[the dakota conflict]

DALLIANCE WITH THE GALLOWS: A COLONIZER’S PRIVILEGE

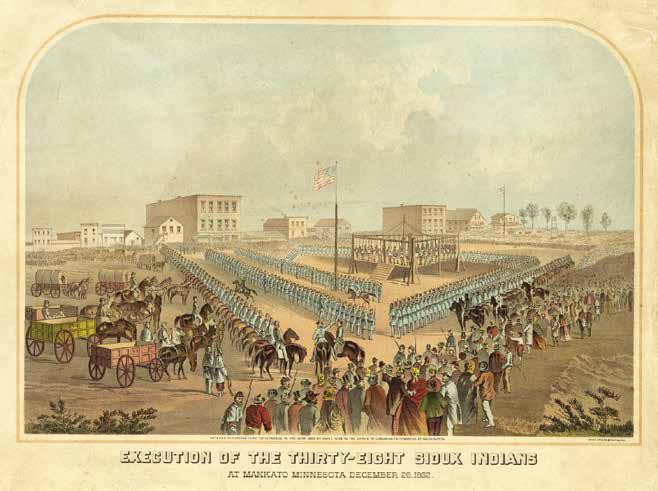

Brooklyn writer Claire Barliant’s “The Hanging in Mankato: Fragments of a Living History of the 1862 Mass Execution of ThirtyEight Dakota Indians,” is a media-piece both geographically and politically removed from the hotbed of controversy surrounding the 150th commemoration of the United States-Dakota War of 1862. Originating as “’Reading History,’ By Waziyatawin a performative reading and conversation hosted by Triple Canopy” in a distant New York art scene, it is a rather unlikely candidate for a responsive essay from a Dakota scholar and activist deeply invested in the interpretation and legacy of this watershed episode in Minnesota and American history. Yet, Barliant’s inquiry into her own family’s brief connection to one of the most spectacular events in world history—the largest, simultaneous mass-hanging from one gallows in world history—offers both curious insight and an honest glimpse into colonial privilege. In many ways, Barliant’s story is a typical American story. An opening excerpt from her nineteenth-century uncle, Pastor Peter Carlson, reveals a family emigrating from Sweden in their pursuit of “God’s will,” the standard Manifest Destiny drama that, in this case, brought them to the Dakota homeland of Minnesota. In this familiar narrative, even if it is not spoken, Indigenous people are a temporary hindrance, soon to be swept away by the march of progress. Once the Indian Wars are over and the Indigenous population has been exterminated, removed, or otherwise rendered powerless, Indigenous people fade into the background, disappearing from the white collective consciousness. As long as white occupation of Indigenous homelands continues unchallenged, white Americans have little reason to devote much thought to past conflicts. Certainly Barliant and her relatives maintained the luxury of never needing to consider what crimes settlers might have perpetrated so that their family could live the American dream. So what was it that broke their historical amnesia and drove Barliant to research the state-sponsored lynching of Dakota warriors? It seems to be curiosity about a family story recently uncovered through genealogical research. The story centers upon another uncle in the Barliant family, Anders Johan (A. J.) Carlson, who served in the Union Army during the Civil War (and presumably in the United States-Dakota War though discussion of this is conspicuously absent in her narrative). It was this military stint that landed him a role as a soldier standing guard during the mass hanging the day after Christmas in 1862. Barliant’s foray into the past was prompted by a concern over A. J.’s response to the hanging—whether he actually vomited after viewing the hanging and why he relied on impersonal sources to describe that gruesome day. Once she began venturing down that investigative path, she was both fascinated by what was for her a chapter in the distant past, and driven by a desire to acquit her ancestor of responsibility for his participation in the hanging. She was not only looking for some kind of evidence of her ancestor’s renunciation of this terrible event, however, she was also looking for her own absolution. While questions of memory, history, and culpability routinely figure into my research, it mattered little to me whether A. J. Carlson was sickened by what he saw, or whether, as a victim of trauma he had repressed memories of the hanging and in his denial chose to recite impersonal accounts. Perhaps if his experience as a soldier keeping guard during the hanging triggered a lifetime’s actions of justice toward Dakota people, I might be interested in how he felt about the hanging. I would be interested in what aspect triggered remorse and a desire to make

12