As of 1st October 2021

Patron

Monty Don

President and Vice Presidents

President The Countess of Darnley, Lord-Lieutenant of Herefordshire

Vice Presidents Mr L Banks CBE, DL

Mr T Davies

Mr E M Harley

Mrs B Winser

Mrs Marie Clarke

Mr Roger Beck

Trustees

Mr B Hurrell, (Chair)

Dr W Bullough (Vice Chair)

Ms D Beaton

Mr J Bharier

Mr R Cryer

Mr P Ford

Mr P Garner

Ms R Hadaway

Mr J Hardy

Mrs A McLean

Mr S McMaster

Mrs E Overstall

Mr N Smith

Mr M Williams

Company Secretary (non-Trustee) Vacant

Solicitors

Messrs Gabbs, 14 Broad Street, Hereford, HR4 9AP

Land Agent

Mr Peter Kirby M.R.I.C.S., Messrs Sunderlands and Thompsons, Offa House, 2 St. Peter’s Square, Hereford, HR1 2PQ

Volunteers

Once again the Trust extends grateful thanks to all its volunteers who have worked hard to deliver a vast amount of work to help conserve the county’s wildlife. Thank you all.

Helen Stace Chief Executive

Andrew Nixon Conservation Senior Manager

Sophie Cowling Senior Project Officer (Lugg Living Landscapes)

David Hutton Ice Age Ponds Project Manager

Claire Spicer Catchment Advisor

Sarah King Community Engagement Officer

Sam Price Nature Recovery Network Officer

Charlotte Bell Wildlife Monitoring & Data Officer

Esther Clarke Nature Reserves Team Manager

Paul Ratcliffe Reserves Officer

Trevor Hulme Reserves Officer

Pete Johnson Reserves Officer

Lewis Goldwater Reserves Officer

Ian James Conservation Volunteer Support Officer

Amanda Eckley Finance Manager

Averil Clother Finance & Admin Officer

Alexsandra Mikula Finance Officer

Frances Weeks Communications and Marketing Manager

Chris Jones Membership Development Officer

Debbie Bean Retail Officer

Julia Morton Engagement Manager

Karen Roberts Outdoor Wellbeing Officer & Engagement Officer

Hannah Dunn Nature Tots Coordinator

Caroline Braid Nature Tots Coordinator (Maternity Cover)

Annderley Hill Volunteer Coordinator

Katherine Manning Queenswood Visitor Experience Manager

Liz Bunney Queenswood Visitor Centre Assistant

Guy Beasley Cleaning Assistant

- Peter Garner

I must start by apologising for the delay in producing this 86th edition of The Flycatcher. Due to the Covid pandemic our opportunities to meet with others have been greatly reduced, and as a consequence recruiting authors for Flycatcher articles has been more difficult. However, I hope you will consider the wait to have been worthwhile, and you find this edition both informative and entertaining.

I have been Flycatcher editor for twenty five years and yet I have never before published an article as long as Denise Foster’s contribution about Herefordshire Bats. I did consider trying to reduce it, but as I read it through I was so impressed I soon realised an abbreviation was unnecessary and inappropriate. For those of you who keep former editions of Flycatcher, this article by Denise is a sequel to the one she and David Lee wrote in 2015 (Issue No. 81). The diversity and strong populations of bats in Herefordshire is an encouragingly positive indicator of the relative good condition of the nvironmental health of the county.

Many people consider farmers and conservationists to be opposed to each other, but this is not the case in our beautiful county. Tony Norman who is a senior member of a large farming family in the west of the county has, once again, written a wonderful article entitled “Pollards”, which will help many readers to gain a greater understanding of the role of such trees in the rural landscape.

In a very helpful article, Bob Hall, who is the county butterfly recorder, describes the county’s different butterfly populations, explaining which species are prospering and those which unfortunately are not.

Jo Weightman is county recorder for fungi and has written many interesting articles for past editions of Flycatcher. This year she has highlighted some of the most colourful cupfungi.

David Taft, who has helped me greatly with the layout of this year’s edition, has written his regular article entitled, “Notes from my garden”. David has a large and unusually wild garden high on the western side of the Malvern Hills above Colwall: he is fascinated by the tiny insects that very few people ever even notice. I quite often go for walks with him, but we never get very far because he is intent on looking under every large stone or piece of rotting wood that we pass. If someone was to follow him with a video camera I’m sure they could make a new nature series for television that would fascinate all who watched it.

Charlie Long has written a variety of articles for Flycatcher and this year she demonstrates her breadth of interest in the natural world by revealing the private lives of her local badgers. She has accompanied her fascinating insight of badger lives with some very special pictures.

In the Lugg Meadows close to the previous Herefordshire Wildlife Trust headquarters at Lower House Farm there is a wonderful population of Fritillaries, and Heather Davies has explained about these magnificent plants and has emphasised their wonderful attraction. I hope that any of our readers who have never been to see them before will make a diary entry to do so next spring – late April/May.

I wonder how many of our readers know where the Yazor Brook flows. After reading Nichola Geeson’s article I expect those who didn’t will be that little bit wiser and encouraged to explore another of “hidden Herefordshire’s” special jewels.

Equally revealing is an article describing another riverside habitat close to Hereford. Bartonsham Meadows are so close they might even be described as part of the city, and I hope, that after reading this article they will receive the careful management our wonderful city deserves.

- Brian Hurrell

Dear Reader,

In my introduction to last year’s Flycatcher in February I started by apologising that my report would be very much in the same vein as my contribution for the March 2019 issue . How things have changed. However, as so much has already been said by others, in all sorts of ways, about the difficulties of operating throughout the pandemic, I want to concentrate on the positives and achievements for Herefordshire Wildlife Trust, the wildlife and people of Hereford. This is not to demean but rather extol the excellent dedication, hard work and persistence of our staff, our volunteers and our members.

We have pressed on in the challenging environment, concentrating our efforts on our main “drivers”. These are to ensure that Herefordshire becomes a county richer and more diverse in wildlife, involves local people in our work and concurrently improves their health and wellbeing in a variety of ways. This has involved continuing to put pressure on both local and central policy makers to take appropriate action to combat and reverse the factors that are influencing climate change and its deleterious effects. The work we have done in partnership with the Wildlife Trusts national body and with other national environmental agencies and NGOs has been helping to ensure that policies and practices for extending wildlife preservation initiatives, improving land management and agricultural processes, really do contribute to environmental enhancement throughout the UK. We know we cannot do this alone and we continue to work as closely as we can with other similarly minded bodies, our neighbouring Trusts and of course our band of around five hundred volunteers.

So, returning to the restoration and improvement of our county’s biodiversity and engaging our people, we have been running various projects and initiatives throughout the year, some of which will continue into the future. A piece of work that demonstrates the range of joint working that we undertake is the Ice Age Ponds Project, where we are now well into phase two working with landowners. We ran a successful exhibition, have developed trails and information apps and continue to work with supporters to improve and learn from these very interesting, highly valued environmental habitats.

We have gained some additional wonderful reserves such as a highly rated Littley Coppice in the Malverns (a legacy), Rounds Meadow (purchased using money received via a fine on a company for environmental breaches) and Oak Tree Farm (funded from bequests and a very successful public appeal from supporters). The Birches Farm new visitor centre was formally opened a few weeks ago and we continue, with the help of a local group of volunteers, to improve the bio-diversity of the site. We are now mid-campaign to raise funds to acquire Ail Meadow. Please help if you can!

Queenswood and Bodenham Lake continued to be a high priority for us and for members of the public who found them of great benefit and interest during the lockdowns. I must say not without some difficulties and poor behaviour that our staff had to manage. With the help of Herefordshire Council, Verging on the Wild, other interest groups, our Branches and volunteers we have seen much work done on many of our other sites e.g. the Yazor Brook and Bartonsham Meadow. Our volunteers don’t just do conservation work

however, they also help, inter alia, with administration, retail, engagement, youth work and site management.

We continued, as did a couple of Branches, to hold meetings and give presentations but this time through the internet and social media channels. In addition we used the internet to continue to work with children, families, disadvantaged people and groups to improve their environmental experiences and provide training opportunities, work experience, membership experiences and wellbeing projects for many hundreds of people. For all this I and my colleague Trustees (who are also volunteers) are extremely proud and grateful to staff, volunteers and the people of Herefordshire.

