It has been a very busy year and it’s hard to believe this is already the final Dawn Chorus for 2022.

Having thrown off the shackles of the recent Covid pandemic, activity on the Island is busy, as high-profile projects and people catch up on lost time. Guiding numbers are now slowly starting to increase from a low point, as are the shop sales. Income from the shop will help support the ongoing work on the Island.

Our magazine goes from strength to strength with our new editor, Lyn Barnes, as she puts an enormous effort in to make Dawn Chorus a successful publication.

One of the biggest projects undertaken this year – the internal and external painting of the historic lighthouse – is now complete. We will now look at options with Maritime NZ to open the tower more often and we will keep members updated.

Juliet Hawkeswood, our fund-raising manager, continues to score funding wins, with a successful grant recently from Foundation North for weeding, and two donations: the first from The Booster Wine Co for the tuatara survey and a donation from Constellation Brands NZ for the kōkako monitoring programme.

On the education front, it has been enjoyable to witness many more low-decile schools visit Tiritiri under the Supporters’ Growing Minds programme. This is a chance to learn about the country’s ecology and cultural history that pupils may not have had. Congratulations to the Education team for making this possible (see p. 17 for more about the education programmes).

The AGM for 2022 was a lively affair, with lots of healthy debate and discussion from the members on the various constitutional changes, committee elections and a great discussion on the future of the proposed Field Centre (see p. 7). Thanks to our IT team (Malcolm de Raat), we were able to offer a better online experience for those members who could not attend.

With summer approaching fast, I want to now wish our members season’s greetings and I look forward to catching up again with you all next year.

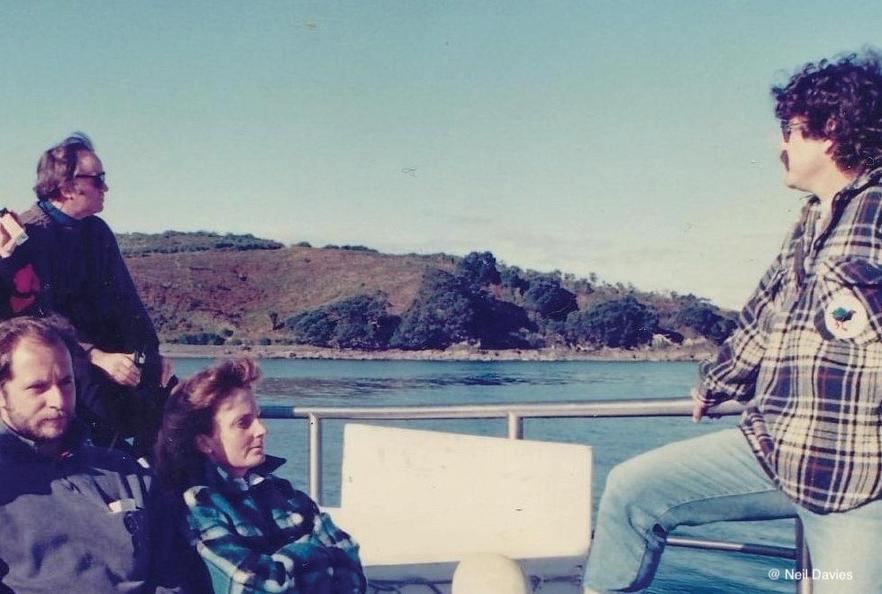

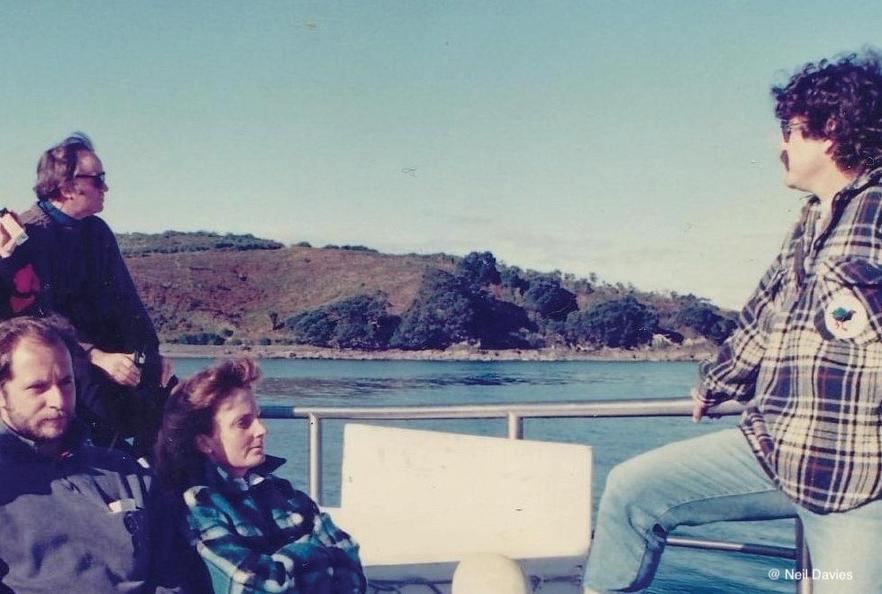

– Carl HaysonEarly champions of Tiritiri Matangi return home on the ferry after taking part in Guides’ Day Out, an education training day for the volunteers. From left, Barbara Walter, John Craig and Ray Walter.

Wandering the tracks with specialists and attending expert workshops were part of a comprehensive programme for Guides’ Day Out on Tiritiri Matangi in late September.

Over two weekends, a number of experts volunteered their time to up-skill the many volunteer guides on their fauna and flora knowledge. There was also a workshop about the maritime history as well as the Island’s, this hosted by John Craig who, along with Neil Mitchell, inspired the transformation from farm to reforestation.

Once off the ferry, there were a number of options for a guided walk in the morning, whether it was with flora expert Warren Brewer, listening for bird calls with Kay Milton and Morag Fordham, checking out a petrel colony with John Stewart, or heading out to search for tuatara, geckos and skink species with Malcolm de Raat, Hester Cooper and Roger Wallace.

After a shared lunch, guiding manager Kim Briggs had organised a selection of workshops, including how to radiotrack a kiwi with Simon Fordham, Mātauranga Māori with Hōhepa Waenga, learning about the ancient life of Tiritiri Matangi with John Sibley and more on translocations to Tiritiri of the various reptiles (for more, see p. 8).

