A

What

We are now into 2024 and the Island has been welcoming many local and overseas visitors, creating a busy time for staff and volunteer guides. As well, many of our biodiversity groups continue to commit considerable hours to the monitoring of the Island’s wildlife and many other volunteers are involved on the myriad of tasks necessary to keep our conservation project alive.

I acknowledge and thank all of you for the contribution you make to the everyday operation of Tiritiri Matangi.

Matters of note from your committee include:-

Discussions are continuing on the provision of a Field Centre in order that we can make progress on this project.

The upgrade of the Kawerau Track is now on our list and needs to be progressed this year.

Grants provide a considerable amount of the annual funding required to operate the Island. A major grant has been received towards the 2024 Growing Minds programme for schools.

Arrangements are in place for the annual concert on the Island on 9 March.

Consideration is being given to how best to recognise the outstanding contributions made by both Mel Galbraith and Ray Walter.

Some members have completed the skills survey but we would like to hear from many more of you, so please take the time to complete this survey.

As a conservation project we rely on many other organisations to assist us in the important work we do. Thanks to the Department of Conservation, Explore Group, sponsors and funders, and our corporate partners, Minter Ellison Rudd Watts, as collectively we work together in the promotion and development of Tiritiri Matangi.

IanWe have recently developed a Code of Conduct Policy and Complaints Process for members of the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi. The Code of Conduct is based on our vision, values, and mission statement outlined in the SoTM strategic plan. Links to these documents are shown below.

Code of Conduct Policy: https://www.tiritirimatangi.org.nz/wpcontent/uploads/2023/12/Final-CODE-OF-CONDUCT-SoTM-1.pdf

It is our absolute pleasure to announce that Wanika Chetty, from Manurewa Intermediate, has been awarded first place for the Tiritiri Matangi Environmental Award. Wanika clearly demonstrates making a positive contribution towards promoting a message of kaitiakitanga with her involvement in, and contributions to, her school Nature Club. In addition to her 100% attendance at Nature Club, Wanika helps in the gardens, with the animals, composts, fruit kitchen, and rubbish system, as well as running the trapline. She also mentors the Year 7s and does the 'yuck jobs', always with a smile on her face.

We are particularly impressed by her mentoring of younger students, ensuring the shared knowledge and skills of the group continue to be passed along. The passion, mahi and knowledge of many individuals, resulting in communities making collective change, truly reflects the values of Tiritiri Matangi.

This quote from Wanika assures us she will continue to make a positive impact for our taiao for many years to come:

'Sustainability means to keep something going. Regeneration means to make something better. Because you never gave up, you got better. Let your passion guide you always.'

Rose Nelder, from Mangawhai Beach School, has been awarded the runner-up’s prize. Rose is a conservation star by not only running the trapline at school, but also encouraging other students to be involved, and running her own trapline - all whilst skipping between the traps! We are truly impressed by the time Rose invests in this mahi and her commitment to sharing this passion with others, both through her school Envirogroup and through a speech she made at her school's annual speech day. It is this passion and commitment of an individual making collective change that aligns with the values of Tiritiri Matangi.

Complaints Process: https://www.tiritirimatangi.org.nz/wpcontent/uploads/2023/12/Final-Complaints-process-.docx-1.pdf

Front

cover: Tony Petericevich - Juvenile korimako/ bellbird Wanika Chetty promoting a message of kaitiakitanga Rose Nelder running the school traplineThe volunteers on the Island bring a wealth of knowledge and come from diverse backgrounds. Yukiko gives her time to guiding visitors and is part of the kōkako team, which involves early mornings finding kōkako nests and observing the birds' behaviour.

Where did you grow up?

I was born in Osaka, Japan and moved to Kyoto. I moved to Palmerston North in 2001 to study teaching at Massey University. In 2003, after graduation, I moved to Auckland to start teaching at Mount Roskill Grammar School.

What were the circumstances that prompted you to become involved with Tiritiri Matangi?

My friend, who is a guide, invited me along to a working weekend on the Island. I met so many bird enthusiasts and learnt a lot about the birds, it was very inspiring. They encouraged me to train and be a guide. I really enjoy being a guide and sharing my passion with the visitors.

What do you enjoy most about being a guide?

I love to share my passion and knowledge about Tiritiri Matangi and its birds. I love how the volunteers show manaakitanga by being caring, passionate and inspirational. They are like a family. I love talking about the environment and Predator Free 2050 Project. Hopefully the mainland will be like it used to be, before invasive predators.

What has been your favourite experience with guiding?

All of my experiences. I enjoy meeting visitors and hearing that they have enjoyed their guided walk and learned about the conservation and biodiversity programme on Tiritiri Matangi. They appreciate what we are doing, and our passion. It is nice meeting them again as repeat visitors some years later.

What is your favourite bird on the Island? Why?

