22 minute read

The Cold War in the Peace Garden State

Cover Photo: Atoms for Peace - The Atomic Energy Commission used a bus to travel the nation, explaining to citizens that atomic energy could be harnessed and put to peaceful use. The bus traveled through North Dakota in 1958. Courtesy of the State Historical Society of North Dakota.

By David Mills

Advertisement

“North Dakota is presumed to have four possible targets which the enemy may strike. They are the Air Force Bases at Minot and Grand Forks, Hector Airport at Fargo, and the State Capitol in Bismarck,” warned the 1960 North Dakota Civil Defense Plan entitled How You Will Survive. The small pamphlet suggested, “In the rural parts of North Dakota, farmers and residents of smaller communities have built root cellars to store foodstuff and as shelter from tornadoes. Whether constructed of concrete or sod, these root cellars are excellent protection against heavy radioactivity.”

The circumstances that required North Dakotans to consider their root cellars as safe havens against radioactivity resulted from the tension between the United States and the Soviet Union after the Second World War, which history remembers as the Cold War. This anxiety between the two superpowers resulted from the inability of the two allies to reconcile their postwar political objectives. The Soviets installed Communist governments in the countries they occupied, as the British and Americans set up democracies in their occupied zones. The atomic bomb also amplified the distrust between the two nations. The United States held a monopoly on the atomic bomb, at least until 1949. In the interim, Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin feared the United States would demand concessions from him through nuclear blackmail. Having just fought a world war that had depleted each nation’s population and treasure, the Americans and Soviets tried to fashion a postwar world that would make them safer. Security for one nation came at the cost of security for the other, creating a cycle of distrust and tension.

The Cold War at the state level was a reflection of national priorities, where the federal government developed programs and pushed them to the state level for implementation. North Dakota participated in initiatives to encourage patriotism among the populace, to fight subversion through anticommunist measures, to employ significant civil defense measures, and to provide acreage for military bases and weapons systems. Citizens in North Dakota embraced many of these initiatives and resisted communism with determination.

