Magda Maaoui

Magda Maaoui

Magda Maaoui

Visit of the Boston Medical Center – Rooftop Farm’s innovative clinical program, the Preventive Food Pantry, where doctors prescribe supplemental foods that facilitate health and recovery for several clinical diagnoses, including cancer, heart disease, and HIV/AIDS – October 2024.

Do No Harm: Dilemmas in Planning for Health

Planners have long imagined themselves as physicians attending to the good health of cities and the communities living in them. Do No Harm unpacks the complex connections between environmental health, public health, and city planning. The course title, a nod to both the Hippocratic Oath and the creed of social reformer Florence Nightingale, represents a challenge to students preparing to manage the discrete, conflicting interests of that most complex of organisms–the metropolis.

This class uses housing as a starting point for a sectional slice of inquiry that spans from the underground to the air that surrounds us. We discuss how the design, policy, geography, ownership model, and maintenance of housing influence various public and environmental health metrics, and what levers are available to planners to influence those outcomes. We explore and evaluate tools of assessment and intervention and identify points of leverage. Within this framework, students are expected to bring their own interests, disciplines, and experience to bear on a semester where our focus ranges from affordable and simple tools at the housing-health nexus (smoke detectors, mosquito nets, and so on) to more complicated questions of ethics, objectives, and priorities.

Course Instructor Magda Maaoui

Teaching Associate Hiteshree Das

Students

Issam Azzam, Aleksandra Banas, Amanda Bendixen, Melissa Berlin, Hiteshree Das, Jazzlynn Derrick, Rachel Fischer, Karthik Girish, Michaela Gwiazda, Brooke Jin, Mike Kaneshiro Chou, Cory Page, Shivangi Varma.

Mid-Term and Final Review Critics Eytan Levi Olivier Faber Tim Cousin

Archival work session co-organized with Loeb Library Special Collections Curator Ines Zalduendo. Students engage with a wide range of historical plans, maps, and archival documents that reveal the evolving relationships–between health and city planning, from the nineteenth century to the present, from Le Cobusier’s analysis of health conditions in slums of Buenos Aires, to urban renewal maps for the City for Boston–November 2024.

9 Teaching about top floors

Magda Maaoui

16 Collaboration with Paris-based Roofscapes

Magda Maaoui, Eytan Levi, Olivier Faber, and Tim Cousin

17

Projects

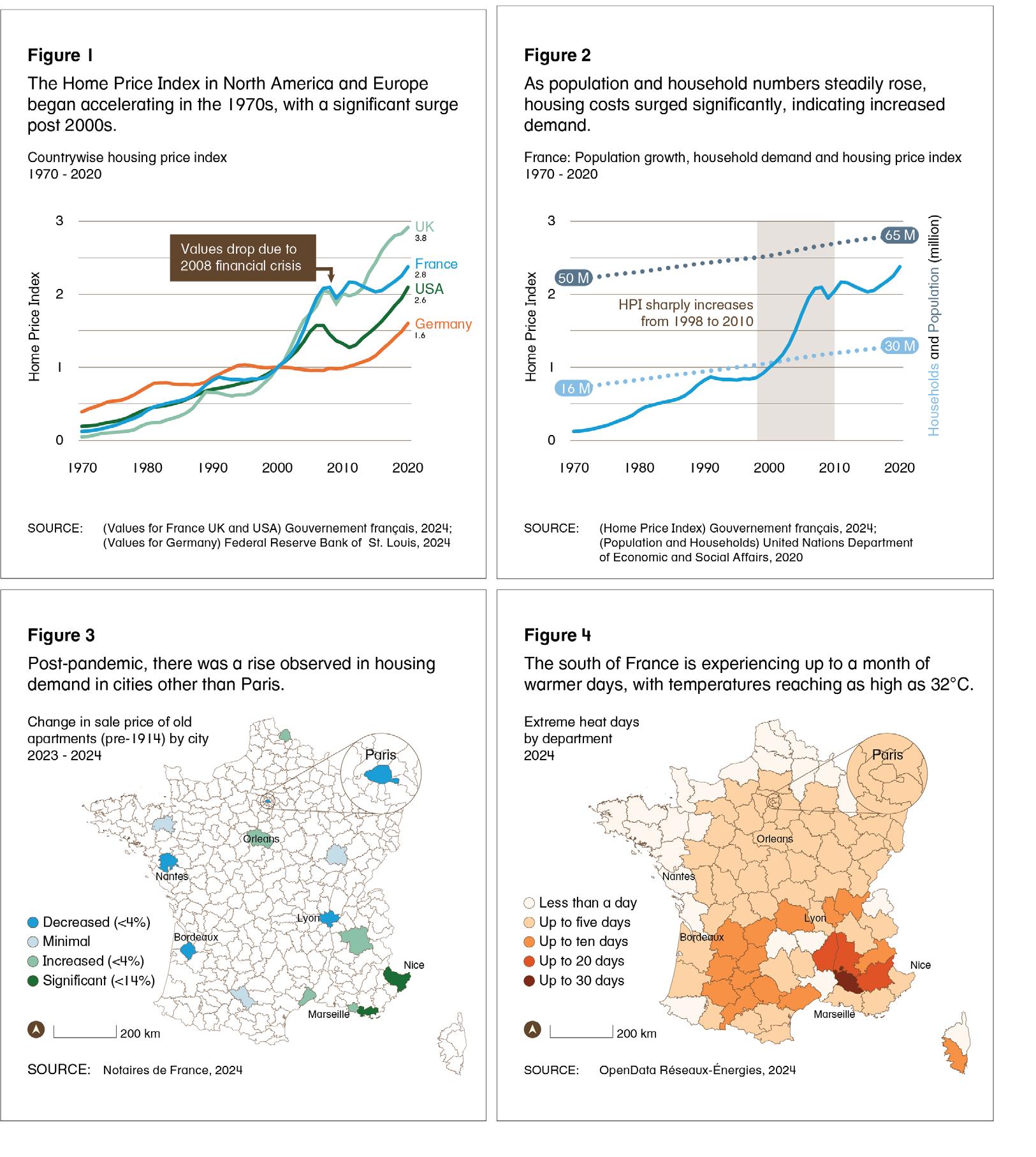

First Assignment: Collecting and Analysing Environmental Health Data

Demographic Breakdown of Chambres de Bonne

Aleksandra Banas, Amanda Bendixen, Jazzlynn Derrick, Brooke Jin and Rachel Fischer

27

Heat Traps in the City

Issam Azzam, Mike Kaneshiro, Cory Page, Shivangi Varma

33

39

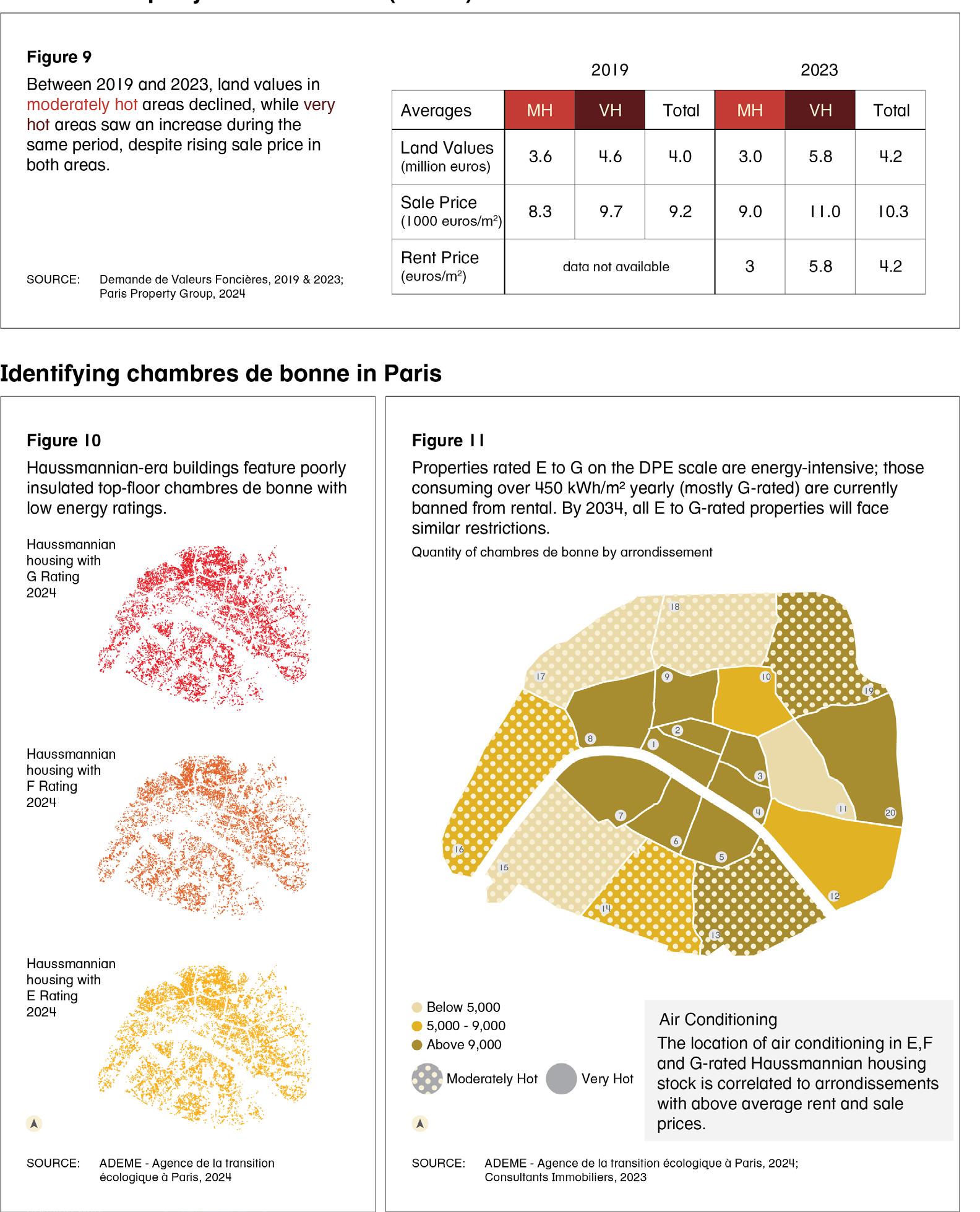

Heat vs. Property Value: A Parisian Perspective

Melissa Berlin, Hiteshree Das, Karthik Girish, Michaela Gwiazda

Second Assignment: Navigating Scenario-planning and Impact Assessments for Health

Greening the Grands Ensembles

Aleksandra Banas, Amanda Bendixen, Jazzlynn Derrick, Brooke Jin and Rachel Fischer

61

81

Strategies for Co-ops: A Proposal for Roofscapes

Melissa Berlin, Hiteshree Das, Karthik Girish, Michaela Gwiazda

From Horizontal to Vertical–Expanding Green Roofs: Habitations à Bon Marché

Issam Azzam, Mike Kaneshiro, Cory Page, Shivangi Varma

by Magda Maaoui Assistant Professor of Urban Planning Department of Urban Planning and Design

Harvard University Graduate School of Design

Source: Parisian spiral stair, 1955, by Paul and Julia Child. Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, Harvard University.

This Fall, I taught a class called “Do No Harm: Dilemmas in Planning for Health”. The class used housing as a starting point for a sectional slice of inquiry that spans from the underground to the air that surrounds us. With students across departments at the GSD and MIT, we discussed how the design, policy, geography, ownership model, and maintenance of housing influence various public and environmental health metrics, and what levers are available to planners to influence those outcomes. Within this framework, students were expected to bring their own interests, disciplines, and experience to bear on a semester where our focus ranged from affordable and simple tools at the housinghealth nexus (smoke detectors, mosquito nets) to more complicated questions of ethics, objectives, and priorities.

Together, we considered the nexus between health and planning as an ongoing process of experimentation, monitoring, learning, and adaptation. We asked: What are the key health issues that should concern those in planning and related fields? Can physical design and planning alone improve health? In a world of finite resources, how do we weigh competing priorities and evaluate the costs and benefits of our interventions? And how can we alleviate the inequities currently experienced by segregated and disinvested communities around the world?

Our work was divided into two streams. In the reading discussions part of the class students learned about famous and infamous stories about how our decisions could harm or heal communities, such as Haussmannian hygienist efforts in France, the rise of air-conditioning in Global South cities, or slum clearance in the United States. In the project part of the class, groups of students developed an approach to addressing an ongoing planning project, using housing as a lever for better health.

