THE MIDDLE OF

State Park. Relax in nature with four impressive waterfalls, great fishing opportunities and a network of hiking and biking trails.

Plan your trip to Marion County.

304.368.1123

State Park. Relax in nature with four impressive waterfalls, great fishing opportunities and a network of hiking and biking trails.

Plan your trip to Marion County.

304.368.1123

Water is life. You’ve undoubtedly heard of this factual maxim or seen it plastered on the back of a Subaru many times around Appalachia. This simple concept is one of the first things children are taught in science class and for good reason. Water is indeed life, and we are teeming with it here in West Virginia. From spring flotillas and summer swimming holes to winters filled with powder days, the Mountain State is blessed—and often inundated—with dihydrogen monoxide year-round. So much so that, sometimes, it can be a bit much. I can’t keep track of the times we’ve had the dreaded “wet exit” on adventure outings, meaning a car full of soggy, muddy gear and the resultant hours of drying and cleaning that follow. But the alternative is the impossible task of cleaning infinitesimal particles of dust out of the deepest nooks and crannies, which we’ve also done following a particularly windy car camping trip in the Utah desert. And I gotta say, I’ll take mud over dust any day.

Editor-in-Chief, Co-Publisher

Dylan Jones

Co-Publisher, Designer

Nikki Forrester

Copy Editor

Amanda Larch

All The Other Things

Dylan Jones, Nikki Forrester

Kevin Adkins, Liz Allen, Art Barket, Rick Burgess, Chip Chase, Gabe DeWitt, Nikki Forrester, Tara Fowler, Abby Holcombe, Dylan Jones, Mark Moody, Jared Seiler, Jesse Shimrock, Molly Wolff, Jay Young, Nico Zegre

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Many of us have heard the spine of the Alleghenies referred to as the birthplace of rivers or the water tower of the East. It’s true—the water that many major cities rely on originates right here on pristine mountaintops in West Virginia. And although we live in an area heralded for its dampness, so much of our water is negatively impacted by the scars of industry with which we are all too familiar. It often seems like our water is under attack from those who want to remove protections safeguarding this quintessential resource. Which I can’t comprehend, because no matter where we may stand on the political spectrum, the hard reality is that we all need clean water to survive.

As the American West becomes increasingly drier in the face of a changing climate, West Virginia continues to look like a better

and better place to be. We’re fortunate that we can turn a blind eye to all the doom-andgloom news of water shortages and depleted aquifers west of the Mississippi. But our wealth of water isn’t without drawbacks. From musty basements to moldy roofs, dealing with all this water poses its own set of challenges. Climate change-driven increases in rainfall mean increased flooding, and towns nestled within the seemingly endless folds of our mountainous topography face a higher risk of flash flooding than almost anywhere else in the country. But still, I have to think that having too much water is more manageable than having no water at all. We can create flood resilient communities, but we can’t create water where it doesn’t exist. Once again, mud is better than dust.

As such, this issue is dedicated to West Virginia’s water: to the rain and snow that swell our rivers with this precious resource, to the adventurous souls who love to play in it, and to the admirable folks who work tirelessly to protect it. I look forward to spending many hours this year interacting with our wonderful waterways, whether it be via swimming, rafting, or just sitting in a camp chair on a hemlock flat along a tannic mountain stream. Water is life, and with each passing year, I become ever more grateful to be spending mine here in Wet Virginia. w

Dylan JonesGet every issue of Highland Outdoors mailed straight to your door or buy a gift subscription for a friend. Sign up at highland-outdoors.com/store/

Request a media kit or send inquiries to info@highland-outdoors.com

Please send pitches and photos to dylan@highland-outdoors.com

Our editorial content is not influenced by advertisers.

Highland Outdoors is printed on ecofriendy paper and is a carbon-neutral business certifed by Aclymate. Please consider passing this issue along or recycling it when you’re done.

Outdoor activities are inherently risky. Highland Outdoors will not be held responsible for your decision to play outdoors.

Wyatt Kappler surfing in the monstrous standing waves of the New River Dries. Photo by Tara Fowler.

Copyright

14

18

22

West Virginia is home to hundreds of waterways that need to be monitored for impacts from development, pg. 14.

28

By Abby Holcombe Nikki Forrester By Dylan Jones34

40

By Dylan JonesPaddlers, rejoice! River access for the Lower Big Sandy is preserved for all following the purchase of land along the classic whitewater run in January 2024 by American Whitewater (AW).

Totaling over 100 acres, the tract runs for nearly 4.5 miles along the river-left corridor of the scenic gorge, protecting the Rockville river access point along with portage routes for the famous Wonder Falls and Big Splat rapids.

The Lower Big Sandy has long been a proving ground for paddlers looking to dip their toes into some of West Virginia’s finest whitewater rapids. Wonder Falls, a 15-foot river-wide waterfall, has provided countless paddlers with their first true waterfall drop, while the consequential Big Splat rapid pushes experts to step up their game. “It’s my favorite stretch of river,” said Charlie Walbridge, a legendary West

Virginia paddler and longtime AW board member. “If you’re stepping into solid class IV, you can work your way down with some portages, or you can really push yourself on the harder rapids.”

The campaign was led by Walbridge and Dave Hough, a retired Cheat River outfitter. The purchase effort was bolstered by financial donations from over 50 whitewater enthusiasts, which helped AW exceed its fundraising goal. In a statement celebrating the purchase, AW said, “We are perhaps the last generation that can purchase and conserve large portions of privately-owned river corridors of our community’s most cherished rivers like the Big Sandy.”

Walbridge said AW plans to transfer the land to the West Virginia Land Trust (WVLT), which will develop a recreation plan for the tract and ensure protection

of this world-class whitewater resource for generations to come. “We are grateful to be able to play a part in the long-term conservation of one of West Virginia’s outdoor recreation gems,” said Adam Webster, WVLT conservation program manager. “The Cheat River and Big Sandy Creek are whitewater rivers that drew me to the Morgantown area and kept me here. This is something that a lot of people have been hoping for through the years, so we look forward to exploring the recreational potential of this property.”

According to Walbridge, donations will help pay for costs associated with the land transfer to the WVLT and help establish an endowment for upkeep of the property. “I really appreciate the WVLT because they’re very recreation-oriented,” he said.

Webster said this tract is unique because it becomes part of a larger protected landscape along Big Sandy Creek that extends to its confluence with the Cheat River at the Jenkinsburg Recreation and Natural Area, which is owned and managed by the WVLT. “Along with our partner groups, like Friends of the Cheat, we are ensuring people can paddle and access the Big Sandy and Cheat River for years to come,” Webster said.

Walbridge said that while most conservation efforts come about because of corporate giving or governmental land acquisitions, this effort was entirely private. “The paddling community is close-knit and willing to pay its way,” he said. “It’s been amazing to see what can happen when people come together.” w

I’m stoked to announce the recipients of donations once again from our 1% for WV campaign, an initiative that donates one percent of our annual print advertising revenue to environmental and social nonprofits based in West Virginia. 1% for WV is our localized version of the lauded 1% for the Planet campaign. Each year, we give these financial donations to groups focused on fighting the good fight right here in the Mountain State with the hope that these dollars will support positive change.

This year’s environmental nonprofit is the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy (WVHC), an organization whose mission is to preserve West Virginia for future generations. The WVHC is one of the Mountain State’s longest running conservation advocacy groups that focuses its efforts on our beautiful and ecologically invaluable Allegheny Highlands. The WVHC also publishes The Highlands Voice, which has been in continuous monthly publication since 1967, and makes those beloved “I ♥ Mountains” stickers many of us have on our bumpers.

This year’s social nonprofit is Appalachian Expeditions (APEX), a fantastic experiential outdoor education program lovingly run by our good friends Alex Snyder and Libbey Holewski in Davis. Under the auspices of APEX, Alex, Libbey, and their staff have taken hundreds of children—and adults—deep into nature to learn about the environment as well as themselves through activities like hiking, backpacking, whitewater rafting, and bikepacking. If you’ve got some kiddos, consider sending them on an APEX trip this summer.

If you’re able, I highly encourage you to bolster our donations with a few bucks of your own to either of these amazing nonprofit organizations. Let’s lift each other up this year! w

There’s a lot to love about living in the mountains of West Virginia, but by far my favorite is the abundance of world-class whitewater rivers. Our complex topography and steep slopes give birth to a whopping 54,000 miles of waterways. This seemingly endless network of streams, creeks, and rivers is a hydrological paradise for whitewater enthusiasts.

