Volume 2 6 009803 763970

For me, the fleeting snapshot-like quality of my paintings evokes a sense of something just having happened; a word just spoken, a stifled cry, a sudden silence. This sense of suspension of time, of waiting, of bated breath is further emphasized by the objects floating in space between the viewer and the canvas. There is a strong sense of cause and effect; of misunderstanding, of things lying just out of reach but tantalizingly close. In the same way that colours at dusk are more vivid when glimpsed out of the corner of your eye, the feelings of obscure familiarity evoked by the objects are seductively accessible. Instead of alienating the viewer, the subject matter serves to invite the viewer into some kind of complicity in the unfolding events.

Caryn Scrimgeour carynscrimgeour.co.za

2 Jack Journal Vol. 2

Barbara gets banned from the Bookclub, 2019. - Oil on linen - 30cm by 80cm.

fromJohn

Keating in Dead Poets Society

by Tom Schulman

“We don’t read and write poetry because it’s cute. We read and write poetry because we are members of the human race. And the human race is filled with passion. And medicine, law, business, engineering, these are noble pursuits and necessary to sustain life. But poetry, beauty, romance, love, these are what we stay alive for.”

3

table of contents

contributors lessons from watching the reinvention of a city Bruce Jack

’n liedjie vannie rieldans Alison Westwood sake Anthony Rose

from trash to treasure Ashley Heather a labyrinth of legacies and musical signposts Josh Hawks gift of the givers Biénne Huisman foraging for mushrooms and other fungi on table mountain Ross Suter

the link between imagination and your wine glass Bruce Jack longing and belonging P. R. Anderson energy of trees 1 Cobus Joubert the national poetry prize Bruce Jack why joe dog makes me uncomfortable Bruce Jack there are none so blind as those who will not sea Aaniyah Omardien

an ode to mama esther and african womanhood Welcome Lishivha stars in the west Greg Mills

turning the tide Patrick Tagoe-Turkson

reverence for the future Frankie Pappas the magic of trees Don Pinnock inspiration and lasting legacies Jamie Goode saving a legacy Angus Sholto-Douglas the art of craft Ronnie Watt plaatje and the friendship of women Matthew Blackman version 1.0 Witold Rybczynski

4 Jack Journal Vol. 2

06 10 20 28 34 36 40 46 54 58 62 66 68 74 80 86 96 102 108 116 122 132 136

94

Editor: Su Birch Design: Allendre Hine & Rohan Etsebeth

editor’s letter

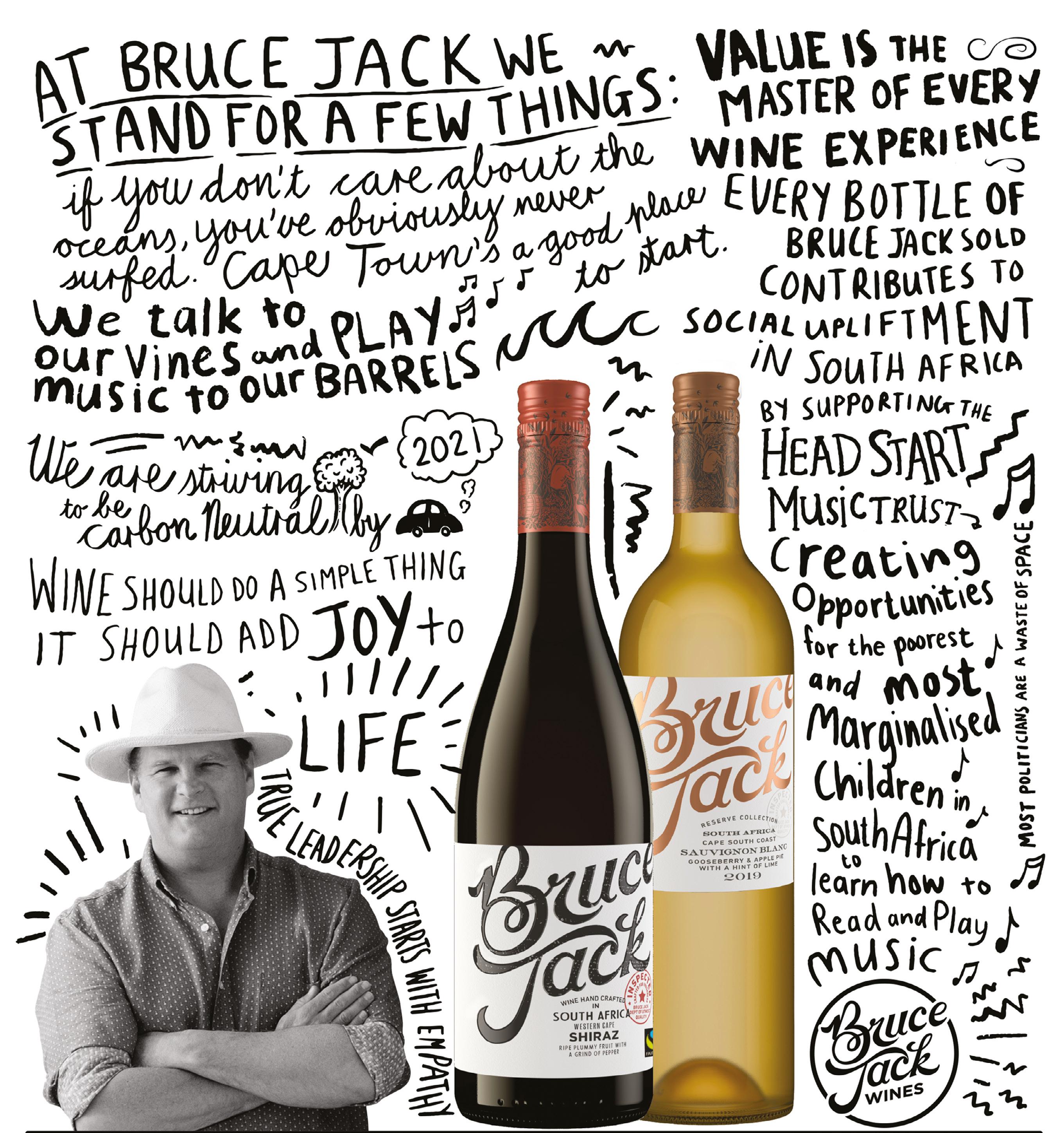

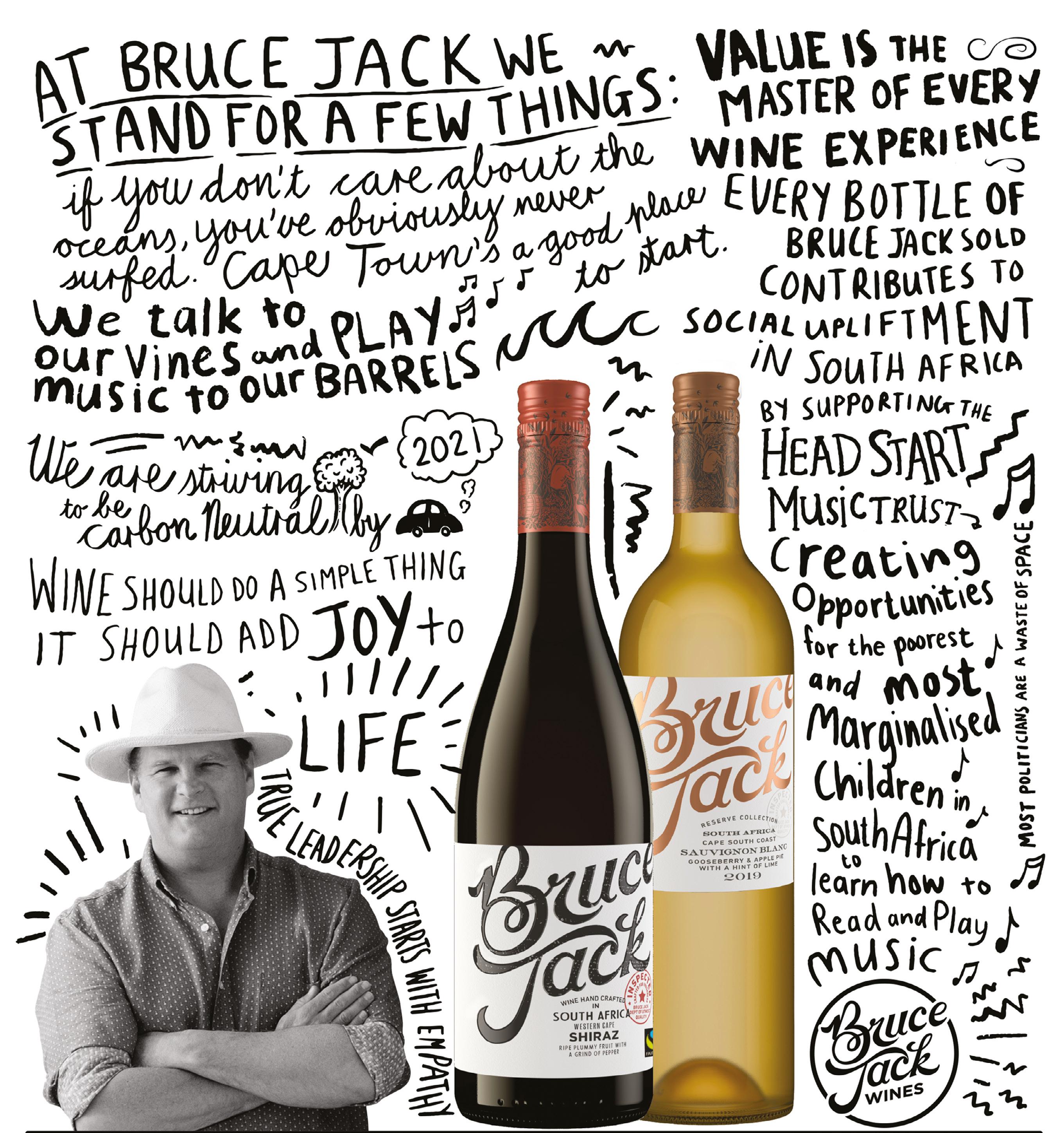

Jack Journal is a magazine about the world of Bruce Jack Wines and the things that we, as a creative business collective and passionate crafters of that ancient staple, wine, are interested in. In a small way it is like the Red Bulletin magazine of the wine world, because it is about the micro-universe of wine and more generally about the things that touch wine.

However, it is different from other product-specific magazines in that it isn’t about trying to sell or even about brand recognition. Instead it is all about welcoming the consumer into the intriguing world of Bruce Jack Wines.

We believe this is important because none of us operates in a vacuum. Our world is tangible, fragile, responsive, challenging, collaborative, sensitive, inspirational, and has context – whether historical, sociopolitical or financial, etc., this context influences us and our work.

Hopefully it will provide insight into what makes us tick – explain why we do what we do, in the way we do it.

But that’s all a bit boring. Essentially, Jack Journal is engaging to read. This volume is quite self-reflective and inward-looking, which partly reflects the state of the world around us. Settle down with an uplifting glass of true wine and dive in. We loved putting this volume together for you.

Bruce

contributors

P. R. ANDERSON

is the author of three volumes of poetry, most recently In a Free State: a Music , described by J. M. Coetzee as destined to be a landmark in South African poetry. He lectures English at the University of Cape Town.

SU BIRCH

is a distinguished international marketing and generic promotions specialist. As CEO of Wines of South Africa, she received the Drinks Business Woman of the Year award. She runs her own marketing business called Thinking Seahorses and has embraced the challenge of producing the Jack Journal. She also volunteers as an English coach in a local township school.

MATTHEW BLACKMAN

is a writer and historian. A co-authored book on the history of corruption in South Africa will be coming out in early 2021. He lives and works in Cape Town.

ROHAN ETSEBETH

designs and illustrates wine labels under the company name of Archival Studio. By the time of this journal going to print he will still not have gotten around to putting his own website up and most certainly will still be looking for the unmute button on Zoom.

JAMIE GOODE

is a prolific, London-based wine writer and book author. He has a PhD in plant biology and is a wine writer who grasps many of the technical aspects of wine production, making him a firm favourite among winemakers. His latest book is The Goode Guide to Wine: a Manifesto of Sorts.

JOSH HAWKS

Josh’s early career with The Streaks and Zap-Dragons saw him share stages with Nelson Mandela, UB40, Crowded House and Duran Duran. Seventeen years with Freshlyground included collaborating with the likes of Stevie Wonder, Aretha Franklin and a global no.1 hit with Shakira. Recent projects include Zulu rock ’n’ roll band The Rockskandi Kings. He is currently studying for a Postgrad dip. through the Henley Business School.

6 Jack Journal Vol. 2

ASHLEY HEATHER

is the founder of ashley heather jewellery, an independent jewellery studio crafting minimalist pieces in silver and gold recycled from e-waste. With a degree in fine arts, 10 years’ experience in jewellery design and a lifelong passion for sustainability, she developed her business as a way of melding these often quite disparate passions.

COBUS JOUBERT

is a farm-raised creative who spent his teenage holidays surfing at the famous Robberg Beach. He now lives in St James, South Africa, with his wife and three children. With his team at Wawa Wooden Surfboards, Cobus builds surfboards inspired by the intuited hydrodynamic genius of the ancient Hawaiian board builders.

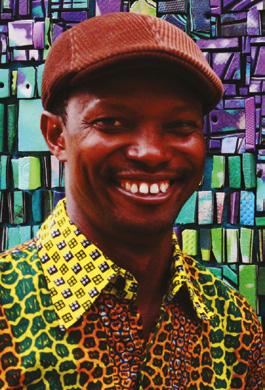

WELCOME LISHIVHA

is a freelance writer whose work has appeared in the Mail & Guardian , Getaway Magazine, Reuters and the City Press where he served as the Arts and Lifestyle Co-Editor. Prior to working for the City Press, he was longlisted for the City Press Non-fiction award and shortlisted for the Gerald Kraak Anthology. He enjoys baking complicated pastries from scratch, trying out new eateries and reading Keats.

