Chair Chat

The warm weather has encouraged many local and international visitors to travel to the Island to enjoy Tiritiri Matangi at its best. The first much-needed rainfall in early March partly filled the Wharf Dam and refreshed the Island's flora. Some more rain on its way will be of immeasurable value to the flora and fauna. Of course, we know the Island is worth a visit at any time of the year, each season bringing its amazing spectacular show of nature.

Our committees, task groups, and hundreds of volunteers help operate the Island. Much of their work is behind the scenes yet essential to the Tiritiri Matangi conservation project. Their ongoing commitment is valued and appreciated.

The Board is pleased to welcome Louise Delamare and Rosemary Gibson as new members to strengthen its governance team. Louise is one of Tiritiri's fundraisers and was introduced to SoTM members in Dawn Chorus issue 138. She brings her legal experience from many different corporate sectors to the Board, and her background in resource management, environmental, property management, and health and safety law will be helpful to our team. Rosemary introduces herself below.

The infrastructure team has completed the staff accommodation and is progressing with the extension to the lighthouse museum.

During March, we had a successful social evening and a Tiritiri Matangi talk by Annette Lees, the author of Walking into the Night

The Department of Conservation is considering tenders to renew the boardwalks on the Kawerau Track. We have been notified that the wharf will shortly be closed for repairs for approximately one week. Other news is that funds will be available from the international visitors' levy to undertake weeding across the Island, which will help to address the ongoing weed problem.

Please continue visiting the Island during the autumn and winter, as the birds, freed from family responsibilities, can be seen enjoying their island home.

Ian Alexander

My name is Rosemary Gibson. My grandparents first introduced me to Tiritiri Matangi 20 years ago. I rediscovered the sanctuary after moving to Auckland and was greatly impressed by the native and endemic birds.

I grew up in Island Bay, a suburb overlooking the Cook Strait. It’s a raw (windy) but beautiful place, and there are a few remaining boats in the bay belonging to the Italian fishermen who settled there. The sea has always been important to me, but I now swim in the warmer waters of the Waitematā, where I live with my partner, young son, and border terrier Bert.

My career has been in law. For the last 12 years, I have worked as a litigator in private practice. Recently, I have focused on working for not-for-profit organisations, and in August last year I joined the Auckland Community Law Centre as a senior lawyer. As a member of Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi, I saw the call for volunteer Board members in Dawn Chorus and put my hand up for what will be a fantastic experience.

I have previously volunteered to check traplines along Te Auaunga Oakley Creek Walkway in central Auckland. I also hold a New Zealand Certificate in Horticultural Services (Level 4) (Landscape Design).

I look forward to contributing to the care and success of Tiritiri Matangi while working on the Board and hope to expand my practical conservation experience on the Island.

Notice is hereby given that the Annual General Meeting of the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi Inc will be held at 7.30pm on Monday 15th September 2025, at MinterEllisonRuddWatts Seminar Room, PWC Tower, 15 Customs Street West, Auckland City. Further details will be published in the August 2025 issue of Dawn Chorus

For many years, staff employed by the Supporters have stayed overnight to work on guide bookings, boat manifests, stocktakes, purchasing goods, and similar tasks. Space in the bunkhouse is often scarce, so staff usually stayed in the extension next to the Visitor Centre. This extension was initially proposed as a propagation area for a mini nursery but was not used as such. It had an improvised bedroom, kitchenette, and a table to work at but lacked toilet and suitable cooking facilities. The absence of these facilities breached NZ WorkSafe standards for staff accommodation.

To bring the space up to the required standard, a broom cupboard needed to be removed to install a bathroom and toilet, and a gas hob needed to be installed in the kitchenette. It seemed like a straightforward plan until Auckland City Council informed us that resource and building consent would be required. This consent process took 18 months to complete and required input from a planner and an architect, making it an expensive and complex undertaking.

Construction began in September 2024, with a planned completion timeframe of two to three months. However, progress slowed during Council inspections. In addition, the consent required installing a comprehensive fire alarm system, not just in the staff accommodation but throughout the entire Visitor Centre. The fire alarm connection became the most expensive aspect of the project, and it was challenging to secure time for fire engineers to travel to the Island and set up the switchboard.

Further delays occurred during the installation of the composting toilet tanks, mainly due to the plumber's unavailability.

Ian Higgins and volunteers helped reduce delays and costs by installing the tanks, connecting them, and filling them with composting materials.

Finally, nearly six months after the project began, the composting tanks, trickle hoses, shower, and toilet are all in place. Special thanks to Ian Higgins and the many volunteers who generously donated their time, significantly reducing the overall cost for SoTM.

The project has brought some side benefits for the Visitor Centre, such as the installation of a professional fire alarm system now fitted in every room. Additionally, wastewater from the tea facilities, which previously drained directly into the bush, is now connected to the composting system.

Although a few paper sign-offs from the Council are still pending, the upgraded accommodation is now available for staff to use. It helps them focus on their work and eases pressure on the bunkhouse. Our Chairperson, Ian Alexander, has 'inspected' the facility and given it his official seal of approval.

Carl Hayson

Hannah Shand is a NZ native bird artist on a mission to raise funds and awareness for endangered birds and the sanctuaries and conservation groups working to protect them. She recently donated her art for some new signage on the Island. Hannah has raised almost $45,000 for bird conservation projects and organisations around the country, and her latest fundraiser is for Tiritiri Matangi! From 1st June to 14th June, 40% of her print sales will be donated to support our work.

Her fine-tip pen drawings highlight the beauty of our native birds. They come in a range of sizes from A4 to A1 and can take up to 16 weeks to produce. She draws primarily from reference photos from her travels throughout NZ, including the following artworks from her time on Tiritiri Matangi: Bathing Bellbird, Kōkako Companions, and Tīeke Aroha.

To check out her work and support Tiritiri Matangi with a print purchase, please see www.hannahshandart.com (please mention Tiritiri Matangi Island in the checkout section).

You can also follow Hannah on Instagram and Facebook at @hannahshandart

Kaia is an outstanding kaitiaki, deeply committed to protecting and supporting native plant and animal life. A dedicated member of the school’s Pest-Free and WeedBuster teams, she brings energy and enthusiasm to every task, inspiring others to get involved. Kaia is a passionate nature ambassador, regularly attending gala days and community events to promote conservation. Her keen interest in the bird and insect species of Tiritiri Matangi fuels her drive to help create a pest-free environment on the Hibiscus Coast.

