Lorena Bello Gómez

Lorena Bello Gómez

Lorena Bello Gómez

Aqua Incognita: Designing for Extreme Climate Resilience in Monterrey, [MX]

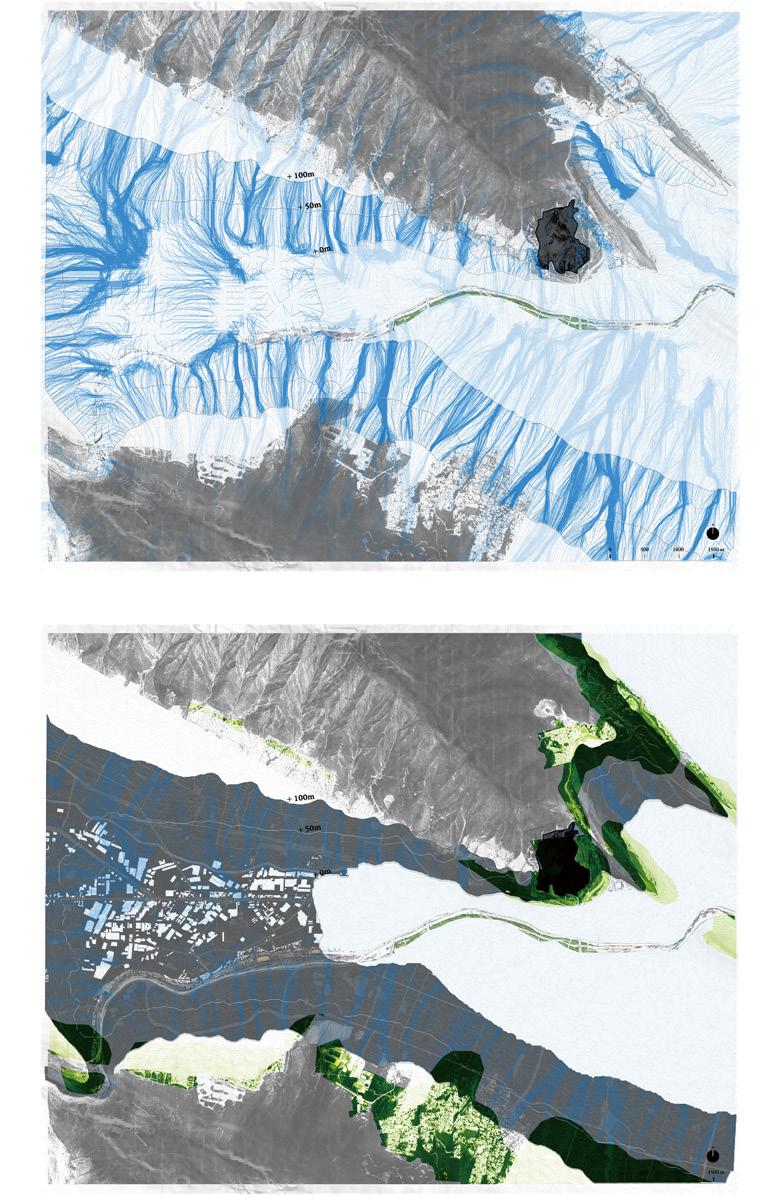

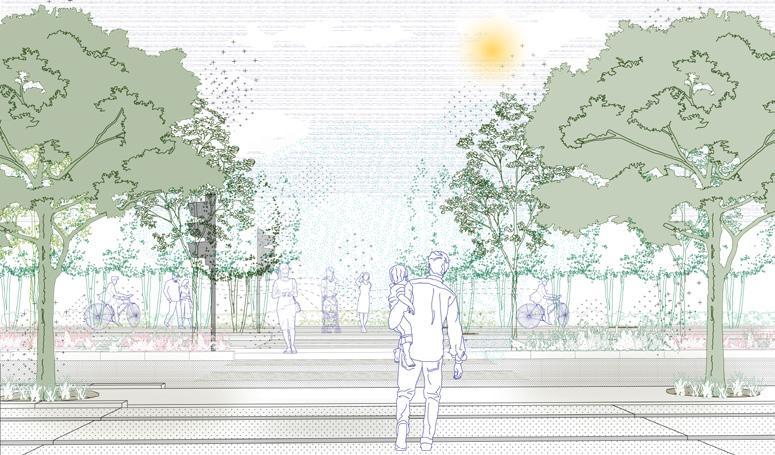

Aqua Incognita continues to engage students in grappling with water-resilient urbanization processes, through the design of systems-based reparative actions in the water-scarce region of Monterrey, Mexico. Mexico’s industrial cradle, and a region undergoing a nearshoring industrial boom, this metropolis of 5.4 million people is threatened by critically unbalanced water regimes. While facing its own version of a Day-Zero crisis in the summers of 2022-3, the city has also withstood recurrent flooding catastrophes over the years. These extreme climatic events are likely to intensify amidst the warming of our planet.

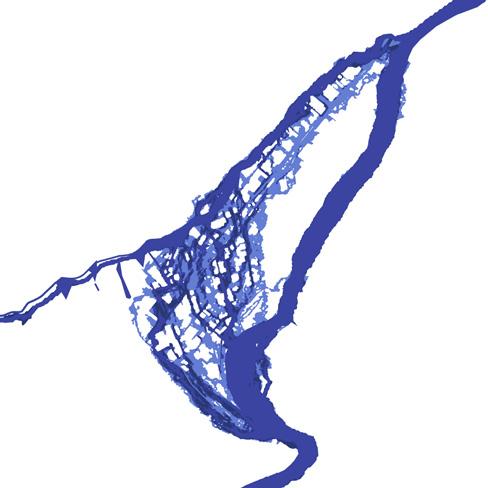

With the objective of catalyzing actions that could trigger a more resilient water future in Monterrey, the studio focuses on one of Monterrey’s most strategic Critical Zones: the Santa Catarina River. The restoration and conservation of this river basin and riparian corridor is key to the future of water security, the reduction of flood risk, and the equitable distribution of safe and healthy biodiverse areas across the city towards climate justice. Achieving these three objectives is part of a contested vision today. The studio has established a collaboration with experts, citizen groups, academia, the government, and the regional conservation institution Terra Habitus (studio sponsor) to push the transformation of this river watershed into a climate-resilient and ecologically stable region in the near future.

Studio Assistants

Samuel Tabory, Rolando Girodengo

Students

Fall ‘23: Sophie Chien, Pie Chueathue, Lucas Dobbin, Annabel Grunebaum, Miguel Lantigua Inoa, Bernadette McCrann, Emily Menard, Ashley Ng, Sanjana Shiroor, Daniella Slowick, Jianing Zhou, Boya Zhou

Fall ‘24: Anne Field, Manaka Hataoka, Mya Kotalac, Donguk Lee, Yuehan Eva Li, Sammy Mansfield, Cory Page, Drummond Poole, Markel Uriu, Yuqi Zhang, Nina Zhao

Studio Instructor

Lorena Bello Gómez

Symposium and Workshop: Urban Hydrological Adaptation. Tec of Monterrey, MX Organizers: Lorena Bello Gómez, Rubén Segovia Experts: Ismael Aguilar, Loreta Castro, Alejandro Echeverri, Ginés Garrido Respondents: Alessandra Cireddu, Nélida Escobedo, Alfredo Hidalgo, Karen Hinojosa, Rob Roggema, Surella Segú

Symposium and Design Charrette: Towards a Radical Ecological Transition Tec of Monterrey, MX Organizers: Lorena Bello Gómez, Rob Roggema, Rubén Segovia Experts: Antonio Azuela, Iñaki Echeverría, Eduardo Marín, Nicholas Nelson, Liz Silver Respondents: Lorena Bello Gómez, Rob Roggema, Lorenzo Rosenzweig, Selene Martínez

Visiting Expert Lecturers

Fall ‘23 Rosario Alvarez, Celina Balderas, Lorenzo Rosenzweig, Liz Silver, Gena Wirth Fall ‘24 Max Piana, Margarita Jover

Semester Critics

Fall ‘23 Carina Arvizú, Celina Balderas, Anita Berrizbeitia, Joan Busquets, Loreta Castro, Ginés Garrido, Maria Elosúa, Matthew Girard, Salvador Herrera, Javier Leal, Lorenzo Rosenzweig, Liz Silver, Luis Zambrano, Robert Zimmerman Fall ‘24 Anita Berrizbeitia, Loreta Castro, Adriana Chavez, Maurice Cox, Gary Hilderbrand, Javier Leal, Nick Nelson, Lorenzo Rosenzweig, Samuel Tabory

Final Review Critics

Fall ‘23 Carina Arvizú, Anita Berrizbeitia, Diane E. Davis, Maria Elosúa, Maria Goula, Salvador Herrera, Gary Hilderbrand, Jungyoon Kim, Liz Silver, Robert Zimmerman Fall ‘24 Salvador Herrera, Jungyoon Kim, Nick Nelson, Max Piana, Chris Reed, Samuel Tabory, Belinda Tato, Ed Wall, Robert Zimmerman

Studio Sponsor

Terra Habitus Fall ´23-24; David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies Fall 24

