Once a week, an article on the defense of the humanities comes across my desk. The author of each piece makes a passionate argument against cuts to humanities education happening in institutions of higher learning across the country. Whenever I read one of these, I wonder why I never see equally vehement pieces in defense of technology, which impacts society on a far grander scale than university history and philosophy departments.

It's a rhetorical question, since the late NYU Professor Neil Postman summed up the answer in 1997 in a college lecture titled “The Surrender of Culture to Technology.” He lamented, "In the culture we live in, technological innovation does not need to be justified, does not need to be explained, it is an end in itself because most of us believe that technological innovation and human progress are the same things."

Is technological innovation the same as human progress? Is current technology designed by people who deeply contemplate the emotional and moral dimensions of the systems they create? Are new technologies interrogated in company meetings by people eager to debate whether their effects, intended or unintended, align with the public interest? Do discourses on social fabric or philosophical explorations of the good life challenge software engineers to rethink the platforms they build?

Of course not. That's not part of their job description. The people whose work equips them to critically examine the motivations behind innovation have been laid off.

Recent GameChanger Ideas Festival scholar Dr. Christopher Belitto summed it up well, “When people say, ‘How did we get here as a nation? You know, split horribly.’ My answer is, ‘What do you lose when you cut the humanities for 50 years? The answer is, you lose your humanity.’”

The humanities are not an exact science with easily measurable data points, but this is their greatest strength. They resist the impulse to reduce human life to algorithms.

The challenge lies in exploring the tension between embracing technological innovation and preserving the core values that define our humanity. You cannot do that without an investment in the humanities. It might not be good business, but it is a must for the common good.

Executive Director & Fellow Lifelong Learner

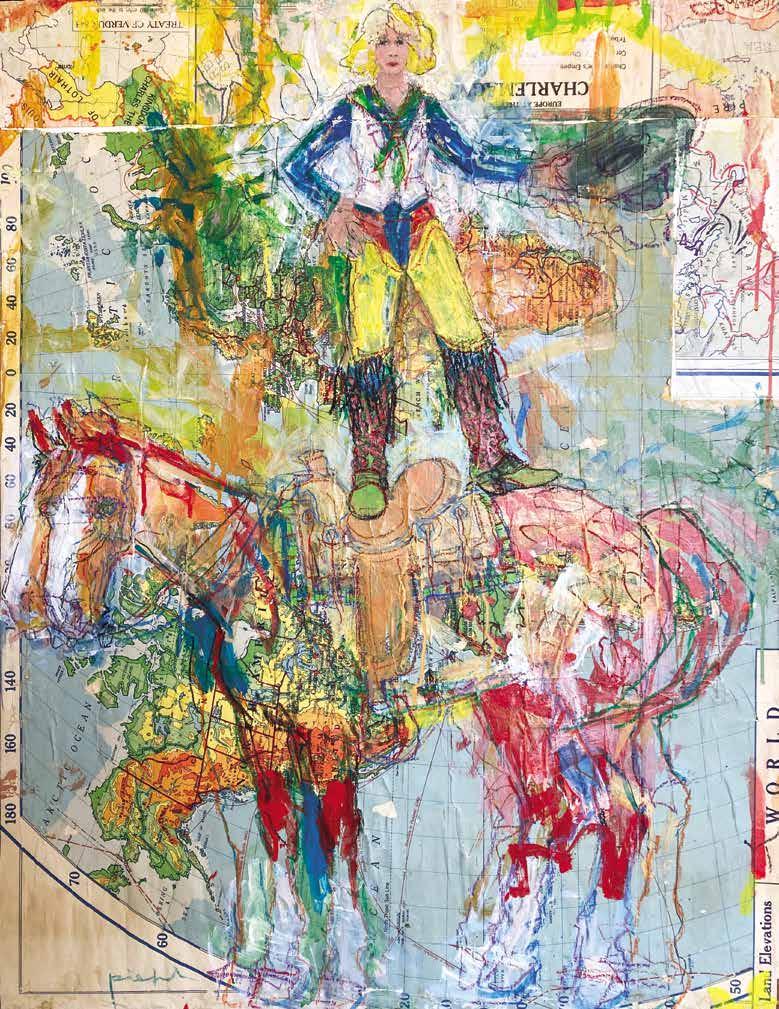

ABOUT THE COVER ARTIST, WALTER PIEHL

Internationally acclaimed artist Walter Piehl Jr. has brought credit to Western heritage through his artistic talents, his preservation of rodeo and Western heritage through his art, and his varied involvement in the sport of rodeo in North Dakota.

It was the 1980s, and we immigrants had to blend in and try not to reveal our origins.

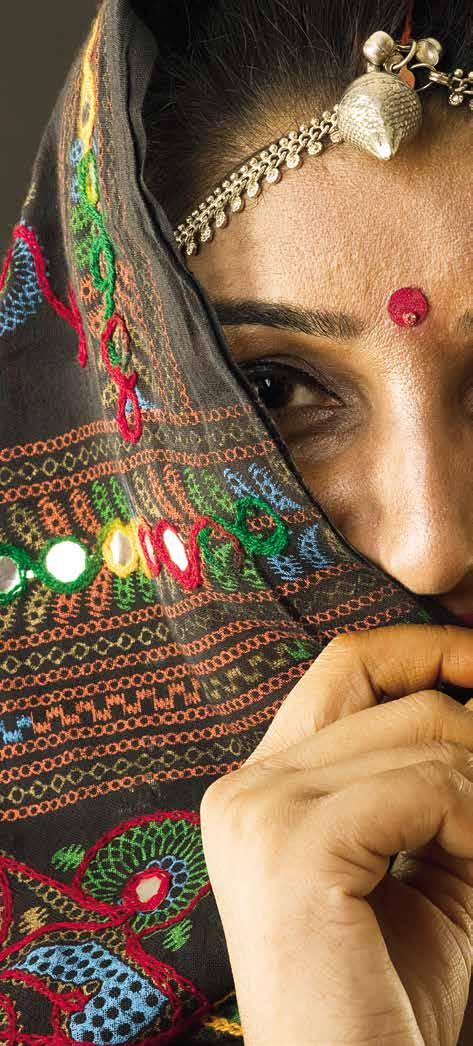

My maternal grandmother’s first name was Sarojini, meaning “lotus pond” in Sanskrit, a very ancient language of India. We affectionately called her “Saro Granny,” and she was a larger-than-life part of my childhood. Granny loved her bindi, the perfectly round dot she wore on her forehead all the time. She grew up in an era when girls in South India, even babies, were adorned with bindis. Some practitioners of Hinduism thought that it was the third eye of wisdom; others believed that it warded off evil. For married Hindu women, it was a mandatory embellishment. Granny got married at sixteen, like many girls from her generation. It was an arranged marriage, beginning with horoscopes being matched to determine if the individuals’ stars aligned. She only got to meet my grandpa, a young lawyer, at a formal “girl viewing” session, amidst a group of hovering relatives. They instantly liked each other and were soon married, settling down in a new home with a garden, in the heart of Madras. After the wedding, Granny religiously wore her big bindi day and night, convinced that it would ensure her a long married life. She wanted to be an “eternal” bride… like the Hindu goddesses, who were always portrayed with bindis. Granny was very particular about this, since both her sisters had been widowed early and their bindis removed forever, a

cruel fate she was determined to avert.

Granny had my mom when she turned seventeen, and I came along when she was just forty! Being her first grandchild, we shared a special bond, and I spent most of my childhood vacations with her. I would watch curiously as she took out this small tin box with a picture of a temple tower on its lid. It had a bright magentacolored powder called kumkum, fragrant like exotic tropical flowers. She would pick up some with her middle right finger and dab it precisely on her forehead, in a perfect circle. Miraculously this dot would stay intact on her all day long, even through the humid summer months in Madras. I thought it was magical, and wondered how she kept it from smudging.

Unexpectedly, we moved in with my grandparents in the ‘70s. Every morning before school Granny would pack my lunch in a tiered tiffin carrier, do my hair in two perfect braids, and paint a small dot on my forehead, which was permitted in my Catholic school with a majority of Hindu girls. My bindi would stay intact all day.

As a young teen, my favorite pastime was hanging out with my grandparents. Granny shared interesting stories from our Hindu epics and took me to many related movies and plays, ensuring I dressed up in my finest Indian silk skirts, with some kohl in my eyes and a nice bindi. “See how

Granny had given up her jewels, but she still had her bindi, perhaps a final appeal to her gods.

it brightens the face,” she would remark. “You look pretty, like a goddess.” I couldn’t refute that—I was the “good” granddaughter and actually enjoyed dressing the part!

Nudged by my grandparents, I got married early and hurriedly prepared to migrate to the United States. Granny tearfully bade me goodbye and gave me a book of her best handwritten recipes and a box of that special kumkum powder. It was the 1980s, and we immigrants had to blend in and try not to reveal our origins. The bindi was therefore reserved for Indian gatherings or home use during festivals. Moreover, we heard about some “dot buster” groups on the East Coast and their attacks on Indian ladies with bindis. It made us reluctant to wear bindis in public!