Biological control agents are an increasingly popular alternative to synthetic pesticides in New Zealand agriculture. However, the traditional pest management methods used in Māori pre-colonial agriculture remain under-researched. My project aimed to explore the potential of native plants as natural biocontrols by examining how peach aphids respond to specific plant extracts. I tested four native species—kawakawa, mānuka, kūmarahou, and horopito—by observing aphid migration patterns in comparison to those exposed to modern pesticides. After a 24-hour observation period, the results indicated that kawakawa and horopito show promising aphid-repellent properties.

Education

Sara Dean, lead educator, reports that during Term 1 an impressive 682 students from Northcross Intermediate took part in the Tiritiri Matangi Education Programme, across 12 separate visits to the Island.

Since 2022, Year 7 students have been making the journey to Tiritiri Matangi, ensuring that over two years every student at the school has the opportunity to experience learning in an 'outdoor classroom'. The programme not only deepens their understanding of Aotearoa New Zealand's native environment, but also creates a meaningful connection to their school's logo — the iconic Tiritiri Matangi lighthouse.

The lighthouse is a powerful symbol for the school, standing for guidance and strength. It represents overcoming challenges and adversity, lighting a way forward, and helping students navigate the world confidently and purposefully. In particular, the head of the lighthouse embodies the value of Whai Whakaaro – obtaining wisdom, forethought, consideration, and fostering strong relationships. At Northcross Intermediate, this means respecting themselves and others, being aware of each other's thoughts, feelings, and needs, and creating a supportive learning environment for all.

Inspired by their visit, a group of students is working on a project to give back — crocheting animals to donate to the Island's gift shop. The proceeds will go toward supporting conservation efforts on Tiritiri Matangi. For the students, the path to success has combined authentic learning with making a meaningful impact on Aotearoa New Zealand's unique wildlife.

We look forward to welcoming students from Northcross Intermediate back next year!

What the students said about their visit:

'I loved that every bird you saw, it would be a special one and some of them you don't see on the Mainland.'

'Our instructor (Fiona) was so nice and told us fascinating stories about Tiritiri Matangi and the creatures that live and thrive there. Also, we saw two giant wētā mating in a tree. It was so cool!'

'I loved seeing all sorts of birds and learning all about them! It was so fun adventuring Tiritiri and seeing all the nature life (birds and bugs).'

Gaye Hayson found her passion for Tiritiri Matangi through her work with the Island's restoration and visitors. Carl Hayson has spent over four decades dedicating himself to Tiritiri Matangi, where he has become a key figure in its conservation journey.

Introducing Gaye

I was born in Birkenhead and grew up between there and Murrays Bay, with Le Roys Bush and Birkenhead Wharf as my playgrounds. I attended Birkenhead Primary and Rangitoto College. I started work as a secretary, moved to hotel reception to work overseas, and spent 18 months in London. Back in Auckland, I worked at the South Pacific and Poenamo Hotels before returning to secretarial work, becoming an executive PA. I later managed accounts and office duties in a small company, loving the team environment.

I met Carl in 1993 and heard about his passion for Tiritiri Matangi. When friends asked where he was, I'd point toward the Island. Eventually, he introduced me to Tiritiri, and I loved it; it had a spirit of its own. It felt like joining a family led by Ray and Barbara Walter.

I worked mainly in the shop with Barbara, Sally, Isabel, and Nan and took on the bookkeeping role when Lois Wilson became treasurer. Carl and I enjoyed spending New Year's Eve on Tiritiri doing the stocktake — a good excuse for a gettogether! Now, I help by collecting raw sugar from Chelsea Sugar for the hihi.

Meeting visitors, helping them shop, and hearing about their guided walks was great. Even now, when I don't visit often, it's lovely assisting people at the Visitor Centre, or lighthouse museum.

When I visit, I love sitting and listening to the birds; their calls still amaze me. I've also become interested in maritime history, helping with lighthouse open days. Learning from Ray was inspiring, and seeing the lighthouse museum grow is wonderful.

As for the birds, I've always loved the takahē, especially Mr Blue and Greg, who would follow me around after visitors left! I also loved the brown teal like Jemima at the Wharf Dam. Then came the kōkako, always a privilege to hear and see. My day is made when I spot a robin.

One favourite memory is when Barbara was giving the ranger's talk with Greg beside her when a young blue penguin raced down the road to the sea on a mission. It was a magical way to start the day.

I was born in Te Kopuru, Northland, and spent my early years on a farm at Forrest Hill, North Shore. I attended Forrest Hill Primary and Westlake Boys High. I worked for 43 years at a scientific products company, becoming Logistics Manager, then moved to a plastics manufacturer as a production planner.

My love of nature began on the farm, fuelled by collecting Gregg's Jelly native bird cards. Later, I attended an Auckland University Continuing Education class on the northern offshore islands, taught by Dr. John Craig.

The class finished with a field trip to Tiritiri Matangi. Seeing my first saddleback hooked me instantly.

On Tiritiri, I met Ray and Barbara Walter, who suggested I join the planting programme. I met many Supporters still active today, and it was great fun. Barbara later encouraged me to help with bird translocations. In 1990, I went to Little Barrier Island to mist-net whiteheads for Tiritiri. In 1992, I helped trap robins near Rotorua, learning a lot about bird handling.

As others took over translocations, I moved into guiding. In the early days, we led groups of up to 30 with just a tape recorder! Finding birds was much harder then. Today's guiding is more professional, with smaller groups and richer wildlife.

The Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi formed in October 1988. Ray and Barbara asked me to join the committee three months later. Except for one small break, I've served ever since, holding most of the elected roles, including Chairperson twice. It's been a challenging and rewarding journey.

My favourite guiding story is the 1991 arrival of the takahē — the roadblocks, the two males, and the success since.

In 1993, my life changed when I met Gaye. After five years, I was finally 'weaned' off my island obsession and became a fully functioning husband! Gaye continues to help and advise me quietly.

My favourite bird is the saddleback — noisy, colourful, and an incredible survivor. Their family behaviour is fun to watch, even if some guides rank kōkako higher.

