art, adventure, music, history, food, poetry, beer, social upliftment, surfing, wine and much more.

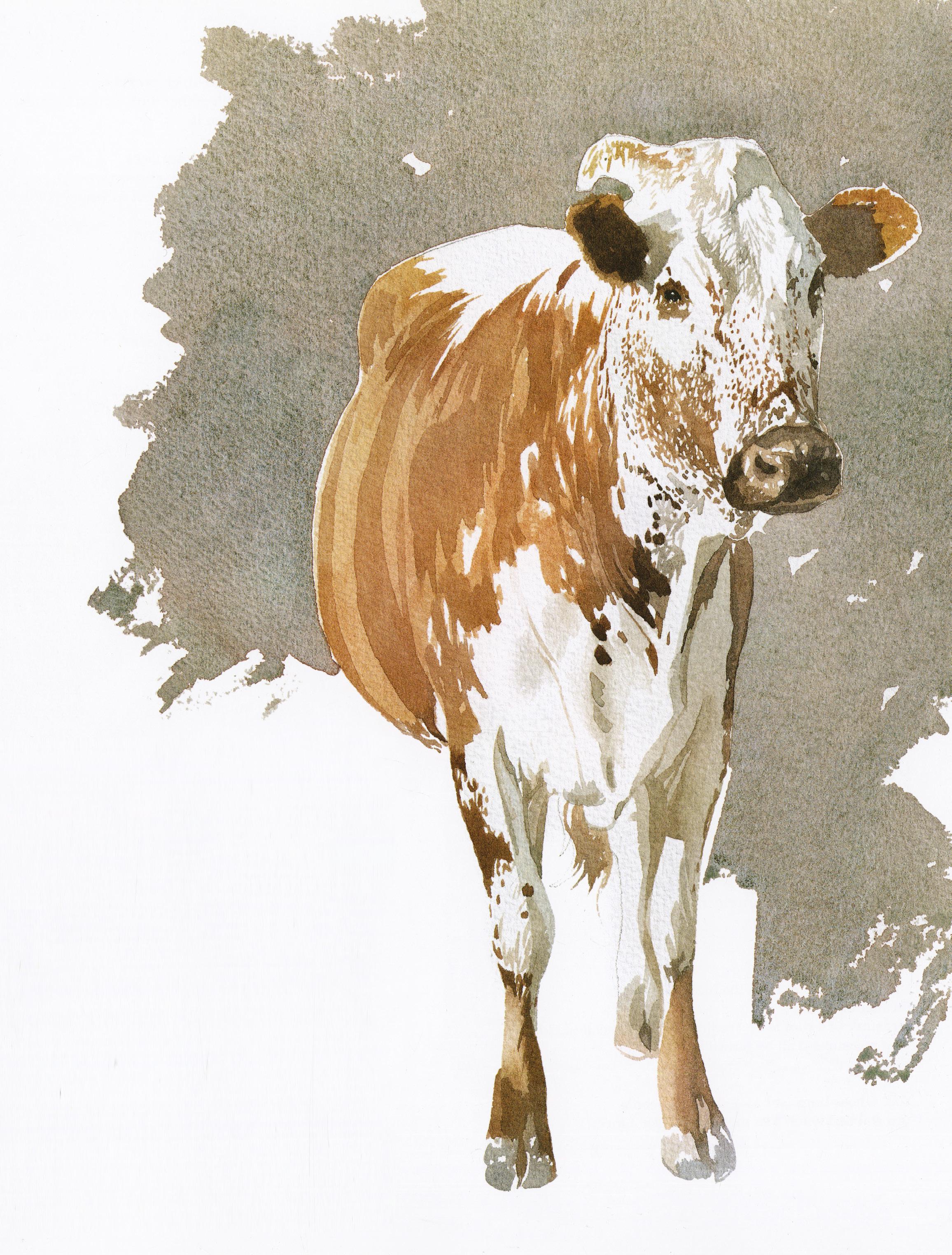

Peripheral vision (no.2). Gabrielle Raaff. Watercolour on Fabriano paper. 73.5cm, 77.5cm. Private collection.

Raaff’s most notable earlier works in watercolour and ink, capturing beach and city figures and aerial Google satellite images of distinctly different South African neighbourhoods, rely on a cool relationship between herself and the subject and revel in the abstract qualities of the view. Working with the ephemeral qualities of watercolour, water-based oil and ink, she layers diluted pigments on substrates such as paper, canvas, raw linen and primed board. Her figural works on paper abstract people into studies of light and dark, devoid of context. The figures imply movement, intention, and a degree of familiarity while existing outside of a place or time.

“My most recent works are a continuation of my interest in photography, and I often use found news imagery as a starting point for my paintings. I consider my personal

act of painting to be a wrestling between intention and chance and an undoing of certainty. Working with the material properties of diluted ink and watercolour – of painting wet into wet and of oil resisting water – determines the means by which a new image is created.

The original photograph is extended, like the sound that manifests an echo, such that a new and multi-layered embodiment of experience or place can be expressed.”

Gabrielle Raaff www.gabrielleraaff.com

2 Jack Journal Vol. 3

Nikos Kazantzakis, Zorba the Greek.

I felt once more how simple and frugal a thing happiness is: a glass of wine, a roast chestnut, a wretched little brazier, the sound of the sea. Nothing else.

3

table of contents

why we produce Jack Journal

Bruce Jack contributors in search of the strange Don Pinnock weaving a living through rugs, the story of oomama bethu (our mothers) Unathi Kondile

legacy of wood how trees live again Melvyn Minnaar

it’s still a tree Bruce Jack for nature and for the people: conservation with a difference Heather D’Alton nguni cattle –a gentle african treasure