Lorena Bello Gómez

Samuel Tabory

Jianing

Water Footprints: Río

Santa Catarina Floodplain

Restoration in Cumbres de Monterrey National Park

Nina Zhao

Cumbres’ Water Forest: Riparian Eco-Restoration Towards Resilience

Donguk Lee

Eroding for Higher Ground: Riverbed Scarring in Monterrey

Mya Kotalac

From Visible to Invisible Sammy Mansfield

La Huasteca 98 Cumbres de Monterrey: Rewilding for a Hydro-Social Commons

Anne Field

108 Reciprocal Futures: The Cumbres National Park and the Origins of the Río Santa Catarina

Emily Menard

114

Erasing the Line while Flooding: Giving Room to the Santa Catarina River

Christopher Lucas Dobbin

128 Industrial Aqua: Hydrological Rearrangement through Hybrid Assemblage

Manaka Hataoka

Las Mitras

142 A Sublime Scar: Recovering the Lost Interface in Las Mitras

Yuehan Eva Li

154 Regenerating Capillaries: Toward a Blue-Green Network along Awakened Living Hydric Soils

Boya Zhou

164 Obispo, Unbounded: From Pipes to Creeks in Las Mitras

Drummond Poole

174 The Poetics of Circularity: Water, Energy, and Regenerative Industrial Near-Shoring Centralities in Monterrey

Sanjana Shiroor

180 Post Industrial Tapestry: Remediating and Visualizing Water Systems within the Industrial Urban Fabric

Markel Uriu

Loma Larga

194 El Río Vivo: Revitalizing Living Riverine Systems for Ecological, Hydrological and Cultural Connectivity

Daniella Slowick

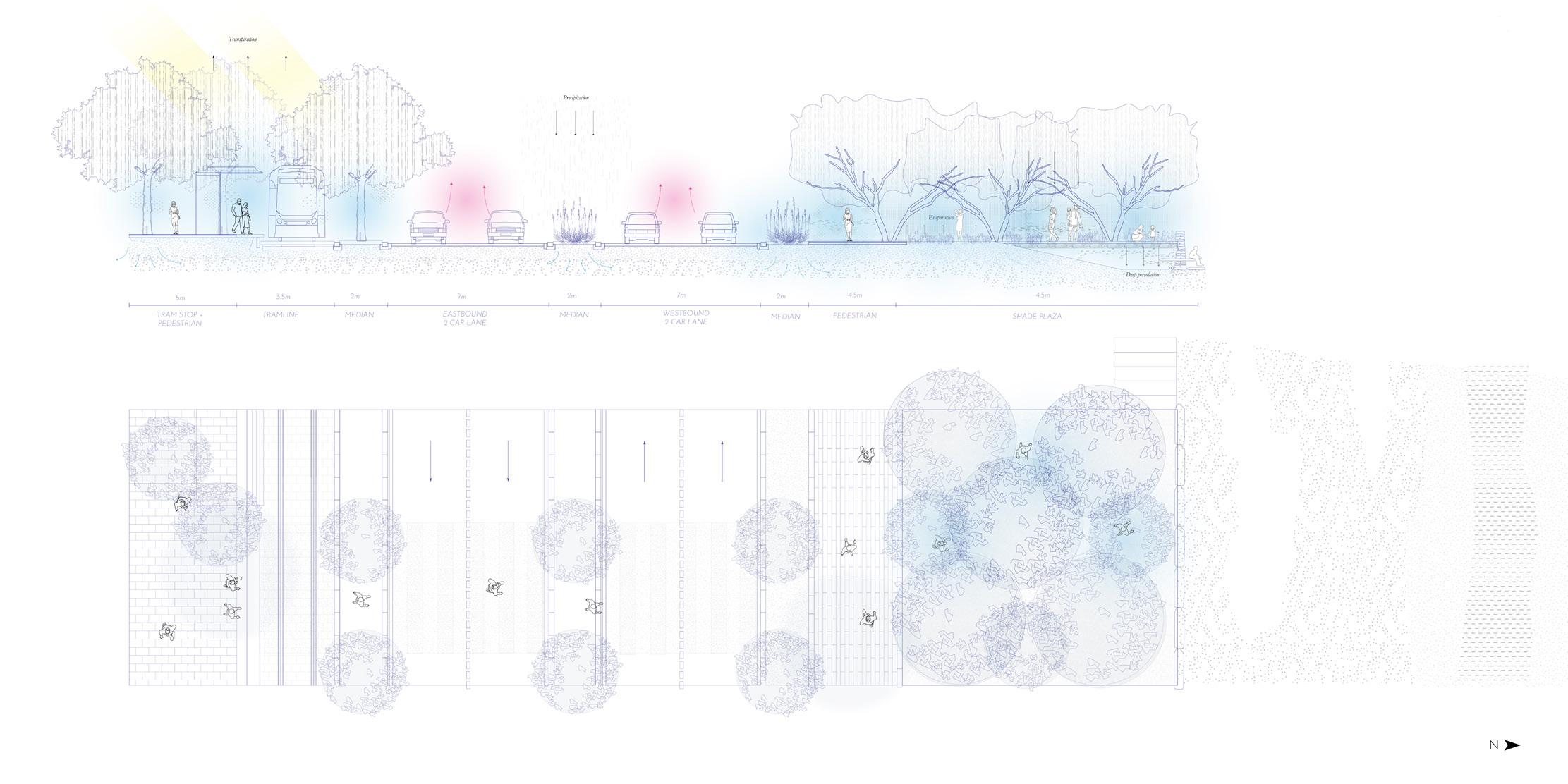

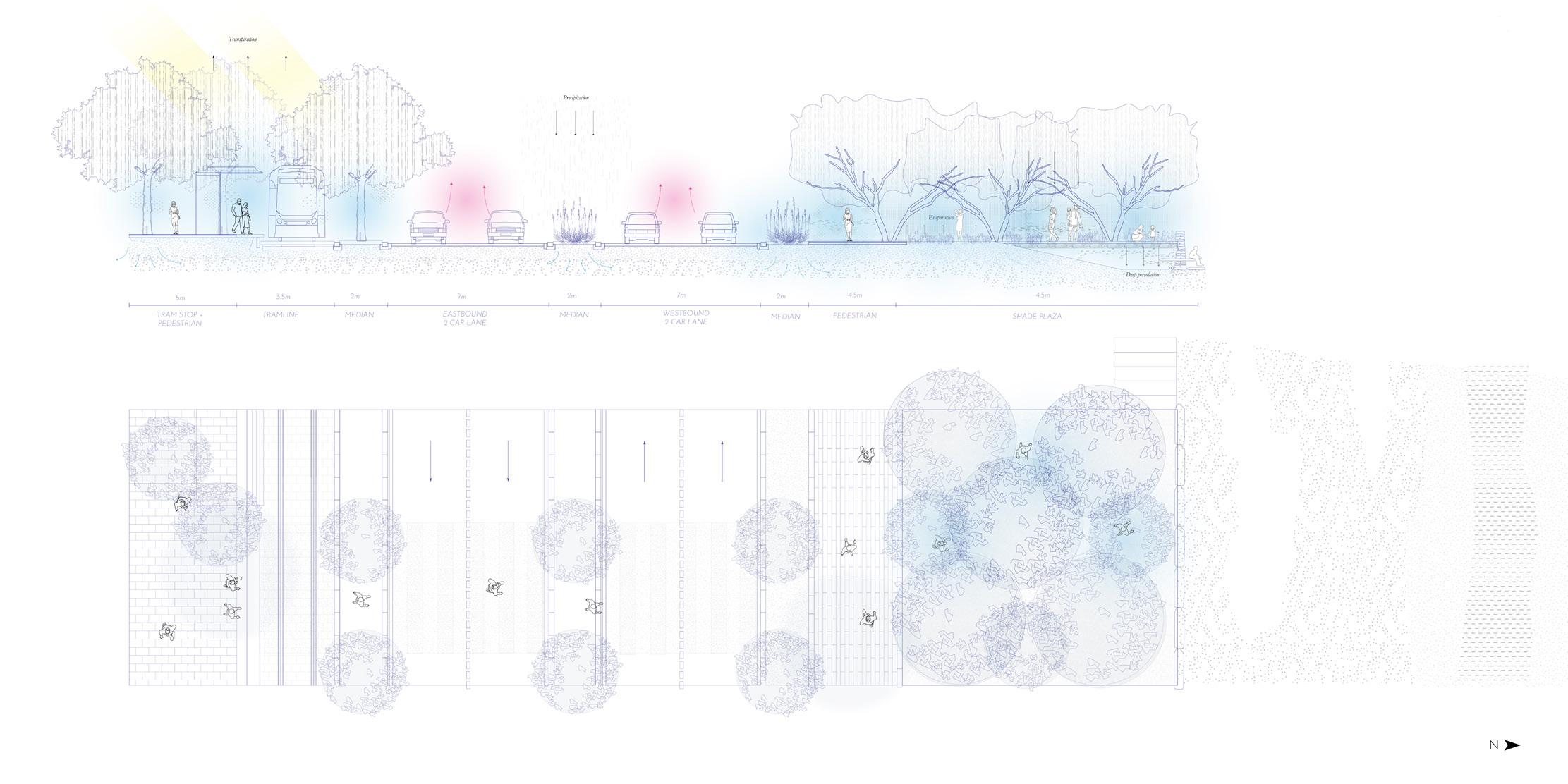

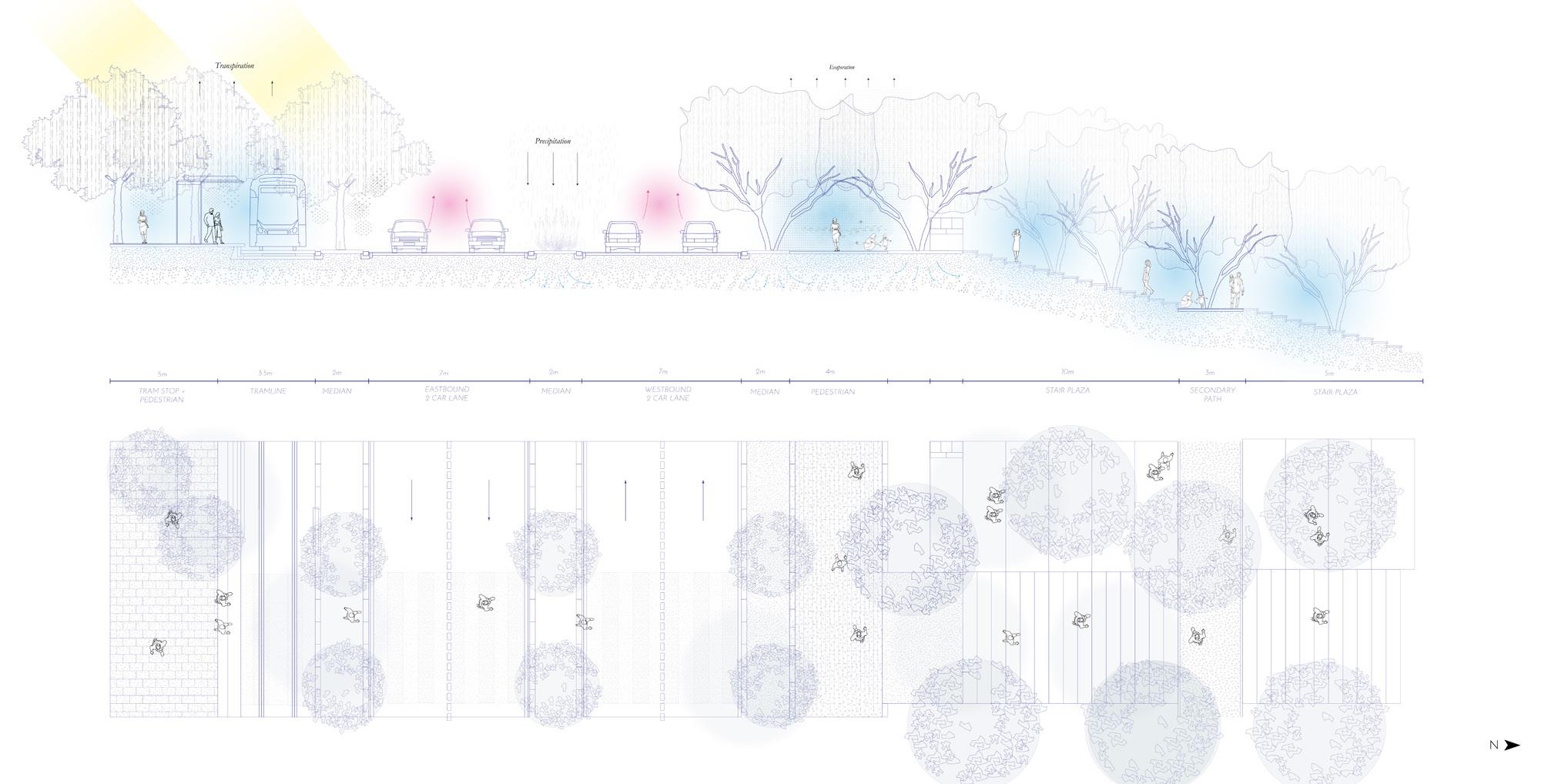

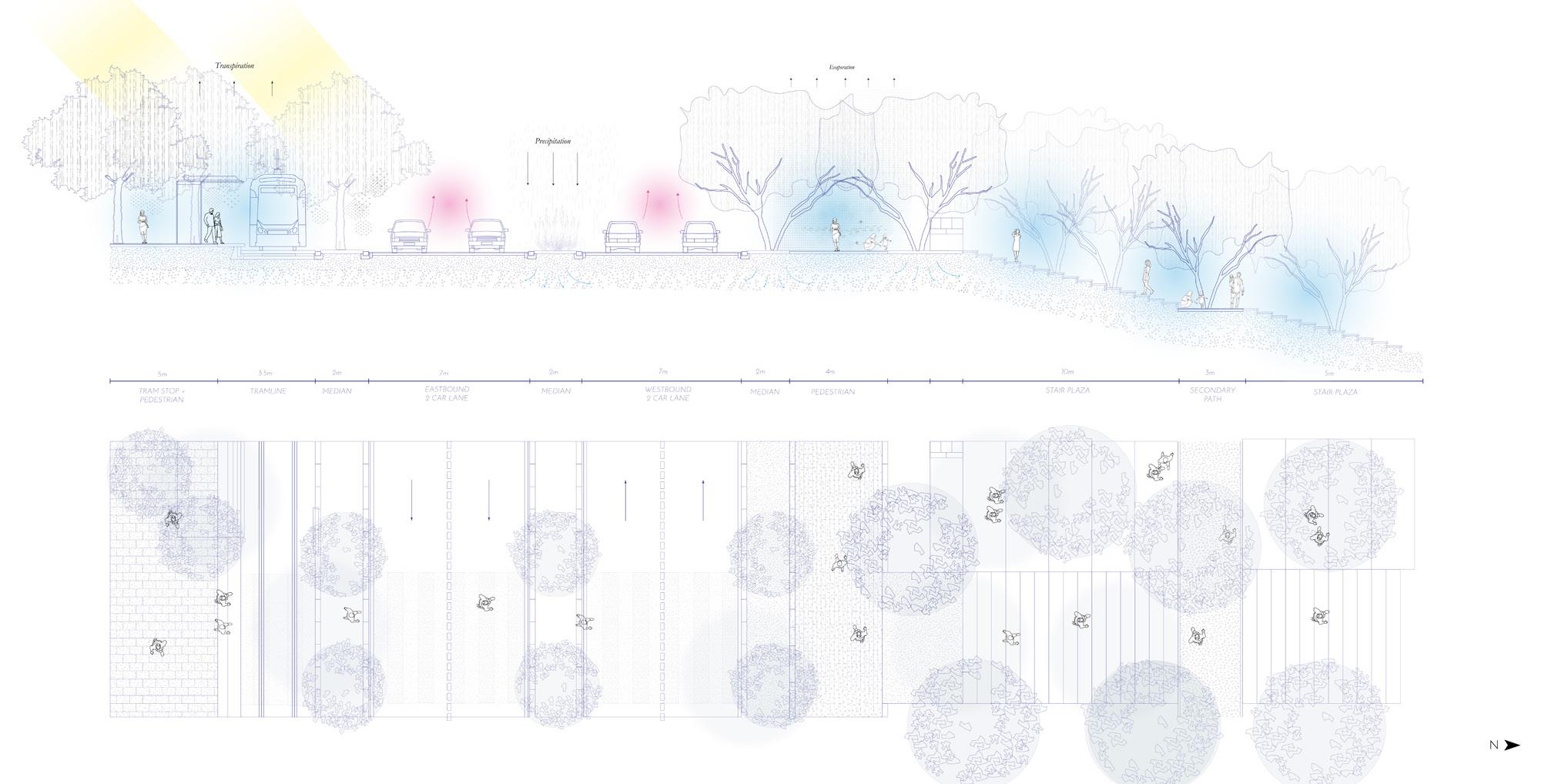

206 Riverine Microclimates:

Shading Santa Catarina’s

Urban Riverfront

Ashely Ng

216 Santa Catarina’s Ojo de Agua: Erasing Concrete River Boundaries at Macroplaza

Bernadette McCrann

222 Bridging Monterrey, Reaching the Río Santa Catarina

Sophie Weston Chien

228 El Gran Bosque de Río: Microclimatic Urban [River]

Forest

Miguel Lantigua Inoa

La Silla

238 Río de Arboles: Giving Room to Trees, Temporary Nurseries, and Micro-Climates in Monterrey

Pie Chueathue

250 La Plaza Verde: Seeding Ecological-Civic Memory in the Río Santa Catarina Riverbed

Annabel Grunebaum

256 From 2D to 3D: Rethinking Surface Water Flow to Mitigate Heat and Flood Risks

Yuqi Zhang

264

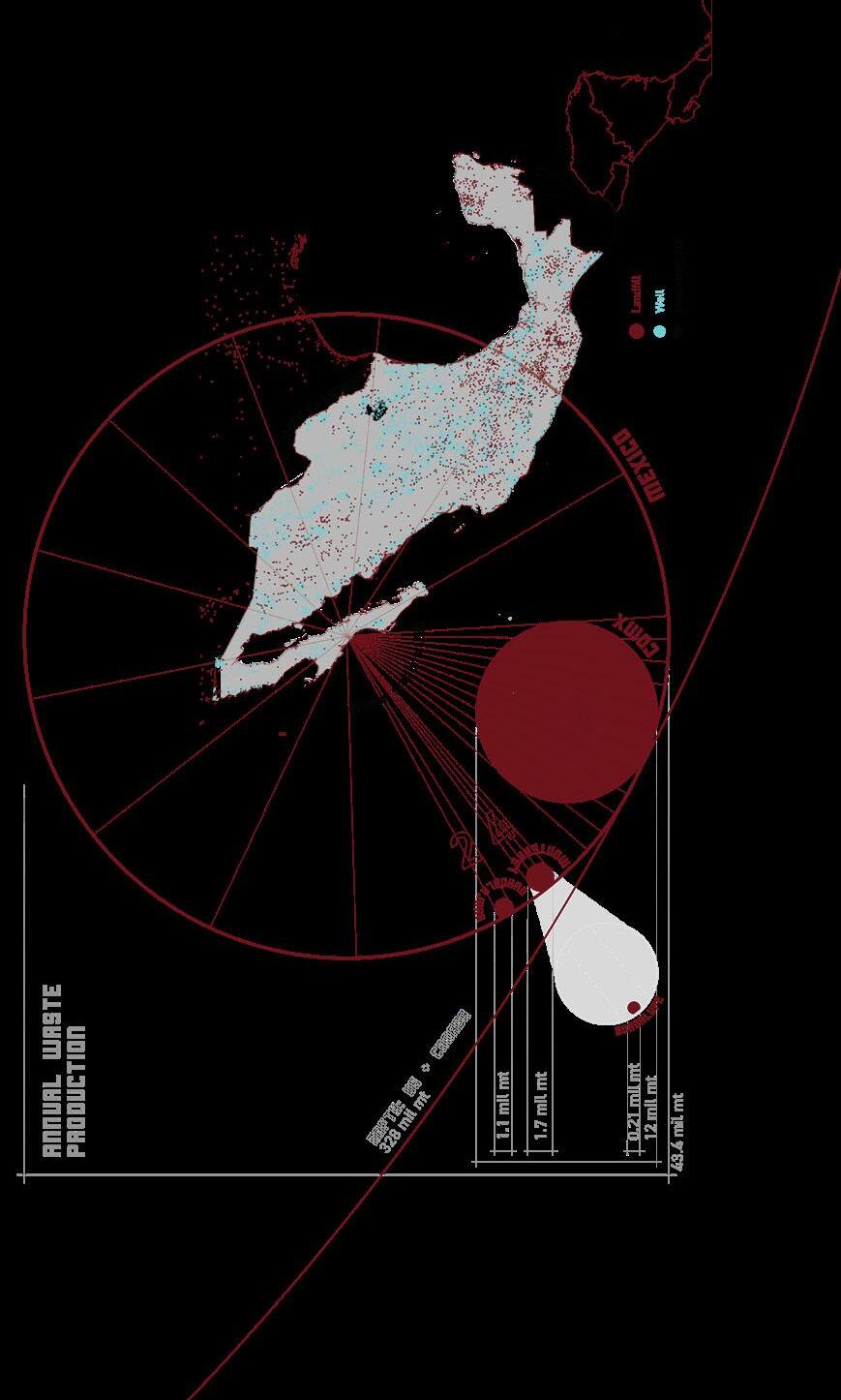

Wasted Water: Dumping on The Río Santa Catarina

Cory Page

280 Acknowledgments

283 Contributors

Embracing

This report is the culmination of two and a half years of sustained collaboration between Lorena Bello Gómez, her students at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, and my new organization, Terra Habitus, one where I am capitalizing all my experience as founder and former CEO of the Mexican Fund for the Conservation of Nature, a leading national environmental Fund I had the privilege to lead from 1994 to 2020.

The collaboration of Terra Habitus with the GSD, thanks to the financial support to Terra Habitus by G-10, a philanthropic alliance funded by Monterrey’s private sector, has reaffirmed my conviction that bridging local expertise and resources with the energy and passion of young, talented individuals, both national and international, is essential to shifting our culture toward conservation and regeneration, envisioning resilient futures for our region.

Below, I summarize this pathway, shaped by ongoing meetings and conversations as we prepared a seminar in Spring 2023 and two option studios in the Fall semesters of 2023 and 2024, each involving immersive field visits to Monterrey. Alongside field research, we organized two symposiums and workshops in collaboration with local universities and students at Tecnológico de Monterrey (ITESM) and Universidad de Monterrey (UDEM).

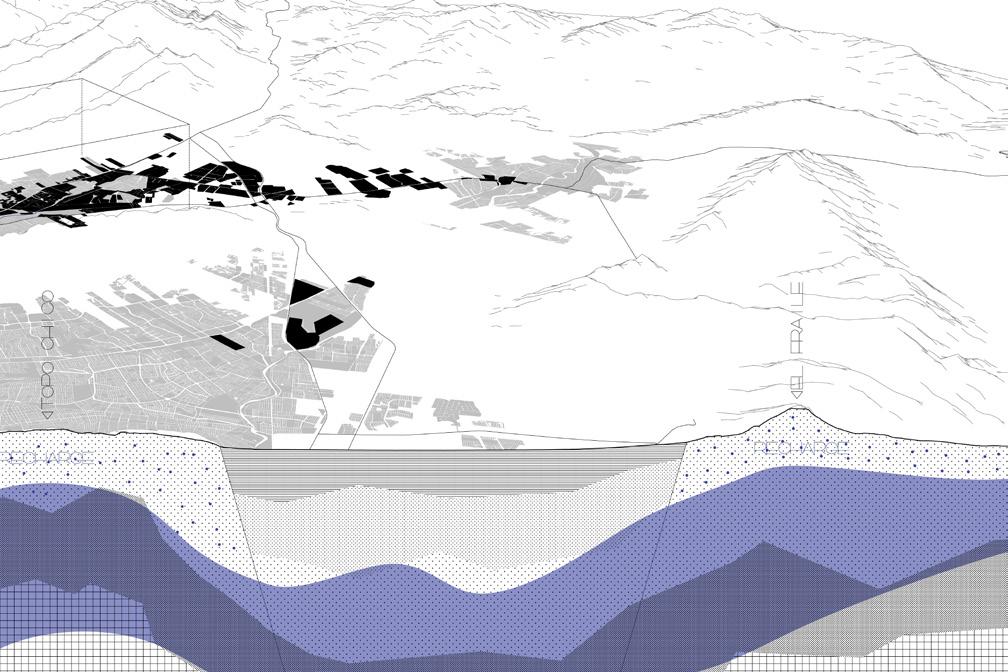

The Monterrey metropolitan area lies between the northeastern edge of the Sierra Madre Oriental and the Tamaulipan coastal plain. With 5.4 million inhabitants, it is a dynamic urban and industrial hub, increasingly recognized for its competitiveness, robust economy, and nearshoring potential. Yet, amid rapid urbanization and industrial expansion, Monterrey faces acute environmental challenges: air pollution, water

Lorenzo J. de Rosenzweig

scarcity, seasonal floods, extreme heat, insufficient public transportation, and a shortage of recreational spaces and urban parks.

Monterrey’s most pressing social and environmental issues are extreme heat in low-income neighborhoods, pervasive air pollution, and the perilous oscillation between water scarcity and flooding.

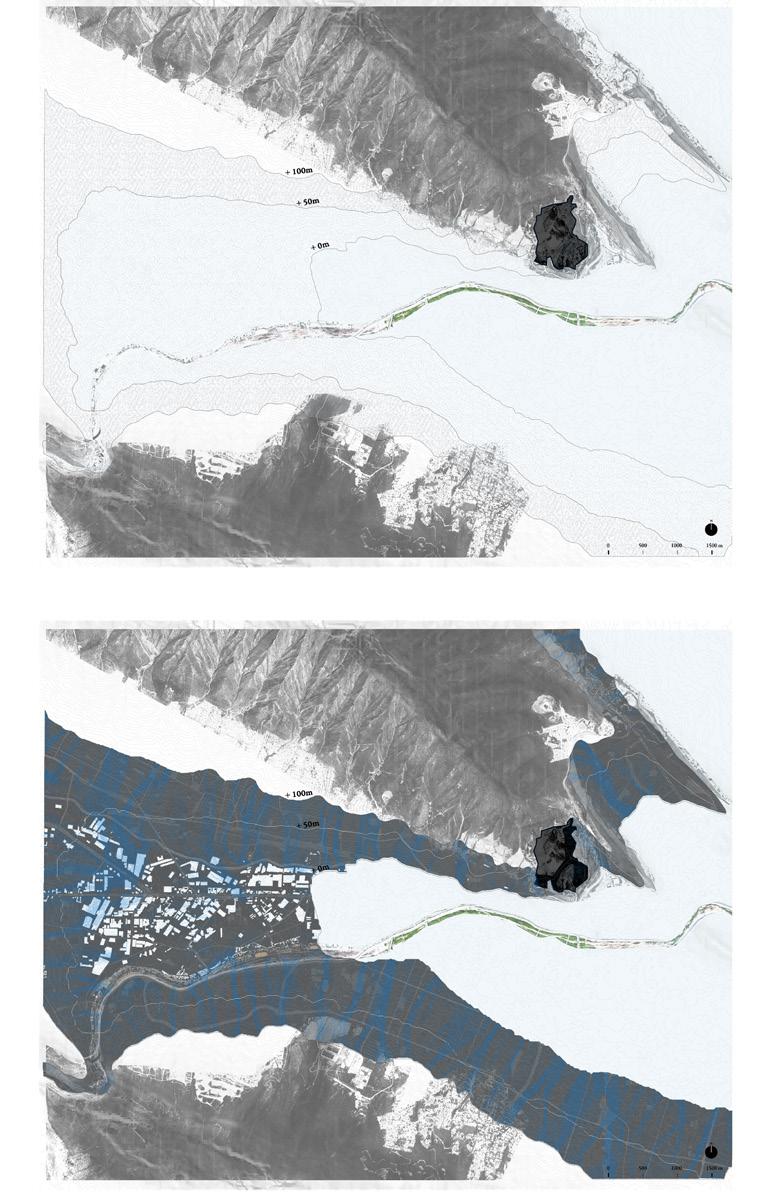

Exacerbated by climate change and rising demand, Monterrey narrowly avoided a Day Zero scenario of water provision in 2022 and 2023, as record-breaking summer temperatures intensified water scarcity. In late June and early July 2024, Tropical Storm Alberto and Hurricane Beryl delivered over 43 inches of rainfall—83% above the annual average—in just a few weeks. These extreme events filled all three major reservoirs (El Cuchillo, Cerro Prieto, and La Boca) with nearly 1.5 billion cubic meters of water, while simultaneously inflicting damage on public and private infrastructure that will require years and 10 billion pesos (approximately $555 million USD) to repair.

This recurring cycle underscores the urgent need for a deeper understanding of the hydrological cycle and improved management of the watershed and its critical aquifer recharge zones. In this new climatic reality, the vast and majestic mountains encircling Monterrey are essential to strengthening water management and resilience. Restoring and conserving these landscapes will play a crucial role in water filtration, flood regulation, and groundwater recharge, serving as vital “naturally distributed storage for water.” Acting as natural reservoirs, these mountains capture and slowly release water through their complex systems of rivers, streams, and aquifers—a capacity that is critical for maintaining water availability during dry periods and mitigating the impacts of extreme weather events.

The forests and vegetation of these mountains are also vital for climate change mitigation, capturing and storing carbon,

stabilizing soils, preventing erosion, and sustaining watershed health. By protecting and restoring these landscapes, Monterrey can enhance its water security and resilience, ensuring a sustainable water supply for its growing population and industry.

Monterrey is still far from being a sustainable and resilient city. Integrating a comprehensive, systems-based regenerative approach can help build an equitable, resilient, and biodiverse urban environment. By leveraging its natural landscapes and fostering a harmonious relationship between urban development and nature, Monterrey can set an example for other cities facing similar challenges. As Monterrey continues to grow, its focus on water resilience, heat reduction, and biodiversity will be key to ensuring a sustainable and thriving future for all its inhabitants, reducing the current gap in equality. It will also help Monterrey realize its potential as a true “BiodiverCity,” integrating biodiversity into urban planning and development, fostering harmonious coexistence between urban spaces and natural habitats, and ensuring that biodiversity flourishes within the city. Urban green spaces, biodiversity corridors, and community gardens for marginalized communities will enhance urban biodiversity and provide all residents with access to nature and green urban areas.

The talent and dedication of 35 students from the Harvard GSD, and the extraordinary leadership and strategic vision of Lorena Bello Gómez, have enabled us to bridge existing knowledge with innovative approaches to address Monterrey’s environmental and social challenges, while advancing biodiversity conservation and enhancing quality of life. Practical solutions for flood risk reduction, heat mitigation, watershed management, social inclusion, and green urban infrastructure provision, as presented in this work, will hopefully seed creative solutions embraced by both government and society.

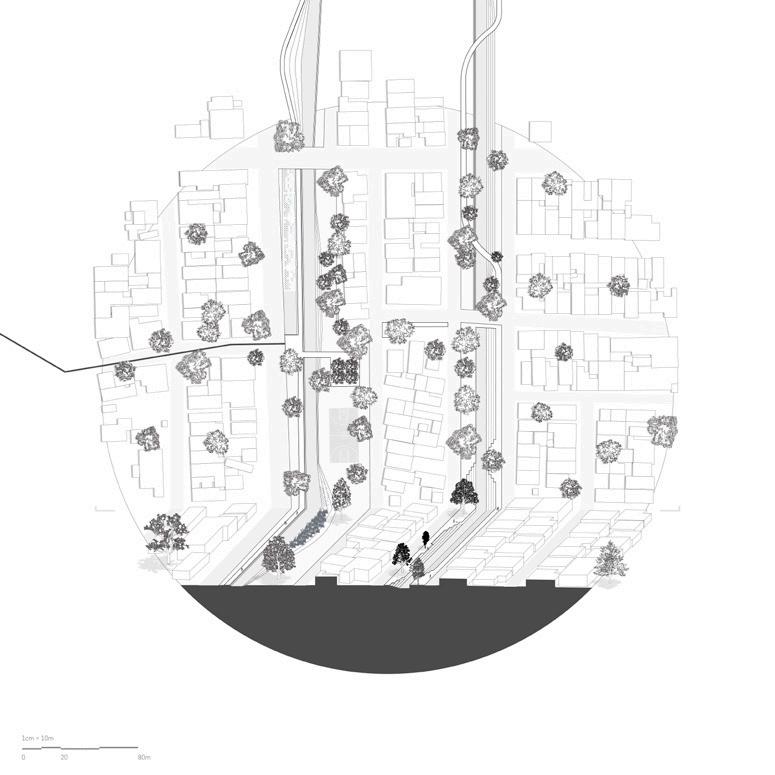

One immediate task—requiring seamless collaboration among academia, civil society, the private sector, and all levels of government, to realize the citizens’ vision of transforming the Santa Catarina River’s urban riparian corridor and its headwaters into a well-managed, safe green infrastructure spanning 1,200 to 1,500 hectares. A comprehensive management plan would integrate its core 700-hectare urban section into a metropolitan park, where nature and recreation coexist for the benefit of both people and the environment.

A second pressing challenge is to design and implement a public-private sustainable finance mechanism—anchored in effective governance and transparency—that leverages voluntary water fees from Monterrey’s more than one million users, alongside private and international resources. Drawing from experiences in both the United States and Mexico, this innovative conservation finance tool could cover the long-term maintenance costs of the Santa Catarina Metropolitan Park and vast priority water basins and aquifer recharge areas, which are essential to strengthening Monterrey’s water resilience. These solutions can serve as a model for other cities confronting similar constraints, challenges, and opportunities—paving the way toward safer, more equitable urban living in harmony with regenerated landscapes, where nature is recognized as a key stakeholder and partner in a truly prosperous future.

“The gods had condemned Sisyphus to ceaselessly rolling a rock to the top of a mountain, whence the stone would fall back of its own weight. They had thought with some reason that there is no more dreadful punishment than futile and hopeless labor.”

The Myth of Sisyphus. Essay on the Absurd Albert Camus1

Globally, many territories are experiencing unprecedented megadroughts due to our humanly induced changing climates.2 As global temperatures rise, water is evaporating at alarming rates, pushing cities like Monterrey in northern Mexico or its capital, Mexico City, dangerously close to a Day-Zero scenario, when millions of taps could run dry. 3 After the airstream shifts from La Niña to El Niño, extreme heat and thirst are suffocated by deadly and costly megafloods. Then, extreme volumes of water downpour onto the broken and impervious soils of urban-rural watersheds designed to drain water as fast as possible: devastation follows.

Addressing the human-disrupted water cycle has become a Sisyphean task in the Anthropocene. But let’s not fool ourselves: expecting a different outcome while repeating the same actions, like Sisyphus, will be both futile and absurd.

In fact, without action, predictions show that by 2050, half of the global urban population will face water scarcity as urban water demand increases by 80%. 4 As early as 2016, two-thirds of the global population (4 billion people) experienced severe water scarcity for at least 1 month each year, with half a billion suffering year-round. 5 Between 2002-2021 droughts affected 1.43 billion people, killed over 21,000, and caused economic losses of $170 billion. 6 Urban heat, known as heatisland, has reached hazardous and deadly temperatures (49C~120F) and worsened air pollution. 7

During the same period, floods affected another 1.65 billion people, caused nearly 100,000 deaths, and resulted in $832 billion in economic losses.8 Contaminated water, poor sanitation and inadequate hygiene are linked to waterborne diseases such as cholera, diarrhea, dysentery, hepatitis A, typhoid and polio affecting countless lives. 9 More severe

pollutants including arsenic, fluoride, lead, fracking chemicals, pesticides, and antibiotics found in water, are associated with various cancers, neurological diseases, and antimicrobial resistance. 10 With water either everywhere or nowhere, the transmission of diseases and threats increase exponentially.