Most memorable moment: sitting alone by Bush 23, watching a deep red sunset over Whangaparāoa, hearing little blue penguins below and seeing dolphins leap offshore — pure magic and a reminder of Tiritiri's spirit.

In 2002, Ray warned that the old lighthouse buildings could be lost without action. I took it as a challenge. With no maritime history knowledge, I learnt from Ray and discovered how special Tiritiri's station is. A small team began restoring the structures with minimal funding. Now, it's a success story, and we're working to restore the foghorn, too. Watch this space!

A few years ago, on my first training day as a guide on Tiritiri Matangi, I was introduced to the phrase 'the supermarket tree'. It describes the year-round food supply pūriri (Vitex lucens) provides to the Island’s birds.

I had previously worked in the botanical world, using both Latin and common names to describe plants, but 'the supermarket tree’ was new to me. It had a ring to it that was hard to forget, so when each successive trainer also used the phrase, I duly adopted it.

It’s an apt description for this bountiful species. However, it wasn’t always this way. Pūriri were notably scarce on Tiritiri Matangi before the 1984-94 revegetation programme. Records show that only two trees existed.

Thanks to widespread replanting, trees are now repopulating naturally across the Island. The 'supermarket shelves' are filling!

Pūriri is endemic to northern New Zealand and extends as far south as the coastal strips north of Opunake in the west and Mahia Peninsula in the east. It grows below 500 metres, where frost-sensitive seedlings prefer sheltered, humus-rich soil. Volcanic is ideal.

In forests, the young plants stretch towards light, producing only a handful of branches below 15 metres. In the open, exposed to the elements, a gnarly, shorter-branched tree develops.

Pūriri grow relatively quickly for 60-odd years and then slow their pace. This results in extremely hard, dense wood. Trunks can grow up to two metres wide and reach at least 20 metres in height. The tree's strength helps it withstand coastal gales and hold a sprawling canopy.

Trees can regenerate from stumps, fallen branches, and logs — a survival technique suited to windy, coastal environments. As a result, you may notice some odd-shaped and widely sprawling trees.

Some of the biggest pūriri trees in New Zealand are up to two thousand years old but, sadly, their strength has historically been an Achilles heel: few such giants are left, due to selective logging, habitat clearance, and introduced pests. In earlier years, its strong wood made the tree ideal for palisades, fence posts, railway sleepers, house piles, and bridges.

Now that the trees are abundant on Tiritiri Matangi, you'll see terminal clusters of nectar-filled, pinkish-red flowers appear on pūriri throughout the year. The main blooms occur in winter when few other plants flower. Each loosely-held cluster holds 12 to 15 flowers.

Tiny hairs at the base of the 2.5cm, tube-shaped flower stop insects from reaching the nectar, leaving it primarily a food source for nectar-feeding birds. Korimako/bellbirds are particularly well-designed for the job, but tūī, hihi/stitchbirds, kōkako, kākā, and tauhou/silvereyes also help. Kākāriki dine on the buds and flowers.

Following flowering, a steady supply of ripe red, 20mm wide, fruit appears, peaking in summer. Kererū, along with tūī, kākā, and kōkako, feast on the juicy cherry-sized fruit.

Kererū are the primary vehicle for pūriri seed dispersal and play an essential role in the tree’s survival and revegetation. No other common endemic bird can swallow fruits greater than 12mm in diameter and disperse the seeds intact.

Pūriri — also a 'real estate' tree

Since becoming a guide on Tiritiri Matangi, I have been reflecting on another characteristic of the pūriri. This 'supermarket tree' turns out to be an all-in-one service: it feeds an ecological village and can also house one!

Many birds, plants and insects benefit. Most notable is the beautiful, green pūriri moth, which lives as a caterpillar inside the tree for up to seven years.

After metamorphosing into New Zealand’s largest moth and leaving the tree, it survives just one or two days, sufficient time to mate and for the female to distribute her eggs. That’s if a perching ruru/morepork doesn’t devour it first!

The empty holes left by the pūriri moth provide homes for wētā and spiders but, once the holes seal over, they leave huge, tell-tale scars on the trunk.

Many other insects live in the pūriri bark and foliage, and they are readily hunted by birds such as tīeke/saddleback, pīwakawaka/ fantail, pōpokotea/whitehead, toutouwai / North Island robin and titipounamu/rifleman.

Although the majority of Tiritiri's pūriri are not mature enough to provide them, given time, large cavities left by broken branches may provide spaces for our cavity-nesting birds to utilise.

Like residents of a multistoried apartment block, epiphytic plants reside on strong branches at varying heights in mature forests. Bushmen referred to these as 'widow makers' as their massive size made them lethal if they fell. One day, Tiritiri's pūriri may provide homes to these impressive plants.

It certainly is a tree that keeps giving. I hope these taonga of the forest will thrive on Tiritiri Matangi – and across northern New Zealand –for generations and centuries to come.

Natalie Spyksma

Now is the perfect time to visit the Island and observe this year's fledglings and adult birds that have recently moulted and regrown their feathers since the end of summer.

Tīeke

Fewer tīeke/saddleback are using our nest boxes than ever, but those that used them in 2024-25 had a higher success rate than usual. Only 17 tīeke laid eggs in nest boxes and, of the 36 eggs laid, 21 hatched. The table below compares this with the previous four years.

As far as we can tell, all 21 chicks fledged successfully. We can never be certain of fledging because, once the chicks are around 14 days old, the box is not visited until a week after the expected fledging date. This avoids the risk of startling large chicks into leaving the nest before they are ready. However, when a nest fails in its latter stages, there are usually clear signs (such as dead chicks in the boxes or nearby), and none were found.

In the previous five seasons, 20-22 boxes had been used, so the figure of 17 in 2024-25 represents a significant drop. Almost as many titipounamu/rifleman pairs (14) built nests in tīeke boxes. As in recent years, many boxes were also occupied by wētāpunga. A more detailed analysis of the figures might indicate whether there is a correlation between other species moving in and tīeke moving out.

Kōkako

The season started with 25 pairs, increasing to 26 pairs by the end of November. Four 'divorces' have occurred since the end of the previous season.

The first nest was found on 3 October, and the season finished with the last chick fledging by mid-April.

Twenty-five chicks fledged, but only 20 of them were banded. Two banded chicks disappeared shortly after fledging, and one banded chick was predated in the nest. Four nests were not accessed, producing five fledglings that remain unbanded. Unsuccessful attempts have been made to catch these fledglings.

