It’s often said that great wines are grown, not made. Our readers demonstrate that concept perfectly: two out of three wineries that read Wine Business Monthly own vineyards.

This issue includes a few articles focused on the vineyard. Nitrogen content in grapes is of interest to winemakers because it plays a major role in the kinetics of alcoholic fermentation and in the wine’s aromas. Another article in this issue delves into the role specific viticultural practices play in affecting nitrogen content. A 10-year study looked at nitrogen and canopy management.

The wheels of academia and research grind slowly but, as another article indicates, progress has been made in the quest to create vines that are resistant to powdery mildew, part of the VitisGen project. That’s a big deal: Powdery mildew is the most significant vineyard disease of all in terms of expenses for control and potential losses. More chemicals, sulfur and other fungicides are used to combat powdery mildew than to manage any other vineyard problem.

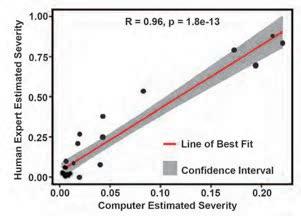

Another piece discusses recent findings on how the third iteration of the VitisGen3 project leverages artificial intelligence and machine learning.

The report from the recent Vinitech show in Bordeaux highlights innovations. Not all of them are available in the U.S. market, yet, but the article provides a snapshot of what could be coming. Much of it involves information technology and automation.

I always enjoy reading the annual selection of “Hot Brands.” The list has evolved through the years but always includes an interesting selection of up-and-coming wines, winemakers and regions. There’s a rundown on various varieties and styles but also discussion of the paths people take on their journeys into winemaking. For some, it’s a family tradition, but most of these winemakers were in other professions. One winemaker on this year’s list was in politics, another in restaurants, another was in mortgage lending, while still another was with the Air Force. One is making wines with students from a local high school, mentoring them on growing the best grapes—in this case Cabernet Sauvignon—possible.

March 2023 • Volume XXX No. 3

Editor Cyril Penn

Managing Editor Erin Kirschenmann

PWV Editor Don Neel

Eastern Editor Linda Jones McKee

Copy Editor Paula Whiteside

Contributors L.M. Archer, Bryan Avila, Richard Carey, Christopher Chen, W. Blake Gray, Mark Greenspan, Michael S. Lasky

Design & Production Sharon Harvey

Director, Analytics Group Alan Talbot

Editor, Wine Analytics Report Andrew Adams

Events Director: Danielle Robb

Web Developers Burke Pedersen, Peter Scarborough

Marketing Specialist Katie Hannan

President & Publisher Eric Jorgensen

Associate Publisher & Vice President of Sales

Tamara Leon

ADVERTISING

Account Executives Hooper Jones, Laura Lemos, Ashley Powell

Account Support Representative Aidan O’Mara

ADMINISTRATION

Vice President – Data Management Lynne Skinner

Project Manager, Circulation Liesl Stevenson

Financial Controller Katie Kohfeld

Data Group Program Manager Rachel Cunningham

Research Assistant Sara Jennings

Public Relations Mary Jorgensen

Chairman Hugh Tietjen

Publishing Consultant Ken Koppel

Commercial Advisor Dave Bellon

For editorial or advertising inquiries, call 707-940-3920 or email info@winebusiness.com

Copyright 2022 Wine Communications Group, Inc.

Short passages can be quoted without permission but only if the information is attributed to Wine Business Monthly.

Wine Business Monthly is distributed through an audited circulation. Those interested in subscribing for $39/year, or $58 for 2 years, call 800-895-9463 or subscribe online at subs.winebusiness.com. You may also fill out the card in this magazine and send it in.

With each Diam solution, winemakers can choose the ideal oxygen level and optimal bottle aging duration depending on their wine profile and wine history. The Diam cork range is unique as it enables winemakers to best meet their consumers ever-changing needs and makes corking the ultimate oenological act.

If the notion of “sustainability” has crossed your mind lately, consider this fact: The typical mature French oak tree will yield about 7 traditional barrels. The very same tree will yield about 500 barrels worth of StaVin barrel alternatives. Our various timeperfected infusion systems are just as meticulously resourceful as how Sioux hunters once harvested their buffalo,

with absolutely nothing at all going to waste. And that includes a whopping savings of 94% in operating costs.

© 2023 StaVin Incorporated, P.O. Box 1693, Sausalito, CA 94966 USA telephone (415) 331-7849 www.stavin.com

®

Bruce Reisch

grape breeder and leader, VitisGen2, Cornell University, “Powdery Mildew-resistant ‘Renstack’ Vines Released to the Public Domain”, page 52

Xavier Zamarripa

Co-founder and President, Vara Winery & Distillery, Albuquerque New Mexico, “VARA: A Collaborative Vision,” page 16

“Before marker-assisted selection, we could only observe whether or not powdery mildew was infecting our grapevine selections. Reliable DNA markers allow us to know which resistance genes are present in each seedling we test.”

“To have the highest expression of what you are going to make, you need to provide your artisans with the best tools and materials.”

Paula Harrell

owner, P. Harrell Wines, “Hot Brands of 2022”, page 12

Brent Stone

COO and winemaker, King Estate, Eugene Oregon, “Oregon Sauvignon Blanc Enters the Flagship Fray,” page 22

“You have a blank canvas because there aren’t a lot of expectations for what an Oregon Sauvignon Blanc should or shouldn’t be.”

“I would love to create a handbook for somebody who wants to get into this business in this way because putting all those pieces together was just challenging. I mean, it took me some years.”

Ben Riccardi

Tegan Passalacqua

owner and winemaker, Osmote Wine, “Hot Brands of 2022”, page 12

winemaker, Turley Wine Cellars, Amador and Paso Robles California, “Old Vines Begin to Capture the Wine World’s Attention,” page 40

“I took everything about the Finger Lakes—bracing acidity, fun hybrid, old vineyard—and I turned it up to 11 in one wine.”

NEW TEXT TK

“The big wineries didn’t want [the Historic Vineyard Society] to happen. They like paying not so much for old-vine grapes.”

Remy Drabkin

Amanda Barnes

owner and winemaker, Remy Wines; Mayor, McMinnville, Ore., “Technical Review: Remy Wines”, page 34

author, The South American Wine Guide, “Old Vines Begin to Capture the Wine World’s Attention,” page 43

“You have to be OK that not everything has to be perfect all the time. That’s part of finding beauty in the shadows, which is not hard to do.”

“Most of the producers in South America are paying at least double what they would for grapes from younger vines as a gesture and to try to retain these old vines.”

Jordan Kivelstadt

managing director, Tubes USA, “Single-Serve Wine-in-Tubes Brings Tasting Room Pours to the Consumer’s Home”, page 72

Herve Duteil

“The wine consumer’s behavior is changing and this idea of both sampling and small consumption, of having a glass instead of a bottle at a time, has fueled a lot of the innovation in the industry over the last few years.”

chief sustainability officer for BNP Paribas Americas, parent company of Bank of the West, New York, NY, “Sustainability Meets Finance,” page 76

“We moved from financing the green [leaders] to financing the greening of the economy. We moved from niche to universal.”

Damian Doffo

general manager, Doffo Wines, “Hot Brands of 2022”, page 12

Erica Landin-Löfving

chief sustainability officer, Vintage Wine Estates, Santa Rosa, CA, “Sustainability Meets Finance,” page 76

“Sustainability is moving from storytelling to data.”

“There’s a concerted effort among wineries that really care to change the stereotype of Temecula Valley. Several are taking the right steps to make change.”

USING BUSINESS AS A FORCE FOR GOOD.

Scott Laboratories is proud to meet high standards of social and environmental impact. Learn more about B Corporation certification at usca.bcorporation.net.

From

crush to

A trusted partner for more than 90 years.

Breakthru Beverage Group, the nation’s fourth largest distributor, signed an agreement to acquire Wine Warehouse, enhancing its national footprint. Wine Warehouse is a multi-generational, family owned and operated, wholesale distributor of wine, beer and spirits. The company was established in 1973 and grew to be the third largest wholesaler in California, a top 10 wholesaler in the country. The deal was Breakthru’s third acquisition in the past year following Major Brands in Missouri and J.J. Taylor in Minnesota.

E. & J. Gallo Winery awarded its retail chain distribution business in California to Republic National Distributing Company (RNDC), the country’s second largest wine and spirits distributor, and is closing Gallo Sales Co. Inc., which formed in 1933. According to media reports, at least 355 workers across seven sites are affected, but Gallo said most employees would be interviewed and offered similar opportunities with RNDC.