I really missed my granny and her big bright bindi during that phase of my life. Phone calls were expensive and infrequent, so we wrote and relied on international snail mail. She would make my favorite snacks and send me care packages with kind, unsuspecting travelers headed here to America. She promised to visit me, but that never happened.

The years flew by and sticker bindis in different shapes and colors became widely popular, especially among youngsters like my two daughters. I would take them to Madras every other summer, and they got to share special times with Granny like I had in the past. She braided their hair, made special treats, and enchanted them with her favorite Hindu stories, like the one where the young god Krishna’s mother urges him not to go out to herd the cows, offering butter as a bribe. She would sing the accompanying verses in Tamil, our native language, an added bonus!

Sadly, time was catching up. Granny developed debilitating arthritis and heart disease which she downplayed and continued working hard, cooking away in her hot, outdated kitchen. She was really shaken up when Grandpa was diagnosed with cancer and her old wish to precede him in death was in jeopardy. When I visited in 1998, they both looked very frail; it broke my heart. They lay side by side in their room on the same poster bed they had shared as newlyweds, over six decades ago. Granny had given up her jewels, but she still held on to her bindi, perhaps a final appeal to her gods. I sadly headed back to my life in the US, expecting Grandpa to pass away soon. I was wrong…six months later I got the shocking news that Granny was no more. Granny’s wish had been granted… she had broken her family curse and kept her bindi intact. Grandpa joined his beloved Saro a month later. Unfortunately, life got in the way, and I could not even attend their funerals. All I have are the precious memories and beautiful artifacts that Granny bequeathed to me, including a small silver lotus-shaped box filled with her favorite magentacolored kumkum powder for my bindis. l

ROOPA MOHAN is a professional storyteller from Walnut Creek, CA, who shares folktales with school groups visiting the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. She also tells multi-genre stories, braiding her childhood memories from India into them. She is also a Chautauqua scholar, who recently portrayed Kasturba Gandhi, after being mentored and trained by Humanities North Dakota.

Have you ever wondered what a lung transplant is like? I never did, because I enjoyed excellent health for almost 70 years, thanks to a lifestyle of no smoking, very little alcohol, no recreational drugs, no chronic disease and no obesity on my health card—and lots of hiking and other exercise. Until my lungs crashed, I was a veritable rock bunny, seeking mountains to climb, high places to traverse, and enjoying views in every direction. My will to live found expression in forward motion, which provided me the indispensable reassurance that I was truly alive.

Not surprisingly, then, I was deeply troubled when my physical ceiling for walking dropped from 17,000 feet in 2012 to sea level by 2020. By then I was dying of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, an incurable disease. My only hope was to receive someone else’s lungs. It was going to be a long and gritty road to awaken me to an appropriate sense of gratitude for my new life of struggle.

My elder daughter found a hospital out west, and we four— my wife and daughters and I— transplanted ourselves there. The November 28, 2020, procedure lasted only three hours. It began with “popping the hood,” as the doctors called the opening of the ribcage. A “clamshell” incision was made from one armpit to the other, just below my ribcage. My breastbone was sawed through sufficiently for my ribs to be propped up high and wide. The old lungs were removed in such a way that kept air circulating into my body and minimized the transfusion of blood. Two anonymous lungs were inserted, one at a time. Then the hood was stapled shut. Done!

But not done. The post-op pain stretched over a month, with ups and downs. Oxycontin made the pain almost bearable in the incredibly noisy ICU, where I spent a week. This epidural vacation was discontinued on the fifth day after the operation, as four drainage tubes were yanked from my ribcage. I was terrified of the pain to come, for hospital practice was to provide only hydrocodone and Tylenol. Utterly drained from having been reduced to a medically manipulated body, I badly needed to regain contact with my spirit. I put on Bach’s St. Matthew Passion. Unexpectedly— note here that I am not a publicly emotional guy—I wept until my bedclothes were soaking. Bach was returning my soul to my

body, lofting me into that grand jet stream of saints—past, present and future. His heart-stretching polyphony reminded me that I have a finite timespan of selfawareness in this grand aerial river, but that I would never be separated from the giver of life. That was my Revelation, the seedbed of my gratitude. This revelation is renewed, with tears, every time I listen to the opening chorus of the St. Matthew Passion

My optimism blossomed. Two days after the transplant I began shuffling with a walker through the hospital wards. I quickly worked up to a mile—17 laps on the polished floors. Three weeks after the operation, I ditched the walker. Once the hood slammed shut on my new lungs, I assumed I could revert to my walking ways and become once again the person I had been—with fresh young lungs, no less! My optimistic recovery moved along an upward trajectory for half a year. I sought out local trails and hills and got to the point where I could walk 5 miles or climb 1000 feet at a time. But then my forward motion mysteriously lost steam. Over the next six months, my lung function declined to the point I was in worse shape than before arriving at the operating table a year earlier, and it took another half year to regain the strength I had enjoyed on this brief hilltop of optimism. And it has been down and up ever since.

I had launched my recovery

with an utterly unrealistic expectation of rapid progress, driven by my strong hunger for normalcy. I had not been informed about possible negative consequences, and they turned out to be numerous and severe. From the perspective of three years out, I see my recovery as a series of scares and adaptations. By “scare” I mean a medical setback that seemed to put me on a steep slope down to debility and death. Medical issues emerged, often unexpectedly, prompting my frantic attempts to understand what was going on. Each scare—there have been thirteen so far—generated moments of angst and terror, but then faded into my psychic backstage as it was addressed. Each required adaptive coping, which for me required laborious learning. I began to understand that there is a serious price to pay for the miracle of not dying. (For a detailed account of these scares, see the online version of this article at humanitiesnd.org/news.)

By the fall of 2021, I had reached the lowest point, or so I thought. I was starving to the point of needing a feeding tube; dehydrating to the point of suffering significant kidney damage (“third stage” or moderate kidney disease); and experiencing side effects which morphed into further scares. Anxious to return home, I transferred my recovery care to a clinic and hospital system in Minnesota. The needed

referrals began immediately and ultimately branched out into multiple specialties. Such wider consultation was needed because I was faced with the worst scare of my entire recovery so far: “chronic” rejection, where the body slowly but surely rids itself of the new lungs. Constantly dizzy, I shuffled about as if a zombie, unrefreshed by miserably broken sleep. My melancholy returned in the form of fatalism about my pending mortality.

Even now I fight to regain lung volume, but the road is bumpy and my stamina and energy are not improving. In all truth, I don’t understand enough of the many scares and resulting changes to distinguish the consequences of the lung transplant from the “accumulation of diminishments,” as theologian Joseph Sittler dolorously termed the aging process. I certainly have lost any certitude about how I will die. But I have learned some gratitude, the hard way, which for me finds expression through my Lutheran faith.

For almost three decades as a teacher, I encouraged students to think of vocation, grace, works-righteousness, inwardcurving selfishness, paradox, and other convictions from the Lutheran tradition as nodes around which to weave their selfunderstandings. My lung disease and transplant have put these

I began to understand that there is a serious price to pay for the miracle of not dying.

convictions to the test in a way that has strengthened my faith, which principally takes the form of gratitude.

First is the venerable notion of living out a vocation. My looming mortality raised the question: why should I struggle so persistently to stay alive? Here I heard a very clear call—not a gossamer voice from the heavens above, but the concrete concern of my loved ones, friends and my congregation. They did not want me to die, simply put. My pastor sought to understand my evolving condition as well as provide support. Congregational members expressed warm concern, especially those in the medical field. My siblings chimed in. For further encouragement, I had only to think of my mother, who struggled for twenty years with the debilitating after-effects of a stroke. I dared not give up. I heard the clarion call: Struggle! Heal! Recover! I had no doubt I was hearing a genuine call to stay alive.

I heard the call to survive most pointedly from my wife and daughters, and with a particularly jarring impact. I had no prior inkling of how strong a protective impulse my post-op vulnerability would elicit from them. A tension developed between my urge to return to my old way of living and their determination to protect

me, especially from myself—a determination for which I was insufficiently grateful. I did not face this tension with grace, and they were bruised as a result. I learned the hard way that I needed to retreat into silence for a day or more, saying nothing while I “deep-listened” to them for what I clearly was not understanding. New medical symptoms only increased the strain on our communication.

Regaining my capacity to breathe was my vocation, but it raised a question of justice. Given the wretched swathe that COVID was cutting through the American population, how could I justify the taxpayer resources required for my care in the hospital and clinic? More bluntly put, what value did I have that justified the massive subsidies covering my medical expenses, when other patients were struggling to cope with inadequate insurance? What made me worthy of staff time needed by other, needier patients? This doubt played out as a doleful theme, particularly during the height of the pandemic.

