SUMMER 2025

Home to iconic Seneca Rocks, Pendleton County is the best rock climbing destination in West Virginia for climbers of all skill levels. Our Via Ferrata at NROCKS is one of only three on the East Coast and is a mecca for climbing enthusiasts. Smoke Hole Canyon, Reed’s Creek, and Entrance Walls are just a few of the other great climbing spots throughout the county. Come find your favorite.

Discover Pendleton County, West Virginia, for yourself. It is always worth the climb.

Miles of hiking, biking, and water trails are waiting to be explored in Berkeley County, West Virginia. Two Audubon Society managed preserves are the perfect locations for bird watchers to spend the day. Serene fishing spots, championship golf, and world-class geocaching make for the perfect adventure vacation.

In the the heart of the Potomac Highlands of West Virginia, discover an untamed, stunningly beautiful mountain village blessed with incredible outdoor adventure and warm, friendly people. Surrounded by the Monongahela National Forest, Petersburg is your guide to unrivaled fishing, boating, hiking, biking, climbing, and more. Discover a better view of your world and your life, in our naturally untamed mountain home.

It seems that artificial intelligence is unavoidable these days. Every major tech company has their poorly named version, incessantly popping up in apps and programs we use every day. Cleverly disguised as digital pals demanding to “Let me do that for you,” these AI chatbots are designed to make your life increasingly efficient and evermore optimized. Cluely, a particularly poorly named and insidious AI app, is an undetectable assistant that sees your screen, hears your audio, and feeds you answers in real time so you don’t have to think up responses to other humans during real-life social interactions, such as a meeting, or even, as the company suggests, during a date. The app goes so far as to use the tagline, “Start cheating. Because when everyone else is, no one is.”

STAFF

Editor-in-Chief, Co-Publisher

Dylan Jones

Co-Publisher, Designer Nikki Forrester

Copy Editor Amanda Larch Hinchman

Pretty Much Everything Else Dylan Jones, Nikki Forrester

CONTRIBUTORS

You might be thinking, why are you rambling on about AI in the letter from the editor for an outdoor print magazine? Shouldn’t you be waxing poetic about your love for trees and skis? The short answer is yes, I should be using this space precisely for that prosaic purpose, but I felt compelled to speak out in defense of genuine human creation. Frankly, I just don’t find the results of generative AI to be very interesting. Whatever writing it spews out is typically pedestrian, robotic, and unpolished—immediately recognizable as repackaged drivel. A great line in a BBC article titled “The people refusing to use AI” puts it perfectly: “Why would I bother to read something someone couldn’t be bothered to write?” And don’t get me started on the clichéd horrors of generative AI “art.” From humanoids with seven fingers to pictures of the New River Gorge Bridge that don’t look like anything like the New River Gorge, or even a real bridge for that matter, I am not in any way impressed with the outputs of these programs. Programs, mind you, that have blatantly broken copyright law by stealing from the collective cornucopia of art, wisdom, knowledge, and beauty created over millennia by billions of

unique human minds.

This isn’t to say that AI in general is evil incarnate. Like any invention, it has positive applications, mostly pertaining to its use in processing massive amounts of data and searching for patterns to advance scientific and medical research. But daily use of ChatGPT to replace the need for critical thought and problem solving does not fall into the realm of what I consider to be beneficial to society. Also worthy of mention are the immense energy demands and environmental impacts of AI: an internet search with ChatGPT uses 10 times more energy and emits 340 times more carbon dioxide than a standard Google internet search.

As such, I am hereby making a commitment to you, dear reader, to refuse to use generative AI in all aspects regarding the creation of Highland Outdoors . The writing and photography that appears in our pages has always been, and will always be, lovingly crafted by real, authentic, and genuine human minds. To drive this point home, I tasked Kai, my best five-year-old friend and fellow Lego master, to draw the art you see above, using this prompt that I could have easily dropped into an AI program: Draw a picture of Dylan riding a bike in Canaan Valley with a fire-breathing dragon flying overhead. The result, I must say, is quite magnificent. Because I truly believe that the creative output of a five-year-old pal is inherently more interesting than the output of the world’s most powerful chatbot. w

Dylan Jones

Kim Ayers, Art Barket, Roger Bird, Eric Brumbaugh, Nikki Forrester, Rosalie Haizlett, Chris Jackson, Dylan Jones, Karen Lane, Kai MargoliesMoore, Boyce McCoy, Vernon Patterson, Mike Paugh, Terry Priest, Kurt Schachner, Katja Schulz, Jesse Thornton, Mark Wenzler, Jay Young

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Get every issue of Highland Outdoors mailed straight to your door or buy a gift subscription for a friend. Sign up at highland-outdoors.com/store/

ADVERTISING

Request a media kit or send inquiries to info@highland-outdoors.com

Please send pitches and photos to dylan@highland-outdoors.com

Our editorial content is not influenced by advertisers.

Highland Outdoors is printed on ecofriendy paper and is a carbon-neutral business certifed by Aclymate. Please consider passing this issue along or recycling it when you’re done.

Outdoor activities are inherently risky. Highland Outdoors will not be held responsible for your decision to play outdoors.

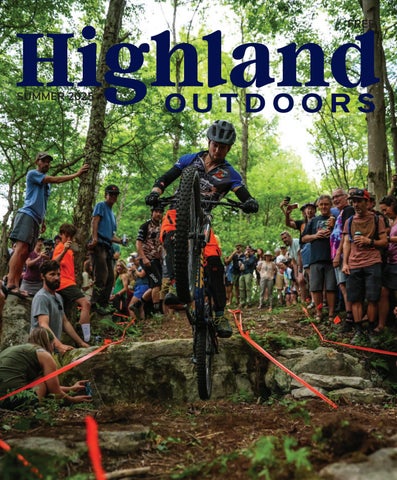

COVER

Peter Denbigh wheelies himself to the top of the podium at the 2024 Run What Ya Brung trials competition at the Canaan Mountain Bike Festival. Photo by Boyce McCoy.

Copyright © 2025 by Highland Outdoors. All rights reserved.

By Nikki Forrester and Dylan Jones

A Virginia-based company wants to build one of the world’s largest data center complexes in Tucker County, West Virginia. If the proposed facility is fully built out, it will span 10,000 acres across Tucker and Grant counties—more than half the size of the Dolly Sods Wilderness and more than four times the size of Blackwater Falls State Park.

To power this massive data center complex, the company, Fundamental Data, wants to build a gas- and diesel-fired power plant between Davis and Thomas. This plant would be located less than one mile from the local elementary school and within two miles of 90% of the homes and businesses in the two towns. The plant will have 30 million gallons of diesel fuel stored on site, and the company has already stated that leaks are possible.

At Highland Outdoors , we cherish our public lands, clean air, water, local businesses, and our vibrant community. The proposed power plant and data center complex threatens the health, safety, economy, and quality of life for everyone who lives in and visits Tucker County. This project would irreversibly harm our environment and the outdoor recreation resources we love. For these reasons, we strongly oppose Fundamental Data’s proposed power plant and data center complex.

We have many concerns about this project. The facility would generate harmful amounts of air, noise, and light pollution. Data centers consume massive amounts of water—water that we need to support our residents, visitors, and local businesses. It would also make Tucker County a less desirable place to live and visit, collapsing our tourism economy and putting more than 900 local jobs at risk.

Information has been hard to obtain given Fundamental Data’s refusal to discuss their plans with the public and their highly redacted air quality permit application. But we know the power plant would emit carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, and other hazardous air pollutants. These toxic air

pollutants are known to cause asthma, heart disease, and other respiratory diseases. Children and older adults are particularly at risk.

Canaan Valley frequently experiences temperature inversions that trap cold air for days or weeks. While this weather phenomenon is excellent for winter recreation, these inversions will also trap air pollutants from the power plant, concentrating exposure for people who live and recreate in Canaan Valley.

Along with air pollution, the facility could cause an immense amount of noise pollution. In other towns with data center complexes, residents describe constant noise that sounds like a jet that never takes off. In North Carolina, residents that live next to data centers experience migraines, hearing loss, vertigo, vomiting, and panic attacks. Despite expressing our concerns, Fundamental Data has not provided any information about the levels of noise that will be produced by the facility or how that noise pollution will be mitigated.

This facility also threatens our dark skies, as data centers emit excessive amounts of light and operate 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. Light pollution is linked to depression, heart disease, sleep loss, and cancer in humans. Wildlife are also greatly impacted by light pollution, including the millions of birds that migrate over the Mid-Atlantic every year. Blackwater Falls State Park is recognized as a Dark Sky location, making it a premier destination for stargazers and astronomers. Light pollution puts our state’s beloved natural areas at risk.

Which brings us to our tourism economy. Tucker County relies on tourism to support local jobs and businesses, including this magazine. In 2023, tourism generated $85.3 million in revenue and supported 910 local jobs in Tucker County. Those numbers continue to grow every year. In contrast, 70% of the revenue generated by the power plant and data center complex will go to Charleston. Of the 30% that would be remitted to the county

commission, not a penny of that revenue will go to our public schools, roads, healthcare, or other essential services and infrastructure.

On average, data centers only provide 30 to 35 permanent jobs. But there are no guarantees that any of these jobs would go to Tucker County residents or West Virginians at all. Many power plant and data center projects are constructed by skilled out-of-state workers who already work for the company leading the project. Fundamental Data has not provided any information about the number of jobs that will be created, how much they would pay, and whether they will go to local people.

We love Tucker County and we’re proud to live here. We treasure the pristine landscapes, clean air, fresh water, and stunning night skies. We are so fortunate to be surrounded by endless outdoor recreation opportunities. We find solace in listening to bird songs, croaking frogs, and leaves crunching beneath our feet. Above all, we fill our hearts by spending time with all the passionate, creative, and caring people who call Tucker County home. Fundamental Data’s power plant and data center complex would destroy everything we love about living in Tucker County. It threatens the health, safety, and livelihood of our public lands, clean water, and vibrant community. The costs are too great.

But this is not just a fight about Tucker County, this is a fight for every community in every county in the state. This may be one of the first proposed data center complexes in the state, but it certainly won’t be the last. The West Virginia legislature passed a bill that fast-tracks data center development and usurps the power of residents and local officials. We believe every community has a right to decide what happens in their community. We will never stop fighting to defend the right of West Virginians to protect their health, safety, public lands, and quality of life. w

To learn more about this project and to get involved, visit tuckerunited.com

For generations, Appalachian forests have provided for families, shaped communities, and stood as a testament to resilience.

The Family Forest Carbon Program helps landowners like you continue that legacy—offering financial support and expert guidance to improve forest health while keeping your land in your hands. Put your mark on the land, keep it healthy, and get rewarded for responsible stewardship.

Now enrolling landowners up and down the Appalachian range.

