the SENSE OF PLACE issue

In the introduction to their book, Senses of Place, anthropologists Keith Basso and Steven Feld write that sense of place is “the experiential and expressive ways places are known, imagined, yearned for, held, remembered, voiced, lived, contested and struggled over.”

by Mark

Holmanby Brian

StriefelGiven the rancorous tone of our world, the “contested and struggled over” part of this definition stands out when I reflect on what this place I've called home for over forty years means to me. Distrust, fear, and anger punctuate too many conversations I’ve had with people reflecting on the state of our state. The prayerful part of me lingers on the words “imagined, yearned for, held” because they carry a prophetic hope that this place of extremes in temperatures and temperaments could find a greater purpose and more inclusive vision. As a society, we would do well to learn how to remember with humility and honesty in order to move forward with clarity. Nostalgia is the flimsiest of foundations on which to build a better world.

by

by Mark Vinz

58 AR-15 by David Solheim

59 IF THE WIND by Aimee Geurts

There is still so much I don't know about this place, especially the history of the first peoples whose languages remember and voice ideas that have sustained communities for thousands of years. It's only possible to get a full sense of this place with this knowledge. Humanities North Dakota plays a small part in educating about the history, languages, culture, and issues of the tribes who dwell here. We will continue to partner with Indigenous-led nonprofits, colleges, and educators to do more.

I hope you will use the tools of lifelong learning in the humanities to explore what has been and what is possible.

Much heart,

Brenna Gerhardt Executive Director & Fellow Lifelong Learner

ABOUT THE

Artist Shelley Larson, a long-time Bismarck resident, has always had a love of nature and conservation. She has enjoyed painting since she was a child and over her lifetime has won many awards for her work.

Her paintings feature colorful landscapes with complimentary colors, and she ultimately wants them to bring “happiness” and hope to those going through cancer treatment. “I want to share the joy from my heart with the use of bright colors to create serene landscapes.”

Shelley enjoys all art mediums, but watercolors are her favorite. Many of the pictures she has painted are from their ranch and cabin near Crooked Lake and McClusky, ND, where she shares the love of the outdoors with her husband, Craig. She hopes her paintings encourage endurance, strength, courage, and life. They are a symbol of “hope” on display at the Bismarck Cancer Center, which has been a trusted community resource, providing compassion and care for over two decades.

n the early morning hours of January 29, 1931, a mob broke into the small stone jail at Schafer, North Dakota, and seized Charles Bannon. The mob hanged Bannon from a nearby bridge. It was North Dakota’s last lynching.

Bannon, who was 22 years old, had spent only a few days in the Schafer jail prior to the break-in. He was moved from the larger and more secure jail in Williston on January 23, 1931, so he could be arraigned in Schafer on charges that he murdered the six members of the Haven family. His father, James Bannon, was also confined in the Schafer jail, awaiting arraignment as an accomplice to the murder.

The Haven family lived on a farm about a mile north of Schafer, a village east of Watford City. The family had five members: Albert, 50, Lulia, 39, Daniel, 18, Leland, 14, Charles, 2, and Mary, 2 months old. As of February 1930, the family had lived on their farm for more than ten years. They owned household goods including a piano and a

radio as well as “considerable livestock, feed and machinery.”

No member of the family was seen alive after February 9, 1930.

Bannon had worked as a hired hand for the Havens. He stayed on the Haven farm after the family disappeared, claiming that he had rented the place. He told neighbors that the family had decided to leave the area.

Bannon’s father James joined him at the farm in February 1930. Together, they worked the land and cared for the Haven family’s livestock through the spring, summer and fall of the year.

Neighbors became suspicious by October 1930, however, after Bannon started selling off Haven family property and crops. Bannon’s father then left the area, saying that he was going to try to find the Haven family.

James went to Oregon, where Bannon said the Haven family had gone. James wrote a letter on December 2, 1930, to Bannon from Oregon, in which he advised Bannon to watch his step and “do what is right.”

Full article with footnotes can be found at ndcourts.gov/about-us/history/north-dakotas-last-lynchingCharles Bannon

In December 1930, Bannon was jailed on grand larceny charges. In the course of the investigation that followed, authorities discovered that the Haven family had been murdered.

On December 12, 1930, Bannon gave a statement to a deputy sheriff in which he admitted involvement in killing the Haven family, but claimed a “stranger” acted as instigator.

The next day, in a lengthy confession to his attorney and his mother, Bannon admitted killing the Haven family in a violent fracas that followed Bannon’s accidental shooting of the eldest child, Daniel. Bannon suggested in this confession that he was forced to kill Leland, Lulia and Albert Haven because they tried to kill Bannon after he shot Daniel.

After Bannon confessed, authorities tracked down his father James in Oregon. James was accused of complicity in the murders and extradited back to North Dakota.

In a final confession that he wrote out himself in January 1931, Bannon again admitted killing the rest of the Haven family after accidentally shooting Daniel. In this confession, however, Bannon did not claim that he acted in self-defense when he killed

the other members of the family—instead he said he killed them because he was scared.

In his last two confessions, Bannon stressed that he acted alone in killing the Havens. Bannon tried to convince authorities that his parents, in particular his father James, knew nothing about the murders. Nonetheless, the authorities kept James in custody.

Bannon, his father James, Deputy Sheriff Peter Hallan, and Fred Maike, who was in jail on theft charges, were present in the Schafer jail on the night of January 28-29, 1931. A crowd of men in masks arrived at the jail sometime between 12:30 and 1:00 a.m. on January 29, looking for Bannon.

The sight of lights flickering through his windows woke Sheriff Syvert Thompson, who lived near the jail, and he went to the scene to investigate. The mob captured him and led him away from the jail.

Thompson and Hallan said that the crowd numbered at least 75 men in at least 15 cars.

The mob battered down the front door of the jail and overpowered Deputy Hallan. After he refused to tell them where the keys to Bannon’s cell were, the mob escorted Hallan out of the jail. Using the timbers they had used to break down the jail door, the mob began work battering down the cell door. Witnesses said the mob appeared disciplined and wellorganized, going about their work as if under strict orders.

Maike told investigators that the mob had so much trouble trying to break down the cell door that they almost gave up. After the mob broke the door down, Bannon surrendered and pleaded that his father not be harmed.

Members of the mob brought in a rope and placed a noose around Bannon’s neck. They dragged him from the jail. The mob put Deputy Hallan in a cell with Bannon’s father and Maike, who had been left alone.

Outside, Sheriff Thompson heard the men demanding that Bannon “tell the truth” or face hanging. Bannon told them that he had told the truth.

After taking Bannon, the mob shoved Sheriff Thompson into the jail cell with Hallan, barricading the door. Thompson and Hallan were not able to free themselves until after the mob dispersed.

The lynch mob first took Bannon to the nearby Haven farm, planning apparently to hang him on the spot the family died. The caretaker of the farm ordered the crowd off the property, threatening to shoot if the mob did not leave.

The mob took Bannon to the bridge over Cherry Creek, a half-mile east of the jail. The new high bridge was built in the summer of 1930. Bannon was pushed over the side of the bridge with the noose still around his neck. Authorities said the lynchers use a half-inch rope, with one end tied to a bridge railing and the other tied in a standard hangman’s knot by someone with “expert knowledge.”

Bannon was buried in Riverside Cemetery in Williston.

Governor George Shafer called the lynching “shameful” and ordered an immediate investigation.

Attorney General James Morris (later a Supreme

Court justice), Adjutant General G.A. Fraser, and Gunder Osjord, head of the Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, were sent to the scene. Morris interviewed witnesses and examined evidence from the lynching.

The rope used was of special interest to Morris. He said that the noose had been tied by “someone with expert knowledge.” He also pointed out that the rope had a thread of red hemp running through it, which could be a manufacturer’s mark. Morris concluded that “the lynching was well-planned in advance” and that “three or more leaders . . . kept the mob organized and under control.”

Morris said that the governor had ordered the investigators to “go to the bottom” of the lynching. The state investigation, however, was not fruitful: no member of the lynch mob was ever arrested and Morris concluded after less than a week of investigation that it would be impossible to identify any member of the lynch mob.

