The Flycatcher

Issue No 88, March 2025

A natural history journal for Herefordshire

A natural history journal for Herefordshire

5 Local Wildlife Sites in Herefordshire

Toby Fountain

10 Climate change in Herefordshire and its impact Sarah Keefe/ on Biodiversity Rachel Jenkins

13 The Herefordshire Local Nature Recovery Strategy

15 Ledbury swift group

Charlie Alfandary

William Lambourne

16 Carabid beetles – discovering the commonplace Tim Kaye

18 Fungi in winter

Jo Weightman

22 Olchon Valley stream survey 2024 Will Watson

25 Recording wildlife – an opinion piece Ian Draycott

30 Wildlife highlights of 2024

38 Notable fungi records 2024.

Editorial Team

Jo Weightman

39 Notable Herefordshire bird records from 2024 Michael Colquhoun

41 Herefordshire butterfly records 2024

43 Some reflections and highlights of my 2024 moth year

Bob Hall

Robin Hemming

45 Herefordshire’s special hoverfly – Myolepta potens the Western Wood-vase Hoverfly Ian Draycott

All views and opinions expressed in The Flycatcher are the views of the author of each individual article and are not necessarily those of Herefordshire Wildlife Trust.

Photos attributed to author of the article unless otherwise stated.

Editorial team: Ian Draycott, Trevor Hulme, Sarah Keefe, Frances Weeks

Cover image: A tributary of the Olchon Brook in Pengelli Wood (c) Will Watson

Herefordshire Wildlife Trust, Queenswood Country Park & Arboretum, Dinmore Hill, Nr Leominster, Herefordshire, HR6 0PY enquiries@herefordshirewt.co.uk www.herefordshirewt.org

Herefordshire Wildlife Trust is a registered charity no. 220173 and a company limited by guarantee no. 743899

Issue 88 is the first issue of Flycatcher since Peter Garner stepped down as editor in 2024. His role has been replaced by a small editorial team who would like to pay tribute to Peter for his skills and dedication in seamlessly converting Flycatcher from being the main reporting publication for Herefordshire Wildlife Trust to becoming a much-valued natural history journal for Herefordshire. The new team would like to continue with a similar style and balance in the publication and ensure its content is driven by the Trust membership and the needs of the wider natural history community in Herefordshire.

This issue is about capturing some of the important initiatives that are going on across the county that should have a mitigating effect on changes to our wildlife. The Nature Recovery Strategy has been initiated by central government and is driven at local level by Herefordshire Council who have started the process with a major mapping initiative. Rachel Jenkins has done an important review of the local impacts of climate change which is reviewed here.

Several articles describe local initiatives such as Ledbury Swift group set up to help an iconic species in trouble, and an update on Local Wildlife Sites by Toby Fountain. Ways of monitoring change are explored in articles about the various methods of recording wildlife and about setting up a recording group for carabid beetles.

Wildlife Highlights of 2024 includes plenty of good news from the expert recorders around the county. The Flycatcher will also be used to signpost the spectrum of other organisations with an interest in monitoring and conserving the wildlife of our county.

Do give us feedback on what you would like to see in future editions. If you’re interesting in contributing an article do get in touch. Contact: f.weeks@ herefordshirewt.co.uk

Editorial team:

Ian Draycott, Trevor Hulme, Sarah Keefe and Frances Weeks

Local Wildlife Sites (LWS) are parcels of land which are known to have locally significant value for wildlife. In Herefordshire these were initially selected in the 1990s and over 775 separate land parcels were listed giving a combined area of almost 30,000ha, which is approximately 13.5% of the total area of the county.

In Herefordshire a Local Wildlife Site can be any natural or semi-natural habitat: grassland, woodland, heathland, ponds, rivers and streams and can vary greatly in size from large woodlands like Haugh Woods, to churchyards and small roadside verges. They are designated by the local authority however many are also on privately owned land and such a designation does not infer any right of public access so should not be confused with Local Nature Reserves.

Most UK counties will have made an inventory of such sites but there are some variations in interpretation and the criteria used especially regarding community importance and public access. They can also be known as County Wildlife Sites.

Although a Local Wildlife Site does not have the statutory protection of a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) which is a land parcel legally designated by Natural England, a LWS can still have a more ambiguous level of protection within the local planning system. Such protection largely arises from the interpretation of the responsible planning officers and ecologists when reviewing cases of a proposed development. Planners will take account of any biological data collected in a survey of the LWS especially the reports that were initially used to justify the site’s inclusion on the list.

If a survey is out of date, or lacking necessary detail that doesn’t make a strong, scientifically sound case for the site’s biodiversity value, it is therefore easier to dismiss its wildlife value. This was recognised as an issue in Herefordshire because many LWSs have not been properly surveyed for some decades. For this reason a project was set up in 2022 to refresh the supporting database and review the status of LWSs.

This project is an outsourced component of Herefordshire Council’s Local Nature Recovery Strategy (LNRS) which is a legally binding commitment made by local authorities across England to take steps to halt the decline in biodiversity and aid its recovery.

A Local Wildlife Site Panel consisting of representatives of Herefordshire Council, Herefordshire Biological Records Centre, Natural England and Herefordshire Wildlife Trust, was set up to develop the project brief and oversee its implementation. The brief calls for a number of outputs:

• To re-survey a number of Local Wildlife Sites deemed to be of importance and do so in a more rigorous manner, particularly for priority species and habitats. The survey data is then matched against revised criteria to justify continued inclusion on the LWS list.

• To follow up the survey by writing management plans for them in consultation with

the site owners.

• To survey any additional areas with a view to adding any important new sites to the inventory.

• To review and develop a new set of criteria. For example, to help designating traditional orchards as LWS.

• To assist in the mapping of important habitats surveys for Natural England’s Priority Habitats Inventory (PHI) and Herefordshire’s LNRS by helping to assess the ecological character of the county.

The surveys so far have been mostly orientated around defining and classifying the main habitats using the National Vegetation Classification (NVC) system to determine plant communities. However, additional species groups such as birds and butterflies were usually recorded whilst carrying out these general habitat and botanical surveys. Historical records were also utilised from HBRC and other sources.

The survey work across the county covered a combined area of 896.6ha and included 9 newly designated sites, some of which were quite large and included a mosaic of different habitats.

Several exciting discoveries were made in terms of both habitats and species, some of which are regionally significant.

Firstly, as part of these surveys two bird species, the Hawfinch Cocothraustes coccothraustes and the Tree Sparrow Passer montanus were rediscovered as breeding species in the county. The Hawfinch is one of Britain’s rarest woodland birds, with a UK population of just 500 pairs this was the first breeding record in the county for decades.

Toby Fountain and colleague Holly Thompson recording ancient woodland

at a LWS in 2022.

At a LWS such as Brandor Hill there was a mosaic of complex habitats present.

Hawfinch (Coccothraustes coccothraustes) one of Britain’s rarest birds

Tree Sparrow (Passer montanus) a breeding coloney was discovered on a farm in the north of the county

The small colony of Tree Sparrows, with around five pairs, was on a farm in the north of the county. This classic farmland bird is Red Listed as it has suffered a staggering 94% decline since the 1970s. It had not been recorded breeding in the county for ten years.

Another exciting find was a fragment of woodland with a canopy of oak with an open understorey with little or no shrub layer and unusual ground flora composed mostly of mosses, ferns and flowers that favour acidic soils such as violets (Viola sp.). This appeared similar to the National Vegetation Classification communities W11 and W17 which includes the rare Celtic Temperate Rainforest and further professional botanical investigations are worthwhile.

A further project output in 2024 was the creation of new criteria to enable the surveying and designation of LWSs for a wider spectrum of habitats and species groups. Previously we only had criteria for surveying grasslands and woodland on a botanical basis. We have now added new sets of criteria for any site with an important bird fauna and for traditional orchards.

The bird fauna criteria were tailored specifically to a Herefordshire context, with an acknowledgement of the species and species assemblages that are notable for the county. This was peer reviewed by local experts to ensure it was scientifically sound. These criteria were first utilised to a designate Brockhall Gravel Pits, one of the county’s most significant sites for wetland birds, as a new wetland LWS.

Traditionally managed orchards are a high priority in Herefordshire as the county still

has more of this type of habitat than other parts of UK. This is now widely recognised to be a highly biodiverse habitat which hosts many nationally scarce species such as the Noble Chafer beetle Gnorimus nobilis. Surprisingly few orchards have been designated as LWSs and this habitat is particularly vulnerable due to changed management practices and conversion to other land uses. This criteria set was written in collaboration with local orchard expert James Bisset of The Hereford Cider Museum and focuses on features that make such orchards valuable to wildlife such as standing deadwood, presence of mature trees, ground flora diversity as well as the presence of scarce orchard specialist species.

The final output this year was the production of 20 management plans designed to make tangible conservation outcomes for these sites, linking to agri-environment schemes and to other organisations providing advice and consultancy to landowners.

Birtley Knole: a fragment of rare Celtic Temperate Rainforest?

