Jane Webster PhD Researcher Illustrated Reader September - December 2024

My son bought this book as a Christmas gift, thoughtfully looking for any reading on birth that isn’t in the collection on the desk. I have missed this read: a hybrid of history, assumptions and attitudes toward women and childbirth. The midwife, through time and their changing roles. I can see comparisons between ‘Mother as a Verb.’

CONTENTS:

Page 1.....New reading reference

Pages 2-3.....Care Quality Commission National Review of Maternity Services Report 2022- 24.

Page 4-5.....Communication recommendations from the report - highlighted quotes.

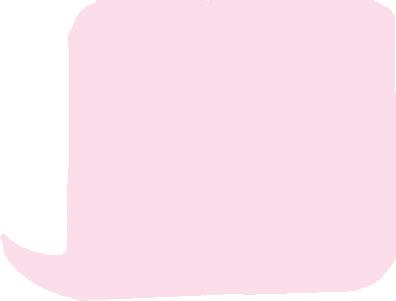

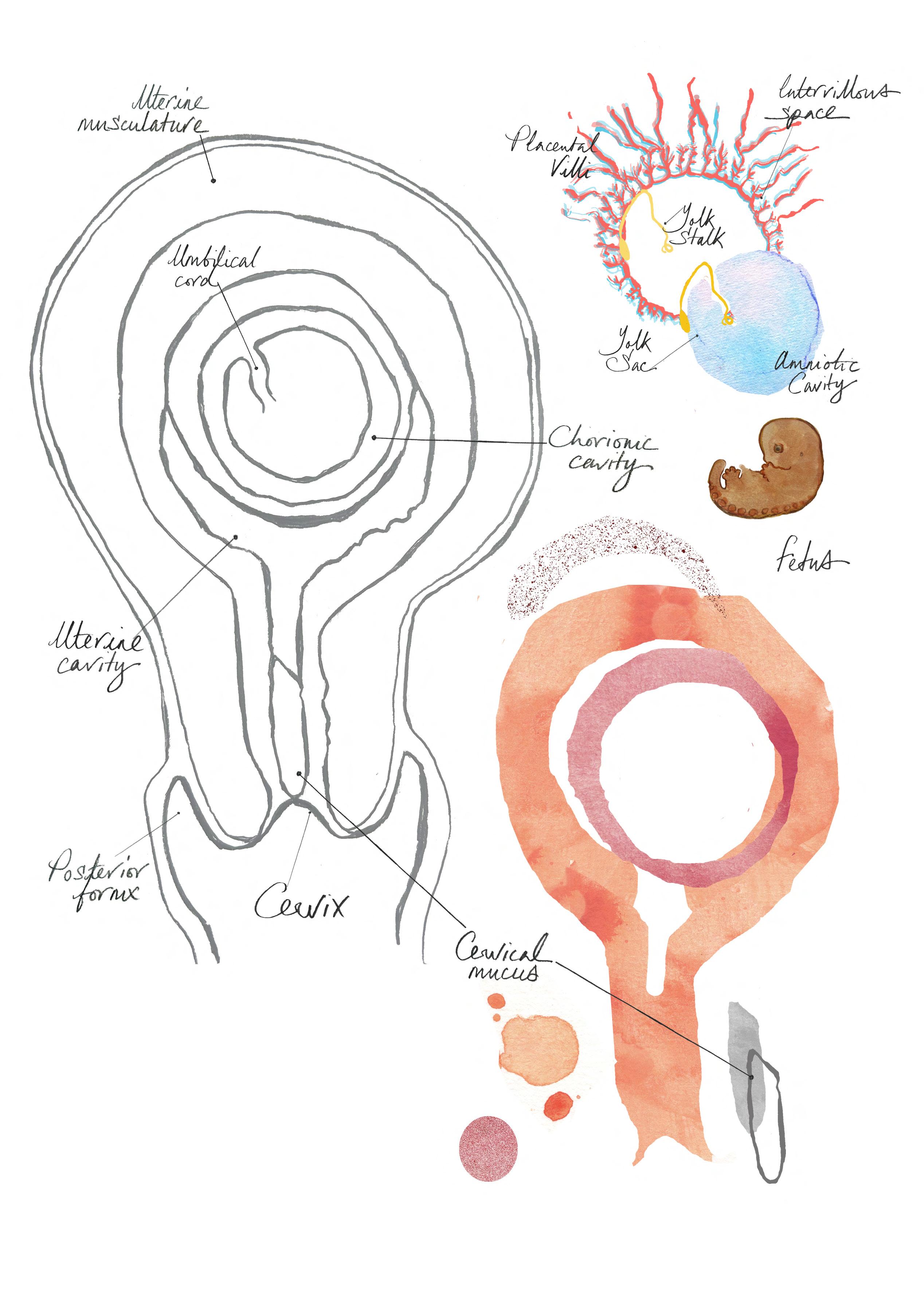

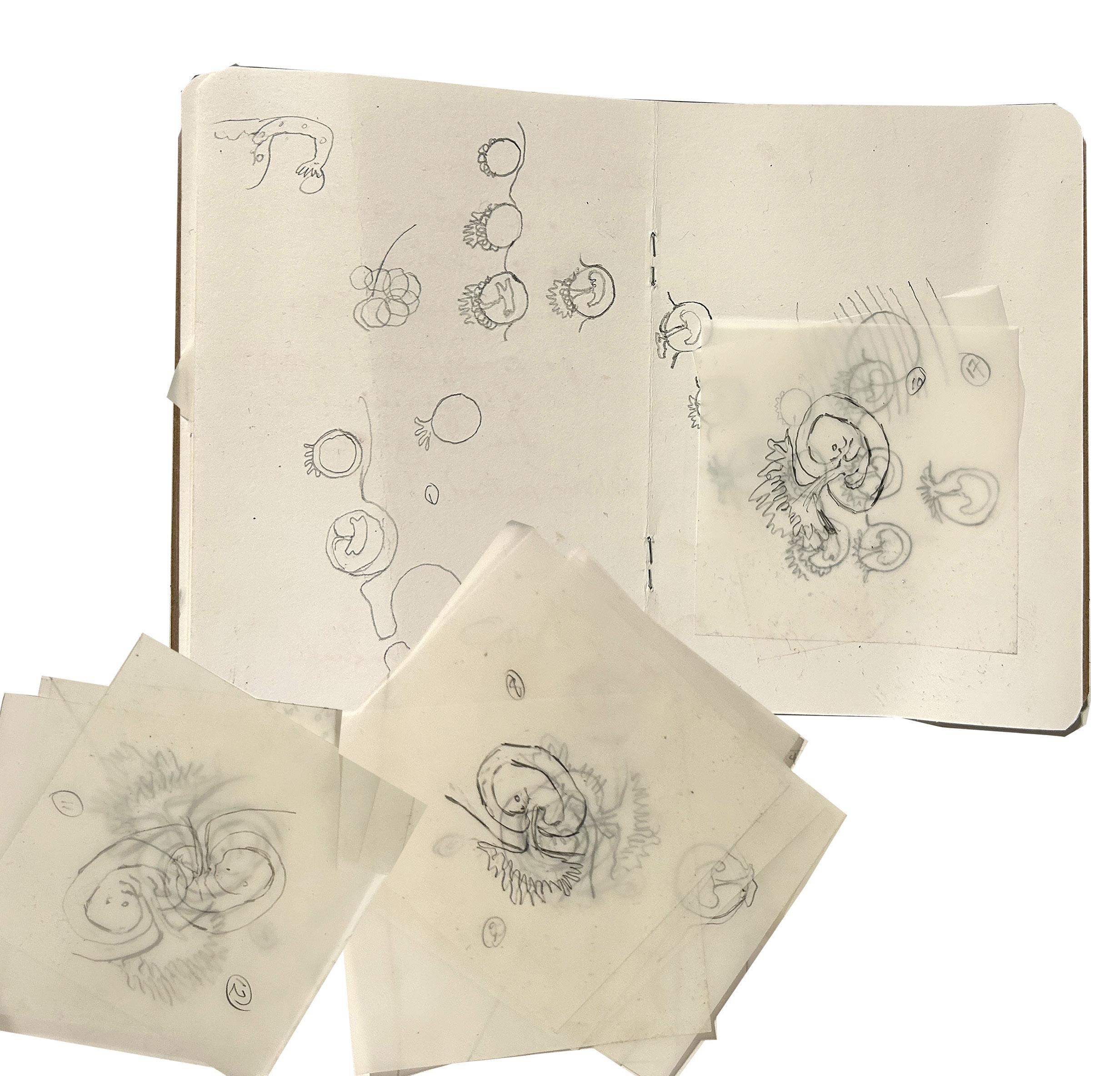

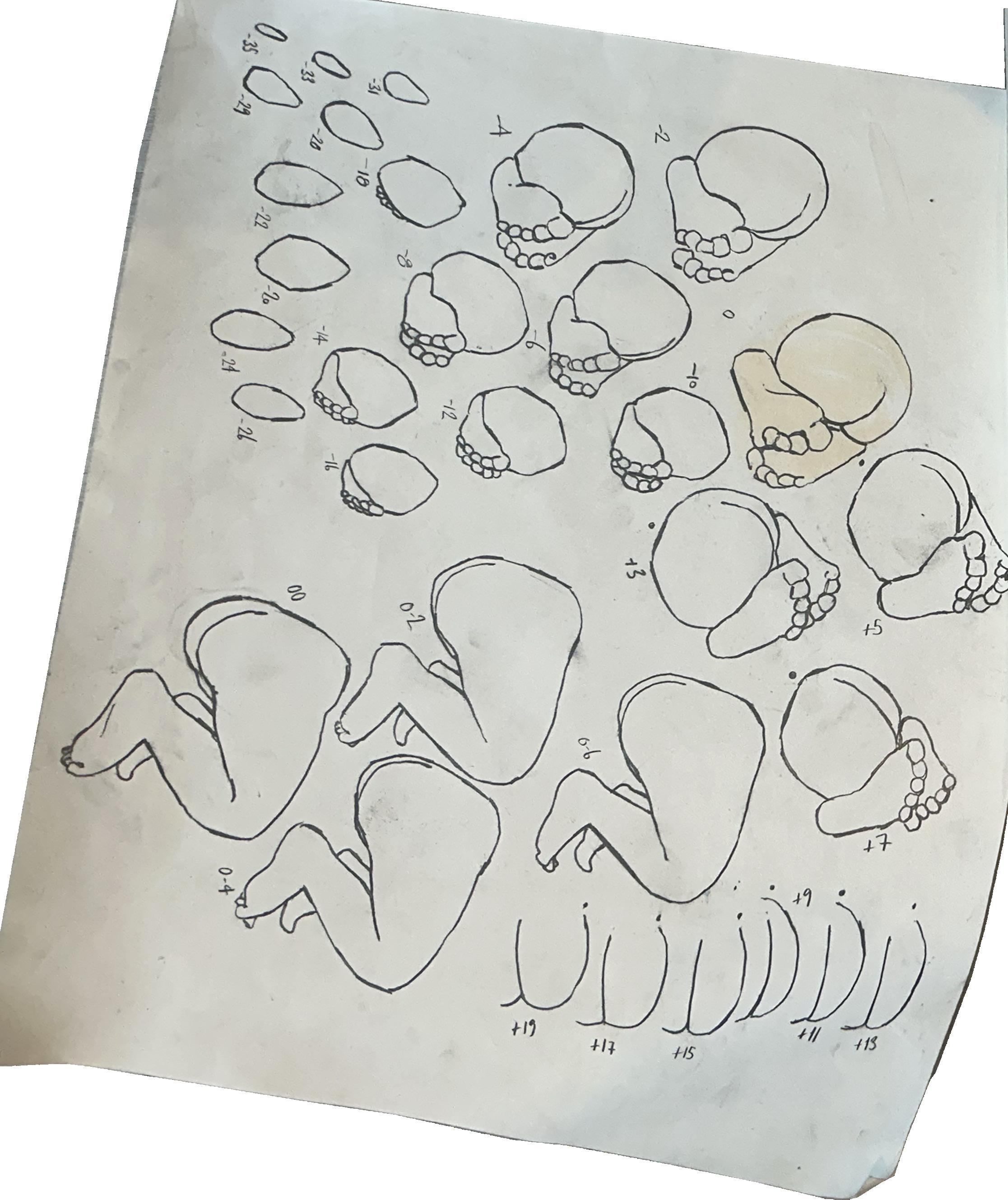

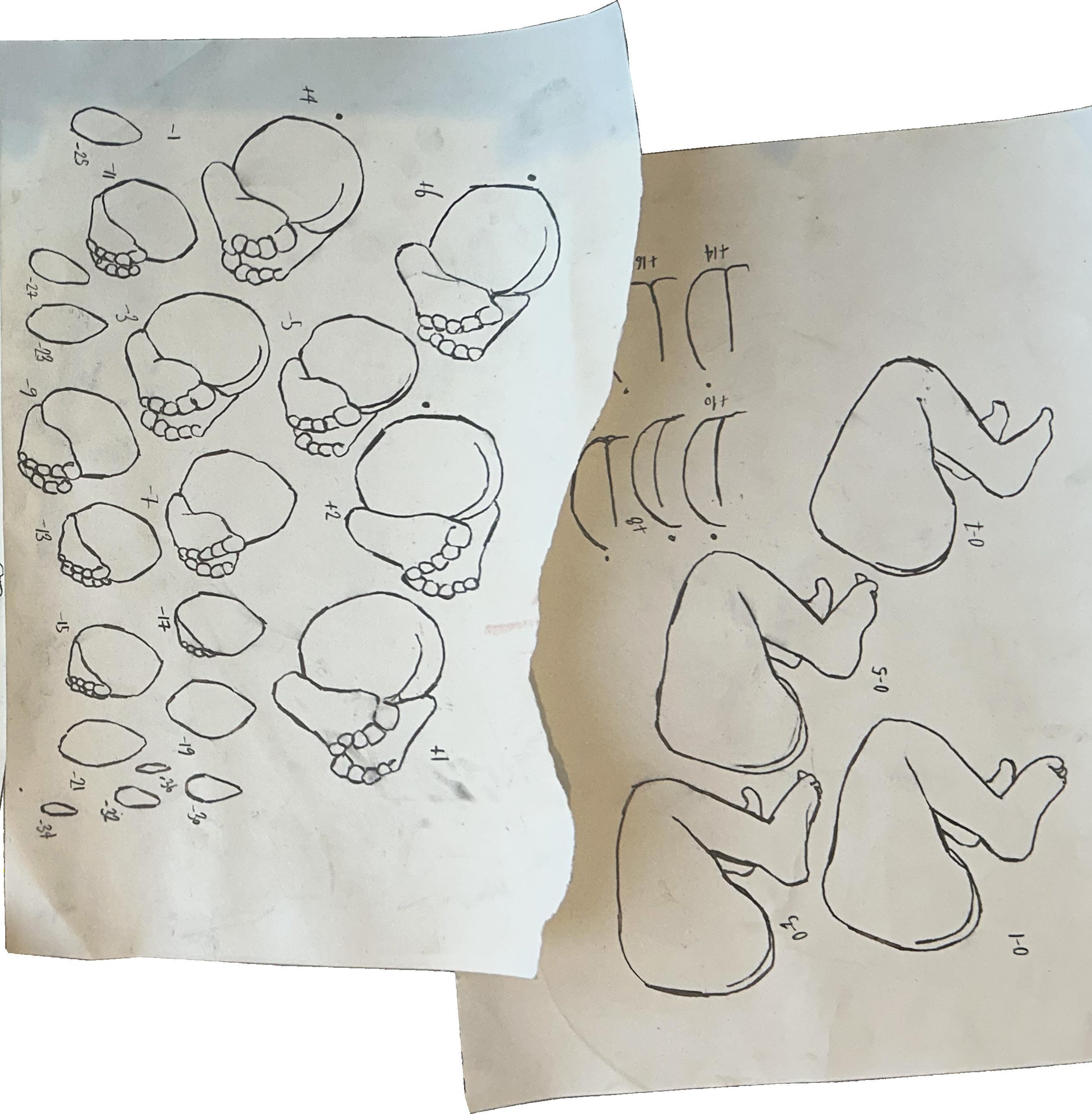

Page 6-7.....Drawn layered visualisation experimentation of representation of the uterus.

Page 8.....Drawing for animation using see through post it notes.

Page 9.....Literature Review continued.

Pages 10-13.....Listening with Andrew Baker- illustrator of ‘Body A graphic guide to us.’

