Chair Chat

We are more than halfway through winter, the Island’s dams are full, and the birds are thriving with an abundance of early nectar and fruits such as pūriri and puahou / five finger.

The Biodiversity and Research Committee is progressing with its long-term pōhutukawa project, with many teams in the field during June and July, conducting bird counts and continuing scientific work. Numerous small teams and individuals are involved in activities both on and off the Island, much of it behind the scenes. Thank you to the membership and fundraising teams, along with Rachel Goddard, for leading efforts in health and safety, IT, and the website. We couldn’t do without you!

I also thank our educators for organising and delivering the conservation message to the many schools visiting as part of the education programme. Bookings remain high, with Term 4 this year and Term 1 next year already heavily booked. Congratulations to the education team and school guides.

To all volunteers involved in various activities supporting the Island’s operations, your ongoing support and interest are greatly appreciated.

In July, Tripadvisor announced that Tiritiri Matangi had been placed in the Travellers’ Choice Awards Best of the Best 2025. This is Tripadvisor’s highest honor. The award takes into account the quality and quantity of traveller reviews and ratings and recognizes the top 1% of all listings.

Congratulations and thank you to all our volunteers and staff whose efforts contributed to this wonderful result.

The following pages provide information about the AGM and elections. Please attend the AGM and support your society.

Ian Alexander

Join us at 7:30pm at the offices of MinterEllisonRuddWatts, Level 22, PWC Tower, 15 Customs Street West, Auckland CBD

A quorum of 30 voting members is required, so we encourage you to attend the meeting. However, for those unable to attend, but who wish to observe the meeting, a Zoom Link will be available on the website from 8 September 2025.

Agenda:

1. Apologies

2. Minutes of the 2024 AGM (posted on the website)

3. Matters arising from the 2024 AGM

4. Chairperson’s annual report (Ian Alexander)

5. Treasurer’s report and financial statements (Peter Lee-Grey)

6. The setting of annual subscriptions for 2025/2026

7. Motions:

i. That the members of the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi Incorporated formally agree to reregister the Society under the Incorporated Societies Act 2022

ii. That the members of the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi Incorporated formally approve the new Constitution dated September 2025

8. Determination of the number of board members to be elected

9. Election of officers

10. Election of board members

11. Notices

12. General notified business

Guest Speaker: Peter Lee-Grey Fellowship of the Wing: the Supporters over the past 35 years — a personal reflection

Refreshments will be served at the end of the meeting.

Cover photo: Male hihi, Tony Petricevich

For translating Te

Other information:

A Member may exercise a proxy vote through another Member, or the Chairperson, and, in either case, such proxies in writing must be in the hands of the Secretary not less than 24 hours before the time of commencement of the meeting.

A Member may notify the Secretary of matters they wish to be raised in general business. Such notification must be provided in writing no less than five days before the time of commencement of the meeting.

For Zoom details visit: https://www.tiritirimatangi.org.nz/news/agm

To view the new Constition (September 2025) visit: https://www.tiritirimatangi.org.nz/news/agm

Access to MERW offices:

The entrance to the building is on the corner of Customs Street West and Lower Albert Street. The doors to the PWC Tower will be locked from 7:25 pm. We advise everyone to be at the venue by 7:20 pm.

The Downtown car park is the closest car park to the office. https://at.govt.nz/driving-and-parking/find-parking/parking-incentral-auckland/downtown-car-park. Alternatively, there are several public transport options: Waitematā/Britomart station is located directly across from the office.

The Northern Express bus terminates on Lower Albert Street, directly beside the office. The ferry terminal is a two-minute walk from the office.

Officers

I have served on the Board as chair for the past two years. It has been a challenging period of improving the governance structure and preparing the organisation for the years ahead. For 27 years, I have been involved with SoTM, including 15 years as a regular guide, volunteering on numerous biodiversity projects, and advocating for the Island through community presentations. I am willing to contribute further to the governance of this remarkable island. I will continue to bring a lifetime of experience in charitable and nonprofit groups to the Board.

Treasurer – Mark Withers

I am a recently retired chartered accountant residing in Gulf Harbour. I am available for the position of treasurer and bring thirty years of experience from public practice as the founding partner of PKF Withers Tsang. My love for Tiritiri stems from boating, and the Island has become a favourite destination. I have served ten years as treasurer of the Auckland Property Investors Association, where I hold a life membership. Additionally, I have served as treasurer for the Lake Tarawera Ratepayers Association and the Rangitane Recreation Association. Through our accounting firm, we have supported the Kiwis for kiwi trust.

I’m a Canadian-born primary school teacher with a passion for environmental education and conservation. I’m standing for secretary at the upcoming AGM, as I have some experience with secretarial duties from my work and other volunteer positions. Having recently joined the Board, I am looking forward to another year of learning the ropes from our more seasoned members!

Hester Cooper This year is proving challenging for many, but Tiritiri remains a refuge for visitors and volunteers alike. Much of my work with the Biodiversity and Research Committee promotes projects that allow members to engage in the Island’s restoration. If you want to help, join our biodiversity database to hear about support opportunities. Many projects are long-term, helping us understand how the Island’s ecosystem diversifies and changes. This allows us to plan future translocations confidently, further enhancing diversity. SoTM has always been at the forefront of conservation projects, relishing the challenge of pioneering new approaches. I look forward to facing new challenges.

Louise Delamare After witnessing firsthand the positive impact the Island has had on my own children and how they have loved being immersed in nature, I have jumped at the chance to be involved in SoTM ever since. As an environmental lawyer and consultant, I bring knowledge and expertise that can contribute to the Island's conservation efforts. I am passionate about giving back to the community and ensuring that future generations can enjoy the natural beauty and educational opportunities the Island offers. I am a current member of the Board as well as one of SoTM’s fundraisers.

Rosemary Gibson I am a lawyer with 13 years of experience. Having been co-opted onto the Board in May, I am now standing for election. I want the opportunity to contribute meaningfully to the work the Board does to support its members and the sanctuary at Tiritiri Matangi.

continued next page

Rachel Goddard Tiritiri is a special place for me, away from the pressures of life in Auckland. I have loved being involved in bird and reptile surveys and getting my hands dirty on working weekends. I enjoy giving back to SoTM through my Health and Safety and IT responsibilities and by being on the Board. I'd like to continue to contribute to SoTM, on and off the Island, for many years to come.

Carl Hayson Having served on the Board in various roles for many years, I believe I still have much to offer, particularly in the areas of infrastructure and historic restoration on the Island. My extensive knowledge and familiarity with the Supporters could be of benefit to the incoming board members.

Andrew Nelson I’ve been fortunate to build a 30-year career working in New Zealand conservation, across various roles within DOC, Auckland Zoo, and Auckland Council. Since 2011 I have contributed to SoTM’s aims as a member of the Biodiversity and Research Committee. At times I have also served on the Advocacy Committee and the Board. While on the Board, I aim to utilise my skills and experience to support the Island’s role in species conservation, uphold Tiritiri Matangi as a premier location for visitors to experience and learn about New Zealand’s unique nature, and ensure that the efforts of the SoTM volunteers serve as an inspiring example of community-led conservation.

Janet Petricevich I started volunteering as a guide on the Island in early 2017. Gradually I shifted from guiding to biodiversity projects. I am a member of the kōkako monitoring team, have served on the Board for two years, and am co-editor of Dawn Chorus. Along with my passion for the Island, I bring a background in accounting and commercial finance to my role on the Board.

