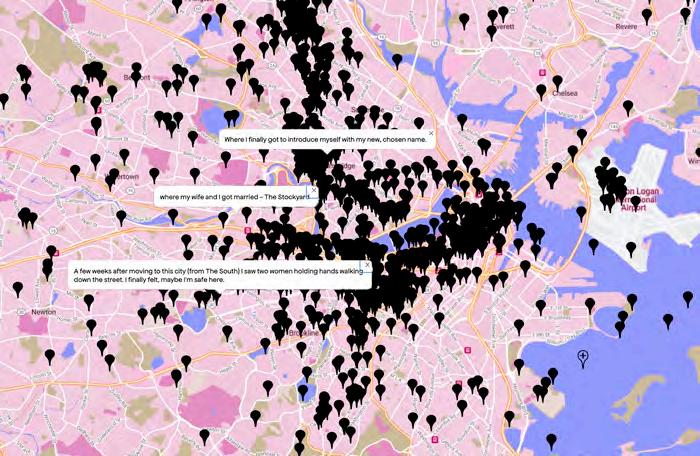

The absence of queer narrative from cultural cognition often leaves queer individuals without a guide to discover their queerness or community. Projects like ‘Queering the Map’ aim to create the maps we do not have. The website allows users to individually add a location to the map and specify its significance. Each location represents one element of an individual’s queer map. Collectively, these locations produce a tapestry of the queer experience. The History Project is a Boston based organization that is committed to the documenting and preserving of New England’s queer communities. Their maps have facilitated in my understanding of Boston’s queer history and made me feel at home in a city I had not realized held so much queer depth.

Mental and physical “mapping” is a fundamental part of the queer experience. Mapping is also essential for the social acknowledgment of queer people within the public realm.

24Ingram, Gordon Brent, Anne-Marie Bouthillette, and Yolanda Retter, eds. Queers in Space, 57.

25Ingram, Gordon Brent, Anne-Marie Bouthillette, and Yolanda Retter, eds. Queers in Space, 55.

our geographies hold the history of queer place - lived, temporal, established, eradicated, violent, remembered. All there, but often invisible. The act of marking - of creating monument - exposes these queer histories and footfalls on the landscape of our urban and rural environments. It makes transparent what is often opaque and encourages queer people to claim public space as queer territory.

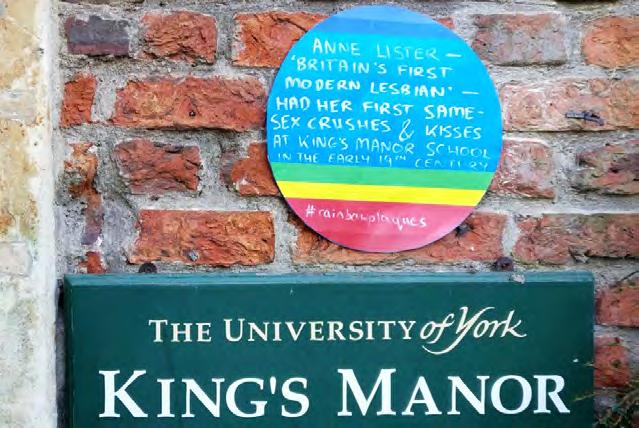

The Proud Little Pyramid designed by queer architect Adam Nathaniel Furman used a recycled Christmas tree structure to create what the artist calls a monumental anti-monument to publicly and expressively highlight the history of Queer London in the late 20th century. The Rainbow Plaques: Making Queer History Visible project aims to commemorate the queer history of places by making it clearly visible in the public realm, challenging the idea of what constitutes historical significance. People can print out plaque templates and create their own monuments, publicly identifying the inherent queerness of a specific public place. Although individual, each gorilla act of marking accumulates to identify a collective queerness within our public realm and consciousness.

To hold space as a marginalized group requires vigilance and resilience. To become monument means to memorialize past and present queer space within the physical realm. It means to hold permanence and establish a space in-between the cis-heteronormative landscape. By persistently creating monument, we can increase our presence within the physical and mental landscape of Boston and help others orient themselves, discover history, and join in queer community.

QUEER ..

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

Pheno men ology

Hope Whynot

It’s like, how many spaces had to be dark? They couldn’t have windows because it was illegal, as it is becoming illegal again, to wear clothes of the opposite gender or to dance with someone of the same sex. I think the beauty is in what we do in those spaces and in what queer people create, and they always create color and warmth, if not light...we always do the best we can.

“ “

In general in life, I like light. My favorite place in my own home is my sunroom, but I’m so used to queer things being in dark spaces, that I don’t particularly mind it.

