Elizabeth Bowie Christoforetti

Elizabeth Bowie Christoforetti

Elizabeth Bowie Christoforetti

Urban Glitch: Systems-linked architecture in a contingent world

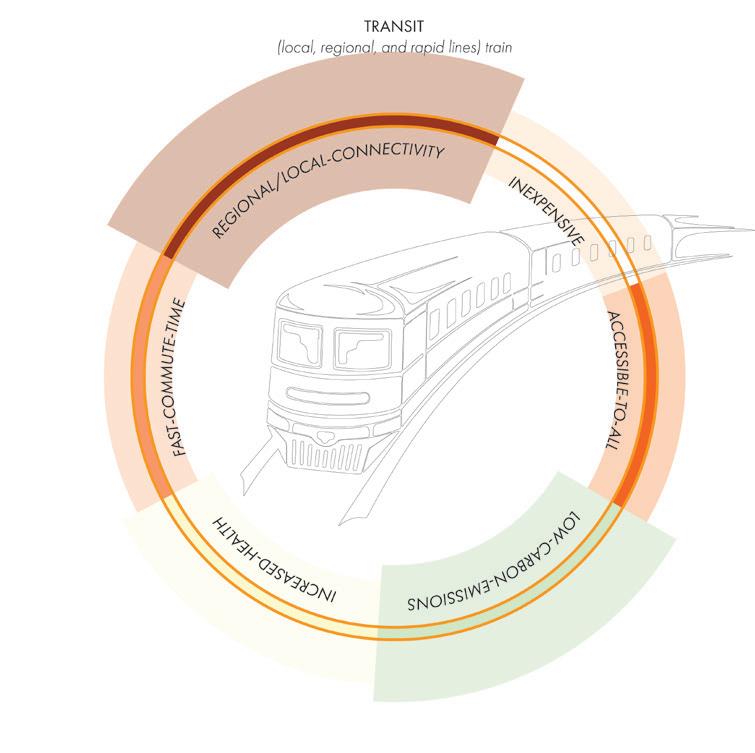

Urban Glitch was a Spring 2024 GSD options studio designed to research the pressing issue of systems-linked architecture in relation to the complex and intertwined ecological, social, and technological imperatives of our time. The studio utilized the program of a public transportation hub to explore the potential disposition of a 21st-century systems-linked architecture, asking how and when design can act in the face of complexity and toward a future of decarbonization.

Studio Instructor

Elizabeth Bowie Christoforetti

Teaching Assistant

Rita Rui Ting Wang

Advising Faculty in Urban Planning

Carole Voulgaris

Students

Nehemiah Ashford-Carroll, Gina Bernotsky, Chandler Caserta, Yixin Du, Connor Gravelle, Aria Hill, Inmo Kang, Ally Lammert, Rita Rui Ting Wang, Hannah Wong, Lanson Xie

AECOM Expert Advisors

Sally Librera, Nancy Lin, Jonathan Rushmore, Kristopher Takacs

Final Review Critics

Meera Deean, Craig Douglas, Grace La, Mark Lamster, Sally Librera, Nancy Lin, Adam Lubinsky, Rosalea Monacella, Angela Pang, Nayeli Rodriguez, Jonathan Rushmore, Kristopher Takacs, Carole Voulgaris, Sarah Whiting

This Spring 2024 GSD options studio was designed to research the pressing issue of systems-linked architecture in relation to the complex and intertwined ecological, social, and technological imperatives of our time. The work of the studio explores the potential disposition of a 21st-century systems-linked architecture, asking how and when design must act in the face of cultural complexity and climate crisis.

In the context of the studio, systems-linked architecture is focused upon infrastructures of energy, data, and transportation. The program is a transportation hub in Boston, MA. The studio begins with a counterfactual “game” that enables an understanding of the circumstances that led to our current condition of carbon-dependent mobility and imagines an alternative condition if just one historical event had taken a different course. This exercise acts as a radically pragmatic grounding mechanism to both situate design as a consequence of real-world contingencies and catalyze architectural imagination as neither the construction of wild utopias nor the acceptance of the existing status quo.

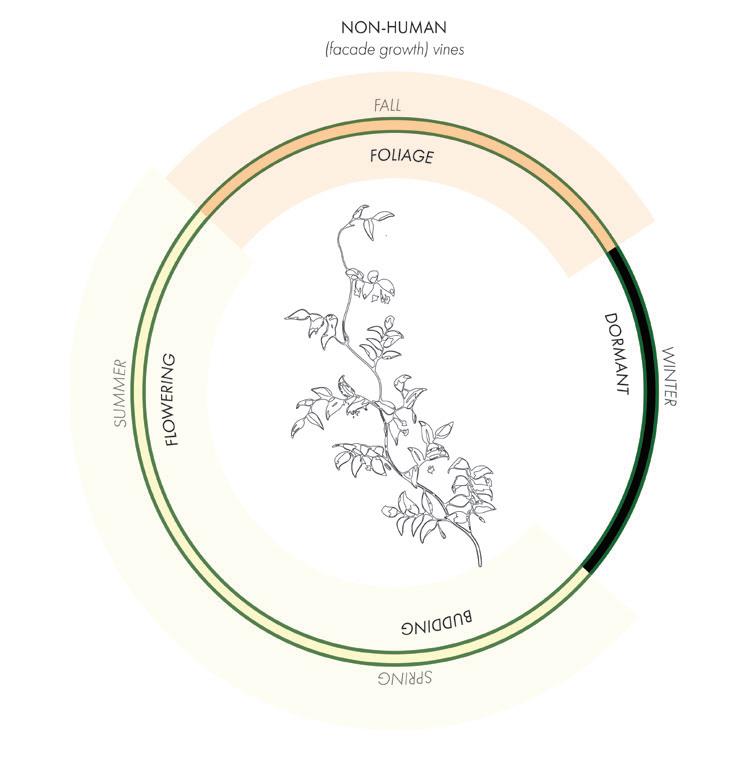

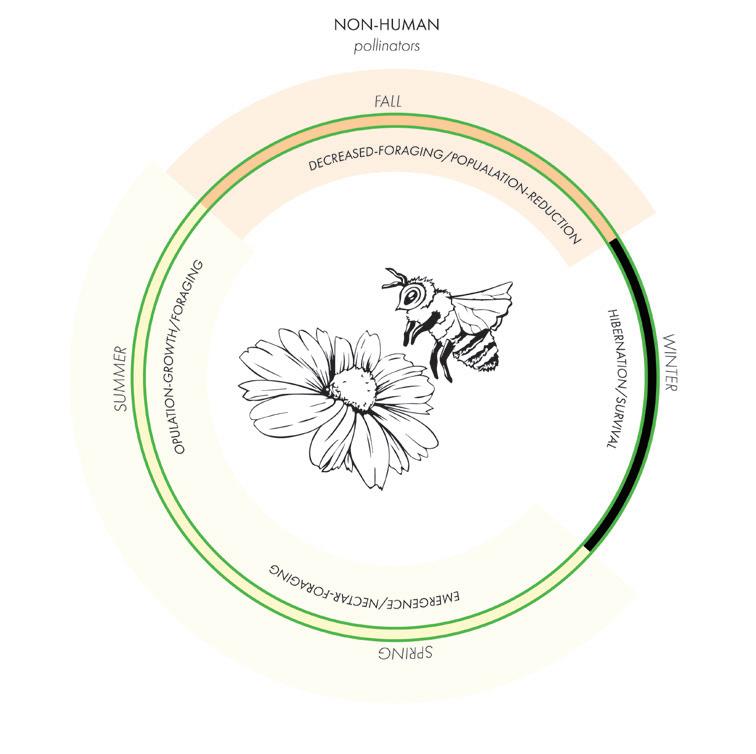

This hopeful work is informed by rigorous attention to the fragile contingencies of our shared world alongside the imagination of a meaningful future for urban mobility and public life in an era of decarbonization. We hope the work of the studio, as well as the methods explored within it, will positively contribute to the rapidly evolving discourse surrounding design for complextity, post-human design, and design for new nature.

The Urban Glitch studio grew out of the practice seminar “Urban Stack,” which I have been teaching at the GSD since 2020. The course focuses on emerging modes and methods of design practice that can grapple with the increasing systemic complexity that architecture must encounter in order to confront the major challenges of our time, namely the intersecting climate crisis and the rise of artificial intelligence.

The work of the first weeks of the Urban Stack seminar focuses upon mechanisms for re-reading or re-seeing urban form through the lens of essential systemic constructs of 21st-century power: capital, technology, and policy. Through a careful and sensitive reading of our environment and architectural precedent through this lens, a narrative of architecture as deeply contingent and linked to invisible systems of energy, finance, regulation, and public will quickly emerges. The course explores methods to navigate and engage the complexities that impact design at the project level as well a ways that design can create impact at the level of systems change, a mode of action that becomes increasingly important as we are called to take an ethical, as well as a cultural, position on the nature of relevant architectural and urban in an era of crisis and complexity.

While the seminar is an excellent environment for analysis and discussion, it is not structured to host sustained design speculation. The Urban Glitch studio, made possible by the support of AECOM, was an opportunity to extend the interests of the seminar into the territory of design imagination; to explore the nature and disposition of a truly systems-linked architecture that embraces contemporary complexity as a way to encounter the pressing challenges of our moment. Early conversations with the well-matched AECOM leadership team yielded a studio program focused upon infrastructures of mobility as way to directly engage both systems-linked design and an architecture focused on decarbonization through the design of shared transit futures an reduced vehicle miles traveled.

From a conceptual perspective, the Urban Glitch studio embraced architecture as anti-autonomous, as an agent of urban change that is necessarily collaborative, connected, and contingent; as a mode of engaged cultural production that requires fresh operational positions to facilitate this agency. The definition and disposition of infrastructure as a system of physical and social path dependencies with deeply embedded cultural and political values was explored and opened as a space for architectural agency and action. In practical terms, the studio addressed the intersection of transportation infrastructure, landscape, and civic architecture.

We collaborated with artists, policymakers, and engineers, among others, to consider the following questions within the context of the design process:

What is the role of the middle scale of architecture in re-programming patterns of urban mobility for an era of decarbonization? Who owns, rents, and maintains our urban infrastructure, and what happens to urban form if variables of use and ownership change? What urban mechanics are contingent or changeable, and what conditions are inevitable factors in the shaping of 21st-century architectural form? What are the opportunities presented by an architecture of dependence in which form must act in concert with the larger conditions and constructs that drive urban change? What is the disposition and agency of a public architecture in an era of private capital? How and when does architecture have the power to act up and down the scales of the built environment?

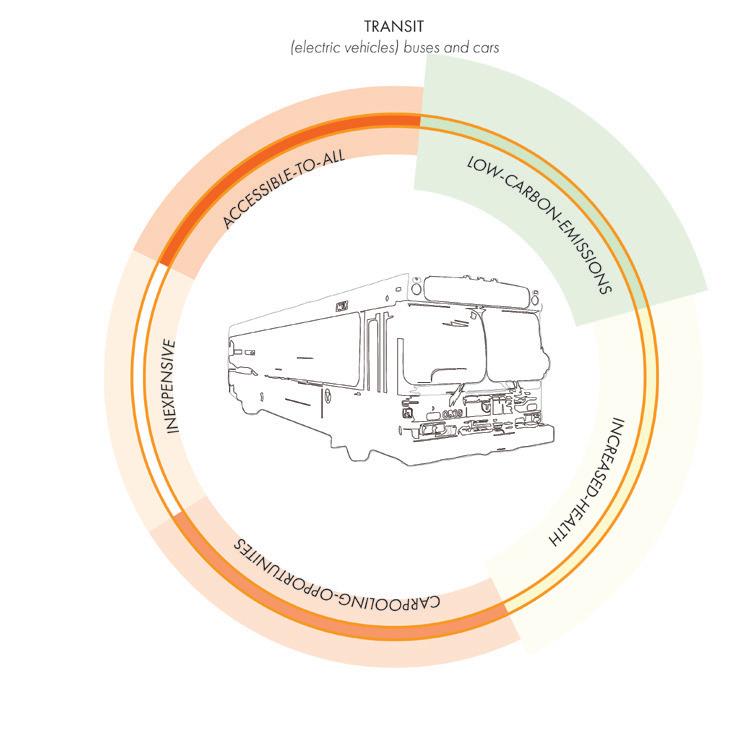

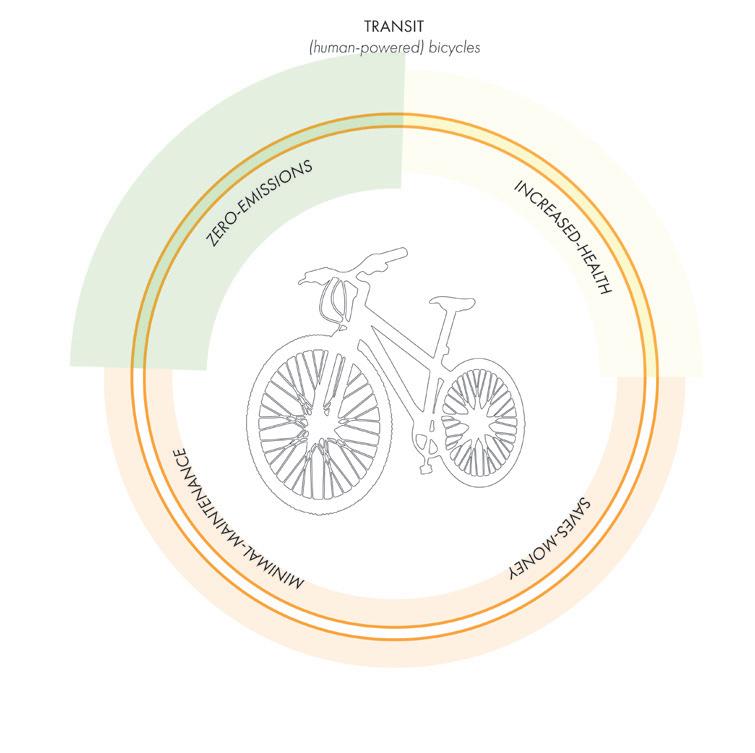

The studio program was a mixed-use transit hub that could accommodate public and private mobility within a paradigm of infrastructural decarbonization. The social dimension of such a program required the students to think critically about spaces of mobility as places for democratic activity where strangers interact regardless

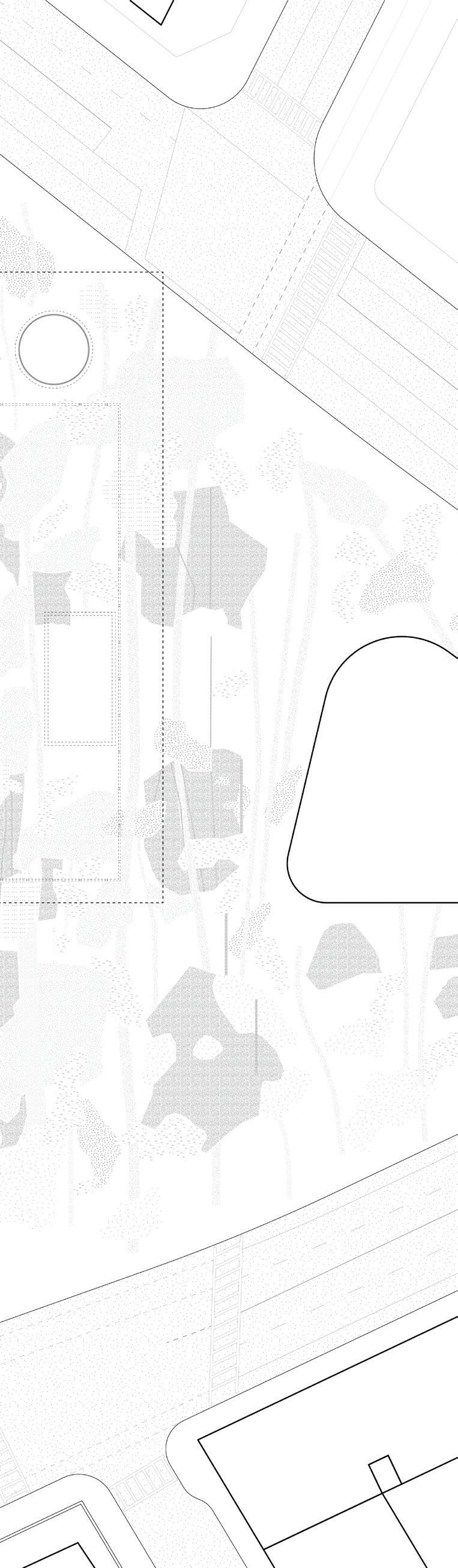

of their political and social leanings, as sites of protest as well as the mundane in-between places of everyday work and life. Studio projects were sited in the Boston area and students chose to situate their design exploration within one of two sites, each to host a distinct mobility hub and program relevant to the given context. Both sites are already affiliated with mobility, and both host a post-industrial landscape—spaces of tangled ecological, economic, political, and social conditions are the opposite of a pure or tabula rasa condition.

The first site is a central public transit node underneath existing I-93 highway infrastructure in Sullivan Square. The station program includes a new train station, busway, and shared mobility infrastructure. Key variables for consideration included transportation infrastructure ownership, management, and composition. The overlap of private and public development ambitions, financing mechanisms,

with the Boston Planning and Development Agency (BPDA) Chief of Planning and his Senior Advisor. Through an extensive discussion and tour of the City Hall model room we learned about the political and practical drivers behind site transformation; about timelines for change and the competing challenges of climate risk and the need for thorough public processes. Students were able to understand the urban mechanics driving design decisions around the scale and nature of our specific sites.

As a way into a more radical approach to the often-codified middle scale of urban form, the studio collectively imagined an alternative present—an urban glitch—in which our architectural imagination is contingent upon altered and re-imagined outcomes to an event and cascading set of decisions in recent history that

and corollary value systems was a rich space for design innovation on the Sullivan Square site.

The second is a peripheral node balancing industrial logistics and public mobility. It is an abandoned dry dock—infrastructure from a different era—located at the intersection of recent residential development, a public waterfront and path system, the Silver Line busway, and historic industrial uses in Boston’s Seaport. Carefully calibrated and overlapping accommodations for bike, boat, bus, and EV servicing were required to be integrated into this civic landscape of hard and soft infrastructure.

To learn more about the complexities and opportunities offered by each site, we met

shapes the current status quo mode of operation and consumption within the built environment. The goal of this counterfactual approach to site construction and design production (see “A Counterfactual Site” on p. 26) was to explore the spaces where current and future decisions are not fixed, where a combination of design imagination and radical pragmatism can impact the deep DNA and embedded path dependencies that shape our built world, and that generate or dissolve design’s capacity to make change at the scales of site and system.

Ultimately, “urban glitch” took on two meanings. It is a method for triggering design speculation by collaboratively imagining an

In addition to municipal planners from the City of Boston, transportation planners and designers from AECOM generously participated as expert planning, design, and engineering advisors across the semester. We were also grateful to have the perspective of local design practitioners actively working on the Boston sites in question and theorists considering the changing nature of infrastructural space within the discipline more broadly. Studio guests presented pragmatic constraints for transportation design, historical context for contemporary spaces of infrastructural operation, and conceptual methods and approaches to creating productive design specu-

alternative present as the set for design and the stage upon which public life unfolds within the project. The site itself is also imagined as a moment of friction—or a meaningful glitch —within the efficiency of the transit and infrastructural landscape. It must awkwardly balance the demand of systemic efficiencies with the meaningful inefficiencies that are essential for human life.

lation and design fiction. Our research also included travel to Amsterdam, a city relevant to the studio for its role in the counterfactual game; its robust transit infrastructure; its blurred perspective on the intersection of the natural and artificial as part of its history of radical landscape engineering and infrastructural transformation. In the Netherlands we explored a system of urban transportation and related infrastructure that yields dynamic forms of personal and shared mobility and a diverse range of buildings to store, charge, and host it. While visiting the

Netherlands, the studio met with historians, transportation designers, architects of infrastructure, technologists, and the director and curator of the Museum of 21st Century Design. Through the lens of art and science, and utilizing many forms of mobility, we explored the Dutch perspective on nature and the role of infrastructure in transforming productive, industrial, and urban landscapes. The studio trip was enormously influential in terms of understanding the dynamic (and pragmatic) challenges of public transportation infrastructure as well as perspectives on the role of biological systems in the continuously oscillating boundary between the natural and artificial in the Dutch landscape.

Given the vast nature of the ecological problem we are confronting, as well as the entangled local conditions of the post-industrial social and physical site, the studio made a point to

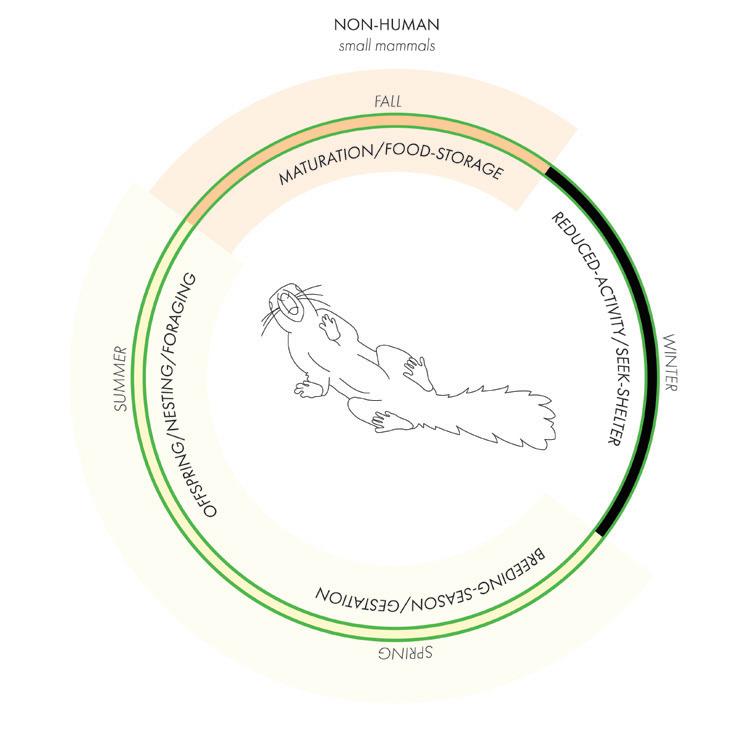

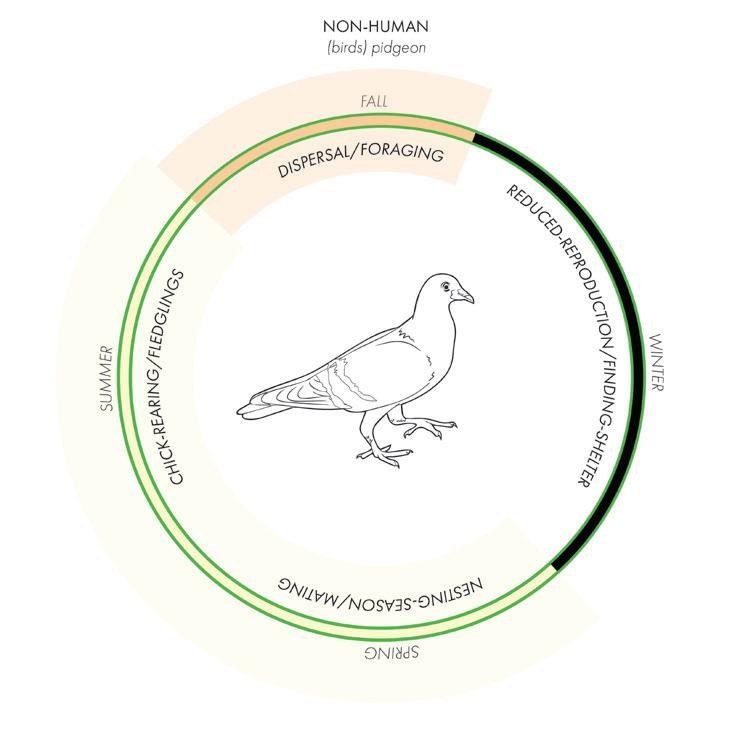

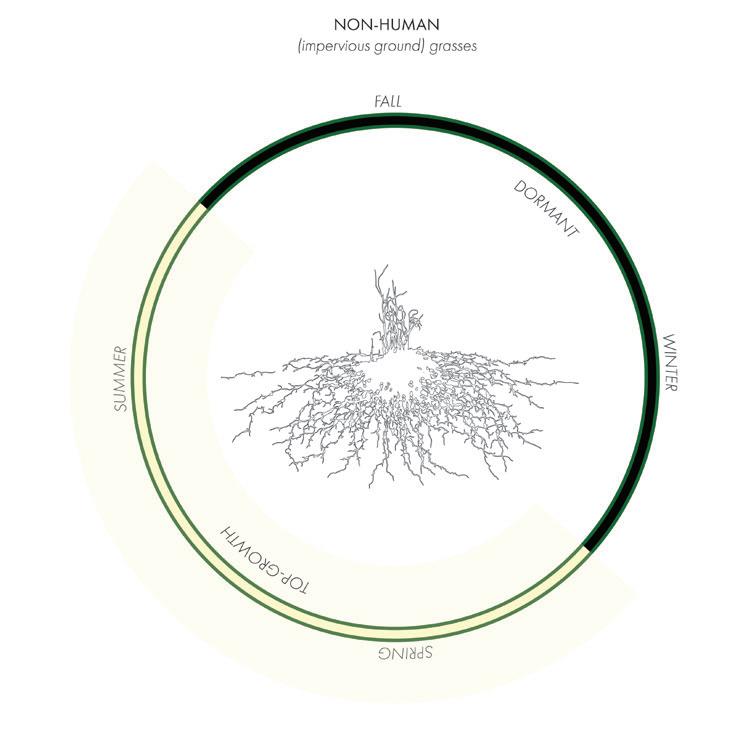

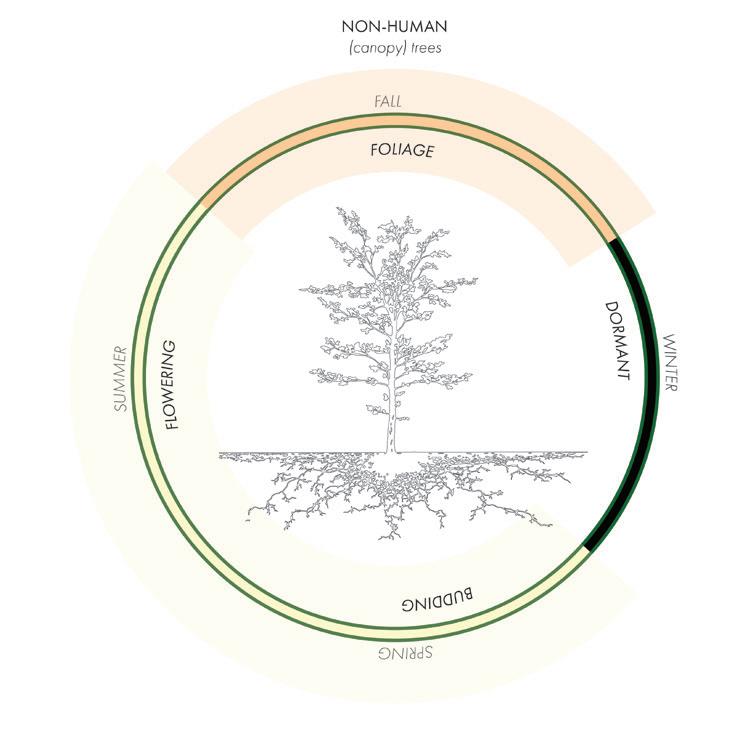

between all actors on the site, from trains and technology to people and fish, are explored throughout the work that follows. In so doing, the students have sketched out a systems-linked architecture that embraces complexity as a temporal, social, biological, and technological construct. Their work yields an architecture

take a position on “the natural.” Unlike the 19th century drive to control, manage, and extract the overwhelming power of the natural world, our own time is overwhelmed by the waste and environmental crisis that this worldview has wrought.

Students have thus taken on the natural and artificial as a bonded pair in the contemporary urban landscape. As such, processes for change over time are embraced as approaches for site transformation and radical interactions

that points toward a new sublime: something that systematically acknowledges the overwhelming condition of our context-in-crisis and yet remains optimistic in its quite and patient effort to make change. This awkward moment holds hope for collaboration through a release of autonomy and the exploration of new relationships that blur the boundaries between architecture, landscape architecture, and urban scale practice.

Boetzkes, Amanda. 2019. Plastic Capitalism : Contemporary Art and the Drive to Waste. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press.

Christoforetti, Elizabeth. 2023. Our Artificial Nature: Design Research for and Era of Environmental Change. Exhibition text for exhibition by the same name. Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Easterling, Keller. 2021. Medium Design : Knowing How to Build the World. London: Verso.

https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezp-prod1. hul.harvard.edu/lib/harvard-ebooks/detail. action?docID=6386631

Easterling, Keller. 2014. Extrastatecraft : the Power of Infrastructure Space. London ; New York: Verso.

Friedman, Batya, and David G Hendry. 2019. Value Sensitive Design. 1st ed. Cambridge: MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/ mitpress/7585.001.0001.

Gallagher, Catherine. 2018. Telling It Like It Wasn’t : The Counterfactual Imagination in History and Fiction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Haraway, Donna Jeanne. 2016. Staying with the Trouble : Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

Schmelzer, Matthias, Andrea Vetter, and Aaron Vansintjan. 2022. “The Future of Degrowth.” In The Future Is Degrowth. United Kingdom: Verso.

Meadows, Donella H., Club of Rome, and Potomac Associates. 1974. The Limits to Growth : a Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind. 2d ed. New York: Universe Books. https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezp-prod1. hul.harvard.edu/lib/harvard-ebooks/detail. action?docID=7012344

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. The Mushroom at the End of the World :on the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Pilot project. eBook available to selected US libraries only. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Winner, Langdon. 1980. “Do Artifacts Have Politics?” Daedalus (Cambridge, Mass.) 109 (1): 121–36.

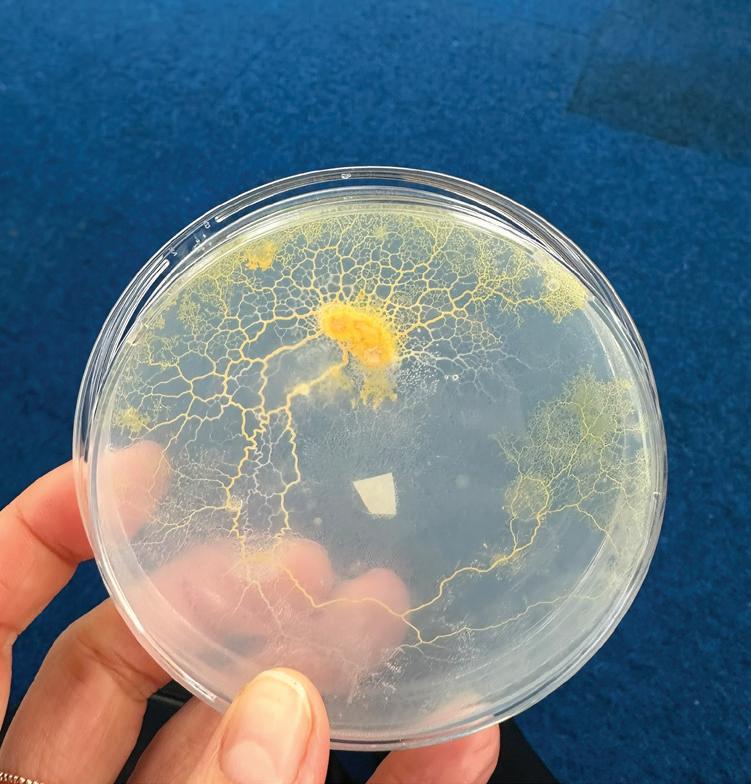

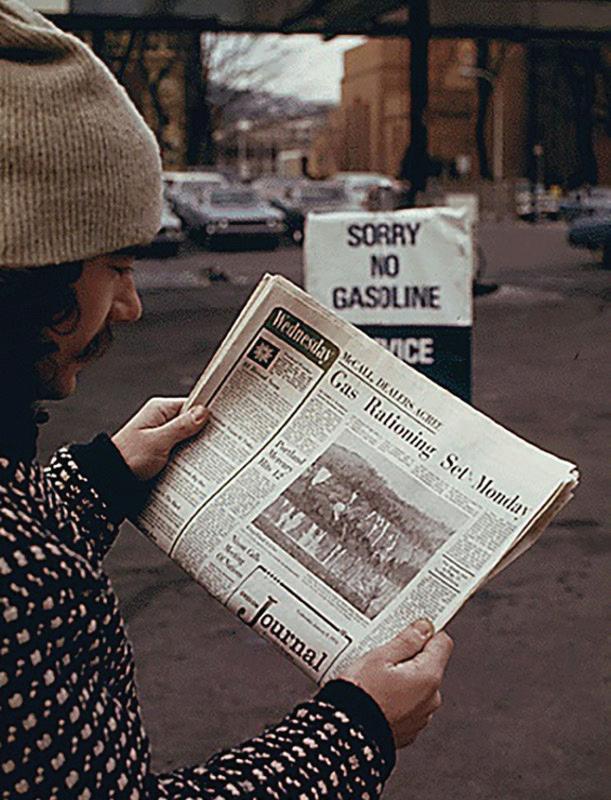

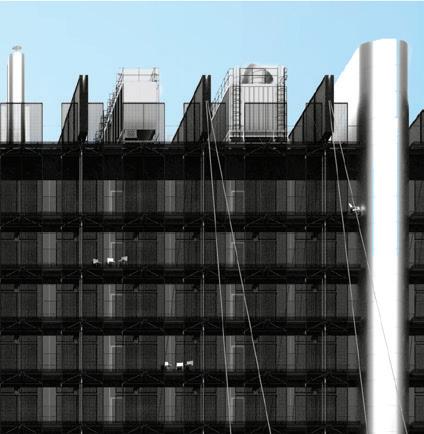

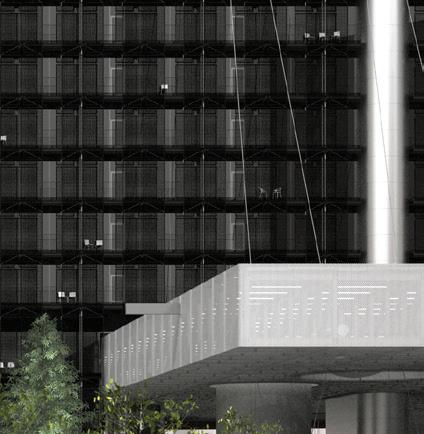

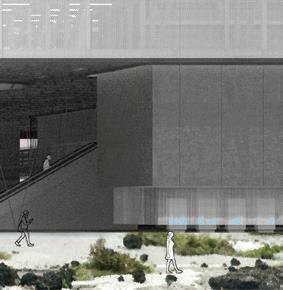

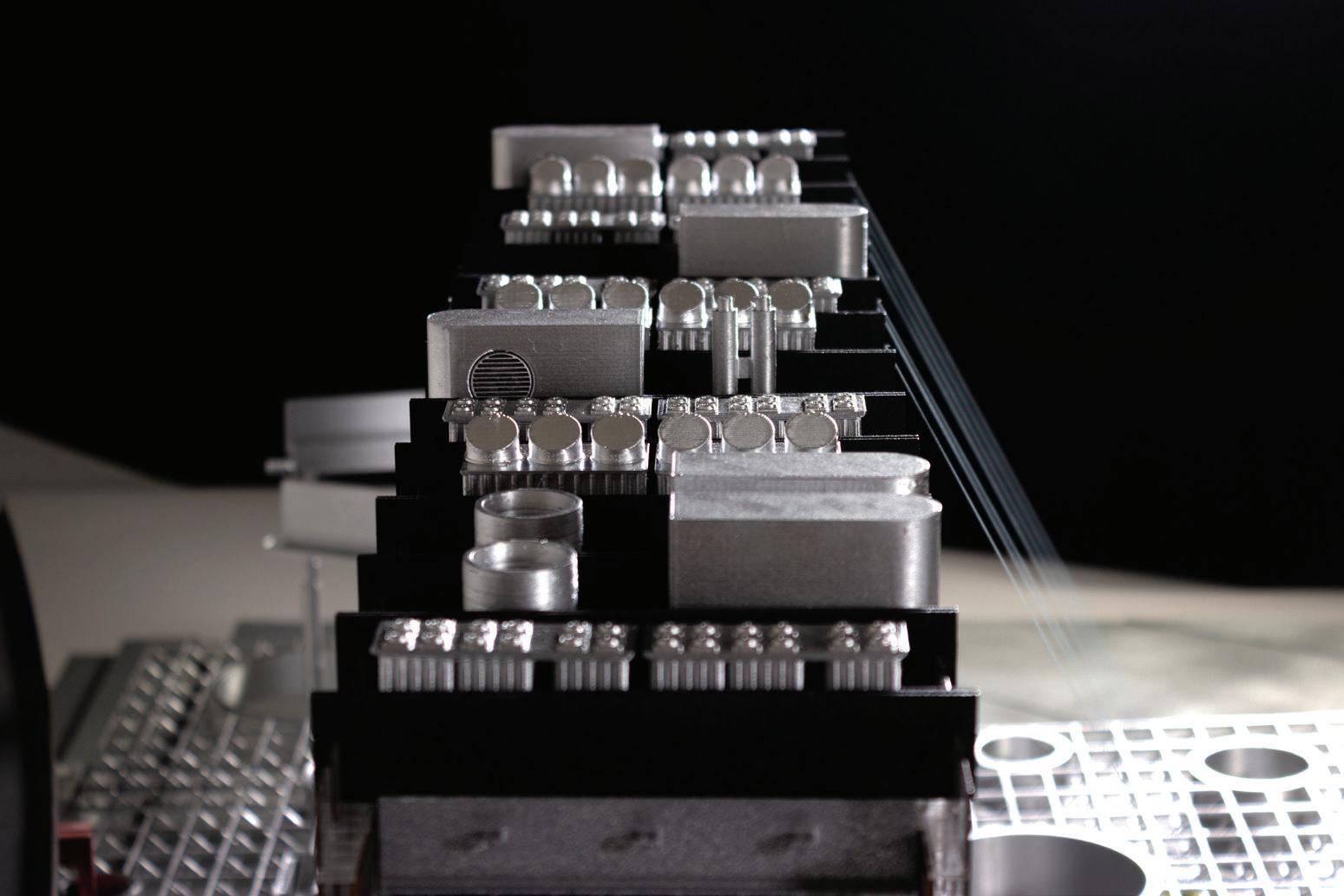

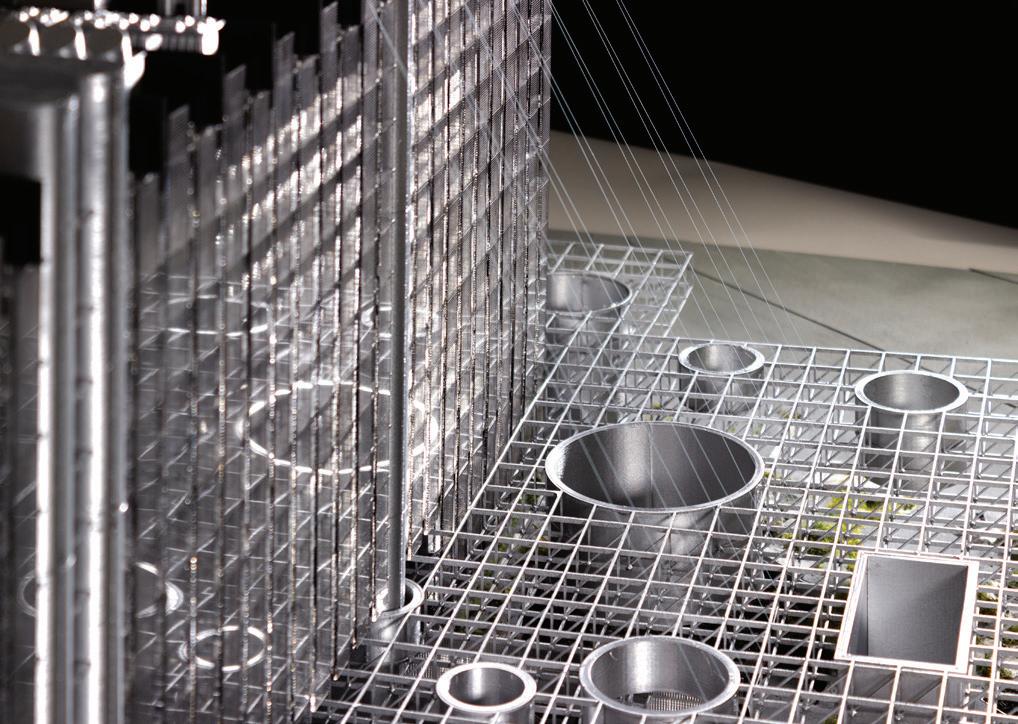

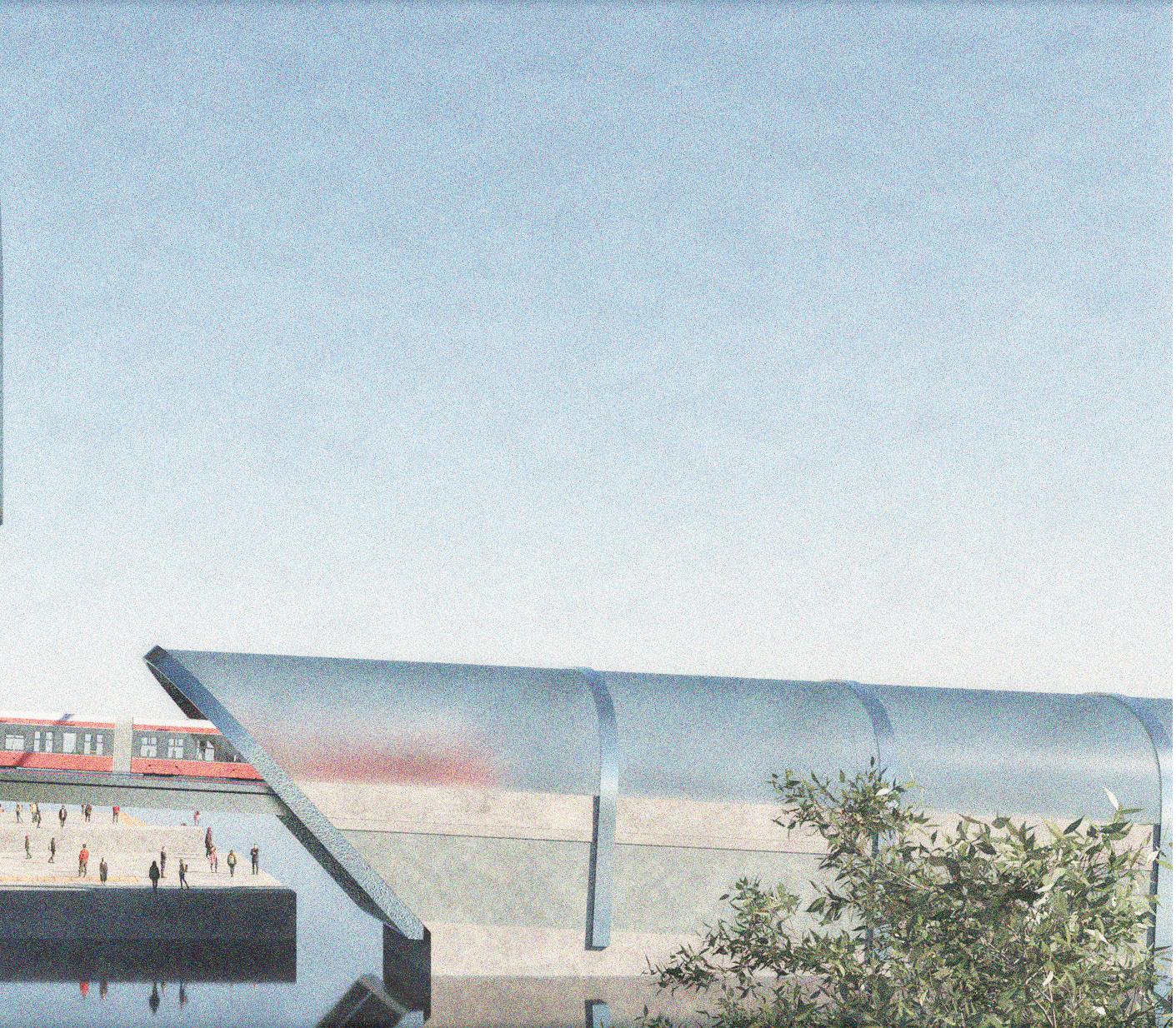

Photographs from the studio trip to Amsterdam. Students explored modes of infrastructural transformation from microscopic growth to systemic standardization. With a focus on infrastructures of mobility, we toured contemporary transit stations (by bike, train, ferry, and foot) and learned about the Dutch history of aggressive landscape transformation across changing cultural value systems and perspectives on the relationship between human life and natural systems.

