An assessment framework of public open space and its functions as they relate to resilience

Universitat International de Catalunya (UIC) City Resilience Design & Management

Written by:

Jesslin Gonzales

Jole Lutzu

Judith Catellanos

Kalipi Aluvilu

Katharina Davis

Katie Becker Schmidt

Laureline Lhullier

Roydan Segura

Zhi Xin Hoo

This report has been developed by the students from the 1st edition of the International Master City Resilience Design and Management at the Universitat Internacional de Catalunya, Barcelona, during a two week workshop on the resilience of public open spaces.

The study has benefited from support and feedback provided by Lorenzo Chelleri (Director - Int. Master City Resilience Design and Management) and Wolfgang Haupt (Coordinator - Int. Master City Resilience Design and Management).

The workshop has been supported from the Rockefeller Foundation 100 Resilient Cities Program, the Barcelona Municipality Urban Resilience Unit and BIT Habitat 22@ Barcelona. A special acknowledgment goes to:

Ares Gabàs Masip (Head of the Resilience Department - Barcelona City Council) and her the team; David Martínez (Coordinator of 22@ Commission from BIT Habitat); Braulio Eduardo Morera (Director of Strategy Delivery at 100 Resilient Cities).

Barcelona, February 2019

This report provides a preliminary framework assessment tool that informs practitioners and policy-makers on improving public open space functions in order to effectively implement urban resilience characteristics, with a special consideration given to vulnerable demographics.

In order to better understand the gaps that exist between design and use, the proposed framework explores the linkages between public spaces both design and uses driven functions in relation to urban shocks and stresses. After having identified these functions and shock/stresses relationship, the assessment framework can provide “a profile” of the analyzed public space, by showing (and measuring) which functions are provided, to whom. In order to assess these performances, the assessment could be run testing different people profiles perceptions about these functions, or city practitioners perceptions, and compare therefore all these different perceptions about public space functions to get where the main gaps, strengths or weaknesses are and how to improve the design or use of public spaces maximizing their resilience performances.

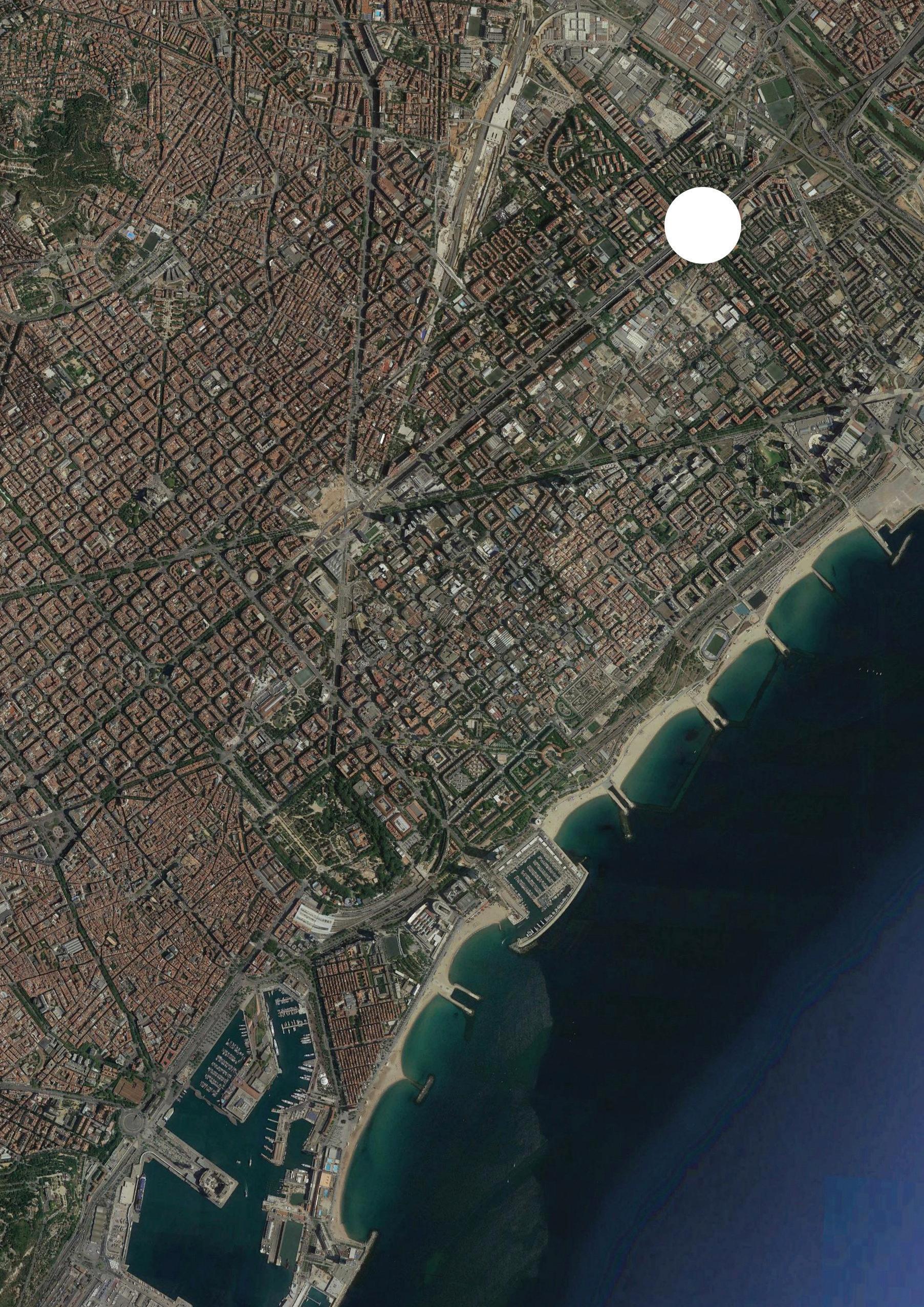

The framework was tested through the evaluation of three case studies in the Barcelona context: Jardins de la Rambla de Sants, La Rambla de Prim, and Joan Miro Parc. Framework testing included desk review of local histories and socio-economic profiles of surrounding neighborhoods of the three public spaces, as well as interviews with park users and urban planning practitioners. The interviews were then mapped to illustrate how different social groups perceive the functions of the public space.