The 1,300+ acre collection of vineyards and land known as the Paicines Vineyards in San Benito County, Calif., was sold to The Wine Group. “The Paicines Vineyards offer a great blend of water security, scale, production, quality, and overall value as an asset to produce coastal red and white winegrapes for our wine programs currently met with strong demand,” John Sutton, CEO of The Wine Group, said in a press release. The Wine Group, headquartered in Livermore, Calif., is America’s second largest wine producer by volume.

Rombauer Vineyards announced the acquisition of a vineyard with 54 planted vine acres in the Sonoma Valley, Calif. appellation. The vineyard, called “Carriger Two” by the Rombauer team, has been a primary source of Sauvignon Blanc since 2014. It sits adjacent to the Carriger One Vineyard, acquired by Rombauer in 2022.

Favia’s Andy Erickson and Annie Favia are partnering with the Huneeus family to build a winery in the Oakville AVA in Napa Valley. They plan to build it on an 86-acre parcel between Opus One and Groth. The property, formerly owned by Clark Swanson, was purchased by the Huneeus family, owners of Quintessa, among other wineries, in 2018.

Scott Laboratories, a winery supplier, became a Certified B Corporation as it entered its 90th year of business. Scott Laboratories was founded by Robert Scott, grandfather of Zachary Scott, current director of Scott Labs. “I believe that B Corp Certification not only validates what we do, it provides a framework to go further,” Zachary Scott said. “The best way to honor our legacy is to challenge ourselves to do more.” The B Corp framework expands the ways in which a company must evaluate itself. Beyond standard business evaluations of inputs versus waste and quality versus efficiency, B Corp Certification forces looking beyond the numbers to reveal the broader impact of business decisions.

Erin Kirschenmann, DipWSET, is the managing editor for Wine Business Monthly and has been with the company since 2012. In addition to production responsibilities for the monthly trade magazine, she writes about business, technology, sales and marketing, and also oversees content and programming for WBM’s symposiums. She speaks on wine industry trends at numerous conferences, including the Unified Wine & Grape Symposium and the World Bulk Wine Exhibition, and guest lectures on wine, media and public relations. In 2022, she joined the Napa Valley Wine Academy as a WSET Level 1 and Level 2 instructor. Erin has served as a judge in the international Concours Mondial de Bruxelles wine competition since 2016 and at several regional competitions. She earned her Bachelor of Arts in communications with a journalism emphasis from Sonoma State University. Find her online via her Instagram, @erinakirsch.

Our Hot Brands surprise us every year. Sometimes, finding the brands we’d like to feature is a challenge—having been in the wine industry so long it’s easy to become jaded, or feel like there aren’t anymore original stories. Family winery? Heard that one. Left the crazy tech world to return to their roots? That’s become pretty common in the North Coast.

But then, there are times when coming up with the list is a cinch. We’ve either been to the winery or stumbled upon a fantastic story. Family winery? Let’s plant a vineyard at the local high school to get more students interested in agriculture. Left a tough industry? She started blending other people’s wines before deciding to do it on her own.

No matter how simple or difficult it may be, our Hot Brands list always attempts to encompass the latest trends in the American wine market.

In 2022, Wine Business Monthly ended up choosing a number of wineries from east of the Rockies or in regions that aren’t always celebrated. We chose wineries that are determined to do well by their communities and be a catalyst for change in a “heritage”-based industry. We found wineries that are using hybrids, a wide array of fermentation vessels and making the best of limited space.

This was certainly an enterprising bunch. Not one of these brands are static—they are all pushing the status quo in their own ways. All of them, though, are dedicated to producing high-quality, premium wines that taste delicious and are more accessible to the average consumer. These aren’t wine geeks’ wines (though wine geeks would certainly enjoy them). They’re meant for everyone to enjoy, to feel a part of the wine community.

The men, women and wines you’ll meet in the following pages are the embodiment of all that is great about this industry. Whittling their stories down to a page was an impossible feat, but we hope you take the chance to try a few of their wines and let the bottles tell you the rest!

2021

Wines

Wine

• Bodkin Wines

• Ulloa Cellars

• Eden Rift Vineyards

Cellars

• 2019

• Dot Wine

• Gonzalez Wine Company

• Walsh Family Wine

• Parra Wine Co.

• Andis Wines

Domaine Drouhin Oregon

& Vineyards

• La Pelle Wines

• 2Hawk Vineyard & Winery

• Sharrott Winery

• Early Mountain Vineyard

• Tarpon Cellars

• Alara Cellars

• Onesta Cellars

• 2020

• Scheid Family Wines

• J. Wilkes

• Thacher Vineyards

• Aridus Wine Company

• Sangiacomo

Amista Vineyards

Vineyard

• Sans Wine Co.

• Ankida Ridge Vineyards

• Stewart Cellars

Cohn Cellars

Winery

• Syncline Winery

• Fujishin Family Cellars

• Presqu’ile

• L’aventure

• Marynissen Estates

• Four Vines Peasant

• Rivaura Winery • SMAK

• Bodega Pierce

• Devium

• Sokol Blosser Winery

• Land of Promise Wines

• The Hilt

• William Chris

• Elk Cove Vineyards

• Smith Story Wine Cellars

• Band of Vintners

• Vidon Vineyard

• Illahe Vineyards

• 2018

• Intrinsic Wine Co.

• 2017

• Wade

• Obvious Wines

•

• Acquiesce Winery

• Lagier Meredith

• Alexandria Nicole Cellars

• Bella Grace Vineyards Winery

• Winery Sixteen 600

• 2016

• Infinite Monkey Theorem Winery

•

• Parrish Family

• Amavi Cellars

• LVVR Cellars

• Dan

• Mi Sueño

• Bartholomew Park Winery

• Becker Vineyards

• Marilyn Remark Winery

Vineyards

• Tangent

• Gruet Winery

Gladiator

• Red Tail Ridge

• Trio Vintners

• Clos Du Val

• 2006

• Bedell Cellars

Wine Cellars

Swanson Vineyards

• Raffaldini Vineyards And Winery

• Sojourn Cellars

• Purple Wine Company

• Kutch Wines

• A to Z Wineworks

• Solorosa

Andretti Winery

Angeline Wines

• Coro Mendocino

• House Wine

• Artesa Vineyards & Winery

• Cheapskate

• Esser Vineyards

• Rock Rabbit

• HRM Rex-Goliath

• Velvet Red

• 2004

• Domaine Drouhin

• 2007

• 2008

• Graziano

• Jeff Runquist Wines

• Willamette Valley Vineyards

• J.R. Storey

• Liberty School

• Black Star Farms

• Incredible Red

• Red Truck

• Three Thieves Bandit

• McManis Family Vineyards

Jewel Collection

• L’ecole Nº 41

• Shannon Ridge

• Ceja

• King Family Vineyards

• Twenty Bench

• Buena Vista Carneros

• Hard Core

• Cartlidge & Browne

• Sofia Mini

• Kunde Estate

• 2005

• Cycles

• Parducci

• Hitching Post

• Seven Deadly Zins

• Screw Kappa Napa

• Sebastiani Vineyards & Winery

• Tin Roof

• Three Thieves

• Jest Red

•

• Oliver Winery

• Graceland Cellars

• Castle Rock Winery

• J Garcia Wines

•

• 2003

• Black Oak

•

As the climate continues to change , and weather fluctuations become wilder, many in the wine world have begun to consider new varieties. In Bordeaux, a slew of new clones and grapes have been approved. In vineyards across the United States, viticulturists are trialing more Spanish, Italian and other warm-climate varieties.

And it’s amidst this altered landscape that some have even looked to French-American hybrids—or even the more traditional all-American varieties.

However, there are wineries and vineyards east of the Rockies who never gave up on these grapes, and one of the most prominent is Chrysalis Vineyards in Middleburg, Va. Proprietor Jennifer McCloud is proud to grow Norton, and might be one of the largest Norton growers in the U.S.

For many in the wine industry, Norton is simply viewed as “lesser than”. First cultivated by Daniel Norton in the early 19th century, Norton is of the vitis aestivalis species and doesn’t have the typical characteristics we would expect from vitis vinifera—but it also doesn’t have the “foxy” characters of other hybrids. What it does have is a lot of anthocyanins and produces deeply colored, rich red wines.

Norton is widely considered “America’s grape” and is a staple in states like Virginia and Missouri, where it has been commonly grown for more than a century.

It is this indigenous variety that Chrysalis Vineyards is dedicated to growing and growing well. McCloud is steadfast in her belief that Norton can produce premium, dry wines. Yes, more international varieties, including Albariño, Nebbiolo, Petit Verdot, Tannat and Viognier, are part of the portfolio, but they certainly are not the focus.