There are some excellent ‘private nature conservationists’ in the county: There appears to be a growing body of private landowners with small to medium sized holdings undertaking exciting conservation initiatives from rewilding and livestock exclusions to the active creation of wildflower meadows, wetlands and shrubby areas. Added together such initiatives represent a substantial area that could become a critical parts of Herefordshire’s LNRS in its aims to get greater connectivity for biodiversity and create more high-quality habitats with notable species.

There is an urgent need to find better ways to encourage and support these initiatives. This will be looked at in the next year of the project. Bringing Local Wildlife Site owners together in a forum could enable exchanges of ideas, recommendations of services and discussion common issues with a collective voice.

If anyone owns or is responsible for an area of land that might merit inclusion as a Local

Wildlife Site we would strongly encourage you to contact Toby Fountain - t.fountain@ herefordshirewt.co.uk. Any biodiversity data can be kept out of the public domain, if preferred, and there is no risk of any change to rights of access.

Acknowledgements:

I would like to thank and acknowledge the great assistance and support from many people in helping with this surveying work, especially from William and Amanada Lambourne.

This is an overview of a talk Rachel Jenkins gave to the Hereford City branch of Herefordshire Wildlife Trust in December 2024. A further article in a forthcoming Woolhope Club’s Transactions publication going into more detail, will be available to all members, alternatively the presentation can be downloaded here: www.herefordshirewt.org/ herefordcitytalks

Climate change has occurred naturally over millions of years, it was only 14,000 years ago that the last ice age retreated creating Herefordshire’s ice age ponds. The pollen samples collected from them provide valuable time capsules as to the predominant tree species over the years.

The last ten years (2014-2023) have been the warmest years on record and 2023, the hottest year on record (subsequent to the talk, 2024 was recorded as being even hotter). When we drill down to data of rainfall and temperature in Herefordshire in 1900-1909 and 2013-2022 and compare the two data sets, winters are now warmer and wetter, and summers hotter than over a century ago.

According to the Environmental Change Network, many species are occurring further north and shifting to higher altitudes. Species with short life cycles are better able to adapt, less so those with low genetic diversity or longer life cycles. Some habitats are particularly sensitive to climate change, especially montane habitats due to temperature changes, where lowland species start to colonise upland areas and outcompete mountain plants. Wetlands are vulnerable to drought and grassland suffers more than forests during drought periods.

The presentation shows examples of Bee Orchid Ophrys apifera, Pyramidal Orchid Anacamptis pyramidalis, Grass Vetchling Lathyrus nissolia and Pale Flax Linum bienne recordings in 1987 and then in 2000 and the locations have moved northwards over that time frame.

There are some interesting examples of how higher water levels caused by wetter winters is affecting trees. The sallow Salix cinerea trees that used to be on the margin of Leech Pool in Clifford are now 8m from the shore as the water level is permanently higher than it used to be. A veteran oak in an ice age pond in Kenchester has been killed by higher water levels as the photo shows.

Drought is also affecting Herefordshire oaks. Oaks are sensitive to dry spring weather because this is when they are laying the earlywood sapwood that will conduct a large proportion of the water supply for the trees in that year. Sufficient moisture in spring means that trees can set up a good band of large lumen vessels in the early wood, but a shortage of moisture results in reduced earlywood formation and small vessels.

If water is in short supply over the summer, the trees suffer because it can’t transfer enough water up to the leaves and the stomata that give off water vapour aren’t sufficiently closed. This can lead to water deficits and often the damaging effects of drought are only seen years afterwards.

For moths, significant changes in their distribution and abundance have been recorded. Most moth species emerge earlier and more species are managing to produce two broods. There are examples of increased numbers in Herefordshire of the Clifden Nonpareil moth Catocala fraxini from when it arrived in 2017 to 76 records in 2023. Scarlet Tiger Callimorpha dominula is a recent arrival that is flourishing and whereas the Garden Tiger Arctia caja is not coping so well with our warmer wetter winters.

Frog and toad populations have suffered from lower summer rainfall and therefore lower soil moisture during the drier summers, notwithstanding loss of suitable habitats and habitat fragmentation.

The climatic changes we’re experiencing cause birds to breed earlier and for summer migrants to arrive earlier. Pied Flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca is arriving earlier at breeding grounds, leading to mismatch between arrival and food availability to feed the nestlings. There are examples of how an owl’s ability to hunt and feed are affected by increased rainfall, and that great tits are laying earlier to coincide with the emergence of caterpillar prey but the food disappears as the caterpillars pupate earlier in the warm weather.

Birds that we’re seeing for the first time in Herefordshire include the Cettti’s Warbler Cettia cetti and Great White Egret Ardea alba. On the other hand, wildfowl such as Common Pochard Aythya ferina, which used to breed here has become rare as it shifts northwards due to climate change.

Finally turning to mammals, the effect of climate change are seen on bats, dormice and badgers. For hedgehogs Erinaceus europaeus, warm winters disrupt their hibernation, drier springs disrupt earthworm prey, and flooding of foraging grounds mean hedgehogs are facing a battle on all fronts. Climate change is making our winters generally warmer and wetter, causing hedgehogs to wake up more often during a season where food is at its lowest. Without enough sustenance to replace the energy they use trying to forage during winter, hedgehogs may starve.

To meet current policy targets for net-zero and biodiversity, The Royal Society estimates that we would need an additional 1.4 million hectares of additional land (equivalent to the area of Northern Ireland) by 2030 and 4.4 million hectares by 2050 (over twice the land area of Wales and 18% of total UK land area).

Trade-offs are needed. These could include a land use change combined with dietary shift to less meat and dairy plus exploring opportunities for multi-functional land use delivering multiple benefits at landscape scale. Rachel has included details of various reports and strategy documents that discuss this topic in the presentation.

Food for thought to end with:

• 71% of UK land is used for agriculture.

• 85% of the land used for growing our food is used to rear animals, providing meat, milk, cheese and eggs, yet these food products only provide 32% of the UK’s calories.

• The remaining 15% of farmland grows plant crops for human consumption provides 68% of the UK’s calories.

• A reduction in meat consumption of 30% would allow the UK to produce the same amount of calories from 30% less land. (Source: UK Food Security Report)

Herefordshire Council are in the process of creating their first Local Nature Recovery Strategy.

It is one of 48 separate Local Nature Recovery Strategies that are being created throughout England. Each of the responsible authorities will provide a bespoke strategy for how to best promote Nature Recovery across the county. The strategies will contain an opportunities map that will be able to be joined up to form a complete picture of nature recovery across England.

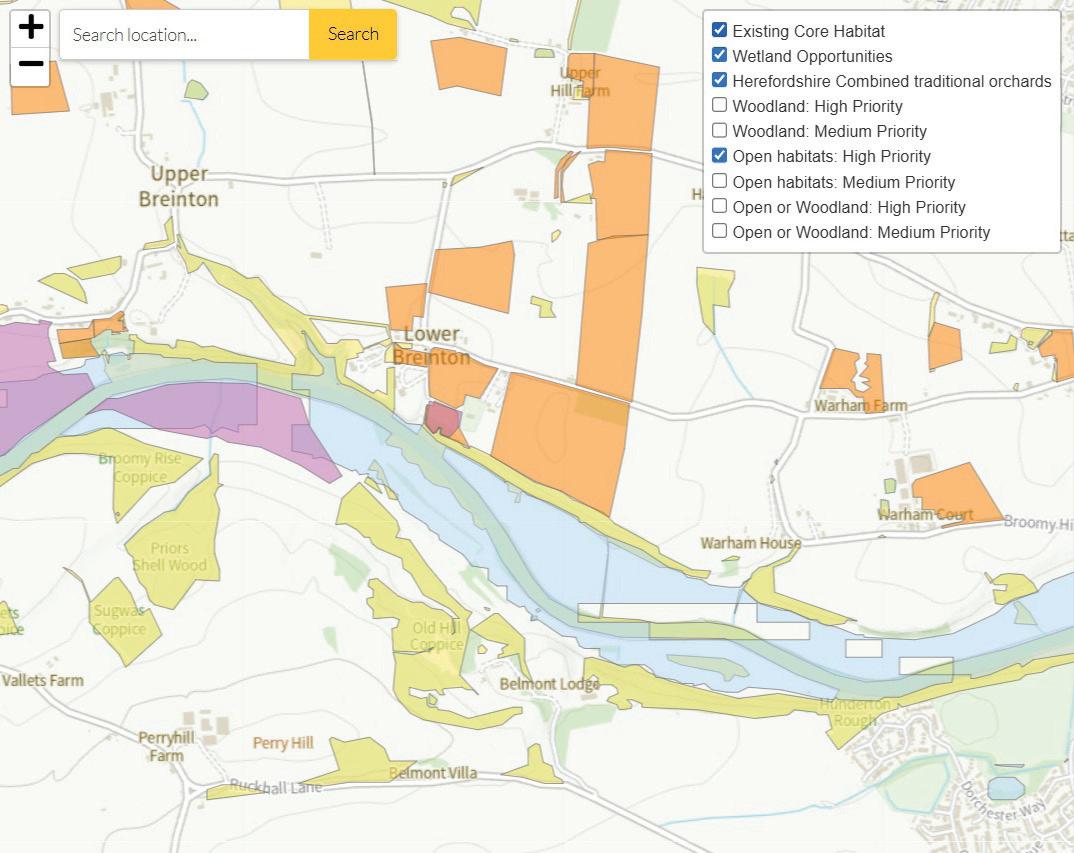

A sample of a draft map centred on Lower Breinton overlaid with three different habitats

The concept is that in order to develop nature rich areas we need to follow the recommendations stated by Professor John Lawton in his 2010 report “Making spaces for Nature”. The report said that existing priority habitats within England need to be more numerous, bigger, better (as in richer) and more joined up. The strategy will identify where focus should be placed to make this happen by identifying areas of high opportunity and nature corridors. It will also help where contributions from biodiversity net gain derived from housing developments is best utilised.