By Dylan Jones

Good-deed-doers rejoice! An anonymous reader recently left us a kind and concise note on the windshield of the venerable HO Mobile while we were out shooting photos for the Dobbin Slashings Preserve feature in this issue. Going out

in the field to produce special stories we get to publish is one of the greatest joys in creating Highland Outdoors, but it’s not always easy work—especially with looming printer deadlines. Despite feeling the weight of the summer deadline on our shoulders, Nikki and I shouldered backpacks to head into Dolly Sods over Memorial Day weekend to campout and shoot photos in the name of journalism. As is the norm on our backpacking trips, we had heavy packs (weighed down by even more camera gear), not enough water, and not nearly enough time to see all the sights. We were feeling physically beat

By HO Staff

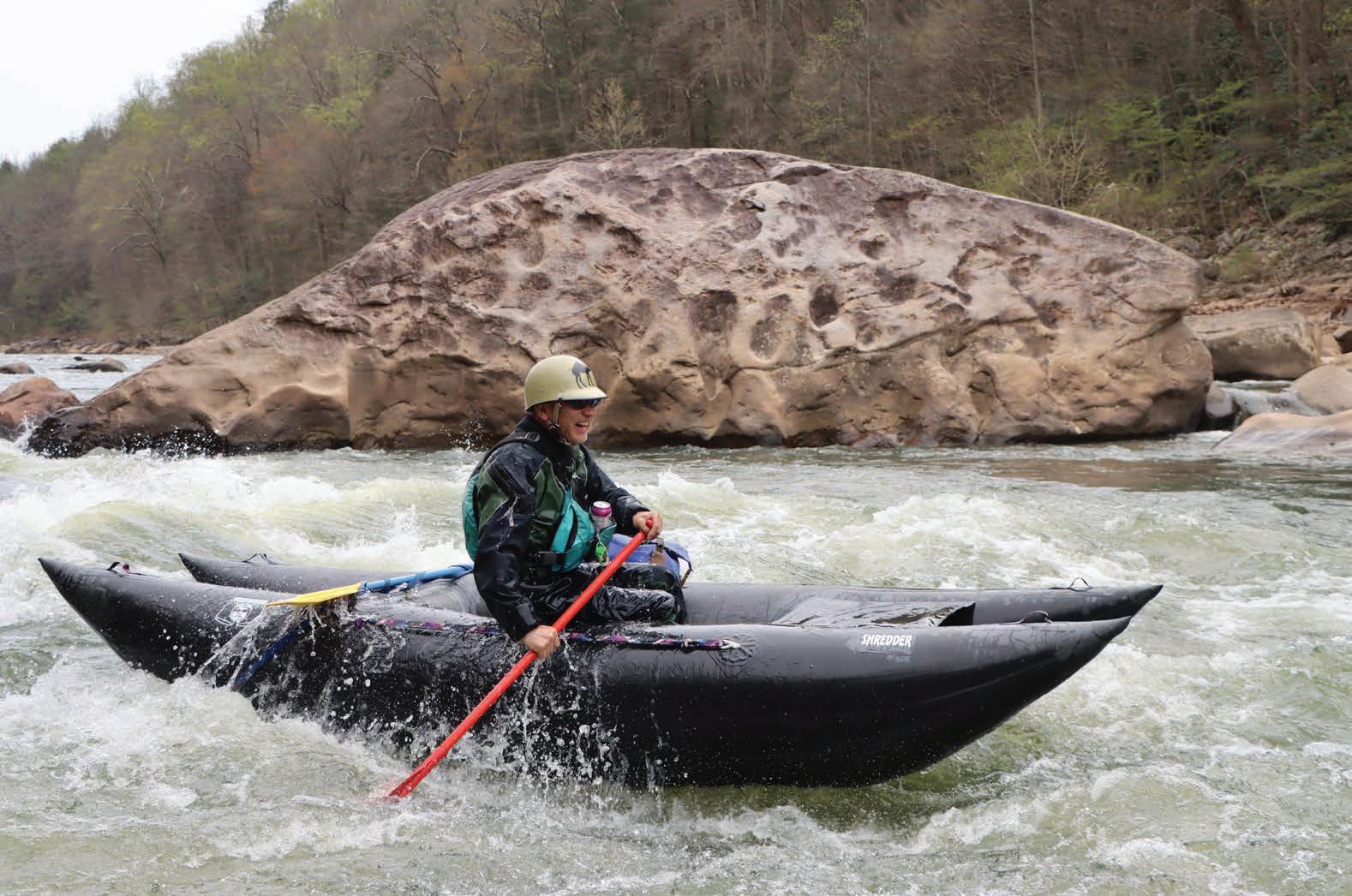

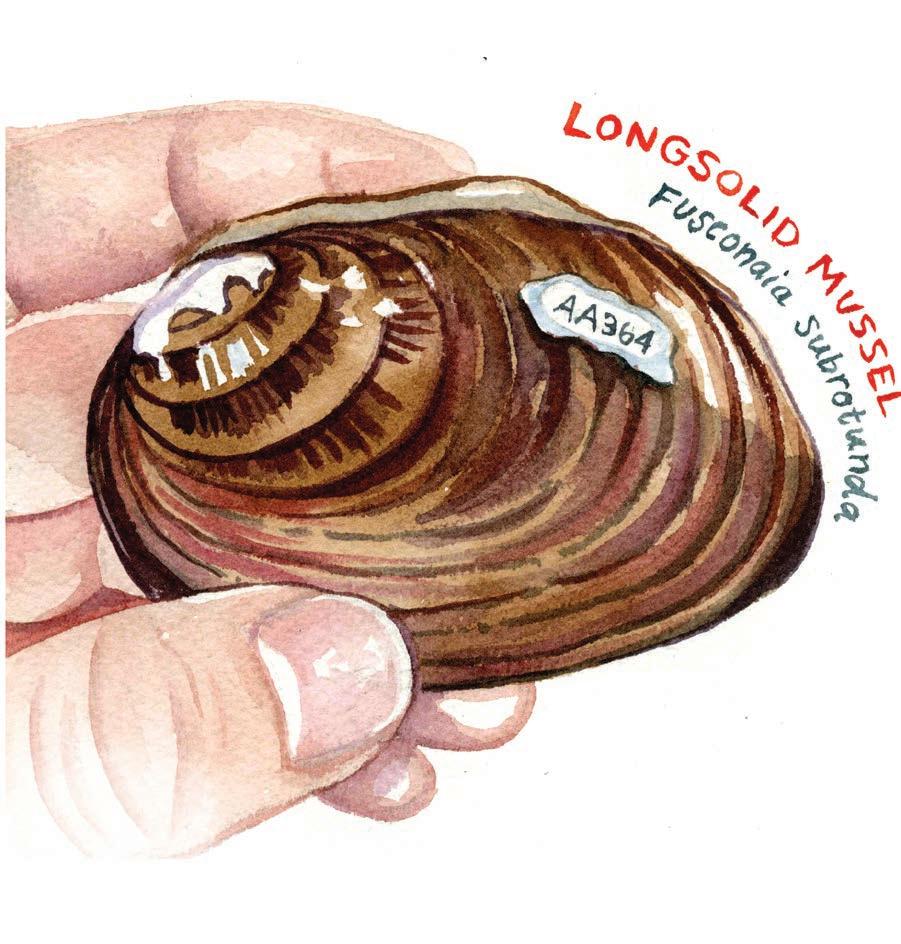

Unfortunately, river lovers, this story isn’t one to rejoice about. American Rivers, a national conservation organization advocating for clean waterways across the country, added the Gauley River to its annual list of America’s Most Endangered Rivers. Each year, the campaign identifies 10 waterways that face imminent threats from pollution or harmful development.

The threat of toxic coal pollution from surface mining on the South Fork Cherry River, one of the Gauley’s main headwater tributaries, is the primary reason for the beloved river’s listing. The South Fork Cherry serves as critical habitat for the endangered candy darter. The Gauley is globally recognized for its world-class whitewater runs, rugged beauty, and critically important biodiversity. Every year, the Gauley River rafting season draws some 40,000 whitewater enthusiasts from around the globe to brave its thrashing rapids and celebrate West Virginia’s vibrant whitewater culture.

The primary culprit in the river’s listing is the South Fork Coal Company, which is currently operating the 3,600-acre Rocky Run Surface Mine site in Greenbrier and

Pocahontas counties. This site includes strip mines, a coal preparation plant, and a network of haul roads for transporting coal. “South Fork Coal is a prolific polluter and violator of laws designed to protect our environment,” said Olivia Miller, program director for the West Virginia Highlands Conservancy (WVHC).

While the mine itself, which sits just outside the boundaries of the Monongahela National Forest (MNF), isn’t illegal, aspects of its operation have resulted in numerous citations. The company has been subject to over 140 enforcement actions by the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) since 2021, and has accumulated over 80 Clean Water Act violations since 2019 for releasing heavy metals—sometimes up to 900% above legal limits—and harmful sediment into the South Fork Cherry River.

The company has also been embroiled in legal battles over its use of US Forest Service roads within the boundaries of the MNF for hauling coal. Although the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in February of 2025 to stall the ongoing lawsuits, it continues to operate the Rocky

and mentally stressed on our hike out, only to come back to our vehicle and find the encouraging note placed under a wiper blade. Reading the note aloud resulted in immediate goosebumps, mushy feelings, and motivation to get home and continue cranking out this issue you now hold. The positive reinforcement we receive from readers is a huge part of what helps us maintain the passion required to produce a print publication in the digital age. We’d like to give a heartfelt thank you not only to whomever left the note, but to all those who’ve provided much-needed encouragement along the way. Although, I must say, the note failed to realize that this issue is, naturally, our best one yet. Onward! w

Run site, pollute the South Fork Cherry River, and transport up to 100,000 tons of coal annually on Forest Service roads. “It’s just mind boggling. There have been over 80 violations of the Clean Water Act, and none of them have been enforced,” Miller said. “Coal companies are not held accountable in this state whatsoever. We need stronger enforcement of existing laws and regulations to stop this illegal hauling of coal through our national forest.”

To encourage regional advocacy, American Rivers partnered with regional conservation organizations including Allegheny-Blue Ridge Alliance, Appalachian Voices, and the WVHC. Through each of these organizations, concerned citizens can submit public comments and pressure lawmakers and DEP officials to protect the invaluable resources of the Gauley River. w

To learn more or get involved, visit wvhighlands.org/protect-the-gauley/

FIND YOUR NEXT ADVENTURE IN THE 63RD NATIONAL PARK — the New River Gorge National Park and Preserve. Hike through miles of scenic trails that lead to some of the most popular views in West Virginia. Or scale the sandstone cliffs on a guided rock climbing trip and take in the Gorge from a new perspective.

Start planning your summer getaway to the New River Gorge in West Virginia.