Eventually, I found comfort in a question—not an answer—posed long ago by the ethicist James M. Gustafson. He asked why intrinsic value was generally privileged over instrumental value. Are we to be valued simply for existing, or because of what value we can

Are we to be valued simply for existing, or because of what value we can generate in our lives?

generate in our lives? I resonated with this philosophical question because I badly wanted to be useful to Creation, this world I live in and cherish, rather than merely ornamental. My unsteady recovery has ramped up the pressure to be productive. I didn’t have physical strength, but there was a solar power system to be built at my church in Minneapolis. I was intent on publishing my father’s letters from Nazi Berlin in the 1930s. And there was our net-zero house to be maintained. So I buried myself in these projects as a way of living out the grace of my extended life. Enforced pandemic isolation without forward progress in these tasks would have left me convinced that I was nothing but a useless, moribund social parasite on this good earth. These projects gave me reasons for living of an instrumental sort, which also likely had a good psycho-somatic influence upon my healing. Not exactly justice, but at least they softened the question of injustice.

At this point, Lutheran theologians might suspect me of works-righteousness, that bugbear of pointless striving for heaven that haunts Lutheran theology. But my projects had nothing to do with salvation, justification or sanctification. As H. Richard Niebuhr argued once in a philosophical vein, all value is always measured

relative to some center (“The Center of Value”). I measure my specifically instrumental value relative to earthly need and the partial vindication of my earthly life which might result. I also have intrinsic value measured relative to friends and family. But all these connections are to be distinguished sharply from my intrinsic and instrumental value for God, for these dimensions of value lie wholly beyond my claim or control. Even as I feared death from lung disease, I never worried about my ultimate disposition, since it was utterly in the hands of a graciously judging God. Grace was taken care of; my job was to help preserve Creation.

Beyond vocation, justice, and works-righteousness, my struggle to remain alive put an arresting new spin on selfishness—the Lutheran conviction that we humans are curved in upon ourselves by our inescapable self-centeredness. My extended recovery reoriented my thinking from my healthy earlier days. For almost seventy years, I had been convinced of my endless health while bounding over mountains. Now, the kaleidoscope of problems I faced hardened me into a projectile bent on a narrow and frankly self-absorbed trajectory. The demise of my old lungs and the implant of the new ones focused me on my mortality,

which is about as deep a pit of self-concern as I had ever fallen into.

It took a long time and some jarring ego bruises to call me out of this pit of mortal fear. The prospect of a “new normalcy” beckoned, but to gain it I needed to put some distance between me and my medical struggle. I began to realize that my healing required distance from my woes, and that is another dimension of gratitude. I took my name off the prayer list at church. I learned to bite my tongue about bringing up my recovery in conversation. I stopped using my condition as an excuse to avoid challenges, particularly of the physical sort. This distancing remains very much a work in progress. I do not want to be seen as a survivor, but rather as a continuation of my old self. I am learning how powerful that ache is, to return to normal. But the doleful Lutheran view of our inevitable inward curving reminds me that the struggle to lean outward will never be won.

Finally, the Lutheran taste for paradox has helped me with that perennial dark question: how should I face my death, whenever it comes? Where is there room for gratitude, given that inevitable ending? Of course, I am called to consent to God’s will as death looms, but I am also called to resist mortal challenges to my health. How can I do both? A paradox arises when two convictions are opposed

to each other yet must both be true. In my Lutheran view, these two imperatives are redeemed from outright contradiction by being anchored in an underlying commonality—much like fractions based upon a common denominator. Both resistance and consent are underlain by a love that will not let go. Each must be pursued in light of the other, much like while driving with one’s foot working brake and accelerator in a coordinated dance to avoid a collision. So I am haunted and comforted by a line from Dylan Thomas—“Do not go gentle into that good night.” My resistance to bodily decay continues in the faith that consent is warranted at the same time. In short, I am grateful for the challenge to struggle, and confident that the outcome will be good, even when resistance finally fails, as it must.

I have described here my ongoing and shaky recovery from fatal lung disease. The medical consequences continue to unspool in scary and depressing ways, and the learning curve of resistance has been extraordinarily steep and difficult. The aim of this article is to make this journey easier for others. Of course, no two journeys are alike, and this article is not meant to be a guide so much as a catalog of possible consequences and sideeffects, veneered with reflections about the consequences for

my inner self. By this point (the journey is hardly over, after all!) I have been sobered by the many scares. I never will be the ‘rock bunny’ I used to be, bounding along mountain trails and seeking high vistas. The major scares may be past, but the prospects for returning to full strength and energy while in my mid-70s are dim at best. The scares continue and likely at some point will put me on a steep slope down from debility to death.

On a happier note, this sobering experience has embedded me more firmly in my earthly home. I don’t long for heaven. I still have a vocation. In pursuing it I remain blessed by the continuing humbling experience of being sustained by loved ones, friends, my congregation, and the pieces of a wider community. And my will to live? The pressure is off. Even if I can no longer hike and run, I am called now to move outward, rather than simply forward. There is ample work to do in all directions. And that is ok. The hiking can wait. After all, Joseph Sittler once said that to live forever is to reside eternally in the memory of God. Who knows? That ethereal place might furnish interesting terrain for endless wandering exploration. l

Read the unabridged article at https:// www.humanitiesnd.org/news

STEWART W. HERMAN, PhD, taught ethics in the religion department at Concordia College in Moorhead, MN, for 27 years. Since his retirement in 2015, he has been a visiting fellow at the Christensen Center on Vocation at Augsburg University in Minneapolis. Upon retirement, he remodeled a 100-year-old house in Minneapolis to produce more energy than it uses.

You have likely heard that North Dakota is a drive-through state, with only rolling farmland and little towns offering nothing but a gas station and a post office. I, however, wholeheartedly disagree with this impression, because the prairie is one of my greatest teachers. While I am Filipina-American, originating from coastal Connecticut, North Dakota is where I’ve called home since 2017. Home became a patchwork of lands, waters, and people offering me joy and courage in the face of racism and willful ignorance. Home became a place of friendship where strangers turn into family and, better yet, co-conspirators for good days and better tomorrows.

North Dakota persists as a home for folks looking for new beginnings: for families from near and far, for young professionals, and for those seeking a slower, quiet chapter. I managed to move to North Dakota in the dead of winter, not once, but twice. When I look at the rolling prairie, I see diversity

in grasses and wildlife. When I look at my community, I am grateful for the movers and shakers organizing for healthier places to live and building meaningful businesses. I am a student of the prairie: learning rural lifestyles, progressive values, and what it means to be North Dakotan. While America is increasingly divisive, North Dakota teaches me to be resilient in the face of adversity (and brutal cold winds) and to stay hopeful that North Dakota continues to be a welcoming home. North Dakota taught me resilience. Resilience can be heroic, capturing the essence of how a person bounces back after major stress. In North Dakota, I witness resilience in our landscape and people. I landed in Bismarck for a job in natural resources with a federal agency, enabling me to mix with other conservation professionals, many of whom have roots in the upper Midwest. Colleagues taught me how to read the prairie, and I quickly learned the resilience of prairie grasses. I knew little of the diversity

I see that much of the hate in the world is outside of my control, yet I'm gifted with a voice to speak truth to hate.

of grasses and forbs, but came to be inspired by watching them turn pale as the temperature drops into winter, then become vibrant again when spring grants reliable warmth.

North Dakota taught me that, like the grasses, I can endure harsh conditions and be lively again. For one, my bones reverberated the cliche “when in Rome, do as the Romans do” as I picked up hunting for pheasants and ducks. A hunter intimately knows the species she pursues, and I began to study the way birds migrate, where they like to live, and what they prefer to eat. Unlike many ducks who migrate to the Gulf Coast, pheasants stay local throughout the changing seasons. Like me, pheasants are not native to North Dakota (we share Asian descent); and with time, I, like they, learned how to hide away from wind chills and stay cool in the beaming sun.

North Dakota taught me how to endure harsh social conditions and still enjoy the warmth of friendships. Living in Bismarck-Mandan, Mercer County, and Oliver County, I grew committed to our state: in addition to working in government, I served and collaborated with several non-profits, launched an outdoors and wellness business, taught yoga, and at the end of the day, learned to make friends wherever I went. While I am often met with open arms, I have also met the harshest flavor of racism in North Dakota.

North Dakota taught me that racism is ubiquitous, both in the grass and on the trees. The hardest part of enduring racism in North Dakota is that folks rarely hold their family and friends accountable for passing judgment on the basis of race or ethnicity. In downtown Bismarck, I walked from the parking lot to my office and got my heart broken by racial slurs. Because my office requested that employees report harassment outside the building, I voiced how a woman called me the N-word, and my manager quickly dismissed it as being not “that bad.” At a party, a man shared with me how an elderly Asian man ordered at a meat counter, speaking gibberish to mock an immigrant with the courage to live in a new place. When a Filipina woman died in a car accident hundreds of miles away, I was asked if I knew her (no, I didn’t) then asked if all Filipinos live in huts (I’ll spare you my response). When walking my own neighborhoods or leading community events, I am met with “Where are you from?” because somehow, a quick glance at me says I cannot be from North Dakota.