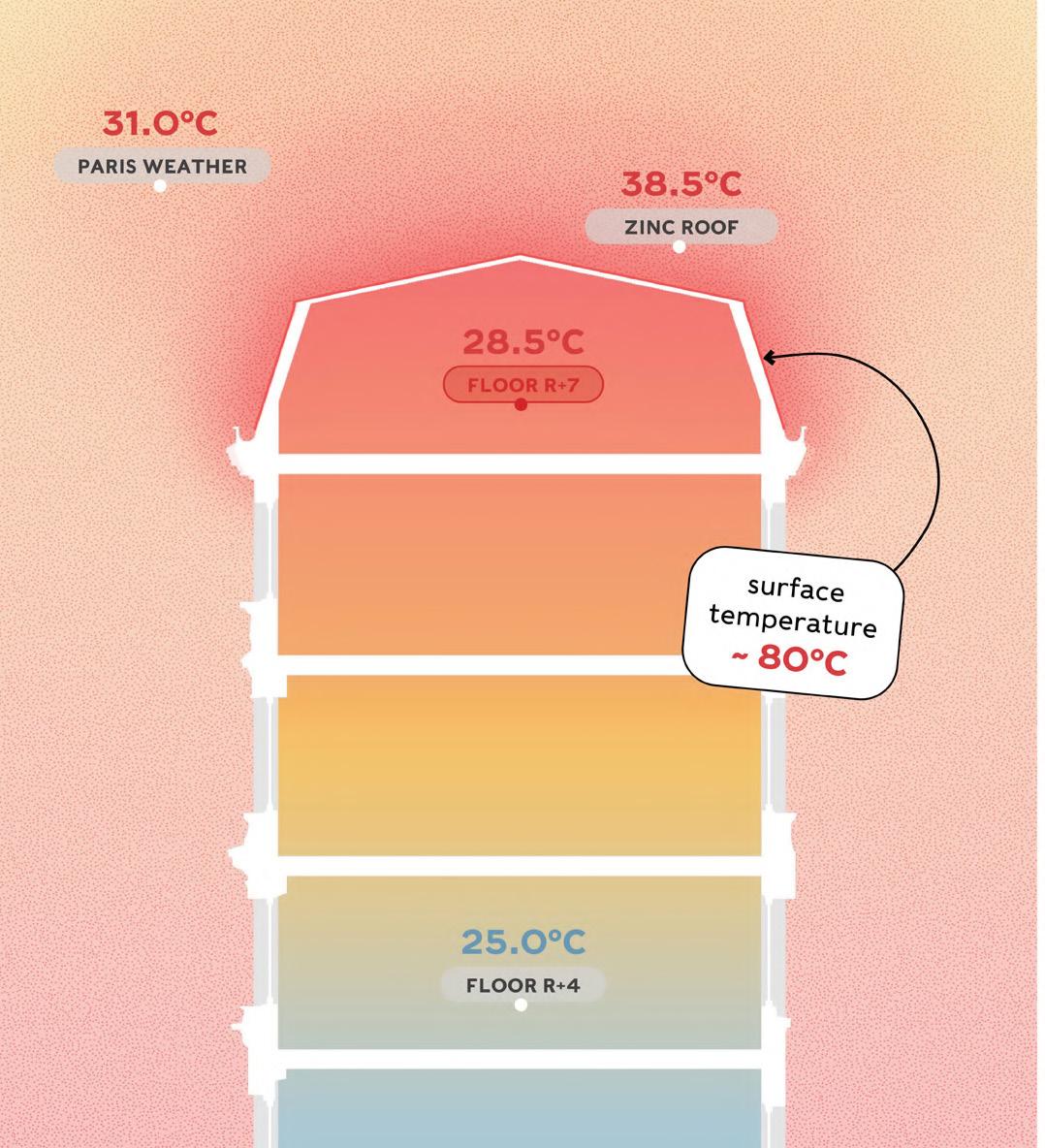

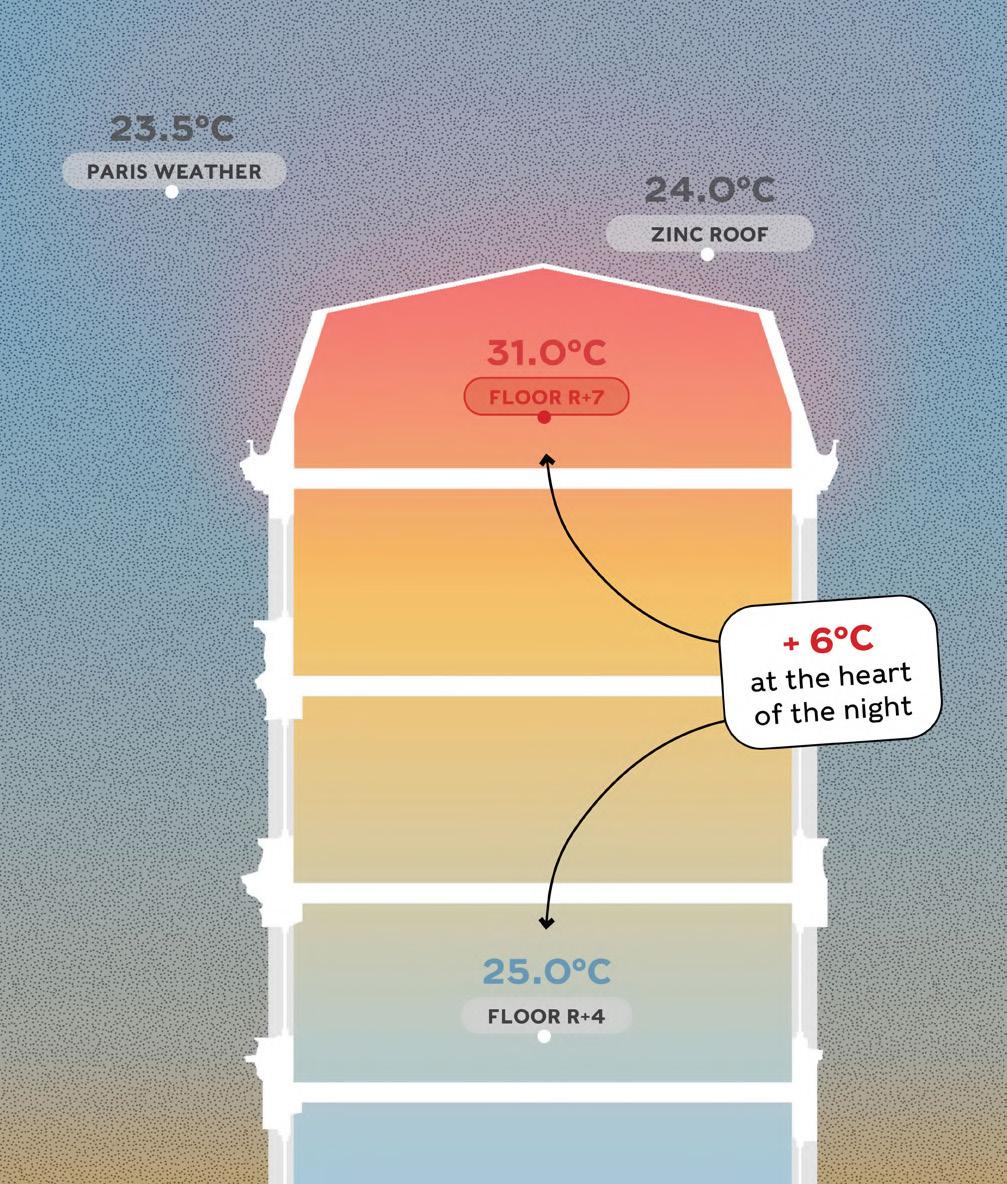

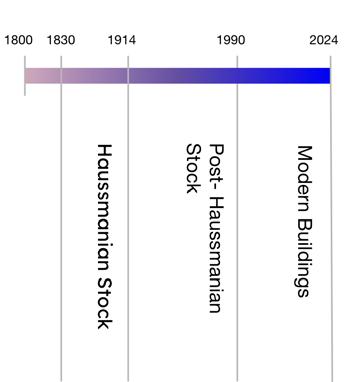

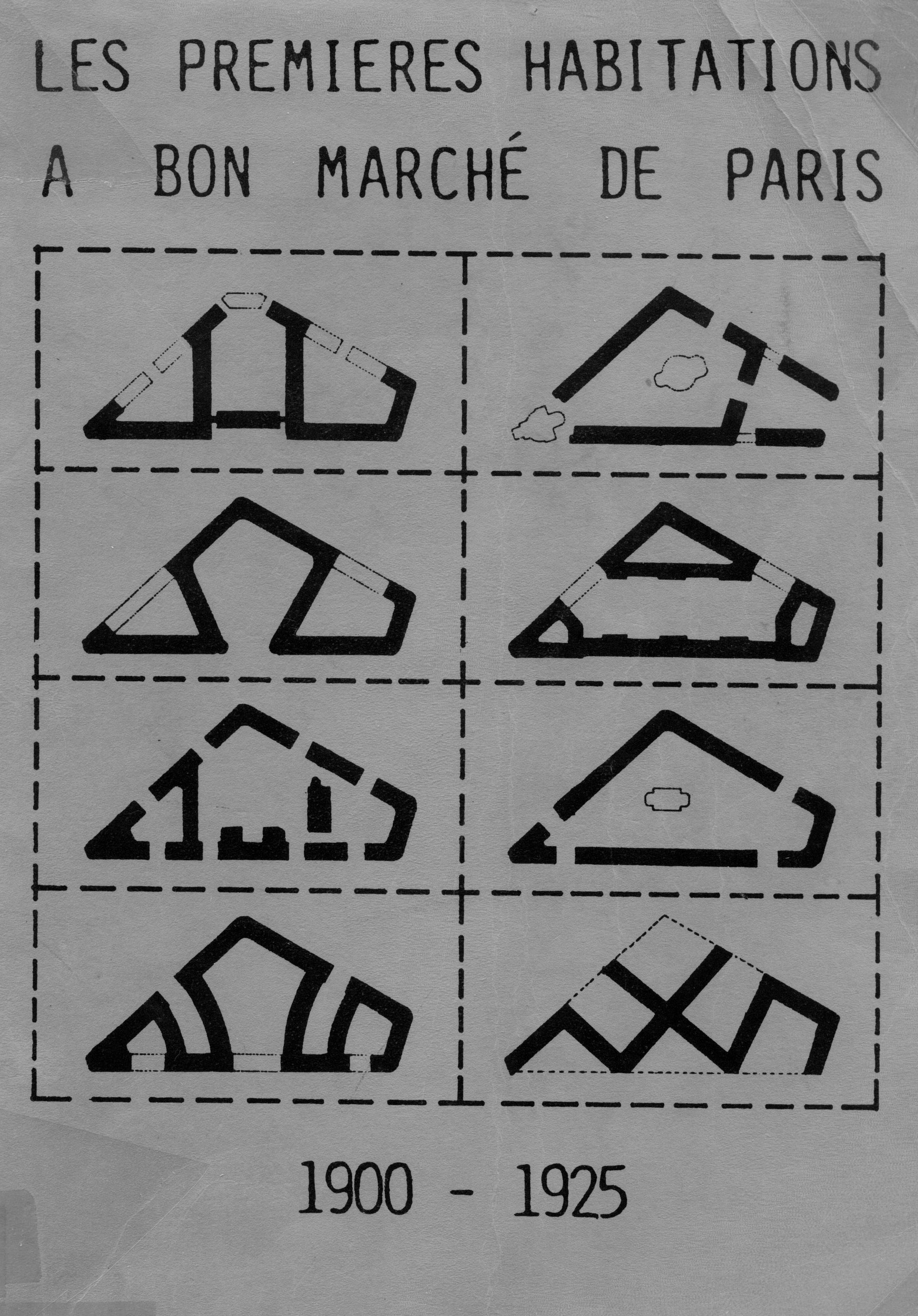

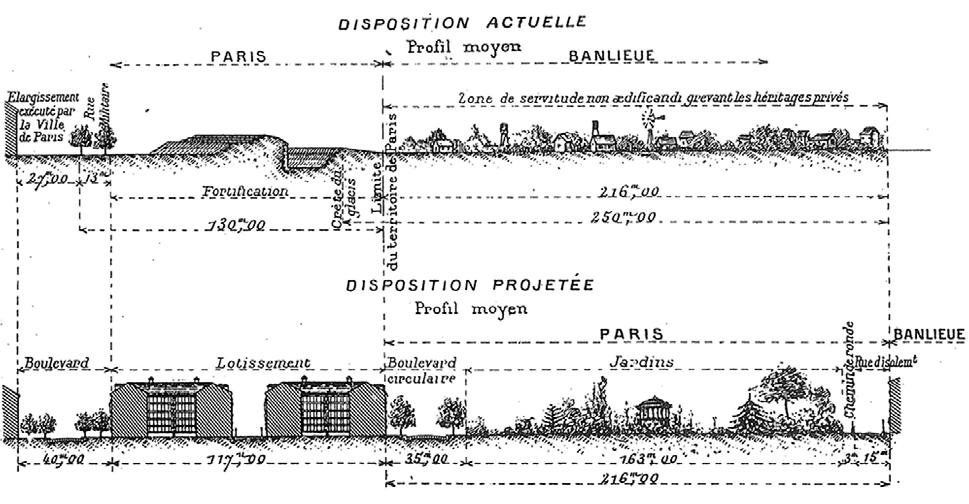

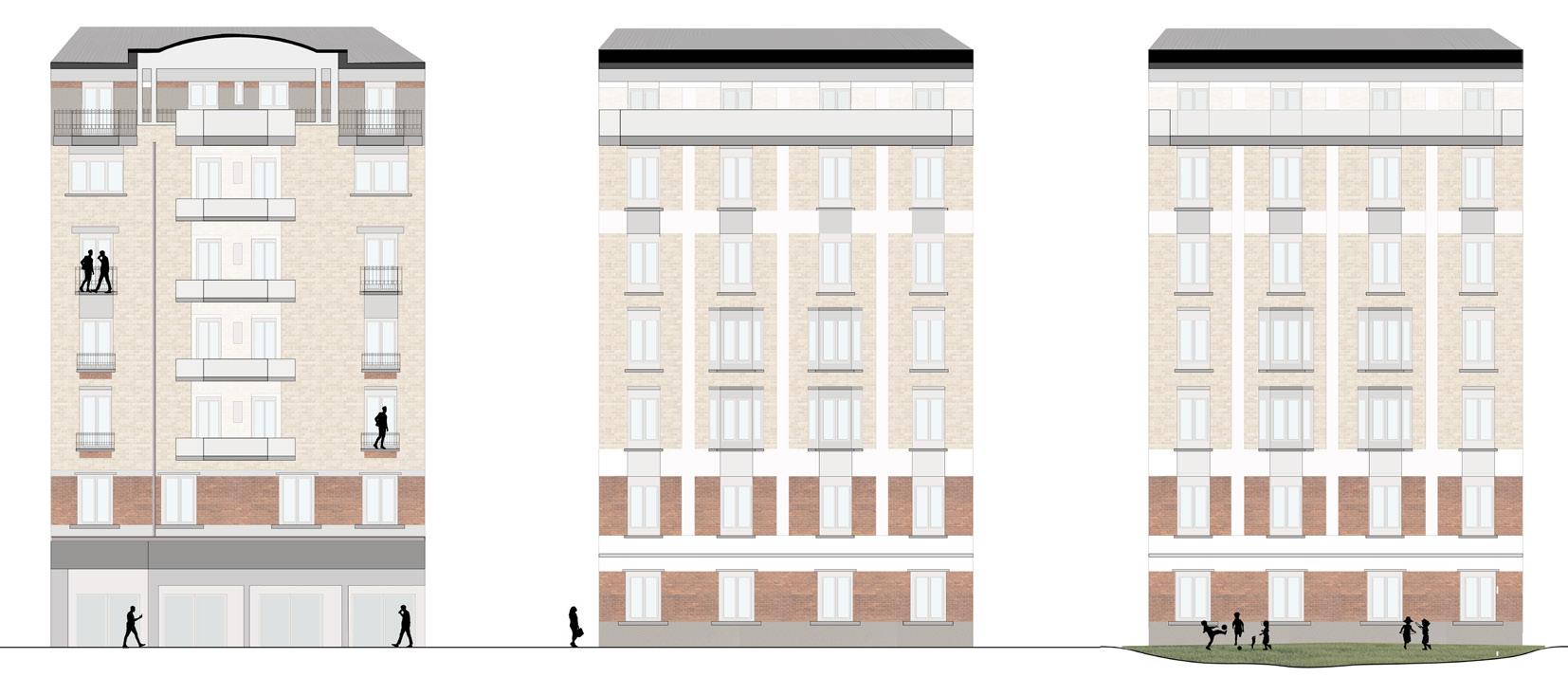

The first iteration of this project-based course looked at top floors and heat, specifically in Paris’s Haussmannian housing stock. We worked with Roofscapes studio, a trio of designers, architects and planners. Through their practice, they intend to address heat for the 4 out of 5 Parisian buildings that have a pitched roof, most of which is in zinc—a material

that increases the capital city’s thermal vulnerability by reaching temperatures close to 80°C in the summer, and making housing units right underneath these roofs unbearable to live in when temperatures rise. And as Roofscapes continued adapting and greening the city’s roofs, which cover up to 38% of the city’s footprint, the class embarked on a dissection of what’s right underneath these Haussmannian roofs, digging into the units located on these top floors, commonly known as chambres de bonne.

Haussmannian buildings are characteristic of the French Second Empire, as the materialization of an essential—and vertical—social division (Pinçon and Pinçon-Charlot, 1989; Maaoui, 2024).1

Haussmannian lower floors are endowed with features praised in real estate listings. Think oak parquet floors, marble fireplaces, large windows and mirrors, moldings, or paneled wainscoting (Jallon et al., 2017).2

Meanwhile, the chambres de bonne are hidden behind the façade of cut stone and the double carriage entrance, at the very top of these same Haussmannian buildings, above the wrought-iron railing balconies, and sometimes accessible only by a steep independent staircase. Because these units were intended for domestics working in lower-floor bourgeois apartments, they are very compact. That’s typically 9 to 15 square meters, serving both as bedroom and living room, with limited space for furniture or storage. If you’re lucky, they will include a kitchenette.

The chambre de bonne has been a common housing option for workers without means, ready to give up space and thermal insulation. They have historically housed domestic workers, low-income families, artists, bohemians, students, or senior residents. What’s essential is that the chambres de bonne inject demographic, social, and even racial diversity within the Haussmannian building. The presence of low-income residents in the top floors, to this day—be they students, young couples, domestic workers, or undocumented immigrants—perpetuates in renewed forms the topos of an ancient vertical urban segregation.

The heatwave episode of summer 2003 also revealed the vulnerability of residents living in poorly insulated, poorly oriented homes under rooftops. It killed nearly 15,000 people in France, and in Paris, more than a thousand victims—many of them lived in substandard housing, particularly in chambres de bonne (Keller, 2011).3 The chambre de bonne is in part housing for the Parisian proletariat, what people call today naturally occurring affordable housing. A proletariat that clashes with the bourgeois floors below and has long been facing health threats due to the substandard insulation of top floors.

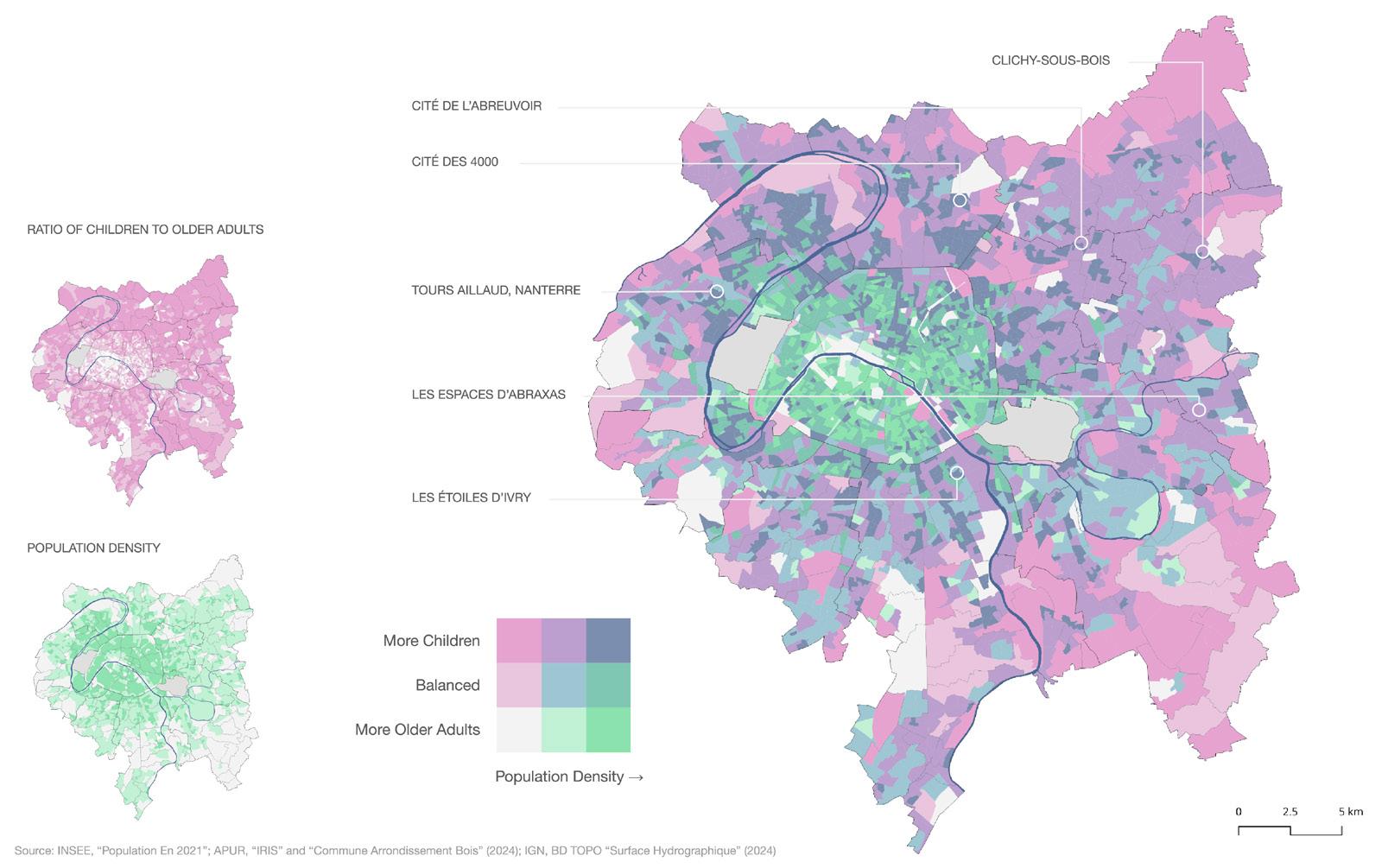

Chambres de bonne, still very much underresearched despite making up a significant portion of the Parisian housing stock, have become a genuine issue in terms of affordability and sustainability. According to a pioneering study conducted in 2015 by the Atelier parisien d’urbanisme, Paris reportedly has 113,000 chambres de bonne, with 80% located in the western districts and 30% in the 16th arrondissement alone. They often offer an affordable and central housing solution, being situated in the most desirable areas of Paris. A law voted in 1954 also facilitated dividing under-occupied apartments and renting out separate chambres de bonne, around the time when Paris saw a steep decline in the number of its domestic workers.

Students were tasked to develop data analysis and planning proposals that complicated Roofscapes’ greening strategies. They first learned about how Roofscapes works to preserve and adapt the historic fabric of existing Haussmannian roofs, while reducing direct solar exposure and overheating, installing modular prefabricated wooden platforms, and planting gardens that cool the air through evapotranspiration, retain rainwater, and support local biodiversity anchors. Through archival research, mapping, policy and economic research, and in dialogue with them, we discussed how greening strategies were a solution for chambres de bonne’s heat problem, but not the only solution, in a place where land use plans, zoning regulations, state subsidies and government mandates all push the envelope for a cooler city, starting with its top floors. Finally, students pitched proposals for an

expansion of Roofscapes’ portfolio beyond the Haussmannian housing stock, and onto the top floors of turn-of-the-century worker housing, middle-income co-ops, and postwar public housing projects in the greater Paris metro region.

The first iteration of this project-based course took us to the top floors of Parisian Haussmann housing. But if we stick with this slice of inquiry, the possibilities are endless. Yes, for many, Paris is synonymous with Haussmann, with 75% of Parisian buildings attributed to him, and Haussmann is synonymous with the invention of the chambre de bonne. It’s a literary reference, think Émile Zola, and a cinematic one, think François Truffaut or Gene Kelly in the 1951 An American in Paris. But it’s also an architectural standard that has been exported elsewhere in the world, notably during the 19th century, the golden age of the global rise of the bourgeoisie, from the terraces of the old Ottoman houses in the Casbah of Algiers (Maaoui et al., 2022),5 to the rooftops of the old Art Deco buildings in Cairo, and into current debates in North America about basement apartments and attached accessory-dwelling units (Maaoui, 2018).6

Teaching about top floors and heat provided an avenue for investigating the unequal distribution of risks to health in the face of climate change (Samuelson et al. 2020).6 The chambre de bonne can offer a panoramic view over the city’s rooftops. It also allows us to take the temperature of the city and “move environmental justice indoors” (Adamkiewicz et al., 2017).7 It sets in motion a rethinking of housing in a context of densification, housing shortage, climate crisis, and ultimately health inequality. It’s an architectural archetype inherited from the historically dense city, which should be rehabilitated for its sustainable future.

Planners have long imagined themselves as physicians attending to the good health of cities and the communities living in them. The class Do No Harm started unpacking the complex connections between environmental health, public health, and city planning. The course title, a nod to both the Hippocratic Oath and the creed of social reformer Florence Nightingale, was

intended as a challenge to students preparing to manage the discrete, conflicting interests of that most complex of organisms—the metropolis. With this course, we proposed top floors as an invitation, just like the black-and-white photograph hints to it, to consider the ways we live and endure worsening thermal conditions today, and a “challenge to imagine how we will transform and inhabit the cities of tomorrow” (Klinenberg, 2002).8

References:

1. Pinçon, Michel and Monique PinçonCharlot, 1989. Dans les beaux quartiers, Paris, Seuil; Maaoui, Magda. 2024. “La chambre de bonne”, in Argounès, Fabrice, Michel Bussi, and Martine Drozdz (eds). Nos lieux communs : Une géographie du monde contemporain, Paris: Fayard editions.

2. Jallon, Benoît, Napolitano, Umberto et Franck Boutté, 2017 (first edition). Exposition « Paris Haussmann : Modèle de Ville», Pavillon de l’Arsenal and Park Books.

3. Richard C. Keller. Fatal Isolation: The Devastating Heat Wave of 2003. University of Chicago Press, 2015.

4. Maaoui, Magda et al., 2022. Habiter l’indépendance : Alger, conditions d’une architecture de l’occupation, Shed Publishing.

5. Maaoui, Magda, 2018. “A Granny Flat of One’s Own? The Households that Build Accessory-Dwelling Units in Seattle’s King County”, Berkeley Planning Journal 30.

6. Samuelson, H. et al., 2020. “Housing as a critical determinant of heat vulnerability and health”, Science of the Total Environment 720, 137296.

7. Adamkiewicz, Gary, et al. “Moving environmental justice indoors: understanding structural influences on residential exposure patterns in low-income communities.” American Journal of Public Health 101.S1 (2011): S238-S245.

8. Klinenberg, Eric (2002). Heat wave: A social autopsy of disaster in Chicago (Introduction). University of Chicago Press, p. xiii.

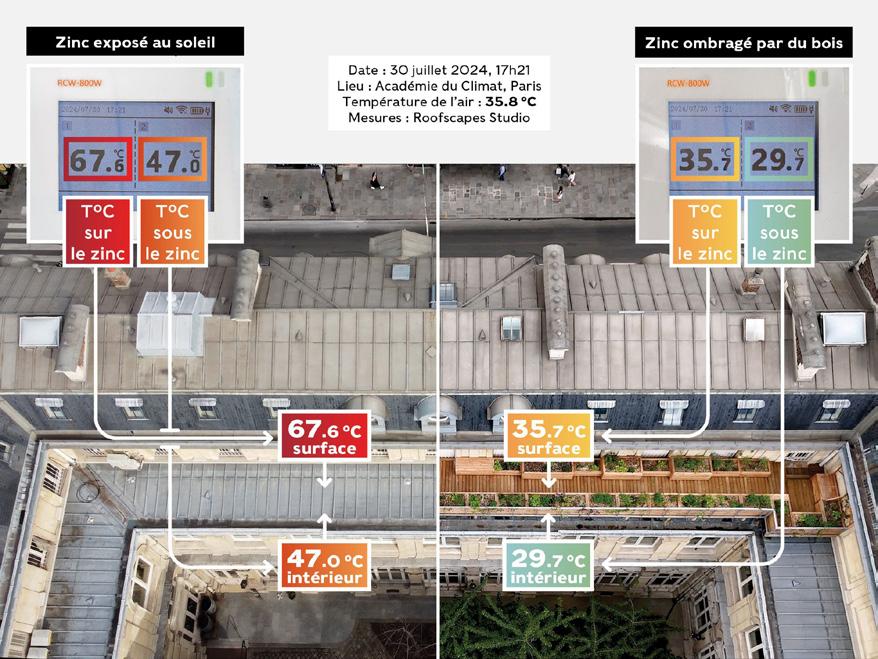

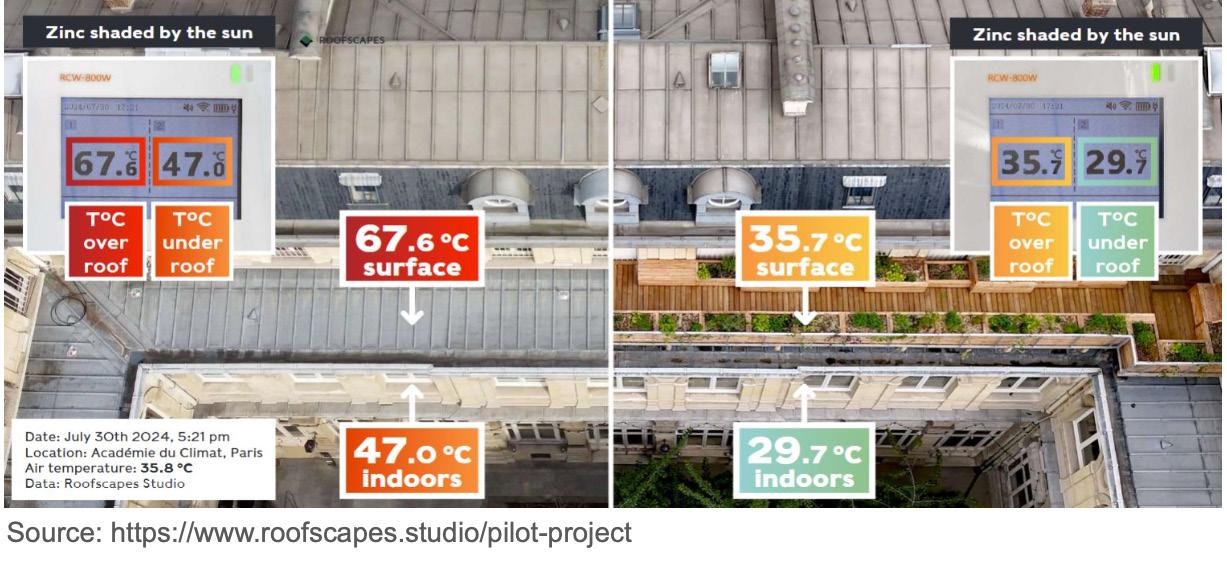

The following diagram shows the variation in temperature recorded by Roofscapes Studio on July 30, 2024, at 5:21pm, on their pilot rooftop installation at the Academie du Climat in Paris. The temperature that day approximated 35.8° C (96.4° F). The average temperature of top floor rooms directly under the bare zinc roof approximated 47°C (116.6° F), when that of top floor rooms under the pilot green roof structure stayed under 29.7°C (85.5° F).

The first time Dr. Maaoui visited the newly installed pilot green roof that Eytan Levi, Olivier Faber, and Tim Cousin had been working on for several months, she thought of the power of in situ field visits hold in our professions. The Roofscapes team is excellent at communicating and disseminating their practice framework, but a visit on that roof, with a live, detailed, thoughtful explanation of the design, construction, and financing of this first roof prototype inaugurated in 2024–that really connected the potential these roof interventions could hold for the capital city’s Haussmannian stock. This roof has welcomed many visitors, including recently elected Mayor Anne Hidalgo herself, a strong supporte of the initiative. The road seems to be paved for an extrusion of the model to other roofs, and the project component of our Do No Harm course allowed students to speculate on what implementation would look like for Haussmannian zinc roofs and beyond that for other housing typologies in the capital city.

Roofscapes, an innovative venture launched at MIT and based in Paris, works on the adaptation of Parisian zinc roofs to climate change and evolving needs in existing buildings. By installing green, accessible timber platforms on pitched roofs, Roofscapes hopes to carry the mission of mitigating urban heat, enhancing biodiversity, capturing rainwater and offering valuable outdoor spaces for communities in dense urban settings. Roofscapes operates through a combination of research, advocacy and built projects engaging with both private and public building owners, like the City of Paris or the Île-de-France Region.

Magda Maaoui, Eytan Levi, Olivier Faber, and Tim Cousin

The work of Roofscapes intersects with the course’s exploration of ethical dilemmas in planning by addressing how interventions on the built environment, and on planning processes, can impact public and environmental health conditions. The adaptation of rooftops involves key considerations of equity in access, cohabitation with non-humans, financing, and natural resource use, all of which highlight the trade-offs and benefits of such interventions.

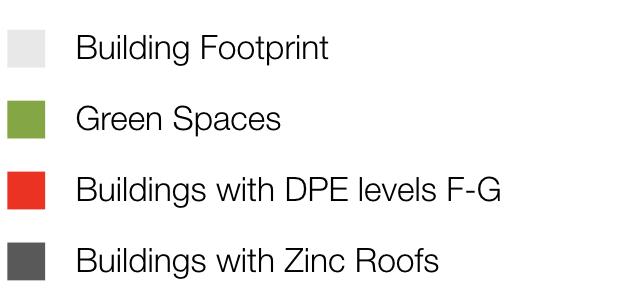

Collecting and analyzing environmental health data involves gathering information on environmental factors—such as air and water quality, pollution levels, chemical exposures, and noise—that may impact human health. This process includes using monitoring tools, sensors, and surveys to capture relevant data, followed by statistical and spatial analysis to identify patterns, trends, and potential health risks. The goal is to understand how environmental conditions affect populations and to inform policies and interventions that promote healthier communities.

