Although we are well into autumn, Tiritiri continues to attract large visitor numbers, including sizeable school groups.

I would like to say a special thank you to our many volunteers and staff, who do an incredible amount of work behind the scenes in many ways to ensure visitors have the best possible experience. Feedback from visitors is positive, and they leave inspired by what they have experienced on this special island sanctuary.

The committee, along with subcommittee chairs, held a budget and planning meeting, looking ahead to the next three years, to determine needs for the development of the Island.

The field centre subcommittee is making progress in reactivating this project, with advice being sought from several experts.

The recent working weekend over Easter has certainly improved the condition of the tracks; a lot of work has been completed. Thanks to the many volunteers for their efforts.

A successful concert with two wonderful bands delivering music, some specifically devised for our island paradise, took place on March 9 by the lighthouse and was enjoyed by all those attending.

It was good to see two of the people who instigated our island conservation project in the 1970s, John Craig and Neil Mitchell, recently. They were on the Island with a conservation group that was interested in what had been achieved through the planting programme.

Many visitors took advantage of the open day on April 20 to learn about the maritime heritage of the Island, visit the museum, foghorn, and watchtower, and climb the steps to the top of the lighthouse. Thank you to Carl Hayson and his team for organising this event and to the Maritime NZ staff who provided briefings on the operation of the light.

Bunkhouse charges for the DOC bunkhouse on the Island are to increase from July 1 to $42.00 per night. The previous supporters' 50% discount will no longer be available. This change will include supporters’ weekends and all occasions when members wish to stay overnight on the Island. Generally, there will be no change to the arrangements for those volunteers involved in the biodiversity programme and track maintenance who need to stay in the bunkhouse.

Ian AlexanderThe motu was alive with the sounds of birdsong, laughter, and power tools this past Easter weekend as our crew of volunteers worked together to complete some big projects. The spirit of tuakana-teina was alive within the diverse group, a beautiful balance of experienced older volunteers sharing their knowledge, leadership and wisdom and new, highly enthusiastic younger folks ready to dig into the mahi and learn from our predecessors.

Together, we dug drainage ditches, gravelled tracks, built safety structures and a special water system for the takahē. We painted and cleaned signs, installed nest boxes and cabinets, and cleaned troughs. Many fadge bags were filled with old materials, which needed to be cut up, cleared away, and taken off the Island. There were sore muscles and tired problem solvers, but we kept each other going with encouragement, jokes, and, of course, the excitement of what manu we were spotting on the job! There was something quite special about the dynamic this working weekend: each volunteer coming from a different walk of life, bringing their own unique set of skills to share, united in our efforts as kaitiaki of this taonga. There were some unforgettable moments, with some volunteers having their first sightings of kōkako and kiwi, and some sighs of relief, realising that the heaviest lifting can now be delegated to the strong young newbies!

As a member of the next generation of volunteers committed to preserving this precious island, I know I speak for all of the rangatahi when I say ngā mihi nui to our kaiārahi.

Entrusting us (as one volunteer so humbly put it, 'the high enthusiasm low-skill group') to do the mahi and manaaki required to keep this island flourishing leaves us feeling humbled and grateful. May there be many more weekends of sharing new ideas and creative problem solving, passing on the mātauranga, and coming together in community for Tiritiri Matangi for generations to come.

Meredith Blogg

Notice is hereby given that the Annual General Meeting of the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi will be held at 7.30pm, Monday 16 September 2024, at MinterEllisonRuddWatts Seminar Room, PWC Tower, 15 Customs Street West, Auckland City. Further details will be in the August issue of Dawn Chorus

Cover photo: Kōkako feeding on nīkau fruit, John SibleyThis issue’s guest guide is Jonathan (JP) Mower. JP grew up in Kawerau, a small town in the Western Bay of Plenty, moving there from England in 1969 (he’s closer to 60 than 50). JP works as a corporate tower concierge but, prior to that, had many years working in the retail industry.

The editors of Dawn Chorus asked JP about himself and his experiences guiding on Tiritiri Matangi. Here are his responses:

How long have you been a guide?

Nine or ten years, I think. I was introduced to the Island by Donald Snook and was hooked by the end of my first buddy guide with him.

What are your other hobbies or pastimes?

I am a pretty keen birder and gardener, and I like to take photographs. I spend a lot of time combining all three. I like to share my photographs on social media. That can take up quite a lot of time if I am not careful.

What attracted you to guiding?

I am keen to advocate for the conservation projects undertaken on Tiritiri Matangi and other Hauraki Gulf islands, and guiding lets me do that. As a guide, you can share your perspective on life and what makes the flora and fauna of this country uniquely special. In a way, guides have an opportunity to get people to see things in a different way, and that can make a real difference to the world.

What has been your favourite experience with guiding?

Well, that’s not an easy question to answer. Being able to be a private guide for Canadian musician Geddy Lee was a fantastic experience. I had to take the ferry to Waiheke so we could take a water taxi to the Island. He came with the main aim of spending time with kōkako and, luckily, I was able to get him exactly what he wanted.

What is your favourite story you would like to share about Tiritiri Matangi?

There are many to share, but the story of the first takahē, Mr. Blue and Stormy, is one of my favourites. They vindicated the efforts made to convince the powers that be that takahē would be successful on the Island, and then went on to be two males who incubated and hatched little Matangi.

What is your favourite bird on the Island, and why?

That would be takahē. I was introduced to them on Motutapu Island and I clicked with them right from the start. They are extraordinary birds who seem to move around the Island at their own pace, regardless of what is going on around them. Their story is a ‘poster child’ story of New Zealand conservation, and Tiritiri Matangi gives us up close and personal time with them.

What is your favourite plant, and why?

Haekaro / Pittosporum umbellatum

They have bunches of large, heavily perfumed flowers, which is quite unusual for a New Zealand endemic plant. If you are lucky, you can catch nectar feeders drinking from the big bunches of pink flowers, and that is a beautiful sight.

What is the quirkiest experience you’ve had on the Island?

Being the person who is most likely

to be the last one on the ferry almost every single time is kind of fun. When I fly somewhere, I am usually the first to get there, but on the Island, time seems to run a little differently for me. What is your greatest environmental concern?

There are many of those, to be honest. I have a great fear that the avian flu that has devastated bird populations around the world will make it here. We have so many species that number only in the hundreds, and that virus could be devastating for them. It has recently arrived in South Georgia and Antarctica, which are very, very close to this country.

Is there anything else you would like to share about guiding?

I read a lot and try to learn things that are not easily found by doing a simple Google search. Quirky things that will pique people’s interest and grab their attention. I find that helps make your storytelling more successful and memorable.