The Federal Council of Churches investigated the lynching in the spring of 1931. The Council found that even though feelings ran high against Bannon in the community, authorities “took the prisoner back to the scene of the crime, put him in a makeshift jail, and thus gave every chance to a mob.” Frank Vrzralek surveyed North Dakota lynchings in 1990 and noted that one similarity among several lynching cases was

“grossly inadequate” protection for the prisoners. On learning of the Council’s work, Morris wrote Rev. Howard Anderson of Williston, who conducted the investigation. Morris wanted to know if Anderson had obtained any information that might help the authorities; Anderson responded that the Council had focused on the circumstances leading up to the lynching. He stated:

It did not come within the scope of my investigation to try to discover who the members of the lynching mob were. That, it seems to me, is the duty of the sheriff and state’s attorney of McKenzie County.

Whether or not these duly constituted officials have performed their duty in this, or to the full in their holding of Bannon, is something you know as well, or better, than I.

After escaping the lynch mob, Bannon’s father, James, was tried for the Haven murders. Concerned about James’ safety, attorney W.A. Jacobsen asked Morris what steps would be taken “to see that this man is kept alive during the time he is in the county.” The trial was moved to Divide County, where James was convicted and sentenced to life in prison.

Jacobsen and E.J. McIlraith, James’ attorneys, argued on appeal that James was not involved in the murders and that the evidence did not support the charges against him. The attorneys pointed out that the “witnesses for the State were so anxious to convict the defendant . . . that they made their testimony to suit the situation, and made the testimony so positive as to convict him, if there was any possibility of doing so.” The North Dakota Supreme Court, however, upheld James’ conviction. James was admitted to the state penitentiary on June 29, 1931. As he left the jail in Minot, he told the guard “you are seeing an innocent man go to prison.” When James sought parole in 1939, Attorney General Alvin Strutz (later a Supreme Court justice) was sent to McKenzie County to

investigate whether the community believed James was innocent. In a report dated May 18, 1939, Strutz concluded that the belief in the community was that James was guilty at the very least of helping cover up the murders. James was released by the state Pardon Board on Sept. 12, 1950. He was 76 years old.

In the wake of the Bannon lynching, State Sen. James P. Cain of Stark County introduced a bill to revive capital punishment for murder in North Dakota. Supporters of the bill argued that the lynching would not have occurred if Bannon could have faced a death sentence. The North Dakota Senate rejected the bill on a 28 to 21 vote.

At the time of the Haven murders, Schafer was the county seat of McKenzie County. Today, all that remains of Schafer is a cluster of buildings, including an abandoned school and the Schafer jail building. A sign stands next to the jail, outlining the history of the jail and the events of January 29, 1931, when Charles Bannon “was taken by an angry mob and lynched.”

Strutz concluded his 1939 report on the lynching with these thoughts:

There is no doubt in my mind but that some prosecution should have been commenced for the lynching of Charles Bannon. No conviction could have been had in McKenzie County, it is true, but the State might have secured a change of venue and, even though no conviction could have been had it seems to me that such a crime should not be allowed to have been committed without at least an attempt to punish those who perpetrated the same. It may not have been a popular thing to do in McKenzie County but on the other hand it would have been the right thing.

Schafer is approximately five miles east of Watford City on North Dakota Highway 23. l

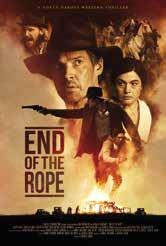

HND: Why this story for a film?

Daniel: End of the Rope is a true story based on the book End of the Rope written by Dennis Edward Johnson. It’s a fascinating true story that asks some interesting moral questions and provides a powerful picture of life in northwest North Dakota in 1931.

HND: Who was the first person you told your idea to?

Daniel: Dennis Johnson and I initially discussed the movie.

HND: Describe the film in three words.

Daniel: Western crime thriller

HND: Most exciting moment from filming.

Daniel: We filmed at the Fairview bridge and tunnel. A beautiful and iconic North Dakota location.

Daniel has an M.F.A. in Acting from Columbia University. He moved to North Dakota in 2015 and began working as a writer and producer. He lives with his wife and five children in Bismarck, where he currently serves as Chair of Dramatic Arts at the University of Mary.

When a family mysteriously disappears from the town of Schafer, North Dakota, suspicion lands on a sociopathic farm-hand, and the entire community rises up to take justice into its own hands. The film is based on the true story of the infamous Charles Bannon case of 1931.

HND: Biggest obstacle while filming.

Daniel: It was a massive logistical undertaking. Hundreds of extras. Dozens of vintage cars. We built the set of an entire town. We filmed in a warehouse converted into a sound studio.

HND: What do you hope people say after they see the film?

Daniel: Powerful and beautiful filmmaking.

HND: Is there anything else you would like to add?

Daniel: Tickets are available to Red Carpet premieres at www.endoftheropefilm.com

Iam closing my eyes because the lights have come back on. These blinding glints across the field of my vision, and the dryness in my mouth, in my throat, remind me of being on the snow-covered prairie delivering mail.

“Dad, they’re not turning the lights out,” my son Cliff says to me. “We talked to them. The lights are always on.”

Those winters delivering mail, the prairie was like a hospital room with no walls, white and bright. I feel again the way I felt when I shoveled my black Ford truck out of the snow, again and again, to make it through the fifty-two miles of my dirt-road route outside Napoleon. Shovel after shovel. My shovel might as well have been a spoon. My heart was as strong as two hearts, my muscles bone-tired. And the wind ripped the moisture from my eyes. But sometimes I would feel a presence alongside me, looking after me.

After enough shoveling, I felt warm. Once I cleared enough snow, I would get in the truck and drive toward the horizon, awash in brightness, the sky indistinguishable from the land. And I felt sure that if I kept driving, I would get right to Heaven with my mail. This was a long time ago.

“They said they’re not turning the lights out, Dad, did you hear?” That’s Janie. She sounds a lot like her mother. And looks like her, too.

My son is here, and my daughter is here. They do not understand me, my children, but their not-understanding does not annoy me the way it usually would because they seem to be far away. On the other side of something. Janie rubs my arms. My arms feel far away, but she makes them

come back when she rubs them. She makes my arms out of nothing. She knows how to do these things that women can do: make something out of nothing. The kinds of things my wife could do. Maggie. I came back from Iwo Jima, uninjured, though minus two tonsils, and I asked Maggie to marry me. I had never had a girlfriend. I had never gone anywhere with Maggie alone. But we got married, and it turned out that I loved her and that she made excellent kuchen. When we were poor those first years, when Cliff was a baby yet, she had a way of making coffee with almost no grounds, coffee that still tasted strong. She was as good as any woman. Like the sky and the earth in Napoleon. Good and real and there.

“I’m thirsty,” I say. My eyes are closed and my mouth is closed. There is something against my lips.

“Open your mouth a little. They took the tubes out so you could drink.”

“I don’t want the tubes,” I say.

“We know, Dad,” Janie says. “They took them out.”

She is a good daughter. Sometimes, I would take her with me on my route, and the farmers waiting by their mailboxes leaned into the truck, and said, “Little girl, do you want to come home with me?” She always shook her head no. She never wanted to go home with them. Then she grew up and moved away, but she’s back now. I’m sorry she doesn’t have a husband because she is soft and patient and would make a good wife.

“How long do I have?” I ask now. Or I might have asked earlier.

“You’re going to make it to Easter, but not Memorial Day,” the doctor says.

“Who cares about Memorial Day?” I say. One day isn’t enough to remember anything. One needs years to do the work of remembering.

I don’t know if Memorial Day is soon or a long time from now. I don’t even know if this is winter or summer. It could be either, or both, for sometimes I feel very cold and sometimes I feel very hot. I was cold before but now I am hot. My blood is stinging.

be in line with the earth, I was in line with them both, and I felt lifted, like the sun was pulling me up more than the earth was pulling me down. I did not mind the soreness or the heat or the thirst.

“My throat,” I say.

“Do you want some ice cream, Dad?” Janie asks.

The lights go out again, and my own blood is burning; there is a terrible sharpness in my gut. It amazes me what the body can do to itself. The pain feels like it must be coming from outside, but it is coming from inside.

“Look, he’s in pain. Look how his arms go up,” Janie says.

“They all do that.” My eyes are closed, and I don’t know this voice, but I know it is a nurse-voice.

