October 2023

October 2023

The global interest-rate hiking cycle is drawing to an end. In the months ahead, the task at hand for central banks is to study the effects of the tightened monetary policy in real time and to readjust it if necessary. Meanwhile, the government of China is striving to fine-tune its economic stimulus measures. Its efforts are likely to at least stabilize China’s GDP growth close to the +5% target.

The US Federal Reserve is attempting to engineer a soft landing, but the Democratic Party, too, is hoping that America’s economy doesn’t falter too much in the quarters ahead when the US presidential election campaign enters the home stretch. That would hurt Joe Biden’s chances of getting reelected. The Republicans therefore will probably try to throw as much sand as possible in the gears of the US economic engine.

Yields on fixed-income markets have risen to new highs in recent weeks. Bond bulls were caught on the wrong foot by this turn of events, but they shouldn’t bury their heads in the sand because the higher that yields climb going forward, the more asymmetrical bonds’ risk/reward profiles become. Stocks have become even

more unattractive than before relative to bonds, but this doesn’t necessarily stand in the way of a year-end equity rally. Window dressing could give another boost particularly to the big US tech stocks in the fourth quarter.

In the fight against inflation, today’s generation of central bankers is entering uncharted territory. The Great Inflation of the 1970s provides illustrative historical visual aids to go by, but the current rate-hiking cycle nonetheless is truly a novelty. It is akin to an experiment in real time with an uncertain outcome. Investors would be well advised not to place too much trust in central banks’ maneuverability.

Sustainability ratings are increasingly affecting capital flows on financial markets and influencing corporate conduct. Less publicized, though, is the fact that ESG ratings from different providers diverge from each other substantially sometimes, making the fundament for investor or managerial decisions and the basis of many academic studies confusing and vague. The sustainability industry is still in its infancy with regard to its information base.

There was another beer-sloshing celebration this year at the world’s biggest public festival. In any event, the renewed increase in the price of beer at the Oktoberfest didn’t turn out to be a fun killer. Even so, though, a 1-liter stein of beer, or actually usually much less than that (plus a big head of foam), cost a frothy EUR 13.75 on average this year. At an increase of 4.2% compared to the prior year, beer price inflation this time around was lower than the general inflation level for once, making beer relatively more affordable for the first time. Over the long term, though, inflation at the Oktoberfest has been exorbitant at an average of 3.9% per annum since 1991, roughly twice the inflation rate for retail beer prices (1.8%). If the price of a 1-liter stein of Oktoberfest beer had kept pace with German consumer price inflation since then (2%), the beverage would cost only EUR 7.68 today in the beer tents. But music, service, and ambiance also have their price.

Since the economic activity outlook has improved, the Fed now envisages just two quarter-point rate cuts next year (instead of four).

The global interest-rate hiking cycle is winding to an end. In the months ahead, the task at hand for central banks is to study the effects of the tightened monetary policy in real time and to readjust it if necessary. Meanwhile, the government of China is striving to fine-tune its economic stimulus measures. Its efforts are likely to at least stabilize China’s GDP growth close to the +5% target.

As most observers expected, the US Federal Reserve left its policy rate unchanged in September in a range between 5.25% and 5.50%, the highest level in 22 years. The Fed also made considerable adjustments to its economic forecasts. It now foresees significantly higher GDP growth for 2024 compared to the last projection in June (+1.5% instead of +1.1%) and a much lower unemployment rate (4.1% instead of 4.5%). It thus implicitly is counting on a soft economic landing. However, at the press conference following the September FOMC meeting, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell demurred from confirming that this desired scenario is also the one most likely to come true. Since the economic activity outlook has improved, the Fed now envisages just two quarter-point rate cuts next year (instead of four). The Fed is navigating along a narrow and bumpy path in wait-andsee mode (see the Theme in Focus article).