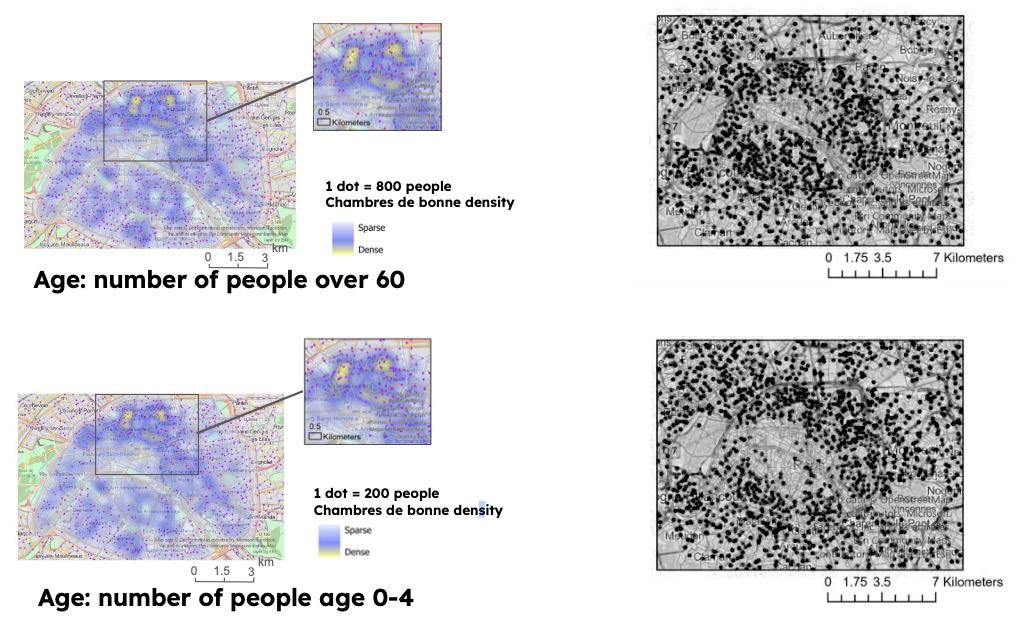

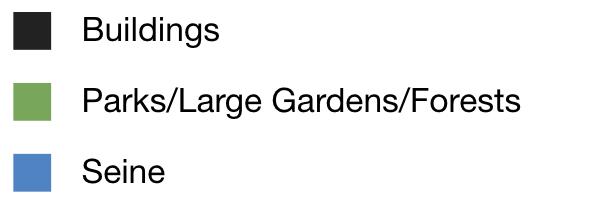

Effective healthy planning begins with understanding the current context. In the Greater Paris area, the exact number of dwellers living directly beneath rooftops has remained unknown for years. Working in teams, students were tasked to use Geographic Information System (GIS) tools and open-source data to map and quantify the number of residents directly impacted by rooftop adaptations. This process helped identify which local communities might have experienced the most significant effects, both positive and negative, of a restructuring of the city as it recently mandated the climate adaptation of its poorly insulated housing stock—a large part of which is represented by Haussmannian top floor units, referred to as chambres de bonne

To deepen this analysis, students were encouraged to develop an understanding of Haussmannian neighborhoods within their broader historical, architectural, and social contexts. By combining this contextual knowledge with neighborhood health

analysis, they examined how urban form, building typologies, and socio-economic patterns intersect with environmental health indicators such as heat exposure, air quality, and vulnerability to climate change. This integrated approach allowed for a more nuanced assessment of how the legacy of Haussmannian design influences present-day health outcomes and informs equitable adaptation strategies.

Key considerations for health-informed planning include exploring how it can address social determinants of health, such as housing, transportation, and access to green spaces. Identifying leverage points within these systems allows students to develop more targeted and effective interventions. Applying a health equity lens ensures that proposals prioritize the needs of vulnerable populations who are disproportionately affected by environmental health issues. Students learned that in order to strengthen planning recommendations, it is essential to provide evidence supporting the potential health benefits of proposed actions. This involves balancing both qualitative and quantitative data from health and environmental assessments. Finally, this first part of the project forced students to also recognize the limitations of planning alone in improving health outcomes, emphasizing the need for interdisciplinary collaboration with other sectors, starting with public health, policy and design.

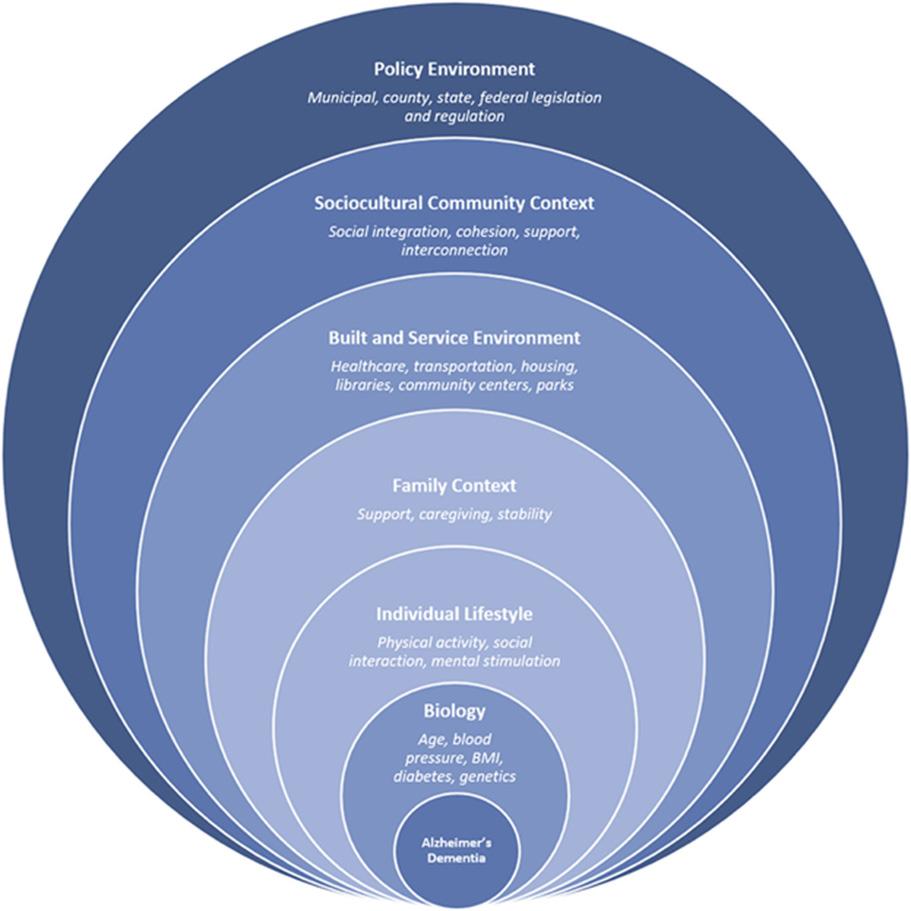

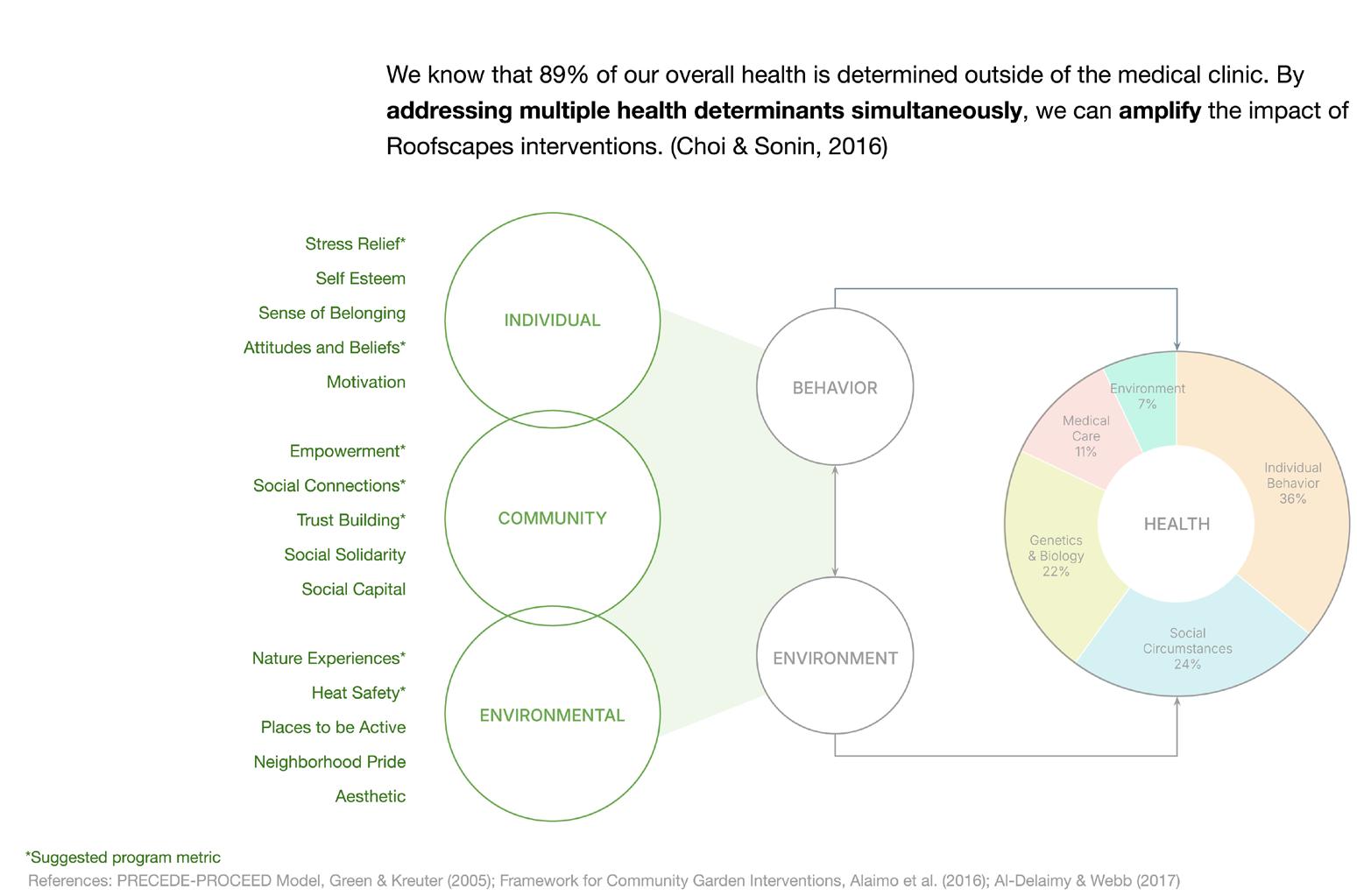

The socioecological model provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the multi-layered determinants of health - the built environment, climate vulnerability, and social inequalities. This model can be applied specifically to the Haussmannian chambres de bonne with respect to the following metrics.

Health risks are not solely due to individual vulnerabilities but are compounded by community layout, institutional neglect, and societal priorities. Residents of chambres de bonne may experience disproportionate biological vulnerabilities due to inadequate living conditions. For instance, older residents or individuals with pre-existing conditions are at greater risk of heat-related health issues. Additionally, lack of proper insulation exacerbates exposure to extreme temperatures, which can lead to heat exhaustion or hypothermia. Finally, due to the small size and limited amenities of chambres de bonne, residents often experience constrained lifestyles. Limited space discourages physical activity, leading to a sedentary lifestyle. Poor ventilation and limited natural light negatively impact mental stimulation and well-being. Over-reliance

on quick fixes for comfort, such as portable heaters or fans, increases energy costs and environmental strain.

Chambres de bonne often house individuals with limited family connections. Many residents are students, low-income workers, or elderly individuals living far from family, leading to social isolation. The lack of space and privacy discourages family visits, further exacerbating isolation. Vulnerable populations, like single mothers or retirees, may struggle to access caregiving or family support during extreme weather events.

The physical and service environment surrounding chambres de bonne poses specific challenges. Poor insulation in these small units results in extreme heat in the summer and extreme cold in the winter. Haussmannian top floors often lack elevators, making them inaccessible to older or disabled residents. Limited access to green spaces or cooling centers exacerbates heat vulnerability, as these units are typically situated far above shaded courtyards. Shared or inadequate bathroom facilities increase hygiene-related vulnerabilities, particularly during heatwaves.

Moreover, the social and cultural dynamics of Haussmannian buildings contribute to health disparities. Residents of chambres de bonne often belong to marginalized socioeconomic groups, such as migrants, low-wage workers, or students, creating a stark divide from wealthier residents living in the same buildings. Minimal interaction between residents of the main apartments and those in the chambres de bonne perpetuates social exclusion. In the end, this limited social cohesion reduces the likelihood of community-led initiatives, such as shared cooling measures or communal support during heatwaves.

Lastly, government policies have a direct impact on the living conditions in these units. The 2022 insulation mandate from the French government requires landlords to retrofit poorly insulated properties, but many chambres de bonne remain exempt due to their classification as “non-primary residences”, insulating the difficulty enforcing the law. Rent control policies sometimes cap rent prices for these units but may discourage landlords from making necessary improvements. Limited enforcement of health and safety regulations allows substandard living conditions to persist in chambres de bonne. Broader urban planning policies often overlook the unique vulnerabilities of these spaces, as they are viewed as ancillary housing, at best considered as naturally occurring affordable housing, at worst as substandard housing.

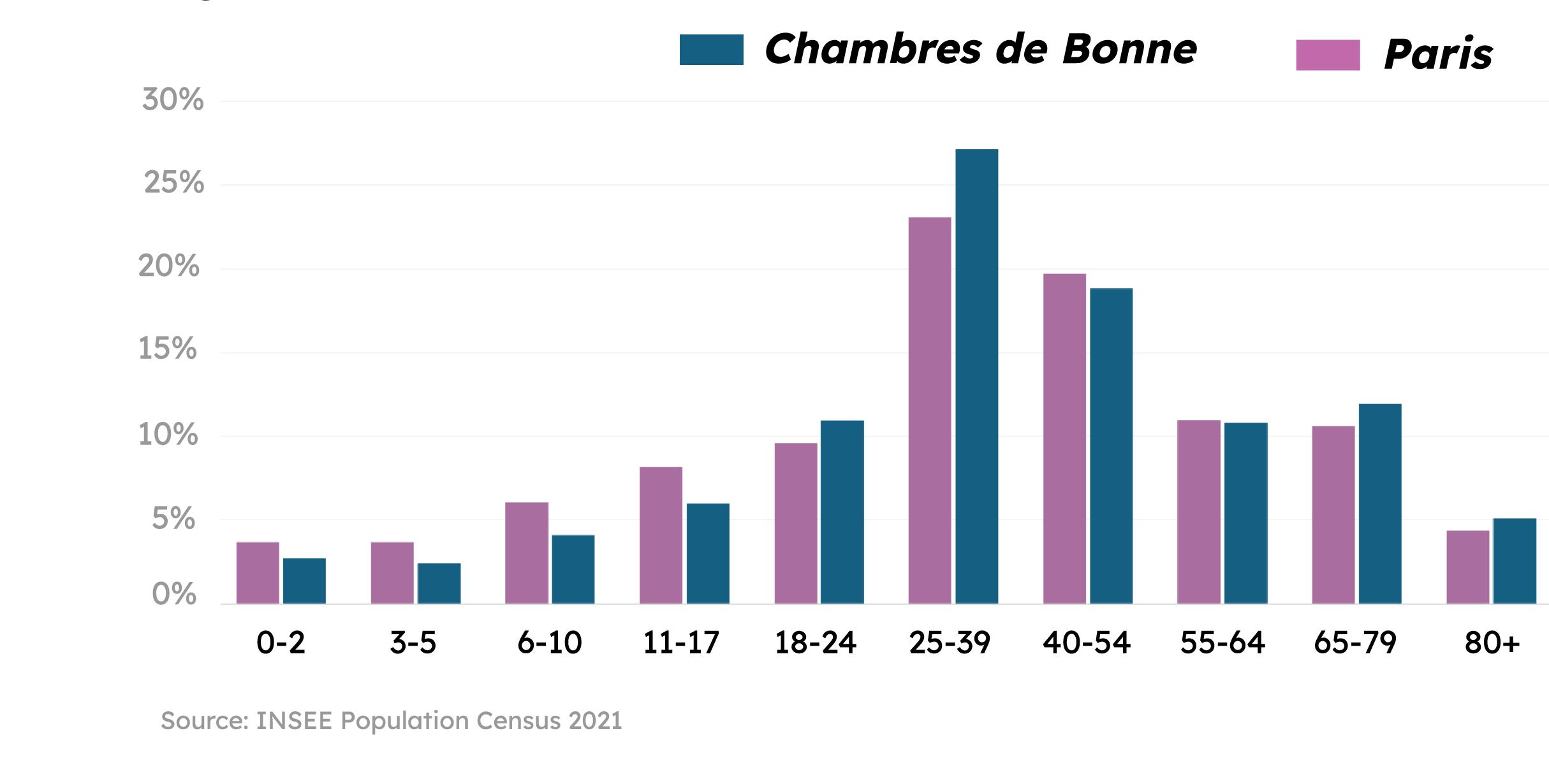

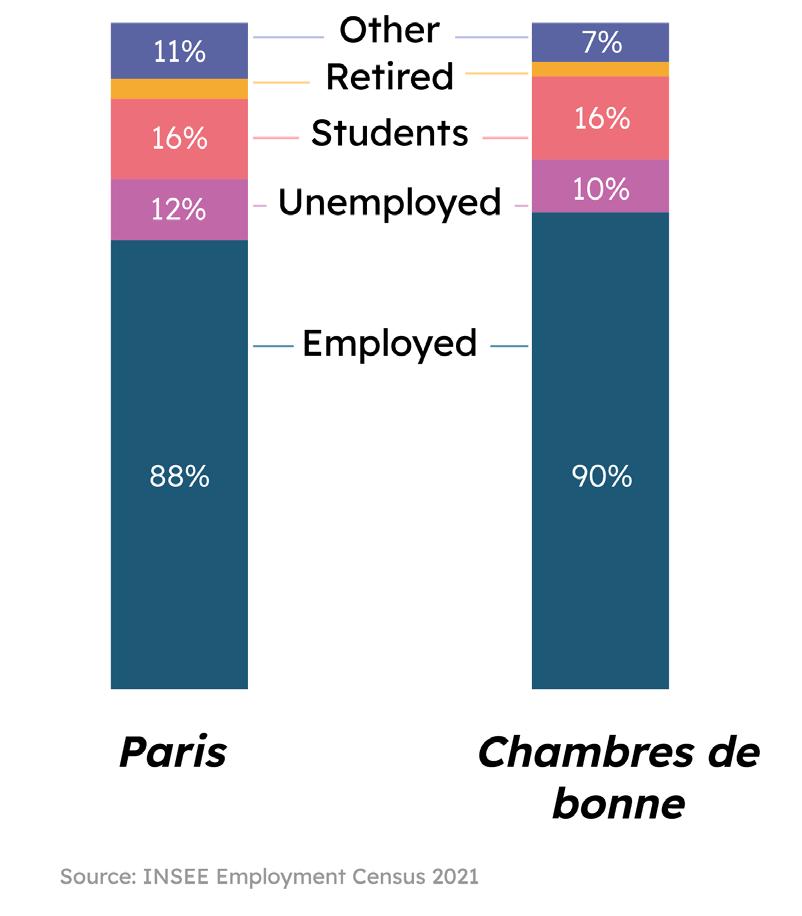

Demographic dimensions of urban heat in Paris’ Chambres de bonne

Aleksandra Banas

Amanda Bendixen

Jazzlynn Derrick

Brooke Jin

Rachel Fischer

The aim of this demographic study of chambres de bonne s is to identify the most vulnerable populations in these spaces. This analysis will inform targeted, population-specific proposals addressing both heat vulnerability and the broader daily challenges residents face. By aligning rooftop interventions with these identified needs, the hope is to enhance their impact and broaden support for these solutions.

This column demonstrates the unique demographic factors of the chambres de bonne.

This column contextualizes the findings from the right column by presenting the greater trends in Paris.

High concentration of people over age 60 arrondissements with a high concentration of chambres de bonne

Areas of very high percentages of single-person households in with a high concentration of chambres de bonne.

Arrondissements with a high concentration of chambres de bonne are areas that have a mixed percentage of immigrants. It’s higher than areas in the center city without chambres de bonne, ranging from 20-40%. One explanation may be a higher rate of expats, but more research is needed to confirm this.

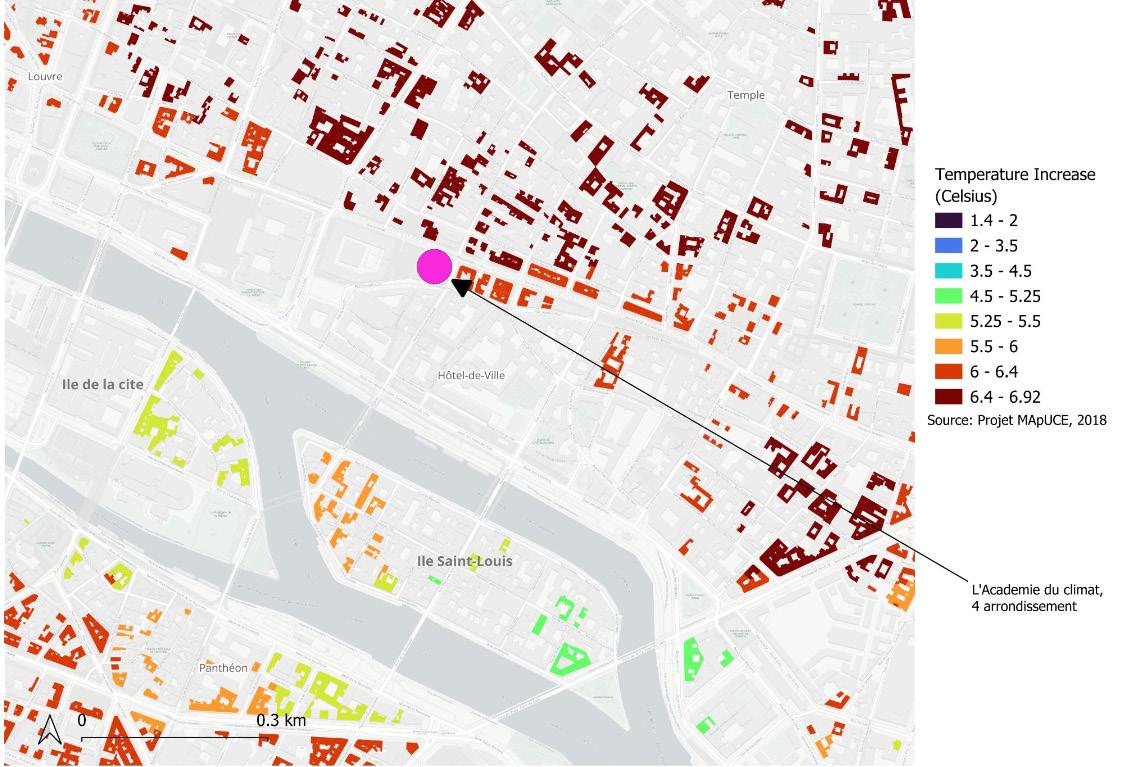

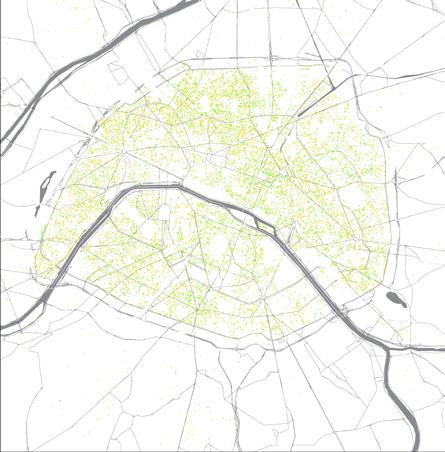

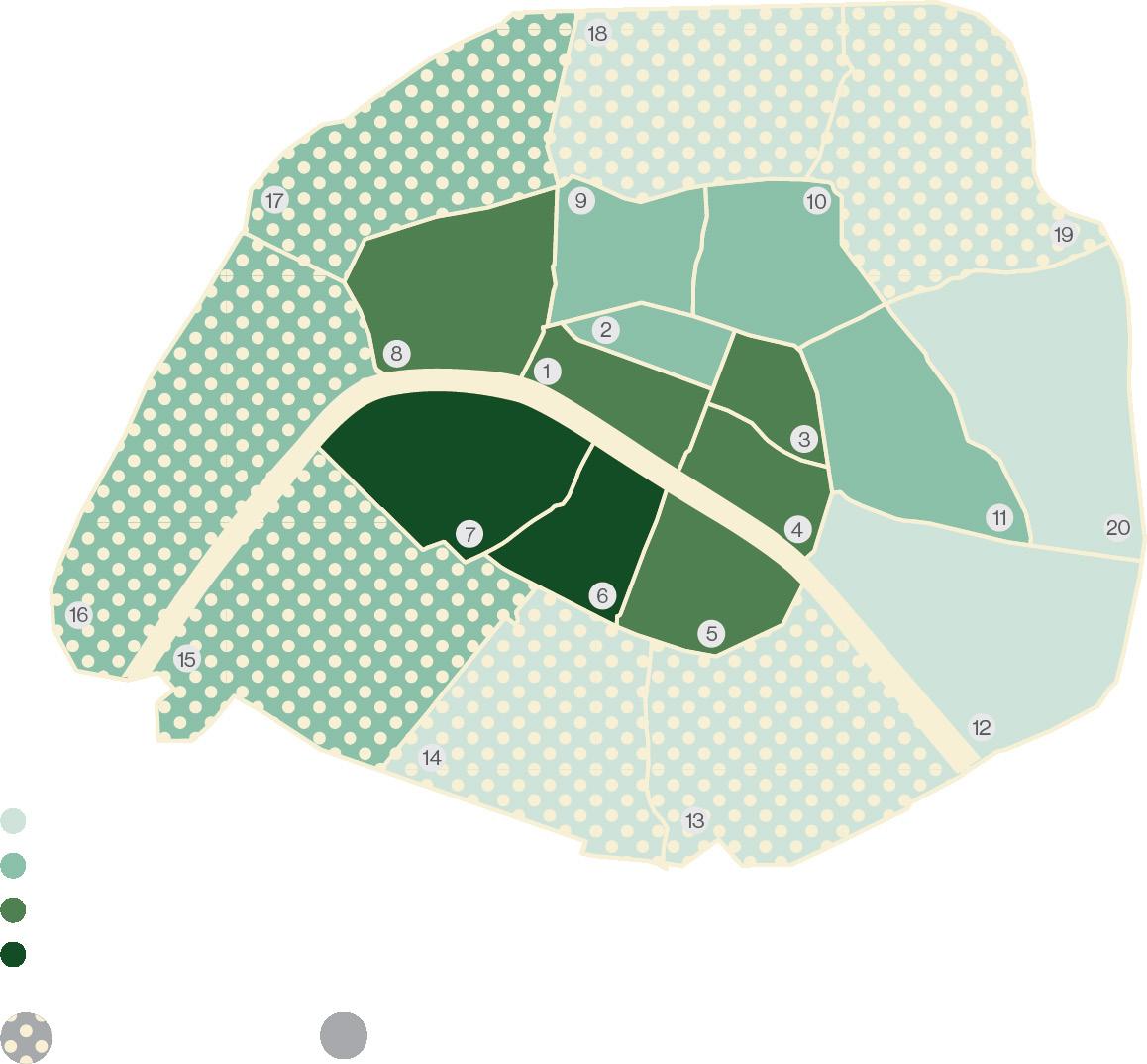

Urban Heat Islands in Haussmannian neighborhoods /Paris metro area

Heat vulnerability in Paris tends to be higher in the central part of the city and lower closer to the edges, likely due to the density of buildings.

