With this Special Edition, we kick off the celebration of Humo Latino Magazine’s Fourth Anniversary by highlighting the work of Robert Glick, who transforms cigar bands into works of art. Featuring one of his pieces, specially created for this cover, is a source of great pride and satisfaction that we deeply appreciate.

Furthermore, over the past couple of years, we have dedicated time to researching the history of La Perla, a century-old Mexican factory whose life came to an end months ago. The founder’s great-granddaughter, Alejandra Corrales Amezcua, gifted us hundreds of cigar bands that had remained in storage, some of them very old.

Thanks to this, alongside a brief profile of the factory –whose history holds enough material for a book– today we present a representative sample. We previously sent the original material to Robert Glick for his work. These pages serve as a preview of the content for our Anniversary Edition, which, as is customary, will appear mid-month.

César Salinas Chávez

Director

Alberto Arizmendi

Editorial Director

GH L

Dominican Republic

Julio César Fuentes

Commercial Director

Honduras

Patricia Pineda

Rolando Soto

Roberto Pérez Santiago

Art Director

Raúl Melo

Publisher

Enrique Quijano Style Correction

Moisés Licea

Web Master

Yoshua Segovia Community Manager

Argentina

Gastón Banegas

Canada

Nicolás Valenzuela Voss

Chile

Francisco Reusser

Christopher Sáez

Michel Iván Texier Verdugo

Colombia

Federico Londoño Mesa

Eduardo Márquez

Cuba

José Camilo López Valls

Humo Latino Magazine reserves the right to reject unsolicited articles that contravene its thematic profile, as well as those that do not conform to its style standards.

The articles received will be approved in the first instance by members of the Editorial Board. We reserve the right to make changes or introduce modifications to the manuscripts, for the sake

© All Rights Reserved. Grupo Humo Latino Any reproduction, total or partial, of this contents, by any process, is prohibited.

global.humolatino.com issuu.com/humolatino

Dominican Republic

Francisco Matos Mancebo

Wendell Rodríguez

Mexico

Aurelio Contreras

Gonzalo Romero

Manolo Santiago

Puerto Rico

Cándido Alfonso

José Luis Acosta

Spain

Luciano Quadrini

Sofía Ruiz

José Antonio Ruiz Tierraseca

Fernando Sanfiel

United States

Anastasia Psomiadi

Blanca Suárez

Lefty Karropoulos

Venezuela

José Bello

Diego Urdaneta

of better reading comprehension, without this implying changing their content.

The authors are responsible for the content published under their signature. Humo Latino Magazine does not assume any responsibility for possible conflicts arising from the authorship of the works and publication of the graphic material that accompanies them.

@humolatinoglobal info@humolatino.com

Four years ago, we decided to embark on the Humo Latino journey, supported by a group of collaborators and friends who joined the purpose of giving visibility to cigar producers and small or boutique brands entering the tobacco industry. The vehicle was, and is, a monthly electronic magazine in Spanish—the language of tobacco—aimed at a broad international audience.

Over time, we have maintained that “true north,” even as our goals and platforms expanded, thanks to the incorporation of some production houses with extensive and recognized trajectories.

Within a few months of our launch, in January 2022, we simultaneously published the Humo Latino Journal newspaper, which ran for eight issues (three in English) and was distributed in eleven countries and/or in the U.S. during the Premium Cigar Association (PCA) Trade Show. We also embraced the Anglo-Saxon market with Humo Latino Global, an electronic magazine that has been published monthly since May 2024.

The original website and social media accounts were joined by their English counterparts; the company, headquartered in Mexico, also established a separate operation in the Dominican Republic. Since November 2024, we have offered the quarterly Spanish print magazine Humo Latino Dominicana, which extends its circulation to other countries, in addition to a special English Print Edition.

Regarding this fourth anniversary and 48 issues of Humo Latino Magazine, suffice it to say that we have dedicated over 5,000 pages to informing our readers about the Tobacco World from an inclusive perspective that, for example, has also highlighted the role of women in the industry.

We recognize and value our sponsors, collaborators, and readers, as we owe our permanence to all of them, as well as the trust of those who have shared their life stories with us –as sources of information– stories that speak of their efforts and aspirations.

This journalistic, human record –which is like planting a seed in the furrow traced by another– has allowed Humo Latino to grow, develop, and move toward its consolidation… and allowed us to live the dream.

Robert Glick

Raúl Melo

An attorney with a law firm in New York, where he has practiced his profession for over three decades, Robert Glick is a cigar aficionado. At the age of 25, drawn by the beauty of their gold details and die-cut reliefs, he began to collect the cigar bands of the cigars he smoked. For some time, a glass container was the destination for dozens of bands that shone inside like coins, but when it exceeded its capacity, Robert had an idea that would change the course of his hobby.

On a table, something as simple as a coaster inspired the lawyer’s artistic heritage to turn it into something more, helped by the aesthetic and elegance that cigar bands could provide. Thus, this piece of wood became the first object his curiosity “intervened upon,” and the result was satisfying.

Over time, Robert’s technique evolved into a kind of puzzle that takes shape piece by piece, with no lines or edges that make it obvious that they are bands. This is how he seeks to set himself apart from other artists and continues to learn to improve.

Born in Queens, New York, and a fan of the Mets, he went to law school in Massachusetts and has no artistic training whatsoever. But he does have the influence of his mother, a woman with a very good eye for art, as well as his father, who for many years was dedicated to graphic design and the creation of various works focused on advertising.

