Jane Webster PhD Researcher

Illustrated Reader January - April 2025

CONTENTS:

Page 1.....Reflection on reader 8.

Pages 2-3.....Tutorial notes and feedback from meeting with Dr John Miers and Geoff Grandfield.

Pages 4-7.....Drawing on location at the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons.

Pages 8-9.....ETHICS Training - Dr Christoph Lueder . Pages 10-11.....Good Practice Training ‘Ethics and Impact part 2.’

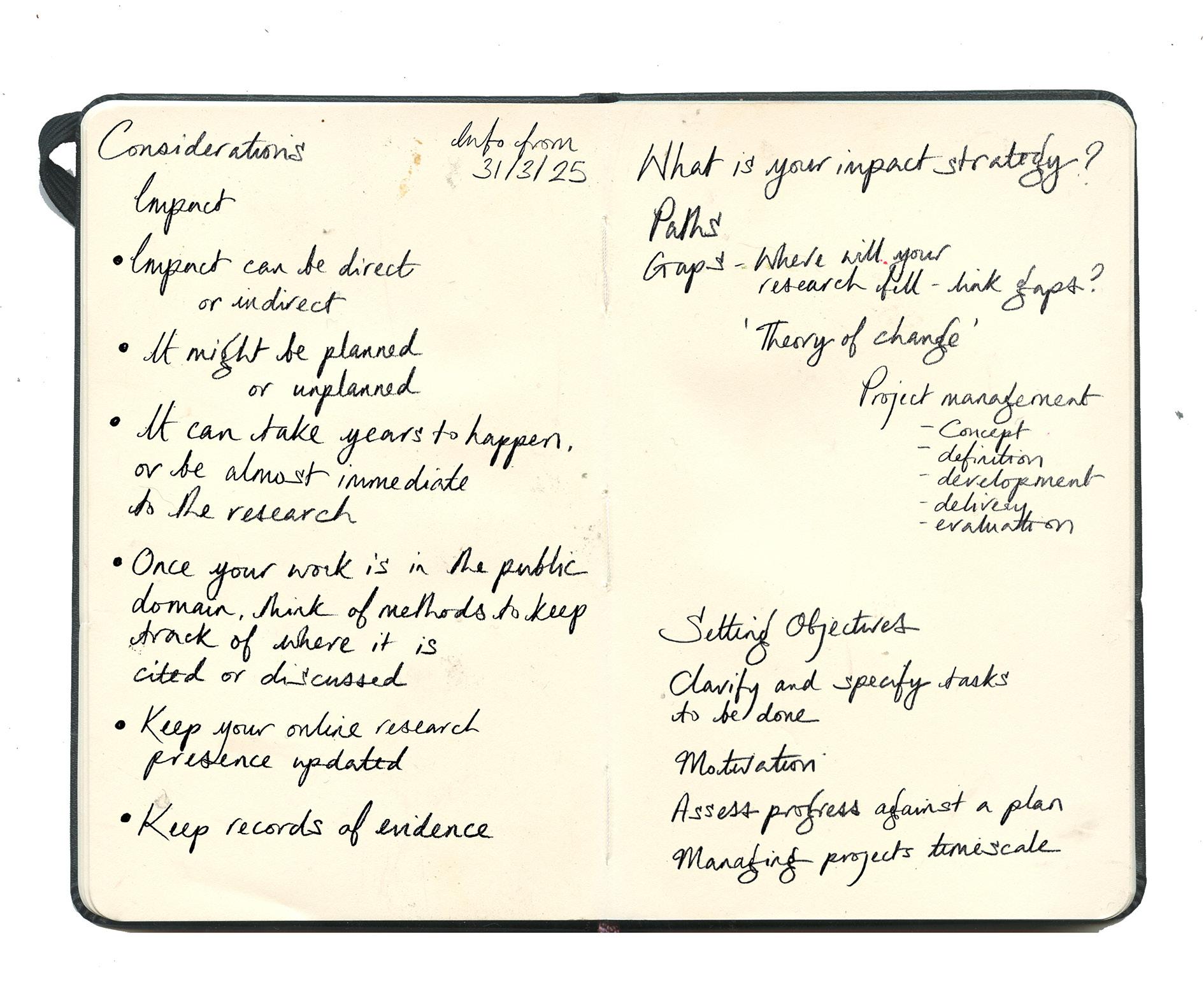

Pages 12-13.....Notes and considerations from the Good Practice in Research training.

Pages 14-15.....Epigeum Ethics Research Training Certificates.

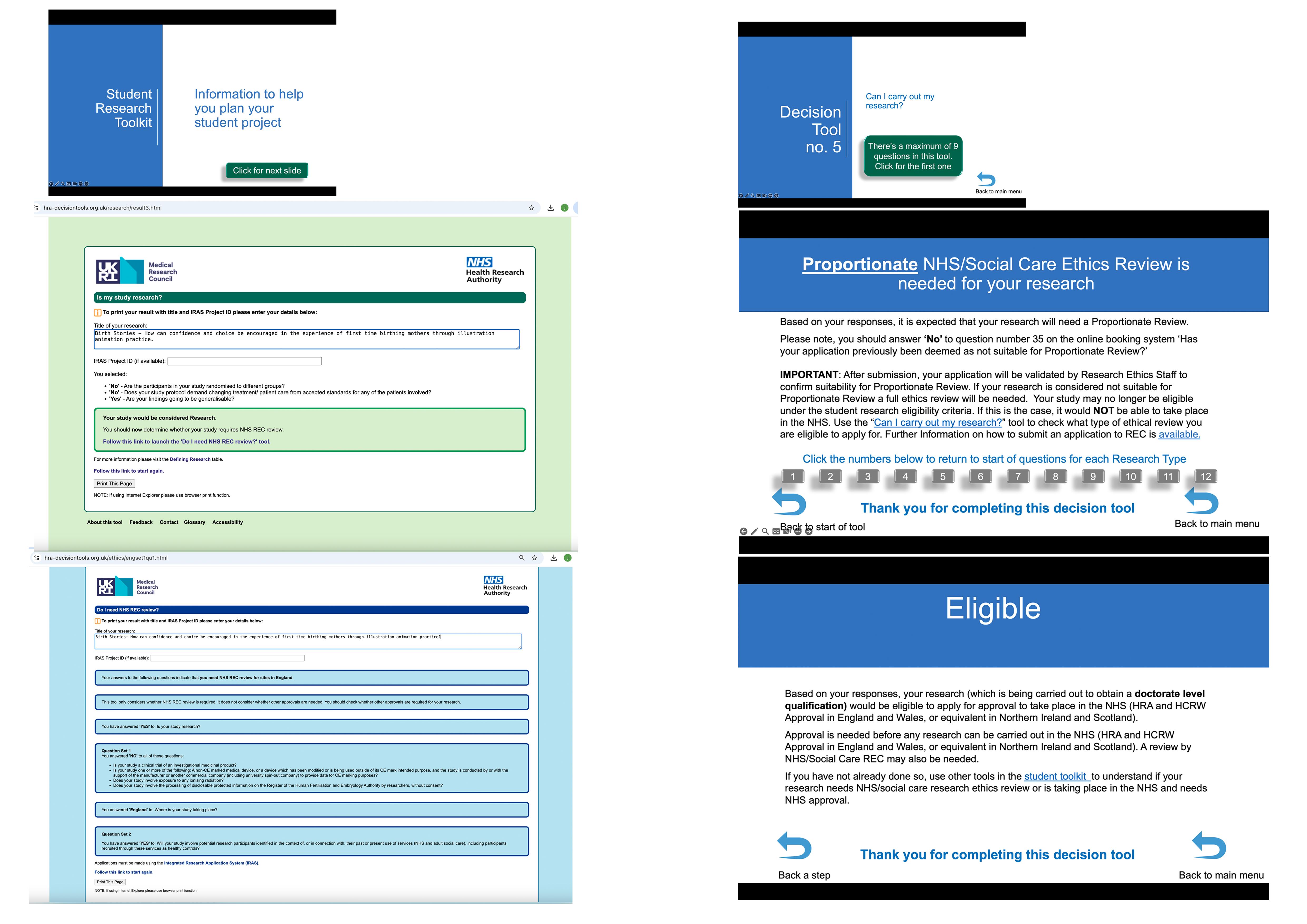

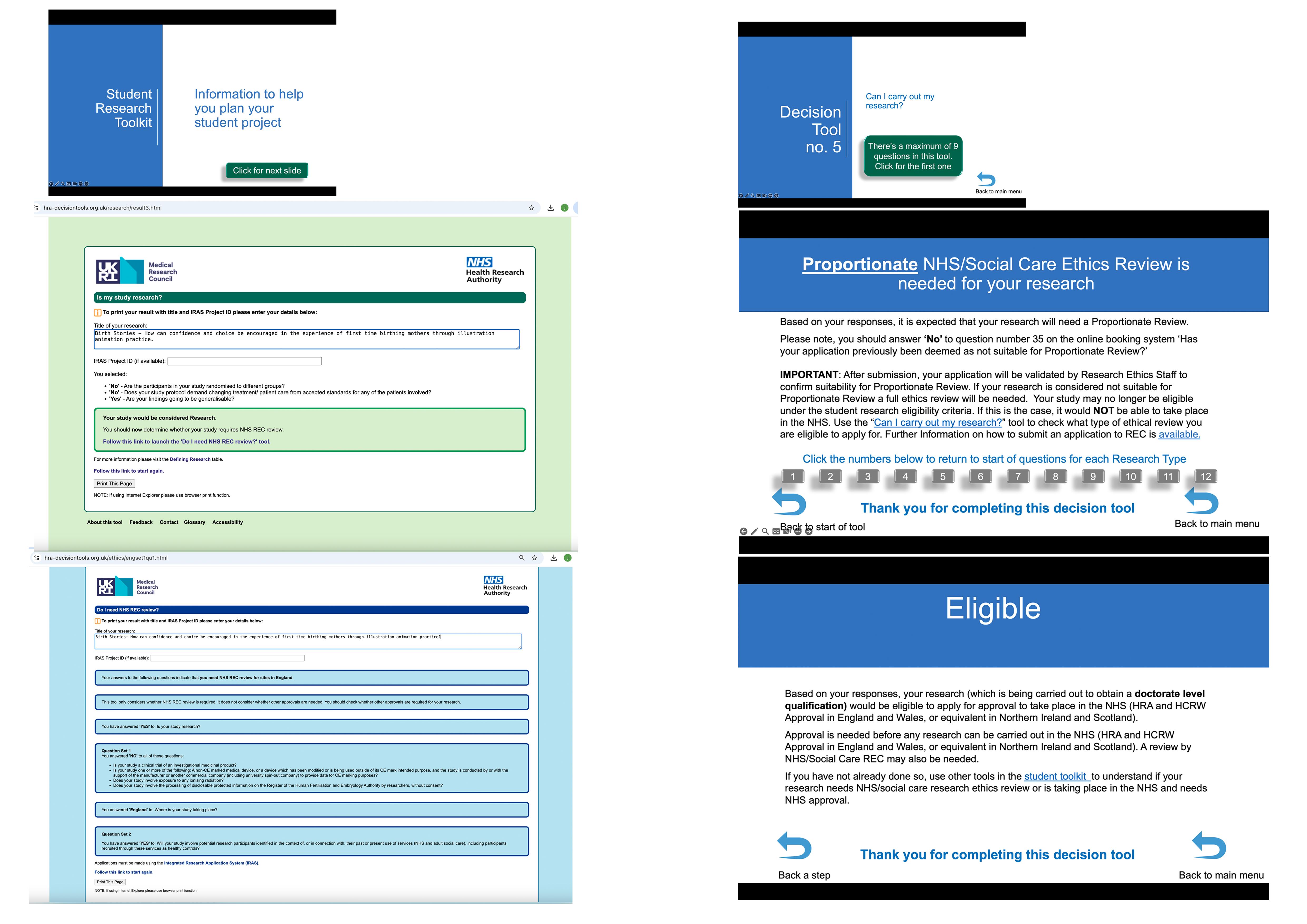

Pages 16-17.....Research Health Authority Toolkit- Is my PhD NHS Research?

Pages 18-22..... Listening with Jenny and baby Marius aged 3 months.

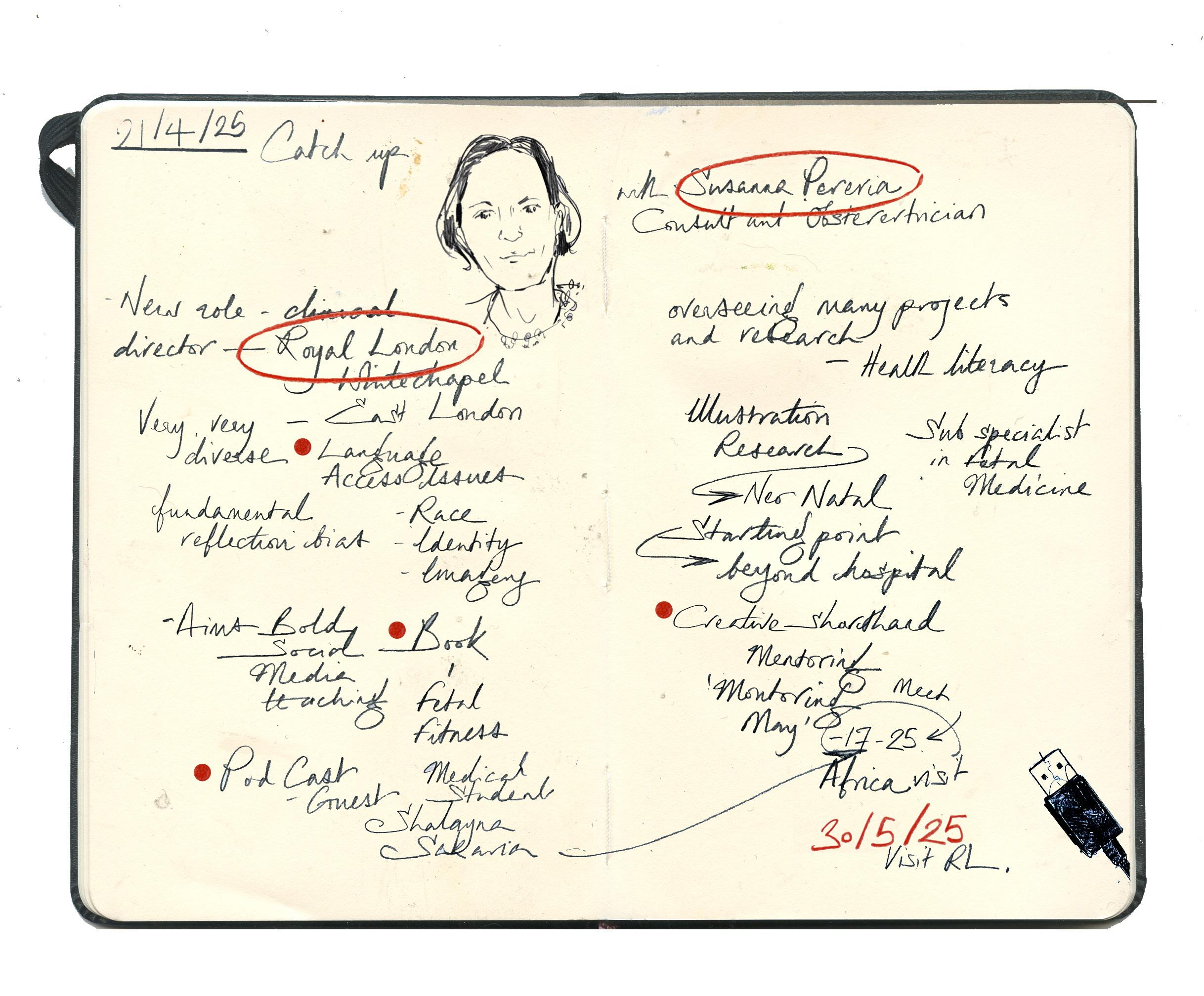

Pages 23-25.....Catch Up with Susanna Pereria.