North Dakota taught me to admire the Indigenous communities who have persisted in North Dakota for generations and who continue to fight the good fight despite systemic hate. My Indigenous friends and colleagues have modeled for me that the prairie is a place to call home even when you are told and shown you are not welcomed here. The bison have been pushed to near extinction due to human pressure, and I look to the bison when I whisper to myself that I belong alongside my white neighbors flying flags of hate and telling me to return where I came from. I also return to the grasses and wildlife, watching them coexist amid their diversity. I bear witness, trusting that I am

not so different from nature: you and I are nature. We are resilient and endure the trials and tribulations stemming from a narrative that America shall stay divided.

North Dakota taught me hope. Despite unsolicited challenges of what I am doing outdoors, in my career, or even at the grocery store, I remain on my two feet. Off-colored jokes and unfounded opinions about my race and heritage are not about me. Working and living alongside neighbors with willful ignorance in their hearts, I did not grow hardy like a cool-season grass. Instead, I grew patient, rooted in the belief that hurt people hurt people. As a yoga teacher and conservationist, I see that much of the hate in the world is outside of my control, yet I am gifted with a voice to speak truth to hate. I have grown confident leading and engaging in difficult conversations. I have also learned that it is ok, if not vital, to turn away from adults unwilling to learn. When hate surprises me where I least expect it, I tune into my resilience.

North Dakota taught me that whether you are the first or fifth generation to call North Dakota home, your friends are there to welcome you; and when hate surprises you when you least expect it, nature is there to remind you of your resilience. In moments when your patience runs low for willful ignorance, remember the resilience of your neighbors—human and non-human—and sit with “‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers,” a poem by Emily Dickinson.[3]

“Hope” is the thing with feathers -

That perches in the soul -

And sings the tune without the words -

And never stops - at all -

And sweetest - in the Gale - is heardAnd sore must be the storm -

That could abash the little Bird

That kept so many warm -

I’ve heard it in the chillest landAnd on the strangest SeaYet - never - in Extremity, It asked a crumb - of me. l

MICHELLE DE LEON is a yoga teacher and public land manager. After working in the outdoors and wellness industries, she founded ResiliOak LLC in 2022 to help busy adults bounce back after stress through coaching and workshops rooted in mindfulness, the outdoors, and community. Michelle can be found hunting, kayaking, and hiking with her dog, Rusty the Toller.

[3]Citation: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/42889/hope-is-the-thing-with-feathers-314

Ours was not an affectionate family. Neither were we given to loud outbursts. We were cut from the fabric of the Great Plains, which lay flat under winds that blow reliably in every season.

The Plains don’t put on airs. It’s beneath them to beckon to you, and their true nature is hidden from all but a chosen few. Against them, the genuine and the impostor are revealed.

Webster describes “plain” as an extensive area of level or rolling treeless country; lacking in ornament, open, unobstructed, evident, obvious, easily understood, clear, candid, blunt, simple, uncomplicated, lacking beauty or ugliness.

Webster was only partly right.

You can see a long way across the wide rolling hills of the Great Plains. They are like earthen waves, rolling endlessly from the leafy green of the East to the jagged mountains of the West. However, to truly see the Plains, you must wade into them and swim far out, duck your head under its water with your eyes wide open, and stay awhile. In time, the Plains may reveal their secrets.

Unless you pay attention, you wouldn’t know the flat, quiet pastures have dozens of plant species. Nesting birds may hide along the path you tread. Wildlife scurries under tall grass, as do colonies of insects. In the neighboring field, enough grain grows to feed a small country.

We live on a hillside, and the rise behind the house is covered in landscaping stones. A pair of killdeers nest there each summer, in the open at the edge of our property. These are not quiet birds. When they have news, no one can ignore their shrieks. Yet, the gray and white birds mostly blend into the rocks as they go about the business of starting a family. They remain hidden in plain sight. I could only find them with binoculars searching the area where I knew them to be.

Last summer, they endured days of intense winds, temperatures near the century mark, and drenching rains. As natives to the Plains, the couple remained steadfastly on their nest for almost a month. Three times the mower from the property above us whisked by the nest. The birds would make themselves known by standing up and puffing their feathers in warning. The mower man kindly let the June grass grow near them.

People of the Plains also have surprising resilience. And, not that they care, but they are just as likely to go unnoticed as the killdeers. Virtues such as integrity, diligence, and bravery come standard. Plains people don’t talk about being honest or having courage. They just do it. A handshake is a legal document. Often, they give others the credit due them. They live by the Bible even if they can’t quote chapter and verse.

Anything less from Plains people is startling and noteworthy.

In The Sound of Mountain Water, Wallace Stegner wrote about the American West: “Just possibly, if our Westerner lived and wrote his convictions he could show the hopeless where hope comes from…”

Stegner might have been writing about people of the Plains. He might have been writing about my own family.

For years, I tried to explain my parents’ prevailing stoic mindset. I finally found a quote that perhaps describes their view of life. Patrick J. Buchanan said, “To view poverty simply as an economic condition, to be measured by statistics, is simplistic, misleading and false; poverty is a state of mind, a matter of horizons.”

Whatever my parents’ horizons had been, they had shrunk. The Depression and Dust Bowl had left them hunkered down. It was all they could manage to survive on a rented farm with a crashing economy and a houseful of kids to raise during the 1930s. They hadn’t done well in the 1940s, either. Then in the prosperous 1950s, Dad’s health began to fail. In spite of their hard work, diligence and integrity, they were never able to do more than scrape by.

When I began to write in the late fifties at age eight, a line in one of my poems was, “My mother works hard, she makes lard.” In my own defense, lard does rhyme with hard, and I had watched her render lard and make lye soap many times. It was a smelly, hot, all-day process.

Dad was a farmer who never owned land, and a fisherman who never owned a boat. He affably drifted along with whatever life dispensed to him, being unwilling or unable to fight against the current.

Perhaps explaining poverty as a matter of horizons clarifies why Mom and Dad sometimes turned down opportunities that might have improved their lives. They taught us kids by word and example to accept our lot in life and that thinking beyond our current circumstances was foolishness.

They’re all gone now, my parents and siblings. Except for me. Their stories inhabit my heart like

Plains people don't talk about being honest or having courage. They just do it. A handshake is a legal document.

cream swirling in a cup of coffee. After a lifetime of writing, it was only natural that I wanted to set down the tales that they told and the anecdotes I remember.

Then a remarkable thing happened just after the last person in my generation passed away, leaving just my husband and me. I had a vision and a healing. I’d had a miserable week of back pain. In addition, my blood pressure was high enough to create a choking feeling in my throat. I’d been to my skilled and gifted chiropractor twice that week with only minimum results. Now I was sitting in church on a Sunday morning with excruciating back pain.

As I tried to focus on the service rather than my pain, I suddenly saw myself at the end of a long string of Larson cousins. There were forty-six cousins on that side of the family. I’m the youngest by seven or eight years. In that moment, it came to me that I am in a place to be a voice for their generation.

Just as that thought came to me, something released in my back. From that moment, the back pain began to leave, and my blood pressure dropped back to normal. If God can speak to our hearts, I believe he spoke to mine that day.

While it’s my honor to record events from the past, it is my delight to be here in the land of the living with my own children and grandchildren, my nieces and nephews and their children and grandchildren. What fun it is to see my mother’s flame red hair appear down the family line in the fourth and fifth generations. To see my dad’s eyes shine out from the little faces of my great-grand nieces and nephews.

My parents were defined by limited horizons, their roots deep in the soil of the James River Valley. However, today many of their descendants travel the world, have exceptional careers, and enjoy much easier lives than my parents could imagine.

As delightful as it is to see them soaring away, it also causes me to wonder. Will succeeding generations have the same grit, the same integrity, the same beliefs that defined, refined and strengthened my parents and siblings?

As St. Paul told the people at Corinth, “Now we see in the mirror dimly, but then face to face.” Perhaps their sad, sunny, mundane and monumental stories will offer a mirror to the future that reflects the light of the past. l

GAYLE LARSON SCHUCK is a native North Dakotan who lives in Bismarck. After graduating from the University of Mary, she spent twenty-eight years working in public relations and development. Schuck is the author of five books including Secrets of the Dark Closet.