impressions

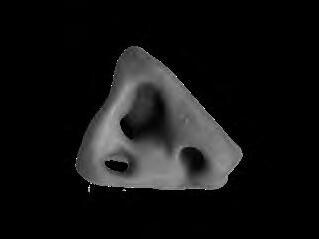

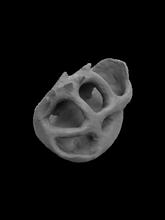

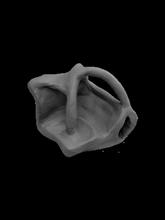

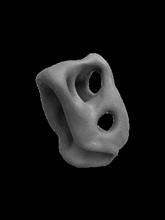

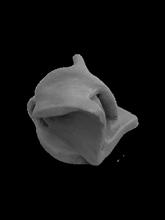

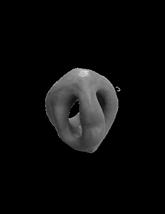

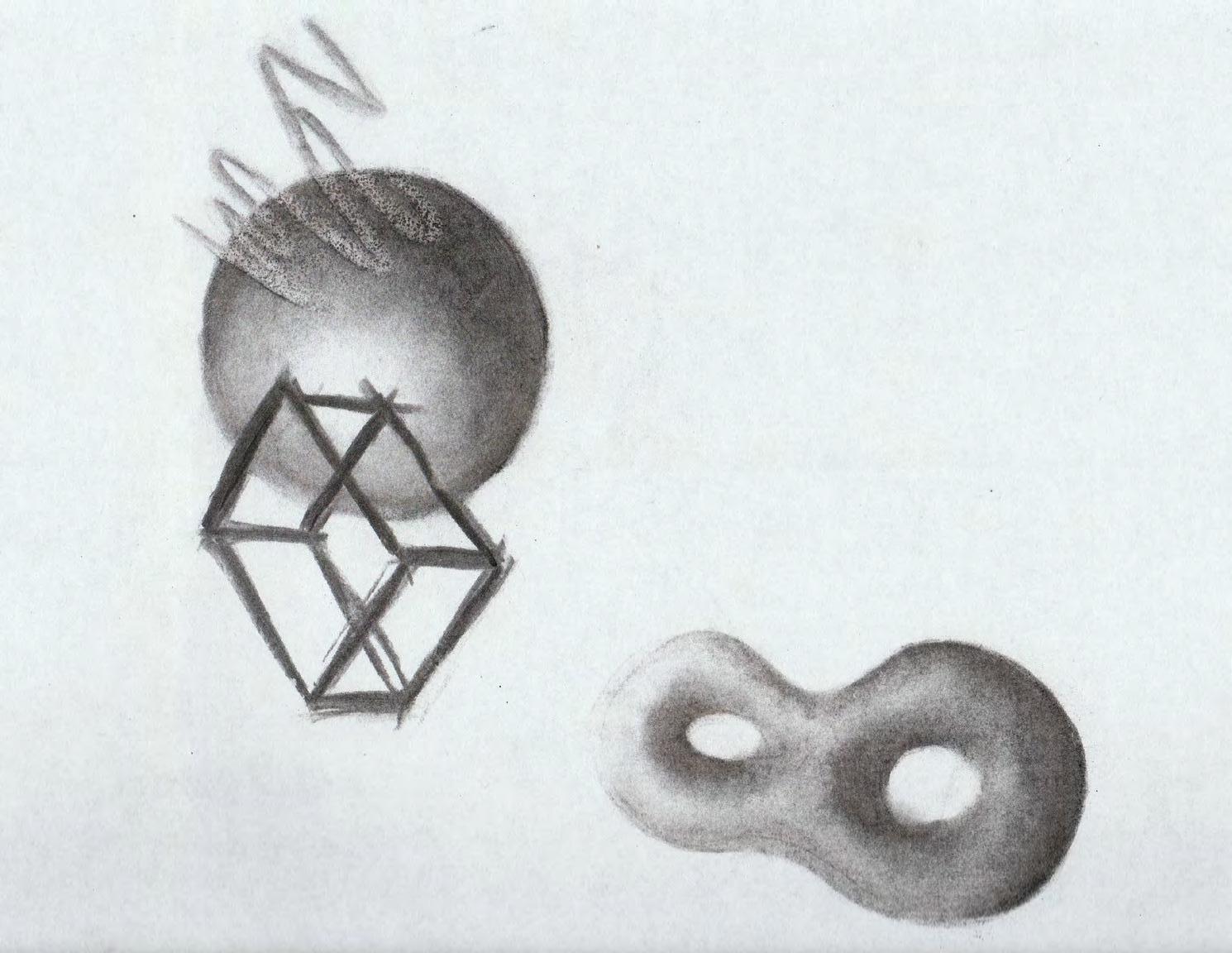

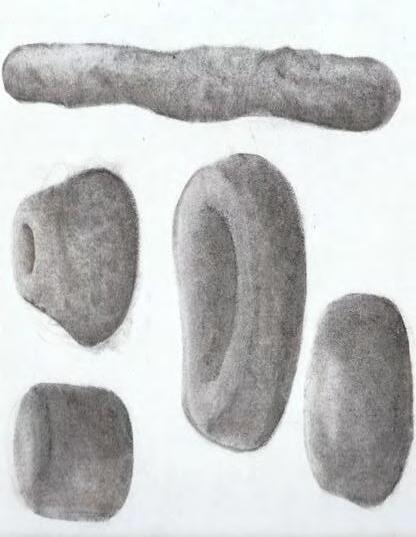

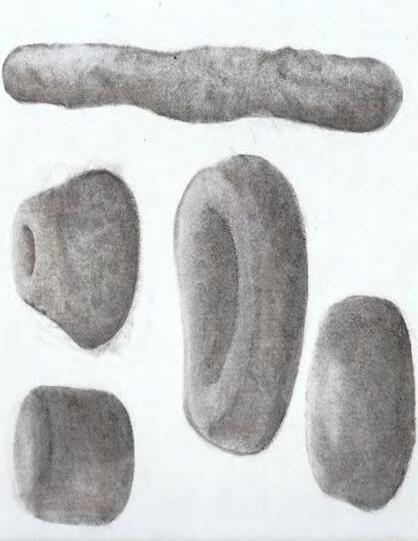

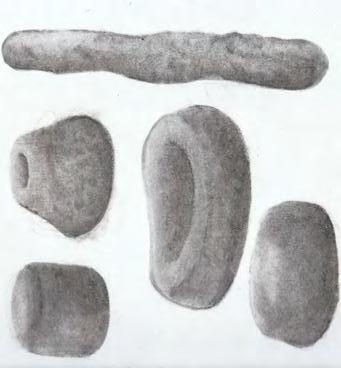

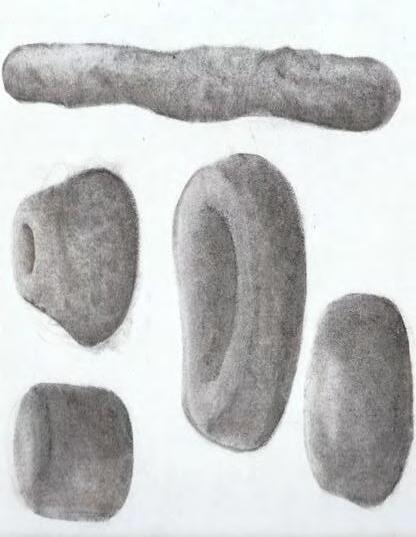

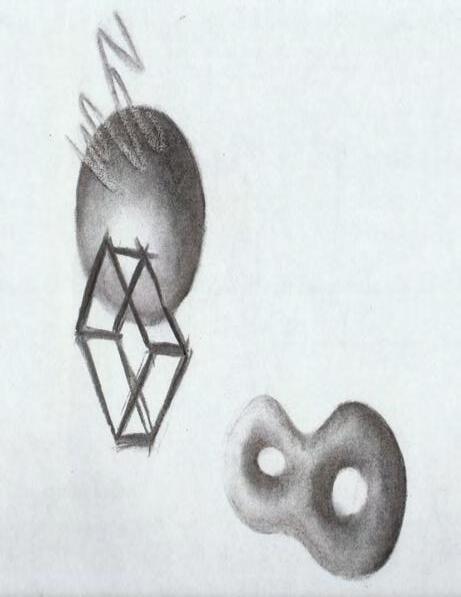

in a primary research study, I interviewed trans individuals in the Boston area, searching to articulate the relationship between queer body and space. In order to capture both dialogue and physical expression, participants told their stories while sculpting with clay.

Seated in their homes, I gave each participant the material, a few tools, and some intentionally rudimentary instruction - here is how to slip and score, here is how to pinch and pull, here is how to add clay and take it away. The dialogue was conversational. The participant needed to be unlimited and uninfluenced by my instruction and inquiry. The resulting sculptural forms and the words used to describe them varied from abstract to symbolic. Each form and story was specific to the individual’s queer experience.

These interviews led to my understanding of queer place as at once autonomous and communal, temporary and transient, claimed, and bodily. Queer places are less about their specific appearance and more about the occupants’ phenomenological experience; more about the queer bodies who mark queer space.

It is through my existence in this ‘flesh of a world’ […] that I experience and interpret [architecture]. 26

“

mark on body, mark on space

ireturn to orientation; I return to lines. “Lines become the external trace of an interior world, as signs of who we are on the flesh and folds and unfolds before others. What we follow, what we do becomes “shown” through the lines that gather on our (bodies) as the accumulation of gestures on the skin.”27 These lines that mark the skin, that mark the history and future of our identities, come through experience. They come through tears, and smiles, and wrinkled brows brought forth by geographical influence - social, cultural, physical. They also come through choices made. Scars accumulated. Lines on chests reshaped to shape a form that feels closer to home, closer to orientation.

The relationship between the queer experience and body is cyclical. Queer experience is dependent on body. The queer body, as any body, is marked by space. Space, in turn, responds, formed by the bodies that inhabit it. Consider for a moment objects in space; “Objects are thought to structure the environment immediately around themselves; they cast a shadow, heat up the surround, strew indications, leave an imprint, they impress a part of themselves” within space.28 Our presence in space as trans people - our breathing, moving, our mobility and perceptibility - influences public space and leaves a mark upon it.

Robin (she/her) is drawn to water. For her, it allows a freedom of the body, to feel connected with nature. The water’s surface breaks at her introduction. It folds around her. Between the water within the body, the skin of the body, and the water that engulfs her, there is no element that is untouched by another. In these moments, the queer body and the queer space hold each other. In these moments, Robin can wash away the weight associated with being trans-femme in America and float peacefully

26 Bêka, Ila, Louise Lemoine, and Juhani Pallasmaa. “The Tuning of Space.” Essay. In The Emotional Power of Space, (Paris, France: B&P, Bêka & Partners Publishers, 2023), 61.

27 Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology, 18.

28 Rendell, Jane, Barbara Penner, and Iain Bordan, eds. Gender Space Architecture, 114.

in the comfort of her own body in queer place.

T (she/they) explores their nonbinary gender identity through drag. There is liberation in theatrical expression. The act of dressing oneself to emulate a gender presentation is to layer a skin on top of your own, to present it in space and allow that space to form around you in response. T’s characters come to be in community through The Queer Theatre Project. These spaces receive queer individually and, in turn, encourage its expression.

The relationship between queer body and space is what makes space inherently queer. To create a queer place, all one needs is themselves and the space in which they exist. Like the bodies that inhabit it, queer place is multi-dimensional. It does not have to look a certain way nor meet a gendered standard. It is infinite in expression and belongs to those who inhabit it. A queer place becomes so because queer people occupy it, molding it to the folds of their bodies.