Surprisingly in comparison, the Swiss National Bank also took a break from raising interest rates at its last policy meeting, but reserved the option to further tighten its monetary policy, though that’s actually not necessary from today’s perspective. At an inflation rate of 1.6% in August, the SNB has already reached its desired inflati-

on target range, and the new inflation forecast for 2025 (1.9% instead of 2.1% previously) indicates that it will stay there in the medium term. Switzerland’s interest-rate differential versus the deposit rate in the Eurozone has thus widened to a new record high of 225 basis points because the European Central Bank upped the ante in September by implementing another rate hike. At the same time, though, the ECB also made it clear that it considers the new interest-rate level appropriate.

The bad news keeps coming for Europe’s largest national economy. After the International Monetary Fund (IMF) this summer dialed down its economic growth forecast for Germany for this year to “recession,” the OECD then also turned its thumbs down on Germany last month. Germany thus appears destined to be the only other G20 country besides Argentina with negative growth for 2023. However, an end to the bad news for the German export engine is in sight at the moment at least from the direction of China. Since the last Politburo meeting in late July, the government of China has initiated a long list of measures designed to support the country’s real estate market and to bolster consumer spending. They are likely to at least stabilize China’s GDP growth close to the government’s +5% target.

Investors shouldn’t let themselves get flustered by the political theatrics.

In reality, shutdowns in the past have had only mild impacts on the stock market.

The Democrats are hoping that America’s economy doesn’t falter too much in the quarters ahead when the US presidential election campaign enters the home stretch. That would hurt Joe Biden’s chances of getting reelected. The Republicans therefore will probably try to throw as much sand as possible in the gears of the US economic engine.

Thirteen months ahead of the 2024 US elections, everything thus far is pointing to a reprise of a familiar duel. Voter polls and indications from the betting market are predicting that Joe Biden will face off against Donald Trump again next year. No genuine Republican opponent to Trump has emerged in recent weeks. Trump’s strongest challenger thus far, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, has continually lost voter approval lately. The numerous court proceedings that Trump is embroiled in could prove to be his biggest (logistical) problem by far in the election campaign. Age, on the other hand, will likely be the biggest challenge facing Biden next year. Biden’s health is the biggest concern within the Democratic Party, followed hot on the heels by the US economy on the Democrats’ list of worries because a recession in an election year would at least considerably reduce Biden’s chances of getting reelected, and the Republicans know that.

Shutdown…

It therefore wouldn’t be surprising if the USA were in the midst of a government shutdown by the time this edition of Monthly Market Monitor goes to press. There at least were few indications of a swift agreement

on a new federal budget prior to the editorial deadline. Forcing a shutdown of the federal government would be one of the few opportunities left for Republicans to throw some sand in the gears of the US economic engine. The last shutdown in 2018/2019, which lasted for a record-breaking five weeks, reduced the USA’s economic output by 0.3 percentage points, according to calculations by the Congressional Budget Office. The bulk of that lost output was recouped after the shutdown ended. A shutdown therefore arguably would not put enough of a brake on economic activity to decide the election, but it probably would act as yet another reminder of just how dysfunctional and polarized the political situation in Washington, D.C., is these days.

Investors shouldn’t let themselves get flustered by the political theatrics. In reality, shutdowns in the past have had only mild impacts on the stock market. There have been 20 US government shutdowns since 1976, and the average performance of the S&P 500 index during those events came to exactly +0.04%. During the last shutdown five years ago, the index actually even gained 10.3%, serving as a reminder that political stock markets are ephemeral.

Asset

Cash

Equities: Interest rates – how high is too high?

back by the USA’s bellwether S&P 500 index through end-September as an example – has stayed within reasonable limits. European stock markets have also been in correction mode lately. In the wider-angle picture, though, the Euro Stoxx 50 has been drifting up and down in a broad sideways channel this year.

Monthly Market Monitor - October 2023 | Kaiser Partner Privatbank AG 10

It would take a breach of the year-to-date low to below the 4,000 level to significantly dim the technical analysis picture.