In an environment of ubiquitous networks, systems, and infrastructure designed to connect and consume across our digital and physical worlds, the identity of architectural form as cultural, ethical, or functional—as artifact, algorithm, or urban component—is murky.

On one hand, architecture can be read a rehearsal and reflection of the systems upon which it is dependent. Invisible systems of finance, policy, and technology shape our built world to yield a set of contemporary typologies that fit seamlessly into the streams of data, energy, and capital that flow through them. This architecture optimizes form, space, and performance for the societal values of its time and place. It is a tool of power to amplify existing orders and modes of living.

On the other, we may see architecture as a bit of friction in the machine, a wrench in the works of the systems that aggregate to shape our contemporary context. This architecture is like the pea in the bedding of the princess in Hans Christian Anderson’s story of the Princess and the Pea. It is a small but insistent actor within the larger infrastructure of comfort, interrupting the purpose of the stacks of soft feather beds and mattresses, which are layered to yield uninterrupted sleep and luxurious rest. This architecture operates within and against the urban systems that surround it, calling attention to their relentless efficiencies and revealing the character or nature of the society that shapes them by causing a disruption, however temporary, within the infrastructures of urban function.

These two architectures co-exist in our disciplinary imagination, one optimizing and one resisting the status quo. Our discipline recognizes the latter as Architecture with a capital “A,” the banner of the historic avante garde. The former is simply building, or architecture with a lower case “a”. Practices of the latter yield culture while practices of the former do not. The latter is a more pure expression of humanity

while the former is complicated, muddled, and shaped by the messy and overlapping systems designed to serve and structure collective human life. The latter Architecture is the 1% (and often for the 1% in a world defined by an increasing wealth gap) and the former is the other 99% of urban form.

But the real-time storyline of the 21st century is not so binary or clean. We are increasingly aware that a world that celebrates the rare and special 1% is a world imagined and shaped by a worldview of colonial hegemony and industrial extraction. The systems created to define and support human life in this paradigm yield climate crisis and social inequity. The worldview and its systemic infrastructure produced the significant works of the architectural canon, which are bound tightly to parallel disciplinary path dependencies and extractive infrastructures of labor, energy, and material use. Regardless of the status of a building as an act of cultural criticism or instrument of capital, it is inevitably a contributing member of a sector that is responsible for 40% of collective global energy consumption. Furthermore, the 99% of buildings with an “a” account for 99% of our collective human experience and consume 99% of the energy we produce. Given the shared nature and magnitude of the climate crisis, the argument to address—in fact, prioritize—systems-linked architecture as an act of human meaning is not difficult to construct.

As awareness of our self-constructed environmental plight grows, so does an awareness that the frameworks we created to imagine and produce our built world reflect an outdated set of inherited values vis a vis conceptions of both nature (to be controlled) and technology (as a tool for control). These frameworks, such as the carbon-extractive energy grid, policy and financing mechanisms prioritizing large-scale and self-similar development types, and the ever-growing highway infrastructure for individual vehicles, yield buildings that are

carbon-dependent infrastructures of energy and capital. Inherited worldviews shaped by a paradigm of power and profit through limitless growth in a finite world also shape the underlying DNA of our profession and discipline. If the frameworks we operate within to understand and create architecture are themselves constructs of an outdated legacy, both the existing and potential structures we have created to imagine and construct our built environment urgently require fresh examination and re-consideration. The implications for our understanding of architecture as an operative and meaningful human endeavor are significant. The imperatives of our time—from environmental change to artificial general intelligence—are vast, overwhelming, and the outcome of a mode of world building that is rapidly crumbling. While the architect was once the self-appointed designer of our world, this role is diminishing in the face of the digital

relevance for our time must engage with the systems of material, labor, finance, and energy that it rests upon; while our discipline maintains its own theoretical frameworks and internal principles, autonomous form as a pure idea apart from worldly externalities is no longer possible.

So how must we act? There is general acceptance that we need to reduce dependence upon carbon, and that we can and must do more to re-situate relationships between and within human communities as well as between humans and non-humans in order to do so in a sustainable and ethical way. Our growing awareness of architecture’s entangled relationships with biological, technological, economic, and political systems requires that we engage with complexity and understand our work in new ways.

As such, the work of the Urban Glitch studio embraces systems-linked architecture with lower case “a,” but does so from a position of critical optimism, imagining that the intellec-

imagination, and our territory of concern is increasingly siloed due to rapidly mounting building complexity and specialization; ethical concerns over material use, supply chains, energy consumption, and human labor; an environment of intensifying regulatory control. The frameworks we have created to ensure intellectual and financial control over our work (namely the discipline and profession of architecture) may not be equipped to support relevant form in that a building that is an authentic representation of our time may in fact be one that yields either no form at all or a strategy for less future building—modes of design that fly in the face of the raison d’etre of both professional organizations and disciplinary structure. At the very least, an architecture of

tual project of design must operate within, but can also operate upon, the systemic constructs that shape our world. It oscillates between the scales of human experience and infrastructural space, and considers what it may mean to create a vast but quiet architecture that accounts for change over time. The work explores what it may mean to be accountable to both human meaning and systems change, and to do so in a way that builds upon both disciplinary and anti-disciplinary histories.

The work acknowledges that our environmental crisis is vast and shared, and that an approach must be collaborative and trans-disciplinary. It offers a reflective perspective on choices not made, laying bare the contingent nature of our built world as a source of optimism

and a mechanism for change. The work of this studio is not diagnostic and it makes no great claims. Instead, it operates upon gaps and contingencies—the places where doors open and close and where small decisions grow long tails of impact—to explore and test the questions that remain unanswered. In so doing, it also tests the disposition of an architecture that works in the background to serve and reveal the values of our time. It fills in overlooked urban space, explores the potentials of re-use and the limits of architectural form to yield real and substantive change in our built world by oscillating between operation at the levels of momentary experience and systemic integration. In simple terms, we ask the following questions:

Is architecture simply accountable to operation within the systems and path dependencies of our regulated world of standards and type-forms, or can it become an agent to re-shape them?

ization and new nature in an alternative present (see “A Counterfactual Site” on the following pages) and rests upon the domains of art and science as much as theory and precedent from our native disciplines of architecture and landscape architecture.

The questions raised in the studio remain open and thorny, a rich territory for cultural imagination and a radically pragmatic platform for a re-consideration of the role and identity of architecture in a time of needed systemic change.

If architecture can act as more than artifact, how might we confront and re-imagine a mode of practice that evades capture by our native disciplinary boundaries? What is the disposition of such and architecture and at what scale(s) is it accountable to what is means to be human, together?

In collaboration with AECOM, the brief was developed to address systems-linked architecture through the program of a transportation hub on post-industrial sites that are vulnerable to climate instability and flooding. The program is devoted to public space and shared mobility with the intersecting purpose of infrastructural decarbonization and social connectivity. The work directly considers a paradigm of decarbon-

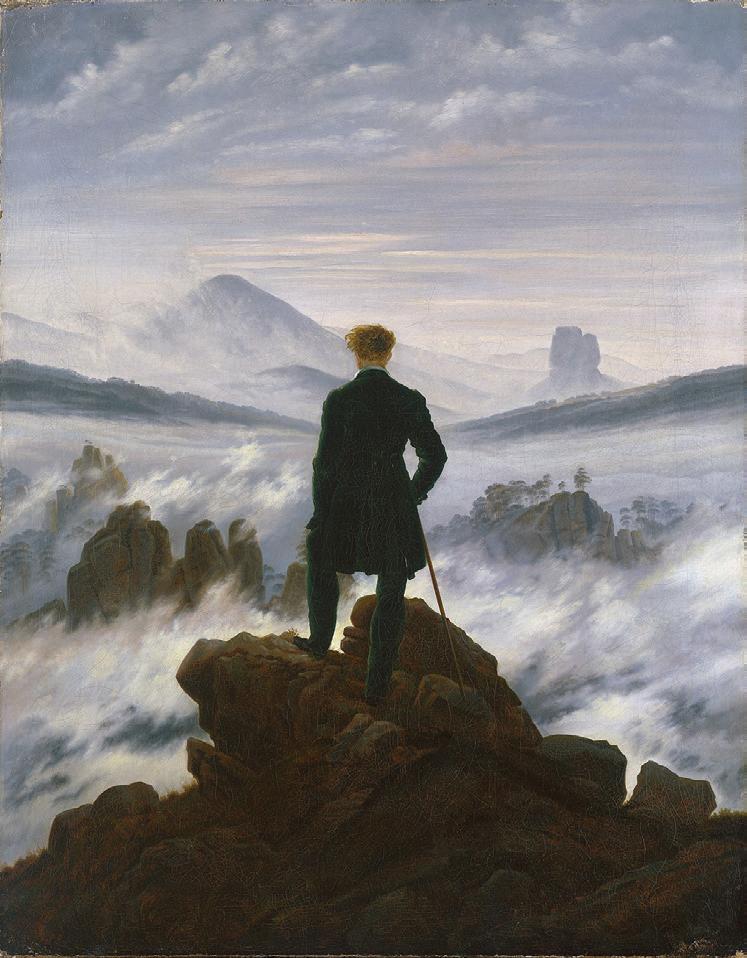

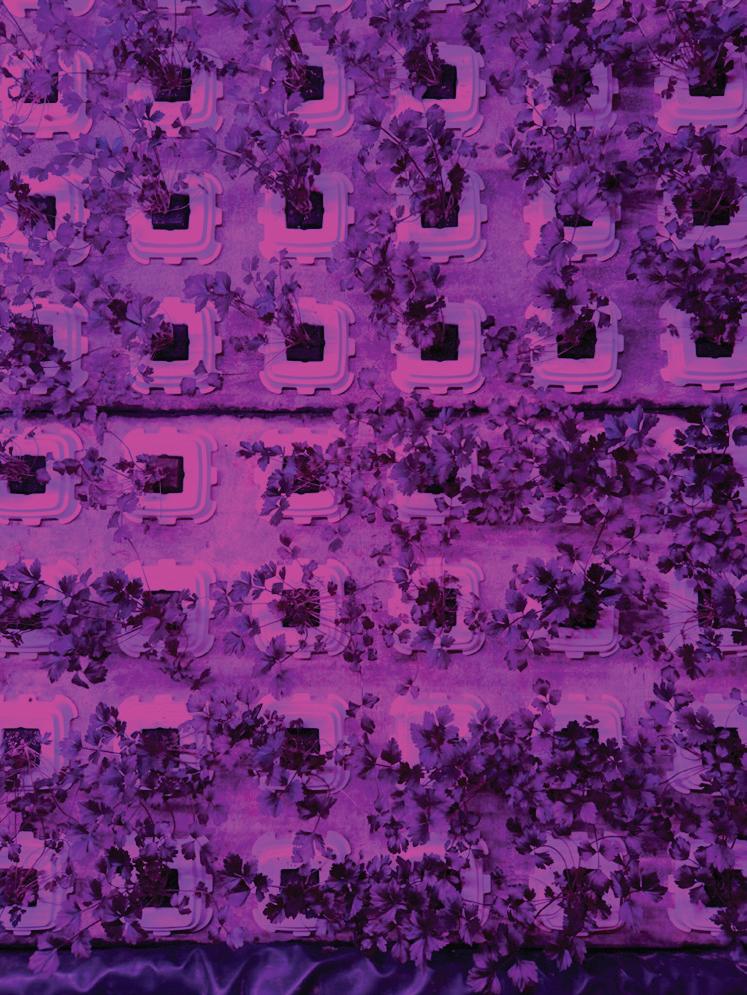

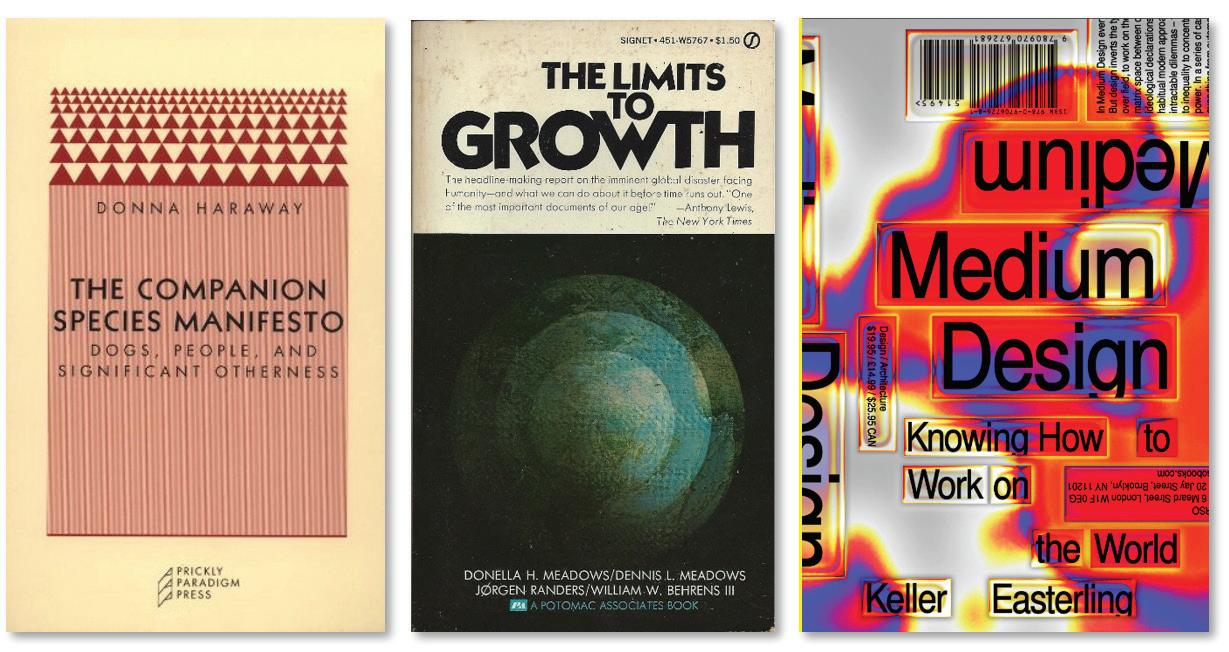

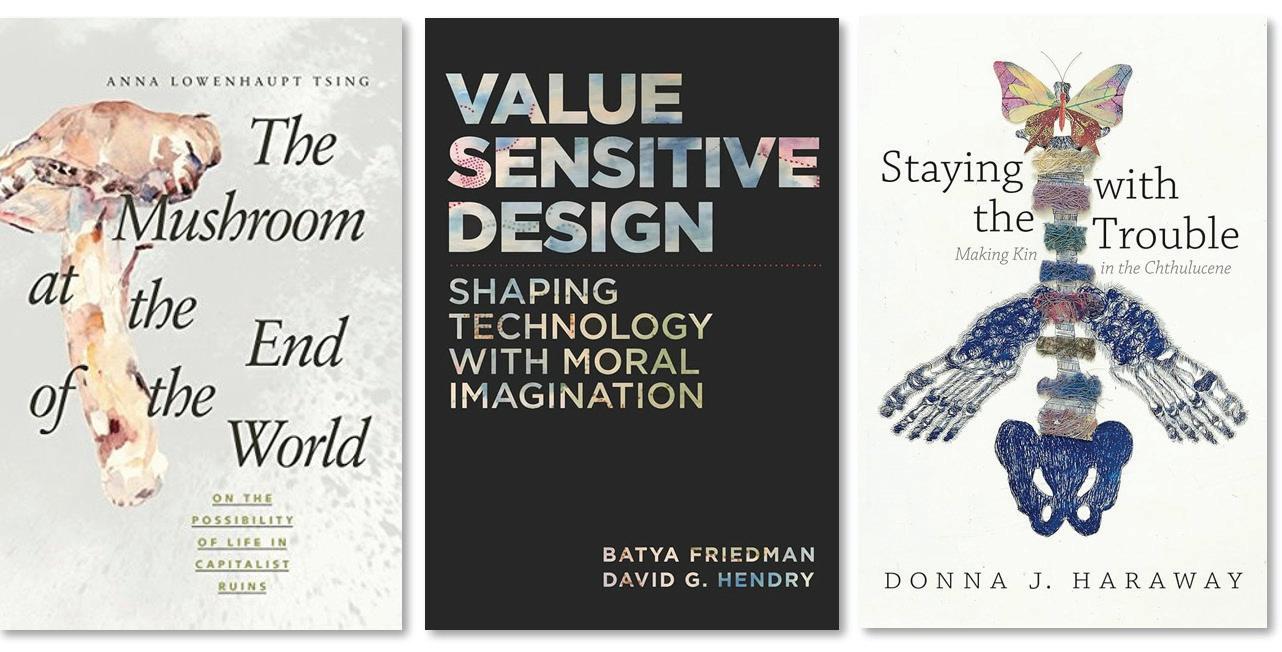

Images of reference from abutting or distant-but-relevant disciplines that informed the construction of the studio brief. Topical material includes positions on unlimited growth in a finite world; relationships between human and non-human species in the built environment; the role of capitalism in the construction of self-limiting systems of design; daylighting and constructing value systems for design.

The studio began with a counterfactual condition rather than a fixed brief:

What if the 1974 OPEC negotiations failed, developing into a longer-lasting embargo? How would the disposition of urban infrastructure in Boston, MA have evolved differently in a condition of forced decarbonization?

Imagined as a design exercise in its own right, the counterfactual game operated as a collective platform to lay bare the fragile and human decisions that drive the disposition of our urban systems and the architecture that serves them. The game yielded a 2024 site context shaped by slightly different decisions: a world of path dependencies and infrastructural relationships different from our own, and rich in their potential to enable design imagination.

The outcome of the counterfactual game, constructed in collaboration with artist Tyler Coburn and urban technologist Siqi Zhu, set the conditions and program for our investigation of transportation infrastructure design. The single-day counterfactual workshop enabled students to collaborate with transportation design experts in both academia and practice to consider the paradigms of causality, determinism, and contingency in our work as designers. It was a productive mechanism to address and construct the role of human (and non-human) agency in project design. The site construction method allowed students to learn from the past to image a better future by deconstructing the variables that shape a site and its reciprocity with the seen and unseen urban context that shape it.

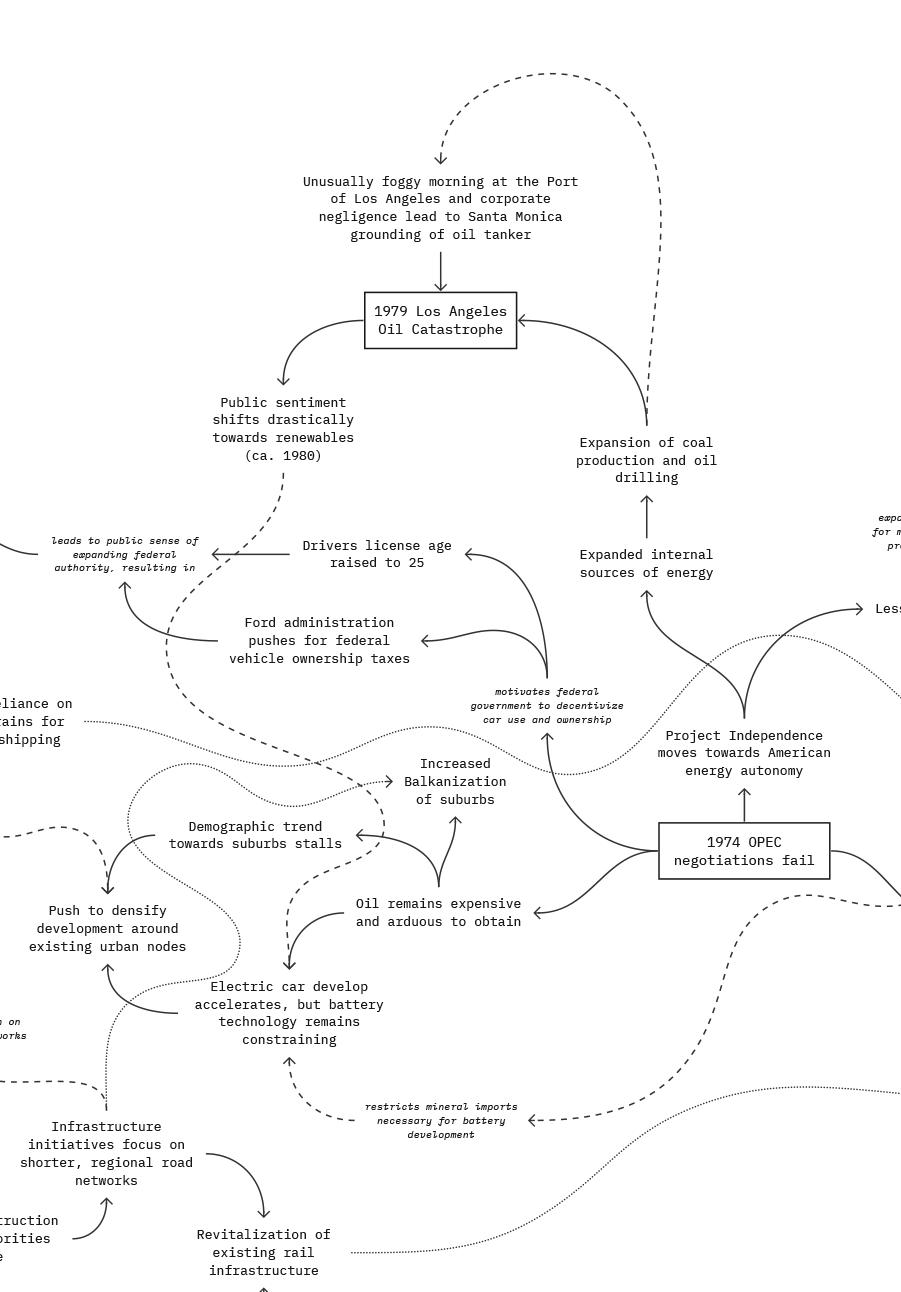

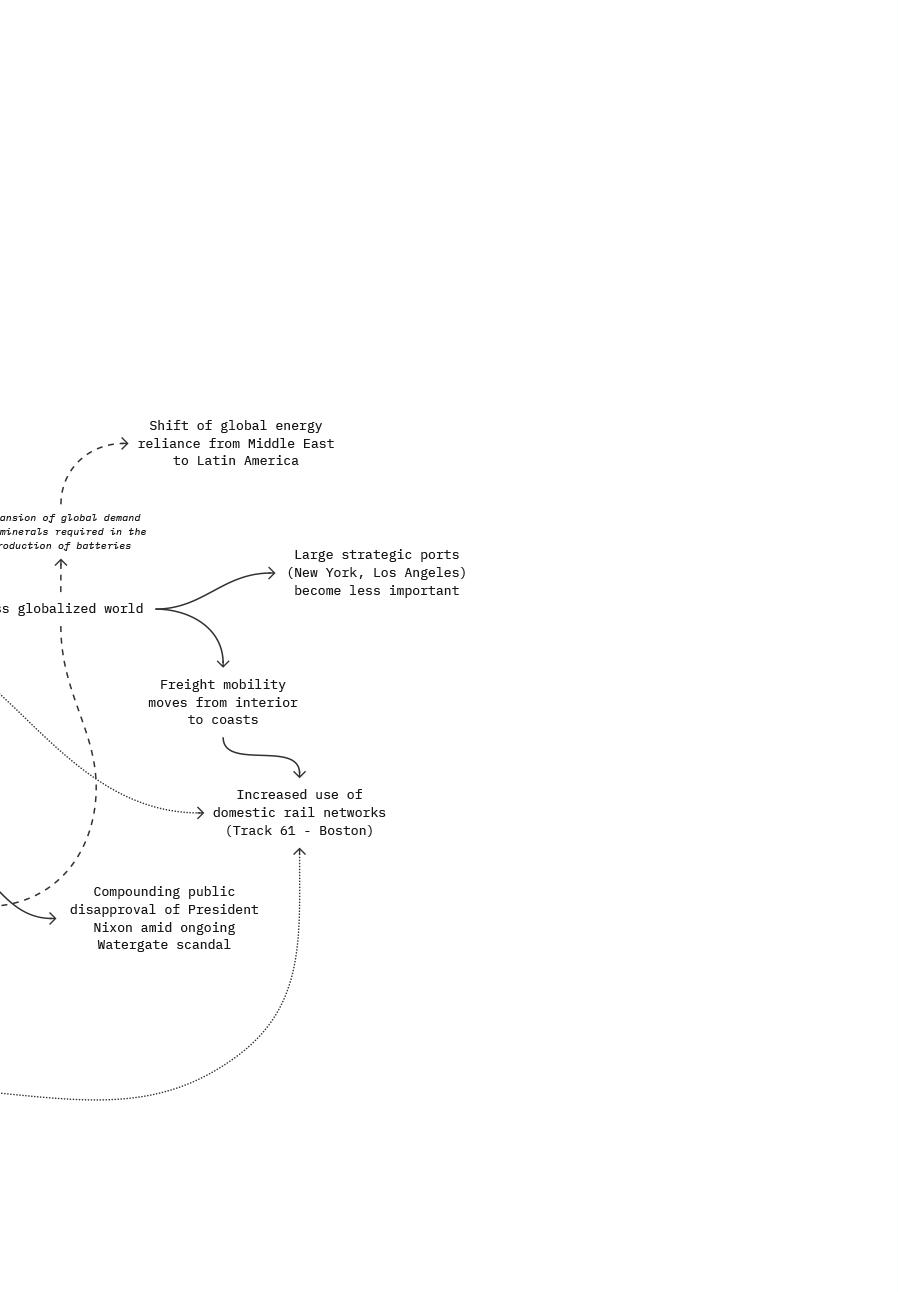

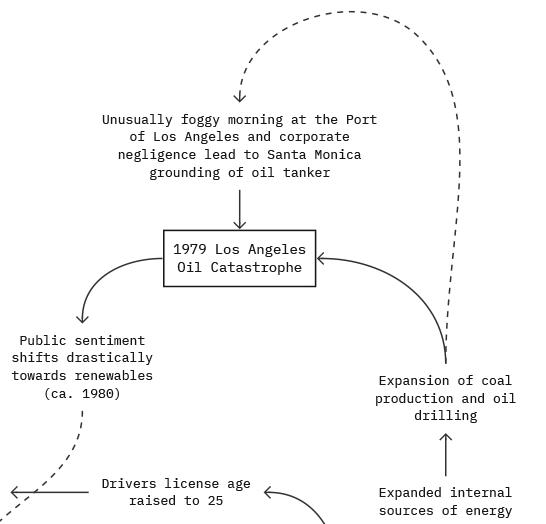

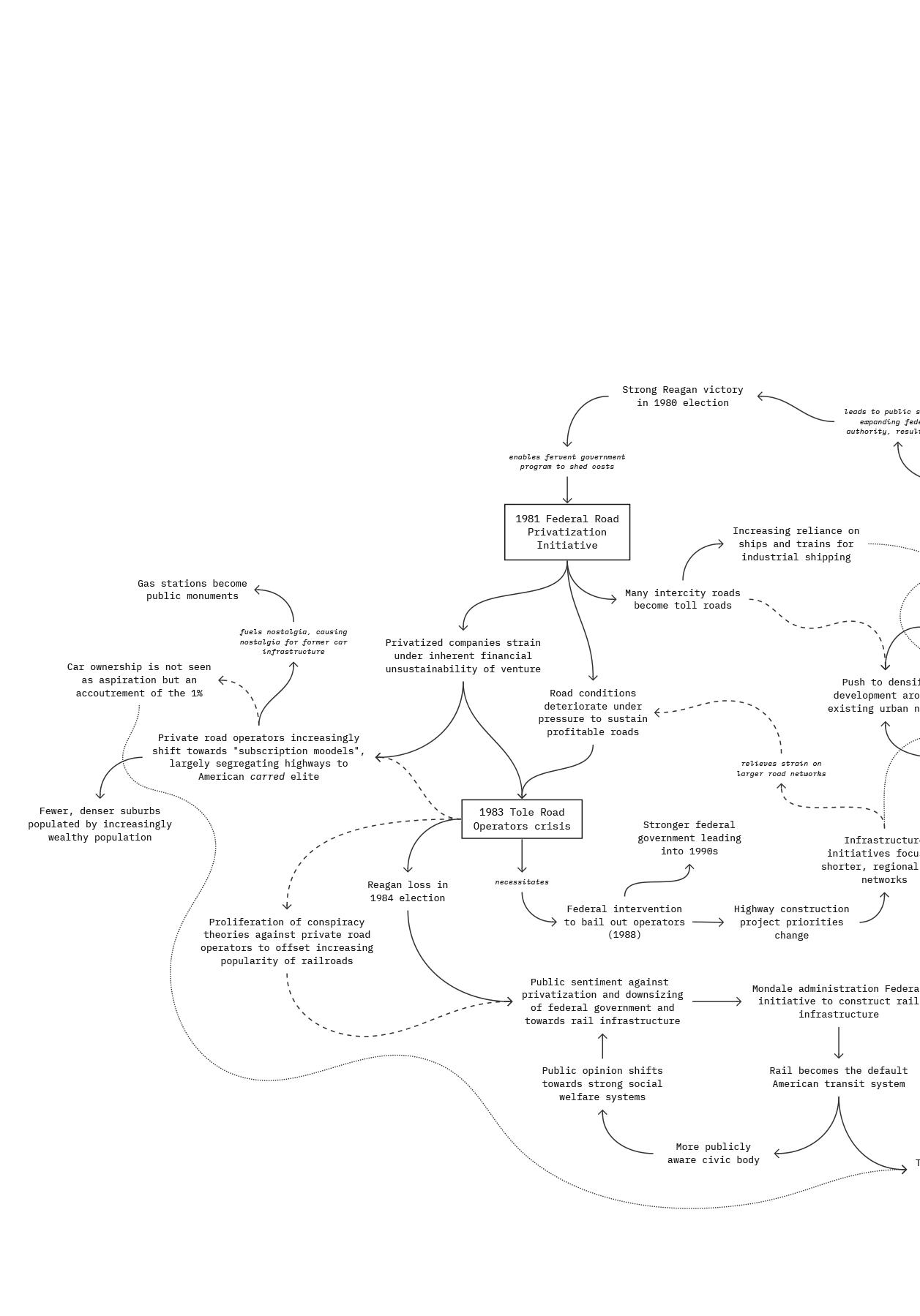

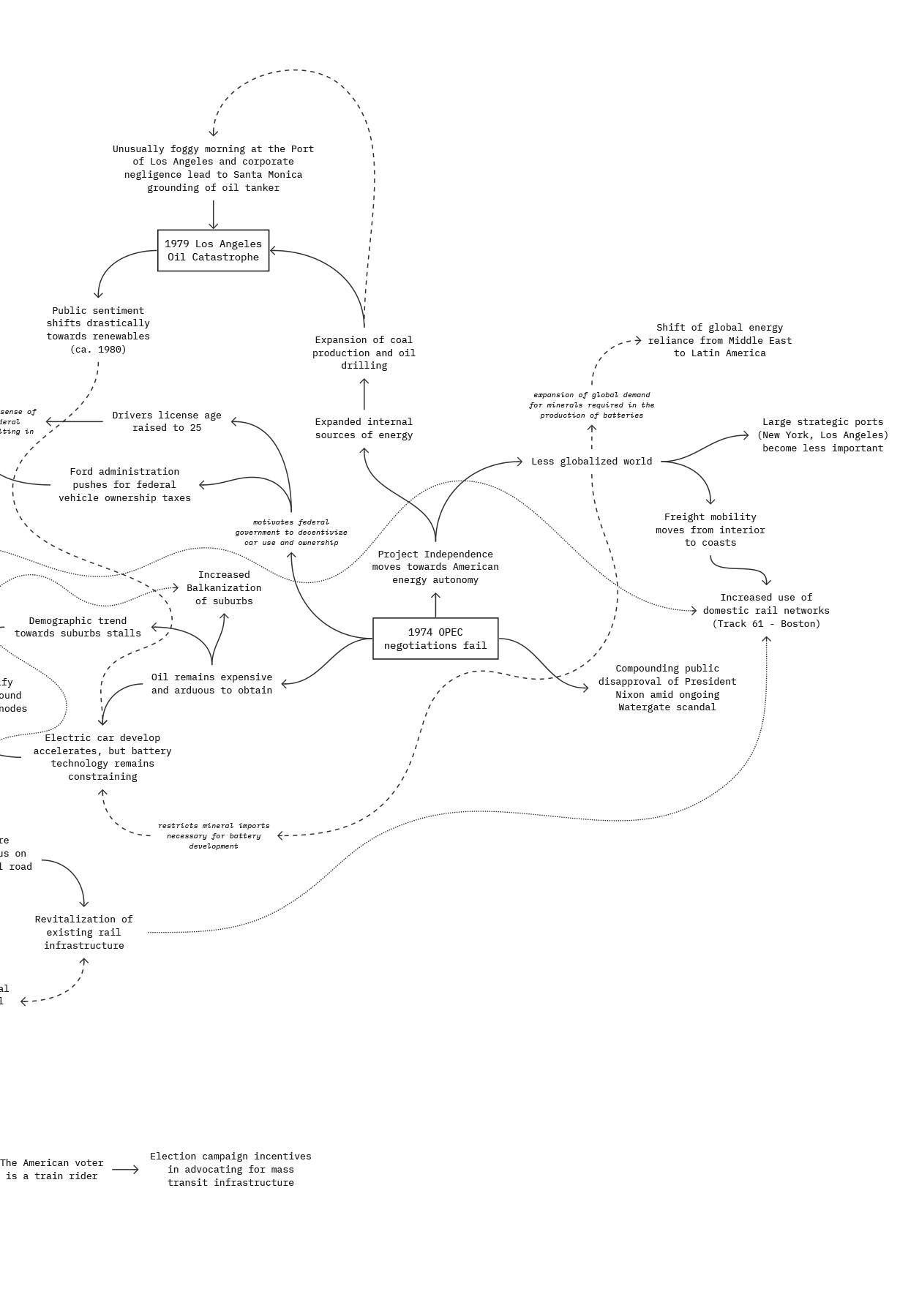

The counterfactual game, recorded on a collective online whiteboard, began with this prompt:

Contingencies surrounding the 1973 Oil Crisis serve as the conditions for our counterfactual game. OPEC’s oil embargo on the US and the Netherlands drove rapid and dramatic change in the ways in which fuel was consumed between 1973 and 1974. Fuel rationing, lower speed limits, and car-free mandates on mobility were suddenly on the table as ways to radically reduce dependence on cheap fossil fuels. While the impact of the crisis was lasting in its global impact, negotiations with OPEC in 1974 resulted in a lifting of the embargo. Ultimately, the impact on patterns of mobility and fuel use in the US were not dramatically altered.

