© Mark Moody

© Kent Mason

© Joel Wolpert

© Mark Moody

© Kent Mason

© Joel Wolpert

© Mark Moody

© Kent Mason

© Joel Wolpert

© Mark Moody

© Kent Mason

© Joel Wolpert

The red spruce forests where you love to play are at risk because of climate change. Over the past 20 years, The Nature Conservancy and its partners have been restoring Appalachian forests by planting red spruce trees. Now we are sourcing red spruce seed for greater genetic diversity in our plantings to ensure our forests can withstand the impacts of a warming planet.

To make a change, donate at nature.org/plantabillion

As the climate warms and gets drier, genetically diverse forests can adapt and thrive. To learn more, visit nature.org/redspruce20

As the climate warms and gets drier, GENETICALLY DIVERSE FORESTS can adapt and thrive. : :

Restore forest CONNECTIVITY with GENETICALLY DIVERSE seedlings for gene flow and animal climate migrations.

© Mark Moody

© Kent Mason

© Kent Mason

© Mark Moody

© Kent Mason

© Kent Mason

Our lives are filled with warning labels reminding us to use the good stuff in moderation. And then there is snow. Particularly, the kind you find at the top of a mountain, on slopes, and in tubing hill lanes. It’s our chance to pile on as many extra servings as we like, without a label reminding us to use only sparingly. Snow – when in doubt, take one more run. Welcome to the Mountain.

snowshoemtn.com

Publisher, Editor-in-Chief

Dylan Jones

Senior Editor, Designer Nikki Forrester

Copy Editor

Amanda Larch

Happy Holidays from your HO Staff Dylan Jones, Nikki Forrester

I can’t believe I’m about to admit this, but I’ve never been the biggest fan of winter. Sure, I have tons of happy memories of snowball fights, sledding adventures, and snow days as a kiddo. But I always thought the best version of myself could be found swimming in a natural body of water on a hot, summer day. And then I met Dylan, the publisher and editor-inchief of this here publication, who transforms into a giddy five-year-old anytime there’s even the mention of snow. On a gorgeous sunshiny day in July, Dylan can regularly be found chatting about how he can’t wait to ski. It’s the only reason he’ll get up before 8 a.m., and by “get up,” I mean launch out of bed with unbridled enthusiasm for the day ahead. Well, I have to say that enthusiasm is contagious, and it all started on my first trip to White Grass in 2016.

Dylan and I rented skinny cross-country skis and embarked up the slope toward Bald Knob. We had no clue what we were doing or where we were going. We awkwardly shuffled our long skis, trying as hard as we could to gain traction in the snow. Our naivety led us to choose arguably the worst possible route up the mountain on a trail called Steep Upper Falls. I remember looking up the seemingly vertical face, wondering how I would ever make it up on my skis. I faceplanted so many times that I eventually gave up and bellycrawled my way to the top of the trail. My hands were frozen, my pants were full of snow, and I was on the verge of tears (and by “verge” I mean I actually started crying). For a brief moment, I was sucked into a void of my own misery.

And then I looked up. Fat, fluffy snowflakes fell on my head and stuck to my eyelashes. They coated every exposed branch and twig. I felt like it was just me and this magical expanse of quiet and calm. I don’t even remember how we ended up getting back down to the lodge that day. I’m sure I had trouble staying upright and I’m sure I looked like a total goof. But I vividly remember that moment staring into the snowy trees, feeling completely insignificant and filled to the brim with a sense of wonder and appreciation.

A true love of winter has slowly seeped into my psyche. I now live in Davis, a place that experiences wintry weather for upwards of six months a year. As the temperature drops and snow settles into Canaan Valley, the collective stoke for the coldest and most ephemeral season begins. Everyone talks about the weather, constantly. We check the forecast 50 times per day, letting the ever positive 10-day outlooks fuel us with optimistic dreams of skiing powder up to our chins. Most of the time, only two inches of funky fluff fall from the sky, but it doesn’t matter, because we’ll go ski with the unbridled enthusiasm of a five-year-old.

Those feelings of pure joy and awe never get old. They’re a constant reminder that winter is a season like no other. It brings out the best in so many people, and even if it’s not the one that brings out the best version of you, I hope you can find some way to get outside and savor the snow while you can. Winter is the most fleeting of the seasons, which is exactly what makes it so wonderful. w

Nikki Forrester

Nikki Forrester

Bob Bell, Ellie Bell, George Bell, Nikki Forrester, Nikki Fox, Dylan Jones, Justin Harris, Tanner Henson, Karen Lane, Nils Larsen, Boyce McCoy, Mark Moody, Cam Moore, Nathaniel Peck, Kurtis Schachner, Rob Stull, Jesse Thornton

Get every issue of Highland Outdoors mailed straight to your door or buy a gift subscription for a friend. Sign up at highland-outdoors.com/store/

Request a media kit or send inquiries to info@highland-outdoors.com

Please send pitches and photos to dylan@highland-outdoors.com

Our editorial content is not influenced by advertisers.

Highland Outdoors is printed on ecofriendy paper and is a carbon-neutral business certifed by Aclymate. Please consider passing this issue along or recycling it when you’re done.

Outdoor activities are inherently risky. Highland Outdoors will not be held responsible for your decision to play outdoors.

COVER

Ellie Bell (aka Tele Bell) executes a perfect telemark turn in fresh powder at Snowshoe Mountain Resort. Photo by Kurtis Schachner.

Copyright © 2022 by Highland Outdoors. All rights reserved.

Lovers of the Monongahela National Forest, rejoice! The Mon Forest Towns Partnership was awarded the Governor’s Award for Regional Cooperation at the 2022 Governor’s Conference on Tourism. This annual award is given to a group, community, or organization that excels in regional tourism development and bolsters collaborative efforts between counties.

The mission of Mon Forest Towns Partnership is to grow a sustainable recreation economy that benefits the gateway towns that surround the 900,000-acre national forest. The initiative currently includes 12 towns across eight counties: Petersburg in Grant County; White Sulphur Springs in Greenbrier County; Richwood in Nicholas County; Seneca Rocks and Franklin in Pendleton County; Durbin and Marlinton in Pocahontas County; Elkins in Randolph County; Davis, Parsons, and Thomas in Tucker County; and Cowen in Webster County.

“I can’t think of a better regional collaboration in the state,” said Cara Rose, executive director of the Pocahontas County CVB. “When you consider that the Mon

National Forest is the largest tourism asset in the state and the fact that 12 communities are all collaborating to develop and market recreation in the Mon, it sets a really strong precedent for regional development in West Virginia.”

Since its inception in 2020, the initiative

has developed a strategic plan, outlined specific priority projects in each Mon Forest Town community, implemented a marketing plan, and installed informational kiosks with area-specific amenities—like the bike pump and tool set at the kiosk in the bike-centric town of Davis.

“Over the past 100 years, the focus in the Mon has been on natural resources. It’s really exciting to think about the national forest becoming recognized for the economic value that recreation brings to communities located within the forest,” Rose said. “Even small communities that aren’t as recreation-focused right now realize that they can be part of this, too. I hope this helps the state recognize what an asset the Mon Forest really is.”

The Mon Forest Towns Partnership is working with West Virginia University Extension, various WVU collegiate programs, Region 4 Planning & Development, the Benedum Foundation, Woodlands Development Group, Downstream Strategies, and the West Virginia Community Development Hub. To learn more, visit www.monforesttowns.com. w

With its acquisition of several large properties toward the end of 2021, the West Virginia Land Trust (WVLT) has officially protected over 20,000 acres throughout West Virginia.

The WVLT is a nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting special places and natural resources across the Mountain State. The total acreage is currently comprised of 22 preserves across 17 counties and 30 conservation easements on privately owned lands.