Kōkako. I have been involved in the kōkako monitoring team for 14 years. It is like treasure spotting to see kōkako. The first kōkako I named was called Takara which means treasure in Japanese. He has Taranaki genes, so he was translocated to Parininihi in 2017. I enjoy hearing stories shared about how well he is doing and how many chicks he has had.

What is your favourite plant/tree? Why?

Rangiora. It is bushman’s friend, toilet paper. I like sharing the story with visitors.

A life-long connection to nature and te taiao (the environment) brought me to the motu. I was attracted to the role of Volunteer and Guiding Manager as I approached retirement because of the alignment between what the Island stands for (conservation, restoration, research, education) and my own personal values. I am always up for a challenge, and I love learning, and the role on Tiritiri Matangi presents me with both. After spending the last half of my career in leadership development, I truly appreciate having genuinely interesting, passionate and knowledgeable people as colleagues in my workplace.

I was drawn to the Hibiscus Coast area by my love of the ocean and nature and have lived here for 21 years. In this time I worked hard with secateurs and slashers to clear masses of invasive pest weeds from my property, establishing a predominance of native plantings as a haven for local birds.

Do you have a favourite story that you would like to share about Tiritiri?

Greg the takahē nagged me to open the lid of his pellets container. When I joined the working weekends, he always came to the morning meeting to check us. He supervised when a new ranger came to the Island.

During working weekends we meet at 9am at the implement shed and Greg would always join the meeting. I remember a guides' day out training day and we all brought shared food. We closed the door to prevent him coming in, so he walked round to the side door and came in through there. One time Greg stood on Jim’s shoes and pulled at the shoe laces.

What is your greatest environmental concern?

It's really sad to hear about marine pollution and how it affects the environment. When the wind blows from the west, the rubbish from the city arrives on the beach. It is so frustrating to find fishing wire, lollipop sticks, and pegs littering the coastline. It's important to reduce pollution and keep our oceans clean and healthy for all marine life.

Anything else you would like to share about guiding?

I always encourage visitors to get involved in any volunteer programme on Tiritiri Matangi. I would love to be an inspiration to visitors so they become guides as well. As a teacher, I also encourage school visits to Tiritiri Matangi.

I am fascinated by the manu on the motu and love that my work includes being able to commune with such rare and special species.

Outside of work I do a lot of biking and have completed many of the great trails around Aotearoa. In the community, together with a small group of neighbours, I work to control invasive pest weeds on the south side of Orewa Estuary. I am also on the Board of the Estuary Arts Centre in Orewa in support of my interest in the arts.

I have an adult son in Auckland and am privileged to have my mother close by in a care facility. I enjoy socialising with local friends and keeping flexible by practising yin yoga.

Each year, since the 2013-14 breeding season, we have counted the seabirds nesting on Tiritiri Matangi.

The counting team, led by Michael and Roy, make up to nine day trips at one- to two-week intervals, when they use a telescope and binoculars to make the counts. They have a series of observation points around the coast, carefully selected to allow them to scan the Island’s headlands, rock stacks and islets where the seabirds nest. Counting nesting pairs can be tricky as the team need to decide whether sitting birds are on a nest or just resting. They are sometimes unable to scan the seaward side of nesting areas and so some nests will be missed.

We have four regular nesters, tarāpunga/ red-billed gull, karoro/ black-backed gull, tara/ white-fronted tern and kāruhiruhi/ pied shag. They are occasionally joined by taranui/ Caspian tern, kawaupaka/ little shag and, just once, matuku moana/ reef heron.

Table 1 shows the NZ threat status and national population estimates for the seven species. In some other countries, but not in New Zealand as far as we are aware, the authorities use 1% of the national population to identify important bird sites. Tiritiri Matangi has been around this level for tarāpunga in five of the last ten years and three of the last ten years for tara. So, the Island is occasionally a significant nesting site for these species.

Species New Zealand threat staus National population estimate

Tarāpunga / redbilled gull

Karoro / blackbacked gull

Tara / whitefronted tern

Kāruhiruhi / pied shag

Kawaupaka / lilttle shag

At risk - declining 27,800 pairs

Not threatened 100,000 to 1 million?

At risk - declining 5,000 to 20,000 adults

Recovering 5,000 to 10,000 pairs

At risk - relict 5,000 to 10,000 pairs

Taranui / Caspian tern Nationally vulnerable

Matuku moana / reef heron Nationally endangered

1,300 to 1,400 pairs

300 to 500 individuals

For karoro there are on average 35 pairs nesting each year, while there are six to ten pairs of kāruhiruhi. Occasionally we have single pairs of taranui and kawaupaka.