• Despite the autumn correction, several factors are pointing to a positive fourth quarter. For one thing, markets are already back in near-term oversold territory. Moreover, the robust upward momentum on the US market this year is also supportive of a year-end rally. Window dressing, too, looks set to exert a buoying effect in the weeks ahead. In order to put their portfolios in the best light, mutual fund managers will likely go on another shopping spree, especially snapping up more of this year’s winners: the big US tech stocks. Investors, howe-

ver, would be well advised not to participate in this portfolio-prettifying game. They would be better advised to already start slowly looking ahead to next year. The risk of a recession will tend to increase in 2024, as will the likelihood of a major stock-market correction. Investors therefore should gradually lock in this year’s gains and should position their portfolios on the defensive side going forward.

Fixed income: Bond bulls in distress

• Diversification also pays off in the interest-bearing asset space. Whoever holds cat bonds in his or her portfolio can delight, for instance, in a value appreciation north of 10% year-to-date. Bond bulls, on the other hand, have gotten caught on the wrong foot in recent weeks. The previous year-to-date yield high of 4.35% on 10-year US Treasury notes turned out not to be the end of the market interest rate uptrend. On the contrary, in fact, the rally in yields and the inverse selloff in bonds actually accelerated once more. At a level of around 4.5% at last look, the 10-year Treasury yield is around 60 basis points higher than it was at the start of this year. This increase has more than eroded the interest coupon, causing 10-year Treasurys to return a negative 3% for the year through end-September. The picture even looks much worse for longer-term bonds. The iShares 20+ Year Treasury Bond ETF, for example, is down more than 10% for the first nine months of 2023. But this is exactly the kind of situation where investors need to keep their cool because the higher that yields climb further from here, the more asymmetrical bonds’ risk/reward profiles become.

• That goes not just for government bonds, but for high-yield bonds as well. Their high absolute yields provide a comfortable risk buffer. Even in a recession scenario, this class of bonds looks set to deliver at least a breakeven return over the next 12 to 18 months. In a better macroeconomic scenario, returns well into double digits can even be expected. Since pinpointing the ideal timing is just as difficult on the bond market as it is on the equity market, a staggered entry into high-yield bonds is advisable. Since cash is earning an attractive rate of interest these days, this strategy entails much lower opportunity costs than in the past under the new interest-rate regime.

Alternative assets: The oil-price rally is not an argument for investing in commodities

• The price of petroleum has risen by around a third to over USD 90 per barrel since the start of July on the back of production cuts by Saudi Arabia and is up a cumulative 15% year-to-date. Whoever wished to profit from this price trend through diversified investment products perforce became acquainted with the pitfalls of such a strategy. To wit, the Bloomberg Commodity Index, in which crude oil has a weight of only 15%, is down 5% year-to-date. The energy-heavy Goldman Sachs Commodity Index at least has posted a gain of around 5% for the same period. We continue to consider this type of investment in commodities an unsuitable strategic portfolio component. The commodities asset class admittedly is benefiting from the new regime of higher interest rates since the collateral return is now well in positive territory and looks attractive on paper. But whoever wishes to hedge against the prospect of persistently high inflation has much less volatile asset categories to choose from in alternative asset segments such as infrastructure or private credit.

Currencies: The SNB springs a surprise

• EUR/USD: Any interest-rate speculation in favor of the euro has dissipated completely since the European Central Bank’s September policy meeting, at which the ECB more or less distinctly raised the prospect of ending its rate-hiking cycle. The weakness of economic activity in the Eurozone, particularly compared to the USA, moved into the foreground instead. The EUR/USD exchange rate accordingly has resumed its downward trend in recent weeks, but the euro looks set to at least stabilize in the near term at its year-to-date low thus far of 1.05 against the greenback.

• GBP/USD: There was a major surprise on the inflation front in the UK in September. The inflation rate came in much lower than anticipated. The Bank of England thus left the interest-rate level unchanged, and market participants subsequently had to lower their expectations also for the British pound to bring them in line with the future interest-rate path. For the GBP/USD exchange rate as well, the year-to-date low at 1.18 is likely to be the ultimate destination of the current downward impetus and a support zone at the same time.

• EUR/CHF: In conjunction with its quarterly monetary policy assessment, the Swiss National Bank likewise kept its policy rate steady at 1.75%, which is on the low side in international comparison. The euro lurched upward in reaction to this surprise and gained 1% against the Swiss franc over the next several days. However, we do not expect to witness a grander revival of the euro because the SNB has no interest in seeing the franc weaken too much.