Our valued and dedicated staff too have continued to benefit from our participation in the Thrive at Work programme, which has been particularly valuable in combatting some of the stresses of the lockdowns and limited working challenges. As Trustees we continue to review our skills base, our diversity and our performance as a Board to ensure we are as effective as we can be. I am pleased to say we recruited three new Trustees and co-opted another during 2020 which significantly strengthened us in these respects.

There is much more information and detail in our Annual Report 2020/21, available online or in print, on our overall management, resources, activities, finances (which were very positive in the last financial year despite or perhaps because of the pandemic!), our engagement activities and much more.

So, to conclude, with our membership (now over 5,800), our sound volunteer base and our outreach to young people we feel we are continuing to achieve our aims and objectives. Our website regularly attracts over 8,000 visits per month, so we are well connected with the public and have a good local and regional profile. I must add that the articles in this edition of Flycatcher, a highly regarded publication, also demonstrate the contribution volunteers can make. They also add to the evidence and confirm the overall value of wildlife to us, the benefits it has to offer and the contribution we can all make to ensure there is continuing progress.

Finally I must add, on a personal note, that twice on one afternoon in the spring there were, very surprisingly, over 30 buzzards circling over my garden and, even more exciting, a pair of Spotted Flycatchers successfully raised four young in my garden, in an old recycled teapot carefully lodged in a tree.

Enjoy this valued and valuable edition.

Brian Hurrell , Chair of Trustees

- Tony Norman

I was keen to write this article because we are just about to lose an enormous amount of our history, our heritage and our wildlife. Why? Well, Ash trees are dying with ‘Ash Dieback’ and with that we shall see the loss of thousands of Ash Pollards - these trees were once common on nearly every farm in the county.

A pollard is a tree with its trunk severed at 6 to 15 feet off the ground; it is allowed to grow again with multiple shoots (to form poles) above the reach of browsing animals. These are ‘harvested’ over periods of several years. This is a very ancient form of tree management that produces many different products, rejuvenates the tree and provides an almost unique form of habitat.

This system has been refined in urban settings to shape the trees, to prolong their lives and by constantly cutting them back reduce the spread of their roots.

Trees were planted (or allowed to grow) often around parish, estate or farm boundaries as markers, along roads, by rivers or streams using the theory that half the tree would be growing ‘off the land’ (in other words half the shade and the roots would be growing over the neighbours’ or ‘waste’ ground). Sometimes they would be planted on Commons (such as Castlemorton Common) where advantage could be taken of ‘Estovers’ (where the owner

of the land allowed wood to be taken). Complications also arose with some owners wanting the ‘timber’ on their land (primarily Oak) while allowing the tenant to use other wood such as pollards.

Here we must introduce another form of tree management known as ‘coppice’- this is where a tree is cut off near the ground (1 to 3 feet) and the resulting vigorous regrowth of shoots is managed in much the same way as on Pollards. Because browsing stock (cattle, sheep, and deer) must be kept away, these generally occur in protected hedgerows, stream-sides or areas of woodland.

Many farms would not have access to coppice woodland so the products they needed were either grown on farm or expensively ‘bought in’. There was a huge demand for wooden items of all sorts, many used and discarded after very few years, so needing constant replacement. Farmers used pollards of Oak (for building and tanning), Ash (poles), Chestnut (fencing and poles) Elm (poles, rails, bark for ‘false leather’) and Willow (everything from hedging stakes, poles, thatching spars, hurdles, wattle down to clothes pegs) but also Lime, Poplar (known in

Herefordshire as ‘Black Willow’ with similar uses), Aspen and just occasionally Holly (cut for fodder). The demand for Hop Poles was incredible – prior to the use of ‘wirework’ introduced at the end of the Nineteenth century – as many as 3,000 poles (up to 18 feet long) per acre were used to grow the hops. The county had around 6,000 acres of Hops in 1850 rising to nearly 10,000 by 1900, and remember that each pole only lasted a few years despite being removed from the ground and stacked in the hop pole arches or pyramids.

Cutting the pollards was an absolute art with the axeman often balanced in the tree swinging his razor-sharp axe within inches of his boots. There never seemed to be an accident and the same axe would be used deftly on the ground to ‘sned’1 the poles, to cut them to length, to split them and to point them (and often to debark them as well or cut them upside down, if they were Willow, to stop them growing in the laid hedges). Whatever products were produced, nothing was ever wasted: even the smallest branches and chips from the axe were collected up and used for kindling, firewood or bundled up into ‘faggots’ for firing the bread ovens.

Often the pollards were shredded up the sides and the tops were left to grow into poles as this Black Poplar from Kingsland shows (above). After a few years the best ‘poles’ would be selected to grow-on with the rest removed. Some pollards are still used today for hedging stakes and ‘truncheons’ (cuttings for establishing more trees). Farmers have been paid £15 per tree through Countryside Stewardship to manage these trees.

Today there are just a few of these trees left; they are beacons for wildlife often on farms that are almost devoid of ancient wildlife habitat. Many of these trees are veterans with a large proportion in the ‘ancient’ tree category. The ones we notice are the ‘lapsed pollards’ some of which may not have been worked on for over 100 years. These trees bear the scars of age with a huge number of crevices, hollows, rots and holes.

Birds: Very many of our farmland birds use them. They are commonly used by Barn Owls for nesting, often being the only suitable place for miles.

Mammals: Commonly used by several species of bats, great hunting for Stoats, Weasels and Polecats, often with a Fox’s earth at the base

Plants: The rotten wood provides a great medium for Bramble, Hawthorn, Rose, Gooseberry and Black Currant which are common with seeds carried in by birds. Yew, Ivy and Holly often provide year round greenery

Around many rural cottages, on smallholdings and on common land, many pollards were ‘shredded’ (cut annually) to add to the meagre supply of fodder either to be eaten by stock during hard summer droughts or carefully dried and stored for ‘tree hay’ to be fed in winter.

1 Snedding is the process of removing side branches and twigs to leave clean poles.

Insects: Again this rare habitat provides material for grubs and beetles with a huge number of moths using the numerous crevices and shelter.

Mosses and Lichens are often growing in profusion and Fungi of all sorts are growing continuously throughout the trees.

This picture shows a series of lapsed pollards near Pembridge. The large Black Poplar overshadows Ash and Willow pollards. The poplar has a Barn Owl’s nest and will receive careful reduction work on the branches to prolong its life.

Fortunately many land owners DO care about their trees and often go to the expense of re- pollarding their trees. They are occasionally cut for firewood and rarely for their original purposes.

On many of these ancient trees pollarding can continue to take place and the trees can be completely rejuvenated. However, it is easy to be too hard and give the tree such a shock that it dies! Advice from a competent tree specialist should always be sought BEFORE any work is done.

These days they are more often recognised for the huge wildlife value that they have so they are maintained by many NGOs 1 and individuals. Just occasionally one sees new Pollards being started but it will be very many years of constant maintenance before they turn into those honey-pots of wildlife that we see today. But we must start somewhere!

- Bob Hall, Herefordshire County Recorder, Butterfly Conservation

2020 was a strange year in many ways. After the severe winter flooding, hot weather in April and May meant that many butterfly species were on the wing 2 or 3 weeks earlier than normal. Examples of this early emergence can be seen from this table of first sightings:

23rd March Holly Blue

3rd April Orange Tip

20th April Pearl bordered Fritillary

24th April Wood White

7th May Common Blue

29th May Dark Green Fritillary

7th June Marbled White

19th June White Admiral

Skippers

These are all small, moth like insects that hold their wings at an angle of 45 degrees to their bodies. Typically they have a rapid darting flight

Ewyas Harold Common remains the only site for Dingy Skipper. Grizzled Skipper, too, are also restricted to one site, Herefordshire Wildlife Trust’s White Rocks nature reserve on The Doward. It is sobering to reflect that even 30 years ago these two species were much more widespread. What has caused the decline of these two species? Their habitat requirements are for herb rich sites with a mosaic of sward heights and areas of sparse vegetation or bare ground providing a warm microclimate. The larval foodplants for Grizzled Skipper include Wild Strawberry and Creeping Cinquefoil, and Common Birds-foot Trefoil for the Dingy.

