CATHOLIC WORKER

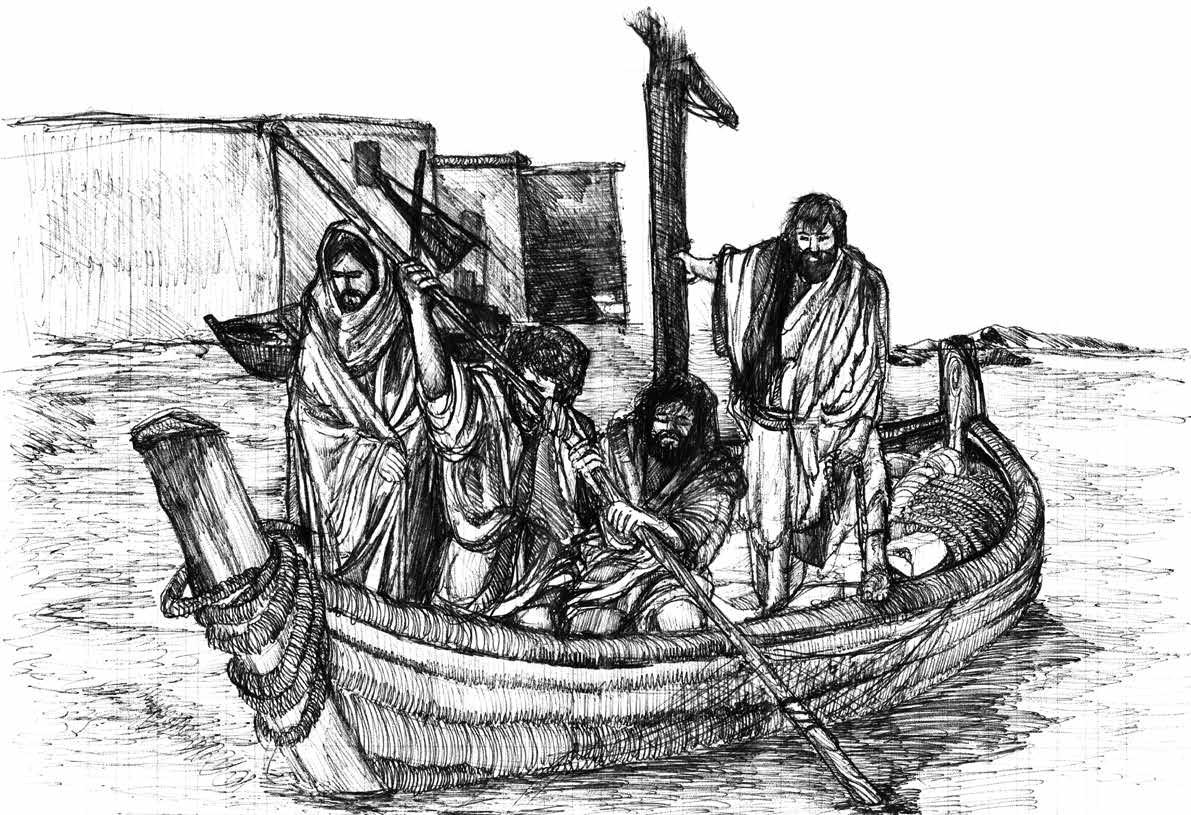

Sometimes we ask ourselves how we can keep going in the midst of the storm around us, the people with all their needs, their anxieties, the traumas they carry with them, their health problem. We have to ask the Lord to be with us each day as he calmed the sea for the disciples during a great storm. We also pray for the ship of the Church in the midst of the tempests of our time.

Three of the Gospels recount the story of the time that Jesus was in a boat with the disciples when a great storm arose. The Lord was asleep. They woke him up and begged for help. Jesus calmed the sea and asked, “Why are you afraid, O you of little faith?”

The possibilities of doing good are overwhelming when one begins to do the Works of Mercy. It almost seems like the crowds that followed Jesus come to those who try to follow as His disciples. Word spreads when you house people, when you give food to the hungry without too many restrictions, when you provide health care for the poorest, do what you can to assist the sick and injured, when you

recognize the Lord’s presence in the poor. More and more people arrive at Casa Juan Diego seeking whatever help they can find. Agencies and referral services keep sending more people. Mark Zwick once said that people are paid $25,000 a year (adjust to inflation to $45,000 a year) to give out our phone number.

We are just a few full-time people, fewer than ever because this is the transition time when some young people have left to pursue their vocations and others have not yet arrived. Parttime volunteers help very much.

Individuals who come across a person in need do what they can, often by bringing them to Casa Juan Diego. In addition to the dedicated doctors who volunteer in our clinic, the assistance of the Harris Health System is invaluable for the sick who come to us. We know that those who help in the parishes are in the same boat as we are (no pun intended) with many coming for help. The Houston Food Bank provides much food. We ask the Lord to be with us in performing the Works of Mercy,

By Louise Zwick

following Matthew 25. The Works of Mercy help to keep us from despair in the face of the realities of poverty, displacement, and violence in our world. The daily practice of the Works of Mercy reminds us to invite the Lord to be with us in our sometimes shaky, certainly vulnerable boat. We were quite surprised recently to discover that some Protestant Christians believe that the teaching of Jesus in Matthew 25:31ff. can only apply to those who have been “saved.” His words that whatever we do to the least of the brethren, the poor, the stranger in a strange land, the sick or in prison, we do to Him, are reinterpreted out of its clear meaning in the Scripture to include only an elite group. Quite different from Henri De Lubac’s and Dorothy Day’s Catholic vision. We wouldn’t have as much work at Casa Juan Diego if we tried to sort out the deserving poor from the rest. However, these misinterpretations also have influence in Catholic circles. We find hope and encouragement in the celebration of the Eucharist.