“We started by making agreements with private landowners to protect their land, but we’ve really shifted in the last

few years to look for parcels with public access opportunities,” said WVLT executive director Brent Bailey.

Eight of the preserves, including the recently acquired 1,006-acre Piney Creek Preserve in Raleigh County, are currently open to the public. The WVLT plans to open all 22 of its preserves to the public as funds allow. According to WVLT communications and marketing director Jessica Spatafore, it takes around $100,000 to open a preserve for public access. “We need volunteers and donations to build infrastructure like trails, signage, and safe parking,” Spatafore said.

Bailey said the WVLT, which wasn’t specifically shooting for the 20,000 figure as a benchmark, was surprised when it tallied its acreage at the end 2021. “We turned around one day and realized we had crossed that threshold,” he said. “Someone added it up and said, “Do you realize how big this number is?””

Just in case you were wondering, 20,000 acres is equivalent to 15,152 football fields. If you’re wondering what 15,152 football fields is equivalent to, you could probably Google it. For reference, Watoga State Park, West Virginia’s largest state park, is 10,000 acres. Arbitrary size compari-

sons aside, 20,000 acres is a lot of land—especially when that acreage is protecting myriad natural and cultural resources across 52 properties.

The WVLT is now wondering what the next 20,000 acres will look like. “We’re exploring how we can really bump up the acreage per transaction,” Bailey said. “We want to provide habitat, protect drinking water, and have diversified trails for all users. When it comes to conservation, bigger is better.”

But whether it’s a small easement on a family farm or a multi-thousand-acre public preserve, West Virginians are passionate about their lands. “This is a cultural thing for West Virginians, whether they grew up here or moved here,” Bailey said. “You can’t expect to have permanent access to trails and rivers unless you’ve somehow protected that land. We’re excited to be riding this wave where what we do protects the land on which recreation is going to occur.” w

We look forward to seeing what natural gems are protected in the WVLT’s next 20,000 acres. To find out more about the WVLT, visit www.wvlandtrust.org.

I am thrilled to announce the first recipients of our 1% for WV campaign, an initiative that donates one percent of our annual advertising revenue to environmental and social nonprofits based in West Virginia. This campaign is our localized version of the lauded 1% for the Planet program. We give 100% of our donations to groups focused on fighting the good fight right here in the Mountain State with the hope that these dollars will support positive change.

This year’s environmental nonprofit is West Virginia Rivers Coalition, a statewide organization whose mission is “conserving and restoring West Virginia’s exceptional rivers and streams.” While its mission statement is water-focused, the organization’s work extends far beyond West Virginia’s riverbanks. We chose WV Rivers for its incredible statewide advocacy via legislative lobbying, its West Virginians for Public Lands campaign, and its programs aiding the local fight against climate change.

This year’s social nonprofit is Active Southern West Virginia, a regional organization whose mission is “providing an ecosystem of physical activity for the residents of southern West Virginia by offering programs led by trained volunteers from within the communities they serve.” We chose Active SWV for its effectiveness in removing access barriers and getting multitudes of West Virginians outside to live healthier and happier lives. w

By Cam Moore

By Cam Moore

All things, like the mighty Mississippi River itself, eventually run their course. It’s been a wonderful two years of proselytizing obscure facts about West Virginia’s glut of superlatives that end with “east of the Mississippi.” So, take a seat and grab a tissue, because this, unfortunately, is the final installment of East of the Mississippi. As such, it’s a good time to reflect on the original premise of this column. There’s an unspoken assumption that the West Virginia highlands are shockingly cool and impressive when compared to other places on the western side of an arbitrary river a thousand miles away. Don’t get me wrong, I like a good geographical factoid as much as the next nerd. However, I think my original premise for this column is bunk on two counts. First, our green Appalachian Mountains can go toe-to-toe (or is it foothill-to-foothill?) with the dramatic landscapes of the West. I’m glad to know the vast sagebrush steppe is out yonder in the windy heartland, although I could live a long and happy life without ever seeing another dustcovered lodgepole pine. But could I live a long and happy life if I never again experienced the autumnal blaze of sugar maples or a gnarled yellow birch hanging over a tea-colored river? Absolutely not. Second, the West is an inherently amazing region, but some of the national obsession with heading west is rooted in the idea of Manifest Destiny; that it lies ‘out there’ somewhere over the horizon, an idyllic place where the sunsets will be brighter and where we’ll become better versions of ourselves. Consider the vibes of two nationally colloquial phrases: the positive promise of going “out west” compared to the negative connotation of heading “back east.” But it doesn’t have to be this way. Imagine walking across the continent from west to east with fresh eyes: leaving the giant sequoia gardens of California, traversing the dusty deserts, passing the imposing Rockies, and crossing the incessantly windswept plains only to discover an Appalachian utopia featuring the largest broadleaf temperate forest on Earth and plateaus cut with churning rivers. Simply put, this place is awesome. Just as important, it is the type of awesome that requires work to reach its full potential. Appalachia’s landscapes have long been exploited to meet humanity’s needs for raw materials. We owe a debt to these lands, and in paying that debt through summoning wilderness to once again bloom from the Earth, we add meaning to our lives, regardless of our location east or west of the Mississippi. You desert rats can go plant lodgepole pines in desiccated cracks in Colorado, but me? I’ll be right here, planting yellow birches in soft moss atop the Alleghenies. w

Cam Moore is a resident of Canaan Valley, the highest large valley East of the Mississippi, and a lover of all things West Virginia.

If you’ve visited our high mountain town of Davis, chances are you’ve found yourself checking your weather app on an hourly basis regardless of the season. Spending time outside to enjoy the wealth of outdoor activities this area has to offer is commonplace among us folks who call this community home. However, living in West Virginia’s highest town doesn’t come without tribulation—we frequently endure some pretty miserable atmospheric conditions throughout the year here in Tucker County. From 34 degrees and rain in November to 62 degrees and no snow in February, the rapidly changing weather here in the Allegheny Highlands is the one true constant. The old saying remains true: if you don’t like the weather, just wait a minute. Or, as a good friend puts it, you have to be comfortable with being uncomfortable.

Even though we tolerate some of the most unpredictable conditions Mother Nature can throw at us, we’re treated to some exceptional weather on occasion too, whether it be a beautiful bluebird summer day with low humidity in August or two feet of the lightest, fluffiest powder in January. Every now and then, the stars align, allowing us to experience some truly extraordinary natural phenomena.

We were treated to just that in January of 2022 during a dry spell when many powder-hungry locals were depressed due to lack of snow on the ground. The weather gods, who were busy neglecting the ski slopes for unbeknownst reasons, decided instead to smile down upon the many ponds of Canaan Valley. While in the middle of a long cold snap of dry, Arctic air, we were greeted with the best natural ice-skating conditions in years. But instead of sitting

inside waiting for snow like other folks, my daughter and I chose to make the most of it by dusting off our ice skates and inviting ourselves over to our friend’s pond.

I’ve played on wild ice plenty of times. When I was younger, I messed around on Deep Creek Lake just over the border in Maryland. In more recent years, I’ve found myself cross-country skiing across Lake Thomas, where the North Fork of the Blackwater River is dammed just above our neighboring town of Thomas. But I had never actually skated on wild ice until our outing in Canaan. When my daughter and I arrived at the pond, we couldn’t believe the scene before our eyes. The ice was smooth and clear as glass, with a wispy dusting here and there of powdery snow. We couldn’t have asked for better ice-skating conditions at a climate-controlled rink.

But reader beware—before you drop this magazine and go careening out onto the closest pond, be sure to check the thickness of the ice or you might end up taking an unintentional polar plunge. Based on my limited research, a general rule of thumb is that ice should be four-to-five inches thick before setting foot on it. Fortunately, some brave ice fisherman were there before us and drilled a few ice-fishing holes into the pond, allowing us to properly check the depth. Based on their work, we could tell the ice was plenty thick and safe for us to skate.

