Timothy Love

Timothy Love

For one of the assignments of Design for Real Estate, students were asked to organize themselves into groups of three or four and propose a topic they would like to research at the intersection of real estate development and design. The open-ended nature of the assignment gave students agency to suggest relevant topics and themes, important for a class that is being developed and refined within the larger context of the now two-year old Master in Real Estate program.

As much as feasible, students with different disciplinary backgrounds, which included finance, planning and design, were encouraged to work together so they could bring their individual perspectives to their chosen topic. The compendium of essays that resulted provides a fascinating snapshot of the preoccupations of students who are, in many cases for the first time, learning about the many ways that financing strategies, regulations, and design considerations intersect to shape individual projects and the contemporary city.

Studio Instructor

Timothy Love

Teaching Associate Elly(Zelin) Li

Zeyad Almajed, Katerina Apostolopoulou, Brittany Arceneaux, Esteban Bolanos, Meredith Busch, Juan Sebastian Castaneda, Ming Hong Choi, Simon Colloredo-Mansfeld, Gordon Cooke, Edwina Dai, Maurice El Helou, Ariel Estwick, Cindy Fang, Jason Fong, Jesumiseun Gbotosho, Abby Glass, Antione Gray, Ryan Han, John Heaster, Joanna Ho, David Hogan, Jake Jones, Robert Kang, Nikhil Kapoor, Terry Kipp, Connor Kramer, Shanice Lam, Mitchell Lazerus, So Jung Lee, Elly Li (TA), Harry Liner, Nathan Lowrey, Lily Ma, Sania Mulk, Raymond Narbi, Victor Ohene, Navya Raju, Sulaya Ranjit, Gerry Reyes Varela, Tal Richtman, Xander Ryman, Tatiana Schlesinger, Mohammad Shwiqi, Ryan Snow, Daisy Son, Amy Tomasso, Dylan Walker, Zihao Wang, Francis Wu, Hanxiao Wu, Ronny Xiong, Hongxin Yang, Emily Yuan, Rui Zhang

If the readers are more interested in a particular project, they can reach out to the instructor for more information.

2 Design for Real Estate Course Description

11 Developer/Architect Collaborations: Different Business Models

Gerardo Reyes Varela, Tatiana Schlesinger, Esteban Bolanos

19 AI on Design for Real Estate

Shanice Lam, Jake Jones, Terry Kipp

32 Big Tech Real Estate: Locational Decision and Design Expression

Sania Mulk, Nikhil Kapoor, Navya Raju

51 Building Cities for All: WinWin Development through Negotiated Entitlements

Katerina Apostolopoulou, Lily Ma, Mohammad Shwiqi

69 The Overbuilt Life Science Sector in Boston

Zeyad Almajed, Robert Kang, Francis Wu

II. Housing

81 Supertall Residential Towers

Dylan Walker, Tal Richtman, Connor Kramer

94 Assessing the Impact of Changing Demographics on Housing Design

Ariel M. Estwick, Antione Gray, Jesumiseun Gbotosho

105 Missing Middle Housing

Brittany Arcenaux, Amy Tomasso, Abby Glass, Raymond Narbi, Ryan Snow

123 Mixed-Income Housing

Ace Kang, Daisy Son, Victor Ohene, Meredith Busch

135 Building Adaptive Reuse as Housing

Rui Zhang, Ryan Han, Sulaya Ranji

III. Building Retrofits and Reuse

151 Beyond Traditional Hospitality

Edwina(Feiyang) Dai, Elly(Zelin) Li, Joanna(Wingsze) Ho

160 So You Want to Develop a Brutalist Icon?

Mitchell Lazerus, Cindy Fang, Emily Yuan

173

Adaptive Reuse and the Future of Hospitality

Hanxiao Wu, Hongxin Yang, Zihao Wang

IV. Cost / Value Considerations

187 LEED, Passive House, and WELL

Simon Colloredo-Mansfeld, Jason Fong, Nathan Lowrey

196

207

Impact of Rising Construction Costs on Design

Ming Hong Choi, John Heaster, David Hogan

Pre-manufactured Building Components

Juan Sebastian Castaneda, Harry Liner, Ronny Xiong

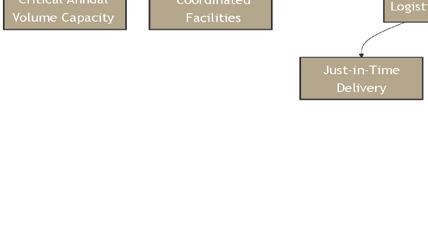

219 The IV-C Opportunities

Maurice el Helou, Gordon Cooke, Xander Ryman

234 Contributors

Architecture is one of the most difficult businesses to understand. While income is very variable and dependent on manpower, expenses are fixed and sometimes eat up most of the profits. Additionally, most of the times income depends on a third party (client) who must pay invoices for the work already delivered and many times the payments won’t come on time to pay for expenses. This is why architects must be very careful in the way they charge for their services. In this section we will explore two of the main ways an architect can charge for his services and analyze the pros and cons of each one.

The first way an architect can charge for their services is fee for service. A fee for service model of business is a payment structure where an architect charges clients based on specific services provided. Depending on the type of architect and the type of work, the fee for service model has different arrangements:

1. Hourly Fees – This is the model where architects charge an hourly rate for their services and can be based on their experience, complexity of the project or region. This method is used for smaller projects or for design and architecture consultants.

2. Fixed Fees – In this model, the architect charges an amount of money for a project and does not charge regardless of time or iterations. This model is very risky because it doesn’t account for project iterations requested by the client/ developer. This arrangement should only be used when the scope of the job is defined at the start of the project.

3. Percentage of Construction Cost –In this model of business the architect charges a percentage of the construction cost of the project. Depending on the type of architect (star

architect, new firm, etc.) the fee ranges from 5% to 15%.

4. Retainer Fees- A retainer fee is an advance payment for the work an architect will do in a project. Retainers are used for services where an architect must be engaged for a long period of time. A retainer can also complement other types of arrangements as it will help maintain the payroll for the initial stages of the project which are normally the longest periods without pay.

5. Per- Project/ Stage Fees – In this model, the architect charges separate fees for each project stage (explained in detail in the next session). This method allows for clarity on payment milestones and helps control costs through the project.

When charging for fees, the architect must understand the efforts required and the associated risks attached to the project. Profitability depends entirely on the type of project an architect is working on and how many hours the project is going to require. To understand the risk, architects must know which stage of design they are working on. According to the American Institute of Architects, there are 5 stages of design. For this article we are going to focus on the following 4:

1. Schematic Design (SD) – The goal of the architect in the SD phase of the process is to develop initial concepts and explore different design directions. In this stage architects use sketches, diagrams, and models to explore different layouts and produce conceptual floor plans, elevations and sketches that reflect the overall project direction.

2. Design Development (DD) – Here the architect redefines the conceptual designs created in SD and develops greater detail. In DD the architect also explores different materials and finishes. In this phase collaboration with engineers and consultants is critical to analyze the feasibility of the project.

3. Construction Documentation (CD) – In this stage the goal of the architect is to prepare detailed construction drawings and specifications for construction. The architect must have precise dimensions, material, specifications and construction methods as well as technical drawings for structure, and MEP.

4. Construction Administration (CA) –During the CA process, the goal of the architect is to ensure that the design is executed correctly by monitoring and reviewing the construction process.

Knowing the stages of design is quite important because based on these stages, the architect must define which type of fee to charge.

The second business model an architect can use to charge for services provides is the share of the profit model. Rather than receiving a fixed fee for services, the architect´s fee is tied to the financial success or profitability of the project. This model aligns the architect’s interest with the project’s success and incentivizes more efficient design. Key features of the share of the profit model include:

1. Profit based compensation- The architect is compensated based on the profit generated by the project. It can be negotiated in addition or instead of a fixed fee. The profit is typically calculated by subtracting the total cost of a project to its total revenues (or final sale value).

2. Incentive for efficiency and innovation – Since the architect’s compensation is linked to the profitability of the project, they have a vested interest in reducing costs, optimizing design efficiency, and increasing the overall value of the project.

3. Risk Sharing - The share of the profit model involves some degree of risk for the architect, as they only earn more if the project is profitable. If the project fails to make a profit or experiences significant cost overruns, the architect may earn less or nothing beyond their basic compensation.

The fee-for-service model is beneficial for clients who prefer clarity and flexibility in pricing, and it allows architects to control their workload. However, both parties must manage the potential risks of budget overruns, and administrative complexity. It is often best suited for smaller projects or when the scope of work is well defined.

The share of profit model in architecture offers opportunities for architects and firms to increase their earnings based on the success of a project. By aligning their financial interests with clients, contractors, or employees, architects can encourage higher performance, innovation, and collaboration. However, the model comes with potential risks and complexities, including financial uncertainty, administrative challenges, and the need for careful negotiation and clear contract terms.

