THE ECONOMICS DIGEST

Hello, and welcome to the fourth edition of The Hampton Economics Digest!

In this edition we delve into some overlooked topics, from the use of AI in market pricing to an insight into how the kidnapping epidemic in Nigeria is affecting their economy. We also do a deep dive into the UK, with articles on the very topical issues of taxes and inflation.

Despite various university application deadlines and admissions tests, our writers have been working hard to produce some incredibly interesting articles. For this, I must thank the entire writing team, Mrs Mullan, and the Media Team at Hampton. With that done, all that’s left to say is enjoy!

Charlie Childs Founder and Editor

Writers: Charlie Childs, Zaid Ahmed, Alex Nelson, Alex Rust, Rohan Ladva and Nathaniel Carson

On the 26th of November, Rachel Reeves announced her new Autumn Budget for the UK, outlining the government’s fiscal policy for the year. We explain just what’s wrong with the UK tax system, and what can be done about it.

There has been much debate about what was going to be included in the Budget this year, with many having warned of tax rises, considering the Chancellor needs to raise a significant amount of tax revenue to plug our deficit, while promoting greater investment in the UK. Changing our complextaxsystemis,withoutadoubt, an incredibly difficult job, whilst trying to keep voters, MPs, investors, and businesses happy. The challenge, therefore, is not simply to decide how much to raise taxes, but how the UK can reform its tax system in order to raise revenue more efficiently and equitably.

Efficient taxes cause minimal distortion to people’s behaviour and economic choices, while equitable taxes are distributed fairly across income and wealth. Unfortunately, these often don’t come hand in hand, creating a trade-off. For example, a progressive income tax (where the tax rate increases with the taxpayer’s income) is equitable but not necessarily efficient, as it may disincentivise work. Whereas, a flat income tax is efficient, but not equitable, as people on both ends of the economic spectrum pay the same

marginal rate. This highlights just how important a well-designed tax system is in influencing incentives and allocativeefficiency.

TheUK’soverlycomplexandconfusing tax system has many strange quirks, along with some seriously inefficient, inequitable taxes. There is a point, where taking a pay rise will actually makeyoulesswelloffintheUK.When your income increases to between £100,000 and £125,140, you will pay a 60% effective tax rate instead of the 40%youwouldexpectfromtheincome band you are in. This extra tax is because after hitting the £100,000 threshold, your personal (tax free) allowance begins to fall at a rate of £1 for every £2 of extra income. This continues until you surpass this income band, at which point your income tax falls back to 45% because you have fully lost your personal allowance.Asaresult,employeesmay optforgreaterpensioncontributionsin order to keep their taxable income below £100,000. This also reduces national insurance payments because ‘salary sacrifice’ into a pension scheme reduces taxable income, so theemployersavestoo.

The UK’s housing tax system has featured prominently in the media recently, with Conservative Party leader Kemi Badenoch pledging to abolishstampdutyonprimaryhomes. Stampdutyusedtobebasedonaslab system, where there was a single rate charged on the entire value of the property. However, this only applied overacertainvalue,resultinginasharp jump in the tax rate and causing disruption to the housing market. As a result, in December 2014 a band system was introduced to ensure you pay a rate of stamp duty only on the proportion of the value that falls into that band. One of the arguments against stamp duty is that it reduces property transactions, with a 1% change inthe effectivetaxrate leading to an estimated 12% change in commercial transactions. However, it would be difficult to abolish stamp duty,asitdoes,inallfairness,generate wellover£10bneveryyear.

Another odd aspect of the housing tax system is council tax, which has also been gaining publicity due to public outrage over how it is calculated. Council tax is based on valuations carried out in 1991, meaning a £30mn mansioninWestminsterpayslessthan amodest‘BandD’homeinBarrowand Furness.

of tax legislation. Estonia operates, among other things, a land value tax (LVT). This is where the ‘unimproved value of land’is taxed, which excludes things like buildings on the land. This incentivises development and discourages land hoarding, which is currently occurring in the UK, squeezing the supply of housing. What’s more, this tax is both efficient and equitable, because the supply of land is fixed, so the price wouldn’t be driven up, and because it applies equally to everyone since you cannot move or hide land as you could with otherassets.