At first, his designs were linear, but then he experimented with more complex objects, expanding the range of materials for their preservation and learning something new with each new piece.

Playing with my favorite bands: a real guitar “intervened upon” with over three thousand bands and antique box applications.

This led to the creation of a home studio and Artdefumar, the Instagram account where it all began, where a sudden flood of followers appeared to enjoy what Robert was doing.

He created pieces on humidors, ashtrays, cutters, and lighters that were a great success among his friends at the Cigar Lounge. Thanks to the industry events he has been invited to, he met and became friends with many of the sector’s leading producers, for whom he has done special work –a list that includes Tony Gómez, Eladio and Emmanuel Díaz, Jorge Padrón, Carlito Fuente Jr., and many other people with whom he slowly connected so that his art would reach such levels that he is now part of the global tobacco family.

For Robert, the most attractive elements of a cigar band are the textures, the gold applications, and the small medals or coins that many include in their designs. This is something that stands out in the vintage style of the La Perla bands selected to adorn the cover of this Special Edition, pieces that date from between 1889 and 1972, “with majestic details that recall royalty,” Glick shares.

At Art de Fumar, the key to the designs lies in the connection that Robert achieves between each band, pieces that –although they have their own discourse and tell a story on their own– are turned into a single work of art by being brought together as one, “in the same way that the industry becomes a big family.”

When working on a flat surface –as in the case of this cover– Robert’s goal is to work with as many different pieces as possible, making sure each one has its own visibility and space, while maintaining a balance that respects its identity.

In contrast, when creating a 3D work of art, such as the selection we previously presented in the Anatomy of a Piece of Art section, the bands lose their individual identity and collaborate with the overall piece. “Maintaining the authenticity of the piece on a cover like this is a challenge, because the goal is for each band to be present, but at the same time form part of a work with others.”

Throughout his years as a smoker and an artist, Robert has had the opportunity to witness the evolution of the premium tobacco industry through the bands of each cigar he has enjoyed. According to his experience, technology has played a fundamental role in these changes.

For him, the technology used to print them, for the die-cutting, and even for cutting them, in addition to the paper and inks used, all make a difference. He points out that there are particular cases like the bands of Arturo Fuente Cigars or the Diamond Crown from J.C. Newman, which, although belonging to the modern era, retain classic and nostalgic designs.

However, in comparison to the bands of La Perla, the textures and paper thickness are very different and make you feel their historical value when you hold them in your hands and work with them with a subtle touch of the fingers. “What I try to do is maintain a balanced mix of old and modern styles when I design, and with that, in addition to expressing something as a whole, I can tell part of the history and evolution of cigar bands over time.”

In this sense, Robert says that the La Perla bands are an example of a style that has unfortunately been lost in the modern era, and for that reason, he especially enjoyed creating this cover. He took the opportunity as a celebration of a past era within the industry, reserving some pieces in his collection of “oils and watercolors” to continue honoring the past through their inclusion in future works of art.

Robert Glick’s studio resembles a small factory with perfect order. Shelves, drawing tables, and workspaces show all kinds of tools and materials, surrounded by dozens of boxes filled with bands sorted by shape and color, as if they were tubes or pots of paint.

In a way, the objects he covers are like 3D puzzles. “The secret is that I take any band and separate the design elements that compose it, which are of various sizes, and organize the pieces. It’s very detailed work, a process that many people would find tedious and that requires special equipment like magnifying glasses, adhesives, tweezers, and so on...”

To achieve perfect designs without borders or blank spaces, Robert uses small clippings from parts of his bands, and during the process, tiny pieces of paper become scraps that invade and dirty the piece. “And instead of using my hand, I intentionally chose to use a paintbrush to clean the surface. With that detail, I create a sensory connection that makes me feel like a painter. It’s the way I express my intention.”

Once the bands are placed, the coating depends on the piece. For example, on an ashtray, he uses a heat-resistant epoxy resin, and on glass pieces, he sometimes adheres them from underneath and then covers them in a different way. He sprays boxes and other objects with matte or high-gloss lacquer, and when he wants the textures to be felt –especially when he’s using bands that contain reliefs and a lot of artistry in their design– he follows a different process.

This is the case with lighters and cutters. He protects them so finger oils don’t ruin them, but if he’s working on a table or a chessboard, he looks for a mirror finish, a leveled surface, that allows them to continue being used for their original purpose. “I feel that each band must be in a certain position that I cannot predetermine. It’s as if they were guiding me, and that’s why I sometimes play a game of cutting a piece and waiting for it to tell me where it wants to be.”

Among many other things, he has covered musical instruments, furniture, masks, shoes, hats, posters, paintings, ceramic figures, antique objects, toys, clocks, and even created advertisements for cigar lounges. When asked directly, he responds that each work is like a child, and although he is very satisfied with his trumpets, shoes, and flags, if he had to choose just a few, the chessboard would definitely be among his favorites.

Robert works alone, with the television on in the background, and when he is not in his role as a lawyer, any place is good to develop his art: the waiting room of an airport, or while traveling on a plane... “in hotels, I get up every morning and work on something, because it’s what I love to do.” In fact, it is his habit to “keep six or eight projects going at once,” because each one requires its own time to be analyzed, to make changes, and even to be discarded. “There are pieces that can take me hours, while others need several months.”