The commodities asset class admittedly is benefiting from the new regime of higher interest rates since the collateral return is now well in positive territory and looks attractive on paper.

Autumn is regularly a period of elevated volatility on financial markets. There are a number of hypothesized reasons for this seasonal pattern. One explanation posits that corporate executives and institutional investors engage in efforts in autumn to manage their stakeholders’ year-end performance expectations. Corporate executives thus try to paint as good a picture as possible of business prospects at conferences for investors or analysts, and institutional investors try to sniff out the right stocks for a potential year-end rally. All in all, this leads to larger trading volumes on equity markets and to greater volatility. Fluctuations this year remained below the seasonal norm at first. The relative calm on the markets reopened a window for initial public offerings. Shares of microchip designer Arm were in hot demand and ended their first day of trading in mid-September up by around 25%. Other IPO candidates are in the pipeline. One thing’s certain, though: volatility is cyclical, and spells of fine weather do not last forever. With a mild delay, the climate indeed ended up turning autumnally turbulent after all in late September.

Relatively calm | A good time for an IPO VIX volatility index

In the fight against inflation, today’s generation of central bankers is entering uncharted territory. The Great Inflation of the 1970s provides illustrative historical visual aids to go by, but the current rate-hiking cycle nonetheless is truly a novelty. It is akin to an experiment in real time with an uncertain outcome. Investors would be well advised not to place too much trust in central banks’ maneuverability.

The lauded changing of the times hasn’t stopped at the gates of central banks and their monetary policies. Quite the contrary, in fact, the inflation shock that was sparked by the COVID-19 pandemic and was exacerbated by the war in Ukraine arguably poses the toughest challenge that the guardians of monetary stability have faced since the 1970s. The current generation of central bankers in office has only textbook knowledge of that decade’s runaway inflation. When former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker raised policy interest rates in the United States to as high as 20% for a time at the end of 1980 and ultimately induced a disinflationary recession, his present counterpart Jerome Powell and current European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde were not even 30 years old yet. Instead of contending with inflation risks, today’s generation of central bankers found itself at times confronted more with the problem of overly low inflation up until the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in the Eurozone, where the ECB under the leadership of Mario Draghi fell short of its desired inflation target of around 2% for years in the aftermath of the European debt crisis. At that time, near-frantic discussion swirled in monetary policy circles over how to creatively nudge

ECB in unfamiliar climes

Inflation is overshooting the central-bank target (by a lot)

up inflation by a few basis points. Viewed in retrospect, those are luxury problems of yesteryear, for in the Eurozone as well, inflation has far exceeded the 2% target by a multiple thereof during the past several quarters. Combating inflation has taken top priority for central banks on both sides of the Atlantic this year and looks set to remain job one for the time being because getting the inflation genie back in the bottle may prove harder than originally thought.

Over the past several quarters, the prescription for combating rampant inflation has been to massively raise interest rates, just like the standard textbook says should be done. The rapid pace and the big steps taken have made the current rate-hiking cycle in the USA the most vigorous one in the last 40 years, with a cumulative policy rate increase of more than 500 basis points within a span of 18 months. The ECB, in turn, entered uncharted territory in September 2023, if not before, when it raised its deposit rate to a historic high of 4%. The interest-rate hikes were supplemented by additional measures designed to drain liquidity from the economy, such as actions taken to shrink central banks’ balance sheets. The logic behind the restrictive

Over the past several quarters, the prescription for combating rampant inflation has been to massively raise interest rates, just like the standard textbook says should be done.

monetary policy course is the same as in previous cycles: the aim is to make money (credit) more expensive to slow economic activity. The resulting decreasing demand for goods and services should then cause inflation to recede, all without risking slamming the brakes on economic activity and ideally culminating in a soft landing. Whether or not this experiment in real time will succeed won’t fully become apparent until 2024, but educated guesses about its probability of success can already be made today.

