11 minute read

Dalliance with the Gallows: A Colonizer’s Privilege

By Waziyatawin

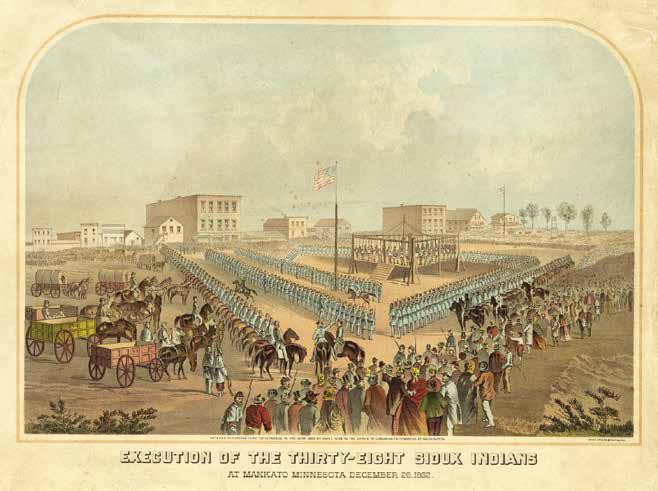

Brooklyn writer Claire Barliant’s “The Hanging in Mankato: Fragments of a Living History of the 1862 Mass Execution of Thirty-Eight Dakota Indians,” is a media-piece both geographically and politically removed from the hotbed of controversy surrounding the 150th commemoration of the United States-Dakota War of 1862. Originating as “’Reading History,’ a performative reading and conversation hosted by Triple Canopy” in a distant New York art scene, it is a rather unlikely candidate for a responsive essay from a Dakota scholar and activist deeply invested in the interpretation and legacy of this watershed episode in Minnesota and American history. Yet, Barliant’s inquiry into her own family’s brief connection to one of the most spectacular events in world history—the largest, simultaneous mass-hanging from one gallows in world history—offers both curious insight and an honest glimpse into colonial privilege.

Advertisement

In many ways, Barliant’s story is a typical American story. An opening excerpt from her nineteenth-century uncle, Pastor Peter Carlson, reveals a family emigrating from Sweden in their pursuit of “God’s will,” the standard Manifest Destiny drama that, in this case, brought them to the Dakota homeland of Minnesota. In this familiar narrative, even if it is not spoken, Indigenous people are a temporary hindrance, soon to be swept away by the march of progress. Once the Indian Wars are over and the Indigenous population has been exterminated, removed, or otherwise rendered powerless, Indigenous people fade into the background, disappearing from the white collective consciousness. As long as white occupation of Indigenous homelands continues unchallenged, white Americans have little reason to devote much thought to past conflicts. Certainly Barliant and her relatives maintained the luxury of never needing to consider what crimes settlers might have perpetrated so that their family could live the American dream.

So what was it that broke their historical amnesia and drove Barliant to research the state-sponsored lynching of Dakota warriors? It seems to be curiosity about a family story recently uncovered through genealogical research. The story centers upon another uncle in the Barliant family, Anders Johan (A. J.) Carlson, who served in the Union Army during the Civil War (and presumably in the United States-Dakota War though discussion of this is conspicuously absent in her narrative). It was this military stint that landed him a role as a soldier standing guard during the mass hanging the day after Christmas in 1862. Barliant’s foray into the past was prompted by a concern over A. J.’s response to the hanging—whether he actually vomited after viewing the hanging and why he relied on impersonal sources to describe that gruesome day. Once she began venturing down that investigative path, she was both fascinated by what was for her a chapter in the distant past, and driven by a desire to acquit her ancestor of responsibility for his participation in the hanging. She was not only looking for some kind of evidence of her ancestor’s renunciation of this terrible event, however, she was also looking for her own absolution.

