ResearchArticle

Contentslistsavailableat ScienceDirect

Flora

journalhomepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ fl ora

Seeddevelopmentandgerminationof Strombocactus species(Cactaceae):A comparativemorphologicalandanatomicalstudy

AldebaranCamacho-Velázqueza,SalvadorAriasb,FlorenciaGarcía-Campusano c , EmilianoSánchez-Martínez d,SoniaVázquez-Santana a,⁎

a LaboratoriodeDesarrolloenPlantas,DepartamentodeBiologíaComparada,FacultaddeCiencias,UniversidadNacionalAutónomadeMéxico,CiudaddeMéxico, 04510,México

b JardínBotánico,InstitutodeBiología,UniversidadNacionalAutónomadeMéxico,CiudaddeMéxico,04510,México

c InstitutoNacionaldeInvestigacionesForestales,AgrícolasyPecuarias,CENID-COMEF,Progreso5,Coyoacán,CiudaddeMéxico,04010,México d JardínBotánicoRegionaldeCadereytaIng,ManuelGonzálezdeCosío,CONCYTEQ,76500CadereytadeMontes,Querétaro,México

ARTICLEINFO

EditedbyAlessioPapini

Keywords:

Aril

Cactaceae

Germination

Seedappendage

Seedling

ABSTRACT

Seeddevelopment,germinationandseedlingestablishmentwerecomparedbetween Strombocactus species, S. corregidorae,S.disciformis ssp. disciformis and S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae, emphasizingtheoriginandroleofthe seedappendage,whichispresentonlyinboth S.disciformis subspecies.Thedevelopmentandmorpho-anatomy ofbothseedsandseedlingswereevaluatedusingstandardlightmicroscopyandscanningelectronmicroscopy. Embryoandseeddevelopmentproceededsimilarlyinallthreetaxa.However,weunequivocallydemonstrate thefunicularoriginandaerenchymaticstructureoftheseedappendage,thearilin S.disciformis ssp. disciformis and S disciformis ssp. esperanzae, whichdifferentiatessoonafterfertilization.Otherdistinguishingfeaturesincludethedelayedgrowthofthetestainthemicropylein S.corregidorae,andtestamicromorphologyinmature seeds.Seedpotentialandproductionweresimilarbetweenspecies,althoughseedefficiencywashigherinboth subspeciesof S.disciformis,whichmayreflectpollinationproblemsin S.corregidorae naturalpopulations.Seed flotationoccursinthethreetaxa,duetothepresenceofairspacesinthelumenoftheseedcoatcellsandthearil aerenchymatic,whenpresent.Neitherphysiologicalnorstructuraldormancyweredetectedin Strombocactus, andahighpercentageofseedsgerminatedinthedifferenttaxa,asnoscarificationordisinfectiontreatments werenecessary.Theabsenceofthearilin S.corregidorae showsthatfurthergenetic,phylogeneticandcomparativeontogenicstudiesthatincludethethreetaxaof Strombocactus andthenearestgenera,suchas Ariocarpus, Turbinicarpus and Epithelantha,arerequiredinordertodetermineifthisstructurewasgainedorlost duringevolutionof Strombocactus. Thisresearchprovidesagreaterunderstandingofthereproductivebiologyof thisendangeredgenusendemictoMexico,necessaryfortheestablishmentoffuturerestorationandconservation programs.

1.Introduction

Cactaceaespecieshaveevolvedadiversityoflifeformsandvarious adaptationstoaridity,whicharereflectedintheirmorphologicaland physiologicalcharacteristics,aswellasintheirreproductiveversatility (Mandujanoetal.,2010; AriasandFlores,2013).Thegenus Strombocactus areshrubsthatbelongtothetribeCacteaeintheCactoideae subfamily(Anderson,2001; AriasandSánchez-Martínez,2010). Strombocactus wasoriginallydescribedas Mammillaria by DeCandolle (1828),andwaslaterproposedasamonotypicgenusby Brittonand Rose(1922) (Strombocactusdisciformis (DC.)Britton&Rose).Currently, twospeciesarerecognized, S.disciformis (DC.)Britton&Rose(withthe

⁎ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress: svs@ciencias.unam.mx (S.Vázquez-Santana).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j. flora.2018.03.006 Received15July2017;Receivedinrevisedform8March2018;Accepted8March2018

Availableonline11March2018

0367-2530/©2018ElsevierGmbH.Allrightsreserved.

subspecies S.disciformis ssp. disciformis and S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae Glass&S.Arias),and S.corregidorae S.Arias&E.Sánchez(Ariasand Sánchez-Martínez,2010).Todate,cactiphylogeniesthatincludethe threetaxaarestilllacking.ThesespeciesareassociatedwithdryenvironmentsintheChihuahuan-Queretaroandesert,haveaveryrestricteddistributionandareexperiencingadeclineinthenumberof matureindividuals(Álvarezetal.,2004; AriasandSánchez-Martínez, 2010).Althoughmanycactihaveefficientreproductivestrategiesand producenumerousseeds,commonlythesurvivalandestablishmentof theseedlingsislow,asin Neobuxbaumiatetetzo (Valiente-Banuetand Ezcurra,1991). Strombocactus exhibitsincreasedvulnerability,dueto lowseedlingrecruitment(personalobservation),aswellastothe

overalldecreaseinpopulationnumbersasaresultofthepressures exertedbyhumanactivity,mainlybyland-usechangeforagriculture andillegaltrade(GlassandArias,1996; Lüthy,2001; Ariasand Sánchez-Martínez,2010; Jiménez,2011).Currently,theyareincluded in AppendixA AppendixIoftheCITES(ConventiononInternational TradeinEndangeredSpecies,2010)andarelistedasthreatenedbythe Mexicangovernment(NormaOficialMexicana, SEMARNAT,2010). ThenaturalrangeofthisgenusincludestheStatesofQuerétaro,HidalgoandGuanajuato(GlassandArias,1996; Anderson,2001; Scheinvar,2004; AriasandSánchez-Martínez,2010).Speciesof Strombocactus appeartocolonizerelativelysimilarhabitats:smallrock crevices filledwith finesoil,onsteepslopesandverticalwalls,and emergeinplaceswithcalcareousshales,preferablyinareasdevoidof vegetationorsparselyvegetated. Strombocactus plantsareoftenobservedgrowingunderthecanopyofnurseplants(Álvarezetal.,2004; AriasandSánchez-Martínez,2010).

Seeddevelopmentalpatternsandgerminationarepivotaltoour understandingofthenaturalsettingsinwhichCactaceaespeciesare inserted,byrevealingsomeoftheinterrelationshipsresponsiblefora successfulreproduction,aprerequisiteforthetemporalpersistenceof thisplantgroupatagivenlocality.Earlystudiesfoundthatcertainseed characteristicswerelinkedtothetypeofseedorfruitdispersersthatare attractedbythem,thustheinterpretationsofthe(easilyobservable) dispersalsyndromehasbeenwidelyusedasasubstitutefordirectobservations(Bregman,1988).However,insomecasestheevidenceregardingthepredictedversustheactualdispersersiserroneous.For example, Ritter(1981) assumedthattheseedsof Frailea aredispersed bywind,howeveritshatshapemayberegardedasanadaptationto transportationbywaterwhenitrains,additionallytobeingdispersed byants(Machado,2007).Thishasopenedthedoortoageneralcriticismastothevalueofseeddevelopmentandanatomyinunderstanding dispersalandgermination.

Manyoftheassociatedcharacteristicssuchasseedshape,size, color,thepresenceofdifferentappendages,aswellasgermination patternandseedlingmorphology,areusefultoidentifydifferenttaxa andunderstandtheirecologicalinteractions(Flores,1976; Gibsonand Horak,1978; BarthlottandHunt,2000; Arreola-NavaandTerrazas, 2003; AriasandTerrazas,2004; Arroyo-Cosultchietal.,2006,2007). Particularly,greaterunderstandingontheoriginandfunctionofthe seedappendage,mayprovidefurtherinsightintotheroleofthese structuresintheevolutionandcurrentdistributionofthesespecies.

Thereareseveraltermsthatdescribeeachoftheseedappendages basedontheontogenicorigin,chemicalcompositionandmorphoanatomy(VanDerPijl,1972; Bewley andBlack,1994; Bewleyetal., 2013; Márquez-Guzmán,2013).However,theterminologyemployed bydifferentauthorsisofteninconsistent,andtermssuchasaril, elaiosome,strophioleandcarunclearecommonlyusedassynonymsof oneanother.In Strombocactus, Bravo-HollisandSánchez-Mejorada (1991) indicatethattheseedof S.disciformis hasanaril,whereas BarthlottandHunt(2000) namedthisstructureasstrophiole. Anderson (2001) statesthattheseedofthisspeciescanbearillate(page35)or strophiolate(page651),whereas Rojas-Aréchiga(2009) mentionsthe presenceofanelaiosome,althoughinlaterworksheusestheterms strophioleandelaiosomeassynonyms(Rojas-Aréchiga,2012).Given theconfusionintheterminologyusedtodescribetheseedappendage, developmentalstudiesthatincludethecharacterizationofthisstructure arenecessarytoclarifyitsorigin,chemicalcompositionandmorphoanatomy,inordertoprovideamoreexactappraisaltypeofappendage anditspotentialfunctionduringseeddispersal.

Thepurposeofthisstudywastodescribeandcomparetheontogeniceventsthatoccurduringseedandseedlingdevelopmentinthe genus Strombocactus togaininsightintothereproductivebiologyofthe group.Attentionwasfocusedontheultrastructuralchangesthatgive risetotheseedappendageinboth S.disciformis subspecies,and flotationexperimentswereperformedtodiscernifthisstructurecouldpotentiallyfunctioninseeddispersalbywater.Inaddition,weexamined

whetherseedproductionandgerminabilitywerecompromisedtoinfer potentialcausesofthelowreproductiveefficiencyfoundinthisendangeredgenusinitsnaturalhabitat.Themainquestionofthisstudyis Whatisthenatureoftheseedappendageandwhatisitsroleduring seeddispersion?

2.Materialsandmethods

2.1.Studyspeciesandsites

Thespeciesof Strombocactus aredistributedinacanyonsystem betweentheStatesofQuerétaro,GuanajuatoandHidalgo(Hernández etal.,2004; Sánchez-Martínezetal.,2006; Hernández-Oriaetal., 2007).Thedistributionof S.corregidorae isrestrictedtothreelocalities intheareaknownasInfiernilloCanyoninQuerétaro,whereas S.disciformis ssp. disciformis hasawiderbutfragmenteddistributionandhas beenreportedinatleast9localitiesinQuerétaro,HidalgoandGuanajuato.Foreachofthesespecies,asinglelocalityinQuerétarowas studiedfrom2014to2017.Thetypeofclimateofthestudiedlocalities isBSk,withamaximumtemperature33.6°C,minimum 3.3°Cand annualmeanof17.3°C;annualmeanprecipitationof506mmandan annualmeanwindspeedof3.5Km/h.Wewereunableto findany specimensof S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae initsnaturalhabitatnear Xichú,Guanajuato(typeofclimateBSh,annualmeantemperatureof 20.9°Candannualmeanprecipitationof579mm),somaterialfromthe livingcollectionoftheBotanicalGardenoftheUNAMandfromThe CadereytaRegionalBotanicalGardenwereusedinthisresearch.

