From 1st March 2019

Patron

Monty Don

President and Vice Presidents

President The Countess of Darnley, Lord-Lieutenant of Herefordshire

Vice Presidents Mr L Banks CBE, DL

Mr T Davies

Mr E M Harley

Dr J Ross

Mrs B Winser

Trustees

Mr B Hurrell, (Chair)

Mr J R Beck (until 10/2019)

Dr W Bullough (Vice Chair)

Mrs M Clarke (until 10/2019)

Mr P Ford

Mrs S Garland (until 10/2019)

Mr P Garner

Mr J Hardy (from 10/2019)

Mrs A McLean

Mr S McMaster

Mrs E Overstall

Mr N Smith

Mr M Williams

Company Secretary (non-Trustee)

Mr M Pakenham

Solicitors

Messrs Gabbs, 14 Broad Street, Hereford, HR4 9AP

Land Agent

Mr Peter Kirby M.R.I.C.S., Messrs Sunderlands and Thompsons, Offa House, 2 St. Peter’s Square, Hereford, HR1 2PQ

Volunteers

Once again the Trust extends grateful thanks to all its volunteers who have worked hard to deliver a vast amount of work to help conserve the county’s wildlife. Support ranges from help to manage and warden nature reserves to providing administrative support in the office and fundraising, from running events to developing and delivering publications, and from monitoring wildlife to contributing to the many and varied committees and groups. Thank you all. Yet again the Trust would not have been able to achieve as much as it has, during the past 12 months.

Helen Stace Chief Executive (from 07/2018)

Andrew Nixon Conservation Senior Manager

Sophie Cowling Living Landscapes Officer

Emma Morrison Fundraising Officer

Laurence Green Orchard Origins Manager (until 11/2019)

Julia Morton Orchard Origins Officer

Philipe Budgen Orchard Origins Assistant (from 10/2019)

David Hutton Ice Age Ponds Project Manager

James Hitchcock Estates Senior Manager

Paul Ratcliffe Reserves Officer

Trevor Hulme Reserves Officer

Pete Johnson Reserves Officer

Lewis Goldwater Reserves Officer

Rose Farrington Queenswood Heritage Gateway Project Manager (Until 12/2019)

Amanda Eckley Finance Manager

Averil Clother Finance & Admin Officer

Francesca de Luca Finance Officer

Beverly Bishop Membership Officer

Frances Weeks Communications and Marketing Manager

Rachel Hibberd Supporter Engagement Officer

Sue Daynes Ledbury Shop Manager (from 08/2019)

Dee White Membership Advisor

Katrina Preston Engagement Manager

Karen Roberts Queenswood Family Engagement Officer (from 4/2019)

Vic Hinsley Engagement Play Ranger (to 11/2019)

Hannah Dunn Nature Tots Coordinator (from 05/2019)

Simone Tiano Retail Manager (to 08/2019)

Debbie Bean Queenswood Visitor Centre & Retail Officer (from 11/2019)

Liz Bunney Queenswood Shop Assistant

Sarah Partington Ledbury Shop Manager (to 06/2019)

Guy Beasley Cleaning Assistant

At a time of heightened awareness that the world’s climate is warming at an alarming rate, that species extinctions are occurring more frequently and a person as young as Greta Thunburg features with enormous impact on the news across the world berating our indulgent materialistic way of life, the wellbeing of our wonderful Herefordshire countryside risks palling into insignificance.

However, this edition of Flycatcher with over twenty contributors, and one still in his teens, confutes any idea that Trust members fail to appreciate the natural wonders of our very special county.

Our first article explains how several well-known lakes and ponds in Herefordshire are relics of the last ice age and as such are of very special value to wildlife.

I have then asked David Watkins to inform readers about the Herefordshire Wildlife Trust reserve at Common Hill where he is the volunteer warden. Following on from Roger Beck’s article, last year about Woodside Reserve, this is the second in a series I hope to continue each year from the wardens of all the Trust reserves.

I’m sure all our readers will be aware of the threat of disease to some of our native trees: in this edition Nick Smith, who works for The Forestry Commission and is one of our trustees, writes about Ash Dieback disease, and offers valuable advice for those who might have Ash trees growing on their land. This is a sad reminder for those of us who can remember the loss of so many of our Elms. However, Tony Norman offers some hope for the Elm in his article.

Regular readers of Flycatcher will, by now, be aware of the meaning of “BOB”. Charlie Long has written an account of this year’s “Bonkers on Botany” outings that have made such a valuable contribution to plant recording in Herefordshire, and which are now flourishing in Worcestershire as well.

Continuing the theme of a concern for the environment, in a very thought provoking article, Liz Overstall debates the effect climate change, and the change in modern farming practices, will have on our Herefordshire countryside.

Ian Draycott has written a challenging article highlighting the narrow perspective so many of us have when “looking at nature”: the loud, the bright, the beautiful and the obvious, but so many less conspicuous small insects with only latin names, go unnoticed and unrecorded. After reading Ian’s article lets hope that Herefordshire can boast more records for a wider range of wildlife: I have certainly been inspired so to do.

If I had enough land I would also be inspired to plant out a small orchard: Philip Budgen’s article about traditional orchards is highly inspirational and full of interest. Continuing on a positive note, Johnny Birks prepares us for the likely arrival of beavers in Herefordshire, and then on a lighter note we can attempt Ian Draycott’s “Herefordshire Biodiversity Challenge”

Following this theme, David Taft deserves high praise for the biodiversity he records in his garden. Regular Flycatcher readers will now be familiar with the “Notes from my Garden” that David contributes each year and, as usual, his observations are fascinating.

At the beginning of this editorial I referred to a teenage contributor, the first for the 24 years I have been editor. If there are many more young people with the knowledge and interest that Jamie has already, the future of our environment is likely to be less at risk than many of us had feared.

Another valuable contribution to the health of our environment is the work carried out by the VOW volunteers. Sally Webster has explained the great value for wildlife of many of our roadside verges.

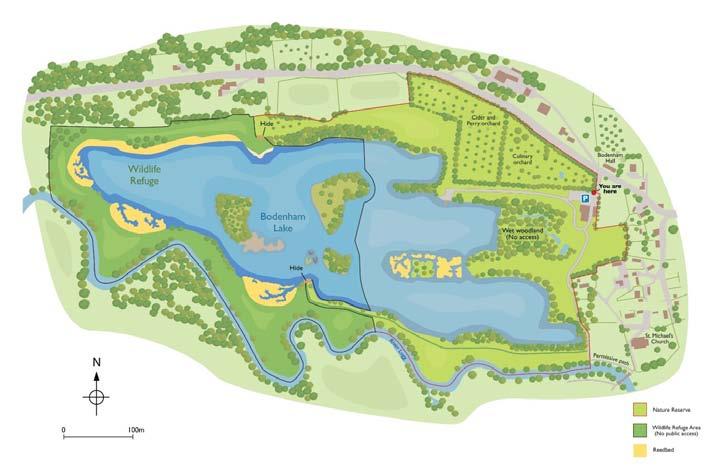

I’m sure many Trust members have now visited our reserve at Bodenham Lake. Sophie Cowling and Wendy Rushton have revealed otherwise hidden exciting occurrences at the lake through the use of trail cameras. I was especially interested to read about the communal fishing activity by the large numbers of cormorants at the lake.

Stuart Hedley, who is now the plant recorder for Herefordshire, has written a full review of “The Rare Plants of Herefordshire” which Les Smith, Mark Jannink and I spent many years compiling. We conclude with our “New Discoveries” section where some of the more interesting records from county recorders are briefly described.

- Brian Hurrell

Dear Reader

I make no apology for starting this report in very much the same vein as my contribution in the March issue last year.

The Trust has pressed on in a persistently challenging environment, both financially and politically, concentrating our efforts on our main “drivers”. These are to ensure that Herefordshire becomes a county richer and more diverse in wildlife, involving local people in our work and concurrently improving their health and wellbeing in a variety of ways.