While questions of memory, history, and culpability routinely figure into my research, it mattered little to me whether A. J. Carlson was sickened by what he saw, or whether, as a victim of trauma he had repressed memories of the hanging and in his denial chose to recite impersonal accounts. Perhaps if his experience as a soldier keeping guard during the hanging triggered a lifetime’s actions of justice toward Dakota people, I might be interested in how he felt about the hanging. I would be interested in what aspect triggered remorse and a desire to make amends for wrongdoing. However, if the event did nothing to change his actions in regards to Dakota people, that is, if he did not work to stop further crimes, then his feelings are irrelevant. For example, if Carlson were disgusted, did it cause him to object when Minnesotans created a bill to forcibly remove Dakota people from our homeland? Did he oppose the unilateral abrogation of US-Dakota treaties, the payment of Dakota annuity money to white settlers, and the theft of Dakota homeland? Did he oppose the implementation of bounties on Dakota scalps? Did he take a stand against the punitive expeditions into Dakota Territory to hunt down, kill, and terrorize the fleeing Dakota? Did he protest the Minnesota Historical Society’s display of Little Crow’s remains after he was killed for the bounty? Did he offer up his family’s land as a way to make amends to Dakota people? If witnessing the hanging had no bearing on his future actions, then he was just another white settler doing what he needed to do to eliminate any threats to his right of colonial occupation. He was just another colonizer benefitting from Dakota extermination and dispossession.

The same kinds of questions might be asked of Barliant. Does her agonizing over her relative’s involvement in the hanging inspire her to work toward justice? I suspect the answer to that question is “No.”

Episcopal Bishop Whipple at Fort Snelling with Dakota Prisoners, Photo by Benjamin F. Upton, 1863.

Encampment of Sioux Prisoners at Fort Snelling, Benjamin F. Upton, 1863.

Barliant is forthcoming, at least, about the personal nature of her journey into the past and her quest for absolution. Not only is this apparent in her musings, through which she attempts to ascribe to Carlson a degree of internal conflict he may not have felt, it is also apparent in the section on her interview with me. In her research, Barliant uncovers no evidence that Carlson felt remorse or disgust at the hanging site. In fact, when she discusses how other bystanders similarly relied on impersonal accounts of the hanging in their own writings “as if reciting from the same script,” she remarks that these witnesses convey “some feeling of triumph and personal satisfaction” about the hanging. In her wording, it is unclear whether such triumphant sentiment was also specifically expressed in Carlson’s account. This does not prevent her from wondering aloud whether his reliance on other sources to provide the account of the hanging was a reflection of memory suppression in the face of trauma, or a form of denial, or simply his shame and disgust at his own complicity that was rendering him mute. Is it possible that A. J. Carlson felt revulsion at the hanging in 1862? Certainly. Further, it is likely that more than a few white observers that day felt some measure of nausea at the site of thirty-eight Dakota men swinging from the gallows—even if they believed in the barbarity of Dakota people and the righteousness of the mass-lynching. Spectators and soldiers with such mixed feelings might have even participated in the “prolonged cheer” that erupted when the Dakota men dropped from the gallows. That Barliant’s own sense of complicity hinges on her ancestor’s reaction thus seems misplaced. Still, she is honest about her own guilty conscience.

Fort Snelling, Minnesota Rendezvous of the Minnesota Volunteers, by W.J. Whitefield, Harper’s Weekly, Sept. 28, 1861.

I often receive inquiries from journalists and researchers about possible interviews, especially on the topic of the 1862 War, and I am generally willing to provide them. I know white people will likely not hear Dakota perspectives any other way. Thus, when Barliant requested an interview and was willing to make the drive out to Granite Falls, Minnesota (the town closest to Upper Sioux), I was happy to comply. It was a familiar conversation. Interviewers are frequently unprepared for the depth of feeling around these issues, especially the lingering pain and anger. Further, they are surprised that we might still want justice. This, too, is a typical reaction. We live in a context in which the occupation and colonization of Indigenous land has become so naturalized it has been rendered invisible. For those of us who still see it, who recognize its many manifestations, anger is a mainstay. Barliant and her mother sensed this anger, but it was not an anger directed specifically at them. It was the dull, tired anger that I feel every time it is clear that a colonizer has really no idea what Indigenous people have lost so that they can live their dreams.

What seemed to be a disappointment for Barliant is that not only did she leave our interview with no exoneration from me, she glimpsed her own naïveté. Upon reflection, however, she was at least honest about our exchange and this is the work’s major strength.

The initial response of white people to these uncomfortable situations interests me far less than what people do with their newfound understandings. After all, everyone has to begin their anti-colonial education somewhere. The question for me was whether this research experience would alter Barliant’s actions— would she be compelled to work for justice for Dakota people? With this in mind, I was not disturbed by her narration of our interview. My disappointment did not come until it was clear to me that the experience had not inspired a larger commitment to justice.

