CATHOLIC WORKER

How does one continue the Works of Mercy in the midst of a pandemic?

How can one help to keep faith and hope alive when people are worried and anxious and ill and some in their desperation become angry and have even sought scapegoats?

We often hear of the importance of developing antibodies to protect from the new Coronavirus. There is a great deal of uncertainty, though, about whether COVID-19 antibodies can actually ensure that the person who has recovered from the illness is immune to another infection. Questions have arisen about whether various antibody tests are accurate. Perhaps Catholic antibodies may offer some of the best protection going forward as we try to rebuild our world in the aftermath of this crisis.

Fr. Antonio Spadaro, SJ, editor of La Civilta Cattolica in Rome, gives us a clue of how to respond when he speaks of the Catholic antibodies that can eradicate the virus of fear that overwhelms many — not only the fear of death from the Coronavirus, but fear of the future, fear and suspicion of strangers, of people who are of different cultures, a fear that contact with the other, “the different,” is a risk of contagion of a different sort than a Coronavirus. Spadaro calls this fear of the future and of the other, a virus of the soul. Presenting the idea that Catholic antibodies can be activated against the virus, the pandemic of fear, anxiety and even hatred in our social and political life, Fr. Spadaro quotes Pope Pius XI, who spoke in 1938 during the Nazis rise to power. He says Pope Pius made it clear at that time how Catholicism possesses

the antibodies to eradicate the virus of nationalism (a nationalism very different from a positive love of country), which has raised its head again in our time. Pope Pius said, “Catholic means universal, not racist, not nationalistic, not separatist. Such ideologies are not Christian, but they end up not even being human.”

As Spadaro puts it, “Unlike marketimposed globalization, the Catholic vision is universal and places the person and peoples at the center, recognizing the other, the outsider and the different as a brother and sister.”

With Catholic antibodies, we can face the viruses around us – COVID-19, but also the viruses of the soul. Catholic antibodies can help us address injustices which have quietly existed, but are now coming into light with the realities of the Coronavirus as it tears apart people’s lives and families and communities.

Glaring inequalities in income, health care, and food insecurity have become more obvious as the crisis has deepened. Reports are coming out each day that the working poor and people of color are suffering more than others from the crisis caused by the Coronavirus. Those who have not been able to afford adequate health care in the past are more at risk. Not only those who are out of work because of stay at home recommendations, but especially those who were already poor are suffering. Aid groups and the United Nations are warning that we are on the brink of a pandemic of hunger. in many countries.

There is a great need for an infusion of Catholic solidarity worldwide.

Pope Francis has also used the terminology of Catholic antibodies on several occasions recently. First, in his unique Urbi et Orbi message at this time of year during the Coronavirus crisis. He spoke of these special antibodies in the context of the storm when the disciples in the boat are afraid. The Lord says to the frightened disciples, “Why are you afraid? Have you no faith?” Pope Francis applies their experience of the storm to that of our lives today:

“The tempest lays bare all our prepackaged ideas and forgetfulness of what nourishes our people’s

souls; all those attempts that anesthetize us with ways of thinking and acting that supposedly ‘save’ us, but instead prove incapable of putting us in touch with our roots and keeping alive the memory of those who have gone before us. We deprive ourselves of the antibodies we need to confront adversity.”

Catholic antibodies can help us to go beyond our own worries to concern for others in the world crises we face now and that we will grapple with in the coming months.

In his article on the web site of the Spanish-language (continued page 8)

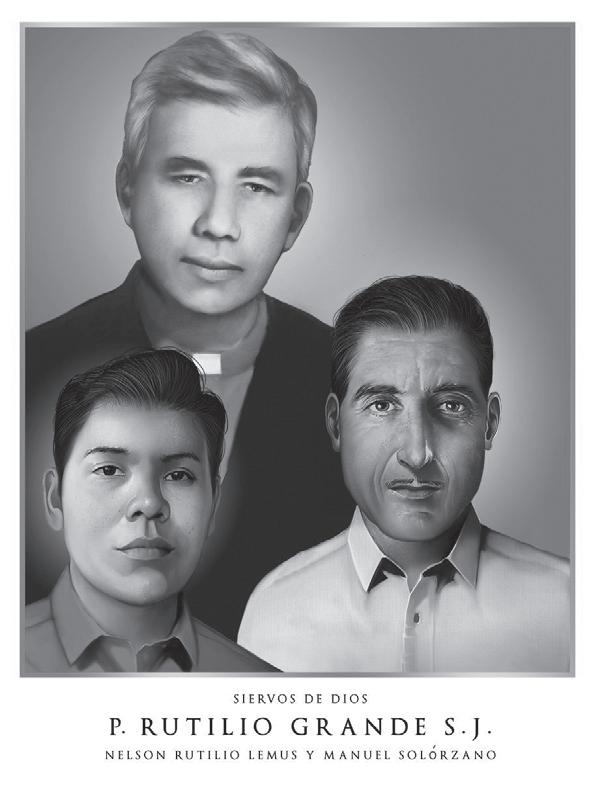

On Saturday, February 22, a Mass of Thanksgiving was celebrated for the promulgation of the degree of martyrdom of Jesuit Father Rutilio Grande and his companions Manuel Soaalorzano and Nelson Rutilio Lemus.

Fr. Rutilio Grande Garcia was assassinated together with the two lay people named above. His death marked a turning point in the life of Saint Oscar Romero.

Reflecting on spending the night at the wake for Father Rutilio, Archbishop Romero said, “That night I felt a divine inspiration to be courageous and have a spirit of fortitude, while in the country, scourged by social injustice, the violence increased: the violence of the oligarchy against the farm workers, violence of the military against the Church which defended he poor, the violence of the revolutionary guerrillas.

Mark Zwick, founder of Casa Juan Diego, attended Rutilio Grande’s last Mass when the Zwick family lived in El Salvador in 1977.

In the time of coronavirus, things at Casa Juan Diego haven’t changed so much as they’ve been clarified. We are still a house of hospitality. We still distribute food, medicine, and other necessities. We still begin our days in prayer. The days, however, are tinged with a particular urgency and intensity that were not as apparent in previous months, and they have helped me to see more clearly how the Houston Catholic Worker operates.