The report measures the benefits provided by public open space functions for the various social profiles across spatial and temporal scales, while considering the synergies and trade-offs that exist within in a specific context.

The analyzed data shows that, in all three cases, the users reported a strong connection between space and social functions. This perception manifested through use of the space for recreation, socialization, and identity. Weak perceptions of environmental and economic functions were observed, presenting an opportunity for focused considerations from designers and policy makers.

Acknowledgments

Executive summary

Introduction

Background

What are public open spaces and why do they matter for cities?

What is resilience and why does it matter for cities?

Linking public open spaces and urban resilience

Methodology and Indicators

Conceptual framework for public open spaces

Case studies: application of the framework

“What defines the character of a city is its public space, not its private space”

- Dr. Joan Clos

Cities have had an increasingly magnetic draw, seeing massive rates of global urbanization starting in the mid-twentieth century. Within the next 20+ years, urban areas, the hubs for social and economic activity, will add an additional 2.5 billion inhabitants. Accelerated urbanization rates will further intensify problems that have plagued cities such as traffic congestions, overcrowding, and air pollution.

Environmental and climatic changes present an additional set of challenging factors including flooding, droughts, heat, sea-level rise and extreme weather events. Barcelona, as a coastal city in an arid region of Spain with an increasing rate of urbanization and tourism, is no exception to these trends.

“What defines the character of a city is its public space, not its private space”, once noted Dr. Joan Clos, the former Executive Director of UN-Habitat. The role of public open spaces and ‘place-making’ as a peoplecentered approach has certainly been rising on the agenda of many urban planners and practitioners. Public open spaces have been recognized as a valuable tool for local economic development, revitalization of neighborhoods and community development.

This working paper proposes that public open spaces play an important role for ever-growing city landscapes and can help manage some of the environmental, economic, and social risks that cities, such as Barcelona, face. We further propose that analyzing public open space through a resilience lens can offer valuable insights for urban resilience building through public open spaces to address the needs, shocks, and stresses of an increasingly urbanized world.

The proposed framework provides a fitting and novel analysis lens to examine the benefits that public open spaces provide, the spatial and temporal scales at which those benefits are realized, and the potential trade-offs among specific functions (i.e. public spaces providing shelter place to sleep for homeless, while decreasing the perception of the spaces safety, or greening an element enhancing resilience to heat waves through the shadow and climate regulation at the expenses of potential gentrification of the surrounding areas because of the land tenure value increase respect to places with no green) or synergies (increase in access/mobility to the spaces fostering functions related to inclusiveness and safety).

Importantly, it also allows us to measure the scale limitations (in terms of impact) that public open spaces have in addressing resilience challenges.

What are Public open spaces and why do they matter for cities?

It is important to make the distinction between general public space and public open space as this framework is designed to apply specifically to public open space. UN-Habitat defines ‘public open space’ as the sum of the built-up areas of cities devoted to streets and boulevards - including walkways, sidewalks, and bicycle lanes, as well as the areas devoted to public parks, squares, recreational green areas, public playgrounds and open areas of public facilities. While public space includes the areas devoted to public facilities - e.g. schools, stadiums, hospitals, airports, waterworks, or military bases - that are not open to the general public. Public open space also does not include open spaces that are in private ownership or vacant lands in private ownership (UN Habitat, 2015).

Cities function in an efficient, equitable, and sustainable manner only when the sum of its complex and multiscalar parts work in a symbiotic relationship to enhance each other. (UN Habitat 2015) In exploring and establishing the link between the quality of the built environment and its value, in health, social, economic and environmental terms, Carmona explains that ‘Place’ is a sociophysical construct. His work confirms the following associations between the quality of place and its place derived value (Carmona, 2019):

that the places in which we live, work, and play will influence, for good or ill, the lives we lead, the opportunities available to us, and our personal and communal happiness, identity and sense of belonging (Speck, 2012; Montgomery, 2013);

that place underpins cultural activities and social opportunities; that place is political, influencing provision of and access to common assets, including to grey, green and social infrastructure (Tonkiss, 2013; Inam, 2014);

that the experience of place is fundamental to our physical and mental health and sense of well-being (Adams and Tiesdell, 2013; Barton, 2017);

that place has an impact on the way we govern ourselves, on our democracy and local decision making, on community togetherness and empowerment (Netto, 2017).

As such, quality (well-designed and maintained) public space, including public open space is critical to the health of any city - in health, social, economic and environmental terms (Carmona 2019).

Fostering resilience in the face of environmental, socioeconomic, and political uncertainty and risk has captured the attention of academics and decision makers across disciplines, sectors, and scales. Resilience priorities have been increasingly focused on cities, often theorized as complex, adaptive systems, because of the particular vulnerability of densely populated, political, economic and cultural centers, the interdependencies of networked infrastructures, and as a result of continued and rapid urbanization.

The complex and dynamic character of urban systems makes a post-disturbance return to a previous status quo highly improbable. Climate change and urbanization will likely exacerbate the already unstable nature of cities. Thus, urban resilience can be understood as operating in a state of non-equilibrium, whereby resilience reflects a system’s capacity to maintain key functions, but not necessarily to return to a prior state.

According to Meerow,

“Urban resilience can be defined as the ability of an urban system, and all its constituent socio-ecological and socio-technical networks across temporal and spatial scales, to maintain or rapidly return to desired functions in the face of a disturbance, to adapt to change and to quickly transform systems that limit current or future adaptive capacity.” (Meerow, 2016)

(see Appendix B for development of urban resilience definitions)

Climate change is one of many types of shocks and stresses that cities face, and climate change-related shocks typically occur in combination with other environmental, economic, and political stresses. As Leichenko states, promotion of urban resilience to climate change will thus require that cities become resilient to a wider range of overlapping and interacting shocks and stresses (Leichenko, 2011). Efforts to build resilience should focus on transforming systems that are inequitable (e.g., poverty traps) or hinder individuals or communities from developing adaptive capacity.