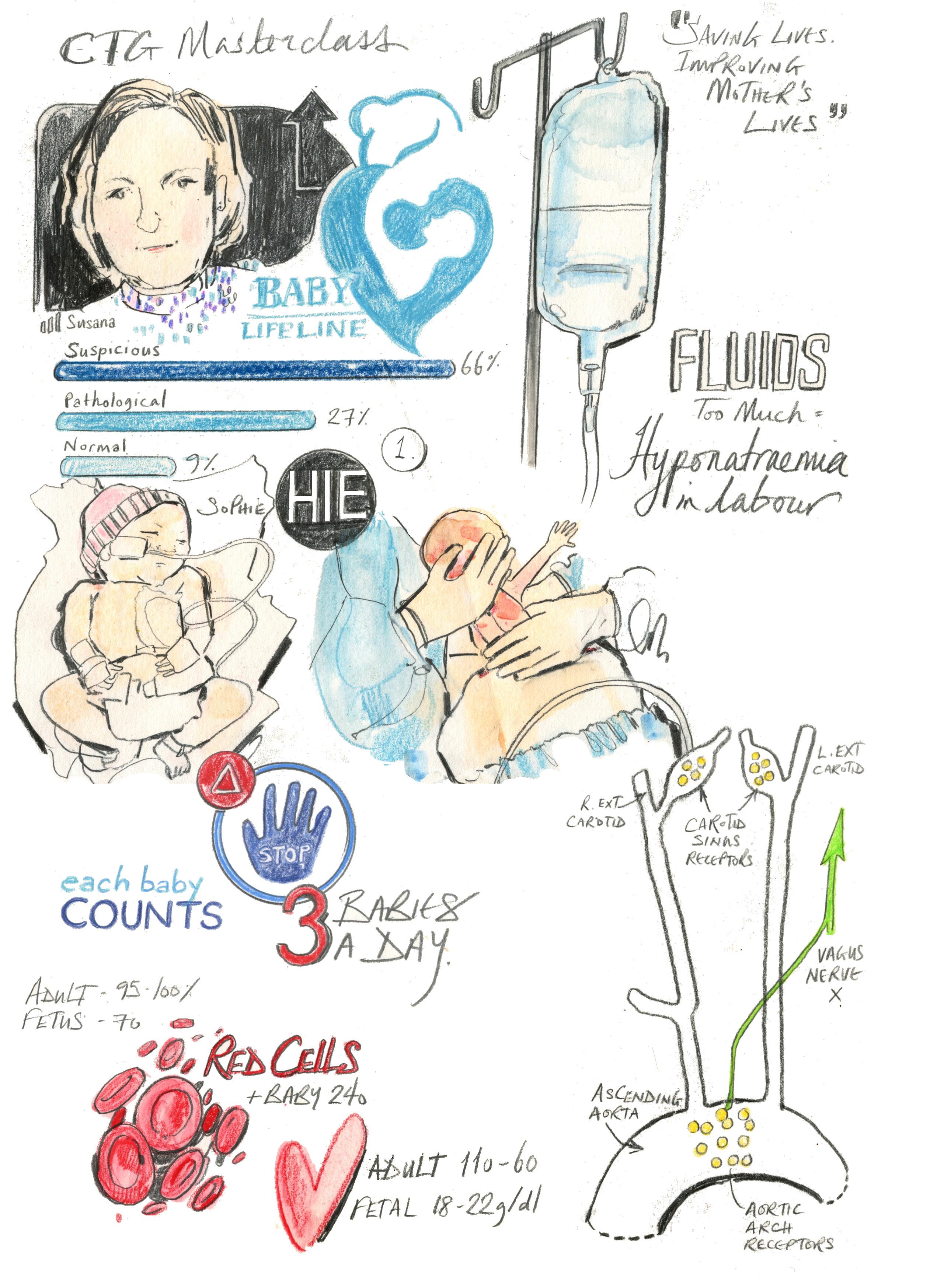

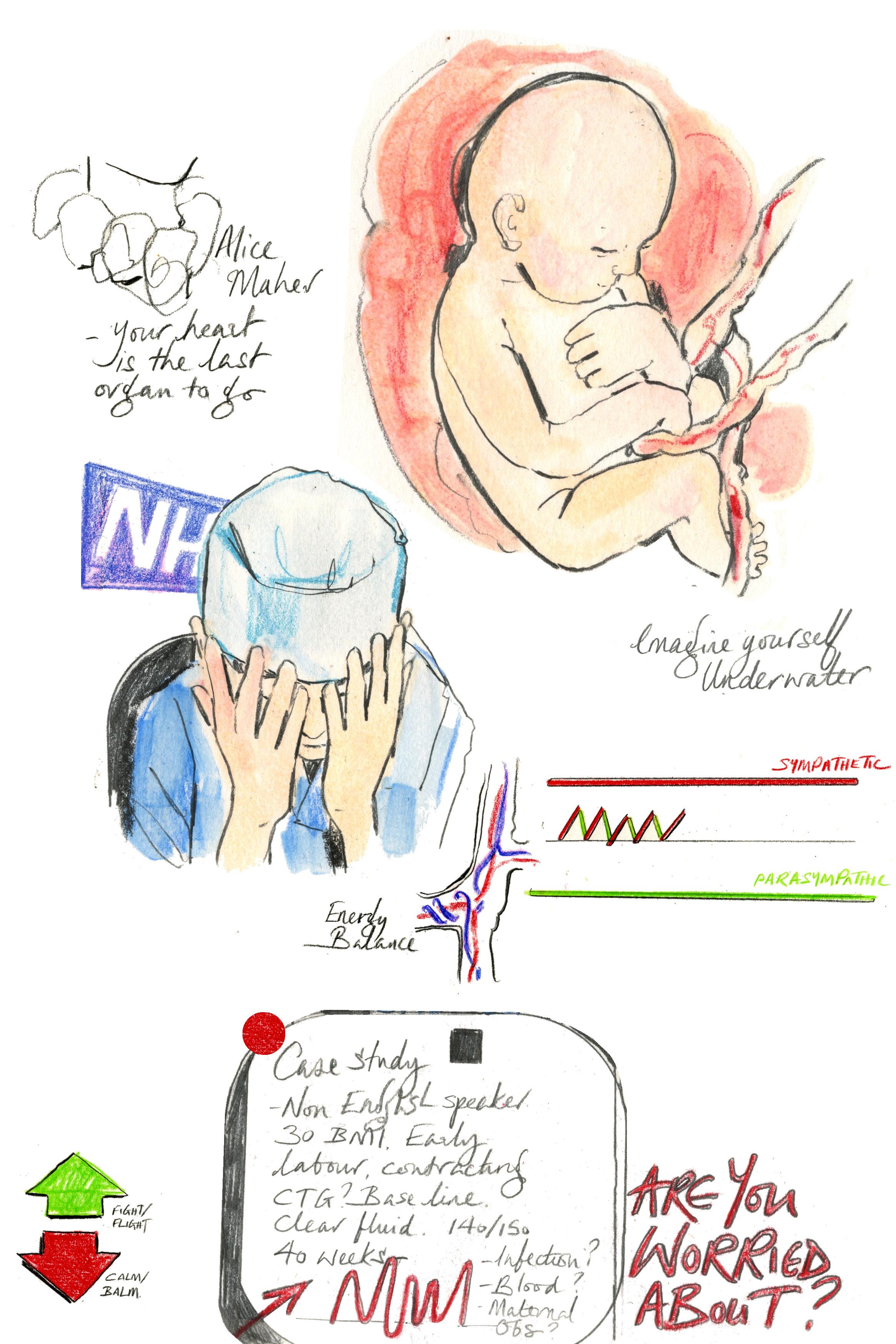

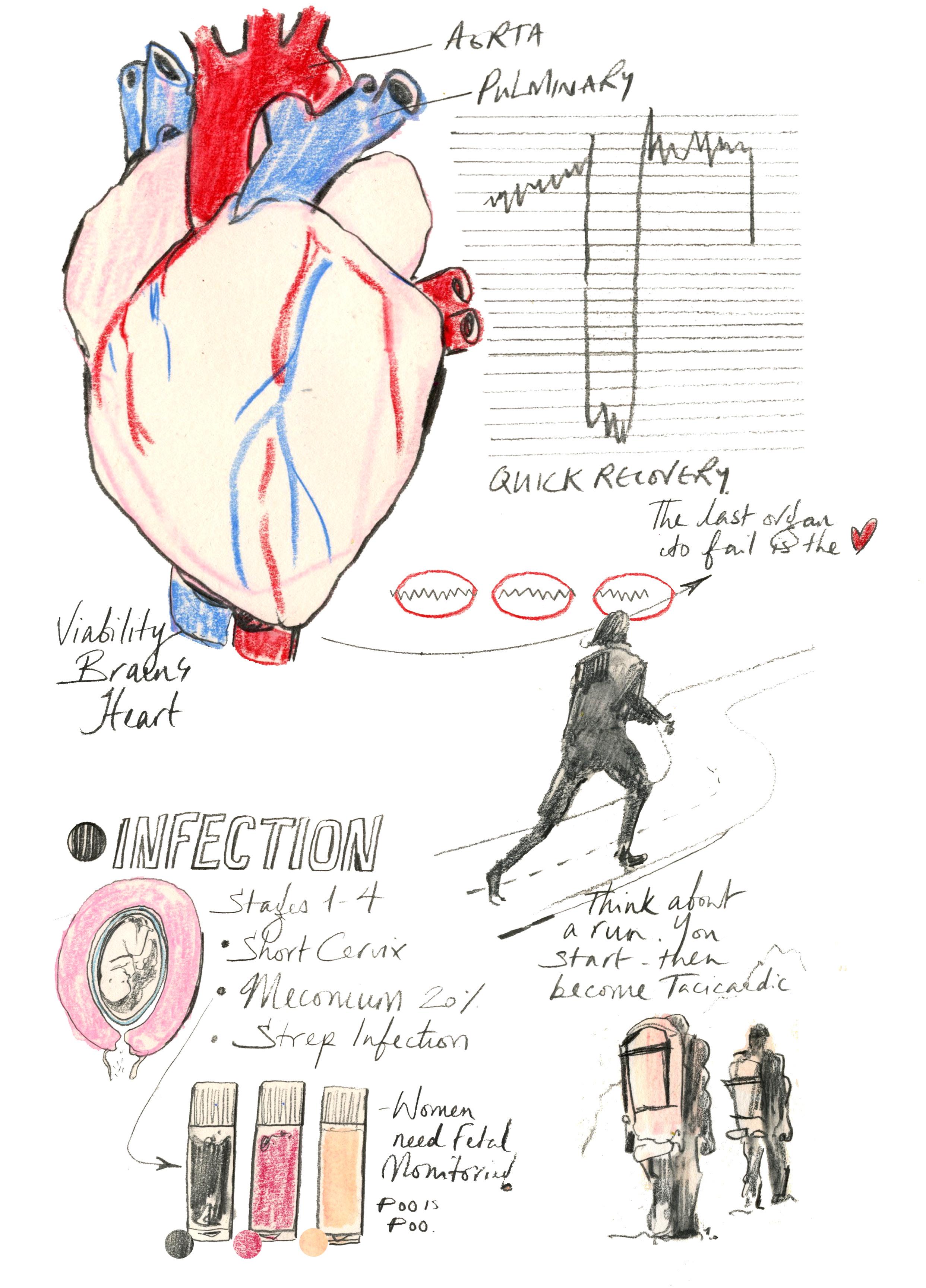

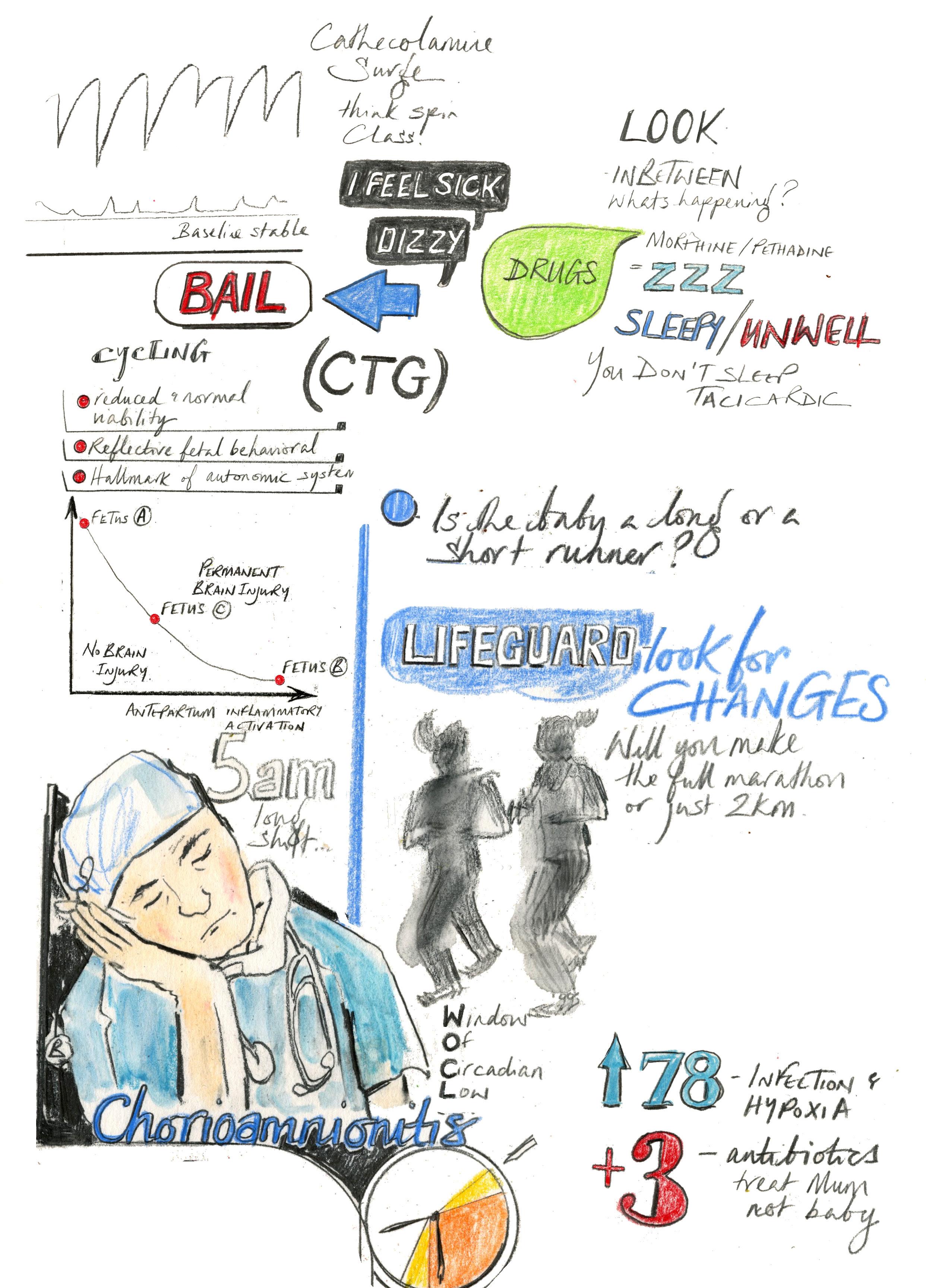

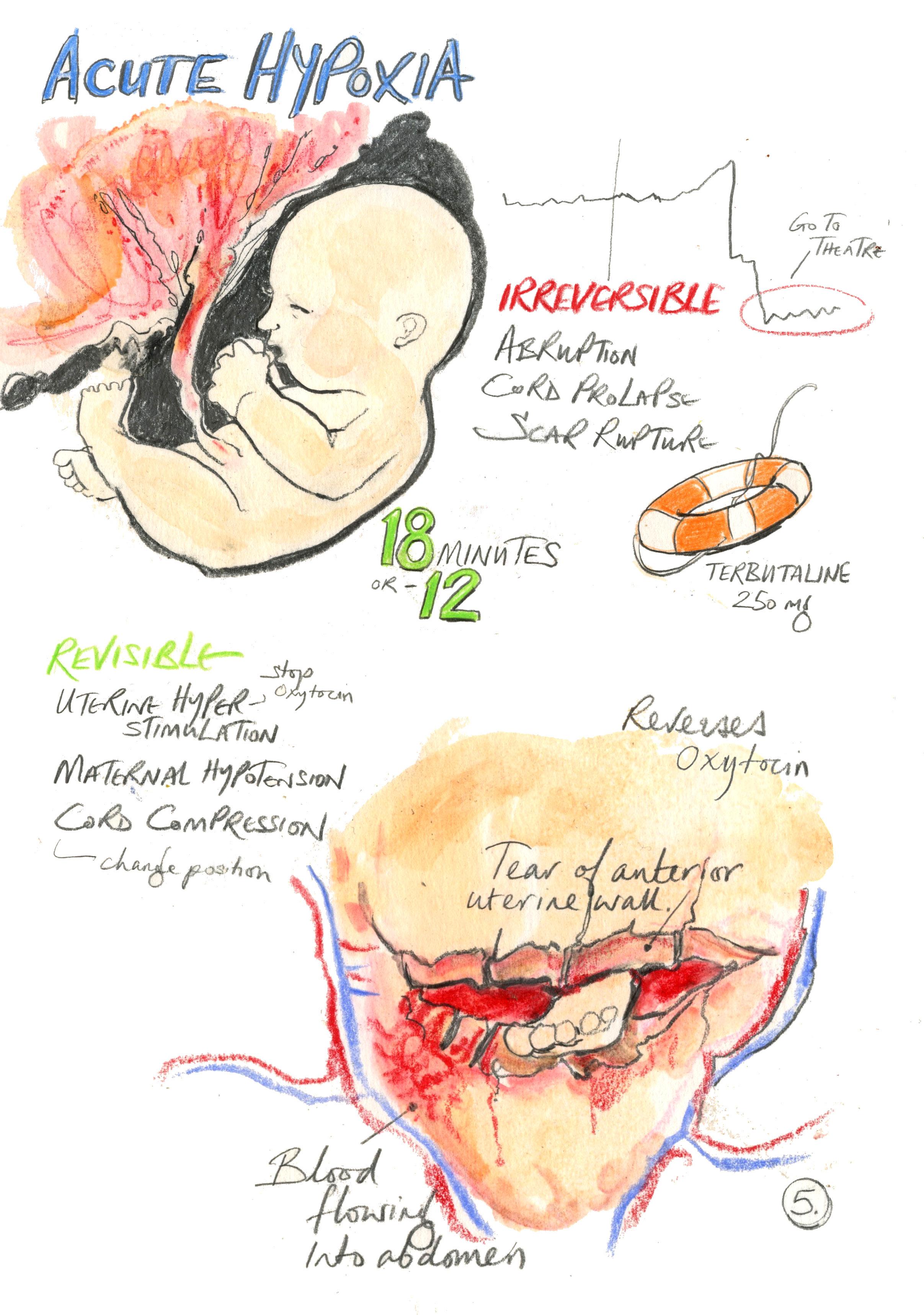

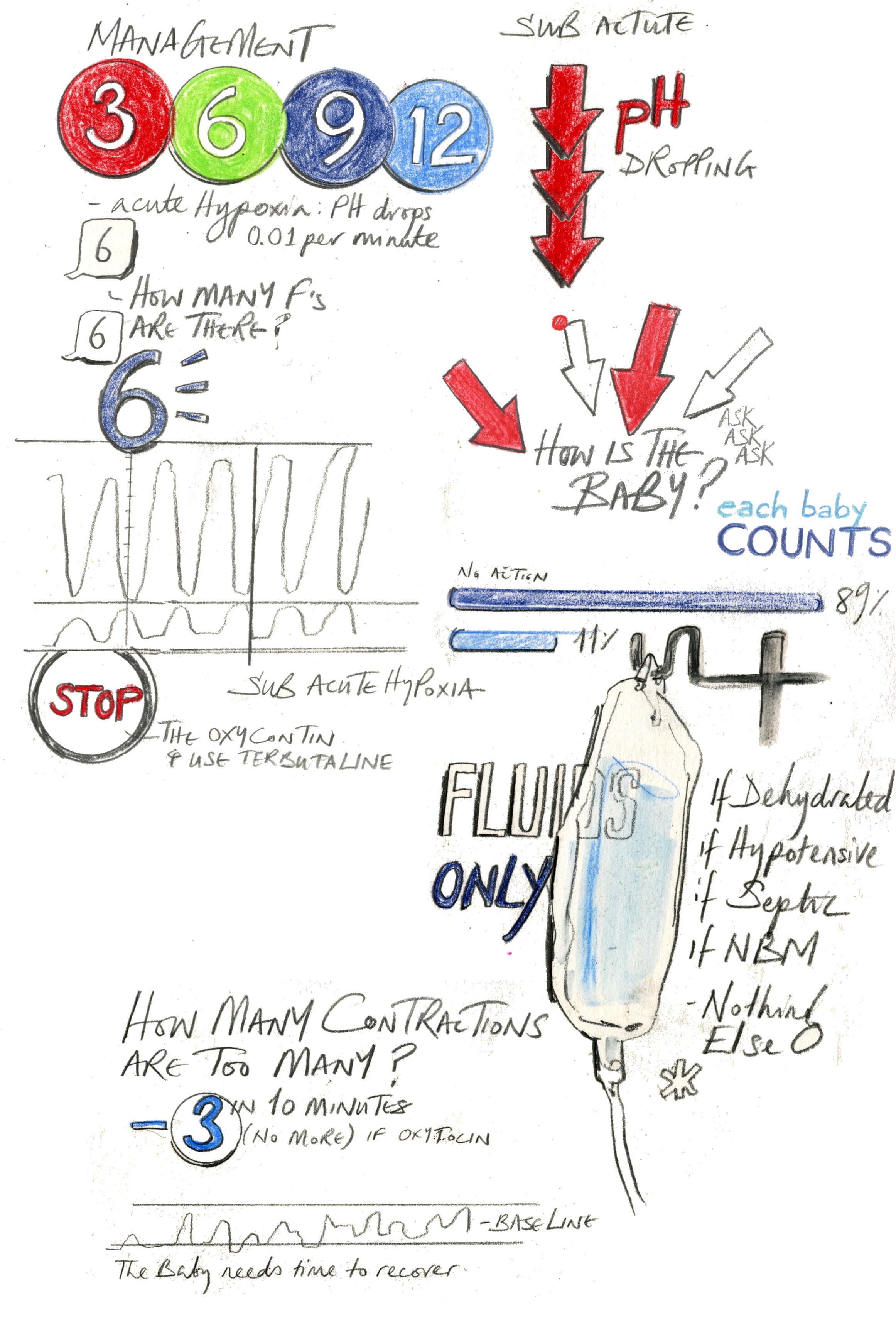

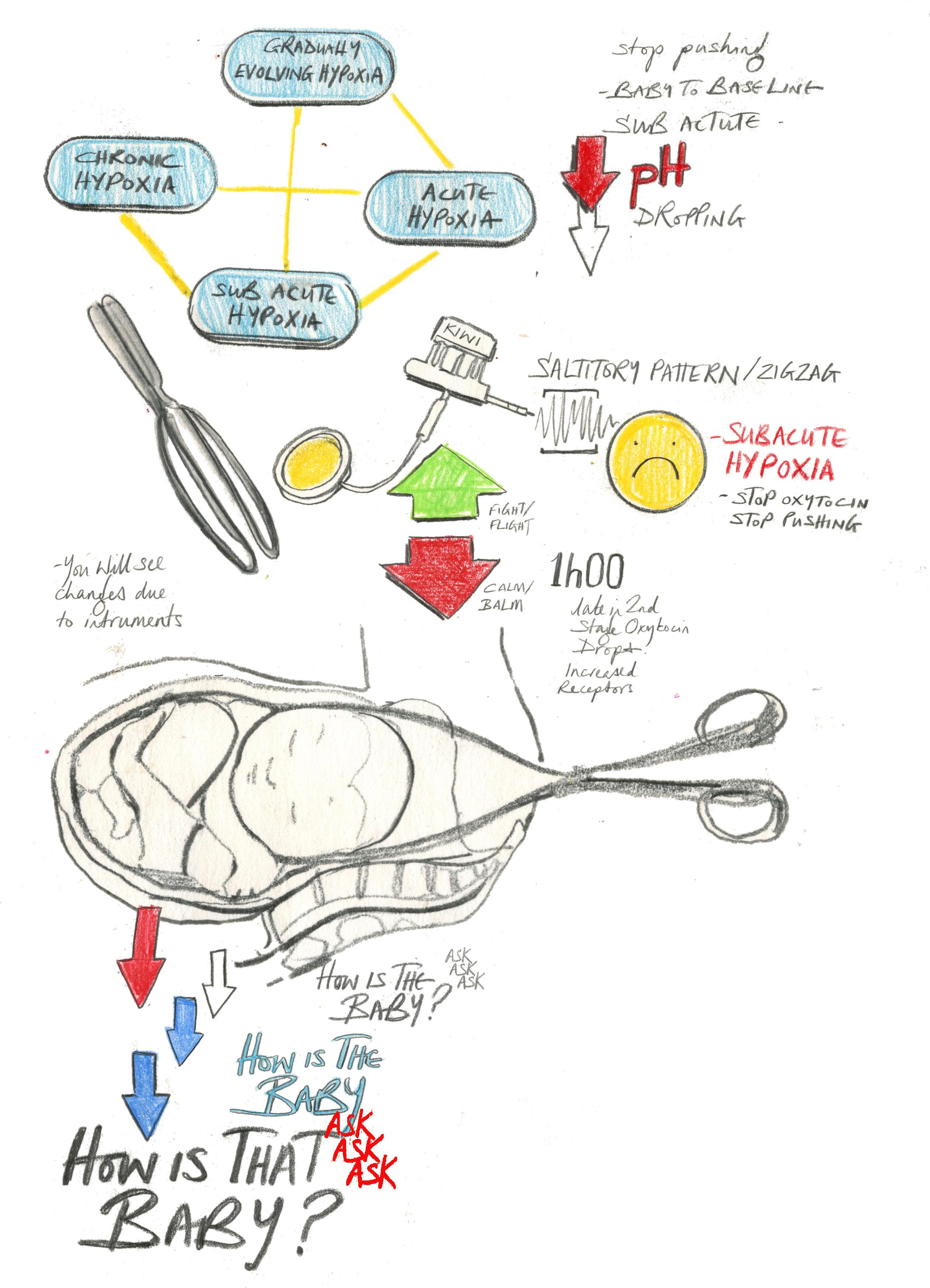

Pages 26-32.....Drawings documenting Susanna Pereria’s CTG Materclass.

Page 33.....Literary Review continued.

Reflections from Reader No. 8

During the academic year, I have felt at times that I have produced little and not progressed with the productivity and creative intention I had back in September; time within the year has been compromised with caring responsibilities, a situation I find myself and my female peers as a ‘sandwich’ carer, you are looking after your family at the same time your parents declining health fall on your shoulders and responsibility. Putting together this 8th reader and looking back through the 6th and 7th, I have been making steady progress and completed training to move on to the next steps. The advice regarding which comes first ethically is Kingston University clearance or the Health Research Authority. As of now, I am aware that the project falls under the label of health research. Pages 16 and 17 illustrate the toolkit for determining what the project constitutes.

I have completed the epigeum trainingcertificates on pages 14 and 15. I attended Christoph Leuder’s impressive ethics training, where he packed in a bucket load of information and answered all of the in-person and online attendees’ various questions to the exact minute the session ended. I have continued reading about the subject and used the report ‘Listen to Mums: Ending the Postcode Lottery on Perinatal Care- A Report by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Birth Trauma as a key text for the issues and failings happening in maternity care within the UK.

Susanna Pereria, who is now the clinical lead at The Royal London Hospital, Whitechapel, London, has a new book published and asked to incorporate two of my illutsrations. In the conversation on pages 22-25 she talks about her new role and the research projects she has set up within her

maternity unit primarily concerned with language barriers and communication to the mothers within the East London area they cover at the Royal London. I am meeting with her and her team on the 30/05/25. I was invited to draw her CTG (cardio toca graph) masterclass, It is used to monitor a baby’s heart rate and a mother’s contractions during labour. These specialist classes are for other professionals who work with birthing women and the content is around reading, understanding and acting on the results of the graph and progress of labour and the stress on the to be delivered baby, pages 26- 32.

Looking back at the three readers I have complied shows a continued committment to the project and a considerable amount of visual and listening progress. The subject of mothers having a better understanding of the narratives and issues surrounding births and especially first hand birth experiences remains in the news and social commentary.

I have had some thoughts about my experience as an advocate for my dad during his range of hospital stays over this past year. One idea centres around quick communication with a patient or family member and and freeing time for health professionals. This large post-note template will have faintly laid out on the paper surface a drawing of the anatomical structures of the specific part of the body. The clinician can then draw and highlight over the issue or the part that needs explaining.

The idea came from talking with a vascular consultant at St. George’s about my dad after his stroke. He was trying to draw a diagram of the head right, and in doing this, he was trying to draw where my dad’s 70 per cent blocked carotid artery was. The carotid artery is the main one that takes the blood from your heart to your brain- so significantly important. He was doing a rather shonky job drawing it with his biro on his lap. We are in a noisy hospital environment; my dad is recovering from a stroke, so he is still weak and confused and also his hearing is impaired. This experience made me think that if there was a visual of the correct structures that don’t necessarily feel clinical, the doctor could add another level of poignant information to that procedure