BIÉNNE HUISMAN

is an award-winning South African journalist with an MA in Creative Writing from Royal Holloway, University of London. She has worked for the BBC, the Sunday Times, Daily Maverick , Getaway Magazine , Open Skies, and more.

ANTON KANNEMEYER

is a satirical artist and co-founding editor of Bitterkomix, an anti-apartheid comic magazine in South Africa. He has exhibited extensively in South Africa, Europe and the USA and his work has been published in numerous publications and catalogues around the world and is held in many permanent art collections, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

FAINE LOUBSER

is a filmmaker, storyteller and environmentalist working with Sea Change Project, Wavescape and GoPro South Africa. She has spent several years committed to learning in nature, with a specific focus on the kelp forests along the Cape Peninsula.

7

GREG MILLS

is the author of numerous best-selling books and heads the Brenthurst Foundation. Previously National Director of the SA Institute of International Affairs, he has directed reform projects in African presidencies like Ghana, Lagos State, Mozambique and SE Nigeria, Kenya, Lesotho, Somaliland and South Africa. He has served four deployments to Afghanistan with the British Army as the adviser to the commander and has his national colours for motorsport. In 2019 he headed the first South African team to participate at Le Mans, driving a Bentley GT3.

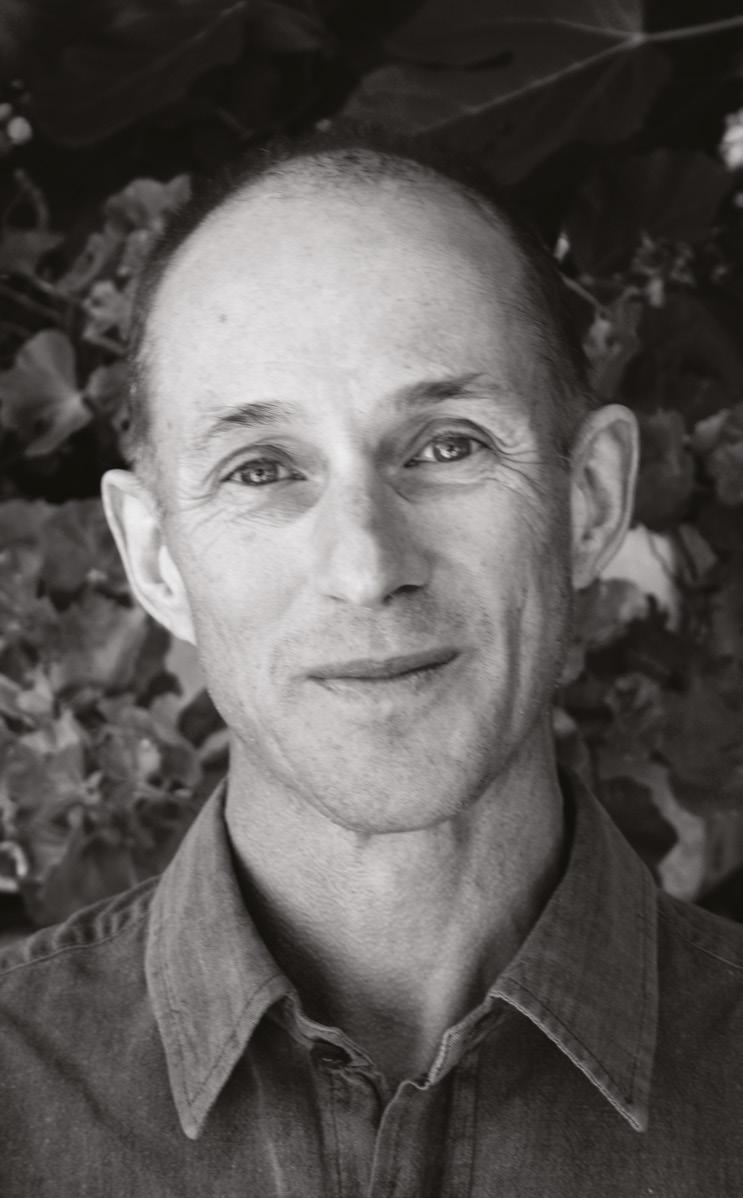

FRANKIE PAPPAS

is an architecture firm making remarkable spaces and places with a very unusual philosophy.

ANTHONY ROSE

A founding member of The Wine Gang, Anthony contributes to Decanter Magazine, The World of Fine Wine, The Financial Times How to Spend It and the Oxford Companion to Wine. In 2007 he developed an interest in sake after visiting Japan as a judge at the Japan Wine Challenge. He is a judge at the Sake International Challenge in Tokyo, teaches a sake consumer course in London and is author of Sake and the Wines of Japan.

ANGUS SHOLTO-DOUGLAS

has spent the last 28 years working in the wild spaces of Africa. Starting in the Sabi Sand Game Reserve then moving to northern Botswana and eventually back to his roots in the Eastern Cape, he established Kwandwe Private Game Reserve (a model 55,000-acre wilderness reserve). He is a trustee of the Kwandwe Rhino Conservation Trust, serves on the board of the Private Rhino Owners’ Association and chairs the Ubunye Foundation, a Community Development organization.

AANIYAH OMARDIEN

Aaniyah’s work connects people and nature. While at World Wildlife Fund from 2001 to 2010, she managed the SA Marine programme. She is the founder and director of The Beach Co-op, a not-forprofit company that evolved from the work of a group of volunteers that started collecting marine debris at their local surf break, the rocky shore at Surfers Corner in Muizenberg, Cape Town.

DON PINNOCK

is an investigative journalist, photographer and travel writer who, realising he knew little about the natural world, set out to discover it. This took him to five continents – including Antarctica – and resulted in five books on natural history and hundreds of articles. He has degrees in criminology, political science and African history and is a former editor of Getaway travel magazine. The Last Elephants is his 18th book. He lives in Cape Town.

WITOLD RYBCZYNSKI

lives in Philadelphia, USA, and is the author of more than twenty books, including Home and How Architecture Works. His latest is Charleston Fancy : Little Houses and Big Dreams in the Holy City

ALLENDRE HINE

is a strategic creator and a lover of crafted design solutions, film, coffee and meaningful conversations. Allendre is graduate of the Red & Yellow School of Logic & Magic.

8 Jack Journal Vol. 2

ROSS SUTER

was born in Cape Town and grew up on the slopes of Table Mountain where he has been hiking and rock climbing since the age of 12. He originally practised as an architect before changing career in 1996 to mountain guiding and training. His business focuses on mountain leadership, walking, hiking, rock climbing, botanical exploration and foraging.

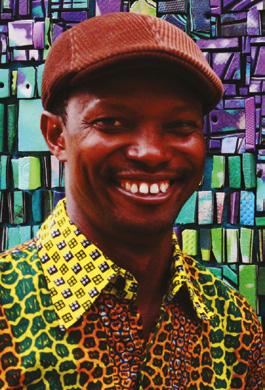

PATRICK TAGOE-TURKSON

is a Ghanian-based multidisciplinary artist. Patrick is best known for his nature art and his works made using found flip-flop debris on the beach. He blends the historical Effutu Asafo flag-making art with his environmental activism. His artwork has been shown in exhibitions throughout the world including the Korean Nature Art Biennale and the Echigo Tsumari Art Triennale, Japan. His works are in permanent collections at the Royal Ontario Museum, Canada, and the Casoria Contemporary Art Museum in Italy.

ALISON WESTWOOD

has been travelling to and writing about Africa’s top destinations for more than 15 years. Her writing and photographs have appeared in various magazines and online publications, as well as a book or two. The Cape is her favourite place in Africa, at least partly because of the wine.

CARYN SCRIMGEOUR

is a graduate in Fine Art from the University of Stellenbosch. She is represented by the Everard Read Galleries in South Africa and London, and her masterful still-life paintings are found in many local and international collections. Her work is inspired by her travels around the world, and her curiosity about how we make meaning in our lives.

RONNIE WATT

is a ceramic arts historian with a specific interest in 20th- and 21st-century South African studio pottery and ceramic art. He started collecting studio pottery in the 1980s. His most recent academic research focused on a contextual history of South African ceramics.

ANDREW VAN DER MERWE

As a surfer, time spent on the beach led to a new art form which Andrew calls beach calligraphy. His way of working is unique in the world, and he has developed his own tools and techniques for the process. The letters are carved into the surface in a way that evokes the ancient way of carving in stone, yet it is all soon washed away by the waves. Occasionally he works on a large, monumental scale using an ordinary rake, but always, like most beauty, the beach work is ephemeral. He also designs wine labels.

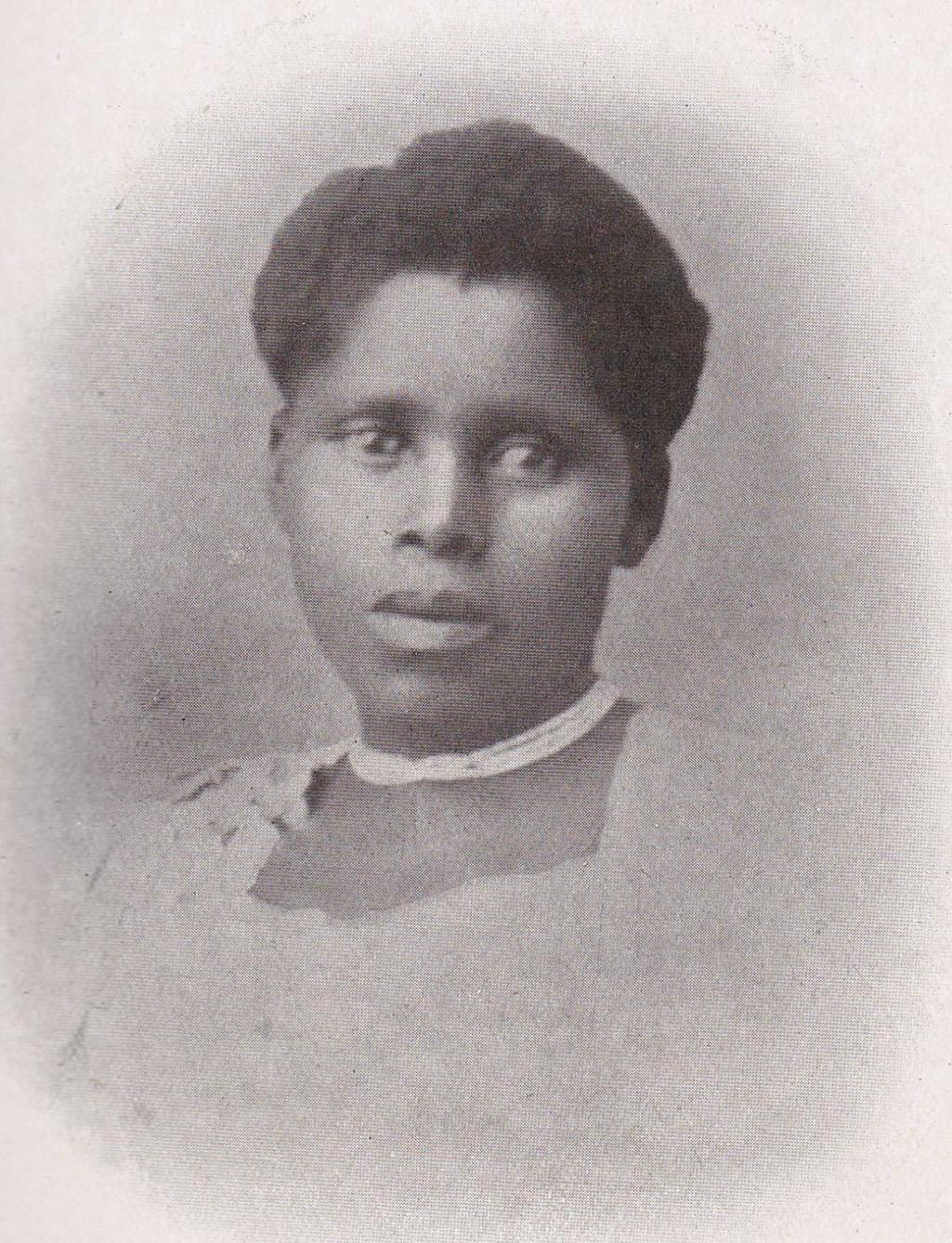

JUDY WOODBORNE

is an internationally awarded printmaker and painter with her own printmaking studio, Intagliostudio, where she teaches classes, runs workshops and curates exhibitions. She has participated in many International Print Biennales and her work is represented in many International Public Collections and Museums. Her ‘Break the silence’ print portfolio is in permanent collections across the world.

SHERYL OZINSKY

has been involved in making things happen in Cape Town for a very long time. She headed up Cape Town Tourism for six years, helping to establish the City as among the world’s favourite tourism destinations. Sheryl, a marine biologist, was involved in starting the Two Oceans Aquarium and establishing Robben Island as a heritage site. Having founded the Oranjezicht City Farm, she then started the Farmers Market at the V&A Waterfront.

9

The Cape Town Waterfront

The Cape Town Waterfront

lessons from watching the reinvention of a city

Written by: Bruce Jack

Written by: Bruce Jack

There is a litany of welldocumented studies detailing how built environments affect all who live in, around and through them. Too often the lack of sympathetic, holistic planning results in a negative experience, with a catalogue of undesirable consequences. Poor design plays a big part in bad planning, as does spatial planning, unsympathetic use of scale, etc. … not to mention ego and nefarious agendas.

I am not just referring to the infamously bad examples like the urban housing project of Pruitt-Igoe in St Louis, Missouri, in the USA. First occupied in 1954, all 33 high-rise buildings proved such a social disaster that they were levelled by explosives two decades later.

As the son of an architect, I am not allowed to say this, but I believe, to a greater or lesser extent, that the vast majority of our built environments are failures. I can hear the gnashing of architects’ and city planners’ teeth just for committing such heresy to paper. I would also argue that positive legacies in this realm are the infrequent exception.

These little miracles of urban upliftment exist at the other end of the scale from Pruitt-Igoe. Instead of destroying hope, they bring happiness. The absolute pinnacle for me are the examples of developments that have saved a deteriorating built environment or crumbling city. Those are so much more difficult than starting with a noble idea like Cadbury Chocolate’s Bournville ‘Factory in a Garden’ vision of the 19th century, because the rot has already set in and success looks impossible.