The fear of scarcity that has swept our world makes itself present, both in the ringing of our doorbell and in my own heart. The bell rings throughout the day as the number of unemployed people grows, repeating the new refrain of our doorstep: “Are you still giving food?”. In response, we’re learning a new rhythm that keeps us on our toes and ever-reliant on God’s grace. We give what we have, then worry that we don’t have enough. We pray, then someone arrives at our door with a car full of food. The cycle repeats itself daily.

The house has been reminding me of lungs, inhaling and exhaling at a rate that intellectually is exhausting but is also the only way to survive. And just as the air that we breathe is a gift and the fact we can breathe is a miracle, this daily rhythm of our house is saturated in the gift, mystery, and mercy of God. In a time of isolation and fear, Casa Juan Diego has been loved and supported by so many. What an honor to be part of a community with ties that aren’t broken by six feet of distance!

If the illusion of youth is invincibility, then perhaps the illusion of adulthood is security. As our preoccupations shift from a juvenile world of needs and wants to those of our loved ones, it is natural to want to secure a future for all our sakes. One prepares for the day when children go to college or when parents need assisted-living, the day when we will finally climb Mount Kilimanjaro or canoe the Amazon, all those things that require years of planning and money, all those things that presume a future. Our thoughts pass from the present moment to these potentiaal futures as naturally as a bird flying over a river.

What the COVID crisis has illuminated mostclearly to me is how quickly these wings of imagination can be clipped, which leave us staring at the endless, chaotic waters of the unknown; these taken-for-granted futures are anything but guaranteed in a time of lockdown and six-feet-apart. So here we are at Casa Juan Diego, bars boarded up and Houston bizarrely traffic-free, struggling to conceive a life post-COVID.

I was supposed to have departed Casa Juan Diego at the end of March for an extended retreat at a monastery before heading back home to Chicago for a wedding. The retreat did not happen, it remains unclear whether my friend’s wedding will go as planned, and the question presses in on us all – what will go on as planned after this? Is this just an unfortunate pause in our lives, or a deeper interruption of the world we had presumed would continue indefinitely? I think it was Dietrich Bonhoeffer who said that to believe in the Gospel is to live a faith of interruptions. And what is COVID but the greatest existential interruption that most of us will ever experience?

In the grand scheme of things the disruption of my plans is of small consequence when it is of course the poor whom are hit the hardest by crisis. Whether war, economic downturn, or pandemic, it will always be the poor, especially the immigrant and foreigner, who are hit the hardest. Hard-up even in the best of times, I’ve seen the proof in the considerable swell of people coming to Casa Juan Diego for food distribution these last few Tuesday mornings, some of them arriving at five a.m. or earlier for a bag of rice and beans and fresh produce. This world of need and solidarity has never been clearer to me, which makes my service here even more of a humbling privilege. What is youth good for if you are not willing to use its energy and health to serve God and neighbor? I am honored to be working alongside such a dedicated group of people responding to the Gospel through the unique lens of their personalities, as well as the larger circle of people donating their time and resources to ensure that Casa Juan Diego has something to give the poor Christ knocking at the door.

In his letter to the Romans, St. Paul speaks of a hope that is not seen – “For who hopes for what he sees?” (8:24). This captures our moment perfectly: we stand on one side of the shore, grounded and staring at the trembling waters, wondering how we will make it to the other side. It is hope that helps us to remember the promise of the other side, only now we recognize – often painfully – that we cannot fly by our own power into the future; it is the Spirit of God that must carry us into this new life.

Casa Juan Diego was founded in 1980, following the Catholic Worker model of Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin, to serve immigrants and refugees and the poor. From one small house it has grown to ten houses. Casa Juan Diego publishes a newspaper, the Houston Catholic Worker, six times a year to share the values of the Catholic Worker movement and the stories of the immigrants and refugees uprooted by the realities of the global economy.

• Food Donation Central Office: 4818 Rose, Houston, TX 77007

• Women’s House of Hospitality: Hospitality and services for immigrant women and children

• Assistance to paralyzed or seriously ill immigrants living in the community.

• Casa Don Marcos Men’s House: For immigrant men new to the country.

• Casa Don Bosco: For sick and wounded men.

• Casa Maria Social Service Center and Medical Clinic: 6101 Edgemoor, Houston, TX 77081

• Casa Juan Diego Medical Clinic

• Food Distribution Center: 4818 Rose, Houston, TX 77007

• Liturgy: In Spanish Wednesdays at 7:00 p.m. 4811 Lillian at Shepherd. (Temporarily Suspended)

• Funding: Casa Juan Diego is funded by voluntary contributions.

EDITORS

Louise Zwick & Susan Gallagher

TRANSLATORS Blanca Flores, Sofía Rubio Damaris Cortez, Carmen Troya Maria del Pilar Hoenack-Cadavid

CATHOLIC WORKERS Dawn McCarty, Maire Abernethy Meg Spesis, Molly Clark, Colleen Teresa Irwin Evan Bednarz, Will Kershner, Sam Tomaso

TECHNICAL DIRECTOR Joachim Zwick

DESIGN Bea Garcia Castillo

CIRCULATION Stephen Lucas

AYUDANTES TEAM Julián Juárez, Manuel Rangel, Manuel Sierra Yohimny Perez, Selvin Herrera, Roberto Narvaes Ramiro Rescalvo, Victor Díaz, Reynaldo Landaverde Felipe Servellon, Pedro Chun, Jonathan Orellana, Gerson Fajardo Marcos Lona, Carlos Hernandez, Antonio Cortez

PERMANENT SUPPORT GROUP Louise Zwick, Stephen Lucas

Dawn McCarty, Lillian Lucas, Andy Durham, Betsy Escobar Kent Keith, Pam Janks, Julia Gallagher, Monica Hatcher Alvaro & Jane Montealegre, Joachim Zwick

VOLUNTEER DOCTORS Drs. John Butler, Daniel Corredor Naggeb Abdalla, Magdy Tadros, Wm. Lindsey, Laura Porterfield