I was fortunate to guide two fully-booked photography walks on consecutive weekends in April with local and international photographers. With breeding and moult completed for the season, the birds were more visible, and we were able to find a good number of species. Photographers love taking their time to find the right shots, so we let the regular guided groups go ahead and avoided the pressure to keep moving. One photographer was attracted by the over-18 rating for the trip, which ensured we could approach the birds quietly and take our time. Another had returned for a second photography walk. These walks suit both beginners and experienced photographers who want guiding with island interpretation mixed with good bird photography expertise and spotting skills.

JP Mower having a post-guiding chill-out with takahē. Photo: Heather Hartles

The bands set up in front of the museum, the majestic lighthouse sheltering concertgoers from the sea breeze and providing a unique backdrop. Hoop opened with a lovely rendition of 'Here Comes the Sun' and charmed the audience with their lyrical folk rock. The volunteers in particular enjoyed their homage to the lighthouse, 'The Brightest in the Land'. Have a listen to it on the Tiritiri Matangi website blog page.

Tweed were rollicking and funny; their whistles would no doubt make the birds nearby curious. The lighthouse takahē family seemed unconcerned and continued their hunt for just the right piece of grass around the back of the museum during most of the concert. The bands joined harmonies at the end of the evening to play a salute to the hard-working kōkako team with a lovely rendition of 'Blue Bird'.

Dancing was done, and, at the end of the evening, the bands challenged the duelling conga lines to a repeat performance. We greatly appreciated Hoop, Tweed, and the team supporting this event. Everyone enjoyed a wonderful evening of great music, dancing, and camaraderie.

We were all excited to welcome a very special VIP to the Island for the concert. Trevor Scott was an assistant lighthouse keeper on the Island from 1958 to 1960 and the principal keeper from 1966 to 1969. He and his family came to watch his grandson play in the band 'Tweed'. Trevor donated a piece of history to add to our museum collection. It was lovely to meet Trevor and his family. He told some wonderful stories of his time on the Island.

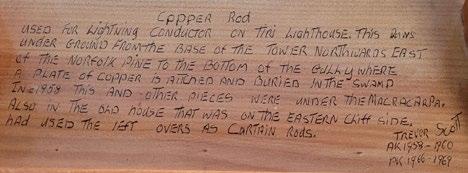

Libby MayTo prevent damage caused by lightning strikes, lighthouses are equipped with metal poles called lightning rods. These rods are attached to a thick copper wire that runs from the top of the lighthouse down to the ground. When lightning strikes the tower, it enters through the lightning rod and travels down the wire into the ground, minimising potential damage.

Trevor Scott shared that he remembers seeing the spare left-over copper rods used to hang up curtains in the lighthouse keeper's house. Trevor constructed a frame to hold a piece of the copper rod and made a model lighthouse, which he has kindly donated to the Tiritiri Matangi Island Museum.

Written on the frame:

Photos:

Libby May

Photo: Talia Hochwimmer

Hoop playing 'Here Comes the Sun'.

Tweed rollicking.

Photos:

Libby May

Photo: Talia Hochwimmer

Hoop playing 'Here Comes the Sun'.

Tweed rollicking.

When Anne Rimmer was browsing through the Tiritiri Matangi Island archival photos recently, she suddenly realised the significance of this black-and-white photograph – it is the very best record we have of the original steps that led up to the lighthouse.

The two original keepers’ cottages, which were built in 1864, stood on the flat area behind the current-day Visitor Centre, where the lawn and picnic tables stand today. A stairway was constructed between the houses to give immediate access to the lighthouse. This was a much easier route for Tiritiri’s keepers to go to work than at many lighthouse stations, of course.

The stairs remained in existence long after the houses were demolished. They were removed some time in the 1970s and taken to Aotea / Great Barrier Island, where their remains were retrieved much later.

From one step and a piece of railing, a replica stairway was erected in the same position as the original stairs. Funding was provided by Devonport Rotary Club North. The stairs

were in position, though not yet painted, at the opening of the Ray and Barbara Walter Visitor Centre on November 13, 2005.

They remain in use today, as evidenced by Tiritiri’s current rangers, Talia and Keith, photographed by Karin Gouldstone in March 2024.

Principal Keeper Peter Taylor took the fine black-and-white photo in the late 1960s. Peter wrote articles about his lighthouse life, supplying the photos to accompany them, and published his memoir of his lighthouse career, ‘As Darker Grows the Night’, in 1975. He died in 2018.

Carl Hayson was delighted to see the old photograph, saying that information on the original stairs has been very difficult to source. Still, we now have a photograph of them to compare to the replica that stands there today.

We don’t yet know the identities of the people who posed for the old photo.

If anyone knows Peter and Marita Taylor’s family, please ask them to contact the editor, as we’d love to know more about the collection of Peter’s photos that we hold in our archives.

Photo:

Photo:

For the first time since the 150 year anniversary in 2015, Tiritiri's lighthouse was opened to the public to view on April 20, 2024

The weather forecast was less than ideal, which deterred some but, despite the rain, there were still many visitors keen to see inside the Island's iconic lighthouse.

Over the course of the day, Maritime New Zealand personnel, along with SoTM's Carl Hayson, guided over 70 people up the lighthouse tower.

Although the view from the top of the tower was limited by low clouds, the experience seemed to be enjoyed by all.

Janet Petricevich The current LED light.

Maritime NZ personnel Dave Pearson, Ashton McGill and Jim Foye with SoTM's Carl Hayson and DOC Ranger Dave Jenkins.

The current LED light.

Maritime NZ personnel Dave Pearson, Ashton McGill and Jim Foye with SoTM's Carl Hayson and DOC Ranger Dave Jenkins.

Photos: Janet Petricevich

The wet weather didn't deter visitors from exploring the lighthouse precinct.

Enthusiastic about lighthouses, from the socks up.

Carl Hayson with the Davis light.

Looking back down the body of the lighthouse.

SoTM members Chris and Peter examine the [now defunct] Davis light rotating base.

Photos: Janet Petricevich

The wet weather didn't deter visitors from exploring the lighthouse precinct.

Enthusiastic about lighthouses, from the socks up.

Carl Hayson with the Davis light.

Looking back down the body of the lighthouse.

SoTM members Chris and Peter examine the [now defunct] Davis light rotating base.

In 1984, 24 tīeke/saddleback from Cuvier Island were released on Tiritiri Matangi. They quickly established themselves with the help of nest boxes, roost boxes and regenerating bush. This year marks the 40th anniversary of their arrival, and, to celebrate this, Barbara Walter shared with me her experiences and stories from the early years.

Dr Tim Lovegrove (Auckland Regional Council Heritage Department scientist) coordinated the translocation from Cuvier Island. The 24 tīeke, comprising six breeding pairs and 12 juveniles, came from five different areas of Cuvier Island and had distinct dialects. In order to preserve these distinctions, they were released in five different areas on Tiritiri Matangi: Bush 1, Bush 2, Wattle Valley, Bush 21, and Bush 22 (see Figure 1).