FACILITATING QUEER PLACE CREATION METHOD OF INQUIRY TERMS OF

method of inquiry

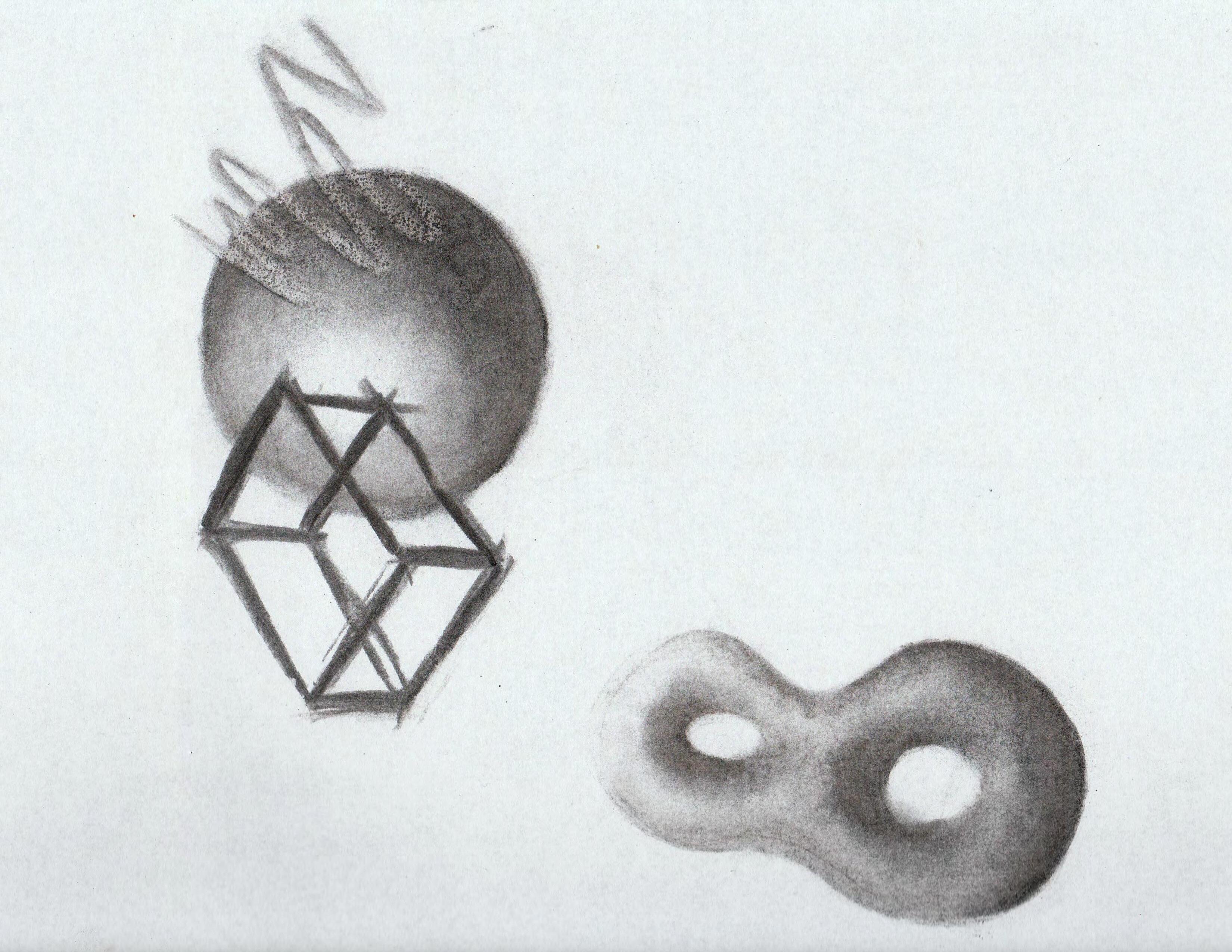

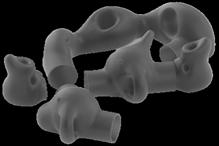

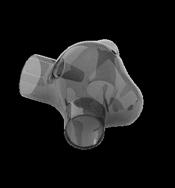

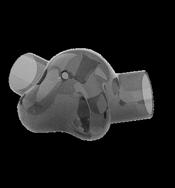

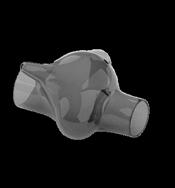

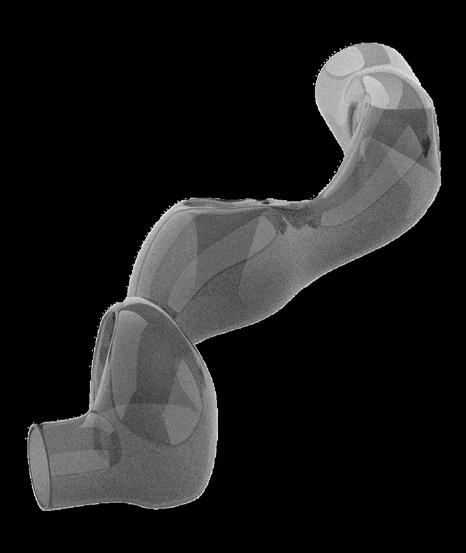

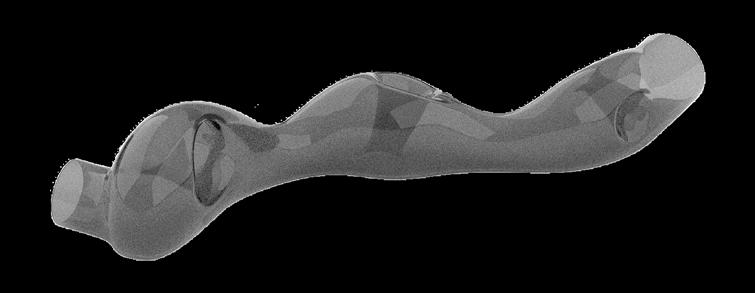

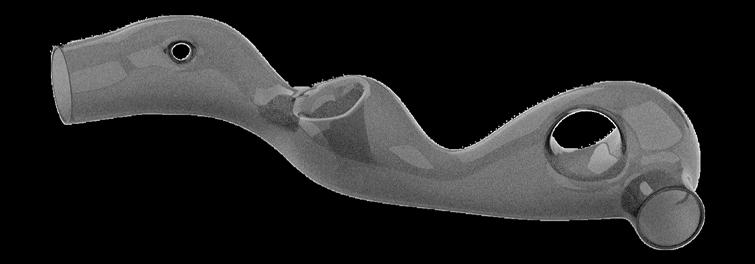

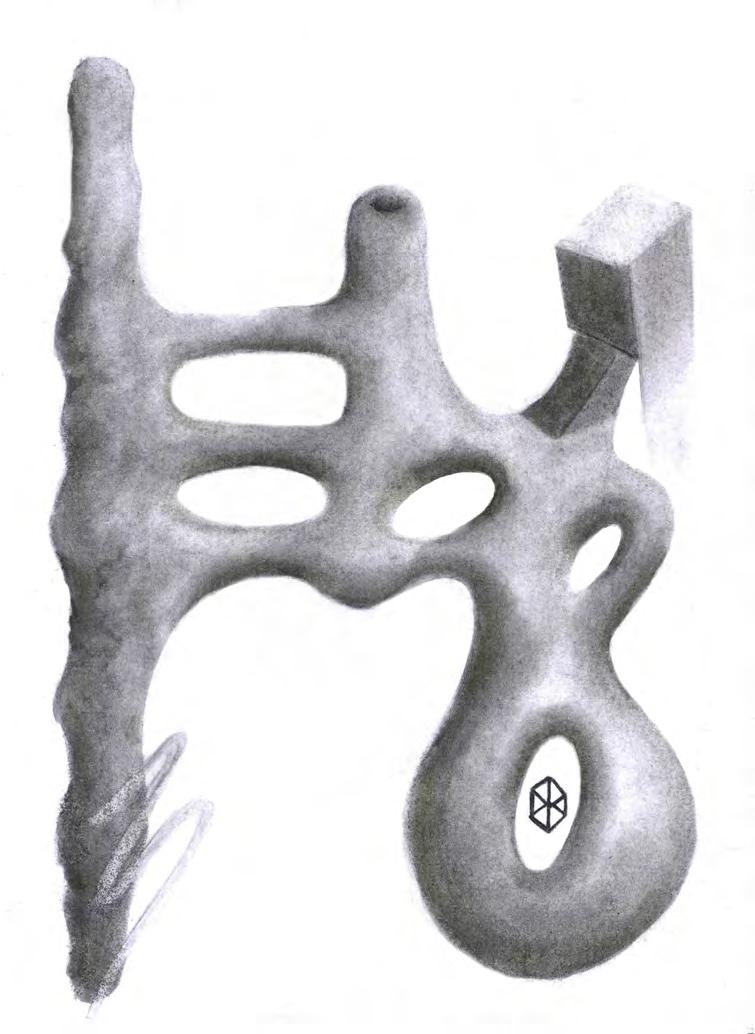

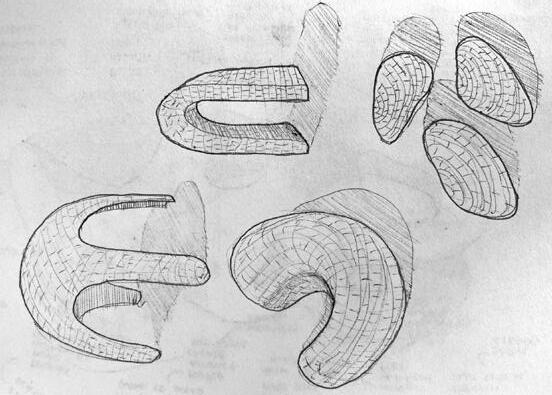

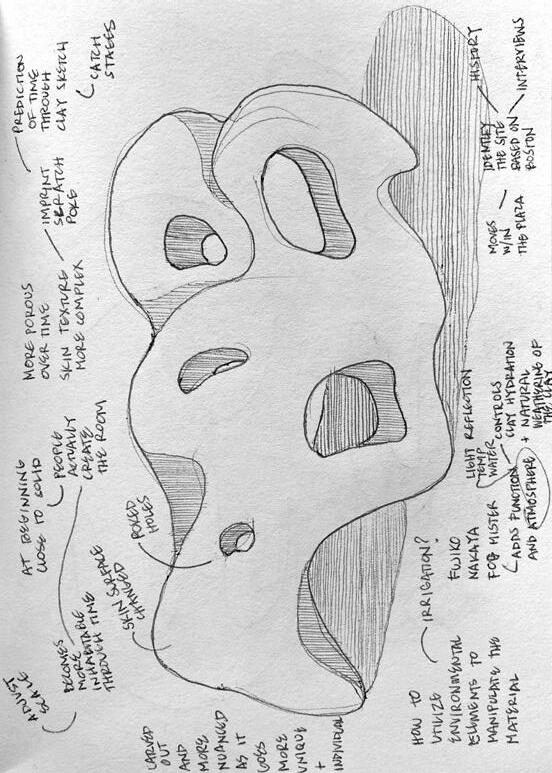

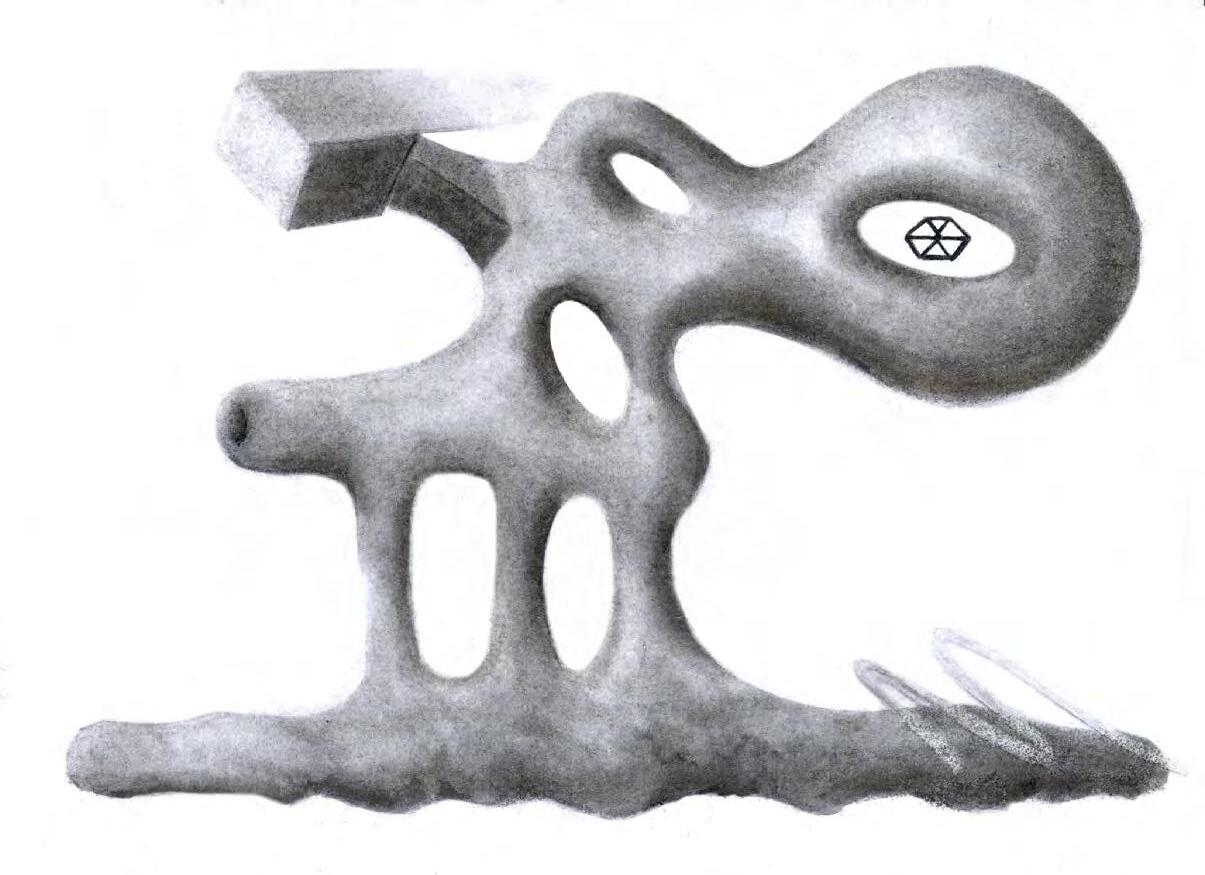

Explore the structural potential of both inflatables and cob to allow for an architecture that is at once temporary and fixed and that allows for the mark of queer hands to be remembered on its surface.

Provide individuals with the means to configure their own space by designing inflatable modules that have different expressions both individually and in combination with other modules.

Ronan Park

Select sites in Boston based on historical queer places - as well as those gathered through primary and secondary research - that have been either lost to time or are temporary and thus, unmarked.

Create a network of queer place monuments that mark the history of the installation and the queer place that came before.

terms of criticism

Does the architecture reflect the queer body in its material expression?

Does the architecture invite autonomous engagement and empower community expression?

Does the architecture embody the transient nature of queer place?

Does the architecture mark the history of the queer place in space?

HOW TO BUILD A QUEER PLACE MONUMENT materials in conjunction FROM SPACE

TO PLACE

mater ials ..

con junc tion in

fabric + atmosphere; body as mobile

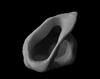

ilook toward materials that embody the malleability of body and space, the essential call and response. Both clay and fabric are deeply influenced by atmosphere and the human hand. Where fabric is elastic, clay holds memory. It is the temporary quality of inflatables and the memory of clay that I wish to construct and memorialize queer place.

Fabric, in its flexibility, can be shaped indefinitely. It is easily manipulated by atmosphere and easily retains and returns to its original shape. To introduce air to fabric, is to witness the shape atmosphere gives the material. When a body interacts with inflated fabric, the fabric bends to the influence, but easily returns to its original form upon the body’s retreat. Queer spaces are also flexible and transformative. The temporary forms of their folds can be quickly forgotten in the introduction of a new environment, a new atmosphere.