However, much of our time and expertise has been directed towards pressuring central law and policy makers to take appropriate action to combat and reverse the drivers that are influencing climate change and it’s deleterious effects. Concurrently much thought and effort, with other national environmental agencies and NGOs, has been going into ensuring that, post Brexit, the rules and regulations for land management and agriculture contribute to both this and environmental enhancement throughout the UK.

So, returning to the restoration and improvement of our county’s biodiversity and engaging our people, we have been running various projects and initiatives throughout the year, some of which will continue into the future.

We know we cannot do this alone and we continue to work as closely as we can with other similar minded bodies, our neighbouring Trusts and of course our band of nearly five hundred volunteers.

A piece of work that demonstrates the range of joint working that we undertake is the Ice Age Ponds Project, where we have successfully obtained and used initial grant funding and now moved on successfully to stage two, with further funding, to explore, learn more and restore and improve these rare and highly valued environmental habitats.

We have gained some additional wonderful reserves such as a highly rated meadow near Colwall and Tretawdy Farm near Llangrove. The former, which is a potential future gift to the Trust, we are managing agents for the owner and the latter, which we were gifted, we have already done significant work on with the help of a new local volunteer group. The Birches has its new visitor centre and improved site management, again with the help of a local volunteer group. Queenswood has seen the Jubilee Room restored to full use, available for local groups to hire and in the early stages of becoming a sustainability demonstration centre for New Leaf, our partners in managing the site.

Queenswood continues to be a high priority with the completion of the Heritage Gateway Trail, which has been hugely popular with our numerous visitors. Work on opening up the glades is starting to show the benefits for flora, fauna and insect life as spring approaches.

We were delighted to receive a national award from the Canal and Rivers Trust for our environmental improvement works at Bodenham Lake where we are continuing, with further grant funding, to provide more island habitats and a new wheelchair accessible hide.

Again with the help of our Branches and volunteers we have seen much work done on many of our other sites and the Yazor Brook. Our volunteers don’t just do conservation work they help, inter alia, with administration, retail, youth work, site management etc.

We have worked with over 6,500 children on environmental experiences and provided training opportunities, work experience, membership experiences and wellbeing projects. For all this I and my colleague Trustees (who are also volunteers) are extremely proud and grateful to the people of Herefordshire.

Our valued and dedicated staff too have been benefitting for our partaking in the Thrive at Work programme and from some greater stability after the upheavals of our organisational changes and our office and workshop relocation. As Trustees we are ourselves carrying out a review of our skills base, our diversity and our performance as a Board to ensure we are as effective as we can be.

So, to conclude, with our membership now over 5300, our sound volunteer base and our outreach to young people we feel we are continuing to achieve our aims and objectives. Our website attracts 3,000 visits per month so we are well connected with the public and have a good local and regional profile. The articles in this edition of Flycatcher, a highly regarded publication, add to the evidence and confirm the overall value of wildlife to us, the benefits it has to offer and the contribution we can all make to ensure there is continuing progress.

- Will Watson, Beth Andrews & Giles King-Salter

In November 2018, we received the exciting news that funding had been approved for the first phase (Development) of a new project to survey and conserve Herefordshire’s ice-age ponds. Just over a year later, the Development phase has been completed and funding for the second phase (Delivery) of the project has been awarded. This will start early in 2020 and should be underway by the time The Flycatcher comes out.

What are ice-age ponds?

The last ice age in Britain was the Devensian Glaciation, which lasted from about 115,000–11,700 years ago. Herefordshire, along with most of southern England, was cold but ice-free for most of this period. At the peak of the ice age, however, approximately 27,000–18,000 years ago, the landscape of northwest Herefordshire was changed dramatically when a large glacier surged down from the Welsh hills and spread across the Herefordshire plain as far as the A49. The advance and subsequent retreat of this glacier probably only took 1,000 years or so, but large amounts of clay, sand, gravel and rock were churned up, transported and dumped during the process. This resulted in the formation of localised areas of glacial deposits known as ‘hummocky moraine’.

As the glacier melted, broke up and retreated, large sections of ice would have been left behind and buried within the glacial deposits. These ice blocks would have melted slowly, taking hundreds or even thousands of years to disappear completely, leaving behind deep, steep-sided depressions known as kettle holes. When these depressions became filled with water, they formed kettle hole ponds that survive to the present. It is still somewhat uncertain, and a matter of active debate among geologists, how many of Herefordshire’s ‘iceage ponds’ are true kettle holes formed by the melting and collapse of buried ice blocks, and how many are simply the consequence of localised variation in the thickness of the glacial deposits resulting in ponds forming within natural hollows.

Ice-age ponds are nationally scarce; it has been estimated that fewer than two percent of lowland ponds are natural and probably only one percent of these are of glacial origin. In Herefordshire, hummocky moraine, and the ice-age ponds within it, is found mainly along the line of the River Arrow in the north of the county and along the River Wye west of Hereford. Similar but less well-known deposits are also found between these rivers in the area around Weobley; we hope to learn more about these during the next stage of the project.

Ice-age ponds can vary dramatically in size; the largest in Herefordshire is the six hectare Pearl Lake near Shobdon, while at the other extreme are seasonal ponds 300m2 or less in area which might dry out for several months each year. A particular characteristic of ice-age ponds is that they are often clustered together with many ponds occurring within a small area. In the area around Kenchester, for instance, almost every field has its own pond. Herefordshire Wildlife Trust’s three reserves at The Sturts, in the Letton area, have many ice-age ponds. However these are unusual in that they occur in relatively flat terrain; they appear to have been formed within the area of a large lake at the edge of the retreating glacier. Large ice blocks breaking away from the melting glacier would have floated away and become grounded in shallow water before being partially or fully buried by the clay, sand and gravel being released from the glacier. After the ice melted and the lake drained away, the depressions left behind became the shallow ponds that still survive today.

The project is a collaboration between Herefordshire Wildlife Trust, Herefordshire Amphibian and Reptile Team (HART), and the Herefordshire and Worcestershire Earth Heritage Trust (EHT). It has received funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund and Kingspan Insulation Community Trust.

The Development phase began with the appointing of David Hutton as project manager in late 2018. It ran until August 2019 and resulted in a number of significant discoveries, including the finding of several rare species and a few species not previously recorded in the county. Detailed surveys were carried out for 15 pond sites by ecologists Will Watson and Giles King-Salter and geologist Beth Andrews, with help from a large and enthusiastic volunteer group. Conservation management plans were produced for these 15 sites; these will be implemented during 2020–21. This vital work will help to conserve these unique sites and ensure that their special habitats and species will be protected into the future. With assistance from the volunteers, we also visited a further 20 ponds within the hummocky moraine areas of north-west Herefordshire. Not all of these turned out to be of ice-age origin, but many additional ponds have also been identified that we aim to survey during the next two years of the project.

Other work carried out during the Development phase included many educational visits to schools within the project area. An ice-age pond conservation strategy was produced, plus a survey form and accompanying manual for use by volunteers in carrying out future surveys. In the second phase of the project we now hope to build on this work and visit a much larger number of ponds, working with more landowners, communities and schools to identify, conserve and protect these unique habitats for the future.

Ponds are our most valuable freshwater habitat type; compared to rivers they support both more species of invertebrates overall and a greater number of rare species (Williams et al., 2010). While both natural and manmade ponds are important for wildlife, ice-age ponds have

a number of characteristics that can make them particularly special habitats. The most obvious of these is the great length of time for which the ponds have been in existence, maintaining continuity of habitat for thousands of years. This has allowed many species of plants and animals to colonise, including slowly dispersing species as well as more mobile ones.

As previously mentioned, ice-age ponds are frequently clustered together in the landscape. This makes it easier for species to move between ponds, creating larger and more robust populations which are better able to persist over the long-term. Coupled with this is the increased habitat diversity provided by multiple ponds in the same area, with deeper, more permanent ponds existing alongside semi-permanent ponds which dry out occasionally, and seasonal or temporary ponds which dry out annually.