Hihi contractor Emma Gray made a scarecrow, complete with DOC uniform, from bits and pieces lying around in the Implement Shed. Named Hazza, his job was to keep the tūī away from the hihi feeders. Tūī are notoriously territorial and chase away the korimako and hihi from the sugar feeders, despite not being able to access the sugar themselves. In the end, Hazza was found to be much more successful at scaring humans around the workshop than scaring away tūī.

IT’S FINISHED! The restoration of the historic lighthouse on Tiritiri Matangi was completed in October with the exterior painting carried out expertly by a team from Abseil Access.

Thanks to grants from the Lotteries Environment and Heritage Fund and the Auckland Council Regional Historic Heritage Fund, plus generous donations, the lighthouse is now fully restored, inside and out, ready to stand proud for another 158 years.

Chairperson of SoTM Carl Hayson said several volunteers contributed to the smooth running of the operation, in particular Ian Higgins, who organised the barges, water tanks and specialised scaffolding.

For Ray Walter, at right, it was a proud moment seeing the work completed. Ray was the lighthouse keeper from 1980-1984. Unpredictable spring weather allowed the abseiling team to carry out the challenging cleaning and painting. This included scrubbing the cast-iron barrel and doing spot repairs for corrosion before the final coats. The finishing touch was the Guardsman Red paint for the timber window trims, door and lettering.

Dear Membership Team, I have sent a donation today. I hope it will help with the painting of the outside of the lighthouse.

I have very precious memories of the lighthouse and its amazing beam. We purchased a section on the beach at Buckleton’s Bay in 1965 and put a very small Keith Hay house on it. The main bedroom had two big picture windows, one looking east across to Kawau and the other looking south towards Martins Bay. Lying in bed at night, I watched the Tiritiri beam sweeping across the end of the Mahurangi Peninsula then across to the southern tip of Kawau. The small house is still there, owned and loved by my daughter and her family, but alas, the magnificent beam has vanished. Best wishes to you all, Audrey Hay

• If you would like to donate to the many SoTM projects on Tiritiri Matangi, see p. 19.

Anyone recognise the tree shown at left? And it's not a karaka! It is similar though, but it is one tree that has intrigued our new Flora Notes writer since she started guiding on Tiritiri two years ago.

Natalie Spyksma (left) says she fell under the spell of plants as an 18-year-old – and they have shaped her life ever since.

Natalie (Nat) trained in a variety of horticultural fields before setting up a garden centre, wholesale nursery, landscaping and café complex in Mangawhai with her husband, Jac. They ran this for 30 years, during which time they raised two children and won both “NZ Garden Centre of The Year” and a Gold Award at Ellerslie Flower Show.

Next came a “catered walking business” on their 16ha-coastal bush property. “Guests walked on handmade tracks and dined on an abundance of homegrown produce. We actively trapped pests, resulting in kiwi and korimako reintroducing themselves on the land,” explains Natalie.

Her first Tiritiri Matangi visit was in 1997 when Natalie took the local garden club there. Once the couple retired to Red Beach two years ago, they both became guides.

Elizabeth Morton (92) had been involved with Tiritiri since 1988, in the planting years. Then she helped in the shop where she was well organised, especially with parcel wrapping. “Lady Elizabeth”, as she was known by her Tiritiri companions, was always immaculate. She took over cleaning the public toilets and, when staying over for Supporters’ Weekends, also the bunkhouse toilets. After the toilet cleaning she routinely took a quick swim and then at 6pm it was time for a whisky.

Dorothy Miskelly (87) was one of our earliest guides, who loved Wattle Valley. She enjoyed guiding school children and was very lucky at seeing kōkako. When not needed for guiding, Dorothy joined Caroline Parker on weeding sessions then, more recently, instead of guiding she manned the Watch Tower to inform visitors of maritime history. At her funeral, in lieu of flowers, she asked that donations be made to Tiritiri Matangi.

John Elliott QSM (84) was a guide on Tiritiri for many years. John also brought his son Finn along, whom he taught to be so knowledgeable about the Island’s history, bird and plant life. Finn was our youngest guide at the age of 14 years. Some visitors weren’t sure about being guided by him. However, they changed their minds after the walk! Finn had inherited his Dad’s charm as well as his knowledge!

– Barbara WalterWe regularly feature science articles by John Sibley, a well-known face to people who frequent the Island. But many Dawn Chorus readers know little about John, apart from his stunning photographs, fascinating facts and detailed diagrams in his Tiritiri Nature Notes articles.

John gained an honours degree in marine biology from the University of Wales in Swansea. He spent a couple of postgraduate years after that working for the university and then completed a postgraduate certificate in education. This was followed by teaching in senior schools in South East England, and then in New Zealand, where he was head of science until retirement nine years ago.

John (below) has two passions: “First, for scientific/wildlife photography and, second, being an ‘explainer’ of amazing science to anyone interested enough to listen!” (See his feature in this issue, p. 14-16).

Ninety-year-old Jean Hawken’s photo of a pepe parariki/common copper butterfly is the feature image for February in the 2023 Tiritiri Matangi Open Sanctuary calendar. And it’s not the first time Jean has won a coveted spot in the annual calendar – her photograph of a kākā taken on the Island was selected in 2021.

“We’re all jealous of Jean,” says her friend and fellow Whangārei Camera Club member Margaret Hooper. “We keep hoping.”

Two other smaller images by Jean also feature in next year’s calendar.

Jean has been visiting Tiritiri Matangi “since long before kiwi were moved onto the Island” and she still goes and stays in the bunkhouse once or twice a year with others in the camera club. She and five others are heading back to the Island in December.

Three other club members also have smaller photos in the new calendar. But it’s Jean who inspires them all.

The retired nurse, who has lived most of her life in Whangārei, developed a love of photography as a child after her mother gave Jean an old camera when she was 11. “I went nursing when I was 18 and bought a new camera then, and also a movie camera that I used for photographing horses at the hunt club and my nursing friends.”

Jean was a member of the local ornithological society and, as part of the tramping club, she used to go to Tiritiri Matangi as a volunteer a couple of times a year, clearing tracks, planting and weeding in the nursery.