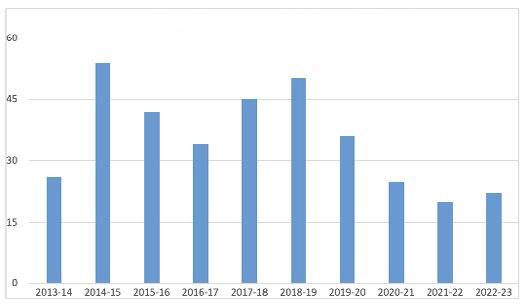

It is important that we continue our annual counts of these seabirds as the two commonest are believed to be in decline. Our annual counts of tara and tarāpunga contribute to counts for the Greater Hauraki Gulf area. It’s also interesting how variable are the counts, as illustrated in figures 1 to 4. While kāruhiruhi numbers don’t vary much from year to year, the karoro range between 20 and 54 pairs, tarāpunga range between 81 and 337 pairs and the range for tara is zero to 107 pairs with six of the ten years at five or fewer. The most recent season’s figures aren’t yet available but are looking extremely poor.

Terns are recognised as species that are quite fickle in their choice of nesting site and it is possible that during our years of low counts some or all of the missing birds are nesting

elsewhere. Gulls tend to be more faithful to their nesting sites so the fairly dramatic variations in annual counts are a challenge to explain. But it’s this variation which makes our counts so interesting and valuable. In the short-term they provide evidence for the birds’ behaviour and in the longterm for changes in population sizes.

Michael Dye, Roy Gosney and John StewartTarāpunga/ Red Billed Gulls Annual Total

Karoro/ Black Backed Gulls Annual Total

Tara/ White Fronted Tern Annual Totals

Kāruhiruhi/ Pied Shag Annual Total

Lots of healthy chicks have been produced, keeping their parents active, and the bird monitoring teams busy. Takahē

The 'lighthouse family' of takahē nested and had their first chick hatched in November 2023. They built another nest and hatched a second chick in early January. Having the same parents have two chicks from two different nests is a first for Tiritiri Matangi.

The older chick has grown quickly and is getting its colours. The younger chick was being assisted by its parents and subadult, Waipuna, as the family moved about the southern end of the Island. However, the second chick was not seen after the second week of January and is presumed dead.

The now family of four are being seen regularly by visitors to the Island. If you see them remember to give them plenty of space.

The takahē family at the northern end of the Island also nested twice. However, they have not hatched a chick this season.

A lot has happened since the last hihi update. Maude Vernet, who was a hihi volunteer, said farewell and has continued her travels in the much drier pastures of Tasmania before returning home to Switzerland. The new hihi volunteer, Sarah Kate, will be here until the end of the season.

After a brief pause in breeding at the start of October, due to the bad weather, the hihi were incredibly busy. Egg laying kicked off again around late November and did not stop until the start of December.

In January, most of the females were finishing off their first clutch, and 12 of the 13 females in the first wave were finishing off their second clutch.

By mid-January, a whopping 70 females had bred this season with 387 eggs laid, 297 chicks hatched, 204 chicks banded and 116 fledglings already flapping around.

Those early-bird females may even try for a third clutch if they aren’t exhausted from raising chicks from their first two nests. It’s shaping up to be a good breeding season. This is only the fourth time the hihi on Tiritiri Matangi have raised over 200 chicks to banding age.

As the blooming pōhutukawa wave swept the Island, the drop-off in sugar water was incredibly noticeable, from over 800L ingested in November to a minimal amount of less than 80L consumed in December. Natural food is important for hihi, and they are known to be a vital pollinator. However, intensive management and provision of supplemental food for the Tiritiri population is still critical to ensure longterm viability.

While the weather has been shifting from wet to dry, the heat and humidity are making those pesky nest mites rear their heads once again, but the team continues to make sure that the chicks have a fighting chance.

Before the breeding season started, we recruited eight new volunteers to help with checking the nest boxes. This has worked extremely well, enabling boxes to be checked every seven to ten days, something we haven’t managed to achieve in recent years. With only two nest boxes currently in use (in early January), it looks like the breeding season for tīeke might be almost over, but there have sometimes been late nests in previous years, so monitoring will continue for a few more weeks.

We shall analyse the records at the end of the season, but so far we can say that 16 boxes have been used by tīeke. Two of the nests failed at egg stage, but around 20 chicks fledged from the remaining 14 nests.

Titipounamu/ rifleman nested in at least five tīeke boxes, and wētāpunga used many as daytime shelters. We suspect that at least one nest failure was caused by a female wētāpunga who moved in shortly after the eggs had been laid. The tīeke abandoned the nest, but a new one was started in a nearby box, probably by the same bird.

The one disappointment is that box 7b, which has been the site of some interesting and mysterious behaviour during the past three seasons (see Dawn Chorus no. 134), has received no attention at all this year. Perhaps something has happened to one or both females who were trying to use it, or perhaps they have found a natural nest site to compete for.

Kōkako

It has proved to be a busy season to date. At the time of writing in midJanuary, we have 26 pairs of kōkako, up from 23 at the start of the season. At one stage in December, we had all 26 pairs either building nests, incubating, or feeding chicks.