Joann Schulte, Jorge Guerreo, Sr. Roseanne Popp, CCVI

Enrique Batres, Darió Zuñiga, Cecilia Lowder, Jaime Chavarría

Amelia Averyt, Deepa Iyengar, Justo Montalvo, Mohammed Zare Joan Killen, Gary Brewton, Serena Shen-Lin

VOLUNTEER DENTISTS Drs. Peter Gambertoglio, Michael Morris

CASA MARIA

Mercedes Berger, Jose Lopez, Justin Seaman

Maged Shokralla, Florence Zare

Juliana Zapata and Manuel Soto

by Dawn McCarty, PhD, LMSW

by Dawn McCarty, PhD, LMSW

Weeks before the formal stay at home orders were issued, we were planning as best we could to take care of our guests and the many community members we serve. Casa Juan Diego is a literal hive of activity throughout the day, with constant interaction of staff with both guests and community. We have on any given night about 100 people living in our Houses of Hospitality, and people come from all over the region every day for food and supports of all types. While the guests staying in our houses are relatively easy to protect from infection by keeping distant from others, protecting the volunteers and full-time staff is another story. If nothing changed, they would continue to interact constantly with the larger community, either by answering and responding to individuals who come to the door for help, in the daily delivery of sandwiches and water to day laborers and homeless men and women, or in the distribution of food, supplies, prescriptions, and more, to hundreds of people a week.

In the first weeks as we were wondering and working on how to keep the six-foot safety zone, my anxiety grew exponentially with every unsettled response to “dos metros entre cada persona!” Spatial distance differs greatly between cultures. I fought hard against my instinct to call for a shutdown of our services to protect the staff and volunteers. It was easy to fall into my place of privilege and safety as both a citizen and a person for whom poverty is voluntary, not forced, and to assume such privilege for others close to me. The full-time staff here are mostly young people just out of college, who are entrusted to our care during their year or two of service, and I was afraid. But I reminded myself that none of them have come to Casa Juan Diego for comfort, not one. Most are giving up privilege and doting parents to be in solidarity, to serve, to love those on the margins. To love them not only in theory and prayer, but also in action. Dorothy Day, cofounder of the Catholic Worker Movement, often quoted Dostoevsky to remind Catholic Workers that “Love in action is a harsh and dreadful thing, compared to love in dreams,” an insight that has never been more relevant. Sharing voluntarily in the vulnerability of the poor, and in this case, the real possibility of exposure to illness, transforms a person for good. The staff may be tired, but they are steady and resolute. They are doing a

remarkable job of protecting themselves and those arriving for help and food, a growing precious and scarce commodity.

Putting it simply, we have adapted. Implementing and following all the new guidelines meant the reduction of some ancillary services, but our main services continue, even as the number of people needing help doubled and doubled again. During these weeks filled with anxiety and grief, my heart has been comforted and inspired by the power of our small community at Casa Juan Diego. To see in action that love for a stranger is stronger than fear, even in the heart of a global pandemic, is a miracle I attribute to the intercession of Dorothy Day, Servant of God.

Casa Juan Diego has a long history of adapting to a changing global context. Founded by Mark and Louise Zwick to serve desperate refugees fleeing civil wars in Central America, the work soon changed to include a growing number of battered women and their children. As the decades passed by, an ever-increasing number of those that are catastrophically sick, injured, or aging in a harsh environment became more and more our focus. Most recently, as the business of detaining asylum seekers for financial profit has accelerated, the work of Casa Juan Diego has expanded yet again to people incarcerated while awaiting their day in immigration court. Depending on ever-changing government policies, some of these families can be released on bail if they have a government-approved sponsor and place to stay.

So, when the immigration authorities call and ask us if we can take in a person or a family so that they can be released from detention, we always say yes. We send a letter to the detention officer that reads like a poem, telling the story and history of Casa Juan Diego in just a paragraph, and ultimately offering what I have come to think of as five magic words, words that must be the answer to a million prayers: “We are willing to receive…” While the time of the coronavirus can be dark and destabilizing, it can be a time of great insight. In “normal” times we naturally get into habitual patterns of thinking and behavior. The drastic changes in our lives that have been necessitated by the virus have the silver lining of encouraging us to see things more clearly. Here at Casa Juan Diego we are long accustomed to seeing the terrible effects of poverty on human beings - the suffering, the shortening of lives, the loss of hope. We get plenty of chances to observe the gross injustices of an economic system rigged to enrich the few at the expense of the many. But now that it is increasingly obvious to everybody that the virus is not an equal opportunity killer, that it preys disproportionately on those on the margins of society, more and more people are coming to see that the suffering, the premature and unnecessary deaths, not just of the undocumented, but of the working class in general, means that just getting back to the way things were will not be enough. To me, the greatest insight of the Catholic tradition is that we are all in this together, that depriving one part always damages the whole. We hurt and heal as one body, a fact that our hypercompetitive economic system wants to hide from us. If our neighbor has a deadly and contagious disease, it is not just her, it is all of us in trouble. Once we see that, it is easier to see that our interdependence is a part of our nature, not just a reaction to a virus. It is literally in our DNA. The revelation that we are never really disconnected, by any border, and that we need each other becomes clearer each sociallydistant day by socially-distant day.

The one thing that I can say with confidence, in a time of great uncertainty, is that when this isolation ends, we will need you, the reader. There will be a reckoning in our economic system, and a need for hands to serve and minds to discern. This is an unprecedented time of clarity and opportunity. Join us as we work to imagine and build a new world out of the ashes of the old.

When my time as a Catholic Worker at Casa Juan Diego concluded, I headed to the Rio Grande Valley, in south Texas, to spend three weeks visiting and volunteering. I had never been to this section of the U.S.-Mexico border before, but I had listened to a number of distressing accounts of [legal] border crossings recounted by our guests.

I had been following coverage of the so-called “Migrant Protection Protocol” (MPP) over the course of the last year. During my stay in the Valley, groups of protesters, positioned themselves next to the Gateway International Bridge that connects Brownsville and Matamoros, Mexico. Their signs read: “Migrant Peril Protocol.”

Dozens of Valley residents had witnessed and imparted to us the horrors of MPP with their voices, writings, and actions long before anyone else arrived on the scene.