Large Skipper are still quite widespread and are found in patches of wild grassland. Their main larval foodplant is Cock’s-foot Dactylis glomerata. Small Skipper, too, are found in grassy areas with the main foodplant being Yorkshire Fog Holcus lanatus and Timothy Phleum pratense. Essex Skipper is the newest arrival in Herefordshire. It is difficult to tell apart from the Small Skipper, it being necessary to examine the underside of the antennae, orange in Small, and black in Essex. A Skipper workshop in the summer of 2016 held at Herefordshire Wildlife Trust’s Wessington Pasture nature reserve found that about one third of the Small Skippers found were in fact Essex Skippers. Essex Skippers are almost certainly under-recorded.

Brimstones are one of the signs of spring, as they emerge from their hibernation in March. This is one of our longest lived butterflies, as they can live up to a year. The females are a pale greenish white unlike the bright yellow of the males. Orange-Tips, too, are very distinctive but only the males have the orange tips to their wings. Cuckooflower Cardamine pratensis and Garlic mustard Alliaria petiolata are the most usual foodplants, but other crucifers can be used. The bright orange of the males is a good example of warning colouration as the wings contain bitter mustard oils.

Green-veined White is fairly common with plenty of records in 2020. Likewise, both Large White and Small White have been found in good numbers. The nationally rare Wood White has strongholds at Haugh Wood and Wigmore Rolls, with smaller numbers found at Lord’s Wood and Siege Wood. There were only a handful of records for Clouded Yellow in 2020.

Footnote: The Making a Stand for the Wood White project has now been completed, but there is no doubting the success of this project, spearheaded by Rhona Goddard, Wood White Project Officer. Targeted habitat management works were carried out in Shropshire, Herefordshire and Worcestershire. Since the project started in 2016, Wood White butterflies have been recorded at 36 sites across these counties, and breeding has increased from 12 sites in 2016 to about 20 in 2019. In addition, a successful re-introduction of Wood Whites to Monkwood in Worcestershire was made possible by the collection of adults from Haugh Wood and another site in Shropshire. Around 2,400 volunteers have attended and supported over 80 events across the three counties, with many of the volunteers being members of the West Midlands branch of Butterfly Conservation.

Gatekeepers, Meadow Browns and Ringlets are all quite common, with Ringlets being the most abundant on the Haugh Wood transects. Small Heath are quite restricted in their habitats in Herefordshire, but are locally common on upland areas such as the Malverns and Hergest Ridge, Kington and the Black Mountains. Speckled Wood, too, is common with plenty of records.

Finally, in 2020, only one record was received for The Wall, now a threatened insect. Marbled White’s preferred habitat is limestone grassland, so there are strongholds of this stunning butterfly in a number of Herefordshire Wildlife Trust reserves in the Woolhope Dome. However, it does have a habit of appearing almost anywhere and discrete and widely separated colonies have been reported.

Dark Green Fritillaries were recorded in good numbers from Haddon Hill outside Kington and in smaller numbers from Ewyas Harold Common and The Malverns. Their preferred habitat is open moorland with grass and bracken mosaic. The hot spot for Pearl bordered Fritillary remains Ewyas Harold Common where good management has been rewarded with high numbers of insects. Smaller numbers have been recorded at Haugh Wood and Coppett

Hill. The Small pearl bordered Fritillary was recorded only from Ewyas Harold Common and Hergest Ridge, and is clearly quite rare in Herefordshire. The Silver Washed Fritillary has a stronghold in Wigmore Rolls and Haugh Wood and the populations seem to be expanding. The female form valezina is one to look out for and occurs in approximately 15% of females.

Footnote: Of interest to Herefordshire entomologists will be to follow the progress of the exciting Malvern Hills Lost Fritillary Project, the aim of which is to re-introduce Pearl bordered Fritillary into the Malverns. The habitat on the Malverns is not very different to that of Ewyas Harold where appropriate management of the bracken and scrub has yielded spectacular results. The project is at an early stage. Spring 2021 marks the start of the captive larval breeding programme.

There were plenty of early records of Commas but not so many of the summer brood. Also, Small Tortoiseshell has shown a pleasing recovery from low numbers two or three years ago. Likewise, Peacocks had a good season in 2020 with large counts of over 50 in Haugh Wood. Hot weather at the end of July caused many to go into aestivation, so sightings were lower from that point. Red Admiral records were low early on, but picked up since then. White Admirals are restricted to just three sites in Herefordshire: Lord’s Wood, Queenswood and Haugh Wood. This last record was the first record for Haugh Wood North for 10 years. This suggests that White Admirals are another elusive butterfly that is under-recorded.

There were plenty of early records of Holly Blue and Common Blue, by contrast, had a poor year in Herefordshire. Purple Hairstreak proved elusive as ever and are almost certainly under-recorded. Green Hairstreak records, too, remain low across the county, but White-letter Hairstreak certainly had a good year in Haugh Wood, their former stronghold, with smaller

numbers found at The Doward, Withan Wood, and Dulas. Brown Argus and Small Copper records are few and far between. Both of these butterflies are in decline. Brown Argus is probably under-recorded as in appearance it is very similar to female Common Blue.

These graphs are based on transect records from Ewyas Harold Common, Haugh Wood North and South, Merbach Common and Queenswood Country Park. Many species showed a marked decline in 2020, although this might be partly due to restrictions caused by the Covid pandemic. The positive news is that Wood Whites continue to do well as do Small Tortoiseshell whose numbers have recovered well from a slump several years ago. The strongholds for Marbled White are on the unimproved limestone grasslands found in the Woolhope dome, but not covered by the transect data. Populations of Holly Blue are always cyclical depending on the numbers of the parasitic ichneumon wasp that predate on the

Holly Blue caterpillars. The cycle is around 4-6 years from peak to trough and back again, so it should be expected that populations will vary. The graph for Pearl bordered Fritillary possibly gives a false impression, as the vast majority of sightings are from Ewyas Harold Common. It is a rare insect in Herefordshire!

Acknowledgements

• John Tilt, West Midlands Branch of Butterfly Conservation for the graphs

• Butterflies of the West Midlands

This has been another strange year. Cold weather in April was followed by cold and wet conditions for most of May. This impacted on butterfly numbers early in the season and so emergence was 2/3 weeks later than in 2020.

Skippers

Dingy Skipper and Grizzled Skipper are still both very restricted in their distribution, with records for Dingy from The Doward and Bringsty Common while Grizzled has been found at The Doward and Wellington G.P. Small Skipper had a maximum count of 20 from Mathon. Large Skipper are quite widespread in the county. A few records of Essex Skipper, but this is almost certainly under-recorded on account of difficulty in identification.

Whites

There were very few early records of Brimstone, but plenty of Orange Tips. There was a large count of 36 Large White from Haugh Wood South. Small White and Green Veined White were quite common with a max count of 14 Green-veined White from Hereford Quarry. Wood White have had a poor year even in their strongholds of Wigmore Rolls ( 17 max) and Haugh Wood ( 25 max). There was a partial second brood of Wood White in Haugh Wood.

Browns

Gatekeeper ( max 100 plus from Moccas Hill NNR), Meadow Brown ( max 44 from Bodenham Lake) and Ringlets all had good breeding seasons. There were good counts of 20 plus Marbled White from Mathon, Nupend HWT reserve, Urishay Court Farm and Yarkhill. Speckled Woods were late emerging and then only found in small numbers. There was a single record of Wall from Richards Castle. Low numbers of Small Heath records from Christopher Cadbury reserve, Malvern Hills and Urishay Court Farm.

There was a maximum count of 12 Dark Green Fritillary from Hergest Ridge. Pearl-bordered Fritillary numbers were down even at Ewyas Harold Common with counts of 40 and 60. There were only two records from Haugh Wood. A record of Small Pearl-bordered Fritillary was received from Anthony Furness from the Olchon Valley in the Black Mountains. Silver-washed Fritillary had a good season with a high count of 21 from High Vinnals and plenty seen in Haugh Wood.

There were few early records of either Comma or Red Admiral, but numbers picked up in midsummer, with a high count of 10 Comma from Haugh Wood. Small Tortoiseshell numbers, too, were generally low except for a fine count of 24 from the Bunch of Carrots Stank. 28 Peacocks were recorded from Haugh Wood in late July. White Admiral were recorded again in Haugh Wood South, a welcome return for this elusive and fast flying insect. Painted Lady records were mostly individuals but were well distributed.