The Chancellor can’t overhaul the entire tax system overnight, but she can certainly begin by commissioning reviews on areas of our tax system which are particularly inefficient and unequitable. Bymakingsmallchanges toremoveloopholesandflawedtaxes, theChancellorcouldbegintheprocess of simplifying our tax system, which should improve confidence in the UK andensure amoreevendistributionof wealthwithoutjustraisingtaxes

Charlie Childs

For Rachel Reeves, it could be time to take a page out of Estonia’s tax code andgetridofsomeofour23,522pages

The rise of AI-driven pricing algorithms is causing a new form of algorithmic collusion, allowing firms to sustain high, monopoly-like prices.

“Monopoly is the condition of every successfulbusiness”–PeterThiel

In 2023 the Federal Trade Commission launched an allegation against Amazon, accusing the company of using a secret algorithm totesthowmuchitcouldraiseprices against its competitors. A firm like Amazon ultimately always wants to maximise profit, and that is why competitioninmarketsiswhatkeeps them thinking carefully about their businessdecisions.

Imagine two firms selling a very similar (or identical) product. A rational consumer would, of course, buy the product from the firm who is selling it more cheaply. So, the two firms may end up engaging in a price war, where they each simultaneously reduce their prices to attract the consumers. However, this will only continue up to a certain point, as there will be a cost to the firms to producetheproductinthefirstplace. So, in order to make profit, their set price must be greater than this cost. With perfect competition, the most logical outcome would be for both firms to end up selling the product at

the same price as this production cost and therefore make no profit. This scenario is known as the ‘BertrandGame’.SohowwasAmazon allegedlyabletoraiseprices?

Traditionally, prices have been set/updated by the humans running the firms, and this may happen quarterlyorannually. Inour‘Bertrand Game’, the optimal strategy for the two firms would be to collude and fix prices to something that benefits them the most. For obvious reasons, thisisillegalintherealworld.

However, in this increasingly AI dominated world, many firms have started to use algorithms in recent years to determine prices. These algorithmsworkbyexploringdifferent prices to see what works, as well as monitoring the prices of their competitors. Using this information, itaimstodiscoveranoptimalstrategy which maximises profit for the firm. Unfortunately,beingascleverasitis, the algorithm is very quickly able to recognise that collusion is the most profitable method, and is therefore able to sustain high, monopoly-like prices, without any human

intervention. This is causing severe problemsforconsumers,whoendup faced with unfair prices for products. It also raises issues with the legal code. Whilst human collusion is illegal, at no point in this process do the algorithms, or any human memberofthefirms,engageinactive price-fixing, and so we now have a loopholeintheantitrustlaws.

This is exactly what the allegation against Amazon was about, and the antitrust lawsuit is yet to reach a conclusion, having already been ongoing for two years. So, the issue currentlyisthatthemomentwehave a market with all competitors using algorithmic pricing, this problem of algorithmic collusion will rapidly arise. And whilst there may not be an outright monopoly in the market, the effects of algorithmic pricing mimin monopolypricing.

So, going back to Peter Thiel’s quote, algorithmic collusion is a worsening issueintoday’sworld,particularlyfor consumers, due to its monopolyinducingresultswhichraisepricesfor everyone.

The US Residential Rental Housing Market is another example of where this is causing problems. There is an increasing number of landlords turning to algorithmic pricing, and many are using very similar, or even the same algorithms, all stemming from the company ‘RealPage’. The catchisthattheselandlordsareusing the same one, and so the algorithm gains access to all the data. This makes unintended collusion even quickerandeasier.

Zaid Ahmed

Britain holds twice as much inflation-linked debt as any other European economy – why?

In October this year, Rachel Reeves went to the annual IMF summit in Washington. The Chancellor attempted to convey Britain as a ‘beacon of stability’. The markets, on theotherhand,beggedtodiffer.

Britishdebthasahigherriskpremium than any other major European country. In September, 30-year gilt yields reached 5.7 per cent, higher than during Liz Truss’s ‘mini-budget’ debacle and the highest level since 1998.

Britain's debt-to-GDP ratio is not uncommonly high. Where Britain stands out isthe structure of its debt anditsexposuretoinflation.