Robert Glick is a perfectionist who performs delicate work with a steady hand and a lot of patience. He is an artist whose greatest pleasure is to observe and listen to the impressions his pieces awaken in people, “because there is no greater reward than enjoying what you do when others enjoy it too.”

For him, working with the La Perla bands was a special challenge because of how old they are and the delicate paper, which, beyond its age, is a finer and thinner material. “A special mention must be made of the fact that there are no more of them, and while I work, I also show respect for their history. Speaking of modern bands, they can be obtained very easily, but that possibility does not exist when you work with such old materials.”

Finally, Robert says he is satisfied with the result obtained for this cover, both as a piece of special edition work and for what it represents as a reflection of the industry, of the different manufacturers, as well as of his passion and performance as an artist.

artdefumar.com/ artdefumar

The story of La Perla, one of the emblematic cigar factories in this industry in Mexico and, for the time being, the longest-running, concluded in 2025 –after 127 years–with the sale of its last building in the city of Banderilla, Veracruz. A source of employment and wealth, it survived the Revolution and the labor union movements of the last century, interspersed with its initial boom and the prosperity that World War II brought to the sector.

Four generations of the Corrales family –now with five men named Andrés– and also women, wives, and daughters, were at the helm of the business, whose decline began in the 1950s after a temporary closure and an economic crisis, compounded by the popular consolidation of cigarettes, taxes, and a changing market whose modernization they could not keep up with, as well as the lack of definitive internationalization of their products and other factors, in a country where tobacco now only implies a past.

However, the leading role achieved by La Perla in other times is present in a rich historical legacy that survives in objects, images, and pieces of paper transformed into valuable art: rings, cigar bands, or vitolas that collectors –vitolphiles– have treasured over the years in Mexico and abroad, mainly in Spain.

A representative sample of the final stock of the company’s graphic materials, gifted to Humo Latino by Alejandra Corrales Amezcua, the founder’s greatgranddaughter and the last person in charge of the factory, accompanies this story.

Caption: Fragment of the Madrazo y Corrales

“Current Prices” list, published in December 1899.

José Madrazo, a Spaniard who left Cuba amid the “revolutionary powder keg,” founded the La Unión factory, Madrazo y Cía., in the port of Veracruz in 1871. This factory was a major reference point in the national cigar industry during the last decades of the 19th century. In fact, one author attributes it as being the very first cigar factory in the country.

The company achieved fame after winning prizes at the National Exposition in 1874 and 1875. According to their promotional material, it was the “Only one awarded at the Philadelphia Exposition (1876), and at the Paris Exposition (1878),” in which they described themselves as a “factory of tobaccos, cigars, and a leaf tobacco warehouse.”

For his part, Andrés Corrales Corrales was born in Santa Eulalia (Santolaya), the capital of the Cabranes council in eastern Asturias. He arrived at the port of Veracruz, where he initially established himself, and was a manager and partner in the El Arte factory. If this is correct, La Perla, by Madrazo y Corrales, emerged from

Propaganda in the Primer Almanaque Histórico, Artístico y Monumental de la República Mexicana for 1884 and 1885.

the merger of the aforementioned companies and initially operated alongside its annex, La Industrial Mexicana.

There is also a version that several partnerships participated in La Perla, which were unified in 1902 as Andrés Corrales y Cía. These included the one mentioned with José Madrazo; a second, with Tomás Pereda; a third, with Santos Ortiz and José Somoano; and a fourth in which the same Santos Ortiz participated, as well as José Corrales García, Francisco Corrales Sánchez, and Andrés Corrales Sánchez.

Regarding Corrales Corrales, we know that he died in Banderilla, but it is unknown if his principal partner ever separated from the company. Without documentation to prove it, and besides his discretion, it has been suggested that José Madrazo also worked in the financial sector.