Through prototyping, and observing the interaction between body and inflatables, I notice our influence on one another. When I move inward, the fabric moves inward with me, when I retreat from the fabric, it follows my movements. This dance between us feels as an extended expression of my bodily movements.

Like unfolding your queer identity and moving through queer place, the fluidity of fabric feels liberating and encourages me to explore expressions of self.

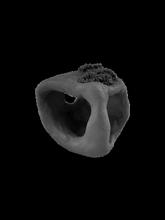

clay + atmosphere; body as monument

the atmosphere-induced material qualities of clay are very similar to that of the body. When wet, clay is malleable. It is moldable and manipulable by the hand. The air changes its cellular structure as it dries to become soft and brittle. When fired, the clay hardens and solidifies. Much like a trans body in space, clay has a call and response between itself and its environment.

Through prototyping, and observing the interaction between body and clay, I noticed how the material retained my touch. Scores and joints, imprints and additions layered upon one another, holding the history of environment on its surface. When I slip and score the surface of the clay, when I press my

hand into it, my imprint remains; my identity is marked on the history of the material. This clay surface is an extened remnant of my bodily movements. Clay has been used in architecture throughout history. It’s elemental form lends itself to the human hand and our desire to build. For this monument, I propose the use of cob. A composite material of subsoil, water, a fibrous organic material (straw), and clay or sand. The combination allows for wet application and the fibrous material creates structural strength. The user layers cob over itself, much like the queer body layers itself in space throughout time. Unlike fabric, clay holds memory. It is not elastic, it holds the marks of the environment impressed upon it. Although transient, space holds the memories of the queer bodies that transformed its identity to that of queer place. Although often invisible, these memories can be monumentalized through the memory of clay.

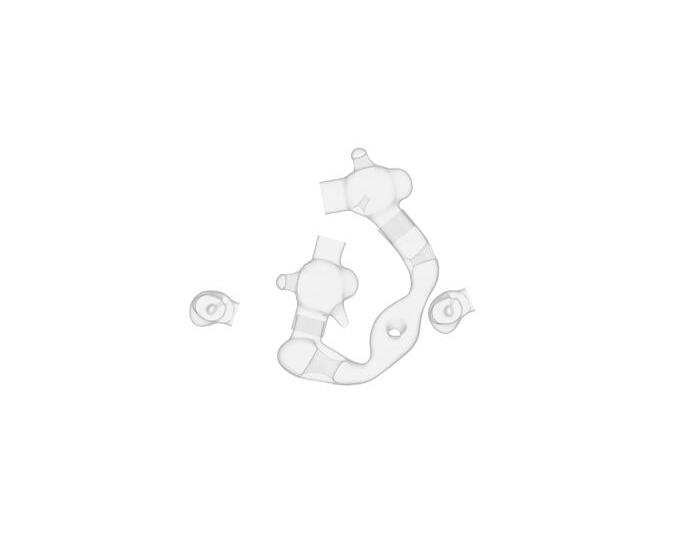

inflatables + cob; from mobile to monument

the performance of gender is repetitive, but not static: a forever evolving understanding of personal identity that is expressed and subsequently interpreted through the current social gender lens. A queer architecture, therefore, cannot be static nor can it be overarching. To manifest a queer architecture is to allow for repeated and varied manipulation authored through both a singular and communal user. It is to facilitate both movement and memory.

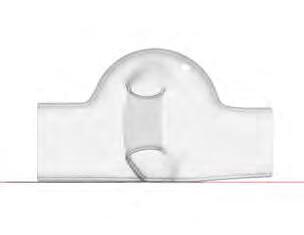

By using inflatables as a supportive substructure and cob as a layered skin, Queer Body; Queer Place harnesses the qualities of both materials to construct an at once temporary and permanent monument.