According to American Whitewater, the nation’s leading whitewater advocacy and river conservation group, West Virginia boasts 260 whitewater runs spread over 1,945 navigable river miles. The high number of runs packed into such a small land area offers the highest concentration of whitewater in the country, bestowing us the lesser-known nickname of the Whitewater State.

But the whitewater superlatives don’t stop there. Many of West Virginia’s most cherished whitewater runs can be paddled year-round, making it one of the most consistently boatable regions in the country. Take three classic runs in the Cheat River watershed known globally for their beauty, quality, and technical challenges: the Cheat Canyon, the Lower Big Sandy, and the Upper Blackwater. According to research by the West Virginia University Mountain Hydrology Lab, the Cheat Canyon runs an average of 280 days per year; the Lower Big Sandy and Upper Blackwater run 180 and 106 days per year, respectively. Spring, naturally, provides the most consistency: 30 days per month for the Canyon, 24 days per month for the Lower Big Sandy, and 15 days per month for the Upper Blackwater.

So, what makes our spring boating so abundant? If you’ve read previous water columns, you already know: copious precipitation and vast, deciduous forests. During the dormant season, when tree transpiration slows, more water remains in the soil. As a result, it takes less precipitation for runoff to happen, resulting in swollen rivers and regularly boatable flows.

While most springtime streamflow comes from rain, snow can also play a role. Last May, a freak snowstorm blanketed the highlands in 20 inches of snow. Skiers and boaters rejoiced, and a handful of dual-sport enthusiasts were lucky enough to ski heavy powder one day and paddle that same water the next as snowmelt filled the Cheat’s channels. It was an historic event that will be talked about for years to come, and yet another example of the magic within West Virginia’s mountains, forests, and waterways. w

Nico Zegre is a forest hydrologist who loves paddling on, swimming in, and telling stories about West Virginia water.

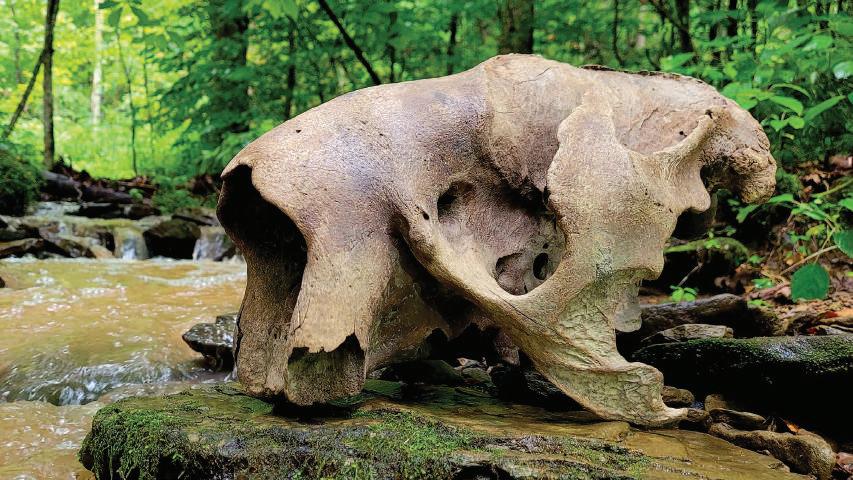

Nothing beats a good ol’ fashioned rock jump into the calming waters of the Cheat River. Photo courtesy Appalachian Expeditions.In May 2022, Kevin Adkins uncovered the skull of a giant ground sloth in a small creek while turkey hunting in Putnam County, West Virginia. In our first story about this incredible find in our Summer 2022 issue, we shared Adkins’s tale of seeking out giant-sloth experts to confirm an identification. With the help of folks from the West Virginia Geological and Economic Survey (WVGES) and Gregory McDonald, a paleontologist in Colorado known as “Dr. Sloth,” the team concluded the skull was most likely from a Jefferson’s ground sloth (Megalonyx jeffersonii ).

Over the past two years, Adkins has made progress toward understanding more about this ancient creature and sharing his discovery with West Virginians. Last summer, he got in touch with the people who owned the land where the skull was found as they were the legal owners. The landowners then got involved with the research process and made the skull available to put on display at the WVGES Museum in Morgantown, where it can be seen today.

In March 2023, the skull was included in a Fossil Days event at the Grave Creek Mound Archeological Complex in Moundsville. “We were more than happy to share it with the public and give others the opportunity to see it for themselves,” said Adkins.

More recently, Adkins shared his unique find with eighth grade students at George Washington Middle School in Eleanor, West Virginia. He gave a presentation and chatted about sloths with the students for nearly an hour. “They were eager to ask questions and seemed genuinely interested about the subject,” Adkins said.

Along with contributing to educational programs, the skull will be loaned to researchers to age the sloth, conduct DNA sampling, and perform CAT scans to look inside the skull without causing damage. Because the sloth skull is so old, it’s been challenging to determine a precise age since carbon dating methods can only date back to 50,000 years ago. “We’ll have to rely on the material found on the skull

for aging,” he added.

By looking at the clay attached to the skull and the blue sediments within that clay, researchers estimated that the sloth skull is at least 700,000 years old. “Right now, we’re assuming that those sediments were, in fact, part of the lake bed of Lake Tight,” said Adkins.

Lake Tight was a massive lake that formed across western West Virginia, Ohio, and Kentucky when the region’s ancient rivers were dammed up by glaciers some 750,000 to 1 million years ago. “The oldest fossil of Megalonyx jeffersonii that has been discovered is about 158,000 years old. If this skull is confirmed to be a Jefferson’s ground sloth, it puts the species in a completely different timeline,” Adkins said. Alternatively, the skull could belong to an older species of ground sloth, Megalonyx wheatley. If that’s the case, it will be one of the largest M. wheatley specimens ever found, according to a WVGES interview with Elizabeth Rhenberg, a geologist at the WVGES.

Because the skull was found in excellent condition in a small creek, Adkins and the researchers think it didn’t travel far to get to the location where it was found; a long aquatic journey would most likely damage the skull. “The skull fossil is all original material. The bone hasn’t been replaced by minerals,” he described.

Although it’s taken some time to get the research ball rolling, the team hasn’t wavered in their excitment about the discovery, said Adkins. “There were so many mysteries behind it: the location, how it turned up, and the condition that it’s in.” Piecing together the puzzle is a slow process. But as Adkins said, “that’s fitting for a sloth.” w

Embrace the beauty of spring in the New River Gorge National Park and Preserve. Explore nature with lush hiking trails or scale the sandstone cliffs on a guided rock climbing trip.

Start planning your adventure in the New River Gorge.

april 13th

may 18th

july 11-13th

aug. 17th

sept. 28th

#1 Rollin Coal

#2 Kate’s Mountain

#3 GRUSK

#4 Lost River classic

#5 High ground gravel

SPONSORED BY:

shinnston, wv

White Sulphur Springs, WV

spruce knob, wv

Mathias, WV

terra alta, wv

wvgravelseries.com

There are nearly 300 named rivers, streams, and creeks that spread their sinuous paths across the Mountain State like the dendritic patterns of tree branches. There are seemingly countless other unnamed troughs, rivulets, and ephemeral drainages that carry runoff to these major waterways at any given time throughout the year.

Many of our state’s great mountain rivers begin their journeys within our borders. This water spills down, eventually making its way to major U.S. cities like Pittsburgh and Washington, D.C., providing drinking water to millions of Americans.

It’s patently obvious that everyone—and everything—needs water to survive. But given the collateral damage caused by the development of industry, energy, and infrastructure, it’s also obvious that much of our natural water supply is tainted. Ask someone to drink a glass of water straight out of a river, and you’ll likely get a response along the lines of “Hell no!”

While there are regulations to protect our water, the reality is that those rules often don’t go far enough. And even when they do, oftentimes state and federal agencies don’t have the resources to enforce them. The WV Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) Watershed Assessment Branch simply can’t employ enough water quality monitors to accomplish the herculean task of keeping tabs on West Virginia’s numerous waterways.

Fortunately, there are throngs of concerned citizens volunteering for the West Virginia-Virginia Water Quality Monitoring (WQM) program. Started in 2013, the WQM is an ongoing collaboration between West Virginia Rivers (WV

Rivers) and Trout Unlimited (TU) that trains volunteers to monitor impacts in their local waterways. These volunteers act as aquatic watchdogs, keeping an eye on the industrial practices that threaten our water supply. “It’s essentially a localized red alert system to effectively identify and document water quality issues,” says TU monitoring and community science manager Jake Lemon.