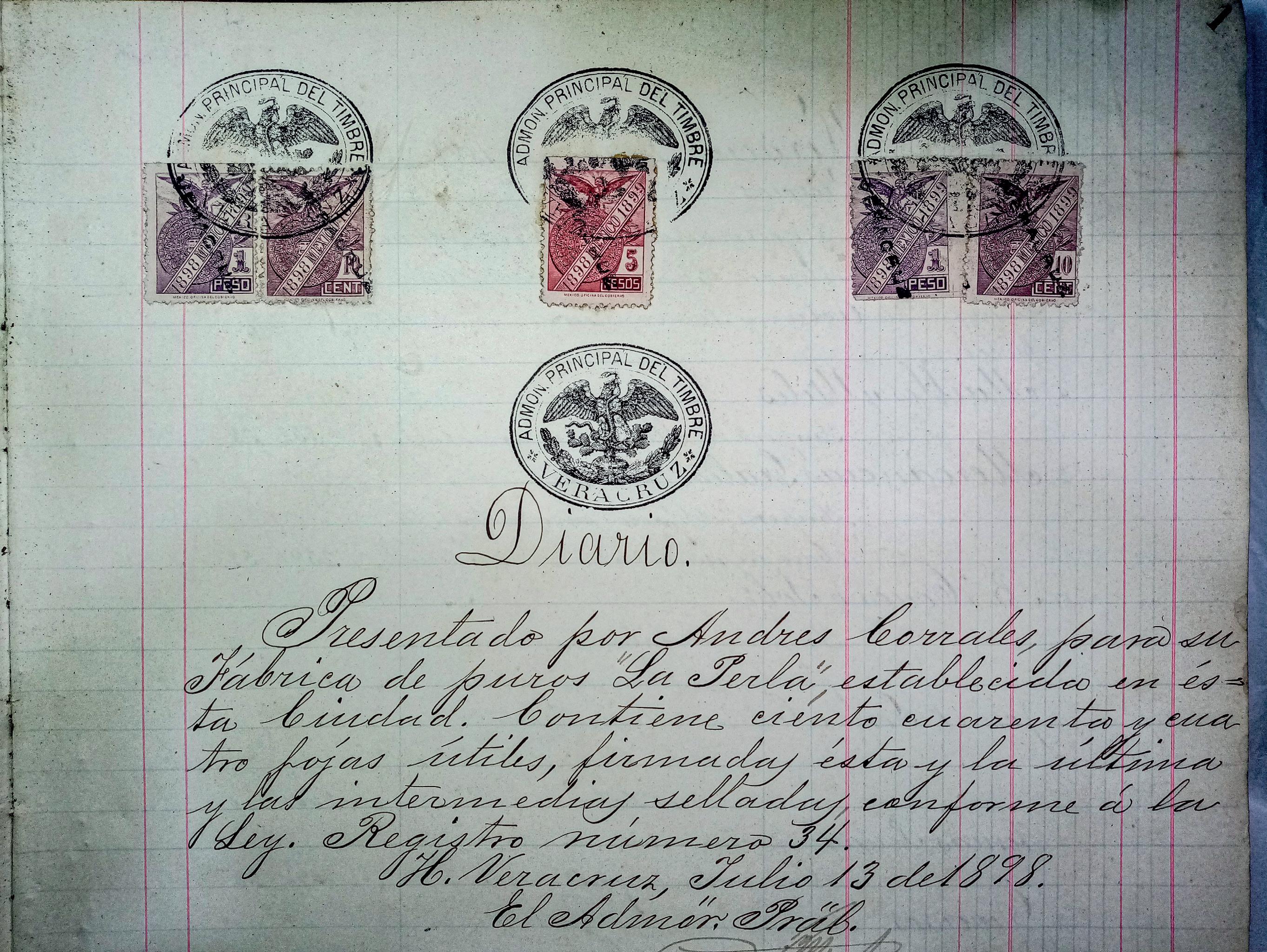

Alberto Arizmendi

On May 12, 1898, the chief administrator of the Stamp Revenue in Veracruz certified registration number 155, corresponding to the La Perla “perilla” cigar factory of Andrés Corrales Corrales, established at 55 5 de Mayo Street in the city and port of Veracruz. Two months later, the Day Book was presented to the same authority, with stamps valued at 7.11 pesos and 144 usable, sealed, and signed pages for the company’s administration.

But he had already registered the name La Perla in 1896, as soon as he arrived in the country from Spain, according to his great-granddaughter Alejandra. This fact is confirmed by the inventory of the

Patent and Trademark Office 1890-1902. (1) Andrés Corrales partnered with José Madrazo in 1897, when the brands Águilas Mexicanas, Regalía Pearson, Flores Americanas, Perlas Finas, and Regalía El Gran Pacífico were authorized in both their names.

On December 1, 1899, Madrazo and Corrales published a list of “Current Prices” headed by the images of La Perla(2) –a “tobacco factory and leaf warehouse”– and La Industrial Mexicana –”Cuban tobaccos and according to consumer preference”– accompanied by coats of arms that, it is understood, correspond to their surnames. They listed 86 regular vitolas (shapes and sizes), plus another 22 for export.

Practically since its inception, La Perla featured the face of a woman as its image, a portrait that has led to various stories and no small number of speculations. She is known as La Muñeca de La Perla (The Doll of La Perla) or La Muñeca de Corrales (Corrales’ Doll). The Valencian vitolphile José Pascual is credited with having identified or linked her to Émilienne André, born in 1870 and renamed Émilienne d’Alençon upon becoming a variety artist in the frivolous Paris of the late 19th century.

Given the number and variety of the brand’s cigar bands and packaging seals on which she appears, it has been written that Andrés Corrales Corrales may have chosen her portrait after meeting her during a trip to Paris, or that they even had a romance. Imagination has also run wild, speculating that the businessman saw her perform, loved her art, and insisted until he obtained permission to reproduce her face as the image of La Perla.

However, our Spanish contributor José Antonio Ruiz Tierraseca, president of the Grupo Vitolfílico del Sureste (Southeastern Vitolphilic Group), dedicated an extensive

serialized article to solving the mystery. He states that the character appears anonymously on an emerging brand, which would do little to help the artist. There is also a lithographic proof sealed by the Gebr. Klingenberg (GK) house that is estimated to correspond to 1894.

He posits that the original, Full Bloom, was actually created by the lithography company Heppenheimer and Maurer (1872-1885) when Émilienne was still a child. When the commission to create something for La Perla reached GK, they saw the model, liked it, modified it with their style, and that was the result.

“Let’s not forget,” he adds, “that by 1898 everything related to Heppenheimer had dissolved into the American Lith. Co.”