2.2.Seedmorpho-anatomy

Flowers inanthesis(n=20)andfruits(n=20)atvariousdevelopmentalstages,fromaminimumof10differentplantsfromeach taxon,werecollectedand fixedinFAA(10:50:5:35,formaldehyde, 95%ethanol,aceticacid,distilledwater).Threeseedswereextracted fromeachofthefruitsandprocessedforlightmicroscopy(n=60); theseweredehydratedinanascendingethanolseries,embeddedin mediumgradeLR-WhiteResin(ElectronMicroscopySciences,Fort Washington,PA,USA),sectionedat1.0–1.25 μmusingaJMC-MT990 ultramicrotome,andstainedwithaqueoustoluidineblue.Inorderto corroboratethepresenceofpolyphenols,thepotassiumpermanganate stainwasperformed(Herrera-Floresetal.,2005).Slidesweremounted withEntellan(Merck)andexaminedusinganOlympusProvisAX70 lightmicroscopeequippedwithadigitalcamera.Forscanningelectron microscopy(SEM)analysis,matureovules,developingseedsand seedlingswere fixedinFAAanddehydratedinagradedethanolseries. SpecimenswerecriticalpointdriedwithCO2 inacriticalpointdryer CPD-030Bal-Tec,thenmountedonmetallicholders,sputtercoated withgoldusingaDentonVacuumDesk-IIsputtercoaterfollowing standardprotocols,andviewedinaJeolJSM-5310LV(Tokyo,Japan) scanningelectronmicroscope.Imagesweretakenfromdifferentseed regions:lateral,dorsalandhilum-micropylar(Fig.S1).Whenpertinent, theseedappendagewasremovedinordertoexposethedetailofthe hilum-micropylarregion.Theterminologyforseedmorphologyused hereisbasedonthatproposedfortheCactaceaeby BarthlottandHunt (2000).Forthemorphologicalanalysisofgerminationandseedling development,200seedsfromeachtaxonwereplacedonPetridishes andcoveredwithmoistened filterpaper.Thedishesweresealedwith Parafilmtapetomaintainhumidity.Foreachtaxonthreegerminated seedsandthreeseedlingsatdifferentpost-germinationtimes(3,6,12, 24handthenevery24h)anddevelopmentalstageswere fixedinFAA andprocessedasmentionedforSEM.

Foreachtaxon,seeddiameterandlength(fromthechalazatothe hilum-micropylarzone)wasmeasuredusingaLeicamicroscopeandthe LASEZversion2.0software.Fourseedsfromeightfruitsfromdifferent plants(n=32)wereused.

2.3.Seedgerminationexperiments

Forthegerminationtests,eightreplicatesof30seeds(fromdifferentindividuals)pertaxonwereplacedonmoistened filterpaperin Petridishes,undera12hphotoperiodat25°C,accordingtoÁlvarez etal.(2004).Seedswerecheckeddailyfor30daysandthenumberof germinatedseedswasregistered.Seedswereconsideredgerminated whentheradicletipemergedfromtheseedcoat(germination sensu stricto).Seedgerminability(%),emergencerateindexandmeangerminationtimewerecalculated.

2.4.Seedproductionpotentialandestimationofefficiency

Tocompareseedefficiency,ovulenumberperovaryandseed numberperfruitwerecountedin S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae (n=10), in S.disciformis ssp. disciformis (n=15)andin S.corregidorae (n=17). Seedproductionpotential(SPP)wasconsideredasthemeannumberof ovulesperovary.Themeannumberofdevelopedseeds(NDS),number ofcollapsedseeds(NCS)andtotalseednumber(TSN,developedand collapsed)perfruitwereobtained.Anestimationofpercentagedevelopedseeds(PDS)wascalculatedusingthemeanvaluesobtainedfor NDSandTSNbytheformulaPDS=(NDS/TSN)×100,andtheseed efficiency(SEf)wascalculatedusingthemeanvaluesobtainedforSPP andNDSbytheformulaSEf=NDS/SPP,theformulasweremodified from Bramlettetal.(1977) and Mendizábal-Hernándezetal.(2010)

2.5.Seed flotation

Seed flotationwastestedusing20seedspertaxon(fromdifferent fruitsandplants)usingtwotreatments:(1)265mlofdistilledwater,(2) 265mlofdistilledwaterand30mgofcommercialpowderdetergent(to breaksuperficialtension).Foreachtreatment fivereplicateswereused. Tosimulatetheeffectofwatercurrentsduringrain,seedsfromeach taxonwereplacedin265mlofdistilledwaterina300mlcontainerand subjectedtoa0.3mljetofwaterusinganinsulinsyringe(commercial), thetimeittookforeachseedtoreachthebottomofthecontainerand returntothesurfacewasregistered.Onlyseedsthathadreachedthe bottomofthecontainerweretimed.Therewere40replicateswith differentseedsforeachtaxon.

2.6.Statisticalanalyses

Numberofovulesandseeds,seedmeasurements,germinability(%), theemergencerateindexandmeangerminationtimewereexpressedas mean±standarddeviation(SD)values.Ineachcase,theShapiro-Wilk normalitytestwasapplied.Differencesinovuleandseednumber,seed measurementsandmeangerminationtimeamongtaxaweretestedfor statisticalsignificanceusingaone-wayANOVA,whereasaKruskalWallis(K-W)testwasappliedtoseeddiameter,germinability(%),the emergencerateindexvaluesandseedresurfacing.Foreachtaxonand ineachreplicate,anarcsinetransformationwasappliedtotheaccumulatedgerminability(%)intimeandthenadjustedtoasigmoidusing theprogramTableCurve2Dv5.01toobtainthemaximumgermination rate(takingintoaccountthemaximum firstderivative).Alldatawere analyzedusingGraphPadPrismversion5.0software.

3.Results

3.1.Ovulemorphologyandanatomy

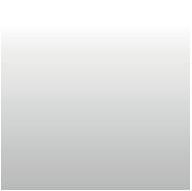

Duringanthesisthematureovulesof S.disciformis ssp. disciformis,S. disciformis ssp. esperanzae and S. corregidorae weresimilar,withdifferencesarisingafterfertilization.Ovulesarecampylotropous,bitegmic,withendostomemicropyle,formedbyaprojectionoftheinner integument(Fig.1A–C).Thefuniculusislong;itsventralepidermisis papillateandfunctionsasanobturator(Fig.1A–D).Theepidermisof

theouterintegumentisenlargedfromthechalazatothemicropyle, slightlygloboseinboth S.disciformis subspecies(Fig.1AandB), whereasitisslightlydepressedandisodiametricin S.corregidorae (Fig.1C).Therapheisshorterinlengththantheantiraphe(Fig.1A–D). Theovulesarecrassinucellate,andthenucellusconsistsof4–5layersof cells;bothintegumentsarebilayered,becomethickenedandmultilayered(upto4layers)nearthemicropylarregion(Fig.1D).The vascularbundleendsatthechalaza(notshown).Theembryosacand nucellusarecurved;inbothspeciestheembryosacisPolygonumtype, heptacellularandoctanucleate,withthreeephymerousantipodes(not shown),abinucleatecentralcellwithalargevacuoleandsmallamount ofcytoplasm,twosynergidsandtheeggcell(Fig.1DandE).Apronouncedgrowthofparenchymaticcellsinthedistalregionoffuniculus wasobservedin S.disciformis ssp. disciformis (Fig.1AandD)andin S. disciformis ssp. esperanzae (Fig.1B),butnotin S.corregidorae (Fig.1C).

3.2.OntogenyofarillateseedsintheStrombocactusdisciformissubspecies

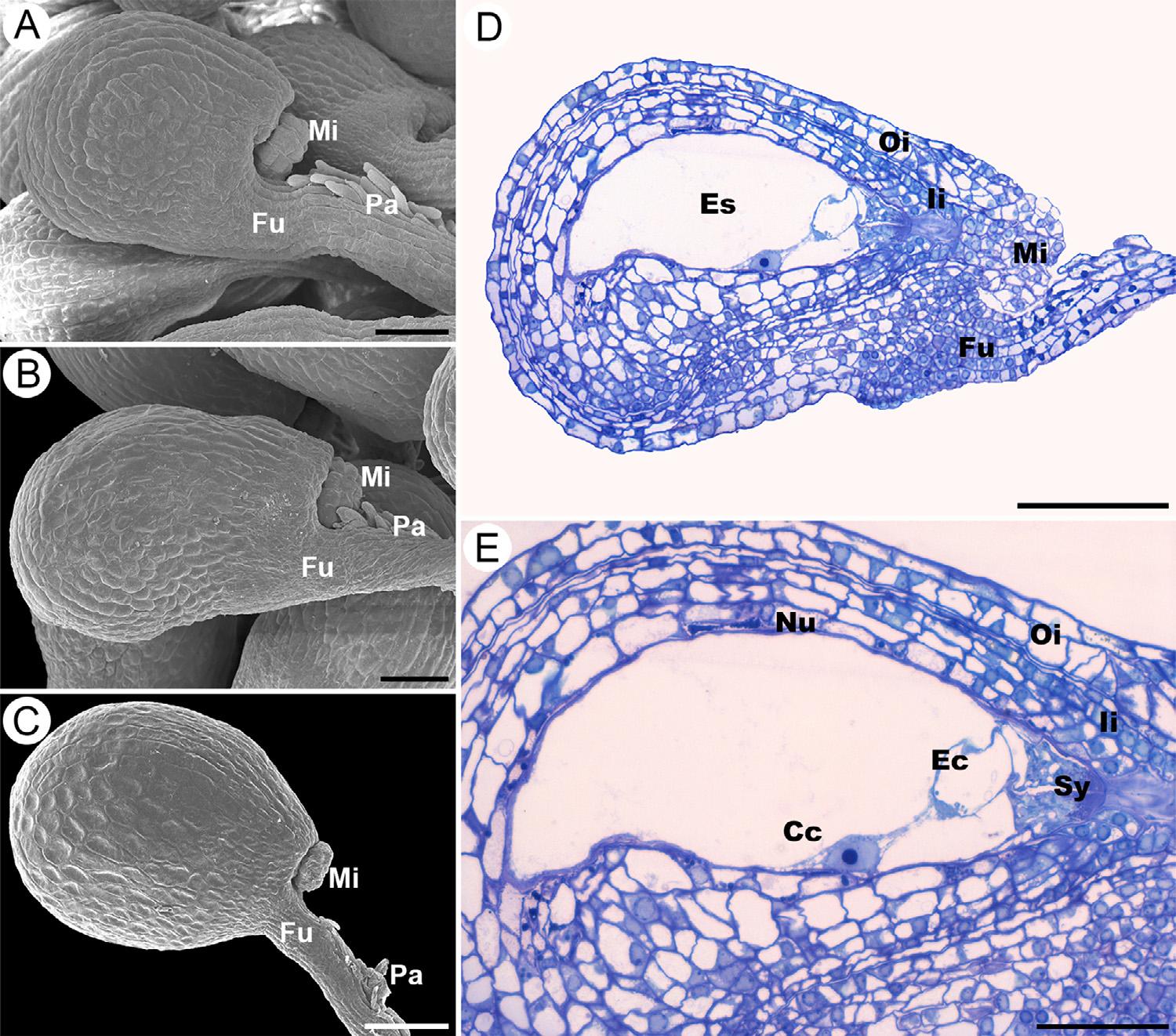

Soonafterfertilization,beforecellulardivisionsofthezygotebecomeapparent,inboth S.disciformis subspecieslocalizeddivisionsof subepidermalcellsinthedistalportionofthefuniculusgiverisetoa distinctiveprotuberance,whichfromhereonwillbereferredtoasa seedappendagetypearil(Fig.2A–D).