Some might ask why we continue to do this work. We try to focus on what Henri de Lubac, SJ (as well as Fr. Onesimus Lacouture, SJ, and Fr. John Hugo of the Retreat given at the Catholic Worker) taught about our supernatural destiny. Their teachings encouraged living with a focus on our final end — following the Nazarene in our daily lives with a supernatural motive, faith lived according to the Gospel that will hopefully lead to the beatific vision with saints and the heavenly hosts. Living with an awareness of that destiny can change our lives completely, as can meditating on the mystery of the cross and the resurrection and how God’s grace can transform our human nature and all of humanity in Christ, in spite of disturbances and tragedies and the difficult challenges in daily life. De Lubac and the Retreat given by Fathers Lacouture and Hugo taught that our “supernatural final end has implications for human life, perfecting continued page 8

• President Biden announced on June 17, 2024, a program to ensure that U.S. citizens with noncitizen spouses and children can keep their families together.

• This new process will help certain noncitizen spouses and children apply for lawful permanent residence – status that they are already eligible for – without leaving the country.

• In order to be eligible, noncitizens must – as of June 17, 2024 – have resided in the United States for 10 or more years and be legally married to a U.S. citizen, while satisfying all applicable legal requirements.

• Those who are approved after DHS’s case-by-case assessment of their application will be afforded a three-year period to apply for permanent residency. They will be allowed to remain with their families in the United States and be eligible for work authorization for up to three years. This will apply to all married couples who are eligible.

• Easing the Visa Process for U.S. College Graduates, Including Dreamers

• President Obama and then-Vice President Biden established the DACA policy to allow young people who were brought here as children to come out of the shadows and contribute to our country in significant ways. Twelve years later, DACA recipients who started as high school and college students are now building successful careers and establishing families of their own.

• Today’s announcement will allow individuals, including DACA recipients and other Dreamers, who have earned a degree at an accredited U.S. institution of higher education in the United States, and who have received an offer of employment from a U.S. employer in a field related to their degree, to more quickly receive work visas.

• Recognizing that it is in our national interest to ensure that individuals who are educated in the U.S. are able to use their skills and education to benefit our country, the Administration is taking action to facilitate the employment visa process for those who have graduated from college and have a high-skilled job offer, including DACA recipients and other Dreamers.

Donations may be dropped off or shipped to:

Casa Juan Diego

4818 Rose Street Houston, TX 77007

• School supplies

• Backpacks

• Flip flops — men and women

• Jeans — men, size 28-34 waist

• Underwear — women, low-cut

• Tennis shoes — men, women & children

• Adult diapers — size medium

• Twin-size sheets

• Blankets

• Rice

• Pinto or black beans

• Coffee

• Skillets, cooking pot with lid for people setting up an apartment

Become a full-time Catholic Worker. Room & board and health insurance provided. Married couples welcome. If you can help, please email us at info@cjd.org.

Casa Juan Diego was founded in 1980, following the Catholic Worker model of Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin, to serve immigrants and refugees and the poor. From one small house it has grown to ten houses. Casa Juan Diego publishes a newspaper, the Houston Catholic Worker, four times a year to share the values of the Catholic Worker movement and the stories of the immigrants and refugees uprooted by the realities of the global economy.

• Food Donation Central Office: 4818 Rose, Houston, TX 77007

• Women’s House of Hospitality: Hospitality and services for immigrant women and children

• Assistance to paralyzed or seriously ill immigrants living in the community.

Casa Don Marcos Men’s House: For refugee men new to the country.

Casa Don Bosco: For sick and wounded men.

• Casa Maria Social Service Center and Medical Clinic: 6101 Edgemoor, Houston, TX 77081

Casa Juan Diego Medical Clinic

• Food Distribution Center: 4818 Rose, Houston, TX 77007

• Liturgy: In Spanish Wednesdays at 7:00 p.m. 4811 Lillian at Shepherd

Funding:

Casa Juan Diego is funded by voluntary contributions.