Norton has proven to be one of the more resilient grapes—a necessity in harsh Virginia climate. In 2020, a hailstorm ripped through the vineyards in

late summer, just before the harvest on the white varieties began. While some of the Albariño, Petit Manseng and Viognier shattered, Norton, a late-ripening variety, was still tough enough to withstand the pelting ice.

The Locksley Reserve is Chrysalis Vineyards’ flagship wine. At $45 it is also one of the most expensive Nortons on the market. Blended with a little bit of Tannat to add chocolate, raspberry and slightly earthy tones, and “a splash” of Petit Verdot, this wine is meant to showcase just how special this grape can be. With just 12 months barrel aging, it is not an overtly tannic wine, but is it certainly suitable for long-term aging.

As the Virginia wine industry continues to mature, the wines coming out of Chrysalis Vineyards have demonstrated that Norton can be part of its future.

The Doffo story began back when Marcelo Doffo emigrated from Argentina to the United States, settling on a piece of land in Temecula. In homage to his Italian roots, he became a garagiste, a home winemaker producing wine out of his garage. In 1997, he purchased an old cattle ranch, installed trellis and irrigation systems by hand, and planted Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah with some Petit Verdot and Cabernet Franc as well. Four years later, he released “Mistura”, a blend of all four varieties.

Today, his son Damian has taken the helm as the general manager and has made Doffo Wines a truly family affair: his sisters Brigitte and Samantha are the tasting room director and events director, respectively.

Taking over for their father wasn’t an insignificant task. Damian recalled all the excitement and dedication for wine and for family Marcelo showed. In addition to being a winemaker, Marcelo was also a single father.

“We want to exude passion in wine and most everything we do,” Damian stated. “We don’t know any other way—that’s how we were taught by Dad.”

It’s a mindset that has carried through the generations, and even Damian’s nephews have started to become involved in the business, serving as bussers or hosts until they reach legal drinking age. The family takes pride in their work.

“We want everything to be well-manicured and taken care of,” Damian said. “It speaks to our quality mindset—even our crews take pride in what we do. It’s all in the details and the details carry through to our winemaking.”

After all, he said, it’s his family’s name on the bottle.

But the Doffos are also committed to Temecula Valley, supporting the community and trying to raise the profile of the region as a place for premium wines.

“We are adamant about using local fruit and showing that you can make good wine from it,” Damian said. “There’s a concerted effort among wineries that really care to change the stereotype of Temecula Valley. Several are taking the right steps to make change.”

As part of that change, Damian knows that it’s essential to keep talent local. Inspiring the next generation to become viticulturists or start a career in wine

has been a challenge in regions across the country—agriculture isn’t nearly as glamorous and certainly does not pay as well as many other positions. Many children watched their parents push through the back-breaking work and decided it wasn’t for them.

Damian wants to change that perception, and he knew that he would have to introduce this career path to young adults much sooner than in college.

The 2020 Val Verde Yote 980 is the first vintage of wine produced from vines tended to by students at Orange Vista High School. Working with the Val Verde School District to launch a viticulture program, Damian and the Doffo team mentored students through a growing season, teaching them how to grow the best Cabernet Sauvignon possible.

Fifty percent of sales will go directly to the Val Verde Viticulture Program, ensuring the continuation of the course.

Synergy is a word used often in the wine world. Typically, it’s used in reference to tannin and acid being in balance with the aroma profile, or finding a brand that resonates perfectly with a certain consumer base.

Sometimes, it’s simply the perfect combination of two people who just want to make really good wine.

Such is the case with eSt Cru, founded in 2020 and run by Paul Muñoz, a marketing and operations expert, and Erica Stancliff, a winemaker known across the North Bay for her dedication to premium wines.

Muñoz, a former marketing manager at Michael David Winery and director of marketing for Oak Ridge Winery in Lodi, is the general manager and uses his experience making brands like Seven Deadly Zins and Freakshow popular to create new labels. Stancliff is the winemaker for her family’s winery, Trombetta Family Wines and consults in her spare time with wineries like Stressed Vines and Pfendler Vineyards.

Muñoz and Stancliff set out to build a brand that would highlight their creativity, shared values and eagerness to produce a wine that would make drinkers say, “Holy shit!”

Sustainability and showcasing wines from areas that don’t receive the recognition they deserve are at the core of this new wine company.

“We’re working with farmers who really care about what they’re doing, who are good stewards of their land and who are actively trying to make a good product without sacrificing the integrity of the vines and the fruit.”

Of course, they also want something that is both fun and high-quality, with as much attention to detail made as if it were an ultra-premium priced bottle—but far more reasonably priced so that anyone can be part of their wine community.

“This project has given me the creative freedom as a winemaker to make wines that I think will have mass appeal for the right reason,” Stancliff explained. “I don’t have a mold that I have to put it into because we’re creating

this from scratch. I get to play with it and make something that I enjoy and that I hope other people are going to enjoy.”

To do all this, eSt has committed to working with anything by Chardonnay or Pinot Noir. Instead, they want to use fruit from varieties and regions that have not traditionally been considered “prestigious” in the past but produce very high-quality wines.

Most of the fruit is coming from Lodi and Clarksburg, where they source Petite Sirah, Petit Verdot, Cabernet Sauvignon, Teroldego, some Chenin Blanc, Grenache Blanc, Albariño and a Cabernet Franc for a Rosé. From the Dry Creek Valley, they’re bringing in Grenache and Mourvedre, and some Syrah from Santa Ynez. By using these grapes from these regions, they’re able to keep price points in the $20 to $45 range while bottling premium wines.

“These growing regions deserve so many more accolades for what they have to offer,” Stancliff said. “They are for serious wine drinkers. They are fun and they are approachable, but they are for people who love wine.”

No Middle Ground is one of the anchor brands, and it’s the marriage of Muñoz and Stancliff’s wine ethos and philosophy—and love for the movie “The Big Lebowski”. They refuse to compromise the integrity of their wines and will always work at the highest standard. It’s the line in the sand they refuse to cross, a reference to the movie and the inspiration for the label.

With No Middle Ground and other core brands, like Clothesline and Staring at the Sun, eSt Cru hopes to show a wider audience that wine can be so many things: exciting, affordable, non-pretentious but expertly crafted, good for the land and for growers and, above all, something to be enjoyed.

“We wanted to stand up and show people that Clarksburg is so much more than Chenin Blanc, that it has serious wines to offer, while also showing this fun, creative side we have,” Stancliff explained. “Paul makes these super-creative labels that make you want to check it out. Then you’ll go home and drink it and be like, ‘Holy shit! That was really good for $35.”

Mathew Bruno grew up as part of a winemaking family—he learned the ins and outs while spending time in his grandparent’s homemade root cellars. His grandfather would pour Bruno and his brother a small glass of 7-Up and add a teaspoon of his wine to turn it a pink hue. It sounds silly, but it made the boys feel like they were part of the winemaking process.

And it worked. In 2008 Bruno decided that he wanted to make some homemade wines as well. He ran out to purchase as many books he could find on the process to make sure he knew what he was doing. He went up to Oak Knoll, hand-picked some grapes, had a winery destem and crush them and he brought them home to ferment and mature in his garage. Bruno caught the wine bug and wanted to make it a career.

“After that first pick and the first fermentation and secondary fermentation at home, I was like, ‘Okay, we’re going to do this in 2009,’” he explained. “I thought about waiting a year, but we jumped right into it.” He received a tremendous amount of support from the family; Bruno’s father, a fellow entrepreneur, supported any project his children begin and served as a cheerleader.

“I learned so much of about business and relationships during the ages of 10 to 18 years old, going to business meetings with my dad,” he said, recalling lessons to, “Treat your clients and employees as they are family and always deliver a product and service that exceeds the highest standard. Most of all with honesty and integrity.”

The product that would exceed the highest standard? For Bruno, that meant making wine from the premier site at the time: Napa. Though his family hails from Central California, he noticed that there aren’t all that many differences between the two—at least when it came to turning to friends for help. “Napa Valley is just another farming community in the sense that neighbors help neighbors. Being a guy coming into Napa, I expected there to be more pushback from locals, but I never had a discouraging word,” he reported.

In fact, Bruno found encouragement and a winemaker in someone he went to junior high and high school with: Stephens Moody. He and Moody played baseball and football together and now, along with Dr. Nichola Hall, have embarked on the latest stage of their friendship.

“I had no idea he had winemaking training and the background he did,” Bruno said. “We hired him from day one and he and Nichola have been with us since. It’s just been a great working relationship and rekindling of a good friendship.”