Cliff is asking the nurse if I have had my morphine shot, and the nurse is saying she will check.

They don’t always do things right. My wife was at this hospital twenty years ago. I know she would have lived longer if Cliff had been here, telling them what to do, but no one thought it was a big problem, what she had wrong with her. Then she died because someone made a mistake, and no one was with her.

I could have bled to death, and what was there to stop it?

“He got his morning shot.” The nurse is back.

“He’s supposed to get an evening shot, too,” Cliff says.

“I don’t know anything about that,” the nurse says.

“I have to go to the bathroom,” I say.

Cliff helps me to the bathroom. I am shocked by my reflection in the mirror. If possible, I look worse than I feel. Whiter than white, in a backless papery gown, and so hunched over. I don’t like it when people don’t stand up straight. It seems disrespectful. To something.

“I can’t straighten up,” I say.

“That’s okay,” Cliff says.

“I’m still taller than you!” I say.

He is holding me, but it is a free fall to the toilet seat. Things still work weakly but getting up again takes the cooperation of armies.

The walk back to the bed is worse than the walk from the bed; the steps I take yank on my gut. I can feel this thing eating me from the inside. Someone needs to reach in with tongs and take out all my organs and all my bones.

me. I was going on seventy then. With my two pensions, I’d stopped having to farm to get by, so it was true that there were no more cows, no more chickens, not even wheat, just long grass that bent and chuffed with the wind, and the government gave me a little money not to plant the land. I donated the money because I didn’t think it was right to get money for not working. But what was here was not nothing.

“Look around!” I said. I showed my grandson where there’d once been a sod hut. I showed him a wooden fence slouching in the grass, the strapping power lines. It was early in my marriage when the power lines came this far into the country, and, the farmhouses lit up, all our wives discovered how dirty everything was. They cleaned and cleaned. After that, we men had to take off our shoes on the doorstep whenever we came inside, even though the dust still rose from our clothes. Even though without shoes, we felt vulnerable and small and like children.

Summers, the mail route was easier, but I had the farm to think about. And it hurt my body, the work I did: heaving the rocks out of the way of my red tractor, bending, standing, seldom taking a break even to drink. I would look up at noon and see the sun right above me. When it beat straight down on me, when I was most unprotected, I felt most protected. I was sore and hot, my mouth was dry, and the sun was smack in the center of the sky, right above my patch of earth. The sun seemed to

My two children are getting along. Cliff is glad that Janie is here, and Janie is glad that Cliff is here. People think sometimes that I am not paying attention, but I have always paid attention. Cliff and Janie don’t always get along, and I don’t blame either of them. Of course Cliff would resent the sister he sees as flighty, a wanderer; Janie would resent Cliff for being dogged and dutiful always. I have resented Cliff sometimes because of how much he reminds me of me.

The pain whites out my thoughts. It is worse than when they took my tonsils out in the tent in Iwo Jima. I wouldn’t have said anything about my tonsils swelling, if the pain hadn’t been so bad, because they didn’t have much equipment. But the pain was bad, so I told them, and they reached into my throat with burning-hot tongs. Snip, snip. I bled and bled.

Then Janie is serving me ice cream: the spoon clicks against my teeth. I feel better. People eat ice cream, and they feel better. I get tired; I nod off; I wake when I get another shot. The hurt of the shot has become the same as relief.

I laugh a little bit.

“He’s laughing,” Janie says. “He doesn’t know what’s going on.”

I know. I know who’s here, and who isn’t. I know Cliff’s son isn’t here. I know Josh let him down. He is not like Cliff, never was.

“What?” The child didn’t understand what I was trying to show him. But all around us was so much: a sprawl of land below a deep cup of sky! Ragged clouds blowing fast. The land in Napoleon felt more like land than the land in other places, the sky more like sky. More there. Maybe because I could see so much of both.

“Your dad is from here. I’m from here,” I said to my grandson. I tried to make him understand. “My grandfather came here with a spoon in his boot.”

There’s nothing here, I remember my grandson saying when Cliff visited me on the farm. This was when his son was a child, not long after Maggie died. I was lonely, so I was glad Cliff brought him: Josh, a little boy with his hair cut like mine when I was in the Navy.

I stood outside with the child and tried to think what I could show him because what he said pained

Imagine! I said. I imagined: he comes as a young man from Odessa, drives his ox and cart who knows how far, gets here. He’s dusty. He’s covered in dust. It must have felt like a mail route that lasted for states and states. It must have been that hard. He brings his spoon and he brings his wife, and his wife brings a rock to weigh down the sauerkraut pot because in Russia rocks were precious. All to get to land that is nothing like Russia, where there are no grapes growing. Where there are so many rocks!

But he built a sod hut, and the earth kept him safe inside itself. It was a good hut: even when cows walked on its roof, which they did, more than once, it did not break. And now that house that

The sun seemed to be in line with the earth, I was in line with them both, and I felt lifted like the sun was pulling me up more than the earth was pulling me down.

even the weight of a bull could not bow is no more, and you, child, are here, made out of something that is gone.

What I am saying is perfect and clear, and the child I am talking to looks at me like he understands everything I am telling him. I suddenly know that this is not happening, not what really happened. I know that because I have never spoken words that were perfect and clear, and no children have ever looked at me like they understand me.

And I am crying because I know I am not on the farm. I sold it not long after Cliff’s visit.

“He’s upset,” Janie says. “Don’t be upset, Dad.” I pipe down by the time the priest sits down and starts talking about his own mother dying in this same room, in the empty bed next to mine. He goes on and on.

“I’ll mail you a pamphlet,” he says, “on grief.”

“Not a good father,” I say.

“You are a good father,” Janie says.

“He’s not a good priest. The man who was just here,” I say. Or maybe he wasn’t just here. Maybe it was after my wife died that a priest visited me and talked all about himself and his own mother. Weeks later, a pamphlet came in the mail with instructions for mourning. It told me not to give away my wife’s things for at least a year. I had already given away all my wife’s things.

Then the room is full again, and the good priest, the one I like, with the hair with white spots like a deer’s, comes and gives me last rites. He wets my hands and my feet and my face with oil, blesses me, and I can feel warmth coming down like wet sunlight.

“There’s nothing to be afraid of,” the good priest says in his pious voice that sometimes squeaks. “You have excellent timing. It’s almost Easter, and every Easter renews the promise that resurrection awaits us all.”

“I don’t know about that,” I say, though, by the time the words escape my mouth, the priest is already gone. I do not know about the resurrection business. A bunch of women show up and see a stone that’s been rolled away from the mouth of the tomb. They go in: no body there. My first thought would have been thieves. Moving a stone out of the way seemed like something a man would have to do to get in. Not

a god, to get out. Couldn’t a god go right through the roof?

“Dad, you’re going to see Mom,” Janie says.

“I don’t know about that,” I say.

“It’s the morphine,” Cliff says. “He knows he will see Mom.”

I don’t know that I will see my wife. When I found out she had died, I felt something drain from me, and I realized that the sense of a comforting and righteous presence I’d had watching me for most of my life was not Jesus or God but my wife. I could feel her attention on me even when she was not there. And then, after she died, I could not feel her watching me anymore: all the snow I shoveled, I shoveled alone. Which made me stop believing in Heaven. If there is a Heaven, I think, I would be able to feel my wife still watching me from it.

Unless, of course, she is busy.

But I have kept going to church, because what else is there to do? What else is there for me? Catholicism is the key I have in my pocket. If Catholicism is the right key, I will be able to open the box, but it might be that I don’t have the right key. Or it might be that I will open up the mailbox, but the mailbox will be empty.

“I won’t have a letter,” I hear myself saying.

“Shhh, Dad. You’ll have a letter,” Cliff says.

I am outside. It is almost noon, and the sun is above us. Cliff is next to me, interlacing his hands behind his neck and looking up. He’s telling me to sell the farm.

“I’m not ready,” I tell him.

“Dad, just consider it while you’re lucky enough to have someone who wants to buy. Otherwise, this land will go back to the buffalo.”

“Don’t talk to me about the buffalo,” I say. It insults me to hear about the buffalo. My grandfather did not wrest this land from nature, I did not spend my whole life moving rocks from it, just so I could surrender it to the buffalo.

“Think about selling, before it’s worth nothing.”