The inflatable provides the necessary support for the installation of the permaent structure. The cob is layered with stiffener coats and sealants and reinforced with a metal mesh. Once the overlay is solidified, the inflatable substructure is deflated, moved and reused on another site.

Mobility within that space is essential, because motion continually stamps new ground with a symbol of ownership.29

29Munt, Sally. Heroic Desire: Lesbian Identity and Cultural Space, 42. New York, New York: New York University Press, 1998.

. . . . ...... . . . . . . . . . ......

. .

from to - ..... .

space place -

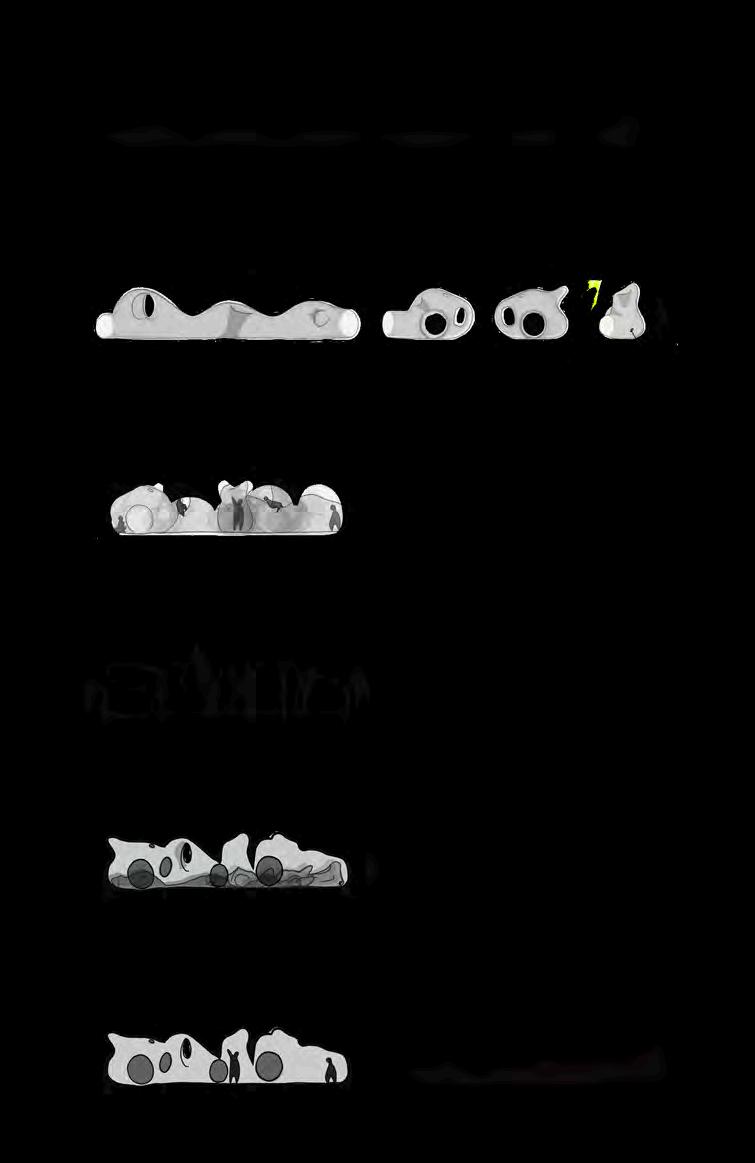

inflate

configure

encase deflate

depart place

from space to place

queer Body; Queer Place is an interactive architectural environment that harnesses the material properties of clay and fabric, influenced by atmosphere and body, to reflect the transformative power of the gender-queer experience.

Inflatable structures are manipulated, moved, and interacted within. Community members then use clay to built a clay encasement around the inflatable. In doing so, the queer place becomes monument and the inflatable continues its transience, moving to create and mark at a once old and now new queer place in Boston.

Some of my interviewees are on a queer kickball team that plays at Ronan field in Dorchester. This field in this neighborhood is not visibly queer. However every Sunday, Stonewall Sports teams flood the field to play kickball. The unassuming acre of grass, mud, and chainlink fence transforms into a colorful wash of queers. Even though the field returns to its unassuming state, for those brief hours on a Sunday afternoon that space becomes a queer place.

I chose this space as a proof-of-concept site. Through the introduction of Queer Body; Queer Place, I create a queer monument in a currently unmarked queer place.

a network of living queer-place monuments

inflated > configured > encased > deflated > departed over time, Queer Body: Queer Place generates a network of living queerplace monuments throughout Boston. Queer geography becomes visible, making the place in-between a prominent fixture in the urban landscape.

meditate

meditate

group group gather

inflatable forms for authorship

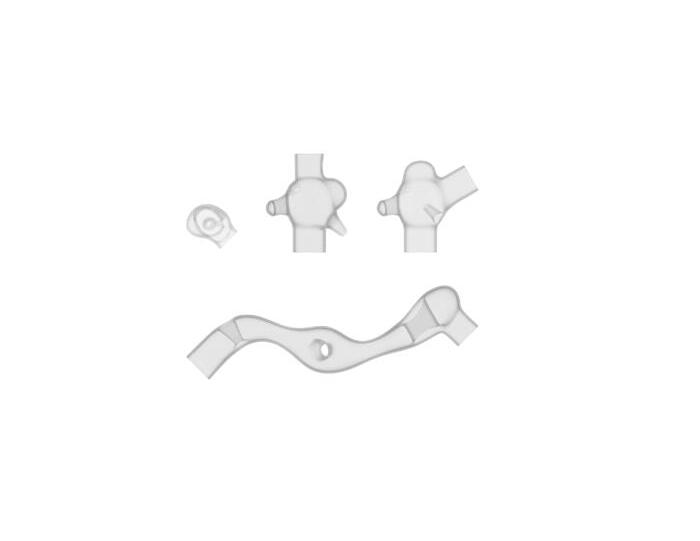

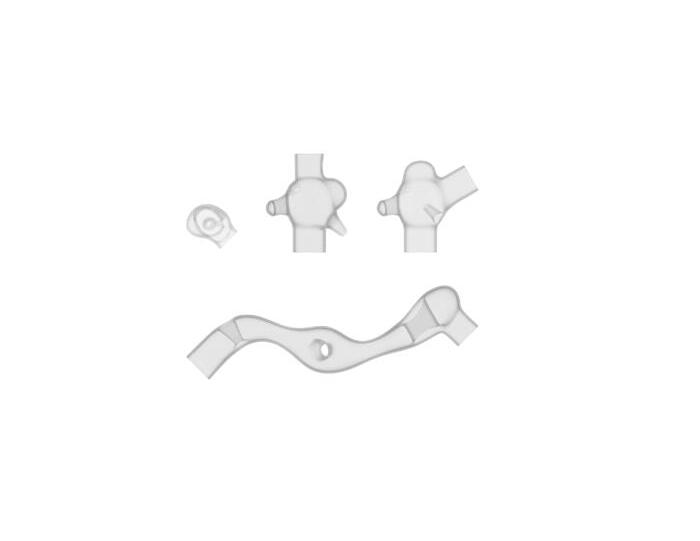

the architecture takes shape in a series of inflatable forms for the user to interact with. They are moveable, changable, interconnecting, and of various scales to allow for individual authorship and programming. The modules are gathered from the forms explored in queer place interviews and research. In addition to the shapes created in the interviews, I have drawn up four specific module designs and three different scales. Each scale enables different types of programming and each module has adjustable components and openings that can interlock with the other modules.

section detail: interactions

meditate > group > gather >

the first series of modules is categorized as meditative. These are forms derived from primary research interviews and are intended to act as furniture on the site. Scaled for single occupant use, they can easily be moved and clustered to facilitate different bodily orrientations and group seating.

meditate > group > gather > configure

the first enclosed module is also categorized as meditative. Intended for 1-2 occupants, these inflatables enable private programming.

meditate > group > gather >

the occupancy of each module is also the number of people required to move it. The medium sized modules hold 1-6 people. The “arm” of the modules are large enough for both interior and exterior occupation, creating a layering affect and a blurring of interior/exterior boundaries of occupation.

section 1|8th

the large module is linear and bendable. It requires the most people for movement, encouraging group programming. The length allows for it to engulf other modules, creating spaces within spaces - a further manipulation of the barriers between interior and exterior.

site 1|8th

section 1|8th

plan 1|8th axon

potential orientations

team debrief

all modules, in their various scales and manipulations, encourage user programming. From a drag performance, to an art market, a group yoga class, to a kickball team debrief, and a lunch date to a solo meditation

market

drag show

components variations

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

o community mark-making

nce configured, the inflatables are encased in the cob overlay. Community members add their marks, layer by layer. Their hands can sculpt, paint, build upon this skin. This form becomes a monument of the queer bodies who shape its expression.

queer Body; Queer Place - with its maliable material and construction methodology - enables community based iteration. What was once temporary queer space becomes solidified queer place, bearing the mark of the queer bodies who created it.