At the start, 360 nest boxes were made by the North Shore Forest and Bird branch, coordinated by Eric Geddes, who used to travel to the Island on a small runabout from Army Bay. There were some differences in how the boxes were made. Some were short and some were long, both types having a V shape for the opening. Later a grill was added to the opening to prevent mynas and ruru from getting in, especially ruru, as they were getting in and stealing the eggs.

John Craig and Marijka Falenberg were the first to monitor the tīeke, and when Marijka finished John asked Barbara to continue with the project. She remembers going out at night with John and Marijka to monitor the nests, and she couldn't keep up with them because they had longer legs than her.

Barbara was tasked with the responsibility of checking the boxes once a week during the season, and twice a week when eggs were hatching. This was quite a laborious task, which required a great deal of dedication, attention to detail, and physical exertion. Ray prepared dinner for them on the days

when Barbara was occupied with checking the boxes. Barbara and Ray also used to band the tīeke chicks in the nest boxes.

Photo: John Sibley

Figure 1: Map of Tiritiri Matangi Island showing the bush areas. Bush 1, 2, 21, 22 and Wattle Valley are circled.

Photo: John Sibley

Figure 1: Map of Tiritiri Matangi Island showing the bush areas. Bush 1, 2, 21, 22 and Wattle Valley are circled.

Tīeke are generally long-lived birds. Five or six of the original birds were still being seen in 1994 and two birds seen in 1998 had been banded back in 1978 and 1979. One female in Wattle Valley lived a long and fruitful life, reaching the impressive age of 21. Despite being a loyal and devoted partner, this tīeke had three different mates during her lifetime. Barbara mentioned that during one breeding season she constructed multiple nests before selecting the perfect one to use.

In 1993, poisoned bait was dropped on the Island to eradicate the kiore (Pacific rat). Prior to this event, it was important to determine whether the tīeke would be likely to be affected by this, so bait was placed in some of the roost boxes. Fortunately, the tīeke showed no interest and the bait drop caused them no harm.

During the early years, tīeke used to lay three or four eggs per nest. However, over time, Barbara noticed that the number of eggs laid gradually decreased. It is now known that this decrease in egg-laying is a natural mechanism that helps regulate the population of tīeke. By laying fewer eggs, tīeke can ensure that the number of chicks hatching each year is balanced with the available resources in their habitat.

By the 1990s, the tīeke population was thriving. As the trees grew taller they had more natural places to build their nests, such as in the punga and harakeke/ flax bushes. In 1991 there were 60 pairs who produced 117 chicks and during the next season, there were 147 chicks.

As a result of this productivity, the Island became a source for translocations to other sites. Barbara described how mist nets were put up and tīeke calls were played to attract the birds to catch them for translocations. The first translocation, to Otorohanga, took place in 1990, and many successful translocations followed (see Figure 2). Barbara remembers Ray being asked to go with the tīeke to Moturoa in the role of kaumātua.

Barbara said that she found herself busy with the planting and handed the monitoring over to Morag Fordham, who had been outstanding and, without her help, the Island’s tīeke programme would not have been the huge success it has turned out to be.

Stacey Balich Photo: Kathryn Jones Figure 2: Map of the North Island showing the tīeke translocationsWhen tīeke/saddleback arrived on Tiritiri Matangi in 1984, it was truly the beginning of an era. Not only did they bring new sights and sounds to enrich the experience of anyone visiting the Island, they also marked the beginning of a project that would consume many working hours over the subsequent 40 years and which continues to this day.

In 1984, only a small fraction of the original bush cover remained, and the planting programme was only just getting under way. This meant there were very few sites where tīeke could nest, so boxes were provided for this purpose. There were 360 boxes, but regularly monitoring this number proved difficult, and, as the bush planted between 1984 and 1994 has matured, an increasing number of ‘natural’ sites has become available. Between 2008 and 2012, the number of boxes was reduced to a level that could be more easily managed by a team of volunteers. Since then, it has been relatively stable at around 150-160 boxes.

Figure 1 shows that, over the past eight years, fewer than 30 boxes per season have been used by tīeke, indicating that a large majority of the birds are using natural sites. Why do we continue to provide nest boxes at all if there are plenty of other sites for the birds to use? Because, although the birds may no longer need them, they have continued to use a proportion of them each year and, in doing so, they provide us with a mechanism for observing their breeding behaviour and gauging their success.

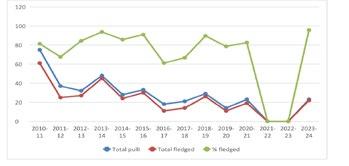

Ideally, to observe all the significant events in the life of a nest (building, lining, egg-laying, hatching, chick growth, and fledging), nest boxes should be checked every seven to ten days. This has been done consistently since 2010, with the exception of the two seasons between 2021 and 2023, when Covid restrictions and the pressure of other work made it impossible. The very welcome recruitment of eight new volunteers in 2023 has enabled regular monitoring to be resumed.

So what can we learn from the years of observation? Figures 2 and 3 are based on data from 2010-11 onwards (excluding the two seasons referred to above). They show that the numbers of eggs and chicks fluctuate from year to year but that there are longer-term trends to observe. Not surprisingly, the number of eggs laid, the number that hatch (Figure 2), and the number of chicks raised to fledging (Figure 3) have declined as the number and percentage of boxes used has declined (Figure 1). But while it is tempting to assume that this is because more natural sites are available, this is

2: Total number of eggs laid in boxes, the number that hatched and the percentage that hatched. The data for 2021-22 and 2022-23 are not included, so the zero records for those seasons should be ignored.

Figure 3: The total number of pulli (chicks), the total number that fledged and the percentage that fledged. Again, the records of zero from 2021-22 and 2022-23 should be ignored.

probably not the whole story.

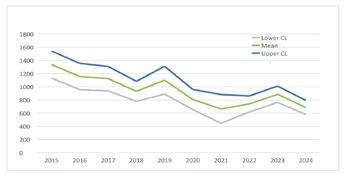

Figure 4 is based on data from the annual bird transect survey, which started in 2015. It shows that, while there have been shorter-term fluctuations, the total population of tīeke on the Island is now slightly more than half what it was in 2015. So the declines observed in nest boxes could simply be a reflection of the decline in population.

Figures 2 and 3 also indicate the percentages of eggs that have hatched and chicks that have fledged. Since 2010, 4060% of the eggs laid each season have hatched, and a more variable 60-95% of the chicks that hatch each season have been raised to fledging. Last season (2023-24) was the most successful on record, with all but one of the chicks hatched in boxes having fledged.