How could it be worth nothing? The sky is such a strong blue that there could be another sky above it, the land so solid there could be another earth

beneath it.

“I’m not going to farm, Dad. Neither is he.” He motions with his chin to his son. Josh plays with the mailbox; the red metal flag squeaks up, squeaks down.

I don’t want my children or my grandson to have to work as hard as I worked. But I want them to want to keep the farm. It would be good for them. It would keep them from wanting foolish things, if they had the farm to come back to. But they go someplace farther when they decide to travel; they go to big cities or beaches. I have never much cared for cities, where buildings are like paperweights pressing down the land. And I was at war on the ocean, and that was enough ocean for me: oceans are full of blasting ships and smoke, dying and bobbing men. The land ringing my flat farm has always been a thousand-mile trench against the ocean. I have felt safe. And sometimes I think that if my children would keep the farm, they would be safe, too.

I sold the farm. I moved to Bismarck to be closer to Cliff. Good thing. His son left and never came back. Cliff was always too easy on him. I was not easy on my children and now, look: they are tending to me.

Sleep is like a dark pond, and I go into it, I come out of it, and I go into it, come out, and sometimes I feel like I am both in it and out of it. Then, I drop suddenly into a depth I had not expected: my whole self sinks under water, as if I have spoons in my boots and rocks in my pockets, and I am surprised to find that once you go deep enough, once it gets dark enough, it starts to get lighter again.

I have nearly made it to another surface: a top of the pond on the bottom of the pond. That’s it, I think. I found it. The light, all this time, has been right there, on the other side of the darkness.

I open my eyes with a start. “When did I die? Before midnight or after midnight?” I ask.

“Dad, you’re not dead,” Cliff is saying. He’s the only one here now, and I’m glad no one else heard me.

“I know I’m not dead,” I scoff. Of course, I know that.

“It’s before midnight. It’s eleven.”

“What would make me go off my rocker like that?” I do not want to go off my rocker. Or, if I go off my rocker, I would like to go back to the farm where I grew up and raised my own family. I would not like to spend my last hours alive thinking that I am dead. That seems a waste of time.

“You’re on some pretty strong meds. You have a drip now,” Cliff says.

They are talking about bringing me to Cliff’s house, but they cannot find a nurse. I know it is hard to find a home nurse in this city because there aren’t enough nurses for all the old people who are always dying. The old people come from the farms to be closer to children and hospitals. An army of old people, marching to cities to die.

“He’s not getting any treatment here. He can’t stay. We have to move him to a nursing home if we can’t find a home health care worker,” a nurse’s voice says.

“I want to stay where I am,” I say. I may say.

I’m on the farm yet. The sun, the sky, the grandson putting rocks in the mailbox, taking them out. I look around. I understand that it is desolate, but there is something in the desolation that is good. Life here isn’t easy, and it isn’t beautiful. But what is there to be proud of if you survive in ease and beauty? If I brag from time to time about my height or my strength or my smarts, it is because these are all things that I eked from this stony patch of earth. I look at those thin trees, the rows of trees planted to block the wind: they’ve got to do many times the work of ordinary trees, to hold down the land, to keep the dust from blowing, because there’s so much land and so much wind and so few of them. Their branches are always shaking as if, from the inside, they are trying to tear themselves apart, raise themselves up: long-dutiful trees, ready for their own assumptions. Those are the trees that deserve admiration.

The land in Napoleon felt more like land than the land in other places, the sky more like sky.

Cliff is shaving my face.

“You came back,” I say to my son.

“I never left,” he says.

It is not good for young children to watch old men die, but my own children are old children now, almost the age I was when I lost everything, my wife and my farm. It is good to watch old men die, at a certain age, because you have to learn how to die yourself. I have watched my brothers and sisters die and my parents die, and my greatest pain is that I did not see my wife die. I suppose it is my turn. There are so few ropes holding me here.

“Are you okay, Dad?” Cliff asks.

“It hurts,” I say. The razor stops.

“I pressed the button, Dad. It should stop hurting soon,” Cliff says.

I can hear the razor scraping against my skin again, but my chin is down somewhere else, at the bottom of a steep slope.

“How does that feel, Dad?” Cliff asks. My hand is on my face. I wonder if Cliff put it there for me. “Better?”

“I know I was hard on you,” I say to my son. “It’s okay.”

“I know I was hard on you, but look how you turned out,” I tell him.

There is a long pause, and I am not sure he heard me. He says, “You’ve been a good dad, and I love you.” I can tell we are alone, because of how his voice sounds. Young. “We’ll all be okay here.

We’ll miss you but we’ll be okay. Don’t worry about us.”

I know what he says is meant to be an untethering, but now I notice that I am dying in the middle of a story that I will never know the end to: who will tend to my children, when they die, the way they are tending to me? Where are their children?

“I’m not ready,” I say. “I’m not ready.” I hold onto the ropes.

“The farm is falling apart. It’s time to let it go,” Cliff is saying, as we look toward the horizon. “You can sell. Go anywhere.”

It is noon. The sun is straight overhead, and light

is coming down over us like the ribs of the umbrella. Our shadows disappear beneath our feet. There is a feeling at this time of day that the sun is not ascending, not descending; it is where it is, and each time it’s there, I think it might stay.

“Come on, Dad. Let go.”

I clutch at the farm with my eyes; I am sure this place is worth more than anyone knows: the sky above the sky, the land beneath the land.

The screen door creaks open.

There is a shadow that changes the weight of the hospital room, and I know someone else is here. I make out a figure framed by door. It looks like my wife’s.

“Dad, I’m back.”

I see my wife on the doorstep. “It’s time,” Maggie says, wiping her hands on her apron. Her hair is in its neat curls, and her spectacles reflect the sun. Children come running. Whose children are these? There are so many of them, all heading for the house together.

“Take off your shoes,” Maggie says.

The children take off their shoes quickly and run in, but I have to sit on the doorstep to unlace my boots, which takes a long time. When I have my boots off, I stand up, I go in through the screen door, and it is bright inside. So bright that I realize I am not inside: I am outside, standing with no shoes under the sun. Light on top of light on top of me. And behold: at last, I am rising; I am dust in the light. I am weightless in the noon. l

Livestream Available

AMBER BURKE is from North Dakota. She is a graduate of Yale and the Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars who now teaches writing at the University of New Mexico in Taos. Her creative work has been published in magazines and literary journals including The Sun, Michigan Quarterly Review, Raleigh Review, Superstition Review, and Quarterly West, and her writing regularly appears in Yoga International.

A s p a r t o f t h e N a t i o n a l E n d o w m e n t f o r t h e A r t s " B i g R e a d I n i t i a t i v e " , w e w e l c o m e T o m m y O r a n g e t o t h e B i s m a r c k s t a g e . F i n a l i s t f o r t h e 2 0 1 9 P u l i t z e r P r i z e a n d r e c i p i e n t o f t h e 2 0 1 9 P E N / H e m i n g w a y A w a r d , T o m m y O r a n g e ’ s b o o k " T h e r e T h e r e " f o l l o w s 1 2 c h a r a c t e r s f r o m N a t i v e c o m m u n i t i e s a s t h e y t r a v e l t o t h e B i g O a k l a n d P o w w o w , a l l c o n n e c t e d t o o n e a n o t h e r i n w a y s t h e y m a y n o t y e t r e a l i z e .

Life here isn’t easy, and it isn’t beautiful. But what is there to be proud of if you survive in ease and beauty?