I hope this doesn’t already exist, as it seems so simple and can be applied to any part of the body, including pregnancy and the build-up to a baby’s birth. From the last conversation with John, he agreed the premise is a straightforward and potentially inexpensive form that could significantly impact the healthcare environment. On asking if he had seen this idea in his work or as a patient, he has not.

“I feel like from the way you’ve described that I can picture it I think that’s just because it is kind of a really graspable idea I’ve certainly I’ve never had anything like that used to explain anything to me although I suppose in a way it’s that there’s that thing like yeah it probably wouldn’t apply necessarily to my condition because I see the MRI scan results but of course the thing with, unlike a blood clot, in my case it’s impossible to kind of point at an MRI scan and go, you’ve got a bit of damage to your nervous system there and that is going to produce this particular effect. But no, I’ve never seen anything like that.”

Medical experts read MRI scans like complex language understood by a fluent speaker. When an A&E doctor showed my dad a scan of his head, he joked, ‘Well, I can’t make head nor tail of that!’ as in the ‘head’ joke.

So, the idea of having a template that gets embellished and curated in real-time. It could show an issue, the process of healing, or change.

What research could back up the value of shared attention? John pointed out the value of a health professional physically making a mark on a diagram or drawn explanation, for example, of a blockage or a clot- that in itself is like a physical metaphor for the flowing of the blood and the blockage.

This way of communicating has implications for explaining issues around the health of mothers and babies. For example-

‘Why is your birth so high risk? Well, it’s because your placenta’s here.’ Or the whole premise of twin-to-twin syndrome, so if you have identical twins, they share the placenta, so you often get one twin that will be much larger than the other and another twin that’s not. And there’s a procedure where a tiny laser cut is made in utero. Explaining that to someone during stress and high risk is quite tricky.

Society is structured to control women; male physicians only became involved with birth almost in the hope that something would go wrong, and then obviously, you’ve got more children, so you have more customers. A lot of childbirth is a lot of waiting, which for those doctors isn’t interesting- ‘I need to be doing something much more important than waiting.’ I think that’s also the way that women often perceive themselves being pushed through this system of, hang on, your body’s not doing quite what we want it to do; we’re going to pump some chemicals in it- or with the premise ‘I’m just going to check your dilation’ often means ‘I’m using this medical implement that resembles a crochet hook and break your waters.’ JW

There’s no specific question on the KUREOS application itself that mentions the NHS. On the Canvas page for postgraduate researchers, there is an ethics page for PGRs in the graduate research school. And that does have a link to a guidance page for projects involving the NHS. It is primarily a general page of ethics guidance with just one paragraph, such as on projects involving the NHS. For projects involving the NHS, you must contact your NHS site provider in advance. The National Research Ethics Service for England works closely with the UK health departments to develop and maintain common UK-wide systems for ethical review of health and social care research. Certain health and social care research projects require a review by an NHS research ethics committee before commencement, so we’re currently looking at that. Then it’s got a link to the HRA site, which you’re already on; the National Research Ethics Service applications are made using the integrated research application system at myresearchproject.org.uk JM

I was discussing this with Susanna Pereira about how we understand an environment when I showed her my drawing of the operating theatre. She went, oh my God, it looks really complicated. And she went, we live here. So it’s like home from home. And it’s like we live here. JW

I had an operation, and they described it as a lab. It is massively high-tech; it resembles a recording studio-type booth where part of the operation is carried out remotely. GG