Many would agree that the above alterations to water and its cycle are among the most impactful and destructive anthropogenic influences on nature. We have transformed water—the most important source of life on our planet—into a source of conflict, food insecurity, migration, pollution, and health threats. 11 At the very core of all processes involving life, water is now central to many processes involving death.

One could say that in a reverse alchemic transmutation, humans have transformed our most precious common resource into a ubiquitous common risk, effectively mutating gold into lead.

In this urgent context, asking the same questions or working with those who have led us to our current situation, will not change the status quo. We need everyone who has a role and interest in finding synergies to help restore a more balanced hydrological cycle— especially in an environment facing increasing liquidity as a result. For this to happen, strategic commitments to water conservation, ecosystemic recovery, socio-environmental equitable health, sustainable water use and the promotion of compact and dense urbanization—instead of boundless standalone housing—are urgently needed.

In Monterrey’s metropolis, this could be an opportunity to implement urban-regional actions that prioritize water security to achieve hydro-ecological resilience at the watershed scale. For this to happen, neither water-scarce communities nor the environment can continue to bear the burden of over-extraction by those who profit at their expense. 12

Instead, as designers, we have the skills to blend the different voices, needs and interdisciplinary expertise into a common spatial framework and vision to restore a more resilient water cycle in this metropolitan region. Monterrey is currently behind, but it could use its delay to learn from best practices and propel itself into a more water-secure and healthier environment in the coming years. Could Monterrey be wise enough to seize this opportunity and achieve greater liquidity? This is the question that we tried to answer in Aqua Incognita III and IV. 13

To find the answer, the Spring 2023 research seminar “Resilience Under New Water Regimes: The Case of Monterrey [MX] Day Zero” met weekly with a visiting speaker and explored Monterrey’s water-related history, culture, urbanization, industry, and politics through readings. 14 By examining global trends and discussions, we studied Monterrey’s Day-Zero as a case study to decipher the “Why” of this water crisis, as well as the “Where,” “How,” and “With Whom” of most impactful actions to restore water resilience. Discussions aimed to understand and critically analyze initiatives from similar water-stressed regions to build the design research foundations for the Aqua Incognita III and IV Option Studios. 15

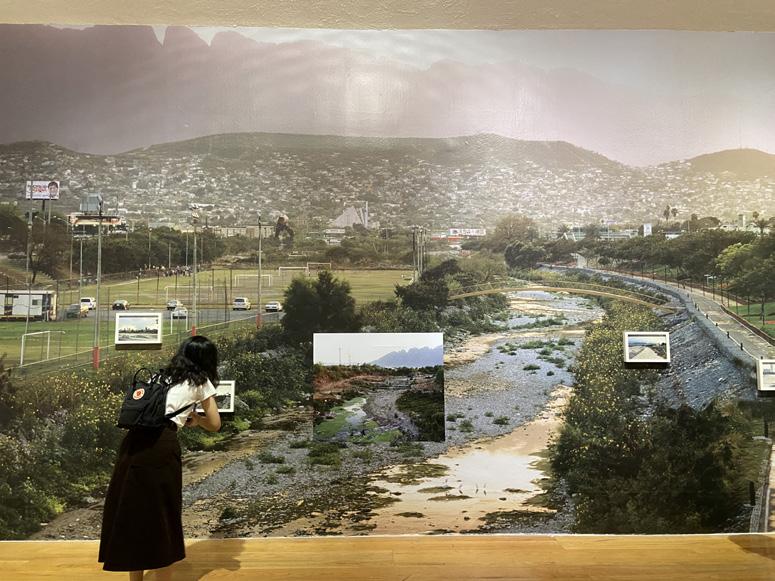

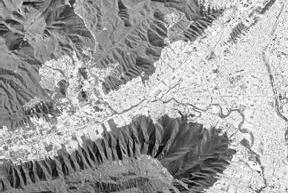

In tandem, Roberto Ortiz Giacoman’s masterful photography offered a glimpse into Monterrey’s sublime mountainous landscape (fig. 1) . Alejandro Cartagena’s critical eye and social conscience shed light on its harsh built environment (fig. 2). 17 Our search was also enriched by the DRCLAS water conference “Mexico + H2O,” which brought experts on Mexico’s water issues to address topics such as water scarcity, restoration, and both flood and drought within the Mexican context.18 Additionally, we knew from our work in the Apan altiplano of the many barriers and conflicting interests that complicate the implementation of necessary actions.19 But we also recognized that extended periods of crisis can be pivotal for mobilizing radical actions toward socioenvironmental change. Especially when our survival is at stake.

Before presenting the critical findings from our two years of design research, which laid the groundwork for the design responses presented in this report, let me summarize the water crisis and how it was averted. This summary includes research and discussions from seminar guests, interviews conducted during three visits to Monterrey in 2022-23,

and participation in conferences on Day-Zero (08/2022) and the Santa Catarina River (08/2023). During a fourth and fifth visit in the Falls of 2023 and 2024, alongside GSD students, we met government officials and participated respectively in the “Hydrological Urban Adaptation” and “Towards a Radical Ecological Transition” symposiums and workshops that I co-organized at the Tec of Monterrey. 20 For those interested in exploring this topic further, please refer to the references annexed to this publication.

Monterrey serves as a paradigmatic example of how urban drought and flood risk are exacerbated by extreme territorial resource depletion and policies that promote socioeconomic and ecological desiccation, all occurring within hydrologically unsustainable pro-growth logics.

Monterrey is a dry-climate city of 5.4 million settled in the larger basin of the Rio Grande, where average annual rainfall ranges between 22.83-25.6 inches (580-650 mm), and evaporation exceeds precipitation. 21 Situated at the “water door” of the Sierra Madre Oriental, before it descends into the Gulf of Mexico’s coastal plain, Monterrey has been urbanized to quickly drain its recurrent floods. Governance and infrastructure challenges have led to a long-brewing crisis, which, in 2022-2023 was exacerbated by six years of decreased rainfall patterns triggered by La Niña. Some citizens received only two hours of water per day, while others (0.5 million) relied on 450 water trucks for over a week. Industry was largely permitted to continue extracting water from the aquifer. But the reality was far more complex than a “good citizenry” versus “bad industry” narrative. 22

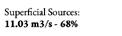

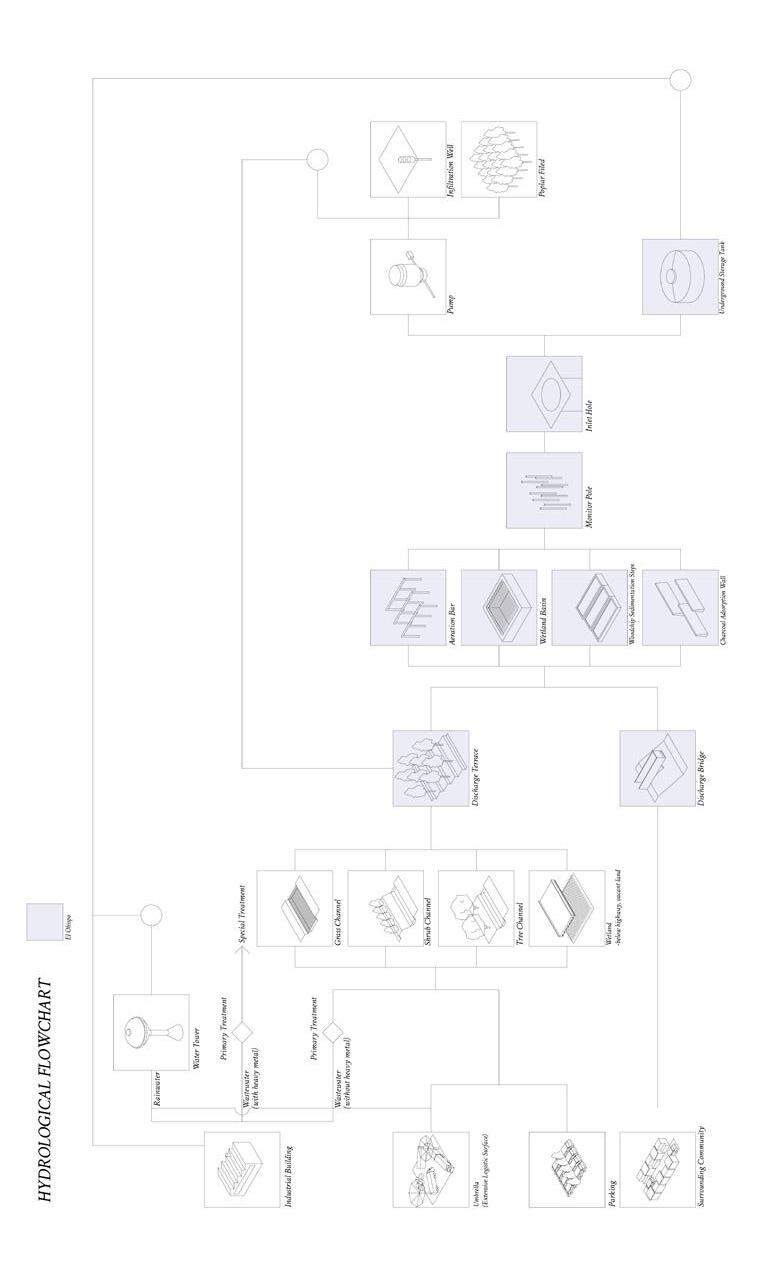

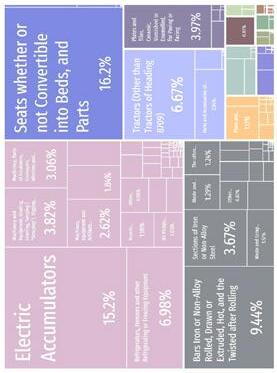

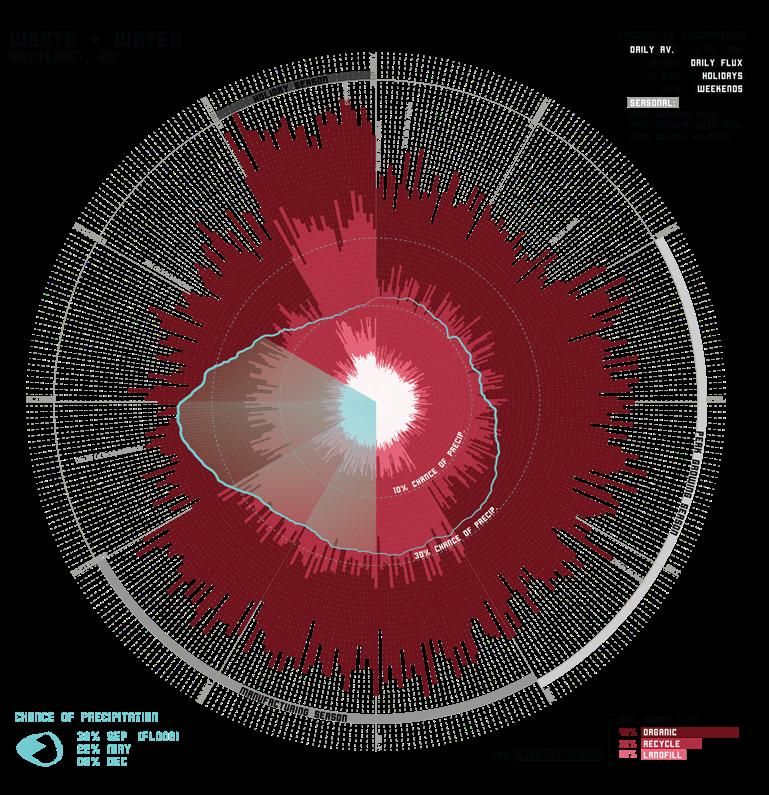

Water provision in Monterrey relies on roughly 60% surface water and 40% groundwater (fig.3). More precisely, out of the 16.18 m³/s of water provision 11.03 m³/s (68%) comes from surface sources such as La Boca, Cerro Prieto, La Mina or Cuchillo dams, while 5.15 m³/s (32%) is extracted from underground aquifers. After accounting for operational losses and leaks, the net water supply is 12.18 m³/s, with 70% (8,52 m3/s) allocated for domestic use, 19% (2.31 m³/s) for public use, and 11% (1.35 m3/s) for industries—as the latter extract directly from the aquifer with national water concessions.

Once used, the 12.18 m³/s are treated, with 8 m³/s sent to the water district of Tamaulipas, 1 m³/s is sold to agriculture, 1 m³/s sold to industry, and 2 m³/s are sold for other uses, leaving only 0.18 m³/s as a buffer. The average consumption per person is 165 liters per day, which exceeds the recommended 100 liters.

Industry is the driving force behind Monterrey’s fast growth and has a significant water footprint due to both virtual water exports and domestic consumption by workers. Additionally, given that the city is situated in the larger agricultural drylands of the low Rio Grande’s coastal plane, irrigation remains a major competitor for water resources.

Engineers explained that the crisis resulted from a shortage of 5.8 m³/s in water supply, caused by several factors: 1) two of the supply dams La Boca (0.92 m³/s) and Cerro Prieto (5.33 m³/s) were nearly depleted by the drought; 2) the new government took office in October 2021 with dams already at crisis capacity; 3) an extreme growth rate of 3,2% (180,000 inhabitants/year) driven by nearshoring, propelling urbanization in areas with limited supply and affecting aquifer recharge; 4) losses from leaks and system deficiencies (4 m³/s); 5) and the lack of automation to reduce pressure based on demand. Additional important vulnerabilities included: 6) the need to transfer 8 m³/s to Tamaulipas’ agricultural water district as compensation for El

Cuchillo dam;23 and 7) the transfer in January of 2021 of 450 million liters (Monterrey’s yearly supply) to honor the 1944 Binational Water Treaty with the US, which was done to suffocate a revolt by farmers in Chihuahua— who had refused to fulfill the agreement to protect their livelihoods. 24

Emergency responses involved a never-ending process of infrastructure expansion including: 1) the installation of 242 water tanks in neighborhoods lacking supply; 2) the drilling of 130 superficial wells and 28 deep wells (3000 feet) under federal emergency concession, to extract from the aquifer; 3) and the construction of a second aqueduct from their largest dam, El Cuchillo, which increased its capacity by 5 m³/s, bringing the total to 10.28 m³/s. Additional measures included: 4) increasing water prices based on consumption (while 50% reducing usage, 30% maintaining usage, and price-insensitive consumers increasing demand by 20%); 5) planning the construction of a fifth dam, Libertad, with a capacity of 220 million m³ to boost supply by 1.5 m³/s; and 6) implementing pressure modulation by dividing the system into 2,500 sectors to provide water where needed, and reduce the 2,500 liters/s (660.43 gallons/s) lost to leaks. These improvements aim to increase water provision to 25 m³/s by 2027 and to 30 m³/s by 2050, potentially through desalination or transfer from the Pánuco

River, both of which are highly unsustainable and undesirable solutions for both their economic and environmental costs.25

And yet, the best emergency response to this “extreme drought,” was another emergency, “extreme rain,” and its consequences: flooding. In June 2024, extreme rains from Tropical Storm Albert and Hurricane Beryl delivered as much water in two weeks as the metropolis typically receives in two years. After a prolonged drought, Regiomontanos celebrated these intense and destructive floods as the only means to refill their depleted reservoirs. So, once again, the extreme drought was averted by extreme rainfall, with an estimated bill of $555 million USD for Monterrey—with a total bill of $7.2 billion in the US according to NOAA. Later that September 2024 our trip to Monterrey was impacted by Hurricane Helene in our fly-in ($78.7 billion) and Milton in our way back ($34.3 billion). 27 (fig. 4)

Landscape Architects possess the skills to design spatial frameworks that tackle multiple challenges by working with natural processes and the ephemeral and cyclical forces of nature, rather than against them

Anne W. Spirn 28

The work presented in this report is motivated by a firm belief that we can escape the Sisyphean “drought-to-flood” destructive cycle in Monterrey. These recommendations are relevant to the current hydrological challenges faced by cities like Monterrey today. Despite significant barriers, this water crisis presents an opportunity to counteract many of the processes that threaten a livable future in an increasingly drier, hotter, polluted air, and less healthy biosphere, which is also periodically devastated by floods.

To uncovering the key incognitas necessary for breaking this cycle required us to look beyond the visible layers, repeated narratives, and usual suspects. In landscape architecture, this approach involves first identifying the underlying causes of complex problems, rather than merely addressing their symptoms with narrowly defined solutions. 29 With the encounters, we planned to project our spatial frameworks.