When these mini miracles brighten urban lives, an oft-quoted common denominator is an individual champion with a bold vision and genius to burn. We think of pioneering

inner-city pedestrianisation initiatives like StrØget in Copenhagen, Denmark. The protagonist for this car-free inner-city experiment was Alfred Wassard, who received death threats for his trouble. When it first opened, the police were on hand to protect him against assassination attempts, and car drivers protested their displeasure in side streets by honking their horns. The architect, Jan Gehl, is now legendary for his visionary insight and planning of pedestrianised inner cities that swayed policy change towards pedestrian- and bicycle-friendly inner-city spaces in many cities around the world.

Architects and urban planners, etc., like to talk about ‘Liveable Cities’, by which they mean the handful of cities that aren’t horrible to live in. This means we mostly have to rely on miracles of rejuvenation to create ‘Liveable Cities’. Perhaps the most famous rejuvenation story is that of a Brazilian city, Coritiba, and an extraordinary man, Jaime Lerner, who happened not only to be a visionary, but both an architect and

12 Jack Journal Vol. 2

the mayor of Coritiba. It is an inspirational story and my father knows it inside out. Many an evening around the dinner table has been spent analysing Coritiba’s reinvention and other successful rejuvenation projects like the Rouse Company’s Baltimore waterfront development in the USA.

The outside-looking-in mythology of these rare and remarkable success stories focuses on the champion catalyst with unstoppable charisma and audacious vision, because it is easier to explain success or failure through the stories of people. But this means we often miss the enigmatic seeds of success and happiness.

Sociopolitical, environmental and economic good timing, for example, are just as crucial as a visionary champion. And cooperative leadership, broad collaboration, committed teams, loyalty and hard work are essential too, but they seldom get the limelight they deserve – maybe because it is challenging to measure the degree of leverage these fluid, dynamic influences have

on an unpredictable outcome.

The reality is that sustainable revitalisation in the most immoveable and socio-impactful of environments relies on a mind-boggling, complex set of interrelated influences. To satisfactorily unpack this is almost impossible.

And then we have luck, whose role is hopelessly unquantifiable, and, in some cases, even culturally uncomfortable to accept –especially in the self-determined world built of minute and certain measurements.

But the lessons and the mysteries are there, waiting less for deciphering and more for acceptance. The mysteries are like the spirituality of place – those poorly understood interacting elements that unexpectedly combine to create social cohesion and happiness.

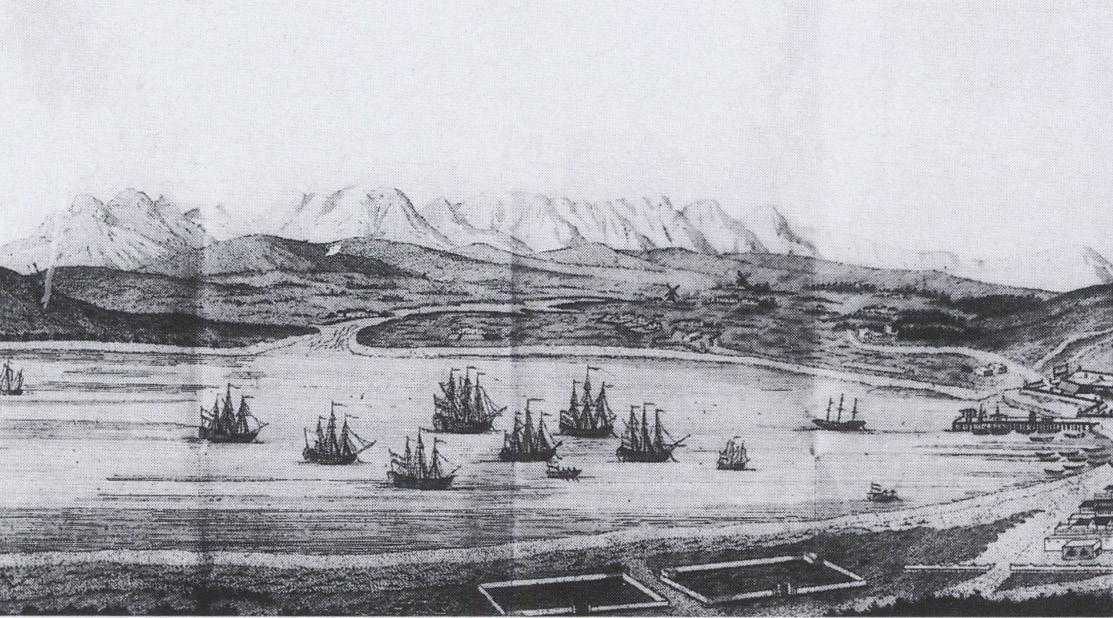

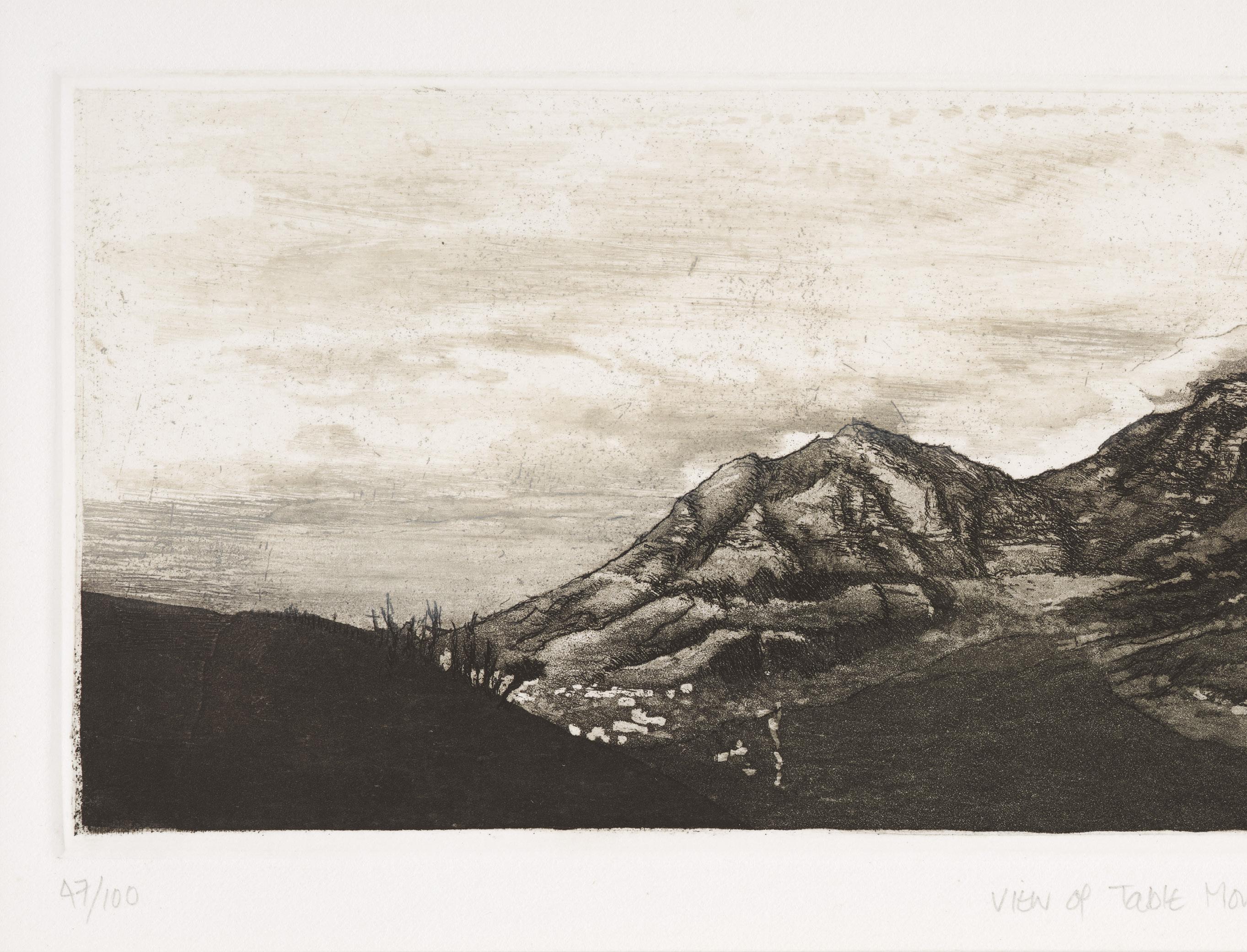

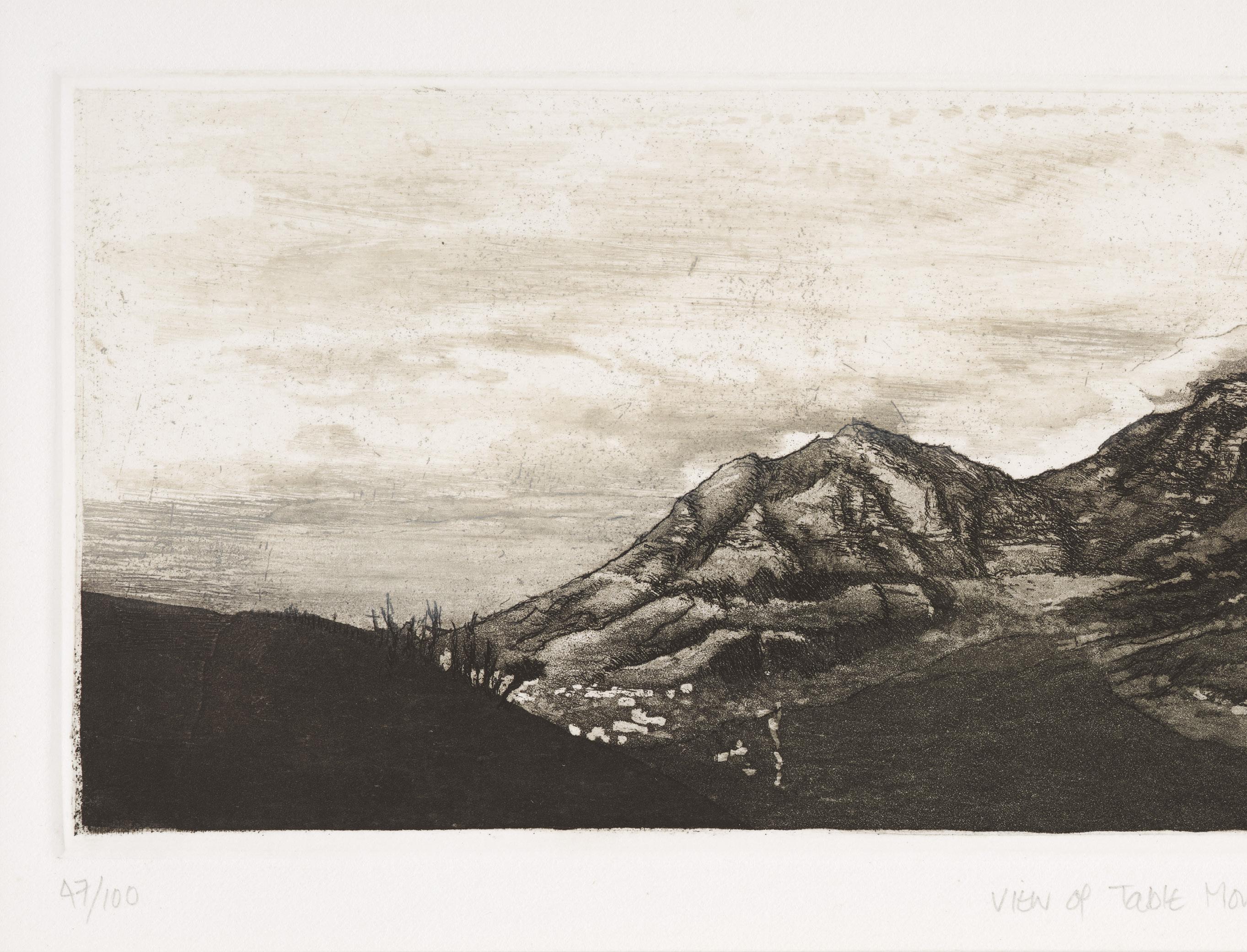

I grew up in the mountain-dominated port city of Cape Town at the southwestern tip of Africa. It is, like the rest of South Africa, a polarised place. Anchored by the brooding granite presence of Table Mountain, it feels suspended in a different reality from the rest of the world, held by

the tension of coexisting radical opposites – awesome beauty alongside revulsion. The peaceful and the violent, like the desperate and the decadent, materialise simultaneously and continuously. And then there is the stubborn legacy of social disunity and economic destruction wreaked by apartheid-era spatial planning.