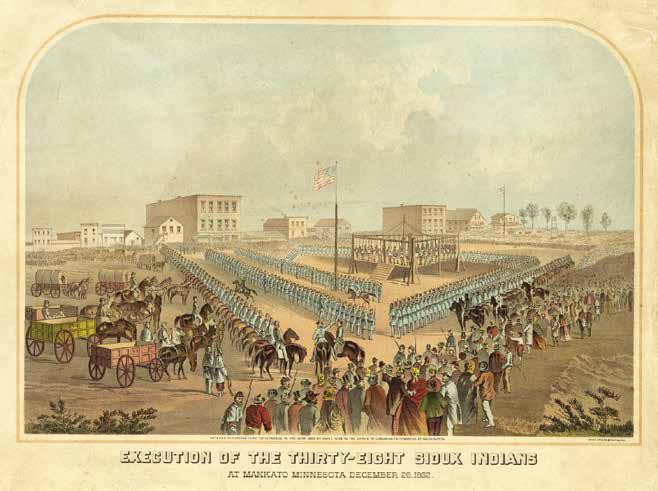

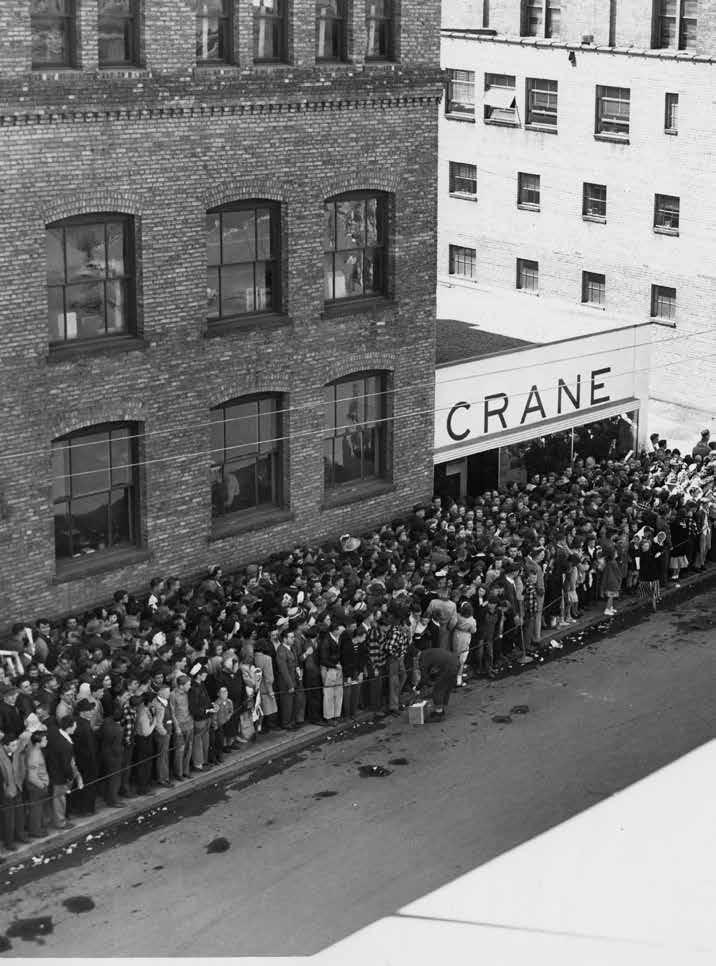

One of the first plans to advance patriotism among American citizens involved a train traveling through every major city in each state, transporting the nation’s most precious documents in 1947 and 1948. The “Freedom Train,” as it was called, carried the United States Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, the Gettysburg Address, and more than one hundred other treasured artifacts. The train left Philadelphia in September 1947, traversed the countryside, and entered North Dakota in April 1948. The train made stops in Bismarck, Minot, Jamestown, Fargo, and Grand Forks, where crowds of citizens eagerly waited in line for hours to view the documents. Residents in Minot broke the “West of the Mississippi” attendance record previously set in Rapid City, South Dakota. Just two days later, Fargo residents beat the Minot record by eighteen visitors. The important point is not that these North Dakota towns had more visitors than cities such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, or Seattle; far more people turned out to see the train in those urban areas, but many could not make it through the display. North Dakotans understood that, while one citizen viewed the display inside the train, others still waited in line, so people needed to get through the exhibit quickly. The record number of people viewing exhibits inside the train was really recognition of good manners.

While the federal government developed plans to enhance patriotism, programs aimed at Communists and subversives moved to the state level for implementation. President Harry S. Truman initiated a loyalty program in 1947, in which millions of Americans eventually signed oaths attesting to their support of the America government and submitted to background investigations. Several congressional investigation committees also emerged, the most famous of which was the House Un-American Activities Committee or HUAC that interviewed thousands of witnesses throughout the Cold War, hoping to expose Communists in American society. Congress also passed a number of laws aimed at suppressing subversive activity, the most effective of which was the Smith Act, passed in 1940, that made it illegal to belong to any organization that advocated the overthrow of the American government and required all immigrant adults to register with the federal government. Nearly every state in the union adopted some or all of these programs and implemented them at the state and local level, as legislatures often had difficulty avoiding these ideas once proposed. The new laws were often a disaster for the civil liberties of citizens, as committees of men and women with the best of intentions often abused the legal system and ruined reputations. North Dakotans never adopted a single law aimed at exposing Communists that infringed on the rights of its own citizens. No statewide loyalty oath, investigative committees, or Communist registration laws ever emerged, much to the credit of the people who lived there. A city council person in Fargo suggested a loyalty oath for the 300 city workers there in 1955, but the rest of the council voted it down, stating that the people of Fargo were already loyal citizens.

Few North Dakotans seemed to fear a Communist insurrection within the state, but many reasons existed to fear a Soviet attack. When the Communists invaded South Korea in 1950, Americans could not help but compare this surprise attack with that of the Japanese in 1941, and reasoned that America might be next. The Soviets had at least 450 bombers and more than 3,000 troop transport aircraft stationed at new airbases in Murmansk and eastern Siberia, poised to attack the United States. American military planners estimated that the Soviets could launch an attack over the Pacific Ocean and strike the West Coast, or fly over the North Pole, striking the northern portion of the United States. These planes could drop nuclear bombs or paratroopers, depending upon their mission. The distances covered were so vast, however, that pilots were probably flying a one-way mission. They might have refueled prior to hitting their North American targets, but would not have the fuel to return home or to meet a refueling aircraft. Other theories suggested that Soviet pilots might try to fly to Mexico, spending the remainder of the war as prisoners, or they might bail out over the ocean to a waiting submarine.