Chambres de bonnes are more concentrated in the parts of Paris with higher heat vulnerability.

Paris

How much can heat mitigation help chambres de bonne occupants?

Roofscapes pilot project

Where is greening needed the most?

The Roofscapes pilot project included a study of temperature variations pre- and postgreening which showed a 17 degree Celsius reduction in indoor air temperature with the addition of a green roof, during a heat wave of 35 degrees Celsius. Their pilot project is located in central Paris, where the heat vulnerability is very high.

Despite its proximity to the cooling effect of the Seine river, in Central Paris there are high densities of buildings with zinc roofs and without many large parks. It is most susceptible to heat and will benefit most from greening. Chambres de bonnes are more likely to be located in these dense areas and experience higher heat vulnerability. Older residents and young residents are more vulnerable to heat and are chambres de bonne s residents in high proportions. Greening would in part help alleviate health risks for these susceptible residents.

Architectural and socio-economic dimensions of urban heat in Paris’ chambres de bonne

Issam Azzam

Mike Kaneshiro

Cory Page

Shivangi Varma

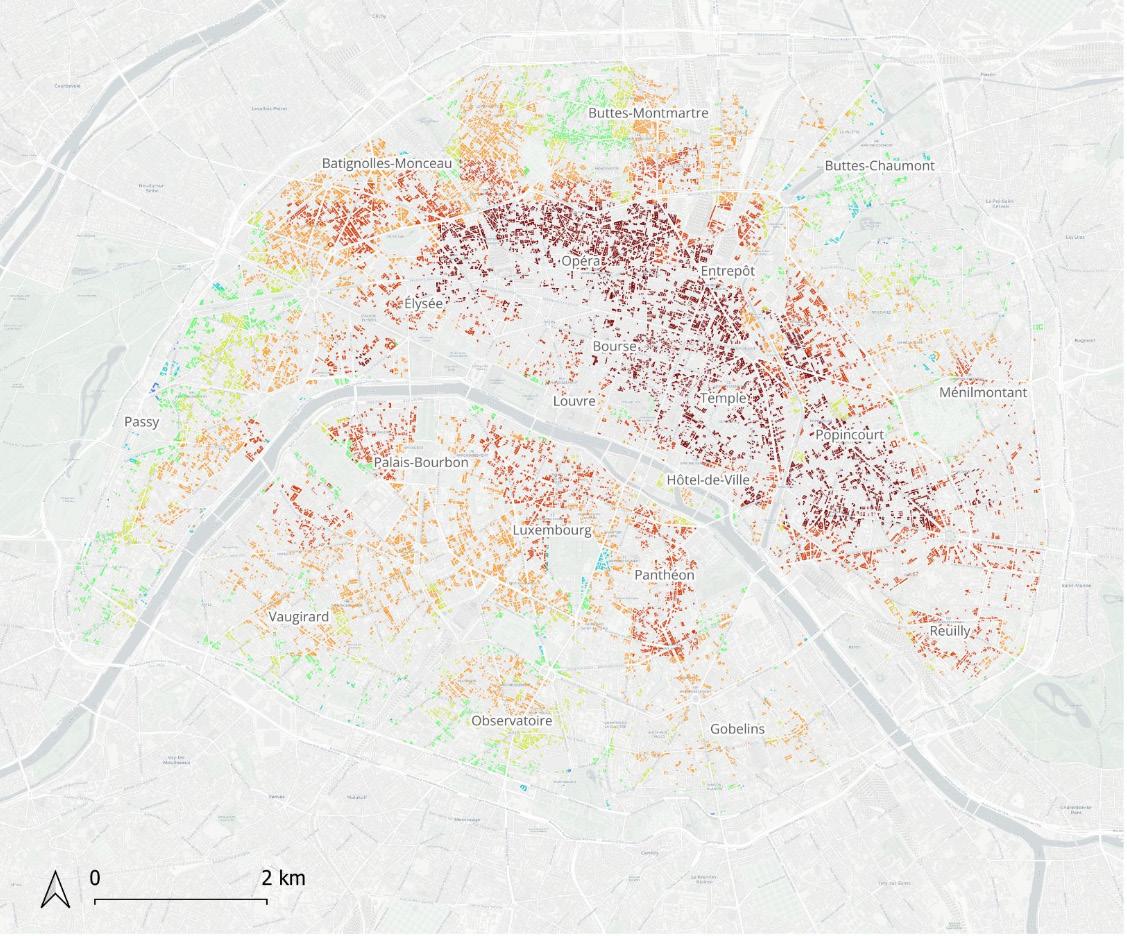

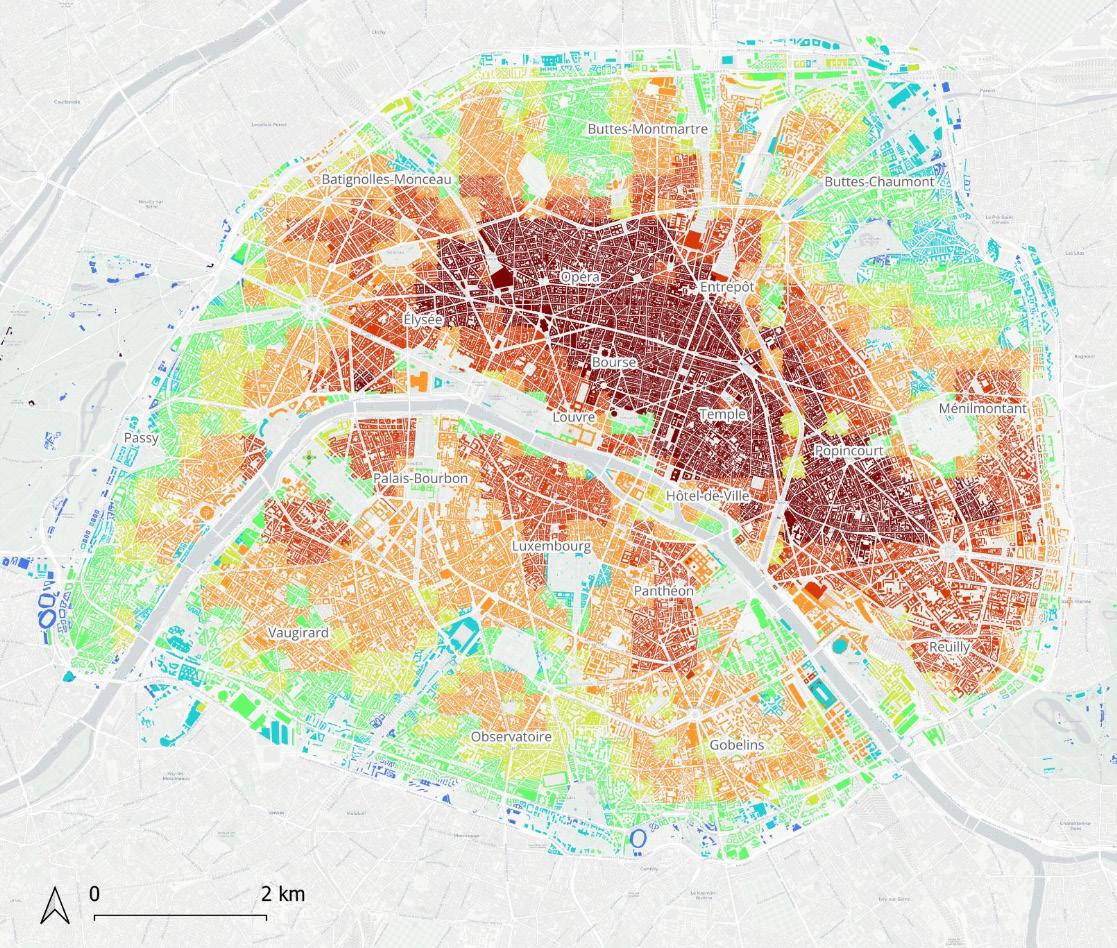

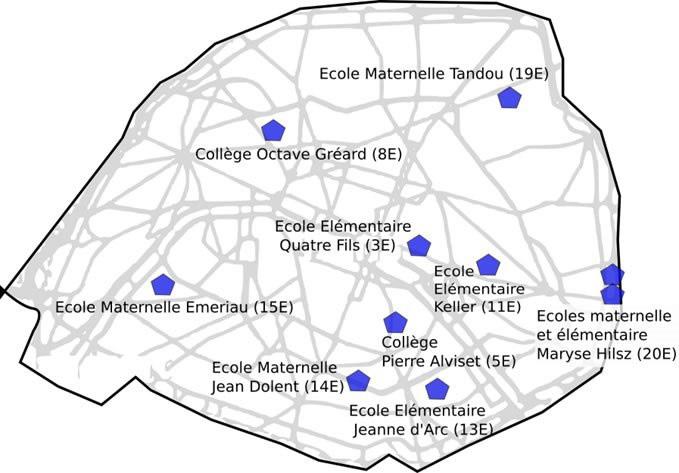

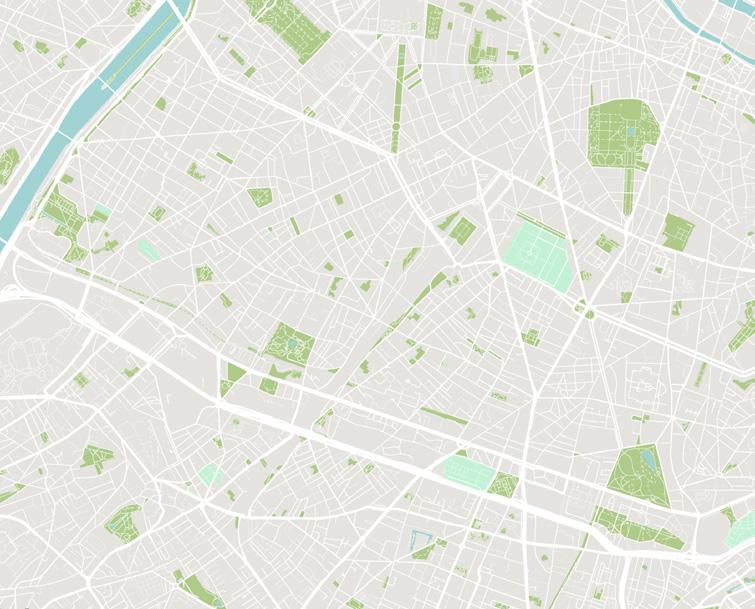

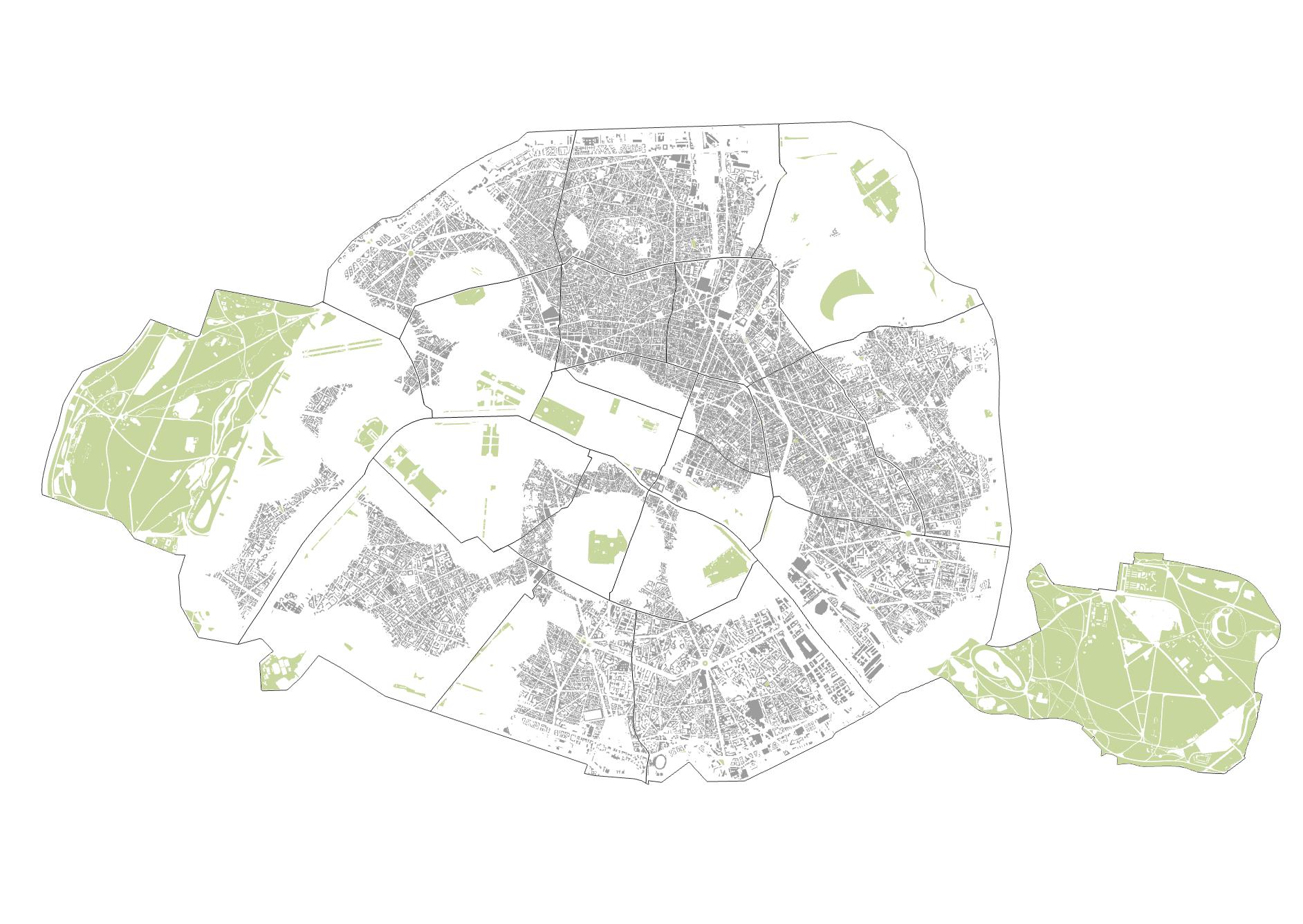

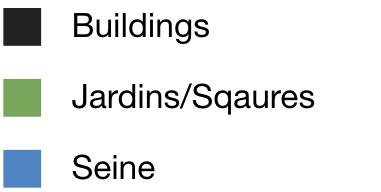

The aim of this architectural study of chambres de bonne is to uncover the hidden mechanisms that contribute to urban heat islands in Paris, focusing on the chambres de bonne as a microcosm of broader urban challenges. By examining the layered interactions between historical and modern architectural styles, and the physical urban environment, alongside socio-economic disparities, our analysis hopes to identify critical areas with an urgent need for sustainable interventions. The findings will inform strategic locations that could be designed to improve indoor thermal comfort, and would also allow an expansive city-wide climate resilience strategy, advocating for a more equitable urban future in the city of Paris, aligning with the goals of Paris’s PLU bioclimatique land use plan.

Voted in december 2024, the PW bioclimatique is the city’s climate-focused land use plan designed to guide urban development toward environmental sustainability, climate resilience, and improved quality of life through regulations that prioritize green infrastructure, energy efficiency, and ecological urbanism.

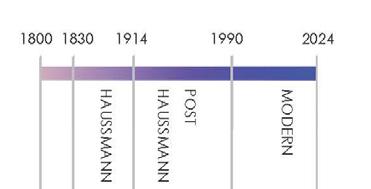

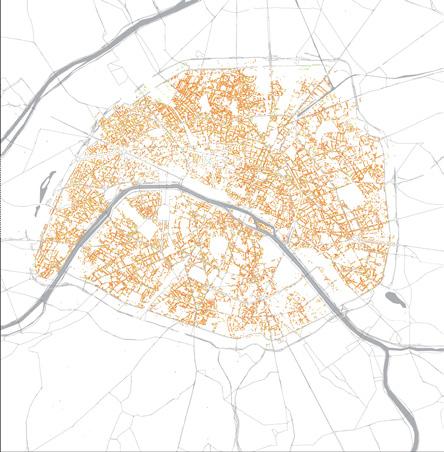

LAYER 1: BUILDING AGE | The first critical layer of architecture is studied through the age of the buildings. Paris’s historical Haussmanian architecture is characterized by mid-rise buildings that emphasize aesthetics and hierarchy, using limestone and zinc. Post-Haussmannian buildings prioritize density with concrete and brick, while modern structures focus on sustainability with advanced materials. We can notice on the map that Haussmanian buildings are spread throughout the city, but are highly concentrated in the city center.

LAYER 2: DPE LEVELS | The study forms a basis by superimposing the Haussmannian building stock with the Diagnostic de Performance Énergétique (DPE) levels. The Diagnostic de Performance Energetique (DPE) is a mandatory energy performance assessment in France that rates a building’s energy efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions to inform buyers or renters about its environmental impact and energy consumption. Heat and DPE levels matter because high indoor temperatures, common in poorly ventilated chambres de bonnes of the Haussmannian buildings, heighten mortality risks, worsen cardiovascular and respiratory conditions, and stress mental health, leading to anxiety, sleep disruption, and cognitive impairment. This impact is especially severe for the elderly and those with pre-existing health issues. When studying the DPE levels in isolation, there is no apparent pattern for DPE levels that can be noticed just yet. However, when we streamline the low DPE levels based on the building age, in this case for modern buildings, we see that there are many modern buildings that are low in their DPE levels (APUR, 2022). This shows that Haussmanian stock (1830-1914) aren’t the only low-efficiency buildings in the city. In fact, the modern buildings (1990 - Present), characterized by sustainable design and materials, are still performing inefficiently.

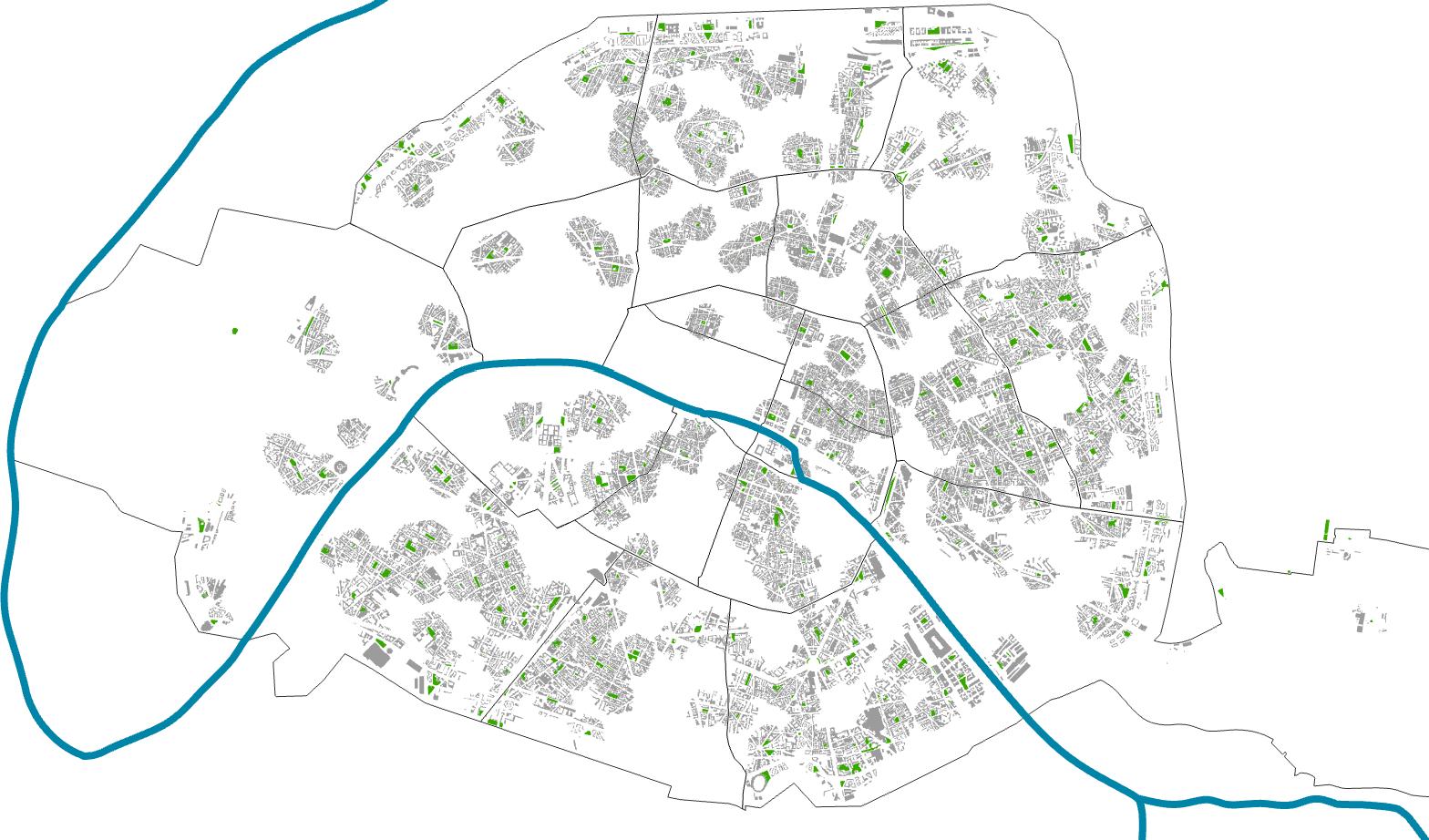

Green spaces play a crucial role in mitigating heat through the “urban cooling effect”, contributing to reducing the temperature in neighborhoods, counteracting the urban heat island (UHI) effect. The distribution of green spaces across Paris is uneven, which can increase the risk of heat-related health complications.

PARKS/FORESTS

PARKS/FORESTS BUILDINGS JARDIN PLAZAS RIVER SEINE/ CANAL

8 MAP SHOWING BUILDINGS LOCATED WITHIN 500 M FROM LARGE GREEN SPACES, PARKS AND FORESTS WHICH ARE OPEN TILL LATE NIGHT/24 HOURS (APUR, 2021)

Most buildings located on the periphery of the city do not fall within the 500 m radius from parks and forests (>15,000m sq. m.), and do not have access to large green spaces after 9pm. This suggests the critical need for green infrastructure to be expanded in areas beyond the city center of Paris.