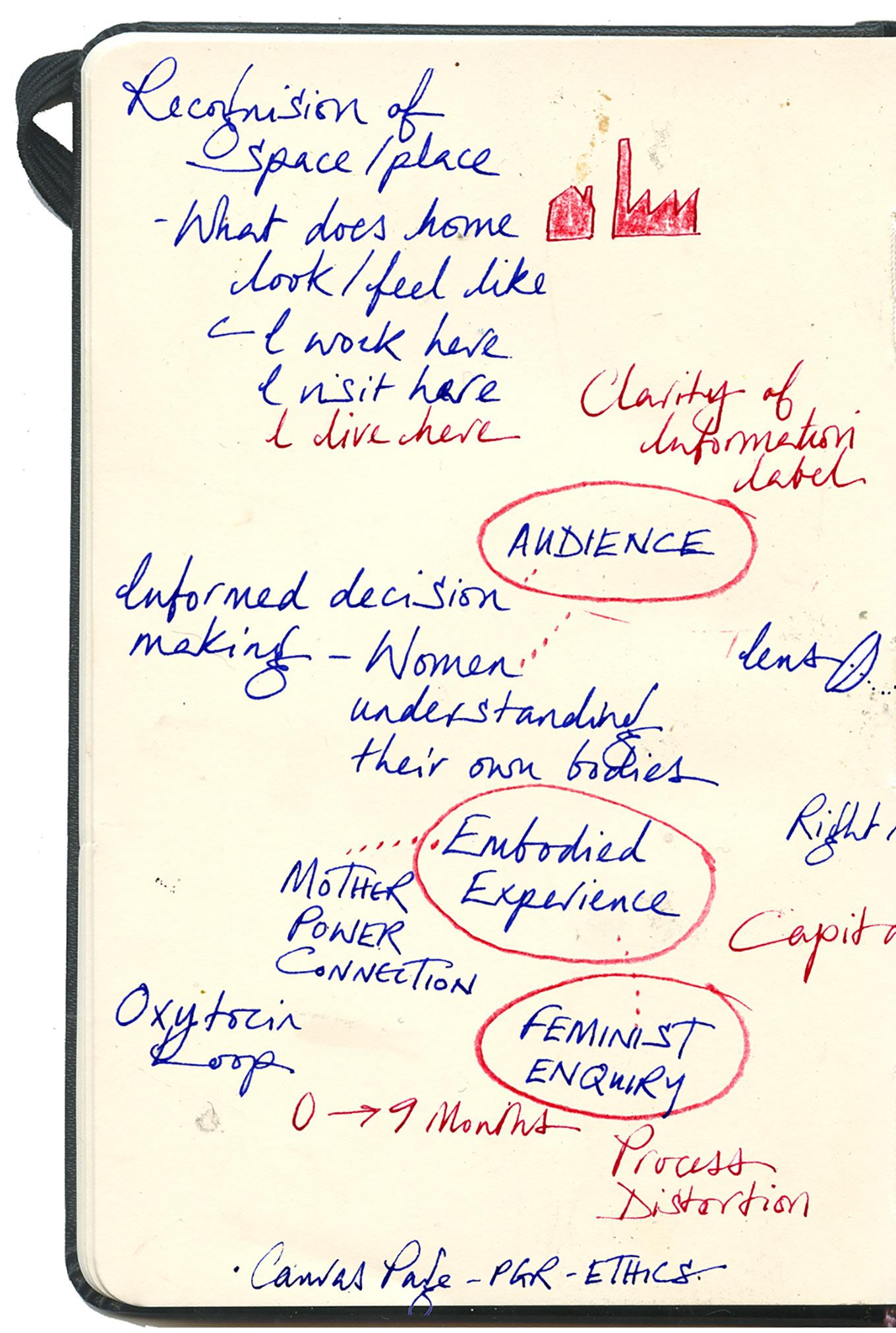

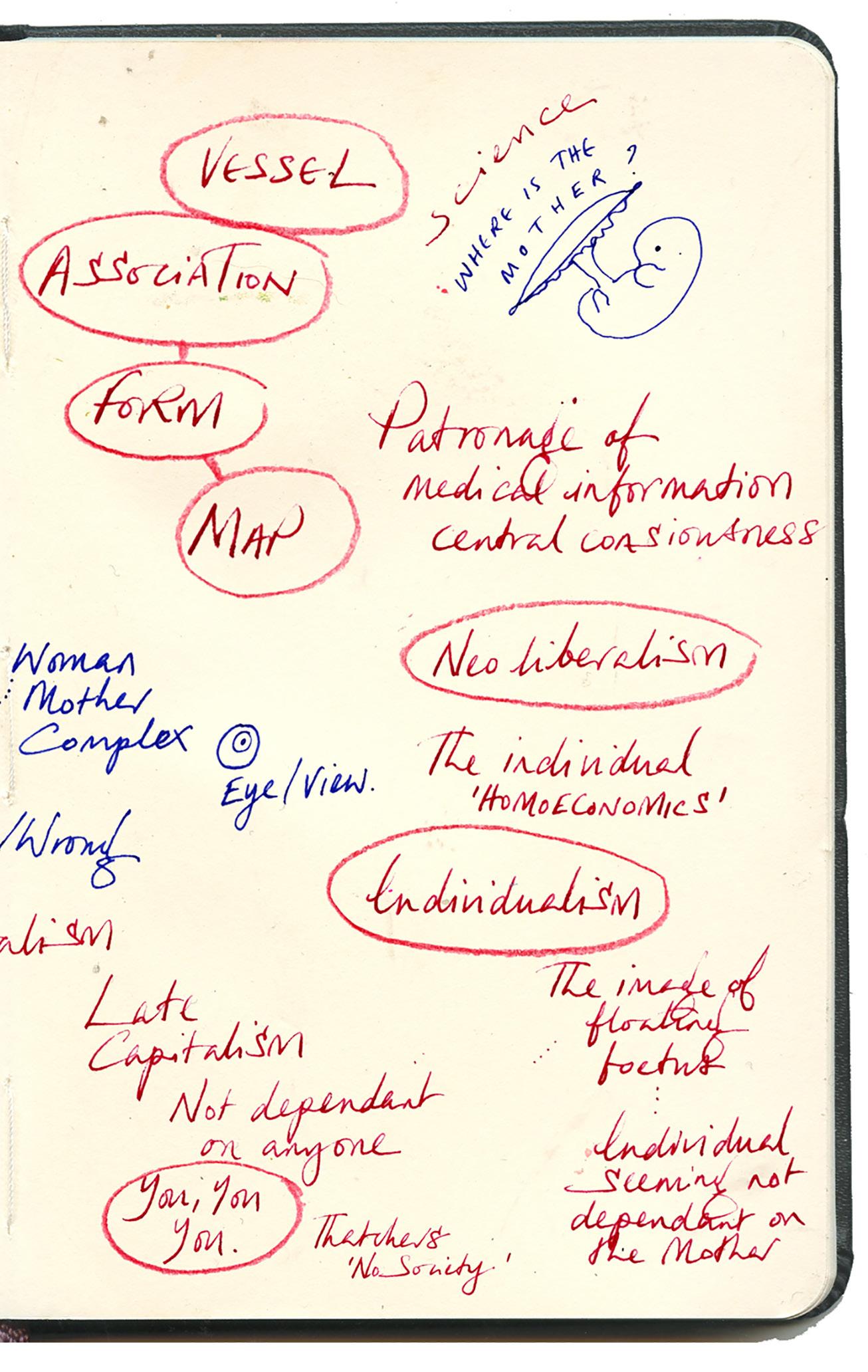

As adults, we’re all completely enmeshed in social obligations, responsibilities, and dependencies. So there’s something like agitation and a bit like a social crisis. So it’s case in point. Whereas, it’s almost like there’s something like actually, so in the months before your birth, it’s the moment when perhaps you’re most obviously and most fundamentally completely dependent on another organism. And so, there is something kind of profoundly capitalist about that image of the autonomous foetus.

JM

Homo economicus- in our society we don’t need to look out for anybody else because you’re an individual. If every individual looked out for themselves, then that’s how the world should function and what screws things up is when people try and create social structures which hold

We all make really informed choices all the time, but when we’re in a different space where we don’t know the rules, we find it really difficult to advocate for ourselves. It comes into comprehension and recognition. In some ways, many first-time mothers are in an unrecognisable space because they haven’t been there. JW

You’ve said several times about the patriarchal nature of the way that knowledge and information are filtered and presented in a certain way for a certain consciousness. In some ways, it’s the origin of some of the problems you’re trying to address, which is about informed decision and choice and being able to effectively, women being able to learn their own bodies. Or is there a central core here of male ownership of knowledge of the human body?

GG

I think about the overall scientific visualisation. This fundamentally impossible image of presenting the foetus as if it’s an independent entity is just where my brain naturally goes; I was connecting that to some wider social critique of neoliberalism that asks us always to think of ourselves as autonomous individuals and to kind of downplay or ignore the way that we’re all connected. GG

How do you want to structure this in terms of your inquiry? You could go into it the way John has: Marxist wants to link it too late capitalist structures basically, or you can go into it as a feminist and say that basically the entire process is being distorted and dangerously distorted and, you know, structured through white male kind of supremacy and things like that. Still, one of the things that I mean is you can describe these lenses as they were. Still, it’s like as a woman, as a mother, as a person with, you know, the experience of complexity with childbirth as well, , these things are kind of incredibly real, it’s this embodied experience that you’ve got.

GG

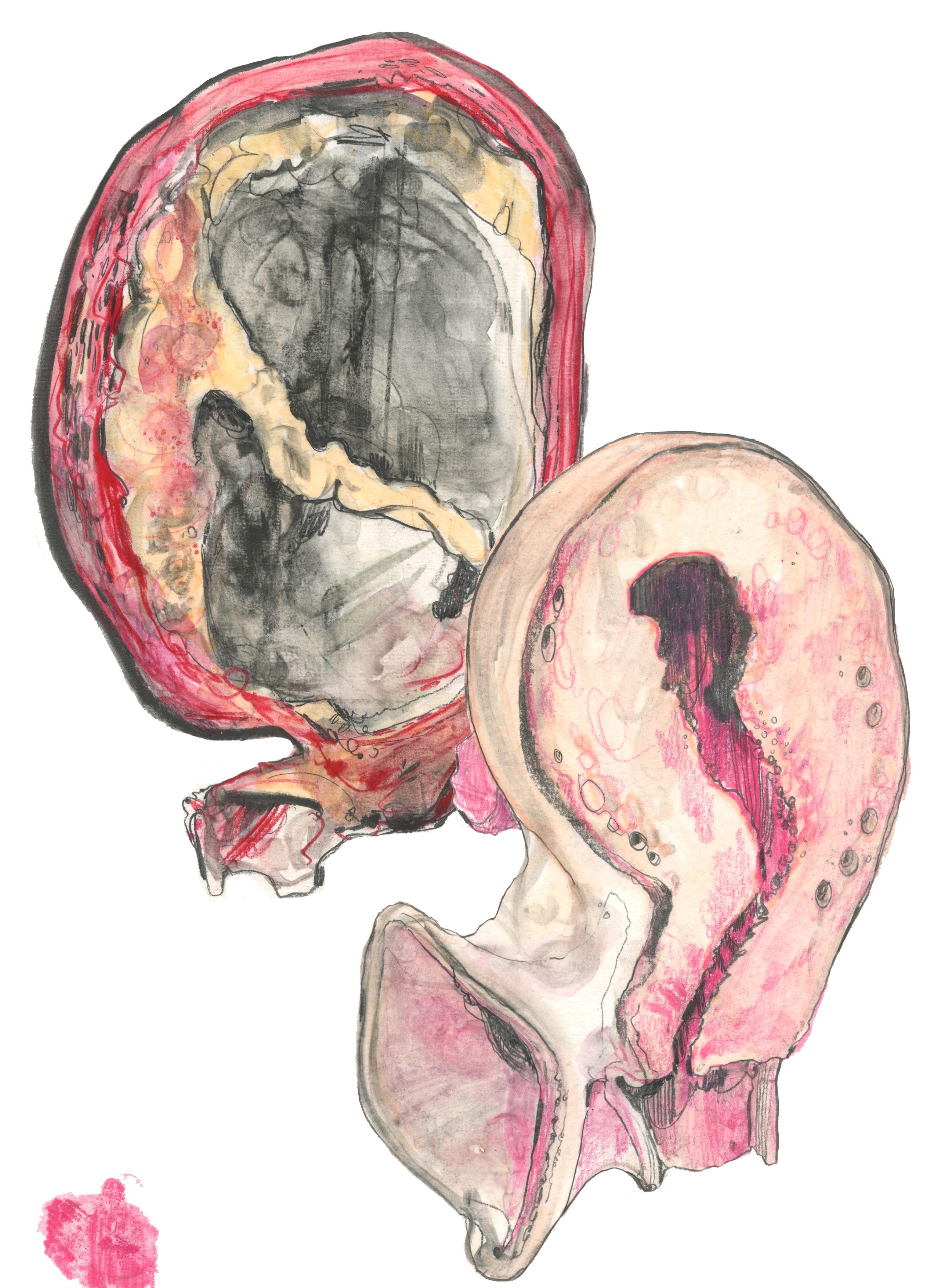

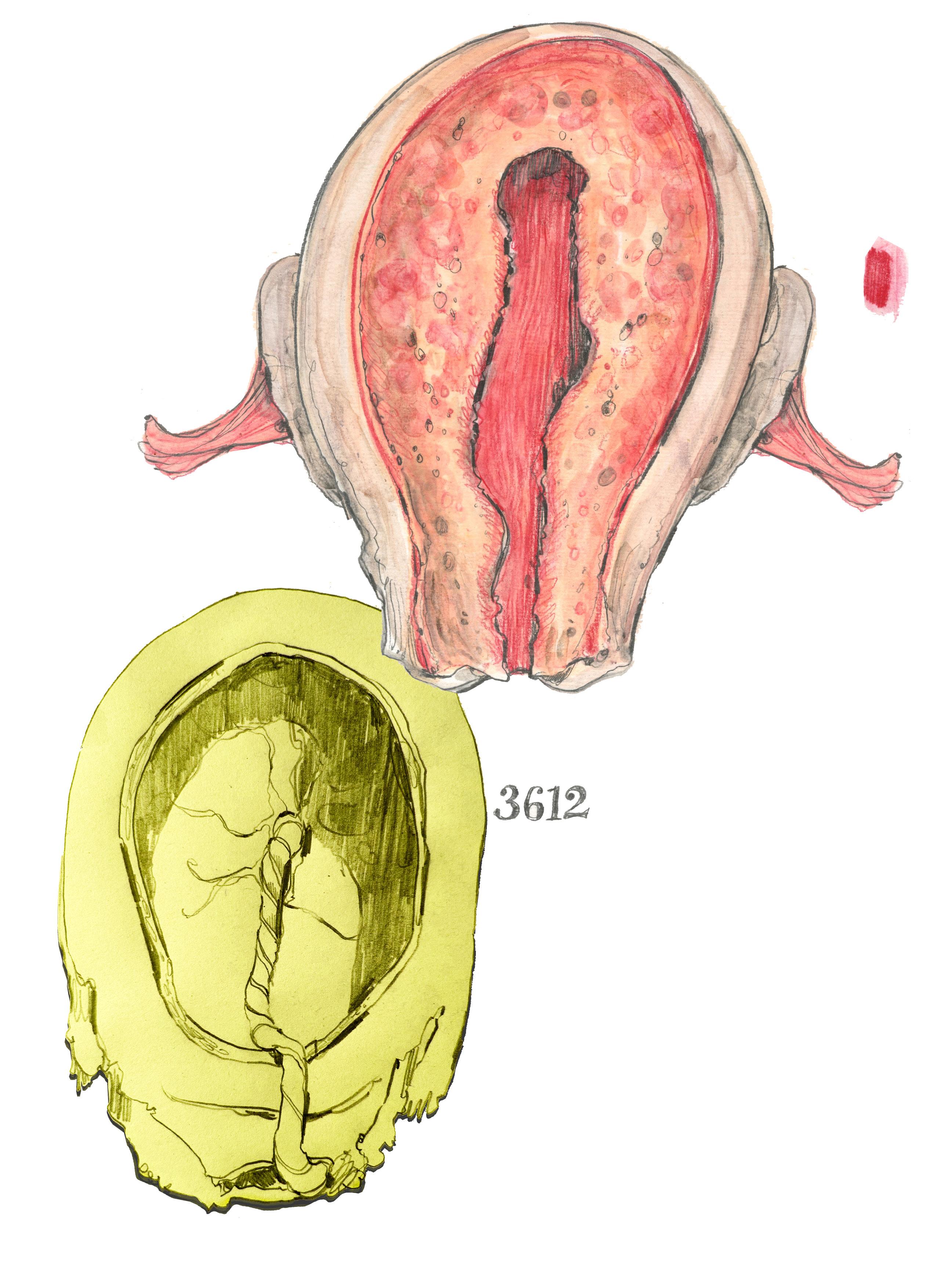

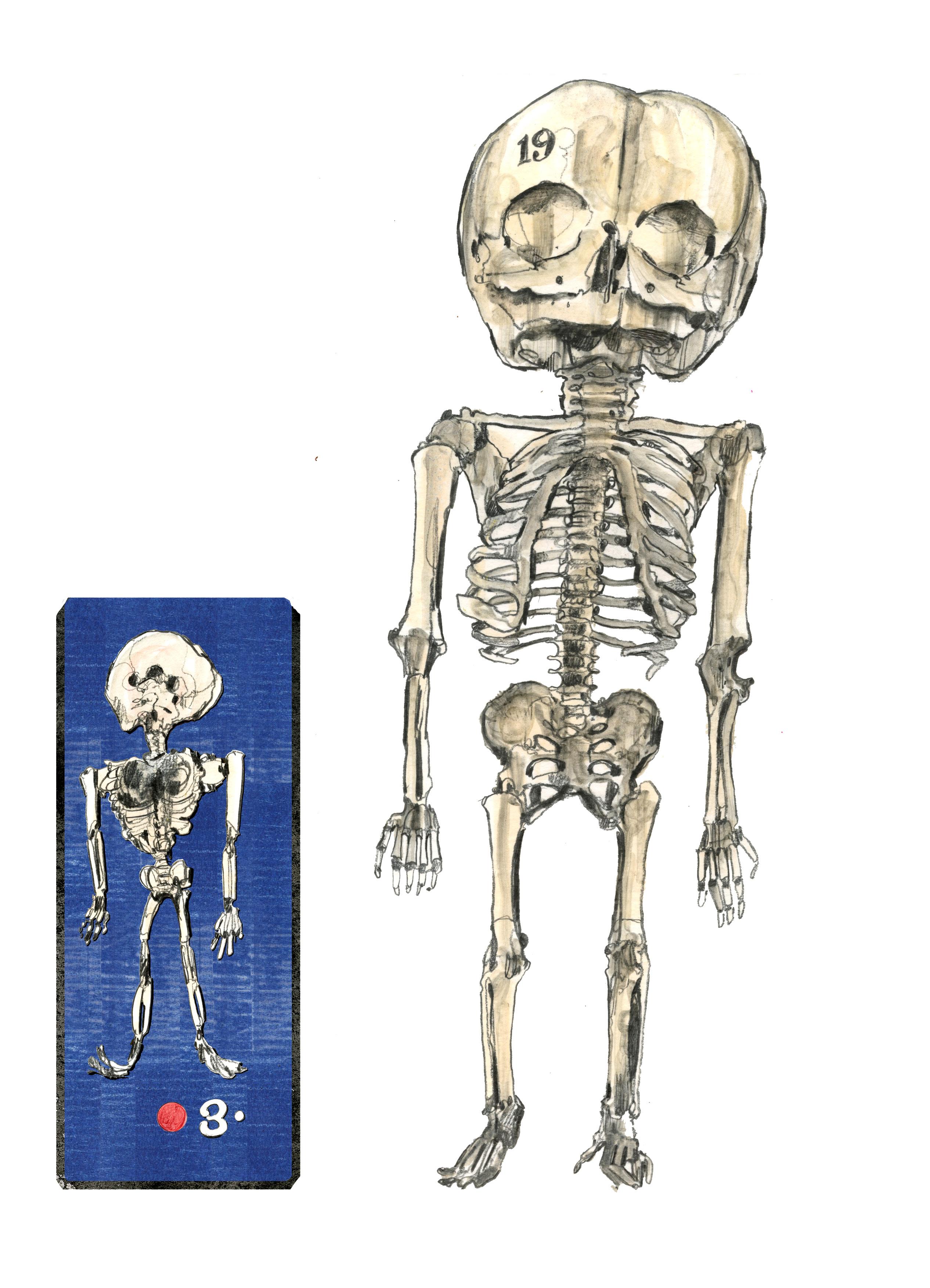

Drawing on location at the Hunterian Museum at the Royal College of Surgeons.