With these thoughts in mind, I reflect on two of the families that I met while visiting the border. Luciana and Samuel (to whom I refer with aliases to protect their identities) are a Honduran couple with a daughter and a son, ages seven and five. I had the opportunity to speak with them, and they helped me understand the inner workings of the tent camp where they stay in Matamoros, in

close proximity of a few thousand other people.

The emphasis on chaos cannot be overstated, according to Samuel. When a family arrives at the camp for the first time, it is their responsibility to figure out how to proceed, often under the direction of those who arrived at the camp before them. They should report to the international bridge in order to express their necessity to seek asylum, at which point they are assigned a number that roughly offers them an indication of when they should return to have their first assessment with an agent of Customs and Border Patrol. These agents are not trained to conduct asylum screening interviews, but they have been assigned this task instead of qualified asylum officers. Before this occurs, though, a family has to steadily, daily, watch and listen carefully within the camp, so as not to lose their spot on “The List” altogether. This is difficult, as migrants are not provided any date or time at which they should return. You simply have to keep track of the progress of “The List” by maintaining communication with your neighbors. And the progress is unpredictable – some days several handfuls of people are processed, and on other days migrants are told to turn around and try again

the following day. If you lose your spot in line because you weren’t present when your number was called into the limited space next to the bridge, it is very difficult to be added to “The List” again.

Even successfully arriving at the bridge when your number is called is tremendously complicated, due to the fact that awaiting this day requires upwards of five months of living in squalid conditions. Access to sanitary bathroom facilities is scarce, parents cook for their children out of empty propane tanks, bathing and laundry are taken care of in the nearby river, which is unclean, and everyone sleeps on the bumpy dirt ground, in a tent if there is one available and totally unsheltered if not.

Luciana and Samuel now face a further challenge, as do many other parents: they chose, under the most desperate and draconian of circumstances, to create a family separation by sending their two children across the international bridge by themselves. Migrants under 18 who present themselves at the border unaccompanied, without their parents, must be admitted into the U.S., under

now in Michigan, living in foster care and waiting to hopefully be placed with relatives in a different state. That process, like all the others, has proven lengthy and onerous. The relatives are undocumented themselves, and are therefore hesitant to participate in background checks. Their daughter has a deportation order standing in her way, too, the result of missing her first expected appearance at the border while she and her father assisted her mother and brother during their final leg of the journey. The family had been separated in central Mexico. (contined page 7)

Kevin is a crucial part of Casa Juan Diego’s volunteer community at this time. At risk to himself (a retiree), he works with the increasingly important food distribution team in this time of food insecurity. Our Catholic Workers have had to orchestrate new procedures to meet rapidly changing food bank guidelines in order to distribute the food safely to a population that jumped from 300 families to 1000 families in the span of two weeks.

How I act and how I think is a test of faith. Curiously, the knowledge that none of us will survive this life on earth motivates me to embrace God’s promises. As a young boy, I realized that our mortal destinies appeared to be cruel. Love everyone, even your enemies - and the more you love, the more you will feel loss when you lose those you succeeded in loving. Then, you also die. How morbid and hopeless.

Over years and years, God’s promises and Christ’s words and actions have slowly given me growing hope, faith, and purpose. However, when life is easy and good, I find myself less motivated to love and follow Christ. Conversely, when life is doubtful and difficult, I so need God’s promises. So much irony in this life. You have to let go of your human desires to gain God’s promises. I claim to be a Christian. I claim to love God above all else. I have no purpose or hope without my Savior. I am bulletproof with Christ.

We fear cancer or any illness that will cause pain and death. We fear death of those we love. We fear global death caused by either human action or natural events. So we fear nuclear war, global warming, plagues and asteroids hitting earth. What do you do when you feel like you are on a sinking ship? In a viral pandemic, do not hoard stuff. Rather, share stuff. Isolate yourself to the extent possible because it is a way to bless the whole world. In other words, stay alone (or with whom you live) except when you are needed to help others. Police, firefighters, EMTs, doctors, nurses, and hospital workers must work. All essential workers related to caring for those in need – old, sick and poor must work smart.

For the Christian it is a time of opportunity to grow in faith. Shake the dust off your Bible and rosary again. Find brothers and sisters of Christ with faith. Read, pray, and meditate. Care for those in need, both spiritually and physically - the same things we should be doing when life is good and easy. Smile and be a light in the darkness. If anyone asks you why you are smiling – proclaim the Good News that resides in your heart. God Speed.

We are living in anxious times. Even before the onset of COVID-19, many felt profound concern in the face of increasing polarization and fragmentation of our communities. Now, with the need for social distancing and selfquarantine, it is almost as if this fragmentation has taken on literal, physical form. These days, searching for a framework to understand the signs of the times, I find myself more and more drawn to Scriptural depictions of God’s people in the wilderness -- in the desert.

As it happens, I am currently in self-quarantine on our family’s land in the country, several miles from the nearest neighbor, 45 minutes from the grocery store. It is poor land, arid and rocky. The solitude can be peaceful and good for reflection, and my husband loves it. But often for someone like me (born and raised in the city) the isolation feels like a wilderness. Nevertheless, I will be here for a while.

When we all became aware of the spread of the novel corona virus, our children asked my husband and me to stay here, rather than returning to Houston. Both children are frontline healthcare workers who have already had encounters with patients who are presumed positive for the disease. They remind me that because of my age and health history, I am at higher risk than others. They tell me that the next few weeks and months will be demanding and it will help them if they don’t have to worry about us being exposed.

Our son drove up from Houston with a load of supplies, but he wouldn’t let me touch him or hug him or get anywhere near him. He wiped all the surfaces down with disinfectant before he left. He tells me not to worry: “Everything will be alright, Momma. I’ll be alright.” Our daughter calls us each day from out of state. She says she is doing whatever work she can remotely, but she is continuing to handle many cases in person. She says, “I have to. This is the work I am called to do.” They do not say they are afraid. They and all their co-workers are in uncharted territory, adapting to new procedures

and new equipment, encountering unexpected impediments and unimagined challenges daily and sometimes hourly. It must feel like they are wandering in the wilderness – in the desert.