Pulli 6 days old. Photo: Kay Milton Figure 1: Number of nest boxes used and percentage of the total available used. Figure

It is clear from all this that the data from the nest box scheme can inform us about annual and longer-term changes in tīeke breeding behaviour and outcomes, but understanding these

Marie and Kathryn share what it is like to be part of the tīeke monitoring team.

Whenever I step off the wharf onto the motu, there is that distinctive feeling of connection: Tiritiri Matangi’s tranquillity, coupled with anticipation of the day’s discoveries to come. As part of the 2023-24 summer tīeke nest box monitoring programme, my track buddy Bronwyn and I have checked boxes in bush areas 22, 23, and Sonya’s Valley.

We began on a spring training day with Kay and John, who briefed the tīeke group on the programme’s kaupapa as we explored the assigned tracks, learning how to check boxes and identify stages of nest building and chick development along the way. Alternating weekly checks, Bronwyn and I thoroughly enjoyed each day, excited to find new nests or eggs and then watching ‘our’ chicks grow. At first, I could only see a huddle of wispy, dark feathers in a nest, but I learned to estimate ‘pulli’ ages as my observation skills improved. We recorded data in a shared spreadsheet to coordinate the mahi efficiently.

Overall, there was the privilege of ‘forest bathing’ in original bush areas and unexpected bird encounters, not only with adult tīeke but with the northern takahē family, kōkako, ruru, pōpokotea, toutouwai, and our ever-present pīwakawaka guides. Beautiful wētāpunga occupied several boxes as well.

Most days, there was enough time afterwards for a dip at Hobbs Beach via the Kawerau Track or to help out at the Visitor Centre. Other highlights included the exceptional pōhutukawa bloom last summer and an early trip when we,

changes requires a much broader range of information on other components of the Island’s ecosystem. Some of this is available from SoTM projects already under way (such as the transect survey mentioned above), some will come from projects planned for the future, and some is available from other sources (such as local weather records). What is certain is that, to understand what is happening to the tīeke on Tiritiri, we just have to keep checking and counting.

delighted ferry passengers, were welcomed to the wharf by a pod of dolphins.

I hope all Tiritiri Matangi’s juveniles from this season thrive and survive the winter, and that another successful breeding season lies ahead. Roll on next summer!

Marie Morrison

I have always loved tīeke, and so I was thrilled to be selected to be a member of the tīeke team. I got a handle on the locations of the nest boxes in the area that I was assigned after a couple of rounds of box checking. It was good to have a second person monitoring the same area of boxes. We could bounce thoughts and ideas off each other, talk about the progress of the nesting tīeke, and fill in for each other if we could not go to Tiritiri on a day we were rostered on.

Each time I went into the bush to check a box, I was conscious of being on tīeke turf. Determining whether tīeke are in a box before you open it involves eyes, ears, and finger tapping. And then you open the lid very slowly. There are such a variety of scenarios you are likely to see – a wētāpunga, a rifleman nest, a Duvaucel’s gecko – but hopefully a tīeke nest will be intricately built and used over time. Highlights for me were seeing nests lined with red tree-fern scales and watching the development of the chicks – so amazing.

I also got to know the calls of the adult tīeke using the nest boxes. It is now fun to walk along the public walking tracks, hear the adult tīeke call, and ‘know’ who the tīeke are that are calling out. Filling out the online data spreadsheet on box status was straightforward, and it was great to be able to go back to it and review what had happened over the breeding season. Bring on next summer!

Kathryn Jones Kay Milton and John Stewart Pulli 13 days old. Photo: Kay MiltonMalcolm de Raat shares some results from the recent surveys of Tiritiri Matangi's Duvaucel’s geckos and tuatara.

Duvaucel’s geckos are thriving on our motu

For those unfamiliar, Duvaucel’s gecko is New Zealand’s largest living gecko species. They can reach a length of 330mm (tip of nose to tip of tail), a weight of 118g, and a lifespan that may exceed 50 years. Like most of New Zealand’s reptiles, they give birth to live young, which are around 80-100mm long, nose to tail, and weigh around 5g. Like our fingerprints, the patterns on a gecko’s head and back are unique and scale up as the gecko ages. This means that a simple photo (yes, even a baby photo) can allow us to track and follow individuals, regardless of age.

In 2006, the initial steps were taken to reintroduce Duvaucel’s gecko (Hoplodactylus duvaucelii ) back onto our beautiful motu, Tiritiri Matangi. Nineteen individuals with radio transmitter backpacks were translocated and monitored. The back packs either eventually fell off or were removed at the end of monitoring.

Seven years later, in 2013, another 90 Duvaucel’s geckos were translocated by Dr. Manu Barry of Massey University. These were a combination of wild caught and ‘cage-raised for release’ geckos. For each of the following five years, Manu led a team of volunteers to survey the population, monitoring their health and progress. This was followed by a five-year pause in monitoring before a final survey at the 10-year anniversary of the 2013 translocation.

For one week in November 2023 and another in February 2024, the SoTM Reptile Team volunteers and two young iwi representatives assisted Manu with the final surveys. This was a huge milestone, completing ten years of monitoring and data gathering since the 2013 translocation.

There is still a lot of data to analyse, and once it is available, we will share it. In the meantime, here are some initial observations from the survey.

The Tiritiri Matangi Duvaucel’s gecko population is thriving. All the geckos

seen and caught were in very good condition, meaning they are healthy and well nourished. There is clearly plenty of great habitat and food.

They are also abundant. While the survey only allowed for a small amount of investigation beyond the original translocation release areas, it is evident the geckos have expanded their territories significantly. We are receiving more and more anecdotes from guides and visitors of Duvaucel’s gecko sightings, both by day and by night, on public tracks. Like wētāpunga, Duvaucel’s geckos are also showing up as sometimes regular, unexpected tenants in some of the bird nest boxes.

Another exciting survey development is the capture of many younger, smaller geckos, indicating strong breeding successes.

During the last survey, conducted in 2017, we caught a total of 141 unique individuals, an amazing result that

exceeded the total number of geckos released in all the translocations combined. This is a very positive stage in any translocation, one that helps to confirm the successful establishment of a population.

During this survey, we caught 79 unique individuals in November and another 140 in February. While Manu still needs to compare the photos taken from both weeks in order to establish an overall number of unique individuals, the total for this survey will be somewhere between 140 and 219, likely a new record.

So, who are the survey individual record-holders? Well, the heaviest male was 87g, the heaviest female was 84g, and she was extremely gravid (pregnant), with two babies on board. The record for the smallest gecko surveyed goes to a neonate (recently born), weighing just 5.5g (pictured).

At just 5.5 grams, this neonate gave us its most disapproving look, for daring to disturb its night-time activities.