Parin Rafiei I am a specialist in climate and sustainability with over 22 years of experience spanning public, private, and international development sectors. Recently I led climate strategy and innovation at Tātaki Auckland Unlimited. Previously I held senior positions at Auckland Council’s Chief Sustainability Office and co-led the development of Te Tāruke-ā-Tāwhiri, Auckland's Climate Plan. My international work includes climate finance and forestry projects with organisations like the World Bank and Standard Bank of Africa. I hold a PhD in Engineering and possess extensive expertise in climate governance, systems thinking, and sustainable development, with a focus on creating resilient, low-carbon communities.

The Board expresses its thanks to Val Lee for her services as secretary from 2023-2025 and to Peter Lee-Grey for his services as treasurer from 2020-2025.

By Ray Walter

Edited by Anne Rimmer

Published by the Walter family

Ray Walter, who sadly passed away in 2023, was a driving force behind the hugely successful planting programme on Tiritiri Matangi in the 1980s and 1990s. Those who worked alongside Ray will remember not only his dedication but also his sharp wit and the many humorous stories he so generously shared. While many of us knew him as Tiritiri’s last lighthouse keeper, few were aware of his long and fascinating career in the lighthouse service that came before. This book brings Ray's stories to a wider audience, offering insight into his life and New Zealand’s lighthouse history.

Ray spent many of his later years working on this book but was unable to complete it. Thanks to information from Lynda Walter and the Walter family, who are funding the project, the remaining chapters are now being finished and edited by esteemed author Anne Rimmer.

The book will be officially launched during a public ceremony on Tiritiri on Sunday, 5 October, this year, with Ray’s family members in attendance.

Ray's entertaining memoirs, related in a relaxed, chatt y style, are an invaluable record of the era of manned lighthouses in New Zealand.

Ecologist and behavioural biologist Mark MacDougall examines the science, secrets, and evolving soundscape of Aotearoa’s dawn chorus by uncovering why birds sing, who starts singing first, and what we have lost and gained in the forest’s morning song.

The dawn chorus likely needs no introduction to anyone involved in conservation in Aotearoa, as ‘bringing back the dawn chorus’ is commonly used as a rallying cry for conservation efforts. Anyone who has stood in the dark at the break of dawn in a native forest and experienced the melodic symphony of birdsong with the full range of vocalists present knows it’s an absolutely magical experience. We’re fortunate here in Aotearoa to have a unique dawn chorus full of talented and melodious singers, making it a taonga well worth protecting.

The dawn chorus is a phenomenon in which multiple bird species sing together rapidly and intensely during the early hours before sunrise, typically in the spring. Why songbirds sing so vigorously at dawn remains a hotly debated question. However, many studies suggest that social interactions between male birds—related to territorial defence, dominance status, and mate guarding—are likely at the heart of dawn singing. Male territory boundaries and dominance ranks relative to their peers can be highly volatile and changeable during the spring breeding season, and it seems dawn chorus singing plays a significant role in mediating these male-to-male interactions every day.

We often imagine monogamous songbird pairs as devoted homemakers fully committed to building a family together, but the reality is somewhat less glamorous. Male birds can be pretty naughty and often sneak off in the early hours to ‘visit’ females in other nests. Tūī are well known for this; on average, about 57% of chicks in any given clutch come from entirely different fathers! Dawn chorus singing seems to serve a key role in deterring these ‘extra-pair copulations’, acting as a sort of ‘back off!’ warning from the male at home.

A fascinating aspect of dawn choruses is that they often display an inherent singing order, where a particular instigator species starts singing first, followed gradually by other species in a predictable pattern. A bird’s position in this sequence can be influenced by various factors, including social behaviours, body size, or the light sensitivity of its eyes. The physical environment also plays a significant role in shaping dawn singing, with stimuli such as ambient light and noise levels capable of shifting the timing of songs. This is a considerable issue when it comes to human-related problems, such as light pollution and noisy roads, which can significantly disrupt the timing of the dawn chorus.

According to mātauranga Māori about ngā manu, the huia was once considered the first singer on the stage. Sadly, along with the piopio, they no longer feature in the lineup. These losses, combined with the arrival of noisy newcomers like blackbirds and thrushes, mean that the chorus today follows a quite different tune from the one heard two hundred years ago. Modern anecdotal accounts suggest that the mantle of the earliest singer has now passed to the tūī.

In 2016, I was fortunate to participate in a research project with Professors Joe Waas and Jenn Foote, recording the dawn chorus of New Zealand birds. We aimed to discover whether our dawn chorus follows a specific singing sequence and whether playing back pre-recorded birdsong could cause the chorus to start even earlier. We set up a transect of recording devices across the pest-free Maungatautari sanctuary, which supports a thriving population of threatened birds such as tīeke/saddleback, pōpokatea/whitehead, hihi/stitchbird, toutouwai/North Island robin, and even a few kōkako.

We found that tūī started the dawn chorus and were later joined by toutouwai and korimako/bellbird. The song initiation times for all the other birds varied considerably, with most of the remaining birds joining across a 12-minute period, while pōpokatea joined the chorus last. Unfortunately, we cannot determine where kōkako fit into the order, as we did not record any of their songs. Tīeke and hihi did not seem to participate in the dawn chorus and only started singing well after sunrise.

While tūī singing first was no surprise, what blindsided us was how much earlier their song shifted as the breeding season advanced. Every other bird kept roughly the same start time for their songs relative to sunrise, but tūī started singing hours earlier (to the point where they kind of messed up our playback experiment!). Increased population densities due to local migrations could account for this shift, as Maungatautari often experiences a surge of tūī into the mountain in late spring. That’s a bunch more ornery males competing for the same territory, which likely means a significant increase in dawn singing.

The dawn chorus isn’t just for show; it’s vital to the social interactions and life cycles of our birds. So let’s continue doing what we can to restore it permanently!

The past breeding season has been a remarkably successful one for hihi/stichbird on Tiritiri Matangi, with 280 healthy youngsters fledged and thriving. That’s not a bad result for a bird which, only a few decades ago, was reduced to a single remnant population on a single island in the Hauraki Gulf and was threatened with extinction.

An opportunity

Hihi disappeared from mainland New Zealand in the late 1800s, and by the 1970s the only viable population was on Te Hauturuō-Toi / Little Barrier Island. Efforts to establish new populations in suitable predator-free sanctuaries had met with limited success. By the early 1990s, only those transferred to Kapiti Island remained viable. Attempts to establish populations on Taranga / Hen Island near Whangārei, Cuvier Island off the Coromandel Peninsula, and Mokoia Island in the middle of Lake Rotorua ultimately failed. However, each failure provided valuable lessons and, with the eradication of kiore / Pacific rats on Tiritiri in 1992, the Island became an obvious candidate for yet another attempt.

Mel’s vision

The Department of Conservation’s (DOC) budget for the project was limited, but the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi (SoTM) committee was eager to contribute resources and volunteer labour to assist. Committee member Mel Galbraith, a secondary school teacher at the time, recognised the potential for this to be an excellent learning opportunity for his students if they could be involved. He discussed his idea with colleagues Graham Jones (also on the committee) and Neil Davies, who was a Tiritiri Matangi volunteer. All three were biology teachers at Glenfield College and were enthusiastic about participating in the project. Mel’s vision extended beyond just biology students; he saw this as a chance to include students from various disciplines, creating a genuinely multidisciplinary educational experience. The proposal was well received by DOC and, with overall supervision from DOC staff at the Auckland Conservancy, the project received the green light. Technical support officer Shaarina Boyd took on the role of liaison between DOC and the school. With that, the project commenced, and the careful planning process could begin.