According to Lemon, TU initially started the program to monitor the impacts of shale gas development on high-quality, coldwater trout streams. TU quickly joined forces with WV Rivers to expand the program into the Virginias and adapt protocol to focus on impacts of pipeline and road construction on warmwater streams.

TU handed over management of the WQM program to WV Rivers in 2018, allowing WV Rivers to get funding from and supply data to the DEP to coordinate when water quality issues arise. “The DEP can’t be everywhere all at once. We like to think of our water quality monitoring program as a compliment to that,” says Jenna Dodson, WV Rivers staff scientist and WQM program manager. “It’s always helpful to have more data.”

Dodson has been in charge of the WQM program for two years. Previously, she coordinated Adopt-A-Stream, a statewide monitoring program in Georgia. “I used to be a volunteer water monitor myself. You can establish a strong connection to a place and see a stream change throughout the seasons,” she says.

The scale of the WQM program is impressive. Over the last decade, 163 volunteers completed 7,913 monitoring events across 525 sites in West Virginia

and Virginia. On average, 2.5 samples have been collected every day since the program’s inception. Volunteers recorded 1,546 monitoring events in 2018, the most in a single year, which coincided with the height of natural gas pipeline construction in the region. “We have great volunteers that are so committed and energized around this,” says Lemon. “In my opinion, this has been the most successful citizen science program that TU has implemented nationwide.”

While there are many threats to our water supply, the WQM sampling protocol specifically checks for impacts ranging from increases in water temperature and sedimentation from erosion to toxic threats like acid mine drainage (AMD) and per-and-polyfluorinated substances (PFAS).

Increases in water temperature, which equate to lower amounts of dissolved oxygen, are particularly hard on native brook trout, which require shaded, cold streams to survive. Dodson also says sedimentation, which often occurs from road and pipeline construction, can clog fish gills, disturb life cycles for macroinvertebrates, and even bond with toxic particles before entering a waterway.

It may be easy to spot the tell-tale orange staining of rocks from AMD or notice an increase in the cloudiness of water, but we can’t see or smell chemicals like PFAS. “You can’t really detect them unless you’re testing for them. Anytime we make our water more polluted, it’s going to be more expensive and difficult to treat the water to be able to drink it,” Dodson says.

Those who like to recreate in West Virginia’s waterways are also at risk of infection from bacteria like E. coli and

a battery of tests for parameters like pH (the acidity of the water), conductivity (how much electrical current the water conducts), and turbidity (how cloudy the water is). They also record the weather, stream level, and water temperature and snap a photo to send with the data submission. The data is collected and curated by WV Rivers before it’s sent to the DEP.

Fortunately, the WQM program tests for all these threats. When volunteers head out on a monitoring mission, they perform

The sampling protocol is rigorous, and some volunteers, like Chris Byrd, sample

certain sites every two weeks. Byrd, who is a longtime angler and TU member, has been sampling since the program’s inception. He currently monitors five streams spanning four counties that face the full gamut of threats from shale fracking, the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, and the construction of Corridor H. “We’re not out trying to stop anything, we just want to make sure things are done right,” he says. “We all live in this watershed together.”

Byrd monitors three of these sites with his friend, Randy Peasley, also a 10-year WQM program veteran. “Someone needs to do it, and it’s a way to give something back. Randy and I are both retired, so there’s a bit of a social aspect to it as well,” he says.

Byrd says that regular monitoring allows scientists to establish a normal range for water quality parameters on a specific stream so that when something goes awry, action can be taken to identify the source of the issue and notify the DEP. But the benefits of regular monitoring go beyond the data. According to Dodson, when project developers are being watched, they are more likely to comply with environmental regulations, like construction of silt fences to control erosion.

Although the WQM volunteer makeup skews toward retired folks, young volunteers have recently joined the ranks, including 26-year-old Molly Sutter. Hailing from Philadelphia and working as a caretaker on a farm in Summers County, Sutter became involved when she and her neighbors noticed impacts from the Mountain Valley Pipeline crossing their local stream of Hungard Creek and the Greenbrier River. “While driving past construction of the pipelines every day, you could see it disrupting the hills and causing a lot of erosion,” she says. “We became concerned about our water. Now that I know this stream and river so well, I care and want to protect them.”

As humanity places ever-increasing

pressure on our natural resources, an increase in passionate citizen watchdogs like Byrd and Sutter can help minimize impacts. But Byrd thinks that monitoring alone isn’t enough—he wants to see our legislature strengthen environmental regulations instead of weakening them. “We lighten up instead of tighten up, but that’s just the political landscape right now,” he says. “I wish people would appreciate what a resource cold, clean water is, and how little you really have to do to protect it.”

Dodson says that despite all the negative press about “forever chemicals” like PFAS and industrial impacts from pipelines, there’s good news, too. Over her time at WV Rivers, she’s noticed an increase in societal awareness about the importance and value of clean water.

To capitalize on these growing public concerns, WV Rivers has teamed up with other watershed groups when interests align. Friends of the Cheat assigns volunteers to monitor streams impacted by the continued construction of Corridor H in Randolph and Tucker counties, and the Warm Springs Watershed Association trains volunteers in the WQM protocol to monitor streams in the path of the new 522 Bypass near Berkeley Springs.

Dodson also pointed to the Chesapeake Bay Agreement, a landmark 2014 accord that established water quality goals for the Chesapeake Bay watershed, a small portion of which lies in Monroe County

in the Eastern Panhandle. According to Dodson, out of all the jurisdictions involved in the seven-state project area, West Virginia has been doing the best on hitting its water quality goals. “I feel like people have their stereotypes about West Virginia, but in this case, we are a leader,” she says. “I want to see a future where all of our waters in West Virginia become swimmable, drinkable, and fishable.”

With the right policies in place and hard work from dedicated groups, it’s amazing how quickly water quality can improve— just look to the amazing recovery of the Cheat River from AMD pollution. In just a few decades, a future where all our rivers run clear, when we don’t have to worry about what’s in the water before we get in, suddenly starts to seem possible.

For that future to happen, we need these aquatic watchdogs to keep eyes on our streams, and we as citizens need to keep putting pressure on our leaders to prioritize clean water for all. “I’d like to see a recognition that water is worth protecting because this is the birthplace of rivers” Sutter says. “Everything relies on water. It’s like the mountains and the streams are saying, ‘We have given you a lot, and now it’s time for you to give back.’” w

Become a watchdog! To get involved, contact your local watershed group to see if there are existing monitoring efforts to join. To join the WQM program, contact WV Rivers to schedule a training session.

In the dark hours before dawn on January 2, 2010, I woke up at 10,188 feet on Mount Rainier to my headlamp illuminating the frosty condensation covering the walls of my tent. It was summit day. I was living in Seattle while training for an Alaskan expedition to climb Denali and descend its runoff by kayak. With a finite window of daylight, there is very little time to waste on a winter bid to reach Rainer’s 14,411 foot summit. I downed a bowl of oatmeal, lightened my pack, and roped up to set off into the darkness. As we ascended the sustained 40-degree pitch of the Furer Finger route, the sun finally began its own ascent over the distant horizon. I was on the lead end of the rope as the couloir began to pinch into an hourglass of stone walls. With each kick into the snow, I kept my eyes locked on the icewall lingering hundreds of feet above. It had not seen

much sunlight yet; I was hedging on its stability. Another kick, another stab, another breath, and then boom—every climber’s worst nightmare. A large chunk of the hanging ice released its grasp and began its explosive descent directly into the guts of our route. I yelled out “Avalanche!” to my partners below and immediately shuffled toward a small rock ledge to my left, digging my crampons into the snow and turning around to pull on my partner’s tag of rope to help them scurry into the miniscule pocket of protection. Within seconds, the maelstrom came ripping down the pitch. I drove my ice ax into the snow, cradled my body as tightly into the rock as possible, and buried my head. My senses were overtaken by the roar of sound as the ensemble of horror passed into the abyss below.