“I’m reminded on the Wattle Track today when I look across and see the cabbage trees we helped plant – it’s all looking wonderful.”

Jean had previously volunteered on Te Hauturu/Little Barrier and dreamed Tiritiri would become the same.

The nonagenarian previously owned an avocado orchard that she

Top: Jean Hawken (above) photographed this pepe parariki/common copper butterfly, which is the main photo for February in the Tiritiri Matangi fund-raising calendar for 2023. Some of the calendars are still on sale through the online shop and at the shop on the Island.

managed on her own. These days she still runs dry stock on her 16 hectares at Maunu, half of which is covenanted land with the QEII National Trust.

Jean’s secret to good health at 90: “Good food, especially homegrown, and keep yourself moving.” Needless to say, she has an impressive vegetable garden.

A wet Auckland night, and live streaming of the Queen’s funeral, did not deter the many Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi from attending this year’s Annual General Meeting. Therefore, the fear not enough Supporters would show up for the 30-member quorum was not an issue.

The meeting was also broadcast via Zoom.

The Chairperson, Secretary and Treasurer were all re-elected unopposed, with Carl Hayson, as Chair, going into his fourth year; Gloria Nash, Secretary, her eighth year and Peter Lee, Treasurer, his third year.

However, voting was necessary to eliminate one candidate to maintain the nine-member Committee. In the end, Supporters voted to re-elect those who had served on the Committee in 2021-2022.

Five of the six motions for proposed changes to the Society’s rules were passed – Motions A, B, C, E and F – (see Issue 130 of Dawn Chorus, page 19, or click the link

here on the electronic version). Motions B, C and E were passed as printed.

There was a slight wording change for motion A regarding ordinary membership. This was in reference to voting rights at a General Meeting commencing after membership has been approved. The meeting approved the motion with the words “two months” being replaced with “eight weeks”.

Much discussion took place in regard to Motion D and after a vote the motion was defeated. This motion would have allowed two adults of a family to be entitled to one vote each. And Motion F - Rule (9A) was approved, with the removal of clause (a) and the renumbering of the next 2 paragraphs to (b) and (c) respectively.

For more details, see the Minutes of the 2022 AGM by clicking here or go to www. tiritirimatangi.org.nz/About, scroll down and click on Reports, and once in Reports scroll down to Admin/AGM reports.

Chairperson Carl Hayson made special mention at the AGM of two people who have made impressive financial contributions to SoTM this year.

Firstly Kay Milton, who at her own expense, printed 100 copies of her Birds on Beanies knitting book, which are sold through the Island’s shop. Kay has also inspired a team who have knitted more than 500 beanies for sale. These volunteers donate the yarn and their time. Carl estimates that the proceeds from the book and the beanies are well over $30,000. (SoTM will cover the cost of the next print run of the beanie books.)

Carl also recognised the efforts of 11-year-old Pippa Wilson from Waiau Pa, near Pukekohe, who built six bird houses from scratch as part of a William Pike Challenge Project to learn a new skill. Pippa used fence palings, and old bike tyres for hinges,

to construct the bird houses. She sold them for $40 each and donated the $240 to SoTM.

Above: Pippa Wilson with her handmade bird houses. Right: Kay Milton wears one of the beanies from her Birds on Beanies knitting book

The SoTM Committee occasionally nominates as life members people who have given outstanding service to the Society.

This year, Chairperson Carl Hayson said the Committee has recognised Peter Lee as a worthy recipient. He said Peter has been a member since 1992, during which time he has served as Chairperson twice, Secretary, and he is currently the Treasurer. Carl also added that Peter is present at many of the Working Weekends where he leads a number of the groups

The Committee’s recommendation was unanimously endorsed by those attending the AGM and Peter was given a round of applause on becoming a life member.

SoTM Chairperson Carl Hayson thanked Juliet Hawkeswood at the Annual General Meeting for her fund-raising efforts in what he said was a very tough financial year due to Covid and the economy. The grants received by SoTM for the last financial year total $448,299.

In his financial report, Peter Lee said the total equity, based on what’s owned and what’s owed by Supporters, is $1,912,255 for 20212022, compared to $1,640,750 for the previous financial year.

For a copy of the full 2022 Financial Report, click here or go to www. tiritirimatangi.org.nz/About, scroll down and click on Reports, and once in Reports scroll down to Admin/ AGM reports.

A survey of Supporters is under way to help decide how to progress the planned Field Centre. This followed discussions at the Annual General Meeting.

The original concept was to construct a purpose-built facility to replace the bunkhouse that could accommodate up to 30, and which would be available to the public, researchers and volunteers. It would include eight two-person chalet bedrooms, a lounge, dining, ablutions and drying area. It was to be funded and built by SoTM, then managed by SoTM as a profit-making venture.

However, Chairperson of SoTM Carl Hayson pointed out at the AGM that costs have escalated significantly. “It would now cost over $6.5m to build.” The original budget in 2017 was around $3.25m.

Architectural drawings and resource consent are in place, plus two independent assessments have been carried out to confirm the centre’s feasibility. At present there is $780,000 in a special fund.

But with Covid and the “funder crunch” over the past two years, plus the fact there are less than two years until the consent

expires, Carl says it is time to reassess. As a result, he, and Treasurer Peter Lee, presented three options:

Option One: To continue with the original concept and try to raise funds.

Option Two: Build a Research Field Centre instead that could accommodate up to eight researchers. This would not be open to the public. It would have only four chalets (three for sleeping and one as a temporary kitchen/dining) plus an ablutions block. This could then be added to in the future.

Option

SoTM member Janet Petricevich told those attending the meeting that the bunkhouse was no longer fit for purpose.

Juliet Hawkeswood, the SoTM fundraising manager, pointed out that unless there was some educational benefit, she would find it difficult to get sponsors.

Peter Lee suggested that one solution could be partnering with a company or organisation to complete the project.

After further discussion and on a show of hands the preferred option was Option 2.

There is a growing interest in Aotearoa to learn Te Reo Māori and to have an increased understanding of Mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge). The first formal celebration of Matariki as a public holiday has further sparked interest in this domain. A number of organisations have become proactive in creating opportunities to improve their competence in Te Reo and Mātauranga Māori understanding.