The three set out to make the first vintages of Mathew Bruno Wines and looked to their neighbors for inspiration, as well as the top vineyard sites.

“Before we make any new variety, we always taste other wineries’ wines and come to a conclusion on the style we want, alcohol content, barrel profile, etc.” he said, adding that once they come to an agreement, they seek out a vineyard that can produce that style, or go directly to the winery to see if there is any extra fruit available.

For the Chardonnay, he didn’t want a 100 percent stainless steel ferment with no barrel, but also not a wine that was over-oaked. He hoped to showcase the mineral characteristics you can find in some Chardonnays.

“We wanted fruity characteristics in our Chardonnay and not one dominant attribute,” he explained. “We wanted a very approachable Chardonnay that had fruity characteristics, a nice blend of alcohol and a hint of the different barrel profiles we have.”

Now, Bruno has also expanded into Sonoma County for his Pinot Noir, doubled production and opened a new tasting room. Bruno recently purchased 5 acres of vineyard land in Oakville, across from Silver Oak and between Opus One and Groth Winery. He’s planting it to 100 percent Cabernet Sauvignon and it will be his first estate wine.

After many years traveling around the world making wine, Finger Lakes native Ben Riccardi started to feel homesick, and moved back to the area just as the region had reached a pivotal turning point. Riccardi and many others would push wine quality further than it had gone before, using new research and production methods alongside traditional varieties to make it happen.

Of course, the route to his success was not straightforward. At first, Riccardi studied chemistry at the Air Force Academy. He ended up returning to New York to study vineyard management at Cornell University and fell in love with winegrapes and winemaking. Upon graduation, he worked at local wineries on Long Island before hopping down to Chile to learn from winemakers in the Maule Valley. For years, Riccardi traveled between the two hemispheres, working one harvest after another.

“Once I had unlocked this combination of a career path, fun, learning and travel and I was excited about learning more about wine, it just all came together,” he recalled

So, after some time spent at Williams Selyem in California and Craggy Range in New Zealand, he moved to Manhattan to work at City Winery New York. And at this point, in 2013, Riccardi recognized that the Finger Lakes had reached an inflection point and wine quality was only getting better.

“I saw opportunity and I wanted to be part of it,” he recalled, thinking his experience making wine in warmer climates could be beneficial to the region. “I saw the potential here, but I also realized that maybe people weren’t doing some of the things I had learned, some of the techniques that I had learned abroad. I just got really excited about the opportunity here.”

The first vintage of his brand, Osmote, produced less than 200 cases of 2014 barrel-fermented Chardonnay. Ten years later, he’s branched out to other varieties and styles of wine, including the hybrids the Finger Lakes are known for, and has his own winemaking facility.

It hasn’t always been easy; like so many others in the region, he’s struggled with finding affordable equipment and sourcing grapes. And, producing a traditional method sparkling wine had always been out of the question—with limited storage space, keeping bottles en tirage for years was impossible. Then he learned about the pétillant naturel style, which definitely was feasible.

“When I started it, I hardly even knew what Pét-Nat was, but I learned about it pretty quickly and thought it was a really interesting opportunity,” Riccardi said. “I saw a tremendous response and it’s become a major part of my winemaking. Working with Cayuga White was a way to be totally unique, totally Finger Lakes and Pét-Nat seems absolutely the right style for that grape.”

In Cayuga White, Riccardi found not just an exceptional grape for a sparkling wine, but a little bit of history to share as well—the grape was developed at his alma mater.

When talking about the wine with consumers, Riccardi emphasizes this heritage: a grape from Cornell University that really only grows in the Finger Lakes, is sourced from a vineyard planted in 1973 and kept in the owner’s family and taps into an old tradition of New York winemakers producing mainly sparkling and fortified wines.

“That’s why I put the Spinal Tap amp dial on the front label,” he explained. “I say to people, ‘I took everything about the Finger Lakes—bracing acidity, fun hybrid, old vineyard—and I turned it up to 11 in one wine.” To ensure a crisp, clean wine, Riccardi disgorges the sparkler.

Riccardi also produces premium wines from more traditional grapes. “I take a lot of pride in making refined Chardonnay and Cabernet Franc and Riesling,” he said. “But it’s also an exploration of where we came from and where we can go with hybrids.”

Ou r Journe y B e gi ns H er e for Enh a nced Na tu ral Cork Q u ali ty

M.A . S il v a's N atu r al Cor k is vertic ally i ntegratedan d f u lly t racea ble. Once ha rvested, thecor k is treat ed usi n g M. A . Sil va 's state of t h e ar t techn ologie s , w hich f urther en hanc e t h e qu a li t y a n d e xp er ie nc e of yo ur fi na l cor k s t oppe r . We i n vi t e y ou to contac t us a nd l ear n mor e abo ut o u r na tura l cor k t od ay!

Paula Harrell fell in love with wine culture while on a student exchange program in Madrid. So, when she returned to San Francisco, she started venturing north into Napa, meeting winery owners and winemakers, building a network of friends and refining her palate over the years. Eventually, she did what nearly every wine lover does—wonder whether she could make wine herself.

Harrell started her winemaking career in a rather unorthodox fashion. “I got into this bad habit of blending other people’s wines at the dinner table,” she recalled. “My family would get so mad at me because we’d go out to dinner and I’d order tastes of different things to try, and then I felt that they were good, but two of them would be better together.”

Her uncle, a wine connoisseur himself, was one of the first to recognize her talent. Even though he’d rib her for blending finished wines at the dinner table and discourage her from the practice, he soon joked that she might benefit from a different career path.

“He goes, ‘You actually have a knack for this. Everything that you’ve put together is better than anything else that we’ve been drinking, but might I suggest you make your own damn wine and stop blending other people’s?’” Harrell said. “When he said that, literally this light bulb went off my head and I was like, ‘Ah, that’s what I’m going to do. I’m going to make my own wine.’”

Using the connections made through her many visits to the Napa Valley over the prior 10 years, she researched and eventually found a place to do custom crush, grapes for sale, and a winemaker to help her produce wine to her exact specifications.

This was back in 2009, when finding facilities, especially in her hometown of San Francisco, wasn’t so simple, and was a long, arduous process she had to face in addition to the usual challenges of starting a wine company. Thankfully, Harrell could rely on her network of not just wine professionals, but those in the real estate and mortgage business—the industry she had spent her career in. She could reach out to restaurants, retailers and event planners to help sell her wines.

“I would love to create a handbook for somebody who wants to get into this business in this way because putting all those pieces together was just challenging,” she said. “I mean, it took me some years.”

Now, Harrell has hit her stride, increasing production from 500 cases to nearly 3,000 cases, and expanded from two bottlings to five. She has contracts with Chase Stadium in San Francisco as well as an airline, and wine club membership has quadrupled since she started. Harrell said that all the hard work at the beginning, even trying to figure out which licenses she would need, was worth the trouble as she has now seen her dream realized.

Through all this, she remains immensely humble and always finds ways to bring her family into the business. Her Three Fifteen Zinfandel, a blend of 85 percent Dry Creek Zinfandel and 15 percent Petite Sirah, is a direct reference to 315 Santa Ana Avenue in San Francisco—the home she grew up in.

“315 was this place that was a melting pot of friends and family and people building genuine relationships and supporting one another,” Harrell described. Her mother, an immigrant from Panama, and her father, a transplant from Oklahoma, would sponsor family members looking to move to the United States, so it always felt like a full house. “It just seemed like it was a fitting name for that wine—and my favorite wine is Zinfandel and Petite Sirah.”

Harrell has lofty goals for the future. When she makes her first Cabernet Sauvignon, she wants to name it “Gregory”, for the uncle who inadvertently inspired her. “I’ll continue to go after big contracts, more airlines,” she added. “I still want to stay a boutique-ish wine company. I don’t need to be the biggest wine company in the world. That’s not really my goal. I’d like to be able to still have a personal touch to it.”

Within the modest exterior of Six Eighty Cellars, you’ll find every winemaker’s dream: A facility that boasts one of every kind of fermentation and maturation vessel imaginable. Not only that, but the winemaker, Ian Barry, also has the opportunity to work with varieties that are uncommon to the Finger Lakes region and treat them with processes most commercial wineries wouldn’t dare to use.

This experimental winery is the brainchild of Dave and Melissa Pittard, Finger Lakes natives and the owners of Buttonwood Grove Winery. Agriculture has always been in Dave’s blood; he grew up helping on the family orchard, Beak & Skiff Apple Farm in Lafayette, NY, which produced apple wine, cider and vodka. It led him to pursue an education at the Cornell College of Agriculture.