Of the 18 remaining banded fledglings, we know we have nine males and seven females. Two of the 18 couldn't be sexed as they were too small to take a feather sample on the day they were banded.

After losing their first chick to predation, Te Rae, who is 19 years old, and her partner Chatters, who is 18 years old, successfully fledged one chick. Parininihi, who is 20 years old, and his 9-year-old partner, Wairua, also successfully fledged one chick.

Four of our new pairings were also successful. Three pairs fledged one chick, while the other fledged two chicks

from two different nests. In their fifth season together, Waitangi and Lyric were finally successful and produced two fledglings.

Ten pairs were unsuccessful and failed to fledge any chicks this season.

The annual Kiwi Call Survey recorded 205 calls over four nights, around 20% below the 14-year average of 254. The recent lack of precipitation may have contributed to this.

The 2025 bird transect survey results

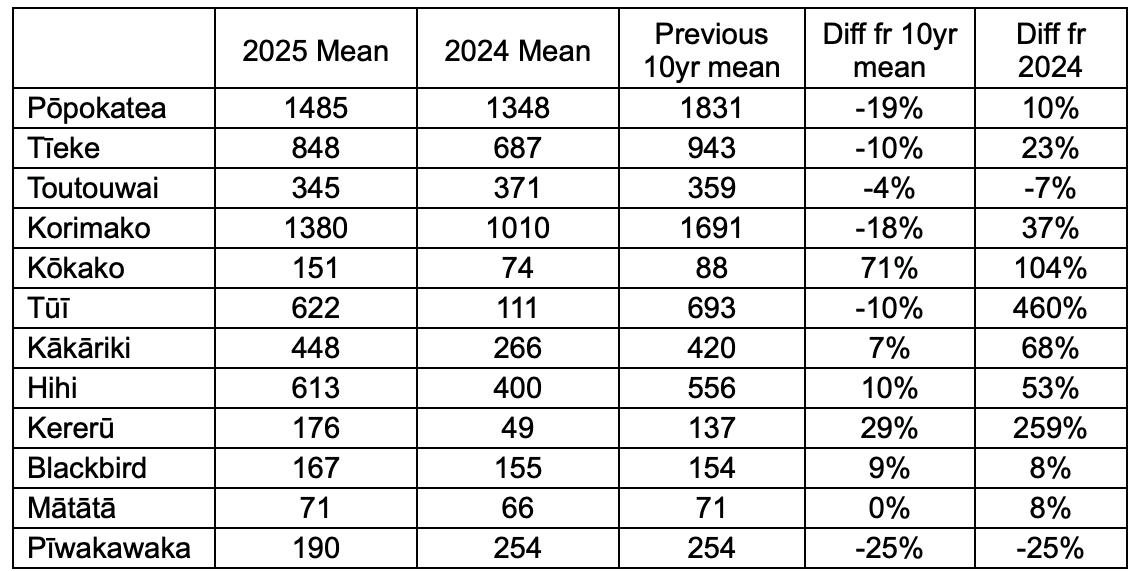

This is the eleventh year of transect counting, and, as always, there have been some interesting changes from last year, although we should really focus on the long-term trends.

The total number of records showed a welcome 37% increase from last year but is still 8% below the average for the previous nine years.

Table 2 shows the mean population estimates for 2024 and 2025, the average of the previous ten years, the percent difference between this year and last year, and the percent difference between this year and the ten-year average.

Our 'big three', pōpokatea/whitehead, tīeke/saddleback and korimako/bellbird, all show increases from last year but are still below their ten-year averages.

The tīeke and pōpokatea populations declined markedly in the three seasons from 2015 to 2017. Tīeke numbers have since followed a more level trajectory, but with marked fluctuations. Pōpokatea numbers have continued to decline, but more slowly, and with less dramatic fluctuations. Both have had moderate increases since last year.

The transect survey overestimates kōkako and hihi, but the trends should be valid. At the time of the transect survey, the actual kōkako population was just short of 100 and was about 30% more than the previous maximum.

Hihi had a record nesting season with about 280 fledglings.

There were dramatic upward swings in the estimated tūī and kererū populations, though not to levels much different from their long-term averages. Both these species are strong fliers and, if necessary, can easily fly to the mainland in search of food, which may explain last year's low estimates. At the time of this year's survey, there was a massive crop of ripening kohekohe fruit, and the canopy was alive with birds gorging on it.

Thanks to this year's count team: Geoff Beals, Kay Milton, Karin Gouldstone, Simon Downer, Luca Kornélia Kósa, Kathryn Jones, Noel Ward, Morag Fordham, and John Stewart.

In March, a tī kāka / reef heron was seen feeding at Emergency Landing. Reef herons are periodically seen around the Island and have been known to breed.

Compiled by Kathryn Jones, with contributions from Morag Fordham, Simon Fordham, Kay Milton, and John Stewart.

Fungi are essential to life on Earth. Without them, we wouldn't be able to eat many plants, and modern medicine, like antibiotics, might not exist. Stacey Balich has been checking out an important new book on their contribution to our world.

Scientists constantly discover new information about fungi, revealing how important and fascinating they are. These weird and wonderful organisms are working hard behind the scenes, and science is just scratching the surface of what they can do.

Fungi aren't just important—they're essential. They help break things down and recycle nutrients, allowing new life to grow. Think of them as the ultimate clean-up crew and the architects of fresh beginnings. Fungi are often the first to show up after damage, quietly rebuilding life from the ground up.

Fungi eat differently from us, or plants, for that matter. While plants are autotrophs (they make their food using sunlight), fungi are heterotrophs. They don't chew or bite. Instead, they release digestive enzymes onto whatever they're growing on (often wood), then absorb the tasty dissolved bits. It's kind of like external digestion.

Fungi are everywhere. In soil, on trees, in the air, and even living quietly inside plants and animals. They're like nature's undercover agents, out of sight but indispensable. When guiding on Tiritiri Matangi, I like to talk about the F.B.I. — Fungi, Bacteria, and Invertebrates. These unsung heroes might not grab the spotlight, but they're doing the hard work behind the scenes, recycling nutrients, breaking things down, and keeping everything in balance.