Gregory Mthembu-Salter

music makes miracles Su Birch the national poetry prize 2020 winners

shweshwe swish and sniff Fiona McDonald

the new nordic food story

Michael Booth

riding high on a wave of wellbeing Alison Westwood

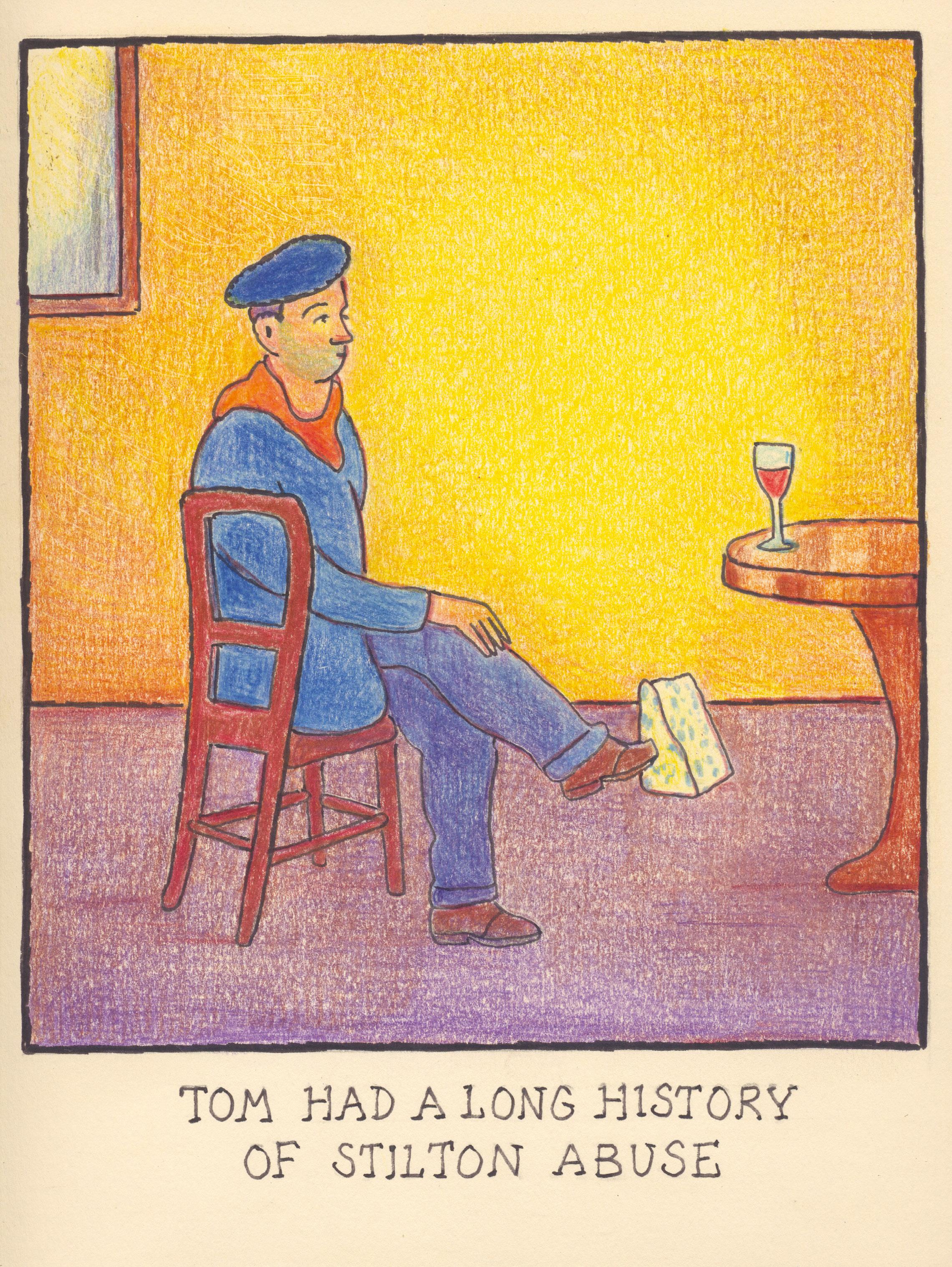

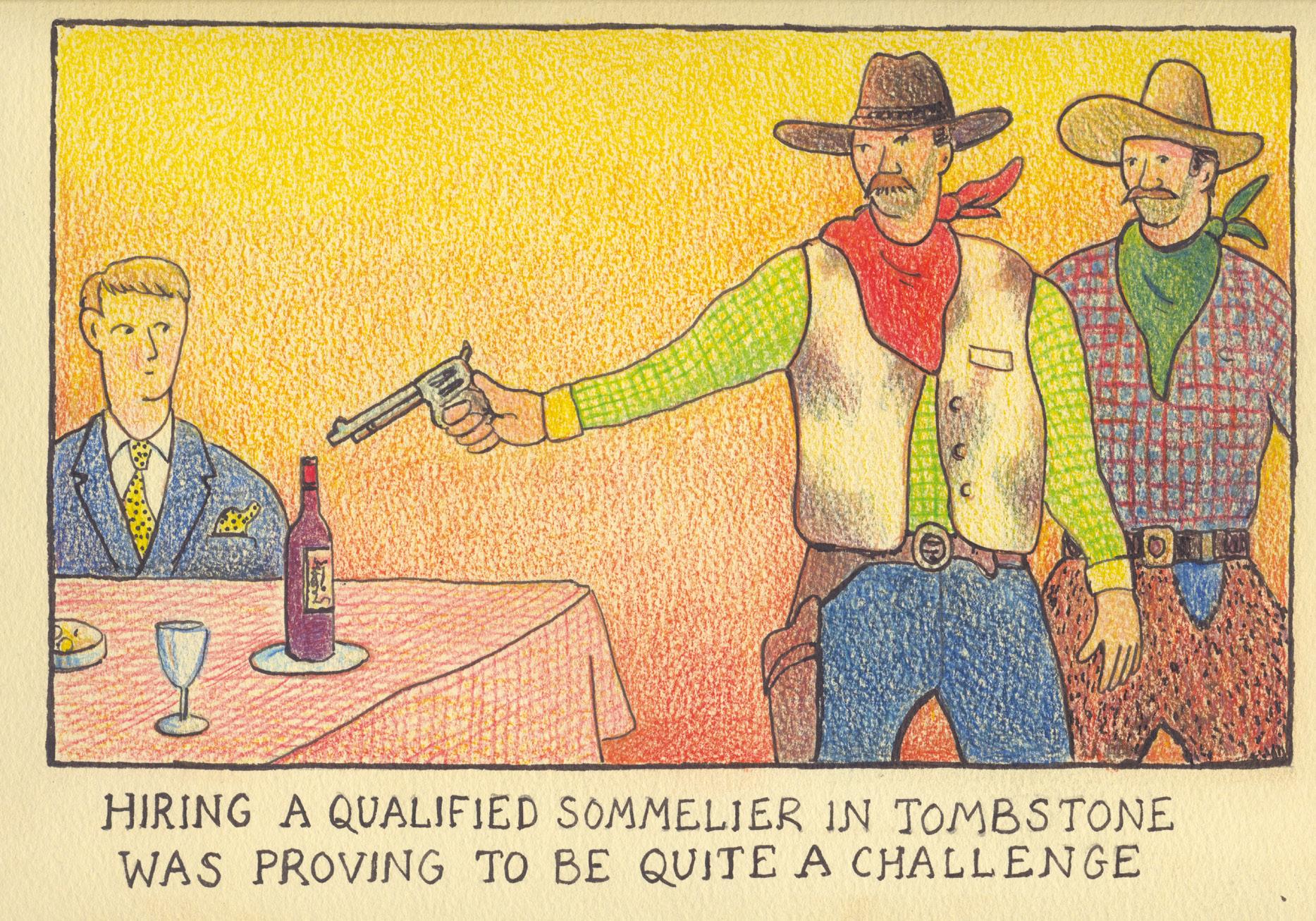

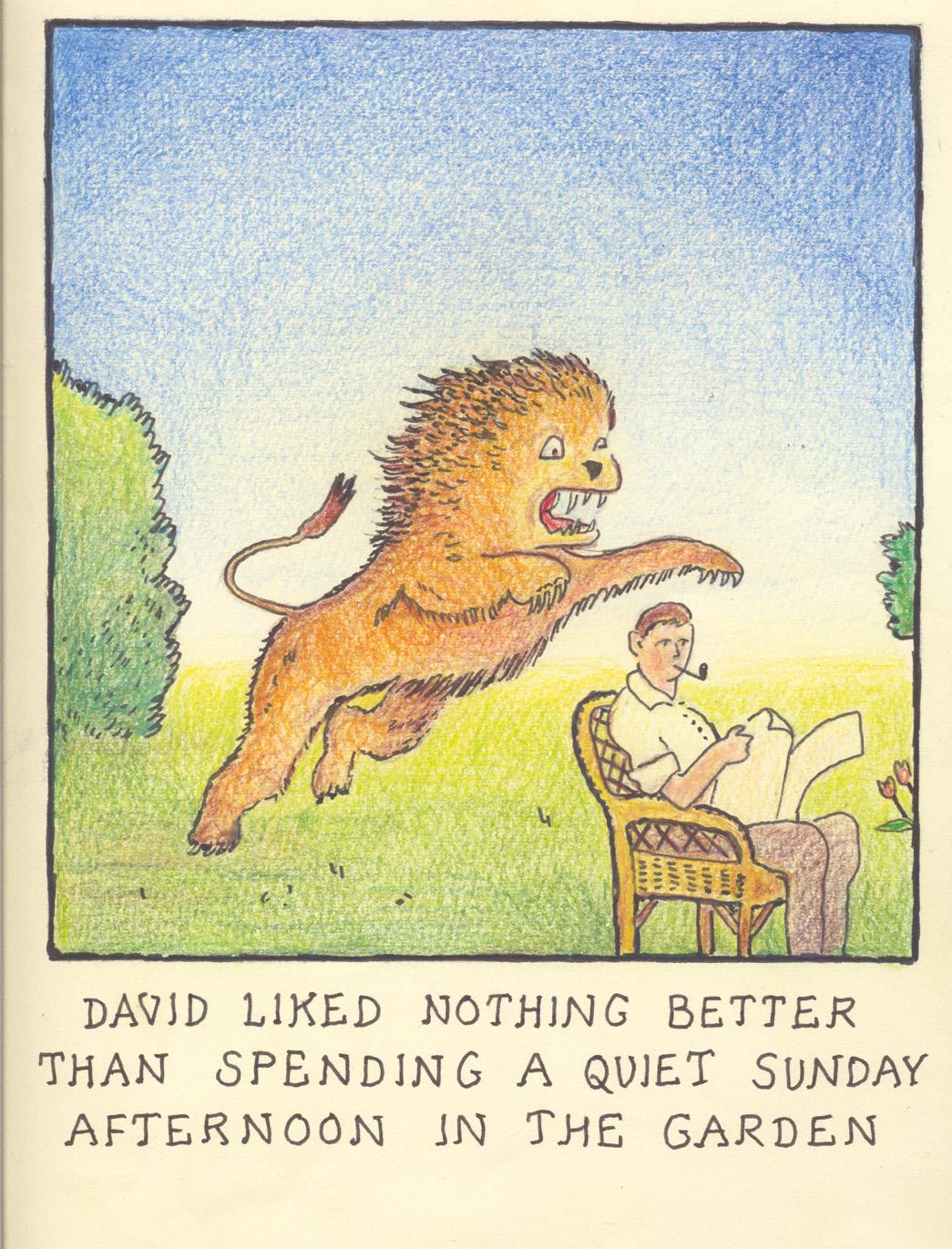

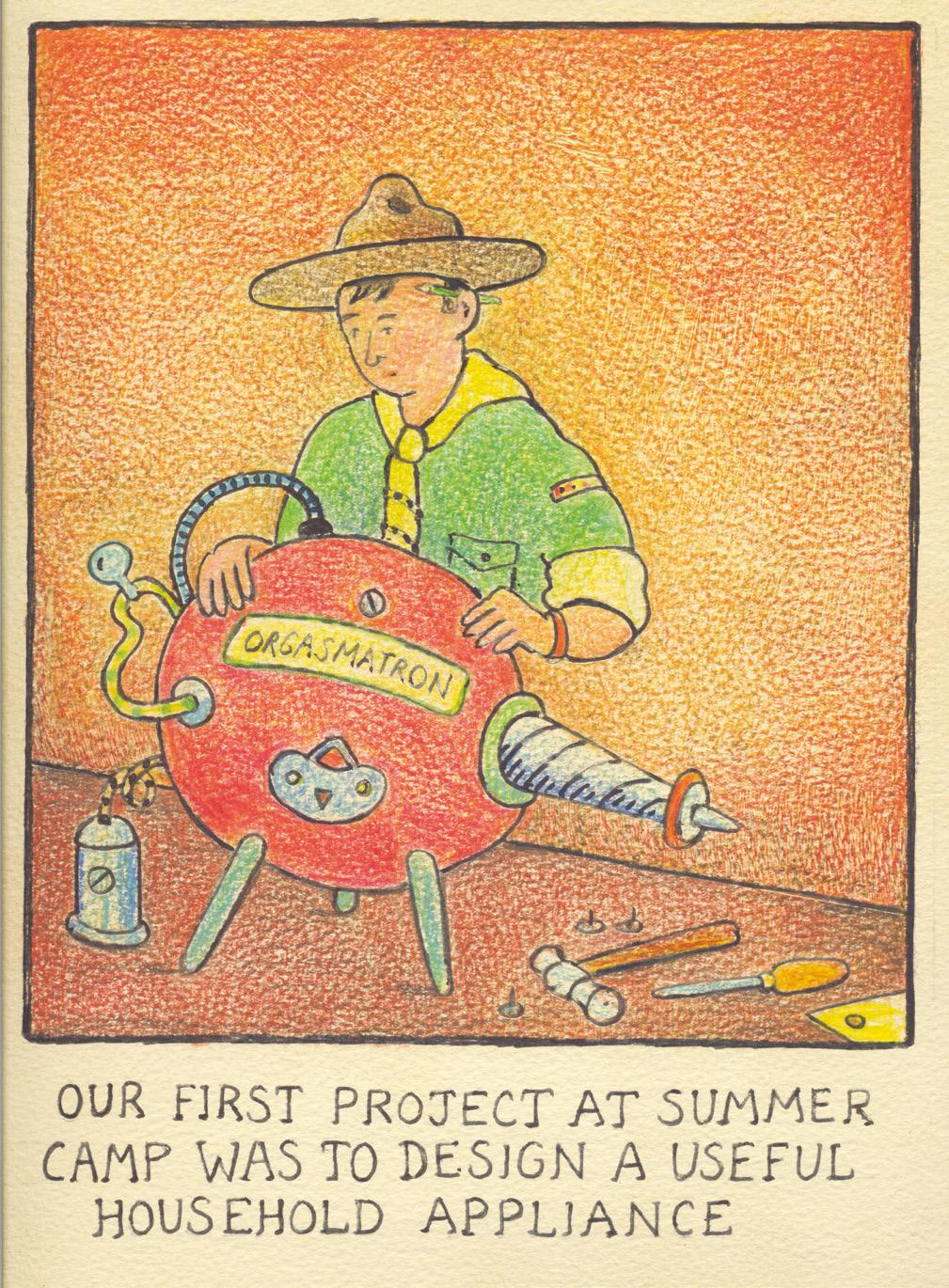

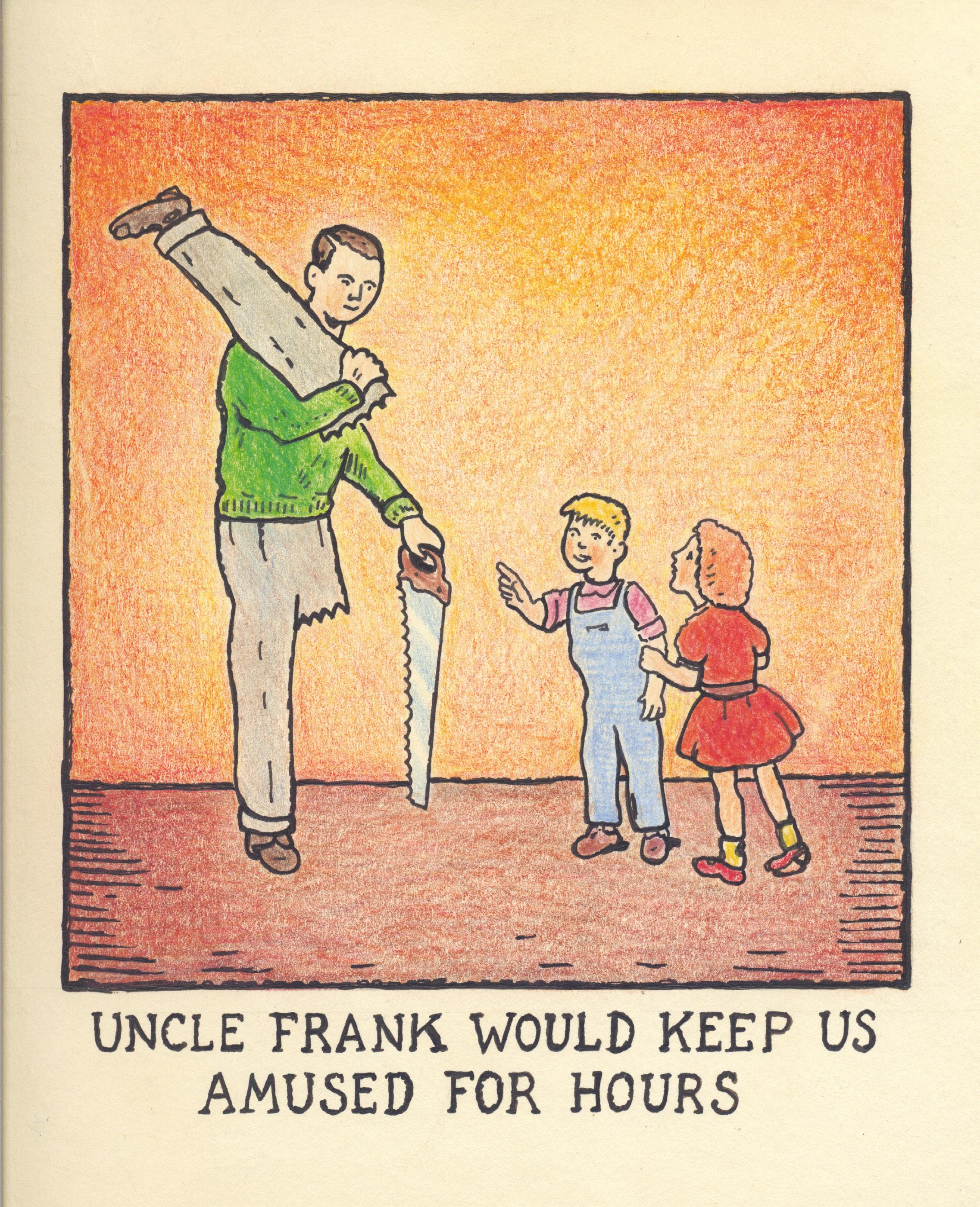

“i never thought of myself as a cartoonist”

Emily Flake

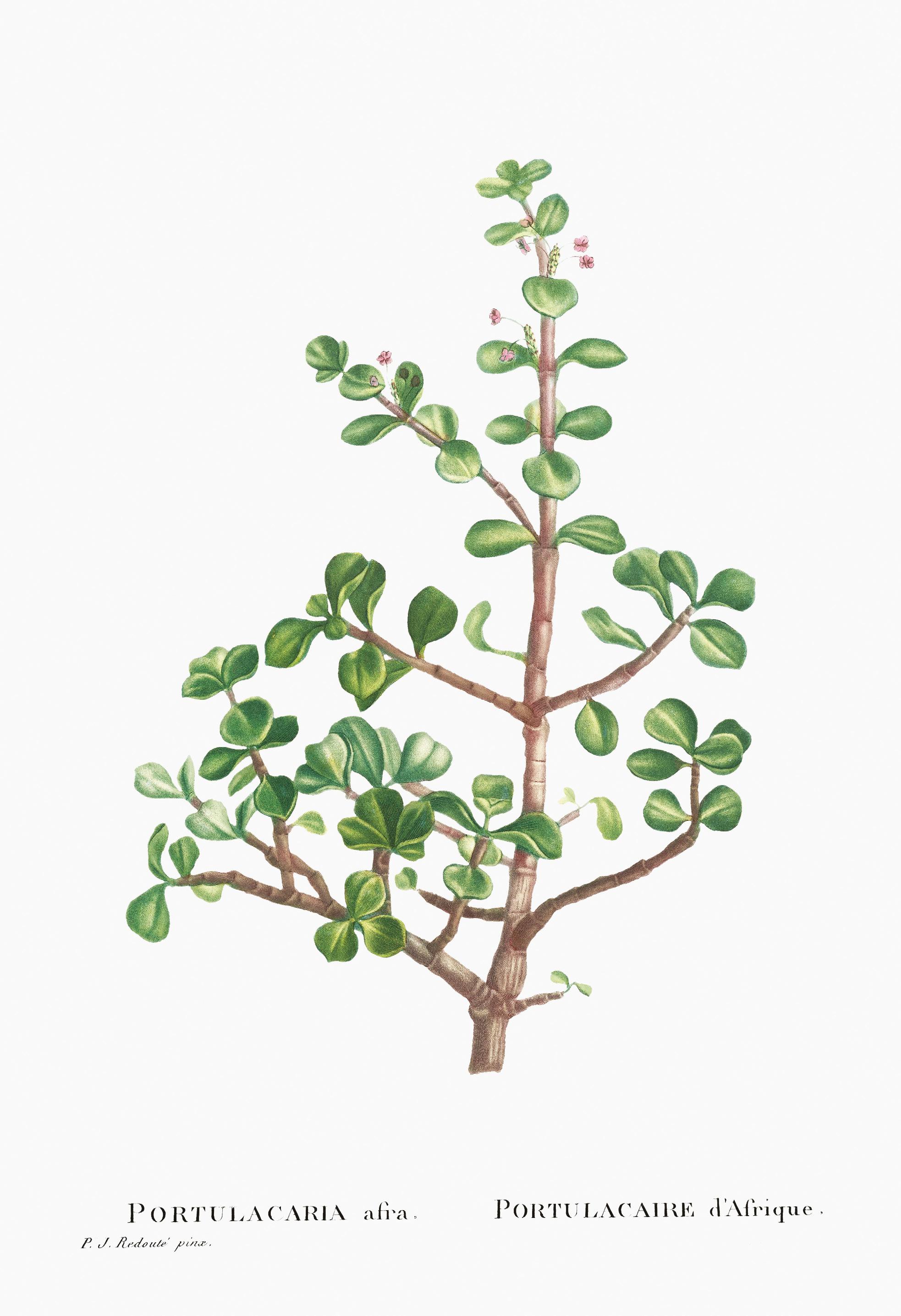

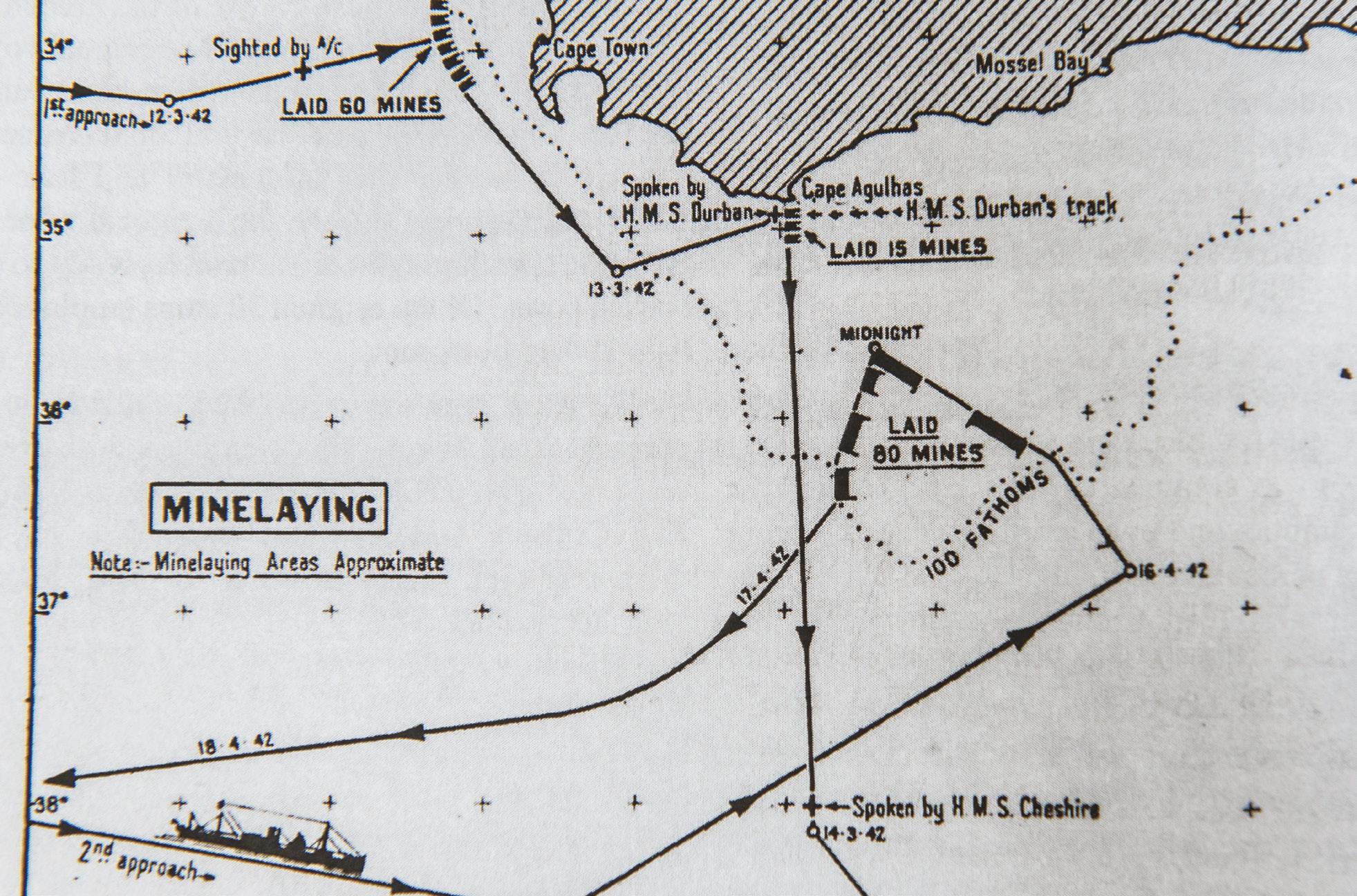

carbon copies Fiona McDonald and Su Birch capitalism with a conscience Biénne Huisman raiders at the cape Justin Fox

4 Jack Journal Vol. 3

06 104 08 12 20 26 38 46 55 56 62 70 80 92 96 100 76

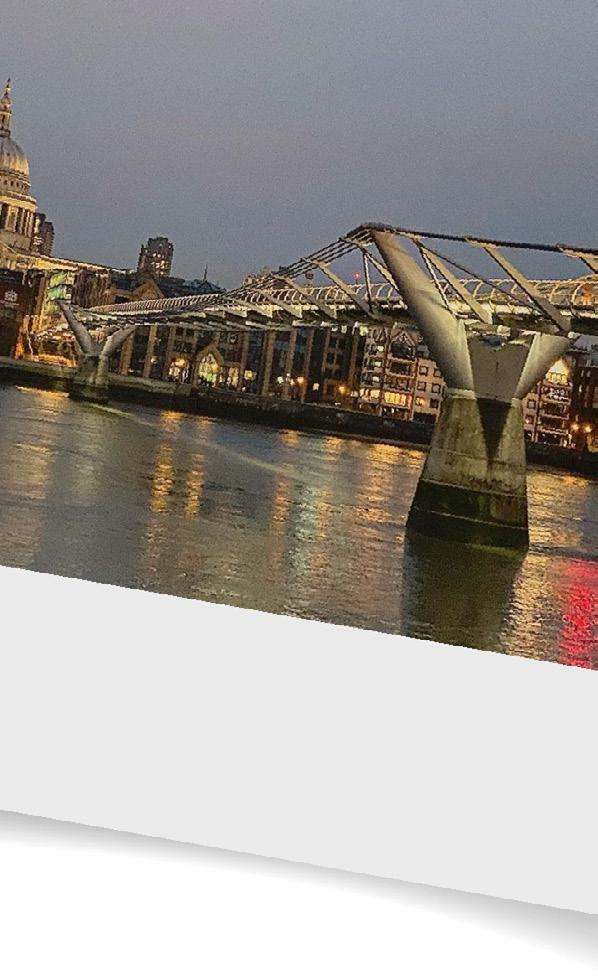

diary of a london restaurant owner 2021 Neleen Strauss a meeting of two worlds Felicity Carter eco-printing. inspired by nature and working with her seasons Rita Trafford

why the best brands are now run by their customers Richard Siddle

playing into silence: a concert guitarist learns the covid art of the online guitar ashram Derek Gripper the knackered mother’s wine guide Helen McGinn and then there was fun Alison Westwood the walk Adrian Kohler we shared what brings us joy Aaniyah Omardien and Monique Rodgers