Addressing resilience for cities is more than identifying and acting on specific climate change impacts. It looks at the performance of each city’s complex and interconnected infrastructure and institutional systems, including interdependence between multiple sectors, levels, and risks in a dynamic physical, economic, institutional, and socio-political environment (Kirshen et al., 2008; Gasper et al., 2011). Public open spaces are examples of dynamic, connected, and open (micro-scale) systems within the complex adaptive urban environment. They represent key elements of successful resilient cities as they help build a sense of community, local culture, economy, and identity, while offering direct responses to climate issues. Polko shows that debates about urban public spaces are multidimensional and multi-objective, focusing on design, environmental, social, economic and political aspects (Polko, 2012).

Meerow et al show that enacting urban resilience is inevitably a contested process in which diverse stakeholders are involved and their motivations, power dynamics, and trade-offs play out across spatial and temporal scales. Therefore, resilience for whom, what, when, where, and why needs to be carefully considered (Meerow et al, 2016).

As such, linking public open space to resilience provides a fitting and novel analysis lens to examine the benefits that public open spaces provide, the spatial and temporal scales at which those benefits are realized and the trade-offs and synergies that exist in making and experiencing these spaces. Importantly, it also allows us to measure the scale limitations (in terms of impact) that public open spaces have in addressing resilience challenges.

Previous attempts to extend the resilience concept to cities (Polko, 2012) and invariably to public spaces, faced a number of challenges. First, due to the complex and multiscale character of cities, resilience has to incorporate many socio-economic aspects, such as human perception, interaction or governance. Second, the current theoretical concept is related to the weak links between social and economic dynamics, governance issue, environmental aspects, land-use patterns and the built environment (Müller, 2011). Our framework builds on these insights.

There is currently no assessment tool that informs architects, urban planners, and policy-makers in the evaluation or design of public open spaces and their ability to foster resilience. This working paper creates a preliminary framework to examine the benefits that public open space provide, the spatial and temporal scales at which those benefits are realized, and the trade-offs and synergies that exist in making and experiencing these spaces. The framework was subsequently operationalized, putting it to test at three public open spaces in Barcelona. The following sections briefly describe the methodology in selecting functions and resilience challenges, analyzing synergies & tradeoffs, interviewing public open space patrons, and designing the perception wheel that visually articulates the framework findings.

The framework was developed through a literature review drawing on relevant research on public open spaces and resilience. The findings informed the identification of key public open space functions and their categories, as well as resilience challenges and their categories. The functions (see Appendix C for function definitions) and challenges serve as the foundation for the ‘public open space perception wheels’, which map users’ and practitioners’ perception of how the functions of a public space enhance or impede the city’s resilience goals.

The framework was then tested through case studies on three public open spaces in Barcelona; that is Jardins de la Rambla de Sants, La Rambla de Prim, and Joan Miro Parc, which were selected to reflect Barcelona’s diversity in topological makeup, risks/ hazards, and socio-economic neighborhood profiles. A series of interviews were conducted as part of the spacial analysis in order to gather user perceptions on open public space functions. The interviews were then mapped using ‘public open space perception wheels’ to illustrate how different social groups and urban practitioners perceive the functions of the public space. This exercise was carried out to inform the designer and policy maker on linkages between built environment and urban resilience challenges.

These efforts resulted in a new conceptual framework that integrates good practices for public open space planning with critical elements from the resilience approach.

The initial literature review focused on the available and commonly cited white and gray studies that covered three strands of literature: (1) exploring the functions, place value, place quality, characteristics and benefits of public open space, including urban public spaces; (2) defining the link between public open space functions and resilience challenges; (3) determining the stresses & shocks that impact cities around the world.

An examination of literature on public open spaces exposed a lack of sufficient research supporting the link between the functions of public open spaces and their impacts on resilience challenges, inconsistencies in the object of measurement (e.g. definition of function, value, or benefits etc), and overlaps in measured spatial scales (e.g. public space or urban space).

Literature explored the functions, qualities, values, benefits, and characteristics of public open spaces. Building on (1) “public space development in the context of urban and regional resilience” (Polko, 2012) which provides an econometric lens on public space planning, (2) “Place value: place quality and its impact on health, social, economic and environmental outcomes” (Carmona, 2018), and (3) The Project for Public Spaces organization “What makes a successful place”, the following inclusion and exclusion criteria for this framework’s public open space functions we developed:

Does this indicator apply to public open space?

Is this indicator applicable to the scale of public open space (vs. urban areas)?

Is this indicator a function of public open space, or just a characteristic or solution?

This criteria iteratively reduced the long list of potential indicators to one of twelve key functions. The functions were then separated into three categories: economic, social, and environmental. These categories are based on features that together define the character of the public space: (1) The range of socio/economic and physical/spatial contexts – or the ‘context for action’ and (2) The key elements that constitute public space – in other words, the ‘kit of parts’ (Carmona, 2008).

access & mobility natural hazard response manmade hazard response diversity

A well designed, green, safe, and accessible public space could support reducing risks from both natural distress, such as floods and fires, and economic activities, such as industrial noise or air pollution (Polko, 2012).

During times of shock, public spaces play a crucial role, where previously private goods are offered for public provision. For instance, during a long drought period, people will use public swimming pools instead of private pools to save water, or reallocate swimming services within still operating private pools as a commons. Public spaces can also become main places for people to convene and help each other during or after disasters or organize themselves to face the threat (Polko, 2012).

ECONOMIC functions:

property uplift connectivity

Public spaces can assume key roles as they can encourage exchanging, and act like “the place of exchanges” (Ozel, 2014).

Public spaces can also play a substantial role in raising self-sufficiency for food and other critical items (Bilge, 2014) and productivity. Public spaces can spur higher economic productivity, and enable higher density development and more efficient land use (Carmona, 2018).

In terms of property uplift, a city can enhance its resilience if it can diversify its economic development. F.ex. The post-industrial city of Bilbao managed to reinvent itself as a cultural center by transforming its urban public spaces through “flagship” projects (Polko, 2012).

SOCIAL functions:

identity

physical & mental comfort

safety & security cohesion & inclusiveness

physical & mental health education

Public space could support civic engagement and social inclusion, build mutual trust between different groups of society and reducing social stratification. A high degree of resilience can be built through exercise and recreation which could play a role in driving forces for individual development which can reduce the risk of getting involved in societal issues such as crimes and drugs (Polko, 2012).