The final strategy will be comprised of 2 documents. One is a map that provides a view of the existing nature designations within the county and all the identified opportunities for nature recovery. And the second is a written document that describes the current state of nature within the county and the priorities and measures that will be proposed to help achieve this goal.

Herefordshire County Council have recently released a first draft of our online map that indicates the current nature designations within the county as well as opportunities for nature recovery across the county. The map has been populated with content using databases from Natural England plus Herefordshire Biological Records Office and other agencies.

There are overlays where areas are categorised according to whether they are Existing Core habitat, Open Habitat opportunity, Woodland opportunity, Open or Woodland opportunity, Wetland opportunity and Traditional Orchard. The category of Open Habitat or Woodland provides the option of having either woodland or open habitat as either option has been found to have the same beneficial impact on nature regardless of which one is selected.

The map is in draft form currently and the Council are looking for feedback relating to its functionality, appearance, accuracy and all other comments that can improve it. There is an online anonymous survey which can be used to relay this feedback. Herefordshire Council wants as many people as possible to fill out the survey to ensure that it is as accessible and useable for everyone.

To view the map and find the survey please go to –Herefordshire Local Nature Recovery Strategy (LNRS) – Herefordshire Council https://www.herefordshire.gov.uk/conservation-1/herefordshire-local-nature-recoverystrategy-lnrs/2

Or scan the QR code

For more information, please go to: https://www.herefordshire.gov.uk/conservation-1/ herefordshire-local-nature-recovery-strategy-lnrs

William Lambourne

The Common Swift Apus apus is a quintessential bird of the British summer, and their screaming calls are a familiar sound in many towns and villages throughout the country. However, since 1995 Swifts have declined in Britain by 66% and are now on the UK Red List, likely driven by poor summer weather, a drop in numbers of insect prey and loss of nest sites.

In response to this decline, Ledbury Swift Group was set up by members of Ledbury naturalists Field Club in 2018 with the aim of monitoring and conserving Ledbury’s breeding Swift population.

The survey methodology is fairly simple – we target known nesting areas in the town, once a week in the evening, during the breeding season and look for Swifts entering/exiting buildings. By identifying nest sites in a particular locality, we can gain a good idea of how many Swifts are attempting to breed in Ledbury during that year.

Every year the group publishes a report, detailing the findings of the year’s survey work. Although we only managed to conduct surveys once every fortnight in 2024, we were still able to produce some good data. A total of 67 nests were located in 28 properties, with 17 of these nests being newly identified in 2024. This number of nests is a marked increase of around 40% over 2023’s results; certainly good news indeed.

Myself and other members of the group also noticed groups of over 50 Swifts around the town, occasionally growing to flocks of nearly 100 birds. Groups of these size were barely, if at all, noted in 2023.

We are always keen for more volunteers to join our band of enthusiastic volunteers, so if you have the odd free evening once a week, between June and July, please do come along. There’s no obligation to come every week; any time you could spare would be really appreciated.

I have very recently set up a Facebook page for our group, which I will keep up to date throughout the Swift breeding season. If you would also like to join our mailing list, then please email me at: ledburyswiftgroup@gmail.com

Editor’s note: Are there other Swift Groups operating in the county? It would be great if a wider network could be set up to help this struggling but iconic species.

The Ground Beetles also called the Carabidae are ubiquitous beetles that everyone will have seen whilst turning logs or stones over. They are usually large (for UK Beetles) predominantly black and run fast. There are thought to be 40,000 worldwide while the UK is host to around 360.

The word ‘Carabid’ is thought to derive from the Greek word ‘Karabos’ which means ‘horned beetle’ which doesn’t really make sense as they don’t have horns but do have large jaws. Most are opportunistic predators but there are a group called the ‘Sunshiners’ (Amara spp) which feed on seeds. They also rely on their long legs to chase down prey. One species, the Snail Hunter, Cychrus caraboides has a narrow head for pushing its way into snail shells. Another Loricera pilicornis has long conspicuous hairs on the antennae with which it traps its springtail prey in the same way that a Retiarus gladiator did in Roman times. Another group, the Springtail hunters (Notiophilus spp) have massive bulging eyes with which to spot their hexapod prey.

With their hardened wing cases and powerful jaws (beetle means to ‘bite’) you would think they had few predators but plenty of animals find them delicious including the Hedgehog who will willingly seek them out over other prey. Many species deter predators by exuding explosive chemicals and the Bombadier Beetles (Brachinus) are the most celebrated in this aspect. I have captured other carabid beetles and foul smells are exuded from a large number of them.

So why should people bother to record carabid beetles? Firstly, there are not too many of them. Trying to grapple with the 1100 or so Rove Beetles is enough to send the seasoned

entomologist crazy but 360 is a challenge without being too daunting. Of course, when you start you learn the common ones first anyway, the equivalent of the blue tit and herring gull for the ornithologists.

Secondly, they are found all year round. Snow and ice will certainly make them harder to find but I have come across them in all seasons so there is no sad end to the season as there is with butterflies for instance.

Thirdly, there are good resources including a key by Luff (2007) and many other resources online. The same cannot be said if you wanted to get into mites!

Fourthly they are fairly easy to ID. Yes, it’s all relative of course and they can easily be confused with other species at first. Indeed, the characteristics that make them uniquely carabid are rather bland (five segmented tarsi, hind coxae forming triangular plates etc) but once you get a feel they are pretty easy to align to a group say the Sunshiners, Thatchers, Black clocks or Pin-palps. Lastly, they are fascinating and attractive beasts that are likely to intrigue the most bug averse person out there.

So what do we know about the carabid diversity in Herefordshire? To date we have records for 167 species in the county which is slightly less than half. This may be partly explained by the fact that quite a few species live on the shoreline or in saltmarsh, though it is more a reflection of the fact that they are poorly recorded. Even a very common species such as the Black Clock (Pterostichus madidus) has only 35 records for the county even though, like the Brown Rat, it must be in every square possible! Of the rare species we have only the Green Tiger Beetle (Cicindela campestris) which people will be familiar with as it flies readily and is green with big eyes!

Predominantly a creature of uplands and dunes it is found at the Doward and the Black Mountains in this part of the world.

There are also four nationally scarce ‘A’ species and 27 Nationally Scarce ‘B’ (relating to the number of 10km squares the species if found in). This is all to be found in a provisional list of the fauna produced this year and accessible on Herefordshire Biological Records Centre website (https://hbrc.org.uk/resources/).

To get to grips with these insects all you need is a pot and a desire to move logs, debris and stones. Many can also be found digging in vegetable beds (though this diminishes your efficiency!). More proactive measures include making pit fall traps with yoghurt or pot noodle pots. Others can be swept with a net as they scuttle up vegetation. This is confined to the Hairy Templed Thatcher Beetle, Demetrias atricapillus and its cousins as most generally prefer the ground, hence the name.

Whatever you do, any queries can be answered by me, Tim Kaye, at tim@clan-cic.org.

While fungi have a seasonal orgy of fruiting in the autumn, looking for them is not confined to those months and I record all year round.

Some fungi are not seasonal and can be recorded or just enjoyed in any month such as the perennial Ganodermas. These large woody parasites colonise living trees and last for many years, decades even, and continue to feed on the fallen corpses. Others, such the Pyrenomycetes, persist for months taking nutrients from dead wood of all sizes from fallen trunks and branches to twigs. Admittedly they are, with one exception, less than spectacular. As the name says, they look burnt but inside those hard, crusty, black knobs hide flask-shaped fruiting bodies.

One particular species, known as King Alfred`s Cake or Cramp Ball Daldinia concentrica at 6cm or more across, is large enough for this fruiting arrangement to be demonstrated in the field. Break one in half and enjoy the darkly iridescent zones inside - a beauty that otherwise passes unseen. The little flasks that contain the spore-producing bodies are lined up in the rind. There are myriad, smaller Pyrenos out there, often restricted to a particular host tree: examples include the Woodwarts Hypoxylon fragiforme on beech, H. multiforme (now curiously re-named as Jackrogersella multiformis) on birch and H. fuscum on hazel.