Thisisfollowedbythe firsttransversalzygoticdivisionthatproducesalargevacuolatedbasalcellandadenselycytoplasmicapicalcell (Fig.2E).Atthistime,theendospermisnucleartypewithachalazal andmicropylardomain.Furthertransversecelldivisionsofthezygote giverisetoathreetofourcelledlinearproembryo(Fig.2F–I).Growth ofthearilissustainedbydivisionsintheapicalportionofthefuniculus, withouttheparticipationoftheinteguments(Fig.2FandH).Although initiallyundifferentiated,bothtestaandtegmenarebilayered,notwithstandingtheexotestaisvisiblyenlarged(Fig.2F).Atthequadrant embryostage,theendospermcytoplasmbeginstoaccumulatestarch grainsneartheproembryoandthemicropyleiscloggedbytheremnantsofthepollentube(Fig. 2G–I).Thearilbeginstowidentakingona “horseshoeshape”,withoutcoveringthemicropyleandthetestaisstill shorterthantegmen(Fig.2JandK).

Whentheembryoproperisintheoctantstage,thesuspensorhas twotiersof4–5vacuolatedcellsthatpushtheembryointotheendosperm.Atthemicropyleregion,thetestahaselongatedcoveringthe tegmen.Theexotestahasthickwallsandcontaindark-stainingsubstancesresemblingpolyphenoliccompounds(datanotshown),whereas cellsoftegmenarecompactlyarrangedandhavethinnerwalls(Fig.2L andM).Theperispermcellsnearthemicropylehavedensecytoplasm andstarchgranules(Fig.2M).Thearilisformedbyparenchymatous epidermisandanaerenchymawithlargeintercellularspaces(Figs. Figure2N, Figure3B).Atthistime,theseedcoatexotestaisformedby globosecells,especiallyneartherapheandantiraphe,whichisparticularlynoticeablein S.disciformis ssp. disciformis.Inthedistalportion ofthefuniculusthearilisenlargedandrounded(Figs. Figure2O, Figure3A).Themicropyleisformedbycollapsedtegmencells (Fig.3C).

Atthebeginningoftheglobularembryostagetheendospermisstill nuclear,theexotestaaccumulatespolyphenolicinclusions,andthearil cellsextendtowardsthedistalportionoftheseed(Fig.3D).Duringlate globularembryostage,theendospermbecomescellularandvacuolated.Theembryopresentsaprotodermisandthefutureradiclemeristemdifferentiatesintheregionadjacenttothesuspensor,whereas cellsofthesuspensorareimmersedintheperispermandendosperm. Theexotestashowsdifferentialthickeningofthecellwalls(Fig.3Eand F).Theariliscompletelyaerenchymatic(Fig.3G)andgrowstowards thedistalportionoftheseed,withoutcoveringthemicropyle(Fig.3H).

Theheartembryostagebeginswiththeelongationofthecotyledons,withtheapicalmeristemlocatedatthedistalendoftheembryo andtheprocambiumatthecenter;thesuspensorcellsarestillpresent (Fig.3KandL).Thearilelongatestowardsthechalaza,coveringabout

aquarteroftheseed,whileleavingthemicropylepartiallyexposed (Fig.3I).Cellsofthearilbegintocollapse(Fig.3J).Theexotestais completely filledwithpolyphenols,evidencingitsroleinhardeningthe seedcoatandprovidingmechanicalstrength(Fig.3K).

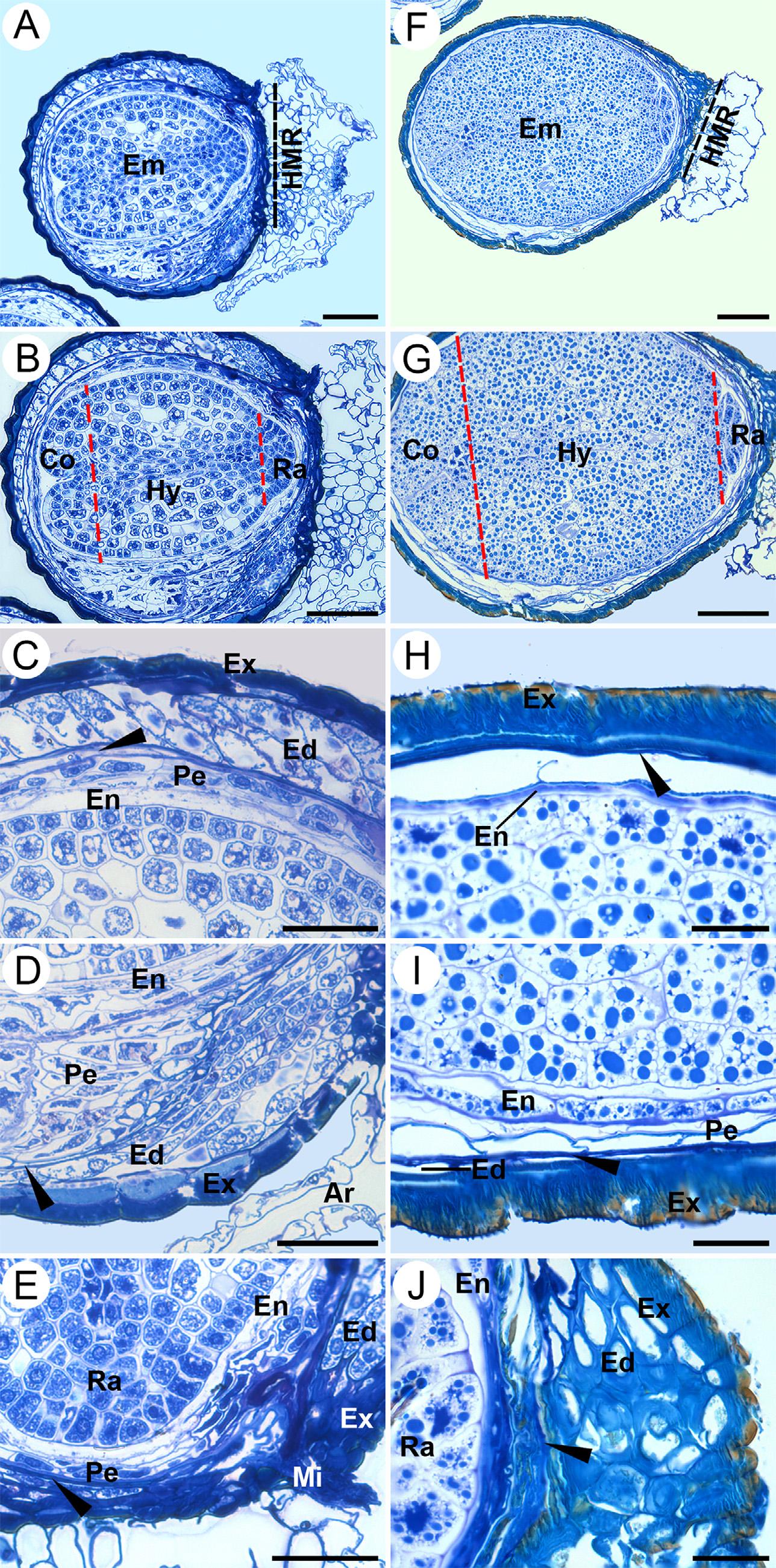

Attheequivalentofthetorpedostage,theseedcoatisformedbythe exotesta,theendotestaandexotegmen.Attheearlycotyledonarystage, thecotyledonsandradicleareclearlydistinguishableandthesuspensor isdegraded(Fig.4AandB).Theseedcoatneartheantirapheisformed byathickexotestarichinpolyphenols,anendotestawithoneortwo celllayers,andadegeneratedtegmen.Theperispermhastwocell layerswhiletheendospermissinglelayeredandshowssignsofdegradation.Theembryocellsexpandtoaccumulatestoragematerialand arevacuolated(Fig.4C).Nearthechalazaandraphe,theendosperm, perispermandendotestaaremultilayered(Fig.4D),whereasnearthe micropyletheyaresingle-layered(Fig.4E).Therefore,theperispermis limitedtotheareaoftherapheandtheendospermisscarceinboth S. disciformis subspecies.

Thematureseedsaregloboseandarillate.The finalstructureofthe exotestaconsistsofadenselayerofdark-stainingpolyphenols(datanot shown)andsclerenchymaticcellswithalargelumen(emptyspace) (Fig.4FandG).Theembryooccupiesmostoftheseedduetoits massiveexpansionduringthelaterdevelopmentalstages;itisstraight andglobose,comprisedmainlyofalargehypocotyl,reducedcotyledonsandradicle(Figs. Figure4G, Figure6).Thehypocotyl-radicleaxis andshortcotyledonscontainmostofthereservematerialthatconsists ofstarchgranulesandproteins,asconfirmedbythelugolandnaphthol blueblackhistochemicaltests(notshown).Neartheantiraphe,the exotestaisthick,theendotegmenconsistsoflarge,irregularlyshaped degeneratingparenchymaticcells,theperispermisabsentandtheendospermisalayeroflongitudinally flattenedcells(Fig.4H).Whereasat thechalazalandrapheendtheseedcoatisformedbycollapsedendotegmen,theexotestahasfully-developedsecondarywallthickenings, andthereisastarchylayerofendospermandabilayeredand

Fig.1. Morphologyofthematureovules.A,DandE Strombocactusdisciformis ssp. disciformis;B, S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae andC, S.corregidorae. (A,B, C)Matureovule,thefuniculushaspapillaeonits ventralsurface.(D)Anatomyofcampilotropous,bitegmicandcrassinucellateovule.(E)Polygonum embryosacshowingtwosynergids,eggcelland centralcell.Cc,centralcell;Ec,eggcell;Es,embryo sac;Fu,funiculus;Ii,innerintegument;Mi,micropyle;Nu,nucellus;Oi,outerintegument;Pa,papillae;Sy,synergids.Scalebars=50 μm(A,B), 100 μm(C),80 μm(D),40 μm(E).

vacuolatedperisperm(Fig.4I).Atthemicropyleregionthetegmenis collapsed,theendotestaismultilayeredandtheexotestaislignified (Fig.4J).