Without hesitation, we strapped on our skates and slipped out onto the ice. There were no Zambonis machines or crowds of people mindlessly skating in circles; just me, my daughter, and a wide-open rink rimmed by snowy mountains, all crafted by Mother Nature. It was perfect.

We smiled, laughed at each other, fell, laughed again, fell some more, and had an absolutely amazing skating session. In our minds, we were as graceful as Olympic skaters, but in reality, we were an icy mess. We simply aren’t that skilled and likely looked like complete amateurs. But that didn’t matter. It was a great father-daughter experience doing something epic that, very likely, won’t happen again for a while. How often can you roll up to a frozen pond in the middle of a beautiful valley and skate until your legs are sore, all while hanging with your kid? My daughter may not agree, but I thought it was pretty damn special.

Even beyond the ice, the conditions were surreal. As the sun began to set, the evening light reflected off the rime ice on Cabin Mountain, producing that beloved Canaan alpenglow. That, coupled with the evergreen forest along the pond’s edge, made for a beautiful setting— perfect for enjoying a post-skate beverage with our friends who stumbled out onto the ice to see what all the commotion was about.

What made the experience even more

special is that this particular pond is owned by my friend’s neighbor, a lifelong Canaan Valley resident in her 90s. When I talked to the pond owner to thank her for allowing us to skate on her pond, her face lit up. She immediately shared stories of when she skated on the pond, long ago, as a little girl. I could see the joy in her eyes from knowing that my daughter was able to experience the same wild ice she had skated on as a kid—two people, generations apart, sharing the joy of a timeless activity in this ancient landscape.

Many old-timers will say it’s not the same as it was when they were kids, that it doesn’t snow as much or doesn’t get as cold as it once did. But the snow can get just as deep, the ice just as thick—you just have to be in the right place at the right time to take advantage of these increasingly ephemeral conditions. In Canaan, that often means you’d better be ready on a random Wednesday at 2:30 in the afternoon. Because if you wait until 2:31, you just might miss it. w

Rob Stull is busy being a RadDad and the self-proclaimed sheriff of Snob Knob, WV.

Every now and then, the stars align, allowing us to experience some truly extraordinary natural phenomena.

.

Three premier ski resorts, small mountain towns and warm, cozy cabins are waiting for you in Tucker County. Averaging 150 inches of snowfall per year and an elevation of over 4,000 feet, we have all the natural ingredients to make our high-mountain paradise ideal for skiing, snowboarding, tubing, sledding and other seasonal activities.

Plan your winter getaway in the valley.

SkiTheValley.com

Growing up in Virginia, I was invariably blanketed in green. Inescapable tunnels of vegetation were both overwhelming and comforting. I was at home among the trees and became an observer of the landscape. I started rock climbing as a child and learned more from climbing outside than I ever did in a classroom. Climbing forced me to observe every handhold and foothold, taking note of each micro grain of crystal under my fingertips. This forced observation serendipitously brought me face to thallus with lichens. This relationship was originally one of annoyance: a tactile feeling of insecurity as my toes slid with the lichens off the edge of a rock face. There is no reciprocity between climber and lichen. We brush and scrape them from their homes and leave chalk graffiti in their wake. Their dust settles to the ground under our packs and dogs and rubber shoes. No longer are their bodies cycling nutrients into the air. And in their final moments, they sacrifice their lives as decomposition transforms their bodies into soil. I never thought of lichens as more than crust until recently.

I was a student of industrial design at Virginia Tech in 2022 and focused my education and thesis on the continuity of design and craft. I was endlessly inspired by the craftspeople of Appalachia (and Indigenous communities within them) and what one could learn from their approach to making objects from regional materials that last for generations. What separates industrial design from other forms of design is the focus on alleviating human pain points. Designers ask, “How can I design this product to help people?” The first steps in this process are research, compassion, and understanding the problems. My specific application of this practice began with climate research.

Half of Americans live in counties with unhealthy ozone and particle pollution, which can be particularly harmful to people with preexisting respiratory conditions like those from COVID-19 or from working in or living near coal mines. Many of these Americans are Appalachians living in valleys where this pollution gets trapped by warm air at ground level between mountains. Lichens die when pollutants are too concentrated in an environment, serving as an indicator species of air toxicity—a canary of sorts— for climatologists and local government employees. Upon reviewing my research, I discovered a question. How can a quilt dyed with lichens grow a conversation around the preciousness of even the most overlooked organisms while educating communities about their surrounding air quality and climate change?

Lichens are complex organisms comprised of a mutualistic relationship between multiple fungi and algae. The algae provide food to the lichen through photosynthesis, while the fungi provide structure. Some lichens also include cyanobacteria that provide food through photosynthesis and fix nitrogen to support the growth of lichens as well as other plants in the environment.

Scientists estimate that 100,000 species of lichen exist. They are abundant most everywhere on Earth, including harsh environments from Antarctica to the world’s hottest deserts. They provide food and shelter for other organisms, and occupy landscapes where no other species

can survive. As important pioneer organisms, they produce acids that chemically weather rocks, breaking them down to form soils for future plants to inhabit.

Because lichens have different tolerances to air quality, scientists can use information about the abundance and diversity of lichen species to monitor air pollution in remote forests, rural hollers, suburban neighborhoods, and crowded cities. But lichens themselves are quite susceptible to climate change and air pollution. Sulfur dioxide and ozone immediately kill species like smooth rock tripe (Umbilicaria mammulata), found across the globe and in abundance here in Appalachia. Certain species of lichens can take hundreds of years to grow larger than a penny—and can live for thousands more—making them particularly vulnerable to overharvesting, habitat destruction, and air pollution.