I lifted my head and opened my eyes. Three feet to my right, where I had just been standing, a razor-sharp, whale-sized fin of ice now barricaded the path of our route. That was my life, but it didn’t flash before my eyes—it was staring right at me. We did ultimately reach the summit that day, but the conversation I had with myself during the rest of the journey was extremely humbling. I realized there was a future I wanted to create for myself that could have been robbed from me that day. It was time to find the right balance of making choices that preserved my dream of building a family while still embracing the spirit of adventure that is so core to my being.

Years have passed since that defining day on the mountain, and the adventures continue to mount. I slowly drifted away from the high-altitude mountaineering realm and shifted more focus to my long-rooted relationship with class V whitewater kayaking. There is still an abundance of risk associated with this activity, but I do believe it is much more calculated compared to the roll of the dice experienced in the alpine.

I’ve been kayaking for over 25 years; I’m often more comfortable in a kayak than I am on my own two feet. I can choose to paddle within my comfort zone or level it up, but ultimately that choice is mine. The river always gives more than it takes. It is a place of concentration where time can either stand still or vanish in front of your eyes. It moves with its own unique cadence—fight it and you will be quickly reminded who is in charge; embrace it and it will carry you through the chaos and into the calmness that always lies waiting below.

Following the flow of the river is what ultimately led me to Liz Allen, the person with whom I now share my calmness

in life. We have spent many years finding our own balance in the outdoors by paddling, hiking, climbing, skiing, and biking as one. But 15 months ago, we decided it was time to level up our life together. Shortly after returning from a paddling adventure throughout the Andean rivers of Chile, we found ourselves staring at the pink plus sign on a little white plastic stick. The greatest adventure life has to offer was about to begin.

Anyone who has ever endured the nine months leading up to childbirth has certainly experienced the continual onslaught of advice from tenured parents. To be frank, most of it flew in one ear and drifted right out the other. With kayaking, I’ve always used guidebooks strictly as a means to find the put-in and the takeout; I never wanted to read rapid descriptions for fear that it would rob the element of surprise which, for me, defines the experience. This read-and-run method is how I began my approach to fatherhood.

During the first few months of Liz’s pregnancy, I felt an unprecedented urgency to purge my system of the ghosts from adventures past. I wanted to paddle hard, I wanted to party hard, I wanted to soak up every ounce of sunlight and howl at every moon available in my last days of “freedom.” As more and more of those days passed, I couldn’t help but observe the way Liz was choosing to spend her time preparing. She was not burning the candle at both ends, rather she had one steady wick. Instead of cramming it all in, she was slowly and methodically researching, designing a nursery, absorbing birthing books, acquiring hand me downs, adjusting her diet, and flowing with the experience. My own appetite for self-destruction began to fade as I watched her spirit begin to blossom, a true foreshadowing of the mother she would soon become.

I was inspired by her peaceful intent. As the dog days of summer settled upon us and the river beds revealed their rocky bones,

I began to find a different flow. I would still jump on the opportunity for a local adventure, but now I was scouting the landscape for family-friendly activities. I would still chase a run on the Blackwater River after a summer monsoon, but rather than join the shuttle party with friends, I would bicycle my shuttle on the rail-trail to see how bumpy it would be for a stroller and how long it would take with a baby in tow. I was suddenly finding just as much enjoyment in exploring trailheads as I was running class V rapids.

Before we knew it, the last week of summer was upon us, and we suddenly found ourselves in the delivery room at WVU Children’s hospital, prepared to welcome our own ray of sunshine into the world. After what can only be described as an all-out war with the divine feminine, Liz gave birth to a happy, healthy Sage Elizebeth Shimrock on the morning of September 15th, and my river of life changed its course forever.

Looking into her eyes for the first time, any selfish thoughts that lingered inside me spontaneously combusted. The immediate shift in priority and purpose can not be described

in words, it is meant only to be experienced. There was no mountain or river on this earth that could dish out the insurmountable wave of emotion that was flowing through my entire being. I had just experienced the true meaning of life.

As we prepared to leave the hospital, I couldn’t believe that I was about to be tasked with transporting the most precious piece of cargo I’ve ever encountered on the wild roads of West Virginia. What once was a mundane daily jaunt suddenly demanded precision and focus. Day one, level one: the expedition of fatherhood had just begun.

The Blackwater Canyon is one of the most challenging stretches of whitewater in the country, demanding every bit of skill one can pack into their kayaking toolbelt. If you’re prepared, the run might go smoothly. If you aren’t, you’re quickly in over your head, thrown right into the maw of pure pandemonium. We quickly realized that parenting was like dropping into the first rapid on the Upper Blackwater. As lifetime adventurers with a knack for adapting to changing conditions, Liz and I found a shred of comfort in this initial

chaos. We quickly developed a rhythm that would begin to cement the road ahead. As this initial rapid was in the rear view, my restlessness for a deep breath of the outdoors was beginning to surface once again. I had plenty of time to think about how I would feel putting myself back in the driver’s seat on class V whitewater now that I had someone whose life depended on me. I wasn’t rushing it, but I often found myself scanning precipitation forecasts while Sage was sleeping peacefully in my arms.

A few days later, the sky squeezed the sponge free of its humidity, and the bones of the Blackwater River sank beneath the thrashing waters once again. I called my crew, loaded up my kayaking gear, gave my little girl a long kiss on her forehead, and looked into her eyes knowing that I was going to do everything in my power to make sure I came home that night.

Arriving at the put-in, I geared up and walked down the steep canyon trail below the falls, staring down the pipe of the class V entrance rapid that I had run countless times in the past. I slid into my kayak, laced up my skirt, and pushed into the water. But I didn’t immediately drop into the rapid below; I found a moment of hesitation as I floated in the tiny oasis of calm water above the drop. I needed to finish the conversation I had started with myself many years ago on that icy slope of Mount Rainier. I had reached my goal of creating a beautiful family, and for the next nine miles, I was about to define my balance with the extreme. I knew the risk; I had calculated it for years. My sword was sharp, my mind was present, my motivation was unwavering. Deep breaths, one stroke, two strokes, dropping in. With a deep breath and three calculated strokes, I dropped in.

What unfolded that day was the most focused run on whitewater that I’ve experienced. Every movement of the paddle carried such intent; every lean and angle of the boat was a beautiful dance with the water beneath. I felt a calmness amidst the chaos and a pure sense of validation that I had found the balance. I no longer needed to chase the path of every rain storm, instead I would cherish the storms I was able to catch and know that my dance with adventure would continue alongside my dance with fatherhood. I didn’t need to challenge the hardest line in the rapid, I needed to find the cleanest line—the line that gets you home.

I have now absorbed five months of parenthood and Sage has found her own stride in the passenger seat on our many adventures thus far. We’ve skied through the blanketed trails of Whitegrass, happily shuffling along the greens and blues while passing by the black diamonds with dreams of the days ahead where we will ski them side-by-side. We take walks along the river’s edge, watching the water drift by with two sets of eyes that will one day float together around the bend downstream. I have no expectations for how her own taste of adventure will unfold, but I know that my new goal, the only goal, is to always make it home so that we may share the journey ahead together. w

Jesse Shimrock’s family and adventures are deeply rooted in Appalachia. He looks forward to watching his daughter discover this magical region in the years ahead.

A kayaker throws an aerial maneuver on the New River Dries. Photo by Molly Wolff.

A kayaker throws an aerial maneuver on the New River Dries. Photo by Molly Wolff.

By Abby Holcombe

By Abby Holcombe

With iconic whitewater found on rivers like the Gauley, Cheat, and the New as their playgrounds, kayakers have long been drawn to West Virginia’s tumultuous waters. The Mountain State’s endless aquatic features provide ample opportunities for water lovers to surf standing waves, execute aerial maneuvers, and explore the hidden depths beneath the surface. From the pioneering efforts of early paddlers to the modern-day feats of up-and-coming locals, West Virginia has played a pivotal role in shaping the sport of freestyle kayaking into what it is today.

Freestyle, unlike traditional whitewater kayaking, is a different way to express fluidity and creativity on the water. While the latter focuses on navigating rapids and avoiding obstacles like holes and hydraulics, freestyle kayaking embraces those obstacles, pushing adventurous practitioners to seek them out for a chance to perform acrobatic tricks. “Freestyle is playing with the currents and rocks of the river in a kayak much like snowboarders play with the jumps and the rails of a terrain park,” says Clay Wright, a five-time International Canoe Federation Squirt Boat World Champion from Rock Island, Tennessee. Wright, who travels to West Virginia every fall for the six-week Gauley River paddling season, has played a key role in developing the sport of freestyle kayaking.