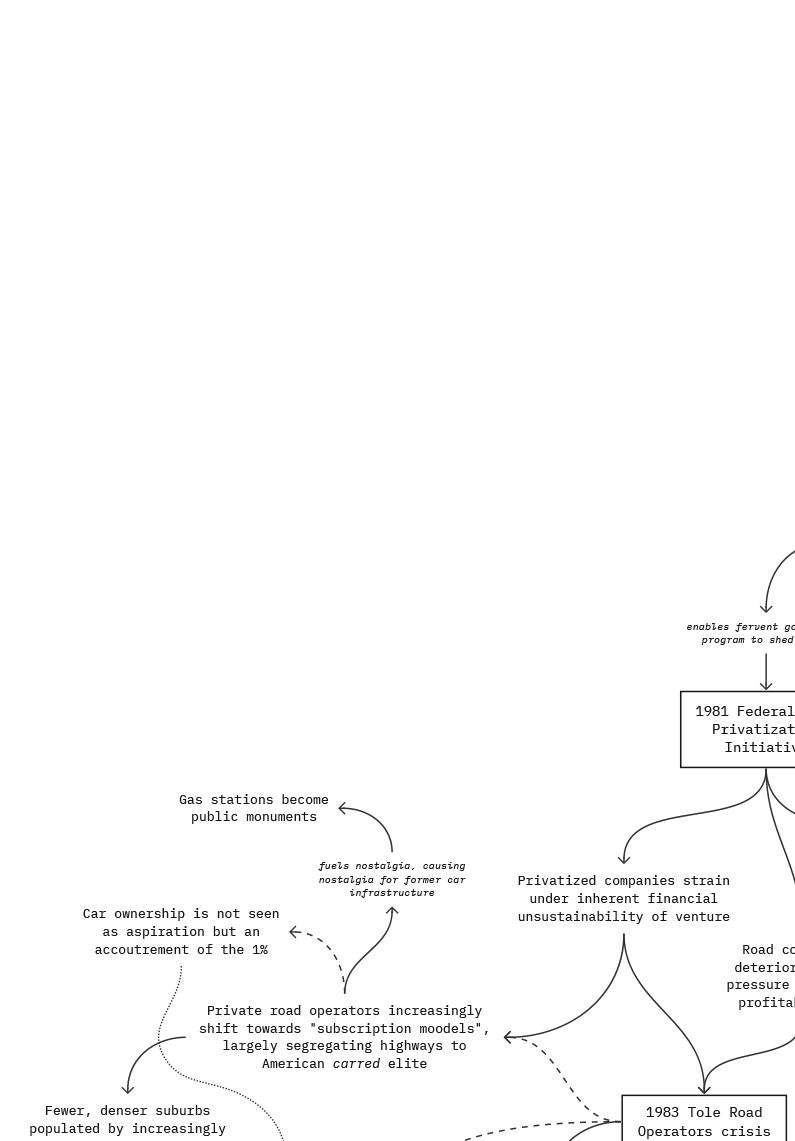

Above and on following pages: Excerpts from Counterfactual Game Workshop, Fall 2024.

But what if the 1974 negotiations with OPEC failed? Would our patterns of development and urban form in the US have changed? To what extent would our transportation infrastructure and transit-oriented development be altered from their current form? And more specifically, what would a mobility hub on our sites in Boston contain? What systems and landscapes would it serve, and in what proportions? What fixed infrastructure would it contend with? Who would own and manage such infrastructure, and to what extent would mobility hubs operate as civic spaces? And what and who would move through them?

Counterfactual game leaders: Tyler Coburn, Siqi Zhu

Participants:

Nehemiah Ashford-Carroll, Gina Bernotsky, Chandler Caserta, Elizabeth Christoforetti, Yixin Du, Connor Gravelle, Aria Hill, Inmo Kang, Ally Lammert, Sally Librera, Carole Voulgaris, Rita Rui Ting Wang, Hannah Wong, Lanson Xie

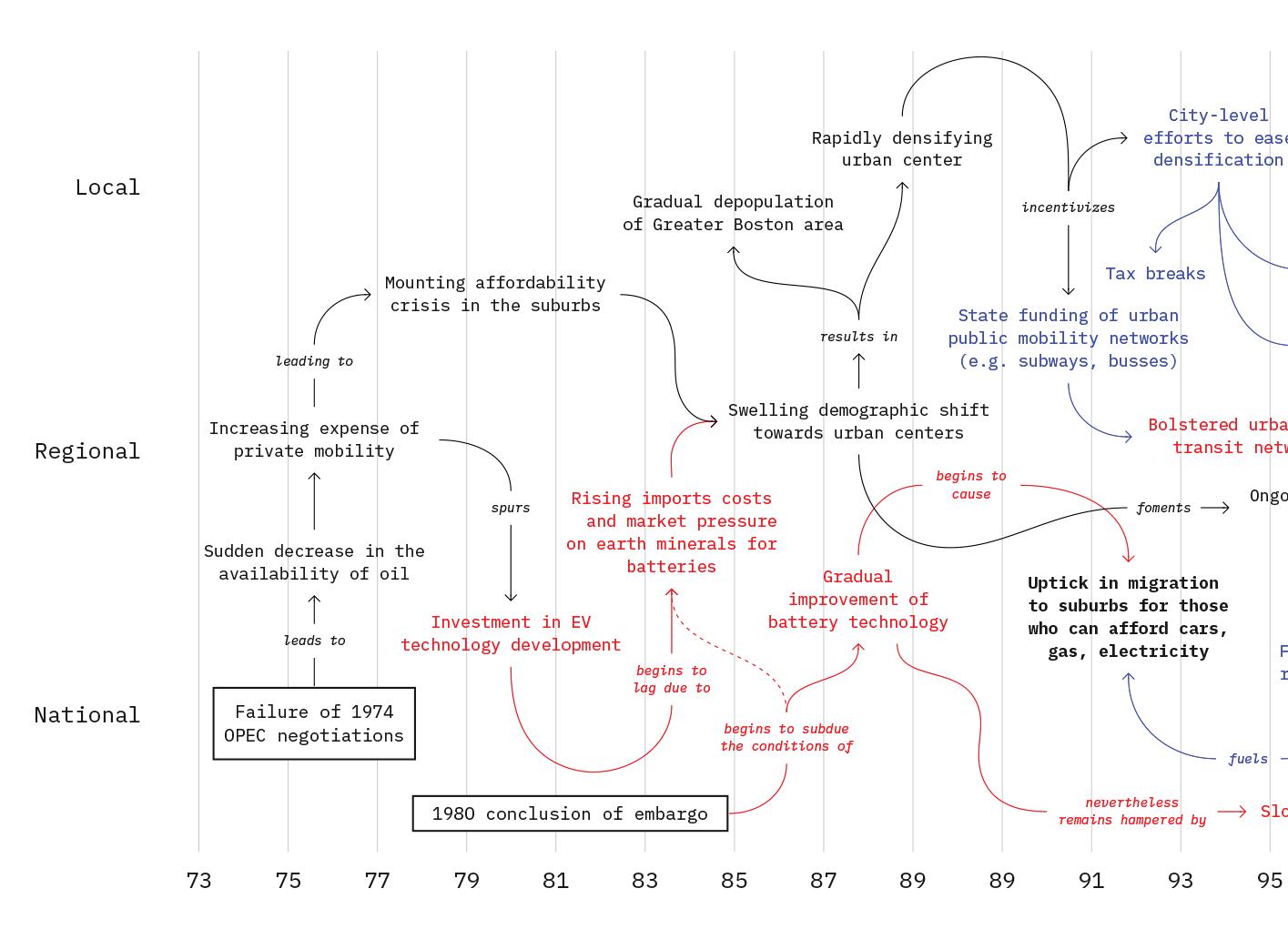

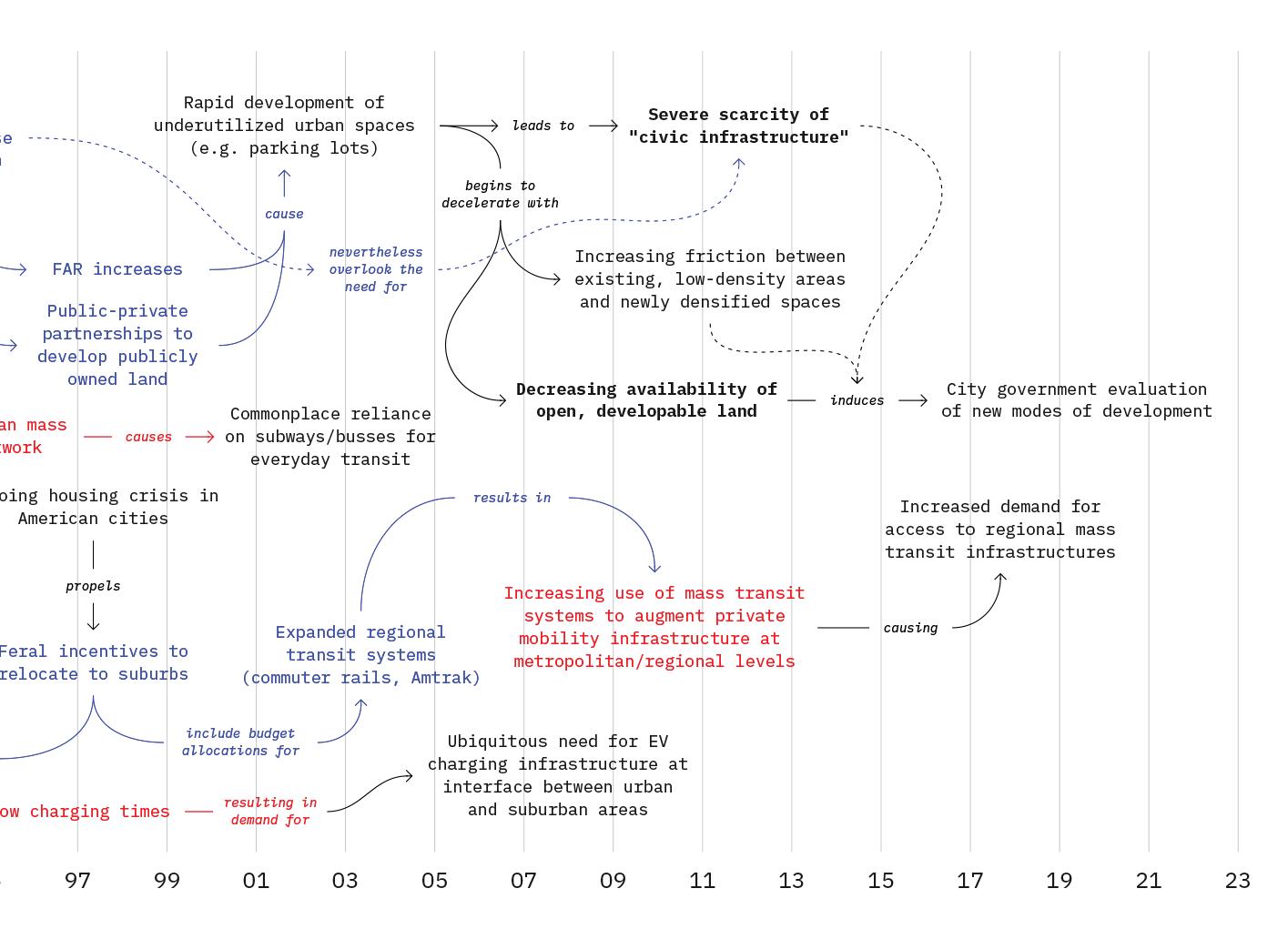

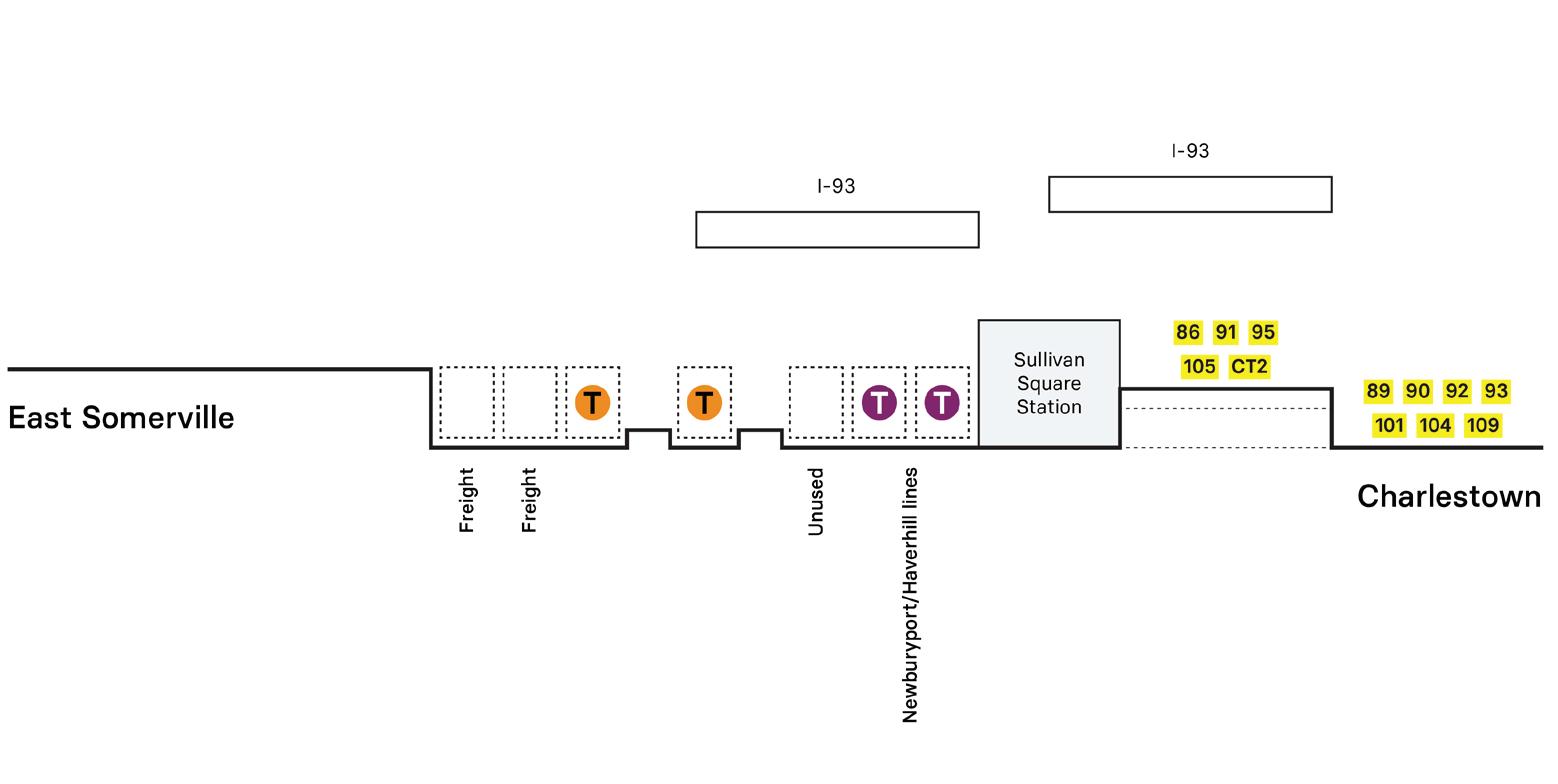

Below: Distilled output of counterfactual game describing imagined transformations in Sullivan Square transportation from 1973 through 2024 (as an alternative present). Created by students Connor Gravelle and Rita Rui Ting Wang.

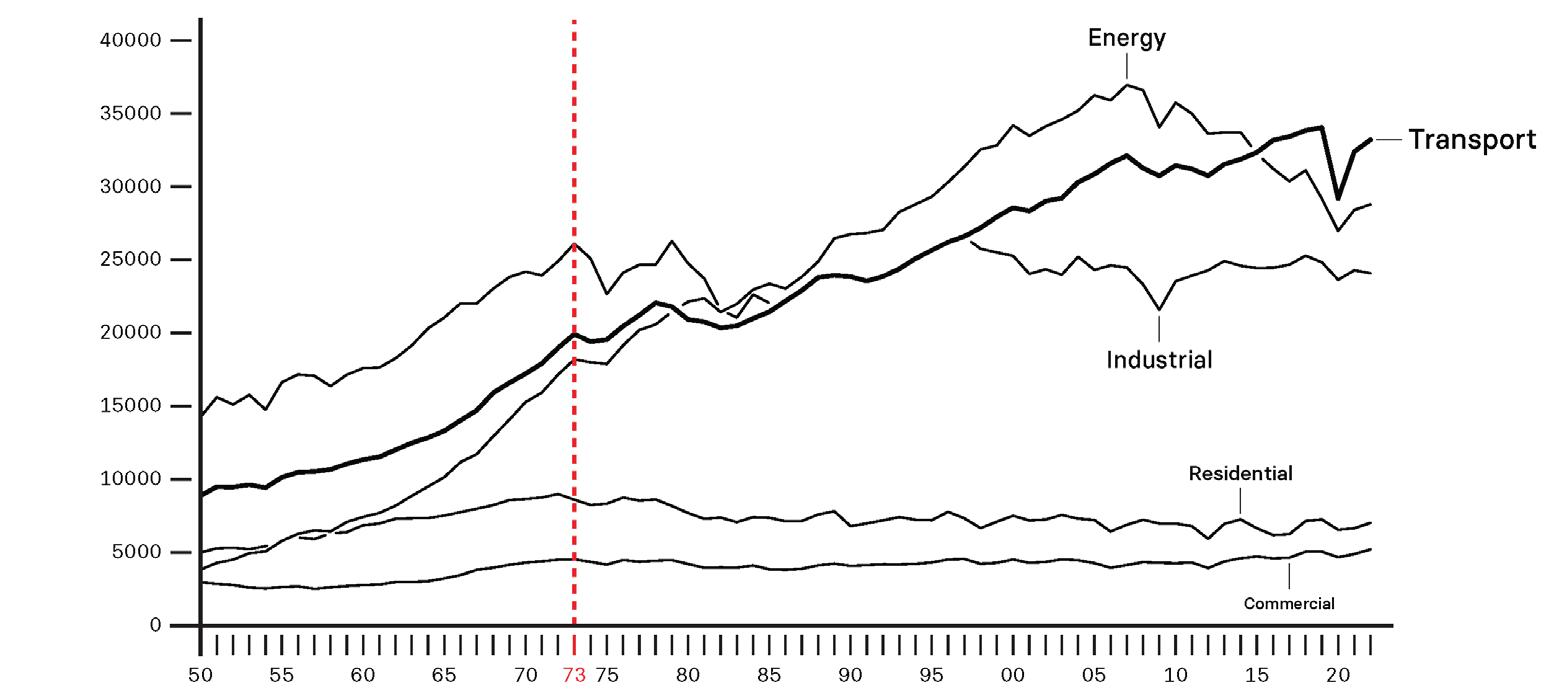

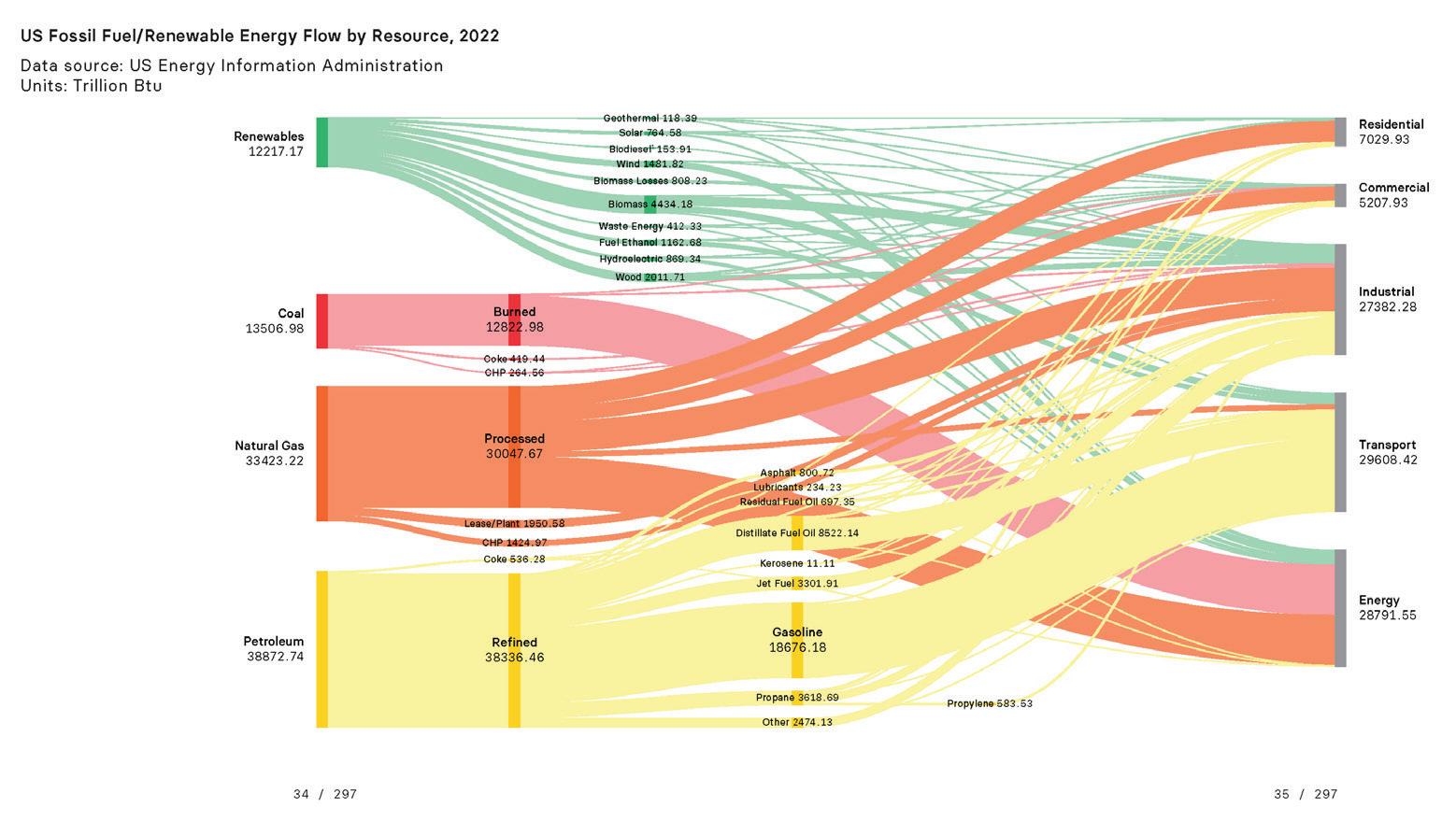

Above: Analysis of US fossil fuel and renewable energy utilization by students Connor Gravelle and Rita Rui Ting Wang in preparation for counterfactual game workshop.

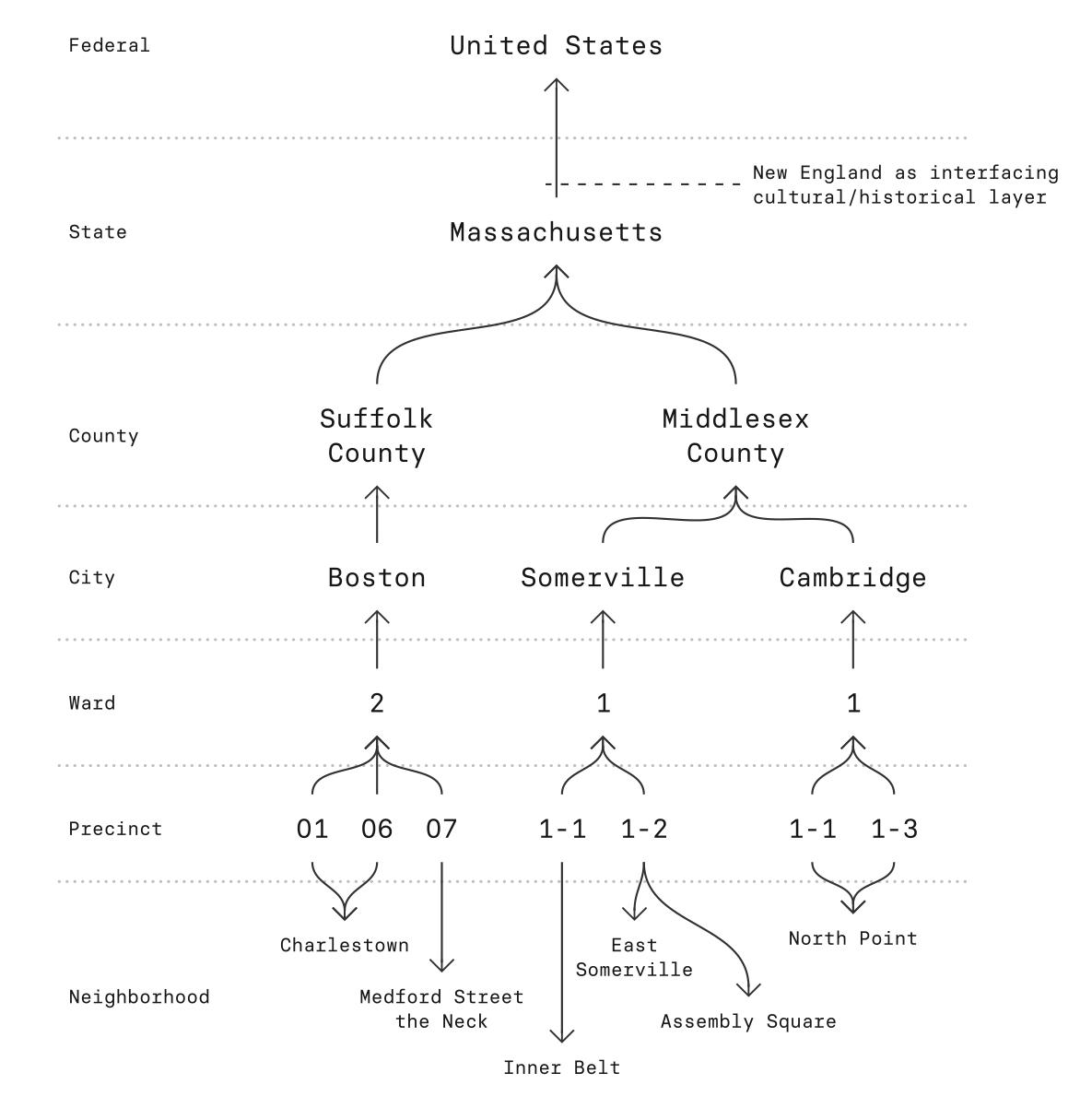

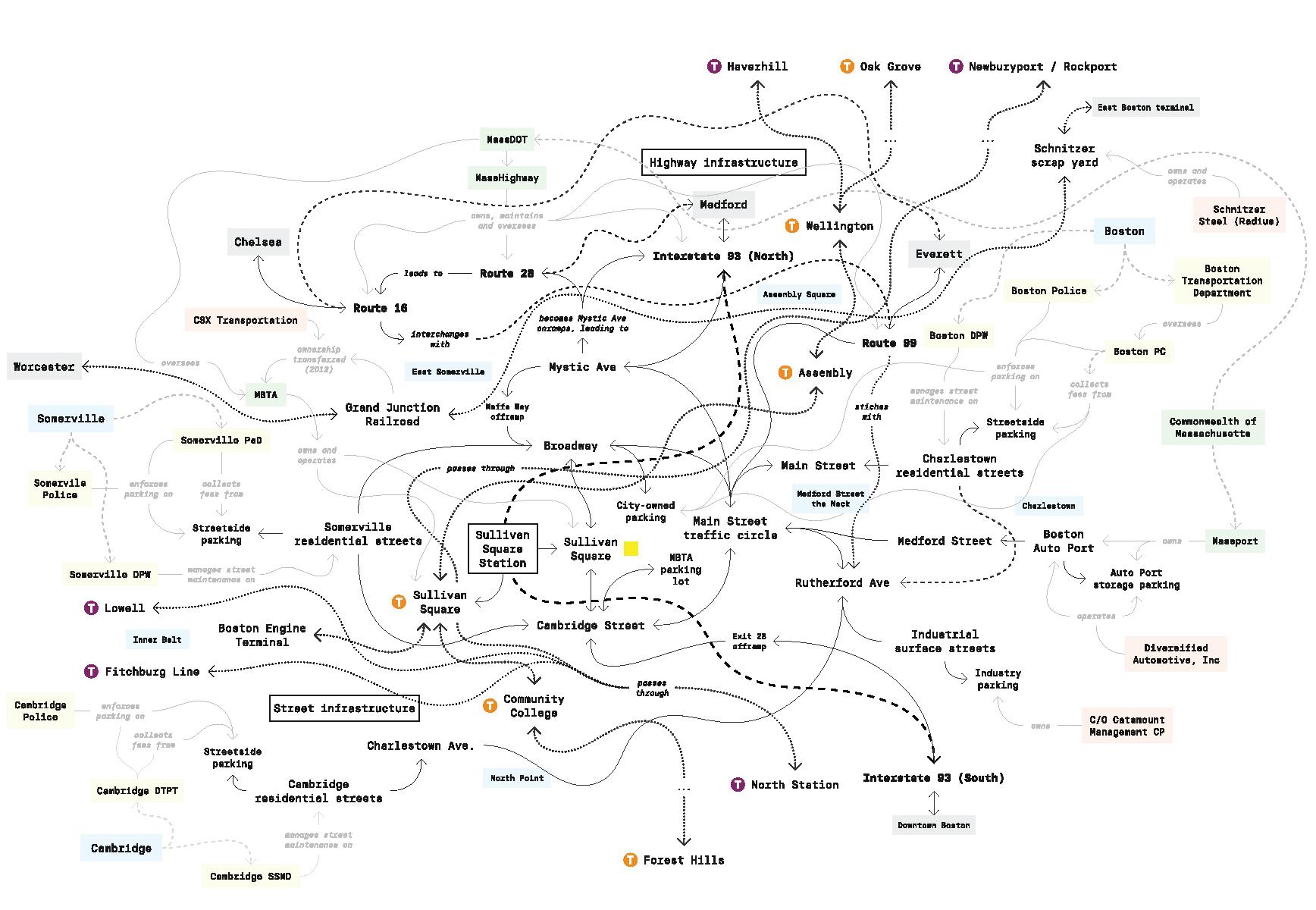

Above: Analysis of governing bodies demonstrating levels at which contingent decisions are made as they trickle down or push up between the federal and local levels, ultimately shaping the capacity of the architectural site.

Studio participants arrived at the counterfactual game workshop with knowledge of the counterfactual prompt and having done individual research on the circumstances of policy and culture that informed essential decisions and contingencies that led to our present condition of carbon-dependant mobility. Once gathered together, and with the leadership of Tyler and Siqi and the input of experience transportation planners and designers, the students constructed counterfactual conditions for their site.

The following brief, written through a collaborative effort by the students as a reflection on counterfactual workshop, was an outcome of the game that became the context for design. The reconstructed narrative addresses the evolution of the Sullivan Square transit infrastructure in light of the counterfactual prompt and the contingencies surrounding the translation of the 1973 Oil Crisis into Boston’s infrastructural network and culture of mobility. It provided a clear context for the students to begin their design work on the Sullivan Square site.

Beginning in the late 1970s, the city of Boston began a process of redevelopment in the Sullivan Square neighborhood. Under the guise of the reorganized MBTA, a significant amount of housing was infilled wherever possible during the 1980s and early 1990s. As the neighborhood densified, a number of city and state initiatives began to shape its urban fabric, often responding to the increasing demand for mass transit and array of disused automotive infrastructure. Before electric vehicles became widely available, a drastic reduction in the use of interstate I-93 spurred neighborhood initiatives advocating for the sequestration of several highway lanes into inter-borough pedestrian park space.

Expanding demand for mass transit accessibility coupled with increased car ownership costs influenced the MBTA’s 1982 expansion of Sullivan Square Station to accommodate Commuter Rail access. This effort required significant reorganization of existing light rail infrastructure to permit platform access in the limited space of the existing station’s facilities, such as the rerouting of Orange Line tracks underground. Other major infrastructural alterations to the area included the recommissioning of nearby canal pathways and the addition of Amtrak access in 2010. The resulting rail and bus connectivity of Sullivan Square Station have lead to its emergence as a major transit hub in the city of Boston, rivaling North Station as a point of transit interchange on the city’s north side.

Still, the question of how to manage the open lot in front of the station remained an open question until only recently. An entanglement of bus lines, subway access, industrial freight transportation and parking facilities has increasingly signaled an obvious need for reconfiguration.

Under the Boston Planning & Development Agency’s 2023 Plan: Charlestown, city planners articulated several clear initiatives for the space:

1. Electric vehicle charging infrastructure must be radically expanded to accommodate a drastically growing number of EVs on the road. Charging times remain constrained by in-development battery technology, requiring on site development to account for not only vehicle parking spaces themselves but also public facilities for their occupants during charging.

2. While Mayor Kevin White’s 1978 Sullivan Square Commission was successful in diffusing tensions between the area’s residents and increased industrial traffic, friction has come

to a head under greater-than-ever population expansion during the Covid-19 pandemic. The BPDA has articulated an ambition to entirely separate industrial and residential traffic on site, using grading and “artificial grounds” to both attend to passing industrial traffic and residential vehicles/pedestrians in separate spaces as well as to mend the historical incision of highway and rail infrastructure that has delineated East Somerville and Charlestown. These design parameters seek to alleviate the pedestrian experience on site, holistically address current water management inadequacies and to speculate on the possibilities of establishing public, civic space for the surrounding area to be used opportunistically by residents at will.

borhood’s clear need, the state legislature has signaled its willingness to adapt state building code to better permit the cohabitation of these uses on site.

Finally, under strict oil conservation laws and the 1980 US Strategic Energy Reorganization Plan, the disposition of the built world in Boston has changed considerably since the 1973-1980 Oil Crisis. Asphalt reuse initiatives, strict energy use considerations and the final stages of a divestment from petrochemical production in the US speak to a cultural landscape that has dramatically diverged from the carbon modernity of the pre-1973 era.

3. Due to the intersection of residential densification and expansion of light industry in the area in correspondence with shifting patterns of urban development in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the area around Sullivan Square has long housed a large amount of mixed-use occupancy. Future uses for the currently underutilized lot in front of the station will need to accommodate these various uses cases in simultaneity. Furthermore, increasing market demands have signaled a decisive shift towards a proliferation of biotech industries both on site and around the general area. Especially in the wake of the Covid19 pandemic, the city’s plans will fundamentally need to negotiate shifting infrastructures of private vehicle use, intense demand for equitable and accessible housing (in both long- and shortterm forms) as well as a reasonable degree of industrial and biotech space. Given the neigh-

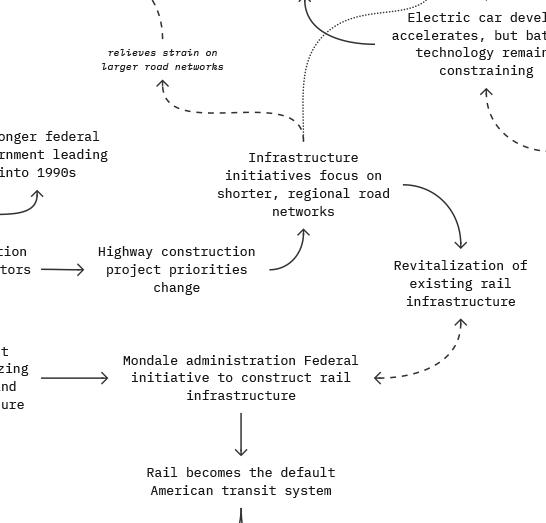

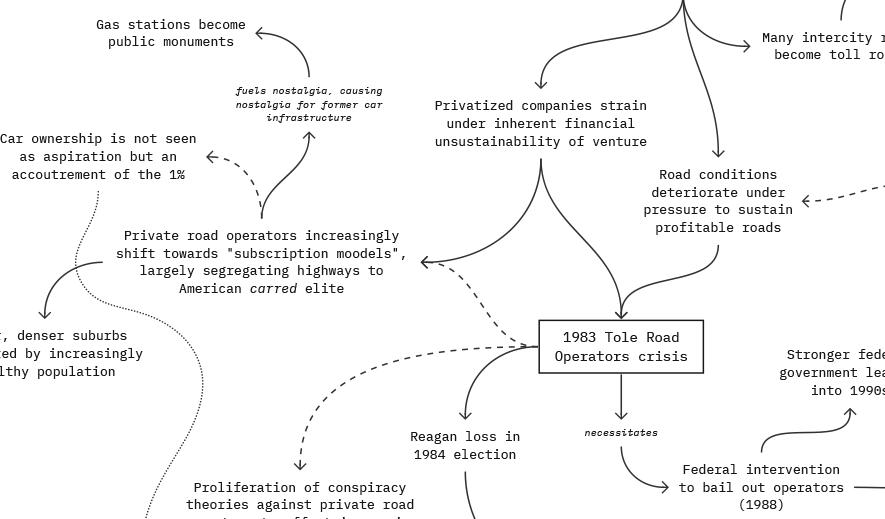

Excerpts from the counterfactual game digital boards examining national and regional level contingencies in the wake of the counterfactual 1973 Oil Crisis decision-making. Student translated the policy outcomes and surrounding social and cultural conditions into site-level impacts.

Counterfactual game workshop output demonstrating originating prompt (1974 OPEC negotiations fail) and the subsequent decisions, events, and consequences that shape an alternative mobility and energy landscape.