There were plenty of early records of Holly Blue and a partial 2nd brood. Common Blue had a poor year with a high count of 10 from Urishay Court Farm. There were 3 records for Green Hairstreak from Coppett Hill, Hergest Ridge and the Malverns. Purple Hairstreak were recorded from Haugh Wood and Newton St Margarets, mostly in late afternoon or evening. Dr Richard Kippax counted 27 one evening in Haugh Wood. White letter Hairstreak were again seen in Haugh Wood and White Rocks, nectaring on Hemp Agrimony or high up in elm trees with a maximum of 4. There were two records of Brown Argus from The Doward and Bodenham Lakes. Small Copper were seen in small numbers in late summer.

An HOC walk in Haugh Wood on August 3rd produced a fine list of 24 species, a remarkable total, given that the Herefordshire list is about 36 species, and at least 6 of those are very rare.

This summary has been compiled with records from these recorders : Liam Bunce , Sarah Cadwallader, Ian Draycott, Tony Eveleigh, Dean Fenton, Toby Fountain, Anthony Furness, Bob and Penny Hall, Peter Hall, Gail Hampshire, Ian Hart, Mike Kimber, Dr Richard Kippax, Jimmy MacDonald, Rachel Mailes, Tom Oliver, Catherine Ponting, Viv Quinn, Jeremy and Katherine Soulsby, Daniel Webb and Richard Wheeler.

Recording

The West Midlands branch of Butterfly Conservation adopted iRecord for submitting records in 2017. The iRecord website is hosted by the national Biological Records Centre. To use iRecord :

1. Go to www.brc.ac.uk/irecord

2. Register user name and password.

3. Click on the Record tab.

4. Select the type of record you wish to submit.

A record must contain 4 essential pieces of information: who, which species, where and the date seen. All records are then checked by verifiers for each county. For Herefordshire the verifiers are currently Ian Draycott and myself.

Website

www.westmidlands-butterflies.org.uk

During the winter of 2019-20 a quiet crisis was taking place in Herefordshire. As everyone wrestled with the fallout from the Covid pandemic, one of the highest floods in living memory was sweeping down the Wye.

The Bartonsham Meadows, situated on the south east of the city and bordered by the Wye, the Hereford to Fownhope road and the Newport railway line, were inundated as usual. The Meadows had been managed as a grazing pasture for well over a hundred years. However, following the (also record) floods of the previous year the Friesian herd had been sold and the land, owned and managed by the Church Commissioners, put down to arable crops. When the floods receded they left behind the usual clutter of wheelie bins and freezers. But to everyone’s dismay, the unprecedented force of the floodwaters stripped tonnes of rich top soil, which, together with the autumnplanted cereal crop, had simply sluiced into the river.

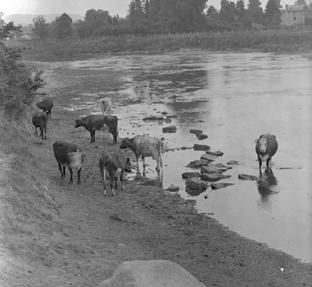

Bartonsham Meadows are floodplain meadows of the River Wye and regularly innundated

Ruth Westoby witnessed the damage with dismay. “The record floods of 2019-20 deluged a floodplain made vulnerable by ploughing and arable farming with devastating results for the river, wildlife, and the hundreds of local people who are deeply attached to them.”

She responded by helping set up the Friends of Bartonsham Meadows. “The Friends was formed in early 2020 following the flood and in response to recent local land management practices, regional flooding, and the global climate crisis.”

Many people despaired of the damage. “In the face of irreversible climate degradation individual action can feel helpless,” agrees Ruth. However, she was convinced that focusing locally, taking small steps, creating networks and working together could be empowering –and perhaps produce long term, beneficial change.

“We are a collective of local residents with backgrounds in ecology, archaeology, activism, history and conservation – and a commitment to the stewardship of this farm nestling in a loop of the River Wye a stone’s throw from the centre of Hereford town.

“We got together in February 2020 specifically to voice concern over the transition to arable from permanent pasture - against the current stewardship scheme - and accompanied environmental degradation that results from farming in this manner on a floodplain: herbicide and manure run-off into the river and topsoil loss degrading the land and river, and reducing biodiversity.”

The Friends of Bartonsham Meadows’ vision is for this small, suburban, riverside farm to be transformed from intensive agriculture to outstanding natural habitat, delivering a broad range of social and environmental public goods.

It’s generally agreed that restoration of the Meadows to traditionally managed floodplain grassland habitat, with additional orchards and Withy beds could deliver an impressive range of benefits: flood mitigation, carbon sequestration, ecological enhancement, improved river water quality, and quality green and blue space for the people of Hereford. The Friends group has pragmatically initiated and maintained a dialogue with the landowners, developed relationships with key decision-makers at local government and expert advisor level, and established a communications network with Hereford residents. “We are extremely grateful for the support of Herefordshire Wildlife Trust without whom we would not have got this far,” says Ruth.

“Our first step was to ask the Church Commissioners to consider making the Meadows over to the people of Hereford on the basis of sale or, preferably, like the Bishops Meadow, gift. The Commissioners, however, are not currently minded to return the land to local management or control due to their financial obligation to manage the funds of the Church. Suggestions have been made that the site could be used for biodiversity ‘net gain’ off-setting, should the Church Commissioners be able to develop other sites they own in Hereford into housing.

The Friends have also lobbied the Church Commissioners to enter a long-term tenancy with Herefordshire Wildlife Trust as the managers of the site, but so far without success. The Friends, alongside Herefordshire Wildlife Trust, and to satisfy the land-owner’s desire for a short-term tenancy, had brokered a plan to see the regenerative farming of a herd of Herefords on the land. This broke down due to unresolved problems with the existing MidTier Stewardship scheme and previous tenancy.

“We are exploring the possibility of pitching to buy the site on behalf of Herefordshire Wildlife Trust. The Church Commissioners have indicated that they see this site being managed in a high tier stewardship scheme. Our discussions continue in our efforts to see this land managed in the best possible way for people, wildlife and the environment.” Ecologist Anna Gundry, a member of the Friends group, lives close to the Meadows. “Our vision is to support the transition of Bartonsham Meadows to sustainable wildlife-friendly management. The current arable regime has left the Meadows with negligible semi-natural habitat, and very limited biodiversity value. The fields therefore present a blank canvas on which new habitats could be developed and environmental and social gain optimised. “The central city location means that they are regularly used by a variety of groups and any new management of the Meadows needs to take into account the varying needs of the local community whilst delivering ecosystem services and providing a diverse and rich environment in which wildlife can thrive.”

She would like to see a mosaic of habitats including willow carr, water bodies and traditional orchards as well as amenity areas being established. However, she says, “the land use most appropriate to the situation and the history of the Meadows is that of the floodplain meadow.”

Anna describes floodplain grasslands as “areas on which traditional hay meadow management has been carried out on seasonally flooded land with alluvial soils. Typically the grassland would be shut up for hay in spring and mown in July. The aftermath is then grazed by cattle, with stock being turned out at the beginning of August. Under this system, meadows received no fertiliser apart from the manure of grazing animals, but of great importance is the winter flooding with its input of nutrients and deposition of silt and decaying organic matter.”

“Deep alluvial profiles accumulate under the meadows with repeated deposition of silt. Winter flooding often leaves the meadows waterlogged for a time, but the underlying freedraining gravel profile allows the water to drain and the meadows to dry out. It is thought that typical floodplain meadows are around 1,000 years old. The Floodplain Meadows Partnership has recorded quadrats with up to 43 species per m2, making this one of the richest neutral grassland habitats in the UK.”

