Contemporary Perspectives on Environmental Histories of Architecture

Hirra Masood

21308588

Humanities Elective 2

Kim Förster

3. Bibliography

Hirra Masood

21308588

Humanities Elective 2

Kim Förster

3. Bibliography

3250 words

Amidst the escalating challenges of climate change across the globe, Pakistan is facing a pivotal moment in its approach to climate adaptation. This comes as a result of the increase in extreme weather events and rising temperatures. Through recent times, there has been an observable towards mechanical cooling and a clear rejection of traditional means to achieve thermal comfort. This ongoing transformation might exacerbate hotter climates across the region and consequently lead to heightened risks of heat-related health issues, increased energy demands for cooling, and greater challenges in maintaining environmental sustainability. Rapid urbanisation and the adoption of modern conveniences have led to a significant reliance on air conditioning and other mechanical cooling systems, in both residential and commercial spaces (Khalid and Sunikka-Blank, 2018). This essay, while addressing immediate comfort needs, aims to question the long-term sustainability of such practices, especially in the context of a changing climate. It intends to assess to what extent Pakistan is prepared for the projected changes in climate, emphasising the shift from passive architectural design methods to reliance on mechanically cooled interiors. By analysing the impact of climate change on socially vulnerable groups and how historic architecture has responded to climate changes in the past. This essay aims to establish a framework for the role of architects, in a nation where rising temperatures are expected to go beyond liveable conditions (Anwar et al., 2022). Additionally, this text will question the rising standards of comfort and reevaluate the extent of which the pursuit of contemporary comfort may be contributing to the environmental challenges Pakistan is currently facing.

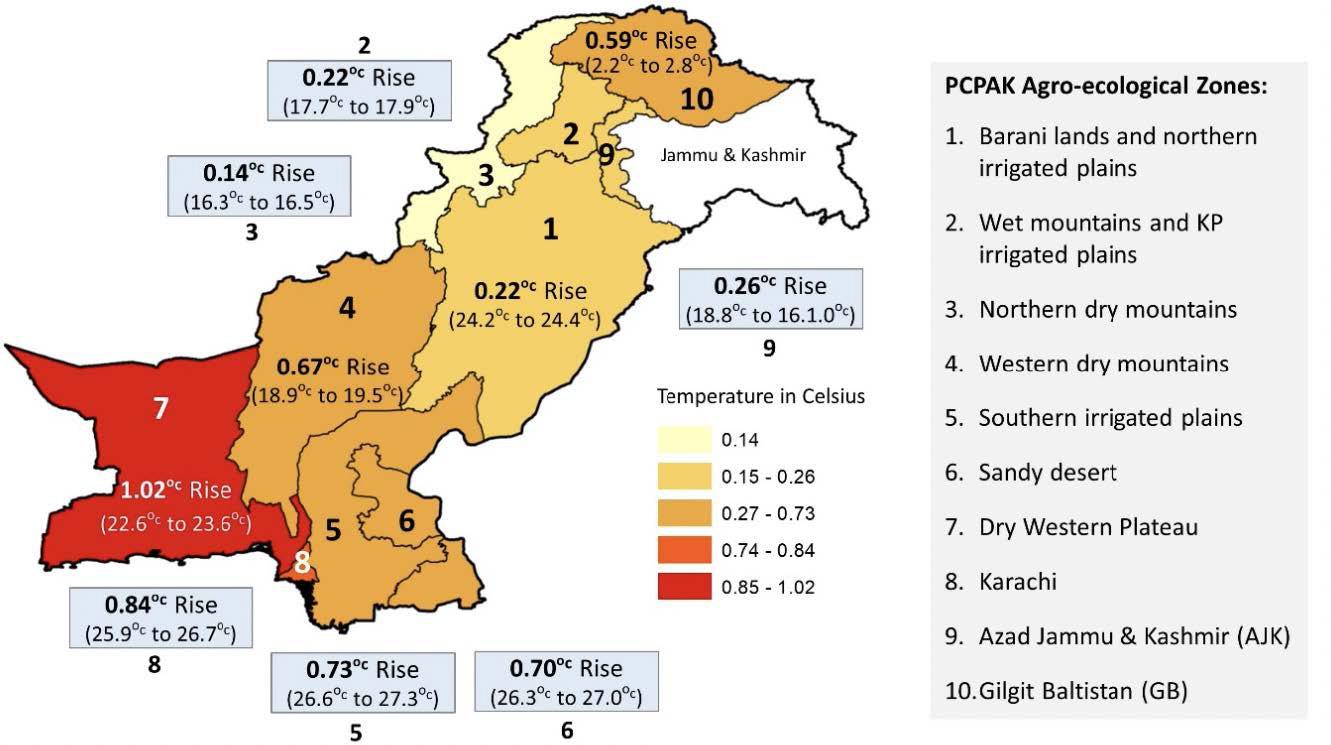

Developing nations such as Pakistan are considered to be particularly susceptible to the consequences of climate change (Nanditha et al., 2023), underscored by the heavy reliance on the agricultural sector by both the economy and the population The importance of agriculture is derived from its role in providing food security, poverty reduction and economic growth through the export of goods to the West (Azam and Shafique, 2017). This dependency becomes unstable when extreme weather events or natural disasters such as floods, droughts or heat waves occur: consequently compromising the food supply chains, employment opportunities, and economic stability. Geographically, Pakistan portrays a juxtaposition of extremes, with one of the globe's largest non-polar glaciers in the north, and low levels of moisture and rainfall in the south. Thus, the effects of climate change and the increase in temperatures vary across the nation (see figure 1). From the time frame of 1901 to 2016 an average temperature rise of 0.5 degree Celsius has been recorded across Pakistan. However, examining the regions individually, the dry Western Plateau region has experienced the highest rise at 1.02 degrees Celsius, followed by the densely populated region of Karachi with 0.84 degrees Celsius (Arif et al., 2019).