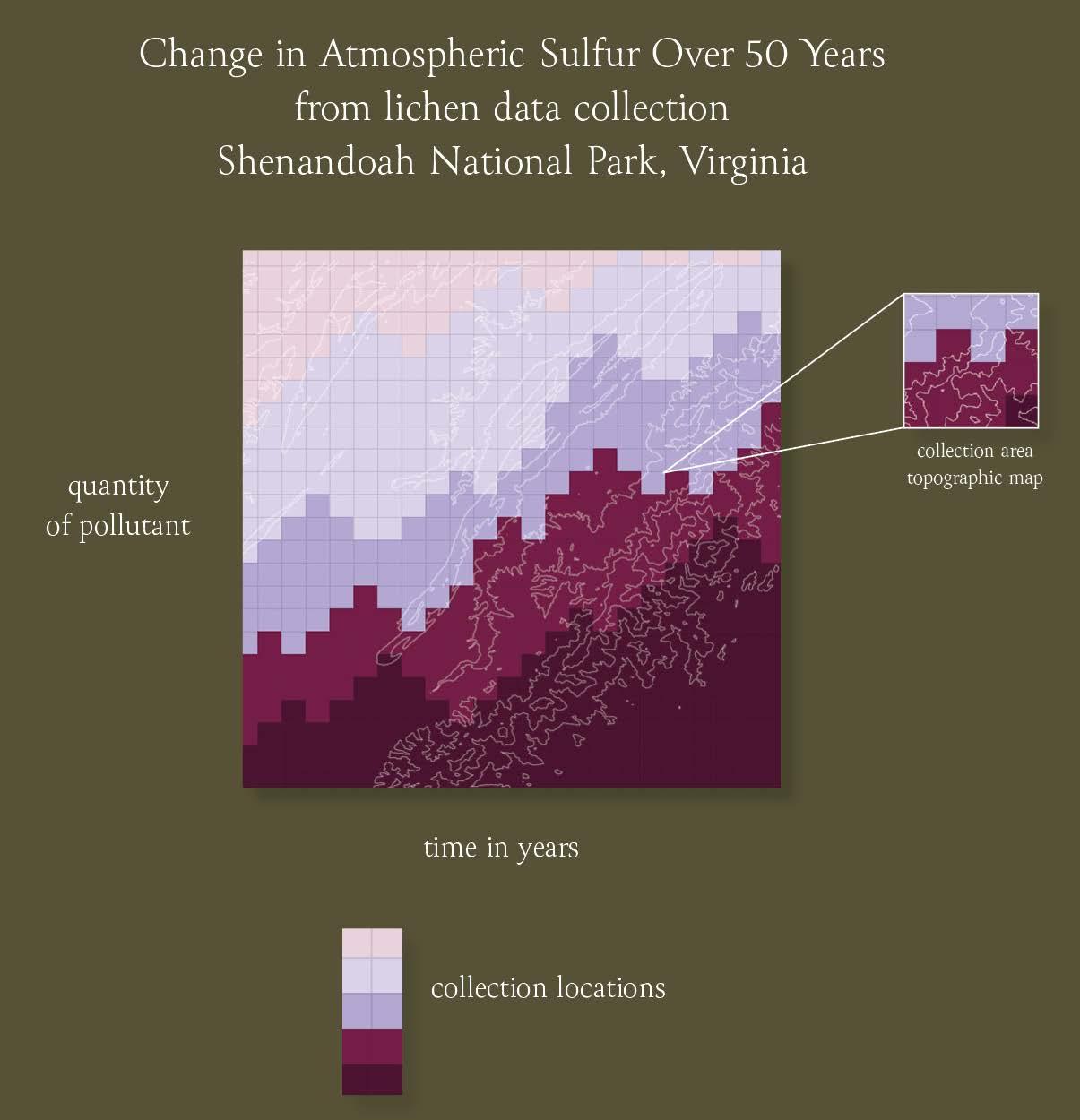

Just as scientists can use lichens to help paint the picture of climate changes across the centuries, artisans have used quilts for hundreds of years as storytelling objects. Their myriad geometries vary across stylized, abstract, and representational patterns of fabric. These qualities make a quilt an ideal object to help visualize complex data. Data visualization is a way to communicate numerical data through graphs and charts; data art takes that visualization one step further by displaying the data in a more abstract way to convey an emotion. The data used for this quilt was collected in Shenandoah National Park in Virginia by James D. Lawrey, a biologist at George Mason University; and Mason E. Hale Jr., a curator of lichens at the Smithsonian Institution. By measuring sulfur accumulation in a common lichen species, the researchers showed an increase in atmospheric sulfur, which is thought to have occurred due to an increase in motor vehicle traffic in the park. A rise in atmospheric sulfur can cause acidification that negatively impacts soils, waterways, and air quality, ultimately contributing to climate change. I used this data to inform the quilt’s geometry and color patterns, and I used the topography of the collection site to quilt the piece together. Ultimately, my quilt is a handmade object with imperfections, more data art than visualization. Unlike the science on which it is based, precision and accuracy were not the objective.

Like a quilt draped over a person, lichens blanket landscapes with patches of color and texture. Oranges, blues, yellows, and greens create a natural textile of sorts high up on rock faces. My lichen dye process began with a conscious practice of “salvage botany,” a technique used by foragers to gather only those lichens found on the ground that were already detached from rocks. After collection, I submerged the lichens in a 1:1 water and ammonia solution and left them to ferment for at least six months or until the liquid was a dark, orange-ochre color. This liquid is known as orcein, or purple/ red lichen dye. The dye color changes from orange to purple when exposed to oxygen. Then, I dipped fiber in the dye for 24 hours and dried it.

I chose cotton and hemp fabrics for maximum color saturation and feel. Cotton thread was also used as well as cotton batting for the internal layer. The quilt was constructed of 576 squares that reflected lichen data from the study. The topography of the data collection area is the quilted portion of the

construction. The colors of the quilt represent different data collection sites and are a visual representation of the increase in atmospheric sulfur. The quilt gives physical form to the liquid dye and

embodies the lichen data through its color and geometry. It combines both properties of the lichens—their dye and the information they reveal—in one dynamic object.

It’s important for me to stress the singularity of this quilt. Lichens are sensitive yet enduring organisms, which is partly why they are such successful indicators of environmental health. Lichen dyes are a controversial craft. The greatest threat to their survival—and to the ecosystems they pioneer—is human activity. The lichens chosen for this project were salvaged from the forest floor, collected after a strong windstorm blew them from their connection points to the rock. And yet this conscious foraging is still not, as the greenwashing trademark says, ‘sustainable.’ I extracted these organisms for education and awareness, or so I convinced myself. I made a finite amount of dye and gave rigor-

ous thought to its application. Even so, making an object for warmth in a warming climate out of a sensitive organism is haunting. These lichens give back to us and our most vulnerable. They have been used in studies to reveal environmental inequalities by showing that low-resource neighborhoods had the highest quantities of air pollution. The lichens give us soil where it never existed. They give us food in times of famine and dye to make royal purples to be traded as gold. But what reciprocity do we practice? How can we live mutually with the lichens as they do within themselves? I suppose this quilt is my reciprocity with the rock tripe. Or at least the beginning. w

Karen Lane is a climber, designer, and photographer living in Fayetteville, WV. The breadth of her work includes fiber arts, product design, and photography of her life as an artist in Appalachia.

After months of anticipation, I am thrilled to share the winning shots from the Inaugural Highland Outdoors Photo Contest. This contest is the fruition of a dream I’ve had since taking over the magazine in 2018. The goal was to build community by showcasing talented photographers and highlight the outstanding beauty found only in West Virginia.

I was beyond impressed with the range and quality of images that we received for our first-ever photo contest. Fifty-two contestants submitted a total of 111 images (31 adventure entries, 47 landscape entries, and 33 wildlife entries), keeping us judges busy and creating some difficult choices when it came to select the winners. I’d like to note that the winning shots you see here are the crème de la crème, and there were plenty of superb shots that came very close to making the cut. We truly appreciate all the photographers who took the time and effort to submit their images. After all, it’s not a true contest without a range of options, so each contestant was very much an integral part of the process.

I’d also like to give a special thanks to our judges: Gabe DeWitt, David Johnston, and Molly Wolff. These professional photographers provided invaluable insight throughout the entirety of the contest. I’m honored to have served alongside them as a judge, and, more importantly, I’m proud to call them friends. I’m already looking forward to next year’s contest.

Dylan Jones, PublisherThis moody image of a solitary angler on Watoga Lake is a perfect showcase of less being more. The sheer simplicity of this photo is why the judges agreed that this was one of the best shots in the contest. The monochromatic color palette is striking; the sharp silhouette of the angler contrasts perfectly with the wispy fog and soft light of the sun; the angler’s pose shows a moment of stillness in between casts and the general incessant movement of the natural world. This image is the epitome of an early autumn morning in West Virginia.

“This photograph was taken at Watoga Lake as fall colors were beginning to hit the area,” Thornton said. “I camped nearby and shot around the lake early in the morning, taking in the spectral forms that were created from uplifting fog that was backlit from the rising sun. This image of the fisherman on the lake was captured by my second camera that I had set up for a short time-lapse sequence, which happened to perfectly capture the ethereal mood of that calm morning.”

This image, taken from a boulder field looking southeast along the ancient spine of the Allegheny Front, was a show-stopper. It has sharp and striking elements throughout the fore, middle, and background. The composition accentuates the depth of field. The perfect light exposure and delicious color palette offer a fresh angle on Dolly Sods, a place many of us have seen countless times.