The Hunter turned his small all-terrain vehicle into the approach to a vast field split by a low grassy peak that extended a half mile ending at a slough hole. The raised hump that divided two areas stretched toward an old tractor sitting next to a tree’s broken and burned stump, just visible on the horizon atop a small island surrounded by cattails. The sky was blue with a handful of wispy clouds, the sun already dipping toward setting. On the island’s edge, the remaining bright yellow leaves of a tightly spaced grove of young cottonwoods shimmered and danced, reflecting the low sun in tiny flashes of light. On one side of the rise lay the unkempt yet uniform rows of a recently harvested field of yellow corn stubble stretching to the edge of the far horizon where the standing stalks of an unharvested field stood. On the opposite side of the berm, an area of wild-looking grassland stretched to the horizon in a raucous yet pleasing mix of a thousand shades of gold, red, yellow, brown, and black swaying in the gentle late afternoon breeze. The pleasant panorama, constructed from the season’s transient blend of light and space, gave everything a glinting gold-kissed hue in the low afternoon sun of late fall. The Hunter listened to the soft rustling of the grasses and caught a whiff of their pleasant dried smell. The only sounds were of the breeze, swaying plants, and the low hum of a combine somewhere past the horizon vibrating through the air. Judging by the dustiness of the skyline, the combine must be just a few miles away. Stepping off the machine, The Hunter turned to reach for a bolt action rifle in a case attached to the ATV. Holding the gun up in the air with one hand, he pulled a clip of shells from his pocket, snapping it into place. Readjusting a small backpack on his back, he slipped the rifle across his shoulder. As he stepped onto the rise, he looked out at the field of dried, swaying plant life, whose desiccated multihued stalks waved in the light wind of the crisp November day, making the pleasant scratching sound of dried grass swaying in the breeze. So much more enjoyable than the wind that whipped and lashed the vast field to and fro the day before when he had to lower his head into the wind to stay

upright and keep windblown soil particles out of his eyes. How quickly something pleasant could turn tortuous by adding just a few miles per hour of wind or a few degrees of temperature. Today was good, though, and he would enjoy it. A nice day can wipe away worry about the past or the future.

The hump, created by the accumulation of soil atop an old fence line of indeterminate age, now buried and covered by a mix of plants, was a dull brown gleaming in the low sun that gave everything a gilded shine. At some point long ago, the soil presumably had come from the grassy field, like a carpet rolled up on one side of a room. Ignoring that wind had stripped a whole field of soil, past farmers had built a fenceline atop the buried one, like a new civilization building atop the remnants of an old one.

When the Hunter’s boss had bought the land from the old farmer, they dug up part of his pasture to plant corn but left the sandier part as grassland in a government program. To remove the fenceline, the Hunter had hooked a giant four-wheel drive tractor to one post with a chain before driving parallel to the fence. As he went, steel posts popped out like toothpicks, ending with a half mile of wire and posts bouncing and jiggling behind the machine like some insane land leveling contraption. Later, he had buried the pile of twisted wire and posts with rocks, picked from the field, as if trying to erase the human and geologic past to create something new.

The top of the hump provided an excellent vantage point to survey the relatively flat topography. He put his binoculars to his eyes and scanned the terrain in all four directions. If there were a deer within range, he could see it standing here. Spinning ninety degrees from the grassy field, he looked closely at the yellowish corn stubble that was just tall enough to hide resting deer. On the

A nice day can wipe away worry about the past or the future.

far edge of the horizon stood the unharvested cornfield, probably where they all were, he thought. But as the day waned, he knew they would be moving from the safety of the field toward the water of the old slough hole with its broken-down, crumbling tractor and shattered tree.

He pulled back the bolt of the rifle to move a shell from the clip into the chamber, and as he did so, checking to make sure the safety was still on. Slinging the rifle on his shoulder again, he began to walk the half mile atop the old fence line, following the game trail along its peak. The well-trod path was kept open by a proliferation of local creatures that used it as the fastest track to the shelter and aqueous salubrity of the slough hole. The ancient, timeless wisdom of life to find the easiest path between two points was worth heeding. Paths first forged by wildlife became human trails and then roads.

Just then, a hen pheasant, blending into the ground until he almost stepped on her, jumped up, giving him a bit of a start, the rapid fluttering of its wings creating musical notes with the air as the brown and black-flecked creature strummed its wings, then glided to the ground. The commotion of the hen had caused something to start moving in the grass ahead of him. An explosion of movement a second later, and a group of small gray and cinnamon colored birds with a smaller half-moon downward curve in their wings took flight, landing hundreds of yards into the deep grass of the field. Watching the small, elegant

partridges land, he was now wondering why he hadn’t decided to bring a shotgun.

He thought briefly about putting away the rifle and pushing through the waist-high tangle of grass on one side of the rise or calf-high corn stubble on the other to chase up something. He quickly pushed the thought aside since stirring anything, let alone shooting, would disturb the peace of his primary goal for the day, the large whitetail buck he expected to see at the slough hole. All year he had been watching it move around the area while working in the fields, seeing it primarily at dusk around the slough hole. Besides, high-stepping corn stalks to avoid getting stabbed in the leg by the razor-sharp spikes or leg pushing through wind-tangled dried grasses interwoven with spiky Russian thistle digging into his legs and thighs wasn’t as appealing as a stroll and high vantage point of the accumulated windblown hubris of human manipulation of nature.

As the sun dipped low, he remembered how he had spied the buck moving slowly near the slough hole the previous day as he dumped the last hopper of corn from the field into the grain cart. Tomorrow, he would take the final truckload on the long round trip to Grain Terminal One, where it would become fuel for some of the machines that grew the corn in the symbiotic cycle of plants feeding machines and machines growing plants.

The crow of a cock pheasant, far off in the corn stubble, brought him back to the moment. Pushing

aside the fantasy of bagging a pheasant, he looked ahead toward the broken and burned remnants of the great cottonwood on the small island. The jagged and scorched remains still stood taller than he did, and he was too young to remember when the tree was struck down by lightning years before. The charred, broken, and hollow remnants of the once great tree still stood high enough to be seen from the road, the charring acting as a preservative that had allowed it to remain for decades. He had heard it had once been the largest cottonwood in the region and had been a striking sight in late fall when its leaves glowed an iridescent yellow in the waning sunshine.

The old farmer, whose family had owned the land for generations before selling it to his boss, who farmed half the county, had allowed people to walk the cattle trail that used to run at the base of the berm to see the natural wonder. That changed the night a combination of wind and lightning took down and burned the old tree whose broken, charred, decaying ruin still held power to instill awe. Standing inside its hollowed shell, one could still reach with outstretched arms and not touch the sides.

Pulling his gun from his shoulder to be ready for a deer to jump up, he continued to walk, stepping high to avoid a burrow dug into the side of the trail. He had been keeping one eye on the ground analyzing the scat and tracks of the many creatures who used the path to get a feel for what things might be in the

area. Walking over the burrow, he thought it might belong to the coyotes he heard yipping in the evenings after he had shut down the machines.

As one of the few raised areas in a mostly flat landscape, the old fence line, perforated with the burrows and holes of various creatures, served as a safe space for animals pushed to the margins of the fields by the constant human disturbance. It was common to hear the barking and yipping of coyotes at night. People said there was a time not so long ago that you didn’t hear coyotes. It was a time when the countryside had more people with more livestock, more guns, and more dogs. In a present that had given way to vast regions growing just a handful of plants and animals, the human environment had given way to one dominated by machines. In the handful of spaces where the machines weren’t, the wild things could thrive within chemically enforced boundaries.

He raised his rifle to his shoulder and glassed the slough ahead of him through the scope. As he slowly moved the eyepiece across the island in the center, he spied the buck he had been watching all year, ambling just between the rusty old tractor and the carbonized stump of the giant cottonwood. It stood there browsing the ground, unaware of him. Was this the moment he had been thinking about all summer? He wavered between pulling the trigger and letting the buck go to savor the anticipation for another season or just letting such a wonderful creature keep

living. Aiming for a moment, he assessed that it was an easy shot. Quietly clicking the safety off, he held the rifle tightly to his shoulder, staring down the scope’s crosshairs to center the slowly moving deer. He tracked it moving through the high tan grasses that denoted the dryer land that followed the edge where the cattails signaled water-saturated ground and shallow water at the slough’s edge. Centering the crosshairs of the scope as it slowly walked, he aimed. When he was sure of a clear shot, he squeezed the trigger, and the gun let out a booming crack, recoiling hard against his shoulder. It always came as a shock to break nature’s relative silence with the violence of sound and action.

In a moment, tension transformed into the mixed joy of success and melancholic regret at striking and watching a fellow creature fall to the ground. He always wondered if he should say a prayer or conduct some ritual to honor the creature that had paid the ultimate price so that he could hang its horns on the wall and eat. He always came up empty since, in his world of cornfed consumerism, deer were resources like corn to be managed and harvested, not beings that deserved some reciprocity.

