R140 incl VAT ADVENTURE, MUSIC, HISTORY, FOOD, POETRY, WINE, SOCIAL UPLIFTMENT, SURFING AND MUCH MORE.

Cover artist: Joshua Miles.

Cover art: Full Moon Agave. A reduction woodcut.

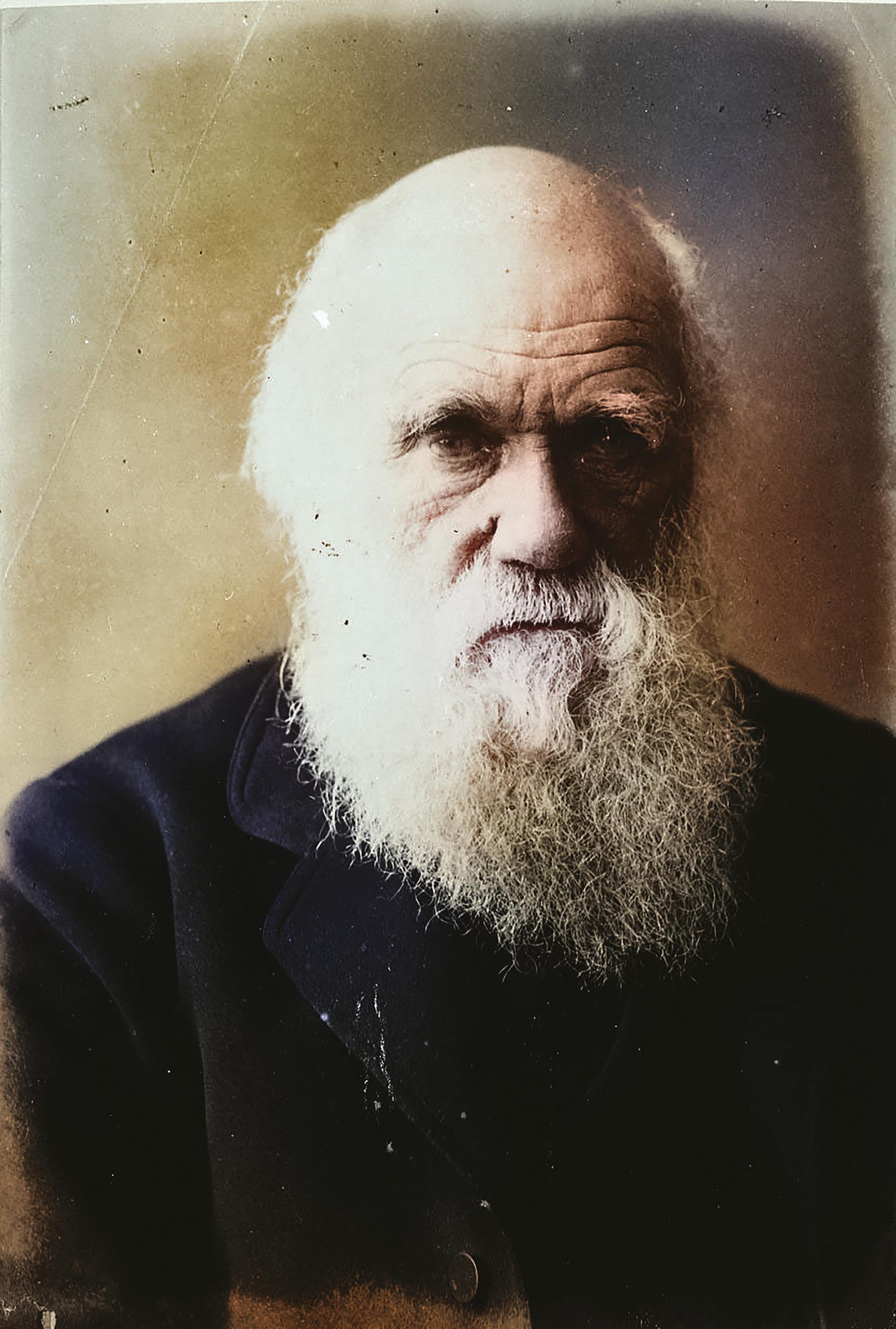

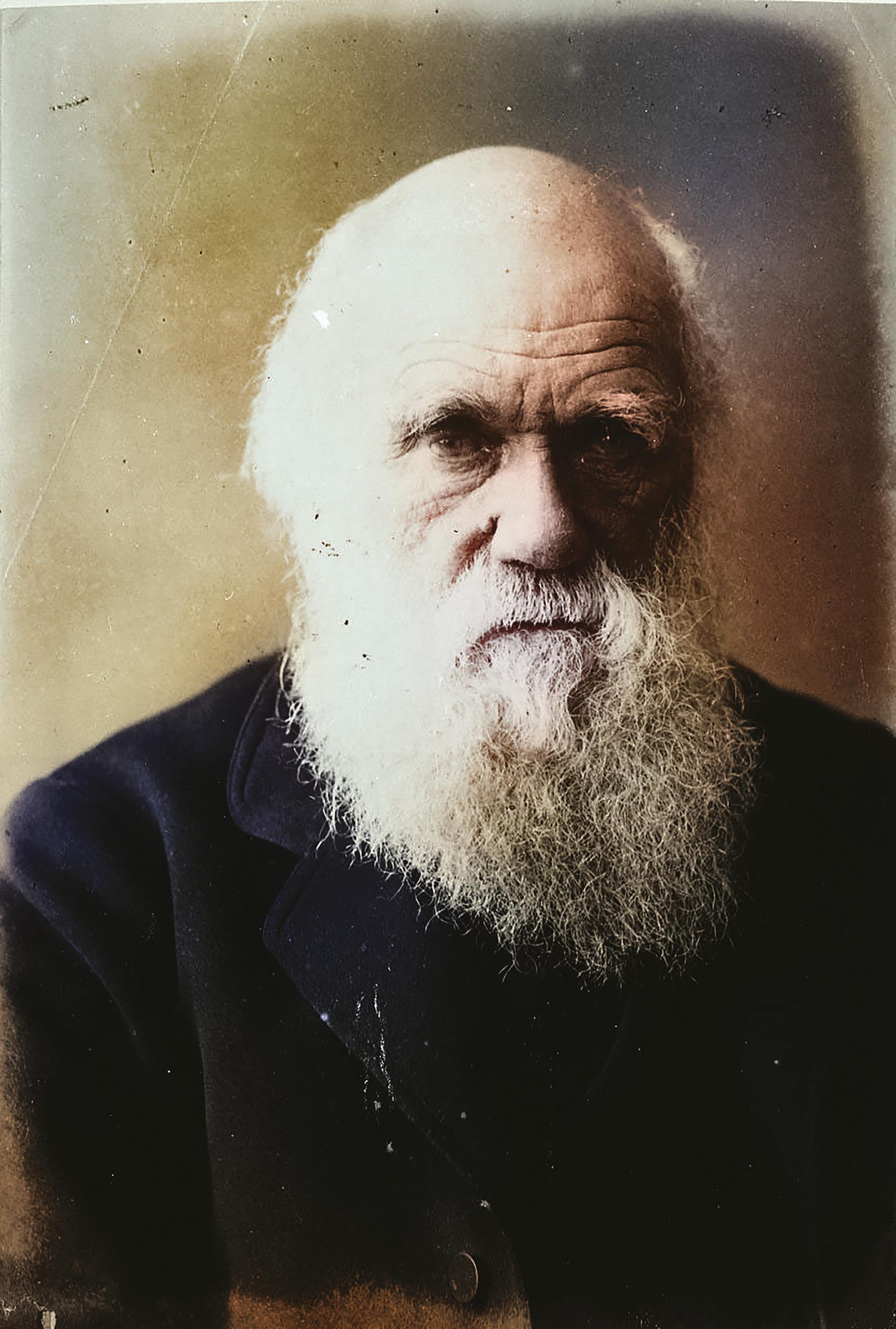

Joshua Miles was born in Ceres in the Western Cape in 1967. He studied fine art at the Michaelis School of Fine Art at the University of Cape Town where he received the Michaelis Prize for best student in his final year.

Joshua is one of those rare artists who has managed to make a living solely from his art. He spent many years painting oils on canvas but his passion has always been with reduction block printmaking.

Joshua’s influences in printmaking started at a young age watching his aunt Elsa Miles, artist and art historian, doing woodcuts and later studying under Cecil Scotness at UCT. He is inspired by the play of light on the landscape which leads him to explore his local areas. He is always hunting qualities of light that evoke emotion. This is often the softer light that brings out the in-between tones and greys most would miss. This love of capturing the play of light is also found in reflections on water or objects. He is also inspired by the impressionist style of loose mark making and the Japanese tradition of printmaking.

After finishing at UCT, Joshua moved to Hermanus where he met his Scottish wife, Angela. They have been married more than 20 years and over the years they have lived and worked between South Africa and Scotland. They work together in the business of selling Joshua’s art and have a home with a studio in both countries.

Joshua is a prolific worker and has exhibited extensively in groups and solo exhibitions and as a result he has work in private homes and collections, not only in his two home countries, but also internationally in America, Australia, France, Italy and Germany.

www.joshuamiles.art

Joshua Miles

Joshua Miles

There is a pleasure in the pathless woods, There is a rapture on the lonely shore, There is society where none intrudes, By the deep Sea, and music in its roar: I love not Man the less, but Nature more.

George Byron

1

Joshua Miles. Quando. Reduction woodcut 265 x 205mm.

table of contents

contributors protecting the pumas Felipe Howard the democracy of print: legacy of sa linocut art Melvyn Minnaar

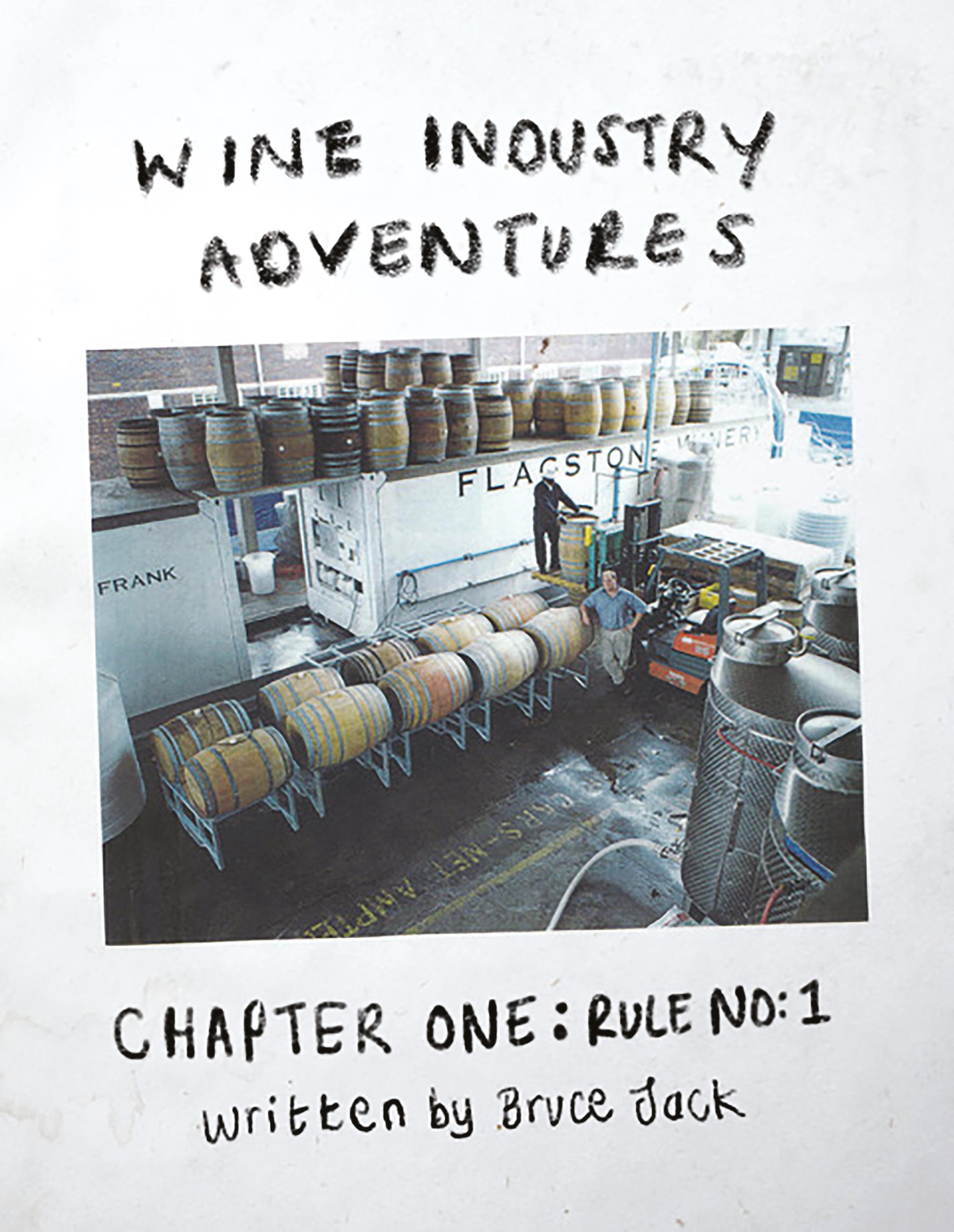

wine industry adventures chapter one rule no: 1 Bruce Jack breaking down barriers in east harlem Jim Clarke

reading the detectives John Higgins grootbos Geoffrey Dean the crypto-feather Chris Marais robert grendon – a forgotten voice in africa Matthew Blackman legacy of trees custom guitars Biénne Huisman

the national poetry prize background, update and 2021 winners the bling’s the thing Anthony Rose in defence of worms Don Pinnock art deco Tanya Farber

red-tailed tropicbird Vernon Head

2 Jack Journal Vol. 4

06 10 18 34 40 46 50 60 66 72

106 120

94 98

78

sea dogs Bobby Jordan humility and the x factor Bruce Jack the billion oyster project Jim Clarke hops on city rooftops Lucy Corne

a young poet no longer Philip Myburgh mothers of invention Alison Westwood the ancient lure of bonfires lives on Jeremy Daniel caribbean paradise Caspar Greef

fiction: the lesson MS Mlandu west coast stoke Justin Fox

nft’s and wine: now and next Simon Pavitt

Editor: Su Birch Design: Allendre Hine

Address letters to the editor: editor@jackjournal.com

Bruce Jack Wines Limited. Registered address: c/o Seles Group, 2a Charing Cross Road, London, England, WC2H 0HF

3

124 134 138 146

149 150 154 160 166 176 162

Jack Journal’s Big Bang

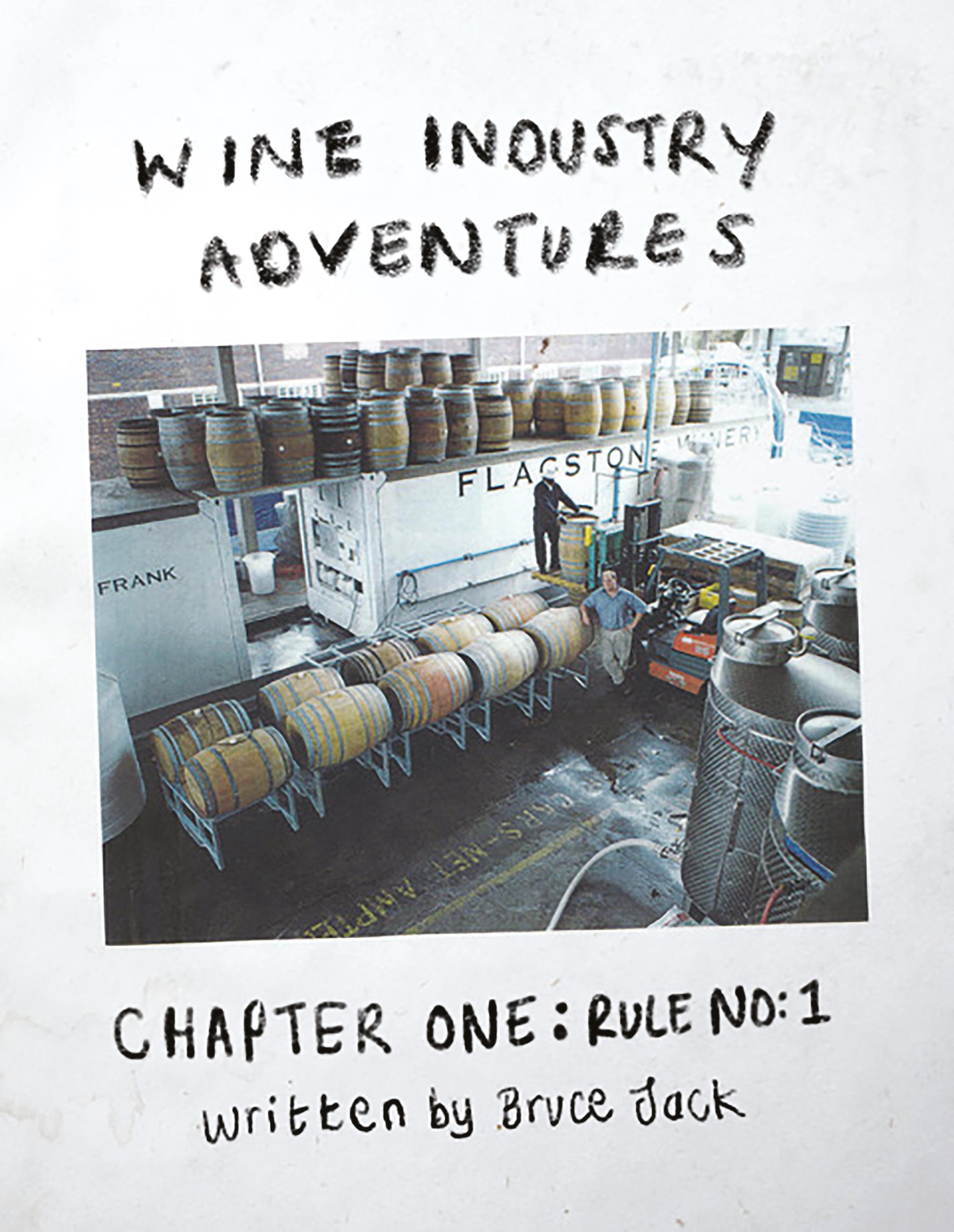

When I decided to leave the corporate wine world where I helped make some juggernaut-sized international brands, I knew what I wanted to do with Bruce Jack Wines – focus on the vineyards and the winecraft. However, there was a problem. Since selling our first winery, Flagstone, in 2008, the world of consumer communication, with which I had had nothing to do for over a decade, had moved on radically. I suddenly had to catch up with how consumers accessed information and interacted with wine producers.

I threw myself into online marketing, social media and the quagmire of ‘influencers’. I did a few online courses that promised to explain how Google search words, website optimisation and Facebook ads worked …

It was awful and depressing. I became suspicious of platforms like Twitter, etc., because by design they amplify negative tonality of the written word – and that most crucial of understanding tools, context, is ubiquitously sacrificed for immediacy, reactiveness, FOMO and clutter.

I discovered to my horror that I was lost in a dense, dark jungle of overwhelming noise, my only guide a capricious gadget called a smartphone designed by organisations

as helpful as they are clearly nefarious.

I am not the only person never to have met an algorithm I trust, be that what pops up on a social media feed or how a large supermarket supply-chain manager is notified by her screen to place another order.

We have witnessed the collapse of global shipping logistics, partly because of the flawed artificial intelligence embedded in international shipping systems. Self-drive cars – originally based on clever code, false-messiah AI and greedy tech investment – have failed to deliver on their promise, the bright buttons at engineering labs now rather quietly reverting to yesterday’s camera technology. And don’t those selfservice book-in machines at airports look forlorn while travelers’ lost baggage piles up like clogging rubbish in a ghetto?

We are told it will all be okay and that the computers will come back to save us from ourselves. I don’t believe this. We all know AI isn’t going to save us from climate change. Which is why, as a winemaker, someone inextricably tied into the warming seasons, and embedded in an ancient craft, I must always champion context and collaboration –the cornerstones that will save us.