Ice-age ponds also tend to have a saucer-shaped, gently sloping profile with broad shallow margins, in contrast to many manmade ponds which are often deep and steep-sided. These broad margins allow the existence of a wide ‘drawdown zone’ – the part of a pond which is submerged in winter but dries out in summer. This area is the most important part of the pond for wildlife, supporting a large percentage of its plants and animals. Aquatic invertebrates and amphibian larvae thrive in the warm shallow water around the pond edges, while a gradient of plant species occurs in response to the length of annual submergence. Soft Rush Juncus effusus, for instance, prefers to be damp but not flooded so it can often be found growing in a ring around the top of the drawdown zone, marking the winter high water level.

Aquatic plants

The submerged aquatic plant Bladderwort Utricularia australis is only known from one site in Herefordshire: the Lawn Pool in Moccas Park National Nature Reserve. Currently it seems to be thriving there; when the pond was surveyed in 2019 it was seen flowering at multiple locations in shallow water around the edges of the pond.

An excellent reference for information about Bladderwort and other local botanical rarities is the recently published book ‘Rare Plants of Herefordshire’ (Smith et al., 2019). One such species is Golden Dock Rumex maritimus, an annual species which likes to grow in the drawdown zone of ponds as they dry out. This species occurs at several of the ponds at Kenchester and was recorded there during the project, but it was not refound at a site in Canon Bridge where it had been recorded in 2011. Golden Dock has a long-lived soil seedbank, however, so there is every chance that it might reappear in future when conditions are more favourable.

Orange Foxtail Alopecurus aequalis is not nationally rare but is scarce within Herefordshire. It is a semi-aquatic grass associated with seasonal ponds and the drawdown zone of larger ponds; it can be seen flowering both in shallow water and on mud as the ponds dry out. It was seen at several ponds during the project, including at Canon Bridge where it was last recorded in 1894 (Smith et al., 2019).

Slender Spike-rush Eleocharis uniglumis is a rare sedge known only from four sites in the county, including one of the Kenchester ponds (Smith et al., 2019). It was refound here during 2019 and also at one of the other ponds nearby. Tubular Water-dropwort Oenanthe fistulosa is not an extreme rarity, but it is ‘Nationally Threatened’ and is a conservation priority species. In Herefordshire it is almost exclusively confined to ice-age ponds. Its continued

Bladderwort, Utricularia australis, flowering in the Lawn Pool, Moccas Park. (Will Watson)

presence in and around the Withy Pool at Kenchester was reconfirmed and it was also discovered at two new sites. These were a marshy field adjacent to the Mere Pool at Blakemere, with over 100 plants counted, and in the drawdown zone of a pond at Canon Bridge.

The aquatic invertebrate highlight of the project was undoubtedly the discovery of a thriving population of the 7–8 mm long diving beetle Agabus undulatus in the Mere Pool at Blakemere. This species has ‘Near Threatened’ status nationally, with the nearest known population over 150 km to the east in Cambridgeshire. This discovery is particularly interesting in that A. undulatus appears to be one of a small number of water beetle species that is either flightless or has very limited flight capability. The isolated population at Blakemere, therefore, is likely to have occupied the site for a considerable period of time, with very little potential for colonising other ponds in the area.

Two species of water beetle with a conservation status of ‘Vulnerable’ were refound during the project. The rarest of these locally is Graphoderus cinereus, a strikingly coloured 14–15 mm long diving beetle which in Herefordshire is known only from the Lawn Pool at Moccas Park. The last twentieth century record from Moccas was in 1973, but it was not seen there again until Will Watson refound it in 2016 (Watson, 2016). When the pond was surveyed during the project in June 2019, two individuals were netted, photographed and returned to the water. The Moccas Park population of this species is completely isolated from the rest of its national distribution, with the handful of other known sites all being south-east of a line from the Dorset coast to The Wash.

The other Vulnerable water beetle refound at Moccas Park during the Project is Helochares obscurus, a species of water scavenger beetle. Despite its rarity this was present in high numbers in both the Lawn Pool and the adjacent Linear Pool. This species has been described as an ‘also run’ glacial relict species – it is primarily associated with ice-age ponds, but also occurs in other high quality wetland sites such as Wicken Fen in Cambridgeshire and the Norfolk Broads. In Herefordshire it also occurs in ice-age ponds at The Sturts. Less rare but also worthy of mention is Enochrus nigritus another species of water scavenger beetle, which was found in a total of nine ponds at six sites during the project. This species is ‘Near Threatened’ nationally, but locally it appears to be frequent in iceage ponds especially in the sites along the Wye Valley. Previously it has also been found in a high quality pond of recent origin in the former silt lagoon at Brockhall Quarry. This demonstrates that E. nigritus is capable of colonising new sites, but it is clear that

Agabus undulatus from the Mere Pool, Blakemere. The wavy yellow lines across the ‘shoulders’ are unique to this species.

Graphoderus cinereus found in the Lawn Pool, Moccas Park, in 2016

Herefordshire’s ice-age ponds provide a vital habitat for this species and are important in maintaining its presence here.

In terms of other aquatic invertebrates, two ponds in Mowley Wood, Staunton on Arrow, were found to support populations of the Mud Snail Omphiscola glabra. This is a mediumsized aquatic snail, 12–20 mm high, which is classified as ‘Vulnerable’ and is listed as a species of principal importance for biodiversity conservation. It favours ponds with high water quality that dry out during the summer, and has declined as a result of various threats including agricultural run-off and temporary ponds becoming shaded by scrub encroachment.

A species of lesser water boatman, Sigara iactans, was recorded in pond seven at Kenchester when it was surveyed in July. This species appears to be a recent colonist to Britain; it was first collected in Norfolk in 2004 and since then has spread across East Anglia, south-east England and the East Midlands. However it does not seem to have previously been recorded in western Britain, so this is almost certainly a new county record for Herefordshire. The population seems to be well established in the pond at Kenchester, with nine individuals collected during the survey.

All five of Herefordshire’s amphibian species were recorded during the project. Four new breeding ponds for Great Crested Newt Triturus cristatus were identified. Three of these were on privately owned farmland at Staunton on Arrow, Norton Canon and Canon Bridge, while the fourth was on National Trust land at the Weir Garden. The latter is within the

well-known complex of ice-age ponds at Kenchester, where a total of over 400 adult Great Crested Newts in 5 ponds was recorded in May 2018. This potentially makes Kenchester the most important breeding site for this species in the county.

Bird recording has not been a high priority within the project so far, and relatively few species were recorded. Some of the more interesting species seen were Green Sandpipers Tringa ochropus at Canon Bridge and at Kenchester, plus a Little Egret Egretta garzetta and two Little Ringed Plovers Charadrius dubius at Kenchester. The latter were very tolerant of the presence of our large volunteer group, and continued to feed along the pond margin a short distance away.

Geological value

Ice-age ponds have the potential to hold scientifically valuable sediments, such as peat, dating back thousands of years. Pollen grains trapped within the peat can be extracted and identified to determine the plant species present at the site in the past. Thus the ponds can be considered natural time capsules, containing a detailed record that can inform us about past climate, habitats and plant distribution. In some cases it is also possible to date the very oldest peat; previous work has given us dates for the last ice melting in Herefordshire of at least 15,000 years ago. During the project, we have so far found peat in four out of the fifteen ponds surveyed in detail. Peat can also preserve animal fossils and human artefacts, although these are much harder to find and study than pollen.

Ice-age pond conservation and management

Unfortunately, only a few ice-age ponds remain in good condition today, and it is likely that all have been degraded to varying extents by farming and other human activities. A large but unknown number of ponds have also been permanently destroyed, resulting in the loss of both plant and animal species and an irreplaceable historical record. These ponds continue to be destroyed today.

During the Development phase, conservation management plans were prepared for 15 iceage ponds. The practical work required will be funded under the Delivery phase and is due to be carried out during 2020 and 2021.