Barliant concludes her piece by recounting her visit to the concentration camp site at Fort Snelling where my Dakota ancestors were imprisoned during the winter of 1862-63. She thoughtfully contrasts the ephemeral nature of our monuments to our ancestors (the prayer stakes with tobacco ties from the last Dakota Commemorative March) with the “sedimented permanence” of the stone monuments of the settlers. She then tells us “The delicate Dakota memorial reinforces a paradox that is hard to accept, that real reconciliation would require a kind of collective amnesia, and possibly a form of cultural integration that many Indians resist. In other words, to forgive and forget is also to surrender. The alternative is to strive for the impossible, which is what Waz wants: the total abdication of US colonization. This leaves the Dakota— and the descendants of settlers—in a precarious position, with no foreseeable resolution. But perhaps this is for the best.” In these comments, Barliant reveals that what she had hoped for was reconciliation between Indians and whites—but reconciliation with no serious consideration of justice. Her solution? Maintenance of the status quo—a space in which the colonizers can continue colonizing with no commitment to justice and where an ineffective “renegade” group agitates from the margins. There is no greater way to ensure ongoing conflict than this suggestion of inaction.

In pitting two extremes against one another as the only two possibilities for reconciliation, collective amnesia (referring to an Indigenous amnesia since the colonizers have already forgotten what crimes they have perpetrated) versus the abdication of US colonization, Barliant is demonstrating a complete lack of will and imagination. While I do not aim for reconciliation within my own work, I have written about the goal of peaceful coexistence between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Peoples and I understand the desire to move beyond a state of conflict. I have spent considerable time contemplating how justice might be achieved in this context (my last book was titled What Does Justice Look Like? The Struggle for Liberation in Dakota Homeland) and I have cited a whole range of possibilities that would bring us closer to peace. Because of this, I find Barliant’s closing comments stunning in their dismissal of the possibility of justice. She decides, from her privileged place as colonizer, what is possible and what is impossible. Fortunately, not all of us will abandon our struggle because Claire Barliant has decreed it futile to try.

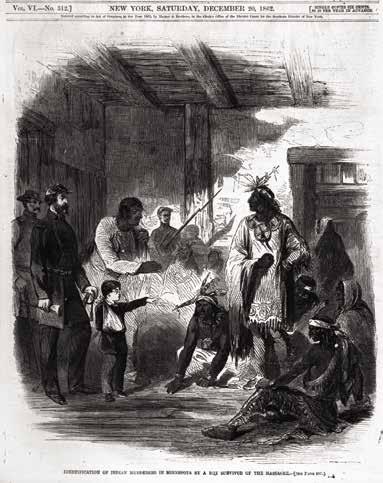

Sioux Trials, White Boy Identifying Indian Who Took Part in the Dakota Uprising, newspaper 1862.

One thing she is correct about is that settler society is on shaky ground, but I do not think she has a clue how shaky. Colonization, which relies on every new generation to continue the subjugation of Indigenous Peoples and lands, is precarious. While most Americans cannot conceive of a future without the US government, or without the US government as an imperial power, a long view of history suggests that the United States will indeed fall—it is just a matter of when. Every day that goes by, the likelihood of this occurring seems to increase exponentially. In this century, as we face the end of the fossil-fuel bonanza, the collapse of the unlimited-growth paradigm of capitalism, and the disastrous consequences of global climate change, the United States and other nation-states will find it increasingly difficult to exist at all, let alone maintain any positions of global dominance. We are witnessing the failure of colonizing society’s capacity for longevity on all fronts. Indigenous people have long recognized the unsustainability and destructiveness of the ways of the colonizers—we have all suffered from it. But we knew it could not last. Thus, when the “impossible” happens, we will be ready. We might even provide a few nudges in that direction.

Claire Barliant is not a bad person and she has certainly helped to bring the story of the hanging to new audiences, but she has also demonstrated that her dalliance with the gallows is fleeting. Like her ancestor before her, she has encountered the unpleasantness of injustice, she has acknowledged the visceral discomfort that accompanies that unpleasantness, and she has moved on. Meanwhile, the colonized are still here, full of pain and rage, and committed to our struggle for justice and liberation.

Waziyatawin is a Dakota writer, teacher, and activist from the Pezihutazizi Otunwe (Yellow Medicine Village) in southwestern Minnesota. She earned her Ph.D. in American history from Cornell University and currently holds the Indigenous Peoples Research Chair in the Indigenous Governance Program at the University of Victoria. She is the author or co/editor of six volumes and including a co-edited volume with Michael Yellow Bird entitled For Indigenous Minds Only: A Decolonization Handbook, released in Fall 2012 by SAR Press.