Tiritiri Matangi and the surrounding islands hold a lot of ancient Māori history. It is great that guides have the opportunity to share Māori stories with the visitors to the Island. Authentic expressions of well-presented indigenous narratives add great value to genuine guiding. To remain culturally safe, it is equally important that personal views/opinions remain silent.

As Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi, we would encourage you to take time to connect and learn about the birds and forests we all love through a Mātauranga lens.

A good starting resource is the book Māori Bird Lore by Murdoch Riley.

Whaowhia te kete mātauranga - Fill the basket of knowledge

Te timatanga o te mātauranga ko te wahangū, te wahanga tuatahi ko te whakarongo…The first stage of learning is silence, the second is listening….

Ngā mihi nui Jerry Norman Cultural Advisor Ngāti Kuri, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Whātua, Tainui

Barry Fraser Chair SoTM Te rōpū whakaruruhau ako Education Advisory Group

Jerry Norman Cultural Advisor Ngāti Kuri, Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Whātua, Tainui

Barry Fraser Chair SoTM Te rōpū whakaruruhau ako Education Advisory Group

Not sure how to say something in te reo Māori? Kupu, the app, has a catch phrase: “take a photo, learn a language”

Former guide Hōhepa Waenga ran two workshops on the Guides’ Day Out on the Island in September (see p. 2) and explained how important it was that guides knew how to say the names of the fauna and flora correctly.

Kōkako or kokako, kererū or kereru: the words sound completely different depending on how we say the vowels, he said. The tohutō (macron) indicates the double vowels or extended vowels sound: ah-eh-ee-or-oo.

Above: Hōhepa Waenga explains to those attending Guides’ Day Out how it is important to break up te reo Māori words. Where there is macron, this indicates a longer vowel sound.

The wildlife enthusiast said the mana of Māori words is in the vowels. “They all need to be said and heard, either in short sound form (A - E - I - O - U) or in their long sound form when seen with a tohutō above the vowel (Ā - Ē - ĪŌ - Ū). The vowel sounds never change. Each vowel is said the same way both in short and long sound form.” Hōhepa recommended checking out Te Aka: Māori Dictionary Online to hear how the vowels sound in familiar words you have heard or seen before. “Break up every te reo Māori word after every vowel,” he explained.

For example: Wha - nga - pa - rā - o - a Ti - ri - ti - ri - Mā - ta - ngi

“Rolling the letter ‘R’ similar to Spanish words is a good tip, as well as remembering the diphthongs – ‘WH’ has a F or PH (like the word phone) sound and the ‘NG’ has a soft ng sound like the words song or thong.

Practice makes perfect and we all make mistakes, said Hōhepa. It’s best to embrace the learning regardless of those small mistakes, he added.

Hōhepa also provided tips on how guides could improve their te reo Māori, by either taking a te reo Māori course or learning online. “Simply listening to Whakaata Māori (formerly Māori Television) or Reo Irirangi Māori (Iwi/ Māori radio stations) in the background can also help with pronunciation,” he added.

A ha ka ma na is “a good song to learn the sounds of our words”

“Whakaata Māori has many TV shows and documentaries that will help not only with te reo Māori but also through our unique storytelling from a Māori world view, a Māori lens.”

Hōhepa also recommended:

• Learning waiata Māori / Māori songs. Perhaps starting with the national anthem and Pōkarekare ana

• Reo Māori Resources from Te Taura Whiri I Te Reo Māori/Māori Language Commission (https://www.reomaori. co.nz/resources)

Tāne Mahuta, the atua (god) of the forests and birds, gathered together all his bird children, concerned about the bugs eating the forest floor and making the trees sick and causing them to die. He needed someone to volunteer to go down to the ground and eat the bugs. So Tāne started asking his bird children one by one.

The tūī said he wasn’t keen because he was too scared. The pūkeko said it was too damp and wet.

The ruru/morepork said it was too dark.

The pīpīwharauroa/shining cuckoo said he couldn’t build a nest down there.

The korimako/bellbird said they liked to sing together, up in the trees with all the other birds, as a choir.

After discussions with Tāne and, taking into consideration what they might lose, for example, their colourful feathers, their smaller beak for eating berries and, in particular, losing the ability to fly, the kiwi volunteered to go down on the ground and eat the bugs on the forest floor.

This came with a lot of elation from the the other birds. However, Tāne was not finished with the others. Tāne said to the tūī that they were cowards for not going down, so he marked them with white feathers by their throat so they went off crying. He sent the pūkeko to the swamps as they didn't like the wet and damp and he told the ruru they could only come out at night as they didn't like the darkness. He told the pīpīwharauroa they would never have a nest of their own and that they'd have to lay in the nest of another bird.

Tāne then turned to the korimako and the other birds and told them that he was taking away all their voices since all they wanted to do all day was sing. This saddened all the birds. Tāne took pity and let them keep their voices but he told them that they could only sing together at one time of the day, that is in the morning as Tamanuiterā (the sun) starts to rise in the east. This time is called te ata or the dawn.

All the birds dispersed after this hui and Tāne turned to the kiwi. He gave kiwi a longer beak for digging in the earth looking for bugs. He said kiwi would also need to be brown to blend in with the ground and he would give kiwi strong legs to burrow and dig into rotten logs and to run fast.

This video produced by Stuff will help develop confidence in pronunciation. (Or type shorturl.at/dkxB9 into your browser.)

Hōhepa would love “everyone to jump on board the waka” and not only learn more about te reo Māori but also share Māori history. He recommended the Te Ara: Encyclopedia of Aotearoa website as the best place for background information, including legends. How the kiwi lost its wings is one of his favourites. Guides at his workshop on Guides’ Day Out enjoyed Hōhepa's version of the popular children's story by Alwyn Owen, which he loved to share when he was a guide.

Tāne thanked kiwi for volunteering to eat the bugs on the forest floor for the sake of the whole forest and all its inhabitants. He said, “Because of this, you will become the most famous bird of this land and people will be named after you.”

And that is the story of how the kiwi lost its wings, became the most famous bird in Aotearoa and how we all became “Kiwi”.

Things change rapidly every spring, as birds go through the annual breeding cycle. By the time you read this, it is likely that many of the land birds will be incubating eggs, and some, like the takahē, will already have chicks. Some of our seabirds follow a different schedule and, by mid-October, are already feeding chicks.