According to accounts from longtime locals, the fledgling sport of freestyle kayaking began in the Cheat River drainage. Brothers Jim and Jeff Snyder, along with their crew of passionate paddlers, pioneered the art of squirt boating, which focuses on maneuvering and performing tricks beneath the water’s surface. Squirt boating then laid the foundation for modern freestyle kayaking.

“The Synder brothers embodied the free spirit that comes with freestyle kayaking,” reflects Corey Lilly, a West Virginia native and esteemed freestyle kayaker. “At that point in time, it wasn’t bound by competition; it was simply about self-expression and exploration of rivers and oneself.”

The Synder brothers were not just kayakers; they were innovators who designed their own boats, paddles, and safety gear, pushing the boundaries of what was possible on the river. Their experimentation with boat designs paved the way for the evolution of freestyle kayaking equipment, from long and thin squirt boats to the shorter, slicey plastic boats that dominate the sport today.

West Virginia’s role in the development of freestyle kayaking is unique, not only because the sport originated here, but also because of the rivers themselves. “There were plenty of access points and the roads often ran parallel to the rivers, making it easy for kayakers to get on the water without having to deal with

Griffin Biggs throws a barrel roll after launching off a precarious ramp as part of the 2023 New River Gorge Race & Rodeo. Photo by Tara Fowler.

Griffin Biggs throws a barrel roll after launching off a precarious ramp as part of the 2023 New River Gorge Race & Rodeo. Photo by Tara Fowler.

the hassle of setting shuttle,” says Lilly. Not only do the big-volume rapids and dynamic hydraulics of the Gauley and New rivers provide the perfect playgrounds for kayakers to hone their skills; the easy access afforded by major roads right along their banks provides opportunities to park and play in multiple spots.

As boat designs progressed and freestyle kayaking put more emphasis on surfing, the legendary waves around West Virginia became essential testing grounds for new designs. After a 2001 flood permanently altered the riverbed on a section of the New called the Dries, a new set of massive standing waves started forming at high water. These world-class waves continue to attract kayakers from far and wide to test their skills and push the creative limits of what’s possible in modern playboat designs. “The largest wave is a beast to surf. It stands about 15 feet tall and 20 feet wide,” says Lilly. “When you catch it, it’s like riding a bull. If you can stay on for a good ride, it’ll be the ride of your life. But if you get bucked, it’s likely to be a big hit.”

Modern playboating, which focuses primarily on performing tricks and maneuvers in hydraulic features, is one distinct discipline within the realm of freestyle kayaking. These paddlers rely on specialized equipment known as playboats, which have shorter

profiles and tapered ends for carving across waves. “It’s the least amount of boat you can get away with that still has enough volume to make you fly out of the water,” remarks Wright, who invented the front flip, known among playboaters as the front loop.

From front and back loops to cartwheels and spins, playboating is a sport where creativity knows no bounds. The repertoire of tricks in playboating is as diverse as it is impressive, with maneuvers boasting evocative names like the Space Godzilla, McNasty, Lunar Orbit, Airscrew, Pistol Flip, among others. But playboating is not just about mastering tricks, it’s about self-expression and individual style. Paddlers infuse their own flair into each maneuver, creating a mesmerizing spectacle that captivates both fellow kayakers and spectators.

Along with throwing acrobatic maneuvers, playboaters seek the artistry of surfing standing river waves. Lilly eloquently captures the essence of surfing in a playboat by describing it as “a feeling of infinity because it never ends.” He further illustrates the thrill of catching that first surf, likening it to the sensation of how he imagines it feels to be “sucked into a black hole.”

On the other end of the freestyle spectrum is squirt boating, where paddlers use specialized kayaks to sink into the depths of the river, much like a submarine. Squirt boaters use an eddyline— the dynamic boundary between swiftly flowing water and the calmer water of an eddy where currents interact—to propel their kayak to the depths of the river. When totally submerged, they continually spin, like a helicopter rotor, to remain underwater for as long as possible.

“Getting in a squirt boat is sort of scary because it’s claustrophobic,” shares Wright, echoing the sentiments of many who have felt the tight confines of these unique vessels. “You basically slide your feet into an encasement made of fiberglass. It’s very tight and kind of painful on the way in.” While the initial discomfort of getting into a squirt boat can be daunting, Wright explains that the boats are often custom-made to fit one’s body. “It’s pretty comfortable once you’re in,” he says. “You become one with the boat.”

The sleek design of squirt boats, with their low volume and precise shaping, allows paddlers to manipulate their craft with unparalleled finesse. This intricate dance between paddler and river is what defines squirt boating—a discipline that requires not only physical skill but also a deep understanding of hydrodynamics and a willingness to play beneath the water’s surface. As squirt boaters explore the hidden depths of the river, they embody the essence of freestyle kayaking, where self-expression and mastery converge in a mesmerizing display of fluidity and grace.

The history of freestyle kayaking in West Virginia is a testament to the spirit of innovation and adventure that defines the sport. From its humble beginnings on the Cheat River to the worldclass waves of the New River Dries, the Mountain State has left an indelible mark on the world of kayaking, inspiring generations of paddlers to push their limits and explore the wild beauty of its rivers. Whether it’s the thrill of catching that first surf or the challenge of mastering intricate maneuvers, the rivers of West Virginia continue to beckon adventurers seeking adrenaline-fueled excitement and unparalleled natural beauty. w

Abby Holcombe is a professional kayaker originally from Colorado. She lives full-time in her van and travels the world chasing whitewater.

National Forest

Feel the cool mountain breeze in the lush Mon Forest, discover the many museums and historic sites, or embrace the culture of a small Swiss village Board a vintage excursion train, access miles of trout streams, and rivers, or pitch a tent under the clear night sky ElkinsRandolphWV

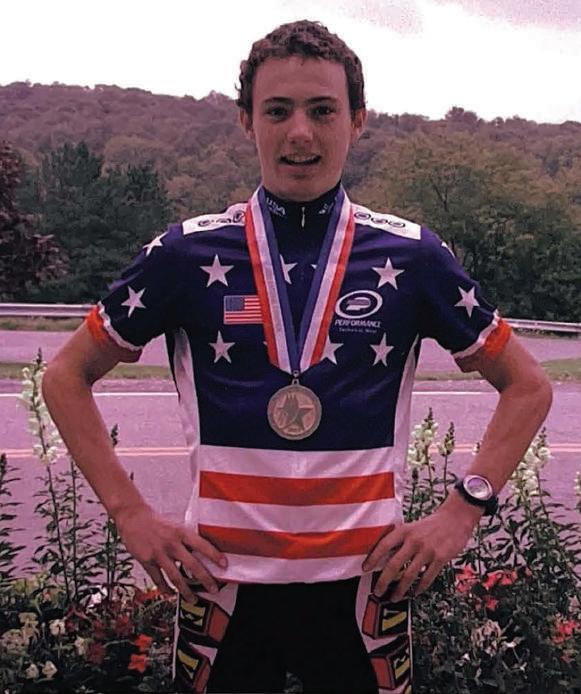

If you live in the town of Davis, West Virginia, there’s a one in 150 chance you’re a national mountain bike champion. This small town, nestled among rugged forests and home to around 600 people, has a special allure for those eager to test their mettle on bikes. Pedaling over slick roots, endless rocks, and expansive bogs is made even more difficult by less-than-ideal weather, which happens more often than not. And yet, the mountain biking scene has thrived in Davis for decades, calling to those who are independent, strong-willed, and hungry for a challenge.

Four stellar athletes have taken their love for mountain biking and competition to the extreme, pushing themselves to their limits to earn the title of National Champion. It’s quite fitting that the people who stand atop the podium have strong ties to the highest (incorporated) town in the state. Whether they were born in Davis or call this place home, these four bikers have been shaped by the terrain and culture of West Virginia and continue to mold the mountain biking community here to this day.

Sue’s first foray into mountain biking began in the early 1990s, when she was a student at West Virginia University in Morgantown. After graduating, her love of mountain biking and interest in snow sports led her to move to Davis and land a job at the local bike shop. “That’s when I got more into racing,” she says.

During the West Virginia Mountain Bike Association (WVMBA) race series, Sue’s technical prowess and competitive spirit

consistently carried her to the top of the podium. It didn’t take long for her to set her sights on bigger races in the region. In 1997, Sue won the expert cross-country race at a National Off-Road Bicycling Association (NORBA) national event at Seven Springs, Pennsylvania. “That was a good indicator that I could win bigger races,” she says.