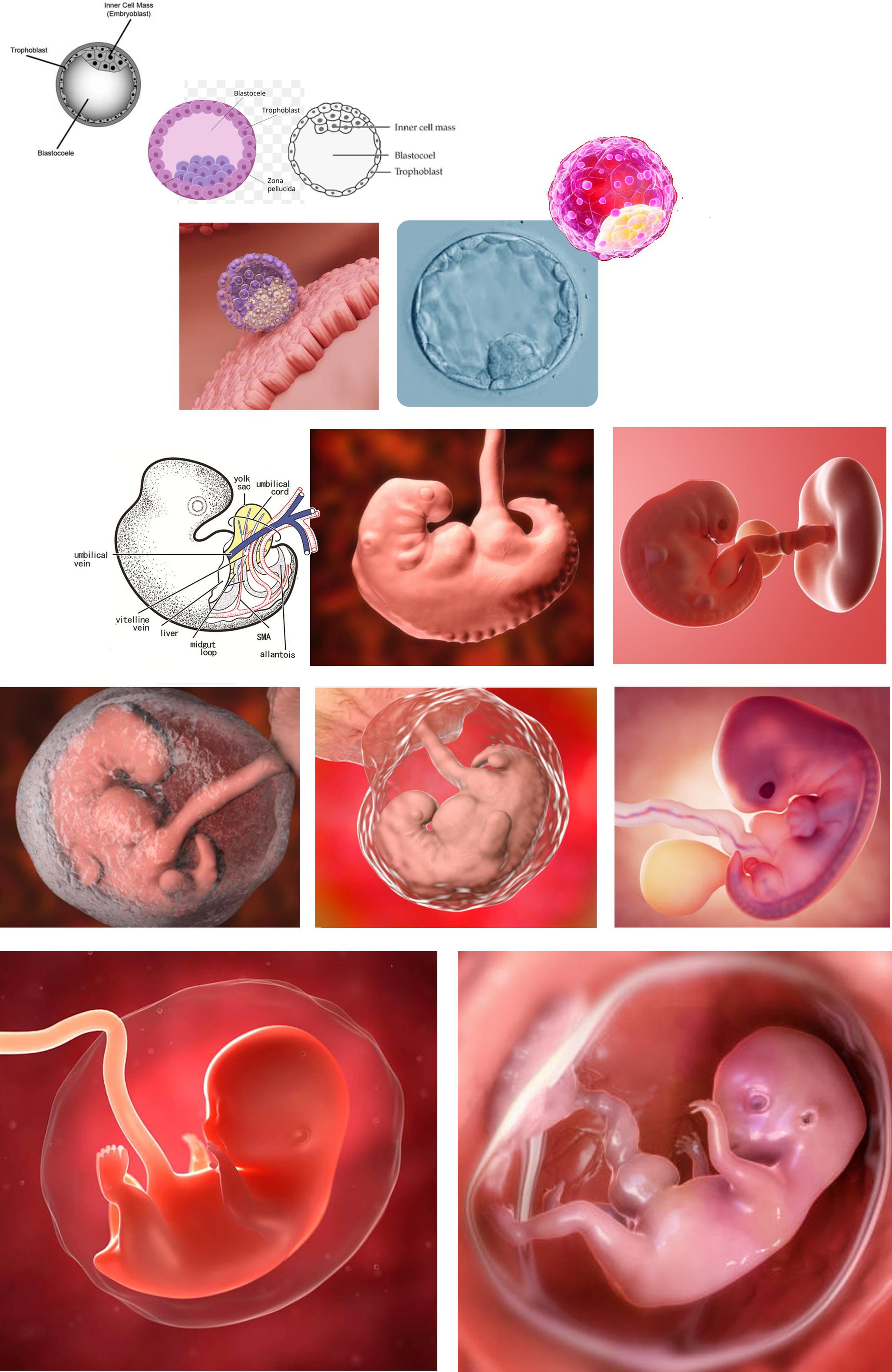

Page 14-17.....Online representation of the developing foetus and body representation.

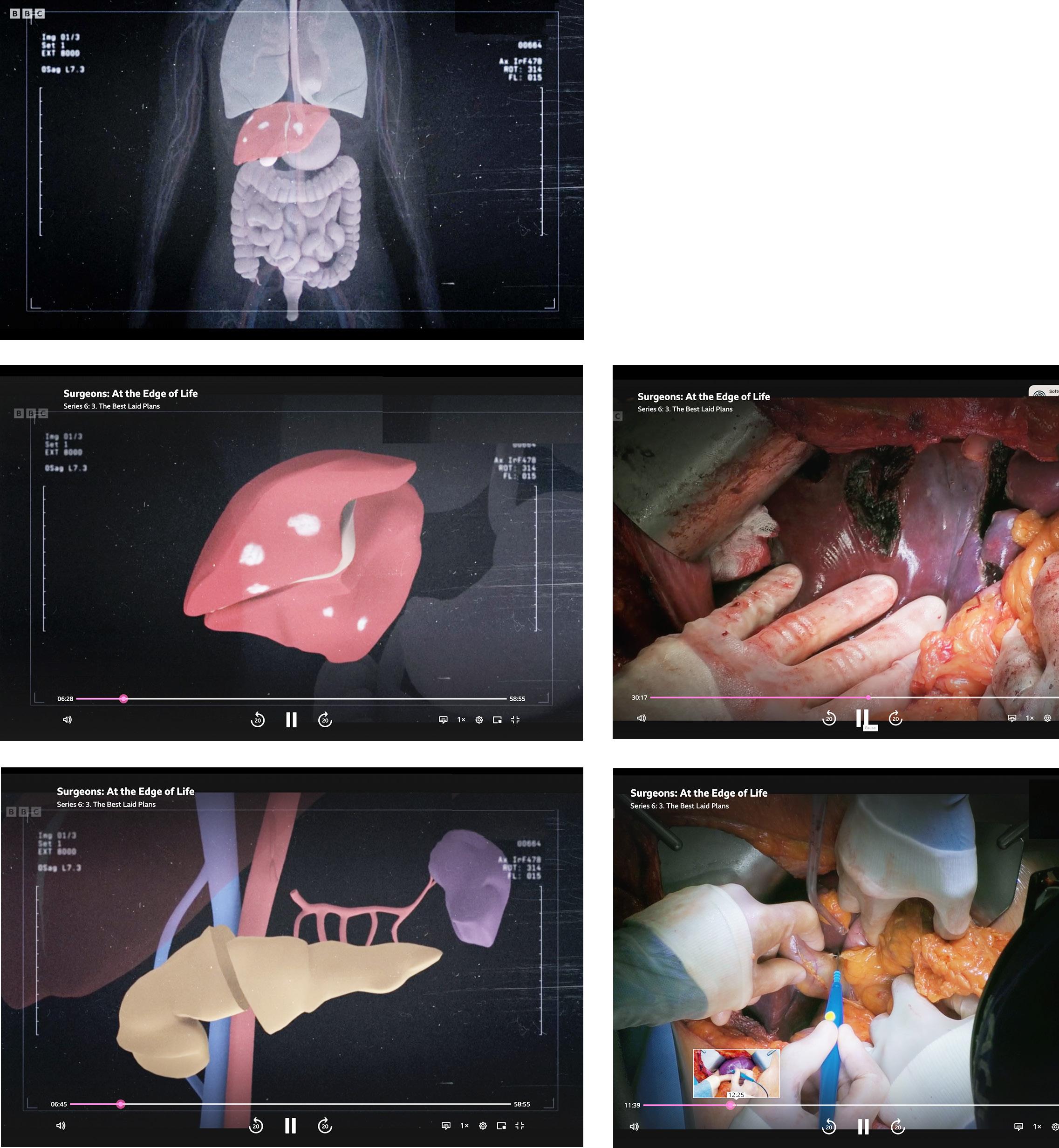

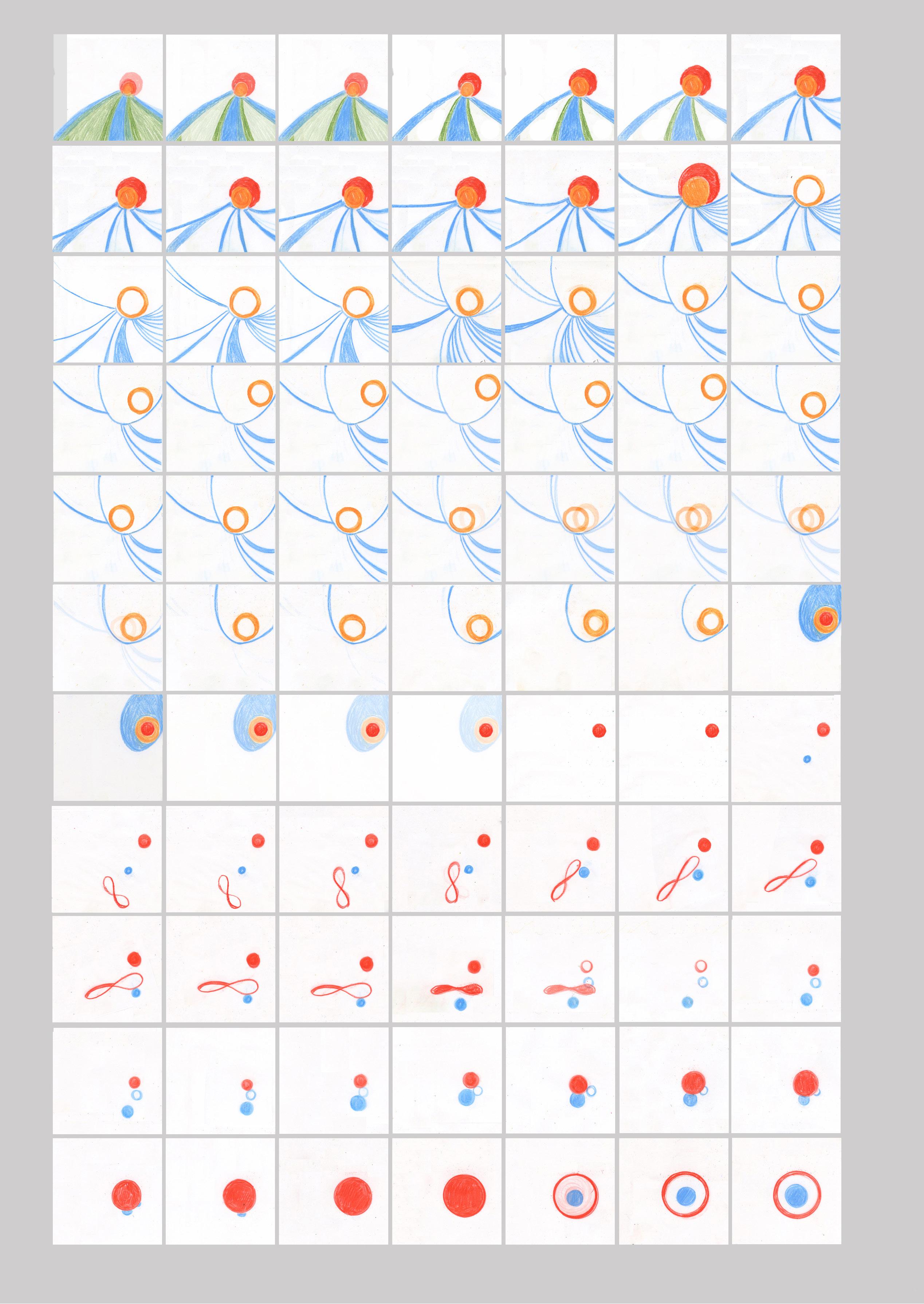

Page 18-19.....Hand drawn cells for experimental animation 1- 154

Pages 20-21.....Hand drawn cells for experimental animation 155- 308

Pages 22-23.....Hand drawn cells for experimental animation 309- 463.

Page 24-25.....Drawing of frames representing a breach birth.

Page 26.....Tutorial with Dr John Miers, notes and annotations.

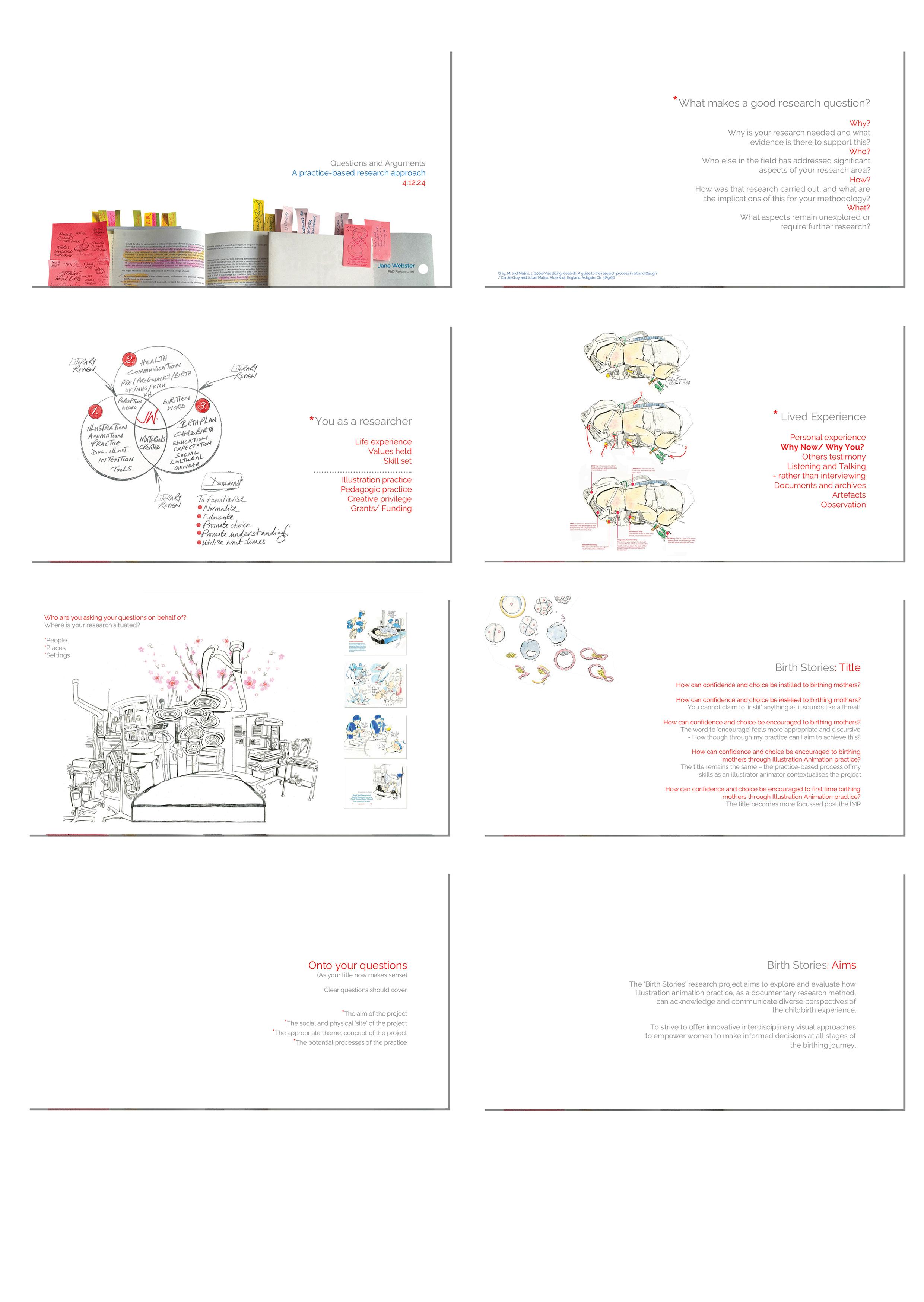

Pages 27-29.....Presentation slides for talk ‘How to formulate research questions and answers.

Page 30.....July - Feedback from Hannah Ballou, reflections from the presentation.

Page 31..... Thoughts about the Virgin Mary.

Page 32..... The HRA- Health Research Authority, proforma for the Patient Information Sheet.

Page 33..... JW Information sheet for participants.

Communication

Effective communication is vital to ensure women are supported to make informed decisions and feel listened to if they raise concerns.

NICE guidance states that services should use clear language, provide timely information and offer regular opportunities for questions. It also highlights the importance of considering people’s individual needs and preferences.

In our 2022/23 State of Care report, weidentified poor communication as an emerging theme from our initial inspections. Now that the programme has finished, we remain concerned that communication is not always good enough, particularly for those with protected characteristics under the Equality Act. Communication is also often the subject of formal complaints received by services, who have a responsibility to ensure all women are given the information they need, in a way they understand it, to make informed decisions and consent to treatment.

Communication challenges

In the feedback we received on inspections and through our Give feedback on care service, negative comments about communication during the maternity pathway outweighed positive comments. Many people told us that a lack of information negatively affected their maternity experiences and sometimes resulted in different birth outcomes than they had envisaged or hoped for:

“Nothing was explained to us at all. Everyone we spoke to had traumatic births during this period. We had been warned that they leave you and ignore you completely, which they did. You have to shout to have someone come and look at you, and fight to be heard”

“They honestly made me feel like I was inconveniencing them and they were rushing through patients. They didn’t take time to ask if I was OK and explain what ANYTHING meant. One even scared the life out of me by misdiagnosing me, luckily me and my midwife caught the discrepancy and queried it. I feel they speak to me as if I’m incompetent and unable to comprehend and then tell me to forget it and not worry when I ask genuine questions/worries.”

In addition, several people told us they felt “fobbed off” and lost trust in the people caring for them:

information to understand the reason for delaying an induction, which increased their anxiety about the consequences for their health and their baby.

On a broader level, a lack of mental health support during the maternity pathway emerged as a theme from our analysis of experiences received through Give feedback on care. Despite a recent focus on perinatal mental health, including in the NHS Long Term Plan, many women felt better communication could have reduced their anxiety. People explained that pregnancy and birth is an overwhelming experience and without clear communication, levels of anxiety can increase. Again, it is important that staff recognise this and care for women in a holistic way to improve the overall experience of having a baby

Listening to women and families

“Some

of

the midwives don’t listen to your concerns and you feel like you’re always being fobbed off or your concerns aren’t being

“I asked several times to be examined, to which I was told there was no need! I couldn’t even sit down my baby had dropped so low, at 7ish I had a bad bleed so someone finally came and examined me and was told I was 7cm!! I had been saying for hours I was progressing and was fobbed off.”