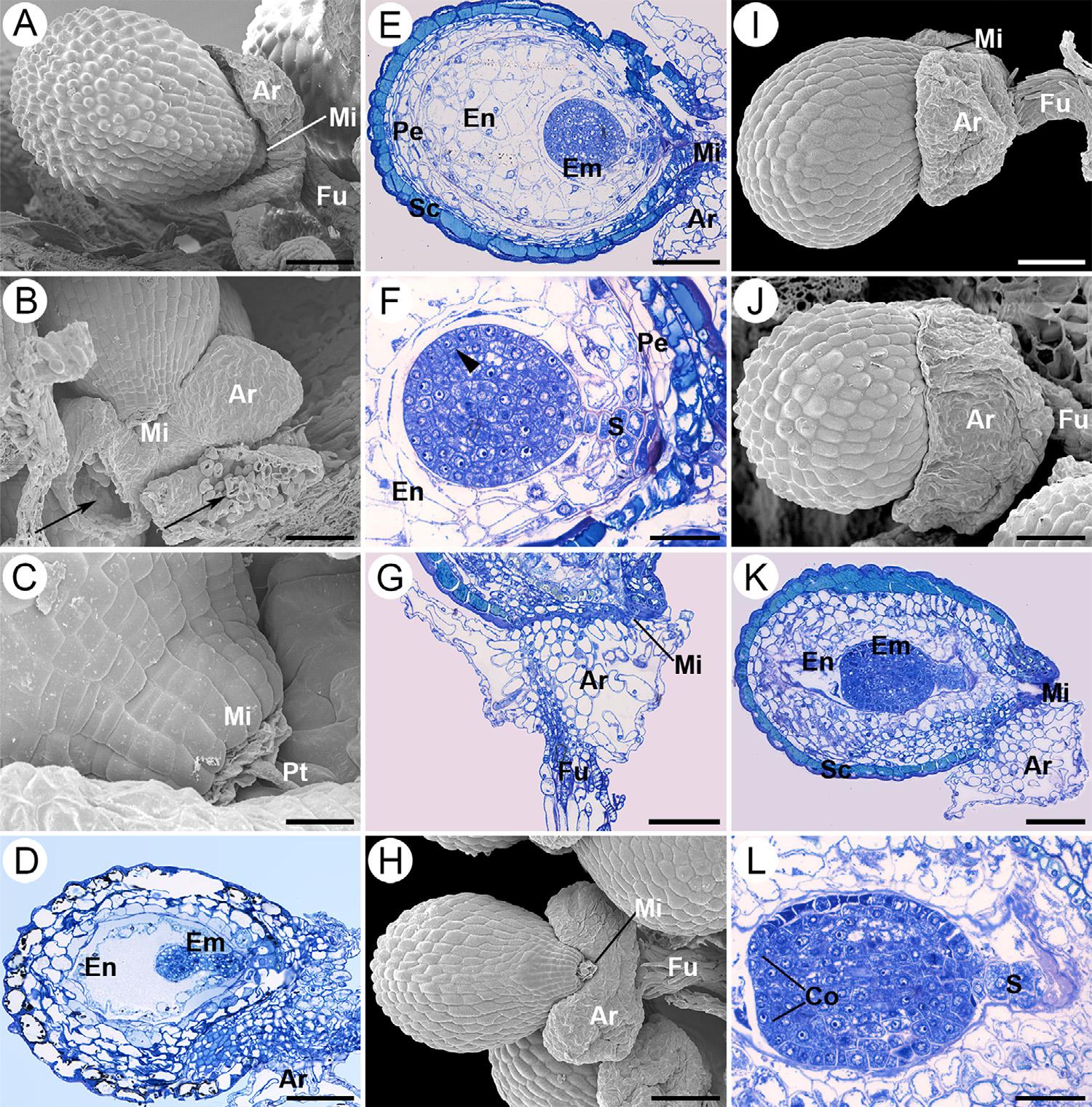

3.3.Ontogenyofthenon-arillateStrombocactuscorregidorae

Seeddevelopmentin S.corregidorae issimilartotheothertaxa, exceptfortheformationoftheprotuberanceinthedistalpartofthe funiculus,whichfailstodevelop,makingtheseedsnon-arillate (Fig.5A–J).Furthermore,incontrastto S.disciformis,wherethetesta coversthetegmenattheearlyglobularstage,in S.corregidorae growth ofthetestaissloweranddoesovercometegmenuntiltheheartstage (Fig.5K–M).Atmaturity, S.corregidorae seeds(Fig.5N–R)haveasimilar structuretoboth S.disciformis,exceptbytheabsenceofthearil. Theseedcoatin S.corregidorae isformedbysclerenchymaticcellswith thickwallsandanemptylumenintheinterior(Fig.5N,O,QandR).

3.4.Seedmicromorphologyandsize

Strombocactus matureseedsareglobosetoovoid,brownish-redin color(Fig.7A,GandM).Micromorphologyrevealsdistinctivecharactersamongthedifferentspecies.Innon-arillateseedsof S.corregidorae (Fig.7AandB),boththemicropyleandthehilumscarcanbe observedtogether,formingasinglecomplex,butseparatedbyabandof sclerifiedtissue(Fig.7CandD).Theoutercellwallsofthetestainthis speciesare flatandtheultrasculptureconsistsoffoldedsometimesreticulatecuticle,whereastheanticlinalcellwallsarestraight(Fig.7E); thecellsofthedorsalsurfacearerectangular(Fig.7F)andthoseofthe lateralsurfaceareirregularlyshaped(Fig.7E).

Seedsof S.disciformis ssp. disciformis (Fig.7G,HandI)havea whitisharilthatcontrastswiththebrownish-redseedcoat(Fig.7G). Whenthearilisremoved,theexposedmicropyleiscup-shapedandthe hilum-areaiswide(Fig.7J).Thepericlinalcellwallsofthelateralarea

ofthetestaarebulgyandslightlyconical(Fig.7K),whereasvery conicalinthedorsalarea(Fig.7L);theultrasculptureconsistsof slightlyfoldedcuticleandtheanticlinalcellwallsaresinuous(Fig.7K).

Seedsof S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae alsoexhibitawhitisharilthat coversthehilum-micropylarregion(Fig.7M–O);whentheappendage isremovedthemicropyleandthehilumscarareexposed(Fig.7P).The periclinalcellwallsoftheseedcoatarebulgingandtheultrasculpture consistsofreticulatecuticle;theanticlinalcellwallsareslightlysinuous (Fig.7QandR),thecellsofthedorsalsurfacearerectangular(Fig.7R) andthoseofthelateralsurfacehaveirregularshape(Fig.7Q).

Inthethreetaxaof Strombocactus,seedsbelongtothe “verysmall” category(accordingto BarthlottandHunt,2000).Seeddiameterwas similarinalltaxa(K-W =5.747, P =0.056),withmean±SDvalues of0.37±0.01mmin S.corregidorae,0.38±0.01mmin S.disciformis ssp. disciformis and0.36±0.02mmin S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae Seedlengthwithoutthearildifferedsignificantlybetweentaxa (F =60.06, P =0.0001),withmean±SDof0.48±0.01mmin S. corregidorae,0.41±0.02mmin S.disciformis ssp. disciformis and 0.46±0.03mmin S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae.Furthermore,whole

Fig.2. Seedmorphologyandontogeny,fromzygote toearlyoctanteembryoin Strombocactusdisciformis A–KandO, S.disciformis ssp. disciformis;L-N, S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae.(A,B,C)Atfertilizationtime, theinitiationofaprotuberanceisobservedatthe distalendofthefuniculus(arrows).(D)Thezygoteis observedandtheotherspermaticnucleuswillfuse withthepolarnuclei.(E)Firsttransversedivisionof thezygote.(F–I)Tetracellularproembryostage.(G) Proliferationofthenucleioftheendosperm,thetesta isshortwithrespecttothetegmen(arrowhead)in themicropyle.(H)Theappendage(arrow)continues toincreaseinsize.Thearrowheadindicatesthe tegmen.(I)Tetracellularproembryo.(J,K)Atthe stageofthetetracellularproembryo,theseedappendagebeginstowidenintheformofahorseshoe (arrows),withoutcoveringthemicropyle.(L-O) Octantstage.(L)Thetestaalreadycoversthecollapsedtegmen(arrowhead).(M)Theembryowitha multicellularsuspensor.Thearrowheadindicatesthe tegmen.(N)Intheinterioroftheariltheaerenchyma startstodifferentiate.(O)Thearilcontinuestogrow withoutcoveringthemicropyle.Ar,aril;Fu,funiculus;Mi,micropyle;Pa,papillae;Pt,pollentube; Em,embryo;En,endosperm;Pe,perisperm;S,suspensor;Sn,spermnucleus;T,testa;Zy,zygote.Scale bars=50 μm(A,B,K,M),80 μm(C,F),16 μm(D,E, I),40 μm(G,H),100 μm(J,L,N,O).

seedlength(includingthearil)alsodifferedsignificantly(F =38.67, P =0.0001)betweenarillateseeds,rangingfrom0.46–0.62 (0.53±0.04)mminlengthin S.disciformis ssp. disciformis,andbetween0.48–0.68(0.57±0.04)mmin S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae

3.5. Seedpotentialproduction

Inordertoassessthereproductivepotentialofeachtaxon,the numberofovulesandseedsproducedwerecounted.Thetotalnumber ofovulesperovarywasconsideredtheseedproductionpotential(SPP). Themean±SDnumberofovulesperovarywassignificantlygreater (F =13.98, P =0.0001)in S.corregidorae (1611±481.1),thanin either S.disciformis ssp.disciformis (1035±253.3)or S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae (933±307.5).However,nosignificantdifferences (F =1.44, P =0.2474)wereobservedinthemean±SDnumberof developedseeds(NDS)perfruit,whichwas838±487.5in S.corregidorae,768±258.4in S.disciformis ssp.disciformis and596±177.6 in S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae. Interestingly,inalltaxabetween94and 96%oftotalseedsdevelopednormally.Toidentifythedevelopmental

stageandpossiblecontributingcausesofseedlossanddiminishedreproductivesuccess,anestimateoftheseedefficiency(SEf)wascalculated.Basedonthemeanovulenumberperovary,SEfin S.disciformis ssp. disciformis was74.20%,whereasin S.disciformis ssp.esperanzae and S.corregidorae itwas63.87%and52.01%,respectively.

3.6.Seed flotation

Inthethreetaxa,allseeds floatedinitiallyindistilledwaterand werestill floatingafter25days(Fig.S2).However,seed floatabilitywas affectedbythepresenceofdetergent;after6days,only67±8.36%of the S.disciformis ssp. disciformis seeds,58±18.91%of S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae and45±32.79%of S.corregidorae seedswerestill floating.Themeantime±SDittookforpurposefullysunkenseedsto resurface(8cm)variedbetweenthedifferenttaxa(K-W =80.82; P< 0.0001),andwassignificantlyshorterforarillateseeds,which wasof2.61±0.53sfor S.disciformis ssp. disciformis (VideoS1),andof 1.74±0.65sin S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae (VideoS2),whereasin S. corregidorae ittook4.72±1.55s(VideoS3).