According to the Global Climate Index 2019, Pakistan has been ranked 8th based on the effects of climate change, contrasting that it accounts for only 0.25% of the global Carbon Dioxide emissions (Ritchie and Roser, 2020). The unprecedented heatwave of March 2022 is a prime example of recent natural disasters taking place in Pakistan, temperatures in the southern provinces of Pakistan rose to 52 degrees Celsius, resulting in 90 officially recorded deaths across Pakistan and India (IANS, 2022). Heat waves in the south of Asia are particularly dangerous as more than 60% of the labour takes place outdoors, as a result, there is limited to no protection from the effects of heat (Butler and Stack-Maddox, 2022). This climate crisis was accompanied by an energy crisis, as heightened temperatures led to increased energy consumption. Despite 20% of the population not being connected to the energy grid, and 45% not having access to a refrigerator. The energy crisis occurred due to 11% of the nation, with access to air conditioning, increased their energy consumption, which prompts us to reflect on the broader implications of air conditioning (Jeffcott, 2023). This catastrophic heatwave was followed by a flood which inflicted widespread devastation, further loss of crops and destruction of livelihoods and infrastructure, causing internal displacement of about 50 million people (Bhutto, 2022). As Pakistan grapples with the formidable impacts of climate change, the need for sustainable practices becomes increasingly apparent, setting the stage for an exploration of both traditional and mechanical means of achieving climate-resistant architecture in a developing nation.

The traditional vernacular architecture of Pakistan dates back to the Mughal Empire, long before the British colonial period. At a time before electricity and mechanical means of regulating interiors, structures were designed based on local climates and the artistry of utilising region-specific materials (Dadlani, 2018). A common element found in Southern Asia are courtyards, locally known as a Havelis, this form is not merely responsive to environmental factors but also contributes to social and cultural elements, found across the Indian subcontinent in many variations and scales (Khan, 2016). Traditional architecture embodies societal habits that influence not only the internal furnishing of spaces but also the placement of rooms within the structure. This adaptability to changing lifestyles over centuries showcases the resilience of these architectural forms in accommodating evolving needs without compromising the implemented environmental strategies. Utilising courtyards and rooftops for sleeping becomes a practical choice in the summer, capitalising on the cooler temperatures that prevail during the night. Havelis achieves thermal comfort by passive design strategies such as stack ventilation, evaporative cooling, and strategic window and door usage. This environmental consciousness contributes to the value of vernacular havelis, showcasing an early understanding of sustainable architectural practices with consideration of local context. Though use of local materials, such as adobe and brick, it reflects on the region's resources and highlights sustainable construction practices. Havelis are emblematic of Pakistan's architectural heritage, adapted and reused over centuries.

Case study: The Seven Sethi Havelis

Located in the city of Peshawar, North-West of Pakistan, the seven Sethi Havelis are a guiding principle for the sustainability of Pakistan’s vernacular architecture and how design is a contributing factor to thermal comfort. Peshawar is known for its frequent earthquakes, therefore the Havelis are constructed with careful consideration to withstand seismic activity. The Sethi havelis create an indigenous framework that combines, societal needs, cultural appropriation and environmental responsiveness. Each of the seven Havelis is designed around a central courtyard; size, orientation and form are based on the location and environmental analysis of the micro context. The Allah Buksh Sethi Haveli was built in 1898 by the Sethi

merchant bankers, presenting strategic design features also found in other buildings across the country. Organised around a central courtyard are rooms with an overhanging roof (see figure 2), calculated and built depending on the summer and winter solaces (Khan, 2010). This allows maximum solar exposure in the winter, where the solace is lower, and protects from overheating in the summer. The external walls are built thicker than the internal walls, as this provides a high thermal mass of external walls. The fluctuation between daytime and nighttime temperatures is mitigated by a high thermal mass, allowing for the absorption of heat during the day and its gradual release at night. This ensures that internal temperatures remain relatively stable, minimising the impact of the external climate. All Sethi Havelis use stack ventilation, which utilises the buoyancy of warm air to create airflow within a building by placing openings at floor and ceiling levels. These openings can be operated by the occupants depending on the desired internal temperature. Other features include a water fountain or other means of sprinkling water on the courtyard, increasing the humidity of the dry summer heat through evaporation. These passive design features suggest that thermal environments can be regulated by traditional design strategies, as they have been established, tested, and adapted through time and with climate changes. Thus, creating a micro climate, ensuring stable temperatures throughout the summer heat. However, one of the Sethi Havelis, The Allah Buksh Sethi Haveli does not implement some of these design features, which might weaken the argument for the effectiveness of traditional architecture in today’s changing climate.