And while I am here in seclusion, the work of Casa Juan Diego continues. The needs of those it serves are more urgent than ever. I suspect that all the full-time Catholic Workers and parttime volunteers (a number of whom are also especially vulnerable due to age and health concerns) will be working to exhaustion. Louise has consulted with one of our volunteer doctors, who is an infectious disease specialist,

By Susan Gallagherdeeply concerned about the changes in immigration policy that leave refugees and migrants and those waiting in Mexico stranded indefinitely. Casa Juan Diego has faced crisis before, but the current situation presents novel challenges. We face uncharted territory, like ones wandering in the wilderness – in the desert.

During our times in the wilderness, when normalcy is overturned and nothing is as we had planned, it is not clear how things will unfold. This need to surrender old routines and to be uncertain of what will happen next is uncomfortable. For the people who have lost income and don’t know how they will feed

with time on my hands, I pulled down McKenzie’s Dictionary of the Bible from my shelf and looked up “wilderness”. “See Desert,” it said. In the entry for desert, I read, “Israel first met [God] in the desert and the story of the desert wandering remains the type of encounter of man and God. …[T]he desert is the place where man meets God, particularly in crisis…” (195-6).

These days do feel like a crisis and it is hard to see the path before us. I think of Thomas Merton’s famous prayer from Thoughts in Solitude: “My Lord God, I have no idea where I am going. I do not see the road ahead of me.

and we have adapted our procedures to protect the health of the Catholic Workers and those they serve. Because, virus or no virus, the injured and chronically ill who depend on Casa Juan Diego must still receive help; their prescriptions must be refilled. Refugees and immigrants must still be welcomed. And with all the economic disruption connected to closing of businesses and social distancing, more of our neighbors than ever will come to receive whatever food we can provide. Our thoughts are with the people held in immigration detention in crowded conditions that don’t allow for sufficient hand washing or social distancing. And, of course we are

and shelter their families (the undocumented families who have lost work will receive no government help) and for the essential workers and healthcare providers who risk exposure to the virus, this time of uncertainty may be a crisis.

Here in the country I am trying to pray, especially the Jesus Prayer, although often I slip into worrying instead. I am taking a lot of meandering walks, wandering around the property. In this, the 40th year of our paper’s publication, I am thinking of the Israelites 40-year sojourn in the wilderness, and of Jesus’ 40 days in the desert. These periods in the wilderness were times of trial and testing, but also of encounter. Back at the house

For some the road will lead to seclusion, for others to active engagement and exposure to risk. For all of us with willing hearts, the road will lead to encounter with God.

If we have seen reason for concern, we have also seen reason for hope. We have all heard stories of some generous and creative responses to the pandemic. My neighbors in Houston have been organizing a system of volunteers to run errands and bring supplies to those in the neighborhood who shouldn’t go out. I know of several businesses who have distributed free food or cleaning supplies to their neighborhoods. Many of us have read about the Texas distillery and the French perfume manufacturer who are making and distributing hand sanitizer at no charge. Essential workers—grocers, drivers, clerks, healthcare workers, IT technicians, first responders, and Catholic Workers — report to work despite the risks. We have all been touched by reports of people in Italy going out on their balconies each evening to sing and make music together.

I cannot know for certain where it will end.” Merton continues, saying that he cannot be certain his choices are the right ones, but that he is convinced that if he truly has the desire to please God, then God will lead him. He addresses God saying “…You will lead me by the right road though I may know nothing about it.”

What else can we do but step out in faith and try to follow the right road through this wilderness, this desert?

Perhaps, in this time of suffering and loss, we will rediscover our need for each other and the importance of nurturing the beloved community. Our path is not clear, but we know we must be present to each other in our grief, encourage each other in our fear, and support each other in hope until these tribulations pass. As we travel together through this uncharted territory that feels like a wilderness, like a desert, we must cling to the certainty that wherever we are going, God will meet us there.

As Merton wrote, “Therefore I will trust You always though I may seem to be lost and in the shadow of death. I will not fear, for You are ever with me, and You will never leave me to face my perils alone.”

Virus or no virus, the injured and chronically ill who depend on Casa Juan Diego must still receive help.

“I have not yet resisted unto blood,” Dorothy Day commented, after surviving a drive-by shooting at Koinonia Farm. She had endured many hardships – jeers, threats, and insults, being shoved into paddy wagons and jailed – but her acts of protest against war and social injustice had never put her life at risk. She had never been shot at. But one night in 1957, when she was keeping night watch at Koinonia, bullets fired from a passing car struck the station wagon in which she was sitting, barely missing her and the other woman who was with her, coming within inches of wounding, if not killing, both of them.

What was this place, this Koinonia Farm, where Dorothy Day very nearly did “resist unto blood”? What had brought her there?

Koinonia Farm was a Christian farming community located outside Americus, Georgia, co-founded in 1942 by Clarence Jordan, a Baptist preacher, and his wife Florence, along with two Baptist missionaries, Martin and Mabel England. It might seem unlikely that Dorothy Day would be drawn to a farm in the Deep South, or to Clarence Jordan, whose Baptist roots were about as far from Catholicism on a Christian spectrum as one could get. But denominational boundaries faded as

Day recognized in Jordan a person whose understanding of the Christian life was very similar to her own. Her impulse toward solidarity with Jordan and his community led up to that historic visit — and that nearly fatal night.

Founded in 1942, Koinonia Farm was named for the Greek word for “fellowship” or “loving

community. It was based on the community life of the firstcentury church: the practice of non-violence; a belief in the equality of all people before God; and sharing a “common purse,” whereby means and goods were shared in common and distributed to each person according to need. All three principles flew in the face of the white mainstream social order of the Deep South in the mid20th century, but particularly was the second, the racial equality practiced by the community, an affront to the notion of white supremacy

and a threat to white privilege in surrounding Sumter County. At Koinonia, located in the heart of the Jim Crow South, white people and black people were living together, working together, sharing meals and worshiping together.

In the 1950s, with the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement, Koinonia began to experience violent persecution from its neighbors.