SELECTED WRITINGS FROM THE NATIONAL EDUCATIONAL ASSOCIATION’S DEPARTMENT OF INDIAN EDUCATION, 1900-1904

by Larry C. SkogenLincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2024

From the Introduction, xxvii-xxxiv

British writer Gilbert K. Chesterton wrote in 1924, “Education is simply the soul of a society as it passes from one generation to another.... The culture, the colour and sentiment, the special knowledge and aptitudes of a civilisation must not be lost, but must be left as a legacy.” This simple passing of the “soul of a society” to future generations is the direct antithesis of what in the United States was called “Indian education.” As Ojibwe writer David Treuer has insightfully stated, “Indian kids went to school to be not-Indian.” Carlisle Indian Industrial School founder Richard Henry Pratt more coldheartedly said that the purpose of Indian education was to “kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

Consistent with these ideas, the US government developed an Indian education policy in the late decades of the nineteenth century that the Native American Rights Fund found “was, at its core, a policy of cultural genocide.” Rather than passing souls to subsequent generations, this policy sought

to eradicate “Indianness” among the Native populations and strove for the “civilization” of American Indians so they would assimilate into the dominant white society. The only way this could be accomplished, write scholars K. Tsianina Lomawaima and Teresa L. McCarty, was to “replace heritage languages with English, replace ‘paganism’ with Christianity, [and] replace economic, political, social, legal, and aesthetic institutions.” The “logical choice” for this “Native American cultural genocide,” they note, was the nation’s educational system.

Two schools of thought dominated discussions by the late 1800s and early 1900s regarding “Indian education” and how best to “civilize” the nation’s Indigenous population. The first philosophy, an Enlightenment-era influenced universalism, had its American roots among the Founders, including Thomas Jefferson, who believed “the Indian...to be in body and mind equal to the whiteman [sic].” Convinced that the continent’s aboriginal people must eventually accept white civilization or perish, he included intermarriage between Natives and whites to his assimilationist quiver. In 1808 he told a visiting Native delegation, “When

once you have property, you will want laws and magistrates to protect your property and persons, and to punish those among you who commit crimes. You will find that our laws are good for this purpose; you will wish to live under them, you will unite yourselves with us, join in our Great Councils and form one people with us, and we shall all be Americans; you will mix with us by marriage, your blood will run in our veins, and will spread with us over this great island.” In the post— Civil War era, this enlightened universalism motivated much of the country’s reform movement to solve the “Indian problem.”

Commissioner Thomas Jefferson Morgan articulated this universalism when he presented his educational plan in 1889 in which he defined Indian education as “that comprehensive system of training and instruction which will convert [Natives] into American citizens.” He and like reformers held that through an educational alchemy American Indians would become productive Christianized Americans. The “secret sauce” of this alchemy was forced total assimilation, or, as noted above, “cultural genocide,” whereby any vestiges of Native lifestyles, religions, languages, and so forth would be totally eliminated from the American landscape. These assimilationists believed that they would be providing American Indians with the profound gift of civilization by eliminating the “tedious evolution,” in Commissioner Morgan’s

words, through which whites had traveled.

The progressive educators, strongly influenced by the era’s scientific racism, represented the second school of thought that directly confronted the universalism of the old assimilationists. The new theory held, education historian Thomas Fallace writes, that societies and individuals “passed through the same linear stages” of “savagery, barbarism, and civilization,” and “non-White individuals and societies were stuck in an earlier sociological-psychological stage... that had been abandoned by the civilized.” Progressive educators believed that American Indians could never become “white.” In other words, there was no way to avoid “tedious evolution.”

“Many white Americans,” historian Jacqueline Fear-Segal notes, “were never able to concede full equality to Indians and progressively situated them within the developing discourse of scientific racism.” Therefore, scientific racism provided a rationale for believing in the superiority of whites. According to Pawnee lawyer Walter R. Echo-Hawk, it “clothed simple prejudice and base racism with the imprimatur of science.”

Francis E. Leupp evidenced this racist viewpoint shortly after he became commissioner of Indian affairs in 1905, when he dismissed what he believed to be the wrongheadedness of the concept of universalism. “The commonest mistake made by his well-wishers

in dealing with the Indian,” he wrote, “is the assumption that he is simply a white man with a red skin.” Leupp and like-minded reformers believed that no amount of transformation would elevate American Indians to the status of white American citizens, who, they believed, were farther along the path of evolutionary advancement. Despite having this low opinion of the intellectual abilities of Natives, Leupp and his ilk liked them and their Indianness. As early as 1900, he wrote, “I like the Indian for what is Indian in him.... Let us not make the mistake, in the process of absorbing them, of washing out of them whatever is distinctly Indian.” This was a decidedly opposing view from Pratt’s “Kill the Indian.”

Differing rhetoric and philosophies notwithstanding, the overall objective in civilizing Native Americans through education was to assimilate them into the religious, economic, linguistic, political, and legal fabric of American society. That is not to say that other—probably larger—motives did not contribute to the drive for Indian education. Historian and Ojibwe writer Brenda J. Child, for example, has argued that, if assimilation were the objective, why establish segregated Indian schools? She maintains that Indian education was more about a “land grab” than assimilation. Her point is well taken when considering how much of federal Indian policy was to facilitate transferring Indian lands to non-Indian hands. In

...no amount of transformation would elevate American Indians to the status of white American citizens, who, they believed, were farther along the path of evolutionary advancement.

sarcastically summarizing the entire “commodification” process of Native lands from colonial to modern times, Canadian historian Allen Greer writes, “All will be well as indigenous land is absorbed into the Euro-American ‘mainstream’ and indigenous people disappear into oblivion.”

Thus, Indian education for assimilation as it evolved in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and the “land grab” are intricately woven together, and Child certainly identified this larger national policy of Indian affairs.

Nevertheless, civilizing for assimilation—to varying degrees— remained an objective among Indian school educators and reformers of the day. All of these approaches required conversion to Christianity, communications in English, and practical skills training to labor in white society. Educators and reformers, however, aggressively debated the degree to which Indian education should amputate students from tribal, including familial, ties in the process of assimilation.

The evolution of this Indian education during the nineteenth century resulted in the establishment of “three institutions—the reservation day

school, the reservation boarding school, and the off-reservation boarding school.” Each institution represented in its own way the philosophical discussions of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The type of institution Native students attended defined the degree of interaction those students would have with their Native communities and families, and how much Indianness would be “killed” or educated out of them. Students enrolled in a reservation day school continued to live within their communities and became instruments by which the rest of the community members were to be uplifted into the dominate white society. Reservation boarding schools offered the same advantage, only in more limited doses, such as during school holidays.

Conversely, the off-reservation boarding school removed students from their communities, often from the geographic region, to be schooled for years at a time in isolation from families and communities. The masthead of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School newspaper best defined the reformers’ view in this approach: “To Civilize the Indian; Get Him into Civilization. To Keep Him

Civilized; Let Him Stay.” These advocates believed that only through total and unbroken immersion into white society, without any opportunity to “return to the blanket”—as “backsliding” into Native culture was derisively called—could American Indian students successfully make the transformation to white society. Dr. Carlos Montezuma, Yavapai from Arizona, went so far as to say, “Away with the reservation schools.” He continued, “You can never civilize the Indian until you place him while yet young (and the younger the better) in direct relations with good civilization.” Such advocates believed that total immersion into white society (the sooner the better) would metamorphose Natives into good American citizens.

Despite the quibbling over the philosophies represented by each of the three Indian educational institutions, there was no disagreement about the ends to be achieved: civilization of the Native American population and its assimilation, to varying degrees, into the dominant white society. Commissioner Morgan wrote in 1889, “This civilization may not be the best possible, but it is the best the Indians can get.

The fact that there was a Department of Indian Education provides resounding evidence that educators believed that there were also chasms too wide to span between the education of America’s Native students and the rest of the population.

They can not escape it, and must either conform to it or be crushed by it.” In 1899 another reformer stated, “[American Indians] must either accept the white man’s civilization or disappear from the earth.” The men and women who worked in Indian education, possessing what Francis Paul Prucha calls “an ethnocentrism of frightening intensity,” used the educational environment to steamroll Native American cultures to ensure conformity to this “gift of civilization.” Robert A. Trennert Jr. writes that “although this promise [of civilization] meant little to Native Americans, the reformers of the late nineteenth century felt honor-bound to carry it out.”

One display of the frightening ethnocentrism and the honorbound dedication to “gifting” civilization to Native students is in the writings of educators from the NEA Department of Indian Education and...published in the Journal of Proceedings and Addresses of the National Educational Association, 1900— 1909. During this ten-year period, Indian school educators gathered with other educators from across

the country at the NEA annual meetings. By 1900 such meetings attracted thousands of educators of every stripe who came together to discuss the educational currents of their respective disciplines and to hear addresses from national speakers. That had not always been the case. Moreover, these educators and the Department of Indian Education to which they belonged were a late, albeit short-lived, addition to the NEA organizational structure and its annual meeting agenda.

By 1857 many of the Northern states had formed statewide teachers’ associations, as well as a variety of literary and professional organizations, all involved in education. These organizations fought for the recognition of the teaching profession, ran institutes to provide professional development for educators, and published a dizzying array of journals dedicated to scholarship. Forty-three leaders of these various organizations came together in Philadelphia in that year to form the National Teachers’ Association (NTA). Predictions for the success of this effort could not have been

good. The nation was hurtling toward a civil war, as disunion and sectionalism militated against the success of any national organization. Regardless, the NTA held its third annual convention in 1859 in Washington DC, where President James Buchanan became the first chief executive to acknowledge its attendees, all whom he invited to the White House.