Are you curious about the colourful characters hiding in our leaf litter? Liv Sisson knows just where to look. In her brilliant book, A curious forager's field guide: Fungi of Aotearoa, she invites us to slow down, look closer, and fall in love with the fungi underfoot. What follows are extracts from her book, printed with permission from the author.

Magnificent mycelium

To understand mycelium, we need to travel through time and space. So hold on to your gumboots — we're going from the garden to the edge of the galaxy here.

If you work in your back garden, you've probably already seen mycelium. It's white and branching, delicate yet strong, like a fungal spider web. It can be seen in clods of dirt, under old logs, and tucked beneath leaf litter. The individual wisps of mycelium are called hyphae. Each one is thinner than a human hair.

Mycorrhizal fungi and mycelium are the side of the fungi kingdom most of us didn't learn about in primary school. But it's in this subterranean realm where things get extra interesting. The sheer amount of mycelium in our soil is mindbending. As is its importance to life.

Mycorrhizal mycelium is the widespread organism in soil. If each bit of mycelium in the top 10 centimetres of soil were lined up in some strange fungal conga line, it would stretch

A delicate basket fungus (Ileodictyon cibarium) emerging from the forest litter, its intricate white lattice structure standing out against the damp, earthy leaf litter of the forest floor

more than 450 quadrillion kilometres. That's literally half the width of our galaxy. Just one tablespoon of soil contains 12 kilometres of mycelium. I can hardly wrap my head around that or even run that far.

Mycelium isn't just something there's a lot of, though — it's also an ancient, life-giving support network.[1] Over 90% of plants have relationships with mycorrhizal fungi.[2] Without these fungal collaborators, plants would struggle to get enough to eat and survive.

At first glance, this doesn't appear to make sense. Plants can make their own food with the sun's rays; surely they're independent individuals? But while plants don't seem to need fungi now, back in the day, they seriously did.

Around 500 million years ago, aquatic plants slowly made their way out of the ocean. Once on land, they began to evolve their root system, which was an arduous task. In the meantime, they relied on fungi in the soil to function in place of roots. Long story short: plants and fungi never made a clean break. They're still entangled in crucial, complicated, sometimes prett y, and even long-distance, relationships.

The role of underground fungus in carbon storage is also often forgotten. In this gnarly climate crisis we have on our hands, fungi are key allies in limiting global heating. When fungi dismantle dead wood, for example, the carbon locked up in that wood shift s to the soil. Our underground ecosystems store up to 75% of all terrestrial carbon, three times more than the amount of carbon stored in living animals and plants.[3] Globally, underground mycelium draws down, or 'sequesters', up to 5 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide yearly. That's roughly equal to the United States' annual CO2 emissions, hidden away in wispy tendrils of hyphae.[4] Carbon can remain stored there for millennia or quickly be released back into the atmosphere. Precipitation levels, vegetation levels, soil texture and land use all affect how long carbon can be stored underground.

As a carbon sink, mycelium plays a crucial role in balancing the global carbon cycle. But as we disrupt and degrade underground fungal networks through agriculture and

Known by many names, Taranaki wool, wood ear, mouse ear, jelly fungus, or cloud ear (Auricularia cornea), this unique jellylike fungus clings to a tree trunk, its ear-shaped lobes glistening with moisture in the forest light

land development, their ability to store carbon diminishes. Working with the land in a way that increases its ability to hold carbon could be a key step in our race against climate collapse. Less tilling, more cover-cropping, and more crop rotation are all strategies that support mycelium's ability to store carbon and limit global heating. A 0.1% increase in underground carbon storage would remove 100 million cars' worth of carbon from the atmosphere.[5]

References:

[1] J.R. Leake and D.J. Read, Mycorrhizal symbioses and pedogenesis throughout Earth’s history, in Nancy Collins Johnson, Catherine Gehring and Jan Jansa (Eds), Mycorrhizal Mediation of Soil, Chapter 2, pp.9-33, Elsevier, 2017

[2] Mark C. Brundrett and Leho Tedersoo, Evolutionary history of mycorrhizal symbioses and global host plant diversity, New Phytologist, vol, 220, no.4, 2018, pp.1108-1115.

[3] Carbon sequestration in soils, Ecological Society of America, 2000.

[4] Serita D. Frey, Mycorrhizal fungi as mediators of soil organic matter dynamics, Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, vol.50, 2019, pp.237-259

[5] Forests and agriculture, European Commissions, Climate Action, https://climate.ec.europa.eu/eu-action/forests-and-agriculutre_en

Although the Department of Conservation is responsible for controlling weeds on Tiritiri Matangi, SoTM supports this vital task, obtaining funding to pay professional abseilers to control weeds on cliffs. Additionally, volunteers tackle weeds in off-track areas of the Island. One of those volunteers, Russell Fulton, shares some history of weed control efforts on Tiritiri.

Weed control on Tiritiri Matangi began with ranger Ray Walter and his family at the start of the Island's restoration programme. Their initial focus was on spraying large infestations of Japanese honeysuckle in southern valleys and controlling weeds around the lighthouse.

In 1998, a more systematic approach was adopted, and the Island was divided into weed control plots for better management and recording. Shaun Dunning established and marked these plots while doing weed control work for several years. However, not all plots were checked annually, and infestations of moth plants and other invasives increased, with Japanese honeysuckle also re-invading. In 2002, new ranger Ian Price decided to search the entire island within one season to map all infestations.

From 2003 to 2005, contractors led by Ian Price grid-searched the Island. I volunteered during the final search, one of the hardest weeks I've ever done! This effort created a comprehensive list of known weed sites, with the intention of checking them annually for regrowth.

Afterwards, much of the effort focused on abseiling to control the extensive boxthorn infestations on the Island's cliffs. Since 2006, an annual follow-up programme has monitored and managed these sites. This ongoing work has been made possible through grants successfully applied for by the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi. Funding plays a crucial role in protecting and restoring the Island's ecosystems.

In 2011, Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi contracted Helen Lindsay to oversee weeding operations. Helen wrote the Weeding Manual and expanded the volunteer programme. The Island was divided into seven zones, each with a volunteer team assigned. Volunteers received three free trips a year to work on their zones.

The 'Tiritiri Matangi Weed Control Manual' states that:

'The objective of the weed control programme is to eradicate all environmentally damaging weeds from Tiritiri Matangi Island where possible and where this is not possible to control them to zero density. Zero density means to control all individuals of a target pest while recognising that re-infestation is possible.'