EDITORS Louise Zwick & Susan Gallagher

TRANSLATORS Blanca Flores, Sofía Rubio

CATHOLIC WORKERS Dawn McCarty, Marie Abernethy Sophia Torcelino, Kevin Mcleod Joachim Zwick, Louise Zwick

TECHNICAL DIRECTOR Joachim Zwick

DESIGN Bea Garcia Castillo

CIRCULATION Stephen Lucas

AYUDANTES TEAM........................... Wilmer Salazar, Ramiro Rescalvo

Julian Juárez, Daniel De la Garza, Juan Manuel Chavez, José Muñoz Dieso Contreras, Carlos Martinez, Alex Giron, Jhon Valencia Wilfredy Martinez, Julio Hurtado

PERMANENT SUPPORT GROUP................ Louise Zwick, Stephen Lucas

Dawn McCarty, Andy Durham, Betsy Escobar, Kent Keith

Julia Gallagher, Monica Creixell, Pam Janks Monica Hatcher, Joachim Zwick

VOLUNTEER DOCTORS................................. Drs. John Butler, Yu Wah Wm. Lindsey, Laura Porterfield

Darío Zuñiga, Roseanne Popp, CCVI, Enrique Batres

Homero Anchondo, Deepa Iyengar, Mohammed Zare

Maya Mayekar, Joan Killen, Stella Fitzgibbons

VOLUNTEER DENTISTS.................Drs. Justin Seaman, Michael Morris

Peter Gambertoglio, Mercedes Berger, Jose Lopez

Maged Shokralla, Florence Zare

CASA MARIA.....................................Juliana Zapata and Manuel Soto

Casa Juan Diego

P.O.Box 70113

By Dawn McCarty, Ph.D., LMSW

When asked what we do at Casa Juan Diego, I used to respond with generalities, abstractions that didn’t really answer the question. Over the years, though, I have responded more and more by telling stories about what happens when Catholic Workers and newly arriving migrant persons interact. Although each story is unique, they do fall into patterns, patterns that have changed over the years. Here are some stories with added context that illustrate what is happening now.

From the medical center: “We have a pregnant woman here at the hospital. Could you receive her? She has been in the country for about two weeks. She had some pain with her pregnancy, but she is OK. She is alone.”

Caring for pregnant women in crisis is always an important part of our work. It is hard work because making sure that we have a healthy baby and mother takes a lot of time and effort for an overburdened staff. But this is where we put our values into action most clearly. This is what it means to us to be pro-life.

Another hospital pleaded with us to receive a mother, new to the country, with her threeweek old. Someone had given the mother and baby a temporary place to stay as a sponsor, but each day told her she would have to leave. The social worker was very concerned about postpartum depression.

Mothers experiencing postpartum symptoms do well at Casa Juan Diego. We are a nurturing community, and a new mother that has been separated from her home and culture needs extra support in every way.

We received a family: father, mother, and daughter, newly arrived from South America. The next morning the man was spitting-up blood. When we got him to the hospital, he was diagnosed with pneumonia. We thank God for Ben Taub Hospital and the Harris Health system.

We are most grateful to the Harris Health System. It isn’t just that they meet individual health care needs, their work protects our entire community through providing access to prevention and treatment.

A young woman arrived at Casa Juan Diego after a long journey. She was offered food. She said she only wanted to sleep. She and the other women who accompanied her on the trip had walked in the Darién jungle in Panama for three days and nights without stopping to rest. They feared for their lives because of wild animals and the possible violence from human attackers.

We see many symptoms of PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) in new arrivals. The physical and emotional ramifications of their well-founded fear and experiences of robbery, physical and sexual assault, and just the toll to a body of walking day after day in a hellish environment causes trauma to all; they all need our vigilant care and attention, some much more than others.

A private hospital called to ask us to receive a man whose foot was badly injured on his journey. He could walk on crutches so he could care for himself. After a few days we were able to unite him with his family.

Over the past year, most migrants arriving at the US border have crossed, mainly by foot, much of the continent and more. The first few days at Casa Juan Diego always includes some level of triage. New guests will need shoes, clothes, ways to contact family if needed, a medical consult, and always a lot of safety and emotional support. We celebrate together the miracle that they have arrived at all.

“I heard that you give out groceries. What do I have to bring to receive food?” Our response is always the same, “nothing”. Our food is humble but nutritious, and we are happy to share it with those in need.

We receive this kind of call several times a day and we speak out often about the great amount of food insecurity in our immigrant community. People that work irregular jobs can’t “prove” their income, and now, post Covid, as food prices rise, our food distribution at Casa Juan Diego has doubled again. We have an insight into the wellbeing of the larger community in this way. It burdens us greatly and motivates us to try our best to keep up with the demand.

continued page 7

By Mattie Jenkins

A particular refrain has tethered itself to me these last months.

I could compare it to the set of keys I carry daily in my right pocket, Notre Dame lanyard swinging happily by my side, keeping me company as I stroll through the house, dodging bodies in the entrada, zipping through the comedor, taking the stairs two at a time, and then back down again, two, three, eighteen times a day. As I open the front door, the port of entry to Casa Juan Diego’s women’s house and food distribution center, my fingers instinctively brush my right thigh, making sure that I won’t be locked out if it closes behind me and I’ve forgotten to prop it with the boulder. Here, these keys are essential, as much a part of my job as orienting guests to the organized chaos of our humble House of Hospitality. The keys and I are inseparable, and no matter how forgetful I am, they always seem to be there, faithfully.

And so it has been with this refrain.

“Love in action is a harsh and dreadful thing, compared with love in dreams.” Dorothy Day liked to re-quote this, from Dostoevsky’s novel, The Brothers Karamazov. But what does it mean? Why is love (specifically: love in action) “harsh and dreadful”? To whom do these words apply?