Based on the AIA Firm Survey 2012, for instance, the overall fee for service averages 4% - 6% of a project’s total value. In a share of the profit model, the net value of these services for architects is well under 1% of total construction costs, putting them near the bottom of the pecking order of the building industry, at least economically. This compensation is at odds with the outsized role that architects typically play in the development of a building project. As a result, for many practitioners the profession is one of long hours with relatively low pay. This is why some architects have been migrating to another type of business model; the architect as developer.

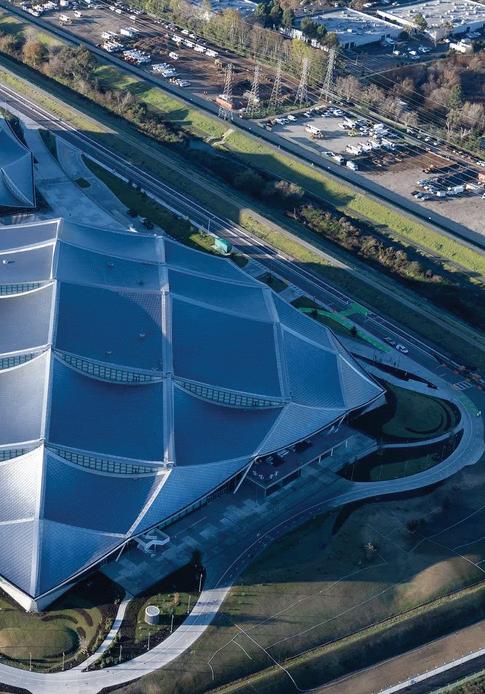

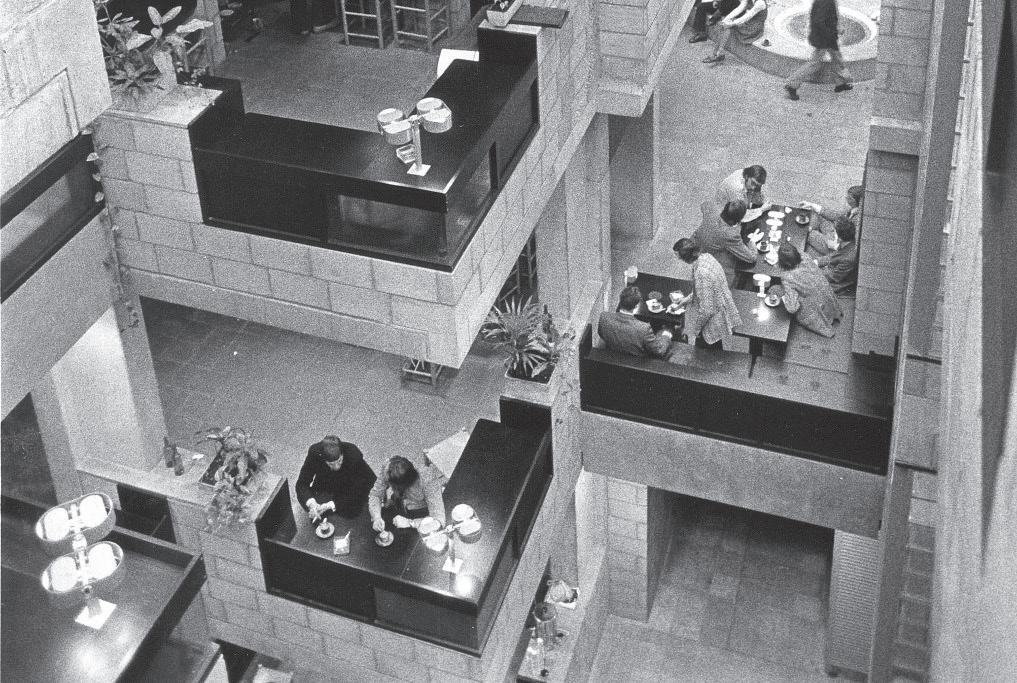

John Portman

The architect-developer approach was pioneered by John Portman since the mid20th century revolutionizing the real estate industry and redefining the architect’s role in the process. This hybrid model, which combines architectural design with real estate development, enables architects to take on greater leadership and control over projects, offering more creative freedom and allowing them to capture more of the value their designs generate. Portman’s innovative approach established him as a key figure in both architecture and real estate.

Early in his career, Portman faced significant challenges in making his mark as an architect. After struggling for three years running his own design firm, he became frustrated with the traditional “passive” process of architecture, where architects depended on their clients and had little influence over the final product. This frustration led him to take control of the entire development process, combining his architectural vision with a deep understanding of real estate. “If I came up with the idea, obtained the site, designed the facility, and held the financing, there would be no question about who would be the architect,” he reasoned, laying the groundwork for his transformative approach (Modern House Productions, 2018).

Portman’s model required him to master every aspect of the development process. He emphasized the importance of broadening an architect’s skill set to encompass feasibility studies, market analysis, and financing mechanisms. Reflecting on his journey, he said, “To accomplish this, I had to learn something about all the elements involved—what makes good real estate, how things are financed, and what makes a project feasible” (Modern House Productions, 2018). His dual role allowed him to make decisions that prioritized both architectural quality and economic viability. “The architect is trained to understand the art, the culture, and the essence of society and humanity far beyond the mundane task of just making money,” he argued, highlighting the unique perspective architects bring when given decision-making power (Modern House Productions, 2018).

Portman’s first successful development in 1956 marked the beginning of his influence on the field. By the time he published his book “The Architect as Developer” in 1976, the concept gained significant attention. His work

began to shape the way architects viewed their roles in the development process, encouraging others to explore it. His projects, such as the Peachtree Center in Atlanta, became symbols of urban renewal, demonstrating how architects could drive large-scale developments that were both innovative and financially successful. Portman viewed architecture as a profound societal contribution, asserting, “Architecture should have a purpose for human existence. If it doesn’t have a beneficial effect on human life, it shouldn’t exist at all” (Modern House Productions, 2018).

The success of the architect-developer model, as pioneered by Portman, has had enduring effects on the real estate industry. In recent decades, architects have increasingly taken on development roles, seeking greater creative control, financial rewards, and direct influence over their projects. Portman believed this approach allowed architects to produce better outcomes than traditional developers, stating, “An architect-developer places the architect in the proper role, one that can produce a better product for society because they understand all aspects of the process and make decisions beyond just monetary results.”

The book “Architect & Developer” by James Petty (2017) also makes a compelling case for architects to adopt a more proactive role in the development process, arguing that this shift can enhance both the built environment and professional outcomes. This shift offers architects the opportunity to directly influence the scope, budget, and success of projects, areas traditionally dominated by developers.

Petty (2017) emphasizes that developers, not architects, largely dictate what gets built in cities. Early decisions made by developers often set the parameters for a project, shaping its potential from the outset. By taking on both roles, architects can ensure their designs are implemented with more creative freedom and greater alignment with their vision. This hybrid model can result in higher-quality buildings and public spaces, as architects are more involved in every stage of the development process, from initial concept to final execution. And as mentioned, it also enables architects to capture more of the financial benefits, improving their profit margins (Petty, 2017).

However, as John Portman stated, transitioning into the developer role is not without its challenges. Architects must adopt an entrepreneurial mindset and be willing to take on the risks associated with development, especially in the early stages. Additionally,

they need to expand their skill set, acquiring knowledge in market analysis, financial modeling, and cost estimation to navigate the complexities of real estate development successfully (Petty, 2017).

In 2018, Jared Della Valle co-founder of Alloy LLC participated in an AIA conference on Architecture, where he discussed the architect-as-developer business model. Addressing a packed room of architecture and real estate developers, he shared his firm’s work and openly explained their decision to adopt this unconventional approach: a general discontent with their experience with traditional architectural practice and a desire for greater control over and compensation for the final outcome.

The foundation for Alloy began in Della Valle’s graduate school years, where he conceptualized the idea for an architect-led development company. His background in both architecture and construction management informed his desire to bridge the gap between design and construction, recognizing early on that developers often needed architects from the beginning of the process until the very end, but without offering architects much value for their time or contribution. This realization drove Della Valle to pursue development as a way to build his own projects and create more control over the design process. Unlike typical architecture practices, Alloy operates as a hybrid, where they purchase properties rather than search for clients, allowing them to focus on what they do best—solving problems and managing projects efficiently (AIA Conference on Architecture, 2018).

Alloy functions uniquely as a collection of six companies: a development firm, a design studio, a construction company, a brokerage firm, a management company, and a community development firm. This multi-faceted structure allows Alloy to approach real estate development differently than traditional firms, using integrated tools like a custom-built, map-based communication platform to streamline processes (AIA Conference on Architecture, 2018). The software helps track properties, zoning data, and news relevant to their projects, providing the firm with a comprehensive overview of their activities. Della Valle’s experience with his first project in 1998—an affordable housing project in New York—marked the beginning of Alloy’s journey into development. Since then, Alloy has expanded its reach, investing over $110 million

of its own capital and managing approximately $430 million in equity (AIA Conference on Architecture, 2018).