By 1870, despite an intervening civil war, the NTA had held eleven annual meetings, changed its constitution to allow women into its membership, and renamed itself the National Educational Association.

Despite these apparent advances, anemic membership numbers continued to plague the organization and hindered its ability to become “one great Educational Brotherhood [and now, Sisterhood].” From its founding in 1857 to 1883, active annual membership never reached 400 members. Under an aggressive new leader during the latter year, membership skyrocketed in 1884 to over 2,700 members, with over 5,000 attendees at that year’s annual

meeting in Madison, Wisconsin. Financial insecurities and struggles to publish its annual NEA Proceedings evaporated. The NEA Proceedings, which included papers delivered at each of the annual meetings, captured the educational currents that represented the academic interests of the members.

Initially, members at the annual meetings met as one group in general sessions but, beginning in 1870, members also met in departments “for the presentation and discussion of papers on specific and technical subjects related to the various divisions of educational work.” The first four departments of the NEA were the Departments of School Superintendence, Normal Schools, Higher Education, and Elementary Education, all established in 1870. Over the ensuing years, the NEA board of directors approved departments based on “the written application of twenty active members of the association for permission to establish a new department,” naming the departments to reflect the function or expertise to be represented by the departments’ members. This process reflects the creation of the NEA Department of Indian Education in 1899.

NEA interest in Indian education began much earlier than the creation of this department. Samuel Chapman Armstrong, founder of Virginia’s Hampton Institute, presented papers in 1883 and 1884 on his school’s experience in mechanical

and agricultural arts for American Indian students. In 1884 and 1895, Pratt spotlighted his school’s work with Native students. William Hailmann, the superintendent of Indian schools, addressed an 1895 NEA general session with his paper “The Next Step in the Education of the Indian.” The NEA was also keen on passing resolutions supporting the nation’s American Indian education initiatives:

1885: We heartily commend the efforts made to solve the so-called Indian problem by educating the young Indians out of the savagery of their parents into the industries and attainments of civilization, in which families shall be set apart by themselves in well-ordered houses with individual possession of land and other property, and enter as proposed upon the duties and accept the obligations of citizenship. 1887: We express our profound interest in the education of the Indians; heartily commend the spirit of liberality shown by Congress in the matter, and call special attention to the important and encouraging results already achieved.

In 1890 a resolution commended Commissioner Morgan and his “plans...for establishing national schools” for Native youth. Moreover, “we hail it as a sign of progress in American civilization, that the United States Government is making this effort to educate all of the Indian race

for future citizenship, and that we pledge our cordial support as educators.” Five years later the NEA members resolved that they “cordially sympathize with Superintendent Hailman’s [sic] appeal to the teachers of the land for active interest on their part in the civilization of the Indians and for a concerted effort to bring the Indian under the same law with the white man in the several states.”

Through papers presented and resolutions passed at its annual meetings, the NEA had demonstrated an interest in American Indian education prior to 1899. The establishment of the Department of Indian Education, however, brought Indian school educators into the fold of national educators, recognizing their unique category just as the Departments of Elementary Education, Natural Science Instruction, Secondary Education, and the rest of the eighteen departments listed in the NEA Constitution recognized those specialties. After 1899 these educators saw their work endorsed with the Department of Indian Education also listed in the NEA Constitution.

The establishment of this department also emphasizes the segregated nature of the education of Native students, as Brenda Child points out. As will be seen, through the years when they had their own department, Indian school educators met in joint sessions with other NEA departments,

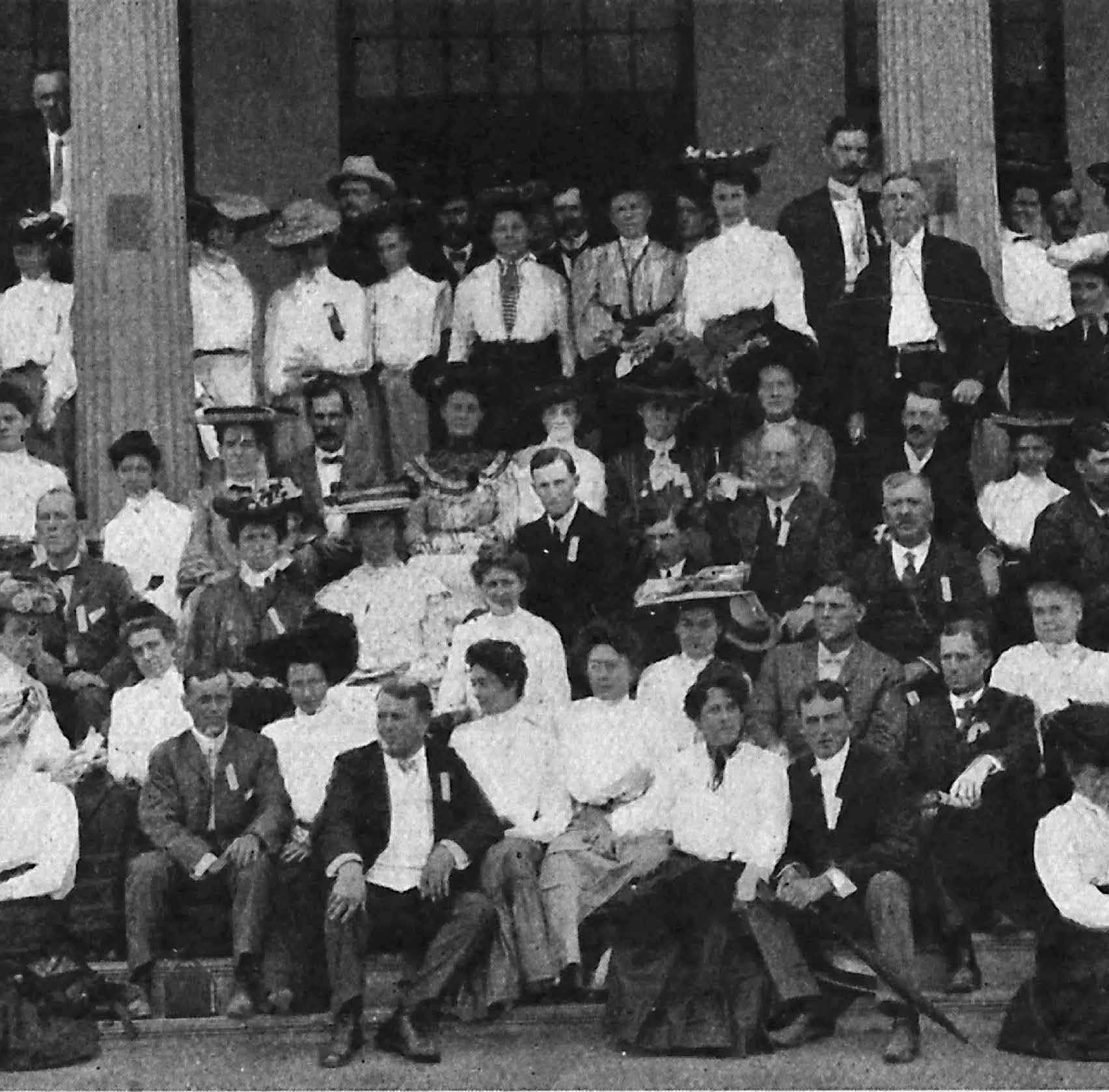

Estelle Reel was superintendent of Indian schools from 1898 to 1910. She was the first woman outside of the US Postal Service to serve as a presidential appointee requiring US Senate confirmation (postmistresses received perfunctory senatorial confirmation). As a director of the NEA, she made the motion in 1899 to create a Department of Indian Education and served as that department’s secretary from 1902 through the last meeting in 1909, when it was disbanded. She believed Native students incapable of higher academics and promoted instead domestic arts training for girls and agricultural and industrial training for boys. Regarding the education of her students, she maintained that it was not “necessary to study useless things in order to get the discipline necessary for doing useful things.”

Undated photograph courtesy of Library of Congress. Bain News Service, publisher. https:// www.loc.gov/item/2014683701/.

such as the Departments of Manual Training and Elementary Education. These joint meetings indicated the commonality in the work of specialized educators in Indian schools or the nation’s public schools. In other words, manual training and elementary education had similarities for both Native and white students. However, the fact that there was a Department of Indian Education provides resounding evidence that educators believed that there were also chasms too wide to span between the education of America’s Native students and the rest of the population.