Six months ago, I would have imperiously asserted that these words apply to those situations in which someone must face “hard love.” That is, love that doesn’t feel soft or gentle, and indeed may not feel like love at all, but is in that person’s best interest (or rather, what I consider that person’s best interest). In short, I probably would have used this maxim to justify not giving the love of God full rein in my life to fall full force upon the human being in front of me, because I am too busy to be bothered or too tired to be kind. Or too apathetic to find love hidden amidst the ordinary.

A dear friend and mentor of mine is frequently heard to state, “Everyone wants to be a hero, but no one wants to be heroic.” We celebrate heroism as a society, and I confess that I have fancied myself a hero; I frequently imagined committing some grand, noble deed. The greater the sacrifice required, the stronger the pull to do it. But the difficulty was that the acts of heroism in my dreams were usually momentary: one choice made at a fixed point in time. They had to be, for “all I have to give” could only be given once. Tragically, this heroic streak has unwittingly wedded itself to my understanding and definition of love: real love has meant being a hero in a conspicuous, limitless sense.

My dreams of love and heroism did not account for interminable sacrifices, such as caring for someone who is dying, whose care requires long-suffering and diligent companionship. They never accounted for standing beside a 16 year old girl as she buried her first child. They didn’t account for the absurdity of being able to do little more than hand someone a sandwich and an apple but not pay their rent for the next month, not to mention giving them dignified work and prospects of adequate healthcare, education, time to rest and enjoy family. They didn’t account for facing the daily tasks of handing out laundry soap, refilling the sugar bowl, answering a litany of questions in the middle of trying to heat up and serve lunch, all under the weight of fatigue that has piled up after strings of late nights and early mornings. They didn’t account for my lack of patience, my frustrations, my need for sleep and quiet time, because to admit need and limitations was to relinquish my role as the hero. My heroic notions did not take into account my limitations, only my vision of who I would want to be.

But the last eight months at Casa Juan Diego have cast new light on Dostoevsky’s words about what it means to love. I have come to see a fuller, more pragmatic picture of love. When the opportunity has presented itself to put love into action, I have time and again been faced with the awareness of how far I have to go. In a nutshell, I have

realized the great gap between the love I imagined in my dreams, and this business of truly acting for the good of the other, and the longer I spend here, the more I realize that this phrase is not to be used lightly. That is, love being harsh and dreadful isn’t a trite quip that I can make to myself or anyone else - it is a serious declaration of what love is, and one earns the right to say what love is after some amount of time experiencing it as harsh and dreadful.

Love in action is harsh and dreadful because it asks me to have an unnatural faith that the act of loving means something, even when I do not see the fruit immediately. Love in action is harsh and dreadful because life is harsh and dreadful. Love in action is harsh and dreadful because it rarely has the satisfaction of feeling heroic. Love in action is harsh and dreadful because it will indeed ask more of me than I am able to give, it will defy my heroic notions as I am confronted by these limitations in the act of trying to love., and so love in action harshly reacquaints me with my identity. Harsh and dreadful love is the faith that even actions taken imperfectly are still love because they are taken with the intent to love, not to be a hero.

But mercifully, this statement hinges on a comparison: love in action is harsh and dreadful compared with love in dreams. Could it be, then, that if I surrender my dreams and definitions of what it means to love and allow an infinitely merciful Savior to be the hero, love in action will pass beyond something harsh and dreadful to something pleasant and blissful? Or perhaps it will always be jarring, as imperfection is reshaped on this pilgrimage to our heavenly home. Either way, I know that I will always need the reminder of Dostoevsky’s words, and it will continue to be as essential to me as my keys are to my job at Casa Juan Diego. And though I will hand over those keys at the end of my time here, this refrain will continue to be my faithful and indispensable companion as I press onward, doing my best to love.

In the Catholic Church a Jubilee Year is celebrated every 25 years. As in other Jubilee Years, many will go to Rome on pilgrimage during the coming year for this event. Pope Francis has announced that the Jubilee Year for 2025 will begin with the opening of the Holy Door of St Peter’s Basilica on Christmas Eve, 2024. Later, on December 29. the Pope will open the Holy Door of St John Lateran, the Cathedral of Rome. On the same day, every Cathedral and co-Cathedral throughout the world will have Mass celebrated by the local Bishop to mark the opening of the Jubilee. The Jubilee Year will close on Epiphany 2026. The celebration of a Year of Jubilee comes from the tradition of a year of Jubilee every fifty years in the Old Testament, which the restitution of land to the original owners, the remission of debts, and the liberation of slaves was decreed. The Jubilee Year is an opportunity to respond to God’s call to turn to him and to pursue justice. In the Jubilee Year of 2000 many Christians joined together to call for cancellation of debt owed by the world’s poorest countries. Excerpts follow:

In the Catholic Church a Jubilee or Holy Year is a special year or forgiveness and reconciliation in which people are invited to come back to a closer relationship with God and with one another. This year’s Jubilee theme is hope. Our Holy Father invites us to hope for our own lives in the fullness of the faith, but especially encourages us to bring hope to others: “Christian hope does not deceive or disappoint because it is grounded in the certainty that nothing and no one may ever separate us from God’s love.” In his announcement of the Jubilee Year, Pope Francis outlines many ways of reading the signs of the times today, working for peace, justice for the poor, and giving people hope. “If we really wish to prepare a path to peace in our world, let us commit ourselves to remedying the remote causes of injustice, settling unjust and unpayable debts, and feeding the hungry.”