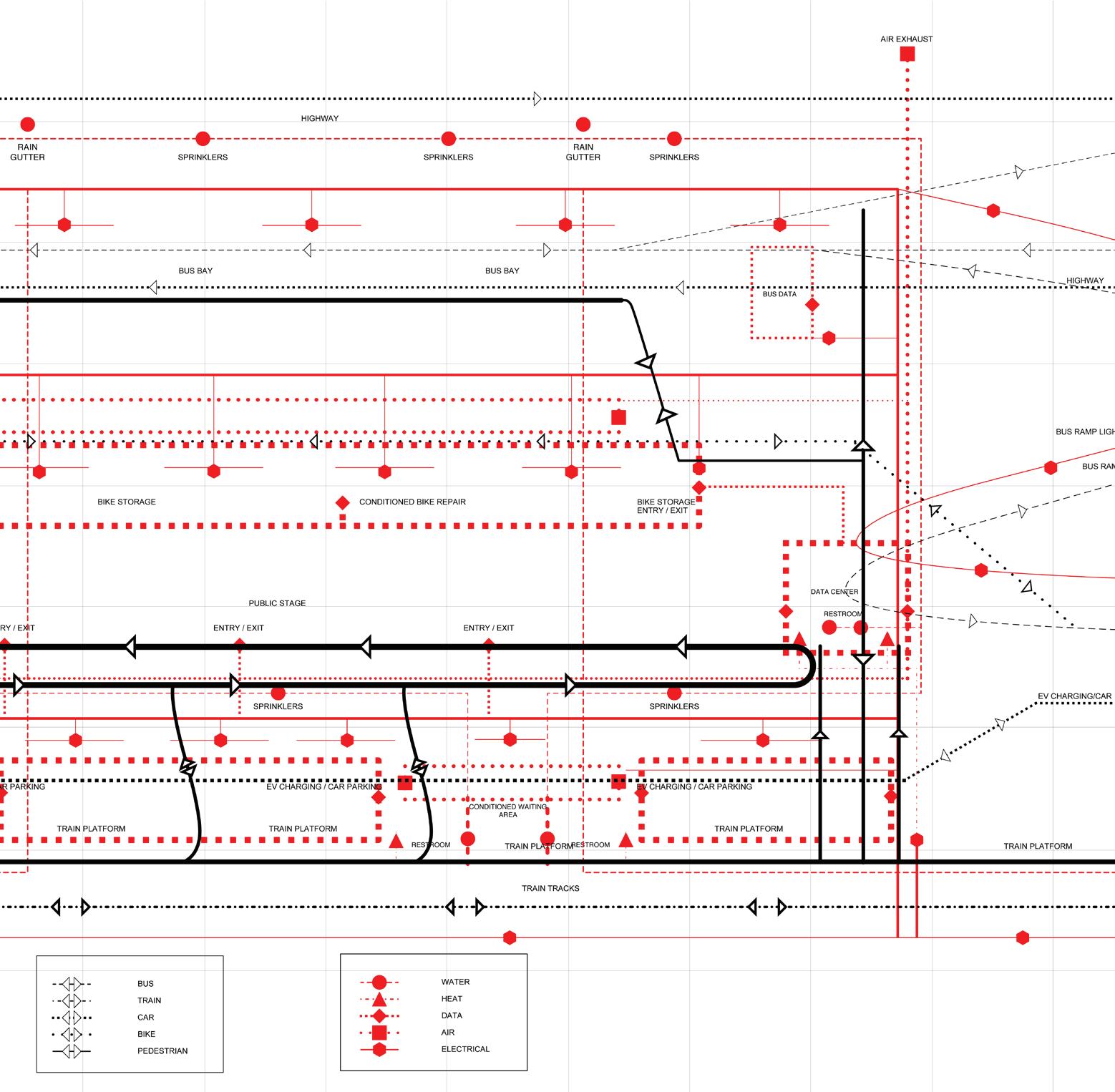

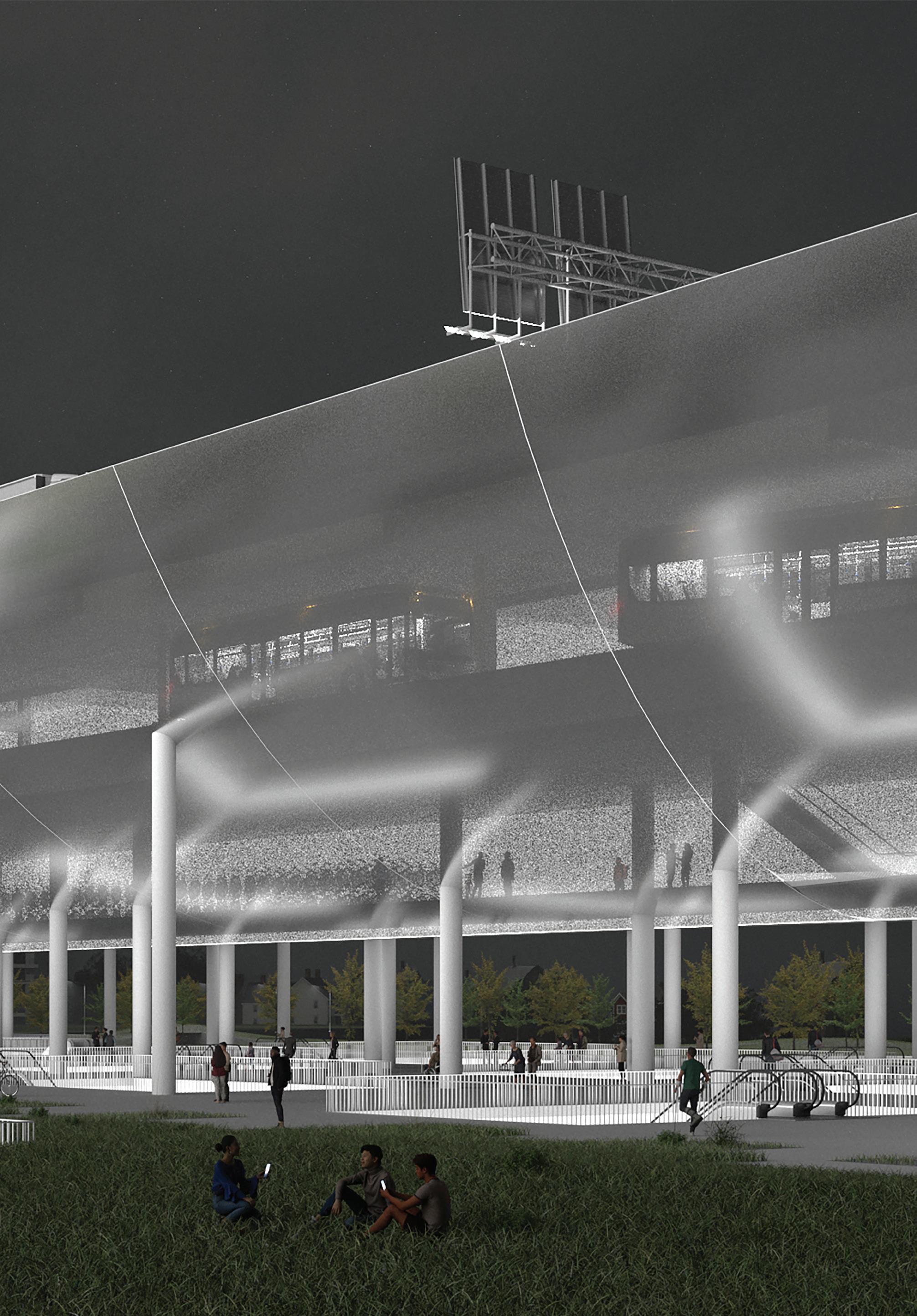

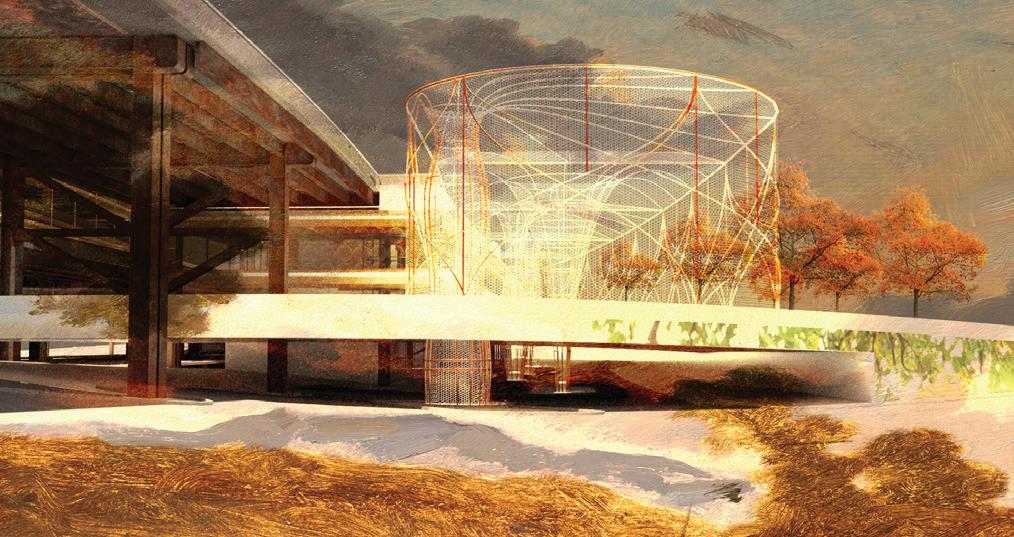

Nehemiah Ashford-Carroll, Chandler Caserta

Site: Sullivan Square

Sullivan Square has been a highly volatile site, one that lies within the modernist vision for America. Now, Sullivan Square is a location to question the post-postmodern, the meta-modern. Defining what it means for something to be public in the 21st century with respect to personal interactions has been altered by the rise of digital space and the internet’s promise as the “new townhall”. However, this promise of digital space as the new public space often falls short in reality, as it creates siloed communities of varied discourse. The physical space of public transit infrastructure can balance the divisive tendencies of physical space by providing a platform for genuine diversity and interaction to occur. This said interaction may occur at varying speeds, sizes, and comfort conditions, creating greater affordances for the user’s authorship of space.

We theorize that in order for public space to be effective and active lies in the ability of infrastructure, transit in this case, to facilitate this interaction where the public spaces ingrained in transit must be accessible and inclusive. Additionally, infrastructural space, physical and digital, often prioritizes speed and efficiency, therefore, deliberate moments of friction and inefficiency are necessary to encourage engagement and reflection on a non-digital and interpersonal level. To explore this complexity, public space becomes a metaphorical stage that hosts unauthored and authored interactions between actors and produces a layered sensory effect supported by the architecture. The accessible ground stitches the neighborhood, formerly divided by modernist planning practices, with a continuous plane allowing the mobility hub to re-establish the neighborhood connection through the site and capture the public with spatial affordances on the site. The ceiling conceals the busy highway infrastructure to produce a contrasting backdrop that heightens the drama felt within the transit hub.

Additionally, to challenge the speed of digital and transit, we use the lens of theater to frame the moments of friction and inefficiency in public space as a stage that hosts unauthored and authored interactions between human and non-human actors to produce a layered sensory effect supported by the architecture. Transit infrastructure, such as cars, trains, and buses are also included as actors and enter and exit frames of viewing in addition to pedestrians. We do this by creating frames of viewing in the ground plane which reduces the public realm into tighter stages and scenes where micro-narratives can thrive.

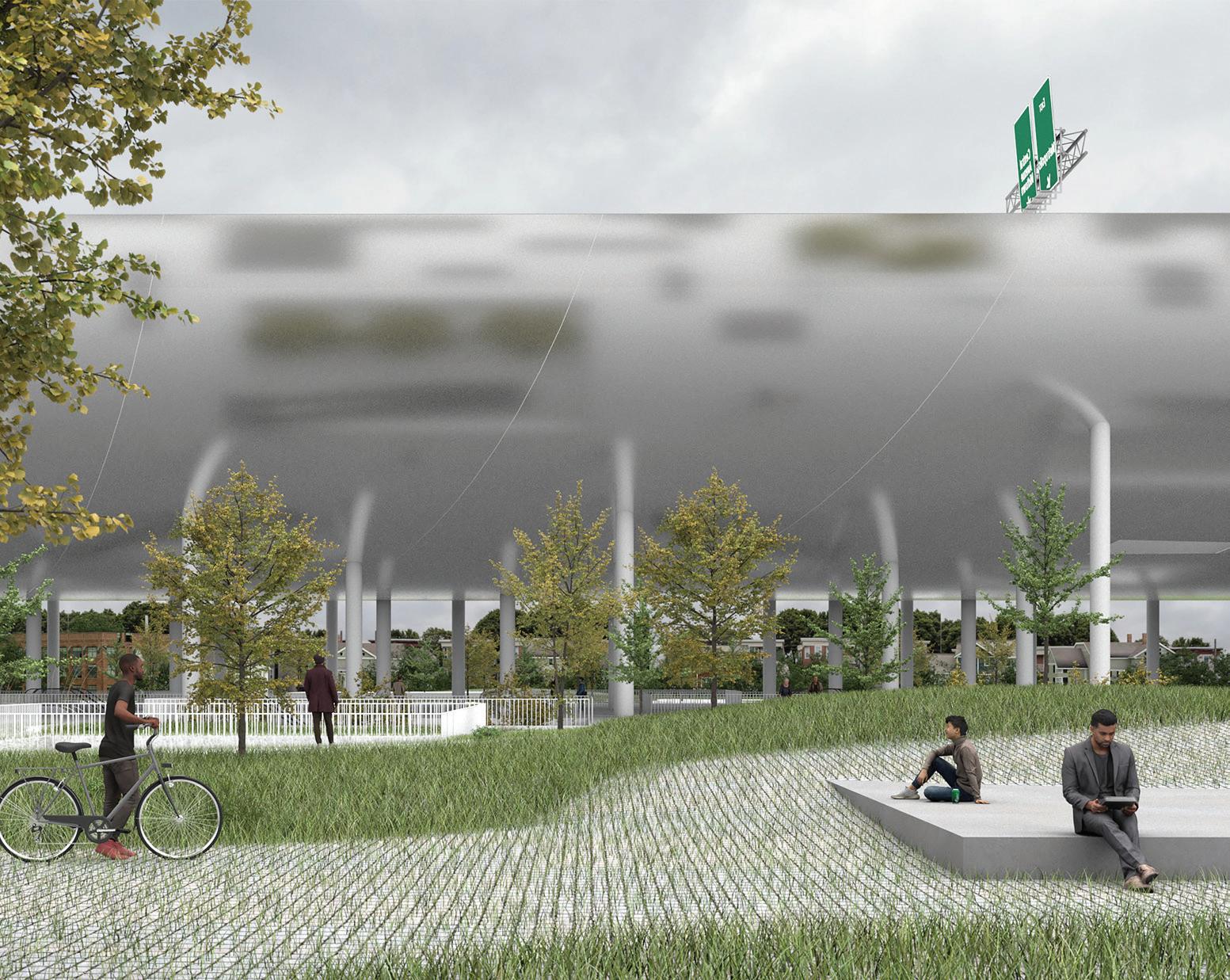

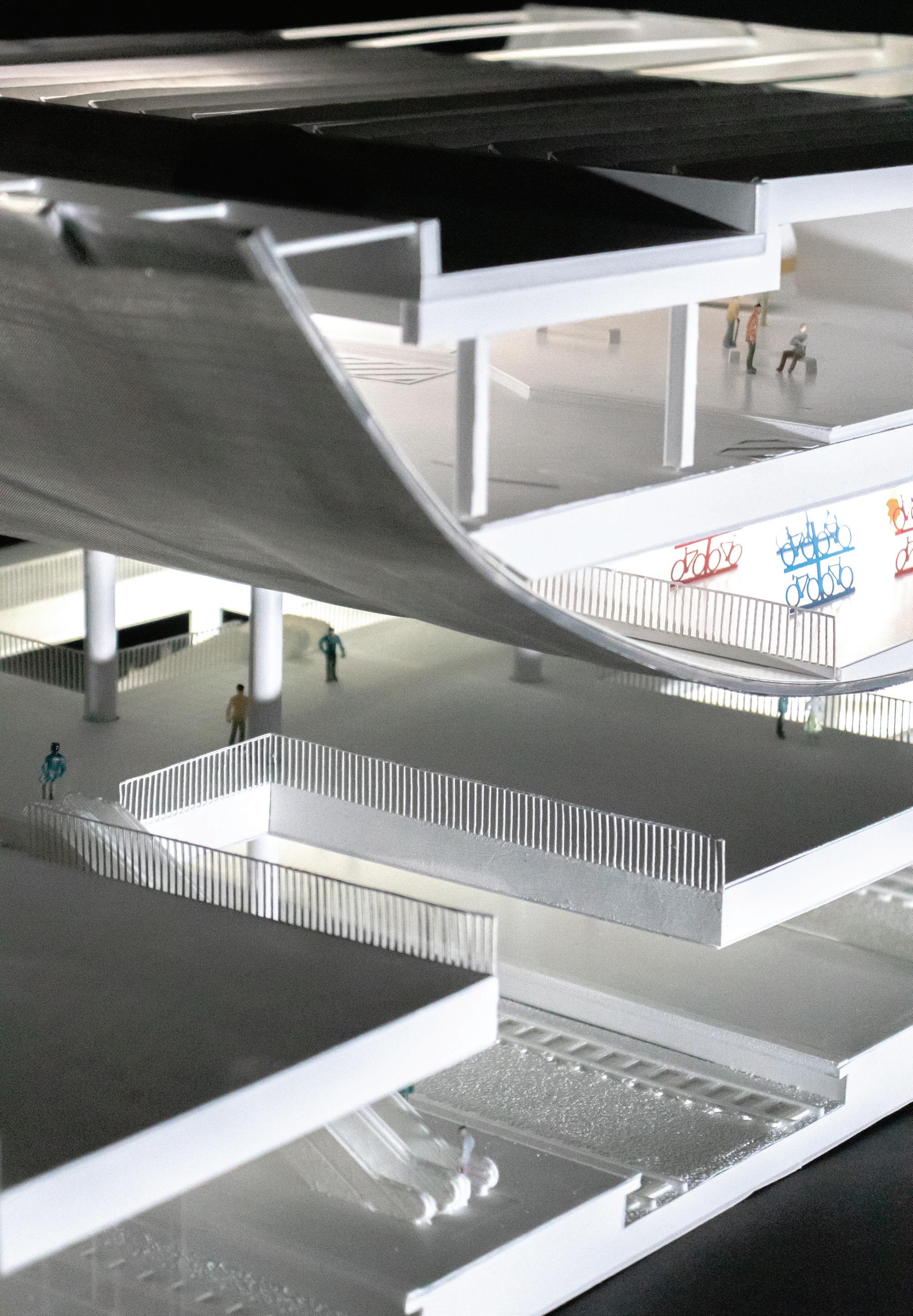

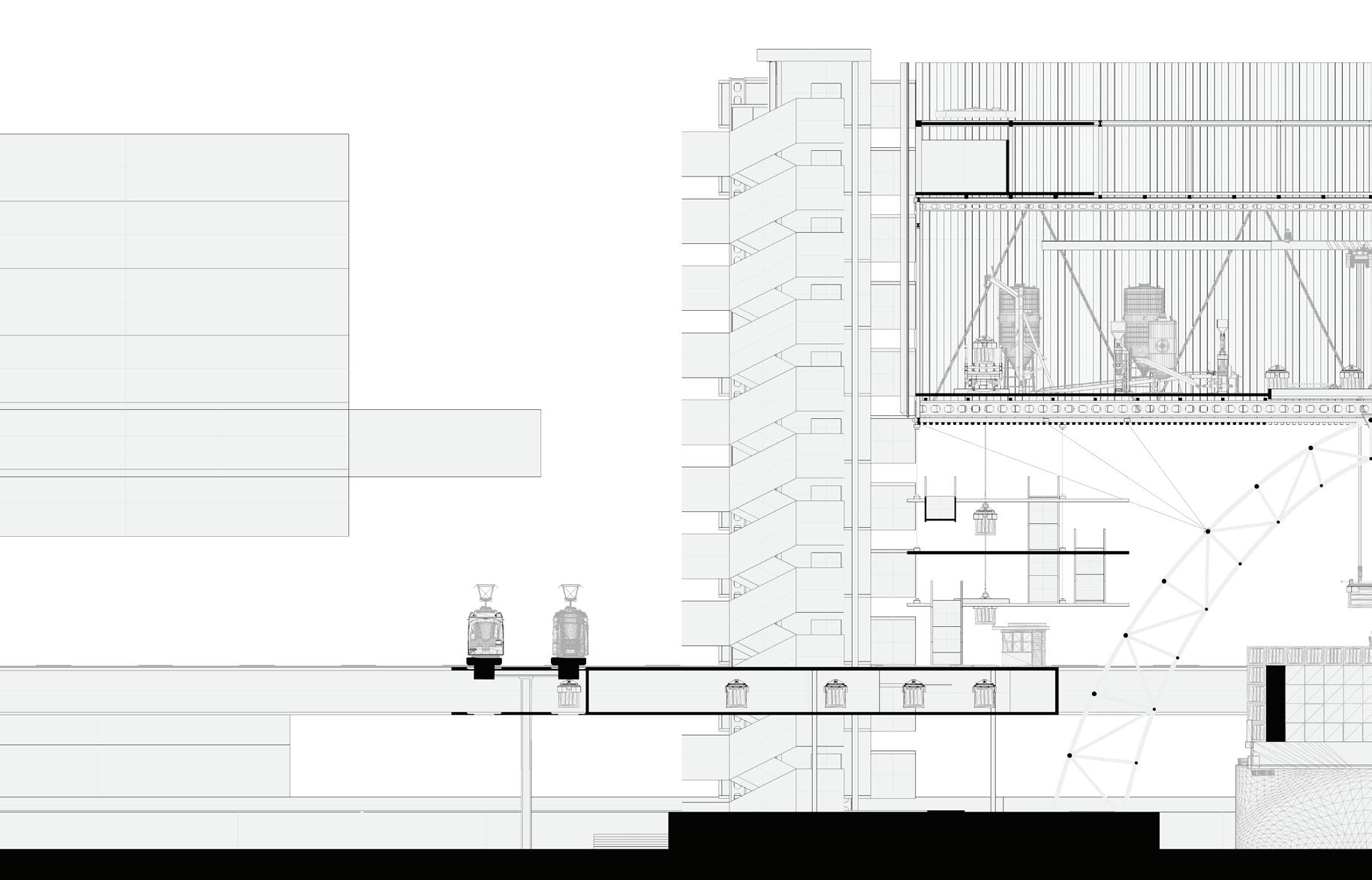

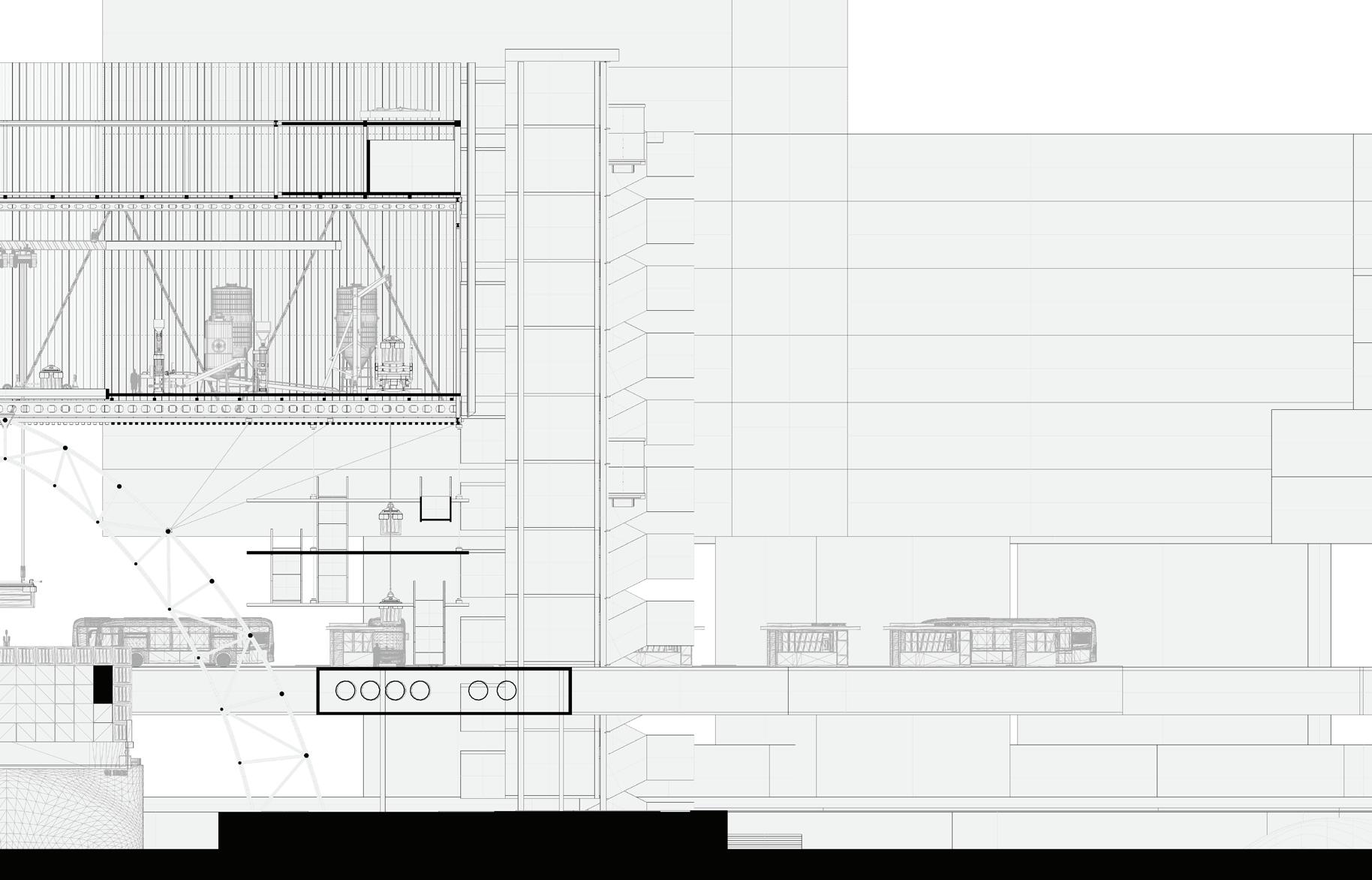

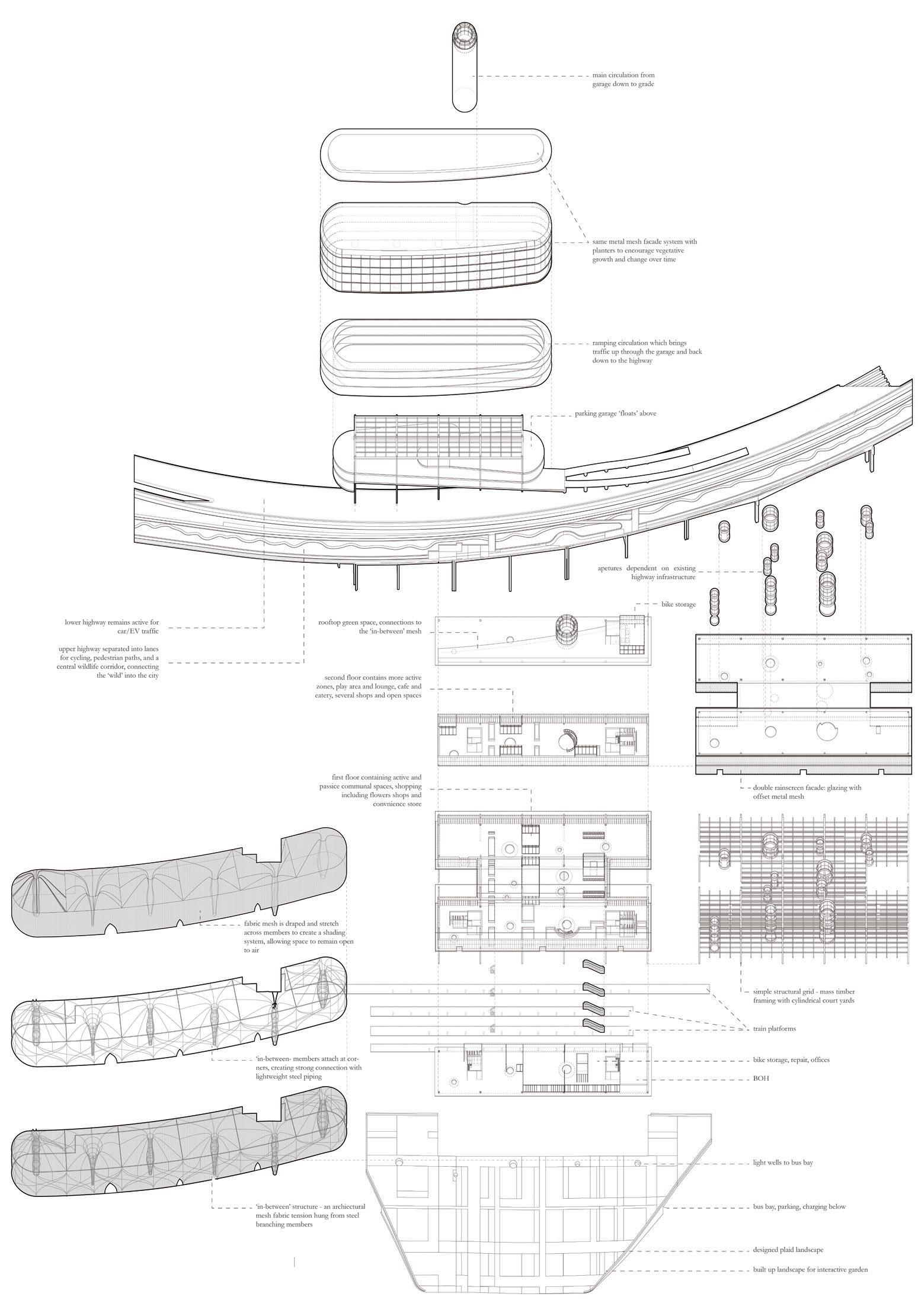

Connor Gravelle, Rita Rui Ting Wang

Site: Sullivan Square

By the 1970s, life in the United States constituted a totalizing petrochemical reality in which oil saturated everything from roadways to toothpaste. In failing to ameliorate OPEC’s 1973 embargo, the country suddenly faced a radical form of fundamental resource scarcity. The petro-austerity of the 1970s-1980s forced a rapid demographic transformation of urban space as exorbitant gasoline prices chastened America’s automobile-dependent suburbs. In seeking to address its swelling population, Boston has focused mostly on low-hanging fruit by incentivizing development through threadbare modifications to existing zoning.