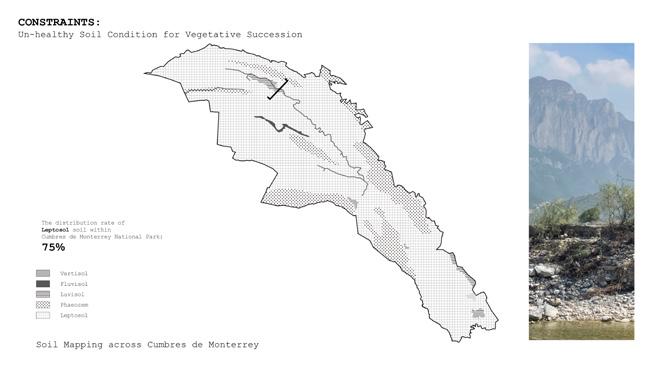

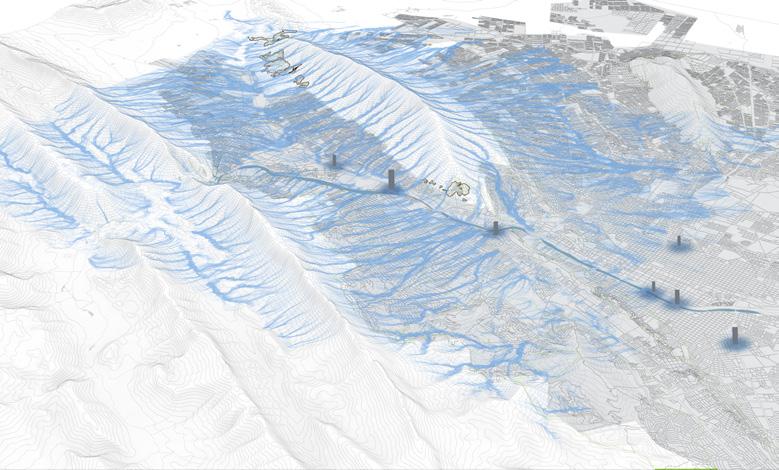

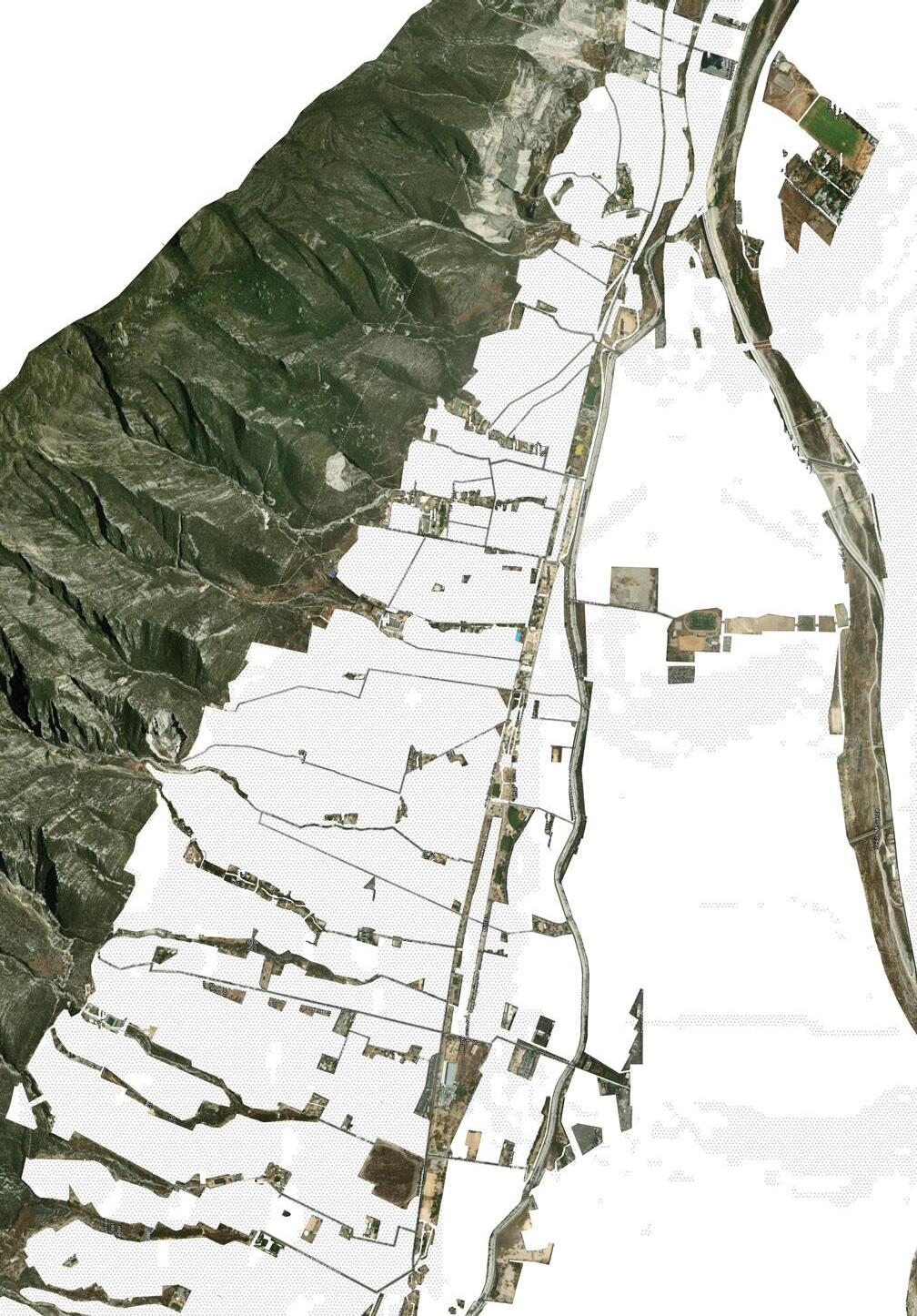

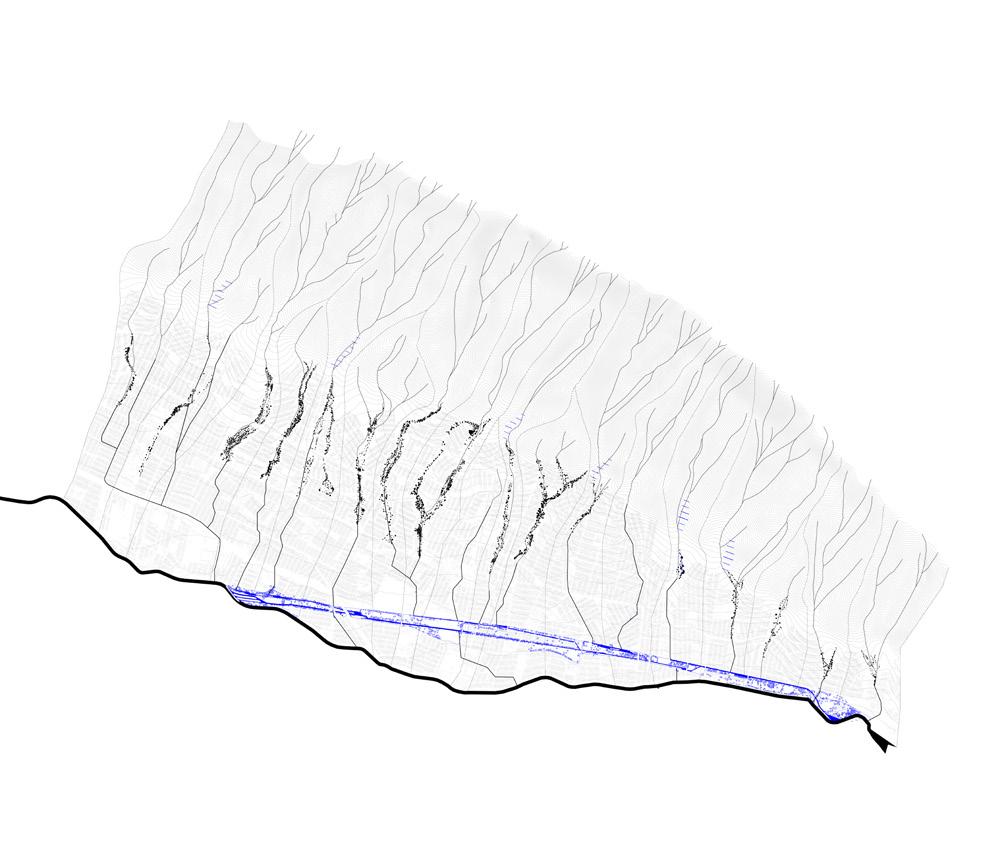

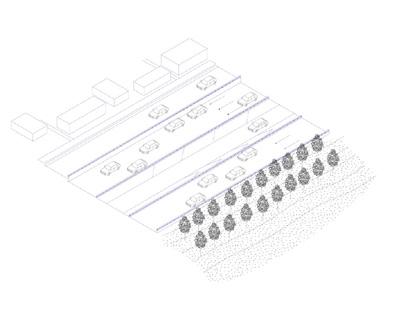

In our search for the “why?” of the crisis, we found that this metropolitan region is trapped in a perilous cycle of endless infrastructural expansion—driven by overexploitation from water-intensive agriculture and industrial growth focused on exports. Such industrial expansion fuels also endless, water-intensive, car-dependent urban sprawl characterized by small, standalone worker housing. Without policies to constrain growth, Monterrey´s metro-region has expanded its footprint by 2.8 times over the last thirty years, while its functional center is being abandoned.30 This trend exacerbates air pollution and flood risk, while reducing water recharge. Additionally, the lack of policies to protect aquifer recharge and curb overconsumption— both by inefficient planning and water management—has led to significant depletion of both surface and groundwater. Simultaneously, policies promoting car infrastructure and rapid drainage have dismantled the natural water network, resulting in the loss of water arteries, capillaries, moisture, wetness, and a vibrant biosphere, while increasing flood risk during extreme rainfall events. These policies have also contributed to desertification and the formation of heat islands in an already heavily polluted air. In the mountains, within Cumbres National Park, heat, drought, and a lack of management planning for twenty-three years since its designation have led to the loss of 2,500 hectares of forest due to fires and the encroachment of its valleys and waterbeds with private villas with swimming pools, or out-of-law new settlements. 31

The above-mentioned unsustainable urbanization processes contribute to water insecurity, flood risk, and human-environmental health degradation with big ecological and economic impact. Consequently, in our search for the “where?” and “how?” of water security and hydrological resilience, we identified various physical points for actions along Monterrey’s water cycle.

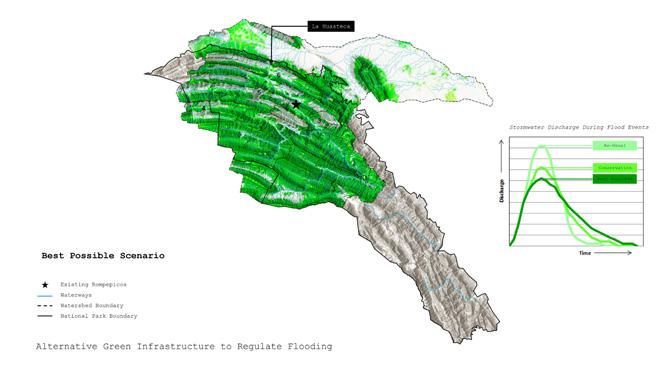

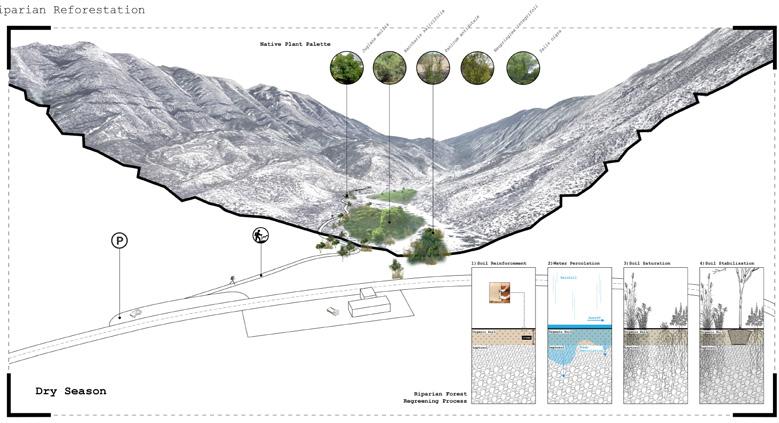

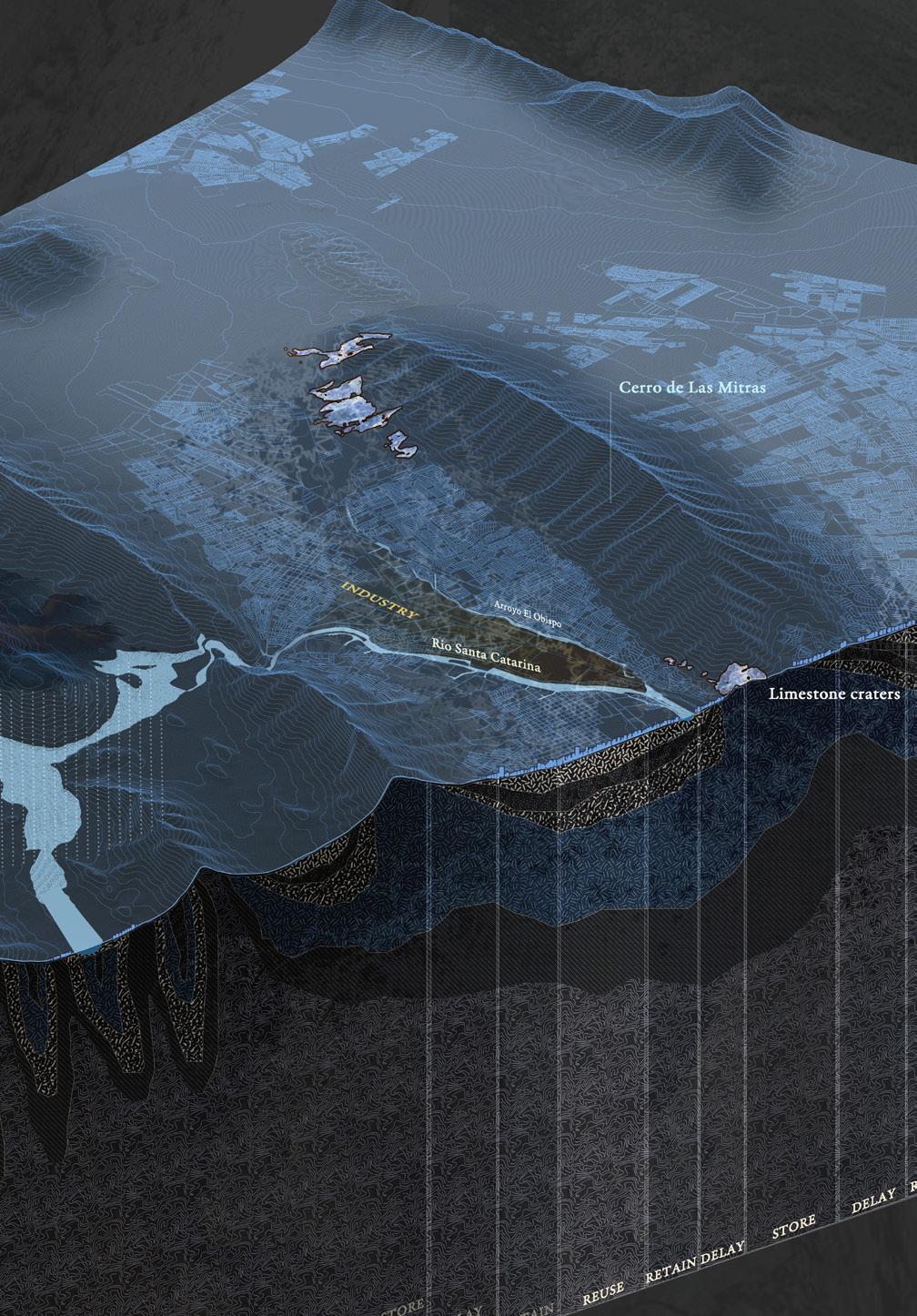

In the mountains, we explored actions towards water conservation, aquifer recharge, and flood risk reduction.

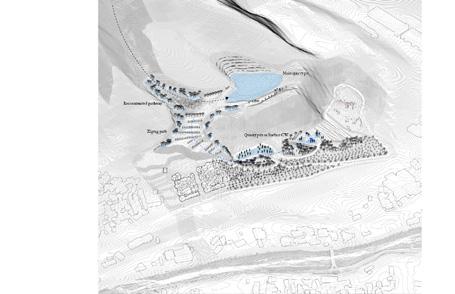

Water conservation and aquifer recharge actions involve regenerative agriculture and reforestation in Cumbres National Park, drawing many lessons from our experience with ejidatarios and farmers in Apan, Hidalgo. 32 Also, indigenous water conservation practices, US National Parks programs that could be reinterpreted for this culturally rich landscape, and successful local models such as Ecological Park Chipinque in Monterrey. 33 For flood risk reduction, we looked for alternative ways to naturally store water and reduce its speed, as well as to discourage riverbed encroachment and urban patterns of urbanization in this sublime and hydrologically strategic landscape. Here, we recognized the importance of La Huasteca, the gateway to Cumbres National Park and mouth of the river into the city, as a cultural icon known for its sublime beauty and sacred origins, its importance to Regiomontanos’ identity, as well as its vulnerability to floods—floods that disconnect and endanger its local communities. 34

In the urban watershed, we explored actions towards urban compactness and water circularity to reduce overall aquifer overexploitation and pollution while recovering Monterrey’s water blueprint and veins as a network of “cool bio-corridors” linking the mountains with an accessible and regenerated metropolitan river park.

For this, we considered demarcating a topographical line above which urbanization would be banned—similar to Santiago de Chile’s approach—to enhance water security through natural infiltration and delay in the middle slopes or piedemonte. 35 We learned that Monterrey’s municipality is already considering a swap program to move homes from these middle slopes. 36 We mapped the water footprint of both industry and housing and proposed policies to tax industries based on their virtual water and workers’ water use. This could promote higher density and direct

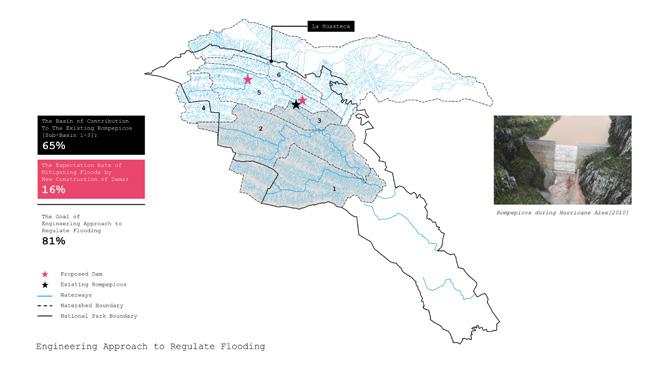

capital input toward watershed conservation. We also examined AECOM’s post-Hurricane Alex plan to reduce flood risk along the Santa Catarina River only understood as a mobility corridor, noting its lack of a regenerative approach to the river as an accessible urban ecology. Based on Monterrey’s original water blueprint, we explored the possibility of circular livelihoods along a regenerated river instead.

Rather than tackling problems in isolation, our spatial framework aimed to integrate all the above actions to enable Monterrey to achieve liquidity in both environmental and socio-economic terms.

Could this framework be the Santa Catarina River watershed?

4. Flowing Commons: The River Santa Catarina as a Climate Resilience Framework

As we explored Monterrey’s hydrological challenges more deeply, it became increasingly clear that balancing this fast-growing metro region with its water cycle and ecosystems towards water security could start by policies to constrain unsustainable growth, in tandem with the regeneration of all its riverine soils and landscapes. Instead of waiting for the next crisis, the government should proactively enhance the ecological regeneration—when feasible—of its original water blueprint. We are certain that this new spatial framework re-connecting the mountains across the watershed with the river valley can improve ecosystemic health and water security, ultimately bringing liquidity back to the metro-region.

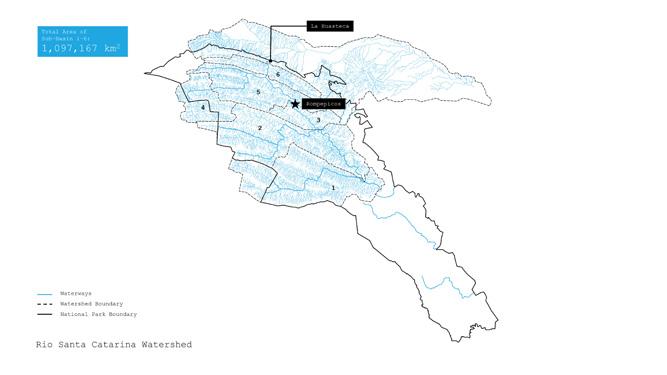

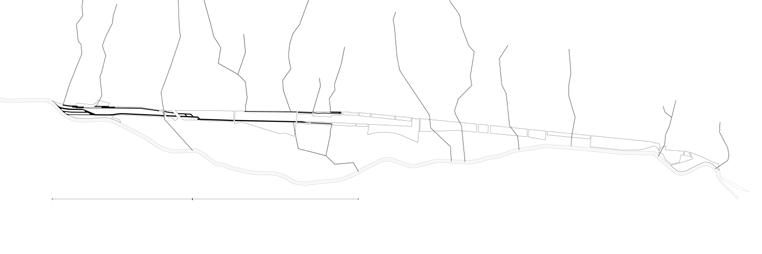

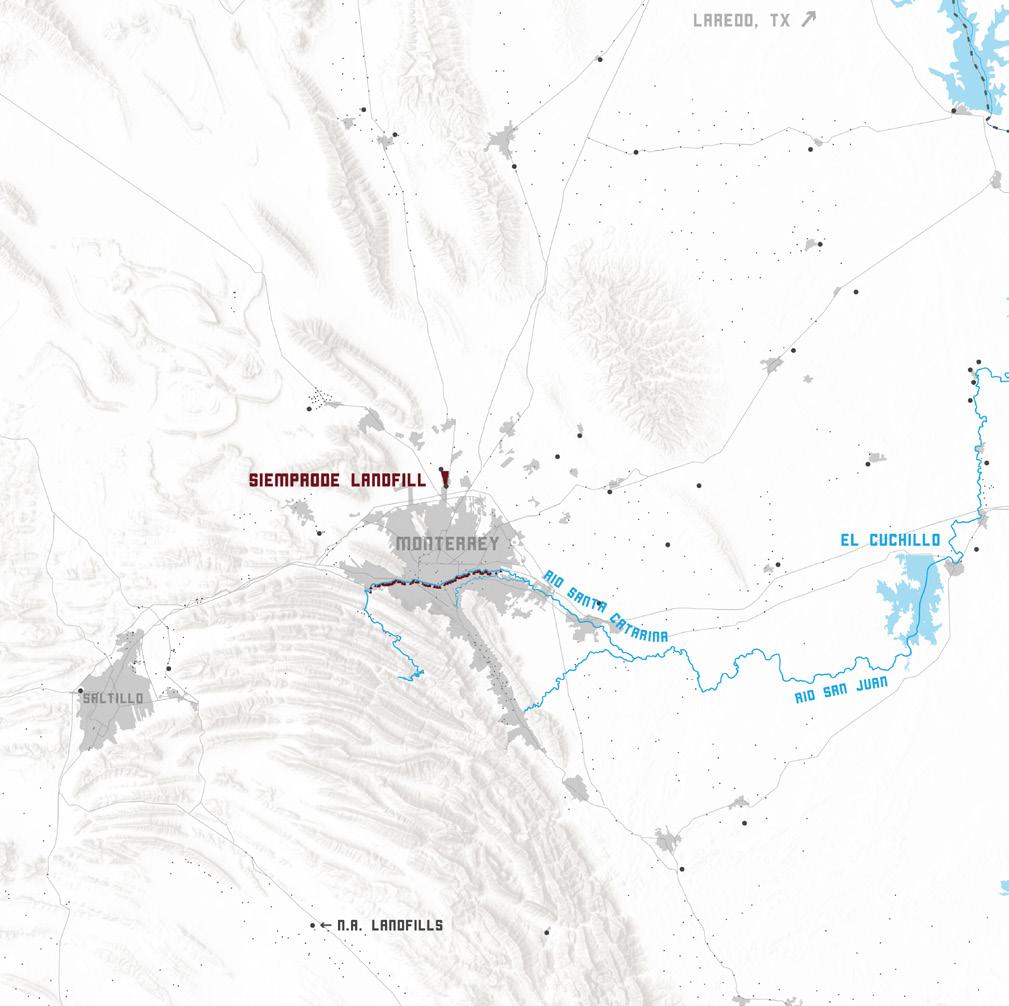

Among this riverine network, the Santa Catarina River stands out for its importance in water security and flood risk reduction as well as for being the most visible part of Monterrey´s extreme fluctuation from drought to flood, linking physically the Cumbres mountains with the metropolis. Flooding has been linked to the Santa Catarina, its Santa Lucía Stream and Ojo de Agua (a spring) since the city’s founding. This flooding vulnerability is increased by its location at the eastern edge of the Sierra Madre Oriental range, source of 90% of Monterrey´s water, and the river´s basin. Due to its seasonality and water overexploitation, the water of the Santa Catarina is often invisible for most of the year, which promotes floodplain urbanization and heightens the vulnerability to catastrophic floods in return. In a warmer and wetter hydrosphere, the riverbed receives water from hurricanes and tropical

storms which drains rapidly through the 1,921.5 km² (192,150 hectares) of the Cumbres National Park canyons and the impermeable urban surfaces of asphalt and concrete.