Other events provided a constant reminder of American vulnerability to attack, as atomic scientists and popular culture continuously warned citizens of the horrors of nuclear war. The scientists felt that they alone understood the terrible potential of this new technology, and sought to educate the public and political leaders. To get their message heard, they consciously adopted a policy of horror and annihilation when discussing the bomb. Anything else, they argued, met with yawns. Thus, scientists largely manufactured the scare over nuclear weapons as a means to create opposition to their use. Movies depicting nuclear accidents or atomic war scenarios, such as On the Beach (1959), reminded citizens that they lived in a nuclear world. Citizens understood the dangers when the Soviets exploded their first nuclear bomb in 1949, a hydrogen bomb in 1953, and launched Sputnik in 1957, which ushered in the age of intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMS). Even more frightening, the United States and the Soviet Union nearly exchanged nuclear missiles during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962. The American people were in the middle of the potential firestorm, the likely casualties of such a contest. The front lines in an atomic war were American city streets.

Fargo Freedom Train – Record-breaking crowd waits in line to board the Freedom Train in Fargo, April 1948. Courtesy of the State Historical Society of North Dakota.

Fargo Freedom Train – Record-breaking crowd waits in line to board the Freedom Train in Fargo, April 1948. Courtesy of the State Historical Society of North Dakota.

Civil defense planners began working shortly after World War II, formulating contingency plans to protect American citizens at home in case of attack through the newly created Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA). The survival plan during the Cold War has gone by many designations such as “Run or Dig,” or more descriptively, “Run Like Hell” or “Duck and Cover.” These monikers describe the various phases national and regional planners used to ensure the survival of the American people. The “Run” appellation refers to the strategy of fleeing a city or dwelling prior to a Soviet attack where plenty of advanced warning seemed likely. The national government partially justified building the highway system through the argument that Americans needed well-constructed routes out of urban areas. “Dig” referred to the realization that citizens could never evacuate major cities fast enough to outrun a Soviet attack, especially once the missile age caught up with the Cold War in the late 1950s. The government encouraged people to find a fallout shelter within the city, or dig their own in their backyard.

Civil defense planners worked to educate the public on the terrors of nuclear war, and the fact that citizens could survive a war if they took necessary precautions. “Bert the Turtle” was a popular character in American films, instructing schoolchildren and adults ways in which they could protect themselves in event of nuclear war. The FCDA printed more than twenty million cartoon booklets with civil defense warnings, and more than fifty-five million wallet-sized cards with the same information. Newspapers and magazines carried articles showing citizens how to construct bomb shelters and stock them with the necessary provisions.

Appropriations were slow, as many officials and citizens doubted North Dakota was even a target for the Soviets. Most believed an attack would target strategic centers outside the state such as government buildings, military bases, or shipping and transportation centers. This indifference to Soviet attack plagued the state for years. The governor appointed Lieutenant Colonel Noel F. Tharalson, a soldier with more than 42 years of state and federal service as head of the state’s civil defense organization in 1955. Shortly after taking charge, Tharalson admitted that his position in the civil defense organization was the most frustrating job he had ever held. “Apathy within the state will have to be overcome before any real program can evolve,” he declared. “If you talk to North Dakotans about the possibility of bombing raids, they’ll laugh and turn their backs. They just won’t believe that an enemy bomber would bother with the wide open spaces around the state.”

Tharalson and others concerned with nuclear war worked tirelessly to prepare North Dakota for the unthinkable. Though people may have feared nuclear war, they did little to prepare for it. Each county had an organized civil defense plan by 1960 that included basic facts about atomic explosions, likely target areas, radioactive fallout, and steps to survive such an ordeal. The counties containing larger cities even published locations of fallout shelters that were available throughout the area. The state also produced a comprehensive plan to assist residents in case of nuclear attack, published in a booklet entitled, How You Will Survive. The booklet included information on using root cellars and basements as short-term fallout shelters, and ways to decontaminate people, animals, and vehicles after an attack. The booklet also included information on evacuation procedures and encouraged residents to leave likely target areas such as Bismarck, Fargo, and the area around the air force bases.