If one focuses the analysis on the two most important central banks, i.e. the Fed and the ECB, the chances of success for the latter look worse because the ECB has to devise an appropriate interest-rate and monetary policy not just for one country, but for 20 simultaneously. In July 2023, inflation rates in the Eurozone countries were still hovering in a wide range between 1.7% (Belgium) and 10.3% (Slovakia). And the ECB’s track record isn’t exactly reassuring. In the continual search for a consensus between hawks and doves on monetary policy, the ECB has repeatedly proven to be a lumbering ocean tanker that oversteers beyond the target and corrects course too late. Two times in the past – during the 2008 financial crisis and the 2011 Eurozone debt crisis – this resulted in poorly timed interest-rate hikes that the majority of economists have since classified as monetary policy errors in hindsight. Today it is already foreseeable that the current rate-hiking cycle will claim victims. Germany, for example, looks set to hold the grim distinction of being the only major industrialized country with negative GDP growth in 2023, according to projections by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The ECB’s monetary policy, though, is at most only part of the explanation for Germany’s recession.

Growth forecasts for the Eurozone as a whole, in contrast, project a stagnation for the quarters ahead with a tendency toward stagflation. The braking effects of higher interest rates on economic activity are already taking a noticeable toll on growth in the form of more restrictive lending by banks, falling real estate prices,

slumping sentiment and orders in the construction industry, and weak retail sales, for example. As for inflation, the interest-rate hikes have already resulted in a significant pullback in survey-based inflation expectations, but headline and core inflation are still persistently stuck above 5% in autumn 2023 despite the recordhigh interest-rate level. In the quarters ahead, inflation looks set to converge toward the 2% target only at a snail’s pace. The disinflation process will likely be slowed in part by the ongoing recovery in the price of oil underway since summer 2023 and, last but not least, by certain second-round effects on wages. Structural factors will also make the job of central banks more difficult. Those factors include a shortage of skilled workers and laborers, rising costs for climate protection, a structural shift toward non-automatable services (in the healthcare sector, for example), deglobalization, and increased statist industrial policy. European central bankers are entering uncharted territory also with regard to these inflation challenges and are doing that with humility. The ECB’s September forecasts project that inflation in the Eurozone will still exceed 2% even at the end of 2025. This mix of growth and inflation points to only one conclusion about the future interest-rate path: rates will have to stay high and restrictive for a longer time in order to reach the ECB’s definition of price stability. Against this backdrop, the obstacles to rate cuts anytime soon seem very high. This means that the (minor) collateral damage that is already hitting some areas of the economy will probably continue to have to be tolerated for the time being. In any case, maintaining credibility in the fight against inflation has been deemed more important in ECB circles thus far. Monetary policymakers are under tremendous pressure that is also being turned up by organizations like the OECD, whose interim economic outlook report in September included yet another stern reminder that interest rates must stay high until inflation has been tamed for good. In contrast to previous cycles in which the ECB reverted back to lowering interest rates after no more than seven months, the interest-rate crest in the current cycle could easily last for 18 months or longer. However, the “higher for longer” motto for the time being is not

If one focuses the analysis on the two most important central banks, i.e. the Fed and the ECB, the chances of success for the latter look worse.

being reflected at the moment in economists’ consensus forecasts or on the interest-rate futures market, where expectations are tending toward a return to falling interest rates in the Eurozone by as early as 2024. Those hopes, though, may meet with disappointment.

A continual revision of expectations has also been characteristic of the United States this year. The recession initially predicted by the majority of economic researchers didn’t materialize, and recession expectations were gradually postponed to next year. Predictions of the terminal interest rate and the forecast trajectory of subsequent rate cuts were likewise repeatedly readjusted. Central bank officials in the USA are navigating in unfamiliar terrain amid a lot of uncertainty, just like their colleagues in Europe are. If one uses reliable past indicators of impending recessions such as the Conference Board Leading Economic Index or the US yield curve as guideposts, one would conclude that an economic contraction is long or soon overdue. Yet economic activity in the USA has stayed robust thus far. A look at the Beveridge curve reveals that the Fed is still situated in the sweet spot of a potential soft landing – the job market is cooling down, but without an appreciable increase in the unemployment rate thus far. However, every hard landing starts out looking like a soft landing.