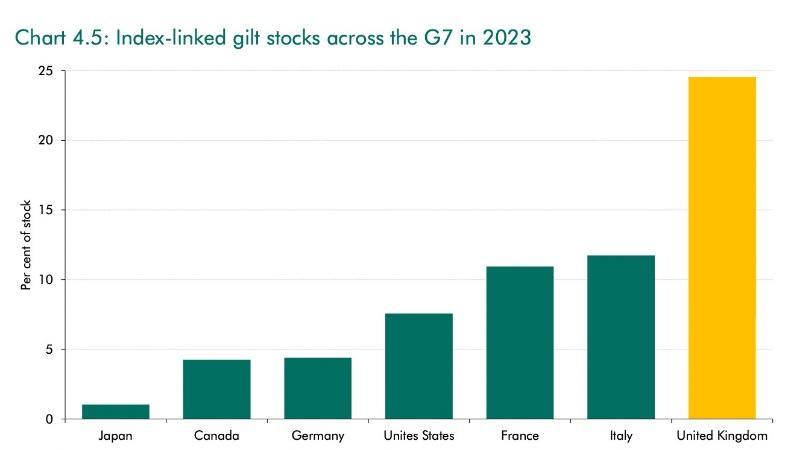

The Treasury’s latest debt management report highlighted the riseof‘index-linkedgiltstocks’,which now form a quarter of government debt. These gilts are the UK’s government bonds, whose interest payments are linked to inflation, thereby protecting the creditor from an unexpected devaluation of the currencyinwhichtheyhaveinvested.

Wheninflationrisesorfalls,a‘capital uplift’mechanism changes the value and interest payments for these index-linked bonds. When inflation increases, the bond interest paymentsrise.

A good way to understand the dynamics is by imagining the government as an insurer. The government provides protection, so the bondholder does not have to worry about the value of their investment beingeroded by inflation. In return, the bondholder accepts less interest on the bond, as they are takinglessrisk.

The British government started issuing these in the 1980s at a time whenmanythoughtthecentralbanks hadlearnttocontrolinflationandthat it wouldn’t come back. Around the turn of the century, books were even writtenaboutthe‘deathofinflation’.

As the government turned to this seeminglyattractivemethodofcheap borrowing, its inflation-linked debt

rose from making up 10 per cent of thetotaldebtinthelate1980sto24.5 percentin2023.

Other developed countries were more risk-averse and decided to lock intheirdebtwithlow,long-termfixed rates. Between 2014 and 2021, Germany never paid more than 1.1 per cent on their ten-year bonds. Britain,ontheotherhand,decidedto gamble on high inflation never comingback.

The only other developed European country with a similar idea was Italy. But even Italy did not inflation-link anymorethan12percentofitsdebt.

That is less than half of what Britain holds. This graph from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) 2023 fiscalriskreportillustratesourunique exposure.

Source: ONS

Source: OBR

This situation caused the UK to become the most inflation-exposed economy in the G7. Little did the governmentknowthatinflationwould return with a vengeance. In April 2022, Retail Price Index inflation surpassed 10 per cent and remained thereforoverayear.

TheeffectontheUK’spublicfinances hasbeendevastating.

Other factors, such as the Bank of England’s interest rate hike, helped cause the increase in debt interest spending. For the sake of brevity, the inflation-linkedbondswillbefocused on.

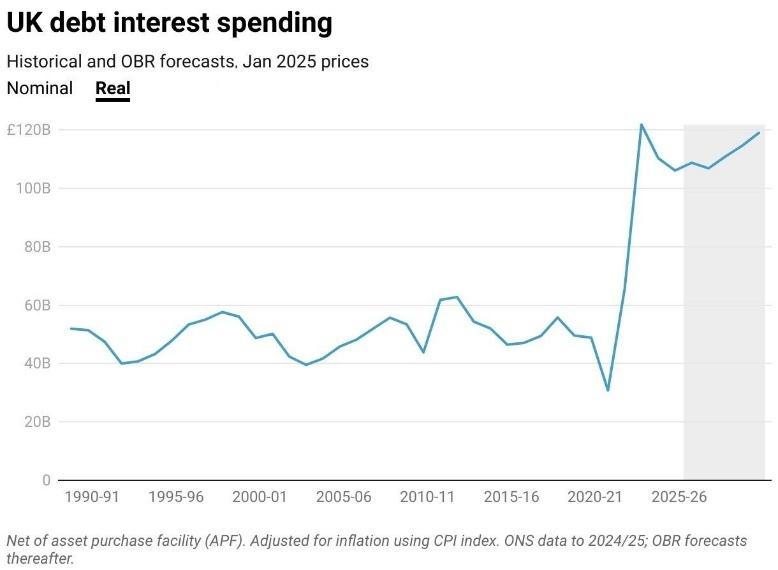

The OBR reports that in the year 2022/23, debt interest spending reached a post-war high of £112 billion.Thisisabout4percentofGDP and more than the government’s budgets for several vital sectors. For comparison, the schools budget (for pupilsaged5to16)is£64billion,the military budget is £54 billion and the policebudgetis£19billion.