“I live in Cumberland, Maryland, so I had to wake up at three in the morning, drive two hours, and then bushwhack in the dark to make it to this spot for sunrise,” Peck said. “You never know what kind of conditions you’re going to get on the Sods. I had been up almost every morning that week and there had been dense fog with zero visibility. It looked like that was going to happen again, but the fog stayed in the valleys to the east and there was just enough sun to light up the clouds looking south.”

This aerial shot of a peak autumn morning in picturesque and pastoral Canaan Valley is certainly an attention grabber. The ghostly fog contrasts nicely against the silhouette of Cabin Mountain, separating the otherwise monotone background from the vivid tones of the foreground forest. Although the judges typically don’t prefer roads in landscape images, something about the appealing emptiness of Route 32 disappearing into the trees adds an inviting quality to this image.

“Last fall, fog hit Canaan every morning during peak foliage, and I’d wake up early and fly my drone right off my deck,” Harris said. “I shot a different composition each day. That morning, I turned south, and the color of the sky was extremely unique. Combined with the fog and foliage, Route 32 added an element to the shot instead of taking away from it.”

Tanner Henson

DECKERS CREEK GORGE, PRESTON COUNTY

Waterfall photos are often a dime-a-dozen, but this wintry shot of one of the larger waterfalls on Deckers Creek immediately stood out. The photo is both framed and exposed well, a tough goal when shooting a winter landscape. The one-second exposure was long enough for the falls to be silky smooth, yet short enough for the water in the plunge pool to have texture and show movement.

“I shot this during a big snowstorm in 2020 when I was just getting into photography,” Henson said. “I was new to long-exposure photography and decided to go for a hike along Deckers Creek and try it out. I felt like I was getting horrible results on the camera’s display screen and left feeling underwhelmed, but once I got home and checked the shots out on the computer, I found what I thought was a pretty decent shot.”

We had quite a few submissions of deer photos, but this shot of a yawning buck provided a sense of personality that is hard to come by with these otherwise omnipresent ungulates. The winning element of this image is the crystal-clear focus, showing incredible sharpness around the eyes—the hallmark of a good wildlife shot. The mid-yawn mug is comedically reminiscent of those classic Budweiser “Whassup?” Superbowl commercials. The judges also liked the subtle feeling of movement provided by the wet snow falling on the antlers.

“My goal was to shoot the sunrise at Pendleton Point, but the sunrise didn’t do anything spectacular,” Peck said. “I happened to have my wildlife lens because there are always deer in Blackwater. I drove laps around the park until I spotted this big buck out in the bushes, and got excited because I usually just photograph does. He stood up, yawned, and was gone in an instant—this was the only sharp image I got of him.”

This close-up image of a snail traversing a pure, white piece of calcite flowstone was taken deep in a large cave system underneath Greenbrier County. The judges liked the choice of the composition in respect to the light source, which makes the snail look translucent. We were struck by the stark contrast of the pure, white stone against the pitch-black background, which places the emphasis on the snail and is reminiscent of the heralded National Geographic Photo Ark series.

“I’m a caver and a former journalist, so I’ve got the constant bug to photograph and document things,” Fox said. “I thought this particular surface snail was so interesting because it’s deep down a drop in the cave, and underground, animals need to have a food source, so I was unsure of what it was doing down there. It was beyond the natural light, so I used an external flash to take a million pictures and then found the best one. I was rooting for the little guy to survive.”

ADVENTURE WINNER

Boyce McCoy

BIG BEAR LAKE TRAIL CENTER, PRESTON COUNTY

This shot of Annie Simcoe mountain biking through “The Pines” at Big Bear Lake Trail Center instantly stood out in the Adventure Category. This photo exudes action, scale, and mood. Annie, with her determined look and bright colors, is clearly the subject of the photo. Typically, a large out-of-focus object in the middle of an image is a big no-no, but the judges felt the large tree in the foreground provides context to the image by making it feel as if you’re there with Annie, flying through the woods on a bike. We also loved the panoramic crop, which provides scale to this picturesque forest without making Annie seem too small.

“At the end of every October, Big Bear hosts a rider appreciation event, and it happened to snow just in time for the ride,” McCoy said. “The Pines section is a major highlight of the Big Bear trail system and catching a rider coming through makes for a great shot. Capturing Annie, isolated among the trees with colors that pop in that environment, was definitely a plus.”

This snap of a kayaker cruising on Indian Creek by Cook’s Old Mill is quintessential Appalachia, candidly showing a timeless summer scene. Cook’s Old Mill, a restored mid-1800s gristmill, is a tasteful juxtaposition to the modern fiberglass kayak, creating an element of time travel. The verdant hues and the pop of pink in the roses scream peak summer, and the peaceful kayaker shows an accessible side of adventure that’s welcoming instead of frightening.

“I’m from Western Kentucky, but was in West Virginia working on a construction project where I did a lot of driving on backroads,” Bell said. “I was out looking for photo opportunities to document the area’s regional history, and saw this lady in a kayak on the millpond and had to snap the image.”

Step by step, I glide my Hok skis straight up the steep edge of the glade, using one long wooden stick, called a tiak, to stabilize. My skis are short and wide, perfect for maneuvering through the tight Appalachian understory. I duck under, climb over, and sidestep through the snowy forest, remembering the art of the triangle with my body and the pole.

I pause. I hear nothing but silence—not the silence of nighttime, ears humming with static, the echo of the day’s noise in your head—but the muted silence only found deep in

a forest blanketed in snow. Every now and then, the silence is punctuated. The oaks creek, turning in their sleep. I am living in a Robert Frost poem, but instead of a horse, I ride on wood and fiberglass. I am fully present, carried forward by skis that echo the ancient arts of the past.

The route below is sparkling with fresh snow and uninterrupted vertical. The forest tells a story of succession with a couple of downed logs and a scattering of saplings and briars. The group—my dad, my partner Ryan, and our friend Kurt —catches up. My dad descends first, bracing on

Above, clockwise from top left: Chokue, a famous old-time skier in the village of Khom in the Altai Mountains, photo by Nils Larsen; Ryan Krofcheck hooting and hollering across the Appalachian backcountry, photo by Kurtis Schachner; a Hok skier descends a slope in Washington, photo by Nils Larsen; George Bell in deep PNW powder, photo by Nils Larsen.

Previous: Ellie Bell (front) and Ryan Krofcheck (back) tour through the woods on Hok skis. Photo by Kurtis Schachner.

his tiak behind him as if he is captaining a raft. He expertly lifts the broad tips of his Hok skis, floating on pillows of powder. I drop in next, creating a braided pattern as I carve in and out of my dad’s tracks. On my way down the silence is broken once again, this time by my vocal eruptions of joy. It is beautiful to know this same joyous sound can be heard across space and time, winter after winter, on snowy mountains around the world.

Hok, pronounced “hawk,” is the Tuwa word for “ski.” The Tuwas are Mongolian tribespeople that live a nomadic lifestyle on the banks of the Kanas Lake in the Altai Mountains, tucked away in a remote corner of China’s Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. Here, the stunning Altai Mountains rise to heights of 14,000 feet in the center of the Eurasian continent, where China, Mongolia, Russia, and Kazakhstan converge. The earliest written record of skiing in Chinese history refers to Indigenous people hunting

on skis in these towering alpine mountains. The Indigenous peoples of the Altai Mountains, like those in Tubek and Kanas Lake, hand-craft skis from Siberian spruce. A pair of skis is carved from a single tree using only an ax and hand planer. Braces are applied to curve the front tips up as the skis cure. The foot bindings are made of rawhide; the climbing skins come from the legs of a horse. The skins were traditionally laced to the ski using rawhide, but now nails are used to affix the skin to the base. Instead of two ski poles, the tiak—the Tuwa word literally meaning “stick”— serves to stabilize and steer on descents while providing a third point of contact when climbing through technical terrain.