The remaining two pairs of takahē on the Island have been sitting on eggs since September. Suspicions were aroused when only Tussie reported to the ranger’s house for breakfast one day. Anatori showed up in the evening, suggesting that nesting had begun. The female normally incubates during the day, with the male doing the night shift.

The northern pair, Edge and Turutu, followed a similar pattern a few days later. We are keeping our fingers crossed for Edge, who did not produce a chick last year. She will be 16 on 11 November, an age by which some takahē have retired from breeding. Hatching is expected mid-late October and we can expect the parents to keep their chicks out of sight while they are very small. Once they become more adventurous, they never fail to delight our visitors as they grow.

Moke, Edge and Turutu’s son from the 2020-21 season, is now settled and doing well in his new home at Cape Sanctuary. Meanwhile, the other young birds recently removed from the Island are now learning the ways of the wider takahē world, particularly how to eat tussock, at the Burwood Takahē Breeding Centre.

For the first time there could be over 20 pairs of kōkako on the Island this season, as some of the young birds who fledged over the past two years start to pair up and establish territories.

In mid-September it looked like it might be an unusually early start to the season, when Te Rangi Pai (partner to Hēmi) built a nest very close to the Wattle Track, in full view of many delighted visitors. Now, a month later, she is still making adjustments to that nest but has not laid yet.

Male hihi are more common on Tiritiri at this time of year. Out of the estimated 178 hihi on the Island in the most recent survey, only 56 were female.

Erenora (partner to Tātākī) has also been seen building, but so far her nest is just a basic platform. A few of the other females have been seen carrying material, but no serious nesting activity has been observed, and even courtship feeding, which intensifies as the time for breeding gets closer, has been seen relatively rarely. All this points to November being the month when nesting gets seriously under way.

Te Hari, our oldest bird at nearly 25, who moved out or was pushed out of his former territory late last summer, is still around and is often seen on public tracks, feeding peacefully. As far as we can tell, he has not yet shown any interest in finding a new territory or partner.

Meanwhile, his former partner Phantom (now partner to Wakei) had a leg injury which hampered her movements for several weeks. She now seems to be recovering well, but we will monitor her progress closely.

Emma Gray has returned to the Island for another breeding season as a hihi contractor, with other volunteers joining her in late October and November. The season began with the usual antics of scrubbing boxes used for roosting over winter and making bucket-loads of sugar water for hungry hihi and korimako, but the main form of entertainment was provided by the pre-breeding survey, whose aim is to find as many individual hihi as possible over a seven-day period.

Emma managed to identify 170 birds; 88 were recorded by the data loggers attached to the sugar feeders, and nine additional birds were seen by other observers. When overlaps are taken into account, this amounts to 178 hihi in total, 122 males and 56 females. A gender imbalance is normal for hihi and varies from year to year.

as they often do, much to the

As of mid-October, the breeding activity is starting to pick up with 15 nests ready for eggs to be laid, an incomplete clutch in one and an additional four almost ready. The first clutch of the season has already hatched two chicks, and the second clutch will hatch around 26 October. Early clutches tend to be more successful than later ones. The female who laid first this season also laid first last season and is the mother of the “traffic light chick" featured in Fauna Notes last February. This chick is now fully adult and has his own territory.

The mainly nocturnal comings and goings of our burrow-nesting seabirds often proceed undetected by human visitors to the Island, but there is a lot to see and hear for those prepared to venture out at night.

Two years ago we installed 29 new nest boxes for penguins. Only two of these were used in 2021-22, but this season six are in use by penguins. As of mid-October, and including the display boxes on the Hobbs Beach Track, there are nine occupied boxes, six of which have chicks and three of which still have unhatched eggs.

Every year we catch and band kuaka/ common diving petrels at the colony at the north end of the Island. The birds are caught by hand as they arrive just after dusk. Because we have been doing this for several years, a good proportion of the birds are already banded.

Of 41 birds caught on 13 October, just over half were new (unbanded) birds, and many of them had quite low weights. This suggests they were young, non-breeding birds prospecting for partners and burrows.

This is my last time compiling Fauna Notes. I have enjoyed doing it for the past nine years, but it’s time for a break. My thanks to all those who have contributed over that time.

– Kay Milton• Thanks Kay for all your years of hard work doing this – and it's great you’re continuing as one of our wonderful proofreaders.

– Ed

The heavier birds are carrying food for their rapidly growing chicks.

It looks possible that the number of breeding pairs is lower than in previous years. As an indication, out of 21 nest boxes, only four are occupied this season, compared with the usual 10.

Visitors leaving the Island on 24 September were entertained by three or four bottlenosed dolphins, including an obvious juvenile, who played around the wharf as the ferry prepared to leave. You could sense their excitement as the engines revved up and their movements became noticeably faster. A larger pod of 20 or so awaited us at Gulf Harbour, cruising just outside the breakwater.

The occupants of the new penguin boxes include, not just penguins, but a tuatara, and a pair of titipounamu (rifleman), who by mid-October had a completed nest.

Compiled by Kay Milton with contributions from Keith Townsend, Emma Gray and John Stewart.

Scientists are studying the flight patterns of kuaka/common diving petrels at Tiritiri by attaching a small logging device to their backs.

These charismatic little seabirds, with their bright blue feet and easily recognisable ‘oo-rup’ calls, breed in shallow burrows around the edge of the Island and on some steep cliff faces. They nest on both Tiritiri Matangi and on Wooded Island in their thousands.

In comparison to other local members of the petrel seabird family, these birds have shorter, more rounded wings, which are well adapted for underwater pursuit of food items, but mean their typical flight pattern shows a fast wing beat and straight-line flight close to the sea surface. Other petrels with longer, narrower wings tend to soar and glide over a meandering flight path.

Their short-winged, rapid-beat flight pattern and diving pattern when feeding is more like some of the northern hemisphere auks than other petrels and this has caught the attention of local academic Brendon Dunphy and Kyle Elliott from McGill University in Canada. The kuaka’s fast wing-beat flight uses more energy than intermittent soaring flight, but they are likely to be more efficient and use less energy when feeding underwater.

The scientists hope to track the birds’ flight and feeding efforts and measure the energy expended at the same time. To do this they will temporarily attach a tiny device called an accelerometer to the feathers on the birds’ backs. The device will record speed and direction of movement above and below the water.