Many people highlighted poor communication during the antenatal pathway, noting they were not given enough time to ask questions. We also heard that staff did not always provide enough information about the harms and risks associated with their pregnancy. Some of these people told us about how they were made to feel like an inconvenience:

This feedback is supported by the findings of our 2023 Maternity survey, which found a 5-year downward trend for respondents saying they were ‘always’ given the information and explanations they needed while in hospital after the birth. This year’s results found 60% of respondents reporting that they ‘always’ received the information and explanations they needed, compared with 65% in 2018.

It is essential that women feel listened to by staff, especially when they are in pain. From April 2024, the first phase of the introduction of Martha’s Rule will be implemented in the NHS. This will allow patients and families to request a review if they feel their concerns are not being listened to. In maternity services, it may help women make sure that their concerns are heard, as during the programme, we were concerned to hear about instances where people felt that staff did not listen to their requests for pain relief. In some cases, this resulted in poor pain management during birth

“The staff weren’t listening to my worry of not having pain relief and managing without an epidural with my mental health as well as my physical health. By the time the midwife took me over to the room, my labour was unbearably painful, and I was told that it was too late for the epidural. I gave birth with no pain relief – not even paracetamol and I was very disappointed and frustrated that they didn’t listen to me when I knew what my body was going to do.”

“I was not listened to by the healthcare professionals during my labour and they were not managing my pain. I was left for several hours despite asking for help.”

“When I first went into labour I contacted [name of hospital] for advice. I contacted them 4 times as I was in agony with the pain but was told to stay at home because it was my first child. I felt I had been stereotyped because it was my first child and didn’t know how much pain I would be in. When I eventually arrived at hospital after deciding just to go in because I was in so much pain I was actually 7cm dilated.”

“Communication should just be better, it would help if the staff remembered that it might be all routine for them, but for patients it’s very much a new and potentially traumatic time. And communicating in a sensitive way goes a long way.”

Communication around induction of labour was a key issue. Inductions are often offered when babies are overdue or if there is a risk to their health. While inductions are becoming more common, it is vital that staff recognise that the process can be difficult for women as some may be disappointed about being induced and the process can be painful. Effective communication therefore plays a key role in shaping the experience

Inductions are often planned in advance and while it may be medically appropriate for someone to wait to be induced, we found that this is not always explained to women. Some women felt they were given insufficient

Even when women asked for help to manage their pain, they were sometimes not given the help they asked for. Through our research interviewing midwives and obstetricians from ethnic minority groups, we heard how false beliefs around physical characteristics and symptoms can mean some people are denied pain relief. Interviewees reported hearing racial bias in pain assessment, for example:

“Black women have thicker skin, so they are less likely have a tear after delivery.”

“You are African, you are tough – you don’t need pain relief, get on with it.”

Stereotyping and a lack of cultural awareness can significantly affect people’s experience of care, as we outline in the section of this report on inequalities.

People whose first language is not English face additional inequalities. Access to and the quality of interpreting services varied and continues to be a theme in patient safety incidents nationally. We found some pockets of good practice, for example in one service, the Non-English-Speaking Team (NEST) hosted an antenatal clinic using translation services with midwifery and consultant support. Home visits could be arranged and information was provided in the woman’s first language, allowing people to make the right choice for themselves and their babies.

However, our interviews with midwives and obstetricians from ethnic minority groups highlighted that having poor or no spoken English was associated with worse experiences of care:

“Staff need to be very mindful that you will get people nodding their head but not understanding. And instead of just choosing to accept that, staff need to make sure that they have understood.”

“My summary is, if you are White you will get good care. If you are not White but you speak English, it’s OK, you will get what you need. If you have poor English –it’s going to be the very basic standard.”

Communication between staff

Multiple studies have shown a link between effective communication and safety in maternity services. Teamwork, co-operation and positive working relationships combined with effective co-ordination are also 2 of the 7 features of safe maternity services identified in research by THIS Institute. Where staff communicated effectively, people told us this had a positive impact on their experience.

A small number of women explained how poor staff hand overs had a detrimental impact on their care.

* notably access to pain relief:

“The lack of continuity of care was also a contributing factor to my difficult delivery and eventual caesarean. There was little hand over between most clinicians during my delivery and no handover between 2 clinicians, this also led to difficulties and unnecessary pain.”

“There was no consistency of care during labour. I had the gel and my contractions were really painful and I could tell that the baby was on the way. The midwife wasn’t listening to us and actively put off examination due to a change-over of staff.”

We also heard from several people who had to repeat information about their medical history, or preferences about their care because of a disconnect between staff:

“There was also a disconnect between consultants, midwives and obstetricians, all of whom seemed to have a different opinion on induction timings.”

“I saw a different doctor from the diabetic team for every appointment, so I had to tell each one my history.

Informed choice and consent

It is essential that women are clear about the risks and benefits of different birthing choices and treatment options. Staff also need to ensure the language they use is accessible so that women know what to expect when they consent to procedures and examinations. Everyone has a right to physical autonomy and integrity, and good communication is vital in empowering people to make informed decisions about their care.

When we found good examples of communication and information-sharing, women praised clear and transparent explanations from staff, which meant that they were able to make more informed choices:

“My second midwife ] was brilliant, I witnessed a team who worked seamlessly together, handing over information about my care which made me feel confident in the continuity of the high standards of care I was receiving.”

On all our inspection visits we reviewed the quality of communication and co-ordination at morning multidisciplinary handover meetings on labour wards. These meetings are critical for staff to understand how to manage current risks across the unit. They are also an opportunity for staff to share learning.

“My husband said that the day my son was born, the maternity department was very busy but I was completely oblivious to this as not one midwife or doctor made me feel like this, I felt like everyone gave me the time I needed and we were able to discuss options, ask questions and make plans about our care.”

“I had loads of questions and anxieties regarding pain relief and labour, and they were able to answer all of my questions and made me feel at ease. I felt as though I was in good hands.”

However, this was not always the case, for example, one person told us about feeling a lack of choice about being induced.

“I was induced. It did feel as though I was being ‘told’ that I had to be induced. When I expressed my reluctance for an induction a consultant was sent to speak to me. It would have been more helpful to understand the clinical rationale and risk v benefits of induction versus waiting. The only explanation I received was that ‘baby is to term and it won’t affect baby being born early’. I felt this could have been explained more thoroughly and would help me to make an informed decision rather than feeling ‘forced’.”

In our interviews with midwives and obstetricians from ethnic minority backgrounds, staff identified other factors, along with language barriers, which can lead to a lack of choice. This included cultural perceptions of authority, where people from some ethnic minority groups may be more inclined (or perceived by staff to be more inclined) to accept the advice of health professionals without questioning it. Concerningly, interviewees also suggested that staff may not always offer choice, because they know they will not be challenged. Perhaps most worryingly, we also heard about perceptions around who is ‘entitled’ to care, and this sometimes affected the level of choice offered.

Accessing digital maternity records

In line with recommendations in NHS England’s 3-year delivery plan most services have adopted digital records and have maternity records apps to enable women to view their records at home. We heard a few positive comments about the functionality of the maternity records apps and how it contributed positively to the maternity experience as people could access their records, store their birth plan and receive reminders about upcoming appointments.

The use of digital technology is not always i nclusive. In our Safety, equity and engagement in maternity report, and through our engagement with MNVPs, Five X More and National Maternity Voices, we heard concerns that reliance on digital technology to engage women and provide them with the information they needed could exclude women who do not have the access to, or skills to use, digital technology.

The [maternity records app] does not update and let patients know about the care and tests they have received. This left me very anxious during my first few appointments and being pregnant for the first time.

The use of digital technology is not always inclusive. In our Safety, equity and engagement in maternity report, and through our engagement with MNVPs, Five X More and National Maternity Voices, we heard concerns that reliance on digital technology to engage women and provide them with the information they needed could exclude women who do not have the access to, or skills to use, digital technology.

https://www.cqc.org.uk/publications/maternityservices-2022-2024/communication

I am continuing to develop a range of visual languages that can be appropriate for the project so that alternatives can be ready once the ethics clearance has been achieved. Developing illustration practice takes time to design the nuances of why a particular opacity works over another and how the scientific or the glossy shine of the imagery found on Getty is more or less appropriate, inviting or communicative. What will ‘talk’ to mothers to engage with accessing the examples or information relevant to their specific birth story?