Jack Journal has had a very long gestation period. It all began in 1987 when a group

of friends and I started an unsanctioned magazine at school called Gray Matter. Illicitly printed on a clunky Xerox machine and stapled together, it caused a mild sensation by lampooning our equivalent of helicopter moms … an irate mother wrote a vitriolic letter to the principal demanding an apology from me, the editor. It was one of the most rewarding moments – I suddenly realised that a well-timed word had as much impact as a well-timed rugby tackle in the ribs. I framed the letter of complaint. What a triumph! Thirty years later, Gray Matter was still being produced by the students.

As an undergraduate, during apartheid, while studying Politics and English, the heady journey continued with a magazine called Ascent produced and published by the Humanities Student Council. I revelled in the deadline-enforced all-nighters, and as co-editor came in for a lambasting from both political extremes at UCT (University of Cape Town) – the agitating young revolutionaries and the conservative right. It was a surreal ride, with an ironic twist – a decade later I learnt that one of those agitating revolutionaries so critical of Ascent was a spy for the apartheid police.

It wasn’t all opinion pieces. We also produced a magazine dedicated purely

4 Jack Journal Vol. 4

to creative writing, called 3rd Ear, and I was thrilled to have poetry published in South Africa’s oldest literary magazine, New Contrast.

After a Masters degree in Literature and a failed attempt at publishing the ‘Great South African novel’, I started working full time in the wine industry, followed shortly by a postgraduate Oenology and Viticulture degree at The University of Adelaide. Thankfully, wine bottles have back labels, and wine businesses have newsletters to write.Various publications also asked me to contribute, so when I didn’t have my head in a tank, or wasn’t vainly trying to sell my wine, I was able to write a bit.

Highlights included a regular column for The South African newspaper in the UK, an insightful gig at Personal Finance magazine

when Bruce Cameron was editor, and a few prefaces for WOSA (Wines of South Africa) publications while Su Birch was CEO (Su is now the editor-in-chief of Jack Journal). I may also be the only full-time winemaker to have written the forward for Platter’s Wine Guide.

As I slowly worked out what was positive in this new, often artificial, world of marketing and communication, and, more importantly, what was not, I came to a conclusion: I had to believe in the intelligent, inquisitive and considered wine drinkers out there.

I knew you couldn’t all have been transformed by snake oil AI into mindless crowd-rating app slaves. No matter what age or nationality, I believe in my heart you are still interested in the rich, diverse context of wine and the joy of discovery. And the only way I know how to reach you, to share this journey with you, is to produce a beautiful and embracing magazine. Thank you for joining me.

Bruce

contributors

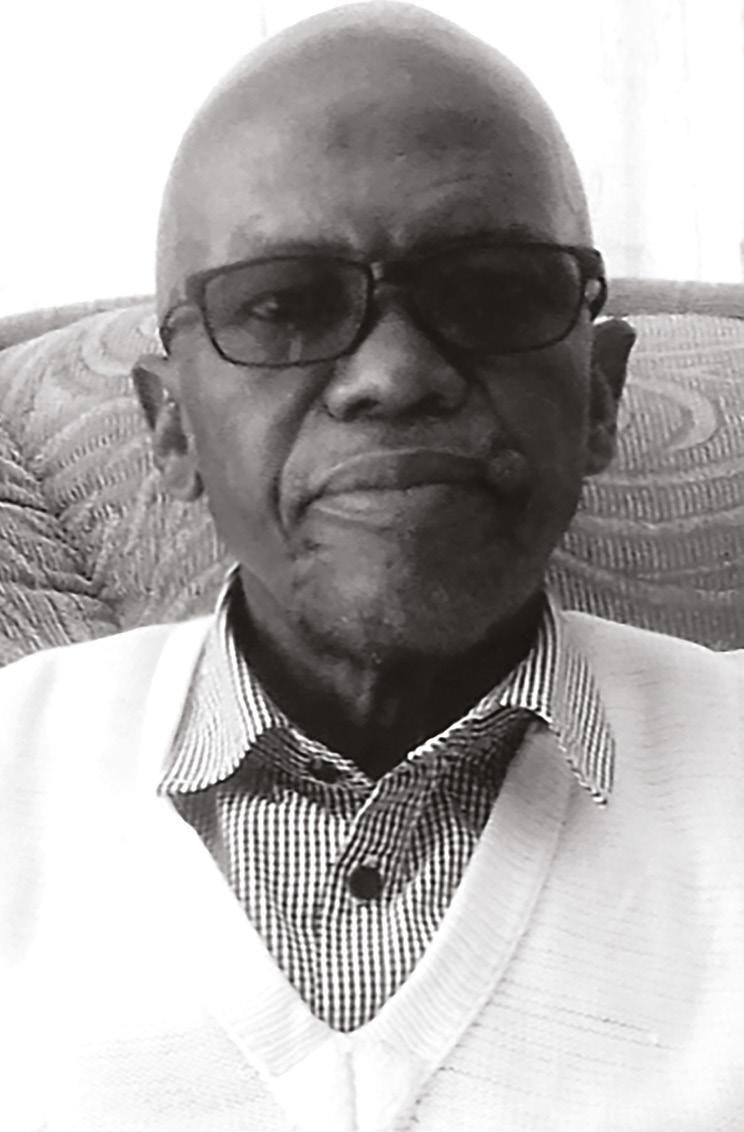

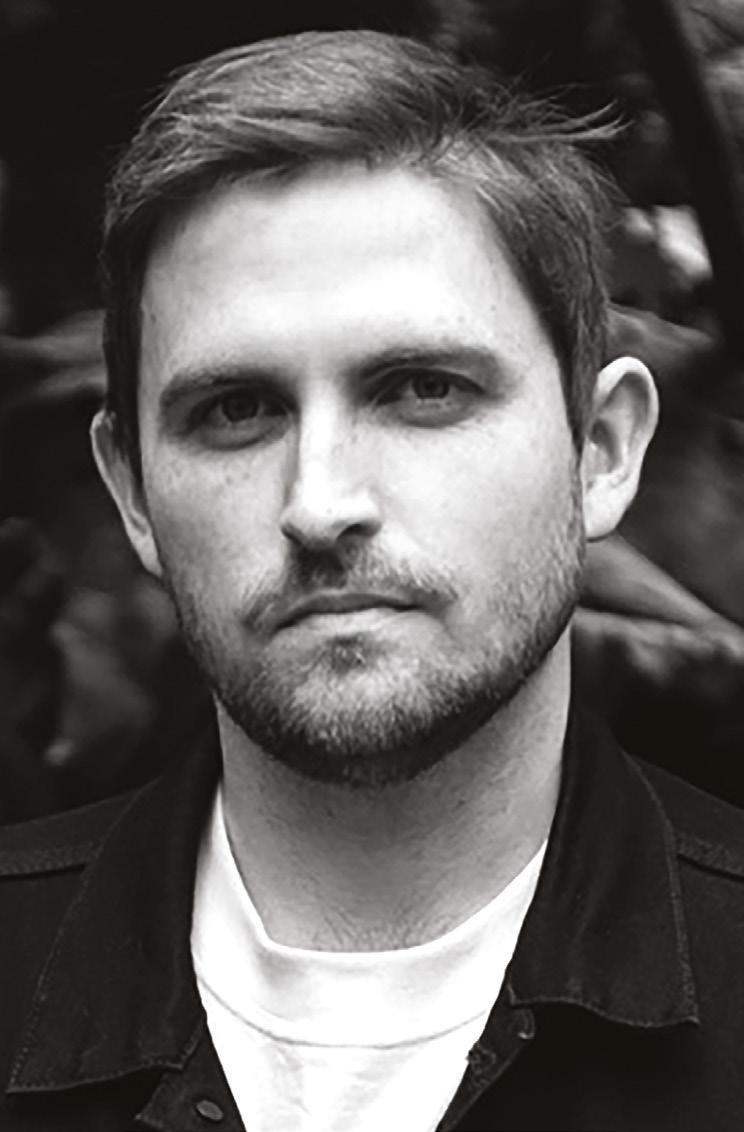

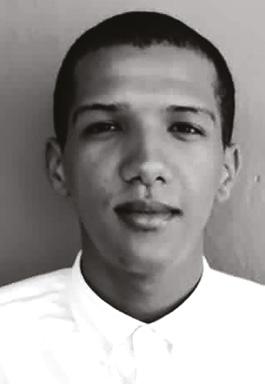

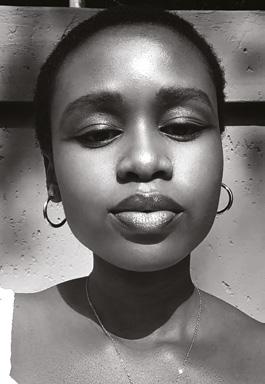

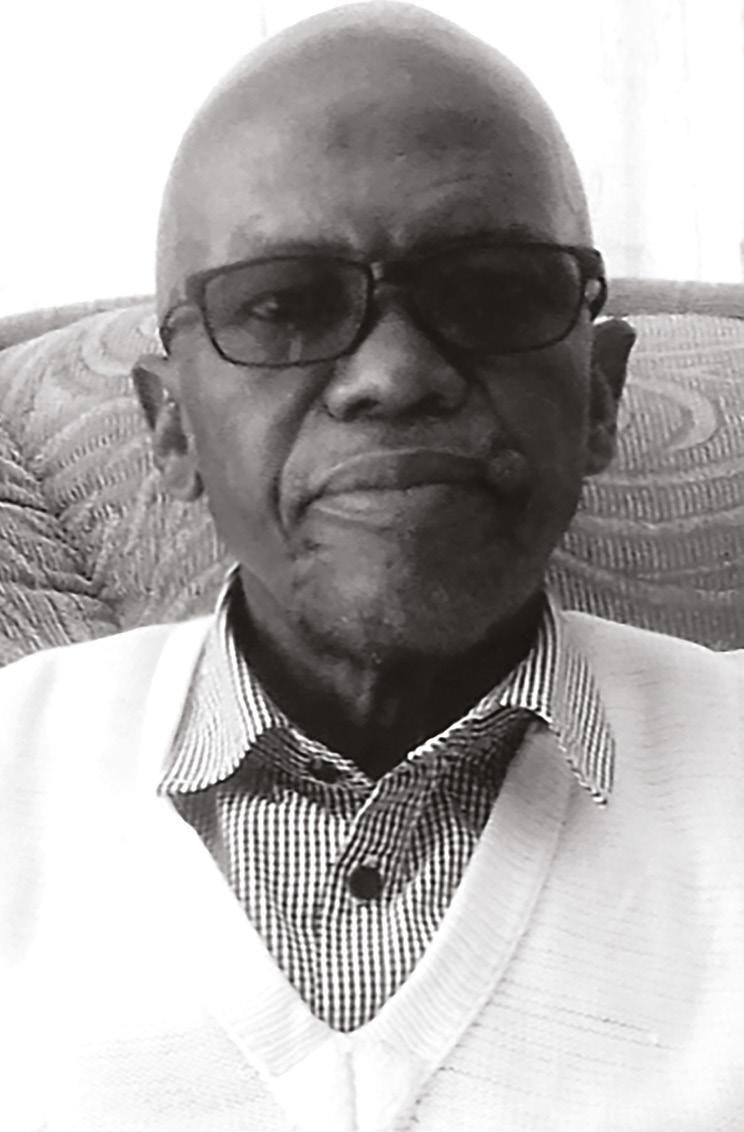

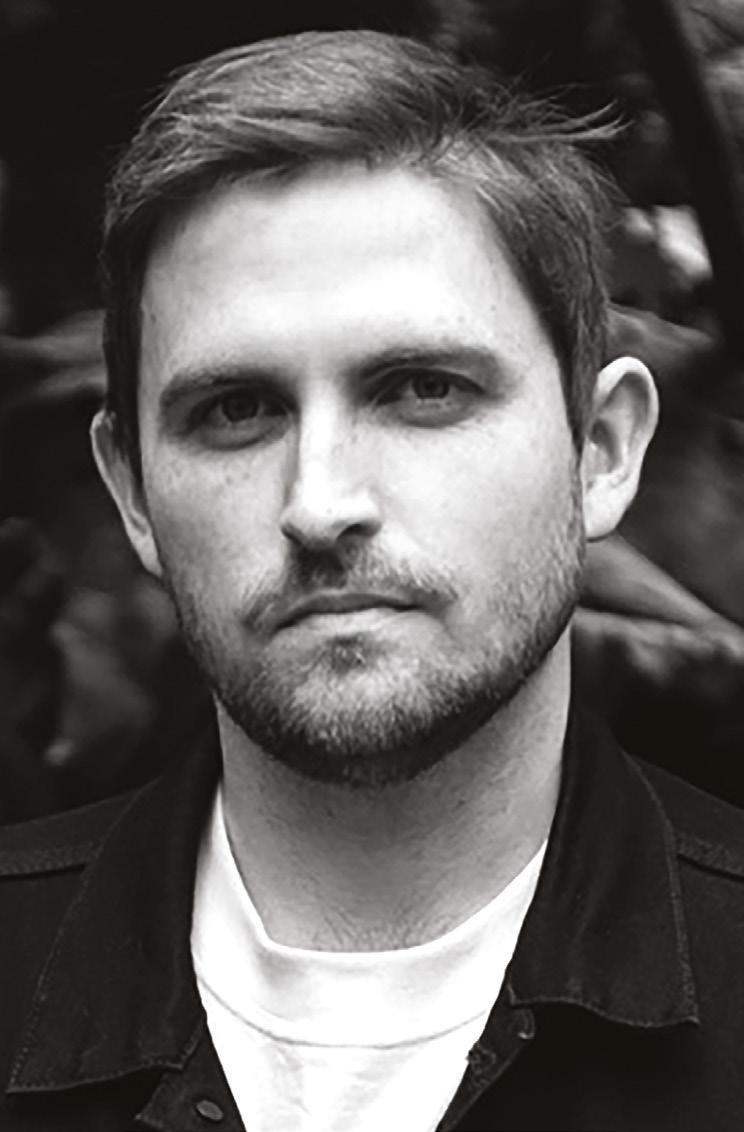

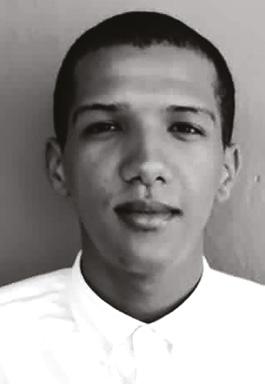

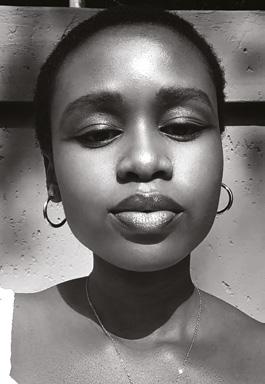

SU BIRCH

Su Birch is a distinguished international marketer. As CEO of Wines of South Africa, she received the Drinks Business Woman of the Year award. She runs her own marketing business called Thinking Seahorses and is enjoying the challenge of producing the Jack Journal. She also volunteers as an English coach in a local township school.

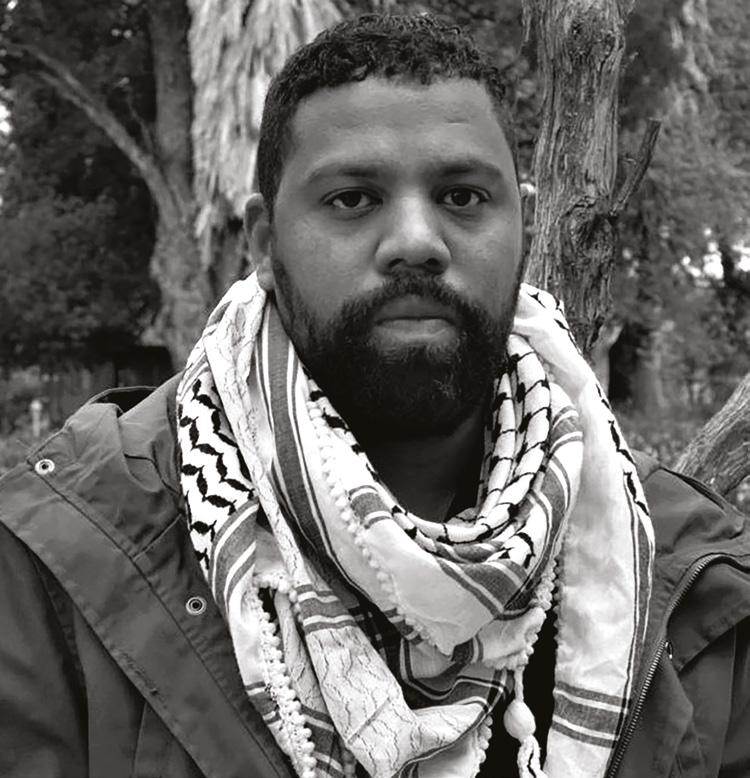

MATTHEW BLACKMAN

Matthew Blackman is a writer and historian. He has co-authored two books with Nick Dall on the history of South Africa. The most recent, Spoilt Ballot s, is a history of South African elections which came out this year. He lives and works in Cape Town.

JIM CLARKE

Jim Clarke has been writing about wine, sake, and related subjects for almost 20 years. In 2020, Jim received the International Louis Roederer Wine Writers’ Award for Feature Writing, and in August of that year Wine Business Monthly named him a Wine Industry Leader of the Year. Jim is the author of The Wines of South Africa , published by Infinite Ideas. He is also the US Marketing Manager for Wines of South Africa (WOSA).

LUCY CORNE

Lucy Corne is a beer writer and the editor of On Tap, South Africa’s only beer magazine. She is Africa’s first certified cicerone – akin to a beer sommelier –and the founder of South African National Beer Day. Lucy is a big fan of pilsner and IPA but also has a deep fascination with traditional African beers.

JEREMY DANIEL

Jeremy Daniel is an author and a scriptwriter for film and television. He is the author of a series of YA nonfiction books for Jonathan Ball Publishing: the Road to Glory biographies of South African sporting heroes. His adult biography Siya Kolisi: Against All Odds (Jonathan Ball Publishing) is a number one bestseller. He also writes business content on the convergence of cloud, mobile, big data and social media for international brands and online publications.

GEOFFREY DEAN

Geoffrey Dean is a wine and travel writer for various publications, as well as being a cricket correspondent for The Times of London, for whom he has covered more than 100 test matches. He judges for the International Wine Challenge and the Michelangelo International Wine & Spirits Awards. A lover of aged rum from his many cricketing trips to the Caribbean, and of single malt Scotch whiskies, he also writes on both spirits.

6 Jack Journal Vol. 4

TANYA FARBER

Tanya Farber is an award-winning journalist and author of bestseller Blood On Her Hands: South Africa’s Most Notorious Female Killers. She has won three international human rights journalism awards, has a Masters degree in journalism from Wits University, and is passionate about science, art and social justice. She lives in Cape Town with her husband, two daughters and four dogs.

JUSTIN FOX

Justin Fox is a travel writer, photographer and former editor of Getaway magazine. He is the author of more than 20 books, including The Marginal Safari, Whoever Fears the Sea , The Impossible Five and Beat Routes. His latest World War II novel, The Cape Raider (Penguin, 2021), is available in bookshops and on amazon.com. Its sequel, Wolf Hunt, is due out soon.

CASPAR GREEFF

Caspar Greeff has been a journalist for longer than he cares to remember (not that he has much memory left after all those beers). For the last 30 months he has been a digital nomad in Latin America, working (he is currently a subeditor for Daily Maverick) and travelling in Belize, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, Ecuador, the Galapagos, Peru and Panama. He is the author of the psychedelic journal The Ayahuasca Diaries

VERNON R.L. HEAD

Vernon R.L. Head is a birdwatcher. He is also a South African poet with an MA in Creative Writing (UCT), a bestselling novelist, and an internationally acclaimed architect. His first book – a non-fiction narrative, The Search for the Rarest Bird in the World –was long-listed for the 2015 Sunday Times Alan Paton Literature Prize. His first novel, A Tree for the Birds, was long-listed for the Sunday Times Barry Ronge Fiction Prize and short-listed for the National Institute of Humanities & Social Sciences 2020 Fiction Prize. And his poetry has been long-listed for the Sol Plaatje European Union Poetry Prize in 2014, 2017, and again in 2019. He writes for a number of international literary magazines.