Whilst vernacular architecture in Pakistan offers a wide range of solutions to the increasing temperatures of the region, it may be argued that romanticizing these traditional practices could hinder progress and modernization. According to Arif et al. (2019) the modernization of the middle-class population in Pakistan has taken a rapid increase, which has raised concerns of exacerbation of economic disparities and environmental challenges. Adapting traditional designs to today’s climate comes with a set of challenges. Traditional designs were often tailored to specific climate patterns that were more predictable in the past. Contemporary climate change presents a threat to the efficacy, as rising temperatures, and erratic weather patterns create an unpredictable weather condition, including irregular rainfall, temperature fluctuations, and extreme events. In addition to that, traditional designs were based on relatively low population density, however, the rapid increase in population requires more efficient use of space. Additionally, the preservation of these design practices might hinder the creation of more efficient and sustainable urban environments, especially in densely populated areas, like Karachi where space is a critical factor.

During the post colonial period, traditional havelis were viewed as indicators of social status. However, with the shift to fully enclosed domestic spaces and conditioned interiors, these structures have transformed into new symbols of power. Architecture in the Indian subcontinent has been progressively impacted by the global west. In western regions, structures are often fully enclosed, as the climate is less prone to high temperatures. On the other hand, in Pakistan the local climate requires enclosed buildings to be mechanically cooled to be occupied as otherwise overheating creates unliveable conditions. The increasing gap between energy demand and production has led to daily power outages for up to 16 hours, this energy

crisis has been a constant issue affecting Pakistan. The national energy production heavily depends on fossil fuels, constituting 64% of its total energy, while hydro power contributes 27%, and the remaining 9% is sourced from other renewable and nuclear power (Sattar and Mubasal, 2023). Consequently, this exposes the country to environmental vulnerabilities and disruptions in energy supply. Energy usage increases in the summer, as many households and the commercial sector have implemented devices such as air conditioners to mitigate the effects of the ever-increasing heat (Rashid et al., 2019). The dual challenge of meeting the needs of internal comfort whilst addressing the impact of increased energy consumption on the environment poses a critical dilemma. This requires a comprehensive approach that provides energy-efficient technologies, such as smart thermostats, occupancy sensors, and advanced HVAC systems. Contrastingly, developed nations have implemented numerous initiatives for energy efficiency, one notable example is The Concerted Action EPBD (Energy Performance of Building Directive) forum.

Although, Pakistan is considered to be a less developed country, energy consumption in the domestic sector accounts for approximately 55%, which is higher than in countries such as Spain or the US, where the energy consumptions lie at about 45% (Sattar and Mubasal, 2023). Operational electricity usage, especially for thermal comfort purposes like space heating and cooling, has a significant adverse impact on the environment. A major factor when analysing Pakistan’s energy consumption is the lack of regulated technological appliances, thus creating a threat to energy conservation. It is imperative for the government, to implement minimum energy performance standards and energy efficiency regulations. Currently circulating fans and lighting appliances fall short of contemporary energy efficiency standards, straining the already overloaded energy supply.

It is important to remember that although the need for energy efficiency in technological appliances is evident, pushing for the adoption of energy-efficient appliances could potentially exacerbate existing socio-economic disparities. Whilst energy conservation is essential, the high cost of these appliances creates a disadvantage for much of the population, which might inadvertently lead to only the more affluent being able to adopt environmentally friendly technologies (Sattar and Mubasal, 2023).

The middle-class demographic accounts for the majority of energy consumption, leading to the socio-economic disparities in Pakistan widening with the effects of climate change. The transition from traditional vernacular architecture to Western-style fully enclosed residences is also primarily witnessed among the socio-economically privileged segments of the population, attributable to their financial capacity. This illustrates the transformative impact of economic privilege on architectural preferences and comfort. As previously there was very limited access to electric appliances, the national manufacturing of air conditioners had increased the availability and thus the demand for ACs in middle-class households. In the early 1980s ACs were considered to be a luxury item, however over time it has become a necessity for many, the spatial configuration of domestic architecture has heavily been influenced by the emergence of technology. Prolonged exposure to mechanically conditioned spaces changes your thermal comfort and therefore makes spaces that one might have considered as comfortable, now uncomfortable. Air conditioning has not only taken a central role in the domestic sector, but it has also become a vital function in cars, shopping malls and offices. Thus, the middle-class population is moving from one conditioned space to another, adding to a prevalent dependence on controlled environments throughout daily life.

During the post-war time of decolonisation, architects like Michel Ecochard provided “development aid” (Avermaete et al., 2014) to newly independent states. Many nations like Pakistan and Guinea underwent a period of modernisation in search of a new architectural

identity, divergent from their colonising nations (Avermaete, 2020). Pakistan in 1947 had a very limitedly developed energy and infrastructure grid. Consequently, the University of Karachi was designed, in the 1950s by Ecochard, to not only create a productive space of comfort but to do so with consideration to the energy and infrastructure constraints at the time. The university building became one of Pakistan’s best examples of resource-conscious architecture, amidst the uncertainties of the climate in Karachi. Working with the hot climate, Ecochard prioritised the considerations of the “direction of wind”, “the provision of shade” and the impact of “topographical conditions” (Avermaete, 2020). The proposed master plan for the university campus was based on the prevailing wind direction (south/

west), this was crucial to allow passive ventilation of classrooms. Sun breakers were incorporated as vertical and horizontal sun shading devices, preventing enclosed spaces from overheating. Green spaces were woven into the spaces between university buildings creating its own micro climate. Undoubtedly, the original master plan of the campus had been designed and executed with a remarkable degree of precision, showcasing a deep understanding of the climatic conditions of Karachi.