Marihi and Themba (one of last year’s chicks) have paired up and are our newest couple. Although she built a nest and laid two eggs these were found broken and the nest was abandoned.

All the other pairs attempted to nest with various degrees of success. Unusually, Te Rae and Dawn, who are both experienced females, abandoned their respective nests part way through their incubation period. Both these birds have since built new nests and Te Rae and her mate Chatters now have a chick.

To date we have had over 20 failed nests. The cause is often unknown but it can be due to either predation or non-viable eggs. Many of these pairs are now renesting.

Shelly and Tama were the first pair to fledge a chick, closely followed by Oran and Haar. Oran was so enthusiastic about nesting that she left Haar to look after the fledgling while she concentrated on nesting again. However, this nest subsequently failed. One of our younger couples, Wai Ata and Awenga, were unsuccessful last season but fledged one chick in

January. Haeata and Hotu are having more luck this season and have one fledgling. Wairua and Parininihi, and Phantom and Wakei both have one fledgling. Five other pairs are feeding chicks.

Two of last season’s youngsters, Moana (Shelly and Tama’s daughter) and UB9 (Pūtōrino and Sapphire’s offspring)

Kōkako feeding records (months / food species omitted where there are too few records) Photo: Jonathan Mower

have taken up residence at the top of Little Wattle Valley / implement shed area. They are often very visible and continue to delight everyone with their efforts learning to sing.

Titipounamu/rifleman

Is it possible to have a plague of titipounamu? If so, then the Island is currently experiencing one.

In the six weeks to 15th January, 150 new birds were fitted with bands, three times as many as for the same period

last year. Of these, 96 were this season’s juveniles.

Guides and visitors are no longer reporting seeing just the occasional bird or family, they are now often reporting multiple sightings. This is clearly the best breeding season since titipounamu were first introduced to Tiritiri, 15 years ago.

The bird feeding project

Thanks to the two dozen Supporters who have contributed bird feeding records via the phone app, we now have 640 records in the database and already we can begin to see how feeding patterns vary through the year.

The most recorded species has been kōkako with 350 feeding sightings. Some of these are shown in the figure on p. 6 (some months and some plants have been omitted because there are too few records). The chart is complex but it’s possible to pick out some details. Kōwhai form a small part of kōkako diet in December and January (long after flowering has ended), kohekohe is only important in March when both fruit

and leaves are eaten, pūriri is the most popular food in October and November, while in January most records were of trackside weeds and grasses. Karo, māhoe, pūriri and trackside weeds are part of the year-round diet. Cicadas are taken in March and clematis in October and November.

For our nectar-eaters, korimako/ bellbird had 57 records, 38 were of nectar, 7 invertebrates, 5 fruit, 2 flowers and 5 unknown. Tūī had 66 records, 38 of nectar, 15 fruit, 6 flowers, 3 invertebrates, 1 seeds and 3 unknown. So, although more than half the records for these two species were of nectar, they also take fruit and invertebrates. The survey doesn’t record consumption of sugar water.

Compiled by Kathryn Jones, with contributions from Emma Gray, Morag Fordham, Simon Fordham, Mhairi McCready, Kay Milton and John Stewart

Kererū feeding on trackside grass Photo: Kathryn Jones Photo: Jonathan MowerAt about the same time this issue of Dawn Chorus hits mailboxes, a treat will be waiting for passers-by on Tiritiri Matangi’s Wattle Track. Beside the steps towards the top water trough, heads of white-tinged, mauve Veronica stricta will be flowering and waving in the breeze.

Confirmation of the identity of these pretty flowers is provided on the sign nearby: 'Koromiko/Hebe stricta' - names that are perhaps more familiar to most of us than their botanical classification.

What's in a name?

Koromiko is one of the beautiful names Māori bestowed on these plants. Others were korohiko, korokio or kokomuka, depending on locality, but koromiko remains the most widely used.

Koromiko was first scientifically recorded on Tiritiri Matangi by botanist Thomas Cheeseman, around 1906. He catalogued the plant as a Veronica, as all the New Zealand members of this genus were at the time. However, in 1929, they were all reclassified into their own genus, Hebe, giving rise to the botanical name, Hebe stricta, for this shrub.

Just to keep us on our toes, new techniques using DNA have resulted in hebes being reclassified back to the Veronica genus. Consequently, Veronica stricta is now the correct botanical name. 'Hebe' is still very much in use as a synonym or common name, as is 'koromiko'.

Worldwide, there are many instances of multiple common names for the same plant, no matter their origin. New Zealand is no exception to this.

To avoid confusion, botanical names provide an international language of identification, description, and classification within the plant kingdom. As science and knowledge evolve, new insights are gained and with them, a reshuffle of the order periodically occurs.

There are over ninety hebe species in the Veronica genus that are endemic

to New Zealand, making it by far our biggest plant group as well as our biggest group of flowering plants.