The Civil Rights Movement in the Deep South involved more than the picketing and peaceful demonstrations Day had been a part of, more than being jailed overnight; people were putting their very lives on the line—and at times losing their lives. Day had known about Koinonia for some time; she was inter-ested in all the centers of Civil Rights activities in the South. But Koinonia held a particular interest. It was more than an outpost of racial equality; it was founded on an understanding of the Gospel very similar to Day’s own.

In the spring of 1957, Day determined to spend the last two weeks before Easter at Koinonia, wanting to share in the suffering of the “beleaguered community.”

In a series of letters to the Catholic Worker she describes her visit. Arriving after a 36-hour bus trip, she learned that there had been

gunfire the night before, and four of the community’s hogs had been shot.

Day wanted to help in the work of the farm, and she was given the jobs of harvesting fruit and vegetables and helping prepare community meals. On her second day she accompanied Florence Jordan and the Jordans’ young son Lenny to buy seed peanuts in a nearby town. In front of the feed store a man began to follow them, “screaming incoherently,” calling them “dirty Communist whores” and “nigger lovers.” They left quickly before a crowd gathered.

In an attempt to limit the damage done to the property at night, the community began to station a night watch of two people out by the highway. The two people would sit in a car near the public road and, if they saw a car approaching, they were to get out with lanterns and walk up and down the road to make their presence known. Because the men were busy with spring planting, the women were taking night watch duty. On the third night of her visit, Day volunteered to keep watch with another visitor, Elizabeth Morgan. As Day later recalled the incident, she and Morgan were sitting in the car, under a floodlight, Morgan playing hymns on

her accordion while Day prayed her breviary. As Day recounted, at 1:30 in the morning a car approached, “slowed up as it passed and peppered the car with shot. We heard sounds of repeated shots—a regular gunfire, and we were too startled to duck our heads. I was shaken of course. There was no other sound from the slowed down car which gathered speed and disappeared down the road.”

Three members of the community rushed to the scene. Ora Brown noticed that Day was trembling and offered Day her coat. Day said, “That ain’t cold, baby, that’s scared.” A decade later she wrote of this experience as “one of situations when I was most afraid.” But she had not come to feel safe, she wrote. “[I]f they want to keep watch, I must help. It is what I came for—to share in fear and suffering.”

Day is widely quoted as saying, “Don’t call me a saint; I don’t want to be dismissed that easily.” Nevertheless, she is in the early stages of being considered for sainthood in the Catholic Church. What is a saint? According to Day, a saint is a person whose life would not make sense if God did not exist. In that sense, both Day and Jordan are easily identified as saints, canonized or not.

My story begins when I left my country for fear the government of my country, Nicaragua, was going to kill me.

When I arrived in Mexico, I was kidnaped by the mafia. They kept me five days in captivity where I was raped by five men, I don’t even know how many times. I was able to escape and, in a way that I could, enter the United States. The Immigration agents put me in custody and I was detained 15 days in a refrigerator cell, where I was mistreated and humiliated only for the fault that I was an immigrant requesting refuge in this country. Later, they took me to tents in the desert that we want to forget. We call them carpas de olvido. I was there with about 800 other women, sleeping on the floor, enduring sun, rain, hunger, and cold, without being able to bathe or change our clothing and brush our teeth, except once a week. All this, and the mistreatment by ranking Immigration officials relentlessly pursuing the 18 year old girls. After being in detention there for 52 days in addition to the 15 days in the other place, Immigration sent me back to Juarez, Mexico. They did not care that I had been kidnapped and raped. They never let me enter the country. I had to enter illegally because the mafia had already found me. I finally arrived and today I will see my husband at last. Thanks to Casa Juan Diego for helping me.

Mark Zwick was fond of saying “The most dangerous part of working at Casa Juan Diego is crossing Durham Drive”. He did so many times a day, going between the various buildings that make up Casa Juan Diego.

Our buildings are bound by Shepherd and Durham Drives – four lanes (soon to be 5 on the Shepherd side) in each direction. An ever-flowing river of North-South traffic in the great sea that is Houston, a sprawling city of drivers. These two massive arteries bring us food and clothing donations, patients for the clinic, volunteers for the houses and garden, deliveries, ambulances, school buses and the many poor who need our help. In the mornings, Shepherd is backed up for half a mile. In the evenings, Durham is the same. Sometimes these thoroughfares are helpful, with nearby traffic signals slowing the rush to our doors when we are distributing food.

On a Saturday night in February, I missed two calls on my phone in quick succession, but caught the third one. It was Louise Zwick, calling to ensure I had been notified that not one, but two vehicles had driven into one of our buildings at the corner of Rose and Shepherd. I headed over.

A dazzling array of blue, white and red lights covered the intersection. A truck had smashed into a tree at the corner, and a small SUV had driven through the perimeter chain-link fence, “bounced” off our wheelchair

ramp, the building, and through a large wooden fence to our garden. Thankfully no one was hurt!

Police officers, wrecker drivers and firefighters did their normal things. People were checked, statements were collected and the vehicles were extracted, not without adding to the mess. No one was arrested. A lot of the mess was due to the severing of a water line to the building when the SUV impacted it (before the cut off valve). The head of the firefighters group helped us search for the water meter for at least 15 minutes with no luck and then they had to go.

And dug. First clearing the spreading mud at the base of the geyser / pipe to get a read on the direction it was going, then at the street to find the meter. Nothing. Next, a series of 3-foot holes every several feet following the line from the house to the street. Rien. We traced it to the edge of the sidewalk, after which it disappeared. We pay the water bill, there has to be a meter! We had someone run over to meet Louise so we could look at the 20 year old survey. Nil. We opened the storm drain cover. We went to the water meters at our nearby buildings and turned them off. Nix. We dug a trench along where the meter should have been, based on the pipe. Nada. We restarted the process that the Captain of the fire truck, with his wisdom and experience, had shown

us: hit the grass with a crowbar in likely spots hoping to find it. Imagine the sound: a dull thud every few seconds. Perhaps with a breath of hope in between thuds. Zilch. We called the City of Houston for help. They said they would send someone out.