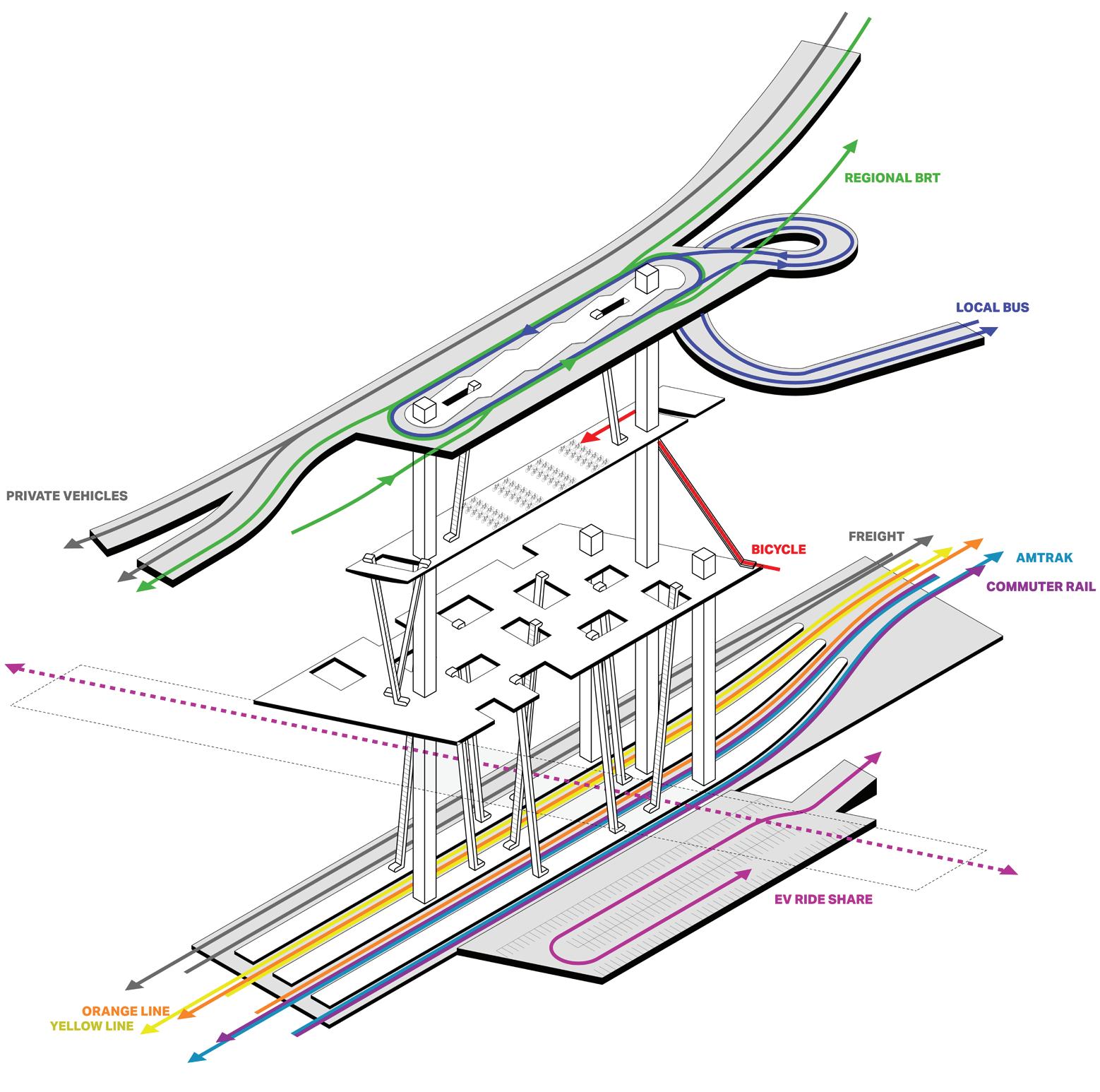

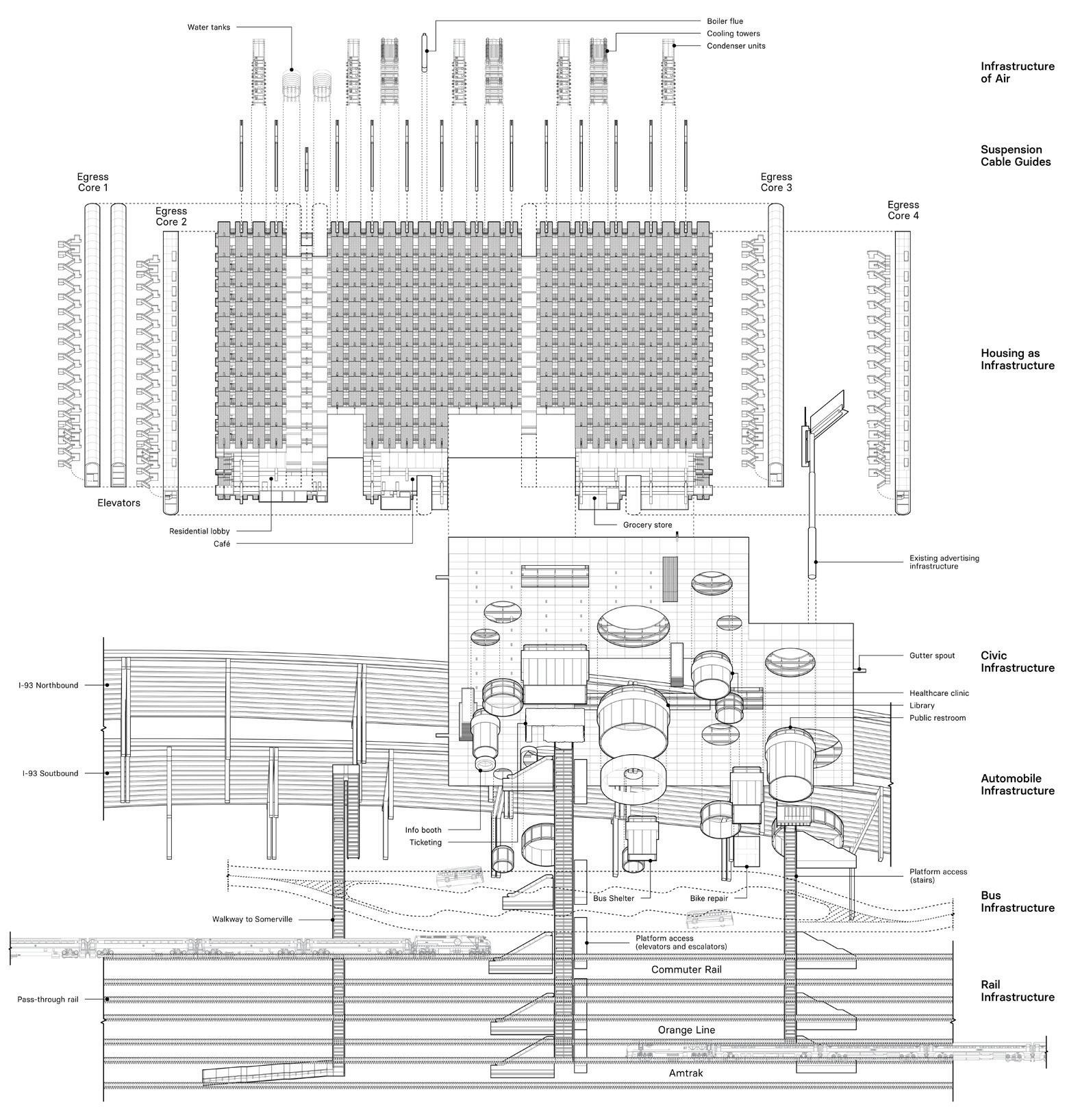

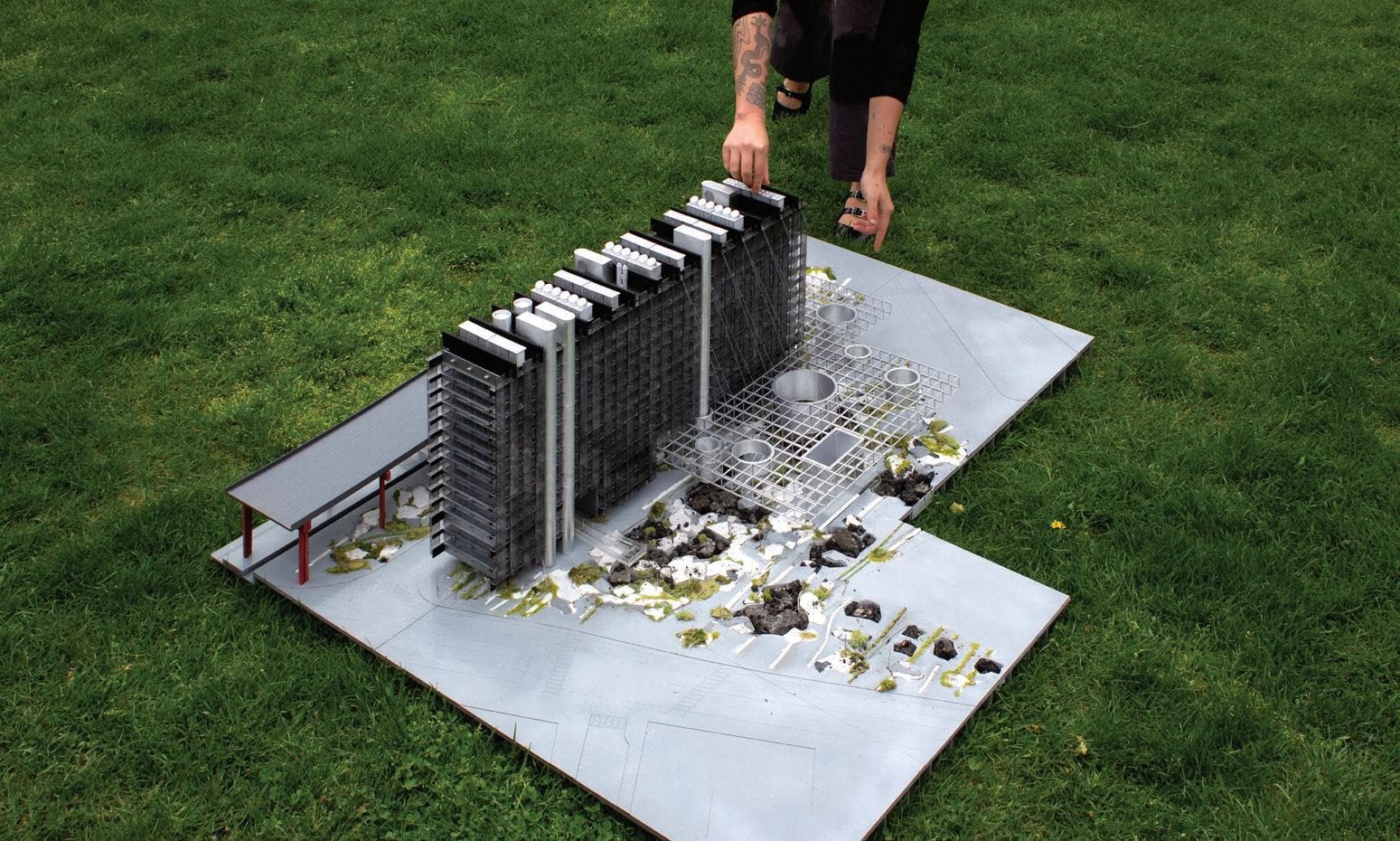

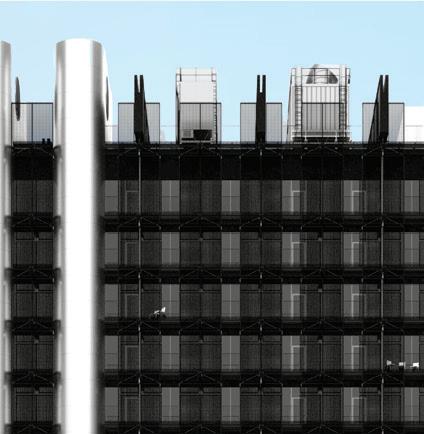

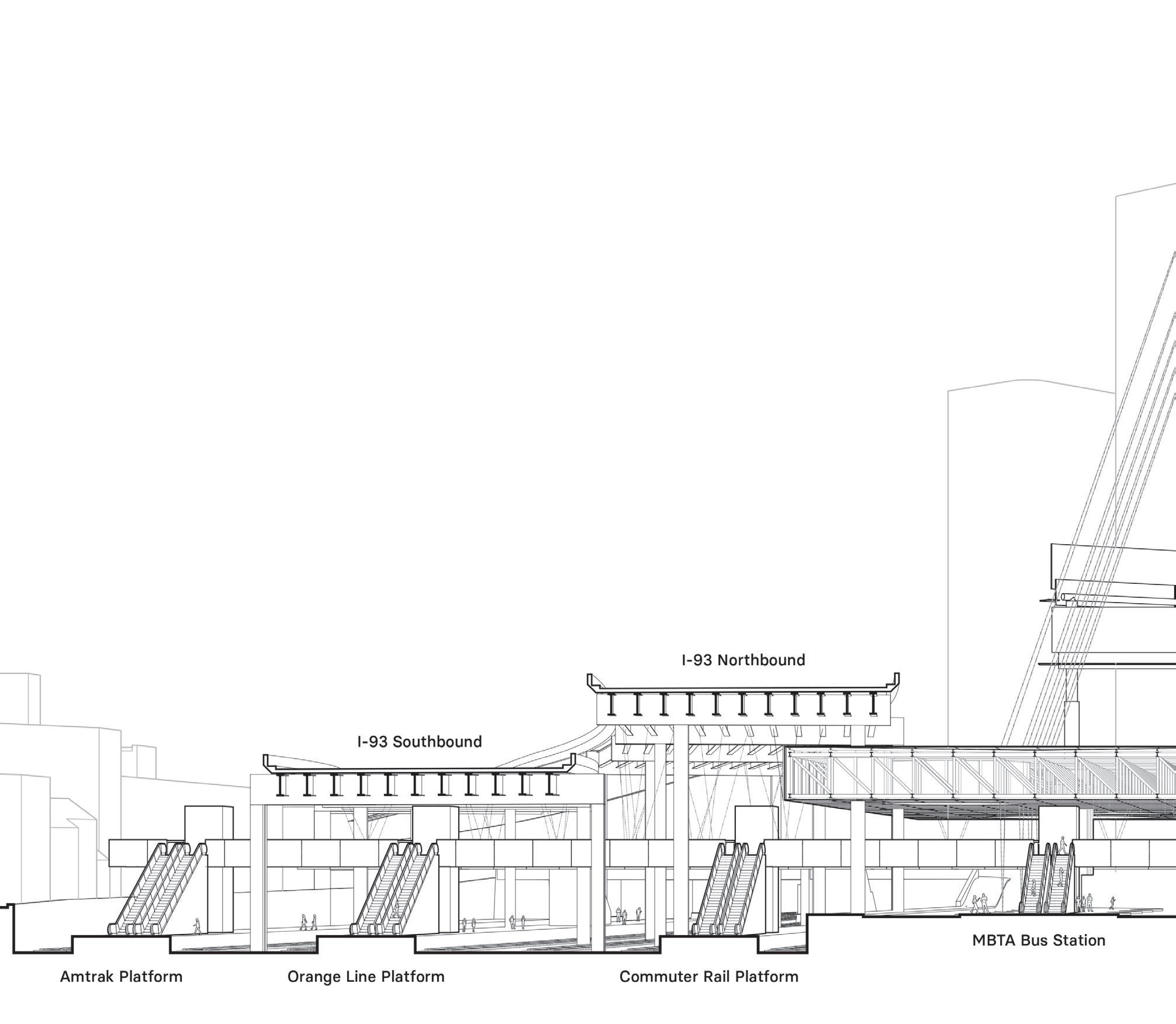

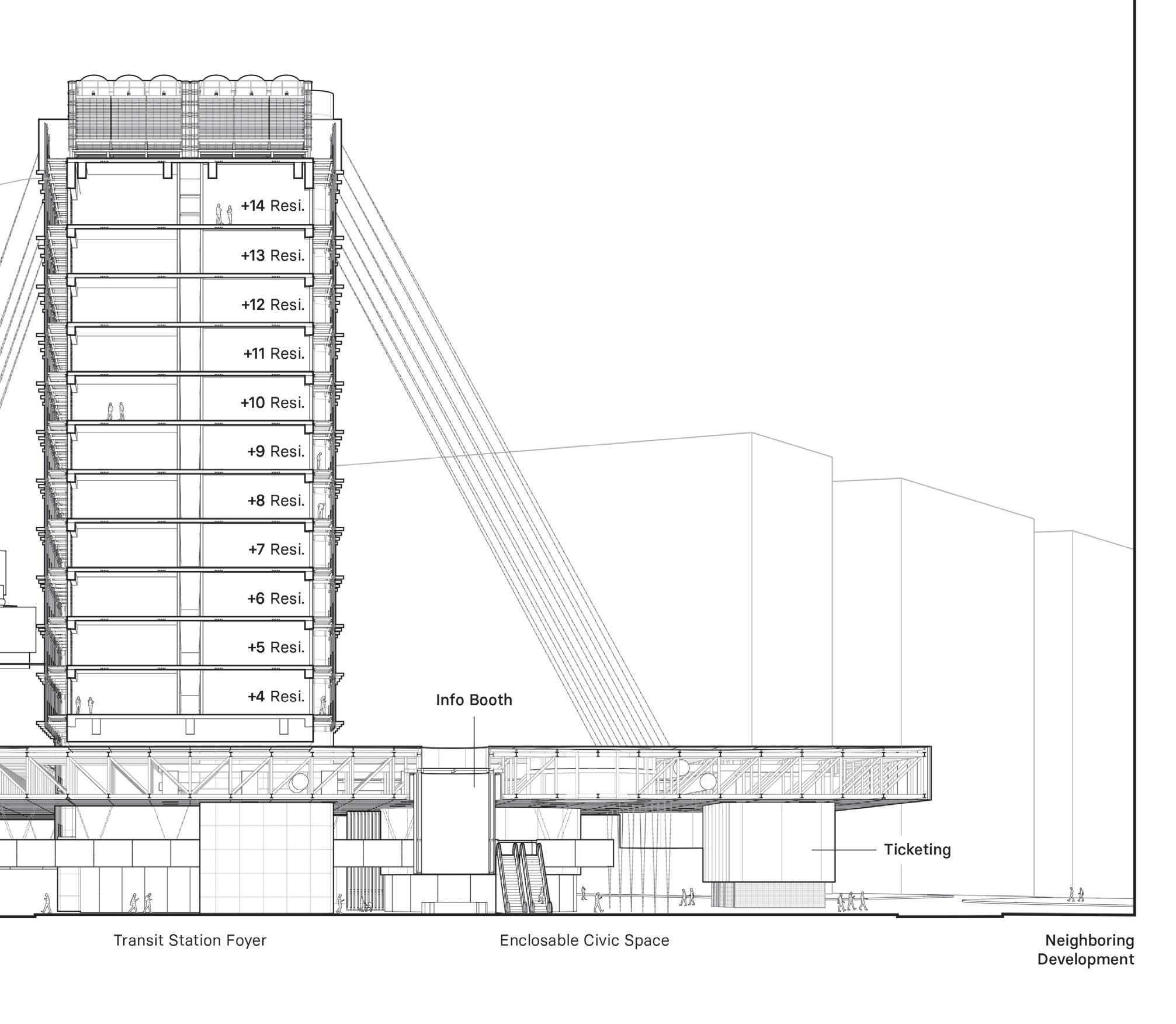

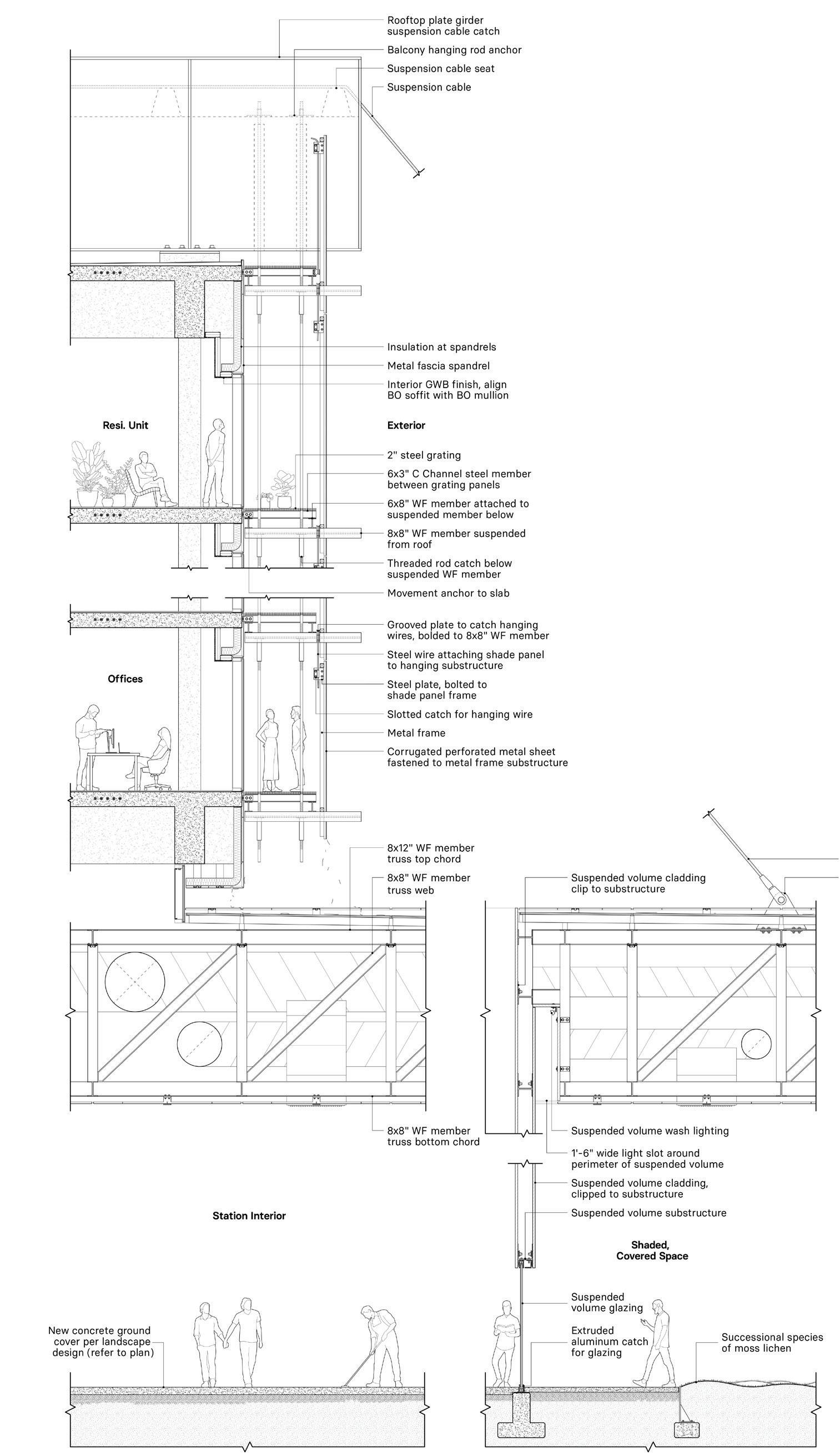

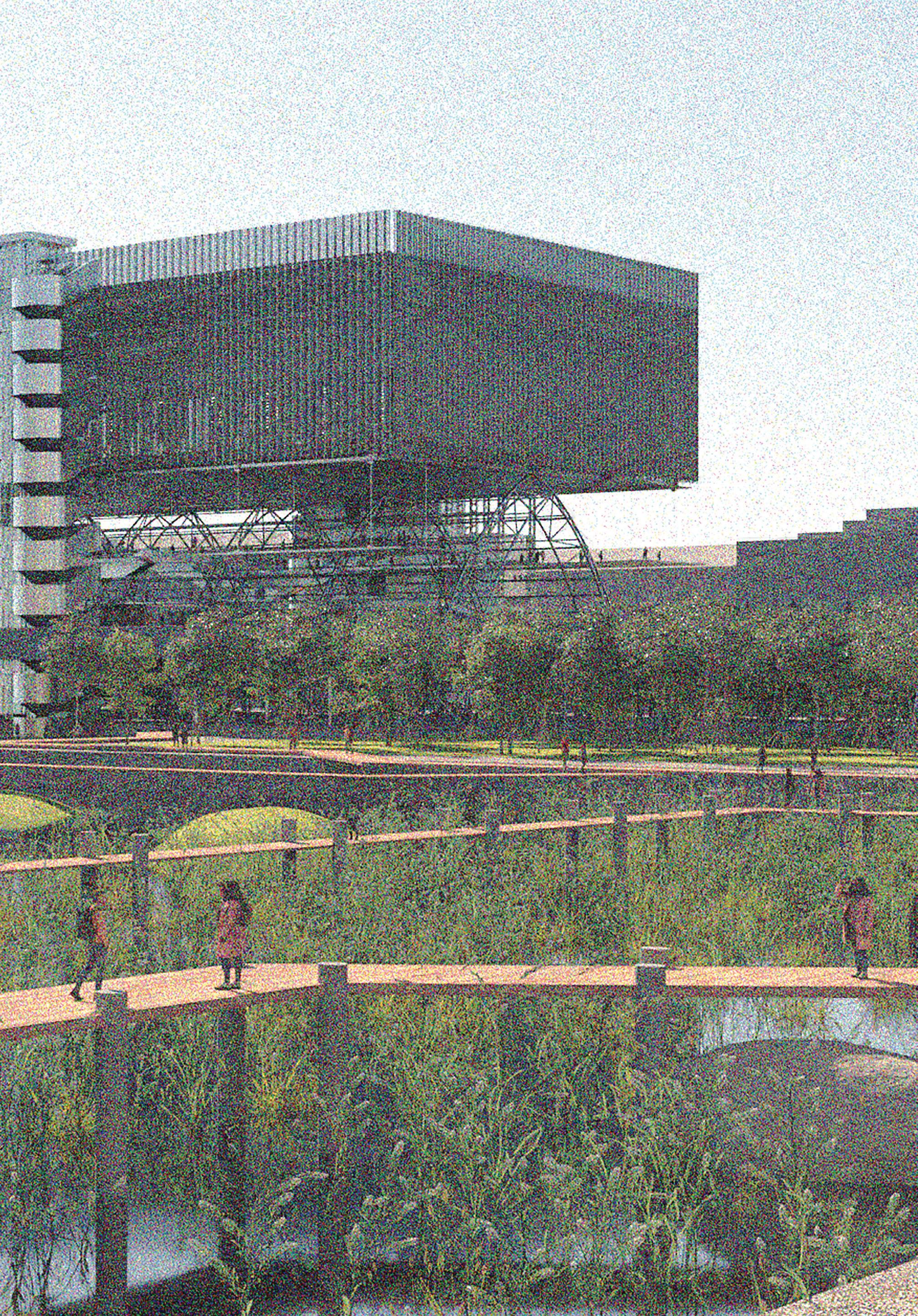

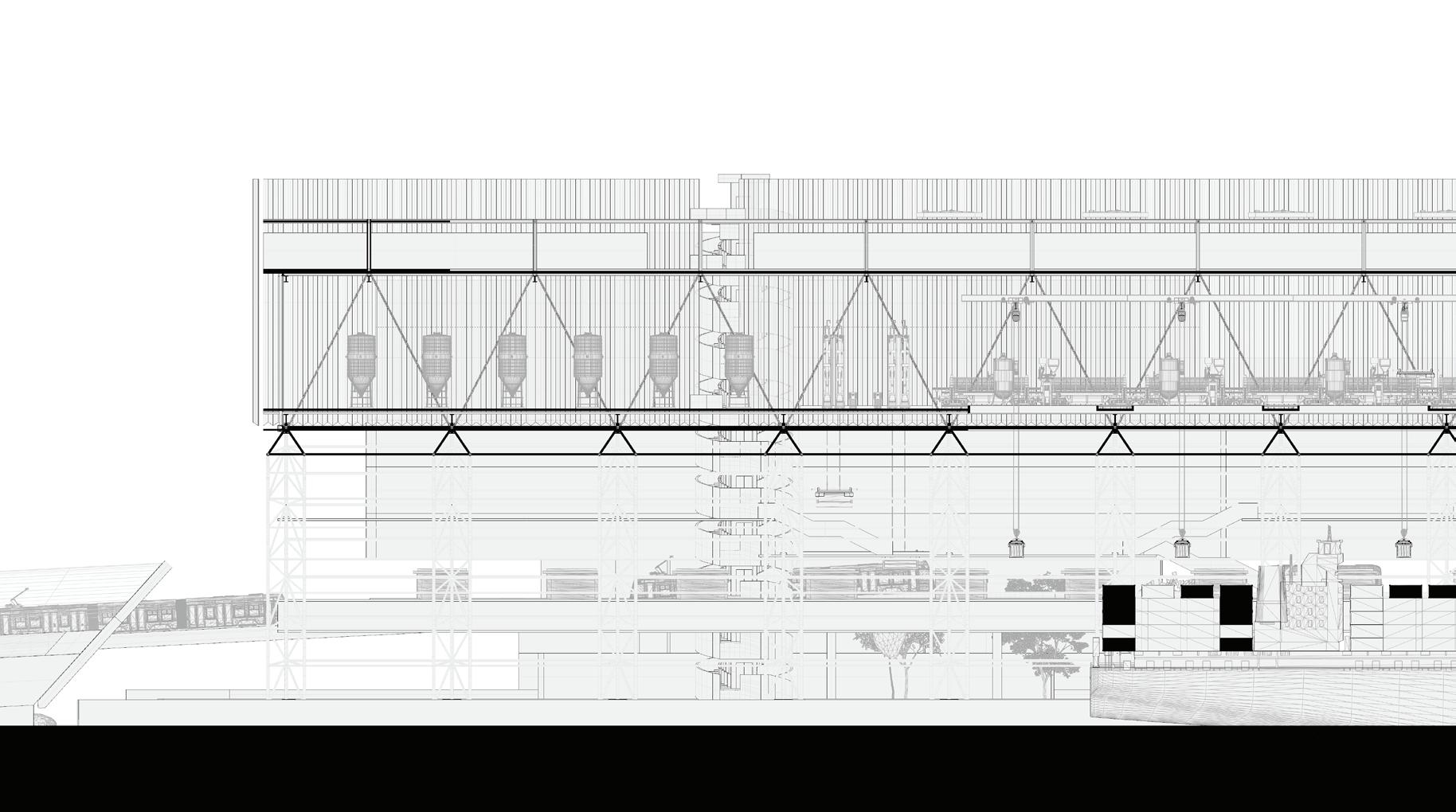

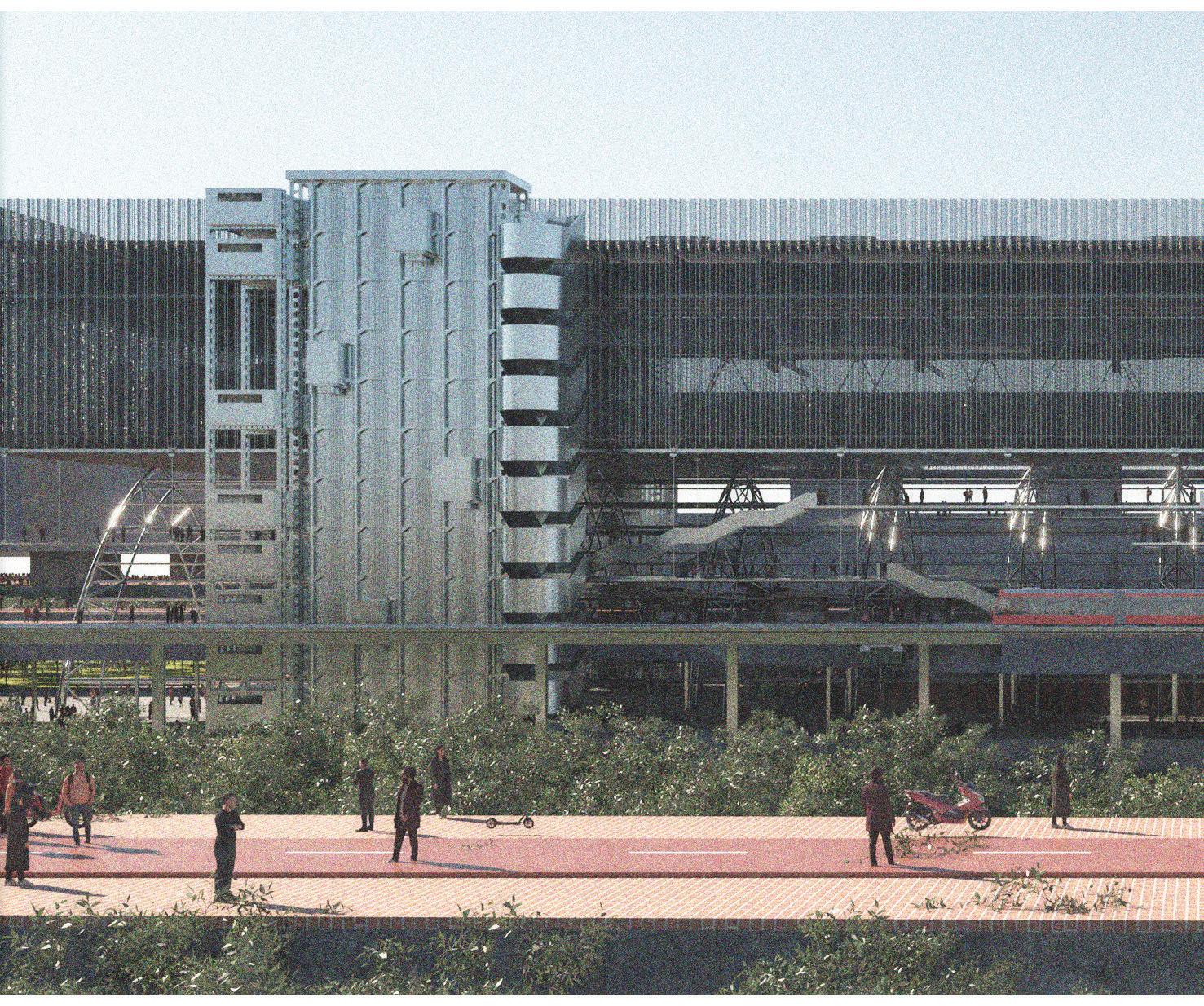

By 2024, the effects of this approach are apparent: the city has become a landscape of hasty private development with little regard for the social fabric necessary in a more crowded, livelier Boston. This proposal for an intermodal transit hub at Sullivan Square refashions how we manage densification and renewal. Situated amid the entanglement of I-93, 11 bus lines and 7 train tracks, the project acknowledges the heaviness of infrastructure to ask if housing can itself be recast as basic civic infrastructure. By suspending the archetypal long-span truss structure of a train station from a midrise housing block, we envisage a series of mediating dependencies between the private and public, urgently needed housing alongside supporting civic services and the anticipation of renewal amid a necessary memory of a petrochemical near past under threat of total erasure.

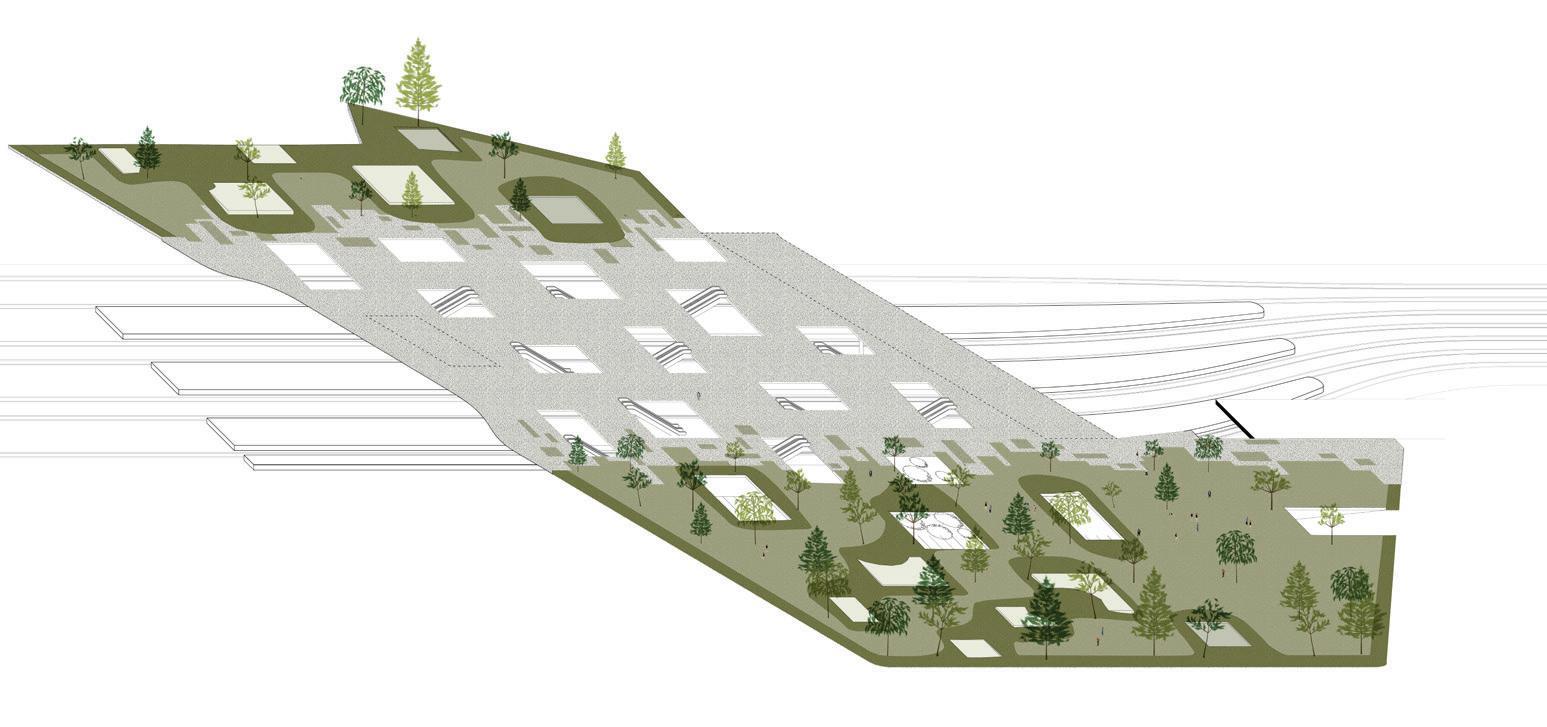

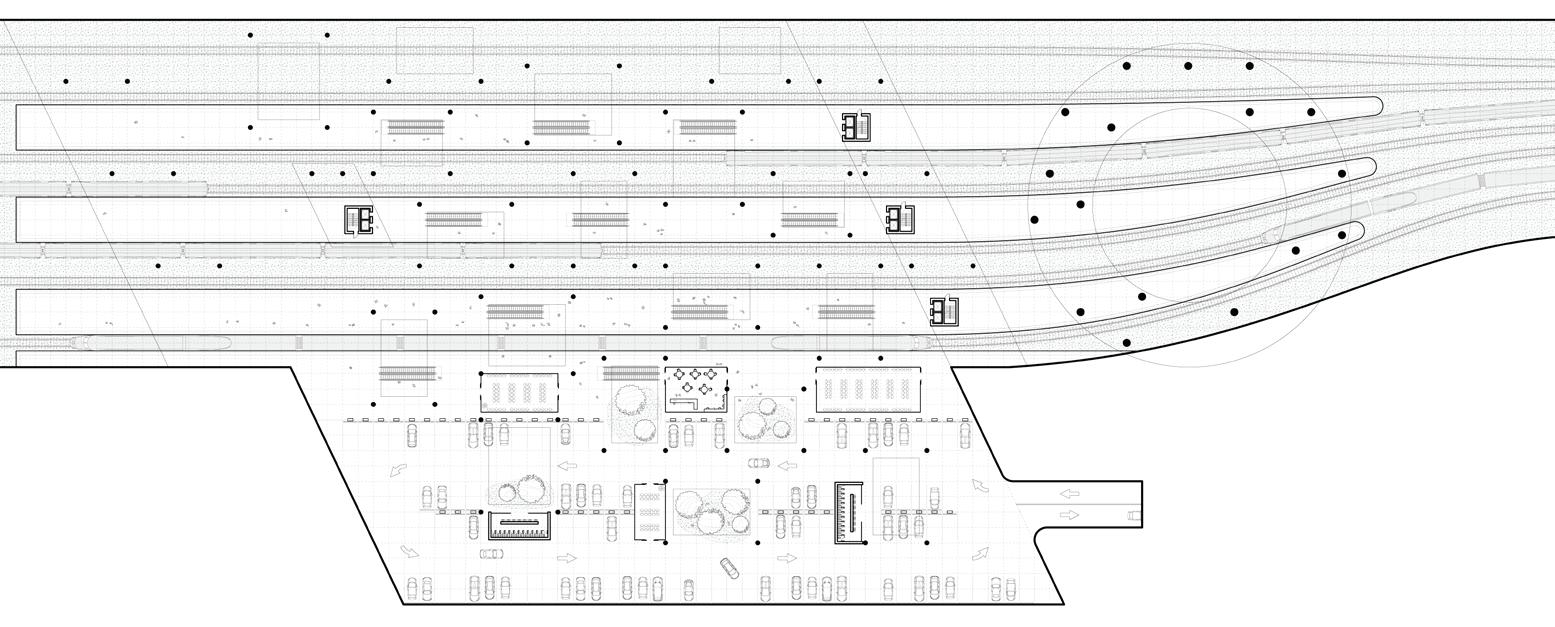

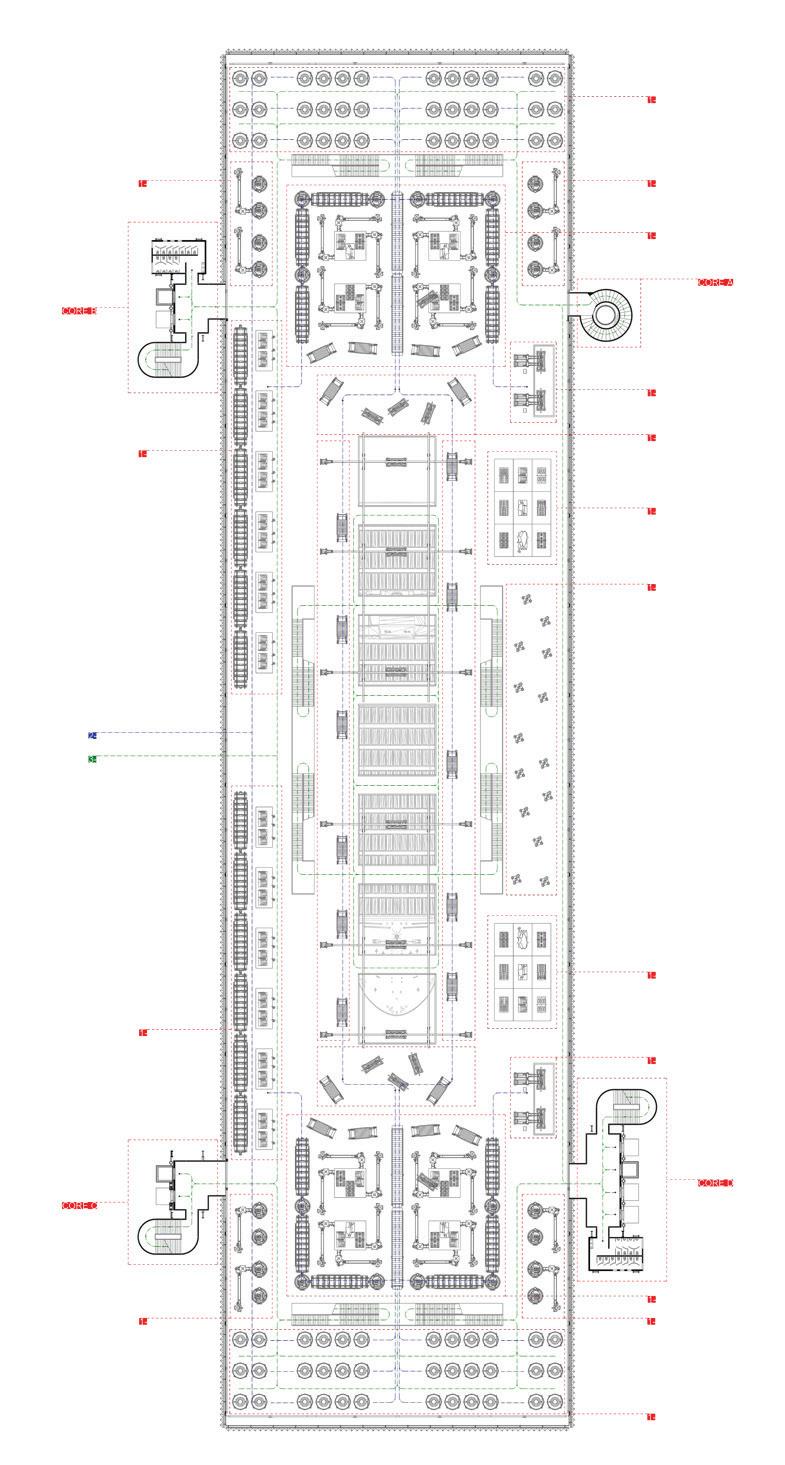

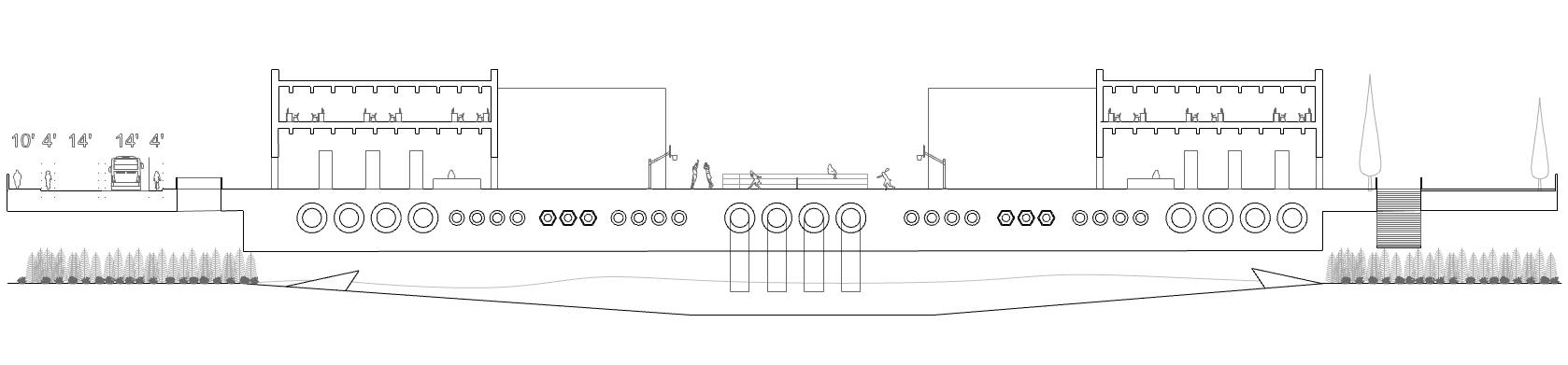

Exploded axonometric view of project components.