Apart from physical destruction, one of the major factors affecting ponds (of all types) today is unmanaged dense growth of trees and scrub around the ponds. Over time, this causes ponds to become heavily shaded and to silt up more rapidly, substantially reducing their habitat value for aquatic plants and animals. Trunks and large branches also collapse into the pond, take root and send up new shoots, potentially leading to the whole area of the pond becoming overgrown. The main tree species of concern are willows, in particular the non-native Crack Willow Salix fragilis and two native sallows, Grey Willow Salix cinerea subsp. oleifolia and Goat Willow Salix caprea.

Since trees themselves are highly important for a wide range of wildlife, the primary focus of management under the project is to repollard existing mature individuals, leaving the trunks and major branches intact as much as possible. In addition there will be the removal of a certain amount of younger growth to increase the amount of sunlight reaching the pond and its surrounds. This will provide improved conditions for the growth of aquatic and marginal vegetation, and will greatly benefit aquatic invertebrates and breeding amphibians.

The Ice-age Ponds Project will be holding events during Spring and Summer 2020. There will be many opportunities to find out more and to get involved, so watch out for more details soon.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank project manager David Hutton and all the staff and volunteers from HWT, HART and EHT who contributed their time to planning and organising the project. We would also like to thank the large number of volunteers who attended training courses and pond visits during 2019, and the landowners and farmers who allowed us to visit and survey their ponds. Finally we would like to thank the National Lottery Heritage Fund and Kingspan Insulation Community Trust for funding the project.

References:

Smith, L., Garner, P. and Jannick, M. (2019) The Rare Plants of Herefordshire. Les Smith & Peter Garner

Watson, W.R.C 2016. Graphoderus cinereus re-found at Moccas Park, England. Latissimus 38: 23–24

Williams, P., Biggs, J. Whitfield, M., Thorne, A., Bryant, S., Fox, G. & Nicolet, P. 2010. The Pond Book: A guide to the management and creation of ponds. 2nd Ed., Pond Conservation, Oxford.

- David Watkins

A two mile trackway of prehistoric origin connects three of our Trust’s reserves2. Together with wooded commons and privately owned orchards, woods and small fields they make up a stretch of countryside where we can all connect, not just with all kinds of wildlife, but also in a way with our predecessors.

Along this route, careful observation on the ground and of maps reveals an iron-age fort, medieval field boundaries, charcoal burner platforms, kilns, quarries, a community of smallholdings and an enthusiasm for cider.

Midway is the Common Hill community, a scattering of perhaps twenty cottages which were once intensive small-holdings linked by this ancient track; here the track is elevated with occasional outlook over a nameless valley rising to Citterdine with Haugh Wood and Bagpiper’s Tump above and beyond.

Almost central to this community is Common Hill Nature Reserve, maintained by volunteers for almost 50 years now with its five small, mostly sloping enclosures in small-holding mode which over the centuries has resulted in wild flower hay meadows, old orchards and half a mile of varied, mature hedgerows. Alongside the through trackway there are ancient banks on which the hedges grow. The hedges include some trees of considerable age: occasional Yews, a coppiced Sycamore 16 feet in circumference at its base and a much coppiced Field Maple 5 feet in diameter. There are many other species in these hedges including Dogwood, Spindle and Wild Service hosting many climbers including the various Bryony species. Less apparent than previously are the hillocks of Yellow Ant nests. The ruins of two cottages

with occasional remnant fruit bush and patches of Snowdrops give insight to a more intensive and domestic history.

After almost 50 years, the Trust also has history here and many will remember those who took the initiative to investigate, acquire, establish and maintain this Reserve in the early years. Prominent in my memory are Joe Bond, Jack Fox and Jim Watkins among many others. Their enthusiasm for continuing this traditional smallholding environment extended to sharing with others, hence the Wildlife Trust Information Sheet for members and signboards and permissive path for all to experience. Many people walk quickly through that part of the Reserve given over to the Wye Valley Walk, a few investigate its hidden areas and some, like volunteers, spend hours re-living a little of open air smallholding life and physical work, as it used to be and some step further back into the history of this place using the tool of their imagination.

This reserve is justifiably renowned for it’s wealth of beautiful Spring flowers. For me, 2019 was the year of the secretive Adders Tongue Fern, the year in which I came to know its full extent and shared this with others by providing illustrative markers from May to July. In my mind it is also the year of Earthstar fungi having discovered two spectacular colonies of different species.

Spending time in this place, often alone, allows intimate and sometimes surprising wildlife moments to occur such as: a Song Thrush singing for three hours celebrating the turn of the year; a slowworm emerging (slowly) to see who is disturbing her patch; a solitary Blue Tit egg in a Dormice tube (!); a beautiful Grass Snake where it “shouldn’t” be; a not so beautiful Bird’s Nest Orchid (a first for Common Hill); a super-active Pygmy Shrew blindly exploring a public footpath; a host of butterflies repeatedly rising from the hay-meadow as patches of sunshine pass over, and of course the first stunningly, bright yellow male Brimstone every year...

Sharing this Reserve with others in 2020 will hopefully extend to a Wild Flower Identification Walk in the Spring and a Fungus Foray in the Autumn, both led by those who know more than I do! Perhaps another article will report our findings.

If these forays or any other aspect of Common Hill Nature Reserve are of interest or if you have observations you would like to share, please contact me on 07970 160910. There is also now a WhatsApp for those who like to share observations or photographs of this wonderful living landscape – more participants are welcome.

1 Common Hill Reserve ½ mile East of the village of Fownhope SO 590 189 2 Nupend, Common Hill and Lea and Pagets

- Nick Smith

A failing and dangerous ash tree near Bredwardine

Many of us have heard of the fungus attacking our widespread ash trees across the UK and in this county. We can already assume its presence in nearly all of our woods and hedgerow trees, and its progressive impact will show more and more over the coming years. So with this article, I would like to try and explain the likely outcomes to our current population of ash, which makes up approximately 20% of the broadleaf species across Herefordshire. The appearance of the Hymenoscyphus fraxineus fungus in Britain has meant that the future of common ash (Fraxinus excelsior) as a woodland tree species is under serious threat. The disease is present in all counties of England, and that the majority of ash trees in either woodlands or outside woods, are likely to be infected with the disease and will decline and die over the next 10–15 years.

There is growing evidence that once trees are infected by H. fraxineus, and the disease has progressed, the trees become also susceptible to secondary pathogens such as Armillaria spp. (honey fungus). These secondary pathogens can result in butt or root rot,

destabilisation of the tree making them prone to falling, and may ultimately be the final cause tree decline and death.

Currently there is no known efficient prevention or curative treatment (e.g. silvicultural or chemical approach) that will alleviate or mitigate the effects of ash dieback. However it has been reported that a low proportion of trees (1-5% of the population) may possess a partial but heritable tolerance to H. fraxineus.

The Forestry Commission National Inventory of Woodland and Trees 2002 has been used to explain the various data sets below and that Table 1, is the information extracted to give an overall summary to the growing areas of conifers and broadleaves in this county. The county has a woodland composition of approximately 12% of the area of the county is covered by woodland of differing history, size and mixtures.

Table 1 Woodland area by principal conifers and broadleaves and woodland size

source Forest Research, Forestry Commission Crown Copyright 2002 - National Inventory of Woodland and Trees - Hereford.

Table 2 gives a very good picture of the current estimated areas of woodlands which are ash and how important this species is in ecological terms, as well as being threatened by the disease.

2 Woodland area covered by Ash and woodland size

Data source Forest Research, Forestry Commission Crown Copyright 2002 - National Inventory of Woodland and Trees - Hereford.

Ash trees within woods cover a very large part of our woodland composition and may be found as intimate mixtures or as pure ash woods of high forest canopy or coppice origins. All ash will be threatened by the disease whether in managed woodlands or unmanaged woods, and the threat from ash dieback will enter via the canopy trees, coppice working or pollarding, with the seedlings, younger growth being more susceptible to the disease. Table 3 is a summary of the number of ash trees living outside woodlands and how important they are in relation to many other broadleaf species within hedgerows, clumps and linear lines of trees and that we will become solely dependent on the Oak tree, after the loss of many ash trees in our landscape.