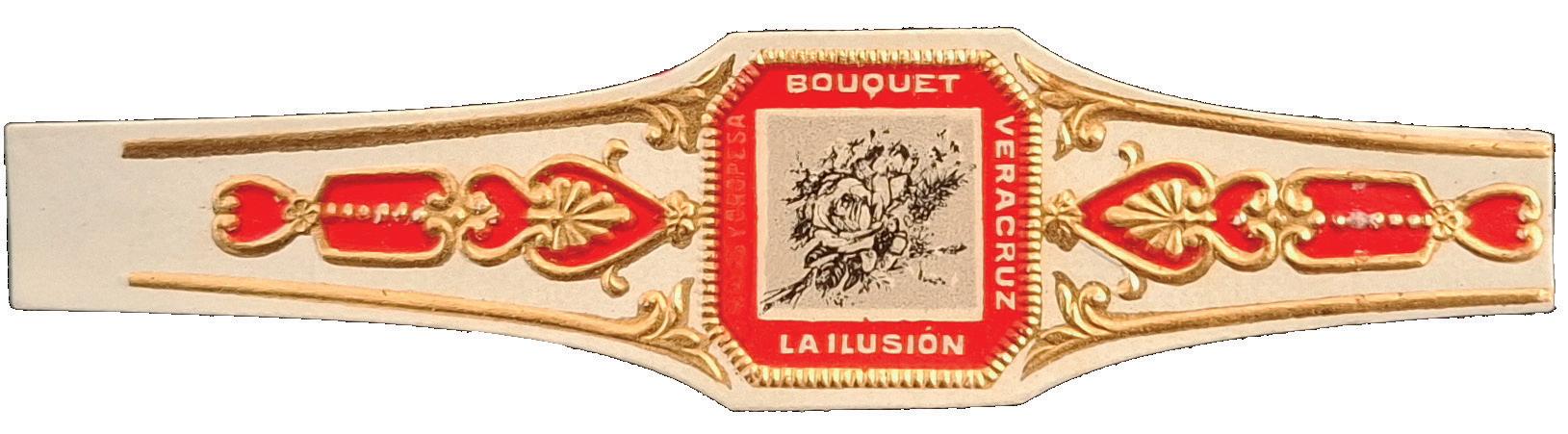

By April 1902, a new poster titled Gran Fábrica de Tabacos La Perla (The Great La Perla Tobacco Factory) included the portraits of the partners, flanked by the gold medals obtained at the Universal Exposition of 1900 in San Antonio, Texas, and at the PanAmerican Exposition held in Buffalo, U.S., a year later. Announcing themselves as leaf tobacco warehousemen and tobacco manufacturers, they presented their annexed brands La Ilusión and La Camelia.

The price list, per thousand, included 99 vitolas for which they specified the container and its capacity, as well as the approximate weight in kilograms. They also detailed the cost for placing bands, shipping costs, and other charges, as well as the presentation of their products with lead foil and bands; bands only, and in bundles. The address of the establishment was listed as 27 Playa Street,(3) in addition to a warehouse at 1 Lerdo Street.

“Current Prices” list, 1899.

Over the years, La Perla featured bands on its products under different company names: A. Corrales, Andrés Corrales, Madrazo y Corrales, Madrazo y Corrales Sucr., Andrés Corrales y Cía., and Andrés Corrales, S.A. These names corresponded somewhat to the company’s evolution and changes in its ownership structure.

Regarding their provenance, the bands from the earliest period originated with the German lithography companies Gebr. Klingenberg (GK) and Hermann Schott (HS). They were later printed in the U.S. by Consolidated Lithographing Corporation (C), at Galas de México in the capital city, and finally at the family’s printing press in Xalapa, where a Chandler printing machine and a Thompson-style diecutting machine were used.

Of the jobs commissioned from GK, an entry in the Administration Book dated May 17, 1899, records a payment of 668 pesos. Below are some samples corresponding to different eras:

La Playa Street in the port of Veracruz, at the beginning of the 20th century.

By then, they had also put a workshop into operation in the city of Xalapa, the state capital, at 2 Second Zamora Street. It is also recorded that in the same year, the construction of a full-fledged factory was completed at 82 of the old Colón Street, now Úrsulo Galván. (4) They maintained the slogan that appeared on the first poster: “Ready to give any requested order for fancy vitolas, for which we have the most skilled laborers in this area.”

It was shortly before 1907 that La Perla would move to Banderilla(5) –a small town, an “unimportant” municipal seat, but close to Xalapa and located on the main road between the port of Veracruz and Mexico City, where, since 1892, a station of the Interoceanic Railway operated, connecting it with the rest of the country.(6) Here, a building specifically designed for the factory was also constructed, at 92 of the current Benito Juárez Street.

The factory on the old Colón Street, now Úrsulo Galván, in Xalapa, Veracruz.