The much more conspicuous Oyster Fungus Pleurotus ostreatus and Sulphur Tuft Hypholoma fasciculare are a different kind of all year rounder capable of appearing in any month when conditions are right. They do require a large piece of dead broadleaf wood, a stump, a fallen trunk or a major branch and so long as the host is thoroughly damp, will take advantage of the available nutrients and produce their fleshy fruitbodies. My database holds records of them in every month of the year.

Dead, wet herbaceous stems are always worth investigating and winter is a prime time for looking. Dead nettles provide a fertile hunting ground - and are always to hand. It is hard not to find the little black pyramids of Nettle Rash Leptosphaeria acuta near the base of the stem– but keep looking and you will find waxy orange patches, mini-goblets, forests of black hairs with globules on the tip, mini-gravestones with horizontal grooving. The list is a long one but you will need a x10 hand lens to see these little wonders.

Fungi forming ‘white paint’ on the underside of small fallen branches, sticks and twigs are nearly all best left to a specialist. However, one that can be identified easily in the field is Netted Crust Byssomerulius corium. The underside looks like tripe or a candlewick bedspread and gives its presence away by spreading up the sides of the stick a short way forming a narrow white ridge.

Gill-bearing, fleshy species normally rot away in a week or so but two in particular that emerge late in the old year actually endure for some months. One is Bitter Oysterling Panellus stipticus a little fan-shaped fungus with a pale ochraceous cap and gills. In shape and size like the short-lived Crepidotus spp, this species is made of tougher stuff and, having shed its spores in the autumn, lasts for months on large pieces of fallen wood, often in large colonies on the cut face of felled timber. I have records of it from October through to May when it finally disintegrates.

The second with an endurance record is the Split Gill Schizophyllum commune a fungus with a clever strategy. Probably appearing months previously, it is still sitting it out in the winter months, producing spores whenever conditions are right for germination.

The edges of the gills are split in two and can be held vertically or horizontally, vertically to allow spore dispersal on damp days and horizontally to block spore discharge when it is dry. This species has a very hairy upper side and like the Panellus is fan-shaped.

A whole group of wood-dwelling fungi are equally able to control spore discharge in response to climatic conditions These are the jelly fungi, a very disparate group that include the large shapely Jelly Ear Auricularia auricula-judae and Tripe Fungus A. mesenterica while other smaller ones form simple blobs. These jellies operate a shrink and swell, stop and start policy throughout autumn and winter.

Holly Parachute Marasmius hudsonii, a pinhead-sized species restricted to rotting holly leaves is adept at making the best of things. It revives on re-wetting even in January and February, going from a shrunken and collapsed condition to upright with a delightful crew cut coiffure.

The winter and early spring is also a good time to look for rusts on ferns. Ignore the brown dead fronds and choose instead those halfway between green and brown. Look for tiny white powdery heaps on the underside.

Several well-known fungi bridge the gap between December and January, between the old year and the new. They include Velvet Shank Flammulina velutipes, Olive Oysterling Sarcomyxa serotina (the word means ‘appearing late’) and The Goblet, Pseudoclitocybe cyathiformis. I remember seeing the latter emerging bravely through the snow on Bircher Common one January and still standing there several weeks later.

There is a Scalycap Pholiota on my winter list. Most Pholiotas are golden and autumnal but Winter Brownie P. oedipus (now renamed as Meottomyces dissimulans) comes later. It is a small species, muted in colour so does not catch the eye in the same way as its more showy relatives. Search for it among damp rotting leaves and woody debris, especially under poplar and ash. The cap is yellowish grey and slimy, the gills grey-brown and the stipe (stem) pallid. Records (only a few) date from December to March. I suspect it is under-recorded in the county.

Readers will be very familiar with the Scarlet Elf Cup Sarcoscypha austriaca or S. coccinea. Initials start to appear in late autumn but they are little more than white promises of things to come and the scarlet is barely visible.

To find them at their showy best, walk in February beside a stream or a good wet patch where fallen wood is moss-covered. Final identification in the field is not possible as the two species can only be separated under the microscope by their spore and hair characters. S. austriaca has blunt ended spores and crisped hairs while S. coccinea has rounded spores and straight hairs.

When I lived in Kent, I used to look for and find Spring Hazelcup Encoelia furfuracea in most woods in the winter months. Here in Herefordshire this little brown cup fungus seems much less common. It emerges through the bark of moribund and usually still standing hazel poles. If the black pustules of Hazel Woodwart Hypoxylon fuscum or blackhead Diatrypella favacea are present, making the branches look measley, then this fungus may also be on the pole. If Bleeding Broadleaf Crust Stereum rugosum or Hairy Curtain Crust S. hirsutum have moved in, it is too late. The cups emerge in tight clusters, scurfy on the outside and open as best they may in the crowd. When fully expanded, they are about a centimetre across.

Finally, a challenge - do please look for Alder Goblet Ciboria caucus (formerly amentacea). This fungus has a mid-brown, goblet-shaped cup 5-10mm across on a distinct stalk. It arises from old, often buried, alder catkins. Most of my finds have been in February and March. Note that by March the new current year’s catkins may have fallen and should be ignored.

Finding this fungus merits a G&T when you get home.

Last spring I was invited by the owners of Olchon Court, a privately owned farm in the Olchon Valley, to carry out an aquatic invertebrate survey.

The focus of the survey was on the streams which flow off the escarpment of the Black Mountains into the Olchon Brook (see cover image.). The site was first visited on 29th April 2024 with the purpose of assessing the habitat potential. It was visited again on the 8th May. The largest of the streams was dip netted for 3-minutes and all the macro-invertebrate sample collected and counted. The samples were divided into families in line with the Riverfly Partnership extended Riverfly Recording Scheme. Where possible samples were identified down to species level.

The most significant find was the Golden-ringed Dragonflies nymphs. They were found in two locations in the main stream and a stream just 150 metres to the north. According to the British Dragonfly Society there are only 9 records for Golden-ringed Dragonfly in Herefordshire, mainly covering the Olchon Valley. However, there were previously no breeding records, so my survey has found the first breeding records for this species within Herefordshire. Golden-ringed Dragonflies are widely distributed in the UK but are restricted to acid streams and rivulets which are restricted to the west of the county.

Golden-ringed

The Giant Lacewing larva is not listed as one of the main families in Riverfly, but its larva is semi-aquatic often found in mosses beside streams. This is described as being a ‘local’ species nationally. There are only a few records in the county, and this may be the first breeding record.

Several large perlid stonefly nymphs identified as Dinocras cephalotes were found in the main stream. This species has a preference for fast-flowing stoney streams and as a consequence is widespread in Wales, Cumbria and the Peak District, it was also recently found in the headwaters of a stream on the Herefordshire Plateau but is most likely to be mainly confined to the west of the county.

Family Species Common Name Recorder

Water Beetles

Elmidae Limnius volckmari a riffle beetle Will Watson

Elmidae Elmis aenea a riffle beetle Will Watson

Hydrophilidae Cercyon sp. scavenger water beetle Will Watson

Total no. of water beetles 3

Odonata (Dragonflies)

Cordulegastridae Cordulegaster boltonii Golden-ringed Dragonfly Will Watson

Total no. of dragonflies 1 Shrimps

Malacostraca Gammarus pulex Freshwater Shrimp Will Watson

Total no. of shrimps 1

Sphaeriidae Pisidium sp. Pea Mussel Will Watson

Total no. of bivalves 1

Veliidae Velia caprai Water Cricket Will Watson

Total no. of aquatic bugs 1

Trichoptera (Caddisfly)

Hydropsychidae Hydropsyche contubernalis a caseless caddis Will Watson

Philopotamidae Philopotamus montanus Non-gilled caddis Will Watson

Sericostomatidae a bushy-tailed caddis Will Watson

Limnephilidae Halesus sp. a cased caddis Will Watson

Limnephilidae Drusus annulatus a cased caddis Will Watson

Total no. of caddisfly 5

Plecoptera (Stoneflies)

Perlidae Dinocras cephalotes a large stonefly Will Watson

Perlidae Perla sp. a large stonefly Will Watson

Taeniopterygidae Brachyptera sp. a stonefly Will Watson

Glossosomatidae Agapetus sp. a stonefly Will Watson

Total no. of stoneflies 4

Ephemeroptera (Mayfly)

Heptageniidae Ecdyonurus dispar Autumn Dun Will Watson

Heptageniidae Rhithrogena germanica March Brown Will Watson

Baetidae Baetis vernis Medium Olive Will Watson

Baetidae Baetis muticus Iron Blue Will Watson

Baetidae Baetis rhodani Large Dark Olive Will Watson

Total no. of Mayflies 5

Flatworms (Turbellaria)

Planariidae Crenobia alpina Alpine Flatworm Will Watson

Planariidae Polycelis sp. a flatworm Will Watson

Total no. of Flatworms 2

Tipulidae (Craneflies)