The descendants of those original skiers in the Altai still use skis for transportation, hunting, and, not surprisingly, fun. Nils Larsen, one of the developers of the Altai Skis brand—the maker of the modern Hoks on which we ski today—traveled to the Altai

forward by skis that echo the ancient arts of the past.

Mountains to learn about the Indigenous skiing history and techniques. These modern Hok skis and tiaks honor the time-tested design and features of the original ancient skis. Altai’s Hok skis have steel edges and a permanent nylon climbing skin affixed to the underfoot portion of the ski base. This permanent skin is an ode to the horse skin on traditional skis. The bindings can be a three-pin, telemark-style binding that requires a specialized boot, or universal bindings that use ratchet straps to hug the tops of your everyday snow boots. The modern tiak is typically made from the straight wood of the lodgepole pine.

Because ancient skis were arduous to create and relied on limited resources, they were designed to be a do-it-all ski, ready for all tasks and conditions. The parallel features of the modern Hok follow that concept. The ski’s slow and steady nature works well in the varying conditions of the Appalachian snowpack— those thin and wishful December snows, deep January powder,

and crusty March freeze-thaw crud. The modern Hok really shines in tight Appalachian tree skiing, an environment where speed is scary. But it’s more than just a toy for fun—Hoks can also function as utilitarian winter tools for watering livestock, gathering firewood, and hunting.

For the Indigenous people of the Altai Mountains, who refer to their skis as “wooden horses,” survival depends largely on the use of both skis and horses for transportation. Ancient accounts tell of hunters running down prey in deep snow on skis. When their horses die, they use the skin on their skis, creating a cycle. In death, the horse becomes part of the ski, which is a tool that allows these mountain people to thrive. As the horse lives on through the ski, so too can the ancient Hok live on through its modern counterpart.

I am living in a Robert Frost poem, but instead of a horse, I ride on wood and fiberglass. I am fully present, carried

My dad still makes regular trips to British Columbia to ski with Larsen, who introduced him to Hoks and the mission of the Altai Project. My dad instantly fell in love and soon gifted me a pair of Hoks. The skis translate beautifully from the big mountains of British Columbia to the ancient hills of West Virginia. The Hok has provided a fresh experience on slopes I’ve skied hundreds of times. I love meandering through the familiar forests of my childhood at a slower pace, able to take it all in and see them from a new perspective. My connection to these hills has deepened as I use the patient pace to identify trees, study wind patterns on the snow, and teach my friends the art of Hok skiing. I still hunt for north-facing powder, able to go steeper and connect even deeper. The experience of Hok skiing transcends functionality, venturing deeper into the philosophical realm and strengthening the soul of skiing. It serves as a bridge to the skiers of the past and those of the future, connecting us across generations and cultures through the universal language of sliding on snow. w

For a deeper look at Hok skiing, check out Nils Larsen’s documentary Skiing in the Shadow of Genghis Khan – Timeless Skiers of the Altai.

The red spruce (Picea rubens) is the epitome of the West Virginia highlands; its flagged branches atop the Allegheny Front are iconic to all those who’ve set foot on the ancient spine of the North American continent’s oldest mountain range. The rich, green color of spindly needles on stubby branches harkens back to harder times when life in Appalachia just wasn’t that easy. It’s safe to say the red spruce is my favorite tree, one that grows only in the highest portions of the Central Appalachians, and a tree that means home to so many West Virginians.

My love affair with red spruce trees began early in my teenage years when I cut my backpacking teeth in Dolly Sods. A friend and I went up in early June, only to be greeted by thick fog and snow. As we huddled under the dense branches of a wind-battered spruce in the high plains, I was immediately grateful for this tree, although I didn’t yet know exactly what

kind of tree it was. I took a dendrology class in college and learned about all sorts of conifers and hardwoods, but my heart remained up on the Sods, huddled under that spruce, cooking ramen over a stove with my friend. That spruce is still there—a testament to what these trees can endure when faced with the harshest of conditions.

Now, as an avid skier in my late-thirties, I’ve spent countless hours cross-country ski touring among the thick stands of red spruce, just as in love with them as I was two decades ago. There’s nothing quite like meandering through the Appalachian majesty of a red spruce forest in the dead of winter (although cold weather makes me feel the most alive, so perhaps we should change that phrase). The most gnarled red spruces that patiently grow atop the backbones of the Alleghenies have much in common with us backcountry skiers, preferring to spend their days getting blasted with incessant

subzero winds and covered in a thick crust of rime ice and snow. While a skier picks their route, a seed doesn’t choose where it grows, although I’d like to think those particular ridgetop spruces standing tall in the bald meadows did just that. The spruce is the epitome of resilience. When I’m going through a particularly rough patch—whether it be during a bushwhack or a work project—I think like the spruce. Stand tall. Go with the wind, not against it. Bend, don’t break. These daily affirmations help connect me to my favorite landscapes, and in doing so, become part of them.

But, like all things, spruce eventually succumb to the elements. When a mature red spruce tree falls, it creates a hole in the thick canopy, allowing seedlings to sprout and compete for light in a (slow) race to close the gap once again. Red spruce saplings are surprisingly shade tolerant and can rest somewhat dormant while waiting for their chance to steal the limelight—some trees only a few feet in height can be decades old. Pay attention when walking in a red spruce forest—you may just stumble upon an area carpeted in hundreds of small red spruce seedlings,

often growing on the rotting detritus of the fallen giant. Look up, and you’ll undoubtedly find a gap in the canopy. When I find one of these areas, I like to lie down next to the cadre of seedlings and stare up at the hole in the canopy to get a feel for what these seedlings experience. Yes, I know trees don’t have eyes, but I do, so please excuse my ill-fated effort to anthropomorphize our woody brethren. I like to think that they’re a group of children, playing together in the midst of the towering adults, thinking One day, I’m going to grow up to be that big.

Most healthy red spruce forests in West Virginia exist in insular communities called spruce islands. This isn’t a product of Mother Nature’s grand design, instead it is the unfortunate result of the destructive clear-cutting of the early 1900s. Red spruce once covered over 1.5 million acres of the West Virginia highlands— hardwoods were rare, and deer, with exponentially less food on which to browse, were even rarer. After the slash-and-burn sprees of the early loggers, the red spruce began their slow recovery on the mountaintops where they could establish themselves before faster-growing hardwoods stole the light. Now these spruce islands remain fragmented, making it incredibly hard for species like the Virginia northern flying squirrel, Cheat Mountain salamander, and native brook trout to migrate between their requisite

habitats. Fortunately, various groups of dedicated folks and organizations are working hard to restore the region’s once dominant spruce forests and connect those disparate islands.

One late night at a campfire after I had consumed a bit too much whiskey, a persuasive friend had me convinced that Bruce Springsteen, upon learning of the importance of red spruce trees in the fight against climate change, had recently started a spruce restoration nonprofit called Spruce Springstrees. I initially rejected the cockamamie idea, but after his relentless objections, I yielded, suddenly in love with the concept. Of course, he was yanking my chain, but nevertheless the name and the sentiment for which it stands live on in our lexicon. Every time I plant a red spruce tree—we’ve planted upwards of 20 seedlings so far on two acres of mountaintop property we own—I think of The Boss himself, hands in the dirt, planting a red spruce atop some remote hill in West Virginia.

I encourage you to volunteer for a legitimate red spruce planting event and join the fray. That’s right, we need you to spring some spruce trees from the fertile soils of Appalachia and help our fake nonprofit reach its lofty goal of planting one bajillion red spruce seedlings. Who knows, perhaps one day your grandchildren’s children will be walking through a vast forest of towering red spruce, talking about those elder activists who came before them and worked tirelessly to connect the now-distant spruce islands. w

THERE’S NOTHING QUITE LIKE MEANDERING THROUGH THE APPALACHIAN MAJESTY OF A RED SPRUCE FOREST IN THE DEAD OF WINTER.