The adaptation of buildings over time is an integral process, reflecting the occupant's needs, technological advancements, and evolving societal preferences. Over the years, due to the growth of the university, rooms and buildings have been added and the overall masterplan adapted to a new era. These changes not only accommodated the increasing number of students but also changed the thermal dynamic of interiors. With the emergence of air conditioning, condenser units can be found attached to internal and external walls, releasing hot air into corridors and external communal spaces. It contributes to the warming of peripheral zones, counteracting the intended cooling effect indoors and potentially exacerbating outdoor heat levels. Due to the frequent load shedding in the summer and dependency on air conditioning for internal spaces to be occupiable, students reserve outdoor spaces for relief from the heat (Macktoom et al., 2023). The semi-external corridors, with concrete screens designed for cross-ventilated cooling, have undergone modifications of filling in and thus creating a sealed space (see figure 3). In order to meet the demands of the university's growth, new buildings now obstruct the natural wind patterns in these pathways. Although it is undeniable that buildings are subject to change, Macktoom et al. (2023) argue that these adaptations lack sensitivity to the original architectural design and that such practices inadvertently diminishes the effort of Echochards' contextually relevant design. It is crucial to acknowledge the change in climate and its impact on the needs of the university occupants. Reevaluating architectural interventions that pre-date widespread adoption of mechanical comfort as the standard approach to designing habitable spaces, is vital to allow Pakistan as a nation to move away from fossil-fuelled comfort.

Comfort as a broader concept is sought after not only in Pakistan but around the world. When put in the context of spaces, it protects us from the unpredictability of the outside, including the climate and weather. But where does comfort fit in a perpetuating climate crisis? Conditioned spaces provide us with consistency, normalcy, and predictability. It gives us the ability to be in control, contrasting to the environment where humans have little to no agency. However, the extent to which we can afford comfort and stability varies disproportion-

ately across global socio-economic dynamics (Barber, 2019). As the climate crisis diminishes the availability of stability and comfort in the natural world, architects increasingly focus on designing the built environment to minimise carbon emissions yet maintain comfort. The relationship between comfort and the climate crisis is a difficult one, as one seeks stability in the unpredictability of the other. Thus, comfort increasingly becomes a scarcity for the majority population.

In the context of Pakistan, the availability of comfort is tightly linked to socio-economic factors, as access to cooling technologies, a key component of comfort, in an increasingly warming world, tends to be stratified. However, design strategies present in vernacular architecture might provide a starting point, as they are known for achieving some degree of comfort without compromising environmental sustainability. Embracing these time-tested strategies can serve as a foundation for contemporary architects to explore innovative solutions, this does not necessitate a rejection of modernization. Instead, Macktoom et al. (2023) underscores the critical need for Pakistan to invest in infrastructure that can withstand the challenges posed by climate change. The availability of renewable energy sources, that do not strain finite resources and contribute to environmental degradation, are crucial for Pakistan to ensure participation and address the forthcoming challenges posed by climate change.

It is evident that Pakistan stands inadequately prepared to confront the impending challenges of climate change. The prevalent reliance on mechanical cooling, while addressing immediate comfort needs, appears to divert the society away from sustainable adaptation strategies, exacerbating environmental issues and intensifying the risks associated with rising temperatures. In light of this, to claim traditional architecture and its design strategies to be the solution, in providing some degree of comfort in a rapidly warming country, is a compromised strategy. Pakistan's preparation for the forthcoming changes in climate requires a multifaceted approach, that does not only aim to educate professionals but also the wider community. It is undeniable that architecture and systems implemented within architecture contribute significantly to the warming of Pakistan. Thus, continuing to mechanically cool interiors with the current technology will not only exacerbate the heat but also strain the already unreliable energy grid. Prioritisation of middle-class comfort comes with the cost of increased natural disasters that disproportionately affect the less fortunate portion of the population. Traditional design strategies can form a foundation for architecture in Pakistan. While they might not provide the same comfort as HVAC systems, they have proven to have worked for vernacular architecture of the past. In addition to that, context-specific designs might decrease the need for technological appliances to create thermally comfortable spaces. The adaptation to impending climatic changes in Pakistan necessitates a collective responsibility across all social classes. These initiatives should highlight the interconnectedness of individual actions with broader environmental impacts, emphasizing that everyone, regardless of social class, plays a crucial role in building a resilient and sustainable society. It is essential to shift societal expectations and imperatively reconsider the pursuit of the desired comfort. Instead, encourage a cultural transition towards embracing some degree of discomfort to provide a sustainable level of comfort for future generations.

Reflecting upon “Building on Ghost Acres: The London Coal Exchange, circa 1849,” by Aleksandr Bierig, architecture is used as a medium to symbolise the importance, power, and need of fossil fuels such as coal in the seventeenth century. It is referred to as ‘ghost acres’ due to its pivotal role in the socio-economic transformation of England as well as the uncertainty of how coal is formed and how it was sourced, it also highlights the dramatic changes it had on the environment. It questions the extent to which the use of coal and industrialisation allowed society to exert control over the environment/nature. While also considering the power coal held over society and thus its human affairs. Similarly, coal mines became vital to the rapid urbanisation of London, which led to an increase in rural-to-urban migration and a natural increase in population. The Coal Exchange displayed paintings of coal ships and scenes of coal mining in north-eastern England, in an attempt to highlight the historical and geographical origins of the coal trade in London. However, the author argues that the paintings displayed were inaccurate and rather a glorification of coal mines instead of presenting the reality of child labour and the ‘dirtiness’ of the sourcing.