He arrived at the slough’s edge, where the buried fence line ran to

the edge of the small island. Due to the frosty nights, It had lost its pleasant herbaceous smell, most evocative on still evenings as the fog settled over it. Stepping across the squat land bridge formed by the buried fence line barely rising above the cattails’ fluffy heads, he moved onto the tiny island. He looked at the old tractor, a heaping hunk of metal whose once bright paint was faded after decades in the sun and beginning to erode to spots of rusty roughness. The Hunter could see that the head was removed from the engine as if someone had attempted to fix it or salvage parts. Three carcasses, a plant, an animal, and a machine lay within feet of one another on the tiny island. For a moment he imagined the great Tree of Life broken, its four-legged fruit splayed on the ground due to the excesses of the dead tractor. In some parallel reality of the multiverse, the same tractor thrived next to a healthy deer and tree. A different world was only as far away as the imagination.

Stepping past the tractor, he leaned the rifle against its engine, catching a whiff of its pleasant fermented mix of old dirt, organic matter, grease, and oil that gave it the distinctive smell of forgotten old machines. Walking toward the buck, the Hunter noticed it lay on something higher than the surrounding shades of brown

In a moment, tension transformed into the mixed joy of success and melancholic regret ...

grass and still green leafy spurge. The deer lay on its side, legs splayed outward, looking peaceful. He kicked the tips of his boots as he walked and hit something solid just before reaching the deer. Removing his pack as he knelt, he felt the edges of something hard buried beneath season after season of layered dried grass, wrapping it tight like the arms of a wicker chair. Intrigued, he grabbed the deer by the legs and rolled it off. He pulled a short knife out of its sheath and began to slice the dead grass stalks that cocooned the metal in a tangle in various states of decomposition toward grass made humus at its bottom. Pulling the iron remains of an old walking plow from decades of slowly being buried and consumed by the earth, he stood it up in its natural position.

As he knelt, gazing for a moment at the unique find and catching his breath from the exertion, he noticed for the first time a sky crisscrossed by the tracks of aircraft contrails moving in every direction and others stretching from ground to sky of a type he had never seen. It was common to see the Air Force from nearby bases doing things in the sky. Watching them broke up the long days sitting on the tractor, but this was more than usual. For so much activity, it was still oddly quiet, just a low rumble, barely audible below the drone of the distant combine and the rustle of the remaining golden leaves of the small cottonwoods at the edge of the island. The display of looping contrails and rising rockets danced in a strangely quiet show

across the dimming blue of the sky; shimmering, evanescent fluffy white lines breaking through the slow transition from blue to orange to darkness. A plastic bag caught in the branches of one of the small cottonwoods, fluttering in a chaotic unnatural way, fractured the trance of the almost silent ballet in the sky, his mind returning to the moment.

The setting sun spread light out in deep reds and oranges touched by wisps of purple, and the shadows of the tractor and the shell of the dead tree were getting longer. The relatively warm afternoon air had turned cooler, tinged with the touch of comfort that comes with the pleasant moment of the day’s completion between light and dark.

The lengthening shadows of the tractor and tree spurred him to work on gutting the deer. He began to cut open the chest cavity, regretting that he had used his knife to cut out the old plow. He pulled out a small sharpener and gave it a few quick strikes to refresh the blade. He sliced the chest cavity, splitting the pelvis and pulling it open to reveal the warmth inside, like turning on a small heater.

He began to pull the innards from their viscous attachments on the sides of the body cavity, using his knife to trim as he went, his hands warmed by the action. He pulled the guts out and dragged them to the side into a pile. The coyotes would eat well tonight, and that spot would sprout something new in the spring from the blood and fluids that soaked into the ground.

His hands warmed from the body of the deer, but feeling the chill because of his lighter dress; he decided to start a fire. Even though it was an unseasonably warm hunting season, whatever that meant anymore, the chill in the air was enough that he wouldn’t have to rush back and could hang the deer in the garage and pull off the hide before the body cooled down fully. So many things had been turned upside down by weather that no longer followed old rules, but this was a nice moment, and he would savor it.

Tipping the old plow back on its side so that it lay somewhat flat to form a fire ring, he gathered some dried fallen wood from around the old cottonwood stump. Breaking up tiny twigs, he made a small pyramid in the center of the half circle formed by the plow. Pulling a piece of crumpled paper from his pocket, he placed it in the center, setting it alight with a match from his other pocket. The flames quickly engulfed the dry wood, and he began to pile successively larger pieces onto the growing fire. Soon, he was collecting larger chunks pried off the broken tree by dragging uncut deadfall to the edge that could be slowly fed into the fire as needed. When he finished, he could grab the unburned ends and throw them in the little spot of open water at the center of the slough.

Reaching inside the body cavity of the deer, he cut out one of the tenderloins and rinsed it with water from a bottle in his pack. Shaping a makeshift skewer from a stick, he sculpted it

quickly to clean the bark, offering fresh, clean wood to push the meat through. Using a relatively clean piece of the wood he had gathered, he cut the meat into cubes before skewering and placed them over the fire to cook, not directly over the fire, but off to the side to slowly cook, fashioning a makeshift spit from some sticks. He took out cans of spaghetti and beans from his pack, opening them with a small knife in his pocket. Pouring the contents into the small pot, he mixed them with a stick and set them on one side of the flame. He then walked over to the small rock pile and looked for something to use as a plate to put everything on. On the glaciated prairie, most stones were roughly spherical, lacking flat sides or sharp corners unless broken. He found a soccer ball-sized piece of granite with a flat side sheared off, possibly by striking the old plow long ago.

His little meal cooking and smelling good, he stopped and sat down on the springy cushion of grass and pulled a small thermos from his pack, pouring himself a cup of coffee. Taking a long sip, he stared at the deepening colors of the sunset laced with fluffy contrails and considered the present moment. The colors of the little fire almost matched those of the waning evening, crackling and glowing in shades of red, orange, blue, and yellow that blended with the sunset at its edges. The tip of the sun was disappearing, and the sky just had that slim edge of light along the western horizon tinged a deep orange, turning dark. The opposite sky was already

beginning to show a few stars of the slow transition from day to night. The moon’s outline began to appear as part of the seamless daily handoff between the sun and moon.

The gentle cacophonies of insects and birds that made sundown so pleasant in warm months were gone in the frozen evenings, replaced by a new harmony of a few titering sparrows and the squawk of a crow in the nearby quivering grove of cottonwoods. Relaxing, he watched as the diminishing light at the world’s edge was slowly giving way to the new world of stars on the far edge of the heavens to his back—the daily ending of one world and the beginning of another.

Before long, the tenderloin skewer was sizzling. Taking it off the fire, he put it to the side to cool on the plate rock. It cooled fast on the cold stone, and he tested a piece chewing slowly. Next, he grabbed the pot with a glove and set it on the rock to cool. He took a bite of the mixed beans and spaghetti. As he chewed, he looked off in the distance toward the now dark, blood-red sky and the slim line of the remaining glow of the dipping sun. Enjoying the convivial moment by the fire, roasted venison, with beans with spaghetti, the sky flashed bright, and his vision went blank. Before his brain could even wonder what had happened, a wave so hot it incinerated all wondering washed over him. He never saw the impressive mushroom cloud curling upward in a mix of reds, oranges, grays, and blacks above

the last sliver of the setting sun. The tractor stood as a silent witness, the only thing not made of earth left standing in a landscape that stretched as far as eyes could see if there had still been eyes to see.

People returned to the place long after the trees and grass started to grow again. In that place, new people began to call things by new names. The iron brick of the tractor, the lone landmark that hadn’t been burned away by nuclear fire, stood out in the terrain. To that lonely place, with its old tractor, revered as one of the magical feats of the mistshrouded past when machines transformed and consumed the world, they gave the name: Lone Tractor Plain.

The world moved on. The memory of what had come before carried on in myth, story, and fragmentary texts in an old tongue few could read. In this new world, the sun rises and sets, the stars and moon shine, the wind blows, and life bursts forth in every imaginable color. On Lone Tractor Plain, generations of life come and go, and the tractor endures; the tractor abides. l

MARK HOLMAN lives in Williston, North Dakota, where he enjoys writing in his spare time. This story is a prequel to “The Tractor and the Tree,” published in the 2020 Sense of Place issue.