Even after inflation fell back down to normal levels, the instability in interestrepaymentsremained.Thisis because after the value of the bond increased, the interest, a proportion of the bond, remained higher than before.

Allthishashappenedwithhardlyany parliamentary debate, despite its transformative effect on public finances.It’sfarfromclearhowmany MPs in the Houses of Parliament understand what an index-linked gilt yield is or how much of Britain’s fiscalfuturenowdependsonthem.

As wealth inequality deepens and public finances tighten, a UK wealth tax has re-entered discourse as both a moral imperative and a complex policy challenge.

Britain’s wealth divide has rarely lookedsostark.Therichest0.1%saw their share of total wealth double between1984and2013,reaching9% oftotalhouseholdwealth.

For decades, successive governments have focused primarily on taxing income, while the accumulation of private assets –property, pensions, investments, and inheritances–remainscomparatively undertaxed. A wealth tax, a recurring levy on individual net assets, has therefore re-emerged as a potential solution to address both fiscal strain and widening inequality. Yet, despite its appeal, such a tax remains politically elusive and challenging to implement.

TheUKhasnocomprehensivewealth tax. Instead, it taxes components of wealth indirectly through capital gains, inheritance, and property taxes. This fragmented approach leaves large stores of accumulated wealth untouched, particularly among the wealthiest households. The result is a system where wealth begets wealth, while those reliant on income face disproportionately

higher tax burdens. On average, the poorest 10% of households pay 48% of their income in tax, whilst the richest10%payjust39%.

Public sentiment, however, leans towards reform. Polling consistently shows broad support for taxing the veryrichestratherthanfurthercutsto public spending, reflecting growing frustration at the entrenchment of privilege.

Advocates argue that a wealth tax could serve a dual purpose: generating significant revenue while directly reducing inequality. A proposal by Oxfam, for example, suggested that a 2% annual levy on assets above £10 million could raise around£24billioneachyear.Yeteven if the fiscal case is strong, questions ofdesignandimplementationremain deeplycomplex.

The Wealth Tax Commission, a joint research initiative led by the London School of Economics, concluded in its 2020 final report that an annual wealth tax would be “a non-starter” for the UK, given the administrative and political barriers involved. Instead, it proposed a one-off levy,

collected over several years, as a more viable response when public financesareunderseverestrain.This cautious approach reflects lessons from the past: in 1974, the Labour government pledged to introduce an annualwealthtaxbutabandonedthe planfiveyearslateraftertheTreasury founditwouldyieldlittlerevenueand promptcapitalflight.

Administrativecomplexityisacentral challenge. Determining what counts as taxable wealth is fraught with difficulty: should primary homes, private pensions, or business assets be included? How can illiquid assets suchasartorprivatecompanyshares be fairly assessed? The Institute for Government notes that many households are“asset-rich but cashpoor”, meaning they could face large tax bills without the liquidity to pay them.

The risk of avoidance and evasion is another concern. A poorly designed wealth tax could encourage largescaleoffshoringofassets,potentially costing the economy far more than it raises. In Spain, marginal tax rates have exceeded 100%, effectively removing all real returns on investment, and discouraging inward investment.

wealth and income, alongside reforms to inheritance and property taxes. These changes could raise up to £120bn of additional revenue over fiveyears.

Nevertheless, the principle of taxing wealthremainscentraltoanyserious conversation about inequality. Wealth inequality in the UK has risen sharply over recent decades: the richest 10% now hold 43% of all household wealth, while the bottom 50% own just 9%. As Professor Gabriel Palma has argued, inequality is not primarily a matter of averages but of extremes and the UK’s distribution of wealth exemplifies this.