The company is built on the principle of taking significant risks, a critical difference between architects and developers. With projects that involve millions of dollars and multiple facets of real estate development, Alloy spends around $120,000 a month on legal fees and relies on various consultants to manage the complexity of its work. Della Valle and his team also oversee all aspects of development, from architecture to construction and brokerage, often wearing multiple hats at once (AIA Conference on Architecture, 2018). The firm now handles approximately 2 million square feet of development and over 1,100 units, managing its projects with the same team of architects that started the company.

Della Valle’s approach to Alloy has led to a robust, flexible office culture where each team member is expected to be a “swiss army knife,” contributing across different aspects of the business (AIA Conference on Architecture, 2018). Despite having only one person with formal real estate training, the team of architects handles all facets of the firm, from acquisitions to construction. The firm’s commitment to blending architecture with development has paid off in the form of meaningful project returns. By taking on significant risk and managing multiple roles, Alloy creates value not just through the physical buildings but through the process itself, ensuring a resilient hedge against market fluctuations (AIA Conference on Architecture, 2018).

In the end, Della Valle’s journey reflects a deeper belief in the architect-developer model. He emphasizes that the key to success in both architecture and development is the ability to control the process from start to finish. By handling everything in-house—from design and construction to brokerage and project management—Alloy has not only differentiated itself from typical firms but has also proven that architects can lead the way in the development world.

Real estate development firms approach their projects with distinct operational strategies, shaped by their goals, market focus, and scale. Some firms integrate architectural expertise directly into their operations by maintaining in-house teams, while others rely on external consultants, engaging them as needed. These approaches each have strengths and weaknesses that reflect the differences of development in different contexts.

This sub-title examines the pros and cons of both models through two case studies: Related Companies, a prominent real estate firm with an in-house architectural department, and WinnCompanies, a leader in affordable housing development, which relies exclusively on external architects.

Case Study: Related Companies is a powerhouse in the American real estate industry, known for transformative projects like Hudson Yards in New York City. The firm’s operational model includes an integrated architectural department, which plays a critical role in ensuring alignment between design, financial goals, and market needs.

The Benefits of the In-House Model Streamlined Collaboration: By embedding architects within the organization, Related facilitates seamless coordination between design, construction, and marketing teams. This integration was evident in the Hudson Yards project, where architects collaborated closely with external experts, including Diller Scofidio + Renfro, to create a project that balanced cuttingedge design with practical considerations (Architectural Digest, 2019).

Brand Consistency and Identity: Related’s in-house team helps establish a cohesive design language across its portfolio, which strengthens the company’s brand. This consistency has been especially impactful in its luxury residential and mixed-use developments, where tenants often seek properties that reflect a distinctive design ethos. As Related states on its website, “Our buildings continue to redefine sophisticated urban living, contributing to the economic viability and quality of life for our residents, tenants, and communities” (Related Companies, 2023). During a conference for Master of Real

Estate (MRE) students at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design, Kimberly Sherman Stamler, President of Related Beal, the Boston office of Related Companies, expressed her gratitude and enthusiasm for having an in-house architectural team. She emphasized that this vertically integrated model enables them to deliver the best possible product by combining the expertise of external architects with the in-depth knowledge their in-house architects possess about the company’s layouts, designs, and financial pro formas. She believes this approach is crucial for minimizing rework and change orders in projects, ultimately allowing them to deliver products that not only satisfy their customers but also make financial sense.

Long-Term Cost Efficiency: While maintaining an in-house team involves significant fixed costs, for a firm with Related’s scale and steady project pipeline, these costs are diluted across multiple developments. This efficiency becomes especially evident in projects like Hudson Yards, where the scale of operations justifies the investment in architectural staff.

Adaptability to Market Changes: An in-house team enables Related to respond quickly to changing market conditions. During the Hudson Yards project, design adjustments were made efficiently to accommodate evolving tenant needs and regulatory requirements.

The Drawbacks of the In-House Model

High Overhead Costs: The fixed costs of maintaining a salaried architectural team can be a burden during economic downturns, as evidenced during the recent slowdown in luxury markets. Firms like Related must carefully manage these costs to ensure profitability during periods of reduced activity.

Risk of Design Stagnation: Architects working exclusively within one firm may become overly aligned with internal priorities, potentially leading to repetitive or less innovative designs. Related mitigates this risk by partnering with external architects like Zaha Hadid and Rockwell Group, but smaller firms may not have the resources to adopt a similar approach.

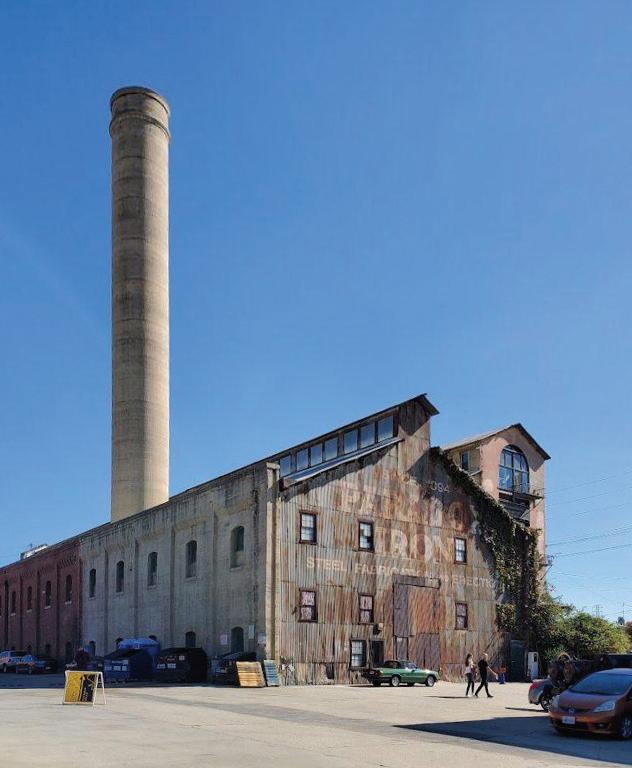

Case Study: WinnCompanies, based in Boston, represents a contrasting approach to development. Specializing in affordable housing and adaptive reuse projects, Winn operates without an in-house architectural team, relying

entirely on external consultants for design. This lean model aligns with its focus on operational flexibility and cost control.

The Benefits of the Lean Model Operational Flexibility: Winn’s reliance on external architects allows it to scale operations up or down based on demand. During periods of low activity, the firm avoids the financial strain of maintaining a salaried architectural team. “In-house architects, while valuable, represent a significant fixed cost, which becomes a liability during market downturns,” noted Larry Curtis, Winn’s President and Managing Partner (L. Curtis, personal communication, November 18, 2024)

Diverse Design Perspectives: By partnering with specialized architectural firms, Winn ensures that each project benefits from unique expertise. This approach has been particularly successful in adaptive reuse projects, where unique design solutions are often required to address site-specific challenges. Curtis attributes Winn’s success to the “diverse character and personality” that each project reflects (L. Curtis, personal communication, November 18, 2024).

Focus on Core Competencies: Winn prioritizes its strengths in project management, financing, and community engagement. By outsourcing design, the firm directs more resources toward these core areas, enhancing the overall impact of its projects.

The Drawbacks of the Lean Model Dependence on External Firms: Relying on external architects can lead to delays if the design team is unavailable or fails to align with the project’s goals. This dependency introduces inefficiencies, particularly in the early stages of development.

Higher Per-Project Costs: Although Winn minimizes fixed costs, outsourcing design services often results in higher expenses on a per-project basis, especially for large or complex developments.

Potential Vision Misalignment: External architects may not fully grasp Winn’s strategic objectives or community-focused mission, leading to designs that require additional revisions. This misalignment can slow the development process and increase costs.

The in-house model employed by Related is well-suited to firms with consistent project pipelines and high activity levels. During economic booms, this model maximizes efficiency and brand consistency. However, during downturns, the fixed costs associated with an architectural team can be challenging to sustain. In contrast, Winn’s lean model provides greater flexibility, allowing the firm to minimize costs during low-demand periods while scaling operations as needed.

Related’s in-house team fosters consistency and reinforces the company’s brand identity. However, this model risks creative stagnation without external input. Winn’s reliance on external architects allows for diverse and innovative designs but sacrifices the cohesive design language that an in-house team provides.

Related’s integrated model excels in efficiency, enabling faster design iterations and better alignment between departments. By comparison, Winn’s approach may face delays in the early stages of development, as external architects acclimate to the firm’s objectives.

The decision to maintain an in-house architectural team or adopt a lean model depends on a firm’s size, market focus, and operational strategy. Related Companies exemplifies how an in-house model can enhance brand identity, operational efficiency, and design quality, particularly for large-scale luxury developments. Meanwhile, WinnCompanies highlights the flexibility and cost-effectiveness of outsourcing, making it a compelling choice for firms in cost-sensitive markets.

Ultimately, the right approach depends on a firm’s ability to navigate macroeconomic cycles and align its operational decisions with long-term goals. Whether prioritizing in-house expertise or external collaborations, success lies in leveraging the strengths of each model to meet the challenges of a dynamic real estate market.