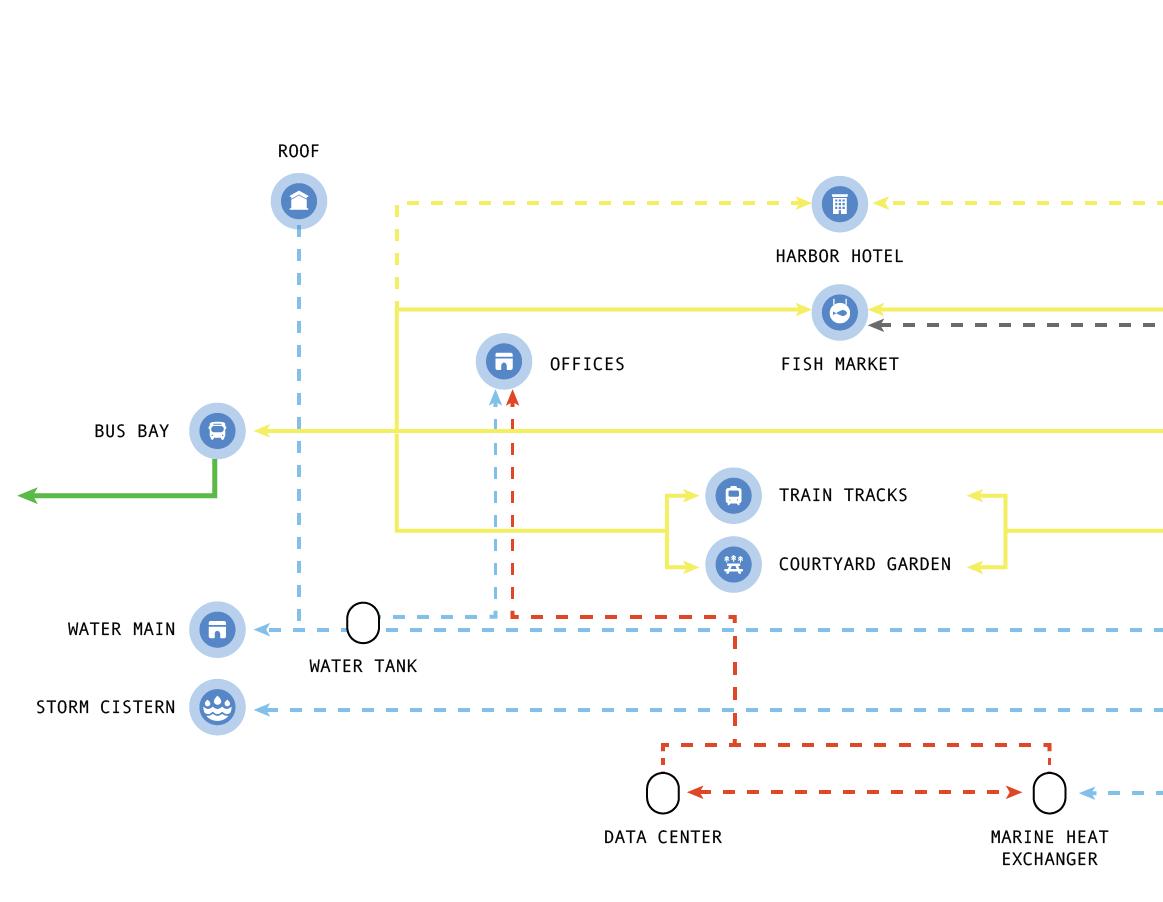

Below: Systems map of site connectivity to regional transportation infrastructure.

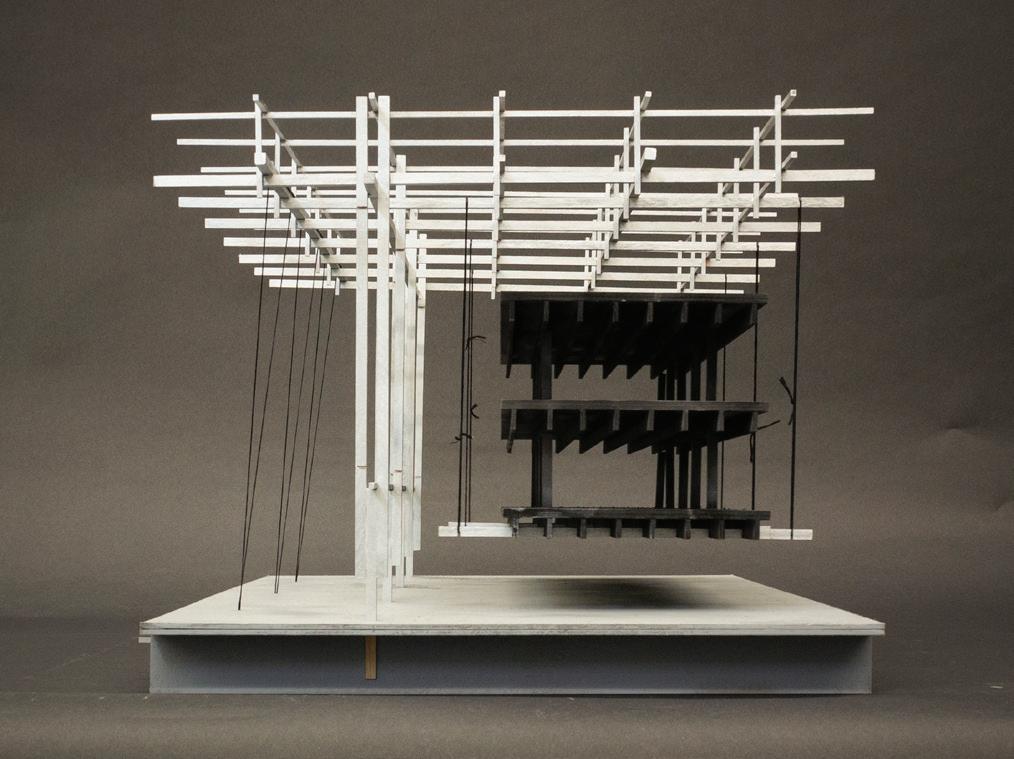

Left: Structural studies testing interdependencies between site and building elements.

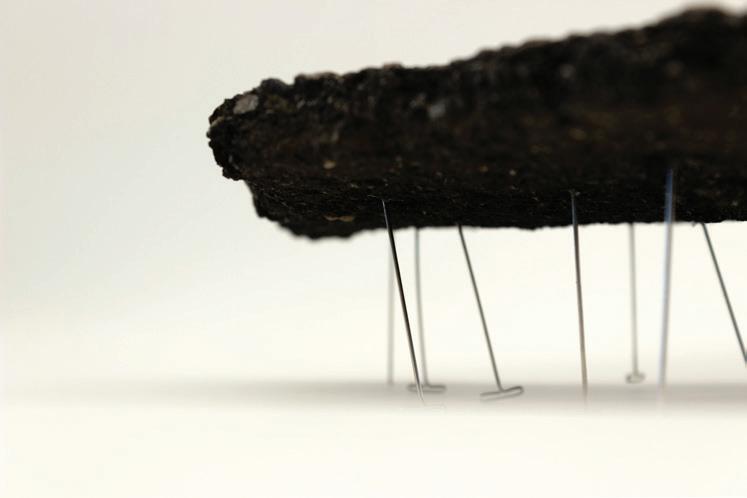

Below: Material studies exploring re-use and re-appropriate of asphault as a dominant existing site condition.

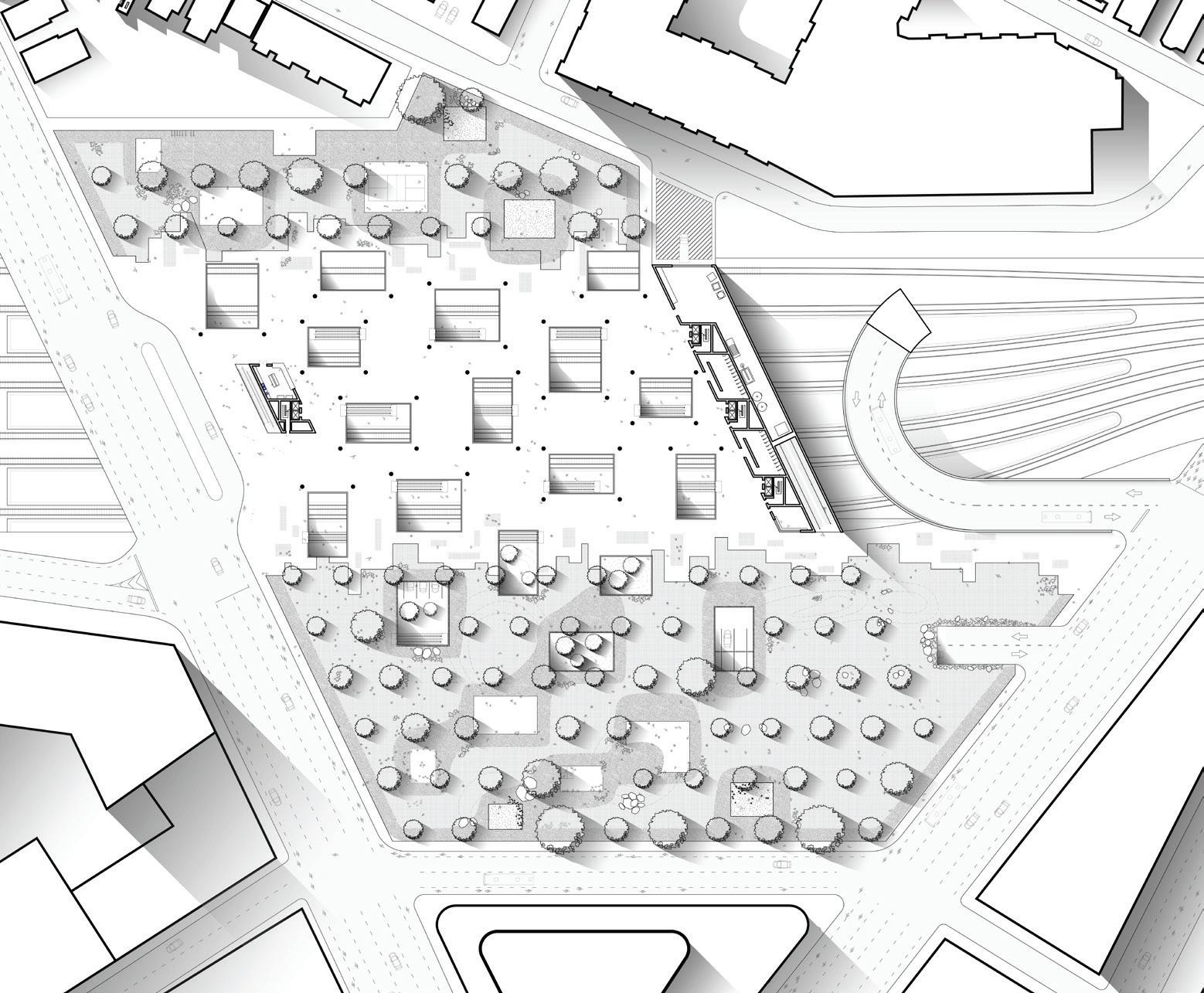

Aria Hill, Lanson Xie Yixin Du

Site: Seaport Drydock

The metropolis is hurting. Recent developments in market-driven urbanism coupled with the repercussions of seemingly interminable fossil fuel extraction radically transformed the integrity of cities. As Matthew Soules describes it, “occupancy” is now the “fulcrum of 21st-century finance capitalism.” High-end residential units that are “owned but empty” foster a type of “zombie urbanism” in city centers, effectively crushing our desires for a vibrant metropolis.

The “everyday” is pervasive. So much so, that it quickly becomes banal. The “exit” sign. The loading dock on the backside of the building. The maintenance man cleaning the tower windows. These elements of the mundane are often absorbed into the slick, glassy architecture for which the market advocates. What opportunities are ripe for rediscovery and celebration amidst the capitalist machine? How can the pervasive banal of industrial cities provide novel architectural responses?

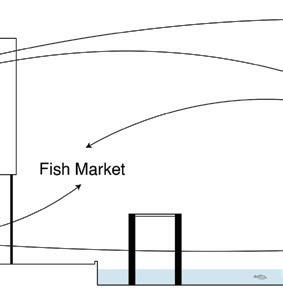

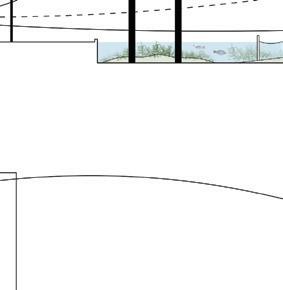

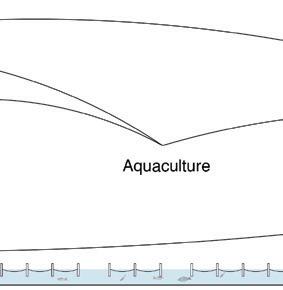

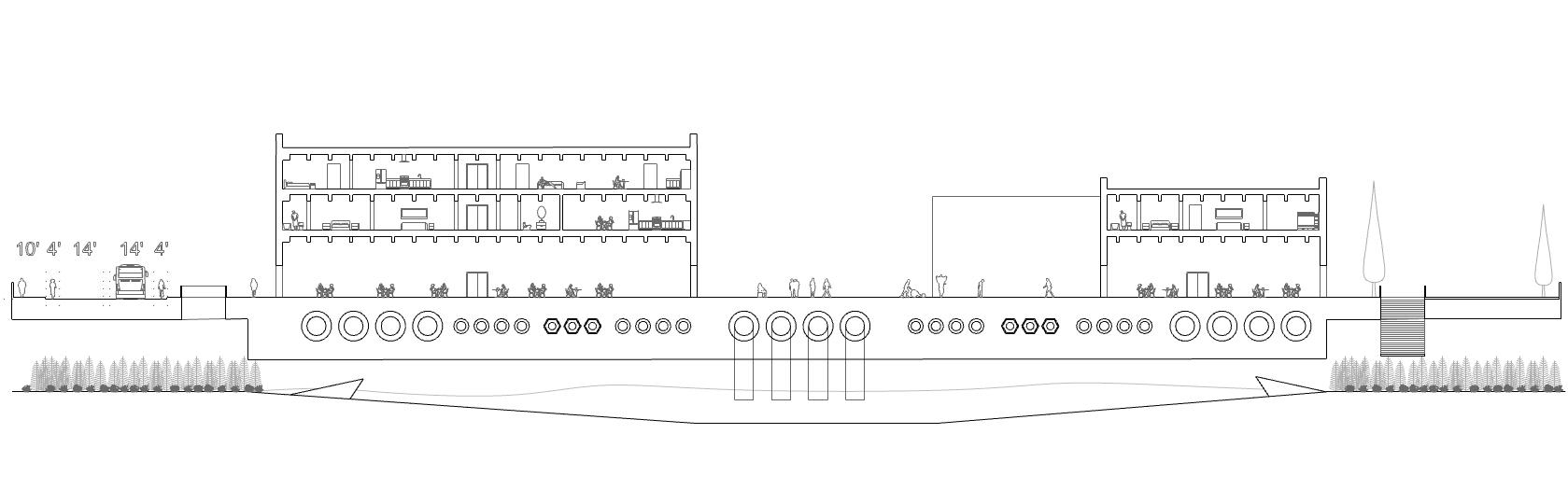

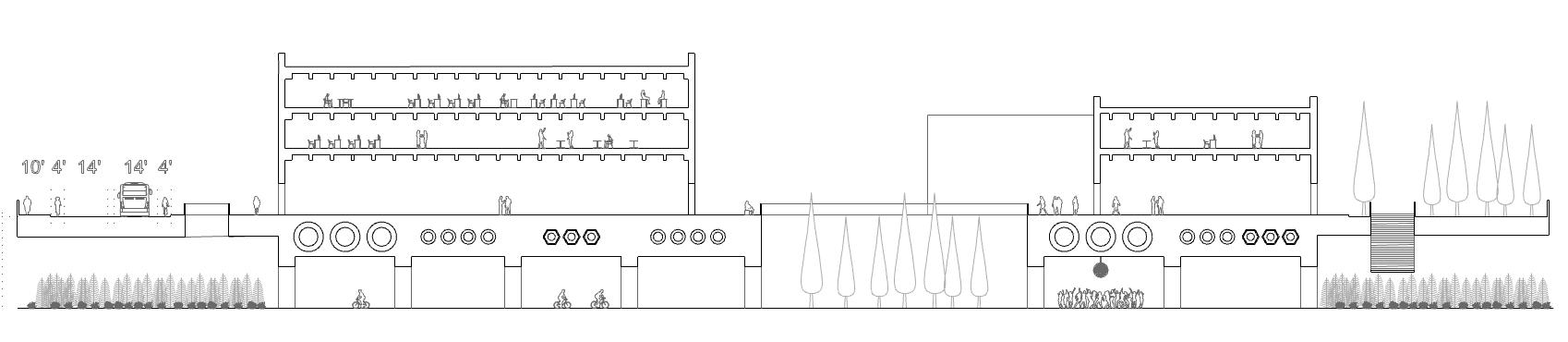

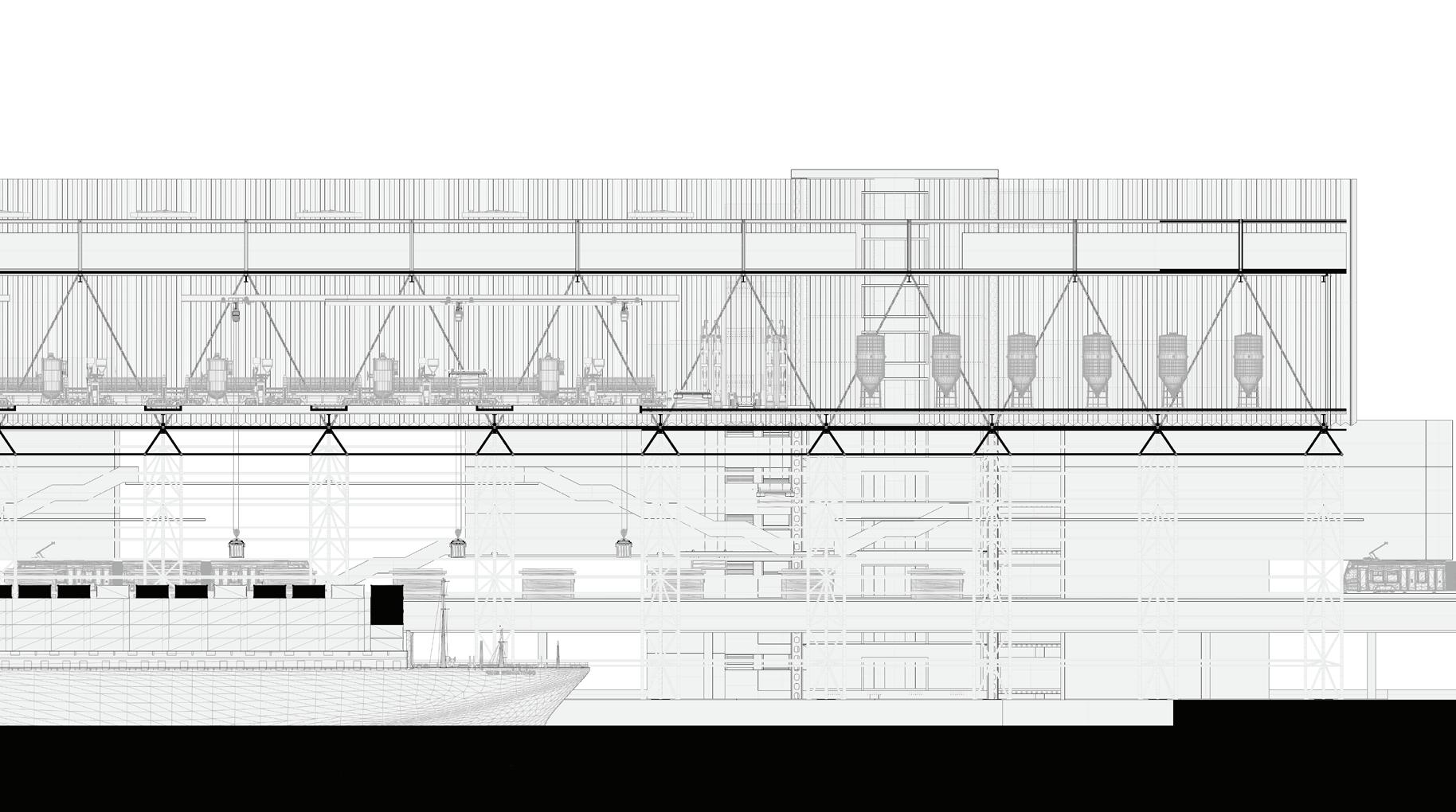

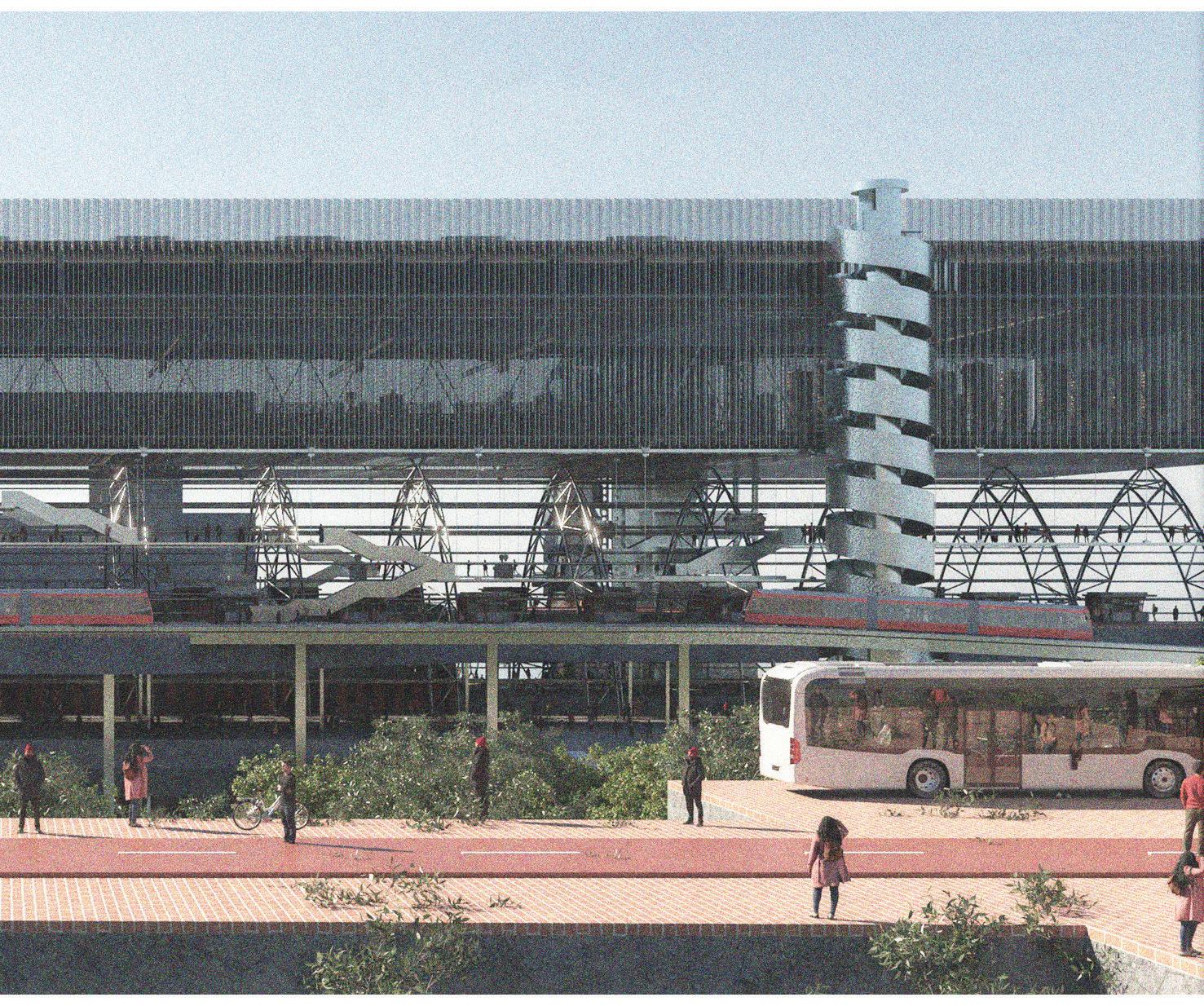

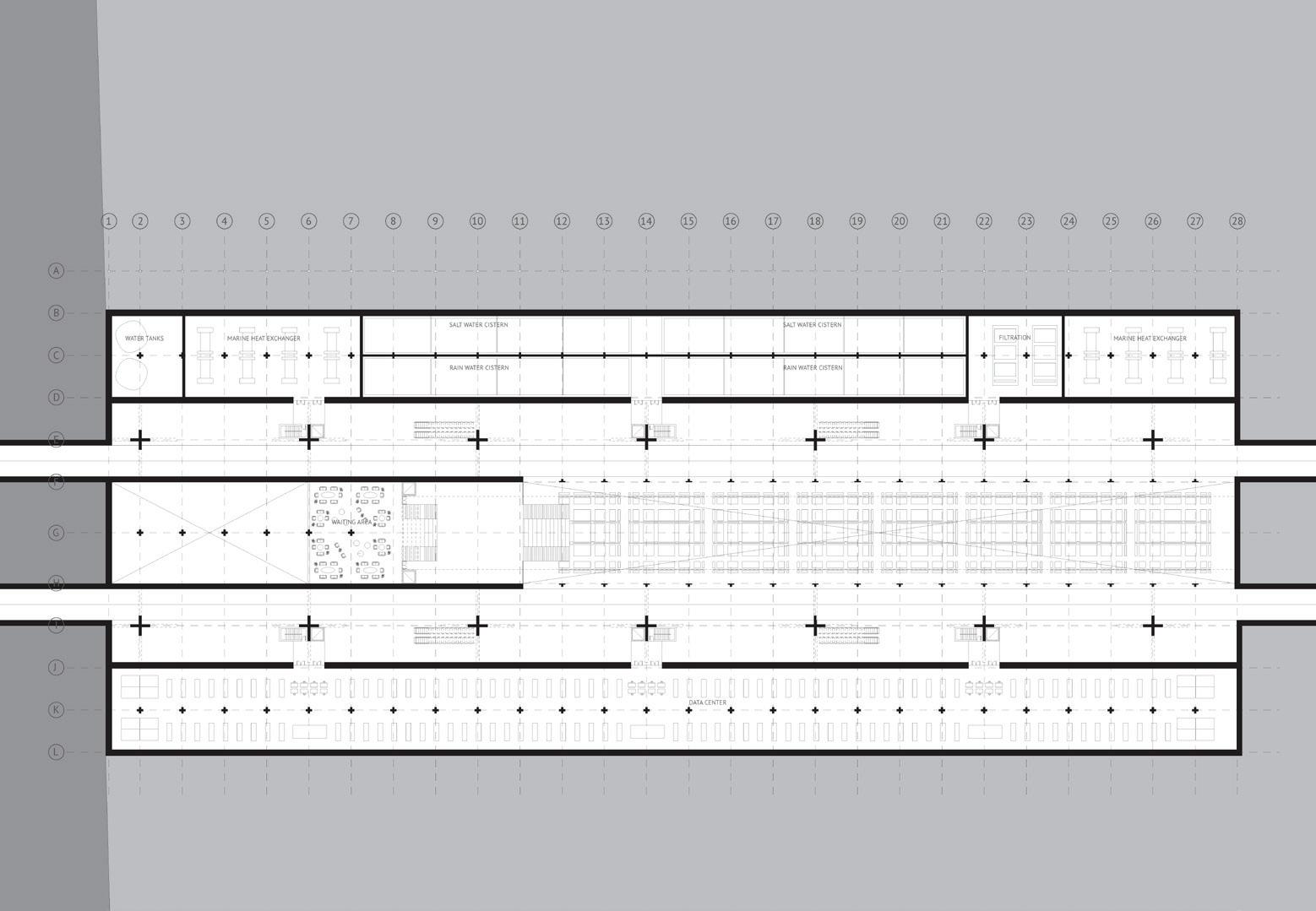

Under counterfactual conditions, Dry Dock II will be transformed into a new urban center with accessible public transportation facilities, higher density residential areas and more multi-functional industrial zones, while revitalizing the existing Track 61 railroad system. Given existing site conditions and the impending deluge of storm surge in this area, a new datum elevation will be established at +28’ to unify the city’s elevation. This new “sealevel” will be the base for a new city interface, with a flexible, floodable space at grade. Roofs and other infrastructures will be traversed in a multi-height landscape.

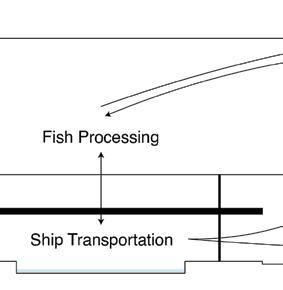

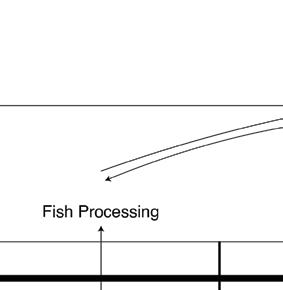

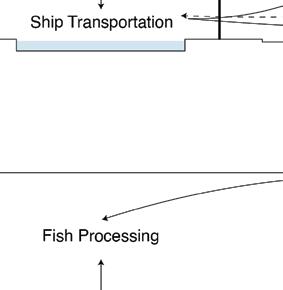

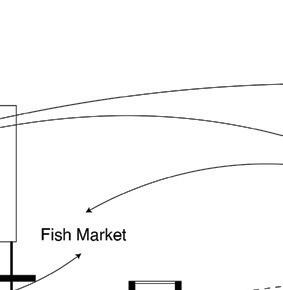

Dry Dock II serves as a transportation hub for the Seaport District, assuming three modes of transportation: rail, bus, and ferry/ship, and is an important hub for regional transportation and production and consumption. Additional programs on the site will include a fishing processing plant.

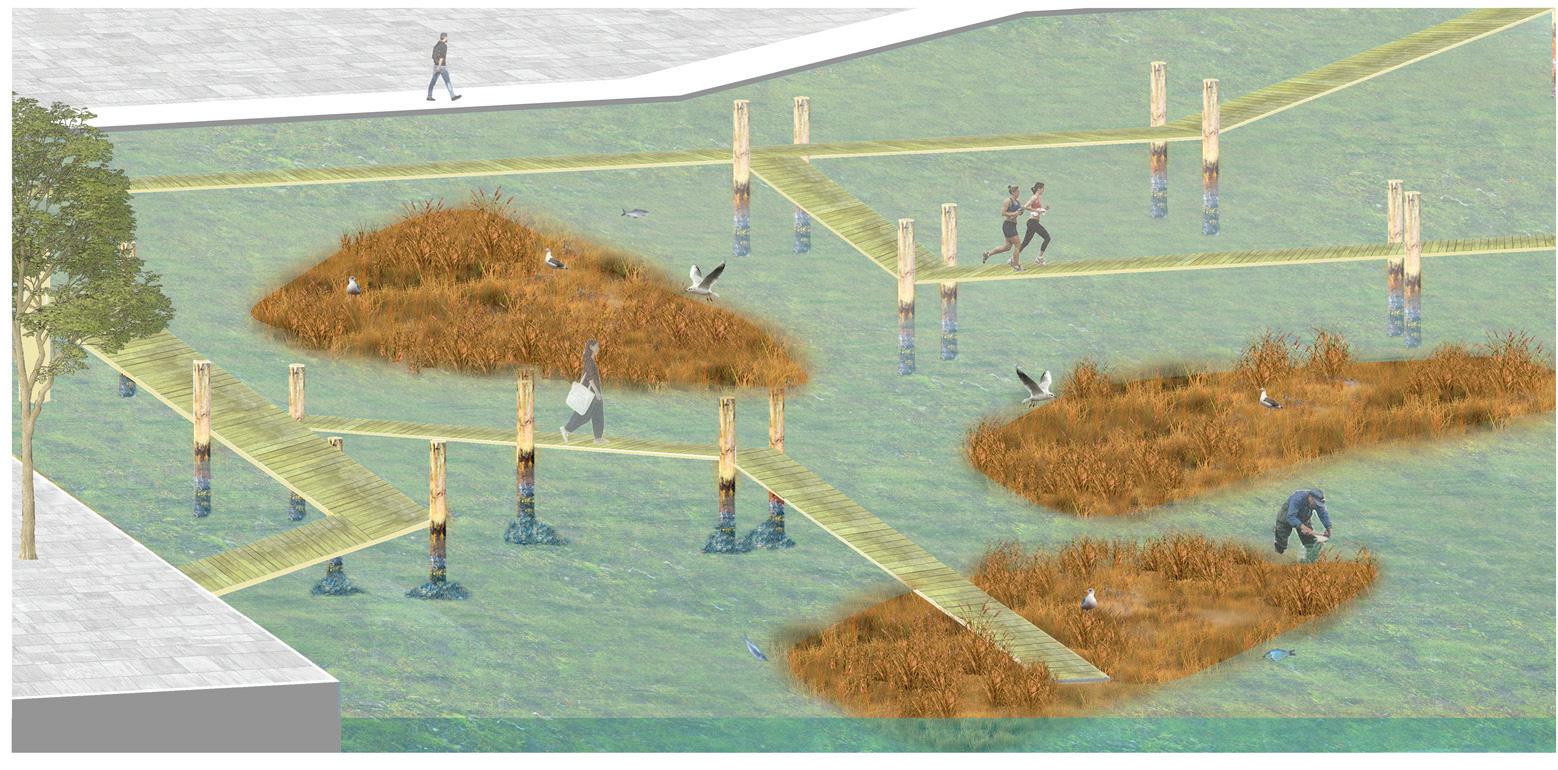

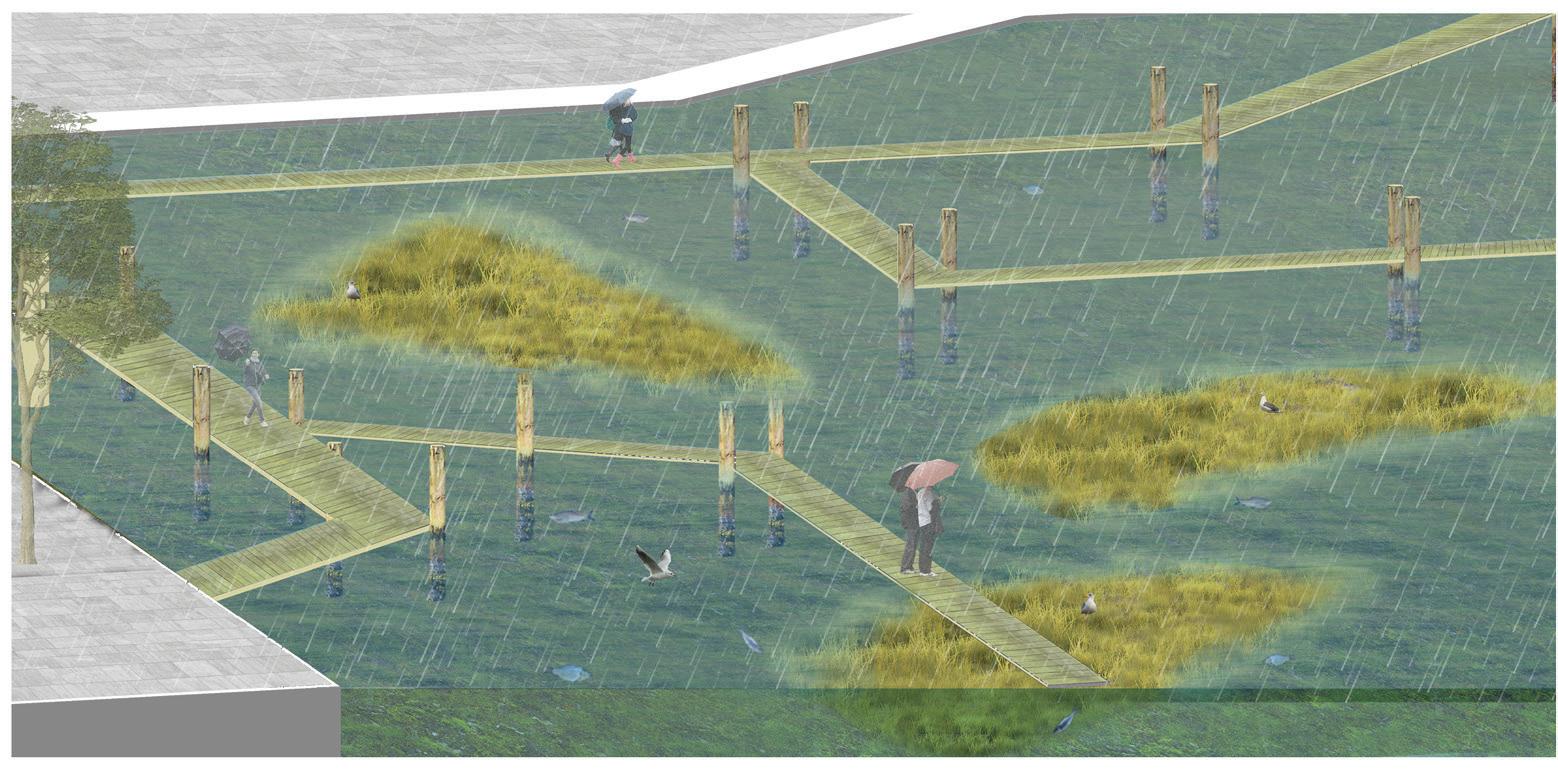

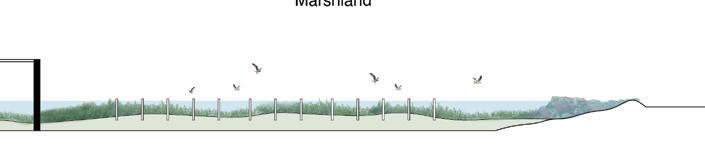

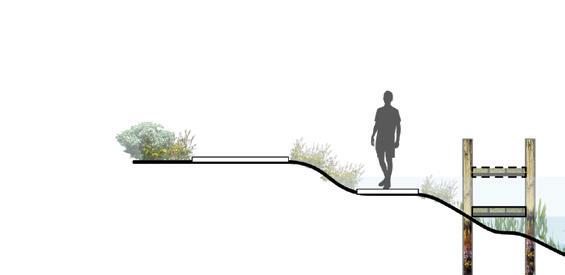

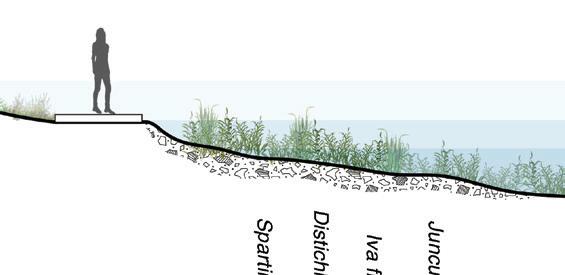

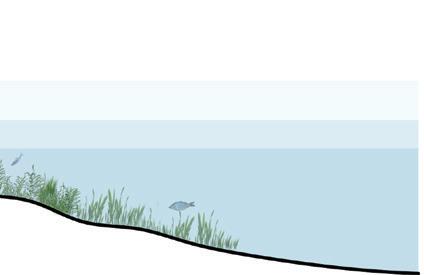

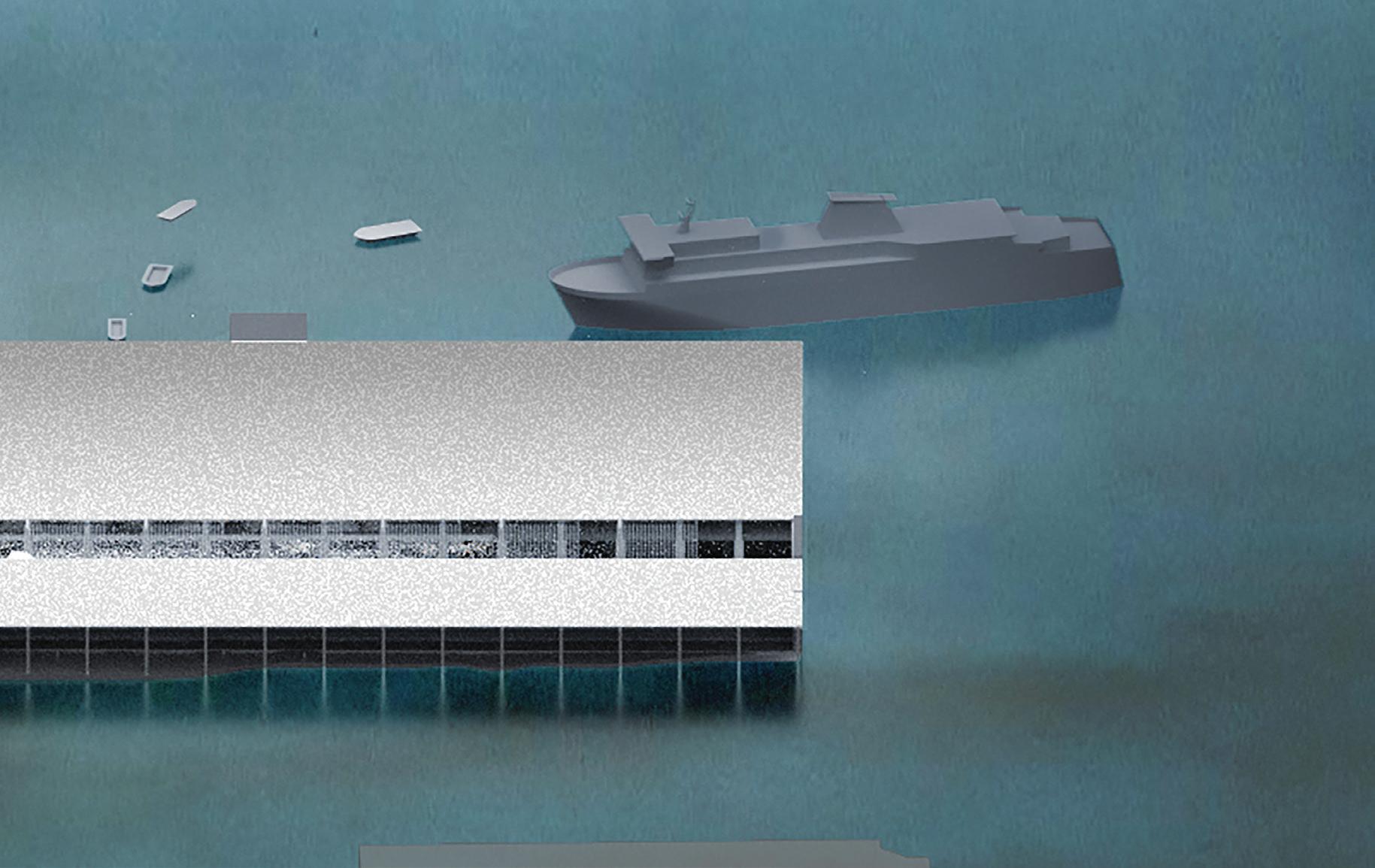

Remediated and reclaimed post-industrial shore line provides a recreational and productive landscape calibrated to handle increasing climatic fluctuations. Depiction of dry seasons (above left) and wet seasons (above right).