The next strand of literature focused on key resilience challenges that can be addressed by public open spaces. According to Müller (2011), one must distinguish between shocks and “slow burns”, which are typical for systems undergoing transformation. The 100 Resilient Cities shocks and stresses list is the basis of the resilience challenge indicators for this public open space framework. As the indicators had been identified and defined by local stakeholders representing the 100 Resilient Cities members, the indicators are subjective and localized and may need to be altered to fit local context.

The following selection (and exclusion) criteria for this framework’s resilience challenges are:

Does this indicator apply to public open space?

Is this indicator applicable to the scale of public open space (vs. urban areas)?

This criteria iteratively reduced the long list of potential indicators to a list of thirty key resilience challenges, which were then categorized across environmental & climate, social, urban, and economic categories. The categories were developed using the work of Meerow on defining urban resilience (Meerow et al. 2016).

The list of public open space functions and the list of public open space resilience challenges were combined to create a matrix that allows practitioners to visualize how various public open space functions can contribute to resilience building. public open space functions - resilience matrix

CATEGORY FUNCTIONS

MOBILITY

IDENTITY

PHYSICAL & MENTAL COMFORT

SAFETY & SECURITY

COHESION & INCLUSIVENESS

PHYSICAL & MENTAL HEALTH

EDUCATION

PROPERTY UPLIFT

CONNECTIVITY

Landslide

Hazardous material accidents

Gender inequality

Ethnic inequality

Displaced populations // immigrants Population growth // over population

Crime or violence

Drug or alcohol abuse

Aging population Youth disinfranchisement Urban blight

Aging infrastructure Uncontrolled urban development

Traffic congestion Energy insecurity Infrastructure failure Unemployment Homelessness

Declining population // human capital flight Undiversified economy Lack of investment

With public open spaces serving multiple functions, there is the possibility that one function enhances (synergy) or inhibits the performances (trade-off) of other functions. In regards to scale, this framework specifically explores synergies and trade-offs of functions within the realm of public open space. However, it is understood that the “cause” of the synergy or trade-off occurs at the public open space in question, but the “affect” may be felt at various scales including the public open space itself, the surrounding neighborhood, or even the urban fabric at large.

“Fuzzy Cognitive Mapping (FCM)” was used as a tool to explore possible trade-offs and synergies between functions. At the current stage, trade-offs and synergies between functions and resilience are not discussed in great extent, due to their complexities, and will need further exploration. However, there are some prominent examples that increasing certain functions lead to trade-offs in resilience challenges, i.e.: property uplift may lead to gentrification in neighborhoods which possibly causes homelessness, declining population or human flight. This has, in turn, adverse effects on the resilience of urban communities.

&

PHYSICAL & MENTAL

SAFETY & SECURITY

COHESION & INCLUSIVENESS

PHYSICAL & MENTAL EDUCATION

PROPERTY UPLIFT CONNECTIVITY / / / / / /

The figure on the next page shows the globally applicable framework tool, represented as a perception wheel. The first iteration of the framework consists of three function categories that include twelve functions as well as four resilience challenge categories that include thirty stresses & shocks. The public open space perception wheel evaluates how the public open space is utilized from user and practitioner perspectives, addressing not only what functions are being met within the space, but also for whom.

The perception of X user group towards the presence of Y function is documented and visualized by the shaded sectors of each sector in the wheel. The four layers in each function sector, radiating outwards, indicate how frequently the performance was perceived; 25%, 50%, 75% or 100% (see figure below). The functions-resilience challenges matrix and the synergies and trade offs matrix are also used with the wheels, further assessing which resilience challenges are met through the functions of the public open space.

The aim is to provide valuable insight on the benefits and shortcomings of the public open space as it pertains to resilience, guiding future design.

Interviews are carried out among the most vulnerable social profiles to obtain their perceptions towards the open space (e.g. youth, women, elderly and disabled users). Those individual user perceptions are aggregated and visualized accordingly on the wheel.

By aggregating the results of different user groups, a overall user perception wheel of a particular public open space is produced.

The wheel is also intended to integrate perceptions from practitioners including architects, urban planners, landscape designers, engineers, and environmentalists. The practitioners’ wheel may account for certain functions that may be overlooked by the general public such as infrastructural presence of a retention basin.

The final wheel, shown above, integrates the perception of both users and practitioners, serving as a comprehensive tool to represent the functionality of the public open space in terms of resilience.

02 Rambla de prim, la mina

03 PARC JOAN miro, eixample

Barcelona has long been an exemplary model for its urban development, constantly rethinking and evolving its approach in order to transform its urban space and everyday life of its citizens. This has resulted in a variation of public open space, with purposes of openair activities, strengthening relationships with nature or urban environment and surrounding architecture, acknowledging the city as a place of collective life and a monument to be preserved, as well as conserving its collective history. Spaces such as these, have resulted in developing a remarkable urban quality.

Field studies were conducted, as part of the space analysis, in order to gather user perceptions on public open space functions. This exercise was carried out to inform the designer and policy maker on linkages between built environment and urban resilience challenges. This research, concerned with promoting inclusive spaces and reducing vulnerability, identified four social profiles in the most need of consideration (elders, handicap, women, and children).

These demographics were identified by the City of Barcelona as the most vulnerable. Researchers carried out the field study on three different open spaces with the target of interviewing the four most vulnerable social profiles.

The spaces included Jardins de La Rambla de Sants, Rambla del Prim in La Mina neighborhood, and Parque Joan Miro in Eixample.

These spaces were selected to represent varying public open space typologies and socio-economic neighborhoods. The surveys were conducted during the afternoons of Friday 8th & Saturday 9th 2019.

Interview questions were designed to uncover the functions that attracted these users to the space, determine which functions are perceived as missing and if there was an understanding of a linkage between public space and reducing risk to climate change stresses and shocks. The questions were simplified for the brevity of the interview and to avoid leading the interviewee into biased answers. Three questions were designed to uncover the user perceptions.

Results of the survey are presented in the findings part of this section.

demographics of survey participants:

Jardins de La Rambla, Sants

Rambla de Prim, La Mina

Parque Joan Miro, Eixample

Gender: 56% of the participants were Female and 44% were Male

Social Profiles: 28% Youth, 34% Women, 25 % Elderly, 13% Handicap

Gender: 52% of the participants were Female and 48% were Male Social Profiles: 18% Youth, 52% Women, 20% Elderly, 9.5% Handicap

Gender: 53% of the participants were female and 47% were male Social Profiles: 21.6% Youth, 37.8% Women, 27% Elderly, 13.5% Handicap

1. 2.