I became Helen's unofficial deputy, helping organise weeding weekends, when we booked the bunkhouse for up to ten volunteers. These weekends were highly successful. Getting ten trained people into a site for 15 minutes was far more effective than three people working for an hour. In two days, we could cover most of the active sites. Some of these volunteer teams are still functioning today.

In recent years, I've focused on controlling carrot weed on Coronary Hill after it spread when regular mowing stopped, creating dense white summer displays.

I've also targeted hedge parsley, a smaller, burr-producing weed established above Hobbs Beach and spread along tracks and the lighthouse area. After six years of concerted effort, it's now largely under control, with very few seedlings remaining.

Successful weed management demands good access. Most weed sites aren't conveniently located near the main tracks used by birders and visitors, so over the years a network of access tracks has been developed to allow volunteers and staff to reach remote weed sites and conduct surveillance. These tracks are vital for the success of weeding efforts, enabling us to monitor and control infestations regularly before they spread. Without maintained access, some weed sites could be left unchecked for years, allowing invasive plants to re-establish and undermine restoration efforts.

Track maintenance is a significant and ongoing task, particularly when the tracks pass through thick flax.

Flax presents three major challenges: there are often no permanent objects to attach marker tape to, making routes hard to follow; wasps infest flax from January to March, posing a serious risk of stings to anyone pushing through; and flax grows vigorously year-round, quickly obscuring tracks if not regularly cleared. In some cases, access can be lost altogether. For example, the track to a weed site in Sonya's Valley is now blocked by a two-metre-tall wall of flax, making it inaccessible without significant work. Re-establishing the track will require a full day of clearing, timed carefully to avoid the wasp season for safety.

Thanks to years of persistence and teamwork, we have a lot to celebrate:

Some major weed sites are now under control, with hardly any seedlings emerging.

Our volunteer-led programme continues to thrive, with dedicated teams protecting key areas.

A vital network of access tracks keeps even the hardest-toreach sites within our care.

Together, we're making a real and lasting difference. Thank you to everyone who's been part of the journey!

The most common and problematic weeds targeted include:

Arum Lily – Still popping up in gullies.

Banana Passionfruit – Found near Doug’s Alley; new plant discovered February 2025.

Bone Seed – Bright yellow flowers in spring; found above Fisherman’s Bay and Coronary Hill.

Boxthorn – Controlled on northern cliff s via abseiling.

Brush Wattle – Managed in Wattle Valley and on Coronary Hill.

Gorse – Controlled mainly on the north side to prevent track spread.

Japanese Honeysuckle – Persistent around Coronary Hill and the lighthouse.

Mile-a-minute – Active sites below the Visitor Centre and on the east side of Coronary Hill.

Moth Plant – 30 monitored sites; new plant found January 2025 behind Hobbs Beach.

Periwinkle – Seedbanks around the lighthouse and cliff s.

Sweet Pea Bush – 12 known sites near Sylvester Wetlands and North West Point.

50% Explore ferry to Tiritiri Matangi Island

Embrace the wild beauty of winter on Tiritiri Matangi

Offer Valid from 1 June to 31 July 2025

Olga Brochner and Kevin Barker invite you to look beyond the bush and birds and turn your gaze to the sky. They explore the stunning nighttime wonders visible from Tiritiri Matangi during autumn, offering tips on what to spot and maybe inspiring you to try a little stargazing from your backyard as well!

On Tiritiri Matangi, you must look all around to see what's about, including up, during overnight stays. The glow from Auckland's lights south of the Island lessens the view looking south. But on a moonless night, it is an impressive sky viewed from the Island. What night sky objects might you be able to see from Tiritiri Matangi in autumn?

If you stay overnight on Tiritiri Matangi during autumn, make your way to the area under the lighthouse. The bright beam will not be visible, and you can enjoy the night sky. Begin as the sky is darkening. It is too early to go kiwi and tuatara spotting! Use these star maps (by NZ astronomer Alan Gilmore) to help you get oriented: https://www.rasnz.org.nz/in-the-sky/the-evening-sky/aprilevening-sky-1

https://www.rasnz.org.nz/in-the-sky/the-evening-sky/mayevening-sky

At first glance, the night sky may seem like a sea of twinkling stars, but some patterns can help you navigate around the sky — and our Earth, too. These patterns and pointers help guide you, just like the track signage on Tiritiri Matangi.

Start by looking to the northwest for the familiar constellation of Orion, often represented as a hunter with a belt and dagger. In New Zealand, we also call the central part of Orion 'The Pot' because Orion's three belt stars form the base of the pot, and the dagger becomes the pot handle. Even if you don't know this constellation, it's relatively easy to find, as it's unusual to see three bright stars in a straight line. At this time of year, Orion is heading west, and 'the pot' appears to be lying on its side. By late autumn, Orion dips under the horizon shortly after twilight.

Once you've located Orion, grab your binoculars and check out the magnificent Orion Nebula in the handle/dagger region. It's a gas cloud where new stars are currently forming. Unaided, it looks fuzzy, but binoculars reveal more detail.

Orion also features several bright stars, including brilliant white Rigel and orange Betelgeuse. That orange hue is seen more easily in Tiritiri Matangi's darker night skies.

Return to Orion's three belt stars, as they will help find other objects. Following them towards the horizon (downwards), you'll head to the constellation of Taurus, which includes the Hyades cluster. Further down and west is the Matariki/ Pleiades star cluster. In this region, we can see the planet Jupiter in early autumn. It appears as a bright star and sits below Orion between the prominent open clusters, Hyades and Matariki/Pleiades.

You may see a few small bright points of light objects around/ near Jupiter with binoculars. These could be the four Galilean Moons of Jupiter that Galileo Galilei first discovered looking through a telescope in 1609. Back then, most thought the Earth was the centre of the universe, so seeing objects orbit Jupiter caused quite a stir.

'Planet' means 'wandering star', reflecting what the ancient astronomers believed they were — stars that didn't stay with associated stars to form a pattern. Today, we know planets are not stars, and the ones we can see are 'our neighbours' in the Solar System.