Photography lovers, rejoice! I am thrilled to announce the fourth installment of our annual photo contest. It feels like just yesterday I looked over to Nikki and said, “I think we should run a photo contest.” She nodded in agreement, and I immediately followed up with, “How do we do it?” This, of course, led me on a meandering journey to discover the nuts and bolts of how to host a photo contest in a print publication. And while it wasn’t always easy, it’s always been a lot of fun. Shooting my own photography and publishing the outstanding work of other photographers is my favorite part of this job. I’d like to give a special shoutout to David Johnston, who was integral in guiding me through the process of designing and running the contest. He was a judge our first year, and I am stoked to welcome him back to the judges panel this year, along with two other perennial contest winners Kim Ayers and Nathaniel Peck.

Our 2024 photo contest was yet another successful endeavor that saw 60 individual contestants submit a total of 102 images. As has become the norm (and no surprise given the wealth of talent in the Mountain State), I was once again impressed by the range and quality of the images we received. I’d like to send a heart-felt thank you to all the photographers who submitted images and to the judges who helped comb through them. I know there are thousands of talented photographers throughout Appalachia, and I am calling on you once again to send in your best shots—or at least encourage your pals to do the same. You don’t have to be a published photographer to have a chance. If you think you’ve got a special shot, it’s got a shot at winning. And if you’ve submitted before, please consider doing so again. As always, we’ll publish the winning images in our Winter 2025 issue. Thanks in advance to this year’s judges, and to everyone who submits their photos. Good luck!

Dylan Jones, Editor-in-Chief

We know rules aren’t fun, but we live in a society, and we need rules to keep things on track. If you’re planning to submit a photo, please read this section carefully.

We’re West Virginia’s Outdoor Magazine, and our lovely state is worthy of its own photo contest. As such, submissions must be from locations in West Virginia. Any photos found to be from out-of-state locations will be disqualified.

Do not submit an image with a watermark, signature, or logo. This helps maintain anonymity during the judging process. Any photographer who submits an image with a watermark will be asked to remove it and resubmit. If that cannot be accomplished, the image will be disqualified.

We will not accept any photos showing abuse, misuse, or degradation of wild animals, plants, or landscape features.

We will not accept any photos showing illegal activities. If we have reason to question the legality of anything depicted in your image, we reserve the right to disqualify it.

Please do not send photo illustrations or images depicting altered reality, including any photos created using artificial intelligence. This also includes abstract images or clearly altered (Photoshopped) images. Panoramas and composite images are OK so long as they do not clearly misrepresent reality. Any image deemed to be a photo illustration will be disqualified.

If your photo contains a recognizable person or minor under the age of 18, the person or the minor’s parent/legal guardian must sign a photo release form. If we decide a release form is needed, we will contact you following your submission. This is easy to do and shouldn’t deter you from submitting your photograph.

Send us your most spectacular photos showing off West Virginia’s beauty. There are only two rules here: locations must be in WV and there can’t be any people in your images (animals are OK, but photos with a wild animal as the primary subject should be submitted under the wildlife category). Buildings are acceptable if they showcase historic and/or cultural elements or if they are part of the landscape.

The wildlife category is for, you guessed it, photos of our amazing flora and fauna. Plants, bugs, bears—it doesn’t matter. If it’s wild and it’s living, it’s fair game for your submission. A few rules here: keep it wild! We will not accept photos of domesticated animals, captive wild animals, or wild animals feeding at manmade food sources. And just like the landscape category, no humans!

So, what about us crazy hominids that like to do radical activities in the great outdoors? Cue the adventure category! This is for any photo that shows human-powered adventure in the mountains (no motorized recreation, please). Whether it’s a high-speed capture of a skier, a photo of an angler casting in a mountain stream, or a snap of adventurous souls being dwarfed by our big landscapes, we want to see it!

There will be eight winning photographs. All eight photographs will be published in our Winter 2025 issue.

The overall winner will receive: $350 and a one-year print subscription.

The overall runner-up will receive: $250 and a one-year print subscription.

Each category winner will receive: $125 and a one-year print subscription.

Each category runner-up will receive: $75 and a one-year print subscription.

» All submissions must be received by August 15, 2025.

» Submit all entries directly via email to dylan@highland-outdoors.com with Highland Outdoors 2025 Photo Contest Submission in the subject line.

» You may submit one photo per category for a total of three photos per entrant. Do not submit multiple photos for a single category.

» Maximum file size: 4 megabytes (MB).

» To ensure that photos are judged fairly, please size your photo(s) for viewing on a screen. Please submit vertical images close to but no larger than 2,400 pixels (PX) on the vertical side. Please submit horizontal images close to but no larger than 2,400 PX on the horizontal side. If a panorama or other oddly sized image is chosen, we will work with you to size it properly for print. If your image is selected, we will ask you to send a high-resolution file with specific parameters.

» We prefer photos to be submitted in the sRBG colorspace. If that’s over your head, or you’re unsure how to change the colorspace of your photograph, no worries.

Photographer’s Rights and Use of Images by Highland Outdoors

The photographer will retain all rights to their submitted photo(s), regardless of selection for publication. If submitted photo(s) are selected for publication, the photographer agrees to grant Highland Outdoors permission to publish the photo(s) in its Winter 2025 print publication as well as the digital version of the article that will appear on www.highland-outdoors.com. Highland Outdoors may use any winning photograph(s) for use in materials promoting our Winter 2025 issue and our 2026 photo contest. Basically, we don’t own your photos—you do!

As always, I am honored to have a fantastic panel of judges joining me to help select the winning photographs. To celebrate the fourth rendition of our photo contest, I thought it would be apropos to pack the panel with the three winningest photographers from the last three years. As such, I present to you an all-star lineup of winning photogs who’ve dominated the pages of the mag over the years!

Kim Ayers is a wildlife photographer who currently resides on the Greenbrier River in Alderson, WV, where she can often be found exploring the back roads of Summers and Monroe counties with her husband, leaning out the sunroof of a car in her overalls with camera in hand. Her love for photography began with her children’s sporting events, and the image that ignited her passion for wildlife photography was also her first published photo that appeared in the Pocahontas County Visitors Guide. Since then, she’s continued to sharpen her skills and learn from her mistakes along the way. Kim is a Tamarack Juried Artisan and is a regular winner in the Wildlife category of the Highland Outdoors Photo Contest.

David Johnston has enjoyed the privilege of photographing the great outdoors all over the country. When he retired, he headed straight for the West Virginia highlands. Now a resident of Dryfork, WV, he specializes in landscape photography with a focus on panoramas, astrophotography, and botanical macros. He is a juried artist with Tamarack Marketplace and has exhibited at Tamarack: The Best of West Virginia, the West Virginia Culture Center, the annual Cortland Acres Photography Exhibit, and the North American Nature Photography Association’s annual showcase. He serves as a liaison for the Cortland Acres Exhibit and is the coordinator for the Dolly Sods Wilderness Stewards, which is dedicated to preserving Dolly Sods and other West Virginia wilderness areas.

Dylan Jones is co-publisher and editor-in-chief of Highland Outdoors and lives in Davis, WV, with his wife and mag co-publisher Nikki. Nothing makes Dylan happier (besides a perfect powder day at White Grass) than making Highland Outdoors West Virginia’s premier publication for outstanding nature and adventure photography. Besides Highland Outdoors, he’s had his images published in Freehub Magazine, National Geographic Explorer’s Journal , Wonderful West Virginia , Harvest Hollow, Adventure Journal , Garden & Gun , and West Virginia ArtWorks. He’s exhibited images in the annual Cortland Acres Photography Exhibit and maintains a dusty gallery in the corner of Stumptown Ales in Davis—you should probably stop in and buy a piece!

Nathaniel Peck is an avid nature photographer who focuses his lens on the dramatic landscapes, wildlife, and caves of the Allegheny Highlands region. His love for wild spaces started while growing up on a farm in the mountains of Western Maryland. Photography continues to be Nathaniel’s way to share the beauty of his home with everyone. He hopes his images can inspire the next generation to help protect the last wild places in the East. Nathaniel’s work has been published in Nautilus Quarterly, The Maryland Natural Resource Magazine, Allegany Magazine, and, most importantly, Highland Outdoors. He won gold in the 2024 Bird Photographer of the Year Contest and was the grandprize winner of the 2022 Highland Outdoors Photo Contest.

By Mark Wenzler

West Virginia has more than its fair share of mysterious creatures, from Mothman and the Flatwoods Monster to Wampus cats and, of course, Bigfoot himself. Most frequently spotted during twilight hours deep in foreboding hollers, these creatures have eluded me for as long as I’ve sought them out. But on a perfectly fine afternoon last June, standing high atop West Virginia’s tallest peak, I did happen to see a shark slowly stalking a skeleton sporting a tie-dyed skull.

While it may sound like I was hallucinating, I wasn’t the only one who saw it. I spotted this bizarre duo in the skies among many other airborne oddities during the annual Spruce Knob Kite Festival.

Topping out at 4,863 feet, Spruce Knob is not only the highest summit in the Mountain State, it’s also the highest ridge in the Allegheny Mountains, which run for about 300 miles from north-central Pennsylvania through western Maryland and

eastern West Virginia. This rugged mountain range can receive high winds year-round, as evidenced by the many wind-deformed red spruce scattered across its rocky ridges. As the proud owner of a wind-damaged tent, I can attest that you could probably fly a small appliance in the skies above these ridges.

The Spruce Knob Mountain Center, where the Kite Festival takes place, is tucked into a protected shoulder of the mountain, with expansive high meadows perfect for flying kites. Its large Mongolian-style yurts, with evocative names like Almaty and Ulan Bator, give the campus an otherworldly feel that’s fitting for being atop the roof of West Virginia. The setting also creates a perfect backdrop for the phoenix, flying dragons, and other mythological creatures that fill the sky at the kite festival.

Held on the last Saturday of June, the Kite Festival is a free event hosted by Experience Learning, a nonprofit outdoor education center. The meadows and forests of the Mountain Center offer an ideal location for Experience Learning to deliver a robust offering of programs, including outdoor education, adventure and stewardship courses for kids and adults, and opportunities for kids from underserved communities—both from within West Virginia and surrounding cities—to get outside and enjoy the rugged Appalachian wilderness.

While Experience Learning has been around for about 10 years, it continues the legacy of several preceding organizations, including the Woodlands Institute and the Mountain Institute, dating back to 1972. Experience Learning has remained true to these roots by focusing its curriculum around a wilderness-based “learning beyond the classroom” approach.

Vicki Fenwick-Judy served as Executive Director in 2017 when Experience Learning emerged from the Mountain Institute. At the time, Vicki understood that wilderness and adventure-based programming did not always feel accessible to the local residents who live adjacent to Spruce Knob, many of whom had long wondered what folks were up to on the mountain.

Vicki and her team created the Kite Festival in 2019 to welcome both their neighbors and the broader community with a family-friendly event. “We wanted people to come and see who we really are, that our campus is open to everyone. We thought, if they come for the Kite Festival, maybe they’ll return as campers,” she said.