Free-branching and reaching 3-4 metres in height, koromiko is one of the tallest in the genus. It naturally occurs north of Manawatu and in Marlborough in sunny, open, coastal to sub-alpine habitats, where, as a pioneer plant, it will establish quickly on regenerating land such as coastal slips, roadside banks, forest and scrub margins, and dry stony streambanks.

Koromiko can show considerable seedling and geographic variation in both leaf form and flower colour. Generally, it’s characterised as having elliptic to linear leaves (straight, pointy leaves) that are deep green on top and paler underneath.

In summer, masses of tiny flowers appear in clusters (inflorescences) on lateral stalks up to 20cm long. These protrude well beyond the leaves. The flowers are bluish/purple to lilaccoloured when freshly opened, but

quickly fade to white as they mature. Insects are attracted to the flowers, which in turn provide a food source for birds, which helps with pollination.

Small dark seed capsules appear in abundance once flowering finishes. When the seed ripens inside, the capsules split open, dispersing their contents on the wind to new sites.

Both Māori and early settlers used koromiko leaves as a treatment for dysentery, diarrhoea, and stomach aches. It was made into medicine through a variety of techniques, or simply chewed in its raw form.

There are records that tell of soldiers being sent dried leaves during both World Wars, for the treatment of such ailments.

It was considered good for kidney and bladder problems as an ingested medicine. Poultices made from young tender shoots were used to treat ulcers.

Other uses included combining the leaves with kawakawa (Piper excelsum) and karamu (C oprosma robusta) to line hāngi (earth ovens).

A vast array of leaf forms and flower colours have seen hebes become popular garden plants the world over. Most varieties are small shrubs or ground covers, scattered in habitats from mountain to sea. Many hybrids and cultivars are now in production, widening their never-ending appeal to gardeners.

On Tiritiri, however, koromiko are a rarer treat. Less than 1,000 were added to the small, existing population during the 1984-94 planting programme and they were recorded as 'occasional' in the 2013 Cameron and Davies survey.

As the Island’s forest cover grows, their preferred habitat will diminish, confining them to the remaining margins, slips and newly disturbed sites sunny enough for their survival.

This is simply the flow of an evolving ecosystem.

For now, enjoy the spectacle of these flowers when you do get the chance to see them on Tiritiri – the Wattle Track being a good place to start looking.

We’re now looking for entries for our photographic competition (and ph otos for our 2025 Calendar). The categories are:

•

•

All photos must have been taken on Tiritiri Matangi Is land . You retain image copyright and can enter up to four photos in each category. Entries close April 30, 202 4 .

Details and image use policy are at :

Natalie Spyksma

Various stages of flowers

Photo: Neil Davies

Photo: Natalie Spyksma

A bumblebee feeding on koromiko flowers

Photo – Geoff Beals

Photo –Aaron Skelton

Natalie Spyksma

Various stages of flowers

Photo: Neil Davies

Photo: Natalie Spyksma

A bumblebee feeding on koromiko flowers

Photo – Geoff Beals

Photo –Aaron Skelton

Before 2019, I had taken only a passing interest in the Island’s population of kororā/ little penguin, but then we had a donation of 29 wooden penguin nest boxes from Brendon Dunphy of Auckland University.

I thought the best location for the boxes would be along Hobbs Beach Track, just inland from the track, and placed them there. Many of the boxes were visible in the bush and, unfortunately, visitors to the Island were opening the box lids, which probably explains why none of them were occupied. For the next season, I moved the boxes further inland and out of sight.

It seems that it takes a year or two before the kororā will decide to nest in a new box, but it was obvious that ‘house inspections’ had been taking place. And, while Covid interrupted box checking, we had evidence of nesting in 2021 when three boxes were occupied, two of which produced chicks. Five boxes were occupied in 2022, each had two eggs laid, but only four chicks fledged – a very poor success rate likely due to a lack of food.

In the 2022 season, I was contacted by the New Zealand Penguin Initiative.

They were hoping to encourage kororā monitoring around the country and the use of a range of standardised methods, from basic observations through to identifying individual birds using PIT tags (transponders) and subsequently following those individuals through their lives, recording longevity, partners, nesting attempts and chicks raised. I was keen to adopt the ‘gold standard’ by marking individuals and monitoring them. Having completed the required training, I have begun to mark our nesting birds. Males have larger bills than females so, when a bird is caught for marking, I measure the bill and then we know its sex (see photo below right).

Once they have their PIT tags, their identity can be verified using a detecting wand which is passed over the bird’s back and will pick up and display the unique ID number if a tag is present. Gerhard Wette and Jonathan Mower have taken on the task of weekly checks on the nest boxes.

Tagging the birds is already showing interesting activity. In 2023, one pair, 15295 (male) and 46623 (female) were recorded in box 26 between the 13th July and the 18th August, but they had switched to box 24 by 25th August and promptly laid two eggs. Box 3 was first occupied by a pair on the 17th September, by which time many other pairs already had hatched chicks.