While the federal government tried to interest people in preparing for nuclear war, the air force directed a civilian organization, known as the Ground Observer Corps (GOC), charged with watching the skies and reporting any aircraft to headquarters, called a filter center. Air Force General Ennis C. Whitehead reconstituted the GOC in February 1950, which had served a similar role in World War II. Early estimates showed the organization required 160,000 volunteers to operate the 8,000 observation sites located throughout the northern portion of America. During the existence of the GOC between 1950 and 1959, some 800,000 observers stood watch at 16,000 observation posts. The organization was so popular with citizens that by 1955, every state in the nation operated a GOC program. Observers occupied old buildings, rooftops, or observation towers and scanned the sky for low flying aircraft, twenty-four hours per day, each day of the year.

Bismarck Shelters - Officials in North Dakota began marking Fallout Shelters. Coincidently, this photo was taken October 19, 1962, three days before President Kennedy’s announcement. Courtesy of the State Historical Society of North Dakota

The GOC in North Dakota was especially important, as a Soviet bomber fleet could pass through the state on its way to other targets. It was a matter of pride for many communities to build an observation post out of donated funds, labor, and materials, and then operate the observation post with volunteers. New Hradec, North Dakota, a town of thirty-five residents, accomplished the impossible by establishing an observation post that required one hundred volunteers. Residents recruited volunteers from outlying areas, and swelled the ranks of observers 125. Stanton, North Dakota, used a more creative method to meet its personnel requirements. Mrs. Rueben Sailor, head of the GOC in the town, assigned observation duties to a different volunteer family each day.

Volunteers were continuously in short supply, because observation posts and the filter centers required so many people to meet commitments. Radio broadcasts helped to recruit volunteers, as did ice cream socials held at the filter centers and observation posts. Minot had a more creative way to recruit volunteers. It staged a “bombing raid” when a local pilot dropped balloons over the city with requests for help. Each balloon carried a free ticket to see Invasion USA (1952), a popular movie viewed throughout the country that illustrated what might happen if Soviet bombers struck an American city. Nationally, newspapers and magazines also helped in the recruitment effort, but North Dakota publications brought the issue closer to home. The Golden Valley News portrayed a drawing of a Soviet soldier conducting an orchestra with musical notes floating by. The caption read, “Do the Russian leaders really want peace or to lull us into a sense of false security?” The Minot Daily News carried an advertisement that read, “WARNING: Russian War Planes in a Single Raid Could Attack All of the Most Critical U.S. Targets Leaving Millions Wounded or Dead.” Each notice also contained several paragraphs proclaiming that the Soviets possessed a considerable number of bombers and nuclear weapons that could wreak havoc upon the American population. The United States military was on alert and working hard, but the nation needed GOC volunteers.

Not everyone could serve in uniform during the Cold War, but the opportunity to serve in the GOC gave many citizens a sense of pride in serving their country. Radar improvements gradually reduced the reliance upon civilian volunteers by 1958 and eliminated the requirement for twenty-four-hour alert. Federal authorities disbanded the GOC by early 1959, while numerous closure ceremonies throughout the state marked the end of the proud tradition of the GOC in North Dakota.

Some citizens worried about the possibility of nuclear war, but the Cold War brought tremendous economic opportunities to the state. Federal assistance had generously helped the state during the Great Depression, and some believed it could do so again. Senator Milton Young relentlessly pursued federal dollars and was quick to realize the implications the Cold War could hold for his state. The Bismarck Capital revealed in 1951 that Senator Young had orchestrated a survey of existing airport facilities, passing the information to the air force in hopes of bringing a military base to North Dakota. When air force officials responded with interest, it sparked a controversy within the state as communities maneuvered to locate a base in their vicinity. Several cities, including Bismarck, Grand Forks, Jamestown, Minot, Williston, and Wahpeton, contacted their political officials seeking information, while Fargo’s mayor traveled to Washington to discuss plans with military leaders.

Bismarck BOMARC - Air Force BOMARC missile displayed in downtown Bismarck, North Dakota, as part of the “Crazy Days” shopping Initiative in July 1962. Courtesy of the State Historical Society of North Dakota.

Not much happened until November 1953, when the air force determined that its military requirements included an increase in the number of air force wings, requiring the construction of new air bases, the reactivation of old ones, and the expansion of existing facilities. Air force officials notified North Dakota political leaders on February 25, 1954, that they intended to establish two air force bases within the state. Initially, the military identified sites in Fargo and Bismarck as the most likely locations for the future bases because of the existing facilities there, contingent upon satisfactory agreements with the local communities.