The planet Mars is also visible during autumn. Mars can appear as a bright orange-red object. Unlike stars, planets usually don't twinkle. Mars is seen to the north, close to the two bright stars Castor and Pollux, the twins of the Gemini constellation. To locate Gemini, head from Orion's belt stars through Betelgeuse, which points in the general direction of Gemini and Mars. Then, keep heading northeast; you'll find Praesepe, an open star cluster (also known as the Beehive), quite a sight viewed through binoculars in a dark sky. It is part of the constellation Cancer. This area of the sky doesn't have many bright stars at present, but see if you can spot

the star Regulus, the brightest star in the Leo constellation. Leo appears as a sickle shape, which was interpreted as a lion's head in the Northern Hemisphere. Although no cats are allowed on Tiritiri Matangi, this constellation dominates the north-eastern sky throughout autumn.

Above Leo is a squished-looking square, the constellation of Corvus, supposedly a crow. Spotting Corvus adds another bird to your Tiritiri Matangi list!

Now, back to Orion's belt. Head up from it overhead to the Zenith, where you'll find the brightest of all stars, Sirius. Sweeping the unaided (naked) eye or using binoculars through this region is rewarding, as you are looking at a spiral arm of our galaxy, the Milky Way. It is rich in a myriad of star clusters and nebulae. Here, you'll find the Southern Cross (more correctly, the constellation Crux) and the two pointers, Alpha and Beta Centaurus. However, as stated earlier, heading south goes towards Auckland's sky glow. The Crux constellation is small but has bright stars. Look for a kite shape to help identify it. Or use the pointers Alpha and Beta Centaurus, also bright, to help locate it.

From the Crux, look to the west. Here, Tiritiri Matangi's darker skies will help you see two fuzzy patches: the two Clouds of Magellan. Yes, named after the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan, these are the large and the small Clouds of Magellan (LMC and SMC). They are small galaxies which orbit our Milky Way galaxy. The LMC is approximately 160,000 lightyears away, and the SMC is 200,000 lightyears away.

You can see the great globular cluster 47 Tucanae close to the SMC with binoculars. It's one of the sky's most famous globular clusters and a personal favourite of Olga's! It appears as a fuzzy star with one's naked eyes; binoculars reveal a tight ball due to the glow of 47 Tuc's thousands of stars. Look sort of above the LMC and SMC to see another very bright star, Canopus, an important star for navigation.

Heading into the winter night sky, Orion is 'replaced' with the Scorpius constellation, which appears to chase Orion away. Scorpius rises in the east as Orion sets in the west. Scorpius will also help you find your way around. And if you are up late enough, you may notice Scorpius rising in the south-eastern sky.

We all know Tirititiri Matangi is a magical place to step back in time to see restored habitats and an opportunity to see rare endemic New Zealand birds and reptiles. Tiritiri Matangi's night sky offers a chance to see stars, constellations, clusters, planets and galaxies that are not always visible from lightpolluted sites: give it a go if you have a chance!

The following website will help you identify what will be in the Auckland night sky tonight: https://www.timeanddate.com/astronomy/night/newzealand/auckland

The historic diaphonic foghorn, located near the lighthouse area, has sat mute in recent years. Carl Hayson explains how the foghorn was silenced and the work currently underway to restore its boom.

The long hiatus since the COVID lockdowns has meant that the 1952 Lister motor, which powers the compressor filling the large air tank, has lost all engine compression after not being run and maintained since 2019. Lister engines must be run regularly to keep them in good working order.

In addition, the air tank was developing rust over the top of the tank and safety valves and was in serious need of TLC. Work is now underway to save the foghorn unit from further deterioration and to bring it back to working order. It is, after all, the last operating foghorn in New Zealand.

Because motor repairs required expert help, Shaw Diesels (NZ’s Lister agents) arranged to order brand-new parts from the UK, including cylinders and valves. Shaw Diesels has also overhauled the cylinder head, which will be installed along with the other parts soon. The Rano Community Trust Ltd helped fund this specialist engineering work.

Our fundraisers applied successfully to the Auckland Regional Heritage Fund for financial support for the air tank. This funding enabled us to engage Geoff and Martin Love, professional painters who have painted many historic structures on Tiritiri, to come to the Island to strip the rust off the tank and repaint it with marine-grade enamel paint. They have done a terrific job, saving the tank from further degradation.

In addition, while waiting for the paint to dry, they generously painted the watchtower deck free of charge.

It is anticipated that the Lister engine will be operational again soon, and we look forward to having the foghorn back in action, with our volunteers sounding it for many years to come.

The two photos above capture the tank in its weathered state, showing extensive rust and flaking paint from years of exposure. In contrast, the bottom photo (left) reveals the transformed result: a fully stripped, smooth-surfaced tank, freshly coated with durable paint, restoring both its appearance and protection.

All photos by Geoff Love

The diaphonic foghorn on Tiritiri is the only one of its type left in place in New Zealand. Four horns were initially established at the harbour entrances in Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin, but only Tiritiri's now remains.

The Auckland Harbour Board built and funded it in 1935. It ran reliably for nearly 50 years before being replaced by an electrical horn in 1984. It operated by air force-fed from a large tank through valves and a trumpet. Its booming sound could be heard over 16 km away.

By 2002, the building and machinery were dilapidated, but a group of volunteers, the ToiToi Trekkers, restored both to bring them back into operating condition. Once again, the foghorn has deteriorated due to lack of use. Because it has a unique history in New Zealand, it is worth restoring once again for public education and demonstrations.

Planting on the southern slopes of Coronary Hill in 1984 marked the beginning of Tiritiri Matangi's 10-year planting programme.

Glenfield College year 12/13 biology students and staff made their first trip in June 1984 on the 'Ngaroma' from Auckland via Devonport. This trip marked the beginning of a long association with the Island.

Typically, on these school visits, the group was divided into two. One group worked on tracks in the morning, while the other spent several hours planting trees. After lunch, the groups swapped.

Mary-Ann Rowland pays tribute to Tiritiri's beloved friend, who passed away peacefully on April 23, 2025.

Martin will forever be known for his sense of humour, his photographs, and his kindness and generosity in sharing them. He started working in the UK as a newspaper photographer, after which he spent 10 years in the Merchant Navy with the New Zealand Shipping Corporation, bringing immigrants to NZ, later working as a purser and then in their catering business.

