International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

K. Venkatesh1 , Dr. Addagatla Nagaraju2, * , Akkela Krishnaveni3 , B. Prakash4 , Ayesha1 , G. Snehalatha5

1Lecturer in CSE, Government Polytechnic for Women, Medek

2Lecturer in EEE, Government Polytechnic for Women, Siddipet

3Lecturer in EEE, SRRS Government polytechnic, Sircilla

4Lecturer in CSE, Government Polytechnic for Women, Siddipet

5Head of EEE Department, Government Polytechnic, Cheriyal

Abstract - The convergence of hardware and software in ElectricVehicles(EVs)hascreatedatransformativeplatform for innovation, performance, and sustainability in the automotiveindustry.Thispaperexploresacomputersciencedriven approach to hardware-software integration in EV systems, emphasizing embedded computing, real-time operating systems (RTOS), virtualized control, data communication protocols, cybersecurity, AI-based optimization, and software-defined vehicle (SDV) architectures. Drawing on contemporary developments and research,weproposeamodularintegrationframeworkthat enhances scalability, reliability, and adaptability. This interdisciplinaryfocuscontributestotheevolvinglandscapeof smart,secure,andautonomousEVtechnologies.

Key Words: ElectricVehicle,Hardware,Software,System

1.INTRODUCTION

Overthepasttwodecades,cloudcomputinghasemergedas thethirdmajorwaveofdigitaltransformation,followingthe rise of personal computers and the Internet. It has revolutionizedhowcomputational resourcesareaccessed andutilized.Recently,therapiddevelopmentoftechnologies like the Internet of Everything and 5G offering high bandwidth and ultra-low latency has accelerated the digitalizationandelectrificationofautomobiles.Thedemand for computing power and the complexity of automotive software have surged dramatically. For instance, in 1970, electronics comprised just 5% of a vehicle’s total cost; projectionsnowindicatethiscouldexceed50%by2030[1].

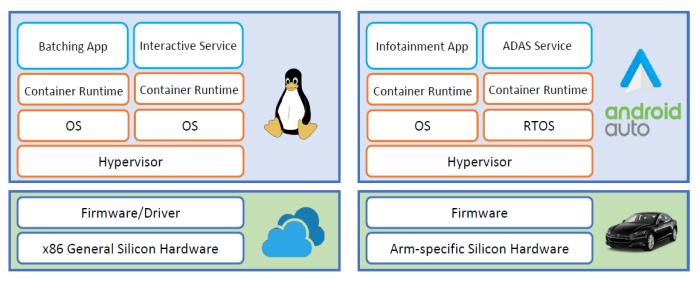

As illustrated in Figure 1, the architecture of cloud computing platforms and intelligent electric vehicle (EV) systems share considerable similarities. Increasingly, EVs arebeingviewedasthenextmajorcomputingplatformand a new frontier for innovation. Government initiatives and regulatoryframeworksarealsocontributingsignificantlyto thisshift.Notably,theU.S.governmentannouncedin2022 itscommitmenttoinvestseveralhundredbilliondollarsto strengthenEVinfrastructureand domesticmanufacturing [5].

Figure 1: Similarity between the Modern Cloud Platform and Electronic Vehicle Infrastructure

Moreover,heightenedawarenessofenergyconservationand environmental sustainability has led to increased global acceptance of EVs. This includes battery-powered electric vehicles (BEVs), plug-in hybrids (PHEVs), and fuel cell vehicles.Inthefirsthalfof2022alone,globalsalesofBEVs and PHEVs reached 4.3 million units representing yearover-yeargrowthof37%and75%,respectively.Projections estimatethatEVsaleswillrisebyanother57%,totaling10.6 millionunitsbytheendof2022[3].

This paper focuses on critical computer science elements thatdrivethisintegration,providingacomprehensiveview of the computational and architectural challenges and opportunities. Electric vehicles have emerged as a key solutiontoglobalenvironmentalandenergychallenges.As EV adoption accelerates, the need for intelligent control, robust safety, and real-time optimization becomes paramount.Unlikeinternalcombustionenginevehicles,EVs areprimarilycontrolledbyembeddedcomputingsystems andrequireintricatecoordination betweensoftwarelogic andphysicalcomponents.