Moreover, the tougher stage of the fight against inflation still has to be faced. Pushing inflation down from a level of 3%–3.5% to below 2% could take longer than supposed. But if short-term market interest rates stay above 5% and thus well in restrictive territory for a protracted period of time, this is bound to make itself felt in areas of the economy that are sensitive to interest rates and will likely adversely radiate to other sectors as well. Rising corporate credit default rates and mounting payment arrears on consumer loans (car loans, credit card debt) have already been observable in recent months. In order to engineer a successful soft landing, the Fed would have to lower interest rates anticipatorily before the inflation target has been reached. That kind of maneuvering has very rarely succeeded in the past.

Implications for financial markets (and for investors) Investors therefore would be well advised not to place too much trust in central banks’ maneuverability. In 2024, the risk of a US recession looks destined to slowly increase with each quarter in which interest rates stay persistently high. If a recession comes to pass, historical patterns suggest that it would inevitably be coupled with a major stock-market correction that would also spread to European markets. Investors who would like to escape such a correction face the same problem that central-bank officials are confronted with: the pro-

A look at the Beveridge curve reveals that the Fed is still situated in the sweet spot of a potential soft landing.

blem of timing. The last quarters before a recession are often very good times on stock markets during which investors can reap, or miss out on, big performance gains. Since tactically maneuvering around a potential downturn in stock prices doesn’t pay off in the majority of cases, it’s inadvisable to undertake large-scale experiments of that kind. Other strategies, though, are recommendable, such as holding a somewhat higher cash allocation, for example, which thanks to the new interest-rate regime can be invested at interest in the

money market and can be used for a “buy the dips” strategy. Qualified investors can further refine this simple strategy in the current environment by employing options – this not only enhances the return, but also increases investment discipline. Last but not least, investors should also think outside the box of liquid asset markets. In the private-markets space, the private credit asset class benefits from higher interest rates and at the same time possesses defensive qualities that will likely come to bear in a recession scenario.

Providers of ESG ratings have also gained increasing influence in recent years.

Sustainability ratings are increasingly affecting capital flows on financial markets and influencing corporate conduct. Less publicized, though, is the fact that ESG ratings from different providers diverge from each other substantially sometimes, making the fundament for investor or managerial decisions and the basis of many academic studies confusing and vague. The sustainability industry is still in its infancy with regard to its information base.

The rating agencies Standard & Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch rank among the most influential institutions in the global financial market (alongside central banks). They rate the creditworthiness of governments and corporations and thus have a big influence on their financing costs. They also decide whether the credit standing of a bond issuer is sound enough for a coveted investment-grade seal or needs to be classified in the more speculative high-yield (or junk) bond segment. The important role that credit ratings play in the world of finance owes in large part to their standardization and comprehensibility, which is reflected in a very high correlation (99%) between the ratings from the different providers.

Providers of ESG ratings have also gained increasing influence in recent years. In the Principles for Responsible Investment community, 3,826 institutional investors (as of end-2021) with over USD 100 trillion in combined assets have pledged to integrate ESG information into their investment decisions. Sustainability investing continues to enjoy growing popularity, particularly in Europe, thanks in part to a regulatory tailwind and despite greenwashing scandals and a decline in performance in recent quarters. This means that more and more investors are thus relying directly or indirectly on outside opinions from specialized ESG rating providers like Sustainalytics and Refinitiv. Moreover, a growing number of academic studies use ESG ratings as a basis for their empirical analyses. ESG ratings are thus increasingly influencing decision-makers and could potentially have

far-reaching effects on securities prices and corporate policies.