The data analysis is complete, the report has been reviewed, and the final version has been submitted and accepted; an awesome milestone to achieve after a lot of hard, yet fun, work.

Naturally the report contains a lot of very sensitive information so, in the interests of protecting our reptilian friends, the full report cannot be widely distributed.

The good news is, we will be releasing a redacted version which will contain most of the report, suitable for distribution to a wider audience. The better news is, we can share some of the information in this article.

When setting up the translocation, the Tuatara Recovery Group set criteria to be used to measure the success of the translocation. These criteria were to be applied at the five-year anniversary and the ten-year anniversary. The Recovery Group acknowledged the timescales and targets were arbitrarily chosen.

The 2009 survey caught 30 unique tuatara, 23 founders and seven islandborn. The 2014 survey caught 31 unique tuatara, 22 founders and nine islandborn. While there was verified proof of tuatara breeding, and plenty of tuatara sightings, these survey numbers were insufficient to meet the ‘population has established’ criteria level.

The 2023 survey caught 73 unique tuatara, ten founders and 63 islandborn. This is a massive step up in numbers and in accord with regularly reported volunteer and visitor sightings. Excitingly, for several of the founder tuatara caught during this survey, it was the first time they had been recorded since being translocated.

The 2023 survey has provided sufficient capture/recapture data to allow us, for the first time since the translocation, to calculate a population estimate for the Island. That estimate is 370 individuals,

over six times the size of the original translocation population.

Despite the huge success of the survey, only 8.2% of individuals caught fit the criteria ‘tuatara in the 120mm –180mm SVL (snout-vent length) size range’. Applying the Recovery Group guidelines for this criteria, this is ‘cause for concern’.

However, the report concludes ‘… the tuatara population on Tiritiri Matangi has established and is thriving …’ because:

Out of a sample of 73 animals, 63 animals were island-born (86.3 %), with island-born animals occupying a range of sizes from small through to very large – which indicates many breeding events over 20 years.

Island-born individuals are far larger and heavier than their founder counterparts at a much younger age, indicating that island-born tuatara are growing faster, are healthier, and have access to abundant food resources.

A consequence of faster growth is that young tuatara on Tiritiri are more likely to grow rapidly through the 120mm180mm SVL size class than on islands

where tuatara are naturally present, but where food resources are limited and growth is, therefore, possibly slower. The lack of tuatara on Tiritiri in the size range of 120 mm – 180 mm SVL may therefore be more of a function of how long young animals remain in that size range. Compared to tuatara in the size range 120 mm – 180 mm SVL on other islands, similar aged animals on Tiritiri may simply already be much larger.

The core areas of tuatara occupancy on the Island seen in 2009 and 2014 have grown in extent and in abundance of animals. Overall distribution has extended into areas where no tuatara were found in 2014.

Overall, the total number of tuatara that may be present on the Island (circa 370 individuals) is, at a minimum, six times the size of the original founder population (60 adults).

As with any research, one of the first things concluded is that more research is required. Consequently, in addition to the five-yearly surveys already planned and permitted, there will be some additional surveys targeted to answer some remaining questions.

Nominations are sought for Chairperson, Secretary, Treasurer and up to nine committee members for the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi to be elected at the Annual General Meeting.

If you are keen to become further involved in the management of our outstanding organization, do consider a role on the committee. Meetings are held every six weeks at a central location. Nominations (including a nominator and seconder) must be received in writing by the Secretary on or before 31 July 2024. Send to PO Box 90-814, Victoria St West 1142, or secretary@tiritirimatangi.org.nz. Please include a photo and brief resumé for inclusion in the August issue of Dawn Chorus

'Gary', one of the Island's founding tuatara, was caught in the March 2023 survey. Photo: John SibleyI have a favourite spot on Tiritiri Matangi’s Wattle Track. It’s in the valley, where the boardwalk intersects a watercourse. The spot exudes a calm energy that, if you’re lucky when visiting, is accentuated by the thrill of seeing kōkako or kererū, or the daintier forms of hihi and korimako.

It’s filled with a bounty of elegant, architectural shapes and bold coloursbeautiful browns and greens, soft pink, mauve, and red, depending on the time of year.

Welcome to the ‘nīkau grove’.

A recent resident of Tiritiri Matangi Nīkau palms (Rhopalostylis sapida) are endemic to New Zealand. Their name, given by Māori when they first arrived on these shores, comes from the Polynesian word ‘nīkau’, which references the fronds (leaves) of the coconut palm.

The palms grow throughout the North Island in coastal lowland and hilly forests. They can also be found in coastal South Island regions north of Greymouth and Banks Peninsula, as well as on the Chatham Islands, where they claim the title of the world’s most southerly palm species. A second species in the Rhopalostylis genus, R. baueri, is also found on Norfolk Island.

Nīkau are relatively new to Tiritiri Matangi and were introduced to the Wattle Track and other forested valleys during the 1984-1994 planting programme. Seed was sourced from Hauturu / Little Barrier Island and Warkworth. Now, 40 years later, they are regenerating in suitable, shady, moist sites.

Nīkau remain at ground level for their first decade, producing a crown of pinnate (divided into two rows of leaflets) fronds before a solitary trunk slowly pushes skyward, ultimately reaching 15-20 metres high, some 100 years later.

Annually, new fronds sprout from the crown’s apex in a spiral, affording each one light and space, while old fronds detach from the crown’s base, leaving behind a distinctive brown trunk scar and a maximum of fourteen fronds in the crown.

Each frond completely encircles the trunk at the attachment site and stacks snugly inside the others, forming the distinctive bulbous shape below the crown.

Flowering begins when the palm is between 15 and 20 years old and starts at the site of the last frond detachment, where a green club-shaped spathe is exposed. Within a few days, the spathe releases a large drooping flower inflorescence (cluster) with up to 40 cream, finger-like branches, each clothed in a multitude of tiny pinkish-mauve buds and flowers. A close inspection will show the flowers arranged in groups of three: one female and two males.

Their musky scent and sweet sticky nectar attract insects and birds such as tūī, korimako and hihi to help in the task of pollination. Within a week, the male flowers have shed their pollen and fallen, leaving the pollinated females to grow their fruit into large green berries that ripen to red 12-18 months later.

While flowering can occur sporadically throughout the year, the main season is from November to May, and the main edible berry season is from February to November.

Many birds benefit from this almost year-round food supply, be it in the form of insects, flowers, nectar, or fruit. However, it is kererū, who can swallow the whole berry in one gulp, that are the main distributors of nīkau’s large seed to new habitats.

On Tiritiri Matangi, it’s always a thrill if you catch kōkako, tīeke, hihi, or kākāriki foraging from the crown to the ground amongst these beautiful palms. The boardwalk at the nīkau grove provides a wonderful platform from which to observe the spectacle.