Kuaka around Tiritiri Matangi feed on small crustaceans and krill over an area bounded by Te Hauturu/Little Barrier to the north and Coromandel to the east. They catch their food making shallow dives of about 20-second duration, up to 80 times per hour. Adults arriving at the colony just after dark to incubate their single egg or feed their chick can weigh up to 190g but only around 130g by the time of their departure up to a day later.

– John StewartClick here to see a three-minute video on YouTube about the kuaka/common diving petrel, or type this link into your browser: tinyurl.com/2med387n

In this issue, we introduce Natalie Spyksma as our new flora expert on Tiritiri Matangi. Here, she shares her knowledge about two intriguing trees on the Island.

On the Wattle Track, just up the steps from the Nīkau Grove, are a couple of straightbacked trees with an interesting story. With their glossy leaves and berries, Elingamita johnsonii summon you to take a closer look.

At first glance, Elingamita johnsonii (commonly called elingamita) could be mistaken for the better-known karaka (Corynocarpus laevigatus) as their leaves are similar. However, on closer inspection, elingamita has a much shorter petiole, or leaf stalk, and their fruit are also different.

Karaka has elliptical orange berries when ripe, whereas elingamita’s are globe-shaped – and take one to two years to ripen from green to red. The berries hang in terminal bunches of up to 20, with each berry measuring 17-20mm across. Once ripe, they are said to taste like an oily, salty apple! The trees on Tiritiri always seem to have some berries to observe.

Elingamita are endemic to the Three Kings Islands, a wild, rugged, windswept group of islands 50km northwest of mainland New Zealand. They were first discovered in 1950 by Major M E Johnson, a plant enthusiast and decorated WW1 hero. While exploring the precipitous West Island, he spotted

Elingamita johnsonii, the plant that now bears his name, growing in the understory of the prevailing pōhutukawa forest and coastal bush. Most were shrubs or small trees, with the largest displaying a canopy spread of about 4.5m.

The rest of the name, elingamita, is after SS Elingamite, which was wrecked on West Island in 1902. The ship was sailing from Sydney, carrying gold and silver coins to replenish bank supplies in New Zealand. Many have tried to recover the treasures, including Kelly Tarlton.

Major Johnson went on to make a further seven trips to the Three Kings in his boat, Rosemary. However, it was on his second trip, when he was accompanied by botanist Professor Baylis from the University of Otago, that they gathered seeds from elingamita. These were later propagated by the Mt Albert Plant Diseases Division of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR).

So how did these two striking specimens end up on Tiritiri? Records show they were planted some time between 1984 and 1994 and are catalogued as “a cultivated native species outside its geographic range”.

Originally,

but has since been changed to the Primulaceae family. Their genus is Elingamita GTS Baylis and the species, E. johnsonii

Elingamita are primarily dioecious, having separate male and female trees, though occasionally hermaphrodite trees occur. The small, terminal clusters of flowers will sometimes appear as early as August but are more common in summer months. Female flowers are pale yellow to pink, whereas the males are yellow to yellowish-pink. The green berries follow a few months later.

The Three Kings Islands are currently rodent-free, but dire consequences could be spelt for Elingamita johnsonii should fire or rodents take hold on West Island.

Perhaps you could give them a helping hand in the survival stakes and consider planting one in your own garden. Just remember you’ll need both a male and female tree to get the berries. If you have room for a grove, a ratio of one male to five females should do the trick.

Recently, elingamita were planted on the roof of the new Hundertwasser Art Centre in Whāngarei’s Town Basin. They make excellent tub specimens if space is limited.

It’s the season for these strange, hollow, tubular creatures in the sea around Tiritiri Matangi – some are so big that divers can fit inside them. Many perform a vital role feeding our seabirds, explains John Sibley.

Tunicates are soft, barrel-shaped, transparent animals that take water in at the front end and shoot it out the rear end, like a jet engine. They filter microscopic algae out of sea water to eat, using delicate mucus nets secreted by an organ called an endostyle. They are capable of capturing particles down to the size of 1.5 microns (millionths of a metre).

There are several “designs” within the tunicate group: the freeswimming salps, larvaceans and pyrosomes, and the sessile, or static, sea squirts, which attach themselves to rocks and pier piles.

Salps: You might have noticed one member of the tunicate group, a species of salp appearing in the sea around Tiritiri from early spring through to summer called Thalia democratica (see photo above). This group is called tunicates because they possess a tough, outer covering or “tunic”, which is made of a flexible sugar polymer – a type of cellulose – which is unusual for animals.

Tunicates in turn belong to a larger group called chordates, which includes vertebrates like ourselves. All chordates have several features in common: a dorsal hollow nerve cord, a stiffening “backbone” rod called a notochord (morphed into a vertebral column in vertebrates), a pharynx (throat) with gill slits, a tail that extends past the anus, and an endostyle organ that exudes a sheet of delicate mucus, forming a filter-feeding sieve (in vertebrates, this has morphed into the thyroid gland). Some tunicates have larvae which look like tiny tadpoles or fish, with all the features above.

Top: Salps like this species Thalia democratica are often seen in the waters off Tiritiri. Above: The anatomy of a salp.

Salps seem to materialise overnight in great numbers, looking like joined-up strings of crystal beads, called “aggregates” or blastozooids, which drift near the surface of the sea. They don’t appear to be doing very much as they float about, but appearances can be deceptive. They are busy feeding and, while they are doing this, they are also quietly engaged in sexual reproduction – all the while plotting to launch a massive attack on the microscopic phytoplankton in the area, filtering out even the smallest “nanoplanktonic” algae with their slime nets.

There is only one problem, though. Sexual reproduction is a relatively slow process when it comes to trying to rapidly scale up the size of your population to take advantage of a super-abundant phytoplankton food supply. And where there is food, there will be competitors – other species which may be much better adapted to exploiting this phytoplankton resource. They plainly need some sort of advantageous “edge” over the other filter feeders.

However, salps are clever – they have a trick up their invertebrate sleeves to magically inflate their numbers. They clone themselves –making billions of identical copies, called oozoids, all with hungry mouths to cash in on the phytoplankton bonanza.

Several other free-swimming tunicates turn up in our plankton samples around Tiritiri on a regular basis.