Parallel to this does the analogy of opening pandoras jar imply that the industrialisation is an event in the past that once unleashed cannot be undone, While it might not have benefited the whole population the increased usage of fossil fuels has led to an increase in environmental hazards to the nature as well as the population. It is questioned whether the power to destruction could be equal to the power of production, in other words, did the industrialisation cause as much harm as it did good?

This argument prompts me to contemplate whether the contemporary construction of new buildings carries similar dualities of good and harm. Or is it possible that the relentless pursuit of constructing new buildings may not align with the concept of Sustainability?

• Bierig, A. (2022). ‘Building on Ghost Acres: The London Coal Exchange, circa 1849.’ In Förster, K. (ed.) Environmental Histories of Architecture, Montreal: CCA.

• Wrigley, E.A. (1967). ‘A Simple Model of London's Importance in Changing English Society and Economy 1650-1750.’Past & Present, No. 37, July, 44–70. / Wrigley, E.A. (2010). ‘Introduction.’ In Ibid. Energy and the English Industrial Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1–6.

Invisible danger, with the naked eye pollution, is non-existent in the first instance, however, scientific research has shown the origin and the consequences of pollution, not only to humans but also to the planet. The representation of pollution in architecture shifted during the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. Initially, architecture was seen from an ‘aesthetic’ perspective as a ‘protector’ of humans from pollution, however, in modern times it could be considered to be a cause of pollution. Calvillo draws parallels between the marginalization experienced by queer communities and the often overlooked, marginalized aspects of environmental issues. He refers to Rob Nixon’s concept of ‘slow violence’, as the exposure to toxicants and pollution over extended periods disproportionately affects the poorer community. He criticises the techno-scientific approach to ‘saving’ the environment, questioning whether sustainable solutions add to pollution as many technological solutions resolve an increased consumption of energy. Pollution itself is a complicated term, what do we classify as ‘pollution’? As something that harms us might be a vital part of nature, who can identify pollution? Pollen is needed for many processes in nature, yet a large part of the population suffers from hay fever, thus pollution is also created by nature. Overall, pollution comes in many shapes, forms and scales, considering the wider image architecture can be a protector but also a cause of pollution.

The concept of ‘slow violence’ especially intrigues me as it shows the subtle yet cumulative impacts of human activities on the built environment and ecosystems, highlighting the imperative for sustainable design and long-term planning to mitigate the gradual but profound consequences over time.

Contrasting to the previous reading, Gissen suggests that architecture does not simply isolate itself from pollution or shield itself exclusively against it. Instead, is it an essential component of the modernity of architecture, it provides an ‘aesthetic’ approach to the issue of pollution. He argues that the form, technology, and functionality of buildings have been historically influenced by the environment and pollution. Thus, it provides a fresh perspective on the role of architecture in relation to pollution, by arguing that pollution could become a pathway for architects to integrate representational, formal, and historical ideas into their designs, and represent human life in pollution.

• Calvillo, N. (2022). ‘Toxic Nature: Toward a Queer Theory of Pollution.’ In Förster, K. (ed.) Environmental Histories of Architecture, Montreal: CCA.Wrigley,

• Gissen, D. (2012). 'A Theory of Pollution for Architecture.' In Borasi, G. / Zardini, M. (eds.) Imperfect Health: The Medicalization of Architecture, Montréal / Zurich: Canadian Centre for Architecture / Lars Müller Publishers, 117–132.

As air conditioning is increasingly being implemented in the global south, I wonder how long we will manage to cool interiors whilst the same technology is heating our planet. The rise in demand for ACs in the south is mainly due to the increase in population and wealth, middle class households have grown used to moving from one conditioned space to another, as not only interiors are being conditioned but also the external public realm. Examples of Singapore and Doha as representatives of the Global South, highlight how the unequal distribution of wealth and cooling reflects global disparities. He shows that both cities benefit from the availability of fossil fuels and promote dependence on air conditioning. Chang emphasizes that the demand for air conditioning in the Global South will exponentially increase due to climate change and population growth. This poses a serious challenge as conventional air conditioning contributes significantly to global carbon dioxide emissions. He suggests that alternative, energy-efficient cooling technologies must be explored to meet the world's cooling needs without further warming the planet. Similarly, this reading focuses particularly on the cities of Singapore and Medan. It discusses the shift in construction materials from traditional wood and bamboo to brick and reinforced concrete and the resulting influence on microclimates and inhabitants' comfort. It brings forward the idea that sustainability of buildings relies significantly on the behaviours of individual users, emphasizing the importance of public awareness and collaboration with government initiatives for effective state coordination. Particularly in Singapore, the government must rethink sustainable ventilation systems for urban mass housing, centralizing the air-conditioning system in buildings in order to reduce energy consumption.

Gunel examines Masdar City, a sustainable city in Abu Dhabi designed as a "Spaceship in the Desert, this city was designed as a part of a plan to promote renewable energy and clean technologies, aiming to reduce dependence on oil. Masdar City is presented as a modular city, implying the idea that it could be implemented in other regions, however, there are significant challenges to its global applicability. The high cost of $22 billion for its development, the unique economic circumstances of the oil-rich UAE, and the political stability provided by the government of Abu Dhabi are crucial factors that may not be replicable in other countries. The concept of Masdar City as a "spaceship in the desert, to me, implies that it could serve as some kind of protection from the outside world in the future. There is an ongoing debate among Masdar Institute students about the city's elite sustainability and its potential as a global prototype. I receive it as an isolated and lonely city, as there is nothing around but sand, some aspects of it I am sure could be implemented elsewhere, however, a little further research shows to date only 25% of the city has been developed, and it makes a home to a sixth of the expected residents.