“I think of prisoners… I propose that in this Jubilee Year governments undertake initiatives aimed at restoring hope; forms of amnesty or pardon meant to help individuals regain confidence in themselves and in society; and programs of reintegration in the community, including a concrete commitment to respect for law. “This is an ancient appeal, one drawn from the word of God, whose wisdom remains ever timely. It calls for acts of clemency and liberation that enable new beginnings: “You shall hallow the fiftieth year and you shall proclaim liberty throughout the land to all its inhabitants” (Lev 25:10). This institution of the Mosaic law was later taken up by the prophet Isaiah: “The Lord has sent me to bring good news to the oppressed, to bind up the brokenhearted, to proclaim liberty to the captives and release to the prisoners, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor” (Is 61:1-2). Jesus made those words his own at the beginning of his ministry, presenting himself as the fulfilment of the “year of the Lord’s favor” (cf. Lk 4:18-19).

“Signs of hope should also be shown to the sick, at home or in hospital. Their sufferings can be allayed by the closeness and affection of those who visit them. “Inclusive attention should also be given to all those in particularly difficult situations, who experience their own weaknesses and limitations, especially those affected by illnesses or disabilities that severely restrict their personal independence and freedom. Care given to them is a hymn to human dignity, a song of hope that calls for the choral participation of society as a whole.

continued from page 5

“Echoing the age-old message of the prophets, the Jubilee reminds us that the goods of the earth are not destined for a privileged few, but for everyone… Here I think especially of those who lack water and food: hunger is a scandal, an open wound on the body of our humanity, and it summons all of us to a serious examination of conscience. I renew my appeal that “with the money spent on weapons and other military expenditures, let us establish a global fund that can finally put an end to hunger and favor development in the most impoverished countries, so that their citizens will not resort to violent or illusory situations, or have to leave their countries in order to seek a more dignified life”. [8] “Another heartfelt appeal that I would make in light of the coming Jubilee is directed to the more affluent nations. I ask that they acknowledge the gravity of so many of their past decisions and determine to forgive the debts of countries that will never be able to repay them. More than a question of generosity, this is a matter of justice. It is made all the more serious today by a new form of injustice which we increasingly recognize, namely, that “a true ‘ecological debt’ exists, particularly between the global North and South, connected to commercial imbalances with effects on the environment and the disproportionate use of natural resources by certain countries over long periods of time”. [9] “As sacred Scripture teaches, the earth is the Lord’s and all of us dwell in it as ‘aliens and tenants’.” ( Lev 25:23).

“In our journey towards the Jubilee, let us return to Scripture and realize that it speaks to us in these words: “May we who have taken refuge in him be strongly encouraged to seize the hope set before us. We have this hope, a sure and steadfast anchor of the soul, a hope that enters the inner shrine behind the curtain, where Jesus, a forerunner on our behalf, has entered” (Heb 6:18-20). Those words are a forceful encouragement for us never to lose the hope we have been given, to hold fast to that hope and to find in God our refuge and our strength. “The image of the anchor is eloquent; it helps us to recognize the stability and security that is ours amid the troubled waters of this life, provided we entrust ourselves to the Lord Jesus. The storms that buffet us will never prevail, for we are firmly anchored in the hope born of grace, which enables us to live in Christ and to overcome sin, fear and death. This hope, which transcends life’s fleeting pleasures and the achievement of our immediate goals, makes us rise above our trials and difficulties, and inspires us to keep pressing forward, never losing sight of the grandeur of the heavenly goal to which we have been called.”

“Signs of hope should also be present for migrants who leave their homelands behind in search of a better life for themselves and for their families. “May the Christian community always be prepared to defend the rights of those who are most vulnerable, opening wide its doors to welcome them, lest anyone ever be robbed of the hope of a better future. May the Lord’s words in the great parable of the Last Judgement always find an echo in our hearts: “I was a stranger and you welcomed me” for “just as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers and sisters, you did it to me” (Mt 25:35.40).

To read the entire document: Spes Non Confundit, Bull of Indiction of the Ordinary Jubilee of the Year 2025: https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/bulls/documents/20240509_spes-non-confundit_bollagiubileo2025.html

By Dorothy Day

God is on the side of even the unworthy poor, as we know from the story Jesus told of His Father and the prodigal son. Charles Péguy,in God Speaks, has explained it perfectly. Readers may object that the prodigal son returned to his father’s house. But, who knows, he might have gone out and squandered money on the next Saturday night; he might have refused to help with the farm work, and asked to be sent to finish his education instead, thereby further incurring his brother’s righteous wrath, and the war between the worker and the intellectual, or the conservative and the radical, would be on. Jesus has another answer to that one: to forgive one’s brother seventy times seven. There are always answers, although they are not always calculated to soothe.

By Dorothy Day

Within The Catholic Worker, there has always been emphasis placed on the works of mercy, feeding the hungry, clothing the naked, sheltering the harborless, that it has seemed to many of our intellectuals a top-heavy performance. There was early criticism that we were taking on ”rotten lumber that would sink the ship.” “Derelict” was the term used most often. As though Jesus did not come to live with the lost, to save the lost, to save the lost, to show them the way. His love was always shown most tenderly to the poor, the derelict, the prodigal son, so that he would leave the ninetynine just ones to go after the one.

continued from page 3

Child Protective Services called to ask if we could take in a woman so that she could be reunited with her infant. She had been beaten by her husband and called the police. After the police intervention, she had nowhere to live, so CPS removed her baby. Now the baby is three months old and becoming reacquainted with the mother at Casa. We were glad to receive her.