In 2014, Ken and Diane Riemer, the former owners of Buttonwood Grove Winery, decided to sell the property and the brand. The Pittards saw this as their chance to enter the wine business. Since then, they have continued the legacy by building a new winemaking facility, expanding the vineyards and creating new hospitality opportunities with a summer music series and on-site cabins for overnight stays.

Departing from the norm, Pittard also wanted a brand that was devoted to creativity, to playing with offbeat vinifera varieties as well as winemaking techniques and vessels. He looked to a piece of land just down the road from Buttonwood Grove that rises 680 feet from Cayuga Lake and in 2020 purchased the perfect spot to establish Six Eighty Cellars.

The Pittards are committed to farming sustainably, even in such an extreme environment. While spraying is a common, and necessary, practice, Dave is trialing an organic, algae-based fungicide to protect the grapes. The hope is to preserve the land for his kids and boost the reputation of the Finger Lakes.

Centered on the premise that the past can inform the future, the Pittards and Barry are determined to use traditional winemaking methods and vessels and bring them into the 21st century. While there are some barrels and stainless steel tanks, the beauty of this cellar is in its wide array of fermentation vessels: A terracotta cigar, cocciopesto opus, clay clayers, and a concrete tulip from Italy; vin et terre sandstone vessels in egg and jarred form from France; and an appetite to trial any vessel they can get their hands on.

Some of those offbeat varieties (for the region) that the two plant and ferment include Chenin Blanc, Gruner Veltliner and, in the future, Gamay. The hope is to not only differentiate their portfolio but to see what else the region has to offer. Barry uses minimal intervention on these varieties to highlight the bracing acidity and fresh fruit inherent to the grapes and the region.

Of course, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Cabernet Franc and Riesling are also planted; but in these typical Finger Lakes varieties they use atypical methods to produce rather unexpected styles. Think a semi-carbonic Cabernet Franc, a Merlot made as a Pet-Nat, or a Riesling that was wild-fermented in a sandstone egg.

Take the 2020 Cabernet Franc Appassimento, for example. In the traditional Valpolicella style, grapes are partially dehydrated prior to fermentation. The wine is then split between two older French oak barrels and an Italian terra cotta “cigar” before being blended again. The Cabernet is mostly dry, with just 2.2 percent RS.

While working in politics, Jill Osur realized that at every great event she attended, there was some great wine on the table. She immediately began a quest to find her preferred style and instead discovered that wine can be a conduit to great conversations, community building and fundraising.

She left the political landscape for a much tougher industry: distribution. Osur found employment with a small distributor working to build brands and compete against the larger players, like Southern Wine & Spirits.

One of the brands she helped grow was Myka Cellars and Osur eventually left the distributor to work directly with the winery. They built two brands, employed 54 people and quickly became the fastest growing wine group in El Dorado County.

“But then, like so many people, it took a crisis to change your path,” Osur said. She, like so many Americans, followed the murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, and while sitting at home under COVID lockdown asked herself, “What am I doing as a leader in the wine industry to be part of the solutions I wanted to see.”

Growing up in a Jewish family, Osur said she was taught tikkun olam—repair the world. “I was very used to standing up and speaking out for social and racial justice issues, and yet I found that I had become very tame in an industry that is steeped in tradition and dominated by men,” she said. Then, after she posted about the Black Lives Matter movement on the winery’s social media page, she was asked by the winery’s largest investor to resign.

It made her rethink how she uses her voice. Osur turned to the numbers: 10 percent of winemakers across the country are women. Only 0.1 percent are Black. Female winemakers make 70 cents on the dollar to their male counterparts. All this and yet women make 67 percent of wine purchases.

She wanted to disrupt the industry, and be the change she wanted to see. After giving herself permission to do something daring but that truly aligned with her integrity and voice, she launched Teneral Cellars, a 100-percent

woman-owned and -run company on a mission to reshape the wine industry to reflect its largest consumer and give back.

Teneral is the moment in which a dragonfly comes out of its cast and is in its most vulnerable state; Osur chose this as the winery’s icon because it represents the transformation she wants to see. “Its wings are colorless, and it can’t fly, but within a few days it gets its full colors and spreads its wings and takes off with amazing power, grace and grit,” she explained. “We all have that power within us. We just have to claim our power, spread our wings and fly.”

Her company only uses sustainably farmed grapes, purchases supplies from companies that are owned by women or people of color, works with a female-owned distributor and donates 10 percent of profits to organizations that empower women and fight for gender and racial justice—attempting to harness the power of business for good.

Every quarter, her advisory board, made up of an incredibly diverse group of women, helps her choose a new theme based on the charity they would like to support. In 2021, the first full year of operation, the company gave more than $51,000 to organizations like the National Women’s Law Center, the Endometriosis Foundation of America, Generation W, World Central Kitchen and several local charities. Themes for these El Dorado wines centered around influential women like former Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg and tennis great Billie Jean King.

“I feel like I can use wine as a conduit for change. We do a lot of virtual experiences. We even bring in some diversity, equity, inclusion and belonging training because wine allows people to relax a little bit so they can open up to have those necessary conversations,” Osur said. She’s working to find a home for Teneral in the Sierra Foothills, a place for women to gather for wine and wellness retreats or for community events.

“I love hosting and using wine as an amazing vehicle for creating the kind of change I want to see in the world.”

Like many college students, Joshua Klapper worked in restaurants when not in class at the University of Southern California. Unlike others, however, he worked on the sommelier team at Sona, an establishment that had just received a grand award from Wine Spectator for its wine list. Because of the tasting opportunities this afforded, Klapper knew that he wanted to do more in the wine business and looked to other sommeliers, like Michael Bonaccorsi, MS, for inspiration.

“I just felt like I wanted to explore something different,” he said. “An easy jump at the time was to start making a little wine.” Klapper then followed in the footsteps of other Los Angeles-based sommeliers branching out into enology.

He reached out to some well-connected friends in the industry to purchase grapes and, with the help of another winemaker, began making blends in 2004 out of his garage. When he graduated in 2006, he had already spent years visiting wineries in the Central Coast, bottling his own wines, and knew that restaurant work, while fulfilling, was not the way forward.

“I decided to take a sabbatical from the restaurant business and worked my first harvest. That was when I fell in love, and I realized I wasn’t just going to buy juice from other people or have other people make my stuff. I wanted to be the chef,” he said. “I was 26, I’d been working 60 hours a week in restaurants, going to school full-time, working really hard. I was like, ‘If I work hard doing anything for myself, at least I’ll be in control of my own destiny. It may take me longer to make money or be successful, but I’ll ultimately be happier.’”

Klapper knew from the outset that he wanted to make Burgundian-style wines—those with lower alcohol—and chose Santa Barbara County as his home, thinking that would be the easiest place to do so. Following a conversation with some of the best winemakers of the Central Coast, he concluded that only Burgundy can be Burgundy, no matter the alcohol level. This realization about terroir led him to instead seek out sites where “magic happened”.

“I can’t exactly put my finger on what it is, but I know that the wines are exciting from those places,” he said. “I like making wines that are generally

interesting, that have tension, that have that balance of acidity, richness, deliciousness and complexity, but I don’t like interesting for interesting’s sake. Interesting has to be delicious.”

For something to be nteresting it must also have character—whether it’s a sense of place or sound. In 2012 Klapper named his brand Timbre, which means the character of sound, or what makes our voices sound different. “Five hundred decisions are made for even a pedestrian wine. When you make it a fine wine, maybe it’s even more decisions,” he said. “All those decisions as a winemaker add up to your voice.” This is the idea behind Timbre.

Leaning into this theme, each wine has a musical term as its name. Klapper thinks of the 2019 Lead Vocals like Mick Jagger or Madonna—someone who is iconic not just for their voice, but for their personality as well.

“That’s how we’ve always thought about Bien Nacido Vineyard. Lead Vocals came from own-rooted vines that were planted in 1973,” he explained. “Finding own-rooted Pinot Noir is very rare. It was just this unique thing because it is so old, and it has a unique expression.”

The 2019 vintage, however, was the last from these old vines, as the block was torn out and replanted for the next vintage. This last bottling is a special one for him.

“You’ll never see a sale on that wine at my winery, or any of the Lead Vocals wines I made over the years—just like you wouldn’t see a sale on RomaneConti. It’s a special place and time in a bottle.”

For 12 years, Remy Drabkin, owner and winemaker at Remy Wines, made all of her wine in a rented facility in McMinnville, Oregon. When her landlords informed her in 2021 that they would not renew her lease for the 2022 harvest, she was left with a difficult decision. Should she scramble to find a new place to rent? Or should she finally move forward with her long-held intention of converting an old barn on her property into a winery?