Thepaperoutlinestheroleofsoftwareengineeringpractices indevelopingdependableEVsubsystems.Fromautonomous driving to thermal control, computer science facilitates reliable interaction between sensors, actuators, and datacentriccloudplatforms.Amodulardesignpatternisusedto managehardwarevariabilityandenablescalableupgrades.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

Motivation. However, despite being a rapidly developing computing platform, research and analysis related to EVs remain insufficient, particularly within academia. Firstly, with the exponential growth of computing power in hardware chips and software complexity within the automotive industry, investigating EV hardware and software has become crucial to keeping pace with technologicaladvancementsandinnovations.Secondly,as EVsgainpopularity,thereisapressingneedtoexplorethe hardware and software of EV platforms to support their development and integration into the next-generation transportationecosystem.Thirdly,EVsconfrontnumerous challenges,suchaslimitedcruisingrange,extendedcharging times, inadequate supporting infrastructure, network security risks, etc. Understanding these challenges can motivatetheexplorationofsolutionsandinnovationsinEV technology.Inthisarticle,weanalyzethecurrentstateofEV technologydevelopment,focusingontheglobalEVmarket anditstrends.WedelveintothehardwaresystemsofEVs, encompassing various energy subsystems, charging infrastructure, high-efficiency control subsystems, powertrain subsystems, power electronics, and chip technology.Additionally,weexaminenumerousmainstream EVsoftwarearchitectures,technologies,developments,and applications.Furthermore, weaddressthelimitationsand challenges of current EV platforms that necessitate improvementinfutureEVtechnologies.Tosummarize,this paperhasmadethefollowingcontributions:

•WesystematicallyexaminedEVsystems,encompassingthe historicalevolutionofEVs,primaryarchitectures,modules, technologies, developments, and applications in both hardware and software. Additionally, we scrutinized the mostadvancedtechnologiescurrentlyinuse.

•Weanalyzetheconstraintsandobstaclesencounteredby existing EV platforms and explore avenues for enhancing futureEVtechnologydevelopment.

• We aim to draw attention from scholars in this domain towardtheadvancementofvehiclecomputing.Meanwhile, wehopethisworkcanbettershedlightonfurtherresearch onelectricvehicleplatformsandrelatedtechnologies.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 brieflydescribestheelectricvehicle’shistoryanditscurrent development status. Section 3 studies the existing key componentsandtechniquesinhardware,suchastheenergy subsystem,controlsubsystem,sensors,etc.TheEVsoftware technologyiscoveredinSection4,includingvirtualization, hypervisor,OS,autoapplications,etc.Section5summarizes thispaperwithaconclusion.

Electric vehicles (EVs) boast a legacy spanning over a century. In 1873, British chemist Robert Davidson

constructed what is recognized as the world’s first operationalelectricautomobile.Fromthelate1800sthrough the 1920s, EVs experienced their first significant era of growth.Atthattime,internalcombustionengineswerestill intheirinfancyandfacednumerousperformancelimitations [4]. However, after the 1920s, advancements in gasolinepowered vehicles and a lack of adequate EV technology causedelectriccarstodeclineinpopularity.

This trend reversed in the 21st century, driven by substantial technological progress in battery systems, electric motors, and vehicle control mechanisms. These innovationshaverevitalizedtheEVmarket.Asconventional fuel-powered vehicles contribute to energy depletion and environmentaldegradation,electricvehicleshaveemerged as a cleaner alternative. Increasing global emphasis on sustainability,includingcarbonneutralityandpeakcarbon policies, has accelerated EV adoption rates. For example, globalEVsalesexceeded6millionunitsin2021 upfrom just2%ofmarketsharein2019toapproximately10%[7].

In the U.S. state of Georgia, the EV sector has also seen considerablegrowth.FollowingthecreationoftheGeorgia ElectricMobilityandInnovationAlliance(EMIA)inJuly2021 [6],majormanufacturerslikeBlueBird[2],Rivian[8],and HyundaiMotorGroup[4]haveexpandedtheirinvestments inelectricvehicleproductionandsupportingsupplychains across various counties in the state. According to the SouthernAllianceforCleanEnergy,Georgialeadsthenation with 27,817 newly announced EV-related manufacturing jobs,encompassingvehicleandbatteryproductionaswellas charginginfrastructuredeployment.

Electric vehicles offer several distinct advantages over traditional fossil fuel-powered automobiles. They are significantly more environmentally friendly, producing no tailpipeemissionssuchascarbondioxideornitrogenoxides. They also operate much more quietly, reducing noise pollution. Furthermore, EVs have a simpler mechanical design,whichresultsinfewermovingpartsandtherefore lower maintenance costs. Despite these benefits, EVs still faceseveralchallenges.Limitationssuchasshorterdriving ranges,extendedchargingtimes,andthelackofwidespread charginginfrastructureremainbarrierstomassadoption.