The wreckers finally pulled the SUV out, as they had the truck earlier. The police provided a copy of the accident report and left. The lights were gone, the traffic passing as normal. I sent all our people home and sat on the porch with one of our several men named Manuel, speculating on how the cars had ended up here, the nature of the magic water line, and whether whacking grass with a crowbar could become a competitive sport.

After a while, I asked one of our guests to come back and we could think it through together, with his knowledge

of construction. We started from the top, checking two more adjacent water meters, digging yet another hole and walking the building perimeter. As we walked, he worked on his grass-whacking technique. Imagine our surprised delight when instead of the sound of crowbar on sod, we heard metal on plastic, just a few feet from where our trench ended. Eureka!

The water pipe, magically, zigged under the sidewalk for about 6 feet before emerging. The cover to the water meter had at least an inch of grass grown over it.

We called the City to cancel the technician visit 30 minutes later. They said they did, but still their technician arrived about 9 a.m. the next morning. They could only admire our digging work before going to their next Sunday call. Our plumber arrived shortly after and put in a new pipe and valve to the house. The fences took a bit longer.

Thousands were left behind on the January day that Gabriela left for the U. S. The Supreme Court has declared that these migrant people will continue to wait, constantly endangered and pleading only for security. Continued from page 4

Still in Matamoros, Luciana and Samuel regularly fluctuate between gratitude and anguish. They are thankful for their children’s safety, that they are well-fed and not living outdoors anymore. They miss them terribly and truly don’t know if they will ever see them again. With uncertainties stacked against them, Luciana and Samuel nevertheless search for hopefulness with pertinacity. I also met Gabriela (alias) and her two daughters. Gabriela is a survivor of relationships marked by domestic violence, substance abuse, and economic instability. Her parents are Guatemalan, and all of the life she remembers was lived in the country’s rural highlands, but she was born in the 1980s in

southern Mexico during the Guatemalan Civil War. Gabriela waited for months in Matamoros, in a tent just beside the chain-link fence where volunteer teams from Catholic Charities of the Rio Grande Valley set up tables of supplies. To be a migrant in the camp is to queue ceaselessly for foodstuffs, potable water, diapers, bars of soap, and whatever else groups are able to bring. Gabriela’s older daughter, around 11 years old, was her mom’s best helper and defender. She longed for the chance to attend school and learn English, but in the absence of many educational outlets there, she kicked cans, played clapping games, and tenderly assisted her mom with her younger sister, who is almost

two. Gabriela allowed her older daughter to wander and forge new friendships, but very minimally. She was terrified that her daughter would be subjected to some of the same violence that she herself has known, as she heard the stories of rape, kidnapping, and murder unfolding in and near the camp.

Likely due to her Mexican citizenship, Gabriela was granted admission into the United States. She called me via WhatsApp to let me know that she and her children were living near Houston. Family members received them at first, but the financial stress and privacy issues that developed were too much to bear, so she has since moved out, begun work as a dishwasher, and is

struggling to make ends meet in her own small apartment. Gabriela’s tent was left behind on the morning she rose early to boldly head to the bridge with the girls, but undoubtedly another family is already using it as their new home. She and her daughters have found relative safety in the U.S.; her daughter can study, at least until their court hearing, when they may very well be given a deportation order.

(continued from page 1) periodical Vida Nueva, Pope Francis quoted from Global Pandemic and Universal Brotherhood: Note on the Covid-19 Emergency, by the Pontifical Academy for Life, emphasizing that this pandemic needs to be treated with the “antibodies of solidarity”. He expressed his hope that society might find “the necessary antibodies of justice, charity and solidarity” to work together to combat not only this epidemic, but also the epidemics of hunger, war, poverty, environmental devastation, and indifference to suffering.

Not to mention that the rebuilding that must take place after the coronavirus cannot happen well if countries turn to arms sales and war instead of justice, charity, and solidarity.

Often with everyone focused on the Coronavirus, taking time to think of those who are seeking asylum from war, violence and extreme poverty in their countries, as well as the undocumented already here in the United States may take second or twentieth place. But their plight is real.

At Casa Juan Diego we are familiar with the realities on the ground in Houston Texas, with the vulnerability and precarity of the undocumented.

Casa Juan Diego is in a unique position to know of the institutionalized inequality and the difficult economic situation that affects undocumented workers even before a disaster hits, because we talk to the people each day. We see a part of the economy that few others see. The needs are often overwhelming for us.

The undocumented are at the heart of the Houston economy. The Coronavirus crisis is especially hard for the immigrant community because of the places they work and because they have no savings. There is no safety net for them. Many work in restaurants across the city, they clean houses and watch children while others are working, and they clean hotels. - those jobs are gone now.

Day laborers who fill many temporary jobs are in a precarious position. Many of the undocumented work in construction where work has decreased; those who continue to work are not able to do social distancing and are exposed to contagion.

It is ironic that farmworkers, who have been neglected for so many years and have always worked under very difficult conditions, have been named essential workers as the economy has had to shut down in many places because of health concerns. The U. S. Catholic Bishops have long advocated for better working conditions for farm laborers. Dorothy Day supported Cesar Chavez in his organizing of farm workers for better pay and better working conditions.

All of a sudden, this spring farm workers have been deemed essential to our food supply and have been asked to continue working. A large percentage of farm workers are undocumented.

It is even more ironic, or better put, very sad, that the large agribusinesses who are receiving many billions of dollars from the federal government during this crisis are asking to lower the wages of farm laborers. These wages should instead be raised because the work at close quarters does not allow for social distancing and the workers are very much at risk for becoming ill.

In meat-packing plants across the country with large COVID-19 outbreaks, the poor, many immigrants, are asked to work shoulder to shoulder without pro-tection, chopping hogs and chickens at a very fast pace. The plants have been ordered to reopen. Some say we will have to choose between the welfare of workers and an abundance of meat. We encourage our readers to follow LULAC’s campaign for meatless Mondays until the workers are given protection.