June of 2024 was just my third time attending the Kite Festival, but I’ve made the Mountain Center my base camp for many hiking, biking, and running adventures over the years. If you see a wind-battered tent with a bike next to it, it’s probably me hunkered down inside.

The Kite Festival is an opportunity for Experience Learning to give back to the many communities that help make its work possible. It’s a day where old friends reunite and new friends are made under a sky filled with remarkable flying contraptions of every variety imaginable: an octopus, a crab, a turtle, a butterfly, even a fighter jet. During the monster kite demos, giant kites, each as long as a school bus, take to the skies. If you can imagine a shape, someone has figured out how to make it fly. Attendees can bring their own kite, try a kite, or buy a kite on site from local vendors. In addition to kites, there’s a science, technology, engineering and math festival for kids of all ages, with multiple vendors, activities, and regional nonprofit educational programs. Grabbing the reins of a colorful kite is the perfect opportunity to introduce little ones to the marvelous physics of flight.

After wrangling a tethered aerodyne for a couple of hours, folks tend to work up a mighty thirst. Fortunately, the Kite Festival features a fine selection of West Virginia craft beer and cider, along with local food trucks and vendors.

And when the magical twilight arrives, if you’re not off searching for Wampus cats, you can gather around the bonfire and stay for an evening of live music and camping in the serene mountaintop meadow.

If you’ve never been to Spruce Knob Mountain Center, the Kite Festival offers an ideal chance to visit one of the most unique alpine venues anywhere. I’ve come to think of it as West Virginia’s own Shangri-La. But unlike the Tibetan Valley of the Blue Moon in James Hilton’s 1933 novel “Lost Horizon,” this earthly paradise can be found on Google Maps. I hope to see you high up on the mountain this June. I’ll be the guy tangled up in the kite strings. w

The fourth-annual Spruce Knob Kite Festival will be held on June 28. Mark Wenzler is chair of the board of trustees at Experience Learning. He’s also a part-time resident of Tucker County and is terrible at flying kites.