1 American Institute of Architects. (2024). 2024 AIA firm survey report: Infographic. American Institute of Architects. https:// www.aia.org/sites/default/files/2024-11/ AIA_2024_firm_survey_report_Infographic. pdf

2 American Institute of Architects Conference on Architecture (2018). AIA Conference on Architecture: Self-initiating your work at A’18 Jared Della Valle. YouTube. Retrieved November 14, 2024, from https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=XBeHmYS6H2g

3 Architectural Digest. (2019, March 5). Hudson Yards: A case study in urban design. Retrieved from https://www. architecturaldigest.com/story/hudsonyards-nyc

4 Modern House Productions. (2018). Architect as developer: A viable business model. YouTube. Retrieved November 27, 2024, from https://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=ZR4XUT3RIOk

5 Related Companies. (2023). Our commitment to architecture and design. Retrieved from https://www.related.com

6 Richards B. David, FAIA. (n.d.). Setting fees: What to consider. American Institute of Architects. https://www.aia.org/resourcecenter/setting-fees-what-consider

7 Richards B. David, FAIA. (n.d.). Charging for services. American Institute of Architects. https://www.aia.org/resource-center/ charging-services

8 Petty, J. (2017). Architect & developer: A guide to self-initiating projects. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform.

It is important to recognize the broad landscape of AI use for design processes. Softwares are observational and analytical, while others also provide generative, futurelooking scenarios. We have identified 8 areas of impact of AI on design and real estate: early stage planning, building documentation, drawing optimization, compliance checking, building energy management, parametric design, paperwork automation, and risk identification.1

visualization software. Next, we discuss those implications and influence on the landscape of employment within design and real estate and stakeholder engagement. Then, we examine some of the challenges of AI implementation in the fields of architecture and real estate. Lastly, we discuss the role of big data and predictive analytics in shaping urban spaces, and offer our perspective on the future outlook of AI advancements in real estate design.

AI design programs, like Delve, seek to optimize the highest and best use of a site based on predetermined parameters. At Delve, the most efficient forms of massing are generated and evaluated using criteria such as space utilization, structural feasibility, energy efficiency, solar exposure, and views. Furthermore, the platform translates these massing results into financial performance metrics, creating a standard pro forma excel sheet that includes key indicators like Net Operating Income and Cash Flow to Equity Investors. This combination of form generation and financial analysis gives AI the potential to streamline early design and investment decisionmaking processes.

In this thought piece, we specifically examine AI that aids in the architectural design and real estate conversations, software that generates initial design concepts and transforms early-stage architectural planning. We first explain AI-driven optimization, then provide an overview of existing

1 itransition. Artificial intelligence in architecture: 10 use cases and top technologies. 2023. https://www.itransition. com/ai/architecture

The massing designs produced by Delve are primarily biased toward market-driven building typologies, as these are the most desirable forms for public and private sectors alike. The responsibility falls on the designers to ensure that the AI is fed the appropriate typologies and relevant building codes, making it possible for the program to generate contextually accurate and code-compliant forms. Since building codes and market-driven priorities are always evolving, it is the role of the architectural team, not the software, to advise necessary updates, demonstrating the ongoing importance of human oversight in the AI-driven design process.2

2 TestFit. “Prologis Invests in TestFit, Deploys AI

Despite its promising capabilities, AI in design and real estate still faces limitations. For instance, while Delve can generate a pro forma from its massing recommendations, but the reverse process where a financial pro forma serves as an input that informs the design does not yet exist. Similarly, while the software can produce iterations based on specific parameters, it cannot yet translate a designer’s perspective drawing, axonometric, or traditional plans and sections into a viable massing model with financial projections.

These gaps illustrate that while AI technology offers significant opportunities, it remains reliant on the continual input and expertise of designers. AI may suggest a framework for design and financial success, but its full potential is yet to be realized, as it requires further advancements to support a more reciprocal relationship between design intent and optimization.

AI cannot explain its own results or the reasoning behind its decisions, leaving the interpretation and understanding up to the reader. This underscores the continuing importance of designers and real estate professionals. While AI can generate designs, it cannot communicate the underlying rationale. While it can assess options, it cannot critique them. While it can propose scenarios, it cannot negotiate the nuances of those outcomes. Therefore, the present and future roles of the built environment thinkers are to aid in decision making and to offer critical evaluations that AI alone cannot provide. 3

The rise of AI in architecture and real estate does not eliminate the need for fundamental knowledge in these fields. Although technology can automate tasks like zoning research or pro forma creation, professionals still need to learn the underlying principles that enable effective decision-making. For instance, architects will still be required to understand zoning laws and regulations, even if AI can provide this information instantly. Similarly, while AI may optimize solar orientation and maximize views, designers must understand the principles behind these strategies to make informed adjustments or to evaluate the AI’s suggestions. It is in fact the learning of these “basic” processes that enables one to be able to use these AI platforms

Software.” 2023. https://www.testfit.io/news/prologisinvests-in-testfit-deploys-ai-software.

3 Jinhua Zhao, Lecture at MIT on AI’s Influence in Mobility and Urban Planning, November 2024

effectively to begin with.

In real estate, the ability to construct and analyze a pro forma will remain crucial, despite AI’s ability to generate a complete financial analysis at the push of a button. Without an understanding of how schematic design and financial modeling work, professionals would be unable to recognize whether an AI-generated solution truly meets the goals of a project or aligns with broader market, regulatory, or community considerations.

Ultimately, AI should be seen as a tool that supports professionals rather than replaces them. It offers efficiency and computational power, but the human elements of critical thinking, negotiation, interpretation, and communicating with other humans remains irreplaceable.

Adoption of AI in the real estate industry has been very nuanced. A Deloitte study indicated that over 70% of real estate companies were planning to adopt some form of artificial intelligence in their business. That being said the report indicates that the primary application of this artificial intelligence is market research and forecasting.4 Other areas of focus in the industry are more repetitive tasks such as due diligence, lease analysis, and document preparation. Design specifically has had several entrants into the space and is in the early innings of adoption and real impact. One of the primary incumbents in the space, TestFit AI, asserts that 50% of the top 10 multifamily developers are working with TestFit. To what extent, the article is unclear, but what is clear is that this concept is intriguing enough to command significant attention. So much so that the world leader in industrial real estate, Prologis, made an investment into TestFit.5

AI and automation has typically been thought to be best with companies that have a high amount of uniformity or repetition. For example, assembly lines were an ideal target for technology like robotics automation since a simple task was completed over and over again.

4 Deloitte. “Real Estate Predictions 2021: From Location, Location, Location to Location, Insights, and Experience.” n.d. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/ global/Documents/Infrastructure%20&%20Capital%20 Projects/gx-real-estate-predictions-2021.pdf.

5 TestFit. “Prologis Invests in TestFit, Deploys AI Software.” 2023. https://www.testfit.io/news/prologisinvests-in-testfit-deploys-ai-software.

One of the challenges with AI design companies is that although these tasks are somewhat repetitive, the details of each task are anything but repetitive and require significant judgment. As TestFit AI CEO commented “Real estate development is innately bespoke. Every piece of land is unique, requiring every building to be a prototype.”5 In the early phases of development there are multiple inputs that are not cut and dry. For example, while current zoning may be easy to ascertain, the probability of a rezone is

of the progress in AI and real estate technology is likely hindered by the drastically different culture and strategy of these two industries. Like most technological advances there needs to be a business application to move the innovation forward. While there are clear applications, the execution has likely been challenged by lack of traditional developers buying into and engaging in the feedback loop of these new technologies.

highly dependent on past experiences with that municipality and other similar projects in other municipalities. This is one reason why real estate development is difficult to break into because of the high reliance on previous experience that can drive success.

Another barrier to implementation arises from the “old school” mentality of real estate development. In broad terms, real estate has historically been a very late adopter of new technology. Another Deoitte study in 2021 of real estate firms found that “most respondents admit their firms’ core technology infrastructures still rely on legacy systems.”4 Unless there is a clear value proposition real estate companies are unlikely to adopt new technology. The technology industry on the other hand has a strategy that is quite the opposite. Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg made famous the phrase “move fast and break things” when referring to the industry strategy.6 Some

6 Business Insider. “Mark Zuckerberg’s New Values for Meta Show He Still Hasn’t Truly Let Go of ‘Move Fast and Break Things.’” February 16, 2022. https://www.

TestFit AI was founded in 2015 in Dallas TX and has generated significant interest in recent years. Notably Prologis recently made a headline investment into the company. While the details aren’t fully released the company website states that TestFit AI raised a $20M series A round that was co-led by Prologis.7

The primary use of TestFit AI is for site design and building massing. The tool will auto generate building or site designs and rank them based on parameters fed into the software. This is meant to help architects, developers, and planners both save time and generate ideas that might not have been typically explored. The software’s click and drag functionality makes it extremely user friendly. It is also worth noting that TestFit has a Revit plugin to businessinsider.com/meta-mark-zuckerberg-new-valuesmove-fast-and-break-things-2022-2.