Floodplain meadows have a vital role to play in flood alleviation, nutrient capture and carbon capture. Floodplain meadows are being studied by the Open University who have produced extensive resources available at www.floodplainmeadows.org.uk

The Meadows’ history is long and intriguing. Bill Laws is chair of Bartonsham History. “From serving a siege army during the Civil War to providing a site for the city’s first swimming pool, the Meadows have played a big role in Hereford’s history,” he says. In its pre-railway days the thirteen fields that made up the Meadows included orchards, a hopyard, a thriving river wharf, slaughterhouse and a timber yard. There were mills in the river and a generous

riverside path wide enough to serve the hauliers heaving barges into the city. The sheltered south east edge was bordered by Withy beds that serviced local basket makers and the northern side by the Row Ditch, now a Listed Monument, which, in 1645, stood between the advancing Scots Army and the city’s doomed Royalist defenders. Recent archaeological excavations suggest the Ditch also served the ‘drowners’, the agricultural engineers who managed the Meadow’s irrigation systems. Their efforts extended the grazing season, ensured a good summer hay harvest and helped control flooding.

This made the Bartonsham Meadows a valuable resource and gives credence to the theory that the land was once part of the ‘home farm’ associated with the Anglo-Saxon Mercian kingdom. (The Mercian Lords have been linked to the lost chapel of St Guthlac on nearby Castle Green; the name ‘Barton’ may come from the Old English beretun or baertun, a demesne, corn (or ‘barley’) farm retained for the lord’s use.)

The Meadows continued to benefit their post-Domesday landowners, the local Church, until 1866 when they were traded to the Church Commissioners in return for the endowment of a new church, St James. By then the city’s sewage works had opened on the south-eastern side of the Meadows and, although Herefordshire suffered badly during the late 19th century agricultural depression, the Meadows’ meat, dairy, orchard fruit and hops benefited from being close to their city markets.

Bill Laws points out: “In 1913 swimmers enjoying the river at the Bassom, the municipal bathing station which stood on the west side of the Meadows, were delighted by an aerial display from the pioneer air ace Bentfield Hucks who landed his monoplane here, offering £5 flights over the city.

“Around 1920, after gifting the Bishops Meadow to the city for use as a public park, the Church Commissioners let the Meadows to the Matthews family. Until recently, and down three generations, they ran the Bartonsham Dairy, grazing their cattle on the Meadows.” Although agricultural improvements saw two large ponds drained, the apple orchards felled and many of the old hedgerows grubbed up, the Meadows continued to serve as pasture grassland until, by 2019-20, as the tenancy came to an end, the Meadows were ploughed and put down to arable crops. Currently while the future of Bartonsham Meadows is under discussion, the land is lying fallow.

This ‘rest period’ has had some curious results, at least according to Dick Jones. He’s a member of both the Friends and Herefordshire Ornithological Club. “This year saw the return of a bird long absent from the meadows, described by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds as a ‘little brown bird larger than a sparrow but smaller than a starling’muted wows and whoops of joy!

“This bird, if it is to be described as an LBJ (little brown job), should have an A++ rating. It has quite rightly starred in poetic literature for hundreds of years and inspired Shelley, Wordsworth, Hogg, Clare, and Rossetti to wax lyrical. This bird is of course the skylark.” Dick is convinced that if the Meadows were returned to becoming floodplain meadows it would encourage the return of other absentee bird species such as lapwing, curlew and yellow wagtails. As the trilling of skylarks continued over the Meadows throughout the summer of 2021 Dick called for the bird to be given more protection. “As an ambassador for Friends of Bartonsham Meadows this bird can almost single-handedly achieve one of the Friends’ objectives in providing a socially elevating benefit to the locality: Hail to thee, blythe spirit!”

Another voice supporting the notion of turning Bartonsham Meadows into a floodplain meadow is that of the Hereford Wildlife Trust City Branch. The Branch’s Mo Burns explains how the Branch was launched in 2017 with a seminal presentation by John Clark, Herefordshire Wildlife Trust’s Development Director at that time, on ‘Wildlife conservation in Hereford City: our blue & green corridors’.

“John outlined the potential for the city to become a nature reserve in its own right: through better protecting our urban waterways, joined up green corridors, increasing tree canopies and in effect, working to enrich and connect green spaces, and all the bits in between, so animals, insects – and human animals - can more easily travel safely through them. So, we were very pleased and supportive when the Friends of Bartonsham Meadows was formed with the aim of restoring this environmentally important and strategically placed urban ‘oasis’ that has the potential to contribute so much towards our vision of a city rich in wildlife. This project, along with hopefully many others, in time will help join the city’s green and blue natural resources together and further connect people to nature through community involvement; through citizen science opportunities; through nature walks with schools; and through a multitude of other – as yet unappreciated – ways. And essentially, it will allow 95 acres of natural floodplain meadowland to regenerate and be managed as it historically always was, with the pulse of nature firmly at its heart.”

Interactive map

Rhys Ward, a student of Conservation Science at the University of the West of England, created a series of interactive maps to illustrate possible floodplain meadow and heritage restoration. This plan provides a range of ecosystem services such as flood mitigation, carbon sequestration and enrichment of biodiversity. This landscape opens up an opportunity for multiple habitats to be restored and developed: habitats such as hedgerows, orchards and farm ponds can be restored to their historical positioning along with new reed beds and designated wildlife zones. Link to interactive map: www.friendsofbartonshammeadows.org

Writers

This piece is a collaboration by the Friends Committee: Charlie Arthur, Chloe Bradman, Mo Burns, Anna Gundry, Dick Jones, Bill Laws, Jeremy Milln, Rhys Ward and Ruth Westoby.

Art contributions

Julia Goldsmith

aRISE. 60 Objects from the River Wye

“The river flows, swells and floods. Detritus and lost objects were strewn among the trees and river banks. The objects lost to the river over years are raised from the river bed and washed along in the high waters and flung back onto land as the levels subside. They have lived a life of their own, been marked and changed their form. Collectively the objects speak of escalating climate chaos. Over three walks I collected 60 objects from a 600m stretch of the River Wye by the Canary Bridge in Hereford. My installation suspended the objects at the highest levels of the river over 60 months from January 2016 to February 2021. The highest ever recorded level is 6.11 metres on 17th February 2020.”

Instagram: @juliamarygoldsmith

Sally Stone

Ananda Hill

BA Contemporary Design Craft Student at Hereford College of Arts

“I live on Eign Road and walk in the meadows most days with my dog. The prints were inspired by the plants I found growing there through spring and summer, and this further developed into finding out about their medicinal history and use in the Anglo Saxon “Nine Herbs Charm”.

Instagram: @ananda_c_hill

Stunning litter pieces discovered by Hereford College of Arts Student Sally Stone. Instagram: @sally_stone_creative

Contact details for the Friends group

www.friendsofbartonshammeadows.org/ info@friendsofbartonshammeadows.org

Head to our website and click ‘Join us’ to join our mailing list for our monthly newsletters and other regular updates.

Search ‘Friends of Bartonsham Meadows’ on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube to follow us and join the community around our growing project

- Charlie Long

In past editions of Flycatcher I have written a round-up report of our wonderful Bonkers on Botany escapades across the county. I am pleased to say they are back up and running this year, but the 2020 outings, like most other activities, were cancelled during the lockdowns. So now for something completely different. As I write this on a warm, sunny day in July, it’s hard to think back to the prolonged winter of 2020-2021 we enjoyed (or endured, depending on your opinion of snow) – those short days and long nights of continuous snowfall and sub-zero temperatures. Often thought of as a “closed” season for many ecologists (except maybe the enthusiastic bryologist or the winter migrant birder), the winter months can be a quiet period of hibernation and a time to catch up on lost sleep from a frantic spring and summer trapping various amphibians, struggling to identify sedges and analysing bat calls. By the New Year, the spring birds have not yet arrived from their warmer second homes and only a few bulbs are beginning to poke their heads up. Underground, however, is an entirely different picture; one that I was privy to observing and studying during January and February this year, at a fascinating site in Herefordshire with rather a lot of mammal holes. 152, to be precise. Our job was to work out if, how and by whom these holes were being used.

First, a bit of background on the badger Meles meles and its ecology. Badgers are members of the mustelid family, which also includes weasel, stoat, polecat, otter and pine marten – generally the long-bodied, stumpy mammals (though pine martens are pretty leggy!). Badgers are predominantly nocturnal mammals, often emerging at dusk or later, but can also be observed during the quieter hours of the early morning in the summer months. When not active, badgers usually lie up in an extensive system of underground tunnels and nesting chambers, known as a sett.