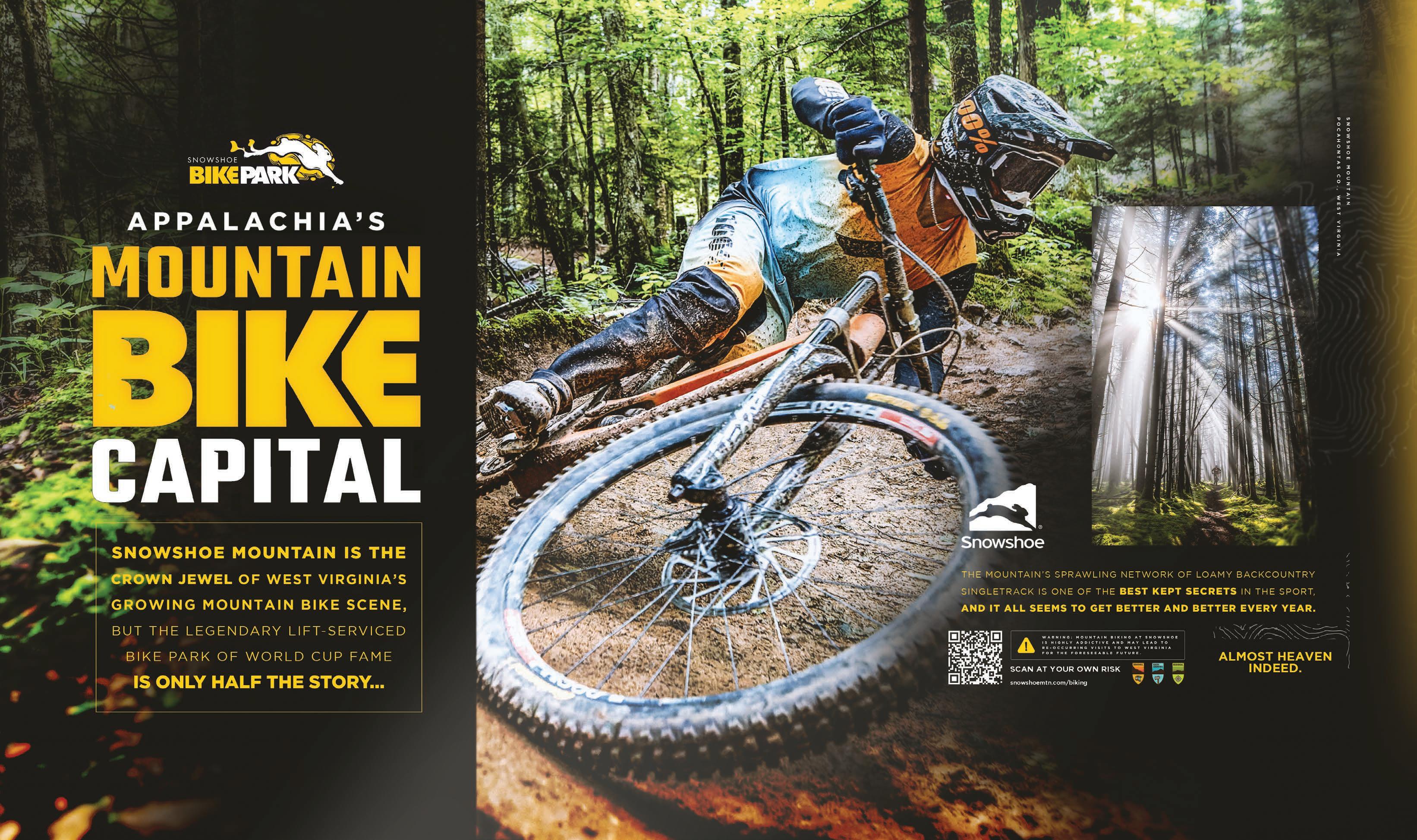

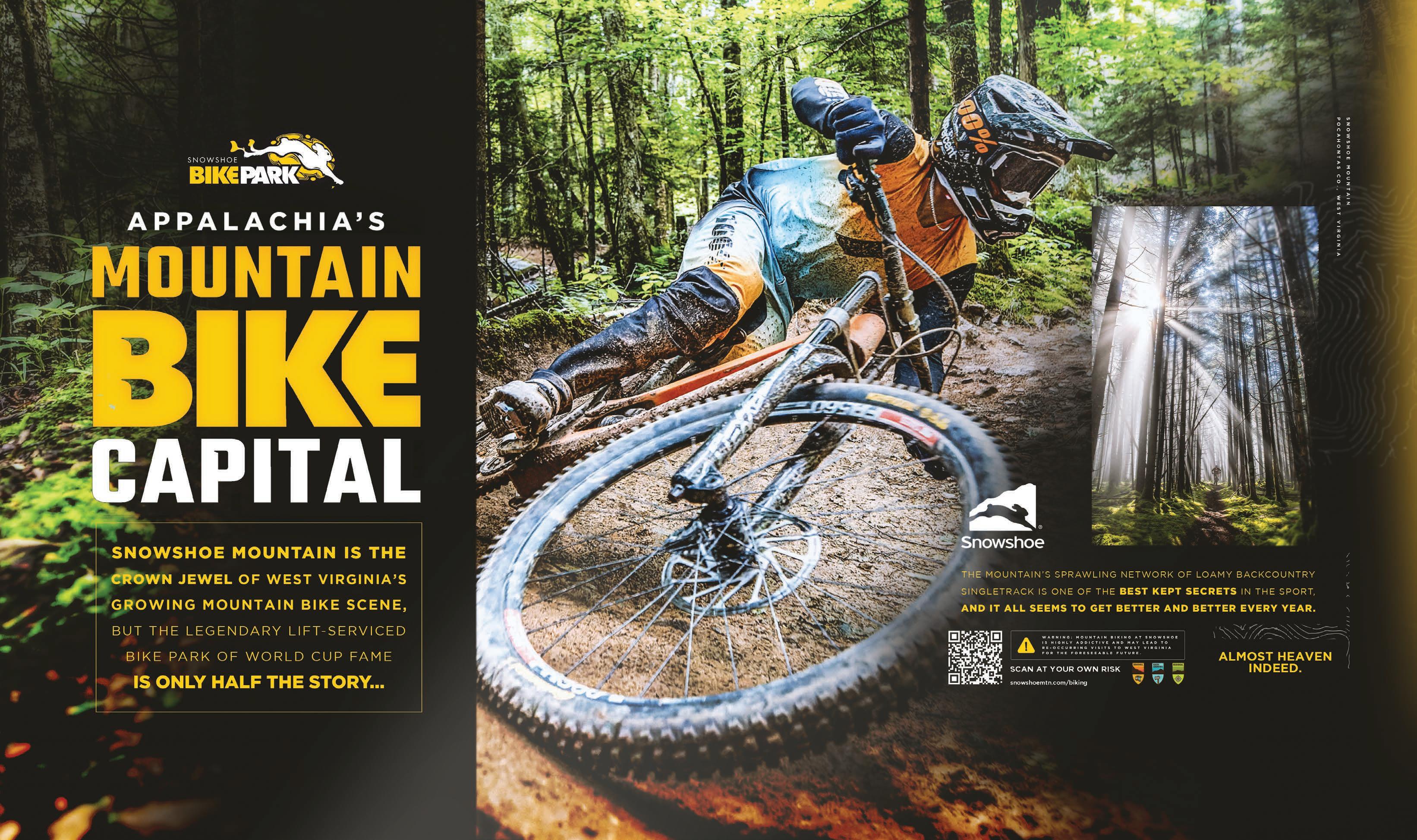

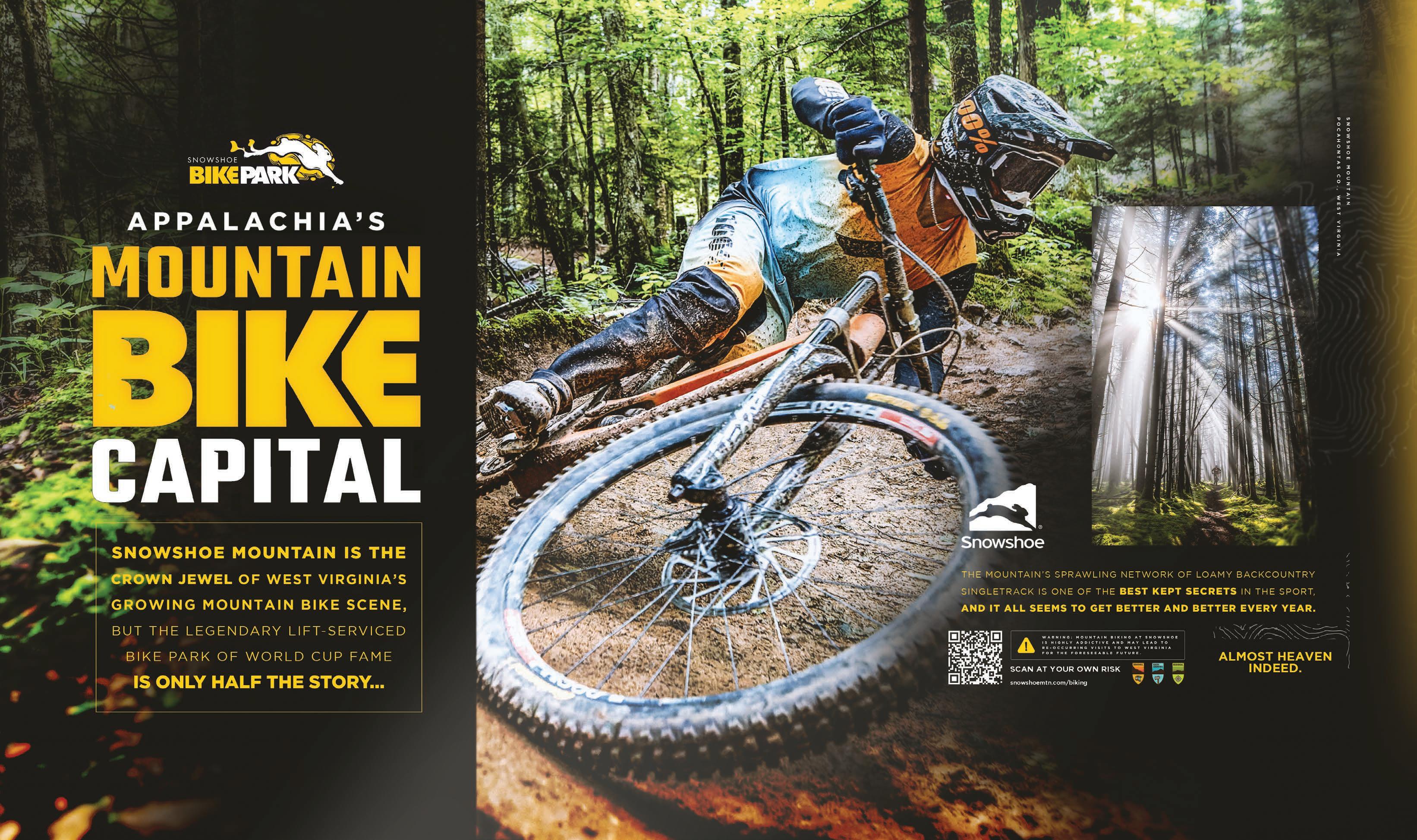

THE ULTIMATE R &R MOUNTAIN BIKING GETAWAY.

Cacapon State Park’s world-class trails have a smile-making ride for every style and skill. Enjoy black diamond downhills, blue rocky tech, green flowy berms, old-school Appalachia singletrack, drops, jumps, and everything in between. After the ride, refuel in our local breweries, restore your sore muscles in our legendary spas and do it all again the next day!

Words and photos

by

Art Barket

The mighty Cheat River begins its journey where the rushing waters of the Black Fork and Shavers Fork rivers merge in the historic town of Parsons in Tucker County. The mainstem of the Cheat flows north past the small towns of Saint George, Rowlesburg, and Albright before entering the rugged wilderness of the Cheat Canyon in Preston County. As the canyon walls rise, the placid cobblestone riverbed steepens and fills with massive boulders and bedrock ledges. The ensuing stretch offers a whitewater playground for skilled paddlers stacked with legendary rapids. Although the Cheat Canyon is best explored by boat, hikers can head down to the rocky banks by hiking the Allegheny Trail, which runs the length of the canyon on an old railroad grade above the river.

Over millennia, the seemingly random boulders of the Cheat Canyon have fallen from cliffs high above the river or have been pushed downstream by biblical-scale floods. The last major event to tumble house-sized boulders through the canyon was the infamous 1985 Election Day flood, when the Cheat rose 30 feet in one day, killing 38 people and causing millions of dollars in damage to

homes and infrastructure. The erosive effects of the rushing water, coupled with wind and time, have steadily sculpted these rocks, creating some amazing spectacles that resemble familiar forms.

As humans, our brains are wired to seek out patterns in nature, like stars forming constellations, or clouds resembling animals. While searching for a word to describe this phenomenon, I came across “mimetolith,” which is defined as a natural rock feature resembling a living form, typically a human face, head, or the form of an animal. This relatively new term, which is a combination of the Greek words mimetes (an imitator) and lithos (stone), was coined by Thomas Orzo MacAdoo and first printed in 1989. Among the myriad rocks scattered throughout the Cheat Canyon, a number of them have become well-known mimetoliths, named by local paddlers that frequent the rushing rapids. w

Art Barket is an avid whitewater kayaker and admirer of rocks. He feels right at home battling the rapids of the Cheat Canyon, which he’s been paddling and exploring for over 20 years.

Three hundred million years ago, during the Carboniferous Period, much of what is now West Virginia was a tropical environment comprised of swamps and forests. During this period, Lepidodendron, a large tree-like vascular plant, flourished here. The fossilized imprints left by Lepidodendron plants resemble the tail strike of a mighty dragon (or a tire track to motor sports enthusiasts). The Lepidodendron went extinct some 250 million years ago. Much of the plant matter from Lepidodendron and other plants during this period decayed in the swamps and bogs, creating the vast peat deposits that eventually compressed into coal. Fossilized imprints of many plant species can be found in the sandstone boulders throughout the canyon. In a striking wall at a rapid called Fossil Falls, an exposed limestone layer provides evidence of an ancient seabed where one can find thousands of fossilized shells and other small sea creatures.

A bit less magical than the Tail of the Dragon, and yet more relevant to modern life, is this surprising shape that has been dubbed Beer Can Rock. I recently discovered this imprint while scouring the riverside rocks for interesting finds just like this. I have no idea what process might have caused this formation, but it appears to look exactly like the top of a beer can —and even has the tab to crack it open. For decades, cheap beer has been the preferred beverage of raft guides and river cruisers, and Beer Can Rock offers the perfect spot to eddy out and crack open a cold one.

This large porcine rock sits in the large pool preceding the Tear Drop rapid. Composed of Pottsville sandstone, Miss Piggy’s permanent smile means she’s always happy to see everyone who passes by. Likewise, paddlers are always happy to see Miss Piggy, as she marks the end of a long flatwater stretch and the start of the best series of rapids in the Cheat Canyon, including Tear Drop, High Falls, Maze, and The Coliseum.

Turtle Rock resembles a giant turtle shell with a turtle head sticking out just above the water. This giant Pottsville sandstone boulder fractured perfectly to create the head and neck of the turtle. Turtle Rock can be found just below Elephant Rock and Pete Morgan’s rapid, which was named for the guy who ran a gas station in Albright that served as the go-to for paddlers seeking river level information in the 70s and 80s. Interestingly, there is an old hand-carved gauge featuring lines and Roman numerals on the backside of Turtle Rock. The history of this seemingly ancient gauge is unknown.

Armadillo Rock is one of the largest boulders found in the Cheat Canyon. This house-sized mimetolith resembles the scaled head and body of an armadillo. Armadillo Rock is composed of Pottsville sandstone and chokes down the entire flow of the river to a rightside channel, forming a fun series of wave trains. The sculpted backside of the armadillo is covered with eroded potholes that formed over millennia as cobblestones washed over the boulder. Rocks caught in these small depressions are swirled around by water, slowing carving away the rock and sculpting the armored creature we see today.

The Cheat River Guardian faces strongly upstream, forever keeping a stoic and watchful eye on the canyon. You can find the Guardian at the bottom of the mighty High Falls rapid, where the river tumbles down a set of bedrock ledges and slides. As I stare at this rock, I see a warrior wearing a Trojan-style battle helmet. The face and helmet stand out so much that this mimetolith appears to have been carved by humans. This impressively large rock feature doesn’t get much attention since it sits on the bank opposite an impressive cliff with waterfalls that trickle into the canyon.

The Fist sits midway through its eponymous rapid. This striking boulder takes the form of a triumphantly clenched human hand. The rock is aggressively poised upstream and faces paddlers as they brave the rapid. The proceeding ledge is fast and steep, and paddlers need to keep it upright to avoid getting knocked out by the Fist. During the 2025 Cheat River Massacre-Ence downriver race held in May, the Fist rapid was the site of carnage: two kayakers swam at the same time, and one of their boats swamped and sank to the river bottom.

Elephant Rock is one of the most spectacular and awe-inspiring rock formations in the Cheat Canyon. Just below the exciting Coliseum rapid, the Cheat slices through a layer of Loyalhanna limestone, creating this amazing herd of elephants marching through the canyon. The Loyalhanna limestone is a unique layer of rock that is actually a mixture of sandstone and limestone. The striped, layered columns of limestone resemble the legs of the herd, while the centerpiece of the formation creates an uncanny resemblance to trunks and heads. Early paddling pioneers, awed by these stone columns, named the Coliseum rapid due to the resemblance with Roman architecture. Coliseum is the hardest rapid in the Cheat Canyon, rated as a solid class IV at medium flows, and can turn into a rowdy class V rapid at high water.

By Dylan Jones

We’re snaking through the crowded branches of a shady red spruce forest, trying to make our way back out into the open. Picking a path through the understory is slow going, and we’ve been whipped in the face and had our hats snatched by the needleless twigs more than enough times.

Nevertheless, it’s a beautiful day in the mountains. Temps hover around 60 degrees; the air is crisp with zero humidity and a steady breeze. It’s the rare type of Appalachian day where the smell of arid duff reminds me of alpine summer hikes in the Tetons. My wife, Nikki, and I pop out of a small hole between the branches at the edge of the spruce stand and enter a shrubby meadow awash with bright sunlight. The only visible paths through the thick brush are braided game trails that deer and other fauna follow on their endless quests for food and water.