The hard mahi

The ‘Noah’s Ark’ approach to establishing a new population is, of course, far from guaranteed in the real world, and releasing a few males and females into the bush will almost certainly fail. A vast and comprehensive range of factors must be considered, and any risks should be mitigated as much as possible. This is why it takes quite a while to develop a transfer proposal. Eighteen enthusiastic Glenfield College students volunteered to help write the proposal, planning to do so by speaking with research scientists and conducting some of their own research. Several questions needed answers. Did the Island have suitable food in sufficient quantities throughout the year? What about competition with other species like korimako/bellbird and tūī? Would they need nest boxes? How many? What design? The list of questions went on and on, and each one required a satisfactory answer.

Students conducted a plant survey on Tiritiri, and one of the conclusions was that the New Zealand gloxinia/taurepo (Rhabdothalmus solandri ), used by hihi as a winter nectar source on Hauturu, was in short supply on the Island. Consequently, over 100 plants were propagated and later planted by students during various weekend field trips. Two other species that were important hihi food sources on Hauturu had been planted on Tiritiri in 1984/85 — Alseuosmia spp and haekaro (Pittosporum umbellatum) — to supplement nectar sources for birds during winter and spring. Under the supervision of DOC and teachers, these students made a very significant contribution to the final translocation proposal document; in fact, they practically wrote the entire thing.

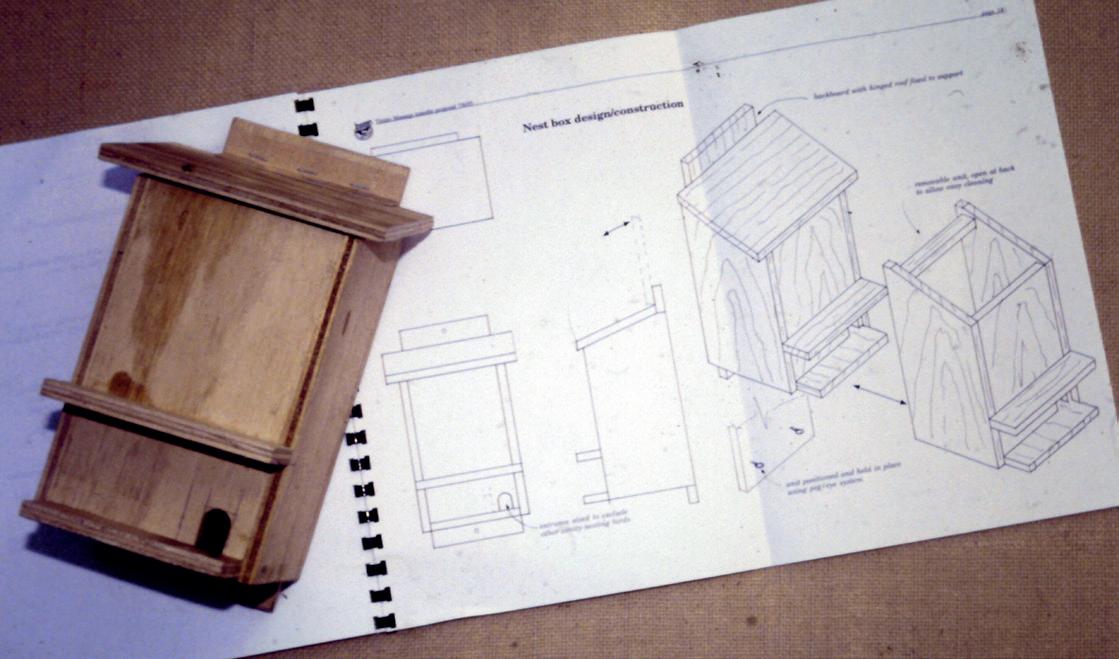

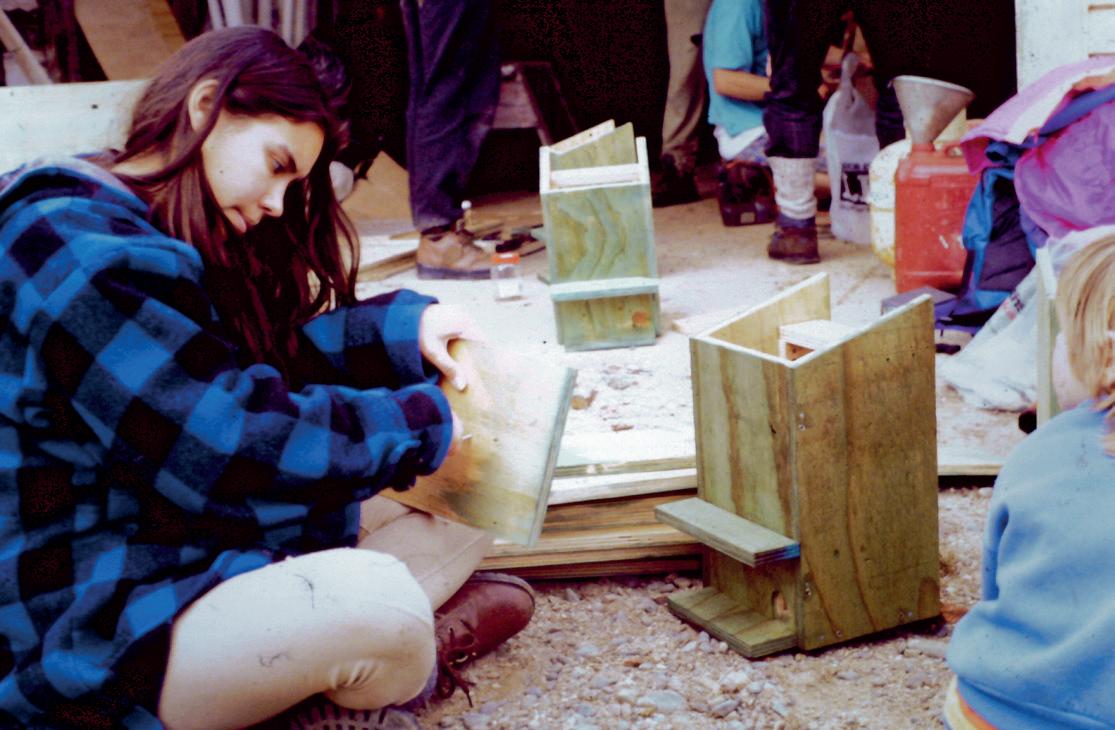

The young, regenerating forest on Tiritiri provided very few suitable tree cavities for hihi to nest in, so it was clear that many nest boxes needed to be supplied for the new population. Past experience from Mokoia Island showed that young hihi often left the nest boxes too early, which probably contributed to fledgling failure. The likely causes were mite infestations and blowflies attracted to fouled nests. Mel Galbraith’s plan allowed multiple disciplines to participate in the project, offering an opportunity for the school’s technology department to get involved under the supervision of woodwork teacher Frank Whitfield. He gathered a team of students to build 50 nest boxes, designing a modified version that would be easy to sanitise between broods. The boxes were delivered to Tiritiri in kitset form and assembled on the Island.