3. What brings you here?

What would you improve in this space?

Regarding the hotter summers and heavier rains, what can this space provide you?

The neighborhood of Sants is known to be one of the most vibrant working-class areas of Barcelona, by the time the original small village grew and was annexed by the city of Barcelona in the 19th century, it had flourished into one of the most industrialized areas of the city. Along with the historical industrialization, Sants was the epicenter for social movements such as Catalan anarchosyndicalism and simultaneously developed a strong cooperative movement.

As a result of the neighborhood being home to some of the most important Spanish manufactures, one dominant driver of the way Sants’ urban fabric developed, was a network of important roads and railways that served as the south entrance to the city of Barcelona.

One of the big urban renewal projects, of the 1980’s, included the tearing down of defunct industrial buildings in order to create public parks. Resulting in unconventional landscapes and projects such as Parc de l’Espanya and Parc de l’Excorxador.

The most recent urban project, Jardins de las Ramblas de Sants, in construction from 2006 to 2016, is an incredible addition to the process of urban transformation in the neighborhood. Where there was once train and metro tracks dividing the neighborhood into two practically unconnected part, which had led to urban defects, in terms of noise pollution and a deterioration of the surrounding areas, you now find an 800-metre-long raised and landscaped boulevard.

identity:

Name Location

Construction

Architect

Size

Particularities

Materials:

Jardins de Rambla de Sants

Barcelona Sant, Carrer del Rector Triado

2016

Sergi Godia, Ana Molino Arquitects

48 400 m2

Linear park

analysis of the public open space

The support structure for the construction is a container made of prefabricated concrete sections in a diagonal sequence that imitates the form of a Warren truss, recalling images of old train bridges.

The structure creates large triangular open spaces that are closed in with glass, preserving the views of the trains through the city, while reducing noise to a maximum. Large planted slopes from the lowest-lying surrounding areas, which rise up to the roof level. These slopes “anchor” the building to its surroundings, allowing for the plant life from the roof to spill down onto the side streets, and they support pedestrian ramps that provide a “natural” access to the roof.

The project’s objectives also include the incorporation of the improvement of the transverse pedestrian permeability by building adapted routes – with ramps, lifts and escalators – as well as the improvement of the environmental conditions in the district against noise and vibration.

The layout of slopes and pedestrian paths allows the creation of a quality urban space in which the central axis is perceived as a wide green avenue on the roof of the railway corridor, converting this degraded space into a central focus for the Sants district, a large green corridor that connects the resulting free spaces in the railway area both longitudinally and transversely.

TYPOLOGY:

Urban elements Green space Recreation Services

Large pergolas, photovoltaic panels

High density of trees, shrubs , ground cover

Playground, exercise stations, café/Bar, gathering area

Elevators, adapted ramps, stairways, escalators

Uses:

Young perception wheel

Woman perception wheel

Elderly perception wheel

Disabled perception wheel

Aggregated user perspective wheel

Social functions were by far the most predominant user perceived public open space functions in our analysis, of Jardins de la Rambla de Sants. Identity, such as the sense of pride and belonging to the place was very evident. As well as all activities related to Physical and Mental Health, such as walking, exercising and even mundane actions like enjoying the sun on a Saturday afternoon. Targeted social profiles also addressed actions related to comfort, cohesion, and inclusiveness.

As demonstrated by the overall aggregated wheel, there was a severe lack of functions falling under Safety and Security. Throughout the interviews, women specifically mentioned the need for better solutions in order to feel safer in early mornings or late at night.

Practitioner perspective wheel

Regarding environmental functions, Accessibility & Mobility is particularly important in this context, considering one of the main objectives of this urban renewal project was to connect two different parts of the neighborhood that had been previously divided by the railways. This function, developed as a design solution, showed to be very successful as it was one of the first functions mentioned by users, specifically community locals. In contrast, to other types of environmental or economic functions which were generally less perceived.

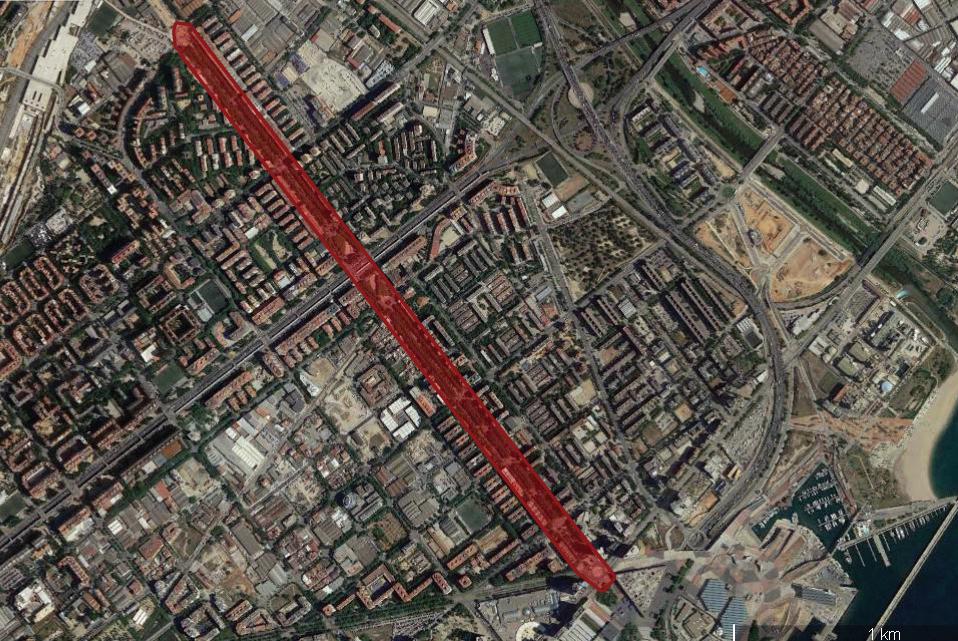

La Rambla del Prim, inaugurated in 1992 and located 6km northeast from La Rambla de Barcelona, cross-cuts and defines a long narrow neighborhood known as El Besos i El Maresme. The rambla stretches 2.7km from The Forum Park to a rail line at the north.