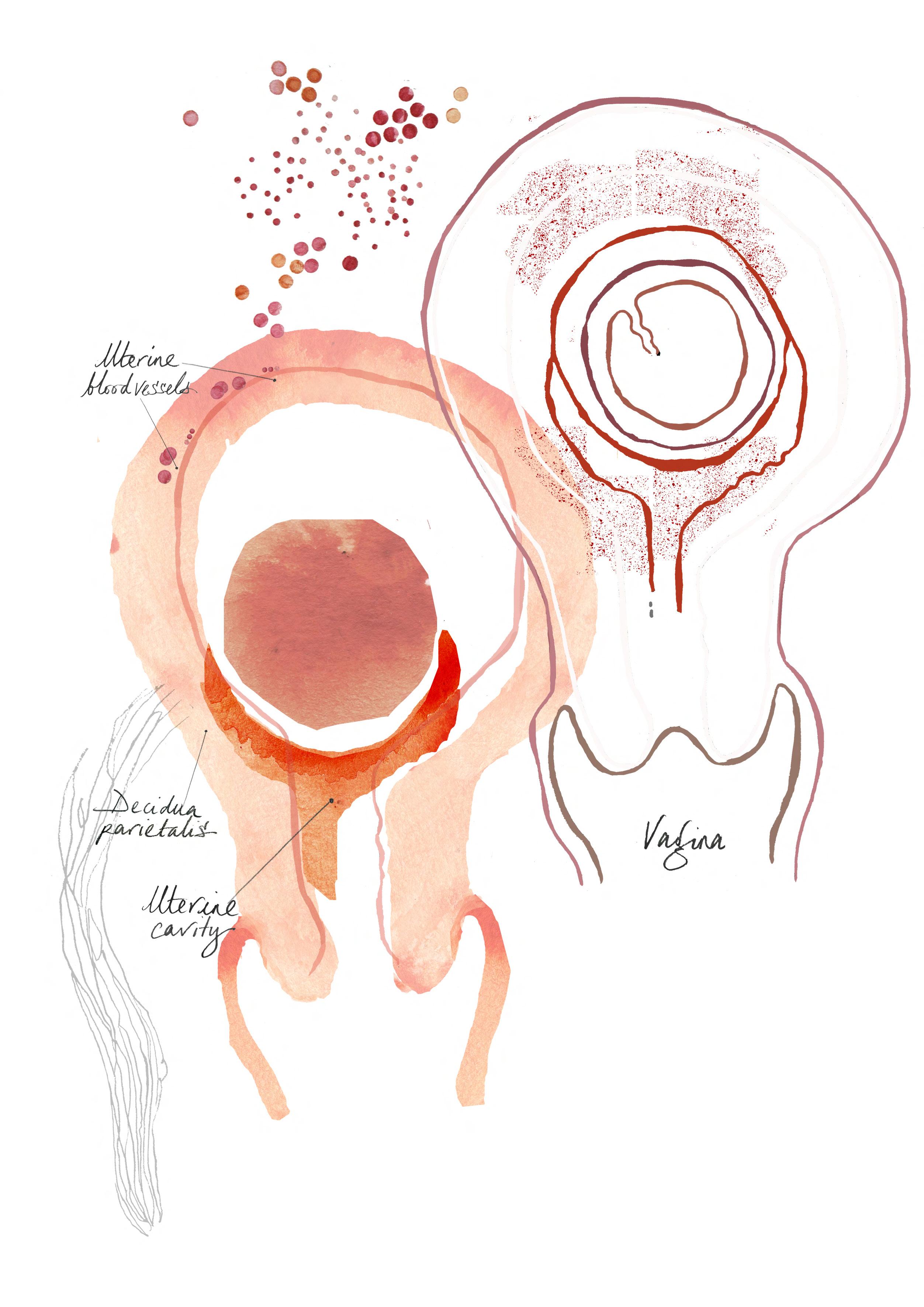

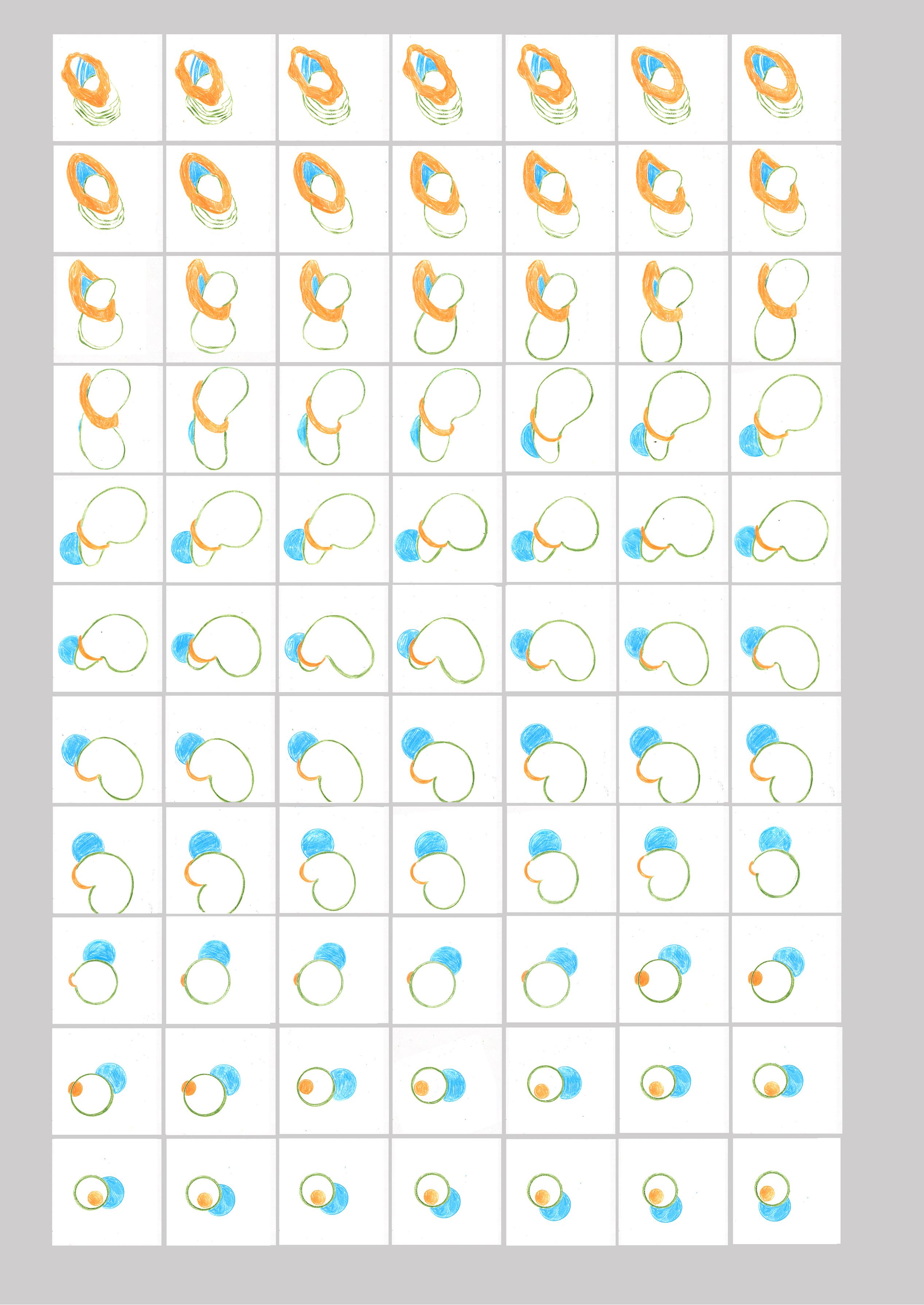

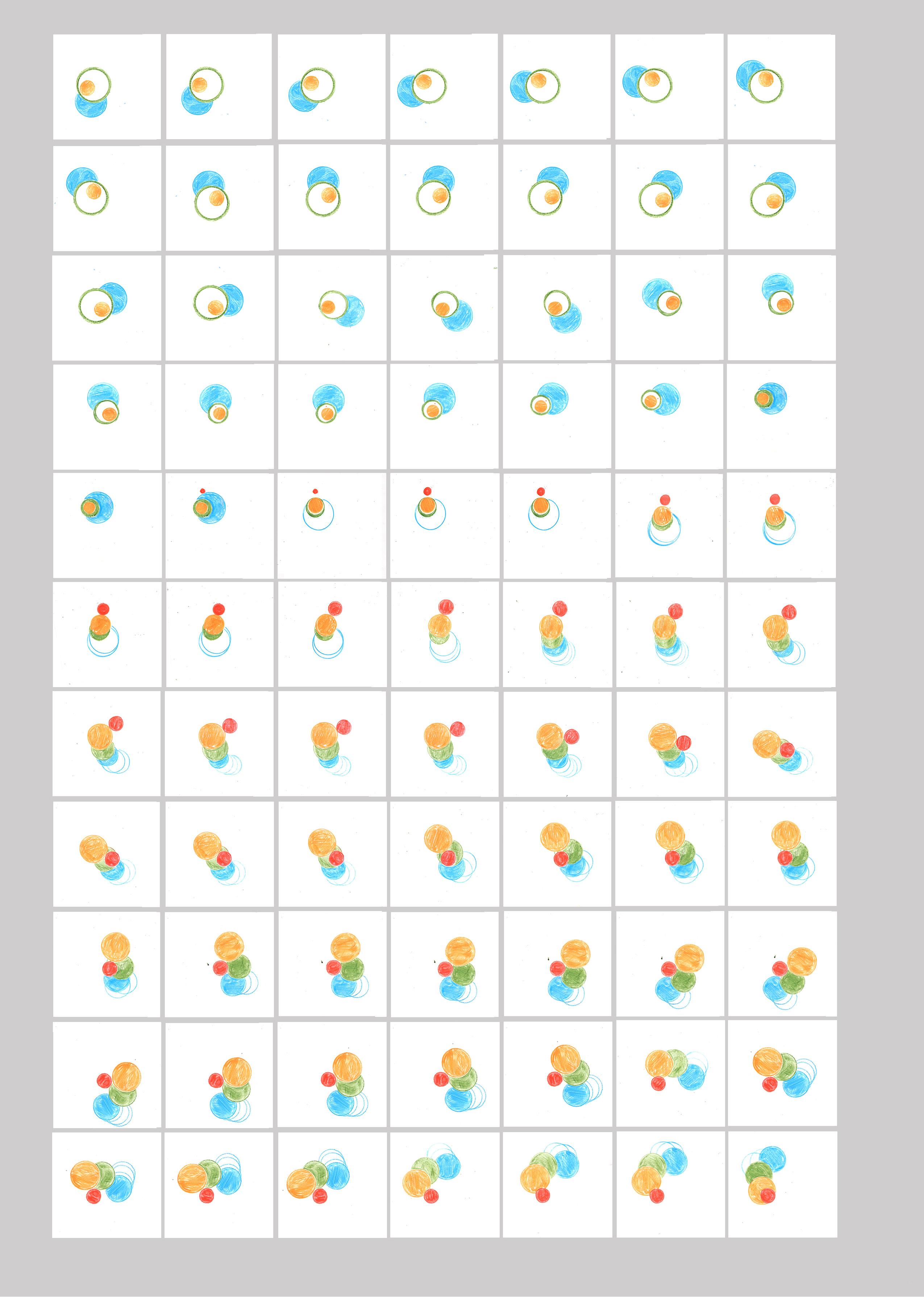

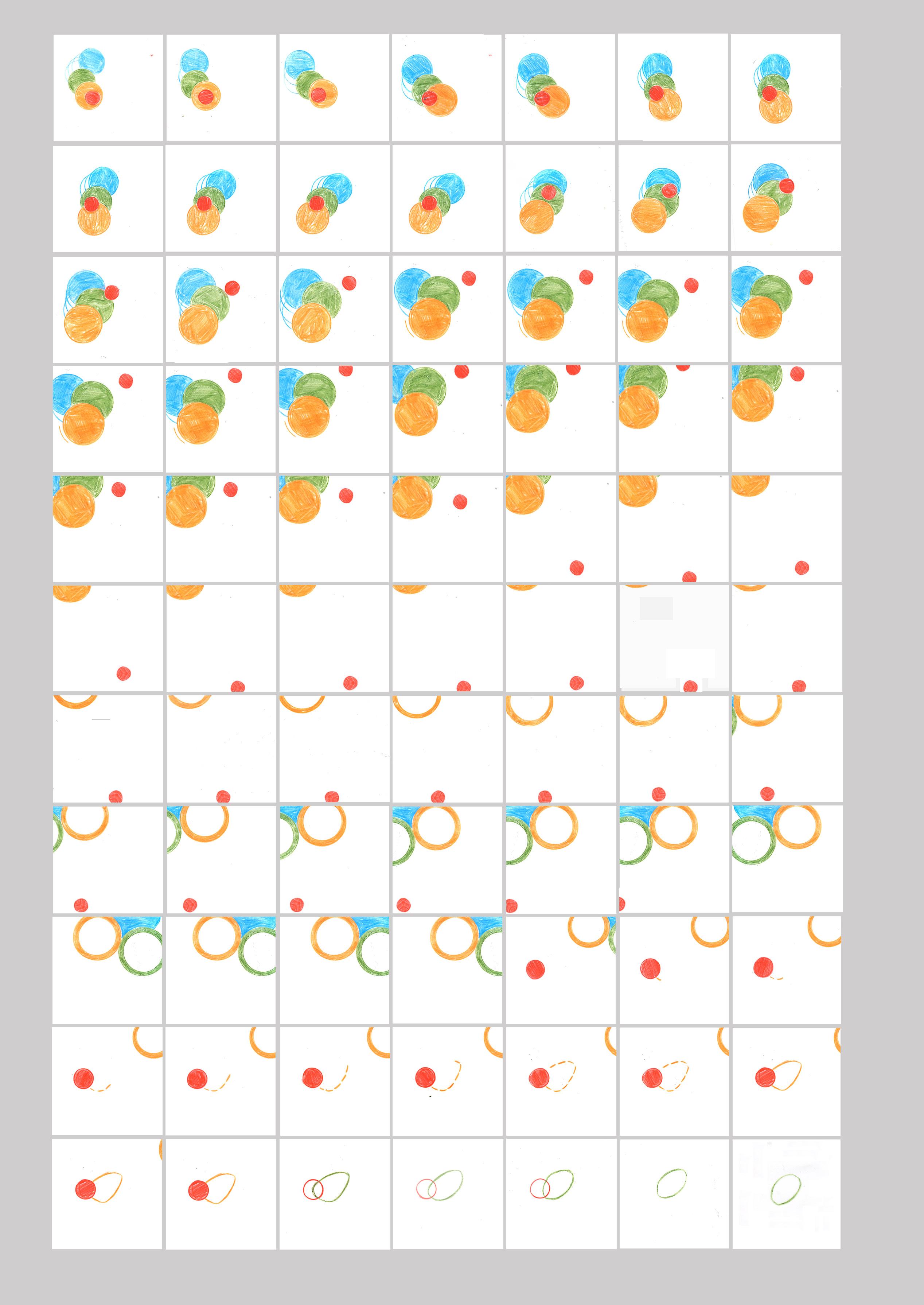

Drawing for animation.

I have discovered clear Post-it notes, ideal for stop-motion drawn experiments. I have used this material to create a 500-frame experimental ‘stream of consciousness’ animation, where I have not concerned myself with anything other than the transition of colour and movement. The cells are evidenced later on this reader.

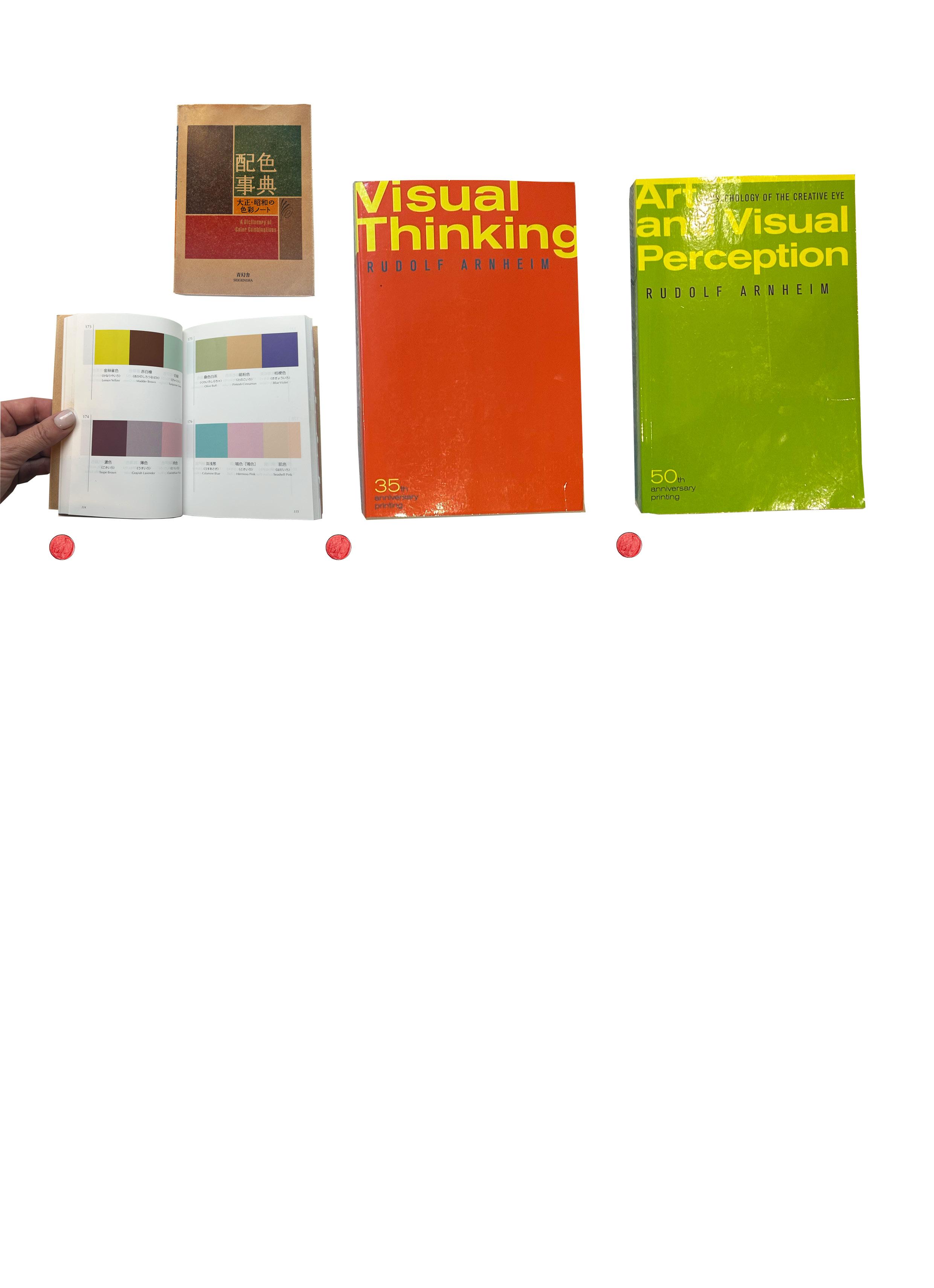

A Dictionary of Colour Combinations

Various Seigensha Art Publishing 2011

ISBN 978-4861522475

This pocket-size book is a rich resource for any creative. I have recommended it to countless numbers of students, who either demonstrate a sophisticated or bold sense of colour use. Or, most often, for the other end of the spectrum - where we work predominantly digitally, and students no longer have the luxury of mixing colour and randomly picking at computer colour swatches—students with, at best, a hitand-miss, pick-and-mix understanding of colour calibration and association.

Japanese artist Sanzo Wada (1883–1967) was a teacher, costume and kimono designer. He worked during a turbulent time in avant-garde Japanese art and cinema. Wada was ahead of his time in developing traditional and Western-influenced colour combinations, helping to lay the foundations for contemporary colour research. This pleasingly scaled book is based on his original six-volume work from the 1930s, offering 348 colour combinations as attractive and sophisticated as the book’s hand-held print and design layout quality.

It is a beautiful reference tool as the range of colour combinations - is wild, suggesting 4, 3 and 2 colour groupings of suggestions few of us would be confident going there. This book allows students to work boldly with colour and a broad space to experiment to gain confidence.

Rudolph Arnheim

Universitu of California 1969

ISBN 978-0-520-24226-5

A six-month marathon of a text has been a crisscrossing of enlightenment and questioning. The fact that Arnheim wrote the book 35 years ago shows its continuous relevance in a visual world that is arguably more complex than that of 1969. The writing and tone were more accessible than I thought, and the chapters are titled to allow the reader to make sense of and build upon the theory. The importance of images in the understanding and contextualisation the world we inhabit is made clear through the chapters. The written text takes time to export and absorb in relation to drawings, stalling the creative process of unpacking and organising information. I was unaware of the term ‘Gestalt’ psychology- and the difference from cognitive psychology. Cognitive is focused on mental processes such as memory, perception, and problem-solving. Gestalt examines the mind and body holistically, the idea that human perception is not just about seeing what is present in the world around us- being heavily influenced by our motivations and expectations.

As designers, we focus on the hierarchy of information and how the design talks to an audience; we are working with the focal object - an image, an object, and the space this sits in inhabits within the negative space of a page or a physical space. The association of imagery in relation to other elements is presented such as an image with a caption or title or as a sequence. Having a long track record of teaching and creating imagery as an illustrator, this text makes sense and has been enlightening;

much seems common sense. I wish I had been aware of the book much earlier in my career in a reassuring feeling that intuitive decision-making as a visual practitioner is something to be trusted.

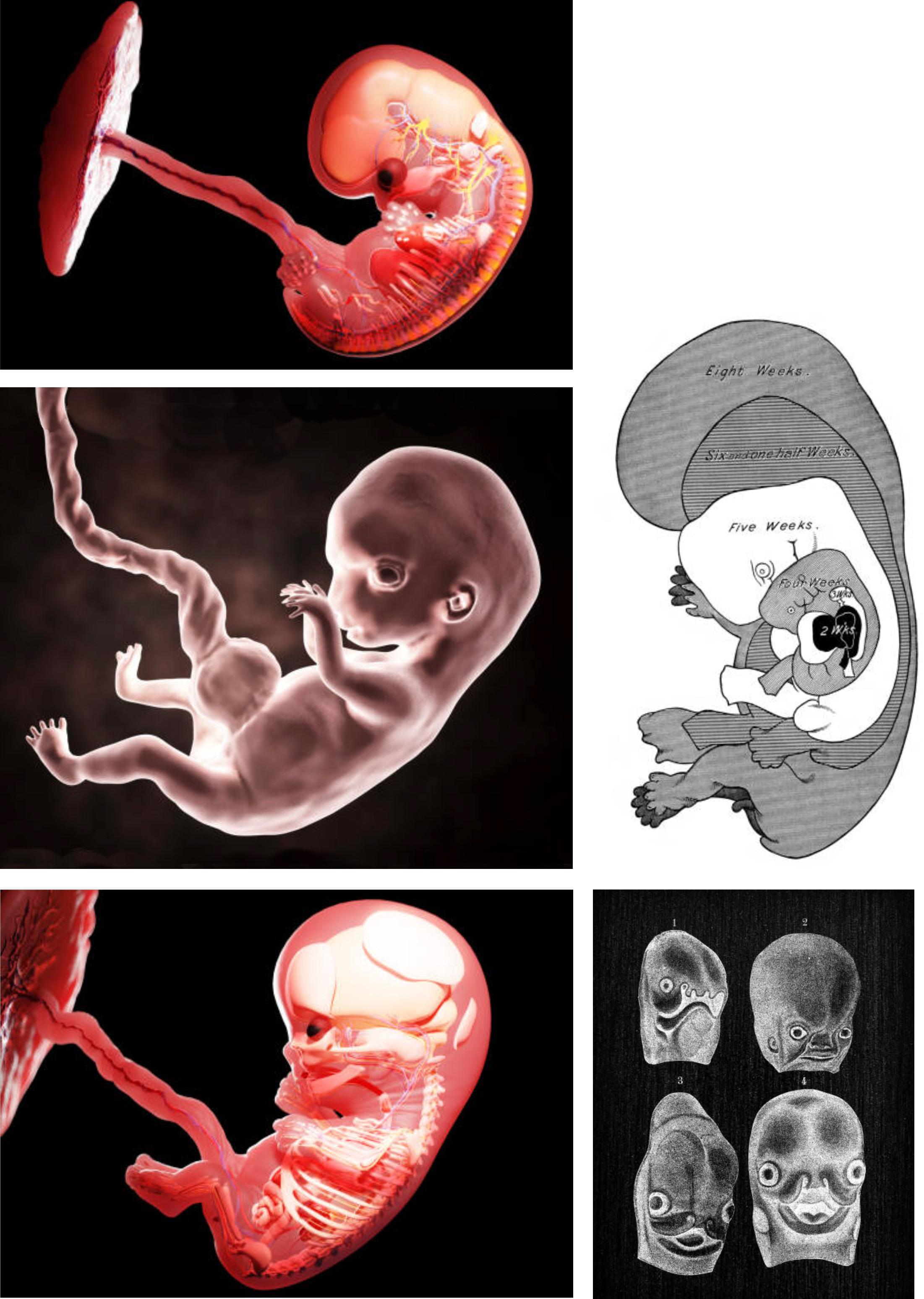

Regarding my research project, the book’s takeaway is from the last chapter, Vision in Education: Focus on Function. Here, the reality or sense of reality or realism in a drawing allows the viewer to receive the information with a sense of belief. We believe in the information that a map offers, as we are brought up with the assumption that a map is an accurate representation of a physical space. Page 314 touches on how Da Vinci successfully represented his anatomical drawings. He visually describes the muscles and tendons as analogies of use as function or as an inventory of an invention through spatial relationships. In looking at other examples of visual representation of the body- especially the representation of embryology and pregnancy on sites such as Getty and the BBC, Arnheim’s Visual Thinking text has provided a thought-provoking sense of grounding to start looking at and considering the loaded and ingrained ‘baggage’ that the association of visuals has to us as viewers in the presentation and the tone of the imagery.