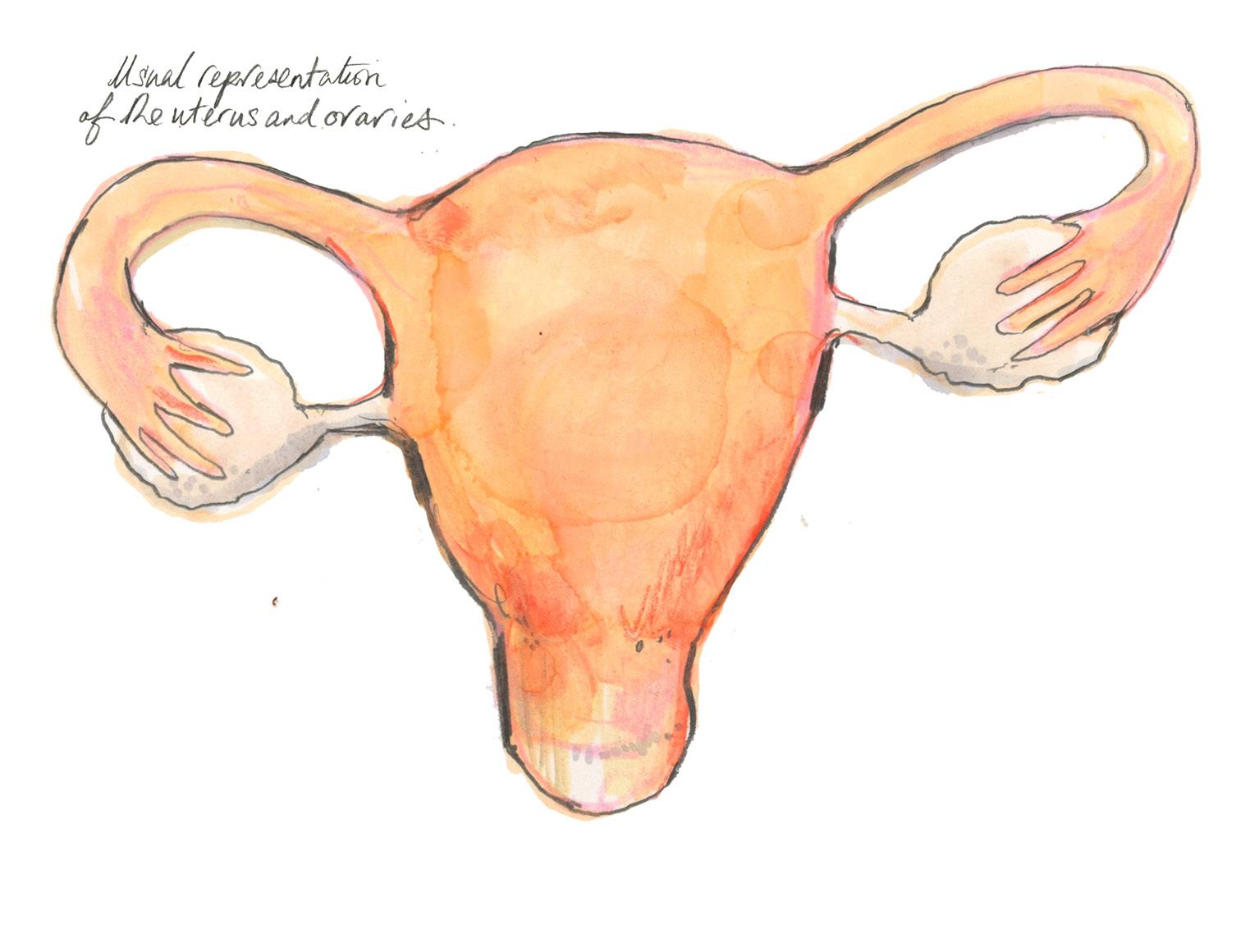

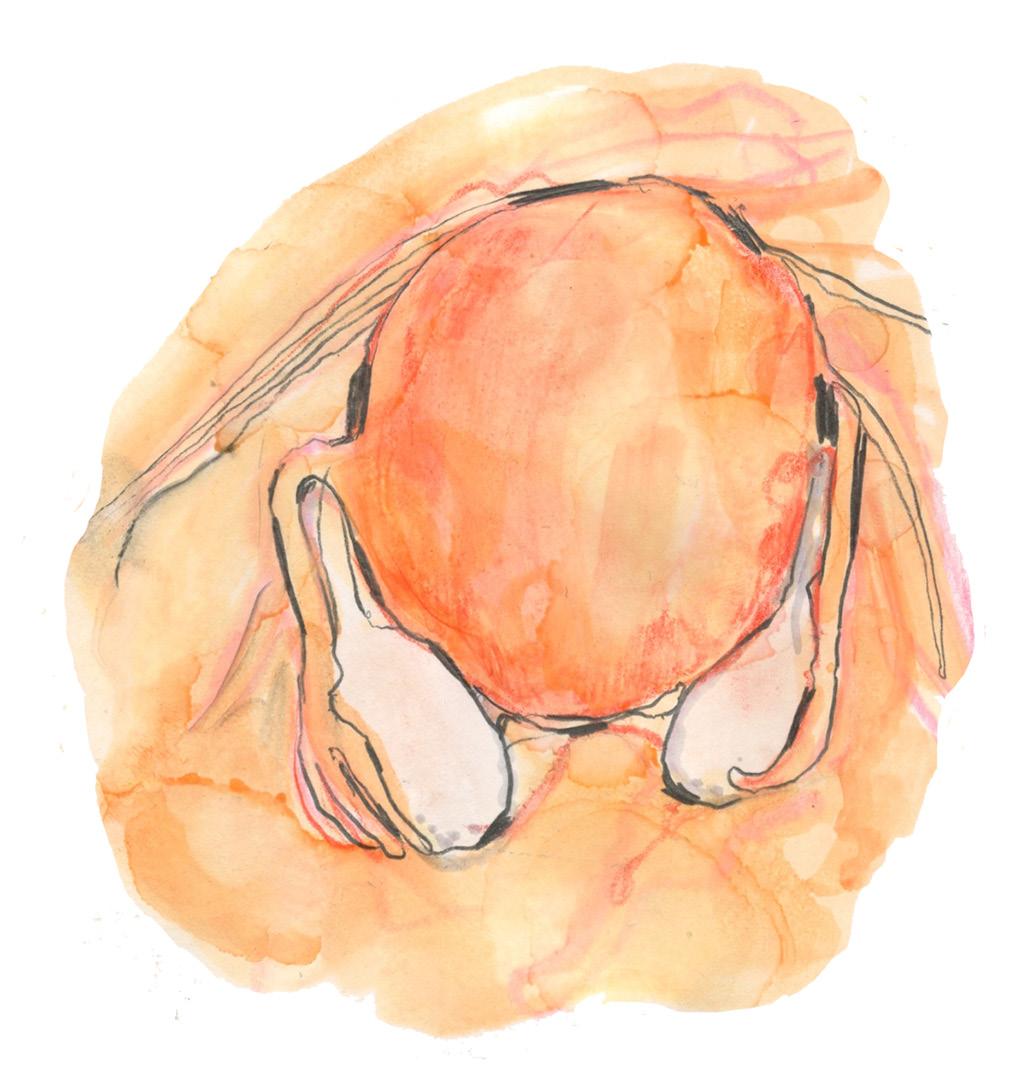

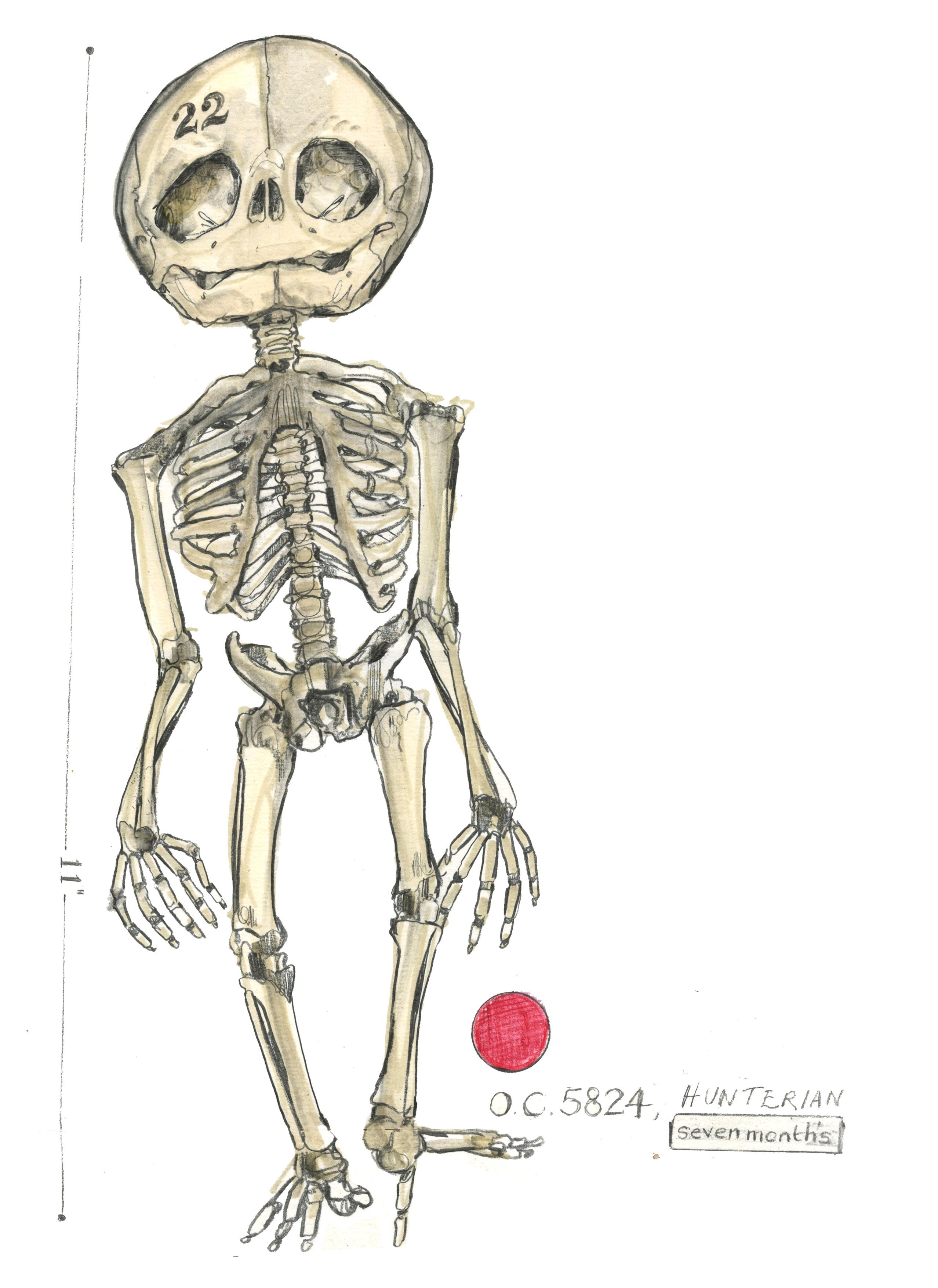

Specimens from anatomist John Hunter’s 18th Century collection. These are drawings of the uterus within the collection. On the next page, there are skeletons of babies at 3, 6, and 7 months gestation.

ETHICS Training - Dr

Christoph

Lueder 20/03/25 Knights Park TK502

We will start with a brief overview of the research ethics process, during which you are welcome to interrupt and ask questions. Then, we will make time to speak about specific questions that arise from your research applications you’re working on and from research you’re planning for the future. Some of you have either a pending application or received a favourable ethical opinion some time ago; looking at you, Alex, and are carrying out the research. I’ll keep the overview of the processes succinct if that’s okay with you.

To reiterate, I’ll review things that most of you might already know. So it’s a requirement to undertake two courses. There are online quizzes available through Epigeum. If you click on here, we can go there. We can find these courses in ethical research. And the two courses that you are asked, hello, good morning, to undertake becoming an ethical researcher, so it does take a bit of time, but it’s also well-spent time. Apologies. I found those quizzes and courses quite valuable.

They are not specific to the discipline, but they’ll go through several case studies and principles of ethical research.

You can also find research ethics for PGRs on the Canvas page, which gives you an overview of the process and the available forms. I will just now go through the most critical parts of this process. This is all the guidance. A pre-application checklist helps you understand whether you have completed all the necessary attachmentsThere’s a guide.

Focus on three key elements to keep this succinct. One is a participant information sheet. That’s where you are explaining your research to your participant in language that they’ll understand, including all the information, but also thinking a bit about how to communicate, how to communicate in a way that will make sense to them, and perhaps break down some academic jargon into something that’s more generally understood. I like to use visual information quite a lot. That’s an excellent way of communicating, and I will show you some examples of participant information sheets.

We have an informed consent form. That’s a place where you can ask your participants whether they want to remain anonymous and whether they feel their name should be cited, and they’ll be informed that they can withdraw from your study. There are many other things. So it’s a valuable element. There are circumstances in which it is advisable to seek oral consent. So, there’s a situation where it can be very awkward to present people with a piece of paper to sign, and it’s perfectly acceptable to have a conversation and seek verbal consent. I’ll move that to the second part, where we’ll discuss research.

I recently completed a research project where I was working with Avery Fletcher on a film with every flagship on the film, so we recorded the content at the beginning of the film. We gave people plenty of time to read the information and have a conversation about it, and then, at the beginning, someone just said, okay, are you happy with the information we’ve provided you with? Are you happy to proceed? If people say yes, then it’s recorded. That’s not always the case; we’ll have an informed consent form because recording audio content might be more appropriate. There’s a data management plan spelling out how you will store the data if you have promised anonymity to your participant, then how you will safeguard that, and finally also, how you will conserve the data once the research project has concluded; there’s a possibility to either store metadata on the Kingston data repository, which is different from the Kingston research repository. So, in the data repository, you could store metadata or even the transcript of the interviews or work you carried out. So these are the information sheets that I’ve used. The first is a single-page one where we just asked people for statistical information and didn’t record any names, so we kept that simple. I didn’t include an image of a comparable previous research project, so they see, okay, the data is represented as a series of graphs and statistics and not identifiable to a person.

The second one is interviews carried out on site, in place, so to speak, in apartments and houses that have been transformed. And so I just, in place, again, used images to explain to them what the data will be gathering and also how it might typically present. I think that’s a way of trying to make those more accessible.

Alex Passoli, who is here, has allowed me to share her information sheets. I’m just going to share those with you. They’re wonderful. So Alice is working with children and has a process, again, that’s bespoke to two different age groups. This illustrated version is for younger children, where Alice has made this beautiful series of scenes that take the child through the process. And it’s the same thing you would also talk about with the adult participant: how it engages the child and makes research ethics part of the research process. In terms of research ethics, if it doesn’t become some onerous task that’s appended or annexed to the research, if it starts to help you with your research, establishing a trustful relationship with the participant will also improve the answers you get. And so it’s good to use that process, to be transparent about what you’re doing and to explain it in a way your respondent will understand. In this case, that’s very lovely. And then there’s another one. Then there are, this is an example, where we have experts involved -here’s one sheet for professionals, which is somebody that you might, in your disciplines, they may be curators, or artists, or illustrators, so somebody that you actually will be likely more familiar with research and with speaking in public,

with disseminating their work in public, as opposed to the previous sheet, which is about inhabitants, what people who live in a flat, where I think one needs to take responsibility also for them perhaps inadvertently divulging information that they wouldn’t want to share. As researchers, you have a responsibility to spend a bit of time trying to understand what the different participants might expect from your research and how they might react to it. And so this is reclaiming the autistic voice by doing workshops, but let’s not go into too much detail with this part. One aspect is following on from your research, whether focus groups, practice-based engagement, or interviews. There is something that has recently been called restitution, restitution of knowledge to the communities, taking a term from colonial studies and realising that research often is extractive, that we are taking a lot from the people we are interviewing without always acknowledging and without always seeing what’s in there, in the process for them, because that’s research that we benefit. It’s going to be your PhD; it’s going to be your publication. So, restitution means giving back to the community and the individual.

So, there are different ways I’ve done interviews about architecture, around homes, and about people’s informally constructed or informally transformed homes. I’ve made booklets, and we always talk with local partners. The local partners visit the families or respondents and share that information with them. So, there are different ways of showing appreciation. Other researchers have screened a film for the participants, so they also had an opportunity to close the feedback loop, as they say, and to share their reactions, which is so valuable for you as a researcher.

We also did this with an automated model in the form of crystal bases. You have this informed content form and the data management plan, and I will go to the research data repository.

It’s not the research repository. So, you see colleagues who have shared datasets here. You can browse your time and see how they have navigated this. Sometimes, there is a policy consideration between protecting your respondents’ privacy and your interviewees’ privacy and making data available to other researchers. So this is Zoe Bather in the Berlin Pathways to Graphic Design practice. I recommend looking through some of those to make this more tangible.

So that’s where we’ve got our data management plan. We have the application process. It’s good to chase the supervisor. Sometimes, these things get stuck, and usually, the reason is that the supervisor has assigned them off. We won’t see anything until the supervisor has signed it off. Also, you need to attach the certificates of completion to the FPGEO training because otherwise, it won’t be forwarded so that we won’t see it. If they could be tempted to join as a reviewer, the KSA College of Ethics Reviewers, let them know that we’re welcome.

Everybody is also helpful if the supervisor has some experience reviewing applications. It will help them advise their students and make this process more integral to research than something that feels like an add-on. So you have about 20 working days maximum. We use very quick and supportive reviewers who review much faster. If you have more reviewers, the reviews will be quicker again. We should return the feedback much faster, but within a maximum of 20 working days, you typically have one round of revisions.

So you are asked to make some changes, which will also take time. You’ve got those elements. So here, I shared this presentation so I won’t read it all out now. It’s been helpful in previous meetings with top and PhD students to respond to precise queries related to the research project. It’s been conducive for me to reflect on those. If I couldn’t answer them directly in those sessions, I have added them to the research ethics reading list. So that’s how this reading list has been developed. It’s all come out of conversations with individuals or during these seminars. It now has quiet sections, links to KU guidance, an introduction to research methods, and a little book on design research ethics. Within Pauline Robson’s real-world research, a chapter centred around researching with children. There are some technicalities around that, such as the age bands and things like that. Gilding competency: when is the child competent to give consent? They must always be asked in the UK, not just the parent. We’ve got interviews using various media and audio-film transcripts. We’ve got oral history with links to the Oral History Society, which publishes quite extensive guidance on interviewing and oral history on their web page.

Researching with vulnerable communities and participants. Meg Jensen, our colleague Meg Jensen, has co-authored the Expressive Life Writing Handbook with Shearwood Campbell, which we’ve shared here, and we’ve got a few more texts. It’s also helpful to reflect on who exactly is vulnerable or considered vulnerable under those definitions because it can be a patronising term. Vulnerable in ethics means somebody who cannot look out for themselves. And that can be very patronising if you declare everybody as vulnerable just because of their race or religion. So we need to be more precise about that. And there are other terms, such as marginalised communities, that are more appropriate than vulnerable communities in that context because it’s clear that they are being marginalised. It’s not a lack of capacity on their side, but rather society is marginalising them. It’s a huge difference. So, these marginalised groups can decide whether they want to participate as individuals or groups and whether they want to participate. So it’s essential to make that differentiation and to not patronise research with neurodiverse. We just heard about Charlie Wilson’s application, which I shared with you. It’s excellent that Charles has been working with us also to give his perspective on the Curious

Project, research with community struggles, scholarly activism, active scholarships, what is a participant as opposed to a respondent, informant, contributor, co-researcher; you can look it up there, autoethnography, payments and benefits to research participants. It’s often a means of getting a more representative sample because otherwise if you think about people who might be unable to afford to spend time on research, they would be excluded. And so there have been colleagues, PhD students applying to either the Techne funds, your technical students or the KU funds for remunerating payments. The other important part is the benefits. Can you share something with your participants that will benefit them genuinely? Or that virtual appreciation?