Drabkin opted for the latter, even though she had only a year to get the project done. But Drabkin, who is also the mayor of McMinnville and the co-founder of Wine Country Pride, is no stranger to overcoming challenges and mobilizing people to make things happen. She quickly built a team to meet the goal of having a functional winery in place by September 2022. In the process, she also helped spur the creation of a new concrete formulation (dubbed the Drabkin-Mead Formulation) that is billed as carbon negative—making it possible to transform one of the most potent greenhouse-gas-emitting products in construction into a carbon sink.

Drabkin’s mother was the first culinary director of the International Pinot Noir Festival and stayed in that position for 15 years. Many of her parents’ friends were winemakers. Given that, it’s perhaps not surprising that Drabkin began telling people she planned to be a winemaker when she was only 6 years old. Her dream was helped along by her parents’ purchase of a 29-acre property in the Dundee Hills AVA in the mid-1990s. Though they had no intention of making wines themselves, they understood the property, which has patches of Jory soil and is located near big names like Sokol Blosser and Archery Summit, was a good investment. Drabkin suspects they were already thinking about her future and believed the property was an investment in her as well.

However, making the property habitable kind took a tremendous amount of work. It had been abandoned and in foreclosure for several years. Everything was overgrown with blackberries. There was an antique apple orchard that had to be taken out. (Some trees were so fragile that if you picked an apple, the whole tree often fell over, Drabkin recalled.) The site had also been used as a dumping ground. “We pulled something like 30 tractor tires off the property,” she said, along with railroad ties and numerous other bits of detritus.

Slowly, the family unearthed the property and the 1900s-era house, which they then both lived in and rented. Drabkin made some of her first wines in it, and the home currently serves as Remy Wines’ tasting room. The building didn’t have enough room for a full-scale winery, which is what led Drabkin to her warehouse in McMinnville.

The property outside of McMinnville also had an open-sided garage that was built around 1940. In the 1960s, a pole barn was constructed over the top. Drabkin’s long-term plan was to build a winery there—a goal that became a necessity in 2021.

Drabkin had known John Mead, a local contractor and owner of a concrete surfaces company called Vesuvian Forge, for years and has always loved his aesthetic. He had also walked the property and discussed the project previously, so he was the first person Drabkin called about the potential winery project. He was confident he could make the project happen in the timeline and began pulling a full team together.

As she thought about out her goals for the winery, Drabkin was clear that she wanted functionality and the ability to improve her winemaking process. She also wanted to focus on sustainability, but “sustainability is not just environmental,” she said. “It’s about workplace safety, workplace happiness, and equity and diversity. It’s about getting out of small pockets of culture and being really intentional about being cross-cultural. It ties in with how I live my life and try to build a community that lets people thrive.”

While the building has several notable features that make it welcoming, the environmental sustainability features are the ones that are most readily apparent when looking at the 5,000-square-foot facility. The winery is made with the principle of adaptive reuse in mind, meaning much of the building features many salvaged and second-hand materials.

Rather than tearing down the existing barn, the construction team saved as much of the existing structure as possible. In addition to adding exterior walls, they build a second story on existing load-bearing walls inside and reinforced the existing trusses by sandwiching them between new trusses. That made the roof strong enough to hold a water collection system to feed the fire suppression pond and support the future installation of solar panels if Drabkin chooses.

When possible, materials from the original structure that were removed found homes elsewhere. A pair of pillars that used to be in the main structure were put to use holding up an outdoor utility porch. Large pieces of concrete were repurposed into a bench.

The stairs to the second story are made with metal grating that was found on the property and welded together by students in a technical education class at local Dayton High School. The railings and banisters are made from old pallets.

Pallet wood also lines the walls of Drabkin’s office. She first got the idea for using it when she built out baR, a now-closed tasting room in McMinnville. At first, she was nervous to cover the walls with second-hand wood, she recalled. “But as we started picking out pieces of pallet wood, that’s when we noticed these pieces with ink, with numbering, with all these little details that were from the life of that product. They had all this beauty.” It speaks to the idea that “you have to be OK that not everything has to be perfect all the time. That’s part of finding beauty in the shadows, which is not hard to do.”

The centerpiece of her office’s décor is an old riddling rack mounted with custom metal braces. Before starting her own company, Drabkin worked at Argyle Winery, Oregon’s first sparkling wine house. During her brief tenure, Argyle was switching from traditional riddling racks to machines and sold some of the old wooden racks. “I bought this for $50,” she marveled.

The staff offices were built between the building’s original trusses, making them long and narrow. The builders added gables so the offices have plenty of natural light, which cuts down on energy costs and also makes for a more enjoyable work environment. Reclaimed doors salvaged from the property were hung to make barn-style rolling doors. The offices are lined with reclaimed wood that came from the garage demolition and another project.

The interior doors for the lab and other parts of the building were purchased at the non-profit ReBuilding Center in Portland. The sinks are almost all second hand. (The bathroom has a decorative sink made by Mead’s Vesuvian Forge.) The windows are new but have a high U-value, and the walls and ceilings contain around a foot of insulation. When the ductless heat pumps throughout the facility are turned on, it should maintain a fairly consistent temperature with minimal energy usage.

Storage space in our brand spanking new South Napa building

29,000 square feet, ready for your full or empty barrels

Full-service solutions for your wine and beverage needs

• Bulk wine storage

• Bottling

• Custom crush winemaking

• Canning and beyond bintobottle.com

carbon dioxide that’s been sequestered is chemically released back into the atmosphere,” Mead said.

Heating the limestone and other ingredients takes a tremendous amount of energy, most of which is created by burning fossil fuels, so there’s a double whammy of emissions. For every pound of cement that’s produced, a pound of carbon dioxide is released into the atmosphere. According to the Global Cement and Concrete Association, concrete alone produces 7 percent of the world’s total greenhouse gas emissions, making it the biggest carbon culprit in most construction projects.

Concrete companies know they have a big part to play in reducing the carbon footprint of their product, both for the long-term survival of human civilization and the short-term survival of their industry, said Michael Bernert, vice president and co-owner of Wilsonville Concrete and a major partner in creating the new concrete formulation. Holcim in Canada has already developed several products, including OneCem and NewCem Plus, that have significantly shrunk the emissions associated with making concrete. But there’s only so much any technology can do to because breaking apart virgin limestone and heating it to high temperatures is always going to cause enormous carbon emissions. Concrete is one of many products that must look to net carbon emissions—finding ways to sequester or trap more carbon in the built environment than they release into the atmosphere—as the solution to the environmental damage it causes.

One way to do that is to mix in biochar, which the International Biochar Initiative defines as “a solid material obtained from the carbonization theremochemical conversion of biomass in an oxygen-limited environment.” Biomass is organic waste that often comes from things like agricultural and forestry waste, yard clippings and food scraps. If these carbon-rich items are left laying out in places like fields, forests and landfills, they slowly decompose and emit gases such as carbon dioxide and methane—a gas that has a warming capacity 80 times higher than carbon dioxide over a 20-year period.

To avoid these emissions, this organic matter needs to be removed from the carbon cycle. That’s where biochar comes in. When organic waste is pyrolyzed (burned at a very high temperature in an oxygen-starved environment), most of the volatile compounds that would cause it to offgas are burned off. What remains is the energy created from the burning (enough to carry out the

General contractor Mead estimates the cost for all the sustainability features made the project about 1.5 percent more expensive than it might have been otherwise. The fact that Drabkin preserved so much of the original structure helped cut down on overall expenses. Recycling materials, such as metal and wood, lowered disposal costs. Those cost savings made it possible to include slightly more spendy features such as the high-efficiency windows and added insulation. Noting that 1.5 percent is the amount someone might spend on high-end countertops or appliances, he called green construction “totally accessible.”

To help Drabkin fulfill her goals around worker safety and increased efficiency, the facility has numerous utility hookups scattered throughout the winemaking area. Instead of wheeling around tanks of CO2 and nitrogen on hand trucks or running long hoses for hot and cold water, employees can attach lines to these hookups and get access to most of the things they need.

Drabkin is particularly proud of her “equity bathroom,” which has multiple stalls, is ADA compliant and is accessible from both the interior and exterior of the building. When harvest crews come to work, they will have full access to the facilities instead of relying on portable toilets. “This is a basic human function. We should all be able to wash our hands,” said Drabkin.

When Mead committed to working with Drabkin on the winery project, he also asked if she would be willing to try out a new concrete formulation that included biochar. He had been experimenting with biochar in concrete for products such as his countertops and fireplaces, but his formulation wasn’t strong enough for structural uses.