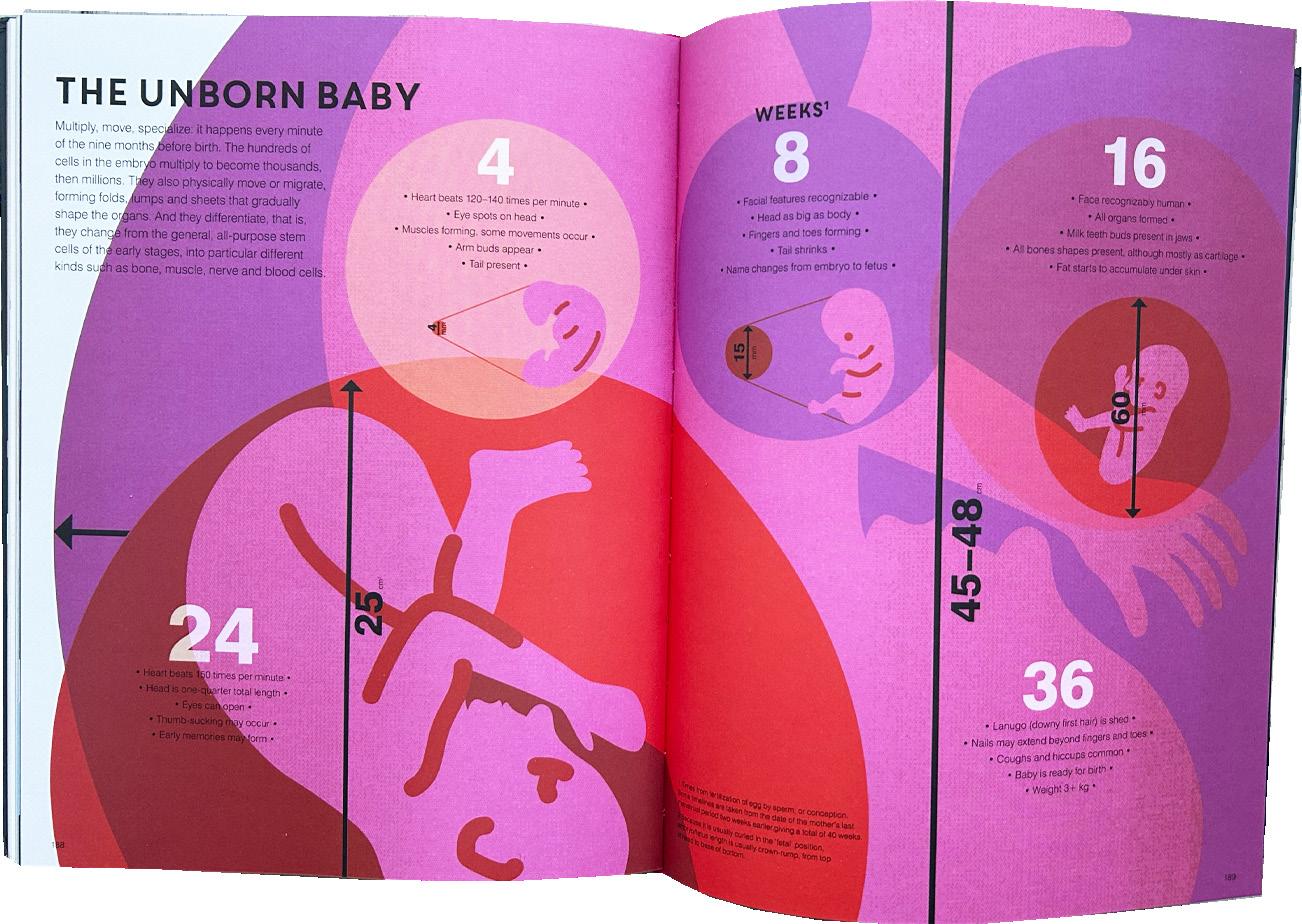

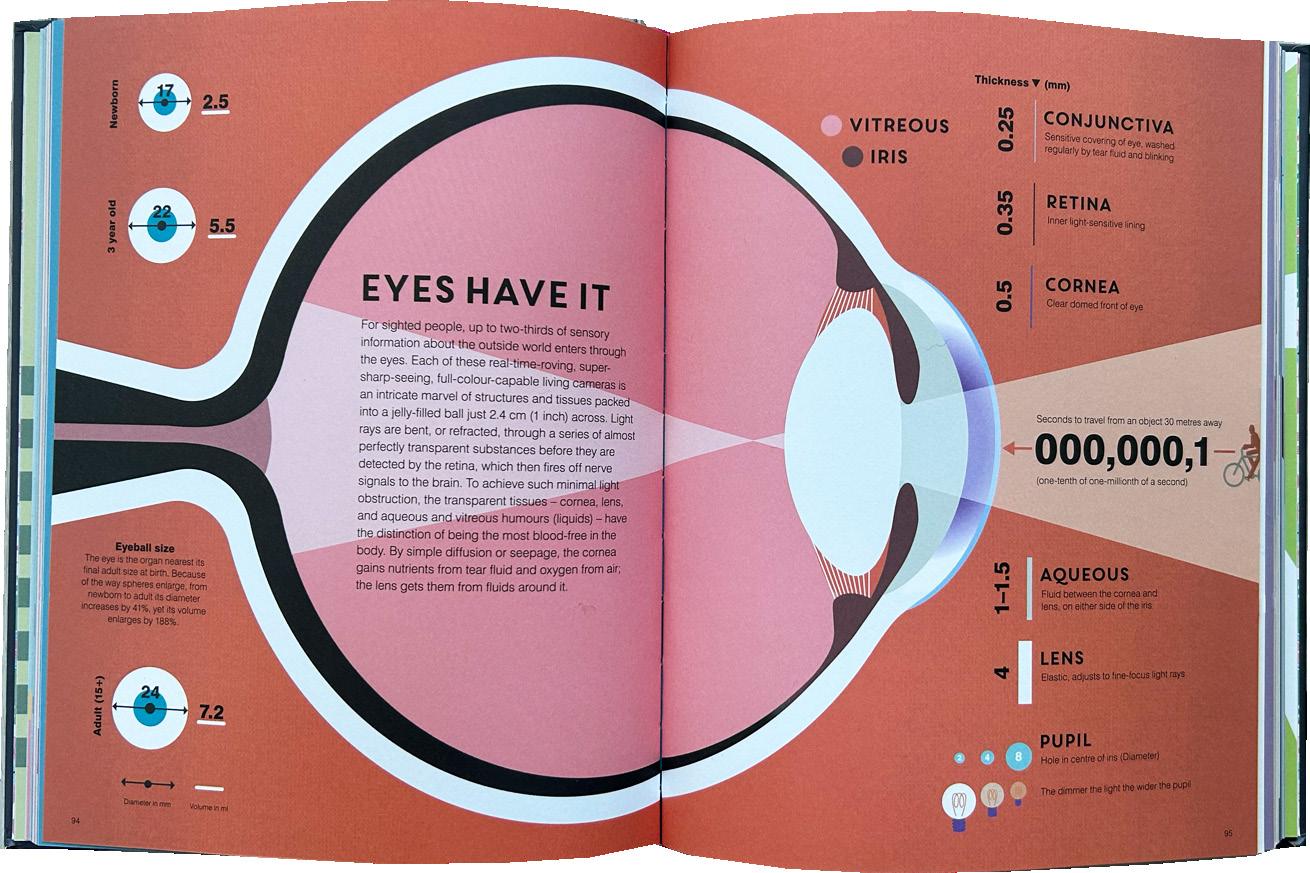

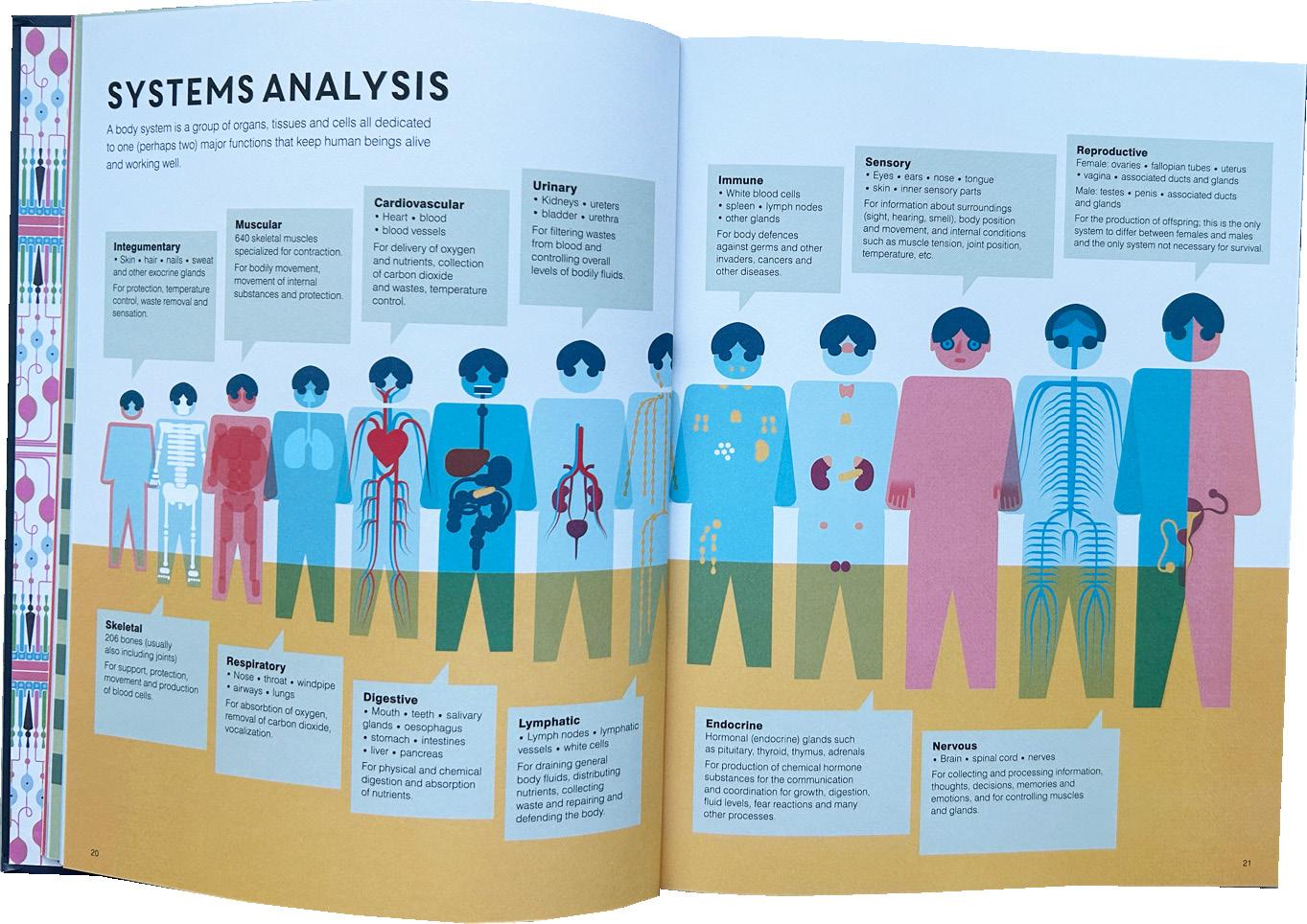

BODY- A Graphic Guide to Us.

Steve Parker & Andrew Baker

Aurum 2016

ISBN 978-1-78131-593-2

Listening with Andrew Baker - Illustrator of BODY- A Graphic Guide to Us.

JW -Red

AB- Black

So, Jane I hear that you are doing a PhD.

I am indeed, which is why I wanted to talk to you as an award winning illustrator to you about your book. I have just started my third year.

I don’t know how you’ve been getting on with it so far. How does it feel?

I’m working very hard. And I feel so passionate about the subject, so that is the reason I wanted to talk to you about your experience.

It is your subject, isn’t it- the body?

Yes! And it is really weird just going back realising I went back to things that I was looking at 30 years ago.

Well I remember you bringing in to Epsom your kind of physiology objects were they teaching aids about the body for kids.

So it’s kind of gone full circle and then so basically I’m doing a project which is about women understanding choice and confidence in the process of going through their pregnancy, but also through birth, where obviously everything is not normally as anything you want. So I’m making animated examples of like, we’re going to move you into another room, this is what this room is going to look like, this is what these machines are going to be, or you know, your baby’s got a hernia and some of its bowel

is on the outside and this is what it’s going to look like when it’s born and this is what we’re going to do.

I mean yeah Linda has some stories to tell, I was witness to them and you know both of Linda’s births were problematic in different ways. And I don’t know if we also like it, but it’s very, encouraging that you could solve a whole bunch of myths.

There is a lot of gate holding and we don’t see images of babies being born so we have no understanding of what that looks like and if you look at birth materials on social media such as Instagram, all the posts are covered as it’s deemed so offensive to see a vagina having a baby coming out of it and not having something an implement being put in it. So there’s a huge lack of visual information of what births in all shapes and form look like? So I am exploring how drawing can be a tool for this communication.

Yes, well I do maybe feel like I’m not really qualified to talk about that kind of stuff. But I mean I did do a section on pregnancy in the body book. I don’t know if you’ve seen that book.

I have seen your body book, which I have here. You’re under the label of being an excellent medical illustrator.

One of the students told me this- I mean, I don’t know where this has come from.

Well if you look for, if you look for medical illustrators, you’re up there as an award winning medical illustrator.

Well that’s very interesting but that must be just it must be mostly from that must be it and I think there was I was covered in some review of interesting medical instructors but they had lots of different people doing different kinds of work and I think that is the start of it.

I know your work as being explanatoryshowing how thinks link up, and how things work- info-graphics with humour and it feels handmade, it feels like it’s had a hand with it because it’s textured. I was looking at it the other day thinking why does it look like this? And you know the fact that it doesn’t look shiny, it looks beautiful on uncoated paper it’s not glistening.

I think working on it was quite the process. Can I just tell you a little bit about how I designed this book? Yeah, please. It came out of the blue and it was after D&AD I was just leaving and I was actually having a cup of coffee down at a little, it’s that market isn’t it, near, what’s it called, you know where it is.

Spitalfields?

Spitalfields market! I’m no longer a Londoner anymore! So I was having a coffee there with Martin or somebody, and my phone rang and was Andrew from Debutart -who never calls, always emails. He ran it by me and he said it’d be a lot of work probably about a year’s work and I kind of slightly bought to the prospect anyway I went home sat down with Linda worked out and he was 200 pages of illustration and you don’t have a year to do it. • I wanted to know what that actually meant and I thought this is really going to be impossible. But if I don’t do it, and I see it in the shops and somebody else has done it, I’ll just be beside

myself with jealousy. So I just said yes and originally the fee was going to be something kind of decent, like, for £34,000. Obviously by the time I ended up getting paid I think it was about £20,000. But it came out of the blue, it was just, it was from Aurum Publishing, based in Islington. I went in to see them and I can’t remember the name of the woman who commissioned me, no, we should explain. We really want you to do it. We’ve seen your illustration. It’s friendly, it’s colourful, it’s informative. You haven’t done that much info-graphics, but we obviously can see that you would be good at it. I said, oh, that sounds very nice. I like to use test pages. And there was the children’s book fair, I think it was...?

Was it Bologne?

Yes, Bologne.

So I prepared, I think, I think it was about 10 spreads of that within about two weeks. And that was it, they loved them, and they went down well at Bologne. I did all the graphic design. That’s the key to the book, actually, Jane, is the fact that I did it all for myself. It was the writer, Steve Parker, there he is, who I never met. An older guy who’s done loads and loads and loads of books on all kinds of subjects. He sent me a bunch of facts on each section, facts and figures, that I bought. So I had quite a lot of control over the content. I then had control over the layout. I then had control over the typography and where the typography went, which is why it looks quite nice. There’s a lot of plates of hand and smoke and mirrors going on there in terms of the design because I would realise that a really big eyeball is a beautiful thing to look at, and I would then articulate all little things around it. I would realise that a knee joint wasn’t such a beautiful thing as an eye to look at, so I would do a typology of them on a page and lay them out fairly quickly. So I was led by the visuals, what I thought would look really attractive.

It looks beautiful the book. I haven’t got it. I want to get it from World of Books. I found a similar one that’s really beautiful, that’s all about taste and about how all different things go together in terms of processes and flavours.

Oh is it? This is Nora Rowe?

It looks like the same publisher?

Is it Aurum? With an A on the side? Yeah. Yeah, so it’s a good little set of them. After I finished this, they came back to me and said, we really love it. I met the publisher and said, oh we really love it, I think it’s one of the best books ever on the human body. Oh we’d love to give you some more work. And about a week later I got a phone call saying, would you like to do another book? And I said, well, here’s what it is. And they told me and it sounded quite interesting. And then they said, but it’s going to be half the price. And I just kind of went.