The following year, Sue earned her pro license, landed sponsorships from Dirt Rag Magazine and West Virgina Tourism, and began training more seriously. “When you move up to the pro class and start racing against your peers at the national level, you realize how much smarter and harder you have to train to compete successfully. Once I hired a coach, it really helped me learn how to train and gain the fitness to race better.”

Just two years later, in 2001, Sue secured her first National Championship title at the NORBA national final at Mount Snow, Vermont. At the time, racers competed in a series of five races at various locations across the country and earned points depending on their performance. Whoever earned the most points at the end of the series was awarded National Champion along with the coveted stars and stripes jersey. Now, National Champions are crowned based on a single event hosted by USA Cycling.

“Before the race, I was confident. I didn’t think about blowing it, I was just thinking charge, charge, charge,” she describes. Sue won the pro cross-country short track, which was a roughly 20-minute race plus three laps. It’s an action-packed event, featuring lots of passing and cheering spectators. Upon winning, she was elated.

“There are so many races in between where you didn’t win, but winning a National Championship is really special— you always have that title.”

That title launched Sue into the next stage of her career as a professional mountain bike racer. She joined the Trek-Volkswagen World factory team and upped her training regimen. “It’s super fun trying to get to the top. There’s so much hope and promise,” she describes. “But it also puts expectations and pressure on you.”

Over the next decade, Sue held her own as one of the best mountain bikers in the country. In 2003, she became National Champion in pro short track again. But perhaps her most lauded year was 2006, when she became National Champion of short track and super D, which is a mix of cross-country and downhill that she describes as “aggressive and sketchy.” That same year, Sue became World Champion of the solo 24-hour race at Conyers, Georgia.

Even with four National Championship wins, two Pan-American Championships, and a World Champion title under her belt, Sue didn’t sit back and rest on her mountain laurels. In 2018, she secured her fifth National Champion title in the master’s enduro event at Snowshoe, West Virginia. She attributes this success not to any physical place or ability, but rather her passion for the sport. “I don’t think it’s Davis that produces National Champions. I think it’s the people’s personalities that draw them to those kind of events and to an area like this. We’re independent, stubborn, driven, and competitive. And this place is fiercely independent, challenging, and gnarly. If you can ride here, you can ride anywhere.”

Today, Sue can often be found effort-

Clockwise from top left: Sue Haywood celebrating her 2001 National Championship victory; Nick Waite became a National Champ that same year. Zanna Logar rose to the top at the 2023 National Championship race. In 2018, Jason Cyr earned his first National Champion title.

All photos courtesy the riders.

Clockwise from top left: Sue Haywood celebrating her 2001 National Championship victory; Nick Waite became a National Champ that same year. Zanna Logar rose to the top at the 2023 National Championship race. In 2018, Jason Cyr earned his first National Champion title.

All photos courtesy the riders.

lessly pedaling across the technical trails of Davis, cheering on her friends, and pointing out fluffy patches of moss. While her joy of mountain biking is rooted far deeper than the highlights of her racing career, there’s still a glimmer of pride that shines through when she talks about her achievements. “It’s funny; it definitely feels like ancient history now. But on those couple of days, I was the best in the country. I had one day of excellence that I’ll have for the rest of my life.”

Nick was born in a cozy apartment above what is now Stumptown Ales in Davis. His parents owned the building and lived in the apartment, along with Laird Knight, who started the Canaan Mountain Series. Being surrounded by avid cyclists, Nick hopped on a bike around age two and has navigated the ebbs and flows of biking ever since. “All the fun adults around me were into biking. I would say I loved it, but just like anyone who rides mountain bikes, there’s periods of misery that come along with it,” he says.

Nick got his first mountain bike in the late 1980s and spent most of his childhood riding with any adult that would let him tag along. He shifted gears to focus on rollerblading before diving head-first into mountain bike racing in 1999. After performing well in various state and regional races, Nick began competing in national events. “That’s when I decided to give it my full focus. I became obsessed with the idea of the pursuit,” Nick says.

He spent the fall running cross-country for Preston County High School and the winter riding and cross-country skiing. “I came out swinging that next spring and went from being in the middle of the pack to winning all the races,” he recalls. His quick rise to the top nabbed him a spot on a premier junior mountain bike racing team, an invitation to a NORBA talent camp, and a spot at the Olympic Training Center in Chula Vista, California in 2000. “It was a big step for a kid from Davis.”

In the summer of 2001, Nick traveled the country competing in the National Championship series. “They were the biggest races that happened in the U.S., period,” he says. “Of course, my favor-

ite ones were on the East Coast.” In August, he became the junior cross-country mountain bike National Champion at Mount Snow, Vermont. He recalls the two-hour race being rooty, rocky, and brutally hot.

A year later, Nick turned pro and launched himself even further into the racing world. Starting in 2004, he raced for the U.S. National Team and competed in World Cup events across Europe. He also ventured into road racing, which offered more opportunities for sponsorships. “That’s probably when the ultimate burnout started to happen,” he says. “Being a bike racer is not normal life. It’s magical and very difficult at the same time.”

On top of the physical and emotional demands of a professional racing career, Nick began struggling with an injury in 2002 that reduced the capacity in his left leg to what felt like 50%. “It felt like I was riding up a hill with someone hanging on the back of my seat, not aggressively but enough where I was like this is terrible, stop it.”

Toward the end of 2008, Nick decided he wanted to try out a more normal life. When his racing team contract wasn’t renewed, he moved to New York City to become a bike messenger. “I was out on my own. I would do jobs and get paid directly for the effort as opposed to a monthly stipend or having to rely on prize money. I felt useful on a bike for the first time in a long time.”

But the racing scene drew him back in the following year. Nick moved to Harrisonburg, Virginia, where he lives today, and focused on racing alongside building his small business, Pro-Tested Gear. Nowadays, he vacillates between periods of enthusiasm for racing and excitement to pursue other aspects of his life. As with most things, a bit of distance from racing provided some clarity. “Years removed from the experience, I can now see how special it was. It’s something to be proud of,” he says.

Beyond racing, Nick’s roots in Davis have left a lasting impression on him. “I’m not afraid of cold, wet rides on slimy roots and rocks or of losing my shoe in a bog because that happened all the time,” he laughs. “I was born into this random, pop-up community of cyclists. It’s a huge reason why I was able to accomplish what I did.”

For Jason, racing mountain bikes is more about hitting personal goals and having fun with his friends than pursuing a professional career. His interest in mountain biking was sparked in the mid-1980s, when he started working at a bike shop in Enfield, Connecticut. “The cool guys in the shop had mountain bikes, and they got me into it,” he says. As a long-time BMX and motocross racer, picking up mountain biking added yet another arrow in his quiver of athletic pursuits.

In the early 1990s, Jason joined the Army and, with his mountain bike in tow, began competing in races wherever he was stationed. “I really like the competition of racing. It’s not necessarily about trying to win, but about doing as well as I personally can do,” he describes. And to perform at his best, he has to train, which is fortunately something he loves to do. “I like that headspace. I go grind out miles; that’s where I do my best thinking.”

In 2004, after his deployment in Afghanistan, Jason moved to Davis so he could spend as much time as possible in the woods and on the snow. He’s lived here ever since. Over the years, Jason says he’s competed in roughly 20 National Championship races across a range of disciplines from cyclocross to cross-country to marathon to downhill. “Enduro is probably my favorite discipline just because it’s how I ride with my buddies. It’s party-paced uphill and then you go as hard as you can on the downhills.”

In 2018, Jason earned his first National Champion title for the master’s enduro race at Snowshoe, West Virginia. Enduro races typically involve three to six timed stages that are mostly downhill, punctuated by transfer stages where the rider must pedal or catch a lift back uphill.

About halfway through the National Championship enduro race, riders could check their times and strategize for the next stages. Jason was close to the top, but his good friend Harlan Price was in the lead. “I had to get my game plan together. Usually, I race at like 80 percent of my capacity because you can’t win if you crash and don’t finish,” he says. “In the last stage, Harlan had made a mistake, but I hadn’t yet. I was completely off the brakes

and on the edge the whole time. We were less than two seconds apart after nearly 30 minutes of racing. That’s definitely one of the closest races I’ve ever had.”