3.7.Seedgermination

Ahighpercentageofseedsgerminatedinalltaxaandnosignificant differenceswereobservedbetweenthearillateseedsandthosenonarillate(K-W =2.686, P =0.261),thereforethearildidnothavean effectongerminability.In S.disciformis ssp. disciformis meanseedgerminationwas97.08±3.75%,whereasin S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae and S.corregidorae itwas92.08±7.75%and96.67±4.36%,respectively.Furthermore,meangerminationtimewasalsosimilar

Fig.3. Ontogenyofarillateseeds(earlydevelopment).A,C,DandJ, Strombocactusdisciformis ssp disciformis; B,E–I,KandL, S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae.A–C,Inoctantstage;D,earlyglobularembryo stage;E–H,advancedglobularembryostage;I–L, heartshapeembryostage.(A)Inoctantstagethearil continuestogrowwithoutcoveringthemicropyle. (B)Intheinterioroftheariltheaerenchymabegins todifferentiate(arrow).(C)Remainsofapollentube seenenteringthemicropyle.(D)Youngglobular embryosurroundedbynuclearendospermand perisperm.(E,F)Differentiationoftheprotodermis (arrowhead)andasuspensor;thecellularendosperm andperispermsurroundtheembryo.(G)Theaerenchymainsidethearilcontinuestodevelop.(H) Advancedglobularembryostage,thearilextendsin cup-shapetowardsthedistalzoneofseed,themicropyleisfree.(I,J)Thearilcontinuestoincreaseits sizetowardsthechalaza.(K,L)Thecotyledonsbecomevisibleandthesuspensorislarger.Ar,aril;Co, cotyledons;Em,embryo;En,endosperm;Fu,funiculus;Mi,micropyle;Pe,perisperm;Pt,pollentube; S,suspensor;Sc,seedcoat.Scalebars=100 μm(A, B,H,I,J),20 μm(C),80 μm(D,E,G,K),40 μm(F, L).

betweentaxa(ANOVA, F =0.882, P =0.428),lasting 5.27±0.06daysfor S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae,5.29±0.04days for S. disciformis ssp.disciformis and5.31±0.06daysfor S.corregidorae.Thehighestemergenceratewasreachedby S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae (32.37±5.98seedsd 1),althoughnosignificantdifferenceswereobtainedwith S.corregidorae or S.disciformis ssp.disciformis (29.50±4.49and28.91±6.49seedsd 1,respectively; KW =2.015, P =0.365).Inalltaxa,seedgerminationbegins2–3days afterimbibitionwhenthetestabreaksallowingtheemergenceofthe radicle,causingtheformationofacirculargroovearoundthehilummicropylarareaknownasoperculum,whichiswherethetestacomes off (Fig.8A).Duetotheexpansionofthehypocotyl,alongitudinal grooveisformedinthedorsalportion,whichextendsfromthemicropyletothechalazathroughtheantiraphezone(Fig.8FandK).In S. disciformis ssp. disciformis (Fig.8G)and S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae (Fig.8L),theemergingradiclepushesthroughtheoperculumandthe aril,whereasin S.corregidorae theradicleemergesthroughtheformer (Fig.8B).

Thearil,whenpresent,causestheradicletocurveassoonasit emergesfromtheseedcoat,whilethehypocotylexpandsradially (Fig.8G).Inthethreetaxa,theradicleisshortandbroad,andexhibits numerousroothairsthatformatashortdistancefromtherootmeristemandgrowalongtheperipheryandlengthoftheradicle,rendering thecellelongationzoneinconspicuous(Fig.8BandL).Theseedcoat opensintwoirregularvalves,duetothewideningandelongationofthe hypocotyl(Fig.8L).Boththecotyledonsandhypocotylturngreen 2–3dayspost-germination,indicatingstrongmetabolicactivityand chlorophyllsynthesis.Theradiclestopsgrowingearlyandthenumber ofroothairsincreases(Fig.8C).Attheshoot,smallcotyledonscover

theapicalmeristem(Fig.8CandH).Theseedlingisglobose,witha muchwiderhypocotylthancotyledonsorradicle(Fig.8D,I,MandN). Stomatadevelopearlyinthehypocotylandcanbeseenasdepressions intheepidermis(Fig.8I).Later,podariabegintodifferentiateinthe

Fig.4. Ontogenyofarillateseeds(latedevelopment).A–E,Seedsof S. disciformis ssp. disciformis atcotyledonarystageembryo;F-J,Mature seedsof S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae. (A,F)Wholeseedswiththearil coveringthehilum,butthemicropyleisfree;dottedblacklinesindicatethehilum-micropylarregion.(B,G)Thewholeembryosshowing shortcotyledonsthatarebroadatthebase;theradicleisshortand broad;theembryocellsarevacuolated.(C,H)Antiraphezone.(D,I) Raphezone.(E,J)Micropilarregion;arrowheadsindicatetheremnants ofthetegmen.Ar,aril;Co,cotyledons;Ed,endotesta;Em,embryo;En, endosperm;Ex,exotesta;HMR,hilum-micropylarregion;Hy,hypocotyl;Mi,micropyle;Pe,perisperm;Ra,radicle.Scalebars=80 μm(A, B,F,G),40 μm(C,D,E),16 μm(H,I,J).

apicalregion;theseareverysmalland flattened,andtheareolacanbe distinguishedattheaxil(Fig.8E,JandO).

Fig.5. Ontogenyofnon-arillateseedsin S.corregidorae.(A,B)Afterfertilizationnoprotuberanceis seeninthedistalpartofthefuniculus.(C–F)Atthe beginningoftheglobularembryoandnuclearendosperm,thetegmenstillsurpassesthetesta.(G,H) Atearlierglobularstagetheperispermismultilayeredandtheendospermbecomescellularized; remnantsofpollentubearestillobserved.(I,J) Whentheendospermisabundantandcompletely cellularthesuspensorhasabroadbase;theexotesta andendotegmenbecomelignified,whereastheendotestaandexotegmenareparenchymatic.(K)At earlyheart-shapedembryostagethetestabeginsto coverthetegmen.(L)Duringheartembryostagethe testaformsthemicropyle,closetothehilum,butno appendageisobserved.(M)Heart-shapedembryo stage,thecotyledonsbegintoappear,thecellular endospermiscopiousandtheperispermstartsto collapse;theexotestathickens.(N)Longitudinal sectionofmatureseedwithoutseedappendage;the embryoisstraight;thedottedblacklineindicatesthe hilum-micropylarregion.(O)Theembryohasshort cotyledons,butisbroadatthebase;theradicleis shortandwide;dottedredlinesindicatethelimitsof hypocotyl.(P)Antiraphezone.(Q)Raphezone.(R) Micropylarregion;arrowheadindicatestheremnantsofthetegmen.Co,cotyledons;Ed,endotesta; Em,embryo;En,endosperm;Ex,exotesta;Fu,funiculus;Hi,hilum;HMR,hilum-micropylarregion;Hy, hypocotyl;Mi,micropyle;Pa,papillae;Pe,perisperm;Ra,radicle;S,suspensor;Sc,seedcoat.Scale bars=100 μm(A,B,E,K),80 μm(C,G,I,J,M,N, O),40 μm(D,H),50 μm(F,L),16 μm(P,Q,R).(For interpretationofthereferencestocolourinthis figurelegend,thereaderisreferredtothewebversionofthisarticle.) A.Camacho-Velázquezetal.

4.Discussion

Inthisstudywepresentadetailedanalysisofthedifferentstages involvedinseedandearlyseedlingdevelopmentin S.corregidorae and twosubspeciesof S.disciformis, theonlyknownrepresentativesof Strombocactus,avulnerablegenusnativetocentralMexico.Weprovide newseedcharactersandvariationsinseedcoatanatomyandultrasculpture,whichrepresentanewandeffectivewaytodifferentiate betweenthetaxa.Furthermore,weprovideunequivocalevidenceon theoriginandnatureoftheseedappendagefoundexclusivelyin S. disciformis ssp. disciformis and S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae,anddiscuss itspotentialusefulnessintheidentificationandclassificationofthe membersofthisgenus,aswellasitsroleinseeddispersal.

4.1.Comparativeseedandseedlingmorpho-anatomyinStrombocactus

Theearlystagesofembryogenesisandendospermogenesisappear similarinthethreetaxa,howeverdifferenceswereobservedinthe patternofmicropyleformationandinseedappendagedifferentiationin bothsubspeciesof S.disciformis.Incacti,themicropyleisformedbythe tegmen,however,asmaturationprogresses,growthofthetestacell layergraduallyovertakesandenclosestheseed,eventuallycrushingthe tegmen(Corner,1976).In Strombocactus,thetimerequiredforthetesta toovertakethetegmenduringitsdevelopmentdiffersnotablybetween taxa,whereasinboth S.disciformis subspeciesthisoccursearlyinthe octantembryostage,in S.corregidorae thegrowthofthetestaisnot completeduntiltheheartembryostage.Ingeneral,thereareveryfew researchpapersdescribingseedandseedlingdevelopmentinCactaceae (Ganong,1898; Engleman,1960; FloresandEngleman,1976; Almeida

etal.,2013),sowecouldnotcomparethisinformationwithwhatoccursinotherrelatedspeciesnorascribeitsphysiologicalsignificance, notwithstandingitwasastablecharacterwithineachtaxon.

Atmaturity,theseedproperalwayslooksmoreorlessrounded, containsanembryowithawelldevelopedhypocotyl,shortcotyledons andradicle,theperispermislimitedtotherapheend,andtheendospermisscarce,similartoothergloboseCactoideaetaxa,suchas B. liliputana (BarthlottandPorembski,1996)and Astrophytummyriostigma (Engleman1960; Johrietal.,1992).In Strombocactus,thehypocotyl increasesnotoriouslyitssizeandaccumulatesreservematerial,even theshortradiclecontainsreserves.Thereductioninperispermand endospermvolumeisconsistentwithascenarioinwhichthefunction ofreserveaccumulationtosustainrapidgerminationhasbeentransferredtotheembryonictissues,whichagreeswiththenotoriousincreaseinsizeofthehypocotylandreductionofcotyledons(Johrietal., 1992; BarthlottandHunt,2000; Ritzetal.,2012).Itwasrecently shownthatduringembryogenesisandgerminationin Cereusjamacaru, reservesaremovedtotheembryoaxesandcotyledonsbeforeseed dehydrationtakesplace(Alencaretal.,2012).In Mammillaria and Parodia thehypocotylhasassumedthefunctionofaccumulatingreservesalmostcompletely,andconstitutes90%ofthevolumeofthe embryo(BarthlottandHunt,2000).