Tipulidae Tipula sp. Cranefly larva Will Watson

Total no. of craneflies 1

Total number of

Aquatic Invertebrate Species

Non-aquatic species 24

Staphylinidae Stenus bimaculatus a Rove beetle Will Watson

Neuroptera Osmylus fulvicephalus Giant Lacewing Will Watson

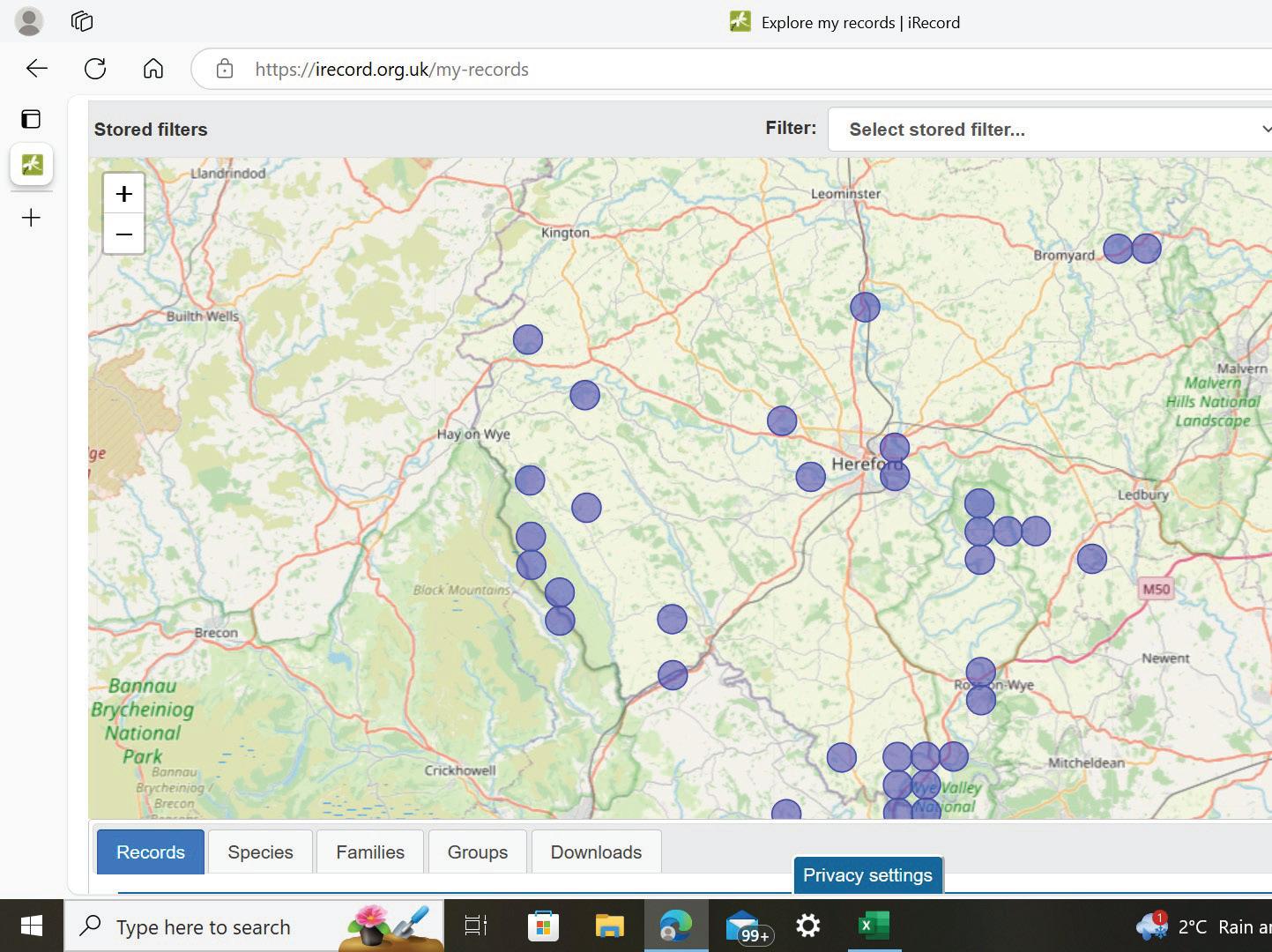

Like many amateur naturalists, I have always kept records of what I’ve seen. For me it’s been a bit of an obsession that started as a teenager with a diary of bird notes, but this habit has persisted and now it’s the only way I can look back to find out where I was on any date over the last 60 years. As my interest in natural history has broadened, I found myself making ever more detailed lists of my sightings covering a whole range of different taxa groups from flies to bryophytes. I have realised this is my most effective way of learning and remembering.

So now I’m burdened with a large number of spreadsheets, and all this takes up my time to keep up to date and organised but despite this, I sometimes struggle to find what I need to recall. Actually, I also want to be better at sharing relevant observations with anyone else that might be interested in a particular group of organisms, and I also want any scientific or conservation value they may have to be captured and used. By this I mean that my observations should contribute to monitoring the abundance/scarcity, geographical distribution and population changes of some species on both a local and national scale.

So now I’ve finally had to embrace some more up-to-date ways of doing things and have a more serious look at the ‘online resources’ available. However, this has created a new level of complexity because, even in quiet Herefordshire, there seems to be so many different organisations, websites and smart phone apps all encouraging me to submit my wildlife data. At times this can feels like a minefield, so this article is about my experiences so far with them and some personal views about their merits and what I’ve ended up doing. Before looking at these choices I wanted to get an overview of how wildlife recording works in UK. This is more correctly termed ‘Biological Recording’. It may sound silly but first we should all remember that no one owns our biodiversity, so no one has exclusive rights to the information or data generated from it and (with a few safeguarding exceptions) it should all be placed in the public domain.

That said, the government has an obligation to monitor biodiversity which it does by analysing data generated and freely given by the members of a host of voluntary sector organisations. The coordination of this is through a network of governmental bodies (Defra, Joint Nature Conservation Committee, Natural England, etc) and starts with the Biological Records Centre (BRC) who are part of Centre for Ecology and Hydrology who in turn are associated with Natural Environment Research Council. BRC are tasked with managing a set of National Recording Schemes for all the taxa groups that make up our biodiversity. They also provide a measure of public access to this data through another associated organisation the National Biodiversity Network (NBN) using a website now called the NBN Atlas.

Most of these National Recording Schemes are actually operated by voluntary sector organisations that focus on certain taxa groups many of which are familiar to most amateur naturalists.

There are too many to list here, but it includes Butterfly Conservation (BC), Botanical Society of the British Isles (BSBI), British Trust for Ornithology (BTO) etc. They have the expertise to do the surveys and verify the species identifications for each taxa group. Some of these organisations delegate this task to a county level either to a local organisation such as Herefordshire Ornithological Club or by appointing a County Recorder such as BSBI and BC. This does not usually happen with the smaller, less popular taxa groups.

Another layer also exists in many counties where biodiversity data is used for local purposes such as environmental assessments for planning applications. Here the councils may set up a Local Records Centre, such as we have with Herefordshire Biological Records Centre (HBRC), which may collect data separately or have links to other sources. Local Record Centres can act as a useful focal point to stimulate biological recording in a county.

So back to the question of what to do with my own wildlife information. It seems to boil down to the following main options:

• Send the relevant parts to a set of County Recorders and experts in the National Recording Schemes.

• Send everything to HBRC using their online form. – a local approach

• Enter everything online HWT’s web portal Nature Counts – a local approach

• Enter everything online to the web portal iRecord - a national approach

• Enter everything online to the web portal iNaturalist – an international approach

• Use some of the other bespoke web portals for defined taxa groups (especially for bird and mammal records)

To decide which of these options to use I ask myself several questions. What type of information will I be passing on and how many records does it involve? Can I then access my own records later and use it as a database of my own information? Will the information provided contribute to local or national monitoring and conservation purposes? Does the data get placed in the public domain and is it transferable between recording schemes? Are there additional benefits such as feedback from experts on identification, status and scarcity of the species involved?

For the taxa groups where I only usually send in occasional records, I have been directly messaging the County Recorders that I know, and this has provided me with helpful feedback and confirmation/rejection of my own identifications. This has worked well for

vascular plants, fungi, butterflies and moths. Sometimes an email with photo attachment is enough but when a lot of records are involved, such as with Lepidoptera, a bespoke spreadsheet is used or alternatively a set of iRecord entries in conjunction with personal contact.

If I was concerned about either an area of land under some form of development threat or if I had found something rare and special to Herefordshire, I would certainly want to ensure HBRC knows about it. However, they should also be able to trawl information submitted to other sources such as iRecord so I want to avoid duplication. They also don’t have the resources or technology to provide me with automatic access to my own submitted records and may struggle to process lots of raw data.

If my recording was focussed on HWT reserves or was part of a special survey and I wanted to share information with HWT staff or others working on this site, it would be best to use the Nature Counts. This website is actually a customised portal to iRecord, so it also has the benefit of linking to National Recording Schemes and on to BRC/NBN. I am currently unsure if submitting the same data directly to iRecord can still be picked up in the same way.