There are too few shelters and supports for women that are battered, an issue made worse for new migrant women that don’t understand our laws or trust the authorities. Women can’t leave abusive partners if they have nowhere to go.

“We have just arrived in the United States. Could you help us with a place to stay for a few days?” Many young men come to us. Some come with their wives and children. Others are here to try to help their families in their home country. Their anxiety to work is palpable and heartbreaking at times. They don’t understand their new reality.

Some of the asylum seekers that have been processed at the border and allowed to legally remain in the United States pending their day in immigration court have family, friends, or sponsors in the U.S. willing to support them until they can get a work permit. They stay with us a few days until we can reunite them with their families. Increasingly, though, those who show up at our door have no one to help them. They are ineligible for any kind of government support; they cannot work to support themselves without a work permit. Getting one is a bureaucratic nightmare, possibly taking more than six months depending upon your home country. A Catch 22 - they are legally in this country but cannot legally work. Those who are willing to hire them take advantage of their desperate situation and offer work that is dangerous and demeaning, and often just refuse to pay them (or pay fairly) when the job is done. Preventing and protecting new arrivals from exploitation takes much of our time and attention.

In all these interactions, and the hundreds more each week, we work in solidarity with migrant persons, asylum seekers, and refugees that are needing help now; trying to set an example as Catholic Workers of a society that is more compassionate and more equitable, one loving Act of Mercy at a time. You are welcome to join us.

it into a ‘new creature’- making it holy. “(Peters, p. 237). These priests clarified that a life of faith with a supernatural perspective in mind could not be confused with trying to identify the nationstate and its institutions as sacred, on a par with salvation history.

In the light of that supernatural destiny and the plan of God for the salvation of all people, it is hard to understand the turn today toward supernationalism, harsh authoritarianism, rejection of whole groups of people, and Machiavellian plots, far from the prayer of the Nazarene that we all may be one in His name.

The importance of the theology of Henri de Lubac cannot be underestimated in these times when there is a concern about dictatorships and conflating Christianity with extreme nationalism. The threats of authoritarianism and exclusion of people on the basis of ethnonationalism of today remind us of the crises of the twentieth century. De Lubac’s insights and his courage were remarkable in confronting those realities. It turns out that theology does make a difference in real life.

Jesus said, My kingdom is not of this world. The challenge, the question of the possibility of confusing the reign of God with a very imperfect nation is not new.

Henri De Lubac, one of the most important theologians in the twentieth century, brought the insights of the Fathers of the Church to not only theology, but to the problems of tyranny in his time. De Lubac was not always understood or appreciated. His theology was criticized by those who wanted to keep the neoscholastic status quo in theology, and for a significant time he was forbidden to teach.

We have been aware of how de Lubac was “alienated by the politics closely associated with the neoscholastic model in France among the clergy, where neoscholasticism sometimes went hand in hand with support for the far-right nationalist and royalist movement known as the Action française, condemned in 1926,” but De Lubac was also a part of the resistance under Hitler. Benjamin Peters pointed out how the opponents of De Lubac’s theology used neoscholasticism to attack his early work. His main critic, Fr. Garrigou-La Grange, O.P., later supported the Vichy government, the Nazi regime’s takeover of France, in contrast to de Lubac’s courageous writings and stand against Hitler’s regime. (See Benjamin Peters, Called to Be Saints: John Hugo, the Catholic Worker, and a Theology of Radical Christianity (157-158).

including the following: “Through his work, a believer’s itinerary emerges: a faith which is attentive to the problems of the times, rooted in the experience of God, nourished by Scripture, and attached to the life of the Church. “

Recent books and articles about Henri de Lubac’s work are bringing to us a deeper understanding of his faith, even mysticism, and the relevance of his insights in theology and Church history for the crises in today’s world. His immersion in the Mystery of Christ and his study of the Fathers of the Church permeated de Lubac’s work, and his understanding of the social nature of the Eucharist and the Body of Christ brought to the world a new awareness of the meaning of history and the common destiny of humankind.

Susan Wood, SCL, described his mysticism as one with a perspective somewhat unusual in the way mysticism is often understood: “De Lubac’s

continued from page 1

Not only is De Lubac considered by many to be one the most important theologians, if not the most important theologian of the twentieth century, he also continues to influence studies of secular history. In researching how secularization and the secular nation-state developed, historians have since 1957 been citing de Lubac’s theological work. These studies are quite relevant to the problems of extreme nationalism (to be distinguished from patriotism) to today’s political realities.