PARKS/FORESTS

7 MAP SHOWING ALL BUILDINGS LOCATED MORE THAN 500 M AWAY FROM LARGE GREEN SPACES, PARKS AND FORESTS (APUR, 2021)

The presence of green spaces within 500 meters from buildings has been associated with lower daytime temperatures and improved air quality, which could alleviate some heat stress for residents in dense urban fabrics.

Most buildings have access to green spaces that are smaller in size and closed in the evenings, thus creating lack of cool spaces in hot summer months specially during nights. 0

SMALL GREEN SPACES BUILDINGS BUILDINGS

9 MAP SHOWING BUILDINGS LOCATED WITHIN 250 M FROM SMALL OPEN SPACES (<10,000 SQ. M.) WHICH ARE NOT OPEN 24HRS (APUR, 2022)

Property values dimensions of urban heat in Paris’ Chambres de bonne

Melissa Berlin Hiteshree

Das

Karthik Girish Michaela Gwiazda

The analysis explores heat and property values in Paris’s housing market, focusing on the chambres de bonne in Haussmannian buildings (1851–1914), that are now influenced by the Energy performance diagnostics (DPE). The diagnostic de Performance Energetique (DPE) is a mandatory energy performance assessment in France that rates a building’s energy efficiency and greenhouse gas emmisions to inform buyers or renters about its environmental impact and energy consumption.

Navigating scenario-planning and impact assessments for health involves exploring different potential future developments—such as changes in land use, climate, or transportation— and evaluating how these scenarios might affect public and environmental health. This process includes modeling potential outcomes, identifying health risks and benefits, and assessing the impacts on different populations, especially vulnerable groups. The goal is to inform decision-making by predicting how planning choices could shape health outcomes, and to guide strategies that promote healthier, more resilient communities.

This process involves creating detailed models to explore how different planning scenarios—such as new housing developments, transportation changes, or climate adaptation strategies— might affect public and environmental health over time. These models help identify both the potential health risks, like increased air pollution or reduced access to green space, and the possible benefits, such as improved walkability or better access to services. Special attention is given to how these impacts vary across populations, with a focus on vulnerable groups who may face greater exposure or have fewer resources to adapt. By assessing these differential impacts, planners can prioritize actions that reduce health inequities and promote well-being for all residents.

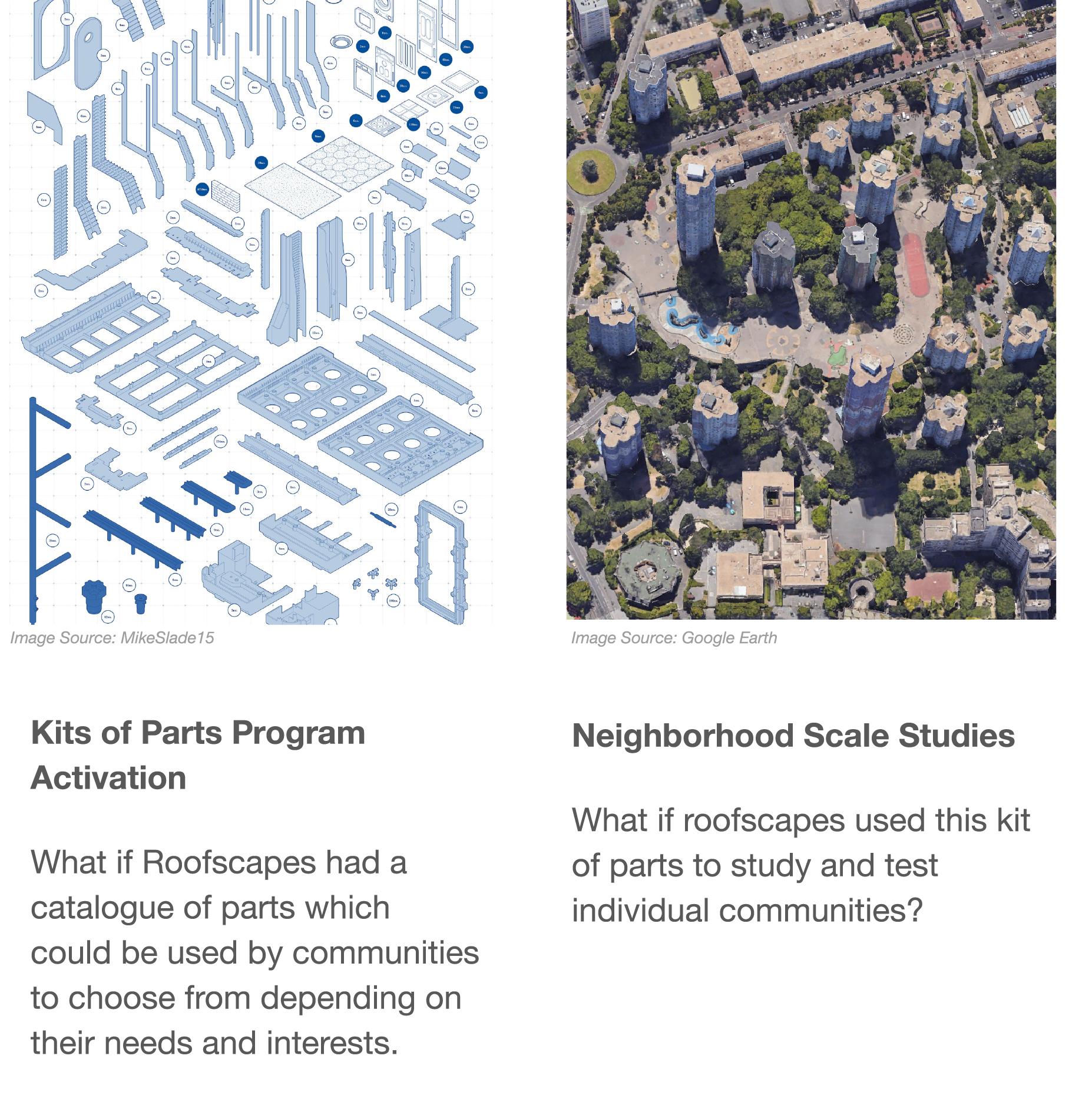

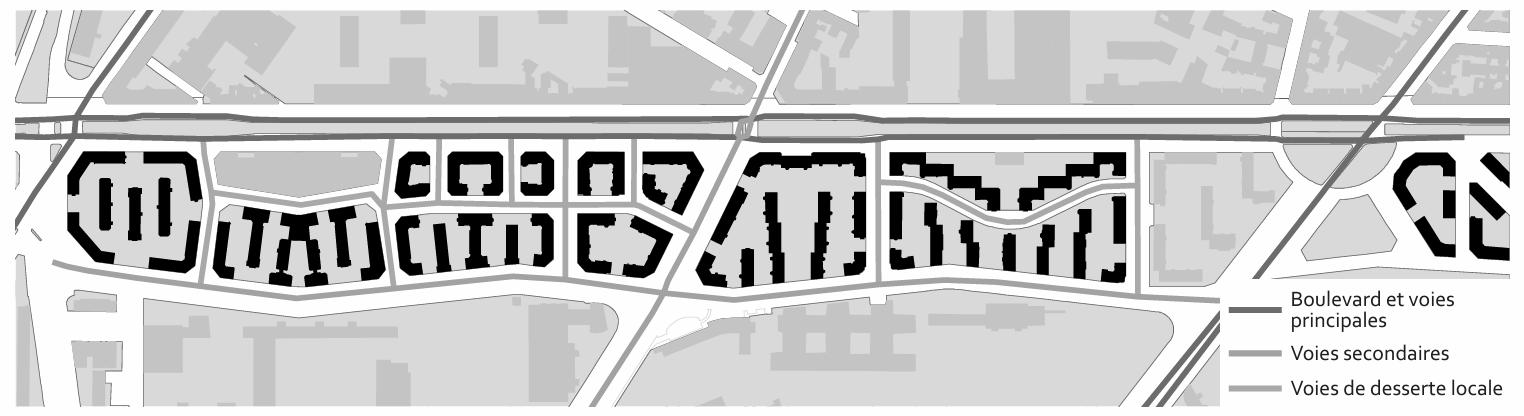

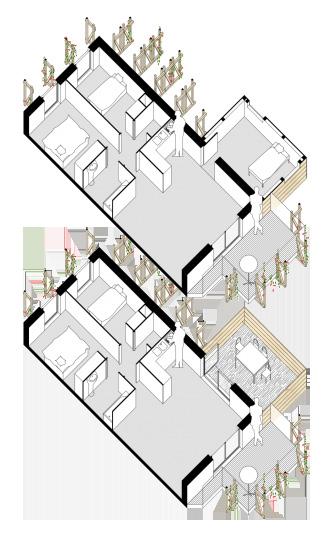

In the first part of the semester of the course Do No Harm: Dilemmas in Planning for Health, students analyzed the roofs of the Haussmannian housing stock, which represents ~60% of the Parisian fabric, within city limits. For the second part of the project, they pushed the envelope and asked what other residential typologies could be a priority focus for Roofscapes. Parisian practitioners have data on 32.2 million sq.m. of rooftops with information on typology (material, albedo, slope), current and potential uses. Out of the 128,000 roofs which have potential for solar energy installations and/or greening and and/or urban agriculture projects to be carried out, proposals explored (1) interwar HBMs or Habitations à Bon Marché, (2) modernist public housing grands ensembles located in the suburbs, and (3) central city middle-income co-propriétés (or co-ops).

Building on this expanded focus, students examined how each residential typology presents unique opportunities and challenges for rooftop adaptation in terms of climate resilience, energy efficiency, and health equity. By considering factors such as building ownership structures, socio-economic profiles of residents, and existing environmental burdens, the project aimed to identify where interventions could have the most significant impact. Scenario planning and health impact assessments were integrated to evaluate how rooftop transformations could contribute not only to environmental goals but also to improving physical and mental well-being, especially in middle-income and underserved communities.

Magda Maaoui

The goal of this phase of the course was to combine a health-focused analysis of the Paris metropolitan region with the development of actionable proposals and detailed implementation strategies. Students were tasked with identifying health disparities linked to the typologies they zoomed in on, and using this insight to inform planning interventions. Through this process, they translated data-driven health assessments into concrete, site-specific proposals that addressed both immediate needs and long-term goals, considering feasibility, equity, and impact at each step.

Implementation of rooftop adaptation proposals requires careful consideration of the broader city and regional context, including regulatory frameworks that may influence feasibility. Different housing typologies present distinct challenges—such as ownership models, structural limitations, and maintenance responsibilities—that must be addressed within each proposal. Students also examined the trade-offs between competing land uses, the need for public infrastructure, and the rights of private property owners. Understanding which municipal organizations and stakeholders are involved allowed for strategies to better align priorities and promote collaboration. Finally, proposals explored how green infrastructure could be effectively integrated and phased over time to ensure both practical implementation and long-term impact.

A strong implementation framework would combine policy, design, and community engagement strategies to ensure proposals are both feasible and impactful. Students assessed necessary legislative changes and governance models to support rooftop adaptation, while also exploring programs and incentives—such as financing mechanisms or civic engagement tools—to encourage participation and investment. Conceptual designs for buildings and public spaces illustrated how interventions could be integrated physically, while phasing plans connected short- and long-term actions to specific costs and responsible stakeholders. Throughout, community engagement played a central role, with an emphasis on informing, involving, and empowering local residents and partners in the implementation process.

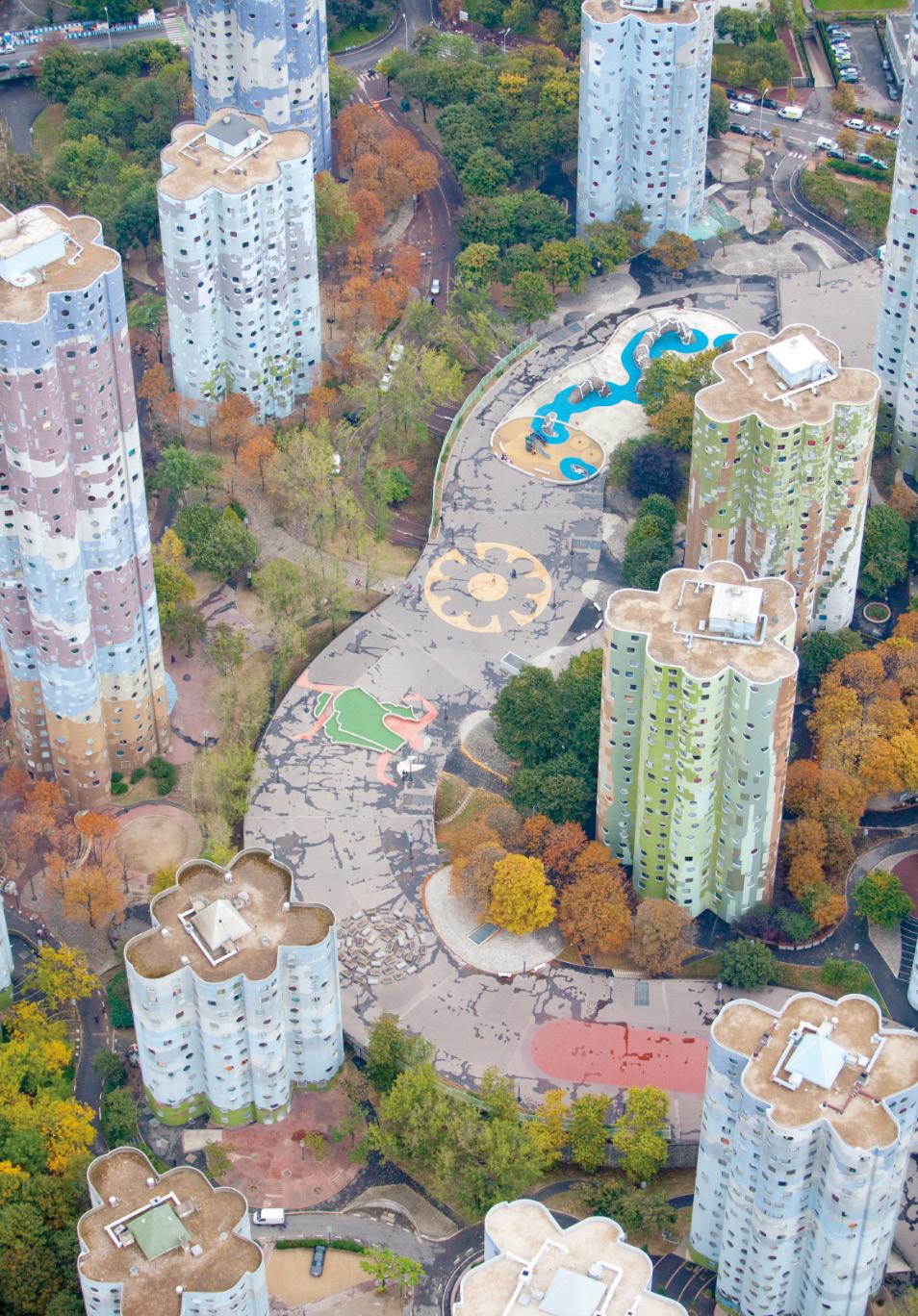

By grands ensembles, we refer to large-scale housing developments, often built in the mid-20th century to accomodate growing urban populations, typically characterized by high-rise apartment blocks and uniform architectural styles. Many of these propels pioneered innovative greenings strategies, like the Etoiles d’ Ivry, pictured above, and designed in the 1970s by architects Jean Renaudie and Renee Gailhoustet, The project integrates 40 social housing units with staggered planted terraces.

Aleksandra Banas

Amanda Bendixen

Jazzlynn Derrick

Brooke Jin

Rachel Fischer

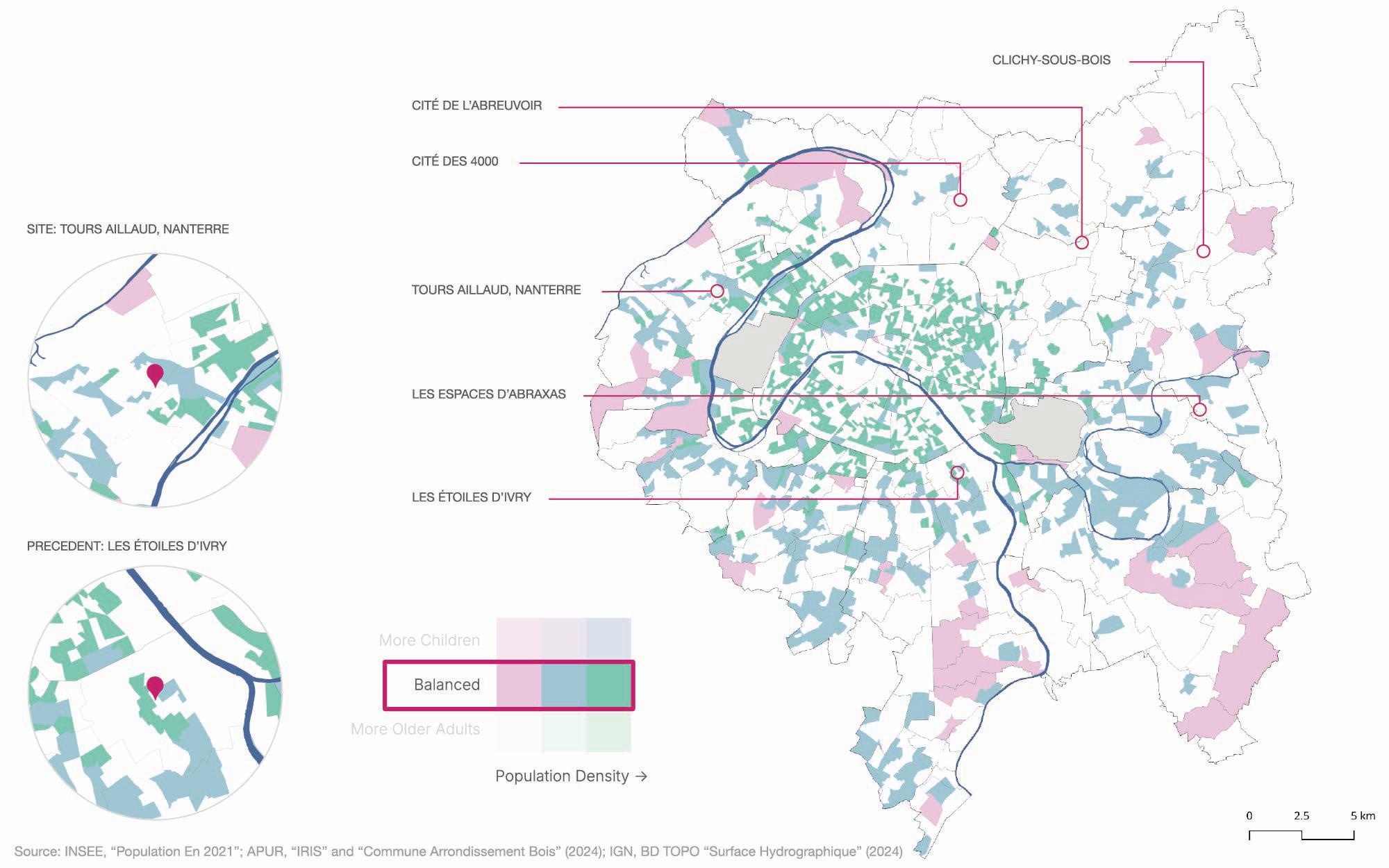

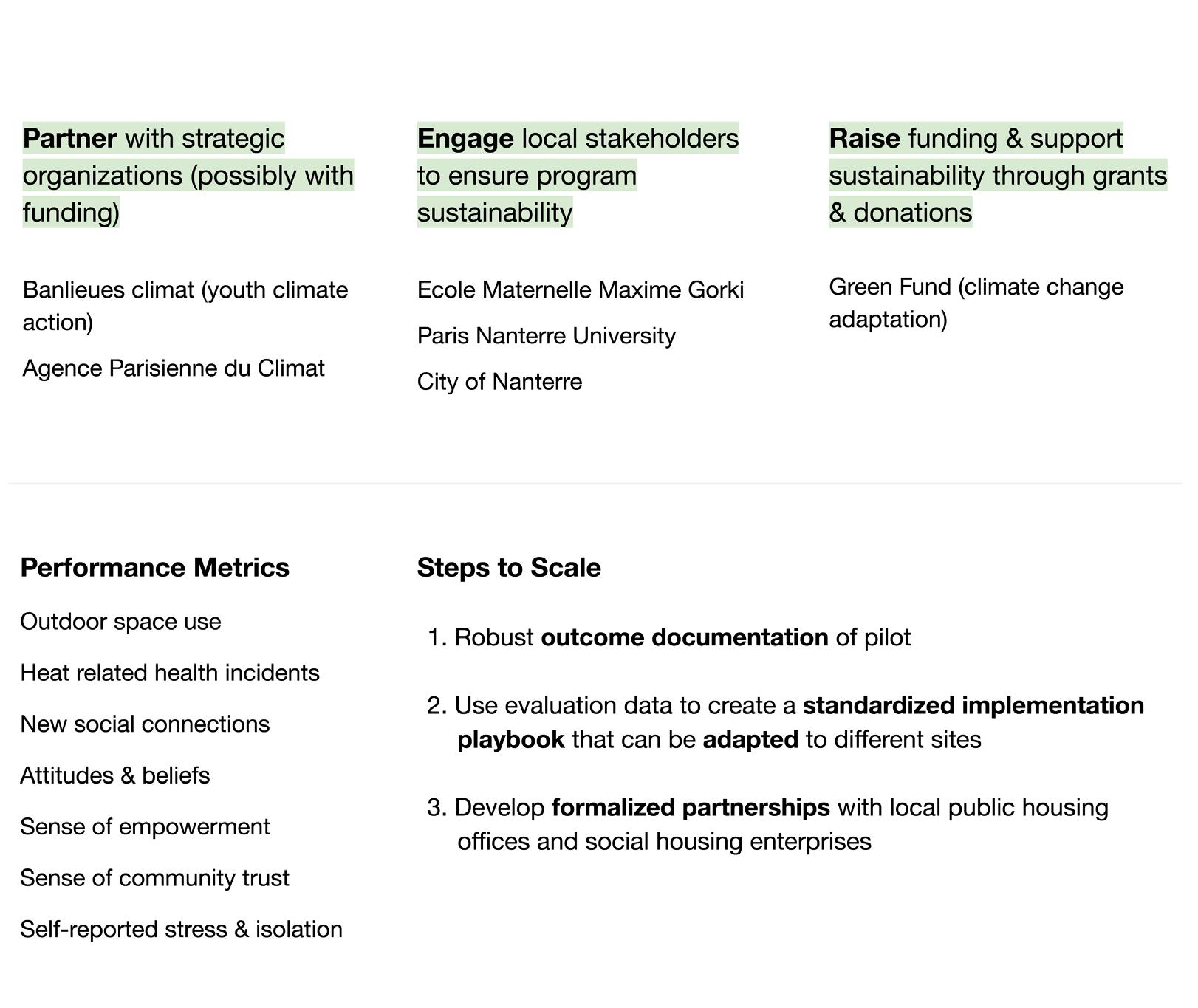

After analyzing the demographic data of the Haussmannian stock, which showcases the intersection between age and heat vulnerability, our team decided to focus on interventions and typologies that could serve multigenerational communities: the Grand Ensembles found on the outskirts of Paris.