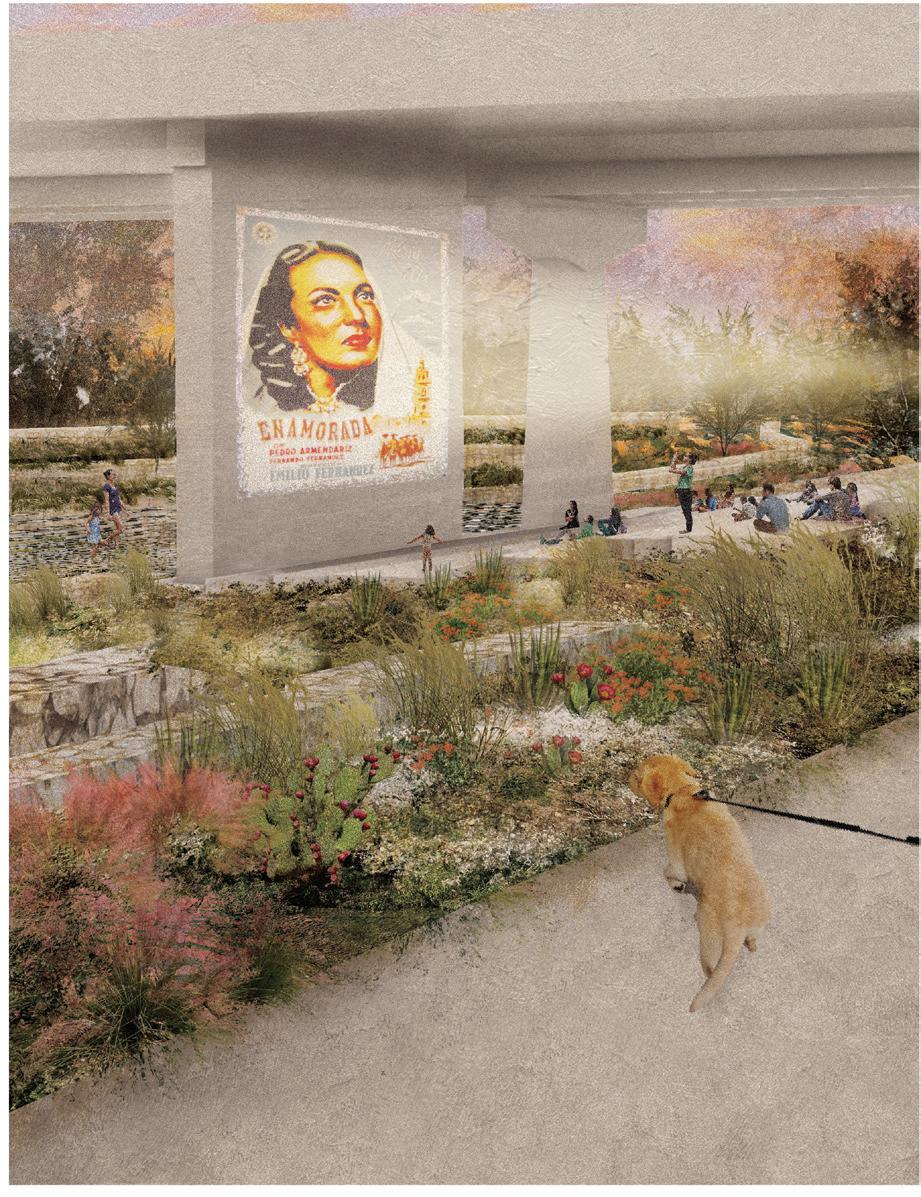

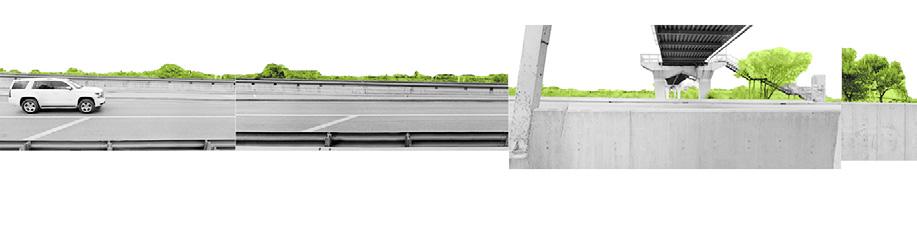

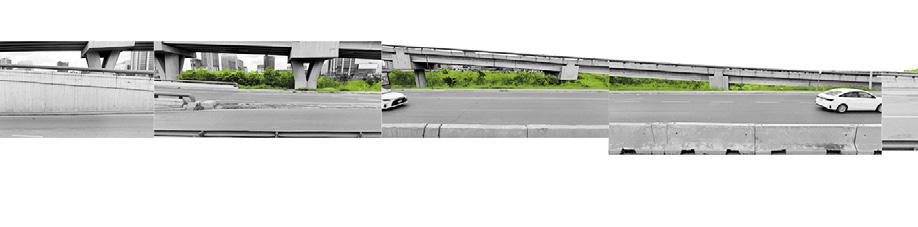

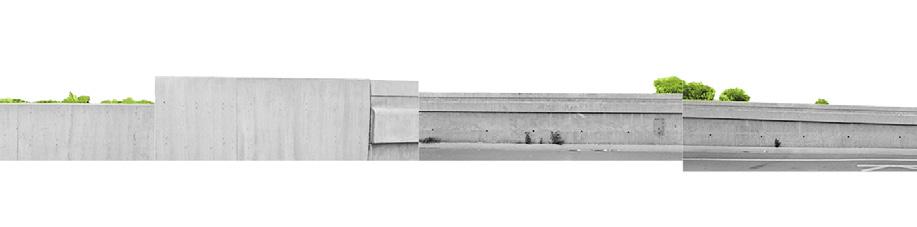

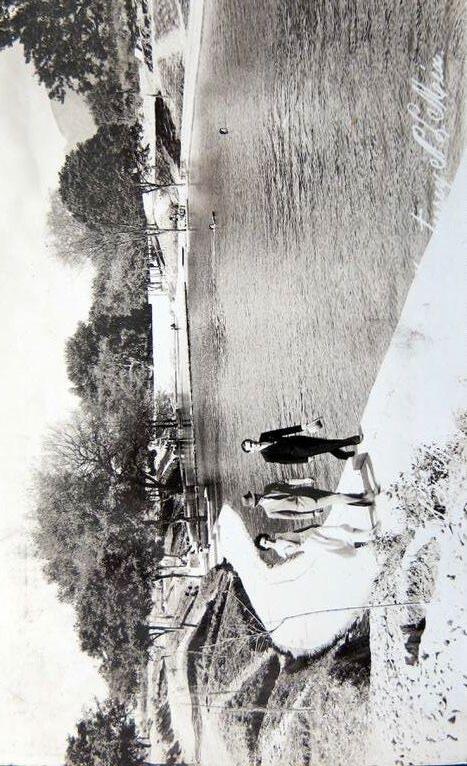

While it remains invisible as a mobility and flood control channel for several months or years, the Santa Catarina periodically bursts with water during hurricanes and tropical storms, reminding citizens of its liquid nature. When dry, the riverbed forms part of the living memories of contemporary Regiomontanos serving as a public space where they have learned to drive, play football, golf, or attend events like circuses, concerts, or visits from Pope John Paul II. (fig.5) However, since its destruction during Hurricane Alex in 2010, the river has evolved into an unmanaged, naturalized riverbed—altered more recently by tropical storms Alberto and Hurricane Beryl in 2024. Additionally, this urban wild is inaccessible and is constrained by 10-lane asphalt highways on both sides. Sadly, studies show that the river receives a high number of pollutants from illegal discharges and dumping sites which are washed away when it floods.37 So, accessibility to the river is not enough.

The future of the Santa Catarina River was extremely contested in the summer of 2023, when, fearing a potential shift to El Niño and the catastrophic hurricanes associated with it, the government began removing all trees from the Santa Catarina riverbed. However, the action was halted by a court decree following citizen mobilization conforming the collective “Un Río en el Río.” 38 They had already opposed the construction of an elevated

viaduct “segundo piso” on top of the existing highway—further impeding a pedestrian connection with the river. While cities like Boston have already paid 10.4 billion dollars back in 2007 to tear down these failed infrastructures this unnecessary mega-project is still being considered by Monterrey’s government these days and is experiencing the same opposition.

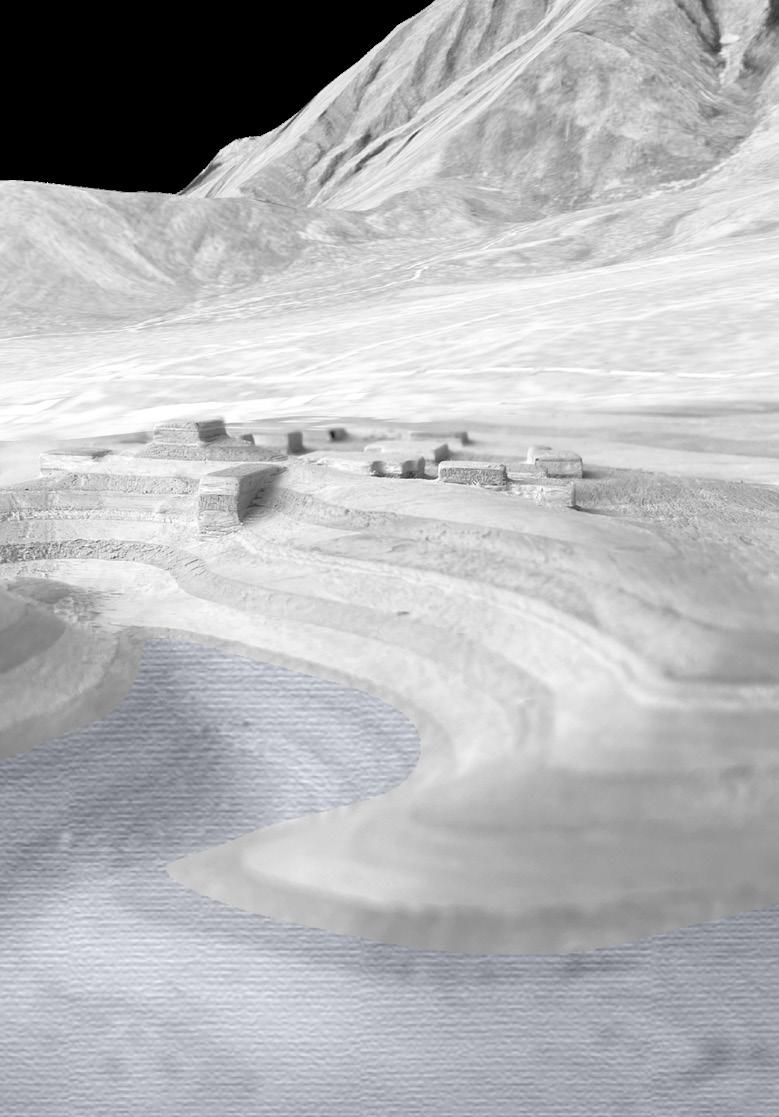

Later that October of 2023, during our first studio visit, the government announced plans to construct two additional spike dams in Cumbres National Park to reinforce the existing Rompepicos and to reduce the impacts of extreme flooding events. Some fear that these dams could bring a sense of security, promoting in turn the encroachment of the riverbed even further. Besides, more communities will be uncommunicated during floods.

So, in our search of “With Whom?” we started to see that strengthening our collaboration with Terra Habitus, with its significant capacity in nature conservation; as well as with the Tec of Monterrey, itself connected to industry and the government; the UDEM school of design, already working on a 50 hectares pilot at the Santa Catarina riverbed at San Pedro Garza García; and several forceful citizen groups, were collectively a forceful way to push the political will towards the design-led regeneration of Monterrey’s riverine landscapes in the years to come, and with it addressing an important front toward water security.

Would we be able to transform the Santa Catarina into a Flowing Commons?

5. One Vision. Three Regenerative Actions. Seven Principles Towards Resilience

“All rivers have fundamental rights and are living entities that possess legal standing in a court of law. Among other rivers have rights to: a) flow, b) perform essential functions within its ecosystem, c) be free from pollution, d) to feed and be fed by sustainable aquifers, e) regeneration and restoration.”

Universal Declaration of River Rights 40

Monterrey is far from recognizing the Santa Catarina as a living entity with fundamental rights. Santa Catarina is not yet a legal person, a subject of rights, a living person, or a living being or entity. 41 Yet, all the eco jurisprudence written by “The Rights of Nature” is already redrawing the rights of our environment globally—as one can explore in their monitor.42 More important, we understand that promoting those rights will promote hydrological resilience for Monterrey´s metropolitan region. And so, we translated them spatially to draw our vision. In a similar manner to Robert McFarlane´s recent book Is a River Alive?, written “with the rivers” who run through its pages, our vision was drawn “with the Santa Catarina River” for this water body and corresponding arborescent network to become a Flowing Commons, able to sustain life and those of the creatures than depend on its water. 43 An if well is true that due to overexploitation this river has diminished its water flow, Regios should learn that the river is the visible sensor of their water balance and cycle.

According to environmental lawyer Antonio Azuela, who joined our second symposium in Monterrey, a way to implement actions spanning the 1,200 to 1,500 hectares of Santa Catarina´s headwaters and the urban riparian corridor would be through the transfer of “custody” from the State to the municipalities:

“Streams, lakes, and lagoons that are national property, as well as the federal zone of hydraulic infrastructure located within the boundaries of populated areas … The Commission may enter into agreements with the governments of the states, the Federal District, or the municipalities for the custody, conservation, and maintenance of the federal zones referred to in this article.”