Inthematureseed,ultrastructureofthetestaalsovariedbetween thetaxa,in S.corregidorae thetestaisformedby flattenedcellwalls, withfoldedandreticulatecuticleinsomeareas,whereas S.disciformis ssp. disciformis exhibitsgloboseconicalcells,andaslightlyfoldedcuticle.Interestingly,althoughin S.disciformis ssp.esperanzae theouter cellwallsarealsoglobose,thecellsare flatterwithareticulatecuticle, andtheoverallappearanceiscloserto S.corregidorae.Thesecharacters maybeusedtodistinguishbetweenthe S.disciformis subspecies,asit hasprovensuitabletoidentifycloselyrelatedtaxainotherCactaceae, Orchidaceae(BehnkeandBarthlott,1983)andLoasaceae(Nogueraand Jáuregui,2006);however,furtherphylogenetictestingisnecessaryto validatetheirusefulnessasdiagnosticcharactersinthisclade.

Aftergermination,thethreetaxaof Strombocactus formabroadand

Fig.6. Diagramofa Strombocactus embryoshowingthemeristematic zones.(A) Strombocactus embryo.(B)Closeuptothechalazaregion. (C)Closeuptothemicropylarregionofamatureseedof S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae.Theredboxesindicatetheshootapicalmeristem.The purpleboxesindicaterootapicalmeristem.Scalebars=40 μm(B,C). (Forinterpretationofthereferencestocolourinthis figurelegend,the readerisreferredtothewebversionofthisarticle.)

shortradicleanddeveloproothairs.Thenewlyemerged Strombocactus seedlingsaresmallinsize,about0.5mmhigh.Thisisalsocharacteristic oftheseedlingsof Turbinicarpuspseudomacrochele,acloselyrelated species(Álvarezetal.,2004).The Strombocactus seedlingsareglobose, asin Ariocarpusretusus and A. fissuratus (Buxbaum, 1950),emphasizing theroleofthehypocotylinwaterandnutrientstorage.

4.2.Originoftheseedappendage

Theseedappendagedescribedin S.disciformis ssp. disciformis and S. disciformis ssp. esperanzae,doesnotexistin S.corregidorae,orinother relatedgenera,suchas Ariocarpus, Turbinicarpus and Epithelantha (Bravo-HollisandSánchez-Mejorada,1991; BarthlottandHunt,2000; Anderson,2001; Scheinvar,2004).Basedonourobservationsofthe funicularoriginofthisstructure,theappendageispositivelydefinedas anaril,sinceitoriginatessolelyfromthefuniculus(VanDerPijl,1972; Zhangetal.,2011; Silveiraetal.,2016).Intheliterature,thetermaril isoftenusederroneouslyandinterchangeablywithseveralother structures,suchasthestrophiole,caruncleorelaiosome,eventhough theirontogenyandchemicalnaturediffers,whichformanyspecieshas notbeenclarified(Buxbaum,1955; Engleman,1960; Bravo-Hollis, 1978;Bravo-HollisandSánchez-Mejorada,1991; Barthlottand Porembski,1996).Thestrophioleisformedfromtheraphezoneofthe ovule(VanDerPijl,1972; Karakietal.,2012; Silveiraetal.,2016), whereasthecaruncleisa fleshystructurethatisformedfromtheintegument,nearbythemicropyle(VanDerPijl,1972; Zhangetal.,2011, 2014).Ontheotherhand,thetermelaiosomereferstoanystructure withnutritivecontent(irrespectiveofitsontogeneticorigin)thatrepresentsarewardfordispersers,mainlyants(HughesandWestoby, 1992; Lealetal.,2007; Linhart,2014).Althoughthepresenceofan elaiosomehasbeensuggestedinvariousgeneraofCactaceae,suchas Parodia, Aztekium, Rebutia, Notocactus and Gymnocalycium (Bregman, 1988),specific developmentalstudiestoclarifyitsnaturehavenotbeen performed.

Intheparticularcaseof Strombocactus,theseedappendagehasbeen

commonlymentionedasastrophioleandisusedasadiagnosticcharacter(Scheinvar,2004; AriasandSánchez-Martínez,2010; RojasAréchiga,2012),notwithstandingitsabsencefrom S.corregidorae (amongothermorphologicalcharacters).However,thestructurewas namedastrophiolewithoutperformingpriordevelopmentalstudiesto demonstrateitsorigin.Ourresultsclarifytheoriginofthearilinthe S. disciformis subspeciesandopensthedoortoitsuseasaninformative taxonomiccharacterforfuturephylogeneticstudies.Furtherontogenic studiesneedtobeperformedinthevariousspeciesoftheCactaceaein ordertoclarifyiftheappendagesarehomologousstructures.

4.3.ArilfunctioninStrombocactus

Ithasbeenarguedthatthemainfunctionofthearilisfordispersal byants,sincetheappendageisusuallyassociatedwithsofttissuesand

Fig.7. Seedmicromorphologyinthegenus Strombocactus.A-F,Non-arillate S.corregidorae;G–L, arillate S.disciformis ssp. disciformis andM-R, S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae.(A,G,M)Lateralviewofthe seeds,whicharebrownish-redcolor;thearilispale yellowwhenpresent.(B,H,N)Lateralviewofthe seedsshowingtheirmicromorphology.(B,N) Flattenedseedcoatcellsin S.corregidorae and S. disciformis ssp. esperanzae respectively.(H)Globose testacellsin S.disciformis ssp. disciformis. (C)Hilummicropylarviewof S.corregidorae seed.(I,O)Hilummicropylarviewinboth S.disciformis subspecies,itis coveredbythepapiraceousarilseedappendage.(D) Detailofthehilum-micropylarregionof S.corregidorae.(J,P)Detailofthehilum-micropylarregionin both S.disciformis subspecies,thearilwasmanually removed.(E,K,Q).Detailofcellsofthelateralzone; straightand flattenedcellsandreticulatecellwallsin S.corregidorae (E)and S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae (Q),butglobosecellsandstriatecuticlein S.disciformis ssp. disciformis (K).(F,L,R).Detailofcellsof thedorsalzone;straight,rectangleand flattened cellsandreticulatecuticlein S.corregidorae (F)and S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae (R)butroundedand globosecellswithstriatecuticlein S.disciformis ssp. disciformis (L).Ar,aril;Hi,hilum;Mi,micropyle. Scalebars=100 μm(A,B,G,H,M–O),50 μm(C,I, J,P),30 μm(D),20 μm(E,F,K,L,Q,R).(Forinterpretationofthereferencestocolourinthis figure legend,thereaderisreferredtothewebversionof thisarticle.)

lipidreserves(VanDerPijl,1972; Bregman,1988; Rojas-Aréchigaand Vázquez-Yanes,2000).Furthermore,insomespeciesofthefamilyEuphorbiaceaetheelaiosomeservesasasupportstructureusedbyantsto transporttheseedstotheirnests(Lealetal.,2007).However,in S. disciformis thearilisnot fleshyanditdoesnotcontainreserves, thereforeitdoesnotconstituteanelaiosomeanddoesnotrepresenta rewardfortheants.Our fieldobservationsshowedfruitdispersalby Atta sp.ants(VideoS4,Fig.S3),althoughwedidnotdetectthe movementofindividualseedstosuggestthearilplaysaroleinanemochory.Inthecactus Denmozarhodacantha,antscarryawayindividualseeds(EggliandGiorgetta,2015),however,itisnotclear whethertheseseedshaveanappendage,althougharticlephotosare suggestiveofitspresence.

Alternatively,thearilmayfunctionasa flotationsstructurefor dispersionbywater;seedsbelongingtothegenera Astrophytum

(Sánchez-Salasetal.,2012), Espostoa, Frailea, Gymnocalycium and Matucana have flotationmechanisms,mainlyabroadanddeephilum, smallandlightembryos,thintestaandnaviformshape,thatallowthem tobetransportedbyrunoff causedbyheavyrains(Bregman,1988).In theparticularcaseof Selenicereuswittii, seedshaveanairchamberthat allowsthemto float(Barthlottetal.,1997).Thepresenceoftheaerenchymainthearilof S.disciformis supportsitsroleasa flotation structure;however,ourdataonseed flotationdidnotshowdifferences betweenarillateandnonarillateseeds.Thismaybepartiallyexplained bythepresenceofairspacesinthelumenofsclerenchymatictestacells inboth S.corregidorae asin S.disciformis. Moreover,observeddifferencesintestamicrosculpturingcouldalsocontributetoseed floatability,sincesurfacestructureisknowntoimpactonhydrophobicity (wettability),keeping/trappingairbubblesunderwater,watermovementundertensionandreducingdraginmovingobjects(Barthlottand

Fig.8. Morphologyofseedlingsofthegenus Strombocactus.A–E, S.corregidorae;F–J, S.disciformis ssp. disciformis, andK-O, S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae.(A,F,K)Seedsduringgermination,slotsoriginatearoundthehilum-micropylarregionand throughouttheantiraphezone;germinationisbyan operculum.(B,G,L)Theradicleemergespushingthe operculumandarilin S.disciformis ssp. disciformis and S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae,andonlytheoperculumin S.corregidorae.Theseedcoatfractures creatingtwovalves,byhypocotylgrowth.Theradicleisshort,hashairsanditcurvesuponleaving theseedcoat.(C,H,M)Intheapicalpartofthe seedlingsthecotyledonsareobservedandlongroot hairsareseenintheradicle.(D,I,N)Theseedlings areglobose,thehypocotylcontinuestogrowradially andsomestomataareseenasdepressionsinthe epidermis;theroothaslongroothairs;atthistime someseedlingshaveremnantsofseedcoatandaril. (E,J,O)Intheapicalregionofyoungplantsare observedverysmalland flattenedpodariawiththeir areoles.Al,areole;Ar,aril;Co,cotyledon;Hy,hypocotyl;Op,operculum;Ra,radicle;Rh,roothairs; St,stoma.Scalebars=100 μm(A,C,F–H,K–M), 200 μm(B,D,I,N),500 μm(E,J,O).

Hunt,2000; KochandBarthlott,2009).Thiscouldhavehadanimpact onseedresurfacinguponsubmergence,inwhichthemoreconvexcell shapes,asthoseobservedin S.disciformis,togetherwiththepresenceof thearil,maybemoreeffectiveintrappingairinthecavitiesbetween cells,therebyreducingwettability,contributingtotheobservedoverall lowerresurfacingtimeoftheseeds.Thiscouldhaveasignificantimpact onseeddispersalbyallowingseedstoremainafloatwhensubjectedto watercurrentsandturbulenceonasmallscale.

Dispersionisessential,itisthemeansbywhichthepopulationsofa certainspeciescanexchangeindividualsorcolonizeemptysites(Cain etal.,2000)andthushaveagreateropportunitytoincreasegenetic variationamongpopulations.Thespeciesthathaveawidedistribution andan “effective” dispersalsystembymammalsand/orbirdssuchas Hylocereus and Stenocereus,tendtoshowstrikingand fleshyfruits. Whereasgenerathathavedry,small,unattractivefruitssuchas

Ariocarpus, Aztekium and Turbinicarpus usuallyhaveareduceddistribution(HernándezandGómez-Hinostrosa,2011),whichmayalsobe thecaseof Strombocactus.Therefore,alternatedispersalstrategiesare occurringwhichmustbeunderstoodinordertofurtherconservation efforts.