Grands Ensembles are social housing complexes built after World War II in response to the growing postwar population and lack of development in rural areas of the region. The goal of the Grands Ensembles was to create commercial hubs outside central Paris and create a more egalitarian society with subsidized housing to the lower and middle class. While the Grands Ensembles were built as creative, highspec apartments meant to be desirable for urban living, they often fall short of serving the true needs of the public.1

This housing typology has long been associated with immigrant communities due to longstanding and impactful patterns of spatial

segregation, stigmatization, and discrimination, resulting in notable social disparities among residents.2 Yet, the spirit of these communities is strong– and their residents have a history of pushing back against mistreatment by local authorities, most recently in protests ignited in 2023 in response to the police killing of 16-yearold Nahel M., a former resident of Tours Aillaud.3

At this moment, climate change impacts are increasing and disproportionately experienced by the same communities grappling with the wounds of police violence and social inequities, there is a meaningful opportunity to advance both climate adaptation and community healing. Grands Ensembles are known for their spacious flat roofs and large concrete plazas, providing ideal conditions for greening interventions. Our intervention focuses on a specific grand ensemble, Tours Aillaud in Nanterre, western Paris, designed by French architect Émile Aillaud. The complex was built between 1974 and 1981 with 2,000 social housing (HLM) apartments.4

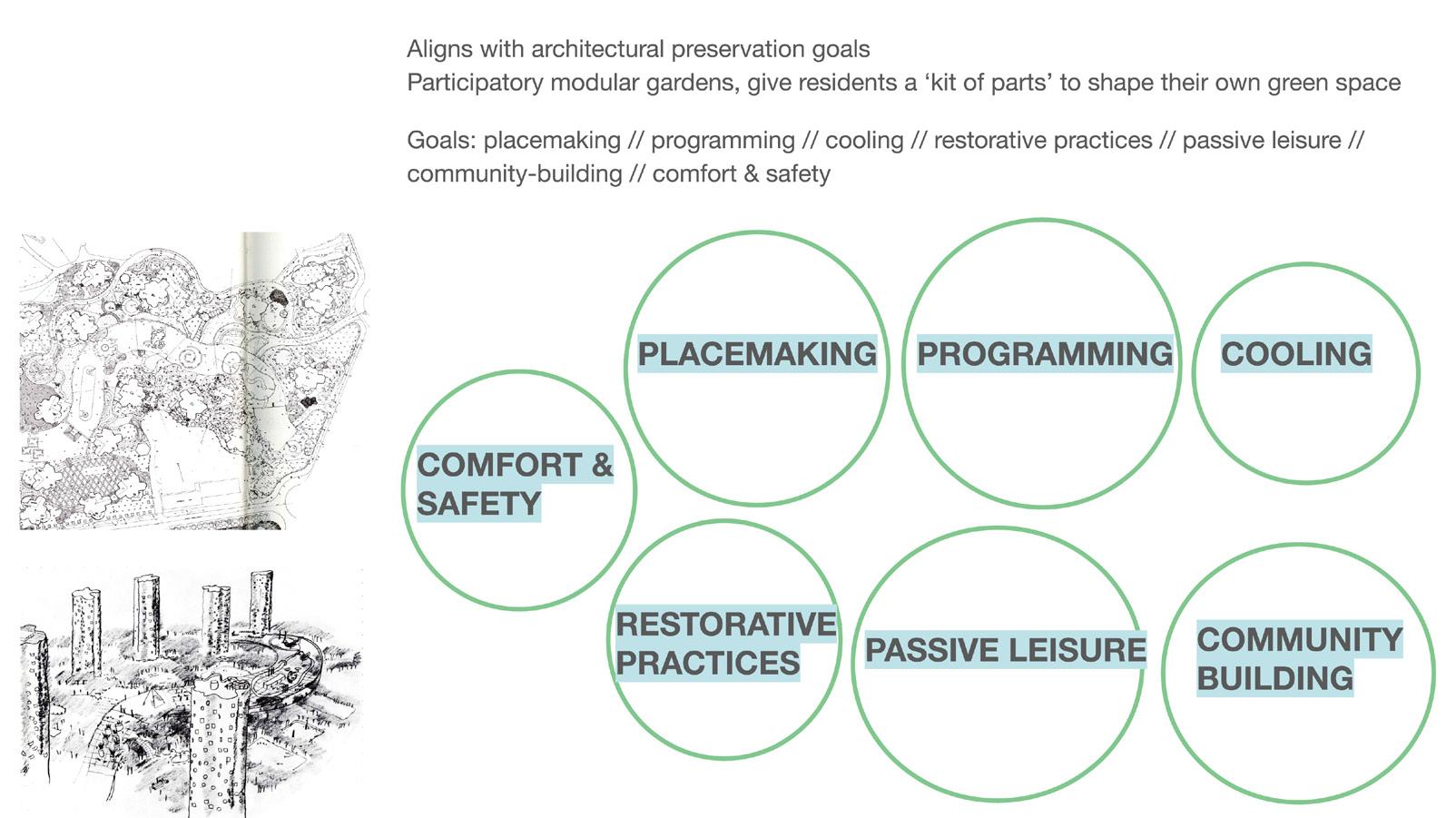

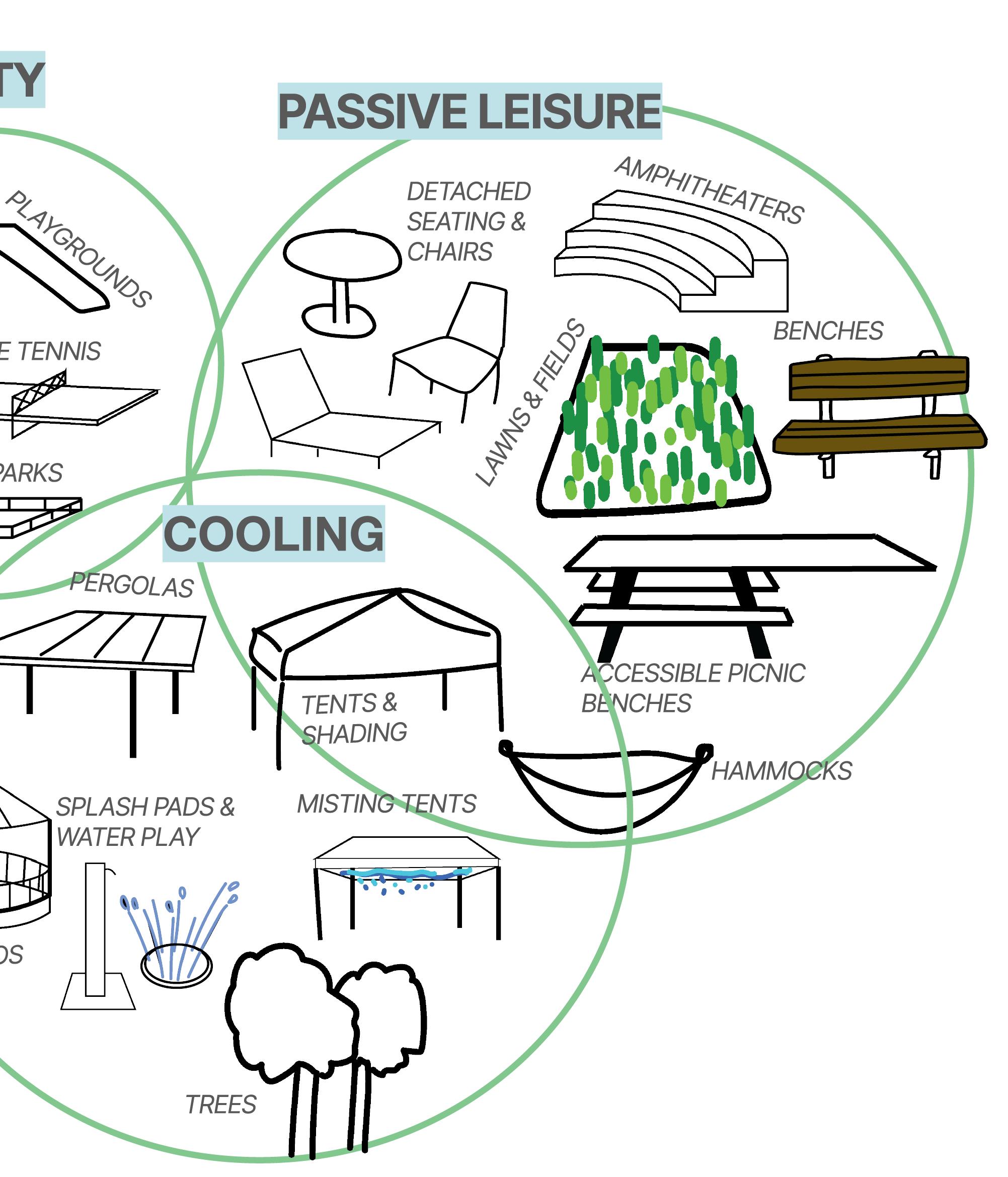

Our team proposes a toolkit of scalable greening and restorative strategies in the Tours Aillaud, in order to address climate vulnerability, appropriate for the landscapes, communities, resources, and challenges specific Parisian banlieues. We aim to cultivate spaces for multi-generational community-building and re-building neighborhood investment and trust. The project focuses on multigenerational communities, heat mitigation and climate adaptation, and design and programming strategies that foster health-promoting social connections.

In each phase of the intervention, our goals remain the same: placemaking, programming, cooling, restorative practices, passive leisure, community-building, and comfort and safety. For phase 1, we recommend greening the plaza directly outside the towers, which aligns well with architectural preservation goals.5 As part of this phase, we suggest a visioning process with community residents to shape their own green spaces, similar to the process employed by OASIS Courtyards in Paris.6

In phase 2, we suggest greening the nearby Maxime Gorki School rooftop with their partnership. With phase 3, we suggest programmatic activation of these two spaces with options like climate resilient day camps and intergenerational daycares, and lastly, in phase 4, we propose a feasibility study for the greening of the tower rooftops.

This intervention supports the residents of Tours Aillaud in several key ways. It prioritizes the building of multigenerational community ties, fostering stronger social bonds across age groups. With a restorative approach, it aims to advance health justice at the neighborhood scale, addressing the specific needs of the local population. Recognizing that suburban contexts differ significantly from those in central Paris, the programming at Tours Aillaud is tailored accordingly, reflecting the unique spatial and social dynamics of the area. Additionally, while recent renovations have treated Tours Aillaud primarily as a heritage landmark, this intervention re-centers the focus on its role as lived-in housing—a place where people make their homes and shape everyday life. If the first focus of this intervention is multigenerational programming serving youth and older adults, this program also benefits everyone whose health can benefit from environmental and behavioral interventions.7 We know that 89% of our overall health is determined outside of the medical clinic, so by addressing multiple health determinants simultaneously, we can amplify positive outcomes for all.8 Much research has shown the positive biopsychosocial outcomes associated with similar multigenerational greening interventions.9 10

Individual Level Change Community Level Change Environmental Change

Stress Relief*

Self Esteem Sense of Belonging Attitudes and Beliefs* Motivation

Empowerment*

Social Connections

Trust Building*

Social Solidarity*

Social Capital

* indicates a suggested program metric

Nature Experiences*

Heat Safety*

Places to be Active

Neighborhood Pride Aesthetic

References:

1. Alaimo, Katherine, Alyssa W. Beavers, Caroline Crawford, Elizabeth Hodges Snyder, and Jill S. Litt. 2016. “Amplifying Health Through Community Gardens: A Framework for Advancing Multicomponent, Behaviorally Based Neighborhood Interventions.” Current Environmental Health Reports 3(3):302–12. doi: 10.1007/s40572-016-0105-0.

2. Al-Delaimy, W. K., and M. Webb. 2017. “Community Gardens as Environmental Health Interventions: Benefits Versus Potential Risks.” Current Environmental Health Reports 4(2):252–65. doi: 10.1007/s40572-017-0133-4.

3. Atelier Parisien d’Urbanisme (APUR). 2024. “Commune Arrondissement Bois.”

4. Atelier Parisien d’Urbanisme (APUR). 2024. “IRIS.”

5. Butts, Donna M., and Shannon E. Jarrott. 2021. “The Power of Proximity: Co-Locating Childcare and Eldercare Programs.” Stanford Social Innovation Review

6. Children Nature Network. “Case Study: France | Les Cours OASIS, Ville de Paris | C&NN.”

7. Choi, Edwin, and Justin Sonin. 2016. “Determinants of Health Visualized.” GoInvo.

8. Climate ADAPT. 2024. “Paris Oasis Schoolyard Programme, France.”

9. Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. 2019. “Suburban Paris Complex Undergoes Major Renovations – CTBUH.”

10. Direction du patrimoine. 2011. Les Grands Ensembles: Une Architecture Du XXe Siècle. Paris: Carré.

11. Erikson, Lars Hinnerskov. “Superkilen: Welcome Europe’s Strangest Public Park | CNN.”

12. Green, Lawrence, and Marshall Kreuter. 2005. Health Program Planning: An Educational

and Ecological Approach. 4th ed. Boston, Mass.: McGraw-Hill Humanities/Social Sciences/ Languages.

13. Institut National de L’Information Géographique et Forestière (IGN). 2024. “BD TOPO.”

14. Institut National de la Statistique et des Études Économiques (INSEE). 2021. “Population En 2021.”

15. Keller, Richard C. 2013. “Place Matters: Mortality, Space, and Urban Form in the 2003 Paris Heat Wave Disaster.” French Historical Studies 36(2):299–330. doi: 10.1215/001610711960682.

16. Kirby, Paul. 2023. “France Shooting: Who Was Nahel M, Shot by French Police in Nanterre?” BBC, June 29.

17. Lyell, Kelly. n.d. “‘Built by Teens for Teens’: New Activity Center in Old Town Fort Collins to Open in June.” Fort Collins Coloradoan

18. Ministère de la Culture. 2014. “Grand Ensemble Des Tours Nuages Du Quartier Pablo Picasso.”

19. Ministère de la Culture. 2021. “Atlas Des Patrimoines.”

20. Nanterre.fr. n.d. “Ecole Maternelle Maxime Gorki.”

21. Onur, Zeynep. 2023. “French Banlieues and the Consequences of Spatial Segregation.” Center of Excellence in Housing and Urban Research and Policy (CHURP) at Howard University.

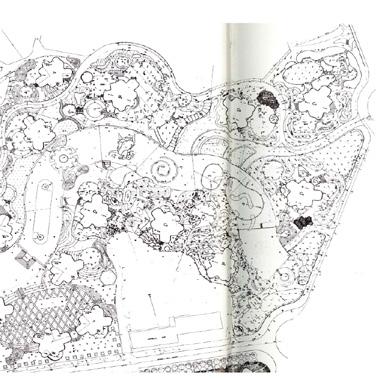

22. Plan for plaza by Architect Emile Aillaud (n.d.), in Chanteloup Les Vignes, Quartier “La Noé”, by Emile Aillaud, Fabio Reti, and Gilles Aillaud. Paris: Fayard, 1978.

23. Projet Modélisation Appliquée et droit de l’Urbanisme: Climat urbain et Énergie (MApUCE). 2018. “Les données d’ilot de chaleur urbain urbaines.”

24. Roofscapes. “Maintenance Guidelines.”

25. The Safer Parks Consortium. 2023. Safer Parks: Improving Access for Women and Girls doi: 10.48785/100/151.

26. Stevens, Joshua. 2015. “Bivariate Choropleth Maps: A How-to Guide.” Joshua Stevens, Geographic Communicator.

27. Visions of the Future: Paris’s Grands Ensembles. RICS.

28. Wilensky, David A. M. 2018. “Tawonga Evacuation Is a Sign of Climate Change.” J.

Multigenerational Neighborhoods

The intersection between age and heat vulnerability led our team to focus on interventions that can serve multigenerational communities.

Post WWII social housing complexes in the outskirts of Paris. Built to establish commercial hubs outside of Paris, eradicate slums and create a more egalitarian society.

These rows of high-rise public housing units built in and around major French cities were anticipated as the “miracle solution” for a fire housing shortage.

After the 1970s, public discourse has defined these public housing projects either as the failure of the country’s housing, social welfare, and modernization effort or cost it as an important part of the country’s architectural heritage.

Focus Areas

Multigenerational Communities

Heat mitigation & adaptation

Fostering social connection

Source: Direction du patrimoine. 2011. Les Grands Ensembles : Une Architecture Du

Constructed: 1974 - 1981

Location: Nanterre, Western Paris

Architect: Émile Aillaud

Site Status: Modern Heritage 1

Quantity: 18 towers comprising 2,000 HLM apartments

Other names: Cité Pablo Picasso, Tours Nuages

Developments: Renovation of outdoor spaces in 2007, update of façades began 2019

Recent Event: 2023 protests of police killing of Tours Aillaud resident, 16 year old Nahel M.

1. Ministére de la Culture. 2014. “Grand Ensemble Des Tours Nuages Du Quartier Pablo Picasso.” Plateforme Ouverte Du Patrimoine. https://pop.culture.gouv.fr/notice/merimee/EA92000017

Image Source – (top left): Anna-Maria Mayerhofer. (2020) https://www.sosbrutalism.org/cms/19749541, (top right): Source: Daily Photo Stream. (2010) https://dailyphotostream.blogspot.com/2010/08/giant-snake.html

Housing Typology:

Priority Population:

Problems Addressed:

A toolkit of scalable strategies to address climate vulnerability through greening and restorative practices, appropriate for the landscapes, populations, and issues of Parisian banlieues.

We aim to cultivate spaces for multigenerational communitybuilding and re-building neighborhood investment and trust.

Grands ensembles, social housing projects of Greater Paris. Known for expansive flat roofs and large concrete plazas.

Vulnerable populations living in grands ensembles who are disproportionately likely to be immigrants, including children, young adults, and older adults in particular.

Social and environmental heat vulnerability

Youth summer activities / enrichment for older adults

Social solidarity

Social isolation

Health disparities

Strategic Orientation:

Low-cost / high-impact public space adaptation and greening options suited to community co-design and flexible programming.

Phase 1: Greening the plaza directly outside the towers

Phase 2: Greening nearby school rooftop

Phase 3: Programmatic activation

Phase 4: Feasibility studies of greening tower rooftops

How does this intervention serve the residents who live in Tours Aillaud?

The intervention focuses on multigenerational community-building

It is restorative - it aims to promote health justice on a neighborhood level

Programming for suburban scales will be different than urban scales

Recent renovations have focused on Tours Aillaud as a heritage site rather than as housing, where people live

Phase 1: Greening the Plaza

Imagine these tool kit components as a menu of “sticker to use during a visioning process for residents to mix and match to explore features they want included in their space.

PRECEDENT: OASIS Courtyards in Paris

• Funding: European Regional Development Fund – Urban Innovative Actions Initiative (UIA

• Method: Co-design process

• Principles: increasing vegetation and natural materials, retaining water

• Pilot: 10 target schools, focusing on the most vulnerable, programmatic events

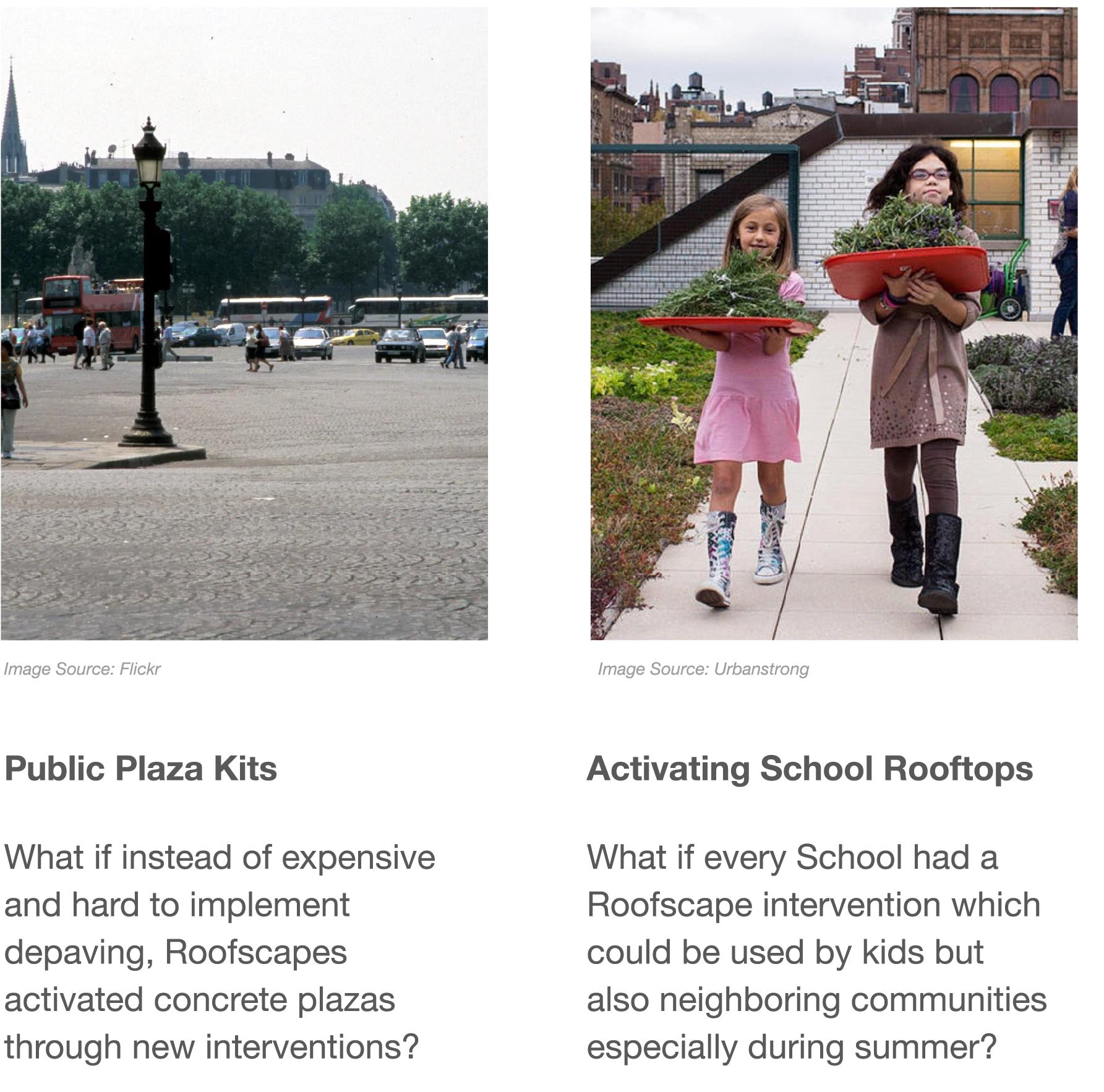

the School Rooftop

Goals: placemaking // programming // cooling // restorative practices // passive leisure // community-building // comfort & safety

Pilot Location

Challenges

• Gaining access to rooftops and cooperation with school

• Need for maintenance ecosystem + employees or volunteers Use

• Logistics of who can use, how to include them, when/ how to open or close the space Co-benefit

• Cooling of classrooms directly underneath

• Day camps

• Heat resilient strategies for children, global camp adaptations to climate change

• Multi-generational community-building

• Intergenerational daycare movements

• Night teen hangout spaces

• Temporary activations and visioning processes

• Does the structure have sufficient integrity for intervention?

• Who lives right under the roofs?

• Are the roofs accessible?

• Will residents be able to go up and use the roof?

Greening the Plaza + Programmatic Activation

Greening the School Rooftop

In Paris, co-propiertes, or co-ops, refer to shared residential buildings where–individual apartments are privately owned, but common areas like stairwells, roofs, and courtyards are jointly owned and maintained by all the residents. Co-propiertes are present throughout all 20 arrondissements, as they are dominant form of residential ownership in Paris, across buildings of vaious ages.

Our proposal aims to motivate efficient and equitable renovation solutions for cooperatives in the 14th arrondissement by leveraging combined insulation, tariffed on-bill financing and tiered payment systems. This proposal will drive collaborative decision-making through strategic cost-sharing with the city and reduced risk to individual owners.

Thermal strainers (EFG-rated units) are facing declining property value and rental bans, creating financial strain for owners and complicating the housing market dynamics for Paris. Without energy renovation work, nearly one in two homes in the Paris region will soon be banned from renting. Parisians are selling off lower-rated apartments to avoid paying the cost of renovation.

Residents in the 14th arrondissement have different motivations than the sale value and rental bans that concern many owners throughout Paris. Middle-income families call the 14th arrondissement home. We focus our attention on Plaisance, where many residences have been owned by families for multiple generations. The neighborhood has a strong trend of long-term occupancy. The data shows long-term family retention, with stable housing stock, minimal turnover, and increased vacant dwellings or second homes. In 2021, the majority of households were families. Residences in the 14th arrondissement are mostly primary residences. Most residents want to stay in their homes as long as it is affordable.

Copropriétés are buildings where individuals own their own unit and the condominium association, or resident collective, owns the common spaces. These are an interesting case study for renovations because the condo association needs to agree on the work, and individual owners must contribute much of the financing. Ma Prime Rénov’, a state aid that allows households to finance energy renovation, covers 30-45% of renovation costs, with the rest funded by unit owners. Some individuals are eligible for additional income-based subsidies. Others must take out loans to cover the upfront financing. Residents may be discouraged from voting for the renovation if their utility savings will be disproportionately low compared to other units. In the case of installing a green roof, the upper floors will have the highest reduction in heat loss and therefore the highest utility bill savings. First floor owners may be less eager to contribute an equal amount for lower utility savings.