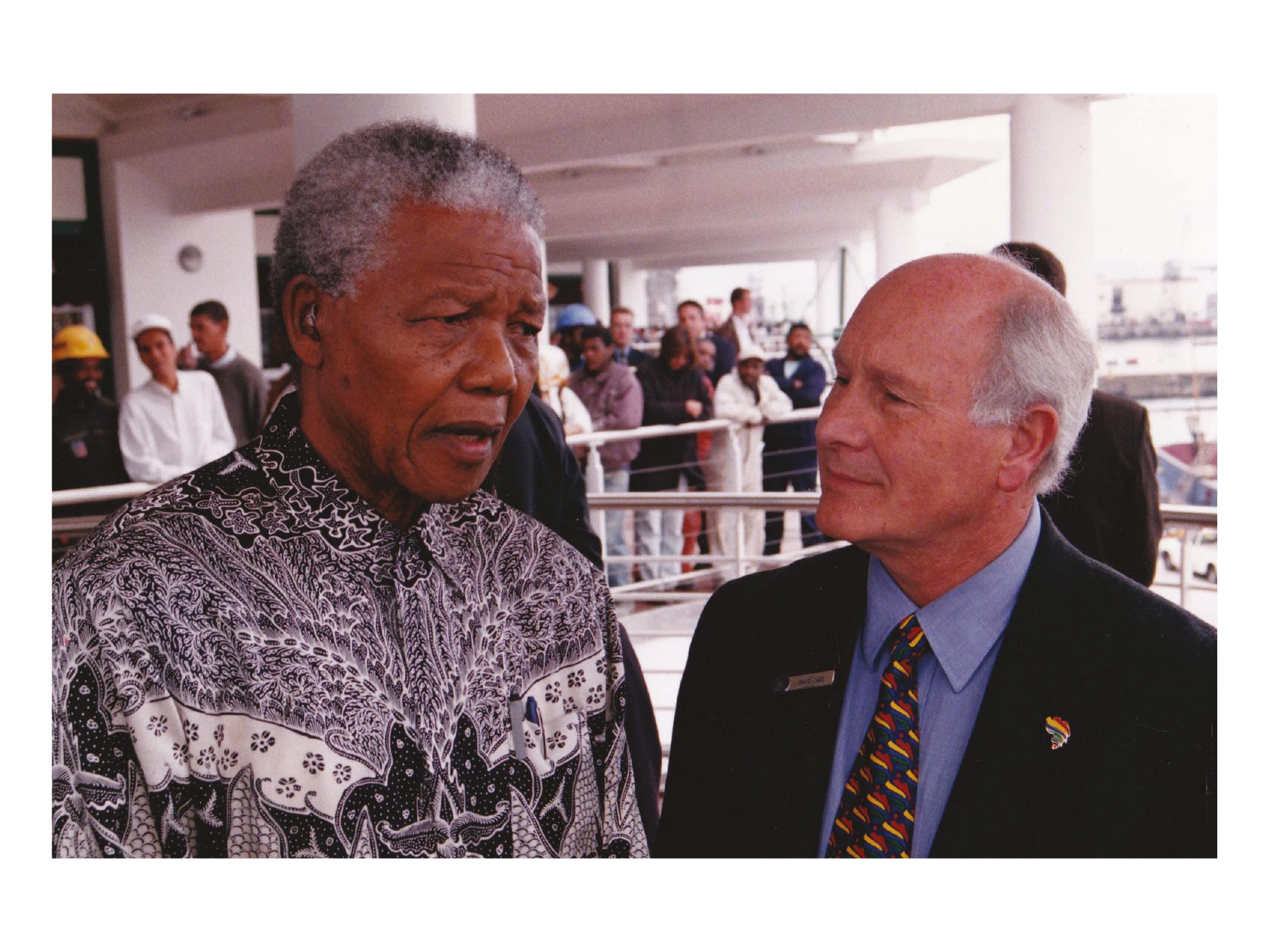

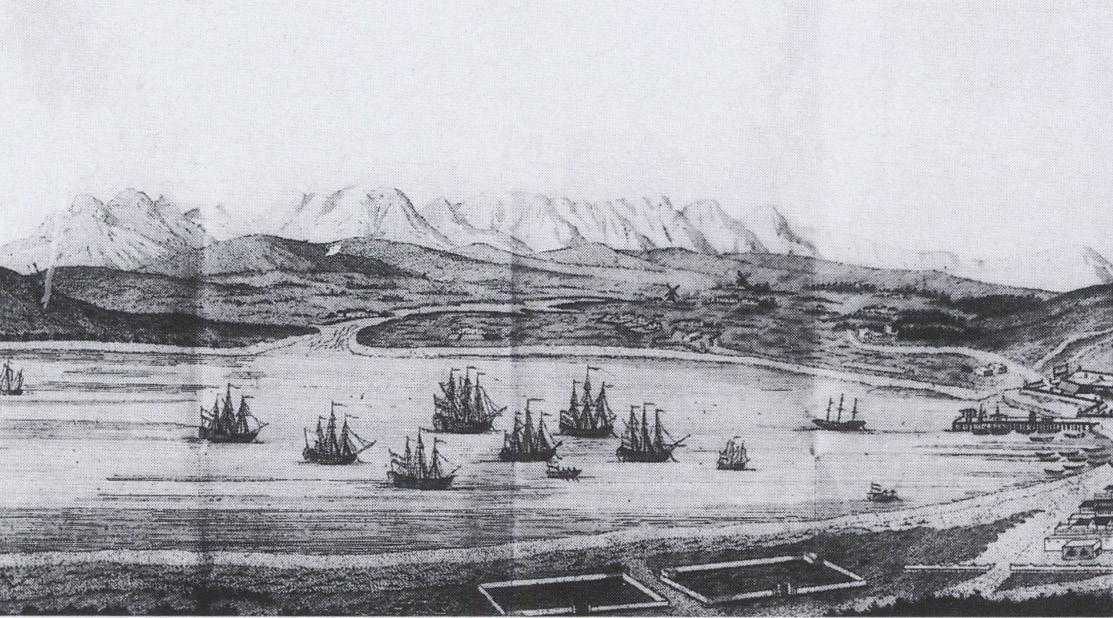

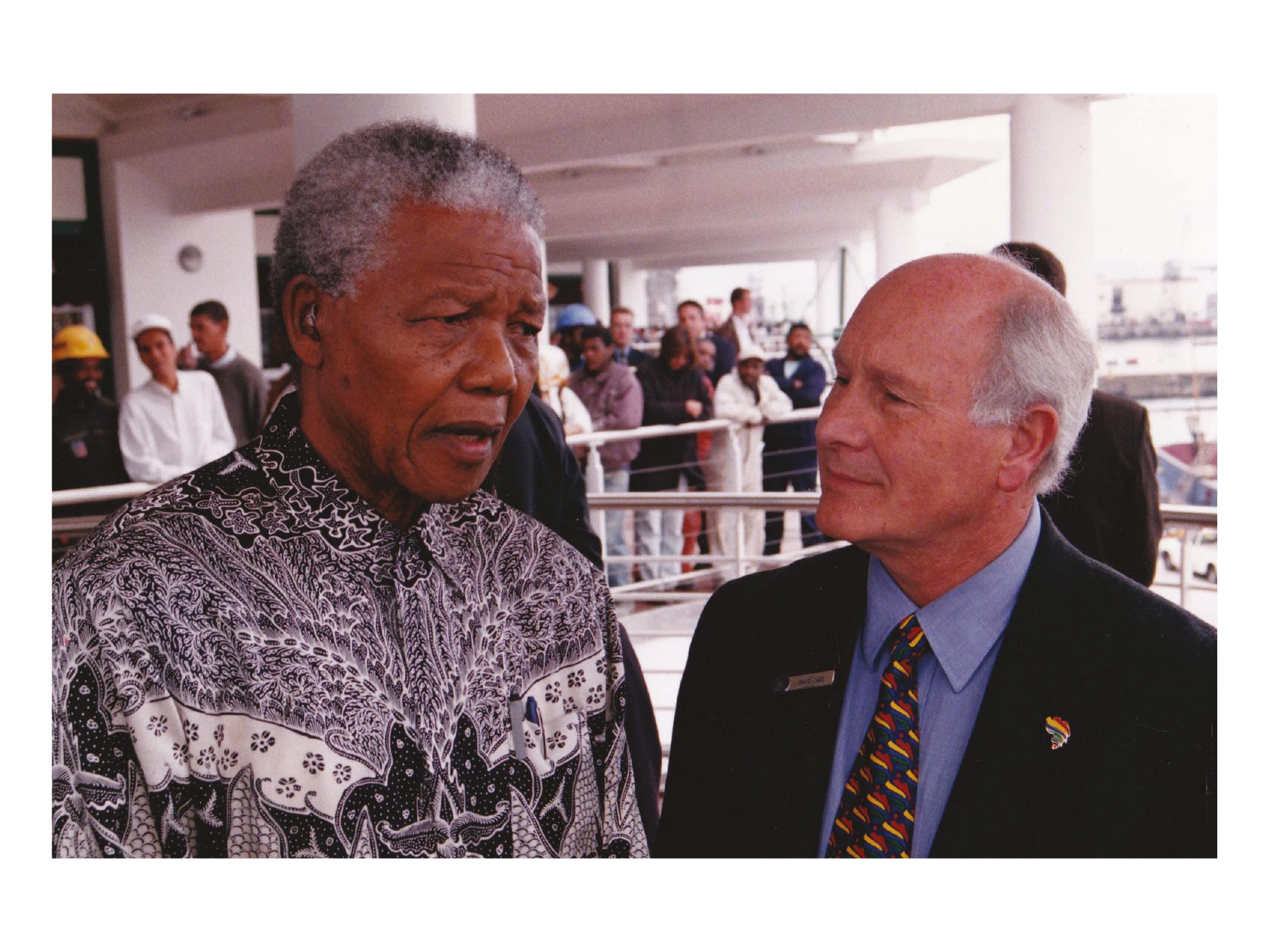

Against this backdrop, our own miracle of inner-city rejuvenation took place, and I had a unique view of it unfolding. I was backstage as the Victoria and Alfred Waterfront was conceived, and I watched it transform Cape Town from the inside looking out. This unique insight was possible because the man who orchestrated it is my father, David Jack.

Recent figures show that Cape Town’s Waterfront is the most visited tourist attraction in Africa, with over 24 million visitors annually. While conceived primarily as a place for Cape Town’s locals, it has become a must-visit tourist destination. On most measurable levels – economic or social – the V&A is an unprecedented

13

>

globally significant success. The momentum it has created has rejuvenated the City Bowl and the Western Cape. It created thousands of indirect and direct jobs and provided a welcoming, culturally sensitive, relatively crime-free, clean, embracing space for all Capetonians.

But these miracles of the built environment don’t happen in a time bubble. Context is required to unearth the mysteries and the lessons. My father’s father, James ‘Stan’ Jack, was head of investments for Goldfields of South Africa, and so my father was born and attended boarding school in Johannesburg. Both sides of my family are almost exclusively of Scottish origin, with the Jacks having been involved in South African mining in some way or another since the mid-19th century. But instead of becoming a mining engineer, my father chose the University of Cape Town and architecture.

Here he excelled, met my mother on a blind date, and won a scholarship to study further at the Architectural Association in London, focusing on urban design in developing countries. He further excelled in London and won a Rockefeller Fellowship to the University of Los Angeles, USA, where he completed a master’s degree in urban planning. It was here that he became intrigued by waterfront and marina developments and visited as many as he could all around the USA and Canada to study them first-hand.

On completion of his degree, he was snapped up by the Californian architectural practice of Charles and Ray Eames, and so I should have been a Malibu grommet, not a Muizenberg one, because there was no intention to return to apartheid South Africa. Unfortunately, my grandfather-to-be, Stan, was diagnosed with cancer, and my parents reluctantly headed back to Africa, where I popped out some months later. Stan lived on for another decade and they stayed as a result.

On his return to Africa, David Jack was an unknown but landed a job at Anglo American Properties, then developing the groundbreaking Marina da Gama in Cape Town’s southern peninsula. Our first house was the old servants’ quarters of the Sandown-on-Sea Hotel on Surfers Corner, Muizenberg, a stone’s throw from the marina development.

Sheryl Ozinski worked with my father in different capacities on various key projects and has known him for 30 years. I asked her to provide me with some of her memories of the waterfront project, but she started with the marina development because it was here, she believes, that David Jack developed his unique way of working.

‘David Jack is not a follower. He didn’t simply change our environment for the better, he created important models for change. And he did that successfully, not just once or twice, but many times during his career.

‘It was during the development of the Marina da Gama project that David worked with many of Cape Town’s professional teams to provide a set of design parameters, while they built one of the city’s first iconic developments.

‘David understood that no single professional discipline can possess all the skills needed to address the complex issues facing South Africa’s towns and neighbourhoods. He knew that planning and design are multifaceted, and that these professionals needed to acquire extra competencies through collaboration. He envisioned a holistic development practice that included architects, town planners, engineers, geographers, urban designers, landscape architects, community leaders, biologists, environmentalists and historians, amongst others.’

This collaborative philosophy was something drilled into me at an early age. When he heard me criticising a rugby teammate at under-11 level, he took me aside after the game and said: ‘Everyone is trying their best out there. If they make a mistake, it isn’t on purpose. Criticising them won’t help, it will just make them more nervous and more likely to make mistakes in the future. Rather, encourage someone who has made a mistake and restore his confidence. In that way he is less likely to make the same mistake in the future and the whole team performs better.’ I kid you not. That’s a true story and even though I was 10 years old I remember it vividly. And that was exactly how he ran his multidisciplinary teams. His genius was not in putting these teams together, but in how he facilitated their interaction.

My father eventually became City Planner, a role he carried out for 14 years.

His team were responsible for overseeing all planning and also initiated many of the City’s own projects – including protecting and rejuvenating many heritage buildings earmarked for demolition and car parks. A favourite project was the pedestrianisation and greening of Church Street and St Georges Street (now St Georges Mall) in the Cape Town CBD. This project linked the old Company Gardens of the 17th century at the top of town all the way to the foreshore, in a similar way that the famous Ramblas in Barcelona works.

He helped facilitate the inspirational ‘Greening of the City’ initiative that saw over 1 million trees planted by the City Parks Board, and he made it his mission to bring life back into the CBD by redeveloping the stalls on the Grand Parade in front of the City Hall, etc. The projects were many – some small, like bringing the famous Cape flower sellers back into town. All were focused on revitalisation of the city around people. Unknown to most, he also worked tirelessly behind the scenes to keep the head offices of major companies in the city. His intervention helped stop many of the oil companies and, importantly, national retailer Woolworths from relocating to Johannesburg, for example.

Growing up, my sister and I would jump into his car on Sundays and drive around the peninsula with him for most of the day, inspecting contentious developments and progress-checking others. We spent more time on building sites than most kids, and it is little wonder that my sister studied architecture at university. It was on these car trips that he would regale us with stories about our city. He knows the origin of almost every building in Cape Town –who built it, why they built it, etc. – but he also knew contextual facts like why there is tension between National Government, Provincial Government and Local Government and how to align them, or why certain streets exist where they do, or that Hout Bay was first called Chapman’s Chance, or the history and practices of forestry management on Table Mountain, etc. I doubt anyone possesses as much detailed knowledge about the humaninfluenced environment of Cape Town.