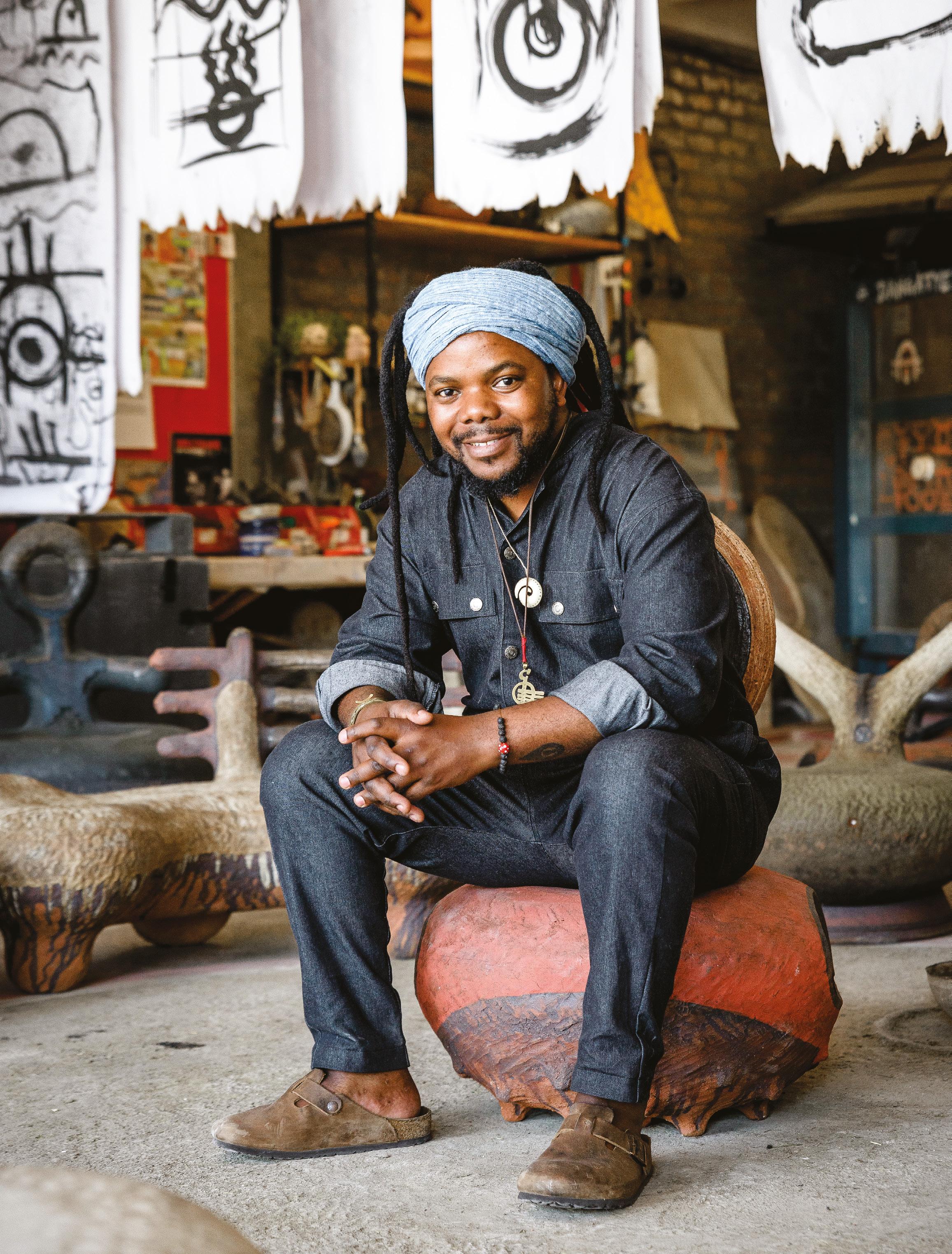

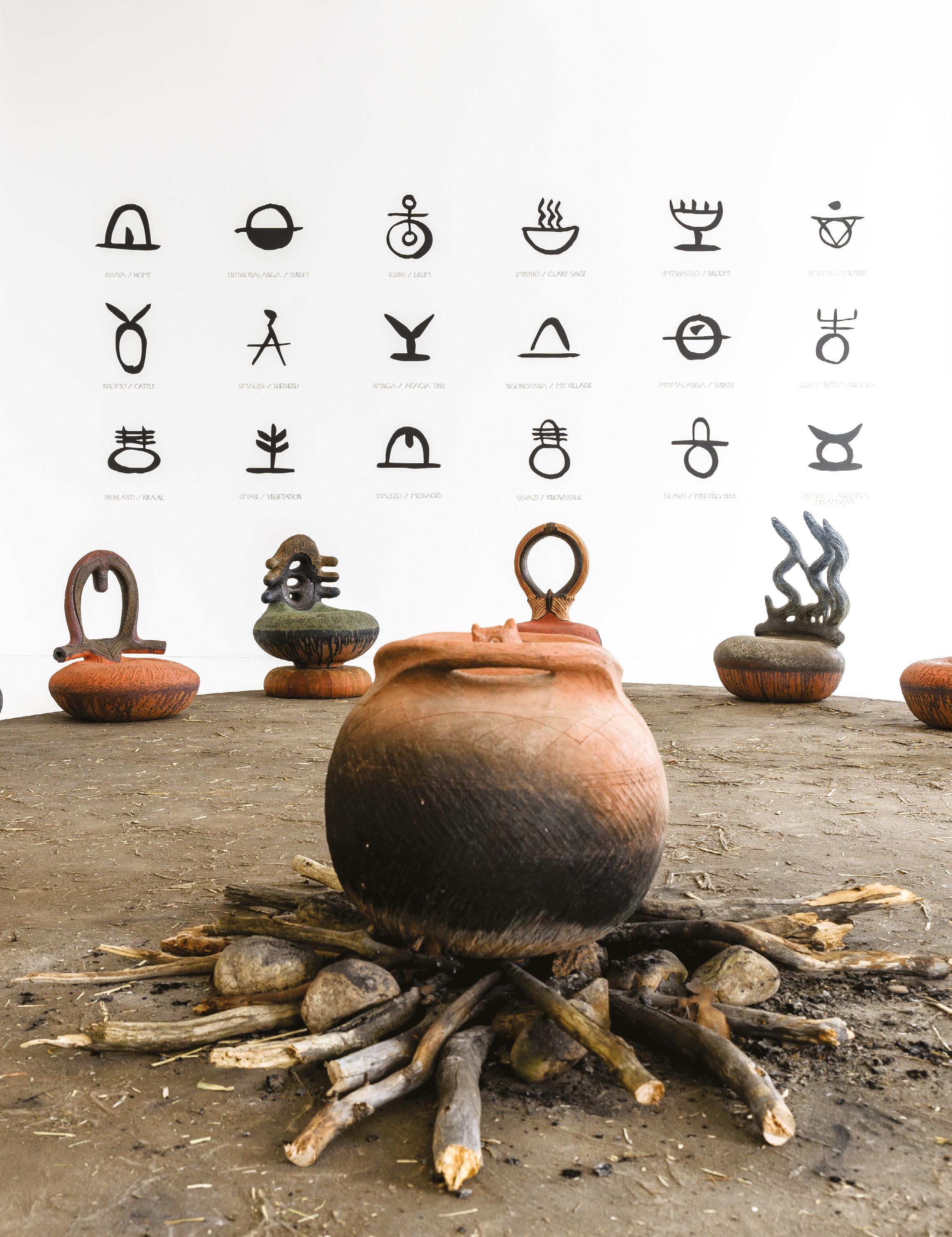

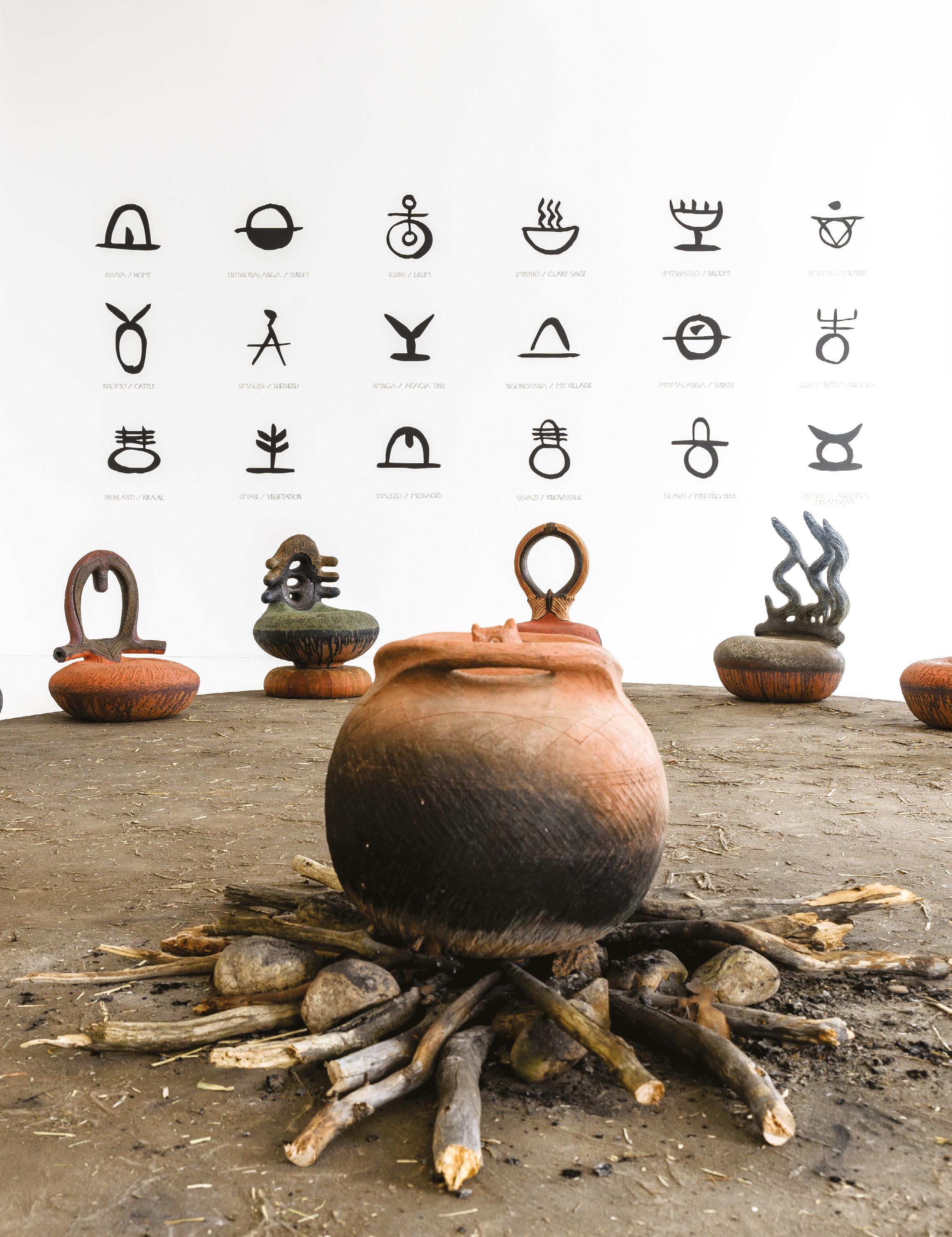

andile dyalvane the gift Su Birch liquid history Lucy Corne

a salute to the sun Fraser Crighton

foods of the world Emile Joubert

the scent of empires – chanel Nº5 and red moscow Karl Schlögel

5

114 118 122

130 132 136 140 152 160 162 164

110

126

144

why we produce Jack Journal

This is a wine magazine that embraces the things around wine, things that touch our wine world, rather than being a wine-centric publication. Wine is central to so much of what we do, and when crafted within this multiplicity of influences, wine is enhanced by them.

Despite what the scourge of social media vainly portrays, we are not defined by our circumstances, appearance or even talents. Rather, it is our fears, dreams, insecurities, resilience, irrationality and empathy that set our course on this multidimensional trajectory through life. These, and other building blocks of our character, make us and others interesting. Of course, Luck, and her conspirator, Timing, merrily wreak havoc and happiness along the way, dealing out both opportunities and dead-end disappointments. And all the time there is so much beauty … weaving in and out and around our fumbling and fuming.

I am still some years away from a well-considered philosophical stance on this mesmerizing journey, but I have

made enough mistakes to know that the omnipresent unfairness and fragility of life is what makes it so addictive and precious. And so we need to let our meandering minds explore.

Psychological and Cognitive Science studies have proven many times over that we walk among fellow fantasists. We have survived excruciating odds just to be sentient and here. And we battle on, hard-wired to procreate, because our brains have constructed a fantasy of existence, so we believe it is not only bearable, but sure to improve. On the other hand, true realists, of which there are a few, are unavoidably depressed.

This fascinating facet of our curious minds means that we lack the ability to reason properly about most things. While we now accept that this is another survival trait, it means reasonable-seeming people like you and me are very often irrational. This shocking revelation (led by Stanford University research academics in the 1970s and replicated many times since) adds spice to our exploration.

It also explains why the technological revolution of connectedness is both so freeing and so damaging. Clear communication is no longer enough. Fact-based insight and rational arguments hardly compete for the limelight. Truth, never a requisite of political or neocapitalist success, is now even less evident. And over the din of our collapsing ecosystem the new screeching soapbox, social media, is overwhelmed by a cacophony of ill-informed, unquestioning (often unthinkingly regurgitated) semi-opinions.

This riptide of bilge is not, in itself, a bad thing. What role it will play in the ongoing development of our coping and survival strategies as a species remains to be seen. But, if you are reading this, you are not alone in believing that we also need to keep offering a counterpoint, a balancing buffer against the flood of fools. This doesn’t mean trying to swim against the riptide, which like an ocean riptide will always drown you. We must swim perpendicular to the inescapable

6 Jack Journal Vol. 3

wash of senseless noise that’s sweeping so many out into the deep sea of idiocy.

We can do many simple things. We can read to small children. We can force ourselves to remain inquisitive. We can try to see things from another perspective. And we can practise patience (if not acceptance) when it comes to views that challenge our beliefs. We can read widely and surround ourselves with people who think before they talk. We can be inclusive and generous and forgiving. And we can keep exploring.

And this is why we produce Jack Journal

Jack Journal is an authentic voice – it reflects our vision as a family-owned, but widely collaborative, wine business. It is informed by our own dreams and isn’t trying to be popular or popularist.

Jack Journal was born of an intense desire to find meaning in things and to explore this chaotic thing called life. It is not trying to be idealistic or superior. It is naturally inclusive and not dumbed

down – which is precisely how we make wine.

Jack Journal is reflective of the signposts along this wine journey that point to delicious wanderings, often resulting in revelation, offering solace and adding joy – and these are the same reasons we craft wine.

Bruce

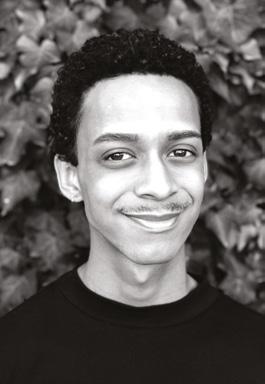

contributors

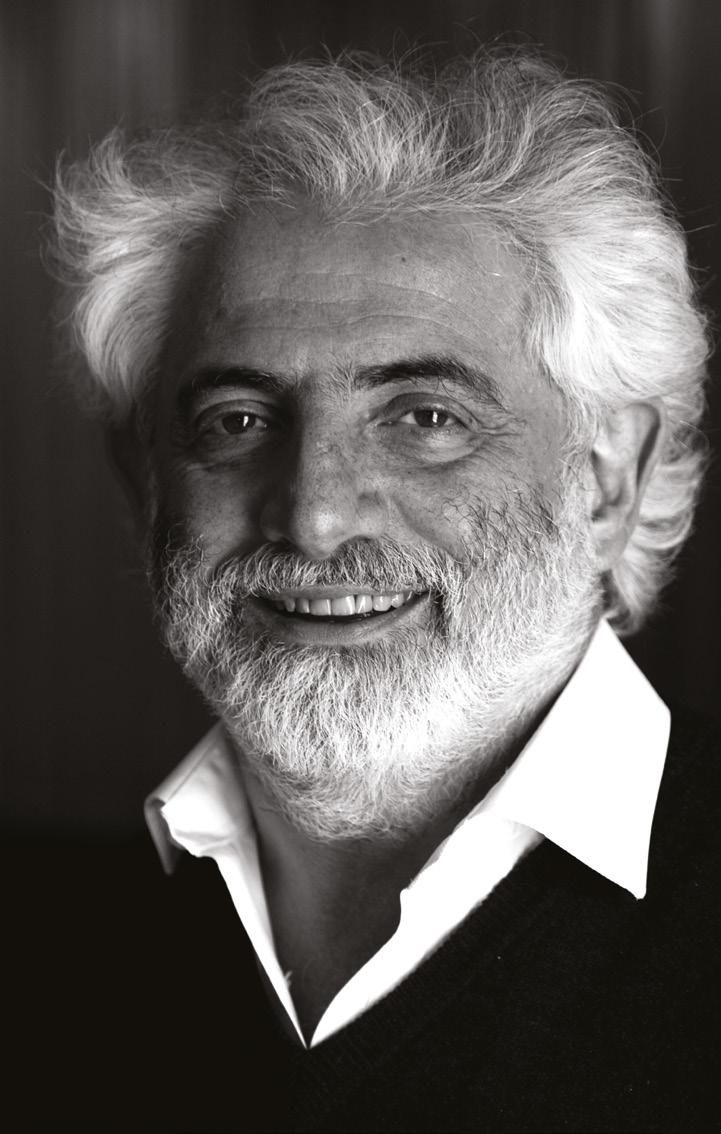

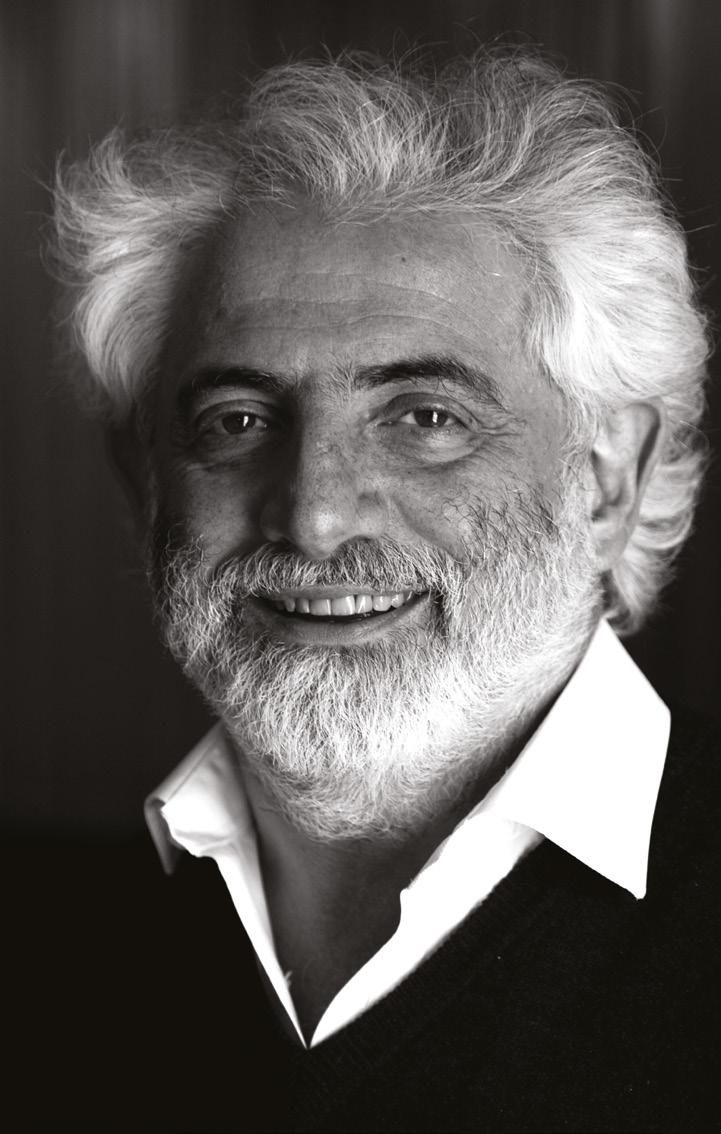

MICHAEL

BOOTH

is the author of seven non-fiction books including the international best-selling, award-winning The Almost Nearly Perfect People, and Sushi and Beyond He writes regularly for a wide range of newspapers and magazines around the world including The Sunday Times, Monocle and Condé Nast Traveller www.michael-booth.com.