The benefits don’t always have to be monetary, but it’s helpful to think about what could you share with them, what might help them, especially if you think about community struggles, or for example, if you share with them, as an architect now speaking, a careful documentation of the spaces they’ve constructed for themselves, they’ll have something to show, as opposed to the many documents that those who have more power will be able to pay for. So you might think about what, in each case, could be helpful in some way. Researchers work remotely with participant data; are they intelligent? Including also the tools that use AI. There’s some information here when you use transcription software. Also, students have looked into it.

What happens to the data? How can you be sure that the data will remain confidential? Different transcription software have different terms of reference that tell you what they will do with the data. Once again, we can discuss whether it concerns your current research steps. Managing risk to the researchers, where there have been police undertaking research with former inmates of prisons, and so on. There’s also a research presentation by David Carpenter, which is helpful. It’s a presentation that, for example, was under-explained and also helped to establish that you don’t have to use a written form in all cases. So, it’s good to have something to go by. And this is a document with his presentation where he’s covering things like, for example, seeking consent verbally.

Good Practice in Research 2 – topics Issues for level 2/3 PhD Students’, ’Press and social media and ‘Ethics and Impact part 2’ 31/03/25

Cilla Harries

The repository is a digital space where you can store data and email addresses to ask how to go about that with more support.

Jane, why don’t you go first because you’ve got your camera on.

Hello, I’ve reached the stage where I was saying it’s not as easy to find the actual place to upload your. At the moment, I’ve done the training, but I don’t know where to upload those. If you have a link for that, that would be helpful.

I’m going to the slide deck here. I will give you the link to it in the chat, and then we can also have a quick look. Let me see how to apply for ethics research. Here we go. That’s guidance, ethics guidance.

Let’s see- KUREOUS stands for Kingston University Ethics Research Ethics Online. How to apply;

Create a project - and then a standard ethics application is created. So it’s got various fields where you work your way through to upload the different information. So these are the other sections along here and then when you’ve finished it all, I mean I recommend that you download a copy and share it and discuss it with your supervisor, and then when you press the button submit when everything’s there, you are signing to submit and then it goes through to your supervisor via email. They check and confirm they’re happy with your submission.

You have to upload the PDF of your training here, and then you keep working your way through, so you put your title in it. Then go to the next page, etc. All right. Great. Thank you

Noreen- Would you like to come on and share any queries?

I appreciate that. I was the only one in my group with the ethics approval requirement, but it was helpful that you went through that for Jane because I’ve completed my ethics training; I was curious, so I wanted to thank you. It was a good refresher to see you do the demonstration.

So thank you for that. We have a few minutes left; I will quickly return to the ethics slides to see if we can pick up anything else.

The link is on the Canvas page here. Generally, you discuss any issues with your super visor, and if your supervisor is unsure, they will contact the ethics lead in your faculty. James Bruner has become the faculty ethics lead for HSSCE. Mircea and Pedro will take turns chairing the ethics committee. There is some guidance on how to use the

portal. Generally, the portal is intuitive in how to fill it in, but on the same page, you can also get this link here, which can guide you through it.

If you’re the person who likes to read the instructions in advance, yeah. This will take you through each step. So you might want to have this open as you go through, and you see, as you can see, we’ve got the creator project, et cetera

And if you’ve got, if you’re thinking, well, I need to do that bit, then I’ll need to do that bit. What would work best? You should do two separate applications. If you’re unsure if you will recruit enough people for your study or something, you might want to say; if I can’t recruit people through that mechanism, I will recruit people through this mechanism. So if you’ve already put it in as a plan B, C, or D, and that’s approved, you can work through those yourself. You can amend the application if you think of something after and want to change. So once you’ve already had one approved, you’ll have a little box for amendments, and you can submit those. So don’t feel pressured to get the whole of your PhD approved right from the start. You should go through one step at a time. So that’s the step-by-step guide. So that’s in the chat for you and in the slides. I’ll just come back to the slide deck.

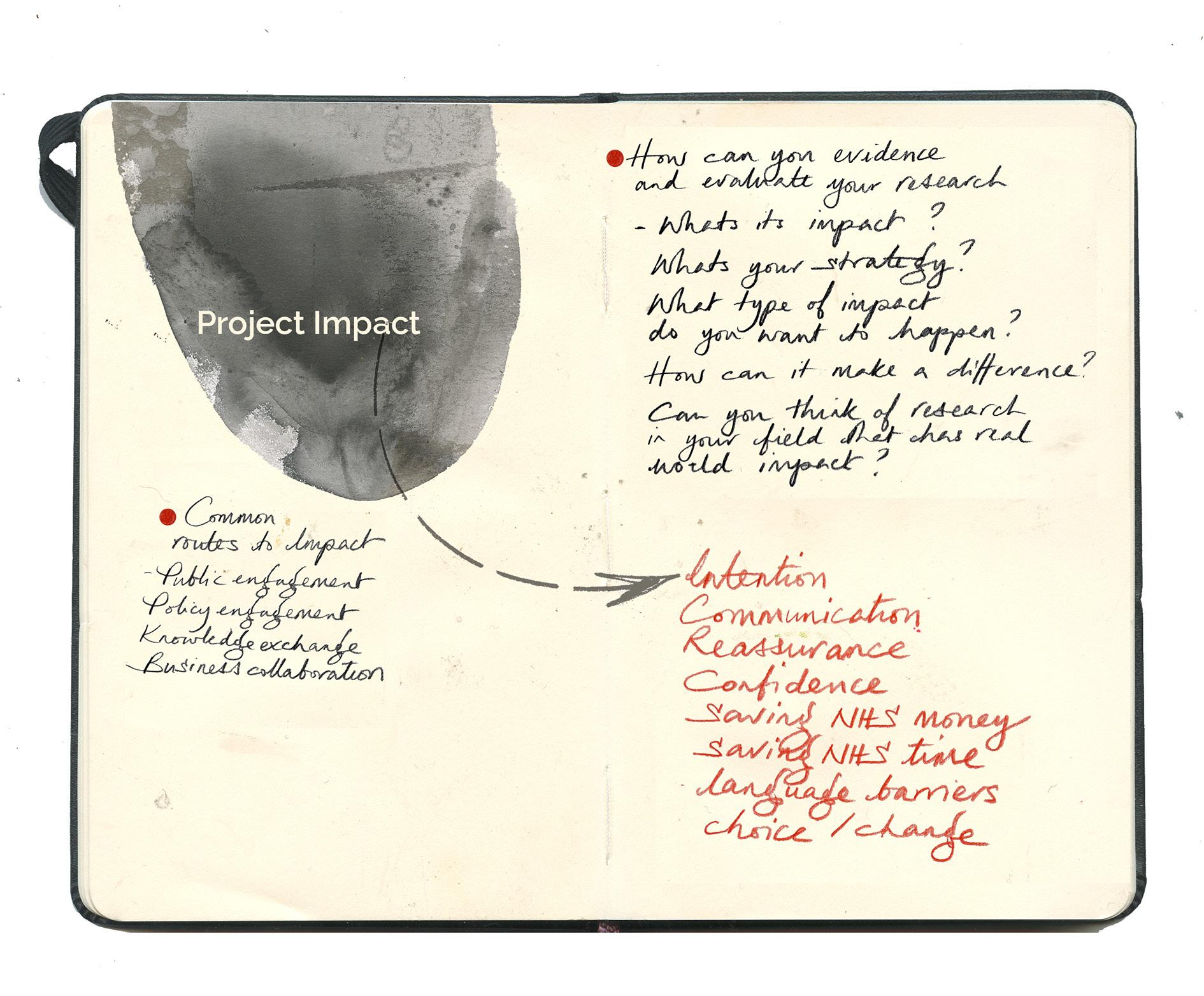

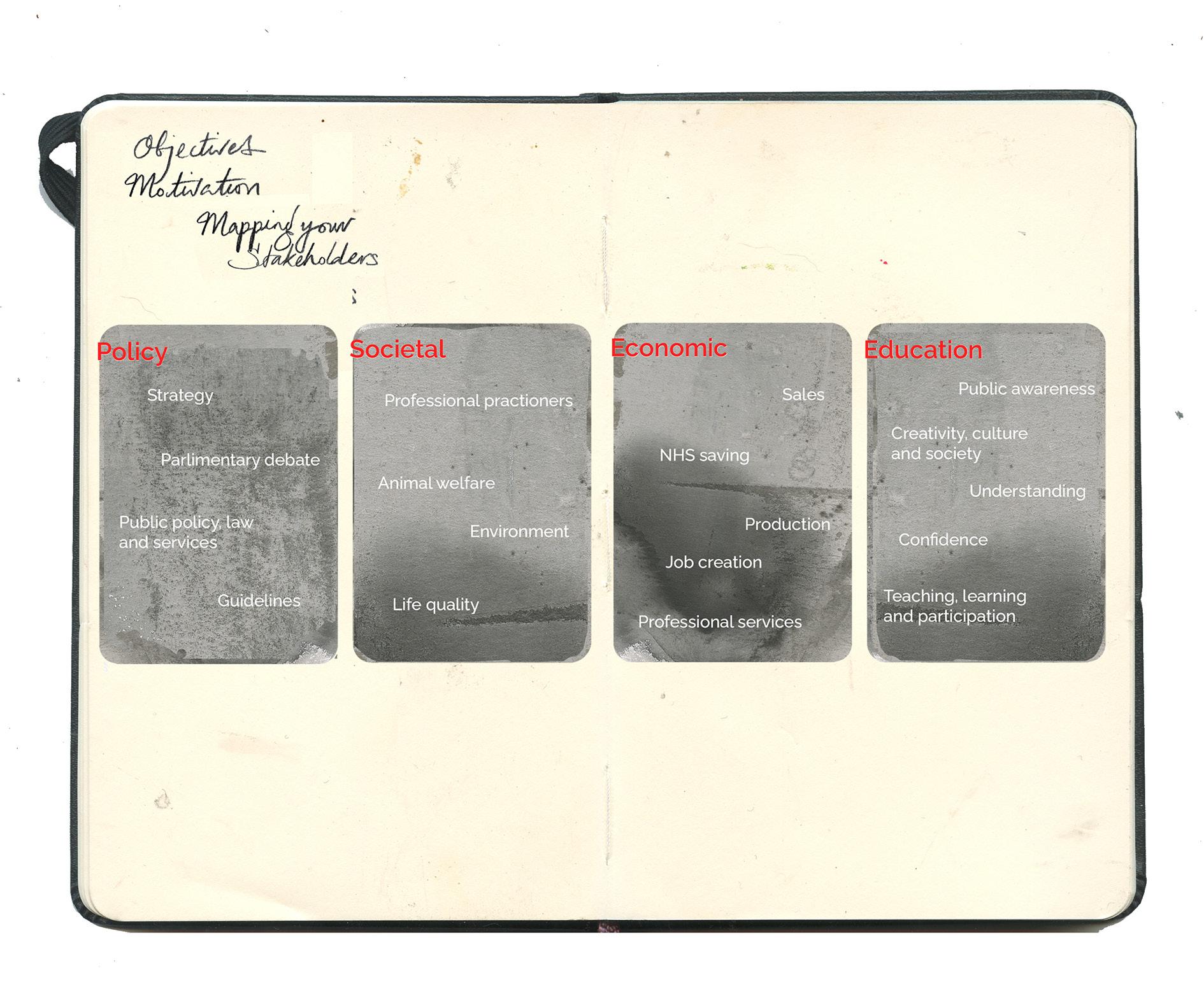

So, Research Excellence Framework at Kingston University. This session is titled Research Impact Facilitating Factors and Evidence Methods, so you may remember from your induction program into the PhD that we were thinking about what is the definition of research impact and what is the motivation behind your undertaking this program of study and research impact is all about enhancing the visibility of your research, solving real-world problems. It’s also an important part of the funding for research. So what I’m going to do very briefly is to briefly recap our definition or evolving understanding of what research impact is. Still, then I want to move quite quickly on to thinking about these facilitating factors and evidence methods, that is, you know, what is the strategy that you might have in place or what are the ways you might be thinking about actually building research impact into the work that you might be doing. So yeah, hopefully, this will be useful to you, and I’m going to whiz quite quickly through the first slides here as we’re thinking about definitions of research impact. Still, the PowerPoint will be available to you afterwards, so you can return to any of this. So you’ll recall that research impact is really thinking about the effect of research, how or benefit to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, environment, quality of life, crucially beyond academia. And so it’s all about the difference we make and, importantly, the evidence for it. and research impact stretches across a whole number of different areas. Your work may touch on some of these, maybe crossing over several of them from education, environment, health issues,

technology, etc., to the economy. The kind of impact you might be engaged in can have quite a breadth, too. You might be working closely with professional practitioners, you might be working more on a policy level trying to influence reform or guidelines, you might be working with educational organisations trying to raise public awareness of a particular issue, or you might be working with business to drive forward economic growth in a particular area. There are various ways in which your research may engage with these and aim to have a real-world impact and effects. So, some of the common routes to good impacts are those different approaches: public engagement, policy engagement, knowledge exchange and dissemination of your research findings, and business collaboration. I think a lot of research impact often comes through partnership work, so there may be informal collaborations that you’re involved in, there may be formal partnerships that you’ve established as part of your research project, people that you’re working with outside of or indeed inside and that may be interdisciplinary perhaps as well. All of those routes can bring impact through your project. So how do we go about planning an impact strategy then? You know I consider you to be more seasoned researchers now as you’re in the second and third year of your doctoral project and this may be more or less at the forefront of your mind as you’ve been designing and defining your research question your hypotheses and your methodology and immersing yourselves in your literature review I wonder you might want to reflect at this stage you know to what extent is research impact a factor in the work that I’m undertaking? Is it still a motivational part of what I’m doing, to what extent, and what is my aim?

Am I taking a sort of strategic approach?

And it isn’t easy, I think, to research impact work. Some of the questions to think about or things to bear in mind really is to try and pursue what you think might be most valuable and realistic in terms of approaches to research impact and maximising the So to reflect on the gap into which your research maybe can make a contribution and to think carefully about what the scale of that contribution might be and to take a strategic approach to this you know you can bring all your skills of project management and theories of change to the impact strategy part of your project. So, define the need for change carefully and then work backwards from that to understand what steps and processes you can implement to get there, having a strategic approach to the development, delivery and critical evaluation, the evidence thing and the evaluation of how effective your impact is proving to be.

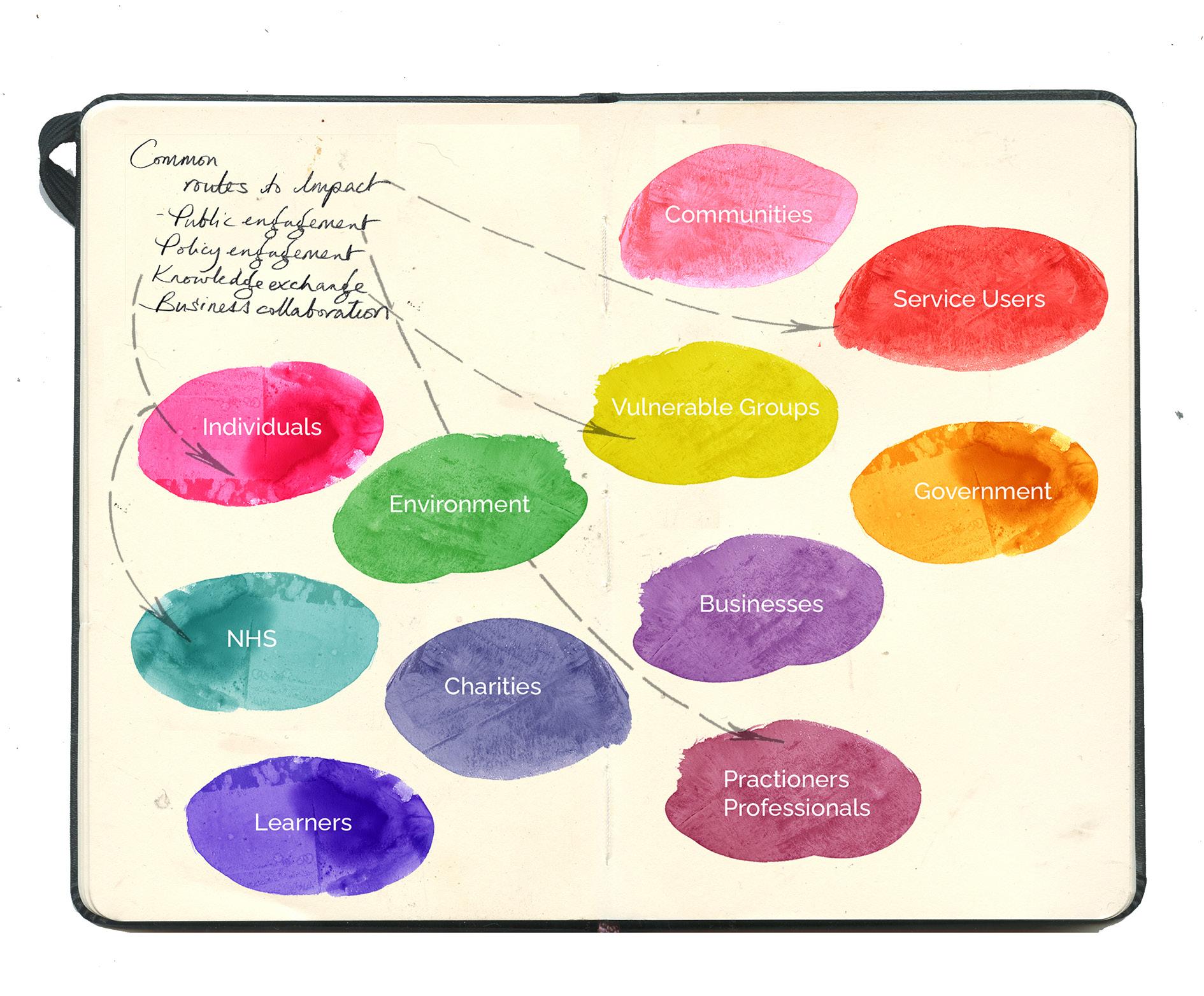

One of the first steps I will take when thinking about your strategy and where you intend to have an impact is to map out your stakeholders. You’re probably already very aware of who your project stakeholders

You’re probably already very aware of who your project stakeholders are. Still, it’s worth continually reflecting on and refreshing this. Individuals go through particular parts of government, business, and maybe the charitable sector. What are the groups and individuals that are important to you and have a potential stake in the work that you are doing? And then, in terms of evidencing and evaluating impact, a couple of ideas here are to find out, try, and find out what changed through your research and interventions. That may be something to come in the future, but thinking about how to get there is important. And consider how you might provide evidence and communicate that change. And crucially, what data needs to be gathered.