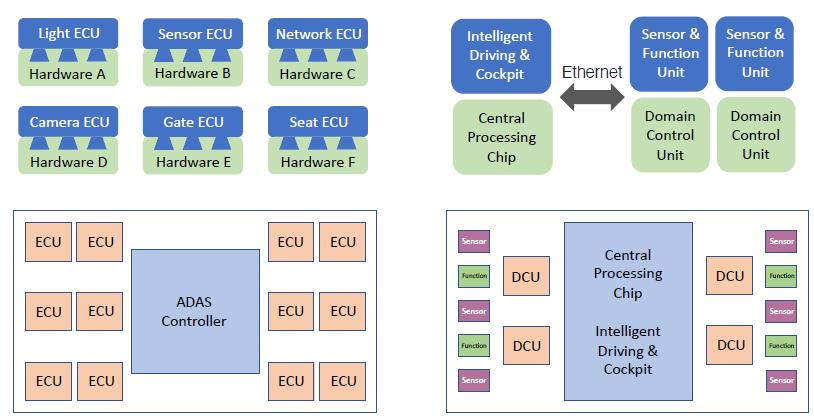

Unlike the rapidly evolving information technology (IT) sector,theautomotiveindustrytraditionallyprogressesata much slower pace. Legacy vehicle systems rely on a distributedelectricalandelectronicarchitecturecomposed ofnumerouselectroniccontrolunits(ECUs),whichareoften constrained by limited processing capabilities, low data transmission efficiency, and complicated wiring harness systems.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

However, the rise of next-generation communication technologiessuchastheInternetofEverythingand5Ghas significantly propelled the electrification and digital transformation of automobiles. These advancements have driven a surge in hardware computing power and led to exponential increases in software size and complexity. In response, the automotive industry is shifting from the conventional distributed ECU architecture to a more centralizedanddomain-orientedcomputingmodel.

In traditional architectures, each ECU is typically sourced fromdifferentsuppliersandoftenlacksinteroperabilityor standardization across systems. But as vehicles become smarter, the proliferation of ECUs has rendered this fragmented model inefficient. Centralized computing architecturesarenowessentialtoaddressthischallengeand to support the emerging concept of software-defined vehicles (SDVs), where software updates can redefine vehiclefunctionalitythroughoutits lifecycle[11].Figure2 illustratesthisevolvinghardwareparadigm.

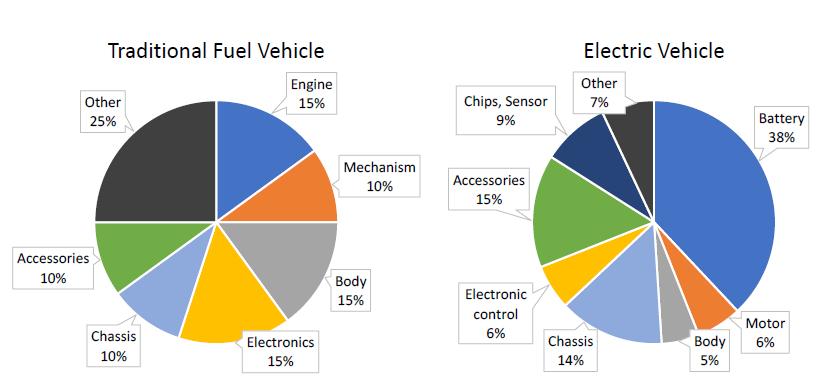

Thehardware platformin electricvehiclesforms the core infrastructureoftheentiresystem.TakingtheTeslaModel3 asareference,crucialcomponentsincludethebatterypack, centralizedcontrolunit,thermalmanagementsystem,power electronics,intelligentdrivingprocessors,asuiteofsensors, vehicle body structure, and tires. The cost structure of electric vehicles diverges significantly from that of conventionalinternalcombustionengine(ICE)vehicles.As seeninFigure3,traditionalICEvehiclesallocatethebulkof their costs to mechanical elements such as the engine, chassis, and drivetrain. In contrast, smart EVs primarily invest in batteries, motors, controllers, and various highperformanceelectronicsystems[8].

Charging System

Electric vehicles (EVs) utilize several types of battery chargingsystems,includingACcharging,DCcharging,hybrid AC-DCsystems,andwirelesschargingtechnologies[9-12]. EV charging infrastructure is commonly categorized into threelevels:

Level 1 charging uses a standard 120V AC householdoutletandtypicallydeliversarangeof3 to5milesperhourofcharging.