Of the eleven pairs found nesting in the boxes, all laid two eggs. Six pairs hatched two chicks, three pairs hatched one chick and two pairs failed to hatch a chick. All seemed to be going well until the second half of October, by which time we had chicks ranging in age from a few days to around six weeks. Sadly, all the chicks then died within about

two weeks. It is likely that the parents were unable to find enough food to keep themselves and their chicks alive. The situation on Motuora, about 20km north of Tiritiri Matangi, was very similar and there were reports from other Gulf sites of many failures and of starving chicks.

While nesting, kororā only have time to feed within about 20km of their nest sites, so their annual breeding success is a good indicator of the abundance, quality and accessibility of food available within that distance.

Kororā can live for up to 25 years, so local populations can withstand a few bad breeding seasons as long as there are also some successful times. We know that there have been previous times on Tiritiri Matangi when breeding success was very low. Over the next few years our monitoring programme will help to provide vital information on whether populations in the Gulf are stable or in long-term decline.

John Stewart Photo: Jonathan Mower.

Photo: Jonathan Mower.

Photo: Jonathan Mower.

Photo: Jonathan Mower.

For some time now the conservation status of our kororā/ little penguins has been described as ‘at risk – declining’ nationally. On Tiritiri Matangi the kororā breeding season this year has been the worst since monitoring began four years ago. John Sibley explores why.

Over a brief period in October 2023 all kororā chicks in the Island's monitored nest boxes died of starvation, abandoned by parents who were unable to catch enough fish to feed them.

This pattern seems to have been replicated all over the Tīkapa Moana/ Hauraki Gulf. Back in May 2023, I reported in a Dawn Chorus article that the plankton situation off Tiritiri seemed to be improving. Unfortunately, this did not continue and several months passed when there was little of the usual ‘bread-and-butter’ species available to feed the

fish that sustain the kororā.

Kororā forage for small fish and arrow squid within a 20km radius of the Island. Their prey fish are mainly ‘bait fish’ i.e. jack mackerel Trachurus novaezelandiae, Australian anchovy Engraulis australis, Pacific pilchard Sardinops neopilchardus, myctophids (small deep sea lantern fish that come to the surface at night), and arrow squid. Kororā can switch their diet between prey species when the need arises. It would appear, however, that the numbers of all these prey species have been low around Tiritiri this season.

Plankton sampling

I have been conducting plankton sampling around Tiritiri wharf twice weekly since December 2020. Of the 30+ species and groups recorded in the Tiritiri plankton, three are of particular importance because of their numbers. I have concentrated my research on these three ‘keystone’ plankton groups which sustain the bait fish kororā rely on when feeding off the Island.

These species/groups are:

1. The Cladoceran crustacean Penilia avirostris. This species makes up the bulk of the zooplankton biomass.

2. The combined group of all the copepod crustaceans. There are more than 20 species present in the Gulf.

Photo: John Sibley.

Photo: John Sibley.

Photo: John Sibley.

A dead kororā chick

Solmaris is one of the most common cnidarians found in the waters around Tiritiri and forms an important component of the plankton there

Photo: John Sibley.

Photo: John Sibley.

Photo: John Sibley.

A dead kororā chick

Solmaris is one of the most common cnidarians found in the waters around Tiritiri and forms an important component of the plankton there

3. And lastly all species of salps and cnidarians (all loosely described as ‘jelly’ organisms). In terms of biomass, Penilia tends to outweigh the copepods and jellies combined by a factor of three or four, most of the time. So Penilia forms the most critical component of the plankton around Tiritiri and the inner Gulf.

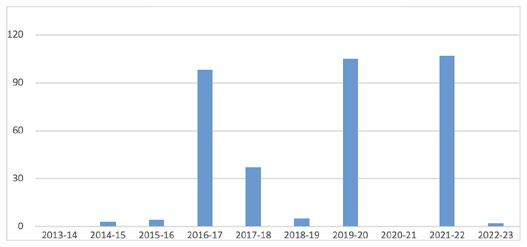

In each of the accompanying graphs, I have divided the three years of data up into six-month periods/segments, each consisting of approximately 30 hauls of plankton collected during that period.

Famine periods: Graph 1 above shows the percentage of samples over the three years where there were ten or fewer individual plankton organisms per m3 of sea water sampled. These extremely low concentrations could cause the fish that feed on them to move away from the Island at these

times, to find better feeding conditions further offshore, leaving our penguins hungry.

In the case of copepods and cnidarians, initial low numbers in plankton hauls have shown a steady improvement during the past three years. However, the main component of the zooplankton, Penilia, has shown irregular patterns of occurrence at these low levels. Of concern was a marked occurrence in the last six months of 2023, where it was either absent altogether on some occasions, or present in very low numbers.

Feast times: Graph 2 shows the three-year trends at the other end of the spectrum where plankton has been abundant during this time. The graph shows the percentage of samples in each six-month period where there were 500 or more individual organisms per m3 of water.