…but are very divergent

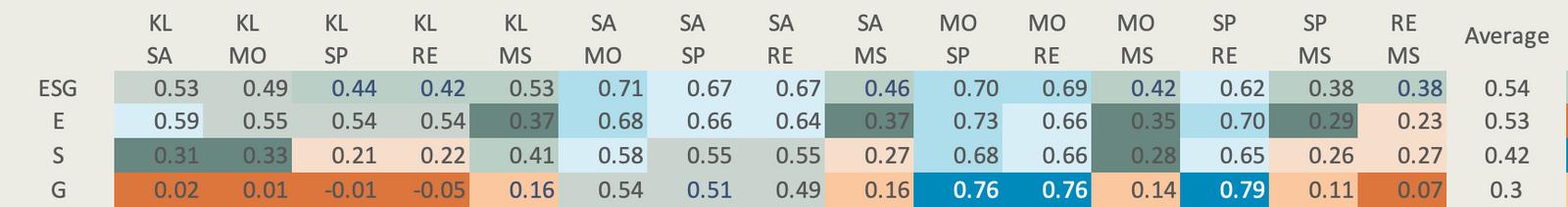

So far, so good – and no problem? Not necessarily! Because as analysts1 already illuminated several years ago, ESG ratings from different providers disagree with each other, substantially sometimes. A more recent study published last year by F. Berg, J.F. Kölbel, and R. Rigobon (MIT Sloan, University of Zurich)2 reconfirmed this discrepancy. It found that although correlations between ESG ratings from six prominent providers (KLD, Sustainalytics, Moody’s ESG, S&P Global, Refinitiv, and MSCI) are not completely inexistent, they are nonetheless low, with coefficients ranging from 0.38 to 0.71. The authors of the study probed deeper into these rating divergences and mapped the different rating methodologies onto a common taxonomy of categories. This way they were able to detect three main causes of the divergences between ESG ratings:

• Weight divergence (6%): ESG ratings diverge from each other because rating providers weight the three main categories – environmental, social, and corporate governance – as well as their subcategories differently. For example, the working conditions at a company may have a higher or lower weight than the company’s exhaust gas emissions, depending on the rating agency.

• Scope divergence (38%): ESG ratings differ from each other because they focus in part on different (ESG) attributes. Some rating agencies, for instance, include companies’ lobbying activities in their evaluation of the G (governance) aspect of ESG while others do not.

Sources: F. Berg et. al (2022), Kaiser Partner Privatbank

Motley rating mosaic | Aggregate confusion raises a lot of doubts

Correlation between ESG ratings

Motley rating mosaic | Aggregate confusion raises a lot of doubts

Correlation between ESG ratings

• Measurement divergence (56%): ESG ratings diverge from each other because different rating providers measure the same attribute using different indicators or different information bases. This third factor is the largest cause of ESG rating discrepancies, accounting for 56% of overall rating divergence. According to the authors of the study, measurement divergence is driven in part by a “rater effect” (which is also known as the “halo effect”): when a company receives a high score in one ESG category, it often receives high scores in all of the other categories from that same ESG analyst (the rater). In contrast to conventional credit ratings, in which each individual analyst usually appraises only one partial aspect of overall creditworthiness, ESG ratings for a company are usually formulated entirely by a single analyst. The analyst’s subjective perception of the company thus has a substantial impact on the final rating.

The divergence between ESG ratings highlighted once more by this latest study has a number of (important) implications. First, it impedes the main purpose of sustainability ratings, which is to judge the ESG performance of companies or mutual funds and portfolios. Second, the rating divergences reduce the incentive for companies to strive to improve their E, S, and G performance because they send them vague signals about necessary remediation actions and about how favorably they would be received by the financial market. Consequently, it’s likely that many an effort or investment to improve ESG scores doesn’t get undertaken by companies in the first place. Third, given the rating confusion, it seems very questionable to make CEO compensation contingent on achieving specific ESG ratings. If managers align their companies’ operations to optimally meet the ESG criteria set by rating provider X, they may end up receiving much lower scores from rating providers Y and Z. This dilemma could

cause companies to fall short of the actual ultimate goal of comprehensively improving their sustainability.

Divergent sustainability ratings also at a minimum challenge one of the basic premises put forth by ESG advocates, who postulate that corporate sustainability efforts are fundamentally relevant to enterprise value and influence investor preferences and stock prices. Rating divergences, however, at the least are likely to dilute this influence. And, finally, divergent ESG ratings also present a challenge for academia – the choice of a specific ESG rating provider can greatly affect the findings of a study and the resulting conclusions drawn from them. To come straight to the point, due to the divergences, any decisions based on today’s ESG ratings contain an extra element of uncertainty.