No.

As illustrating it - it nearly killed me doing it. I worked every single day except Valentine’s Day and Christmas Day. Oh my god. For nine months and I worked until news night started. From when I got up in the morning at seven until when news night started. Shit. And well, yeah, I was making this with you and Watson and the like. But, and it was too much for me, actually. And in the end, I think I, you know, this

is probably why I’m here in Edinburgh, because I kind of just came out of that thinking, I had that exhibition at the Coningsby Gallery. I just kind of thought, do you know what, I think I’ll fly it. I think I need to change it. I think I’m done. Yeah, I produced something really good. Time for a break. Yeah. You know, kind of like an extreme case of resting on my laurels. Yeah. I thought I just need a break. I’m not getting satisfied by being a Middlesex and I’m not getting satisfied by my inspiration work., I was getting grumpy, really grumpy, I was tired, I didn’t want to do, I was dependent on academia, it didn’t value anything that I did in terms of my illustration work. I did one little talk about the landscaping comics up here in Edinburgh, and I got more attention for that than for any piece of illustration, including the body work.

Gosh

I thought, this is pathetic. That bit of research took me a few nights’ work. That’s like the same as one illustration. Yeah. And that’s what they value. You know, it was ridiculous. I mean, I suppose if I’d been, you know, smarter, I’d just thought, I’ll just do a lot more of that. But I just thought it was a sham. And, um, so now I’m at the art school here where it’s just teaching art

Lovely, It’s what we all want to do.

So there you go, so that’s the story of the body book.

Did you work in a way that, I mean did you work at it in a way that you’d solve like any other brief? Say for example a financial or a business to business brief?

No, it was, it was a, the whole thing was completely new process to me. So I would get the,double page content each morning open up the brief and, I knew I had to complete a double page a day. I would get the copy for that day- so say it was pregnancy I would... or the growth cycle of the baby I would wipe overnight, I would wipe the slate clean of my mind and I would come to this next subject I would spend the first hour just reading through all the copy it’s very systematic just read through it and I would kind of think okay I know this is all about I’ve got it some of it was very difficult like DNA and I had to watch lots of videos to figure out what he was talking about anything I could understand I would research through the plethora of online videos. The better ones were the ones that were for children. Yeah. In fact, it possibly says something about my level of intellect. The ones that were aimed at children were just far more direct, and would get to the next stage which was to gather lots of visual material. That was all online. And in fact the pregnancy area, I have to say Jane, was disturbing because what I hadn’t banked on when I started researching was there’s lots of... it is a controversial area, the whole thing of the age at which the foetus could be aborted, for example. So there’s a huge amount of online propaganda. Yeah. And I saw things there which I wish I’d never seen, the most disturbing things I think I’d ever seen online. And I try not to think about it actually. They were really horrific images. Have you probably encountered them?

Absolutely, I mean if you look at Getty images they’re all made by men and they all look a bit like a shiny car that’s forming a new trove but also yeah it’s, I mean it’s, we live in a patriarchal society don’t we and so you know, women’s bodies are sort of weaponised, aren’t they?

I didn’t probe into it at health classes at all. I quickly did a bit of a googling about the size of babies, it came up with pro-life information of foetuses and they’d show dissections of them. It was really really gross. I find it very disturbing actually. I don’t know if it’s just what I’d click on. Well it was obviously what I’d click on. I don’t know how widely disseminated it is. I don’t know what I was searching for six weeks or something like that. Really to try and research, because what I would do is I would try and collect around the, you know, I’m working in Illustrator and around my art board to set it with, I would just pop in the title of the page then I would put in lots and lots of imagery that I thought was going to be relevant, which I’d kind of get, browse on my own, put all of this stuff that I thought could work and help me as reference. Obviously what I wasn’t doing was what I think medical strokes is true medical stress is they would go to the source and they would be dealing with the human body you know obviously you’ve got all the great masters in mind who sat there watching what is being dissected or probably did some dissecting themselves and here I am just looking at the results of medical science and work online and some property down there. And just filling it down. So all the hard work for me. I mean I did go to some museums. In Edinburgh there’s the Socialist Hall Museum and I spent some time there kind of getting to, you know, kind of just seeing if there was anything I could take from real life. And obviously you’ve gone and drawn in all of those.

So a completely different process of processing and understanding the information.

So I gather all around pages of my art book and then I’m trying, as I say, trying to distill it down visually starting with what I thought would be really picking out the lesson that was key to the story of that page but also it was going to look really good. And not like any other page in the art of the whole book. So I mean if I look at that section, let’s see, I’ll take you through the pages. It’s this section. Growing body. Yeah, so I’ll take you through these pages, I haven’t looked at these for a little while- So this is all about your. yes, a bit of DNA whizzing around. all of this stuff inside out

So you can see the largest cell and the smallest cell together in the body.

Is that on there? I don’t know.

Did you know a baby girl is born with all of her eggs ready to go in her ovaries, as she gets older, after puberty the number and the quality diminishes?

I did not know that- this shows that I had to scan learn the range of information of the book in a pretty superficial way to cover the range of content and subject.

What I find really interesting is you see you’ve got there you’ve got the embryo and the implantation is if you watch any videos it goes to that right and then it jumps back out and it looks like the 2010 spaceman floating in space lit from behind and I can’t find any visual or any animated reference which shows how the blastocyte goes into the uterine wall and then how it then comes back out to then form a foetus -with the placenta, and I have looked yes Number 21 you got there yeah He’s actually well actually the Baby goes further into the uterine wall and then comes back out.

Like I say- I certainly wasn’t the expert on everything body wise. I suppose one of the weird things is I had no, um, there was no editing. I don’t think they came back with any, changes to the content that I had drawn.

Wow. That’s quite dreamy, isn’t it?

Yeah, I mean, I just kind of thought I’d probably got it all right. In fact, I have spotted one or two mistakes subsequently, and you’ve pointed another one out. But they’re very minor. There’s a mistake with an optic there. I mean there’s probably loads, but my niece, who is a medic - said I am a body expert. It’s strange to be called that, she said it’s really good and that all medical courses should have it on their reading list.

Let’s work out why does it look really lovely? So your colour palette is kind of, it feels quite retro doesn’t it? It feels quite, like, I was looking at like the colours that you use and why it feels non-confrontational. I mean that looks brilliant because you’ve got pink, purple, red all together. Wildly clashing but vibrant colours.

Andrew is showing me the page below

What I did here is I tried to approximate the exact sizes as much as I could with my research. So that if you have the book on your lap, you’re picturing the baby at those stages.

I don’t think anybody’s commented on that colour wise, what I was interested in is showing like what this is what the size the baby would we in the way that you would have the book on your lap. So, you’ve got the full term one here, you see the head?

Oh yes- at 36 weeks. I didn’t see where the hands here. It’s beautifully designed Andrew. So, you like you’ve created a pink baby there I mean obviously babies aren’t that colour, did you consider at all whether to you know in terms of what colour the baby would be?

No. I suppose it never crossed my mind actually. I suppose of course I just kept thinking of Ray and James, my babies.

From my research, there are hardly any images of black and brown babies in utero.

Interesting. certainly in Walthamstow where Ray and James was born, that would be the, it being a little white baby, although they’re all funny colours, they are, aren’t they? But Ray and James would have been in a minority. Yeah, that’s interesting. But I mean, all those images are very crisp and clinical and they’re the opposite of grisly reality. When Ray was born, the scene of mayhem in the hospital room looked like a famous image by George Grosz, it looked like that. And no one tells you that there’s going to be that, no one tells you that, you know, you’re going to poo yourself, no one tells you that, or as a partner that you are going to witness that either.

I mean, there’s so many awful instances of non-consensual harm of people breaking your waters or going I’m just going to cut you without a conversation going I don’t want you to. You’re so vulnerable.

You’re in a vulnerable position. You’re exhausted, might not have eaten for days, you’re full of various drugs, you’re thinking you might die, and you’re surrounded by the medical paraphernalia, plus a whole bunch of people coming and going, a lot of people you’ve never seen before. No, different shifts. And you’re utterly powerless.

I remember when I had Jonas, it was so long and drawn out because it was an induction and he was 18 days overdue. I still get his birthday wrong because I thought in my head he’s born on the 26th of March. He wasn’t, he was born on the 28th. But I had so much epidural I couldn’t see. And that was really upsetting. And then when he was born he had a mid-line birth abnormality in his neck which was quite upsetting because it wasn’t picked up and then when I had Elsa, it’s completely different I had her seven weeks early my placenta came away and I nearly bled to death and they thought she was going to have cerebral palsy.

• Basically coming out of a near-death experience you’ve been told that your child isn’t ‘perfect’ is not what you were expecting, What struck me about the whole process was just how visceral, honestly. this is all yeah oh this is it’s partly why it’s yeah probably the most memorable thing ever happened to me because it is maybe for the partner actually because it’s full of all these drugs but for me it’s one of the most memorable thing because you’re living in absolute fear for your partner’s life and your unborn child.f.

My dad got the choice of would you want us to save your wife or your baby and obviously he said well my wife I’ve got a three year old at home.

That’s the kind of thing you don’t want to ever hear. Yeah, that is absolutely shocking. But reading the literature, it was all like, how would you like to have a baby? Like- how you’d like to have a coffee? A bit like having a really nice toilet where you can go for a nice little poo really, isn’t it? It’s like, you just think it’s going to pop out. But obviously for some people it kind of does. Yeah. Yeah, my sister’s second child just shot out like a, I don’t know, like a cannonball.

But, you know. I think if your body doesn’t, this is from my research, if your body doesn’t do what it’s expected to do in the timings of a very like precise time and obviously everyone’s bodies are different then you’re in for a shit time because your body’s in that then you’re speeded up with drugs and your body’s not ready yeah and you’re not listened to and such yeah.

Hhhmm I’m wondering if that could be of any use to your research? I suppose I take my hats off to the amount of stuff that’s been done by other researchers, by proper researchers. Yeah. Illustration, the kind I was saying, is built on the work of others, that work is, comes in all forms, really. I find that some of the little scribbles by doctors are completely artless, but are obviously needed to get that key information across in the time of an appointment or consultation. In this book things like DNAs little scribbles and jottings where they would get a like clarifying idea these things were very important for me because I can make them beautiful I mean I realised that there was very... had there any beautiful images of chromosomes. I thought well I... I liked it because I thought I might be the first person to make a really beautiful page of chromosomes, you know, maybe I am, I don’t know, I feel I did a really good job on that but I’m going to make this really beautiful.

Well they’re great because they’re stripy.

I also thought it was a way of showing that you could unravel this thing, because of the way I drew it, it would have been the length of the chromosome which is really long, you can stretch it out. And it appealed to me. When I was a kid in school, I really liked maths. It appealed to that kind of illogical part of my mind. And I suppose probably what you are thinking, or you have to address this answer, is the opposite.

The work that I’m commissioned to do tends to feel like, have a slightly kind of romanticised look about it, feels quite feminine, it doesn’t feel digital, even though I put everything together digitally, you know, it feels like quite, I don’t know, painterly and such.

So are you doing visual work for the PhD?

Yes, it’s a practice-based PhD.

So how are you going to, have you started doing drawings?

I’ve started doing, I’ve done a lot. And I can send you if you’re interested. I’ve done, so one of the things, even from someone understanding having a blood test, and people just, so, yeah, it’s all, the whole thing is actually all, you

know, it’s like, what does this look like?

Yes. So, bit of animation, Andrew?

Oh yes, yes, very nice. Yeah.

So I’ve been doing these... Obviously in more blood, you know. Maybe I need more blood. So I’ve been creating these readers, I’m on the seventh of these, which is documenting the process of my research and what I’m doing. So these are some drawings from the Royal College of Surgeons. This is a huge amount of work. I’m just, it’s my happy place and then this was my upgrade. So I’ve basically done like a hardback book for, yeah, my upgrade. So it’s like, you know, what does it look like to have a blood test? Because for some people it’s the first time they’ve ever gone to a medical setting. So the premise is I’m doing it for medical practitioners who need to have something explained to their people. And then also for birthing women who might need to understand certain things, like I don’t want a blood test, the needle’s massive and don’t you take loads of blood out. It’s like no, here’s a little film to show exactly what it is. What actually happens when if now, what is a graze or a third degree tear? I wish someone would show me what that place looks like. So one of the things I’m doing some drawings in is a thing called mental canvas. So it’s almost like you can walk around a room as if it was a stage. So you could go, look, we’re going to need to move you into somewhere that’s got a bit more specialist medical equipment. And it’s going to look like this. You can just walk around here. And this is the equipment. So if you pressed on this, it would go what this equipment can do, why it’s there.

So in the end, are you thinking this is going to be something that you would give to pregnant women to look at?

So yeah, the premise being to roll it out in these two hospitals that I’m working with.

• So I guess that’s the important thing, isn’t it? Because the audience is always going to be women, and on the most hand, they are not doctors or medical practitioners. You are going to be making something that’s going into the public domain.

I am trying to say its important to be thinking about keeping it kept to the point yeah is not just in terms of the content but also in the length. So these being like 30 second things so things that so you know when you’re having a baby there’s lots of times when you’re like kind of empty time where you’re in waiting rooms and obviously people scrolling through a phone so the premise being that all of this information would be have no print costs it would everything would be on a phone

It sounds great- communication about the body is so important, I have been approached by some pharmaceutical companies- and it’s been designed for men. It was about the clotting process, the clotting cascade. And the truth that would help people didn’t have the right chemicals for clotting. It was for quite a massive fee, which feels as if it’s all made up isn’t it? That was quite an interesting project, and I got almost as much as I did for the body book, for a fraction of the work!

There’s, the stuff that I’ve done for Pharma, it’s so well paid, but it’s such horrible work to do, because you’ve got all these lunatics that are

all like totally invested in it, and they’ve got six figure salaries, and they have to explain why they think that this is a shit version of Jane Webster’s work because they’ve asked me to redraw it so many times I totally hate it.

• I didn’t have that with the ones I’ve worked for, they’ve been pretty nice to me. I once worked for an old company for my sins and I really wish I’d just thrown it back at them as they were a pretty awful client. I think what you are doing sounds well needed, yes there a massive range of information out there, more and more as social media adds a billion other threads. What I think is important to women and the families supporting them - is that the information is medically correct and helpful, and offers a reality that is both accurate, but not terrifying. That is a hard ask I think.

Thanks Andrew, I believe wholly in the research project, but I can’t say that I don’t wildly swing from feeling- yes this is great and my project potentially will make a massive difference, to thinking- how is anything original any in the world, and is this an enormous waste of time? I hear that is a healthy non- sociopathic approach to a PhD research project. So at least I am not that? I thought, I’ve got these skills as an image maker and as an illustrator. I need to do something with them that’s helpful to the world and not just drawing a sexy bunch of tomatoes for higher end super markets.

Well, you’re the perfect person for it. Obviously, your drawings are going to look great, they have a reality but a sensitivity to them, from what I have seen, the sequencing of them is so glorious. And how you, I mean, I don’t know if you, who’s looking at it with you?

As in, who are my supervisors?

Yes, who is supporting you through your project?

I am lucky as at Kingston as my supervisors are made up of Dr John Miers, he is an expert in narrative comics, autoethnography, health communication- he has the most astonishing knowledge of research, and approaches that will work for you as a researcher. I have Dr Hannah Ballou- she is a comic and performer who works with the subject of motherhood, and feminism embodied in the autoethnographic performative form. I have Geoff Grandfield too, as you know from working with him at Middlesex he is the narrative voice of film noir and understands composition and illustration like the back of his hand. I am in the same department as John and Geoff- so it is easy to field questions and feel supported from all of them. I speak to other PhD students who seem to have a dreadful or a very tentative and unsupported experience.

Look Jane let me know if there is any other way I can support you, just give me a shout.

Thanks Andrew, your book is so complex, but looks so effortless- which shows how beautifully designed it is.

Speak soon, come up to Edinburgh!

Sounds great.

Online representation of the developing baby.

On these following few pages, I have put together a range of imagery in the public domain, visual examples of a foetus in utero, and the formation and implantation of a blastocyte in the womb lining on the successful implantation of a developing embryo. The images- taken online from Getty predominantly have shared visual similarities—pink, shiny, floating forms. Most are lit from behind, with a reminiscence of a spaceman floating in space attached to the ‘mother ship’ by the umbilical cord in how an astronaut on a space walk is tethered to the craft or space station. Safe but alone in their quest to develop and grow. The film poster Gravity 2013 is an excellent example of this aesthetic

If we think of a Diet Coke advert, the can is shiny, with a dewy drop sliding down the side of the cylinder. An iPhone is sleek, glossy, and even ‘Rose Quartz.’ A psychological fetish for shiny internal objects in the body is called ‘splanchnophilia.’

Within all of these images, there is an absence of the mother joining and supporting their developing baby instance; the non-mother is a blue, watery blob behind the plastic surface of the baby’s flawless surface.