In a few cases I may take photographs of some organism but do not have a clear idea what the species is. iNaturalist is a good choice here as it uses artificial intelligence software to get to the right ballpark then a user peer review system to take it further to ‘research grade’. At this level, it will automatically be passed to iRecord for verification by the National Recording Scheme and go on to the BRC/ NBN datasets. However, this can still be a bit hit and miss and for difficult groups I have found some specialist Facebook groups better at getting identifications agreed.

For most records that I submit I am fairly confident that I know what the species is and so I enter these records directly on the iRecord website usually with a macro photo that shows the identification characters. Even so, getting verification can also be a hit and miss affair with some National Recording Schemes being very prompt in sending feedback, and occasionally a correction, but other schemes do not respond.

However, at least I know the information has been deposited to the right place and even unconfirmed records have value and can now be shown in the NBN Atlas.

The other reason I use iRecord is that there is a facility to download a detailed spreadsheets of all my records over the years with which I can do any searching or sorting for the analysis I fancy seeing. (yes, getting nerdy now!)

These days the only bird sightings I report are on those rare occasions that I find something that may be unusual for the county. I’m not sure what I would do if I ever found a real rarity (other than panic and probably contact the county recorder directly) but for uncommon

observations HOC operate an easy-to-use web tool for entering daily bird news (see link below). To be certain any bird observations are used for national monitoring and research purposes.

BTO’s BirdTrack would be better especially for survey work. An option I’ve recently started using for ‘recreational birding’ is eBird, a tool from Cornell University in USA which related to the more familiar Merlin app (an identification aid). This is cleverly designed and ideal for keeping a detailed record of site visits, as well as regional and country lists and also for adding bird photos but its data may be less useful for monitoring UK trends. I haven’t done a recent comparison with BirdTrack which also has a download facility for your own records so I’m not making recommendations.

There are a host of other specialised websites and apps that I haven’t looked at such as Mammal Mapper from the Mammal Society or some of the apps which are trimmed down versions of websites for ease of use on a smartphone.

I probably record a wider selection of organisms than most people and currently I seem to use a rather inefficient mixture of most of these routes. I don’t expect this to change much as there’s no panacea in sight …. and so, I still keep writing all my own notes as well!

References and links

National Biodiversity Network https://nbnatlas.org

iRecord. https://irecord.org.uk

iNaturalist. https://www.inaturalist.org/

Herefordshire Biological Records centre. https://hbrc.org.uk

Hereford Wildlife Trust - Nature Counts https://record.herefordshirewt.org

Herefordshire Ornithological Club. https://Goingbirding.co.uk/Herefords/birdnews.asp

This section has been assembled from the combined efforts of many people putting records into the public domain or passing them to the loose network of local specialist organisations. Not everyone can be acknowledged in this review but at the end of this section is a list is of organisations mentioned, websites and acronyms used.

Our particular thanks must go to those county recorders and taxon experts who have verified and summarised this information and all at rather short notice. We have not covered every taxon group and would be pleased to hear from anyone who may be willing to act as a correspondent for another group in future issues.

Stuart Hedley, the county recorder (BSBI) has prepared a very comprehensive report on his botanical highlights of the year which will be published in the 2025 issue of Transactions of Woolhope Naturalists Field Club (volumes usually published the summer after the report year). He starts with an overview of the various current recording methods and pays tribute to the individuals and to HBS who provide BSBI with input. The report includes many items of positive news such as rediscoveries of lost species or new sites for some uncommon ones but also mentions some concerns about habitat damage and disappearances.

He discusses one site in the west of the county where new populations have been found of Stemless Thistle Cirsium acaule and Large Thyme Thymus pulegioides, both scarce plants and on the edge of their British ranges, additionally finding there one of the healthiest UK populations of the near-threatened Flea Sedge Carex pulicaris.

Also in the west, he mentions the precarious populations Globeflower Trollius europaeus and Pillwort Pilularia globulifera and sites with healthy populations of Upright Chickweed Moenchia erecta and Autumn Lady’s-tresses Spiranthes spiralis.

In the northwest of the county good finds include two less well-known wild roses, the Small-flowered Sweet-briar Rosa micrantha and Sherard’s Downy-rose R. sherardii, Smooth-stalked Sedge Carex laevigata and Pale St.John’s-wort Hypericum montanum. Mark Lawley found Perfoliate Pondweed Potamogeton perfoliatus in the Teme at Downton Gorge on a day in June when Natural England organised a bioblitz recording event.

Globeflower Trollius europaeus A Foulds

Along the banks of the Wye in the centre of the county Stuart talks about the continuing occurrence of specialist riverside plants like Flowering Rush Butomus umbellatus, Water Chickweed Stellaria aquatica and Yellow Loosestrife Lysimachia vulgaris, Slender Tuftedsedge Carex acuta, Sand Spurrey Spergula arvensis and the complex of Mint Mentha species. Also of note were two or three small populations of the Wood Club-rush Scirpus sylvaticus.

Astonishingly 2024 marked the rediscovery of Crested Hair-grass Koeleria macrantha, a very rare plant in the county, not just at a known site where it was last seen by Francis Day in 1951, but also at a new site near the Monmouthshire border.

His report contains much more than this and is a great read for anyone with a passing interest in botany and even includes a comment about the ongoing saga of the elusive Ghost Orchid.

The county list has grown by at least four species with the discovery of Palmate Germanderwort Riccardia palmata and Welsh Pocket-moss Fissidens celticus in Olchon Valley and with Spreading-leaved Beardless-moss Weissia squarrosa and Tender Feathermoss Rhychostegiella litorea from a site near Abbey Dore. All are accepted as first VC36 (Herefordshire) records by the BBS thanks to Mark Lawley and helped by the excursions of Border Bryologists group and the Herefordshire Winter Recording Group (HWRG).

Left: Fissidens celticus

Right: Riccardia palmata

Other good finds in 2024 include Plagiochila brittanica, Plagiothecium latebricola and Rhychostegiella teneriffae.

The ‘unoffical’ county list of bryophytes covering 372 mosses and 107 liverworts can be found on HBRC website. This needs some work to update because around a quarter of these species have not been seen this century and there are few active bryologists in the county.

Jo Weightman has provided a short note (page 38) listing some notable fungal finds in the year. When Jo says ‘notable’ she really means it; not only are most of the species on her list first Herefordshire records but one, a waxcap, has only just been described and another is awaiting scientific determination.

Jo has been the county recorder (BMS) for many years and her expertise has put Herefordshire on the mycological map at national level and stimulated interest of many people. She has recently announced that she has stepped down from this role and David Williamson has taken over. We wish David well and expect an appropriate tribute can be paid to Jo in due course.

The Herefordshire Fungus Survey Group (HFSG) runs a series of local field meetings to uncover more about this important group of organisms.

We are not aware of anyone doing focussed Lichen and/or Slime Mould recording in the county although the HWRG blogsite does note some interesting records such as the Slime mould Physarum album.

For those interested in mammal of our area the website of The Herefordshire Mammal Group includes useful links to extracts of their last Atlas work with a review of the status of each species.

Herefordshire Ornithological Club (HOC) do a fine job of collating information from many observers about the county’s bird populations. Michael Colquhoun, their county recorder, has prepared a useful summary of uncommon visitors during 2024 on page 39. This includes some lesser-known scarcities seen in the county such as Tundra Bean Geese, Bonaparte’s and Caspian Gulls and some irruption species such as Waxwings and Hawfinches that have been noted during the year.

We are hoping to give better updates of these groups in the next issue. Waxwing Bombycilla garrulus

Bob Hall the county Butterfly recorder (BC) has provided a summary of Herefordshire records for 2024. See page 41. He reports on an exceptionally poor summer for this group this year leading BC to declare a ‘Butterfly Emergency’. However, there were still some highlights with early season species such as Grizzled Skipper and Pearl-bordered Fritillary doing OK and new reports of Small Pearl-bordered Fritillary, White Admiral and Green Hairstreak in various areas.

At the time of writing Peter Hall, the county Moth recorder (BC), is still receiving and processing the large number of records from Herefordshire’s network of enthusiasts using light traps and other methods of checking on our moth fauna. He reports that over 650,000 individual moth records are now in the county database! However, Robin Hemming has stepped in with a personal note on his reflections and highlights from 2024 and this includes an amazing number of immigrant species from his garden in late Autumn – See page 43.

Further information about both butterflies and moths of the county can be found from the excellent websites managed by BC including the new West Midlands Moth Atlas. Summaries of the year will also appear in the BC local members group newsletter

A population of the Rufous Grasshopper Gomphocerippus rufus was first noticed on Little Doward in late summer 2023 and they still seemed to be doing well there in 2024. From NBN maps this appears to be the first county report and the most north westerly UK population, although this may represent an ongoing range expansion in the same manner as some other orthopterans such as Roesel’s Bush-cricket Metrioptera roeselii which is now being reported widely across the county. Does anyone have a county-wide overview of the status of our orthopteran species?