It’s taken some time for me to get to know Charlie Waters, in part because she’s a profoundly humble person. When I first moved here, I mostly knew of her as the person who taught my friends how to ski or who inspired them to move to West Virginia. Over the years, I’ve gotten to know Charlie while biking in Davis, skiing at White Grass, and jogging through Canaan Valley. And each time we chat, I discover something new.

She’s an accomplished athlete in nearly every outdoor pursuit, and she hasn’t slowed down one bit since moving to West Virginia in 1981. She’s a wonderful artist who is endlessly inspired by the patterns she observes outdoors, from tree bark to snow resting on leaves. And she’s a dedicated teacher and mentor, who has helped countless people explore West Virginia’s expansive hills and hollows.

While chatting for this article, I learned yet another thing about Charlie. She is deeply thoughtful about her place in the community and the changes that are happening as we invest more heavily in West Virginia’s outdoor recreation economy. Our conversation about her adventures in the Mountain State, lifelong investment in experiential learning, and hopes for the future is a gentle reminder to bring kindness, humility, and an open mind wherever you roam.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What’s your coming to West Virginia story?

I grew up on a farm in rural Illinois, outside of Chicago. I went to college at the University of Illinois, which had an artist-in-residence program. One artist owned a farm with friends in Terra Alta in Preston County. Another artist took us on a trip down the San Juan River and backpacking in the Grand Canyon. That was my first introduction to adventuring and whitewater. After a few years of coming out to Terra Alta during school breaks, I decided to move to West Virginia. I wanted to be a river guide, practice experiential learning, and do small-scale farming—all of which seemed more exciting than failing school.

How did you end up in Tucker County?

I was a river guide for Appalachian Wildwaters for about 12 years; eight of those were full-time. I guided on the Cheat, Tygart, New, and Gauley rivers. I met Tom Preston through guiding, and his wife Janet told me about White Grass Ski Touring Center. It was White Grass’s second year and they were looking for another cook, so I applied for and got the job. I would spend the weekends in Canaan Valley, and then drive back to the farm in Preston County, which I still own with my college friends. There was a small community of people in Davis and Canaan, so I decided to move there in 1981. We worked on the rivers in the summer and at the ski areas in the winter. I also got a part-time job at East-West Printing. We were all figuring out how to make a living. We had this running joke that the only reason we lived here was that we didn’t have enough money to leave—which was pretty true. There really wasn’t any place to go out, so we went biking, skiing, boating, and had potlucks. Every once in a while, we would splurge and go out to Sirianni’s Café.

What’s your most memorable paddling experience?

I was a halfway decent paddler, but I would freak myself out. One of the worst things I did was paddle a ducky down the Upper Gauley. I swam most of the major rapids. Then I open-boated it and swam a good number of the rapids again. When you paddle above class III whitewater, you have to totally believe in yourself. I realized that I just wasn’t cocky or confident enough. It wasn’t scary necessarily, but it was stupid. Once I figured that out, I had a lot more fun paddling the New, Cheat, and Lower Gauley rivers.

How did you get into mountain biking?

I came to West Virginia with a road bike. Alice Fleischman and I went out on a mountain bike ride once, and I just remember her flying downhill so fast. I thought, I gotta learn how to do that. Eventually I got a mountain bike and I’ve been mountain biking ever since.

The coolest thing that I’ve done recently was a three-day, 240-mile gravel biking trip from Canaan Valley to Fayetteville. I started on a rainy, 40-degree day. I got about a half mile from my house and put a garbage bag on in an attempt to keep my clothes dry. I kept biking even though the weather didn’t get much better until the next afternoon. I was kind of anxious the whole time because I was traveling by myself, but I kept meeting people along the way who were really nice. The second day I ended up biking 80 or 90 miles because I didn’t want to climb three big hills on the last day. I pedaled all the way through the Williams River and into the Cranberry. I ended the second day with a long descent into the Cranberry in complete darkness—it was thrilling.

Where did you learn how to ski?

I first cross-country skied when I was 10 or 11 years old. My older brother

and sister-in-law took my sister and me to this really cool place called Black Hawk Ridge in Wisconsin. It was a cross-country ski trail system with rustic cabins and a lodge. We spent the weekend there, skiing on wooden skis. I went home and immediately bought a pair of cross-country skis so I could go ski around the golf courses in Illinois. But I really learned to ski at White Grass, backcountry style, with all the best skiers we’ve collected here through the years. Terry Peterson taught me how to telemark ski. We learned through a lot of experimentation and failure, but we had a great time and were always pushing ourselves to get better. One of my skiing highlights was racing the American Birkebeiner, a 50K classical or freestyle ski race in northern Wisconsin. In the end, I enjoyed training at White Grass and Timberline more than the racing.

How has your experience of outdoor adventure changed over time?

I would like to say that I’ve mellowed out a little bit, but I don’t think that I have. I biked Splashdam (an impossibly rocky trail in Davis – editor) last night and it was just so fun and exhilarating. I actually feel like I do more now than I used to do. Maybe I’m a little more committed to playing outside now because I feel like if I want to keep being able to do it, then I gotta keep doing it. I never really cared about speed or high-performance; I was always more into spending a boatload of time outside. I still want to go for a three- or four-hour bike ride or ski rather than a shorter outing.

What was your path into outdoor education?

After moving to West Virginia, I went back to school at Davis & Elkins College and got my undergraduate degree in recreation education. I taught a backpacking class, a whitewater paddling class, and a cross-country ski class for D&E’s recreation department. That led me to get a job at the Mountain Institute on Spruce Knob as a field instructor during the summer. In the winter, I taught cross-country skiing at White Grass and downhill skiing and snowboarding at Timberline. Eventually those experiences morphed into running an outdoor education program with some friends called Adventure Skool.

How was working at the Mountain Institute?

It was probably the most intense and influential job I ever had. The Mountain Institute was an international non-profit organization with an outdoor education program near Spruce Knob. It was hardcore. We would camp in rain or snow, and sometimes both, for five days at a time. Our rain gear wasn’t very good and it was often really cold. People can handle a lot more adversity than they think they can, but only if they don’t have the option to bail out. This was true for the instructors as much as it was for the kids! We’d always debrief at the end of each trip, and it was so interesting to learn that the kids who had the most profoundly miserable experiences were often the ones who said it was the best experience they’d ever had.

Why did you start Adventure Skool?