Developing a carbon-neutral or carbon-negative concrete, he knew, had the potential to revolutionize the industry and construction as a whole. Concrete is made with a mixture of sand, gravel and cement. Cement is responsible for binding the mixture together, and the main ingredient in cement is calcium carbonate, which comes from natural deposits of limestone. The shells of the fossilized sea creatures that make up the limestone have absorbed and trapped carbon for centuries. However, “when the limestone is baked at 2,500° F, the

pyrolyzation process again) and a solid but porous substance that looks a lot like charcoal.

To further sequester these sources of atmospheric carbon and other gases, the biochar needs to find an economically viable use. It has been used in agricultural applications for years because it can be buried in the ground, which removes it from the carbon cycle and also makes the soil better able to retain water and nutrients. Alternatively, “it turns out building with concrete is one of the things that’s happening on a big enough scale to make a difference for our atmosphere,” said Mead.

The challenge with developing a biochar-laced concrete for structural purposes was getting a building owner to accept the risk of using it. It’s difficult to be the first to try an experimental product—especially if that product is a foundational component of a very expensive construction project. But Drabkin signed on as a partner from the get-go, and Mead put the wheels in motion to develop what would become known as the Drabkin-Mead Formulation.

Mead knew that Bernert had been working on strategies to get the carbon footprint of concrete as low as possible. The two started comparing notes and came up with the technical pathway of using biochar in concrete. They reached out to other people, including experts at Holcim, Oregon State University and the Athena Sustainable Materials Institute, who offered advice, reviewed technical specifications and helped them refine their plans.

One of the people they contacted suggested using a specific type of biochar called Our Carbon in their formulation. While biochar can be made from many things, this one come from drying and pyrolyzing municipal waste, which includes both human and food waste, Drabkin said.

For her, using biogenic carbon would help with another problem beyond the need to shrink concrete’s carbon footprint. Due to her time in elected office, she was acutely aware of the cost for disposing of food and human waste. Her small town recently signed a seven-figure contract with a company that provides waste disposal services. If this waste could be transformed into a resource, it would save cities a tremendous amount of money. Those dollars could then be reinvested in the technology to dry and pyrolyze waste.

“My lens isn’t just wine,” said Drabkin. “I’m always thinking about how we fold things into larger system.” While it wouldn’t make sense for all cities to invest in the technology to create biogenic carbon, they could become part of cooperatives or regional partnerships that run the machinery and return the finished product to communities. With a ready source of biogenic carbon, cities could then rewrite their design standards to require carbon-fixing concrete in municipal projects—and provide the biogenic carbon and instructions for using it at little or no cost to contractors.

“It creates this closed loop where the city can say, ‘You have to use a carbon-neutral product, but we’re creating the source,’” she said. “You can put an RFP out to your normal suppliers, so you’re not cutting anyone out.”

Mead and Bernert sourced their biogenic carbon from the Bioforcetech Corporation in California. They were delighted to find that its addition improved the concrete’s performance as well. “When we started doing our tests, all of a sudden our concrete was setting faster and testing harder,” and performing on par with conventional products, said Drabkin. Those results remained consistent even as the concrete was exposed to a variety of stressors,

Arangethatisonaverage20%lighterthansimilar ultrapremium bottles

EGOCLASSE

Height(mm/in):315/12.40

Weight(g/oz):865/30.50

EGOGRANDCRU

Height(mm/in):325/12.79

Weight(g/oz):820/28.92

EGOCONICA

Height(mm/in):308/12.12

Weight(g/oz):650/22.93

Experienceouruniqueknow-how, discoverourproducts

707.419.7200

with the best consulting winemakers in the world: Bordeaux, Rioja, Stellenbosch, Sonoma and Napa Valley.

including heat, cold, abrasion and submersion in wine and cleaning chemicals. (The biggest test that remains, Drabkin pointed out, is the test of time.)

The performance benefits of the Drabkin-Mead Formulations are in active research right now, Bernert said. “What we can definitively say is the biogenic carbon increases the durability of concrete because of a mechanism called internal curing. Cement needs water to be hydrated. Once you combine cement and rocks, you add water and that makes it stick together.” As the concrete sets, that water begins to evaporate, and it leaves the concrete at the top more quickly than it does in the middle. That causes faster shrinkage on the outside edges of the concrete than in the middle, which can weaken the finished structure.

“The beauty of using biochar in concrete is it absorbs massive amounts of the water,” said Bernert. “It’s two times greater than lightweight sands that are specifically added to concrete for their water absorption capacity. That water slowly leaves the biochar and hydrates those cement particles, so you get uniform hydration.”

Mead said working with the concrete, which makes up the 5,000-squarefoot slab floor at Remy Wines, was easy. “The concrete went in like any other concrete. The fact that it was different was not obvious when you think about things like the workability, the transport and getting in through the concrete pumps. The Solid Carbon adds a little bit of pigmentation, but other than the color, it behaved like any other concrete.”

The biggest difference is its impact on the planet. “Remy’s slab sequesters over 10,000 pounds of carbon dioxide,” Mead said, and should do so permanently.

From the beginning, the team planned to make the Drabkin-Mead Formulation open source so others could copy it. “We weren’t looking for a product to keep close to our chest and capitalize on,” said Drabkin. “We were looking for a product that could make a real impact on the environment.” Anyone interested in learning about the formulation can get technical specifications on the website for Solid Carbon, a new joint venture by Mead, Bernert and others to create zero carbon concrete products in the built environment.

Bernert said he can’t stress enough how important her commitment was to making the project happen. “Her courage allowed us to demonstrate we can do this. That Remy was willing to take a risk means every project after this is easier.”

For her part, Drabkin said it felt like the right thing to do. “I believe that we really all can make a difference,” she said. “Sometimes you just have to do that. You have to show people it’s possible.” WBM

When I was given the opportunity to collaborate and learn about barrels and wood from such an experienced team, I thought: why should I not do it?! Only progress can come from that.

Owners/Principals

503-864-8777

Appellation

Dundee Hills AVA

Vineyard Acreage

7 acres planted (29 acres total)

Varieties Grown

Pinot Noir, Lagrein

Sustainability Certification(s)

LIVE Certification

Sustainability Practices (not certified)

No till, overseed, dry farm

Soil Type

Jory Silty Clay Loam, Carlton Silt

Loam

Rootstocks

3304

Additional Varieties Purchased

Dolcetto, Sangiovese, Carmenere, Malbec, Tempranillo

Tons Used vs. Tons Sold

100% Used

Year Built

Original part in the 1940s, added on in 1960s, adpative reuse building complete in 2022

Size (square feet)

5,000

Architect

Bruce W. Kenny

Contractor

Vesuvian Forge

Stryker Roofing - Roof (woman-owned)

Simpson Electric

Interior Design

None

Landscape Architect

Remy Drabkin

Flooring

Made with the Drabkin-Mead Formula in partnership with Vesuvian Forge, Lafarge Labs, and Wilsonville Concrete

HVAC

Husky

MACHINERY

Deleafer

Harvesting Equipment

Tractor Mowers Mower

Pre-pruners

By-hand

Pruning machinery

By-hand

Rotary tiller/cultivator

WINEMAKING

COOPERAGE

Barrels

Cadus

Françcois Frères

East Bernstadt Cooperage

Quintessence

Giraud

Used Barrels

Used barrels are sent to ReWine for refurbishment/ reuse

WINERY EQUIPMENT

Bottling Line

Small lots hand-bottled

Bottling Line

Casteel Bottling

Fermentors

1.5 ton fermenters

Filtration System

Willamette CrossFlow WINEMAKING No enzymes

Label Design

Nectar Graphics

Label Printing

Press Packaging

Warehousing(Case Goods Storage, Pick, Pack & Ship)

OnSite

Banking

Citizens Bank

PR Agency

Play Nice PR

Vinitech-Sifel, France’s largest wine industry tradeshow, took place in-person in Bordeaux for the first time since the pandemic forced organizers to host a virtual event during COVID-19 lockdowns. About 42,000 visitors and 750 exhibitors attended the event held Nov. 29 to Dec.1, 2022 at Bordeaux’s Parc des Expositions-Lac.

Robots designed to cultivate, spray and harvest returned en masse. So too did barrels, tanks, cultivating tools, glassware, packaging and other goods. Topics discussed at Vinitech included climate change, labor shortages, global supply chain costs, inflation costs and vineyard land conversion into other uses. Vinitech is an opportunity to showcase emerging new products and this year was no different.

Here is a sampler of products a jury of experts recognized with silver and bronze medals and citations. Instead of a gold medal, the jury awarded an innovation prize and €5,000—about $5,400.