Co-propriété owners and residents in the 14th arrondissement have different motivations to invest in renovations. They are more likely to undertake such renovation work if the renovation improves the long term comfort of their homes as heat intensifies, or if the investment reduces utility bills, does not require upfront costs, does not require the risk associated with loans, especially if an owner sells their unit or is billed relative to each unit’s resulting savings.

Our proposal has three complementary components.

1. Combined insulation renovation

A packaged renovation links roof insulation or green roofs with another global insulation renovation (i.e. windows, interior walls, exterior facades). This helps equalize the benefit of insulation across the building instead of targeting upper units, and it maximizes the effect of future renovations such as heat pumps.

2.

The utility company pays the remaining upfront cost after Ma Prime Rénov’ subsidies as a loan against the building. The loan is paid back as a surcharge on unit utility bills, never to exceed each unit’s savings.

Therefore, residents continue to pay the same amount while experiencing greater comfort. This has additional benefits:

• The utility bill decreases once the loan is paid off

• The loan is passed onto future residents if the owner sells their unit

• The home value increases, especially once the loan is paid off

3. Tiered contributions

The overall loan against the building will be divided according to each unit’s respective utility savings. For example, if a top floor unit is saving 20% on their utility bill and a first floor unit only 5%, the top floor will pay 75% more than the bottom floor on their monthly surcharge.

The neighborhood will benefit from reduced heat island effects and heat expulsion from the building .

Tenants will be more likely to vote in favor of a renovation if the cost feels fair, they do not have to pay an upfront cost, and they do not need to assume the risk of a person-linked loan.

The Paris government is responsible for raising significant financing to cover upfront costs. It also assumes the risk of unpaid loans. Still, occupants who would benefit the most may be discouraged from voting in favor if they feel that the higher cost to them is unfair.

This proposal aims to motivate uptake of building renovations that upgrade building energy efficiency in a working class neighborhood home to many families. Our proposal targets longtime residents who would most benefit from improved thermal comfort and air quality but who are less considered in the current model of sanctions and incentives. Our model encourages low-risk investment in the community’s future.

References:

1. Agence de l’Environnement et de la Maîtrise de l’Énergie (ADEME). “Guide de l’isolation thermique des façades.” https://www. ademe.fr/guides/isolation-thermiquefacades.

2. Agence Nationale de l’Habitat (Anah). “DPE Logements Existants: Etiquettes DPE.” Last modified 2024. https://www.anah.gouv.fr/ dpe-logements-existants-etiquettes-dpe.

3. Agence Nationale de l’Habitat (Anah). “MaPrimeRénov’ Copropriété.” https:// www.anah.gouv.fr/.

4. Buildings Performance Institute Europe (BPIE). “How to Stay Warm and Save Energy: Insulation Opportunities in European Homes.” Last modified December 2011. https://www.bpie.eu/publication/ how-to-stay-warm-and-save-energyinsulation-opportunities-in-europeanhomes/.

5. Complete France. “French Property Renovation Costs.” Last modified September 25, 2019. https://www.completefrance.com/ french-property/what-are-the-costs-ofrenovation-in-france-8346396/.

6. Electricity Regulatory Commission. “Electricity Prices in France: December 2024 Report.” https://www.cre.fr/en/ electricity-prices-december-2024-report.

7. European Commission. “Renovation Wave.” https://energy.ec.europa.eu/topics/energyefficiency/energy-efficient-buildings/ renovation-wave_en.

8. Financial Times. “Two Dead After Huge Explosion at Eni Fuel Depot Near Florence.” December 9, 2024. https://www.ft.com/ content/9fb44a42-66f6-4c84-a94709b394878280.

9. France Rénov’. “Tout savoir sur la rénovation énergétique de votre copropriété.” Last modified February 2024. https:// france-renov.gouv.fr/sites/default/ files/2024-02/202402-synthese-renovationenergetique-copropriete.pdf.

10. Google. “Google Maps Street View of [Building Address].” https://www.google. com/maps.

11. Green Roofs for Healthy Cities. “2023 Year End Report.” https://greenroofs.org/yearend-report-2023.

12. Institut Paris Region. “Without Energy Renovation Work, Nearly One in Two Housing Units in Île-de-France Soon Banned from Renting.” https://www. institutparisregion.fr/nos-travaux/ publications/sans-travaux-de-renovationenergetique-pres-dun-logement-franciliensur-deux-bientot-interdit-a-la-location/.

13. Le Parisien. “Thermal Sieves: In Case of a Poor Energy Performance Certificate (EPC), What Depreciation to Expect for Your Property?” Last modified December 15, 2023. https://www.leparisien.fr/ immobilier/passoires-thermiques-encas-de-mauvais-dpe-a-quelle-decotesattendre-pour-son-logement-15-12-2023U3ECMFF6NJBULJLWTDKKC2X3QI.php.

14. Le Parisien. “Thermal Sieves: Why the Ban on Renting Them Is a Real Time Bomb.” Last modified November 23, 2024. https://www.leparisien.fr/immobilier/ passoires-thermiques-pourquoilinterdiction-de-les-louer-est-uneveritable-bombe-a-retardement-23-11-2024RFK7LHI6IVHGRNVI7COSDZW6KU.php.

15. Muspratt, Ashley, and Jon Blair. “UtilityLed Acceleration of Residential Efficiency & Electrification Retrofits: Introducing Tariffed On-Bill Financing.” Center for EcoTechnology, 2022. https://www.cetonline.org/ utility-led-acceleration-of-residentialefficiency-introducing-tob-tariff-on-billfinancing-electrification-retrofits/.

16. National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE). “Complete Data File: Commune of Paris 14th Arrondissement (75114).” Last modified October 8, 2024. https://www.insee.fr/ en/statistiques/6455994?geo=COM75114#ancre-POP_T3.

17. National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE). “Full Set of Local Data: Commune of Paris 14th Arrondissement (75114).” Last modified October 8, 2024. https://www.insee.fr/en/ statistiques/6457611?geo=COM-75114.

18. National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE). “Population Evolution and Structure in 2020: Commune of Paris 14th Arrondissement (75114).” Last modified June 27, 2023. https://www.insee.fr/en/ statistiques/6455996?geo=COM-75114.

19. Property Records. “[Building Address] Property Details.” https://propertyrecords. example.com/building-address.

20. Roofscapes. “Maintenance Guidelines.” https://roofscapes.com/maintenanceguidelines.

21. SeLoger. “SeLoger: Votre Site d’Annonces Immobilières.” https://www.seloger.com/.

22. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). “City of Paris: Climate Leaders.” https://unfccc.int/ climate-action/un-global-climate-actionawards/climate-leaders/city-of-paris.

23. Urbanstrong. “France’s Famous Eco-Roof Law – Too Green to Be True?” Last modified February 29, 2016. https://urbanstrong.com/ blog/frances-famous-eco-roof-law-toogreen-to-be-true.

24. Wikivoyage. “Paris/14th Arrondissement.” https://en.wikivoyage.org/wiki/ Paris/14th_arrondissement#/media/ File:Paris_14e_arrondissement_-_Quartiers. svg.

25. Yale Environment 360. “Paris Heat Waves and Climate Change.” Last modified July 15, 2019. https://e360.yale.edu/features/parisheat-waves-climate-change.

Drive efficient and equitable insulation renovation solutions for cooperatives in the 14th arrondissement by leveraging innovative strategies such as combined insulation, tariffed onbill financing, tiered payment systems, collaborative decision making through voting, and strategic cost-sharing with the city.

While no proper correlation can be evidenced between the two metrics, in very hot areas, the sale prices of apartments reach up to €14,000 per m2, while in moderately hot areas, prices can be as low as €9,000 per m2.

SOURCE: Meilleurs Agents, 2024

Thermal strainers are facing declining property value and rental bans, creating financial strain for owners and complicating the housing market dynamics for Paris.

SOURCE: Le Parisien, 2024

Without energy renovation work, nearly one in two homes in the Paris region will soon be banned from renting.

SOURCE: L‘Institut Paris Region, 2022

SANS TRAVAUX DE RÉNOVATION ÉNERGÉTIQUE, PRÈS D’UN LOGEMENT FRANCILIEN SUR DEUX BIENTÔT INTERDIT À LA LOCATION EN ÎLE-DE-FRANCE, EN 2018, 2,3 MILLIONS DE RÉSIDENCES PRINCIPALES ONT UN DIAGNOSTIC DE PERFORMANCE ÉNERGÉTIQUE CLASSÉ E, F OU G, SOIT 45 % DU PARC FRANCILIEN DE RÉSIDENCES PRINCIPALES. CES LOGEMENTS, DIRECTEMENT CONCERNÉS PAR LA LOI CLIMAT ET RÉSILIENCE, POURRAIENT ÊTRE SOUMIS À DES INTERDICTIONS QUANT À LEUR LOCATION, SANS RÉNOVATION. CES INTERDICTIONS ENTRERONT PROGRESSIVEMENT EN VIGUEUR, EN FONCTION DE L’ÉTIQUETTE ÉNERGÉTIQUE DU LOGEMENT, ENTRE 2025 ET 2034. DANS LE CONTEXTE FRANCILIEN D’UN MARCHÉ IMMOBILIER TENDU, UNE MEILLEURE CONNAISSANCE DE CES LOGEMENTS EST INDISPENSABLE POUR CIBLER LES ACTIONS PRIORITAIRES À METTRE EN ŒUVRE, ET AINSI MASSIFIER LA RÉNOVATION ÉNERGÉTIQUE.

Dans un contexte de forte hausse des prix de l’énergie, les performances énergétiques des logements représentent un enjeu majeur. En Île-de-France, les tensions sur le marché du logement sont fortes et pourraient encore s’amplifier si les habitations les plus énergivores du parc ne sont pas rapidement rénovées, sans quoi elles ne pourront bientôt plus être louées. En effet, la loi Climat et résilience vise la disparition des logements à faible performance énergétique. Après le gel des loyers des logements étiquetés F ou G, entré en vigueur en août 2022, des interdictions de louer s’imposeront en 2025, 2028 et 2034, frappant progressivement les logements de classe G, puis F, et enfin E. La loi Climat et résilience renforce aussi l’information sur la performance des logements en imposant la réalisation d’un audit énergétique pour chaque vente. Quantifier, localiser et caractériser les logements énergivores constituent donc des priorités afin que soient identifiés les enjeux de rénovation pour baisser les émissions de gaz à effet de serre (GES), améliorer le confort d’usage des logements et préserver

Without energy renovation work, nearly one in two homes in the Paris region will soon be banned from renting.

SOURCE: L‘Institut Paris Region, 2022

Professionals, middle-income families, and students live here, with tourists drawn by its cultural hubs, green spaces, and vibrant café and entertainment scenes.

SOURCE: INSEE, 2022

The 26–50 age group dominates the workforce, mainly in managerial roles.

1000 residents

SOURCE: (Calculated from hourly wage) INSEE, 2022

15 to 25 years

26 to 50 years

Average Income € 25,756 Average Income € 44,556

Above 50 years

Average Income € 60,348

Long-term occupants indicate stability in tenure patterns.

SOURCE: INSEE, 2019

Majority of residents are tenants in flats and social housing.

SOURCE: INSEE, 2019

In 2021, family households make up the majority in the 14th arrondissement, accounting for 42.8%, including couples and single parents.

SOURCE: INSEE, 2022

Majority of workers live and work in their residential zones, indicating dependence on housing and linking local availability with living and employment needs.

SOURCE: INSEE, 2022

Despite fluctuations, data shows long-term family retention, with stable housing stock, minimal turnover, and increased vacant dwellings or second homes.

SOURCE: INSEE, 2022

Speculative reasons for change in main residences

• Death of homeowners

• Shifting to other dwellings

Between 1971 and 2005, 170 new houses were constructed, bringing the total to 908 in 2005. Additionally, 20,800 flats were also constructed during this period.

SOURCE: INSEE, 2022

Generational residences

Apartments have been owned by families through multiple generations for a long time and will most likely continue to be so.

SOURCE: INSEE, 2022

SOURCE: United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, 2018 City intent

Prevalence of families

The third Paris Climate Action Plan (2018) defines a 2020-2030 plan for the reduction of emissions and energy consumption adaptation to climate change.

In 2021, most residences were family households (couples with children and single-parent families), many residing in 3room or 4-room homes.

SOURCE: INSEE, 2022

(26.9%)

“The vast majority of existing buildings are ill-suited for the extreme climate of the 21st century: poorly insulated, poorly sited, dependent on air-conditioning to keep them habitable.”

SOURCE: Yale Environment 360, 2023

Investment in better insulation reduces utility costs longer term.

SOURCE: Buildings Performance Institute Europe, 2023

SOURCE: Yale Environment 360, 2023

We identified 18 EFG-rated residential co-ops, predominantly located in Plaisance. These co-ops were primarily constructed between 1975 and 2000.

SOURCE: ADEME - Agence de la transition écologique à Paris, 2024

14th Arrondissement

CO-OPS HOUSING

Existing

Selected for piloting based on:

• Energy rating (E, F, and G)

• Built Period (1975 - 2000)

• Co-ops

SOURCE: IpswichMA.gov

Tenants on higher floors typically endure significantly higher temperatures. This also means that lower floors might end up paying higher tariffs for heat levels that they are not experiencing.

Under embargo until July 24, 2024 5pm CET

SOURCE: Roofscapes, 2024

Image:

Image: July 9, 2023, 2:00 a.m.

Combining insulation is one of the most efficient renovation approaches. It increases the benefit of other renovations. Combining roof insulations with other benefits will help the entire building.

SOURCE: Anah, fichiers détaillés MaPrimeRénov’ ; Fidéli 2021 ; Tremi 2020. Calculs SDES

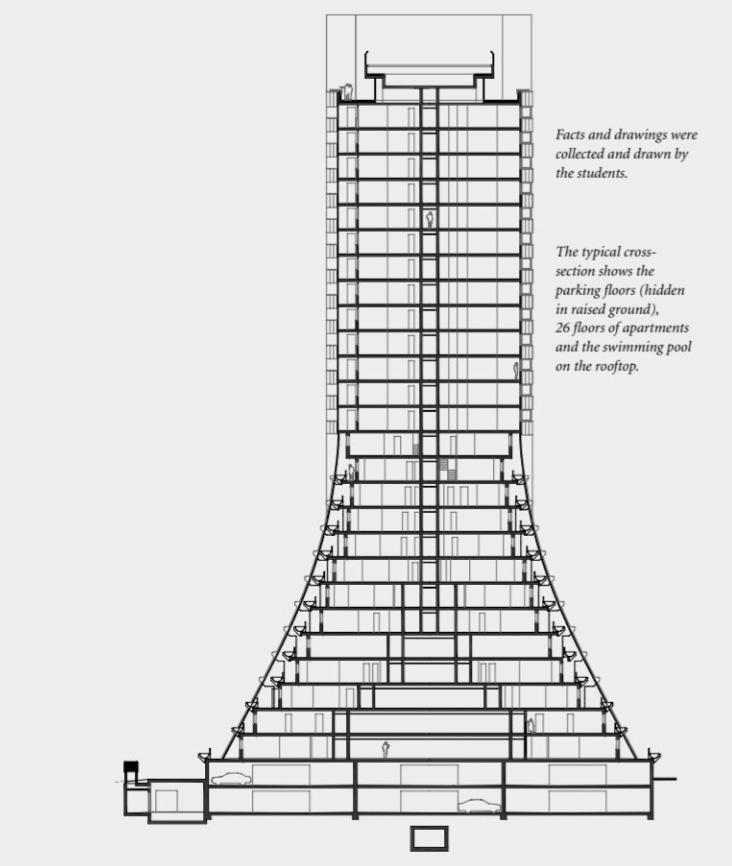

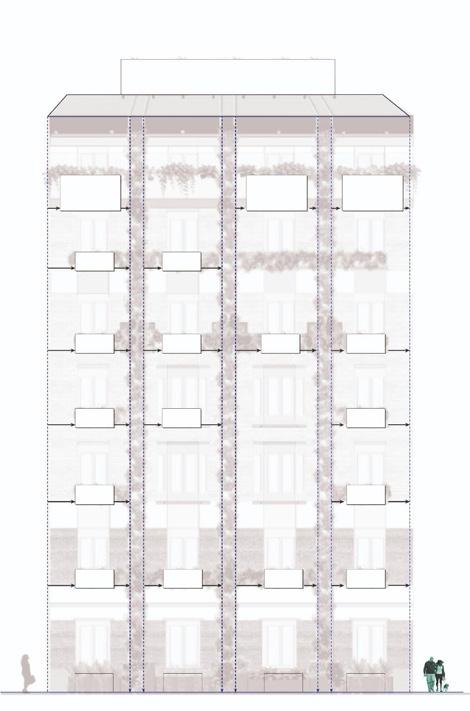

Heat Pump , Ventilation, ESC

During the summer of 2023, Roofscapes, a Paris-based startup launched at MIT and working on the climate adaptation of existing buildings, carried out a thermal study on a typical Haussmann building, with the aim of understanding the impact of climate change and increasing summer heat on the livability of Parisian housing. At a time when the French capital has already entered a climate different from the one for which it was built, the Abbé Pierre Foundation makes the link between illhousing and summer discomfort, speaking of a new form of social injustice(1). Against this backdrop, the aim of Roofscapes’ research is to granularize the understanding of the thermal phenomena that governs housing in the greater Paris, and to inform public stakeholders of the necessity of addressing heat resilience upstream. Indeed, a reactive rather than proactive attitude would lead to massive deployment of air conditioning, the impacts of which are already well known: urban temperatures rise by several degrees during heat waves, and electricity consumption in a city like Paris doubles(2)

Heat Pump, ESC

Exterior Wall, Roof Insulation

Roofscapes carried out air temperature measurements during the summer of 2023 using thermal probes in various areas of an Haussmann building, including:

Interior Wall, Roof Insulation

Ventilation, Wood Heating System, ESC

30cm above the zinc roof, outside (R+8) in a dwelling unit under the zinc roof (R+7) in the heart of the building (R+4)

Ventilation, Wood Heating System

Wood Heating Boiler, ESC

Each sensor was programmed to take around thirty measurements per day. Roofscapes thus received and compiled over 10,000 data points, which were then compared with the temperatures recorded by the Paris weather station, located in the Parc Montsouris(3)

Ventilation, ESC

Wood Heating System, Window Replacement

Wood Heating System, ESC

Costing One Building 17 Buildings

Stakeholder Role

France Rénov' Maintains current role - subsidizing and supporting coordination for renovations

Électricité de France Administers loans and charges tarif on utility bills

Roofscapes Installs green roofs

Third party mediator

Supports co-ops associations to understand the process and benefits, administer the vote, navigate the process, and administer tiered payment process

Combined Insulation

Maximizes utility savings across building and benefits from multiple renovations.

Decreases heat expulsion to the neighborhood.

Tarifed on-bill financing

Prevents upfront costs, so bills stay same with additional benefits. Minimizes risk of defaulting on loan.

High funds can be arranged for costs.

Tiered Payment

Motivates vote in favor of renovation because residents are paying proportionate to their savings.

Residents City

+ Cooling the Neighborhood

+ Cooling the building + Recreation

+ Property Values + Gardening

+ Insulation

- Utility Costs

+ Insulation

- Utility Costs

+ Insulation

- Utility Costs

+ Insulation

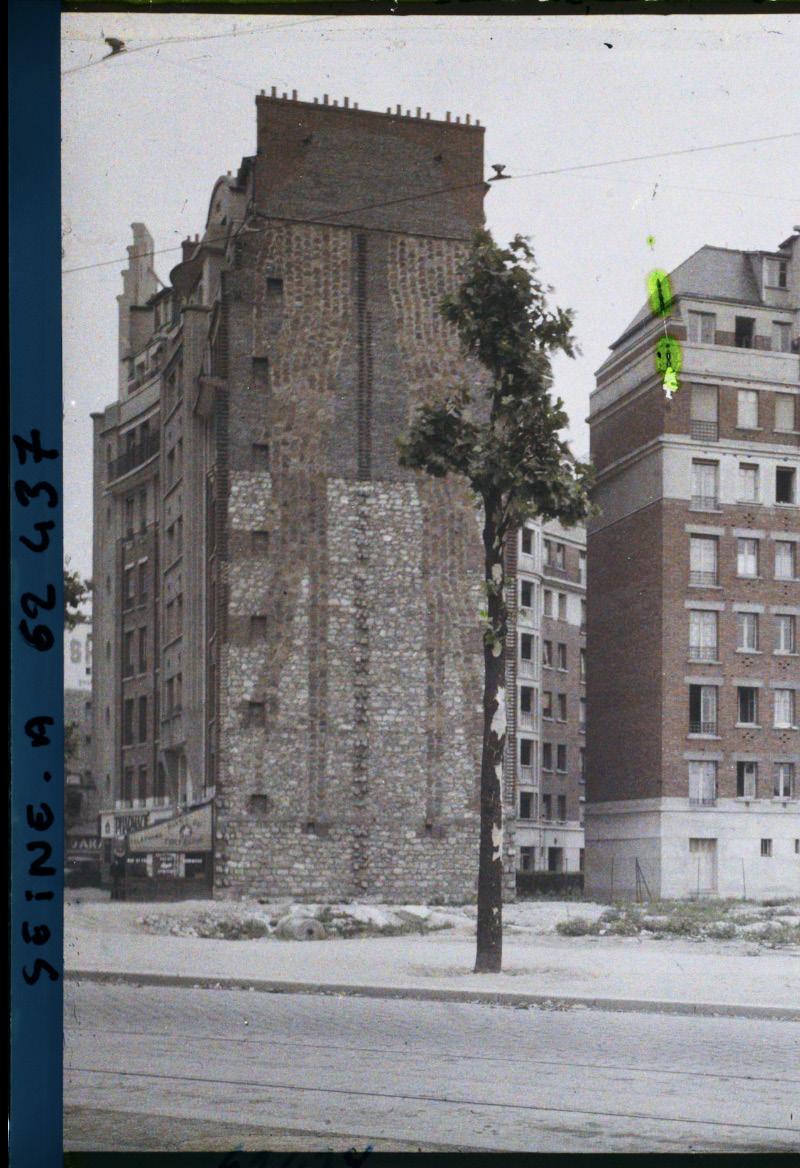

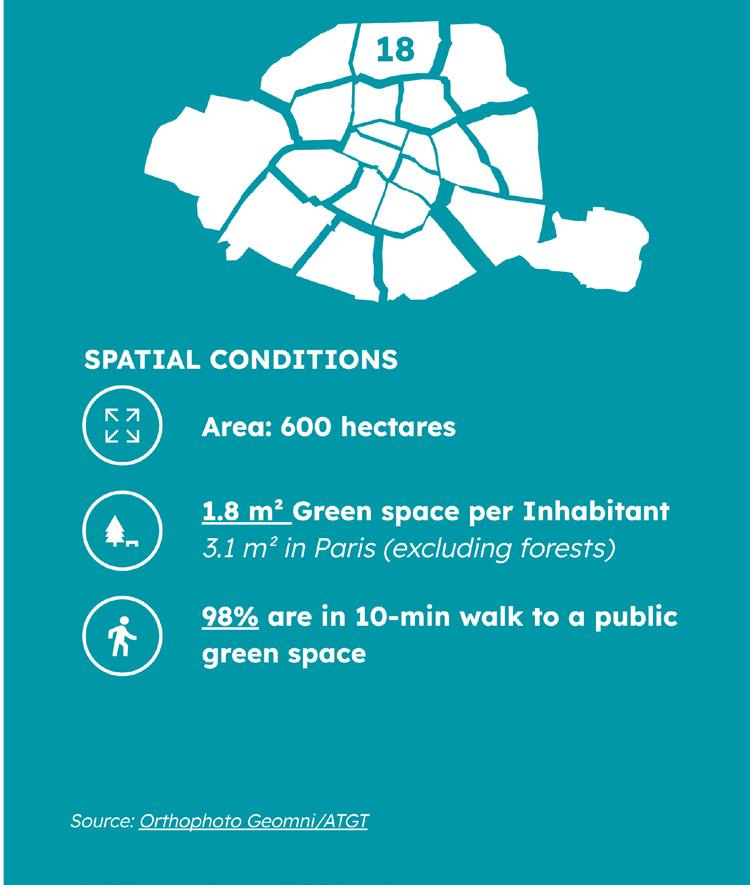

- Utility Costs

Habitation à bon marché (HBM) were early forms of social housing built from the late19th to mid20th century to provide affordable homes for working-class families, often characterized by robust brick architecture are located in the city’s outer arrondissements, in linear formations running parallel to the peripherque ring road encircling the city, mostly beacuse was more available there. These buildings often form continuous block or courtyards, with uniform red-brick facades and modest decorative element, reflecting both functionalist design and a desire to create orderly, healthy housing environments for the working class.