SU

BIRCH

is a distinguished international marketing and promotions specialist. As CEO of Wines of South Africa, she received the Drinks Business Woman of the Year award. She runs her own marketing business called Thinking Seahorses and has embraced the challenge of producing the Jack Journal. She also volunteers as an English coach in a local township school. www.thinkingseahorses.com.

FELICITY CARTER

is the Executive Editor at Pix, the wine discovery platform launched in late 2021. Previously she worked for Meininger Verlag, Europe’s biggest wine and spirits publisher, where she built Meininger’s Wine Business International into the world’s premier wine business magazine, with correspondents from 30 countries and subscribers in 38. Her work has also appeared in The Age and Sydney Morning Herald newspapers in Australia, and in The Guardian USA , among others. She is an international wine judge and speaker. www.pix.wine.

LUCY CORNE

is a beer writer and the editor of On Tap, South Africa’s only beer magazine. She is Africa’s first Certified Cicerone – akin to a beer sommelier –and the founder of South African National Beer Day. Lucy is a big fan of pilsner and IPA but also has a deep fascination with traditional African beers. www.lucycorne.com.

FRASER CRIGHTON

moved to South Africa from the UK in 2010 after training as a winemaker. As real beer wasn’t a thing at that time in South Africa, Fraser decided to change that and 12 years later he is still brewing craft beers.

Instagram: @fraserchrightonphotos

HEATHER D’ALTON

is a conservation communications specialist. She spent more than a decade working as a business journalist in London, Johannesburg and Cape Town before changing tack to follow her love of nature. She’s the co-owner of LoveGreen Communications, where she works with wonderful clients who care deeply about our natural world. www.lovegreen.co.za

8 Jack Journal Vol. 3

JANNEKE DE KOCK

works as an illustrator and designer for Archival studio in Cape Town. www.archival.co.za

ROHAN ETSEBETH runs Archival studio, a small design and illustration studio that mostly does packaging design. He has finally put some work on a website. www.archival.co.za

JUSTIN FOX

is a travel writer, photographer and former editor of Getaway magazine. He is the author of more than 20 books, including The Marginal Safari, Whoever Fears the Sea , The Impossible Five and Beat Routes. His latest World War II novel, The Cape Raider (Penguin, 2021), is available in bookshops and on amazon.com. https://justinfoxafrica.wordpress.com

DEREK GRIPPER

creates original music from his diverse influences and spent many years performing and recording his own translations of Bach’s violin and cello music, infusing his interpretations with his lessons from the oral traditions of Africa. He has transcribed note-for-note the complex compositions of Malian kora player Toumani Diabaté and has found a way of playing them on six-string guitar. He has performed with classical guitar legend, Paul Williams, with Diabaté and his Symmetric Orchestra, and with Trio da Kali at Carnegie Hall.

ALLENDRE

HINE

is a strategic creator and a lover of crafted design solutions, film, coffee and meaningful conversations. Ali is a graduate of the Red & Yellow School of Logic & Magic. She is the main designer on Jack Journal www.behance.net/Alihine

BIÉNNE HUISMAN

is an award-winning South African journalist with an MA in Creative Writing from Royal Holloway, University of London. She has worked for the BBC, the Sunday Times, Daily Maverick , Getaway magazine, Open Skies, and more. Instagram: @biennehuisman

9

EMILE JOUBERT

is a communication consultant in the Cape wine industry who writes fiction in his spare time, having published various short-story collections.

ADRIAN KOHLER

is one of the world’s leading masters in puppetry. He is co-founder and artistic director of Handspring Puppet Company. Their productions have graced many a global stage including the West End and Broadway. He has not quite managed to retire yet but when he is at home, in South Africa, he enjoys a morning swim in the Kalk Bay tidal pool. www.handspringpuppet.co.za

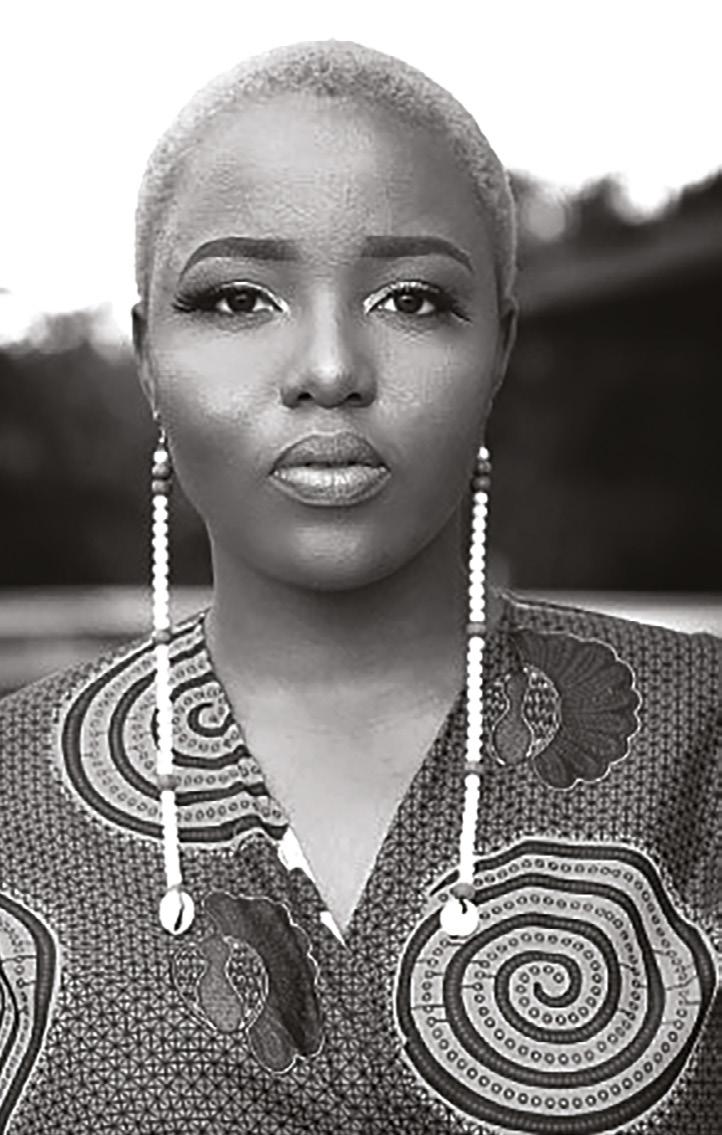

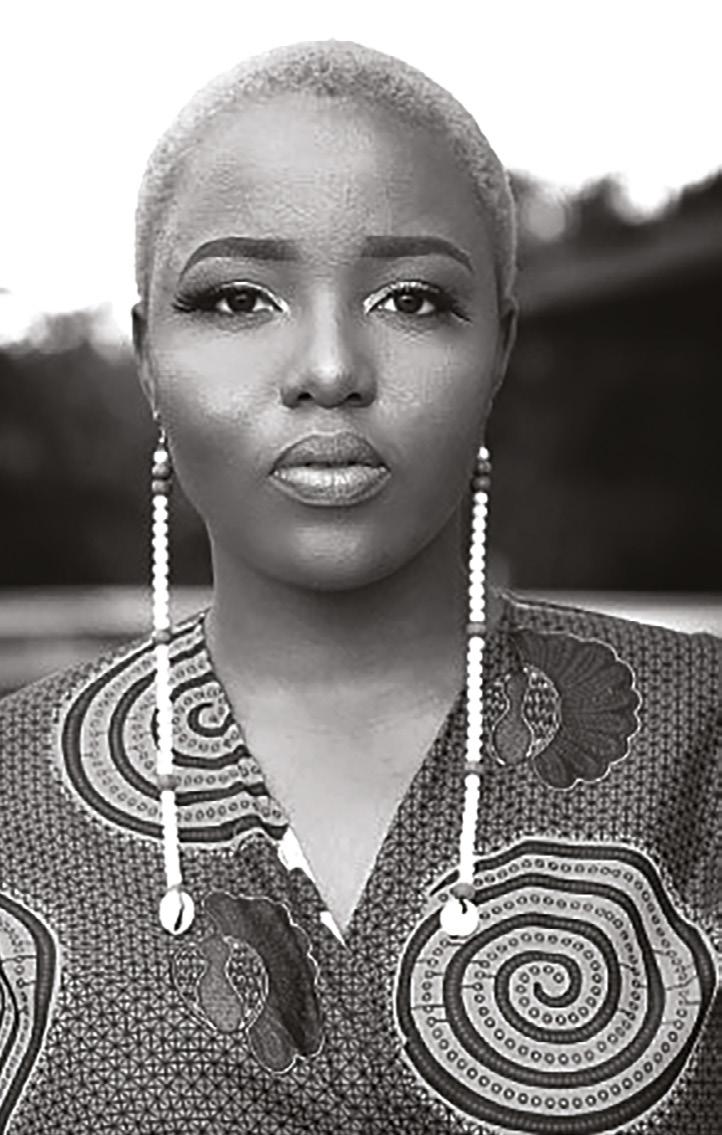

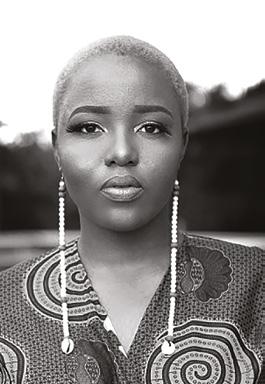

UNATHI KONDILE

is the founding editor of South Africa’s first daily isiXhosa newspaper, Isolezwe lesiXhosa , and the weekly Iphepha Lam newspaper. Kondile is currently based in the Eastern Cape where he continues to develop rural community journalism. He holds an MA in Media Studies (UCT) and has freelanced for a number of media companies locally and abroad.

Instagram: @unathikondile

FIONA MCDONALD

Words and wine are how Fiona McDonald earns her crust. Trained as a news journalist, she accidentally got involved in wine and life took a fortuitous turn, via vineyards, cellars, editorship of WINE magazine for eight years, and ultimately led to her chairing tasting panels at global competitions such as the International Wine Challenge, International Wine & Spirits Competition, Concours Mondial de Bruxelles and Decanter World Wine Awards. Locally, she writes and tastes for the annual Platter Guide when not disappearing down fascinating internet rabbit holes ...

MELVYN MINNAAR

has been writing about art, wine and related existential issues for various local and international publications for many years. The creativity that underpins these subjects is an enduring personal passion. He has served on a number of cultural bodies and institutions. Veritas honoured Melvyn in 2018, recognising his history of cultural involvement, opinions about art and wine, the politics of such and his appreciation for talent.

HELEN MCGINN

is a drinks writer, international wine judge and the author of the award-winning Knackered Mother’s Wine Club blog and book. She spent almost a decade as a UK supermarket buyer and writes about drinks for the Daily Mail and appears regularly on BBC1’s Saturday Kitchen and ITV’s This Morning as their wine expert. Her best-selling debut novel, This Changes Everything, was published in February 2021, and her second fiction book, In Just One Day, was published in August 2021.

GREGORY MTHEMBU-SALTER

is a researcher and writer who lives in Scarborough, near Cape Town. After paying lobola in cows for his own marriage over 25 years ago, Gregory became drawn to the rich theme of South Africans and cattle, eventually writing a book about the subject, entitled Wanted Dead and Alive. Gregory runs Phuzumoya Consulting, specialising in research on political and economic landscapes of Southern and Central Africa, and particularly the Democratic Republic of Congo.

AANIYAH OMARDIEN

Aaniyah’s work connects people and nature. While at World Wildlife Fund from 2001 to 2010, she managed the SA Marine Programme. She is the founder and director of The Beach Co-op (TBC), a not-for-profit company that evolved from the work of a group of volunteers who started collecting marine debris at their local surf break, the rocky shore at Surfers Corner in Muizenberg, Cape Town. www.thebeachcoop.org

10 Jack Journal Vol. 3

DR DON PINNOCK

is an investigative journalist, photographer and travel writer who, realising he knew little about the natural world, set out to discover it. This took him to five continents – including Antarctica – and resulted in five books on natural history and hundreds of articles. He has degrees in criminology, political science and African history and is a former editor of Getaway travel magazine. The Last Elephants is his 18th book. He lives in Cape Town.

GABRIELLE RAAFF

is a full-time contemporary artist living in Cape Town. She works with ethereality, using ink, watercolour and water-based oil to express the form and emotion of her subjects. She has had five solo shows, exhibits extensively locally and abroad, and is preparing for her next solo show in the first quarter of 2022.

KARL SCHLÖGEL

is a historian, writer and Professor Emeritus, living in Berlin. Besides visiting scholarships to Budapest, Oxford, Uppsala and Los Angeles, he travelled for decades in Russia and Central Europe writing about cities, Stalinism and urban cultures. Among his many books are: Moscow 1937 (Cambridge 2012), In Space We Read Time (New York 2016), Ukraine. A Nation on the Borderland (London 2016), The Soviet Century (forthcoming, Princeton). He has won many awards including the ‘Orden pour le mérite für Wissenschaft und Künste’.

RICHARD SIDDLE

is an award-winning business editor with over 25 years’ experience working across diverse fields including wine, drinks, computing, grocery retail, convenience and travel. As well as running his own editorial and business consultancy, he launched a B2B website for the premium wine trade, http://www.The-Buyer.net, with his business partner, Peter Dean – a digital-only platform that provides insight and analysis to help drinks producers understand and work more closely with the trade buyers they most want to work with, be it distributors or sommeliers and restaurateurs.

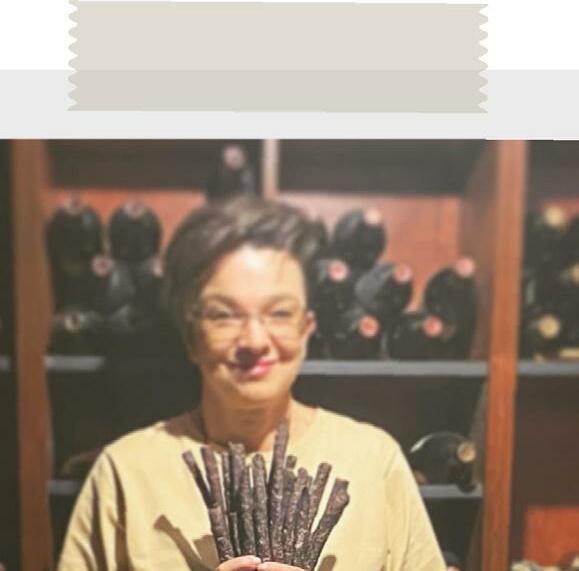

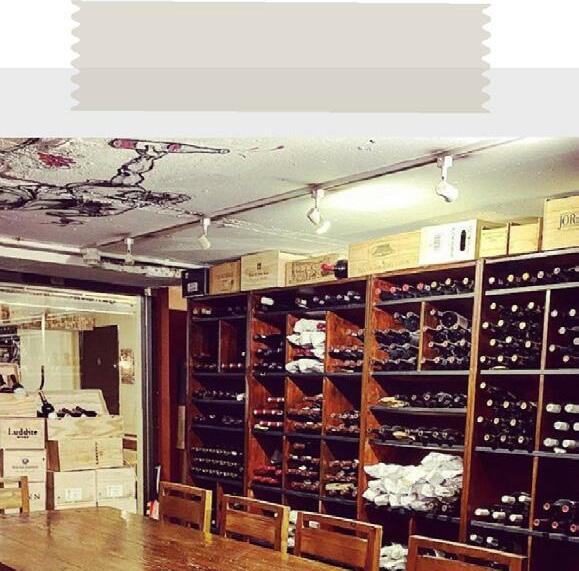

NELEEN STRAUSS

Neleen is the owner/manager of High Timber restaurant, London. She loves test cricket, safari, Negronis and opera. She knows her opinion is not a fact, but loves debating.