Vinitech’s special jury prize—and recipient of a €5,000 check—went to Mo.Del. The company presented Viti-Tunnel, an automated covering system designed to protect multiple rows grapevines from rain and disease pressure, as well as hail and frost.

Viticulturist Patrick Delmarre, who once worked in the Napa Valley, came up with the concept in 2016 so that his grapegrower clients would no longer

Harvest is on the horizon. You need tanks and you need them now, but compromising on quality to get them fast is not how great wines are made.

We’re ready. Our Letina stainless tanks – jacketed, single wall, variable, you name it –are built in Europe and in stock in our Pacific Northwest warehouse, ready to ship. Want more info? Call us today, or visit:

have to rely on pesticides to protect their vines from powdery mildew and other diseases.

Testing, which has taken place for the past four years at 10 sites around Bordeaux and validated by the French Wine and Vine Institute / Institut Français de la Vigne et du Vin (IFV), has indicated that fungicide use can be reduced by as much as 90 percent. The company may be ready to sell its first Viti-Tunnel in two years, Delmarre said.

The system entails a retractable 120-micron cover commonly found in agricultural fields, held tent like. The cost is about €30 to €40 per linear meter— about $32 to $43 per 3.4 feet. The goal is to reduce this cost to €15 to €20 per linear meter—$16 to $21 per 3.4 feet.

Delmarre said the special prize announcement has drawn interest from investors. Mo.Del may even have enough money to experiment Viti-Tunnel in the United States and other countries, he said.

Taransaud embedded a thermoregulating system in the staves of the barrel and earned a silver medal for the creation. Water runs inside a silicone tube incorporated within the staves to control the liquid’s temperature. The barrel is connected to a water source.

The system’s goal is to ensure that temperature inside the barrel remains homogeneous, thanks in part to the large wine/barrel surface, explained Thierry Six, who works in research and development at Taransaud. No additional equipment to regulate the temperature is needed, which makes cleaning easier and improves sanitation.

The thermoregulating barrel can hold anywhere from 1,500 to 3,000 liters and has been tested for about a year. Six said that it may be on the market by late 2023 and larger barrels may also be produced.

Taransaud North America (TNA) distributes Taransaud products in the U.S. The French company is based in Cognac.

Flex-key’s smart hose system was awarded a silver medal. The system monitors the hose, including when it’s connected, disconnected and maintained. Goals include increased safety, pollution prevention and cost savings.

The product was not in the U.S. as of late 2022. Its worldwide distributor is Trelleborg.

Scientists from the French Wine and Vine Institute, in collaboration with colleagues from France’s National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment (INRAE) have created an automated micro-fermentation system for red wines, managed by a robot.

The new system—known as Vinimag received a silver medal. Vinimag, created in 2022, allows scientists to quickly obtain data on multiple samples of red wine, all at once. The robot manages up to 60 micro fermentations contained in French-press like containers.

The system overcomes one challenge: how to deal with must and red wine extraction when the amount of fruit is limited, said Marie-Agnès Ducasse, Minicave project coordinator at IVF. Fruit samples can be frozen for a year under a set of protocols.

Previous micro-fermenters created two decades ago handled juice only— white or rosé juice samples without must.

One of the stated goals is to select varieties adapted to climate change conditions. Other applications include yeast selection.

The team of French scientists was inspired by work carried on by The Australian Wine Research Institute. The product is not available in the United States.

Parsec received two medals for its new programs: A silver medal for Quadr @ and a bronze medal for Nectar.

Quadr @ monitors wine production data thanks to a native-web software and tracks all operations in the cellar.

Nectar monitors CO2 recovery and re-use during the fermentation process and then analyzes the wine’s fermentation.

Parsec’s U.S. distributor is ATPGroup.

“Knowledge in Your Pocket” or KYP by Vyvelis is a new digital notebook for the winemaker. It received a bronze medal.

The digital notebook shows data, including temperatures and tasting notes, organized in a simple way to help winemakers make decisions, explained Pau Inzirillo, Vivelys’ solutions developer. Modeling gives precise data on the fermentation and a history of the data in the cellar, Inzirillo explained.

The program, introduced in 2022, has been tested in Argentina, Chile, France and the United States, Inzirillo said.

The sustainably manufactured Wild Glass™ range o ers a natural glass look and organic and deliberate aesthetic imperfections. Nearly all of the Wild Glass™ material is Post Consumer Recycled (PCR) glass.

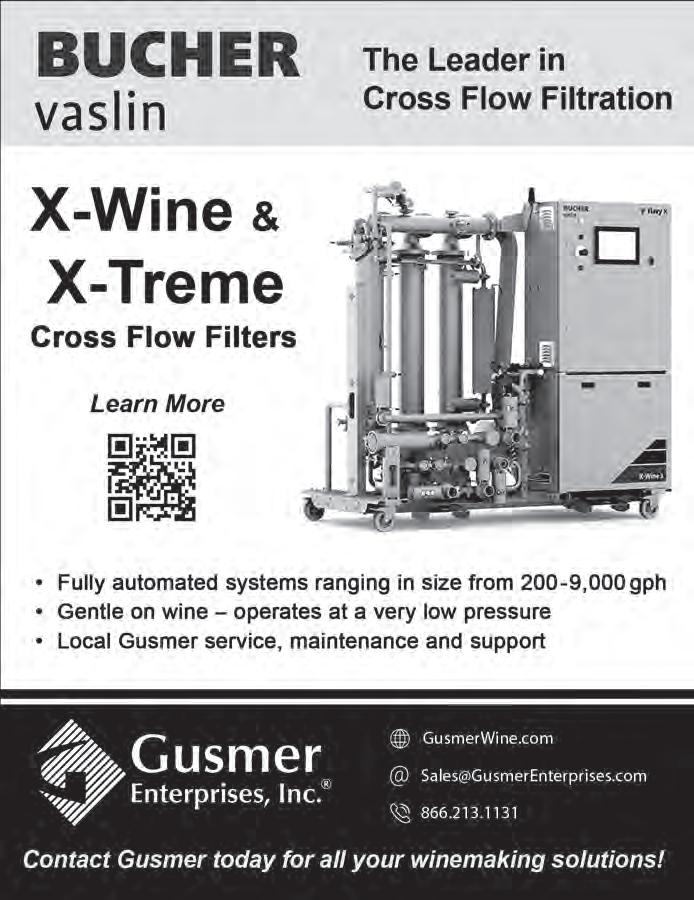

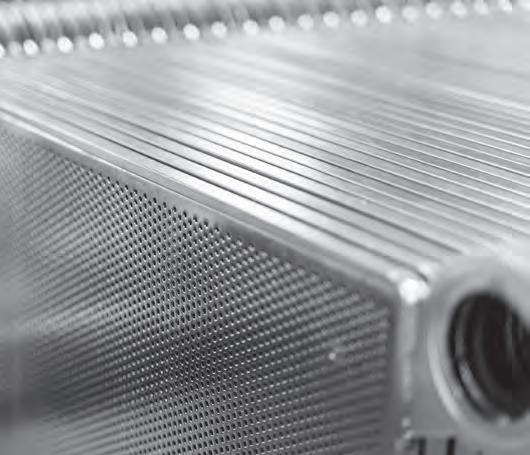

Bronze medalist Flavy FGC is a large-capacity filter system for big wineries designed to save energy. water and cleaning chemicals, according to the company. Flavy FGC also recovers more wine than other filtration system. It was designed for wineries or bottling plants that filter wines at less than 100 nephelometric turbidity units (NTUs). The machine is expandable.

The filtration system initially relies on pressure from the head tank—instead of its pump—to operate the filter. It saves energy by not running a pump immediately, said Benoit Murat, a Bucher Vaslin representative based in Bordeaux. A sensor monitors the pressure. The pumps kick in when pressure runs low.

Flavy FGC operates on low pressure. As a result, the membrane does not plug as much as other machines, Murat said, thereby making cleaning the membrane faster and easier. The larger filter is for the wine while a smaller filter continuously filters the retentate. The permeate is used to backflush the system. At the end of the cycle, the liquid left inside the filter is pumped and filtered to minimize wine losses.

The first two Flavy FGC systems were installed in Bordeaux late 2022, Murat said, and should be available in the U.S. in 2023. Bucher Vaslin’s distributor for filtration systems in the United States is Gusmer Enterprises Inc.

AMB Rousset won a silver medal for one of its new products: a multi-purpose tractor implement to pull and replant vines in one tractor pass. Vitipince could also be used for other tasks, such as planting trees in forests, the creator said.