Table 3

Numbers of living broadleaf trees outside woodland by species and habitat feature type

Principle Broadleaf

Species only and excludes conifers

Data source Forest Research, Forestry Commission Crown Copyright 2002 - National Inventory of Woodland and Trees - Hereford.

Therefore, forestry practices can play a key role in conservation strategies by retaining trees with exceptionally low damage levels from which tolerant regeneration may result. In severely damaged stands the retention of these tolerant ash trees may, however, not be beneficial for future stand development due to numbers being too low for successful regeneration, or justified from an economic perspective. Nevertheless, it is still recommended that the best trees be retained (i.e. those with minimal crown damage) to facilitate possible long-term adaptation of ash populations to H. fraxineus through potentially tolerant genotypes.

Therefore we should adopt some broad principles to our approach of management;

• Maintaining as far as possible the values and benefits associated with ash woodlands.

• Securing an economic return where timber production is an important objective.

• Maintaining as much genetic diversity in ash trees as possible with the aim of ensuring the presence of ash in the long term.

• Minimising impacts on associated species and wider biodiversity.

• Managing the health and safety risks from dead and dying trees.

Current advice recommends that land managers should already be identifying their ash tree population, assessing ash tree condition, monitoring for any change over time, and be planning mitigation for the expected loss of a large proportion of ash trees. Such works should look to minimise the loss of ash trees as a habitat used by other species and as an important tree in the landscape by, for example, undertaking compensatory tree planting with site appropriate species in advance of the expected loss of ash trees.

Land managers have a duty to comply with the law, and should be acting now in their preparation to deal with the likely increased risks from ash dieback on their ash trees. In particular, their focus must be on Ash trees growing within ‘high risk’ locations, like those adjacent to highways, service network infrastructure, buildings, or in areas or routes frequently used by the public.

It is important to note that poor condition of an ash tree canopy might not always be a result of ash dieback. Other problems such as drought stress, waterlogging, root damage, or other pests and diseases can cause ash trees to become stressed and to decline and the inherent strength of an ash tree may be severely affected by the disease and by associated secondary pests or pathogens; these may create high risk felling conditions for any operators working on or adjacent to that tree.

Most importantly, keep written notes from the monitoring work; they will provide evidence of your awareness of the risks and your assessment of them, should a tree failure incident occur which affects someone else.

Advice can be sought from suitably qualified and experienced tree consultants. Both the Arboricultural Association and the Institute of Chartered Foresters maintain directories of registered practitioners and consultants.

Public safety is likely to be one the biggest management issues for owners of ash in woodlands as the disease weakens or kills trees over the coming years, particularly as infected trees are likely to have considerable amounts of dead wood in the crown. Trees infected at the base by H. fraxineus, and associated secondary pathogens, may rapidly lose their structural integrity and anchorage in the soil because of butt and root rot. For example, ash colonised by Armillaria spp. begin to pose risks to forest workers and visitors within two years of basal necrosis formation, and after five years, about half of affected trees are likely to have sufficient decay to be assumed hazardous. Trees in areas with high levels of public access or other recreational use need to be monitored carefully for risks to safety, and some felling or pruning of dead or dying trees is advisable if risk assessments show they are a hazard.

Where more than 50% of the crown is infected and survival of the tree

depends on epicormic shoots, felling should be considered because the tree’s economic value is declining as they have become seriously infected. Where less than 50% of the crown is infected, trees should be regularly monitored to ensure appropriate management. However, managers should also assess the risk of Armillaria attack, primarily by checking for basal lesions caused by H. fraxineus. If timber production is an important objective, felling should be considered if Armillaria is present on the site as this can cause root and butt rot of the trees.

In all cases any apparently tolerant trees should be retained, as should a proportion of dying or dead trees where it is safe to do so. Conserving environmental benefits may mean lower levels of intervention could be appropriate, where conserving environmental benefits is the key objective, but active intervention by felling diseased trees can also increase species and structural diversity.

Its always best to consider active management by some of the below points:

• Open up the woodland to allow earlier natural regeneration from other species. Encourage structural diversity. Let more light into the stand in a controlled fashion to help prevent the establishment of non-woodland flora.

• Potentially allow tolerant trees to be identified.

Planting ash is currently not possible because we still have import and movement controls on all ash (Fraxinus) species, as there is a general consensus that this is unacceptable risk presently.

Encouraging regeneration of ash: the percentage of potentially tolerant trees is likely to be very low but with careful management these could regenerate and the species could continue to exist at low levels in mixed stands, but consideration should also be given to other species already present in the stand if they will meet management objective Regenerating a stand using coppice shoots from infected felled trees is not recommended as recent observations in other parts of the country have shown that over 80% of coppiced ash dies within four years.

Planting alternative species: the choice of species to be used for restocking in place of ash must always be guided by management objectives, site conditions, and current stand composition and designation status of the site. On brown earth soils, the range of alternative broadleaved species is wide and includes aspen, beech, birch, cherry, field maple, hornbeam, lime, oak, rowan, sweet chestnut and sycamore. On other sites the choice is much more restricted. For example, on ground-water gleys, alder, aspen, oak and willow are possible alternatives.

One strategy to improve the resilience of woodland to both disease and climate change is to increase the species, genetic and age diversity of woodlands. Developing stands of mixed species and age may make woodland less vulnerable to disease, and adopting a continuouscover approach, where practicable and appropriate, could be one way to achieve this. We all need to be aware of the potential environmental gain the ash tree has provided and that we need to plan ahead carefully as to finding the right species in the right locations to replace ash, to help keep that important integrity of our woodland structure or individual field trees in the landscape.

Introduction

Many of us over the age of 60 will remember the iconic tree of the shires. Massive statuesque trees in the hedgerows and clumps in the fields. They held the noisy rookeries and were the classic backdrop to so many rural activities ably captured in those old pictures of English rural life.

They provided the food and shelter for many fungi, mosses, lichens and hosted 80 species of invertebrates such as the White letter Hairstreak butterfly.

The English Elms showing the typical figure of eight shape (Nature Photographers Ltd, Alamy Stock Photo)

In the UK the hardwood timber from the Elm was the second in importance to the Oak. We sat on Elm kitchen chairs, at Elm tables, used the coffers, the sideboards and the implements made of the wood. A whole industry was set up to produce this furniture and the ‘bodgers’, far from the meaning of the present day word, produced exquisite Windsor chairs that held pride of place in many country homes. The resistance to splitting made it ideal for the hubs of the many cartwheels in use and the planks were common on the floors of those wagons and the coffins they occasionally carried. The wood lasted extremely well underground or underwater and was used as drainage pipes and for making locks and wharfs in canals and harbours. The massive Elm keel of The Mary Rose can be seen in Portsmouth dockyard. Elms were once known as the ‘Worcestershire weed’ and mature trees once numbered @1000 per sq. km. in the Severn and Thames valleys.

In Great Britain, the only truly native species is the Wych elm (Ulmus glabra) which has a more northerly and westerly distribution. The Wych Elm multiplies by seed and never suckers but will regenerate from coppice stools.

The Field elm (U. minor), found mainly in central and southern England reproduces mostly by suckers. It was introduced in prehistoric times by man and is said to have been much bolstered by further introductions from Spain by the Romans for supporting their vines- a practice continued in Italy until well into the Twentieth century.

The Field elm includes clones such as English elm (U. minor ‘Atinia’, previously known as U. procera). Both Wych elm and Field elm can hybridise and naturally occurring hybrids are frequent.

Over the years many cultivars and some exotic species were also planted as ornamental street, garden, and park trees.

During the twentieth century there were two pandemics (1920s and 1960s) of Dutch Elm Disease (DED) (The name "Dutch elm disease" refers to its identification in 1921 by Dutch phytopathologists). This was caused by two entirely separate but related species of microfungi, Ophiostoma ulmi and O. novo-ulmi

Sadly, by the early 1970s most of the mature Elms were nearly all dead, over 25 million trees were lost. Struck down by the deadly fungus carried by beetles (Scolytus spp.) that laid their eggs beneath the bark of the tree. The trees were cut down and destroyed, leaving a huge gap in any country dwellers life.