Article 117. National Water Law 44

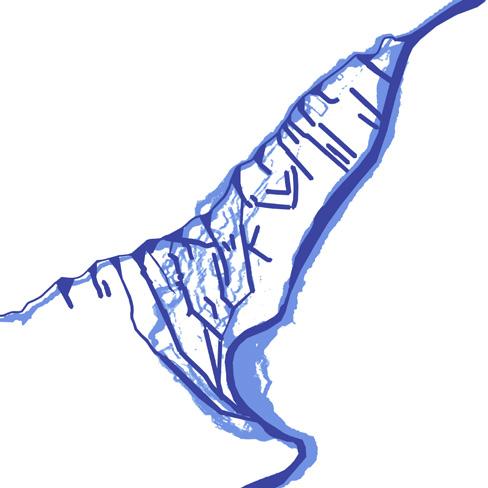

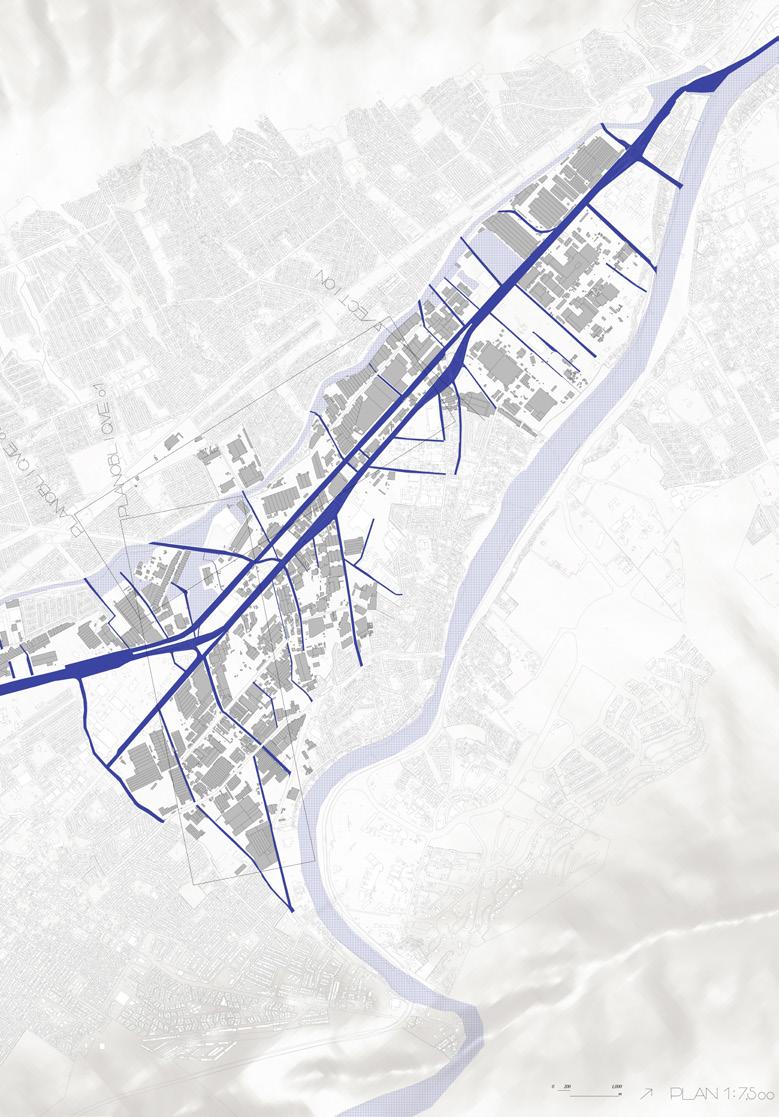

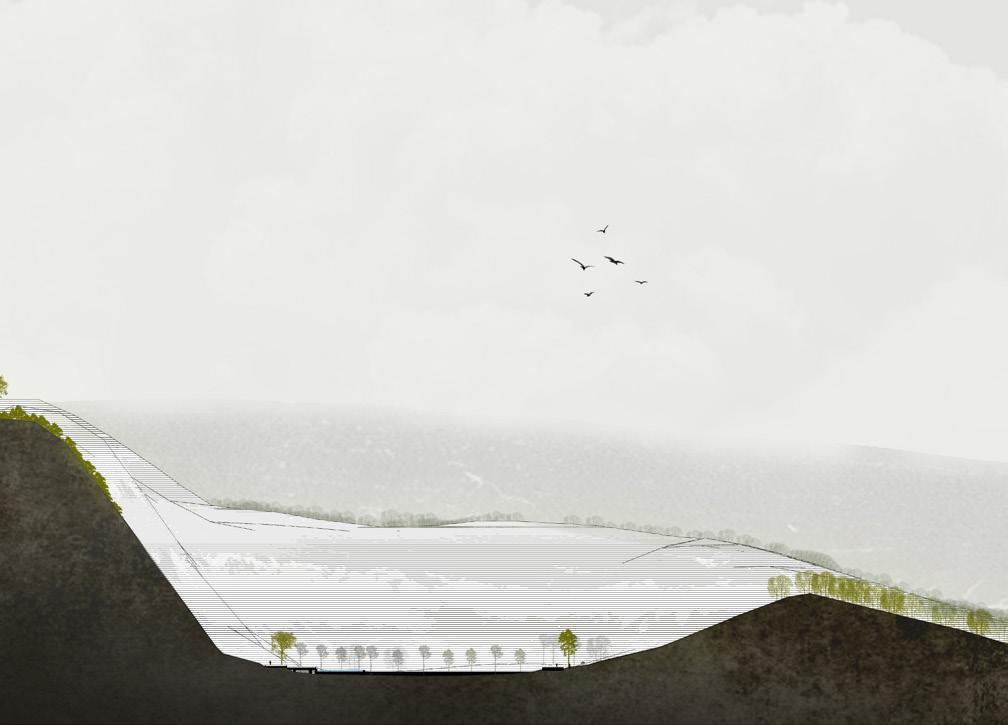

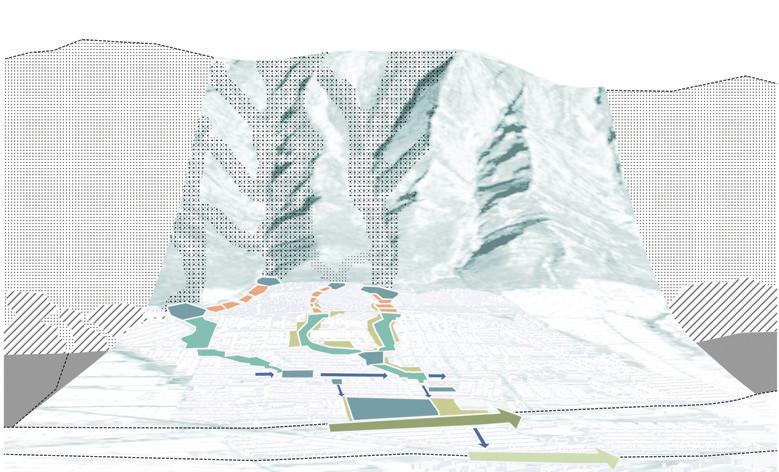

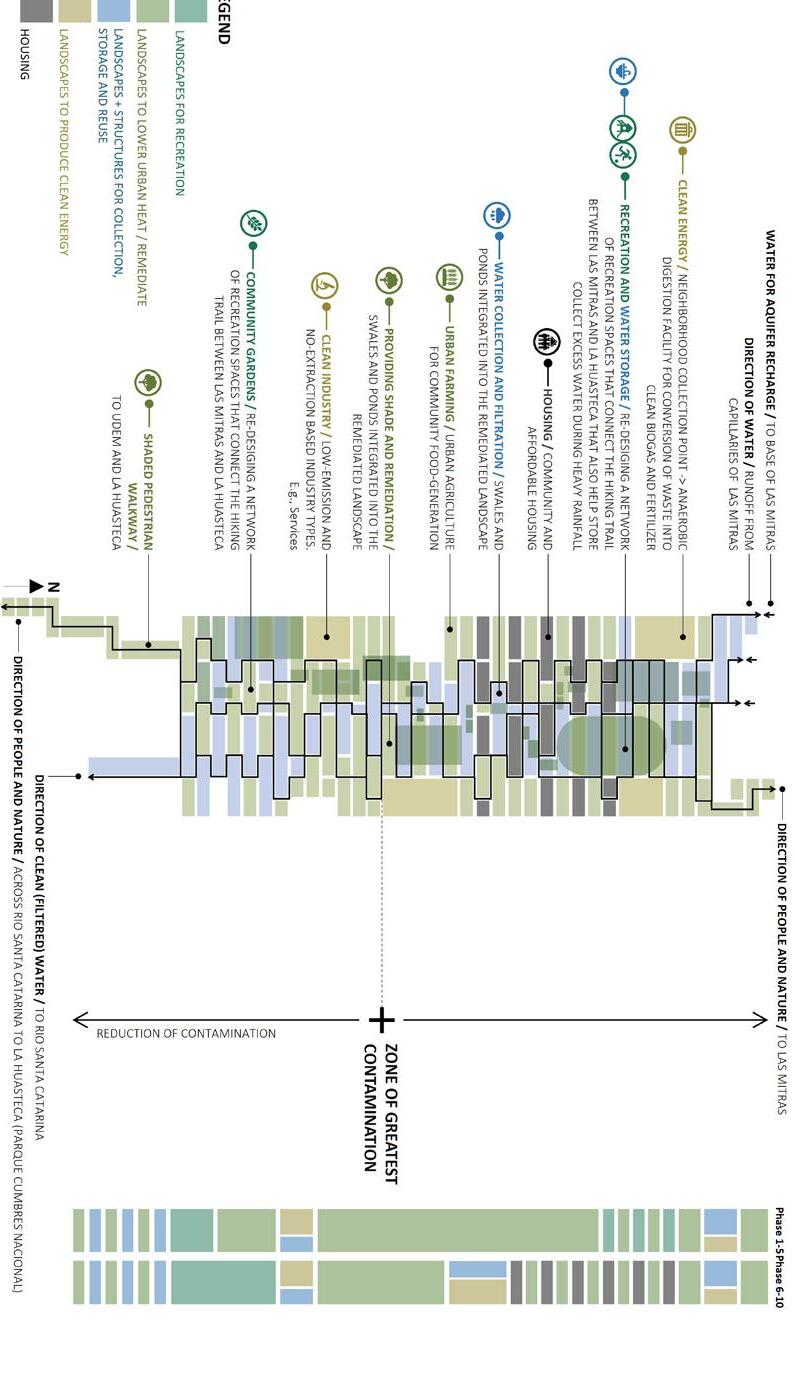

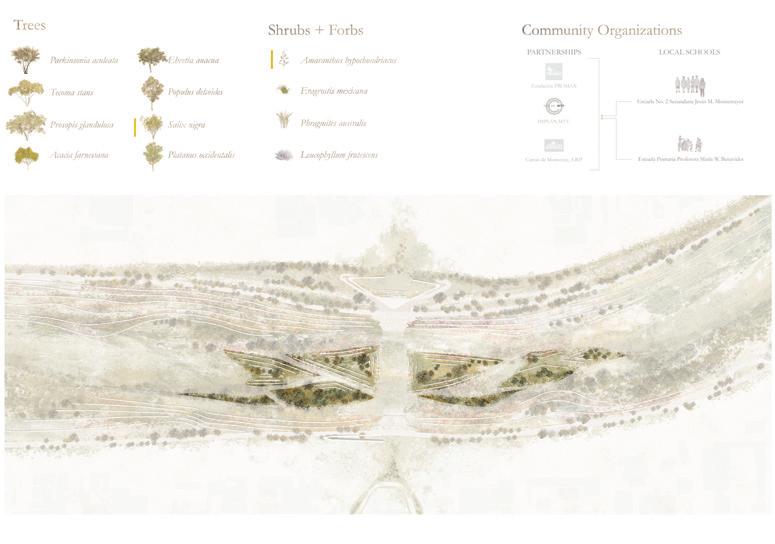

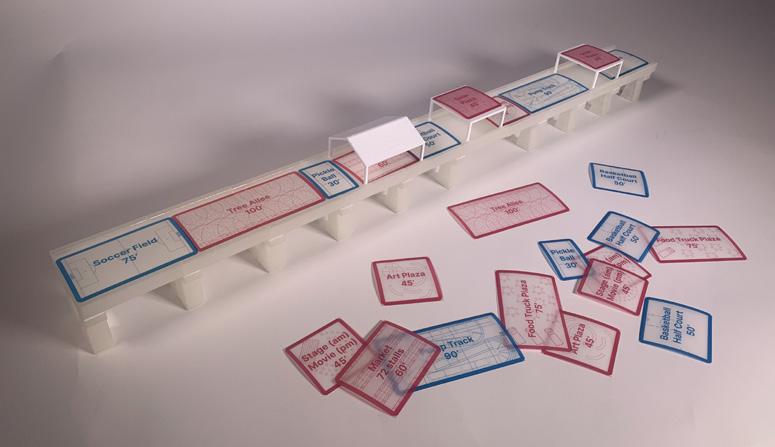

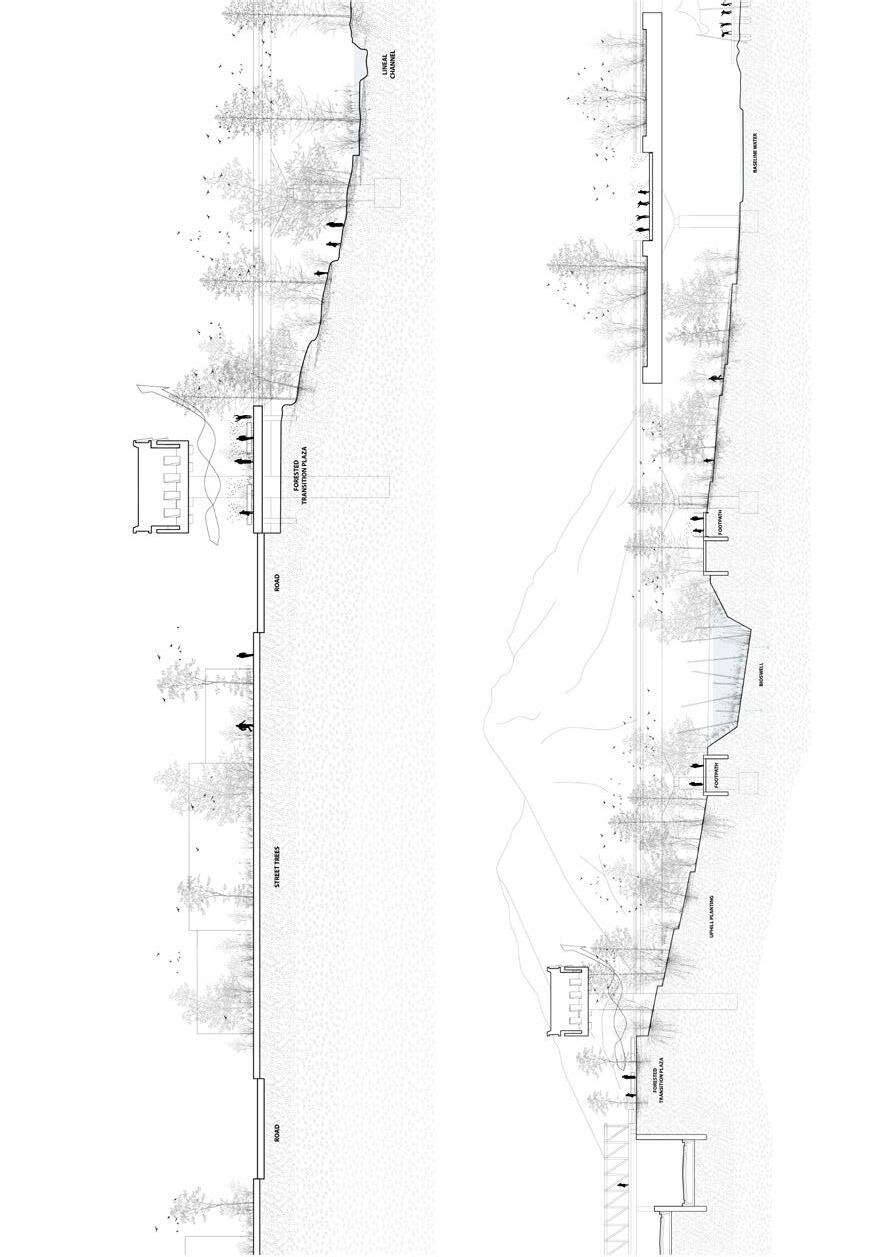

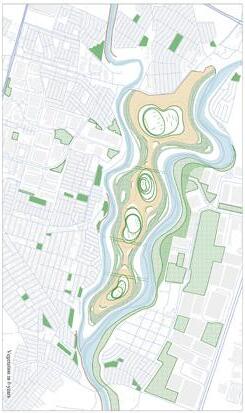

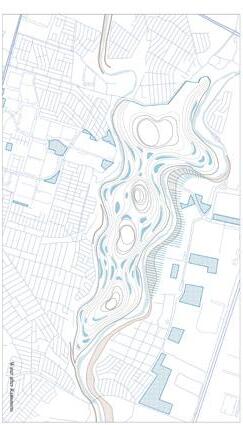

Flowing Commons aims to enhance water security and climatic resilience for all living communities in Monterrey´s metropolitan region through nature-positive regenerative actions. It does so by establishing the Santa Catarina River watershed as a spatial framework for climate resilience to promote: 1) regenerative actions in the mountainous headwaters for natural water storage, infiltration, delay and flood reduction; 2) regenerative actions in the urban watershed to enhance blue capillaries or “cool-bio corridors” linking the mountains with an accessible and regenerated metropolitan river park (approx. 700 hectares of riparian corridor from Santa Catarina to Juárez); 3) and regenerative actions to reduce pollution and aquifer overexploitation overall. For this to happen the dual nature of the river must be addressed, its mountainous and urban condition, to understand how to regenerate their living or dormant soils to enhance the water cycle while bringing continuity along and across this riverine landscape and watershed. We learned from several cities that had successfully implemented projects to regenerate their main water bodies and or rivers, including: The Trinity (Dallas), Buffalo Bayou (Houston), the Seine (Paris Olympics), Los Angeles (LA), Mapocho (Santiago de Chile), Chattahoochee (Atlanta), Besós (Barcelona), Manzanares (Madrid), Medellín (Medellin), Yamuna (New Delhi), Rhine (The Netherlands), and Wadi Hanifa (Riyadh). These case studies were helpful to understand the actors, visions, values, actions, timelines and participatory processes behind them (see case studies p 36).

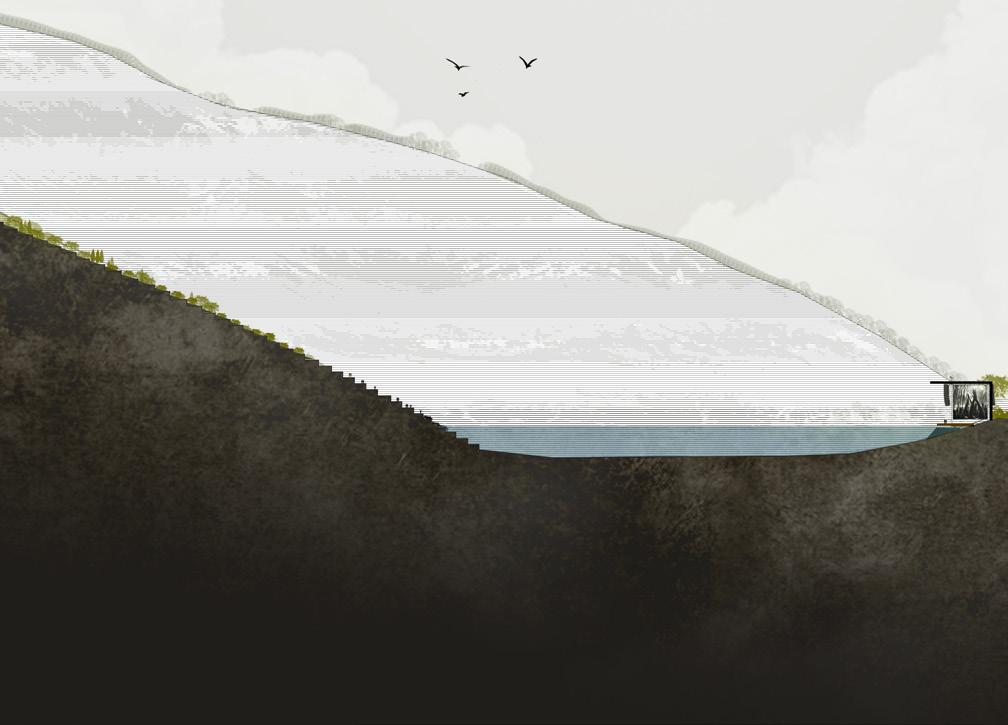

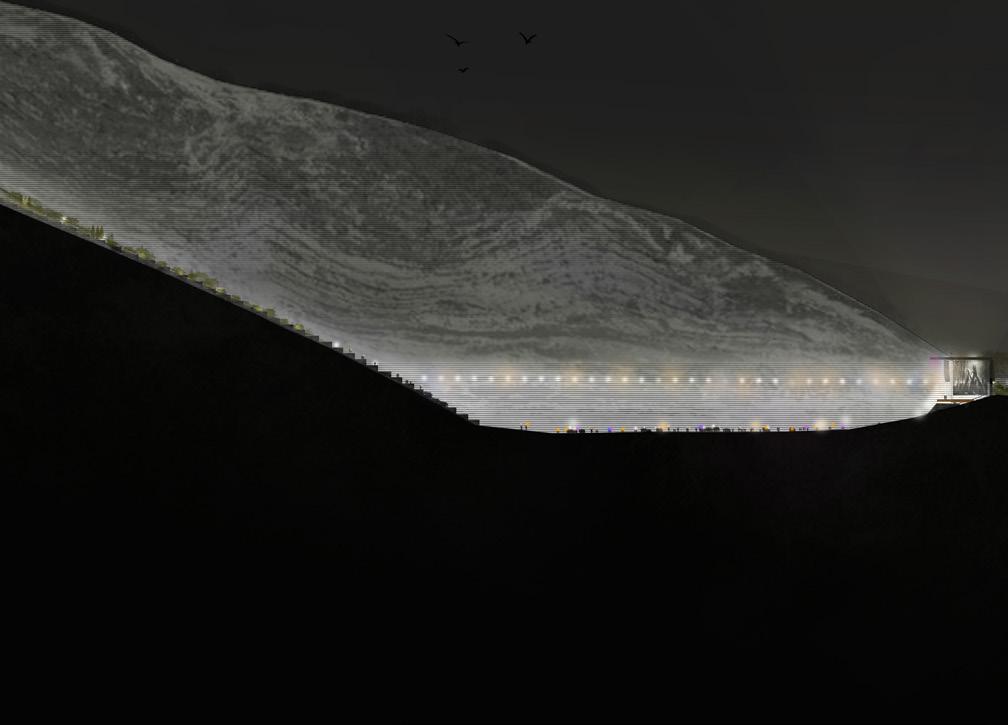

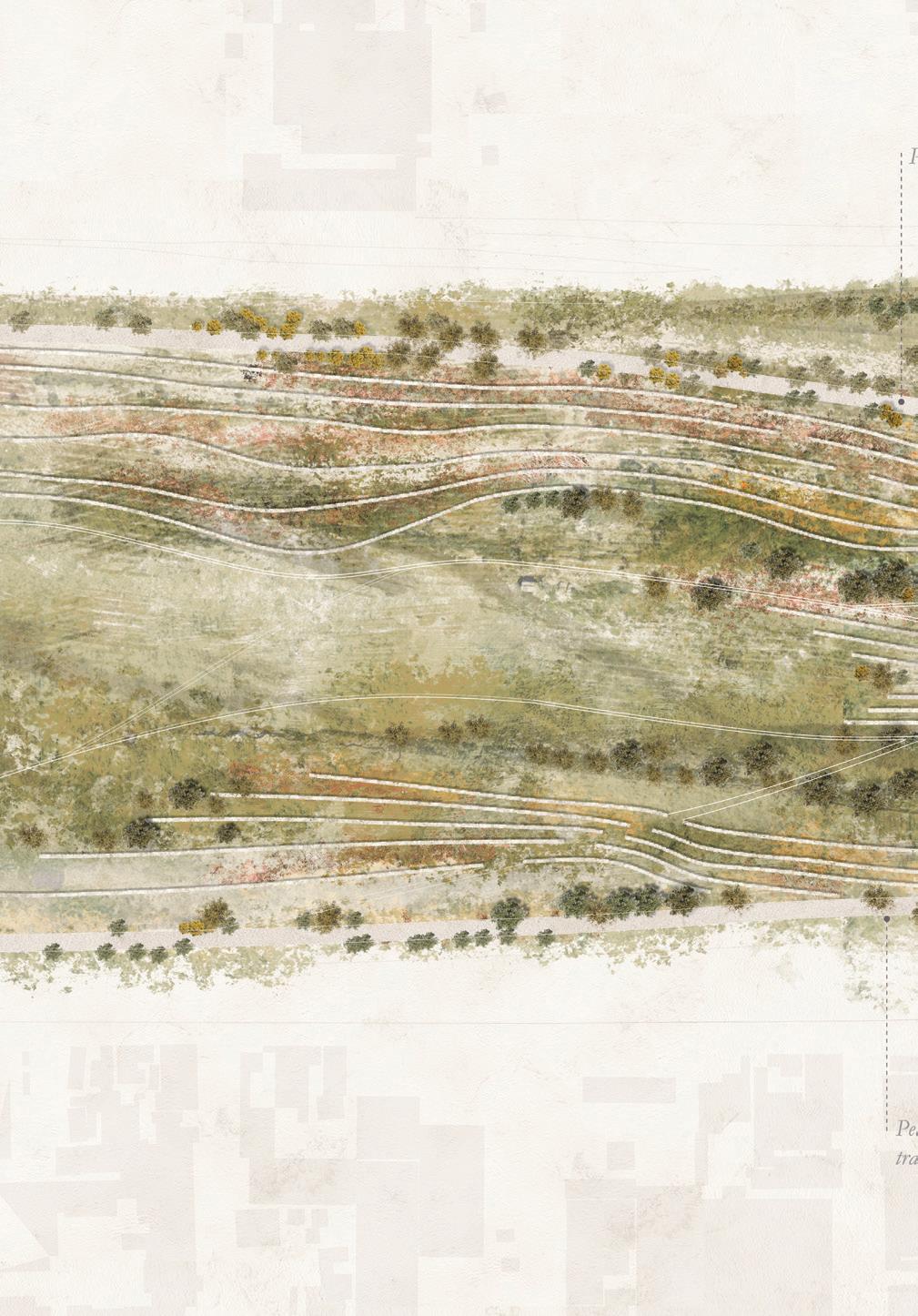

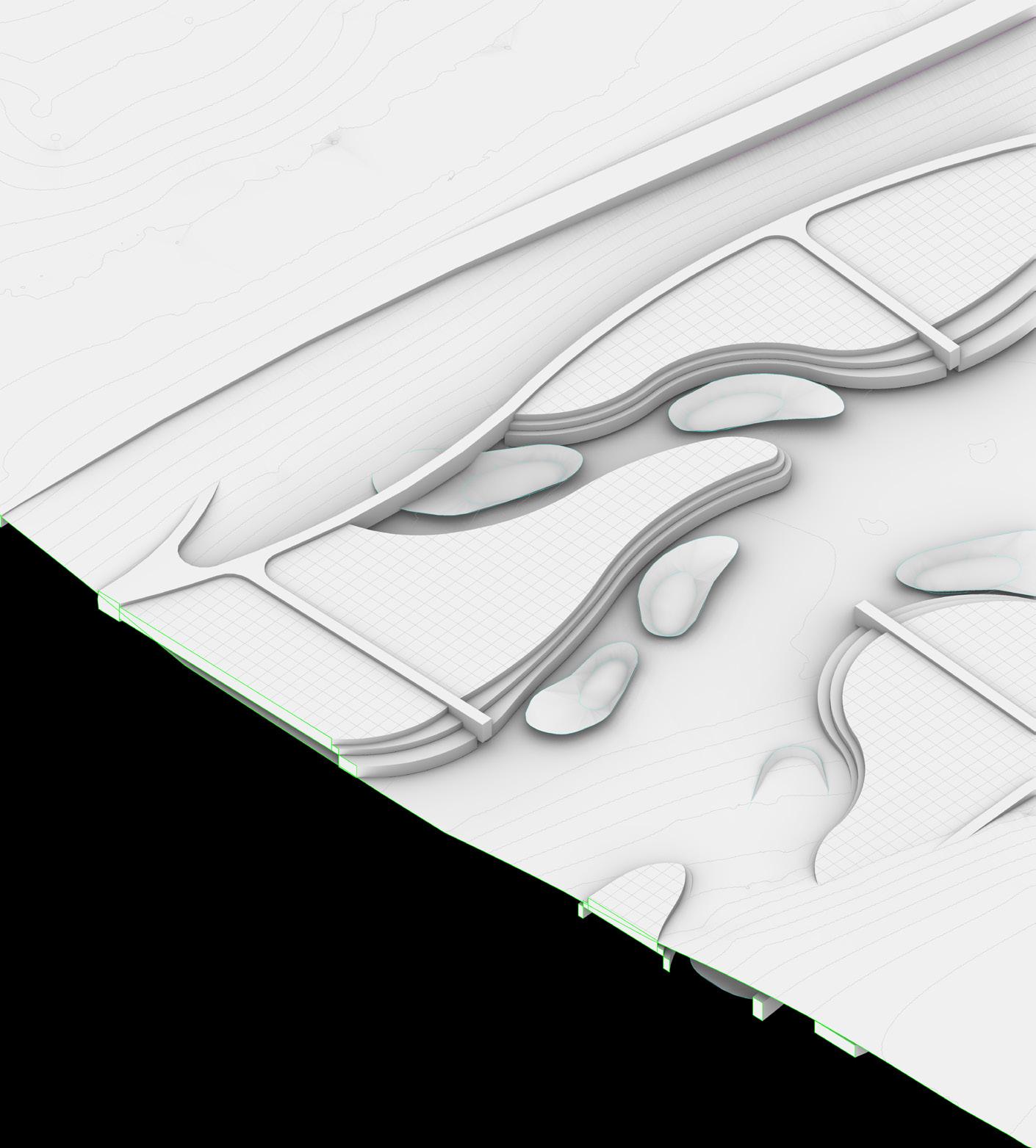

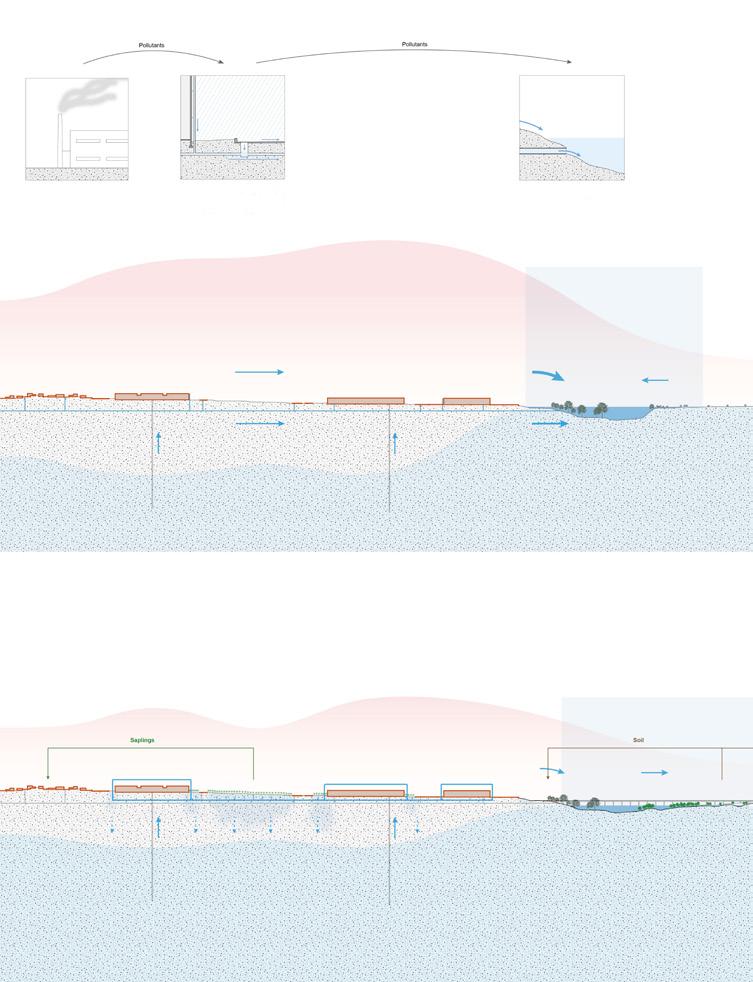

In the river’s uplands and headwaters, at the Cumbres National Park, we explored more distributed and decentralized process-based strategies toward flood reduction. Not all upland storage is equally beneficial. Traditional methods, such as dams, reservoirs, and concrete canals, have been used for years to manage upland water storage by slowing the flow of peak water. However, these structures often become clogged with silt and offer minimal benefits to the natural environment, as most vegetation and wildlife cannot access the stored water.