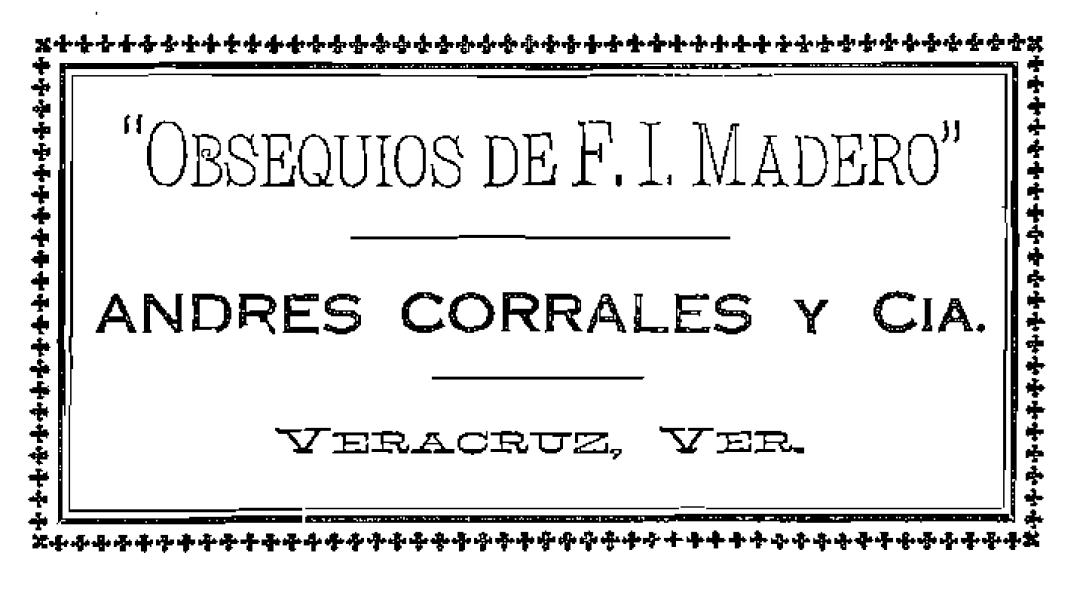

Certificates 11,242 and 11,243 of the Patent and Trademark Office reserved the names or slogans “Victorias de F. I. Madero” (Victories of F. I. Madero) and “Obsequios de F. I. Madero” (Gifts of F. I. Madero) –alone, or combined with other words– on May 18, 1911, in favor of Andrés Corrales y Cía., as trademarks to distinguish all types of manufactured tobaccos, especially cigars.()

They could be used on bands and labels, engraved or represented on boxes and packaging, with any size, font, alignment, and colors, including metallics. Ultimately, they could be used in any way deemed best to promote a product and evidence its origin.

The first cigar bands appeared without the President’s image.

On May 20, a telegram was sent on behalf of the company to Ciudad Juárez, addressed to Francisco I. Madero, requesting authorization to use his portrait on the La Perla cigar bands, and cordially congratulating him(). This occurred days after the capture of Ciudad Juárez, which forced the resignation of the dictator Porfirio Díaz on May 25.

This is confirmed by the attendance of its worker representatives at the First Congress of Workers of the Tobacco Industry in Mexico City in July 1906. (7) This was a time of growing social movements, which in this case favored the registration of the Tobacco Rollers Union of the La Perla factory by the Central Board of Conciliation and Arbitration, subordinate to the then-Syndicalist Federation of the Jalapa Region.(8) ***

Between 1911 and 1919, the area was affected by the revolutionary movement,(9) suffering the disturbances caused by carrancistas and zapatistas, joined by the hacendados’ “white guards,” until the Federal Army of President Venustiano Carranza finally managed to pacify the area.(10) In any case, the tobacconists included cigar bands with characters from one side or the other, which allowed them to navigate the changing situation.

The Banderilla Tobacconists Guild was one of the clubs supporting Madero.

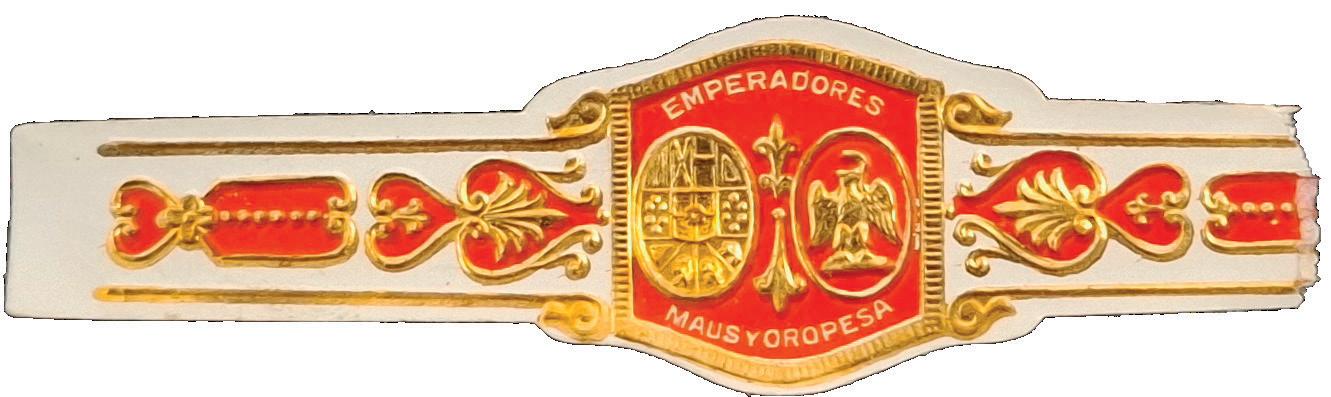

During the first two or three decades of the 20th century, Madrazo y Corrales –and later Corrales y Cía. Sucrs.– wholly absorbed different brands registered by other entrepreneurs, such as La Camelia. They also gained control of the La Ilusión brands from Veracruz, which were owned by Maus y Oropesa. They went on to purchase the brands of Bernabé García; the Peláez

factory from Puebla; the La Esperanza factory from Teocelo; and around the 1950s, they acquired the workshop and brands of El Toro from Alfonseca Sucrs. in Xalapa.

The obtained collection also includes cigar bands corresponding to Alonso y Cía. from Xalapa; Flor Fina –without further reference– from Veracruz; Juan O. Roux y Cía.; La Competencia; and others that remain unidentified. The following sampling excludes those from major companies, which are addressed separately.