JOHN HIGGINS

John Higgins was formerly Arderne Chair of Literature at UCT and is currently a Senior Research Scholar at its Centre for Higher Education Development. His most recent academic writings include ‘Getting Academic Freedom into Focus’ and ‘Montage’, and he is also the co-author (with the artist Hanien Conradie) of 40 nights/40 days from the lockdown , a book comprising 40 hand-painted postcards and texts put together in the first two months of lockdown. Every month he convenes an online meeting, through UCT’s Centre for ExtraMural Studies, of The Detectives’ Club and The Poets’ Club, with each month focusing on a particular author and text.

7

ALLENDRE HINE

Allendre Hine is a strategic creator and a lover of crafted design solutions, film, coffee and meaningful conversations. Ali is a graduate of the Red & Yellow School of Logic & Magic. She is the designer on Jack Journal

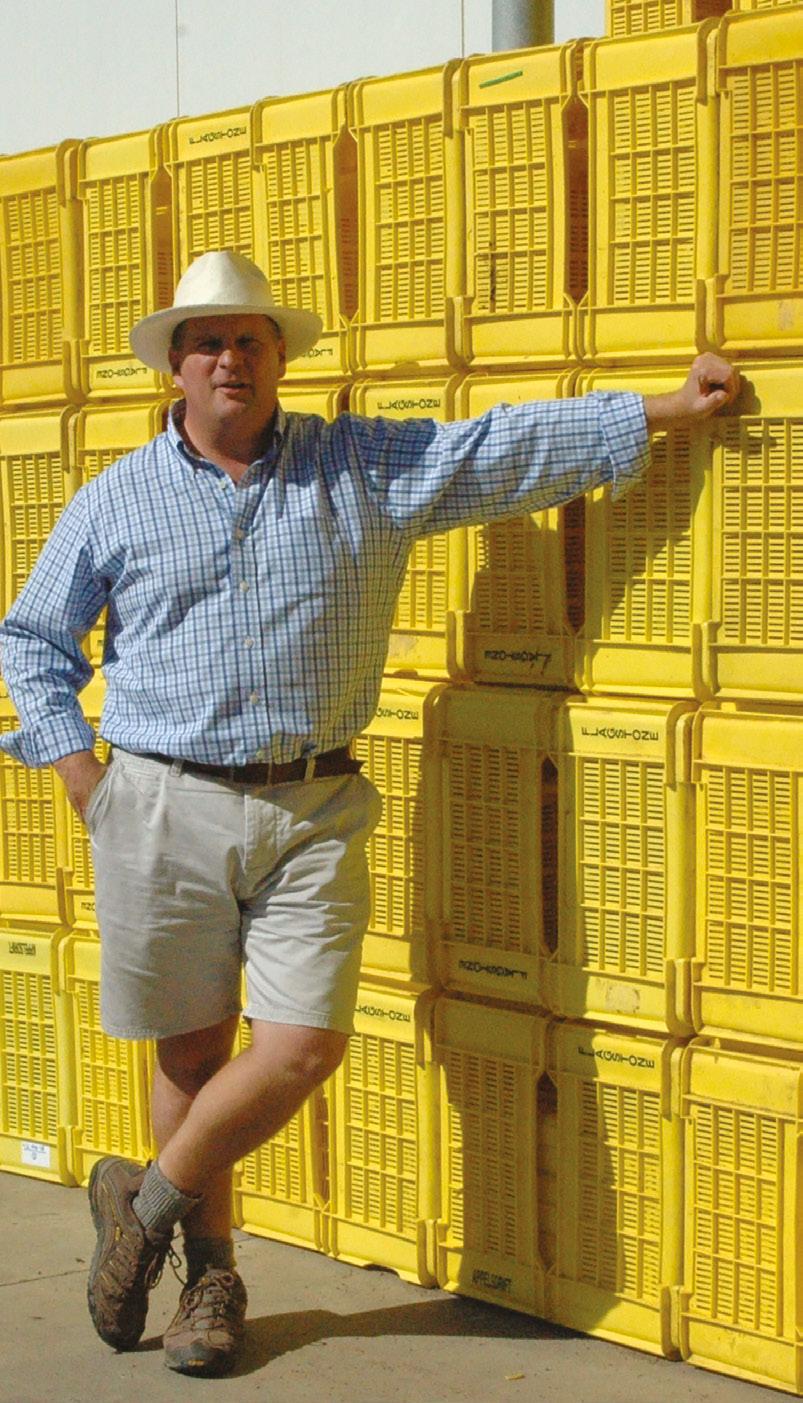

FELIPE HOWARD

A keen kayaker, mountain biker and SUP surfer, Felipe Howard owns his own travel company and created the award-winning Patagonia Camp, a 20-yurt hotel located on the outskirts of Torres del Paine, which received the Avonni Innovation Award in 2009. He has helped establish and contributes to the Chile Outdoors guide. He loves travelling with his family whenever he can, showing the world to his children.

BIÉNNE HUISMAN

Award-winning journalist Biénne Huisman is happiest finding the world’s special bits, and writing about them. She holds an MA in Creative Writing from Royal Holloway, University of London, and has contributed to BBC World Arts, the Sunday Times, Daily Maverick , and more.

BOBBY JORDAN

Bobby Jordan is a Cape Town-based journalist with an interest in most things, not only seals. He is employed by the Sunday Times newspaper, and was once warned not to keep writing about fish. As a writer, he is happily working his way up the food chain.

CHRIS MARAIS

Award-winning journalist and indie publisher Chris Marais has worked in the South African media landscape for decades as a newspaper reporter, feature writer and magazine editor. In the past 15 years, Chris and his partner Julienne du Toit have focused exclusively on telling the story of the Karoo. They have published six books and written more than 300 magazine features, exposing the vast and varied narrative of South Africa’s dry heartland to readers all over the world. Operating from the river town of Cradock, they own and manage the premier website of the region: www.karoospace.co.za

MELVYN MINNAAR

Melvyn Minnaar has been writing about art, wine and related existential issues for various local and international publications for many years. The creativity that underpins these subjects is an enduring personal passion. He has served on a number of cultural bodies and institutions. With a history of cultural involvement, opinions about art and wine, and an appreciation for talent, he was honoured by Veritas in 2018.

8 Jack Journal Vol. 4

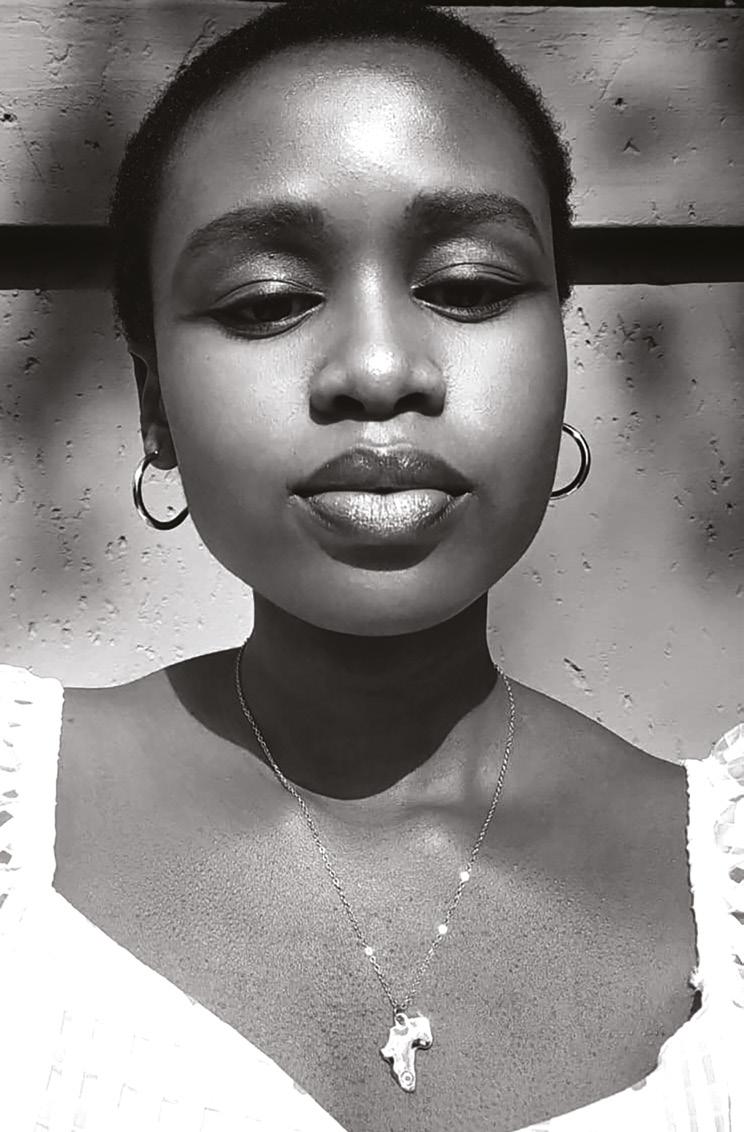

M. SOGA MLANDU

M. Soga Mlandu was born in the district of Mount Frere and lives in Mthatha in the Eastern Cape. M. Soga Mlandu has published many isiXhosa school books as well as English books of essays, short stories and poems. Soga edited South Africa is Part of Africa written by Kenyan author, Anthony Kambi Masha. In 2013, he was the Mellon writer-in-residence at Rhodes University and is the recipient of four South African writers’ awards.

PHILIP MYBURGH

Philip is part of the Myburgh clan who have lived on Joostenberg Farm for generations. Two years ago he published his debut collection, Fifty-two | Twee-en-vyftig and is now working on his next collection of English, Afrikaans and isiXhosa poems, which will go by the name A young poet no longer. When not scribbling in his notebook, he works as an advocate in Cape Town.

SIMON PAVITT

Simon Pavitt is the founder of the boutique consulting firm Capstones Co, which manages extraordinary passion projects, and has almost 25 years of experience in fast-paced, dynamic business environments under his belt, including as the Chief Marketing Officer of a Formula One team. Simon is the Chief Operating Officer of the London Technology Club, an exclusive network of over 90 private investors, VCs, family offices, and institutional partners such as UBS, Barclays, and LGT. He is publishing his first book, Capstones: The blueprint for meaningful passion projects, later this year.

DR DON PINNOCK

Don Pinnock is an investigative journalist, photographer and travel writer who, realising he knew little about the natural world, set out to discover it. This took him to five continents – including Antarctica – and resulted in five books on natural history and hundreds of articles. He has degrees in criminology, political science and African history, and is a former editor of Getaway travel magazine. The Last Elephants is his 18th book. He lives in Cape Town.

ANTHONY ROSE

Wine correspondent of The Independent from 1986 to 2016, Anthony contributes to Decanter magazine, The World of Fine Wine , The Real Review and The Oxford Companion to Wine, and is the panel chair for Southern Italy at the Decanter World Wine Awards. His most recent books are Sake and the Wines of Japan (Infinite Ideas, 2018) and Fizz! Champagne and Sparkling Wines of the World (Infinite Ideas, 2021), the latter of which was nominated this year for Drink Book of the Year by the Guild of Food Writers.

ALISON WESTWOOD

Alison has been travelling to and writing about Africa’s top destinations for more than 15 years. Her writing and photographs have appeared in various magazines and online publications, as well as a book or two. The Cape is her favourite place in Africa, at least partly because of the wine.

9

the_jack_journal @The Jack Journal FOLLOW

US ON SOCIAL

Torres del Paine in Patagonia.

Torres del Paine in Patagonia.

11

12 Jack Journal Vol. 4

Raya and her cub.

protecting the pumas

Written by: Felipe Howard Translated by: Su Birch Photography by: Felipe Howard

At Cerro Guido, situated in the pristine landscapes of Torres del Paine in Patagonia, a conservation project to protect the puma and explore ways for wildlife, the gauchos, and ranching culture to co-exist is attracting a lot of attention. High-end tourism is a powerful tool in sustainable conservation, and recently I had the chance to visit Estancia Cerro Guido and experience this first-hand.

On day one, Pía Vergara, Director of Cerro Guido Conservation, greets us with a smile: ‘We have a surprise for you.’ She had just contacted her team of trackers, who had left earlier from Casa Puma. It is 8am and the Paine massif is sharp in the clear winter light.

After a short drive, the vehicles stop and we all meet the trackers: Mirko Utrovicic, Alfredo Rivera and Gino Pereira. They are also accompanied by Nicolás Lagos, scientific

advisor to the project. Only 100 metres away is a puma, imposingly reclining with her cub on a rock. We are handed powerful binoculars to follow their movements. Pía excitedly tells us that it is Raya, one of her favorite pumas, with her three-month-old cub, whose birth was recorded on 27 May 2021.

While we watch how the cub plays around her mother, Raya looks carefully towards the pampas. One of the trackers who has also been looking in the same direction quietly points out another puma crossing the bushes surreptitiously but very determinedly. It is a male. He advances and crosses about 50 metres from us, ignoring us completely. The scene plays out very fast. The male reaches Raya and the cub, trying to attack the little one. We hear loud roars, we see the bushes move; Raya manages to drive the male away, and begins following him without pausing. We would never see the cub again. Raya would follow the male towards the summit and we would become spectators of their movements from a distance.

During the day we move towards the upper part of the area, while the trackers split up to position themselves in different locations so as to never lose sight of the two pumas. Alfredo stays down, while Mirko and Nico go up to another sector. This is how we are able to see the pumas from the ledge, watching them under a cliff about 40 metres away. Raya follows the invading puma all day. We feel privileged, so lucky to be watching the scene. Pía is very worried about Raya’s cub. She explains to us that the males want to impose their offspring into a territory, so they try to attack and eliminate offspring that are not theirs and then try to mate with the female and thus leave their own offspring. In fact, Raya had two cubs this year and one of them was never seen again – the harsh laws of nature.

The Cerro Guido conservation project started from scratch in January 2019 as a way to protect the pumas and to manage a coexistence with the gaucho and cattleraising culture that is so typical and deeply rooted in the Magallanes Region – two

13

Palomo and sheep with the Torres del Paine behind them.

Palomo and sheep with the Torres del Paine behind them.

15

16 Jack Journal Vol. 4

Torres del Paine in Patagonia at sunset.

Travelling to Cerro Guido is not just going to see pumas, as Pía Vergara told us – it is seeing wildlife, it is living in and knowing the work of an estancia, it is meeting the gauchos, it is participating in this experiment to achieve coexistence between fauna, wildlife and the livestock world.

worlds that have always been in conflict. The approach is multi-pronged: introducing methodologies to protect the livestock, introducing conservation tourism, and scientifically measuring the impacts of their efforts. The project did not expect such good results in the short term given the history with the pumas, but with 30 camera traps installed, they have come a long way.

Says Vergara: ‘This is more than coming to see pumas – we are in a kind of laboratory, testing tools that can protect livestock and make coexistence a reality. We want to obtain real, scientific data from these methods and then make them available to neighbouring farms and the entire region, to protect not only the puma but all the fauna. This is a project that requires a lot of collaboration.’ Vergara is also a nature photographer and passionate about this region. ‘The conservation originates with the puma because of its importance, symbolism and meaning and the need to conserve these animals. The idea is to make the Cerro Guido conservation project sustainable through tourism, which is why we want to show our activities.’

We don’t only see pumas: in searching for them, we often came across majestic condors, snow-covered rheas, flamingos in the lagoons, as well as foxes and a type of rare llama called the guanaco in the pampas. All far away from the tourist crowds that you can sometimes find in Torres del Paine. ‘Look, Felipe, to the east, next to a square stone with lichens, under the crack – there is another puma.’ I take the binoculars and I see the stones covered with lichens; they are all square to me, everything looks the same and I have a hard time finding the puma, which camouflages itself very effectively. The eye of the trackers and Pía is impressive; part of the tourist experience is feeling that emotion of patiently observing until you find a puma. Look at the sky, the movement of birds, look for signs.

For five days we lived the experience in the field. We stayed at the Estancia Cerro Guido hotel, the base for all these excursions and part of the conservation project. It’s an old house, renovated, very warm, cozy and with the decor of the period and a privileged view of the Paine: a true ranch that currently operates as such. The hearty breakfasts were the start of our explorations.

Their personalised snacks kept us going during the day. We observed the Paine from another perspective, from the Sierra del Toro, from the condoreras cliffs – home of the condors, landscapes with lights that change day by day, sunrises and sunsets with the towers as a backdrop, or the immense Sierra Baguales, yet another treasure.

We participated in several routines of the scientific experiments that aim to change some of the methodologies in the management of cattle pastures. We saw the Foxlights, LED solar-powered lights that, at night, project random multicoloured patterns into the valley, imitating the movements of torches held by humans. We visited the different locations where camera traps have been installed, following the footsteps of nature and the intuition of the trackers. We accompanied our guide, Alfredo, in his work looking for these cameras, and we saw his emotion when, on checking the memory cards on his phone, he found when a puma had passed by, with the exact date and time of its movements. It had passed by two days earlier. Alfredo’s smile and joy when he saw the puma on the phone infected us all.

We also loved his connection with Palomo, one of the dogs of the Great Pyrenees species that has lived with the sheep since he was a puppy. The flock has accepted Palomo and he will defend the sheep from attacks by the puma. Palomo played gently among the animals with Torres del Paine behind him; a postcard.

Travelling to Cerro Guido is not just going to see pumas, as Pía Vergara told us – it is seeing wildlife, it is living in and knowing the work of an estancia, it is meeting the gauchos, it is participating in this experiment to achieve coexistence between fauna, wildlife and the livestock world.

For more on the conservation of the puma.

17

18 Jack Journal Vol. 4

Written by: Melvyn Minnaar

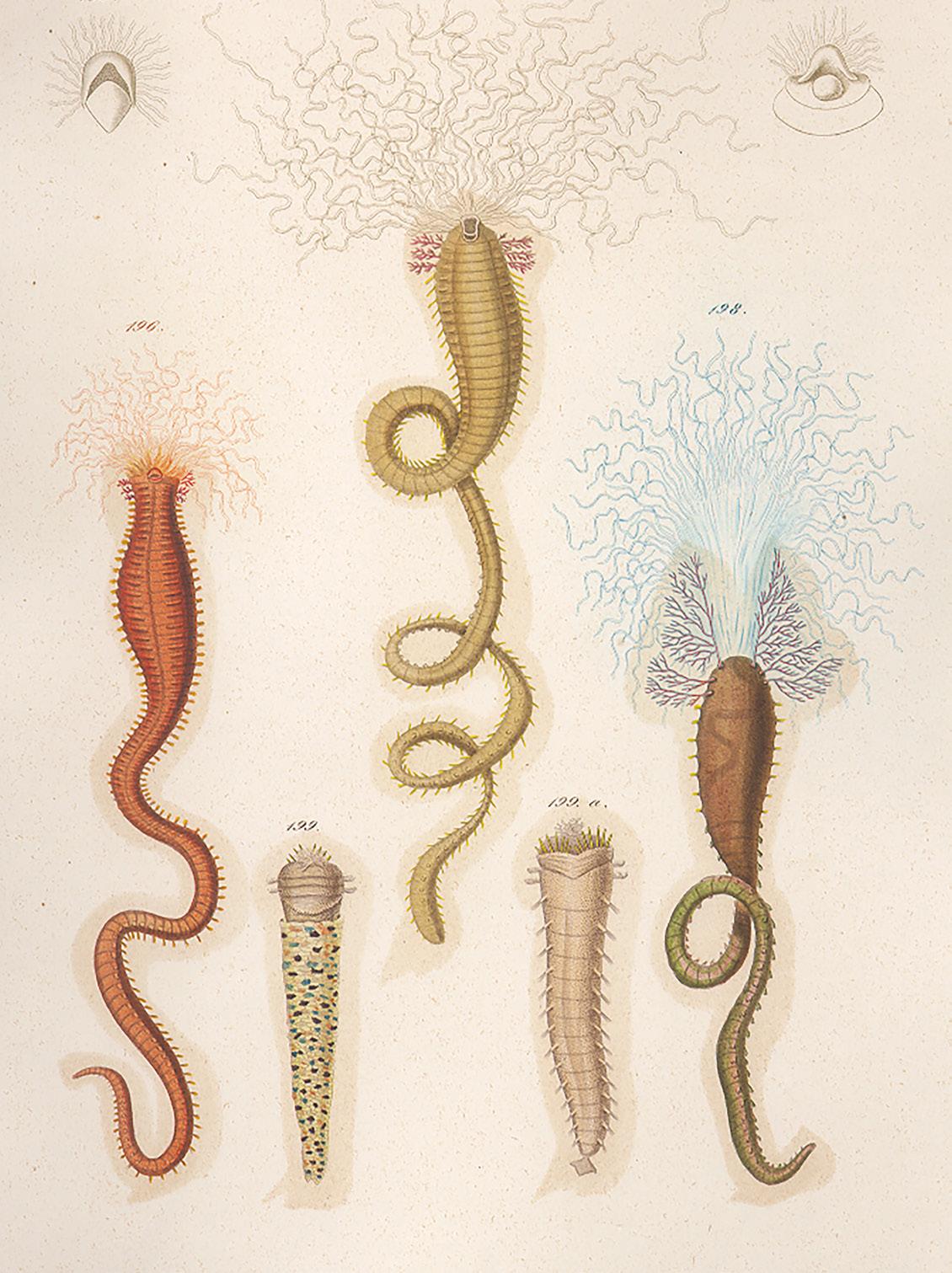

The word ‘print’, both as a verb and noun, has a strong association with process and procedure. It also suggests access, multiples and format. Metaphorically, it conjures up notions of communication, spreading stories, moving messages – reaching many. Indeed, the limit of that reach is only determined by how many are printed and where they land up.