This architectural intervention is a contribution to the rich queer spatial history and an expression of gratitude to those who have contributed before and along side me. My trans identity is known because of you.

“

In personhood, Becker

conclusion “

To be open to oppositional ways of knowing that teach us how to transgress we must free the imagination. It is our capacity to image that lets us move beyond boundarieswithout imagination we cannot reinvent and recreate the worldthe space we live in so that justice and freedom for all can be realized in our liveseveryday and always. 30

bibliography: books + articles

Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, objects, Others. Durham, NC: Duke Univer sity Press, 2006. Bêka, Ila, Louise Lemoine, and Juhani Pallasmaa. “The Tuning of Space.” Essay. In The Emotional P ower of Space, 55–72. Paris, France: B&P, Bêka & Partners Publishers, 2023. Bongiovanni, Archie, and Tristan Jimerson. A Quick & Easy Guide to They/Them Pronouns. P ortland, OR: A Limerence Press Publication, 2018. Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge, 2006. Catterall, Pippa, and Azzouz Ammar. Rep. Queering Public Space: Exploring the Relationship Bet ween Queer Communities and Public Spaces. London, UK: Arup, 2021. Davis, Chloe O. Queens English: The LGBTQIA+ dictionary of Lingo and Colloquial Phrases. New Y ork, NY: Clarkson Potter, 2021. Fitzgerald, Tom, and Lorenzo Marquez. Legendary Children: The First Decade of RuPaul’s Drag R ace and the Last Century of Queer Life. Penguin Publishing Group, 2020. Gowen, Amy, and Pauline Augstoni . “L as in Walking.” Essay. In Rights of Way: The Body as Witness in Public Space, 7 5–95. Eindhoven: Onomatopee, 2021. Hooks, Bell. Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black. South End Press, 1999. Human Rights Campaign. “Human Rights Campaign: Extremists at CPAC Laid Bare Hatred at Root of Vile Legislation T argeting Trans People,” March 6, 2023. https://www.

hrc.org/press-releases/human-rights-campaign-extremists-at-cpac-laid-bare-hatred- at-root-of-vile-legislation-targeting-trans-people.

Ingram, Gordon Brent, Anne-Marie Bouthillette, and Yolanda Retter, eds. Queers in Space

Communities, Public Places, Sites of R esistance. Seattle, WA: Bay Press, 1997. Library of Congress. N.D. “Research Guides: LGBTQIA+ Studies: A Resource Guide: 1969: The Stonewall Uprising.” Libr ary of Congress Research Guides. https://guides.loc.gov/ lgbtq-studies/stonewall-era.

Munt, Sally. Heroic Desire: Lesbian Identity and Cultural Space. New York, New York: New York Univer sity Press, 1998. Menon, Alok V. “What We Are Is Free.” NYC LGBT Community Center, New York, New York Mar ch 29, 2023. Rendell, Jane, Barbara Penner, and Iain Bordan, eds. Gender Space Architecture: An Inter disciplinary Introduction. London: Routledge, 2000. The History Project. Improper Bostonians: Lesbian and Gay History From the Puritans to Playland. Boston, MA: Beacon Pr ess, 1998. “2023 Anti-Trans Bills: Trans Legislation Tracker,” n.d. https://translegislation.com/.

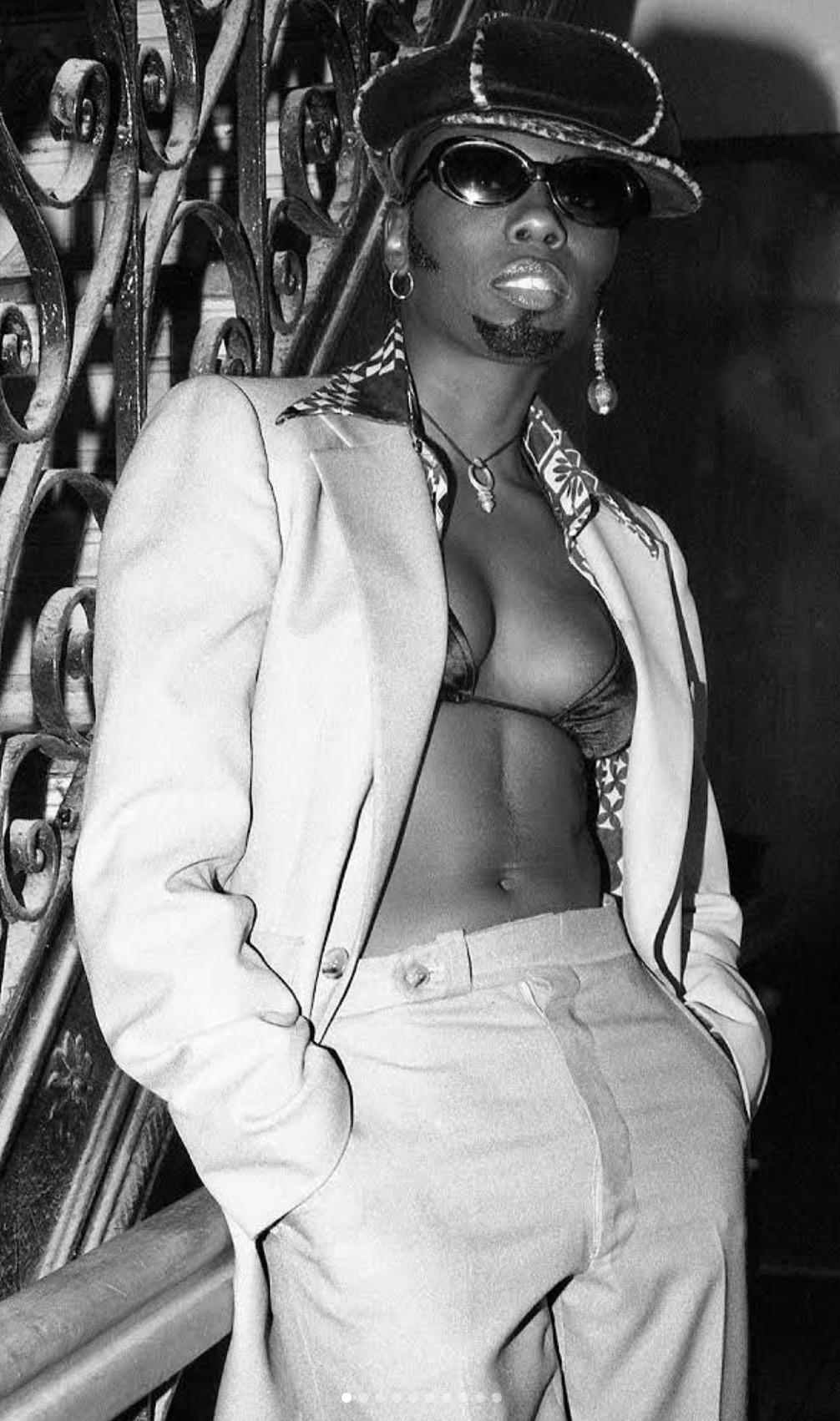

bibliography: images Carle, Lewis. “Sylvia Rivera (with Christina Hayworth and Julia Murray).” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution. 2 000. Accessed December 9th, 2023. https://npg.si.edu/ blog/welcome-collection-sylvia-rivera. Delmonte, Irma. “‘Anne Lister –Britain’s first modern lesbian’, King’s Manor, University of York.” Rainbow Plaques Project. August 11, 2020. Accessed December 9th, 2023. https://www.sahgb. org.uk/features/rainbow-plaques-making-queer-history-visible. Furman, Adam Nathaniel. “Proud Little Pyramid.” June 24th 2021. Accessed December 9th, 2023. ht tps://www.dezeen.com/2021/06/24/adam-nathaniel-furman-proud-little- pyramid-kings-cross-london/#. Goblinhole69. “Goblin Hole 2023.” Instagram, April 22, 2023. Accessed December 9th, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/CrUzhVVMtZE/. Gwenwald, Lesbianherstoryarchives. “MilDred Gerestant ‘Drag King Dred’ NYC 1997. ‘Death does not scar e me for my spirit is everlasting.’” Instagram, April 26th, 2021. Accessed December 9th, 2 023. https://www.instagram.com/p/COIVItIJyOe/?img_index=1. Gwenwald, Lesbianherstoryarchives. “Transsexual Menace, 1994.” Instagram, March 31st, 2022. Accessed December 9th, 2 023. https://www.instagram.com/pCbyMSWTJ2ct/?img_ index=1. Hammer, Hausofyesterday. “Briar and Rusty go to the Movies.” Instagram, August 3rd, 2023. Accessed December 9th, 2 023. https://www.instagram.com/p/Cvfc4GXRZwt/. Lgbt_histor y. “The Transsexual MenaceNew York City.” Instagram, November 1 5th, 2016 Accessed December9th, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p

Philomène, Laurence. “Non Binary Portraits.” August 21st, 2019. Accessed December 9th, 2023 https://www.itsnicethat.com/articles/laurence-philomene-photography-210819.