Not long before news became readily available about the new virus, Casa Juan Diego welcomed a new baby. The young mother was overjoyed, but exhausted. Catholic Worker staff and volunteers quickly began to help, feeding the baby, changing diapers, so the mother could have some rest. The joy of new birth of this baby girl permeated our whole house of hospitality. The father of the baby is pursuing every avenue he can to try to be released from Immigration detention so that he can rejoin his family. (a very difficult proposition). Another woman who is a guest of Casa Juan Diego has been waiting for the release of her husband for many months. We wrote letters of support for him in the hope that he could be released from detention to Casa Juan Diego. Sylvia (name changed to protect the innocent) had one child already living with her here. In the time of waiting, Sylvia had her baby. Day after day, Sylvia has hoped for her husband’s release. She was devastated to find out that instead of the hoped-for release, he was deported in mid-April. Why? And why now?

When there was still time before a large spread of the virus in detention centers, advocates begged for release of immigrants detained in privatized prisons. Was it the virus of the soul that caused the decision makers not to act, but to hint that

instead of the spread of the Coronavirus within the United States, it was the immigrant population coming to the border that was causing the danger? And why were thousands of immigrants in detention in the first place, when there are other ways to monitor them without jailing them? The distressing reality of the lucrative private prison industry (on the stock market) and the prison corporations’ lobbyists seems even more cruel and unjust now. This must change. The United States cannot allow profit on human suffering. Advocates for immigrants in detention have decried the conditions in detention centers from the beginning of awareness of the contagion of the Coronavirus. People are crowded together, they do not have the opportunity to wash their hands, let alone practice social distancing. And deportations continue.

Guatemala has reported that half of deportees from the United States have Coronavirus (Los Angeles Times). They are worried about the effects on their poor countries of cases deported from the U S.

What is all this desire to jail and deport people, to rid our countries of the poor, the stranger - the workers who build our houses, trim our trees, care for our lawns and our children, harvest and prepare our food? And more important than their contributions to our society, the immigrants are human beings with all the dignity that that implies.

Some citizens might wonder why the protest against deportations. Aren’t people just being sent home? That is the argument presented by those who deport so many.

Observer from a distance might have forgotten the situation of violence or devastating poverty that impelled people to leave in the first place and deters people from returning. When they are returned, they suffer again. Deported migrants are targeted by the cartels, by corrupt groups that prey on migrants but especially on those who are deported.

Massive deportations create not only human misery, but death. These cruel realities were documented long before the present crisis.

In addition, the countries who receive huge numbers of deportees are destabilized by the influx of homeless, penniless people. If our goal is to deter immigration, destabilizing the sending countries is not a good idea.

The Poor Will Always Be with You

In the light of these realities, we can turn for perspective to the prophetic words of the Holy Father from his homily on April 6. Pope Francis asked at Mass that day for everyone to pray for the serious problem of overcrowded prisons.

In his homily, he reflected on the Gospel reading (Jn 12:1-11) in which Mary – the sister of Lazarus and Martha – anointed Jesus’ feet with expensive perfumed oil.

The anointing of Jesus’ feet provoked an angry response from Judas who said the money should have been given to the poor. Jesus replied, “The poor will always be with you.”

Pope Francis said while Judas appeared to think of the poor, it was not because they mattered to him. What he cared about was money. He held the common purse and was a thief.

The Pope said there is always someone with these characteristics, pointing out that frequently less than half of the money given in charity for the poor goes to the poor. His comments were very interesting to those of us in the Catholic Worker movement, where there are no salaries.

“This story of the unfaithful administrator is always current: they are always around, even at a high level. We think of some charitable or humanitarian organizations that have many, many employees, with a structure full of people and only about 40% of donations make it to the poor because 60% goes to pay many salaries. This is a way of taking money from the poor.” – Matthew 25 Pope Francis expressed what has been hiding in plain sight, that many poor people are victims of structural injustice in today’s global economy, of economic and financial systems.

He reminded us that Jesus’ question to each of us on the Day of Judgment will be: “How did you treat the poor? Did you feed them? Did you visit those in prison, in hospital? Did you help the widow and the orphan? Because I was there.”

The Pope said we will be judged according to our relationship with the poor:

“If I ignore the poor today, leaving them aside and acting as if they didn’t exist, the Lord will ignore me on the Day of Judgment.

“When Jesus says, ‘You always have the poor with you,’ He is saying, ‘I will always be with you in the poor. I will be present there.’ And this is not acting like a communist. This is at the center of the Gospel: we will be judged on this.”

We pray that our Catholic antibodies will help us respond to Jesus in the poor and help us all to create a civilization of love – beyond pandemics.

Meditation from Urbi et Orbi 2020 by Pope Francis https://www.vaticannews.va/en/pope/ news/2020-03/urbi-et-orbi-pope-coronavirusprayer-blessing.html

Migrating to Prison: America’s Obsession with Locking Up Immigrants by Cesar Cuauhtémoc García Hernández The New Press, 2019

Baby Jails: The Fight to End the Incarceration of Refugee Children in America by Philip G. Schrag

Oakland: University of California Press, 2020

Deportation To Death: How Drug Violence Is Changing Migration On the US-Mexico Border by Jeremy Slack

Oakland: University of California Press, 2019

Coronavirus Policy: Activating the Antibodies of Catholicism by Antonio Spadaro, SJ, La Civilta Cattolica, March 16, 2020

Bottled water

Cooking Oil

Canned tuna

Canned chicken

Maseca

Coffee

Ground Beef

Chicken

Spaghetti

Canned tomatoes

Masks

Adult diapers

Baby wipes

Twin size sheets

Bed pillows

Towels

Dishwashing liquid

Men’s deodorant

Shampoo

Toothpaste

Besides advocating for policies of solidarity in this difficult time and assisting as many are doing with pro viding food for the poor, the hungry, readers can help Casa Juan Diego by following Mark Zwick’s advice in his three-time campaign over the years at the Houston Catholic Worker: No New Clothes for a Year. Afer observing so often the large quanities of used clothing donated, Mark asked people to fast from buying clothes for a year and donate the money to the poor or to the Church. Casa Juan Diego is not able to accept used clothing at present (we are overwhelmed trying to prepare bags of food for hundreds and hundreds of people). We don’t have the buttons at present, but years ago Mark had buttons made up for people to wear saying “Don’t Make Fun of My Clothes: No New Clothes for a Year.”