The competition to attract military bases continued. When local officials heard that the air force was looking to locate two bases within the state, officials in Bismarck, Jamestown, Washburn, Minot, Devils Lake, Fargo, Grand Forks, and Valley City all asked their congressional representatives to help them petition the air force and secure a base near their community. Most of these cities even sent delegations to Washington to press their cases. When officials in Minot asked Senator Young for his assistance in securing an air base for their city, Young told the representatives that the air force was not considering Minot as a possible location and reiterated his stance of strict neutrality in the site selection. Rumors also persisted that the officials were looking for a site to locate the new air force academy. A number of cities, including Mandan, Minot, Grand Forks, Jamestown, and Devils Lake all sent letters to North Dakota political leaders and to the Department of the Air Force, expressing their desire to host the academy, and listed the numerous attributes their locations might have to offer. Communities continued their battle to attract air bases, even though Fargo and Bismarck appeared to have the best chance of securing the bases by expanding their existing facilities. Tension among other cities intensified when Fargo and Bismarck announced that they were having difficulty acquiring the necessary land. Other communities, specifically Grand Forks and Minot, had no such problems, and let officials know their position.

Air force officials announced on June 11, 1954, that they had an obligation to taxpayers to construct the bases at the lowest possible cost. When two or more locations existed within the area of requirement, other factors become important, such as the availability of land at little or no cost. Five days later, air force officials announced that the new bases would be located in Minot and Grand Forks, not Fargo and Bismarck as initially announced. Citizens throughout the state demanded clarification in the disappointment and confusion that followed the announcement. Officials acknowledged that they had originally considered the existing facilities at Fargo and Bismarck, but admitted these sites were only marginally acceptable, as they presented little opportunity for expansion. Additionally, military planners explained that these locations were too far south to engage enemy aircraft effectively, and needed locations farther north. Air force officials maintained that donating land had helped in selecting Minot and Grand Forks, but it was not the overriding factor.

The air force bases with their jet fighters reflected the changing technology of the era, but the missile age brought a new dimension to the Cold War. When the Soviets launched Sputnik, the first satellite to orbit the globe in 1957, it terrified American government and military officials. A missile that could launch a satellite into space could also carry a nuclear warhead to the United States. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev’s claim that the Soviet Union turned out nuclear weapons “like sausages” did little to alleviate these fears. What American planners did not know was that the Soviet Union had only six long-range nuclear missiles even as late as 1959. As Khrushchev’s son Sergei observed, “We threatened with missiles we didn’t have.” Khrushchev’s bluster led President John F. Kennedy to rally against the “missile gap” that he believed had developed under the Eisenhower administration. Only after taking office did Kennedy learn the truth, the United States was far ahead of the Soviets in long-range missile construction.

Notwithstanding the lack of missiles on the part of the Soviets, the United States proceeded to deploy hundreds of nuclear missiles throughout the Great Plains. North Dakota, often jokingly referred to as the third most powerful nuclear state in the world, became home to 300 missile silos, as Grand Forks and Minot Air Force Bases controlled 150 silos each. The 455th Strategic Missile Wing was operational by April 1964 in Minot, and in Grand Forks, the 321st Strategic Missile Wing was operational by December 1966.

Simply acquiring land for the missile sites was a tremendous undertaking. Officials from the Corps of Engineers and the Department of the Air Force published advertisements in regional newspapers announcing their intent to buy land for the missile sites, and held public meetings to answer questions throughout the state. Once the officials had acquired all of the necessary sites, they began construction. There was no guarantee, however, that the military would build the missile silos near the bases in North Dakota. Senator Milton Young, as one might expect, played a key role in getting the missiles assigned to his state. In fact, in his adopted hometown of LaMoure, North Dakota, a Minuteman missile shell still stands, which the senator dedicated in 1972 for the twenty-fifth anniversary of his Senate election.

The United States Air Force was not the only military organization keeping the skies clear of enemy bombers. The North Dakota Air National Guard (NDANG) formed in January 1947, shared this mission. Air force officials were quite skeptical about forming an air guard unit in a sparsely populated state, but the unit grew to appropriate size after officials organized the unit as the 178th Fighter Squadron, with facilities at Hector Field in Fargo. The decision to form the unit in Fargo was not without debate, however, as Grand Forks, Jamestown, Minot, Devils Lake, and Wahpeton all requested the fighter squadron. Jamestown, adamant in its desire for the fighter squadron, refused to make commitments to any other national guard unit until officials decided where the flight unit would go. Air force officials settled the debate, insisting on Fargo because of the excellent facilities there.