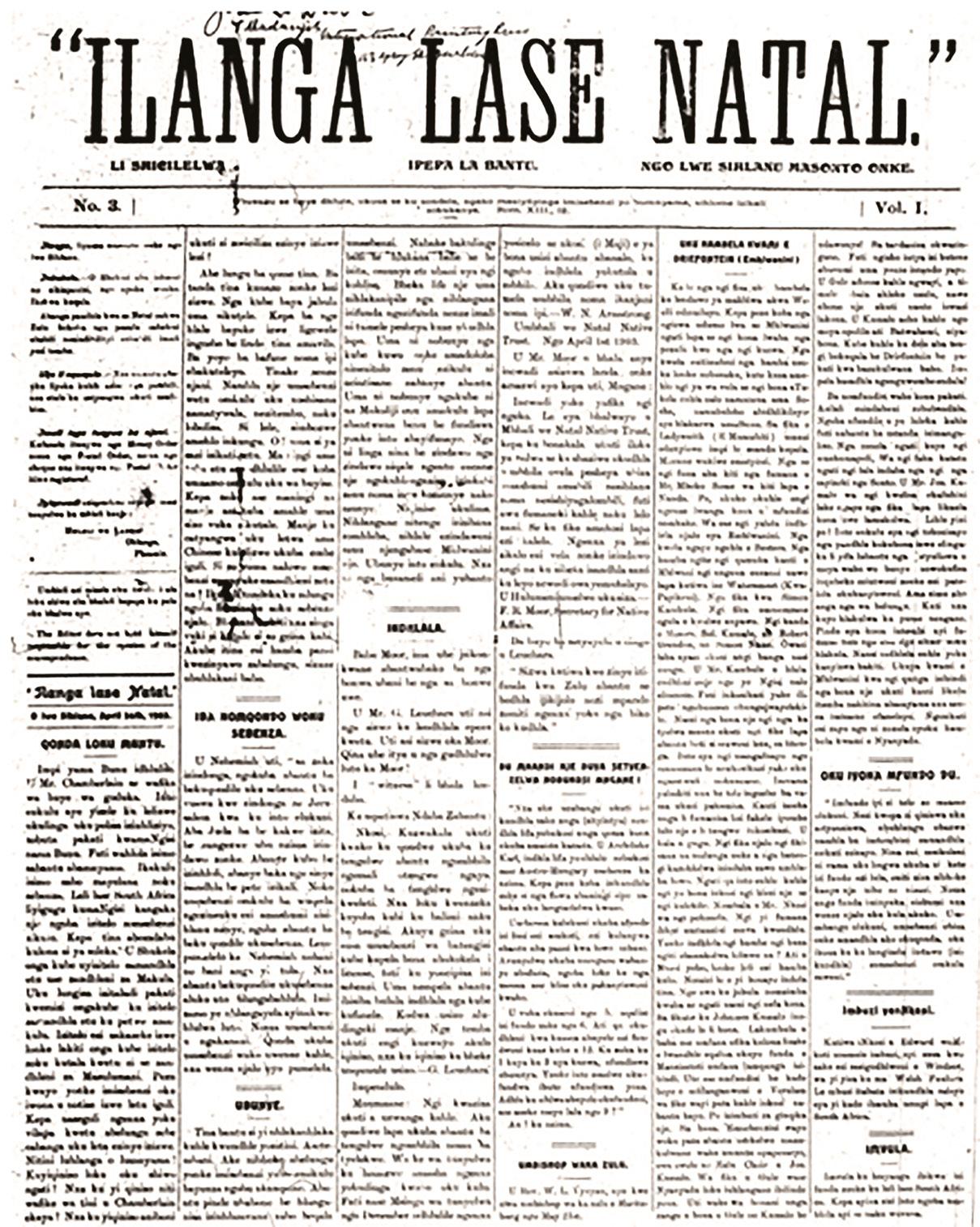

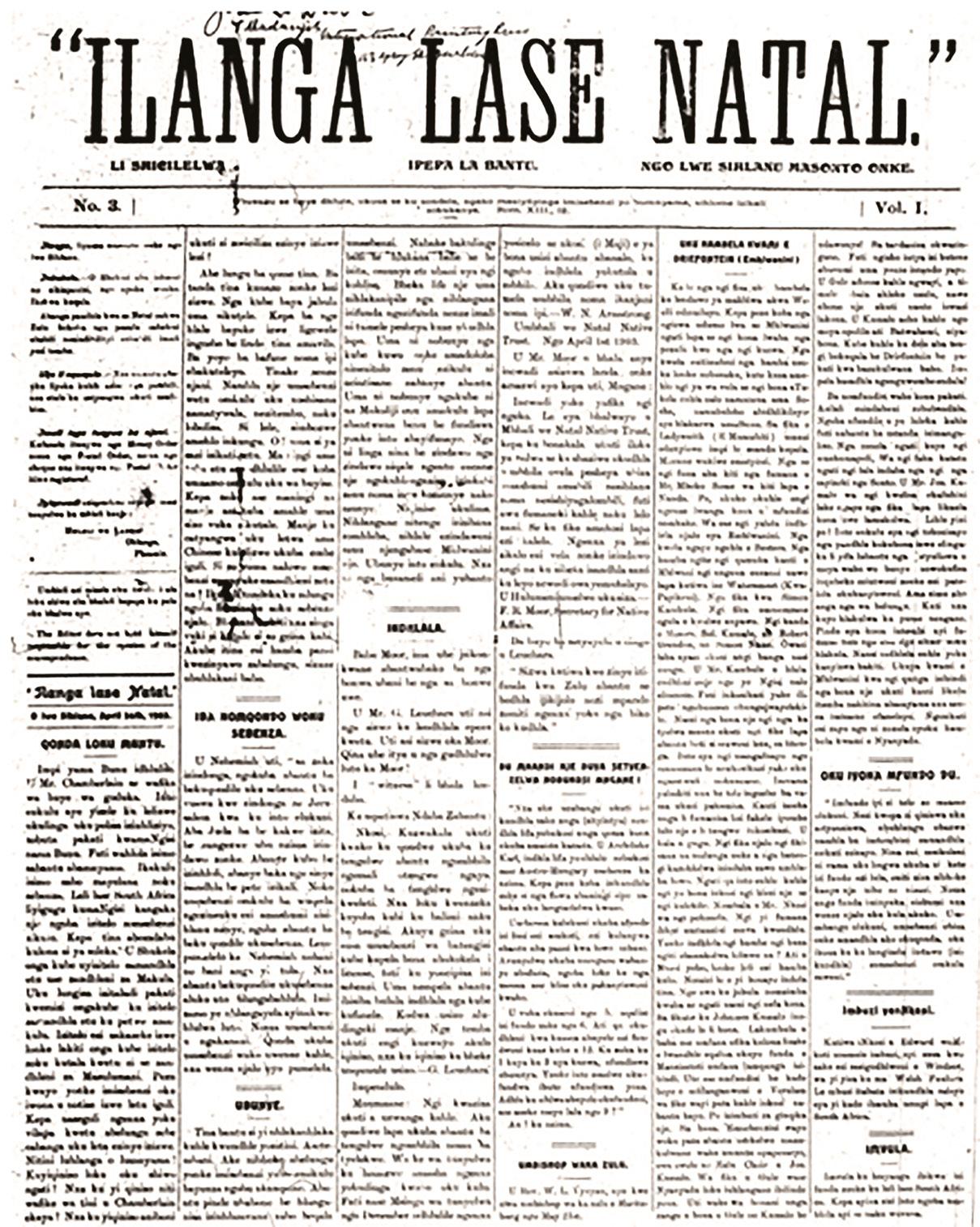

From newspapers to books, to posters to brochures, the physical print marks the very essence of an open society, in conversation and debate with itself. Democracy at work.

Print can be many things, but in the world of art it occupies a niche. One step away from the most simple of artistic visual gestures – the drawing – it empowers the artist to reach more, extending the audience.

Western art usually credits the Nuremberg artist Albrecht Durer (1471–1528) as the first print master.

Both as creator and theorist, his work and influence defined the process during the Renaissance. He worked with wood and metal – the first producing woodcut prints, the second engravings or intaglio prints.

Multiple copies were made, in the first instance, by cutting out into a wooden board the part of the illustration not to be seen. The remaining surface would be inked and printed onto paper. This is known as relief printing. In the second manner, also called etching, the opposite is done: with intaglio (‘incised’), the grooves cut into a metal plate with a burin are filled with ink, the surface wiped clean, and the print produced from those inked grooves.

The handsome, clever Durer, connected to many of the well-known contemporaries of the time, including Raphael and Bellini, revolutionised printing as a sophisticated medium for artists. He unlocked the power of the process. Ownership of the artwork – in other media, like a painting, singular and elitist – opened up with more than one of the same possible. The stories to tell, the visual messages to be seen were less limited and not exclusive.

This is the democracy of art that echoes all the way to the valleys and townships of South Africa, coinciding with the awakening about 60 years ago of a particular black political-artistic awareness and invention.

The simplicity of the process and the print is the trick. Inexpensive in terms of media (wood – free; linoleum – handy), relatively easy in terms of hands-on manipulation, the potential was obvious to unlock.

It starts as simply as teaching preschool children to cut and print patterns with potatoes and ink. It can end up as some of the most sophisticated multicoloured, multilayered imagery in a combination of methods in the process that is called relief printing. Somewhere between these is what many have called South Africa’s own art tool, the one that we have polished to exquisite power: the linocut print. This method has suited us better than any other. For many reasons. For many purposes. For it literally and figuratively brought art and expression to the people – and their freedom.