Unfortunately, there is no simple solution at hand for doing away with the aggregate rating confusion involved in sustainability investing. Although the various ESG rating agencies could agree to use the same ESG categories and attributes as well as identical weights, the biggest contributor to the confusion – measurement divergence – cannot be eliminated so easily. Comprehensive, universal, and binding regulatory guidance on collecting and measuring ESG-relevant data that arguably would be needed to end measurement divergence is not in sight anytime soon. It’s up to regulators to harmonize existing ESG disclosure requirements and to establish and promote a common taxonomy of ESG categories. Efforts undertaken to this end in Europe are the most advanced thus far, but even the EU taxonomy is still far from fully developed. The investment experts at Kaiser Partner Privatbank are well aware of the glaring ESG ratings jungle. ESG ratings accordingly form only one part of a much more comprehensive sustainability analysis in our sustainability strategies.

Unfortunately, there is no simple solution at hand for doing away with the aggregate rating confusion involved in sustainability investing.

*1)

Sustainability at a high level Kaiser Partner Privatbank was awarded the rating “Master” for sustainability in private banking by the renowned independent testing firm FUCHS | RICHTER Prüfinstanz. The highly personalised advice and the knowledge of the advisors in this area were highlighted as “outstanding”.

2)

A.K. Chatterji, R. Durand, D.I. Levine, S. Touboul (2016): "Do ratings of firms converge? Implications for managers, investors and strategy researchers" * F. Berg, J.F. Kölbel, R. Rigobon (2023): "Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings"

• October 8 to 12: Internet Governance Forum

Internet governance issues will be discussed for the 18th time this October in Kyoto, Japan. This annual multilateral forum brings a variety of government, private-sector, and civil-society stakeholders together, providing a platform for dialogue and the development of best practices. This year’s agenda includes subjects such as artificial intelligence and cybersecurity.

• October 13: World Egg Day

Even (chicken) eggs have a lobby. Since 1996, World Egg Day has been celebrated every year on the second Friday of October. This source of protein really doesn’t need to advertise anymore. In any case, from a health standpoint, eggs have a better nutritional reputation today than they did 40 or 50 years ago. But a yearly reminder about animal welfare certainly can’t hurt.

• November 1: US Federal Reserve FOMC meeting

The USA’s central bank has raised its benchmark federal funds rate by more than five percentage points in the space of less than one-and-a-half years. Now it’s time to let the bitter medicine take effect. Fed officials took a break from raising interest rates in September and are expect to do the same at the FOMC meeting in November. Patience is called for, though, because in the attempt to get inflation back below 2%, the last few yards are likely to be the toughest ones.

This document constitutes neither a financial analysis nor an advertisement. It is intended solely for informational purposes. None of the information contained herein constitutes a solicitation or recommendation by Kaiser Partner Privatbank AG to purchase or sell a financial instrument or to take any other actions regarding any financial instruments. Furthermore, the information contained herein does not constitute investment advice. Any references in this document to past performance are no guarantee of a positive future performance. Kaiser Partner Privatbank AG assumes no liability for the completeness, correctness or currentness of the information contained herein or for any losses or damages arising from any actions taken on the basis of the information in this document. All contents of this document are protected by intellectual property law, particularly by copyright law. The reprinting or reproduction of all or any parts of this document in any way or form for public or commercial purposes is expressly prohibited unless prior written consent has been explicitly granted by Kaiser Partner Privatbank AG.

Publisher: Kaiser Partner Privatbank AG

Herrengasse 23, Postfach 725

FL-9490 Vaduz, Liechtenstein

HR-Nr. FL-0001.018.213-7

T: +423 237 80 00, F: +423 237 80 01

E: bank@kaiserpartner.com

Editorial Team: Oliver Hackel, Senior Investment Strategist

Roman Pfranger, Head Private Banking & Investment Solutions

Design & Print: 21iLAB AG, Vaduz, Liechtenstein