Queering the Map. “Queering the Map.” 2023. Accessed December 9th, 2023. http:// queeringthemap.com.

Scheffer, Lesbianherstoryarchives. “The NYC Dyke March.” Instagram, June 25th, 2023. Accessed December 9th, 2 023. https://www.instagram.com/p/Ct6m_hzre7v/?img_index=1.

Scheffer, Lesbianherstoryarchives. “1998: Marching past Bryant Park.” Instagram, June 23rd, 2 023. Accessed December 9th, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/

Ct1ZGEArSyD/?img_index=6.

Scheffer, Lesbianherstoryarchives. “the First Annual NYC Dyke Pride March. 1993.” Instagram, June 2 3rd, 2023. Accessed December 9th, 2023. https://www.instagram.com/p/ CfSG21wpqyy/?img_index=1. Zaman, Soraya. “N.D.” July 26th, 2019. Accessed December 9th, 2023. https://birdinflightcom/ en/inspiration/project/20190726-american-boys-soraya-zaman.html.

IMAGERY

APPENDIX mind maps precedents DESIGN ITERATIONS interviews

GENDER

buildings/ interiors

rural/urban open space

clothing

the trans-ness of architecture

social groups environmental power institutional communal political spatial spheres its relation to the physical self and the body orientation queer space theory gender sensative planning how we reside in space

What material elements reflect those of the body?

moved removed lost to time transformed by time

how does my gender relate to my experience of architecture? architecture of systems digital spatial spheres movie sets illusion in the physical world the surreal objects qualities of space defy physics, the rational, the logical spaces confine or expand symbolic unexpected the temple the bed the vehicle “any object that represents, enables, and embodies movement” drifting in and out of sleep wander/meander spaces that once existed but no longer do spaces described in literature spaces of the unconscious/ subconscious how does the point of view influence our experience of space? spectator subject participant the camera obscura

DREAMS

dreams psychological scaffolding dreams as another dimenson of architecture clay hydrates absorbs transforms structural of the earth moldable

“the consecration of space for ritual purpose” the pillow emerged from stone

MATERIAL

GENDER

how does gender relate to the experience of architecture?

environmental power

institutional political

SPACES

queer space theory gender sensitive planning how we reside in space

public/private open space

interior/exterior

social physical

orientation

the trans-ness of architecture

moved removed lost to time transformed by time

architecture of systems spatial spheres the surreal qualities of space defy physics, the rational, the logical spaces confine or expand symbolic unexpected spaces of the unconscious/ subconscious how does the point of view influence our experience of space?

its relation to the physical self and the body

psychological dreams as another dimension of architecture clay

hydrates absorbs transforms structural of the earth moldable

DREAMS

What material elements reflect those of the body?

spectator subject participant the camera obscura

WITHIN CONSTRAINTS

ENESS: Airship Orchestra

Harmonitrees: Sky Macklay

SOUND RESPONSE

INFLATABLE PRECEDENTS

Numen: Latex Karlsruhe

“The whole aspect of strangeness hiding within the familiar, of borders that are not fixed, of bodyspace mimesis, is entrenched firmly in the terrain of perceptual uncanny where objects come alive.”

‘We want a clean city, but a not sterilized one. We want a city that is inclusive and not exclusive. We want a city to live in, to use, but we also want to be able to transform it. We want to inhabit our city and we want to do it our way’.

ELASTIC RESPONSE

PHYSICAL

Numen: Void Seoul

“Entering the installation, the body weights of temporary inhabitants open a limited, personal space in front and behind the person inside. Moving away from the entrance, the space moves with the body, closing the former opening and the connection to the outer world.”

Iteration

CASEY

B How does your experience of gender influence the way you move through the world?

C I fear for my safety more when I am in public - specifically after cutting my hair. I was living as nonbinary but, with long hair, I was presenting more feminine. Now, I’m more aware of my surroundings. I’ve had some weird moments with men in particular. But I feel freer, too. It’s nice to feel like you are able to represent yourself even if you don’t always feel safe. Its authenticity is meaningful.

B What comes to mind when I ask about queer space?

C Creativity; so much creativity comes from struggle. Because you have to get creative when you don’t have access to all the things or all the opportunities. So, I think queer people are creative when it comes to space. More Specifically, there is Queeraoke, which feels like a queer space. There are two other queer nightlife spaces that I used to go to when I was first coming out at 22, but have been shut down since. So I feel like that is part of the experience, the transience of our spaces. A lot of the spaces that have felt the most comfortable to me are my friend’s homes. I feel safer being queer in private.

B We’ve talked about privacy and darkness in queer space. Do you think that these nightlife spaces feel more private because of their darkness?

C I think so. Queeraoke is a very small, very intimate space. There’s a bouncer who isn’t checking ID’s as much as they are checking homophobes. So I feel like there is an element of protection that makes something feel more private, even if it is public.

B You also mentioned transience as a quality of queer space. Can you say more?

C Well, when I played softball at my Catholic High School, people would accuse members of the team of being lesbians and it wasn’t great in that way. And you know, a lot of people since then have come out, including me. There were actually two girls on our team who had a secret relationship that they kept from the whole team. It is interesting because we played all over the Boston area, like we definitely played in Dorchester, but our presence was only temporary. Those spaces are only queer for a short minute when the team is there. They’re not permanent; they’re not our spaces. It shows that you can actually experience homophobia - like deep rooted homophobia - in the exact same places that there is queer joy.

B So the space is transient; it’s queerness is dependant on who’s occupying it. What are other places in Boston that feel queer or have queer symbolism to you?

C Bookstores and coffee shops; Trident for example. I had my first date with Gracie there and they have poetry readings, which is very queer.

B You’re moving to a new home and setting up your room - your own ‘cave’ of sorts. How does the space speak to your queer identity?

C It is so ridiculous, but I went to a very fun antique store with all these trinkets and things. I want to make one wall that is kind of maximalist with lots of different areas of art and design. So I have found some really fun, vintage things. Like this calendar from the 40s with a photo of a naked woman kneeling. And a clock that belonged to someone’s 96 year old grandma and a Peacock made out of shells. Everything is weird and fun and creepy. I’m so excited to put my little eclectic collection of things on the walls.

B You describe your art collection as fun and weird and creepy. It makes me think about how queer people are drawn to the unconventional.

C Have you seen Pink Flamingos? It’s this indie avant-garde film with these drag queens that are trying to be the filthiest people in Baltimore. It was highly regarded because it brought a new element of queer camp that said, we’re seen not just as flamboyant and fun and over the top, but we’re also seen as dirty and wrong and ugly. And it really played into that narrative and flipped it on its head and made it a positive thing to be queer in those dirty little ways.

B Can you tell me about what you are making?

C I have a couch. I have an ear; I covered a few of the essential categories. There’s no real reason for it exactly, but I was forming the clay and it started to look like an ear. And I was like, oh, that’s cool. When I was first coming out, I got a whole bunch of ear piercings and they made me feel really happy. And then, I wanted the ear I made to be a space, so I put a couch there.

B Perhaps you’re saying something about listening. The couch made me think about the times when you, me, and Maddie would sit in our living room and hang out. Those moments where you sit and shoot the shit with other queer people.

C That was really nice. Yeah, totally.

B You talked about piercings. What about those experiences feel tied to your coming out journey?

C I feel like there’s an adrenaline rush associated with getting a new tattoo or piercing, and there is this sense that you can do something

impulsive. You can be different than who you were. It was nice to have that feeling in a time in my life where things were rough. Almost like, I’m just going to get a bunch of piercings and have a little bit of joy for a little bit of time. I’m making ambiguous phallic objects now around the couch because I feel like that’s what this needed, like in terms of the balance of the piece you know. The whole thing is giving ‘cave’ and I feel like the phallic objects add to the cave ambiance in a way that I like... maybe I will turn them into fingers. IDK, they are fluid.

B I like your ear couch cave situation. To close it out, what is the queerest color?

C Yellow; like the color of Lala in Teletubbies.

hope

B How does your experience of gender influence the way you move through the world?

H I bump into a lot of men. I don’t move for men; I move for women - just be nice to women always. I’ll hold the door open for men, though. I do all these little things to subvert expectations. I give men the chivalry that they never got and I get in their way when they deserve it. Also, sometimes I feel safer now because I stopped getting catcalled as much when I cut my hair and started presenting more masculine. There is a safety in that. I think feminine women go through a lot of shit and I am fortunate enough not to go through that. I just don’t navigate the world like that in Boston and men typically leave me alone.

B When I ask about queer space, are there sepcific spots that come to mind?

H Yeah. Last night I went to the first part of the Trans Quinceanera event at Harvard. It was a dinner conversation with Lia “La Novia Sirena” Garcia who is a trans artist and activist. It was like a workshop-style, intimate conversation in the Harvard LGBTQ office, which is in a basement. It felt so representative of so many queer spaces that have been in - like, really dark rooms. These spaces may not be the first choice of land and not in a place with a lot of windows, but they are colorful and warm. In that way, it does feel like home, because it’s what we make out of the cut-offs. It made me think of a lot of the queer performance spaces I’ve been in that are similarly dark. It’s like, how many spaces had to be dark? They couldn’t have windows because it was illegal, and is becoming illegal again, to be wearing clothes of the opposite gender or to be dancing with someone of the same sex.