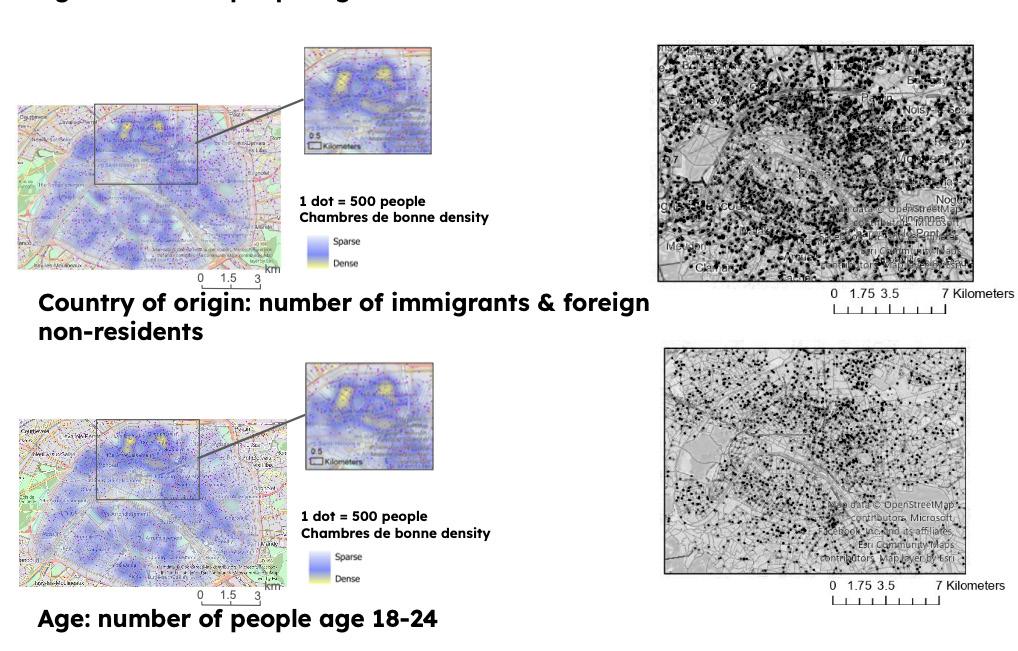

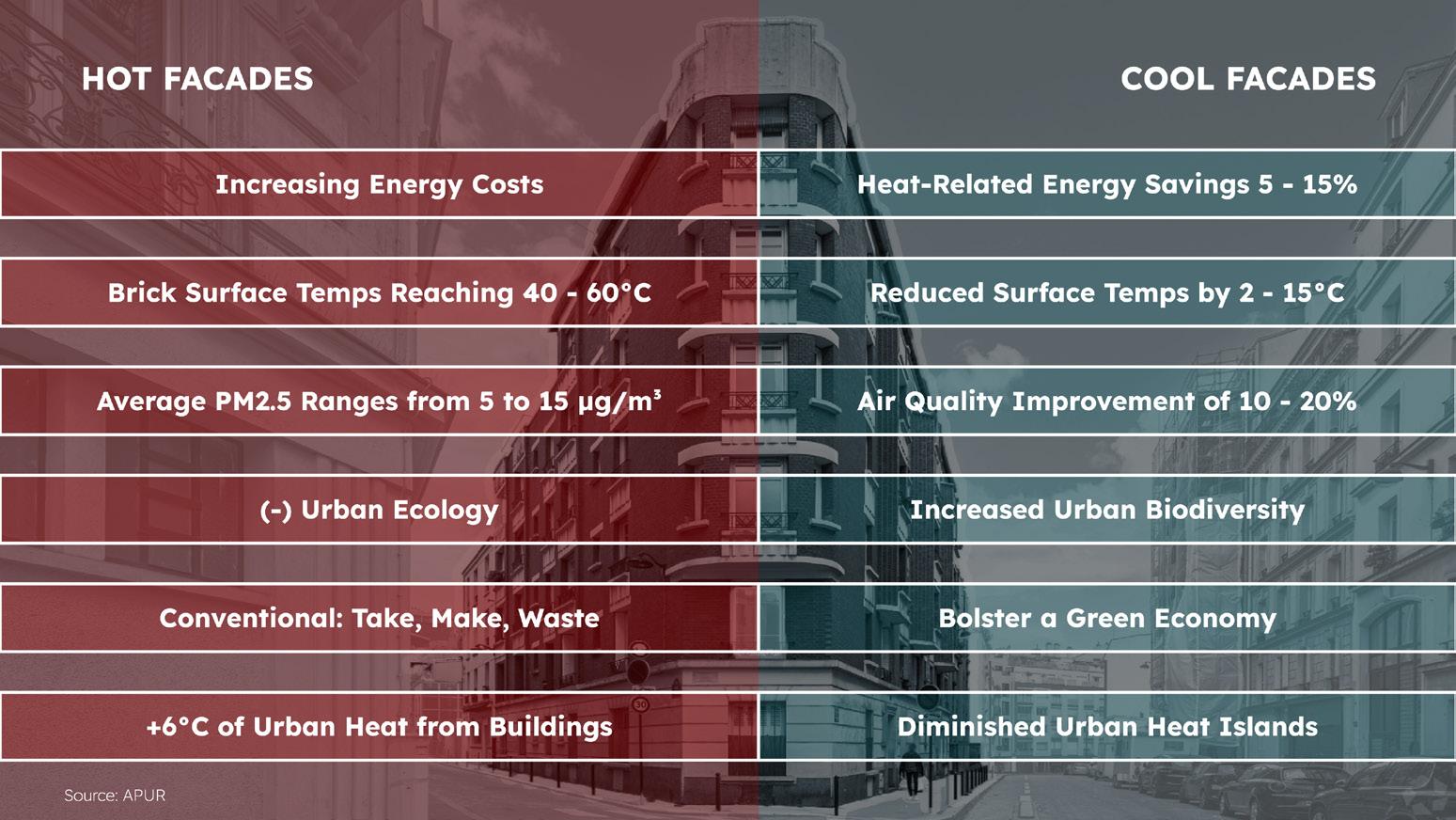

Our analysis of DPE levels across Paris expanded our focus beyond the chambres de bonnes. The study categorized the city’s building stock into Haussmanian (1830-1914), post-Haussmanian (1914-1990), and Modern (since 1990), revealing consistently low ratings for all three typologies. This diagnosis compelled us to widen our proposal from the Haussmannian buildings in the city center to the Habitations à Bon Marché (HBM) along Paris’s periphery, particularly the 18th arrondissement due to its critical lack of accessible green spaces. Our analysis has previously shown how the uneven distribution of green spaces in Paris has exacerbated the issue of heat retention in the city, highlighting a broader public health concern.

The 18th arrondissement combines high population density, limited green spaces, and a high poverty rate, leaving low-income and immigrant communities disproportionately exposed to urban heat island (UHI) effects.1 These vulnerabilities highlight the need for equitable climate adaptation strategies targeting HBM housing stock. Originally designed for working-class families, HBMs prioritized light, ventilation, and durability but now suffer from aging infrastructure, making retrofitting essential.2

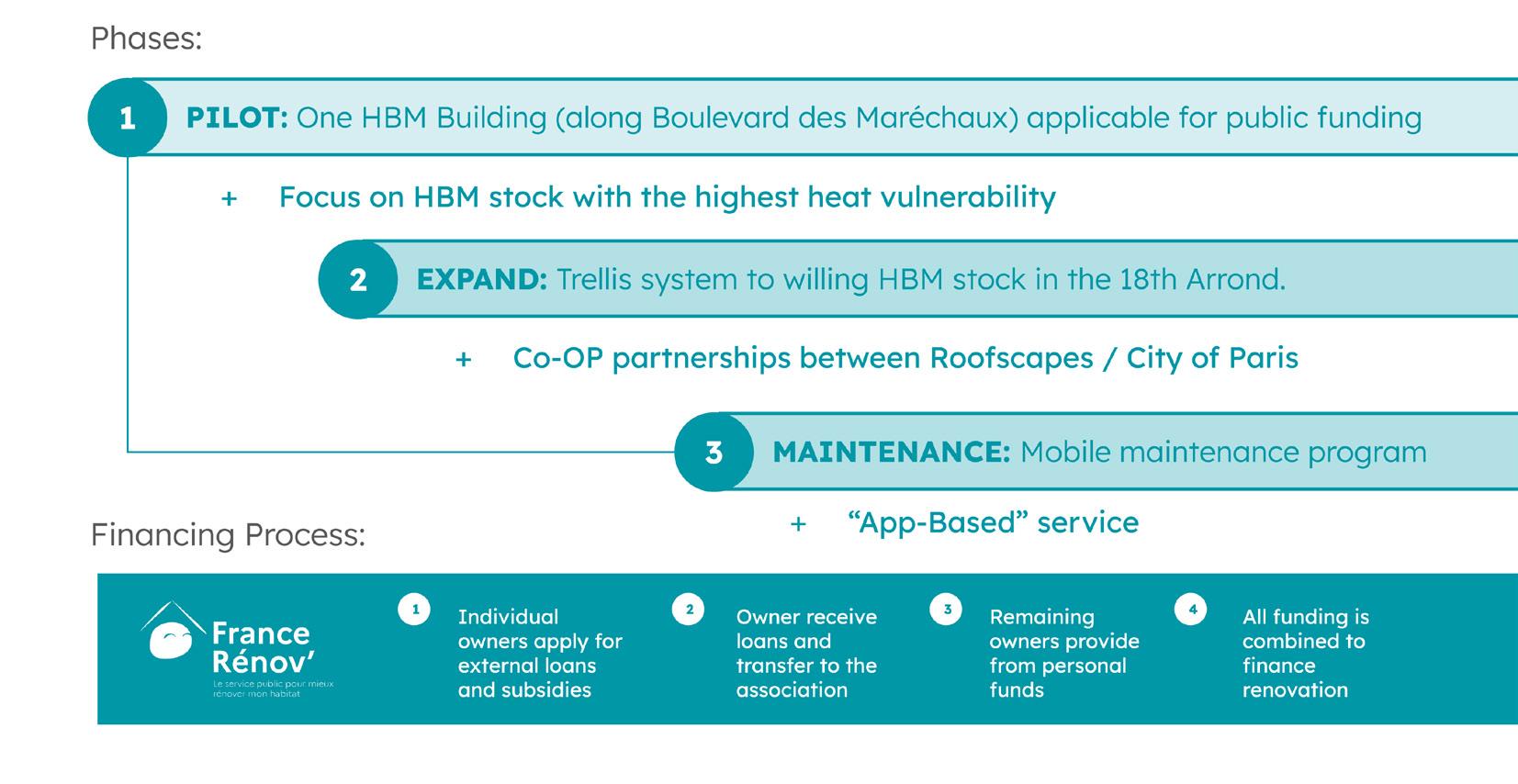

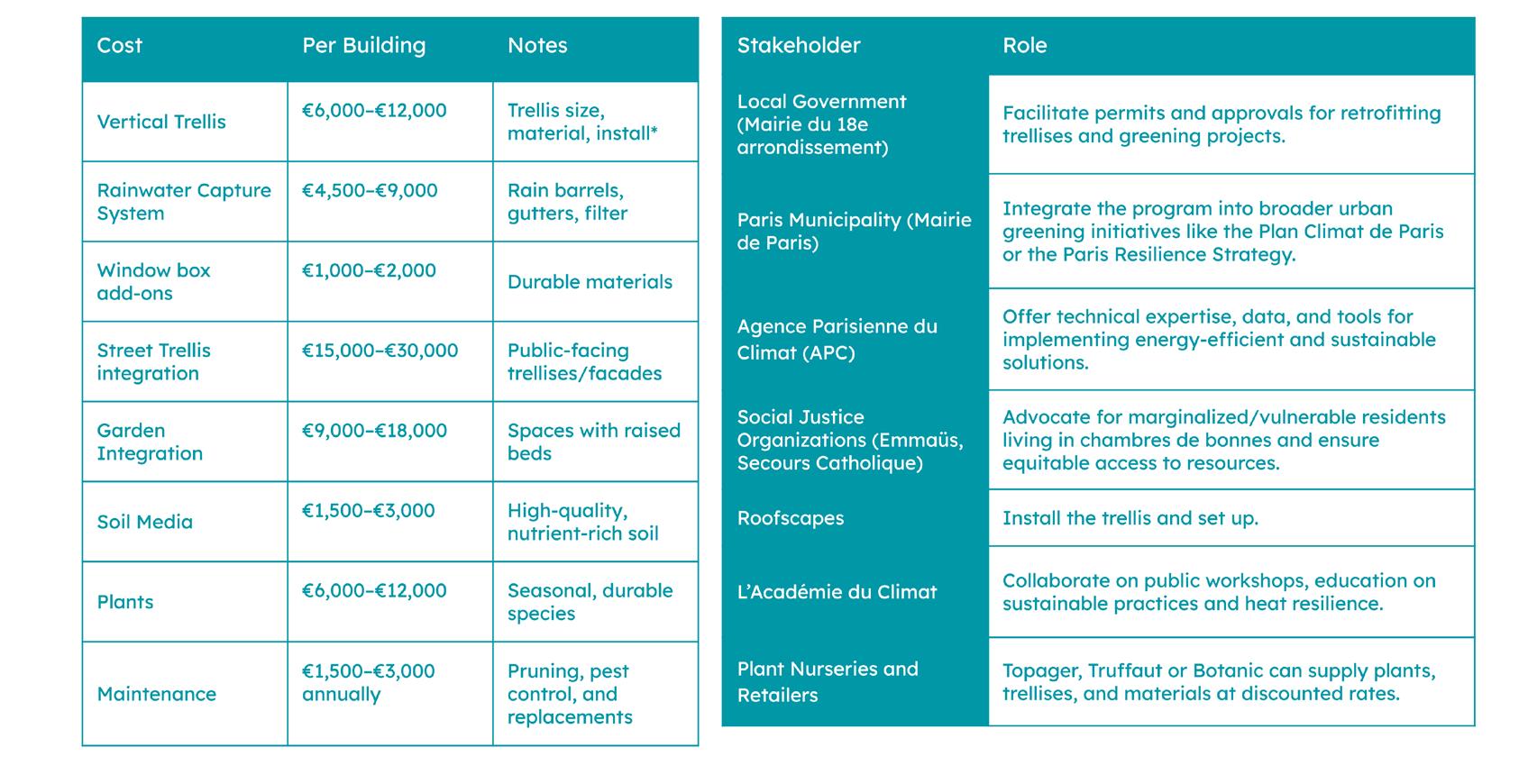

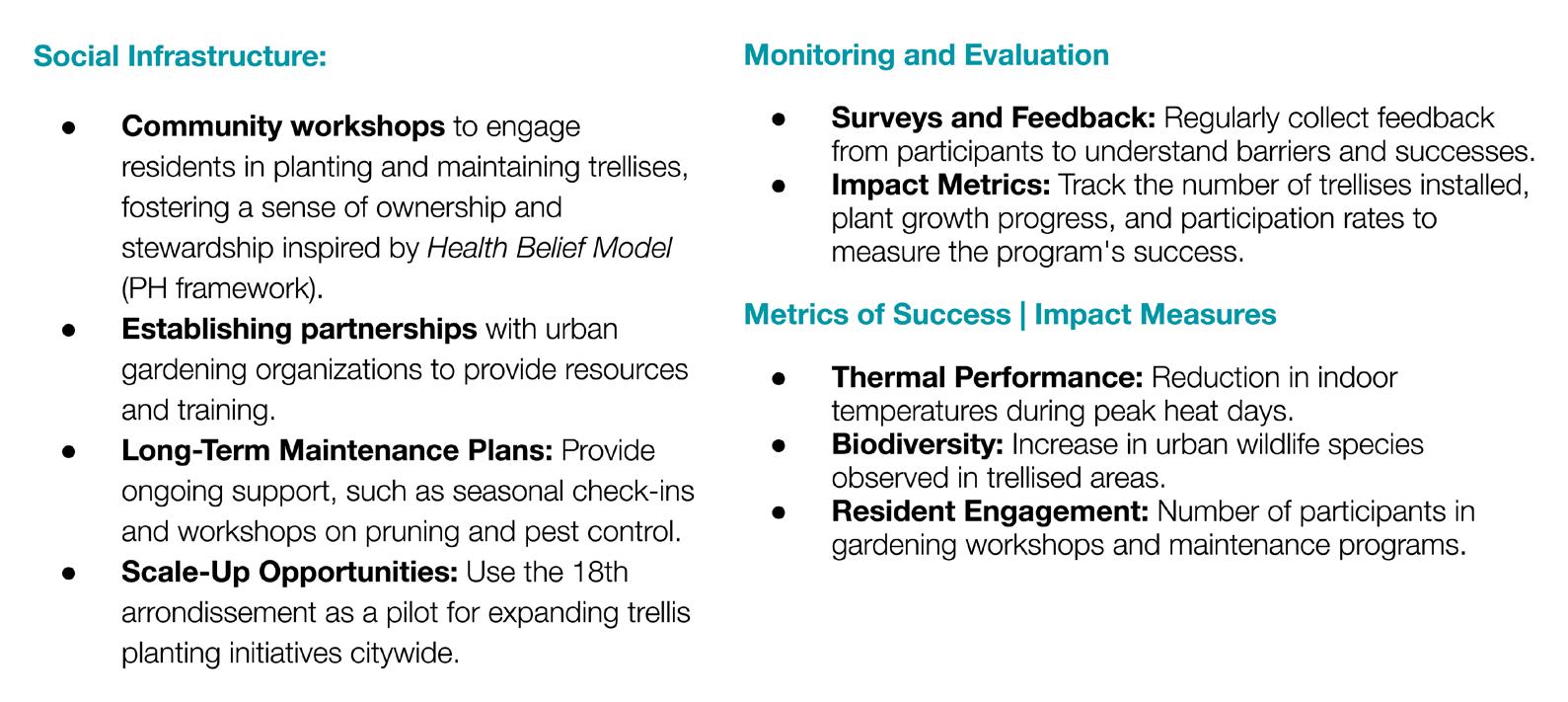

As an extension of Roofscapes’ core tenets— reuse, climate mitigation, spatial equity, and collaborative urban futures, we propose modular green trellis wall systems to transform HBM facades into living walls. This strategy provides multiple benefits: enhanced thermal comfort, reduced UHI effects, improved air quality, and water runoff management. The modular design integrates rainwater harvesting systems to irrigate the façades and balconies, creating a cost-effective and scalable solution for urban resilience. Material innovation underpins the project’s sustainability goals. The project employs pressed recycled plastics that offer durability, weather resistance, and vibrant aesthetic potential while contributing to the circular economy and complying with EU sustainability regulations.

The goal of our project is to expand Roofscapes’ scope from the green roof typology. It aims to connect the roof to the ground for more equitable access among the buildings’ residents and activate streets and public spaces for the passersby. The 18th arrondissement’s combination of climate vulnerability, dense population, and HBM concentration close to the peripherique ring road provides a unique opportunity for innovative, equitable, and scalable climate adaptation solutions. This initiative sets a precedent for urban resilience and social equity in Paris and beyond by reimagining iconic building typologies.

1. Al-Kodmany, K. (2023). Greenery-Covered Tall Buildings: A Review. Buildings, 13(9), 2362. [https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings13092362]

2. Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

3. Brown, A. (2019). Vertical Gardens and Social Equity: A Pathway Towards Healthier Communities. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 43(5), 832-850.

4. Cardoso, R., et al. (2018). Structural and Material Characterization of a Haussmann Building. Urbanism. Architecture. Constructions.

5. Coutts, C., Horner, M., & Chapin, T. (2010). Using geographical information system to model the effects of green space accessibility on mortality in Florida. Geocarto International, 25(6), 471–484.

6. INSEE (2023). Statistical Data Overview 2023. [https://www.insee.fr/en/ statistiques/8068514?sommaire=8068801] (https://www.insee.fr/en/ statistiques/8068514?sommaire=8068801)

7. James, P., Banay, R. F., Hart, J. E., & Laden, F. (2015). A Review of the Health Benefits of Greenness. Curr Epidemiol Rep, 2(2), 131-142. doi: [10.1007/s40471-015-0043-7](https:// doi.org/10.1007/s40471-015-0043-7). PMID: 26185745; PMCID: PMC4500194.

8. Lee, S., & Kim, J. (2018). Exploring the Relationship between Vertical Greening Systems and Social Equity: A Case Study in Seoul, South Korea. Sustainability, 10(8), 2791.

9. Millward, A. A., & Blake, M. (2024). When Trees Are Not an Option: Perennial Vines as a Complementary Strategy for Mitigating the Summer Warming of an Urban Microclimate. Buildings, 14(2), 416. [https://doi.org/10.3390/ buildings14020416](https://doi. org/10.3390/buildings14020416)

10. Rocque, R. J., et al. (2021). Health effects of climate change: an overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open, 11, e046333.

11. Sallis, J. F., Floyd, M. F., Rodrıguez, D., & Saelens, B. E. (2012). Role of built environments in physical activity, obesity, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation, 125, 729–737.

13. Smith, J. (2020). Vertical Gardens: A Sustainable Solution for Urban Environments. Journal of Sustainable Development, 8(2), 45-62.

Our proposal aims to address urban climate challenges by focusing on the Habitation Bon Marché housing stock in the 18th arrondissement.

To reimagine urban greening, we propose expanding beyond horizontal green roofs to the vertical plane with modular green trellis wall systems. This initiative addresses a critical gap: the 18th is the city’s furthest district from 24/7 accessible greenspaces, leaving residents disproportionately exposed to heat stress and climate risks. Transforming the iconic HBM facades into living walls, the project enhances thermal comfort, mitigates urban heat (indoors and out), and improves air quality, offering scalable, cost-effective solutions for urban resilience and equity.

Buildings at a distance > 800 m 20,000 sq. m. + green spaces

Building Age

DPE Levels F-G

Zinc Roof

Greenspaces by Scale and Type

Buildings at a distance > 800 m

20,000 sq. m. + green spaces

Building Age

DPE Levels F-G

Zinc Roof

Short Distances Hot Day

Jardins + Squares

<10,000m^2

Not 24hrs (lunch) 250m distance

Open Spaces + the River >15,000m^2

River Seine

9pm- or 24hrs 500m distance

18th Arrondissement

Image source: Union Habitat

La fondation Rothschild et les premières habitations à bon marché de Paris : 1900-1925

Source:

Architects: Harry Gluk with Requat & Reinthaller & Partner, Kurt hlaweniczka

Construction: 1973-1984

Inhabitants: 10,000

Apartments: 3,180

Size of Lot: 220,000 m²

Housing Footprint: 40,500 m²

Architects: Maison Edouard François

Construction: 2021

Inhabitants: Up to 770

Social Housing Apartments: 100

Size of Lot: 24,250 m²

Social Housing Footprint: 17,144 m²

Materials and Plants

Connects to green roof

PRIMARY SPECIES

Trachelospermum jasminoides (Star Jasmine)

Rosa ‘Paul’s Himalayan Musk’ (Rambling Rose)

Hydrangea petiolaris (Climbing Hydrangea)

Hedera helix (Common Ivy)

Clematis armandii

Flowering Plants (Balconies)

-Pelargoniums (Geraniums)

-Petunias

-Lavender

Herbs (Balconies)

-Basil, Thyme, and Oregano

-Mint

-Chives

Pressed recycled plastics - HDPE

Vegetables and Fruits (Balconies)

-Cherry Tomatoes

-Strawberries

-Salad Greens (Lettuce, Arugula)

Climbers and Trailing Plants (Façade)

-Morning Glory

-Ivy

-Succulents