4.4.Seedproduction

Seedproductionisanimportantindicatorthatallowsustorecognizethepotentialforreproductivesuccessinagivenspecies.All threetaxaproduceahighnumberofovules,rangingbetween933and 1611,whichweresignificantlyhigherin S.corregidorae thanin S.disciformis subspecies.However,whenthesevaluesarecomparedwith seedsperfruit,thistendencyisreversed,with S.disciformis ssp. disciformis presentingthehighestestimatedseedefficiency,followedby S. disciformis ssp. esperanzae,andlastly S.corregidorae;inthelatter,nearly 50%oftheovulesdidnotformseeds.Therearemanypotentialcauses forthisdiscrepancy;lowseedefficiencymayresultfromovuleabortion (unknowncauses)orinadequatepollination,fromlownumberof pollengrainsreachingthestigmatoproblemsinpollengermination andpollentubegrowth.However,post-fertilizationbarriersmayalso beinvolved,resultingfromembryoabortioncausedbytheexpression ofhomozygouslethalgenesasaproductofinbreeding,whichis commoninsmall,isolatedpopulations(Mandujanoetal.,1996).Ifthe latterwerethecase,embryoabortionmustoccurattheearlieststages sincemalformedseedsdidnotsurpass6%inanyofthetaxa.External factorssuchastheattackbyherbivoresandpathogensmayalsoreduce seedefficiency(López-UptonandDonahue,1995),howeverdamaged seedsorfruitswerenotobservedinthestudiedpopulations.Fieldobservationsshowedthatin S.disciformis ssp. disciformis flowerswere visitedbymanypollinators,mainlybees(datanotshown),whereasthe S.corregidorae studiedpopulationswerepoorlyvisited(personalobservation).Because S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae wasgrownunder greenhouseconditionshandpollinationswereperformed,howeverefficiencydidnotdifferfrom S.disciformis ssp. disciformis.Weconsider thatthemaincausebehindlowseedefficiencycouldbetheresultof inefficientpollination;howeverfurther fieldstudiesmustbeundertaken,especiallyin S.corregidorae.

4.5.Seedgermination

Inthestudiedtaxa,seedsgerminatebyanoperculum,asreported forthesubfamiliesCactoideaeandPereskioideae(Bregmanand Bouman,1983).Accordingtothedifferent germinationvariantsproposed, Strombocactus wouldbeincludedeitherasthevariants3(Cereus) and4(Notocactus),oracombinationofboth,sincethereisanoperculumwithoneormorerowsoftestacells(variant3)ornone(variant 4).

In Strombocactus,germinationbeginswithinthe firsttwodaysof imbibition,thusitisfeasibletoassumethatthisprocessdependsexclusivelyonreachingappropriatemoistureconditions(Rojas-Aréchiga andVázquez-Yanes,2000)andthatnoinhibitorysubstancesarepresentthathindertheprocess.Inthethreestudiedtaxa,over90%ofthe seedsgerminatedwithinthe first fivedays,whichcontrastswithpreviousreportsbyÁlvarezetal.(2004)whomentionlowgerminabilityin S.disciformis,rangingfrom25–82%,andwhichtook12daystobe completed.Theseauthorsappliedapre-germinativedisinfectiontreatmentwhichmayhaveaffectedseedviability,sinceoverexposure(time andconcentration)tocommercialbleachandotherdisinfectantsare knowntodamageembryonictissuesandaffectgerminability(AlvarezPardoetal.,2006; Billardetal.,2014),althoughwecannotruleoutthe influenceofotherunidentifiedfactorsthatmayhaveimpactedonseed viability(seedmanipulationandstorage,maternaleffect,etc.).This showsthat Strombocactus seedsdonotexhibitstructuralorphysiologicaldormancy.

Thepresenceofthearildidnothaveaneffectongerminability,

unlikeinthesubfamilyOpuntiodeaewherethearilissclerifiedand impermeabletowateranditsremovalisnecessarytofacilitategermination(BregmanandBouman,1983);furthermore,thisstructuredid nothavetheroleofahydrophilouslayerasin Notocacteae (Bregman andGraven,1997),anditsremovaldidnothaveadeleteriouseffecton germination.Thissupportsthehypothesisthatin Strombocactus thearil hasadifferentrole,mostlikelyassociatedtoseeddispersalbywater.In thisstudywe findthatneitherseednorseedlingdevelopmentiscompromisedandifproperpollinationoccurshighseednumbersandgerminabilitycanbeobtained,suggestingthereareotherpost-germinative factorsthataffectseedlingestablishmentandsurvival(Álvarezetal., 2004),therebyinfluencinglownumberofindividualswithinpopulations,whichmustbeconsideredinfuture fieldstudies.

5.Conclusions

Aspartofanongoingstudyintothereproductivebiologyinthe genus Strombocactus, endangeredcactiendemictoMexico,weprovide insightintothemorpho-anatomyassociatedwithseedandearlyseedlingdevelopment.Weshowthattheseedappendagepresentin S.disciformis ssp. disciformis andin S.disciformis ssp. esperanzae isanarilthat originatesfromthedistalpartofthefuniculusandisaerenchymatous. Thepresenceofthisappendageexclusivelyinboth S.disciformis subspeciesisafundamentalcharacterthatmakesitespeciallyusefulto distinguishthisspeciesfrom S.corregidorae. Althoughthisstructure mightbeimplicatedinseeddispersalbyants,itcouldalsobeassociated withwaterdispersal,supportedbythepresenceoflumenspaces,which mayprovide floatabilityandpromoteresurfacingofsubmergedseeds. Testamicrosculpturingalsodifferedamongthestudiedtaxa,providing anewcharacterfortaxonomy,aswellasinsightintootherstructural featurespotentiallyinvolvedindispersal.Seedsinthesetaxagerminatedvigorouslyanddonotappeartohaveanyspecialrequirements, whichshowsthatgiventheappropriatemanagementtheymaybe suitablecandidatesfor insitu and exsitu propagation,restorationand conservationprograms.Ontogenicstudiesprovideabetterunderstandingofplantreproductivebiology,andareanecessaryframework tocomprehendtheevolutionofhomologousstructures,aswellasthe roleofmorphologyinecologicalinteractions.

Acknowledgements

ThisworkwassupportedbytheProgramDGAPA-PAPIIT(IN223814)andCONACyT(101771)toSVS.Thispaperconstitutesa partialfulfillmentoftheGraduatePrograminBiologicalSciencesofthe NationalAutonomousUniversityofMéxico(UNAM)forA.CamachoVelázquez,whoacknowledgesscholarshipand financialsupportprovidedbytheNationalCouncilofScienceandTechnology(CONACyT), andUNAM.WearegratefultoSilviaEspinosaMatíasandAnaIsabel BielerfortechnicalsupportonSEMandLightmicroscopypictures; PatriciaOlguínSantosforhersupportduringgerminationexperiments; LeticiaBonillaforstatisticalanalysis.WearegratefultoRocío Hernández,AlbertoCarrasco,NadiaCastro,CésarGonzález,Ikal Paredes,SandraRiosandFernandaRodríguezfortheirhelpin field work.ToJerónimoReyes(JB-IB-UNAM)andMagdalenaHernándezM. (JBRCadereyta)fortheirhelpwithbiologicalcollections.Theauthors alsothankanonymousreviewersfortheirvaluablecommentsonthe manuscript.

AppendixA.Supplementarydata

Supplementarydataassociatedwiththisarticlecanbefound,inthe onlineversion,at https://doi.org/10.1016/j. flora.2018.03.006 .

References

Álvarez,R.,Godínez-Álvarez,H.,Guzmán,U.,Dávila,P.,2004.Aspectosecológicosde

doscactáceasmexicanasamenazadas:implicacionesparasuconservación.Bol.Soc. Bot.Méx.75,7–16

Alencar,N.L.,Innecco,R.,Gomes-Filho,E.,Gallão,M.I.,Alvarez-Pizarro,J.C.,Prisco,J.T., Oliveira,A.B.D.,2012.Seedreservecompositionandmobilizationduringgerminationandearlyseedlingestablishmentof Cereusjamacaru DCssp. jamacaru (Cactaceae).An.Acad.Bras.Cienc.84,823–832

Almeida,O.J.,Paoli,A.A.,Souza,L.A.,Cota-Sánchez,J.H.,2013.Seedlingmorphology anddevelopmentintheepiphyticcactus Epiphyllumphyllanthus (L.)Haw.(Cactaceae: hylocereeae).J.TorreyBot.Soc.140,196–214 Alvarez-Pardo,V.M.,Ferreira,A.G.,Nunes,V.F.,2006.Seeddisinfestationmethodsfor in vitro cultivationofepiphyteorchidsfromSouthernBrazil.Hortic.Bras.24,217–220 Anderson,E.F.,2001.TheCactusFamily.TimberPressPortland,Oregon Arias,S.,Flores,J.,2013.LafamiliaCactaceae.In:Márquez-Guzmán,J.,Collazo-Ortega, M.,Martínez-Gordillo,M.,Orozco-Segovia,A.,Vázquez-Santana,S.(Eds.),Biología deAngiospermas.PrensasdelaFacultaddeCiencias.UniversidadNacional AutónomadeMéxico,MexicoCity,pp.492–504 Arias,S.,Sánchez-Martínez,E.,2010.Unaespecienuevade Strombocactus (Cactaceae)del ríoMoctezumaQuerétaro,México.Rev.Méx.Biodiv.8,619–624 Arias,S.,Terrazas,T.,2004.Seedmorphologyandvariationinthegenus Pachycereus (Cactaceae).J.PlantRes.117,277–289. Arreola-Nava,H.J.,Terrazas,T.,2003.Especiesde Stenocereus conaréolasmorenas:clave ydescripciones.ActaBot.Méx.64,1–18

Arroyo-Cosultchi,G.,Terrazas,T.,Arias,S.,Arreola-Nava,H.J.,2006.Thesystematic significanceofseedmorphologyin Stenocereus (Cactaceae).Taxon55,983–992

Arroyo-Cosultchi,G.,Terrazas,T.,Arias,S.,López-Mata,L.,2007.Morfologíadela semillaen Neobuxbaumia (Cactaceae).Bol.Soc.Bot.Méx.81,17–25

Barthlott,W.,Hunt,D.,2000.SeeddiversityintheCactaceaesubfamilyCactoideae.Succ. PlantRes.5,1–173

Barthlott,W.,Porembski,S.,1996.Ecologyandmorphologyof Blossfeldialiliputana (Cactaceae):apoikilohydricandalmostastomatesucculent.Bot.Acta109,161–166

Barthlott,W.,Porembski,S.,Kluge,M.,Hopke,J.,Schmidt,L.,1997.Selenicereuswittii (Cactaceae):anepiphyteadaptedtoAmazonianIgapóinundationforests.PlantSyst. Evol.206,175–185

Behnke,H.,Barthlott,W.,1983.Newevidencefromtheultrastructuralandmicromorphological fieldsinangiospermclassification.Nor.J.Bot.3,43–66

Bewley,J.D.,Black,M.,1994.Seeds.PhysiologyofDevelopmentandGermination, second ed.PlenumPress,NewYork