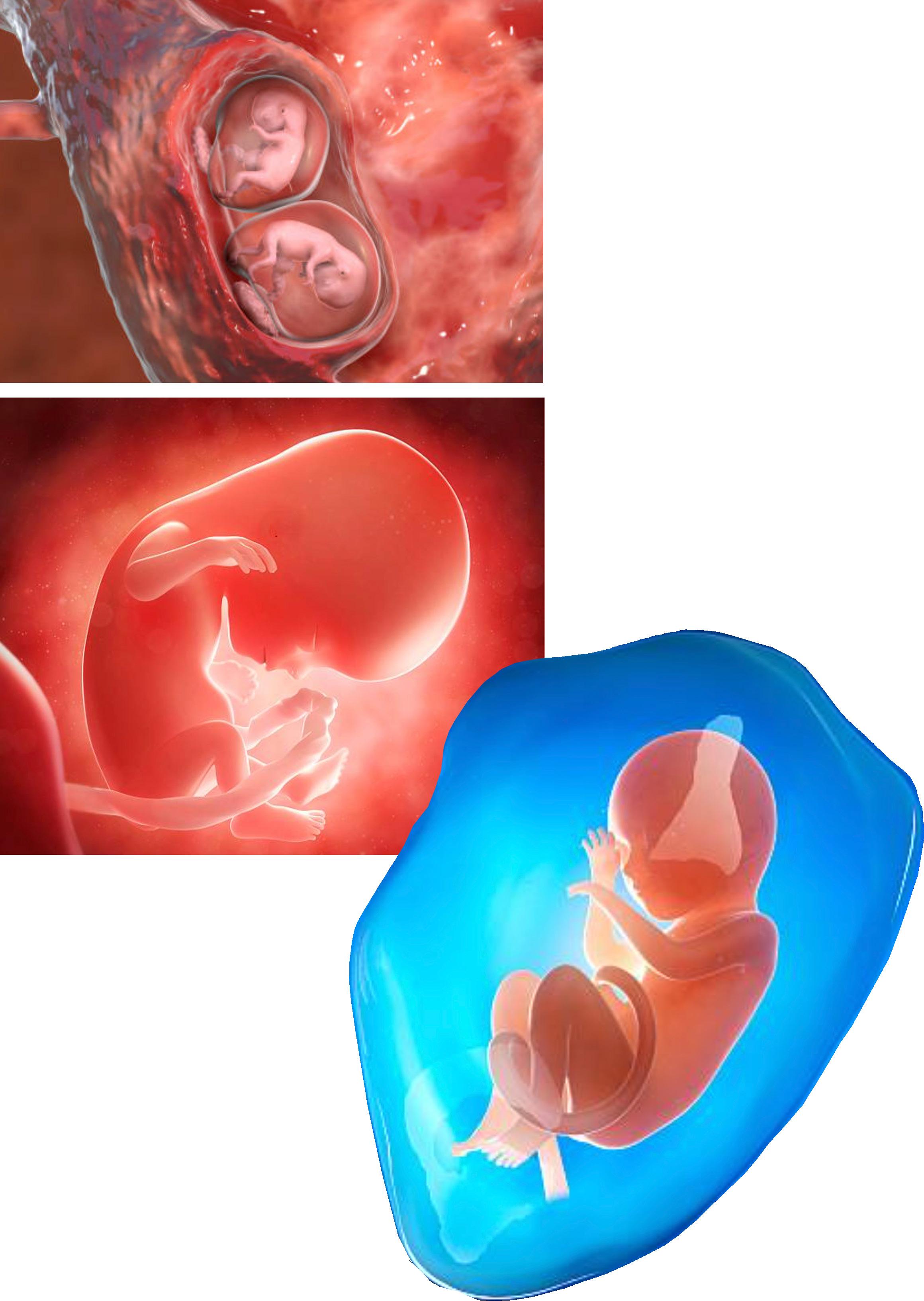

On the next page are examples from a BBC programme called ‘Surgeons at the Edge of Life,’ within the one-hour programme, leading medical teams take on cases that most hospitals don’t have the expertise to take on or attempt. The visuals are CGI and take the viewer on a film journey of setting the scene and what needs moving, removing, replacing, and re-plumbing. The surgical scenes from the theatres are incredibly graphic. The viewer is privy to see most of a woman’s head scooped out, eye socket, eyeball, and cheek removed.

The first image shows a map of the body, contextualising where the operation will take place through the use of colour for the organ(s) featured and the mono tones to represent the location site.

We assume the environment of a uterus to be dark, as there is no internal light source. Research shows babies’ eyes have developed enough by 32 weeks to track large objects. By 34 weeks, the first colour a baby can see is the red inside the womb and the placenta; this is a dim hue as there is no internal light source. I find the lighting of these images intriguing, and the babies glow with luminescence; the light reflected on the amniotic sac again suggests the glow of light from the sun with a view from a spaceship.

The shininess of the developing fetus is odd. The aesthetic of the surface being wet sometimes feels like the form could be a product- a car prototype. There is little that feels organic within these images. From reading about the promotion of products through an advertising lens, we as consumers are drawn to products and objects associating shiny things with luxury, wealth, and a need for fresh water.

These are tamer examples here, showing sections of a diseased liver being removed and a pancreas dissection. I have lined up the diagram with the live-action operation to compare the visual forms. The show has a guide for graphic content, but the imagery is much more arresting and shocking than the censored imagery on the Instagram posts of birth advocates. Again, you can easily access imagery of objects being inserted into vaginas, but not a baby coming into the world through one.

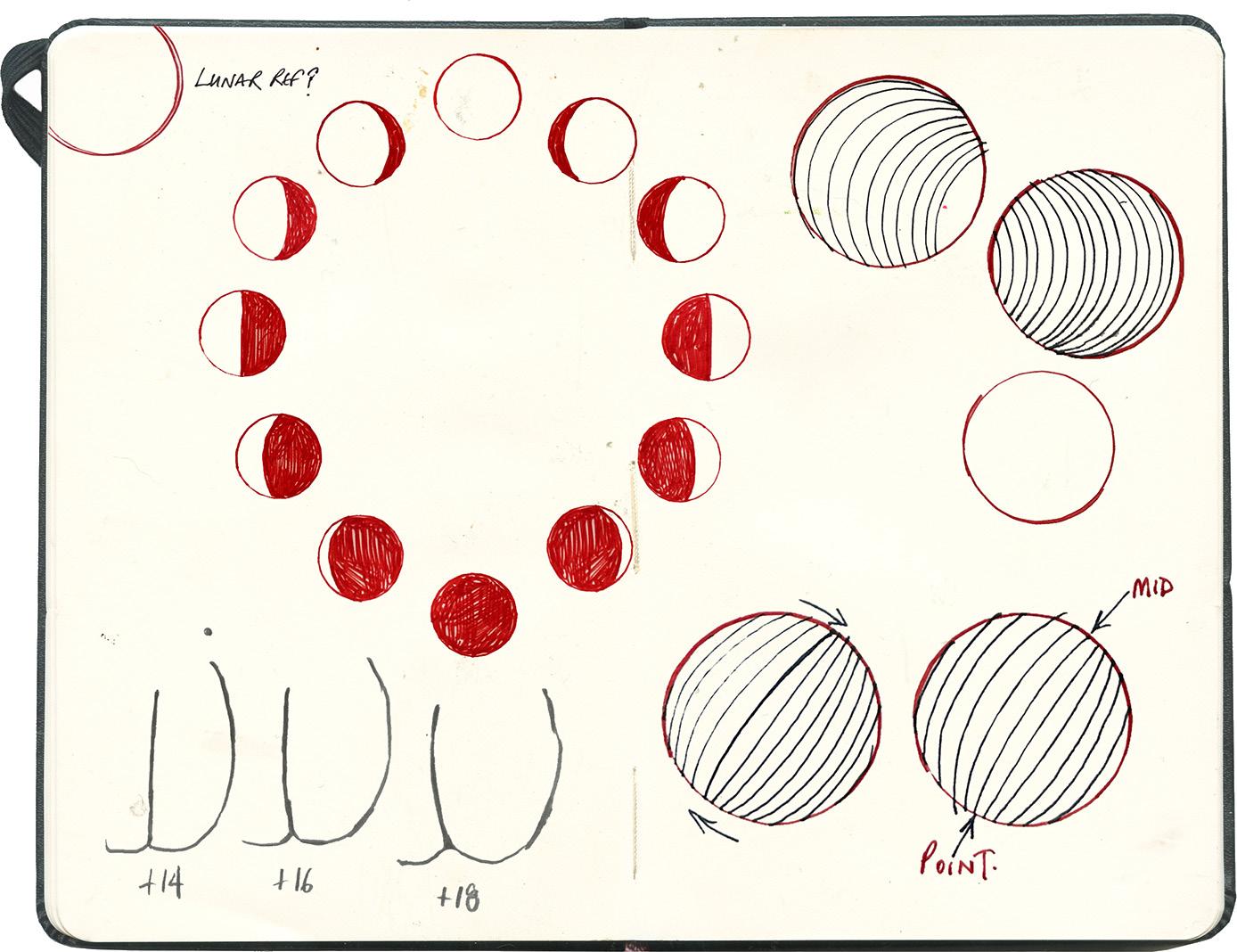

Following the IMR, I have had several stop-starts. As I was new to animating my illustrations, I made headway and then struggled with the complexity of what I was trying to convey. So, instead, I used the advice I would give students, where the project’s content can be parked to one side. The process is explored without judgment until after the exercise is complete— approaching it as a stream of consciousness, which has no narrative, and the point is to get to know how elements move and morph, what frame rates to choose and such considerations.

So it’s been quite cathartic as it’s had nothing to do with bodily forms; it has focused on movement. In a subconscious language, it looks rather cellular in how things move through the frame. It’s been a beneficial creative cleansing process, and has helped me not over think and work in a much more intuitive way. I chose a limited colour palette, free and marks and a circle-maker as a formal shape. These limitations can be a helpful and informative guide to navigating new processes that can be overly complex.

The short 500-frame animation runs on a loop as the first frame is mirrored by the last, meaning the frame and the in-betweens can be experimented with in Photoshop and AfterEffects, allowing more of an experimental process technically as well as through the materiality of drawing. I have been able to apply the simple principles to a sequence of a breech birth, using the lunar cycle to base the missing frames as the baby moves position as the leg begins to descend.

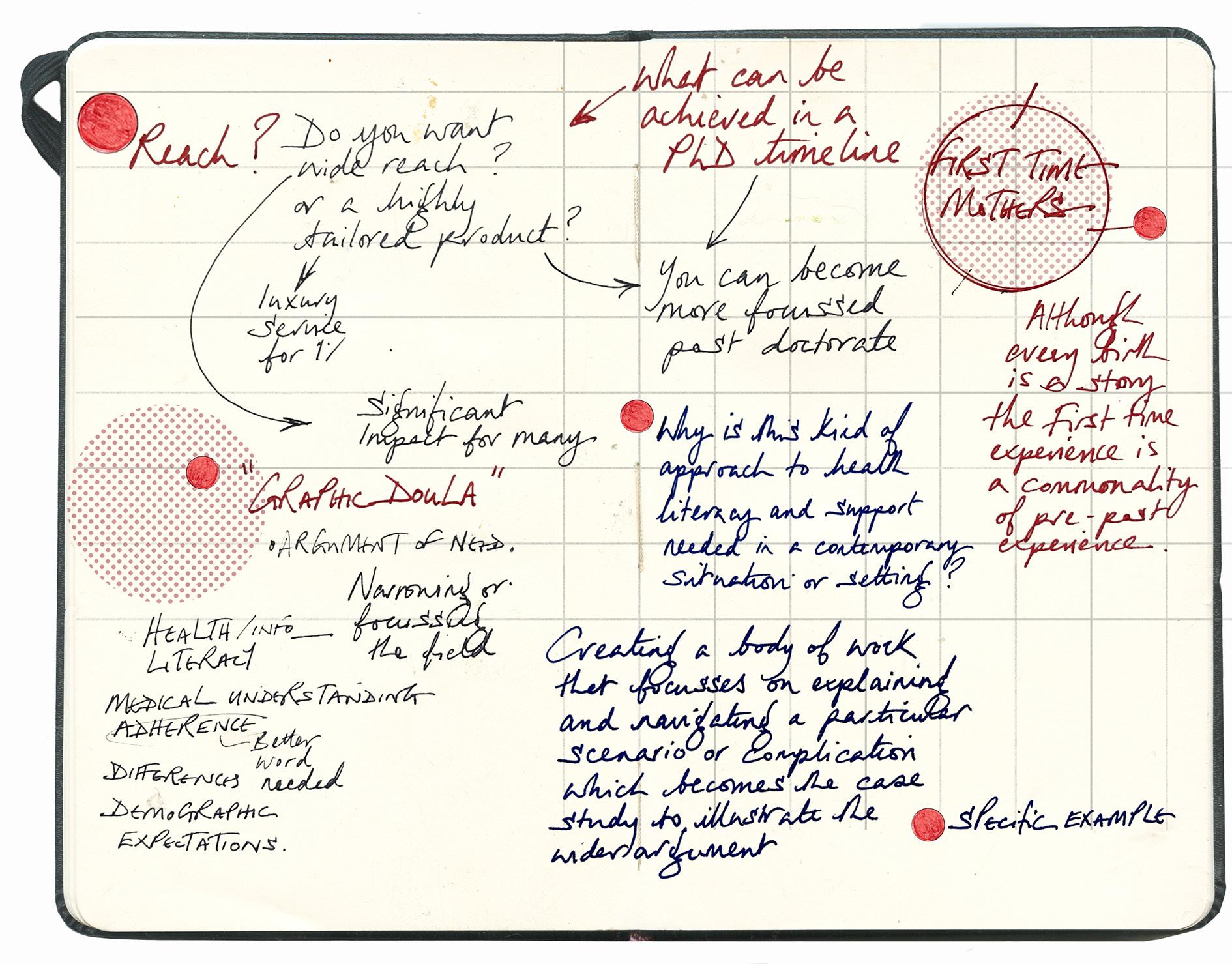

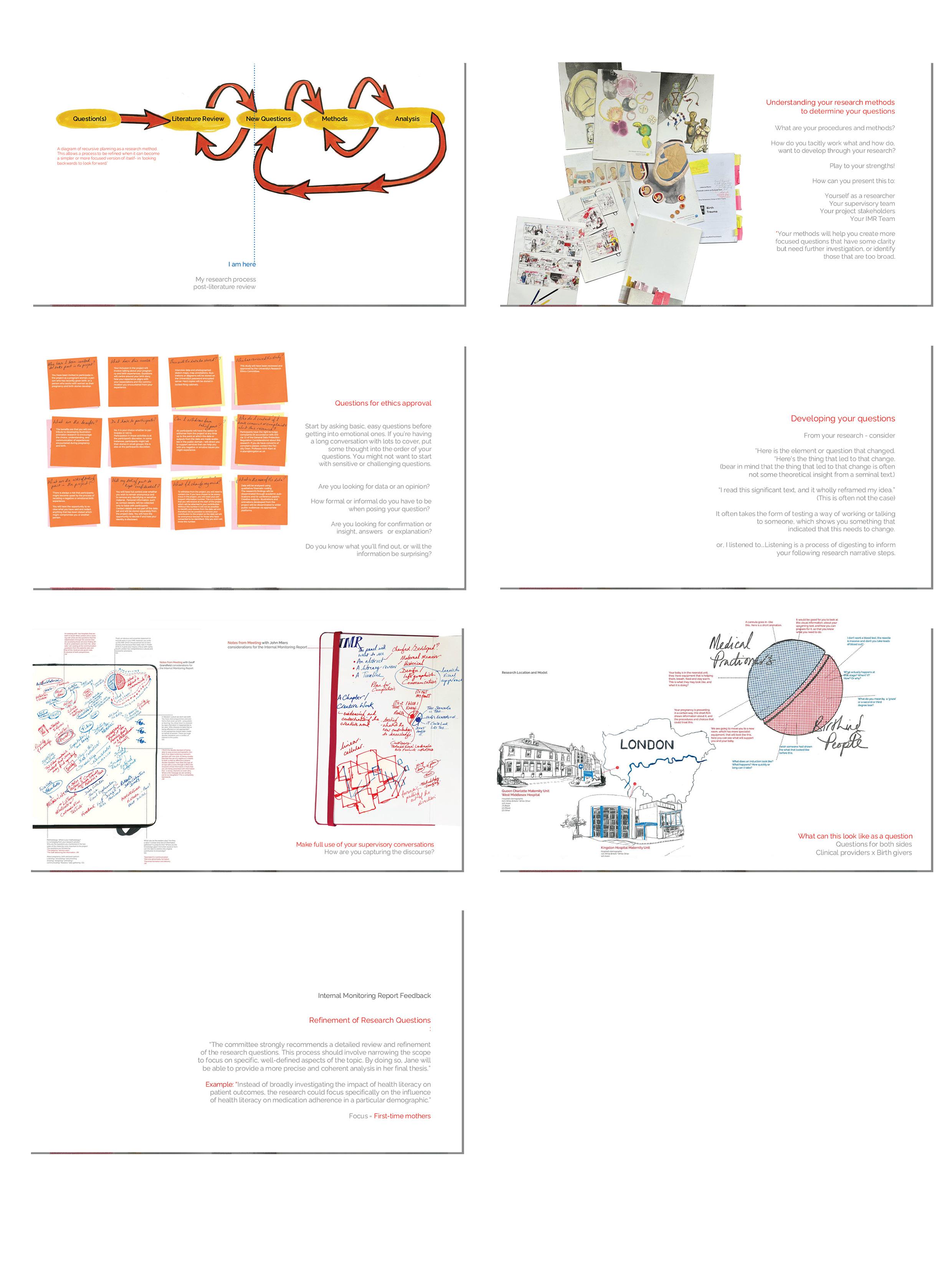

Tutorial notes and feedback from meeting with Dr John Miers. 19/11/24

Think about the time scale and what can be identified, achieved and measured within your research project. So here’s a specific example, here’s how it works, here are my reasons, here are my justifications for believing that this can then be extended more widely. And then also, in practical terms, if this is something you want to then carry on with afterwards, framing it in that way, when you conclude the thesis and say, yeah, there is my contribution to knowledge, that kind of sets you up for writing your postdoc proposal. In this instance you can be working in an academic capacity and space, the next stage could be within the context of the NHS.