Specific to Abu Dhabi’s cliamte unsuitable for global use

Argument Map-Inhabiting the Spaceship: The Connected Isolation of Masdar City (updated)

Presentation Notes

• spaceship analogy- Masdar City reimagines the desert as an uncharted frontier,

• spaceship as a finite, technically sophisticated, and insular habitat for an exclusive group of beings facing an outside world of crises.

• Norman Foster intended Masdar City being to maintain the lives of its residents by relying on renewable energy and clean technologies, performing the role of “a spaceship in the desert

• “man with a brush,” in maintaining the effectiveness of solar panels.

• references the film “Interstellar” to explore the concept of connected isolation and the preservation of lifestyle in a spaceship, reflecting on the broader implications of human habitation and survival.

• budget of $22 billion, feasible only for oil-rich countries like the UAE.

• doubts about its affordability and practicality in other countries with different economies.

• government served as a steady source of financing

• Chang, J.-H. (2022). ‘The Air-Conditioning Complex: Histories and Futures of Hybridization in Asia.’ In Förster, K. (ed.) Environmental Histories of Architecture, Montreal: CCA.

• Roesler, S. (2022). ‘Epilogue 7. Singapore as a Model? Urban Climate Control in Practice.’ In ibid. City, Climate, and Architecture: A Theory of Collective Practice, KLIMA POLIS, vol. 1, Basel: Birkhäuser, 213–227.

• Günel, G. (2016). ‘Inhabiting the Spaceship: The Connected Isolation of Masdar City.’ In Graham, J. / Blanchfield, C. (eds.) Climates: Architecture and the Planetary Imaginary New York / Zurich: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City / Lars Müller Publishers, 361–371.

The historical rise and fall of Asbestos as a building material is the most suitable example of the concept of ‘slow violence’. Once it was celebrated as a versatile construction material, valued for its fire resistance and insulating properties, however, the subsequent revelation of its severe health risks and environmental consequences led to a precipitous fall. The International AC Review played a crucial role in shaping the discourse around asbestos in the architectural sector, promoting it for social housing and in developing countries. It provided a platform for architects to show of their work with asbestos and thus present it beautified in architecture and products rather than revealing its toxicity This reading made me wonder whether there are building materials we are using today, that might be deemed toxic in the future. Whilst the awareness of materials such as cement being harmful to the environment exists, there is little awareness in the architectural sector of materials being toxic to human health in particular. It also reinforces the role and responsibility of architects and architectural literature in promoting and circulating information. The International AC Review’s role in perpetuating a beautified image of asbestos accentuates the need for architectural education to emphasise ethical considerations and accountability.

The main argument presented is that the design and organization of office spaces have a significant impact on the health and well-being of office workers. While office workers may not face the same obvious hazards as industrial workers, they are still exposed to serious dangers from chemical and psychological risks. The movement raises awareness about the potential health hazards in office environments, such as indoor pollution, poor air circulation, and exposure to specific office technologies. Materials, such as photocopier toner, correction fluid, and other office supplies, were scrutinized for their potentially toxic ingredients. The impact of spatial office design is often overlooked, as traditional notions of office environments are considered to be safe and protected from the outside. The movement illustrated that even in the seemingly harmless office environment, serious health risks can exist. Overall, this promotes the revaluation of spaces and the consideration of environmental and health factors posed on the occupant. Additionally, it goes beyond the confines of offices, and encourages design with the mental wellbeing of the potential users in mind.

• le Roux, H. (2022). ‘Circulating Asbestos: The International AC Review, 1956–1985,’ In Förster, K. (ed.) Environmental Histories of Architecture, Montreal: CCA.

• Murphy, M. (2000). ‘Toxicity in the Details: The History of the Women’s Office Worker Movement and Occupational Health in the Late-Capitalist Office.’ Labor History, 41(2), 189–213.

Doucet presents the importance of environmental sciences and post-humanist approaches in architecture, she does this by analysing the case studies of the Aviary by Cedric Price and the Dolphin Embassy. Both precedents showcase innovative approaches to promoting respectful relationships between humans and animals. The Aviary included a mechanical bird and an artificial tree to meet the needs of birds. The Dolphin Embassy, on the other hand, put forth this intriguing concept of a floating lab designed to facilitate interaction between humans and dolphins. The author also introduces the idea of architects being like fiction writers- both are dreamers aiming to bring new worlds to life. This concept highlights how architects, in their designs, get all speculative and creative, letting them imagine different futures and challenge the stereotypical ways of doing things.

Haraway's ideas, on the other hand, encourage a shift in thinking about architecture, urging us to consider the complex entanglements of human and non-human actors in the creation of built environments. Her argument of accountability brings forth the need for responsible and responsive relationships with the environment. She does this by using examples from her own life, such as her relationship with her dog. Her concept of coexistence implies the idea of "companion species," referring to the mutual dependence and interaction between different species. It makes me contemplate how to deal with animals and how we can understand their interactions. Whilst during typical studio projects we are encouraged to enforce accessibility, this reading sheds light on inclusivity beyond the human species, reconsidering the impact on diverse species and ecosystems of our actions on the environment and its inhabitants.

• Doucet, I. (2022). ‘Interspecies Encounters: Design (Hi)stories, Practices of Care, and Challenges,’ In Förster, K. (ed.) Environmental Histories of Architecture, Montreal: CCA.