Level 2 operates between 208–240V, offering significantlyfasterchargingspeeds rangingfrom 28to80milesperhour.Thesechargersareoften installedinhomes,workplaces,andpubliclocations.

Level 3, also known as DC fast charging or supercharging,suppliesbetween400and900Vand can provide 3 to 20 miles of range per minute. Tesla’s V3 Superchargers and ABB’s Terra 360 capable of adding up to 100 km in under three minutes are examples of this fast-charging tier [14].

TheonboardchargerinanEVistailoredtothespecifications ofeachvehicleandtypicallysupportsinputvoltagesranging from110Vto260Vinsingle-phasesetupsand360Vto440V in three-phase systems. The output voltage of EV battery packs generally falls within the range of 450V to 850V. Wirelesschargingisa neweralternative, lesswidespread, whichusesamagneticfieldgeneratedbetweenfloorandcar matstotransferenergy.PluglessPowerpioneeredthiswith a system delivering 20 to 25 miles per hour of wireless charging.

The battery pack serves as the core energy reservoir in electricvehicles.ItstoresDCpower,whichisthenconverted intoACbytheinvertertodrivetheelectrictractionmotor

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

[16,27].SeveralbatterychemistriesareavailableintheEV market,eachsuitedtodifferentusecases:

1. Lead-acid batteries: These are cost-effective and perform well in cold climates, but their low energy density,shortservice life, bulkiness,andsafetyissues limittheirusetolow-speedorutilityvehicles[21,25].

2. Nickel-MetalHydride(Ni-MH):Knownfordurabilityand established technology, Ni-MH batteries offer better performancethanlead-acidtypes.However,theirlarge size,lowervoltageoutput,andmodestenergydensity confinethemtocompactorhybridEVs.

3. LithiumIronPhosphate(LiFePO₄): Widelyadoptedin current EV models, LiFePO₄ batteries provide strong thermalstability,highsafety,moderatecost,andalong operational lifespan. Their drawbacks include limited driving range, reduced cold-weather efficiency, and slowerchargingspeeds[15].

4. TernaryLithium(NMC/NCA): Thesebatteriesexcelin energy density, lifespan, and low-temperature performance, making them ideal for premium EVs. However,theirhighcostisamajorbarriertobroader adoption.

5. Sodium-ionbatteries(emerging):Stillinresearchand earlydevelopmentstages,sodium-ionbatteriespromise improved safety, affordability, and high retention capacity. Their limitations include greater weight and reduced energy density compared to lithium-ion alternatives[9].

The onboard charger enables AC power from an external sourcetobeconvertedinto DCpowersuitableforbattery charging.Itsoutputpowercapacityisvehicle-dependentand typically falls between 3.7 kW and 22 kW. For instance, Tesla’sintegratedonboardchargerisspecificallydesignedto align with its high-performance battery specifications, allowing faster and more efficient charging within the AC infrastructure.

PowerElectronicsController:

Thepowerelectronicscontrollerisapivotalelementinthe electric vehicle (EV) architecture. It acts as the interface betweentheenergystoragesystem(battery)andtheelectric motor, ensuring efficient and controlled energy transfer. Typically, this unit combines both inverter and converter functionalities.Duringregenerativebraking,thecontroller captures the kinetic energy and converts it into electrical energy to recharge the battery pack. When the vehicle accelerates, signals from the throttle are sent to the

controller, which in turn adjusts the inverter's switching frequencytoregulatemotortorqueandspeedbyconverting directcurrent(DC)fromthebatteryintoalternatingcurrent (AC)forthetractionmotor.

Inrecent developments, multi-level inverterarchitectures have been implemented to enhance efficiency, minimize harmonic distortion, and increase power density. For instance,theTeslaModelSemploysasiliconcarbide(SiC) multi-level inverter, which offers improved thermal performance and switching capabilities. However, these advancementsalsointroduceincreasedsystemcomplexity, higher manufacturing costs, and more demanding computational requirements in the control algorithms, presentingchallengesindesignandintegration[25].

The DC/DC converter plays a crucial role in managing voltagelevelswithintheEV’selectricalsystem.Ittransforms high-voltage DC power from the main battery pack into lower voltage DC suitable for auxiliary systems such as lighting,infotainment,airconditioning,windshieldwipers, and navigation units. These systems typically operate on voltagesrangingbetween12Vand48V.