It was in 1988 while working for the City that he was invited to become the CEO of the first ever public-private partnership –

14 Jack Journal Vol. 2

the development of Cape Town’s Waterfront, known by all Capetonians as ‘The Docks’. Cut off from the city by a freeway, this run-down, seedy area was notorious for belligerent stevedores, prostitution, rats and crime. It was not only an insalubrious eyesore but cost the South African taxpayer over R2 million a year. In many quarters it was considered a hopeless situation. Not for my father – this is what he had been preparing for all his life and he jumped at the opportunity. He knew what would help save Cape Town from a design and urban planning perspective – she had to be reunited with her sea, through her people.

Sheryl recalls: ‘When the Victoria & Alfred Waterfront Company was formed and work started in 1989, most Capetonians said “it will never happen” and those few who were lobbying for the Waterfront were regarded as dreamers.’

As my father went around Cape Town

outlining his vision, he was met with cynicism and antagonism. Some restaurants in the neighbouring Sea Point felt threatened and a campaign called ‘Duck the Fox’ was started, which was typically myopic of the time, but still hurtful.

This attitude partly reflected the negative mindset – the apartheid nationalist government was in the dying throes of their tenure, but not going down without a fight. On 12 June 1986 – four days before the 10th anniversary of the Soweto Uprising – a draconian, country-wide State of Emergency had been declared. Detention without trial, curfews, torture, banning of political funerals, banning of certain indoor gatherings, and political murder, etc., ensued. News crews with television cameras were banned from filming in areas where there was political unrest. This meant both national and international coverage of police brutality and the

government’s attempts to contain unrest were largely unreported. The country was imploding, and tensions ran high. An estimated 26,000 people were detained between June 1986 and June 1987 – many of these died.

A young reporter for the largest local newspaper, Willem Steenkamp, recalls going to one of my father’s presentations and being impressed by the vision and excited by my father’s passion for his project.

When he filed his report, the editorial team mocked him for his naivety, cut the report down to a paragraph and apparently ran it near the sports section at the back of the edition.

But David Jack had kick-started his vision and he was determined. With the stoic support of Brian Kantor, an economics professor, who had been named Chairman of the V&A Waterfront, and the loyalty and connections of Arie Burggraaf, the most

15 >

David Jack showing Nelson Mandela around the Cape Town Waterfront, 1995.

senior harbour engineer at parastatal Portnet, my father knew it would work. His inner team believed in him and backed his audacious vision.

Sheryl explains: ‘The job was to rejuvenate the City’s historic harbour by restoring abandoned buildings, bringing together a mix of local retailers, restaurants, hotels, offices, residential and museums, all co-existing side by side.’

Of course, this meant simultaneously managing the economic development alongside the physical development, the successful execution of which required skills and inner resources not expected of most architects.

‘Unlike many other waterfronts in the world, David’s focus from the start was on attracting locals. For him, authenticity was everything – restoring historic buildings in the local vernacular style – whilst adapting them for new purposes and retaining an authentic link to the past. Most importantly, David wanted to ensure the continuation of the working harbour, which provides vitality and a rich maritime experience – from shipping traffic to the Synchrolift and Robinson Dry Dock, to fishing boats and tugs – this was to be a real peoples’ place, not a theme park. For me this aspect was the most interesting and David supported the work I did together with the Cape Town History Project in the development of story boards and a walking tour that presented alternative perspectives on the dockland and broader Cape Town history.

‘When I first met David, I was nervous, not knowing what to expect. But I needn’t have been. I encountered a modest man with great ideas and high ideals. It was obvious that David Jack was doing what he loved. He was passionate and curious and excited about the work at the Waterfront and I admired his sense of purpose and meaning. When I asked him if I could play a role in making his dream of the Two Oceans Aquarium a reality, he answered by quoting Nelson Mandela: “There is no passion to be found playing small –in settling for a life that is less than the one you are capable of living.”

‘David gave me a chance to do the work I loved. On 13 November 1995, the Two Oceans Aquarium was opened to the public – a feat that was only possible

thanks to David Jack and the thousands of hours committed by passionate professionals and volunteers.’

A distinguishing feature of how the development of the V&A Waterfront progressed was the way my father structured his multidisciplinary planning process. The team directly employed by the V&A Waterfront was always small and fleet-footed. It was his utilisation of external review boards, professional consultants and key outside individuals that allowed him to put together a dream team of the very best developers.

Sheryl again: ‘I remember the large boardroom in the Port Captain’s Building always being full of people in business suits carrying drawings and plans. Krysia, David’s hard-working secretary, would never let me peek inside, but I later learnt that these were David’s famous Design Review Meetings, where professionals worked collaboratively across many disciplines to bring the vision to life. Only by realising the benefits that closer working with people from other disciplines could bring was this ever possible. David has the uncanny ability to bring the last bit of inspiration, talent or ability out of each professional, and that is really what has made the Waterfront such a success.’

This was a difficult and potentially disastrous development model to adopt, because many big egos were involved. Most in those Design Review Meetings, for example, were leaders in their fields, owners of their own practices, with strong characters and strong opinions.

It sounds like a nightmare to most developers, which is why this model is seldom adopted and why, when it is, it often fails. The secret was the way in which my father managed these interactions. I was present in a few –left alone and ignored, at the other end of the room with my homework. I experienced it first-hand, but the stories are legendary – like a magician, he not only coaxed the best ever work from the best in the business, but he somehow managed to secure alignment and inspire an incredible sense of ownership and loyalty.

The Waterfront was also different from other waterfront developments around

16 Jack Journal Vol. 2

>

A distinguishing feature of how the development of the V&A Waterfront progressed was the way my father structured his multidisciplinary planning process. The team directly employed by the V&A Waterfront was always small and fleet-footed.

Scan to find out more about the Two Oceans Aquarium

17

Cape Town Two Oceans Aquarium

18 Jack Journal Vol. 2

Californian Redwoods. Photography by Victoria Palacios via Upsplash

the world because it was conceived and planned around people, but not just an academic understanding of sociology or even psychology; rather this came about through how David Jack reads people. The direction of development was continuously tweaked as he carefully analysed what worked best through his unique lens. In a way, the early phases of development were an ongoing, real-time design experiment, the many outcomes of which were immediately felt by him, then analysed – all to ensure the best eventual outcome for all involved, especially for the Capetonians who would utilise the space.

Sheryl found this practice unusual, but fascinating: ‘The V&A took its shape as a result of David’s practice of carefully observing social behaviours and patterns and then adapting the project accordingly. He watched people walk, he watched them shop, and he watched them interact and socialise. He worried through challenges and constantly sought ways to make the Waterfront encourage rather than discourage social interaction.’

I remember the early years, walking around with my father and getting frustrated that it took so long to make it from one spot to another. In one instance he stopped and made me watch a hundred people cross an open space between two restaurants. Then he turned to me and said something like, ‘The reason most people cut out that corner and go the long way around is because the relationship between them, in this environment, and the scale of the building at the corner is wrong. We will plant a tree there.’

While the built environment is often what alienates us, it is the carefully designed and planned spaces in-between that can make us feel welcome once again. In David Jack’s mind the spaces are just as important as the buildings.

Sheryl: ‘I will never forget David walking around talking to tenants, customers, builders, security personnel, local and overseas visitors – all the while picking up any litter he encountered. If the Managing Director could pick up litter, then so could everyone else. It was a valuable lesson.

‘My own career took many turns, but I found myself at the V&AW again – this time working with the Robben Island Museum as the island was transformed from political

prison to World Heritage Site. When the Museum opened its doors in 1997, the first tour ferries departed from the original departure building at Jetty 1, with its unfriendly façade of red bricks, wrought iron doors and barbed wire fencing. This was the time that I got to know David as a compassionate person who wanted to turn our common suffering into hope for the future. Quite simply, he wanted to do good.

‘I am back at the V&AW, this time as a tenant, operating the Oranjezicht City Farm Market. I’m fortunate to see David from time to time, when he pops by. He never ages – he still has that twinkle of curiosity in his eye. He tells me he can still touch his toes, make a good cappuccino, peel a prickly pear, and at a push ride a horse and milk a cow – but prefers to drive his 1965 model Porsche.’ Numinosity is a beautiful word – it means the sense of blissful awe a place inspires in those who are fortunate to experience it. This could be a cathedrallike cave open to the crashing sea, an ancient forest of giant trees, or, in very rare instances, a building or city space. Those who have stood in front of the Acropolis in Athens, before the crowds arrive, will know what I mean.

We will never understand all the mysterious reasons why some urban or building design really works. It is usually easier to work out why it doesn’t work. But what we can attempt to do, if we care about our collective happiness, is to consciously scratch below the surface of this sort of success – where the spirituality of place makes us feel welcomed and happy. We can learn from them.

In the case of Cape Town’s V&A Waterfront, I have learnt lessons I try to utilise in my own business. I love learning from how people interact with my wines – why they react positively or why they sometimes don’t grasp the whole package. I continuously tweak my house style, my label design and my communication in an attempt to give consumers a sense of belonging. This makes me feel fulfilled and I believe it benefits the consumer. And business collaboration is the cornerstone of my business philosophy, as it was with my father.

It is not an easy path. I can see why no

one does business this way in the wine industry. Margins are so small and the pitfalls so prevalent that true collaboration takes a huge amount of trust and belief in my vision – a vision that to some is so long-term that it doesn’t always seem anchored in the commercial reality of this cut-throat industry.

Over and above this, watching my father struggle and eventually succeed in realising his dream for Cape Town taught me that if your vision is as egoless as possible, and if it is truly designed to spread joy, success against impossible odds is possible.

Most importantly, I learnt that it is not in the concreteness of the wine industry that we find beauty and joy – not in the scale of businesses, the turnover and profit, not even in the weight of the bottles, or the awards won at wine competitions.

Rather it is in the empty, mysterious spaces between all these measurable things – in the silence between sips, as flavours and aromas explode on your tongue, firing a thousand neurons deep in your brain, and in the initiatives outside of winemaking, like the social upliftment projects many of us are passionate about. And, I hope, in projects like this magazine, which, with any luck, is like that tree my father planted in the corner of that empty space between two restaurants – an out-of-the-box additional element that provides welcome and belonging.

Scan to find out more about the Cape Town Waterfront

19

’n liedjie vannie rieldans

(A Little Ditty about the Riel Dance)

Written by: Alison Westwood Photography: Courtesy of ATKV.

It’s midnight in the Great Karoo, The stars are out, the moon is new. It’s New Year’s 1952, Klein Johanna’s at the riel.

In a circle, on the dry sand, The crowd is clapping, hand on hand. A ramkie guitar leads the band, They’re ready for the riel.

Pieter van Rooien trots on first. Of all the dancers, he’s the worst – Been working on a mighty thirst, But now it’s time to riel.

Next come Stoffel, Jaap, and Arrie –that man dances dangerously! They say he kicked cracks in concrete, Last time he danced the riel.

Bow-ties, waistcoats, ostrich feathers In their hats – so smart and clever. Watch how they vlerksleep together, When they dance the riel.

Three girls skip in, then another, Klein Johanna cheers her mother: Kappie, dress, and apron over, She’s dressed up for the riel.

The liedjie starts, this one is funny: It’s about a naughty tannie Who stole all the farmer’s money While he watched the riel.

Knees like rubber, lungs that aren’t pap, Toes dug in to throw the dust up, Vellies tough enough to vastrap –That’s what you need to riel.

Feet too nimble to make them out, All leap and kick and turn about: Then ‘Askoek!’ everybody shouts – That’s how you dance the riel.

Johanna watches them all night. Next morning, somewhere out of sight, She tries to gooi her feet just right, And learns to dance the riel.

***

Johanna’s old now – seventy-seven. Verneukpan’s not exactly heaven, But she’s smiling, laughing even, When she talks about the riel.

‘I can skoffel, you must believe –I was champion at ATKV. Come to Kenhardt on New Year’s Eve, And then we’ll dance a riel.

‘My son Flippie’s got two left feet, But man, that boy can keep a beat. His blikviool sings something sweet, When he plays the riel.

‘I taught his daughter Elsa well, Since she was just a little girl.

Really, you should see her twirl, When she dances riel.

‘Now Elsa’s in a winning team – They took gold in 2018. It’s the best thing you’ve ever seen When they dance the riel.

‘She said, “Ouma, I saw the sea, Thousands of people cheered for me. My face was even on TV, When I danced the riel.”

‘And those kids from Wupperthal way, Who flew out to the USA, Thirteen medals, they won – sien jy? For dancing in the riel.

‘They say it comes from long ago, The San, the Khoe-Khoe – well who knows? But samesyn will always grow, When we dance the riel.’

The wireless twangs an old refrain Of love and mischief, hope and pain. She jumps up, she feels young again –Old Johanna dances riel.

22 Jack Journal Vol. 2

GLOSSARY

ASKOEK: (ash cake) or askoek-slaan (hitting ash cakes) is a characteristic dance move of the riel. Dancers strike their heels together, mimicking the sound made by removing excess ash from bread baked on coals.

ATKV: The Afrikaanse Taal- en Kultuurvereniging (Afrikaans Language and Culture Association) was historically an all-white affair, but when apartheid ended, it opened up to include all ethnic race groups who spoke Afrikaans. The establishment of their annual rieldans competition in 2006 was critical to the riel’s revival. Participants have grown from a handful of groups to hundreds of dancers from all over the Cape.

BLIKVIOOL: A tin-can violin.

KAPPIE: A bonnet in the style of the colonial era.

GREAT KAROO: A sparsely populated inland semi-desert stretching over more than 400,000 square kilometres.

GOOI: Literally, to throw.

KENHARDT: A small town in the arid Northern Cape at the heart of the region’s sheep farming community.

KLEIN: Little.

LIEDJIE: ‘Little songs’ are performed by a singer accompanying the band. Each liedjie tells a story about something in the community’s lived experience, which the dancers also try to depict in their performance.

OUMA: Grannie.

PAP: Flat, like a car tyre.

RAMKIE: A home-made stringed instrument, similar to a lute or guitar.