7 CoStar. “World’s Biggest Warehouse Developer Looks to Expand Beyond Commercial Real Estate.” 2023. Testfit.io. https://www.testfit.io/news/costar-worldsbiggest-warehouse-developer-looks-to-expand-beyondcommercial-real-estate.

better integrate with existing software that is an industry standard. According to the company website as of November 14, 2024 over 650 deals are evaluated on TestFit per week. TestFit does not currently charge for its technology, but there is anticipation that this will change in the future. With a solid foundation and significant investment it seems this software is poised to make meaningful progress in the space.

Delve was created by Google initially as part of Sidewalk Labs. Sidewalk Labs was created with the goal of creating a city in Toronto, Canada that could be a forward thinking city incorporating technology in new ways. Delve was initially included to assist in the planning and public engagement of the project. Although Sidewalk Labs was eventually dissolved, Delve continued on.

Delve has continued to progress its planning functionality with a site yield analysis but has added additional functionality. Two other options include a highest and best use analysis and a solar feasibility study. The highest and best use analysis includes considerations like parking, costs, rents, cap rates, and values. All 3 options include a wide variety of asset class options including retail, residential, community, office, education, hotel, and other. This can further be defined by a building type option. The residential building type options have 13 distinct building types including low density, medium density, and high density ranging all the way up to skyscrapers. Something unique about Delve is that it has a focus on helping the environment and has multiple features like solar feasibility and a carbon emission output.

Deepblocks is another company that aims to help with front end feasibility. It does have functionality to generate 3D models on sites similar to the previous technologies. It also has a feature to assist with site selection. Parcels are loaded into the system and the user is able to filter sites based on input criteria including lot size and zoning. The technology appears very user friendly.

The software also has market data included and the user can use this data to facilitate market analysis. This software comes with many applications, but does also come with a price. The current pricing for one city is $280 per month with other options that cater to a more nationwide or corporate client. It also appears the company is working on a more interactive experience where the user can input prompts similar to ChatGPT and the software will run the analysis requested for the user.

There are multiple companies that are

developing in this space of generative design, even more than are discussed here. It does seem to be very early but these companies have significant backing both financially and from a business perspective. As AI evolves these companies will also evolve but it is clear that this concept is gaining steam.

Visualization Tools and Their Role

Technology associated with the real estate industry is rapidly evolving. This has spurred visualization tools as key drivers that revolutionize how projects are conceptualized, communicated, and developed. Platforms such as Delve by Google are leading this transformation. Delve utilizes algorithms to create design options that account for multiple variables, such as: land use, density, sustainability, and financial feasibility. While these tools enable developers

and architects to visualize potential project outcomes more accurately, they also can bridge the gap that often exists between stakeholders. This can lead to better-informed decisionmaking during the design and planning process of the development.8

Given that significant advancement in visualization software has taken place, it’s now possible to develop realistic 3D models and simulations that can be easily modified and linked to local city zoning. Delve, for instance, uses machine learning to analyze thousands of design iterations and provides a data-backed approach to project planning.9 By utilizing these technologies, real estate professionals can visualize a range of design outcomes, compare the pros and cons of various scenarios, and choose the optimal solution for project goals and constraints. This is essential for large-scale urban development projects, where even minor design flaws can have a long-term impact on local communities.

These types of new technology can go beyond simple aesthetics. They enable a deep understanding of how design choices can impact overall project performance. The software can factor in environmental considerations, energy efficiency, and financial returns for projects. This revolutionary approach helps ensure that the final design aligns with the developer’s vision while also meeting crucial regulatory requirements and community needs. The ability to generate quick iterations instantaneously means that design decisions can be beta tested and optimized in real-time.10 Due to this, the software can save both time and critical resources during the planning phase of the project.

The development process involves a diverse set of stakeholders, and each have not their own priorities and concerns with the particulars of a project. Developers focus on financial feasibility, architects on the design and functionality, city officials and residents on the impact the development will have on the community. Visualization tools become a bridge that aligns varying interests by providing a common ground that can be seen, not just imagined. When all parties involved can ascertain a realistic portrayal of the project and understand how

8 Azure Magazine. “Inside 307, Sidewalk Toronto’s Experimental Hub.” Last modified June 19, 2018. Accessed November 9, 2024. https://www.azuremagazine.com/ article/sidewalk-labs-307/.

9 Ho, Brian. Interview by Jacob Jones, Terry Kipp, and Shanice Lam. November 6, 2024

10 MIT Technology Review. “Using Data, AI, and Cloud to Transform Real Estate.” Last modified October 16, 2023. Accessed November 9, 2024. https://www. technologyreview.com/2023/10/16/1081609/using-data-aiand-cloud-to-transform-real-estate/.

different design choices will impact outcomes, a sense of shared purpose and collaboration is fostered.11

Due to architectural knowledge barriers, it can be a challenge explaining complex architectural concepts to clients and stakeholders during the planning phase of the project. These tools can enhance communication between all parties and help get to a place of alignment on planning and design quicker than the traditional process. The use of AI-driven visualization tools helps to paint a clearer picture of what the completed development will look like.9 These tools also show how it will function, and how it will impact the surrounding environment. They impart realworld data into the design elements, such as sunlight patterns, traffic flow, and pedestrian movement. Developers and architects can anticipate potential issues and make informed adjustments before construction begins, which can minimize the risk of costly changes later in the development process by implementing this data-based approach. This ensures that the development is well-suited for the intended use. In the early stages of community engagement, visualization tools also garner better collaborative processes. By demonstrating a 3D model, project proposals can be better communicated and realigned with community goals that can become invaluable to fostering support for project approvals. When all parties can see and understand the design in the same way, it can lead to more productive discussions around community needs and project feasibility.

In conclusion, the role of visualization tools in real estate development cannot be overstated. These new technologies aid in creating appealing designs backed by data-driven decisions. They can align financial, sustainability, and community goals by improving communication across project stakeholders. Visualization software is setting a new standard by improving project conceptualization, efficiency and collaboration within the industry. As these tools continue to evolve, they will play an even more integral role in shaping the future landscape of real estate development.

Urban spaces are being transformed in how they are optimized and conceptualized by big data. They are using the implementation of predictive analytics in real estate development

11 Realeflow. “AI in Real Estate: Trends & Use Cases.” Accessed November 9, 2024. https://blog.realeflow.com/ artificial-intelligence-real-estate.

and design by leveraging massive datasets.11

On account of this, developers and architects can make more informed decisions that enhance economic performance of a project. Remarkably, these data sets can also aid to the overall livability and sustainability of the built environment. As cities continue to expand, they face complex challenges. The role of data in molding design choices is becoming increasingly important. Big data intends to tackle issues such as climate change, population density, and vital resource management.12

Big data has been proficient in offering unprecedented insights into the real estate industry. By revolutionizing analytics, insights into market trends, consumer behavior, and environmental impacts, they have completely transformed how data is digested.10 Today, predictive models can help developers forecast how a development will perform under various conditions and scenarios. To better understand what should be built and how spaces can be best used to serve the community, these models analyze vast amounts of data from sources like social media, real estate listings, transportation networks, and environmental sensors.13

Predictive analytics can help identify patterns in demographic shifts, helping developers anticipate demand for different property types and adjust their projects accordingly.12 These models can also forecast trends that influence property values by evaluating economic trends. Predictive analytics consider job growth or shifts in the local housing market.10 This transformation in data allows developers to design their projects in a way that not only maximizes returns, but also hints where they should invest.

Data-driven urban planning can help address issues of resource management and sustainability. Analytics can be used to: design energy-efficient buildings, optimize waste management systems, and ensure adequate public infrastructure. Predictive models can even help developers evaluate how different building

12 McKinsey & Company. “The Potential in Real Estate Analytics.” Accessed November 9, 2024. https://www. mckinsey.com/industries/real-estate/our-insights/gettingahead-of-the-market-how-big-data-is-transforming-realestate.

13 Asper Brothers. “AI for the Real Estate Industry: Best Artificial Intelligence Tools and Trends.” Accessed November 9, 2024. https://asperbrothers.com/blog/ai-forreal-estate/

spread: Graphic by Shanice Lam

materials will affect energy consumption over time.11 This allows them to choose options that reduce environmental impact and operating costs. As cities become shrewder and more connected, the prominence of data in urban design will only continue to expand. Big data will propose resolutions that are both economically viable and environmentally sustainable.12

One of the most enlivening developments of data-driven design is the capability to incorporate various types of data and implement them in a unified approach.10 This integration allows for better understanding of the factors that influence urban development. Demographic data can reveal insights into population density, age distribution, and cultural preferences.11 Understanding these key metrics enables developers to create spaces that better meet the needs of specific communities. Whether it’s housing for young professionals, better suited amenities for families, or accessibility features for elderly residents, being able to visualize the data makes for more suitable communities.13

Economic data is also crucial, revealing patterns in household income, employment rates, consumer spending, and job creation. This information helps developers determine the best use for a site and predict its financial success. As climate change becomes a growing concern, environmental data plays a critical role in sustainable design.10 Developers need to consider factors like air quality, temperature, and water resources. Analyzing this data allows for informed decisions that reduce environmental impact and enhance project durability. For example, buildings can be oriented to optimize natural light, cutting down on energy consumption. This data-informed approach to sustainability is becoming the norm in modern real estate projects.13

In conclusion, the impact of big data and predictive analytics is set to expand as more datasets become available and are integrated into the design and planning process. These technologies provide essential insights into market behavior, resource allocation, and economic needs, ultimately shaping urban spaces that are well-prepared for the future.