Instagram: @hightimberrestaurant

RITA TRAFFORD

is a qualified chef, an unqualified artist, a mother of two wonderful children who have recently flown the coop, a doting (not all the time) wife to a talented winemaker, parent to three foster dogs, and proud mamma to a few chatty free-range hens. Living with all this against a backdrop of mountains, vineyards, old oak trees and spectacular fynbos, one can only be in awe of the surrounds.

ALISON WESTWOOD

has been travelling to and writing about Africa’s top destinations for more than 15 years. Her writing and photographs have appeared in various magazines and online publications, as well as a book or two. The Cape is her favourite place in Africa, at least partly because of the wine. Instagram: @alisonwestwood

Editor: Su Birch

Design: Allendre Hine & Rohan Etsebeth

Jack Journal is a Bruce Jack Wines production. Please contact the editor at editor@jackjournal.com with comments, questions and ideas for articles.

Bruce Jack Wines Limited. Registered address: c/o Seles Group, 2a Charing Cross Road, London, England, WC2H 0HF

11

in search of the strange

There are mountains you climb to reach the top. But there are other mountains, and other reasons to climb them. Don Pinnock found two of them in northern Madagascar.

Written by: Don Pinnock Photography: Don Pinnock

The Avenue of the Baobabs is a prominent group of Grandidier’s baobabs lining the road between Morondava and Belon’i Tsiribihina in western Madagascar.

‘The way to cook a tenrec,’ Zakamisy explained as we stomped up through the dripping mist forest, ‘is to first boil it then peel it to remove the prickles. After that you grill it.’

Tastes a bit like pig, evidently.

The conversation about tenrecs had begun back in Antsiranana, Madagascar, where Zak said he thought he could root one from the underbrush. Not to eat, you understand, just to regard. Tenrecs are mammals best described by what they’re not: they aren’t shrews, platypuses, hedgehogs or guinea pigs, but have something in common with all of these. I couldn’t wait to see one.

Right then, though, we were heading up a trail to Amber Mountain. The forest was dark, dense and full of things with names like dragon trees, flaming Katys, polka dot plants and outrageous, balletic orchids with tongue-twister titles like Aerangis, Jumellea, Bulbophyllum and Phaius. It all seemed to belong to some remote epoch. In this landscape it wouldn’t entirely surprise you to see pterosaurs gliding through the trees and velociraptors sprinting across the trail ahead. But the more we hunted for tenrecs, the more they weren’t there.

‘They’re not fady,’ Zak explained, after another fruitless forage in the soggy leaf litter. ‘Lemurs are fady, so are chameleons, but not tenrecs. So they get eaten.’

We had time on our hands, maybe another 10 hours of hard climbing, so it seemed okay to begin yet another conversation about the complexities of Malagasy customs.

‘What’s fady?’ I asked.

Zak, you must understand, is not your common sort of guide. His father was a musician fairly famous in northern Madagascar but he died when Zak was quite young. Zak and his six sisters were brought up in a peasant village by his mother and beloved grandfather, who was both a champion bare-knuckle boxer and a storyteller.

In his youth the old man had been press-ganged by the French into building the road to the top of Amber Mountain upon which we were walking – though after 50 years of neglect it was a mere precipice-hugging, tangle-foot path.

Zak learned French, then English, then Italian, and decided growing rice and mangoes wasn’t for him. His ambition led him, eventually, to York Pareik who ran a

travel outfit named King de la Piste. A piste, in case your French is as lousy as mine, is a dirt road.

Zak soon learned the Latin names of almost every Madagascan plant and creature. So now – in his late 20s, with a head full of tribal customs, hundreds (maybe thousands) of traditional stories and a fine grasp of modern ecology – he’s a sort of Renaissance man.You ask him a question and you invariably get a very full answer plus peripheral anecdotes.

To radically paraphrase his answer, fady is a taboo system so complex that neighbouring villages and even close neighbours don’t necessarily share it. Taboos can vary from family to family, community to community or even person to person.

Perhaps eating pork is fady, or digging a grave with a spade which does not have a loose handle is fady (not too much contact between the living and the dead). In the Imerina area it’s fady to hand an egg to someone; it must first be put on the ground. In many areas it’s fady to work in the rice fields on Thursdays, or work at all on Tuesdays.

Places are also fady, and all over Madagascar you will see trees or rocks lovingly cloaked in bright cloth, or bowls full of money beside certain objects. We even came across a skeleton in a cave with a platter of coins beside its grinning skull.

A close relative of fady is vintana, which cuts up time into good times and bad times to do things, which means people might suddenly stop what they’re doing and sit down for an hour or two.

Some things, though, are generally agreed to be fady, like chameleons and lemurs. Chameleons, from tiny scraps of rainbow to huge, metre-long dragons, are everywhere and, in the forests, lemurs hurtle all over the place or sit and stare at you. Some will even steal your lunch.

It’s just a pity there’s no taboo on slaughtering rain forests – only about 10 per cent of them are left and vast areas of the island are either eroded ruination or rice paddies. Well, there you are. But just then, no tenrecs.

Now to the purpose of my trip: I’d come to Madagascar to explore two mountains, one entirely cloaked by some of the surviving rainforest, the other ripped to shreds by water. I was filled, to quote Kipling, with

a ‘satiable curiosity’ about an island where almost everything was endemic, volcanic or just plain odd.

Any trip necessarily begins in Antananarivo because that’s where international flights land. It didn’t take me long to realise it wasn’t Africa. Antananarivo is a traffic jam clamped round a curious, pointy-roofed city surrounded by endless rice paddies. It takes a while to get anywhere, but the people along the roads are charming and mostly beautiful Indo-Malayan or MalayoPolynesian, so it doesn’t matter. Coming in from the airport, I just sat and gawped at all the delightful strangeness.

But my mountains – Ankarana and Amber Mountain – were in northern Madagascar, so I flew out next day to Antsiranana and King’s Lodge.York, who owned the lodge, was seriously laid-back. He had a fleet of elderly but serviceable Range Rovers and year-old twins who keep him and his wife, Lydia, awake at night. There was a time, he confessed as we clutched cold Three Horses beers and watched the afternoon sun get swallowed by a volcano, when he wore his hair long, sampled interesting substances and travelled the world in dangerous public transport. Then he found Antsiranana and decided he’d arrived at his Shangri-La.

I couldn’t argue with him about that.

Next day Zak packed up our kit and victuals, loaded up a shy cook named Bridget and set off on the most grimy journey I have ever experienced – and I live in Africa.

Madagascar’s not dubbed the red island for nothing. When forests are slashed and burned, the oxidised laterite soil beneath them is singularly infertile and soon erodes, spreading fine ruddy powder over the whole island. In the rainy season, roads are a quagmire; when they’re dry, each bump produces an effect not unlike hitting a fat bag of bright red flour.

When we arrived at the spiky buttresses of Ankarana, we were astonishingly red, with our personal colour showing only where dark glasses had been. Each rivulet of sweat made the mess even more surreal and sticky.

Well, never mind all that. Let me tell you about Ankarana. On an island of strange things it has to be near the top of the strangeness list. It’s a limestone massif sticking abruptly out of the plain and covered in razor-sharp limestone karst

14 Jack Journal Vol. 3

15

Zakamisy was the rare sort of guide whose deep knowledge turned his surroundings into magic.

16 Jack Journal Vol. 3

Madagascar is home to about half the world’s 150 or so species of chameleons.

Tenrecs aren’t shrews or mice or hedgehogs but seem a bit of all those.

17

The trail up Amber Mountain goes through dark, dense forest.

pinnacles known locally as tsingy. Instead of going round it, rivers chose to run through it, forming caves, canyons and eerie underground tunnels.You can walk through several hundred kilometres of these things. In places, huge caves have collapsed, forming isolated pockets of river-fed forest with sunlight streaming down from above. Creatures you’ll find nowhere else on the planet live in there.

We hiked through the inky black caves, some with twinkling stalactites and stalagmites, then climbed up the mountain to view the forests and rivers from above. A troop of rare crowned lemurs came to investigate. I bent down to photograph one, and three others jumped on my back to see what I was doing. Fady works wonders in the trust department.

We camped at the foot of the tsingy, watched the setting sun turn them orange, and Zak produced some local rum. It was spittingly awful. When I refused to drink it, Zak told me a story which seemed to justify getting motherless on bad booze and opened up a later discussion about why the Malagasy are a nation of grave robbers.

There was once a mamalava (rum drunkard) whom nobody respected. He was around during a famadihana, a time of year when, for some reason or other, corpses are exhumed, their bones dusted off, danced with and carried to some other place (I saw empty graves all over the place).

When the skull was unearthed, it began to move this way and that. Everyone ran away in fright. But the mamalava took a closer look and saw it was being moved by a little tenrec in the brain cavity. He called everyone back and after that they all approved of his rum habits.

‘And that,’ said Zak triumphantly, ‘is why it’s good to drink Malagasy rum!’

Well, maybe.

Next day we headed through more red dust to Amber Mountain. It’s a thing apart, a great volcanic massif covered in ancient mist forest with its own wet microclimate quite unlike anywhere else around it. Manokan Ambre, as it’s called, towers over the northern tip of Madagascar with, more often than not, a soggy cloud frown across its peak.

We overnighted in a very neat, clean hut at Roussettes Forestry Station and hit the trail in a light drizzle at an ungodly 05h00

the next morning. Half an hour after passing an atmospheric little waterfall (sacred, of course) near the hut, we were gazing down into the forest-cloaked mouth of a crater lake named Mahasarika.

The forest was … weird. A glance at the statistics will tell you why. Madagascar has around 10,000 plant species of which about 80 per cent are endemic. It has eight species of baobab whereas the whole of Africa has only one. Of the 258 species of birds, 107 are endemic. Then there are lemurs – 30 species. They’re primates that look like monkeys with foxy faces and cat eyes. And tenrecs, which Zak promised …

We hiked past huge pandan trees (Pandanus sp.), fluffy topped Araliaceae literally dripping with epiphytes, many of them orchids, huge manaries (Dalbergia sp.), massive tree ferns (Cyathea sp.) and spooky dragon trees (Dracaena sp.).

A turkey-sized Madagascar crested ibis, the bane of tenrecs and chameleons, scratched in the understorey, a monticole played hide and seek in the upper branches of a manary, and Madagascar bee-eaters buzzed through the mist-edged glades. Lurid lichens sprouted from the rotting trunks of trees thrown down by the area’s violent cyclones, and in the stream beds Boophis frogs muttered contentedly.

The place was simply glorious, and we had it all to ourselves.

Around five hours deep we came upon a moody crater lake which appeared suddenly as we stepped out of the forest onto its grassy apron. From there it was a slippery, tough climb out of the crater and up to the summit, marked by a neat concrete pillar and a plaque with the words ‘Pic D’Ambre’. My GPS registered an elevation of 1,488 metres and, in case you like exact locations, it read S12°35.778, E43°09.188. In the swirling mist we couldn’t see a thing.

Nearly an hour later, after we’d munched the scrambled-egg sandwiches and fruit Bridget had prepared, the murk suddenly lifted. Below us was a great crater – I think it was the one named Renard – and beyond that the Mozambique Channel. There’s just something about the view from the highest point of anywhere that makes it worth the pain.

Twelve hours after starting, we were back in the hut. My feet hurt and I was suffering

from the strange emptiness I often feel after climbing a mountain. Maybe I looked glum.

Zak, ever perceptive, handed me a glass of rum and said: ‘Would you like me to tell you a story?’ He gave me no time to reply.

‘There were once three friends, bon? A duck, a chicken and a dog. They lived together in a village. Once every week they’d take the taxi-brousse to the market in Antsiranana. But one week, when they were halfway to the market, the taxi driver he told them that because of the cost of gaz-oelie, the fare had gone up from 300 francs to 500 francs.

‘The duck he had the extra cash, the dog was rich anyway, but the chicken he had only 300 francs. So when they arrived in the market, the duck got off and paid 500 francs. The chicken paid 300 and told the driver that his friend, the dog, would pay the rest. The dog had a 1,000-frank note. The driver took it, got in the taxi-brousse and just drove off.

‘That is why, today, when you see a duck in the road, it’s not worried about the car, the chicken always runs away shouting and flapping, and the dog he chases the car going ‘woa, woa woa’ …

‘Are you feeling okay now?’ Zak asked, looking at me with his wise, serious eyes all etched about with smile wrinkles.

‘Yes, sure. Fierce rum, though. Do you think if I drank it I could spot a tenrec?’

‘Well, we could try …’

For more about the tenrec

18 Jack Journal Vol. 3

Let me tell you about Ankarana. On an island of strange things it has to be near the top of the strangeness list.

19

Tsingy de Bemaraha, Madagascar.

Weaver Nomtheliso Ngxoni. Photography by Cheryl McEwan.

Weaver Nomtheliso Ngxoni. Photography by Cheryl McEwan.

22 Jack Journal Vol. 3

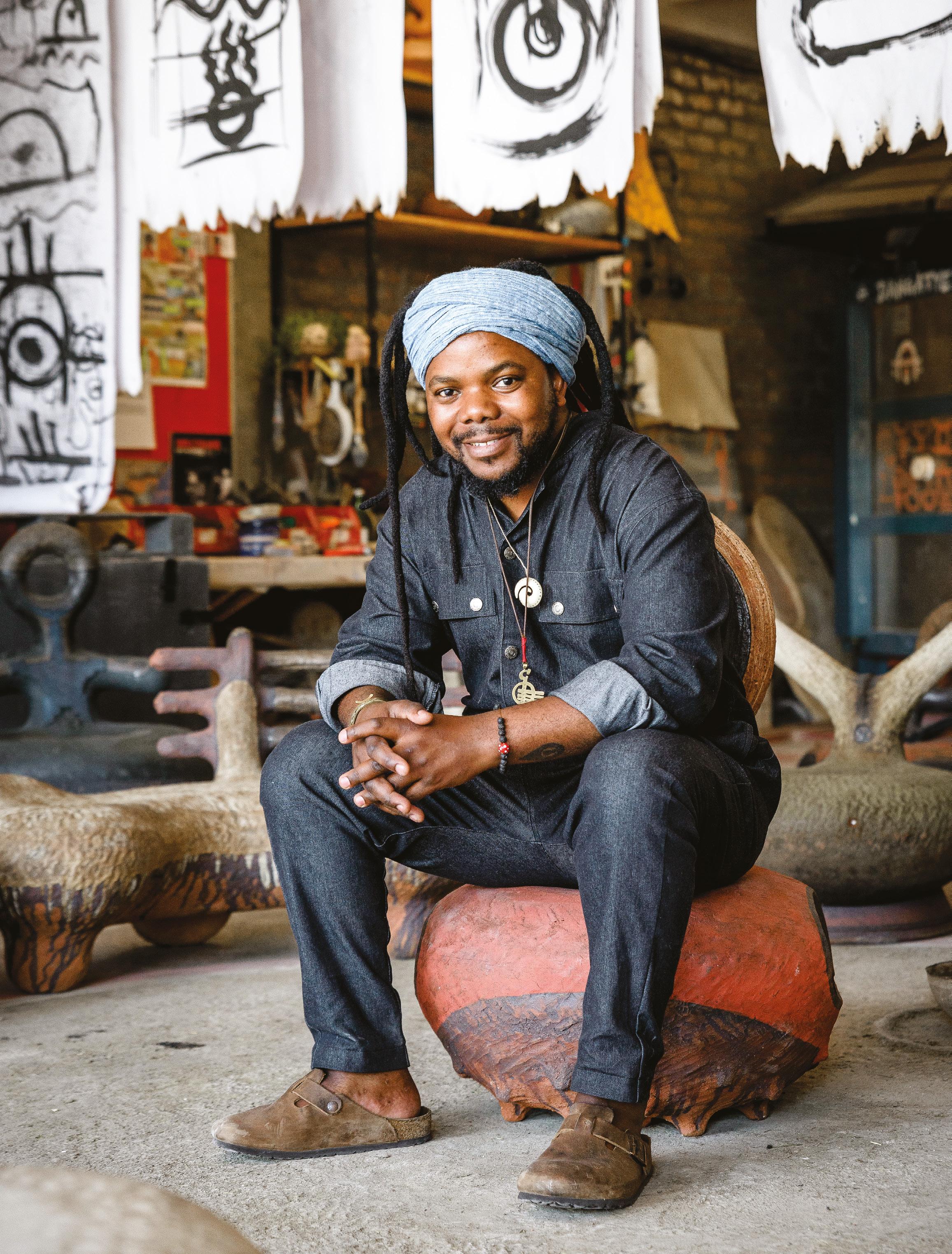

Rich Mnisi. Photography by Stephanie Veldman for Southern Guild.

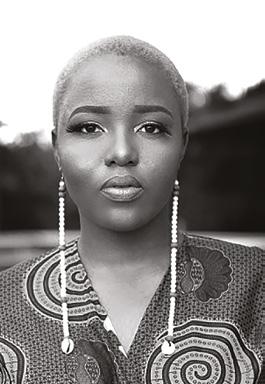

weaving a living through rugs, the story of oomama bethu (our mothers)

Written by: Unathi Kondile

Rich Mnisi, South African designer darling, stares boldly out from the pages of November’s Wallpaper* magazine, which features his extraordinary solo exhibition titled Nyoka (The Snake).

Behind him in the photograph is a colourful rug, still on the looms of weaving studio Coral & Hive. His exhibition features a range of objects including seating, lighting and a beaded console, but it is this imposing rug in its finished form that has everyone talking.

Rich has named the rug Nwa’ntlhohe (Pure Beauty). It is over 5 metres wide and curves organically around splashes of colour and a big blue mound of extra-long tufting that invites you to lie down, curl up and chill. It was woven on Africa’s largest loom, in natural fibres (karakul and mohair), by two master weavers, Nokwaka Dyani and Funiswa Sibeko.