Even the first gay prom I went to was in Boston City Hall in the basement. It’s just always in somebody’s basement.

B Can you speak to lighting in queer spaces and how you experience it?

H In general, I like light. My favorite place in my own home is my sunroom, but I’m so used to queer things being in dark spaces, that I don’t particularly mind it. I think the beauty is in what we do in those spaces and in what queer people create, and they always create color and warmth, if not light. Like if light is some combination of color and warmth then, I don’t know, maybe we don’t have that third piece of it, but we always do the best we can with what we have, ya know?

B Are there public places that feel safe or feel queer?

H Kickball come’s to mind. That’s outside.

B What makes that space feel queer and safe, even though it is just a standard spor ts field?

H It’s the people who are in the league. It used to be in Jamaica Plain, which is a very queer friendly neighborhood. So that definitely felt safe, like people are used to seeing “visibly” queer people out and about, and it’s not a problem. Now, because the league is too big, they moved it to Dorchester. In the context of Boston and JP specifically, I don’t think Dorchester will be fine. I’m from closer to that area and it’s not quite as queer friendly as JP. I don’t think there will be problems, but I think I will probably be a little more cautious.

B Cer tain places, like JP and Somerville, feel queer. I’m wondering, what is it about those places that queer people flock to?

H I mean, I think you have to consider the

schools, in particular, the graduate schools. Somerville got all the Harvard outcasts which built up that neighborhood and made it queer. And then there’s Tufts, which has always felt queer to me.

B So it is the people occupying the space that make it queer. Does it ever feel like a take over? Do you ever feel like you’re coming into a space to take it over and reestablish it as queer?

H I’ve been to flannel takeover events that are explicitly for that purpose. It is funny because one of them was at a random downtown bar and there where straight people just there to watch a sports game that looked pretty confused. A lot of times at those events, if the straight people are there when the queers get there, they don’t stay. I think at some point they realized that the space is no longer for them - as all default spaces are - and then they feel weird about it and leave.

B You mentioned the Space Pussy event. Can you tell me about it?

H Well, I don’t think Space Pussy is explicitly marketed as queer, but it feels queer because of the number of queer people there and the general vibe. I would describe it as a punk performance space that had burlesque, spoken word, a film-based performance, and an art installation. There was also a kink presence with a cage were people were making out/doing mildly suggestive things all night. Space Pussy just seems like queer cannon to me.

H If I think about queer Boston spaces like Goblin Hole and Space Pussy, it seems like we are naturally attracted to what others would see as grotesque little creatures - like aliens. At the Trans Quinceneara event, Lia Garcia compared herself to a vulture, which I think is a bird that a lot of people would think is ugly. It is interesting that she was attrached to vultures and was talking so positively

about their attributes - like survival and that sort of thing. Like, you know, we are the people who get the rescue dogs with one eye.

B I feel like queer people are drawn to the things that non-queer people would see as ugly par tially because of that, because it’s like we recognize our own experiences in the underappreciation and disregard of those animals.

H Yeah, Space Pussy also had all these other details - like there was a zine you got with your ticket and the tickets themselves were painted on receipts. And there were all these colors and art on the walls and people were dressed like aliens. It was at the Rollins Community Center in Brighton, but it’s literally just some person’s house. Their name is Gray or something and they were dressed as a cute little alient in a vest, so that felt pretty queer to me.

B What are other places in Boston that feel queer or have queer symbolism to you?

H Tattoo shops. Rusty’s shop. I have 50 hours of work from Rusty. When I started going to him, he identified as a straight woman. Then, in the time-frame that I was getting tattooed by them, they started taking drag classes and learned how to roller-stake. They came out and got top surgery, and like, my own life was changing so that’s a really sweet memory for me. He was very intentional when he made that tattoo shop. It is beautiful in there. He doesn’t play heavy metal and only has queer employees. He wanted that space to be different. You know, tattoo shops are traditionally very male dominated spaces, if you think of like the old Sailor Jerry tattoos and stuff. So what Rusty made is really very anti-that and it is really nice.

B What about your tattoo experiences feel tied to your gender?

H Ownership over my own body and

rejecting the feminimity that I felt forced into. Whynot Hope was my first tattoo. I had just found out in my early 20s that it was my original name and I didn’t think I was going to go back to that name. I wasn’t identifying as nonbinary at the time. So, as a way to commemorate it, I got it tattooed on me. Even still, I got a lot of flowers that are traditionally feminine, but I felt like it really towed the line for me in a nonbinary way. I have other tattoos, obviously, but the flowers take up the most amount of space. When I started getting tattoos, they all had really personal meanings, but it was only in retrospect that I realized how much gender stuff I was working out with them.

B You and T have a home together. What has it been like creating the space with her?

H T has been on a really beautiful journeyas have I - to find herself and that hasn’t shown up a lot in our space and I think that’s interesting. For me, it has. The choices I make, the colors I choose, the art I put on the walls - a lot of that has had to do with my own evolution and gender presentation. And for her, her style has changed, but she really doesn’t care about her interior. She prefers nothing. She would be one of those guys - just a recliner and a TV.

B So what decisions have you made in the space?

H So, in our bedroom specifically, I had a custom wood bed frame made and it has these lanterns. It is not quite my style anymore, but very much was my style when we got it, and I still really enjoy it. So I have this very cozy, custom bed frame, but on the wall, I have a piece of art by Danny Capo, who’s a tattoo artist. It is a man with one of those old razor blades but it is in the traditional tattoo style. Underneath that, in a similar but more Japaneseinfluenced style, I have a dom with a whip and her sub kneeling and they both have tattoos. That is the only artwork we have on the walls and then we

have a mini projector to watch TV. And that is pretty much it.

B So T is the minimalism, but what makes up the minimalism is you?

H Pretty much. And, because we’re the only ones who live there, the whole house is like my bedroom.

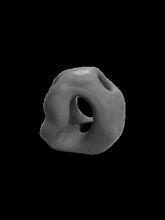

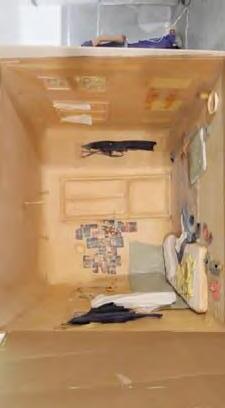

B Can you tell me about what you are making?

H I’m trying to make a box that is eventually going to be closed in. But, I’m trying to put fun things in the box and having a hard time making the fun things. But no one will see them, so I guess it doesn’t matter. So it’ll just be a box.

B Would you like strategic help? What objects are you looking to make?

H I don’t know. Ok, so I was going to make an alien head because of Space Pussy. A lot of things that are coming to mind don’t actually capture the full spirit of what I want to say. I feel limited by the means of expression.

B OK, OK. Tell me more.

H I don’t know. Maybe because I’m not a very physical artist, but I feel a lack of control about how people would interpret an alien. Like, I’m not trying to say that queer people are aliens. We just like that shit. The event was called Space Pussy and there was like, a cage that people were in. But if I make a cage, it’ll look like I’m trying to say that we are boxing people in. But I’m not. I’m trying to say that they made this cute cage so that they could, like, make out in front of people and like it is so much more expansive than I can capture. And yeah, I’m having a lot of feelings about it. Because I am just going to hand you a box and no one is going to know all the things I feel about the box and how I feel about queerness and I’m really struggling.

B It doesn’t all have to be fully represented in your piece of work. Clay provides one expression, but conversation provides something else. Is that OK?

H Yeah, I feel better about that. OK, it’s crumbling. That’s a metaphor for something. We’re going to keep it crumbling, cool. But I just feel like squares are not queer, so I had to make it a circle. I made the little alien. That is supposed to be a triangle. This is a little squishy little Caterpillar just for funsies. Maybe I’ll make some glasses because I’m feeling inspired. How do you make a star? You know what, though? There is no color, which feels limiting in some degree based on what I was saying earlier. Like. I can’t dress it up in a way. There seems to be some sort of metaphor in the fact that this whole entire time I’ve been trying to create an enclosed space and it doesn’t want to happen. Maybe that’s the metaphor: the resilience of queer people, especially in terms of visibility. Like, it is trying to be seen. It’s not trying to hide all of my little bits and bobbles. Which feels beautiful, feels like it’s leaving some room for light to get in, but he’s also trying to make that closed off space without any windows that I have experienced over and over again in queer life. You know what, this is a flower. It almost looks like a flower.

B Do you want to make it a flower? What do you envision it looking like?

H Or it could just be that in my mind, we could call it a day. Which, yeah, that’s what’s going to happen. It’s going to be that in my mind and we’re going to cal it a flower.

B A flower cave. What do you think is the queerest color?

H Oh, it’s got to be like yellow, green, purple; the alien colors.

ARIEL SHE/HER

ROBIN SHE|THEY