The suckers of those trees still survive in our hedges- trying to grow into trees. They get to about 20 feet high and the trunk six to nine inches in diameter only to be struck down again by the disease.

But– since the 1990s, it has been apparent that isolated, small populations and individual trees have survived and may be avoiding, tolerant or resistant to DED. With other native species such as Ash and Oak under increasing pest and disease pressures, there is currently much interest in re-considering Elm with an objective of conserving, improving and ultimately restoring the tree back into the landscape.

in progress

A different species, The European White Elm (Ulmus laevis) has been found to produce a chemical that mostly protects it from the beetle. The tree is host to much of the ‘Elm’ wildlife. It is able to grow in very wet conditions but unfortunately does not have the quality of timber or the ‘form’ that we would expect of an Elm.

Since 2000 there have been trials in the UK of ‘resistant’ elm cultivars and selections from breeding programmes in France, Spain, Italy and the United States. Also, cuttings from some surviving British mature elms have been established and potentially promising individuals have been tentatively identified. They have not only been rigorously tested by infecting them with very heavy doses of the DED fungi, but their form and suitability for planting in different circumstances in the UK has been checked out. Of course, there has not yet been time to assess their mature form or value for timber.

Unfortunately, the Forestry Commission (nor anyone else in the UK) has been able to do the sophisticated research needed to produce these cultivars, they have been imported on a small scale and some have been propagated and multiplied by a few nurseries and dedicated individuals. Today these are starting to be marketed and there are still a few that are being imported (nobody likes doing this but they are unobtainable otherwise). The trees have to undergo rigorous testing and they come in under a specific plant passport number.

Several Wych Elm and a few Field Elms, hybrids and cultivars have indeed survived to maturity around the county – some may be naturally resistant but from experience elsewhere in the country, very few are – when put to the fungus test- they have often survived by sheer luck.

The Herefordshire Tree Warden Network have managed to obtain some European White Elms and 4 cultivars for distribution around the county. https://htreewardens.org.uk/ projects/elm-planting/

Eventually plants should be readily available from local nurseries and they will hopefully be the forerunners of returning the Elm to our Herefordshire countryside.

Many of these trees have been planted experimentally by Hampshire & IoW Branch, Butterfly Conservation and a few other tree specialists- they have been found to host the White letter Hairstreak (Satrium w-album).

• National Status: Scattered colonies throughout England and Wales. Pop. Trend since 1976 -96%

• Habitat: Elm trees in all suitable habitats such as woodland edges, hedges and even solitary Elms in gardens. Trees with open, sunny aspect are preferred.

• Flight Period: Late June to mid-August.

• Larval Food Plant: Flowering (over 20 years) Elm.

• Wingspan: 25-35mm

Further Reading:

• Andrew Brookes, Butterfly Conservation Trials Report 2019

• www.hantsiow-butterflies.org.uk/downloads/Disease%20resistant%20elm%20 cultivars%20BC%20trials%209th%20report%20August%202019.pdf

• Karen Russell and Richard Buggs. Where are we with Elms? Future Trees Trust 2019

• Esmond Harris. The European White Elm. Royal Forestry Society

• David Herling http://www.resistantelms.co.uk/

• https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elm

- Charlie Long

2019 was another successful year for Bonkers on Botany (BoB) outings, attracting an impressive array of keen and friendly botanical enthusiasts and offering a last chance to target sites for collecting those all-important records for the Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland (BSBI)'s 2020 atlas. Of course, it helped that those sites also happened to be located at some beautiful spots around the county. Five sites were visited between June and September, this year covering some of the more under-recorded areas of the west of Herefordshire.

The first gathering took place around the fascinating Kilpeck Castle. Despite having delayed this meet-up to June, in an attempt to guarantee some more reliable weather, we were met with a huge downpour upon having climbed up to the exposed top of the castle ruins, clustering around the old stone walls in attempt to shelter from the driving rain. This customary awful weather did not dampen our spirits and we were treated to a variety of habitats and a few notable species.

Within the churchyard and surrounds of the well-known Kilpeck Church, we came across some small patches of the tiny sea mouse-ear Cerastium diffusum known to occur inland on open sandy places, as well as on the coastline habitats which the name would suggest. This species is distinguished from its more common and widespread cousins found in Herefordshire, such as common mouse-ear C. fontanum and sticky mouse-ear C. glomeratum, by its annual life cycle, the presence of long glandular hairs on the sepals, and the fact that it has four petals. Needless to say, a bit of detective work was required in order

to confirm this species.

Another interesting plant species found at Kilpeck (and, incidentally, one that can also be found in dry, open ground as well as coastal areas) is the small-flowered buttercup Ranunculus parviflorus. We were lucky enough to have Stuart Hedley among our group during this visit; he had recorded this species a few years prior and managed to re-find a vegetative patch, growing among the short grassland surrounding the castle ruins, to show the group. Small-flowered buttercup is another annual species, which differentiates it from some of the commoner perennial buttercups, as well as it having a more rounded leaf shape.

The next meeting was a trip out west to Brilley, where the group spent a pleasant Saturday in mid-July botanising around this western nook of the county, located close to the Welsh border. The notable botanical finds of this trip included a few plants of trailing St John’swort Hypericum humifusum and grey sedge Carex divulsa growing on a roadside bank, as well as a patch of small sweet-grass Glyceria declinata, found in a ditch. A few non-native plants of interest were also recorded: phacelia Phacelia tanacetifolia, which is a blue/mauveflowered plant of the borage family, originating from California and naturalised throughout the British Isles, and narrow-leaved ash Fraxinus angustifolia, which is sometimes grown as a street-side tree and features the two subspecies angustifolia and oxycarpa.

The third excursion took us to another church, this time at Preston-on-Wye. We scooted round the churchyard collecting records, noting the occurrence of little ferns, such as wallrue Asplenium ruta-muraria and black spleenwort Asplenium adiantum-nigrum along the wall; also stopping to discuss the differences between the willowherbs Epilobium spp. that we could find on site. We compared the glandular hairs on the upper stem of American willowherb E. ciliatum; the short fruit of the handily-named short-fruited willowherb E.

obscurum; and the hairiness but small size of hoary willowherb E. parviflorum

The other interesting habitat on this visit was the large pool located just opposite the church, which featured several interesting marginal species. Dotted around the edge of the pond was water chickweed Myosoton aquaticum, with its beautiful blue anthers, along with pink water-speedwell Veronica catenata. We continued the watery theme and walked down to two further pools, passing an impressively large badger sett on the way, where we recorded wood small-reed Calamagrostis epigejos, a tall reed-like grass with bushy inflorescences, growing along the path. Within one of the pools was an abundant mass of curly waterweed Lagarosiphon major, an invasive non-native aquatic species which originates from South Africa but has found its way into many British water bodies and slowflowing water courses.

Next, to Burrington Meadow: a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI) which was designated for its marshy grassland habitat. Notable species spotted in the grassland here include pepper-saxifrage Silaum silaus, which is not restricted to wet habitats but is a characteristic species of old meadows; fen bedstraw Galium uliginosum, identified by its downward-pointing prickles on the stem and leaves; and lesser pond-sedge Carex acutiformis, one of the tall sedges which can often form dense stands and which was seen in abundance at this site. Not only was imperforate St John’s-wort Hypericum maculatum present in the wet grassland, but also its hybrid with perforate St John’s-wort H.perforatum, which is named as des Etangs’ St John’s-wort H x desetangsii. This hybrid is partially fertile so is able to backcross, resulting in a mind-boggling range of ‘intermediates’ which can display varying characteristics between both of the parent species.

The damp conditions of this site meant that we were also presented with a range of willow species growing along the boundaries of the grassland, the characteristics of which we were able to compare. White willow Salix alba helpfully has a white appearance from a distance, and up-close, a silky underside to the leaves, which also have serrated margins. Osier S. viminalis was also present; this species is known for its long leaves, whereas the grey willow S. cinerea ssp. oleifolia on site was identifiable from the rusty-red hairs on the underside of its leaves.