Although cigarette factories had existed in the country since the mid19th century, it was around 1910 that consumption became so widespread that companies like El Buen Tono were producing more than one hundred million packs a year. The technological development that accompanied the use of machinery allowed the multinational British American Tobacco (BAT), which entered Mexico through the Compañía Manufacturera de Cigarros El Águila, to almost completely dominate the market by 1928.(11)

Nevertheless, during the 1920s and 30s, the improvement of Banderilla allowed for industrial development, and La Perla’s production was high, as it not only supplied the national market but also engaged in export. Andrés Corrales Corrales had acquired the entirety of the company, and over the years, he had also bought and absorbed many others, remaining at the head of the business until his death in 1935.

Propaganda from El Buen Tono, the cigarette factory that began the popularization of cigarette consumption.

In the book Monografía Descriptiva de la Ciudad de Veracruz. Apuntes históricos, geográficos, estadísticos, guía práctica para el viajero y el hombre de negocios (Descriptive Monograph of the City of Veracruz. Historical, geographical, statistical notes, practical guide for the traveler and businessman) (1900) by the editor Francisco J. Miranda, the Professional Directory (Commerce, industries, authorities, public offices, railways, maritime commerce, etc.) provides a list of tobacco companies.

Among them, La Ilusión, owned by Maus y Oropesa, S.C., is advertised as a factory, leaf tobacco warehouse, and manufacturer of its own brand of cigars for export. Located at 22 Vicario Street in Veracruz, a “view” of the building’s façade is shown. Its absorption by Andrés Corrales y Cía. removed this company from official documents at the end of the first decade of the century.

On some cigar bands used by La Perla, the names of Maus y Oropesa were suppressed or crossed out.

As a product of his marriage to the Mexican Clara Sánchez, their only son, Andrés Corrales Sánchez, took charge of La Perla. Since World War II was also a period of prosperity,(12) the factory developed on a large scale: “Large quantities of quality Habanos were sent to the north of the country, and likewise, by rail, to Mexico City, as well as to private individuals in Oaxaca, Mérida, and

abroad.” The raw material was obtained in El Valle Nacional, Oaxaca, and San Andrés Tuxtla, Veracruz, thanks to exclusive growers who guaranteed the quality of the tobacco.(13)

Rail cars full of cigars went to the northern border, where the largest buyer was the U.S. military. La Perla was a source of employment that even led to the migration of workers, but this phenomenon lasted for a short time, as unionists took the opportunity to demand improvements and progressively increase their benefits, so much so that between 1940 and 1950 they maintained a constant threat of a general strike that finally occurred in 1951, when the establishment remained closed for a year. (14)

Records show that Corrales Sánchez, a member of the Chamber of Commerce of Xalapa, stated that despite his benevolence toward his workers, he lacked the economic means to modify the collective bargaining agreement and satisfy their “excessive demands.”(15)

This company operated under different denominations or trade names: between 1885 and 1892, B. García y Cía.; from approximately 1893 to 1903, Bernabé García y Cía. Sucesores; and from 1904 onward, B. García or simply García, as both names are found indistinctly on the wings of its cigar bands. Its primary brands were La Rosa de Oro and La Flor de Bernabé García.

Based on an analysis of its vitolario (cigar portfolio), it has been written that the founder must surely have been

Spanish and of Asturian origin, given the texts found on the bands, such as Mineros, Flores de Asturias, and Glorias de Pelayo, among others.

Although this company predates La Perla, it eventually became its property, as confirmed by a pair of lithographic paper slips from the La Flor de Bernabé García brand, which bear the text “Prop.: Andrés Corrales y Cía.” and include the registration number 155.

But the businessman’s life was brief, and in 1952, his wife, Julia Elena Correa Bretón, or Doña Julita, took the reins and integrated a new company: Andrés Corrales, S.A., with her children Andrés, Julia Elena, and María Concepción, as well as her nephew Ignacio Hinojosa Correa. (16) However, after its reopening, La Perla never flourished again: “A new, more severe economic crisis was generated between 1965 and 1968, when it almost disappeared. This situation, stemming from a lack of government support, transformed it into a traditional microbusiness.”(17)

When Doña Julita passed away, in 1991, her son Andrés Corrales Correa took over the factory. After experiencing a “good” period during the sixties and seventies, with warehouses full, its final decline

began in the following decade. The sale of its products decreased, and they were left only with the national market, where some distributors, like Casa Petrides, located in the Historic Center of Mexico City,(18) were promoting its flagship product: Canalejas.(19)

The account of this final era is provided by Lucía Alejandra Corrales Amezcua, the founder’s great-granddaughter, who, starting in 2007, was responsible for the family business after her father’s death. She explains that they simply stopped being competitive against other companies with more financial and commercial resources that were able to dedicate themselves to export.

Covering payroll forced her to reduce work hours to practically a half-shift, and this was compounded by the seniority of many cigar makers, who retired around 2012 after 40 to 50 years with the company. By buying less raw material, they also hurt the growers, from whom they primarily obtained the Sumatra variety, so she recalls her father getting tobacco from regions other than Los Tuxtlas.

On the other hand, she decided to keep her job as a professor and dedicate her free time to the factory. “Even in my dad’s time, the business wasn’t profitable. For years, he had owned a printing press in downtown Xalapa and used it to get resources to keep the company going, practically as a family memory.”