Not to be left out, the art department took on the challenge of designing a logo for the project, and student Julie McGregor created the winning design, which was subsequently used on all letterheads, pamphlets, stickers, and labels, thereby branding the venture professionally. The English department saw this as an excellent opportunity to engage in journalistic writing, and the Māori department was also keen to participate in the translocation of this taonga. None of this comes cheap, and again students were involved in applying for sponsorship from various sources. With their own branded stationery on which to write their applications, their submissions were well crafted and professional. The Lottery Grants Board, NZ Glass Environmental Fund and DuPont all provided funding, helping to offset many of the costs. After a few months, the transfer proposal document was submitted and approved by DOC. All that was left was to carry out the plan.

All systems are go

DOC’s approval for the project meant that the completed nest boxes could be transported to the Island and installed in strategic locations by the same team of volunteer students who made them, all in preparation for the translocation itself. Additionally, previous experience and research had shown that, until there was enough nectar year-round from plant sources, the birds would require supplementary feeding in the form of sugar water. A company, Perky Pets, from the United States, donated 20 hummingbird feeders that they believed could do the trick. Another consideration was the competition from the honey-eaters – tūī and korimako/bellbird. Tūī are particularly aggressive in this regard, so caged enclosures were designed to allow smaller birds to come and go while excluding the tūī. With design modifications, these types of feeders continue to be used today.

The team of biology students chosen to carry out the transfer needed to be well-prepared for their roles, which involved extensive training in bird capture and handling techniques. Mist nets were set up on the school grounds and, under the supervision of teachers and DOC’s technical support officer, a significant number of sparrows and blackbirds were caught and released in the dim light of dawn before school. After several of these early morning sessions, the students gained confidence and skill in disentangling birds from mist nets and handling them with minimal stress.

Come the school holidays, two teams of students were well prepared for a fortnight of capturing hihi on Hauturu. Access to the Island is by permit only, and the physical logistics of getting people and equipment on and off the exposed boulder beach are both weather-dependent and challenging. The goal was to capture a total of 40 birds, consisting of 20 females and 20 males, place them in the aviary near the accommodation block, and prepare for the final transfer to Tiritiri.

The first team of nine students went out with teachers Mel Galbraith and Neil Davies and got straight to work setting up three mist nets at intervals along a ridgeline track. With three students per net, there were plenty on hand to rally when a bird was caught. Each target bird was placed in a small black cloth bag and quickly taken down the track to the aviary, where a DOC staff member would be waiting to band each bird, carry out health checks, and collect feather and blood samples. There were also many non-target species that had to be dealt with. Kākāriki and tūī show no sense of humour when caught in a net, and all those weeks of net practice and bird handling at school certainly paid off. By the end of the week, about 25 birds were happily flitting about in the aviary, leaving the incoming team to complete the capture quota. The outgoing team was replaced by a team led by Graham Jones, and by the end of the second week, a full house of 20 males and 20 females was in the aviary, ready for transfer to their new home. The student teams had succeeded in achieving their goal and could take pride in a job well done.

Fly my

Everyone had their fingers crossed for good weather on the release day, which was scheduled for September 3rd 1995. Over 300 visitors attended, including students from Glenfield College, members of the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi, and the general public.

The distant throb of a helicopter sent a wave of excitement through the crowd gathered on Coronary Hill, and very soon, the Heli-Tranz aircraft touched down with its precious cargo. On board were Shaarina Boyd from DOC and representative members of the tangata whenua, Ngati Wai.

After a heartfelt karakia performed by the father of one of the Glenfield College students, the three cages were carried to their release sites, each accompanied by a group of supporters. With all preparations completed and a final blessing given, it was now up to the hihi themselves.

Go forth and multiply, little birds!

The transferred birds were closely monitored after the initial release. Early surveys showed that only 17 had survived, which caused serious concern. Feeding stations were fitted with cameras that were activated by a small switch on the perch. The perch also functioned as a weighing scale and, since each bird was banded, the photographs offered a good indication of which birds were gaining or losing condition. In the end, the birds managed to settle in and, after a slow start, the population began to increase. Thirty years later, the Tiritiri population is thriving.

Once one of the world’s rarest birds, it is now unusual not to encounter one when visiting the Island. Although they still rely on supplementary feeding, their recovery has been a significant success. Lessons learnt from the Tiritiri population have enabled the successful establishment of other managed populations at Zealandia in Wellington, Tarapuruhi Bushy Park in Whanganui, Maungatautari in South Waikato, Rotokare in Taranaki, and Shakespear Regional Park in Auckland.

All of the Glenfield College students involved in the project should feel proud of what they achieved. In December 1996, they won the Tearaway Conservation Shield at the Young Conservation Awards, a significant recognition of their efforts. Wherever they are now, these students can reflect on the crucial role they played in saving a species. For Mel Galbraith and his team, this project demonstrated that valuable learning can be gained through collaboration and hands-on citizen science.

In this special piece, Professor John G. Ewen from the Zoological Society of London reflects on 30 years of dedication, science, and teamwork behind the successful return of hihi to Tiritiri Matangi.

It’s nearly 6.00 p.m. on a warm summer’s evening, and over the rhythmic buzzing of cicadas, I hear the welcoming rumble of an approaching quad bike. I am tired, nearing the end of a two-hour observation of one of only four breeding female hihi on the Island. She is due to lay a precious egg the next morning, hopefully the first of a clutch of up to five, and the males know it… two hours of secretive behaviour from a female attempting to avoid overly amorous suitors, valiant attempts from her mate to provide protection, and constant territory incursions from every other male on the Island. Trying to record all of that is a juggle, to say the least. I have spent six hours in that female’s territory over the day. Similarly, every day, with each female as they finish building their nest and lay precious clutches of eggs. Each egg will be a small white beacon of hope— hope that the birds will like their new home and will successfully settle in. Fast forward 30 years, and that hope has well and truly been realised. Tiritiri Matangi Island is basically hihi heaven.

My watch ticks over 6.00 p.m. and I 'down tools'. Waiting for me along the top edge of Bush One is another researcher, Phil Cassey, with some fishing gear, two cold beers, and a book by Stephen Jay Gould. We're off to relax, catch dinner, and discuss evolution. Later in the evening, this studious behaviour will morph into computer gaming thanks to Shaun Dunning and his tech-savvy ability to link our three dinosaur computers for… WarCraft! Inevitably ending in two of us, extremely grumpy at our poor military skills, storming off to cool down with the kiwi along Wharf Road. Each day… rinse and repeat. This was how the summer of 1995/96 unfolded, and I will never forget it. Four precious female hihi, twelve male hihi fighting over them, and a bunch of memorable characters living on a beautiful island in the Hauraki Gulf, with Ray and Barbara Walter as our guides to the Island, conservation, and life in general.

These are stories from the first Tiritiri Matangi hihi breeding season that I enjoyed alongside another MSC student, Lynette Wilson, from the University of Auckland (I was at Massey University, supervised by Professor Doug Armstrong at the time). Together, we spent our days studying these birds and learning our trade as we went. I have been fortunate to stay involved, more or less constantly, ever since. Each researcher, contractor, or volunteer will have their own stories of life on the Island and working with this wonderful species. As the birds have thrived, so have the many people who have come and worked with them. Many are now establishing themselves as today’s research and conservation leaders both in Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally.