On coming to NZ, he worked in various catering businesses until his retirement in 2003, when he picked up his camera again and gave so much of his time to Tiritiri Matangi.

No matter the occasion — a bird release, historic day, birthday, or Guides' Day Out — Martin would be working in the background quietly taking photos, and a few days later they would be on his SmugMug site for all to see. He had a great eye and was quick to see the funny side and catch that, too!

Less than two weeks before he went into hospital, his family brought him out to Tiritiri, and we bundled him into one of the four-wheel drive vehicles with his camera and a massive smile on his face to take him around the Island.

We went everywhere you could drive to and saw at least forty toutouwai, were serenaded by four kōkako, met the takahē and came across untold tīeke, hihi, korimako, pīwakawaka, kererū and quail. Looking back, it seemed as if all the birds had come out to say their farewells. Just by chance, many of his non-feathered friends were also on the Island and were able to spend time with him. The following day, I checked in to see how he was, afraid that we had worn him out, and Irene said, 'Yes, he was tired, but a good tired.'

by Stacey

Nature is always changing! Can you spot clues that a new season is here? Are flowers blooming? Do birds sound different? Is the air warmer or cooler? Start your own nature journal to track the changes you see! Read the seasonal stories from Tiritiri Matangi, explore what’s happening around you, and answer the questions below!

In spring, Tiritiri Matangi bursts into life. Kōwhai trees bloom, their golden flowers drawing tūī and korimako to sip nectar. Harakeke sends up tall flower stalks, feeding hihi and tīeke. Birds gather twigs, weaving intricate nests in preparation for new life. In the early morning, a dawn chorus of birdsong greets the breaking day. Skinks bask in the warming sun, and fresh green shoots emerge across the forest floor.

Summer brings abundance and warmth. Pōhutukawa trees burst into red bloom, attracting tūī, tīeke, korimako, and hihi. Confident takahē chicks forage with their families. Kororā / little blue penguins begin their annual moult along the coast. Geckos emerge to feed on nectar, while young birds test their wings and call for food.

Winter is quieter, but life continues. Birds forage more to conserve energy, feeding on fruit from trees like pūriri. Fungi thrive in the damp. At night, ruru call and kiwi search for insects. Hidden in trunks, pūriri moths complete their life cycle, awaiting emergence.

Can you find the answers to these questions below?

In autumn, fledglings become independent. Beneath the canopy, fungi emerge, their shapes and colours decorating the damp forest floor and breaking down organic matter. Kohekohe trees start to flower, offering late-season nectar for birds.

1. How do kōwhai and harakeke plants help birds like tūī, korimako, hihi, and tīeke in spring?

2. Why do fungi grow well in winter, and where can you find them?

3. What changes happen to young birds in autumn?

The Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi (SoTM) is a volunteer Incorporated Society that works closely with the Department of Conservation to make the most of the wonderful conservation-restoration project that is Tiritiri Matangi. Every year volunteers put thousands of hours into the project and raise funds through donations, guiding and our island-based gift shop.

If you'd like to share in this exciting project, membership is just $30 for a single adult or family; $35 if you are overseas; and $15 for children or students. Dawn Chorus, our magazine, is sent out to members every quarter. See www.tiritirimatangi.org.nz or contact PO Box 90-814 Victoria St West, Auckland.

SoTM Contacts:

Chairperson: Ian Alexander chairperson@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Secretary: Val Lee secretary@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Treasurer: Peter Lee-Grey treasurer@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Board: Meredith Blogg, Hester Cooper, Louise Delamare, Rosemary Gibson, Rachel Goddard, Carl Hayson, Janet Petricevich, Mark Withers

Operations Manager: Debbie Marshall opsmanager@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Guiding and Volunteer Manager: Gail Reichert guidemanager@tiritirimatangi.org.nz, 09 476 0010

Retail Manager: Ashlea Lawson retail@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Membership: Rose Coveny membership@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Educator: Sara Dean

Assistant Educator: Liz Maire educator@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Fundraisers: Rashi Parker and Louise Delamare fundraiser@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Social Media: Bethny Uptegrove socialmedia@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Dawn Chorus co-editors: Janet Petricevich and Stacey Balich editor@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Island Rangers: Talia Hochwimmer and Nick Fisentzidis tiritirimatangi@doc.govt.nz, 027 536 1067

Day trips:

Weather permitting, Explore runs a return ferry service from Wednesday to Sunday from Auckland Viaduct and the Gulf Harbour Marina. Bookings are essential.

Phone 0800 397 567 or visit the Explore website: www.exploregroup.co.nz/

Overnight visits:

Camping is not permitted and there is limited bunkhouse accommodation. Bookings are essential: https://bookings.doc.govt.nz/

www.tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Tiritiri Matangi Talks - The Sometimes Missing 'F' Word: Fauna, Flora and Fungi

Monday 9th June 2025

Speaker Peter Buchanan

7:30pm at Unitec, Building 115, Mount Albert

Annual General Meeting

Monday 15th September

7:30pm at MinterEllisonRuddWatt s Seminar Room, PWC Tower, 15 Customs Street West, Auckland City.

Working Weekends 2025

Labour Weekend, 25th - 27th October

Enquiries to the guiding and volunteer manager

Supporters' Weekends 2025

5th-6th July

6th-7th September 4th-5th October

Enquiries to the guiding and volunteer manager

Tiritiri Matangi Talks - Save this date

Monday 1st December 2025

We offer a full-day learning experience in a pest-free environment for years 1 to 13. Tamariki and rangatahi can get up close to endangered taonga species where they learn about community conservation and how people can work together to provide protected habitat. This then inspires students to take action in their own neighbourhoods.

Our educators offer a range of education experiences on the Island, which are closely tied to the NZ curriculum. At the senior biology level, there is support material available for a number of NCEA achievement standards. Tertiary students have the opportunity to learn about the history of the Island and tools of conservation as well as to familiarise themselves with population genetics, evolution and speciation.

Subsidies are available for schools with an EQI 430 or more via our Growing Minds programme. Information on the education programme is at: https://www.tiritirimatangi.org.nz/education-programmes/ Bookings are essential.

Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi wishes to acknowledge the generous support of its sponsors

Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi welcomes all types of donations, including bequests, which are used to further our work on the Island. If you are considering making a bequest and would like to find out more, please contact secretary@tiritirimatangi.org.nz