The train departs well after midnight, and by dawn, we roll into the first snow squall. Four days in a train sounds straightforward, but North Dakota storms completely erase the landscape, and by Minot, a full-blown blizzard halts our progress. The early blizzard will hold us up twelve hours, according to the engineer. Truthfully, I need those twelve hours to reload. I need some time to get my confidence back. I’m fearless in Browning, why not the world?

The train chugs into town. I stare through the window at snow blowing parallel to the train, lifting up over the top into a swirl on the other side, changing directions like the thoughts inside my head.

I close my eyes. The falling snow disappears, replaced by my own swirling doubts, yet there’s nothing out there that I can’t face, step by step.

I need my feet firmly planted, and my eyes open, all of the time.

The porter’s familiar limp moves up our aisle. I’ve heard about Minot’s side streets, places that few outsiders see. Channeling those thoughts, John asks a simple question.

“Hey, Charlie, what would you advise for supper here?”

Our amiable black porter thinks a minute. His eyes scrunch at both sides, and his constant smile widens a bit.

“You a little adventurous, John? ’Cause the best places here call for a little adventure. The best places here is on Third Street, ‘High Third.’ ”

“Charlie, I would say a little adventure might be in order tonight, so what can we get on Third Street?”

“Y’all can get anything you want on High Third,” Charlie says, “and I mean anything. Saul’s is an excellent choice. Try Saul’s Barbeque. Tell ’em Charlie asked about Luella and her pet mouse, ask ’em about that.”

Charlie laughs, maybe remembering some dalliance from the past.

“What do you mean anything?” I ask. “Anything might get John in trouble?”

“Not that John looks to stay out of trouble,” John says.

“Well, you do have a pretty lady on your arm, so you don’t need none o’ that. So let’s say a little liquor even though it’s Sunday, and a card game if that catches your fancy.”

“Oh, no,” I say.

Charlie laughs out loud again. “Men likes poker,” he says, “all of ’em, black men, too.”

The storm has already passed through Minot, and a warm south wind reminds us that it’s only October after all. We walk up Main Street as directed, past Saunder’s Drug Store, and across Central Avenue.

Peals of laughter halt us at the door, temporarily propped open by a slim brunette waving at some friends inside. She holds the door open for us.

“Are you going in? Good luck with Al, and don’t say I didn’t warn you about his jokes. Nothing’s sacred in this town.”

I shrug my shoulders and pull John inside the Terrace. Glass blocks scatter natural light around an elegant circular bar. To our right, a hundred bottles of wine and liquor wait for purchase inside a glass display case.

“You come in for the joke?” a large man asks. “Well, it’s no joke. I’m Al, Alfred Emil, and that was my neighbor, Bette. I’ve been trying to ask her sister Bernice out for some time. Bette always promises to line us up, but she’s kinda protective of her big sister.”

“Maybe her sister needs protecting?” I ask.

“Oh, Bernice can take care of herself. Anyway, I went to the doctor today, and he wrote me a prescription, are you ready?” Al sits on a leather bar stool nearest the door. From the looks of his biceps, I guess he owns a farm or works the railroad.

“Sure,” John says. “I’m definitely ready for a joke.”

“Alright, I go to the doctor about all my aches and pains, and he looks me over a long time, and he writes me a prescription, you know what it says? It says ‘Prescription to cure a bachelor’s

aches; deliver to the man ten yards of silk—with a woman wrapped in it.’ ”

The small crowd erupts again, more to Al’s delivery than the joke itself. His mischievous smile and his exaggerated gestures endear him to anyone he meets. Al buys us each a beer, a Schlitz, because that is what Al thinks everyone should drink.

I quiz him a bit about this woman he wants to date.

“You got to see Bette on the way out, just change the black hair to blond. One sister is as beautiful as the other. Their mother died young, and those girls kinda raised each other, so they’re pretty tight.”

“Bette’s beautiful, that’s for sure,” I say. “You live around here?”

“Southwest about thirty miles. You traveling through?”

“Headed east,” John says. “All the way to New York.”

“Best food around is over that direction a few blocks.” He motions west with his thumb. “Any business along Third Street.”

“We’re heading to Saul’s,” John says. “How’s that?”

“My personal favorite,” Al says. “Saul’s barbeque could make a grown man cry.”

“As long as I can keep us out of trouble,” I say.

Al looks around the room.

“Keep your nose clean. Saul’s is a fun-loving place.”

Twenty minutes later, we thank Al for his hospitality. He directs us west on a path already trampled through the snow toward “High Third.” Brick buildings hold the smell of coal smoke and vehicle exhaust.

John pulls me close, and I feel warm. He walks in deeper snow and guides me down the beaten path. A slushy pool blocks our way, and he carries me in his arms. I wonder how our lives would change if this war ended today.

The Avalon, the Coffee Bar, the Twilight Inn, the Parrot―Third Street bustles with brightly lit signs that overlook a broad river valley north and west. Cars pack every side street despite the storm. We walk into Saul’s Barbeque. The floor is worn clean, the odors smoky-tasty, the atmosphere abuzz with lively chatter. This isn’t a church convention crowd for sure, but some of those folks are here, the fun ones that don’t talk about High Third when they leave.

Saul’s menu sums up his establishment well. John holds it in one hand. The index finger of his other hand taps some interesting offerings: pork hocks and cabbage, pork rinds, sausage and grits, chicken feet. We order the smoked pork hocks. John mentions that Charlie the porter sent us, and a shot of whiskey accompanies John’s coffee.

Middle-aged businessmen crowd the tables, along with a few couples, and a handful of military men. Four black waitresses rush about, keeping tables full and customers satisfied—our waitress visits near the end of the meal. John deals an imaginary card deck by his lap where nobody else can see. The young black waitress studies him. One hand drops to her hip, the other rests on our table.

“What’choo trying to show me?”

“Charlie the train porter sent us over. He loves everything about this place.”

“Describe Charlie for me,” she says.

“Well, he’s about your height, twice your weight, with a hearty laugh almost like a crow, and he said to ask about Luella’s pet mouse if that’s helpful.”

“Oh, you know, alright,” she says, her voice dropping. “And I’m Luella, by the way. Tell you what, make sure there’s an extra dollar in your tip, and you both want to use the washroom down that hall to the right.”

“John and Abby here, Luella,” John says.

“Nice meeting you, John and Abby.” She departs with practiced sway.

“C’mon John,” I say.

“Oh, just for an hour, Abby. We’ve got nothing else going on for the next ten hours.”

The tip turns into a five. The washroom holds a toilet and sink opposite a broom closet, but one minute after we close the door, the broom closet opens from the other side, and a muscular black man eyes us both. He’s stout, athletic, handsome, and well-dressed.

“You friends of Charlie?”

“Yes sir, we are,” John says, “John and Abby from Montana. We’re acquaintances of Al Emil, too. He bought us a Schlitz down at the Terrace, told us a bad joke.”

The man looks us up and down.

“Well, come on in, John and Abby, I’ve got a chair for you, sir. Ladies are not allowed at the tables, but you are welcome at the bar, and we have anything you might like to

drink tonight.”

He leads us through a false door sealed from the backside with wooden blocks. We walk down a stairway and into a lively poker room filled with cigarette smoke. Two black girls in skimpy outfits hustle drinks out to four crowded gambling tables.

“Right over here, sir. My name is Saul and welcome to my establishment.” A familiar laugh roars above the rest. Al Emil slaps his cards down on the nearest table.

“He beat us here,” John says.

“He’ll beat you in cards, too,” Saul says. “Don’t tell me I didn’t warn you.”

“John plays pretty well,” I say. Saul smiles. “Not tonight. I’m gonna start you off at a different table.” He motions John toward an open chair.

I sit down next to a pretty blonde at the bar. She looks familiar.

“Oh, another gambling widow for the night. They take us out for supper, and this place just pulls them away. My name’s Bernice.”

“I’m Abby, nice to meet you, Bernice. You’ve been down here before?”

“Oh, several times. My husband and Saul were good friends, which isn’t really a good thing, but whatcha gonna do?”

“You know Al Emil?”

“Everyone knows Al Emil.”

“Let me buy you a drink, Bernice.”

“Well drinks aren’t cheap, dear. It’s Sunday, but Saul has no liquor license anyway. You know, this place started during prohibition

and didn’t bother with a license when the government changed their minds.”

“You live in Minot, Bernice?”

