5 minute read

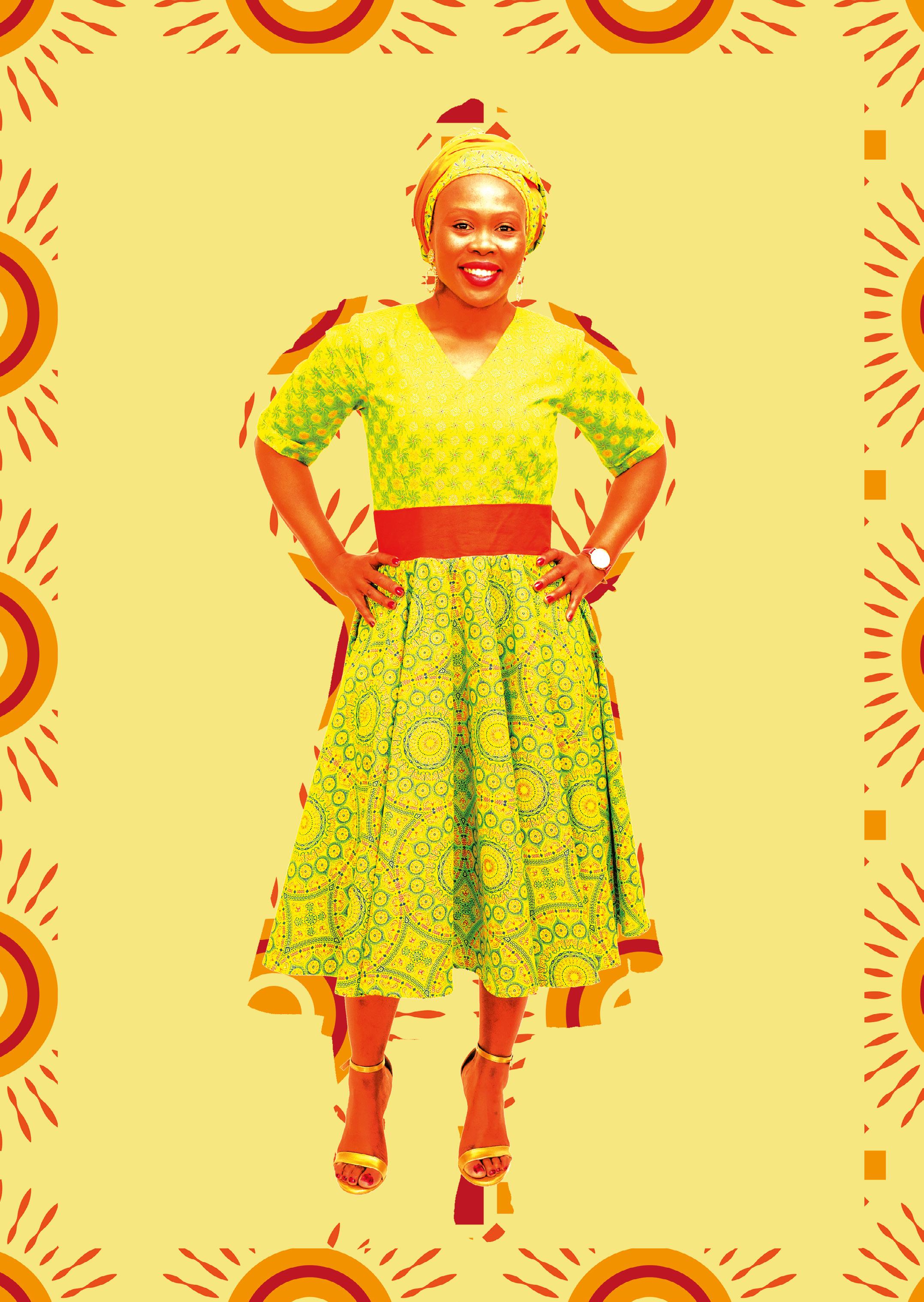

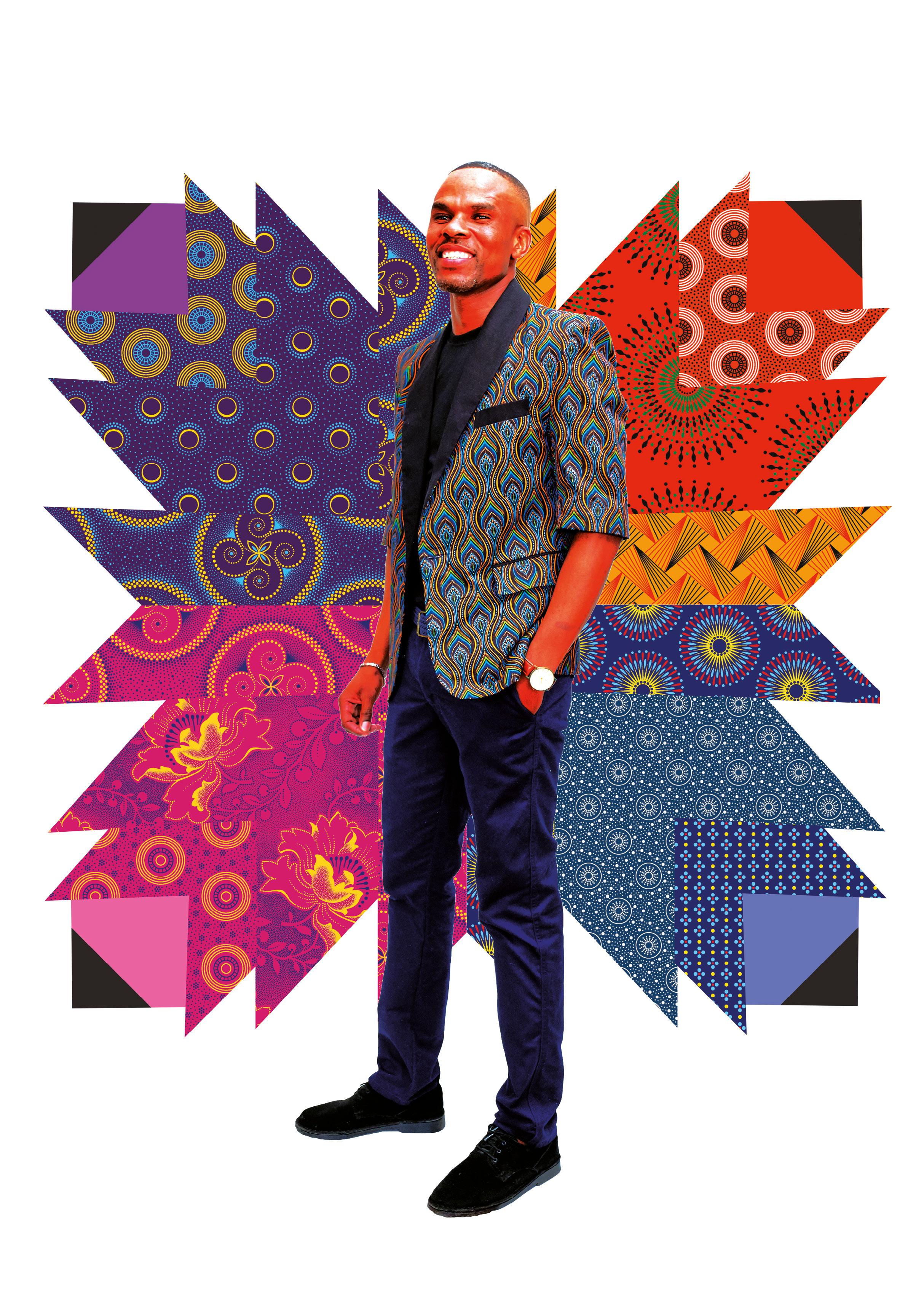

Shweshwe swish and sniff

shweshwe swish and sniff

Written by: Fiona McDonald Photography: Nicholas Schlemmer Artwork: Allendre Hine

Advertisement

It’s the quintessential South African fabric. Originally only available in an indigo blue hue, shweshwe now comes in brown, red, yellow and other vibrant tones. Fiona McDonald looks at this material’s interesting history and popularity.