19

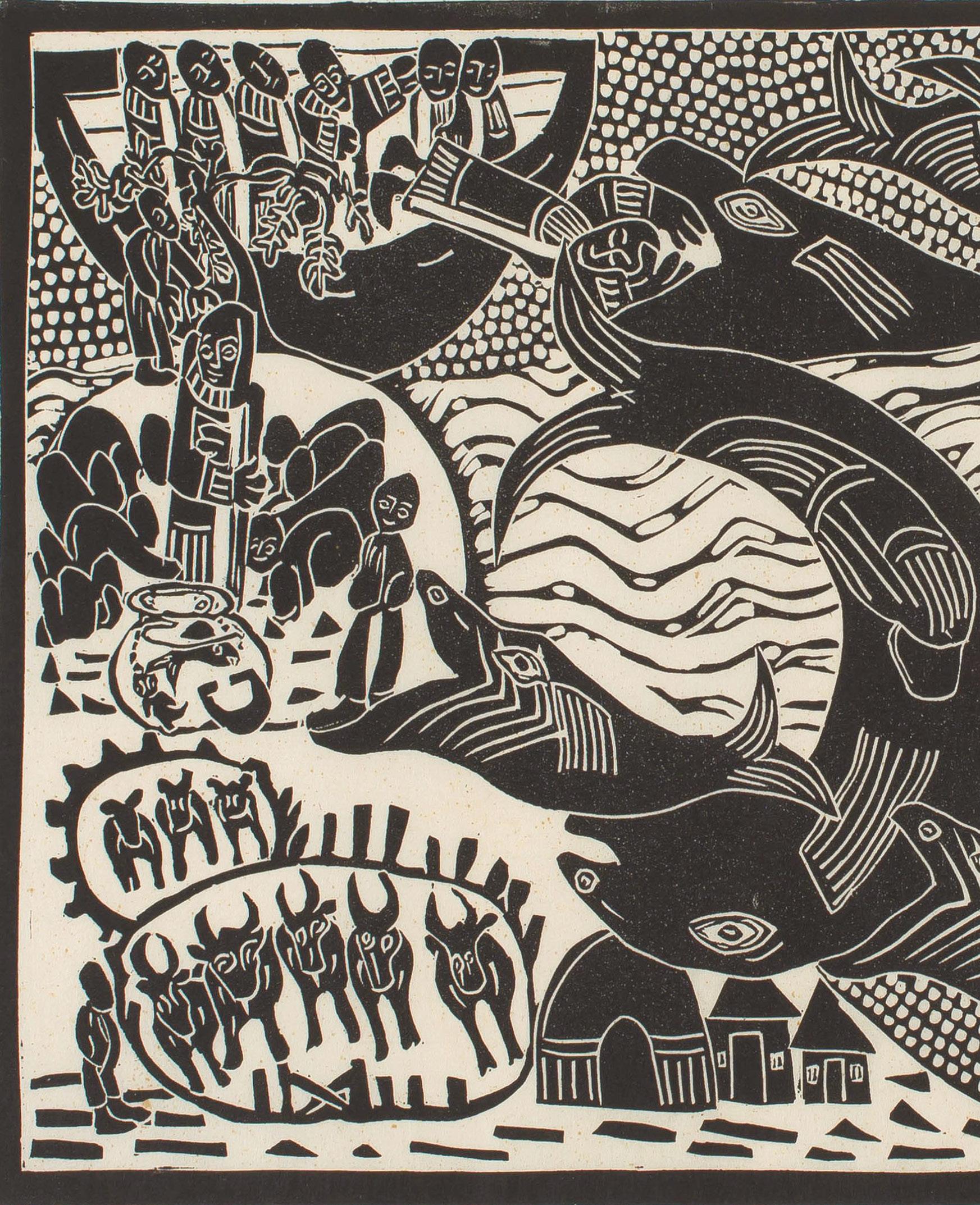

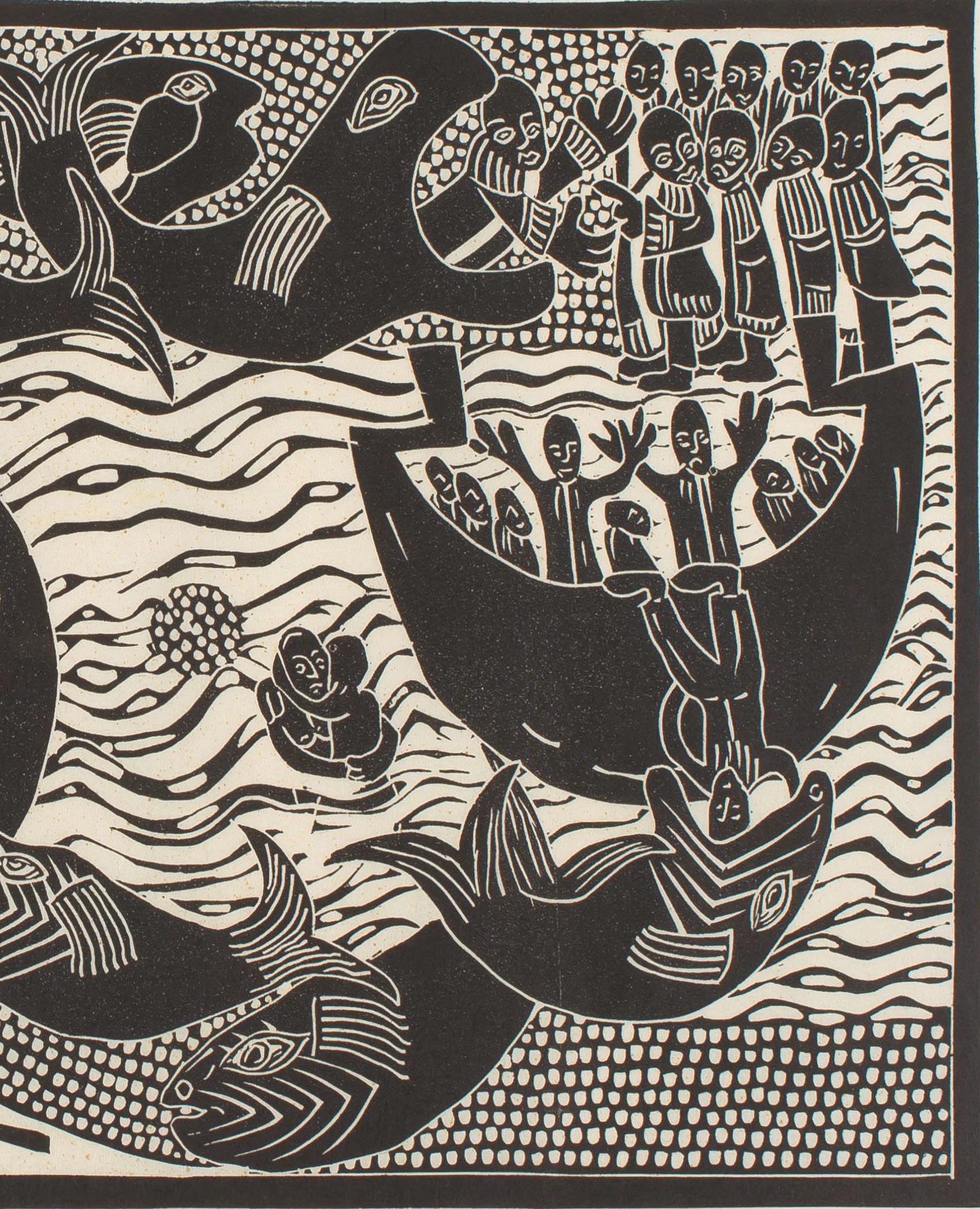

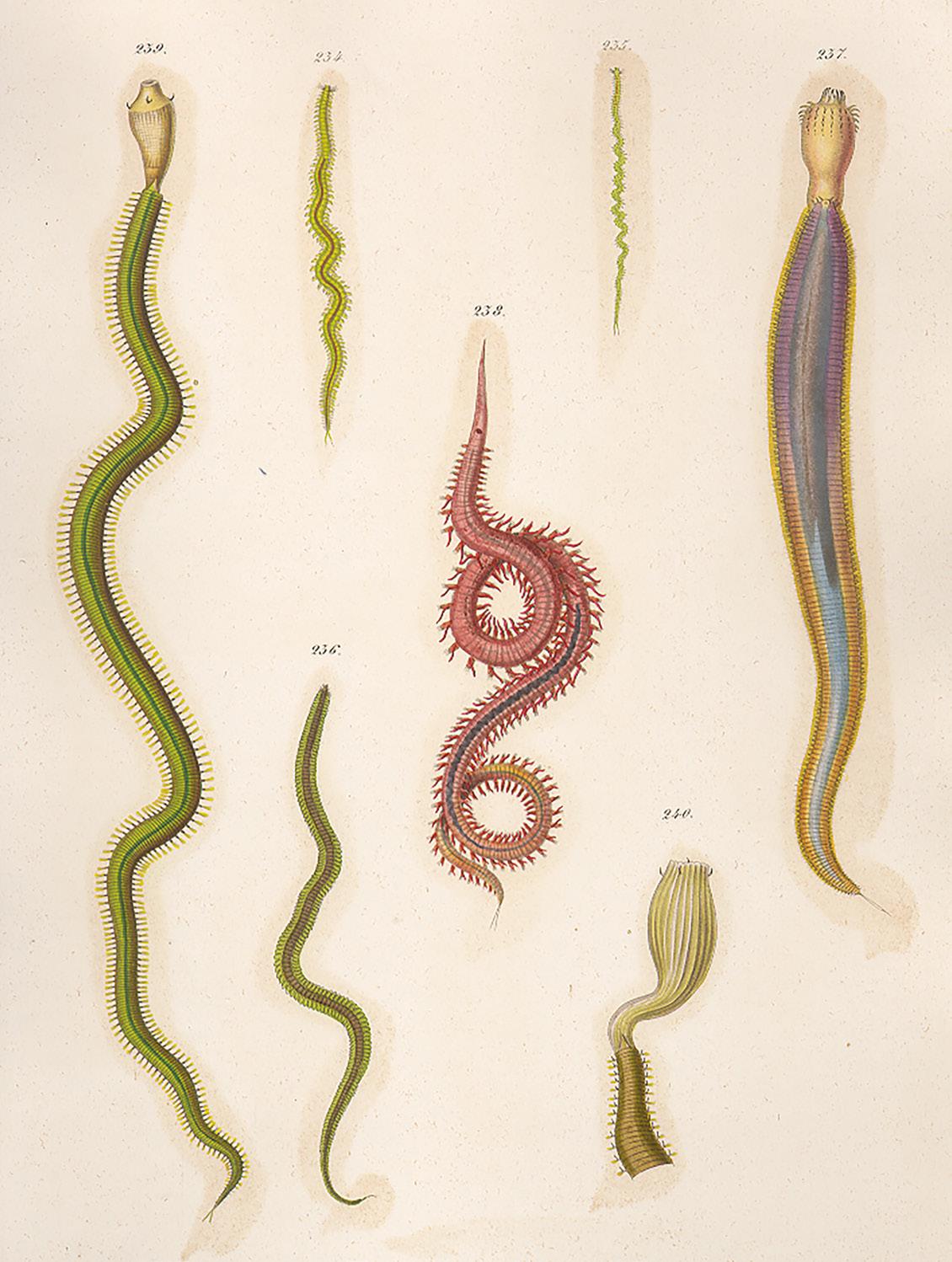

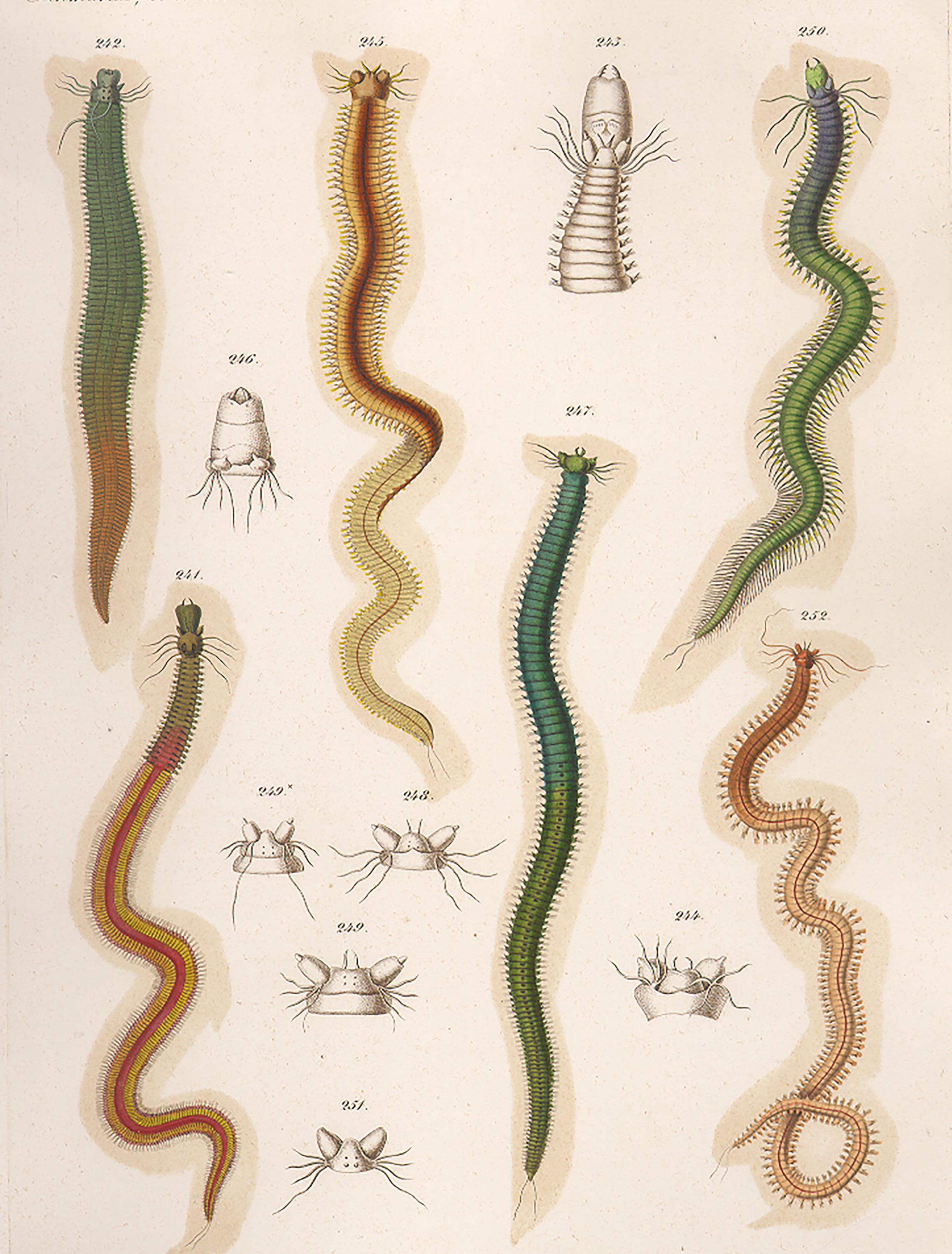

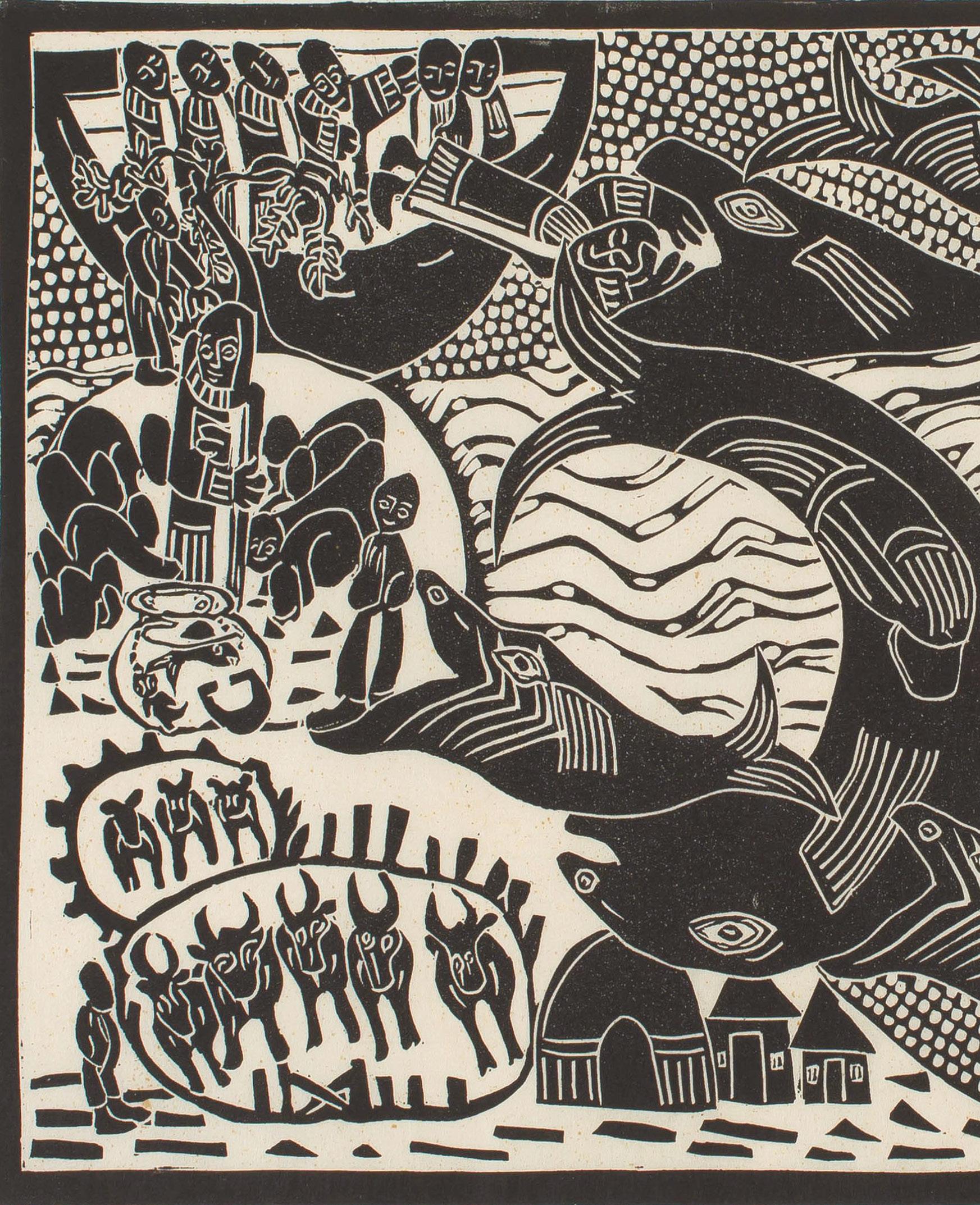

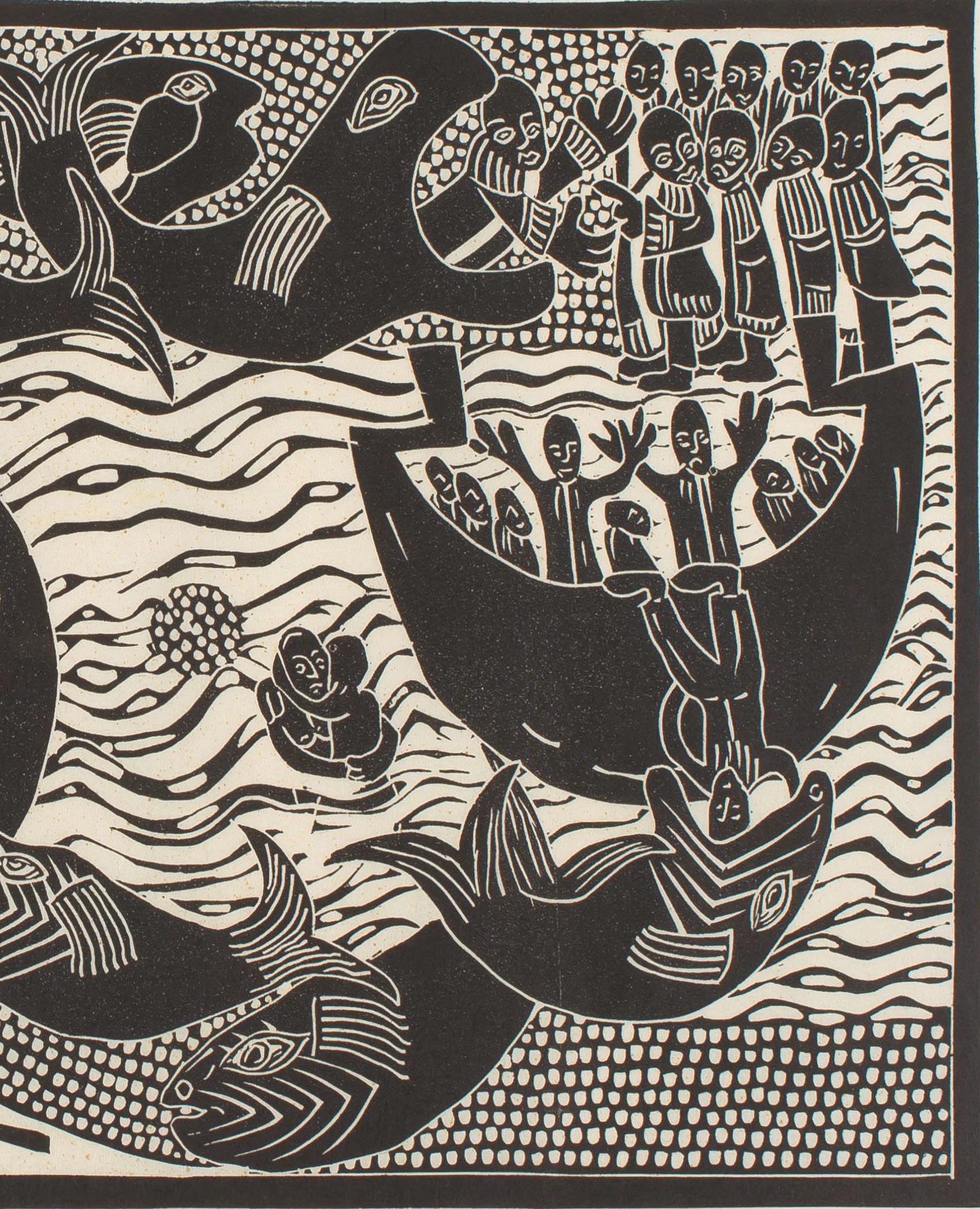

The story of South Africa’s linocut print tradition has numerous roots and branches. It is anchored in the deep, rolling country side where it produced art as a parallel to subsistent rural life and branched out into the townships as vibrant manifestation of political clout.

In the early 1960s, Peder Gowenius, a Swedish art teacher, together with his artist wife, Ulla, established what was to become famous as the Rorke’s Drift Arts and Craft Centre at a church mission in KwaZulu-Natal.

It was an era when black South African artists had no mainstream presence, even though the famous Polly Street Art Centre in Johannesburg, where artists like Cecil Skotnes tried to bridge the gap, had exposed many people of colour to the creative industry.

Beyond its skill teachings of weaving and pottery – ‘creative usefulness’ according to Gowenius’ socialist motto – the Rorke’s Drift centre developed naturally into the field of printmaking. Linoleum was cheap and available.

Azaria Mbatha is the first of numerous names that established and continued the linocut printing trails from here. Among many protégés are artists such as John Muafangejo, Kay Hassan, Sam Nhlengetwa, Thami Jali, Kubeka, Cyprian Shilakoe, Gordon and Eric Mbatha, Thami Mnyele and Sandele Zulu. Later, Gowenius wrote:

‘Some men tried painting but it was a futile exercise … in desperation I tried one last thing, linocut printmaking. Azaria Mbatha’s delight when we rubbed the print with the back of the spoon and peeled off the first proof was the turning point. There is a surprise moment in the graphic printing process, something magical happens …’

The artist and activist Lionel Davis, a Capetonian who was imprisoned on Robben Island in the 1960s, played a key role in the establishment of the collection of prints now carefully housed at the University of the Western Cape’s Centre for Humanities Research. This remarkable collection comprises mostly linocut prints made by many known and unknown artists during the great days of Cape Town’s Community Arts Project (CAP). Davis

was one of the original inspiring teachers when CAP started in 1977 (its work ceased in 2008).

CAP was known for the political punch of the art produced by teachers, students and hangers-on in the run-up to Mandela’s release in 1990. It was here that the humble linocut print bloomed as South Africa’s art medium with clout: a vibrant visual tool for social transformation.

The method and manner of the simple print had carried its political potential over centuries. Here, uniquely South African, it was a vital tool in the urgent political message demanding change. It was used for posters, handouts and ad hoc flyers, making the most of the instant power of both its bold imagery and quick method of production.

The artist, esteemed printmaker and academic John Roome says linocut prints lend themselves to resistance and protest art because they are cheap to make and easily reproduced: ‘The medium is so basic and relatively affordable that artists who do not have access to expensive or fancy equipment can make great prints. That’s why South African artists turned to this process to get their message across during the struggle years.’

Roome is passionate about the medium: ‘Despite the prevalence of digital printing these days, I think the handmade and “raw” quality of lino still has tremendous appeal. It is such a gutsy medium. The graphic strength and directness of the medium makes it really appealing and powerful.

‘Personally I love lino and woodcut printing because the cutting process is kind of meditative, and the end results are more often than not slightly unpredictable but just about always very rewarding.’

In South Africa, the cultural reward is an illustration of creative democracy.

To find out more about the wine, There are Still Mysteries.

To find out more about the art works.

To see more of Joshua Miles’ art.

20 Jack Journal Vol. 4

21

There Are Still Mysteries. Pen Jack. This linocut is the inspiration for Bruce’s wine label ‘There Are Still Mysteries’ Pinot Noir.

22 Jack Journal Vol. 4

Azaria Mbatha: 1941-2018. Untitled. Linocut on paper. 63 by 93cm. Strauss & Co.

23

24

John Muafangejo: 1943-1987. Zululand: Natal Where Art School Is. Linocut. 78 by 97cm, Strauss & Co.