Thisconverteristypicallybidirectional,allowingittoalso direct power from low-voltage sources back to the highvoltagebus,especiallyduringregenerativebraking.AsEV technologyevolves,demandsforhigherefficiency,thermal stability,andcompactpowerdensityinDC/DCconverters areescalating.Advanceddesignsnowfocusonincorporating wide-bandgapsemiconductorssuchasGalliumNitride(GaN) and Silicon Carbide (SiC) to boost efficiency, reduce switchinglosses,andenablefastervoltageregulation.Future innovationsaimtodeliverconverterscapableofprecisely regulatingvoltagelevelsacrossdiverseoperatingconditions, whichiskeytoimprovingsystemreliabilityandextending componentlifespan[18].

Electric Traction Motor:

At the heart of an EV’s propulsion system lies the electric tractionmotor,responsibleforconvertingelectricalenergy intomechanicalmotion.Severalmotortechnologiesareused in EVs, each offering distinct benefits. Common types include:

DCMotors

BrushlessDC(BLDC)Motors

InductionMotors

PermanentMagnetSynchronousMotors(PMSM)

SwitchedReluctanceMotors(SRM)

The Tesla Model S, for example, utilizes a three-phase AC inductionmotor,whiletheModel3incorporatesaninternal

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

permanentmagnetsynchronousreluctancemotor.Eachtype hasuniqueadvantages:

BLDC motors are compact and efficient but more expensive.

Induction motors are robust, require less maintenance,andaremore cost-effective,making them a popular choice for high-performance vehicles.

PMSMs offer superior torque density and energy efficiency,thoughtheyinvolvehighercostsdueto theuseofrare-earthmagnets.

Switched Reluctance Motors provide a low-cost solutionbutareplaguedbyissueslikehighacoustic noiseandtorqueripple,limitingtheiradoption[35].

Amongthese,three-phaseACinductionmotorshavebecome aleadingoptionduetotheirbalancedmixofperformance, efficiency,andlowoperationalcosts.Thesemotorseliminate the need for brushes and commutators, resulting in less maintenanceandenhancedreliability.

Electronic Chips:

Semiconductors are central to the transition of modern vehiclesintointelligent,autonomousplatforms.Onaverage, a contemporary vehicle is embedded with approximately 1,400 semiconductor components sourced from key supplierslikeInfineonTechnologies,NXPSemiconductors, and Texas Instruments [1]. These chips perform a wide variety of functions, ranging from power management to controlsystemsanddataprocessing.

Acriticalclassofautomotivesemiconductorsincludespower devices such as metal–oxide–semiconductor field-effect transistors (MOSFETs). These are predominantly used to regulate vehicle functions like acceleration, regenerative braking, and electronic steering. As vehicle electrification and connectivity have advanced, so has the demand for enhancedprocessingandstorage.Thestoragerequirements insmartEVshaveexpandedsignificantly fromgigabytes (GB) to terabytes (TB) especially in the context of highresolutionsensorydata.Forexample,autonomousvehicles operating at Level 4 autonomy can generate and store approximately 2TB of visual and sensor data every two hours, due to increased sensor density and image fidelity. Consequently,memorychipshavebecomeanessentialpart oftheEV’scomputationalinfrastructure.

Modern system-on-chip (SoC) designs consolidate processingmodulessuchasCPUs,GPUs,FPGAs,andneural networkacceleratorsintoasinglechip.TheseSoCsactasthe computational backbone of smart EVs. Tesla’s Full SelfDriving (FSD) chip, for instance, is a prime example. It

integrates components like image signal processors (ISP), general-purposeGPUs,andcustomAIaccelerators.Thischip is capable of processing over 2,300 frames per second, delivering performance that is roughly 21 times more powerful than its predecessor, thereby substantially boostingautonomousdrivingcapabilityandsafety.

Integration of Chips and Sensors in EVs: ModernEVs,suchasthosefromTesla,incorporatearobust sensor suite with eight external cameras and twelve ultrasonicsensorsdistributedacrossthevehiclebody.Data from these units is fed into the onboard SoC for real-time analysis and decision-making. This fusion of sensor input andprocessingpowerunderpinsthevehicle’scapabilitiesin autonomous navigation, safety monitoring, and driver assistancesystems.

Although this paper does not delve into all hardware subsystems,suchasthechassis,tires,orbodycomponents, it's important to acknowledge that these also play supporting roles in sensor deployment, thermal management,andsafetysystemintegration.