RIEL: The riel traces its roots back to indigenous Khoe-San dances, and is distinguished by fancy footwork, animal mimicry, and extravagant courtship displays. The name ‘riel’ is derived from the Scottish reel (an influence that arrived with Europeans) and is used for both the music and the dance. From the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s, the riel was performed at weekend and New Year’s parties by farm labourers in the rural Cape. During apartheid, it was disparaged for being associated with drunkenness, and almost died out. It is now regarded as a cultural link to the nation’s First People and a proud part of South African heritage.

SAMESYN:

A spirit of togetherness experienced at social gatherings, much valued in rural communities.

SIEN JY: You see?

SKOFFEL:

Literally translated, skoffel means ‘to hoe’, but is also used as a synonym for dance.

TANNIE:

Although it means ‘auntie’, any woman can be called tannie.

VASTRAP:

The fast stamping action performed by riel dancers.

VERNEUKPAN:

A 57km long and 11km wide salt pan in the remote Northern Cape. Verneuk is Afrikaans for trick, mislead or swindle.

VELLIES:

Short for velskoen (skin shoes), these tough leather walking shoes are thought to have been based on traditional Khoe-San footwear. The red shoes favoured by many rieldans teams are probably a hat-tip to Afrikaans folk music icon David Kramer, whose rooi vellies were famous.

VLERKSLEEP:

Literally translated, ‘wing sweep’. The moves for the courtship routines in riel are taken from the bird kingdom, where the male will spread a wing and sweep it along the ground while dancing around the female.

WUPPERTHAL:

This tiny village in the Cederberg mountains is home to a famous rieldans team, the Nuwe Graskoue Trappers. With no formal training, they won the ATKV competition and South African Championships of the Performing Arts, and went on to compete in the 2015 World Championships of the Performing Arts in Los Angeles. Their triumphant return with 13 gold, silver, and bronze medals was an inspiration to the new generation of riel dancers and quite literally put riel on the international stage.

Scan to find out more about the riel dancers

23

24 Jack Journal Vol. 2

25

26 Jack Journal Vol. 2

27

28 Jack Journal Vol. 2

Photo: Sake dinner-Restaurant

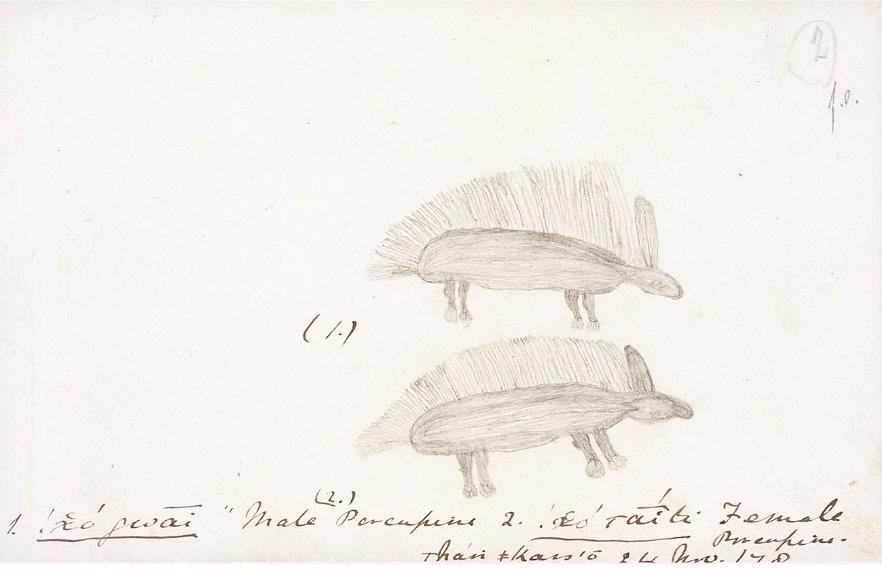

‘A slow clock may never tell the correct time, but a stopped clock is right twice a day,’ says Masataka Shirakashi, the owner of Kenbishi Shuzo in Japan’s Hyogo Prefecture. Kenbishi was established in 1505, 13 years after Columbus discovered America, instead of Japan, as the explorer had originally intended. Historical drawings show 47 samurai drinking Kenbishi sake in 1701; they then set out to settle a score on behalf of their master before committing ritual suicide.

Consumed by Japanese writers, philosophers and politicians and drunk at coming-of-age and wedding ceremonies, Kenbishi’s sake has endured over centuries precisely because this ultra-traditional brewery has had no truck

with passing fads. ‘If two out of a hundred like it, that’s good enough for us,’ says Shirakashi. While it’s a statement that would have any modern-day drinks marketer throwing their hands up in despair, the fact is that the underlying message of ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’ has made Kenbishi one of Japan’s most enduring and distinctive sake breweries.

Endurance is a feature of Japan’s sake industry. More than 900 sake breweries, three-quarters of the 1,200-odd active sake producers in Japan today, are over a century old. One-third were established before the end of the lengthy Edo period (1603–1868). Drink the sake of Imanishi Shuzo in Nara, Japan’s ancient capital, and you are imbibing the traditions of a Japanese sake brewery with records dating back more than nine centuries. Sake brewing has survived, navigated and adapted its way through the challenges and hazards of the centuries to bring us a modern drink which would astonish its forebears as

much as the internet would have Johannes Gutenberg staring in bewilderment.

The families running today’s sake breweries are justifiably proud of ancestors who originally plied their trade in the likes of soy sauce, dried herring production or kimono sales. Traditionally, these families depended on professional master brewers, known as tōji, whose groups formed guilds throughout Japan. The tōji would pass down his skills to the next generation, and the family head would probably know only his surname. In an industry as traditional as sake, changes are almost imperceptible but today’s tōji is more likely to be a family member, and, whisper it softly, a woman perhaps.

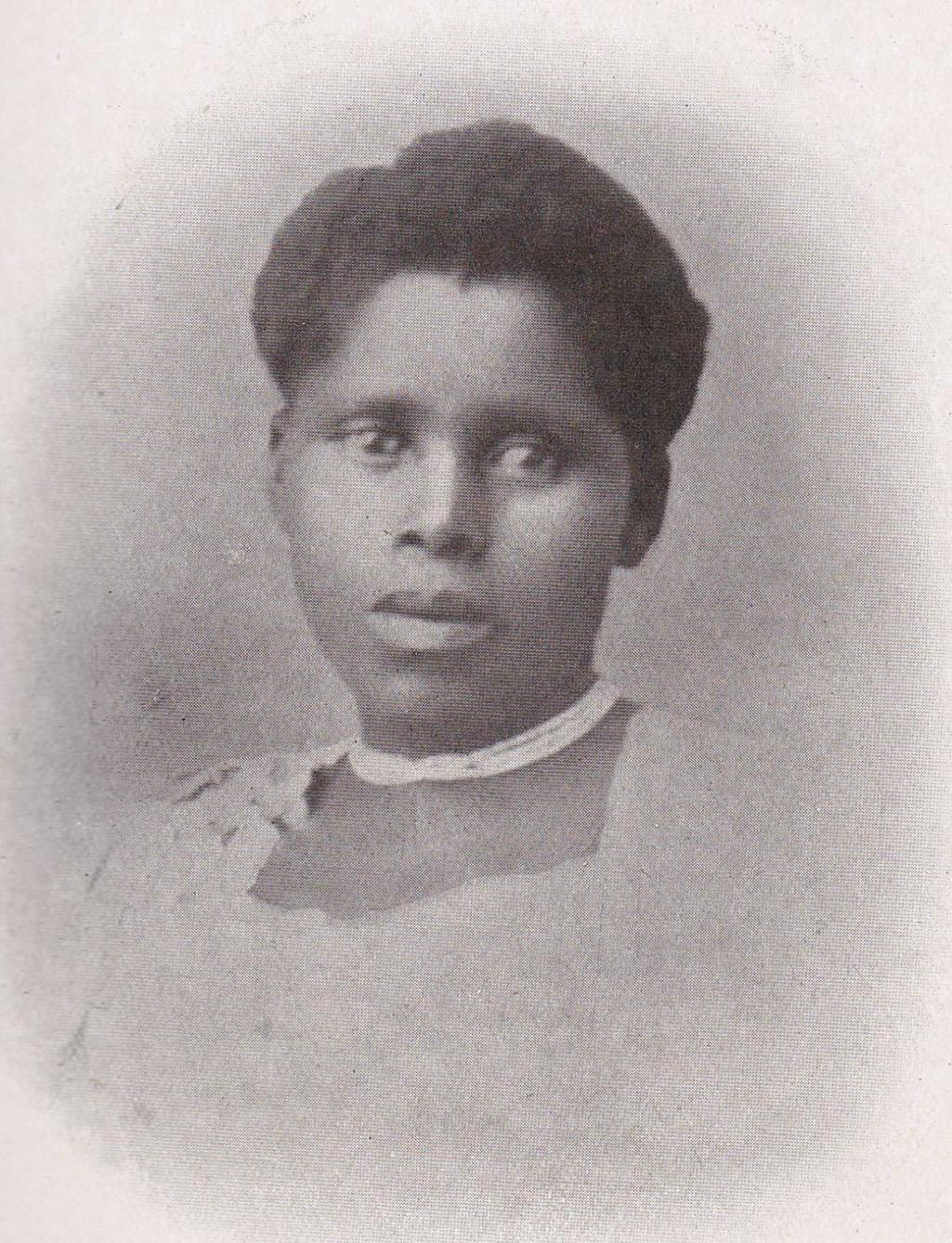

The all-important job of rice milling was once carried out by priestesses (look away now, those of a delicate disposition) chewing the rice grain and spitting into a pot to begin the process of breaking down the enzymes. In the 8th-century Imperial Court in Nara, sake was made for the Emperor and his entourage.

29

sakeWritten by: Anthony Rose Photography: Anthony Rose

30 Jack Journal Vol. 2

Photo: Removing the steamed rice by wooden shovel for cooling down, at Yonetsuru, Yamagata

31

32 Jack Journal Vol. 2

Photo: Miho Imada, head brewer and owner, with Hattan-so rice, Imada Honten, Hiroshima

As the pestle and mortar superseded mouth-chewing, sake-making became the preserve of temples and shrines in medieval Japan, seeping gradually into all aspects of Japanese aesthetics: in the tea ceremony, flower arrangement, painting, lacquerwork, embroidery, porcelain, gardening and Noh theatre.