Rapid advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and budding technologies are mapping out the future of real estate development and design. Through offering fresh breakthroughs

Shanice Lam, Jake Jones, Terry Kipp

in areas of efficiency, sustainability, and community engagement, these innovations are poised to disrupt traditional industry models. Real estate professionals must adapt to these new methodologies that are refining industry standards. As AI continues to expand its capabilities, it sets the stage for more data-driven, integrated, and forward-thinking approaches within the real estate community.14

In ways that were previously unimaginable, artificial intelligence technology is estimated to revolutionize the real estate industry, Most notably in the areas of design, development, and city planning. AI systems will be able to interpret streams of data from connected devices and sensors located throughout the urban area. This will increasingly occur as smart city infrastructure becomes more widespread. Real-time analysis can unlock insights into everything from pedestrian movements to energy consumption. For example, AI could automatically adjust building temperature settings based on real-time weather data or alter traffic patterns to ease congestion in highdensity areas.13

AI advancements are also likely to enhance predictive modeling for the built environment. AI helps developers by analyzing past trends and forecasting future market shifts. This capability allows for a proactive approach instead of reactive regarding demographic and environmental challenges. Enabling developers to future-proof their project and adapt to changing conditions. As these technologies mature, they will become indispensable tools for developers who aim to create sustainability in high-performing urban spaces.15

Due to the complexity of AI technology, many of these solutions are siloed and require multiple platform subscriptions to utilize the technology. In the future, there will be a likely consolidation where AI companies acquire other platforms to streamline the integration and use of data to provide a more well-rounded product that can better cater to developers and architects. This will allow for the more rigorous financial AI products to merge with data-backed design products to help create a more robust platform that synthesizes information in a

14 Applied Sciences. “Blockchain’s Grand Promise for the Real Estate Sector: A Comprehensive Review.” 12, no. 23 (2022): 11940. Accessed November 9, 2024. https://www. mdpi.com/2076-3417/12/23/11940.

15 McKinsey & Company. “The Power of Generative AI in Real Estate.” Accessed November 9, 2024. https:// www.mckinsey.com/industries/real-estate/our-insights/ generative-ai-can-change-real-estate-but-the-industrymust-change-to-reap-the-benefits.

uniform way and creates an easier platform for designers and developers to use.16

Beyond the developments of AI, another disruptive technology is augmented reality (AR), which can radically transform how properties are marketed and experienced by end consumers. AR will allow potential buyers or tenants to visualize a space fully furnished or how design elements would look in real-time. This technology will also aid in construction and development, which will allow architects and developers to overlay digital models onto physical spaces to ensure accuracy and identify potential issues before finalizing the design.17

In addition to new technologies shaking up the real estate world, one must include the Internet of Things (IOT). Specifically in construction and property management there are several ways this new technology is proving helpful. For instance, IoT enabled buildings will provide developers and property managers with data on energy use, occupancy levels, and equipment performance. Not only does this improve overall tenant satisfaction, but this information can be used to optimize building operations and reduce maintenance costs. One example of the utilization of the IoT is that their sensors can detect when a piece of equipment needs servicing. This enables predictive maintenance that prevents breakdowns and extends the lifespan of building systems. These technologies may integrate AI to track and measure user experiences and make for more efficiency planning during the design process.15

AI and related technologies are not just tools for improving efficiency; they are drivers for redefining industry standards within the built environment. Sustainable design is a major area for this transformation as building designs become more optimized for energy efficiency, reduce waste during construction, and may even suggest different building materials that will have a lower environmental impact.13

While the AI era is setting new standards, it is raising concerns in areas of ethics, equity, and access. For example, how do AI-driven developments take into account a prospective community that will benefit all members and

16 RealInsight. “Data-Driven Decision Making in Commercial Real Estate: RealInsight’s Role in Shaping the Future.” Accessed November 9, 2024. https://www. realinsight.com/blog/data-driven-decision-making-incommercial-real-estate-realinsights-role-in-shaping-thefuture/.

17 International Journal of Novel Research and Development. “Augmented Reality in Real Estate: Enhancing Property Exploration and Client Engagement.” 9, no. 5 (2024): 917–920. Accessed November 9, 2024. https://www.ijnrd.org/papers/IJNRD2405592.pdf.

not just the affluent? How can we safeguard against biases within the AI algorithms that may promote social inequalities? Addressing these questions will be critical as the industry continues to embrace and implement these new technologies.10

In conclusion, the future of the built environment is being shaped by advancements in AI and other emerging technologies. By embracing these changes and redefining industry standards, real estate professionals can develop spaces that are not only feasible but also have a more significant impact on local communities and the environment.15

AI & Design Optimization

1 itransition. Artificial intelligence in architecture: 10 use cases and top technologies. 2023. https://www.itransition. com/ai/architecture

2 Ho, Brian. Interview by Jacob Jones, Terry Kipp, and Shanice Lam. November 6, 2024

3 Jinhua Zhao, Lecture at MIT on AI’s Influence in Mobility and Urban Planning, November 2024

Real Esate in Practice

4 Deloitte. Real Estate Predictions 2021. 2021. https://www2.deloitte.com/content/ dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/ Infrastructure%20&%20Capital%20 Projects/gx-real-estate-predictions-2021. pdf.

5 TestFit. “Prologis Invests in TestFit, Deploys AI Software.” 2023. https://www.testfit.io/ news/prologis-invests-in-testfit-deploys-aisoftware.

6 Business Insider. “Mark Zuckerberg’s New Values for Meta Show He Still Hasn’t Truly Let Go of ‘Move Fast and Break Things.’” February 16, 2022. https://www.businessinsider.com/ meta-mark-zuckerberg-new-values-movefast-and-break-things-2022-2.

7 CoStar. “World’s Biggest Warehouse Developer Looks to Expand Beyond Commercial Real Estate.” 2023. Testfit.io. https://www.testfit.io/news/costar-worldsbiggest-warehouse-developer-looks-toexpand-beyond-commercial-real-estate.

8 Azure Magazine. “Inside 307, Sidewalk Toronto’s Experimental Hub.” Last modified June 19, 2018. Accessed November 9, 2024. https://www.azuremagazine.com/article/ sidewalk-labs-307/.

9 Ho, Brian. Interview by Jacob Jones, Terry Kipp, and Shanice Lam. November 6, 2024

10 MIT Technology Review. “Using Data, AI, and Cloud to Transform Real Estate.” Last modified October 16, 2023. Accessed November 9, 2024. https://www.technologyreview. com/2023/10/16/1081609/using-data-aiand-cloud-to-transform-real-estate/.

11 Realeflow. “AI in Real Estate: Trends & Use Cases.” Accessed November 9, 2024. https:// blog.realeflow.com/artificial-intelligencereal-estate.

12 McKinsey & Company. “The Potential in Real Estate Analytics.” Accessed November 9, 2024. https://www.mckinsey.com/ industries/real-estate/our-insights/ getting-ahead-of-the-market-how-big-datais-transforming-real-estate.

13 Asper Brothers. “AI for the Real Estate Industry: Best Artificial Intelligence Tools and Trends.” Accessed November 9, 2024. https://asperbrothers.com/blog/ai-for-realestate/

14 Applied Sciences. “Blockchain’s Grand Promise for the Real Estate Sector: A Comprehensive Review.” 12, no. 23 (2022): 11940. Accessed November 9, 2024. https:// www.mdpi.com/2076-3417/12/23/11940.

15 McKinsey & Company. “The Power of Generative AI in Real Estate.” Accessed November 9, 2024. https://www.mckinsey. com/industries/real-estate/our-insights/ generative-ai-can-change-real-estate-butthe-industry-must-change-to-reap-thebenefits.

16 RealInsight. “Data-Driven Decision Making in Commercial Real Estate: RealInsight’s Role in Shaping the Future.” Accessed November 9, 2024. https://www.realinsight. com/blog/data-driven-decision-making-incommercial-real-estate-realinsights-role-inshaping-the-future/.

17 International Journal of Novel Research and Development. “Augmented Reality in Real Estate: Enhancing Property Exploration and Client Engagement.” 9, no. 5 (2024): 917–920. Accessed November 9, 2024. https:// www.ijnrd.org/papers/IJNRD2405592.pdf.