Whilehardwareremainsfundamental toEVperformance, the importance of software in the automotive domain is rapidly accelerating, especially in areas like vehicle connectivity,automation,andintelligentfunctionalities.Over recentyears,thecomplexityofbothautomotivecomponents and their embedded software has increased considerably [13].

Centralized Architectures and Service-Oriented Approaches

Intraditionalsystems,individualECUsareresponsiblefor specific functions such as lighting, sensors, seating, and networking.Thesefunctionsinteractthroughdistinctsignal pathwaysacrossbuseslikeCAN(ControllerAreaNetwork). The emerging model, however, emphasizes a serviceoriented architecture (SOA) where software services are decoupledfromhardwaremodulesandaredeployedacross aunifiedcomputationalplatformusinghigh-speedprotocols likeEthernet.

Virtualization, a key enabler in cloud computing, is now being adapted for in-vehicle systems to manage growing systemcomplexityandcomputationaldemands[18].Though originatingintheclouddomain,vehiclevirtualizationdiffers inseveralcriticalaspects:

1. PerformanceOrientation:

While cloud virtualization is optimized for scalable resource allocation, automotive virtualization must

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

prioritize real-time responsiveness and functional safety.

2. ResourceConstraints:

Unlike cloud servers, in-vehicle systems have constrainedprocessingpower,makingefficientresource usageacriticalrequirement.

3. Hardware-SoftwareCoupling:

Cloud architectures favor layered abstraction. In contrast, vehicle virtualization involves tightly integrated hardware-software interactions, requiring tailoredsolutionsforeachhardwareconfiguration.

In contemporary EV electronic and electrical systems, multiple ECUs offer distinct functionalities, each with varying criticality and performance requirements. For example,theinstrumentcluster,whichdisplayskeyvehicle parameters,mustoperateinclosesynchronizationwiththe engine control system, necessitating low-latency, highreliabilityprocessing.

Ahypervisorservesasavirtualizationplatformthatenables multipleapplicationsorentireoperatingsystems(OSes)to operateconcurrentlyonasinglephysicalhardwareunit,as thougheachwererunningindependently[10,17].Itactsasa mediatingsoftwarelayerbetweenthehardwareandvirtual machines,allowingforefficientabstractionandpartitioning of hardware resources. Through the hypervisor, systems with differing operational requirements ranging from mission-critical real-time processes to general-purpose applications can coexist on the same platform while maintaining robust security isolation and reliable system performance.

The hypervisor facilitates flexible resource allocation, allowingvarioussoftwareenvironmentstosharethesame hardwareplatformwithoutcompromisingsystemintegrity. This is especially critical in electric vehicles (EVs), where safety-critical control systems must be securely isolated fromnon-trustedorentertainment-basedsoftwarelayers.

Several companies are at the forefront of developing hypervisor solutions tailored for the automotive industry. These include Wind River Systems, Green Hills Software, Continental AG, Mentor Graphics, Blackberry, and Sasken Technologies.

WindRiverHypervisorisawell-establishedembedded hypervisor recognized for its compact design, low latency, and optimized execution. It offers robust partitioning mechanisms, enabling strict isolation between software components with varying safety levels.Importantly,itsupportsreal-timeperformance

guaranteeswhileallowingforsystemcustomizationand innovation.

Green Hills Software offers a hypervisor known as µvisor, which integrates with ARM Cortex-A9-based processors. This solution uses para-virtualization and incorporatesacertifiedreal-timemicrokernel,enabling theconcurrentexecutionofmultipleguestOSes,suchas Android.Itsscalableandefficientarchitectureensures thattheseOSesrunonsharedhardwarewithoutmutual interference. Furthermore, hardware-enforced partitioningensuresthateachvirtualmachinecanreach its optimal performance levels, even within complex automotiveenvironments.

Blackberry QNX Hypervisor stands out as the most widelyadoptedopen-sourcesolutionintheautomotive domain. Built upon a microkernel architecture, it is engineeredtomeetthefunctionalsafetyandreal-time demandsofkeyvehiclesystemslikeinstrumentclusters, advanceddriver-assistancesystems(ADAS),andvehicle controlmodules.Withasignificantmarketshareinthe RTOS segment, QNX has become the industry benchmark for multi-OS vehicle environments. It is deployed by leading automakers such as BMW, Ford, GM, Toyota, Mercedes-Benz, Honda, Volkswagen, and Bosch,amongothers.