The story of Tiritiri Matangi’s hihi is a rich one. The project has provided the most studied species on the Island (to date, more than 60 scientific papers have been published on this population), one of the most translocated birds from the Island, and the bird that has inspired the most researchers through their studies on the Island. Throughout this, hihi, and

those studying them, have formed close bonds with DOC staff, Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi, and many others who should share in celebrating 30 years. All of this started with a bird in need and continues to be judged primarily by how the birds are doing. The project relies heavily on passionate individuals, and this began on Tiritiri Matangi with Mel Galbraith and students from Glenfield College. We (birds and people) are forever grateful. Professor Doug Armstrong initially led the research and has continued to inspire the work we do. The work itself requires substantial resources and, for 30 years, we have appreciated support from a range of funders. We thank you all. Species recovery takes a community, and the community supporting hihi remains vibrant and strong. Once you join it, you are a hihi family for life!

Our work continues. In recent years, this effort has expanded alongside the birds to provide a national perspective through the Hihi Conservation Charitable Trust. Please visit our website (www.hihiconservation.com) and contact us if you're interested in assisting. Tiritiri Matangi’s hihi population is 30 years young, and we are confident it will remain central to hihi recovery. It’s a bright, hihi-coloured future, and I hope you will continue to enjoy watching it unfold as much as I will.

Researchers who studied for PHD or MSC qualification working with the Tiritiri hihi population (alphabetical by surname):

PHDs: Caitlin Andrews, Patricia Brekke, Alienor Chauvenet, Laura Duntsch, Victoria Franks, Alex Knight, Kate Lee, Matthew Low, Ashleigh Marshall, Fay Morland, Hui Zhen Tan (current), Rose Thorogood, Leila Walker

MSCs: Sarah Bailey, Alistair Baxter, Antonia Dalziel, John Ewen, Ella Hamblin, Qianyu Huang, Benjamin Keningale, Naomie Lagesse (current), Troy Makan, Elena Mather, Sarah Nichols, Julia Panfylova, Louise-Marie Poirier, Kate Richardson, Rose Thorogood, Lynette Wilson

The results of the 2025 competition, with the judge’s comments on the winning entries, are listed below. Thank you to all who entered and congratulations to the winners.

FAUNA

First: Nicole Koch, Kōkako

This is a well-taken image with good sharpness on the subject and good exposure, allowing us to see the beautiful feather detail and tonalities on the body of the bird. I enjoyed the fact that you have included the environmental detail, which gives context to where this special bird lives on the Island. A nice diagonal composition all adds up to a very pleasing and excellent storytelling image. Well done!

Second: Lucy Schultz, Tūī

Third: Nanette Felton, Pōpokatea

FLORA

First: Jen Burgin, Tī Kōuka

This image beautifully details the riot of flowers on this plant. There is plenty of sharp detail in this cluster of flowers, and you have filled the frame to allow us to see this beautiful floral display. A well-taken and composed image. Lovely!

Second: Kay Milton, Māhoe Bark

Third: Neil Davies, Orange Pore Fungi

Kingfisher

First: Kay Milton, How to Age a Kingfisher

I enjoyed your capture of the engagement of these two volunteers in their task. I felt this image beautifully captured the true meaning and worth of the work that these, and all the other volunteers and rangers, carry out on the Island. This image so well conveys the care and love that you all put into your efforts on this special island haven. So heartwarming, and very well done!

Second: Martin Sanders, Farewell to Tiritiri

Third: Carol Bates, Ascending the Lighthouse

First: Chester Yip, New Zealand Pigeon

A good, sharp image of this bird showing the environment in which it lives. Well done!

Second: Ariana Eccles, Mushrooms

Third: Ethan Fullam, Korimako

First: Karin Gouldstone, Sunrise Behind Lighthouse

This is a lovely, evocative image of a sunrise on the Island. We get the feel of this special time of the day in an image that is compositionally well thought out, with all the elements nicely arranged in the frame. The exposure has been well judged to capture the warm lighting of this time of day. Well done!

Second: Alison Forbes, Sunrise on Tiritiri Matangi

Third: Kristy Andrews, Lighthouse Night Sky

With the kōkako population on Tiritiri close to one hundred, the chances of observing them on the Island are increasing. Janet Petricevich, a member of the kōkako monitoring team, introduces us to some of those you might encounter on our guiding routes, Kawerau, Wattle, and Moana Rua, and explains how to identify them.

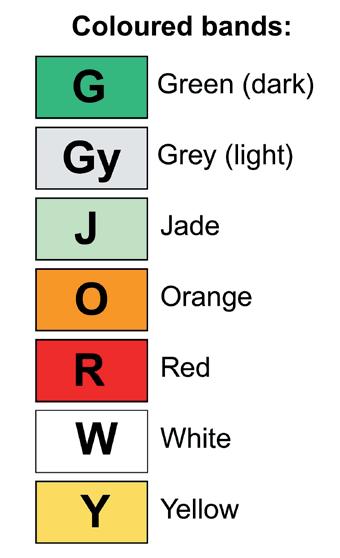

As the Tiritiri kōkako population is monitored, most birds on the Island are banded, assisting the monitoring team in identifying individual birds. To read a bird’s leg bands, begin with the top band on the bird’s left leg, followed by the bottom-left band, then the top band on the bird’s right leg and finally, the bottom-right band. Each banded kōkako on Tiritiri has one metal band (M) containing a unique identifying number (part of the DOC-administered banding scheme) and up to three coloured bands. See the table (right) for key to colours.

While young single birds tend to roam the Island and may therefore be found almost anywhere, the three guiding routes all pass through the known territories of established pairs.

Te Rae (OM-JO) and Chatters (G-M)

Koto (RM-JG) and Apato (GM-JR)

Te Rae and Chatters’ territory is located in the lower part of the Kawerau Track, near the kōkopu pond. Te Rae is the daughter of the last wild-caught Taranaki kōkako, Tamanui. She hatched at the Mount Bruce Wildlife Centre (now Pūkaha National Wildlife Centre) in 2006 and was translocated to Tiritiri in 2007. Chatters hatched on Tiritiri during the 2006/07 season. He is either the son or grandson (we are not sure which) of two of our founder birds, Cloudsley Shovell (Cloudsley) and Te Koha Waiata.

Many of the kōkako that were translocated to Taranaki in 2017 were descended from Te Rae and Chatters. If you are interested in the history of Taranaki kōkako, you may enjoy this YouTube video, 'Kōkako - The story of Tamanui': https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mPXa67wFu_U

Phantom (W-M) and Wakei (WM-YY)

The top of the Kawerau Track, around the bird feeders, is territory belonging to Phantom and Wakei. Phantom hatched in the 2008/09 season, the daughter of Cloudsley and Te Koha Waiata. In 2010, she paired with a founder bird, Te Hari, and remained his partner until the summer of 2022, when she was found with a new mate, Wakei. Te Hari was 24 by this time, which is old for a kōkako. Wakei hatched in 2020, the son of Discovery and Sarang; he is Phantom’s grandson. They bred successfully in the 2023/24 season, but the team believed they were unsuccessful in the 2024/25 season after Phantom’s third nest failed late in the season, and we ceased monitoring her. Imagine our surprise when she was seen feeding a young, unbanded fledgling in April 2025!