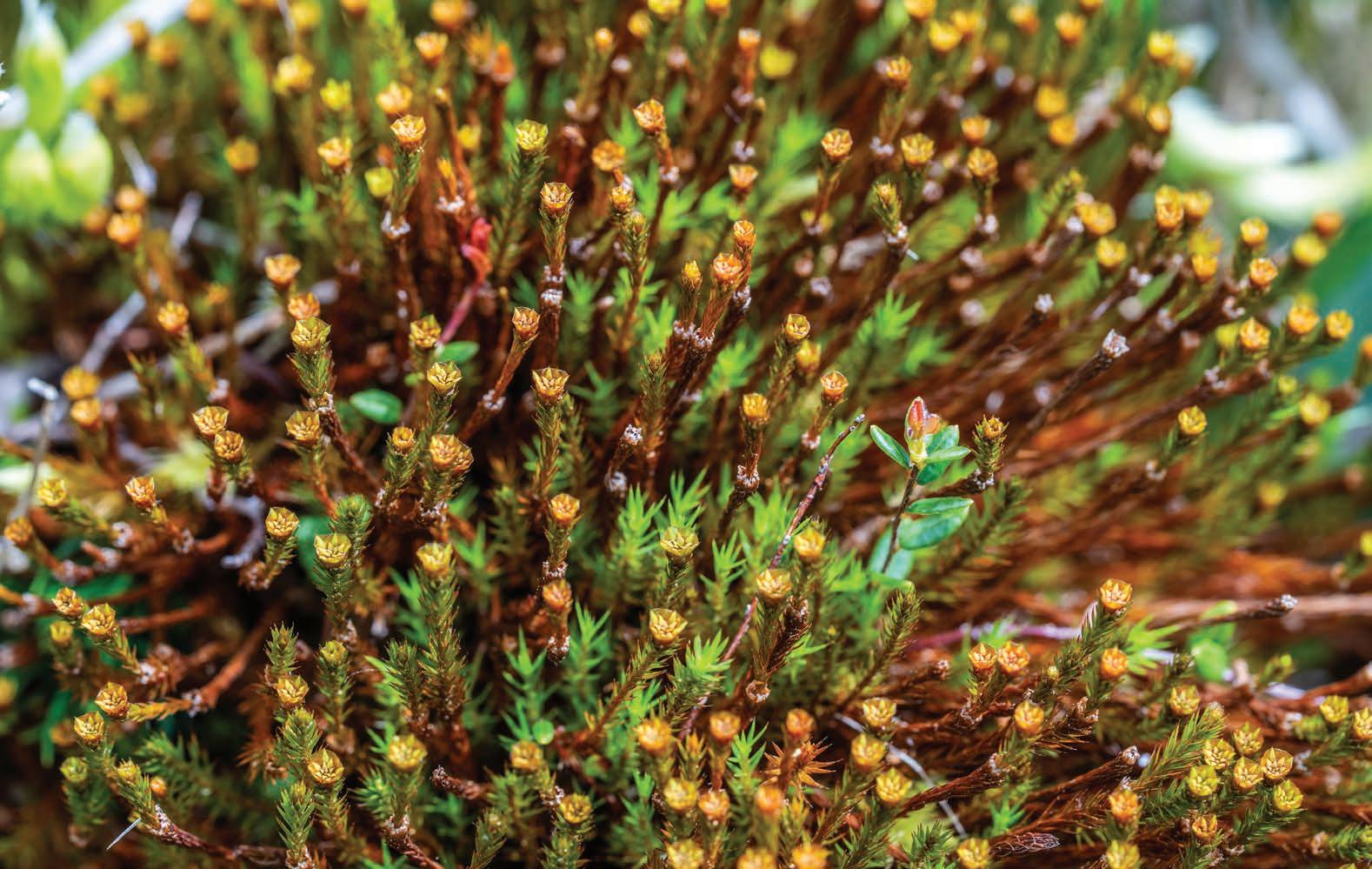

It’s mid-May, and most of West Virginia’s deciduous forests are already enveloped in the monotone green of summer. But here at 4,000 feet, the highlands atop the wind-battered spine of the Allegheny Front are just coming back to life after a long, hard winter. The late-spring tableau still assumes an autumnal color palette: the young leaves of scrubby maples are still quite red, and the tender quaking aspen leaves are so fresh that they’re yellow. The herbaceous layer of the meadow bursts with hues reminiscent of a coral reef: crunchy mats of turquoise reindeer moss, spongy hummocks of blood-red sphagnum, and neon-green shoots of unfurling fiddleheads. Sun-bleached white chunks of Pottsville sandstone, weathered into grotesque shapes with potholes stained orange from algae, punctuate the scene.

While we only drove an hour and hiked up a single ridge, it feels as if we’ve traveled thousands of miles to northern latitudes. The

sun’s rays seem to radiate a little more energy at this elevation, and I imagine the plants are having a photosynthetic party, collectively celebrating a full day of not being enveloped in the thick fog or beaten down by the driving rains typical atop the Front.

We’re deep into our inaugural exploration of the Dobbin Slashings Preserve, a 1,393-acre property situated atop Cabin Mountain in Tucker and Grant counties that represents a huge conservation win for The Nature Conservancy (TNC).

Here, the meandering ridgeline of Cabin Mountain is part of the Eastern Continental Divide, splitting the mountain’s hulking mass between two major watersheds. To the north of the Dobbin Slashings Preserve, the Stony River originates and flows into the Potomac River watershed, eventually reaching the Atlantic Ocean. But the centerpiece of the preserve is the Dobbin Slashings bog, an 800-acre wetland complex featuring myriad plant communities and a wealth of rare species. This spectacular wetland creates the northernmost headwaters of Red Creek, a pristine high-elevation stream that drains the Dolly Sods Wilderness. Red Creek is a tributary of the Dry Fork of the Cheat River, which joins the mainstem of the Cheat and several other rivers along its aquatic journey to the Mississippi and the Gulf of Mexico.

While headwater stream protection is always a noble conservation cause, the big attraction of the Dobbin Slashings bog for TNC is its high concentration of rare plant communities. “The initial interest in the property was in the high-elevation peat wetlands, including several unique wetland types that host rare species that are tracked by the [West Virginia Division of Natural Resources],” says Mike Powell, director of land management and stewardship for the West Virginia chapter of TNC. “There’s also a significant red spruce forest on the southern part of the property, which is one of the largest intact red spruce forest ecosystems on the plateau [of the Allegheny Front].”

Longtime West Virginia ecologist Elizabeth Byers penned an even more verbose description of the tract during an exploratory mission to catalogue the bog’s ecology in August of 2023: “It has an open shrub and herbaceous, beaver-influenced, central portion, bordered by seepage fens and peaty shrub swamps, with a few small remnants of forested peaty swamps on the southwestern margin.”

Additionally, the natural bowl of the bog creates a frost pocket, which is a landscape feature that traps cold air on clear, calm nights. Powell says that David Carroll, a meteorology professor at Virginia Tech who monitors a weather station in the northern, undeveloped end of Canaan Valley, believes that Dobbin Slashings bog could be the coldest spot in West Virginia when

atmospheric conditions are just right. In the first three days of June this year, Carroll recorded three sub-freezing mornings in a row at his professionally equipped weather station in Canaan. It’s plausible that Dobbin Slashings, 1,000 feet higher than the station on the valley floor, hosted even colder temperatures on each of those mornings.

Dobbin Slashings bog is one of the largest wetland complexes in Central Appalachia and was the largest remaining unprotected wetland in the region until TNC’s acquisition of the property in November of 2024. TNC purchased the tract from Western Pocahontas Properties (WPP), the largest private landowner in Tucker County. WPP maintains ownership of land north of the preserve, including the Stony River headwaters.

According to Powell, the deal, like most large-scale conservation acquisitions of this scope, was “several years in the making.” Unlike the Big Cove tract in the northern end of Canaan Valley, which TNC purchased in 2023 and transferred to the Canaan Valley National Wildlife Refuge (CVNWR) in February of 2024, TNC will maintain ownership of the Dobbin Slashings Preserve as a flagship tract to highlight its successes in conserving critically important ecological regions in the Central Appalachians.

TNC, a global organization, is heavily invested in conserving what it considers to be the four most ecologically critical regions for the fight against climate change: the sprawling grasslands in Kenya, the lush Amazon Rainforest, the cloud forests of Borneo, and the ancient forests of the Appalachian Mountains. Like these other incredible natural wonders, Appalachia is home to some of the greatest biodiversity on the planet. The mountain range’s north-south orientation and east-to-west-facing slopes offer multiple migratory corridors for species to respond to pressure from a rapidly changing climate.

Dobbin Slashings bog, and much of the Dolly Sods area, has been subject to a harsh history over the last century. The region was first settled and farmed in the late 1700s by the Dahle family, German immigrants who undoubtedly suffered through some hardscrab -

ble living while grazing sheep atop the notoriously windy and wintry plateau.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the entirety of the Allegheny Front—and the majority of Central Appalachia—was completely deforested by a relentless logging spree that left no sapling standing. George Dobbin was an early white settler of the region who built the Dobbin House settlement in what is now Blackwater Falls State Park. He also formed the town of Dobbin on the North Branch Potomac River in Grant County, and transported timber from the Allegheny Front down the mountain along what is now the infamously muddy Dobbin Grade trail in Dolly Sods. In the early 1930s, the remaining brush, called slash, was piled up and set ablaze across 25,000 acres. Some of this slash burning occurred in the bog, hence the name of Dobbin Slashings. The hungry flames consumed everything and smoldered until the soil was burned down to the bedrock.

In the mid-1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps planted red spruce saplings upon the barren wasteland, ushering in the ongoing recovery of the high-elevation red spruce ecosystem. In October of 1943, fire and flame returned to the bog, this time as part of the national WWII effort. The U.S. Army created the 60,000-acre West Virginia Maneuver Area, where artillery units trained for mountain operations in Italy by using the open plains atop the Front for bombing drills.

Long after the last bomb exploded in the bog, a new threat appeared. In 1970, the Davis Power Project was proposed: a pumped-storage hydroelectricity system that would have required damming the Blackwater River and turning Canaan Valley into a nine-mile-long lake. The upper pool of the system, which would have water pumped up into it so it could flow back down to turn hydroelectric turbines, would have been created by damming Red Creek where it flows out of the Dobbin Slashings bog. Fortunately, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in favor of those opposing the project, paving the way for the creation of the CVNWR in 1994.

But despite its tumultuous history, the Dobbin Slashings bog has made a remarkable recovery. “That’s another part of why this property is so special,” says Powell. “It’s really hardy and really resilient. It’s been logged and burned and bombed and degraded, and it’s still a really special place with significant reforestation, restoration, and recreation opportunities.”

The Dobbin Slashings bog and its surrounding slopes are home to over 400 priority plant and animal species of greatest conservation need. There are several rare plant communities, each a mouthful to recite: blueberry–bracken fern shrub swamp, bluejoint wet meadow, cottongrass fen, cranberry–beakrush peatland, red spruce–three-seeded sedge peat wetland, and silky willow shrub swamp. “Being able to protect a large swath of high-elevation wetlands with surrounding uplands, along with the opportunity to reforest those uplands, really elevates the conservation value of the property,” says Powell.

Rare plant species include balsam fir, several types of sedges, creeping snowberry, northern club moss, small cranberry, and northern stitchwort. Rare insects include the spreadwing damselfly, the black-tipped darner dragonfly, and a handful of other insects and spiders. Several spider species were described as new

state records, meaning the first time they were identified as being present in the state.

The boreal stitchwort, a type of flowering plant typically found in Northern Canada, finds the southernmost extent of its range in the bog and at TNC’s Bear Rocks Preserve just to the east. The southern rock vole, an adorable short-tailed mouse typically found in the Great Smoky Mountains, finds the northern extent of its range in the preserve. These two range extremes are a nod to the Allegheny Front’s importance as both an ecological transition zone and a critical corridor for these imperiled species—and many others—to be able to move in response to a changing climate.