A more sustainable alternative is Distributed Natural Storage (DNS), which stores water throughout the upland landscape in numerous natural water stores like soil, shallow aquifers, and wet meadows. 45

This decentralized approach leverages the natural features of a healthy ecosystem to slow down water rather than stop it completely. By allowing water to infiltrate the soil and be gradually released, DNS reduces the risk of floods and enhances water supply reliability over time. This approach is not only cost effective compared to heavy infrastructure but also benefits wildlife and vegetation, making the ecosystem more resilient to challenges like wildfires. Storing water in soil, wet meadows, and shady riparian areas and wetlands reduces the water’s erosive energy, but it also reduces evaporation, increasing aquifer recharge. The overall effect is of a more forested, more absorbent and aqueous mountainous landscape and National Park that is inhabited by farming communities that enhance water conservation and improve their livelihoods as result.

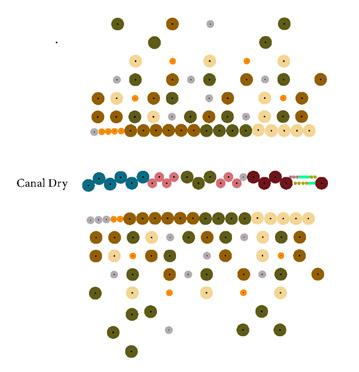

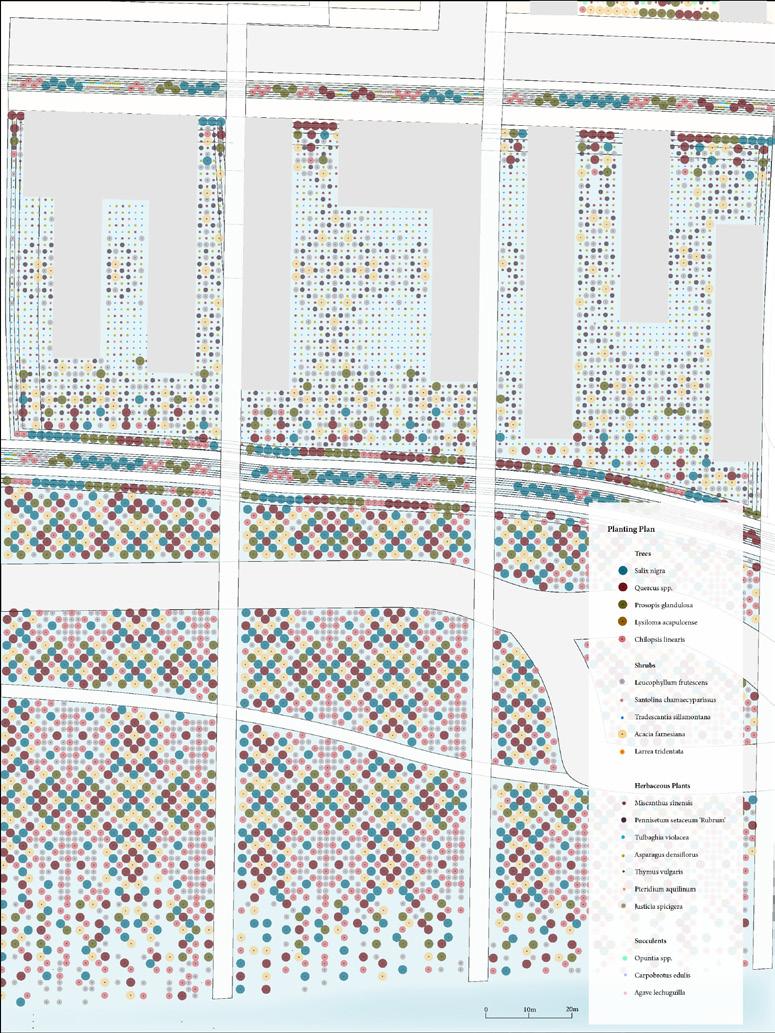

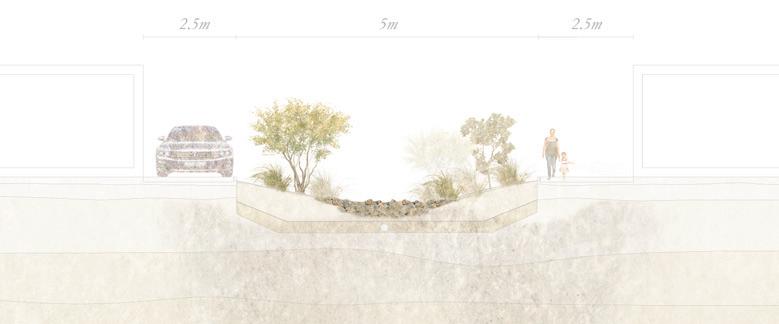

Recognizing the river’s significance under its legal status as a river in the custody of the municipalities, or a newly formed water metropolitan area, within the urban watershed, we are proposing a comprehensive accessibility and vegetation strategy to regenerate the Santa Catarina River, transforming it into a vital component of climate resilience and living nature within the city as a Metropolitan River Park. Additionally, under the broader framework of capillarity and urban forestry, this initiative aims to create a flowing commons that not only reduces flood and heat risk but also enhances the overall hydrological performance of the watershed. For this, our framework includes the careful selection and design of major streams, that as “cool biocorridors” will thread the adjacent mountains with the river or run in parallel to it. These blue threads will serve as essential pathways for wildlife, fostering biodiversity and ecological connectivity between urban and natural landscapes. By integrating these natural systems into the urban fabric, we seek to improve socio-ecological wellbeing, providing residents with cooler, livable and living spaces while promoting a healthier, more resilient environment for future generations.

Overall, for this to happen we need to promote a new water culture in Monterrey, one that departs from a mechanized conception of water as a commodity, to understanding water as a source of life. Urban citizens, industrialists and farmers will benefit from policies that enhance a more sustainable and less polluting way of benefiting from water. A Clean Water Act in Monterrey could promote such culture. In the mountains, soils could do the work of filtering, cleaning and storing this water in the

aquifers, safeguarding it from fast evaporation in the open air. In the urban area, high-quality reclaimed water produced in Community Water and Energy Resource Centers or CWERCs by district, could start a process of clean water recirculation that would expand the capacity of aquifer provision in return. 46

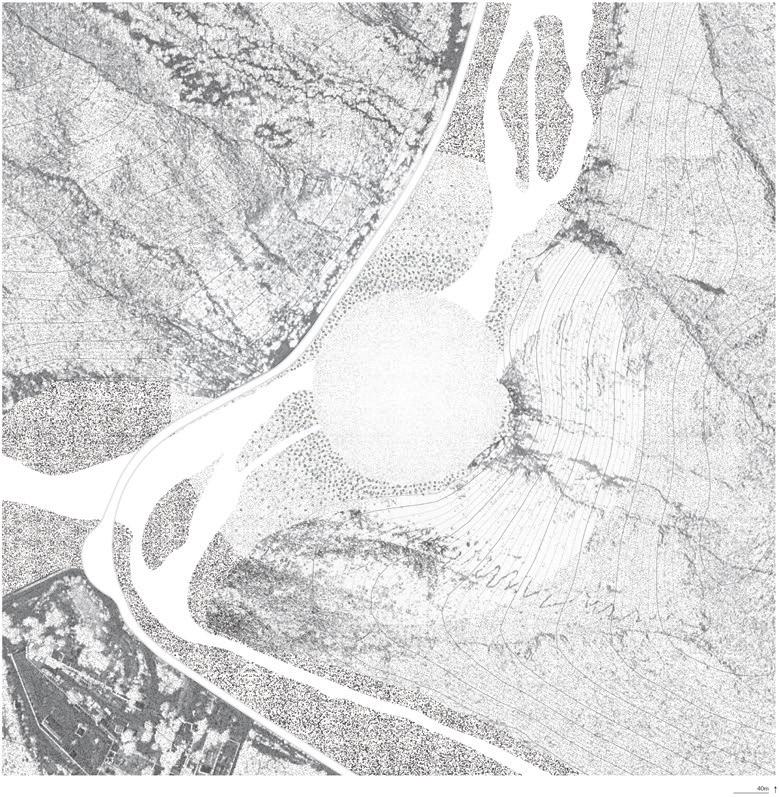

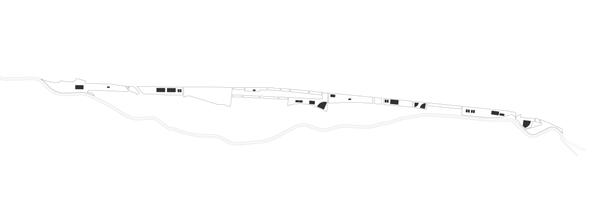

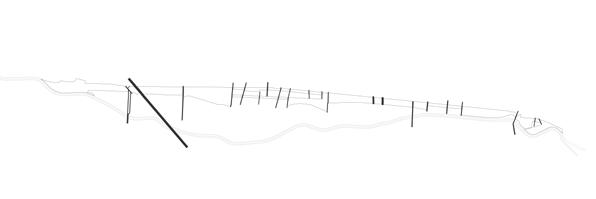

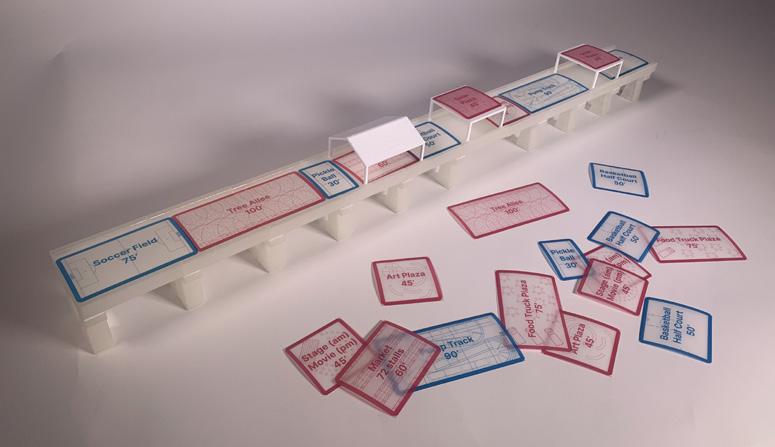

The extended scale of a project dealing with water scarcity and abundance in an urban region, but through the lens of an urban river, requires an ability to telescope from macro to micro scales. Conceptualizing the Santa Catarina as a flowing commons requires multiscale and multi-disciplinary thinking. Out of our analysis we were able to characterize different areas of intervention in relationship to their geography, land use, urbanization status, their water regimes and the pollution of their soils. The first of these areas or micro-watersheds, stretches from the Rompepicos lamination dam to the Huasteca Canyon in Cumbres National Park; the second is the Huasteca Canyon, together with its urban door and river mouth into the metropolis; the third is Las Mitras’ southern watershed with its Obispo stream, its active or obsolete industrial fabric and its scarfed slopes; the fourth is along the Loma Larga and the Macro Plaza; a fifth comprises La Silla’s watershed by both Fundidora Park and the merging of La Silla and Santa Catarina rivers as sites of intervention. The joint exploration of case studies, the field work, and joint workshops at Monterrey’s Tec allowed us to formulate a set of values that could serve as guiding principles of the individually designed interventions that you will discover in this publication. These principles ensured that the plethora of individual design solutions will target the mutual goal of hydrological resilience in Monterrey. These principles, made manifest in the many design projects explored in this volume, are: 1) Visibility and invisibility: caring for water; 2) Ephemerality and recurrence: designing with floods; 3) Mutualism and reciprocity: effects beyond localized boundaries; 4) Capillarity and porosity: reclaiming water’s blueprint; 5) Circularity and recirculation: waste becomes source; 6) Connectivity and immersion: a living nature; 7) Equity and justice: everyone gains.

P1. Visibility and invisibility: caring for water. It is difficult to enhance an empathic relationship with a body of water, when its water disappears from months to years, only to return as a destructive flood. Destructive and deadly floods in 1909, Gilbert in 1989, Alex in 2010, and the most recent, Albert in 2024 stigmatized the Santa Catarina as alternately absent or all-too-present. It is time for an empathic return to the Santa Catarina as a source of life and liquid wealth, and almost all projects pursue this aim. The currently accepted culture of overscaled concrete structures to reduce water impacts, especially in the mountains, must shift, as this culture promotes a paradoxical urbanization in the National Park. The invisibility of natural storage could instead enhance water security and reduce encroachment overall. The projects that respond directly to principles of invisibility are: “Incognito Dams” and “From Visible to Invisible”.

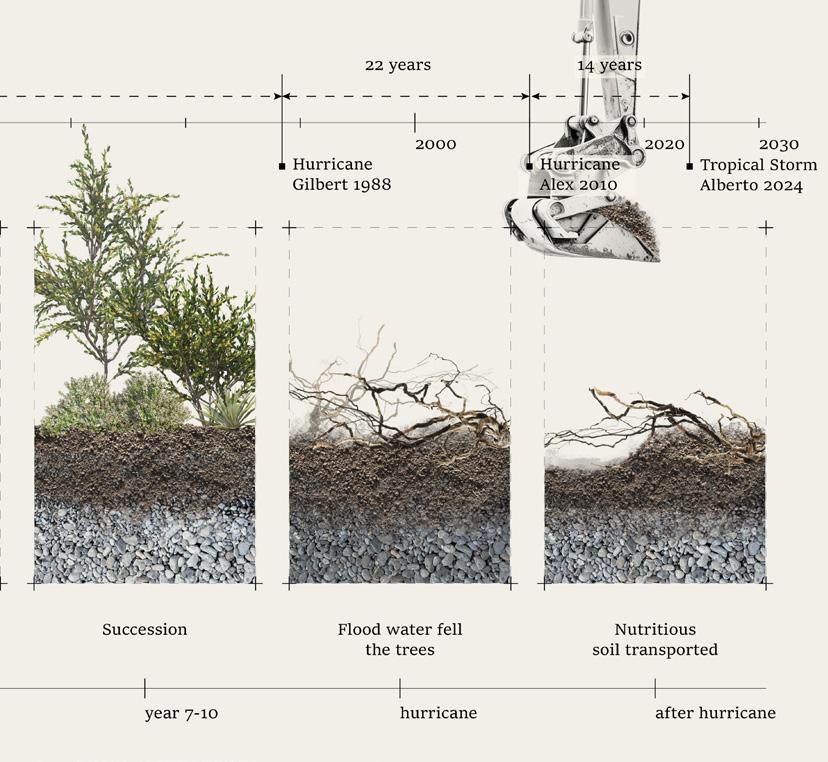

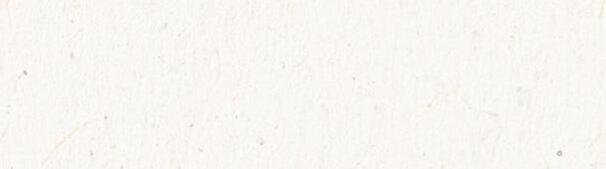

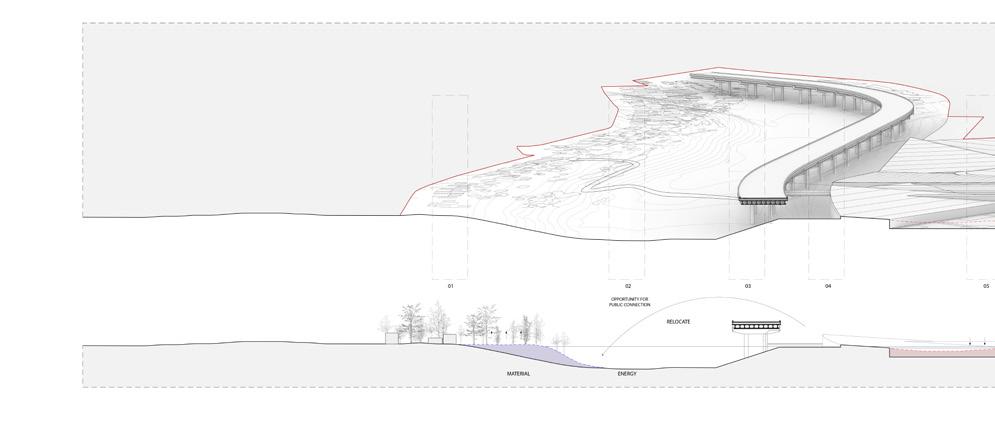

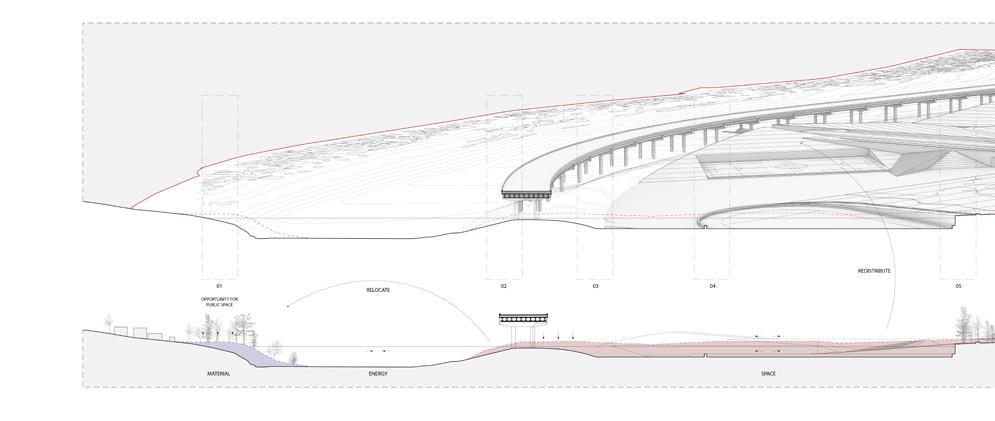

P2. Ephemerality and recurrence: designing with floods Water invisibility promotes the encroachment of anthropogenic activity into the riverbed and erases the necessary room for the river to perform its cycles naturally, including flooding. Instead of fighting and resisting floods, design should embrace the strength and dynamics of the flood as an opportunity for active regeneration. Even as they fill in reservoirs, floods are also moments of material movement and energy that could rebuild higher ground or regenerate riverine forest with deposited silt. Equally importantly, the ephemerality of the flood could be considered for planting strategies. Several projects: “Eroding for Higher Ground,” “Water Footprints,” “Erasing the Line While Flooding,” “Un Río de Arboles,” “From Two Dimensional to Three Dimensional,” design with floods to rebuild ecology.

P3. Mutualism and reciprocity: effects beyond localized boundaries. Water is a flowing, interconnected network without physical boundaries. Water is ocean, is air, clouds, rain, is above and below ground in an interconnected cycle. So, like the butterfly effect, actions in the mountains affect the ocean and vice versa. So too, every action accounts to improve the network, just as Monterrey’s water access is entangled with the US through transboundary agreements increasing its vulnerability to water security. Creating more natural reserves to enhance its aquifers is an intelligent strategy to pursue and the river will improve as result.

Projects such as “Reciprocal Futures,” “Rewilding for a Hydro-Social Commons,” “Santa Catarina Green Again,” and “Wasted Water” follow these principles.

P4. Capillarity and porosity: reclaiming water’s blueprint Water structure is arboreal. Just as trees have branches, root systems and veins, water expands infinitely to bring life and moisture to our territories. Soils are the medium for water to flow horizontally to enhance water bodies, in the case of clay, or to flow vertically through sand, to recharge aquifers. Focusing on the small, networked filaments of an urban watershed, rather than on the arterial quality of the river itself, as well as on the conditions of permeability and porosity of the soil is key to confronting the endless and impervious surface of sprawling Monterrey. The urbanization of the mountains should stop and protecting water veins where urbanized or daylighting creeks in other areas should follow. “Regenerating Capillaries,” “Obispo Unbounded,” “A Sublime Scar,” and “Santa Catarina Ojo de Agua” all address these principles.

P5. Circularity and recirculation: waste becomes source. Water is a circular system, but it is still unsustainably used once, in linear fashion, by the city. Very different from nature that recirculates water continuously, a metropolis like Monterrey still discards polluted water into the environment. Due to its recurrent flooding, water is seen as a threat, simply to be moved out of the city as fast as possible. Design for circularity in such a context needs to be capable of thinking about reuse, of creating loops around flows of resources moving from linear to metabolic, and to shift into a culture of finite resources where extraction should be limited. Circularity is especially critical when it comes to water. Projects that respond to the need of recirculation are “The Poetics of Circularity,” ‘Wasted Water,” “Industrial Aqua,” “A Sublime Scar,” and “Post Industrial Tapestry.”

P6. Connectivity and immersion: a flowing and cool living nature. Descending to the river to swim separates pre-industrial from industrial times. This quintessential act of descending and immersing ourselves in water, goes back to our original swim in amniotic liquid before being born. If a river is given the right to flow clean, we will recover our right to flow with it. This immersion could be possible in the rainy season in Santa Cata -

rina’s headwaters, and projects like “Water Footprints,” “Eroding for Higher Ground” or “From Invisible to Visible” all have swimming in mind. That immersion, into a cool riverine forest, could also be possible in the urban river by designing with the flood in mind to reforest the borders. This connectivity will oblige mobility to change: there is no question that urbanization and mobility should tend towards compact urbanization and collective means of transport in Monterrey—if Regiomontanos were to push for their right to extend their lives and those of new generations. “Riverine Microclimates,” “Bridging Monterrey Reaching the Río Santa Catarina,” “El Gran Bosque de Río,” “Río de Árboles,” and “La Plaza Verde” respond to these principles.

P7. Equity and justice: everyone gains. Monterrey faces severe climatic impacts and deep social inequality. Rethinking its relationship with the river offers a chance to reconfigure ecological systems in ways that prioritize marginalized communities by reconnecting them first and then turning the river into a source of resilience. Moreover, the regeneration of the urban river for denser, more just urban development would counter sprawl that burdens low-income residents with long, costly commutes and limited services. More important, a regenerated Metropolitan River Park could be accessible to all citizens along the 52 Km from Rompepicos to Guadalupe. Projects responding to these principles were: “El Río Vivo,” “Río de Árboles,” “A Sublime Scar,” “Obispo Unbounded,” “Wasted Water,” “Bridging Monterrey.”

Like Macfarlane in Chennai, we went to Monterrey

“in search of the ghosts, monsters, and angels … the ghosts of rivers that had to be killed for this city to live. The monsters that these rivers take as terrible forms when they are resurrected by cyclones. The angels who watch over the lives of the rivers where they survive, and those who seek to revive those who are dying.”