After Rich had been to see the rug on the looms, Funiswa commented:

‘We were excited to have Rich Mnisi, indoda ende (tall man), visit the looms to learn our craft.’ Nokwaka was very curious to see this particular rug come to life. It took 12 weeks to weave, so she felt it was like her baby. When she and Funiswa went to the exhibition to see the rug in situ at the gallery, they commented: ‘Making this rug taught us even more about patterns, design and creativity. We had fun. And, also, it’s nice to be famous for a bit!’

The stories of these women who weave are typical of many oomama bethu (our mothers).

‘I was born in Gatyane, a village in the Eastern Cape province. My beginnings are there; it is where I grew up herding cattle, fetching water from the river, weaving ingobozi (Xhosa baskets made with thatching grass) and stuff,’ says Nokwaka. ‘Here at Coral I was given in-depth training on spinning, weaving, patterns, following designs or what is called tapestry. I mean today I can easily weave together Nelson Mandela’s face on a rug.’ Through this job, Nokwaka has been able to put her second daughter through the Cape

Peninsula University of Technology, and her eldest son is ‘heading to the mountain’ in December to become a man.

Funiswa, the co-weaver of the Mnisi rug, was also born in the Eastern Cape, near Lusikisiki. ‘My father didn’t want me to go to school. He had no son, and I was the middle one of the children, and he said I had to look after the goats and cows. In the end, my father agreed I could go until I could write my name. After that no more school. I cried as all my friends were going to school. I even stopped speaking for a while.’ In 2003 Funiswa got work weaving full time. She didn’t know any English when she started, but she learned fast and today she is proud of her English because people understand her now and don’t laugh at her. She loves to weave, to know the rug is coming from her hands. ‘This job at Coral & Hive is taking me far … it is forever … it’s like a life for me,’ she says. Funiswa’s son is doing his third year in Natural Medicine at the University of the Western Cape, and her other two children are still at school.

Funiswa and Nokwaka are only two

23

24 Jack Journal Vol. 3

From left to right Neliswa Sinuma, Nokwaka Dyani and Madida Ntseheseng. Photography by Johnny Frattasi.

examples from the many success stories behind the looms and spinning wheels. Another is Ntombomfutshane ‘Ntombi’ Mtana, who hails from rural Centane’s Gqungqe village where she was an avid netballer and bead maker.

‘Traditional women tend to decorate their ankles with various colourful beads in the Eastern Cape. So, in my spare time as a child I would make those amanqashela (ankle bracelets) using a needle, thread and various beads to create beautiful jewellery for people like my aunt,’ says Ntombi, who moved to Cape Town in 1992 where her entrepreneurial flair saw her once running a popular shebeen in Harare, Khayelitsha. After getting married, she shut down the shebeen and looked for something more secure. Ntombi trained as a weaver, but today she sits behind the spinning wheel and dubs herself as an expert on the different types of wool they work with, from karakul wool to mohair. Life for her has become more stable.

Nomtheliso Ngxoni was one of the first employees at Coral & Hive and also comes from the Eastern Cape, Ezingqolweni

village near Lady Frere. She relates the entire rug weaving process as being similar to the traditional weaving techniques of producing izithebe (traditional Xhosa placeholder mats) and amakhukho (traditional grass floor mats). ‘What we do here today is similar to what we used to do with imizi (grass from riverside), weaving to make all sorts of things at home. It’s just that here we are now doing it the modern way!’ laughs Nomtheliso.

Thembisa Sam is the youngest of the 25-strong all-women team. She was born and raised in East London’s Nxarhuni village. She dropped out of high school and took up a job as a cleaner before getting married in 2005. Today she sits high up on the looms, weaving some of the best rugs. The biggest rug she’s ever produced was a colossal 6 x 4.5 metres. ‘For me this is familiar territory – I used to braid people’s hair part-time. So now I am weaving wool full-time,’ says a smiling Thembisa. ‘My husband lost his job, so this job has enabled me to support our entire household.’

Nazeema Solomon is the head weaver

at Coral & Hive and a partner in the business. Naz, whose hands were once described as ‘unsuitable for this kind of work’ by her first employer in the 1980s, has trained over 500 weavers across South Africa and Botswana. Looking at her hands, they are still soft and have no signs of ever having done any manual labour. A beautifully aged pair of hands that still deftly feed the mohair through the strings that make up the warp as the complicated geometry of the pattern emerges. Naz has nearly 40 years experience as a weaver and she supervises all the rugs as they emerge on the loom. She also trains new staff for the expanding business, creating yet more opportunities for women who weave.

25

Pure Beauty. The Rich Mnisi rug is 3.75 x 5m. Photography by Christof van der Walt for Southern Guild.

Coral & Hive

the new nordic food story

Written by: Michael Booth Photography: Ditte Isager & Irina Boersma

Written by: Michael Booth Photography: Ditte Isager & Irina Boersma

The first time I ate at Noma, I didn’t realise.

I mean, of course I realised that I was eating at a restaurant called Noma (the name is a conflation of NOrdisk MAd –mad is Danish for ‘food’). It was on the ground floor of an old warehouse beside the harbour in central Copenhagen. The building dated from the mid-19th century and had been used back then, legend has it, for storing whale meat and seal skins. In 2004, when Noma opened, the renovated building was home to the embassies of the Faroe Islands, Greenland and Iceland but, still, it was in a rather desolate part of the city. A bit of a schlep. Few went there, certainly not tourists or casual diners.

What I didn’t realise was what Noma meant, what it would become, how it might be possible for a kitchen in a city as cursed by shitty food as Copenhagen was at that time to change the world forever. Back then, the Danish capital had a dead-end dining scene with a handful of stiff, stuffy classical French and Italian restaurants that literally boasted about flying in produce from Liguria and Paris every week. Yet within a year or so, it really was a burgeoning culinary destination, with people travelling from around the world just to dine in its restaurants, and one leading Spanish chef quoted as saying that if, in cooking terms, Spain had been ‘the new France’ during the previous decade, the 1990s, then the Nordic countries were the next Spain. That chef was Ferran Adrià of El Bulli.

But I didn’t realise any of this as I enjoyed the tasty, though relatively conservative plate of – if memory serves – pork and celeriac. I do remember the waiters telling me that all the produce used in the kitchen was ‘locally sourced’ from the Nordic region, but some of the seafood was from thousands of kilometres away in northern Norway and Iceland, which didn’t seem very ‘local’. It was true, though: there were no tomatoes, no olive oil, no truffles or foie gras – the kind of thing that the other posh restaurants in the Danish capital felt obliged to serve to justify their prices.

I think I wrote a fairly nice review about Noma in a guidebook, complaining about the cost of wine, and that was it. But in the weeks and months afterwards, something nagged at me. It was kind of cool that they were sourcing ingredients from the Arctic

29

– sea birds and sea urchins, seaweed and musk ox. Perhaps more than a gimmick even. So I returned to Noma, and found things had already moved on: this time, for the first course the waiter invited us to dip the tip of a metre-long bullrush into a yoghurt sauce; we ate a musk ox tartare with our bare hands. Among the other fifteen or so courses were a fat, juicy langoustine tail from a Danish fjord, served on a warm stone with an oyster emulsion; a cook-it-yourself duck egg brought to the table with a piping hot skillet and an egg timer; and an ancient purple carrot from Jutland, braised in butter for two hours.

I interviewed the chef, René Redzepi, then aged 27. He was half Danish, half Macedonian, with an indie band hairstyle, friendly but with a pent-up energy. Redzepi was part of a generation of young Nordic chefs who had spent the past few years on the culinary equivalent of the Grand Tour, which at that time usually included stints at El Bulli and Heston’s place, perhaps time with Thomas Keller in California, and of course brutal stages at the Grande Tables of France, before returning home.

Redzepi gave me a blade of grass to taste, and looked at me expectantly. I chewed on the cognitive dissonance: it tasted of coriander. ‘Isn’t it amazing?’ he said. ‘It is a type of grass from Sweden. There’s lots of it growing within miles of here just across the water, but, you know, it is far, far easier for me to get fresh mangoes from the Philippines or wherever. Would you believe they sent us French asparagus the other day? Danish asparagus is the best in the world! Did you know that truffles grow wild on [the Swedish island of] Gotland? We are looking into getting hold of some.’

So I wrote my piece about the birth of New Nordic cuisine in Copenhagen. By chance, I was the first foreigner to do so, and Redzepi was kind enough to give me much more of his time over the years including, later on, to take me out to the wilds of Amager, the island adjacent to the Danish capital, to hunt for onion cress, wild horseradish, elderflowers, yarrow and goosefoot. He even claimed I could eat ground elder, a weed that had shown a triffid-like dedication to taking over my garden. ‘The young leaves are very good steamed.’ So many food writers have

followed since that someone once joked we should all have been given T-shirts: ‘I’ve Been Foraging with René Redzepi’. But his approach was a kind of revolution.

It seemed we had a movement on our hands. It had a manifesto too, signed by a few other like-minded Nordic chefs, and the co-owner of Noma, Claus Meyer. The New Nordic Food Manifesto was clearly inspired by Danish cinema’s Dogme movement but instead of no artificial lighting or special effects, it pledged to use local, seasonal produce, less meat, more organic and biodynamic produce.

Soon after all this, I moved to Paris and enrolled in cooking school. To be a food writer, to stand in judgement about the world of professional chefs, I thought I really ought to at least try and put myself in their shoes. But over the years, word began to reach me, even in the French capital, bastion of classical European cooking, about Noma. Chefs in Paris raised a few eyebrows when I told them that eating local, seasonal produce was a revolution in Denmark: this kind of approach was like breathing to them. But eventually even the French chefs embraced the Nordic movement and most ended up making the pilgrimage to the chilly North to see what all the fuss was about.

By the time I returned to live in Denmark a few years later, the New Nordic movement was in full flood. Noma had two Michelin stars but was never awarded a third, I suspect because, by then, the restaurant was being lauded by the rival 50 Best Restaurants list, which it topped three years in a row. Chefs around the world were now chanting the local, seasonal mantra, exploring the produce in their backyards, finding stuff to eat that no one had eaten before (some of which probably should have remained uneaten – I’m looking at you, reindeer moss).

In 2011, Redzepi asked me to host the first MAD Foodcamp Symposium, Noma’s food festival of ideas. On stage I introduced an amazing line-up of the world’s leading chefs and food ‘thinkers’, including Alex Atala,Yoshihiro Narisawa, Massimo Bottura, Iñaki Aizpitarte, Andoni Luis Anduriz, Harold McGee, Daniel Patterson, and the godfather of foraging, Michel Bras. I will never forget the team-building day we spent beforehand, cooking together

30 Jack Journal Vol. 3

Redzepi gave me a blade of grass to taste, and looked at me expectantly. I chewed on the cognitive dissonance: it tasted of coriander.

“Isn’t it amazing?” he said. “It is a type of grass from Sweden.

Seaweed crisp dressed with garden flowers, radish and horseradish.

31

34 Jack Journal Vol. 3

3

1 2

In 2017 the restaurant reopened, reinvigorated in a purpose-built urban farm location a kilometre away from the original location, on the edge of Christiania, Copenhagen’s famous ‘hippy commune’.

in the outdoors – with Magnus Nilsson tending the grill and Bras kindly showing me how to use a mandoline without slicing off the tops of my fingers. The event itself was held in a circus tent on a piece of wasteland even further out in the harbour, where once they built ships. The restaurant’s magic touch would end up reviving that part of the city too, incidentally: it’s now home to the superb restaurant Amass, overseen by a Noma alumnus, Matt Orlando.

Other Noma alumni began to transform Copenhagen. First to open, in 2011, was Italian-Norwegian Christian Puglisi, whose ‘kælder’ restaurant, Relæ, not only led a wave of restaurants serving refined, innovative food free from the usual Michelin fripperies of thick white linens, extravagant wine lists and smarmy maitre d’s, but also sparked the gentrification of one of Nørrebro’s least salubrious streets, Jægersborggade. Many of the young international chefs who had flocked to work in Noma’s kitchen – and they were mostly foreign chefs; Danes tend to be less prepared to put in the hours that a kitchen like this requires – eventually returned to Australia and Chile, the UK and the USA, pretty much everywhere, to apply the lessons and techniques they had learned –traditional Nordic techniques of pickling, drying, fermenting – to their own native larder. Claus Meyer moved on too, falling out with Redzepi, but going on to build his own food empire, with supermarket lines, and delis and other restaurants in Copenhagen, New York and, weirdly, La Paz.

restless Redzepi decamped: popping up in Mexico, Japan and Australia before closing down for good in the original whale warehouse. In 2017 the restaurant reopened, reinvigorated in a purposebuilt urban farm location a kilometre away from the original location, on the edge of Christiania, Copenhagen’s famous ‘hippy commune’. Now, the menu changes with the seasons, in summer and winter featuring virtually no meat.

The food at Noma is genuinely lifechanging. And every time you eat there, it changes your life in a fresh way. You’ll think about the meal for months if not years afterwards. From time to time, I still think of one particular dessert, made from plankton, three years after eating it.

In the past year, Noma has had to react to Covid, of course. Once again, there was a dramatic pivot: it reopened as an alfresco burger and natural wine bar, prompting mile-long queues.

‘During the lockdown I asked myself: What did I miss the most?’ Redzepi told me the day before Noma reopened as a burger joint. ‘I didn’t miss sitting down to a ten-course meal. I missed the buzz of people just enjoying being together.’

As always, this restless, questing man, icon of a movement, hero to thousands of chefs around the world, judged the zeitgeist perfectly. Pretty great burger it was, too.

Opposite page: Photography: Ditte Isager

1. A grilled onion with chives and walnut oil, young garlic with beechnuts.

2. A layered cake of berries, elderflower, rose and herbs.

3. An oyster with fennel flowers, cracked pepper and a nasturtium flower, served with squeezed tomato juice.

Meanwhile, I travelled further in the region, meeting other pioneering Nordic chefs in Oslo, Stockholm, Reykjavik and Helsinki – people like Geir Skeie, Bocuse D’Or-winning Norwegian chef, who had worked with Michel Rostang in Paris, and Stockholm chefs Björn Frantzén, who went on to win three Michelin stars, and Mathias Dahlgren, who was there at the beginning and helped draft the New Nordic Food Manifesto (he also made me try Swedish fermented herring, surströmming, because it was, he claimed, ‘delicious’. He lied.).

In Oslo, Danish chef Esben Holmboe Bang opened Maaemo and rocketed to the top of the global culinary hierarchy, also winning three stars.

Always a step ahead, Noma and the

35

Michael Booth

Noma

A

36 Jack Journal Vol. 3

skewer of a grilled Danish black lobster with barbecued roses.