Insummary,hypervisorshavebecomeessentialinmodern electricvehiclesoftwarestacks,enablingsecure,modular, and efficient multi-OS deployments on limited hardware platforms.Theirroleispivotalinsupportingtheincreasing demandforcomputationaldiversity,functionalsafety,and real-time responsivenessin today’sintelligentautomotive systems.

Inelectricvehicles(EVs),theoperatingsystem(OS)formsa foundational software layer that manages both hardware resources and application software, while also offering standardizedinterfacesfordevelopers.Asmodernvehicles are equipped with numerous electronic control units (ECUs) includingsystemsformotors,batterymanagement, infotainment,anddriverassistance theOSmustefficiently coordinatereal-timeoperations,taskscheduling,andinterprocess communication across heterogeneous hardware platforms.

Giventhediverserequirementsofautomotivesubsystems, twoprimarytypesofoperatingsystemsareemployed:

Real-TimeOperatingSystems(RTOS):Theseareusedin safety-critical applications such as airbag deployment systems, braking control, and battery management systems. These components demand deterministic timing behavior, where even millisecond-level delays

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

canleadtohazardousfailures.RTOSensuresminimal latency and strict task prioritization, thus supporting life-criticalfunctionalityinvehicles.

Time-SharingOperatingSystems(TSOS):Theseareused innon-criticalbutresource-intensiveapplications,such as infotainment systems and navigation interfaces, wheremultitaskinganduserinteractivityareessential. For instance, a driver might simultaneously use GPS navigation and initiate a phone call both functions managed seamlessly by a TSOS with multiplexing capabilities.

Amongtheleadingoperatingsystemscurrentlyadoptedin electricvehicleplatformsare:

AndroidAutomotiveOS(AAOS)

AAOS has rapidly gained traction as an in-vehicle infotainment (IVI) platform. Unlike Android Auto, which mirrors a smartphone interface, AAOS is an embedded automotive variant of the Android operating system that runsnativelywithinthevehicle’sheadunit.Itisemployedin EVslikethe2021VolvoXC40Recharge,2020Polestar2,and the 2022 GMC Hummer EV. One of the key advantages of AAOSisitsintuitiveuserinterface,optimizedforin-vehicle screens, as well as its compatibility with downloadable applications directly from the car's interface without requiringatetheredsmartphone.Moreover,AAOSleverages Android’s widespread ecosystem, reusing familiar APIs, developmenttools,andprogramminglanguages(e.g.,Kotlin andJava),thusfacilitatingthecontributionofalargeglobal developerbaseandexpeditingapplicationdevelopmentand deployment.

Withtherapidriseinpopularity,electricvehicles(EVs)are nowrecognizedasemergingcomputationalplatformsand centraltothenextwaveoftechnologicalinnovation.Unlike traditional internal combustion engine (ICE)vehicles, EVs offer notable benefits such as enhanced performance, reduced maintenance, eco-friendliness, and an improved driving experience. However, these advantages are accompaniedbysignificanttechnologicalandinfrastructural challenges.

This paper provided a comprehensive overview of the current state and future direction of EV technology. We examinedthecorehardwarecomponents includingenergy systems,powertrains,electroniccontrolunits(ECUs),and chip-level technologies and outlined prevalent software architecturesandtheirrole inthe evolvingEV ecosystem. Furthermore, we discussed emerging trends, ongoing challenges,andpotentialtechnologicalbreakthroughsinthe domain.

While various policy, regulatory, technical, and marketbasedbarriersstillhinderthefull-scaledeploymentofEVs, we hope this review encourages greater academic engagement and innovation in electric vehicle platform development. As a continuation of this work, our future research will focus on the co-design of software and hardwaresystemsaimedatbuildingintelligent,reliable,and energy-efficientEVinfrastructuresforthenextgenerationof mobility.

[1] M.E.ElSharkawi,ElectricVehicleSystems,Wiley-IEEE Press,2013.

[2] HadiAskaripoor,MortezaHashemiFarzaneh,andAlois Knoll.2022.E/EArchitecture

[3] Synthesis: Challenges and Technologies. Electronics (2022).

[4] Victor Bandur, Gehan Selim, Vera Pantelic, and Mark Lawford. 2021. Making the Case for Centralized Automotive E/E Architectures. IEEE Transactions on VehicularTechnology(2021).

[5] Samarjit Chakraborty, Martin Lukasiewycz, Christian Buckl,SuhaibFahmy,NaehyuckChang,SangyoungPark, Younghyun Kim, Patrick Leteinturier, and Hans Adlkofer. 2012. Embedded Systems And Software ChallengesinElectricVehicles.InDesign,Automation& TestinEuropeConference.IEEE,Dresden,Germany.