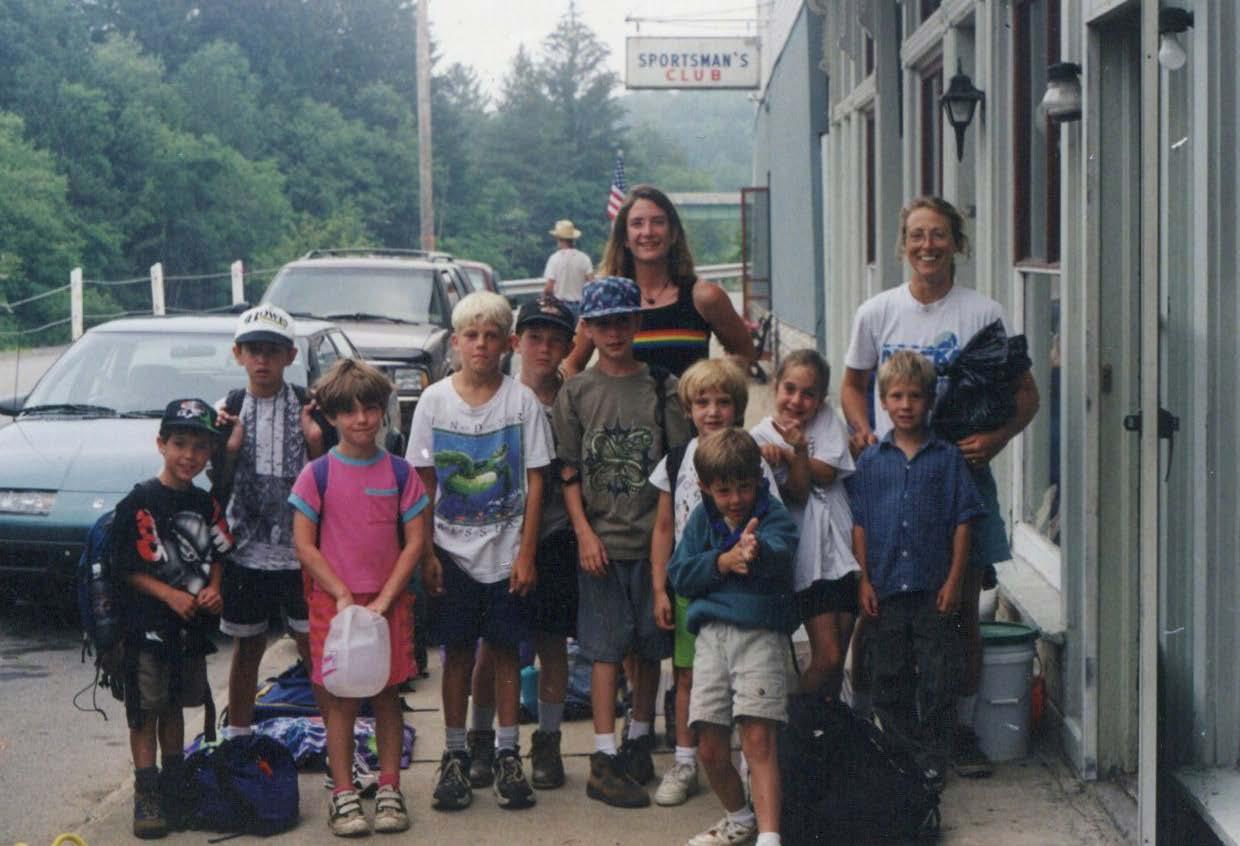

The Mountain Institute worked with private school kids from Washington D.C., Baltimore, and Pittsburgh. I thought it was a shame that the West Virginia outdoors were being used for other kids, but not our own. So, I started Adventure Skool with Carrie Hawkins and Dave Clark. Then Stacy Kay and Sue Haywood helped out. We ran five-day sessions for kids ages six to 12. We paddled the Cheat, climbed at Seneca Rocks, mountain biked, and taught them camping and navigating skills. We ran Adventure Skool for seven years, which brought a lot of people together who wanted local kids to have access to outdoor adventures.

A few friends and I took adventure and outdoor learning into the public school system as part of an AmeriCorps program sponsored by the Canaan Valley Institute. I worked with Shannon Anderson and Vicki Fenwick-Judy to develop a program called Fifth Grade Connections, where we led outdoor trips for fifth graders in Tucker County. We organized activities around natural history, local culture, geology, stream studies, and art.

A thread that has gone through everything I’ve done from my adventuring to teaching is a real belief in experiential learning. I first heard about experiential learning in an education class at the University of Illinois and thinking, “That makes so much

sense. I’m going to move to West Virginia and do my experiential learning as a river guide and back-to-the-lander.” It didn’t look or feel like success for a long time. I didn’t make much money or have a real job by most people’s definition, even though the work I did wasn’t easy. But it was an exciting way to educate myself, and it’s something that I’ve kept as part of my teaching practice.

Are you still a student of experiential learning?

I think so, particularly with my long bike and ski trips. I bike to places that are somewhat unknown, where I don’t know what I’m going to encounter. I don’t always like taking risks, but it’s a cool challenge that keeps a person young and interested in life and not complacent.

What’s kept you here for so long?

I left twice to go to Alaska, which made me realize how accessible West Virginia is for such a wide variety of activities. You don’t have to drive five hours to go skiing or boating. Until a few years ago, West Virginia was relatively undiscovered, which I loved. I am definitely struggling with the change that’s happening here. It’s becoming more populated and more people want to use outdoor spaces now. It makes sense that new rules need to be imposed to mitigate the impacts, but it’s also sad to let go of a time when I could ski and bike anywhere with my dogs. Not everything about West Virginia has changed, but I worry about losing that feeling of remoteness. That’s why I’ve gotten into gravel biking—I can go to more remote places.

A lot of people are attracted to this place because of the beauty, openness, freedom, and community. And I think people move here because they want to be part of this community. But it’s important to take the time to learn how this place works instead of trying to turn it into wherever you came from. This is a lesson I had to learn, and still have to learn on a regular basis, as I am also an outsider in many peoples’ eyes, especially working in our public school system. People have loved this place for a lot of years, and not always in the same way. We’re at a critical point now where we need to figure out how to keep this place special. w

Howdy, friend. We sincerely hope you’ve enjoyed this issue, because we really enjoyed creating it (and every issue before it). We can’t believe this is our 17th issue, especially when factoring in the topsy-turvy uncertainties and struggles of the last two-and-a-half years. Like many of you, we muddled through, emerging stronger than ever. But to help us continue to survive—and thrive—we need your support.

Although we plan to continue offering Highland Outdoors for free at 150+ distribution points across West Virginia, your support makes the magazine more sustainable. First off, we’d like to give a heartfelt thanks to our 344 past and current subscribers across 30 states and D.C. From dealing with rising paper and shipping costs to increasing rates for our fantastic contributing writers and photographers, your support has kept us humming along since we launched print subscriptions in March 2021. But the reality is that we need more subscribers to make Highland Outdoors truly sustainable. Our goal is to reach 1,000 subscribers, a benchmark that would make us feel a little more certain about the future.

Over the years, we’ve heard readers of beloved magazines that had to close say, in retrospect, “If I had known they were gonna go under, I would have subscribed.” While we aren’t on life support yet, this is our appeal to you to help us avoid getting to that point. The last thing we want is to shutter our doors, or even worse, sell Highland Outdoors to someone that doesn’t understand what West Virginia’s adventure culture is all about.

If you live in another state, a subscription is the best way to guarantee that you’ll receive every issue. If you know someone who will love the magazine, consider getting them a gift subscription. And if subscriptions aren’t your thing, we have plenty of HO merch available at the Highland Outstores on our website.

We’d also like to give a shoutout to all our advertisers. The past two years haven’t been easy for them, and we’re eternally grateful that they not only summoned up the moxie to survive, but also kept the magazine alive through their support. Please take a second to peruse the pages of this and previous issues to make note of the phenomenal group of local businesses and organizations that trust us to help amplify their voices. If you’re able, please consider making an effort to support them in return, whether it’s grabbing a meal or a beverage, booking a special trip, buying some new gear, or donating to a meaningful cause.

So, please subscribe if you’re able by scanning the QR code below or by visiting our online store: www.highland-outdoors.com/store. And if you’re unable, no worries—the moral support we receive from readers is just as important and motivates us to keep cranking out better and better issues. If you’ve made it this far, thank you! We sincerely appreciate your time and attention. We wish you many happy (and safe) adventures in 2023.

Big Love, Dylan Jones and Nikki Forrester

Big Love, Dylan Jones and Nikki Forrester

This was my first foray into photographing kayakers in the harrowing rapids of the Upper Blackwater River with a drone. As challenging as it was, the photographs we created that day, like this shot of Jared Seiler navigating the pitch-black waters between snow-covered boulders, inspire me to continue to pursue whitewater and reinforce my appreciation of the beauty in the wilderness of the West Virginia highlands. Photo and caption by Mark Moody.