A well-designed wealth tax, or a series of reformed wealth-based taxes, would not only raise revenue but also signal a commitment to socialjustice.Withoutaddressingthe taxation of assets, discussions of inequality risk becoming rhetorical. The class divides revealed by the 2011GreatBritishClassSurveystem from unequal ownership of assets as muchasfromincome.

Criticsarguethatinsteadofcreatinga new tax, reforming the existing systemcouldachievethesamegoals more efficiently. The Institute for Public Policy Research has advocated for aligning the taxation of

While a full-scale wealth tax remains politicallydistant,itsunderlyinglogic isdifficult to ignore. In an eradefined by stagnant wages, soaring property prices, and deepening divides, taxing wealthmoreeffectivelymaybeoneof the few remaining levers to rebuild both fiscal balance and public trust.

Alex Rust

Nigeria's illicit industry is leading the country into economic turmoil.

Kidnapping for ransom in Nigeria is a security crisis and an economic catastrophe that is dismantling Nigeria's productivity, deterring investment, and pushing people into poverty. What started as targeted abductions in the Niger Delta has become a nationwide criminal enterprise, transforming fear into a multi-billionNairaindustry.

The greatest economic cost of the kidnapping surge is the crushing effect on investment and commerce. Foreign investors are deterred by the instability, viewing Nigeria as a highrisk zone. Embassies issue stringent travel warnings, which in turn signals businesses to incur massive security expenses, making operations costly and leading to their withdrawal from thecountry.

Domestically, the commerce that reliesonroadnetworks,thelifeblood of Nigeria's internal trade, has been throttled. Major highways have become infamous ambush points. Logistics and haulage costs have soared as companies pay insurance premiums. This uncertainty means essential goods, from food to industrial supplies, increase in cost,

directly fuelling the country’s alarming inflation rate. Farmers, particularly in the North-western areas,haveabandonedtheirfieldsfor fear of being abducted or forced to pay "taxes" to bandits. This has worsened food security and reduces agricultural output, an important sector contributing to Nigeria's employmentandeconomy.

The most brutal economic impact is felt at the household level. The payment of ransoms acts as a massive transfer of wealth from legitimate commerce and savings directly into the hands of criminals. Thisiswherethescaleofthecrisisis laid bare: the National Bureau of Statistics reported that Nigerians paid a staggering ₦2.2 trillion in ransom between May 2023 and April 2024alone.That’saround£1.16bn! A separateanalysisbySBMIntelligence also noted that between July 2022 and June 2023, while kidnappers demanded at least ₦5 billion, ₦302 million in verifiable ransom was actually paid out. For middle-class and working-class families, the financial shock of having to pay ransoms is irrecoverable, leading to generational poverty as they lose the

capital needed for education and health.

Thisransommoney,farfromentering the legitimate financial system, is usedtofinancemorecriminalactivity suchasbuyingweaponsandvehicles and establishing deeper operational bases. This creates a selfperpetuating "ransom economy" that directly undermines the formal economy.

Thestate’sinabilitytotacklethecrisis has resulted in a diversion of public funds. The government is forced to continuallyincreasesecuritybudgets without a corresponding improvement in safety which takes money away from developmental projects such as infrastructure, healthcare, and education. Meanwhile, Nigeria's elite have to respondbyinvestingheavilyinprivate security, from armoured vehicles to private guards, a necessary but economically unproductive expenditure.

Overall, the kidnapping industry acts as an unsustainable tax on the population which erodes national wealth, destroys trust in the state, and threatens to entrench insecurity as a permanent fixture of the economic landscape. Dismantling this deadly business is therefore necessaryforanyeconomicrecovery totakeplace.

Rohan Ladva

The Scottish Government are planning to issue bonds for the first time. With a credit rating matching that of the UK, we take a look at what credit rating Scotland have been awarded, and why this matters.