A feeding mackerel showing Planktonfiltering gill rakers

Photo: Copyright Alex Mustard: naturepl.com.

Penilla avirostris

Graph 1: Frequency of low plankton counts over 3 years.

Graph 2: Frequency of high plankton counts over 3 years.

A feeding mackerel showing Planktonfiltering gill rakers

Photo: Copyright Alex Mustard: naturepl.com.

Penilla avirostris

Graph 1: Frequency of low plankton counts over 3 years.

Graph 2: Frequency of high plankton counts over 3 years.

Copepods and cnidarians are rarely found in plankton hauls in extremely large numbers, although during the three years of the study cnidarian numbers have shown a modest improvement. However, the trend for Penilia is concerning, with the percentage of instances where there were good numbers in hauls decreasing, from being stable 40-50% of the time initially, down to about 10% of the time in the last six months of 2023.

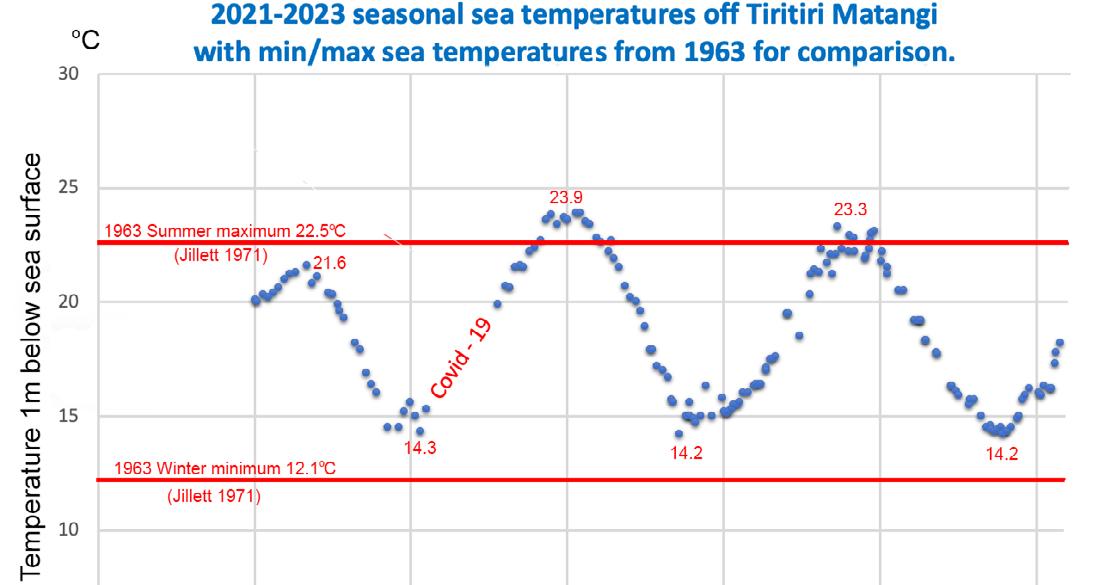

Sea surface temperatures: Graph 3 shows the sea temperature trends off Tiritiri over the three-year period. Recent seasonal temperature trends (blue dots) are compared to 1963 figures (red lines). Summer maximum temperatures appear to be variable and slightly higher, but present day winter minimum temperatures seem to be more greatly influenced, and are consistently around 2.1 °C higher than 60 years ago.

These recent marine ‘heatwaves’ brought about by climate change appear to have had a significant effect on the health of the plankton native to the Gulf. The winter minimum temperature is a barrier, critical defence against the successful invasion and survival of new exotic warm water species constantly being washed into the Gulf from the tropical north by the warm East Auckland Current. In previous years, these species would have not survived the winter here. Now, they could cling on through our milder winters and may start to proliferate, changing the ecology of the Gulf as they do so.

Sedimentation and storm events have also had an effect on kororā (and many other seabirds) who are visual feeders. Sediment can obscure their fish prey and is ranked the third highest threat to Aotearoa/ New Zealand’s marine habitats (after ocean acidification and climate change).

The cyclone (Gabrielle) in February 2023 brought vast quantities of terrestrial debris down rivers into the Gulf.

Much of this was in the form of fine, low-density organic particulate matter, which settles slowly during fine weather, only to be stirred up again in even slightly rough seas, obscuring sunlight and hiding prey fish. The September/ October 2023 release of approximately 258,000 tonnes of raw sewage into the Gulf, from the Parnell sinkhole incident, would also have considerably increased the sediment load. The piper fish in the photo below are no more than 3-4m away from the camera but are almost invisible. It may take a year or more for this sediment load to drop significantly, as it is slowly flushed out of the Gulf.

Tīkapa Moana/ The Hauraki Gulf may well be right on the brink of a tipping point, where the combined effect of marine heatwaves, sewage pollution and overfishing causes parts of the local food web to collapse, forcing the kororā to move away, or face starvation.