As you turn onto Ridge Road at the top of the Kawerau Track, you are entering the territory of Koto and Apato. Koto is the daughter of Te Rae and Chatters. Apato is the grandson of Pureora and Crown, two wild-caught Waikato birds who were translocated to Tiritiri in 2008. Apato is short for ‘Apatosaurus’. This pair has been together since 2018, has produced numerous offspring, and is highly proficient at confounding our attempts to locate them during the breeding season. They are generally extremely relaxed around people for the remainder of the year.

Kopakopa (YM-GJ) and Noel (M-R)

If you hear kōkako singing from the bush above the wharf as you disembark from the ferry, it is most likely to be this pair. Their territory includes the ‘Shortcut’, past the Wharf Dam. Kopakopa is a young bird, the daughter of Pureora and Crown; she hatched in the 2022/23 season. Noel‘s name comes from the time he hatched, around Christmas in 2008. He has a mix of Taranaki and Mapara bloodlines. He was paired with a Taranaki descendant named Rehu from the spring of 2010, but was found with his new mate at the beginning of the 2024/25 season. They successfully fledged two chicks this past season.

Te Rangi Pai (RM-GR) and Hēmi (RM-WR)

Te Rangi Pai and Hēmi are two of the most ‘visible’ birds on the Island, with their territory located right in the middle of the Wattle Track, around the Nīkau Grove and Blackmore

Seat water trough. This territory is where the founder birds, Cloudsley and Te Koha Waiata, made their home. Hēmi is Cloudsley’s grandson, and Te Rangi Pai is his younger sister. They are excellent advocates for kōkako on the Island, as they seem to enjoy public attention (they are probably the most photographed birds on the Island), but have never managed to breed, perhaps due to their familial relationship.

Honey (RM-YY) and Hēnare (YM-JW)

At the top of the Wattle Track, you might encounter Honey and Hēnare. Honey hatched on Tiritiri in 2015/16, but we are uncertain about who her parents were (there were three possible pairs). From 2017, she was partnered with Rimu, a wild-caught Waikato bird translocated to Tiritiri in 2010. Although we do not know Rimu’s age, he appeared slightly ‘tired’ at the end of the 2023/24 breeding season, so it was not too surprising when Honey was discovered with her new mate at the beginning of the 2024/25 season.

Dianella (GyM-GyR) and Te Kōkī (RM-W)

As you walk along the Cable Track and then through the Inner Coastal link, you may encounter a young kōkako pair, Dianella and Te Kōkī. Both of these birds carry under-represented genes in the Tiritiri kōkako population, and the monitoring team is eagerly awaiting offspring from this couple.

Shelly (RM-R) and Tama (RM-WG)

Shelly and Tama’s territory is the bush above Emergency Landing Dam. Keep your eyes and ears sharp for them as you wind your way down ‘the zigzag’. Until 2022, Shelly was partnered with Waipapa, a wild-caught bird from the Waikato region, but he disappeared sometime during the winter of 2022. Shelly and Waipapa only managed to fledge one chick successfully in the four years they were together. She has enjoyed more success with her new partner, Tama, having four of their offspring successfully fledge. Their first, Moana, narrowly escaped the ferocity of Cyclone Gabrielle, which destroyed the nest she had been occupying.

Luna (YM-GG) and Themba (YM-GW)

Luna and Themba are a young couple residing in the Lighthouse Valley. You may encounter them as you walk from the East Coast Track towards the Visitor Centre. Luna is one of Te Rae and Chatters’ offspring, meaning she has many relatives on the Island, while Themba is one of only three of Honey and Rimu’s offspring on Tiritiri. They paired for the first time during the 2024/25 breeding season. Their first nest failed, but they succeeded with their second, a commendable achievement for a young pair.

We often observe young, single birds along Ridge Road, at the top of Wattle Track, and around the Visitor Centre during winter and into spring. They form loose groups as they explore the Island in search of territory and a mate, so it is a splendid time to visit the Island and engage in a bit of kōkako spotting.

One of the things I love most about the Proteaceae family of plants is their flowers – from the showy heads of protea to the spidery flowers of grevillea and the draping macadamia nut flowers. The rewarewa tree (Knightia excelsa) is no exception. Its clusters of lipstick red, yellow-tipped flowers – and their clever pollination process –are fascinating. In fact, there are many quirks about rewarewa that make them one of the most intriguing trees on Tiritiri Matangi.

A southern hemisphere family, most Proteaceae species are found in Southern Africa and Australia. Fossilised pollen evidence shows that New Zealand once had numerous species. But now there are just two: Toru (Toronia toru) and the more well-known Rewarewa, or New Zealand honeysuckle. Both are the only species in their respective endemic genus and, of the two, a few hardy rewarewa live on Tiritiri Matangi.

Rewarewa – standing tall and staying the course

Growing in a conical shape up to 35m high, rewarewa is the tallest member of the Proteaceae family. It’s a fast-growing but long-lived pioneer species: its shape helps it outpace its neighbours and gain height dominance and sunlight in regenerating forests like Tiritiri Matangi. Slower-growing trees will eventually surpass rewarewa, leaving only a few mature specimens to survive once the forest matures.

A pollen-studded tūī gathering nectar from the base of a rewarewa flower. The picture also shows two unopened red buds, numerous yellow-tipped female styles, and numerous curled ribbon-like outer sheaths (perianth) with yellow male anthers attached.

and Davies’ 2013 survey noted only four wild trees near the Kawerau Track and no wild seedlings.

As with most Proteaceae, rewarewa have specialised roots that help them to grow in poor, nutrient-deficient and dry soil. These dense clusters of short, fine horizontal rootlets look a little like clumps of fuzzy cobwebs. They grow in the surface soil and leaf litter, producing chemicals that help release nutrients to feed the tree. Clever!

A few wild rewarewa were first recorded on Tiritiri Matangi during Alan Esler’s surveys in the 1970s. However, Cameron

Less than 1000 plants were added in the 1984-94 revegetation programme. A few are visible near the Wattle Track, including one with a sign before the steps to the top water trough. Find others along the firebreak between the Wattle Track and the road, where they create an ‘avenue effect’ as they grow above the surrounding vegetation.

And if you’re lucky enough to spot this New Zealand protea in flower while visiting, pay close attention.

Inside the world of rewarewa pollination: a slightly bonkers, ingenious process

Like other Proteaceae, rewarewa flowers have many parts. What looks like one big spiky head is in fact a cluster of up to 80 individual flowers, attached on short stalks, along a 10cm long central axis. In the botanical world, each flower is deemed ‘perfect’ because it has both male and female parts.

While this is not uncommon, it’s rewarewa’s fertilisation process that is quite technical and nuanced. It’s all geared up to avoid self-pollination within the perfect flower. How does it do this? A well-timed domino effect in the flowering season.

Red, tube-shaped buds, covered in velvety hair, first appear on the tree in autumn. From spring through to summer, one by one, the top of each individual bud opens slightly to reveal the tip of the style, the female tube that carries pollen to the ovary for fertilisation.

The outer sheath then cracks into four segments. As it bursts fully open, each segment curls down to the central axis like a ribbon, taking with it the male parts of the flower and opening access to the nectar at its base.

This unfurling is not before a delicate and unusual transferral takes place within each bud: pollen is passed from the anthers (male pollen-producing organ) onto the tip of the female style.