There seems to be no specialist local group studying beetles in the county but there are a number of enthusiasts collecting and collating records of this order. Tim Kaye has been working to clarify the status of the various terrestrial beetle families in the county and has now prepared a Carabidae (ground beetle) checklist (see HBRC website). Reviews of more to families to follow.

The Woodland Trust/Buglife carried out another survey for the critically endangered Cosnard’s Net-winged Beetle Erotides cosnardii (family Lycidae) on Little Doward. Anecdotally, 2024 has resulted in more individuals being found than have ever been seen before in the whole of UK!

Some other notable finds around the county include:

• The Hypericum Pot Beetle Cryptocephalus moraei, listed as Nationally Scarce B.

• The ground beetle Patrobus assimilis, was a first county record from Ivington.

• The soldier beetle Malthodes fuscus - 2nd county record at Ashperton, Nationally Scarce

• The Ant Beetle Thanasimus formicarius (Cleridae) - 1st county record at Peterchurch

• Scymnus haemorroidalis (Coccinellidae) - at Dorstone. Fewer than 3 county records.

New sites have been also found for the uncommon Rugged Oil Beetle Meloe rugosus, a species where the adults can best be found at night by torchlight on some grasslands in mid-winter.

Perhaps the most exciting beetle report of the year was that of the stunning Bee Chafer Trichius fasciatus in the west of the county. There is one unconfirmed and very old record of this species in the county, but there are now very few known sites in England where this rare western and northern species continues to exist!

Bees: There is no expert group in the county, however following a solitary bee identification course in 2023 and a review of known records, a provisional county checklist has been assembled covering 108 bee species. This is available to download from the HBRC website and informal plans are being made to better understand the status of these species in the county.

Herefordshire may well be a national stronghold for Long-horned Bee Eucera longicornis with more records coming to light in 2023 and 2024 from species-rich meadows, especially in the south and west of the county. Other notable bee records in 2024 were the Large Meadow

Mining Bee Andrena labialis (2nd County Record) and two scarce bumblebees, the Large Garden Bumblebee Bombus ruderatus and Red-tailed Cuckoo Bee Bombus rupestris. The Red-tailed Mason Bee Osmia bicolor whose wigwam-building habits were featured on BBC’s Wild Isles documentary was also found at another county site suggesting it may not be that uncommon here.

Again, there is no expert group operating in the county and most records seem to come from visiting specialists. However, in 2024 a review of all known VC36 records has put together a provisional checklist of 1,207 species (available to download on the HBRC website). Apparently, some old surveys especially along the River Monnow have found quite a number of species not known from anywhere else in UK and their current status isn’t really known.

Of the 129 species of Hoverfly (Syrphidae) recorded in the county one is very special to Herefordshire and is also critically endangered. This is the Western Vase Hoverfly Myolepta potens*, which is almost only known in UK from this county (see article page 45).

Another exciting record received by HBRC is that of the rather stunning red and black Cranefly Tanyptera atrata, a nationally scarce species recorded in May from the far west of the county.

The Dashed Slender Robberfly Leptogaster guttiventris* and the Fleshfly Metopia argyrocephala are just two of quite a number of apparent county firsts found in 2024 with other new records are mainly from the tricky families of Muscidae and Tachinidae. It has to be said that with so few people looking properly at flies adding to our local knowledge base is not that difficult!

Barklice or booklice are a group in the order Psocoptera with 99 UK species. Most are rather small and although many are distinctive enough, they often get dismissed as small flies or beetles so are seldom looked at properly and identified.

Although largely ignored few species are recorded in Herefordshire and one collected by the river at the bioblitz at Downton Gorge is likely to be Elipsocus moebiusi which is listed as nationally scarce. By contrast Lepinotus patruelis is very common but hardly ever reported and can be a nuisance in stored products such as bird seed. Both are probably first county records in 2024.

Tim Kaye has commented that his record of the Springtail (Collembola) Pogonognathellus longicornis at Weston-under-Penyard is surprising in that this hasn’t been recorded before in the county despite it being the largest springtail in the UK. National mapping data still shows where recorders are found, and this one is likely to occur in all corners of VC36.

Similarly, with Woodlice (crustaceans - order Isopoda), one species Haplothalamus danicus, is a fairly common species nationally but in Herefordshire a recent find represents only the 4th county record. Even common and easy to identify species such as The Common Shiny Woodlouse Oniscus asellus and Common Rough Woodlouse Porcellio scaber are not being recorded.

The Hidden Herefordshire project also stimulated an interest in Myriapods and species such as the millipede Boreoiulus tenuis, had only its 5th known county record in 2024.

No mention has been made here of a number of other important invertebrate groups such Elipsocus moebiusi

as, plant bugs, wasps etc and whole phyla such as Arachnids (spiders etc) and terrestrial molluscs (snails etc) and various worms.

There may be a problem in Herefordshire with finding a good forum to share information and knowledge and it is this that stimulates further study and ultimately the conservation of these groups. Anyone willing to become a correspondent for any particular taxon group for future issues please contact the editors.

Note:

It should be mentioned that it can be difficult, and slow, getting records of some invertebrates properly verified and accepted by national experts. However, being unconfirmed doesn’t mean they are incorrect, so credible ones are still listed here. Where a record of an uncommon species has been confirmed by the appropriate National Recording Scheme this section will mark those species with an asterisk*.

Organisations and Groups (with acronyms) mentioned in the text.

Botanical Society of Britian and Ireland (BSBI) - https://bsbi.org/

Woolhope Naturalists Field Club (WNFC) - www.woolhopeclub.org.uk

Herefordshire Botanical Soc(HBS)https://sites.google.com/view/ herefordshirebotanicalsociety/

British Bryological Society (BBS) www.britishbryologicalsociety.org.uk

British Mycological Society (BMS) https://www.britmycolsoc.org.uk/

Herefordshire Fungus Survey Group (HFSG): www.herefordfungi.org

Herefordshire Ornithological Club (HOC). https://www.herefordshirebirds.org/

Herefordshire Mammal Group. https://www.herefordshiremammalgroup.org

Herefordshire Winter Recording Group (HWRG). https://winterrecording.wordpress.com/ Butterfly Conservation (BC). Websites: https://butterfly-conservation.org/in-your-area/west-midlands-branch/ https://westmidlandsmoths.co.uk/ www.westmidlandsmoths.co.uk/ https://westmidlandsbutterflyconservation.wordpress.com/

Kavinia alboviridis – a crust on a bit of fallen wood. Under the lens seen to have wellseparated greenish spines on a whitish base layer. 1st Herefordshire record for a rarely recorded British species. Mowley Woods, 25.09.24. Accessed to the fungarium at RBG Kew.

Megalocystidium sp - a nondescript crust on a stick, only distinguished by a pronounced smell of almonds. Little Doward, 16.10.24. A new British species, yet to be formally described.

Postia guttulata – this bracket fungus is by no means new to the county as we have 24 records from 9 sites to date. It is also well known in the New Forest in Hampshire but only from a handful of records elsewhere. The collection made in Downton Gorge 29.06.24 was young enough for the pileus growing edge to be producing the droplets which give it its name. These clear droplets inevitably broke on handling and then, remarkably, stained the growing edge red.

The Devil’s Fingers Clathrus archeri appeared in large numbers in Brockhampton Park and was also seen on Bringsty Common.

Melanogaster ambiguus, one of the false truffles, was found in the litter under an oak on Bringsty Common, 13.11.24. 1st Herefordshire record.

Scaly Sawgill Neolentinus lepideus – as its name says, a very scaly toadstool with serrated gills. It occurs on dead conifer wood, often when it is worked wood. Recorded on an old railway sleeper at The Flits NNR, 14.08.24. 2nd Herefordshire record.

Gliophorus reginae - a new to science waxcap described in 2013 and found since then in a handful of counties in England, Wales and Ireland. Now it has been seen on unimproved grassland near Leysters in Herefordshire. First Herefordshire record, 10.11.24.

Michael Colquhoun

The start of the year saw modest numbers of Waxwings reach the county during a year which saw a moderate irruption into Britain. Approximately 60 were recorded at Mortimers Cross and 30 at Shobdon Court Pools.

Lower Lugg Meadows had a series of unusual Gull records with Bonaparte’s, Caspian, Yellow-legged, Greater Black-backed and Mediterranean all recorded in February and March. Up to 10 Black-tailed Godwits were also present intermittently.

Caspian gull Larus cachinnans

Four Black-necked Grebes were present at Brockhall on the 19th March, but the star of the first quarter of 2024 was a male Slavonian Grebe in full breeding plumage at Hartleton Lakes on 24th March. Elsewhere modest numbers of Brambling were recorded and Ring-necked Ducks maintained their presence. A White-tailed Eagle (part of the reintroduction scheme) near Leominster and an Osprey on 31st March at Leintwardine were notable raptor records.

The second quarter of the year was busy with Sandwich Tern and Garganey at Brockhall on 23rd April being notable records. Whimbrel were spotted quite frequently in April and May, largely at Wellington, but also at Kenchester. Pools A Grasshopper Warbler at Bartonsham Meadows was a surprise longstaying visitor and its characteristic call was frequently heard, much to the delight of the local population.