Once primarily used for agriculture, the area was irrigated by the two small tributaries of the Besos river known as la Horta. The river was then converted into a street that separated the neighborhoods of Besòs and Maresme.

Mass migration primarily from Andalusia in the mid20th century led to the rapid, unplanned development of the neighborhoods flanking the La Rambla De Prim, resulted in a lack of facilities and public services as well as common use of low grade construction materials. The latter resulted in degradation of the area in structural quality and appearance.

However, major revitalization efforts including the Centre Civil de Besos in 1993, the Parc del Forum and its Barcelona Museum of Natural Sciences in 2004, and the Platak de Llevant in 2006, marked a drastic transformation in the neighborhood. The Rambla de Prim now acts as a tree lined, sun-shaded walkable artery, connecting citizens to the numerous urban developments along its path.

identity:

Name Situation

Construction Context Size

Particularities

material:

Originally named «La Horta»

Walking avenue built over a small river

Built on the former agricultural lands irrigated by the river

Affordable housing built in 50s/60s for southern Spanish immigrants

2.7km walking avenue spanning 7 city blocks from Forum Park to Diagonal del Mar

Residential walking avenue with minimal commercialization and tourism

of the public open space

The Rambla de Prim is divided into three distinct segments, South, Central and North. The southernmost block begins at a traffic laden roundabout, which acts as an access barrier to the Forum Park. The adjacent neighborhood is currently undertaking major construction projects of modern high rise buildings, servicing the influx of visitors arriving for the events.

The next three blocks are densely populated by a diversity of trees and bushes, raised grass pitches that act as a barrier from the traffic, and expansive gathering spaces where the street intersections have been converted for walking. This neighborhood shows signs of urban decay and little has been invested to modernize the buildings. However, this was the most verdant and utilized section of the Rambla de Prim. The last two blocks before the highway include a playground, skate park and a fountain.

The intersection of the highway with the Rambla de Prim marks a definitive transition in the typology of the walking avenue. The two blocks following the highway mirror the playground and fountain of the southside, but the neighborhood begins to show signs of development and modernization. Here in the northern blocks the diversity of green coverage and physical separation from the streets wanes and disappears. The shops and cars become part of the walking avenue as the barrier feature has been lost in the absence of the raised grass beds and columns of bushes lining the outer edge of the southern rambla. The northernmost block is under construction for the addition of two playgrounds, and the completion of pavement for the walking street. The Rambla de Prim abruptly ends at this unfinished space and is cut off from further development by the rail lines.

TYPOLOGY:

Urban elements Green space Recreation Services

Water fountains, benches, sculptures, amphitheater seating, street lights

Trees, shrubs, raised grass beds

Playgrounds, skatepark, walking path

Walkway, through-way, gathering space

uses:

San-Marti district

interviewee demographics:

San-Marti district

Young perception wheel

Woman perception wheel

Elderly perception wheel

Disabled perception wheel

Aggregated user perspective wheel

In Rambla de Prim the social functions of a public open space account for the largest perceived functional dimension by the users. The functions of Cohesion and Inclusiveness and Physical Mental Health, were the most cited function and were expressed by users intentionally seeking the space for social interactions and access to sun and fresh air. Comfort and Identity were also functions that related to the recreational use of the avenue. Within the social functions the aggregated perception wheel highlights a lack of safety and security and the educational function.

Practitioner perspective wheel

IDENTITY COMFORT

The following dimensions of the wheels highlight perception gaps of economic and environmental functions. Within the economical functions dimension of the Rambla de Prim Connectivity was acknowledged to a low degree, as the space was used for workers on break, and bicycle couriers passing through .The environmental functions of Accessibility & Mobility of the Rambla are acknowledged by the users, while The Natural Hazard Response function is not recognized.

The neighborhood of the Eixample has been constructed between the old city (Ciutat Vella) and what were once surrounding small towns (Sants, Gràcia, Sant Andreu etc.) in the 19th and early 20th centuries. It is characterized by long straight streets, a strict grid pattern crossed by wide avenues, and square blocks with chamfered corners.

Behind ‘’Las Arenas’’, the bullring of Barcelona, the parc Joan Miro occupies four blocs of the urban grid of the the Eixample neighborhood designed by Ildefons Cerda. With the arrival of democracy, a policy designed to create more green areas was set up. Many areas occupied by obsolete installations were converted into parks. Situated on the site of the old slaughterhouse of the city it is also called is also called “Park of the Escorxador”. This is the first large urban park of the post-Franco period in Barcelona.

The project was the work of the architects Antoni Solanas, Màrius Quintana, Beth Galí and Andreu Arriola, and was inaugurated on May 12, 1983. The park is dedicated to Joan Miro, a famous surrealist artist of Barcelona. One of its most famous sculpture, Dona I Ocell, or the woman and the bird, takes place in the heart of the park.

In 2006, a remodeling was carried out by Beth Galí, Jaume Benavent, Andrés Rodríguez and Rüdiger Würth, in which a parking lot and an underground water tank were built, and the roof was adapted as a green area.

identity:

Name

Situation

Construction

Context

Architect

Size

Particularities

MATERIAL:

Original name ‘‘Parc l’Escorxador’’

Southwestern edge of the Eixample Esquerra Barrio

On the former plot of the municipal slaughterhouse,dismantled in 1979

1st urban park of the post-Franco period

Architect Beth Gali

2 blocs of Eixample _ 47 100m2

Joan Miro sculpture (1982) mosaic breakthrough

Aim to address new social needs

analysis of the public open space

The park has two distinct areas: a large square at street level, and the park itself, located on a lower level, with shady trails of pergolas with climbing plants, and a grove of Mediterranean trees mainly populated with pines, poplars, palms and oaks, planted symmetrically.

Next to the street Vilamarí there is a pond in whose center is the Joan Miró Library, which has a curious door formed by two steel doors in the shape of children walking, which bears the name of School and was designed by the architects of the park .