The feedback from the IMR and this conversation has given me the incite to focus my project and think about ‘narrowing’ down to first-time mothers and the improvement of their experience and understanding of the communication relevant to their healthcare needs and choices. JW

Hannah used specific phrase, about being- bridging the gap in communication and care between busy clinicians and birthing mothers. And that’s also a pretty good description of what your project is aiming to do. Are you even providing a visual or a graphic doula? JM

Potentially a nice concise way of looking at and presenting the project. JW

In your write-up - you may make broader arguments for how the kind of graphic treatment or this graphic doula that you’re creating,

*Why this kind of approach to health literacy and support is needed in a contemporary situation?

*What are the broader arguments that you might be referring to health information literacy and such?

*Why this kind of approach is needed in today’s health system? JM

The panel give an example, and that is just an example. Instead of broadly investigating the impact of health literacy on patient outcomes, the research could focus specifically on the influence of health literacy on medication adherence in a particular demographic. JM

The area of focus on a particular complication makes it easier for you to look at how different demographics experiences that and make sure you reach them. JM

In general, narrowing is always a good thing. It always helps to make a project more manageable, and one thing; there’s the particular paragraph where it starts with the committee strongly recommending a detailed review and refinement of the research questions. This process should involve narrowing the scope to specific, well-defined topic aspects. JM

As in more focussed? That makes sense as from the research so far, the range and potential is huge- this is something that is at that forefront of my mind following that feedback. JW

‘How to Formulate Research, Questions and Arguments.’

Feedback from Reader 6- Dr Hannah Ballou

‘One thought I wanted to float from the last reader: you mentioned doulas, who are undoubtedly unaffordable for the majority of service users. However, their entire profession is ostensibly centred on bridging the gap in communication and care between busy clinicians and birthing mothers. An experienced doula who has attended many births might be a useful resource/perspective for this research, and they might also make use of the tools you’re creating.

My other questions are about how much you agree with the narrowing the panel recommends. But we can talk about that another time.’ HB

Reflections

Teaching and studying.

I was invited to contribute to this online session led by Ersi Ioannidou for students early on their PhD journeys titled ‘How to Formulate Research, Questions and Arguments.’

As a researcher in my third year, I returned to what I would have found helpful at that stage. My initial thinking was to see the questions coming from one side and to become formed from reading a particular ‘enlightening text.’

The importance of engaging with the research is acknowledging the changes in your question as you become increasingly engaged in the subject. From a tutorial with John, he highlighted that in very general terms- students can find it challenging to understand the forming and development of research questions because often, particularly at the early stages, researchers have a misconception that you begin your PhD narrative by coming up with a sense of perfect research questions. I made two illustrations, the first shows how we potentially divide up the topic and then ‘it’s a case of just like slotting things into shelves or boxes,’ but of course, what happens is that the size and shape of the questions into suitable question-sized boxes.

Once you become more familiar with the content you are addressing, the second illustration shows how your perceived question-shaped bookcase is at odds with the reality of thinking that you can slot your questions neatly into the structure. What you’ve got are things that are enormous and other elements that don’t scale up and wither away. From developing the talk, I have found that particular findings from the listening sessions and questions have highlighted the back-and-forth nature of communication and the perspective of the two sides of my project.

I wanted the presentation to premise that the more you can do to break it down and acknowledge, ‘here’s the thing that changed, and why?’

Then, ‘here’s the thing that led to that change.’ I have often found that it is not necessarily a theoretical insight that comes from, for example - when I read this significant text, which re-framed my question and premise. Within the talk I wanted to cover how mapping your literature review can establish what has developed from one part to the next, in the books explored within my literature review, the established journey of being able to ascertain certain piles of association with certain colours has proved helpful, in terms of my project- illustration practice, context, history, design, mapping and infographics, literature, personal and lived experience and what do each of these offer to each other. I wanted to visualise what this journey could look like as a diagram, this was a helpful ‘mapping’ exercise. Questions- Literature review- new questions, methods and analysis. These are all intertwined, and feedback and feedback feed forward from each other. As an illustrator, my default is to do just that - how do established questions become new questions after your literature review?

I intend to visually describe this as mixing the three primary colours as circles- red, yellow and blue. As you research these, they spin into secondary colours, green, mauve and orange, and the spaces between them mix to show how new coloursor questions become established.

Planning the presentation prompted reflection on my IMR’s feedback and the research question’s refinement as the project matured. The focus of concentrating on first-time mothers, in hindsight, now seems obvious, but it took making the presentation to realise this. As titled, the privilege of learning whilst teaching provides a reflective space to plan and communicate the journey of contextualising the research process.

Some thoughts about the Virgin MaryPost Christmas conversation with John Miers

JW- I was in a church a few weeks ago, looking at a stained-glass window of the Virgin Mary. It was pretty mad that this is a narrative that we’re fed from being young. I remember being, I only ever made it to be a sheep, or maybe I was an angel with an eye patch, but my daughter was Mary in year two, and I was chuffed that she got that role, yeah, with the plastic baby. I was looking at the stained glass window and thinking, how insane is that? That she is the mother, the Madonna, but there was no seminal fluids, there was no pain, no faecal mater, there was certainly no blood, She’s just totally serene, not traumatised or torn, not sick or terrified, she’s a bit tired, but just the whole premise of that identity being presented as such a monumental load of bullshit. And that’s what is premised to millions; possibly even a billion little girls, globally.

I had an interesting conversation with someone the other day who was talking to about the content of my PhD project. He said, oh, he said, I’ve got a friend; he and his wife had like a really hot relationship, you know, a really kind of intense - you know, very sexualised relationship. He said after he saw her give birth, that completely put him off; it was just the idea of how could

you, well this person used the words ‘suck my cock and then kiss the baby’s head?’We are all of well-known notion about women falling into the spaces of being the Madonna and being the whore.

In the case of the Virgin Mary, she exists to reinforce the idea that is a woman’s role. It’s clean, not painful, and pure, and everything’s fine, and even if you’re in a stable, you know, basically in a farm shed, you’re still fine.

Continuing looking at, and thinking more about the presentation of the Virgin Mary, I find that it is a weird thing that many medieval painters represent baby Jesus as a kind of tiny formed wizened old man, which looks like, or is potentially just a stylistic aesthetic. However, that obviously the presentation the character of a ‘mother as a virgin’ apart from its biological nonsensicalness; it’s a profound separation between the woman’s sexual being and the woman as a mother, and because she is a venerated holy figure, it reinforces or creates a number of ‘anaphorian,’ (this word is from John Miers) and moralistic positions regarding its set up, and a perceived cultural conflict between the idea of being in any sense of sexual being and being a caring,

providing and giving mother. Which of course presents itself as a being deeply problematic and is misogynistic in today’s society where thankfully the reality of these conflicting shapes of femaleness and motherhood are challenged.

JM- So there are a few things here- you might look into what this tells us about social attitudes towards motherhood. What does the fact that it had to be a virgin birth for the mythology?

What does that tell us about attitudes towards, controlling female sexuality and aspects associated with that? It’s not something I’ve read up on specifically, but you, I mean, that has surely got to be a fairly major strand of feminist criticism just because it’s such an obvious, widespread figure. This potentially is a huge field and could be a different PhD research project.

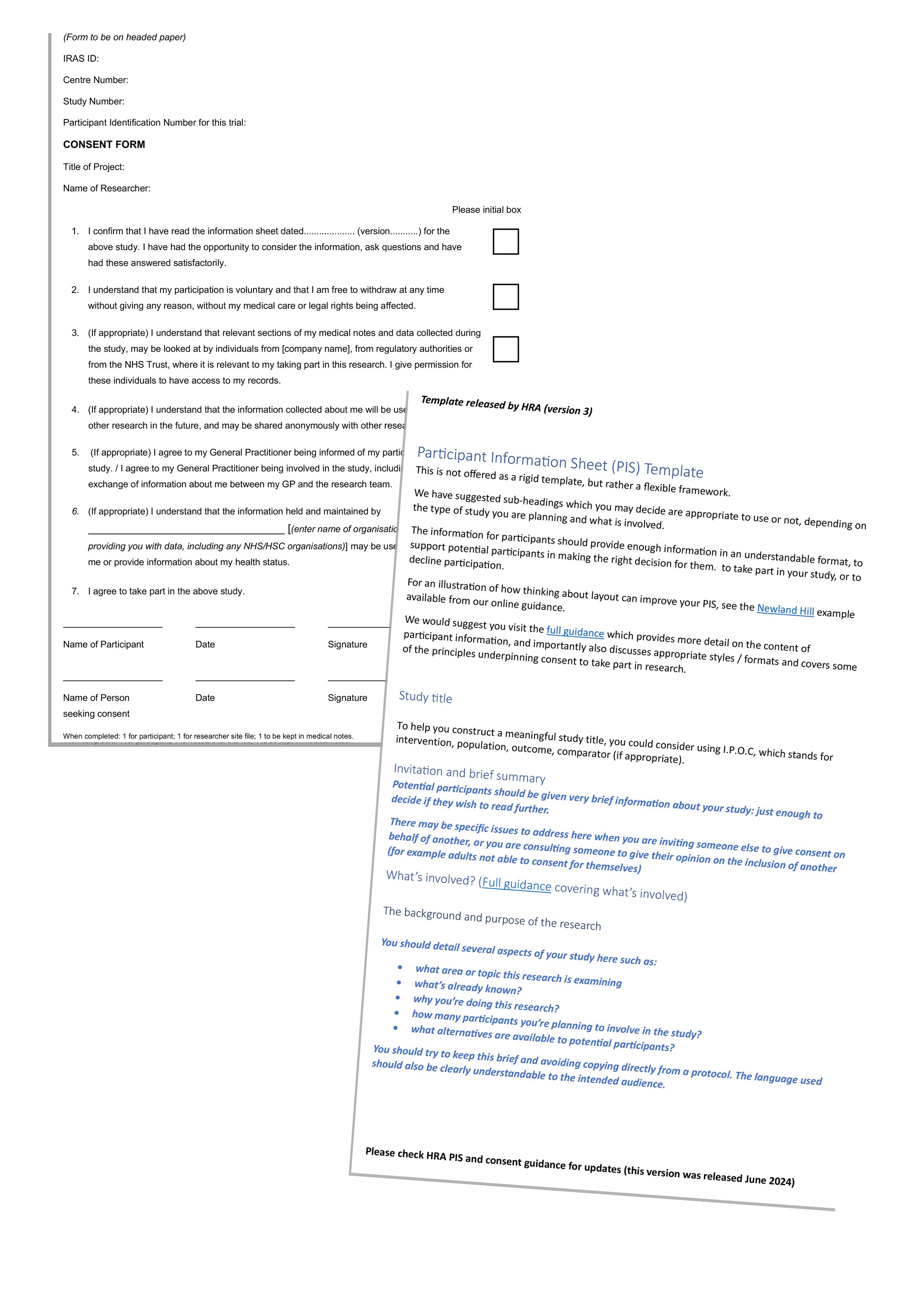

The HRA- Health Research Authority, which is part of the NHS. Above is the proforma for the Patient Information Sheet acronym of (PIS)

To the right is version 3 of an exemplar of considerations and questions included in the Patient Information Sheet.

Next page Birth Stories Research Patient Information Sheet developed from Reader 6 32.

Kingston University Research Ethics Committee

Researcher name: Jane Webster

Supervisors: Dr John Miers, Dr Hannah Ballou, Mr Geoff Grandfield.

PhD Study Title: Birth Stories-

‘How can confidence and choice be encouraged in the experience for first time birthing Mothers through Illustration Animation practice?’

Your participation in this research project, an essential l part of my PhD research, is highly valued. Before deciding whether you want to participate, it’s important that you understand the significance of your role and what your participation will involve. Please take time to read the following information carefully and discuss it with friends, family, and people you trust if you wish. If anything is unclear or if you would like more information, please don’t hesitate to contact me using the details below.

What is the purpose of the study?

The Birth Stories research project centres around creating advocacy around birth for women through clear visual communication in the form of illustration and animation regarding the choices and narratives in pregnancy and childbirth. Through the collection of stories and experiences of birth stories, from those experiencing pregnancy and birth and those working with pregnant women.

Why have I been invited to take part?

You have been invited to participate in the project as a pregnant woman, someone who has recently given birth, or someone who works with women as their pregnancy and birth stories develop.

What will happen if I take part?

If you choose to participate in the study, you will be asked to interview me, Jane Webster. I am a PhD student at Kingston University. In the interview, I will ask to listen to your pregnancy experiences and thoughts about giving birth. If you have given birth, I will ask to hear about your birth story and experience. I will also ask you what you found helpful and unhelpful about your maternity and postnatal care and how you think maternity experiences could be improved for women. Questions will centre around your birth story, how your experience aligns with your expectations and the communication you encountered from your experience. You and your story will guide the interview.

Participation will take place in a location of your choosing. The interview will last about 30-60 minutes, but it could be longer or shorter, depending on how much you want to say. The interview will be audio-recorded with your consent. I am the only person who will listen to the recording. I will use it to type up (“transcribe”) your interview. After the interview is transcribed, your recording will be permanently deleted. I will not include any identifying details in the transcript, such as your name, place names, etc..

You can stop the interview or the recording at any time.

Do I have to take part?

Participation in the study is entirely voluntary; you should only participate if you want to. Once you have read the information sheet, please contact me if you have any questions to help you decide to participate. You can discuss with someone you trust whether to take part in helping you decide. If you choose to take part, I will ask you to sign a consent form, and you will be given a copy of this form to keep.

Will I receive any compensation for taking part in this study?

London public travel expense costs can be reimbursed. If you do not wish to travel physically, your interview can be conducted online on Teams or Zoom.

What are the risks of taking part?

It is essential that you feel safe and supported through your participation in this study. There is always a risk that a participant can become upset when recalling a negative or emotional birth experience. Before listening to your birth story, I will ask if I can contact anyone for you should you feel upset. You will have the opportunity to take any breaks or end the interview at any time. After the session, I will check how you are and direct you to support services to help you with any negative or emotive issues you might experience. You will have the chance to review what you have said and redact anything that might compromise you or another person.

What are the benefits of taking part?

The benefits are that you will contribute to developing illustration animation research to encourage the choice, understanding, and communication of experiences encountered during pregnancy and birth.

What if I change my mind about taking part?

All participants can withdraw from the project at any time until the data or outputs from the data are made available in the public domain. To withdraw from the project, you will need to contact me. If you have chosen to be anonymous in the project, you will need your participant information number. You will receive this number at the start of the project, which will be attached to your contribution. With this number, it will be possible to identify your stories from the data set and, therefore, remove your contribution to the project, as the data set will be anonymous. Only you and I will know this number.

Will my information be confidential?

Your data will be processed per the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and destroyed at the end of the research project timeline. You will have complete control over whether you wish to remain anonymous and to remove any identifying or sensitive material. No information that could identify you will be published. Personal information, such as contact details, will be collected only to liaise with participants. Contact details are not part of the data set and will be stored separately from the project data.

What is the use of this data?

The research data will be analysed using qualitative/thematic coding. Qualitative research data is descriptive, relates to language, and is interpretation-based—it can help us understand why, how, or what happens behind behaviours. The research’s findings will be disseminated through academic publications and conference papers. Creative outputs, such as illustrations and animations developed from the project, will be communicated to broader public audiences via appropriate platforms.

How is the project being funded?

Kingston University is funding the project as I am a Senior Lecturer in Illustration Animation at Kingston School of Art.

Who has reviewed this PhD research study?

This study will have been reviewed and approved by the University’s Research and Ethics Committee.

If I have any concerns or complaints about this research, who do I contact?

Participants have the right to lodge complaints (In accordance with Article 77 of the General Data Protection Regulation Considerations) about this research. If you do have concerns or complaints, please contact the Faculty Dean, Professor Amir Alani, at m.alani@kingston.ac.uk

What will happen to the results of the study?

The results will be summarised in my dissertation as part of the requirements for a PhD. They may also be published in peer-reviewed illustration and design journals, conferences, and to interested organisations that work with the visual communication of pregnancy and birth.

You can indicate on the consent form that you would like to receive a summary of the study by email.

Who should I contact for further information?

If you have any questions or require more information about the study, please contact me using the following details:

Name: Jane Webster

Email: j.webster@kingston.ac.uk

Phone: 07812 170332

Thank you for reading this information sheet and considering taking part in this research.