The unit received its first “real world” mission within a few months of activation. The winter of 1948-49 was particularly hazardous, when North Dakota suffered one of the worst blizzards in history. Snow blocked the roads, isolating farms and towns, and Governor Fred Aandahl activated the NDANG to provide relief. The effort, known as Operation Haylift, primarily involved dropping hay bales to isolated livestock and providing food and supplies to stranded farms. The NDANG used C-47 transport aircraft to deliver more than 8,000 hay bales to suffering livestock over a thirty-one-day period. The situation was so desperate that the North Dakota governor asked the neighboring states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Iowa to bring their C-47s to North Dakota and help with the effort. The Canadian Air Force even helped in the effort. An “airlift” of volunteer civilian aircraft began dropping supplies to stranded towns throughout the west and northern plains, or parachuting more delicate supplies such as units of blood plasma where needed. Twenty small airplanes outfitted with skis enabled pilots to land and evacuate ill citizens. At other times, the pilots flew reconnaissance missions, to find livestock or to drop supplies to needy ranchers. Several pilots crashed and died for a variety of reasons, generally due to poor visibility. Major Donald C. Jones, the commanding officer of the NDANG, died when his F-51 fighter crashed while seeking out those in distress.

This event played out in North Dakota at the same time the United States and other allied nations used C-47s and other aircraft to bring food and supplies into Berlin in the international crisis known as the Berlin Airlift, when Stalin closed all routes into the city. Each volunteer pilot on the northern plains could identify with the pilots providing the lifeline to the residents of Berlin, and the comparisons between the Berlin Airlift and the North Dakota Haylift were unavoidable. As in Europe, flight crews came from different countries, with different type aircraft, but with the same mission.

The NDANG received an air defense role in 1954, and turned in their F-51s because of this new mission, receiving instead T-33 jet trainers, then F-94 fighter interceptors. The NDANG was responsible for defending American skies from Duluth, Minnesota, to Great Falls, Montana, and continued to receive the latest jet aircraft throughout the Cold War. Most remember this unit by its nickname, the “Happy Hooligans.” It came about after Lieutenant Colonel (later Brigadier General) Duane S. “Pappy” Larson took command of the 178th in the 1960s. Members of the unit joined his nickname “Pappy” with a popular comic book character “Happy Easter,” whose own band of men were called the Hooligans. The result became the “Happy Hooligans,” which denotes the unit to this day.

As technology changed the face of warfare, the missile age presented a number of problems for United States forces. While having missiles for offensive means reassured military planners, the threat of numerous incoming nuclear missiles accounted for the many sleepless nights for citizens around the country. The Soviet Union and China were closed societies, with little opportunity for American planners to ascertain the exact numbers of missiles each country held, but estimates suggested a Communist attack could devastate the United States. The answer was the Stanley R. Mickelsen Safeguard Complex that housed an antiballistic missile system to knock Soviet or Chinese missiles from the skies. Congress authorized the construction of such a site in northern North Dakota that used radar to detect incoming missiles. Once identified, the system launched its own nuclear missiles against the inbound ones.

Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, a period of relaxation of Cold War hostility took hold in both the United States and the Soviet Union, until the Cold War ended with the restructuring of the Soviet Union in 1989. Looking back, the Cold War had two major implications for North Dakota; it provided a strategic location for a number of military facilities and demonstrated the resolve of citizens to protect their state and nation in their own way. Citizens there embraced the programs that fostered patriotic feelings, but avoided ones that promoted trouble. Military bases provided an economic stimulus for the state, allowing citizens to abandon their dependency on eastern interests and guard their own interests. Though the Cold War demanded great sacrifice, North Dakotans benefitted from the experience.

Dave Mills grew up in Maryland, received his bachelor’s degree from Frostburg State University, then served in the U.S. Army for fourteen years. He settled down in Minnesota, received his Ph.D. from North Dakota State University, and currently teaches at Minnesota West Community College. He is working with a publisher to bring out his book, Cold War in a Cold Land: Fighting Communism on the Northern Great Plains, which explores the Cold War in North Dakota, South Dakota, and Montana.