But it’s not just the palms and the birds that frequent the spot that make this such a special, energetic place.

Sometimes, during heavy rain, water rushes down the valley and leaves a calling card of piled debris through the grove. At other times, the large, bulbous shapes of decaying fronds fall and loiter. Strewn across the space, they wait for nature’s next move in the ultimate process of recycling.

When you stop and take in this spot, it feels like it’s teeming with life, colour, elegance, and the power of nature.

Natalie Spyksma

Titipounamu/rifleman

These are the end-of-season figures for riflemen.

This, our 15th breeding season since riflemen were first introduced, saw 213 individuals caught, consisting of 107 juveniles, 72 adults, and 34 previously banded birds recaught. This has, by far, been our most successful season.

Kōkako

We have 13 fledglings for the season: eight males, four females, and one whose sex is unknown as Skye and Bátor’s nest could not be accessed.

Discovery and Sarang were the only pair to successfully fledge two chicks. They are both females and have been named Rondo and A Cappella.

The other two female fledglings were produced by Wai Ata and Awenga and Pūtōrino and Sapphire and are named Kiri and Iorangi.

The eight male fledglings (with the parents’ names in brackets) are Tāne (Shelly and Tama), Tūpari (Oran and Haar), Wedel (Haeata and Hotu), Rōreka (Wairua and Parininihi), Tuatahi (Phantom and Wakei), Kiseki (Rehu and Noel), Fonn (Te Rae and Chatters), and

Nuka (Jenny and Slingshot).

The season ended with 25 pairs, as, despite having successfully fledged a chick (UB10)*, Bátor and Skye have separated. Marihi, who had paired up with Themba (Honey and Rimu’s son from last season), has left him and is now with Bátor. Skye has been seen in the same area on her own, and UB10

has been sighted only once and was alone.

The two youngsters, Moana and UB9, from last season are still together in a small area at the top of Little Wattle Valley / implement shed. As suspected, the recently caught and banded UB9 is a male and has been named Hēnare. It will be interesting to see if they remain together as a pair in this area.

*We use the term UB (unbanded) until each kōkako has been given his or her own combination of coloured bands and a numbered metal band.

Results of the 2024 annual bird transect counts

In February, we completed the tenth consecutive year of transect counts of the forest birds. Our survey team walks slowly along fixed routes through the bush, counting every bird they can detect within ten metres on either side of their route. There are 20 transect routes spread throughout the Island’s bush, and each one is counted 16 times. The results are used to calculate the average number of birds per hectare and estimate the total population of each species.

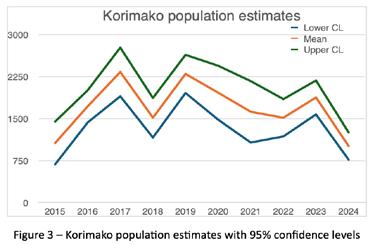

This year, the total number of records (not the same as the total number of birds) was down almost 30% from last year and continues a long-term decline since the high point of 2019 (Figure 1). The counts are dominated by the fortunes of our ‘big three’, pōpokatea/ whitehead, korimako/bellbird, and tīeke/saddleback, with population

estimates of 1,348, 1,010, and 687, respectively. Changes in their annual population estimates are shown in figures 2, 3, and 4. Pōpokatea and tīeke are now at about half their population sizes in 2015; the korimako estimate is also at an all-time low but was at a similar level in 2015, with many large fluctuations between then and now.

Table 1 shows the population estimates for more species together with the change this year from the average of the previous nine years. There are some interesting variations in the fortunes of the different species. Tūī and kererū show the largest declines, but they are both strong fliers and can easily move to and from the nearby mainland at Whangaparāoa when food is in short supply on the Island. We sometimes see tūī first thing in the morning circling high into the sky before setting off on their daily commute.

Toutouwai / North Island robin, pīwakawaka/fantail, and manu pango/ blackbird populations are around the long-term average.

One species not mentioned so far is titipounamu/rifleman. The survey showed a doubling of their population estimate, but it doesn’t work well for them because some of our surveyors are unable to hear their high-pitched calls, which is the main way they are found and identified. Fortunately, we have confirmation of a dramatic increase in the population from the monitoring carried out by Simon Fordham, which indicates there are now many hundreds on the Island.

The hihi estimate is unlikely to be accurate because hihi are inquisitive and fly towards people walking through the bush. The lower-than-average estimated population is at odds with what we would expect, as there was a higher than usual number of breeding females and one of the higher annual nesting success rates.

The long-term declines in the estimated populations are interesting but not necessarily concerning. It may well be that the impacts of cyclone Gabrielle and the heavy rainfall of early 2023 are still impacting some species, and we have had several very dry summers since 2019. It is also possible that bird populations are gradually changing to levels that may be sustainable. We know that introduced populations often show a pattern of strong growth up to a peak, beyond which they decline to fluctuate about a lower average. Part of the value of the annual transect surveys is their illustration of the often dramatic annual fluctuations in bird numbers. We need to keep on counting to be able to follow both short- and long-term changes.

While wandering the Generator Track, looking out for ruru and wētāpunga, my attention was drawn to a kerfuffle in the leaf litter just to the side of the track.

There, to my delight, was a kōkako rolling and jumping around, wrestling with small sticks and Norfolk pine needles like a playful puppy. She grabbed the sticks with both feet and rolled around with them on her back. The play was quite curious, as at times she would leap up and then eye a stick as if expecting it to respond.

After a couple of minutes of rambunctious activity, she hopped up into the low branches of a tree to have a post-play snack on a leaf before moving further into the bush.

Meeting Karin Gouldstone at the ferry and sharing the leg band combination (YM-GG), we found that this bird was Luna (a bird that she had named), a young kōkako from the 2022-23 season. Simon Fordham also shared that Luna was the first chick of that season to be banded on December 13, 2022. It was so wonderful to see a very content young kōkako behaving in a way that is not often seen!

A second unusual sighting involving a kōkako involved Moana (YM-JR), who was seen digging into rotting wood with her beak.

A few people have seen kahukura / red admiral butterflies on the Island.

Compiled by Kathryn Jones, with contributions from Morag Fordham, Simon Fordham, Virginia Nicol, and John Stewart Photo: Virginia Nicol Photo: Kathryn Jones Photo: Kathryn Jones A kahukura / red admiral butterfly. Moana (YM-JR) holding rotting wood she'd dug out of a branch.Tiritiri Matangi Nature Notes

The world in which the ancestors of today’s tuatara appeared, 250 million years ago, was vastly different from today’s environment. John Sibley explores the evolution of tuatara.