Robert Macfarlane

47

The Santa Catarina River and its capillary network is a ghost in some parts, and it definitely returns like a monster from time to time. There are many angels taking care of this ghost and there is no doubt that they will continue fighting to keep it/him/her alive. It is my hope that these lines can help all those good angels. Monterrey stands at the edge of being able to break its Sisyphean water cycle of repeated fast drainage and repumping back to the city. Of continuous expensive reconstruction after flooding events. Wiser water care through hydrological regeneration could bring the city beyond Sisyphus to a more restorative, sustainable era in which Monterrey becomes a healthier ecosystem with retained moisture, cooler environments, that are more environmentally just. The Santa Catarina River is the key to life in a healthier environment and our designed visions could be critical to bringing this new era to fruition. (fig.6)

1. Albert Camus, The Myth of Sisyphus and Other Essays, translated by Justin O’Brien. (New York: Vintage Books, 1991) Originally published as Le Mythe de Sisyphe: [essai sur l’absurde] (Paris: Gallimard, 1942)

2. A. Park Williams, et al. “Rapid Intensification of the Emerging Southwestern North American Megadrought in 2020-2021.” Nature Climate Change, vol. 12, no. 3 (2022): 232–34. (Link)

3. See: Maria Abi-Habib et al, “Mexico’s Cruel Drought: Here You Have to Chase the Water.” The New York Times, Late Edition (East Coast), August 3rd, (2022)

4. Richard Connor & Michela Miletto, The United Nations World Water Development Report 2023: partnerships and cooperation for water; executive summary, (Peruglia: Unesco World Water Assessment Program, 2023) (Link); see also: IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change): Summary for Policymakers. H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.), Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Geneva, IPCC, pp. 1–34. www. ipcc.ch/report/ar6/syr/downloads/report/ IPCC_AR6_SYR_SPM.pdf

5. Mesfin M. Mekonnen & Arjen Hoekstra, “Four billion people facing severe water scarcity,” Science Advances, 2 (2) (2016). (Link)

6. Richard Connor & Michela Miletto, Idid.

7. WMO. (2022) WMO Air Quality and Climate Bulletin. Geneva

8. CRED (Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters). 2022 Disasters in Numbers. (CRED, 2023) https://reliefweb. int/report/world/2022-disasters-numbers.

9. UN-Water. Summary progress update 2021: SDG 6 – water and sanitation for all. https:// www.unwater.org/sites/default/files/app/ uploads/2021/12/SDG-6-Summary-Progress-Update-2021_Version-July-2021a.pdf

10. Ibid.

11. Richard Connor & Michela Miletto, Idid.

12. Maria Kaika, ‘Don’t call me resilient again!’: the New Urban Agenda as immunology … or … what happens when communities refuse to be vaccinated with “smart cities” and indicators. Environment and Urbanization, 29(1), (2017), 89-102. https://doi-org.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard. edu/10.1177/0956247816684763

13. Liquidity understood as capacity to cover current liabilities.

14. Harvard GSD Spring 2023 Seminar: https:// www.gsd.harvard.edu/course/resilienceunder-new-water-regimes-the-case-ofmonterrey-mx-day-zero-spring-2023/

15. Harvard GSD Option Studio Fall 2023: AQUA INCOGNITA: Designing for extreme climate resilience in Monterrey, [MX] ( https://www.gsd.harvard.edu/ course/aqua-incognita-designing-for-extreme-climate-resilience-in-monterrey-mx-fall-2023/); Harvard GSD Option Studio Fall 2024: AQUA INCOGNITA IV: Designing for extreme climate resilience in Monterrey, [MX] (https://www.gsd.harvard. edu/course/aqua-incognita-iv-designing-for-extreme-climate-resilience-in-monterrey-mx-fall-2024/)

16. Find Roberto Ortiz Giacoman’s work here: https://www.robertortizphoto.com/

17. Find Alejandro Cartagena’s work here: https://alejandrocartagena.com/

18. David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies Spring 2023 Water +H2O Conference. https://drclas.harvard.edu/event/ mexico-h2o-challenges-reckonings-and-opportunities

19. Lorena Bello Gómez, “Critical Zones: On Liquid Disappearance, Aquifers, and Climate Justice. Aqua Incognita: Deciphering and Reimagining Liquidity in the Mexican Altiplano (Cambridge, US: Harvard Graduate School of Design), 10-25.

20. Co-organizer: Rubén Segovia (MArch II’17) in 2023, and Rubén Segovia with Rob Roggema in 2024. Both symposia at added to this publication.

21. Alessia Kachadourian. Mapeo hidrogeológico de la cuenca río Santa Catarina. Evidencias en superficie de los sistemas de flujo regionales subterráneos del agua. 2023 (Monterrey: Terra Habitus)

22. Kate Linthicum, “Taps Have Run Dry in Monterrey, Mexico, Where There is Water for Factories but not for Residents,” Los Angeles Times, July 22 (2022)

23. Ismael Aguilar-Barajas, Dustin E. Garrick,Water reallocation, benefit sharing, and compensation in northeastern Mexico: A retrospective assessment of El Cuchillo Dam, Water Security, Volume 8, 2019, 100036, ( https://www.sciencedirect.com/ science/article/pii/S2468312418300403 )

24. For the problem in 2020 see https:// www.gob.mx/conagua/prensa/el-trasvase-de-la-presa-el-cuchillo-solidaridad-no-compromete-el-abasto-de-agua-para-la-zona-metropolitana-de-monterrey

; For the problem with Chihuahua see: https://www.texasstandard.org/stories/ texas-mexico-rio-grande-basin-water-reservoir-deliveries-chihuahua-state-treaty/

25. Data provided by Juan Ignacio Barragán during his Zoom presentation in the 2023 Spring seminar.

26. Hurricanes´ economic impact by NOA: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions/ events/

27. Ibid.

28. Anne W. Spirn, “Reclaiming Common Ground: Water, Neighborhoods, and Public Spaces.” The American Planning Tradition: Culture and Policy, edited by Robert Fishman. Washington, DC and Baltimore, MD: Woodrow Wilson Press and Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000, 297-313

29. Anne W. Spirn, “Rebuilding Urban Communities and Restoring Natural Environments.” Planning for the New Century, edited by Jonathon Barnett. Washington, DC: Island Press, 2001, 165-201

30. Roberto Ponce, Expansion Urbana de Monterrey Analysis. Published in: https:// www.expansionurbanamty.mx/ The population density decreased by 40% in the last 30 years. From 1990 to 2020, the population of the Metropolitan Area doubled, from 2.6 to 5.2 million inhabitants. During the same period, the urban footprint increased from 363 to 1,029 km², meaning it grew by 2.8 times. Instead of consolidating the already developed areas and densifying, we abandon the existing development to build in areas that are increasingly distant from the functional area of the city. While the center lost 263,558 inhabitants between 2000-2020 its peripheral municipality Garcia increased from 13,000 to 397,000 from 1990-2020.

31. SEMARNAT published the Management Plan in January 2023, while CONAMP declared the Cumbers National Park in 2000: https://www. dof.gob.mx/nota_detalle.php?codigo=5676308&fecha=03/01/2023#gsc.tab=0

32. Lorena Bello Gómez. Aqua Incognita: Deciphering and Reimagining Liquidity in the Mexican Altiplano (Cambridge, US: Harvard Graduate School of Design)

33. Link to Chipinque’s biodiversity program: https://www.chipinque.org.mx/biodiversidad; forestry: https://www.chipinque.org. mx/proteccion_forestal; research: https:// www.chipinque.org.mx/investigacion

34. Regiomontanos are people from Monterrey, Mexico.

35. Jorge Pérez Q. et Al. Estudio para la definición de áreas de protección natural y/o patrimonial, en el piedemonte Andino del sector oriente. (Universidad de Chile. Facultad de Ciencias Agronómicas. Laboratorio de Ecología de Ecosistemas, 2016)

36. Class presentation by urbanist Salvador Herrera (SPURS´23-25) in Fall 2023.

37. Martínez-Quiroga, G. E., De León-Gómez, H., Yépez-Rincón, F. D., López-Saavedra, S., Cardona Benavides, A., & Cruz-López, A. Alluvial Terraces and Contaminant Sources of the Santa Catarina River in the Monterrey Metropolitan Area, Mexico. Journal of Maps, 2021, p. 17(2), 247–256.

38. You can learn of the agenda and activities of “Un Río en el Río” in social media at #Unrioenelrio.

39. H Virginia Greiman, “The Big Dig: Learning from a Mega Project” ASK Magazine, 39, Apple Knowledge Services. NASA, July 15, 2020. https://appel.nasa.gov/2010/07/15/ the-big-dig-learning-from-a-mega-project/.

40. The Universal Declaration of Rights of Rivers can be found here: https://www. rightsofrivers.org/#declaration.

41. O’Donnell, Erin, et al. “Repairing Our Relationship with Rivers: Water Law and Legal Personhood.” A Research Agenda for Water Law, Edward Elgar Publishing, 2023, pp. 113–38.

42. Eco Jurisprudence Monitor site: https:// ecojurisprudence.org/dashboard/?map-style=political

43. Macfarlane, Robert. Is A River Alive? First edition., W.W. Norton & Company, 2025.

44. From 1994 to 2000, Antonio Azuela served as the Federal Attorney for Environmental Protection in the Mexican government.

45. See: Lancaster, Brad, and Joe Marshall. Rainwater Harvesting for Drylands and beyond. Volume 2, Water-Harvesting Earthworks. Rainsource Press, 2008; Peter Skidmore and Joseph Wheaton. “Riverscapes as Natural Infrastructure: Meeting Challenges of Climate Adaptation and Ecosystem Restoration.” Anthropocene, vol. 38, 2022, p. 100334

46. Look at our work with students in the Creating Environmental Markets Class with Robert Zimmerman in Spring 2024: The Laredo Resilience Project. Accessible here: https://rgisc.org/the-laredo-resilience-project/

47. Macfarlane, Robert. “Ghosts, Monsters and Angels” (India) in Is A River Alive? W.W. Norton & Company, 2025, p. 124

How to Ask the Right Question: Praxis in Design Research for Regional Climate Resilience

In August of 2022, the outlines of the Monterrey Aqua Incognita III and IV studios started to take shape. We had been invited to visit Monterrey by a friend and architect who had grown up in the city, with the idea that it might be generative to develop a landscape architecture design studio focused on the urban challenges faced by the region of some five million people. Following our two-plus years of work on water challenges in an agro-industrial region in the Apan plains of central Mexico, on the very far outskirts of Mexico City’s urban agglomeration, the possibility of developing a new project that would pick up many of the same themes held much promise. Additionally, the topic of Monterrey and its water scarcity challenges had been in the air of Mexican policy discourse as a possible harbinger of what might come for other parts of the country facing similar challenges. Following a visit to Apan in late July 2022 to present findings from the Aqua Incognita I studio that Bello Gómez had conducted at the GSD in the fall of 2021, we flew from the temperate high-elevation climate of Mexico City to the heat of Monterrey.

This initial visit was brief but productive. We met with officials from the Water and Drainage Department for the State of Nuevo Leon, the agency responsible for water provision in Monterrey’s metropolitan region. We arrived in the midst of a crisis: officials more than once stepped out of our meetings to take phone calls from the governor’s office, as the city was in the grips of an acute Day-Zero water shortage event. We also attended a conference on regional water scarcity organized by a prominent daily newspaper in Mexico. And we met with academics and local civil society leaders.

In a series of site visits to better understand the physical and ecological configuration of the region, we arrived at the imposing rock face of La Huasteca, along the valley floor of the Cumbres de Monterrey National Park, and travelled out to the existing

Rompepicos flood control “spike” dam. We slowed to a crawl in late afternoon traffic surrounded by tractor trailers in the workingclass suburb of García on the western edge of the city, trying to more fully understand the extent of low-slung industrial and suburban sprawl in the region, and observing the upstream conditions of the Río Pesquería, which flows along the north edge of the city. Our exposure to the more centrally positioned Río Santa Catarina gave us a sense of the daily experience of residents going about life in Monterrey. We caught glimpses of the dried-up river here and there as we crossed the city’s bridges back and forth, over and over again, and as we drove along the highway-like roads that border and constrain the river. We left on a Saturday afternoon for our return to Boston with much food for thought and a sense that the design studio would have many—perhaps too many— important challenges to address.

What could or should the studio be about, really? Would it be possible to frame a focused and coherent entry point suitable for project-based design work while still speaking to the full complexity of the expansive and multi-layered water challenges facing Monterrey? Should we focus on scarcity or flooding? Maybe both? What about sprawl? Could a landscape architecture design studio expect to tackle this set of unwieldy and expansive challenges? Would a planning component in parallel be beneficial? Who might sponsor such a studio? What sort of political environment would students be walking into? Was there an audience ready and willing to engage with design proposals for the region’s future and its relationship to water? At what sort of scale would studio participants work, and which specific challenges would students address?

None of these questions had obvious answers. To move forward in determining the focus and contours of the studio, we continued having conversations with people we had met in our initial visit to Monterrey. One

such meeting was with Lorenzo Rosenzweig, CEO and founder of Terra Habitus, a local non-governmental organization focused on regional conservation. Rosenzweig had spent his career working to leverage resources for conservation efforts in Mexico, not least during his tenure as president of the Mexican Fund for the Conservation of Nature. Part of his work with Terra Habitus was now focused on developing policy proposals for protecting the Santa Catarina river shed as an important urban-regional ecological asset under the project banner Rio Ciudad, and in the process, cultivating major private industrial donors to support the cause.

A collaboration between Terra Habitus and the Harvard Graduate School of Design seemed like a productive and generative way to move forward. But could we frame the river as the key focal point for Monterrey’s broader water challenges? The river was not necessarily the only or even the central point of entry to this broader complex of concerns. A web of ecological, political, and economic relationships and entanglements stretched to the limits of the broader metropolitan region, to its immediate mountainous headwaters, to its regional aquifer, and to the US border and beyond. The Río Santa Catarina is a tributary within the larger Rio Grande watershed, thus creating both current and potential future entanglements with binational water sharing treaties. We needed also to acknowledge the Monterrey region’s economic entanglements with the broader NAFTA (now USMCA) zone, as an industrial and manufacturing hub tightly linked into cross-national “nearshoring” trade relationships with the United States and Canada.

Those economic entanglements cannot be separated from the city’s water challenges. The city has grown and is growing, in large part because of its legacy and ability to continue capitalizing on its reputation as a critical economic engine in Mexico, meeting key manufacturing and logistics platforming demand from the US and Canada, and, in the process, providing a hugely significant base of urban employment in northern Mexico. As the city grows, more pressure is put on its water supply. Demand grows. Extraction grows. Impermeable surface coverage grows. We were left with the question: could the river provide an entryway into this intricate brew of topics and challenges?

A research seminar offered at the Graduate School of Design in the spring of 2023 focused on the Day-Zero challenge in

Monterrey and the goal of pursuing resilience under new extreme water and climate regimes. The seminar’s syllabus is attached to this report. The seminar was a next step in analytically sorting out the river’s role in, and potential connection to, Monterrey’s larger water and climate challenges. Designing a 14-week framework of topics and developing a roster of guest speakers promoted an active and ongoing conversation that brought additional interlocutors into our discussions. Over the course of the semester, we were able to get updates from, and think alongside, key partners in Monterrey. The seminar also offered a chance to hear from designers and experts who have worked on similar challenges in other contexts, both in Mexico and globally. Students engaged with concerns of water and growth; with aquifer health and the science-policy interface; with urban river regeneration and design projects; with water-sensitive urban green infrastructure practices; with the agriculture-water-industry nexus; with flood risk during extreme storm events; and with questions of equitable resource distribution and service provision. The seminar addressed a range of interconnected topics in Monterrey’s water crisis, and it created a repository of student-led research projects and joint analysis that established a base on which design proposals could further build.

As the seminar progressed in Cambridge, public conversation about many of these same themes was continuing to emerge and evolve locally in Monterrey. By early summer 2023, it was clear that the river, as both a challenge and opportunity, was gaining traction on the agendas of political and industrial sectors in the city, not least because of their interest in preparing Monterrey as a site for games of the 2026 World Cup, the so-called NAFTA World Cup, to be hosted across Mexico, the United States, and Canada. Various proposals began circulating in public discourse, with opposed camps coalescing around positions that sought major redevelopment efforts within and around the river, or those that sought to leave the channelized segment of the river untouched, intentionally letting it return to a “natural” state. After the federal water agency started razing trees and clearing vegetation along a portion of the riverbed in the summer of 2023, further controversy erupted over the appropriate role of the river as a symbolic, economic, and ecological asset in the city, representing larger debates about the future of the region and the many contested visions

of residents, politicians, NGOs, environmental activists, and business elites. “Un Rio en el Rio” (“A River in the River”) emerged as a prominent rallying call among those opposed to tree removal in the riverbed.

The Monterrey studio, broadly conceived as a space for serious design work about the ecological and urban challenges of a city like Monterrey, was now also becoming a vehicle for working with a topic that was actively in motion, a topic of great urgency in the lives of real people. The studio was emerging as an opportunity to integrate not just concerns of aesthetics, hydrology, infrastructure, and sound ecological functioning, but also of values, of politics, of questions about growth and limits, about equity and distribution.

It was increasingly possible to make the case that the studio could take up the river as a central thematic and ecological entry point, capitalizing on increased public attention, while still doing justice to the broader complexity of interconnections, linkages and entanglements in which the river is bound up. We began to articulate a project framing that, in the tradition of the ongoing Aqua Incognita studio analytic, sought to establish connections between “the seen” and the “not seen” of regional watersheds, to seriously engage with the uncertainty of the risks being faced, but also to not disallow the possibility of opportunities for change emerging under such conditions of uncertainty. Suddenly, it was entirely plausible, even compelling, to use the charismatic and nearly inescapable presence of the river as a feature of daily life in the city, as a means of grappling with the linkages that emanated from it. Such work would require centering the river, but

also tracing its relationship with its more rural headwaters, thinking about its explicitly urban watershed and the role it plays in the regional built environment, seeing its riverbed as a site of great ecological but also social potential, recognizing the catastrophic flood risk the river poses during extreme storms but also its attractiveness as a potential urban amenity to anchor different patterns of development. It became clear that we could shape a studio that, through the means of individual design projects, could collectively grapple with these multi-scale and multi-disciplinary challenges.

Getting to the “right” question and brief for this studio was not a neat or straightforward process. It was somewhat messy, long, and contingent, just like climate and resilience transitions more generally tend to be. Developing the brief required deep, sustained, and rigorous exploration. But it also required the flexibility to think about and adapt to evolving on-the-ground realities, constraints, and opportunities. It was a process that built on the questions we had already been asking, but it also pushed us to pose new ones. Ultimately, this publication illustrates not only the ongoing legacy and ethos of the Aqua Incognita studio series, but also the type of praxis in design-research that we think is necessary to make the design disciplines even more relevant to broad and urgent challenges like urban-regional climate resilience. As we look ahead to another iteration of the Aqua Incognita studio, and the broader line of design-research inquiry it embodies, we can only hope that our understanding of the “right” question keeps evolving.

Globally, the world is experiencing a period of unprecedented drought, the worst in 1200 years according to NASA. With rising global average temperatures, water is evaporating at high rates, with cities around the world, including in Monterrey in northern Mexico, coming dangerously close to reaching sustained Day-Zero scenarios where millions of taps could run dry. While drawing on global trends and discussions, this research seminar will use Monterrey’s water crisis as a paradigmatic example where the drought is exacerbated by extreme resource depletion and policies facilitating socio-economic and territorial desiccation, both embedded within widespread pro-growth logics.

Monterrey is a dry-climate city of five million, where challenges in governance and infrastructure have led to a longbrewing crisis that has now been pushed to the brink by six years of decreased rainfall patterns triggered by La Niña. Some citizens are receiving only two hours of water per day, while others rely on water distribution trucks. Industry has largely been allowed to continue extracting water from the aquifer. But the reality is more complex than a “good citizenry” vs. “bad industry” narrative. Through readings, writings and/ or mapping exercises, we will examine the many forces that are contributing to water crisis in Monterrey, (MX), and study different initiatives that–in the fields of landscape architecture, architecture, urban planning and design—are trying to foster wetness in water-scarce and desiccated territories.

The course is open to students in all programs at the GSD, with the hope that a transdisciplinary dialogue will foster more innovative strategies toward water resilience across scales.

This research seminar is intended to lay the conceptual foundation for a subsequent project-based Option Studio to be offered in the fall of 2023. One of the objectives of the spring seminar is to arrive at a framing for

Instructor: Lorena Bello Gómez, PhD

Teaching Fellow: Samuel Tabory, PhD Candidate

Spring 2023: HIS 4498

the water resilient initiatives that could be further investigated through design later in the year.

The class will meet once a week, structured around a visiting speaker, readings, and discussion on a range of topics intended to generate new knowledge as well as critical questions about the history, cultural traditions, urbanization, politics, governance, and water related practices in Monterrey, Mexico. These topics will help us contextualize our discussion of prior and current efforts to recover from water crisis or disaster in Monterrey and elsewhere. Students will be expected to produce a final research paper or design strategy that leads to a critical rethinking of past practices to increase water resilience in the near future.

Proposed projects could range from actionable designs to experimental interventions and speculations, including but not limited to: design prototypes, sustainable urban design models and policies, naturebased solutions, blue-green infrastructures, regenerative agricultural practices, financing mechanisms, alternative governing institutions, regulatory water redistribution, and so on. With the justification of its impact on Monterrey’s water resilience, they can target any scale within the Santa Caterina sub-watershed, its near shoring region, or the Rio Grande bi-national watershed. Students can decide if they want to work in pairs or individually. In the first two weeks of class, we will have discussions about how the work might be organized, with some collective conversations about common entry points. In this same time period, we will also ask students to determine which particular geographic site they will target for further research.

Previous page: Group picture after second symposium in Fall 2024 at the Tec of Monterrey Campus. Special thanks to Rubén Segovia. Credit: Roxana C. Elorriaga

Act I: Water crisis: Why?

Week 1 (Jan 30th) - Introduction to Day-Zero crises

Events of August 2022 in Monterrey, other day-zero scares and scenarios

(Cape Town, Mexico City, elsewhere)

Guest: Juan Ignacio Barragan

Week 2 (Feb 6th) - Nearshoring and water unbalanced urbanization

Resource demands of nationally important urban-regional economies driving macro-economic growth. Resulting unsustainable low-density urbanization into areas with no water supply.

Roberto Ponce, PhD