Graph 2: Sea temperature trends over 3 years.

Graph 2: Sea temperature trends over 3 years.

Seabirds are unique in that they breed on land, but spend the majority of their lives out at sea. Because of this, they have developed specific physical and biological adaptations that allow them to fly, float, swim, dive and thrive in the marine environment. It’s truly remarkable! Enjoy the seabird facts and help them below to find their way back to Tiritiri Matangi Island.

When the seabirds come ashore they bring a gift from the oceans with them, nutrient rich guano (poo). Guano has a high content of nitrogen, phosphate and potassium, all key nutrients for plant growth.

Overfishing depletes fish stocks and impacts the availability of food for seabirds.

Plastic pollution is a huge problem for seabirds because it can be mistaken for food and can lead to injury, suffocation, or death. It also affects nesting sites and food sources.

The feathers of seabirds are densely packed and coated with waterproof oils. This prevents them from becoming waterlogged, allows them to stay buoyant and maintain their body temperature.

Approximately one-quarter of the world's seabirds breed in New Zealand and 10% are endemic (found only in New Zealand), making it a hub of seabird diversity.

Following the removal of rats from Tiritiri Matangi and other islands around Tīkapa Moana/ Hauraki Gulf seabirds are returning, establishing the region as one of the world's most significant seabird areas.

Kāruhiruhi/ pied shag Tara/ white-fronted tern Tarāpunga/ red-billed gull Kawaupaka/ little shagThe Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi (SoTM) is a volunteer Incorporated Society that works closely with the Department of Conservation to make the most of the wonderful conservation-restoration project that is Tiritiri Matangi. Every year volunteers put thousands of hours into the project and raise funds through donations, guiding and our island-based gift shop.

If you'd like to share in this exciting project, membership is just $30 for a single adult or family; $35 if you are overseas; and $15 for children or students. Dawn Chorus, our magazine, is sent out to members every quarter. See www.tiritirimatangi.org.nz or contact PO Box 90-814 Victoria St West, Auckland.

SoTM Contacts:

Chairperson: Ian Alexander chairperson@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Secretary: Val Lee secretary@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Treasurer: Peter Lee treasurer@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Committee: Hester Cooper, Rachel Goddard, Carl Hayson, Janet Petricevich, Michael Watson

Operations Manager: Debbie Marshall opsmanager@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Volunteer and Guiding Manager: Gail Reichert booktoguide@tiritirimatangi.org.nz, 09 476 0010

Retail Manager: Ashlea Lawson retail@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Membership: Rose Coveny membership@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Educator: Sara Dean

Assistant Educator: Liz Maire educator@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Fundraiser: fundraiser@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Social Media: Stacey Balich socialmedia@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Dawn Chorus co-editors: Janet Petricevich and Stacey Balich editor@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Island Rangers: Talia Hochwimmer and Keith Townsend tiritirimatangi@doc.govt.nz, 09 476 0920

Day trips: Weather permitting, Explore runs a return ferry service from Wednesday to Sunday from Auckland Viaduct and the Gulf Harbour Marina. Bookings are essential. Phone 0800 397 567 or visit the Explore website. Call 09 916 2241 after 7 am on the day of your trip to confirm the vessel is running.

Overnight visits: Camping is not permitted and there is limited bunkhouse accommodation at $20 a night for members ($40 for non-members). Bookings are essential. For further information: www.doc.govt.nz/tiritiribunkhouse or ph: 09 379 6476.

Supporters' discount: Volunteers doing official SoTM work get free accommodation but this must be booked through the Guiding Manager at guiding@tiritirimatangi.org.nz or 09 476 0010.

SoTM members visiting privately can get a 50% discount but must first book and pay online. Then email aucklandvc@doc. govt.nz giving the booking number and SoTM membership number (which is found on the address label of Dawn Chorus or on the email for your digital copy). DOC will refund the discount to your credit card.

School Education Programme: We offer a full-day learning experience in a pest-free environment for year 1 to 13. Tamariki and rangatahi can get up close to endangered taonga species where they learn about community conservation and how people can work together to provide protected habitat. This then inspires students to take action in their own neighbourhoods.

Our educators offer a range of education experiences on the Island that are closely tied to the NZ curriculum. At the senior biology level, there is support material available for a number of NCEA achievement standards. Tertiary students have the opportunity to learn about the history of the Island and tools of conservation as well as to familiarise themselves with population genetics, evolution and speciation.

Subsidies are available for schools with an EQI 430 or more via our Growing Minds programme. Information on the education programme is at: https://www.tiritirimatangi.org. nz/education-programmes/ Bookings are essential.

Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi wishes to acknowledge the generous support of its sponsors

Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi welcomes all types of donations, including bequests, which are used to further our work on the Island. If you are considering making a bequest and would like to find out more, please contact secretary@tiritirimatangi.org.nz