A Whooper Swan at Wellington in May was a remarkable sighting. White Storks were seen at Ross and Cradley, almost certainly from the reintroduction programme. At Yatton, a Corncrake was heard in a flower covered meadow that reminded the County Recorder of the machair in South Uist. Ring

Ouzels were seen on Garway Hill in April, a Ring-necked Duck became a long-stayer at Bodenham Lake.

The third quarter of the year was quieter although Redshank at Kenchester and a Greenshank at Winforton in July were notable. Ten Black-tailed Godwits at Brockhall on 16th July were recorded, the site also hosting Marsh Harrier on 29th July. Another Marsh Harrier was seen at Wellington on 24th August. The final month of the quarter saw further Whimbrel, a Grasshopper Warbler on Hergest Ridge and a possible Honey Buzzard at Bartonsham. Seven Ring Ouzels were seen on the Darrens on 15th October on their migration south.

The last three months of the year saw the irruption of Hawfinches from Fenno-Scandinavia reach the county with 20 at Shobdon Arches, up to 30 in the Yew trees at Walford Church and a scattering of sightings of single birds at other sites. A Whooper Swan at Letton on 16th November was earlier than expected and at the same site Great White Egrets assembled in numbers with ten recorded on 28th November.

A scattering of unusual geese (White-fronted at Kenchester on 9th November, Pink-footed at Tidnor Lane (29th November) were eclipsed by two Tundra Bean Geese which arrived on 14th December and stayed for a few days. The final notable record for the year was a Green-winged Teal found on the new workings at Wellington on the 30th December.

These reported sightings are yet to be reviewed by the Rarities Sub-committee.

Dingy Skipper and Grizzled Skipper are still both very restricted in their distribution, with 9 records for Dingy only from Ewyas Harold Common while Grizzled has been found at The Doward as well as Ewyas Harold Common. 29 records for Large Skipper which are quite widespread in the county. 41 records for Small Skipper with a maximum count of 27 from Mowley Valley and 15 from Garway Common. A few records of Essex Skipper, but this species is almost certainly under-recorded on account of difficulty in identification.

There were over 100 records of Brimstone, but the summer brood was low in number. Plenty of Orange Tips in April and May with a large count of 11 from Viv Quinn. There were over 120 records for Green Veined White with a max count of 17 from Devereux Park. Large White were again common with a high count of 20 from Wigmore. There were over 140 records of Small White with a high count of 14 from Wellington. Wood White have had a very poor year even in their strongholds of Wigmore Rolls (max 9) and Haugh Wood. Wood White were also recorded in Mowley Wood. There were no records of Clouded Yellow.

Browns

Gatekeeper had a good year with over 140 records. There was a high count of 35 from Haugh Wood. Meadow Brown also had a good year with nearly 200 records including an astonishing count of 100 from Tom Oliver at Urishay Court Farm. Ringlets (25 from Haugh Wood and Mowley Valley) also had a good breeding season. There were good counts of 35 Marbled White from Urishay and 30 from Newton St Margarets. A Total of 42 records submitted. Speckled Woods were widespread with a high count of 18 from Pinnacle Hill Malvern. There were 3 records of Wall from Herrock Hill, Mowley Valley and Olchon Valley. Low numbers of Small Heath records from Hergest Ridge Hill (30) and other spots near Kington.

There was a maximum count of 5 Dark Green Fritillary from Hanter Hill, with smaller numbers seen at Ewyas Harold Common. Only 4 records in 2024.

Pearl bordered Fritillary numbers were good at Ewyas Harold Common with a high count of 168. This is the only site in the county apart from the re-introduction site on the southern part of the Malverns. There, 27 mating pairs were seen following a further re-

introduction. Small pearl bordered Fritillary were recorded from Hanter Hill with a high count of 3.

26 records for Silver Washed Fritillary: they had a fair season with a high count of 12 from Wigmore Rolls.

There were over 100 records for Comma with a high count of 5. Red Admiral have had a most wonderful late season extending well into autumn with over 200 records. There were 41 records for Painted Lady. Plenty of Peacocks with a high count of 49 from Robin Hemming at Dymock Woods, 41 from Wigmore and 30 plus in Haugh Wood.

Small Tortoiseshell numbers too were generally low with only 64 records for the whole season. White Admiral: only two records this year from The Doward and Dymock Woods.

Blues

There were plenty of early records of Holly Blue but a poor 2nd brood. There was a high count of 8 from Haugh Wood South. Common Blue had a very poor year in most places; Tom Oliver had a high count of 5 from Urishay Court Farm, compared with a 100 in 2023. There were 2 records for Green Hairstreak from Hergest Ridge and Malvern. Purple Hairstreak were recorded from Kempley, Haugh Wood and Marcle Ridge, but only 7 records all told. White-letter Hairstreaks were not seen in Haugh Wood but 2 were recorded from Holywell Dingle. An egg was seen at Mowley Wood. There were 3 records of Brown Argus. Small Copper were seen in small numbers in late summer, totalling 26 records.

Summary

Undoubtedly, the wet weather in the early part of the year had an impact on insect larvae and adults. Wet weather in June would have affected the breeding success of at least some of the early butterflies and impacted on the numbers of 2nd or summer brood.

These Herefordshire butterflies are in great trouble: Brown Argus, Dingy Skipper, Grizzled Skipper. Common Blue, Green Hairstreak, White letter Hairstreak, Small Pearl bordered Fritillary, Small Tortoiseshell and Wood White.

Butterfly Conservation declared a Butterfly Emergency in September after announcing the results of the Great Butterfly Count. This showed huge declines in many species. The average number of butterflies seen on set surveys was down to 7 from 12 in 2023. Suspicion also falls on the continuing use of neonicotinoid pesticides which have major long-term impacts on many insects.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to all recorders for submitting their records. There are now too many of you to be mentioned individually!

Verification

Thanks to Martyn Davies and Rachel Mailes for their great assistance in checking records.

2024 was a year that never really delivered of its promise. I record moths regularly in my Bodenham garden moth traps. The results are always a reflection of both the weather and the changing climate conditions. The year started well, with a mild spring and no real cold periods. In early March I recorded a Small Eggar and a Lead-coloured Drab. Small Eggars only emerge if conditions are right and can remain as pupae for several years until they get a mild spring. They have only been recorded in the Bodenham area in Herefordshire and are rare. Mid March I recorded my first migrant species of 2024 with a very early Dark Sword Grass. April saw the first of a record number of Silver Clouds, their UK stronghold being the Wye Valley. The mild Spring continued into May, with a very good showing of Puss Moths and all three species of the Kittens (Poplar, Sallow and Aspen). The common Hawkmoths appeared and on May 12th my second ever Dewick’s Plusia, a species just beginning to colonise the county. At the end of May a Lilac Beauty graced my trap, a lovely moth I hadn’t recorded for several years. It used to be regular.

The Summer was poor for moths. Mainland Europe was experiencing record heat. Sadly, while they basked, we endured record cloud cover and persistent North and Easterly winds which blocked most of the immigrant species arriving. June produced four species of Clearwing moth in my garden: Lunar Hornet Moth, Yellow-legged Clearwing, Red-belted Clearwing and Currant Clearwing. The latter being new for the site. A Red-necked Footman was my first for 10 years here. In early July there were glimpses of migrant activity with both European Corn Borers and Olivetree Pearls appearing, after the rare occasions when Southerly winds brought the moths into Southwest England. Garden Tiger Moths still hang on here in Bodenham and Waved Blacks thrive on the rotting wood I leave around. Two Least Carpets, a Kent Black Arches and Obscure Wainscott appeared, all species

spreading North with global warming. A Pine Hawkmoth here and another at Brampton Bryan confirmed this handsome species has spread throughout the county. August produced two more migrant Olive-tree Pearls plus several Pammene spiniana, a micro formerly considered extinct in Herefordshire that has been regular in my garden in recent years.

September and early October were quiet but still produced some interesting species, most notably several Clifden Nonpareil, my second Herefordshire Radford’s Flame Shoulder, a Delicate, Scarce Bordered Straw and three Whitepoints – all migrants or colonists only just appearing in mid Herefordshire.

My Scilly holiday in mid-October was plagued by clear nights, full moons, and gales but did lead to my moth highlight of the year with a magnificent Death’s Head Hawkmoth, a long dreamed of first for me!

On returning from Scilly, the blocking weather conditions finally changed, allowing a settled, Southerly airstream. This period in late October into early November has become an excellent time for moth trapping in recent years. The long hoped for immigrants flooded into the moth trap for two weeks from October 26th. During that period I recorded a total of 243 immigrant moths, involving 18 species. Nothing was new but the numbers were unprecedented. They included 59 Olive-tree Pearls, 2 Vestals, 2 Gems, 29 Radford’s Flame Shoulders, 1 Pearly Underwing, 15 Dark Sword Grass, 17 Delicates, 2 Scarce Bordered Straws, 3 L-Album Wainscots.