25

26 Jack Journal Vol. 4

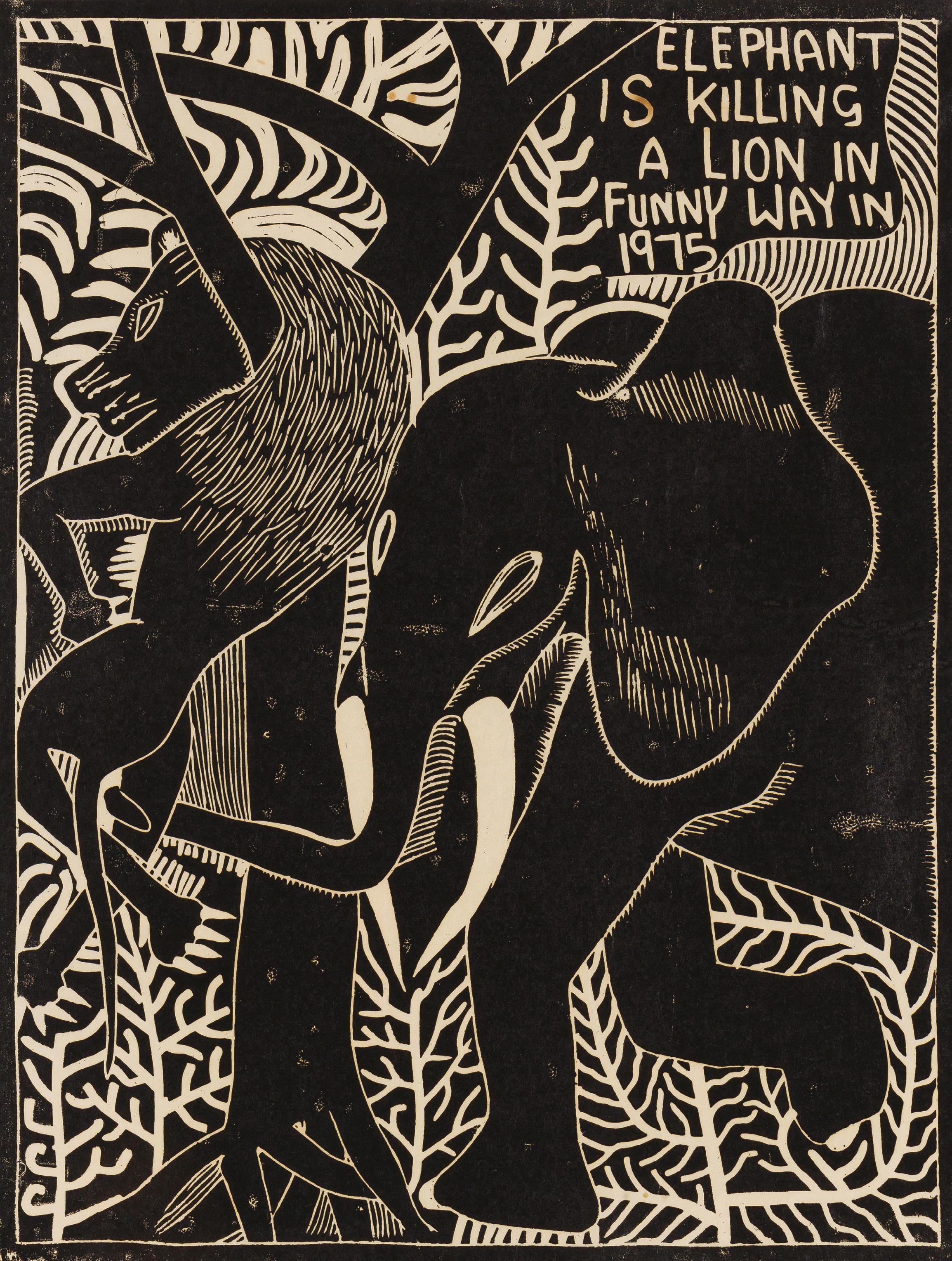

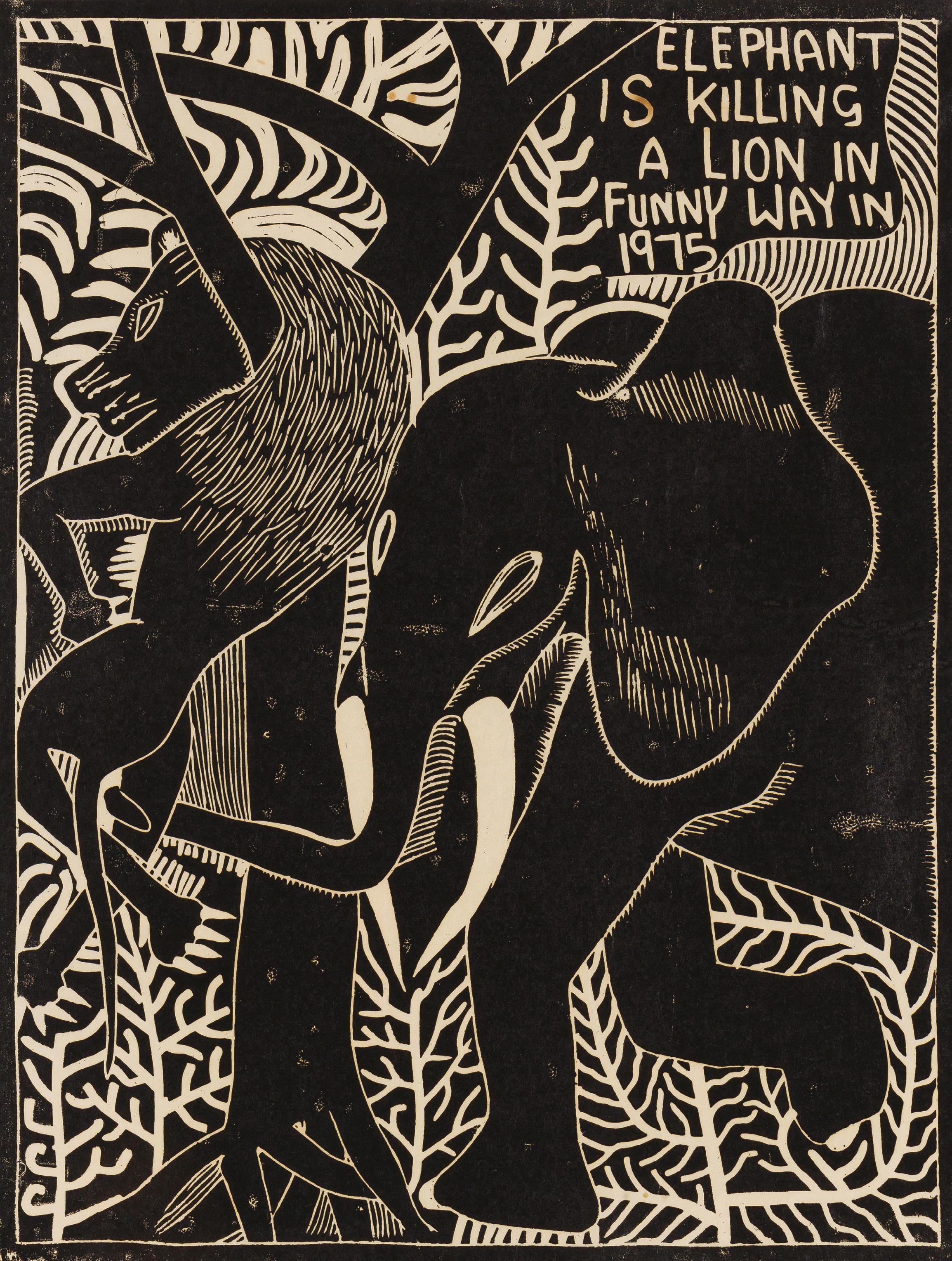

John Muafangejo: 1943-1987. Elephant is Killing a Lion in Funny Way in 1975. Linocut on paper. 45 by 34cm. Strauss & Co.

27

Artist unknown. Linocut. From the Community Arts Project Collection.

Crossroads. Sydney Hollow. Linocut. From the Community Arts Project Collection.

28 Jack Journal Vol. 4

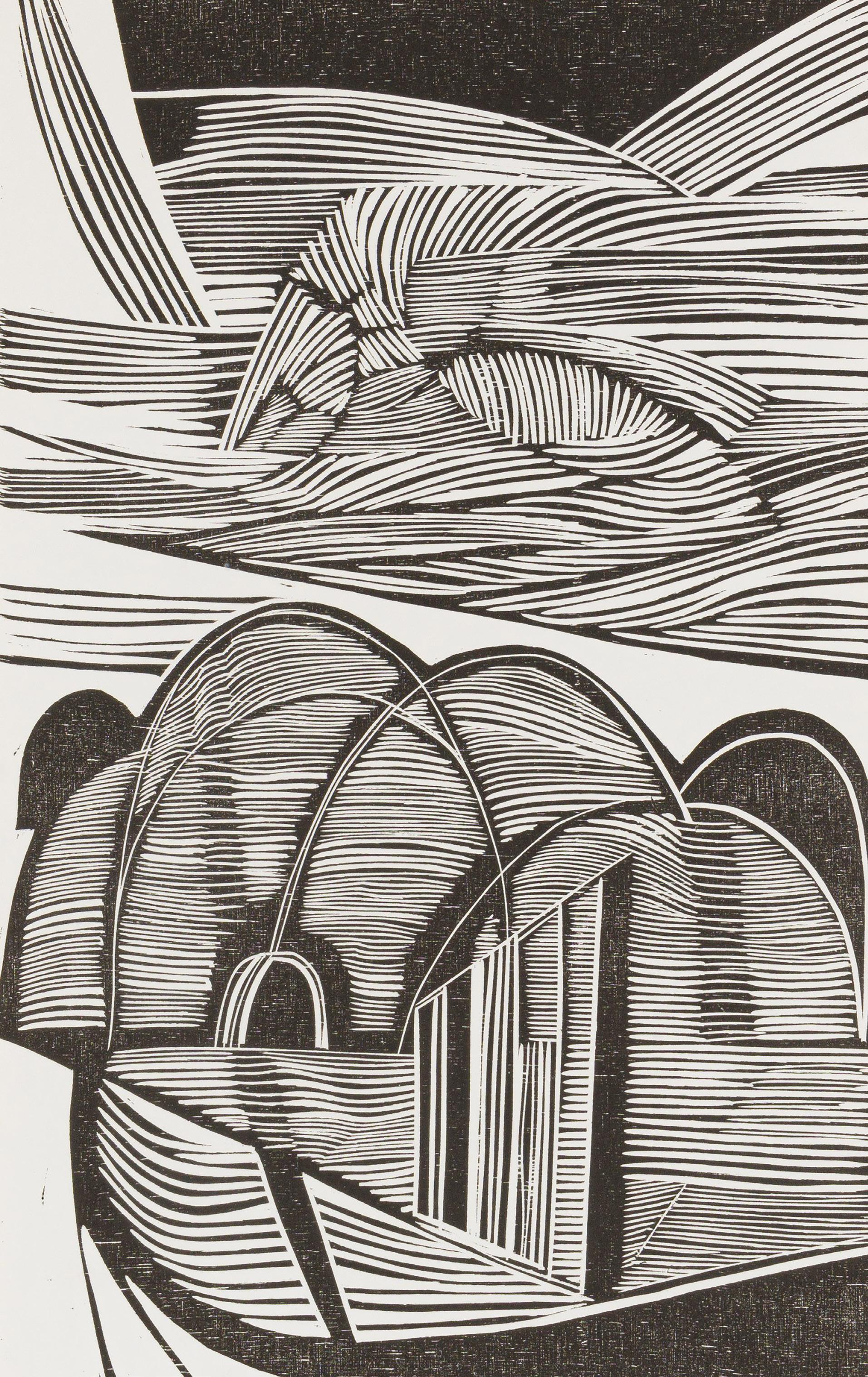

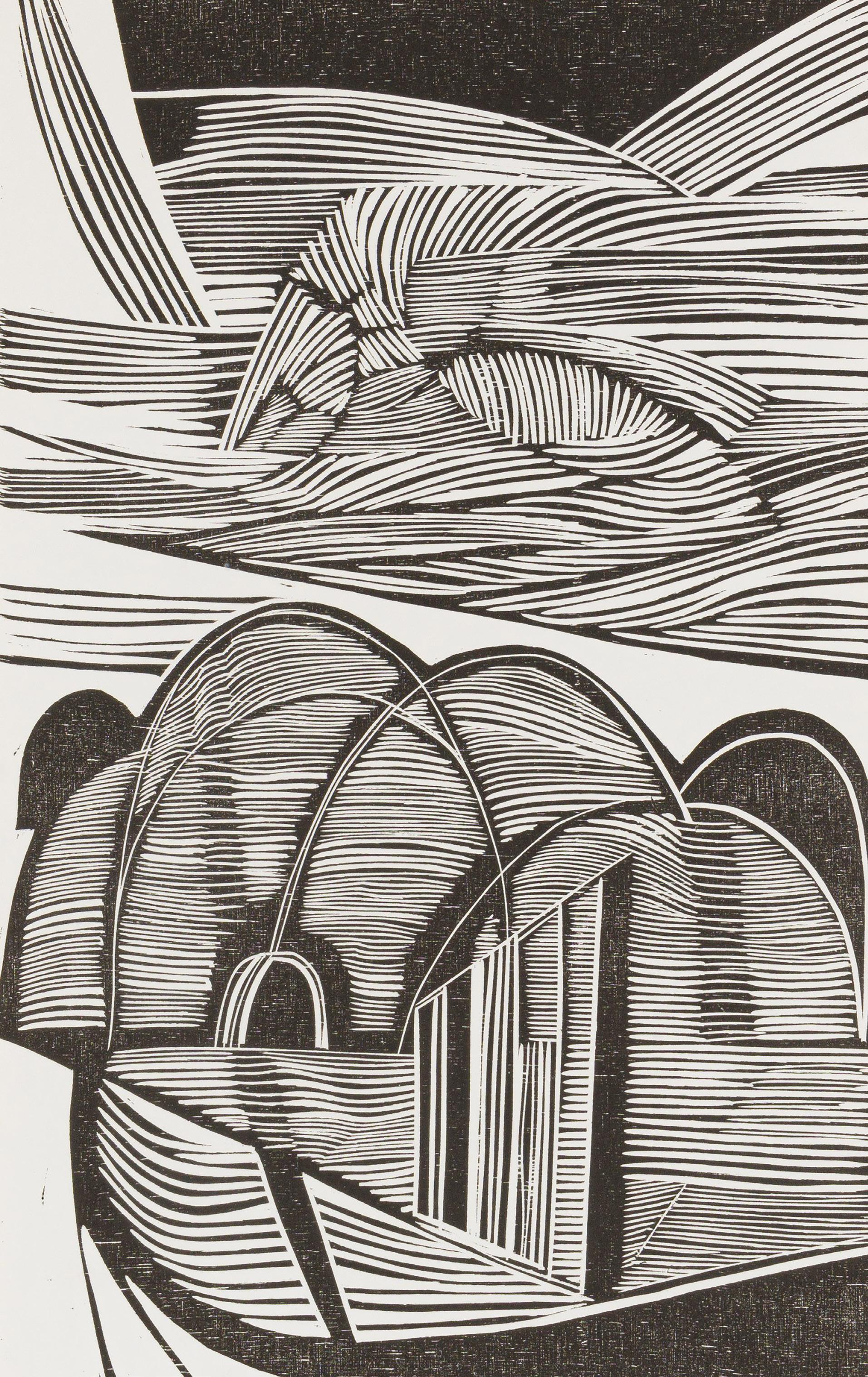

Cecil Skotnes 1926-2009. British Traders Settle. Woodcut on paper. 50 by 33cm. Strauss & Co.

29

Cecil Skotnes 1926-2009. Kwabulawayo Kraal. Woodcut on paper. 102 by 78cm. Strauss & Co.

x 55

Journal Vol. 4

30 Jack

John Roome. Aloe: Three Tree Hill, hand-coloured linocut print on Fabriano paper. Dimensions 37

cm, dated 2021. Edition of 10.

31

Joshua Miles

When John Roome talks about ‘a gutsy medium’ and its ‘graphic strength’, he may well be describing the outstanding print art of Joshua Miles.

The 55-year-old artist has defined his visual work with one of the trickiest of methods: reduction printing. Often described as ‘suicide printing’, this is a multicolour relief process in which the surface of the medium – a single block of wood or linoleum – is systematically cut away as layer after layer is printed in one required colour, each separate, working step by step towards the completed whole in full colour.

It is a challenge – which can also be seen as an aesthetic scuffle with the medium –that suits the artistic temperament of Miles. Once a student at the UCT Michaelis School of Art, where he studied with Cecil Skotnes, he won the celebrated Michaelis Prize in his final year.

Like the spoon-rubbing that once launched the magic and career of Azaria Mbatha way back at Rorke’s Drift, Joshua Miles, too, started his colourful career in that inventive manner. Today he is a master of the press. Hailing from a family where creativity was admired and inspired, his appealing imagery celebrates the landscape and the real.

32 Jack Journal Vol. 4

The 55-year-old artist has defined his visual work with one of the trickiest of methods: reduction printing, often described as ‘suicide printing.’

Joshua Miles. Kayamandi word wakker Reduction linocut 935 x 290mm.

33

Joshua Miles. Getting Ready. Reduction woodcut 700 x 350mm.

34

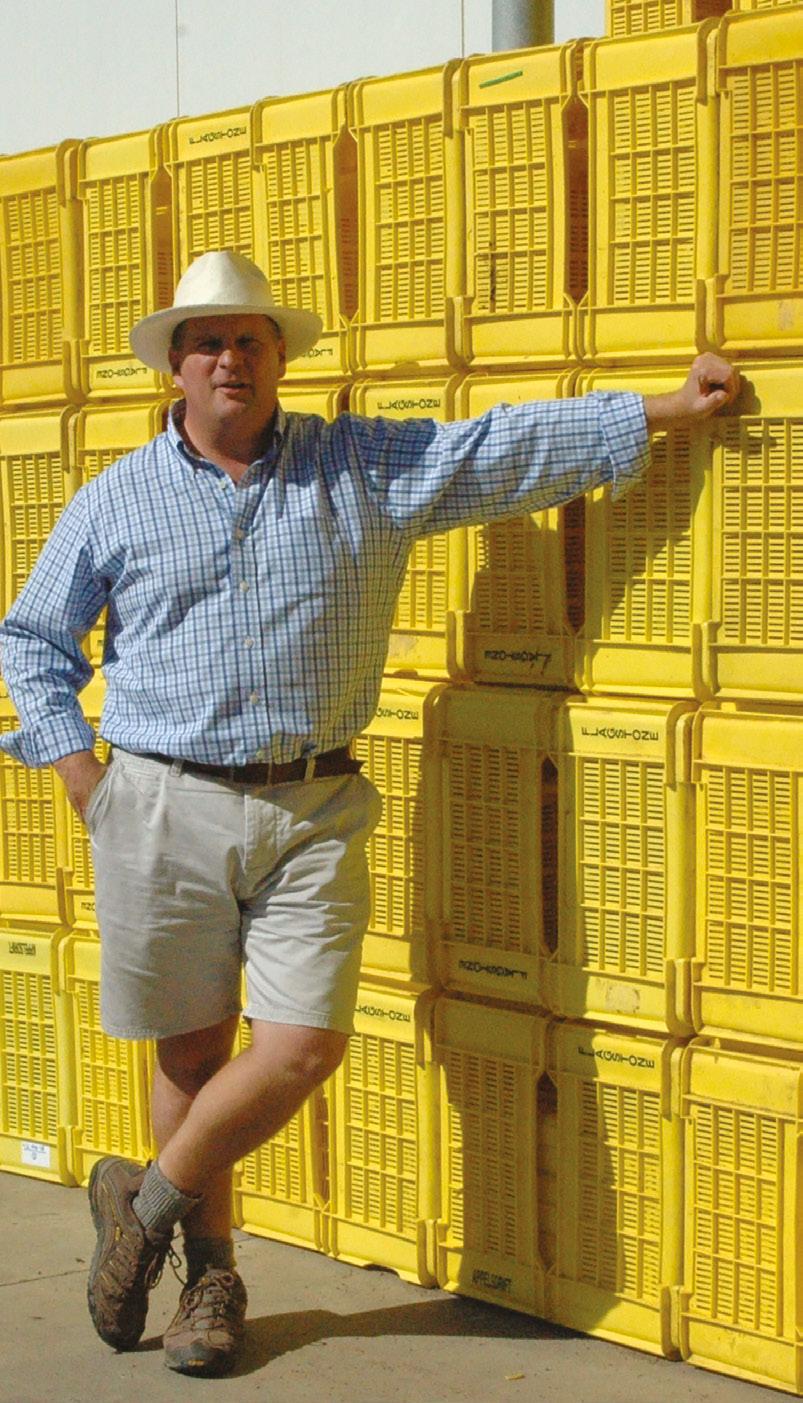

A few months after my winemaking studies at the University of Adelaide, two things occurred that I remember with such hyperreal clarity that it feels as though they happened a few seconds ago. Like many, I remember exactly where I was when I heard that the Princess of Wales had died. I was piloting a Ford F150 pick-up truck along the beautiful Route 116 in Sonoma County, listening to KRSH Radio. It was a clear day with no wind and I was winding along the Russian River.

I had landed a dream Sonoma vintage job at Flowers Vineyard and Winery on Camp Meeting Ridge overlooking the Pacific. I arrived a month before the grapes, and my first job was to wire the office lights from the electrical board through two storeys of conduit, the whole place smelling of recently set cement – the smell of a freshly built dream.

About a month into harvest I woke before sunrise to find the chief winemaker, Greg La Follette, fast asleep on the big Persian carpet beneath the boardroom table. He had driven a load of Pinot Noir grapes through the night from a mystical vineyard on the far side of San Francisco. Greg had only hired me thinking I was Australian, and up until that point hadn’t done a great job of hiding his mild disappointment.

I cooked us some scrambled eggs and woke him with a coffee.

As the ridge caught the first rays of light and the ranch ruffled itself awake, he suddenly asked: ‘Do you really, more than anything, want to be a winemaker?’

I answered unequivocally: ‘Yes, sir.’

‘Well, then, Bruce,’ he said, ‘you are inviting chaos and destruction into your life.’ He smiled a sad sort of smile through sleep-squeezed eyes.

A shaft of sunlight caught the suspended dust between us. I had no answer to that foretelling of doom.

‘As a winemaker your life will be screwed up …’ he continued, taking a long sip of coffee. I heard the chillers in the barrel room kick in. ‘… but there is one rule that might

save you.’ He seemed to be addressing his younger self. ‘The only thing that gives meaning to your crazy existence is how you craft wine. In the end that might be the only thing you can ever truly hold onto with certainty.’