The badger is a social species; individuals live in mixed-sex social groups which are also known as clans. Each social group usually has a main sett where the majority of the group live most of the time, but there may be additional holes scattered around the territory that are used less frequently, or perhaps only occasionally or seasonally, for example during the breeding season, or where particular food resources become available. To help us work out the dynamics of a group of badgers within a site, sett status is typically classified according to the following categories:

• Main sett - large, well established sett with continuous use by a single badger clan; these setts are where cubs are normally born and reared.

• Annexe sett – typically smaller than a main sett with fewer holes, usually in close proximity (i.e. 30 – 150 m) to a main sett and linked to it by well-worn paths.

• Subsidiary sett – small sett with few entrances, often of seasonal or intermittent use, a little further from the main sett, and with no obvious connecting paths to the main sett.

• Outlier sett – usually only one or two holes with little spoil outside, sporadic use, and with no obvious paths connecting to other setts. You can imagine that badgers aren’t great at reading the manual and in many situations these definitions are blurred, depending on the habitat available.

Badgers can live in social groups consisting of two to over 30 adults, but on average the number is usually around five to six individuals, comprising a dominant breeding pair and several additional adults, yearlings and cubs. However, social group compositions can vary immensely; for example, from all-male groups to clans with several breeding individuals.

Each clan defends an area around their main sett as a territory. Territories can extend to as little as a few hectares, but may reach to over 200 ha where food resources are scarce and environmental conditions are more extreme, such as in the Scottish Highlands. In a typical lowland farmed landscape such as Herefordshire, 20-50 ha would be reasonable.

The badger is not a fussy eater and enjoys a varied and seasonal diet, although a large proportion of this is made up of juicy earthworms. They also eat other invertebrates, plants and tubers, fruit, cereals, eggs and small mammals, including rodents and hedgehogs. Badgers leave their faeces in collections of shallow dung pits; a group of dung pits forms a ‘latrine’. As well as being distributed within their territories, badgers also use latrines to mark the territory boundaries. This is of course to the delight of mammalogists, who are obsessed with poo as a means of tracking and identifying animals.

In the UK, mating can take place at any time of year but badgers, along with many other mammal species, have developed a clever technique of surviving the winter; delayed implantation, where the implantation of blastocysts (fertilised eggs) is often delayed until late winter, allows for a spring birth, when food resources become more available. This is usually followed by mating, often occurring between February and May. Usually, just one female badger in a social group breeds, although sometimes two or more may do so. Litters of two to three cubs are born in the nest, blind and hairless, normally in February. Cubs appear above ground after about eight weeks, and weaning takes place at about 12 weeks. By late summer they are usually feeding independently but can be adversely affected by drought at this time, sadly causing starvation.

So now we have swotted up and read the textbook on badgers, how do we go about finding them? A good place to start is being familiar with their tracks and signs out in the field (or woodland) and being able to distinguish these from other mammals. Below is a brief picture gallery of some field signs to look out for. Note that some of the photos feature “soft blocking” sticks; this method is commonly used by field ecologists (not required for the casual observer) and involves placing several sticks vertically and horizontally across each sett entrance and monitoring for disturbance. Sticks placed at an appropriate width (e.g. 12-15 cm) will allow smaller mammals, such as rabbits, to pass through the gaps leaving the sticks intact, while badgers will trample/disrupt them as they exit/enter the sett.

Badger holes are often approximately 25 cm in diameter, and rounded or flattened-oval in shape (Plate 1), whereas red fox Vulpes vulpes and rabbit Oryctolagus cuniculus holes tend to be smaller and are often taller than broad (Plate 2). Rabbit holes usually have droppings outside the entrance and fox earths often have a distinctive (read: nasty) odour. A word of warning: both rabbits and foxes may occupy a temporarily uninhabited badger sett, and rabbit warrens and/or fox earths may later be taken over by badgers. Other useful field signs are badger guard hairs; these are black-and-white and triangular in shape, which can be felt easily by rolling the hair between thumb and forefinger, just as you would do to feel the edges of a sedge stem (if you were that way inclined). The hairs can often be found scattered outside a hole where a badger has been sitting the previous night having a good old scratch. Footprints in mud or snow are a good field sign to get familiar with (Plate 3); as are dung pits and latrines (badger poo tends not to be coiled/twisted in shape like most other mustelid species). Look out for bedding material (Plate 4) and even tree trunks used as scratching posts which feature tell-tale claw marks. Main setts can also have ‘play areas’ where badger cubs and adults have compacted the soil through extensive use.

Plate 1 (above): Active badger sett entrance, flattened-oval in shape and free of debris with well-used, smooth path.

Plate 2 (right): Rabbit burrows are usually rounded and often taller than broad; droppings can be found near the entrance.

Plate 3: Badger footprint (only four of the five toe pads can be seen clearly in this photo). Sometimes claw marks are also visible in the print.

Plate 4: Example of bedding material, which has recently been dragged over the top of and into the sett entrance. Discarded old bedding from the previous season can sometimes be seen around the sett entrance.

Now we have a pretty good idea of what constitutes a badger sett and whether it might be active, it’s incredibly valuable (but also fun) to use motion-activated cameras in the hope of recording badgers using the holes, or displaying various interesting and amusing behaviour outside of them. Sometimes it is possible to identify an individual by its colouration, or a distinctive marking, but it’s often very difficult to determine the sex of the individual as males and females can change shape and size throughout the season.

For our study, we had enough cameras and time to place up to seven camera traps outside a range of sett entrances and monitor them for around five weeks, checking the SD cards once a week. We were careful to place the camera close enough to the hole that it would be within the triggering range to record an animal emerging out of, or entering, the hole, but not too close that its trigger delay would miss the animal completely. There are several other factors to consider in deciding how to place a camera, like making sure it is sufficiently discreet, but that it won’t be triggered by swaying vegetation… It doesn’t take long, flicking

through hundreds of video clips of a twig shaking about in the wind, to realise that a camera might need some adjustments in its positioning!

Below are a few stills from video clips recorded by our cameras. Among the vast amounts of footage of badgers sitting scratching themselves outside the sett entrance, some behaviours which usually indicate breeding were recorded: individuals dragging bedding material into the sett, and courting/play-fighting/grooming behaviour between two adults, as well as lots of scent-marking. A whole host of “non-target” species were also recorded – birds, rodents, muntjac, fox and a persistent pet cat doing the rounds of the site, which showed up on almost every camera.

Whilst we weren’t able to record any cubs emerging from the setts (they usually appear above ground in April-May), I’m pleased to report that the site is still being monitored by a group of dedicated volunteers who have since sent some fantastic stills of cubs recorded on their camera trap.

The badger is protected in Britain under the Protection of Badgers Act 1992; this legislation protects badgers and their setts. The badger is also protected under Schedule 6 of the Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 (as amended) relating specifically to trapping and direct pursuit of animals. For these reasons I have not disclosed the location of the setts studied for this article, but I would encourage anyone interested to follow that mammal trail crossing your path when you’re next out on a walk, and see where it takes you. It’s a real privilege to peer into the lives of these interesting and entertaining animals.

Clark, M. (1988). Badgers. Whittet Books Ltd. Essex.

Harris, S., Cresswell, P. and Jefferies, D. (1989). Surveying Badgers. Mammal Society. Kruuk, H. (1978). Spatial Organisation and Territorial Behaviour of the European Badger Meles meles. Journal of Zoology. London 184: pp 1-19

Kruuk, H. (1989). The social badger: ecology and behaviour of a group-living carnivore (Meles meles). Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Neal, E. & Cheeseman, C. (1996). Badgers. T. & A.D. Poyser Ltd. London. Thornton, P. (1988). Density and Distribution of badgers in South-west England: a predictive model. Mammal Review, 18: pp 11-23.

- David Taft

Some strange natural history events were noted during spring 2020 during the first lockdown induced by the first wave of the pandemic. Widely reported, the feral goats on Great Orme decided it was so quiet and peaceful with glorious weather that it was ideal to go for some days out. So they started visiting their local town Llandudno. Similar, although less dramatic events occurred elsewhere.

Was the occurrence of Snakeflies in my garden a related phenomenon? It was so very quiet in my lane high on the Malvern Hills that sitting in the sun with my elevenses took on a special aura. The adjacent woodland normally muffles sounds from a distance, making it a quiet place, but now the near silence revealed all sorts of normally imperceptible sounds. The shrews and voles, squeaking and moving through the grass on my wild flower bank leading to the front gate, were heard again for the first time in many years by my old ears. The slightest breeze, designated number 1 on the Beaufort scale (called light air) caused hardly any movement of the Ash tree leaves, but I could hear a gentle soughing sound; delightful. But, perhaps they were talking to one another. Poor chap I hear you say; he sat too long in the sun. Anyway what has this to do with Snakeflies which sound like another sun-induced hallucination?

At the time I had not heard of them either, but I have since verified that they are scientific fact not fiction. See the picture below.

During a spell of garden work after my elevenses, which necessitated rolling my sleeves-up – honestly – I felt the slightest sensation on my lower arm. I quickly looked, fearing it might be a sneaky Deerfly, Horsefly or Cleg weighing me up for a snack of blood. There I saw an exquisite looking fly with crystalline transparent wings, a long neck and a body coloured royal blue with hints of purple and bright gold cross bands between the tergites of the abdomen. Finally, and quite literally, the abdomen terminated with a long slender slightly up-curved ovipositor, making it a female whatever. She remained still apparently happy

I took the attached photos and left the open moth pot and Snakefly in the sun and went to look at my pictures. When I returned she had flown away, but three hours or so later whilst I was gardening again after lunch, she or a female relation landed on my other arm. It reminded me of the unpredictability of bus services: having lived here over 30 years this is the first and only time I have observed these insects; but twice in one day!

Snakeflies (order Raphidioptera) are represented by four species nationally, each in a separate genus, whereas in Europe there are 75 species and several hundred worldwide. They are all characterised by having a long prothorax (neck), which gives them their common name. Their two pairs of wings are similar in size and they have a thicker leading edge and a dark patch towards the outside of the wing known as a pterostigma, named after the stigmata; the wounds of the crucifixion. They rest with their wings over each other along their body in the manner of Damselflies or Lacewings.

The purpose of the long neck is not known, but the female’s ovipositor is used to lay eggs in and under crevices in bark, where the larvae live out a predatory life style eating beetle and other insect larvae. They are about ½ inch or a little longer, excluding the female’s ovipositor. This needle like ovipositor gives them their Latin name: Raphidas is from the Greek and means needle-like. The adult fly is also predatory having strong biting mandibles, for mainly munching aphids and the like. The reason that they are rarely seen is because the adults prefer to live high in trees, rarely coming down to lower parts, and only on hot days, which today was, despite being only the 20th May. There are only about 200 records on the national database for the species Atlantoraphidia maculicollis which came to see me. It is associated with Pine trees, and I have a mature Larch plantation across the road with a few Pines in the mix, which probably accounts for their presence.

Looking back, I think that whilst I had heard the trees whispering, the Snakeflies had also heard them say it was a hot and quiet day; a good one to come down from the tree tops and explore the Covid-19 world. That reminds me of another expression or two, - ‘it is an ill wind that blows no good’ or ‘every cloud has a silver lining’. Anyway, without the indirect effects of the pandemic I may never have seen these secretive creatures.

- Nichola Geeson

The Yazor Brook winds its way towards Hereford from the west side. Within Hereford it separates a little, with some sections underground, and as Eign Brook it joins the River Wye east of Bartonsham Meadows. It is a wildlife and community asset that needs some care and management to keep it healthy, because a healthy brook is full of life, and not too overgrown so that the light can’t penetrate. It should be protected as far as possible from agricultural and urban pollution, and Citizen Science projects within and beyond Herefordshire Wildlife Trust can help enormously to maintain and improve such habitats.

The Yazor Brooks Restoration Project began in 2017. For more details see: www.herefordshirewt.org/loveyourriver. With this, Herefordshire Wildlife Trust are working with the Environment Agency and the Wye and Usk Foundation, plus the practical expertise of “Bugs and Beasties” for local interventions. Some of the recent activities are described below.

One indicator of brook health is the species that live in it. So, as Citizen Science volunteers we contribute to the the Riverfly Partnership’s national monitoring programme. This means that we take regular samples, identify the numbers of a small range of riverfly species we observe, and our results are added to a national database. We return to the same sites each time and stand in the brook to carry out a three minute kick sample into a net. The contents of the net, including some gravels, sediment or weed are transferred via a bucket to a white tray. The white background helps to make the small organisms more visible. After a few minutes everything settles, and it is easier to see which small beasts are moving around.

Usually, by far the most numerous are the busy freshwater shrimps, Gammaridae. If they are few or absent, then there is often little else in the sample either. The other species we look for and record are mayfly larvae, cased and uncased caddisfly larvae, stripy-legged blue-winged olives, (Ephemerellidae), other olives (Baetidae), flat-bodied stone clinger (Heptageniidae) and stoneflies (Plecoptera). Numbers present are estimated, and those numbers generate a score. Sometimes we transfer our finds to an observation tray to observe more closely and so that we don’t double-count them. The “score” system helps to iron out any small differences in the ways volunteers record their species, and make our results comparable with others across the country. We use a standard recording form at each site so that it is easy to provide input into the national data base.

Using a lens helps us to appreciate the beauty of, for example, a cased caddis that has found tiny, sparkly gravel pieces to adorn its body; or the rippling gills of a mayfly larva. We learn that some of the species, such as the blue-winged olive, may have distinctive ways of moving. The watery world is utterly captivating! We also note other species we can recognise, from the occasional minnow to snails, leeches, and worms.

In July 2021 some of us agreed to test the water of the brook at various points on a regular basis, particularly for phosphates and nitrates. We were invited to join with the Friends of the Upper Wye https://www.fouw.org.uk/citizen-science to help establish where these nutrients enter the brook system, and how pollution hotspots can be cleaned up. As I write, it is early days but it will be very interesting to see how P and N levels may change with water levels, or seasons, or other factors. Outside of Hereford City, agricultural manure can be an issue, but farmers are encouraged to do all they can to prevent pollution, e.g. by not allowing livestock to enter the water, not leaving manure, e.g. from chicken sheds close to waterways, and not spreading manure on fields when heavy rain might wash it into water courses. Within the city, the brooks receive surface water outfalls, particularly from roads that may be contaminated from vehicles and businesses. Sometimes piping mistakes might mix domestic waste water with surface water, and introduce detergents that include phosphates. Preliminary testing suggests that unfortunately there are sources of P entering the brook across Hereford, with high levels exceeding 200 micrograms per litre found frequently. We would hope for levels less than 100 micrograms per litre (= 0.1 milligrams per litre).

During winter 2020/21 volunteer teams cleared sections of the brooks of debris and over-hanging boughs to let in more light, in collaboration with Herefordshire Council’s contractors, Balfour Beatty. We know there are otters because their spraint is seen quite frequently, and to encourage more, a “holt” that they might use was engineered. The flora along the brooks is mainly determined by Council mowing, strimming and other management regimes.

In spring and summer 2021 some of the plant species growing on long lengths of the banks were identified and listed. Although nettles, brambles, and common “weeds” can easily become abundant, there are places with surprises. On a stretch near Widemarsh Common we were pleased to note Round-leaved cranesbill Geranium rotundifolium, Water-plantain Alisma plantago-aquatica, and Water figwort Scrophularia auriculata. The Water figwort was also seen on some other stretches. The vibrant yellow of Marsh marigold, Caltha palustris, was only seen in one location near Huntington hamlet. Basic lists of plants identified so far are now held by Herefordshire Wildlife Trust’s City Branch.

Hereford does not have many parks north of the River Wye, but green spaces are very important for exercise and the mental wellbeing of city residents. So, we are delighted that Herefordshire Council have agreed in principle that the former Essex Arms playing field on Hereford’s City Link Road, which has Yazor/Widemarsh Brook flowing through it, should become an urban wetland park under management by Herefordshire Wildlife Trust. This is such an exciting project because it can provide a range of habitats to increase biodiversity along the brook corridor and floodplain. Even left as wasteland as it is now, we know it supports many different plants, animals and birds, including kingfishers. It is also hoped to include a pedestrian and cycle path across the park, to link central Hereford and the new university NMITE with the Medical Centre, the Station and student accommodation. In addition, keeping this low-lying land free from building will provide a sink to help mitigate against flood risk. Plans are currently at a very early stage, and progress will depend on funding opportunities.