Bewley,J.D.,Bradford,K.J.,Hilhorst,H.W.M.,Nonogaki,H.,2013.Seeds.Physiologyof Development,GerminationandDormancy,thirded.Springer-Verlag,NewYork Billard,C.E.,Dalzotto,C.A.,Lallana,V.H.,2014.Desinfecciónysiembraasimbióticade semillasdedosespeciesyunavariedaddeorquídeasdelgénero Oncidium Polibotánica38,145–157

Bramlett,D.L.,BelcherJr.,E.W.,DeBarr,G.L.,Hertel,G.D.,Karrfalt,R.P.,Lantz,C.W., Miller,T.,Ware,K.D.,YatesIII,H.D.,1977.ConeAnalysisofSouthernPines – A Guidebook.Gen.Tech.Rep.USDAForestService,Asheville,N.CSE-13. Bravo-Hollis,H.,Sánchez-Mejorada,H.,1991.LasCactáceasdeMéxico,secondvol UniversidadNacionalAutónomadeMéxico,MexicoCity Bravo-Hollis,H.,1978.LasCactáceasdeMéxico, firstvolUniversidadNacional AutónomadeMéxico,MexicoCity

Bregman,R.,Bouman,F.,1983.SeedgerminationinCactaceae.Bot.J.Linn.Soc.86, 357–374

Bregman,R.,Graven,P.,1997.Subcuticularsecretionbycactusseedsimprovesgerminationbymeansofrapiduptakeanddistributionofwater.Ann.Bot.80,525–531

Bregman,R.,1988.FormsofseeddispersalinCactaceae.ActaBot.Neerl.37,395–402 Britton,N.L.,Rose,J.N.,1922.TheCactaceae,thirdvolTheCarnegieInstitutionof Washington,WashingtonD.C

Buxbaum,F.,1950.MorphologyofCacti.Section1.RootsandStems.AbbeyGarden Press,Pasadena,California

Buxbaum,F.,1955.MorphologyofCactiSectionIII.FruitsandSeeds.AbbeyGarden Press,Pasadena,California

CITES,2010.Convenciónsobreelcomerciointernacionaldeespeciesamenazadasde faunay florasilvestres.UNEPApéndicesI,IIyIII

Cain,M.L.,Milligan,B.G.,Strand,A.E.,2000.Long-distanceseeddispersalinplantpopulations.Am.J.Bot.87,1217–1227

Corner,E.J.H.,1976.TheSeedsofDicotyledons, firstvolCambridgeUniversityPress, Cambridge DeCandolle,A.P.,1828.Revuedelafamilledescactées.Memoir.Mus.Hist.Nat.17, 1–119.

Eggli,U.,Giorgetta,M.,2015.Floweringphenologyandobservationsonthepollination biologyofSouthAmericanCacti.1. Denmozarhodacantha.Haseltonia20,3–12 Engleman,M.E.,1960.Ovuleandseeddevelopmentincertaincacti.Am.J.Bot.47, 460–467

Flores,E.M.,Engleman,E.M.,1976.Apuntessobreanatomíaymorfologíadelassemillas decactáceas:I.Desarrolloyestructura.Rev.Biol.Trop.24,199–227

Flores,E.M.,1976.Apuntessobreanatomíaymorfologíadelassemillasdecactáceas:II. Caracteresdevalortaxonómico.Rev.Biol.Trop.24,299–321

Ganong,W.F.,1898.Contributionstoaknowledgeofthemorphologyandecologyofthe Cactaceae:II.Thecomparativemorphologyoftheembryosandseedlings.Ann.Bot. 12,423–474

Gibson,A.C.,Horak,K.E.,1978.SystematicanatomyandphylogenyofMexicancolumnar cacti.Ann.MissouriBot.Gard.65,999–1057

Glass, C.,Arias,S.,1996.Anewsubspeciesof Strombocactus fromtheSierraGordainthe northeasternportionofthestateofGuanajuato,México.Brit.Cact.Succul.J.14, 198–204

Hernández,H.M.,Gómez-Hinostrosa,C.,2011.MappingthecactiofMexico.Succ.Plant Res.7,1–128

Hernández,H.M.,Gómez-Hinostrosa,C.,Goettsch,B.,2004.ChecklistofChihuahuan DesertCactaceae.Harv.Pap.Bot.9,51–68

Hernández-Oria,J.,Chávez-Martínez,R.,Sánchez-Martínez,E.,2007.Factoresderiesgo enlasCactaceaeamenazadasdeunaregiónsemiáridaenelsurdeldesiertochihuahuenseMéxico.Interciencia32,628–734

Herrera-Flores,T.S.,Cárdenas-Soriano,E.,Ortíz-Cereceres,J.,Acosta-Gallegos,J.A., Mendoza-Castillo,Ma.D.C.,2005.Anatomíadelavainadetresespeciesdelgénero Phaseolus.Agrociencia39,595–602

Hughes,L.,Westoby,M.,1992.Effectofdiasporecharacteristicsonremovalofseeds adaptedfordispersalbyants.Ecology73,1300–1312

Jiménez,S.C.L.,2011.Lascactáceasmexicanasylosriesgosqueenfrentan.Rev.Digit. Univ.UNAM12,1–23 Johri,B.M.,Ambergaskar,K.B.,Srivastava,P.S.,1992.ComparativeEmbryologyof Angiosperms, firstvolSpringer-Verlag,Berlin

Karaki,T.,Watanabe,Y.,Kondo,T.,Koike,T.,2012.Strophioleofseedsoftheblack locustactsasawatergap.PlantSpec.Biol.27,226–232.

Koch,K.,Barthlott,W.,2009.Superhydrophobicandsuperhydrophilicplantsurfaces:an inspirationforbiomimeticmaterials.Phil.Trans.R.Soc.A367,1487–1509 López-Upton,J.,Donahue,J.K.,1995.Seedproductionof Pinusgreggii Engelminnatural standsinMexico.TreePlanters’ Notes46,86–92 Lüthy,J.M.,2001.TheCactiofCITES.AppendixI.CITES,Berna Leal,I.R.,Wirth,R.,Tabarelli,M.,2007.Seeddispersalbyantsinthesemi-aridCaatinga ofnorth-eastBrazil.Ann.Bot.99,885–894

Linhart,Y.,2014.Plantpollinationanddispersal.In:Monson,R.K.(Ed.),Ecologyand Environment.Springer,NewYork,pp.89–117

Márquez-Guzmán,J.,2013.Semilla.In:Márquez-Guzmán,J.,Collazo-Ortega,M., Martínez-Gordillo,M.,Orozco-Segovia,A.,Vázquez-Santana,S.(Eds.),Biologíade Angiospermas.PrensasdelaFacultaddeCiencias.UniversidadNacionalAutónoma deMéxico,MexicoCity,pp.137–149

Machado,M.C.,2007.Fascinating Frailea,partI:generalimpressions.CactusWorld25, 5–11

Mandujano,M.D.C.,Montaña,C.,Eguiarte,L.E.,1996.Reproductiveecologyandinbreedingdepressionin Opuntiarastrera (Cactaceae)intheChihuahuanDesert:why aresexuallyderivedrecruitmentssorare?Am.J.Bot.83,63–70

Mandujano, M.D.C.,Carrillo-Ángeles,I.,Martínez-Peralta,C.,Golubov,J.,2010. ReproductivebiologyofCactaceae.In:Ramawat,K.G.(Ed.),DesertPlants.SpringerVerlag,Berlin,pp.197–230 Mendizábal-Hernández,L.D.C.,Alba-Landa,J.,Márquez-Ramírez,J.,Ramírez-García, E.O.,Cruz-Jiménez,H.,2010.Potencialdeproducciónyeficienciadesemillasdedos cosechasde Pinusteocote Schl.etCham.Flor.Veracruz.12,21–26. Noguera,E.,Jáuregui,D.,2006.Micromorfologíayestructuradelacubiertaseminalde cuatroespeciesdeLoasaceaeJuss.presentesenVenezuela.Rodriguésia57,1–9 Ritter,F.,1981.KakteeninSüd-Amerika,bandIV.F.Ritter,Selbstverlag,Selbstverlag Ritz,C.M.,Reiker,J.,Charles,G.,Hoxey,P.,Hunt,D.,Lowry,M.,Stuppy,W.,Taylor,N., 2012.Molecularphylogenyandcharacterevolutioninterete-stemmedAndean opuntias(Cactaceae-Opuntioideae).Mol.Phylogenet.Evol.65,668–681

Rojas-Aréchiga,M.,Vázquez-Yanes,C.,2000.Cactusseedgermination:areview.J.Arid. Environ.44,85–104

Rojas-Aréchiga,M.,2009.¿Quéeselelaiosoma?Bol.Soc.Latin.Carib.Cact.Suc.6, 10–12

Rojas-Aréchiga,M.,2012.LaimportanciadelasemillaenCactaceaeparaestudios taxonómicosy filogenéticos.Bol.Soc.Latin.Carib.Cact.Suc.9,15–18

Sánchez-Martínez,E.,Chávez-Martínez,R.J.,Hernández-Oria,J.G.,Hernández-Martínez, M.M.,2006.EspeciesdeCactáceasPrioritariasParalaConservaciónenLaZonaÁrida Queretano-Hidalguense.ConsejodeCienciayTecnologíadelEstadodeQuerétaro, Querétaro

Sánchez-Salas,J.,Jurado,E.,Flores,J.,Estrada-Castillón,E.,Muro-Pérez,G.,2012. Desertspeciesadaptedfordispersalandgerminationduring floods:experimental evidenceintwo Astrophytum species(Cactaceae).Flora207,707–711 SEMARNAT,2010.NormaOficialMexicanaNOM-059-ECOL-2010.Protección Ambiental-EspeciesNativasdeMéxicodeFlorayFaunaSilvestres.Categoríasde RiesgoyEspecificacionesparasuInclusión,ExclusiónoCambio.DiarioOficial.2ª Sección,MexicoCity. Scheinvar,L.,2004.FloraCactológicadelEstadodeQuerétaro:DiversidadyRiqueza. FondodeCulturaEconómica,MexicoCity

Silveira,S.R.,Dornelas,M.C.,Martinelli,A.P.,2016.Perspectivesforaframeworkto understandarilinitiationanddevelopment.Front.PlantSci.7,1919

Valiente-Banuet,A.,Ezcurra,E.,1991.Shadeasacauseoftheassociationbetweenthe cactus Neobuxbaumiatetetzo andthenurseplant Mimosaluisana intheTehuacan ValleyMexico.J.Ecol.79,961–971

VanDerPijl,L.,1972.PrinciplesofDispersalinHigherPlants,seconded.SpringerVerlag,NewYork

Zhang,X.,Zhang,Z.,Stützel,T.,2011.ArildevelopmentinCelastraceae.FeddesRepert 122,445–455

Zhang,X.,Zhang,Z.,Stützel,T.,2014.Ontogenyoftheovuleandseedwingin Catha edulis (Vahl)Endl.(Celastraceae).Flora209,179–184