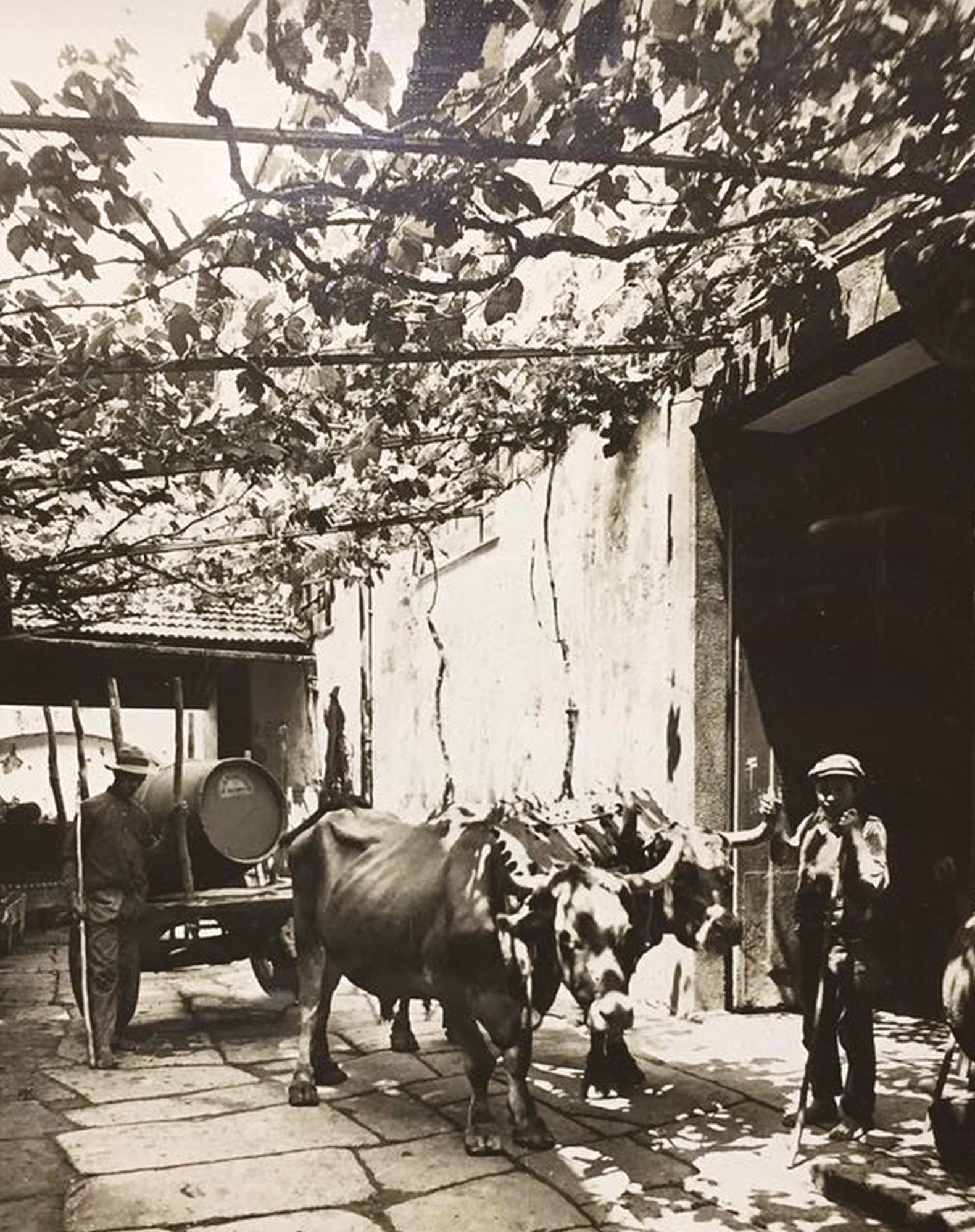

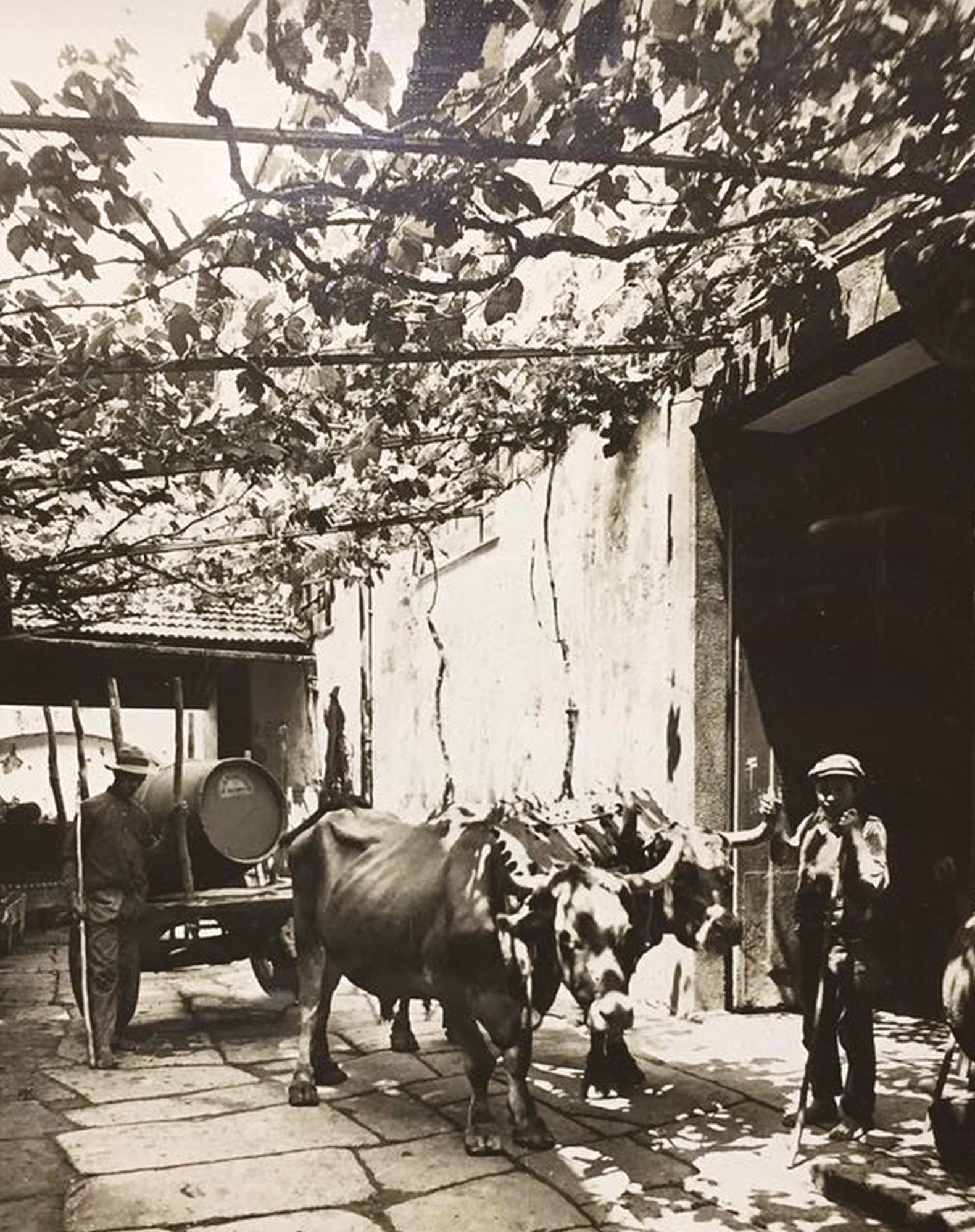

The basic techniques of sake brewing in use today were largely developed during the Edo period.This prosperous era saw continued expansion and improvement. Nada in the central Japanese prefecture of Hyogo became, and remains, the engine room of sake production. Efficient waterwheels replaced the pestle and mortar. In an ancient version of the Beaujolais Nouveau race, ships known as taru-kaisen raced each other to get their cargo of 2,000 barrels of sake to Tokyo’s (then Edo) thirsty population.

At the end of this lengthy isolationist period, Japan opened its doors to inquisitive foreigners lured by a country whose enigmatic charm had for so long obscured what the Western writer Lafcadio Hearn described as ‘a Fairyland … an era forgotten, a vanished age as ancient as Egypt or Nineveh.’ Visiting the country in 1878, bella Bird recorded the custom of drinking sake at a Shinto wedding ceremony: ‘The two girls who brought in the bride handed round a tray with three cups containing sake, which each person was expected to drain till he came to the god of luck at the bottom.’

Thanks to a talented group of pioneers, sake took a number of giant leaps forward after the turn of the century. In 1908, Riichi Satake invented a power-driven milling machine capable of milling the rice grain all the way down to its central starch core. Founded in 1904, the National Research Institute of Brewing made a significant contribution to improvements in quality, stability and scientific solutions to brewing techniques. In place of the laborious pole-ramming technique for getting the sake fermentation going, the more rapid, streamlined sokujo method was developed. Yamada Nishiki and Gohyakumangoku, the two rice strains that account for around two-thirds of today’s sake production, were developed in 1936 and 1957 respectively.

Rice shortages at the start of WW2 led to the government taking control of the sake industry in 1939 with the aim of producing maximum sake from minimum rice. Before

the war was over, breweries were forced to make sake with the wholesale addition of distilled alcohol. Thanks to the resulting ‘triple sake’ – two parts added alcohol to one part naturally produced alcohol – the quality and image of sake suffered badly, leading to a near-terminal decline in consumption and a stigma that has taken decades to eradicate.

Yet with typical Japanese resilience, sake has not only recovered from a spiral of decline but made rapid progress. The early 1970s saw a burgeoning of Jizake, local sake, leading to the ginjō boom of the 1980s in response to demand for a light, smooth, easy-to-drink sake. Old heads have rolled in favour of a younger, more open-minded generation with a formal sake education and experience of industries abroad such as wine. They are more supportive of local rice growers and more flexible in crafting new styles of sake adapted to a revival of interest from a younger generation of consumers.

In Akita, for instance,Yusuke Sato, the young head of the Aramasa brewery, is making waves with an almost wine-like sake commanding prices that other brewery owners can only dream of. Art of Sake, a start-up with four sake brands, is on a mission to revive small artisan sake breweries and put their trendy undiluted, unfiltered, unpasteurised sakes on the map. The young Japanese football star, Hidetoshi Nakata, is turning heads with his Japan Craft Sake Company, and Richie Hawtin, the acclaimed international techno DJ based in Berlin, has created a sake label, Enter Sake, with a focus on bringing young people into sake. Champagne producers too are getting in on the act. In a joint venture with Ryuichiro Masuda of Masuizumi, Richard Geoffroy, former chef de cave of Dom Pérignon, released his first ultra-premium sake this year, IWA5, made in the Toyama foothills of the Japan Alps. The ripple effect of new-wave premium sake is being felt in countries as diverse as Australia, the USA and the UK, where local craft sake breweries are springing up in response to demand. The brewer who perhaps best embodies the spirit of innovation is Philip Harper, Tamagawa’s head brewer in Kyoto Prefecture and Japan’s only British brewer. A welcome breath of fresh air, he has no time for the old shibboleths, favouring a simple set of enduring values with which few would argue: that what sake boils down to is flavour and fun.

SAKE BOX

Q: What is sake?

A: Sake is a fermented drink made from rice, kōji (moulded rice), yeast and water.

Q: What is kōji?

A: Kōji (more accurately kōji-kin) is a micro-organism, a mould, whose enzymes break down the starch in the rice and convert it to fermentable sugars. Kōji is the steamed rice with the kōji mould propagated on it.

Q: What is rice polishing?

A: Rice polishing, or milling, is the first step in the four-stage process of milling, washing, soaking and steaming needed to prepare the rice for fermentation.

Q: What is the polishing ratio?

A: The more the rice grain is polished, the higher the grade of sake. Premium grades of sake correspond to polishing ratios. Daiginjō, with at least 50% of the rice grain removed, is the highest grade of sake.

Q: Sake or saké?

A: Sake is English (pronounced sah-kay), saké is French.

Q: What is the alcohol content of sake?

A: On average 15–17% ABV.

Q: Should sake always be drunk from a traditional Japanese cup (ochoko) or is a wine glass acceptable?

A: Sake can be drunk from any vessel you like.

Q: Is it okay or naff to drink sake warm?

A: Despite a prejudice in some quarters against hot sake, it’s fine to drink sake warm, or even hot.

Q: Is sake better drunk with food, or on its own?

A: Sake is low in acidity and high in umami (savouriness), a versatile drink matching both Japanese and many Western foods.

Q: Should sake be drunk right away or cellared?

A: Most sake is best drunk young.

Q: Is sake good for your health?

A: Sake doesn’t contain sulphites or preservatives but, like any alcoholic drink, should be drunk in moderation.

Scan the QR code to buy the book, Sake and the Wines of Japan by Anthony Rose

33

34 Jack Journal Vol. 2

Photography by Aler Kiv via Upsplash

from trash to treasure

ashley heather jewellery handcrafted in gold and silver recycled from e-waste

‘We believe that while some metal mining may always be necessary, ultimately our most important extraction operations should be happening in recycling centres and scrapyards rather than in sensitive ecological areas and ancestral lands.’

ashley heather jewellery is a jewellery studio that celebrates sustainability by crafting individually designed pieces utilising silver and gold reclaimed from circuit boards. Sustainable studio practices include everything from the manufacturing

process through to the packaging.

‘Our refining process begins with manually dismantling the waste electronic products. All the non-electrical components are sent their separate ways for recycling.

The circuit boards are run through a shredder before being fed into the furnace. All the metals are collected as a sludge. The precious metals are separated and purified before being melted a second time to ensure a pure, high-quality material. The recycled metals start their

new life in our Cape Town studio where, using traditional goldsmithery techniques, they are meticulously handcrafted into minimalist, easy-wearing jewellery.’

Scan to find out more about ashley heather designs

35

a labyrinth of legacies and musical signposts

Written by: Josh Hawks

Written by: Josh Hawks

37

38 Jack Journal Vol. 2

John Lennon’s line ‘I read the news today, oh boy’ seems to have taken on rhetorical resonance. Like a theremin (that glissandosounding aerial of an instrument associated with eerie soundtracks), the digital news and social-media performative space is a high-frequency din as shrill as my tinnitus. I scan the latest from the Orange Vulgarian, the High Priest of Fake News, who, in 1,267 days, has (according to Fact Checker) made 20,055 false or misleading claims. I surmise that it might have always been this way, since the Ancient Assyrians; empires and their art of telling people what they need to know – the time-honoured balancing act – or giving them cake. The US corporate sector is eating it up. Billionaire wealth has gone up by nearly $600 billion since the beginning of the pandemic. Jeff Bezoz made $13 billion in one day. South Africa has its own voracious version of a feeding frenzy on show. The Revolution will consume every brick from the foundation like a biblical plague of locusts. Thinking about cake, I have a flashback to the 2007 pre-Polokwane Conference and I’m watching ANC heavyweights gulping from bottles of Moët behind the stage at the stadium in Athlone. I am with Freshlyground, and we are there to perform. I watch Mbeki cut a single slice from the ANC’s 94th birthday cake and walk down to the crowd for a symbolic feeding of the rapturous multitude. There has been a blast in Beirut; nearly 3,000 tonnes of ammonium nitrate left to solidify in a dilapidated warehouse seems like a metaphor for South Africa’s crisis of inequality. I look for something to stem my anxiety and give me colour, but I catch a story about white cricketers discussing whether black lives matter, and anti-vaxxers apoplectic about Gates and the Rothschilds. It’s suddenly 1928 in Berlin and Goebbels is overseeing the placement of movie cameras and microphones to enhance the image of the Führer, but I slip even further back to 1517, and another anti-Semite, Martin Luther, is about to nail his 95 theses up on the church door. Luther, like Goebbels, knew how to use new technology to absorb and advance a cause – in Luther’s case the Gutenberg printing press, enabling the first viral media campaign around Germany and beyond. Like the Catholic Church, then, it seems

we have no way to counter the information onslaught and are in a crisis of sense making. Then I see a very colourful Sho Madjozi on a BBC video insert, riffing on the legacy of Tsonga music, fashion adornments, and the age-old struggle against European determinations of what beauty and hair are supposed to be. She has annexed her traditions and performed such an original spin that she is now signed to one of the biggest labels in the business. I already feel as if I am in a labyrinth of past and conflicting legacies, but consider my European ancestors arriving in Africa describing their culture as civilisation and thus unchanging and final. Then I consider my own musical journey, rooted in Africa. The first time I lowered the needle onto spinning vinyl as a six-year-old in 1976, I heard a Mellotron and Strawberry Fields I didn’t know then that the Mellotron was the first sampler on record, nor that the reason for Lennon’s voice slowing at one minute in was because George Martin had slowed and spliced one of the takes in order to marry two. Neither did I know then that The Beatles were influenced by Little Richard, Chuck Berry and early rock ’n’ roll, a black art form, rooted in slaves from Africa, that needed a white face to go mainstream in Elvis Presley. Carole King’s Tapestry was another record in a threadbare collection, and years later I would have the fortunate experience of standing in the wings at Radio City Hall and watching Aretha Franklin up close singing (You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman. Aretha –the culmination of the slave-era field holler, the call-and-answer song sung in the fields to compress time and pain; the so-called Negro Spiritual – the Queen of Soul. Another seminal musical moment two years later was my father giving me a cassette. On the one side was David Bowie singing Changes and Suffragette City but on the other was something called Exodus by a bloke Bob Marley and his band The Wailers. It was like nothing I had heard or felt before – the emphasis on the third beat of the bar and what sounded like a coke bottle being played on Jamming. My bible at age thirteen was Stephen Davis’ Reggae International and it was there that I discovered the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Africans, I learnt, were selected for their physical superiority, as they had some

immunity to malaria, and their labour produced massive profits and wealth for their owners. Those first twenty sent to America in 1619 aboard The White Lion from the Kongo were selected too for their iron-working, masonry, glass-making and farming skills. They arrived with their traditions and, through extraordinary resilience and innovation, went on over the generations to pioneer the banjo, the modern drum kit and an assortment of fiddles and string instruments, and lay the foundation for bluegrass, country, ragtime and jazz. The twelve-bar blues, the forerunner to rock ’n’ roll, was based on a Yoruba drum pattern. Rock ’n’ roll, the big hitter that spawned thousands of bands and an industry worth $50 billion today. Music has been my teacher and guide and has taken me into shacks in Nyanga East as a teenager, a boereorkes in De Aar, villages in Zimbabwe, performance stages across Africa, Europe and the USA; she is the language that transcends boundaries. As I look at Sho, I consider the immense contribution from Africa, in her blood lines, her song lines, her blood, and I can hear Bob singing ‘One good thing about music – when it hits you feel no pain’.