TYPOLOGY:

Few lights, benches, statue

Mediterranean trees

Garden square of expanse of grass

Playground, basketball court & Pétanque areas

Free WIFI transmitter, “off lead” area for dogs

Car park and rainwater tank underground

Library surrounded by water

2 open-air snack bars

uses:

district demographics:

Eixample neighborhood

interviewee demographics:

various origins | various social classes | all ages

Young perception wheel

Elderly perception wheel

Woman perception wheel

Aggregated user perspective wheel

In Joan Miro Park the social functions of a public space are largely perceived by the users. Identity, Comfort, Cohesion and Inclusiveness, and Physical and Mental Health are the most filled function of the Park. The aggregated perception wheel shows though a lack of safety and security.

The economic functions of the Joan Miro Park is not perceived whereas it exists from an objective view.

Practitioner perspective wheel

IDENTITY COMFORT

Regarding the environmental functions. Accessibility & Mobility and Diversity of the Park are acknowledged by the users.

Though whereas the water tank plays a crucial role to prevent flooding, the Natural Hazard Response function is not recognized by the users. Awareness campaigned could help the public to understand the importance of the Park for the neighborhood when flash floods happen.

The conceptual framework was developed to map how the spatial functions of public open space impact resilience challenges. This framework, incorporating many socio-economic aspects, such as human perception, interaction or governance, offers the opportunity for practitioners to make strategic use of public open space to enhance resilience across the city.

The application of the framework to three case studies in Barcelona offered interesting, preliminary results .

Operationalization of the framework also revealed some of the limitations of the model.

The first iteration of the framework, which consists of three function categories that include twelve functions as well as four resilience challenge categories that include thirty stresses & shocks, may need to be further refined with a more extensive literature review. A preliminary scan indicated that linkages between public open space and resilience challenges have not yet received much scholarly attention.

Improved sampling could significantly improve the validity of the perception results. Whereas interview sampling was limited to a few days, more extensive field research should be carried out based on the time, day, week and season. Another limiting factor was the limited understanding of climate change by parc users, even when the questions were framed in terms of weather impact rather than climate change. Trust and proper report with the interview candidates are also difficult to establish. Perhaps the framing of the questions and interview techniques could be refined.

Determining the appropriate scale for the function of public urban spaces posed another challenge for the analysis. Future research can further refine whether the functions and resilience challenges shall be considered at the scale of the public open space or the urban area. This is largely a question of the perceived/expected impact of functions on resilience in the respective urban area. Additionally, the identification and aggregation of functions most relevant to the wheel posed a challenge as the many functions were difficult to prioritize.

Moving forward, once the conceptual framework tools have been refined and passed the ‘proof-ofconcept’ stage, the tools could be consolidated into a more user-friendly, interactive digital application. Additional parameters, such as vulnerability factors based on geographical context using GIS or demographics data, could be incorporated to make it a context-sensitive and hence a more comprehensive and holistic tool. Possible synergies and trade offs could be visualized according to their impacts on public open space to ease in decision making process.

Folke, Carl. “Resilience: The emergence of a perspective for social–ecological systems analyses.” Global environmental change 16.3 (2006): 253-267.

Meerow, Sara, Joshua P. Newell, and Melissa Stults. “Defining urban resilience: A review.” Landscape and urban planning 147 (2016): 38-49.

Carmona, Matthew. “Place value: place quality and its impact on health, social, economic and environmental outcomes.” Journal of Urban Design 24.1 (2019): 1-48.

Davoudi, S., Shaw, K., Haider, L. J., Quinlan, A. E., Peterson, G. D., Wilkinson, C., et al. (2012) Resilience: A bridging concept or a dead end? “Reframing” resilience: Challenges for planning theory and practice interacting traps: Resilience assessment of a pasture management system in Northern Afghanistan Urban resilience: What does it mean in planning practice? Resilience as a useful concept for climate change adaptation? The politics of resilience for planning:A cautionary note. Planning Theory & Practice, 13(2), 299–333

Leichenko, R. (2011). Climate change and urban resilience. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability, 3(3), 164–168.

Helen Pineo, Nici Zimmermann, Ellie Cosgrave, Robert W. Aldridge, Michele Acuto & Harry Rutter (2018) Promoting a healthy cities agenda through indicators: development of a global urban environment and health index, Cities & Health, 2:1,27-45, DOI: 10.1080/23748834.2018.1429180

Briggs, D.J., 1999. Environmental health indicators: framework and methodologies. Geneva: World Health Organisation. [Google Scholar]

Innes, J.E. and Booher, D.E., 2000. Indicators for Sustainable Communities: A Strategy Building on Complexity Theory and Distributed Intelligence. Planning Theory & Practice, 1 (2), 173–186.[Taylor & Francis Online], , [Google Scholar]

Balsas, C.J.L., 2004. Measuring the livability of an urban centre: an exploratory study of key performance indicators. Planning Practice & Research, 19 (1), 101–110.[Taylor & Francis Online], [Google Scholar]

Greenwood, T., 2008. Bridging the divide between community indicators and government performance measurement. National Civic Review, 97 (1), 55–59.[Crossref], [Google Scholar]

Pencheon, D., 2008. The Good Indicators Guide: Understanding how to use and choose indicators. Coventry: NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. [Google Scholar]

Lowe, M., et al., 2015. Planning Healthy, Liveable and Sustainable Cities: How Can Indicators Inform Policy? Urban Policy and Research, 33 (2), 131–144.[Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar])

R.R.J.C Jayakody , D. Amarathunga and R. Haigh. (2016). The use of public open spaces for disaster resilient urban cities.

ÖZEL, B. (2014). Rethinking the role of public spaces for urban resilience: case study of eco-village in Cenaia.

Heterogeneity in the usage of the concept of resilience is partly rooted in the differing intellectual origins and lineages of the different research traditions, but diversity of interpretation is also noteworthy within each of the subgroups described below:

Holling used resilience to describe the ability of an ecological system to continue functioning—or to “persist”—when changed, but not necessarily to remain the same. Non-equilibrium resilience sparked a rich body of work at the socio-ecological interface (Folke, 2006). Holling definition was the starting point from which the social-ecological resilience perspective has developed and fits with the dynamics of complex adaptive system. A complex adaptive system consists of heterogeneous collections of individual agents that interact locally, and evolve in their genetics, behaviors. Biological diversity is essential in the self- organizing ability of complex adaptive system both in terms of absorbing disturbance and in regenerating and reorganizing the system following disturbance.