[6] Cagla Dericioglu, Emrak YiriK, Erdem Unal, Mehmet UgrasCuma,BurakOnur,andMehmetTumay.2018.A Review of Charging Technologies for Commercial Electric Vehicles. Journal of Advances on Automotive andTechnology(2018).

[7] JianDuan,XuanTang,HaifengDai,YingYang,Wangyan Wu,XuezheWei,andYunhuiHuang.2020.BuildingSafe Lithium-ion Batteries For Electric Vehicles: a Review. ElectrochemicalEnergyReviews3,1(2020),1–42.

[8] MulugetaGebrehiwotandAlexVandenBossche.2015. RangeExtendersforElectric Vehicles.Editorial Board (2015).

[9] Marco Haeberle, Florian Heimgaertner, Hans Loehr, Naresh Nayak, Dennis Grewe, Sebastian Schildt, and MichaelMenth.2020.SoftwarizationofAutomotiveE/e Architectures: A Software-defined Networking Approach. In 2020 IEEE Vehicular Networking Conference(VNC).IEEE,1–8.

[10] PeterHank,SteffenMüller,OvidiuVermesan,andJeroen VanDenKeybus.2013.

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056

Volume: 12 Issue: 07 | Jul 2025 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072

[11] A.Sangiovanni-VincentelliandM.DiNatale,"Embedded systemdesignforautomotiveapplications,"Computer, vol.40,no.10,pp.42-51,2007.

[12] NVIDIADRIVE,"NVIDIADRIVEAGXPlatform,"[Online]. Available:https://developer.nvidia.com/drive

[13] J. Dittmann, "Automotive Ethernet and Zonal Architectures,"SAETechnicalPaper,2020.

[14] AUTOSARConsortium,"AUTOSARPlatformOverview," https://www.autosar.org

[15] H. Kopetz, Real-Time Systems: Design Principles, Springer,2011.

[16] Tesla Inc., "Model 3 Thermal Management," Technical Whitepaper,2021.

[17] Nagaraju,A.,&Boini,R.(2025).TransformerLessNonIsolated High Gain DC/DC Converters for Solar Photovoltaic System Applications. GMSARN InternationalJournal19,199-219.

[18] Nagaraju,A.,&Boini,R.(2025).TransformerLessNonIsolated High Gain DC/DC Converters for Solar Photovoltaic System Applications. GMSARN InternationalJournal19,199-219.

[19] Nagaraju A., Rajender B., (2023). A Transformer Less High Gain Multi Stage Boost Converter Fed H-Bridge Inverter for Photovoltaic Application with Low ComponentCount.J.Eng.Sci.Technol,18(2),2023,pp. 1038-1054.

[20] Addagatla, N., & Boini, R. (2023). A High Gain Single Switch DC-DC Converter with Double Voltage Booster Switched Inductors. Advances in Science and Technology.ResearchJournal,17(2).

[21] Nagaraju, A., & Krishnaveni, A. (2017). Modified MultilevelInverterTopologywithMinimumNumberof Switches.IJSTE International Journal of Science Technology&Engineering,3(09).

[22] Nagaraju, A., & Krishnaveni, A. (2017). Modeling of Direct Torque Control (DTC) of BLDC Motor Drive International Journal of Science Technology & Engineering,3(09),413-419.

[23] Nagaraju,A.,&Krishnaveni,A.(2017).PSIMSimulation ofVariableDutyCycleControlDCMBoostPFCConverter To Achieve High Input Power Factor. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET),4(3),882-888.

[24] Krishnaveni,A.,&Nagaraju,A.(2017).POWERANGLE CONTROL SCHEME FOR INTEGRATION OF UPQC IN GRIDCONNECTEDPVSYSTEM.

[25] RAO, V. M., NAGARAJU, A., KRISHNAVENI, A., & NAGARAJU, S. (2022). A paper on barriers and challengesofelectricvehiclestogridoptimization.

[26] Krishnaveni,A.,&Kodela,M.(2021).SIMULATIONOF 6KW VARIABLE DUTY CYCLE CONTROL BOOST PFC TOPOLOGYINDISCONTINUOUSCURRENTMODE.

[27] KrishnaveniA,RajenderB,(2024).ASingleSwitchHigh GainMultilevelBoostConverterwithSwitchedInductor Topology for Photovoltaic Applications”, SciEnggJ 17 (Supplement)008-016.