A key part of research impact is gathering your data early on and throughout the impact plan. Then, evaluate your impact activities continuously to improve and apply corrective action if necessary. Things to remember then is that impact can be direct, or it might be unintended, it might, there may be impacts of your work in areas that you didn’t expect or anticipate, it might be planned or indeed unplanned, it can take years often to happen. Instead, it’s less likely to be the research. Once your work is out there, people will take it and can take it in various directions and to different ends. Once your work is in the public domain, consider methods to track its impact. Where is it being cited or discussed? Many online tools can help you do that, and it’s very worthwhile. Of course, you are probably doing this for other reasons as well. Still, by keeping your online research presence updated, you can extend your professional network and contacts in ways that can be really advantageous to potential future research impact work and partnerships. As I mentioned, keeping records of evidence is valuable, so to give you an example, if you are running various events throughout the course of your project, perhaps you’ve organised a seminar or research seminar on the topic. How are you going to keep a record of that?

The number of participants involved, the events’ dates, feedback from the events, what people said about it, and how they were impacted or challenged by it. That might be considered part of the evidence of public engagement and knowledge exchange, which may be the first step in an impact strategy. Some examples here of PhD project work at Kingston specifically tried to have a real-world impact. In this case, this project was developing toys to help children with complex needs learn how to understand and communicate about death, breathing, grief and loss, and the project worked with the British Toymakers Guild. So, you can look at other examples online on the university website, they’re worth looking through as you develop your impact strategy. What would be most helpful is if we have some time for you to discuss your thoughts on research impact in relation to your project -to what extent is it something that you’re engaging in?

Regarding your project. To what extent is it something that you’re engaging in? And questions explicitly four and five here. What is your impact strategy? How will you evidence and evaluate your research impact?

Mentioning citations is really helpful here. For everyone to think of, the Google citation tool is very useful. If you’ve published your work, this is something for the future because you can log into Google Scholar and see how many people have cited your paper, and some of the things can show where your work’s having an impact. Yes, that’s tremendous. My research background is in the humanities for the whole world of vaccine development. Still, we’re more aware of how research has accelerated in the world of vaccine development during the pandemic in recent years. And yeah, another, well, Scylla, you could speak to this, I’m sure. Still, the processes behind tracking, developing, and evaluating vaccine development’s impact must have been quite an exciting area to have been in and continue to be.

Also, if it’s in your field, have an ORCID account or a ResearchGate account, those platforms you work on accelerate the impact and the citation rate. Have you heard of those? ResearchGate and ORCID are common ones. There are other ones in different disciplines.

Stakeholders -Can a wide range of stakeholders could benefit from your doctorate? From education impacting modifying and then statistically to an interdisciplinary approach to auto-ethnographic methodologies. There was an impact on communities and individuals in health for research in illustration animation on the child pathway. Also, it impacts the environment with an AI approach to map making for mapping out disasters worldwide. It also affects the business world in terms of the digital twin model. I have an economic impact on the industry. It’s tremendous to hear such a breadth of real-world engagement and impact. Is your research relevant to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. How the United Nations wants to see progress and change in improving the world.

Notes and considerations from the Good Practice in Research training - Ethics and Impact part 2.

Listening with Jenny 12/02/25

I’m here with Jenny and listening to her birth experience. Jenny has just rocked up with a 12-week-old bundle of gorgeousness called Marius, and I didn’t know this, but Jenny had Marius at home, which is exciting!

I just knew I wanted to have a relaxed birth. Kingston has an amazing home birth team. Wow.

When I registered that I was pregnant with Kingston, they had a little tick box that said, “Do you want to hear more about home births?” Then a lovely lady rang me up, and I was like, OK, immediately.

God, he’s so chilled out.

He’s a super chill baby. And I think he’s just in the home birth.

You’re right.

Yes, because his heart rate didn’t spike during birth. We had a pool at home and were mad, but it was lovely. He didn’t have any pain relief. So he had just pure oxygen, endorphins, and water. So it was an amazing experience.

That’s incredible. Congratulations.

Thank you.

Were you full term?

Nearly. So I was 38 weeks when Marius came. But I had gestational diabetes, so they were threatening me with a hospital bed and with induction at 40 weeks. I was telling the baby, it’s OK, you can come out; I don’t care that I’ve not finished my work; you can come whenever you want. Whenever you want, whenever you want.

Wow, so tell me about how that works—the home birth.

So they sign you up, come, and do a booking appointment like you would have at the hospital. But they come to your house, I made some cookies, and we had tea, and it was just really, it felt like, call the midwife. Oh yes, they come to your house, and every appointment is at home, apart from scans. It’s just really nice because you get the same midwife, so they endeavoured for you only to see two midwives. That’s amazing. In the whole process. Yeah. I saw a few more because my birth was long, so they had to change multiple times.

Hold on, I’ll let you get this chap out of his wool outfit.

I’m so pleased you’re speaking Norwegian to him. Does it feel natural?

For animals and babies, you have to speak Norwegian.

He’s such a lovely strong boy! Please make sure that you look after your back as he gets bigger; lifting car seats and all, can really damage your back.

I’m doing my best, but I feel like I’ve fallen apart! My muscle tone has gone, and it’s all bulging. I will start exercising and regain some strength in this poor body!

So we’re going back to 38 weeks. Go through what’s happened.

So yeah, you get every appointment at home. The snag was that I developed gestational diabetes. They wanted me to have a hospital birth. But then they said, because I was really against it, and they were like, well, you can be in the birth centre. So I talked to my midwife about that, and she said, well if you’re in the birth centre, it’s essentially the same as having your child

at home. It’s the same level of care, and it’s the same. You’re just as safe at home as you are in the birth centre, and I live so close to Kingston Hospital. Yep. She said, ‘I will, obviously I have to say, we recommend that you have your baby in hospital, but I think you’ll be fine.’ The consultant really wanted me to book an induction.

Who was your consultant?

He’s called Adam Jakes. OK. Have you come across him? No, I have heard of the GDM specialist.

That’s interesting.

He was adamant that I booked an induction date, but I didn’t want to because I felt it would jinx it.

An induction is horrible.

Have you been induced?

Yeah, it was awful.

And then you had an emergency C-section, right?

Yes, the first one was 18 days over my due date, and I was beside myself. Then, Elsa was two months early. So, we went from two extremes.

Yeah, that is extreme. The consultant called me a fruit loop and did not want to do an induction workshop.

Really? That’s incredibly rude.

I felt infantilised. He was nice enough, but just the way that he spoke. And then I said, well, I’ve talked to my midwife, Nicole, and she said I’ll be OK with my health and how I’m doing. And that she would be happy for me to go to 41 weeks before any intervention; he immediately just shot me down and said, well, she’s not a doctor; she’s speaking out of turn. I was like, I’m not going to do this. But then, if it went over 40 weeks, I would start, you know, thinking about it. I would, of course, do what was best for Marius, but at the same time, I’ve done many things that I’ve never done before, and I’ve done a lot of reading. Yeah, and where did you find that information? I read some of the NICE guidelines primarily through Millie Hill’s Positive Birth Book. Have you come across that?

Yes, and then I read some of Sam’s- a Danish cousin, Anja, like a birth, it’s not special, but it’s called the On Your Biome method. Have you ever come across it?

No, I haven’t heard of that.

So she has her birth preparation courses in Copenhagen, where it’s a pain-free birth situation like hypnobirthing, but it’s more physical. You do loads of exercises to train your body to hold this pain. To understand it, understand how the oxytocin loop works, not to hold tension, and to allow your body

what it needs to do. She’s brilliant.

Wow.

I also was talking to a friend who’d been induced. I had a friend whose waters had broken, and then she was induced, and then she was being induced for three days, and it didn’t work.

Did she have to have an emergency section?

Yes, she did, but in the end. I have another friend who was started with the pessary, and then they quickly went through the drip, or if she’d been on the drip. They wanted to do something else, and she’s a nurse, and she was like, ‘no, let’s just go straight to C-section, I know where this is heading, I am knackered, I can’t deal with this,’ but she feels robbed of her birth, from the way that she was treated. That is so sad, isn’t it? So I talked to loads of friends, had babies, read Facebook threads, and just absorbed a lot of information about the induction experience and what that potentially feels like.

Do you feel that as you had done that reading and that you’re an intelligent woman from a Scandinavian background, you’re more used to advocating for yourself?

Yes definitely.

Do you think that it helped you to be able to go? No, I want this. Sorry, I have asked you three questions in one place!

Being a stubborn person who has always been taught to ask why, it doesn’t matter who it is or what sort of authority they have, you ask why, and that helps. Because you go, why? And if someone doesn’t have a good answer for you, I keep my count on that. You know, rather than blindly going with what the doctor says because they’re not always right, they’re just interested in their statistics often.

That’s interesting you say that.

They want their hospital to come out with some good rather than what, like looking at individual cases and with my diabetes, which was the main crux of the problem; however, my readings were so low, like they were touching above what was deemed as being diabetes. Anyway, I managed it well. So that doesn’t affect the safety of your birth; it just regulates or helps regulate the hormones. So even when I said, ‘Look at my sugars,’ he had just complimented me on my sugar levels because he could see them in an app. So he could see them while they were working. He said, yeah, but there’s been a period of elevated sugar levels, and we don’t know what the placenta’s doing. There’s no way of knowing what the placenta’s doing. But I felt in myself that because it was caught early at 28 weeks, the readings were low from the start, and I managed it successfully and fastidiously because I really wanted a home birth. My sugar levels didn’t spike. So, that made me more confident to say no to what he was saying. I also felt like, look, you’re a man!

So I thought I’m going to wait it out against your will, you know, and you are going up against my midwife, who I’ve seen all of my pregnancy, and it’s like, Adam Jakes, I don’t know you from, well, Adam! I mean, he was pleasant enough, but then he called me a fruit loop, and I did not appreciate being called a fruit loop.

That’s incredibly rude.

It was such a different experience, in contrast to having my lovely midwife appointments at home to then going into the hospital to deal with the GDM midwives and doctors and stuff.

So you felt that they were not as kind? No!

They didn’t have the same amount of time for you?

They didn’t listen to me. I felt that nothing was individualised. However, I spoke to one of the midwives I saw, and she took a long time to explain different things. You know, she’s like, you have any questions? And let me get my list out. She’s like, oh, one of those.

Oh, did she say that?

No, but you can tell by how she’s like, oh, list. She explained a lot of things and made me feel at ease.

That is good.

But they still really wanted me to go to the hospital. And then they wanted me to stay in hospital. When I said I was going to have a home birth, they wanted me to come in and stay in for 24 hours to monitor Marius. Right. But that surely defeats the object of you, well, exactly.

You’ve just had a baby in the calmness of your home.

So I said to them that I would come in because I don’t know how to spot a hypo and jaundice in a newborn. At 38 weeks and 5 days, I started to feel like, is this it? Is this it? I don’t know.

How are we supposed to know?

So I rang my friend Em, who has been through labour and has a baby and was pregnant. I was like, is this labour? What does labour feel like? Do you think this is labour? If you think you’re in labour, you’re probably in labour.

It actually takes quite a long time to establish and takes several days.

I’ve done a lot of work on my body, like a lot of yoga stuff, to know my body, know my body well. Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. So I just felt like this isn’t something I’ve ever felt before. So, my friend had just come up from Cardiff, and we were going to go, like, try shopping in Pennington for lunch and stuff. I was like, I’m just going to stay in, and she put a tens

machine on me. And we just watched Christmas films. This was on the Sunday. I’d done a massive batch of cooking on Friday and Saturday. So you’ve got your body going; it’s time. Yeah, like, ooh, the lasagna is in the freezer. I repeat, the lasagna is in the freezer. And then, yeah, I just went to labour, and it was ramping up until midnight, and then it went away. And then it started up again at 5 am, and I had to go in to have his little heart monitored because I hadn’t felt him that morning. I went in, and I’m so glad I didn’t have to have a birth in the hospital because it was horrible going into the hospital. And I saw a registrar who was, like, just kept telling me that she didn’t think I was in labour. Yep. And I was still going on about this induction at 40 weeks. I was like, look, I’m 38 weeks, and I’m in labour now. So I’m not sure that you are. It’s all good signs, but I don’t think you’re actually in labour. It’s really strange, isn’t it, that, you know, not trusting women to understand their bodies and their level of pain and their level of, you know, your body.

Yeah, it’s good.

Exactly! Everyone’s labour has got to be different because everyone’s body is different. Yeah, when away from that, my contractions stop. Because of this, let’s go for breakfast. Relax and get back into it about the oxytocin guardian. So I’d read loads about oxytocin and the oxytocin, just a little about how it works. I didn’t know exactly how it worked, but I knew you had to stay in the dark, be comfy, and not get stressed. I was thinking about doing something you might look at on your phone, which might help you think about how that might move around your body. That’s a good idea- a visualisation of oxytocin.

Yeah. Because it’s almost like the premise of, if you’re wheezy, don’t breathe through your mouth, breathe through your nose, because you can’t hyperventilate through your nose. It’s annoying because you’ve got a blocked nose, but that whole premise of understanding what that might look like.

That’s really fascinating because you read things, and it’s hard to visualise how they work physically.

Yes, because your breathing might differ from the next person’s.

I just got back in; we had some food.

What happened after?

We went for a walk in the park. It was absolutely miserable weather! It was on the 20th of November. When time and the contractions started up again, they got pretty intense, but they didn’t get to the frequency that they wanted. So that day, I rang the midwife and said I was due down in Britain on a Thursday. Can someone just come and see me? To see what’s going on. So my regular midwife wasn’t available that day, but this lovely woman called Sarah came in. And she sat with me, and she paid attention and said, I think you’re definitely in labour. I’m not sure how long it will be

because everybody’s different. She gave me some excellent physical movements to do, like shaking the parties and watching the quadrille with the scarf, the jiggle, and the whole business. Some other movements I can do are walking around, walking, and moving to get the pelvis going. I said I’d come back later, probably. I’d imagined this would be on this night. And I’m like, shit!

This was on the Monday?

We got going again, and we called her out in the evening, and she came. And she sat with us for a couple of hours. She did an examination- she said, you’re only one sentence dilated, but your cervix is almost flat. So, most of the work has been done; you need to open up now. I didn’t know what that meant, but I found it positive. You will not have this baby immediately, so I will go back home and get some sleep. Just call me if you need me. And if you go over midnight, then Nicole, who’s my midwife, she’ll be back on.

Incredibly, they’re just like on call.

I know. Yeah. It’s just that whole thing on call. Yeah. And then, um, we went to sleep, and then, at night, we called Nicole down. She came out, checked and said It’s not quite time yet, as you are two centimetres now. But call me again if you get to me before midnight and you can call me again, which we did. She came out in the day and saw me on Tuesday, so I just slept in my little nest all Tuesday. So Sam made a little nest for me in bed, and I had baths. Then I had the TENS machine on after the bath and just slept with this massive pregnancy pillow coiled up. I was in that with blankets on top, and the dog held up with me. I was just in there with a hot water bottle, and he would just come running. Every time I had a contraction and push on my hips, it tickled, and he was a fantastic birth partner and new father.

Excellent.

He thoroughly looked after me. By Tuesday night, I started getting more intense contractions, and then by 3 or 4 am, the pain became really intense, and the contractions didn’t stop. They were just like really intense. But they were only like 2 in 10 minutes, but they were quite long. So I rang up, and they said, well, you’re not. We’ll send someone at 9, and they’ll just come and check on you. Rachel would arrive at 9. I was like, OK. It’s 5 am, something has changed, and it just got incredibly intense. And we rang up again, and the midwife said, OK, no one’s available right now, but we’ll send someone as soon as possible. So Rachel arrived at 7.30- 8 am. And she’d been in early for unknown reasons like she wasn’t supposed to be on call yet. So she came and did a genetic fluid test, which came back negative, so my water hadn’t come yet. And just as she came in and said, oh, your test is negative, there was just like a gush of water, and the nature of the contraction changed. I got stuck in the living room, and they filled it, and then I climbed

in and he was born by 11.30 in the morning.

What an infant!

It was more painful than what I could handle. And by the end, I was like, gas in there. How does it work? And my midwife was like, I don’t think you’d want it at this stage. Because she knew it was only half an hour till you’d be born. You feel a bit sick; you might not want to feel that way when he arrives.

Fair enough.

And the placenta arrived at 12. Hang on -I’m going to feed him.

Okay.