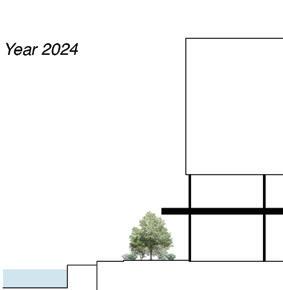

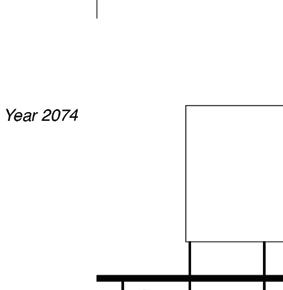

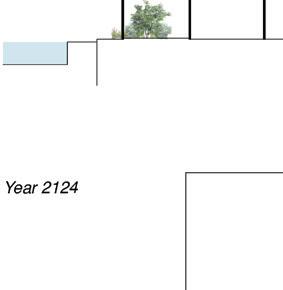

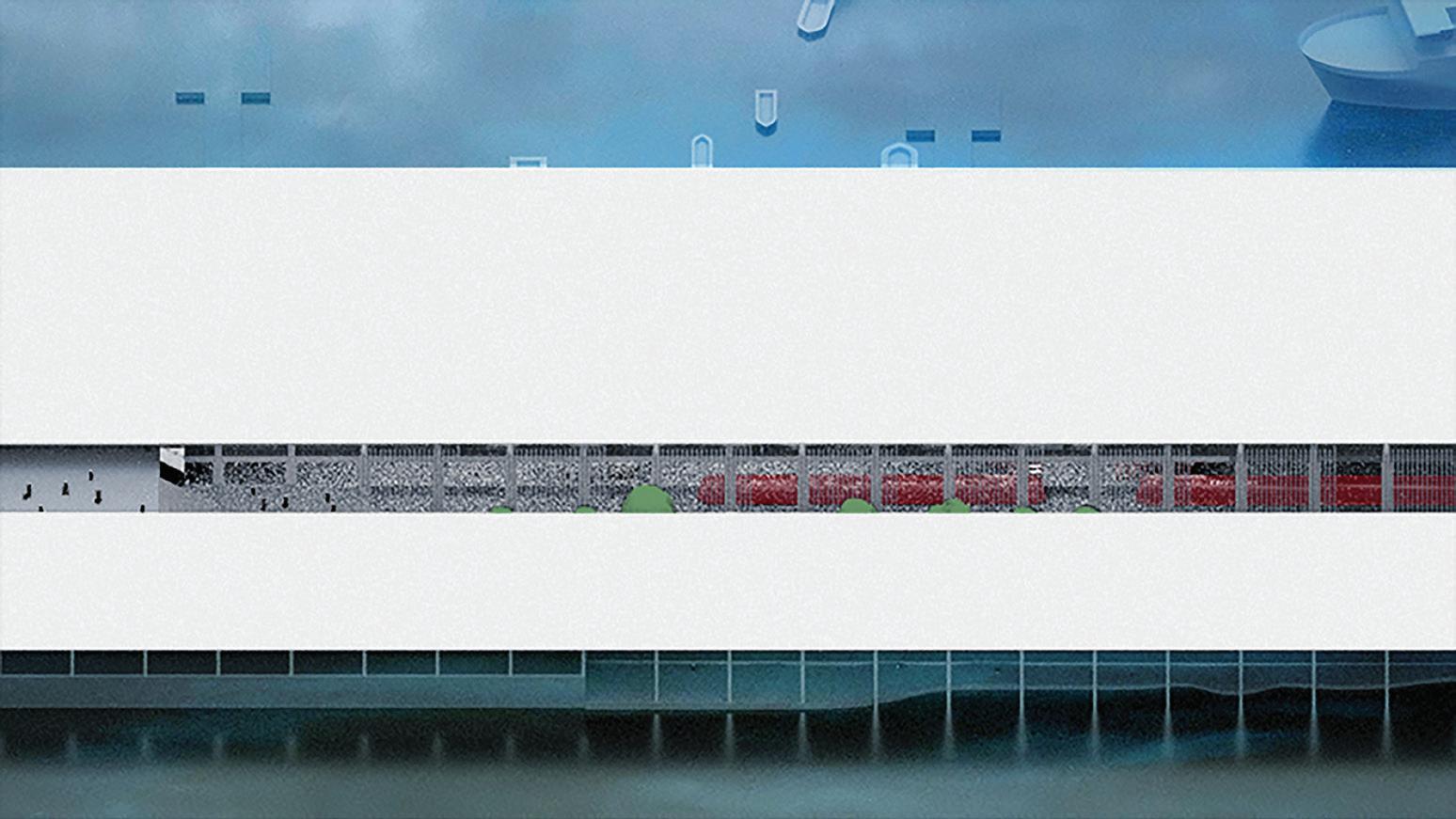

As flooding becomes more frequent the site as a social space of mobility and maritime industry (plan of fish processing program and mobility hub at left) gradually migrates upwards in elevation to occupy a new, higher ground level.

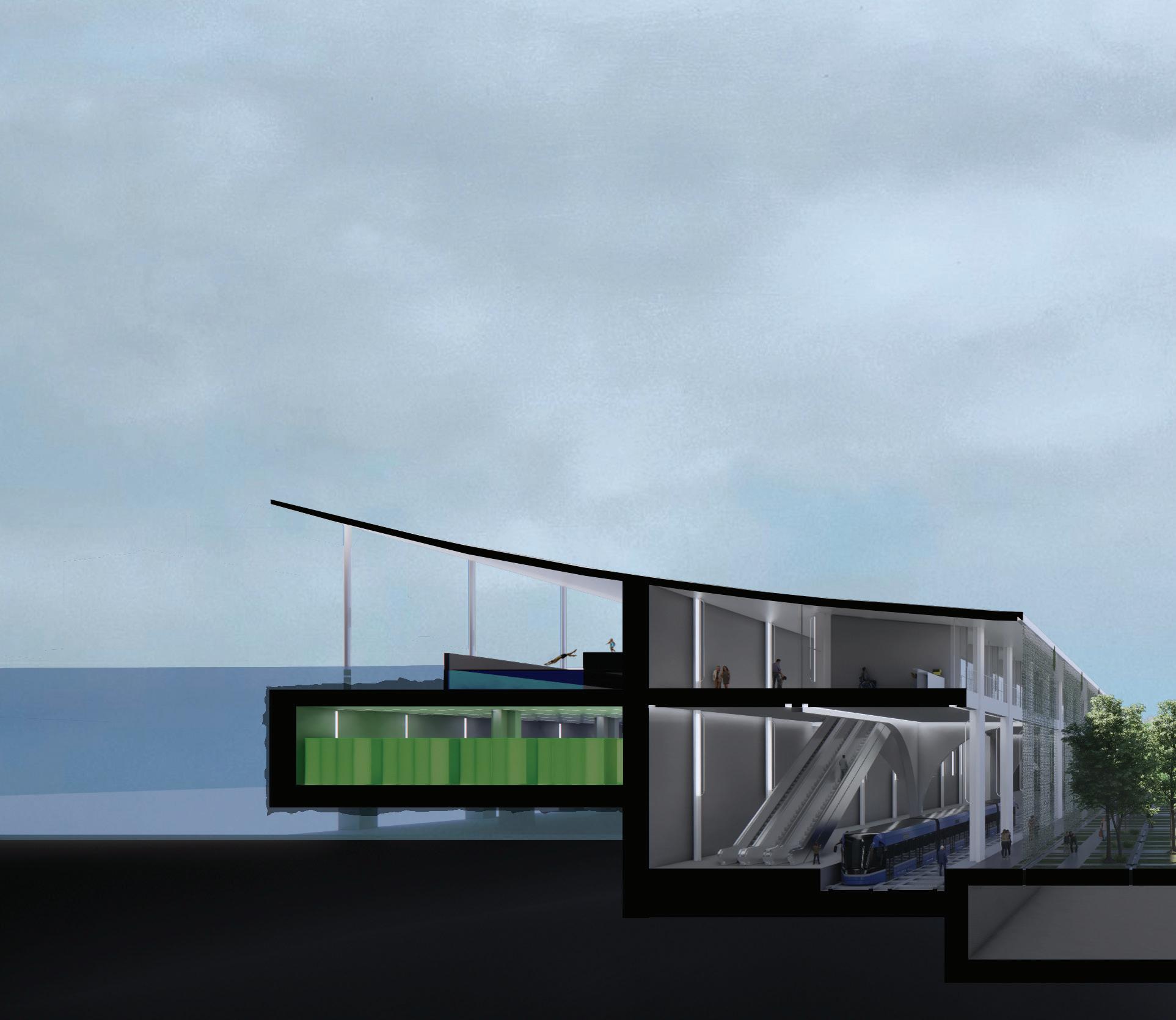

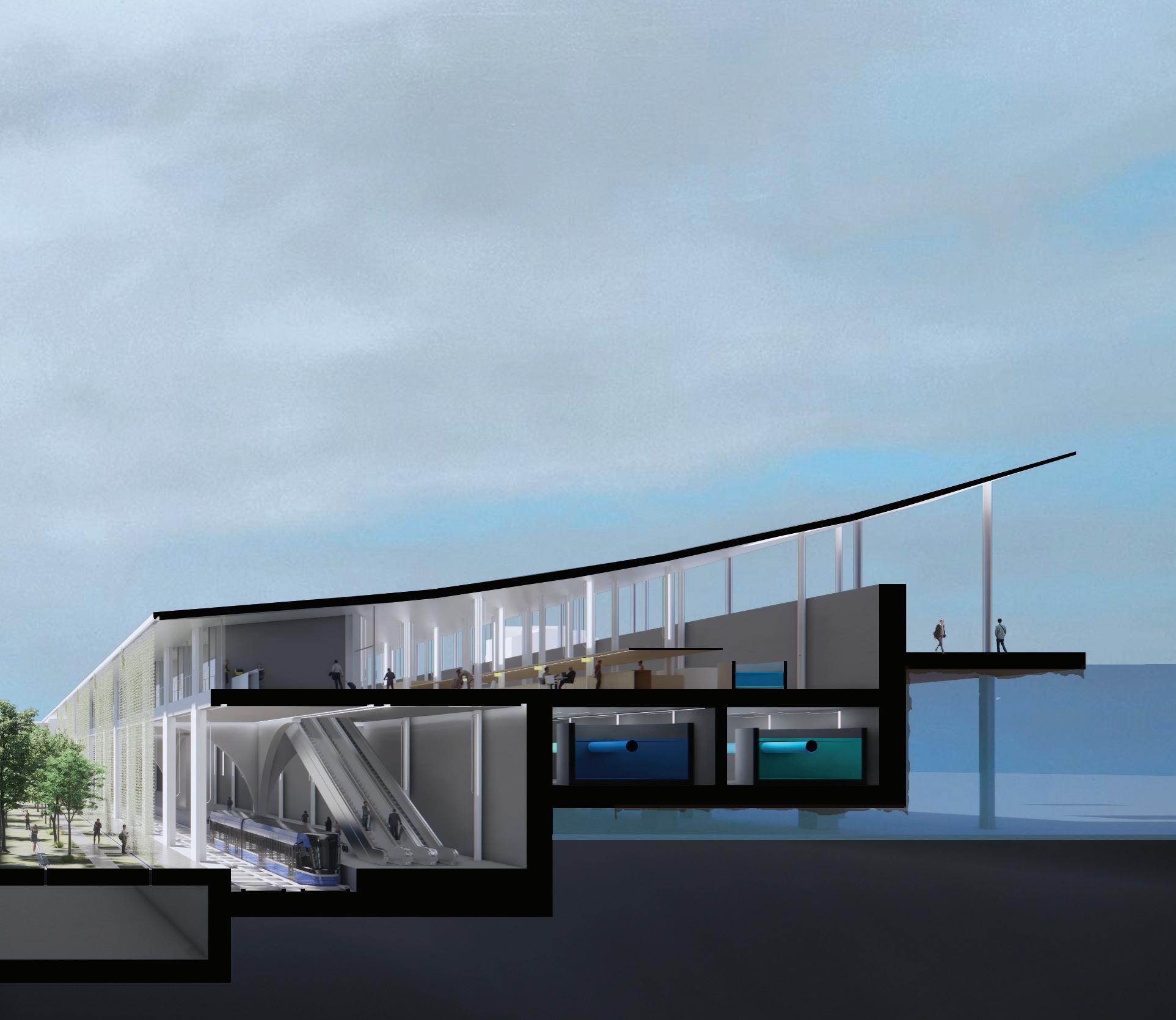

At right: Urban sections showing the end state of the surrounding elevated urbanism and mobility in 2124.

Below: The landscape at grade evolves into a marshland ecosystem, shown below as it transforms over time.

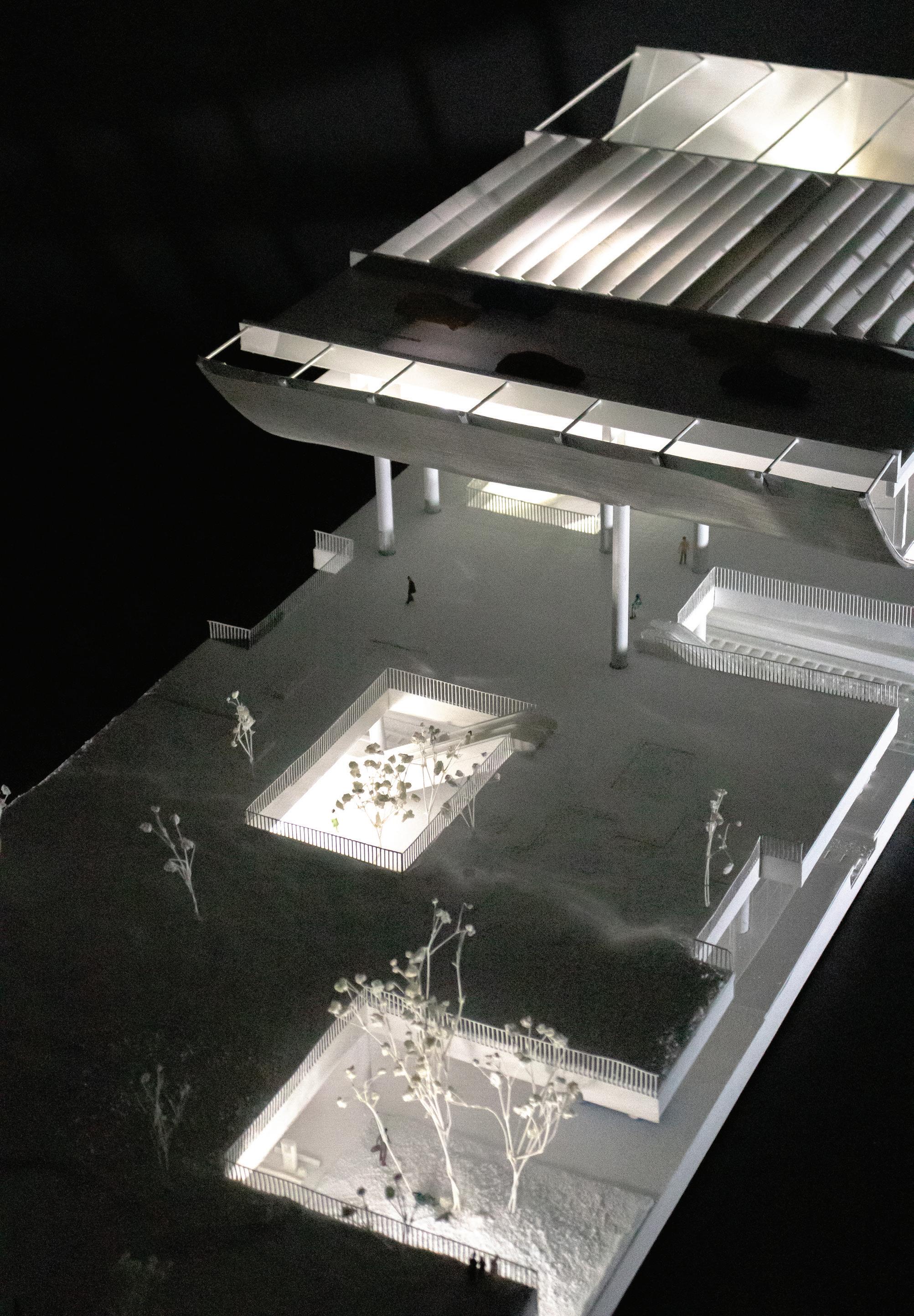

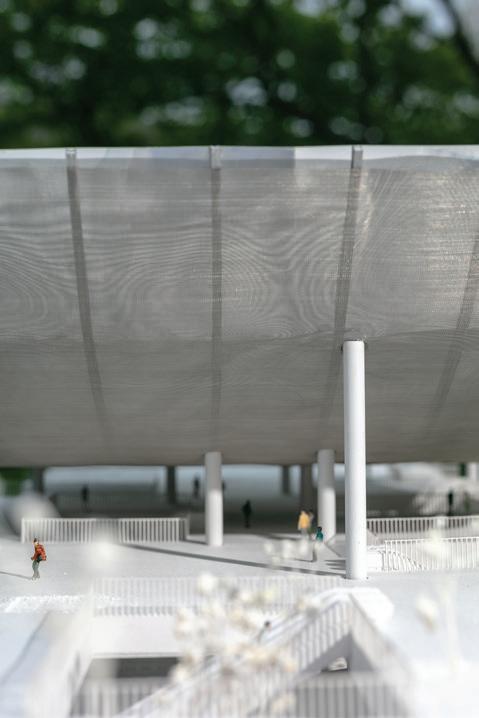

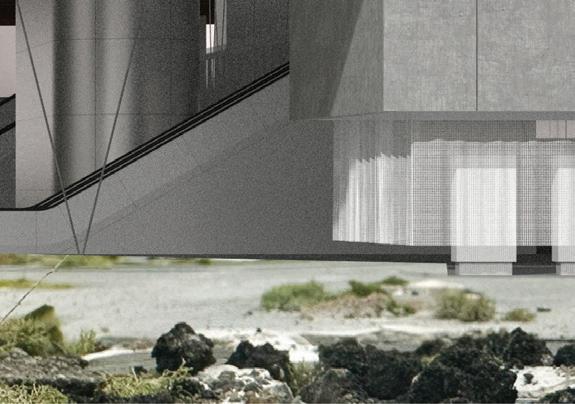

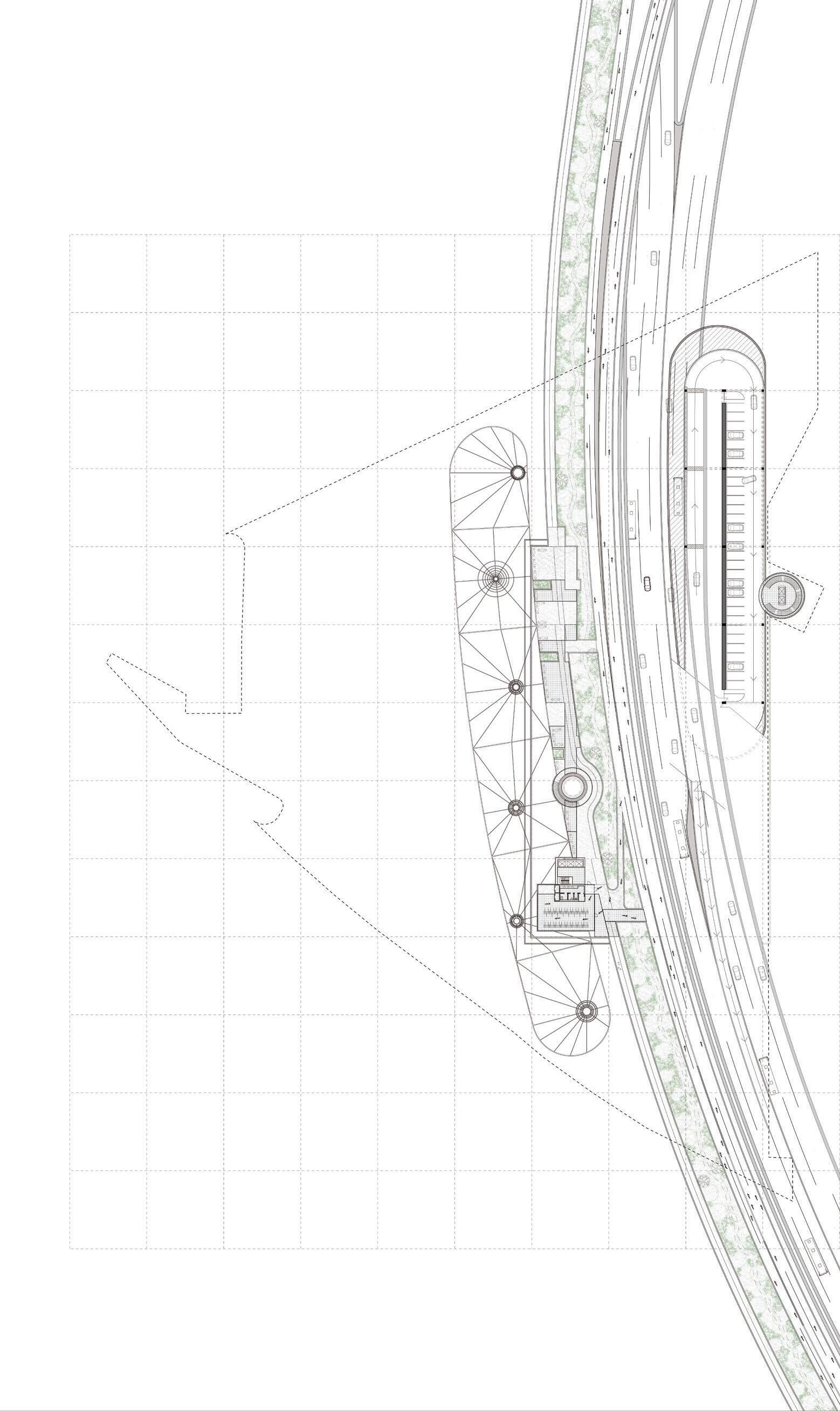

Inmo Kang, Hannah Wong

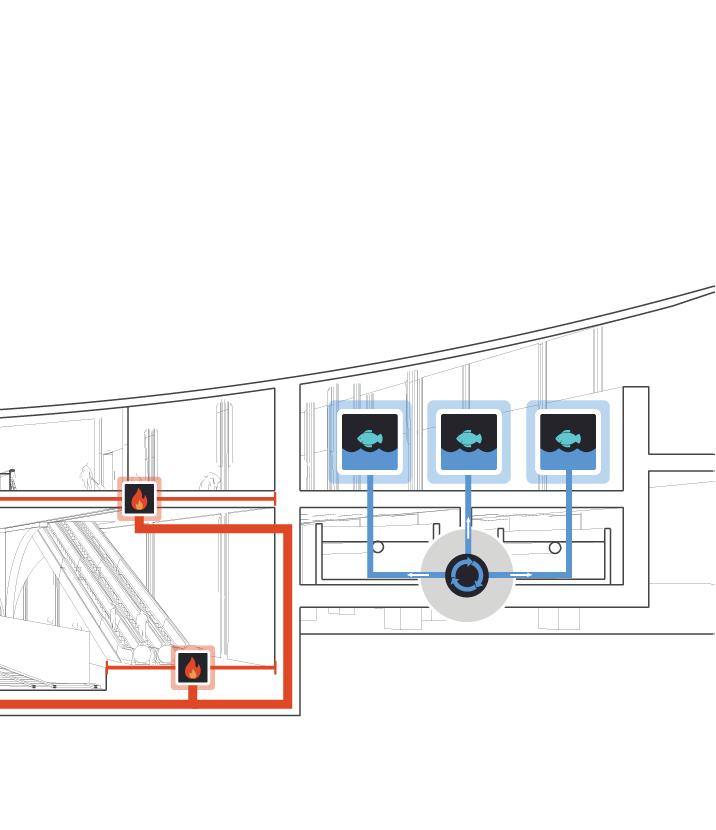

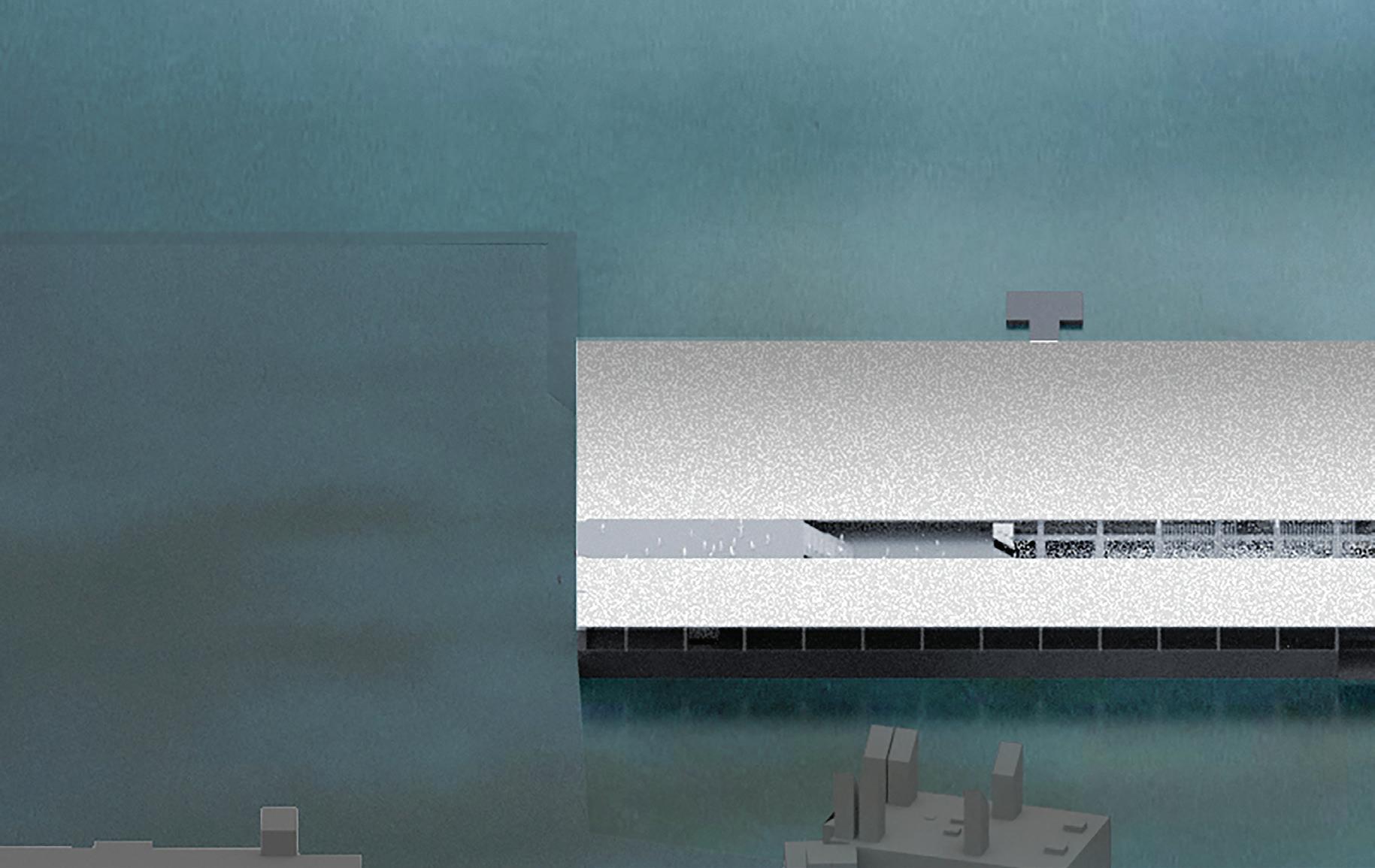

Site: Seaport Drydock

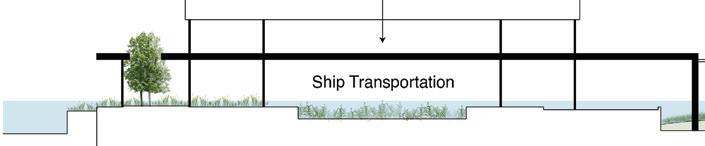

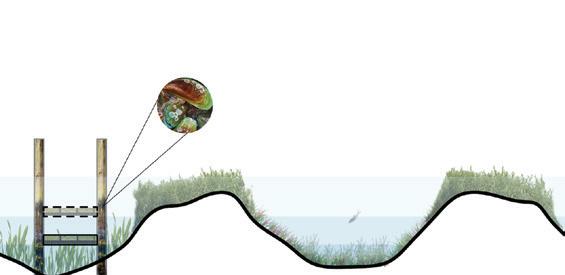

Boston Waterfront Mobility Hub is focused on interactivity and engagement between people, infrastructure, and the harbor. With the inevitable challenge of sea level rise and storm surge and how it could isolate the Seaport, we have created an oxymoronic island, recharging the existing dry dock, for connection, in both transit and social sense in an ever-disconnected area in the face of sea level rise. Our site operates as a link/connector/junction between modes of transit, civic and industrial infrastructure, and human water utilization with the marine ecosystem.

We believe that making a robust and resilient transit hub begins by challenging the existing notion of infrastructure as a perfect, non-destructible system; infrastructure is in fact, “common, negotiable, potentially perishable.” The infrastructure must adapt in tandem with social and environmental changes to continue to serve as a destination for the public. When imagining the imminent future, a new destination of connection, both in physical and social sense, must provide a new sense of togetherness (the “New Sublime”,) not just among citizens but also with species, water, and energy.

To accommodate the necessary adaptations across time, we combined the historical context of the Clean Water Act, Chapter 91, and Seaport’s maritime industrial history with our predicted counterfactual future needs for resilience and transience in the wake of sea level rise. The hub facilitates the integration of these disparate elements by generating productive frictions and symbiotic dichotomies between humans and non-humans to create a sense of plurality and civic freedom.

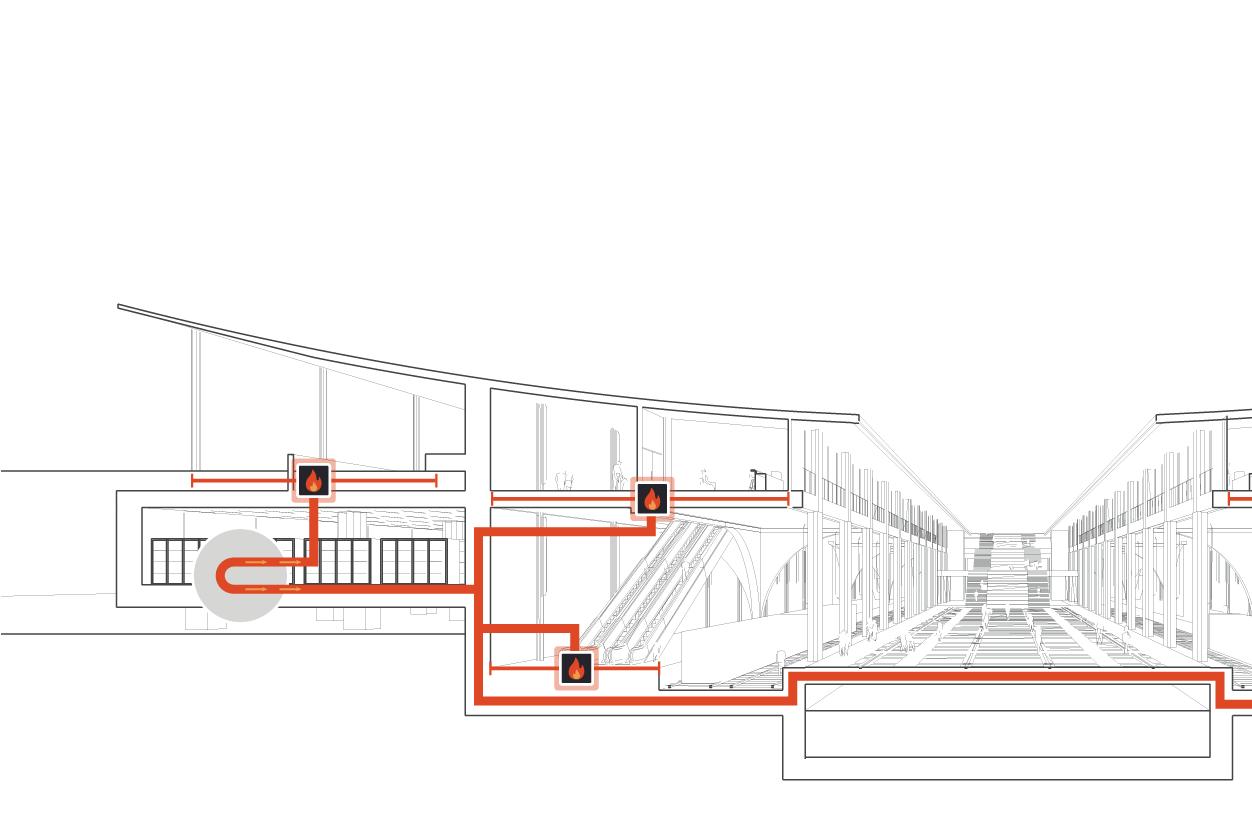

The hub operates at three scales: the macro-scale of transportation, the meso-scale of program and building systems, and the micro-scale of the human experience. Our site physically connects people to one another through transit, but also creates connections on site through integrated and interactive systems and programs. By fostering different types of connection, the hub allows for continued and evolving forms of civic engagement and fascination. We hope not to develop ever-enduring, utopic system, but instead to create resiliency in the face of fallacy, to adapt and adjust in the inevitable occurrences of an ever-changing world.