“Right on Main Street over a clothing store. My first husband wrapped his drunken carcass and our new car around a tree a few years back, so I’m raising a little girl myself. Her name is Dorothy.”

“So, you and Al got a thing going?”

“I work as a railroad ticket agent and help the girls down here on weekends. Al here treats Dorothy and me very well. He’s a gentleman, and after the first man, I know what I want.”

“I’m glad you found him, Bernice.” I look around the room and laugh. “We met him downtown at the Terrace. He’s quite a character, a very likable character. He keeps looking over here at you. All the men sneak a peek over here every couple minutes.”

“How about you, girl, and this handsome serviceman, bestlooking guy in the place. He couldn’t take his eyes off you when he followed you in, let me tell you that. He keeps glancing over here, too, gonna lose his butt at cards.”

“His name’s John, and we met a few weeks back.”

“You really like him.”

“Oh, I don’t know.”

“Well you make a perfect couple, this big handsome guy and a beautiful redhead, almost like a picturebook. I can tell right away you know your way around men, too, around people. You’re a little salty. Redheads always come out a little salty.”

“I don’t know about that either.”

“You’re sitting in an illegal gambling hall, drinking bootlegged liquor with a stranger, and you could own the place.”

“Actually, my confidence needed a boost, and you sure are helping. You see, I’ve never left Montana until now, never done anything to speak of, and now we’re riding a train to New York. John must return to the war, and I’ll volunteer as a nurse.”

“I’ve been all over, girl,” Bernice says. “My father Bill liked to travel, and I can tell you right now, you’re spirited, bright-eyed, good looking—you can get anything you want anywhere you want it. Use those eyes, use those curves, a little demure smile. Never, never let them see you sweat.”

“Anybody ever see you sweat, Bernice?”

“Not since I grew up enough to know how men work. I married too young, thought that men made all the decisions, but that’s what they want you to think. They’ll do anything you want IF you let them make the decision that you lead them to.”

I laugh a long time at her words. She’s beautiful, that’s for sure, not with the haughtiness that usually accompanies beauty. She’s lived her share of heartache. She’s cleaned manure off her shoes. She’s coughed on dust along gravel roads, cried during childbirth, and buried an unwholesome husband. She’s a good sister to the brunette named Bette and probably a very good mother too.

“You’re right, Bernice. They’ll do

anything you want if you let them make the decision that you lead them to. I know you’re right, but I never heard it in words. Thank you.”

“You are most welcome, my dear. Just remember that the men are in charge, but they’re still men. Think about how you look at them, then hang on certain things they say. Derail their agenda, then rebuild it very slowly.”

“Have you rebuilt Al’s agenda?”

“Al has no idea what his agenda even was six months ago.”

“It wasn’t all that hard then?”

“No. Listen, Abby, men have good traits and bad traits. You don’t want any of them at face value, yet with a few adjustments, they will wind up tolerable to wonderful, depending on your needs. You have it in you—your natural beauty, your ease around people, your spark. Men want an equal, although most men like control, too. Give them both.”

“Play them.”

“In a sense, because they play you, too. We all offer ourselves to others, even you and I. We share what we want, then maybe something comes of it. You control your own destiny.”

“Oh Bernice, this advice is all wonderful. Now, where does a girl freshen up down here?”

“Let me show you because this is a place where a girl should not freshen up alone.”

A roulette wheel spins round and round. “Come on red, gotta be red,” a white-haired man chants. His handlebar mustache gives him an air of distinction. “Good

evening, Bernice, nice you could join us tonight.”

“Thank you, Leonard. Here, let me touch your chips for luck.” She leans over a bit further than necessary, pats the chips, kisses his cheek.

Beyond the bar, Bernice swings another door outward into a lighted tunnel. The wooden floor shows signs of frequent use by a drinking crowd―cigarette butts, bottle tops, and even a broken red shoe. I perceive the direction as north.

“Right down here, Abby. There should be two drinks waiting for us when we return, gin-tonics, my favorite.”

Bernice locates a fully functioning bathroom framed in large wooden timbers. There’s even spray cologne and a mirror near the door. We take turns using the toilet and Bernice leads on our return.

“Leonard buys you drinks sometimes?”

“Leonard’s on the city council, which means Leonard drinks free. He’s also the fire chief. Say the cops plan a raid down here. They all get ready at the station, all these extra men and everything. However, the fire station shares the same building, get my drift?”

“I get your drift, Bernice. So how does Saul get rid of liquor bottles and stuff, you know, without alerting the law?”

“Take a lookie here, girl.”

She does a one-eighty, back toward the bathroom, and continues down the passage away from the poker room. A

single suspended wire connects light bulbs every twenty feet, illuminating damp walls, old pipes, and rusty metal.

“These tunnels started out as service corridors, running steam all over this part of town from the power plant. Once abandoned, the tunnels were condemned and blocked off until all the businesses on Third just cleaned ’em back out.”

She stops at a dark passage forking right.

“Can you smell it?” She reaches around the corner and lifts a flashlight but the beam hardly cuts the darkness.

“It smells awful.”

“That’s where everyone dumps their trash, the stuff they can’t put out, like liquor bottles and Lord knows what. Saul took us on a little tour once. What you have back here is an old underground coal mine, a pit.”

“Their own private dump.”

“And I’m not sure what all lands up there, maybe a body every now and then, that’s what Saul alluded to. He’s never done it, although he’s heard talk. Man loses at poker, spouts his mouth off about going to the cops, you know, the underworld operates here like any place.”

“I’m not surprised.”

“You’re new, dear, you and your man, and I want to look out for you. This town doesn’t follow the rules so keep your fun secret and make sure you both get out safe.”

“Thanks, Bernice. I love a little adventure.”

“C’mon then. I’ll show you some

more. I’m good friends with Erma, the lady that does laundry for lots of the girls. I help her out on and off, so I know my way around. Turn back down this tunnel here.”

“Not as tall as the last one.”

“It’s all old heating tunnels. They fixed some of them up to move things business to business.” We walk further away from Saul’s into a narrow hallway leading to another restaurant, bigger and brighter than Saul’s Barbeque.

“This is the Avalon,” Bernice says. “They have the secondbest chicken in town, and this place is packed at one in the morning. You can get things at one in the morning that you can’t get anywhere else.” We’re staring at a diamond sky from the rear hotel entrance. A row of houses populates the street behind us, and the valley stretches out immediately beyond.

“I heard that,” a skinny waitress says. “Who’s the meanest man in town, Bernice?”

“Not Al Emil, that’s what I think,” Bernice peers down the hallway until the black waitress reaches her.

“How’s y’all doing this evening, Bernice? And who’s got the best chicken?”

“Fine, Etta. Your tag’s sticking out. Just a second. There, got it. The Parrot’s got the best chicken.”

“Heck, Bernice, our chicken’s always been better than the Parrot.”

“How’s Erma’s little boy doing, Etta?” Together they look out the window.

“Still colicky, up half the night.

She turns on that porch light,” Etta nods, “and one of us goes over and walks with her. I’m thinkin’ babies might be a little too much work.”

“She’s lucky to have you girls.”

“We all love Erma. She takes good care of us, too.”

There’s movement on the porch, the brief flame of a cigarette.

“Her husband, Selmer. He’s out there smoking now, but sometimes he’s outside with that child half the night.”

“I need to stop over and see Erma,” Bernice says.

Etta walks back into the kitchen. Bernice shrugs her shoulders.

“Out the front door then, Abby.”

Bernice leads down the hotel corridor. We pass a crowded lunch counter where an elderly man in a black bowtie greets us in passing. Bernice pulls the door shut behind us, and I find my directions accurate; the Parrot Inn sign glows almost two blocks south.

“C’mon, let’s get back.”

“So this little boy with colic, does she swaddle him tight?” I ask.

“I don’t know, Abby, it’s the first I heard about the baby’s colic.”

“Swaddling really helped with babies in the hospital. Anyway, what else happens above-ground on High Third?”

“Alright, across the street and up those three stairs, that’s Tuepker’s Grocery. All they sell is canned goods and bread; their ‘blind’ because the grocery business covers for gambling and drinks downstairs. The owner kinda runs things on Third, ‘the

Mayor’ we call him.”

“What’s a blind?” I stop.