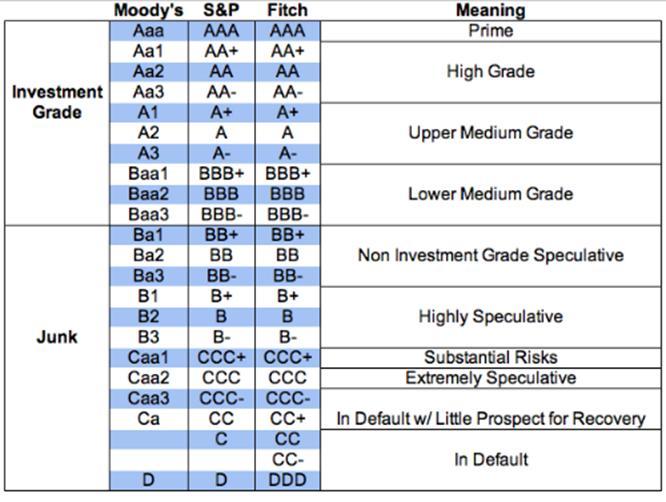

On the 12th of November, Scotland were awarded credit ratings by Moody’s (Aa3) and S&P Global (AA), identical to the United Kingdom’s, as the Scottish National Party (SNP) pursue their policy to issue government bonds. They say that doing so will raise capital for infrastructure projects, as well as strengthening their push for independence – although both agencies said their ratings were strengthened by Scotland’s intrinsic linktotheUKthroughdevolution.

Firstly, we must understand what these ratings actually mean. Countries are assigned a ranking basedonthefollowingmetrics:

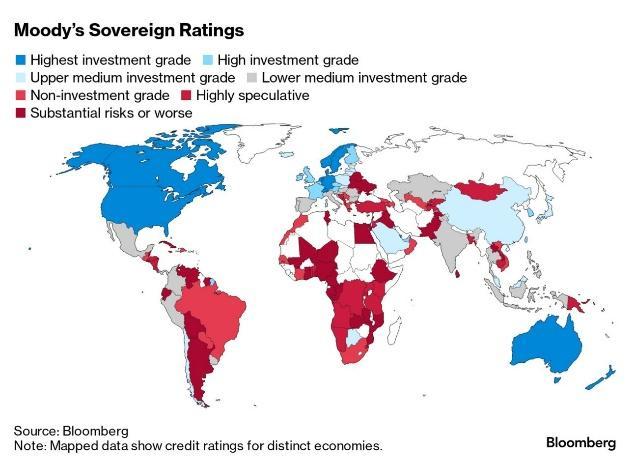

The further up the chart shown, the betteracountry’screditrating.Onlya few countries, such as Australia, Denmark, Germany and Norway, have the highest-grade bonds from themajorcreditratingsagencies.This meansthatbuyinggovernmentbonds from these countries is perceived to be very low risk: the chance of the bond defaulting is relatively low. This increases certainty for that country’s bonds, and therefore the price of borrowing for those countries decreases (i.e. they can borrow at lower interest rates). Conversely, it is much more expensive for countries likeEgypttoborrow,asitisperceived that any bond issued is relatively likely to default. Therefore, the credit ratingawarded to acountry iscrucial to government finances and their ability to raise capital. Scotland’s newly awarded ratings will be welcomed, with an equivalent or higher Moody’s Rating than the likes of China, Estonia, Japan and Saudi Arabia. The following map shows creditratingsacrosstheworld.

Source: Zolio

Scotland has a number of desirable economic factors which have played into this rating. Its very low national debt, strong core industries (including whisky and agriculture), and interconnectedness with the UK have all contributed to its score. Among the problems that Scotland must tackle over the coming years anddecadesisitsincreasinglyageing population,whichisrisingfasterthan the UK average. Furthermore, if Scotland did successfully pursue independence, the resultant trade barrierswiththerestoftheUK(byfar Scotland’s biggest trade partner) could significantly weaken economic growth and certainty in the economy, much like the UK leaving the EuropeanUnion.EvenifScotlanddid then sign new trade deals (primarily with the EU), the short-term effects couldbedamaging.

has up to now taken on debt through a mechanism designed so that it could borrow at the same rate as the central Westminster government. Even though there are strict limits on HolyroodborrowingandScotlandwill mostlikelyhavetoborrowatrelatively high interest rates – Scotland’s market is less attractive due to the abundance of UK government bonds –itisahistoricstepforScotland,who have not issued a bond of their own accord since the late 1600s. A strong credit rating, like the one Scotland has been awarded, is a significant steptoachievingtheirtargetofraising enough capital to fund infrastructure projects and boost growth north of theborder.

Still, it seems unlikely that Scotland will separate from the rest of the UK, at least in the foreseeable future, so its credit rating would appear stable for now. Since devolution, Scotland

Nathaniel Carson