The style is left exposed and extends into a stork-like structure, ‘presenting’ the pollen to birds for incidental collection as they brush past looking for nectar at the flowers’ base. The bird then transfers the pollen to another flower. On Tiritiri Matangi, this is a job for tūī, korimako/bellbirds and hihi/stitchbirds. Elsewhere, silvereyes, kākā, introduced honeybees and possibly a few remaining bats, also oblige.

Now, you might wonder why the flowers’ own pollen, perched on its style, doesn’t accidentally pollinate itself. Not to be outsmarted, rewarewa has yet another clever trick!

The pollen-receiving organs that sit at the end of the style, the stigma, only mature once their own pollen has gone.

In perfect unison, nectar production at the flowers’ base then reaches full peak, ensuring a continued supply of sweet rewards for birds who dust introduced pollen onto the now ‘receptive’ stigma.

This pollen then travels down the style to the ovary, where fertilisation takes place.

How sophisticated! This endemic tree surely is one to marvel at. There is a whole, complex design system operating within what looks like a single flower head. It’s for this reason, and the many more quirks outlined above, that I always have time for rewarewa. We are lucky to have this beautiful Proteaceae in our midst.

The fruit and foliage

The rewarewa fruit develops into a 4-5cm long, dry woody pod which, after about a year, splits open, exposing winged seeds for dispersal by wind. Rewarewa’s distinctive foliage is remarkably like its Australian cousin, the macadamia nut, being linear and markedly toothed around the edges. New shoots and the undersides of young leaves are covered in rusty-red tomentum.

The photo to the right shows young autumn buds, linear tooth-edged leaves, and opened canoe-shaped seed pods.

There have been some surprises from the Island's kōkako, and its tīeke and hihi are on the move.

Kōkako

The season of 2024-25 was the longest and most productive ever for the Island's kōkako. On 17 April, Phantom (in heavy moult) was observed and photographed feeding her fledgling. She had clearly decided to try again after her previous nest was predated. To our knowledge, Tiritiri has never had a kōkako fledge a chick this late in the season. Phantom is 16 years old; this is quite impressive for a lady in late middle age!

Wai Ata and Awenga fledged two chicks just before Christmas, but by 2 January 2025, only the first fledgling, Huna, had been seen. It was assumed that their second fledgling had not survived. It was a welcome surprise when, in early June, their second fledgling, Werewere, was sighted and photographed.

A total of 25 fledglings have been recorded this season. Their names, genders, band combinations, and the names of their parents (in brackets) are as follows:

Quill (GG-GyM), male (Noel and Kopakopa)

Puiaki (YW-GyM), female (Noel and Kopakopa)

Huna (JG-GyM), male (Awenga and Wai Ata)

Werewere (GJ-GyM), sex unknown (Awenga and Wai Ata )

Electra (JR-GyM), female (Honesty and Miro)

Nilah (RY-GyM), female (Sarang and Discovery)

Puoro (RJ-GyM), sex unknown (Sarang and Discovery)

Hikari (WG-GyM), female (Apato and Koto)

Hime (WJ-GyM), female (Apato and Koto)

Titok (WR-GyM), female (Hotu and Haeata)

Mardle (WY-GyM), male (Whistles and Te Hia)

Kawata (YG-GyM), female (Paraninihi and Wairua)

Comet (GyY-GyM), male (Hēnare and Honey)

Rocky (GyW-GyM), male, (Tama and Shelly)

Hihana (YJ-GyM) male, (Chatters and Te Rae)

Sombra (YY-GyM) male, (Rēkohu and Yindi)

Shadow (GyGy-GyM), sex unknown (Rēkohu and Yindi)

Tāwera (GyJ-GyM) male, (Themba and Luna)

Rākautū (JJ-GyM) male, (Bátor and Marihi)

The five unbanded fledglings (Ub11-Ub15) will not be named until they have been caught, banded and sexed.

Have you ever seen a hihi that appears to have a bit of string hanging out of its mouth, like the one in the picture? It is actually its tongue!

This is a peculiar phenomenon known as a ‘sublingual oral fistula’ (SLOF). Essentially, it is a small hole that forms on the underside of their bill, and eventually their tongue (long and adapted for nectar-feeding) can poke through the gap.

This condition was first formally described in hihi in the 1990s, but it is not exclusive to them and has been observed in several other bird species around the world.

A 2007 study on Tiritiri found that about 10% of the adult hihi population consistently have some form of SLOF, even if it does not always result in the tongue poking through. However, the reason why these holes form remains a mystery! Even if this sounds a bit unpleasant to us, we know that birds with a SLOF can still feed successfully, especially on insects, fruit, and at feeding stations. They continue to live for many years.

The one in the picture likely hatched in 2016-2017, so is currently the ripe old age of eight. They also successfully raise young - even if the chicks can get a bit sticky from sugar water during the process!

Further reading: Low, M., Alley, M. R., and Minot, E. (2007). Sublingual oral fistulas in free-living stitchbirds (Notiomystis cincta).Avian Pathology,36(2), 101–107.

May this year was ‘translocation time’ when Tiritiri could share some of its thriving bird population with other sites. Tīeke and hihi were on the move this time to nearby Shakespear Regional Park.

The first hihi translocation to the Park in July 2020 was unsuccessful, but birds from last year’s translocation have done remarkably well. Fifteen of the twenty females moved in May 2024 were still present at the start of the nesting season and produced 60 offspring.

Forty birds from Tiritiri have now joined these to supplement the population. There is a strong likelihood that they will successfully establish themselves in the Park.

Tīeke numbers had been increasing in the Park before a stoat incursion five years ago. The stoats are now gone, and tīeke numbers are once again on the rise. The extra 30 birds we’ve just sent there will give a useful boost to their recovery.

May is a great time to visit the grey-faced petrel colony at the 'Petrel Station’ on the Kawerau Track. During this period, breeding birds return to the Island, reunite with their partners, and reclaim their nest burrows. At the same time, many younger birds also visit. Some of these birds will be ‘on tour’ and will visit numerous sites across the Gulf and beyond.

In previous years, we have successfully caught and banded some of them. On a good night, we might catch 20 to 30 birds. This year, some members of the translocation team were enlisted for an attempt to catch more.

Over four amazing nights, 149 ōi were captured at the 'Petrel Station’ as well as 30 kuaka/diving petrels at the north-east colony opposite Wooded Island.

Catching ōi is not difficult, but it is rather hazardous for the inexperienced bird handler. The birds often sit around on the ground, and can be called in using high-pitched yodels, but they have sharp claws and a strong beak which can cause painful scratches, as some of the less wary catchers discovered.

Eighteen of the ōi were already banded, so their origins could be determined. There were birds from Tiritiri, Motuora, Shakespear, and the Noises.

In previous years, birds from Tāwharanui and Te Henga on the west coast have also been seen. Some are now breeding on Tiritiri, while others have just been visitors and will breed elsewhere.

Ōi can live up to 40 years, so there are decades of opportunities to follow these individuals’ lives. It will be interesting to see how many of the 149 are observed again and where.

As part of my final year of a Bachelor of Applied Science (Biodiversity Management), I, Naiomi, have been extremely fortunate to focus my undergraduate research on the kororā, or little penguin.

My research examines their nesting habits, with particular focus on vegetation cover, nest types, proximity to the shoreline, and nearby urban features. I will be collecting data from as many sites as possible, including Motuora, Mount Maunganui, Oamaru, and Akaroa.