Several recent studies of de Lubac’s work including those of Sarah Shortall, Andrew Prevot, and Eugene Schlesinger, emphasize de Lubac’s study of the shift in language in medieval theology from the use of the terminology of the early Church about the Eucharist as the Mystical Body, to applying that term rather to the Church. Rather than speaking of the three bodies of Christ, medieval theology with its scholastic distinctions, wrote of only two. In his book Corpus Mysticum, De Lubac argued that this shift happened at least partly because of the hope of one medieval Pope of a renewed theocracy based on this concept. De Lubac contended that the medieval shift in theology to describe the Church as the Mystical Body of Christ , a theology that was not closely associated with the Eucharist, was open to misinterpretation and even the political use of ecclesiastical words and symbols.

mysticism is a discovery of spiritual meaning in historical realities. It is thus a mysticism of the incarnate rather than an escape to something otherworldly or disembodied.” (Susan Wood, quoted by Andrew Prevot, “Henri de Lubac (18961991) and Contemporary Mystical Theology” in A Companion to Jesuit Mysticism, edited by Robert A. Markys. Brill, 2017 (280).

Shortall defines the terms: While Jesus is one person, the three bodies of Christ presented by the Church Fathers are 1) the physical body of the Christ of the Incarnation who died on the cross, was resurrected and ascended into heaven, 2) the Eucharist, and 3) the Church. The early Church used the term Mystical Body to refer to the Eucharist. It is fascinating to read with Sarah Shortall, a professor at Notre Dame, how Catholic theology influenced the development of the secular state. She shows how historians fairly recently discovered through de Lubac’s writings that the shift in medieval theology affected the idea of the divine right of kings and facilitated the transition to an almost divine view of the newly emerging secular state. The historians quoted by Sarah Shortall, Ernest Kantorowicz and Marcel Gauchet, studied de Lubac’s book Corpus Mysticum, and cited it extensively in their interpretation of the rationale used to make the new secular nationstate seem sacred.

De Lubac was named a cardinal by Pope John Paul II in 1983. The French bishops have begun his cause for beatification. With the announcement of the opening of his cause, the Jesuits put out a statement about his life of faith and his work,

Benjamin Peters called De Lubac’s mysticism “practical mysticism” (155).

Shortall describes the way in which nations mimicked and took advantage of the language that medieval theologians and some Popes had used to describe the Church. She brings the idea of Kantorowics that somehow with the development of secular states, this morphed into the king being one “sacred” body and the nation-state being another — two bodies instead of the three bodies of Christ in earlier theology. The concept of the

King’s two bodies was, according to Kantorowicz, a “legal fiction”: an individual, mortal body and an immortal body politic. Shortall points out that some nations, with these concepts equating the Church as a juridical body like any other, even called their countries a “mystical body” appropriating the term to hallow their own institutions.

The appeal to theocracy continues to be a concern as not only Christian(?) nationalists but some sincere young Catholics become enamored of this idea.

De Lubac was very aware that the political dangers of misunderstandings of the mystical-body theology were not limited to the medieval past. He was concerned that calling the Church the Mystical Body might be playing into the hands of those who would use it to support an extreme nationalism which would harm many people. He observed that the terminology was being used by Catholics in the liturgical movement, especially the German liturgical movement in the nineteen thirties, appealing to the desire for community and bringing people together. He was concerned that this could be confused with the “goals of earthly communities like the nation, race, or class” and could be used to support authoritarian and fascist regimes.

These dire predictions turned out to be true. Karl Adam, a theologian widely read at the time, who wrote the book The Spirit of Catholicism, actually put together the concept of the Mystical Body with the ideology of the Third Reich in an article in 1933, “to argue that ethnonational identity (something he defined in terms of ‘blood purity’) was in no way incompatible with the universality of the Church.”

De Lubac sought, as Shortall describes it, “to carve out a way for the Church to be in but not of the secular public sphere, and to articulate a Catholic alternative to both liberalism [classical liberalism, not to be easily equated with political liberalism today] and the growing threat of ‘totalitarian’ ideologies. He found the resources for this model by turning back to the work of the Church Fathers, who had been overshadowed by the dominance of neoscholasticism. He was also drawn to the ecclesiology of the Church Fathers, which allowed him to frame the Church as the only human institution capable of transcending the excesses of both liberal individualism and totalitarian collectivism.”

Shortall suggests that de Lubac’s idea of conceiving of the Church as a ‘mystical body’ not closely linked to the Eucharist risked not only its being misused politically, but also led to the weakening of the idea of solidarity among members of the Church. For de Lubac, “Its effect was to individualize Eucharistic piety and dilute ecclesial solidarity by disarticulating the celebration of the Eucharist from the edification of the ecclesial community.”

In Corpus Mysticum, de Lubac famously declared, “Quite literally, the Eucharist makes the Church… Through its hidden power, the members of the body achieve unity among themselves by becoming more fully members of Christ.” The Church Fathers

had understood that the mystery and significance of the Eucharist lay not just in an individual communion with the divine, but the Eucharist was thus an indispensably social affair.