The bog offers refuge for 25 bird species of greatest conservation need, including the American woodcock, American bittern, green heron, northern harrier, and veery. The grounds are also known habitat for bald and golden eagles. “The property provides breeding habitat for those birds; the secluded nature of this site gives them relatively uninterrupted space to forage and feed and do their nesting activities,” Powell says.

Additionally, peatlands are of interest to conservationists for their outsized role in sequestering carbon into soil for long-term, natural storage. “When you think about climate resilience, these wetlands store a lot of carbon, so that’s one of the big drivers of protecting these high-elevation peatlands in addition to the spruce forests and their soils, which also play an outsized role,” Powell says. Forested wetlands store nearly 20 times as much carbon as upland forests because of the ancient peat deposits, some of which

can be upwards of 10,000 years old. “These ecosystems are the two heavyweight champions at sequestering carbon.”

In 2023, Powell and a group of ecological scientists went up to dig a horizon pit to study the soil composition. A soil scientist interpreted the red spruce soil layers, while a mycologist found the mycelium that produces truffle mushrooms, which in turn are eaten by the once-endangered West Virginia northern flying squirrel that lives among the red spruce canopy. “That was a really neat trip; it was with people I consider my mentors and these young people that are grabbing the reins and learning all the science, it’s just amazing to see,” he says.

Securing the protection of the Dobbin Slashings bog was only the first step—now the property needs to be managed in a way that fosters climate resiliency and mitigates current and future impacts. Powell says TNC plans to hire professional crews to plant 60,000 native red spruce and balsam fir trees on the property to make sure the bog can continue to function ecologically as both a giant sponge and carbon sink.

Many Dolly Sods afficionados are equally interested in TNC’s recreation management plan. The Dobbin Slashings Preserve serves as an important connector between the CVNWR and the trails in Dolly Sods, and Powell says TNC plans to work with land managers to develop a system that will connect 80 miles of existing trails around the tract. “It’s an important recreational connector

between public lands, and we want to work with our partners to potentially take some of the pressure off of the east side of Dolly Sods, where parking is limited and crowds are large.”

Although the property is open to the public, there aren’t any officially marked or mapped trails. A historic network of unmaintained jeep and hunting trails has led to erosion and sedimentation of the wetland. Because of the wealth of rare species that are sensitive to impacts, Powell says there are no plans to authorize camping on the property. “We want to develop professionally built, sustainable trails higher up around the property, so that people can enjoy the wetland without negatively impacting the native vegetation. As a land manager, I find a lot of value in projects like Dobbin Slashings and Big Cove, where there’s this intersection of recreation and conservation,” Powell says. “Both the natural world and the human world benefit from our work.”

It’s hard to capture the scale of the landscape in a single image. But feeling compelled to try, I bogwhack out as far as I can go, water rushing into my high-top Goretex boots, before the murky, tannic water becomes too deep for my own taste. I snap a series of images that I’ll later stitch into a single panoramic photo on my computer. I sling my camera back around my shoulder and stand there in awe. The forward march of time seems to freeze. It’s totally silent; only the faint breeze on my skin gives any inkling of change in a raw place that, right now, feels timeless.

Nothing is forever, and this bog will undoubtedly face myriad changes, whether wrought by humans, animals, or geologic

processes. But I take a bit of cosmic comfort knowing that, despite the inevitable acceleration of entropy, this place is safe for now. Nikki joins me on a hummock, and we share the view—and the sentiment—before retreating to higher, dryer ground. We traverse the bog’s rim to the west and north, gaining a commanding view atop a sun-bleached scree slope that emerges from the barren edge of Cabin Mountain like the spine of an ancient skeleton. I can see down and across the entirety of the wetland to where we stood knee-deep in the bog a few hours ago.

Turning to the west, I see nearly all of Canaan Valley, gazing a thousand feet down upon the human development that houses my friends, local businesses, and places I love to play. It’s amazing to know that just up and over the mountain, this place sits isolated, protected from said development for what I hope is a very long time. I consider what it would have looked like as a lake had the proponents of the Davis Power Project been successful.

Although it’s only around two square miles, it’s two square miles of one of the rarest landscapes in all of Central Appalachia. For decades, people wanted to take something that can’t be found anywhere else and turn it into more of something that can be found everywhere: the sterile, manicured, artificial landscapes of industry. But conservationists were able to notch another win, and now we all have a spectacular place to go simply exist and commune with the timeless wonders of our natural world. w

Dylan Jones is co-publisher of Highland Outdoors and is eternally grateful for all the exemplary humans who work tirelessly to protect places like Dobbin Slashings. Viva la Boglandia!

By Nikki Forrester

Krista Noe could barely contain her excitement. “There’s the snappy single sync,” she says to the tune of a catchy jingle while shimmying her shoulders. This firefly species, which synchronizes its flashes, has only been found one time in West Virginia. “My favorite species is probably the blue ghost—but don’t tell the other fireflies.” Blue ghosts are extremely small fireflies, not much larger than a grain of rice, that produce a steady green glow. From far away, their glow can appear blue, hence the name.

Noe began studying fireflies when she joined the West Virginia Division of Natural Resources (WVDNR) in 2022. She still remembers her first official firefly outing. “I was on the heels of Pyractomena dispersa , which is one of the orange-glowing ones,” she says. As an elusive species, little was known about where it occurs. Walking into an open field, Noe and her colleague spotted several species of fireflies, including the one they were seeking. “That’s when it all started for me. Then I went deep down the rabbit hole.”

Now, Noe is one of the state’s leading firefly experts. During the summer, she can frequently be found walking through the woods at night without a headlamp or flashlight. Because adult fireflies use their glowing patterns to find mates, their eyes are finely tuned to their dim glows and, as a result, extremely sensitive to bright lights. “It’s amazing,” she says. “You just have to trust that the path is there and follow the light.”

West Virginia is home to 29 known species of fireflies. They occupy a range of habitats, from lawns and open meadows to hardwood forests, wetlands, and stream banks. Each species has a unique flashing pattern, similar to a fingerprint or birdsong. Some firefly species produce steady green glows, while others emit orange flickers or distinct yellow flashes. Adults of a few species, including the winter firefly, don’t glow at all, relying instead on pheromones to find mates.

The Mountain State is also home to two species of synchronous fireflies. “They all start flashing at about the same time and then they all shut off for the same amount of time. It moves almost like a wave through the woods,” says Jakob Goldner, a terrestrial invertebrates entomologist at WVDNR. “Their displays can be very spectacular. But most fireflies in large concentrations are spectacular.”

Fireflies or lightning bugs are flying beetles in the Lampyridae family. Although we typically think of them in their glowy adult form, they spend the vast majority of their lives as wriggly, worm-like larvae crawling around underground, in leaf litter, or beneath tree bark. In West Virginia, fireflies live for one to two years, but only survive for two to three weeks as adults. Fire - Jesse Thornton

fly larvae consume snails, slugs, worms, caterpillars, and other soft-bodied invertebrates. Most are voracious hunters that inject their prey with neurotoxins to immobilize them and then secrete digestive enzymes that liquify their prey before eating them.

While not all adult fireflies glow, all of the larvae do. “We think the purpose is to deter potential predators,” says Candace Fallon, a senior conservation biologist at The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. “It’s a warning that says, ‘Hey I’m toxic. Don’t eat me, you’ll regret it if you do.’” Several firefly species produce defensive compounds called lucibufagins that make them unpalatable to predators like spiders and birds.

In species that can’t biologically produce these defensive compounds, female Photuris fireflies have a more macabre way of protecting themselves. They mimic the flash patterns of male fireflies that produce lucibufagins in order to draw them in. Once an unsuspecting male ventures too close, the female attacks, consumes the male, and steals his lucibufagins in order to defend herself and her eggs from predators. “They call them the femme fatales of the firefly world,” Noe says, noting that capturing fireflies can be a risky gamble. “If you put a few of them in a jar, it might be all well and dandy. But if there’s a female Photuris in the mix, then it could be a crime scene that you’ve created.”

One of the wonderful things about fireflies is that almost everyone has a story about them. Whether you remember catching fireflies as a child or recall seeing a magnificent display of flashes as an adult, these glowing creatures never cease to amaze. “They are just so magical,” says Fallon. “Every time I bring people out in the field with me, my favorite moment is when the very first firefly starts flashing. Without fail, everyone starts whooping and hollering.”

But over the years, Fallon has heard countless tales from people who saw fireflies all the time as a kid, but no longer see them. In 2018, Fallon and her colleagues decided to start conducting inventories of fireflies to see if they could backup these reports. They partnered with firefly researchers and other conservation groups, surveying 132 of the 177 firefly species known to occur in the U.S. and Canada. “Something we found when we did the assessments was that we don’t actually have population data for any of the firefly species. We have no baseline to say 100 years ago or 50 years ago, these were the estimates.”

This lack of historical data may reflect the fact that studying fireflies in the wild is extremely difficult. Imagine walking into a vast field at night without using any lights to guide your way. Tall grass tickles your feet as you stare into a flat backdrop of distant trees beneath a starry sky. After adjusting to the darkness, you see a faint glow blinking in the grass, then another in the tree tops. All of a sudden, you’re surrounded by flashing lights, each moving in a different direction before disappearing into the landscape. To accurately identify a firefly species, you have to determine its unique flash color and pattern by tracking a single individual as its light blinks on and off. “It’s really hard to anticipate where it’s going. And then you need to record the length of time of the flash, how many flashes, and if there’s a break between them,” Fallon

describes. “If you’re at a site with multiple species and hundreds or thousands of individuals, it becomes nearly impossible to track them all.”

In 2020, Mack Frantz, a zoologist with WVDNR, launched a community science survey to track firefly sightings in West Virginia. Noe joined the effort two years later, creating videos, handouts, and other resources to help enthusiastic participants hone their firefly identification skills. One resource, a flash chart, shows the flash colors and patterns of 22 firefly species over a 12-second interval. For instance, the heebie-jeebies produce one yellow flash every second, while the dot-dashers produce a green flash followed by longer, green glows before going dark for four seconds. Some species have two types of patterns, and, complicating things even further, fireflies change the speed of their flashes depending on the temperature. “It’s a very technical skill to identify a lot of these fireflies from flashes,” says Goldner. “I still have to call Krista at 11 o’clock at night when I’m in the field and saying, ‘What is this? What am I looking at?’”

Although the learning curve can be steep, Noe and Fallon say that with some time, patience, and a smidge of knowledge, you can begin to see the patterns, making the process of identifying fireflies much easier. For instance, a general rule of thumb is that the tiny species with yellow flashes come out earlier in the evening. “As the evening shifts and it gets later and darker, you see more Photuri s. They’re the ones that light up green,” Noe says. Instead of trying to scribble notes in the dark, Noe and her colleagues speak into recorders, using distinct tick sounds to represent the different types of flashes and the timing between them. They also take notes about the weather and habitat. Fireflies don’t flash or glow when the temperature is below 50 degrees or raining. “But if it’s raining in the evening, and then it stops, they love that,” Noe says.