In the dim and distant days of English grammar lessons, onomatopoeia was a fiendishly difficult word to spell. Understanding it was so much easier: it’s a word that mimics the sound of the object or action it refers to.

To my mind, shweshwe cloth is a great example: it perfectly describes the gentle ‘swish-swish’ that the fabric makes when stiff and new. For

generations, enterprising Xhosa woman of the Eastern Cape and their counterparts from Lesotho have sewn garments from this distinctly patterned fabric – and they knew that shweshwe cloth should be felt and sniffed before purchase, because the real-deal shweshwe should be slightly stiff, should swish when rubbed and also have a faint acidic aroma.

In the last decade, shweshwe has crossed over and become trendy – a symbol of Africa in vogue. Few people appreciate that it’s a specially trademarked material and that Eastern Cape-based Da Gama Textiles ensured the survival and ownership of shweshwe in 1982, when it bought the sole rights to one of the most popular brands from a company in Manchester, even going so far as to have the copper rollers crucial to the printing process shipped to South Africa.

Shweshwe has a fascinating history, one which is tied to the historical popularity of the colour indigo – which was, incidentally, identified in the 1660s by Sir Isaac Newton as part of the seven colours of the visible spectrum when he conducted an experiment with a light shone through a glass prism. (And that’s why we learned the mnemonic ‘Roy G Biv’ in science lessons, describing the order of the colours: Red, Orange, Yellow, Green, Blue, Indigo and Violet.)

Ancient Phoenicians and Arabs knew all about real indigo as far back as 2300 BCE – the colour extracted from sea snails and also plant sources (Indigofera tinctoria) was rare and thus valuable.

In her article ‘Shweshwe: a true blue passion’, Cynthia de Villemarette wrote that ‘designs are created using a discharge

process, unlike modern printed fabrics where colour is added to the surface. With Shweshwe, the cotton cloth is first entirely dyed, thoroughly penetrating the fibre. Then the cloth is passed through copper design rollers, which emit a mild acid solution, removing colour with pinpoint accuracy. One of the characteristics of shweshwe is the intense use of picotage, tiny pin dots that create not only the designs, but also texture and depth. It is because of the difficulty and expense in creating these designs that they fell out of favour with American and European manufacturers, who chose instead to move to printing processes. Da Gama Textiles of South Africa is the only known manufacturer of fabrics still using the discharge process … The reverse side of the fabric will be a solid colour because it was dyed. Da Gama also prints its seal on the back to help you identify it.’

The South African garment and textile industry has been hard hit by cheap fabric imports – and shweshwe cloth hasn’t been unscathed. Fabrics from Pakistan and China are inferior quality imitations, and that’s where local woman know exactly what to look – and listen and smell – for! The real shweshwe should be a solid colour on the reverse side of the fabric, ideally with a trademark logo. It should be slightly stiff from the starching process – hence the swish-swish sound – and it should also have a faint acidic smell (and even taste) because of the method used to print the design.

The origin of the name of this material apparently has a link to King Moshoeshoe (pronounced onomatopoeically as Mashweshwe), long-time ruler of Lesotho who died in 1870. History has it that he was given some distinctive indigo cloth by

Historic evidence of settlers’ clothes in museums in places like Graaff-Reinet and Qonce (previously King William’s Town) show that printed indigo blue fabric was popular locally hundreds of years ago, even among slaves and soldiers at the Cape. German settlers referred to it as ‘blauwdruk’, or blue print, because it was similar to a material popular in Germany in the 19th century. The Xhosa initially called the cloth ujamani, although nowadays it is universally known as shweshwe.

Since 1982, when Da Gama textiles obtained the rights – and rollers –for the most popular designs, the Three Cats versions, new colours have been introduced, namely brown, red and even yellow.

As the years go by, it’s through the efforts of people such as local fashion designers Amanda Laird Cherry, Nkhensani Nkosi of Stoned Cherrie and Craig Native that the fabric continues to win new fans to its historical designs and ever more trendy applications.