• Haraway, D. (2008). ‘Part 1: We Have Never Been Human.’ In Ibid. When Species Meet, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1–42.

Tavares calls for a reconsideration of the connection between society and the environment, complicating the interweaving of architecture and history, and challenging assumptions about modernization. Balée calls for a critical and operative engagement with environmental relations beyond the themes of energy and climate change. One of the most important concepts highlighted is the idea of "constructed forests”, challenging traditional notions of wilderness and natural habitats. He emphasizes that human nature is neither entirely destructive nor entirely ecological and that there are sustainable management strategies that can increase biodiversity while also being economically viable. Nature is presented as a “socially determined and culturally specific” (Tavares, 2022: 8-3) concept, challenging the traditional Western view of nature as a universal and neutral concept. Additionally, he touches on the disappearing cultural forests and villages of the Ka'apor community, as they are facing threats from logging and invasion. This reading inspires me to critically rethink the relationship between architecture and the environment, challenging the view of architecture being separate from nature.

Similarly, Tsing emphasizes the importance of understanding the interconnectedness of human and non-human lifeways and the impact of human activities on the environment. The idea of “capitalist ruins” is especially intriguing to me; as modern capitalism has led to the long-distance destruction of landscapes and ecologies, resulting in environmental damage. However, as part of the Western population, one is not aware of the destruction caused elsewhere. We had started this series and ended it with the concept of the Anthropocene, this reading in particular the unintentional mess humans have made of the planet. Overall, it urges me to rethink my actions, and makes me wonder whether to continue to build is the direction I want to go into, as no matter how sustainable a building is, it does ultimately have an negative impact on the environment.

• Tavares, P. (2022). ‘Architectural Botany: A Conversation with William Balée on Constructed Forests,’ In Förster, K. (ed.) Environmental Histories of Architecture, Montreal: CCA

• Tsing, A. (2015). ‘Part 1: What’s Left.’ In Ibid. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 11–43.

Cover Page

• Schultz, K., Chatterjee, A. and Lee, S. T. T. (2023) ‘A Billion New Air Conditioners Will Save Lives But Cook the Planet.’ Bloomberg.com. [Online] 17th May. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2023-05-17/air-conditioners-save-lives-in-india-heat-waves-but-worsen-global-warming.#

• Siddiqui, Z. (2021) Early heatwaves foreshadow uncertain future in South Asia. The Third Pole. [Online] [Accessed on 18th January 2024] https://www.thethirdpole.net/en/climate/early-heatwaves-foreshadow-uncertain-future-for-millions-in-south-asia/.

Essay

• Anwar, N., Khan, H., Abdullah, A., Macktoom, S. and Fatima, A. (2022) Designed To Fail? Heat Governance In Urban South Asia: The Case Of Karachi A Scoping Study Designed To Fail? Heat Governance In Urban South Asia: The Case Of Karachi -A Scoping Study 2 Acknowledgement.

• Arif, G. M., Riaz, M., Faisal, N., Mohammad Jamal Khattak, Sathar, Z. A., Mabood, A., Sadiq, M., Hussain, S. and Khan, K. S. (2019) ‘Climate, population, and vulnerability in Pakistan: Exploring evidence of linkages for adaptation.’ Population Council, January, pp. 11–30.

• Avermaete, T. (2020) ‘Monuments of Country, Climate and Culture: Michel Écochard and the Design of the Postcolonial Tropolis.’ Tropical Architecture in the Modern Diaspora, (63) pp. 32–39.

• Avermaete, T., Maristella Casciato, Yto Barrada, Takashi Honma, Mirko Zardini and Centre Canadien D'architecture (2014) Casablanca Chandigarh : a report on modernization. Montréal: Canadian Centre For Architecture ; Zürich.

• Azam, A. and Shafique, M. (2017) ‘Agriculture in Pakistan and its Impact on Economy―A Review.’ International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 103(2005-4238) pp. 47–60.

• Barber, D. A. (2019) ‘After Comfort.’ Log, (47) November, pp. 45–50.

• Bhutto, F. (2022) The west is ignoring Pakistan’s super-floods. Heed this warning: tomorrow it will be you. the Guardian. [Online] https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/sep/08/pakistan-floods-climate-crisis.

• Butler, L. and Stack-Maddox, S. (2022) Climate change made deadly heatwave in India and Pakistan 30 times more likely | Imperial News | Imperial College London. Imperial Collge London News. [Online] [Accessed on 14th January 2024] https://www.imperial.ac.uk/news/236696/climate-change-madedeadly-heatwave-india/.

• Dadlani, C. B. (2018) From stone to paper : architecture as history in the late Mughal Empire. New Haven Ct: Yale University Press.

• IANS (2022) 90 people died in 2022 due to heatwave spells in India, Pakistan: Study. www.business-standard.com. [Online] https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/90-people-diedin-2022-due-to-heatwave-spells-in-india-pakistan-study-122052400052_1.html.

• Jeffcott, S. (2023) Powering Up Pakistan: CLASP’s Two-Year Plan to Tackle Energy Crises & Climate Change. CLASP. [Online] [Accessed on 14th January 2024] https://www.clasp.ngo/updates/powering-up-pakistan/.

• Khalid, R. and Sunikka-Blank, M. (2018) ‘Evolving houses, demanding practices: A case of rising electricity consumption of the middle class in Pakistan.’ Building and Environment, 143, October, pp. 293–305.