The final visit of the year, in early September, took place in King’s Caple. More pond habitats offered the group a range of species to explore, such as greater spearwort Ranunculus lingua and pond water-crowfoot R. peltatus. Other notable species were often recorded on the road verges and field gateways, reflecting the importance of these sometimes ignored habitats which can function as a bit of a refuge for many declining species. Some of the species recorded here include dwarf mallow Malva neglecta, small-flowered crane’s-bill Geranium pusillum, fig-leaved goosefoot Chenopodium ficifolium and white horehound Marrubium vulgare.

So, another lovely season of botanical forays: in total the group collected over 800 records which not only will fill some dots on the map for our county’s contribution to the national atlas, but hopefully will have provided some nice trips out for anyone who likes spending an evening pottering about looking at plants. As I write this, on a cold, foggy January day, I am dreaming of this year’s botanical escapades, which will be planned over the coming weeks. We hope to provide another varied season of sites, normally taking place on a weekday evening with the occasional Saturday outing for those sites which may warrant a little further exploration. If you are interested in coming along, please contact Heather Davies at heatherbelle.sanctuary@gmail.com to be added to our email list.

- Liz Overstall

I was scrambling along the bank of the Dulas Brook yesterday, marvelling at the newly sculpted banks. Heavy rain this year, and numerous flood events, have changed the nature of the stream. It is almost unrecognisable. Yes, it follows roughly the same course, but it is markedly deeper, and stonier than before. The stream bed has been scoured by violent abrasive action, as weeks of surface flood water has ripped across the meadows picking up soil and sharp stone particles, then pebbles and small rocks. I mark a couple of pebbles and am amazed how far they move downhill.

By the time the floodwater gets to the stream the flood is shifting larger rocks, weighing several kilos, and carving out channels between slabs of rock that have possibly never been exposed before. Uprooted trees and torn branches create log jams, forcing the water to career around them, carving lofty new banks on either side. The position of the former bank is marked by posts and wire that now hang loose over the water, or are carried off to knit the log jams together into an impenetrable tangle. The riparian world of the Dulas Brook has been disassembled and remade anew. All is changed.

People are afraid of change, perhaps rightly so, because change means uncertainty. Yet change is normal, an intrinsic part of life on earth; environmental change being the motor behind evolution, the cause of extinction, as well as the proliferation of species. Perhaps that sends a chill down your spine? So it should! We are faced with the prospect of very rapid change.

We lament the losses of our wildlife populations. Fewer cuckoos, and then no cuckoos where once dozens sang. One year pied flycatchers, and then none. Where are the insects, and those vital pollinators? The hares have vanished from our hill, and the curlew that once nested in the meadow above have also gone, although - even now - we sometimes hear migrants pass overhead, so there’s hope yet. So sometimes I feel despondent, sometimes I feel deeply angry.

The National Biodiversity Network (NBN) State of Nature Report is sad reading, showing the populations of key UK species are down by 13%, and that the area occupied by more than 6500 species has shrunk by 5% since 1970. Why? Intensive farming is the main culprit, with global warming coming second. I come from a farming family. The landscape we think of as “natural” today is almost entirely manmade, and for millennia it is ploughs that have dictated the shape and size of fields. Square to begin with, created by Neolithic ard ploughs that just scratched the soil. (Some of those fields can still be seen in Herefordshire.) Then Saxon ploughs came along, pulled by teams of oxen, cutting deep furrows, creating rectangular fields. Difficult countryside had to wait for the invention of nineteenth century steam ploughing engines which, working in pairs, did for much of the remaining natural habitat of the Midlands and the Fens and plenty of other areas too. My grandfather ploughed with horses, my father with a Massey Fergusson tractor, but my engineering in-laws developed those steam engines and proudly claimed vast areas of Warwickshire for agriculture.

Today those fields are ploughed and cultivated by the largest agricultural machines ever devised. Individual farmers cannot afford to buy these monsters: agricultural economics is forcing farmers into Crop Share syndicates where neighbours join together to hand over their fields to super -contractors who now farm entire landscapes by satellite. That is what has happened to our family farm in Cambridgeshire. Hedges and trees disappear overnight. The machines rule, but then, they always did.

We must feed the cities, and with most of the population now living in urban areas, that is pertinent. But whilst high-tech agriculture is the biggest threat to the natural environment; global warming is the biggest threat to the survival of humankind. We need to be rapidly expanding wild, natural areas for carbon sequestration. Equally we need to stop the destruction of the natural systems that are the foundation of life on earth, focussing on insects, fungi and soils rather than glamorous mammals. (No offence to pandas.) Will this happen?

Farming is dictated by agricultural policy, and the Agriculture Bill is going through Parliament for the second time as I write these words, however it does not seem to adequately address the issue, that agriculture itself might be the problem. The Environment Bill, which went through Parliament last week, mentions Local Nature Recovery Strategies (LNRS), Plans and Local Recovery Networks but without clear legal duties to obey. Years of austerity has had a serious impact on environmental protection, and unless adequate cash is provided for DEFRA, Natural England and other organisations to carry out this vital work, the countryside will not see the protection it urgently needs to be resilient to climate change.

- David Taft

In my last notes I started by discussing how the ‘beast from the east’ had affected local wildlife here in my garden high on the Malvern Hills. In comparison, the weather in spring 2019 was relatively mild, with each month starting with a wet fortnight and ending with a dry sunny warm spell. Although not dramatic it certainly produced some surprising wildlife observations.

Late February was really sunny and warm and insects began to appear unseasonably early. As usual I was monitoring hibernating Small Tortoiseshells (Aglais urticae) in my woodstore where they were spread around the ceiling, hanging upside down with their wings folded over their backs. They had as usual started to appear at the end of September and had reached four in number by the middle of October, and remained in exactly in the same spot throughout the winter. Although one specimen was joined by a hibernating group of Herald (Scoliopteryx libatrix) moths he did not move.

On a glorious day of the 24th February whilst enjoying a coffee sitting on the patio I decided to check on their hibernating status. Whilst noting that all four were still present, one specimen opened its wings, paused for a few seconds, launched itself into the air and flew straight past me and out through the open doorway. It had been hibernating through most if not all of October until nearly the end of February, approximately five months and yet within five seconds of appearing to wake-up it flew out into the sunshine without any hesitation; this I find to be quite remarkable for such a fragile insect. Another specimen awoke and flew the following day, which left two specimens hibernating. On the 27th February I was fortunate to see two Small Tortoiseshells in the garden undertaking their upward spiralling display flight, like two people chasing each other up an invisible spiral staircase. I assume this was the pair from the wood-store.

My continued monitoring revealed nothing more until a third specimen awoke at the end of March. On the 17th April the final Small Tortoiseshell was still apparently asleep and I was beginning to think it may have died. This specimen was right at the back of the wood-store, where it was coolest and darkest, but by now we had enjoyed so many lovely spring days I felt it should have awoken from its slumbers. So, after lunch I collected a small bird feather and went to the wood-store and carefully lifted the butterfly from it’s upside down position on the ceiling. It seemed aware of what was happening and held on to the feather. The return to the patio took about five seconds and on the way its wings opened, and I placed it on the table in full sun. I bent to pick up my camera to take a photograph and it flew away before I could focus. So, this specimen had been asleep for at least six and a half months, before I disturbed its slumbers.

I pondered why there was such a difference of nearly two months between the first Small Tortoiseshell to wake and the last one. I did not find any references to this in reports and literature, but thought up a possible scenario which I think is likely. See what you think!? Variation in populations of any organism is natural and normal, and with spring weather being so notoriously fickle it benefits the butterfly to have early and late awakeners so that not all of them will be caught out by a sudden deterioration in the conditions. An early emergence may increase the length of the breeding season, but the emerging butterfly needs to not only avoid bad weather, but to find flowers on which to feed and nettles on which to

lay its eggs, and too early a start may end up fruitless. So, this is I suppose an instance of not putting all your eggs in one basket.