Although some of the retired cigar makers agreed to work on the side to earn extra money, the number of employees gradually decreased, and in the end, there were only four rollers, one packer, and an office assistant. The last sale to a distributor was in April 2013, shortly before it closed, although it should be noted that in the following years, small batches were sporadically made for weddings and other social events.

Despite the difficulties, Alejandra remembers that in return, she gained some joys, as happened at the Banderilla Fair, where they broke the record for The Largest Cigar in the World with a piece more than 26 meters long. Another, when she was younger, was the celebration of La Perla’s centennial, which took place on May 16, 1998 –four days after the official date– and included the unveiling of a commemorative plaque at its facilities.(20)

1. DIARIO OFICIAL, Volume LXI, no. 13, July 15, 1902, p. 132. Ministry of State. Office of Development, Colonization, and Industry. Patent and Trademark Office, Inventory of registration by progressive numbering of trademark files corresponding to the law of November 28, 1889 of the Ministry of Development, Second Section, received July 22, 1903. The registration file for La Perla, number 1673, consists of 14 pages.

2. The iconic image of the brand appears, with a woman whose identity is a separate topic.

3. The 8th street of La Playa –currently Landero y Coss Avenue– replaced Calle de Los Cuernos (Horn Street), known as such between the 17th and 19th centuries for housing the butcher shop and slaughterhouse, where the horns of the slaughtered animals were piled up. Data and photograph from 1900, in Veracruz Antiguo, [https:// aguapasada.wordpress.com/2013/12/06/nueva-veracruzcalle-de-los-cuernos/](https://aguapasada.wordpress. com/2013/12/06/nueva-veracruz-calle-de-los-cuernos/) Photograph from 1867, at [https://www.pinterest.com.mx/ pin/412642384590904258/](https://www.pinterest.com.mx/ pin/412642384590904258/)

4. ROMERO RAMÍREZ, Raúl, 1999. “El papel informal en el desarrollo de la región de Banderilla, Veracruz (1940-1994),” in Vázquez Palacios, Felipe R. (Coord.). Las interacciones sociales y el proselitismo religioso en una ciudad periférica, CIESAS, Mexico, pp. 19-62.

5. GONZÁLEZ SIERRA, José. Monopolio del Humo. Universidad Veracruzana, Center for Historical Research, Institute of Humanistic Research, 1987. According to sources, it is not possible to document the exact dates of the factory’s transfer to Banderilla or the closure of its headquarters and/or branches in both the port of Veracruz and Xalapa. It is sufficient to note that in various official documents La Perla appears at one or another location between 1913 and 1930.

6. ROMERO RAMÍREZ, Raúl. Op. Cit.

7. MELGAREJO VIVANCO, José Luis. Breve historia de Veracruz. Universidad Veracruzana, Xalapa, Veracruz, 1960. pp. 232-233.

8. VELASCO FUENTES, María Trinidad. Actores locales y reforma agraria en el centro de Veracruz. Un análisis sociopolítico, 1915-1941. Universidad Veracruzana, Institute

for Social Historical Research, Master’s Thesis in Social Sciences. Xalapa, Veracruz, June 2020.

9. On April 22, 1911, the revolutionary faction led by Cándido Aguilar confronted federal forces and took the town of Banderilla, where they destroyed the Interoceanic Railway line. President Francisco I. Madero granted the individual the rank of brigadier general, and in his time, President Venustiano Carranza granted him that of commander of the Mixed Division. (DE LA PAZ REYES, Karina. Veracruz, pionero en la Revolución Mexicana, in Universo. Universidad Veracruzana: [https://www.uv.mx/ prensa/reportaje/veracruz-pionero-en-la-revolucionmexicana/](https://www.uv.mx/prensa/reportaje/ veracruz-pionero-en-la-revolucion-mexicana/)

10. MELGAREJO VIVANCO, José Luis. Op. Cit.

11. GONZÁLEZ SIERRA, José. Op. Cit.

12. As with many other factories, the legend circulates that the British Prime Minister, Sir Winston Churchill, came to try their cigars.

13. ROMERO RAMÍREZ, Raúl. Op. Cit.

14. VELASCO FUENTES, María Trinidad. Op. Cit.

15. Ibid.

16. FERNÁNDEZ MANOVEL, José Luis. El Prestigio de una Marca: La Perla, de Andrés Corrales, in Revista de la Asociación Vitolfílica Española (AVE), no. 100. Madrid, Spain, March-April 1966. The author cites as a source for some data Doña Julita and her daughter Conchita, whom he interviewed personally.

17. ROMERO RAMÍREZ, Raúl. Op. Cit.

18. Casa Petrides, owned by Tracíbulos Petrides, was on the current Madero street, but his brothers Zenón and Nicolás established Hermanos Petrides on República de Uruguay street. “It was a time when the Historic Center of Mexico City had a unifying character: ‘There were up to two tobacconists per block, but also many taverns, bars, and restaurants.’” MARMOLEJO, Roberto, in: Foropuros: [https://www.foropuros.com/threads/la-favoritatabaquer%C3%ADa-de-ciudad-de-m%C3%A9xico.9475/] (https://www.foropuros.com/threads/la-favoritatabaquer%C3%ADa-de-ciudad-de-m%C3%A9xico.9475/)

19. Various La Perla bands allude to José Canalejas Méndez (1854-1912), a Spanish liberal lawyer and politician who was assassinated while serving as President of the Council of Ministers.

20. Un siglo de la Gran Fábrica La Perla de Tabacos, in Diario de Xalapa, Friday, May 29, 1998.