As Prevot writes, “One of de Lubac’s central concerns here is to resituate Catholic Eucharistic devotion in the full Christian reality of ecclesial existence and thereby to combat the dangers of an overly individualistic or abstract Eucharistic piety. Nevertheless, in the end, de Lubac does not call for a reversion to the previous terminological practices but rather a more adequate awareness…of the entire interconnected threefold body of Christ.” Prevot (292)

Francis

De Lubac’s “The Eucharist makes the Church’ can help us to understand that Communion is not meant to be individualistic. In the Angelus this year on the Feast of Corpus Christi, Pope Francis reflected on the meaning of the Eucharist for our lives and the lives of others, beyond personal consolation. Excerpts follow:

“The Gospel of the liturgy today tells us about the Last Supper (Mk 14:12-26), during which the Lord performs a gesture of handing over: in fact, in the broken bread and in the chalice offered to the disciples, it is He who gives Himself for all humanity, and offers Himself for the life of the world. In that gesture of Jesus who breaks the bread, there is an important aspect that the Gospel emphasizes with the words “he gave it to them” (v. 22). Let us fix these words in our heart: he gave it to them. Indeed, the Eucharist recalls first and foremost the dimension of the gift. Jesus takes the bread not to consume it by Himself, but to break it and give it to the disciples, thus revealing His identity and His mission. He did not keep life for Himself, but gave it to us; He did not consider His being as God a jealously-held treasure, but stripped Himself of His glory to share our humanity and let us enter eternal life (cf. Phil 2:1-11). Jesus made a gift of His entire life. Let us remember this: Jesus made a gift of His entire life. Let us understand, then, that celebrating the Eucharist and eating this Bread is not an act of worship detached from life or a mere moment of personal consolation; we must always remember that Jesus took the bread, broke it and gave it to them and, therefore, communion with Him makes us capable of also becoming bread broken for others, capable of sharing what we are and what we have.We are called to become people who no longer live for themselves (cf. Rm 14:7), no, in the logic of possession, of consumption, no, people who know how to make their own life a gift for others, yes. Thanks to the Eucharist, we become prophets and builders of a new world: when we overcome selfishness and open ourselves up to love, when we cultivate bonds of fraternity, when we participate in the sufferings of our brothers and sisters and share bread and resources

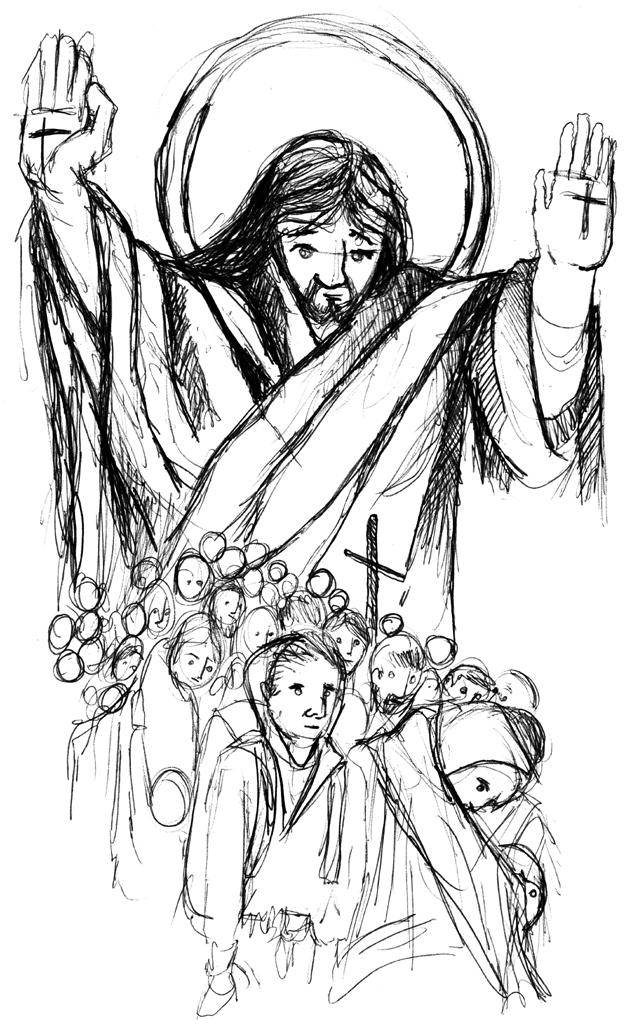

Artist: Fritz Eichenberg

with those in need, when we make all our talents available, then we are breaking the bread of our life like Jesus.”

REFERENCES

Henri de Lubac, SJ, Catholicism: Christ and the Common Destiny of Man. Ignatius Press, 1988.

Henri de Lubac,SJ, Corpus Mysticum: The Eucharist and the Church in the Middle Ages. Paris, 1944. University of Notre Dame Press in English, 2006.

Benjamin T. Peters, Called to Be Saints: John Hugo, the Catholic Worker, and a Theology of Radical Christianity. Marquette University Press, 2016.

Andrew Prevot, “Henri de Lubac (1896-1991) and Contemporary Mystical Theology” in A Companion to Jesuit Mysticism, edited by Robert A. Markys. Brill, 2017.

Eugene R. Schlesinger, Salvation in Henri de Lubac: Divine Grace, Human Nature, and the Mystery of the Cross. University of Notre Dame, 2023.

Sarah Shortall, “From the Three Bodies of Christ to the King’s Two Bodies: The Theological Origins of Secularization Theory” Modern Intellectual History, Vol. 20, Issue 3, September 2022 https://www.cambridge.org/core/ journals/modern-intellectual-history/ article/from-the-three-bodies-of-christ-to-the-kings-twobodies-the-theological-origins-of-secularization-theory/ B656DD46715495626101EF2200F1047D

Thanks to Noemí Flores with help in editing this article.