Extreme climate events and gradual climatic changes are regarded as shocks or stressors (fast or slow moving variables) that affect cities and urban networks. Climate change is one of many types of shocks and stresses that cities face, and climate change-related shocks typically occur in combination with other environmental, economic, and political stresses. As Leichenko states, promotion of urban resilience to climate change will thus require that cities become resilient to a wider range of overlapping and interacting shocks and stresses.

Although resilience can be measured in many different ways, some key characteristics of resilient cities, populations, neighborhoods, and systems include: diversity, flexibility, adaptive governance, and capacity for learning and innovation. In order to contribute to long-term urban sustainability, efforts to promote urban resilience to climate change, including both adaptation and mitigation strategies, need to be bundled with broader development policies and plans.

(Leichenko, 2011)

Turning a crisis into an opportunity requires a great deal of preparedness which in turn depends on the capacity to imagine alternative futures: just such a capacity which does, or ought to, define planning in broad terms. For Davoudi, planning is thus about being prepared for innovative transformation at times of change and in the face of inherent uncertainties put the emphasis on “fluidity, reflexivity, contingency, connectivity, multiplicity and polyvocality”. In this sense, resilience discourages fixity and rigidity in the same way as interpretive planning discourages the modernist “will to order. It recognizes the ubiquity of change, inherent uncertainties, and the potential for novelty and surprise, while advocating the exploration of the unknown and the search for transformation. (Davoudi, 2012)

This literature focuses on questions of how different types of institutional arrangements affect the resilience of local environments and how resilience thinking can influence the development of improved governance mechanisms for promoting adaptation to climate change, such as new types of social contracts and community-based adaptation efforts. Some of the many characteristics of urban governance that are identified as promoting resilience include: polycentricity, transparency and accountability, flexibility, and inclusiveness. But rather than prescribing a single ‘best practice’ arrangement, the governance literature advocates a diversity of approaches, suggesting that effective institutional arrangements take many different forms.

Emphasis is placed on enhancing the capacity of cities, infrastructure systems, and urban populations and communities to quickly and effectively recover from both natural and human-made hazards. Other hazard resilience studies develop models of community resilience based on a wide range of quantitative indicators or measure variations in resilience of towns within specific regions based on characteristics of households. Recent studies also identify mechanisms and strategies to increase hazard resilience of poor urban communities in developing world cities.

CATEGORY FUNCTIONS DE F I NI TI O NS

ACCESS & MOBILITY

Accessible for less mobile, good signposting, access by foot, adequate parking, adequate public transport

Opportunities for walking; reduced car traffic and supports more pedestrian activities

Easy to gain access to and move around in; urban spaces that are available for use all the time

Minimize the use of energy (for transportation) and maximize use of local labour, by implementing new urbanism principles, such as walkability, connectivity, mixed-uses and diversity, increased density, green transport and so on ...open spaces and streets with an objectives to provide safe assembly spaces, to provide the basic emergency services and utilities, such as first aids, fresh water, electricity, and communication and to become visually improved points with an improved way finders even in night time.

The most common way to protect the flood prone areas from land encroachment and to control the future development, is keeping flood-prone areas for open space purposes.

These preserved tsunami hazard areas through the development setbacks, can be potentially used for open-space uses and confine the uses to conservation, open-space, or scenic easement.

MANMADE

HAZARD

RESPONSE

Disadvantages caused by human activities. such as industrial noise and air pollution

DIVERSITY Supporting a greater diversity of species and a greener built environment.

IDENTITY An increased sense of pride, local morale, social resilience and community life, and enhanced social capital (social and political engagement) generally.

COMFORT

SAFETY & SECURITY

NATURAL HAZARD RESPONSE ECONOMIC

COHESION & INCLUSIVENESS

PHYSICAL & MENTAL HEALTH

EDUCATION

PROPERTY

UPLIFT

CONNECTIVITY

Better-maintained benches, shelters, public toilets, green, well kept and attractive, confident and safe, walkable space, good street lighting, police on the street, adequate parking and signage, traffic calming

Reduced airpollution, heat stress, traffic noise and poor sanitation, and reduced exposure of lower socio-economic groups to the effects of debilitating neighbourhoods.

Perception of personal security, child physical safety, Freedom from intimidation, A well cared for place – looks safe, Low level disorder is acceptable (e.g. drunkenness), Visible police presence

Reduced burglary from homes, lower street crime,less fear of crime, and stronger perceptions of safety.

Feeling of safety and security both physically and psychologically. Protection from traffic, crime, and unpleasant encounters Civic engagement and social inclusion

Mutual trust between different groups of society

Reducing social stratification and willingness to live in gated-communities

Activities of institutions as place and scenery of cultural, educational, political and other social events.

Provides a venue for social events, social interchange and for supporting the social life of communities

Reduce incidents of crime and anti-social behaviour

Adequate facilities for teenagers, Tolerant of minority groups, Welcoming to all users

Reduced stratification and greater integration of social groups and larger social networks locally, with stronger social support. Inviting, welcoming to all users, free, and open. Urban spaces that encourage a diversity of users and activities.

Lower obesity, less type 2diabetes, lower blood pressure, reduced heart disease, lower rates of asthma and respiratory disease, faster recovery from illness, and from fatigue.

Increased walking (for both travel and recreation), increased exercise, sport and recreation, and more cycling.

Less stress and more psychological restfulness, reduced depression, anxiety and anger, reduced psychosis.

Delivers learning benefits to children, creative play, and reduces absenteeism

Increased child independence and positive play behaviours, and enhanced learning and educational achievement.

Influenced by access to views, trees and open space, lower pollution, mixed use (up to a point and as long as homes are not too close to retail), walkability, neighbourhood character, access to public transport (if not too close to homes).

Influenced by urban greenery, walkability, public realm quality, external appearance, street connectivity, frontage continuity; all leading to increased retail viability.

Influenced by walkability, external appearance, design innovation and street connectivity.

with local facilities, amenities and employment opportunities reducing the need to travel further afield and supporting local economic and social resilience.

Strengthening linkages between producers, consumers and a city, taking advantages from urban public spaces, they are more conscious of risk, more responsible for a place.