It was an incredible, incredible birth because the oxytocin had been allowed to do what it wanted to do; the beta-endorphins fully kicked in, which then meant that I was high as a kite on my own hormones. I had this visualisation of the moon, which was like a rope around the moon, and I was pulling the moon towards me; with every contraction, I was pulling the moon down from space. It was the most beautiful thing that ever happened in my life. When you tell people, they think you’ve gone mad, but it was. But how lovely to hear a positive experience where a comparison could be if it were a flower coming into bloom. You would give it time, but you wouldn’t be there like trying to squeeze it open or ‘sweeping it’ open.

I had my waters broken when I didn’t want them- so it hurt, as I was tense -and it was painful.

Then do they leave you there to be in pain?

The pain subsided quickly, but the feeling of being tricked lasted.

And I think from what I’ve read and talking to people, it is this kind of, you think you’re a labourer, and then you’re told you’re not. And that’s so damaging to this oxytocin loop. Of course, it is. Yeah. If you get questioned on how your body works and you start doubting it, how is your body going to believe it’s safe? Safe, well yes, that’s such an interesting word, isn’t it, ‘safe.’ So, what I’m looking at at the minute is I’m looking at how we have an utterly patriarchal set-up for being told about our bodies. Yes, the doctor knows, like the way he shut my midwife down, obviously she wasn’t there, but I just felt really like, what’s the word, like he took my power away. I mean to do something where you feel empowered.

It’s so important to feel empowered.

How are you supposed to do it if you don’t feel empowered? He would not have been allowed to be a home birth here if he had been in the breach position.

Or if he was back to back?

Would they allow that?

I don’t know.

I’m intrigued by that.

(Jenny shows me a video of Maruis’ birth)

Oh my God, look at him; he’s just swimming up there. Wow! You look great!

Poor Sam looked like a ghost because he’d been awake for so long.

Oh, look! And then they let him swim to you, that’s how giving birth should be done. You smashed that out of the park! That’s amazing- you look like a goddess.

I felt like a goddess. I felt like a goddess.

That’s quite a big pool to fill. So, what are they filling the pool up with?

A hose? A hose, yeah. You lift it to the kitchen tap.

Look at that, that’s amazing.

And also he’s the right temperature. And the lighting’s nice. And there’s not lots of noise or beeping. No. Beeping around you. Exactly. Nobody’s like discussing any medical things around you. No, they haven’t whisked them away and gone. Do you want to cut the cord? No. No. Did you leave the cord attached? Yeah, until it went white.

Gosh, that’s just, and lots of women are so sleep-deprived because it’s challenging to sleep in the hospital. They keep waking you up to take your, all your different, you know, and such. Wow, that is incredible.

I slept between every contraction, even in the pool.

Really?

My body just knocked me out. So I was well-rested when he arrived. I wasn’t that tired. I felt funny because I’d just given birth. Yeah.

Sam was way more tired than me because he’d been awake for three days. But I had slept a fair bit like the whole Tuesday I was asleep.

Because if you’d been in hospital, you wouldn’t have slept. Or you would have had abysmal quality sleep.

Yeah, and I wouldn’t have been able to enter that space—the sort of oxygenating rattle.

Yeah, you wouldn’t have been able to pull the moon down. So, no stitches?

Yes, stitches, yes. But it is straightforward, say, a grade-one tear.

But it didn’t end up with an episiotomy?

No- I didn’t even feel the tear because of the water and the warmth.

I didn’t even know what an episiotomy was until a doctor said, we’re just going to cut you.

I sincerely hope that things have changed and pregnant women are aware of the procedure. My friend had to have one, and she had to sit on a little doughnut.

This woman who was sewing me up said to me, you might not want to wriggle because your husband will thank you afterwards.

Oh, is she joking?

No. I mean, this was a long time ago.

No, it’s not that long. Within the millennia, right?

Yeah, 2006. 19 years. But yeah, it was... I’d had an epidural, and I’d had so much topped up. I couldn’t see. It’s like I’d taken ecstasy. I couldn’t see a thing, and I couldn’t stop throwing up. It was grim.

I have one birth injury, and it’s that I’ve had, like, um, my nerve has been damaged to the bladder, so I can’t feel when I need to go to the loo.

That is interesting.

I’m having some investigations done because... It knows it’s taken quite a while to work correctly, but it’s still not firing. No one talks about these things.

About other things afterwards. Like, you know, even like tears. I remember my poor friend; they described her as a fourth-degree tear, and they described it as a Michael Palin. ‘Pole to pole?’

I mean, outrageous. A pole to pole? That’s such a horrible, dehumanising thing. That is such a dreadful phrase to describe such a traumatic event. I’m going to get his bladder issue back up and running. I am good; I am seeing a neurologist on the 27th. And we’ll see what happens.

Do you feel like you’ve been looked after afterwards?

The six-week check up was very much like tick boxes. When I brought up some of the issues, the doctor showed more interest and then listened.

Is your mum enjoying being a granny? Is she hands-on?

No.

No?

No, Not yet, but maybe because he’s so little. Yeah. It’s tricky, and he’s, you know, he’s so dependent on me. So, she doesn’t think anyone can take him off me. No.

And how did Fergus take the news?

He hated it. He didn’t speak to me for the first few weeks! He was...What have you

done? Poor dog toppled off his little pedestal as my baby! He’s only just forgiving me now.

That’s really funny, isn’t it? Dog rage. I can imagine. Oh Jenny, congratulations. It’s astonishing that you go from- you’ve never had or held a baby, to you have a baby, and suddenly it’s like the most natural thing in the world? How heavy is he?

He’s about 7 kilos now. My friend who had the long induction, her one-year-old, was 7 kilos.

Just watch your back. When Jonas was 20 months old, I put him in the car seat and slipped my L5 disc. And my back’s been wrong since. You can hear that nerve damage because I’ve got a prolapse L5 disc. It means that I can’t feel the middle of my foot.

It’s so weird, isn’t it, when you suddenly can’t feel something that you usually can’t feel?

So when do you need a wee? It doesn’t come out?

No.! It fills and fills and fills, and I realise it’s been eight hours, and I should go to the toilet. So, I keep going to the bathroom and seeing what happens.

Gosh.

Thankfully, it can still go- on the topic of not being told something; my friend spotted in her notes, months after she’d had her baby, that there was a potential retained placenta after her C-section, and no one told her. She requested a copy of her notes, and it just said, potential retained placenta, because a piece was missing! The time they realised that the doctor had stitched her up and the placenta had gone to the bin for the incinerator.

Amazingly, all the stories come as soon as you’ve given birth or are pregnant.

Yeah yes.

Is that good or bad? So, is it good or bad that these kinds of horror stories or narratives come out? Like, did your mum tell you about your birth, for example?

Not until I was pregnant. Right. No, not really. I knew that I’d had been breech and that she’d have to have a C-section, but she’s not told me what the birth process was like.

So that’s interesting. Yeah, I think it’s really sad that there’s not that safe space to speak of your birth with people who haven’t experienced it.

There’s no, well it hasn’t been at least a rule in society where you can speak about it. And we have to pretend. Or it’s just in the dark with other mothers. Yeah, and we have to pretend that, oh, I mean, you were lucky, it was a good experience. You hear so many heart-wrenching stories that there are just simple things they could do to make it easier.

Can you think, maybe not now, this minute, but if there’s anything you can think of, and you think I’m fresh out of this experience, what could have made it easier?

The bed and the home section of it were amazing. And it felt like they were really mindful of my space. Because obviously, they come into your home. So they’re incredibly polite, and they go easy in your space. They’re very aware. But when I was in the hospital, I felt like I was being just poked and prodded and sent places and told to bring your notes, put your notes there, have you got, like it just felt really barky.

Like? Have you done a sample?

Quite barky! Yes- like pee in this. Yeah. When you suck your blood, and then you’re trying to anticipate something, and then no, obviously, we’re not doing that today. It just felt real; they felt really medicalised and stressed.

It’s interesting, isn’t it, because they live in that environment.

Yeah. And you visit that environment. That environment is their home. I felt like I was in there too. The opposite was when the whole midwife came into your space and existed with you. And they allow your birth partner. And that was interesting because I remember you meeting Dan. But Dan was the guy I shared the studio with. And he said he’d never felt like such a spare part in his life as Catherine had their first baby. He was just in the room but felt like he had no role and had nothing to do apart from patting her head and being shouted at. But Sam, so I talked to Sam about it afterwards. How did you feel about this experience? What was it like for you? He said that he felt really like he was part of the team; he was, you know, wielding the side to catch the poo in the pool. He was hands-on, and we had those three days together. I think that not to be so, to be treated like the adult you are, not like some stupid woman who’s now a vessel for a baby that must come out safely. That’s the feeling I had after being at the hospital. I was a vessel; the only important thing was that the baby came out.

Yeah, so you’re secondary.

Yeah, but my experience with the GDM, how I wanted my birth, seemed irrelevant to the consultant. He was just like we just need to get the baby out safely. It was not like we’re gonna keep you safe. Or we’re going to make you feel that you’re safe and know that you’re safe and that your health and your mental health and all these things like you’re about to go through the most significant monumental physical and mental shift in the next few days. Let’s look after you a bit.

Exactly. Thankfully,

I think you know what I mean.

Yeah. You’re quite determined.

A lot going on in there, so when I got the

DDM diagnosis, I started having panic attacks. Oh God. Because I was just really like...I got really worried about it.

Isn’t that’s quite late on to get it, isn’t it?

It’s at 28 weeks when they usually check for it.

If they’re not worried, I requested some assistance with my mental health, and that hasn’t come until now, really, but I was referred by my GP to St George’s and got seen by a psychiatrist there, the perinatal team at St George’s, and that’s been good. She’s really looked after me, and I feel like I’ve been put into a fortunate loop of being looked after.

Do you have a support group of pram facers? Other Mum faces?

Yeah, I have a couple of people there. I like... Weirdly, you get thrown into, like, mean girls’ club.

Yeah, and you can feel really judged.

Yes, my health visitor said, “ oh, come along to the breastfeeding clinic. I’m like, well, it’s going well, I don’t need to go, I don’t want to. That’s not me. I don’t hang out with people that I don’t like, yeah or just because we have one thing in common.

My friend Emma, I rang to ask if I was in labour. She gave birth in COVID. That must have been hideous, she was in labour, active labour, not active labour, but she was like, actively labouring, her waters had broken, and she was not progressing. Still, because of the, um, pandemic, they didn’t have enough beds because they had to space everyone out, so she was put on an induction ward, so she was on this massive ward with all these women that were being induced. She was progressing, so she felt like they were sending daggers her way because she was labouring. They were waiting for labour. She was on she. Was her labour was 53 hours, and Greg wasn’t allowed in until she was in active labour. So, she was all alone On this ward, and she said she had a really stocky midwife. It wasn’t her regular midwife and she was really awful with her and just kept telling her not be a baby, and That is just awful. She was being really like heckled by the midwife.

That’s terrible -I am sure lots of questionable and awful practices occurred in the pandemic. I think it must have been an awful time for all birthing mothers, fathers and other partners and for all of the medical staff. Oh Jenny it’s been so fantastic to catch up with you both and to hear such a positive birth story, where you have really been clear about what you wanted and how you have advocated fro yourself.

Thanks Jane

See you soon, I don’t suppose you fancy coming into to talk about children’s books?

Sure! I would love that- I’ll need to bring Marius with me.

How is your PhD going?

Well, it’s going well. I love the subject, obviously, most of it, because I’m doing it part-time. So I’m a year and a half in three or four years. So I’ve got to the stage where I’ve done all the reading. I know exactly what I want to do, so I narrowed it down to a mother’s experience, and how illustration and animation practice can help confidence and choice in the quickly changing world, you’re in when you have your first baby.

Oh, it’s so lovely to hear from you. The plan is to work with Kingston Isleworth- The Princess Charlotte.

Do you know that I’m now based at the Royal London Hospital? Yes. So, do you want to get a more diverse range of women? I now work for a population with a very different background. They don’t speak English and sometimes don’t even read their own, so images are essential.

Do you know what, Susanna? That would be

amazing because Kingston’s population is not very diverse.

It’s not diverse. It’s very educated, and images help, but they are not as fundamental as they are for what I am currently doing. Also, I have been reflecting on how our images are very biased regarding colour and dress code.

Also, women come in different sizes. Some cultures encourage women to be fuller sized as it shows they can feed their families well.

There is something there that will be useful for you. I am introducing someone to you because I now have a medical student with whom I’m working a little bit, and she’s very talented from the illustration point of view. So she’s the one who did the cover for my book, which is beautiful. So she has a unique skill set by having this very artistic, creative mind and hand and being a medical student simultaneously. So, I told her I had spoken with her already about you, and it would be nice for me to introduce you.

Sometimes, even conversations can unlock some. I am also changing a bit direction in terms of being a bit bold and braver to have a more presence, you know, in social media, etc., because I want the message to be out of what I do and how I teach, and images are so crucial for all of that. I have been thinking a lot about illustrations and how to pass images and concepts. So good to connect again with you. So the image I’ve chosen to put on the book is the one in theatre.

Yes, absolutely, please do. I will send you the version of the book as soon as I have something I have acknowledged you here.

I am flattered that you feel that encompasses what you want—yes, and how the book will look.

Oh, amazing. It looks gorgeous.

Your image really stands out, as all the other images are more corporate. Yours is palpable, so I wanted something more realistic but imagery with sensitivity in the book—which your image will serve.

Thank you so much. So, with this project, I’d have to get Kingston University Ethics clearance before the NHS, but it turns out it’s the other way around. And NHS clearance is a challenge. I can retrospectively, so it’s not like I can’t have conversations with people. Still, there’d be more clinical side people like yourself and like your colleague here, but to then be talking to, you know, women who are having these first-time experiences. I mean, fortunately, because I’ve been teaching for so long. All the lovely students I taught 15 years ago are popping out babies everywhere. They’ve had a very different experience. Most of them are white, and they’re educated, and they understand things visually. But the whole premise is that the whole project can be accessed by a phone, and it’s two sides whether you want to look for certain things or whether your clinician says, actually, I’d like you to look at this so the whole premise is to stop people having to Google stuff so maybe stop having consultants to have to draw bad diagrams with biros. It’s been really interesting with my father being ill over the last year. He had a stroke last year; during a conversation at St George’s where this guy was, this consultant was trying to explain to my dad about, you know, the carotid artery in your neck is 65% fuzzed up. And also, my dad had just had a stroke. He also can’t hear.

So, I’ve got loads of ideas of how this project, initially testing stuff in a kind of academic capacity, but then also in terms of, my whole premise is to save the NHS money and in time and also like people not understanding things like gestational diabetes tests. It’s a complete waste of money when you know your lady might have had chewing gum or thought you misunderstood that a sugary drink isn’t what you need to drink.

I’m thinking about something else: Otherwise, we have a research project, and again,

I can liaise with you brilliantly because sometimes just connecting with things that already have some ethics or can accelerate your work is brilliant. So, there’s a project about health literacy for women in East London. Again, I can put you in contact with that team.

Amazing.

Again, literacy doesn’t mean only letters. No, exactly.

Images are very much part of literacy. And what I realised, as the clinical director for the place, is that part of the improvement that the hospital needs and that the population deserves is not necessarily inside the hospital. No. Because, you know, the outcomes where I work now are very different from those at Kingston. That’s not necessarily because what we do in the hospital is very different. However, the starting point of education, hygiene, and nutrition is very different. Yes. So, if we want to elevate the outcomes, we must go beyond the hospital. Yeah. Yeah. And part of it is health education. So again, your PhD, ideas, and drawings are very special in that field.

So please come and visit me at some point. I’d love to. Royal London is a long train journey, but it’s not too difficult from Kingston. So that’s one idea. The other one is that I can put you in touch by email with these people, on a Zoom call, or something like that.

We can arrange a meeting on a Zoom call so I can introduce you to them.

That’d be great—amazing. My intentions would be more helpful with women whose English is limited.

The population is very, very interesting. Communication goes above and beyond the physicality of things. There’s a cultural meaning, a social meaning to stuff that sometimes we don’t even understand if we don’t translate. I mean, the wonderful thing about drawing and especially, you know, drawing for animation or even, you know, things I was looking at, there’s a program where you can look at, so you could draw what a theatre looks like yeah but you can draw it, and it’s almost like, looks like a stage set so that when you’re looking at it on an iPad, it’s almost like you can walk around it. So with the understanding of like, what is this, what’s it, what’s it gonna do, or you could press them, it’s called mental canvas this program, or you could press it. Then, in, you know, my native language, it would be this because I remember your comment. I’ve used this a lot throughout the premise of this project. It is like I remember I drew the operating theatre, and you went, wow, it looks complicated.

We forget this because we live here. I that was such a, you know, yeah, so we don’t realise do that when you step into someone else’s natural environment it’s so different and also if then if the level of You know kind of intervention or the other thing that is also Which links with what I do if there’s

something that potentially interests you is because I do work with sick babies, sick mums and babies that need to go to the neonatal unit. The parents’ anticipation of understanding the neonatal unit’s environment is also very interesting.

This was where Elsa was born; I had a placental abruption, and Elsa was born six weeks early. I was so well treated at Kingston. They gave me counselling, and we were so lucky because we lived near the hospital; she was still in the bag, and she didn’t have a brain injury, and she survived, and I survived, so I would so really from the experience of being in that situation of like having this like teeny weeny baby and just you know we were lucky other babies didn’t survive.

If, at some point or somehow, you can involve my medical student in a bit of your creative side, it will benefit her because she’s trapped between two worlds. And I told her, look, you have a unique skill set. You are exceptional and can bridge the gap where very few people can. And if there is something that she can collaborate with you on, even to help with your PhD and have some knowledge on that, That would be knowledge on that. Absolutely, but also maybe mentoring her in... she probably doesn’t realise that she’s really talented at both these things, and she probably doesn’t realise that she’s a unicorn.