37

40 Jack Journal Vol. 3

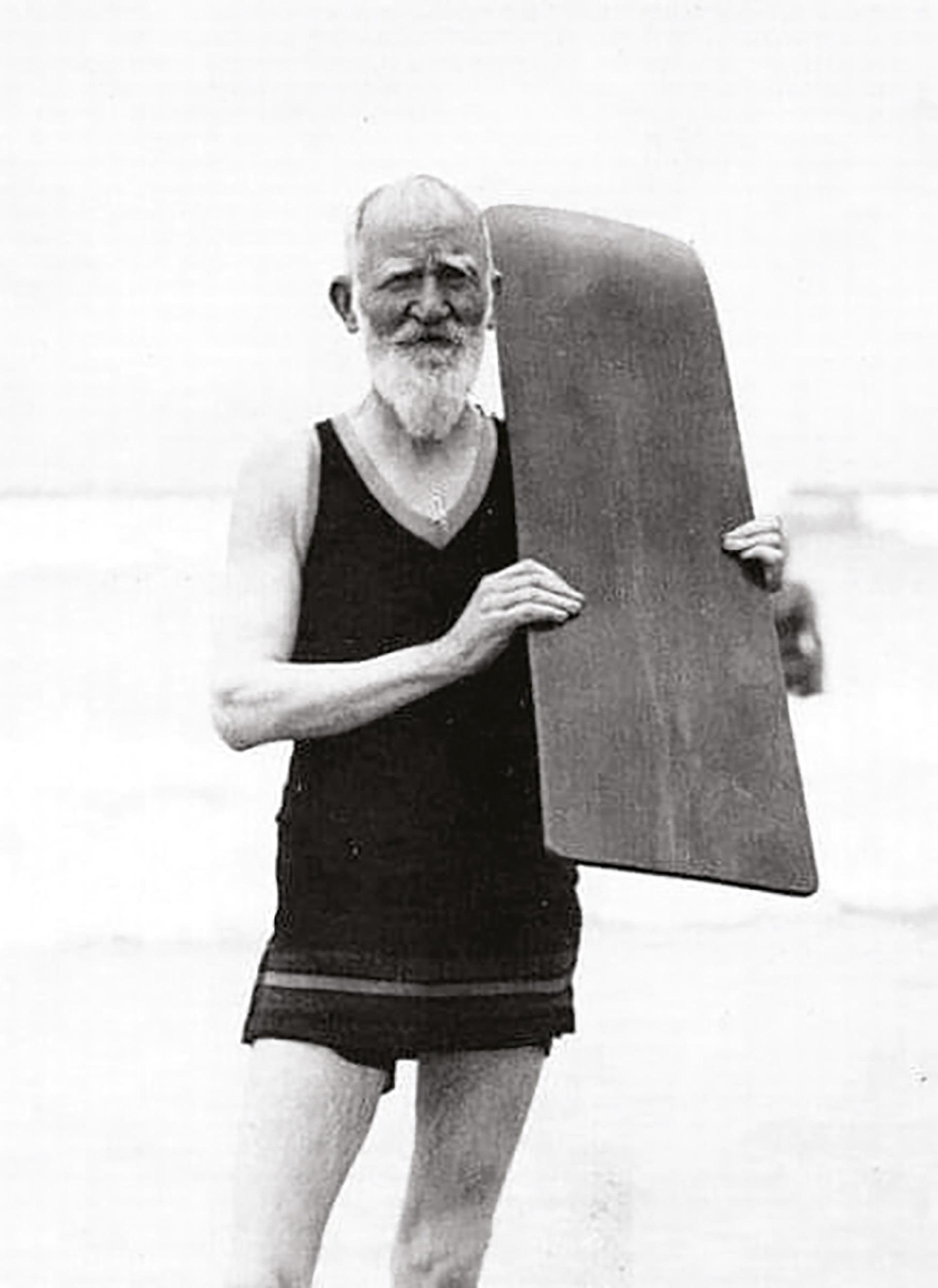

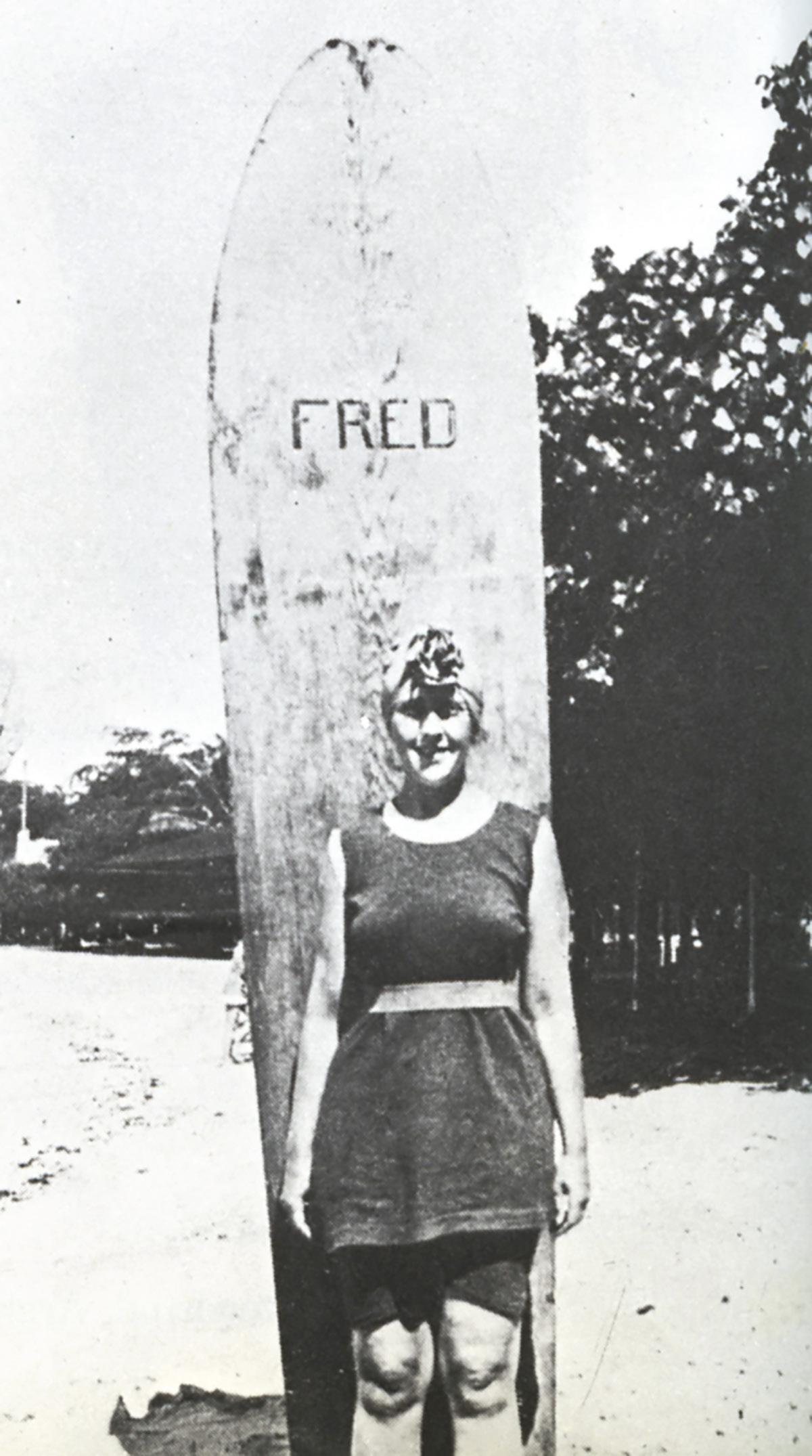

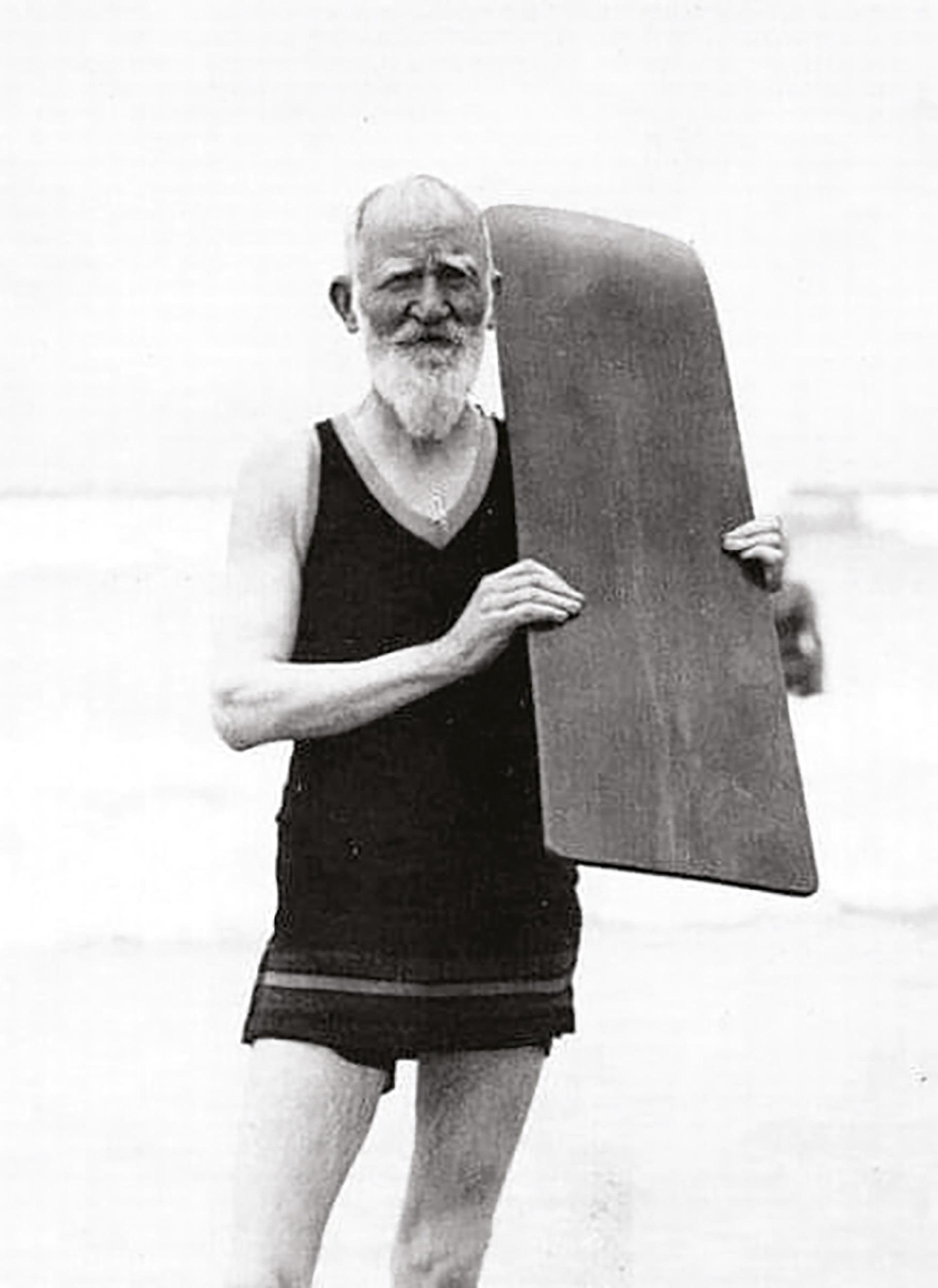

riding high on a wave of wellbeing

A passionate group of surfers is transforming access to mental healthcare by giving traditional therapy a sea change.

Written by: Alison Westwood Photography by: Tao Farren-Hefer

On a sunny Saturday morning in 2008, a small white Golf with a large stack of surfboards pulls up outside Masiphumelele township in Cape Town. The children waiting on the pavement eye them curiously. Although they live so close to the sea, surfing is practically unheard of in this ekasi. But Tim Conibear and his friend Apish Tshetsha are about to change that. Little do they know, but the waves they catch today are going to propel them along for more than a decade.

Just three or four kids join Tim and Apish for that first surf lesson, but the next weekend, 15 are waiting. Tim and his Golf have to make several trips to the beach. The weekend after that, more than 40 aspirant surfers are standing on the pavement. Tim replaces the Golf with an old pickup truck,

and he and Apish create Masiphumelele’s first ever surf club. It’s still going strong today.

But that’s not where this story ends, because Tim is insatiably curious, and he thought it was a little strange that so many children were willing to wait hours for a chance to surf. So, he started asking, why do you come? He got the obvious answers (surfing is fun, we meet new people), but he also got an answer he wasn’t expecting: ‘We can talk and people listen to us.’

This poignant reply sent Tim down a rabbit hole of research, and what he discovered was heartbreaking. Beyond the obvious indignities and discomforts of township life lurks a darker shadow: constant trauma. The statistics told Tim that children in South African townships endure eight traumatic experiences every

single year – serious events, like the death of a loved one, the incarceration of a parent, witnessing community violence, physical or sexual abuse. And for Masi’s community of 60,000 people there were just two social workers and not a single psychologist.

So, in 2011, Waves for Change was born. The idea was simple. Tim and Apish would train local young adults from township communities to do what they were doing. Identify children in need and take them to the beach for a surf – but most importantly, create a physically and psychologically safe space where they could work through their challenges. With the help of universities and psychologists, Waves for Change integrated evidence-based practices into their programme, creating a special blend

41

42 Jack Journal Vol. 3

43

44 Jack Journal Vol. 3

of sport therapy and behavior activation therapy.

Over the course of the year-long programme, children meet every week to learn positive behaviours, such as sharing, recognising emotions, and how to ask for help. And they discover, step by step, the deep connection to nature, the sanctuary, and the sense of accomplishment that surfing provides. ‘The great thing about surfing is that you can select your risk category,’ says Tim. ‘You can choose your level of challenge and overcome it. It takes bravery, it takes strength, it takes confidence.’

By the beginning of 2018, Waves for Change was reaching 1,000 children every week (that’s now grown to 1,800). They wanted to know what impact they were having. So, they did a study of 200 children from the same background, half of whom took part in the programme, and found statistically significant evidence that the children on the programme were becoming more optimistic, engaged and resilient.

Another study, conducted with the Laureus Sport for Good Foundation, measured the children’s Heart Rate Variability (HRV). This is regarded by researchers as a relible marker for resilience and behavioural adaptation. Improvements in HRV were found within the first two months, and were sustained throughout the rest of the programme. The results showed that children who previously shut down under stress had learned to feel and risk more, while those previously in constant fight-or-flight mode responded to adversity more calmly.

Thanks to its focus on research and evidence, Waves for Change has transitioned from a surf initiative into a globally recognised child-friendly mental health programme, and has won multiple awards. In July 2021, they not only won the MTN Award for Social Change, but also the bonus award for having the best evidence of advanced Monitoring and Evaluation Practice. ‘When we talk about surf therapy, we’re starting to talk about it with more authority,’ says Tim. ‘It does work.’

But the same curiosity led them to ask why. And what they discovered was surprising. ‘Surfing is our sport,’ says Ashleigh Heese, Waves for Change Partnerships Manager, ‘but we realised that the therapeutic benefits of surfing could be present in other group physical activities.’ Research identified

the core ingredients of their service –and access to the ocean isn’t necessarily one of them.

What really matters turns out to be this: access to a caring adult, a safe space, the opportunity to learn and practise new skills, tools to regulate wellbeing, and connection to a social support group. ‘So, the question became: how can we translate this and share it more widely?’ says Heese, whose current mission in life is to extend access to the service.

Their answer was to partner up with people all around the world who are doing similar work. As The Wave Alliance, Waves for Change is now working with 23 international partners in 12 countries to introduce impactful surf therapy programmes to their communities. ‘In each instance,’ says Tim, ‘vulnerable people are being connected to caring adults, achieving something they never thought possible, and it is working.There are health outcomes that you can benchmark with therapy.’

In fact, it’s working for a wide range of population groups: post-conflict communities, children with autism or disabilities, young offenders coming out of prison. In each instance, they’re seeing similar results. And, it’s not only surfing. There are skateboarding programmes, yoga programmes, even rally driving. ‘We’re working with a gardening programme in Somalia now,’ says Tim, ‘and that’s performing even better than the surfing.’

On a sunny Saturday morning in 2021, a throng of laughing children launches their boards into the surf in Cape Town. And in Gqeberha, East London, Liberia, Buenos Aires, Peru, Costa Rica, Sierra Leone.

In Johannesburg, a posse of skaters applauds one another’s stunts. In Mogadishu, hopeful green shoots reward a group of young gardeners. For all these people, poverty, violence, disability and depression have lost some of their destructive power. This wave of wellbeing is rippling across the planet, and it’s lifting up everyone who catches it.

45

Over the course of the year-long programme, children meet every week to learn positive behaviours, such as sharing, recognising emotions, and how to ask for help. And they discover, step by step, the deep connection to nature, the sanctuary, and the sense of accomplishment that surfing provides.

Waves for Change

48 Jack Journal Vol. 3

Adam Birch. Photography by Southern Guild/Justin Patrick.

legacy of wood how trees live again

Written by: Melvyn Minnaar Photography: Courtesy of Southern Guild

One of the most powerful statements about the process of art-making is also one of the most vivid: Michelangelo’s description of his job as releasing the angel from a block of marble. It’s a concept that puts a dizzy spin on what drives an artist. The alchemy of media transformed into art.

Locally, the great Shangaan artist-mystic Jackson Mbhazima Hlungwani, who died in 2010, traced the forms of ancestors, of spirits, of God, in the trunks of the trees around him and when those were felled, he brought them to another life, to form.

Adam Birch, self-described as woodsman and sculptor, has defined himself in that matrix – an echo of both the Renaissance master sculptor and the African woodcraftsman of our recent time. It is a calling founded in nature.

The 45-year-old Birch has garnered a wide following that stretches from the

grand lodges of deep Africa to the design expos and studios of first-world cities. It signifies acknowledgement of real and unique talent. When you come face to face with the extraordinary form and shapes of his ‘furniture’, it is the tactile presence of the wood, the pieces’ visual stature in three-dimensional space, that inevitably invite a response of cheer, optimism and wellbeing. It is similar to that shamanic charge, nature speaking up through the hands of a fine crafter.

If both the names ‘Adam’ and ‘Birch’ lead to the forest, the young, farm-raised graphic art student had somewhat of a mission. After completing the fine arts degree at Stellenbosch, the reality of needing a job led to an unusual apprenticeship: tree care and surgery. It was a challenge and adventure, he admits, that set him off. On the eve of his first solo exhibition titled ‘Bifurcation’ three years ago at the esteemed Southern Guild Gallery in Cape Town, he told Wanted magazine how pruning an ancient camphor tree in Kirstenbosch inspired

him. ‘I kept a forked piece of that timber and months later I carved a chair into it, and that was the beginning of a long, happy journey.’

The thrill of working in the giant trees and the power tools suited his spirit of creativity and invention. And the sensitivity of the natural environment was a built-in given. Only naturally fallen, or needed to be felled, trees are taken as his medium.

Sculpture as object in three-dimensional living space was always his creative destination after the arts degree, and in a sense working with trees brings the concept home: the aesthetic of the forest lies in the manner in which trees find their balance in nature – growing in the direction of the light, upright or adapting to circumstances organically in harmony with their surroundings.

The matter of balance is a classic code in sculpture. And so is the awareness of where it is placed or constructed – how it features in the three-dimensional space in which it finds itself.

That line leads directly to the objects

49

50 Jack Journal Vol. 3

Photography by Southern Guild/Justin Patrick.

Birch crafts. A seat, say, carved from whatever piece of a tree he had identified, must fulfil a function to succeed at his intention. It needs to be balanced for comfort, despite or perhaps because of its shape. It requires a fine sense of inventive poise.

Yet if the woodsman succeeds as welladmired sculptor – as he is – the root of that achievement is constantly traced back to the origin: the once living tree, no longer anchored to the earth, but destined for a new life and a carrier of all its history, the energy of its growth, and thus mystery.

Bruce Jack, who acquired Adam Birch’s first sculptured chair, hewn from blue gum wood, is drawn to that individuality. ‘I think his pieces have a sort of energy that is unusual, unlike sculpture made from other materials – as though the tree has been given a second life through the considered handling and care of creating.’

The ‘second life’ is a key concept in what we could call the legacy of timber, and it could be quite practical – such as the ‘furniture’ that Birch carves – or like the magnificent ancestral thrones that Jackson Hlungwani made. (Much admired by Birch, the splendid overview of Hlungwani’s art, ‘Alt and Omega’, is on view at the Norval Foundation until January 2022.)

Like Hlungwani did, Birch delves deep into the timber heart of Africa. In his creative process many local craftspeople are drawn in.

He recently spent eight months working at the Xigera Safari Lodge in Botswana’s Okavango Delta, producing custom articles. Among these is an eye-catcher like the ‘Swept Server’ created from Eucalyptus cladocalyx. An elegant, simple and functional piece, yet it makes a powerful statement about that second life. Indeed a legacy relived, alive among us.

51

Southern Guild

52 Jack Journal Vol. 3

Swept Server. Eucalyptus cladocalyx. Photography by Southern Guild/Hayden Phipps.