Estelle Reel, the superintendent of Indian schools from 1898 to 1910, was the alpha and the omega of that department. An incredibly active member of the NEA after joining in 1894, she was the driving force in creating the Department of Indian Education. Without her it is likely there would not have been one, or, if there were, it would look very different from what existed. The NEA Department of Indian Education was her department. She organized its meetings and established its agendas, invited its speakers, and served as its secretary for all but two years of its existence ensuring that the educators’ papers, edited by her, were published in the NEA Proceedings, and oversaw the last meeting of the department after its single-decade journey with the parent organization. l

LARRY C. SKOGEN, PhD is an Independent Historian and President Emeritus at Bismarck State College.

A native of Hettinger, ND, Dr. Larry C. Skogen holds degrees from Dickinson State University (BS in secondary education), University of Central Missouri, Warrensburg (MA in history), and Arizona State University, Tempe (PhD in history).

Retired from a career in the US Air Force, Dr. Skogen has been involved in education as a high school teacher and as a college faculty member and administrator in a variety of military and civilian institutions, including the United States Air Force Academy and the New Mexico Military Institute. In 2007 the North Dakota State Board of Higher Education appointed him as the sixth CEO of Bismarck State College (BSC). In 2013 he was selected as the interim chancellor of the North Dakota University System and returned to BSC as president in 2015. He retired from that position and became president emeritus in 2020.

He is the author of Indian Depredation Claims, 1796-1920, published by the University of Oklahoma Press in 1996, and in 2024 the University of Nebraska Press published his To Educate American Indians: Selected Writings from the National Educational Association’s Department of Indian Education, 1900-1904. A second volume of this work covering the years 1905-1909 is forthcoming.

by Jean Rezab

by Jean Rezab

Dr. Paul Richmond looked around the exam room from the hard plastic patient chair. He resolved to be on time for his own patients in the future.

Would Riley find an aneurysm? A clot? Some other reason for his hallucinations? She’d been the best in their graduating class and became a respected neurologist, while he opted for family practice.

The door opened, and he let out a deep breath.

Riley walked in and held out her hand. “Hi, Paul.”

He grasped her hand. “Hi, Riley. Thanks for fitting me into your busy schedule.” She set his MRI films on the desk in front of her and sat down. Her shiny black hair bobbed just below her chin as she gazed at him. “No problem. You’re always at the top of my list. How else would I have gotten through med school?”

His strained laugh echoed in the small room. “You helped me too. You’d have managed, driven as you are.”

“That’s me. But let’s talk about you. I looked at the films before I came in, and everything looks fine.”

“Nothing?” There must be a reason he kept seeing and talking to Amy even though she died two months ago.

“I’m sorry, Paul. I know you think there is a medical reason you keep seeing your daughter, but I can’t find one. We’ve done all the tests I can think of that would cause hallucinations.” Her soft voice held only sympathy.

“Maybe I’ve got some psychiatric problem? Is that what you’re telling me?” His loud voice cracked. “I know you’re doing what you can. I don’t believe I’m imagining her because of some need I have to see her again. I miss her a lot.” He lowered his head and stared at his hands clenched in his lap.

Riley wheeled her stool away from the desk and faced Paul directly, a few feet away from him on his own patient chair. “Have you thought there might be a third option? Something other than a neurological or mental problem?”

At her words, he raised his head. He didn’t try to hide the tears pooling in his brown eyes. “Such as?”

“That she’s really there?”

“What?” Paul was confused. “But you know she died in that car accident, Riley.”

Riley’s face showed a compassionate understanding. “I know. But I meant, what if she came back from Heaven?”

His confusion remained—a maelstrom of

“She's been sent back to Earth to comfort you.”

confusion—and he didn’t know what to think. His daughter was real? From Heaven? “What?”

“From Heaven. She’s been sent back to Earth to comfort you.” Riley waited while he absorbed the idea.

It took a few minutes of silence while he tried to wrap his mind around what she’d said. He’d always pictured Amy in Heaven with Samantha. They’d been in the same vehicle crash. They both died at the scene, and he couldn’t say goodbye to either of them. It seemed more likely that he imagined seeing Amy than that she was real and came back to comfort him. He missed Samantha as much as Amy. “Then why don’t I see Samantha? Why is it just Amy?”

“I don’t know.” Riley shook her head. “It’s only a thought, Paul. I know it might be hard to believe, but I’ve seen some interesting things in my life. I don’t think you’re hallucinating. You don’t hear or see anyone else. Amy only comes to you when you’re having a hard time and need some moral support. That’s what you said, anyway?” Her brows lifted in question.

“Right. Whenever I want to have another drink, she appears. But how would she even know? Even if she’s from Heaven, she can’t read my thoughts.”

He didn’t even want to know half of his own thoughts since his daughter and wife had been killed.

“Have you thought about taking a vacation? You haven’t taken a vacation in a long time.”

Not since the Grand Canyon. But Riley didn’t need to say it out loud. The Grand Canyon trip turned out to be one of those magical vacations, exactly as the brochures pictured. One of those times that would be forever etched in his mind and heart no matter how much time passed or how many other things happened to him. Just him and Samantha and Amy.

Any issues that came up on the trip, they laughed away. They relaxed for the first time since Amy was born and felt like a settled couple for the first time in their marriage. Paul’s position at the clinic and Samantha’s interior design firm were successful. Three weeks later, they were gone, and he was on his own.

“Paul, what are you thinking?”

“I don’t know what to think. Maybe I do need a psychiatric consult,” Paul said.

“Maybe. I can refer you to Dr. Ted Whitaker. He’s seen some interesting things in his life. It’s rumored he has visions himself.”

“What?” Paul felt his head about to explode. When he entered the exam room, he’d never have guessed Riley would suggest a psychic psychiatrist. Or that Paul really saw his daughter. “Do you believe in Heaven?”

“Of course. I grew up believing, and nothing I’ve seen has changed my mind. I’m betting Samantha and Amy are in Heaven. But that doesn’t preclude Amy from coming to see you now and then,” Riley replied.

“And you believe I could be seeing my daughter for real, and not in my imagination?” He and Riley hadn’t discussed religion much in the time they

He sat in the driver’s seat, numb. No obvious reason. None. No reason why he saw Amy, except she might be real and from Heaven.

were in med school. Every class they attended was scientifically based.

“Definitely. Look, Paul, I know this is hard to believe, and I’m not sure I should have even suggested it to you. See Dr. Whitaker. He’s a great psychiatrist. He won’t bring this up with you like I did. He’ll listen, and he’ll tell you if he thinks you’ve got a medical problem, or if he thinks you’re imagining your little girl into existence to comfort you, like an imaginary friend. Or if he thinks you have schizophrenia or any one of several conditions. You know them yourself. You’ve studied some of them and looked up the rest since this started happening. That’s all he’ll do. Unless you bring up the question yourself, he won’t bring up visions.

“He’s a private man, and it’s not his way to push his opinions of apparitions onto others. Not many people even know about his visions. It’s a well-kept secret for obvious reasons, so please keep the information to yourself. If you don’t want to see him, then try Dr. Isabel Dacey. She’s traditional but not narrow-minded. She’ll consider all the angles and give you her honest opinion.”

Paul agreed to start out with Dr. Dacey. Riley said she’d send his test results to her; and if he changed his mind and wanted to see Dr. Whitaker, to let her know.

He stumbled out of the room and made it to his black Ford Escape. He sat in the driver’s seat, numb. No obvious reason. None. No reason why he saw Amy, except she might be real and from Heaven.

“God, help me,” he prayed, banging his head on the steering wheel until he realized someone tapped his arm.

“Daddy.”

He turned his head to the right, and there she sat in the passenger seat beside him. She had on a pair of purple leggings, a lilac-colored short-sleeved dress, and white sneakers with butterflies on them. Her blonde hair was one long braid down her back. He thought she might be cold, as it was fifty degrees outside. Spring in Bismarck, North Dakota, remained chilly with occasional warm days.

“Aren’t you cold?”

“No. It feels the same to me all the time. No matter where I am,” Amy said.

“Where do you go when you leave me?”

“All around.”

“All around where?” Paul asked.

“Here and there.” She shrugged.

“At the hospital?” He looked around outside his vehicle at the other cars in the parking lot, realizing someone might be watching his weird display. From the head banging to the talking to himself. No one was around. Just him and the big parking lot, with the cars and the trees with bare branches. Chilly, fresh, and wonderful when Amy visited with him.

“Yes. I see the new babies here in the hospital. And Hannah,” Amy said.

“Who is Hannah?”

“I don’t know for sure. She comes to see the babies sometimes and talks to Sheldon.”

“You see Sheldon?” Paul knew Sheldon Carlisle was the director of the NICU. Amy visited the very sick baby nursery. Why?

“Yes, I see him.”

“Do they see you?” Paul asked.

She laughed. “No, silly. Only you can see me.”

“Why? Why am I the only one who can see you?” He felt like the seven-year-old, not Amy. He had so

many questions and so few answers.

“Because God sent me here to help you.” She put her hand on his forearm again.