From Pangaea to Aotearoa

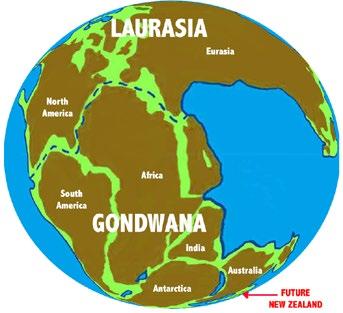

The Triassic period (252-201 million years ago) was the first part of the Mesozoic era, dubbed the ‘age of conifers and dinosaurs,’ although the first dinosaurs did not in fact appear until well into the Triassic period. Today, it is hard for us to imagine the world as it was back then, devoid of flowering plants and even birds. The Gondwanan forest would have formed an endless carpet of plain green conifers and ferns.

This was a time of great climatic, tectonic, and evolutionary upheaval. The earth was on average warmer than it is today, and dominated by a colossal supercontinent called Pangaea, composed of Laurasia in the north and Gondwana in the south. At the end of the Triassic period tectonic forces would rip this land mass apart, separating Laurasia from Gondwana. If viewed from space, the shapes of present-day continents would already have started to become recognisable. At this time, the land mass that would eventually form Aotearoa consisted of a mere shard of submerged oceanic crust, which tectonic forces were pushing westwards. Above water there may have been a chain of small offshore islands near the coast of Australia. The flora and fauna on this protoAotearoa would have been thoroughly Gondwanan in nature.

From Tetrapoda to Tuatara

Pangaea: Adapted. Redrawn from several sources. Non-profit use.

The now extinct ancestral ‘stem reptiles’ (sometimes called ‘ancestral amniotes’) were the predecessors of the dinosaurs and modern reptiles, as well as birds and mammals. Recent research using modern DNA analysis shows that 250 million years ago the ancestors of the tuatara diverged from this stem reptile line. [1] Pre-dating the dinosaurs (which started to appear near the middle of the Triassic period) was an older group of reptiles called the Rhynchocephalians (Gk = ‘beakheads’). These were the ancestors of our present-day tuatara.

Fossil evidence shows that at one time the Rhynchocephalians were widely distributed across Pangaea, but by the early Jurassic period, 100 million years ago, their distribution had begun to contract to their present geographical range. The most recent fossil record is from Argentina about 70 million years ago.

Tuatara belong within this ancient Rhynchocephalian group. Today’s tuatara are sole survivors of a subgroup of the Rhynchocephalians – a family called the Sphenodontidae (Gk = 'wedge-teeth') which is a mere 19 million years old. Therefore, it would be inaccurate to say that modern tuatara pre-date the dinosaurs, however their lineage does. Tuatara still deserve their ‘living fossil’ status, retaining many ancient features lost by the ‘modern’ lizards, skinks, and geckos. The most recent (2020) genetic studies suggest that the rate of tuatara evolution has been unusually slow (contrary to previous studies). [1]

Source: Nature. Gemmell, N.J, adapted. Non-profit use.

The primitive teeth of the tuatara are not set in bony sockets as in other reptiles but are continuous outgrowths of the skull and jaw bones. However, they are not mere bony projections; they have enamel, dentine, and pulp cavities. Unlike modern reptiles, the teeth are not replaced as they wear down. Uniquely amongst the reptiles, tuatara have a double row of teeth in the upper jaw which interlock with the single row on the lower jaw. This gives them a firm grip on prey, and their ability to slide the lower jaw forward and backwards produces a sawing motion, efficiently cutting insect exoskeleton chitin as well as bone. Their skulls have also retained primitive features, including large holes called fenestra, used to accommodate chewing muscles. Modern lizards do not have the same arrangement.

Tuatara are well known for the possession of a ‘third’ parietal eye. Most other reptiles, amphibians, and some fish also possess these. However, when taking a close-up look at a tuatara’s head, most people are disappointed. At best, their parietal eye resembles a dull scale in the centre of the forehead, and it could easily be overlooked. It is unlikely to have any overhead predator perception role. Other modern reptiles have a much clearer eye-like structure visible. Parietal eyes are light sensitive extensions of the brain (just as regular eyes are), positioned beneath a hole or foramen in the skull. They often have rudimentary lenses and retina-like layers which are sensitive to light. They are linked to the pineal gland in the brain which secretes melatonin to regulate diurnal rhythms such as sleep/activity, temperature regulation, and breeding. Although humans do not possess a parietal eye, we do have a pineal gland deep in the brain, which also secretes mood-regulating melatonin, the amount secreted influenced by the amount of daylight received by our eyes.

Like our primitive native frogs, the tuatara has no outer ear, unlike other modern reptiles. Sound waves transmit through the bony skull to the inner ear where, it is thought, only low frequencies are perceived.

Tuatara skull. Redrawn from several sources.

Pineal eye structure - Spencer 1886.

Public domain.

A European common lizard with a prominent pineal eye.

Modern gecko have distinctive external ears.

Tuatara skull. Redrawn from several sources.

Pineal eye structure - Spencer 1886.

Public domain.

A European common lizard with a prominent pineal eye.

Modern gecko have distinctive external ears.

The tuatara skeleton also retains primitive features harking back to the first reptiles and, like the crocodiles, they still possess remnants of bony ‘body armour’ in the form of flat gastralia, rib-like plates beneath the abdominal belly skin, derived from ancestral scales. Their spinal vertebrae still retain an archaic ‘fishy’ flexible notochord rod, which runs through the centre of each vertebra and along the length of the backbone, below the spinal cord.

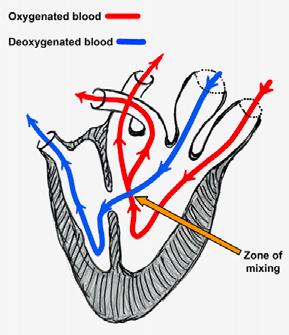

Non-profit use. Adapted.

The heart structure of tuatara [2] is the most primitive and inefficient of all living reptiles. Like many lizards, the heart ventricles which pump the blood are not separated by a complete septum, so oxygenated and deoxygenated blood is not separate, as it is in mammals and birds. This, coupled with their extremely simple lung structure (a single sac without alveoli to increase surface area), limits sustained exertion. They sit mostly motionless, with only brief periods of rapid movement to escape predators or catch prey. This primitive inefficiency means tuatara live life in the ‘slow lane,’ with just one heartbeat per minute and one breath every 20 minutes at rest. Their low metabolic rates enable them to last extended periods between meals. This is a distinct advantage in the cool temperate climate of Aotearoa. Few other reptiles can endure the low temperatures tuatara seem to enjoy and, consequently, they avoid competition for food with other reptiles. However, life ‘on the edge’ can be precarious. Having long lives and slow reproductive rates is a risky survival strategy. It can take a female up to three years to provide a developing egg with yolk, and a further seven months to form the leathery shell. Recently introduced predators, competitors, and changing environmental conditions could tip them into extinction. New Zealand’s isolation no longer offers protection.