Earlier that year, Jason retired from the Army, giving him more time to focus on training and racing. He earned a master’s degree in exercise physiology and launched Cycle Strategies, a coaching company for cyclists. In 2023, he won a second National Championship in master’s enduro at Rock Creek, North Carolina, beating his competition by a cushy 31 seconds. “I think the thing that sets me apart from other competitors is my head. I spent most of my career as a Special Operator in high-pressure situations, so when it comes time to execute, I can just stay focused on the task at hand,” he reflects.

Riding in Davis has also upped his mental and physical stamina. “The terrain here is so gnarly. We just have old hiking trails and dirt bike trails that are pretty blown out.” He notes that the technicality of the trails, combined with a community that loves to ride regardless of the weather, really helps in a race setting. “You get used to riding and training in all these crummy conditions. When you go to a race and the weather is just awful, you have a great result because that’s just the norm.”

From learning how to balance on a Strider bike to winning the junior cross-country National Championship last year, mountain biking has always been a part of Zanna’s life. Growing up in West Virginia, she frequently embarked on adventure

rides with her friends and family. “Learning to ride in Davis helped me build this amazing base of skills and a love for riding my bike,” she says.

In middle school, Zanna started racing as part of the National Interscholastic Cycling Association. “That’s when I fell in love with racing and realized this is what I want to do for the rest of my life.” Even if she doesn’t win, she thrives on setting goals and trying as hard as she can to achieve them. “There’s no limit. You can always get better and faster,” she says.

To improve her skills and advance her racing career, Zanna moved to Virginia in 2021 to attend the Miller School of Albemarle. She also races for the Gravity Academy mountain bike team and is coached by the program’s founder, Cory Rimmer. “We plan out my week, which usually includes a ride every day, intervals, and gym workouts three times a week.” Her training schedule for each season is built around two events where she wants to have peak performances, one of which is the National Championships.

Zanna competed in her first National Championship races, in the cross-country and downhill disciplines, in 2022 at Winter Park, Colorado. At that point, she had only been training for about six months. “It was a big shock for me because I had never raced on that level before. It was the first time I saw how far I could take it. That fueled my fire,” she says. Immediately after the race, Zanna doubled down on her training, with the goal of winning Nationals in 2023 at Bear Creek Mountain Resort, Pennsylvania.

The 2023 cross-country race featured huge climbs and long, technical descents. “I knew there were seven girls that all had a chance of winning, and I kind of included myself in that, but deep down I was like, it’s never going to happen.” Instead of being discouraged, Zanna decided to give it everything she had.

The race began with a tiny loop followed by a slick, technical climb into the woods. Zanna was one of just two riders who made it through the slippery section clean, and within just five minutes of the start, she found herself in first. She took a brief second to look back, only to notice there wasn’t a single girl on her tail. “It was a surreal moment. Then I had to make a decision of whether to push as hard as I could for the rest of the race, not knowing if I could hold that pace, or to let them catch me and the play the game,” she recalls.

Zanna chose option one and led the pack for the rest of the 45-minute race.

“Sometimes I wish I had a receipt of all my thoughts during the race,” she says. “At one point, I convinced myself that there was somebody in front of me and I wasn’t in the lead just to keep me going because it was the hardest race I’ve ever done mentally and physically.” When she saw the finish line in sight, she was hesitant to lift her arms up in celebration because she was convinced someone was in front of her.

The uproar of the crowd sent the unequivocal signal that Zanna had won, accomplishing a goal that she says seemed impossible just the year before. Beyond winning the title, participating in a National Championship event brought a new perspective to her life as a mountain bike racer. “There are thousands of people there, and everyone wants the same thing as you. Sometimes kids in my school or people I hang out with don’t understand how I approach training and why I eat healthy and go to bed early. But at Nationals, everyone understands what my goals are. We’re all part of something bigger.”

This year, beyond aiming for another National Championship title, Zanna is eager to get faster on the bike and learn more about why she’s doing specific workouts. But her ultimate goal is to keep her relationship with biking fun. “Davis has a super strong community of people who really love being on a bike. What made me fall in love with the sport is the people, the laughs, and how much fun everybody has. That’s really stuck with me.” w

Nikki Forrester is co-publisher of Highland Outdoors. She has yet to compete in a mountain bike race, but she is the proud threetime winner of the Canaan Mountain Bike Festival scavenger hunt.

Words and photos by Dylan Jones

Words and photos by Dylan Jones

We’ve been sauntering through a delightful forest of black cherry trees rising from a thick carpet of ferns for several miles, but now we find ourselves ensconced in the dark, damp, shady womb of a balsam fir-red spruce swamp. Carefully stepping over mossy hummocks and avoiding deep vernal pools of tea-colored water, I wouldn’t be surprised to spot a dinosaur stomping through this primordial landscape. We suddenly emerge from the shade to a sprawling meadow filled with the brilliant yellow fireworks created by millions of goldenrod flowers. In the distance, a stand of white trunks and mint-colored leaves reveals the unmistakable sight of a clonal quaking aspen grove. A calm, meandering stream

slices through the landscape. The current is barely discernable by wavering water grasses visible just below the tannic surface. The meadow stretches for miles before it terminates at the base of a thousand-foot mountain, its steep face verdant with the canopies of countless hardwood trees all the way up to its bald, bony spine.

We’re perched on the banks of the Little Blackwater River in the pristine northern end of Canaan Valley, taking in the grandiose view of the region referred to as Big Cove while on a hike guided by staff from The Nature Conservancy (TNC). TNC purchased this tract of land, which includes the Little Blackwater’s wetland complex and its surrounding buffer forests, in 2023 and trans-

ferred the property to the Canaan Valley National Wildlife Refuge (CVNWR) in February of 2024, ensuring that it remains pristine for generations to come.

Canaan Valley is considered one of West Virginia’s most treasured landscapes. This giant bathtub-shaped bowl in the highlands is renowned for its geological and ecological significance. It’s also a recreation hotspot, hosting three ski resorts and a bevvy of trails dispersed across a patchwork of public lands including Canaan Valley State Park, the Monongahela National Forest, and the CVNWR.

The undeveloped northern end of the valley, however, looks as it might have a thousand years ago. Until recently, this nearly 2,000-acre tract was privately owned by a land holding company, inaccessible to the public and at risk of being logged or sold at any moment. But with the recent acquisition of the tract and its addition to the existing CVNWR, this stunning landscape is now owned by all Americans and preserved in perpetuity. As a citizen who takes immense pride in our robust public land systems, I couldn’t be happier to feel a sense of ownership and see this globally critical conservation effort come to fruition.

“There are places in the West that rise in similar importance, but they’re mostly protected and in public ownership. In the East, where lands are much more fragmented, the call to action is much more eminent. In West Virginia, we still have opportunities to make big conservation gains happen,” said Mike Powell, director of land management and stewardship for the West Virginia chapter of TNC.

But the goal of the conservation effort to protect the Big Cove region extends far beyond Canaan Valley. Connecting Canaan’s fertile valley and towering rim to other tracts of public land in Central Appalachia effectively stitches together a large swath of protected lands that serve as a critical corridor for myriad plant and animal species to move as they adapt to a changing climate. Which, Powell said, “is already happening. We’re documenting species moving, some are moving 37 feet upslope, and 11 miles north, per decade.”

Powell added that the Allegheny Front, which runs north from Seneca Rocks all the way to the Allegheny National Forest in Pennsylvania, is critical for Neotropical bird migration. “From a biodi-

versity standpoint, this tract is super important, not only for the species that call it home now, but the species that might call it home in the future,” Powell said.

Several years ago, TNC, which is a global organization, identified what it considers to be the four most critical regions for conservation on the planet: the vast grasslands of Kenya, the thick forests of Borneo, the sprawling Amazon rainforest, and our home here in the ancient Appalachian Mountains. “These areas were identified as super important both in terms of biodiversity and carbon sequestration,” Powell said.

temperature in the Lower 48 states in the winter months. On January 22, 2022, this weather station logged a frigid -30.7 degrees F—the coldest temperature ever recorded in the valley. Because of these extraordinary conditions, Canaan is the southernmost range of cold-adapted plants typically found much further north.