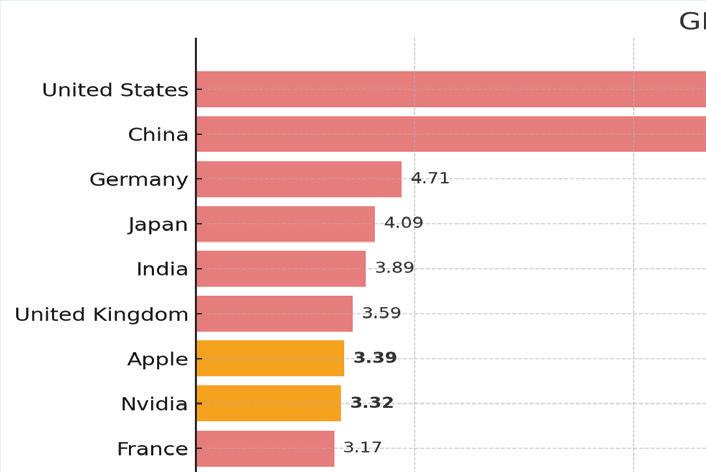

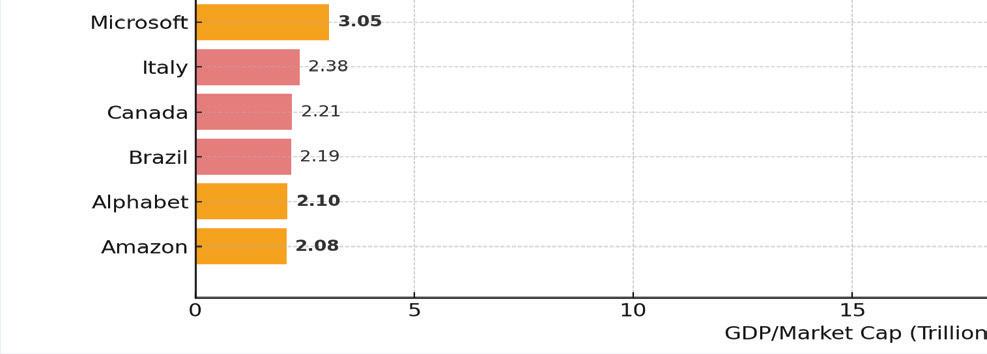

Big Tech companies—Amazon, Google, and Meta—are no longer just tech innovators; they are economic titans, weaving themselves into the very fabric of modern urban life. Their financial power is staggering, with market values that surpass the GDPs of entire nations. Consider Amazon: its market cap, towering at over $1.3 trillion, outstrips the economy of Mexico. Apple, meanwhile, is so vast that it eclipses the economic output of some continents.1 Yet these numbers tell only part of the story. Beneath the surface lies a quieter, equally transformative narrative—how these companies shape the places we live and work.

Over the past decade, Big Tech has fueled nearly a fifth of global leasing activity, but their influence stretches far beyond square footage.2 When Google purchased 111 Eighth Avenue in New York City for $1.8 billion in 2010, it wasn’t just a transaction—it was a declaration.3 This move anchored Google in the heart of Manhattan and signaled Chelsea’s transformation into a burgeoning tech hub. The purchase sent ripples through real estate markets, redefined the neighborhood’s character, and highlighted a broader truth: the tech industry has become a driving force behind urban evolution.

In San Jose, Google’s Downtown West project offers a vision of what these transformations can look like. The project promises to turn the city center into a dynamic, tech-driven urban core, complete with tens of thousands of jobs and a thoughtfully woven

1 Wallach. “The World’s Tech Giants, Compared to the Size of Economies.” Visual Capitalist, July 2021. https://www. visualcapitalist.com.

2 “Tech-30 2024 Measuring the Tech Industry’s Impact on U.S. & Canadian Office Markets.” CBRE Insights, November 2024. https://www.cbre.com.

3 Bagli, Charles V. “Google Buys Big Building in New York.” The New York Times, December 23, 2010. https://www. nytimes.com.

mix of residential and commercial spaces.4 Yet, the narrative here is not without tension. Projects like Downtown West embody a delicate balance—bringing prosperity to one group while stirring fears of displacement among another. Amazon’s HQ2 in Arlington, Virginia, tells a similar story but with sharper contrasts. Announced with much fanfare, the project redefined the city’s real estate landscape almost overnight.5 Property prices soared, development surged, and local governments reveled in the promise of economic growth. But as Arlington’s skyline grew, so did concerns about housing affordability and community displacement. These stories reveal the dual-edged impact of Big Tech’s real estate decisions. On one side, they offer cities a lifeline—a chance to thrive in a competitive global economy. On the other, they force communities to grapple with difficult questions: Who benefits from this growth? Who is left behind? These questions linger in the streets of Chelsea, the corridors of San Jose’s city hall, and the neighborhoods of Arlington.

Real estate decisions by Big Tech companies are anything but routine. These choices are blueprints for the future, influencing the flow of talent, the vitality of neighborhoods, and even the identity of entire cities. For these technology titans, selecting a location is not just about finding a physical space—it’s about crafting an ecosystem that aligns with their vision, values, and long-term strategies. These decisions are multifaceted, involving an intricate balance of economic considerations, workforce priorities, infrastructure needs, and community engagement. Each project, from Amazon’s HQ26 to Google’s Downtown West, tells a story

4 “Downtown West Development.” Real Estate with Google, November 2024. https://realestate.withgoogle.com.

5 Teo. “Amazon HQ2 and Its Impact on Arlington.” The Washington Post, 2024. https://www.washingtonpost. com.

6 “Amazon’s HQ2 Aimed to Show Tech Can Boost Cities.

of negotiation, ambition, and the ever-shifting dynamics between corporations and cities.

Key Location Decision Factors:

1. Economic Considerations:

At the core of every location decision lies the promise of economic transformation. For Big Tech, selecting a location is rarely just about square footage—it’s about unlocking opportunities that align with their long-term ambitions. Tax incentives, subsidies, and land costs often tip the scales in favor of one city over another, driving fierce competition among governments eager to attract these corporate powerhouses. Amazon’s HQ2 search exemplifies this phenomenon. Cities across the United States launched an unprecedented bidding war, each hoping to host the tech giant’s ambitious expansion. Ultimately, Virginia triumphed by offering performance-based incentives worth $573 million and committing to infrastructure improvements that underscored the state’s readiness for innovation.7 Arlington’s proximity to the nation’s capital and its burgeoning tech ecosystem further cemented its appeal.

Yet the allure of tax breaks and subsidies is just one side of the equation. Real estate costs play an equally decisive role. While Silicon Valley continues to symbolize the zenith of tech innovation, escalating costs are prompting companies like Google and Apple to explore more affordable markets such as Austin, Texas. Here, a unique blend of reasonable land prices and an emerging tech culture offers fertile ground for expansion. However, the arrival of Big Tech often triggers unintended consequences. In cities like Seattle and San Francisco, the rapid rise of property values following tech expansions has exacerbated housing affordability crises and fueled displacement.8 This dual-edged impact illustrates the tension between growth and equity, a challenge cities must navigate as they vie for tech investment.

2. Workforce Considerations:

Talent is the heartbeat of Big Tech, making workforce availability the lifeblood of their decision-making. These companies don’t just look for spaces to work—they seek environments that can sustain a perpetual flow

Now It’s on Pause.” Wired, April 2023. https://www.wired. com.

7 Jim Tankersley and Ben Casselman. “Amazon Names Locations for New Headquarters.” The New York Times, November 13, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com.

8 Laura Bliss. “How Big Tech’s Real Estate Boom Affects Housing.” Bloomberg CityLab, May 2021. https://www. bloomberg.com/citylab.

of innovation. Silicon Valley, for instance, owes much of its magnetic appeal to institutions like Stanford and UC Berkeley, which churn out the engineers, programmers, and designers who fuel tech’s relentless progress.9 Google’s sprawling Mountain View headquarters and Apple’s stateof-the-art Cupertino campus are testaments to the importance of proximity to such talent pipelines.

But talent today demands more than a job— it demands a lifestyle. Big Tech campuses have evolved into ecosystems designed to attract and retain top-tier professionals. Apple Park, often called “the spaceship,” goes beyond functionality to inspire. Its green spaces, wellness centers, and environmentally conscious design reflect a deeper commitment to the values of its workforce. These workplaces are not just built for productivity; they are statements of identity, blurring the line between corporate strategy and cultural expression.

3. Infrastructure and Connectivity:

Big Tech thrives in places where connections—both physical and digital—are seamless. Access to robust transportation networks, reliable energy grids, and cuttingedge digital infrastructure are non-negotiables. Amazon’s choice of Arlington for HQ2 underscores this priority. Proximity to Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport offered the convenience of global mobility, a crucial consideration for a company with a far-reaching workforce.

Public transit, too, plays a decisive role. Google’s Downtown West project in San Jose is a striking example of transitoriented development. Designed to reduce car dependency, it prioritizes sustainability and accessibility, proving that innovation isn’t confined to technology—it extends to how we move. Similarly, Facebook’s Menlo Park campus incorporates bicycle-friendly infrastructure and improved public transport links, creating an integrated network for employees and the community alike.