Doliolids: Doliolids belong to the same class as salps, but are much smaller, at 2-5mm in length. They, too, form an important component in the diet of our seabirds.

Larvaceans: These tunicates are tadpole-like (they look like the larvae of sea squirts – hence their name) and their notochord (proto-backbone) stiffens their beating tail, which propels them along and provides a filter-feeding current through a strange temporary barrel-shaped tube of mucus in which they live.

The delicate mucus barrel is shed and discarded several times a day, and its remains sink slowly to the seabed, forming deep sea “snow” where the carbon contained in it is trapped. They occur in such unimaginable numbers in the open oceans that they contribute significantly to the global ocean “carbon-pump”, which removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and transfers it to seabed sediments where it is safely locked away. They are an important ally in the fight against climate change. Whenever they appear in our Tiritiri plankton samples it is always as naked “tadpoles” without their mucus “houses”. Their presence in our plankton samples indicates the inflow of oceanic water into the Hauraki Gulf, bringing nutrients and diluting urban pollutants.

Pyrosomes: Their name means “burning bodies”, as they are bioluminescent. Their large colonies are windsock-shaped tubes, and colonies can sometimes grow large enough for divers to climb inside. They propel themselves slowly through the water, feeding as they go.

The sexual blastozooid stage of Thalia.

So these strings of beads are only one part of their life cycle and, looking closer still into the clear Tiritiri sea water, you might be rewarded with a glimpse of much larger, single individuals – the “cloners” are called oozooids. These are up to 10 times larger than the individuals, making up the aggregate “strings”. Their function is to feed, and then produce a string of identical clones of themselves, looking like a coiled string of flat coins inside their bodies (see photo, top, p.14). When the time is right these strings (or “stolons”) are released into the water. They immediately swell up into strings of aggregates, up to a metre long, as water is rapidly absorbed.

For the rest of the marine food chain, salps can be bad news. Dense swarms of salps can effectively clean up nearly all the available phytoplankton food in a large area of sea, leaving nothing for other plankton feeders. But it’s not all bad news though, as both manifestations of their life cycle form important food items for our seabirds, fish and even turtles in warmer, northerly regions. They are used by marine biologists as indicators of oceanic water influx into places such as the Hauraki Gulf.

Bioluminescent pyrosomes.

These tunicates are sometimes washed up on Tiritiri’s shores, looking like lumpy, gelatinous pipes. Each member of the colony resembles a diminutive salp in its construction and layout, and their collective feeding currents are their means of propulsion.

Sea squirts: Ascidians are sessile tunicates, and they possess yet another variation on the hollow, gelatinous tube theme, but literally with a twist. Instead of a “straight-through” tubular design, their hollow bodies are twisted back on themselves to form a U-shaped structure with two openings or siphons next to each other: one inhalant, the other exhalent.

At low tide, when touched, they contract their bag-like bodies, squirting water out of their siphons – hence their common name. They have the usual mucus net over their pharyngeal gill slits, which form a “branchial basket” structure to catch their food. Again, some species are solitary (often clump-forming), such as Clavellina (right). Others are colonial, with several individuals sharing parts of the tubular tunicate design like the exhalent siphon, which becomes enlarged as a central atrium, as in Botryllus schlosseri (above), where the colonies resemble tiny castle ramparts. In this photograph the central exhalent atrium can be seen shared by 8–10 members of the colony that surround it.

Some ascidians are delicately coloured – the “jewels” of rock pools, rivalling the cup corals in their splendour. Others are exotic pests, such as the invasive Japanese sea squirt.

Tunicates are a fascinating group of animals to study. Their origins go way back to the first multicellular life forms on Earth, back as far as the Cambrian explosion 500 million years ago.

Primitive chordates, such as the amphioxus and lamprey, share many tunicate features, including a rod-like notochord, a dorsal nerve cord and pharyngeal (throat) gill slits – and other features, too. Like the amphioxus and lampreys, vertebrates are chordates also, where the notochord has become the vertebral column. Some pharyngeal gill slits have been repurposed as jaws.

Vertebrate spinal cords also lie dorsally in relation to the main axis of the vertebrae, and the layout of their blood systems follows the same basic pattern as the primitive chordates.

It is not only the students but the parents who accompany their children who are overwhelmed when they first wander the tracks around Tiritiri Matangi. That was certainly the case for the pupils and parents from Flat Bush Primary School, shown here, on their day out recently.

By the end of the year, around 1000 students will have visited Tiritiri in 2022 as part of the Growing Minds programme. It covers the costs for decile one to six schools. Flat Bush Primary is at the lowest end, with a 1A decile rating. The programme, which was launched in 2012, has been funded since 2016 by the Joyce Fisher Charitable Trust, along with generous donations from Supporters and visitors. So far, 7000 of these students have experienced the magic of Tiritiri.

But the Growing Minds programme accounts for less than 20 per cent of the number of students who experience the inspirational environment. Although numbers dropped during the past two years with Covid, they have bounced back, which means educators Barbara Hughes and Liz Maire are busier than ever. Robyn Davies (at right) joined the Education team in February as the programme administrator, to help with the escalating number of bookings.

The Education team caters for groups from pre-school age to tertiary level, from the Far North to the Bay of Plenty in the south. To ensure groups make the most of their experience, Barbara and Liz organise a team of guides from their 300odd volunteer database. The women also create stimulating educational resources and offer a wide range of activities once students reach the Visitor Centre.

Education programme administrator Robyn Davies (above) has a background in IT, specialising in systems integration and training.

More recently Robyn has been involved with managing her local football club and, although she no longer plays, she still enjoys a Saturday morning refereeing junior games. Since 2010 Robyn has volunteered with the fairy tern programme at the Waipu Wildlife Refuge, preparing nesting sites and monitoring the birds during the breeding season, along with assisting with education programmes for local schools. “It’s very rewarding to see how the results of small changes can lead into huge differences in the recovery and sustainability of our natural habitats and wildlife,” says Robyn.

Kānuka, mānuka, harakeke, māhoe, kawakawa and puahou were amongst the first trees planted. Certain trees were planted early because they flowered and this provided nectar for the birds. Others were planted because they were tolerant of the conditions, including soil that had been degraded by cattle.