53

Voodoo 2. Eucalyptus cladocalyx. Photography by Southern Guild/Adriaan Louw.

54 Jack Journal Vol. 3

Untitled. Eucalyptus cladocalyx.

it’s still a tree by bruce jack

I met Adam through my parents who had construed a complex deal – involving a mobile mill, free board, lodging and much wine … etc. – with Adam to chop down trees on our family farm and mill them into timber. He did a great job, charmed my mom, and we have put the timber to good use. Then, in 2006, my wife invited Adam to exhibit his side-line business – his extraordinary furniture/sculpture, at an exhibition she immaculately curated called BIARA. Since undergraduate days at Stellenbosch University, every artist in whom she has seen potential has gone stellar. There were, of course, many times when we lacked the resources to buy a piece of art from an artist whose burgeoning genius she recognised, and BIARA gave her an opportunity to collect together, in one exhilarating exhibition, many of the future stars. Adam was one.

Towards the very end of the opening night, I found myself chatting to Adam – he was puffing energetically away at a ciggie (perhaps somewhat unnerved, not having sold anything yet) and I was sipping energetically away at a Shiraz (half relieved I had not bought anything, and half concerned this was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity). I was sitting on one of his pieces of furniture/sculpture and he was standing a few feet away, half in the veranda light, on a perfect spring evening, with a brooding Table Mountain eavesdropping over his shoulder. We were the stragglers.

‘It’s clearly a chair, buddy. Why pretend it’s a piece of sculpture?’ I goaded.

‘Well, if you are buying it, it’s what you want it to be, I guess,’ said Adam.

‘I love this chair, bud, but I can’t afford it,’ I said truthfully. ‘I am a winemaker, not one of those private equity chaps …’

We both scanned the inside rooms looking for personally cut, expensive suits. It didn’t look hopeful.

‘You must see it’s more than a chair, Bruce,’ and there was a serious look in his eyes. He continued after a pause: ‘And I have not really made it. No, I was only a small part of making it. The tree was already made.’

‘You okes trying to be philosopher artists!’ I dismissed him with a sneer. ‘It’s a chair, buddy. I am sitting on it. It’s a chair.’ I paused. ‘Okay, it’s a particularly beautiful chair, but don’t push that arty stuff too much.’

Adam took a long drag and smiled. ‘It’s still a tree,’ he said.

I thought about this, and I believe the Shiraz helped me ponder. I could hear people clearing up the glasses in the gallery. ‘Which is better than a throne or a sculpture,’ I eventually agreed.

‘Yip,’ he said through his smile and then, comforted by the knowledge he had landed a customer, went in search of more Shiraz so that we could celebrate.

And that’s how I came to buy the first Adam Birch sculpture/ chair/throne/… tree he ever sold.

Now it’s fun to think we own something that will be worth many bitcoins, or dollars … or whatever people will measure financial exchange with in the future, and that’s a nice testament to my wife’s genius. However, my satisfaction comes from knowing that our precious everydays are made more rewarding by something so beautiful in our place of shelter – not just because it looks cool, but because it has been transformed in such a sensitive way –a way that will always reflect the mystical strength, magical beauty and awe-inspiring majesty of a tree. I get daily happiness from that. This is not just timber repurposed. This is something special.

Many years later, Adam heard about our HeadStart Trust and called me up and offered to visit the farm with his crack tree-felling team once again and work for a week, felling fire-damaged pines along our mountain boundary and tidying up hero trees around the homestead – FOR FREE. This team is the SWAT team of arborists – and they don’t come cheap. The deal was that the money we would have paid for this difficult and often dangerous technical work must be donated to HeadStart Trust, and that any extra firewood produced as a by-product must be donated to the local Napier community (our nearest village) in winter for much needed fuel. We have done so in his name.

55

Aerial view of the Nuwejaars Wetlands. Photography by Dirk Human.

Aerial view of the Nuwejaars Wetlands. Photography by Dirk Human.

58 Jack Journal Vol. 3

Blue Crane, the national bird of South Africa, thrives in the farmlands of the NWSMA. Photography by Fraser Crighton.

for nature and for the people: conservation with a difference

Written by: Heather D’Alton

‘The Strandveld just smells different; I love the smell –of the flowers in the vlei, of the rain when it touches the dry ground, of the animals in the veld. Over the mountain from us, it’s barren in summer. But there’s always life in the Strandveld.’

For Dirk Human, founder of the Black Oystercatcher Wine Farm, and one of the founding members of the Nuwejaars Wetlands Special Management Area, there’s nowhere else he would rather live. Dirk is the fourth generation in his family to be born and raised in the Strandveld, close to Africa’s southernmost tip. His farm is nestled between a series of intricate wetlands and rivers, a haven for wildlife and plants.

It’s not only Dirk who recognises the value of this region. These wetlands and lakes, known as the Nuwejaars Wetlands, have been called ‘highly irreplaceable’ by conservation experts. The wetlands provide water to those living downstream. They

support a natural world that is critically threatened, including fynbos and renosterveld. And they’re home to frogs, mammals and birds found nowhere else in the world.

In fact, this farming area is in the heart of a conservation estate, with Agulhas National Park situated just to the south, and De Mond Nature Reserve to the east.

Dirk says: ‘We saw this landscape in which we live, and said we wanted to take it back to its natural state.’ That’s one of the reasons that Dirk and a number of farmers in the area first met up in the late 1990s, to see how they could work together to protect it. This was the start of the Nuwejaars Wetlands Special Management Area, or NWSMA.

Now, more than two decades later, around 47,000 hectares are protected forever through signed title deed restrictions, with 25 landowners and the Moravian missionary town of Elim together conserving the region. They employ a team of conservationists who work across the landscape. Game that became locally extinct in past centuries has been reintroduced. Agricultural areas are fenced out, and animals and plants can move

between farms in conservation corridors. And through funding support from WWF South Africa, the Hans Hoheisen Charitable Trust, and the Overberg District Municipality, wetlands are being cleared of invasive species and rehabilitated, and ongoing research and monitoring informs their conservation activities.

Still, this is a conservation area with a difference. Dirk, who is also the Chair of the NWSMA, says: ‘Farmers continue to farm here. You can’t split agriculture and conservation in our area – we’re both. Through our farming, we produce food. And at the same time, our biodiversity works for us.’

Other wine farmers here agree. Strandveld Vineyards and The Berrio are also members of the NWSMA. All the wineries here benefit from the Strandveld’s cool climate, with the cool ocean winds easily reaching the vineyards, keeping the grapes compact and packed with flavour. This terroir may well have contributed to these wineries becoming multi-award winners. Strandveld’s 2017 First Sighting is a Platinum Medal winner, with 97 points at the Decanter

59

Hippo have been reintroduced after being hunted to extinction locally around 150 years ago.

Photography by Elizabeth Knobel.

Photography by Elizabeth Knobel.

60 Jack Journal Vol. 3

The Berrio, Black Oystercatcher and Strandveld Vineyards are all members of the NWSMA, and form part of the Agulhas Wine Triangle.

World Wine Awards. Their Pofadderbos Sauvignon Blanc has been awarded five stars in Platter’s Wine Guide on several occasions. And The Berrio Sauvignon Blanc 2006 was recently awarded the Best of the Museum Class Trophy at the 2021 Old Mutual Trophy Wine Show.

For Conrad Vlok, winemaker at Strandveld Vineyards, becoming an NWSMA member was a no-brainer. ‘I’m a nature lover. From the start we wanted to farm in a way that was as green as possible. We have never sprayed our vineyards to kill insects, because our birds do that for us. So it simply made sense to become a member. Of course, many evenings drinking whisky with Dirk also contributed.’

Francis Pratt is the co-owner of The Berrio brand with Bruce Jack. Francis bought his farm in 1994, and along with Dirk, Conrad and others, is one of the pioneering wine farmers here. Growing up in Swellendam, a strong agricultural hub, he had a different take on farming when he first arrived in the Strandveld. But farming in this conservation area changed the way he experiences nature – to the point that Francis now serves on the Executive Board of the NWSMA. ‘In other parts of the Overberg, farmers often plough right up to the river, and when you do, you’re seen as being a good farmer. But those guys have no respect for nature,’ he says.

‘Being part of the NWSMA has played a big part in making me more aware –to really experience the wetlands, and to see everything that lives in these wetlands.’

And there’s good reason to be excited about the creatures that live here. A stunning discovery recently created a buzz among amphibian conservationists, when a subpopulation of the Critically Endangered Micro Frog was found in these wetlands. That makes it only the fifth subpopulation of this tiny frog (no bigger than a person’s thumbnail) left in the world. Other populations have all but disappeared as their habitat is lost to urbanisation and agriculture.

Conrad says it’s discoveries like these that give this wine route, known as the Agulhas Wine Triangle, its unique character. ‘The NWSMA’s research, where we’re finding Micro Frogs, and finding out more about Cape Leopards, offers a great tourism spin-off. We now have a wonderful story

to tell of the conservation benefits here –and people like to hear about these good news stories.’

Dirk says this model of conservation – where agriculture and conservation work in tandem – is the only viable option here, in a world where farmers must provide food using productive lands, without transforming any more natural areas. ‘The only way to conserve effectively is to do it at scale, across farms, with farmers working together.’

That’s easier said than done, however. Farmers are known to mind their own business. But that’s again where the Strandveld’s uniqueness comes into play. According to Dirk, ‘I love the nature of this area. But it’s also the people who make this area special. We’ve suffered together here, so we’re closer as a result.’

Francis can’t quite let his neighbour’s comment pass. He quips at Dirk with a laugh: ‘Well, I’m definitely a little “gatvol” of you!’

But in the Strandveld, this captures just how easily farmers get on. Dirk is undeterred. ‘That’s why we work so well together, and why, through the NWSMA, we can determine our own destiny.’

61

I’m a nature lover. From the start we wanted to farm in a way that was as green as possible. We have never sprayed our vineyards to kill insects, because our birds do that for us.

NWSMA

Strandveld Vineyards

The Berrio Wines

Black Oystercatcher Wines

62 Jack Journal Vol. 3

Nguni herd grazing near Dundee, KZN. Drought and coal mines have left cattle in this area increasingly bereft of water. 63

Nguni herd grazing near Dundee, KZN. Drought and coal mines have left cattle in this area increasingly bereft of water. 63

Nguni wander contentedly near Nieu-Bethesda in the Eastern Cape. Their owner practises holistic planned grazing to build the soil.

64 Jack Journal Vol. 3

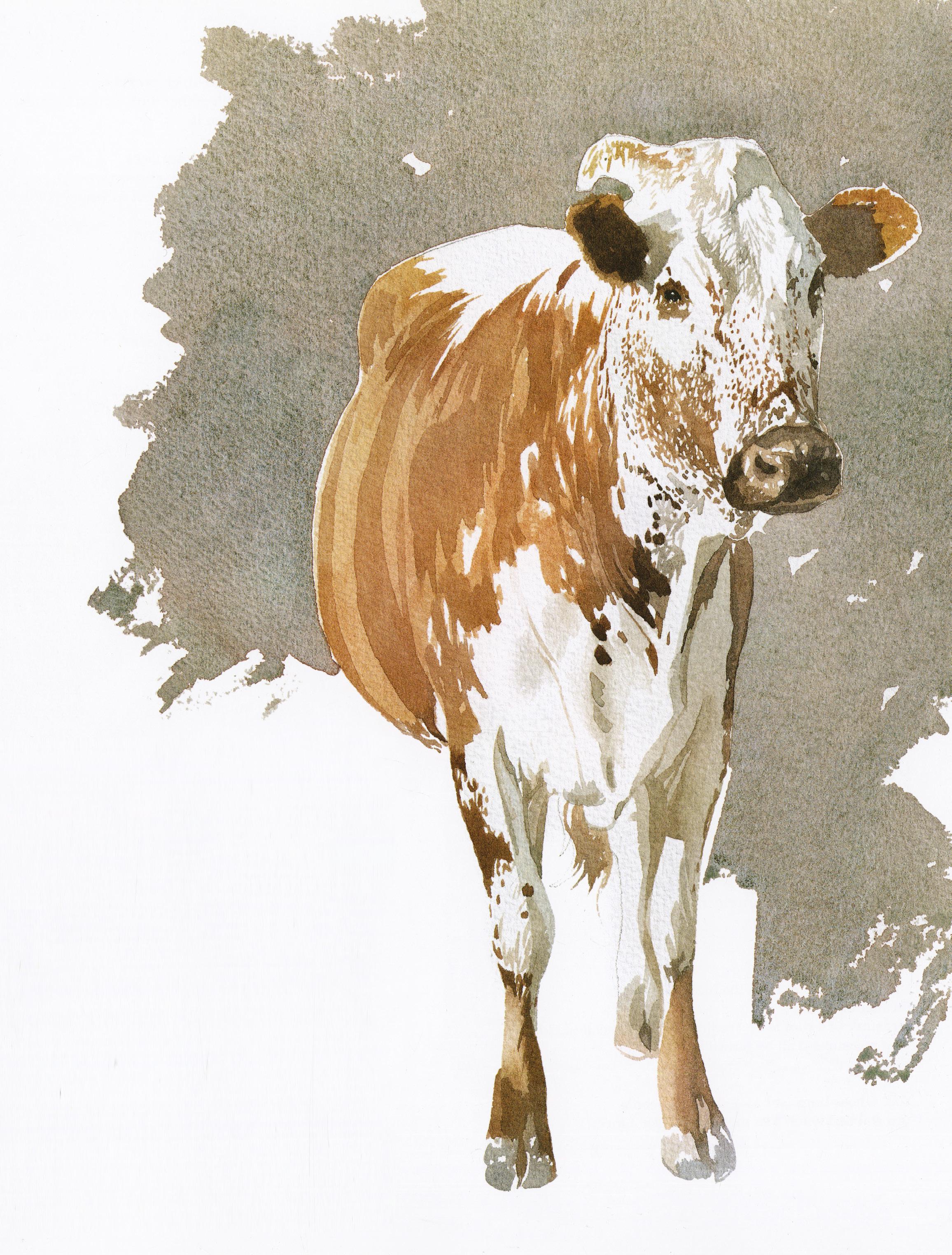

nguni cattle – a gentle african treasure

Written by: Gregory Mthembu-Salter Photography: Gregory Mthembu-Salter Illustrations: Leigh Voigt

Fifty years ago, the Nguni breed looked as if it might be dying. Across South Africa, and in neighbouring Lesotho and Eswatini too, there seemed to be fewer and fewer of these trim, modestly framed and mild-mannered cattle, with their wonderful, distinctive hides.

Commercial farmers and abattoirs had little respect for Nguni, because of the low volumes of meat and milk the cattle yield, and even in the herds of subsistence farmers, Nguni were becoming increasingly mixed with other breeds. Eswatini’s late king, Sobhuza II, noticed this with rising concern and eventually asked Tim and Liz Reilly –who, famously, also established the country’s national parks – to identify and preserve remaining pure Nguni, assigning them several members of his royal court to assist.

The Reillys came with an attractive offer – two mixed-breed cattle for every one Nguni – and had soon purchased 20 cattle. The couple immediately liked them, at first for the cows’ beauty, but later when they saw how capable they were of fending for themselves, how alert and intelligent they were, and how sociable. The Reillys went on to acquire a larger and larger Nguni herd, and in 1981 formally applied to the South African Stud Book Society to have Nguni cattle recognised as a breed. The application was approved in 1983. In 1986, the Reillys founded the Nguni Cattle Breeders’ Society, which remains active today.

In this Anthropocene era of climate breakdown and global heating, the benefit, and indeed the blessing, of an indigenous cattle breed that can more or less cope – so far – with both is much more obvious than it was back in the 1970s and 1980s. But the antipathy of abattoirs to Ngunis because of their compact size, and because they do

not fatten up as much as other cattle when stuffed with maize, molasses, and hormones in feedlots, endures.

As a result, there are still commercial farmers out there who want to bulk up and to ‘improve’ the Nguni. One such attempt is the PinZ²yl. The PinZ²yl has been bred by the Van Zyl family on their huge ZZ2 farm in Mooketsi, Limpopo Province (which is otherwise famed for its tomatoes), and is a cross between Nguni and the Pinzgauer, a much larger-framed breed that hails from Austria. A farm manager there once assured me that the PinZ²yl has retained all the best qualities of a pure-bred Nguni while at the same time inheriting the Pinzgauer’s bigger frame. Perhaps he was right. But the Nguni has been slowly evolving as a breed for many hundreds of years, and the idea that you can make the cow significantly larger now without upsetting any of the subtle, delicate balance in the breed that has gradually emerged over all this time

65

Nguni cattle are described and classified according to perception of what the colour and markings resemble or signify. The Zulu descriptions are rich in imagery and metaphor that often relate to the natural surroundings.

Thuthu u(lu)thuthu [hot ashes]. Ash-grey coloured beast.

66 Jack Journal Vol. 3

The one-horned cow that has drunk the dregs of beer.

67

Bafazibewela inkomo [the beast] ebafazi [which is the women] bewela [crossing over]. This colour pattern brings to mind an image of a woman lifting her skirt to wade into water.

68 Jack Journal Vol. 3

seems, well, far-fetched.

Unlike most European breeds of cattle, Nguni have never historically been bred to provide lots of meat or milk. Instead, African livestock farmers over the ages have been content to accept whatever progeny their cattle deliver without trying to influence the result. Going further, many perceive communications from their family ancestors in the shape of their new-born calves’ horns and the colour of their hides. Indeed, this is but a small part of the myriad connections that these livestock farmers perceive between themselves, their ancestors and their cattle.

One farmer living in Zululand I spoke to explained it this way:

Our cattle bring our family together. Both when they are alive and when we slaughter them. It brings harmony to us. Everyone has a role in the ceremonies, and when everyone comes to celebrate, it makes the occasion important and brings joy.

Another told me: