He re fo rdshire Wildlife Trust

October 2021

November 2022

Herefordshire Wildlife Trust

Editorial Peter Garner

Chair’s Report Alison Mclean

Obituaries Edward Clive

The Restoration of Berrington Hall Pool Will Watson

A Wilder Herefordshire: Local Wildlife Sites Sam Price

Goat’s-Beard Hybrid Hillary Ward

Notes from my Garden David Taft

The Wye in Crisis Andrew Nixon

Regenerative Farming Methods Richard Thomas

New Arrivals in Herefordshire 2022 David Taft

Elm trees in Eastern Herefordshire David Taft

Hedges in Herefordshire Tony Norman

Celebrating Seven Years of Successes in the Lugg Valley Andrew Nixon

All views and opinions expressed in The Flycatcher are the views of the author of each individual article and are not necessarily those of Herefordshire Wildlife Trust. Photos attributed to author of the article unless otherwise stated.

Editor: Peter Garner

Cover illustration: Dawn Cooper

Herefordshire Wildlife Trust, Queenswood Country Park & Arboretum, Dinmore Hill, Nr Leominster, Herefordshire, HR6 0PY enquiries@herefordshirewt.co.uk www.herefordshirewt.org

Herefordshire Wildlife Trust is a registered charity no. 220173 and a company limited by guarantee no. 743899

From 1st December 2022

Monty Don

President and Vice Presidents

President Mr E M Harley OBE, Lord-Lieutenant of Herefordshire Vice Presidents Mr T Davies

Mrs B Winser

Mrs Marie Clarke

Mr Roger Beck

Debbie Beaton

Jake Bharier

Joseph Cole

Richard Cryer (Treasurer)

Mike Dawson

Jacob Dowling

Jim Hardy

Alison McLean (Chair)

Jane Seabrook

Mr M Williams (Vice Chair)

Messrs Gabbs, 14 Broad Street, Hereford, HR4 9AP

Mr Peter Kirby M.R.I.C.S., Messrs Sunderlands and Thompsons, Offa House, 2 St. Peter’s Square, Hereford, HR1 2PQ

Once again the Trust extends grateful thanks to all its volunteers who have worked hard to deliver a vast amount of work to help conserve the county’s wildlife. Support ranges from help to manage and warden nature reserves to providing administrative support in the office and fundraising, from running events to developing and delivering publications and from monitoring wildlife to contributing to the many and varied committees and groups. Thank you all. Yet again the Trust would not have been able to achieve as much as it has during the past 12 months without your help.

Jamie Audsley

Chief Executive

Claire Spicer Head of Conservation

Sarah King Senior Conservation Projects Officer

Gregory Leighton Farm Advisor

Charlotte Bell Severn Treescapes Woodland Advisor

Sam Price Nature Recovery Network Officer

Holly Thompson Wildlife Survey Trainee

Toby Fountain Wildlife Survey Trainee:

Esther Clarke Nature Reserves Team Manager

Lewis Goldwater Reserves Officer

Trevor Hulme Reserves Officer

David Hutton Reserves Officer

Pete Johnson Reserves Officer

Paul Ratcliffe Reserves Officer

Laura Beardsmore Conservation Volunteer Support Officer

Amanda Eckley Finance Manager

Aleksandra Mikula Finance Officer

Natalie Sidnell Operations Officer

Laura Matty Business Administration Apprentice

Liz Speake Fundraising Manager

Frances Weeks Communications and Marketing Manager

Chris Jones Membership Development Officer

Debbie Bean Retail Manager

Nicky Davies Ledbury Shop Assistant

Molly Reese Ledbury Shop Assistant

Cathy Dentist Hereford Shop Assistant

Julia Morton Engagement Manager

Hannah Dunn Nature Tots Coordinator

Caroline Braid WildPlay Engagement Coordinator

Alithea Waterfield Engagement Support Officer

Tracy Price Community Organising Officer

Max Smith

Queenswood and Bodenham Lake Manager

Liz Bunney Visitor Centre Assistant

Patricia Doree Visitor Experience Assistant

I’m not the best at adapting to modern ways, so the decision that The Flycatcher should now be published “online” initially left me feeling somewhat disturbed and unhappy. However, I was soon able to see the many advantages, and I felt completely in favour when it was explained to me that those who wished to have the usual hard copy format could do so for the very reasonable cost of £4. So, if you have a collection of past copies and have sufficient space on your bookshelf you can order a published copy in the same format as previous years.

I hope this new arrangement will allow those of you who like to maintain a collection of past copies (perhaps as a source of reference) to do so. Whereas, I have been assured that more members are likely to read flycatcher on-line, and the Trust will be saved the cost of publishing and postage. I would welcome a response from members.

Publishing The Flycatcher online is a minor change for the Trust compared with the changes in personnel. We must all be grateful for the wonderful contribution to the work of Herefordshire Wildlife Trust made by Helen Stace, Andrew Nixon and Sophie Cowling, but such dynamic people will always move on, and we can be reassured by the fact that the enhanced reputation of The Trust has attracted wonderful replacements such as our new CEO Jamie Audsley.

Several of the articles in this edition have been written by those who have contributed before. I am so grateful to David Taft who has once again written, “Notes from my Garden”. I think, in a few years’ time, we should encourage David to have this sequence of articles published. He writes so well, describing many aspects of wildlife that many of us could experience if we researched our everyday observations more thoughtfully. For this edition he has also contributed two more articles; one about Elm trees, and the other records the observation of two interesting insect species; one new to Herefordshire and the other only previously recorded on The Doward.

Will Watson is another frequent contributor to The Flycatcher and this year’s article about Berrington Hall Pool will, I’m sure, considerably increase their 2023 visitor numbers. It is helpfully informative, wonderfully descriptive and beautifully illustrated: I was very excited to receive it from Will.

Tony Norman is another quite regular contributor to The Flycatcher, and to be able to include his article on hedges with its conservation theme is very exciting.

I mentioned earlier that Andrew Nixon was leaving the Trust, but as a farewell he has written two articles for this edition of The Flycatcher. We wish him well with his new post with Natural England. He has written about “The Wye in Crisis”, which unfortunately, is very disturbing. However, unless these problems are brought to the attention of those of us who care about such things, little is likely to change. I feel it is typical of Andrew to include a second article full of positivity - “Celebrating Seven Years of Successes in The Lugg Valley”.

Hilary Ward’s well illustrated article about Goat’s-beard and a very rare hybrid was a fascinating surprise to me, even though I have spent years recording the plants of Herefordshire.

Two further articles could not be more in tune with the aims and objectives of

Herefordshire Wildlife Trust. Sam Price describes our Local Wildlife Sites and Richard Thomas has explained how farmers can achieve a positive future for the natural environment with “Regenerative Farming Methods.”

While putting together the articles in this edition of The Flycatcher I was hugely encouraged to feel very optimistic about the countryside and environment of our beautiful county.

This is my first introduction to this excellent publication as the new Chair of Herefordshire Wildlife Trust. I took over from Brian Hurrell earlier this year after his six year tenure as Chair amid a total of ten years as a trustee. I want to pay tribute to Brian’s tremendous contribution to the work of the Trust. He has provided calm stability in some turbulent times as well as a wise and consistent focus on achieving the best outcomes for wildlife in our county.

In this year we have also said goodbye to our valued CEO Helen Stace (to a very busy retirement!). There is not room here to list Helen’s many achievements. However, I just want to say that as a knowledgeable and committed conservationist and as a passionate advocate for the natural world, Helen has been an inspiration to members, staff and volunteers as well as an accomplished and thoughtful leader of the trust for four years. She will be greatly missed.

In her place I am really pleased to say that we have recruited Jamie Audsley, who comes to us from the RSPB and started in post at the beginning of August. He has already got to grips with starting a refresh of our strategy to ensure we are ready for the challenges and opportunities ahead; and to make sure that we are doing all we can to contribute to the national Wildlife Trust goals of having 30 percent of land managed for nature by 2030 and one in four people taking action for nature too. You will no doubt be all hearing more from Jamie in the near future!

As well as saying goodbye to Brian Hurrell, three more Trustees come to the end of their terms of office this year, including Peter Garner (editor of The Flycatcher), Will Bullough (woodland expert and dedicated naturalist) and Pete Ford (our former Treasurer). We thank them all for their tremendous contribution to the work of the Board over many years and their uncompromising commitment to the general work of the Trust. We look forward to their remaining firm friends of the Trust in the years ahead.

I want to pick out just a few of the achievements of the Trust in the last year. You can read more about what we have been up to more comprehensively in the Annual Report which is available on our website.

We were gifted a new nature reserve – Weobley Wildlife Meadows – and the local community have been greatly involved helping with many improvements, including planting an orchard and improving the sward.

We purchased Norton Wood Orchard with the support of the Mumford Trust. This reserve includes remnants of several small orchards and five ice age ponds!

Wildflower seed and green hay harvested from various sites have been strewn at Oak Tree Farm, Common Hill and Littley Coppice.

At Bodenham Lake we installed a new easy access hide and the new island attracted nesting birds including ringed plover and an oystercatcher.

Last year 590 volunteers donated 1,460 hours to supporting wildlife.

With new recruits we now have 57 reserve wardens.

We have resumed our programme of walks and talks, public events and children’s activities. And we have launched Team Wilder, building stronger connections between local community groups taking action for nature.

Our membership now stands at over 6,700 members – the highest ever! And for much of this year we have been the fastest growing Wildlife Trust in the country in terms of membership. Look ahead, there are many challenges – particularly the state of our rivers, the continuing under-resourcing of environmental agencies and the threat of further de-regulation of environmental controls. However, there are also many opportunities. Under the new agricultural system, the transition to paying farmers for public goods will itself stimulate new markets for water, carbon, nutrients and biodiversity.

The threat to the natural world sometimes feels overwhelming, but wherever I go I hear people’s care, concern and commitment to action. What could be more powerful?

I hope you enjoy this latest edition of The Flycatcher.

In recent months Queenswood Arboretum has lost two longstanding and exceptionally knowledgeable advisers in David Davenport and Lawrence Banks. Both gave freely of their time and expertise and made very significant contributions to the arboretum.

David Davenport CBE DL, who died in June aged 87, was the owner of the Foxley Estate, only a few miles to the south west of Queenswood and famous as a birthplace of the picturesque movement in landscaping. After a first career in the Grenadier Guards, David took over the estate, continuing and improving its tradition of producing very high quality timber. His experience as a forester led to him being President of the Royal Forestry Society in 1989-91 and later a recipient of its gold medal. He was an advocate of high pruning to improve tree quality and he became UK agent for Silky Saws, known as Silky Fox in this country, after the name of his estate.

He was a trustee of the Queenwood Coronation Fund for 40 years and he made a huge contribution to the planting and management of the arboretum in that time. He was exceptionally tall, with a very gentle manner, and his advice was delivered in a characteristic soft voice that was none the less effective for that. We send our condolences to his widow, Lindy, and his three children. His son, James, is continuing the family involvement as a current trustee of the Coronation Fund.

Lawrence Banks CBE DL, who also died in June, aged 84, was the owner of the renowned Hergest Croft gardens at Kington. He inherited from generations of plantsmen but with his wife Elizabeth, the renowned garden designer, he maintained and developed Hergest into one of the greatest woodland gardens in the country. He was a lifelong supporter of the Royal Horticultural Society and as its treasurer he drove major changes. He was a recipient of their Victoria Medal of Honour, the RHS’s highest award to horticultural experts and limited to as many members as the years of Queen Victoria’s reign.

Lawrence was one of the most knowledgeable plantsmen of his time and he possessed a superb memory for trees. His wide friendship among tree enthusiasts globally, particularly as a key leader of the International Dendrology Society, was very helpful for Queenswood and led to its being one of the only IDS accredited arboreta in the UK. We send our condolences to his widow and two sons, who continue to run Hergest Croft.

The National Trust property of Berrington Hall and its park and pool are located four kilometres to the north of Leominster on the western edge of the Herefordshire Plateau; the largest and highest of the county’s isolated flat topped hills. To the west of the pool are the Herefordshire Lowlands. The Ridgemoor Brook is situated 500 metres to the west within a wide floodplain which was formed before the last glaciation by the proto-Lugg and Teme1. 300 metres east of Berrington Hall there is a wooded ridge, known as Long Wood, which forms the eastern boundary to the estate. The ridge is composed of harder sandstone of the St Maughan’s Formation from the Early Devonian Period. Three springs emanate from the surrounding higher ground. There are at least two small streams running through the park.

In the 1770s, Thomas Harley, who acquired the estate, appointed the famous landscape architect Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown to lay out the park with spectacular views to the west towards Wales and the Black Mountains2. It was his last commission. The pool was created in a natural hollow on the lower slopes of the plateau. The presence of fenland peat suggests that there was probably a marsh and possibly smaller pools present before its construction. Capability Brown constructed a five metre high dam to the west so that water could be impounded from the small streams which he had piped and directed into the pool. Some of the spoil from the construction of the pool was used to level the land to the north to create an open flowing vista from the Hall to the pool. The pool is 360 metres long by 220 metres wide and covers an area of 6.6 hectares (14 acres). Two islands were created, the round Main Island, and the smaller Rat Island to the north-west. The islands cover an area of about 2.1 hectares and both are wooded with tree canopies extending over the water. The total area of open water is 4.5 hectares and as such it is one of the largest areas of open water in the county. From the direction of the Hall the viewer is presented with the appearance that the pool is narrower towards the south. The pool was constructed so that the Hall is reflected in the water when viewed from the south.

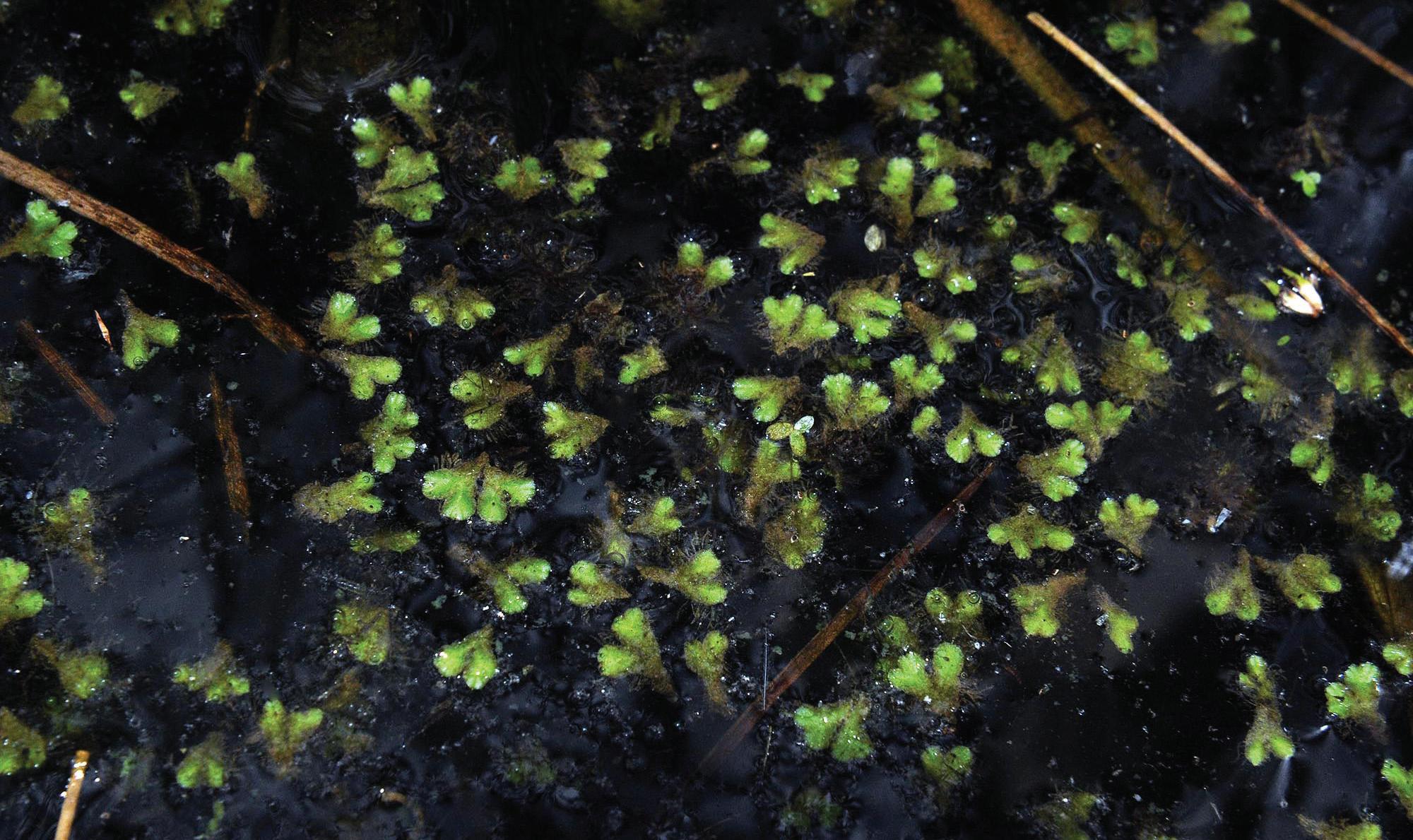

In 1969 the pool was designated as a Site of Special Scientific Interest on account of it being one of a very few sizeable areas of open water in Herefordshire and because of its large heronry, at the time one of only two such breeding sites in the county3. The pool also has relatively rich and diverse flora in comparison with other lakes in Herefordshire. 46 species of aquatic plants were recorded during a detailed survey in 20124. According to the scoring system developed by the Freshwater Habitats Trust, it places the pool in the very high category for UK still water bodies5. The pool has several distinct aquatic plant communities. In the open water there are beds of native White Water-lily Nymphaea alba covering large areas of the pool. This is a local species in Herefordshire with just 29 records6. Around the margin, swamp vegetation has developed to the north and south of Main Island. The swamps are dominated by Lesser Bulrush Typha angustifolia with occasional Reedmace Typha latifolia. Branched Bur-reed Sparganium erectum is locally abundant especially along the east margin. Yellow Iris Iris pseudacorus is occasional in occurrence. On the upper margin of the pool is a zone of marsh vegetation which is broadest to the south where there is locally abundant Reed Canary Grass Phalaris arundinacea, Great Willowherb Epilobium hirsutum and Meadowsweet Filipendula ulmaria. Notable plants include Lesser Waterparsnip Berula erecta, which is rare in the county and the uncommon floating liverwort Ricciocarpus natans which was found to be plentiful in 2012 among the swamp margin to the north of the pool. This was the first county record for over 75 years.

The diversity and richness of the site’s flora is also matched by its animal life. A bat survey carried out the Herefordshire Mammal Group, under Natural England licence, in 2016 found 12 species of bat within the park with the main bat activity centred around the pool7. A significant finding was that of three Bechstein’s Bat Myotis bechsteinii roosts with the largest roost in a tree on Main Island; presence of juvenile bats demonstrated that a maternity colony was also present. Bechstein’s Bats are one of the rarest bats in western Europe. It is classified as near threatened and is on the IUCN Red List.

103 bird species were recorded around at the pool over a 20 year period by British Trust for Ornithology8. In addition to Grey Heron, Little Grebe, Moorhen, Coot, Sedge Warbler, Reed Warbler and Water Rail are regular breeders. The amphibian population has not been well studied but we know from seeing large shoals of Common Toad tadpoles in 2022 that they breed successfully in the pool. Up to 50 Common Frog spawn clumps have been seen in the pool at any one time. Six Smooth Newt tadpoles Lissotriton vulgaris were netted in August 2012; the relative population size of these amphibians within the pool is presently unknown. In 2012, 63 species of aquatic invertebrates were recorded over several visits. This included 20 species of water beetle which are all classed as Lower Risk Least Concern9, 14 species of aquatic bug, 13 species of dragonfly, six species of mollusc, four species of leech, one species of flatworm, one species of mayfly, one species of alderfly, one species of cranefly and one species of caddisfly. At least 20 Red-eyed Damselfly Erythromma najas were seen mainly basking on White Water-lily pads in August 2022. Also significant are the large numbers of common species of dragonfly present. In July 2012 over 100 Common Blue Damselflies Enallagma cyathigerum, and over 25 black-tailed skimmers Orthetrum cancellatum and, on 24th September, 20 common darter Sympetrum striolatum were present. The site is of local importance for Odonata. According to the scoring system developed by Freshwater Habitats Trust the recording of 63 species places the pool in the very high category for aquatic invertebrates; this is because more than 50 species were recorded at the site.

In spite of the relative richness of the pool in the early 2000s there were clear signs that all was not well. Concerns were expressed about the water quality as the roadside drainage to the A49 main trunk road had been directed into the pool. This would have resulted in chemicals toxic to the wildlife entering the pool. In 2012 the Highways Agency re-routed the roadside drainage away from the pool.

There were also large numbers of Common Carp Cyprinus carpio in the pool at the time with few, if any, other fish species present. Common Carp have been cultivated and moved around the world for hundreds of years and have been introduced into the pool. They are predatory on a large number of aquatic invertebrates and have a negative effect on species diversity and can cause local extinction of aquatic invertebrates. They also stir up the bottom sediment leading to increased turbidity particularly during the summer months when they are active.

The other main issue was the spread of the Lesser Bulrush swamp. It was noted that it was spreading further out into the open water covering a greater area. In the south-east of the pool the channel between the main island and shore is very narrow and to the east of the island this swamp vegetation has closed the channel completely. There was also a very broad swamp to the north-east of the pool which was nearly contiguous with the island. The cause of its more rapid spread was the gradual silting up of the pool. This meant that water wasn’t able to circulate around the island as had been planned. If left, the swamp vegetation would soon cover a greater area than that of the open water.

The numbers of breeding Grey Herons on the main island had also declined since a high of 20 to 30 breeding pairs in the 1990s, to a low of just eight breeding pairs in 2012. The exact cause of the bird’s decline is not known but it is likely to be connected to these significant management issues (see below).

The majority of the fish were removed by seine net in November 2012 by Furnace Mill Fisheries with over 75 large Common Carp being taken out, and used for restocking elsewhere after full health checks. The average fish weight was 5½ pounds or 2.4 kilograms. The heaviest fish was 13 pounds in weight or 5.9 kilograms. This showed that the majority of fish present were too large to be caught by the herons. This imbalance in the fish population could have contributed to the heron’s breeding decline. In order to redress the balance Roach Rutilus rutilus, Rudd Scardinius erythrophthalmus, and European Perch Perca fluviatilis, all native species, were added to the pool.

It took a further seven years to tackle the issue of the invading swamp vegetation. The National Trust finally managed to obtain funding from the National Highways through their Environment and Wellbeing Designation Fund. Berrington Hall Pool was dewatered and de-silted between November 2021 and February 2022 with the work being carried out by WM Plant Hire Ltd. at a cost of £260,000. The work was carried out with consent of Natural England and had been preceded by a water and sediment analysis carried out by ADAS, and an updated copy of the management plan10. During the de-silting approximately a third of swamp vegetation was removed and this included the unblocking of the eastern channel around the island. In total, many cubic metres of silt were removed and deposited in an area of plantation in Moreton Ride mainly below the dam. During the de-watering, all remaining large carp were removed by Furnace Mill Fishery, some for restocking. The de-silting was a major operation and at its peak there were four diggers in action each with a 30 metre reach.

It was thought that the bird population might suffer. 38 bird species were recorded between November 2021 and February 2022. When the water was drawn down below the levels of the swamp, the fish had nowhere left to hide and were easy pickings for the birds. Great White Egret was seen on five separate occasions and sometimes up to five Grey Herons were present on the pool taking advantage of this situation, Kingfisher also took advantage and was also a regular winter visitor. One of the strangest things witnessed was Mute Swans feeding on young fish fry. The Water Rail stayed put and was seen foraging on the bare mud.

The exposed mud also attracted a pair of Green Sandpipers which were present for the duration of the work. As the water was drawn the Swan Mussels Anodonta cygnea started coming to the surface in order to breath. It was a great surprise to see 100s of them along the margin of the pool as we hadn’t been aware of their presence before. They are the largest freshwater bivalve in the UK, and those at Berrington didn’t disappoint with the largest reaching 20 cm in length.

We managed to rescue 70 of them, returning them to the section of the pool which had been de-silted. Dozens of the mussels had been predated with evidence of canine teeth along the shell margin; the likely predator was Otter Lutra lutra which also left their tell-tale track signs across the mud. The de-silting work was completed in late February 2022. As if on schedule we then had steady periods of rain and it was amazing how rapidly the pool filled up just in the space of a couple of weeks. In February in time for the heron breeding season the pool was again restocked with Roach, Rudd, Perch and this time also Pike Esox lucius. The management work didn’t end there: following advice from an aftercare plan11 the bare gaps along the bank where the diggers loaded silt onto dumpers had to be filled with aquatic plants. The aquatic plants were obtained from the silt of settling lagoons in Moreton Ride which had began to sprout with all manner of native aquatic plants. Yellow Iris Iris pseudacorus was favoured for gap filling as it won’t spread across the open water like the Bulrushes and Branched Burreed which were not replanted in gaps. Water Mint Mentha aquatica, Brooklime Veronica beccabunga and Pink Water Speedwell Veronica catenata were also favoured for gap filling. It is hoped as a consequence of careful replanting and control measures there will be less aquatic plant management needed in future.

The pool has recovered remarkably quickly. For the first time in decades (possibly living memory) the water actually cleared. There was a risk with all the rich organic sediment in partial solution after de-silting that the pool would be taken over by algae. In the event we saw an increase in algae on the base in June but this declined in a couple of weeks.

What happened next in July and August was a botanical transformation. The entire base of the pool was colonised by submerged aquatic weed. First to appear was stonewort (probably Chara vulgaris) around the margin, then Fennel Pondweed Potamogeton pectinatus, Curled Pondweed Potamogeton crispus and Hornwort Ceratophyllum demersum appeared in great abundance. There was also frequent Horned Pondweed Zannichelia palustris a nationally declining species of aquatic plant. Seven submerged species were noted in total, as well two newly recorded species; Broad-leaved Pondweed Potamogeton natans, and Unbranched Burreed Sparganium emersum

Unfortunately, in addition to the submerged species spreading, the emergent plants also began to march across the pool including in areas which had only months before been desilted. Branched Bur-reed was the main culprit; no doubt it was the clear water conditions that favoured this burst of flora activity. The decision was taken, again with Natural England consent, to apply contact herbicide to these emergent plants which are growing in the wrong place.

So what future plans are there for the pool? The intention is now to maintain the pool in good condition and not allow the management to get behind schedule. So, regular smaller scale management will be carried out on a regular basis to maintain the pool in optimum condition. Ideally we will rely on hand management techniques; such as the removal of emergent species from the margin where and when they threaten to spread into the open water, but if that is not effective then herbicide treatment may again be considered. The other thing we want to continue is the biological monitoring and the water analysis of the pool. A detailed biological survey was not carried out in 2022 because it was thought that the pool would still be recovering. However, a full survey is planned for 2023. It will be interesting to see how these results will compare with the surveys carried out in previous years.

1. Brandon, et.al (1989). Geology of the country between Hereford and Leominster. British Geological Survey. Her Majesty’s Stationery office.

2. National Trust (2022). Berrington Hall website. Available at: https://www.nationaltrust. org.uk/berrington-hall(accessed August 2022).

3. Natural England (1969). Berrington Hall Pool, SSSI Citation.

4. Watson. W. R. C. (2013). Berrington Hall Pool Management Plan and Biological Survey 2012. Unpublished report commissioned by the National Trust.

5. Williams, P.J., Biggs, J., Barr, C.J., et.al. (1997). Conservation assessment of wetland plants and aquatic macroinvertebrates. Pond Action and The Institute for Terrestrial Ecology.

6. Anon. (February 2001). An Atlas of the Vascular Plants of Herefordshire. Herefordshire Botanical Society.

7. Foster, D & Lee, D. (2016). Berrington Hall 2016 Bat Breeding Report. Herefordshire Mammal Atlas, Herefordshire Mammal Group.

8. Cooke, T. (2021). BTO volunteer conducting the Wetland Bird Survey. Personal communication. 21st March 2021.

9. Foster, G.N. (2010). A review of the scarce and threatened Coleoptera of Great Britain Part 3: water beetles. Species Status No. 1. Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservation Committee.

10. Watson. W. R. C.2021. Berrington Hall Pool Management Plan 2021. Unpublished report commissioned by the National Trust.

11. Watson. W. R. C.2022. Berrington Hall Pool AftercareManagement Plan 2022. Unpublished report commissioned by the National Trust.

‘A Wilder Herefordshire’ began in Summer 2021 and runs until 2023. It includes a number of projects which all contribute to nature’s recovery across the country, primarily through increased and improved surveying, monitoring and data collection. This project is grant funded through the Green Recovery Challenge Fund. The Local Wildlife Sites team is one of the sub-projects encompassed by ‘A Wilder Herefordshire’.

Local Wildlife Sites (LWS) are areas of land that are especially important for their wildlife. They are some of our most valuable wildlife areas in the UK. LWSs in Herefordshire reflect the county’s local character and distinctiveness and, since first selected in 1990, have played an important role in maintaining and enhancing wildlife in the county by supporting a rich diversity of habitats and providing networks and corridors across our landscape.

LWSs are identified and selected locally by partnerships of local authorities, nature conservation charities, statutory agencies, ecologists and local nature experts, using scientifically-determined criteria and surveys. Their selection is based on the most important, distinctive and threatened species and habitats within a national, regional or local context.

LWSs are found on public and private land and include a vast range of semi-natural habitats from species-rich grasslands, ancient woodlands, fens and orchards to rivers and stream

corridors. They complement the existing statutorily protected sites and form the core of a resilient ecological network.

There are close to 750 LWSs in Herefordshire, many of which have not been re-surveyed since their initial selection. The role of the LWS team within the project is to investigate the condition of these sites and to re-establish their pertinent infrastructure and systems within the county.

The LWSs team consists of one full time member of staff, the Herefordshire Wildlife Trust’s Nature Recovery Network Officer Sam Price (leading the project since October 2021 until it ends in March 2023), and two part-time Wildlife Survey Trainees Holly Thompson & Toby Fountain (with us since February 2022 to February 2023).

Given the state of the LWS system at the start of the project, there was a significant amount of desk-based work to accomplish before the beginning of the surveying season. While the LWS database was made available to us, no ownership information was available. Thus the first action of the project was to gather appropriate resources and use those available to identify the ownership and management of the sites in order to be able to contact land owners to obtain permission to survey. Simultaneously, an appropriate storage system was created on the Herefordshire Wildlife Trust computer system in order to store all generated data for each individual site.

Once the Wildlife Survey Trainees began in February, their initial role was to assist the project’s Wildlife Monitoring & Data Officer Charlotte Bell in the digitization of historic records kept by the Trust in an effort to modernise our data storage solutions.

In April, they undertook some desk-based training in the use of the Geographic Information Systems (GIS) being used by the project and plant identification training was arranged with county recorder Stuart Hedley for the whole team, to prepare for the imminent survey season. With their training complete, the team set about contacting landowners, arranging surveys and getting out on site. The first surveys started later that month.

Common spotted orchid captured in a quadrat (c) HWT

Attempts have been made to develop a surveying form, using the ArcGIS Survey123 app, in order to follow lessons learned by Gloucester Wildlife Trust, enabling surveying to be done by skilled volunteers in the future and enabling data to feed directly into GIS systems and reduce the amount of digitizing needed. This is currently a work in progress as the survey form is being actively refined as the team get out and survey.

To date, the surveying has focussed on grassland sites as these are some of the most at-risk sites in Herefordshire from unsympathetic management. We are now beginning to diversify into woodland surveys as the grassland season comes to a close. Writing in mid-July, we have so far visited 26 sites and are scheduled to have visited a total of 52 by the end of August. In parallel, our partner organisation, Herefordshire Meadows, is also undertaking to survey and report on a number of potential new grassland LWSs, which will be submitted for assessment

Concurrently, we have also been working on re-establishing the LWS Panel and LWS Partnership within the county. The role of the LWS Panel is to be the decision-making body regarding the creation and development of selection criteria, the evaluation of new and existing sites as well as to advise on national guidance, surveying and monitoring. The role of the LWS Partnership is to support the surveying of existing and potential LWSs and to communicate their importance to the wider community through their stakeholders.

The first meeting of the re-established LWS Panel was held in May, persisting since on a monthly basis to evaluate the re-surveyed sites and discuss the selection criteria that are being re-examined and developed to match the contemporary needs of the system. The re-established LWS Partnership is due for its first meeting in September.

Over the winter months, as the surveying quietens down, the LWS team will be focusing on the development of management plans for the sites surveyed as well as liaising with the landowners of those sites in order to submit them to the Habitats Index. The LWS Panel will be evaluating the developed criteria against all the survey reports collected in order to adjust the criteria thresholds to an appropriate level to reflect the natural character of Herefordshire.

Holly Thompson completing a survey (c) HWT

As a part of “A Wilder Herefordshire”, our project feeds into the development of Herefordshire’s Nature Recovery Strategy. The data that is gathered through the resurveying of LWS will also be ultimately used to feed in to the Nature Recovery Network map and through this we are also able to encourage and support landowners and managers in improving the management of their LWS for the benefit of nature and the communities that may be involved with them.

Through the engagement the project generates with different organisations and individuals, we hope to foster the interest and buy-in that will be necessary in order for the LWS system to survive on its own without our intervention as the ultimate goal is for the work we do to outlive the timeline of the project and continue on without our intervention. The training that the Wildlife Survey Trainees receive through this project aids in enabling more individuals to gain the experience needed to break in to the conservation industry in these challenging times. Empowering local people (both Holly & Toby live within the county) to work for the benefit of their local area is greatly beneficial as local knowledge and personal buy-in go a long way in enthusing others about the work that we do.

We live on the Herefordshire/Worcestershire border in West Malvern and this year I made an exciting discovery in the garden – a hybrid Tragopogon (a cross between T. pratensis and T. porrifolius) referred to as T. x mirabilis.

The native Goat’sbeard (Tragopogon pratensis) grows in our meadow and has seeded into the garden. Other common names include Meadow Salsify and JackGo-To- Bed-AtNoon (this refers to the plant’s habit, on sunny days, of closing the flowers by noon).

Some years ago I acquired a plant of Purple Goat’sbeard or Salsify (T. porrifolius). This species is a native of the Mediterranean region but it is widely naturalised in temperate Europe.

The hybrid has an attractive flower and like its parents is good at attracting insects.

A paper published in AOB Plants. 2015 states that hybrids between Tragopogon pratensis and T. porrifolius have been studied in experimental and natural populations for over 250 years. During this time it seems that the hybrid has not established as a new species. Records also show Tragopogon species seed from Mid-Roman middens in York, dated between 150 and 200 AD. Carl Linnaeus experimented with crossing these two species in 1759. The table below shows the variety of colour and form which can arise.

The Botanical Society of Britain and Ireland (BSBI) Atlas shows three records for Hybrid Tragopogon in 2020 onwards and 25 between 2010 and 2019. Prior to 2010 there were less than 30 records. Most hybrids were found in the Southeast of England with occasional records from other parts of the country and a couple in Wales. No records from Scotland or Ireland.

A paper published by researchers in the Czech Republic refers to studies of a distinct population of Hybrid Goat’s-beard in and around Roudnice, in the north part of Central Bohemia, which is perennial (unlike the biennial parents) and fertile. It is thought that this population has been known for 100 years.

It is doubtful whether ‘my’ hybrid will display the features of the Czech plants but I will try a couple of experiments: 1) leave this year’s hybrid in situ and see if it is perennial; 2) collect seeds and see if they germinate and grow on into hybrids

It is possible new hybrid plants will appear here next year from a crossing between T. pratensis and T. porrifolius. I will certainly continue to grow both parents.

Last year I concentrated on hoverflies, an attractive group of insects which appear in early spring and continue through summer into autumn. The pandemic had forced me to spend more time at home and this had given time for an intense study of smaller garden wildlife. It revealed a much greater diversity of insects than I had imagined, existing here right on my doorstep. This discovery included more than just hoverflies and so I shall also write about some of the other attractive and interesting species.

I have previously mentioned that in recent years I have started to see various insects for the first time, which appears to be as a result of climate change, especially the generally milder winters. One such example, which appeared again in 2022, is the fascinating and exotic Humming-bird Hawk-moth (Macroglossum stellatarum). The photograph shows how whilst hovering in flight, it has rolled out its proboscis to suck the nectar from the Buddleja.

The depicted specimen shows the first one that I recorded in the garden, and although I have since seen them every few years, with one this summer; this is the best picture I have managed. The latest UK published moth atlas (up to 2016) shows the distribution of each moth species, indicating that over 1/3rd of all records for this species have occurred since the millennium. It is known that in some winters, along the south coast of England, it can hibernate and survive appearing in warm spells in every month. Normally it arrives from April onwards, as a migrant from the Mediterranean region spreading north and west into central Scotland and even into Ireland. It is worth noting that unlike our other native Hawk-moths this is unusual in being active by day, although it also comes to moth lights at night like the rest of its nocturnal relatives.

I would like to try to convince you to take a more interested view of beetles, many of which are handsome creatures when looked at closely, often with bright iridescent colours. Whilst

many are small like the pollen-beetles, there are enough larger species, so easily seen when they are on flowers eating nectar; especially the large white flower-heads of umbellifers like Cow Parsley, and later in the year Wild Carrot.

A group of beetles known as the longhorns is one of the most distinctive and commonest groups, with several species likely to be seen in gardens. The term longhorn refers to the antenna, which are often as long as the body and carried projecting forward from the head in a V-shape.

A regular garden visitor and a species that lives up to its name is the Black-and-Yellow Longhorn Beetle (Rutpela maculata). Its larvae develop in deciduous deadwood, and so adults are often found near wooded areas and can be seen from May until September. The 18mm long (3/4 inch) adults are often seen on umbellifers and brambles, and when on umbellifers they seem to become pre-occupied, enabling close inspection.

The yellow and black pattern of the wing cases (elytra) is variable and can cause some confusion with other similar species, but the orange bands on the joints of the otherwise black antennae are definitive. The picture shows a specimen enjoying some summer sunshine and basking on a Tutsan leaf, decidedly a handsome and eye-catching beetle.

Another longhorn beetle I have only seen once in the garden was during summer last year. It is a similar sized species to the Black-and-Yellow above but seemed smaller, probably due to its subdued colouring. But, when viewed closely the legs and antennae were bright cobalt blue-grey with black rings on the antennae, which gives a striking appearance. This colouring is unique and cannot be confused with any other species; it is the Golden-bloomed Grey Longhorn (Agapanthia villosoviridescens).

It is described as a species of moist meadows and hedgerows, but I found it on my rough grass bank sitting on a leaf in sunshine. It is normally to be found on flowers like

umbellifers and in the months of May and June, but may be found a little later in the summer. It has an unusual life cycle as it grows as a larvae from an egg laid in the stems of herbaceous plants like thistles and hogweed, where it lives eating the stem contents before retreating to the crown of the plant for winter hibernation. In spring it finishes its growth by eating some of the plant roots. Although widespread it is local, but gradually spreading its range from eastern and central England. It seems that so far there are only four records for Herefordshire; but keep an eye open for this remarkable beetle especially on umbellifer flower-heads, where so many insects like to spend sunny days.

A final longhorn although it has relatively short antennae in comparison, it is nonetheless part of the family. The Wasp Beetle (Clytus arietis) is aptly named as it looks superficially like a wasp and is around 12mm long (1/2 inch).

This species is again one that is associated with woodland as the larvae live on fallen and dead wood, and may spend several years eating this not particularly nutritious diet. It is said that adults have been recorded emerging from furniture the process takes so long! The adults are apparently very capable flyers and can appear on flowers a long way from their woodland home. They appear in my garden which is surrounded by trees on three sides; but not every year, and when I see them it is usually only one.

They occur commonly throughout Europe although not in the extremities of Scotland or at all in Ireland. Some years they are scarce and sometimes locally common. But, adults are out and about from May to July, and as they come to flowers to feed you may be lucky to see one almost anywhere.

Now for something different! I occasionally see a very distinctive insect in the garden and quite often on the surrounding Malvern Hills where its bright appearance would seem to make it impossible to miss. It is a Froghopper within the larger group of insects known as true Bugs (Hemiptera) as they all have a rostrum: mouthparts in the form of a piecing beak-like tube, enabling them to suck sap from plants and occasionally juices from animals.

The Red-and Black Froghopper (Cercopsis vulnerata) shown below is one of these fascinating insects. Whilst the shade of red seems to vary somewhat, they are

so distinctive as to be virtually impossible to confuse with anything else. Truly an insect once seen, never forgotten! They are about 10mm (around 1/3 inch) long but seeming larger with their bright colouring. As their appearance makes them highly visible it is likely to be aposematic (a warning) to would be predators that it is distasteful or poisonous, but I cannot find any reference to this quality.

I have usually seen them in spring, but they can be seen from April to August and are found in woodland clearings and open countryside. The nymphs (larvae) apparently feed on roots underground. This insect is found throughout Britain and so far does not seem to be affected by changing climate, and I seem to see it as often now as always.

Also with a bright colouring another insect that is the now frequently seen around the Malvern Hills and in my garden is the Scarlet Tiger Moth (Callimorpha dominula). This beautiful day-flying moth has during the last decade or so been increasingly reported in and around the area. Hopefully, many of you will soon see this delightful moth if you have not done so already. Again their bright colours are a warning to birds that they are distasteful.

This is a moth that regularly flies during the day as well as at night. My pictures show a mating pair resting on a Box shrub in a secluded corner. The moth appears from late May, through June and into July, and is often seen associated with Green Alkanet, one of its food plants. The Scarlet Tiger was once mainly found only in south and south-west England, but has recently been spreading into the Midlands. The caterpillars feed initially on Green Alkanet or Comfrey and the moth only started to appear locally since the millennium, when Green Alkanet also started to appear.

I can remember a time in the early 1990s when Green Alkanet was not seen, and now it is everywhere, with its brightly coloured blue flowers from early spring and through summer, and if trimmed by the highways department I think they start to flower again after some rain even into autumn. Anyway the moth arrived shortly after the Green Alkanet it seems, although Comfrey, its other food-plant, was already here!

Later in the summer its caterpillars can be found in considerable numbers, as they are hairy and brightly coloured, predominantly yellow and black. They sometimes eat all the leaves of Green Alkanet, leaving just a skeleton. Their hairiness and bright colouring acts as a warning to birds, and they are left alone. The caterpillars hibernate during the winter and finish growing the following spring, before finally pupating and emerging as an adult moth from late May onwards. Strangely when larger the caterpillars will also eat Stinging Nettle as was the nearly fully grown specimen opposite, which I found in my garden on Stinging Nettle in April.

Yet another insect whose range has been changing with the climate is the hoverfly shown below which is about 16mm long (2/3 inch) with a yellow and black abdomen supposedly mimicking a wasp. It is the Wasp Mimic Hoverfly (Volucella inanis). However, it is twice as tubby as any wasp I have ever seen. This species is slightly smaller than the similar Hornet Mimic Hoverfly. The photograph shows a female as the eyes are wide apart and not touching, and she is feeding on native Wild Marjoram growing on my grass bank. These hoverflies were only found in the south-east around the Home Counties, but in the late 1990s they started to expand their range and numbers and started to appear locally 10 years or so ago. However, I still only see occasional specimens, so they can hardly be called common as yet. They will occur on the blossoms of Buddleja and are therefore well worth looking for, as well as their larger Hornet Mimic relation. They are on the wing from July to September and even into October. Late in the year they can be found with a range of insects on the newly opening flowers on Ivy, such a vital source of nectar and pollen at the beginning and end of the year for so many insects.

Now for one of the smallest Hoverflies, called confusingly the Long Hoverfly (Sphaerophoria scripta); it is typically about 5-7mm long (1/4 inch), as can be seen from the specimen feeding on the minute flowers of Black Medick. I suppose it looks long as it has a slender body when compared to many hoverflies. The specimen below is easily identified as a female due to the tapered end to the abdomen, whereas males have a rounded almost bulbous end to their abdomen. The genus Sphaerophoria contains 11 species in the UK and they are considered difficult to separate from each other, especially the males. But, I am confident about this female as it has been confirmed and is the commonest species.

Female Long Hoverfly (Sphaerophoria scripta 16th July 2020, on Black Medick.

This brightly coloured group of small hoverflies are noticeable for that reason; many small hoverfly species are generally dark and easily overlooked as something more ordinary! The larvae of this species feed amongst ground cover plants on aphids. The hoverfly larvae would be so small that I would think an aphid would be a huge banquet?! This species is visible from spring to autumn and is also thought to be a partial migrant, especially in northern England and Scotland.

It is a common species locally, especially in grassy areas, and should be looked for on all sorts of flowers, especially small ones where there is often less competition from other larger insects.

I have decided that if you have read this far and coped with beetles I would mention wasps, especially as I have just discussed a handsome hoverfly that mimics the black and yellow wasp that is to most of us ‘The Wasp’.

However, it is worth mentioning that there are several thousand species of wasp in the UK and most of these are overlooked due to their minute size or confusion with flies and bees. There are some eight species that are black and yellow and look sufficiently alike as to be identified as ‘a wasp’ by casual observers. It is worth noting that these are social species, and the Queens and workers form a colony which later in the year will be joined by males. Colonies usually die at the end of the year and are started afresh each spring in a new location by a single queen who has hibernated through the winter. Bees are generally considered to have evolved from wasps, and of course Bumblebees have this same basic social structure. Honey Bees are also similar in this regard but are different in that the colony does not die at the end of every year. Honey Bee colonies may continue almost indefinitely whether domestic in a hive or wild in a hollow tree. Sorry I digress!

The typical yellow and black wasps are generally despised by most people for what I guess

are two main reasons. They are not hairy and cuddly like bees, and they have a habit of interrupting late summer picnics, especially when sweet sticky items of food are involved. However, if you put this out of your mind and look at them in spring they are as interesting as any other insects visiting spring flowers. They are then, with a little effort and perhaps a digital camera/phone to record them, able to be identified into their individual species. Spring is a good time as insects are often preoccupied with feeding after their winter slumbers and busy looking for a desirable potential residency for the new season, and so allow a close approach and photographic opportunities. Also, most are queen Bumblebees or Wasps and so there is no confusion with the differences of workers and males that appear later. The picture below is of a queen Saxon Wasp (Dolichovespula saxonica) on 5th April 2020.

Saxon Wasp! I hear you say. Yes, this is one of two typical yellow and black species that has arrived since the 1980/90s and is spreading. Having arrived in the south-east it is now scattered across Scotland and Wales. I first saw them in my garden in 2017 and they are now an annual occurrence in spring. I have not seen them during summer, but by then I am looking at too many other things to perhaps notice them. They are distinguished from other species by their abdominal bands with the black shallow triangle and adjacent black dots being reasonably distinctive. A second feature is the lack of a black mark in the yellow face. Facial marks and patterns are often important diagnostic features with wasps, and so a photograph of the face and abdomen is always useful.

Lastly, something that I am sure you will all appreciate, and enjoy. A female Kestrel (Falco tinnunculus) came and visited the garden and settled in an Ash tree that had dropped its leaves for autumn, although other trees in the background were still hanging on to autumn colour. She lacks the grey head that is a feature of the male Kestrel. After a few minutes I realised she was looking intently at something on the ground, as she twisted and bobbed her head from side to side.

Kestrels are birds that haunt and hunt open areas like the Malvern Hills where I invariably see them when walking on the tops. They will often be seen hovering looking for small rodents and shrews. As I live on the west side of the hills, I face the prevailing southwesterly winds, and I therefore often see kestrels facing into the wind assuming a stalled angle in such a way that they are motionless as if hanging from above on an invisible thread. They will twist their wings and tail, and the tail is used as a steering rudder or fan compensating for the changes in wind strength and turbulence. They also have a small feather known as the alula which is effectively their thumb and this can be seen raised and projecting forward from the front of the bend in the wing known as the elbow. It is used to adjust and smooth the flow of air over the top of the wing and stabilise their hovering

pose. Birds will sometimes remain like this for several minutes without needing to flap their wings at all, and their wings, body and tail will be twisting and adjusting while their head and eyes remain stationary and fixed on the ground below.

This is, of course, the source of the other old countryside name of ‘Windhover’ for this delightful small falcon. Of course, it was this habit that inspired Gerard Manley Hopkins to write his fascinating poem ‘The Windhover’.

The eyesight of these birds is such that they can see ultra violet frequencies, which are invisible to us; scientists claim this would enable them to see mammal urine in their preferred hunting habitat. You may wonder what advantage this might be, but apparently many small mammals use urine as they move around to mark their territory and this is visible in the ultra violet and so it helps Kestrels to locate them. But as can be seen from this bird, they will sometimes do the lazy thing and watch from a handy nearby tree. After quite a few minutes the Kestrel swooped down quickly onto my patio where it had seen either a Wood Mouse or a Bank Vole. I should explain that my patio slabs are bedded on five points of mortar to level them, and that underneath are a lot of clear spaces which are easily accessible from above via the gaps between the slabs. This provides a lovely place for mice and voles to live and breed, especially as bird seed is conveniently put on some of the slabs over their heads and so becomes mouse and vole food.

What happened next was almost comical, as the Kestrel tried putting her head down between the gaps in the slabs to see where her potential meal had disappeared. She hopped around the patio repeating this process in several likely places, before giving up after a few minutes and flying away. Unfortunately, I failed to get an in-focus picture of this strange behaviour.

As I am surrounded by woodland, seeing a Kestrel close-up is a rare treat as they are birds of open spaces. Having just re-read ‘The Windhover’ poem I am now feeling poetic and artistic, and think the picture below should be entitled ‘Symphony in Brown’.

- Andrew Nixon

- Andrew Nixon

Concern for the condition of the River Wye remains very high profile. What started as a problem predominantly around agricultural pollution has broadened out with growing anger both locally and nationally with water companies and their regular practice of releasing untreated sewage into our waterways. For a long time, the Wye and Lugg were in the national spotlight but this has now spread to many other rivers across the UK.

It is widely reported that phosphate pollution has two main sources: waste water treatment works (WWTW) and agriculture, with each contributing approximately 25% and 65% respectively. Other figures have been circulated but they are usually broadly similar. Phosphate pollution is problematic because it encourages algal blooms which can shade out other aquatic plants and when it dies the algae drops to the bottom of the river and smothers gravel beds. A healthy river would have an abundance of water crowfoot growing in vast beds and the River Wye was designated a SSSI and SAC in part because of the abundance of water crowfoot habitat. These beds are now largely lost from the Wye with phosphate pollution and more extreme winter flood events getting most of the blame. These water crowfoot beds are important parts of the river ecosystem, providing a nursery for small fish and important sources of invertebrates, both of which are essential to the food chain.

A significant proportion of this phosphate comes from sewage treatment works with outfalls from WWTWs delivering phosphate-rich water to the river. There are periods during high rainfall when combined storm overflows permit untreated sewage to enter the watercourse. This has received significant national attention this year with public outcries at the frequency of these events. Increasingly, Welsh Water are installing phosphate stripping technology on their sites which helps to reduce the amount entering rivers. Many of the issues at treatment works can be addressed and work is ongoing, albeit more slowly than is desirable and at significant cost to us the water users.

However, the majority of the phosphate comes from agriculture, which is a much more difficult nut to crack. The issue stems from overapplication of manures, essentially applying more phosphate to the land than the plants can use. Some manure is washed directly into watercourses during heavy rain events and residual phosphate can build up in the soils, ultimately entering watercourses when soil is eroded. Identifying, the sources can be difficult as it is a dynamic picture and pollution sources are usually diffuse. Recent research suggests that the legacy phosphate in our soils will prevent us meeting our phosphate targets for many years, even if we were to stop applying manures today. There will not be a quick fix.

Much of the manure comes from intensive poultry units (IPUs) and is particularly high in phosphate. There has been much condemnation of the ever increasing number of IPUs given planning permission across Herefordshire and Powys as they are blamed for introducing ever more phosphate to the catchment. The origin of the phosphate is the poultry feed which is often imported from overseas and in itself is not from sustainable sources. Research by Lancaster University through the RePhoKUs project has calculated an excess of 3000 tons of phosphate is added to land in the catchment every year from all sources.

To get things back into balance we have to reduce the amount of phosphate coming into the catchment and/or export phosphate out of catchment to other areas where it is needed. Actions such as moving to low phosphate poultry feed are being considered and proposals to ship manure/phosphate to the east of the country (where there is a phosphate deficit) has also been suggested. As previously stated, ongoing upgrades to Waste Water Treatment Works to strip phosphate from waste water is also underway. There are some ‘solutions’ that we need to be wary of. It is often stated that using the manure in Anaerobic Digesters is one way to get rid of phosphate. This isn’t true. The amount of phosphate that comes out of an AD plant is equal to the amount that goes in. The digestate can then be spread on the land in the same way as manure. Similarly, the creation of a pyrolysis plant to effectively burn the poultry manure also results in no net reduction but could be useful in making it more transportable to other areas.

Even if we do get an overall phosphate balance in the catchment we will still need much better nutrient management on farms and landholdings. Localised over-application will no doubt still continue as well as poor land management, resulting in soils and phosphates washing into our watercourses.

Working with nature is critical and natural habitats have an important part to play. Managing floodplain as species rich grassland means far fewer inputs being added to the land, reducing overland flows and providing better absorption of nutrients. They can also play a hugely important role in boosting biodiversity, capturing carbon and regulating floodwater. Similarly, good soil health is crucial. We know that heathy soils have a complex ecology with microorganisms and fungi playing an important role in unlocking nutrients

and making them available for plant growth, reducing the need to add fertilisers. Furthermore, the creation of other habitats such as wetlands, hedgerows and woodlands can interrupt the flow of water, allowing suspended silts to settle out, absorb nutrients and also provide those additional benefits to wildlife and natural flood management. Herefordshire Wildlife Trust are actively looking to acquire sites where we can undertake work to generate and demonstrate these benefits. We have also worked closely with landowners throughout the Lugg catchment to support them to undertake similar work.

A good example of how nature can provide solutions is the recent creation of an integrated constructed wetland by Herefordshire Council. The wetland has been developed adjacent to the Luston Waste Water Treatment Works, intercepting water from the outfall and putting it through further treatment before it enters the River Lugg. The wetland is a series of vegetated pools which captures phosphate in growing plant material whilst also providing a wetland habitat. Developers pay the Council to offset the phosphate associated with their sites and the money is used for the creation of further wetlands. Currently the Council hopes to construct three sites. It must be remembered this only reduces phosphates in order to provide offset or ‘headroom’ for new housing to be developed. All three wetlands combined would offset approximately 350kg of phosphate per annum. Currently we have a phosphate surplus of 3,000,000 kg across the catchment. So it is not a solution for the river but a novel means by which development can continue with no net adverse effect on water quality. Work to improve the river’s water quality needs to continue in parallel to address the source problem.

The water quality problems are not going away for some time and work needs to continue from all involved to find and apply the solutions. We mustn’t also forget that there are many other problems affecting our rivers and we need to make sure that we continue to tackle issues such as invasive species, damage to the banks and channel and barriers to migration.

‘Regenerative farming methods’ is an adventurous title for this article, but I will do my best to navigate my way through the issues and explain why now, more than ever, change is needed and why the conservation lobby needs to work with agriculture to make positive change for all.

I started my journey into ‘regenerative agriculture’ around eight years ago. I clearly remember being in the sheep shed, mid-way through lambing, at around nine pm, suckling lambs, feeling tired and wondering why I was doing that particular job, at that particular time, when to coin a phrase, the newly born lamb only has one job. To be born, stand up and suckle its mother. There was probably a multitude of reasons why we had an issue with some of our lambs at that time, but it set in train a period of thinking and learning for me to bring us much closer to farming with nature.

I now prefer the term ‘agroecology’, because it seems the phrase ‘regenerative agriculture’ has been highjacked by almost everyone, from multinational food production companies to agribusinesses. By its very nature regenerative cannot be defined and therefore not certified, it is just a set of principles that we will at some point have to follow, in order to try and produce healthy food from healthy soil.

It is probably not overstating the situation to suggest that modern, western agriculture is underpinned by fossil fuels and in particular nitrogen fertiliser. In most of those farming systems nitrogen fertiliser is the main emitter of greenhouse gases, notably carbon and nitrous oxide. Now I don’t want to get into a debate about what gases, how long they last in our atmosphere and how bad this all is for the future of the planet, but I think few people can debate against the need to reduce our reliance on fossil fuels. The elephant in the room, however, is that of food production. The commonly quoted statistic is that several billion people (between one and four, depending what reference you use) are alive today because of the work of Norman Borlaug and the so called ‘Green Revolution’. However, whilst the ethical discussion around that is fraught with complication, we all know the current situation is unsustainable, never mind regenerative. At some point the change will come because not only will energy and resources be a limiting factor, our ecological and biodiversity crisis will continue to spiral. I remember reading an article about Chinese apple farmers having to hand pollinate their trees, because of the decline of bees. How have we got to a point where that is even a thing? So, bringing things a bit closer to home, how do we get from the current model to one that is more sustainable and hopefully regenerative? Well, if we follow the principles of regenerative agriculture and try to move towards a place where our farm systems rely less on fossil fuels, I think we are heading in the right direction. They are: do not disturb the soil, keep the soil surface covered, keep living roots in the soil, introduce diversity (plants and animals) and bring grazing animals back to the land.

There are people who are stuck in the mistaken belief that everything will be ok if we get rid of all the cows. I think it helps at this juncture to quote a graphic, or perhaps ‘meme’, I saw on social media recently. There was a picture of a cow eating grass and a few lines of text saying something along the lines of ‘imagine thinking cows eating grass is killing the

planet, cows eating grass is the planet’. A second quote, from Nicolette Hahn Niman a former vegetarian and the author of ‘Defending Beef’, is appropriate here too. “It’s not the cow, it’s the how”. Like so many things, the devil is in the detail and it is the system which those cows are in that counts. For millions of years the great grasslands of this planet evolved in the context of the symbiotic relationship between the ruminant animal and the grass. You simply cannot have one without the other. It is quite typical of humans, because we think we are so clever, to now blame the cow for the problem we have created ourselves by poor management. After all, the cows managed quite well thank you very much before we came along and stuffed it all up.

Eight years on, my father and I are trying to get as close as we can to running our small farm in an agroecological and regenerative fashion. We do not use any artificial fertiliser, use a very small amount of herbicide on our small arable acreage and, where possible (which is most of the time), move our animals every day, trying to mimic the movement of the great herds across the great expanse of grasslands of the Midwest of the US, or the Serengeti. It is a bold claim, but perhaps the most powerful tool we have in a grassland situation is that of rest.

Rotational grazing underpins almost everything we do here and it is not a new concept. Most dairy farmers have been using some kind of grass management for decades. Strip grazing, where an electric fence is moved in front of the cows every day, or after every milking has been a common technique for a long time. The seminal work on grass

management in a temperate climate was published in 1959. Written by a Frenchman called Andre Voisin, his work set the standard that everyone else works to. Prior to him a Scottish agriculturalist called James Anderson wrote about daily rotation of cattle in 1777. ‘There are no (or very few) new ideas under the sun’!

The difference is that in 1777, animals moving daily in small fields, or paddocks, were contained by stone walls and probably watered by lots of small bodies of running water. Today we have the luxury of polywire for electric fencing and polypipe for water. The psychological barrier provided by an electric fence gives a really easy and hugely flexible way of controlling how much area is available to the animals for any given period of time. I could go into a bit more detail here, but suffice to say that using these two pieces of technology we can move animals through our fields and use the back fence, that is to say the one behind them to make sure they do not re-graze the grass as it grows, before it is able to fully recover.

That principle of recovery, or rest, is the key one. A grass plant is said to be able to be regrazed after three days. So, moving twice a week is sufficient. We try to move every day, or every second day, depending on the field and the group of animals. It is perhaps surprising how quickly the animals learn that they are moved everyday and I think we have built up a level of trust with them. Once they are on a daily move, they understand that they will move to fresh grass and are actually quite pleased about that!

So, it is almost more important where the animals are not, than where they are and that is where making space for nature and the role of our farm ecosystem is really important. We have a rotation length, or rest period of around 30 days in the spring, increasing to 45 and then 60 days in summer time. If it is particularly dry, meaning slower growth, we try to push the rest period out even further, towards 90 or 100 days. It is not always an easy concept to get your head around, but by building longer rest periods in, we can make the most of the sunshine that hits the farm every day and remove the need for synthetic fertiliser. Those

of you interested in farmland birds will know that birds like the skylark need around seven weeks being undisturbed to be able to hatch and rear a brood of chicks. Seven weeks being fifty days means that we are building in a rest period that is helping our farmland birds as well as our grassland production.

So, leaving these longer rest periods as well as employing shorter duration grazing events means that there will often be forage left behind. We do not want to eat all the grass that is available in every paddock, because the process that makes all this possible, photosynthesis, needs chlorophyll. The old phrase is grass grows grass, so we try to leave some forage behind. By doing that we not only help the grass recover quicker, some will not be eaten at all and have an opportunity to go to seed. We also leave some areas ungrazed all together, along with our three metre wide wildlife corridors, or laid hedgerows. This provides food and habitat for other small birds and mammals. We do make silage for our cattle to eat in winter, but we try to limit that to one or two cuts. We make hay too, and try, where possible to allow the field to go to seed before it is cut. We want the grasses and herbs to go to seed to regenerate our pastures, but we also recognise that a longer period of undisturbed growth is important to creatures like voles and mice.

I was moving a group of cattle last autumn into a field with quite tall grass. As the cattle moved in, the insects got up and as they rose into the air we were joined by a host of swallows, swooping and diving for the feast. It must have been the last day for the swallows before they flew south for the winter, so that was probably why there were so many. We lost count at around 150. Nature has a gain from this kind of grazing and there is also a gain for the farmer too. We do not need to use chemical fly repellent on our cattle, because we are moving the cattle daily: they are rarely near the hatching flies and our wildlife is taking care of them for us. That is how nature designed the system to work, if only we can work with it to benefit the farm and the wildlife.

There are many other examples of how we can design our farms to operate as an ecosystem, with our wildlife. Dung beetles are a very important part of any ecosystem, and yet they are largely ignored. Unfortunately some of the anthelmintic wormers commonly used by farmers can kill them and other soil micro fauna. Animal welfare has to be a large consideration when deciding whether or not to treat sheep and cattle, but if we change the way we graze and test the faeces of the animals, we can see if using those wormers is necessary. If the dung beetles process the dung of the animals, we don’t need to harrow the fields to break down the manure, we have fewer flies, so we don’t need to use fly treatment and the really valuable nutrients that the ruminant animals provide as a by-product of their grazing go back into the soil. So, you see, it is all one big cycle.

Integrating trees and diverse pastures back into the farmed landscape can benefit all stakeholders. Farmers, livestock, wildlife and the public. It is a bit like Pandora’s Box, once you have opened it and you understand how farming and nature can work together, you really cannot go back. We have seen numbers of birds and mammals increase here over the past few years and we are starting to monitor that. Unfortunately our hares have been victims of yobs and their dogs, but field mice and voles are doing well, along with the skylarks and the yellowhammers. I am fairly sure that we have at least two family pairs of the latter and surely more will get established as we plant more hedges and provide more habitat and food. I saw a snipe in early autumn in one of our permanent pasture fields, something I don’t see very often.

We are laying hedges on something like a twenty year rotation, double fencing and only flail trimming a few hedges sparingly to encourage them to bush out. We are planting trees

Tree planting (left) and bushy hedgerows (right) all contribute to the farm ecosystem

and guarding the ones planted by our wildlife: jays and squirrels do have a role after all! We leave some brash behind for habitat when we prune a tree or lay a hedge and we have some fenced-out wild areas that are left alone. We leave standing dead wood in our woodland and orchards to provide habitat for our wildlife and I can confidently say we have quite a good woodpecker population, green and great spotted. Like many arable farmers we have some wild bird strips along our hedges. These diverse planted areas have many small and large seeds that will help to fill the hungry gap our farmland wildlife has through what can be a long winter.

Our old ‘standard’ apple orchards are a great haven for wildlife too. We graze the grass under the trees and pick the apples, but some are always left behind. If you walk through the orchards at dusk you can see the bats flying around and often hear owls calling to each other. We also have quite a lot of bramble encroachment into the wilder areas of our woodlands and the hill fort which sits in the centre of the farm. Not only do we get the pleasure of some very tasty blackberries, they provide quiet habitat for all sorts of wildlife. It is that diverse mixture of habitats right across the farm that allows the wildlife to flourish and us to work in a land-sharing way. Of course, we need to remain profitable and I do not see why that should be such a bad thing, we all have a family and bills to pay. By working with our farm, our land, our wildlife, our farm ecosystem, I believe we can farm in an agroecological manner. Many farms are heading in a similar direction. After all the inflationary pressures we are all facing at the moment are certainly no less in agriculture. My call to you as conservationists? Perhaps you can get involved with a local project on a local farm, help to put some guards around some tree saplings, plant some trees, lay a hedge, do a bird or butterfly count or a plant species count in a hay meadow. We can improve our farm environment and we can only do that if we work together.