39

Gift of the Givers supplying boreholes to drought -stricken South African farmers.

Gift of the Givers supplying boreholes to drought -stricken South African farmers.

42 Jack Journal Vol. 2

Photo: Dr. Sooliman hands out food parcels 2020.

gift of the givers

Written by: Biénne Huisman Photography: Courtesy of Gift of the Givers

In South Africa’s deep, rural reaches, they are a familiar sight: large green trucks bearing the words ‘Gift of the Givers’. As these vehicles approach over rickety roads, dust in their wake, people rush to their doorways; children dance and adults blink away tears. The sight of these trucks elicits pure joy, for they come bearing essential gifts: animal fodder and tanks of water, food parcels, blankets and sanitary pads.

Recently Gift of the Givers featured in the Netflix series Captive, which relayed the story of Afrikaans teacher Pierre Korkie and his wife Yolande, a hospital relief worker, who were abducted in Yemen in 2013.

Gift of the Givers managed to negotiate Yolande’s release, while sadly her husband was murdered.

Since 1992, Dr Imtiaz Sooliman’s Gift of the Givers has saved hundreds of thousands of people from disasters, droughts, floods and famine, in South Africa and around

the world. Today, using four mobile phones, Sooliman presides over 550 staff, including 140 in South Africa and 236 in Syria, where he runs a hospital in the war-torn north.

By the end of August, Gift of the Givers had collected R3 million to help Lebanese people left homeless in the Beirut blast. Over the years, Sooliman’s teams have helped Sri Lankan victims of the 2004 tsunami, performed life-saving surgery in the aftermath of the 2010 Haiti earthquake, and assisted homeless Malawians in the floods of 2015.

Speaking to Jack Journal from his Pietermaritzburg home, Sooliman’s words are rapid. The founder of Africa’s largest humanitarian aid organisation is alert, with an air of slight bemusement. In between anecdotes of his globe-spanning operation, he likes to crack a joke.

‘So the older residents in the deep rural areas – my staff tell me they all know my name,’ says Sooliman. ‘It is a heavy weight on your shoulders, it’s a responsibility. I can’t let people down. I made a joke to my wife. In Islam, ladies wear coverings on their face, you know, a burka. So I told her: “I need to wear a burka, I need to

cover my face.” I mean, all these people recognise me: people I pass when I walk in the streets; the petrol attendant, the street sweep, complete strangers. In King William’s Town, we would be on a programme in a deep rural area; the moment our trucks come over the hill, they start shouting: “Amanzi, amanzi!” (water), and they start dancing because they know food parcels and water are coming.’

In South Africa, Sooliman’s trucks have assisted farmers, doctors, schools and orphanages. Most often, they help people living on the fringes of society, overlooked by politicians. Gift of the Givers have rehabilitated local bees and tortoises, and have launched a massive carp fishing project along the country’s south coast. They have fitted out numerous hospitals to better fight COVID-19.

‘The sad part is that the people who need help the most, who have the most difficulty, are so humble,’ says Sooliman. ‘When they contact me, well, it comes through the system – they are very polite. The first thing they’d tell you is: “Look, we are in great difficulty. But we know you can’t help everybody. If you could possibly come to us, we’d be so

43

44 Jack Journal Vol. 2

Beirut explosion, Lebanon, 2020

Nepal earthquake relief, 2015

To date, the organisation has delivered 650 truckloads and 160 train carriages of fodder to drought-stricken areas around the country. They have drilled 400 boreholes in the past two years.

grateful.” They’re so patient, you know.’

Gift of the Givers first started drought relief in the North West in 2015, then expanded to other parts of the country. ‘I must be honest with you,’ says Sooliman. ‘There was a lot of skepticism at first; for example when we went into Sutherland, the farmers were saying: “Is he coming to convert us? Does he want our sheep, will he turn our churches into mosques?” Because they couldn’t understand that we were giving without wanting anything in return. After a few years, they finally realised that we’re doing it without expectation.’

To date, the organisation has delivered 650 truckloads and 160 train carriages of fodder to drought-stricken areas around the country. They have drilled 400 boreholes in the past two years.

Sooliman, 58, was born in Potchefstroom. He qualified as a medical doctor at the former University of Natal medical school in 1984, where he rubbed shoulders with formidable peers like Health Minister Dr Zweli Mkhize, his deputy, Dr Joe Phaahla, and Dr Vejay Ramlakan, the late president Nelson Mandela’s doctor, who himself passed away in August.

It was a meeting with a Sufi teacher in Istanbul on 6 August 1992 that laid the blueprint for Sooliman’s humanitarian organisation.

‘The moment I made eye contact with the spiritual teacher, I fell in love with

a man I didn’t even know,’ he recalls. ‘It was as if our souls spoke. He said to me in Turkish, and I don’t speak a word of Turkish: “My son, I’m not asking you, I’m instructing you to form an organisation. You will serve people of all races, of all religions, of all colours, of all classes, of all political affiliations and of any geographical location. You will serve them unconditionally, not expecting anything in return. Not even a thank you.”’

The Knysna fires of 2017 were a turning point for Gift of the Givers –this was when local media and corporates took notice.

‘Strangely enough,’ says Sooliman, ‘I had a truck of water on its way to Cape Town, because of the drought there. The truck had reached Three Sisters, when I heard about the Knysna fires. I stopped the truck at 1am in Three Sisters. I said: “Turn around and go to Knysna.” At 6am Gift of the Givers were the first providers of water in the area, as the local firefighters had run out.

‘From there we sent in a whole team; we took up a whole warehouse. In 24 hours, we had converted a car park into a logistics centre. We had teams on the ground. We had our own trucks, we had our own fire people. We had our own life-support paramedics, our own ambulances. We moved patients from Knysna to George and to Plettenberg Bay. We helped 20,000 families with food parcels. These were not only people caught in the fires, but also other poor people in the area who didn’t have food to start off with. When you’re doing food distribution, you don’t discriminate.

It was from here that local corporates understood our capability.’

One of the organisation’s ongoing projects is fishing in Groenvlei Lake in the southern Cape. The freshwater fish are being used to fill dinner plates.

‘We were told that there’s this invasive fish, carp, in this lake,’ says Sooliman.

‘Our contact spoke to the environmental people, the municipality people, all the different people associated with the fish. I said: “Did you test the quality of the fish?” So they sent a sample to be tested locally; then they sent it to Pretoria for specialised testing. It came out a hundred

percent successful.

‘The fish was brilliant, no problems. There is so much of the stuff, we have taken out 180 tons already. I mean you can feed the whole southern Cape. So we’re taking the fish to the local feeding centres. Alternatively, we wrap them up and give them to people to take home, to cook.’

As more and more South Africans turn to Sooliman and Gift of the Givers for help, the organisation’s pioneer gives all credit to God. ‘The spiritual teacher told me everything would be done through me, not by me,’ says Sooliman. He said: “You will know. You will just know what to do.” And it is true. We’re always in the right place, at the right time. I like to tell a joke. I say: “God Almighty, you do all this stuff through me, and you give me all the credit?”’

He adds that in 28 years, the organisation has never formally asked for funding. ‘The teacher told me: “You will never look for money and people from all over the world will come to you.” And they have.’

Scan to support Gift of the Givers or visit www.giftofthegivers.org

45

46 Jack Journal Vol. 2

47

48 Jack Journal Vol. 2

Photo: Ross Suter

foraging for mushrooms and other fungi on table mountain

There is something instinctively appealing and very fulfilling about foraging for food. It is like going on a treasure hunt, and the thrill of finding edible organisms is like finding the treasure! Success requires experience, observational skills, an affinity for the seasons and weather patterns, the will, the work ethic and the ability to sink deep into nature to the point of attaining a heightened awareness and level of intuition.

Written by: Ross Suter Photography: Ross Suter

The net result is incredibly therapeutic and revitalising, because this deep immersion in nature is all about being in the present. It is an antidote to the stressful urban lives many of us live. The process of foraging also reconnects us with knowledge about our natural environment that has mostly been lost in modern-day society.

Foraging has been an essential part of humans’ survival for hundreds of thousands of years. Historical records reveal that the harvesting of mushrooms and other types of fungi for both food and medicinal purposes has been practised for at least 6,000 years in China. In Roman times, the porcini mushroom was sought after for its fine flavour. In South America, the Mayans consumed certain mushrooms for their psychoactive properties as part of religious/ spiritual ceremonies.

In South Africa, people of British

and European origins have foraged for mushrooms for a few hundred years, but the San, the Nama, the Khoikhoi, the Bantu and others had been doing this for millennia.

In the Cape Town environs, and elsewhere in South Africa, many fungi were introduced with the soil of sapling trees and grasses that were brought here from Britain, Europe, North America and elsewhere in the world, mostly by the British in the 19th century. These trees were introduced either for their aesthetic and shade-offering appeal, or as part of creating plantations of pine and eucalyptus trees for timber. Efforts to grow these trees from seed proved difficult because the soil here didn’t have the mycelium (thread-like ‘root’ systems of fungi) that these particular trees needed (creating symbiotic relationships) to help them get nutrients from the soil. The

solution was to import saplings instead. The soil they arrived with contained a wide range of fungi mycelium and spore which were then introduced to the soils here, thereby allowing these exotic trees to grow properly.

Capetonians are blessed to have Table Mountain rising up high above the city, accessible from all sides to those who choose to walk or run in the hills or climb its cliffs. The mountain is part of a World Heritage Site, a status declared by UNESCO for the Western Cape, which hosts the Cape Floristic Region – the most diverse of the world’s six floristic regions. About 70% of the plants growing in this region are endemic. The mountain has roughly 1,500 different flowering plants (more than the entire United Kingdom) that are mostly part of the Fynbos vegetation group, but also include plants from the Renosterveld

49

50 Jack Journal Vol. 2

Photo: Ross Sutter

Chicken of the Woods (Laetiporus sulphureus) grows on oak trees in midsummer in the Western Cape.

Photo: Ross Suter

vegetation type. Sadly, 98% of this latter vegetation group has been lost, mostly due to the agricultural practices associated with the growing of wheat, making it the most threatened vegetation type in the world.

Part of the mountain’s history includes the establishment by the British, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, of pine plantations and stands of eucalyptus trees for commercial timber, plus the planting of oaks, chestnut, poplar and other exotic trees on the lower slopes. As a result, a range of exotic mushrooms have been growing in the Cape Town area for at least 150 years. Some are edible and delicious, some not, and some have toxins that, if consumed, are hallucinatory, poisonous or deadly. The toxins in some mushrooms are among the most potent found on earth, so it is very important for foragers to know exactly what they are picking for the pot and which ones to avoid.

Foraging for mushrooms not only involves exercise, fresh air, quiet and meditative time, but edible wild mushrooms add great flavour to meals, and they also have a range of nutrients beneficial to general health. Other fungi are used for their medicinal properties, such as antibacterial, antiviral, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and even as a remedy for high cholesterol and for certain types of cancer. Of further appeal is the fact that the harvesting of fungi/ wild mushrooms is completely sustainable, and has no negative impact on the natural environment.

If you are interested in mushroom foraging on Table Mountain, get a good reference book such as Gary B Goldman and Marieka Gryzenhout’s Field Guide to Mushrooms and Other Fungi of South Africa (Struik Nature, 2019) and link up with an experienced forager to give you guidance for at least your first few outings.

Happy hunting!

Scan to find out more or visit www.highadventure.co.za

51

52 Jack Journal Vol. 2

53

54 Jack Journal Vol. 2

the link between imagination and your wine glass

Being a winemaker, designing a wine label and remaining sane is surprisingly difficult. This is why there are so many average labels around and why so few designers make this a niche speciality.

Written by: Bruce Jack Art: Lady Margaret Tredgold

Wine-producing countries often have a kind of label look – France is dominated by the Bordeaux and Burgundy look, and these are entrenched by so many wannabe wines from elsewhere (including the south of France) copying said look. They are staid, conservative and predictable. That works for them. Italy also has a specific look and feel, as does Germany – all have developed over many years and in a specific direction. I love the Spanish idiom that has emerged in the last 20 years – Spanish producers generally have excellent taste when it comes to wine label design. The bold colours and balanced negative space of that sun-baked, flavourful, generous country seeps into the language of their wine label design.

Of the New World countries, South Africa is developing a confident, cuttingedge label visual language. This has some thing to do with a growing confidence in the wine producers, but probably has

more to do with a handful of exceptionally talented designers who have established a minimum standard of excellence in South Africa over the last 30 years – Anthony Lane, Brian Plimsol and Rohan Etsebeth spring to mind, but there are others.

When labels are produced that fall short of this standard, they stand out terribly, like amateur floundering. As a result, it is rare to see badly designed labels from South Africa – a commonplace occurrence in the rest of the world. Just one long walk past the thousands of stands at Prowein (the world’s biggest wine show) will prove my point.

‘Never judge a book by its cover’ and ‘You can’t taste the label’ are both aphorisms I live by, but I am a wine nerd, so I guess that comes with the territory. The reality is that you can’t survive at the sharp end of the wine business with badly designed labels. And anyway, I like welldesigned things – it indicates that the