With that, he stood and rubbed his eyes. The Mexican picking team were assembling outside with viticulture manager, Greg Bjornstad.

He pulled on his RM Williams and walked towards the door, then turned as I was clearing the plates and cups away.

‘Vint With Honour. That’s Rule no. 1, Bruce! Whatever happens,Vint With Honour!’ he stated brightly, his fist in the air. Then he turned like the Charge of The Light Brigade into another day of ‘Crush’.

Six months later, I was working as a cellar rat at Grant Burge Wines in the Barossa Valley where, one sweltering February day, I met an eccentric man with a flamboyant moustache. He cycled through the winery on a swanky bicycle, waving regally at the staff. Tanunda in the 1990s was more used to pub brawls and golfing tourists. Without dismissing the world-class pie shop, Tanunda was essentially a hard-grafting, hard-drinking, agricultural village. One didn’t expect strange-looking men on racing bicycles.

‘Where’s my tank?’ he shouted across the crushpad to Craig Stansborough, the head winemaker.

That’s how I learnt we were making a massive Shiraz blend for this strange man – ‘Naturally Australian’ it was called. What a terrible name, I thought.

As it turned out, the man with the moustache was a fellow South African called John Geber. A few years later, I was back in Tanunda, working for him and learning why ‘Naturally Australian’ was a name that actually worked.

But first I had to learn a lesson in perspective.

It was 2001, and my business, Flagstone Wines, was three vintages old. I had been invited by a big bank to present my wines to a group of wealthy private clients. I was sitting next to one of the asset managers, a beautiful young lady hosting our table. We were about the same age – early 30s.

When I sat down after introducing the first two wines, I noticed that she hadn’t touched her wine glasses.

‘They really are nice wines. I promise,’ I smiled and took a swig of my glass. She half smiled back and turned to talk to the person on her other side.

After presenting my last two wines, I saw she hadn’t touched those either. Full of zeal, I touched her forearm. She turned, the stress of the evening showing at the corners of her eyes.

‘Please,’ I implored her, ‘just smell them!’ and I gave her my warmest smile.

She cocked her head, then stood up to turn away. The adrenalin of presenting was pumping through me, so I stood as well. ‘Just smell them. I promise you, they are amazing.’

She turned to me. ‘Mr Bruce, thank you for attending. It has been most entertaining.’

‘That’s actually my first name,’ I mumbled, but her eyes held such a ferocity that I sank back into my chair.

After the obligatory crème brûlée and professed thanks from the CEO, the guests filed out of the mansion to their smart chauffeur-driven cars curved like a black cat’s tail in the circular driveway. I waited at the door for her.

‘I guess wine dinners are a real drag if you don’t like wine,’ I said, unable to hide a slight accusatory tone.

The staff were clearing up behind us and the endless Mozart CD loop had eventually been silenced. She looked at me with that directness. ‘When I was a young girl my father used to sometimes come home late and beat my mother so badly she couldn’t leave the house for a week. Sometimes he would beat me.’ She wasn’t blinking. ‘The smell of alcohol was on his breath and when I smell alcohol, I remember those moments.’

I stood there looking back at impenetrable, dark eyes. ‘I am sorry,’ I eventually managed.

‘Rule no. 1, Mr Bruce,’ she said flatly, ‘your reality isn’t the same as that of others, especially when it comes to alcohol.’

Until that instant, I was a rabid wine evangelist, spreading the gospel about the awe-inspiring, life-changing magnificence of fine wine.

That crushing paradigm shift on the front steps of that big mansion has forever tempered my fervour. Ever since then, I have been constantly aware of the huge responsibility that sits on my shoulders as a winemaker. We can only ever craft wine that is authentic, healthy and made with

35

love. We can only ever preach moderation. It is our continuous duty to educate, demystify and contextualise wine for the consumer. Wine is both the most sophisticated form of alcohol and the most storied beverage humans have ever consumed. It is by far the oldest form of drug we use and it is as varied, richly nuanced and interesting as the differing environments and craftspeople that influence how it is made. Crucially, it is a reflection of life itself, a confusing crucible of good and evil, an exciting journey of danger and joy. The Ying and Yang of wine is what makes it true. Winemakers play an integral role in creating this reality and we must always be on the side of light.

Back to John Geber, the man with the flamboyant moustache; and fast-forward to 2004. John had just bagged the bluestone Barossa landmark, Chateau Tanunda, in what can only be described as the valley’s deal of the century. It is an extraordinarily handsome building. On its completion in 1890, it was the biggest building in the southern hemisphere and it still takes my breath away. Dilapidated and in need of loving restoration, the Chateau was clearly undervalued and unappreciated when John pounced.

I took the job as John’s winemaking consultant because I needed the money. I had exhausted all financing facilities for my business and had run out of cash. All businesses need cash, but young wineries need more than most because of how much gets tied up in equipment, barrels and wine. As anyone who doesn’t inherit a wine business, or start with oodles of money, knows, running out of money a few years into the adventure is a fairly normal misstep on the winemaking journey. My solution, a common one, was to get a consulting gig. I sold my car to pay salaries for a few months and took a job halfway around the world in Australia. The plan was to earn some hard currency and hopefully keep Flagstone afloat.

I was tasked with cleaning up the winemaking side of the Chateau, cataloguing the barrels and fixing the wine quality issues I found. Since then, I have been so proud to watch how John and his team have put the Chateau’s wines firmly on the international wine map. After a rewarding three-month stint

at the Chateau, I joined John on one of his overseas sales trips. He collected me from Geneva Airport and we drove to a meeting with the buyer at Switzerland’s Co-op supermarket.

After pleasantries and a review of sales, John started talking price for the following year’s supply. At one stage he melodramatically pulled off his shirt and put it on the table with the key for the car.

‘You’ve taken all my margin, my friend; here’s my bloody shirt and car as well!’

This drew a wry smile from the buyer, who I suspect did business with John as much for the Geber Theatre as for the wine itself.

A pattern for the next 10 days soon emerged. We started early, fuelled with coffee and what biscuits we unearthed in the car. We drove for many hours and many miles each day, visiting all the main supermarket buyers in mainland Europe with a boot-load of samples. We never booked accommodation, but when we got tired, we turned off the freeway, found a small village and inevitably had to wake up a B&B owner for a room. We stayed in the cheapest accommodation we could find and only ate at truckers’ stops or petrol stations.

‘Always do selling trips on the cheap, Bruce; it keeps you sharp, keeps you hungry. You can’t let yourself become soft. Otherwise you get sloppy, you lose your edge. We don’t take prisoners.’

I also learnt that John, despite being a sole operator, was the biggest supplier of Australian wine to Europe at the time. But mostly, I learnt about Rock & Roll.

‘Your problem, Bruce, is that you are too clever for your own good,’ he said as we pulled out of a small village just before sunrise one morning.

I stopped rummaging in the glove compartment for biscuits and looked at him quizzically.

‘How many people in the world love watching tap dancing?’ he continued.

‘No idea,’ I answered, not quite sure I was prepared for a Geber lecture so early in the morning.

‘Compared to Rock & Roll, not very many …’ he mused, half to himself, ‘not because tap dancing is less demanding or takes less practice. It almost certainly takes more of both ... and that makes it even more ironic.’

‘I guess you don’t see 60,000-seater sports stadiums sell out to tap dancing concerts,’ I ventured.

He smiled his slightly maniacal smile, which meant he was moving in for the kill: ‘So why on earth do you tap dance, Bruce?’ he charged.

‘I don’t,’ I defended myself.

‘Of course you do. You’re a bloody tap dancer! Look at your branding – fancy, overly clever, self-indulgent marketing names like Music Room, Longitude and Free Run … you’re wasting your time. More depressingly, you’re losing all those customers who would love to taste your wine, but they are walking right past you, on their way to a rock concert!’

We drove along in silence for a few minutes, looking into the rising sun for signs to the freeway.

‘I presume you want sell-out wine stadiums?’ he asked eventually.

‘Of course, but I don’t know how to … and, I’ve got no fallback,’ I said honestly.

‘Well, my boytjie, you’d better learn how to Rock & Roll,’ he looked at me and winked. ‘That’s Rule No. 1!’

‘I am not sure where to begin,’ I admitted.

‘Start by calling your wine Bruce Jack,’ he countered without hesitation.

‘That’s a bit narcissistic and arrogant,’ I pointed out.

‘People buy wine from people, Bruce, not corporations or whimsical intellectuals. Get over yourself. Stop worrying about what people think of you. And find those biscuits, I need breakfast.’

Our self-perception is influenced by what others believe – or at least what they tell you they believe. This partly explains how we find our place in the world. It’s also how we lose our place in the world … it all depends on whom we listen to.

Like you, I know that lady luck also plays a big role – sometimes she deals you a bad hand, sometimes you get a break.

I quickly realised how lucky I was to be driving around Europe with John. I clearly wasn’t a quick learner when it came to marketing and, along with John Geber’s accurate insight, I also believed I needed some luck. Towards the end of 2004 I was still furiously tap dancing in circles, unable to get ahead of the curve. It meant travelling for about four months of the year to try and sell wine. And each time

36 Jack Journal Vol. 4

I depressingly drove off to the airport, I left a young family behind – this time I was on the way to Canada.

Despite my bribe of two bottles to the check-in lady, I was placed near the back toilets, against the tapering side and the last window of the fuselage, known at this end as the fusel-small. My fellow row passengers groaned as they saw me shuffle down the aisle towards them.

‘Oh, no, a fat one,’ the lady gurgled, not quite under her breath.

She swapped her middle seat with her husband, who was already twitching for a cigarette.

Newton’s fourth law of motion states that the cabin crew’s patience thins towards the back of cattle class. While I am sympathetic to their travails, this doesn’t stop me being a bit demanding on the wine front. I need my medication to take the edge off each turbulent jolt of paranoia bumpy flights ensure.

My neighbour hates flying, so we find something in common, and together clear out anything in the small bottle category we can wrangle from the prison wardens of the sky.

On arrival, it’s September 2004 and 5°C. After presenting a tasting to a group of Ontario journalists, I somehow get wedged in a swanky, subterranean Toronto bar (purple barstools and yellow lava lamps) with a guy called Donnie and his minders: Paula’s an ex-cop with what looks like a big stainless steel handgun, and Frank is an ex-ice hockey professional with a squashed nose that shunts to the left when he smiles.

Donnie’s ‘in construction’, he tells me, ‘and a bit of mining – that sort of thing’. We are halfway through the cocktail list (he’s buying for anyone in the room who can keep up), when the manager invites us to help interview Playgirl hopefuls for the new Canadian Playboy TV Channel.

Luckily, I had already bought tickets to see the seminal wine-nerd movie, Sideways, which happened to be premiering at the Toronto International Film Festival that night, so I decline the invitation.

‘You gotta be kidding, Jack,’ Donnie rolls his eyes to the bar.

I don’t remind him that Jack is not my first name. ‘Sorry, sir, the truth is I am a wine nerd.’ I try to explain.

‘Cool!’ exclaims Paula. ‘You know wine. Wow!’ And gives me a high five.

‘You wine nuts are fucking crazy!’ Donnie interjects. ‘Last week some cheerleader insisted I bathe her in champagne! Hell …’ he physically winces. ‘Cost me a fortune.’

We all agreed, however, that it was a fun use of champagne.

Broken-nosed Frank leans across the bar and, in a lilting Newfoundland twang, sings a ditty that ends: ‘Rule No. 1, man, follow the fun, the mun will come …’

Even the mobsters are friendly in Canada,

37

I think, as I pull on my beanie and bid adieu to my new friends.

The next morning I am on a short one-hour hop to Halifax, Nova Scotia, to give the winemakers’ address at the Nova Scotia Liquor Corporation’s annual banquet wine dinner. To understand the Canadian market in 2004, say the word ‘Corporation’ like you would say ‘Illuminati’.

On arrival, it’s 0°C and two big guys in puffy ski jackets share a cigarette outside arrivals. As soon as they see me, the one comes over, sticks out his hand and says: ‘Welcome to Nova Scotia, sir.’ He helps the other guy put my bags in the back of his buddy’s taxi and waves us goodbye.

‘Do all you guys always help each other with the luggage?’ I ask.

‘Sure, it doesn’t cost anything to help oot.’

This is great. On the trip into town, I ask as many questions as I can, the answer to which might potentially include the word ‘oot’.

I am not a fan of gala dinners with hundreds of people when I have to talk three-quarters of the way through them. To drink or not to drink? Seated with me at the head table is Joan Carol, of the pioneering Penedès biodynamic winery, Parés Baltà, and next to him sits Jesus.

It only takes a few glasses before I say: ‘Hey, Jesus, you must be named after the best winemaker in the world.’

‘Well,’ replied Jesus meekly, ‘I am actually only the export manager for North America and India.’

Jesus, it turns out, sold shedfuls of vino from a massive winery in Valencia called Gandía. I can’t help myself and suggest he develops a new brand for India called Mahatma Gandía. I find this very funny, but I suspect the fourth glass of maple syrup wine is helping.

Suddenly my name is called and I weave off to the podium, convincing myself that if Dylan Thomas could do this sort of gig wasted, so could I.

During the subsequent pub crawl, we walked for miles through what I suspect would be classified a blizzard – 90cm of snow was an impressive sight the next morning as the taxi slid and crunched its way to the airport, where I learnt that no more flights were leaving until the snowploughs turned up.

That night I found Jesus. He was snowed

in as well. I found him in the hotel restaurant and we drank a bottle of Guigal Grenache Blanc and a ripper Shiraz from Mount Langi Ghiran. We swapped hairy travelling salesman stories, compared websites and agreed that any show where the vivacious Patrizia Torti was showing her equally mesmeric Torti Estate Pinot Nero from the Oltrepò Pavese hills was worth a second visit.

Then he said: ‘Jack, my friend …’ ‘It’s Bruce actually,’ I corrected him. ‘Yes, yes, whatever,’ he placated me. ‘It’s muy importante time …’ and he started waving at the waitress who was trying to study for her accounting exam. ‘Es hora de Rioja – it’s time for Rioja!’

The Muga started rounding out the evening when Jesus grabbed me by the shoulder and said in a tone of revelation: ‘Regla número uno, my friend; Rule no. 1 … is simple: Only value is of concern. Fashions come and go … but no matter the price of the wine … it is value, or it is not. It makes the customer happy, or not … value is not a price, it is measured in your customer’s happiness.’

We poured another glass of happiness. ‘Yes, Jack, my friend, this is it, and it is simple.’ It turns out Jesus was right and it changed the way I thought about pricing forever. I would only ever charge what was fair and what I was certain would represent unbeatable value to my customer. It felt as if I had found the drummer for my rock band.

Jump to Germany 2010. I had sold Flagstone and was working for Constellation Wines, then the world’s biggest wine company. Markus Eser (my German sales contact) and I had just re-launched the Kumala brand. Three gruelling 18-hour days of agency meetings, press conferences, sales presentations and heavy dinners were behind us.

I don’t see many toothpaste factory managers getting on a plane to sell their product halfway around the world –why does the wine industry demand this of winemakers? Besides, they don’t teach you sales and marketing skills at Agricultural College …

Snow speckled the windscreen as we swooped out of the dark forest and onto the glistening Autobahn. It was late. We were both tired. We were listening to Stevie

Nicks on the radio and arguing about the origins of Fleetwood Mac, when I heard a disconcerting shudder coming from the engine of Markus’s brand-new Audi A5.

‘That’s coming from your engine, buddy!’ I said.

‘No way, man, must be that French car next to us.’ He was still sniggering when his car started lurching violently as the engine bucked and screamed. He pulled it hard over to the slow lane.

The car came to a grinding halt; the engine sounding as if it was eating itself. Smoke had started billowing from the front wheel arches; followed by the first licks of flame – like the hot, orange tongues of snakes eagerly smelling the snow.

‘Get out! Out!’ I screamed. I grabbed my laptop and my jacket off the back seat. Markus only had time to grab our phones, but had no time to retrieve his jacket or bag, never mind all the wine samples in the boot. In a few seconds, the car was full of dense, black, acrid smoke. As we jogged away, it became a very expensive bonfire.

‘We wouldn’t have got a child out of a baby seat,’ I said, my words wrapped in condensation.

Standing alongside the Autobahn in the middle of a freezing night somewhere deep in the German countryside, with one tweed jacket to share against the cold, I said: ‘Luck, my friend. We just used up a lot of luck.’

Markus looked into the night with its flecks of soft snow. ‘Yes, my friend, we are lucky, and sometimes not so lucky … but tonight, we are lucky.’ And I remember thinking that summed up this industry pretty well.

To be continued …/

38 Jack Journal Vol. 4

39

Contento Dishes & Drinks. Photography by Michael Tulipan.

Contento Dishes & Drinks. Photography by Michael Tulipan.

41

42 Jack Journal Vol. 4

Yannick Benjamin.

breaking down barriers in east harlem

Written by: Jim Clarke Photography by: Mikhail Lipyanskiy

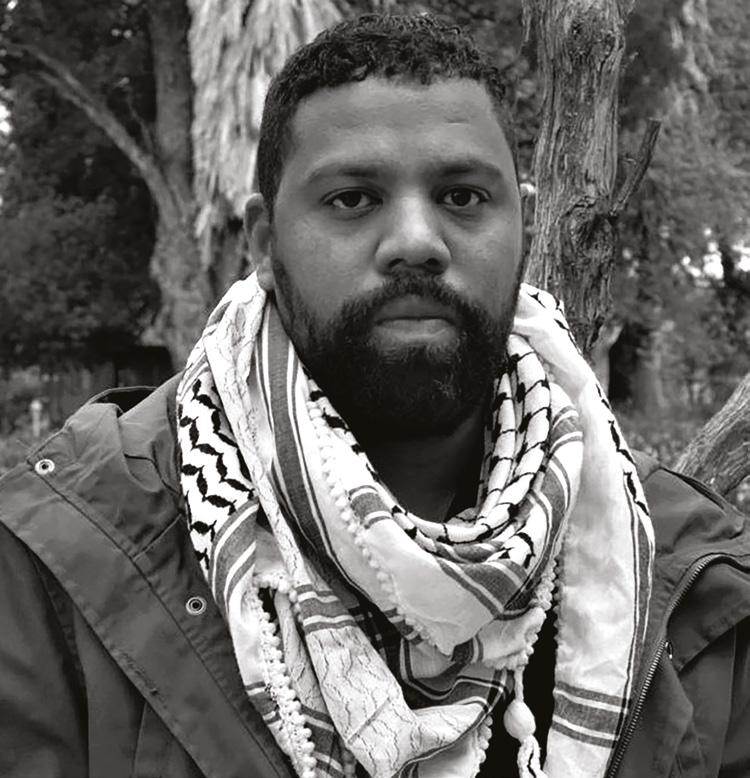

In light of the pandemic, any restaurant opening is cause for celebration, but in New York few new restaurants have been as impactful and cheered as Contento. Chef and partner Oscar Lorenzzi’s Peruvian cuisine has been drawing customers from all over to their East Harlem location, but so has the hospitality. In 2003, a car accident left partner, beverage director, and managing director Yannick Benjamin without the use of the lower half of his body, and his experiences have inspired a previously unheard of level of accessibility and inclusivity in everything the restaurant does.

What inspired you to pursue a career in hospitality and wine?

My entire family was in the restaurant business. My father’s from the north of France, from Brittany, and my mother was born and raised right in the heart of the Medoc in Bordeaux. Growing up, I would spend half my summer in Bordeaux, right in the middle of the vineyards. I remember the smell of fermentation, the smell of the cave, and it all seemed so interesting. And I actually had a terrible crush on Sam Malone and the whole team of Cheers; they just seemed like they had the best life.

After your accident, did you think a career in hospitality was still within reach?

My accident happened on 27 October 2003, and I got discharged from inpatient rehab on 9 January 2004. But I remember at the time calling my mom, saying: ‘Can you bring me some wine books?’ I remember getting the layout of the

restaurant Atelier, where I was working. It was a pretty spacious restaurant because it was in a hotel, so I was like, ‘if you move table 27 to the left and get rid of this table, then I can get around.’ I had no idea how challenging this was going to be – that took time.