In West Virginia, fireflies begin flashing around late April, reach a peak of activity in June, and stop flashing toward the end of July. The first species to begin its mating display is the spring treetop flasher, which produces one yellow flash every three seconds. Big dipper fireflies, which are the most common species in the state, are the last ones at the party. They continue flashing until August, and Noe has even seen a few flash into September.

The WVDNR received many responses to their community firefly survey, showcasing the community’s passion for studying fireflies, but it was tough to validate all of the information they received. The team is taking a brief hiatus this year to restructure the project around a single firefly species in the hopes of making the survey more approachable. In the meantime, they’re continuing their efforts to monitor the state’s 29 known firefly species and discover new firefly species as well.

“In the past, we’ve taken more of an inventory approach because we didn’t really know what we had,” Noe describes. Now that the team has a better grasp of which species occur in the state, they’re switching gears to establish some baselines and evaluate which firefly species are at risk.

Left: Fireflies have large, sensitive eyes that are finely tuned to spot flashes from potential mates. This sensitivy also makes them vulnerable to being blinded by light pollution. Photo by Terry Priest. Right: A light pollution map of the eastern U.S. West Virginia is one of the few remaining places with dark, starry skies. Map courtesy Earth Observation Group, NOAA National Geophysical Data Center. Previous: During the summer, fireflies of many species flock to meadows and forests to show off their flashy displays. Photo by Jesse Thornton.

“Across the world, there seems to be this pretty consistent trend of a 1 to 2% decline in various insect species each year. We don’t know what’s happening with fireflies, but it’s not outrageous to think that something similar is happening to them,” says Fallon.

According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, one in three North American fireflies are at risk of extinction. This risk is driven by a variety of factors, including habitat loss, pesticide use, climate change, and especially light pollution. “Light pollution is a really big issue, because they need to see each other,” says Noe. “Their heads are mostly eyeballs, so even a flashlight or a passing car headlight can be blinding to them.” And if fireflies can’t see one another, then they can’t mate and produce the next generation.

The good news is that there are plenty of individual actions we can take to help protect fireflies. “You can literally turn off the light and the threat is no longer there,” says Fallon. For those who use outdoor lighting at night, it’s beneficial to use motion sensors or timers so the lights turn off when they’re not in use. Even the simple act of closing your blinds or curtains at night prevents the light from inside your house from spilling outdoors.

Because firefly larvae live in leaf litter, rotting logs, and tree bark, keeping your lawn a little messy and wild can go a long way toward protecting these glowing wonders. Some beneficial actions include mowing your lawn less often, keeping leaf litter and fallen branches on the ground, reducing or avoiding the use of pesticides, and letting a portion of your yard grow wild. The

nonprofit Firefly Conservation & Research even offers certified firefly habitat signs for people who create firefly havens around their homes and businesses.

While it can be extremely tempting to capture fireflies and observe their flashes up close, it’s best not to hold them for too long. “One thing we don’t always think about is that our bodies are much bigger and much hotter than a lot of small animals. Just holding a small animal in your hands can be enough to elevate its body temperature to a dangerous level and kill them,” Goldner says. “And if an animal is freaked out and stressed and scared, it is more likely to get sick or act abnormally. There are a lot of reasons to be very gentle and kind to our wildlife.”

And I’d argue that it’s worth taking the time to be a bit kinder to these creatures so we can continue enjoying their brilliant displays for generations to come. In the Mountain State, we’re particularly fortunate to have expansive swaths of dark, starry skies. Take a look at a light pollution map and you’ll see a West-Virginia-shaped hole in the midst of glowing metropolises. These dark skies are critical resources not only for fireflies, but also for us to feel that unique sense of awe that comes from staring at a vast field of flashing, flying beetles. “Looking at a good display of fireflies reminds you that this is a good planet,” Goldner says. “In the whole universe, this is the only place where we get to see fireflies.” w

Nikki Forrester is co-publisher of Highland Outdoors. Even though she’s still struggling to identify firefly species in the wild, singing the snappy single sync tune keeps her spirits high.

By Dylan Jones

The name says it all. Come one, come all, and put your skills to the ultimate two-wheeled test on whatever (steel, aluminum, carbon, or titanium) steed you rode in on. Welcome to the Run What Ya Brung Trials, where anything and everything goes, so long as you—and your bike—make it through in one piece.

Designed to test your balance, strength, endurance, and bravery amidst the heckling gauntlet of a rowdy crowd, this creative cycling competition has become the social centerpiece of the annual Canaan Mountain Bike Festival.

Entering its 17th year, the Canaan MTB Festival is held in the mountain bike-centric town of Davis and is the brainchild of local cycling legend Sue Haywood. Haywood modeled the grassroots festival after the Shenandoah MTB Festival in Stokesville, VA, of which she has fond memories during her formative days as a pro racer. “It was a really special community event,” Haywood says. “Everyone camped together, there were big group rides in

Top left: Fashion is just as important as performance at the Run What Ya Brung trials competition.

Top right: A rider keeps it between the tape. Photo by Dylan Jones.

Bottom: Sue Haywood rocks an apropos tattoo before dropping down a rock slab. Photo by Boyce McCoy.

Previous: David Krut catches air off one of The Thunderdome’s spectacular rock features. Photo by Boyce McCoy.

the day and group meals at night. There was trail work and plenty of partying and loads of inspiration.”

Nowadays, the Canaan MTB Festival features group rides, skills clinics, trail work, and a fundraiser for the Blackwater Bicycle Association (BBA), the local chapter of the International Mountain Bicycling Association. The event is meant to showcase the town of Davis’s offerings of lodging, camping, restaurants, and, of course, old-school trails. “Our fest is very grassroots and organic,” Haywood says. “It’s all about getting people stoked and engaged by rolling out the red carpet for our mountain bike visitors.”

The “observed trials” style of riding originated in the mid-1980s and was modeled after the amazing feats of motocross trials courses. Observed trials take place on segmented obstacle courses strewn with rock gardens, tight turns, and large boulders. Each section is marked out with taped lines that riders and their wheels must stay inside of. One rider at a time attempts each segment, with the goal of making it through without dismounting. “You can stop, you can balance in place, but you cannot put your foot down. If you do even one miniscule dab, it’s a point against you,” says Roger Bird, an OG racer who now calls Wisconsin home. The goal, akin to golf, is to complete all the segments with the lowest score.

Bird was a regular in the Davis mountain bike scene during the 1980s. In those days, national-level events, like the legendary Canaan Mountain Series, required riders to compete in a variety of disciplines. “If you wanted to do well on the overall standings, you had to be able to do everything on a bike, including trials,” says Bird. The best riders had a full quiver of athletic skills, including the ability to stay balanced at a complete stand-still (called a track stand), ratchet the pedals to avoid pedal strikes, modulate the brakes, hop on the rear wheel, and pivot on the front wheel.

“You often have to hold the brakes and hop the bike when pedaling isn’t even an option, since you might be in a wet stream bed or on top of a three-foot boulder,” Bird says. “You essentially have to assume the role of an acrobat, because the balance is a bit of a high-wire act.”

The Run What Ya Brung Trials event started in 2013 and was originally held in the backyard of the late Eric Erbe, a beloved local who was famous for his brute strength and love of moving big rocks—a perfect skillset for creating trials courses. Riders aren’t allowed to practice any moves before they compete, creating an exciting and sometimes nerve-wracking spectacle. One memorable course segment called The Alligator Pond had a skinny wooden beam precariously placed over a kiddy pool filled with murky water. “That was a standout moment,” says Haywood. “It wasn’t the hardest move, but nobody wanted to get wet in this pond.”

Trailbuilder Zach Adams has been instrumental in designing the course segments. He’s also the official scorekeeper every year—something Haywood says is a “really important job, you’ve gotta be able to count all the dabs and keep track of the points.”

“A dab is a dab is a dab,” reiterates Adams. Every touch of the ground or an obstacle with your hands or feet counts as one point against you. If you put a foot down and reposition, that’s a dab. A hand planted on a tree is a dab. And they can add up quickly. Riding outside of the tape and coming back is three points against you. It costs five points to stop and restart the segment. Finally, there’s a penalty of 15 points for skipping a segment. “I don’t think we’ve ever had anybody skip a segment, everyone always wants to at least try to complete it,” Adams says.

After Adams tallies the riders’ scores, he hops on his bike to ride each segment. Judging and competing requires laser-focus. “It’s tough, especially when there’s a lot of chaos going on like people screaming and stuff. I kind of get tunnel vision when it’s happening, but the key is to not take it too seriously,” he says. The event is, as Adams puts it, “really loosey goosey. The point is for it to be a fun spectator activity.”

Whereas traditional observed trials requires specific bikes that are made for jumping around, Run What Ya Brung is a trials event that anyone can do on any style of bike—so long as they have the skill. “Trials gets so specific to where you just can’t do the moves on a regular bike,” says Adams. “It’s super creative, but it’s inaccessible to most people.”

Adams’s course segments range from slow and balance-oriented, to fast and flowy lines that require power and endurance. “How you set the tape really matters,” he says. “Do you roll through something? Do you have to stop and move each wheel individually? How much power do you need for the lead-up? Is the move exposed? How does the segment look? Some rocks are more intimidating than they are challenging.”

For the past two years, the event has been held at The Thunderdome, a natural playground that features giant boulders, rocky crevasses, and steep lines perfect for riders of all styles to show off their skills. The arena is part of The Thumb, a trail system just east of Davis on Camp 70 Road that is maintained by BBA. “People that ride here in Canaan tend to do well because it’s a lot of the slow, balance-oriented technical riding,” Adams says.

“It’s fast, it’s crowded, it’s intense,” says Bird of the Run What Ya Brung Trials format. “And, quite frankly, it’s a lot of pressure. I think the intimidation factor keeps some of the more amateur riders away.”

That intimidation wasn’t enough to deter Peter Denbigh, who took home the win at last year’s event. Denbigh, who lives in Staunton, VA, showcased his style and grace on the course, completing segments with controlled hops, wheelies, and the lowest number of mistakes. “I’m 45 now, so I never thought I’d be the old guy, but here I am and I gave it a shot,” Denbigh said. “Thank goodness none of it was too crazy. It was so fun.”

Denbigh started mountain biking in 1992 when his parents, who were ski instructors at Canaan Valley Ski Resort, started hitting the trails in the summer. Denbigh was in the crowd during a trials competition on Camp 70 Road and immediately fell in love with it. He tried to mirror the moves, and paid the price. “I shed lots of blood, sweat, and tears over the course

of many years, but I stuck with it and started figuring some things out,” Denbigh says.