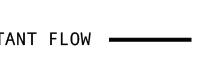

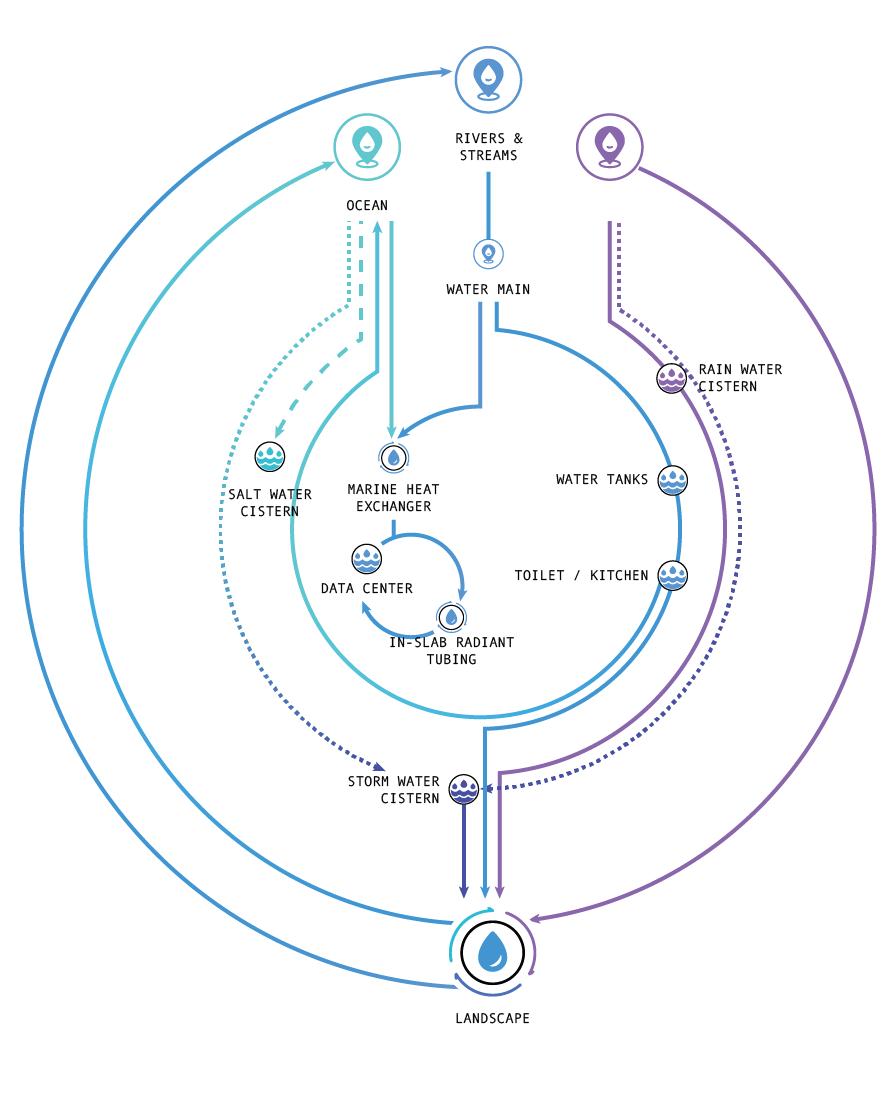

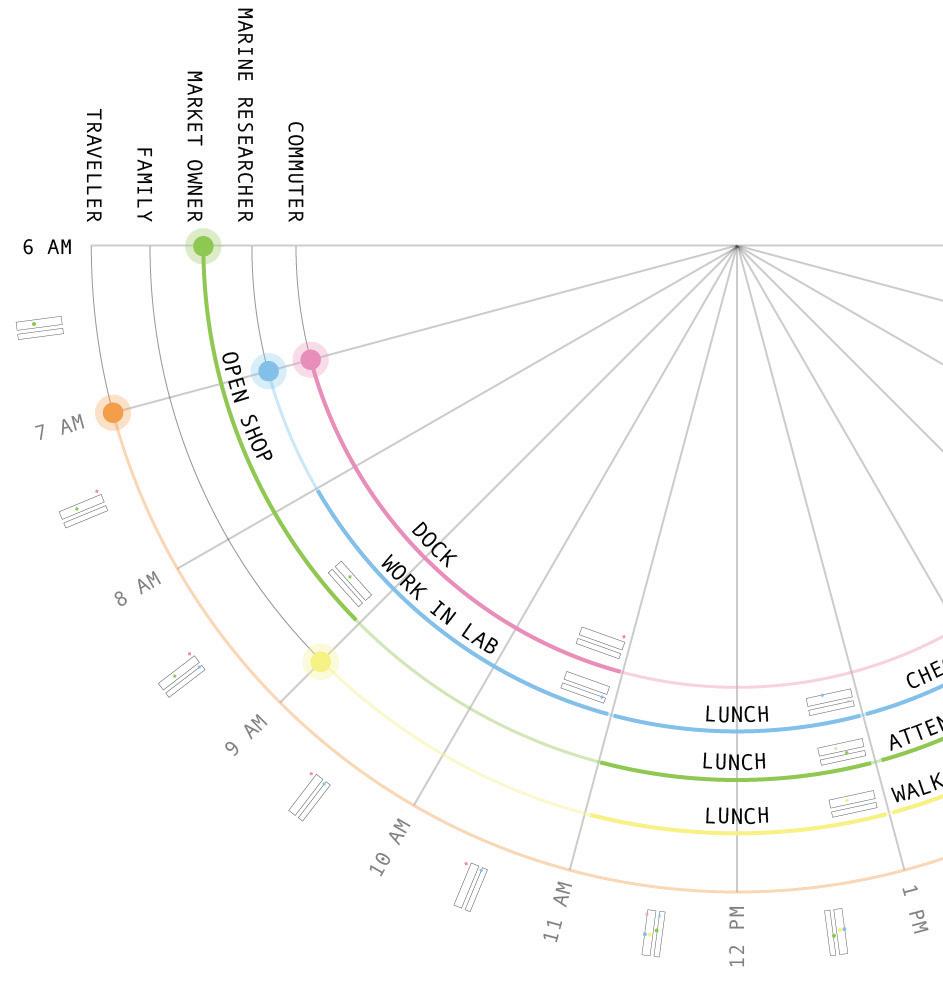

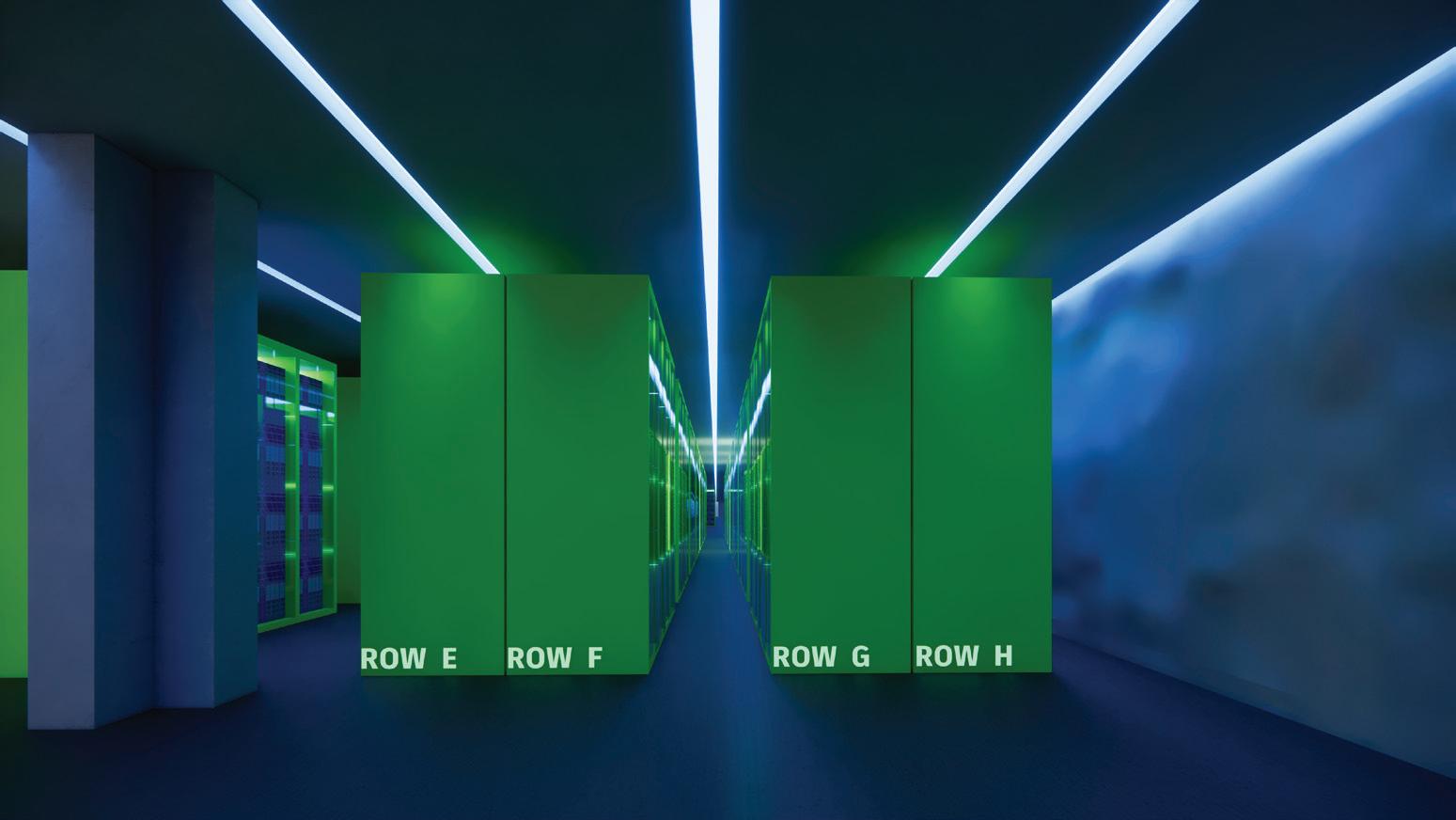

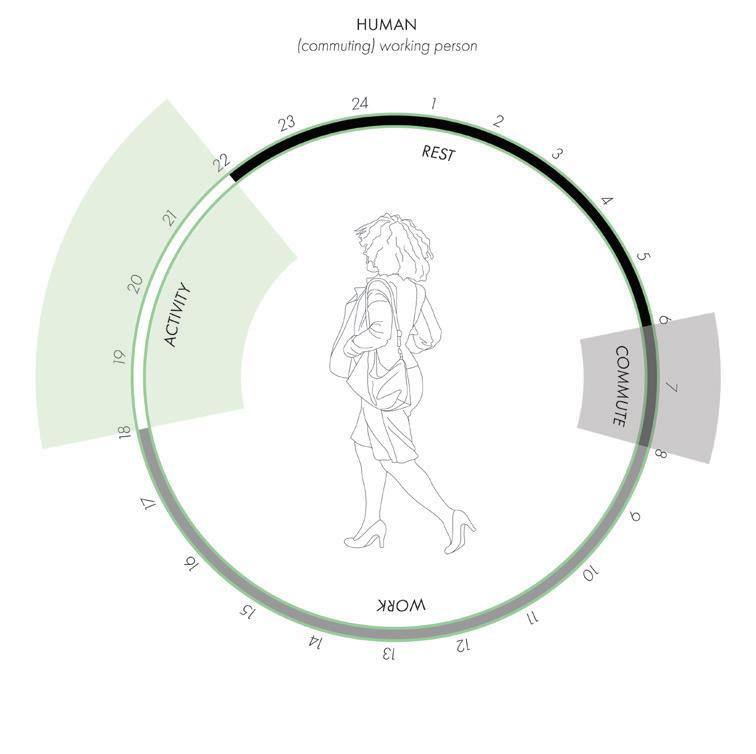

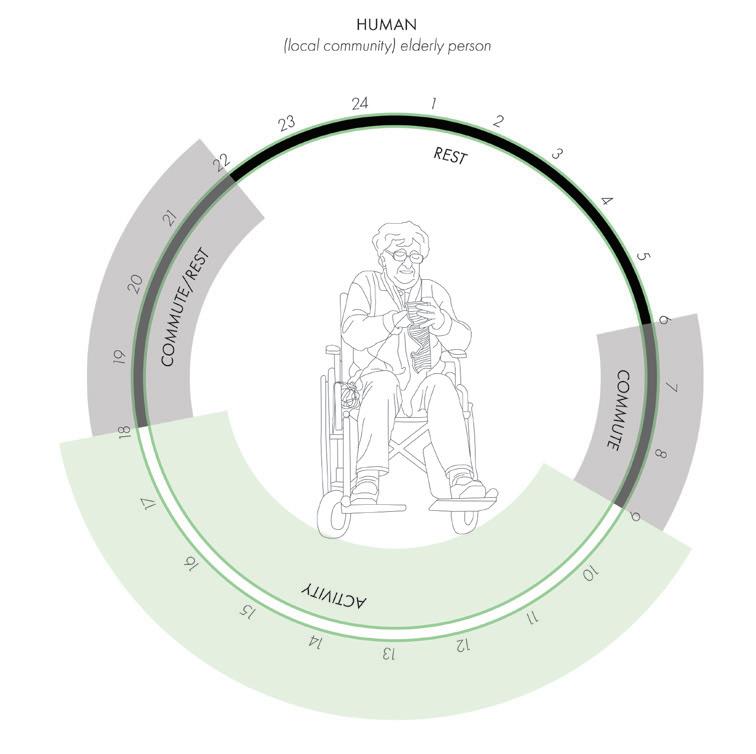

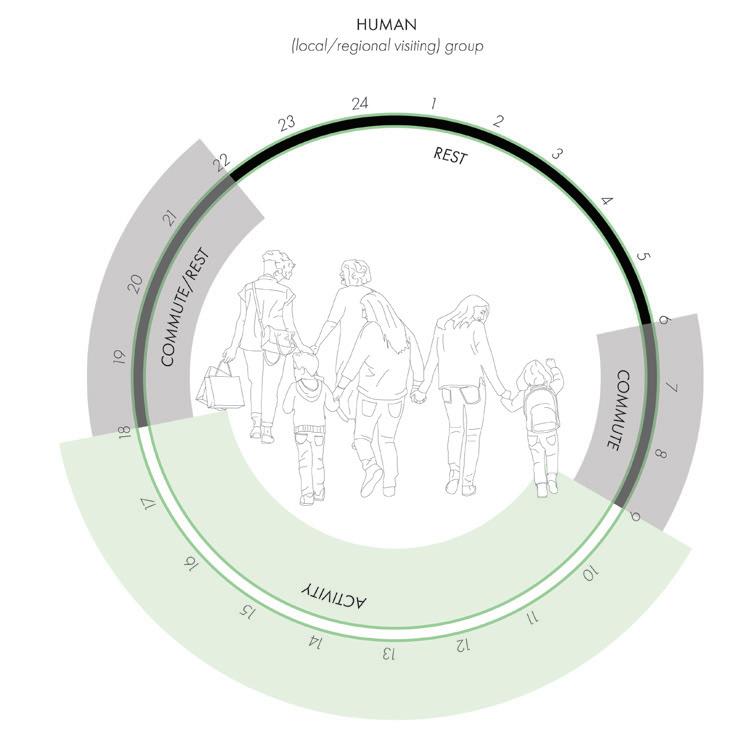

Diagrams (clockwise from above) demonstrate site program and systems in section view; the overlapping actors in the cycle of a typical day; a study model of life above and below sea level; a study of the water sources and flows throughout building architecture.

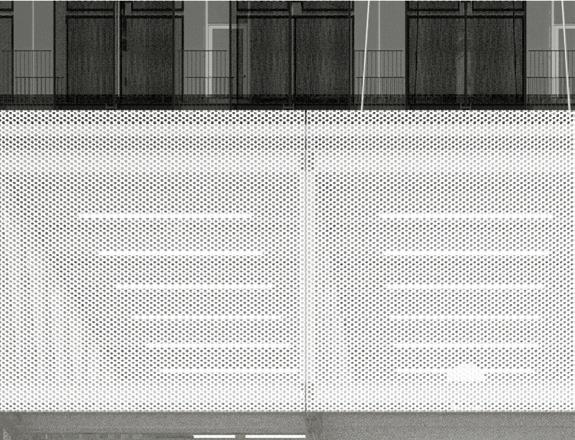

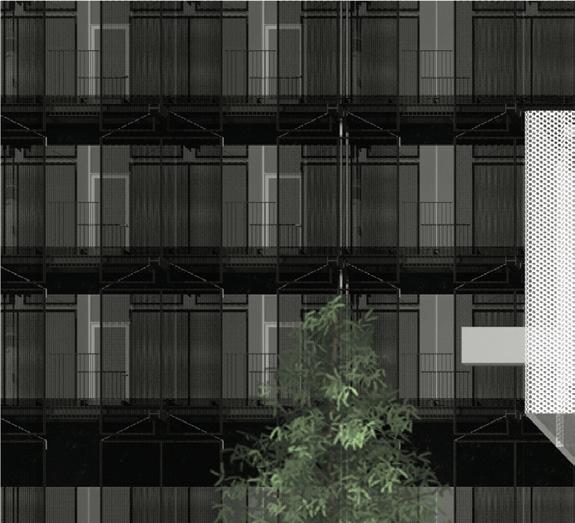

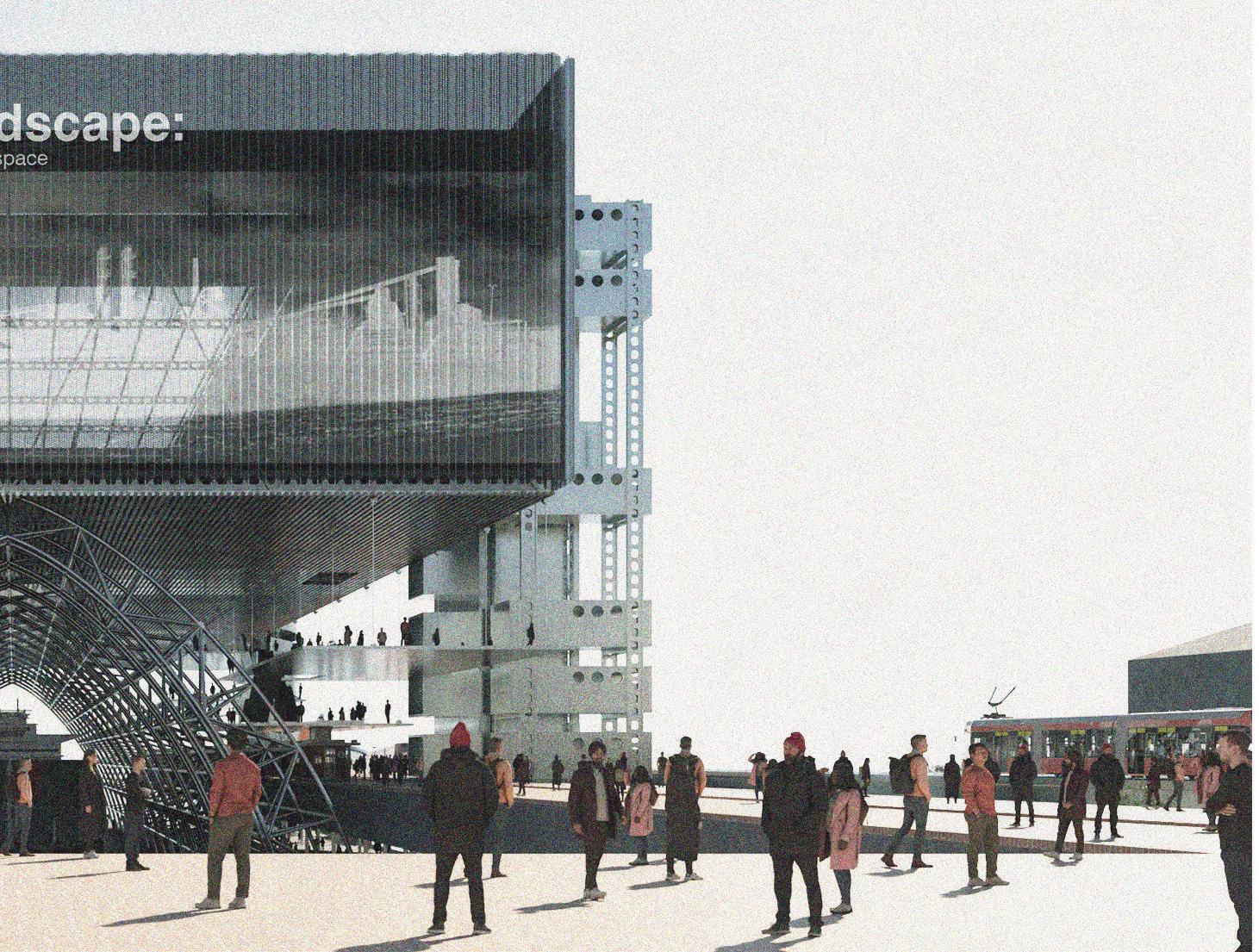

Gina Bernotsky, Ally Lammert

Site: Sullivan Square

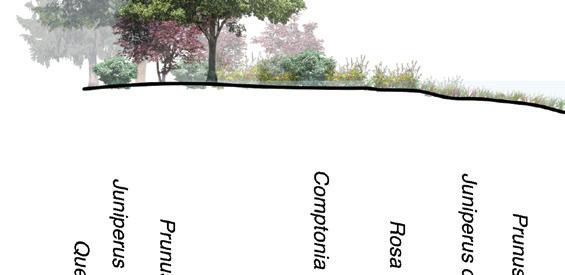

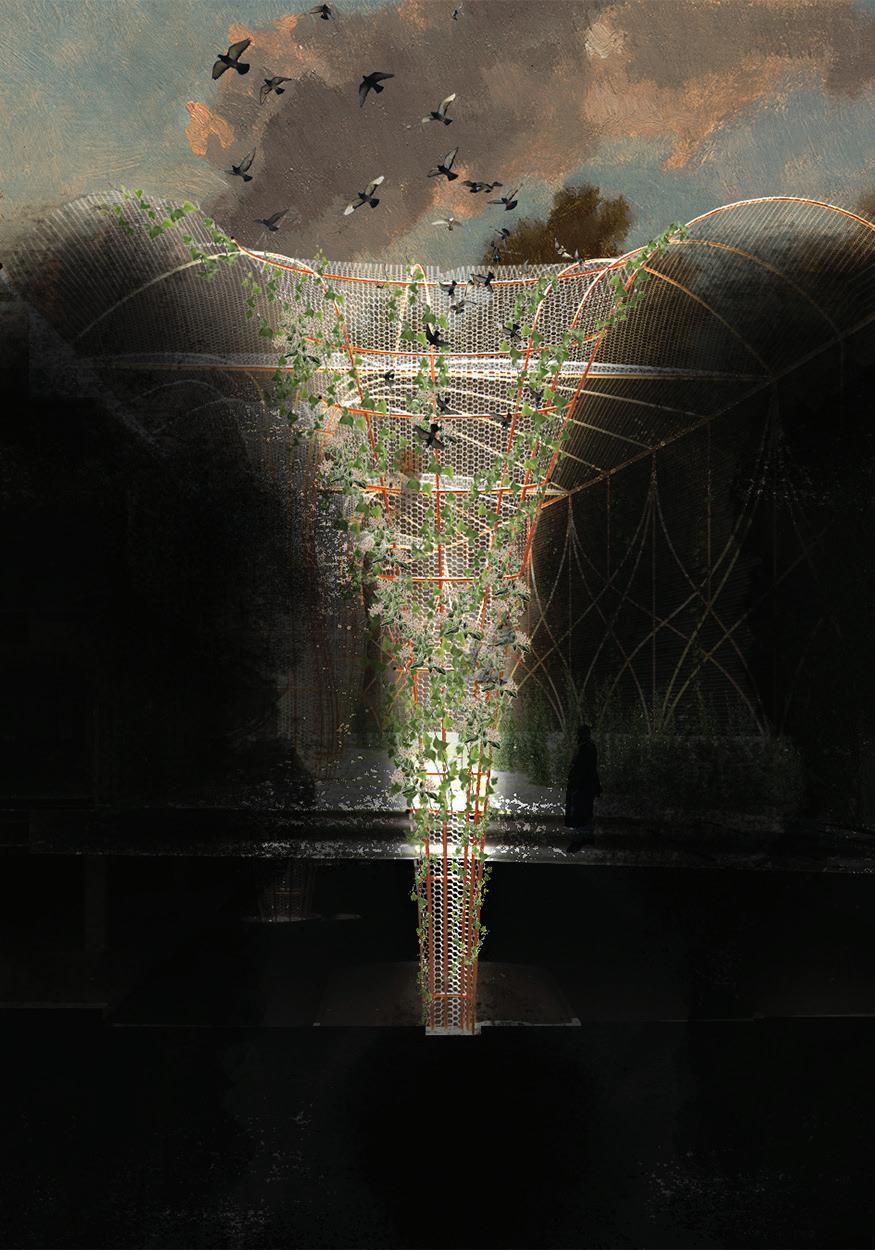

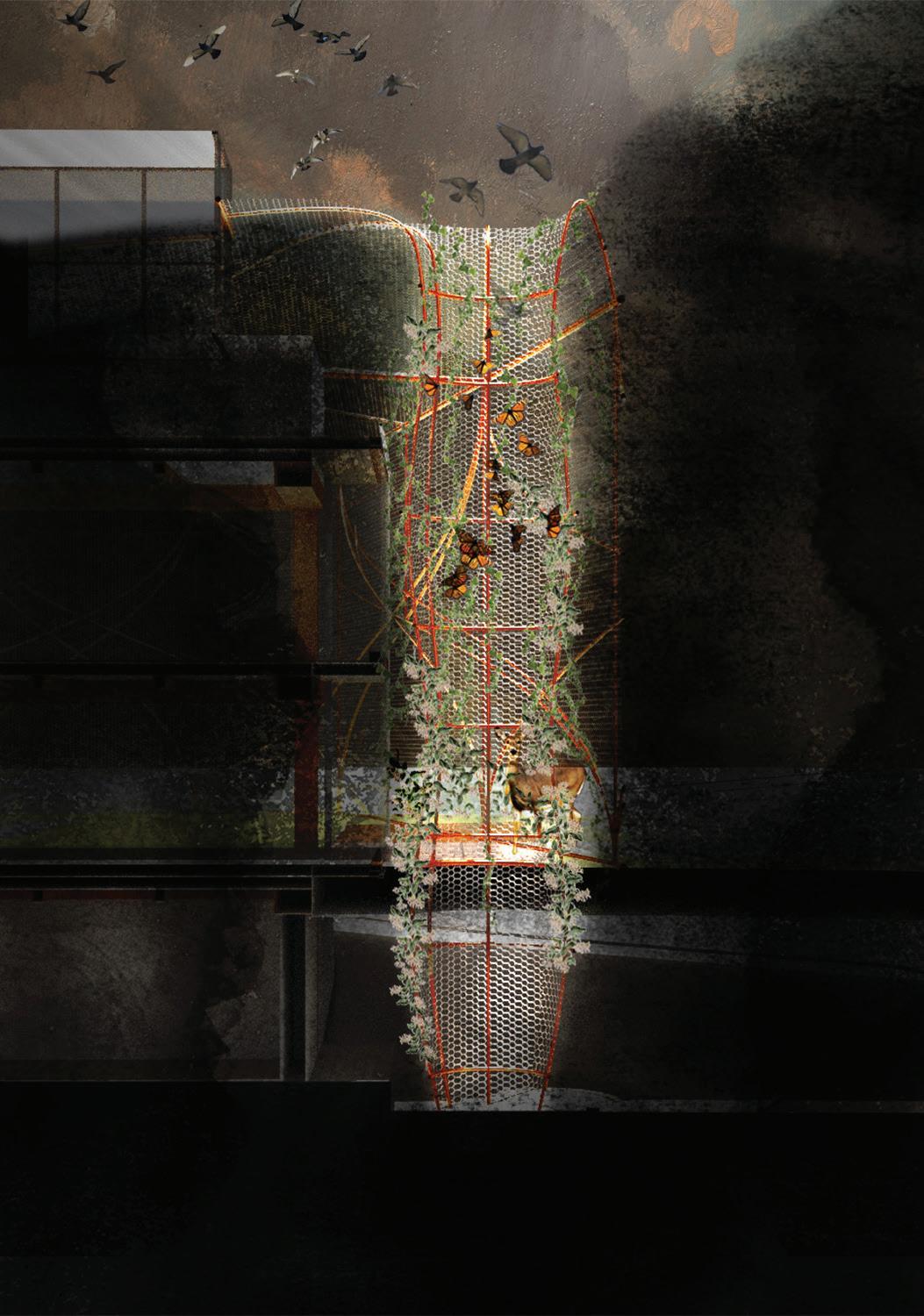

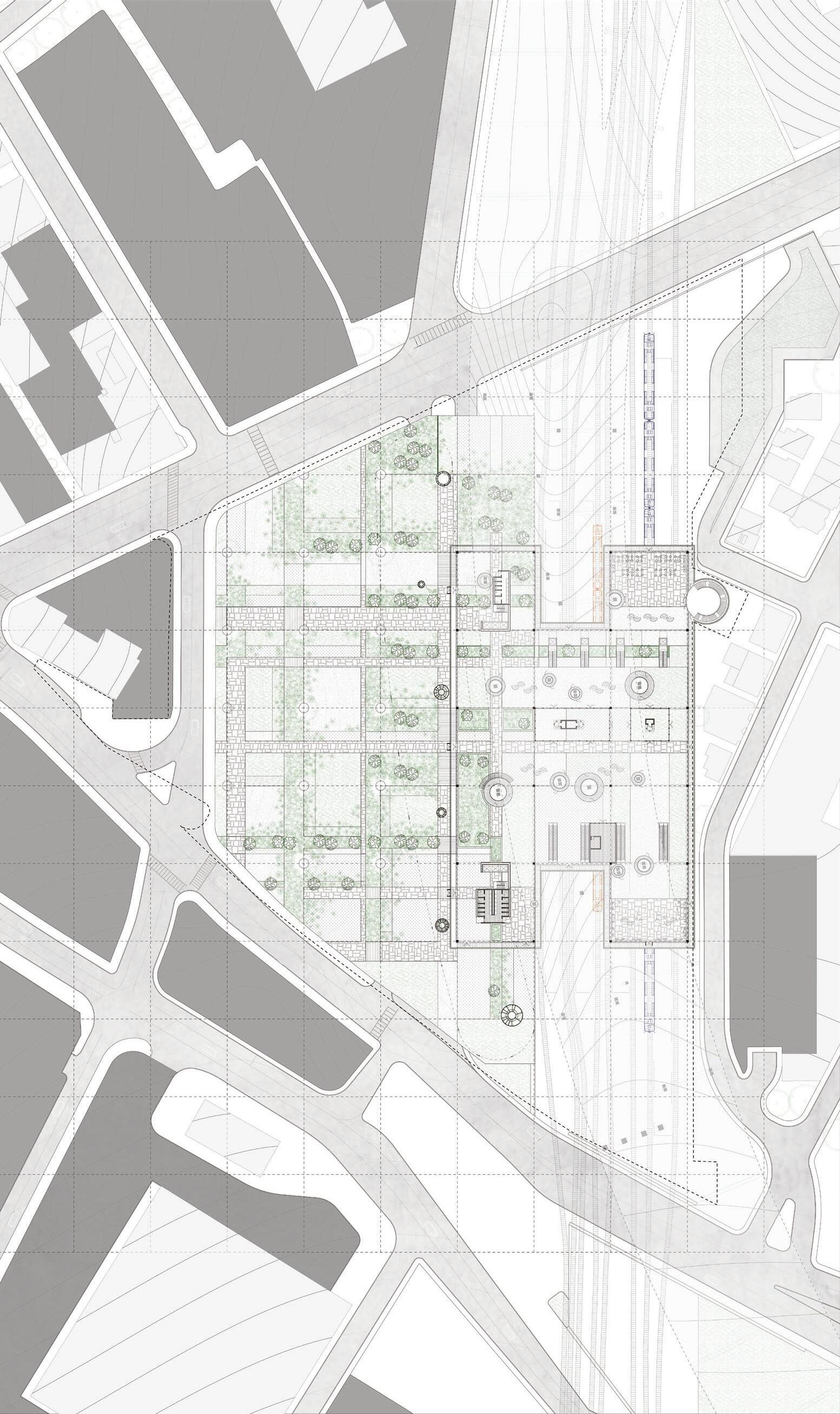

Situated at the nexus of humans, transportation, and the natural world, Sullivan Square in Charlestown is a laboratory for experimentation for a design paradigm focused on defining a new urban synthetic nature by challenging the notion of human dominance over space, advocating for harmonious co-occupation of both humans and nonhumans. Sullivan Square is a reimagined mobility hub and community activation center characterized by accessible, comfortable, and vibrant spaces, starkly contrasting to its current state. The proposed intervention involves curating systems that enforce an idealized ecological approach to landscape urbanism, constructing a layered facade system reminiscent of old botanical greenhouse structures, invoking a dialogue between species, and promoting coexistence.

Within this structure, visitors will encounter an immersive experience akin to stepping into a Victorian glass box, a microcosm presenting an unnatural synthetic habitat yet a captivating scene that compels engagement and encourages curiosity. As society shifts towards mass transportation, electric vehicles, and sustainable mobility, the project questions what the meaning of “nature” within the urban context has become. This vision includes extending human-powered mobility trails, reintroducing an extension of the OrangeLine Train, and adding a commuter rail stop to stimulate regional activity. This facilitates a stronger connection and increased accessibility on a local and regional scale. By integrating a synthetic ‘natural’ element into the urban fabric, the project invites reflection on the essence of nature and our evolving relationship with it in a rapidly changing world.

A multi-level mobility hub settles between exiting infrastructure, bridging previously disparate urban spaces, elevations, and opportunities for inter-species growth and transformation. The multi-layered and porous building envelope carefully calibrates habitats for animals and plants as well as human occupation.

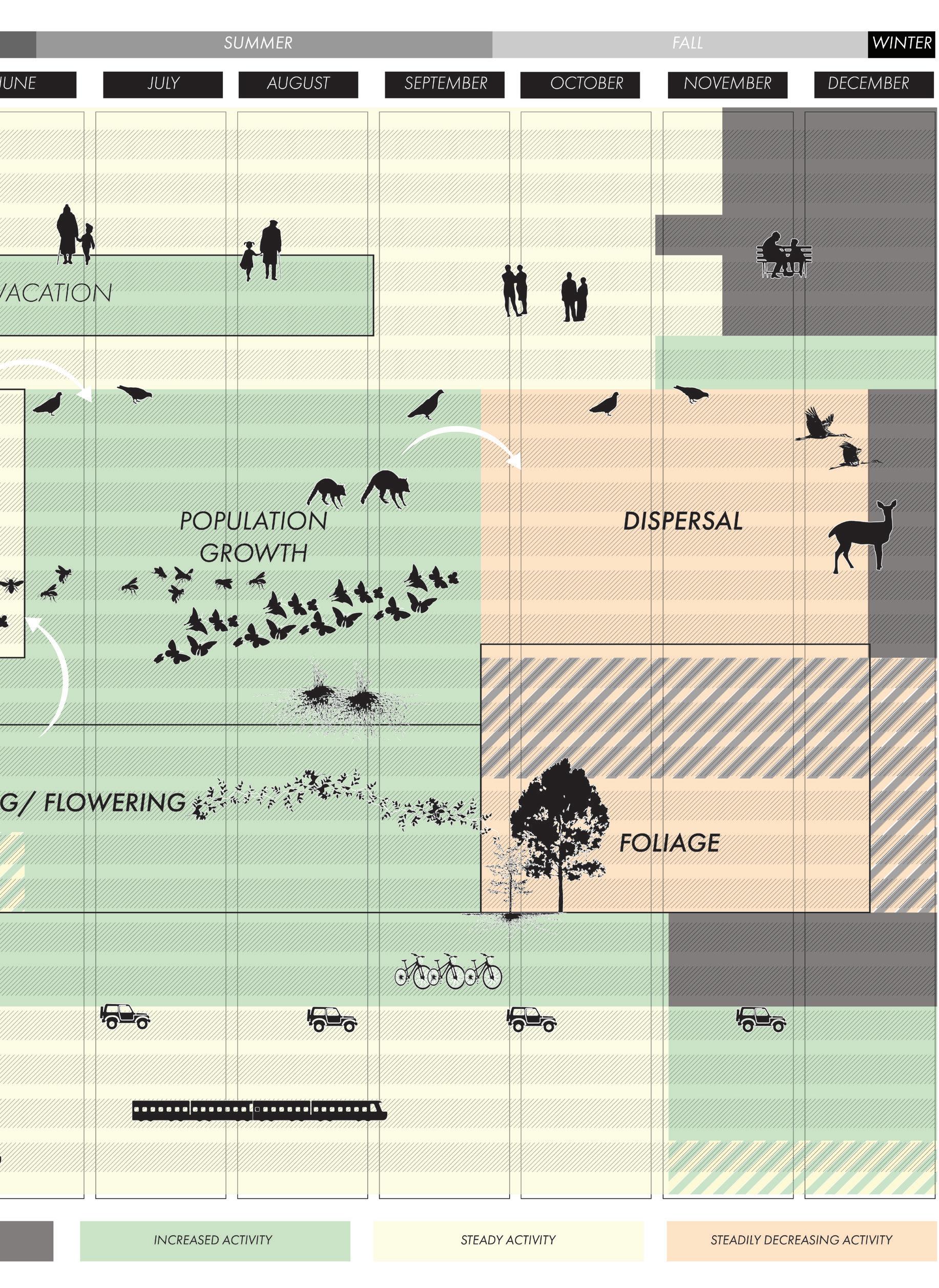

Many human and non-human actors, from birds to trains to commuters, occupy the site. Their interactions are carefully calibrated across season and time of day.

Global risks encompassing economic, environmental, geopolitical, social, and technological dimensions are increasingly impacting infrastructure and the built environment. It is imperative that our design and engineering practices evolve to develop innovative methods, tools, and solutions to address the complex urban challenges our industry faces. Beyond traditional concerns in urban design, architecture, and engineering disciplines, we must now consider additional objectives and underlying questions related to the climate crisis, energy, finance, regulation, and public will.

As the world’s trusted infrastructure consulting firm, we recognize both the urgency of these challenges and our responsibility to act in an impactful and enduring manner. This commitment is exemplified by our decadelong support and collaboration with Harvard Graduate School of Design, in leading the transition toward a more sustainable and equitable future.

Nancy Lin, AECOM Global Business Line Director of Operations, Buildings + Places

This year, the research and design of infrastructures of mobility provide a valuable opportunity for students to investigate the often-invisible systems interconnected with design and architecture. Concurrently, it challenges the role of architecture in the contemporary urban context. Through the Urban Glitch: Systems-Linked Architecture in a Contingent World, not only the projects but also how the studio was conducted fostered rigorous dialogue. Key issues relevant to the future of cities, including the creation of amenities and services, the integration of diverse communities, the facilitation of multiple mobility modes, the establishment of public spaces as social centers, the management of water, and the pursuit of decarbonization, were explored, debated, and tested in design.

It is a privilege to work continuously in partnership with Harvard Graduate School of Design to elevate the essential discourse on our urban environment. Furthermore, to prepare practitioners who will spearhead future transformations, leveraging digital tools to achieve better design and more efficient decision-making while understanding the trade-offs from economic, environmental, social, and political perspectives, is undoubtedly paramount.

Elizabeth Bowie Christoforetti

Elizabeth is Assistant Professor in Practice at the GSD and the founding principal of Supernormal, a design studio that focuses on architecture, urbanism, and design research. Elizabeth served as studio instructor for Urban Glitch, which she designed to explore the unmet challenges of architectural scale design as it confronts systems-level constraints, controls, and impact.

Sally Librera

Sally is a seasoned transportation professional at AECOM with experience in large-scale transit operations and infrastructure projects. Sally traveled to the GSD several times over the course of the studio and her expertise was invaluable to the students as they navigated the complex operational challenges of transportation design and related political and regulatory infrastructures.

Nancy Lin

Nancy Lin is a professional leader in the transformation of the built environment with over 25 years of experience in urban design, architecture, landscape design, construction administration, and project management. She currently serves as the Global Business Line Director of Operations for Buildings + Places at AECOM.

Tyler Coburn

Tyler is an artist and writer based in New York, known for his interdisciplinary practice that encompasses performance, installation, writing, and sound. His work critically engages with contemporary issues in computing, manufacturing, and urban design, exploring tensions between waged and leisure time, individual identity and the social media public, as well as the virtual world and its complex material infrastructures.

Carole Turley Voulgaris

Carole is an Asssociate Professor of Urban Planning at the GSD. Her research focuses on understanding the factors that influence individuals’ and households’ travel decisions within urban environments, and how transportation planning institutions utilize this information to inform plans, policies, and infrastructure designs. Carole’s deep knowledge of the factors driving transportation behavior was key to the success of the counterfactual game and the studio as a whole.

Siqi Zhu

Siqi is an urban planner, technologist, and strategic designer based in New York City. He serves as the Director of Urban Technologies & Planning and an Associate Principal at Sasaki, where he leads the firm’s planning and urban design practice in the city. His work focuses on integrating technology into urban design to create responsive and resilient solutions for urban development challenges.

Urban Glitch: Systems-linked architecture in a contingent world Instructors

Elizabeth Bowie Christoforetti Report Design

Rita Rui Ting Wang Report Editor

Rita Rui Ting Wang

Dean and Josep Lluís Sert Professor of Architecture

Sarah Whiting Chair of the Department of Architecture Grace La

Copyright © 2024 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without prior written permission from the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Text and images © 2024 by their authors.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to AECOM for the support, dialogue, and expert feedback from inception to completion. The collaboration was invaluable and we are grateful.

The editors have attempted to acknowledge all sources of images used and apologize for any errors or omissions.

Harvard University Graduate School of Design 48 Quincy Street Cambridge, MA 02138

gsd.harvard.edu

Studio Report

Fall or Spring Year

Harvard GSD Department of Architecture

Students

Nehemiah Ashford-Carroll, Gina Bernotsky, Chandler

Caserta, Yixin Du, Connor Gravelle, Aria Hill, Inmo Kang, Ally

Lammert, Rita Rui Ting Wang, Hannah Wong, Lanson Xie