Recently, I had the privilege of spending a day on beautiful Tiritiri Matangi to gather data on the Island’s kororā nests. I documented details from around 40 nests and was delighted to see signs that some penguins might soon be coming ashore to lay eggs.

A sincere thank you to Karin Gouldstone and all the volunteers and supporters who made me feel so welcome.

by Stacey

There are only a few thousand hihi/stitchbirds left, which makes them even rarer than brown kiwi! We have approximately 400 hihi living on Tiritiri Matangi. Enjoy the fun hihi facts below and see if you can unscramble the words to find the hidden word!

A long time ago, hihi lived in many places in northern New Zealand. But by 1890, they were only found on Te Hauturuō-Toi / Little Barrier Island due to predation and habitat loss. In September 1995, 37 hihi were carefully moved from Te Hauturu-ō-Toi to Tiritiri Matangi to help bring them back.

Male hihi are easy to spot because they wear a bright yellow band on their chest. They also have a shiny yellow stripe on their wings and the brighter the stripe, the healthier the bird. Female hihi look different. They’re mostly greyish-brown, but have a white bar on their wings.

A study on Tiritiri Matangi showed that hihi need special colour pigments called carotenoids to stay healthy. These pigments are found in the bright fruits of plants like coprosma, māhoe, and tī kōuka / cabbage trees.

Because hihi are so sensitive, they’re like little forest detectives! If something isn’t right in the forest, the hihi are often the first to be affected. In fact, they were one of the first native birds to disappear from the mainland. That’s why looking after hihi helps us keep the whole forest healthy too!

On Tiritiri Matangi, the Hihi Conservation Charitable Trust helps care for these special birds. They carefully monitor the hihi to make sure they’re healthy, have enough food, and are raising chicks.

A watchful female hihi looking around

Hihi love to eat sweet nectar from flowers, along with small fruit and insects. To help support them on the Island, we provide special sugar feeders, white plastic containers with bright red bottoms. The hihi use their long tongues to reach the sugary water inside, just like they would with a real flower.

Hihi breed during spring and summer, when the weather is warmer. The breeding season lasts about three to four months, from September to February. They build soft, cupshaped nests in tree holes or nest boxes. The female lays one to five eggs at a time and can have up to four clutches of eggs in one season. She keeps the eggs warm by sitting on them. This is called incubating. Once the chicks hatch, the male helps feed and look after them.

Unscramble the words to find out the letter in the circle. Once you have circled the letters enter them below and unscramble them to find the hidden word.

llasnd

uagrs

llowye

seotrf

earctn

ssceitn

wfoelr

iihh

riutf

rnoaitdep

seredef

The circled letters

The Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi (SoTM) is a volunteer Incorporated Society that works closely with the Department of Conservation to make the most of the wonderful conservation-restoration project that is Tiritiri Matangi. Every year volunteers put thousands of hours into the project and raise funds through donations, guiding and our island-based gift shop.

If you ’d like to share in this exciting project, membership is just $30 for a single adult or family; $35 if you are overseas; and $15 for children or students. Dawn Chorus, our magazine, is sent out to members every quarter. See www.tiritirimatangi.org.nz or contact PO Box 90-814 Victoria St West, Auckland.

SoTM Contacts:

Chairperson: Ian Alexander chairperson@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Secretary: Val Lee secretary@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Treasurer: Peter Lee-Grey treasurer@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Board: Meredith Blogg, Hester Cooper, Louise Delamare, Rosemary Gibson, Rachel Goddard, Carl Hayson, Janet Petricevich, Mark Withers

Operations Manager: Debbie Marshall opsmanager@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Guiding and Volunteer Manager: Gail Reichert guidemanager@tiritirimatangi.org.nz, 09 476 0010

Retail Manager: Ashlea Lawson retail@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Membership: Rose Coveny membership@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Educator: Sara Dean

Assistant Educator: Liz Maire educator@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Fundraisers: Rashi Parker and Louise Delamare fundraiser@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Social Media: Bethny Uptegrove socialmedia@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Dawn Chorus co-editors: Janet Petricevich and Stacey Balich editor@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Island Rangers: Talia Hochwimmer and Nick Fisentzidis tiritirimatangi@doc.govt.nz, 027 536 1067

Annual General Meeting

Monday 15th September

7:30pm at MinterEllisonRuddWatt s Seminar Room, PWC Tower, 15 Customs Street West, Auckland City.

Dawn Chorus Guided Walk

Saturday 4th October

Bookings through the Explore website

Book Launch – The Lights in my Life

Sunday 5th October

Bookings through the Explore website

Tiritiri Matangi Talks – The history and future of seabirds on Tiritiri Matangi

Monday 1st December 2025

Speaker: John Stewart

7:30pm at Unitec, Building 115, Mount Albert Working Weekends 2025

Labour Weekend, 25th-27th October

Enquiries to the guiding and volunteer manager

Supporters' Weekends 2025

6th-7th September - fully booked

4th-5th October - fully booked

Enquiries for 2026 to the guiding and volunteer manager

Day trips:

Weather permitting, Explore runs a return ferry service from Wednesday to Sunday from Auckland Viaduct and the Gulf Harbour Marina. Bookings are essential.

Phone 0800 397 567 or visit the Explore website: www.exploregroup.co.nz/

Overnight visits:

Camping is not permitted and there is limited bunkhouse accommodation. Bookings are essential: https://bookings.doc.govt.nz/Web/

We offer a full-day learning experience in a pest-free environment for years 1 to 13. Tamariki and rangatahi can get up close to endangered taonga species where they learn about community conservation and how people can work together to provide protected habitat. This then inspires students to take action in their own neighbourhoods.

Our educators offer a range of education experiences on the Island, which are closely tied to the NZ curriculum. At the senior biology level, there is support material available for a number of NCEA achievement standards. Tertiary students have the opportunity to learn about the history of the Island and tools of conservation as well as to familiarise themselves with population genetics, evolution and speciation.

Subsidies are available for schools with an EQI 430 or more via our Growing Minds programme. Information on the education programme is at: https://www.tiritirimatangi.org.nz/education-programmes/ Bookings are essential.

Tiritiri Matangi Open

Sanctuary 2026 Calendar is now available to order!

For just $20, enjoy the unique species of Tiritiri Matangi all year round, wherever you are.

Our beautifully designed calendars are eagerly awaited and make a lovely addition to any home or office. They also make excellent Christmas gift s.

All proceeds from our calendar sales go towards the funding of SoTM’s conservation and education programmes on the Island.

Thank you to everyone who helped create the 2026 calendar; from the photographers to the designer and the SoTM volunteers, your contributions are greatly appreciated.

To order your calendar, please visit our website, send us an email, or call us during shop hours.

Scan the QR code for links to our online shop, social media and more.

https://www.tiritirimatangi.org.nz/online-shop retail@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

+64 9 476 0010 during shop hours

Mon-Tue: Closed

Wed-Fri: 11:00 am - 2:00 pm

Sat-Sun and public holidays: 10:30 am - 2:50 pm

Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi wishes to acknowledge the generous support of its sponsors

Heritage donors and bequests World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) Fullers360 Peter Lorimer bequest

Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi welcomes all types of donations, including bequests, which are used to further our work on the Island. If you are considering making a bequest and would like to find out more, please contact secretary@tiritirimatangi.org.nz