Without a doubt tuatara are supreme survivors, whose ancestors have endured three major global mass extinction events down through the ages. Will they be able to meet the challenges of the present-day mass extinction event caused by humans?

References:

[1] Gemmell, N.J., Rutherford, K., Prost, S. et al. The tuatara genome reveals ancient features of amniote evolution. Nature 584, 403–409 (2020). https://doi. org/10.1038/s41586-020-2561-9

[2] J.R.Simons May 2010. Journal of Zoology 146(4):451 – 466. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1965.tb05219.x

A freshly moulted adult showing breeding colours.

Photo: John Sibley

Belly armour provided by bony gastralia.

A freshly moulted adult showing breeding colours.

Photo: John Sibley

Belly armour provided by bony gastralia.

The Tiritiri Matangi lighthouse is the oldest lighthouse still in operation. Search the diagram to find the words highlighted in the text below. Visit the blog on our website to find out more about the Davis light. Have fun!

The Tiritiri Matangi Island lighthouse is a listed Category 1 historic place. It comprises the tower itself, as well as three keepers’ houses, a workshop, three foghorns, and a signal tower.

It was first lit in 1865, brought over from England on a sailing ship. The prefabricated cast iron tower and light were designed by Maclean & Stillman and manufactured by Simpson & Co. Construction. Twelve bullocks hauled the 75 tons of material up the Island

The second-order dioptric light used a Fresnel lens with thick glass prisms to focus the relatively weak light from an oil lamp. The lamp initially burned canola oil and was fixed so the light shone in all directions. The lamp was progressively upgraded to paraffin, pressurised kerosene in 1916, an automatic acetylene lamp in the 1920s, and electricity in 1955. In 1882, a red glass panel was fitted over a portion of the light beam to warn shipping to avoid Flat Rock near Kawau Island.

From 1965-1984, Tiritiri was the brightest light in the southern hemisphere. The old Fresnel lenses were replaced by the Davis Marine Light with a xenon bulb. Every 15 seconds, the Tiritiri Matangi light swept a brilliant beam across the bedroom walls of Auckland’s North Shore.

The lighthouse was automated and demanned in 1984. Ray Walter was the last lighthouse keeper, but he remained on Tiritiri Matangi to manage the restoration project and was the DOC Ranger until he retired in 2006.

Today, solar panels and batteries supply electricity to a 1.2-million-cp light, with a diesel generator backup.

by Stacey

by Stacey

The Davis light men, 1965.

Photo: Geoff Beals

Photo: P Taylor

The Davis light men, 1965.

Photo: Geoff Beals

Photo: P Taylor

The Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi (SoTM) is a volunteer Incorporated Society that works closely with the Department of Conservation to make the most of the wonderful conservation-restoration project that is Tiritiri Matangi. Every year volunteers put thousands of hours into the project and raise funds through donations, guiding and our island-based gift shop.

If you'd like to share in this exciting project, membership is just $30 for a single adult or family; $35 if you are overseas; and $15 for children or students. Dawn Chorus, our magazine, is sent out to members every quarter. See www.tiritirimatangi.org.nz or contact PO Box 90-814 Victoria St West, Auckland.

SoTM Contacts:

Chairperson: Ian Alexander chairperson@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Secretary: Val Lee secretary@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Treasurer: Peter Lee treasurer@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Committee: Hester Cooper, Rachel Goddard, Carl Hayson, Janet Petricevich, Michael Watson

Operations Manager: Debbie Marshall opsmanager@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Guiding and Volunteer Manager: Gail Reichert booktoguide@tiritirimatangi.org.nz, 09 476 0010

Retail Manager: Ashlea Lawson retail@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Membership: Rose Coveny membership@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Educator: Sara Dean

Assistant Educator: Liz Maire educator@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Fundraiser: fundraiser@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Social Media: Stacey Balich socialmedia@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Dawn Chorus co-editors: Janet Petricevich and Stacey Balich editor@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Island Rangers: Talia Hochwimmer and Keith Townsend tiritirimatangi@doc.govt.nz, 09 476 0920

Day trips:

Weather permitting, Explore runs a return ferry service from Wednesday to Sunday from Auckland Viaduct and the Gulf Harbour Marina. Bookings are essential.

Phone 0800 397 567 or visit the Explore website: www.exploregroup.co.nz/

Overnight visits:

Camping is not permitted and there is limited bunkhouse accommodation. Bookings are essential. For further information: www.doc.govt.nz/tiritiribunkhouse

Supporters' Weekends

13th July, 7th September, and 5th October

These weekends are led by guides who show off the Island's special places. All enquiries to the Guiding and Volunteer Manager.

Working Weekends

King's Birthday Weekend - 1st June (fully booked)

Labour Weekend - 26th October

All enquiries to the Guiding and Volunteer Manager.

Tiritiri Matangi Talk

Monday 10th June

Wētāpunga recovery programme revisited

Chris Green PhD | Honorary Research Associate

Te Papa Atawhai - Department of Conservation

7:30pm at Fickling Centre, 546 Mount Albert Road, Three Kings, Auckland

Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi Winter Deal:

- 50% discount for Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi for travel between 01 June – 31 July 2024

- Maximum 2 Adults (including member) and 3 children per booking.

- Promo code: SOTIRI24

July School Holidays Deal: Kids Go Free

- Valid for travel 3-28 July 2024 (based on days of operation during the month of July).

- Maximum 1 child per full paying adult.

- Promo code: KIDSFREE24

Direct bookings through reservations only via email or phone. Members to be verified through Tiritiri Matangi portal.

School Education Programme:

We offer a full-day learning experience in a pest-free environment for year 1 to 13. Tamariki and rangatahi can get up close to endangered taonga species where they learn about community conservation and how people can work together to provide protected habitat. This then inspires students to take action in their own neighbourhoods.

Our educators offer a range of education experiences on the Island that are closely tied to the NZ curriculum. At the senior biology level, there is support material available for a number of NCEA achievement standards. Tertiary students have the opportunity to learn about the history of the Island and tools of conservation as well as to familiarise themselves with population genetics, evolution and speciation.

Subsidies are available for schools with an EQI 430 or more via our Growing Minds programme. Information on the education programme is at: https://www.tiritirimatangi.org.nz/education-programmes/ Bookings are essential.

Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi wishes to acknowledge the generous support of its sponsors

Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi welcomes all types of donations, including bequests, which are used to further our work on the Island. If you are considering making a bequest and would like to find out more, please contact secretary@tiritirimatangi.org.nz