Kānuka, mānuka, harakeke, māhoe, kawakawa and puahou were amongst the first trees planted. Certain trees were planted early because they flowered and this provided nectar for the birds. Others were planted because they were tolerant of the conditions, including soil that had been degraded by cattle.

Match the plants with their pictures.

Match the plants with their pictures.

by Stacey

Tiritiri Matangi Kids,

mānuka harakeke māhoe kawakawa puahouPhotos: Neil Davies, Geoff Beals, Oscar Thomas, John Stewart, Megan Rothney, Martin Sanders

Plants make carbohydrates from raw materials, using energy from light. This process is called photosynthesis

During photosynthesis, energy is absorbed from sunlight and used to convert carbon dioxide (from the air) and water (from the soil) into a sugar called glucose. Oxygen is released as a by product

Plants help clean the air we breathe, filter the water we drink, provide food, fibre, shelter, medicine and fuel Manu, ngārara and te aitanga pepeke need plants for food and shelter Plants play a key role in helping to protect against global warming because they reduce the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which has an indirect cooling affect. Tree planting is one of the simplest and most effective ways to tackle climate change

Plants help clean the air we breathe, filter the water we drink, provide food, fibre, shelter, medicine and fuel Manu, ngārara and te aitanga pepeke need plants for food and shelter Plants play a key role in helping to protect against global warming because they reduce the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, which has an indirect cooling effect. Tree planting is one of the simplest and most effective ways to tackle climate change.

Fill in the blanks on the photosynthesis diagram.

Fill in the blanks on the photosynthesis diagram

1 mānuka . 2 puahou. 3 māhoe. 4 harakeke. 5 kawakawa.

The Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi (SoTM) is a volunteer Incorporated Society that works closely with the Department of Conservation to make the most of the wonderful conservation restoration project that is Tiritiri Matangi. Every year volunteers put thousands of hours into the project and raise funds through donations, guiding and our Island-based gift shop. If you’d like to share in this exciting project, membership is just $25 for a single adult, family or corporate; $30 if you are overseas; and $13 for children or students. Dawn Chorus, our magazine, is sent out to members every quarter. See www.tiritirimatangi. org.nz or contact PO Box 90-814 Victoria St West, Auckland.

Chairperson: Carl Hayson chairperson@tiritirimatangi.org.nz, 027 3397105

Secretary: Gloria Nash secretary@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Treasurer: Peter Lee treasurer@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Committee: Stacey Balich, Hester Cooper, Malcolm de Raat, Barry Fraser, Rachel Goddard, Val Lee, Jane Thompson, Ray Walter and Michael Watson Operations manager: Debbie Chapman opsmanager@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Guiding and shop manager: Kim Briggs guiding@tiritirimatangi.org.nz, 09 476 0010

Membership: Rose Coveny membership@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Educator: Barbara Hughes Assistant educator: Liz Maire educator@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Fundraiser: Juliet Hawkeswood fundraiser@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Social Media: Stacey Balich socialmedia@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Dawn Chorus editor: Lyn Barnes editor@tiritirimatangi.org.nz, 021 407 820

Island rangers: Emma Dunning and Talia Hochwimmer tiritirimatangi@doc.govt.nz, 09 476 0920

Working Weekends are a chance for members to give the Island a hand. Travel is free, as is accommodation in the bunkhouse. Book through guiding@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

For the latest information on events on the Island, visit the SoTM website www.tiritirimatangi.org.nz

The best way to donate is via the website, https://www.tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Follow the DONATE tab for information on how to make a donation either by credit card or by internet banking. Donations to the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi are taxdeductible in New Zealand. In order to send you a receipt for tax purposes, we need to know the donor's full name and address. When making a donation by credit card, you provide this information via the online form.

If the donation is made using internet banking, this information can be provided to the Membership team with a quick email to membership@tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Support for Tiritiri Matangi from memberships and donations is much appreciated.

Day trips: Weather permitting, Explore runs a return ferry service Wednesday to Sunday from Auckland Viaduct and the Gulf Harbour Marina. Bookings essential. Phone 0800 397 567 or visit https://www.exploregroup.co.nz/tiritiri-matangi-island/tiritirimatangi-island-ferry/. Call 09 916 2241 after 6.30am on the day to confirm the vessel is running.

School and tertiary institution visits: The Tiritiri education programme covers from pre-school (3-4 year-olds), to Year 13 (17-18-year-olds), along with tertiary students. The focus in primary and secondary areas is on delivering the required Nature of Science and Living World objectives from the NZ Science Curriculum. At the senior biology level there are a number of NCEA Achievement Standards where support material and presentations are available. For senior students the Sustainability (EFS) Achievement Standards are available on the NZQA website. There is huge potential in that these standards relate directly to Tiritiri in various subject areas: science, economics, tourism, geography, religious education, marketing, health and physical education. The Island also provides a superb environment for creative writing, photography and art workshops.

www.tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Tertiary students have the opportunity to learn about the history of Tiritiri and tools of conservation as well as to familiarise themselves with population genetics, evolution and speciation. Groups wishing to visit should go to www.tiritirimatangi.org.nz/schoolvisits.htm or contact schoolbooking@tiritirimatangi.org.nz. Bookings are essential.

Overnight visits: Camping is not permitted and there is limited bunkhouse accommodation at $20 a night for members ($40 for non-members). Bookings essential. For further information: www.doc.govt.nz/tiritiribunkhouse or ph: 09 379 6476.

Supporters’ discount: Volunteers doing official SoTM work get free accommodation but this must be booked through the Guiding and Shop Manager at guiding@tiritirimatangi.org.nz or 09 476 0010. SoTM members visiting privately can get a 50% discount but must first book and pay online. Then email aucklandvc@doc. govt.nz giving the booking number and SoTM membership number (which is found on the address label of Dawn Chorus or on the email for your digital copy). DOC will then refund the discount to your credit card.

Capture your memories of Tiritiri Matangi with this beautiful calendar featuring the Island's spectacular fauna and flora.

Christmas presents solved – and support for a wonderful cause, all in one.

To place orders, go to our Online Shop at www.tiritirimatangi.org.nz or email shop@ tiritirimatangi.org.nz

Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi welcomes all types of donations, including bequests, which are used to further our work on the Island. If you are considering making a bequest and would like to find out more, please contact a member of the Committee.