• Khan, S. M. (2010) ‘Sethi Haveli, An Indigenous Model For 21st Century “Green Architecture.”’ International Journal of Architectural Research: Archnet-IJAR, 4(1) pp. 85–98.

• Khan, S. M. (2016) ‘Traditional havelis and sustainable thermal comfort.’ International Journal of Environmental Studies, 73(4) pp. 573–583.

• Macktoom, S., H. Anwar, N. and Ahmad, M. (2023) After Comfort: A User’s Guide - Soha Macktoom et al. - Heatscapes and Evolutionary Habitats. www.e-flux.com. [Online] [Accessed on 15th January 2024] https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/after-comfort/568093/heatscapes-and-evolutionary-habitats/.

Bibliography

• Mehmood, S. and Jan, Z. (2022) ‘Adaptive Reuse Of Heritage Buildings For Conservation, Restoration And Tourism Promotion: A Case Study Of The Sethi Haveli Complexes In Peshawar.’ Pakistan journal of social research, 04(03) pp. 804–814.

• Nanditha, J. S., Kushwaha, A. P., Singh, R., Malik, I., Solanki, H., Chuphal, D. S., Dangar, S., Mahto, S. S., Vegad, U. and Mishra, V. (2023) ‘The Pakistan Flood of August 2022: Causes and Implications.’ Earth’s Future, 11(3).

• Rashid, S. A., Haider, Z., Chapal Hossain, S. M., Memon, K., Panhwar, F., Mbogba, M. K., Hu, P. and Zhao, G. (2019) ‘Retrofitting low-cost heating ventilation and air-conditioning systems for energy management in buildings.’ Applied Energy, 236, February, pp. 648–661.

• Ritchie, H. and Roser, M. (2020) ‘CO2 and Greenhouse Gas Emissions.’ Our World in Data, May.

• Sattar, S. and Mubasal, M. (2023) Pakistan’s Energy Use: High Inefficiency and Distorted Consumption. Aptma. [Online] [Accessed on 17th January 2024] https://aptma.org.pk/pakistans-energy-use-high-inefficiency-and-distorted-consumption/.

Reading Diary

• Bierig, A. (2022). ‘Building on Ghost Acres: The London Coal Exchange, circa 1849.’ In Förster, K. (ed.) Environmental Histories of Architecture, Montreal: CCA.

• Wrigley, E.A. (1967). ‘A Simple Model of London’s Importance in Changing English Society and Economy 1650-1750.’Past & Present, No. 37, July, 44–70. / Wrigley, E.A. (2010). ‘Introduction.’ In Ibid. Energy and the English Industrial Revolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1–6.

• Calvillo, N. (2022). ‘Toxic Nature: Toward a Queer Theory of Pollution.’ In Förster, K. (ed.) Environmental Histories of Architecture, Montreal: CCA.Wrigley,

• Gissen, D. (2012). ‘A Theory of Pollution for Architecture.’ In Borasi, G. / Zardini, M. (eds.) Imperfect Health: The Medicalization of Architecture, Montréal / Zurich: Canadian Centre for Architecture / Lars Müller Publishers, 117–132.

• Chang, J.-H. (2022). ‘The Air-Conditioning Complex: Histories and Futures of Hybridization in Asia.’ In Förster, K. (ed.) Environmental Histories of Architecture, Montreal: CCA.

• Roesler, S. (2022). ‘Epilogue 7. Singapore as a Model? Urban Climate Control in Practice.’ In ibid. City, Climate, and Architecture: A Theory of Collective Practice, KLIMA POLIS, vol. 1, Basel: Birkhäuser, 213–227.

• Günel, G. (2016). ‘Inhabiting the Spaceship: The Connected Isolation of Masdar City.’ In Graham, J. / Blanchfield, C. (eds.) Climates: Architecture and the Planetary Imaginary. New York / Zurich: Columbia Books on Architecture and the City / Lars Müller Publishers, 361–371.

• le Roux, H. (2022). ‘Circulating Asbestos: The International AC Review, 1956–1985,’ In Förster, K. (ed.) Environmental Histories of Architecture, Montreal: CCA.

• Murphy, M. (2000). ‘Toxicity in the Details: The History of the Women’s Office Worker Movement and Occupational Health in the Late-Capitalist Office.’ Labor History, 41(2), 189–213.

• Doucet, I. (2022). ‘Interspecies Encounters: Design (Hi)stories, Practices of Care, and Challenges,’ In Förster, K. (ed.) Environmental Histories of Architecture, Montreal: CCA.

• Haraway, D. (2008). ‘Part 1: We Have Never Been Human.’ In Ibid. When Species Meet, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1–42.

• Tavares, P. (2022). ‘Architectural Botany: A Conversation with William Balée on Constructed Forests,’ In Förster, K. (ed.) Environmental Histories of Architecture, Montreal: CCA

• Tsing, A. (2015). ‘Part 1: What’s Left.’ In Ibid. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 11–43.

• Smog: LHC Directs Govt To Impose Emergency In City (2023) The Friday Times. [Online] [Accessed on 19th January 2024] https://thefridaytimes.com/01-Nov-2023/smog-lhc-directs-govt-to-impose-emergency-in-city.

• https://www.facebook.com/thoughtcodotcom (2019) The Great London Smog of 1952 Kickstarted Focus on Air Quality. ThoughtCo. [Online] https://www.thoughtco.com/the-great-smog-of-1952-1779346.