So, what have we discovered about the health of Yazor Brook? There are natural changes in populations depending on factors such as time of year or brook level and flow rate, but most sites have “average” populations. The levels of the brooks are not always related to current weather conditions because there are complex underground connections, both piped and natural, and some sites are clearly affected by water from local outfalls. Any brook in an urban environment has a certain amount of pollution, but we aim to help keep that to a

minimum. Surface water washed from roads has many small polluting particles from tyres and exhausts, but reedbeds might provide a filter before water reaches the brook and reduce the impact. Some businesses or homes may be using chemicals and detergents outdoors that get washed into water courses, so our monitoring may identify any such issues. Our work is making a difference to enhancing the wildlife of the brooks, but there is still a lot to do!

- Jo Weightman

Most fungi live their lives unseen. The majority never put out a fruiting body at all. The rest form aerial bodies in a wide range of shapes including cups. Nearly all cup fungi can only be found by examining rotting vegetation with a hand lens. However, a small number are large, easily seen and very beautiful.

This site by the City Link Road, with Yazor Brook flowing through it, would make an ideal urban wetland park. Looking towards Hereford Medical Centre and the Station. (M. Burns)

From January onwards the Scarlet Elf Cup Sarcoscypha can take you by surprise. When I saw my first one I thought it was a chewed and discarded plastic ball. It is possible to see the initials, the baby cups, of this species in late December but the best time is January and February. Typically it grows on fallen, often mossy wood on the ground in damp places and at up to 6cm across is unmissable. The fungus is what is “says on the tin”, cup-shaped and scarlet inside. The outside is white and fades to a dirty cream. I am delighted to get records of a sighting but the down side for me is that there are two species, S. austriaca and S. coccinea and they look alike in the field (Plate 1). Under the microscope S. austriaca (which is by far the most common of the two in Herefordshire) has blunt-ended spores and crimped hairs on the outside. S. coccinea has rounded ends to the spores and straight hairs. Both brighten a dark winter woodland.

Sowerbyella radiculata is not as common as the Scarlet Elf Cup but is equally eye-catching, large, up to 10 cm across, bright yellow inside, white underneath and with a short white stem. I saw my first in a flower bed in front of Charles Darwin’s house at Downe in Kent when it was recorded as var. kewensis, the name given to large forms under broad-leaved trees. I recall one collection made in deep litter on a woodland path in Mallins wood near the Wye that so blended with the dry autumn leaves that most of the forayers had passed it by. There are six sites in the county for this species which is very uncommon in Britain and Europe.

In March I home in on cedar trees hoping to find Geopora sumneriana (Plate 3). This cup is more quietly coloured and half-buried so I have to walk carefully and with peeled eyes. It begins as a closed sphere just below the surface of the ground and at maturity splits open at the top revealing the pale, opalescent inside. It still grows at Hampton Court where it was first recorded in 1882. There are five other sites in the county but there are many cedars, the only host for this beautiful species. Do you know a cedar? Please look next March.

Sarcosphaera coronaria grows in a similar half-immersed manner, splitting into lobes at maturity and exposing the violet-rose hymenium (spore-producing layer) inside (Plate 4). I saw it once in Kent when in bare ground under some beech still standing after the adjacent conifer had fallen during the 1987 storm. This Red Data species, listed as Near Threatened, is mainly limited to the south of England but has been recorded in Shropshire and Gloucestershire and should be looked for here. Most British records have been under beech but with some associated with conifer.

Otidea onotica is yellow to apricot both inside and out (Plate 5). In shape it is less of a cup and more of an ear, being split on one side and often more erect. It often grows in an untidy cluster of cups and ears and can swarm in deep litter. It is common and occurs in all kinds of woodland throughout the British Isles.

On the other hand Caloscypha fulgens (Plate 6) is truly rare, being listed as Vulnerable on the GB Red List for fungi. The few records are widespread across the southern half of the country with none in Herefordshire. It occurs in litter and debris under both broad-leaved and coniferous trees. Look out for a yellow-orange cup – you may well think you have found the Otidea described above - but it is a proper cup and stains strongly blue when touched.

Many of the large cups are some unexciting shade of brown and then are likely to be one of the Pezizas. Most require examination under the microscope. Just one or two can be named on the spot. P. succosa for example when broken produces a yellow juice, and P. vesiculosa (Plate 7) grows on animal bedding, straw bales, compost and dung. This second species, which is sandy in colour, can grow quite large, perhaps up to 10cm and may develop into more of a saucer than a cup often with irregular swellings inside. Brown cups on plaster are likely to be P. domiciliana or P. varia.

Another saucer-like species is Disciotis venosa which occurs in woodlands in the spring. It is dark brown, spreads flat to the ground and is deeply veined (Plate 8). When broken, the flesh smells strongly of bleach. In Herefordshire it is an occasional find, perhaps passing unseen on account of its dark colour.

Cups have been the theme. The last species in this selection, the White Saddle Helvella crispa, is one of a suite of variations (Plate 9). Imagine a white cup raised on a tall ribbed stem. The cup falls open and back, forming a saddle. Then the former cup collapses into a wilderness of hollows and ridges. You may find this fungus in the middle of a wood, sometimes in a clearing but commonly at the edge of a woodland path as it favours a disturbed situation.

These cup-style fungi are all ‘shooters’ – they shoot their spores. The other fungi you see, whether they are toadstool, bracket, crust, coral, jelly or ‘hedgehog’ all drop their spores – a self-defeating dispersal method for a cup. So the strategy is to fire off the spores into a passing breeze. These cups, and their myriad tiny cousins, are collectively in the Ascomycetes, or Ascos for short.

- Denise Foster and David Lee; Herefordshire Bat Research Group

Introduction

Herefordshire is known to be rich in bat species and 15 of the 17 UK breeding species have been recorded in the county. In addition, a 16th species, the cryptic Alcathoe bat Myotis alcathoe, new to science in 2001 and only confirmed in Britain in 2009, has been recorded from DNA analysis of a dropping collected near Worcester and so the species is also likely to be present in Herefordshire. Thus only one of the known British breeding species, the grey long-eared bat Plecotus austriacus– at the very limit of its European range in the southern counties of England – is likely to be absent from Herefordshire.

Table 1: The bat species of Herefordshire

serotinus Serotine E.ser

Myotis alcathoe Alcathoe bat M.alc

Myotis bechsteinii Bechstein's bat M.bec

Myotis brandtii Brandt's bat M.bra

Myotis daubentonii Daubenton's bat M.dau

Myotis mystacinus Whiskered bat M.mys

Myotis nattereri Natterer's bat M.nat

Myotis species Myotis species Myo.spp

Nyctalus leisleri Leisler's bat N.lei

Nyctalus noctula Noctule N.noc

Nyctalus species Nyctalus species Nyt.spp

Pipistrellus nathusii Nathusius’ pipistrelle P.nat

Pipistrellus pipistrellus Common pipistrelle P.pip

Pipistrellus pygmaeus Soprano pipistrelle P.pyg

Plecotus auritus Brown long-eared bat P.aur

Rhinolophus ferrumequinum Greater horseshoe bat R.fer

Rhinolophus hipposideros Lesser horseshoe bat R.hip

Baseline Bat Atlas

In 2014, following a meeting of interested parties held at the Herefordshire Biological Records Centre (HBRC), it was decided that an attempt should be made to produce a county mammal atlas to cover the first two decades of the millennium. Atlases of the six mammalian orders were to be prepared individually and in June 2016 the present authors

(DF and DL) produced the first of these - a baseline atlas for the Chiroptera, compiled from records available up to the end of 2015, to inform the existing state of bat records in Herefordshire. Distribution maps were produced for individual bat species at a resolution of 1km (based on Ordnance Survey ‘monad’ grid squares). The main maps showed the distribution of records post-millennium (2000-2015) with earlier records (1960-2000) mapped separately, for comparison.

At that time a total of 12,406 records were available from HBRC and a further 1,144 records were obtained from the National Biodiversity Network (NBN) – a grand total of 13,850 records. Of these 12,746 were dated 2000-2015 with only 1,104 (8%) from the period 1960 to 2000.