At 13 miles long and five miles wide, and with an average valley floor elevation of 3,200 feet, Canaan Valley is the largest high-altitude valley east of the Mississippi. This giant bowl is a frost pocket, meaning cold air sinks down and pools on clear, calm nights. It’s not out of the ordinary for the Big Cove region, which hosts a professionally monitored weather station, to log the coldest

“Big Cove is one of the very special places of West Virginia,” said Elizabeth Byers, a senior wetland scientist at the WV Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). “It’s a hotspot for rare plant communities, especially the balsam fir-red spruce swamps, which probably look very similar to the way they would have looked to Native Americans a thousand years ago. It’s an extraordinary piece of our state heritage.”

The Big Cove wetland complex that feeds the Little Blackwater is considered by DEP to be an exemplary wetland, meaning it ranks in the top 2% of wetlands statewide for its biodiversity. The National Wetland Condition Assessment, a collaborative survey of the nation’s wetlands, considers Big Cove one of the least-dis-

turbed wetlands in the country. It now serves as a benchmark for assessing the quality of other wetlands. “That means it’s our responsibility to protect it, because these plants don’t have large populations outside of West Virginia. It’s not as though the surrounding states can pick up the slack if we don’t conserve them,” Byers said.

Besides its status as a critical refuge for rare plants and migratory birds, the Big Cove region is unique because of its deep and incredibly rich organic soils—some of which Byers said contain peat deposits up to 10,000 years old, dating them almost to the Pleistocene epoch. “These habitats have been relatively stable for millennia, which is why they’re home to so many rare species. That’s what happens when a place is allowed to follow natural processes over thousands of years,” she said.

Peatlands are high-priority conservation targets because of the immense amounts of carbon dioxide sequestered in their anaerobic deposits—the lack of decomposition below the peat’s living surface means carbon can’t be released back into the atmosphere. Forested wetlands store a whopping 20 times as much carbon as upland forests because of those ancient organic deposits. “We’re talking orders of magnitude more carbon than even a mature natural forest, and it’s all in the soil,” said Byers.

Byers explained how the quick recovery of the rare balsam fir-red spruce community in these rich soils tells her that human-caused disturbances, like the slash-and-burn logging practices of the early 1900s, were very minimal in the immediate Big Cove wetland complex. Because these wetland conifers grow primarily on nurse logs, hummocks, and tipped-over root balls, it can take upwards of 400 years for a burned wetland to recover to the point that trees can take root. “There was a practice of burning wetlands in the southern part of Canaan Valley, and we know that Big Cove did not burn because those stands are now in excellent shape and hosting rare species that can only grow in the shade of a mature conifer swamp,” she said.

Prior to the recent acquisition, the CVNWR owned Big Cove proper, a small piece of property completely surrounded by the previous owner’s tract, similar to a donut hole. Since the entirety of the northern portion of Canaan Valley was within the refuge’s proclamation boundary—the maximum land area a wildlife refuge can encompass that is set by Congress—the CVNWR has had a long interest in acquiring the surrounding property.

But once a property goes up for sale, it takes quite a bit of time for a National Wildlife Refuge to build the assets required to purchase additional land. Given the slow speed of governmental land acquisition, when the opportunity to purchase the remaining tract in Big Cove suddenly came up, TNC stepped in to buy the property, giving the CVNWR time to acquire the funds. “Part of why TNC does these kinds of transactions is we’re able to be more nimble as a landowner,” Powell said. “When a property like this is in the acquisition boundary of one of our partners, like the refuge, we generally like to see it end up in public ownership. In this case, we were just a bridge to make it possible.”

“It’s great timing for this acquisition as this is the 30th anniversary of the refuge,” said CVNWR refuge manager Bob Frank. “This acquisition now allows access to the interior portion, which the refuge owned but did not have public access to. It’s important that we can protect and manage the entire Little Blackwater watershed.”

Although many species rely on having access to the Big Cove region for survival, people also rely on access to the outdoors for a variety of needs, including hunting for food, playing for fun, and the quintessentially human desire to spend time in nature for mental health. Fortunately, outdoor lovers will be able to do all three in Big Cove. “This will provide additional recreational opportunities for all folks, whether it be hiking, birdwatching, hunting, or a whole host of activities,” said Frank.

According to Frank, the new acquisition is already open to the public for hunting and fishing opportunities, and plans are in place to install several ADA-accessible hunting blinds. “We have a huge deer population in northern Canaan Valley, and this provides an opportunity to remove some of those deer to reduce the effects they have on regeneration of forbs and other rare plants,” he said.

The CVNWR also plans to work with TNC to build new trails crossing the Big Cove region that will allow hikers and bikers to access and enjoy the area in addition to the existing network of trails that cross the refuge. Frank said funds from the Great American Outdoors Act will be used to construct a new trail to connect the Brown Mountain trail system at the end of Camp 70 Road on the western end of the valley to A-Frame Road on the valley’s eastern flank of Cabin Mountain.

Now that the long-term goal of conserving the northern end of Canaan has been achieved, and that effort has stitched together a critical wildlife corridor, I feel I can rest slightly more assured that Appalachia’s amazing flora and fauna will have a fighting chance. As the world becomes increasingly developed, these invaluable species with which we share these magical landscapes must have access to connected tracts of untrammeled land. “I’m absolutely delighted that it is going to have permanent protection; it’s just nice to know it’s there,” Byers said. “Even if you don’t ever visit, it gives you this good feeling that it’s truly a refuge for rare species.”

I strongly believe the act of conserving these corridors via public land is something that should be a source of pride for Americans; the bonus that we have the privilege of using them for our own recreational, educational, and spiritual purposes makes them even more special. “We live in a place of globally significant conservation opportunity, and when we can get conservation combined with recreation, everybody wins,” Powell said. “To me, that’s really hitting the bullseye, and I think this property plays an outsized role.” w

Dylan Jones is co-publisher of Highland Outdoors and encourages you to support conservation efforts in Central Appalachia in any way you’re able.

By Chip Chase

By Chip Chase

s the sun slides higher in the sky, winter starts warming up, and snow gently trickles back to the land. Maple farmers tap their trees, boaters are happily floating cool rivers, and trails are drying out. Spring is in the air! Green again with wildflowers while birds sing their love songs, daylight seems to go on forever. It’s a magical time of year. Meanwhile in the mountains, a few snow lovers still have winter on their minds and seem slow to transition with the seasons.

The inevitable end of winter brings back memories of floaty turns through the kind of knee-deep fluff considered the crème de la crème by all. As spring returns, a wonderfully friendly snowpack can form with a velvety surface from the repetitive freeze-thaw cycle of cold nights and warm

days. Lovingly known as corn or hominy, this flavor of snow peels off magically into kernels that taste so sweet, a delectable dish worshiped by skiers and snowboarders worldwide.

Spring snows, when timed just right, create the kind of conditions where one can fly like an eagle, offering a super carvable surface that’s easy to manage and just fast enough to keep your eyes wide open. Skiing back uphill for another serving is soft and mellow with posi-traction in every step. Many ski areas let the bumps form deeper during this late-season cycle, while tree skiers follow the sun, feel out the snow, and make as many turns as possible.

Timing is everything. Although frozen stiff when the rooster crows at dawn, corn softens as the day goes on. Sunshine melts the top layers into bushels of soft, granular

Dylan Jonescorn. If one waits too late, the heat of the day will overcook it, burning sweet corn into a serving of mashed potatoes. But gorge too long past the dinner bell, and smooth sailing quickly reverts to an icy mass of frozen tracks, scary in every way imaginable.

The search for spring corn is a harvest of the most adventurous type, a journey of discovery as the sun works her magic in and out of the forest. Elevation, exposure, and changing weather combine to create the challenge of finding perfect snow. The first corny days will pop up during one of the many thaws, but prime time comes in early spring when temps drop below freezing by night and climb well into the 40s by day.

Like the best farmers, experienced corn harvesters know how to predict optimal timing and location. The rule is simple: follow the sun. Start your day skiing east-facing slopes, work your way toward south faces, and eventually chase the sunset on north- and west-facing slopes. Trade your insulated gloves, parkas, and longjohns for sunscreen, T-shirts, headbands, and some of the most exciting and gratifying conditions of the year.

As with all adventures, the quest for corn can be tricky. Even the best ski areas post signs stating that conditions may vary. Early in corn season, thawing is of utmost importance as an icy

Above: A group of corn lovers goes for an afternoon adventure on the rocks. Photo courtesy Chip Chase.

Left: Adam Chase makes an impressive telemark turn on some late-season corn.

“Our mantra is all snow must be used, and if you’re a winter enthusiast, no snow patch can go unturned.”