He felt comforted but afraid. Glad she was here. Yet afraid of when she would disappear again. “Did you see God?”

“Of course. He’s in Heaven.”

“Were you in Heaven?” Paul asked.

“Of course,” Amy said as if his question didn’t need an answer.

Of course. Paul did believe in Heaven. He believed Samantha was there too, along with Amy. But Amy was here now. Alone. Confusing.

“Do you leave Heaven to come here?” Paul asked.

“It’s not really leaving. Heaven is kind of here. Kind of there. It’s hard to explain. I blink, and I’m back in Heaven with the other kids.” Amy shrugged.

“So, how do you get here?”

She scrunched up her nose and pursed her lips. “I don’t know. I end up here with you sometimes.”

He could see it wasn’t going to be easy talking with her if he kept asking her how Heaven worked. “Are you a ghost?”

“Of course not, Daddy. I’m your little girl.”

“Of course you are.” He wanted to reach out and hug her, but he didn’t know if that was allowed. l

Rezab, Jean. Chokecherry Valley Comfort, Mary Schmitz, 2023, pp. 6-10. Reprinted excerpt.

JEAN REZAB writes from her home in North Dakota. Having grown up on a farm, she enjoys all things country, especially wildflowers, wheat fields, and winding lanes. She likes to entertain her readers with intriguing mysteries and women’s contemporary fiction.

Early mid-October. The wind out of the Canadian north-northwest grates, stings, burns. Tiny, sifted crystals of snow seep and slowly pack into the brittle, cracked-brown, downwind side of all manner of barren husks. The whiteness lends sheen to the freeze-dried vegetation, rows of sad, unharvested sun flowers, wild rose bushes in disarray, bleached wheat stubble, bent goldenrod, depleted tiger lilies, thick, matted tufts of tall native prairie grass on roughly laid-out plots left alone to die and return as in countless eons past.

“Where do you want to go?”

“Oh, I don’t know. Anywhere. Just a ride around with you is good.”

“But, where? It’s your day. If you had to pick a spot right now….”

“Oh, anywhere you want, but it would be nice to see that old shelterbelt line one more time.”

“Which one?”

“No, let’s just drive around. That’s fine for me.”

Our car crests the highest of three low-lying glacial ridges leading to Highway 66 and we stop, cut the engine, briefly feel the hilltop wind buffeting us. Monotony. The radio is off. Near silence. It’s just after 10 am. The gentle whirring of a car heater bucks up my fears for the low battery.

“Let’s go there!”

“Where’s that?”

“You see that tower with the flashing red lights on it, all the way down south? Let’s go there.”

“You wanna go there? OK, let’s go! That’ll be something new. I’ve never been there.”

“It’s funny. I’ve lived here all these years, nearly 55 years, and have never been there; and yet it’s only a few miles from home. I’ve seen it so many times. Have always wondered why it’s there.”

“Me, too. I’ve seen those flashing lights so many times from this hill and have never gone to see what it is. OK. We’re off!”

The rutted, dried-up mud-puddle section-line trail straight south of Highway 66 ends in a series of manmade cul-de-sacs. Wide-angle field ends fueled by land-hunger simply overstep federally regulated surveying limits. Even “No Access” signs are posted. No one cares much, not even at the county Ag office. We drive along slowly, skirting the problem, take a turn west along rows of ragged shelterbelts (Could these be the ones she was talking about?) and then head miles further south well into an area of tiny glacial lakes already frozen over, brown cattails still vertical, intact though starting to burst open. The car maneuvers well along the curving gravel roads dusted white

early in this season, climbs through low-lying hill country on up and around a number of virgin prairie knolls. Finally, we turn northward towards the big hill and its tower of flashing red lights.

“Those lights are on and it’s broad daylight.”

“Suppose it’s blinking for planes. It’s the biggest hill around for miles.”

“Do you really think we can go there?”

“I don’t know. You still wanna go? Should we go? Yeah, let’s go!”

A feeling of boyish bravado instantly falls victim to the audible crunch of dried grass on the undercarriage and then there’s a decidedly metallic bump shaking the car’s frame. The brake slams down hard just in time to avoid getting caught on a large rock working its way upward through the glacial soil. Back up! Stick it in reverse! Try driving outside of the ruts. Take the center ‘lane’ and the unused, thin shoulder to crawl forward up the hill. Be careful, you fool! What the hell would you do? Leave her all alone in the car perched on a hill miles from anywhere while you waltz off to get help?

“Are you sure we can make this? We can see it pretty good from here. I don’t really need to see it up that close.”

I didn’t answer. She knew why. Read me like

a book. Knew I was afraid for her, for myself, maybe even for the ridiculous situation this would be just two days in the offing from the day, not the nostalgic jaunt of this day, the day. Onward, upward we move until a chain-linked fence begins to dawn just over a small rise. Relief. When unlocked, it’s wide enough only for a small ATV. Saved!

“Guess we can’t go any further. Too bad. Just look at that metal tower, though. Wouldn’t like to have to climb up that thing to make sure the lights are working.”

“You wouldn’t catch me climbing that in a million years. My friend ‘Art’ wouldn’t let me. Have never been here before. Now we can say we’ve been to the tower, can’t we? Ha!”

After ten, fifteen minutes of looking at the dun scenery of early winter far below, spying our town off to the north-northwest and then, much farther to the north, spread across the horizon, the bluishgray line of the Turtle Mountains with its load of memories, fun times with her sister and nephew at the Pearson’s, pow-wows, politicking, summer swimming in Belcourt Lake, Upsilon, visiting Fred and Sarah Fayant. Much closer and yet much more difficult to make out, we barely see the now oddly insignificant crest of our own big hill, the one

where she decided on today’s adventure a few hours ago. Like an old nervous nellie, I hesitantly put the car in reverse. It inches backwards at a crotchety snail’s pace along the narrow trail, avoiding both ATV ruts and the big rock, eventually managing to find flat footing enough to turn around and move head-first off of the big hill with the flashing red lights.

“You can’t even see the farm from here, can you? This is what Helen sees when she looks north.”

“Yeah, I kind of like the idea that we are hidden. How about you?

“Oh, I don’t know. I needed to get off the place. We’re hidden enough. I was always glad to see Gertie and Mary in Fargo. It’s good to get out sometimes.”

Silence.

“Where to next?”

“Oh, I think that’s plenty. We can go back home if you want. I don’t want to keep you too long. You haven’t even seen your friends yet. You’ve got things to do.”

“I’ve got absolutely nothing to do except spend the day with you. Should we grab a bite to eat? Are you hungry?”

“No. Sometimes, I could go all day without eating.”

“That’s not good for you. Well, where next? Let’s go somewhere else, somewhere you like.”

“You decide. You’re always so good at getting out and finding things.”

“But it’s your day. You decide. Don’t make me dictate where you want to go.”

“Dictate? You never dictate. You know that.”

“Well, where should we go? Do you want me to just pick a spot?”

“That’s a good idea. Let’s go where you want instead.”

Well, that grates on ya’, doesn’t it? Bite your tongue. Self-control! This is not the moment to react like some Skinnerian rat. Besides, I’m incapable of telling the real difference between

some forms of innate kindness and a good dose of passive aggressivity. Knuckle under. Keep it light. You’ll thank yourself later on.

“OK. I know a place. It’s in the directly opposite direction. Straight back up north the way we came from but let’s not take the same way, all right?”

“You go exactly where you want to. I’m just along for the ride. It’s good to get out and see some country. I get so sick of the four walls. Anywhere you want. Just go where you want.”

“It’s a secret. I’ll let you guess.”

She still likes a certain level of teasing, gentle ribbing, little jests, simple things that keep it light, merry, fun-filled, prankish albeit with an occasional, good old-fashioned crack aimed at some local blowhard or some really nasty, crusty fellow, a sharp jab to stir the conversation a bit, have a chuckle, just a measured little zinger though never sly enough for it to become mean, rough or certainly not obscene. It seems she rarely laughs that full-throated way anymore. Yet, her penchant for a good, old-fashioned belly laugh remains intact. It’s a kind mirth, one which inevitably makes everyone feel complicit. Like her sisters, she mostly twitters and rolls out expressions from her youth, “My dear little gaspipe,” “Isn’t that just the berries,” or “He should mind his potatoes,” or an occasional “After that, she skidooed.” We drive down and away from the tower, head east across that area of tiny, glacial lakes and return west via Highway 66. At the Belcourt Road, we turn northward towards the Rez.

“Oh, are we going to Torkel and Marie’s? She always had the best plums. Made the best jelly. Picked them right out of the west end of their shelterbelt.”

“You used to put that plum jelly in homemade bismarcks and doughnuts. Man, were they ever good! Remember those meals you sent out to the field?”

“There’s not much left of that place now. Imagine that. It used to be so alive. Are we going there?”

“Nope, but we can if you want.”

“You decide.”

“Nope, we’re not going there.”

“Belcourt, then? Did you want to go there?”

“Nope.”