I think I was probably a year and a half into it when I was like, ‘Shit, this is going to be challenging.’ I have no illusions; I have it better than probably 70% of people in the world that might be paralysed. But there were a lot of hills, a lot of blocked roads, and a lot of places where I had to build my own trails.

That being the case, what was your path back into the industry?

It wasn’t really until late ’04 or ’05, when Jean-Luc Le Dû, who is from the same village as my dad, was opening a wine store. He got connected and it was great to take a few steps back, to really see what the future was going to

43

44 Jack Journal Vol. 4

Photography by: Robin & Sue. Photography by: Robin & Sue.

I knew that if I were ever going to open my own place, it would have to be barrier-free and accessible. Of course, we have braille menus, we have adaptive flatware, we have an accessible bathroom –we have everything.

be. That’s what I needed to do. I needed to fully understand my body and what this new situation was.

But retail isn’t really my thing. Finally, there was a client who happened to be a member at the Yale University Club.

I had heard about an opening as a sommelier there, so I started picking his brain. The money wasn’t going to be very good, but that wasn’t the point. I just needed to get in the door somewhere. So I interviewed with a GM who hired me right then and there. And he said: ‘You don’t remember me, but I remember you. I happened to be one of the judges at one of the sommelier competitions. And I thought you were the best one at service.’

He never asked me what my shortcomings were. His only question was: ‘Is there anything that we can do to make it comfortable for you?’ I didn’t even know how to respond. I worked there for about eight years and made some really great connections; it really gave me the confidence I needed.

And when you were ready to open your own place, inclusion and accessibility were a priority?

I knew that if I were ever going to open my own place, it would have to be barrier-free and accessible. Of course, we have braille menus, we have adaptive flatware, we have an accessible bathroom – we have everything. We have people who work here with whom they can identify. But in addition, everyone else who works here who’s able-bodied is trained. We have people who have come here from the blind and low vision community, who are deaf, and then myself, who teach them proper etiquette and tableside manners and how to deal with people with disabilities. And that’s the most important thing. I think what we’ve done is create a conversation.

Aslina, to give a South African example; wine from people who are really breaking social barriers, people who are getting rid of that unconscious bias most people have of a winemaker looking like me – yes, I’m on a wheelchair, but just the white male, dressed up in a suit. There are people who are black, there are people of colour, there are people with disabilities who also do make wine, and make very good wine.

What can the wine and hospitality industries do to move forward with these ideas?

I think the world has become a much smaller place, and if there’s information you need, be it from the BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Colour) community or the disability community, the access is there. I think the key is to be humble. You’ll never get it 100 per cent right, but as long as you’re giving it 100 per cent effort, that’s what’s important. Be willing to learn.

With Contento coming up on its first anniversary,Yannick is now moving forward with a new project: a wine shop right in the Hell’s Kitchen neighbourhood where he grew up. Now that the pandemic has ebbed, he’s also looking forward to returning to live events for the charity he co-founded, Wine on Wheels. New initiatives include the Solera Project, which will provide training and internship opportunities for people with disabilities in hospitality and wine.

Food from left to right:

1. Contento Octopus, Black Chimichurri, Chilled Cauliflower Gazpacho.

2. Contento Ceviche Clasico, Corn, Onion, Cilantro, Sweet Potato, Leche de Tigre.

There are 61 million Americans with disabilities, with $500 billion in spending power; I think we’ve shown that if you build a place that’s physically open and barrier-free, and more importantly, if you create the culture we have, then people are going to come.

The concept of inclusion makes its way onto the wine list, too. The first section of the wine list is devoted to wines that have a social impact, like

For more on Contento.

45

46 Jack Journal Vol. 4

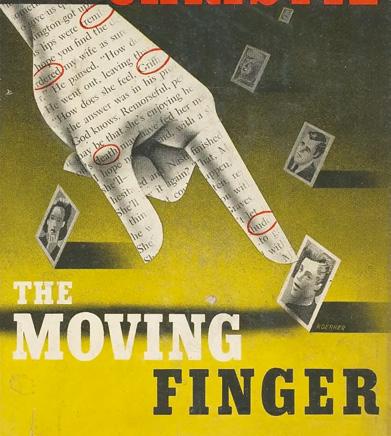

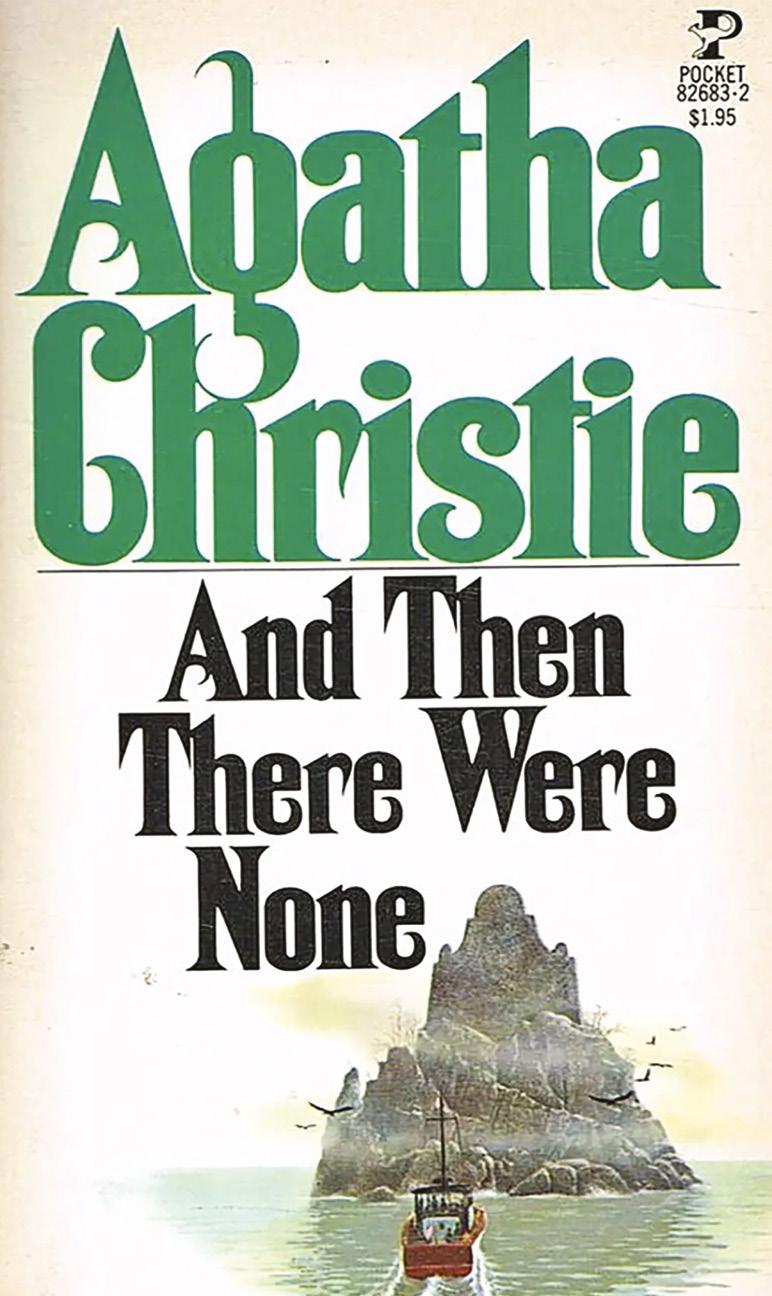

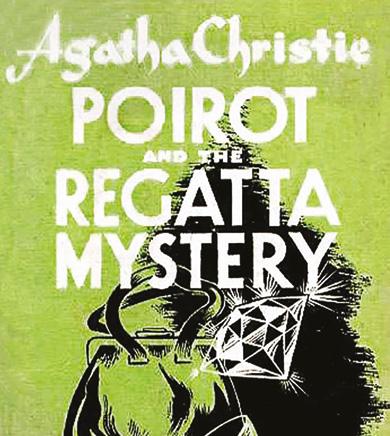

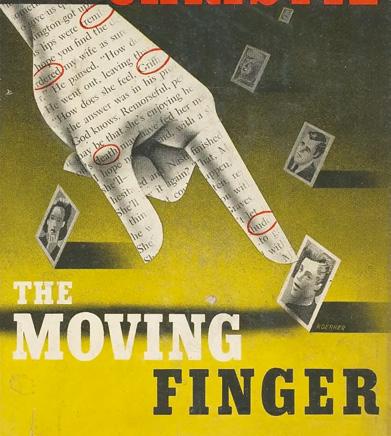

reading the detectives

watching the detectives,

watching the detectives.’ – Elvis Costello

Written by: John Higgins

We are all amateur detectives.

This is so in the simple sense that we try to understand the world around us and also need to make sense of the behaviour of those who are close to us, as well as those who promise (or is it threaten?) to come close either as acquaintances or friends, as potential lovers or stalkers.

That we are all amateur detectives is the source of the immense appeal of detective fiction.

For over a hundred years, detective fiction has been one of the most successful of popular literary genres, making fortunes (and attracting honours) for writers like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, Georges Simenon, Raymond Chandler and Dame Agatha Christie. It continues to do so for a whole host of writers today, including a Lee Child

or a ‘Robert Galbraith’ (aka J. K. Rowling).

The genre has also provided the narrative templates (and even the characters) for so many of our favourite TV or streaming series (Sherlock, Strike, Broadchurch, Killing Eve) as well as for a great deal of cinema. (Anyone ready for another remake of Murder on the Orient Express or Death on the Nile? Absolutely! How many detective series can BritBox take? As many as it can.)

As amateur detectives ourselves, we enjoy reading about someone who can so successfully read the clues and indices of social and psychological life. We like to read about a Sherlock Holmes or a Hercule Poirot because we would very much like to read the world and those around us as accurately and with as much insight as these detectives do.

The clue is the thing; that and the expert knowledge necessary to interpret the clue. The successful detective is usually a hybrid, an unusual combination of sociologist with psychologist.

Like the sociologist, the detective enjoys an insight into the social whole that is denied those like his or her readers who are confined to the fixed perspective embedded in our daily grind. Detectives travel across and between all the social strata while we readers remain stuck in our bubbles.

London cab drivers need to study for years to acquire ‘The Knowledge’ that enables them to find their way to anywhere in the 250,000 streets of that dense and complex metropolis. Our detectives have somehow acquired a similarly detailed

47

‘We’re

They’re

48 Jack Journal Vol. 4

knowledge of their social worlds.

They are as at ease in the palace drawing rooms of a ‘royal personage’ as in the opium dens of the East End (Sherlock Holmes) or drinking fine brandy in the Sternwood Mansion but going on to fight hoodlums the mean streets of Los Angeles (Philip Marlowe). Jack Reacher, while refusing to have a home (or even a backpack) and sometimes referred to as ‘Sherlock Homeless’, is as at home in the overwhelmingly crowded streets of New York (Gone Tomorrow) as in the empty wastelands of Nebraska (Worth Dying For).

‘Come,’ said Hercule Poirot, in Christie’s Appointment with Death. ‘We have still a little way to go!’ He says: ‘We have taken the facts, we have established a chronological sequence of events, we have heard the evidence. There remains – the psychology.’

The psychology. Psychology is not just present in the extreme form it often assumes in one strand of detective fiction. In this strand, the focus might be on the sociopath (think of John D. MacDonald’s Travis McGee novels) or on Oedipal and other family dramas (as do Ross Macdonald’s Lou Archer series or Anne Cleeves’ Shetland novels). Or think of those narratives in which the detective in question may be a psychological profiler and have to deal with a Hannibal Lecter (Thomas Harris’s Silence of the Lambs) or, indeed, a whole succession of variously disturbed killers, as Dr Tony Hill does across Val McDermid’s Wire in the Blood series.

No, the central psychology at work and on display in detective fiction is the everyday sense of psychology that is shared with the amateur reader. It takes in and adopts something like the procedures of observation and analysis present in Freud’s Psychopathology of Everyday Life or Erving Goffman’s Presentation of Self in Everyday Life.

These are the kind of observations available to us in the everyday life of the amateur detective.

Detectives watch with an analytic eye and listen with a therapeutic ear, registering the minutiae of body language and the giveaways of tone of voice. They fulfill Sherlock Holmes’ claim (also that of the therapist) ‘to fathom a man’s innermost thoughts’ by ‘a twitch of a muscle or a glance of an eye’.

All that is needed – it is implied to the reader – is to pay attention. ‘From another

bunch of guys I learned another mantra’, explains Jack Reacher. ‘Look, don’t see, listen, don’t hear.’ These ‘other guys’ surely include Holmes, who constantly repeats to his sidekick Watson: ‘You see, but you do not observe’. That we can also add to this ‘bunch of guys’ one of the greatest of great novelists, Henry James, also suggests the ever closer affinity of the detective story to the realist novel insisted on by P.D. James and Ian Rankin. James’s mantra for the aspiring novelist: ‘Try to be one of those on whom nothing is lost.’

There’s almost nothing to it – for the professional detective. As Hercule Poirot emphasized, interrogation need not even proceed by force. There is no need for the third degree, he insists. ‘No’, he says. ‘Just ordinary conversation. On the whole, you know, people tell you the truth. Because it is easier! You cannot lie all the time. And so – the truth becomes plain.’

Or – the promise of detective fiction is that it can become plain, and visible even to the amateur detective.

And, just in case we readers might begin to make that common move from admiration to jealousy and dislike, we are usually reminded that – as with the sports people we amateurs also admire –professionalism comes at a cost. This usually proves to be a cost we would not be willing to pay.

Holmes, in Conan Doyle’s version, is, after all, unattractively inhuman, and the BBC series Sherlock deals with this by telling us he may be suffering from Asperger’s Syndrome, and therefore still worthy of our now distanced sympathy. Agatha Christie grew to find Hercule Poirot ‘insufferable’, a ‘detestable, bombastic, tiresome, egocentric little creep’. Both authors wished to kill off their lead characters, but brought them back due to the intensity of public demand.

More recently, the formidable Jack Reacher, we gradually come to realise, may well be suffering from some form of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, and his apparently enviable freedom from all constraint and attachment is only achieved at some considerable cost in terms of his real existential isolation. (Indeed, I suspect that it was this growing insight into Reacher’s plight that made his author Lee Child give up the task of writing about Reacher and relinquish him to his brother.)

Our detectives tend to suffer from loneliness, alcoholism, trouble with relationships: just think of a Morse, a Rebus or a DCI Banks. The professionals pay a price amateurs can (hopefully) avoid.

We like – we love – detective fiction because it comforts us with the possibility that our own amateur efforts at reading the world are not only inescapable, but can also, at times, be spot on. Reading detective fiction rewards us with a sense that the world and our place in it make sense.

A clue is only a clue if there is meaning to the world.

49

A stunning display of Erica irregularis , unique to the Grootbos area.

51

52 Jack Journal Vol. 4

Sundowners at the new Garden Lodge.

I have been fortunate enough to visit South Africa umpteen times over the last 30 years, and I am often asked by friends and acquaintances about my favourite lodge or hotel. I do not even have to think about my answer, for one place stands out – Grootbos Private Nature Reserve, a magical place 30km southeast of Hermanus to which I have kept returning again and again after my first visit there 13 years ago.

South Africa has a list as long as your arm of great options, so why does Grootbos lead the way in such a distinguished field? It is hard to answer in one sentence, but suffice it to say that, like a great wine, it has multiple layers to it with so much depth and complexity. There is its exterior beauty, which hits you between the eyes, and then there is its inner beauty, which gradually reveals itself over the course of a stay. So

grootbos

Written by: Geoffrey Dean Photography supplied by: Grootbos

important to the whole ethos of Grootbos is its role in supporting both the environment and the local community. Instrumental in that has been the property’s owner, Michael Lutzeyer, a man of real vision and inspiration, who lives on site with his wife, Dorothee. Lutzeyer’s embrace of social upliftment in the area goes back many years to the first decade of the millennium, when he helped set up a football academy in nearby Gansbaai. Around 120 children, aged between six and 19, from the township flock there after school to improve not just their footballing but also life skills, such as learning English. Lutzeyer’s chance meeting with a Grootbos guest, who worked for Barclays, led to the UK bank building a R2.5m sporting clubhouse after the local council freed up some unused Gansbaai scrubland. Another Grootbos guest knew the then chairman of the English Premier League, Dave Richards, who was persuaded not only to fund the installation of a synthetic football pitch but also to pay an annual subsidy of R800,000 to the newly formed Football Federation of South Africa

(FFSA). With a central aim of promoting the sport among the disadvantaged youth of the country, the FFSA set up their HQ at the Gansbaai academy.

I vividly recall how my first stay at Grootbos in December 2009 coincided with a visit to the lodge and Gansbaai by the then South African vice president, Kgalema Motlanthe. He was in Cape Town for the draw, which was due to take place that evening, of the 2010 football World Cup. In the daytime, he and his entourage came out to see the children in action at the academy. ‘I heard some time ago about the fantastic effect the federation is having on the children in Gansbaai, and I wanted to see it for myself,’ Motlanthe told me at the time. ‘It is so uplifting, and I would like to give thanks to your Premiership for their tremendous support and to Michael Lutzeyer for his role. I am a big football fan and I don’t underestimate what it can do to help our youth and lift all our spirits.’

Grootbos has been attracting acclaim from many quarters, not just for its footballing connection. The 3,500-hectare

53

Ancient milkwood forests.

Ancient milkwood forests.

reserve has been voted The Good Safari Guide’s ‘Best Community Safari Camp in Africa’ on account of its training programmes in horticulture and ecotourism for the local unemployed. These take place at the reserve’s Green Futures Horticultural and Life Skills College, whose plant nursery helps to fund tuition.

David Bellamy, the celebrated conservationist, has described Grootbos as ‘the best example of conservation of biodiversity I’ve ever seen.’ Of the 9,000 plant species found in fynbos, there are 900 on Grootbos alone. More than 100 of these are endangered, and seven were discovered on Grootbos, with four of them thought only to exist in the reserve. These include the Grootbos erica (Erica magnisylvae), and two named after Michael’s father Heiner –Lachenalia lutzeyeri and Capnophyllum lutzeyeri With this extraordinary plant diversity comes enormous insect diversity (over 2,500 different species having been identified, with 26 different ant species exclusive to Grootbos). There is spectacular birdlife (at least 125 species) as a consequence, adding to the feeling that this is a veritable land of milk and honey when you hike or horseback ride through its milkwood forests, cone bushes and sour fig, lobelia and buchu plants. The latter, as one of Grootbos’ botanical safari guides told me, is very good for sore throats and bladder infections.

Equally medicinal are sour fig leaves, which not only soothe cuts, burns and jellyfish stings but also provide crucial refuge for tortoises, who nestle in them during a bush fire as they don’t burn. Grootbos is part of a fire-driven ecosystem, whereby plants use fire to regenerate themselves. Indeed, without fire, some species can become extinct. The last big fire on Grootbos was in 2006, when Forest Lodge sadly burnt down, but controlled burns are carried out now, using firebreaks. In November 2020, a burn of 120 hectares was successfully carried out.

One fabulous panoramic point, high up in Grootbos, is known as ‘God’s Window’ with its sweeping vistas out to sea and of the Walker Bay Conservancy. This is a huge 24,000-hectare area, comprising Grootbos itself, 49 other landholdings of various sizes, and the Walker Bay Nature Reserve by the ocean. Mike Fabricius, general manager of the conservancy, estimates that

55

56 Jack Journal Vol. 4

Local children taking part in sport activities presented by the Football Foundation.

57

Guests explore the reserve by 4x4 in Grootbos’ flagship flower safari.

58 Jack Journal Vol. 4

The sunset landscape viewed from Garden Lodge.

there are around 15 adult Cape leopards plus cubs in it. ‘The spotted eagle owl does very well in Grootbos as it feeds on rodents, which are highly abundant,’ he says.

If leopard sightings are understandably rare, what guests can see on Grootbos are six different species of small antelopes as well as caracals, genets, porcupines and honey badgers.