Other butterfly species were also on the wing in February. Brimstones (Gonepteryx rhamni) which I wrote about in the last ‘Flycatcher’ were regularly in the garden from the 25th February. Our longest lived butterfly these insects which emerged from a pupa in July or August have hibernated through the winter, but not in my wood-store. I assume somewhere more natural is preferred for their hibernation, and they re-appear in the spring looking newly minted. After they have mated and laid their eggs they will continue to be seen into May and sometimes June. I so look forward to seeing these large beautiful pale yellow butterflies, that I decided rightly or wrongly to give them some assistance. Their distribution is tied to the availability of their caterpillar’s food-plant, the Alder Buckthorn (Frangula alnus). This shrub forms part of the understorey of woodlands and its occurrence is patchy and infrequent in this part of England. I bought some small seedlings from a woodland plant supplier to plant in my garden where it meets the woodland edge. After planting, I had a few plants left over which were in their container in front of the garage, when on 20th April as I was parking the car, I saw a female Brimstone. I watched her from close quarters for several minutes as she laid eggs on the underside of the newly emerging leaves. She seemed too busy to worry about my presence and I marvelled at the care she took during egg laying. The pictures I took show how small the leaves were, and I pondered how she found this unplanted Alder Buckthorn. I found several references to the females apparently being able to smell the leaves from distances of a quarter to half a mile.

Continuing the butterfly theme I also saw a Red Admiral (Vanessa atalanta) in flight and taking nectar from the flowers of an ornamental cherry tree on the 24th February. This butterfly like the Painted Lady (Vanessa cardui) migrates from northern Africa and Spain to

visit us every year. Later in the year the offspring of these immigrants attempt a return migration, not remaining here for winter. But, with changing climate there is now increasing evidence that Red Admirals overwinter especially in the south of England. But, unlike Brimstones, Commas, Peacocks, Small Tortoiseshells they do not become completely torpid and consequently during mild spells in winter are more likely to be found on the wing. So I think that the sighting on 24th February is more likely to be a successfully overwintered individual rather than a newly arrived immigrant. I also saw several Red Admirals locally during October 2018 with the final specimen basking on my patio on the 26th. I suspect that these specimens were more likely to be ones attempting to over-winter, and were not planning to return to the continent. But, as the picture of the Red Admiral on the Cherry blossom shows it is important for all insects that hibernate to have access to readily available sources of nectar when they awake.

Now for something different and another discovery from my wood-store; perhaps the article should be entitled ‘notes from my wood-store’. Whilst checking the hibernating butterflies on the 26th February I noticed something hanging from the cardboard in the

gloom at the back. I had my camera with me and so I took a picture for which the flash came on automatically. Looking at the picture on the computer and magnifying it to compensate for the distance I found that it was a bat and not a large moth, as I had initially thought. The strange appearance of its face peering out from between its wings left me in little doubt that it was a Lesser-horseshoe Bat (Rhinolophus hipposideros). Johnny Birks a local mammal expert confirmed the identification and said that the habit of hanging freely from above, rather than against a wall was diagnostic, along with the distinctive facial expression. The facial mark is likened to a horseshoe which gives them their name, and the lesser part describes their diminutive size when compared to the very rare Greater-horseshoe Bat. The horseshoe is part of the bat’s mechanism for making the high-pitched sounds used in echo location. This bat is so small it is not surprising that my first encounter in the gloom caused me to think it was a large moth. They only weigh five to nine grams (around a quarter of an ounce), which is slightly less on average than a Wren, and yet for all their small size they may live 20 years.

I must stress that it is illegal to disturb bats, even their roosts and so I subsequently noted the status of my visitor from the open doorway so as not to enter and disturb him or her. Remaining present during the daytime, other specimens started to appear from 24th April and on one occasion at least four were visible hanging serenely from the ceiling, before they all disappeared on 22nd May. I assumed that this was the end of the story and that they had moved on to their usual summer roosting sites. However, in June bats were flying around the garden at dusk as was often the case, and I wondered if they were Lesser-horseshoe Bat or Pipistrelle as I had previously assumed. Bats feed mainly at dusk and dawn resting during the middle of the night, I presume to digest their meals. So, at around midnight I noted that bats were no longer flying around the garden, and I went to peer into the wood-store from the open doorway. The sight of several bats greeted me. Some were hanging freely from

the ceiling and spinning as if their ankles were made of swivels, whilst others were flying around; I reckoned at least six were present. Subsequently, from time to time I looked in late at night and found this was the normal scenario. However, they were never present during the daytime, and sometime in September they disappeared altogether.

Continuing the bat theme I had another brief encounter on the 26th October when I suddenly became aware of a large bat flying around the lounge. How it found its way into the house is a mystery, but it was large with a wingspan of about 12 inches (30cm). I opened the windows to allow it to find its way out. But, first it flew around every room including the minute cloakroom where its flight control was something to marvel, and then it landed briefly on the hall ceiling lamp enabling me a clear view for a few seconds. It had huge ears nearly as long as its body and shaped like a canoe with a rounded end. There was a clearly visible tragus, the fleshy projection that protects the opening to the inner ear and helps to direct sounds down into the ear canal. I thought this bat was a Brown Longeared Bat (Plecotus auritus) and again I confirmed the identification with Johnny Birks. Unfortunately I was so nonplussed by the whole experience that I forgot to take a picture and the bat left by an open window a few minutes later.

I have recently been looking at hoverflies but still have to photograph most of them to be sure of their identification. When reviewing the photographs on the computer I often find I have photographed something different or unexpected. One of the first interesting flies I came across several years ago was a large fly like a fat overgrown housefly about half an inch long but brightly coloured with an orange-buff abdomen overlaid with brown or dull black markings. It only has a Latin name Tachina fera and is a member of a group of flies which are known as ‘parasitic flies’ the Tachinidae. Although called parasitic flies they are in fact parasitoids, which means that their larva in fact kill their hosts as they develop within them. In recent years to make insects easier to study and encourage lay observers the scientific community has been trying to give many insects common vernacular names. So, this group of flies numbering some 270 species in the UK now has its own website and followers, where they are known as ‘Bristle Flies’. However, some entomologists are calling them ‘Punk Flies’, but whichever name is used it sounds less unpleasant than parasitic flies. When you see the pictures below it is clear why they might be called bristle or punk flies, with their spiky emergent hairs.

The species I first recorded in the garden was Tachina fera, common and widespread and being large and quite distinctive I have noticed it every year since. But, I still take photographs when good opportunities arise, as this fly enjoys feeding on colourful flowers and basking in the sun on a prominent leaf where it can be seen day after day. Consequently, I get many chances for photography, and whilst reviewing 2019’s photographs I came across something that whilst superficially the same was obviously different. This I identified as Nowickia ferox another one of the so called Bristle Flies with the same outline, bristles on the abdomen and general colour pattern, except this fly was much more brightly coloured, as if only gloss paint was used topped off with a layer of varnish. Other distinguishing features are N. ferox has black antennae, eyes and legs whereas in T. fera they are brown. Both these species live in similar habitats and feed on similar prey the larvae of certain moths, but my new discovery Nowickia ferox was until recently found only in southern England. So this is again another example of an insect moving north with our changing climate. But, I doubt that I would ever have noticed this new Bristle Fly if I had not been taking pictures.

In August I had a large brightly coloured fly land on my empty cup whilst sitting on the patio, and whilst I went to get the camera it obligingly landed on the magazine I had put down. So, the picture is nice and clear as a consequence, even if it looks rather artificial. I decided that it most looked like a hoverfly and after laboriously twice going through my guide of the 270 or so British species, I could not identify it.

So, in frustration I posted the picture on iSpot, a website setup by the Open University to help people get their wildlife discoveries identified. Almost immediately somebody suggested it was Phasia hemiptera, which was correct. This of course, turned out to be another member of the Tachinidae parasitic flies. What had thrown me was the use of the common name Bristle Flies for these insects, making me assume that they all had bristles. Phasia hemiptera is an example of a Bristle Fly without bristles, and now I have identified it I shall not be confused again, but this is just one of many examples of how common