Equally vital is digital infrastructure. For tech companies, locations like Ashburn, Virginia—known as “Data Center Alley”—are gold mines. With unparalleled bandwidth and stable energy grids, these hubs serve as the backbone for data-heavy operations, ensuring that the gears of global tech dominance keep turning.10

9 Kenji Kushida. “Silicon Valley and the Talent Ecosystem.” Stanford Research Papers, January 2024.

10 Michael Woolridge. “Ashburn’s Data Center Boom.”

Navigating the intricate web of regulations, environmental considerations, and community dynamics is a complex endeavor for Big Tech companies. These factors significantly influence real estate decisions, often dictating the feasibility and success of large-scale projects. Local zoning laws and building codes can either facilitate or hinder development. In San Francisco, for instance, stringent zoning regulations have posed challenges for tech expansions, prompting companies to explore suburban areas with more flexible policies. Google’s Downtown West project in San Jose exemplifies this, requiring extensive negotiations with local authorities to align corporate ambitions with community needs.

Environmental sustainability has become a cornerstone of Big Tech’s real estate strategies. Apple Park in Cupertino, California, is a prime example, operating entirely on renewable energy and incorporating green building practices. Such initiatives not only reflect corporate values but also respond to increasing regulatory incentives for environmentally friendly developments.11

Google New York headquarters is a repurposed 1930s railway terminal

affordability, ultimately leading to its cancellation. This underscores the importance of securing community support and addressing local concerns in the planning stages. In contrast, Google’s redevelopment of Chelsea Market in New York City demonstrates a more harmonious integration with the existing community, revitalizing the neighborhood while preserving its cultural identity.

The pandemic was a seismic event that upended traditional notions of office spaces, pushing Big Tech to reimagine the role of real estate in a rapidly changing world. No longer is sheer square footage the defining metric of success. Instead, flexibility, well-being, and purpose have emerged as the guiding principles of post-pandemic real estate strategies. The shift is evident in the growing preference for Class A properties, which boast advanced infrastructure, modern amenities, and sustainable features designed to foster creativity and collaboration.12 Big Tech campuses are increasingly being conceived as environments that inspire and support a hybrid workforce. These spaces balance the practicalities of productivity with the need to attract and retain top-tier talent. For instance, Microsoft’s updated campus in Redmond, Washington, integrates outdoor meeting spaces, green roofs, and state-of-the-art technology to meet evolving workplace needs while promoting employee wellness.13 Similarly, Google’s commitment to high-quality office environments is reflected in its acquisition of St. John’s Terminal in Manhattan, a $2.1 billion investment in a sustainable, future-ready campus.14

The pandemic also reshaped lease dynamics. Uncertainty in the economic landscape has made flexibility a critical requirement for occupiers. Companies are now demanding shorter lease terms, scalability options, and access to shared workspaces that can adapt to fluctuating needs. WeWork’s resurgence in the flexible office market highlights the growing demand for agile solutions, especially among Big Tech clients navigating hybrid work models.15

Community engagement is equally crucial. Amazon’s HQ2 project in Arlington, Virginia, faced significant local opposition due to concerns over gentrification and housing

Tech Infrastructure Quarterly, November 2021. 11 “Apple Park: A Model for Sustainability.” Green Architecture Digest, August 2024.

12 CBRE Research. “Post-Pandemic Trends in Office Real Estate.” CBRE Insights, August 2024. https://www.cbre. com.

13 Nat Levy. “Microsoft’s Redmond Campus Reimagined for Post-Pandemic Work.” GeekWire, March 2023. https:// www.geekwire.com.

14 Stefanos Chen. “Google Buys St. John’s Terminal for $2.1 Billion in Manhattan.” The New York Times, September 21, 2021. https://www.nytimes.com.

15 Jonathan O’Connell. “WeWork’s Resurgence in the Hybrid Work Era.” The Washington Post, May 2023.

Furthermore, the digital revolution accelerated by the pandemic has influenced how companies approach real estate. The rise of remote and hybrid work models has challenged tech giants to rethink not only where work happens but how it happens. As physical and virtual spaces blend, investments in technologyenabled environments—such as smart buildings equipped with IoT (Internet of Things) capabilities—are becoming a priority. This shift signals the broader evolution of workplaces into ecosystems of innovation, well-being, and adaptability.

increasingly recognize that their impact extends beyond products and services.16 Sustainability has become more than just a buzzword—it’s a lens through which companies evaluate their operations, and office design is at the heart of this transformation.17

Modern workplaces are no longer mere backdrops for productivity; they shape behavior, influence health, and act as physical embodiments of corporate values. For big tech firms like Google, Amazon, and Microsoft,

of National GDPs and Market Cap of Big Tech

The post-pandemic world has redefined the parameters of success in real estate for Big Tech. Offices are no longer static assets; they are dynamic hubs that must respond to the demands of a workforce seeking flexibility, purpose, and inspiration. In this new paradigm, the emphasis on quality, adaptability, and employee-centric design will continue to shape the future of Big Tech’s real estate footprint.

What makes a workplace truly sustainable? Is it just about minimizing energy consumption, or does it also reflect a company’s commitment to innovation, employee well-being, and longterm environmental goals? Businesses today https://www.washingtonpost.com.

sustainable offices are not only essential platforms for innovation but also benchmarks for the future of work environments.

Big Tech’s Path to Sustainable Workspaces: What does sustainability in office design truly entail, and why is it so vital?

Big tech firms are answering this question by designing workspaces that integrate energy efficiency, renewable materials, biophilic design, and smart technologies.18 These initiatives not only reduce environmental footprints

16 Sebastian Smeenk, “Sustainable Office Spaces: Shaping the Future of Modern Work Environments,” Edge Workspaces, August 30, 2024, https://www. edgeworkspaces.com/sustainable-office-spaces-shapingthe-future-of-modern-work-environments/#elementortoc__heading-anchor-4.

17 Ken Silverstein, “Is Sustainability More than a Corporate Buzzword?,” Forbes, May 1, 2024, https://www.forbes.com/ sites/kensilverstein/2024/05/01/is-sustainability-morethan-a-corporate-buzzword/.

18 Sebastian Smeenk, “Sustainable Office Spaces: Shaping the Future of Modern Work Environments,” Edge Workspaces, August 30, 2024, https://www. edgeworkspaces.com/sustainable-office-spaces-shapingthe-future-of-modern-work-environments/#elementortoc__heading-anchor-4.

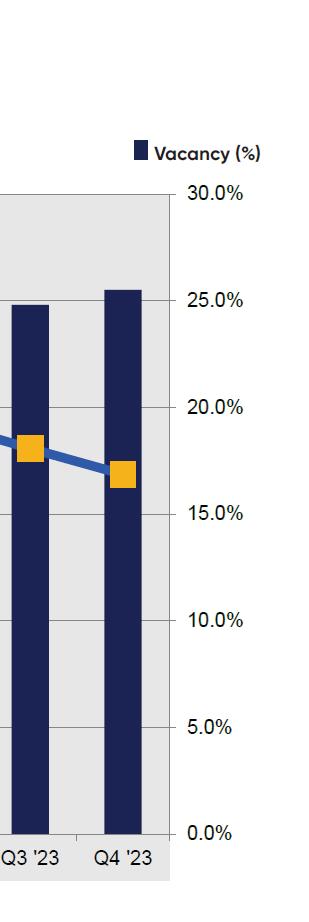

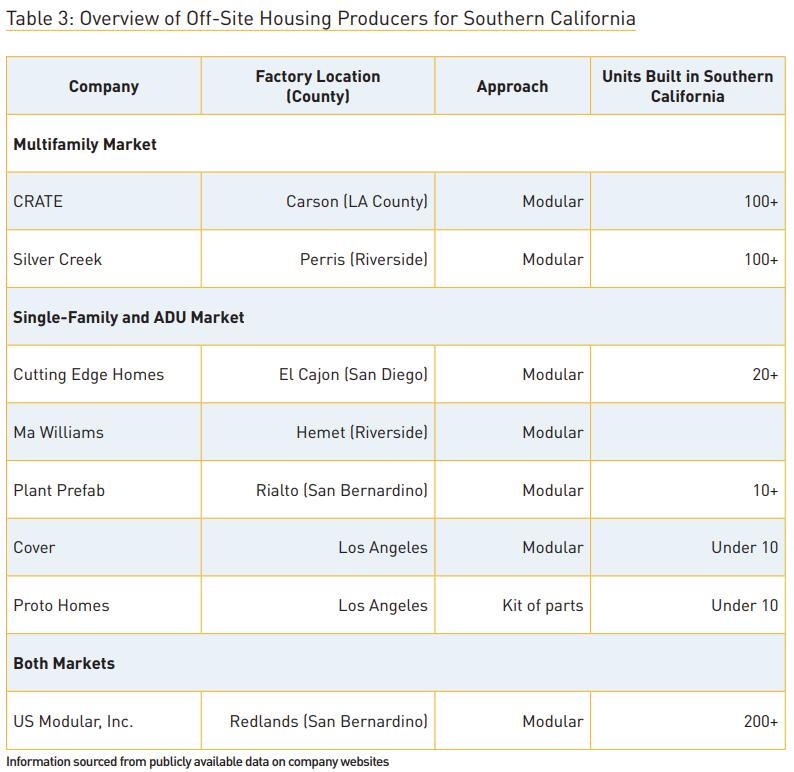

but also create spaces that inspire employees and redefine the possibilities of sustainable design.